Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a ~1 hour talk on the field of developmental bioelectricity from a perspective of cognitive science and the homology between mechanisms of self-assembly of somatic and brain-based intelligence.

CHAPTERS:

(00:01) Framing bioelectric morphogenesis

(06:15) Genomes and body plans

(12:05) Anatomical compiler and homeostasis

(19:23) Brain analogies and tools

(28:13) Cancer and pattern memory

(36:23) Regeneration and electroceutical control

(50:17) Novel morphologies and anthrobots

(57:43) Summary and future directions

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/51 · 00m:00s

Thank you for organizing this amazing meeting. Thank you for giving me the opportunity to share some ideas with you.

What I'm going to do today is talk about some symmetries, what I think are profound symmetries between neuroscience and developmental biology. If you want to see any of the details, the software, the data sets, everything is at this site. Then here are some personal thoughts about what I think all this stuff means.

I'm going to frame today's talk around this question of how does it know? Because when we look at biology, and in particular developmental biology, that's one of the first things that strikes people: how do the cells and tissues and everything else know what to do?

Slide 2/51 · 00m:43s

I'm going to give a few main points. First of all, I'm going to claim that biomedicine and bioengineering boil down to finding out the informational structures of the material of life. That is, how does it know what to do in various circumstances? What kind of mistakes it makes and why? How do we alter decision-making towards specific set points that living material is very good at doing? And for biomedicine and engineering in particular, how do we change these outcomes with the least effort possible?

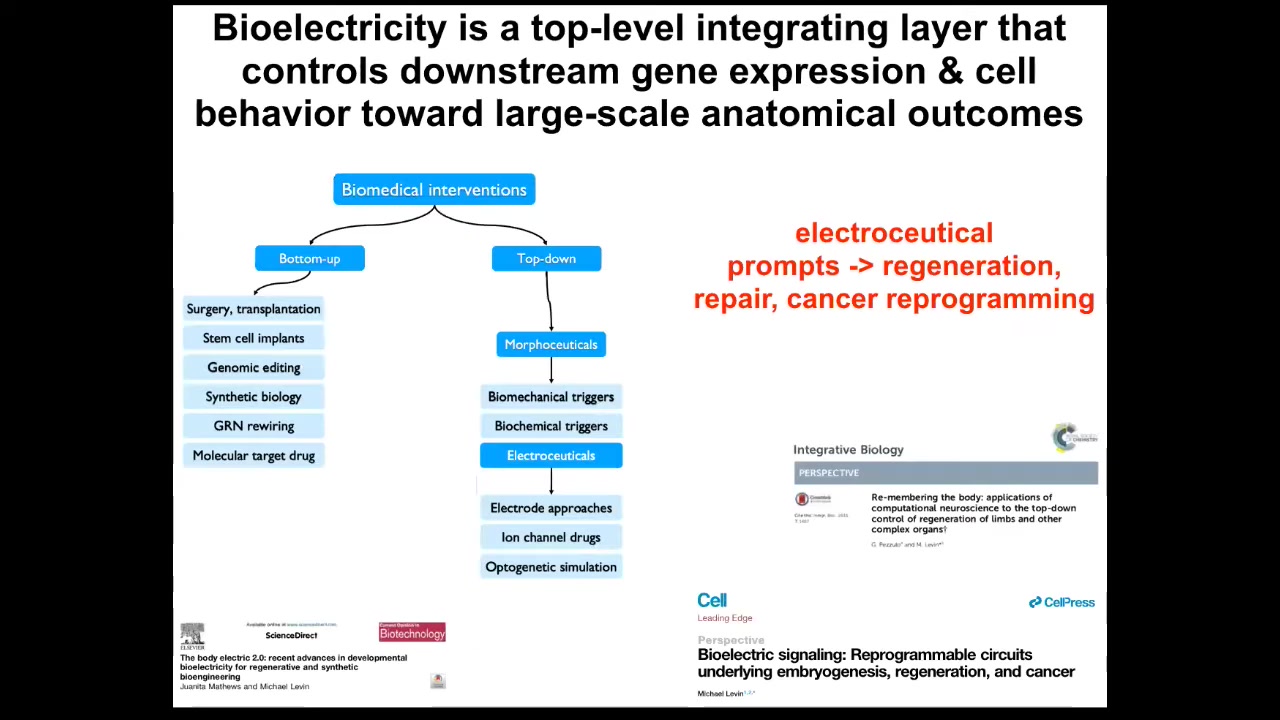

I'm going to make three basic claims: that bioelectricity is a kind of cognitive glue that binds individual cells and other structures towards larger scale purpose; that bioelectricity is also a kind of memory medium, which stores patterns towards which cells and tissues operate, and that we can now reset those patterns; and then towards the end, I'm going to show you some new bioengineering, which I think is a great opportunity for bioelectricity, but it hasn't really taken off yet.

The most obvious thing that anybody first asks when they see this process of embryonic development, where we all start life as a single cell and eventually we become one of these amazing things, the first question arises: how do the cells know what to do? They all have the same genome. The stem cells and everything else in your hand and in your foot are the same. But why does your hand not look like your foot? How does it know when to stop all of these things?

This question of how do they know what to make — I'm going to emphasize the idea that the mechanisms of knowing what to build and how are actually homologous, meaning both in terms of their mechanisms, their evolutionary mechanisms and their algorithms to those that underlie knowing in familiar contexts, meaning behavior, brain-driven behavior. These are some of the exact same mechanisms that operate in those two spaces.

The first clue we get to this is this interesting point that chemistry doesn't make mistakes. Chemistry just does what it does, and the laws of chemistry you roll forwards and that's all. But morphogenesis absolutely can make mistakes. Something very interesting happens in this transition where you go from chemistry and physics to a morphogenetic system that has goals and the ability to fail to meet them, and then to various cognitive and behavioral goals that also can be met or not.

Slide 3/51 · 03m:12s

This kind of thing was appreciated by Alan Turing. He was very interested in intelligence, broadly defined in different embodiments, machine learning and machine thinking. Towards the end of his life he wrote the paper "The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis." We might wonder why someone interested in computation and intelligence would be thinking about chemicals during morphogenesis. I think he actually saw this profound symmetry: the story of the autopoiesis of minds is basically the same story as the autopoiesis of the body, and we have to understand how this works.

Slide 4/51 · 03m:52s

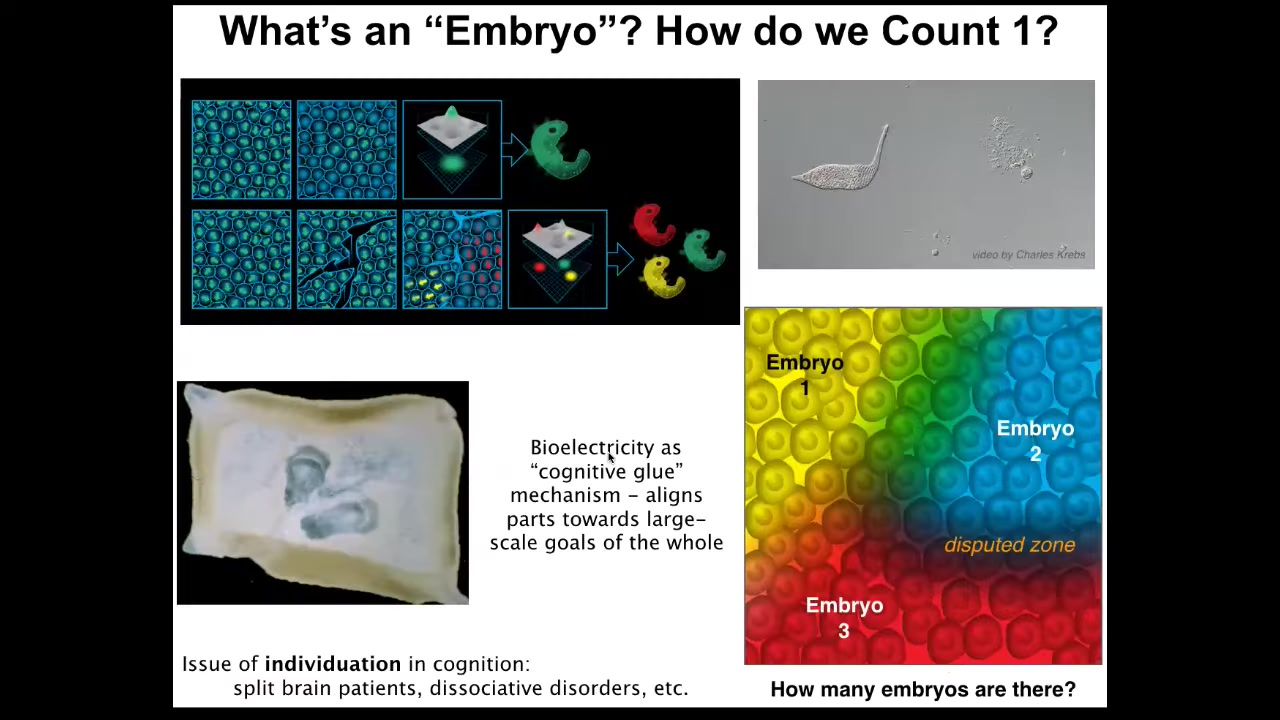

And we encounter the amazing aspects of this self-constructing material very early on in development. This is a single cell. You can see it's very active. It has lots of competencies in its own little cognitive light cone. This is a free living being called the lacrimaria, but we're all made of cells like this. And for that reason, we are all a collective intelligence. We are all made of competent little subunits.

In fact, during embryonic development, when we look at an embryo and we say, there is one embryo, what are we counting? What is there one of? There might be hundreds of thousands or millions of cells. What is there one of that we're counting? But what we're counting is alignment. We're counting commitment of all the cells to the same journey in the anatomical space. What makes it an embryo as opposed to a pile of cells is that they're all committed to the same homeostatic process that's going to get them to a particular region of anatomical space. They're all going to make this thing.

What you can do is you can make little cuts in this blastoderm, and here are some in an avian embryo that I made many years ago. When you do this, each of these little islands, for the time that it doesn't feel the presence of the others, itself organizes into its own embryo. From this excitable medium of this blastoderm, you might get one, two, 0, or up to half a dozen or more individuals. So the question of how many individuals are here is not an obvious question. It is not set by the genetics. It is solved in real time by processes of alignment, by this notion of cognitive glue, these mechanisms that enable individual pieces to align in some kind of problem space, in this case, the anatomical space, to have a shared vision of what it is that they're going to build. And bioelectricity is a really important, it's not the only mechanism, but it's a really important cognitive mechanism that allows wholes to form.

In cognitive science, we already know this is the case because electrophysiology is what makes us more than a collection of neurons. It is what allows us to have memories, preferences, goals, and so on that our individual neurons don't have. And there you have this exact same kind of question about how many individuals within a certain amount of real estate because we have split brain patients and dissociative identity disorders. So this is again very parallel. So we need to understand how all these kinds of decisions are made.

Slide 5/51 · 06m:19s

The standard story is the genome. In fact, more than that, the standard story that we're told is this open-loop process that leans on notions of complexity and emergence, that there are these gene regulatory networks: they make proteins. Some of the proteins do things. They diffuse or they are sticky or they have enzymatic activity. So there's a bunch of physics that goes on in parallel. And then this magical process of emergence happens. And we know this is true. If you have lots of simple rules that you execute in parallel, often the outcome is quite complex. And so the standard story is this open-loop feed-forward emergence of complexity.

Slide 6/51 · 07m:02s

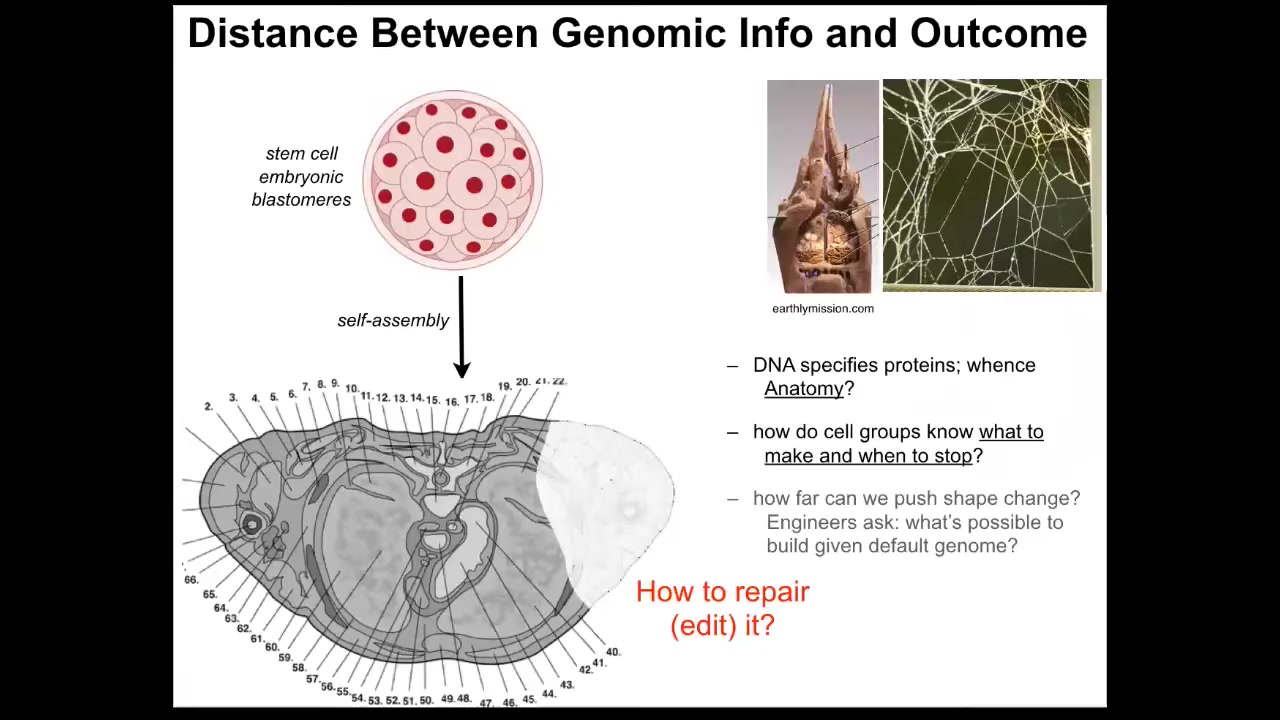

But there's a significant distance between what's actually in the genome and the thing that we really want to understand and control.

This is a cross-section through a human torso. You can see the incredible complexity. Everything is in the right place, the right size, the right shape, next to the right neighbors. What's actually in the genome is not anything about this. What you see in the genome is information about protein structure and some other information about when and how these proteins become expressed. It doesn't say anything directly about the size, the shape, the symmetry of the body or anything like that.

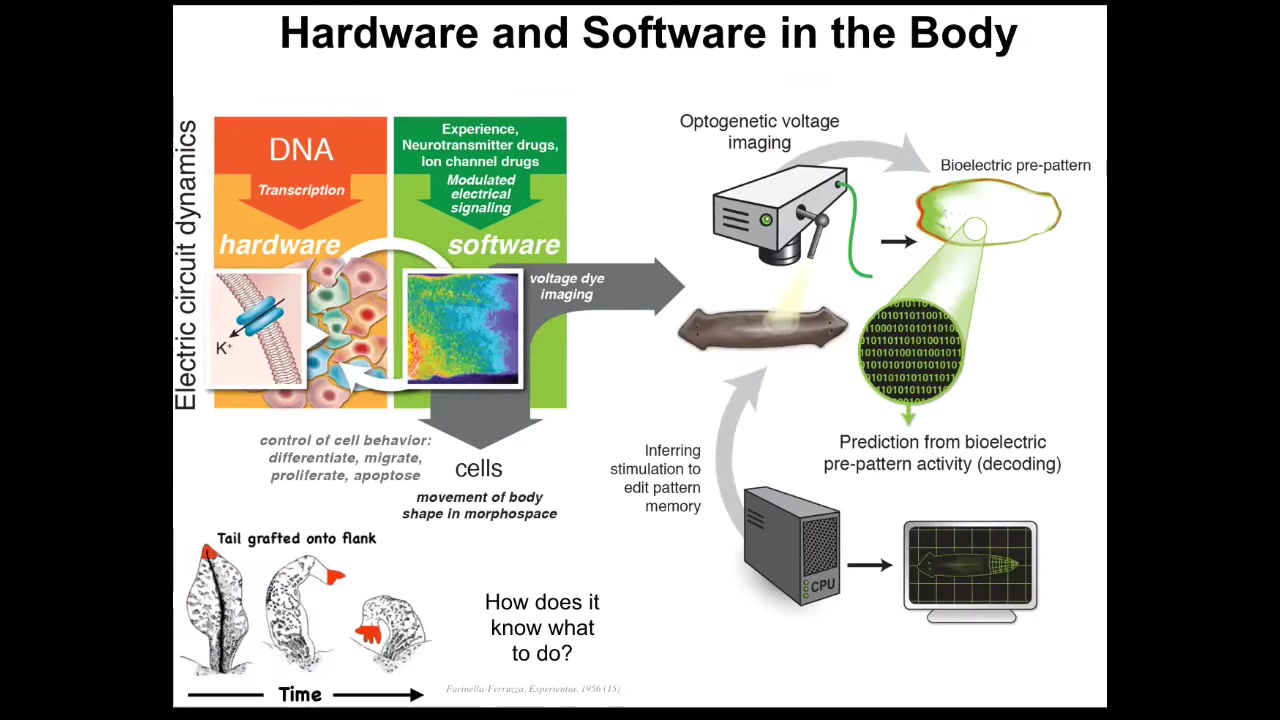

We still have this distance that we need to bridge between what's actually the hardware specification that is in the genome and the kind of physiological software that enables cells to know what to do and when to stop. From that, we can infer how we convince cells to repair things that are missing or damaged. And, as I'll show you at the end of this talk, what can we get them to build other than the default morphology?

