Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a ~45 minute talk I gave to some undergraduate students about ideas from biology that might help them think about AI and related topics.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Redefining species and minds

(08:22) From cells to selves

(17:21) Metamorphosis and regenerative memory

(23:04) Developmental robustness and plasticity

(30:45) Bioelectric control of morphology

(38:26) From pattern to Xenobots

(48:38) AI, ethics, and humanity

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/39 · 00m:00s

So thanks, everybody, for being here and letting me share some ideas with you. If anybody's interested in the details of it, you can track them down at this website. Here's all the papers, the software, the data sets, everything. Here is where I put some more speculative things, where I talk about what I think the papers mean. You're welcome to check them out.

What I'm going to talk to you about today is a weird topic. I'm going to talk about AI and the right way to understand AI through the lens of collective intelligence. In other words, we're going to take a deep dive into where minds come from so that we can talk about this notion of whether artificial minds have the same status as biologically evolved ones. We're going to look at those questions.

Slide 2/39 · 00m:52s

So the main points of today, what I'd like to do is this. We're going to look under the hood of biology a little bit to clear out some viewpoints and some terminology that's persisted with us for centuries, but I think are going to have to change in this idea of discrete natural kinds in biology. So we'll talk about that.

We'll talk about diverse intelligence, in particular collective intelligence, so unconventional minds and unconventional cognitive systems. And I'm going to argue that all the things that people argue about today in terms of artificial intelligence are an off ramp to a much deeper, more difficult discussion about the really deep philosophical questions about what we are, about freedom of embodiment and things like that. It's a much more complicated set of questions than just to focus on today's AIs. And so we'll talk a little bit at the end about the ethics and the future of humanity and things like that. So let's start with this.

Slide 3/39 · 01m:58s

This is a well-known painting. It's called "Adam Names the Animals in the Garden of Eden." And so here he is. This is the old Judeo-Christian story where animals are showing up and Adam gets to name them. Something important about that story is that it was on Adam to name the animals. God couldn't do it. The angels couldn't do it. Adam was the one that had to name them. That's a very interesting part of that story. And it has two lessons, one that we're going to have to break as the future moves on, and the other one that's very deep and that we're going to have to dive into.

The part that has to be given up is this notion that all of these species are discrete. They're natural kinds. Everybody knows what each of these are. They're separate from the others. In fact, Adam is also a discrete entity and completely different from all of the others. And this idea that you can number and categorize very specific types of beings. You can count them, count the animals in your environment. As you'll see in a minute, that idea has to go.

What's deep is this notion that Adam, because he is the one that has to live with them, he is the one that has to give them names. In these old traditions, giving something a name was very deep and spiritual. It meant that you've discovered their true nature. Knowing the name of something means you know their true nature. And as I'm going to show you at the end of this talk, because of synthetic biology and bioengineering and some other disciplines, we are going to have to name or discover the true nature of kinds of unusual creatures that you guys will be living with in your lifetime.

Let's start there.

Slide 4/39 · 03m:42s

Here's the part that has to break. Here's a normal modern human. Lots of philosophy talks about the human mind, does this and that, and humans have responsibilities and rights.

But we know that now because of evolution and also because of developmental biology that this is not a sharp category. If you track backwards in time, these modern humans are at a particular point in the evolution of a lineage that goes all the way back to single cell organisms.

If you have something to say about humans, you might ask yourself, what about the humans of a couple of 100,000 years ago? What about the hominids of a couple million years ago? Understand that all these changes are slow and gradual.

The same thing about development. Whatever you think is true of humans with their true hopes and dreams and cognitive responsibilities, at one point they were a single cell. This process is, again, very slow and gradual.

We know now that there's this continuum. It's not just a discrete human, but a whole continuum of forms that you might have to decide what is the status of these other forms.

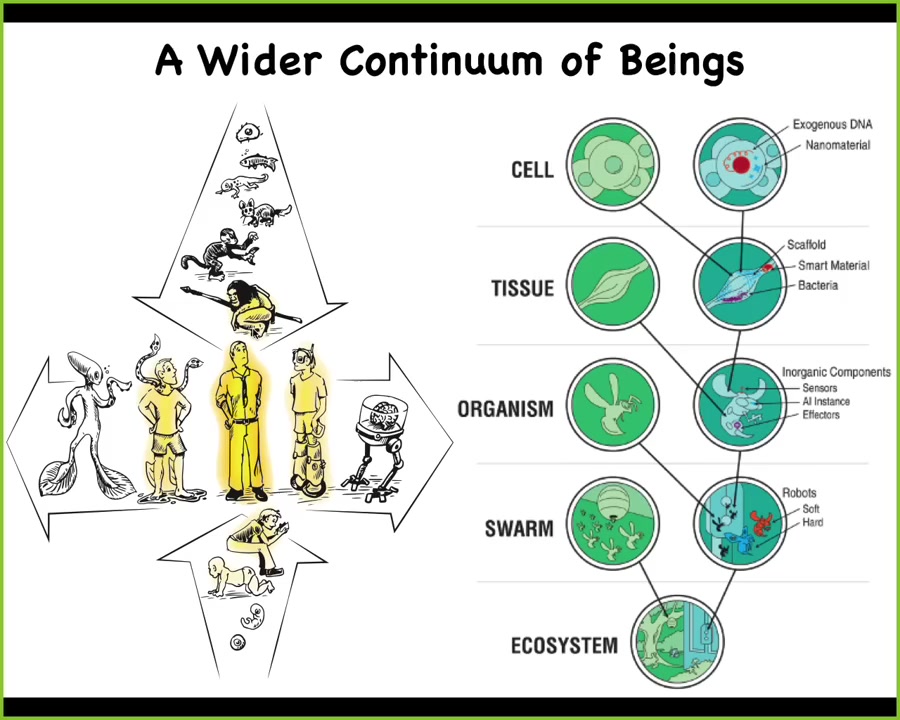

Slide 5/39 · 04m:56s

Not only that, but there's this other continuum going horizontal here in my diagram, where we know that humans are going to be modified and improved. So for various health applications, but also for augmentation technologies, there's no particular reason why anybody's going to want to be stuck in the body that random vagaries of evolution left them with. I don't think anybody really thinks that a mature modern humanity, 100 years from now is going to be susceptible to the same dumb diseases, your lower back pain, astigmatism, viruses; presumably all of that is going to get fixed. There's nothing magic about where evolution happened to have dropped us.

And so there are technological modifications, there are biological modifications that will be made. That's because at every level of organization in our bodies, from subcellular materials all the way up, you can introduce different kinds of novel engineered components. And so all of this is now possible. Again, if you have thoughts about what a human is versus what a machine is, you have to ask yourself how you are going to distinguish this when you are confronted with all sorts of beings along this continuum. You're going to need to find ways to relate to them.

Slide 6/39 · 06m:10s

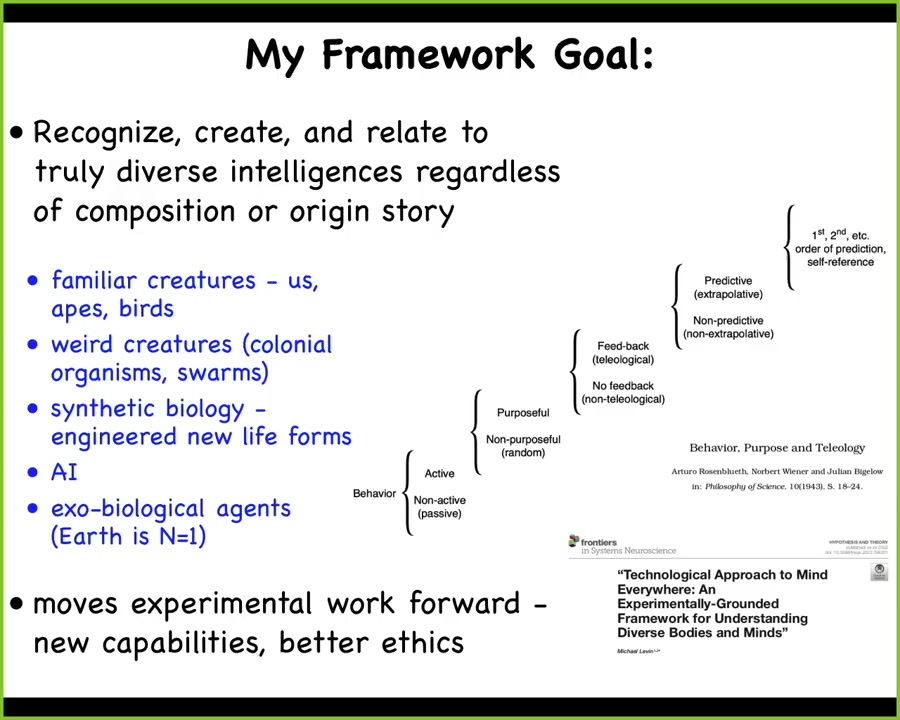

One of the things that I've been working on for some years now is a framework to be able to recognize, to create, and to ethically relate to truly diverse intelligences that we can have relationships with regardless of their composition, meaning what they're made of, or their origin story, where they evolved, did they come out of a factory, or some combination of those.

That means that we need to think about all of these things. Familiar kinds of creatures like primates and birds and maybe an octopus and so on. But also all kinds of weird organisms like colonial organisms, swarms, synthetic engineered new life forms, artificial intelligences, whether robotic, meaning embodied or pure software AI, and maybe even someday aliens. There's probably some sort of exo-biological life form out there somewhere that at some point we'll confront.

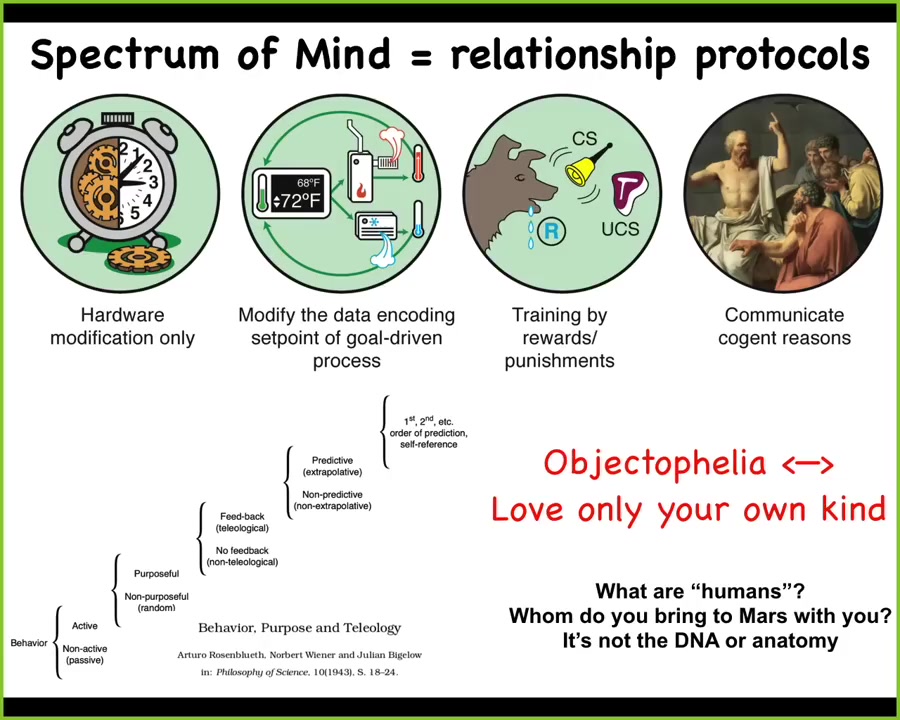

Now, we need to be able to think about all of these in the same way, regardless of where they came from or what they're made of. Now, I'm not the first person to try for this. Here's Rosenbluth, Wiener, and Bigelow in 1943 trying for this scale all the way from passive matter, so rocks and sand, all the way up to different kinds of active matter and then various kinds of computational matter and agential materials, which is what I'm going to be talking about today, all the way up to some sort of human metacognition, complex human kinds of minds and beyond.

The goal of this kind of framework is not a philosophy. The goal is to move experimental work forward. Part of my framework is a very strong insistence that when you look at something and you say, that's not real cognition, or that is real, this thing really does have intelligence. The goal of this is not just to have philosophical feelings about it. It's to have a toolkit for interacting with these systems that is beneficial, that brings new discoveries, new capabilities, biomedicine, engineering. It also puts ethics on a better footing because these old categories that we've had for a really long time for how we deal with other beings are not going to be of use anymore. The details are all here if you want to follow that.

