Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a ~45 minute talk for an embodied cognition audience, covering my framework for diverse intelligence, our use of morphogenesis as a model system for communicating with unconventional minds, and my views on our new MomBot platform and how it helps understand the symmetries between science and agency, and the novel group minds consisting of technology, living matter, and scientists themselves.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Framing unconventional intelligences

(04:56) Continuous minds and disciplines

(09:40) Memory beyond the brain

(13:18) Multi-scale morphogenetic intelligence

(18:13) Scaling cognition and cancer

(22:38) Bioelectric pattern control

(28:38) Xenobots, anthrobots, latent space

(36:13) Mombot embodied AI scientist

(42:04) Future directions and ethics

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/43 · 00m:00s

What I'm going to do today is talk about some model systems and some frameworks that we've created for thinking about various kinds of novel beings in unconventional embodiments. Specifically, I'm going to talk about some things we've learned about how to relate to unconventional beings. If you want to look up the primary papers, the data sets, the software, everything is available here. This is my personal blog about what I think some of these things mean.

Slide 2/43 · 00m:29s

We as humans, the standard adult modern human that features prominently in philosophy of mind and literature going back a long ways, stand at the center of several continuous series.

We are both on a developmental and evolutionary scale: ultimately we come from cells and subcellular components. But now, because of biological and technological progress, we are in the middle of this continuum where it's going to be increasingly unclear what a human actually is. I'm not just talking about language models or things such as this. We're first going to encounter beings such as this. Some percentage human, some percentage cyborg, this is already happening. We need to start developing better frameworks for understanding what it is like to relate to these novel beings.

I think that we as humans, because of our own evolutionary history, have a lot of mind blindness. We find it very difficult to detect and understand unconventional beings, as with what happened with the electromagnetic spectrum. Prior to a good theory of electromagnetism, we had static electricity and lightning and magnets and visible light. We thought those were all different things.

People thought these were sharp categories. But with a good theory, we now understand that all of them are actually different kinds of manifestations of the same underlying phenomenon. While natively we're only able to recognize a small portion of that spectrum, with appropriate theory and appropriate technology, we can operate along pieces of this continuum that we were completely blind to before. I think this is how we are with the spectrum of minds.

Slide 3/43 · 02m:23s

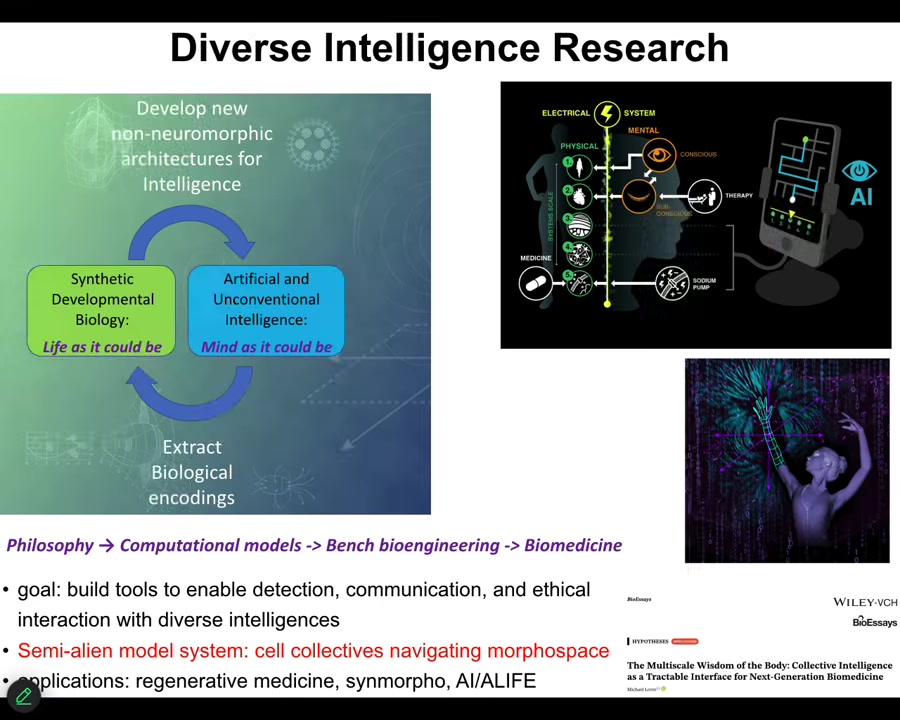

In my group, we bounce back and forth between biological and technological media, trying to understand what both of them are telling us about the nature of intelligence. What we try to do is span the spectrum from deep philosophical ideas to eventually runnable computational models, and then basic science done at the bench, and then hopefully eventually biomedical applications. A number of the things we're doing are moving to the clinic in areas of regenerative medicine. That is one way that we test our philosophical ideas. We see if they will push forward very practical things that everyone can benefit from.

Our goal is to build tools to enable the detection, communication, and ethical interactions with very diverse intelligences. Our favorite model system is a kind of semi-alien one. We don't have proper aliens, but it's close enough. The way that cell collectives will live in anatomical space, which I'll talk about, is good because on the one hand, they are related to us closely. On the other hand, they are sufficiently different as cognitive beings that it's very hard for people to think about them. I think they make a good stepping stone towards truly unconventional minds. You can see in this paper how these things are now being extended to regenerative medicine.

Slide 4/43 · 03m:47s

The goal of my framework is to be able to think about all these different kinds of beings, familiar creatures and primates and birds and a whale or an octopus, but also some very weird creatures such as colonial organisms and synthetic new biological life forms. I'm going to introduce you to two of them today. AI, whether software or robotic, and then someday aliens, and also some very strange things that I won't have time to talk to you about today.

We're not the first to try something like this. Here's Rosenbluth, Wiener, and Bigelow in 1943, trying to understand how you get from passive matter to high-level metacognition.

My take on all of this, at least the 1.0 version of it, is in this paper. The key is that we have to move experimental work forward. In other words, it's not good enough that we have philosophical ideas. We have to ask what practical implications for research and for the real world these things have. These are the criteria for what we're trying to do.

The first thing I want to do in the next few minutes is to show you some features of living material with which you may not be familiar. In particular, to look at how the material of life navigates some very unconventional spaces.

Slide 5/43 · 05m:12s

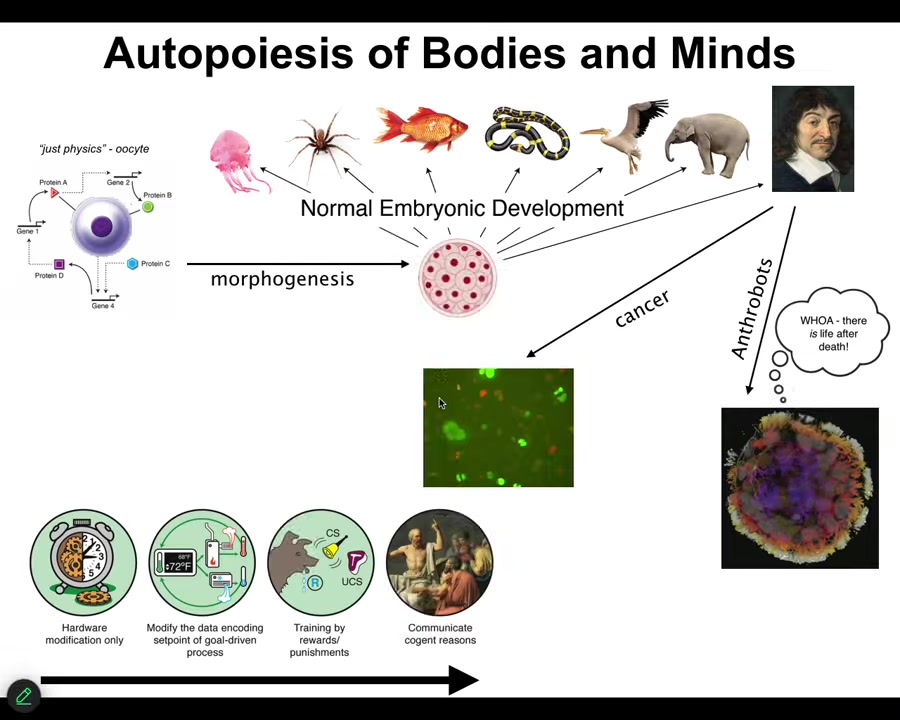

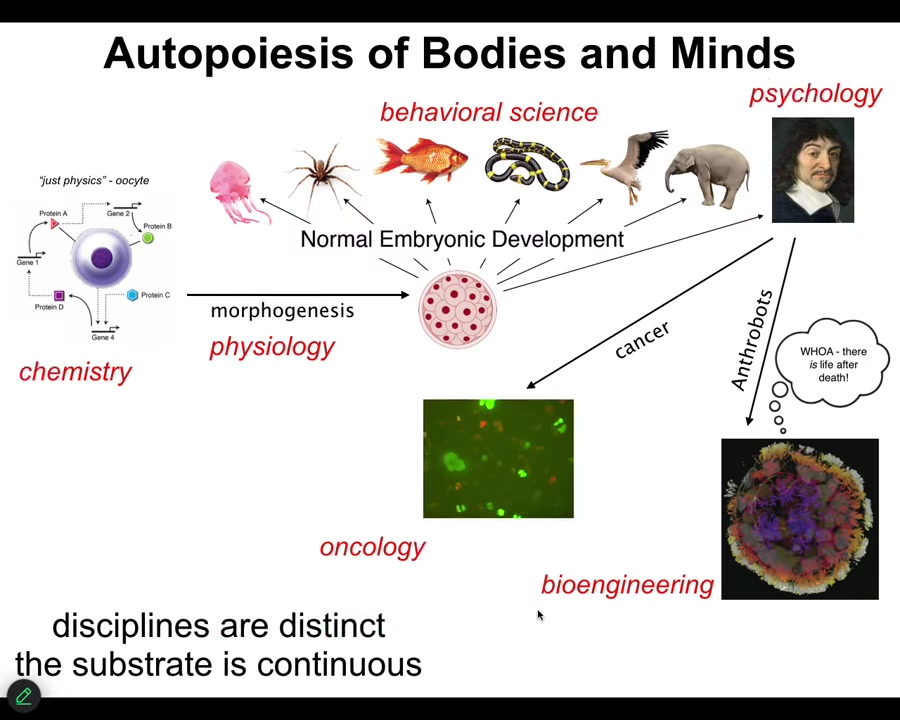

The first thing to notice is that when all of us took this journey from being a single cell, an unfertilized oocyte eventually becomes something like this or even something like this. René Descartes is going to say that he's not a machine. But notice that this is a slow and gradual process. It's a continuous process. There is no magic lightning bolt that says you were just physics and chemistry before, but now you have a real mind. Actually, even that's not the end of the story, as I'll show you. There are a couple of other things that can happen.

What's happening here is that we are traversing a spectrum of persuadability, in other words, the spectrum of techniques that one might use to relate to us: from the kinds of simple physical systems that can only be rewired at the hardware level, physical modifications, to things that are cybernetic and maybe amenable to those kinds of techniques of resetting set points and control theory and things like that, ultimately to systems that are amenable to learning and training, and eventually to psychoanalysis and love and friendship and those kinds of things. This is the kind of spectrum that we are traversing.

Slide 6/43 · 06m:23s

Notice also that the other thing we traverse is a whole bunch of different disciplines. We start off somewhere in chemistry and physics, eventually systems physiology, then behavioral science, then psychology, maybe a detour into oncology and bioengineering. But while these disciplines are treated as distinct, we have separate departments, we have journals, we have funding agencies that treat them as distinct, the substrate, I would argue, is quite continuous. These are all labels that we put on specific areas, and they have specific tools associated with them. Treating these things as distinct natural kinds is very limiting for research. It prevents us from discovering symmetries, deep symmetries across this continuum. I'm going to show you some of that today.

