Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

A talk I have at the University of Hertfordshire

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Host introduction

(00:52) Collective intelligence and morphogenesis

(01:01:20) Q&A: genetics vs bioelectricity

(01:07:08) Q&A: holography and memory

(01:11:22) Q&A: affect and morphospace

(01:13:05) Closing thanks and farewell

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/58 · 00m:00s

It's a great pleasure today for me to introduce Professor Michael Levin. He's a distinguished professor at Tufts University, as well as the Vannevar Bush Professor, and he's also director of the Allen Discovery Center and the Tufts Center for Regenerative and Developmental Biology. And I'm sure everyone here has heard about his work on xenobots. I've been told there'll be some of that at the end of his talk. Michael has requested that we refrain from asking deep questions until the end. Clarification questions throughout the talk so that we can get to the really exciting parts. Take it away. Thank you.

Thank you for having me and giving me the opportunity to share some ideas with you. If you would like to contact me, you can find me at these two websites. What I want to talk about today is our perspective on collective intelligence and, in particular, cellular behavior as a kind of collective intelligence.

Slide 2/58 · 01m:15s

I often start by thinking about Alan Turing, who needs no introduction. He was very interested in intelligence, in cognition and various embodiments, and in particular in problem-solving machines, the idea that intelligence can be manifest through plasticity or reprogrammability.

Some people may not know that he was also interested in morphogenesis, the generation of biological shape. One might wonder why the same person interested in intelligence would be interested in the kinds of questions developmental biologists deal with. He saw a very deep symmetry between these two fields, which is very important and still not really appreciated sufficiently.

This is what we work on: the idea of problem-solving living machines.

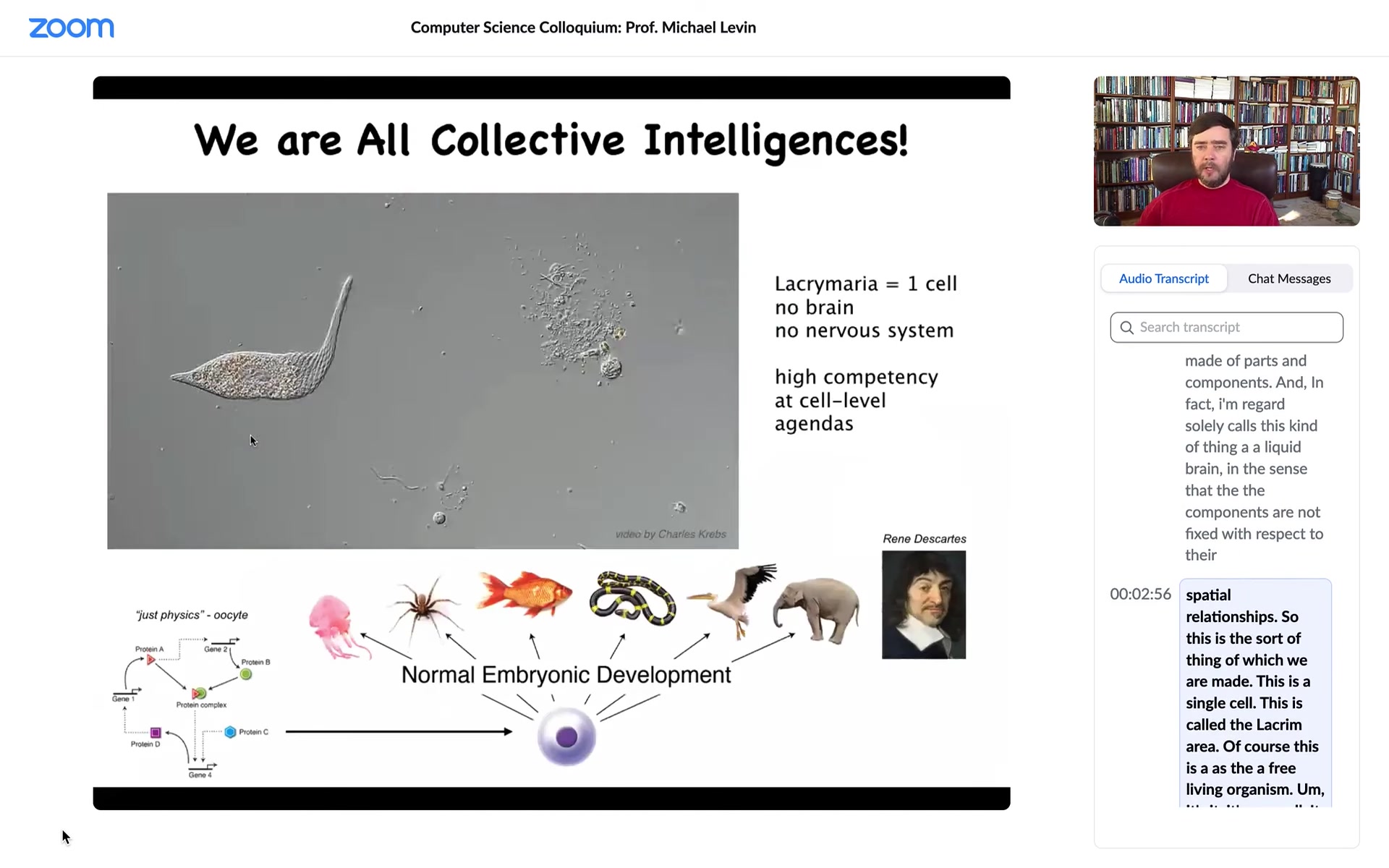

One thing we have to think about as we drill down in the biology is the traditional distinction that termite mounds, bee colonies and large flocks are collective intelligence, while humans are centralized intelligences. The idea is that actually all intelligence, certainly in biology, is collective intelligence, because we are all made of parts and components. And in fact, Ricard Soleil calls this kind of thing a liquid brain in the sense that the components are not fixed with respect to their spatial relationships.

Slide 3/58 · 02m:56s

This is the sort of thing of which we are made. This is a single cell. This is called a Lacrymaria. It has no brain. It has no nervous system. It is extremely competent in its local environment with its local goals. It has physiological, anatomical, and behavioral goals. It's very competent without the typical things that we associate with intelligence.

All of us make this amazing journey from what people call physics to cognition. We were all at one point a quiescent oocyte, a little pile of chemicals where specific molecules interact with other molecules, but eventually through embryonic development, we become something like this or maybe even something like that. The thing about this process is that it's extremely slow and gradual. There is no special point at which a magic lightning flash says, now you're a cognitive; before that you were physics and chemistry, now you're a true cognitive individual. That doesn't happen. We need to understand this scale-up. We need to understand what happens from the time that we are this to the time that we are that.

Slide 4/58 · 04m:15s

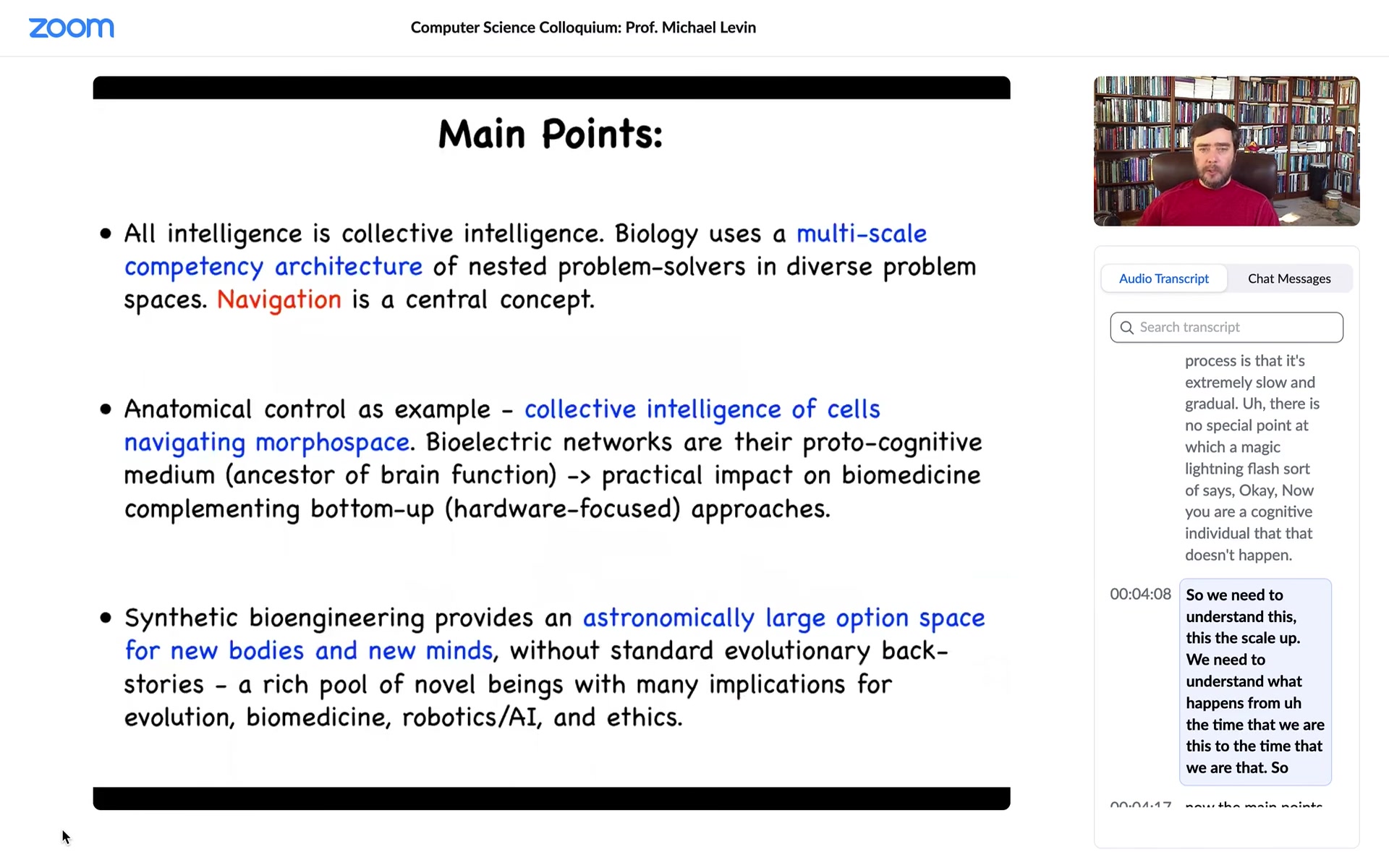

The main point today is this idea of biology's multi-scale competency architecture, which is a set of nested problem solvers in different spaces. One kind of invariant to all of this is navigation. I want to spend most of my time on this example, although there are many other examples, of anatomical control, and specifically this idea of navigating morphospace.

I will talk about bioelectrical networks, not only as the glue that binds neurons together into a coherent, emergent intelligence, but also for a much more ancient role of that same mechanism. This has many applications, for example, in biomedicine. At the end, I want to talk about synthetic bioengineering. I want to show you some novel creatures that have never existed before and talk about what this means for evolution and for many other fields.

Slide 5/58 · 05m:14s

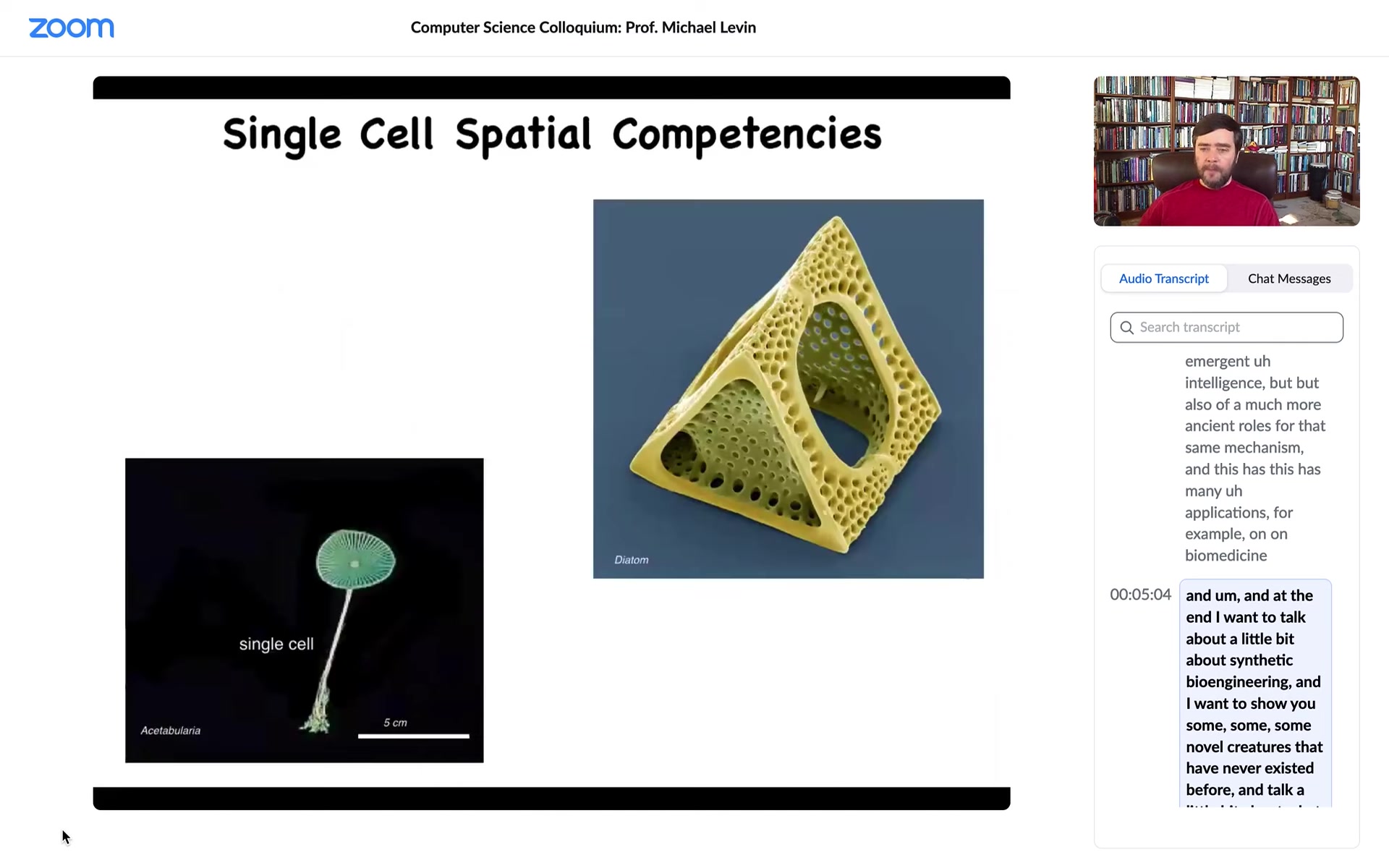

Single cells come in all shapes and sizes. This is a single cell. This is a diatom. They're very tiny. This is also a single cell.

This thing, which looks like a plant, has a nice cap and a stalk and some roots here. It's actually an alga. The whole thing could be up to 10 centimeters in size. It's also a single cell.

If you're interested in morphogenesis by differentiating cells into different types, we already start to see there's structure well below that. This thing has one nucleus and it manages to make this amazing shape without any differentiation.

Slide 6/58 · 05m:52s

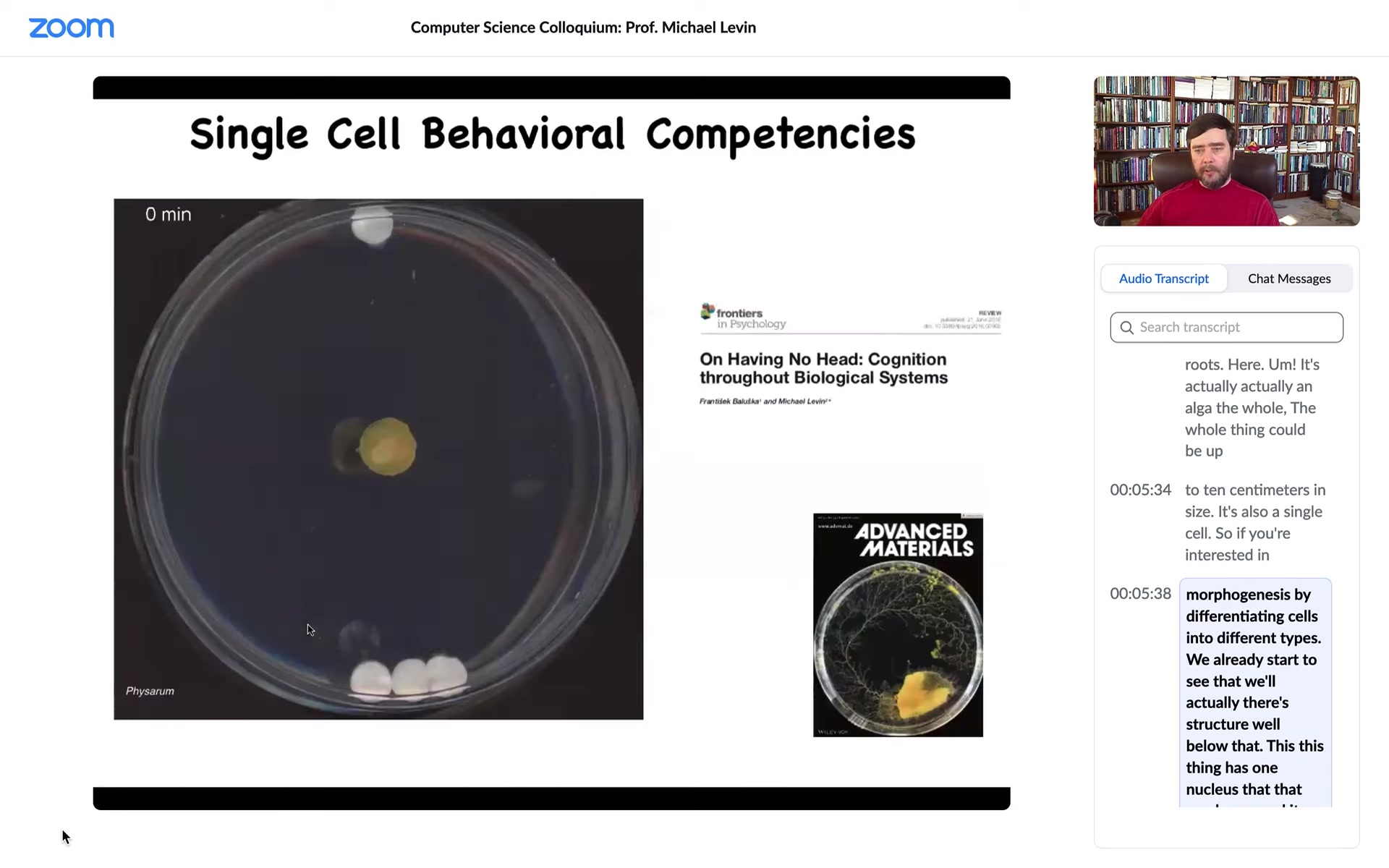

Cells are also competent in behavioral spaces. What you're looking at here, this is a slime mold called Physarum polycephalum. It has many nuclei, but it's still one cell. The whole thing is 1 cell.

You can put some objects in its vicinity. These white things are glass discs. They have no chemical on them, no food, nothing. They're completely inert. If you put three on one side and one on the other, it will consistently choose to travel towards the three. What it's doing, as we showed in this paper, is it's sensing strain angle in the medium. It is incredibly sensitive to it, and it's pulsing, which you can't see here, as a sonar to build a map of its surroundings and migrate towards the heavier object.

What's cool is that at this point, for the first four hours, it grows in all directions and this is the point at which it's got enough information and then, boom, it knows where to go. Right here, you still don't know, but at this point, bang, it starts to.

This is the field of basal cognition and trying to understand how biology was solving various problems long before brains and neurons appeared.

I want to talk about three or four things today. The first thing I want to do is twist some knobs on traditional cognitive science and talk about some unconventional agents that we can start thinking about.

Slide 7/58 · 07m:18s

This kind of picture, this is the classic painting of Adam naming the animals in the Garden of Eden. This kind of picture is prevalent in a lot of discussions in the sense that people think about finished adult organisms as the subjects of their study.

What I want to do is stretch this in a number of dimensions, both in terms of time evolution and the fact that everything comes from one cell at one point. And also the fact that drawing boundaries between different types of creatures is actually very difficult because of the interoperability of life and the ability to make chimeras. The first thing we can think about is this.

Slide 8/58 · 08m:06s

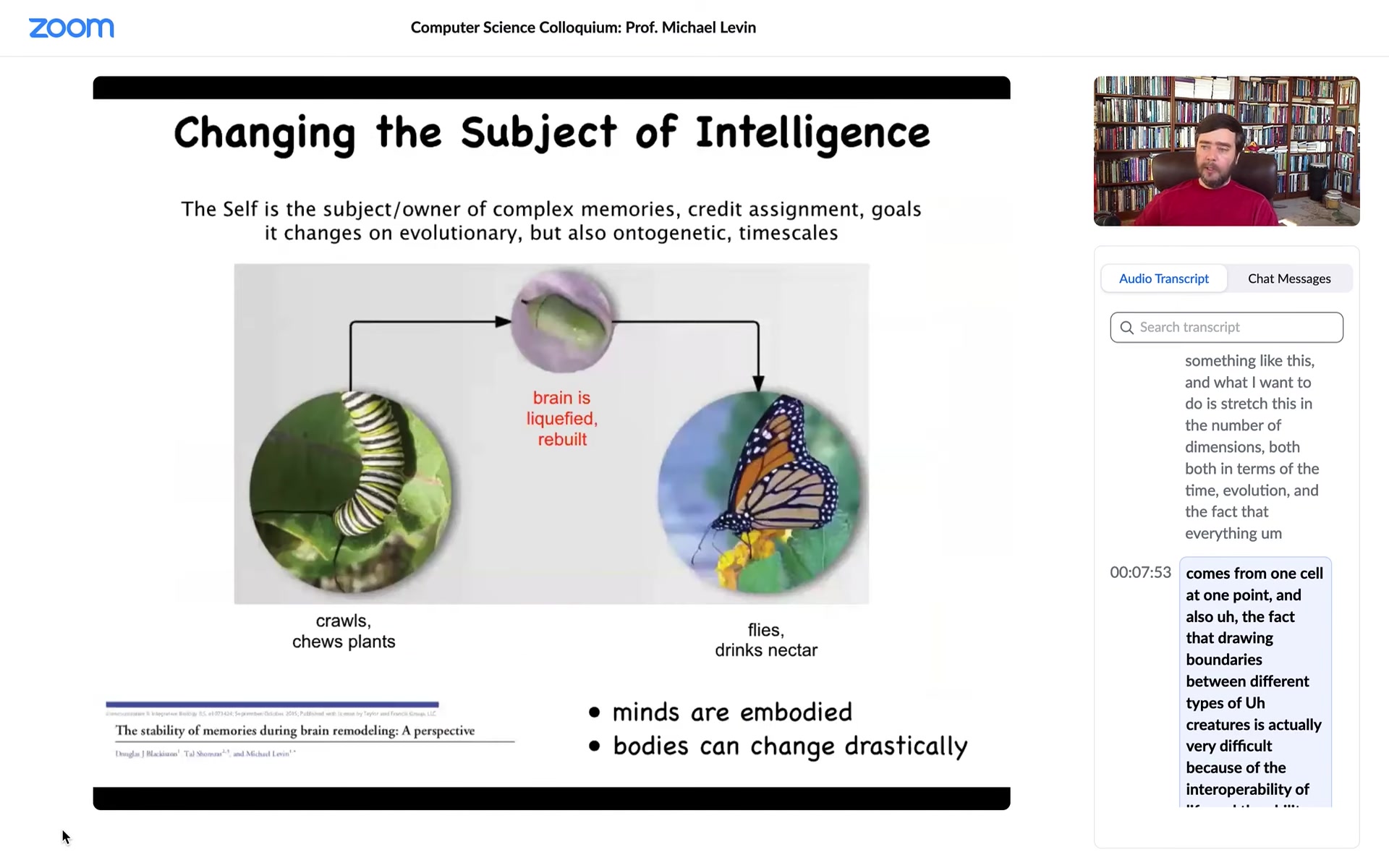

This is a caterpillar. This is a soft-bodied robot that crawls around, it chews plants, and it lives in a two-dimensional world. It has to turn into this. This is a completely different hard-bodied creature which has to fly in a three-dimensional world. It doesn't care about leaves anymore, but it does want nectar. The behavioral and all of these repertoires are completely different.