Slide 7/51 · 08m:05s

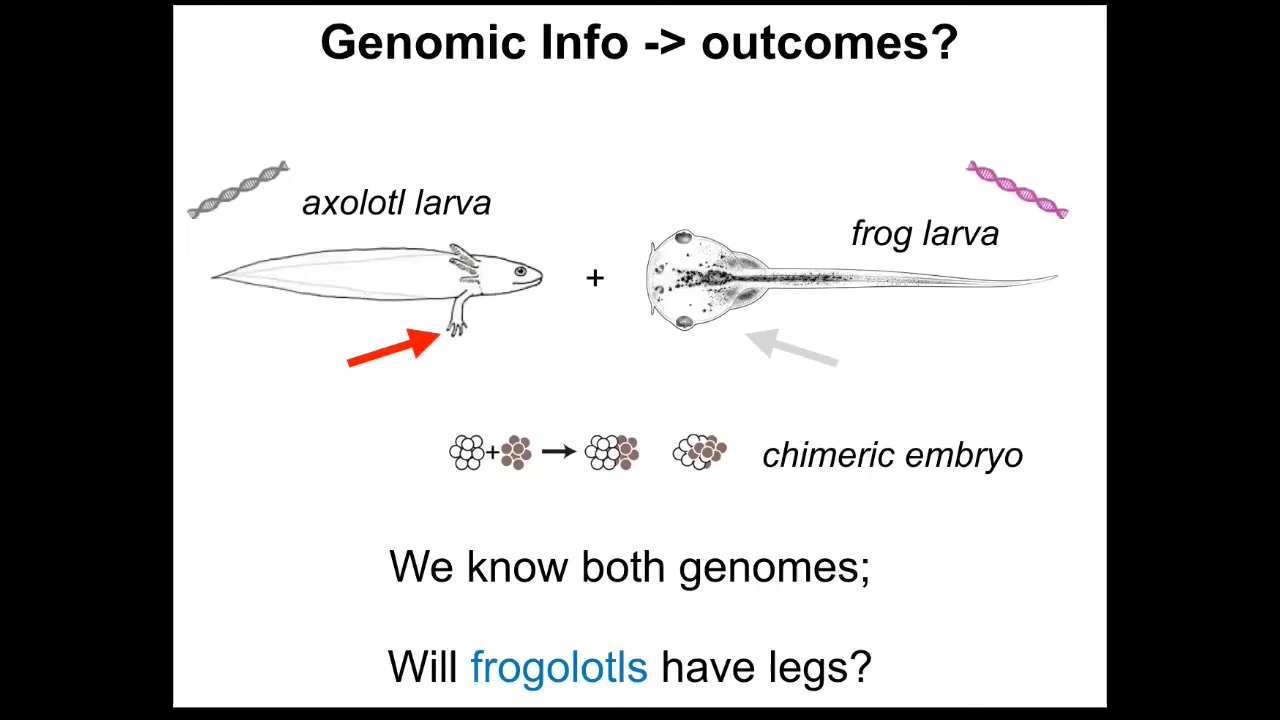

One thing to realize is that the genomic information is insufficient for a broad understanding of shape. As a simple example, axolotl larvae have little forelegs, frog tadpoles do not. In our group, we make something called a frogolotl, which is a kind of combination of frog and axolotl. I could ask a simple question.

We have the axolotl genome; it's been sequenced. We have the frog genome; it's been sequenced. We have all of that. Can you tell me if a frogolotl is going to have legs or not? And the answer is we can't. We have no idea. And if it does have legs, whether those legs will contain frog cells or be made strictly of axolotl cells — we don't know that either.

To be fair, we couldn't even predict the shape of either of these things from their genome, other than by comparing it to the genomes of other animals whose shape we do know. Our ability to predict either static shape or these kinds of novel cases is quite poor.

Slide 8/51 · 09m:03s

The other thing that is not readily discernible from genomic information is the properties of dynamic robustness. For example, this axolotl will regenerate its eyes, its jaws, its limbs, its spinal cord, portions of the brain and heart. If you amputate anywhere along this axis, the cells will grow exactly what they need, and then they stop.

The most magical thing about regeneration is that it knows when to stop. It stops when the correct structure has been produced. It's a kind of homeostatic process where the system can tell it's been deviated, and it will do what it needs to do to get back to where it needs to go.

The capabilities of these systems are not readily predictable. Not only can these systems get back to where they need to be after injury or other external perturbation, but there's some incredible problem-solving competencies within this material.

Slide 9/51 · 10m:00s

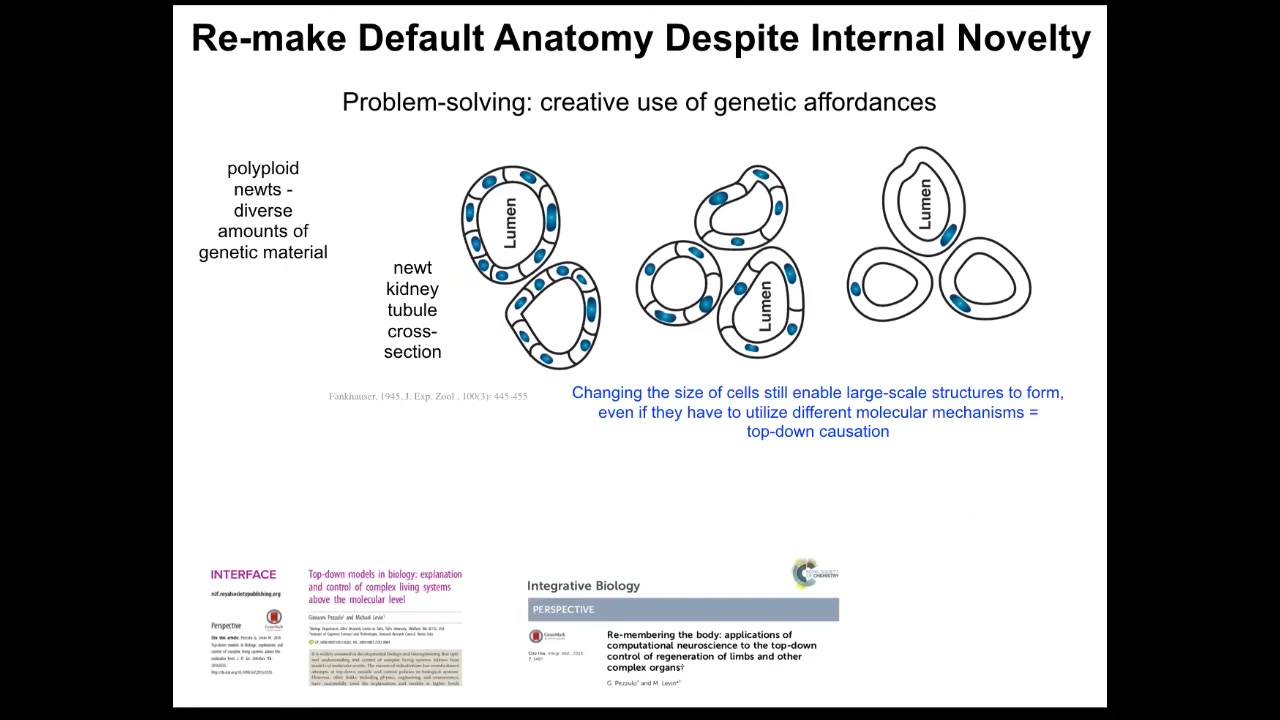

So this is one of my favorites. If you make polyploid newts, meaning extra copies of the genetic material, what happens is that these kidney tubules, which usually have about 8 to 10 cells that work together to line this lumen, the cells get bigger to accommodate the new genetic material. The newt stays the same size, so it uses fewer but larger cells to do exactly the same thing until the cells get truly gigantic. And then it'll use just one cell bent around itself and give you the same structure.

Now, the ability to use different molecular mechanisms, cell-to-cell communication, cytoskeletal bending, the ability to use different affordances in your toolkit to solve a problem you haven't seen before is basically a standard definition of intelligence. It's what's measured on all the IQ tests.

What we have here is the ability of a newt. It doesn't know in advance; the environment has uncertainties, but its own parts are unreliable. You don't know how many copies of your genome you're going to have. You don't know how big or how many cells you're going to have. You have to do the job using different molecular mechanisms.

Different affordances from your genome in ways to solve the problem. Again, all of this is completely not obvious from anything that we're going to get from typical molecular profiling.

Slide 10/51 · 11m:24s

In fact, even below the single cell level, the molecular pathways by themselves have six different kinds of learning capacity, including Pavlovian conditioning. This is something else that we're doing in our group, trying to take advantage of some of these properties for things like drug conditioning and the fact that the molecular pathways inside of cells can learn as well. All of this forms an amazing multi-scale competency architecture where the material has various capabilities at different levels, and all of the different levels have agendas and abilities to solve problems in different spaces, in gene expression space and physiological space and anatomical space.

Slide 11/51 · 12m:05s

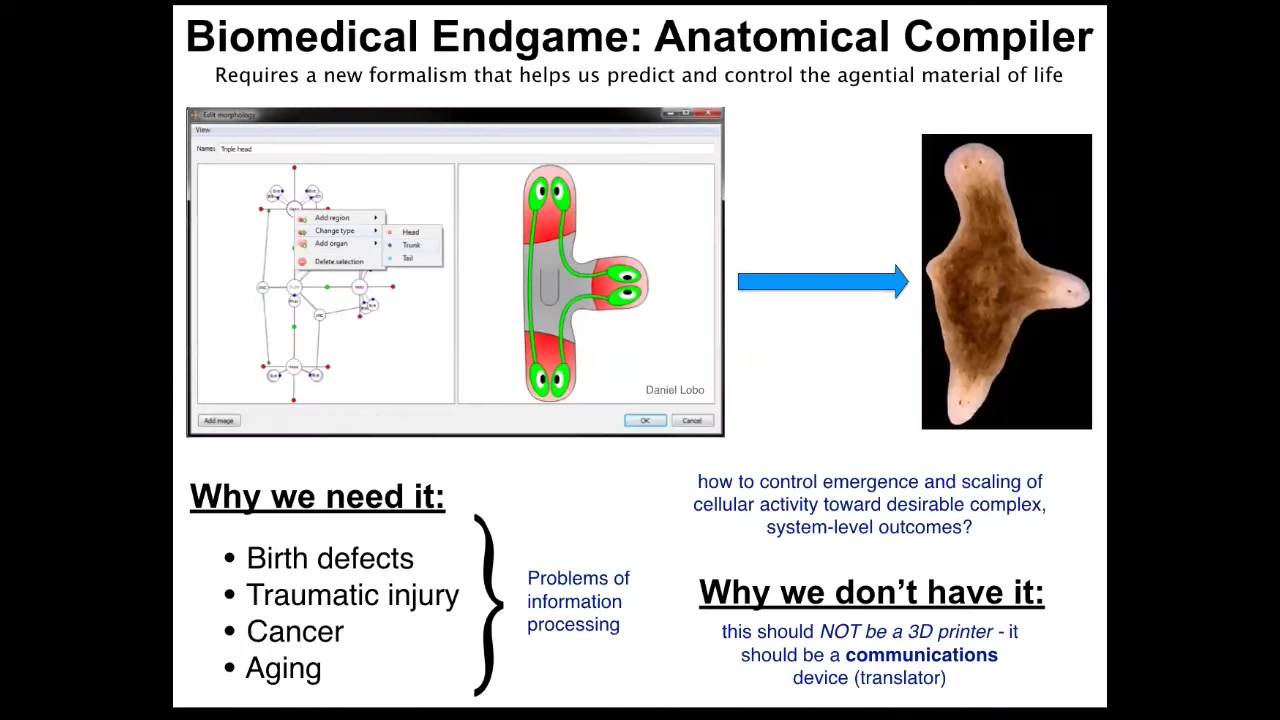

Ultimately, what we would like to do is this. We would like to have something I call an anatomical compiler. The idea is that someday you should be able to sit in front of a computer and draw the plant, animal, organ, biobot, in any shape and configuration that you want. And the system should be able to then, if we properly understood how the material of life works, compile it into a set of stimuli that could then be given to cells to get them to build exactly this, in this case, this three-dimensional flatworm, three-headed flatworm.

The key here is that this is not something like a 3D printer, which is going to build as if it were Legos, build a whole structure. This is a communications device. It's a translator from the goals of the engineer to those of the cellular collective. If we had something like this, all of this would go away. If we knew how to communicate novel goals to groups of cells, all of this would become a non-issue. We're very far away from this. We don't have anything remotely like this. You might wonder why, because molecular biology, genetics, biochemistry have been going very strong for many decades now. Why don't we have something like this?

Slide 12/51 · 13m:21s

And partially, it's because we've been really focused on this idea of the reliability of development. So this happens all the time and it happens correctly almost all of the time. You have eggs and they give rise to a very specific thing. And we tend to think that this is what the genome encodes. This is what the genome is capable of doing. We're still missing the deep lessons of both neuroscience and computer science, where a reprogrammable material is far more than its hardware specification. When you have something like this, what these cells are actually capable of is building things like this.

Slide 13/51 · 14m:00s

It is called a gall. It's made of the actual cells of the plant. You would have no idea that the cells that reliably build this nice flat green structure, very stereotypical. We think that's what the genome does. We'd have no idea that they're actually capable of building something like this until a non-human bioengineer comes along, in this case a wasp, that is able to prompt these cells with cues to build these incredible structures. And so who knows what else they're capable of? Probably the latent space is extremely large.

Slide 14/51 · 14m:35s

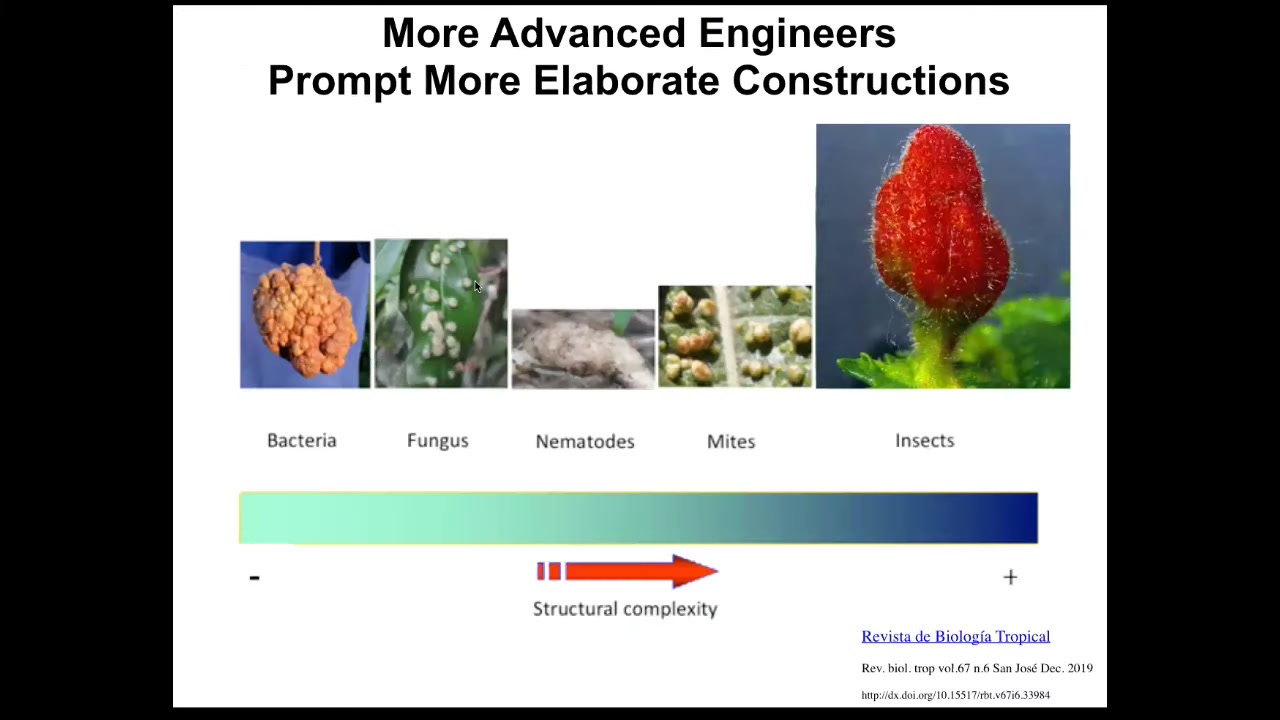

But what we do know is that more advanced engineers produce more elaborate constructions. Bacteria make these kind of featureless blobs. Fungi do something similar. Nematodes are starting to do a little better. There's some kind of non-trivial structure happening here. Mites do the same. By the time you get to insects, you get these incredible, incredible constructs. Clearly the space of possibilities is far wider than the genomic default, than the thing that we see all the time. Presumably it took that wasp millions of years to get to be able to do this.