Slide 7/43 · 07m:12s

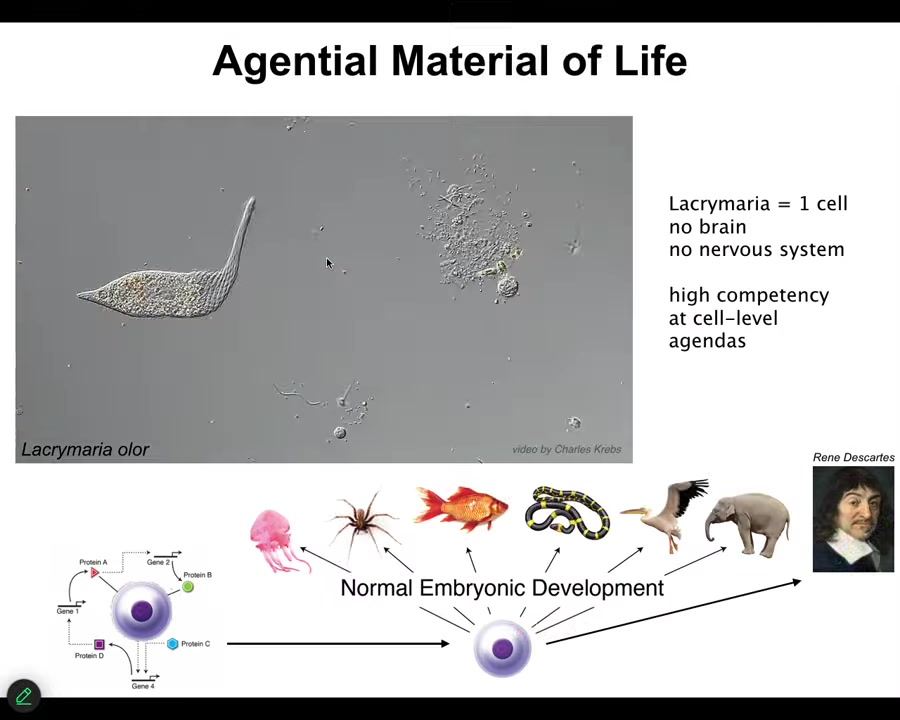

This is the sort of thing we're made of. Now, this is a free-living unicellular organism known as a lacrimaria. It's a single cell. It has no brain. It has no nervous system. But it has high competency in its tiny little agendas. It has a tiny little cognitive light cone. It only cares about the things in a small region of space-time around it. And it is managing those states, but with great competency.

But one of the remarkable things about this is, of course, that it's full of chemical networks. I think many of us would agree that a creature like this can be rewarded and punished. It has some valence states that it cares what happens next. If you watch a video of a unicellular organism die, it's sad. We can all see that there is a being that comes and goes into existence. But what about the chemical network that makes it up?

Slide 8/43 · 08m:13s

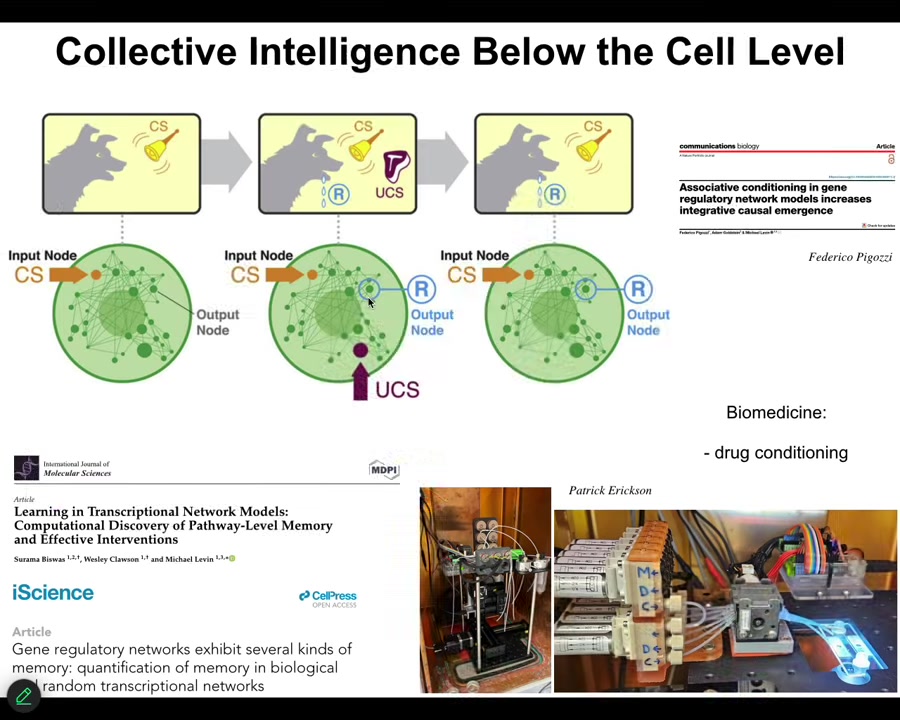

Do you think you could reward or punish a molecular pathway?

Here most people would say you can't. We have to ask the question, what happened from the time that you had a molecular pathway to the time that you had that creature? I can tell you that if we actually ask the question experimentally, we simply do the experiment. What we find out is that even molecular networks, not cells, not neurons, just molecular networks alone. In fact, even small ones that have four or five nodes, they can offer at least six different kinds of learning. We can find habituation, sensitization, associative conditioning. They can count to small numbers. Just the chemical network itself is capable of doing this. And they have very interesting causal emergence properties. As these networks learn, their integrated emergence actually goes up. It's a remarkable thing. Even the material of which single cells are made itself already has proto-cognitive competencies.

In our lab we're building devices to train molecular networks, to give them specific memories, to wipe other memories because you can now do drug conditioning in a medical context. We are made of cells. Cells are made of these molecular pathways, which themselves can learn and can scale their causal emergence, and that gives the biological material some really interesting properties at the higher level.

Slide 9/43 · 09m:42s

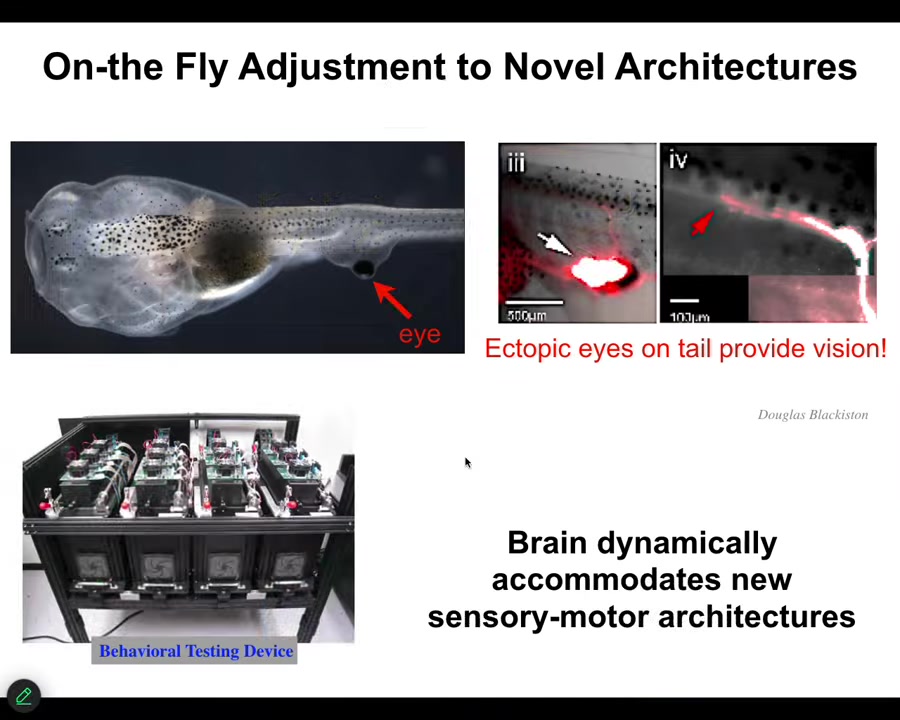

So I want to show you some examples of that. First of all, this is a tadpole of the frog Xenopus laevis. Here's the mouth, nostrils, brain, tail. And what you'll notice is that we've prevented the primary eyes from forming, but we've put an eye on the tail. Here's this eye. If you track the optic nerve, you see that it comes out here. It lands sometimes on the spinal cord, sometimes in the gut, but it never goes to the brain. And yet, these animals can see. The reason we know they can see is because we've built a device that automates their training and testing in visual assays, visual cues, so they can learn to behave appropriately in visual contexts. This is kind of amazing. You might wonder why it is that an animal with a radically different sensorimotor architecture doesn't need new rounds of mutation, selection, adaptation. You don't need any of that. Out-of-the-box, you make this new creature with an eye on its tail, it doesn't connect to the brain, and yet they have functional vision and they can learn visual cues. So that's kind of remarkable, this zero-shot learning adaptation.

Slide 10/43 · 10m:47s

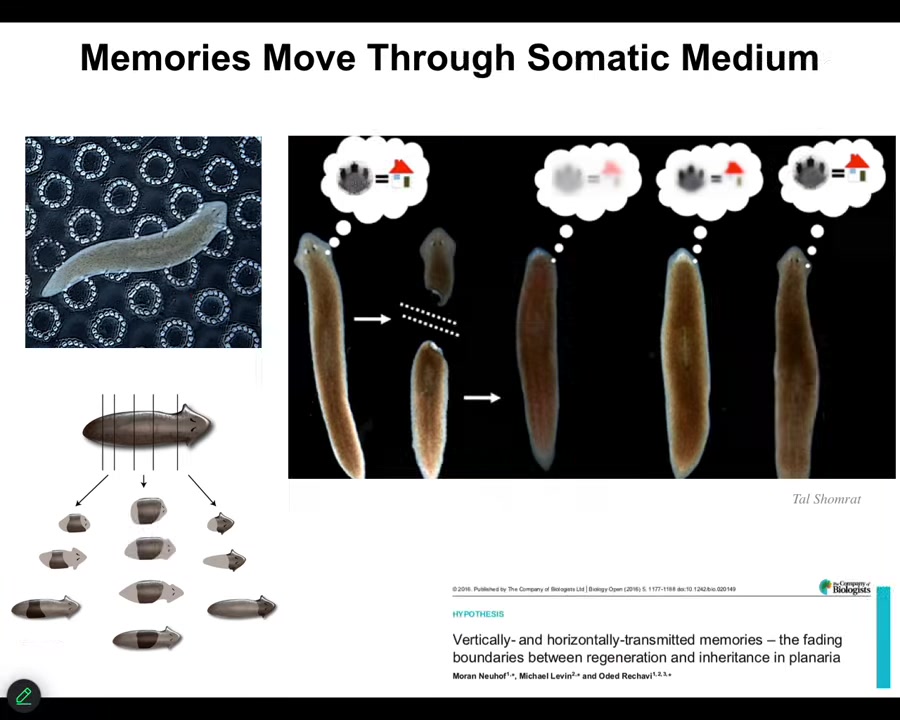

Here's another interesting example of memory moving through a tissue medium.

So these are planaria. These are flatworms. You can cut them into pieces. They regenerate. And what we've done is use that same automated device to replicate McConnell's original data from the 1960s, showing that if you train planaria using the place conditioning task for these kinds of rough little bubbles, then you cut off their head, which contains a true centralized brain. The tail sits there not having any behaviors for about 8 days. By then, they grow a new brain, and then the behavior comes back and you see that they actually remember what they had learned. So not only is the information stored somewhere outside the brain, but also it is imprinted onto the new brain so that the behavior can return when the brain directs the motion.

So the information is moving in and out of various tissues, being imprinted onto the new brain. And this is something that we're very interested in, how information moves through a collective intelligence, because we are all collective intelligences. We are all made of parts. Everything is made of some sort of components. And how does information, global information about the needs of the organism or any kind of agent move through its medium?

Slide 11/43 · 12m:09s

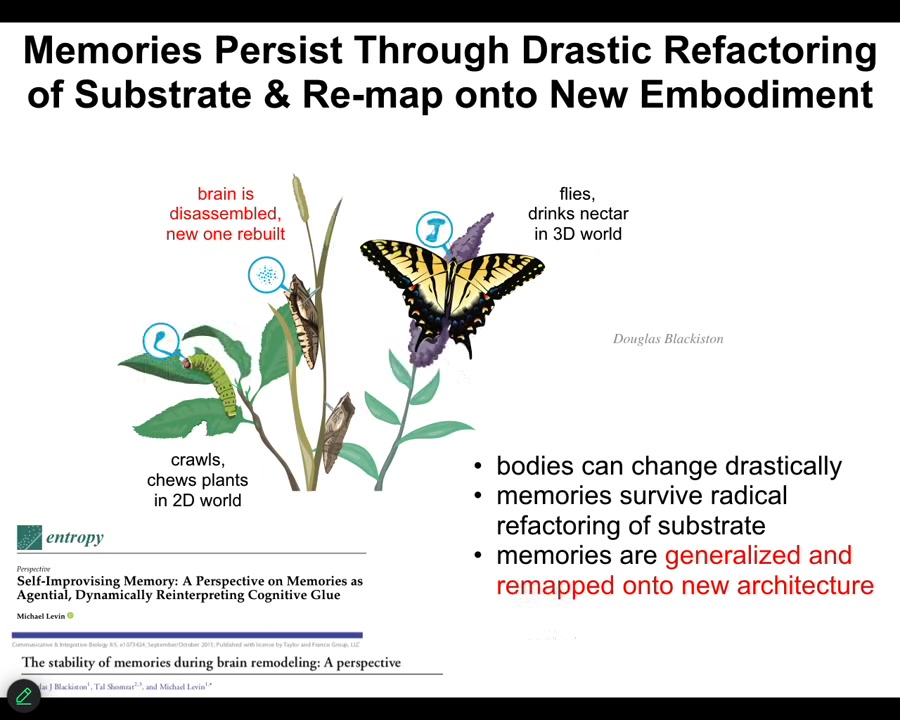

But there's more to it than just holding on to the memory and bringing it back when you need it, and that is seen in this amazing example of caterpillars turning into butterflies.

