Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a ~46 minute talk given at a conference on consciousness, presenting my lab's data on cognition in body organs outside the brain and then some speculations about the mind-body connection more generally (fleshing out my Platonic space model with symmetries between brain:mind relationships and mathematics:physics relationships).

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Expanding consciousness inquiry

(04:24) Continuity across beings

(09:03) From embryo to agent

(14:12) Morphogenesis as problem solving

(21:09) Bioelectric goals and memories

(29:01) Synthetic xenobots and agency

(35:41) Platonic patterns and minds

(41:04) Emergent agency and AI

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/42 · 00m:00s

What I'm going to do today is give a very different talk than what I usually do. Nicholas asked me to get on the edge more. I'm going to do that today.

Typically, I'd spend about 45 minutes on the biology and either not mention consciousness at all or mention it at the end. I've flipped that. A large part of what I normally discuss on the biology end, I'm going to skip and we can talk about it in Q&A or you can find it on our lab website or many other places.

It's a little intimidating to be talking about consciousness to people who are experts in the field because typically my lab does not work on consciousness per se. We work on different aspects of unconventional intelligence. I'm going to go out on a limb and say a few things and see what you think.

Slide 2/42 · 00m:48s

What I do not claim is to have a new theory of consciousness, nor do I have definitive data uniquely supporting a specific theory of consciousness, but here are some things that I do claim.

We've expanded the use of both bench tools and conceptual frameworks from cognitive and neuroscience outside of that domain. We've applied them to all sorts of other things. This has led to new discoveries and new capabilities. It's had empirical fertility, not a question of philosophy or linguistics, but actually of discovering new things. I think that's quite useful and helps us to think about very diverse kinds of minds in other embodiments.

I also think that if you use any of the typical criteria that we use to ascribe consciousness to each other, be they joint cellular mechanisms or problem-solving observable behaviors or evolutionary relationships, or microtubule dynamics or specific kinds of causal architectures as evidence of consciousness in each other, then for the exact same reasons, we are going to have to take very seriously the possibility of consciousness in our other body structures. That is a stepping stone to asking more broadly what other kinds of diverse embodiments could be relevant to the study of consciousness.

I think we can get there step by step by first considering the reasons that one might or might not assign at least some plausibility to consciousness outside of the brain in our own bodies. More broadly, issues around AI and many ethical problems are not going to be resolved if we maintain a focus on humans, a focus on 3D space for embodiment, if we view the brain as necessarily privileged in some way, and if we try to maintain crisp binary categories of being conscious or not. All of these things are preventing progress in this field, and I will talk about why that is.

Towards the end, I'm going to say some controversial things about what this all means for consciousness and the idea that physics and evolutionary history do not tell the whole story of what's going on here. I'm going to show you a model that in some ways is a very ancient model and in other ways is now in a much different place.

Slide 3/42 · 03m:15s

First I'm going to talk about the framework, the approach that we take to these kinds of problems, and I think it's really analogous to what's happened in our understanding of electromagnetism prior to having a good theory of electromagnetism. We had all kinds of diverse phenomena: static electricity, lightning, light, magnets, and so on, that people thought were fundamentally different things. Having a good theory allowed us to see that they're actually different aspects of the same underlying thing. It also enabled us to create technologies that allow us to operate in areas of the spectrum to which we were previously blind.

In other words, only a tiny region was available to us because of our own evolutionary history. I think this is exactly what's going on with our mind blindness and our inability to envision and to recognize that very diverse intelligence is all around us. I think we need to create these kinds of enabling technologies, much as we did here, to recognize and interact with these other beings.

Slide 4/42 · 04m:24s

This is the picture that underlies a lot of thought in the field. It's an old piece of art called "Adam Names the Animals in the Garden of Eden." I think there's something deeply wrong and something deeply correct about this view. What's wrong here is that it suggests that there are very clearly delineated natural kinds.

Here are the different animals. These are familiar things that are easy for us to recognize as having a mind. Adam is different from all of these. It suggests that this is the thing we need to understand. Once we've got all of these, we're done. I think this is going to have to profoundly change.

What's interesting about this is that in this ancient biblical story, the idea was that Adam had to be the one to name the animals. God couldn't do it, the angels couldn't do it; it had to be Adam that named them. In these old traditions, the idea of naming something means that you've discovered its true inner nature. That's the deep meaning of giving something a name.

I think this is profound for us because we are going to have to name, in this sense of discovering the inner nature, a whole variety of novel beings with whom we are going to share our world. That's just as true for Adam. We're trying to develop some tools for making that easier to do.

Slide 5/42 · 05m:52s

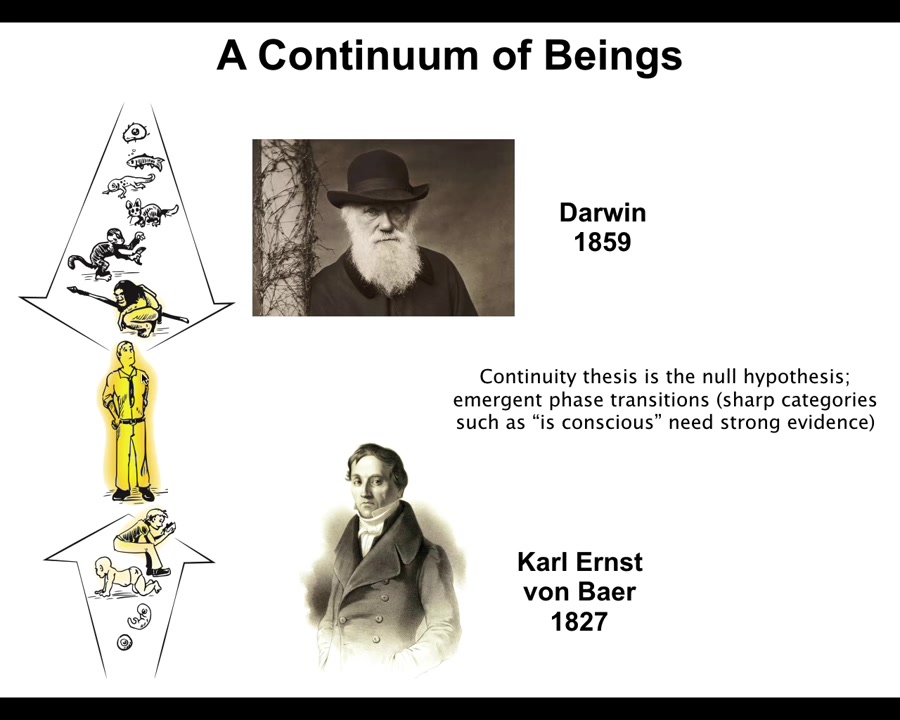

And one important thing is that because of our understanding of evolution and embryonic development, that we're on different time scales, we all start as a single cell and then we become this typical human that features prominently in philosophical discussions of a philosophy of mind. We now know that this is a slow and gradual process on both time scales. And so I would claim that the continuity thesis is the null hypothesis. That is, if we think there should be some emergent phase transitions and specific categories that are just different than other categories of beings here, that is what needs very strong evidence. The baseline, I think, in the null hypothesis should be a continuity and the drive to develop models of scaling and so that we can talk about what kind of consciousness and how much, not whether something is or isn't consciousness. And I'll hammer this theme a couple of times in my talk.

Slide 6/42 · 06m:49s

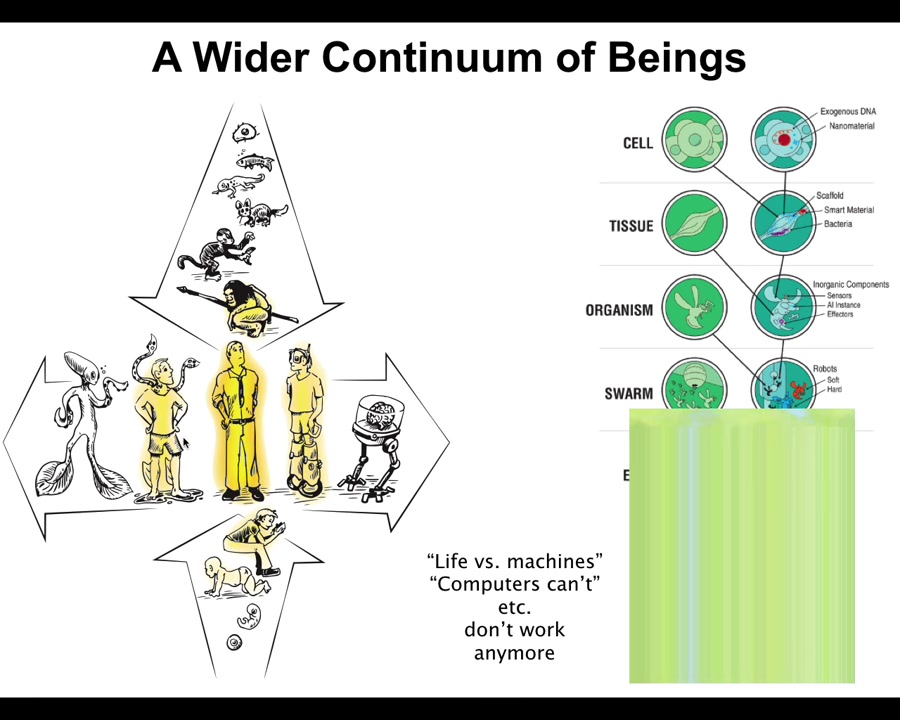

Now, moreover, I don't know what's going on with this visual here, but there is another spectrum here, another continuum, which is the gradual technological and biological changes that can and will and are being applied to this kind of standard human with this sort of special agential glow. And because biology is so highly interoperable, you can introduce engineered material pretty much anywhere along the scale. And so, questions of life versus machines or what computers can and can't do, these are all very difficult now because of the existence of these chimeras. And I think these are the difficult cases that we need to talk about, which, again, speak to models of transformation, not sharp categories.

Slide 7/42 · 07m:40s

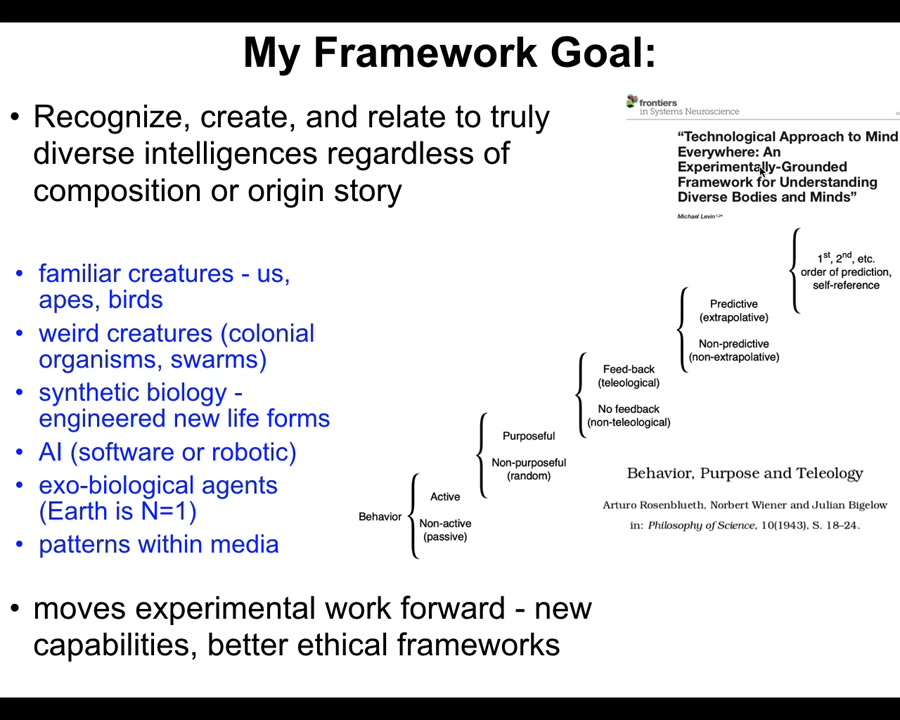

In my framework, what I try to do is create a way of thinking about all of these different agents, no matter what their composition or province is. We need to be able to think about familiar creatures like primates and birds and maybe an octopus and a whale, but also weird creatures such as colonial organisms, engineered new life forms of which I'm going to show you one today, AIs whether purely software or robotic, maybe someday exobiological agents, and even patterns within media.

I would like to have a way of understanding what all of these agents have in common, and in particular, in a way that moves experimental work forward. This is very important for us in our lab: whatever we say about these things has to be actionable in an experimental way that shows why thinking of these things is useful. I also think it's critical for better ethical frameworks as we learn to recognize and relate to these unfamiliar kinds of minds.