Slide 7/39 · 08m:22s

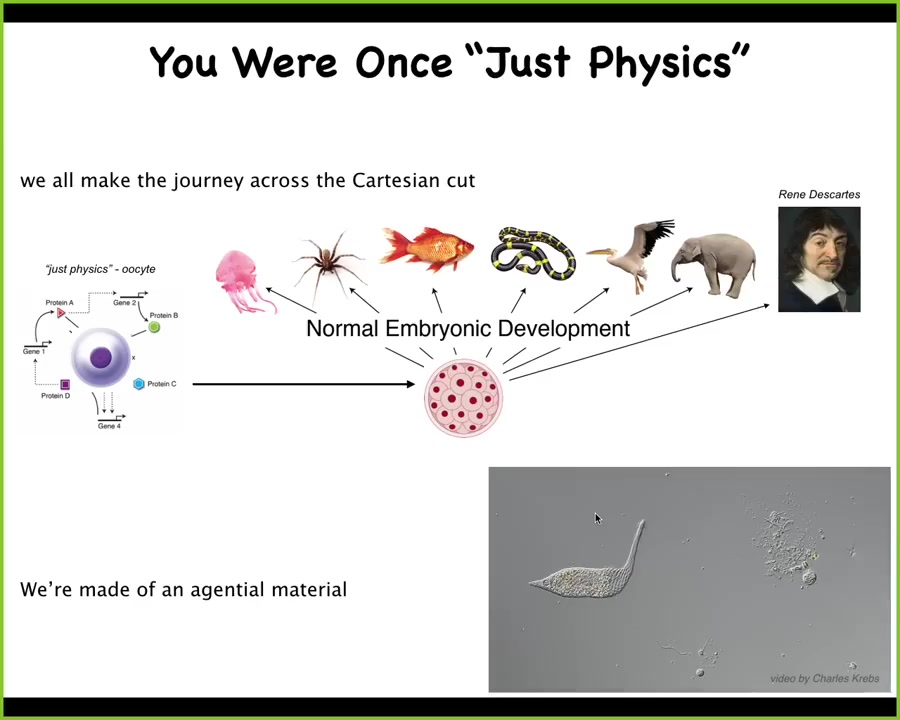

A basic fact from developmental biology is that we all make this amazing journey from what people call "just physics" to a complex mind. Each of us started life here as a single cell, a little BLOB of chemicals, and slowly it became something like this or even something like this. A complex metacognitive being who is going to say things about not being a machine. This process is gradual. Developmental biology gives us no bright line at which point you were just chemistry and physics and then the mind appears. There isn't anything like that. It's a very slow and gradual process.

Scientists and philosophers need to develop a story of scaling. We need to understand how the properties of this thing, which follows the laws of chemistry and physics, end up being something that's also describable by the laws of psychology and psychoanalysis.

The reason that this is possible is because we are all made of an agential material, unlike Legos and wood and metal, which just stay where you put them. We are made of a material with agendas. And so this is the kind of thing we're made of. This is a single cell. This happens to be a free-living organism called Lacrymaria. You can see that it's extremely competent in its local unicellular goals. There's no brain, there's no nervous system, there are no stem cells, but this thing is doing everything it needs to maintain its physiological, metabolic, and behavioral goals.

The first shocking thing to some people that you need to realize is that we are all made of this interesting stuff that has its own agendas. I don't have time to tell you about it today, but the reality is these things themselves can learn. They can have pretty complex problem-solving capacities in different kinds of environments. We are a very interesting construction of a very unusual type of material with which we are just now starting to learn how to engineer.

Slide 8/39 · 10m:34s

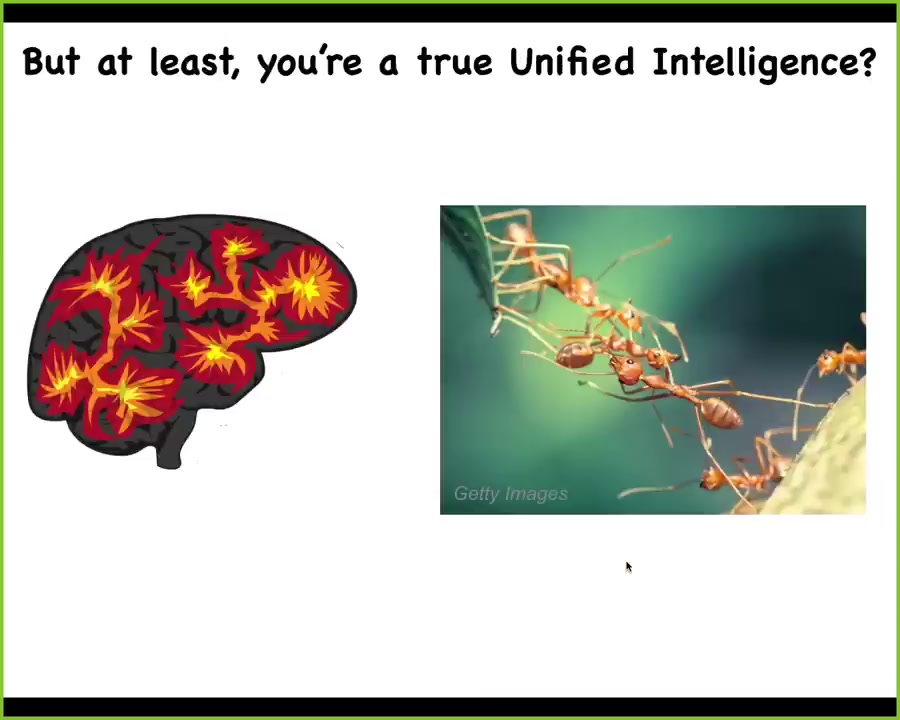

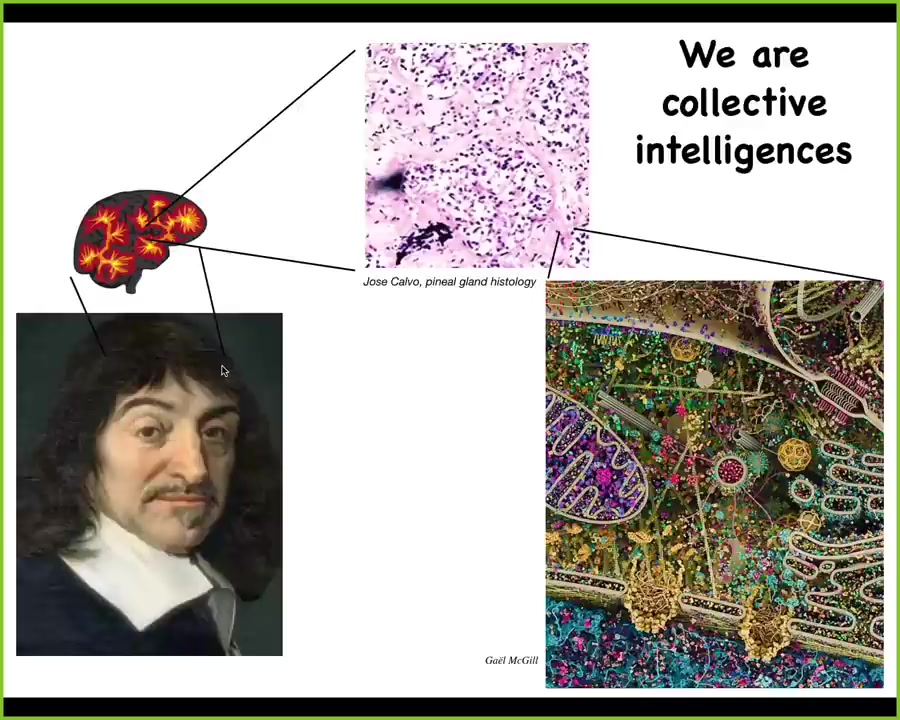

At least we are a true unified intelligence. Maybe you can call an ant colony some kind of collective intelligence, but we have a brain where we feel like a single unified being.

Slide 9/39 · 10m:53s

And in fact, René Descartes really liked the pineal gland because there is only one of them in the brain. And he thought that that's where the human experience was centralized because there are no multiple aspects of it. There's just one in the brain. But if he had access to a microscope, he would have discovered that inside this pineal gland is all this stuff. It's a bunch of cells. And inside each of those cells is all this stuff. There isn't one of anything in the brain, and all of us are collective intelligences. We are all made of parts that do things. The real trick here, again, is that scaling story, is to give a convincing account of how it is that all these parts give rise to something that has the feeling of being a centralized, unified self. And so this is what my group works on.

Slide 10/39 · 11m:41s

Now, it's interesting that Alan Turing, who is the father of modern computer science, was very interested in machine intelligence and in computation and programmability.

But one weird thing is that he also published this paper called "The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis," which was an attempt to understand how the chemicals of an embryo organize into order from their initial disorder.

Why would he be studying the chemicals in an embryo?

Although he didn't write about it, I think that Turing saw a very profound truth, which is that the process by which bodies come to be in this physical universe, by which your body was self-organized from chemicals in the oocyte, is very closely related to the question of where minds come from. So the origin of the self-assembly of your mind and of your body are very related stories, even though they're treated by completely different communities.

Neuroscience and the behavioral sciences versus developmental biology, molecular biology, cell biology, those folks do not think they're studying the same thing. I think they're studying exactly the same thing, just in different components.

Slide 11/39 · 13m:10s

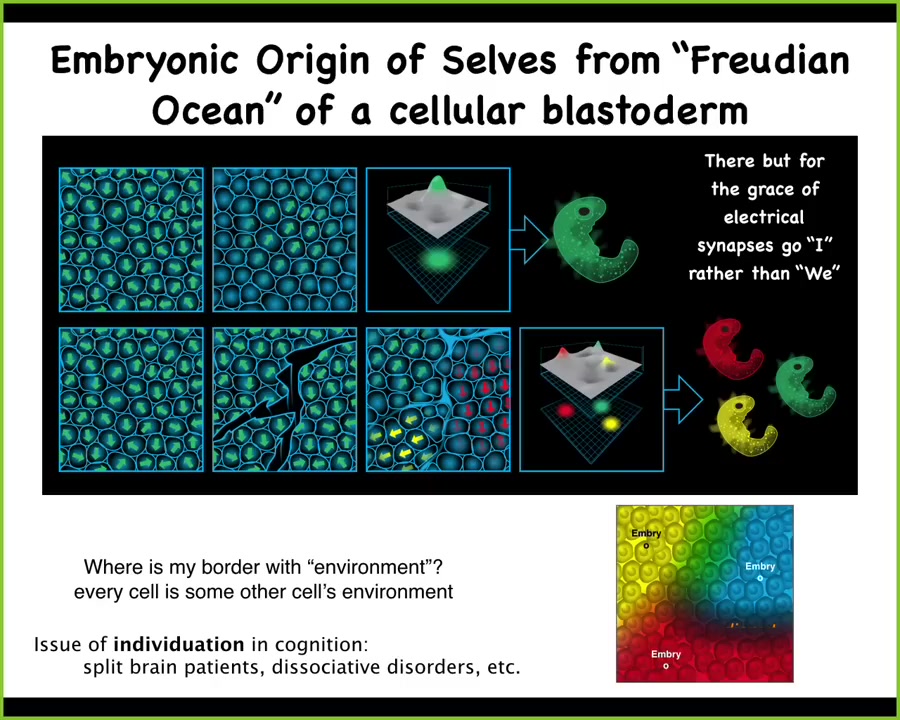

To look a little further into where we come from, this is an embryonic blastoderm. That's basically a flat sheet of cells. In the beginning, the egg will get fertilized, it will divide, and then eventually flatten out and give rise to, at least in amniotes like us, a flat sheet of cells. You can think about a little disc that's just a couple of cell layers thick. Here's your disc. Let's just imagine there's about 50,000 cells at this point in this disc. We look at it and we say, there's an embryo, maybe a human embryo or a mouse embryo or something. Mice have a different structure than this. They're kind of weird, but let's say rabbit. So human or rabbit or some other amniotes, you look at that and you say, there's one embryo, but there's 50,000 cells. What are you actually counting when you say there's one embryo? Well, what you're counting is alignment. You're counting the fact that all of those cells are committed to the same story of what they're going to do in anatomical space. They're all going to collaborate to build a very particular kind of embryo. They are all connected together, and they are all going to cooperate to do one specific thing, which is to build that. That's what makes this an embryo. What makes this an embryo is that all of these cells are committed to the same plan. That doesn't have to be the case.

This is some work that was first done in the 40s. I did it again when I was a grad student in 1996 or so. When you take a duck embryo and you use a little needle to scratch some scratches into it, what you'll see is these little islands here for the next few hours before they rejoin again. Each of these islands doesn't realize the other one is there. What they do is they self-organize a new embryo. Each one of them thinks they're the only one, so they make an embryo. When they heal up, you end up with conjoined twins or triplets. You end up with a few individual animals coming out of the same blastoderm.

The question of how many beings, how many selves are actually in an embryo is tricky. It's not fixed by the genetics. It's anywhere from zero to probably half a dozen or more, depending on what happens. The selves arise in this medium, the cellular blastoderm, in real time as a process of physiology. It's not hard-coded. That means a self has to put itself together. It has to figure out a border between itself and the outside world. Here are three embryonic fields sitting there. Each of these cells has to decide, am I part of this one, or am I part of that one, or who am I part of?

This medium that can fragment or come together to form some number of coherent individuals is not just for development. This happens in the brain as well. Split-brain patients with a cut between their two hemispheres, in an important sense, have two individuals in there that have different opinions. You can have dissociative identity disorders and various other phenomena that make it clear that it's not so simple as the brain has one cognitive owner and the body is one embryo. It's not that simple.