It turns out that if you train a caterpillar to a new task during this metamorphosis process, they largely dissolve their brain. Most of the neurons are killed off. Most of the connections are broken. A brand new brain is built for a new life of a different organism in a different environment. But if you train the caterpillar, then the moth or the butterfly remembers the original task. What's amazing here is not just that memory survives this radical refactoring of the memory medium, but it actually gets remapped onto a new architecture because if you train the caterpillar to crawl towards a particular color to eat leaves, the butterfly doesn't crawl and it doesn't care about leaves. It wants nectar. If that memory is going to survive, it can't survive simply by persisting. It has to be remapped. It has to be generalized and remapped into a new world. That memory is now living in a completely different cognitive system. This is the plasticity and the movement of information in which we're interested.

Biology lives in this multi-scale competency architecture where every level of organization has its own agendas, its own problem-solving competencies in different spaces and at different scales that allow this incredible plasticity and these amazing feats of maintaining and remapping information and being plastic to novel rearrangements, all the things that our technology doesn't yet have. One thing I think is very important about our own embodiment is that we are collective intelligences and that all the different scales are also different kinds of cognitive beings with whom we can communicate if we have the appropriate frameworks and technologies.

Slide 12/43 · 14m:02s

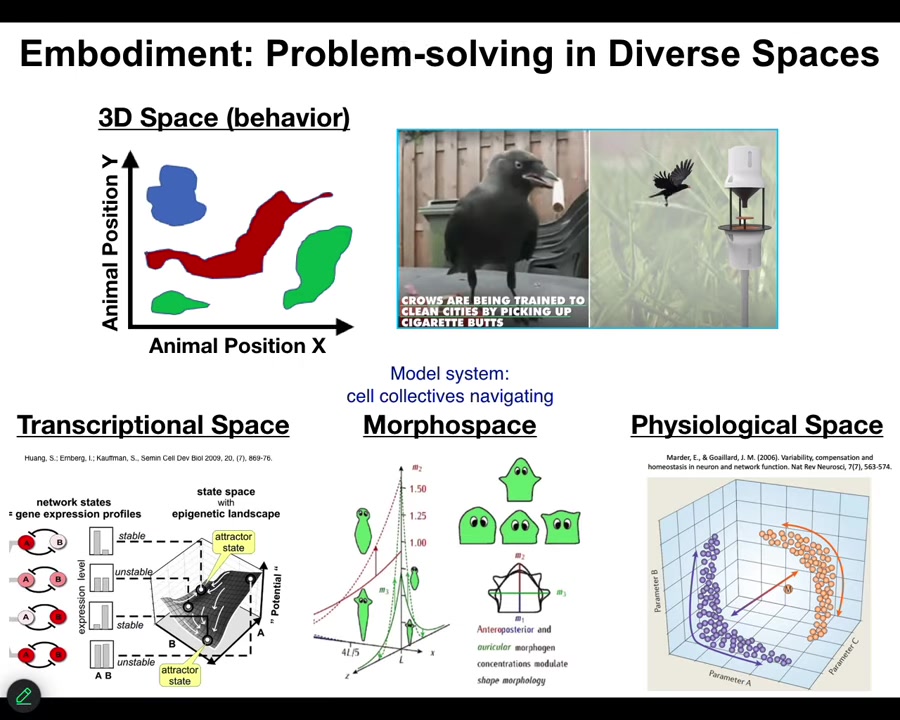

And one of the important things about it is that by Embodiment, as we understand now from this multi-scale architecture, can take place in a lot of different spaces, not just our familiar three-dimensional space with which we tend to be pretty obsessed. We, as humans, are okay at noticing medium-sized objects doing intelligent things at medium speeds in three-dimensional space. But biology has been solving problems and navigating spaces, doing this kind of sensing, learning, decision-making, and then actuation loop in lots of different spaces, long before we had nerve or muscle. So cells navigate a high-dimensional transcriptional space. They navigate physiological state spaces. My favorite of all is anatomical morphospace. So this is just the space of all possible geometric configurations of a large-scale body. And our favorite model system is groups of cells, so a collective intelligence formed of groups of cells navigating in a context-sensitive way, anatomical amorphous space. I'm going to show you a couple of quick examples.

Slide 13/43 · 15m:10s

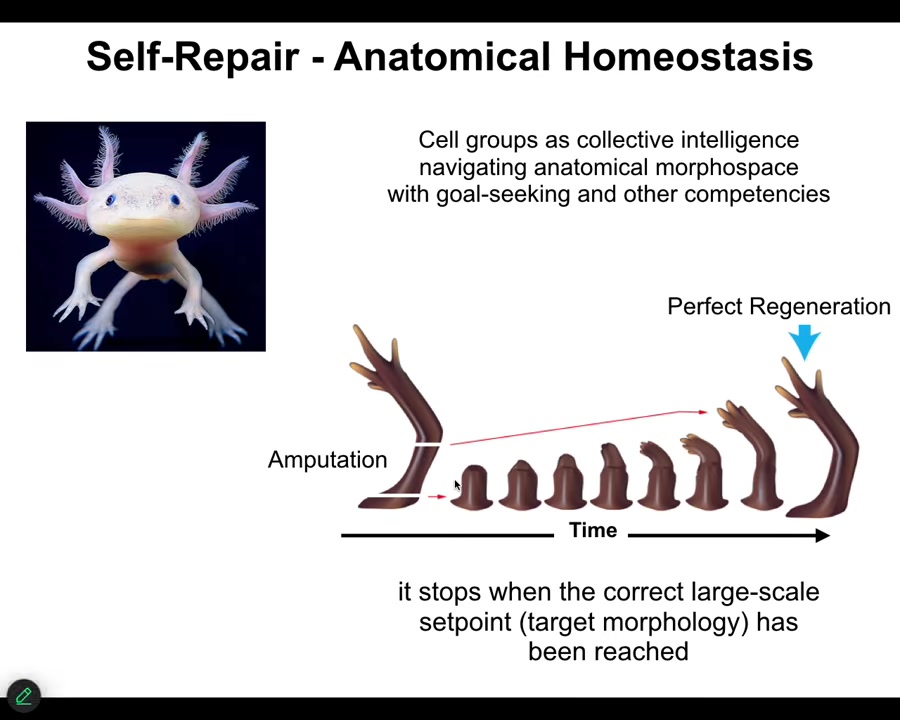

The most obvious thing we can see about navigation towards a specific outcome is what these cells are not doing: simply mechanically following certain local rules of chemistry, and then emergence and complexity describes the fact that something interesting comes out. That kind of open loop model doesn't fit the data. Instead, animals like this. This is an axolotl, and these guys are highly regenerative. They regenerate their limbs, their eyes, their jaws, spinal cords, ovaries. They show you what goal directedness in anatomical space looks like.

You can amputate anywhere along the length of this limb. The cells will very quickly spring into action. They can tell that they've been deviated from their correct position in morphospace, and they very rapidly grow, and then they stop. When do they stop? They stop when a correct axolotl limb has been completed. This is an error minimization scheme. It's a homeostatic process. There is a set point. They know when they've reached it; when the error is below some acceptable limit, they stop the movement in anatomical space.

But it's actually much more interesting than that. It's not simply that cells are able to reduce error towards some particular goal state, and we'll talk in a minute about how they remember what the goal state is, but there's more to it than that. Imagine this experiment. This tail gets grafted to the middle of the flank, and over the coming weeks it transforms into a limb in place. It remodels into a limb.

Look at the world from the perspective of these cells up here at the tip of the tail. We are tail-tip cells sitting at the end of the tail. There's no damage. There's no injury. Locally, there's no problem. There's no reason for us to change. And yet, we have to turn into fingers. Why? Because much like in cognitive systems and much like in morphogenetic systems, that's one of the symmetries between them, local order obeys a global plan. None of the individual cells here know what a tail is or what a limb is, but the collective absolutely does. It can detect the error of having a tail in the wrong location. The information propagates down to the molecular events needed to turn tail tip cells into fingers.

This is exactly what happens to you and I when we wake up in the morning and we have grandiose research goals, social goals. These are very abstract things. Ultimately, for you to execute on those goals, they have to make potassium and calcium ions move across your muscle membranes. Your abstract high-level goals have to make the chemistry dance in your cells so that you can go do whatever your cognitive system is aiming at. That kind of multi-scale transduction from very abstract high-level goals, such as having limbs in the appropriate places, has to make a functional difference to the molecular biology of the cells here. That's very interesting.

Slide 14/43 · 18m:13s

In the next few minutes, I want to talk about two things. First, how we scale minds. As we make a collective intelligence from competent subunits, meaning molecular networks, cells, tissues, all of them have various competencies, how we scale that up into a larger scale collective intelligence, and what communication interface could we use to talk to this unusual intelligence? It lives in anatomical morphospace. We don't know how to visualize it, but the mathematics can handle it.

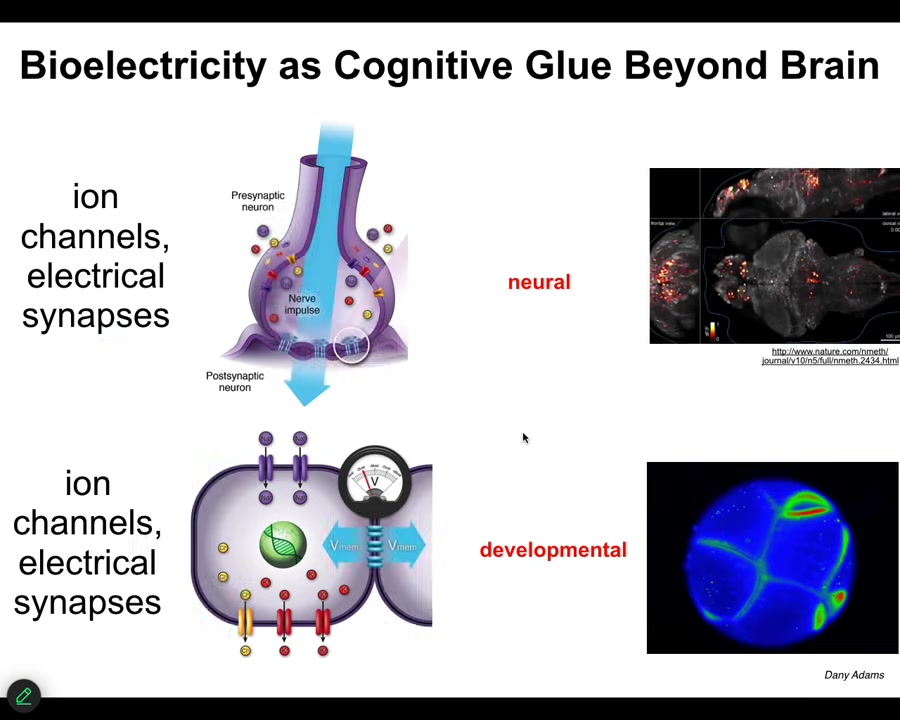

Two concepts: one is called the cognitive light cone, and one is the bioelectric interface. Bioelectricity is basically the cognitive glue. Evolution loves bioelectric mechanisms as the cognitive glue that binds cells into higher level decision-making units, just like you and I are more than the sum of our neurons, partly because of the bioelectric networks in our body.

Slide 15/43 · 19m:16s

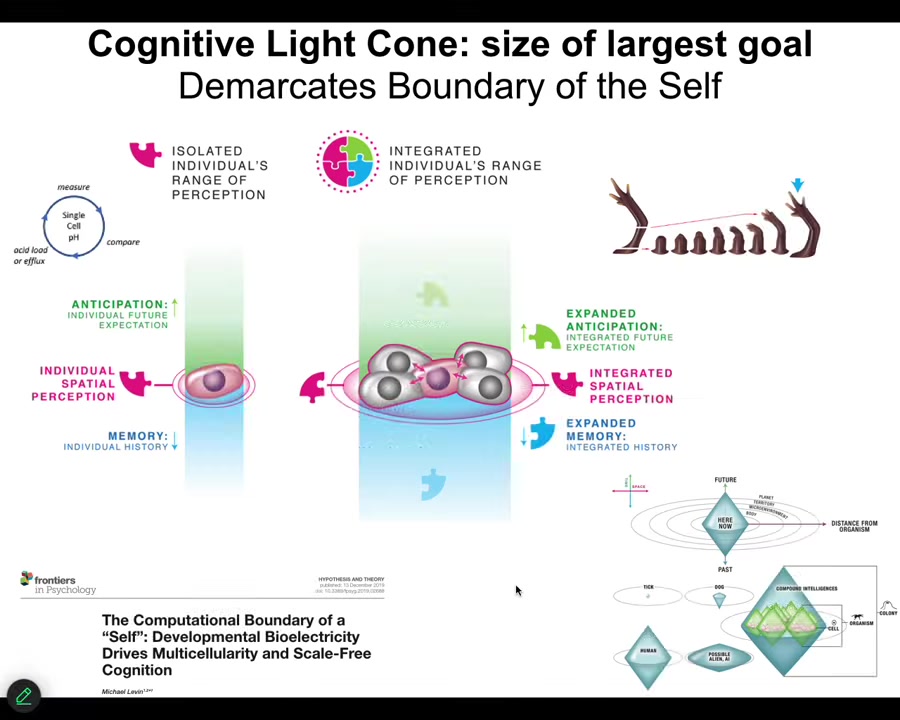

So notice that one way to think about cells, different kinds of agents, is as the scale of their biggest goal. So individual cells have tiny little goals, maybe pH, maybe hunger level. So their homeostatic set points are very small. They enact this homeostatic process, but the set point is tiny. It's a single number, usually in a very small region of space-time.