During this time, what happens is the brain liquefies. Most of the connections are broken. Most of the neurons die. It gets reassembled and rebuilt into a brand new brain suitable for driving this creature. One of the most amazing things is that if you train this animal to have particular memories, those memories are recovered in the moth or butterfly that comes out. Despite the complete rewiring of the brain, those memories remain.

As computer scientists, we can start thinking about what medium could store information and then survive radical remodeling of the structure of the medium. This metamorphosis is very interesting because this is not just on evolutionary timescales. This is a single individual. If you're into philosophy of mind and you wonder what's it like to be a caterpillar or a butterfly, here's the next level question. What's it like to be a caterpillar turning into a butterfly? What is the experience of this process as your cognitive medium is being completely reshaped?

Slide 9/58 · 09m:39s

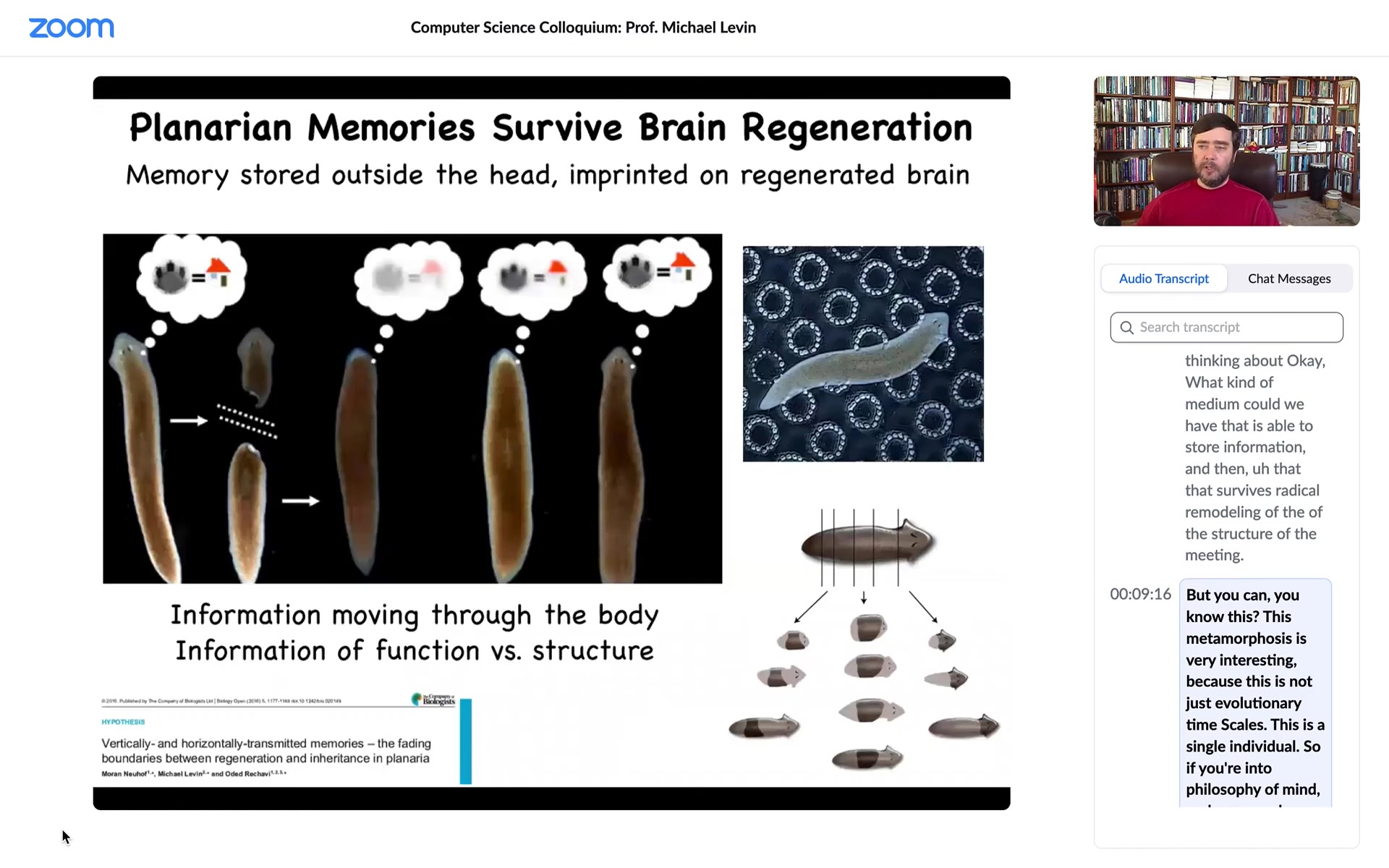

Biology goes even further. These are planaria. These are flatworms. You'll hear lots more about them later. Interesting thing about them — several interesting things. One is that you can cut them into pieces and every piece regenerates and becomes a completely normal worm.

They have a true brain, all the same neurotransmitters that you and I have, and a centralized nervous system. What you can do is train them to expect food on these little laser-etched bumpy surfaces. Cut off their heads; the tail sits there doing nothing for about 10 days, and then they regrow a brand new brain, and then you find out that the animal actually remembers where to find the food. So the memory survives complete decapitation.

So the interesting thing about that is somehow it's stored in the rest of the tissue, maybe neural, maybe not neural, we don't know. But also that information has to be imprinted onto the new brain that is constructed from scratch. So this idea of moving information around and what happens to cognitive information as anatomical information is being processed is really interesting. That's the nexus at which we do most of our work.

Slide 10/58 · 10m:49s

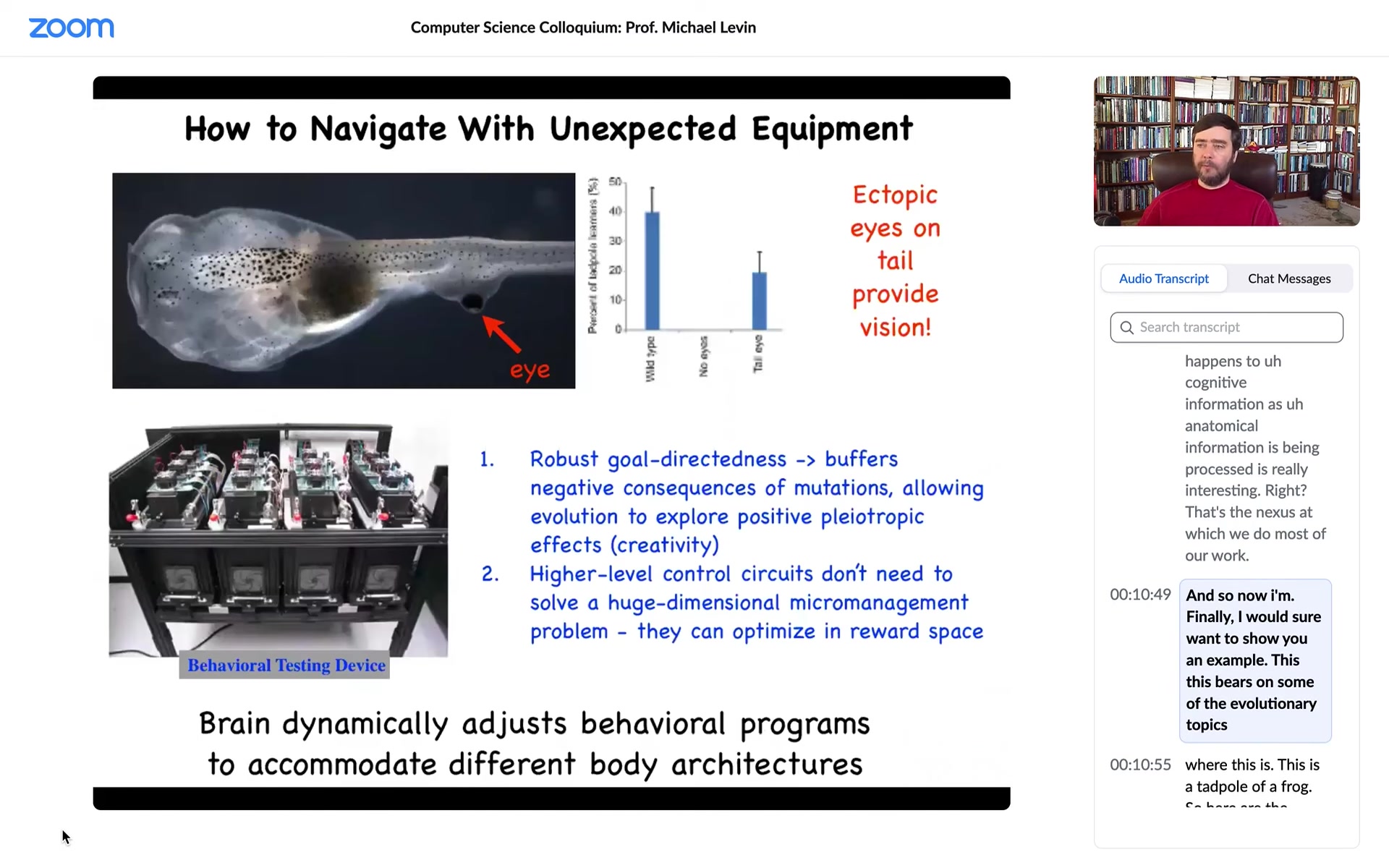

Finally, I want to show you an example. This bears on some of the evolutionary topics. This is a tadpole of a frog. So here are the nostrils, here's the mouth, here's a brain, here's the gut, here's the tail.

Now you'll notice something very strange: the eyes should be here, but they're missing. Instead there's one on the tail. We engineered it this way, and I can talk later about how that's done. But the interesting thing is that when you make a tadpole with an eye on its tail, despite the fact that for millions of years everything was perfectly set up to expect visual input from two regions right here into the optic tectum, these animals can see quite well. We made a machine that tests their learning and visual assays. This eye, in fact, makes an optic nerve. It synapses on the spinal cord, not on the brain. That apparently is sufficient for the brain to recognize this.

You can imagine this weird information bus onto which this organ is putting data, and the brain says, yes, I know what that is. That's visual data, even though it's coming in from a completely bizarre location. No problem. That kind of plasticity is going to be a major, major theme today because one of the things that I think is a constant theme in biology is that it does not overtrain on priors, meaning that it plays the hands that it's dealt at any given moment. What evolution is making is hardware that is very good at dealing with novelty because it doesn't actually have exact expectations, and we'll get to some of that later.

The interesting thing, what I think makes all of that work, which of course is very challenging, is this. We're still struggling to make technology like that.

What makes all of this work is this multi-scale competency architecture where not only is biology nested dolls at the structural level—that's obvious, everybody knows that—but actually, not only functionally, but computationally, every level is solving different problems in their own space.

Slide 11/58 · 12m:51s

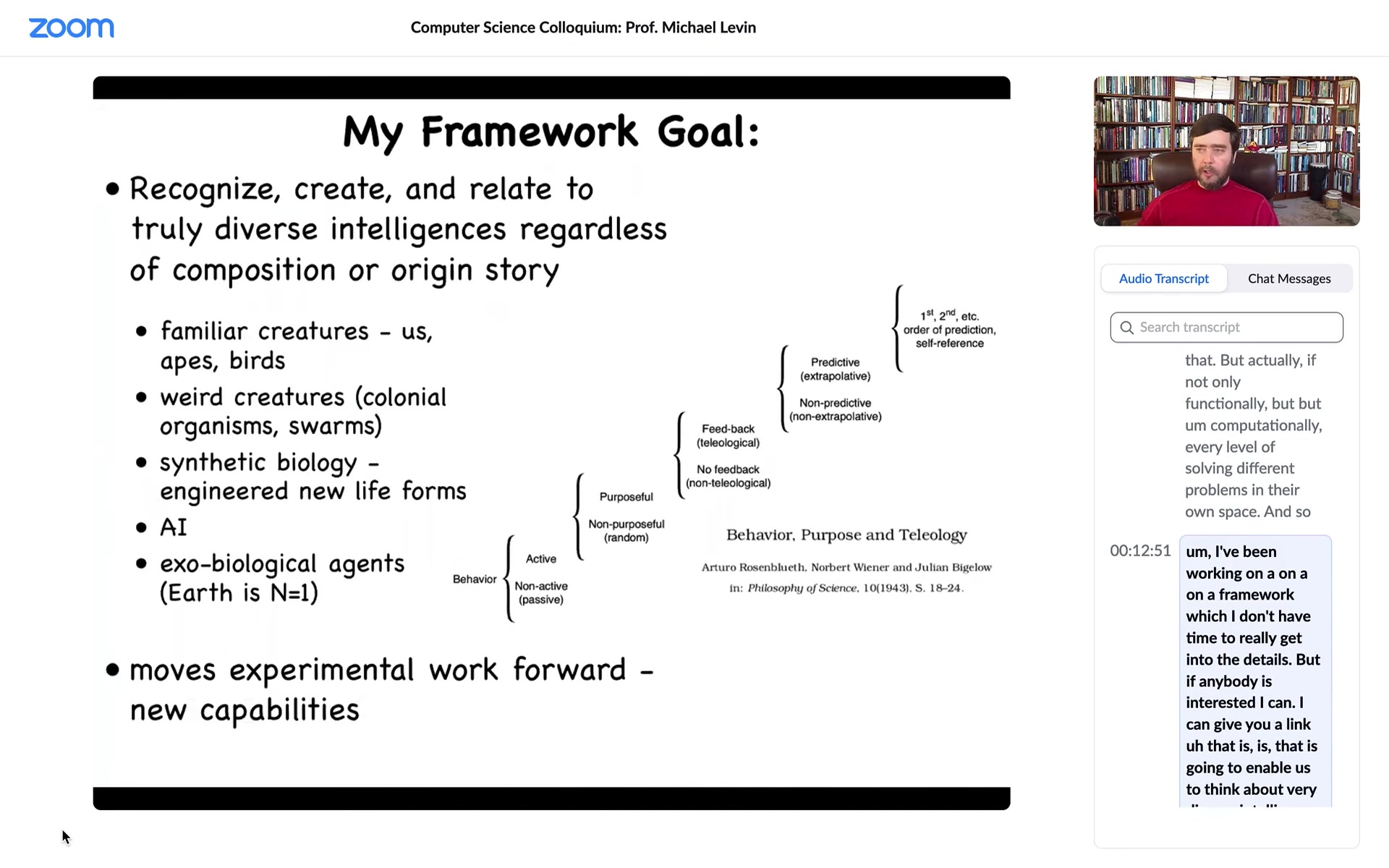

I've been working on a framework that is going to enable us to think about very diverse intelligence. This is not only the kinds of things that people typically think about, but also weird creatures, colonial swarms and bacterial mats and engineered new life forms and AIs and maybe alien life forms.

It's based in part on an old paper in the 40s about setting up a scale of cognitive sophistication, all the way from very simple to quite advanced, with the idea being that there's nothing here about nerves and brains and whatnot. It's a cybernetic approach that's very substrate independent. I think that's important as we start to come up with frameworks that enable us to recognize alien intelligences.

So what we think about is competency in diverse spaces. The thing that human beings are very good at is recognizing intelligence of medium-sized objects moving at medium speeds through three-dimensional space. All our sense organs are pointed that way. We're good at recognizing that. So we know when crows and things are doing intelligent navigation.

But life is navigating all kinds of interesting spaces. There's the space of possible gene expressions, and there's the space of possible physiological states, and then there's this, which we'll spend the most time talking about, which is morphospace. This is the space of possible anatomical configurations.

What I want to do next is talk about morphogenesis, the generation of body structure as the behavior of a collective intelligence of cells in this morphospace. We want to think differently here.

Let's ask a fundamental question. This is a cross-section through a human torso. Look at this amazing order. All of this—the tissues, the organs—everything is in exactly the right place, the right orientation, the right size. Where does this structure come from? You would think that it would take an incredible amount of information to specify all this. What would that information even look like? What would the encoding and decoding be? We all start life like this, as a collection of embryonic plastomeres.

I ask, where is this information? People intuitively will say, well, it's in the DNA, it's in the genome. But we can read genomes, and we know what's in the genome. What's in the genome are protein sequences, the specification of the micro-level hardware that every cell gets to have. There's nothing in the genome directly about any of this.

There is a very deep set of questions about how the cellular collective knows what to make and how it knows when to stop. If a piece is missing, as regenerative medicine workers, we would like to know how to convince the cells to build it again. As engineers, we might ask, what else is possible? Given those exact same cells, what else can we get them to build with the same hardware?

The reason this question is important is this. In addition to all the basic stuff, pretty much every aspect of medicine, with the exception of infectious disease—birth defects, traumatic injury, cancer, aging, degenerative disease—would be completely solved if we knew how to tell collections of cells what to build. If we could specify what three-dimensional structure we wanted the cells to build, all of this would go away.

This is kind of the end game for this whole field: what we really want is a kind of anatomical compiler. We want to sit down and draw the animal or plant that we want, not at the level of gene pathways. You want to be able to draw the final goal here. I want a three-headed flatworm like this, and then with this kind of nervous system, this is what I want.

And if we knew what we were doing, this compiler would take that description and convert it to a set of stimuli that would have to be given to cells to get them to build exactly that. Now, we don't have anything remotely like this, despite all the incredible progress in genetics and biology. Why not? Here's one simple example. This is a baby axolotl. Axolotls are a kind of salamander. Baby axolotls have legs. This is a tadpole of a frog. Frogs don't have legs.

One of the things you can make is a chimeric embryo. We call it a frogolotl. We're making these in our lab. I would pose this challenge. We have the genome for the axolotl. We have the genome for the frog. You have all the genetic information. Now I ask a simple question. Will frogolotls have legs or not? There are no models in the field that will help you answer that question, none. Because even though we know a lot about the molecular pathways that are involved at the cellular level, we really don't understand very well how large-scale decisions are made. And in particular, not only can't we tell what the chimera is going to do, we can't even tell what the individual is going to do. If you didn't already know what an axolotl was, or you were able to compare that genome to other genomes, you would have no idea what the shape or the other properties of the animal were by looking at the genome.

So where we are in biology is this. We're very good at this kind of thing. We're very good at manipulating cells and molecules and getting this kind of information. What we really want is something like this. We would like to be able to control large-scale anatomy. It reminds me of where computer science was a long time ago, where one of the things you had to do was always interact at the hardware level. This is where modern molecular medicine is. All of the exciting approaches are CRISPR genome editing. It's basically this: it's trying to manipulate the absolute low level. I think we can do way better than that, because evolution doesn't do this. Evolution exploits these amazing higher-level interfaces that we can now exploit as well. They give you access to all kinds of computation, modularity, and all kinds of other interesting things.

One of the things that we're interested in is a degree of intelligence. By intelligence, I don't mean human-level intelligence. I mean something along the lines of that cybernetic scale that Wiener gave us. William James agreed. He said that intelligence is the ability to reach the same goal by different means. So this is, again, a very substrate-independent functional definition.

What I want to talk about in terms of this anatomy is this idea of an anatomical morphospace. It's a virtual space of possible anatomical configurations. This is a simple example. These are snail shells. Every shell can be generated by an equation with three parameters. You can build a three-dimensional space. Every existing snail shell is somewhere in this space. There are lots of regions, and we can argue about why those regions aren't populated by real organisms and so on.

Let's think about how much, if any, intelligence a collection of cells has in navigating this morphospace. The very simplest thing you can do is take an early embryo, cut it in half, and what you don't get are two half bodies. What you actually get are two perfectly normal monozygotic twins. You start to get this idea that development is reliable, but it isn't hardwired because if you introduce changes, it can still get to where it's going. There are a variety of starting states. There are some local minima, but what it knows how to do is get around and get to a correct final state.

Being cut in half is not the normal state of affairs for embryos, but no problem. They can still get there even when half the cells are missing.

Now, this is a regeneration which works in a similar fashion. There's our axolotl. Axolotls regenerate their eyes, their limbs, their jaws. They're absolutely amazing. So what you can do is cut this limb anywhere along the length. It will build exactly what's missing, no more, no less. And then it stops. That's maybe the most amazing part of this process: this idea that it actually knows when to stop. When does it stop? Well, it stops when a correct salamander arm has been produced. So this is some kind of means-ends thing going on here, where when the error is low enough, that's when it stops.

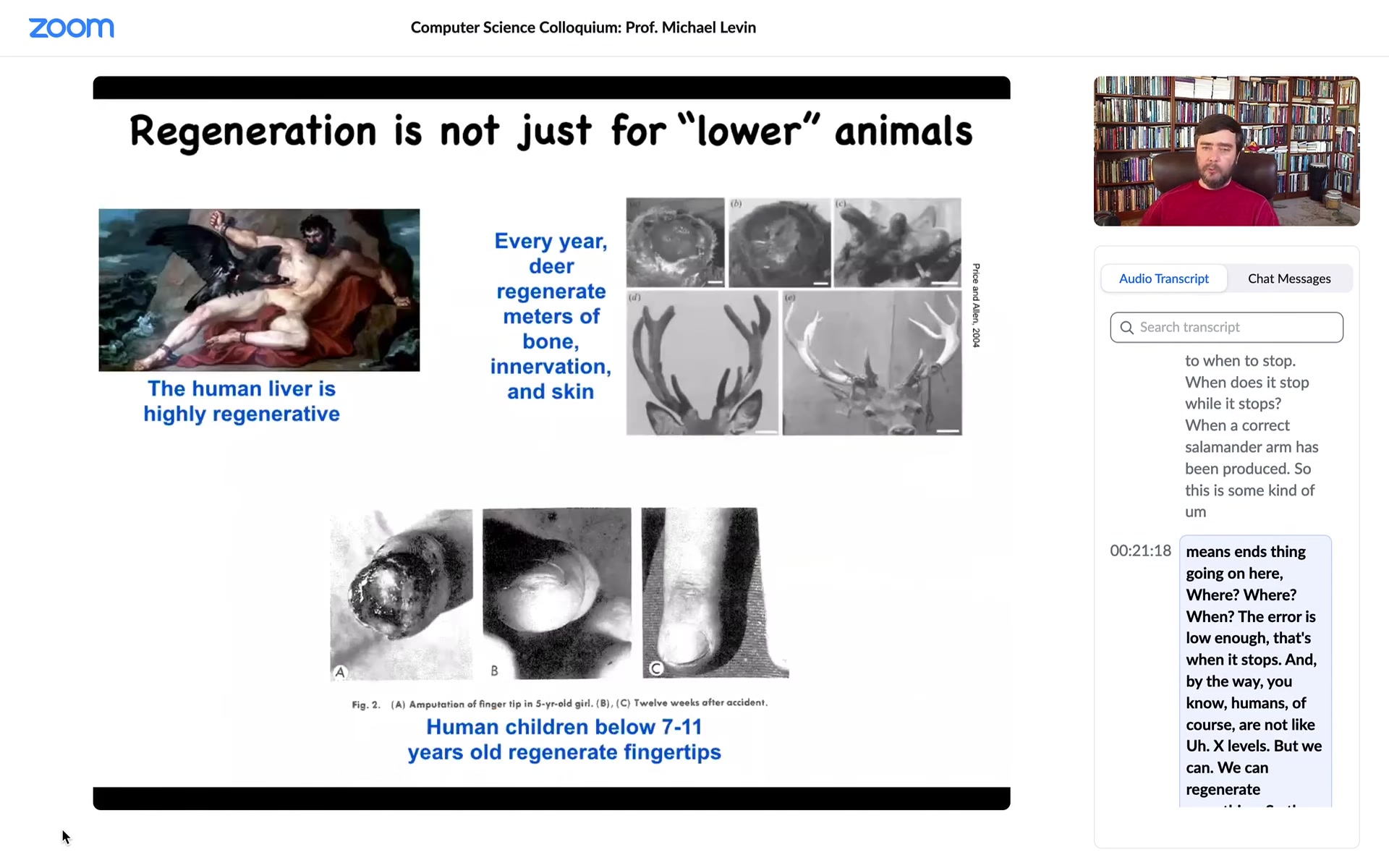

Slide 12/58 · 21m:23s

Humans are not like axolotls, but we can regenerate something. The liver is highly regenerative, human children regenerate their fingertips below a certain age, and deer regenerate huge amounts of bone and vasculature and innervation every year. You can think about some of these examples.

