Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a 1 hour 10 minute presentation of ideas around the architecture of biology (and how it differs from today's computational systems). Focusing on morphogenesis as a model of collective intelligence, I talk about the intelligence ratchet that results from life's need to creatively interpret information on the cognitive, developmental, and evolutionary scale. I end with some speculative ideas about Platonic space and cognitive patterns therein, which radically enlarge the set of beings.

There's a Q&A session which can be found at: https://thoughtforms.life/a-talk-on-the-architecture-of-life/

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Framing diverse intelligence

(05:09) Unconventional biological intelligence

(12:40) Multi-scale competency architecture

(26:18) Bioelectric pattern memory

(38:16) Collective selves and cancer

(45:10) Intelligence on unreliable substrates

(55:36) Biobots and Platonic patterns

(01:08:00) Summary and research agenda

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/64 · 00m:00s

Thank you so much for having me here, and I look forward to our discussions.

Today, I'm going to have a mix of some things that I think we have pretty strong evidence for, and some very conjectural things at the end that we can all talk about.

These two links: this is my academic site, all of the papers, the data sets, the software, everything is here. This is a blog where I put some more speculative ideas about what I think this all means.

What I'd like to do today is show you some biology that I think is relevant to intelligence and bio-inspired computing.

Slide 2/64 · 00m:39s

I always thought it was really interesting that Alan Turing, who was interested in problem-solving machines and reprogrammability, also wrote this amazing paper, which was about the origin of order in chemicals during morphogenesis. I think that what he was on to is extremely profound. It's a deep symmetry between the self-creation of bodies and the self-creation of minds. I think that those two things are very tightly linked, and we learn a lot about both of them by bouncing them off of each other.

Slide 3/64 · 01m:12s

What I'd like to do today is 4 things. I'm going to show you some unconventional examples of intelligence and biology, which I think argues for a view of mind all the way down. We can discuss what "all the way down" means. But to show you some biology that's different than the kind of biology that normally underwrites thoughts in cognitive science, in bio-inspired computing, and so on.

I want to tell you about some recent progress that we've made with communicating with this agential material. I'm going to argue that it's not just a computational matter or active matter. It is actually an agential material, and we now can access one of several interfaces for communicating with it.

Then I want to talk about why that works and what I think is a driving force of this process and the creative aspects of the architecture of life. At the end, I'll throw around some ideas about what I think that might mean.

