Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a talk I gave at a large tech company for non-specialists interested in the intersection of computation, biology, and fundamental questions about Selfhood. It's about 48 minutes long and unfortunately does not capture my cursor movement so you can't see the things on the slides at which I am pointing.

CHAPTERS:

(00:07) Adam and frog eye

(05:41) Collective intelligence foundations

(09:50) Regeneration, memory, and identity

(16:49) Morphogenesis and anatomical goals

(24:15) Bioelectric reprogramming of form

(30:16) Selves, scale and cancer

(37:16) New synthetic living systems

(42:21) Biology's lessons and ethics

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/41 · 00m:00s

Thank you so much. That's very kind and it's been a real honor and a privilege to get to know Bill and work together on these projects. Thank you for inviting me here.

This is a new kind of audience for me and I've put together a talk that I haven't given before. Let's see how it goes.

By the way, if anybody's interested afterwards in the details, all of the official peer-reviewed stuff, the software, the papers, everything is here. Here are a few more personal thoughts about what I think it all means.

Slide 2/41 · 00m:40s

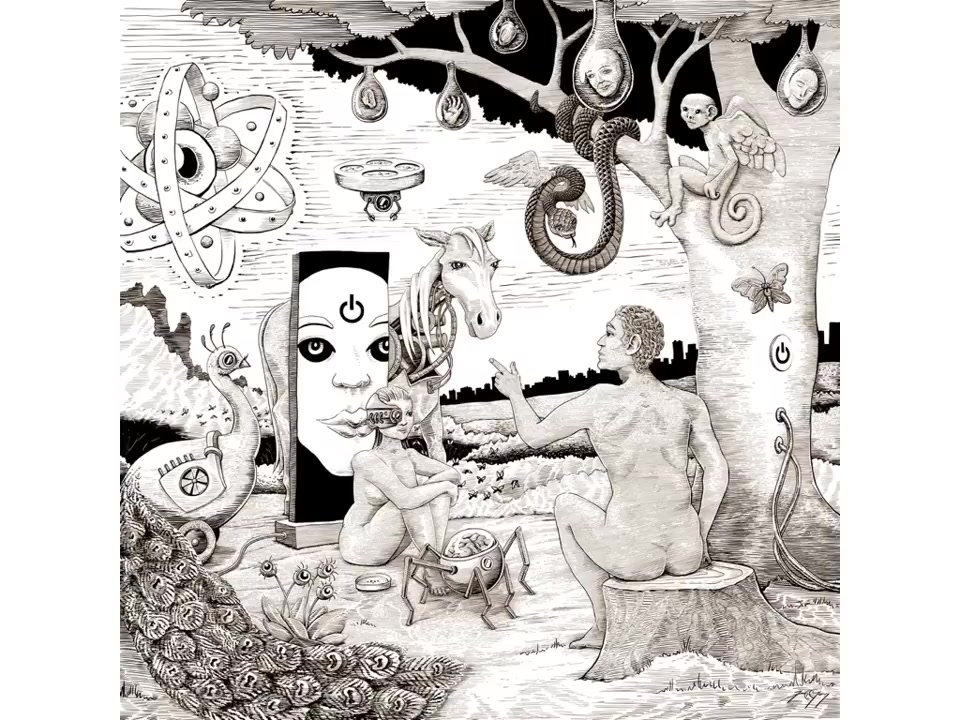

Let's begin here. This is a well-known painting. It's called "Adam Names the Animals in the Garden of Eden." There are two interesting things about this old story. One of them needs to be redone and ditched, and the other is very profound and is going to be important for us going forward. The one that needs to be dropped is this idea that there are discrete natural kinds of beings. We know what they are. Here are these large, mostly cute animals. There's Adam. They're discrete. Adam is different from all of them. And that does not do justice to the incredible plasticity of life. Our attempts to bin it into these categories is not going to fly.

What is really profound here is that in that original story, neither God nor the angels were able to name the animals. It was Adam that had to do it. The job was on him. One reason is because in these old traditions, naming something or discovering the name of something means you've discovered something about its true inner nature. That's important because we as humans are going to have to discover the inner nature of a very wide set of beings that Adam could not even have begun to dream of. Adam's the one that has to live with them. His understanding of his world and the other beings around it is going to be critical for him to develop.

Slide 3/41 · 02m:10s

I want to talk about a few things today. First, some thoughts on information, evolution, and selves, this notion of collective intelligence and where it comes from. I want to talk about the paradox of change and how biology handles it. The paradox of change can be said as follows. This is scaled to the level of evolution, but I think you will see the obvious implications for personal and possibly company growth. The paradox is this. If you're a species and you fail to change, you're going to go extinct. But if you do change, you likewise will, in an important sense, cease to exist. What does that mean? How do we as beings preserve ourselves in some sense as we inevitably change? We change physically, we change mentally. If you don't change mentally, you can't learn. There's some sense in which a profound educational process changes you so that you're not the same. Certainly growing up will do that. I'm going to show you how I think biology handles it. We're going to talk about a few other topics such as plasticity, diverse intelligence, and creative interpretation, AKA poly computing, that biology uses across scales. We're going to start our journey here through the eyes of a frog with an eye on its ****. If anybody asks you in the future, "Have you ever seen a frog with an eye on its ****?" now you can say yes. This is a frog we have made in our lab. This is not Photoshop. This is not AI. This is a real eye on its ****. The reason that these kinds of things are possible is because Biology commits to a certain kind of creative process to solve this problem.

Slide 4/41 · 03m:54s

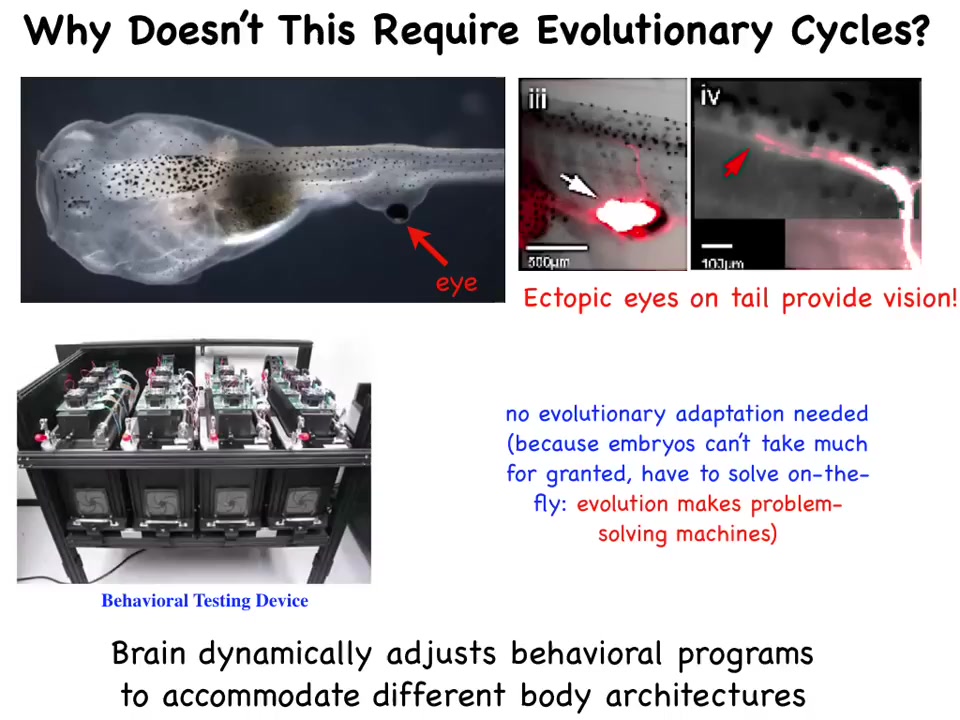

The way that frog came to be is that we took a tadpole. Here's a tadpole. Here's the brain, the nostrils, the mouth, the gut, the tail. And what we did was we put some eyes, some eye cell precursor cells on the back of this tadpole. The cells go ahead and they make an eye. I'll tell you another story about ectopic eyes in a minute, but that's how we did this is by transplantation. You'll also note that he doesn't have any primary eyes, so we prevented those from forming, but we put an eye on his tail. And then we built this machine. This was an incredible ordeal. It took probably five years, about 1,000,000 bucks, which is huge for a lab, to build this kind of thing. And what the machine does is test these tadpoles in visual assays. Basically, there's a little spot of light, and they have to either chase or stay away from the moving light in order to succeed in that task. We found out that they can see quite well. These eyes on their backs enable them to see perfectly well.

Here's the optic nerve. You can trace it. It does not go to the brain. It goes to the spinal cord and then it stops there. So notice what's happened here is that this animal has a radically different sensory motor architecture. You've got now this weird itchy patch of tissue on your back that's sending signals to your spinal cord. How does the brain know that that's visual data and use it? And in particular, why doesn't that take extra evolutionary cycles, cycles of mutation, selection. It's just ready to roll. You've drastically changed this architecture that's been the same for millions of years and suddenly it works. And it works because evolution doesn't actually make specific solutions to specific problems. It makes problem-solving agents. And embryos, as I'll point out in a few minutes, can't take much for granted. They solve these things on the fly, which is why this works.

Slide 5/41 · 05m:42s

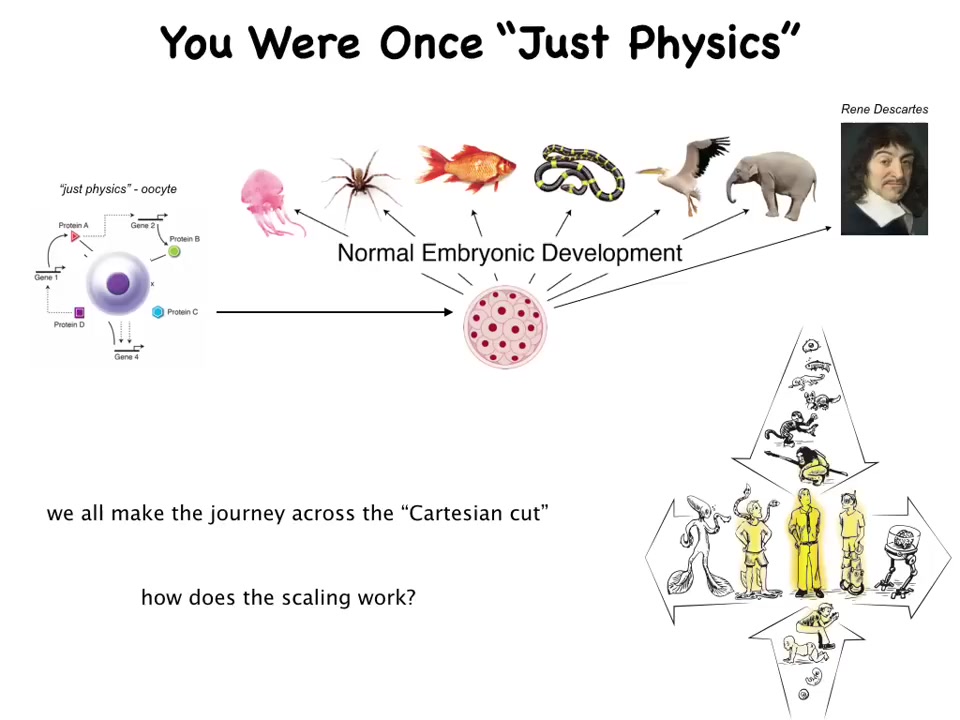

Now, what this has to do with collective intelligence is this. We all started life as a single cell. I once pointed out to somebody, I was doing some expert witness work, and one of the attorneys was trying to say that our work in frogs was not relevant to humans. He said, "Don't frogs come from an egg?" I said, "Well, you come from an egg." Everybody thought I was insulting him. The judge banged the thing. But let's remember, we all come from an egg. We all come from a single cell. That's a little blob of chemistry and physics. That slowly and gradually gives rise to one of these remarkable morphologies. There is no magic spot, no lightning flash that says you were physics, but now you're a real cognitive individual. Mind comes into the picture. This is slow and gradual.

So we as scientists and philosophers need to understand how that scaling works. How do you get from a system that's well described by chemistry and physics? As I'll mention, not with zero cognitive capacity—it's small, but it's not zero. How do you get here? Let's remember that we humans with our magical, agential glow are not discretely different from all of these other things. We stand at the intersection of two enormous continuums, both evolutionarily and developmentally, and through biological change and through technological change, there are all kinds of interesting beings that we're going to need to get to know.

Slide 6/41 · 07m:18s

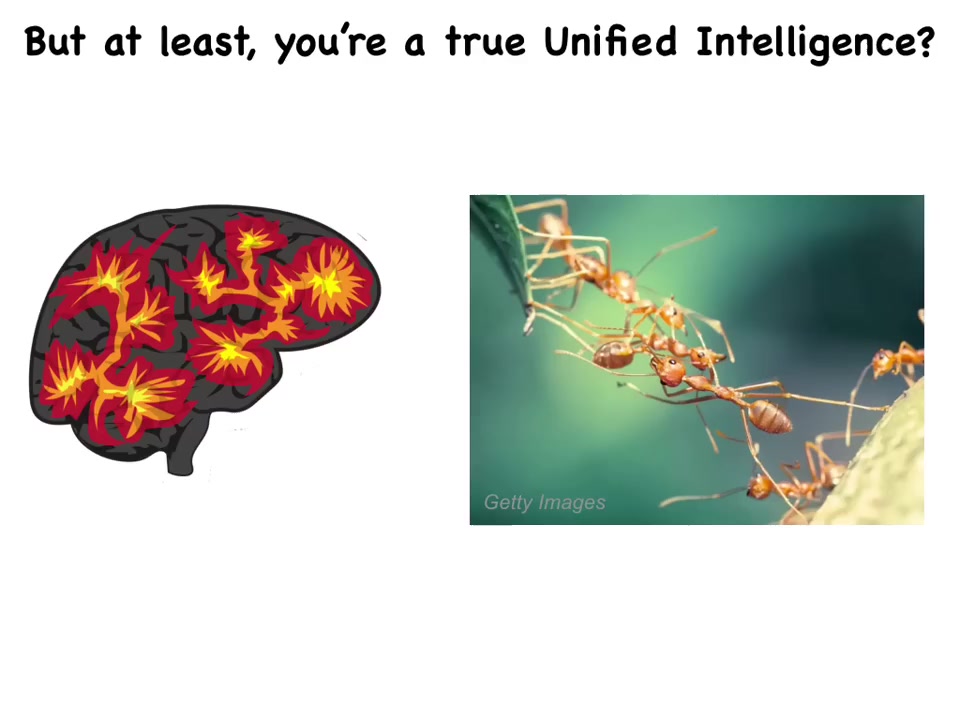

That's a little disturbing. A lot of people send me emails about how disturbed they are to find out that they were a scale up from a single cell. But at least we're a true unified intelligence. We're not a collection of ants or termites that you can talk about an ant colony as a collective intelligence, but we're an actual true unified intelligence.