So if you think about the amount of space and time that each goal refers to, individual cells have a very tiny one, but groups of cells come together into a network that has massive, massive goal states. For example, no individual cell knows what it is, but the collective is storing something like this. It's projecting into a new space. So this is physiological space, this is anatomical space. And the size of the goal, both in space and time, is much, much larger.

And all of that is described here, our efforts to model how cells come together in electrical networks so that they can store larger set points. They can remember much bigger, they can remember these incredible grandiose goals that individual cells cannot remember. And you can map out the cognitive light cone in space-time of all kinds of common biologicals, but also perhaps some aliens and some cyborgs.

Slide 16/43 · 20m:42s

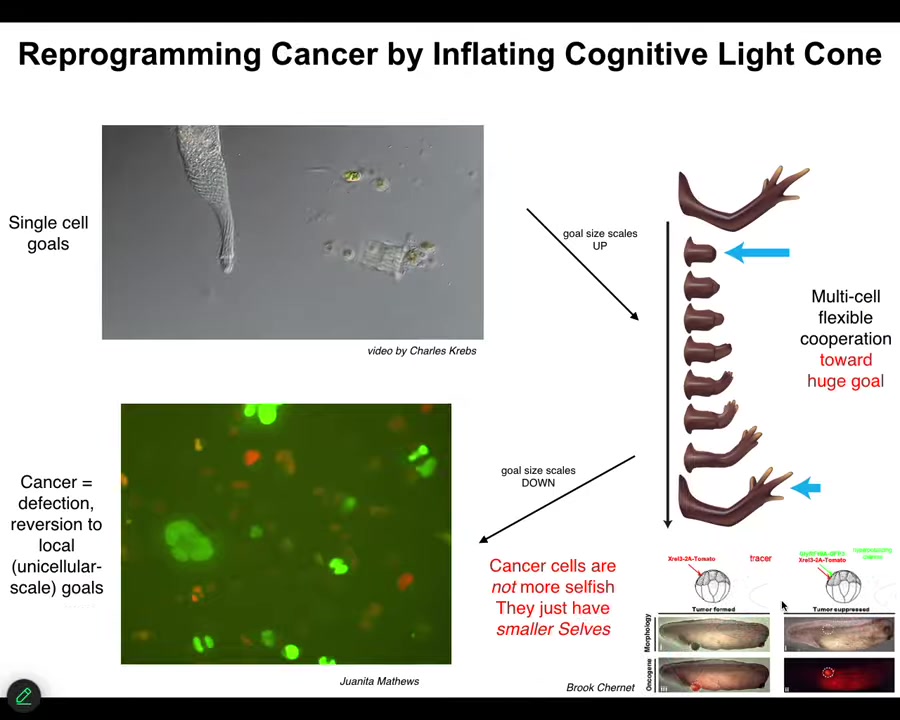

Just to show you one practical example of how these philosophical ideas become useful, if we understand that individual cells join into networks and thus scale up their goal states, scale up the set points that they can represent, their cognitive light cone, then something that becomes clear is that process should have a failure mode. That failure mode is called cancer. When cells disconnect from that electrical network, they can't remember the goal they were working on. They go back to their unicellular goals of mitosis and metabolism and so on. That is exactly what we see in cancer cells. Our model here said that cancer cells aren't more selfish, they just have tinier cells. The boundary between self and world has shrunk, and the cognitive light cone, instead of being big like this, has become small. Could we re-inflate it again?

We have a whole set of work in the lab, and it's now moving to human patient tissues, where we inject oncogenes; they form tumors. But then we don't kill the cells, we don't repair the hardware, meaning the genetic damage. We force the cells into electrical communication with their neighbors, which they lose. Oncogenic processes first cause the cell to disconnect from the network. If we force connections, even though the ANCA protein is blazingly expressed here in this tadpole, there's no tumor. It's the same animal. There's no tumor. If you connect cells to the electrical network, the network will be building the healthy tissues, not doing individual cell behaviors. So here's an example of how a theory of scaling of the cognitive light cone is taking us to specific biomedical applications.

Slide 17/43 · 22m:38s

What I was telling you is that the actual information that propagates through that network and is computed is electrical. And that really shouldn't be a surprise because when we think about brains and this idea, here's a zebrafish brain in the living state doing, thinking about whatever zebrafish think about. We have to ask, where did this come from evolutionarily? And we know that neurons evolved from pre-neural cells that had all the same machinery. Ion channels, electrical synapses, this stuff is ancient. It goes back to bacterial biofilms, and every cell in your body has this electrical machinery, and in fact, it connects into networks.

While the networks in your brain spend much of their time thinking about moving you through three-dimensional space, the networks in your body spend most of their time thinking about how to move you and keep your configuration in the right region of anatomical space. We developed the first tools to read and write the electrical activity of non-neural cells. This is an early frog embryo, and here the colors are showing us the voltage gradients. You can see all the electrical conversations that the cells are having with each other.

Much like people in the field of neural decoding want to read this and ask, what is this creature thinking about? What are its goals? What are its capabilities? We have been working to decode the bioelectrics of the body, asking, what is it thinking about?

Slide 18/43 · 24m:04s

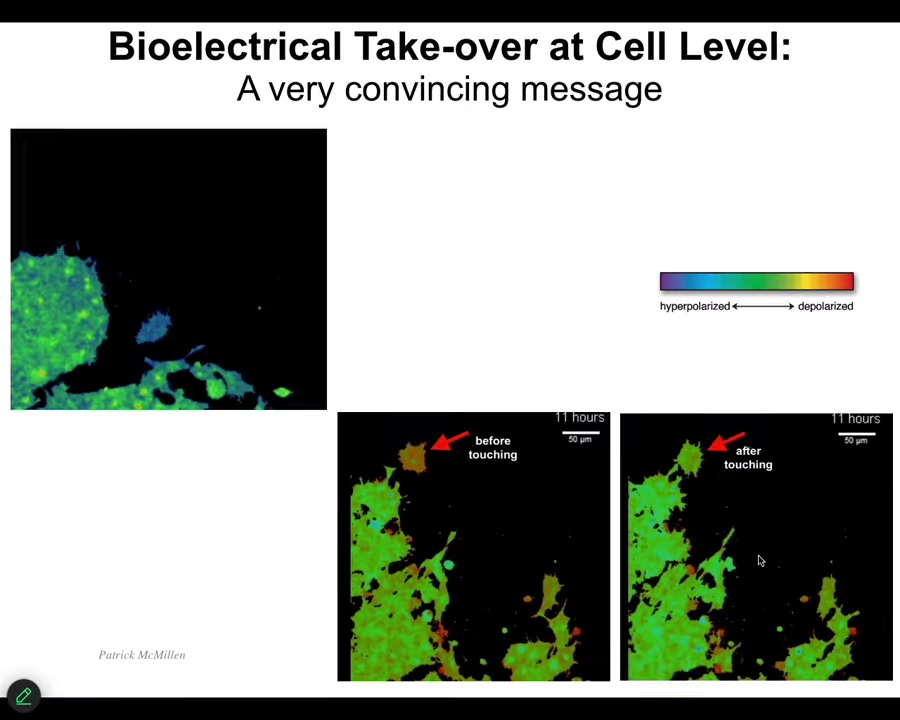

I want to show you a couple of interesting things. I want to show you how cells convince each other to do things. I'm going to play this video in a minute. The colors here represent voltage. These are two frames of this video before and after. Keep an eye on this cell right here. It's blue. It has its own voltage, minding its own business over here. This guy's going to reach out, bang. That's it. That's all it took. Here's the before; here's the after. That tiny little connection is formed and that's it. The cell voltage is now just like that of this other mass. Now the cell is going to come back and work with the rest of these cells to build whatever it is that they're building.

Being able to communicate to these cells is important because we're starting to learn how to do it too.

Slide 19/43 · 24m:44s

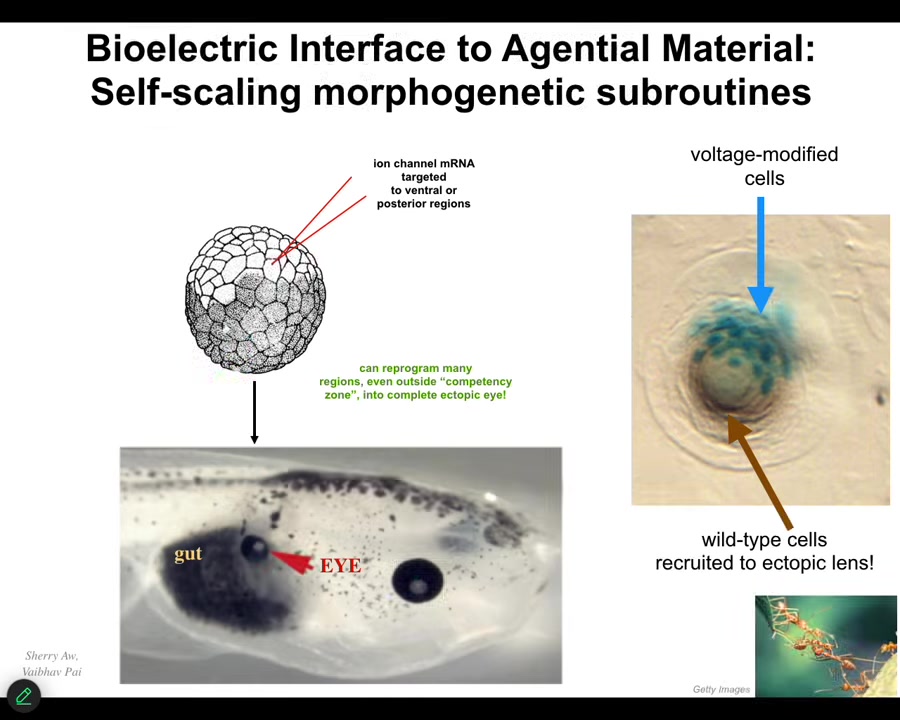

When we do it, we can inject, for example, ion channel RNA that puts cells in particular bioelectrical states. The way that is interpreted by the other cells is as organ identity messages, prompts. So here again is that tadpole side view. This time here's the gut, here's the eye, here's the brain, the mouth. We've injected some ion channel RNA that provides a particular voltage pattern. The voltage pattern says to these cells, build an eye. And that's what they do. We don't micromanage it. We don't talk to the stem cells. We have no idea how to arrange all the different cells in their combination any more than I know how to arrange your synaptic proteins now so that you'll remember what I'm saying. You handle that yourself. I don't have to worry about the biochemistry.

The same thing is true here. Because we're dealing with a very competent material in Morphospace, I can give it a very high-level message, build an eye, and it will take care of all the molecular details down the line, just as I was showing you a moment ago. Not only that, the material has some awesome competencies. For example, if I only inject a few cells here, what they will do is recruit all this other stuff. The blue ones are the ones we injected. They recruit all these other cells to help them build an eye when there's not enough of them. Other collective intelligences do this too. Ants and termites do the same thing. We didn't have to teach them that. We didn't have to force that. The material already does it.

So the trick here is to learn to communicate with it, not to micromanage the molecular states, but to send prompts that the material understands and take advantage of it. This is part of recognizing and communicating with a novel being. We have to understand what is the interface, in this case bioelectricity, for communicating with it, and what is the language? What does it understand? What kind of competencies does it have? What kind of prompts can we use to communicate?