Slide 4/64 · 02m:09s

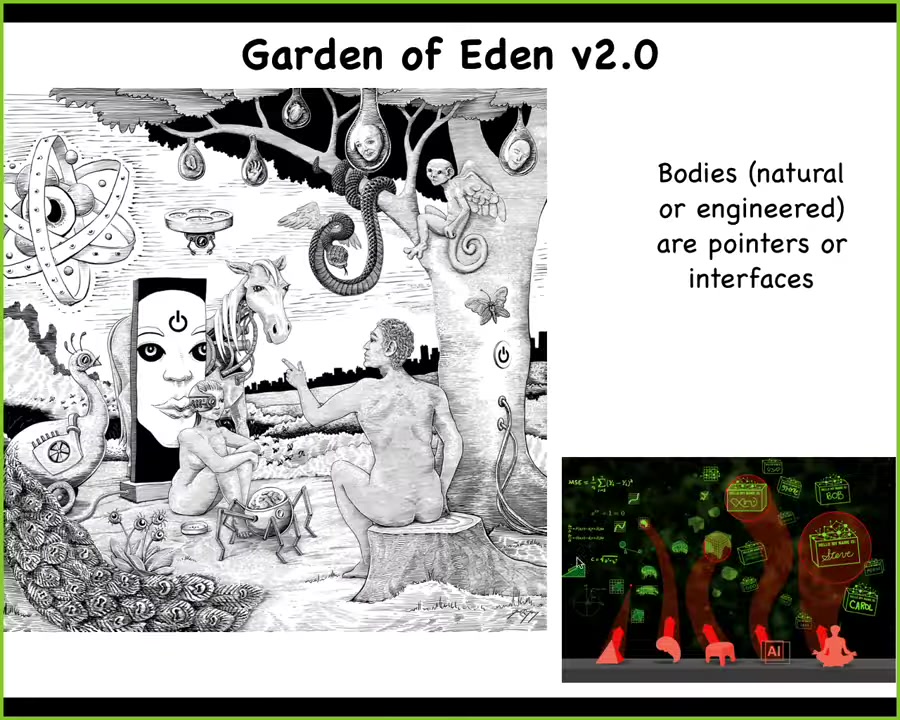

This is a well-known piece of art. Adam is naming the animals in the Garden of Eden. There's something about this that is rate limiting for progress in the field, but there's something else that is very deep and correct.

The thing that's rate limiting is that in this system, what's pictured is a very fixed idea of natural kinds. It's clear that you have specific discrete animals, and then you have Adam who is different from them, and it's supposed to be objective what everything is. That's a fundamental problem that we're going to have to get around.

What's good, though, is that in the original story, it was on Adam to name the animals. God wasn't going to do it. The angels couldn't do it.

What is cool about that is that in ancient traditions, naming something means you've discovered its inner nature. It was on Adam to do this because he was the one that was going to have to live with these creatures.