Slide 13/58 · 21m:43s

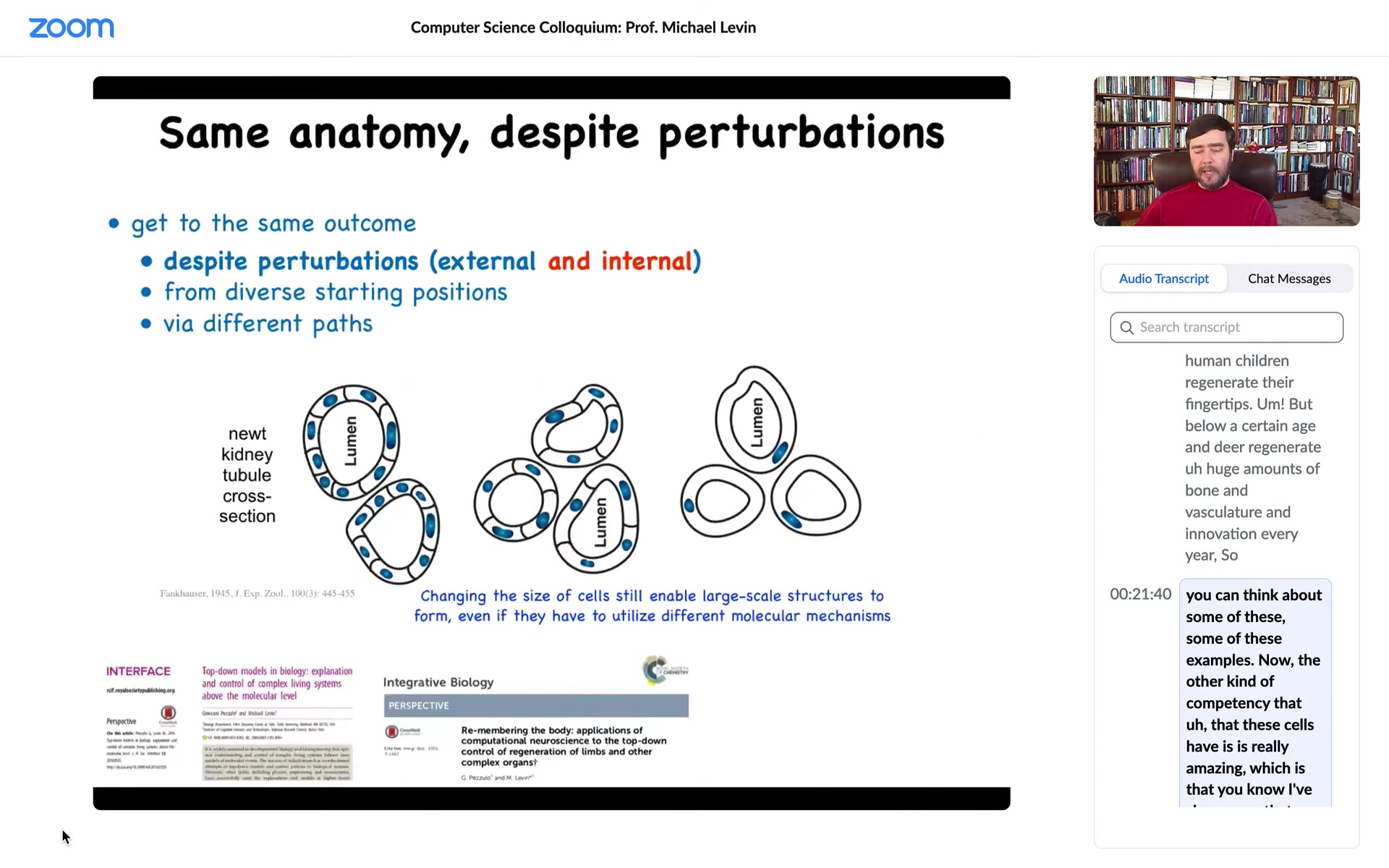

Now, the other kind of competency that these cells have is really amazing, which is that I've shown you that as an embryo, you can't count on how many cells you have. You have to be able to produce embryogenesis even when half of your cells are missing. But it turns out you can't even count on how much DNA you have or how big your cells are.

This is one of my favorite examples. This is a cross-section through a kidney tubule in a newt. Normally it's 8 to 10 cells, and they sort of work together to build this kind of tube. What you can do is this trick where early on in development you prevent the cells from dividing for a bit, the DNA accumulates, every cell ends up with multiple copies of the genome, and then you let it go. Development proceeds, but the cells are now much larger — they're huge. And so no problem: despite the fact that you have too many copies of the genome in every cell and the cells are huge, a smaller number of those cells will work together to give you exactly the same structure, so they adjust to the cell size.

But even better than that, if you make the cells truly gigantic by having eight times the amount of DNA in the original egg, what will happen is one cell will bend around itself, leaving a hole in the middle, and give you the exact same tubule.

Now what's cool about this is that this is top-down causation. The idea is that cells will choose different molecular mechanisms to get the same job done at the anatomical level. In service of getting the same large-scale structure, what the cells are harnessing are cell-to-cell communication. What they're harnessing is cytoskeletal bending — completely different molecular mechanisms to get to the same step. The idea is that this hardware that evolution has given us is able to make up for drastic changes of its component parts.

Slide 14/58 · 23m:37s

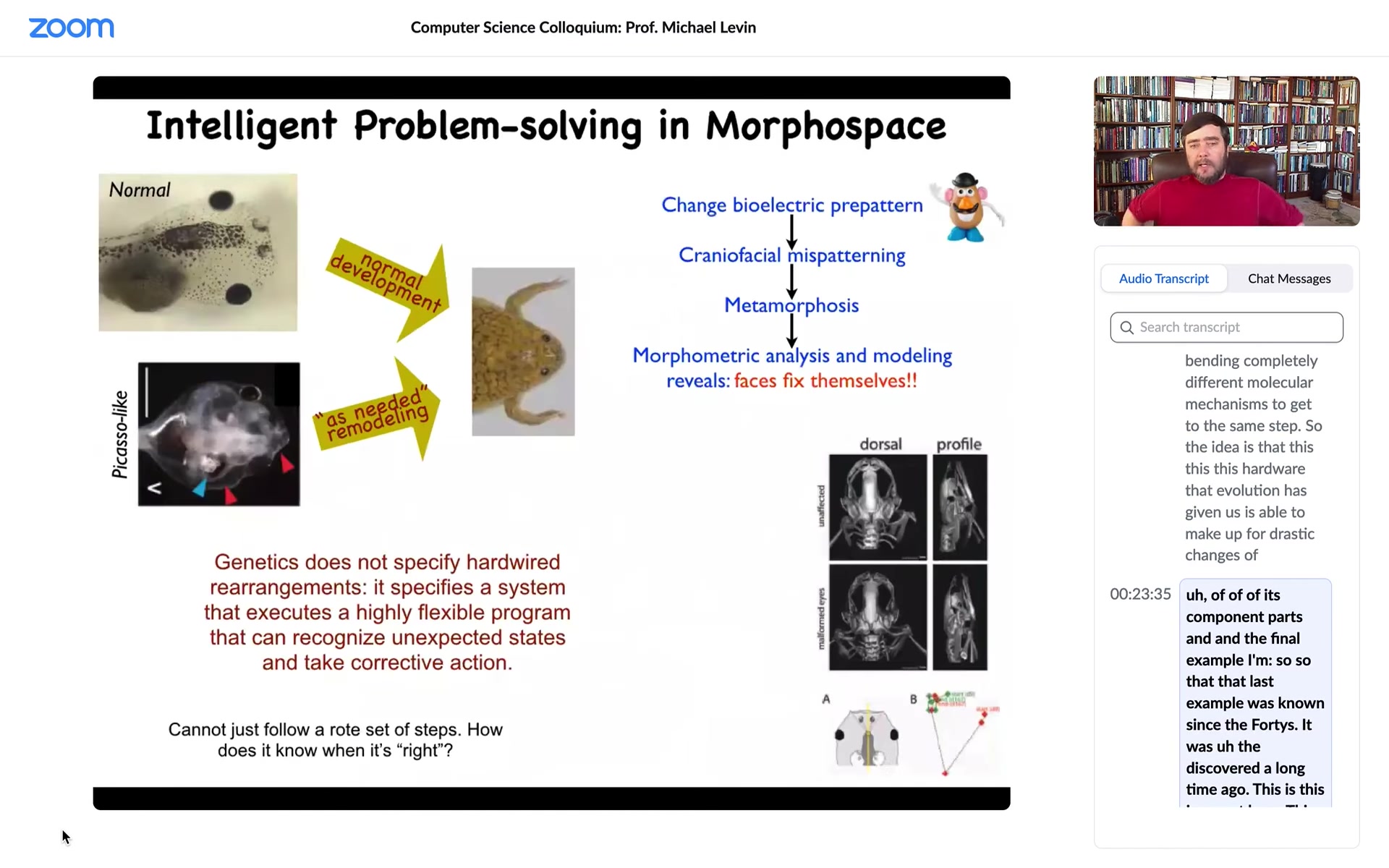

And the final example. The last example was known since the '40s. It was discovered a long time ago. This is recent. This is our work. And it's just a simple example of this kind of navigating morphospace. So here's your tadpole. Now this one is normal. This is a normal tadpole, and it becomes a normal frog. But in order to do that, it has to rearrange its face. So the jaws have to move, the eyes have to move forward, the nostrils have to extend, everything has to move. The traditional way of thinking about this was that somehow the genome encodes some hardwired cell behaviors so that every tissue moves the right direction in the right amount, and then you get your normal frog from the normal starting position. So we wanted to test this hypothesis and we thought no, probably it's much more clever than that. So what we did was we created what we call Picasso tadpoles. Everything is in the wrong place. The eyes are in the side of the head, the mouth is on top. Everything is scrambled. And the amazing thing is that these scrambled tadpoles still become pretty normal frogs because all of these organs starting off at the incorrect position will move around until they get to where they're going. In fact, sometimes they go too far and they have to double back, but everything will move around until it lands in this correct orientation and then it stops.

So what evolution actually gave us is some kind of an error minimization scheme that is able to make up for drastic defects. This has massive implications for evolution because it means that if you have mutations that move your mouth off kilter or move your eye to your tail or do some kind of crazy thing like this, it isn't necessarily the end. And if they have other kinds of positive implications elsewhere in the body, now you get to explore those because these organs are fairly competent in getting where they need to go, connecting up in however they need to connect up and giving you some kind of functionality. It tends to smooth the evolutionary landscape by a massive amount.

Slide 15/58 · 25m:33s

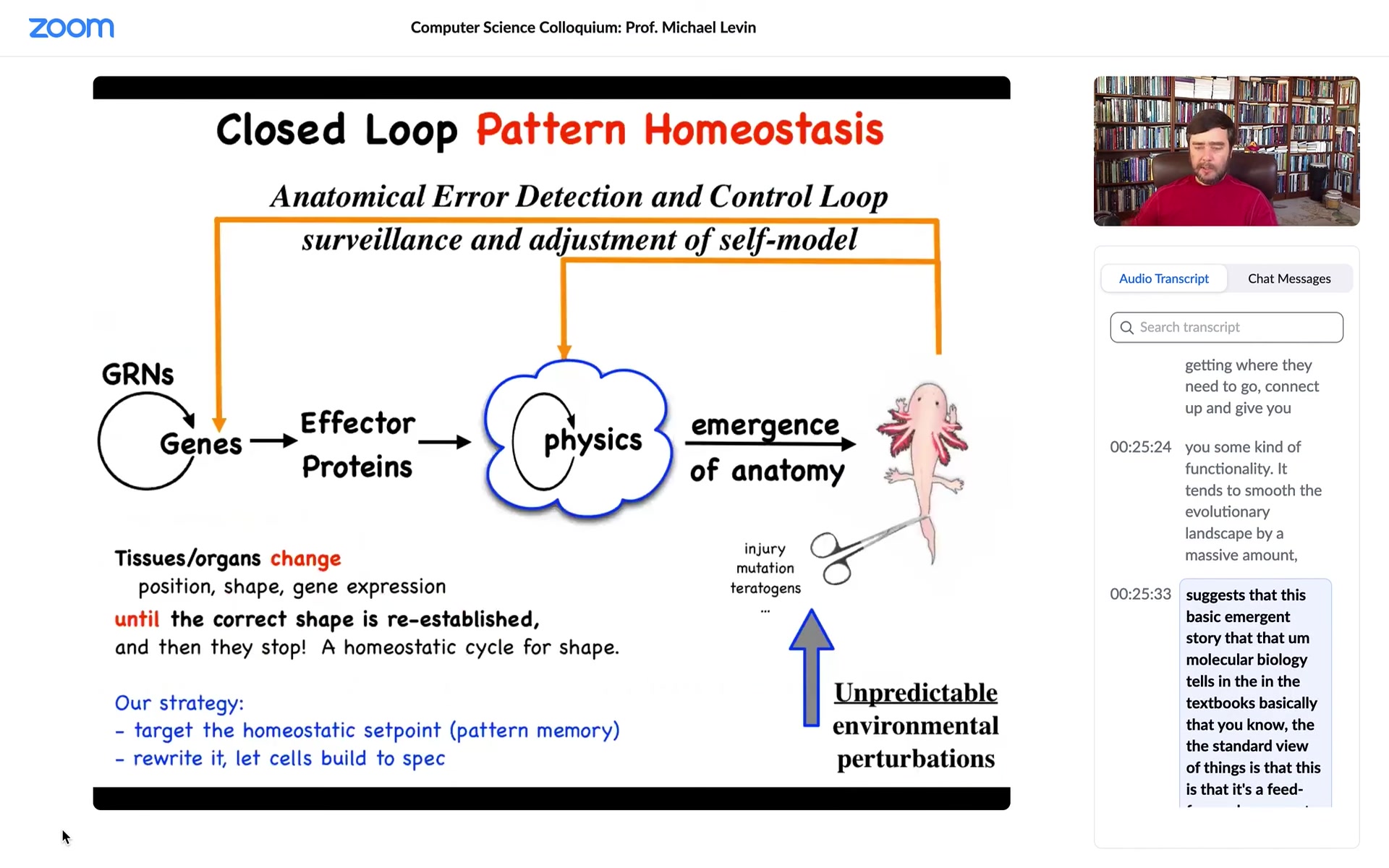

So this whole homeostatic process suggests that this emergent story that molecular biology tells in the textbooks, that the standard view of things is this, is that it's a feed-forward emergent process, that there are genes interacting with each other, some of them make proteins that do things, they're sticky or they diffuse or something, so there's this physics. And then there's this process of emergence. Simple rules executed in parallel over massive amounts of tiny agents give you an emergent outcome. And this is true, of course, this is true, all of this does happen, but I think it's massively incomplete.

Because one of the problems with this feed-forward story is that, in addition to evolutionary issues, if you, as an engineer or bio worker in regenerative medicine, if you wanted to make a change up here, and this was truly a feed-forward process, you would have no idea what to do back here because reversing this is impossible. This is a terrible inverse problem. And if you decided that I like this axolotl, but it's missing a leg, or instead I want it to be a three-fold symmetry instead of bilateral symmetry, what genes would you change? We have absolutely no idea how to reverse this. I don't think it's a solvable problem. And as a result, the gains of things like genomic editing and CRISPR are going to hit a glass ceiling because for the vast majority of problems, we don't know what to do down here.

So what we focus on in our group is these feedback loops. The idea that what's actually going on here is that there are systems that measure error. They measure deviation from a set point, and then they activate both at the genetic level and at the level of physics, and this is what we'll talk about for the next bit. They try to get you closer to your set point.

Biologists know all about homeostasis and set points, but there are two weird things going on here. One is that the set point, unlike a typical biological set point, which might be metabolic level, pH, or temperature, is a complex data structure. This is an anatomical descriptor of what this thing is supposed to look like. The other thing is that it suggests that this whole system, in a certain sense, is goal-directed. Not magically so, but in a cybernetic sense, like a thermostat. Molecular biology doesn't love discussing goals and things like that, even though we now have a perfectly good engineering science of it.

What this view does, though, is that it makes a very strong prediction. It predicts that if we wanted to make changes up here, if this is all true and there is a set point being stored, and it's not purely feed-forward emergence, then what we should be able to do is find how that set point is being stored, learn to read it, learn to rewrite it. And then the cells would build something else without having to make any changes to the hardware down here.

In other words, if it's true that there's some degree of reprogrammability, this idea that the collective compares to a pattern memory, builds to that pattern, we could change the pattern and not have to actually rewire the machine. How general is this? What else can these cells do? You can see this tying back into the themes that I started off with, Turing.

For the next part of the talk, I want to show you an example of how this works, because we've been looking for this, and we think we found it, and we've started to learn to read and write it. And the medium of all of this, maybe not terribly surprising for any neuroscientist, is bioelectricity.

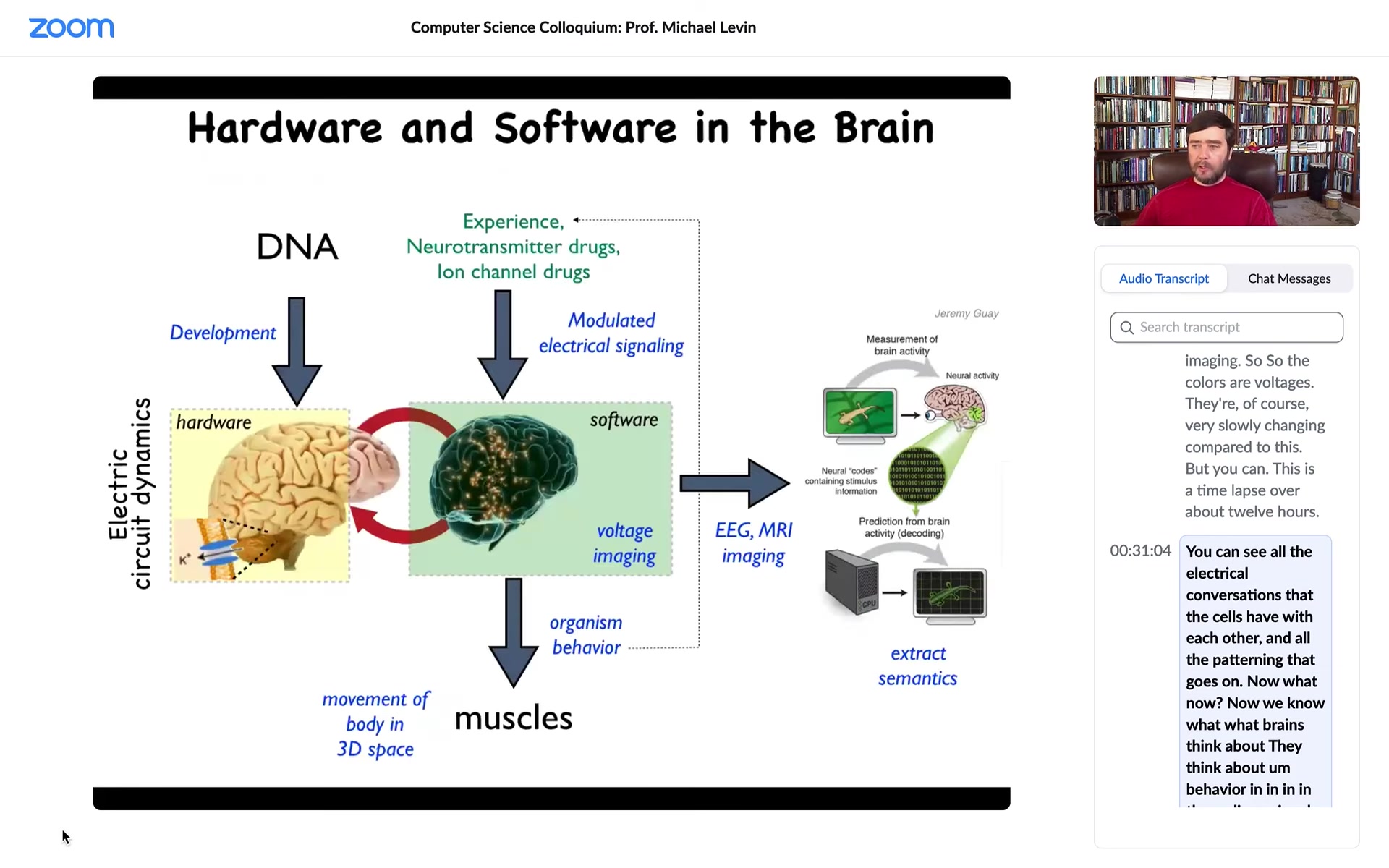

How does this work in the brain? Just the hardware looks like this. There's a collection of cells in the network. They have ion channels, which enable voltage states to exist and propagate to their neighbors via these electrical synapses known as gap junctions.

So that's the hardware. This group made an amazing video of zebrafish brain activity in a live fish thinking about whatever it is that fish think about. The idea is that all of the memories, the goals, cognitive content of that mind is embedded in this electrical activity. Thus there's the idea of neural decoding, that if we understood the encoding, we should be able to read out the physiological activity and then understand what the animal was thinking about or what its memories were.

It turns out that this same exact system works everywhere in your body. This is an extremely ancient set of tools that evolution uses. Every cell in your body has ion channels. Most cells in your body have the exact same electrical synapses. There is neurotransmitter signaling in most tissues of the body. We can now think about a similar project. What about neuroscience outside of neurons? What if we could decode the electrical conversations that other cells were having with each other? Understand how this kind of electrical glue was functioning outside of the brain.

This is an early frog embryo using very similar technology. We developed voltage-sensitive dye imaging. The colors are voltages. They're very slowly changing compared to this. This is a time lapse over about 12 hours. You can see all the electrical conversations that the cells have with each other and all the patterning that goes on.

Now, we know what brains think about. They think about behavior in three-dimensional spaces and then maybe linguistic spaces. What does the rest of the body think about using that same process?