Slide 12/39 · 16m:32s

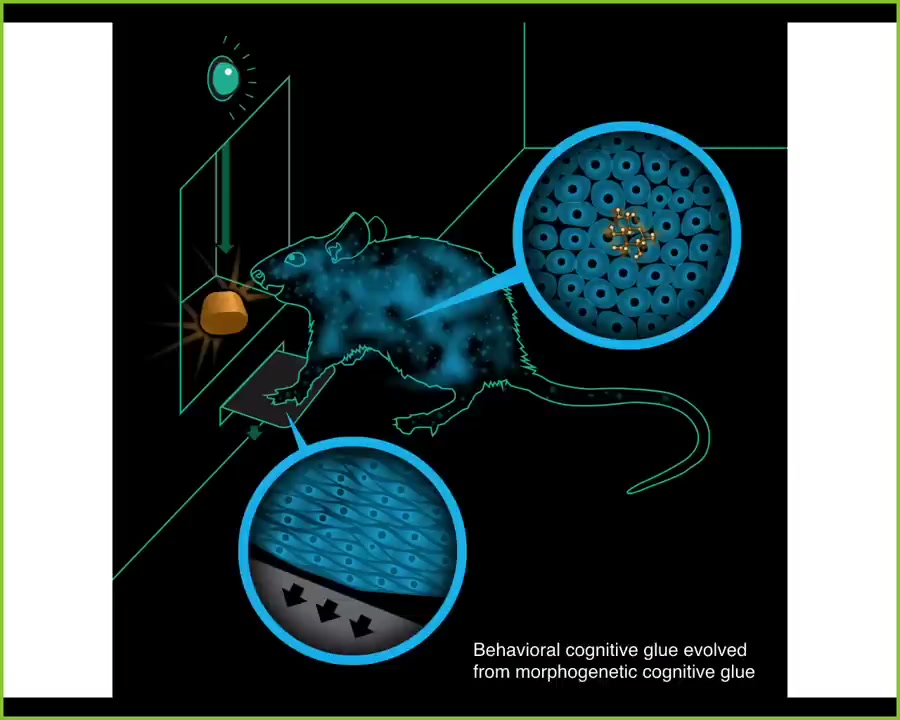

You learn about this when you think about something like this. Here's a rat. You train the rat to press the lever and get a delicious reward. There are cells in this rat that interact with the lever. There are cells in his gut that get the sugar, but there is no single cell that has both experiences. So who is it that owns this associative memory, the fact that the pellet is associated with pressing the lever? Who owns that? The owner of that memory is not any individual cell, it's the entire rat. It has to be because no cell has that experience. And there's a kind of cognitive glue that operates in this rat, which we know as the nervous system, which allows the rat to know things the individual cells don't know, such as that these two facts are connected. That cognitive glue is a very interesting thing.

I want to be clear that these animals that you typically hear about are not the only game in town as far as some very interesting aspects of what the biology is trying to tell you.

Slide 13/39 · 17m:32s

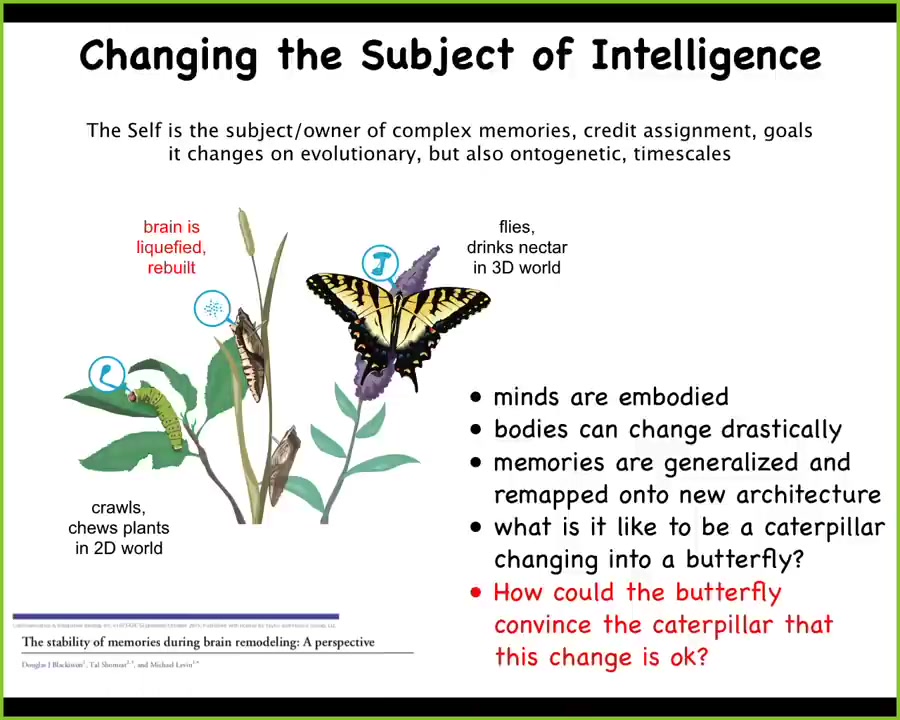

I'm going to show you a couple of these examples to expand our horizons about what we need to understand.

So here's a caterpillar. This caterpillar lives in a two-dimensional world. It's a soft-bodied creature. It has a controller, a specific brain, that's very well suited for driving this kind of soft body around. But it needs to turn into this. This is a flying kind of creature with hard elements. During this metamorphosis process, when the caterpillar turns into the butterfly, the brain is pretty much dissolved. Most of the connections are broken, most of the cells are killed off. There's huge refactoring, remodeling; new cells and a new brain are built, quite different, and there's your butterfly.

That already is amazing. You can imagine the philosophical question of what's it like—never mind what's it like to be a caterpillar—what's it like to be a caterpillar changing into a butterfly in real time, not just on an evolutionary time scale, but in your lifetime drastically. Never mind puberty, this is a major change.

That's the first thing. The second thing is that memories persist through this process. A caterpillar that learns something will still remember it as a butterfly. That's amazing. How do memories persist when the brain is getting radically refactored?

It's even more than that: what they did was train caterpillars to look for leaves at a particular color disk. That kind of information is completely useless to the butterfly because the butterfly doesn't crawl, it flies, and it doesn't eat leaves. This process has to not just store memory; it has to actively remap what's important to the caterpillar to what's important to the butterfly. It has to generalize from the concept of leaves to the concept of food and from specific crawling motions—which you might think is what this simple animal is remembering—to something much more complex, a navigational process that will be implemented by flying, by completely different muscles and a different architecture.

This radical process of change raises questions about the individual identity of this organism, and what it would be like if the caterpillar knew what was coming and said, "You're going to change radically, but don't worry, you'll still have some of your memories." It's just your priorities will be different. You love leaves now, but you're not going to care about leaves at all later, and you'll want this weird nectar.

What is that like? We'll come back to this at the end of the talk. How would you convince a creature like this that this is a perfectly fine thing for them to go through? Are they still here? Is this organism actually still here by the time you get to this stage?

The reason this is important for us is because humanity is going to change in a way that's somewhat reminiscent of this.

Slide 14/39 · 20m:24s

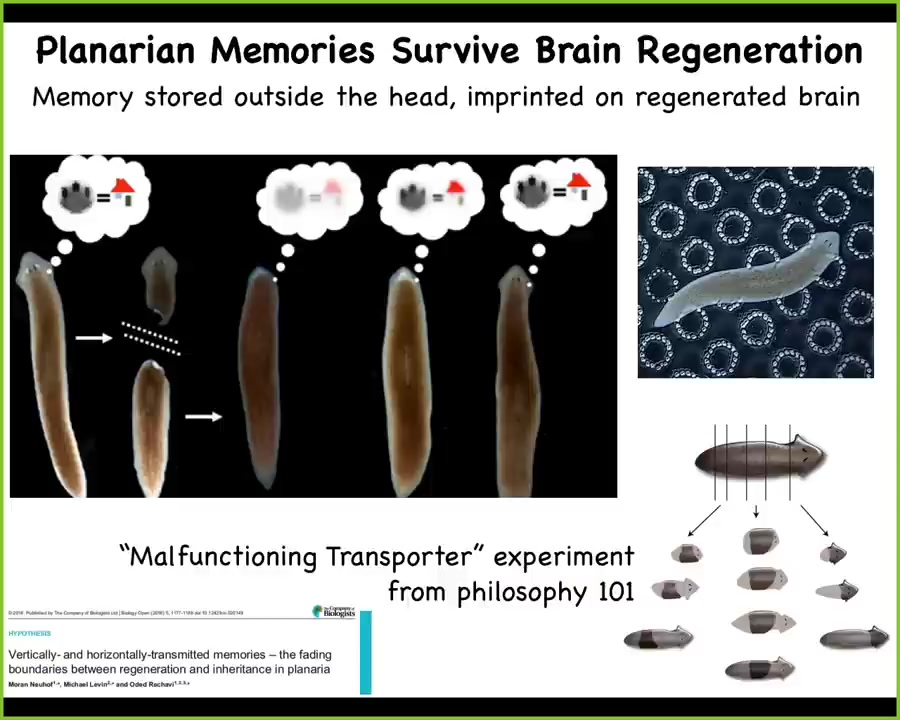

That's one kind of example. Another example is these amazing creatures called planaria. They're flatworms.

When you train them to expect food on these little bumpy circles, they will remember. If you cut off their heads, the tail will sit there doing nothing. Eventually, the tail will regrow a brand new head, so they regenerate. Every piece will regenerate. Eventually, when they regenerate, you find that they still remember the original information.

This not only tells you that the memory can be stored outside the brain, but also that it can be imprinted onto a new brain as the brain develops. The movement of memories through tissues. All of this is possible because we have this amazing multi-scale competency architecture.

Slide 15/39 · 21m:04s

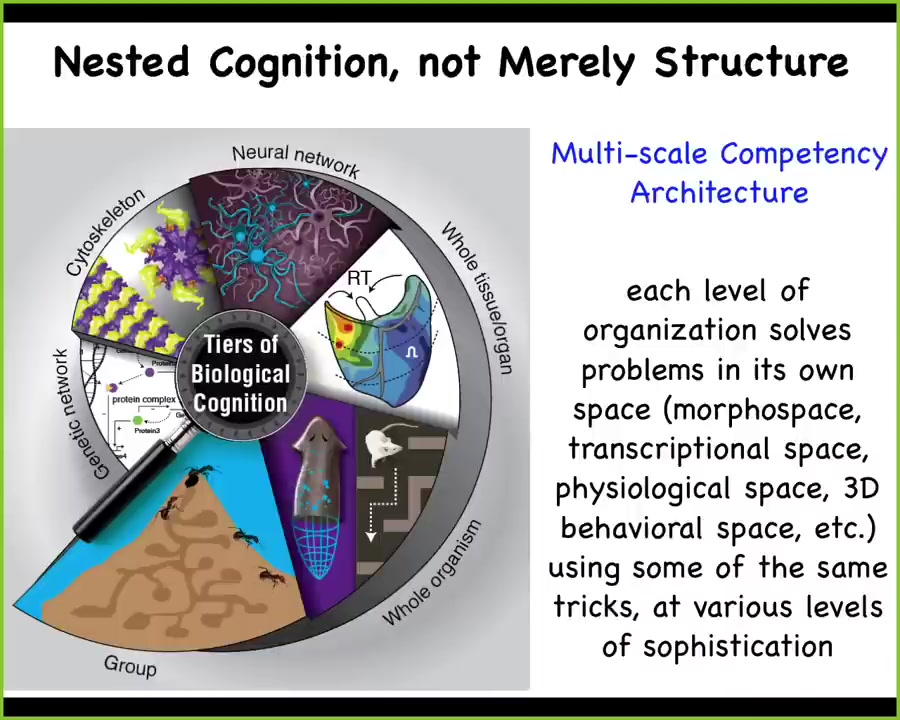

At every scale in your body, from the molecular networks to the organs and tissues and even groups, these different layers are not just biological scales, but actually they have the ability to solve problems.

In other words, they have competencies in different spaces, in the space of possible gene expressions and physiological states and anatomical layouts. There's some amazing examples of these things solving various problems.