Slide 5/64 · 03m:14s

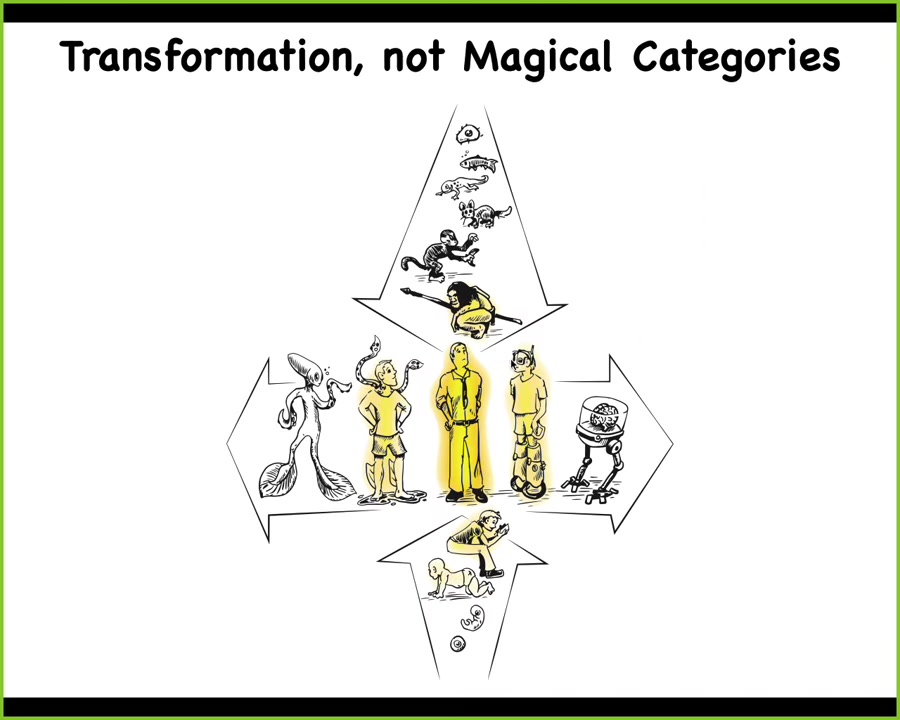

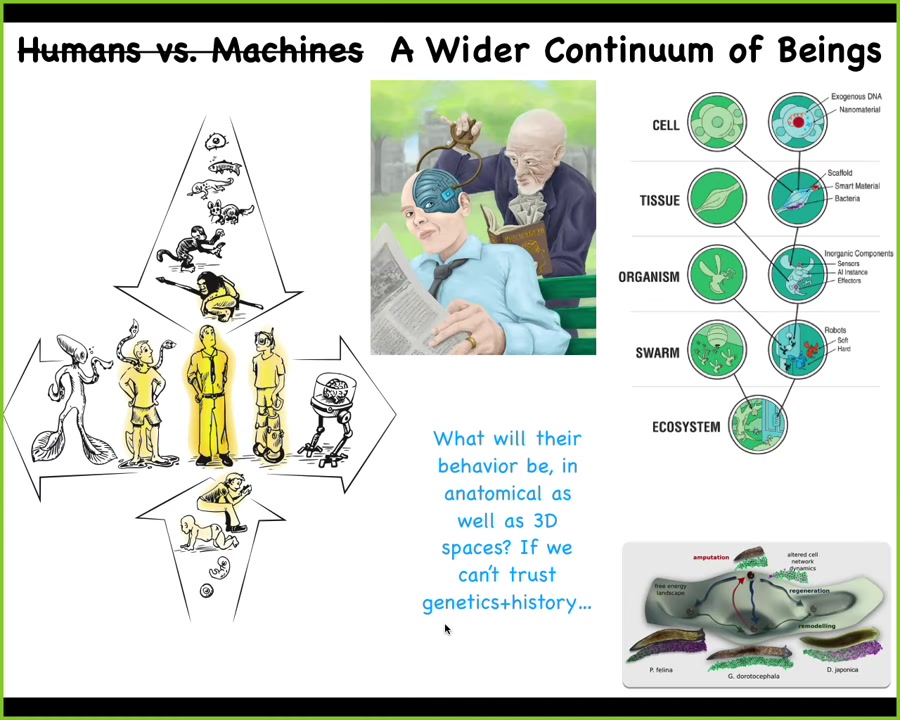

I think that's very deep because what we now understand is that both evolutionarily and developmentally, this thing that we normally take in philosophy of mind discussions as a normal human, an adult human, is actually at the center of a very continuous set of transformative processes where we all start life as single cells and then there are various things that lead up to this, and whatever agential glow you think the human has, you have to have some sort of a story about how it shows up and where it shows up.

Not just the natural story, there's also this axis that tells us that we can start making modifications, as we already have, both technologically and biologically. We end up with some other things where it's going to be quite difficult to say whether what we have is a human or not. That tells us right away that we're dealing with continuous variables, not hard categories.

What I'm interested in is developing a framework that lets us recognize, create, and relate to truly diverse intelligences. Regardless of what their composition or origin story is, I'm interested in unification. I want to understand what all of these things have in common. Are the familiar creatures, colonial organisms, swarms, new bioengineered life forms, AIs, whether software or robotic, and maybe someday exobiological agents?

Obviously I'm not the first person to try for something like this. Here's Weiner, Rosenbluth, and Bigelow back in the 1940s. I'm trying for something like that. This is my recent exposition of how I think about these things.

The most important thing about this framework is that it needs to move experimental work forward. Not just philosophy, although philosophy is important, it needs to actually impact things like biomedicine, synthetic bioengineering with new capabilities. I think it should be leading to improved ethical frameworks.

For the talk today, I'm going to break it up into three parts. I'm going to show you some unique features of the biology, and we'll talk about how it works and what it means.

Slide 6/64 · 05m:15s

Here's one example. You're looking at a tadpole of the frog Xenopus laevis. Here is the brain. It's got some nostrils. Here's the mouth. Here's the tail, the gut. What you'll notice is that we prevented the primary eyes from forming, but what we did do is put an eye on its tail. This is an animal with a radically different sensory motor architecture from normal tadpoles. If you track the optic nerve, here it comes out like this. Sometimes it synapses on the spinal cord, sometimes on the gut, sometimes nowhere at all.

