Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is an ~8 minute very quick introduction about the context for developmental bioelectricity and some examples of how we use it as an interface to control growth and form. In this very short 3 slide introduction at a discussion forum, I tried to explain that bioelectricity is not just more physics we need to keep track of in morphogenesis, nor is it about applying external fields to have effects on cells. It's important in the body, and for biomedicine, for the exact same reason it's important in the brain: because it's the natural medium in which the collective intelligence of cell groups operates, and thus it's a great interface for deploying top-down, high-level interventions: it makes the living material reprogrammable in software, without having to edit DNA. By collaborating with the agential material of life (re-writing its setpoint memories, etc.) we can reach very complex outcomes that are too hard to micromanage from the molecular level. The context is cognition, not physics, with the payoff being the same kind of advance in biosciences as we've had in the move from having to work on computers at the hardware level (1950's) to being able to work in high-level languages or even prompts.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Axolotl regeneration and collectives

(01:32) Reading and writing bioelectricity

(03:30) Cancer as bioelectric failure

(05:02) Preventing tumors via bioelectricity

(06:24) Fixing developmental brain defects

(07:45) Bioelectric limb regeneration

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/4 · 00m:00s

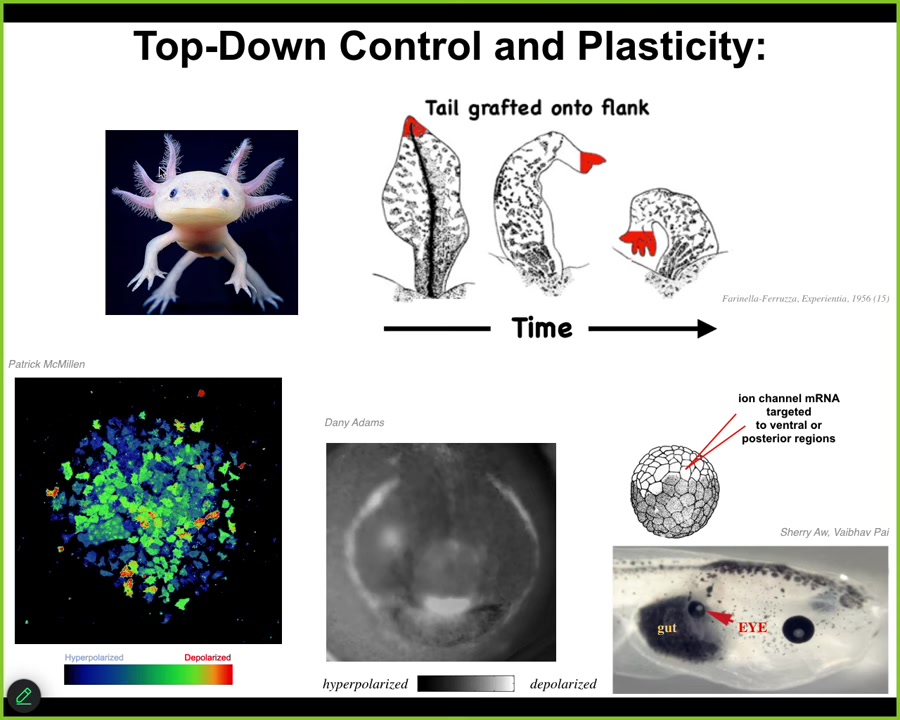

This little creature is called an axolotl. They are incredibly regenerative. They regenerate their limbs, their eyes, their jaws, their ovaries, portions of the brain and heart. But there's something very deep that they're trying to tell us that goes beyond repair of damage. This is an experiment where they took a tail of an amphibian, they grafted it to the flank of that animal. And what happens is that over time, the tail remodels into a limb. Now take the perspective of the little, this little region right here, the cells sitting at the tip of the tail, those cells are becoming fingers. But there's no local damage. There's nothing wrong here. From the perspective of these cells, there is no reason why anything should change. And yet they change because the larger scale system, the larger collective transduces the fact that it senses that there's an error at the body level: a tail doesn't belong here, a limb does. And that information is transduced down through the cellular and ultimately molecular pathways to get this to happen. Even though there's nothing wrong here and no individual cell knows what a finger is or how many fingers you're supposed to have, the collective absolutely does. And so this kind of top-down control, the ability to take a very abstract high-level goal state and have it percolate down to make the molecular biology dance to that particular outcome is what we are trying to manage. We would like to control health and disease states that are way too complicated for us to try to micromanage.