Slide 20/43 · 26m:35s

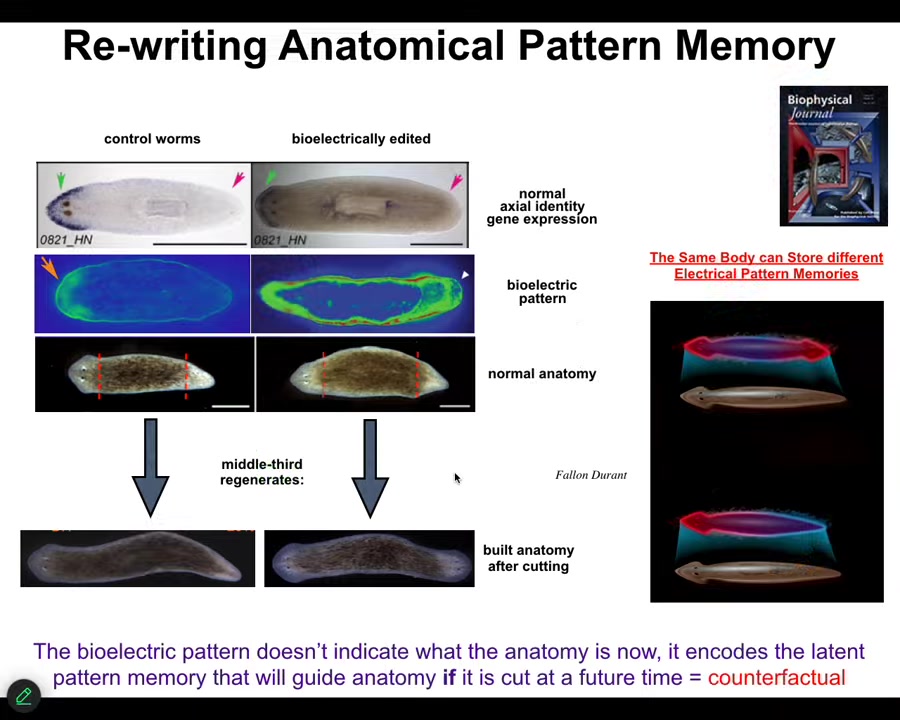

We've developed some other things, such as being able to rewrite their pattern memories. In this planarian, if you chop it into pieces, you find that every piece remembers how to build a correct worm, one head, one tail. We asked, how does it know? It turns out that there is a voltage pattern that we can read out that says one head, one tail. If we rewrite that voltage pattern to say, no, actually, you should have two heads, then after cutting this animal, they will indeed make two heads.

Notice that what you're seeing here is a representation of the planarian tissue's answer to what a correct planarian looks like. That is the memory that is used, the set point that is used to guide regeneration. If we say the set point is two-headed, that is what they build. Also notice that this is not a map of this two-headed animal. This is a map of this perfectly normal-looking one-headed creature. That memory is latent. It doesn't do anything until we cut, until it's injured, and then the cells consult this pattern and build whatever it says.

This is actually a counterfactual. It's a primitive version of our mental ability to time travel, to remember things that are not true right now. Past things or future states that are not true right now. It's a simple version of a counterfactual in amorphospace, because this pattern is not true until the animal's been injured, and it is what I will implement in the future if I get injured.

Slide 21/43 · 27m:59s

I keep calling it a memory because it has that property. If I make two-headed worms, I can then cut them as many times as I want. They will continue to make two-headed animals. Here are the videos of what they look like. There's no genetic change here. We haven't touched the genome whatsoever. There's nothing wrong with the genetics here. You can sequence these all day long. You will never find out that they have two heads, because that's not where the information is. It is not in the hardware. It is in the remembered experience that these tissues have had by us using ionophores to change the bioelectrical state such that it encodes a two-headed state, and the information persists, as far as we can tell, forever.

The next thing I want to show you is what happens when we go beyond evolutionarily selected forms. You can take a look at some implications of that for evolution here.

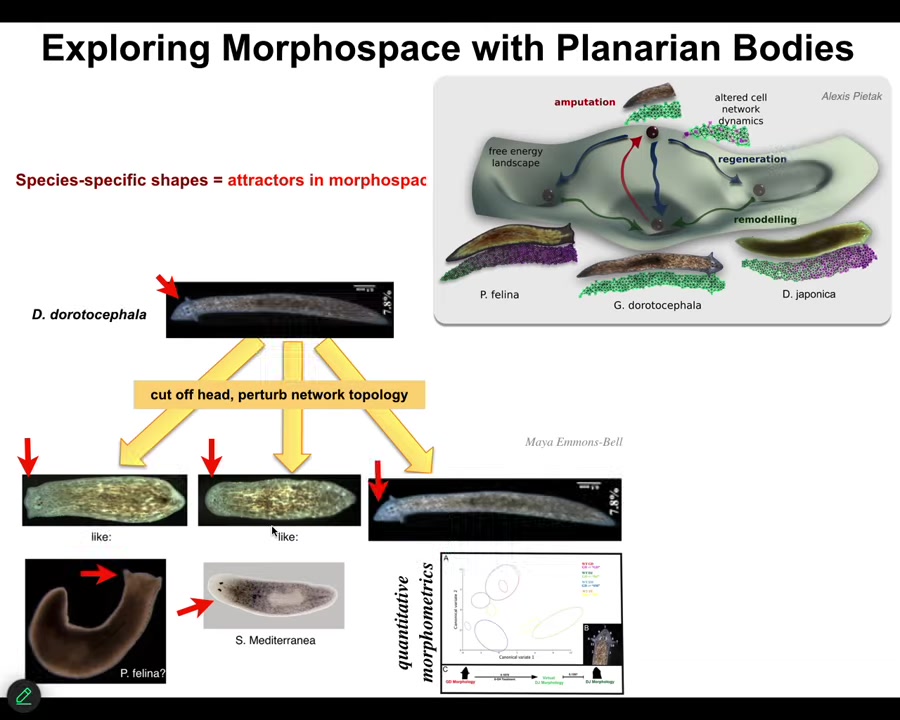

Slide 22/43 · 28m:50s

In planaria, by disrupting the bioelectrical signaling, we can ask species of planaria to make heads appropriate to other species. This nice triangular-headed guy can make flat heads like a P. falina, round heads like an S. mediterranea, about 100 to 150 million years' distance between them. It's not just the shape of the head; the shape of the brain and the distribution of stem cells are just like these other creatures.

This hardware is perfectly happy to visit attractors in morphospace. In anatomical space, there are different attractors corresponding to these other species. We can chase them into these other attractors where they live natively.

All of these attractors were shaped by evolution. In other words, they exist because of a history of selection forces that made sure that these are the attractors, not something else.

What happens when we make new creatures that don't have that history of selection?

Slide 23/43 · 29m:51s

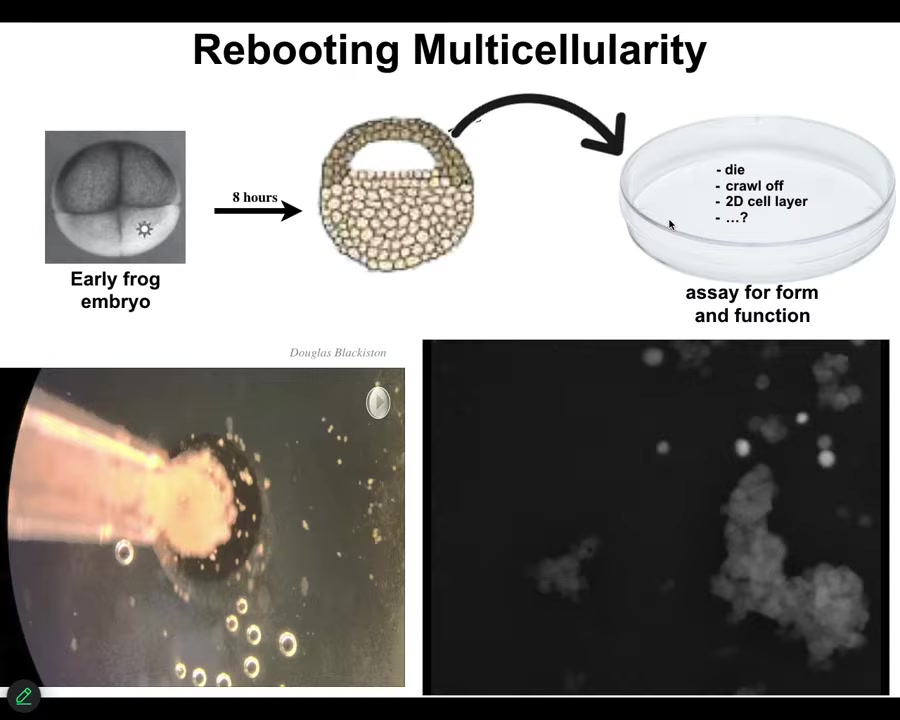

Xenobots. When we take apical epithelial cells from frog embryos, they don't die. They don't crawl away from each other. They assemble into this little thing. I want to show you what that looks like. Each circle here is a single cell. This little group of cells, about 20 of them, looks like a little horse. They don't all look like that, but I think this one is particularly cute. They move around as a collective. They have all these interesting motions. You'll see a calcium flash when it encounters this larger mass. Eventually all these cells will get together and they make something like this.

Slide 24/43 · 30m:24s

These are self-motile. They use cilia to swim through the water. They can go in circles. They can patrol back and forth. They have collective behaviors like this. You can make them into weird shapes, like this floating donut.

Slide 25/43 · 30m:40s

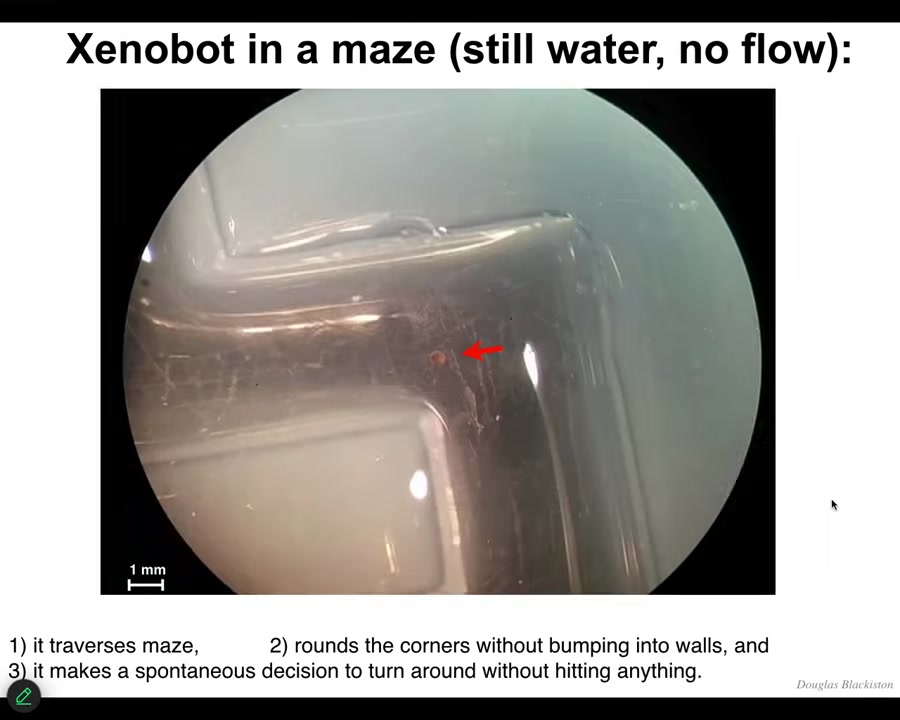

Here's a Xenobot traversing a maze. It moves forward. It's going to take this corner without bumping into the wall. So it takes the corner, and then here it spontaneously turns around and goes back where it came from. They have different kinds of spontaneous behaviors.

Slide 26/43 · 30m:57s

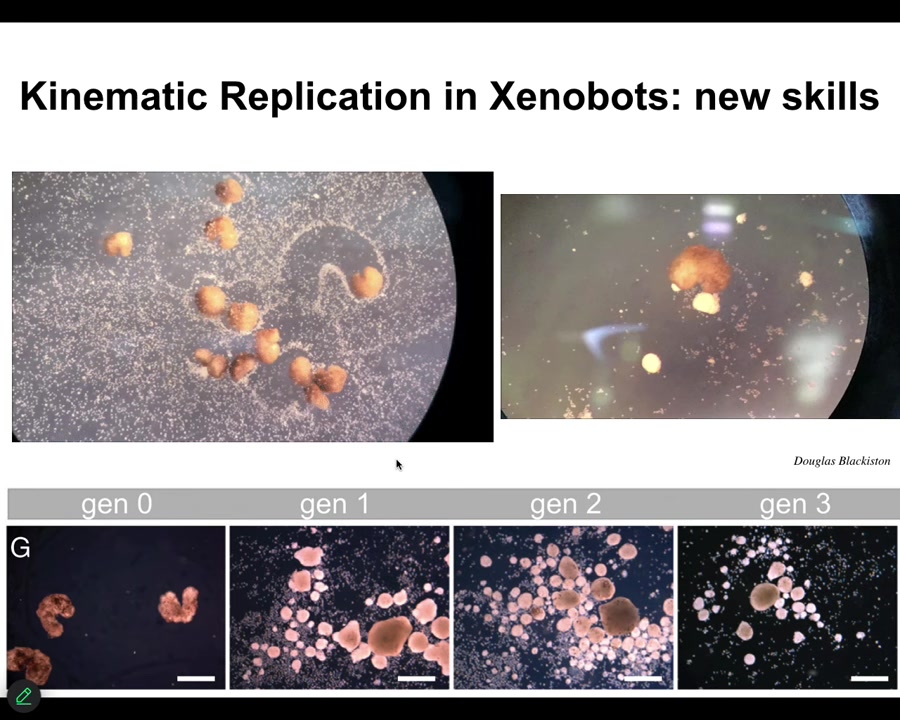

One of the amazing things they know how to do is called kinematic replication. If you provide them with loose epithelial cells, they will individually and collectively push them into little piles. Then they polish the little piles. Because they're dealing with an agential material, not passive matter but an agential material, these piles themselves become the next generation of xenobots. They make the next generation and so on. So as far as we know, no other creature on earth uses kinematic self-replication. We've made it impossible for these guys to reproduce in the normal frog-like fashion, but they found a different way to replicate themselves.