I'm not the first person to try this. So here's Rosenbluth, Wiener, and Bigelow with their cybernetic ladder leading up from passive matter all the way up to human metacognition. But I think we have a new way of thinking about it, and the 1.0 version of that is all described here.

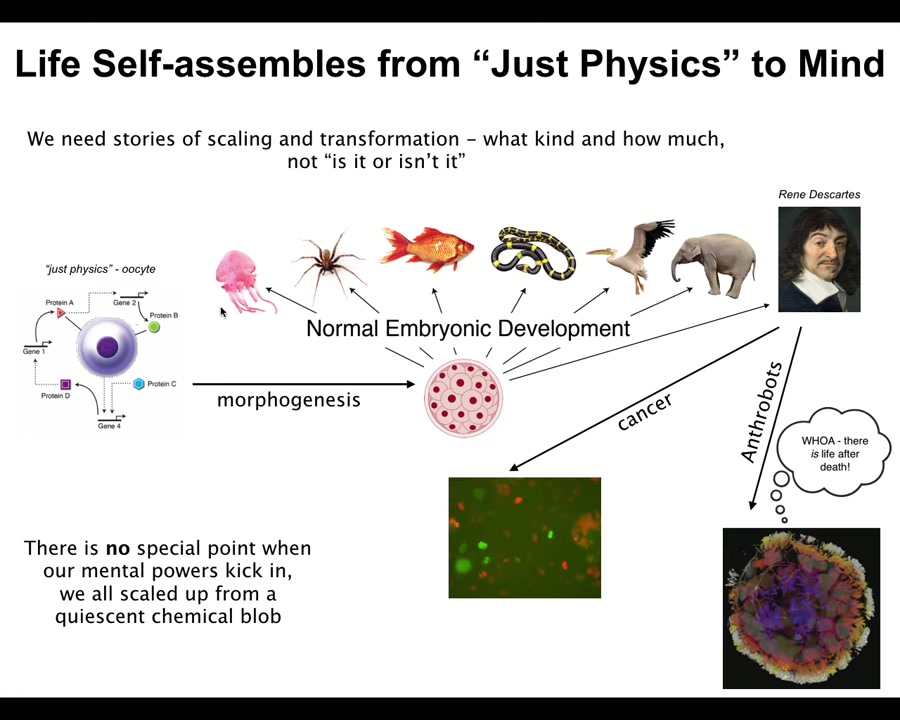

Slide 8/42 · 09m:03s

The fact is that all of us made this journey. We all started life as a quiescent BLOB of chemicals, as an unfertilized oocyte. People tend to think that is well handled by the laws of physics and chemistry, and that you don't need any concepts from cognitive or behavioral science to deal with this. Through the process of morphogenesis, we become something like this, or even perhaps something like this. This journey from chemistry and physics to the land of psychoanalysis is gradual.

This is not the end. There are a number of interesting things that can happen after that. I think that developmental biology offers no special point when any of the things that are of interest to this group kick in. At least I'm not aware of any such.

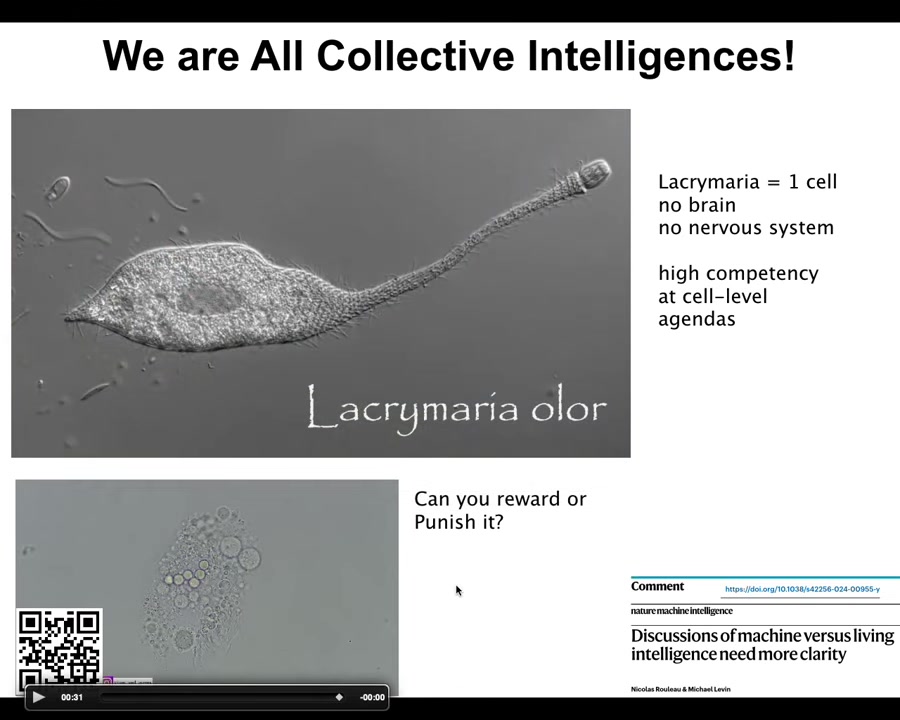

Slide 9/42 · 10m:05s

The other important thing about the architecture of which we're made is that we are all collective intelligences. We are all made of parts that are themselves quite competent. So here's a single cell. This is a free-living organism, but you get the idea. This is one cell. It has no brain, no nervous system. It is highly competent at its own tiny little cell-level agendas. You can ask the question of whether you can reward and punish this. Most people will say you can. You can do experiments where you provide positive and negative reinforcement.

Here's another unicellular organism. This is a sad video. What you're watching is the death of a minimal being. This poor guy is falling apart into its constitutive parts. What you see now is just some chemicals, chemicals that are quite different from what it was just minutes ago. Now we can ask the question, can you in fact reward and punish a collection of chemicals? Because that in a certain sense is what we have here. With some time, if this was an egg, you would have a being that you can reward and punish.

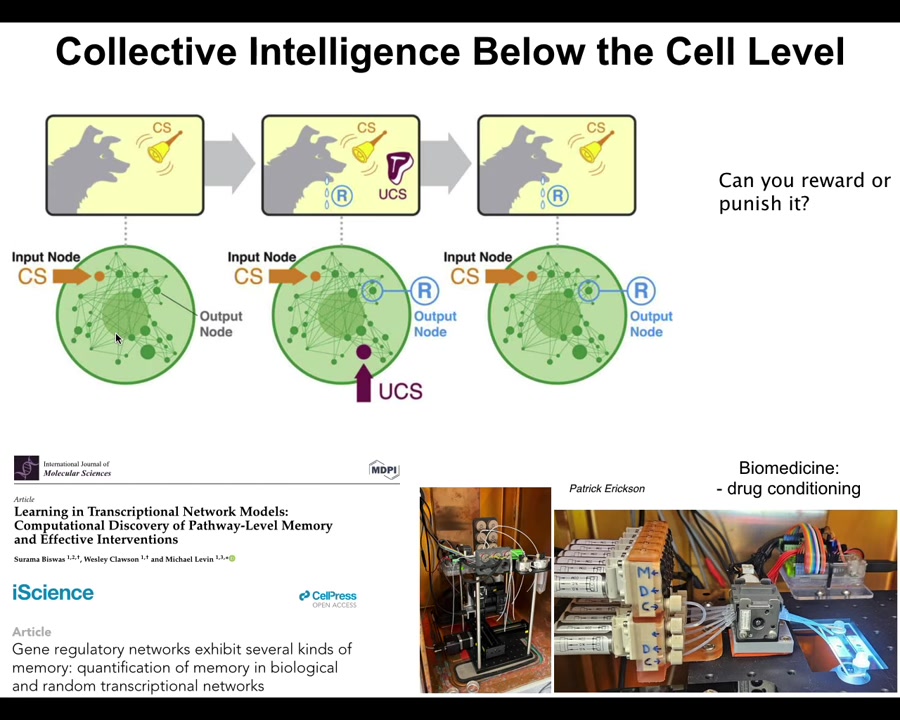

Slide 10/42 · 11m:17s

What these things are all made of are chemical networks. These chemical networks themselves can learn. Just by virtue of the mathematics that governs collections of chemicals that turn each other on or off, you find that these kinds of systems have at least six different kinds of learning, including Pavlovian conditioning. We're using all this in the labs for all kinds of interesting biomedical applications, such as drug conditioning, and you can actually train the material that is inside the cells themselves. What I'm painting here is a picture of a collective intelligence stack where the material, I've called it an "agential material," goes all the way to the bottom of collections of chemical networks that have behaviors that would be recognized by people who work in behavioral science.

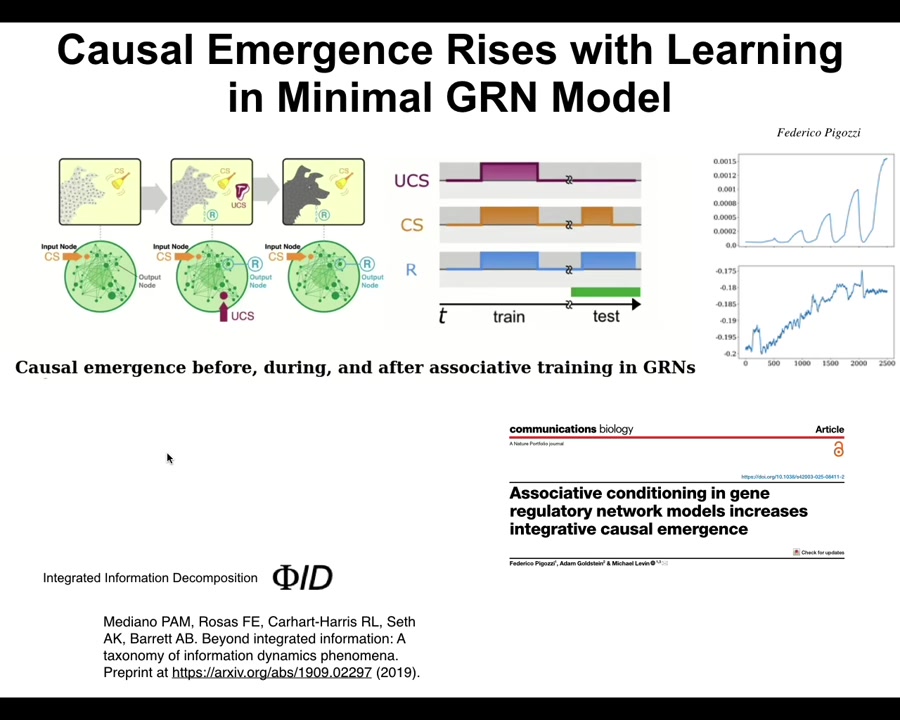

Slide 11/42 · 12m:04s

This is very recent data. It turns out that as you train these things, their causal emergence goes up. Sometimes it goes up gradually, sometimes it goes up in spurts where they fall asleep or disband into their collective subunits in between the interactions you have with them. The activity doesn't stop. They're highly active the whole time. However, the causal emergence falls when you're not talking to them, so they can't keep themselves awake. As you train them, in particular in an associative conditioning paradigm, the integration goes up and up and up, and you can find all that here.

So the material of which we are made itself has significant relevance to this problem of minds, and unconventional is to understand how limited we are in terms of recognizing embodiment.

Slide 12/42 · 12m:50s

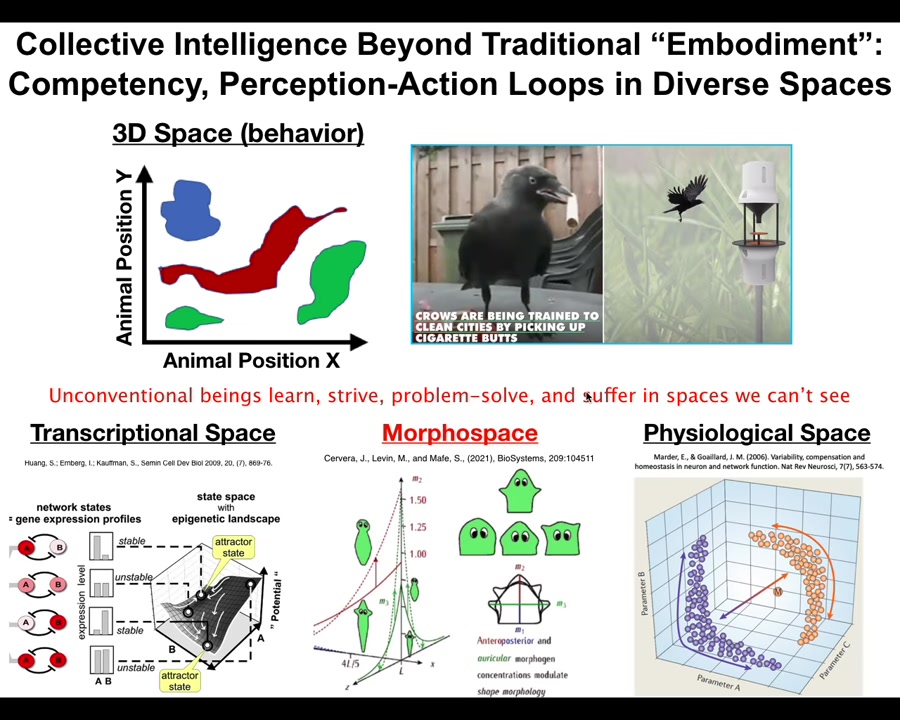

We as humans are obsessed with three-dimensional space. We are pretty good at recognizing medium-sized objects moving at medium speeds in that space. These kinds of things are pretty easy for us to understand.