Slide 15/51 · 15m:08s

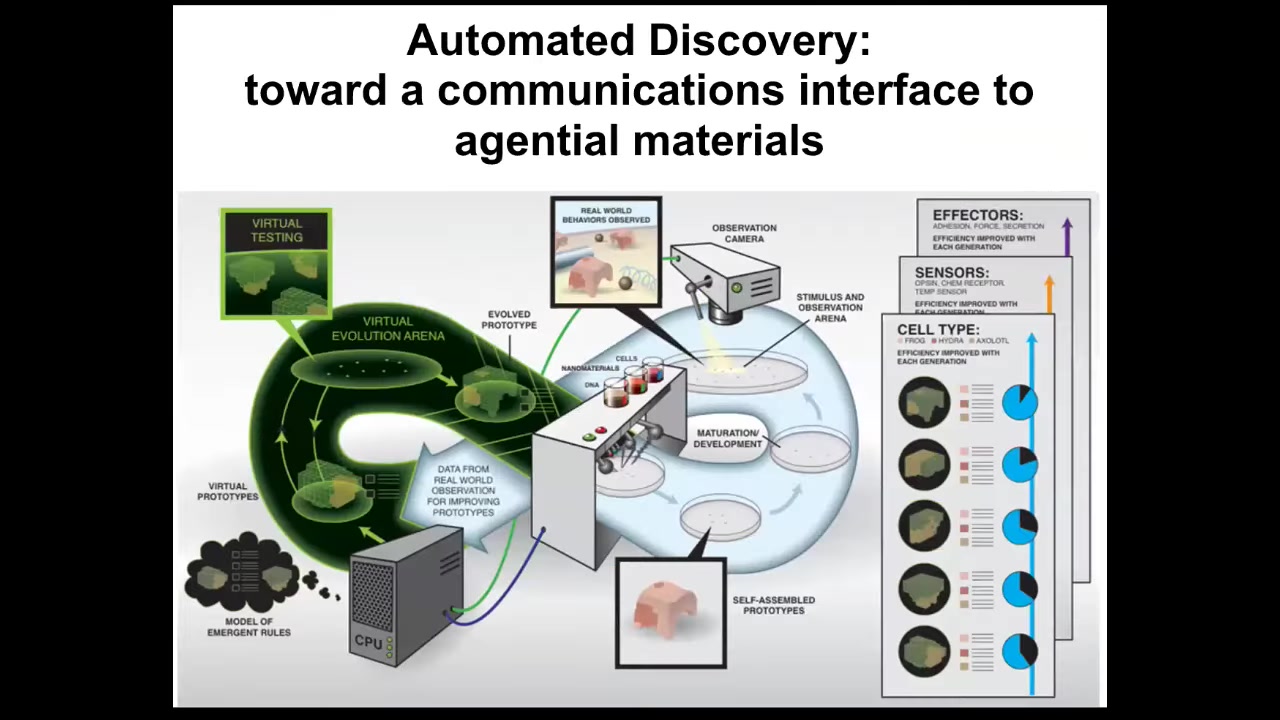

We would like to do it a lot faster. In my group, in collaboration with Josh Bongard, we are building this kind of automated robot scientist platform that is making hypotheses about the laws of morphogenesis, providing stimuli to real cells in parallel, observing the morphogenetic outcomes, revising its hypotheses, and going back. You'll recognize this as the typical cycle that we all do. In science, ideally, this will go a lot faster so that we can start to have some control and understanding of this process.

Slide 16/51 · 15m:43s

Where we are now is that the community is very good at figuring out the hardware, which proteins and RNAs interact with each other. But what we would really like to do is this. One positive control that we can look at is what happened in computer science and information technology. This is what programming looked like in the 1940s and 50s. You had to physically interact with the hardware. She's sitting there rewiring the machine to get it to do something different. This is what most of today's biomedicine, and molecular medicine especially, is all about. Genomic editing, pathway rewiring, protein engineering. It's all about the finer and finer control of the hardware of life.

Slide 17/51 · 16m:27s

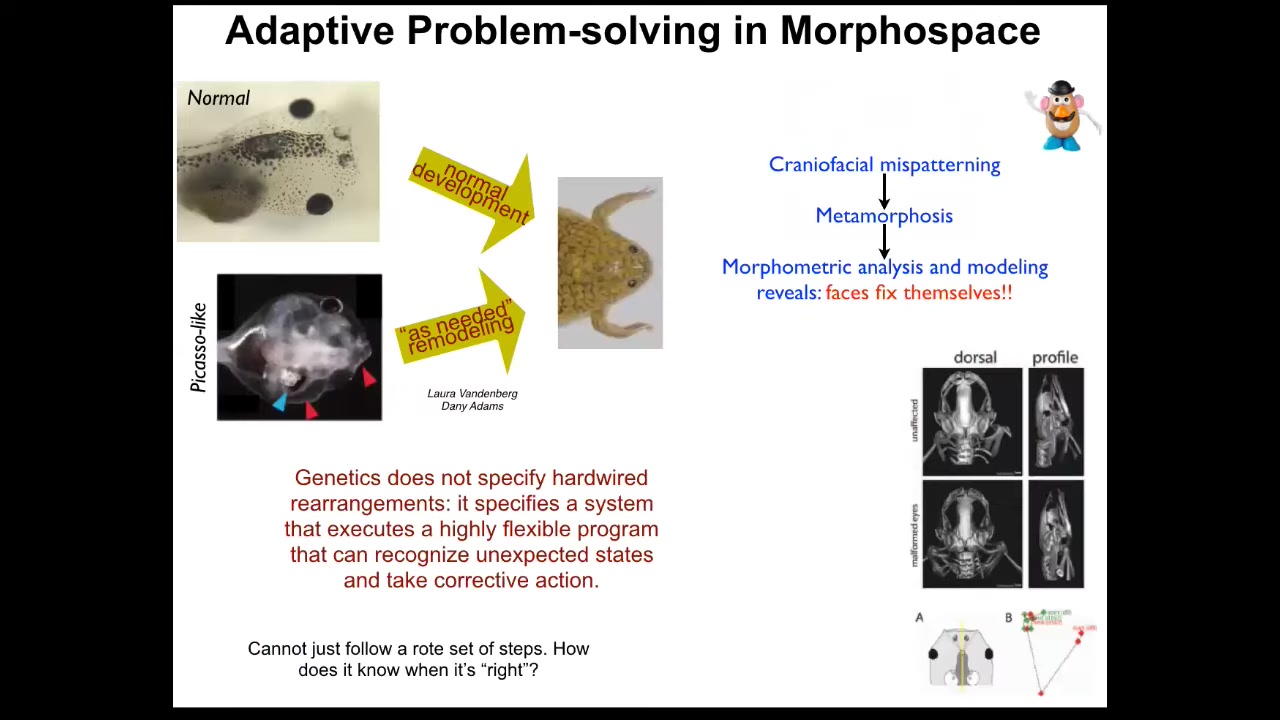

What we really need to understand is things like this. This was discovered in our group by Danny and Laura Vandenberg. Normally you have this stereotypical change of tadpoles becoming frogs and they have to rearrange their face and move their various craniofacial organs. This is not a hardwired process because if you scramble all of them and you make these so-called Picasso frogs, where the eyes are on the back of the head, the mouth is off to the side, everything is scrambled, you still get largely normal frogs because all of these things will adapt to their novel starting conditions. They will move in novel paths. Sometimes they go too far and have to double back a little bit, but they still get their goals met.

What you see is that the genetics is not giving you a piece of hardware that does the same thing every time; it gives you an error-minimization scheme and a system that can recognize unexpected states and take corrective action. That leads to a very obvious problem: how does it know what the right pattern is? If it's going to become a frog from that state or any of the other things I showed you, how does it know what the correct final goal is?

Slide 18/51 · 17m:34s

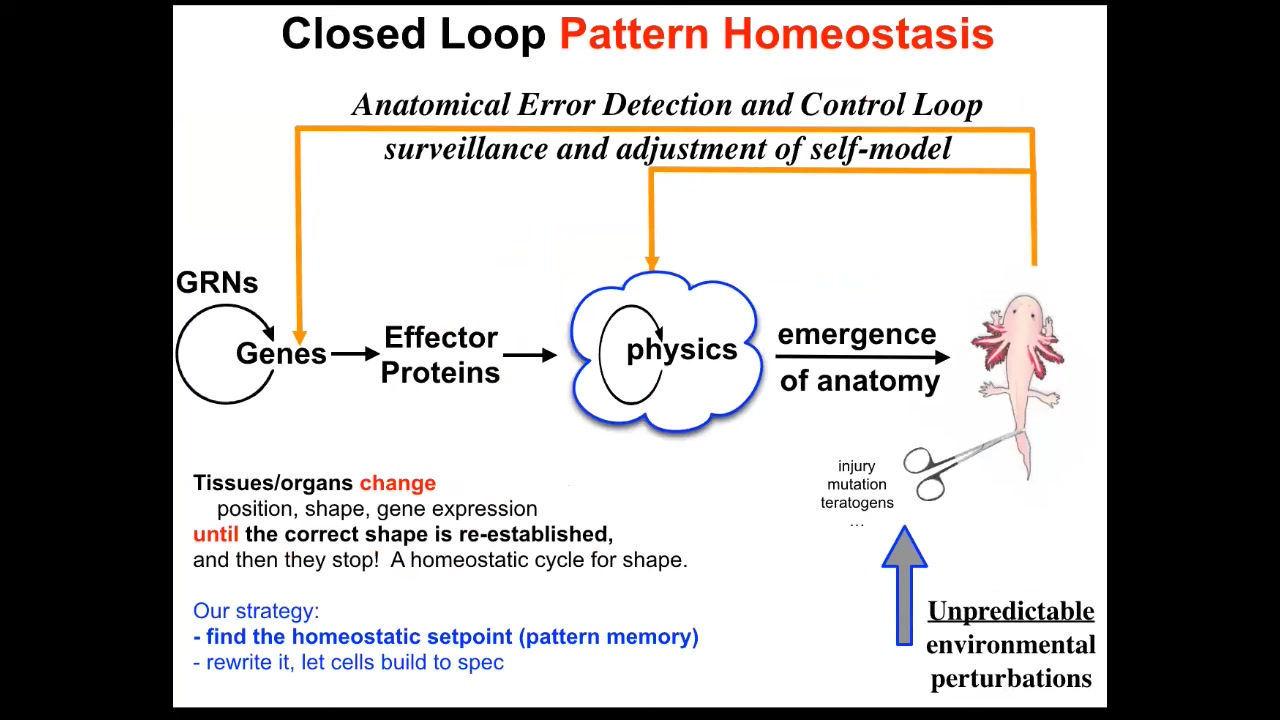

So what we do in our group is augment this kind of conventional open loop with this homeostatic component where deviation from this state, and this is something that typically open loop systems like cellular automata and so on don't do.

When you try to deviate the system from whatever that outcome was, it actually works really hard using all the mechanisms at its disposal. So of course the genetics, but also the physics, work really hard to try to get back there. This is not just injury, but also mutations, teratogens, and many different things.

So what we would like to know then is: how does this work? First of all, once you add this loop, for the first time the notion of mistakes enters the picture. Because until you have a homeostatic loop towards a specific outcome that is willing to expend energy to get back to where it was, there's no reasonable definition of what a mistake is.

Otherwise, it just rolls forward and whatever happens, happens. But now you see that any situation that pulls it away from this state — and that might be a situation that's fixable or one that's not fixable — now allows you to define how hard the system is willing to try to get back. How much stress is the system under, given that you've deviated from its goal state?

And so what we need to understand now is: how does the system know what the set point is? Any homeostatic process has to have a set point, which is with respect to which it's measuring error. And so now we need to understand what it actually means to store a target state in cells. And what does it mean to try to reduce the delta from where you are now to where you are? How could cells possibly execute something like this?

Slide 19/51 · 19m:20s

We have a non-controversial example of that. That is a brain-based behavior.

In the brain, what we have is a bunch of hardware, which is constituted by cells in a network that communicate electrically. On top of this hardware runs some very interesting physiology, which allows that network to do context-sensitive behaviors, to store memories and do problem solving of various degrees of complexity from simple habituation and sensitization all the way up to anticipation and planning. This system is using the remarkable properties of electrical networks and information processing in those networks to move your body through three-dimensional space. It does many other things now that we're humans and we play chess. Fundamentally, it evolved to move you through three-dimensional space.

We see creatures doing clever things, such as these crows that pick up cigarette butts and get a reward when they drop them off. You ask, how does it know what to do? The commitment of neuroscience is that if we were to scan and read out this electrophysiology, we would be able to eventually decode it and extract the cognitive algorithms. We would know what the animal is thinking about, what memories it has, what the goals and preferences are. All of that cognitive stuff is encoded and implemented in the electrophysiology of the brain. That's what these things think about.

Slide 20/51 · 20m:57s

Now, it turns out that this amazing trick is not just about brains. This is evolutionarily very ancient. It evolved around the time of bacteria and then bacterial biofilms. If you ask what those networks think about, I think the answer is they think about the movement of your body configuration in anatomical morphospace. I think what evolution did was pivot some ancient tricks that these electrical networks were doing to navigate anatomical space, and it sped them up quite a bit and then pivoted them into control of motion in three-dimensional space. And you can ask the same kind of questions.

When Farinella grafted these tails to the flank, to the side of a salamander, they slowly remodeled. These tails slowly remodeled into limbs. And in fact, the tail tip here, these cells are in their correct local environment, they're tail tip cells at the end of a tail, but they become fingers. This whole thing starts to remodel to better match a large-scale pattern of what the body plan is supposed to be like. And you can ask exactly the same question, how does it know what to do? It's a very parallel kind of system to what's done in neuroscience. And so we're trying to do exactly the same thing, to do this kind of neural decoding, except not in neurons, and to ask how are the decisions, the memories, the set points and so on, how are these things encoded in the electrophysiology of somatic tissues? Same kind of question, using many of the same tools.

Slide 21/51 · 22m:30s

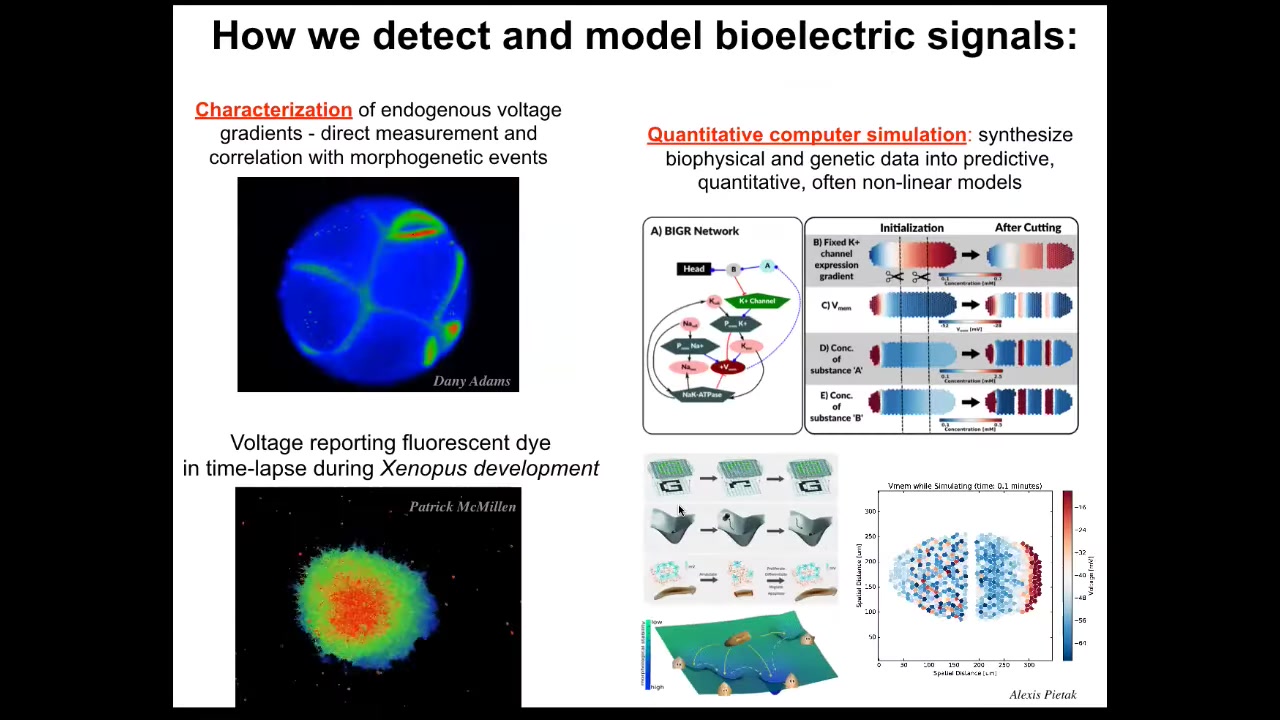

Here are some tools that were developed. These are voltage-sensitive reporter dyes. Here's a movie that Danny Adams made years ago of a frog embryo during the time when all the cells are figuring out who's going to be left, who's going to be right, who's anterior, who's posterior. You can see all the conversations that these cells are having with each other.

Here are some explanted amphibian cells in culture, making some decisions about who's going to stay within this group and who's going to leave. There are important bioelectrical signals that Patrick McMillan in my group is analyzing. We have the ability to use both dyes and genetically encoded reporters to read the electrical information in vivo. We do a lot of computer simulations all the way from the molecular networks that underlie those ion channels up through large-scale network properties such as pattern completion, studied in connectionist computer science. I hope we try to understand how artificial neural networks encode the pattern memories and how they can be repaired.

Slide 22/51 · 23m:35s

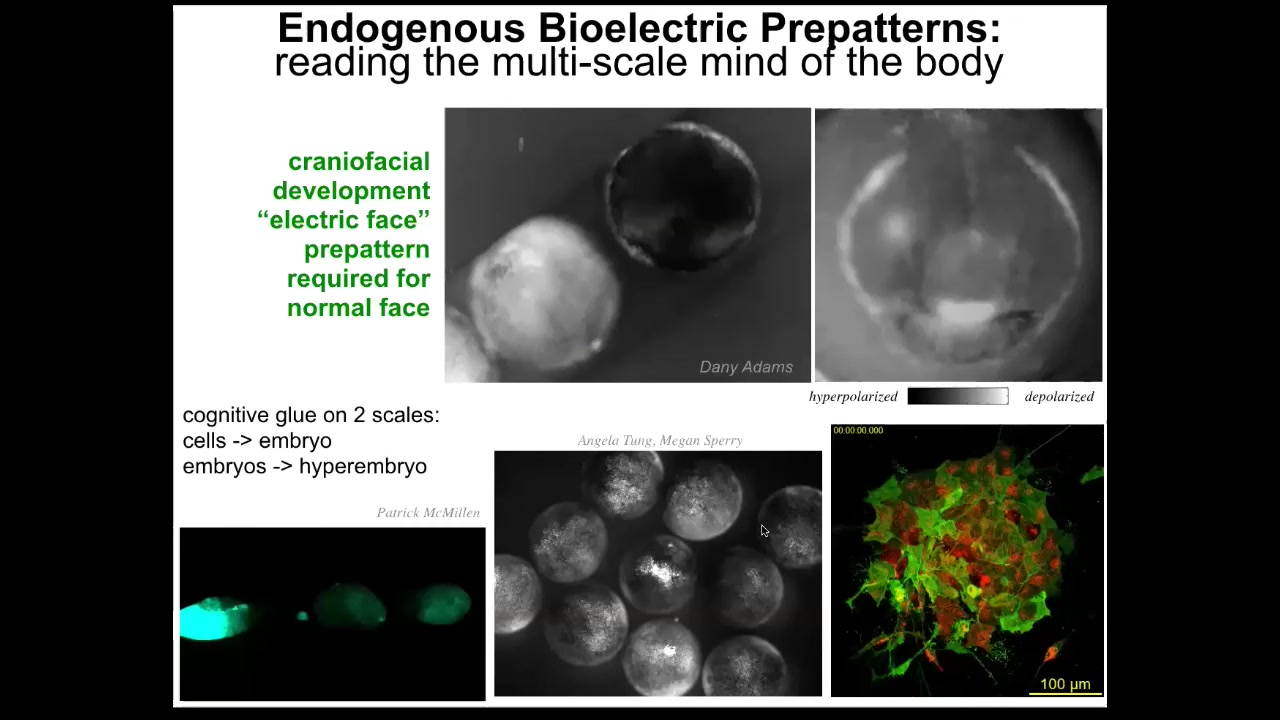

Here are some examples of what these patterns look like in vivo. This again is the famous electric face movie that Danny made, where you can see in a time lapse of this frog embryo putting its face together. Here's one snapshot from that video where you could see a subtle pre-pattern that tells you where the animal's right eye is going to be, here's the mouth, the structure is out to the sides.