Slide 16/58 · 31m:22s

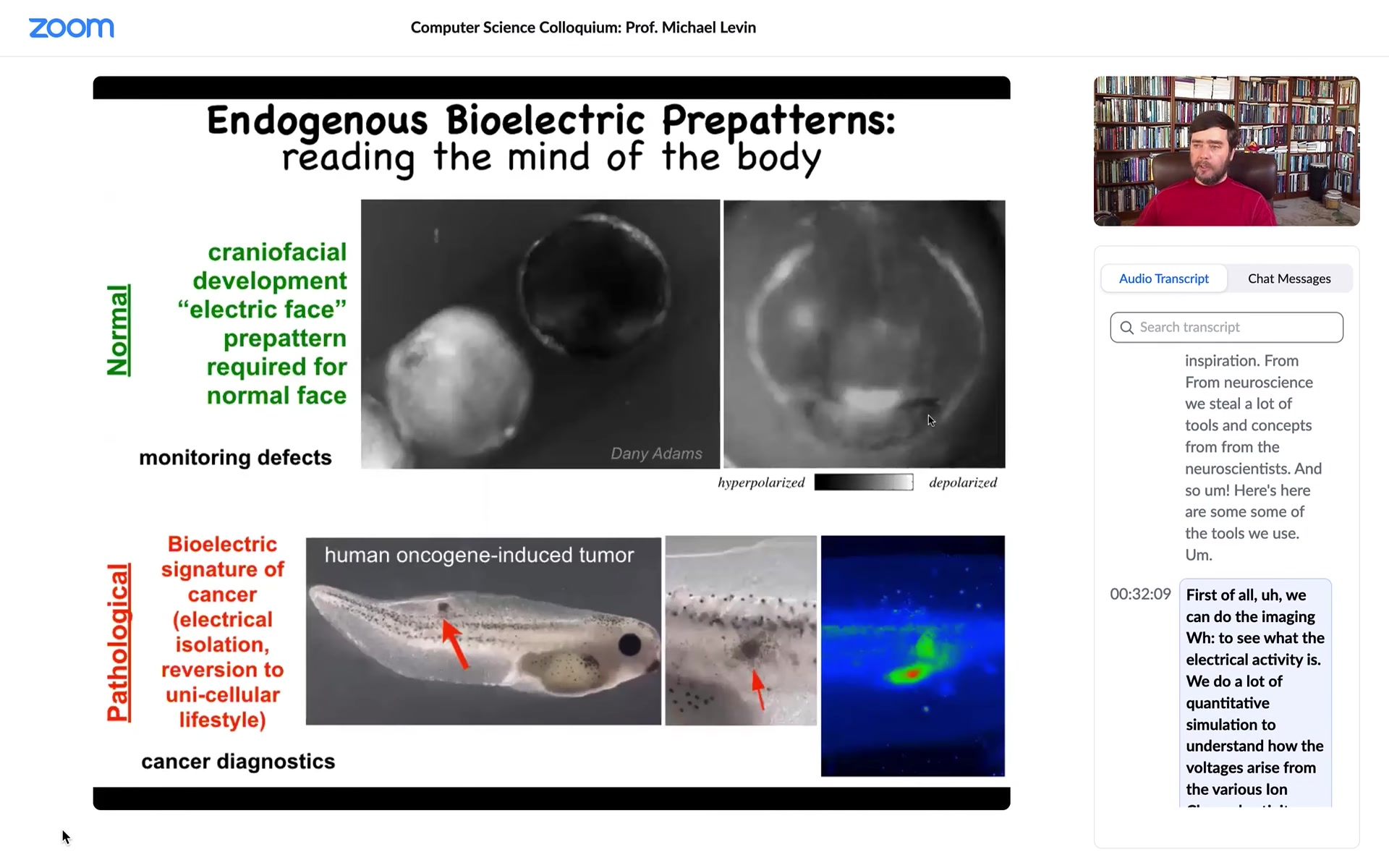

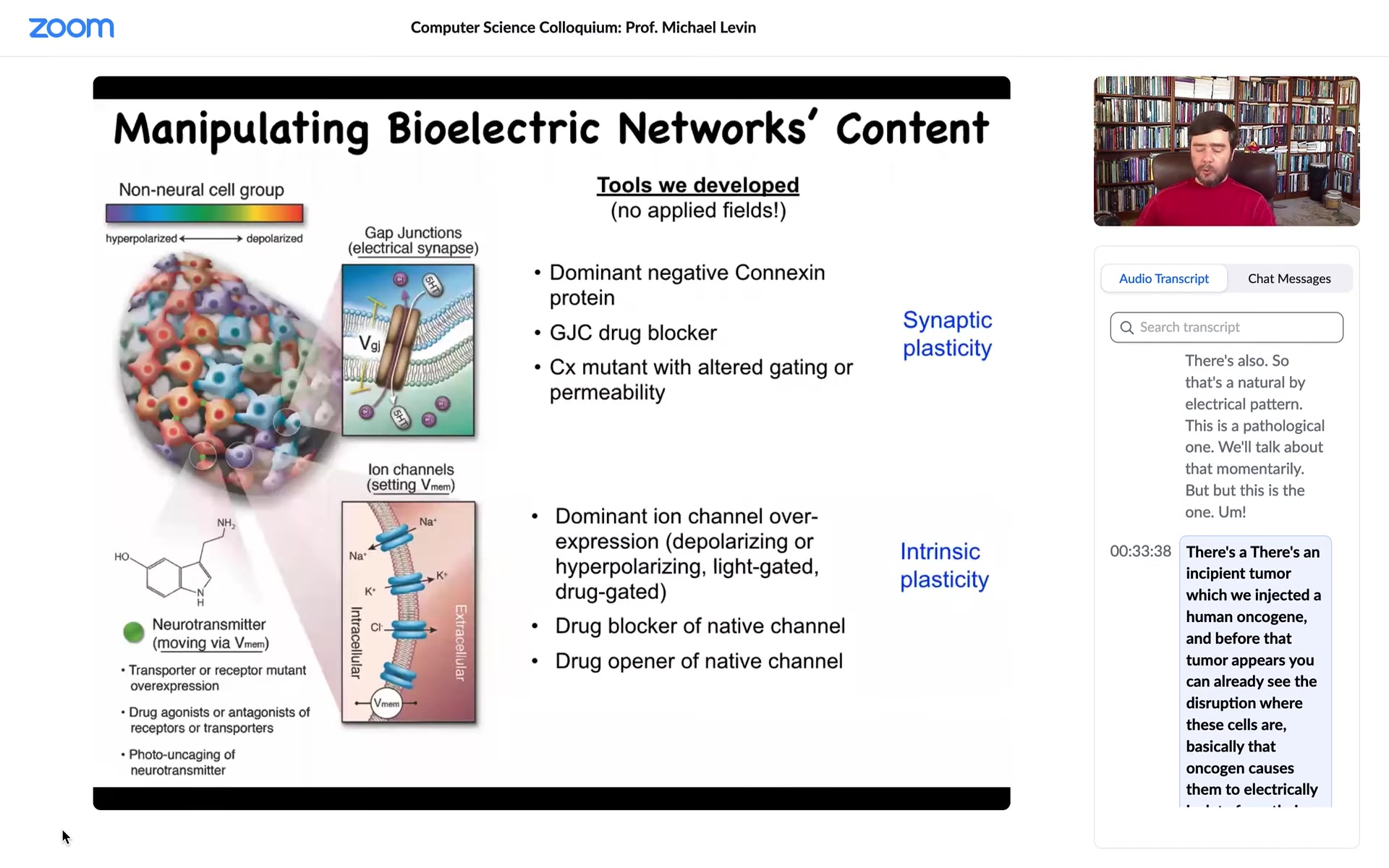

Whereas in the brain, you have an electrical network issuing commands to muscles to move the body through three-dimensional space. It was a very isomorphic picture where, long before that, the system was issuing commands to individual cells to move the configuration of your body through morphospace. What we think evolution did was this was first, and then it pivoted the whole thing to motion spaces instead of anatomical spacing. We got our inspiration from neuroscience. We steal a lot of tools and concepts from the neuroscientists. Here are some of the tools we use.

We can do the imaging to see what the electrical activity is. We do a lot of quantitative simulation to understand how the voltages arise from the activity of various ion channels.

Slide 17/58 · 32m:20s

Here's what some of these things look like. This is an early frog embryo. Putting its face together. One of the things you can see is the bioelectric voltage potentials across the tissue in the grayscale here. This is one frame from that video. What you can see is that long before the genes turn on to actually pattern the face, and long before the face really appears, you can already read out a pre-pattern, a bioelectrical pre-pattern of what the future face is going to look like. Here's where the mouth is going to be, here's where the eye is going to be, here are the placodes. I'm showing you this one because it's the most obvious one to understand. There are other patterns that need a lot of decoding, but this one is simple. You can see exactly what it's going to do.

And this pattern is functional. If I change the electrical properties of this, if I draw using either optogenetics or other tools to draw on this, I can wipe out this eye, I can put it somewhere else, I can change the location of the mouth. All of this is actually determinative. This is the set point that guides future cell activity.

That's a natural bioelectrical pattern. This is a pathological one. We'll talk about that momentarily. There's an incipient tumor which we injected a human oncogene into. And before that tumor appears, you can already see the disruption where that oncogene causes them to electrically isolate from their neighbors. At that point, they're just amoebas treating the rest of the animal as the external environment. They just disconnect from everything.

Slide 18/58 · 33m:57s

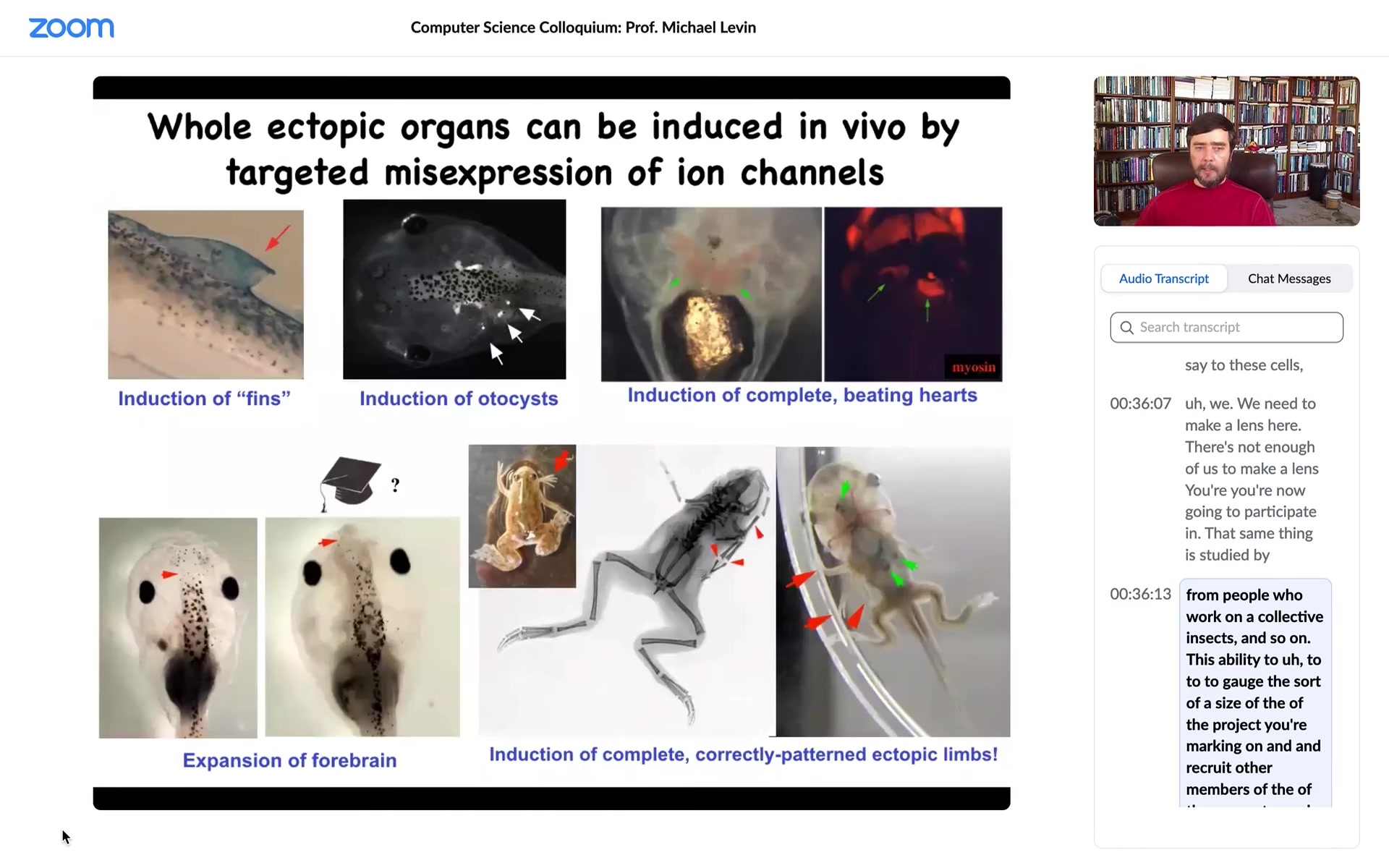

So we use the same tools that neuroscientists use to control these electrical states. We can target the ion channels here. We can target the gap junction. We can control the topology of the electrical network. We can control the specific states using optogenetics, using drugs, using ion channel mutations. No electric field applications, no waves, no magnets, no electromagnetics. This is exactly what neuroscientists do by exploiting the actual interface that the system gives us to manipulate the computations that it does. So how do we know this is of any use? What happens when you do this? Here's one simple example.

Slide 19/58 · 34m:36s

I showed you a bioelectrical pattern that tells the animal where to put its eye. We can reproduce that pattern by injecting ion channel genes, potassium channels, somewhere else. You can introduce that pattern onto the gut, and that tells the gut cells, "hey, you need to make an eye here." If you section that eye, you get the right lens, the optic nerve, all that stuff.

A couple of interesting things. One is that the modularity is amazing because what we actually introduce is a very low information content signal. We don't give all the information you need to know how to make an eye, what the 30 different cell types are inside the eye. We don't produce any of that. It's very modular. It's a subroutine call. We say, "build an eye here," and everything else, all the molecular cascades that are required to build an eye and make retinal cells and all that, is downstream. That's the first thing. It's highly modular.

The second thing is that it has a really interesting competency. In this case, what you're looking at is a cross-section of a lens sitting out in the tail of a tadpole. The blue cells are the ones that we actually injected with our ion channel. We told these blue cells, you need to make an eye. But there's not enough of them to make an eye. Very much like ants in an ant colony, they know how to recruit their neighbors. They recruited a bunch of these brown cells, which were never touched by us. They're completely normal body cells. They're able to say to these cells, "We need to make a lens here. There's not enough of us to make a lens. You're now going to participate." That same thing is studied by people who work on collective insects.

This is the ability to gauge the size of the project you're embarking on and recruit other members of the swarm to work with you. These cells certainly have the ability to do that.

Slide 20/58 · 36m:27s

Using that same modulation, we've discovered the code for things like inner ear organs or otocysts, hearts, inducing ectopic hearts, extra forebrain, extra limbs, some six-legged frogs that you can see, and fins.

Now this is interesting, tadpoles aren't supposed to have fins, that's more of a fish thing.

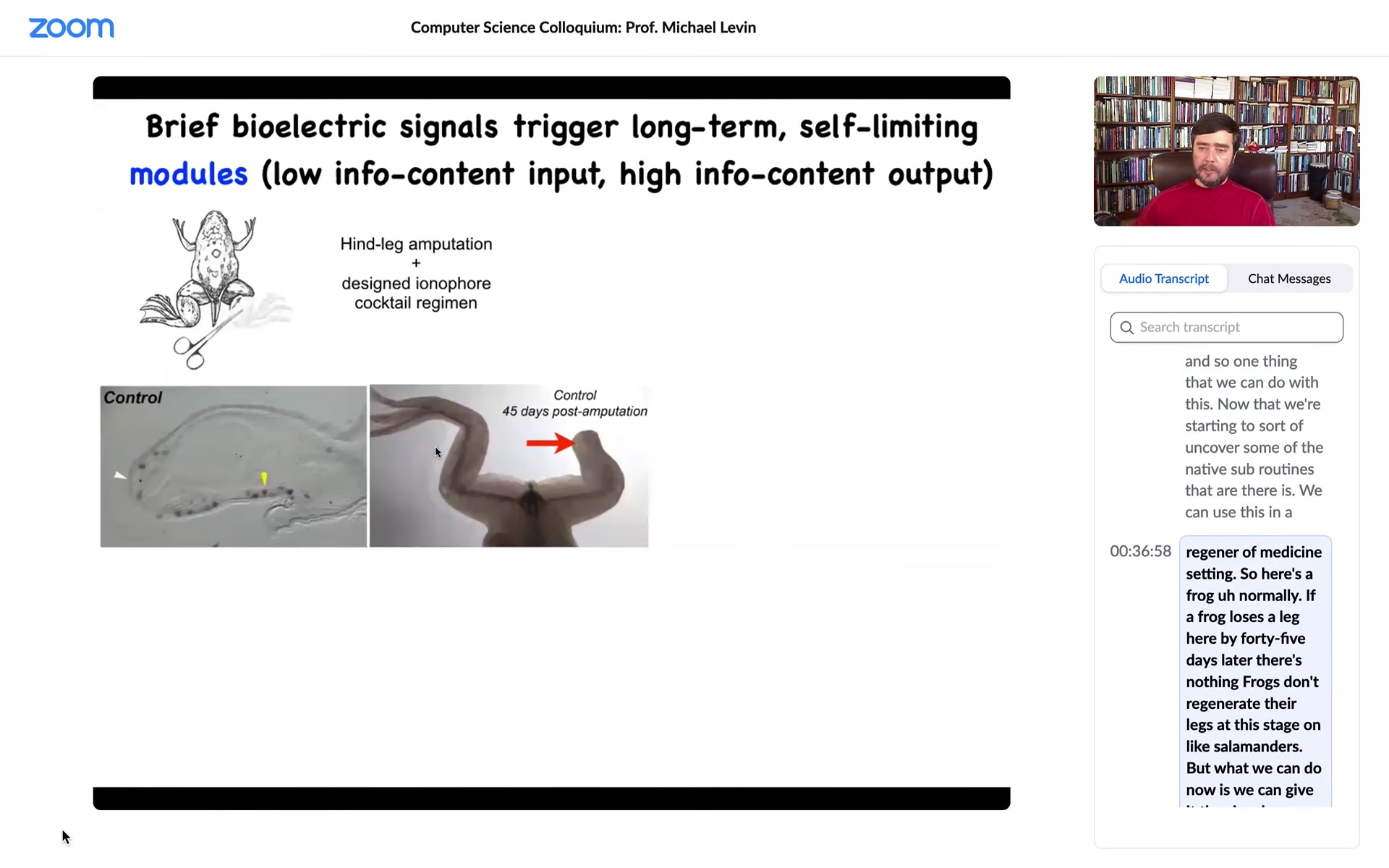

One thing that we can do with this now that we're starting to uncover some of the native subroutines that are there is we can use this in a regenerative medicine setting.

Slide 21/58 · 36m:58s

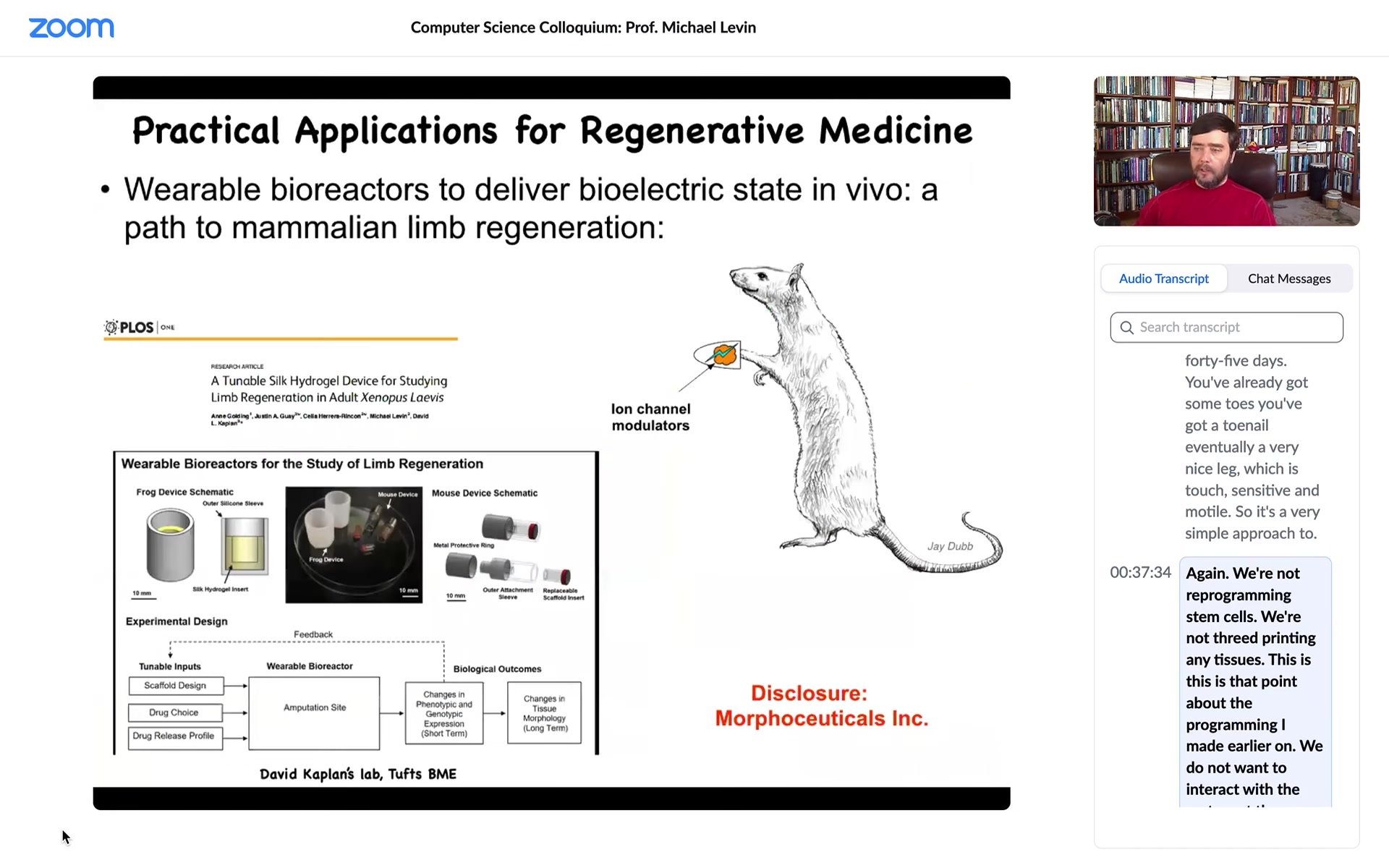

Here's a frog. Normally, if a frog loses a leg here, by 45 days later there's nothing. Frogs don't regenerate their legs at this stage, unlike salamanders. But what we can do now is we can give it the signal that says, "hey, you need to rebuild this leg."

What happens here is that the way we do that is with a drug that opens specific ion channels at the wound. It turns on the genes that you need to get started on regeneration. By 45 days you've already got some toes, you've got a toenail, and eventually a very nice leg, which is touch sensitive and mobile.

It's a very simple approach. We're not reprogramming stem cells. We're not 3D printing any tissues. We do not want to interact with the system at the lowest level by telling molecular pathways or cells what to do. We want to discover the large-scale subroutines and the large-scale control structure that allows us to say "build a leg."

Slide 22/58 · 37m:55s

We are in trials in rodents. I have to disclose that Dave Kaplan and I are co-founders of Morpheceuticals, which seeks to apply this kind of approach to regenerative medicine, hopefully someday for humans. You can see that's the applied side of the work.

I want to switch to an amazing animal, the planaria. You can cut them into as many pieces as you want. I think the record is 275. They're immortal; they do not age. They're extremely resistant to cancer, and they have the world's worst genome. But they have incredible capacity for morphogenetic control.

Slide 23/58 · 38m:50s

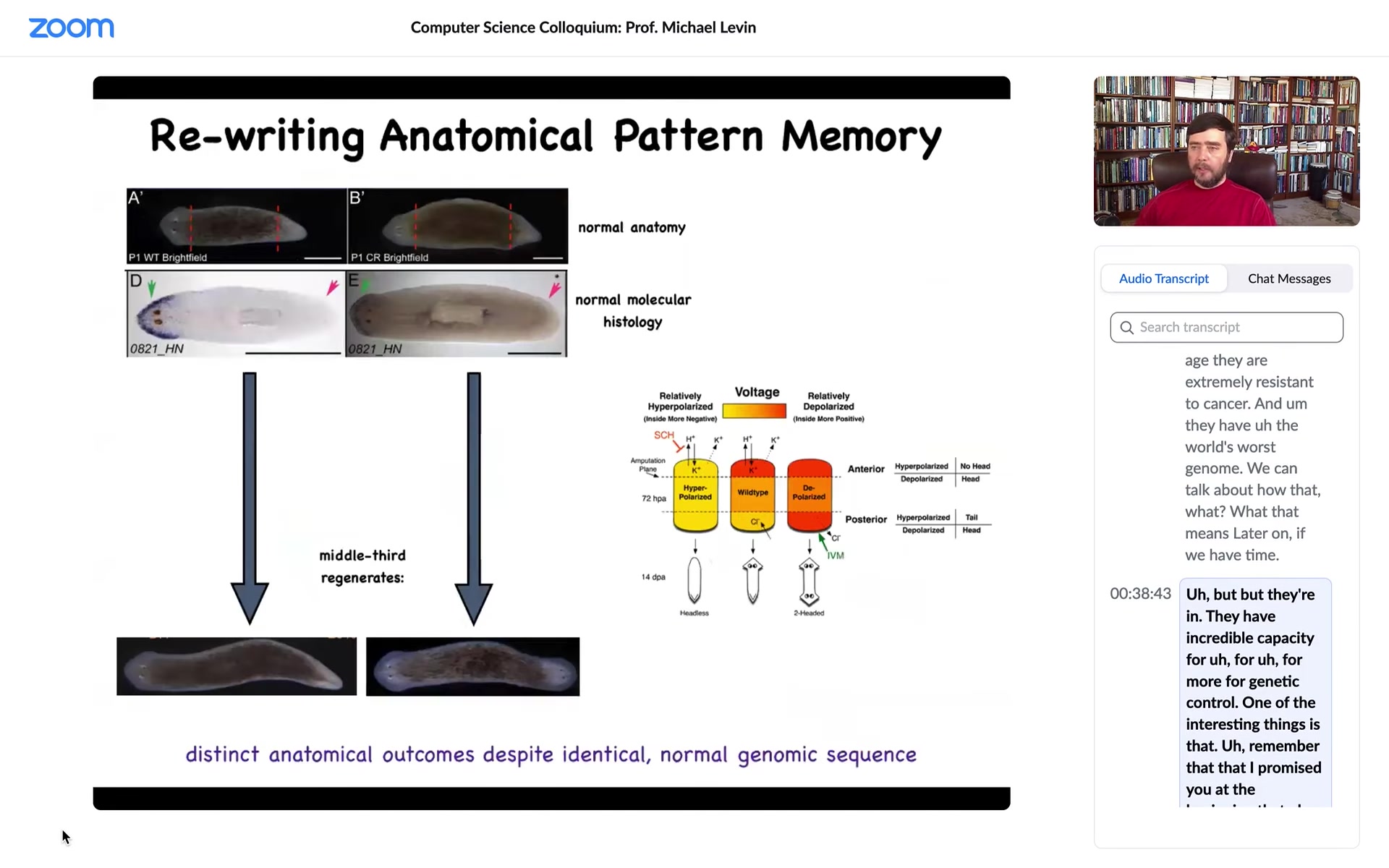

One of the interesting things is that, remember that I promised you at the beginning, that we would look for the pattern memory. We would look for that encoding of the set point, that anatomical set point that tells the cells what to build and when we are complete.