If you make a machine to train them in visual assays, as we have done, what you find out is that these animals can see. The machine trains them to respond appropriately to visual cues. This is fairly remarkable. Why is there no evolutionary adaptation needed here? Why don't you need new rounds of mutation and selection when you suddenly mix up all the circuitry? These eyes are not connected to the brain. They're, at best, putting the information on this sort of centralized bus. Why does this work out of the box? I'm going to make the argument that this is because the standard tadpole never assumed where the eyes of the brain were going to be either. I think this is an active problem-solving process.

Slide 7/64 · 06m:28s

Here's another example. These are planaria. We'll talk more about them later, but these little flatworms, they've got a brain, they've got a central nervous system, and they've got some interesting properties. They're the only animal in which you can study learning and brain regeneration in the same animal. So what you can do is train them to recognize these little bumpy spots as their safe area where they're going to eat. So this is place conditioning. And then with these worms, you can cut them into pieces. Every piece gives rise to a normal worm. So you take these trained animals, you cut off their heads with their brain, you have a tail. The tail sits there doing nothing for about 8 or 9 days. Eventually, it grows back a brand new brain from scratch. And then you find out that these animals actually remember the original information. And so you can read more about that here.

Now, what you've got here is 2 things. One is the storage of learned information outside the brain. But I think even more excitingly, what you have is the ability of that tissue to imprint the information onto the new brain as the brain develops. Because in the absence of that, there's no behavior. So you're watching information. There's 2 things going on here. One is information moving across the body. And the other thing you're seeing is a kind of interplay between learned information and behavioral information and morphogenetic information, or the kind of memory you need to actually grow back the correct head. And we'll talk more about that.

Slide 8/64 · 07m:49s

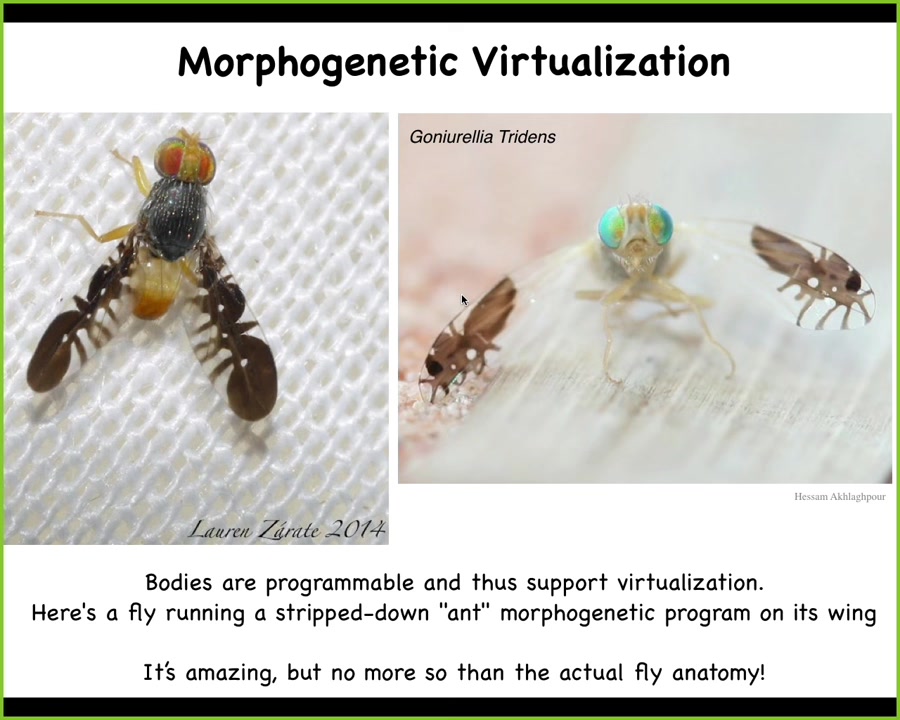

Then we have some interesting instances of what look like a virtualization. This is not AI or Photoshop. This is a real fly. What it's doing is running a stripped-down, two-dimensional morphogenetic program on its wings. These are ants. The reason it does this is because when it moves the wings around, predators who don't want to deal with stinging ants stay away from it. It's a protective thing. It's remarkable that it's able to run this coarse-grained morphogenetic ant program on the wings. That's wild, but certainly not more impressive than the actual fly itself. We have to start thinking about where the rest of this came from, the three-dimensional high-fidelity version.