What you're seeing here is a set of tools that we've developed to monitor the native bioelectric conversations that cells are having with each other. The colors represent voltage states. This is not a model. These are real cells. We do this imaging in vivo. I'm going to show you mostly amphibian data because that's where the techniques work the best. We are now moving everything into mammals. This right here is an image again, this is a voltage map of an early frog embryo that's about to put its face together. Long before the genes turn on to say where the eyes are going to go, where the mouth is going to go, we can already read out that subtle bioelectrical scaffold that tells this unregionalized ectoderm where the different organs are going to be. This is literally an electrical pattern memory that tells all the organs where they're going to be and how many of them there are. Having figured this out, we can take this electrical state and induce it elsewhere. We don't do this with applied fields or magnets or waves. We are using molecular pharmacology and optogenetics to open and close specific channels. We can take a region of the body. Here's a tadpole. You're looking at the side of it. Here's the eye, the mouth, the brain, the gut. We can take a region that would normally be gut and we can say you should be an eye. We can inject some RNA encoding a specific ion channel that induces this bioelectrical pattern that just says make an eye here. Now notice we have no idea how to micromanage the production of an eye. It's got dozens of different cell types, tens of thousands of different genes have to come on and off. We don't know any of that. What we do know is a high level subroutine call that the cells find compelling. And that's important: having received that message, they will orchestrate all of the downstream stuff necessary to build this complex organ. I can show you dozens of examples of this.

Slide 2/4 · 03m:29s

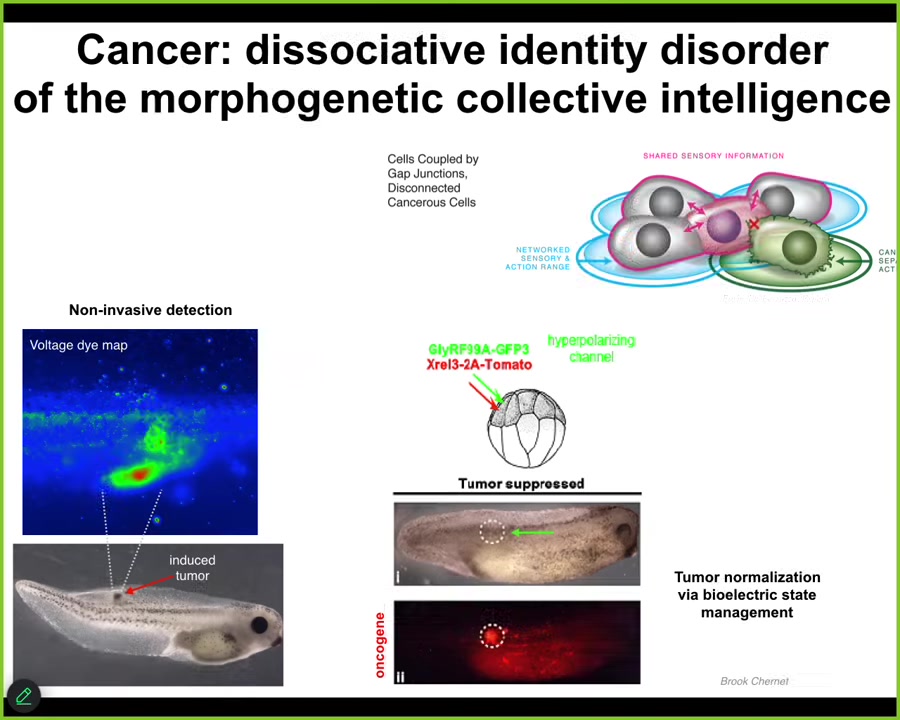

I think I have a couple minutes. I now want to talk about this cancer problem. Why is there ever anything but cancer? How do individual cells, which are very competent on their own, get together and work on grandiose construction projects like building limbs and eyes and hearts and all of that?

It turns out that individual cells connect to each other using native electrical machinery. This is ion channels and electrical synapses, which are not just in the brain. In fact, our brains evolved all their cool tricks by adopting all of this from the way your body was processing information long before we had brains. When cells connect electrically, the resulting network is able to store very large goal states where a single cell can store tiny little goal states like pH level, metabolic state and things like that. Collectives can think about very large goal states such as here's what a limb looks like, here's how many fingers it's supposed to have and so on.

That kind of a system, which operates in embryogenesis, operates during regeneration. It has a failure mode. That failure mode is cancer. What happens is that when individual cells disconnect electrically, they go back to their unicellular lifestyle. Their cognitive lightcone shrinks from being able to be part of a collective working on maintaining healthy organs down to a single amoeba that treats the rest of the body as external environment. It simply can't comprehend the larger goals that the collective was trying to implement.

That led us to noninvasive diagnostics technology, where we can inject human oncogenes into these animals and they will eventually make tumors. Before they do, you can already see, using this voltage-sensitive fluorescent dye, where the cells are going to defect from the body plan that they've been building. All this other stuff out here, you better keep an eye on that as well. Better than just detection and monitoring.