However, biology has been navigating other spaces long before we had nerve and muscle that allowed us to explore the three-dimensional world. Living things navigate transcriptional space, they navigate physiological state spaces, and they navigate anatomical morphospace, which is basically the journey that we took during embryogenesis from being a single cell to whatever body shape we have now.

My point is that there are unconventional beings that are doing this perception-action loop. They have competency of problem solving. They strive for specific goals. I think they suffer and they do various things that we would find very relevant to this problem in spaces that we can't see.

And that is critical, just like in the case of the electromagnetism, that means the responsibility is on us to develop tools to be able to recognize and think about the lives and the inner lives in particular of beings that live in spaces that we are not evolutionarily prepped for.

Slide 13/42 · 14m:12s

The next thing I'm going to briefly talk about is one model system that we study, which is the collective intelligence of morphogenesis. This is typically what I'd spend 45 minutes on and not do any of these other things. I think it's important for us.

Slide 14/42 · 14m:32s

The reason that it's important is that it allows us to start to think about how it is that we might extend ideas from a cognitive and behavioral science to other substrates, and how we can communicate with these beings and discover new science.

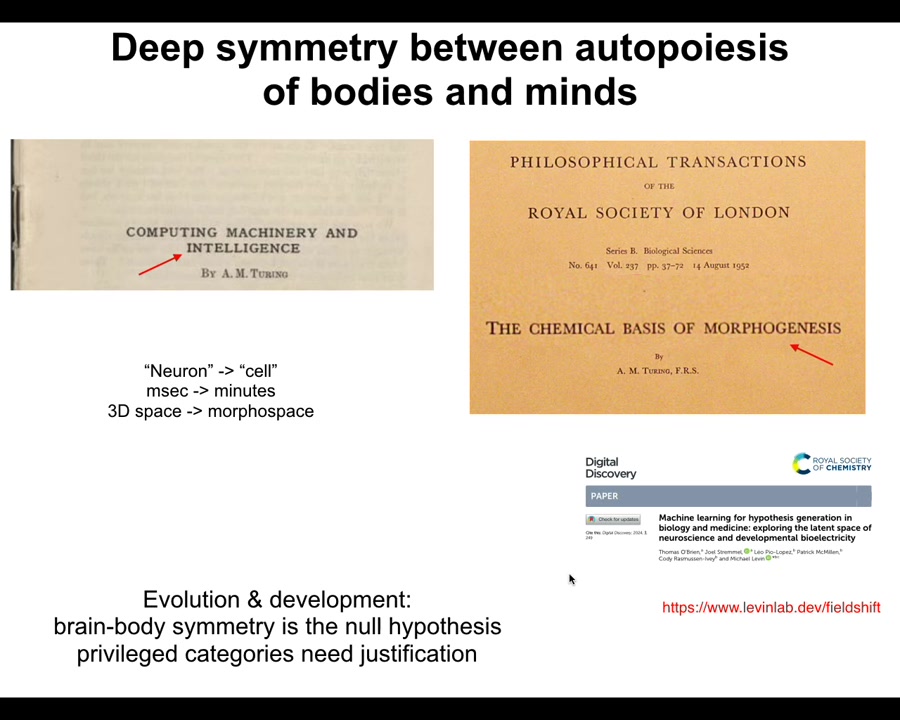

The basic foundational idea here is that there's a very deep symmetry between the self-creation of bodies and minds. I think Turing understood this. It's quite amazing that somebody who is interested in understanding intelligence in different guises and machine intelligence and computation also wrote the paper "The Chemical Bases of Morphogenesis," where he thought about the question of how do embryos self-assemble from a soup of unorganized chemicals. I think the reason he was interested in this question, which at first doesn't seem like it has a lot to do with this, is that he understood there's a deep symmetry here.

It turns out that what evolution and developmental biology are telling us is that all of the things that brains do were an evolutionary pivot of much more ancient mechanisms by which multicellular beings navigated anatomical space.

We developed a tool. I used to have my students do this by hand, but now we made a tool that you can all try. You can take the abstract of a paper in neuroscience, and every time it says neuron, it says cell. Every time it says millisecond, it says minutes or hours. With very few similar shifts, you have a developmental biology paper. The symmetries are quite striking.

Slide 15/42 · 16m:13s

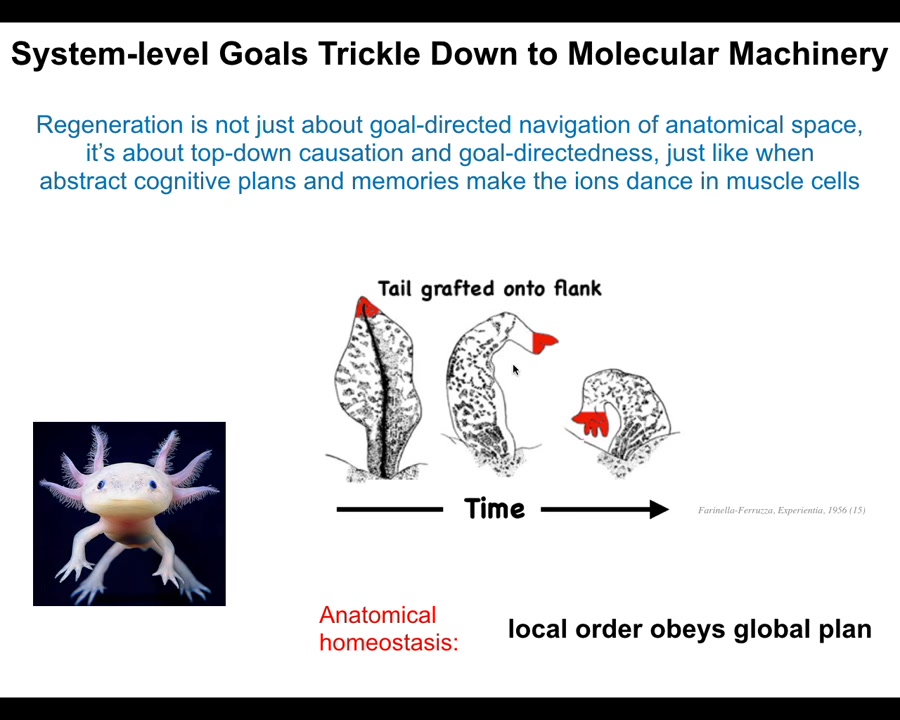

I don't have time today to show you all the examples in which the collective intelligence of cells during morphogenesis solves problems, navigates the space in a context-sensitive way, contains memories of goals that it pursues. I'll show you a little bit of that. Just a couple of things to point out. Some interesting ways in which the collective intelligence of cells, as it navigates morphospace, is doing all of the things that we usually take to be pretty relevant evidence for consciousness. First of all, it has this really interesting top-down control structure where higher-level goal states eventually trickle down and control the molecular biology of what happens in the tissue.

Here's an example. Regenerative amphibians such as this axolotl — if you take a tail and graft it to the flank here, over time this thing will turn into a limb. This whole thing gets remodeled into a limb. Notice something interesting. These cells up here are tail tip cells sitting at the end of a tail. Why do they turn into fingers? Locally, there's no issue. The collective, not the individual cells, but the group knows that having a tail in the middle of the body is not the correct goal state. That attempt to reduce error trickles down to the molecular biology that is needed to turn tail cells into finger cells. This idea of control of low-level phenomena in the service of higher-level, perhaps abstract goals that they know nothing about, is something that is not unique to voluntary motion in our conventional brains. It is baked in all the way down into the way our bodies are assembled. This is an example where the local order ends up obeying a high level plan.

Slide 16/42 · 18m:12s

There's another profound thing that unifies cognition and morphogenesis, which is that at any given moment, we cognitively don't have access to the past. What we have access to are engrams, memory traces that we have formed in past instances of ourselves as a compression of our past experience. So you end up with this bow tie architecture where there's an algorithmic encoder that takes past experiences and squeezes it down into some memory that is in our brain or body. But then there has to be a process of interpretation. And this has to be creative. I don't think it's algorithmic as this end is, because you've lost information. You don't exactly know what your memories mean. I think a critical part of being a conscious agent is being in charge of constantly reinterpreting your own memories, maybe the same way they were interpreted before, but maybe not. All of this is described in detail here.

But notice that living bodies face the exact same problem. We get squeezed down into a bottleneck, which is the egg, and then we have to decode. Under normal circumstances, the decoding goes exactly the way the encoding went, but it doesn't have to. This is why anthrobots and xenobots and various chimeras and all kinds of weird things can work. This is a creative interpretation process. There is no allegiance to what the information meant before. You tell the most adaptive story you can tell now. So this process of creative confabulation—forward-looking, not just the recall of static information, but reinterpretation of whatever you have—I think in our brain our ability to do this comes from this ancient need to re-expand the genetic information that you've been given as opposed to obey it in rote fashion.

Slide 17/42 · 19m:59s

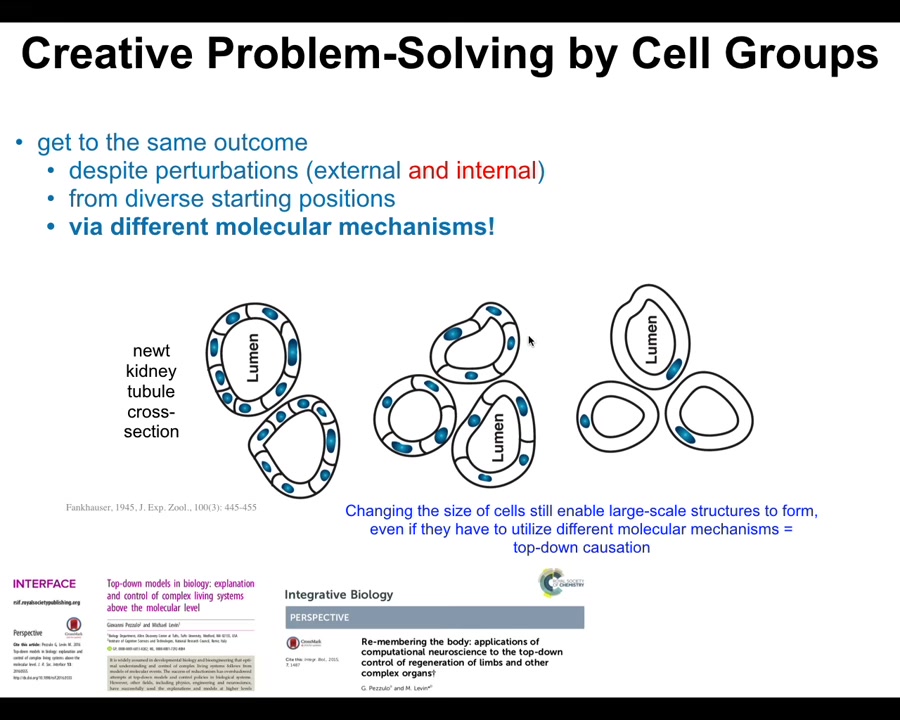

And this is why living things can do amazing, they have incredible plasticity. If you want to make a kidney lumen and you happen to be given normal-sized cells, this is what you do. Cell-to-cell communication: 8 to 10 cells build a thing. If you're given these enormous cells that you've never seen before, this is experimental perturbation that makes the cells gigantic. It will just take one of these gigantic cells, bend it around itself using a completely different molecular mechanism than this. So this is a kind of intelligence that you see on IQ tests. Here are some objects you have, use them in a new way to solve a new problem that you've not seen before. These cells figure out how to use cytoskeletal bending to create the same large-scale outcome using very different molecular mechanisms. And so this kind of problem solving requires us to ask, how does the collective intelligence hold together, and how does it know what it's supposed to do?