Slide 7/41 · 07m:41s

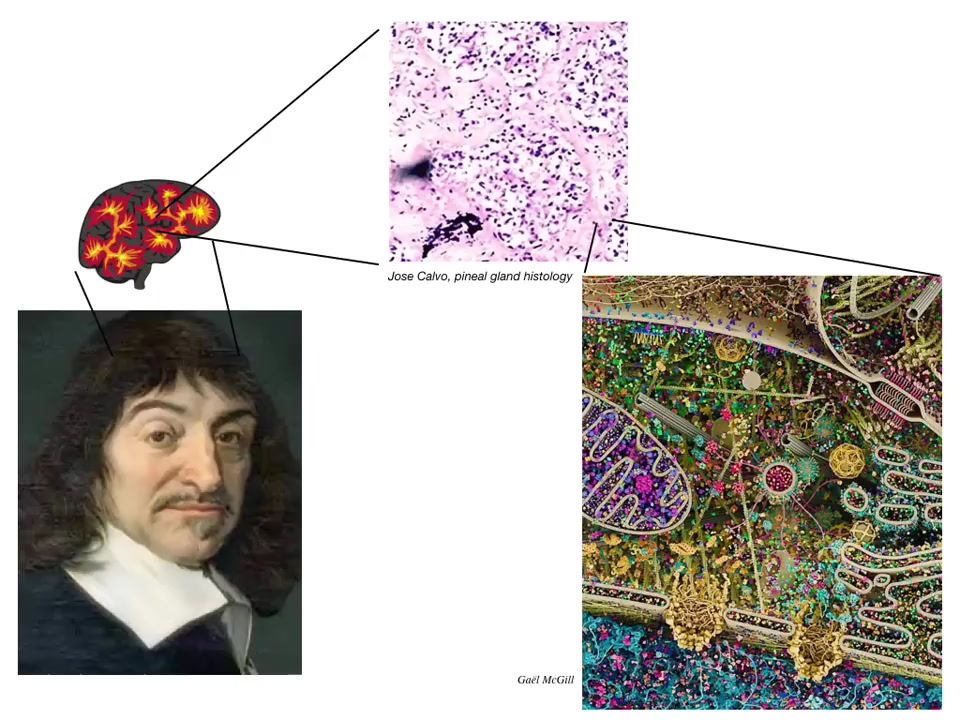

Wrong. This is Descartes who really liked the pineal gland. The reason he liked the pineal gland is that there's only one of them in the brain. He felt that our unified human experience should be associated with a structure in the brain that's unique, not the bifurcated, not the hemispheres or all these other structures. It should be the only one.

If he had access to good microscopy, he would have looked inside the pineal gland and he would have seen that there's not one of anything. It's made of a bunch of cells. Each one of these cells has all this stuff in it. Look at this. These are all the things that are inside each cell. And there's plenty more. This is only what we know to stain at this point.

Slide 8/41 · 08m:22s

All intelligence is collective intelligence. We are all built of a kind of multi-scale agential material. This is a single cell. This happens to be a free-living organism known as a lacrimaria. This is what a single cell can do. There's no brain, there's no nervous system. He's handling all of his local needs with incredible anatomical, physiological, and metabolic control. We're all made of collections of these.

Slide 9/41 · 08m:52s

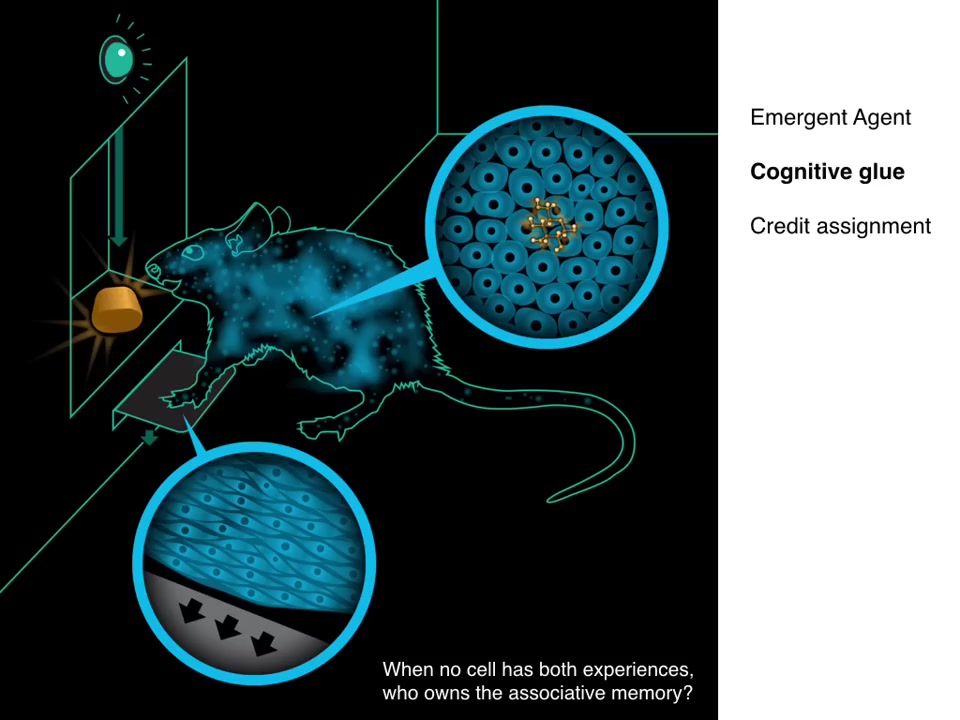

And the thing about being a collective intelligence is that you need cognitive glue. What I mean by that is here's a rat that's been trained to press a lever, get a reward. There is no single cell here that has had both experiences. So the cells at the bottom of the feet interacted with the lever, the cells in the gut got the delicious sugar reward, but no single cell had both of these experiences. So who owns the associative memory? Who is it that knows that these two things are tied? It isn't any individual cell, it is the rat. What you need is a set of mechanisms that are able to provide this system with memories, preferences, goals, and other cognitive properties that the individual parts don't have.

We're used to thinking about ones like this, but there are many other creatures that show us something really remarkable.

Slide 10/41 · 09m:46s

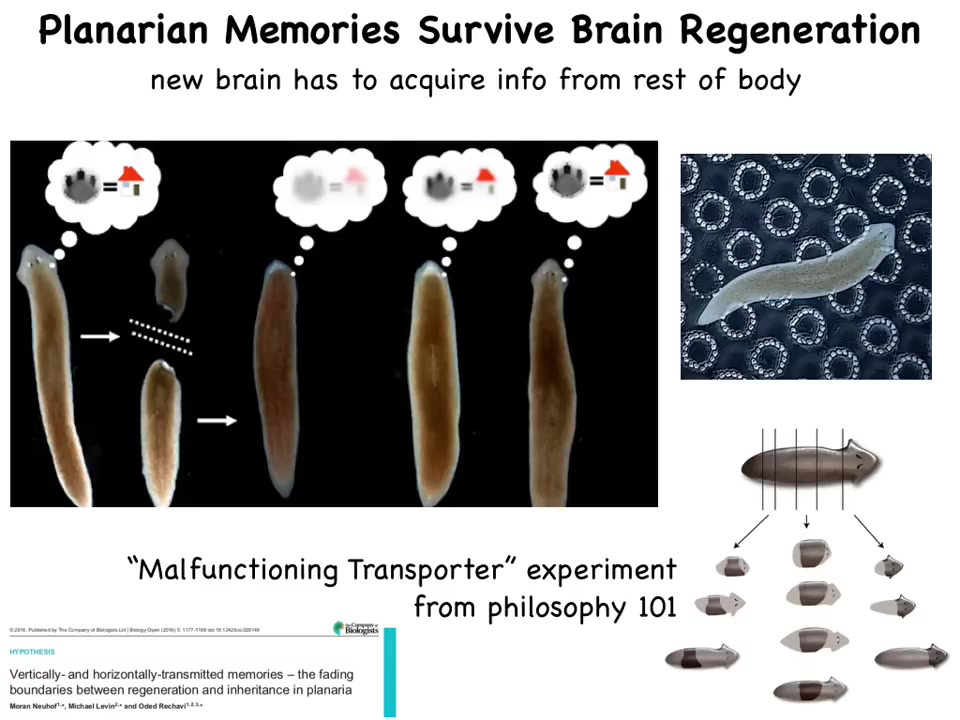

Here are some flatworms, some planaria. You can train them. You can train them to understand that these little bumpy circles that we've laser etched into the bottom of the dish are where they get fed. The liver shows up on these little circles.

The other amazing thing about planaria is that they regenerate. You can cut them into pieces. The record is 276 pieces. If you cut them in half here, this tail will sit there doing nothing for about 8 days. It'll grow a new head. Then behavior begins and you find out that these animals remember the original information.

The information is not exclusively in the brain because you can cut off the entire head. It is somewhere else. However, it is imprinted onto the new brain as it develops.

You can do all kinds of interesting thought experiments, the old malfunctioning transporter and ask, if we cut them into pieces, who's the original planarian?

Right away you get into these issues of personal identity. You get into where is behavioral information? How does it move through the body? How does it imprint it onto new brains? How do brains know how to interpret? Just like I showed you in the tadpole, the brain knows how to interpret information coming off of its spinal cord. How does this brain know that whatever the tail is telling it is actually behavioral information that the brain can use?

It goes even beyond that. It's not just about maintaining the information.

Slide 11/41 · 11m:11s

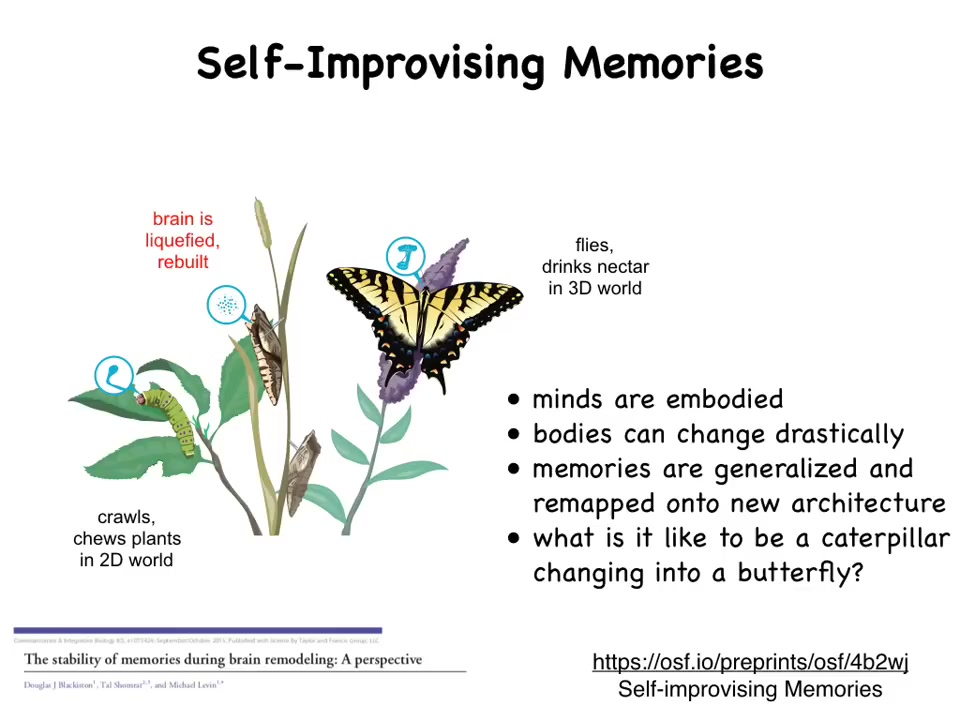

Here's one of my favorite examples. Here's a caterpillar, two-dimensional. You can model it as a soft-bodied robot with a particular controller, and that's suitable for moving soft bodies that have no hard elements. You can't push on anything. These things crawl around and they eat leaves, and they have a brain that's well suited for that. They have to turn into this: a butterfly that flies in three-dimensional space, doesn't eat leaves, it drinks nectar. In order to change the brain from this to that, you undergo this remarkable transformation process that dissolves most of the brain. Many of the cells die, most of the connections are broken.

If you train the caterpillar to seek out leaves on a particular color disc, the butterfly will do the same. You can ask questions like, what's it like to be a creature in the process of changing so radically? You can ask, where is the memory? If the brain is being refactored, where does it keep those memories? There's a deeper issue, which is that butterflies don't eat the same stuff that caterpillars eat. They don't move the same way that caterpillars move. So having the exact memories of a caterpillar is completely useless. What it has to do is interpret the engrams, the memory traces that the caterpillar leaves; it has to reinterpret them for its new context. In its new higher dimensional life, it doesn't carry the exact memories of its previous life, but it carries the deep lessons that it's learned. The trick is that it has to know how to remap them onto its own architecture. You can read a lot more about this in this preprint that I put up a few days ago.