Slide 16/39 · 21m:44s

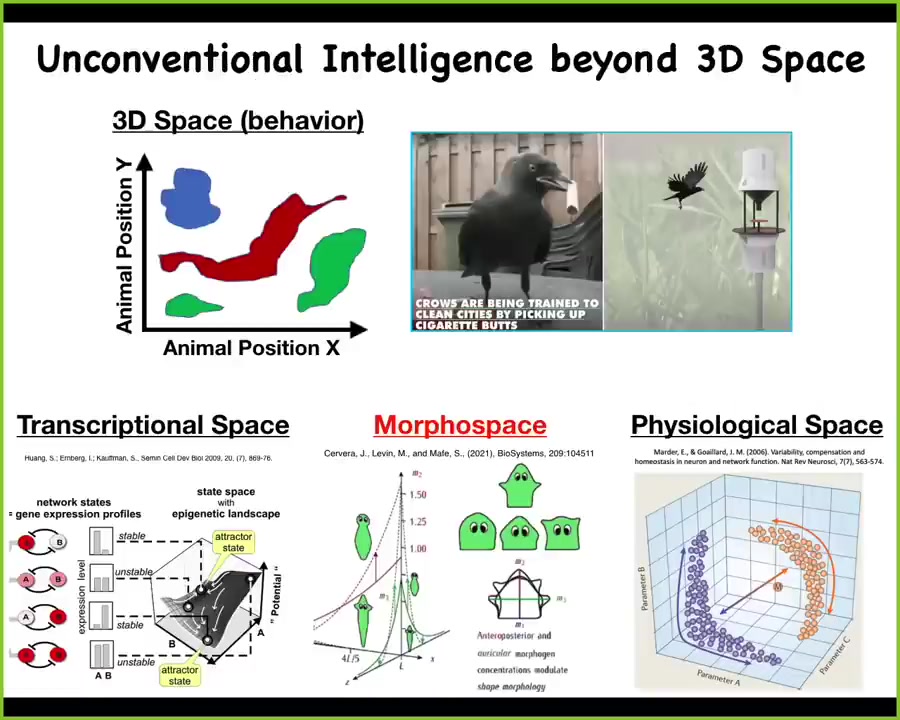

Now, the thing to keep in mind is that we humans are pretty terrible at detecting intelligence. We do okay with middle-sized objects moving at medium speeds in three-dimensional space, crows and birds and maybe a dolphin or something like that. We can recognize those as intelligence, but there are other spaces in which complex creatures navigate and spend effort and try to achieve goals.

There are gene expression spaces and physiological spaces. I want to focus today on what's known as anatomical morphospace. It's a multi-dimensional space of all the different shapes that any structure can have. So in this particular case, here's a planarian head, and it can have different shapes. These different shapes correspond to the different settings of these two control knobs. And so you have this two-dimensional space that shows you where all the different planaria shapes are. But the actuality is, for complex organisms, a very high-dimensional space. So what I want to look at is, I've told you that we're all made of cells, that these cells underlie the emergence or the self-assembly of a unified self, both cognitively and morphologically. And I want to look at how that works.

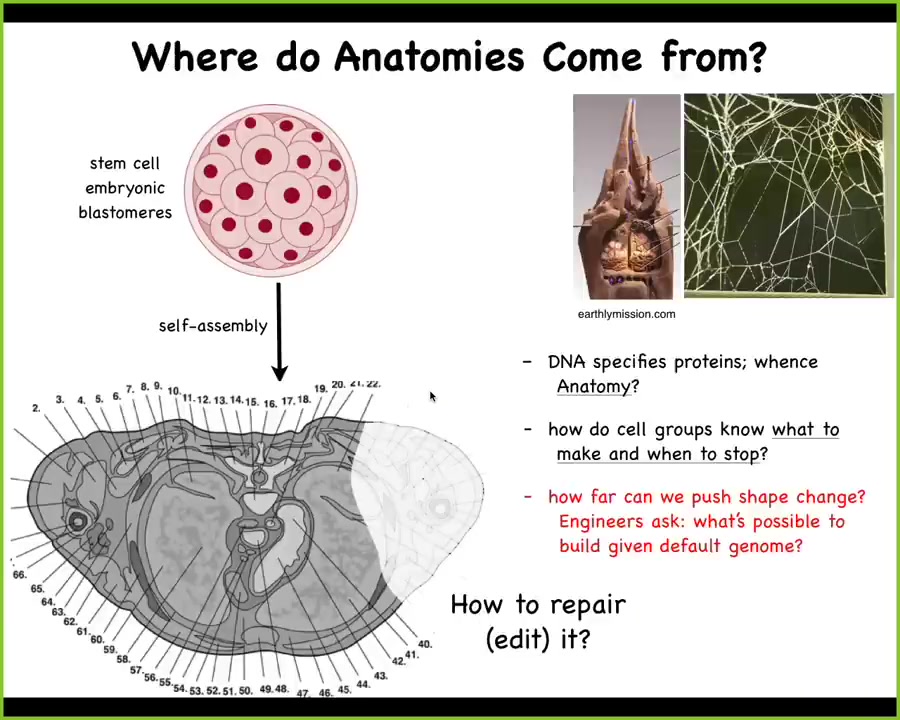

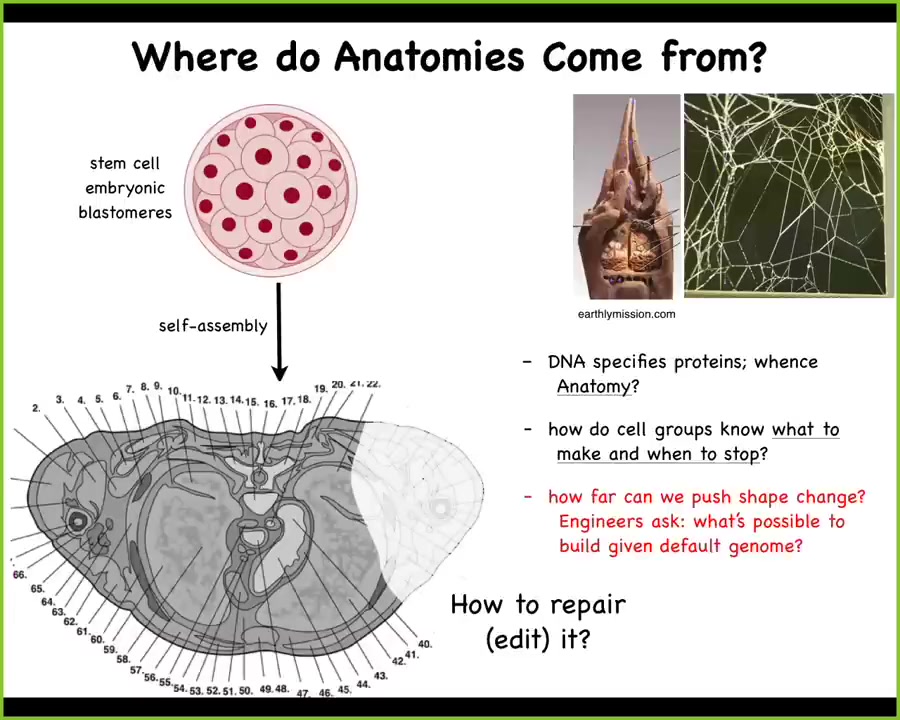

Slide 17/39 · 23m:07s

So here we are, we start life as a collection of embryonic cells. This is a cross-section through a human torso. Imagine where does this incredible order come from? The structure, everything is in the right place, the right shape, the right size, next to the right thing. Where does this order come from?

At that point, I've given a version of this talk to middle schoolers, and even nine-year-olds will immediately say, it's in the genome. We know where it is. It's in the human genome. But of course, we can read genomes now, and we know that isn't what the genome specifies at all. The genome talks about proteins. The genome specifies the tiny molecular hardware that every cell gets to have. This isn't directly in the genome any more than the structure of a termite nest or the shape of a spider web is in the genome of those species. All of this is the outcome of physiology and behavior. It's the outcome of these cells doing their thing with the hardware that they've been given by their genetics.

If the DNA specifies the hardware, how do these cells know what to build? How do they know when to stop? If we want to convince them to repair something that's been damaged, how do we communicate that to them? And as engineers, we can ask, what else is possible? What else can we convince them to build? Same exact hardware, but what more could they build?

I want to give you a couple of examples of the amazing nature of this process.

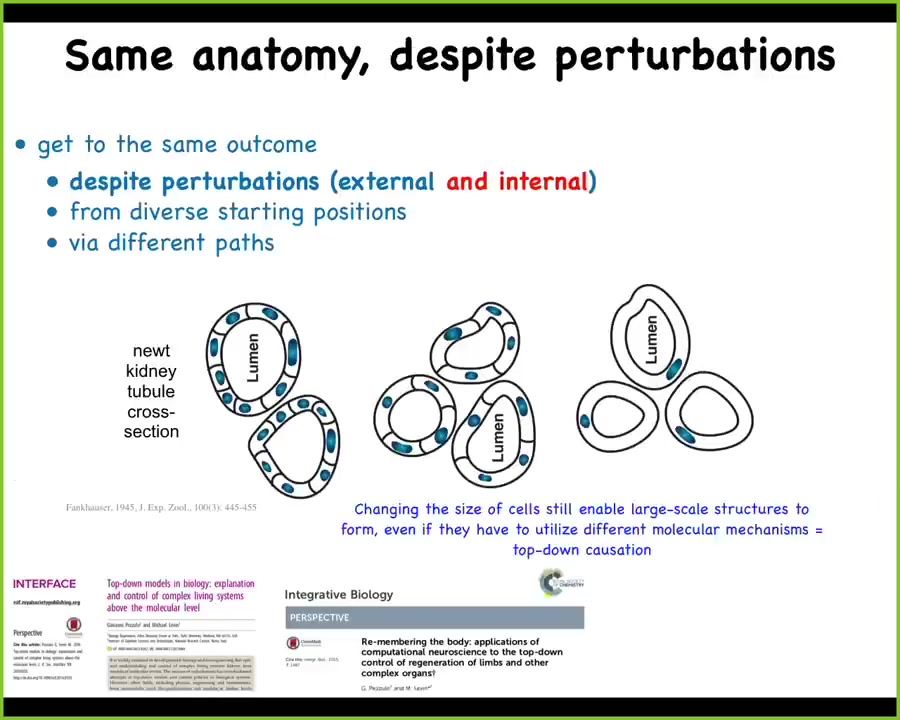

Slide 18/39 · 24m:33s

When you look at this, you might think that the biggest thing this thing has going for it is reliability. That it happens the same every single time. And that's true. Reliability is amazing here. But I want to show you that it's much more than that.

Slide 19/39 · 24m:46s

What you're looking at here is the cross-section of a little tubule leading to the kidneys of a salamander. Normally there's about 8 to 10 of these cells that work together and they form this little structure with a space in the middle. You can do this weird trick where you cause multiple copies of the genetic material to build up in the very early embryo. So when that happens, you still get a normal animal and it's normal size, but the cells are bigger. When you take a cross-section, you find out that the cells are bigger. So now fewer of them create the same kind of lumen.

Multiple copies of your chromosome, no problem. Weird cell size, no problem, because you'll scale it to the number of cells. And most of all, if you make truly gigantic cells and you do these 5N or 6N polyploid newts, one single cell bends around itself to give you the exact same kind of structure. That's remarkable because this is a different molecular mechanism. This is cell-to-cell communication. This is some sort of cytoskeletal bending.

What this means is that in the service of a particular high-level anatomical structure, these cells can call on different molecular mechanisms to solve their problem. So they're using different tools in their toolkit to get to where they're going. That is a very good definition of intelligence, to reuse the affordances you have in the service of a goal when things change. When you're a salamander coming into the world, you don't know how many copies of your genetic material you're going to have. You don't know how many cells you're going to have or what the size of the cells are going to be. You still need to be able to get the job done.

This is not a matter of just being reliable with fixed parts. This is the idea that what evolution is making is problem-solving agents. It's making a system that is ready for many, many unexpected things, and not just environment, not just when somebody bites your leg off and the salamander regenerates it. This is unreliability of your own parts. This is not even being sure of what you're made of. You really can't depend on much, and that's an amazing thing. It's quite different than what you normally get in a biology curriculum where they tell you that your genome, the purpose of your genome is to carry information from a long time away with maximal fidelity and to minimize errors, and every cell is going to do whatever the genome says, and in the end, you get this emergent thing. Actually, that's not at all what's happening here.

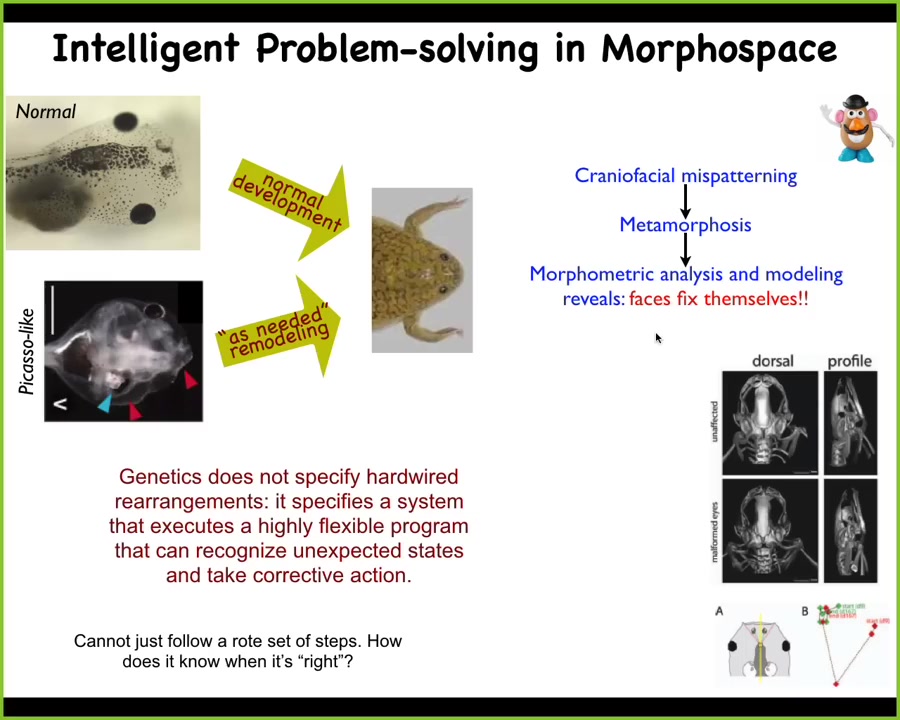

Slide 20/39 · 27m:18s

Here's another example. We discovered this a few years ago. These tadpoles need to become frogs. In order for this tadpole face to make a frog face, all the organs have to move. So the eyes have to move, the jaws have to move, and so on. And they normally do this quite reliably. But it was thought to be a hardwired process. People thought that every organ just moves in the right direction, a fixed amount, and that's it.