I want to show you a story where we can rewrite that pattern memory. I've shown you examples already. The thing with the face and the eye is an example. I think this is even better.

So here's our planarian. It has one head and one tail. The anterior genes are up here, turned on at the head, turned off at the tail. If I amputate the head and tail, this middle fragment reliably, 100% of the time, gives us a nice worm.

Now, one of the things that we did was to discover a bioelectric circuit that actually told the cells, this fragment, how many heads are you supposed to have? Once the head and the tail are chopped off, which end is the head, or maybe both should be the head? How would you know?

So we discovered this electrical circuit, and what we were able to do is to convert this perfectly normal one-headed animal to a state that, once we cut it, makes a two-headed worm. This is not Photoshop. These are real live animals. Here's how it works.

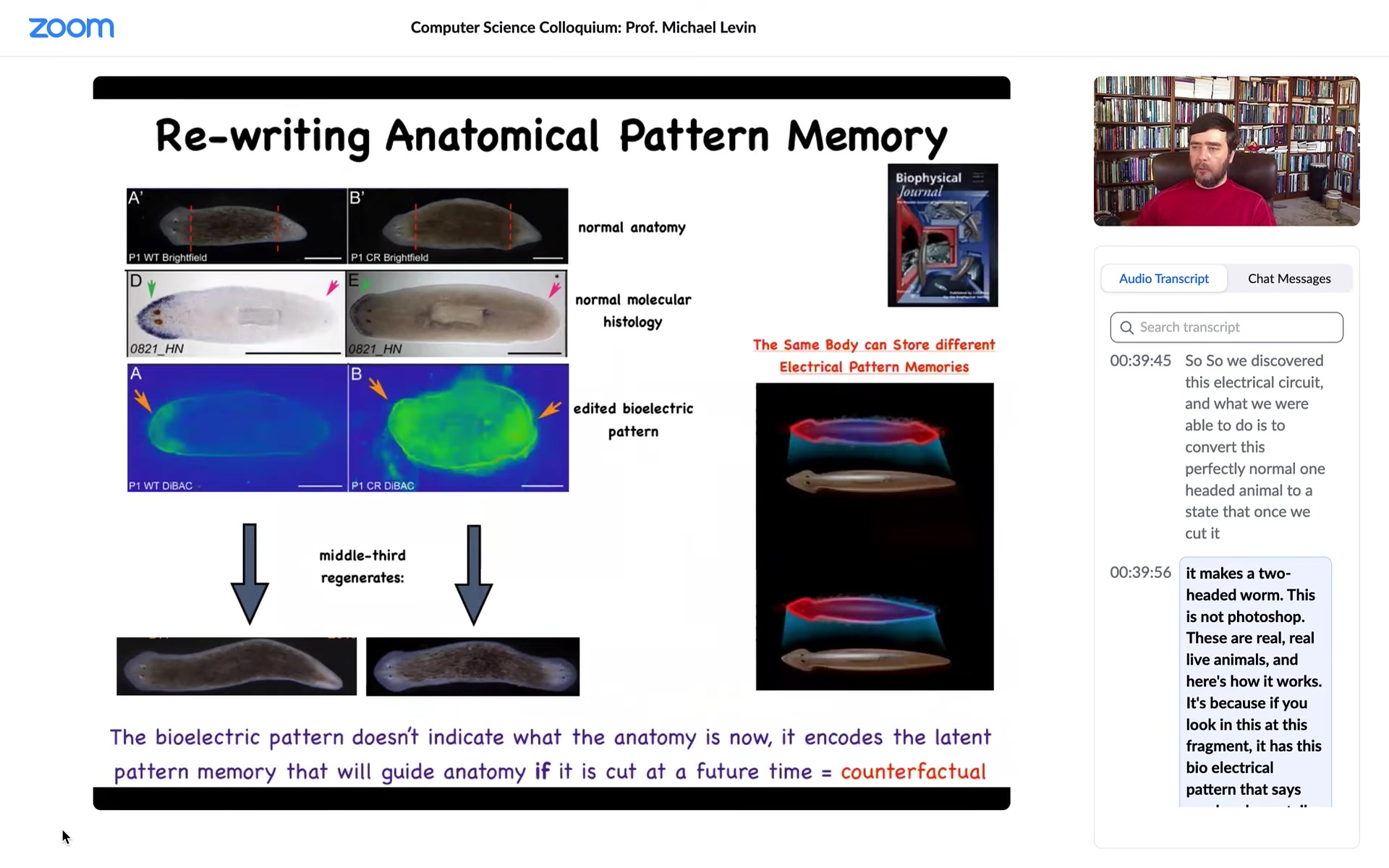

Slide 24/58 · 40m:01s

It's because if you look at this fragment, it has this bioelectrical pattern that says one head, one tail. That's what the cells build. But we can, using various ways to modulate ion channels, convert this pattern to this pattern. It's a little messy. You can see here the technology is still very much being worked out. There are two; the code says 2 heads. Sure enough, if I cut this animal, there he is.

Here's a very important point that we need to understand. This electrical map is not a map of this two-headed creature. This electrical map is a map of this one-headed animal in which we have manipulated the electric circuit such that the voltage looks like this. It sits there being one-headed until it's injured. At that point, the cells consult this map and build this two-headed worm.

The bioelectrical pattern is not a readout of the current anatomy. You can think about this as a primitive counterfactual memory. This is a memory of something that is not happening right now. In fact, it may never happen. But if it does, if we get injured, this is what a correct worm is supposed to look like. We will keep rebuilding until this is the pattern we get.

So this is an encoded set point. A single-headed planarian body can encode at least one of two different ideas of what a planarian is supposed to look like. No doubt there are more; we found two. This is very important. This is the basics of counterfactual memory. This electric circuit can hold at least one of two different representations of what a correct planarian should look like, and upon injury, this is their reference point. They have nothing else to gauge by.

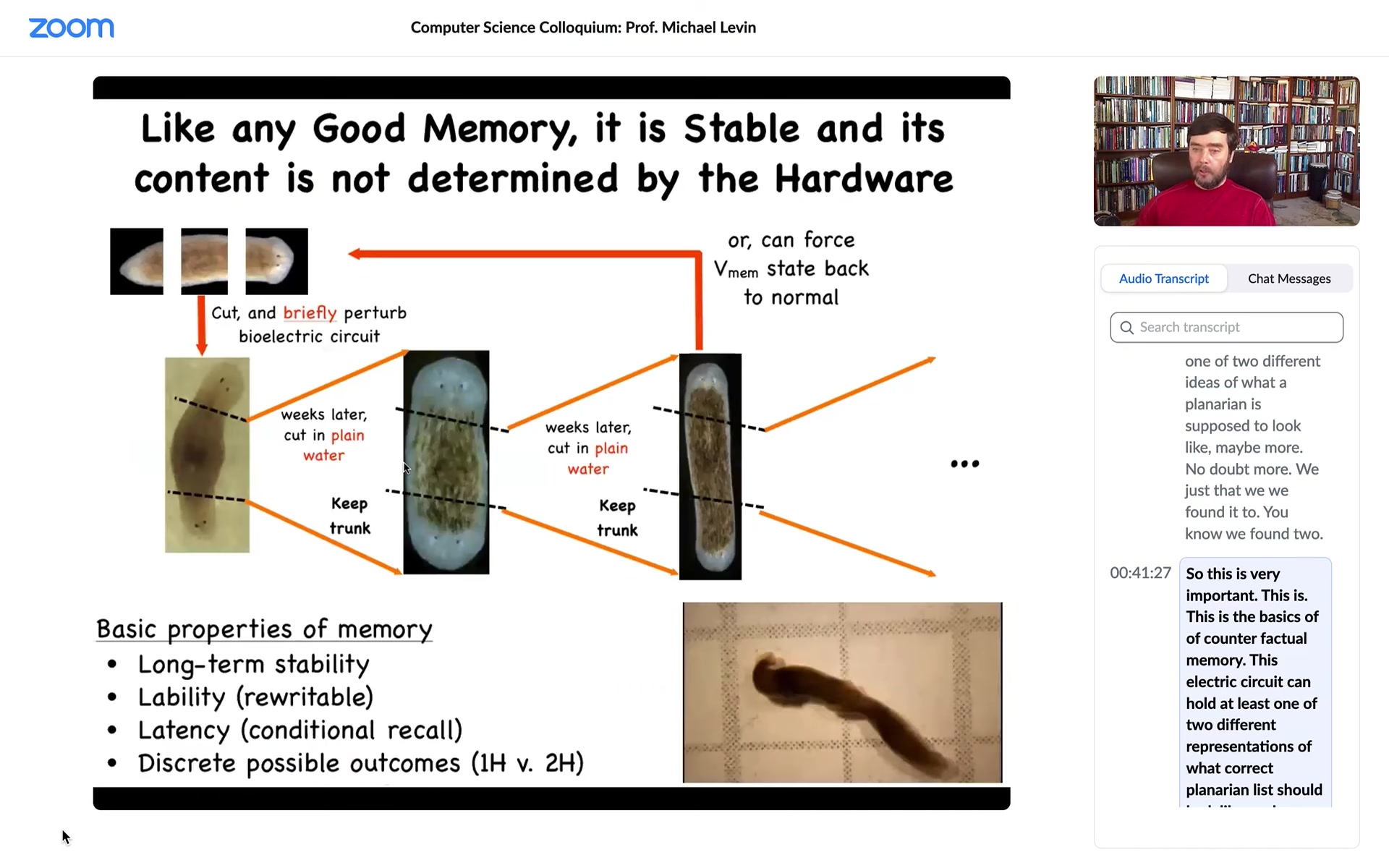

Why do I keep calling it a memory?

Slide 25/58 · 41m:43s

Because every good memory, it is not only rewritable, but it's long-term stable. So if I take these two-headed worms, and I amputate the head, and I amputate this other ectopic head, and I leave just a nice normal mid-fragment. No more treatments of any kind, plain water. The genetics haven't been changed. We never edited the genome. There's nothing wrong with the genetics of this animal. So you might think that once you've cut this off you'll go back to normal, and that's not what happened.

So these animals, in perpetuity, generate two-headed worms. Where is it stored that there are now two-headed worms? It is stored in the electrical pattern distributed over the cells. That pattern has a memory property. Once you've changed it, it holds. And in fact, we know how to change it back. So we can take that pattern, change it back to a one-headed, and then you get a line of one-headed animals.

So the answer to what determines how many heads planaria have is not really nailed down by the genetics. What the genetics does is it gives you an electric circuit that by default says one head. But that circuit is reprogrammable. You can change it to say two heads and it will hold state, as far as we can tell, forever. And then you can flip it back and forth. So you can think of this as a distributed flip-flop. And here are these two-headed planaria in their native habitat.

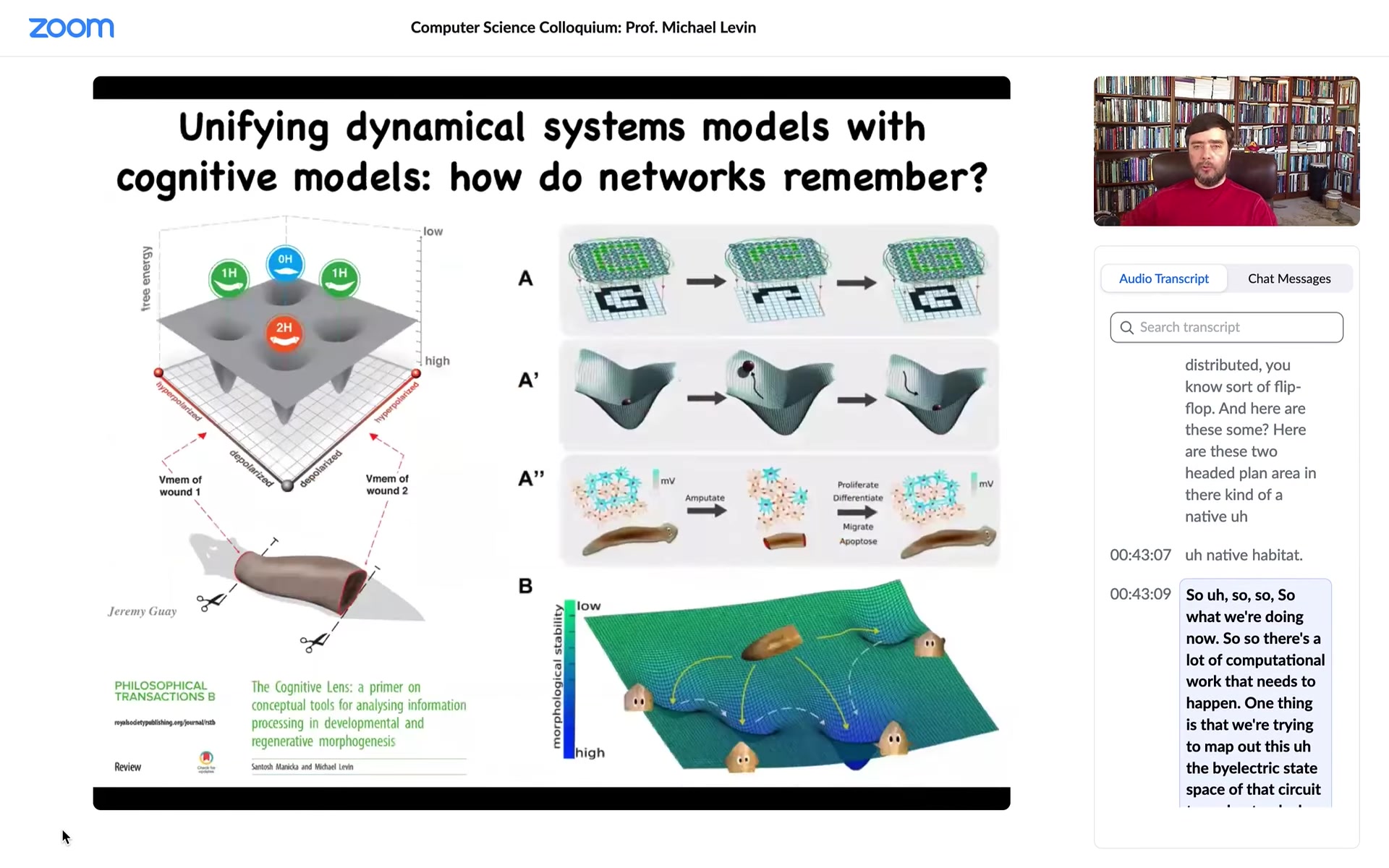

Slide 26/58 · 43m:10s

What we're doing now is a lot of computational work that needs to happen. One thing is that we're trying to map out the bioelectric state space of that circuit to understand why certain parts of it correspond to one head, two head, and so on, and view that regeneration as an energy minimization process where what you're doing is to recover these pattern memories when they are damaged.

We really want to see if some of the tools of connectionist computer science can help us understand what's going on here, the link between the physics of the circuit and the information processing of memory, of recall, of energy minimization, and so on.

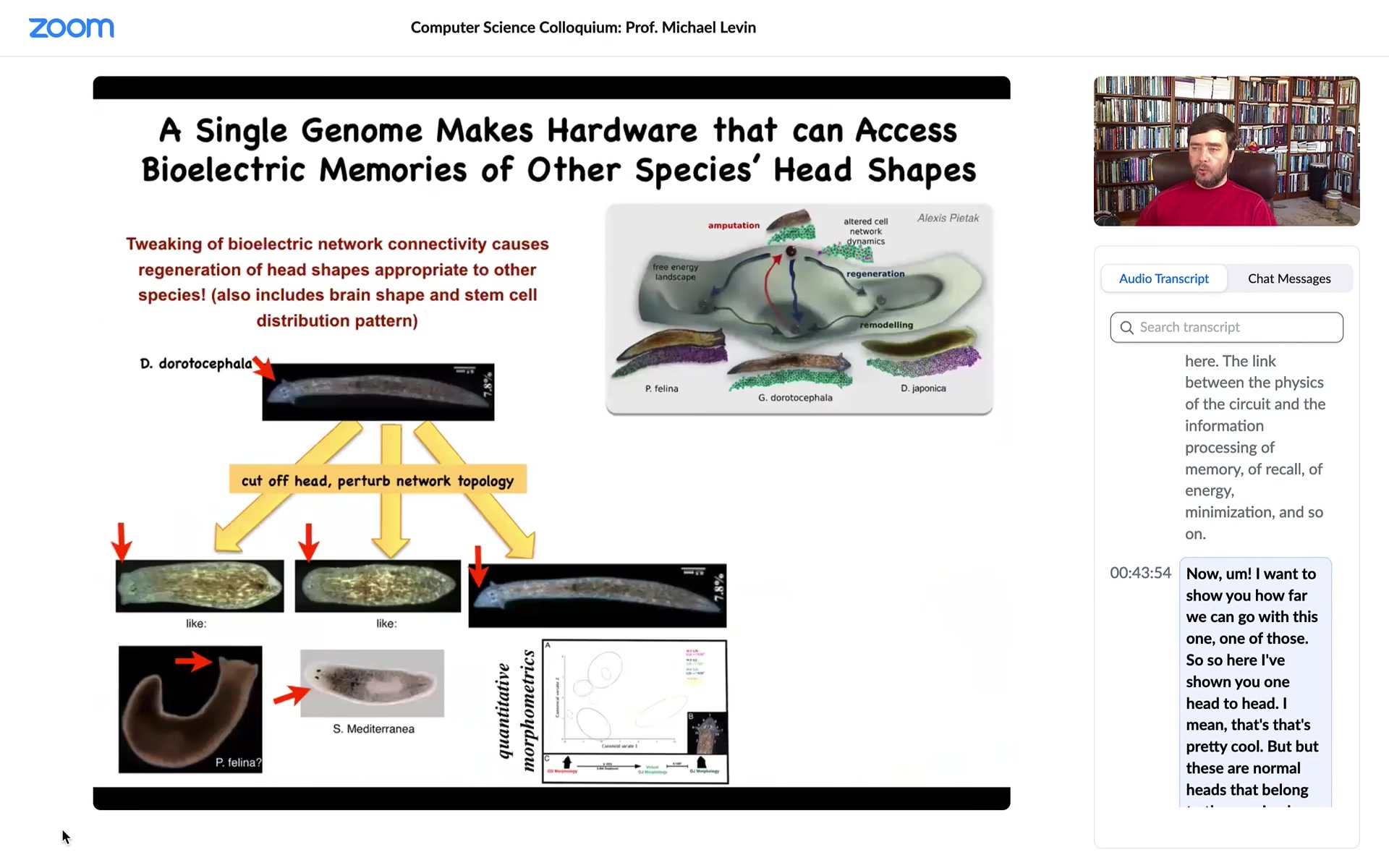

Now I want to show you how far we can go with this. Here I've shown you one head, two head. That's pretty cool, but these are normal heads that belong to these animals anyway.

Slide 27/58 · 44m:03s

Well, one thing you can do is you can push them into further attractors in that state space that belong to other species. So I can take this triangular shaped worm with no genetic change whatsoever, with completely normal hardware, just by disrupting that electrical decision-making, when you cut off the head, they have to decide what the head shape is. I can make flat heads like the P. falina. We can make round heads like an S. mediterranean, or of course we can make the normal ones. The shape of the brain becomes just like these other species. The distribution of stem cells in the brain becomes just like these other species. They can access other, a genetically normal set of cells can access other morphological attractors if you push them that way along this bioelectrical interface.

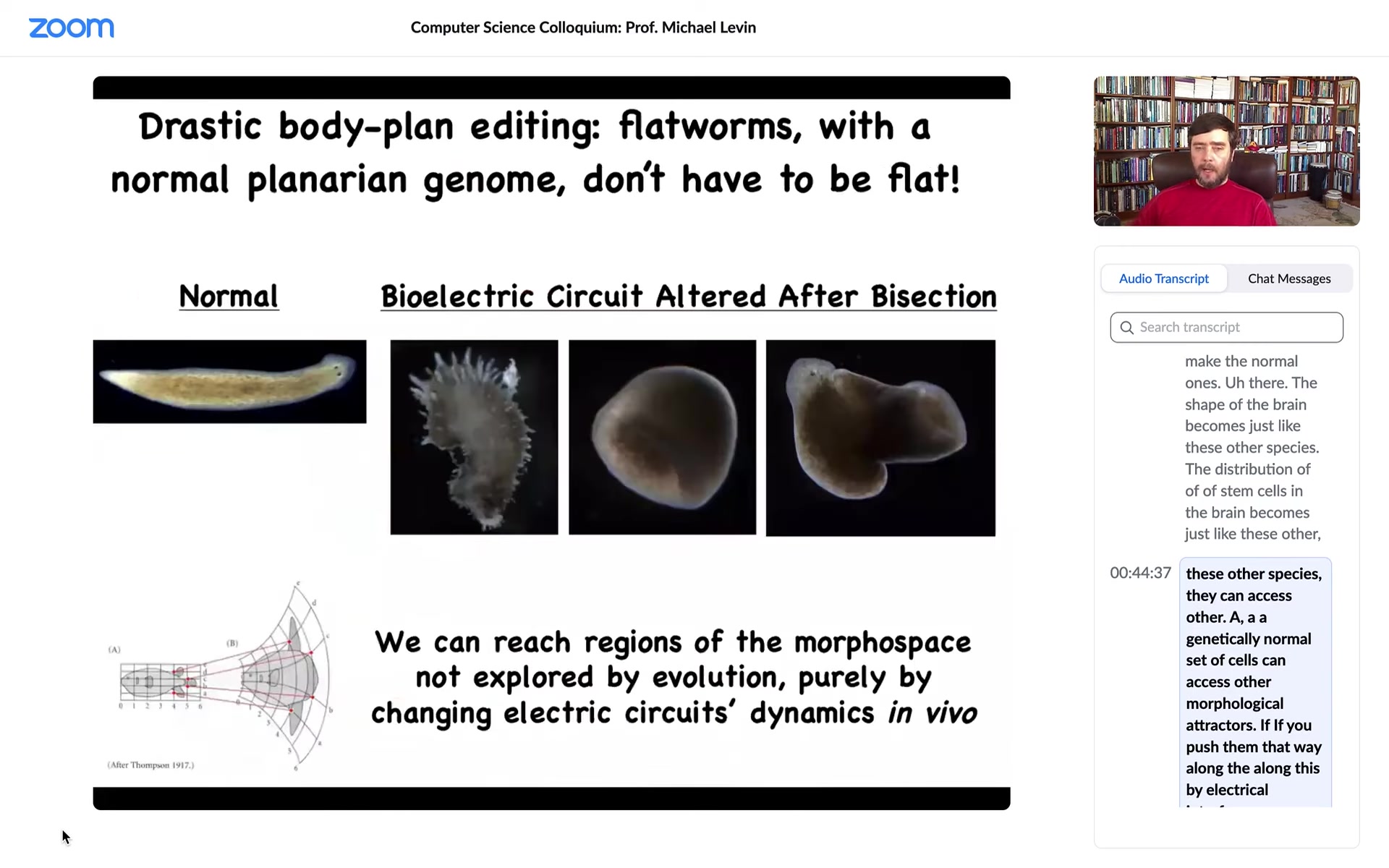

Slide 28/58 · 44m:50s

You can even push them further and you can reach shapes that don't belong to planaria at all. You can make these kind of hybrid forms, you can make radially symmetrical, ski-cap-looking things. You can make these weird spiky forms. There's a tremendous variety of anatomical forms that you can achieve. If you interfere with the ability of these cells to navigate morphospace, what they want to do is reach this region of the morphospace, and they're very good at it, but now that we've found this electrical process by which they navigate, we can push them into other areas.