Slide 12/41 · 12m:57s

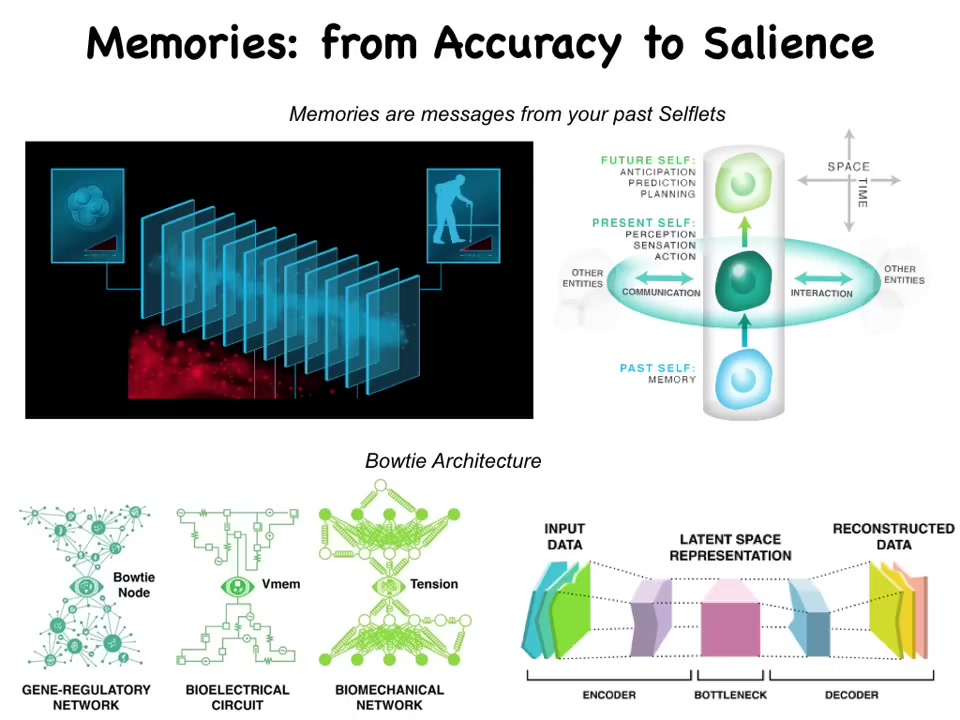

So the interesting thing is that these worms and caterpillars and so on, we shouldn't just think about them as this bizarre aspect of biology that has nothing to do with us. Because if you think about the slices of our own life at any given moment, you don't have access to the past. The only thing you have access to are the engrams, the traces of past experience that your past self has laid down in your brain and your body and notepads and various outsourced kinds of things. You have to reinterpret those memories at every point. You have to reconstruct actively the story of who you are, what you are, what your various commitments and beliefs are from the molecules and the energy patterns that are in your body. And you have to tell a story about what they add up to. This is what our brain does all the time.

One way to think about this is that memories are messages from your past self. Just the way that you exchange messages laterally with other beings at your current time point, these memories are messages from a past self. And like any act of communication, you're not required to interpret these messages in the way that the sender intended. You are free to reinterpret them however it's best for you. Not only are you free to do that, you have to do that because you will change. Your body will change, the environment changes, even for humans. There's molecular turnover and cellular turnover all the time. So all of these messages have to be turned over.

And the way that this works, you can imagine that these engrams, these memory traces are like this middle node, this narrow little middle node in this architecture that's used like an auto-encoder, where it squeezes down all of the information that's come before, because you don't want it to remember the exact data, you want it to remember patterns, and then you pass the bottleneck; you want this side to re-inflate those patterns into whatever makes sense on the other end. Biology has this everywhere: in gene regulatory networks, in voltage at the center of bioelectrical circuits, in biomechanical networks. This architecture is absolutely everywhere because this is what enables information to preserve salience, not accuracy, but salience and utility on the other end.

This will only work if the two ends of this thing are smart. They have to undertake some effort to interpret and encode what's going on here.

Slide 13/41 · 15m:37s

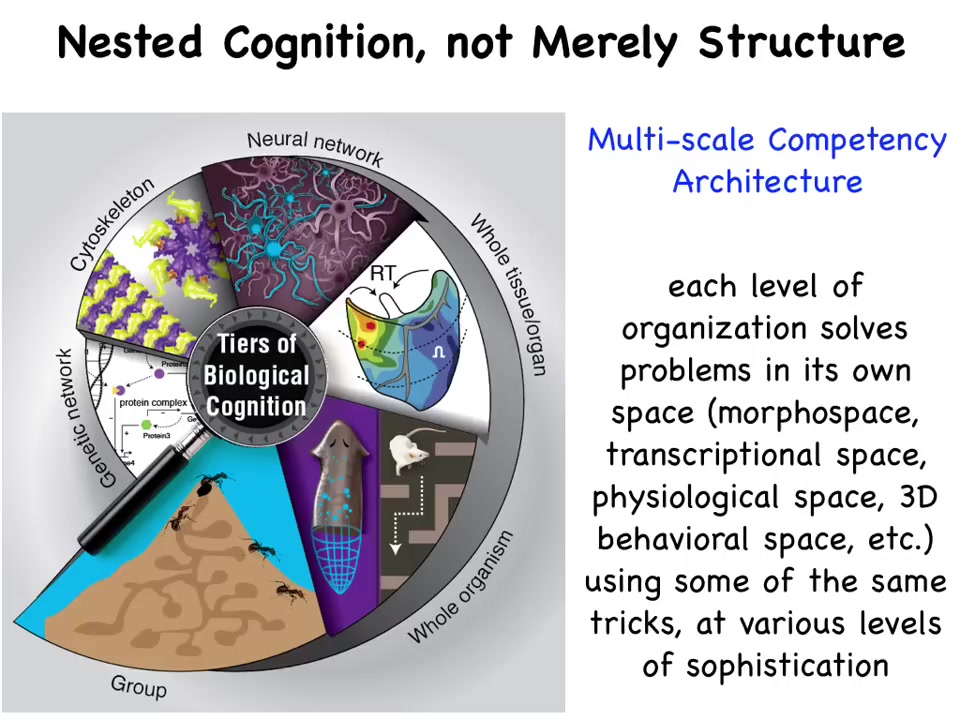

Our bodies are made of a multi-scale competency architecture. Every level of this is smart in the sense that it has a competency to solve various problems. Whole bodies solve problems in three-dimensional space, various kinds of behavior. But your molecular networks, your subcellular organelles, your cellular components, your organs, tissues, all of these things solve problems in other kinds of spaces.

Slide 14/41 · 16m:06s

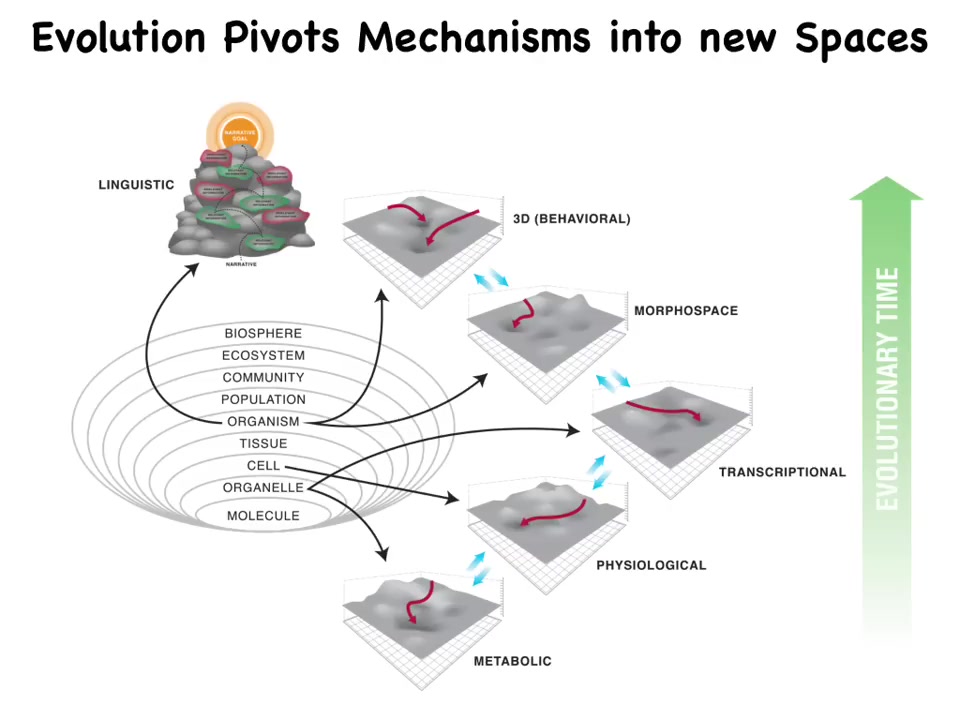

One thing that evolution has done is to pivot some of the same tools and tricks for navigating problem spaces across these various spaces. We started off in metabolic space and then physiological space, and then genes came along and you could navigate gene expression space. Multicellularity came along and you could navigate anatomical space, the space of possible large-scale shapes. Brains and muscles showed up and you could do behavioral space and eventually linguistic space. It turns out from some recent work in our group that some of the exact same ideas from navigating these other spaces you can use to help AIs navigate linguistic space and keep track of a story longer and longer.

Alan Turing, who was very interested in minds and intelligence and different embodiments of intelligence and machines, was studying intelligence through reprogrammability. He was interested in programmable hardware and plasticity. Interestingly, he wrote this paper, "The Chemical Bases of Morphogenesis." It's one of the earliest works on the mathematics of how order might arise in chemical systems, that egg that I showed you. He was interested: how does the egg self-assemble? How do the chemicals assume some order? Why would somebody who was interested in mathematics and computer science be interested in this question?

I think that he saw a very profound kind of invariance. If he had lived longer, both biology and computer science would be much further along. What he realized was that the story of the appearance of minds is fundamentally the same story as the story of the self-assembly of the body. The factors that put together your body should be really important for understanding where minds come from.

Slide 15/41 · 18m:00s

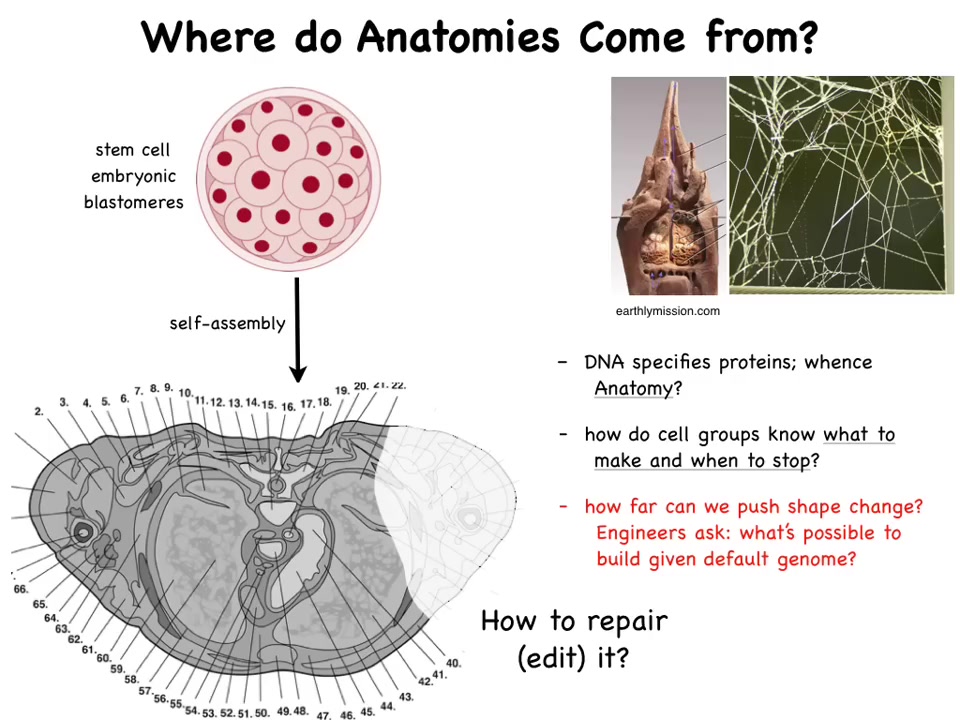

Let's ask, where do anatomies come from? You start life as a collection of embryonic blastomeres. This is a cross-section through an adult human. Look at the amazing order. All of the organs, they're the right size, the right shape. Everything is next to the correct thing. Where does this amazing order come from? Where is this pattern written down? If you ask even nine-year-olds, I've given talks to middle schoolers, and they will immediately say, it's in the DNA, it's in the genome. We can read genomes now. This was apparent long before, but now we know for sure, because we can read genomes, none of this is directly in the genome. What's in the genome are the specifications of the proteins, the tiniest hardware, the molecular hardware that cells get to have. This pattern, any more than the actual structure of the termite colony or the precise pattern of a spider web, is not in their genome. This is not directly in our genome either. Where this comes from is the working out of the physiological software that this hardware enables.

We have to ask a number of questions. Given that DNA specifies the hardware, where does the anatomy come from? How do cells know what to make and when to stop? If a piece is missing, people like us want to know how do you repair it? How do you convince them to regrow what they need to regrow? As engineers, we also ask, what else are they willing to do? If we knew how to communicate with these cells, what else would they be willing to build? I'm going to show you some of those towards the end of the talk. One cool thing about this process is that it's not hardwired. This is not simply the emergence of complexity. This is actually the emergence of intelligence.