Not only is the bioelectric signaling critical for the cells in the structure to know what they're going to make; it's a glue that coordinates the actions of individual cells toward a large-scale structure within one embryo.

These kinds of dynamics also work across scales. For example, here's an injury wave that propagates between individuals. When I poke this one, all of these find out about it.

This is Angela Tungsor, who showed that groups of embryos are better at resisting teratogens than singletons, precisely because they communicate as a larger-scale, second-tier collective intelligence.

You can see in these explanted cells that Patrick made the two layers. You can see the slow bioelectrics that are happening and also the neurons. We have the ability to observe all of this on different time scales and spatial scales.

Slide 23/51 · 25m:02s

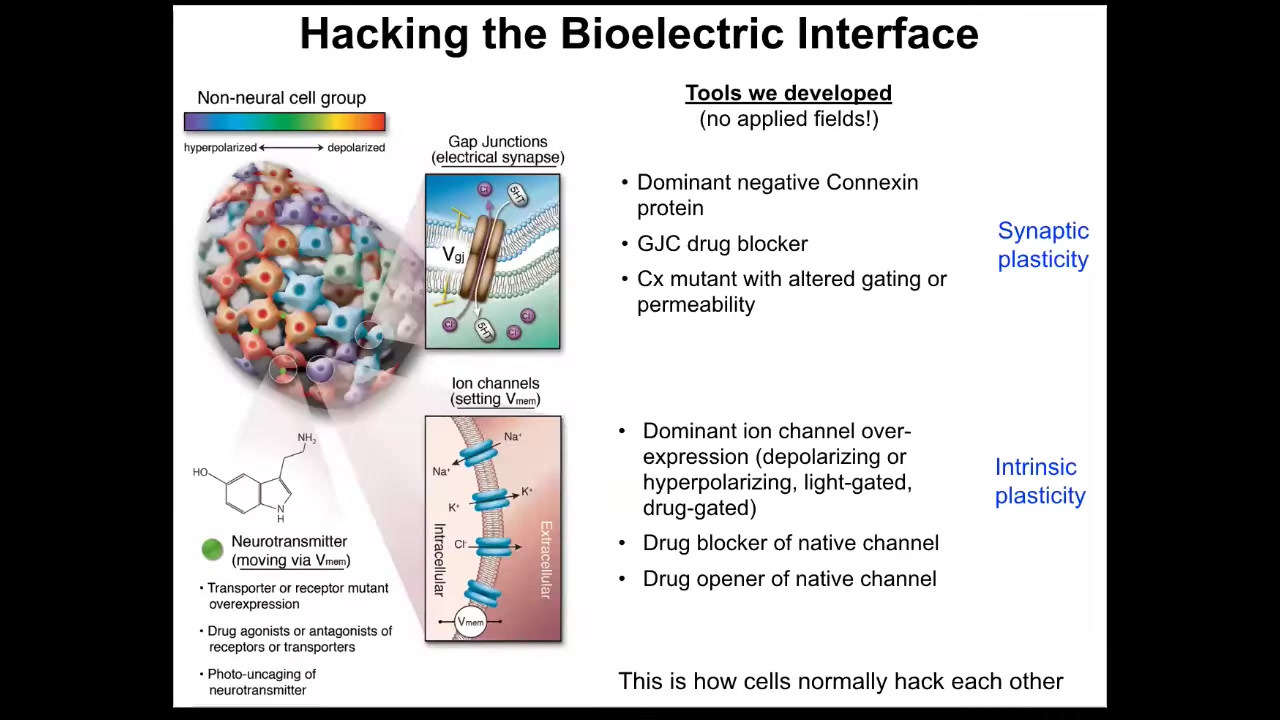

Better than being able to observe these patterns is the ability to modify them. You have to be able to do functional experiments and to insert information into the networks to know what that information is actually doing and to be able to control outcomes. In our group, we do not use applied fields or electrodes, no electromagnetics, no waves, no frequencies. What we do is manipulate the interface that cells are normally using to hack each other. That is, they're not happening because we're so smart. They're happening because we're hijacking a system that already exists by which these cells try to tell each other what to do and synthesize into a larger collective. We can control the connectivity of the cells via targeting gap junctions or the actual voltage states of the individual cells. We do this with optogenetics or with drugs that open and close these different channels. That corresponds to synaptic or intrinsic plasticity in the case of neuroscience. Here are some things that we're doing.

In work with David Kaplan's group, we showed years ago that one thing you can do on a single-cell level is control differentiation. You could tell individual cells to be more stem-like or be differentiated depending on the voltage that you can control.

Slide 24/51 · 26m:25s

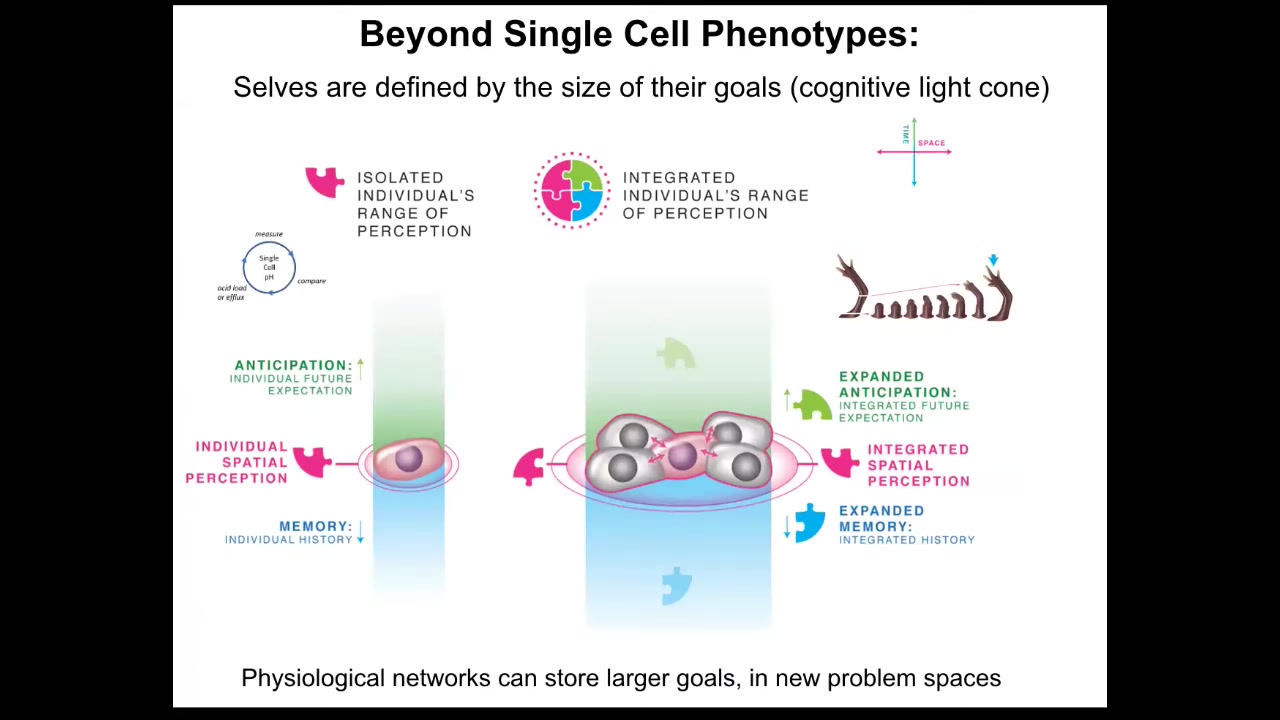

More importantly than individual cell state, the big impact of bioelectricity is not at the single cell level but in its collective forming properties: when you connect cells into a larger network, one of the things you're doing is scaling up their cognitive light cone. And what I mean by the cognitive light cone is simply the size of the biggest goals that they can pursue. So if we collapse space onto one axis and time onto the other, you can see that individual cells have tiny goals. These are things like maintaining pH and metabolic state. They have a little bit of anticipation potential, a little bit of memory going back. Everything in single-cell organisms is concerned with maintaining the conditions at the level of a single cell. Groups of cells, such as tissues, organs, and whole embryos, can have very, very large-scale goals. They can start building things like this.

Slide 25/51 · 27m:25s

During development and during evolution, what actually happens is by joining together, the size of the goals that they're pursuing gets radically increased.

While individual cells only care about what's going on inside their own borders, these cells work hard on this grandiose goal of maintaining a large structure. No individual cell knows what a finger is or how many fingers it's supposed to have, but the collective absolutely knows in a very functional sense, meaning that you can, if you know that they know this, then you will be able to predict that once you introduce damage, it will actually build the right kind of stuff, and that that's when it will stop.

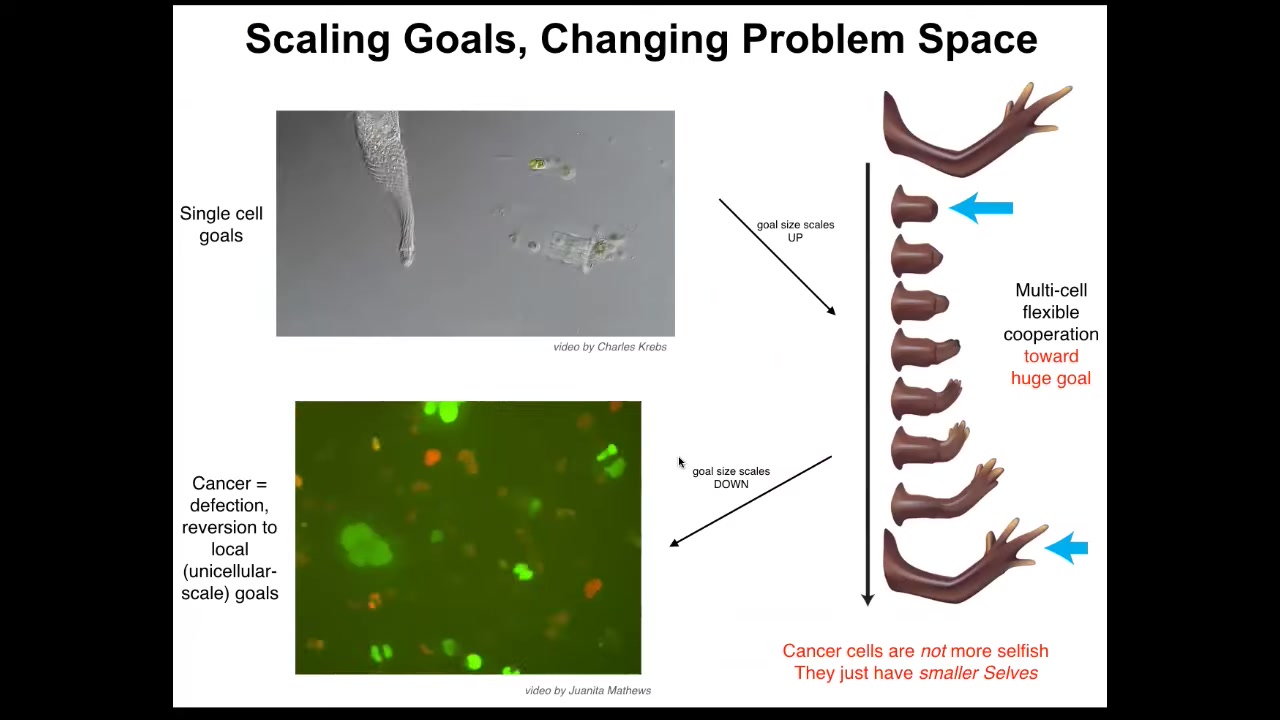

This system has a functional ability to get back to a goal state that is much, much larger than the tiny scalars that individual cells pursue. But of course, this kind of thing has a failure mode, and that failure mode is cancer.

One of the things that happens when cells electrically disconnect from the collective is that they can no longer pursue these large grandiose set points. They basically roll back to their ancient unicellular lifestyle.

Here's a video of some glioblastoma cells that Juanita in our group studies. There have been many papers looking at how these things are traveling back in their evolutionary history to occupy themselves with very small kinds of set points and treating the rest of the body as external environment. What's happened is the border between self and world has shrunk. Now, this failure of this multicellularity does not require DNA damage.

Slide 26/51 · 29m:03s

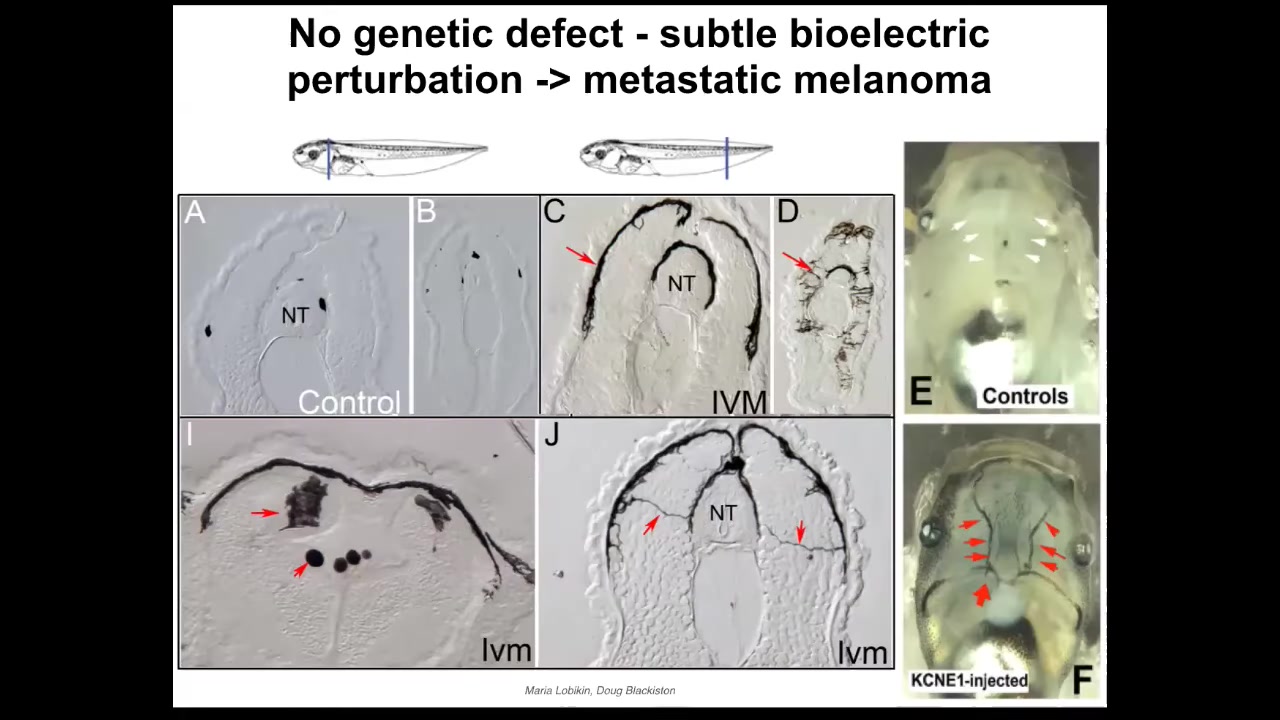

It doesn't require mutations. It can be triggered purely bioelectrically because these networks that keep cells harnessed towards specific goals are in large part bioelectric.

This is some work by Maria and Doug from our group where we showed that if you interfere with the electrical communication between melanocytes, these little pigment cells, and another rare population of cells we called instructor cells because they're the ones who keep these guys under control. If you interfere with that, then these little melanocytes go crazy and they acquire this hyper-invasive morphology. They start to drop down and invade the neural tube, the brain, and the blood vessels. You can see this has a lot of the anatomical and molecular markers of metastatic melanoma. There is no primary tumor here. All of the melanocytes go crazy and do this. And there also is no genetic damage. There are no carcinogens here. There are no oncogenes. But they will turn on a bunch of markers that are associated with the metastatic melanoma. That's all done just by disrupting the electrical coordination between cells. Better than inducing this kind of transformed behavior, you can actually suppress it.