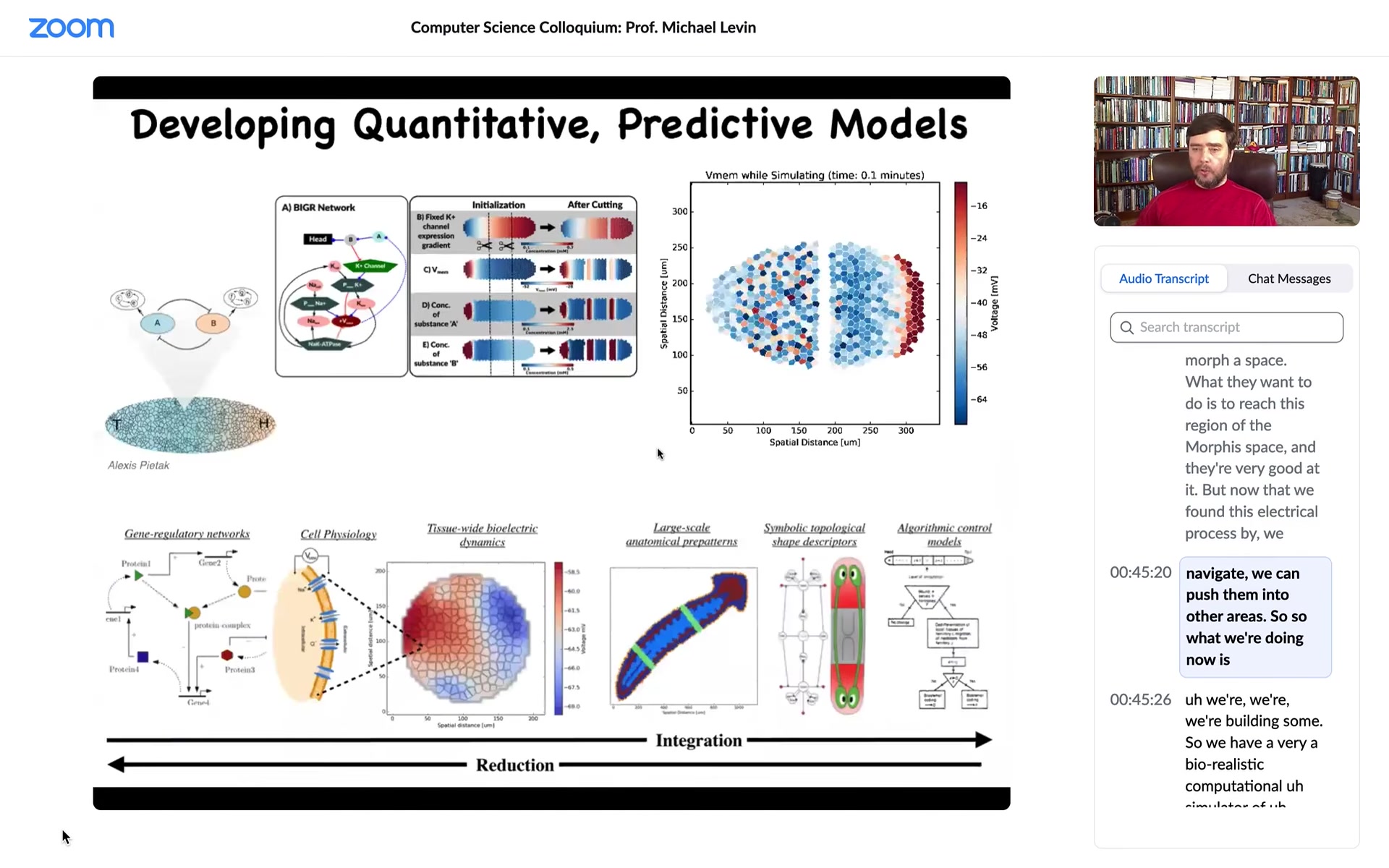

Slide 29/58 · 45m:23s

What we're doing now is we're building. We have a very biorealistic computational simulator of electrical activity; we can look at the circuits at the tissue level, how they rescale.

We're trying, the goal, long-term goal is this full-stack model where we start with the facts of which ion channels are expressed. That's where the genetics plays out and that's your hardware.

But then at the tissue level, what are all the voltage dynamics? They're not obvious because many of these channels are voltage-gated. That's a voltage-gated current conductance. That's a transistor.

When you put these things into circuits, you have all kinds of symmetry-breaking loops. They can do memory as I just showed you. They have all kinds of interesting computations, but are very non-linear, hard to predict.

We want to understand this decision-making of head versus tail versus what else. To the point where we get to an algorithmic model, we're using machine learning approaches to try and extract white-box algorithmic models so that we can say, but what would we need to do if we wanted a fatter worm or three heads or if somebody needed a new finger or a new eye?

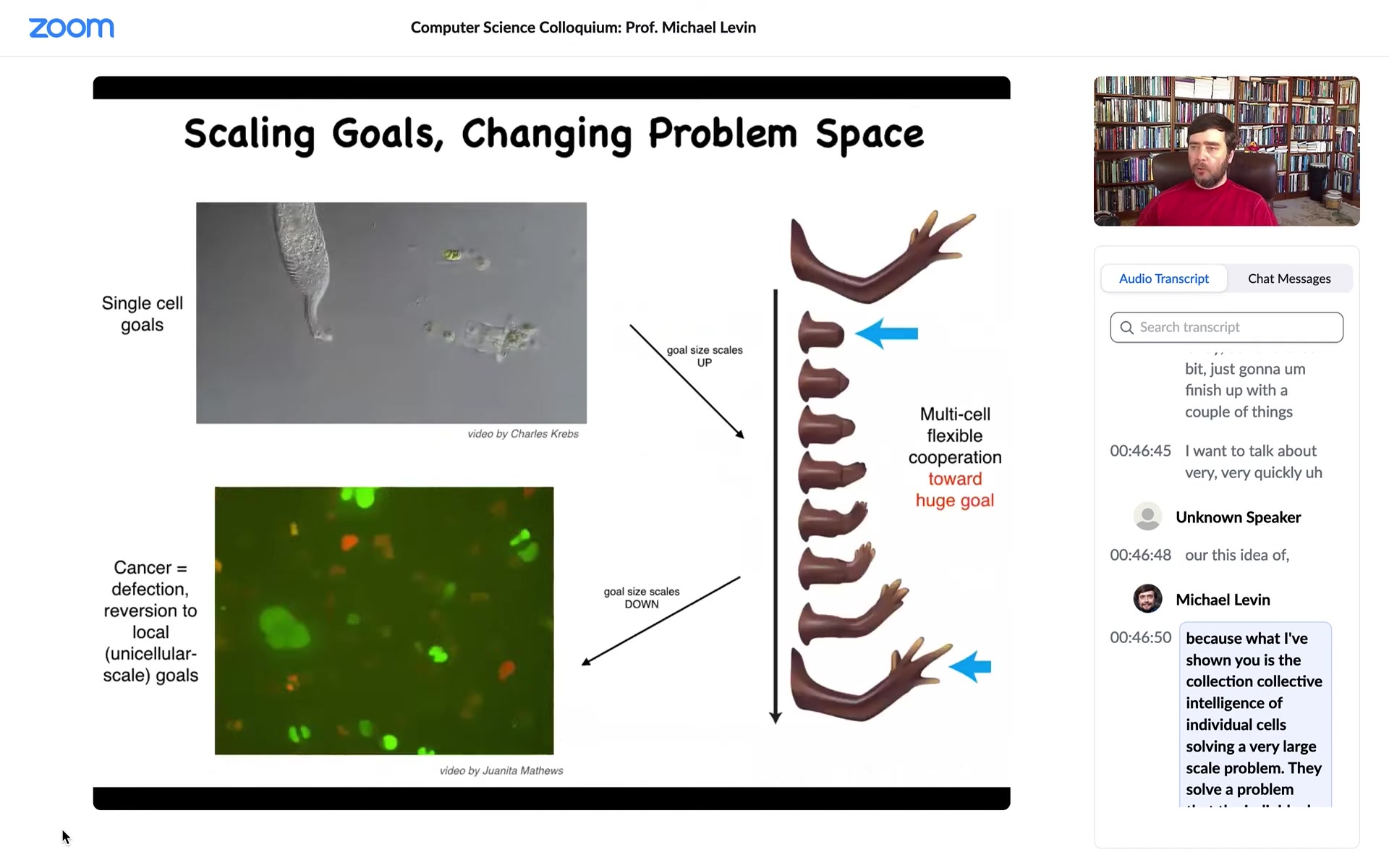

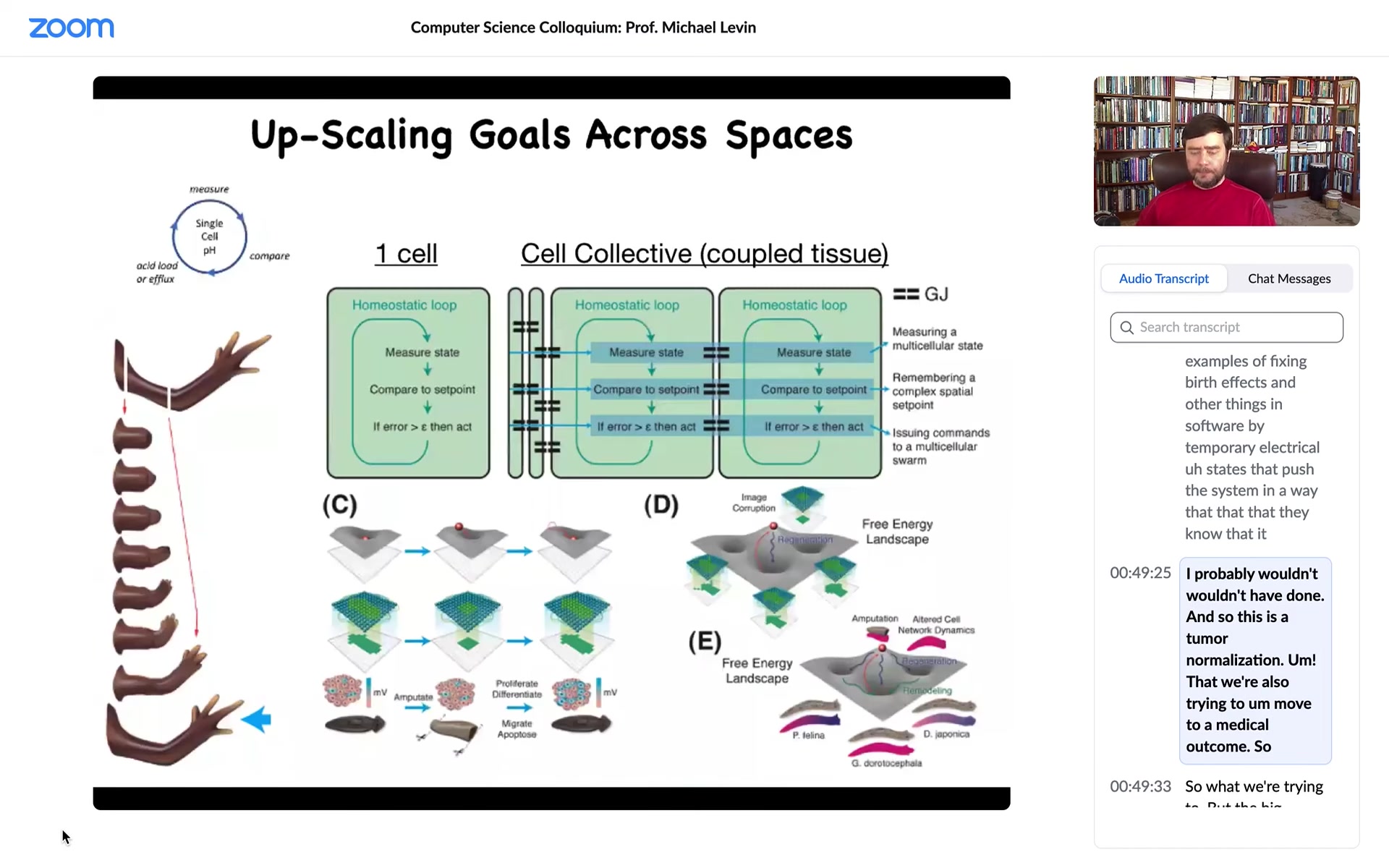

For the last bit, I'm going to finish up with a couple of things. I want to talk very quickly about this idea, because what I've shown you is the collective intelligence of individual cells solving a very large-scale problem. They solve a problem that the individual cells don't have.

Slide 30/58 · 47m:02s

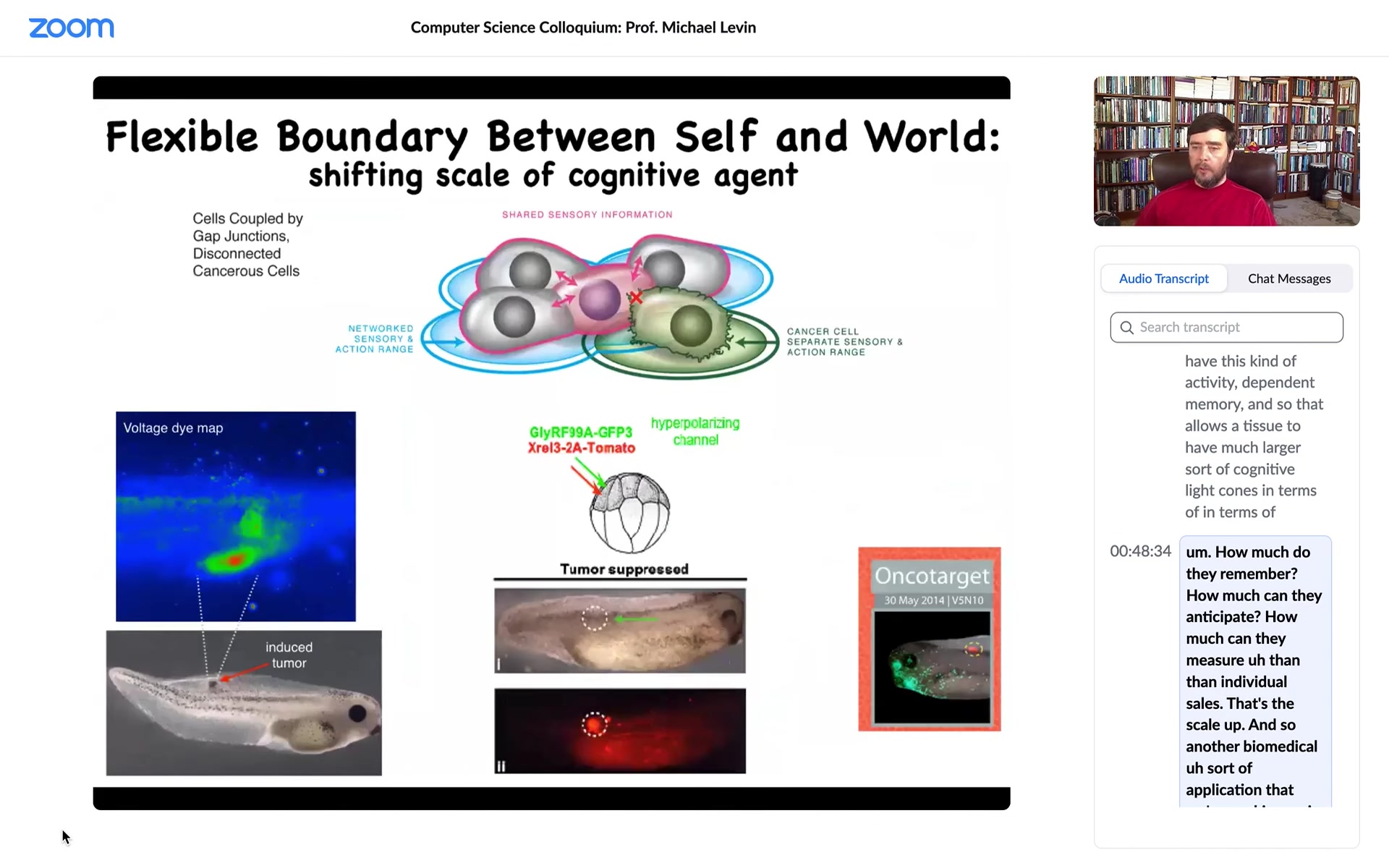

This is what evolution does. Evolution takes these creatures and that enables them to connect with each other to solve problems at the level of anatomical morphospace. For example, if we don't have enough fingers, the tissue knows that and can regenerate the right number of fingers, then it stops. Individual cells have no idea what a finger is or how many fingers there are or anything, but the collective does. What evolution does is this amazing scaling up. But that process has a failure mode. That failure mode is known as cancer.

What happens in cancer is that when individual cells disconnect from this electrical network, they go back to being single-cell amoebas, where their goals are now maximal proliferation and maximal metabolic gain instead of having goals in anatomical morphospace. This is human glioblastoma. These are cells crawling around in culture with no inclination to work hard towards these things.

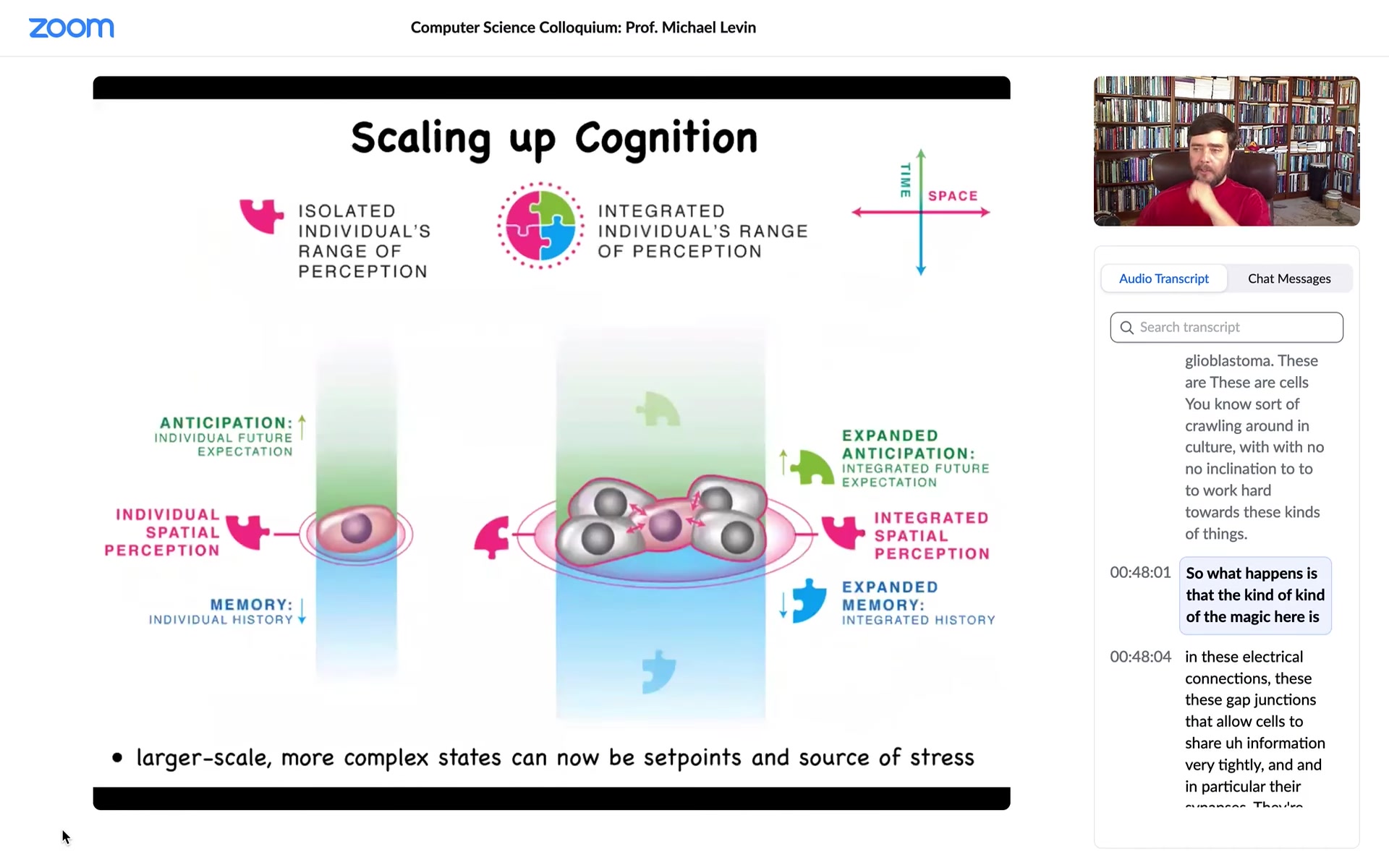

Slide 31/58 · 48m:01s

So what happens is that the magic here is in these electrical connections, these gap junctions that allow cells to share information very tightly, and in particular their synapses, they're called synapses because they are open and closed by prior experiences, meaning that the information that moves through a particular synapse also feeds back, because of their voltage sensitivity, to open and close that synapse. So you have this activity-dependent memory. And so that allows the tissue to have much larger cognitive light cones in terms of how much do they remember, how much can they anticipate, how much can they measure, than individual cells. That's the scale-up.

Slide 32/58 · 48m:40s

Another biomedical application that we're working on is to force that connection. Here is this: we inject an oncogene; normally it would make a tumor. Here it is; the oncogene is blazingly expressed. It's all over the place here. But there is no tumor, because what we've done is we've co-injected a very specific ion channel that forces that cell to remain in electrical connection with their neighbors.

When you force them, even if the genetics are screwed up, I've shown you a number of examples where the genetics is diverting from the actual outcome. What the hardware says is one thing, but you can make changes, and we have lots of other examples of fixing birth defects and other things in software by temporary electrical states that push the system in a way that it normally wouldn't have done. This is a tumor normalization technology that we're also trying to move to a medical outcome.

Slide 33/58 · 49m:32s

What we're trying to do now is to make computational models of local homeostatic loops that started out in bacteria by managing pH and metabolics and things like that. We show how, by connecting these, you have a network of homeostats that are able to control local variables towards set points, and by connecting them you enable the collective to do the same thing, but in a much, much different space.

This is the big area where we need to understand lots more. These are the models we're thinking about.

For the last couple of minutes, I want to talk about this idea of novel organisms. I have to do another disclosure. We also have a spin-off company for biorobotics called Fauna Systems. This is all the work with Josh Bongard at University of Vermont, with whom we've started the Institute for Computationally Designed Organisms.

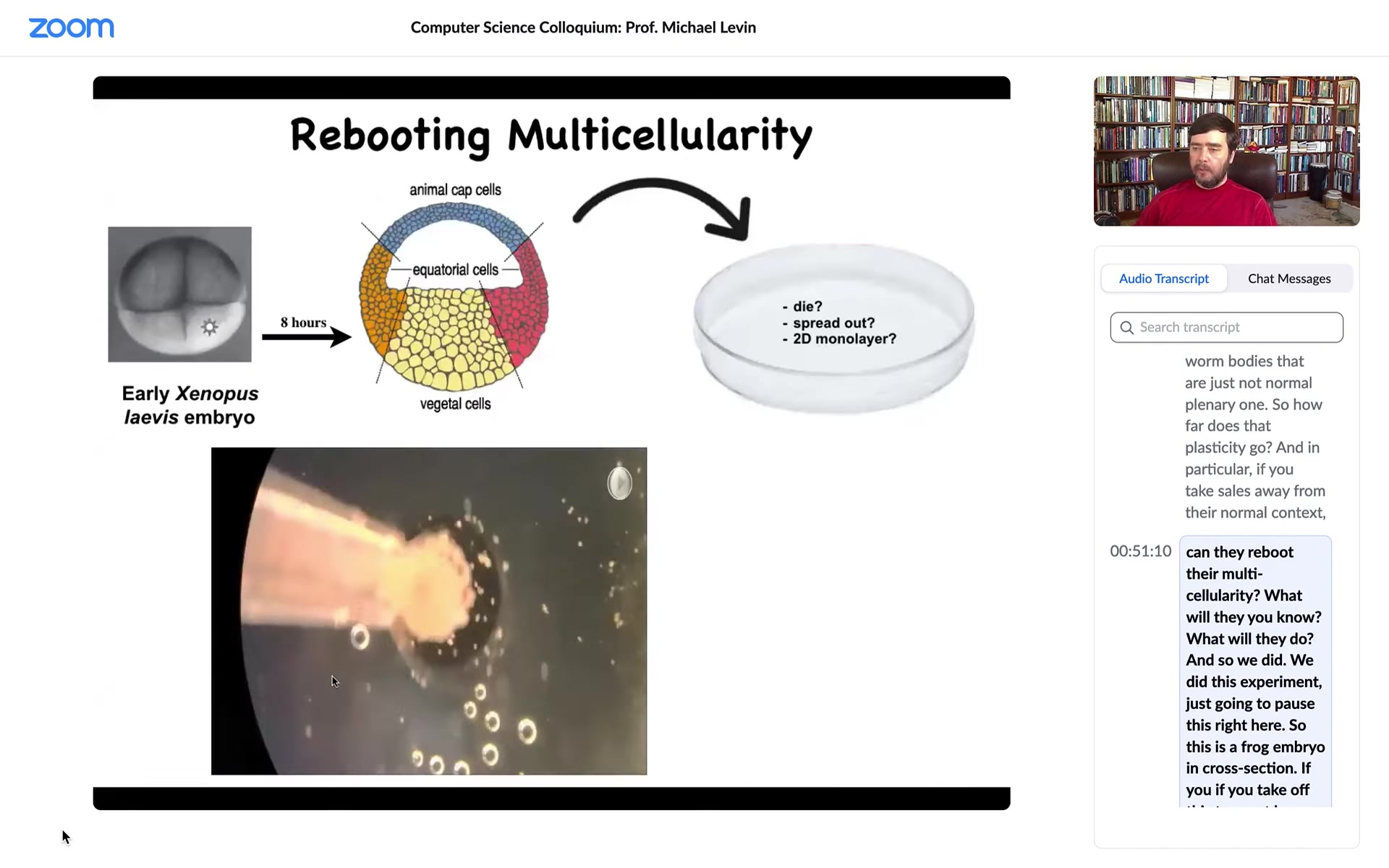

We wanted to ask a simple question: how far does this plasticity go? I've shown you that normal embryos are able to adapt to changes in cell number, cell shape, amount of DNA. You can push them to make worms with heads that belong to other species and worm bodies that are not normal planaria at all. In particular, if you take cells away from their normal context, can they reboot their multicellularity? What will they do?