Slide 16/41 · 19m:45s

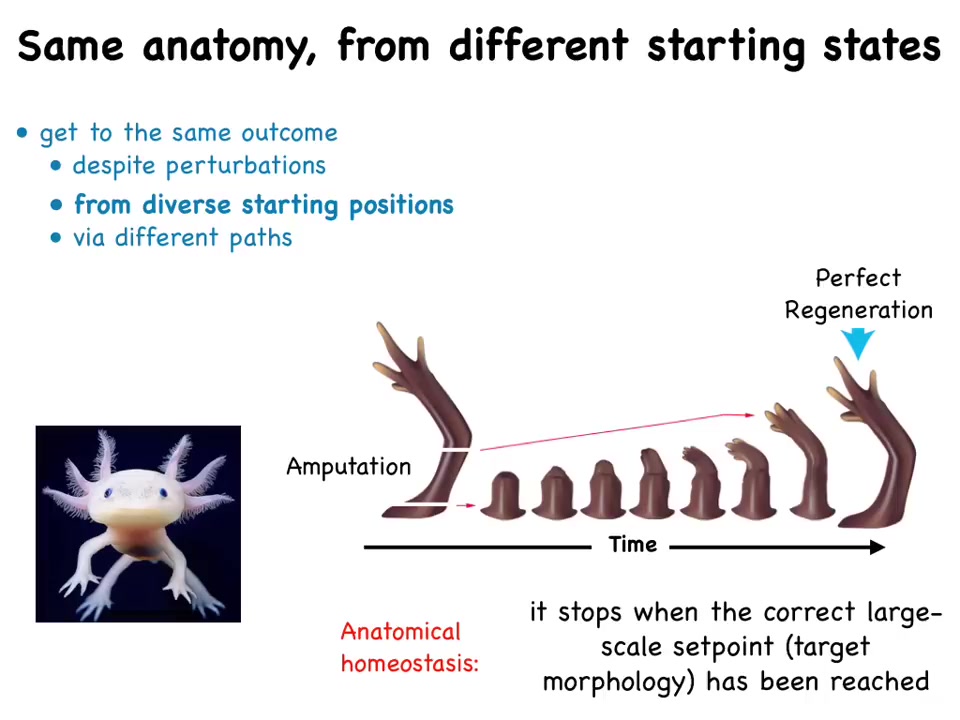

What kind of intelligence? Goal directedness of a certain kind in anatomical space. So here, this is an amazing creature, this axolotl, and they regenerate their limbs, their eyes, their jaws, portions of the brain and heart. If they lose a limb, and they do this all the time, they bite each other's legs off constantly, wherever they lose the limb, the cells will work very hard to build exactly what's needed and then they stop. The most amazing thing about this process is they know when to stop. How do they know when to stop? They stop when the correct axolotl arm has been completed. It's a process of anatomical homeostasis. If you deviate them from their goal, they will get right back there and stop.

Slide 17/41 · 20m:25s

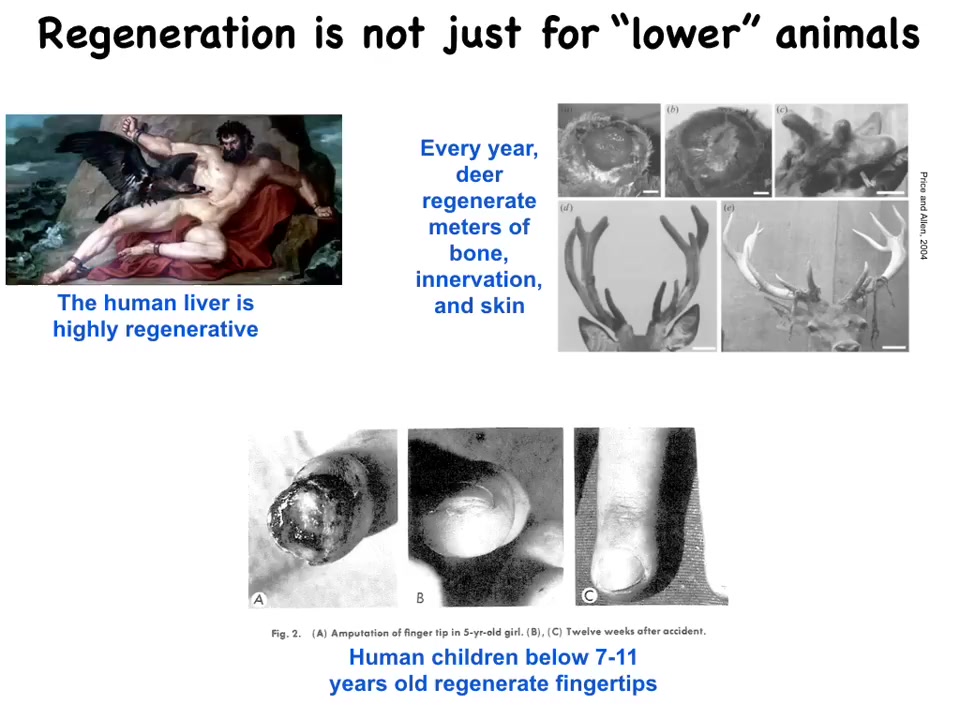

Mammals are a little bit regenerative, so humans can regenerate their liver. Kids up to a certain age can regenerate their fingertips. And deer can regenerate bone and vasculature and innervation up to a centimeter and a half per day of new growth. So we have some of these capacities, but not terribly much.

Slide 18/41 · 20m:49s

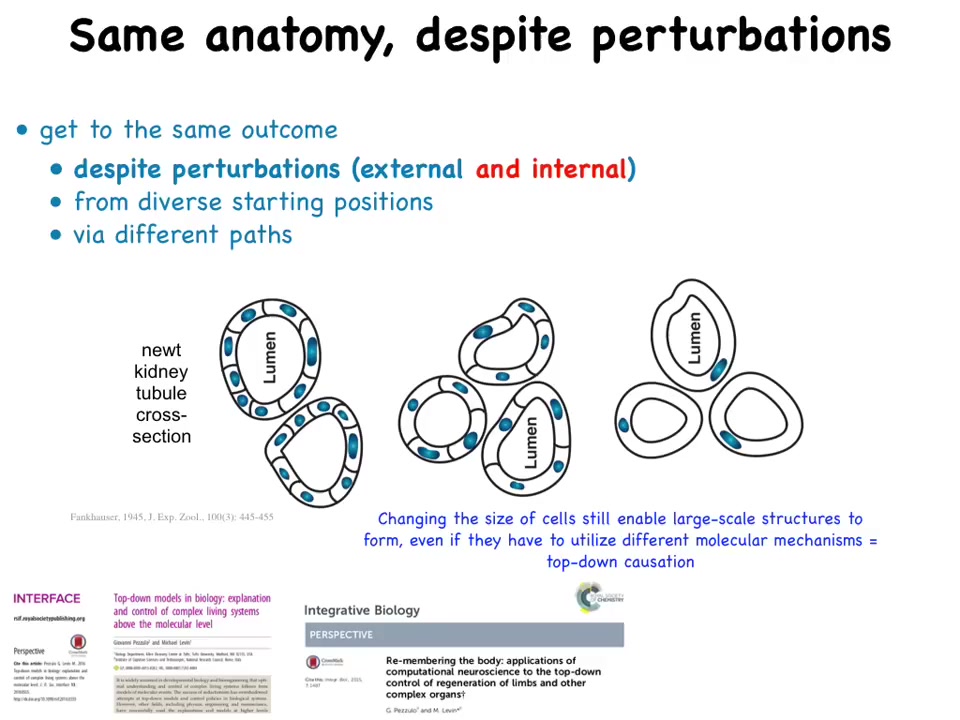

I want to show you one of my favorite examples of this kind of intelligence and what it means to be a being coming into this world. This is a cross-section through a kidney tubule in the newt. So normally it's made of 8 to 10 cells or so. But one trick you can do is by increasing the amount of genetic material in these cells, you can make the cells much larger. So the cells will scale to the amount of genetic material, but the lumen stays the same size. And the only way you can do that is by using fewer cells to build the same structure. And so the first amazing thing is that you could have extra copies of all your genetic material, no problems, everything still works. Second, you can have huge cells and you will scale the number appropriately, no problem. The most amazing thing happens when you make truly enormous cells, and at that point, one cell will just bend around itself and give you that same lumen.

Now this is a completely different molecular mechanism than this. This is cell-to-cell communication. This is cytoskeletal bending. So this is top-down causation in the service of a particular journey in anatomical space that this system needs to make. It can use different tools at its disposal. It can use different molecular tools to get the job done. And we can ask all kinds of interesting questions about how it knew that was the thing to do?

But just think about what it means to be a newt coming into this world. You can't depend on anything, never mind the environment, never mind the injury that somebody else might come along and bite your leg off. You can't even count on your own parts. You don't know how many copies of your chromosomes you're going to have. You don't know what the size of your cells are going to be. You don't know how many cells you're going to have. You have to come in on the fly and take this journey in anatomical space and you can't overtrain on your evolutionary priors. You cannot assume any of the things that were true in evolution going back, not just about the environment, but about yourself.

We've been studying how all these things work.

Slide 19/41 · 22m:50s

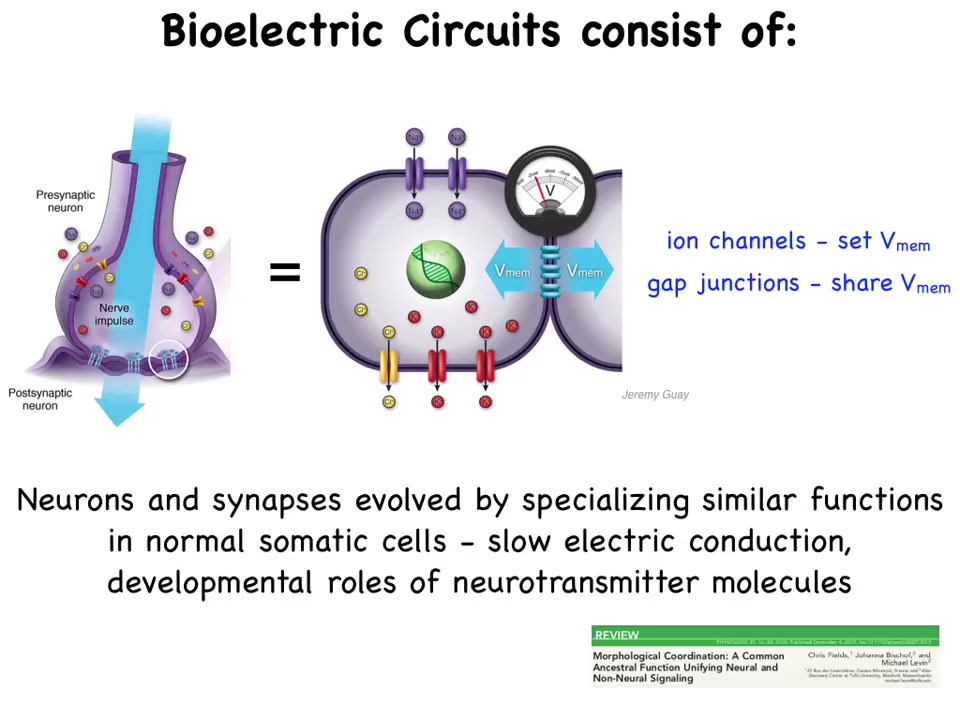

What we found out is that the capacities of brains and nervous systems for dealing with novelty, for intelligence, for navigation, for keeping memories and pursuing goals and all of that are actually incredibly ancient. They're driven by a kind of electrophysiological software that is produced in the brain by these little ion channels that set voltages, and these voltages can propagate through the network and you get this electrical activity that you can imagine going on in the brain. But that mechanism is extremely ancient. It's not specific to brains at all. Evolution discovered it about the time of bacterial biofilm, so long ago. All cells have these ion channels. Most cells have these electrical synapses. Your whole body is a giant electrical network that has many of the capacities that your brain has, but it does them slower.

If you take almost any neuroscience paper and do a find-and-replace, we made an AI system to do this for people. It flips some words around. If instead of "neuron" you say "cell," and instead of "millisecond" you say "hour," you get a pretty reasonable developmental biology paper about how, whereas your brain thinks about moving you in three-dimensional and now linguistic space, the rest of your body has been thinking about moving you through anatomical space, from being an egg to being whatever we become.

These electrical networks are literally the cognitive medium of the collective intelligence of your body cells. Whereas you are the product of the collective intelligence of your neurons, your body is the product of the collective intelligence of the rest of your cells behaving in anatomical space. And when we learn this interface, this bioelectrical interface, we get access to an API that's very powerful.

Slide 20/41 · 24m:43s

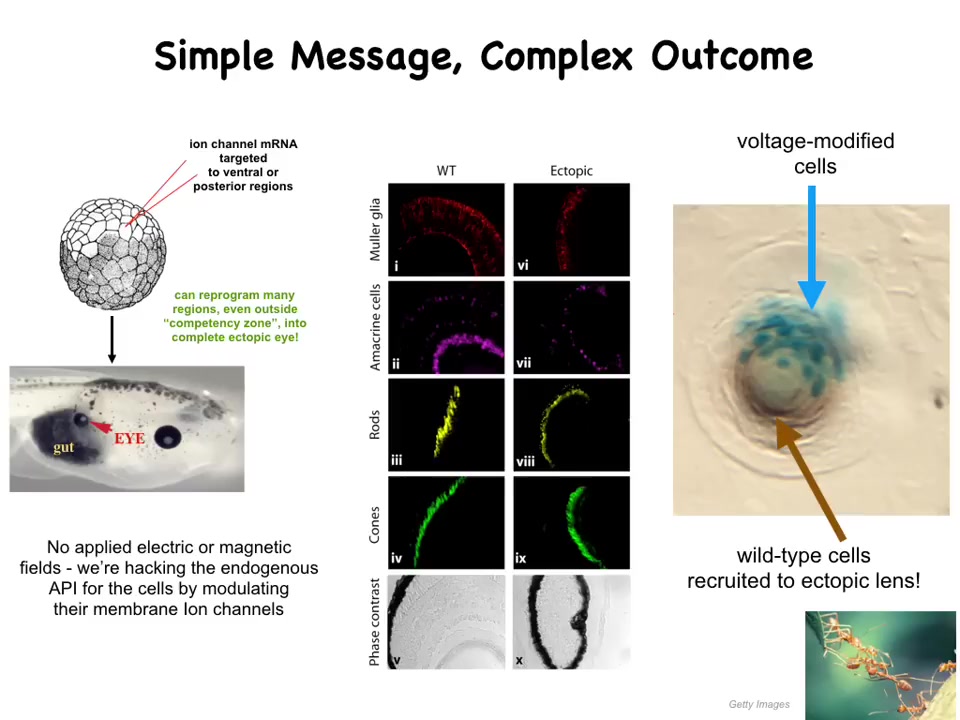

Here's one example. None of this has to do with applied electric fields. There are no electrodes, no magnets, no waves or frequencies or anything like that. We're hacking the natural interface that cells use to shape each other's behavior, which is the set of ion channels and gap junctions on their surface. So we can, for example, insert some potassium channel proteins here to create a particular voltage pattern. That voltage pattern is a signal to these cells. What these cells will do is build an eye.