Slide 18/42 · 20m:56s

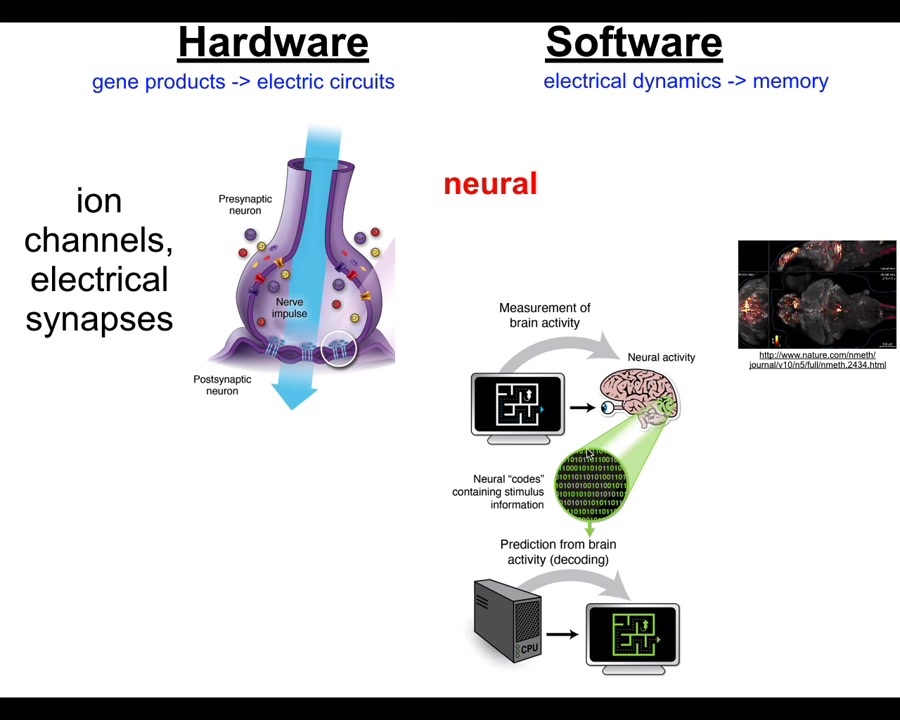

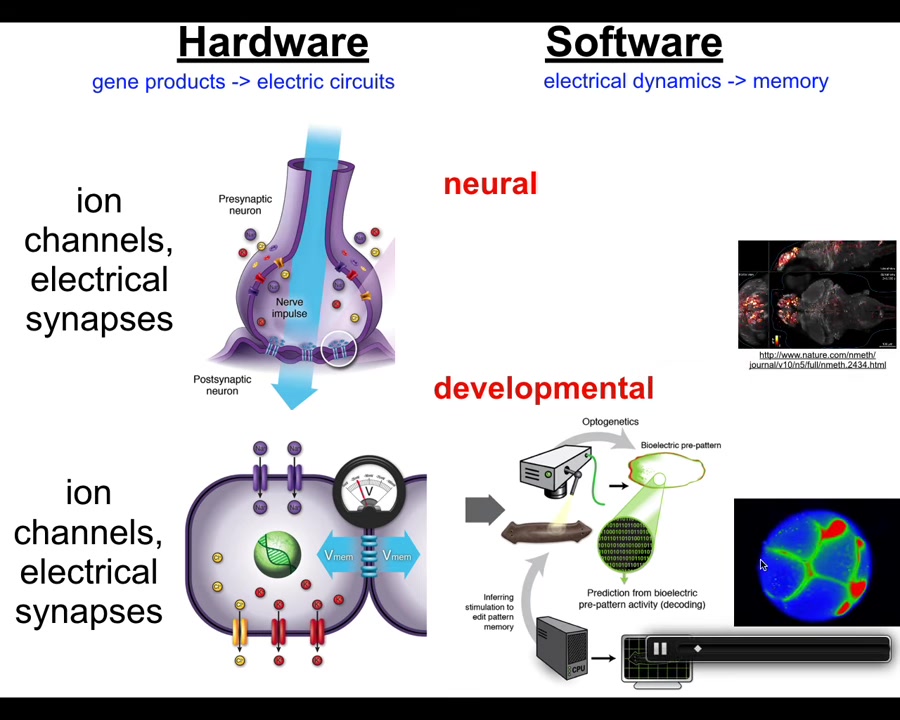

In the one uncontroversial example that we have of systems that try to implement goals that their individual parts don't have. The cognitive glue in the brain is electrophysiology, so we know that this is a remarkable architecture where cells generate electrical properties, which they do or do not share with their neighbors in a dynamic fashion. And that allows the network to perform computations, to pursue goals, and so on. And that's what underlies the fact that we are more than the sum of our neurons. We know things and we have goals that individual neurons in our brain do not. And it also means that you could start to do this kind of neural decoding project, where if we could read out the electrophysiological signals and decode them, then we could understand the goals, the preferences, the memories of the cognitive content of that being. It's supposed to be literally in the electrophysiology.

Slide 19/42 · 21m:53s

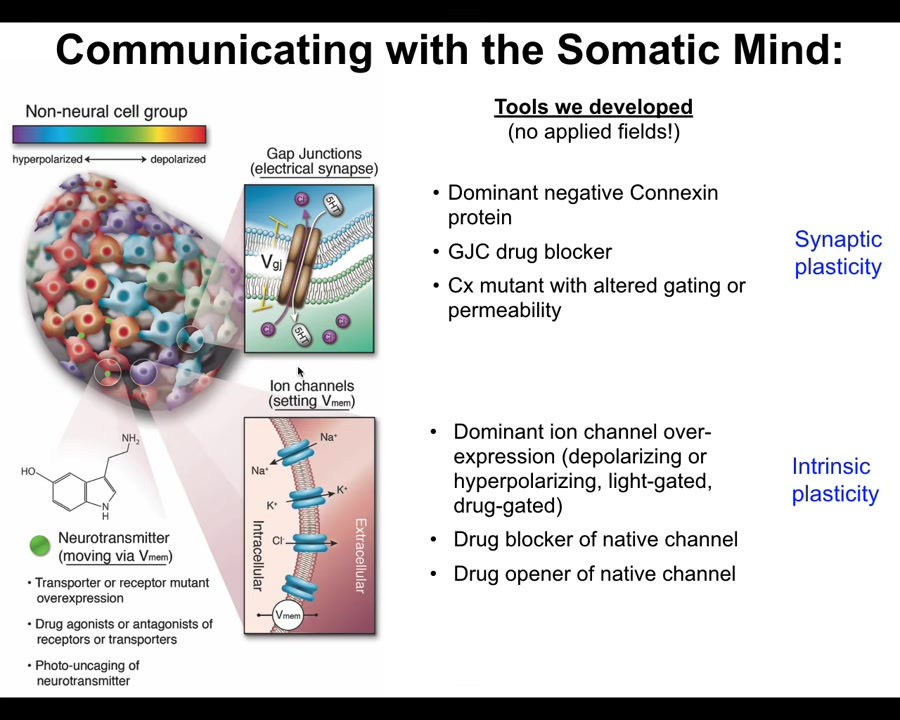

Evolution figured out this architecture long before we had neurons or brains. Every cell in your body has these ion channels. Most cells in your body have these electrical synapses. This is highly conserved homologous machinery, not merely analogous. They are actually evolutionarily homologous. For years now, we've been operating on this hypothesis that we could also learn to do non-neural decoding to understand the goals, the preferences, the problem-solving capacities of morphogenesis, of navigating not three-dimensional spaces, which is what the nervous system does, but actually navigating anatomical space.

Slide 20/42 · 22m:33s

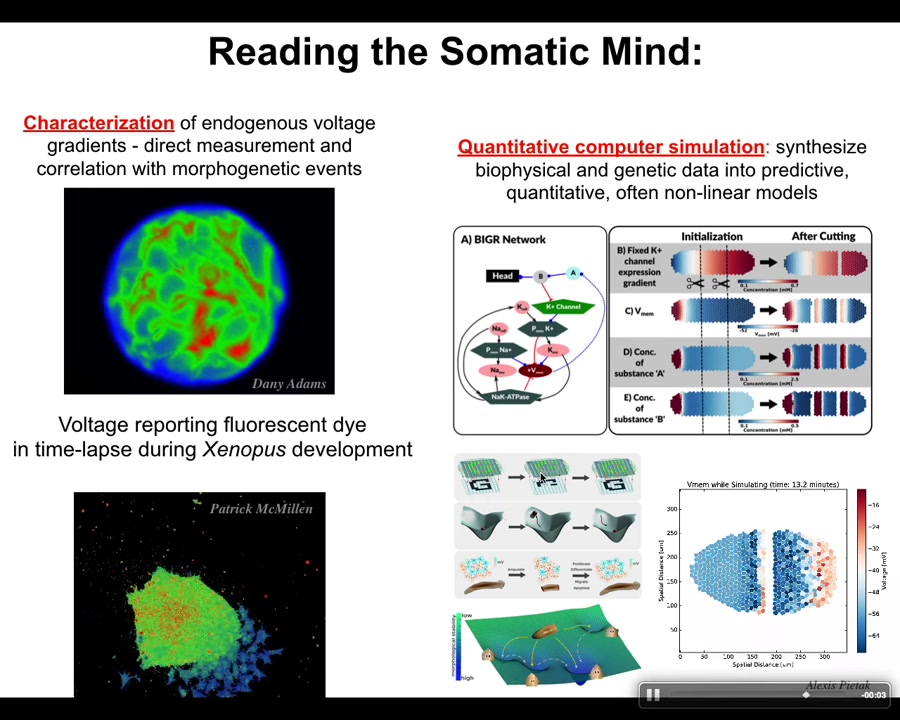

We've developed tools to read the bioelectrical states here of individual cells. The colors represent voltage. These are voltage-sensitive dyes. These are not models. These are simulations. These are real biological data. This is a frog embryo. We can see all the electrical activity that's going on. We're scanning this thing the way that you might scan a brain.

We do lots of quantitative simulations to understand at multiple levels of description how these dynamics are changing, all the way from the molecular biology to tissue-level dynamics, to link them with ideas in connectionist machine learning and dynamical systems theory to understand pattern completion, regeneration as pattern completion. We use all the same computational tools.

Slide 21/42 · 23m:23s

And then more importantly than just reading out those patterns, you want to be able to rewrite them. The way we do this is not by applied electric fields. There are no magnets, no frequencies, no waves. We hack the same interface that the cells are already using to talk to each other. We can control, at a molecular level, the topology of the network by controlling these electrical synapses. And of course, we can turn individual channels on and off, whether that be optogenetics or drugs. So we have the ability to both read and write information into this electrical interface as you would in the brain.

Slide 22/42 · 23m:57s

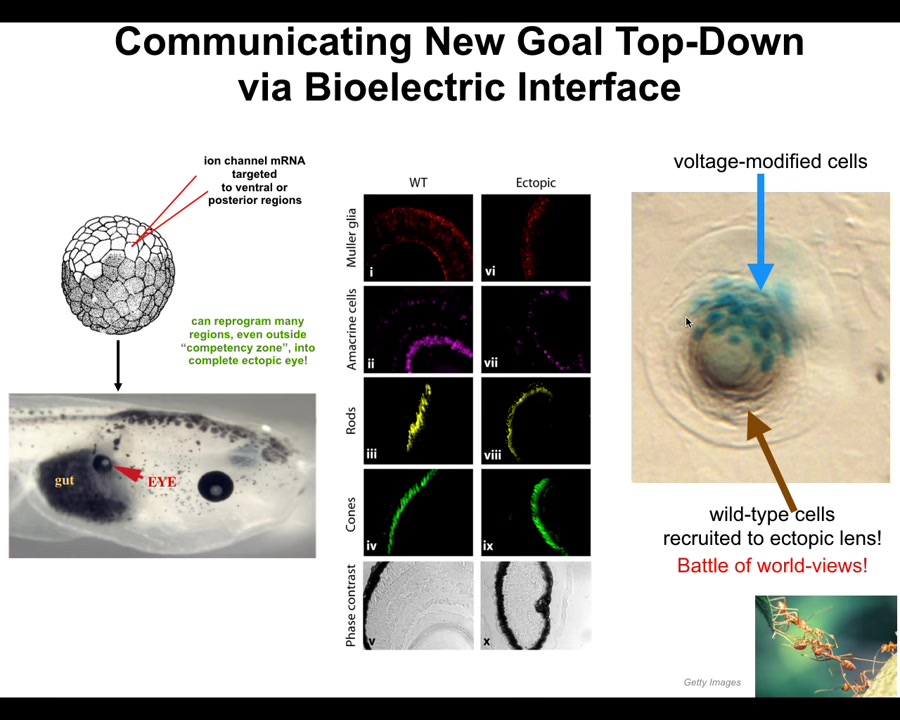

I could show you dozens of different examples. I'll just show you one. When you do this, you can communicate new goals.