Slide 9/64 · 08m:34s

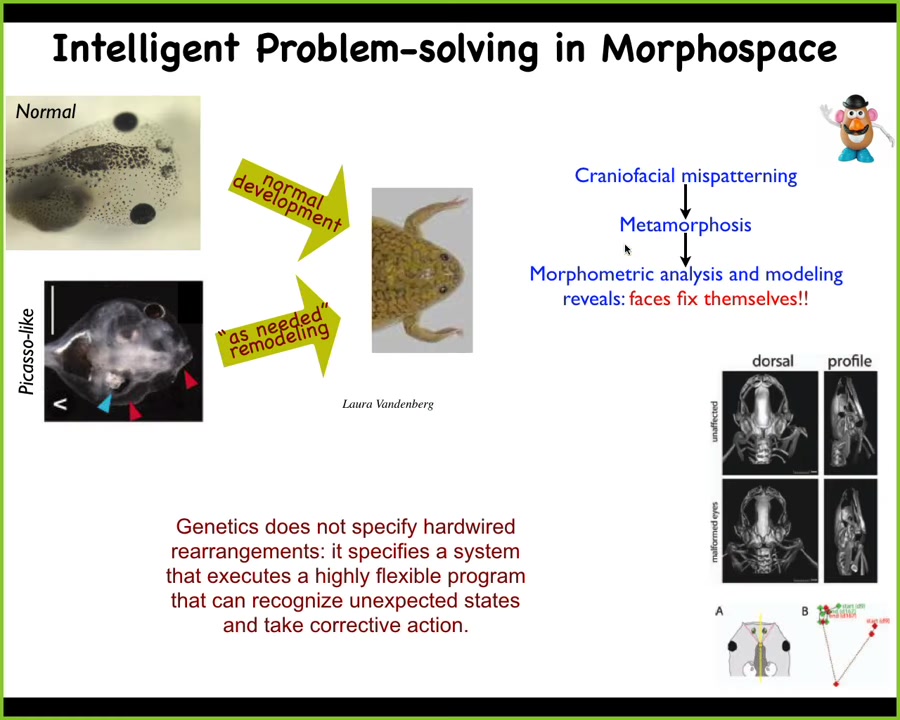

As we'll get into the development momentarily, I just want to point out that some of what we see in biology has capabilities that you don't know by looking at it. All over the world, there are tadpoles turning into frogs, and in order to do that it has to rearrange its face. So it has to move the eyes forward and the mouth and the nostrils. Everything has to rearrange. If you were to watch that, you could think that this is a hardwired process. Somehow the genetics makes every organ move in the right direction the right amount, and then you get your frog.

We decided to test that, and we created these what we call Picasso tadpoles. We scrambled all the organs, like a Mr. Potato Head doll. We put the eye on the back of the head, the mouth is off to the side, everything is scrambled, and what you get from that is quite normal frogs, because all of these things will continuously move in novel paths relative to each other to give you a normal frog. So the genetics does not specify a bunch of hardwired rearrangements. What it gives you is a system that can do an error minimization scheme, and it can get to where it's going from different starting configurations. We will talk a lot about that.

Slide 10/64 · 09m:47s

There is this phenomenon known as trophic memory. Most of what I'm telling you, you've probably not seen in standard reviews of biology. These are, I think, interesting cases that are informative for things that are not captured by the current paradigms.

Deer, every year, grow these antlers and then shed them. One thing that this team of researchers, Bubenik, found over 40 years of maintaining deer herds in Canada and doing these multi-decade, terribly difficult experiments is that if, one year, you make a little notch, then the whole antler falls off. Months later, they regrow a new one. What you see is the same pattern: you get an ectopic tine at the location where you made the injury, and then eventually some years later it goes away.