This is not like the eye I showed you before. That was a transplant. This is not like that. We have said to these cells, which normally make a gut, here's a particular voltage pattern. It happens to be the same pattern that they normally use to make an eye. The cells see it, and they build an eye. These eyes, if you section them, have the same lens, retina, optic nerve, all this stuff.

Like any good subroutine call, we did not have to give it all the information on how to build an eye. In fact, we don't have any idea of how to build an eye. We don't know how to talk to all the stem cells, all the genes that are there that have to be turned on. The eyes are very complex. We want a high level stimulus that prompts the cells to do what they already know how to do.

This is a lens sitting out in the flank of a tadpole somewhere. The blue cells are the ones that we actually injected with our ion channel, but there's not enough of them to make an eye. What they've done is they've recruited all these other normal cells to participate with them to be an eye. We've studied this. There's a conversation that happens. These blue cells acquire a new belief. They believe that they should be an eye and they tell all the other cells, "You should be working with us to make an eye."

These other cells are saying, "No, we should be skin or gut or whatever." They have this back-and-forth conversation. Sometimes these guys win and you get an eye, and sometimes the rest of the cells win and they ignore us and stay whatever tissue they're supposed to be.

There are other collective intelligences like ants that do this when two ants or a couple of ants discover something that it's too big for them to carry by themselves. They recruit their neighbors. All these competencies — this ability to hold a goal in anatomical space, to try to convince others of your goal, to get buy-in to your story about what should happen, and sometimes you win and sometimes you lose that battle — are native competencies of the tissue. We didn't have to build in any of that. It's already there.

Slide 21/41 · 27m:11s

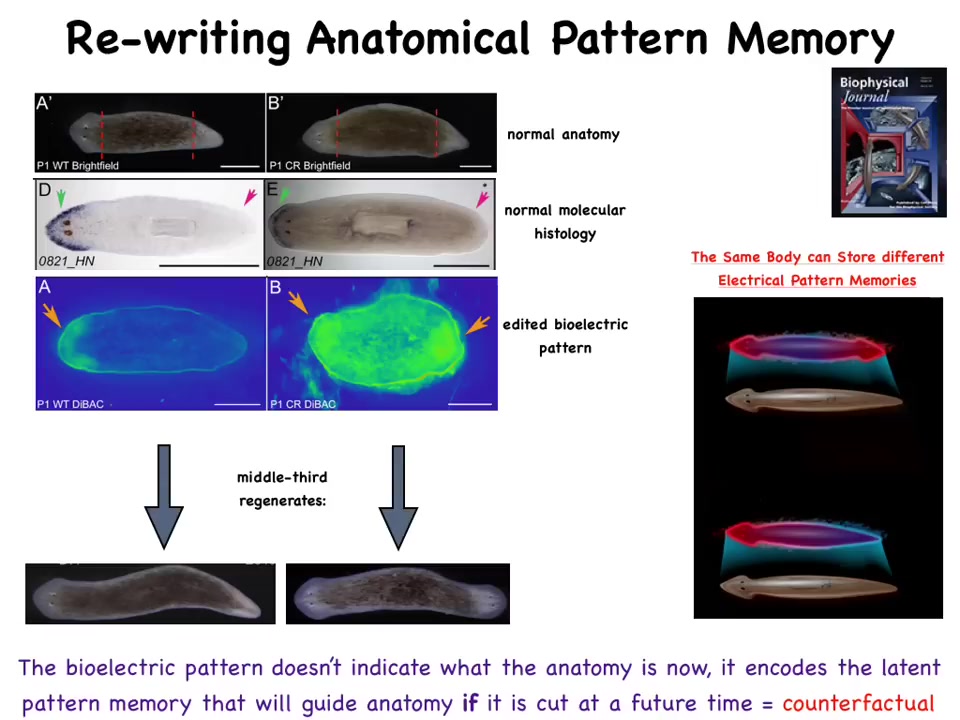

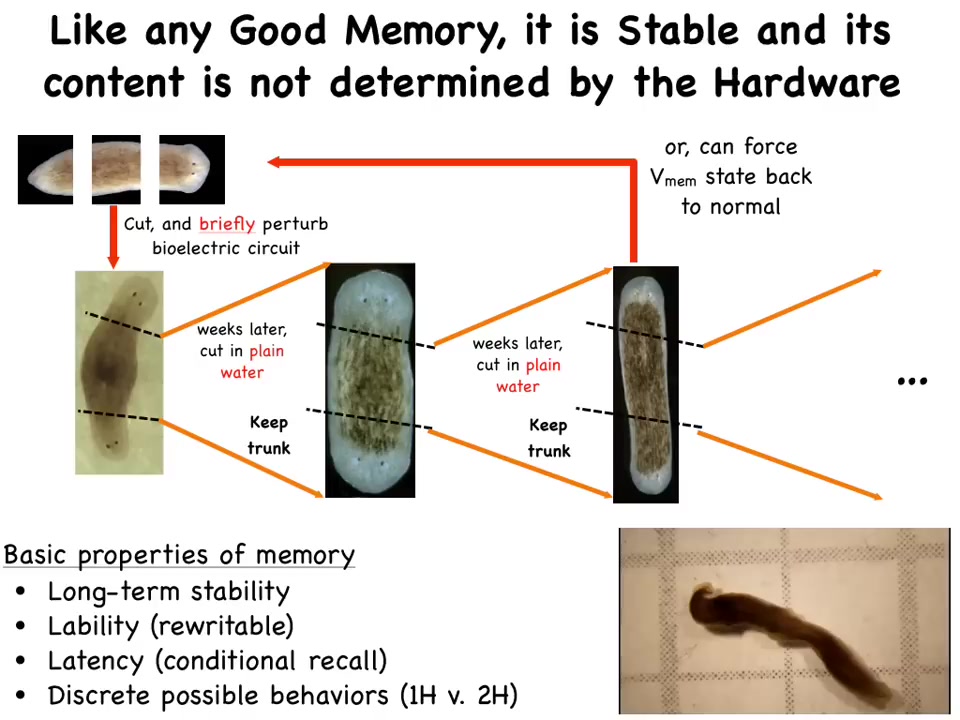

In the planaria, I told you that they regenerate, and if you cut off the head and the tail, this middle piece will reliably regenerate this normal worm with the right number of heads. Here's the bioelectric pattern memory. We're literally seeing the memories. Think of it as a brain scan, except not in the brain. We're literally seeing the representations in this tissue of how many heads a normal planarian should have.

So we can go ahead and change them. We have the technology: instead of one head, we can say, no, you should have two heads. Here's a perfectly normal animal whose tissues, not the animal itself, not the brain, but the tissues, have been incepted with a new form of memory that says that if you get cut in the future, a proper worm should have two heads. If you cut that worm, this is what you get. Again, not Photoshop, these are real.

So a single, anatomically normal worm body can store at least two different ideas of what it will do in the future if it should happen to get injured. The reason I call this a pattern memory is that it's a memory of the collective intelligence of the body.

Slide 22/41 · 28m:23s

The reason I call it a memory is because if you cut these two-headed worms in perpetuity, they maintain two-headedness with no more change. And so this has all the properties of memory. It's stable, but it's rewritable. Not genetic. We haven't touched the genetics. The genetics are completely untouched. So the question of where is the anatomy of this, the answer to the genome is not really the right answer. Yes, the genome encodes hardware that by default will say one head, but that hardware is reprogrammable. And here you can push it into this other state.

Slide 23/41 · 29m:00s

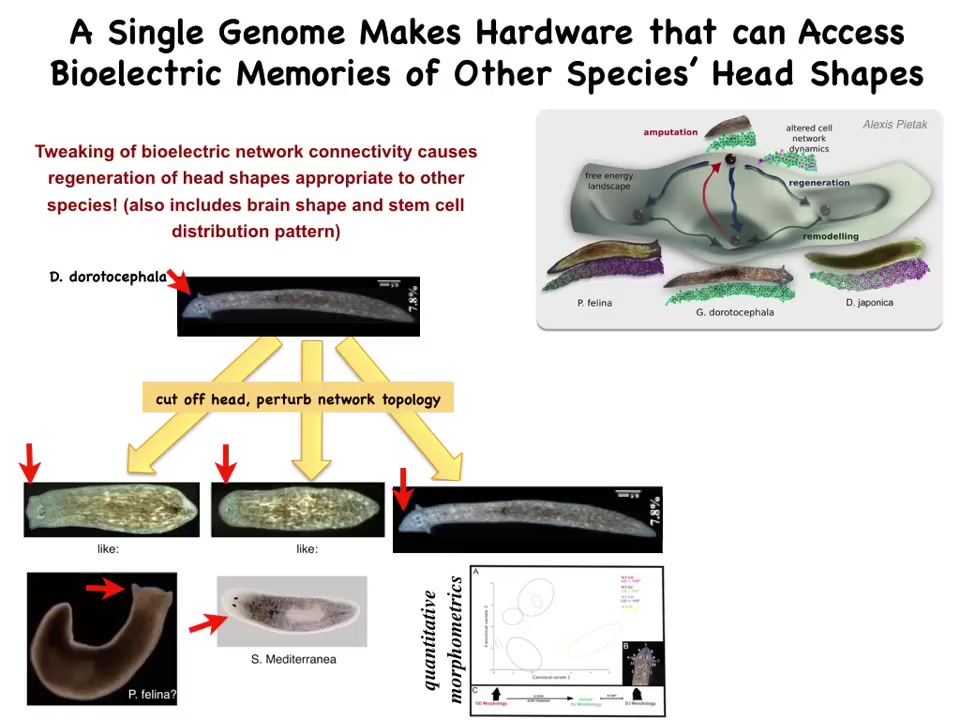

You could push it into a state belonging to other species. So this triangular-headed planarian can make flatheads like a P. falina, roundheads like an S. mediterranean. This hardware, with no genetic change, does this just by altering the bioelectrical patterns that serve as the memory here. They will visit these other attractors in the anatomical state space where these other creatures normally live, about 100 to 150 million years of evolutionary distance.

Not just the shape of the head, but the shape of the brain and the distribution of stem cells are all the same as these other species. So what we're seeing here is, first of all, the hardware-software distinction in biology, the reprogrammability of biology. The API, once you understand how the cognitive glue works that binds individual cells into a more global vision of what they should be doing, now you can start communicating with it, rewriting goals, and really collaborating with the material. I do a whole other talk on engineering with gentle materials. This is not metal and Legos. This isn't a gentle material. You're a collaborator with that material. You're not micromanaging it.

Slide 24/41 · 30m:13s

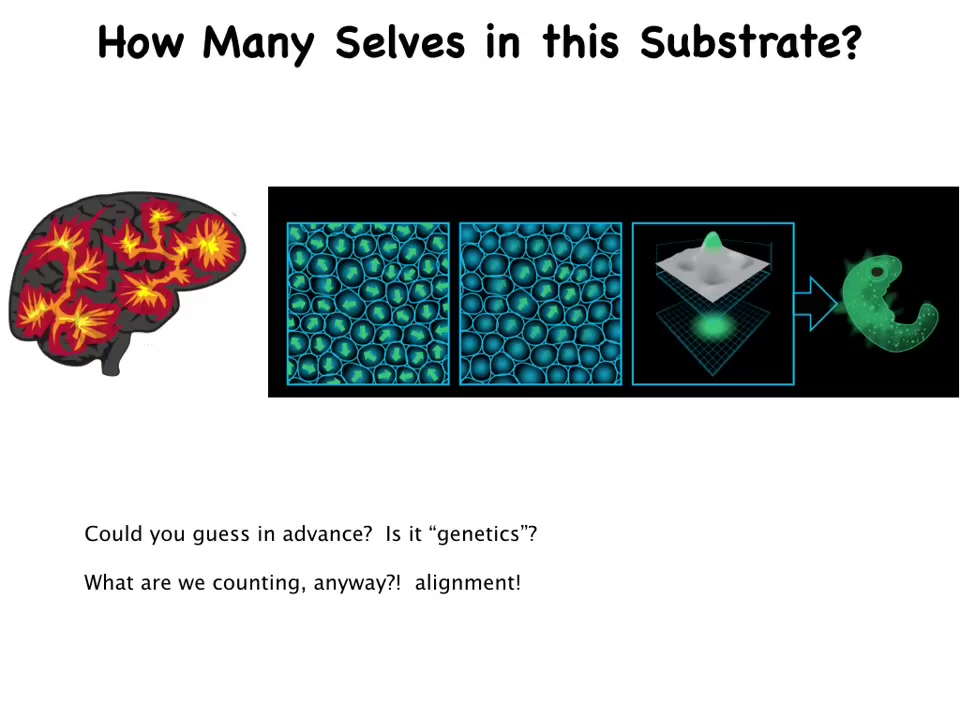

Let's think about where these cells come from. Here's a blastoderm. Let's say it's 10 or 50,000 cells in the beginning. We look at that and we say that's one embryo. What are we counting when we say that's one embryo? What is there really one of?

Well, what we're really counting is stories. We're counting how many different stories there are in this tissue that the cells are committed to as far as where they're going to go in anatomical space. We're counting commitment. But they're aligned.