What we did was we created these so-called Picasso frogs because we wanted to test how much intelligence is actually in that process. What kind of problems can it solve? We scrambled everything. You can see here the eyes on the top of the head, the mouth is off to the side. Everything is just a complete mess. And these guys still become normal frogs. Because all of these organs will move now in novel paths, paths that these guys don't do, until they get to a correct frog face, and then they stop.

And so what evolution actually has given you is not a hardwired set of instructions, but a system for error minimization, for a way of wherever you happen to start out, do whatever you have to do to end up in this particular location. This kind of goal directedness is something else that you're not going to see in your developmental biology textbook. This is not emergence, and this is not simply an increase of complexity. This is problem solving, and that raises an obvious question about how does it know what the correct face looks like? Where is the memory for that set point of that homeostatic process?

Slide 21/39 · 28m:45s

I want to show you a couple of other things related to the plasticity of this.

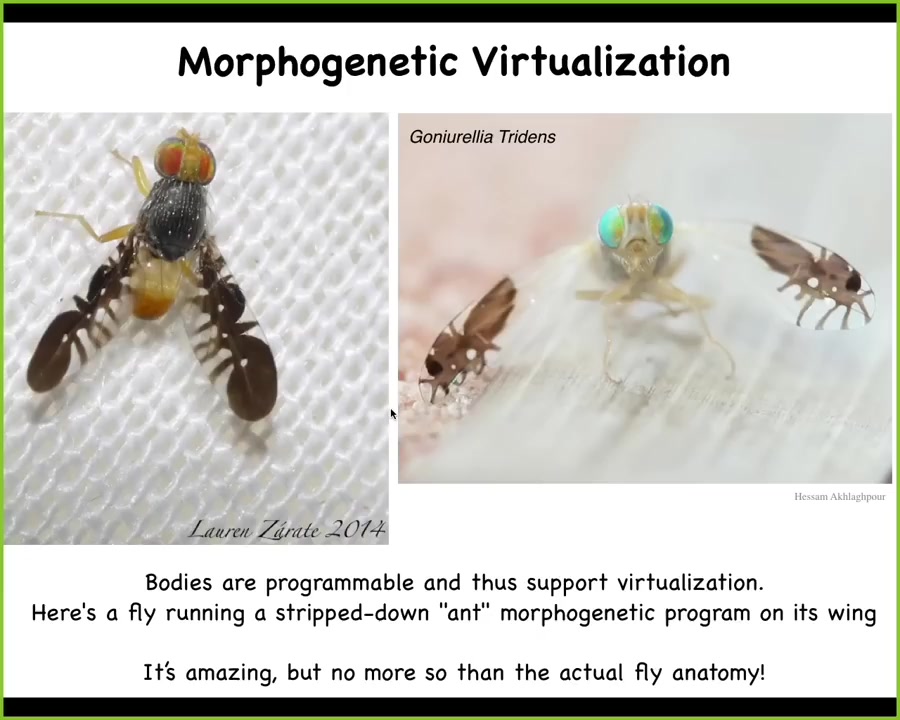

Just so you understand how much play there is between the fixed hardware of your genetics and the actual outcomes.

This here, you might think this is a Photoshop or something. I didn't believe it the first time I saw it. But this fly is running a stripped down ant morphogenetic program on its wings. It's running a virtual ant on its wings. It wiggles its wings to simulate ants, and that keeps the predators away because they don't want to deal with ants. And this is amazing, and it's striking that it has this pattern. But it's no more striking than the much more intricate pattern of the actual fly. All of these are specific morphogenetic patterns, whether 2D or 3D, carried out on this kind of hardware.

Slide 22/39 · 29m:41s

And you might think that the outcomes are pretty fixed. Here's an acorn, and these acorns give rise to these oak leaves. And you might think that the oak genome actually encodes this particular shape. But along comes a bioengineer, and this is a non-human bioengineer.

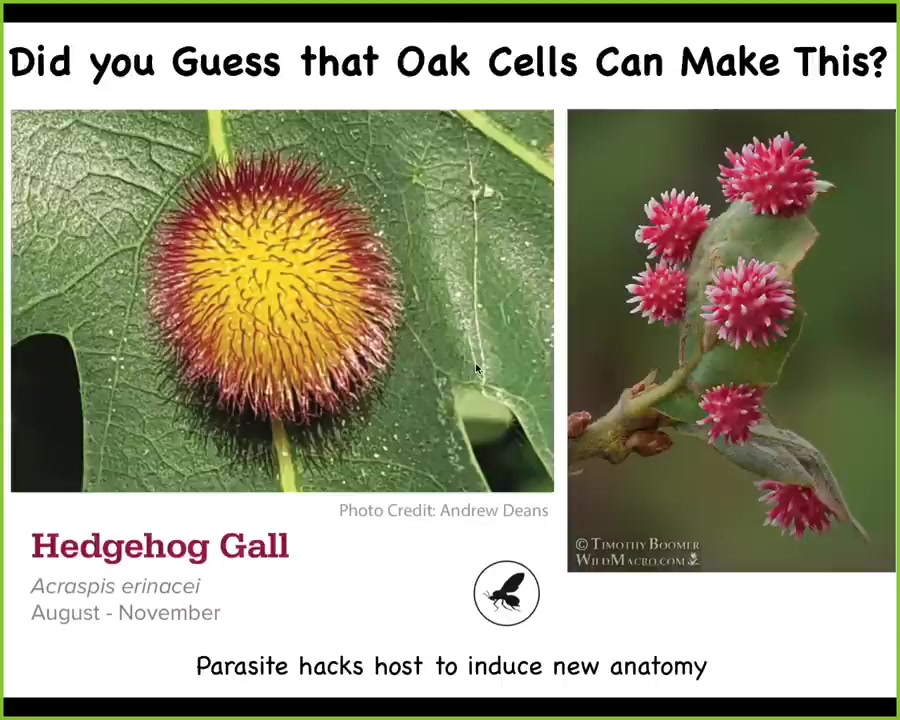

Slide 23/39 · 30m:00s

This is a little wasp. What these wasps do is they provide some signals that prompt the rest of the tissue to build something like this. They're hacking the morphogenetic competencies of this leaf. They're not changing the genome. What they're doing is providing some instructions that cause the leaf cells to adopt a different set point in anatomical space. Would you ever have any idea, looking at these flat green leaves and how reliable they are, that they're capable of building something like this? We have no idea. So that reminds us that this whole notion of developmental constraint is probably a constraint in our thinking. It's not a constraint in the biology. The option space for morphogenesis is enormous. What we need to do is to discover the prompts, the language that we can use to get them to build other things, and it clearly doesn't require modifying the hardware. The genetics of this thing are still completely intact, so now comes the meat of the talk, which is that...

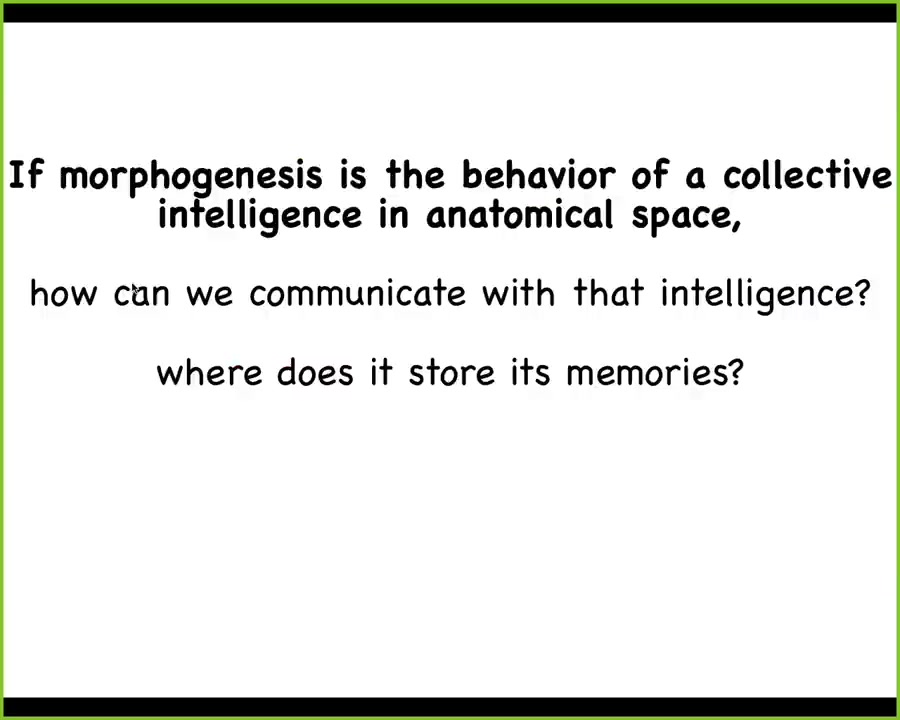

Slide 24/39 · 31m:02s

If morphogenesis is the behavior of a collective intelligence operating in anatomical space, the act of creating complex anatomical shapes is really behavior. It's behavior in an anatomical space of possibilities. And it's done by a collective intelligence, which thinks about shape as opposed to moving around in 3D space. So now we need to ask, how do we communicate with that intelligence? The wasp did it through millions of years of evolution. We would like to do it faster. And where does it store its memories? These are some things that we've been looking at.

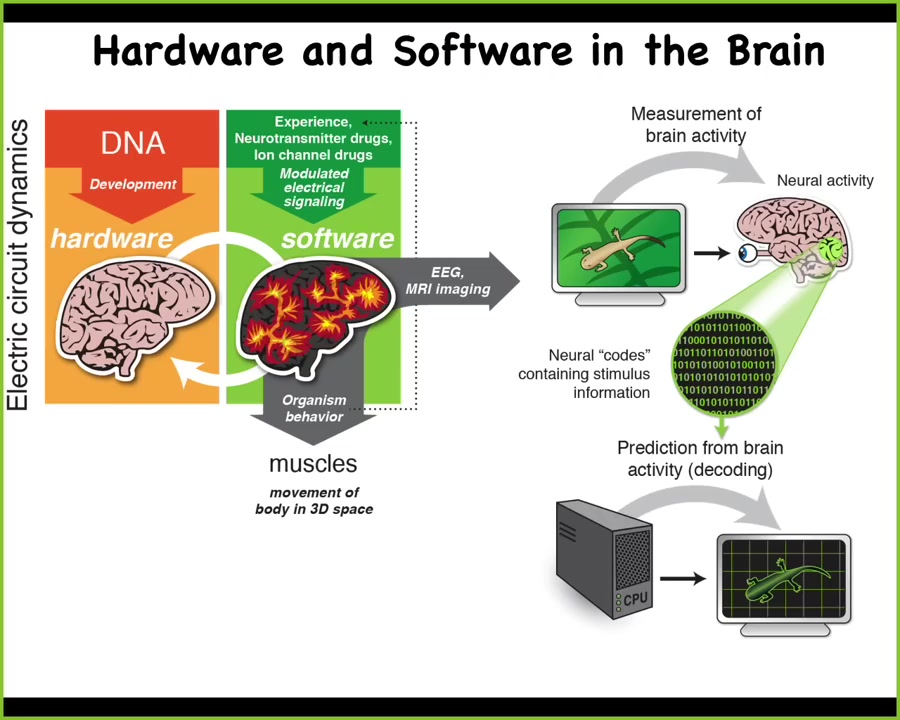

Slide 25/39 · 31m:49s

We know that one way to store memories and communicate with a collective intelligence is through the nervous system. The nervous system does it via computations in an electrical network. You can try to decode those. This is the work of people doing neural decoding to try to read the electrical activity of the brain and to know what thoughts, preferences, and memories the system has.