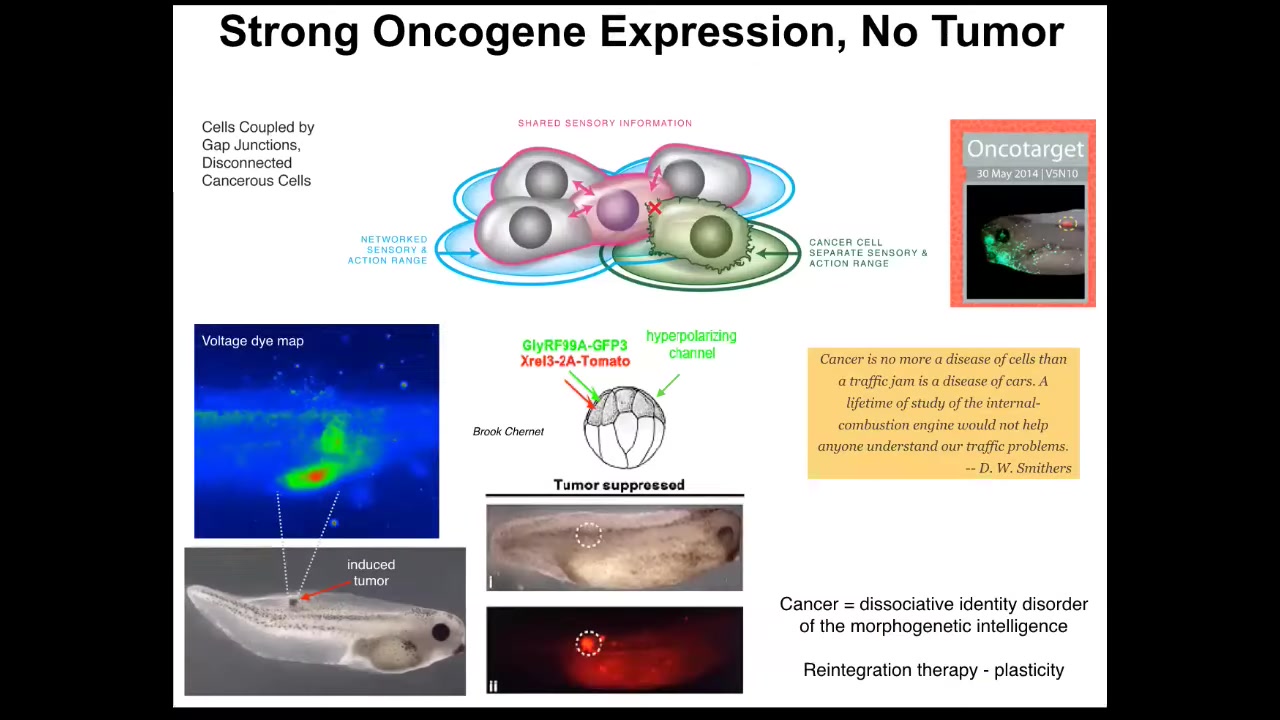

Slide 27/51 · 30m:20s

And this is something that Brooke Charnett showed in our group where you can, first of all, if you do inject human oncogene, so nasty things like KRL and dominant negative P53 and so on, you will get tumors. But if you also co-inject a channel that forces the cells into the appropriate bioelectrical state and keeps them coupled to their neighbors, then you won't get a tumor in a good chunk of the cases. This is the same animal. The oncoprotein is blazingly expressed. You can see it all over the place; it's marked with this fluorescence, but there's no tumor. Because it isn't the genetics that drives, it's the physiology. And once these cells are connected to their neighbors, they're going to keep working on the skin and muscle and everything else that they were doing. We did all this in frogs.

Slide 28/51 · 31m:16s

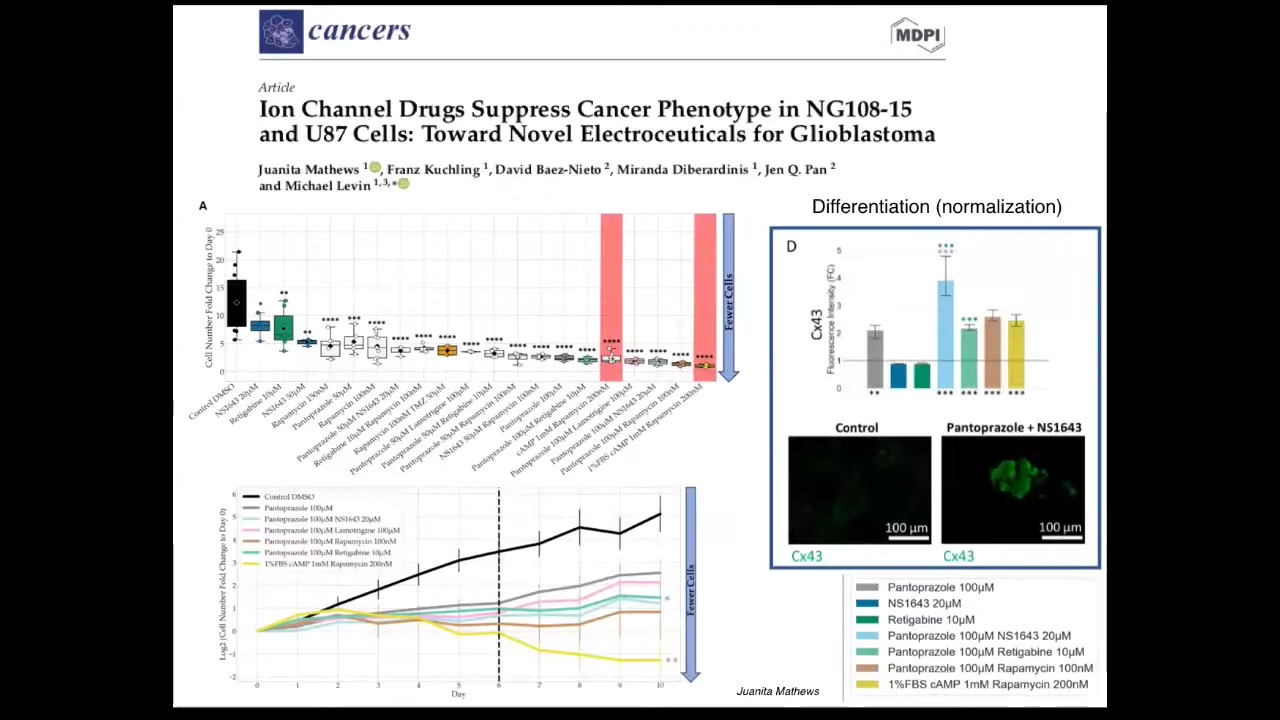

We are now moving, as Juanita showed you yesterday, into humans, into mammalian cells and human cell spheroids. This is some work that she had looking at ion channel drugs as electroceuticals to manipulate the phenotype in glioblastoma cells in vitro. And we're moving into 3D culture as she showed you yesterday.

Slide 29/51 · 31m:40s

We've talked about the importance of bioelectricity in maintaining multicellularity and maintaining a collective commitment to morphogenesis instead of unicellular kinds of lifestyles.

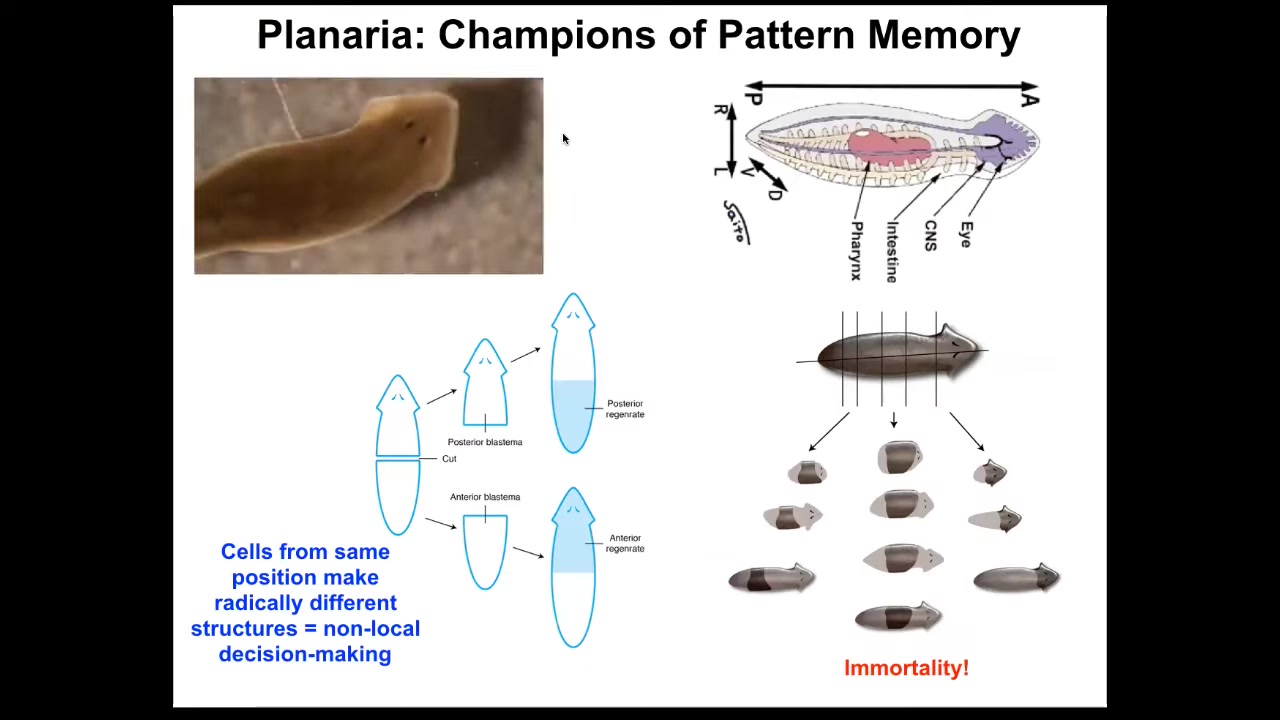

I want to shift now to the role of bioelectrics as a pattern memory. For that, I want to talk about this organism. This is a planarian. This is a remarkable organism. Not only are they incredibly regenerative; you can cut them into pieces. The record is something like 270. Each piece will restore the full worm. They are also extremely cancer resistant and don't age. The asexual forms are immortal.

It's very strange, and it took us years to understand why this is happening: why the animal with the best regenerative capacity, the most cancer resistance, the least susceptibility to aging is the one with the extremely noisy genome. Because of their asexual reproduction, they're mixoploid: their cells have different numbers of chromosomes; it's very noisy. Why is that?

That's a whole other talk.

This is an amazing model system because every piece here has this holographic memory of what the collective looks like and it can rebuild this.

Slide 30/51 · 33m:03s

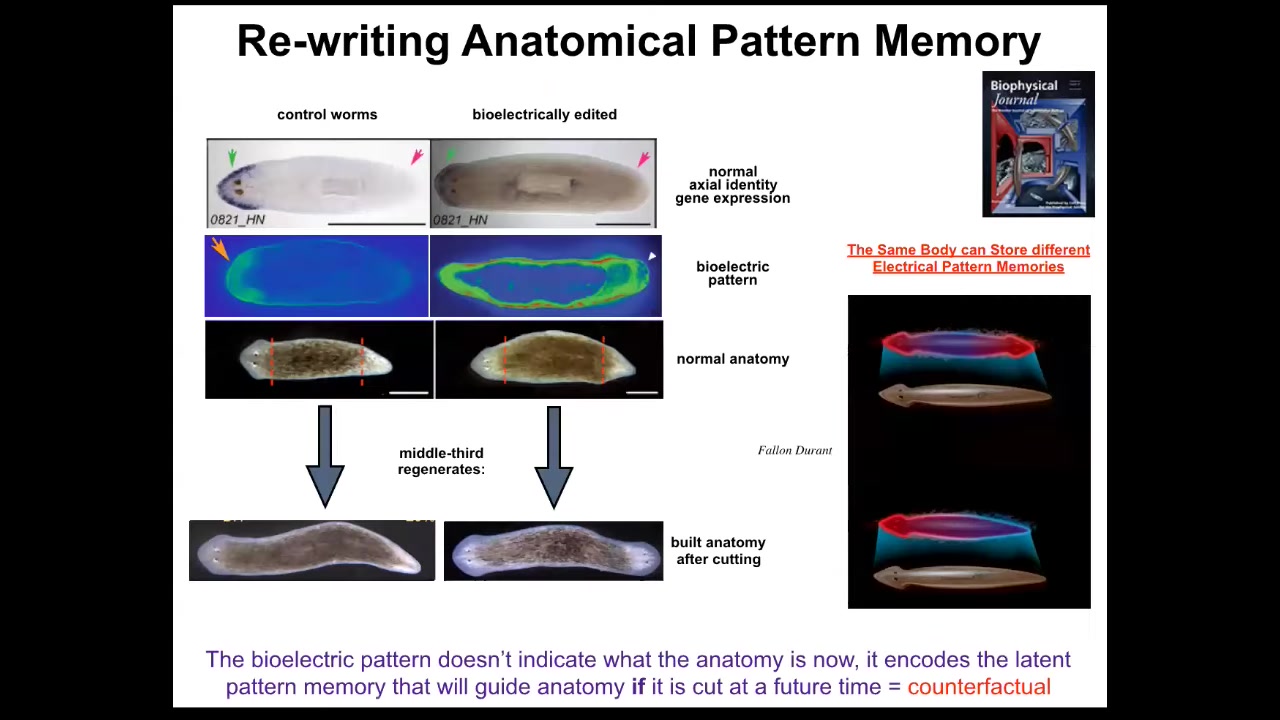

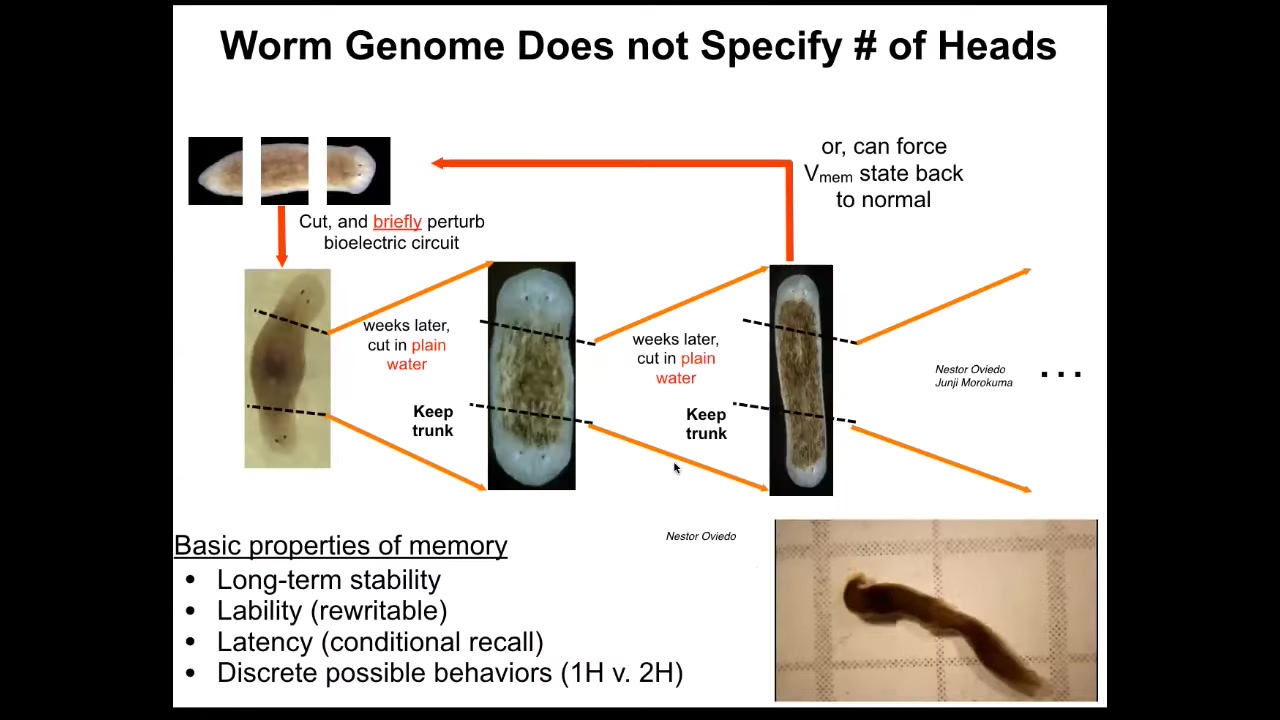

What we found was that individual pieces or whole animals have this electrical gradient that tells them one head, one tail. If you amputate this animal, you get one head, one tail. Remarkably, you can manipulate that gradient using ion channel drugs, and you can move it to this state that says two heads. If you amputate this animal, you will get a two-headed worm. This is not AI or Photoshop. These are real animals.

Something important to note is that this voltage map is not a map of this two-headed animal. This voltage map is a map of this perfectly normal looking, anatomically normal and molecularly normal animal, meaning that if you look at the markers, anterior markers are only on one end, not on the other. Only when you cut this animal do you realize that it had a different idea of what a normal planarian is going to look like.

In other words, the body of an anatomically and molecularly normal planarian can store at least two, probably a lot more, but we've nailed down two representations of what to do if it gets injured at a future time. That's a counterfactual memory. Neuroscientists will recognize this as an early primitive form of the mental time travel that brainy systems can do when they can recall or anticipate things that are not happening right now. This is a pattern that will sit there. It's a latent memory. It doesn't do anything until the animal gets injured. When it does, it becomes relevant because that is the ground truth of what the cells consult when deciding what to build at each end.

Slide 31/51 · 34m:39s

I keep calling it a memory because if you cut these two-headed worms, no more manipulations of any kind, cutting them in plain water, they will in perpetuity continue to make two-headed worms. That pattern is permanently changed. We've not touched the genome. There's not been any genomic editing. If you were to genomically sequence these animals, you would be none the wiser that they have a radically different body plan, architecture, behavior, everything is different.

There is important information that is stored for very long periods of time, possibly permanently. As far as we can tell, it's permanent, although we do know how to set it back to normal now. That is kept in this electrophysiological layer.

It is not genetics. The genetics does not tell you whether the planarian is going to have one head or two. It gives you hardware that settles into a pattern by default that encodes one head, but it's rewritable like any good memory should be. And this should not be surprising to anybody in neuroscience. That is what the purpose of the nervous system is, to be flexible and to store patterns that were not genetically set in stone at the beginning.

So given that we have the ability of cells to interpret these bioelectrical patterns, because the bioelectrical pattern is saying build ahead here, but the other cells have to interpret it and do all of the molecular, the hard work of turning on the various genes and differentiating cells into eyes and brains. Given that cells have the ability to interpret it, can we modify what they're doing?