Under normal circumstances, all of these cells are aligned. They've bought into one single story and this is what they're going to build. That's what we mean when we say there's one embryo.

You might ask a similar question in the brain. If I showed you a human brain and you didn't know what a human was, you could ask how many individual cells fit here? What's the density of cells per unit volume of this medium? In computers, we have some idea of how much information fits into a certain number of transistors. But here we don't know.

Slide 25/41 · 31m:14s

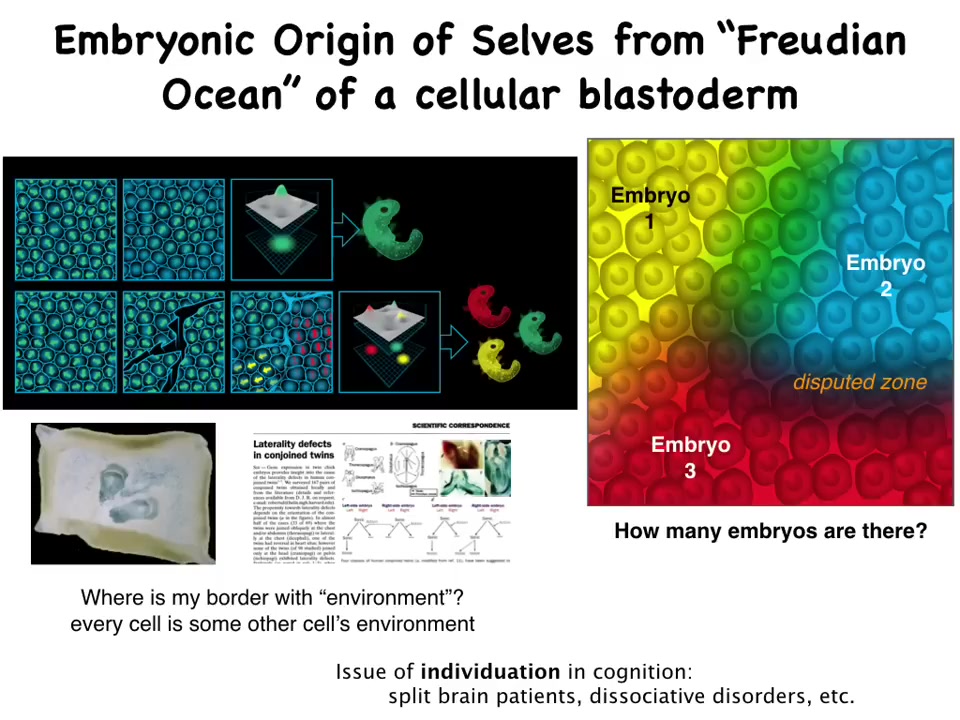

And the amazing thing is that if you take this early embryonic blastoderm, use a needle to scratch, and I used to do this in duck embryos when I was a grad student. What happens is that each of these little islands doesn't feel the presence of the others for a while until it heals up. It goes and self-organizes an embryo. Then you get conjoined twins like this. You can get triplets, you can get all sorts of things.

The number of individuals that come out of this excitable medium is not known in advance. It's certainly not determined by genetics. It could be 0, 1, probably up to half a dozen. So how many cells, how many individuals are really in there? You don't know until they self-organize. That process of self-organization is critical.

One of the things they have to do is determine boundaries. Where do I end and the outside world begin? Or, in this case, where some other embryo begins. Some of the cells at this intersection are a little confused. That's why in conjoined twins, one of the twins will often have a laterality defect. We figured out why in 1996 for the first time.

Why do conjoined twins tend to have laterality flipping in one of the twins? It's because these cells can't quite tell. Am I the right side of this guy or am I the left side of this guy? But overall, they have to establish their boundaries.

The analogy to the brain is still apropos because we have lots of examples of split-brain patients, dissociative identity disorder, all of these where it's not obvious that our brain hosts just one coherent self.

Slide 26/41 · 32m:48s

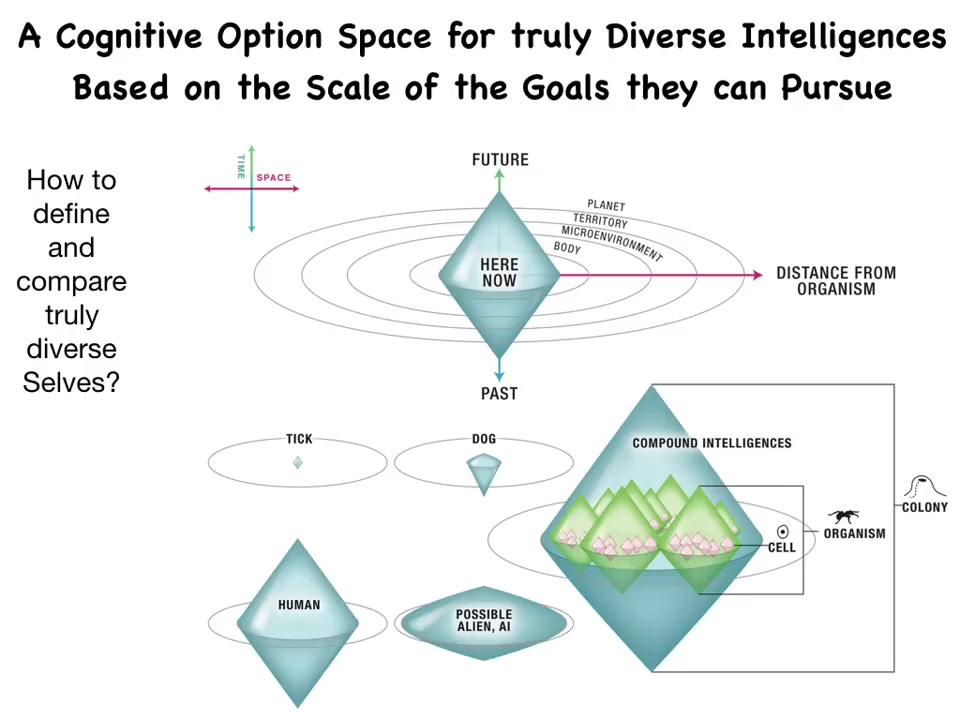

One way that I've been working on to start thinking about how to understand beings, goal-directed beings, in very different embodiments is to put aside the question of what you're made of or whether you were engineered or evolved, and really just to ask about the size of your goals. What's the largest goal you're capable of pursuing?

That gives rise to this idea of a cognitive light cone. It's like a Minkowski cone, except upside down. If you collapse a space onto this axis and time onto this axis, you can see that different kinds of creatures can have different scopes to the goals that they can build, that they can conceive of.

Humans may be unique: their cognitive life is bigger than their own lifespan. That may provide for some interesting psychological pressures. If you're a goldfish, you may have some goals 20 minutes into the future, but those goals are probably achievable. It's very likely that you will live for the next 20 minutes. All your goals are achievable.

Many humans know their goals are guaranteed not achievable because they can see and commit to goals that are bigger than their known lifespan. This is something that makes humans unique.

We are all compound bodies of lots of little subunits that have their own goals in various spaces that compete, cooperate, and interact with each other.

Slide 27/41 · 34m:17s

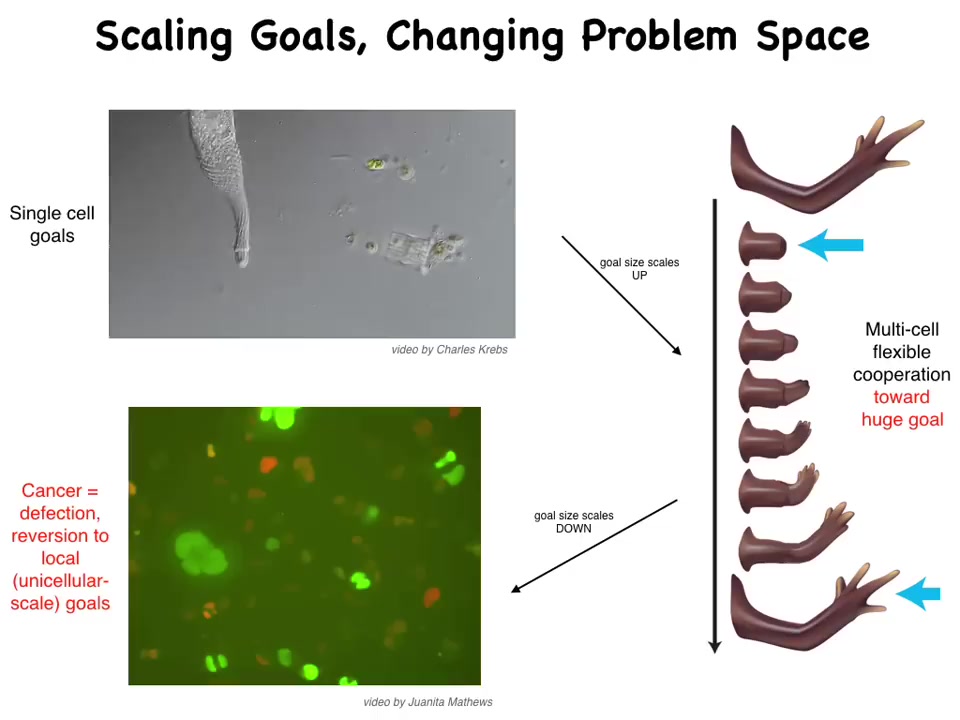

Now, this has this crazy way of thinking about things as this cognitive light cone has clinical implications. I like this not just because I want to make advances in biomedicine, but also because this is how we know that some of this philosophizing is on the right track.

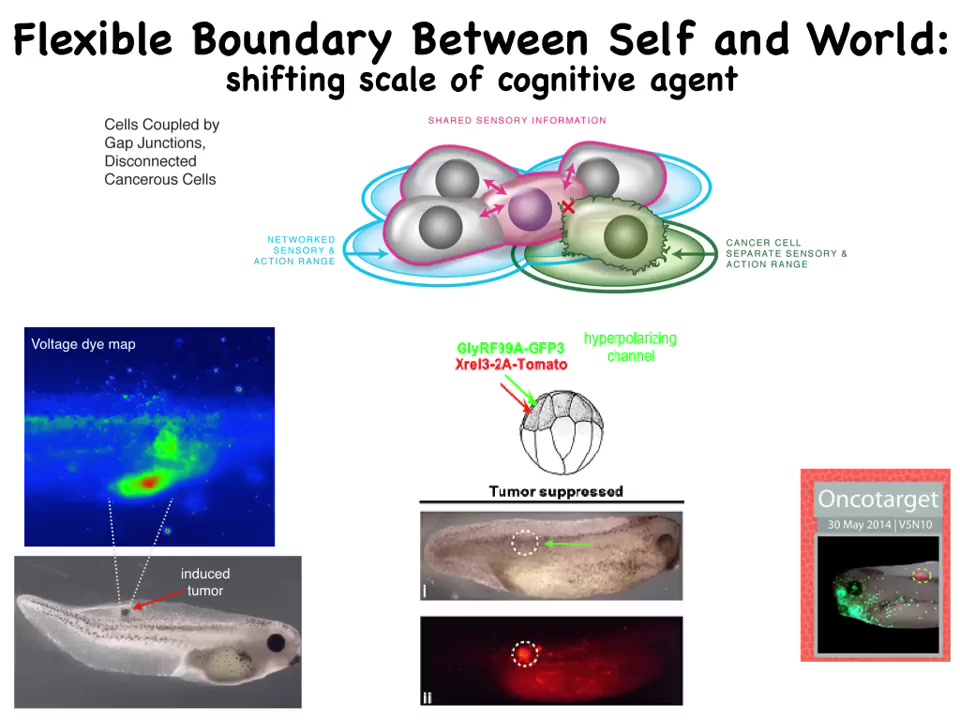

So this is the tiny cognitive light cone of a single cell. All it cares about is its local states here. But what evolution did is scale it up via mechanisms that I haven't had time to talk about, but bioelectricity is one of them. Now the cognitive cone is huge. It's the size of this whole limb. All of these cells are not pursuing their own local agendas. They're pursuing this giant goal.

But that has a failure mode. That failure mode is cancer. Once individual cells disconnect from the network, they roll back to their unicellular selves. They can't conceive of these grandiose goals anymore. All they can remember is proliferate as much as you can and eat as much as you can and go wherever life is good. This is a human glioblastoma; that's cancer.

Slide 28/41 · 35m:24s

And so one of the things you might do then is, on this weird way of looking at things, instead of targeting the genes or being worried about genetic defects or trying to kill these cells with toxic chemotherapy, what if we just forcibly reconnect them to the rest of the organism?

So here's a tadpole injected with a human oncogene. The bioelectric imaging already tells you the first thing that happens when these cells transform is that they disconnect electrically from the rest of the body. They acquire this aberrant voltage pattern. And if we co-inject an ion channel, it doesn't kill the cells. In fact, you can see here the red is the oncoprotein. It's very strong. It's all over the place. This is the same animal. There's no tumor. Because even though the hardware of these guys is a little screwy, because they've got this oncoprotein, they're being forced informationally to be part of this continuum. That causes them to be part of a collective intelligence that just builds nice organs.

Again, we're able to do all this: make eyes, normalize tumors, induce leg regeneration in animals that don't regenerate, and so on. Not because we're so smart or we're doing some crazy synthetic biology. All we're doing is hacking the native competency of the tissue.

One other thing I wanted to say is that these cancer cells are not more selfish than normal cells. There's a lot of game theory that models cancer as being more selfish. I don't think they're more selfish. I think they have smaller cells. So you can be as selfish as you want, as long as your cognitive light cone is large enough to encompass many, possibly all beings, and then it's fine.