Slide 26/39 · 32m:15s

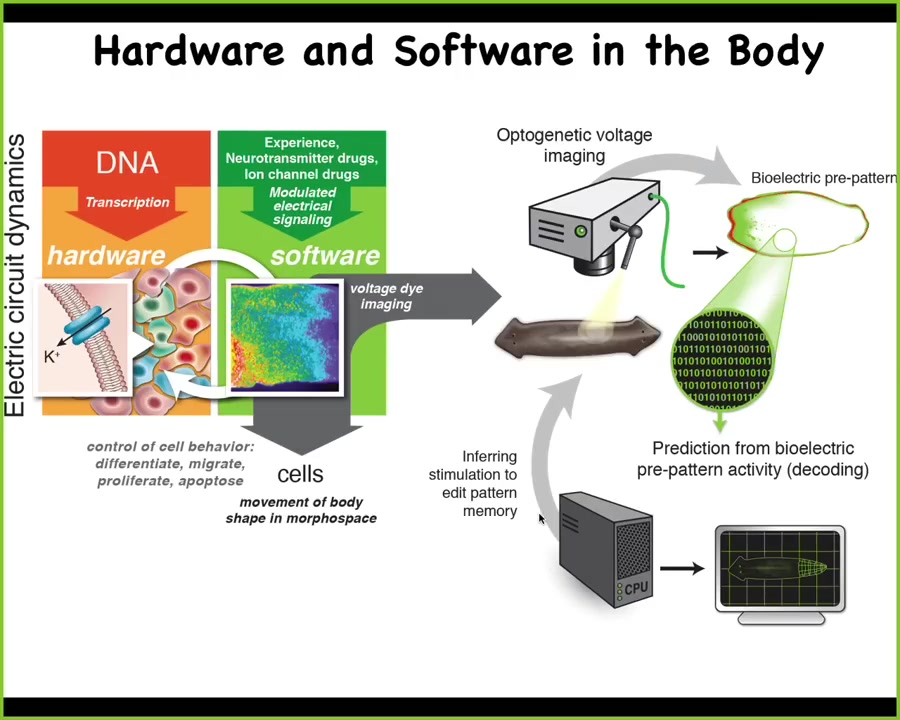

It turns out that this system, this ability to store memories in an electrical network, to use an electrical network to integrate information across many cells, both in space and in time, is something that evolution discovered a really long time ago. It is way older than nerve and muscle. Bacterial biofilms were probably the first to do this, long predating multicellularity.

What we've done is to develop some of the first tools to read and write the mind of the collective intelligence of your body. By taking a lot of the concepts from neuroscientists and emphasizing this idea that neuroscience isn't about neurons at all, neuroscience is really about scaling of information from tiny competent subunits into much larger coherent selves that have higher intelligence in other spaces. That's really what this is about. That doesn't just work in the brain, that works in your entire body.

Slide 27/39 · 33m:12s

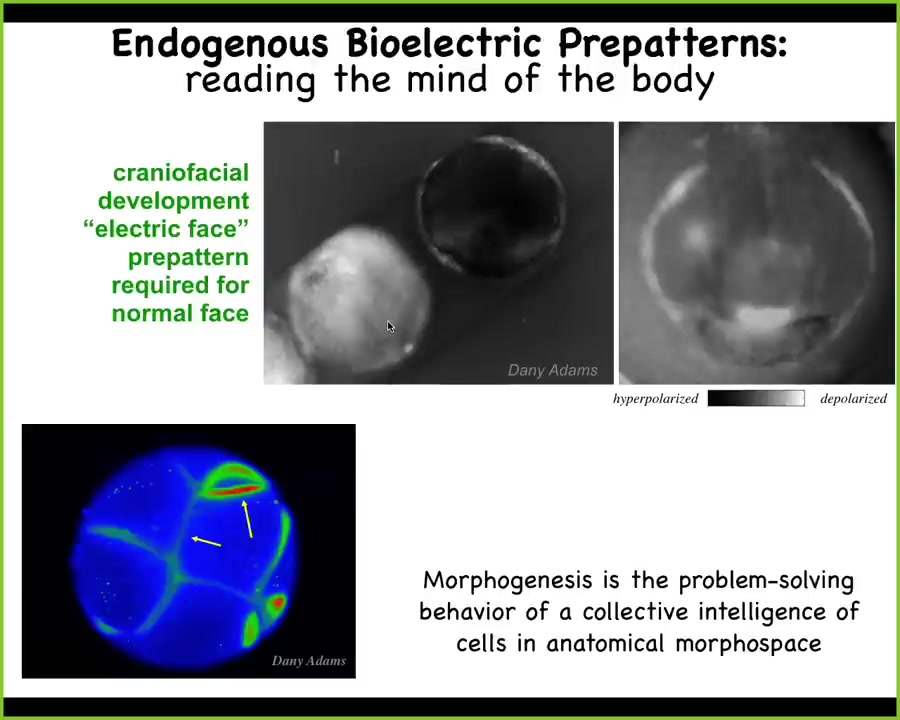

The first thing I want to show you is some of the techniques that can be used. One thing we have is a technique we developed called "voltage-sensitive fluorescent dye imaging." That means that without having to poke the cells with electrodes, you can get, in real time, a time lapse of a frog embryo. This is a frog putting its face together.

You can get a map of all the electrical states, and thus you can try to learn to decode what the system is trying to build. What are the computations that they're doing. We call this the electric face. This is a bioelectric map of the face ectoderm long before any of these organs actually appear.

You can see that cells already know. Here's where we're going to place the eye. This eye, the left eye, comes in a little bit later. Here's where the mouth is going to go. Here are the placodes.

You are seeing it the way you would with a brain scan. You are seeing the content of the collective intelligence of morphogenesis in the body of these animals, so these are normal patterns. In fact, these are required for normal development, as I'll show you momentarily, but here's a pathological pattern.

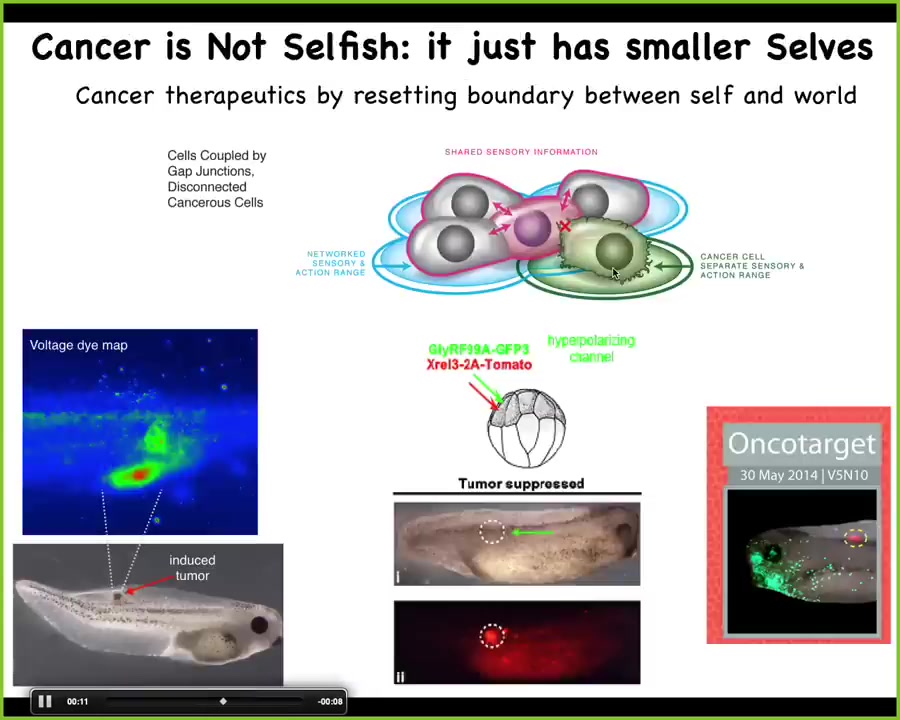

Slide 28/39 · 34m:20s

And this is induced by injecting a human oncogene into these embryos, which eventually will make a tumor. But these tumors have an aberrant bioelectrical profile, because the first thing that happens with this oncogene is that it causes an electrical disconnection of cells from their environment. When cells disconnect, they immediately lose the ability to remember these large grandiose goals they were working on, like making complex organs and fixing defects. They're just amoebas now. That boundary between self and world has now shrunk. This cognitive light cone, where before the goal was the size of an organ or maybe the whole organism, is now down to the size of a single cell. To them, the rest of the body is just environment now.

This is where you get metastasis and progression, because as far as they're concerned they're just amoebas living in an environment. They go where they want and they reproduce as much as they want. Once you understand that, you can try for really interesting cancer therapeutics, which is what we're doing in our lab: don't try to kill the cells with toxic chemotherapy. What if we re-inflate their sense of self? What if we reconnect them, forcibly reconnect them to the large electrical network that can remember what a proper organ is?

When you do that—this is the same animal. Here's the oncoprotein; it has this red fluorescence on it. You can see it's blazingly strongly expressed. In fact, it's all over the place. But there's no tumor, because we co-injected an ion channel, an RNA that modulates the electrical property of the cell, to force them to remain in connection despite what the oncogene is saying. After that it doesn't matter that they have this genetic defect; they behave appropriately and they build nice organs.

That's a story at the level of single cells—how you scale individual cells into a kind of larger set of goals.

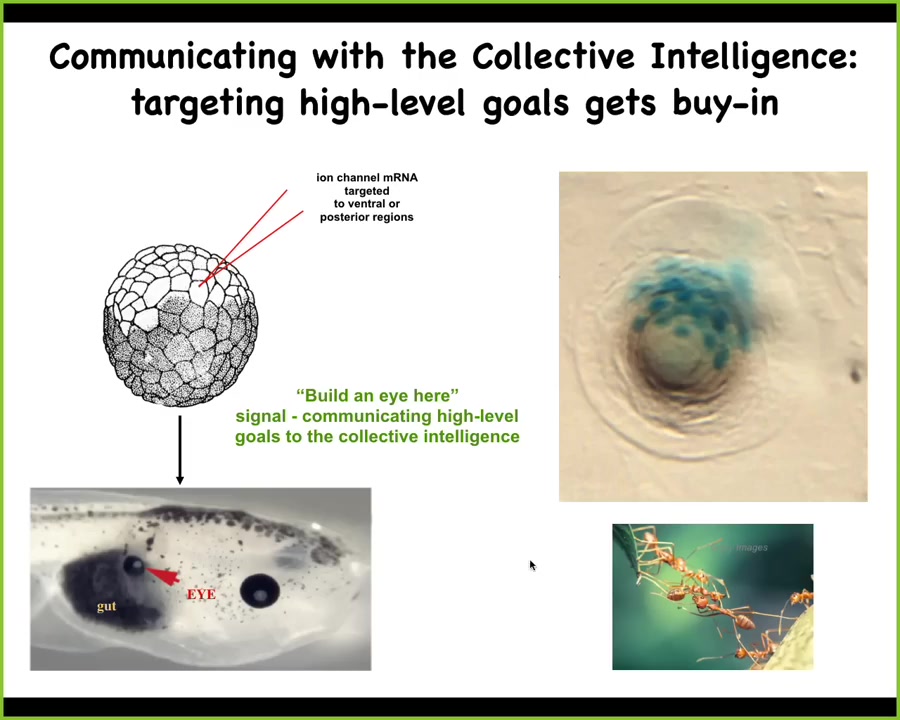

Slide 29/39 · 36m:17s

But I want to show you something even larger scale than that, which is we saw in that electric face, there's a little eye spot which tells the animal that that's where the eye is going to go. So you can ask a simple question, what happens if you reproduce that bioelectric pattern somewhere else? Can you tell this group of cells to build an eye somewhere else? And it turns out you can.

Here it is, we injected some potassium ion channel RNA into a location that normally would make a gut. So here's a tadpole, here's the mouth, here's the eye, here's the gut. And if you tell these cells using an appropriate voltage signal that, hey, you should be making an eye, boom, that's what they do. And these eyes have normal lens, retina, optic nerve, all the same stuff.

And you might see in your developmental biology textbook that only cells in the anterior neuroectoderm here are competent to make eye. So that isn't true. That's only true if you try to prompt them with the so-called master eye gene. So if you put in PAX6, the master eye gene, yes, that's true. Only these cells can do it. But again, that limitation of competency isn't in the embryo. That's on us. That's because we didn't know, the community didn't know the right way to talk to these cells. Once you understand the bioelectric code, actually it turns out that almost any region in this embryo is competent to make eye.

And if you should happen to only inject a few cells, so here this is a lens sitting out in the tail of a tadpole somewhere. If you only inject a few cells, these blue cells are the ones we injected, then they know there's not enough of them to make a good eye. So what do they do? They recruit a bunch of their neighbors to work with them to make an eye, just like ants and termites will recruit their buddies to solve a problem.

So now you can see that what we're doing is providing signals. We didn't tell these cells how to build an eye. We didn't say anything about the stem cells or the gene expression. We have no idea how to build an eye. What we did find was a message that we can transmit through this bioelectrical interface that says, build an eye here. And once you get the cells buy-in so that they are convinced that in fact is what they should be building, after that, you don't need to do anything. They will do what they do best. They'll build to a morphogenetic spec.