Slide 32/51 · 36m:18s

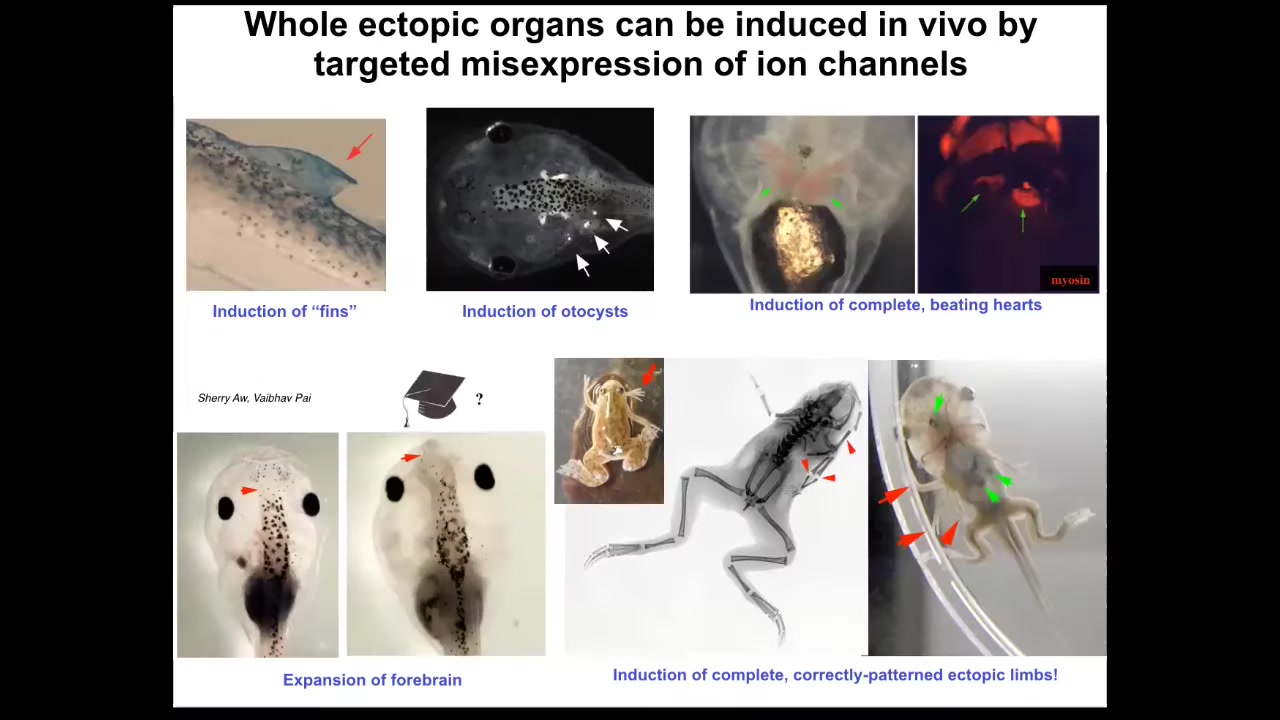

This is one of our earliest applications when we used ion channel RNA. This is Sherry Au and Viphof Pai's work where they introduced potassium channels into the early embryo in different regions, and we're able to tell the cells to build an eye. These eyes have all the right lens and the optic nerve; they have all these things.

Note a couple of important features. First of all, this tells you that the bioelectric signals are instructive. They don't just screw up development or produce errors. They actually communicate organ-level information. The other thing is that it's highly modular. In other words, we didn't tell the cells how to build an eye. We didn't talk to the stem cells. We didn't control gene expression. We have no idea how to do any of that. What we found is a very high-level subroutine call that communicates the idea that this is where an eye should be. Like any good cognitive system, it can take a very simple stimulus and do all of the downstream processing. Hierarchical control does all of the things needed to implement what it wants to do.

We also found something very interesting: if you section these eyes, you can find that only a few of the cells were directly injected by us. Only a few of these cells were directly injected by us. What they did was instruct their other cells to help because there wasn't enough of them to build a complete organ. There's this secondary instruction. Once they're committed, once they've bought into what needs to happen here, they will then do things we don't know how to do, which is to instruct all the other cells to participate.

This is an important part of future medicine. Right now, aside from antibiotics and surgery, we really don't have many, if any, medicines that actually fix anything. We have things that suppress symptoms, but we don't have anything that you take for a while and then you can stop taking it and the problem is fixed. The idea here is that we need to reset set points so that the system itself becomes committed to whatever outcome we want so that we're not trying to micromanage a totally intractable number of moving parts, but actually we get the buy-in of the homeostatic process. There are many collective intelligences that do something like this, not just cells. Ants and termites, if they find something too heavy to move, will recruit their nest mates to help. It's a common thing in collective intelligence.

Slide 33/51 · 38m:50s

So we can make many different organs. We've made ectopic limbs, ectopic hearts in this way by ion channel mis-expression, otocysts, ectopic brains, structures that don't actually belong on a tadpole, such as these kind of fin-like structures.

Slide 34/51 · 39m:18s

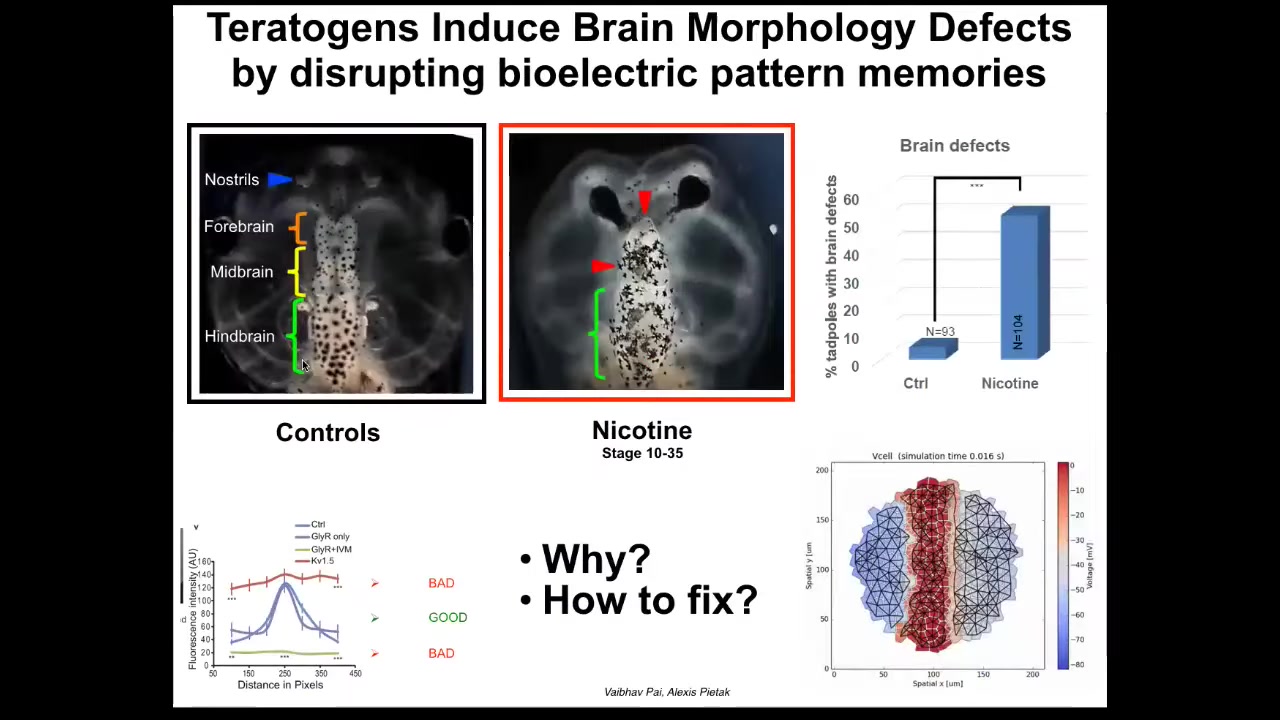

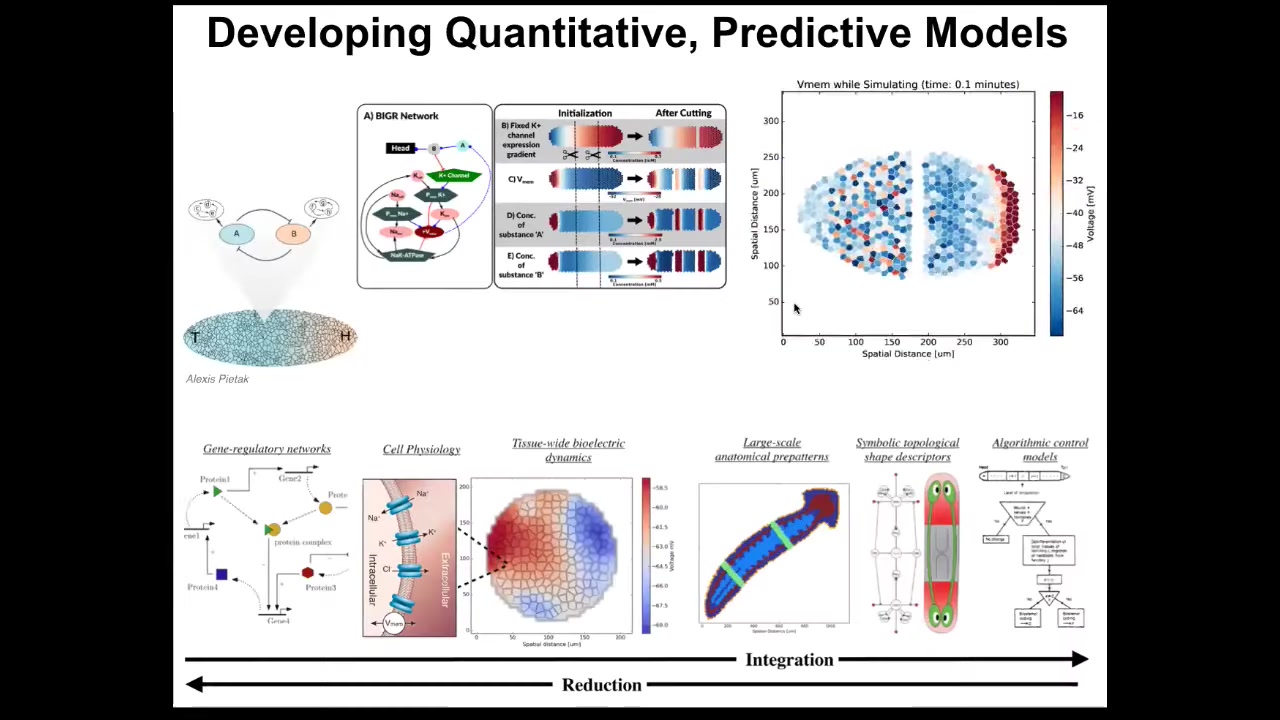

The idea of this, now that we're starting to understand what aspects of the bioelectric properties are controlling downstream outcomes, is that we can start to get really specific and ask, can we induce repair of things that go wrong?

Here is a set of papers by Pi and a few with the modeling by Alexis, where we were looking at the frog brain, and you can see here the forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain, and various teratogens, nicotine, alcohol, lots of other things, produce characteristic defects. Here you can see the brain is damaged. The eyes are connected to the brain; they're not at the right distance. We asked the question, what's actually going wrong here when this happens? Alexis produced this computational model that uses the voltage imaging that we performed to understand what happens to set the correct or the incorrect shape and size of the brain.

Slide 35/51 · 40m:14s

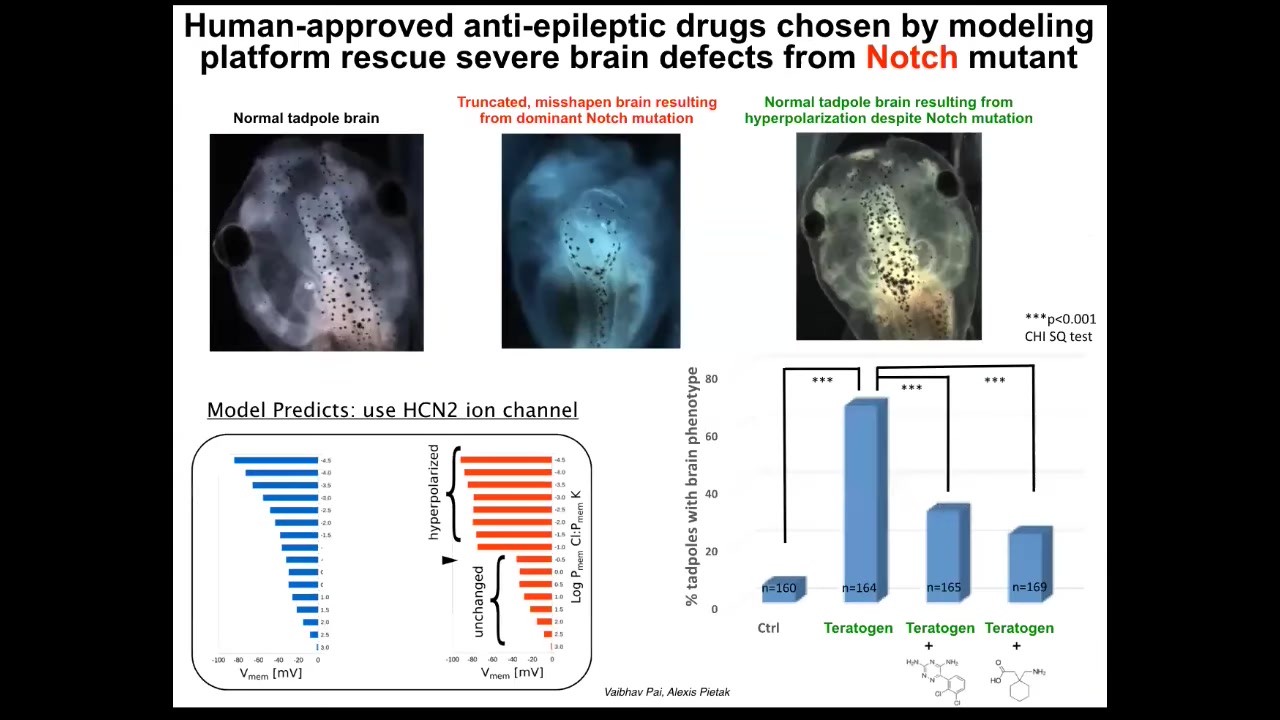

It turned out that once you have a model like this, what you can do is run it backwards and ask the questions: given that what's happening is incorrect, how do I bring it back to the correct state? In other words, what channel do I open or close to get the pattern back to normal? Those are our control knobs.

In particular, for a range of defects of the brain, face, heart, and gut, what we learned is that there's this amazing thing called HCN2. What's cool about HCN2 is that it's a sharpened filter in Photoshop. If you turn on HCN2, it takes fuzzy or diffuse voltage patterns and sharpens them so that the boundaries between regions of different voltage are stronger. In other words, cells that are slightly polarized stay where they are. Cells that are depolarized stay where they are. Cells that are slightly polarized become very polarized.

As a result, you sharpen up all the gradients. And that is enough to take tadpoles that have extremely severe brain defects. So this is a Notch mutation, a very important neurogenesis gene. These animals have no forebrain. The remaining tissue is a bubble filled with water. They have no behavior; they lay there doing nothing. You can override this despite the presence of this dominant Notch mutation and get a brain that has normal anatomy, normal gene expression, and normal behavior. Their learning rates go back to normal by managing the bioelectric pattern.

All we had to do in this case was open HCN2. We did not have to tattoo it in specific cells. We didn't have to manage the fine structure of where it's expressed and how and when; just that sharpening filter alone was sufficient to override the Notch mutation and a bunch of chemical teratogens as well.

So that's one way to start to computationally predict interventions: pick electroceuticals like this, using a computational model of what the bioelectrics are doing.