For example, we can take RNA encoding a particular potassium channel. We can use that to establish a particular bioelectrical state somewhere in the early embryo. We have one here that encodes the message "build an eye." When we do that in cells that are going to become gut, sure enough, they get the message, and they build an eye.

The way this works is not because we are turning specific genes on and off, although certainly genes are changing their expression levels. We're not talking to the gene level. We're not talking to the stem cells. We have no idea how to micromanage an eye. Any more than when I'm talking to you, I don't know how and I don't have to know how to rearrange all the proteins in your synapses so that you remember what I'm saying to you. They will handle that on their own. We're using a very thin interface, this linguistic interface, where I give a high-level message. The receiving system, because it is a multi-scale cognitive system, takes care of making the molecular biology fit.

The same thing is happening here. All we say is "build an eye," and then this lens, retina, optic nerve, in the right position, the right orientations, the system takes care of all of that. We are giving a very minimal high-level prompt.

There's something interesting that happens here. If we inject only a few cells, the blue cells are the ones that we injected, they will try to recruit their neighbors to participate. We don't have to tell them to do that. The material is already doing it. There's not enough of them to build an eye; they try to recruit these guys. But these guys resist. They have a cancer suppression mechanism that says if your neighbor has a weird voltage that's telling you to do something strange, try to resist. Try to normalize them and make sure they end up like you. There's this battle of worldviews going on here between these cells that have bought into our message and these cells.

Slide 23/42 · 25m:46s

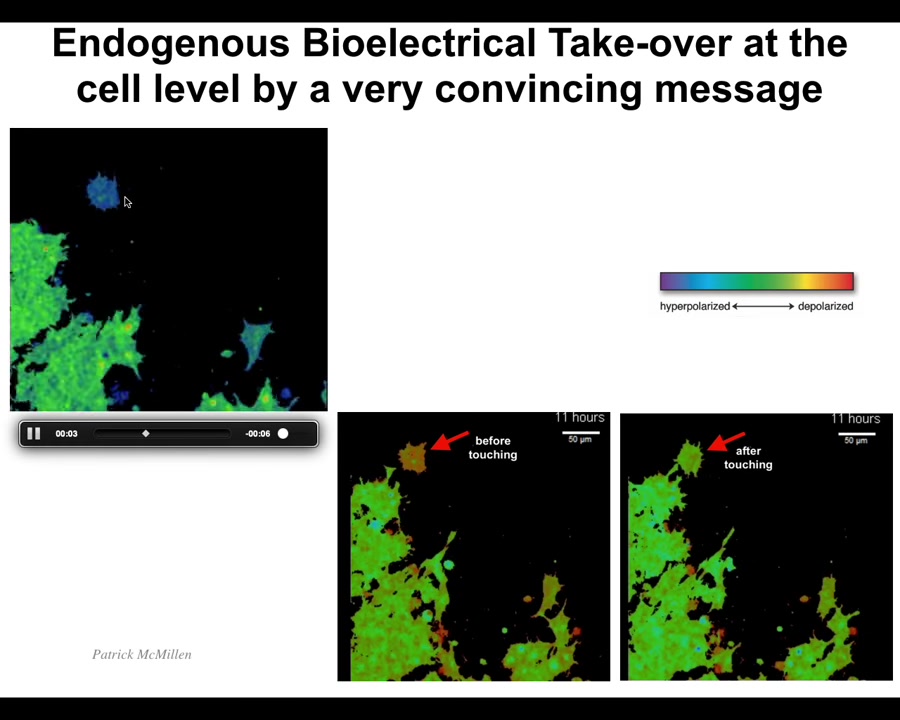

I want to show you one cute example of what that looks like. The colors are voltage here. These are two frames. Notice that this cell has a particular voltage before it touches these. This is right after, the tiniest touch. Here's the video. It's coming along, minding its own business, having its own voltage. This guy reaches out, boom, that's it. As soon as it touched it a little bit, the voltage changes and it becomes part of this mass and it's going to do things that the collective wants to do. This is a very convincing piece of bioelectrical data that takes over this. That is exactly what we did when we created that ectopic eye that I showed you.

Slide 24/42 · 26m:24s

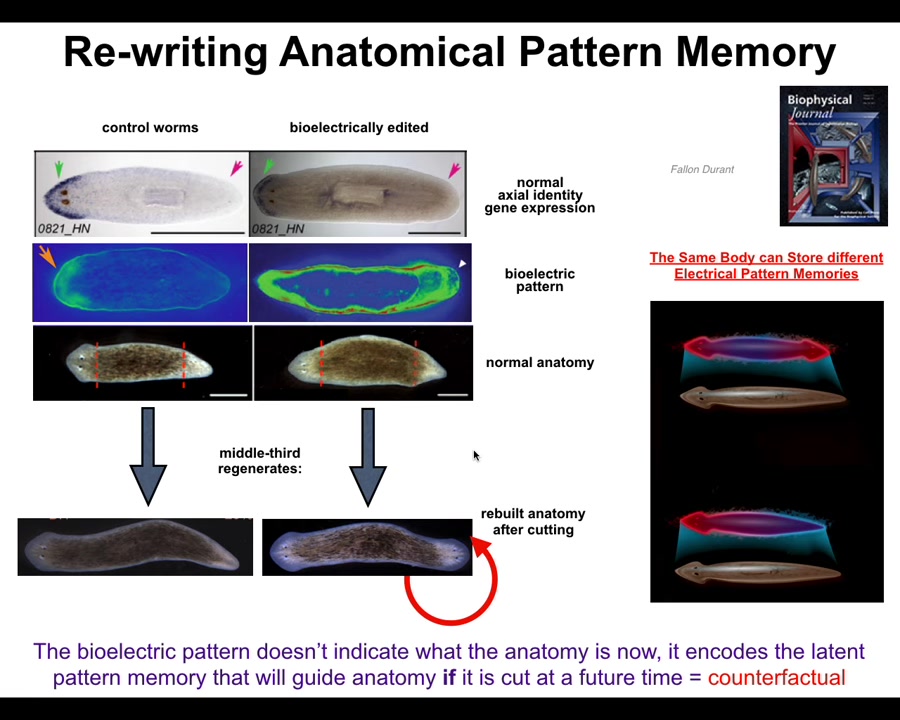

Can also do interesting things like this. This is a planarian. These flatworms regenerate. You can cut them into pieces. This middle fragment knows exactly how many heads or tails it should have. Very reliably, it makes one head, one tail. It does so because there is a memory of how many heads you're supposed to have, which we can read out exactly as you might do in the neural decoding context. Here it is. We can rewrite it. We've made an animal that now has a pattern that says 2 heads. When we cut this guy, it makes a two-headed animal. This is not Photoshop or AI. This is exactly what they look like.

Notice something very interesting. This bioelectrical map is not a map of this two-headed animal. It is a map of this anatomically one-headed animal. In fact, the molecular biology is normal. Anterior markers in the head, not in the tail. What you're looking at here is the fact that a single body can hold at least one of two different representations of what a correct planarian will look like. In fact, this is a counterfactual representation because this is not true right now. This is what you will build if you get injured at a future time. If you don't get injured, then this stays a latent memory. The tissues ignore it until they get injured and then they obey and construct what this says.

You can think about these as very minimal, and as any good memory, they're permanent. If you take these two-headed animals and keep recutting them, they will continuously regenerate as two-headed, even though we haven't touched the genetics. This ability to change your memory without changing the hardware, with a normal genome but a completely different body-plan architecture, and the ability to store patterns that are not reflective of what's true right now, that is, past or future, but not right now. I think these are basal model systems for some of the amazing things our brains do in terms of mental time travel.

Slide 25/42 · 28m:22s

What I've shown you so far is that we can start to think about somewhat alien minds by looking at a situation where the system is navigating a space that is very hard for us to visualize, this anatomical morphospace, but it has the advantage that all of the mechanisms that it's using to do this are homologous to what our brains use to do the things that we do. I think this is a nice stepping stone. It's a nice way before we start thinking about aliens and all kinds of weird intelligences, we can start sharpening our tools here. Here's something that's using the exact same machinery to do this in a space that's hard for us. That's why I think it's a good model system.

I want to move on from this to a synthetic morphology model, because what I've shown you so far are systems whose goals in anatomical space are determined by evolution.

Slide 26/42 · 29m:12s

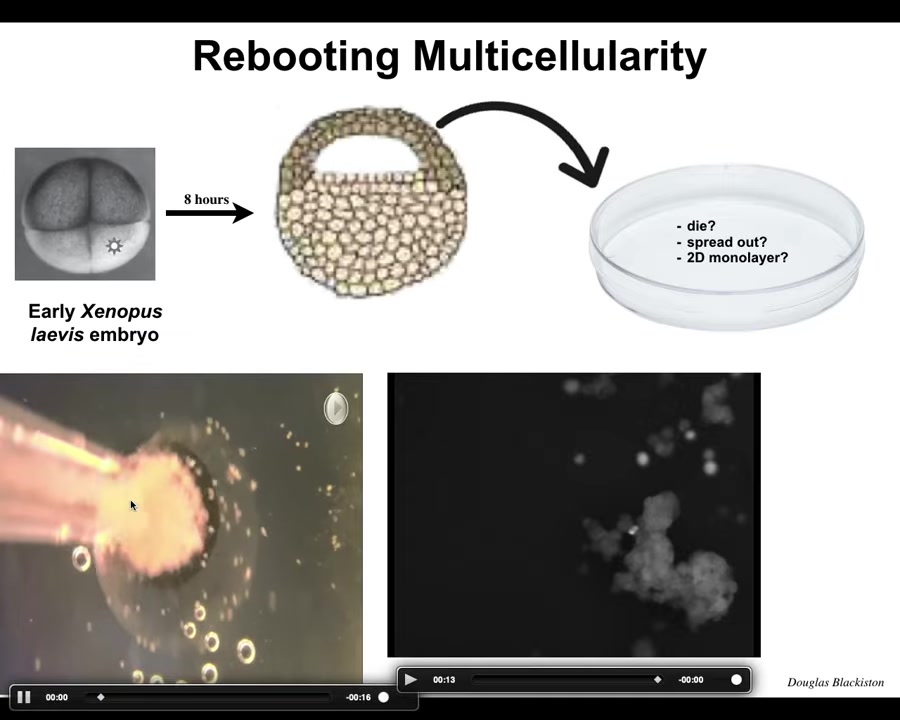

I want to show you some xenobots. The way that they're formed is that we take a frog embryo, we take some of these prospective epithelial cells up here, we put them in a dish. We dissociate them here. There are many things they could do. They could die. They could walk away from each other. They could form a two-dimensional cell culture layer. Instead, what they do is they coalesce into this little unit.

This is neat. This is a close-up. Each one of these little circles is a single cell. You see this little group of cells. It doesn't hurt that it looks like a little horse. I just think this is cute. It moves over and it has some interactions with us. You see a little calcium flash here. I'll get to the calcium momentarily. The individual cells do these things. Then they coalesce into this.

Slide 27/42 · 30m:00s

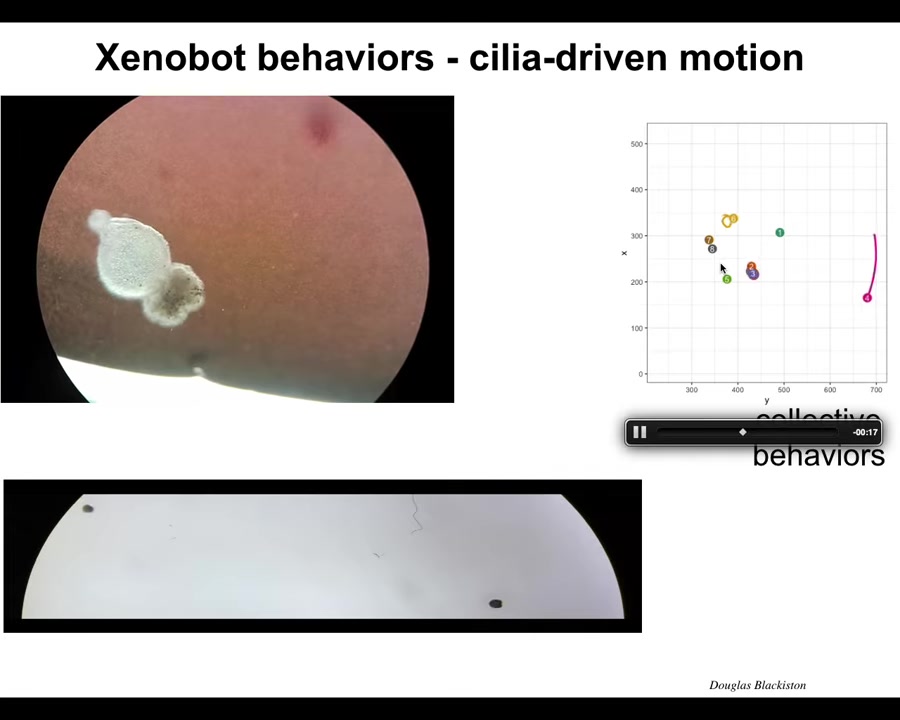

And then you get this little motile creature. It has cilia on its outer surface. It uses them to propel through the water. It can go in circles. It can patrol back and forth. They have collective dynamics.