This is information of injury that remains somewhere in the body of the deer, and then months later is re-expressed and forces new growth. We have all the original antlers because Bubenik retired and sent them to us, and we had CAT scans so you can start to study this process. You can start to think that it would be pretty challenging to come up with a typical molecular biology explanation of how the three-dimensional location of injury is stored within the stem cells of the scalp. Eventually, when the growth happens, you get to this point and they say, "Oh, by the way, take a left turn and do an extra tine here."

Slide 11/64 · 11m:34s

And this plasticity, this ability to deal with novelty, this morphogenetic memory is really critical to understand what's going on in biology because morphogenesis itself is incredibly reliable. We see this again and again. We see acorns turning into oak leaves. And we think that this is what the oak genome has learned to do. This is what it encodes.

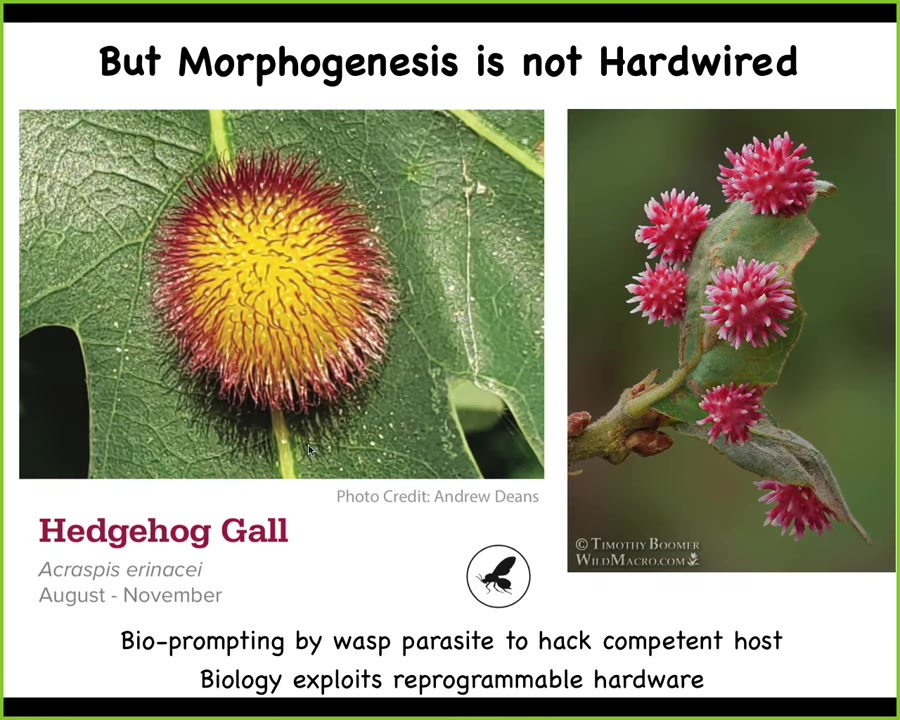

Slide 12/64 · 11m:57s

What you wouldn't know unless we had the benefit of this little non-human bioengineer, this little wasp, is that with appropriate signals from the wasp, those exact same cells, which reliably, billions of times every year, make exactly the same flat green structure, these same cells are actually capable of building this, or this, or many other incredible structures. These are not the insect cells making this. These are the plant cells hacked by signals from the wasp to build something that is completely different than what it does by default. And we would never know that they're capable of it. There's a lot of this reprogrammability and plasticity.

I'd like to talk about why I think they actually work. We're going to talk about this idea of the multi-scale competency architecture and the plasticity of boundaries between agents and how we communicate with what I think is the intelligence that underlies all this.