Slide 36/51 · 42m:13s

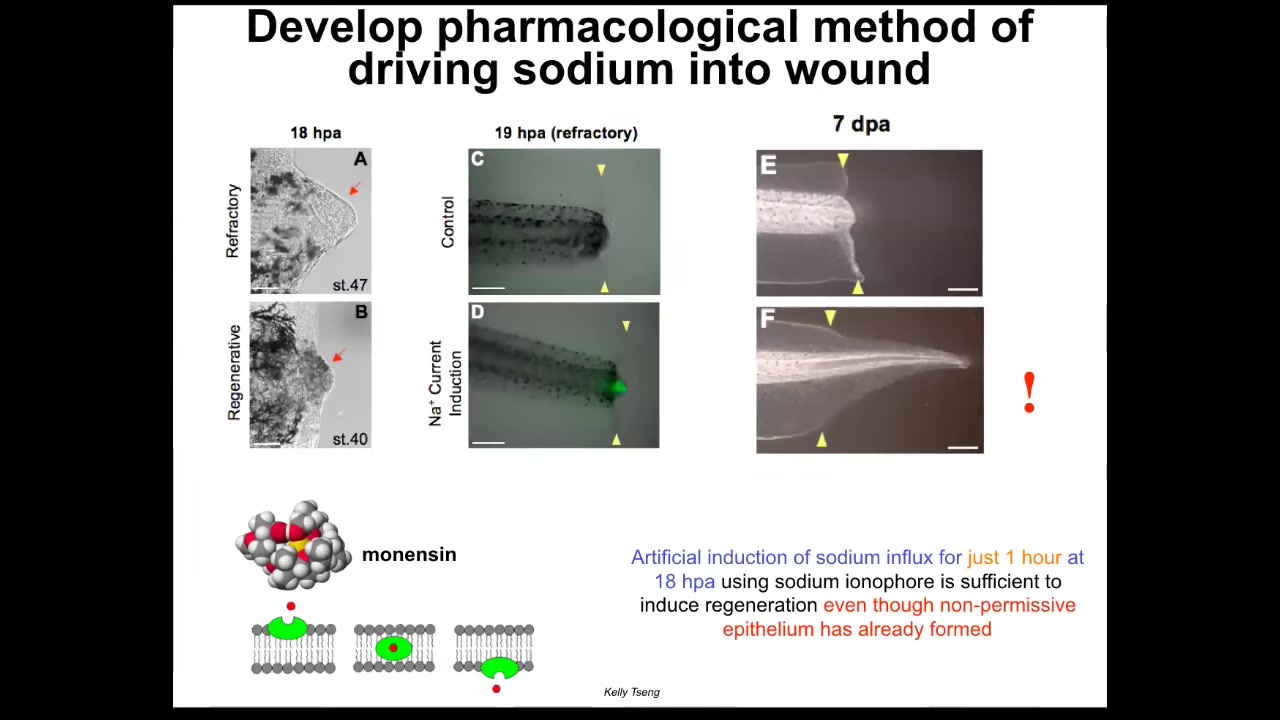

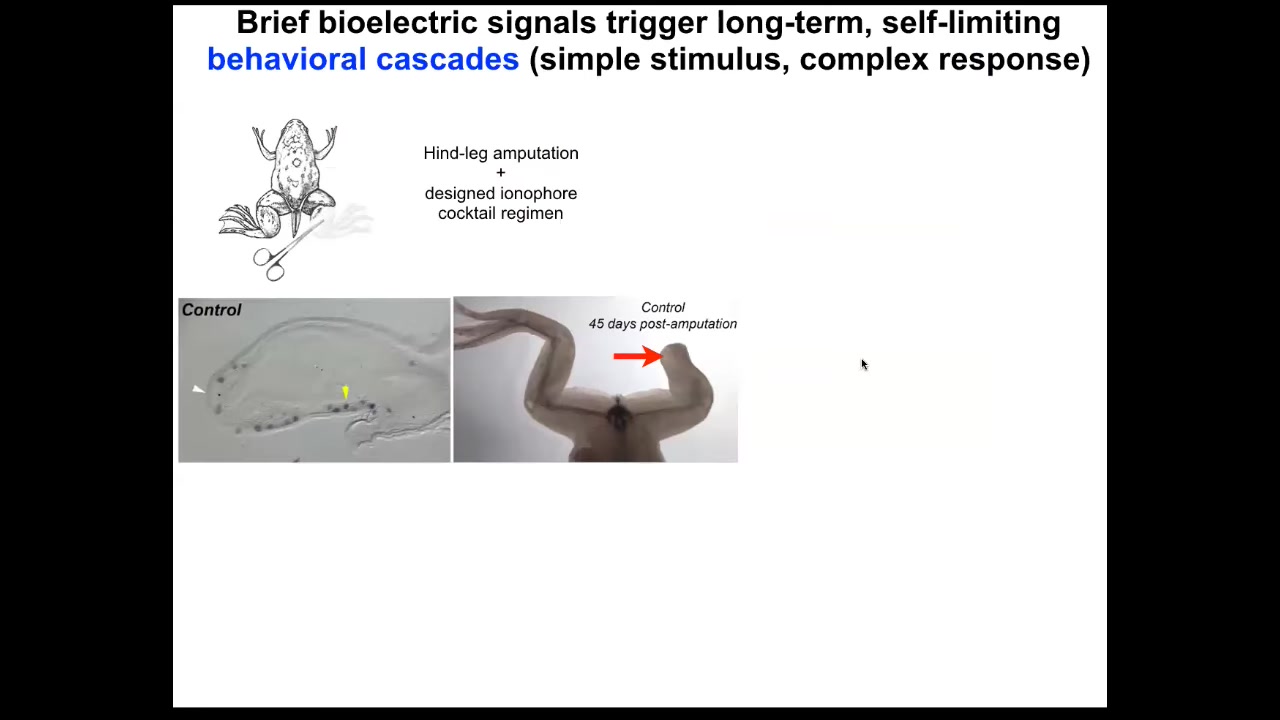

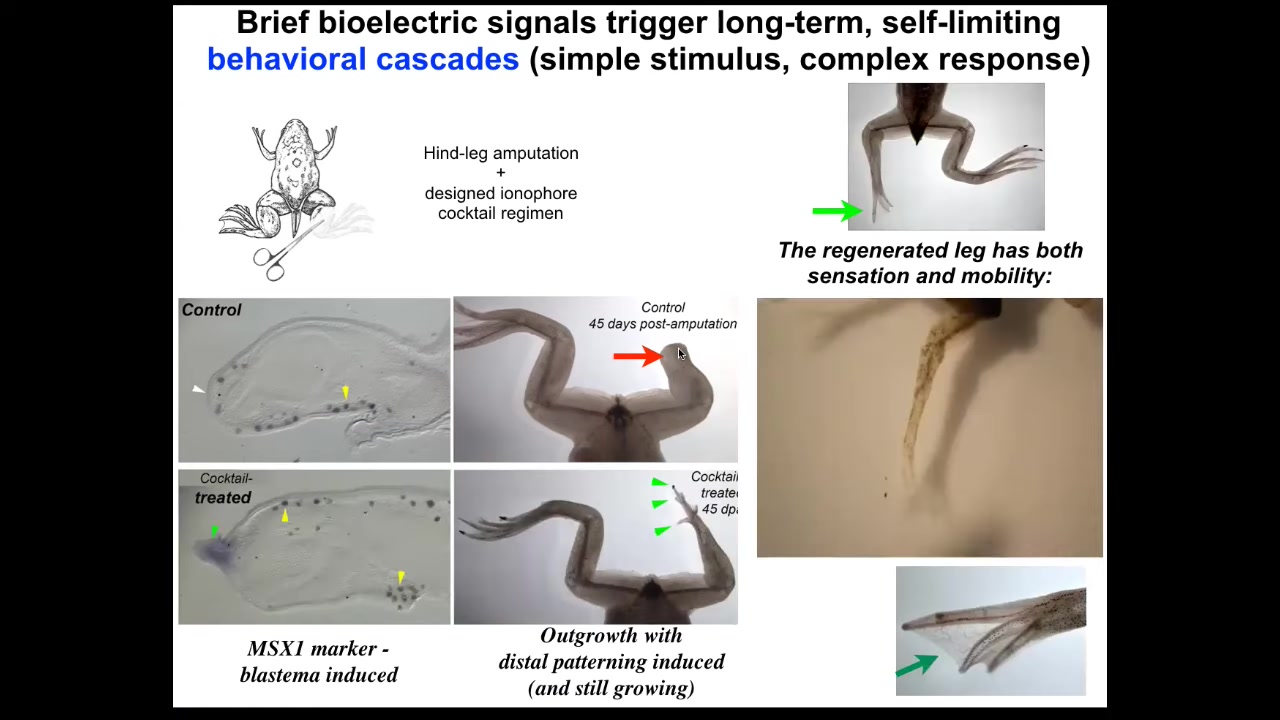

We also have a program in appendage regeneration. Some of Kelly Cheng's work uses very simple triggers. I'm showing you this because it reminds us that very simple triggers in bioelectrics can give rise to very complex outcomes. In this case, a one-hour stimulation with a sodium ionophore, which drives sodium into the wound, kick-starts regeneration at this non-regenerative phase of life even though a normally non-permissive wound epithelium has already formed.

Slide 37/51 · 42m:48s

We took this into frogs. Frogs, unlike salamanders, do not regenerate their legs. What Kelly showed is that after 24 hours of stimulation, compared to what normal frogs do at this point, you get immediate turn-on of pro-regenerative genes such as MSX1.

Slide 38/51 · 43m:02s

By 45 days, you've already got some toes and a toenail. Amazingly, the path that the leg takes to regeneration is not the normal path by which frog legs form. It's quite different, but it gets to the same endpoint because you can see eventually you get a very respectable leg that is touch sensitive and motile. But, as with many problem-solving systems, it doesn't necessarily follow the same path that it did before. It finds a new path to get to where it's going.

Slide 39/51 · 43m:33s

The most recent work from Celia and Narosha had to do with very large adult frogs, which have never been shown to be able to regenerate anything like this. Using a bioreactor, we were able to induce very significant regeneration. The most amazing thing about it is that we only interacted with the wound for 24 hours. It's a wearable bioreactor. 24 hours of treatment gives you 18 months of growth during which time we don't touch it at all.

This underlies the same thing. One amazing thing about cognitive systems is that when you communicate to them, you are not in charge of all the molecular complexity that it takes to make changes in their body. In other words, when I'm talking to you now through this very thin language interface, I don't need to worry about tweaking all of your synaptic proteins so that you understand and remember what you're hearing. You will do all of that yourself. The whole electric network of your brain and body is organized so as to take these low information content stimuli and do all of the downstream steps that it takes. We'll move all the biochemicals around so that the information sticks. That's what's happening here. We did not have to micromanage this 24-hour stimulus to convince the cells that you're going to go down the leg-building path, not the scarring path. That's it. After that, we take our hands off the wheel. That's what we're looking for.

Slide 40/51 · 45m:04s

I have to make a disclosure because Dave Kaplan and I have a spin-off called Morphoceuticals. We're now moving this approach into mammals, where we build various kinds of bioreactors that deliver a payload and allow an aqueous, tightly controlled environment around the wound where all the ion currents can flow and the cells can feel that they're in a protected, almost amniotic-like environment. The payload is ion channel drugs and some other things designed to tip the whole system towards regeneration and away from scarring.

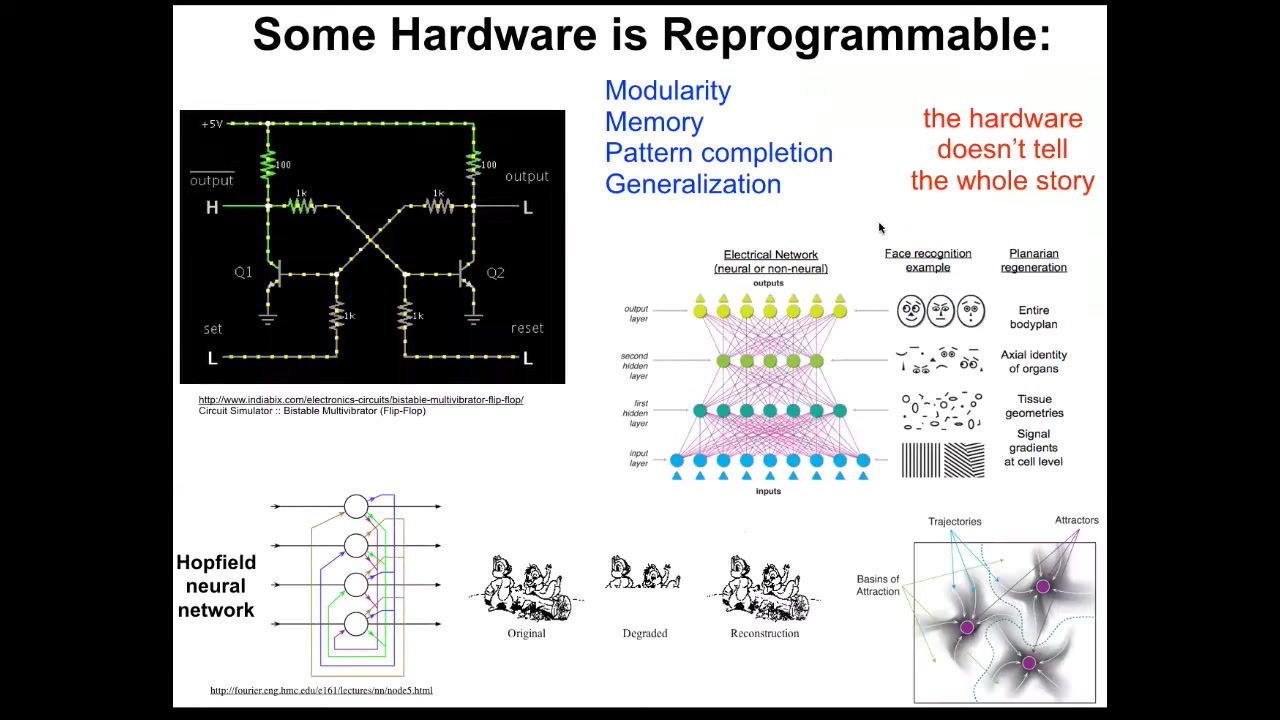

The point of all these examples is that the traditional story that everybody's taught, which is that the cell is the hardware and the DNA is the software, is turned upside down by the work in bioelectricity, which reminds us that the DNA is what sets the hardware. The DNA tells the cell what kind of channels, pumps, gap junctions, and things it gets to have.

Slide 41/51 · 46m:25s

But after that, an excitable medium of cells expressing these things has some very interesting and very important properties that allow self-organization of patterns, memory, computation, and all the things that neuroscientists are used to, which means that much like in computer science, where we know that the simple flip-flop can store two different kinds of information, A1 or A0, not by changing the parts around, simply by temporarily giving a stimulus that changes the way that energy flows through the system, it can acquire different states and carry different information one way or the other.

None of that is visible on an ohmics approach. You could take an X-ray of the system. You could count all the resistors and transistors; you would not know what the information is. That reminds us that biochemical omics does not tell the whole story. We're now applying useful tools from connectionist cognitive science to try to understand how networks of cells can store memories as attractors in physiological space, but also how they can do things like pattern completion and generalization, because the different layers in these systems generalize to larger-scale features.

While you might have chemical gradients at one level, eventually you'll have tissue geometry, axial polarity, organ identity, and things like face patterns.

Slide 42/51 · 47m:33s

The dream here is to be able to have a full stack computational model that goes from the molecular networks that tell you what channels and pumps you have, meaning the targets of your intervention or all these things, all the way through tissue level models that show how it is that these voltage patterns arise, what their properties are in terms of injury and modification, and eventually into algorithmic models.

This comes from Slack's book in 1981. It's an algorithmic model of planarian regeneration, trying to understand what are the steps that it requires to have a proper worm from a little fragment.

This is very difficult, because it's hard to do the inverse problem of knowing what do I do here to get a specific outcome. This is what we're working on now: a full stack integration of these different layers so that we can start to infer interventions and birth defects, regeneration and cancer.

Slide 43/51 · 48m:41s

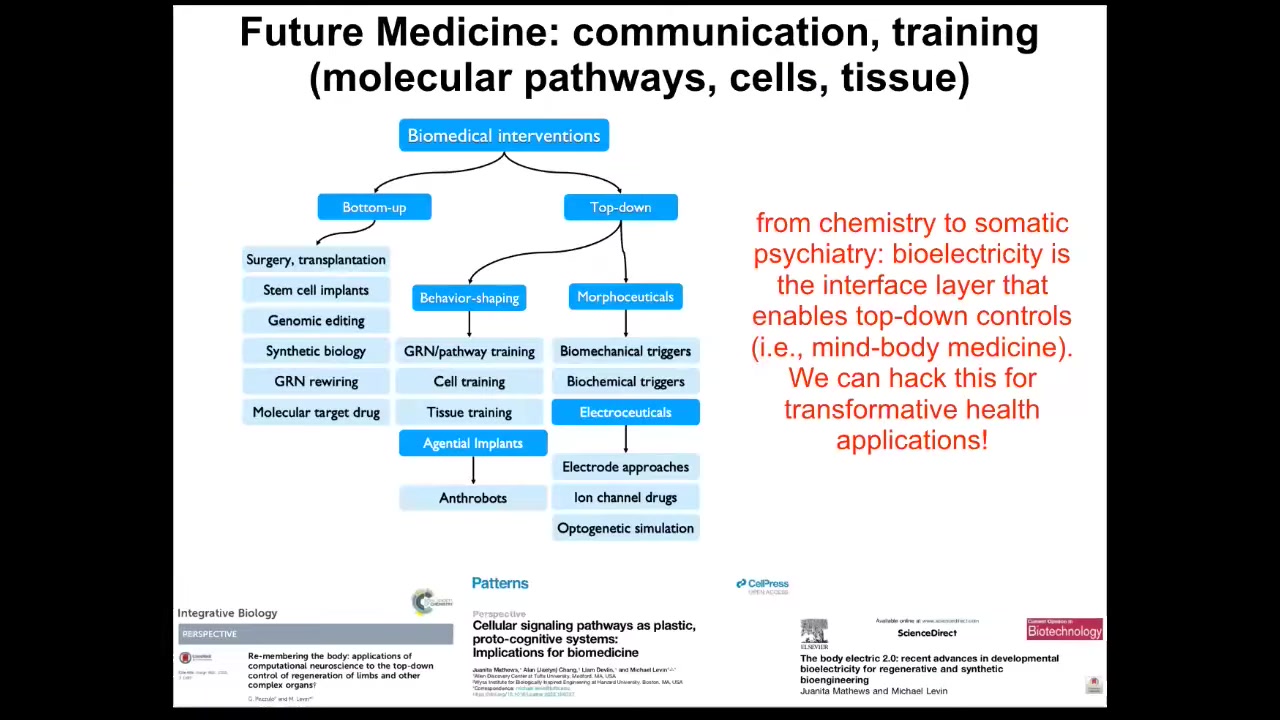

I think that one of the most exciting things about bioelectricity is this: it's not just another piece of physics that needs to be managed the way that biomechanics is. It's a communication interface into the very root of the deep problem here, which is the boundary between self and world. When I showed you that embryo that self-organizes out of a huge number of cells, and you cut it into pieces or don't, every cell has other cells as neighbors, and that whole collective has to figure out where do I end and where does the outside world begin? What are the states that I'm going to work hard to maintain? Are they large states, small states, and in what space — in anatomical space or physiological space? Bioelectricity is this critical integrating layer that controls a lot of downstream things because it provides this multi-scale competency architecture; it aligns the components, which are by themselves active matter and smart, toward higher-level goals.

I think what we're going to have in complement to the kinds of bottom-up systems that are exploited today by medicine is some very interesting top-down interventions that have to do with the use of electroceuticals, which are, I think, a subset of a broader field that will also encompass biomechanics, biophotons, and biochemical signals, and in order not to micromanage the molecular pathways but to convey new information, new set points, and alter the boundaries of the systems that are making decisions about what they're going to do.