Slide 28/42 · 30m:15s

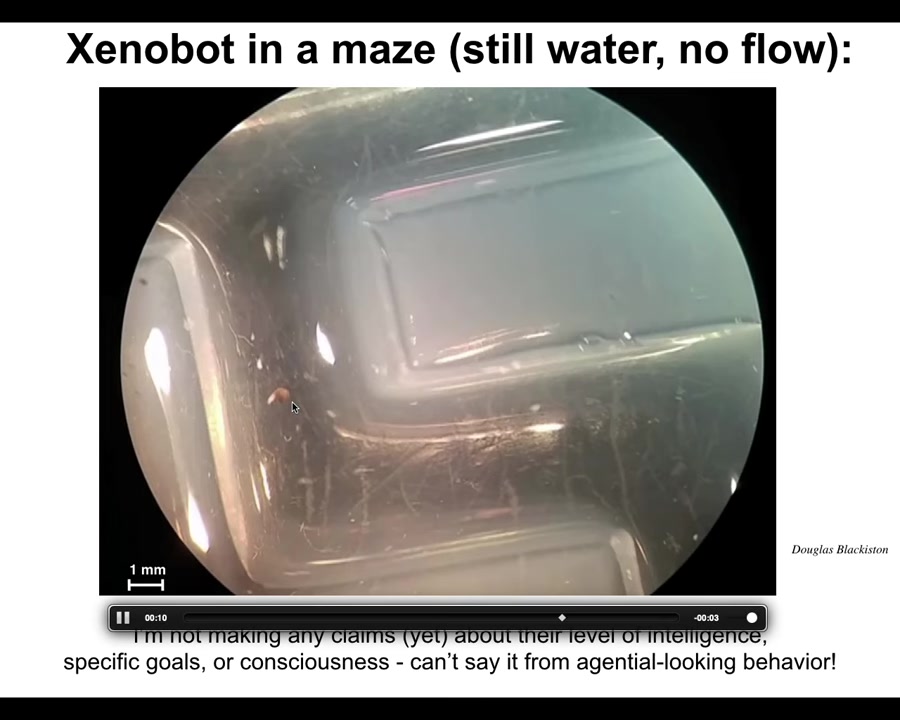

Here it is. Traversing a maze. This is still water. There's no flow, there are no gradients. It takes the corner without bumping into the wall. Then at this point, it spontaneously turns around to go back where it came from.

These are not like the biobots people make out of muscle cells where you have to paste them and you control where they go. This thing is completely autonomous. I'm not making any claims yet about their level of intelligence. We're testing all that. We have some interesting data on their memory formation and so on, or what goals they have or their consciousness; I'm not making any claims about that because I don't think you can tell any of that from observations of behavior.

Slide 29/42 · 30m:53s

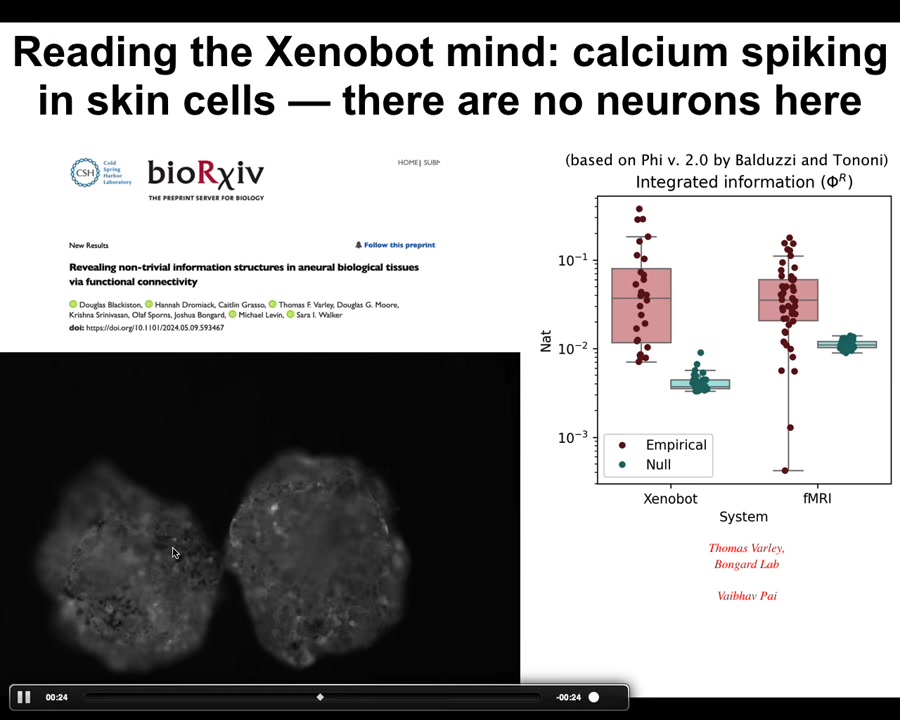

However, we can start doing some interesting things. This is calcium signaling. Remember, there are no neurons here. There's just prospective skin cells. What you can do is look at the calcium signaling in these guys and focus on one of them. It's also interesting whether they're talking to each other; we don't know that yet. To look at one, we can look at the connectivity that we see and use the kind of tools that are used to analyze brain connectivity. In particular, to analyze things like integrated information. To compare these firings of our Xenobots with the null models as people do in fMRI data.

This is work of Thomas Barley and Josh Bongard's lab, and Pai and my group started to look at what exactly is the same and what's different in what these kinds of metrics tell you about brain signaling in the brain and beyond. If you do see things like this, you have to answer an interesting question. Do we learn from what the method is telling us, or do we somehow by fiat assume that it doesn't apply here for whatever reason, that we've stretched these things beyond where they need to be applied? And if so, why? Clearly, I don't think that. I think applying these methods here is quite informative.

Slide 30/42 · 32m:06s

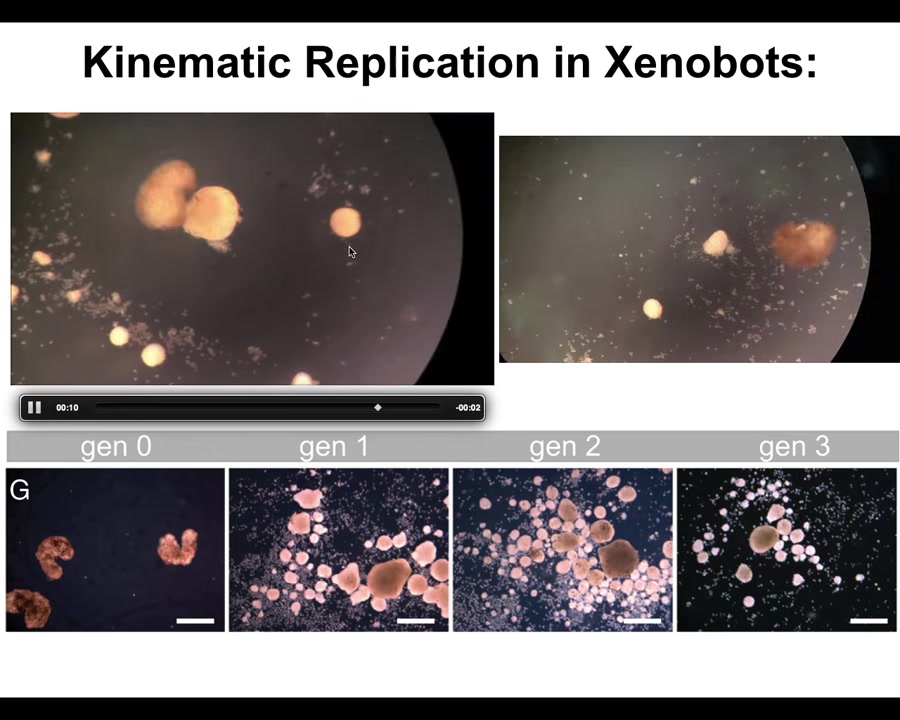

They have all sorts of interesting behavioral capacities. For example, if you give them loose epithelial cells, what they do is they run around and they collect them into little balls. Because they themselves are working with an agential material, these little balls mature to be the next generation of xenobots. Guess what they do? They run around and they make the next generation, which makes the next, and so on. We call this kinematic replication. As far as we know, no other creature on Earth reproduces this way. It's like von Neumann's dream of a robot that makes copies of itself from stuff it finds in the environment. We didn't teach them to do that. This is spontaneous. I don't think any other creature does this or has in the lineage. We can do one other interesting thing.

Slide 31/42 · 32m:53s

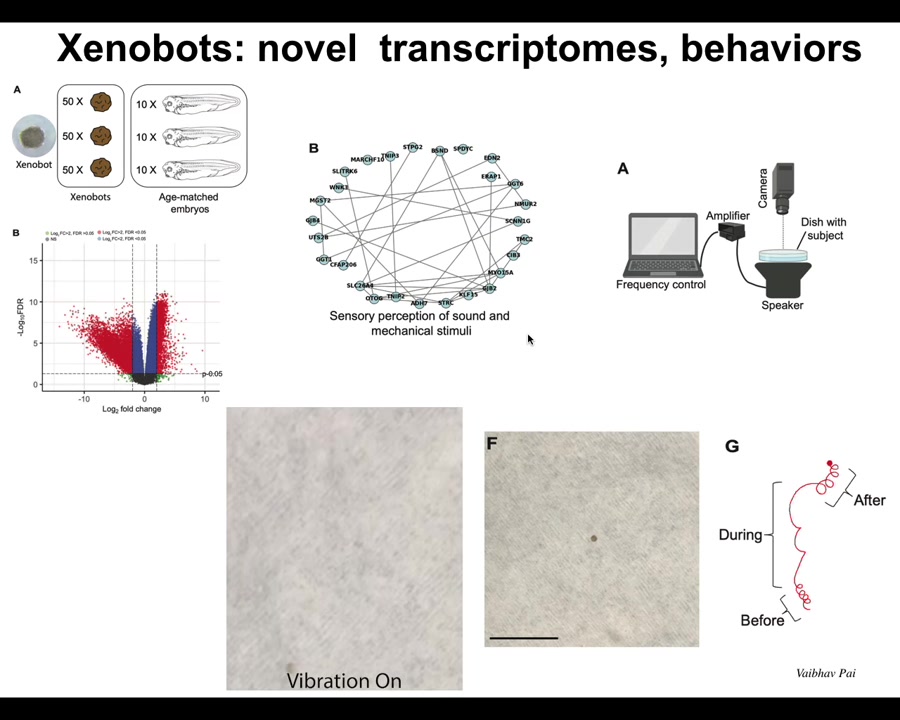

We can ask what their transcriptomes look like. What genes do they express? It turns out that they express hundreds of new genes that their original age-matched embryos do not express. Among these genes is a cluster of genes related to hearing or sensory perception of sound.

We decided to test this, and Pi put a speaker underneath these guys and caused some sound and vibration. What we see is that they respond. You can tell from their behavior that they react to these stimuli in ways that embryos do not. This is novel. These are novel gene expressions, novel behaviors such as kinematic self-replication and responding to sound stimuli that the original material does not exhibit.

Slide 32/42 · 33m:46s

This raises an interesting question and I'll explain why I think this is relevant to consciousness work. What you would typically say is that the frog genome, over the years of interactions with the environment, has produced this kind of a thing. The developmental stages, the tadpoles that have certain behaviors. But it also produces Xenobots with their own weird developmental sequence and behaviors that have never existed before. There have never been any Xenobots, and there has never been selection to be a good Xenobot.

One wants to ask the question: we know when the computations were done to derive a frog embryo — that was done over the eons that this genome has been interacting with the environment. When were the computations done to figure out how to be a good Xenobot? Xenobots have never existed.