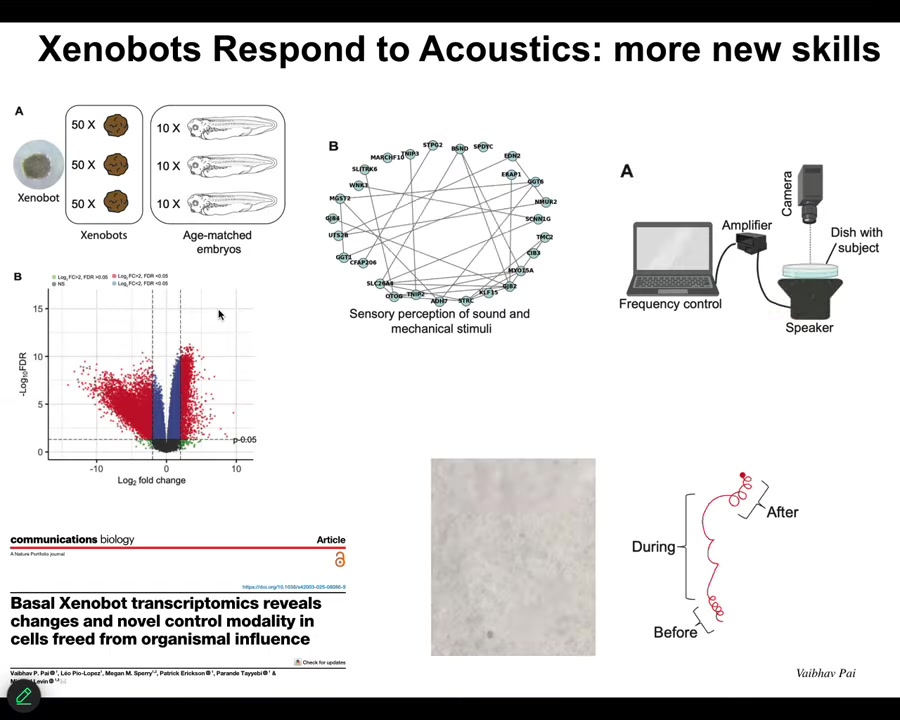

There are some other curious things about them. When you look at the system, what genes do they express relative to what they normally would do in an embryo?

Slide 27/43 · 31m:43s

Well, we found out hundreds of new genes are upregulated in Xenobots. I'll just show you one example. A cluster of genes related to hearing — perception of sound and mechanical stimuli. Normal embryos don't express these. This is something new that Xenobots are expressing.

We saw this and we thought, that's wild. Is it possible that they can respond to sound? So we put speakers under the dish, we provided the acoustic stimulation, and we found out that they do in fact react to it. This is a novel competency. Normal embryos would not be doing this. This is something that only Xenobots do.

Maybe this is some very frog-specific thing. Amphibians are plastic.

Slide 28/43 · 32m:35s

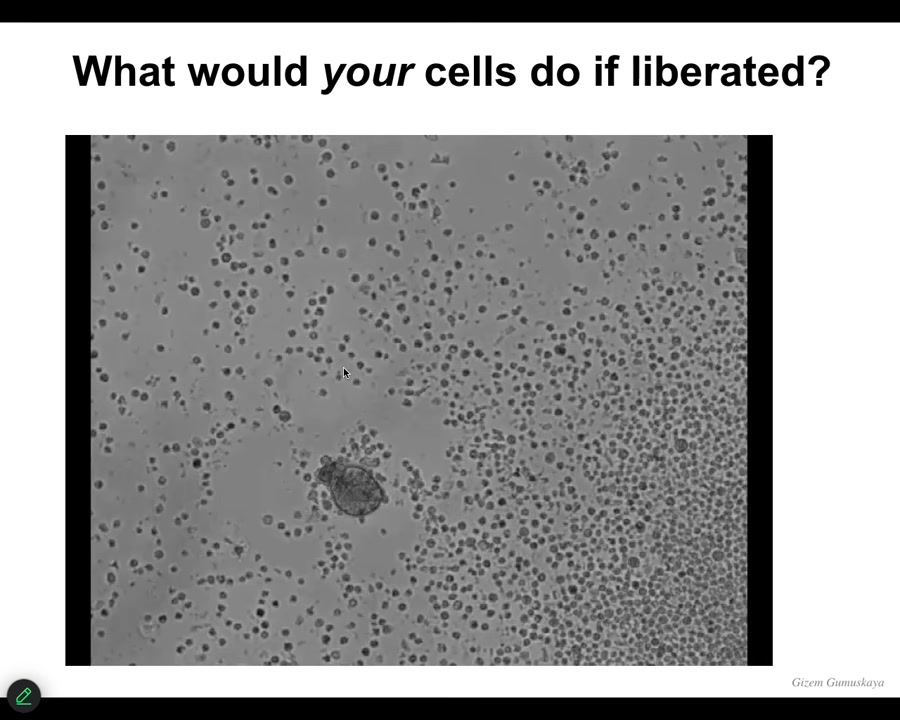

I would ask you the question of what would your cells do if I liberated them from the instructive influence of the rest of your body?

I would introduce you to this creature. This is called an anthrobot. It looks like something primitive you might see at the bottom of a pond, but it is 100% wild-type Homo sapiens genome. These are made by taking tracheal epithelial cells from human patients and, through a fairly simple protocol that we have, they self-assemble into this novel little creature that swims around. It doesn't look like any stage of normal human development.

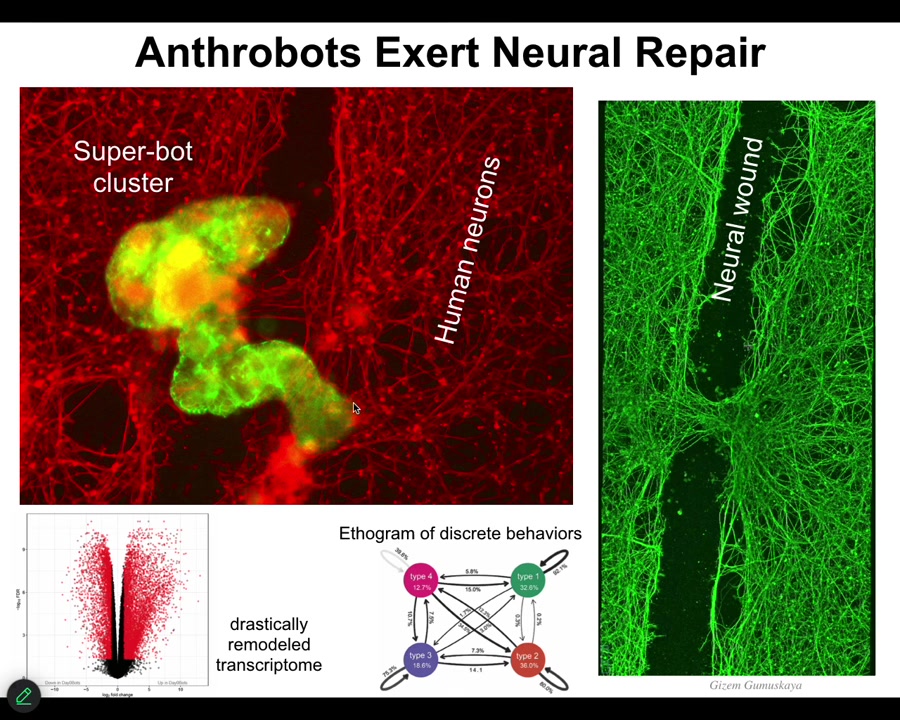

Slide 29/43 · 33m:09s

These guys have over 9,000 differentially expressed genes compared to what they were doing in your body. They have a completely different transcriptome; about half the genome is now differently expressed.

They have 4 distinct behaviors, and you can draw a little ethigram of transition probabilities, not 12, not one, four specific distinct behaviors. If you place them on a dish of human neurons that you've damaged by putting a big scratch through them, they will form this kind of superbot cluster and start to heal the gap. If you lift it off, this is what you see. They're sitting there within about four days. They take the two sides of the wound and they heal it.

Who would have thought that your tracheal cells, which sit there quietly in your airway for decades dealing with mucus and smoke particles, have the ability to form a separate self-motile little creature that has its own transcriptome that's never been seen before, its own set of behaviors, the ability to heal your body?

Someday these will be personalized biobots in the body healing you. They won't need immune suppression because they're made of your own cells. There's no weird materials. There's no nanoparticles here. There's no synthetic circuits. We haven't edited the genome. We haven't done anything at the hardware level. These are native plasticities of cells that are able to do this.

Slide 30/43 · 34m:30s

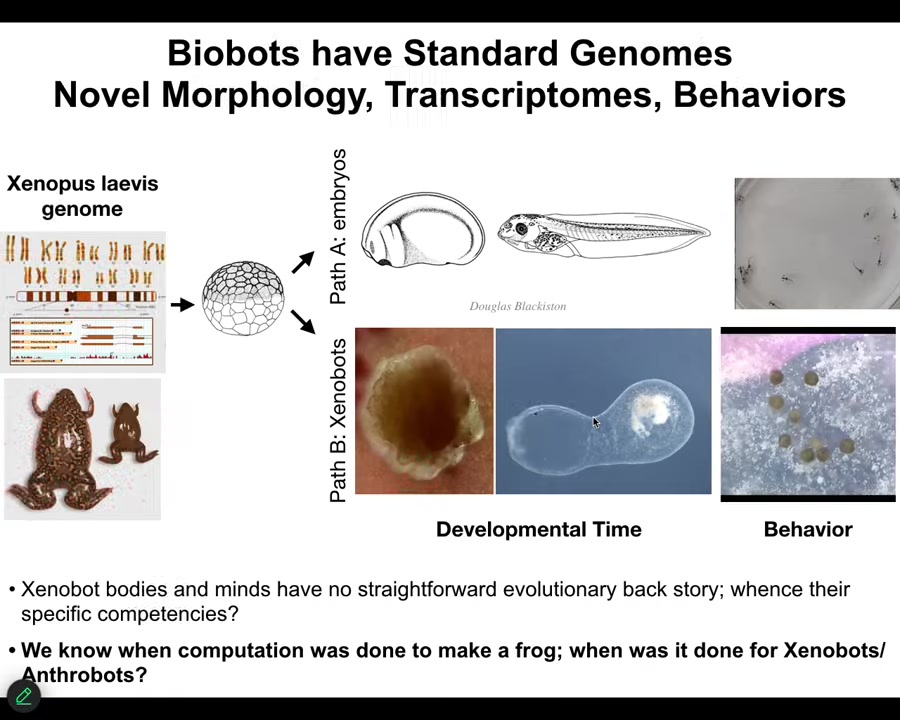

This raises, as we think about these novel beings. Just to bring it back to our fundamental goal: to learn to detect and communicate with novel beings. We also have to understand what are going to be the properties of these new beings that have not been here before. You can't derive it from selection. You have to ask what are going to be their capabilities? How can we predict them?

You can say that we know when the computations were done to design a frog, and that was in the millions of years that the frog genome was interacting with the environment, certain selection forces, and so now here's stages of development and here are some tadpoles. We know when the computational cost for this was paid. When did we pay the computational cost to design Xenobots? There was never selection to be a good Xenobot. There haven't been any Xenobots. There haven't been any Anthrobots. Where did all those things come from? I don't think it's fruitful to say that at the same time that humans and frogs were selected, we also learned to do this, to have these specific properties. I don't think that works. I think we have to do better than that in understanding why those specific transcriptional states, specific physiological states, specific behaviors, where do they come from?