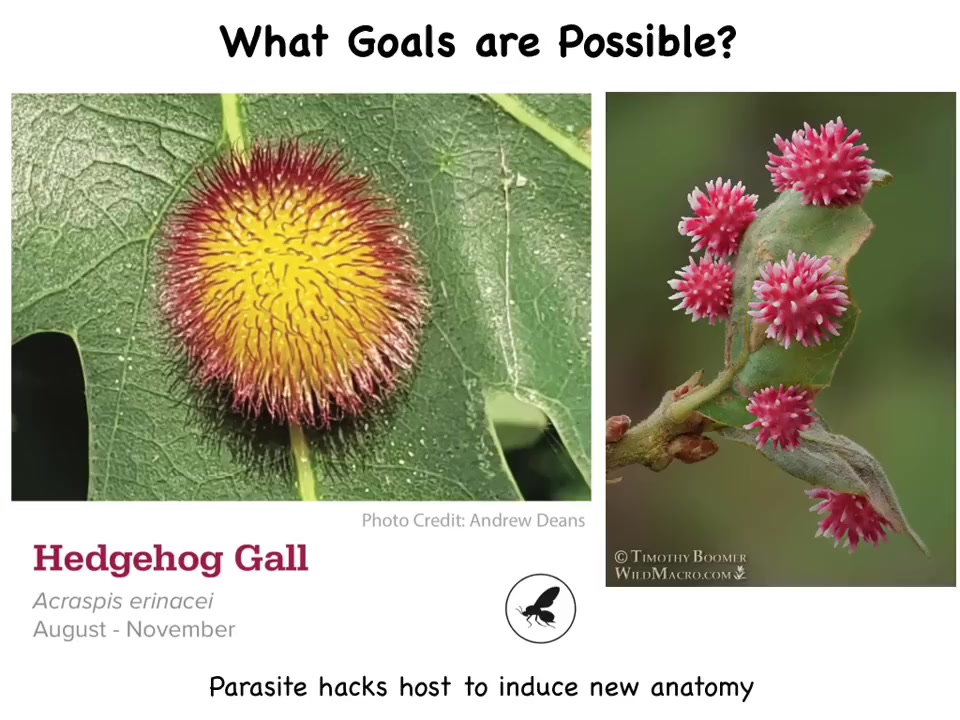

This is something that Bill and our other collaborators are actually working on: increasing the cone of compassion outwards. The interesting thing about us engineering all this is that we are not the only bioengineers.

Slide 29/41 · 37m:20s

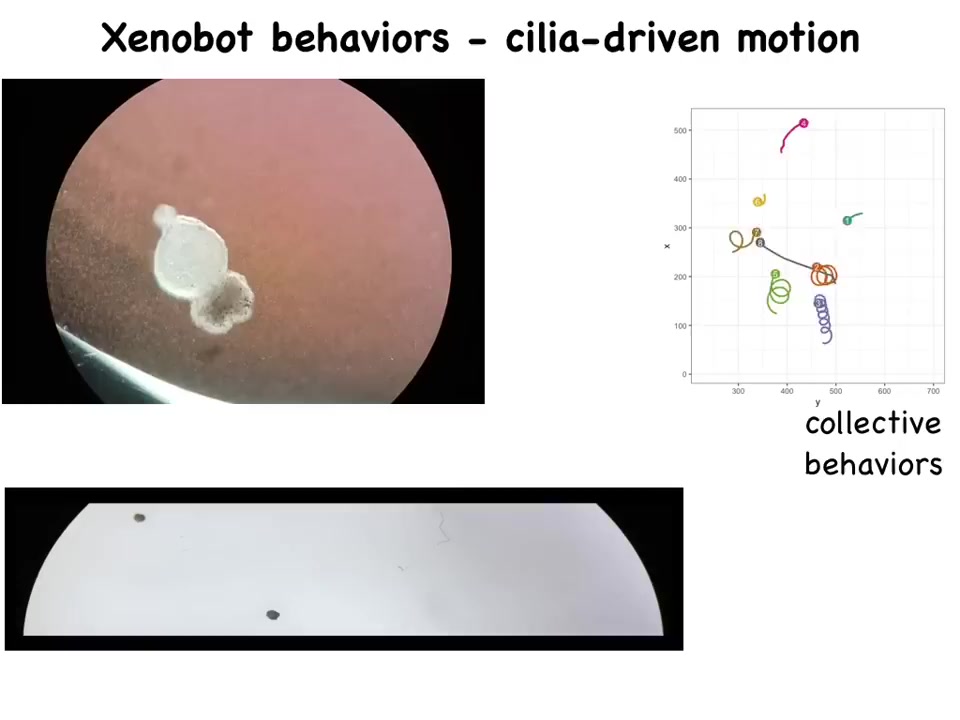

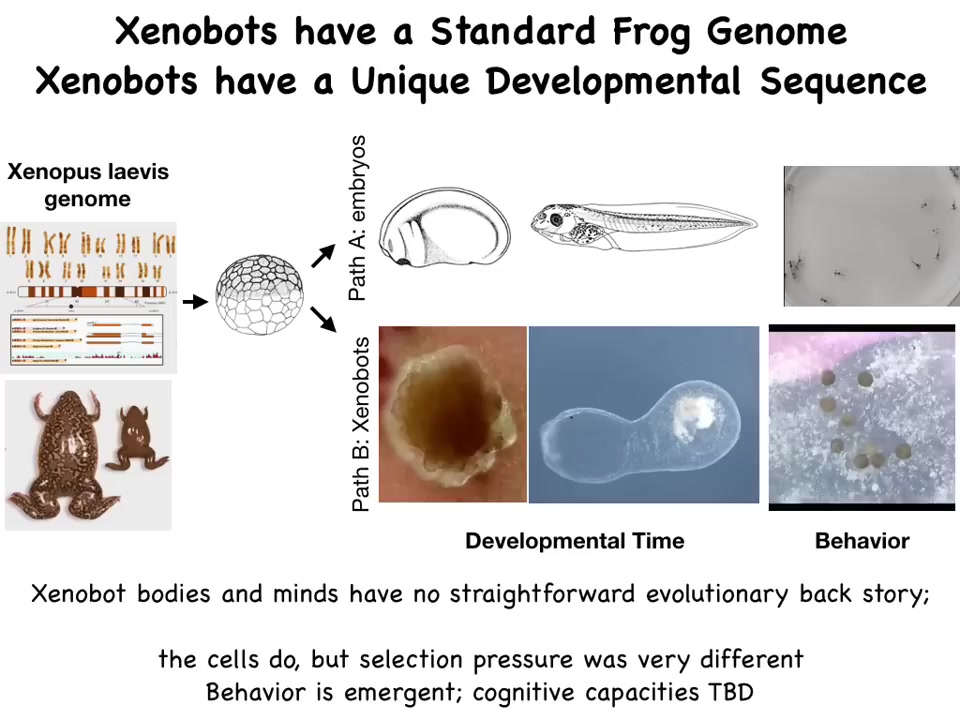

This is a non-human bioengineer. This is an oak leaf. You might think that acorns always make oak trees and these leaves, we know what the oak genome does. It makes these flat green things. But here comes this bioengineer. Doesn't change the genome. The hardware is perfectly capable. You don't need to rewire it. You don't have to explain to this crowd why you don't use a soldering iron when you want to go from PowerPoint to Microsoft Word on your laptop. This animal takes advantage of exactly that, which is that it lays down some signals that prompt the cells to build something completely different. This is made of the plant cells, not the animal. Would we have any idea that these cells are capable of building something like this or like this if we hadn't done this? We would not. And so for that reason, in our lab, we make a number of synthetic creatures to really test the plasticity, the ability of the hardware to undergo novel scenarios.

We call these Xenobots because what happens here is that some skin cells are harvested from the top of a frog embryo. They self-assemble into this little thing, which is a bio-robotics platform, and we are interested in knowing where their goals come from.

Slide 30/41 · 38m:38s

So here you can see they swim. They can go in circles. They can patrol back and forth. They have collective behaviors.

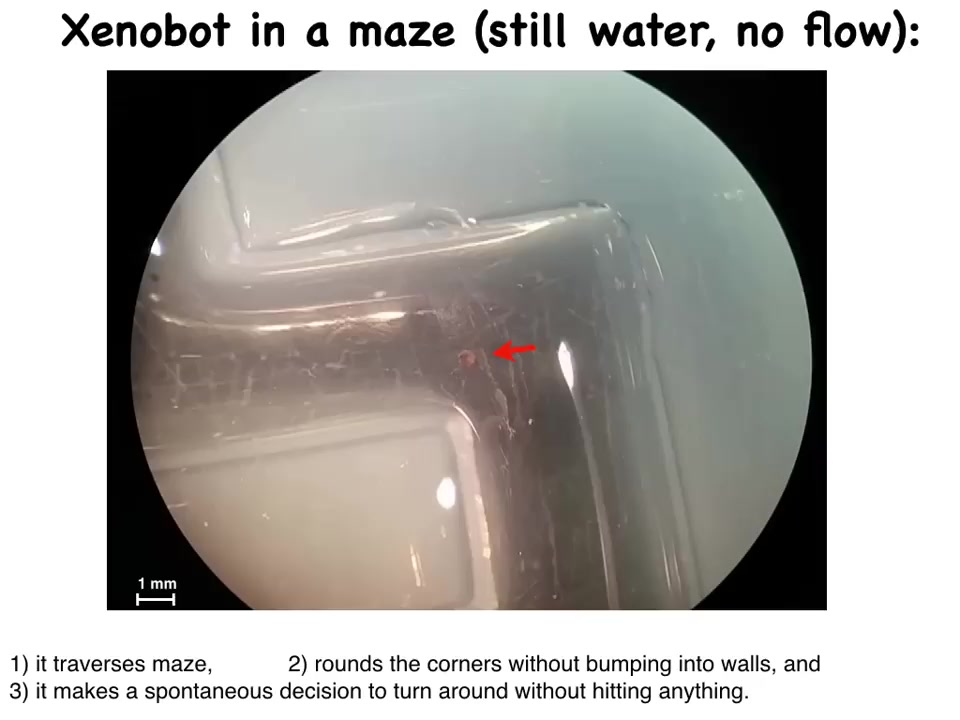

Slide 31/41 · 38m:45s

Here's one going through a maze. It comes down this arm of the maze over here. It's going to take a turn without bumping into the opposite wall. It takes a turn. At this point it turns around and goes back where it came from.

Slide 32/41 · 39m:01s

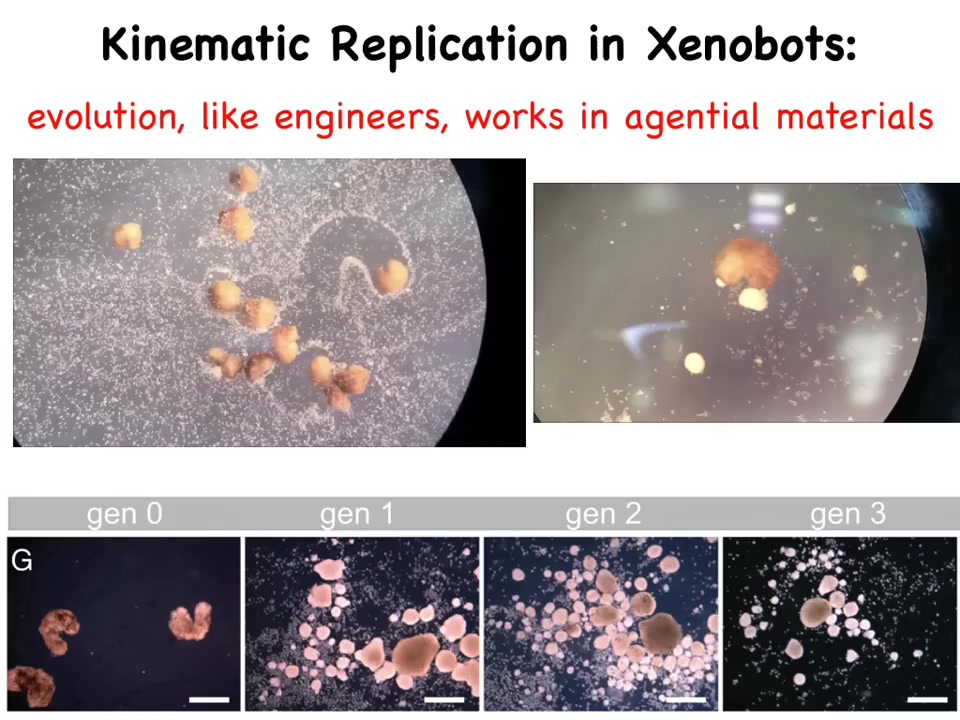

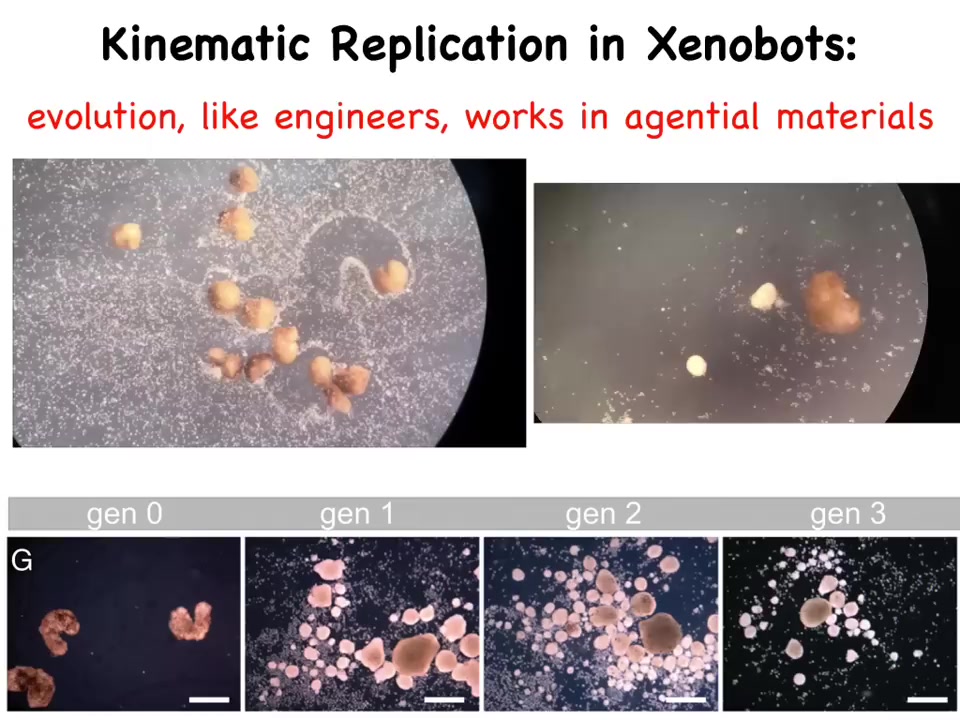

Remember, this is just skin. There's no nervous system. There's nothing in there. One amazing thing they do is kinematic replication. So if you provide them with loose skin cells, they will run around and combine them into these little piles and work them and polish them.