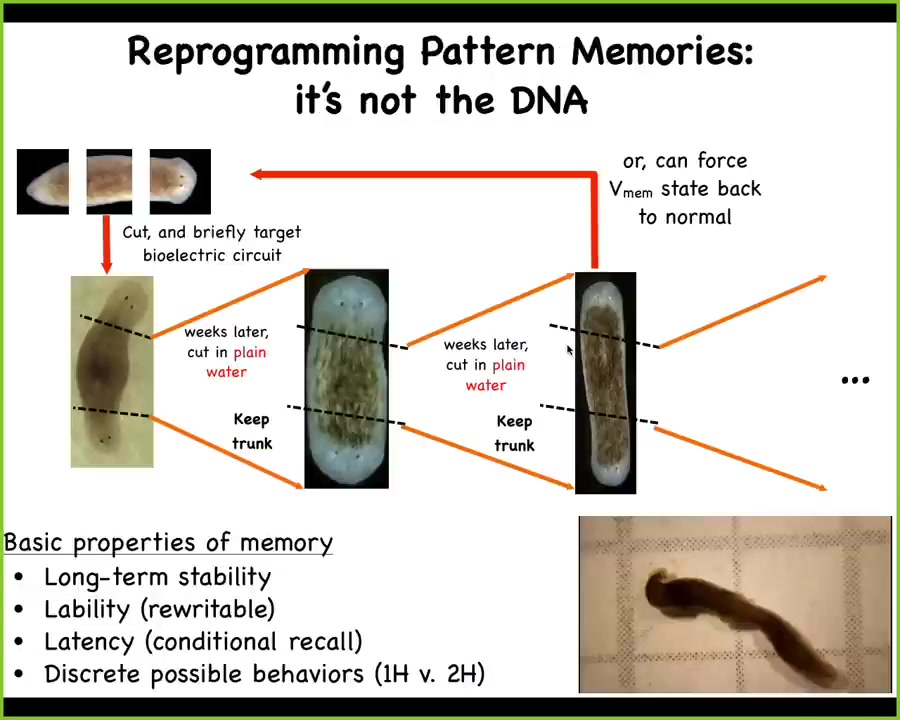

Slide 30/39 · 38m:27s

We know this. I want to show you another kind of pattern memory in these planaria. So here's a normal flatworm. These guys, you can cut them into pieces and they will always regenerate correctly. Every piece normally makes a nice one-headed worm 100% of the time. But there's a bioelectric pattern there that we were able to read out and then we were able to modify. When you modify that pattern, you make two-headed worms. When you make these two-headed worms, what happens is that you have rewritten the memory of what a correct worm is supposed to look like. When these middle fragments go to regenerate, they consult the pattern to say what should a normal worm look like. They see that it says two heads, and they go ahead and they build two heads. These two-headed worms now in plain water, meaning no more manipulation of any kind, are now forever two-headed. If you keep cutting them, they will just continue to regenerate as two-headed. We have permanently changed the target morphology, the pattern to which they regenerate. But we never touched the DNA. There's nothing wrong with the genetics here. If we were to throw these guys into the Charles River, 100 years later, some scientists would come along, they'd scoop up some single-headed worms and some double-headed worms. They'd say, oh, cool, a speciation event. Let's sequence the genome and see what made the difference. There's nothing wrong with their genome. That's not where the information is. That's really important to understand that much as we've been learning from computer science for a really long time now, the hardware, if it's good hardware, does not fully constrain what the software is able to do. This is a kind of pattern memory. It's long-term stable. It's rewritable because we can turn these guys back to one-headed. Here you can see what these two-headed guys are doing when they're hanging out. The question of how many heads should a planarian have is not written in the DNA. What is written in the DNA is the construction of some biological material that by default will develop a pattern memory that says one head. That's what it does by default, very reliably, but you can change it. You can rewrite it. And the fact that biological tissue is reprogrammable in this way is hugely important for biomedicine and for other things. I hope you're starting to see that all the emphasis on genetics and on the genome and all that, it's all very important because you have to understand your hardware, but it's just the beginning. It's the same reason that on your laptop, if you want to switch from Photoshop to Microsoft Word, you don't get out your soldering iron and start rewiring, because it's reprogrammable. Neither does biology. Biology is using an incredibly reprogrammable medium that solves problems and can be communicated with using various interfaces, for example, this bioelectrical interface.

We've talked about the reliability of development and what things do by default. We've talked about various ways to hack, communicate with, and reprogram the collective intelligence of cells so they can build other variants on the form. But where do these goals actually come from? When we called up a second head here, the second head looks just like the first head. Where are these patterns really? If it's not in the DNA, what's the space of possible patterns? What else can we do? We can actually turn these worms into heads of other species, about 100 to 150 million years distance. So triangular worms become round, become flat. You can make the hardware go to other regions of that space that normally belong to other species. Those are all evolutionarily defined forms. Is that it? Is that where the forms come from? They're basically selected for, and then there's a finite set of forms that can be implemented by the hardware. Well, we decided to look at this in a synthetic bioengineering way.

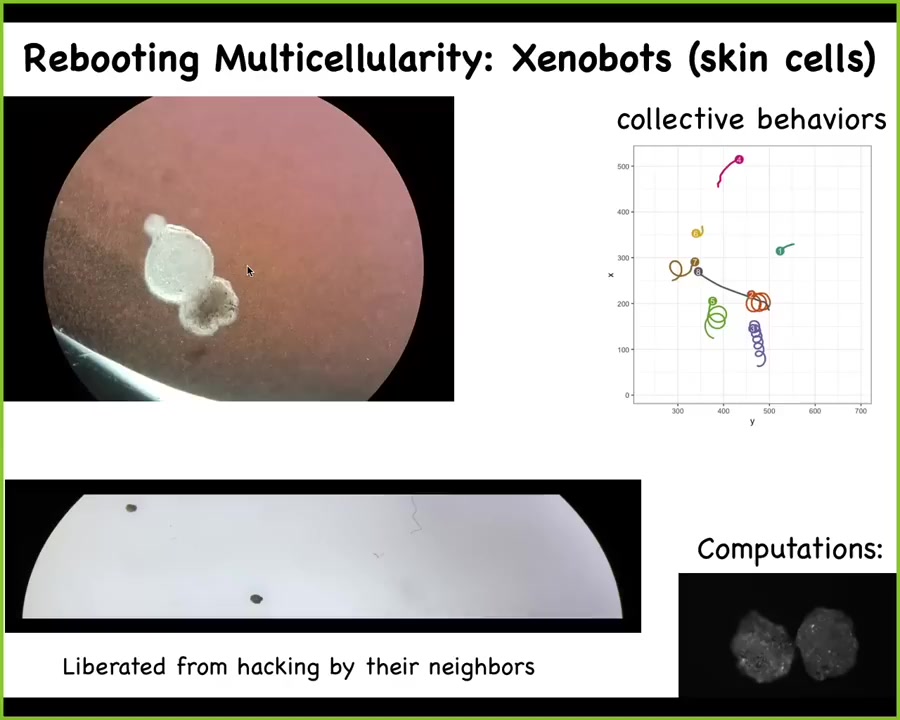

Slide 31/39 · 42m:27s

And what we did was we took some cells, some skin cells from frog embryos, and we let them reboot their multicellularity. We took them aside, we liberated them from their normal interactions with other cells. They could have done many things. They could have died, they could have crawled away from each other, they could have made a flat monolayer like cell culture. What they did instead is they merged into something we then named Xenobots. Xenobot because Xenopus laevis is the name of the frog and we think this is a biorobotics platform.

They start to swim. They have little cilia, little hairs that are normally used to distribute mucus down the side of the frog, but here they row. These guys are rowing to the left, these cells are rowing to the right, and as a result, this thing moves forward. They can go in circles like this. They can patrol back and forth like that. They have various collective behaviors. These two are dancing around. This one's going on a long journey. These ones are doing nothing. They have some very rich calcium signaling. You can see that here, which is usually a sign of some information processing in these cells.

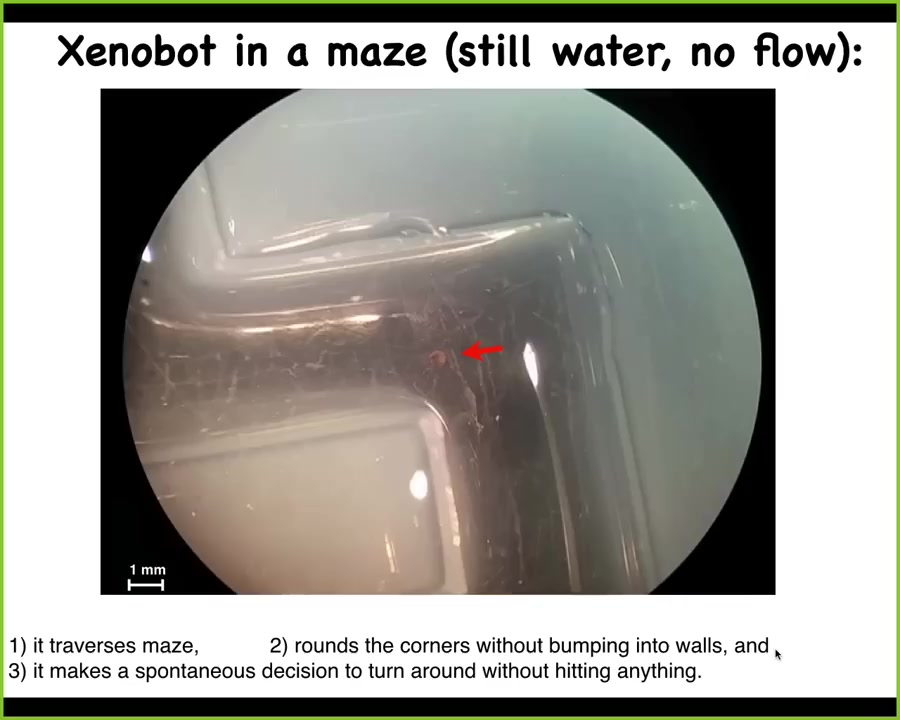

Slide 32/39 · 43m:28s

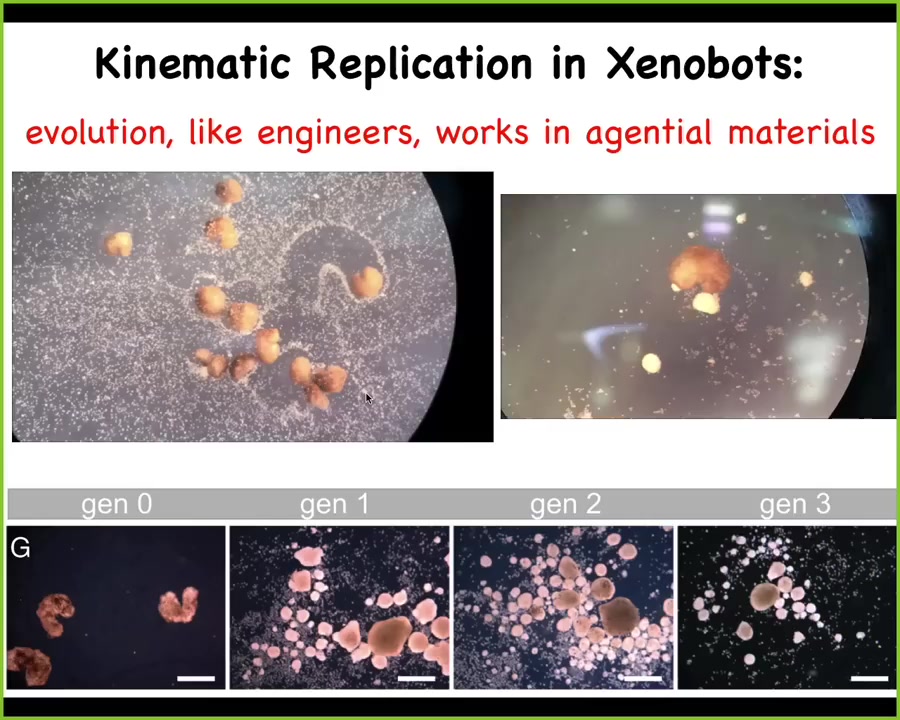

Here's one that is navigating this maze. It's going to take this corner without bumping into the opposite wall. There it is, it bumps. Then here, spontaneously, it turns around and goes back where it came from. It has spontaneous behavior. This is just skin; these are just epithelial cells. They have lots of interesting behaviors that we can talk about. But one of the most amazing things they do is called kinematic replication.

Slide 33/39 · 44m:01s

Imagine we've made it completely impossible for these things to reproduce the normal ****** fashion. They don't have any of the reproductive organs, they don't have any of that. But in this novel configuration they figured out a way to make copies of themselves. Here's how they do it. If you provide them with loose skin cells, this loose material, what they do is they run around and they collect those loose skin cells into little balls like this. Because what they're working with is an agential material, meaning these are not passive pellets, these are cells, for the same reason that we were able to make Xenobots, they make the second generation of Xenobots. These little balls that they make mature, and they run around and make the next generation of Xenobots and so on.

This is kinematic replication. It's kind of von Neumann's dream of a robot that went around and made copies of itself from materials it finds in the environment. There's never been any Xenobots. There's never been any selection to be a good Xenobot. This is not in the lineage of frogs. Where does this come from? Their shape, their behaviors, the kinematic self-replication, all the other things they can do. Where does that come from? It's very hard to say that this was the subject of selection.