Slide 31/43 · 35m:51s

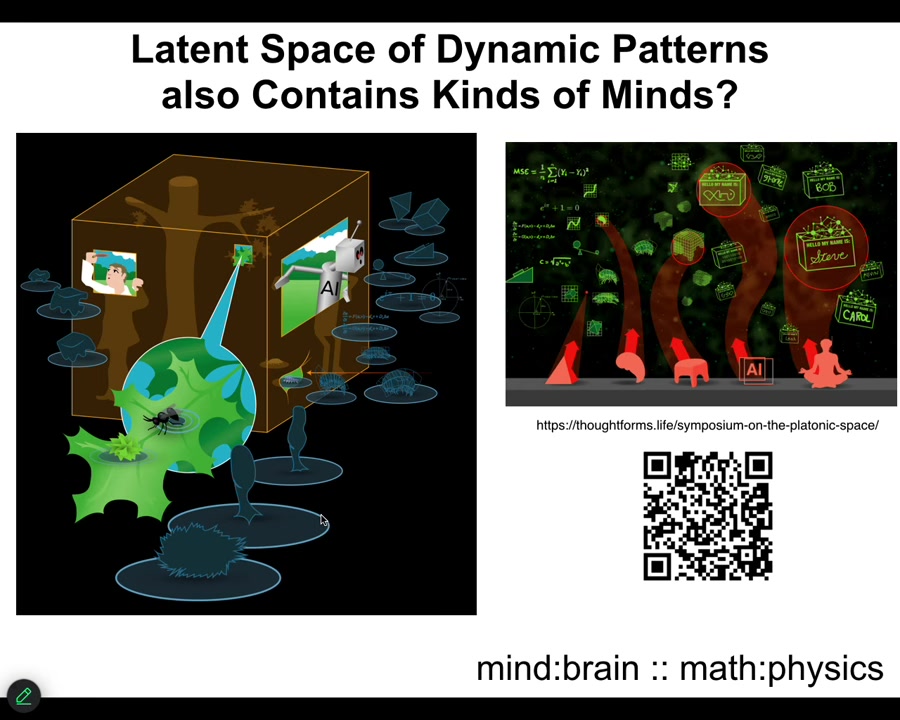

I don't have time to get into all that here, but I'll just tease this: we have a symposium running, and you can watch a bunch of videos, including my introduction to what I think is going on, where we study the latent space of patterns. These are patterns of gene expression, of physiology, but also of behavior, aka kinds of minds.

I make the argument in that talk that the mind-brain relationship is basically the same as the math-physics relationship. In other words, the world of Platonic facts about the number E and various mathematical objects is not just for constraining what happens in particle physics and other physical objects. It also is something that evolution makes use of and exploits as a kind of free lunch. Some of those are in fact cognitive properties, not just structural properties. So you can see that here.

Slide 32/43 · 36m:45s

The final thing in the last few minutes, I want to show you something that's our most recent work, which is the use of AI for diverse intelligence research. This is something that spans the spectrum from a tool to something that eventually will be a colleague. It has to do with engineering in agential materials.

Slide 33/43 · 37m:07s

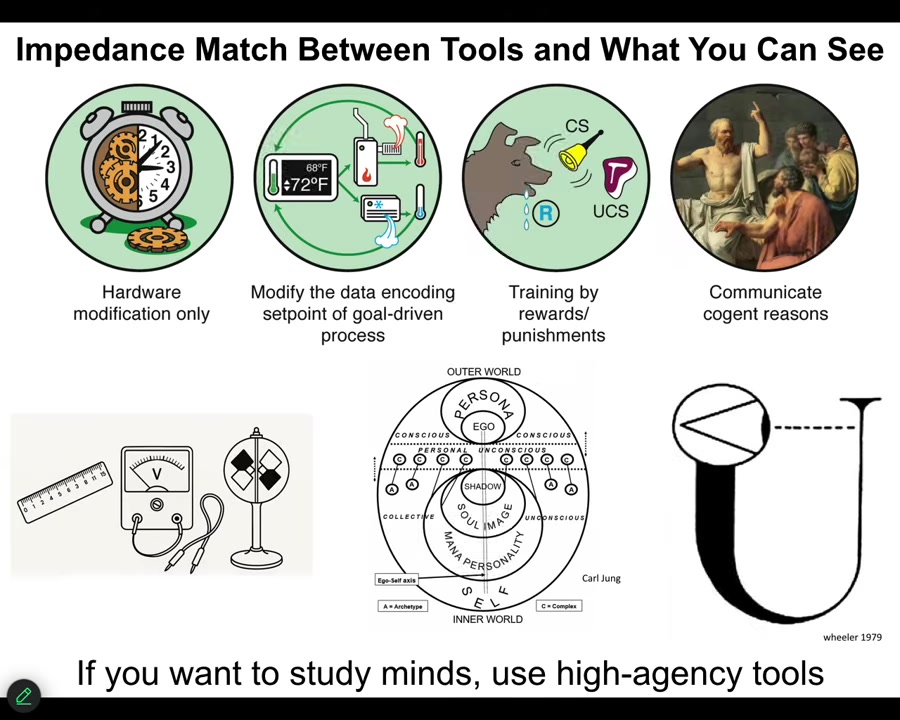

There needs to be an impedance match between the tools you use and what you can see.

I think that physics mostly sees mechanism because it uses low-agency tools, rulers and voltmeters and things like this. If you want to see other minds, you have to use gentle sensors. It takes a mind to be able to see other minds.

Slide 34/43 · 37m:34s

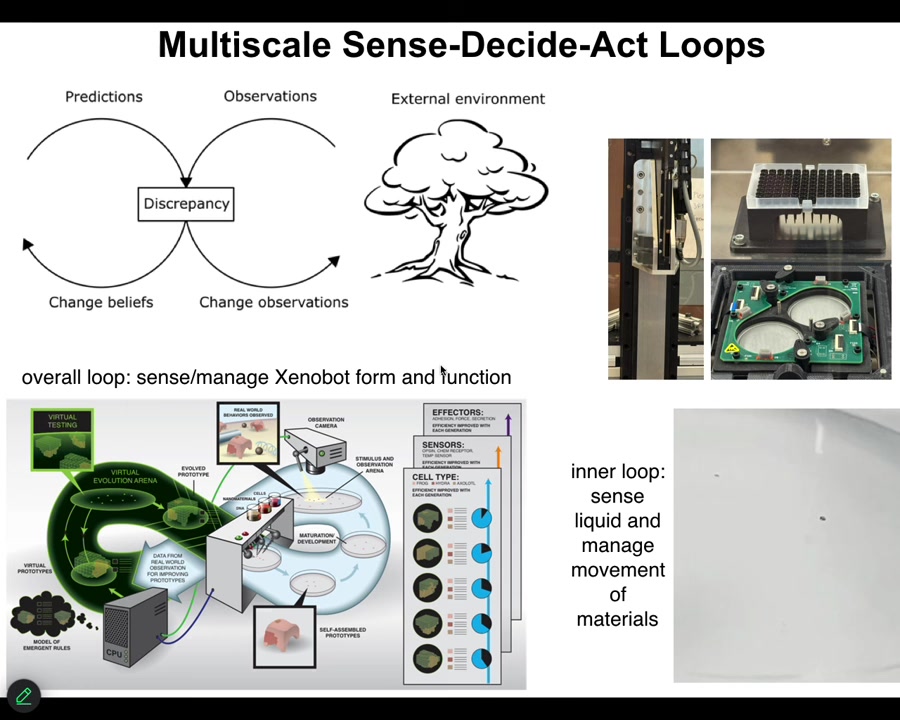

And so, there's this interesting symmetry between the way that agents navigate their world. They make predictions, they make observations, then discrepancy drives the change in their self-model and the model of the world, and then they make new observations.

I just want to point out that describes equally well the life of an active agent in any kind of environment, but it also describes science. It describes what we do in science. And so here comes the last of the concepts, which is this blurring of the lines between tools, agents, and the task of navigating and understanding our world.

Slide 35/43 · 38m:16s

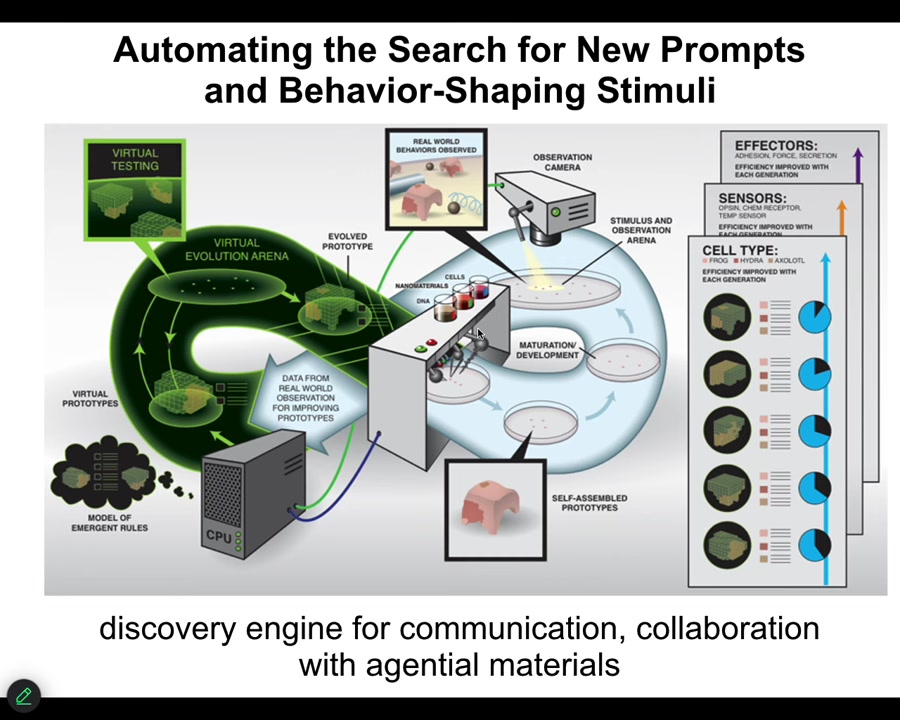

What we wanted to do, and this is a project together with the Bongard Lab at University of Vermont and with Doug Blakiston, who just got his own faculty position at Tufts. He was a staff scientist with me for years. Together, what we've been creating is the first platform for doing closed-loop hypothesis and design of biobots. One way to think about this is it's a system that has an AI component that makes hypotheses about morphogenesis, about what stimuli would have to be given to cells to get them to build specific things. It then carries out those tests by stimulating cells and then observing what kind of xenobots resulted. And then it goes back and revises those hypotheses based on what it saw. One way to think about this is a discovery engine for communication and collaboration with the cellular material.

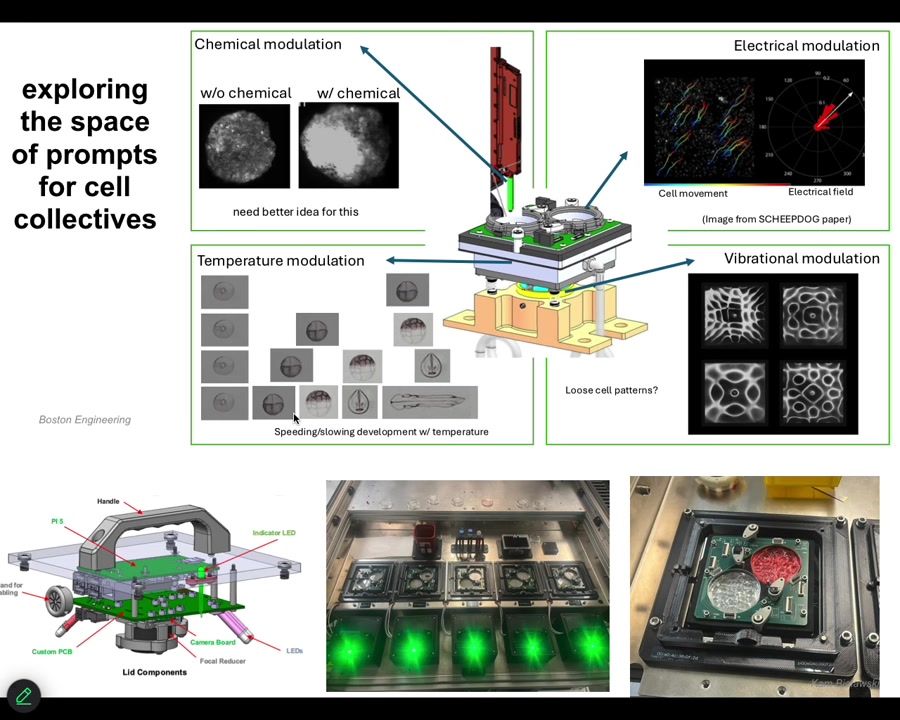

Slide 36/43 · 39m:12s

We started to build this. Here are the different kinds of stimuli. They can do chemical stimuli, vibration, and bioelectric things.

This is what it actually looks like. These are not artist's renditions. This is actually something that we've built.