What we can do then is inject very nasty oncogenes, KRAS, all those kinds of things, if we at the same time manage the bioelectrics. So not kill the cells with chemotherapy, not fix the genetic defect, but simply force the correct electrical state where they stay connected to the rest of the network.

This is what you get. This is the same embryo. Here's the Onca protein. It's blazingly expressed. In fact, it's all over the place, but this is where it got injected. There's no tumor. The reason there's no tumor is because even though the hardware here is broken, the actual functionality is not driven by the hardware state. It's driven by the bioelectric software dynamics that operate in the tissue. As long as the cells are forced to be connected and to have the right state, they are not going to defect and go off and do their own thing.

This is our now strategy. We're doing this in human cancer spheroids and mouse glioblastoma and so on.

Slide 3/4 · 06m:25s

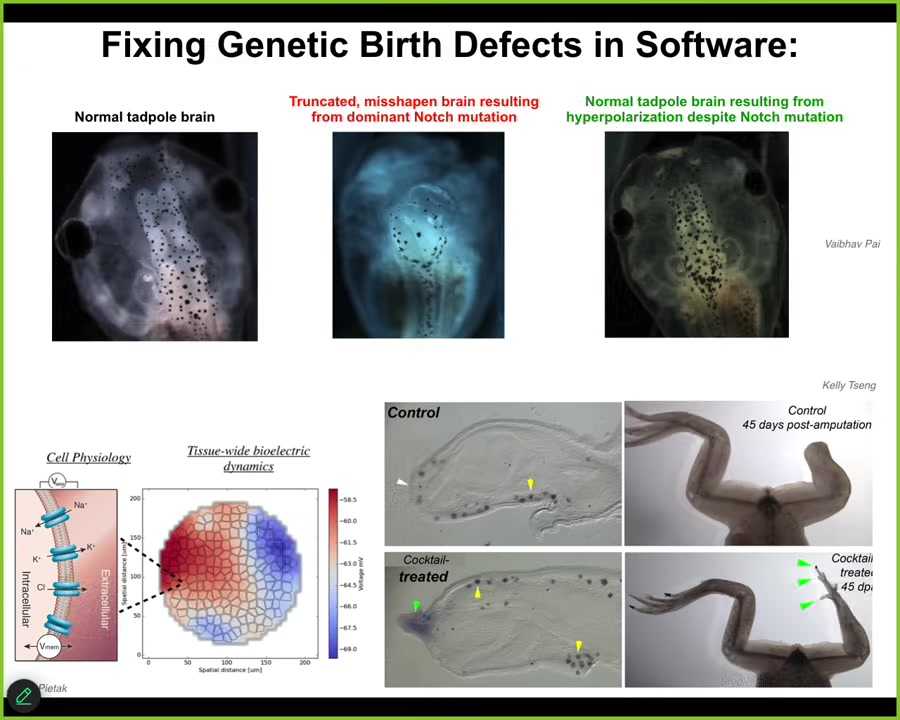

And the final thing I want to show you is, again, to hammer this theme of being able to fix some of these things at the physiological level.

This is the brain of a tadpole. You see forebrain, midbrain, hindbrain. This is a tadpole that's been injected with a dominant mutation of a gene called Notch, a very important neurogenesis gene. The forebrain is gone. The midbrain and hindbrain are just a bubble. These animals are profoundly defective. They have no behavior.

We created a computational model that allowed us to ask the following question. If the bioelectrics are wrong here, what would we have to do? What channels would we have to open and close to get the bioelectric pattern that tells the brain what size and shape should be? How would we fix the bioelectric pattern? The model made a prediction about a very specific ion channel, and when we open that channel using already human-approved drugs, they happen to be antiepileptics. What you get is a complete repair. The brain is normal, the gene expression is normal. Their IQs are normal. They go back to the same learning rates as wild types. We can, at least for some genetic defects. This animal still has this dominant Notch mutation, and it doesn't matter; the outcome is normal.

We can use these kinds of systems again as predictive platforms to say what is the bioelectrical state that will get you what you want.

This is the final thing I'll show you: our limb regeneration program, where adult animals here do not regenerate their legs. We have a stimulus, a wearable bioreactor that delivers specific kinds of electroceuticals, which are ion channel drugs. There is a massive toolkit available of already human-approved ion channel drugs. Within 45 days you've already got some toes and a toenail. This process then runs for a year and a half of leg regeneration, during which time we don't touch it at all. This is not about micromanaging. This is not about stem cells or scaffolds.

On the first day, in the first 24 hours, we have to communicate to the cells: go down the leg-building path, not the scarring path. Then we take our hands off the wheel. That's the last thing.

Slide 4/4 · 08m:33s

The point here is to develop tools. Now we're using some AI tools to learn to communicate novel goals to the system, to get the system to take on those goal states and to reduce error between the current state and the goal state. That's our approach.