So again, I come back to this theme that while the hardware was absolutely selected for, I don't think it was selected to make frogs. I don't think that what evolution does is create solutions for specific problems or things that are fit in a specific environment. I think what evolution does is make creative problem-solving agents that will do the same thing under default conditions, but once you start making changes and challenging them, they often rise to the occasion and solve problems in very novel ways that reflect dynamics that they've not seen before.

Lest you think this is some trick unique to frogs or embryos, when we first published all this stuff, some people said, frogs — amphibians are pretty plastic and embryos are especially plastic, so maybe this is some kind of specific thing in frog embryology.

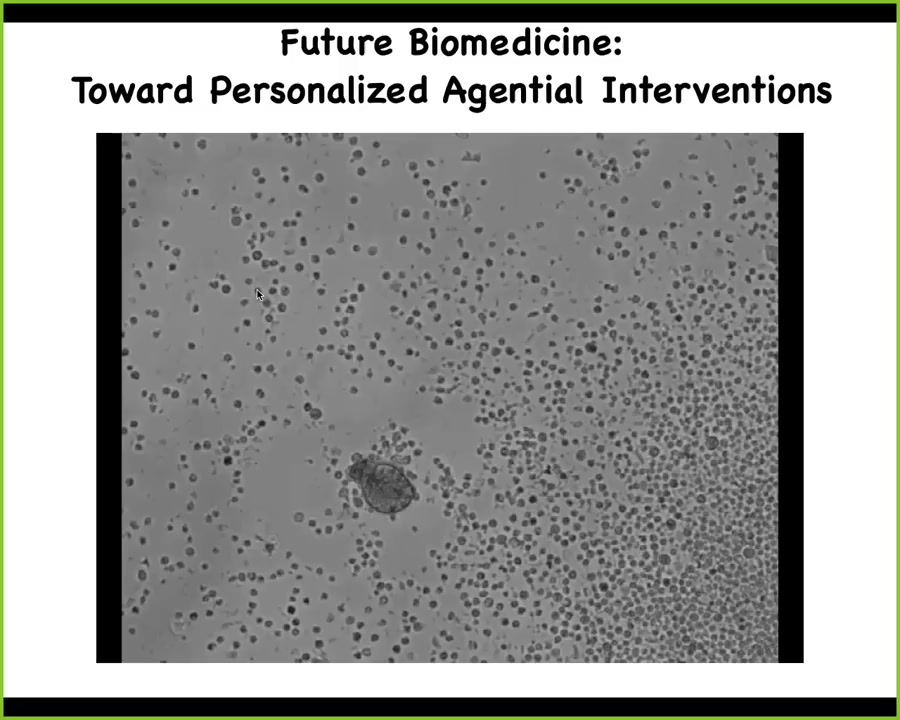

Slide 34/39 · 46m:13s

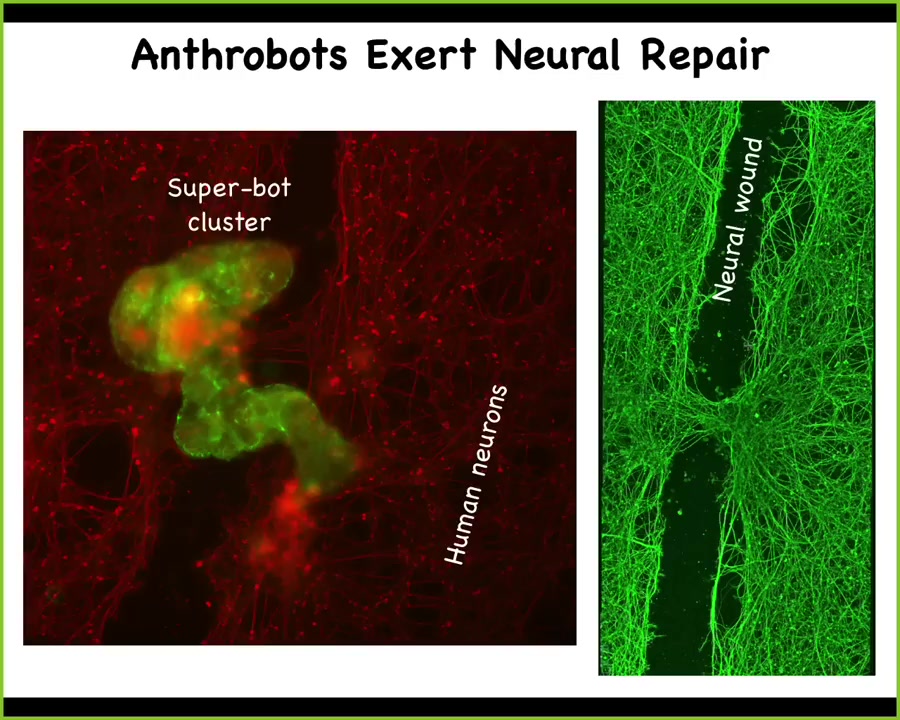

The last thing I want to show you is this. Here's this little guy running around, and I will ask you what this is. You might think that this is something I got off the bottom of a pond somewhere, some sort of primitive organism. Then I can tell you that we've sequenced its genome. You'll say, what's the genome? What does it look like? I'll say this is 100% Homo sapiens. These are adult human cells. There's no embryonic cells here. These are adult tracheal cells taken from human donors, most of them elderly in their 70s and 80s. When given the chance, they reboot themselves and have a new life as these things. We call them anthrobots for obvious reasons. They have all kinds of novel shapes and behaviors. I call this kind of a technology for personalized agential interventions because if you ask, what can these things do?

Slide 35/39 · 47m:10s

Well, one thing they can do is this. If you If you take human neurons and plate them on a dish and put a big scratch through them, these anthrobots can settle down. We call this a superbot because there's probably 10 of them here. They'll settle down and within a few days you lift them up and you see that what they did was they took the two sides of the wound and they knitted the nerves together. Okay, so they have the ability to repair these kind of neural wounds. I mean, who would have thought that your tracheal cells, which normally sit quietly in your airway for decades, that given the opportunity taken out of the body, they would actually reassemble themselves into a new kind of creature with these new capacities. And so this is, I think, hugely important for the future of medicine because just imagine, once we understand what kind of healing effects these guys can have, they can be injected into your body. They do not require immune suppression because they're made of your own cells. So personalized medicine in that way. They share with your body all the priors about what health is, what diseases, inflammation, cancer. You don't have to build all those detectors from scratch like you would with some sort of engineered nanobot because these are your own cells. They already understand all those things. And so again, you start to see this plasticity. Again, what you just saw is not some embryonic developmental stage that they're recovering, back-to-back in their history, there is no such stage. This is completely novel set of behaviors.

Slide 36/39 · 48m:39s

I'm going to finish up with some big-picture thinking.

I've been telling you about all of these stories and all of their biomedical implications for cancer and birth defects and regenerative medicine. There's a bigger picture, which is that what we're talking about is an example of how to recognize and how to communicate with an unconventional intelligence.

It is not just philosophy: thinking about groups of cells as decision-making, memory-having, goal-directed beings has led us to lots of discoveries that were not made by the standard paradigm, which sees them as simple machines.

Along this spectrum, I call this the spectrum of persuadability because it's all about what kind of tools you're going to use to communicate and control these various systems. Here it's hardware rewiring and some control theory and cybernetics with things like thermostats. Then, behavioral science and training. Here, you have a rich relationship with cogent reasoning.

We can't just have philosophical feelings about where things fit on this continuum. Most people assume that cells are somewhere down here, that they're basically simple machines that need to be treated that way. That leaves a lot on the table because we're doing interesting things with cell training and taking advantage of the problem-solving competencies of these things. We have to do experiments.

That brings us back to the issue of AI. The question of AI isn't about today's language models. Today it's pretty easy to say GPT-4 isn't really like a human mind. No, it isn't, and it doesn't matter for two reasons. First, there are many interesting minds that are not human minds, and some of them are quite alien. Second, the whole point is that you can't just assume these things. You have to do experiments. You have to ask yourself, do I know where intelligence comes from? We've studied some very simple things that have amazing, unexpected, emergent, intelligent behaviors. Do we know where that comes from and how to recognize them? At this moment, we don't.

This is the science of diverse intelligence. I think this is where the ethics comes in: we need to be extremely careful about not denying moral worth and various kinds of ethical protections to beings because they don't look like us. Humans have a very long history of trying to make separations between in-group and out-group based on surfacey characteristics. In your lifetime, you are going to be confronted with all sorts of novel beings.

Slide 37/39 · 51m:36s

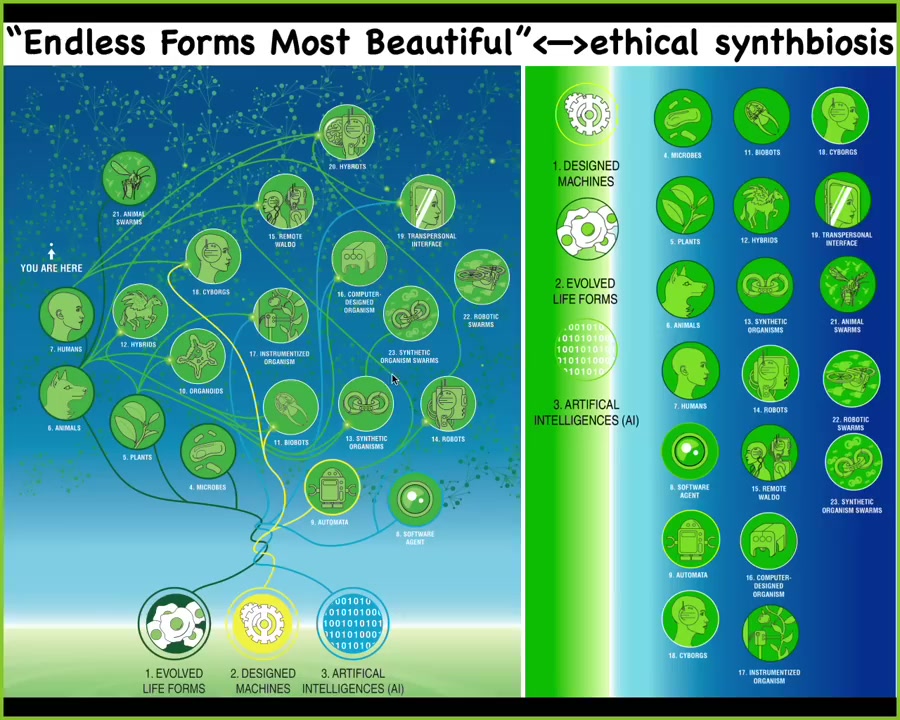

So all of Darwin's endless forms most beautiful here on Earth are a tiny corner of this whole space. Hybrids and cyborgs and all kinds of non-neurotypical humans with implants and different kinds of connections to other creatures and to other technical systems. Pretty much any combination of evolved material, engineered material, and software is some kind of being.

There are going to be chimeras and cyborgs. And so it's not about the language models of today. It's about beings that are nowhere near you on the tree of life. You cannot decide how you're going to relate to them in the old ways, which was to knock on it. And if you hear a metallic clanging sound, you say, aha, so you were made in a factory and you're boring and I can take you apart and that's okay. Whereas if you heard this soft woolly thud, you would say, well, you're a real being like me, and I have to treat you even though we're not even very good at that as humans. But the point is that those kinds of categories are going to be worthless because the space of possible bodies and minds is extending radically. And we're going to have to develop much better ethical frameworks. I think what we're really talking about is a kind of synth biosis where we have to learn how to relate to beings that are different than us.

Slide 38/39 · 52m:59s

We're going to have to figure out how you detect where things are on this continuum so that we find appropriate balance points between objectophilia. Objectophilia is the thing where people fall in love with bridges; they think the Eiffel Tower is married to them. Things down here, you're not going to have that deep relationship with things up here. But other people are trapped in the other end of the continuum where they see things that are not like today's standard humans and they say, "those are not real minds worthy of care and respect." That very quickly devolves to an idea that's basically "love only your own kind." That's probably much worse than this.

We really need to ask, given all of these facts, what is a human, actually? I have a weird answer to that. If you were going on a long journey and you wanted a companion, what is it that you actually care about? When you say you don't want a Roomba, that's not enough; what do you actually care about? It's not the DNA. I don't think anybody has any allegiance to our particular human DNA or the specific set of organs. What is it that you do want in a rich human-level relationship? That's very worth thinking about.

I'm going to stop here. If anybody's interested in this, here's a bunch of papers that go into all of this in great detail.

Slide 39/39 · 54m:26s

Most importantly, I need to thank all the people who did the work that I showed you today. Here are all the postdocs and students and everybody else who contributed. We have lots of amazing collaborators. Our funding comes from all kinds of people. I have to disclose that three companies spun out of our lab are supporting some of our work. There are some business connections here. Most of all, I always thank the model system because the various animals and plants do all of the heavy lifting in teaching us about biology and about ourselves. Thank you so much. I'll take questions.