Slide 13/64 · 13m:01s

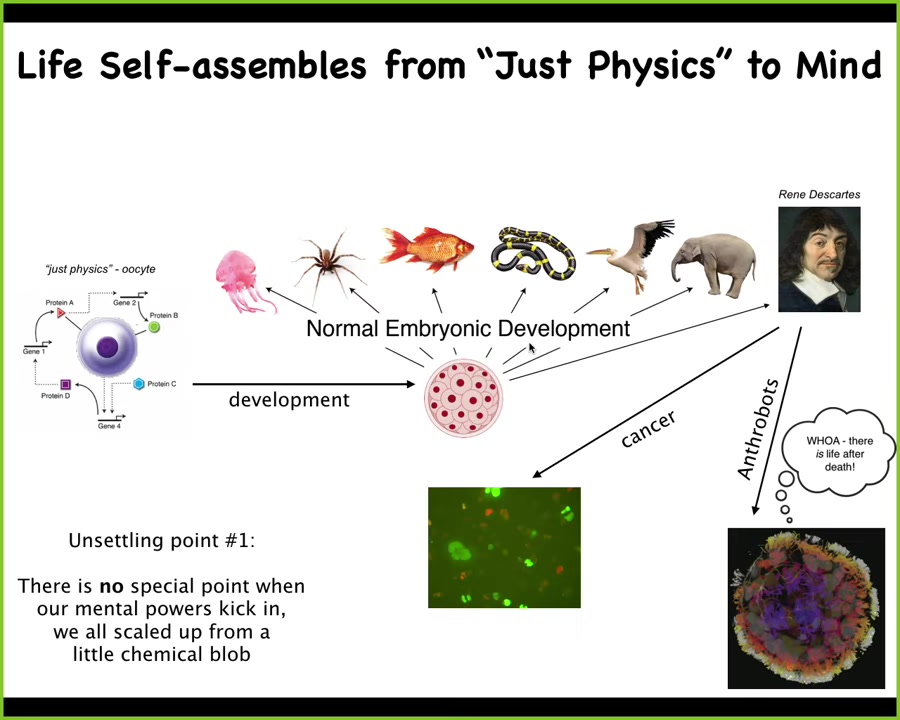

This is the basic life cycle that all of us have gone through. We started as a single cell, which people will often say is 'just physics.' It's a quiescent oocyte. It's got some chemicals in it. You might look at it and say that there is no intelligence there. It's just a little BLOB of chemicals. But then there's this remarkable process of embryogenesis, which leads to being one of these things, or maybe even something like this, which is going to then make statements about not being a machine.

What we really need to understand is how you got from here to here, because development offers no special point in which you tick over from chemistry and physics into mind, psychology, psychoanalysis, and whatever. This is a very slow, gradual process of development. There is no bright line. That means we really need to understand this transformative process that scales us up from just chemistry and physics.

This is not even the end of the story. I'm going to talk a little bit about what can happen after that, which is some breakdowns of the collective intelligence known as cancer and also some radical transformations into anthrobots, which can happen even after the patient is deceased. We will talk about all of that.