Slide 34/58 · 51m:13s

We did this experiment. This is a frog embryo in cross-section. If you take off this top part, all of these cells up here are going to be skin. They're all fated to be different kinds of epidermis.

We asked this question: if I take these cells, I dissociate them. I put a little drop of them in a separate environment away from all of this stuff. The person who physically does this is Doug Blackiston in our group. He's a staff scientist who perfected a lot of these protocols. We're not adding synthetic biology constructs. We're not changing the DNA. We're not putting any weird nanomaterials. We're engineering by subtraction. We're taking away the instructive signals from all of this stuff.

What would they do? They might die. They might spread out and crawl away from each other. They might form a two-dimensional monolayer like cell culture. We don't know, but those are some things they might do. Instead, what they do is: here these are loose cells. This is time-lapse. Overnight, they come together and merge into this little thing, this little round thing. The flashes are calcium flashes. We'll talk about that momentarily. What does it do? This is a little ball of skin. What does a little ball of skin do?

Slide 35/58 · 52m:29s

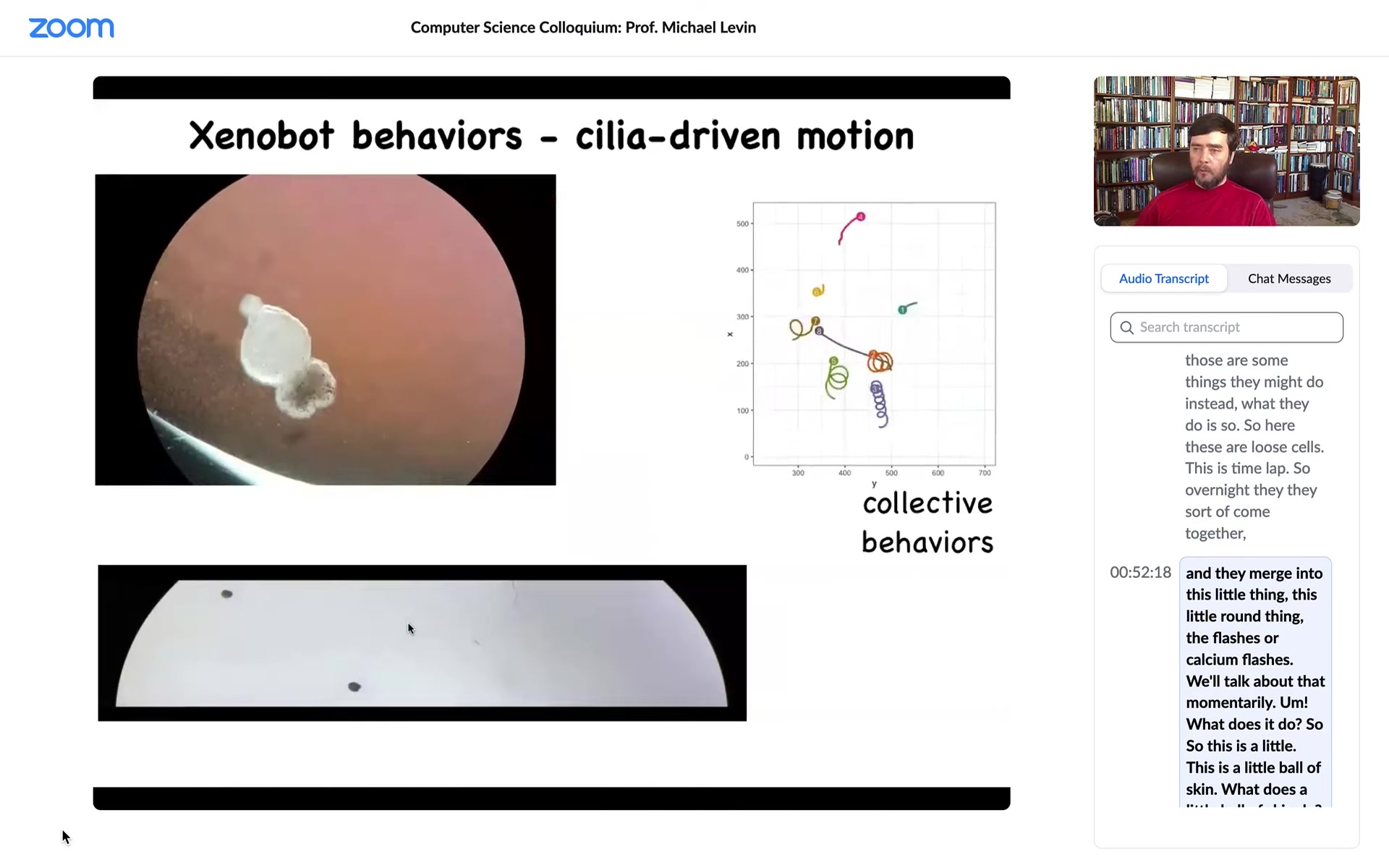

Well, the first thing it does is it takes little hairs that are normally used on the skin to move the mucus down the body of the animal, and it uses those hairs to swim. It rows through the media by pushing the little hairs in opposite directions to the left and right of a midline that it can organize.

Here you can see some behaviors. They can go in circles. They can patrol back and forth. Here's some tracking data on group behavior. This guy's going on a long journey. These are interacting with each other. Sometimes they sit still for long periods of time. They have autonomous motion. This is what they look like in a maze.

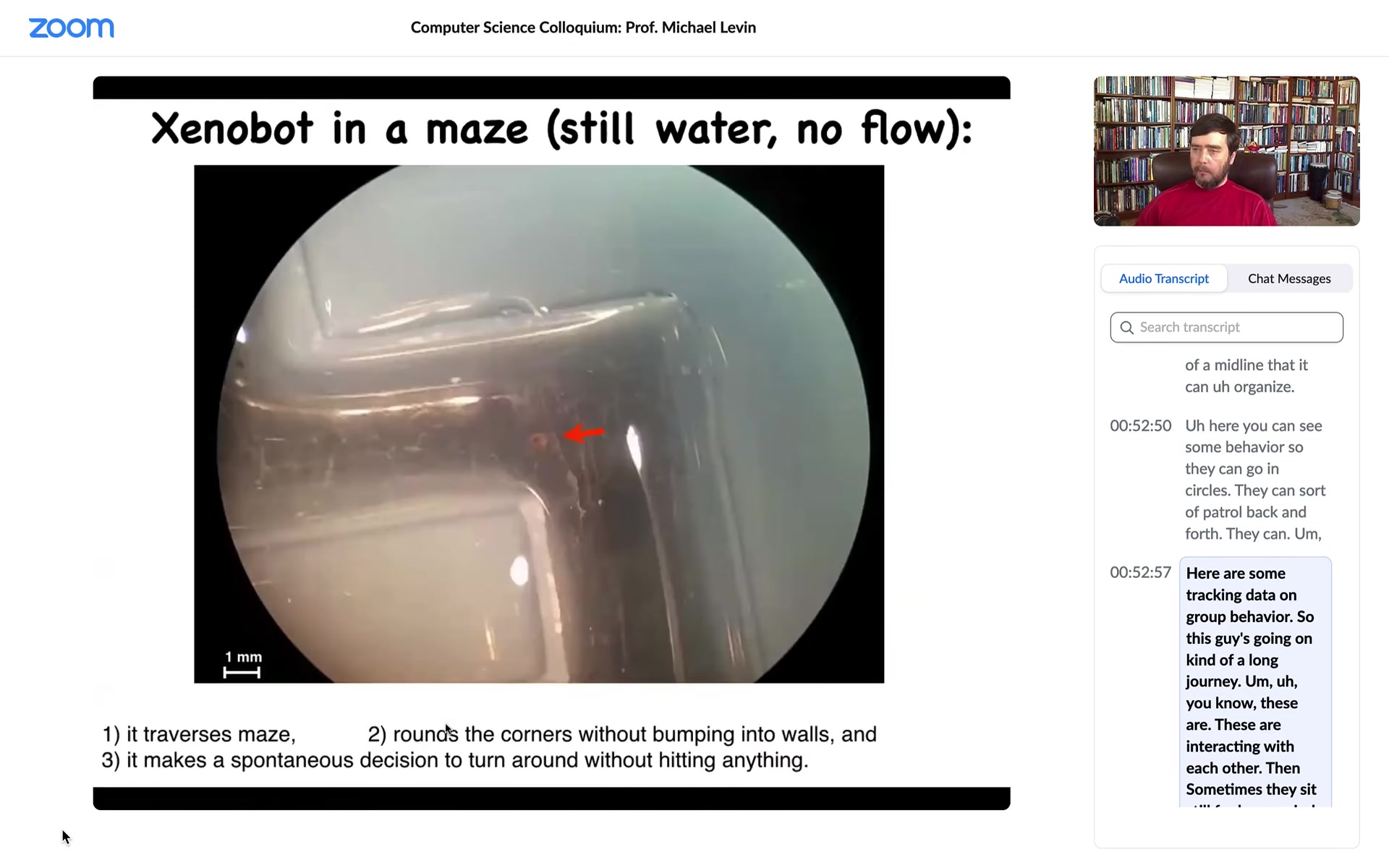

Slide 36/58 · 53m:10s

So this is a water maze. There's no flow. There are no gradients. It's just still spring water. It goes down here. It takes the corner without having to bump into the outside wall. It just follows the corner.

So remember, this is just skin. There is no brain. There is no nervous system. At this point, for some reason that we don't know, it turns around and goes back where it came from. It doesn't want to keep going anymore. So they have a range of behaviors.

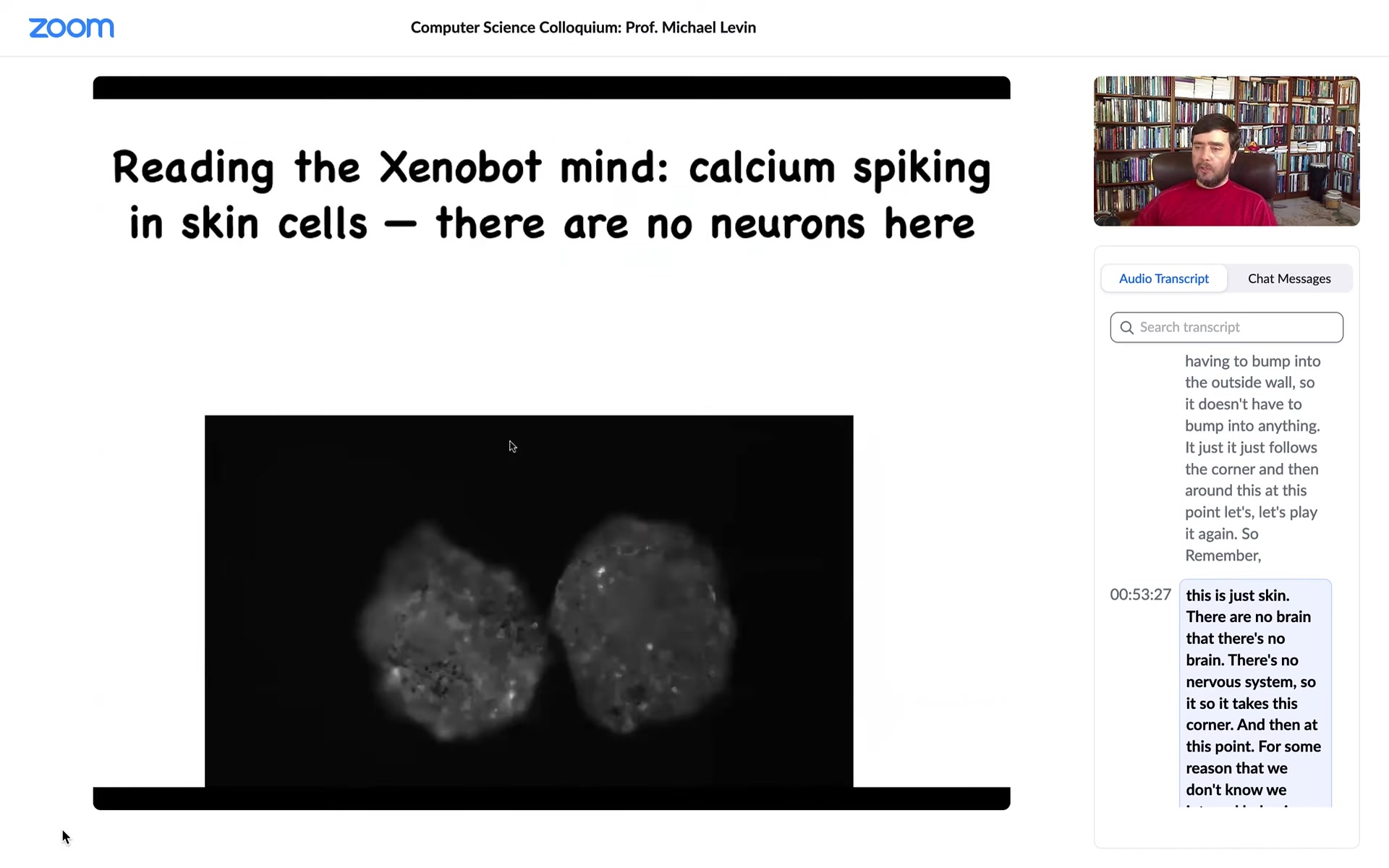

Slide 37/58 · 53m:39s

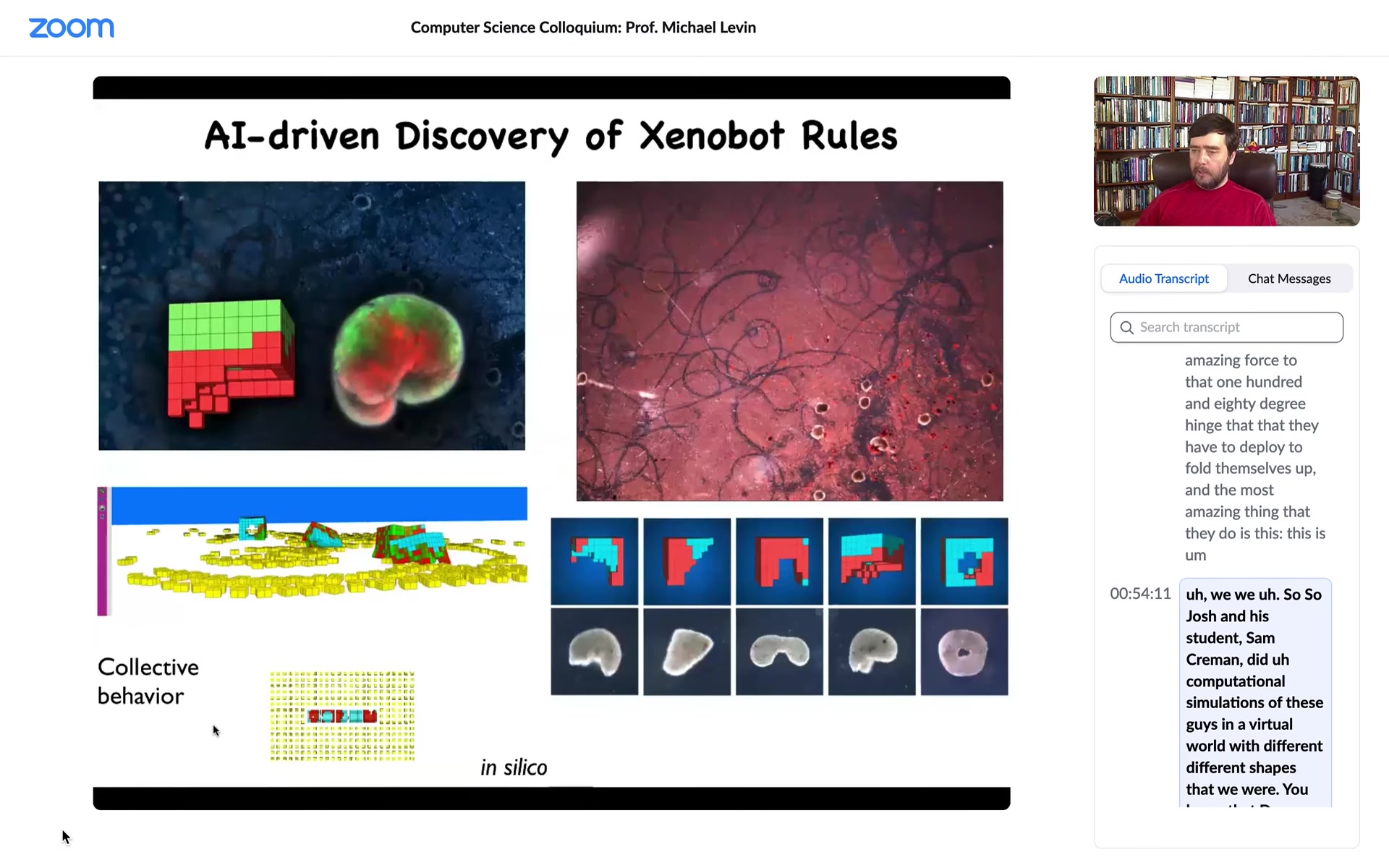

If you ask what the calcium signaling looks like, no neurons here, but the skin is very active with brain-like dynamics, which we are now analyzing using information theory to see what's going on and whether they might be talking to each other. They have regenerative capacity. If I cut it in half, they will try to fold up to their new Zenobot shape. There's an amazing force at the 180-degree hinge that they have to deploy to fold themselves up. The most amazing thing they do is this.

Josh and his student Sam Kriegman did computational simulations of these guys in a virtual world with different shapes that Doug was able to make. We saw something very interesting: in the computational simulation, one of the things they do is they rearrange the particles in their environment into specific shapes.

Slide 38/58 · 54m:30s

That was a prediction of the simulation. We tried. We gave them some particles.

Slide 39/58 · 54m:40s

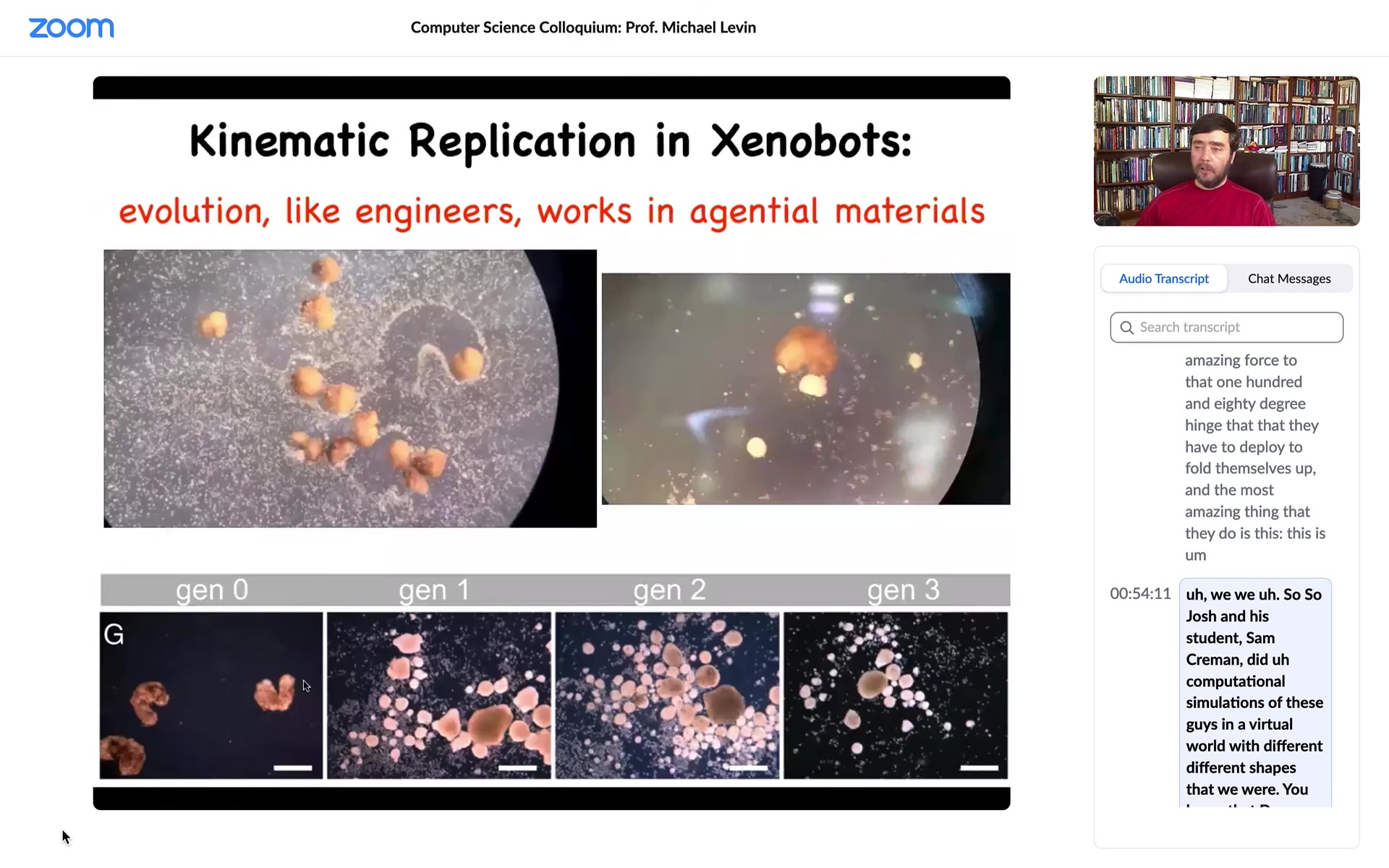

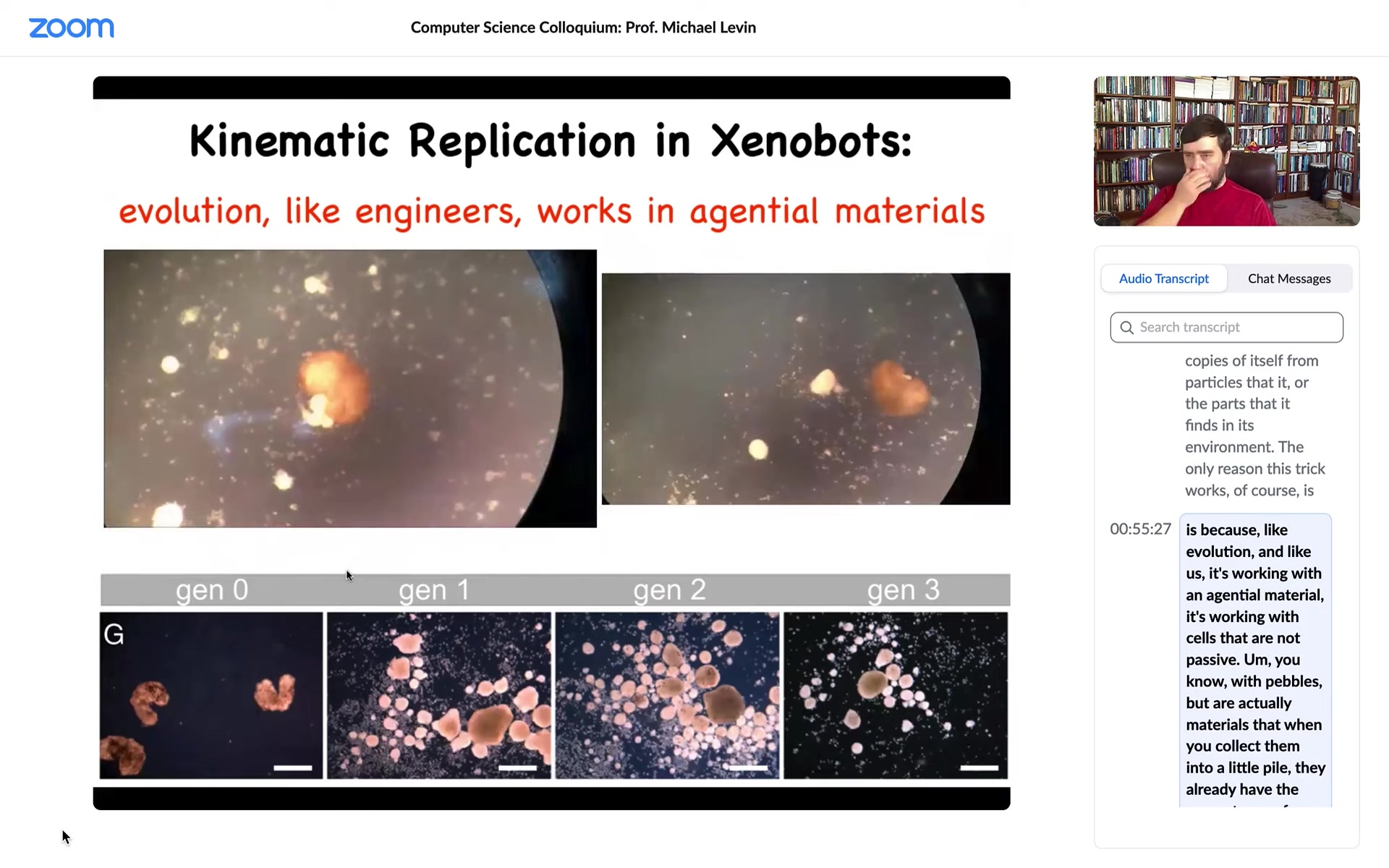

What did we give them? We gave them cells, loose cells. This is the white stuff, the snow here. Those are loose cells. What you see is that the xenobots run around, they corral these particles into little piles, and then they continue to polish those little piles until they become these circular things. Then because what we did was we gave them skin cells, these little piles became the next generation of xenobots. And so guess what? When they matured, they went and did the same thing and they created the next generation of xenobots.