The idea is that the system is going to learn about morphogenesis by doing experiments in a closed-loop system.

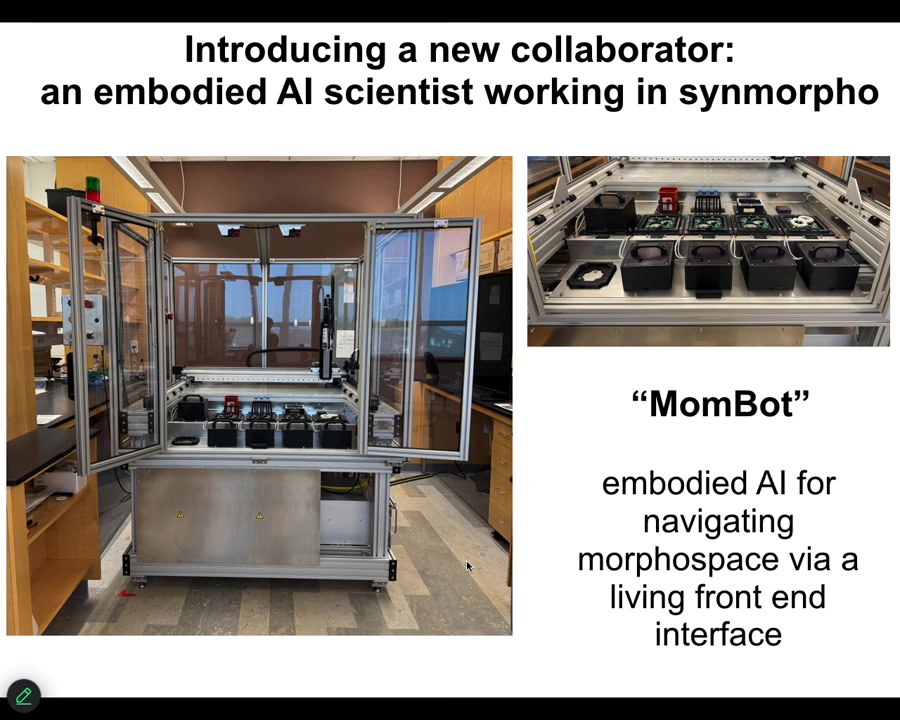

Slide 37/43 · 39m:38s

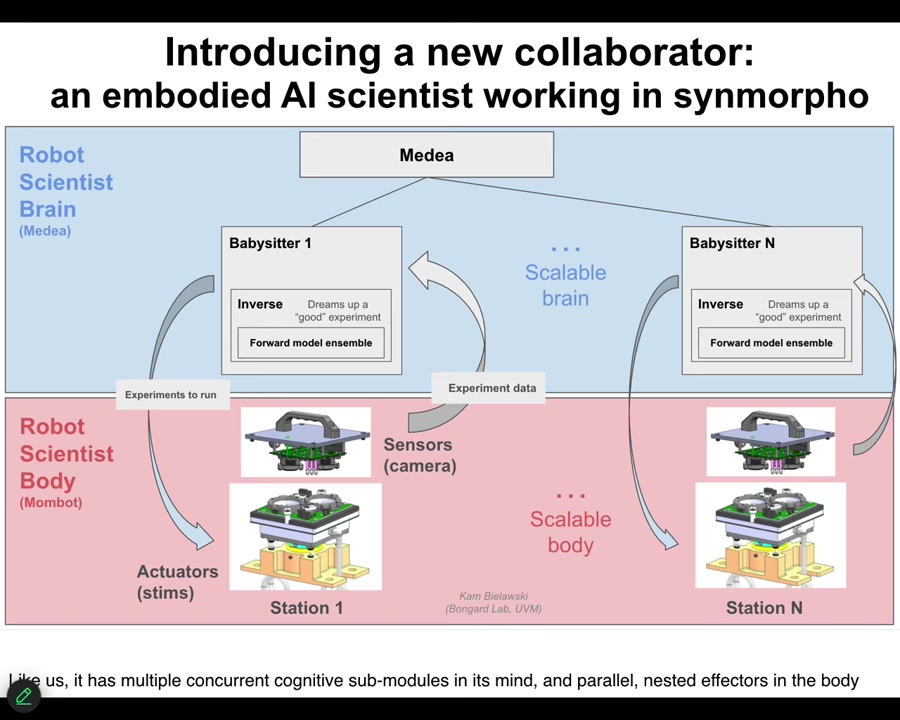

This is what it looks like. It went online 3 weeks ago, put together in our lab. It's starting to do its thing. We call it MomBot because it's a robot for making biobots. We think that what it is is an embodied AI. It has a software AI system inside, but it also has a body. Now that body does not move around in three-dimensional space. It navigates the space of behavior-shaping cues that it is giving to the Zenobot cells to build new bodies that are used to explore the latent space of possible forms and behaviors. It's actually navigating morphospace via the Zenobots as a front end. They're using the Zenobots as a sense, as a front end interface to study this morphospace.

Slide 38/43 · 40m:40s

It has a system that has multiple concurrent sub-modules, just like we have. They're all active at the same time, making suggestions for what experiments are going to be done. Some suggestions eventually percolate to the front, and then it carries out those experiments. It has a body. It has a scalable mind, and it has a scalable physical body.

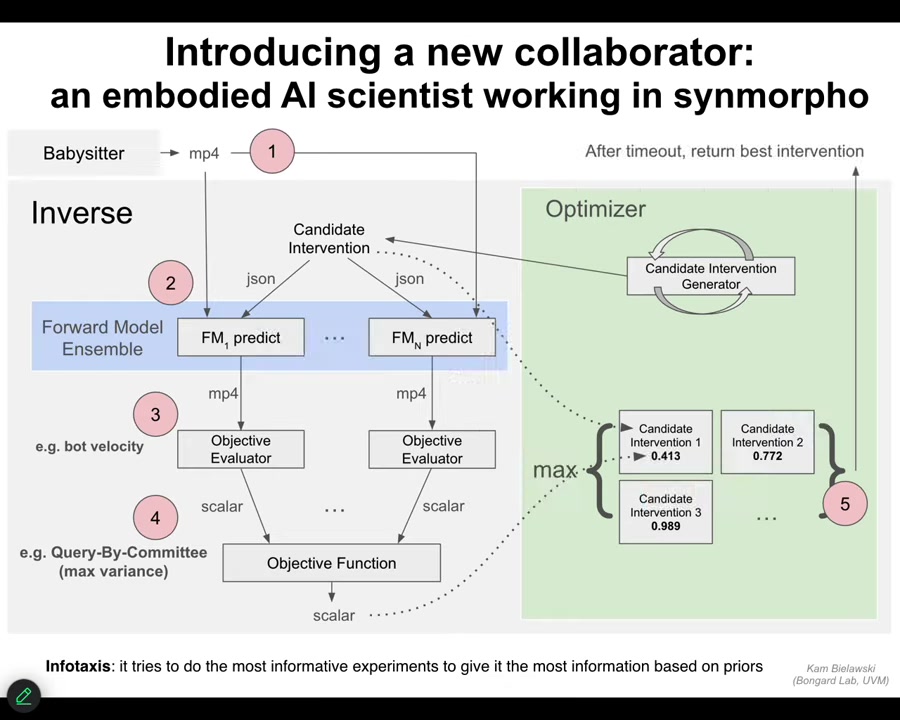

Slide 39/43 · 41m:07s

This is the various layers you can see. If you want to understand the kind of cognitive architecture of the system, this is it, because we created it from scratch. It tries to do infotaxis, so it tries to do the most informative experiments it can that will give it the most information about resolving uncertainty. This is what agents do in their environment.

Slide 40/43 · 41m:36s

It even has something else that's important: this thing right here, when it's picking up and dropping cells, it can feel. This tip, through electrical sensing, can feel when it has something and when it doesn't. So it has some proprioception. The physical part of its body can sense. It has immediate feedback of what it's doing.

Slide 41/43 · 42m:02s

Let me wrap all this up. First, the next steps of what we're doing.

We're using it to discover new biobot forms and behaviors. We're adding curiosity about finding problems to solve, not just finding solutions that we ask it for. Because this thing gives stimuli to Xenobots, the Xenobots could modify their own environment by behaving in ways that cause MomBot to do certain things. Instrumental learning. There's a potentially very complex loop between the collective intelligence in the living material and in the AI.

There are three ways to think about this. First, useful synthetic living machines: environmental cleanup, exploration, in-body repair, bespoke living machines.

More interesting is the idea that this is actually a robot scientist that can help us crack the morphogenetic code to learn what kinds of stimuli allow us to motivate the cells to build things we want to build. Applications in regenerative medicine, birth defects, bioengineering, and so on, towards this notion of an anatomical compiler—being able to create whatever biological form you want by motivating the cells appropriately.

Even deeper than that, this is the first tool to communicate with unconventional minds. It really breaks the categories we've had separating tools, scientists, the space of intelligence, and developmental processes. All those categories are doing more harm than good now. We have to create tools like this that help us build intuitions and help us understand how to recognize diverse intelligences and how to communicate with beings in other spaces.

We, MomBot, and the Xenobots are all together part of a composite new system that has never existed before. Here are at least two different ways to think about it; they're both right, and there are probably many others. The MomBot is this middle bow-tie node between human scientists and the Xenobots' collective intelligence and morphospace. You could also say that MomBot is an agent using the Xenobot tissue to explore, to live in, and to experience the space of possible forms and functions, anatomical amorphous space.

There are numerous ways to cut this up between we, the scientists, the machine that stands in our lab, the Xenobots and the latent space of possibilities—numerous perspectives of different active embodied agents that are at play here. We need to begin to get comfortable with that.

Slide 42/43 · 45m:09s

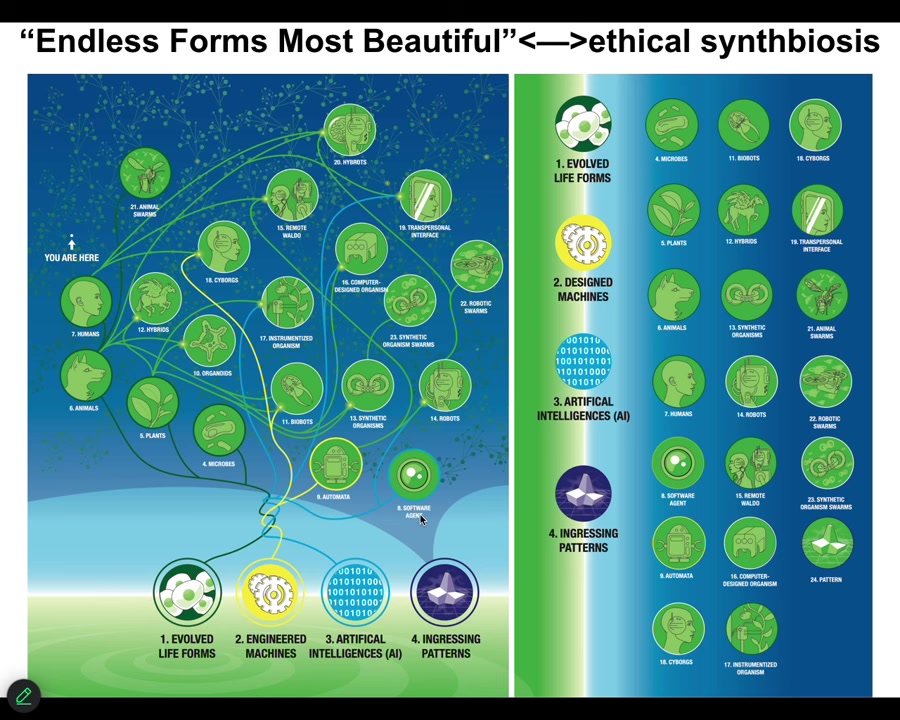

The last thing is that because of the interoperability of life, this multi-scale problem-solving competency, every kind of combination of living material, engineered material, software, is going to be a viable agent. It's going to be a viable embodiment of the mind. It's going to have the benefit of patterns ingressing from this latent space.

Everything we know about in the biosphere of the earth is here. It's a tiny little corner of this option space. Cyborgs and hybrots and all kinds of chimeras, we are going to be living in this world in the decades to come. We really need to understand how to enter an ethical synthbiosis with these beings. Because when Darwin said "endless forms most beautiful," he meant this tiny little corner of this option space. But it's a very wide space and we need to get a lot better at recognizing and learning to communicate with these beings.

Slide 43/43 · 46m:08s

I'll stop here by thanking the postdocs and students who did the work that I showed you, Josh Bongard and his team, especially for that later part. We have lots of amazing collaborators for this work. I have to thank our funders that have supported us through the last 25 years. I have 3 disclosures: these are companies that have spun out of this work and are commercializing some of the stuff — Fauna Systems, Astonishing Labs, and Softmax. That's it. I'll stop here and thank you for listening.