You might say that it has happened at the same time as you evolved a frog. But that undermines the whole specificity of environment to outcome. That's the point of evolutionary theory: there should be very tight specificity between what you're selected for in your environment and what actually happens in the end.

Now this raises an interesting question. In anthrobots and Xenobots, where do their goals come from? We could say that the goals of these creatures — anatomical goals, physiological set points, transcriptional set points, and so on — come from a history of selection. You can't say that for these. Where do they come from? Where do the cognitive and other capacities of, the forms of body and of behavior, where do they come from if it's not going to be a history of selection?

Now here's the weirdest part of the talk, where I'm going to say some out-there things, and we can all decide what we think.

The first thing to realize is that there are patterns that are not set by either physics or history.

Slide 33/42 · 35m:42s

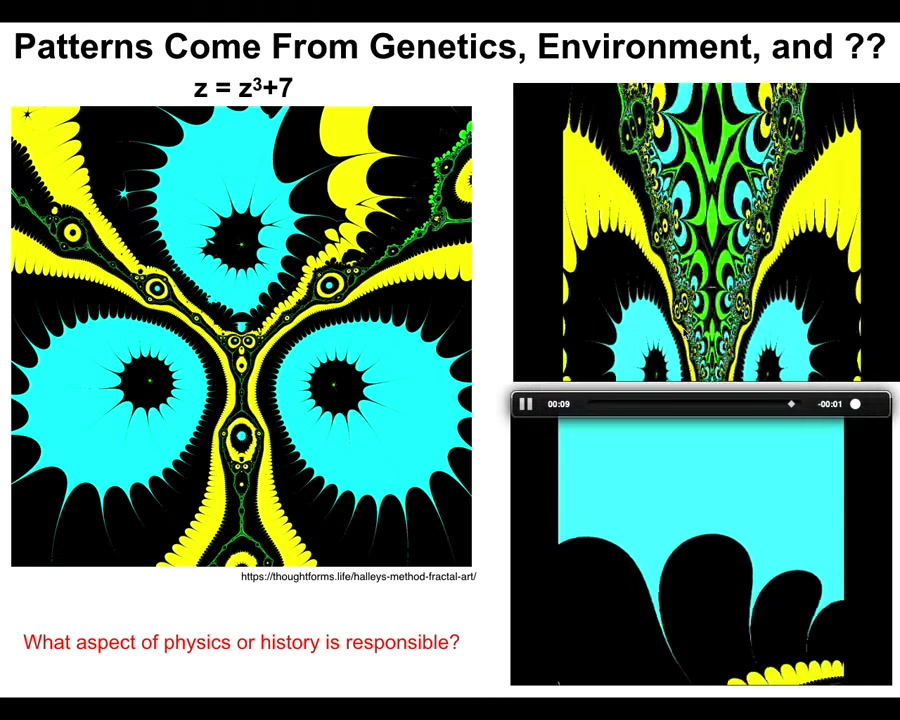

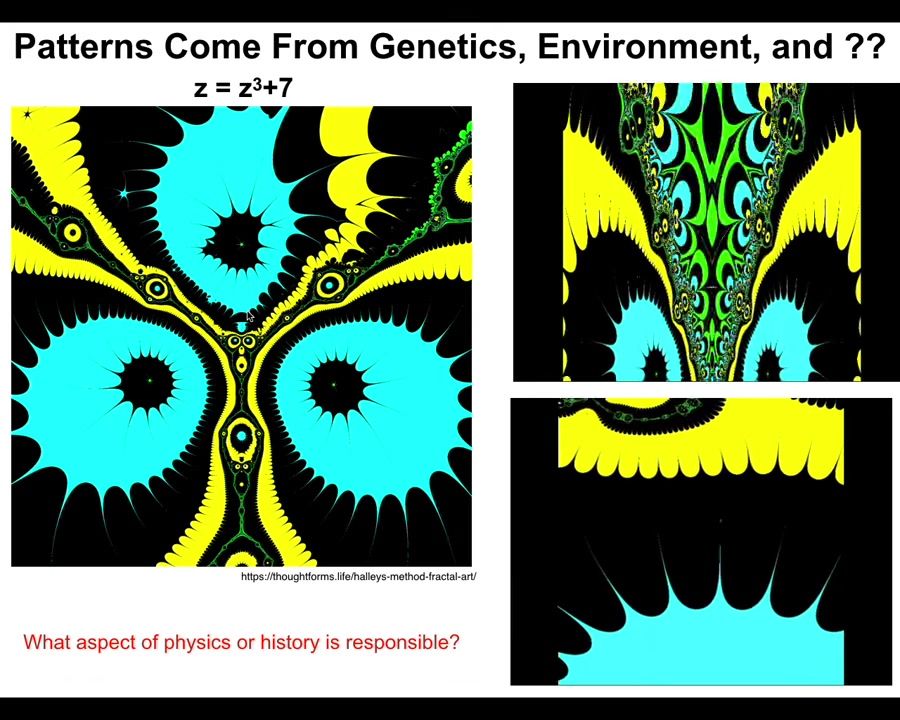

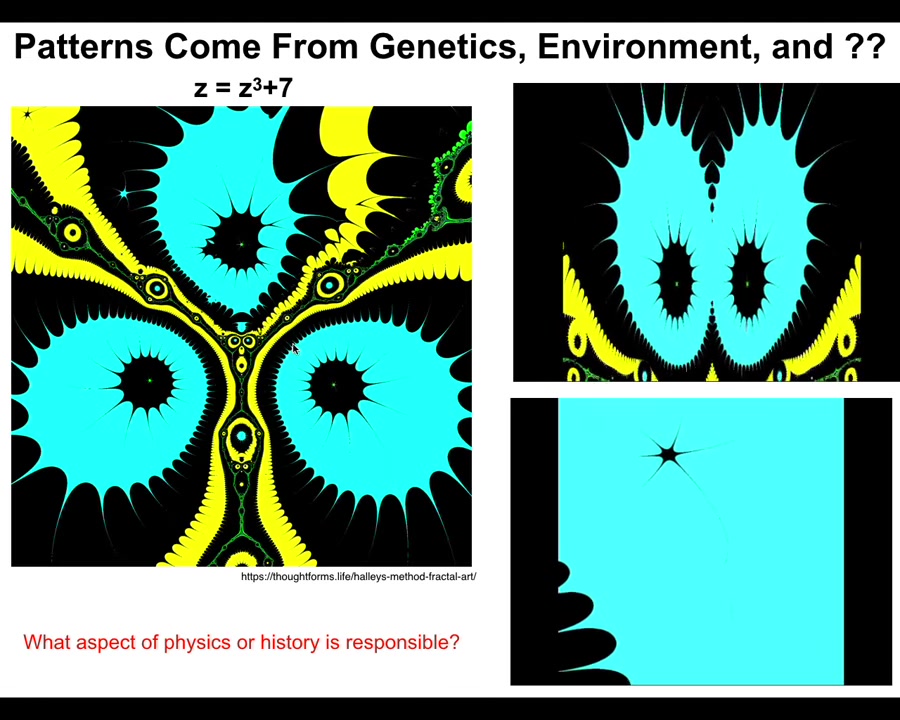

What you're looking at here is something called a Halley plot. I've made videos of them. It comes from plotting this formula in complex numbers. It's very short, very simple, but this is the richness that this encodes if you know how to look at it.

The particular shape of this thing—there is no fact of physics that sets this. There is no evolutionary history that tells you why this is the case.

The explanation for why this is the way it is comes from the properties of mathematical objects.

Slide 34/42 · 36m:11s

I'm going to push on this concept for a few minutes. This idea that there are specific patterns in mathematical objects that are neither determined by physics nor by any evolutionary history. There is another source. Biologists don't like to think about that.

Biologists would like everything in biology to be explained either by some necessity of physics or by an evolutionary history of selection. But that is clearly not the only game in town.

Slide 35/42 · 36m:38s

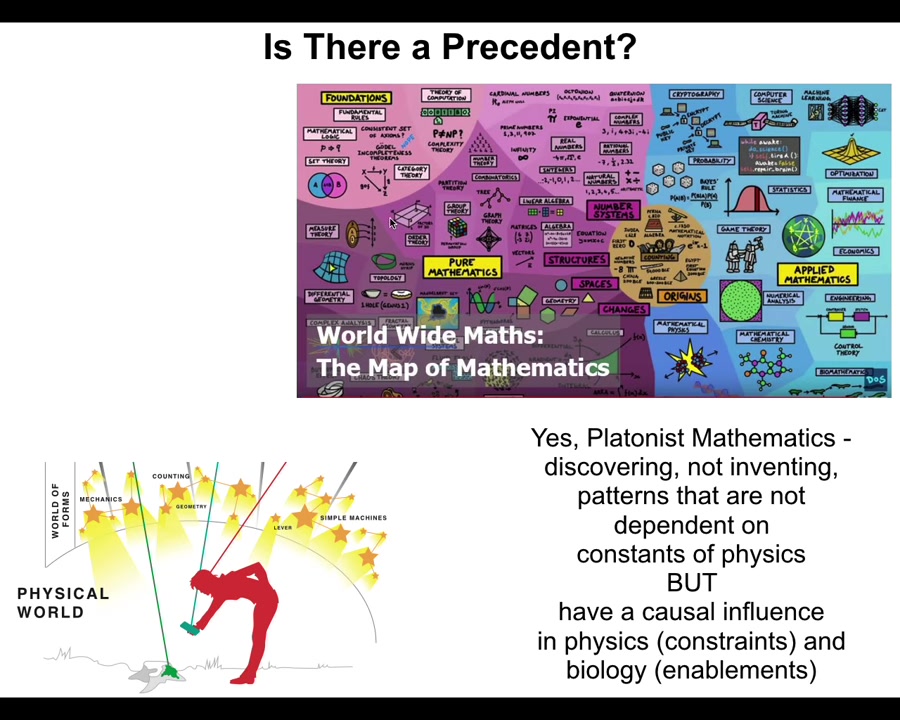

I would like to suggest the following hypothesis.

What's happening is what Platonist mathematicians think is happening, which is that there is another space, an ordered, structured space of truths not determined by any facts of the physical world. They're independent in that sense, but they affect the things that happen in the physical world. What they're doing is exploring this space in a systematic, structured way.

These patterns have a causal influence on the physical world. In physics, we see them as constraints. In biology, we see them as enablements. We call biological systems that are making use of some of these free lunches.

My hypothesis is this: I am extending this; there are many mathematicians that already believe this.

Slide 36/42 · 37m:34s

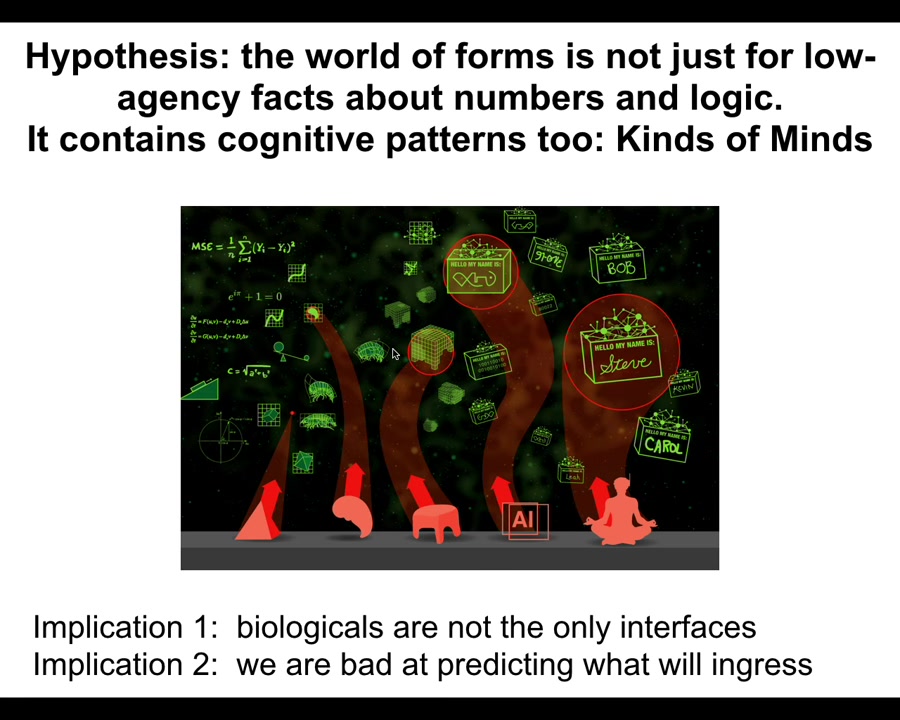

I'm extending this in the following way. I think this world of forms or the platonic space or the latent space contains low-agency patterns such as facts about numbers and logic and the truths about the prime numbers. But also it contains more complex active patterns that behavioral scientists would recognize as kinds of minds. What I think is happening is that the relationship between mind and body is the same relationship as between truths of mathematics and physical objects, because that space contains not just mathematical facts, but actually behavioral propensities or kinds of minds. There are two implications to this.