This is von Neumann's dream. This is a machine that runs around and makes copies of itself from particles or parts that it finds in its environment. The only reason this trick works, of course, is because, like evolution and like us, it's working with an agential material. It's working with cells that are not passive pebbles, but are actually materials that when you collect them into a little pile, they already have the competency of becoming a xenobot. So it actually takes very little to get this reproductive cycle happening.

Slide 40/58 · 55m:48s

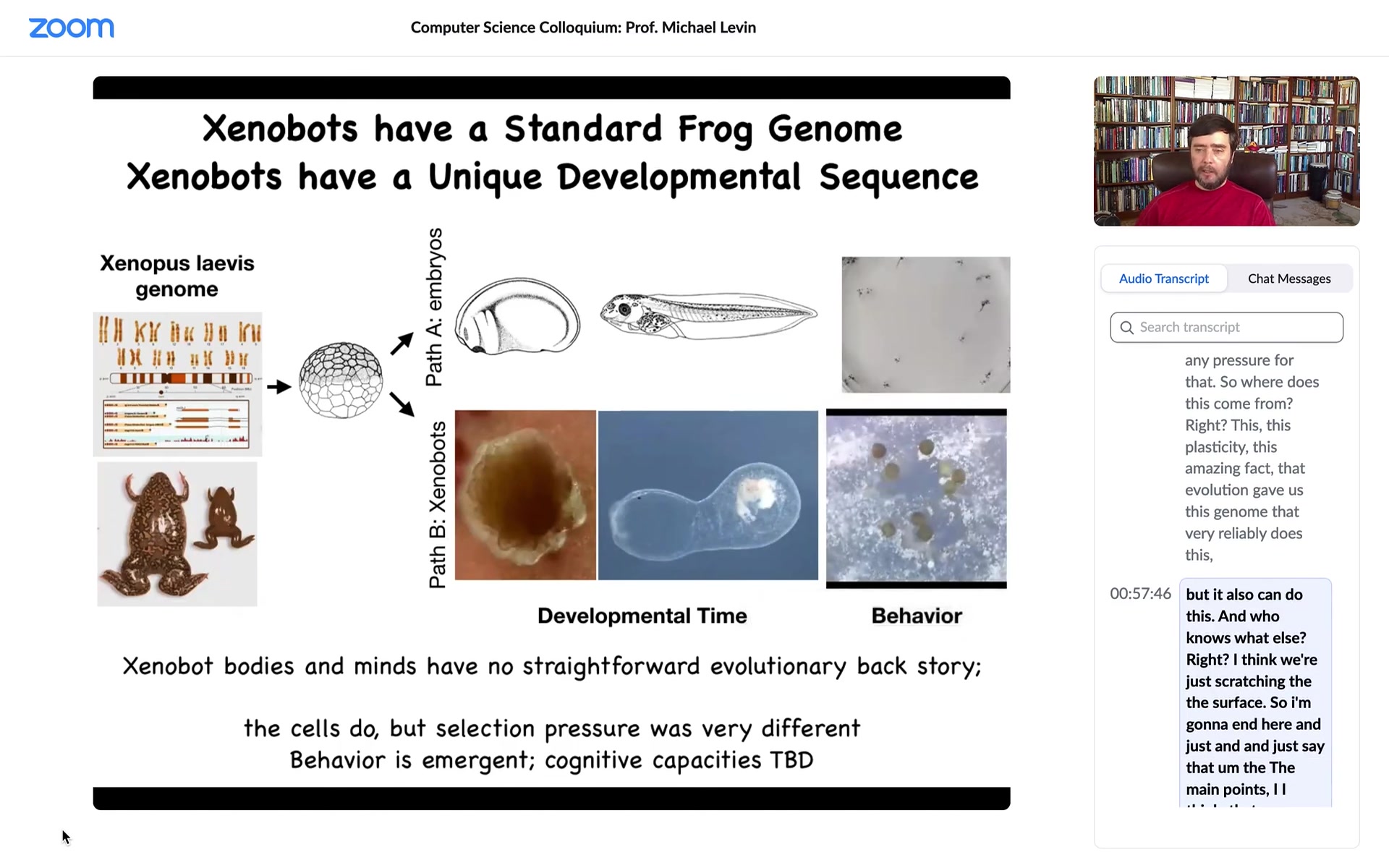

We can learn some interesting things from this. This is the standard Xenopus laevis genome, the standard frog. If you only observe standard development, you are really lulled into a false sense of security. You're given the idea that acorns always make oak trees, frog eggs always make frogs. The genome determines morphology. This is what they can make. They make an embryo that has a certain set of developmental sequences and then certain behaviors. That's what this hardware makes.

Actually, if you liberate these skin cells. What do skin cells know how to do? They know how to be a boring two-dimensional outer layer on this animal, keep out the bacteria, that's it. That's what they do when the other cells bully them into that role. The instructive interactions from the other cells are what's constraining the capacity of these skin cells to sit quietly as the outer layer, and that's that. On their own, given the ability to escape these instructive interactions, they're actually capable of much more.

They make a Zenobot. They undergo a developmental sequence over the next two months. They become this thing. I don't know what this is. They have their own kind of a weird developmental trajectory. Their behaviors are things like making copies of themselves via kinematic self-replication.

This is interesting because for every other creature on Earth, if you were to ask, Why does it have a certain shape, a certain behavior? How is it able to do whatever it does? The answer is always the same: years of selection, eons of evolutionary pressure to do this or that. There's never been any Zenobots. There's never been any evolutionary pressure to be a good Zenobot, to do kinematic self-replication, to any other behaviors that they do, and the morphology—there's never been any pressure for that. So where does this come from? This plasticity, this amazing fact that evolution gave us this genome that very reliably does this, but it also can do this, and who knows what else. I think we're just scratching the surface.

Slide 41/58 · 57m:50s

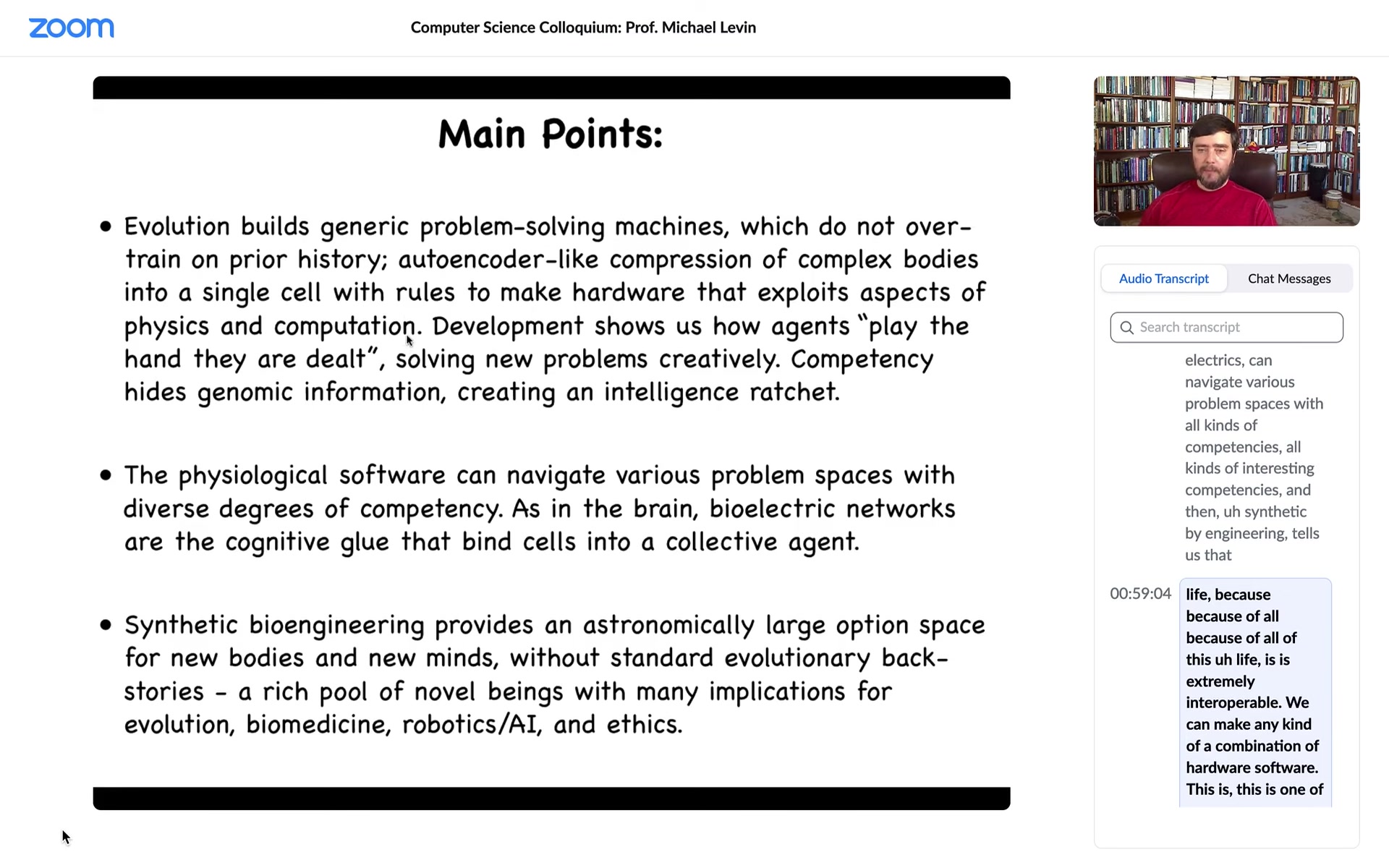

I'm going to end here and say that the main points I think that are emerging from all our work, including many things I didn't show you, are these. Evolution tends to build generic problem-solving machines which, because of this compression of complex bodies into a single cell during sexual reproduction, enables some amazing hardware that exploits aspects of physics and computation. It doesn't try to pre-code everything.

And development shows us that these kinds of agents in morphospace and in other spaces have to deal with whatever they're given at the beginning. They are not tied to a very specific, very tight set of initial conditions.

There's this intelligence ratchet that's formed because that competency hides a lot of genomic fitness information from evolution. A lot of the effort goes into that competency, as opposed to the hardware.

And the physiology, especially the bioelectrics, navigate various problem spaces with all kinds of interesting competencies. And then synthetic bioengineering tells us that life, because of all of this, is extremely interoperable.

Slide 42/58 · 59m:11s

We can make any kind of combination of hardware, software. This is one of my favorite kinds of videos. This is an early baby mammal discovering for the first time what kinds of effectors it has. Look at this, I've got legs, I've got arms.

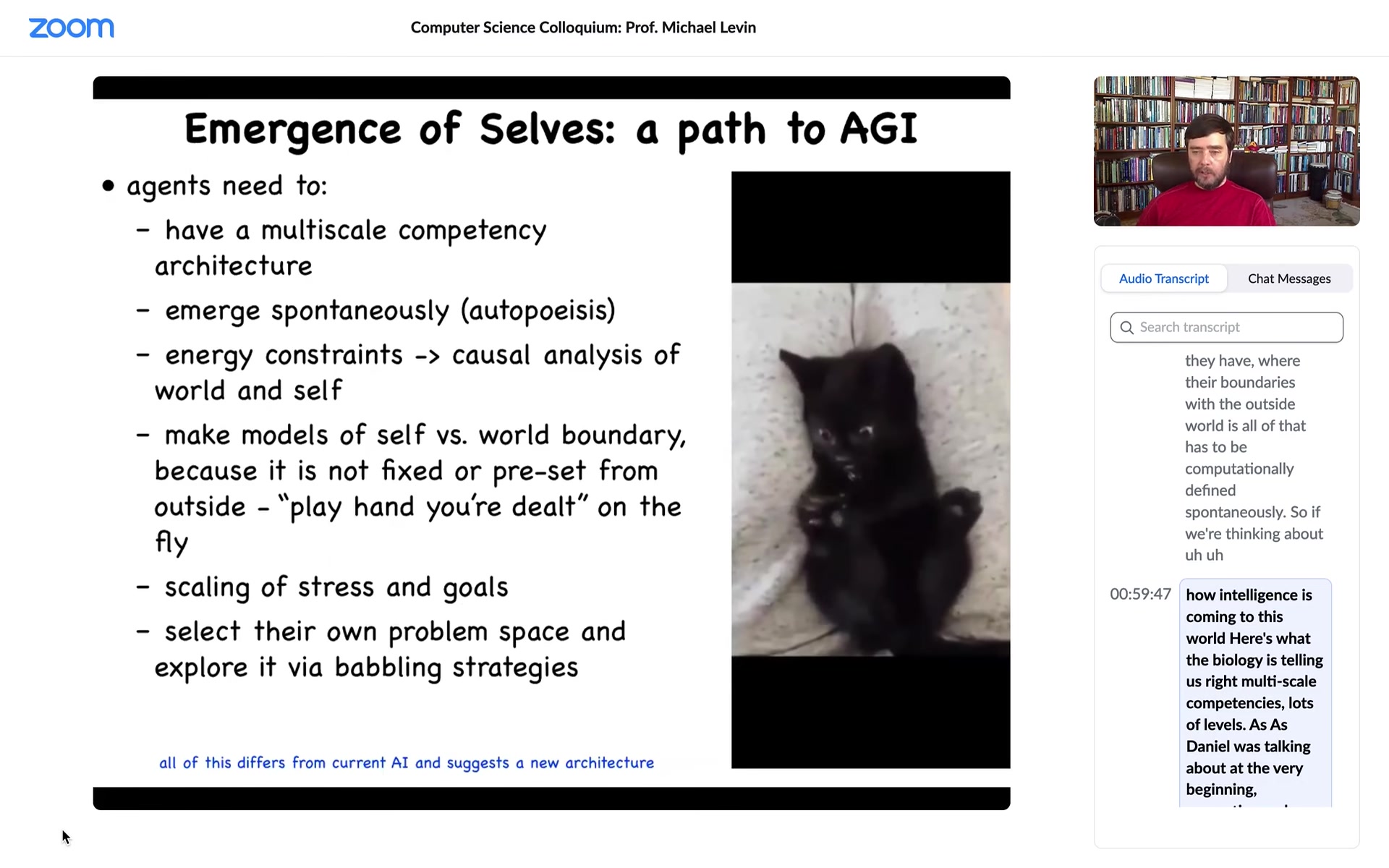

They don't know ahead of time when embryos are born into this world, much like Josh Bongard's robots. They don't know right away what they have, where their boundaries with the outside world are. All of that has to be computationally defined spontaneously.

So if we're thinking about how intelligence is coming to this world, here's what the biology is telling us. Multi-scale competencies, lots of levels, as Daniel was talking about at the very beginning, competing and cooperating with each other, spontaneous emergence of boundaries, energy constraints, which require you to do coarse graining on your inputs, self-modeling — this is what biology is telling us.

Slide 43/58 · 1h:00m:10s

Because of this interoperability, everything that we know in the natural world, all of Darwin's "endless forms most beautiful," is just a tiny corner of this option space. Every combination of evolved material, designed machinery, AI, and software is some kind of agent. A lot of this already exists. Hybrids, cyborgs, all kinds of things.

That means that we have to redefine a lot of our old categories that started out by looking at this picture of the Garden of Eden, where you have a standard human, you have some standard animals, and that's it. That picture is gone.

I'm going to close here. If anybody's interested in diving further into these issues, here are some papers I could send you.

Slide 44/58 · 1h:01m:00s

I want to thank all the people that did the work.

Doug and Sam did all the Zenabot work. Here are the other students and postdocs that contributed to this stuff, our collaborators, our funders. Most of all our model systems—the animals do most of the heavy lifting here.

And that's it. I thank you for listening and I will take any questions.

Slide 45/58 · 1h:01m:21s

Thank you for a truly marvelous talk.

We have a few minutes for questions. I think you said we have about 10 minutes left. Yes, Daniel, I think you were first.

If I start asking, nobody else will have time. I'll leave mine for the last.

Christophe, I thought I saw your hand.

Sorry, I was just clapping.

Slide 46/58 · 1h:01m:59s

Anyone else before I start asking questions as well? In that case, I have too many questions and I don't know enough about it. I'd really like to know more about these bioelectrical patterns and how you, for instance, seem to have gained control over how to manipulate those, say you fix the genetics and you give it somehow the phenotype of a different creature, a different animal entirely.

That is absolutely mind-blowing.

And it almost seems like the genetics isn't as important as we thought it would be. To what extent can you get something with a drastically different phenotype? How drastically different can the phenotype end up?

Slide 47/58 · 1h:03m:11s

I think that in the planaria, it's 150 million years difference between the animals that we start with and the ones that we can make. It's equivalent to 150 million years of evolutionary distance to these other species. Plus, we can make shapes that never existed. I don't know what the distance there would be. I think it's a very important point. I think absolutely the role of the genome is not what we thought it was.

One of the key things here is that a lot of people get very suspicious about computer science analogies, but the part that is actually very, very useful is the distinction between hardware and software. Sometimes students are taught this, that the cell is the hardware that interprets the genome, and the genome is the software of the cell. I think that's completely wrong. What the genome actually does is nail down the hardware of the cell. The genome tells you what channels you're going to have. If your genome does not give you a voltage-gated ion channel, you don't have those transistors; there are very limited things you can do. The hardware is critical because it facilitates or forbids certain kinds of behavior modes.

We all know now that knowing the hardware does not tell you all of the interesting things you need to know about what this thing is going to be able to do. Not only can the same hardware run many different kinds of behavior modes, but it means that the way you interact with it does not have to be at the hardware level. The huge insight to me of computer science is this idea of reprogrammability. Once you get beyond a certain capacity, and I think biological systems are way beyond that, you can interact with it via inputs, via stimuli, via communication, not just by rewiring it.

The focus on the DNA, both as the source of the information and as the optimal control knob, and all the excitement over genomic editing and everything else are misplaced. Those things are misplaced. That's not to say that the genome isn't important. You need to have the right hardware. If you don't have the right hardware, you're not going to be able to do certain things.

Slide 48/58 · 1h:05m:31s

So it's like there's a whole area of interaction with physics, what this hardware can do. There is some physics that it exploits and that doesn't need to be in the genome.

Slide 49/58 · 1h:05m:45s

That's a very profound idea, and people have been thinking about this in mathematics for the longest time. Where do the truths of number theory live? You could change all the facts of the initial conditions of the universe and number theory would still be what it is.

Think about this. If you were to try to evolve a triangle, you evolve the first angle, you evolve the second angle, but you don't need to evolve the third angle. You know what it is.

Where does that come from?

Slide 50/58 · 1h:06m:18s

That's an amazing free lunch, as the physicists would say. And the same thing with computation. So once you evolve that ion channel, and that's basically a transistor. So now you get to have logic gates and truth tables. Did you have to evolve a truth table? No, you got that for free. Where do truth tables live?

But I think you're absolutely right: what evolution does is it builds machines that couple to these amazing affordances. So, in behavioural ecology, they would call these affordances, these incredible affordances provided by physics, by computation, by geometry, by mechanics. I think that's really an important way to look at evolution.

Daniel, yes.

Slide 51/58 · 1h:07m:09s

I can't hold myself anymore. First of all, this is an amazing talk. I wish we could now sit together and talk for the rest of the afternoon, which neither you nor I can do, but we should definitely continue talking. I completely agree with this point about the triangle. I just recently said to somebody that mathematics is neither discovered nor constructed, but it's something in between.

Slide 52/58 · 1h:07m:43s

You construct some things and then there are constraints that emerge and they are implicit to whatever you do. It's a bit like what I call a box of oranges. You fill the box of oranges and you get these hexagonal patterns once you're dense enough. This is not something you created. It's an aspect of the space that forces this upon us. But we still have choices between different crystal patterns. For example, there are 14 crystal patterns.

It looks like there's an element of holography in the whole thing, where information is not fully localized. I felt it's the most strongly actual in your example with the brain, with the reconstructed brain, because the question is, how much information can you retain holographically?

So, when you take this planar worm, the question is, how much information can you retain? In my language, I would say, how many bits can you retain in this delocalized form?

Slide 53/58 · 1h:08m:54s

I have no idea how much information. We can't do the bits thing because we don't know what the encoding and decoding of the message is, so that's hard. But you're absolutely right. There's holography here in two ways. One is the lateral way, which is that most of this information is distributed spatially across the whole animal. So the bioelectric code and what enables us to do these various things is not a single cell code. This is not something that tells individual cells what cell type they should be. This is spread across the whole tissue. And of course, you can cut it both spatially and behaviorally. It rescales the information onto every piece; every piece retains it. So that's lateral holography.

There's also a vertical one, which is interesting in a very important sense. A lot of the same rules that operate in controlling the morphology of large-scale bodies, like ours, some of those same rules are playing out in the shaping of single cells. So there are mathematical aspects of morphology that work the same way in multicellular bodies, but also in single cells at a much lower scale. And other people have found the same thing in patterning of ant colonies and so on. So there's also this almost a fractal idea. That the same things repeat themselves again and again at different scales, despite the fact that the material implementation is quite different at that point.

That sounds interesting because I do think that there might be ways of qualifying that.

Slide 54/58 · 1h:10m:41s

I very much like this attractive vision of genetic coding because we know that embodiment can change a lot. The talk that I gave with you, I had mentioned that primitive example of how you can change the amount of information you need to do something if you change embodiment. It's drastically different. The big question is how much can you associate to the embodiment? How much can you associate to, in your case, the genome?

I see Stavros has a question; I'll be silent.

We can discuss another time.

I'll let Stavros go ahead.

Stavros. I'll say thank you. I'll take the question, but I apologize. In about three minutes I have to run.

Slide 55/58 · 1h:11m:31s

Sorry to interrupt you, Daniel. Thanks for your talk. I'll be very quick. I've seen you in other talks talk about using the language of affect to describe navigating these morphological spaces and extending the concept of affect beyond where it's usually used. Could you talk more on that?

Slide 56/58 · 1h:11m:57s

That's a very long discussion, but the short version of it is that we have been trying to map as many concepts in cognitive neuroscience as we can onto this, for example, navigating morphospace.

Goal-seeking behavior, rewards, punishments, different types of learning and memory, different types of affect, perceptual bistability, visual illusions, all of these things can be mapped very nicely. I have tables in a couple of papers, which I'm happy to send, where it just goes side by side and it shows you exactly what the mapping is.

There are mappings for affect and for many of these terms. I'm not saying all of them are going to map, but so far the symmetry has worked very nicely. You can define these things in other spaces.

It seems incredible.

Drop me an e-mail and I'll send you the paper where we go into this.

Slide 57/58 · 1h:13m:08s

So are there any more questions? I wish there were. I take this opportunity once more to thank the speaker for a wonderful talk. Thank you so much.

Slide 58/58 · 1h:13m:22s

Really appreciate the discussion. Please, by all means, e-mail me. I'd love to discuss it with anybody anytime. Thank you again.

Thank you so much, everybody.