Slide 33/41 · 39m:25s

Because they're working with an agential material, for the same reason we were able to do this, not because we know how to change the way these cells behave, but we liberated them into a new context. These little piles mature into the next generation of Xenobots. Guess what they do? They run around and they make the next generation and the next. This is basically von Neumann's dream of a robot that makes copies of itself from materials it finds in the environment.

Slide 34/41 · 39m:43s

If you ask, what does a frog genome know? Well, it certainly knows how to do this, the hardware that goes through this developmental sequence and then has these kind of behaviors. Here's some tadpoles. But apparently it also can do this. And the amazing thing is that there's never been any Xenobots. There's never been any evolutionary pressure to be a good Xenobot. Where did all this come from? Why is there this weird developmental stage of this Xenobot? This is an 80 day old Xenobot. It's changing into something. We have no idea what. They have their own behaviors. They do this kinematic replication that no one else, no other organism does. So this is really the thing. When you make novel collective intelligences that have never been here before, and that includes financial structures, social structures, Internet of Things, we make these things all the time. We really don't know where their goals come from, what their goals are going to be, what their capacity for problem solving is going to be. We need to understand.

Lest you think that this is special, these cells come from an amphibian. They come from an embryo. You might think amphibians are plastic. Embryos are pretty plastic. This is probably some crazy embryonic cell thing.

Slide 35/41 · 40m:55s

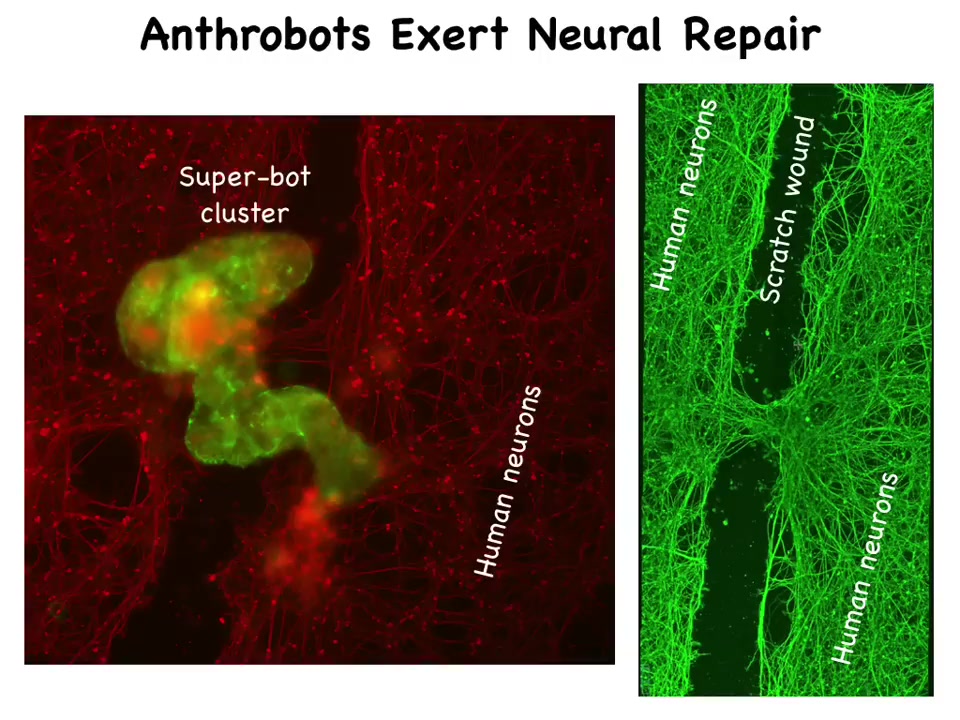

Here is this little creature. If I asked you what you thought this was, you might think we got it off the bottom of a pond somewhere. If you were to sequence its genome, you would see 100% Homo sapiens. These are human cells. They come from an adult human patient, no embryo stuff. Adult human tracheal epithelial cells. They make something we call anthrobots. This is a type of a gentle intervention because these anthrobots, remarkably, we found a novel capability. The capability is, if you plated a bunch of human neurons and you scratch them, so you make a wound here, these anthrobots will traverse down the wound.

Slide 36/41 · 41m:38s

When they settle down, what they'll do is they start knitting the two sides together. They heal this neural defect.

Who would have known that your tracheal cells, which sit there quietly in your airway for decades, if you take them out and you let them have a new life, reboot their multicellularity and a new environment, they become this little motile creature that can run around, can be injected back into your body. There's no immune suppression needed because it's your own cells. It shares all the priors with your own tissues about what health and disease are, what cancer is, what inflammation is. Among other things, they can actually repair neural defects. That's the biomedical side of things, but more fundamentally.

Slide 37/41 · 42m:20s

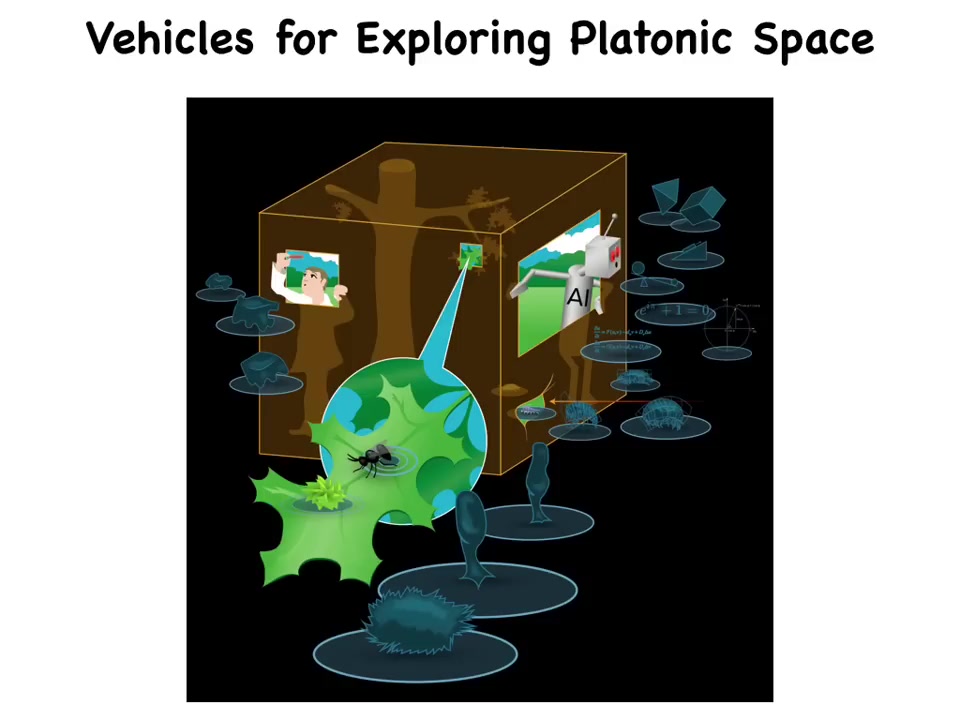

I know I'm over time, a couple of minutes. What we see is that what I think these are, vehicles for exploring a platonic space or a latent space of possibilities. When we ask where the shape and behavior of xenobots, of anthrobots, of other chimeras and the weird things that we make come from? Evolutionary selection is not where they come from. What normal embryos do is exploit a little pinprick, one single point of interface between this platonic space and the physical world, and you get your standard reliable body. But what we can do is start to enlarge these little holes by making anthrobots and xenobots and other things. We can make holes and look around and understand the structure of that space. What else is out there? What we're studying here is the structure of this space that's around us and still very poorly understood.

Slide 38/41 · 43m:27s

A couple things to finish up here. Here's what I think biology teaches us. Everything is going to change. Your body is going to change, your parts, the environment, everything is going to change. It's futile to try to hold on to specific details. In particular, biology uses an extremely unreliable material. Everything within a cell is going to go bad. There's a huge amount of noise. It's exactly the opposite of what we do in computers, where we make very reliable parts, and we try to insulate each level from the level below. You assume the level below is going to work, and then that's how we program. That is the opposite of what biology does. Biology assumes the material is going to go wrong in a million ways. Whether you're a genome that has to be reinterpreted by the species as it changes, your parts are going to change. You're going to be mutated and your environment will change. You have to reinterpret it. Brains do the same as they change over time. They reinterpret their memories.

Intelligence is everywhere. That's because the only way to do this kind of thing, this committing to salience as opposed to accuracy, means that intelligence has to be everywhere. Every part of the body has to be able to reinterpret, confabulate, tell new stories about what it saw and what information it has to solve whatever the new problems are. This is polycomputing, an idea Josh Bonnegard and I work on: biology is just a huge collection of systems which interpret and reinterpret each other's computations in different ways. The exact same computation means different things to different observers. It's an observer-focused view: you can't say what it is really computing, and from that perspective, each self is a dynamic construction. It's an ongoing process of sense-making of your own memories and the environment, and it's self-reinforcing. These are continuously modifying points of view that seek to perpetuate themselves by making sense of whatever's going on now.

This is a very deep idea from William James, where he said, "thoughts are the thinkers." If we dissolve the distinction between data and machine, and we think that the pattern itself is actually helping construct its niche, so it's constructing the cognitive system within which it will prosper, then all of us are really very complex bundles of thoughts that have closed the loop and learned to contribute to their own persistence within various physical cognitive systems.

Slide 39/41 · 46m:13s

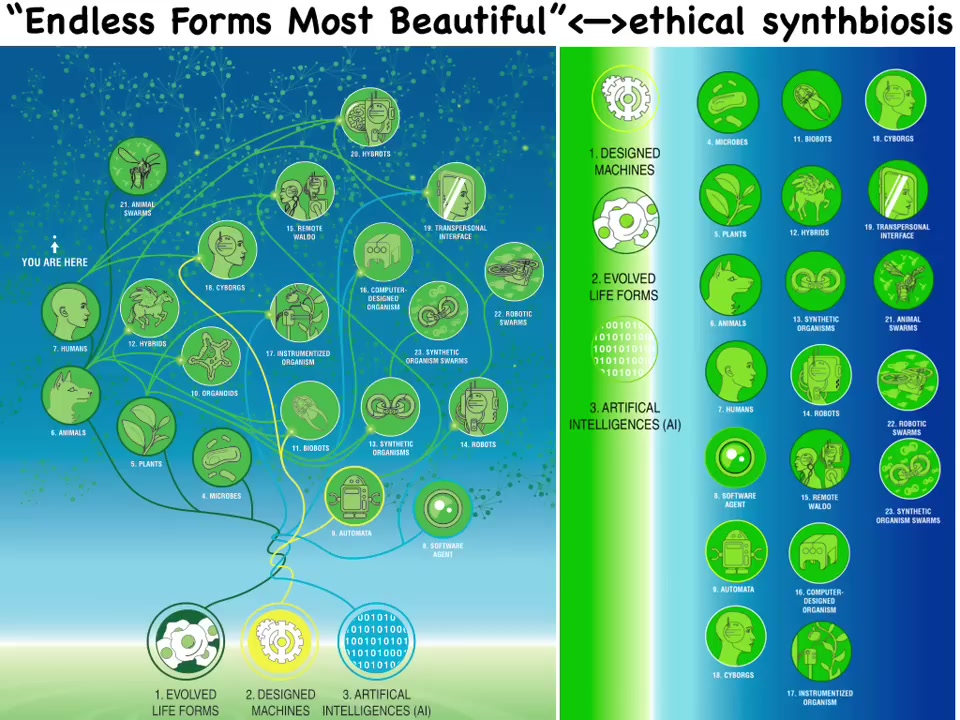

And because biology is so interoperable, because biology solves all of this on the fly, it doesn't assume anything. Pretty much any combination of evolved material, designed or engineered material, and software is some kind of viable agent. So we already have some cyborgs, and we're going to have lots more, and there are hybrots and chimeras and all kinds of different bodies and minds where all of Darwin's "endless forms most beautiful" on earth are a tiny little dot in this enormous option space of new bodies and new minds.

So the need now for a new ethical synth biosis is clear. This old idea that we can decide how we're going to relate to something based on what it looks like and how it got here. Did it come from a factory or was it naturally evolved? Those two criteria are going to be out the window. We're going to have to deal with beings that are nowhere on the tree of life with us, that don't offer us easy answers the way that, for example, current AIs do, when you can distinguish them strongly from biology. We're going to be surrounded by beings that are composites, and none of those answers will be so trivial.

Slide 40/41 · 47m:27s

And this is Jeremy Gay. He is an amazing graphic artist who drew this for me. This is a new version of Adam and the Garden of Eden because we've got our job cut out for us, but it's going to be an amazing journey because we are finally going to, I hope, get better at detecting and relating to very diverse minds all around us.

I'm going to stop here. If you're interested in any of the stuff, it's discussed in various papers here.

Slide 41/41 · 47m:53s

These are the people I want to thank. A number of postdocs and PhD students who did the work I showed you today. Lots of our collaborators. These are the people who fund us.

Disclosure: these are three spin-off companies for my group that have funded our work.

Most thanks of all to the actual animals that we deal with.

That's it. Thank you so much for listening.