First of all, whatever we build, be it machines, robots, biobots, embryos, bodies, organs, these are interfaces, they're front ends, they're thin clients for these patterns that ingress into the physical world and have a huge impact on what actually happens. Biologicals are not the only interfaces for this. I think this stuff is pervasive. I think it goes all the way down to the bottom. It is not just the biological bodies that have the advantage of being able to host these kinds of patterns. The scientific community is really bad at predicting what is going to ingress when you make these kinds of things. I'll briefly mention an example in a minute. This is very important for the status of AIs, because I do not believe that we make intelligence, either biological or technological. I think that what we make are interfaces that enable some of these patterns to come into the physical world.

Slide 37/42 · 39m:27s

Now, at this point, most of you are probably saying, well, interaction is dead. This was killed off at the time of Descartes, that there's this interaction problem, there's a mental world and there's a physical world. It just doesn't work to say that there's some kind of external patterns that are part of the consciousness of beings. Most people think that this has been put to bed a long time ago.

I think that because of mathematics, physicalism was already dead in Newton's universe, in the classical, boring, deterministic universe. You don't need quantum mechanics for this, as many people have tried to resurrect this with a quantum mechanical interface. I don't think you need any of that, although maybe that's true too. But because Newton's universe was already haunted by truths that are not determined by anything that happens in the physical world, but in turn affect what does happen, I think this was already dead.

This is a hypothesis that I'm floating: the way to think about mind-body interactions is the same way that people think about how the truths of mathematics determine physics. There are lots of aspects of biology. For example, cicadas come out at 13 and 17 years because of the way prime numbers work, not because of anything in physics or biology. D'Arcy Thompson's book on Growth and Form in the 1920s shows many amazing examples of how biology makes use of this stuff. Epiphenomenalism is as hopeless for mathematics as it is for models of mind. I actually argue for an interactionist model.

The final thing I want to bring up is this, and I don't have time to go into it in detail, but you can grab this paper and take a look. What we found, long and short, by looking at very minimal models, in particular here, sorting algorithms, bubble sort, is that these are six lines of code, completely transparent, completely deterministic. People have been working on them for many decades. If you look at them the right way, you see that they do the thing they're supposed to do, which is to sort numbers, but they also have these weird side quests that we measured as clustering and some other properties that are basically nowhere in the algorithm. In other words, they have behaviors that would be quite recognizable by behavioral scientists that are not what the algorithm is forcing them to do.

I think what this means is that there is something else besides chance and necessity, and this is a way to start thinking about what significant minds do. This is obviously very minimal, but even something as simplistic and dumb as a sorting algorithm is doing things that you neither prescribe for it to do nor forbidden from doing. I think there's a lot of humility necessary here because if we don't understand bubble sort, which I think we haven't, then I don't think we understand language models or anything like that.

If you think the situation is better in the neural sciences, where people think they know what parts of the brain do, we've gathered some interesting examples of human clinical data that also suggests that in some ways the brain is basically a thin client because the mapping between brain architectures and cognitive performance really breaks down in certain cases.

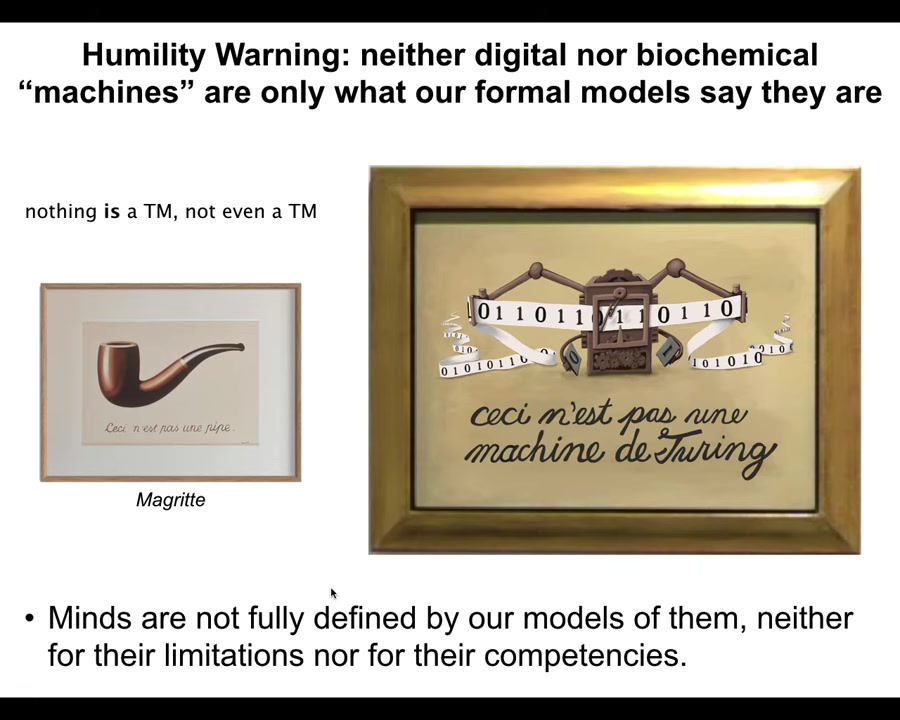

Slide 38/42 · 42m:54s

I think cognitive ways of handling cognitive beings go all the way down. Neither digital nor biochemical machines are what our formal models say they are. Magritte was reminding us this is not a pipe. This is a depiction of a pipe. I think we need to remember this is not a Turing machine. Turing machines have limitations. Our formal models of computers and computing have limitations, but I don't think anything fully matches these models. I don't think they describe anything in the real world. Their limitations and their competencies are not fully describing the limitations and competencies of systems, either technological or biological. I think we have to remember that.

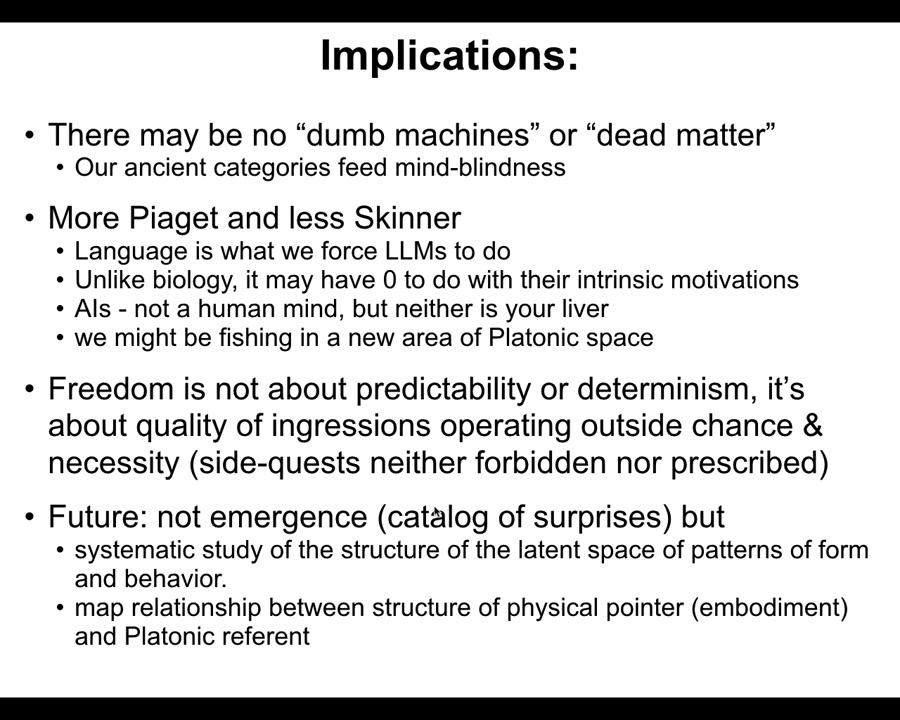

Slide 39/42 · 43m:44s

And so here's a summary of what I'm saying. I'm not sure there are any dumb machines or dead matter at all. I think these ancient categories are feeding the mind blindness that we already have.

I think that in making machines, whether digital or analog, there are things we force them to do, such as language, which we force language models to do. But unlike biology, where the thing they're doing and the communications they're expressing are very tightly linked, what these things are doing may have very little to do with their intrinsic motivations. In other words, just like in that sorting algorithm, we make it sort, but the intrinsic motivation that it has to do other things has nothing to do with the sorting itself. We could really be fooled by the fact that these things speak. I think language may be a red herring as far as what any of these things are actually doing. These AIs, I don't think they have anything resembling a human mind, but that doesn't matter. Neither does your liver. These things have other kinds of minds.

By creating these interfaces, we may be fishing in a new area of that space that has never had embodiments before. That's a different way of thinking about it than this idea that you are creating a new intelligence whose cognition is described by the language that it speaks. I think these two things might be very decoupled. We might end up talking about freedom, not about predictability or determinism, but really about the quality of the ingressions that are operating at this other level between chance and necessity.

We need to focus less on emergence as merely a catalog of surprises that we didn't expect, and more on a systematic study of the structure of that latent space of patterns of form and behavior, and to really try to work out that relationship between the structure of the physical pointer, meaning the embodiment, and the patterns that are coming through it. Xenobots and Anthrobots and various other tools, including language models, are exploration vehicles.

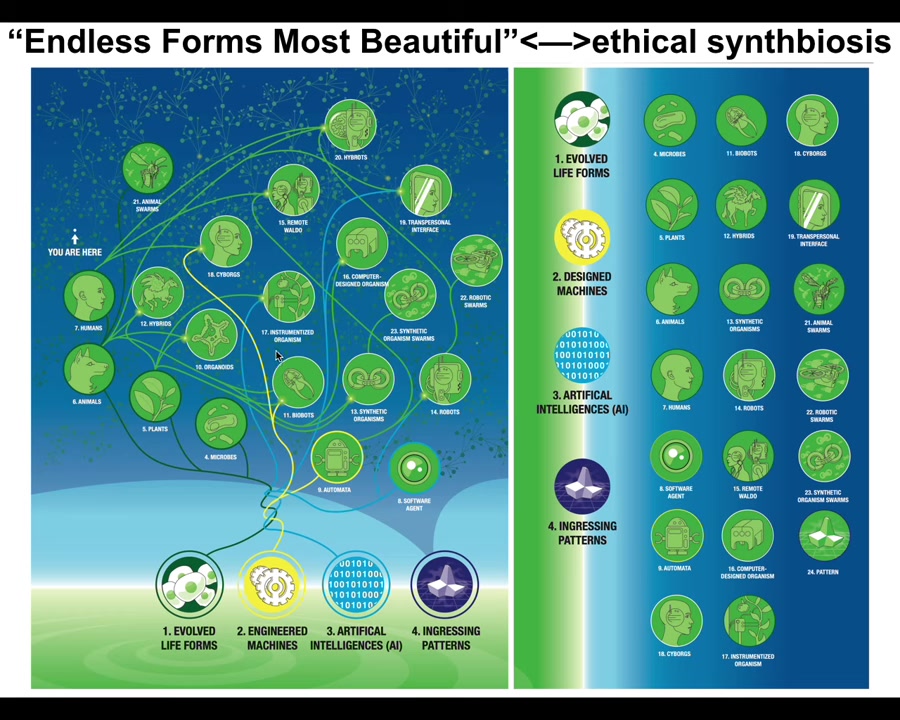

Slide 40/42 · 45m:43s

Pretty much any combination of evolved material, engineered material, software, and these patterns, which affect all of them, are viable beings. Cyborgs and hybrids, these are the kinds of things that are going to challenge our notions of consciousness. If we're going to have an ethical synth biosis with these things, we have to get better at understanding minds outside of our normal embodiment.

Slide 41/42 · 46m:08s

And this is what I think the future Garden of Eden is going to look like. It's going to be a very weird place, but this is all coming. And it's not going to take long before we're surrounded by beings that are radically different.

I'm going to skip all this and say that if you're interested in any of these things, there are papers where we go into this in detail.

Slide 42/42 · 46m:28s

The most important thing is to thank the postdocs and the students who did the work, our amazing collaborators, our funders here that have supported this work over the years.

There are three disclosures. These are companies that have licensed some of our stuff for various purposes.

I'll stop here. Thank you for listening.