Now what I'd like to do in the remaining couple of minutes is move past everything that I've told you up until now, which was about how good these systems are at regaining their normal species-specific target morphology. In other words, even conventional embryos rebuild the entire body from one cell. That's an amazing example of regeneration, where you restore the entire body from one egg cell. All of those cases, whether interfered with by scientists or not, are very good at creating and reaching that correct target morphology.

Slide 44/51 · 51m:12s

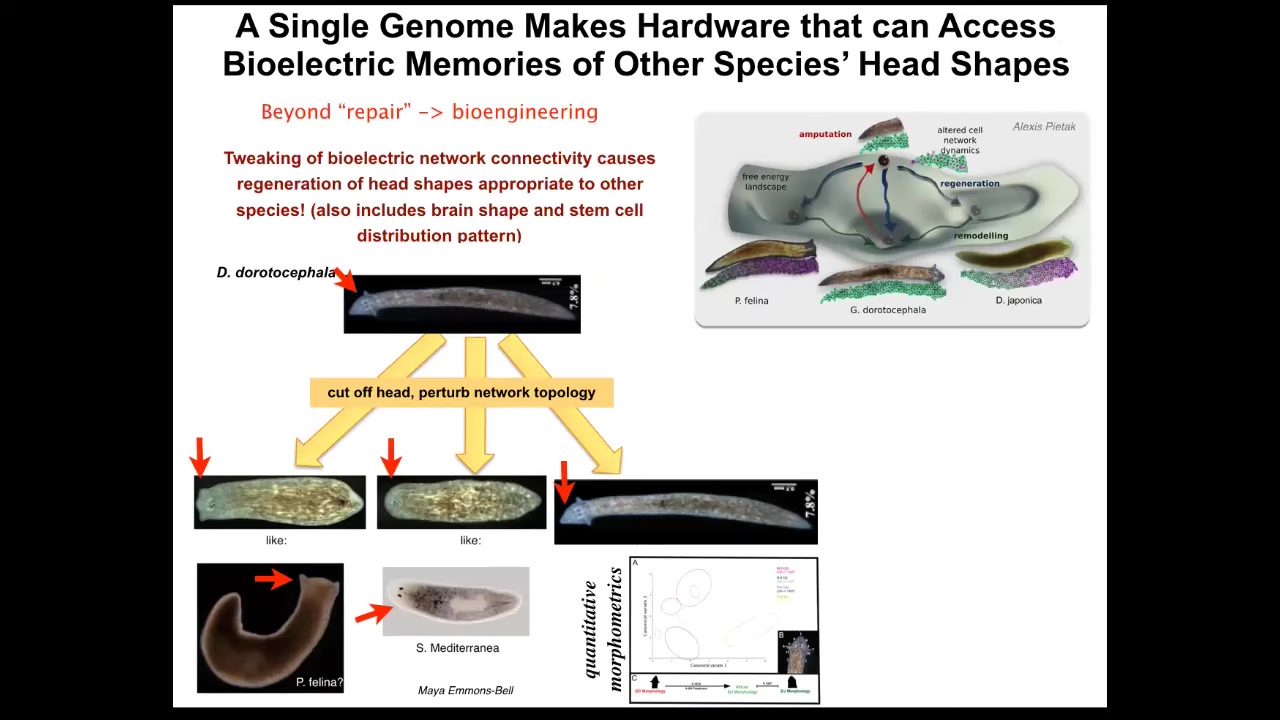

But let's look at a couple of things here regarding the question of plasticity. What else can it make? Beyond repair, let's look at what the possibilities are for bioengineering. The first thing we know is that planaria are very good at restoring their bodies, but the control is not just about the number of heads; if you manipulate the bioelectrical decisions during that regeneration process, you can make the same hardware, meaning the same genome with no genomic editing, visit other attractors in the anatomical space belonging to other species. For example, this guy with a triangular head can be made to have a flat head like a P. felina or a round head like an S. mediterranean. This is about 100 to 150 million years of evolution. Also the brains and the stem cell distribution in the brains become just like those in these other species. The same hardware can be pushed into the attractors belonging to other species. That's weird enough. But what about things that have never existed before? One thing you could say is that these attractors were created by evolution. It shaped other species to be able to do this. This is what we're finding. We're finding other evolutionarily stable strategies that have been rewarded and selected for in the past.

Slide 45/51 · 52m:27s

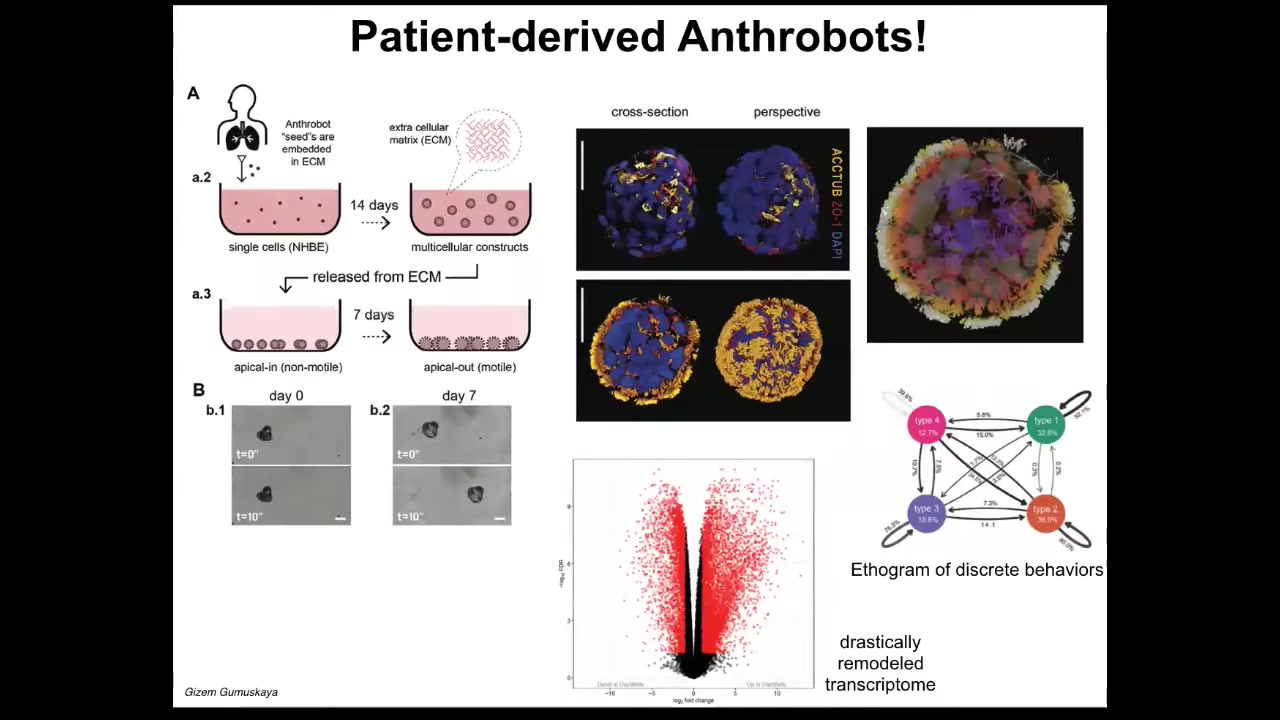

I want to show you a different kind of technology that I think is going to be really important for biomedical interventions. When you look at this thing, you might guess that this is a primitive organism that we got from the bottom of a pond. If I asked you to guess what kind of genome it has, you might guess that it has a genome similar to some of these primitive organisms. If you were to sequence it, you would find that it is 100% Homo sapiens genome.

These are constructs we make from cells derived from adult human patient tracheal epithelia. We call them anthrobots. They self-assemble into this amazing little self-motile proto-organism.

Slide 46/51 · 53m:10s

There's a particular protocol that we use. This is what they look like. The reason that thing was swimming around and moving is because they're covered by little hairs called cilia. These things beat. Normally in your airway, they're moving the mucus around. Here, they're able to row against the water. This is a human version of the xenobots that we made some years back.

There are a few really interesting features about this. First of all, there have never been any xenobots, any anthrobots in history. They don't look like a stage of human development. There has never been selection to be a good anthrobot. This is a novel construct.

One of the things they do is, if you look at the transcriptomics that compares what genes the anthrobots express versus normal, versus the cells they come from, about half the genome—9,000 genes—are significantly altered in their expression. An enormous amount of transcriptional change. They've not been genetically edited. There is nothing wrong with their genomes. There are no scaffolds. There are no nanomaterials, no weird drugs that we're using. They have a different lifestyle. They are freely motile. They live in the same kind of environment physiologically as they did before, except that they're not locked in by other cells. They're free to explore their new multicellularity. They take full advantage of it by transcribing their genomes very differently.

They also have four different behaviors that we can draw an epigram of the transition probabilities between, as you would for any animal. They have some interesting features.

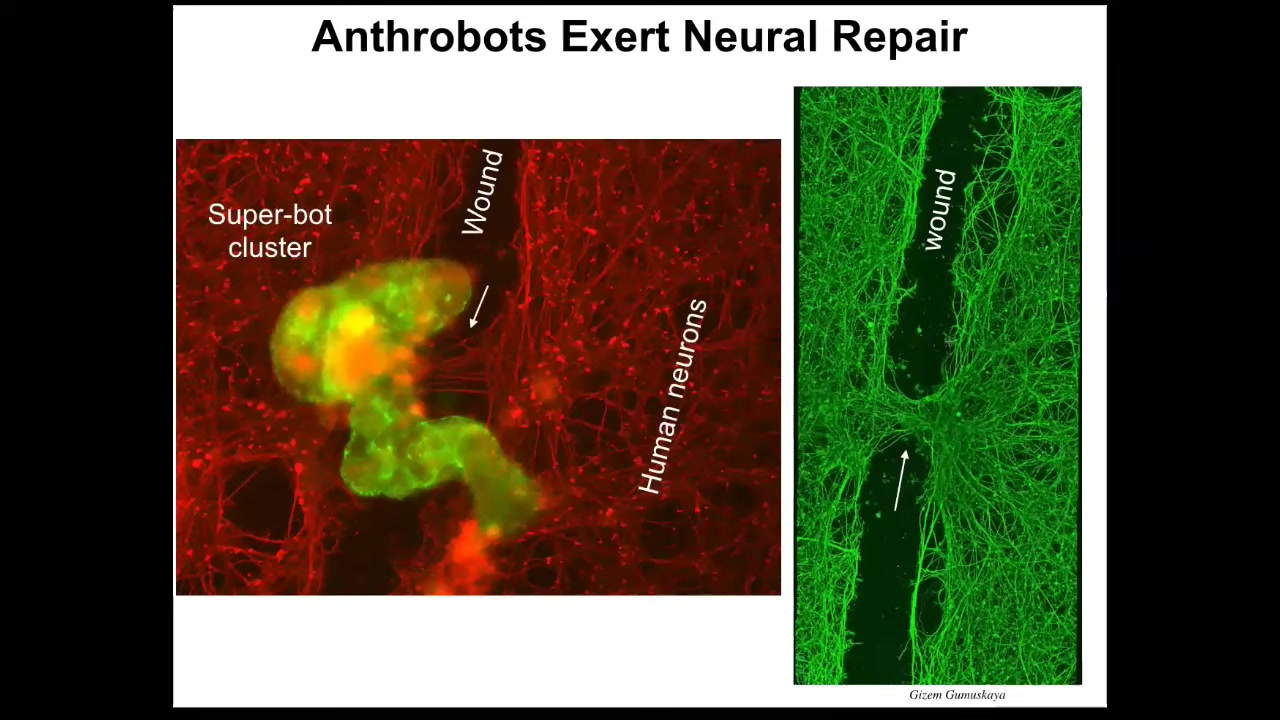

First of all, if you plate a dish of human neurons—these are iPS-derived human neurons—and you put a big scratch through it with a scalpel, what you find is that they traverse the wound, but then they settle.

Slide 47/51 · 55m:00s

When they settle, they can form into something we call a superbot cluster. There's a bunch of them. Over the next four days they sit there and reconnect the two sides of the wound. Here you can see when you lift them up, this is what they were doing. They were healing the gap. Who would have thought that your tracheal epithelial cells that sit there quietly, dealing with mucus and particles in the air, have the ability to self-organize into a multi-little creature? They live for about 5 to 9 weeks, and they have all kinds of capabilities. This was the absolute first thing we tried. They can probably do many other things that we haven't figured out yet.

Slide 48/51 · 55m:42s

The opportunity here is to use them as a kind of agential implant. Mostly drugs are pretty dumb. They have a target and ideally they bind it and that's that. But you can imagine something like this made from your own cells, so you don't need immunosuppression. It has a billion-plus years of shared history with you, so these cells know what cancer is, what inflammation is, what stress is. You could imagine a million applications of using things like this to do helpful things in the body that we have no idea how to micromanage. I suspect we have a lot of things going on around self-training and tissue training. My suspicion is that future medicine is going to look more like a kind of somatic psychiatry than it is like chemistry, because we're going to have to pay careful attention to cells and tissues, what inputs they've received, what memories they form, what set points they are pursuing, what they are capable of pursuing, what their problem-solving competencies are. A huge chunk of that is mediated by bioelectricity. And so I think that we have this amazing capability now in this field in particular to address some of this.

Slide 49/51 · 57m:08s

There are some great tools coming online, in particular some AI tools and things that we're doing around creating systems to actually talk using natural language to gene regulatory networks, to cells and tissues, to organs, and using AI as a translator module to the different layers of information in the body that normally are linked by bioelectricity at different scales.

Slide 50/51 · 57m:44s

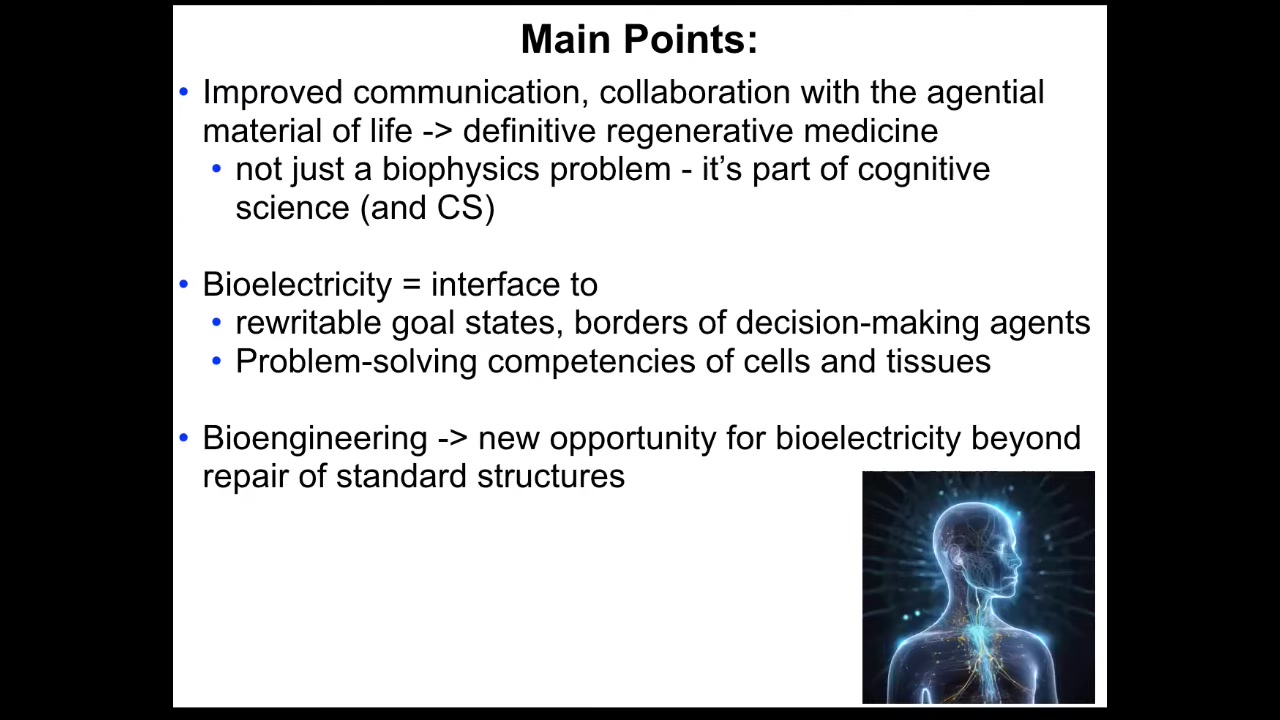

I'll stop here and just summarize the main points. I think that definitive regenerative medicine is going to require improved methods for communication and collaboration with the agential material of life to recognize that we're not dealing with passive matter anymore, that we can take advantage of some of the competencies. For that reason, I think the relevance of bioelectricity is not just as another piece of the mechanics, it's a component of cognitive science and computer science that can let us reach new outcomes that we couldn't do otherwise.

I think that bioelectricity is an amazingly powerful interface to two classes of things. First, rewritable goal states. Second, the borders of the decision-making agents; it's the cognitive glue that makes individual cells into larger scale computational units. In addition to writing these goal states, I think we can also use bioelectrics to learn a lot from the cells themselves as to how they're solving different problems. We have many examples that I haven't shown you today about how cells themselves react to and solve problems that we have no idea how to do. Hopefully we can read and learn from them by using this interface.

All of the things that I've shown you about the Anthrobots and the Zenobots, we have some other things coming soon. All of those things are poised to take advantage and to benefit from everything that's being developed in this field and all the amazing advances in bioelectricity, because they allow us to start to probe not just the stability and the robustness of life towards standard target morphologies, but towards the plasticity to completely new things that have never existed before. To use that as a sandbox for complete control over growth and form in that anatomical compiler that I mentioned at the very beginning.

Slide 51/51 · 59m:49s

I'm going to stop here. I'm going to thank the amazing people who did all of the work that I showed you today. Here are all the postdocs, grad students, and staff scientists who did all of the things that I told you about.

We have incredible technical support and many very valuable collaborators who work with us on these things. We've had different kinds of funding over the years.

Three disclosures that I have to do: Morphosuticals, AL, and Fauna Systems. The most important thing to thank is the model systems, because they do all the heavy lifting, and they're the ones who teach us all about this stuff. Thank you so much.