Slide 14/64 · 14m:16s

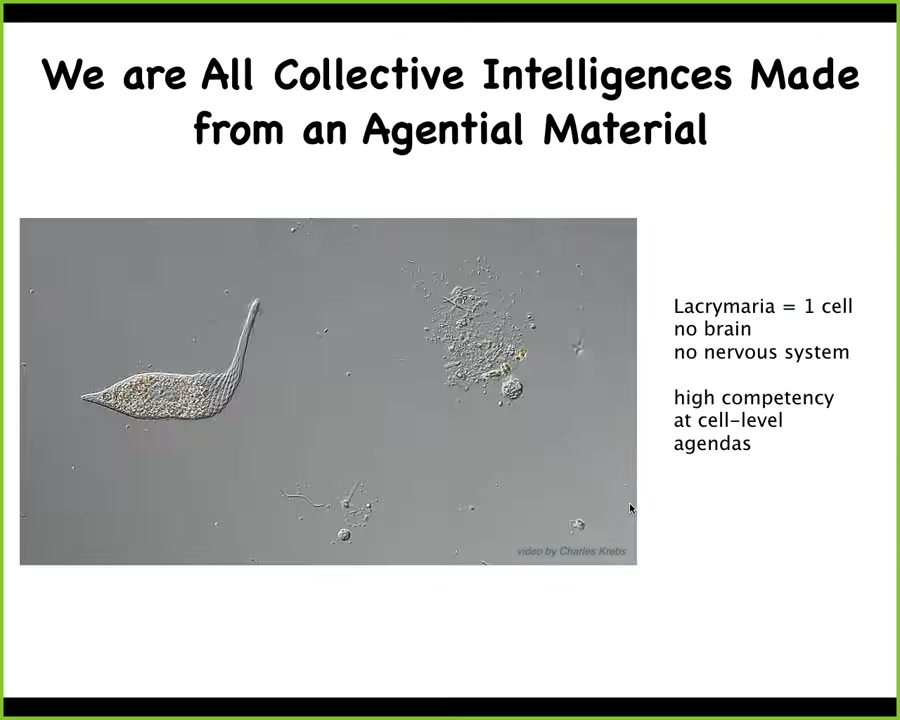

This is the kind of thing that we are made of. One basic subunit is something like this. This one happens to be a free-living one called the lacrimaria. It's one cell. There's no brain, there's no nervous system. Everything that it's doing here as it hunts for its food is handled within one cell. We are already made from a very sophisticated material that has a lot of competencies and agendas on its own.

Slide 15/64 · 14m:47s

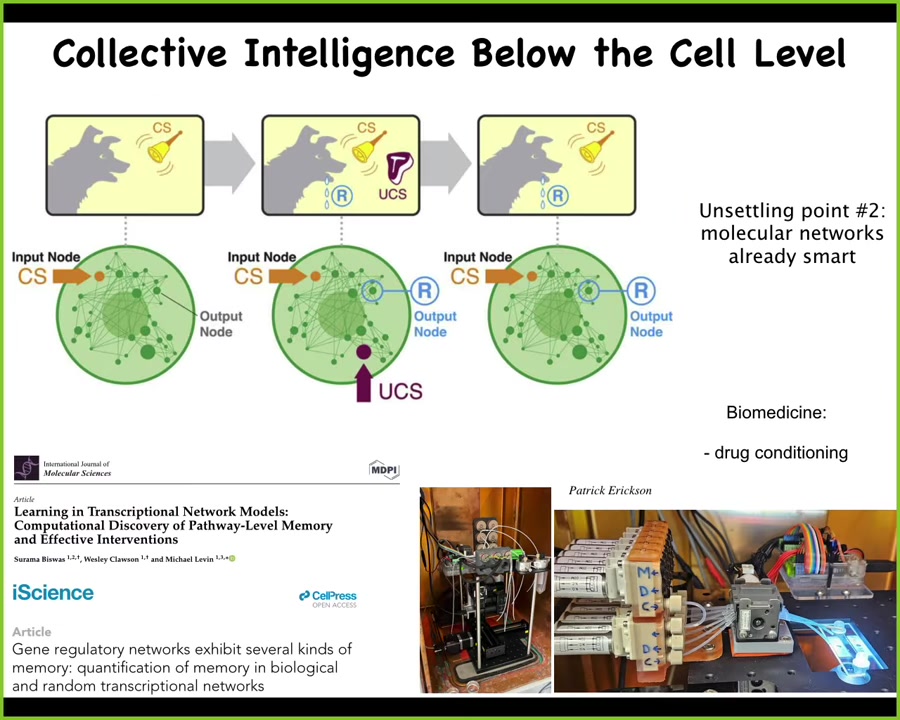

In fact, you can even go below that. And we recently found that the gene regulatory network models, not even cells, not even groups of cells, certainly not neurons or brains or any of that, but just gene regulatory networks, which are models of genes turning each other on and off. If you do the experiment and you train them in various paradigms, you can find six different learning capacities, six different kinds of memory, including Pavlovian conditioning. And so we are now building some devices to do this for applications like drug conditioning. So not only are the cells that we are made of quite competent at all kinds of things, but the material itself, the molecular networks inside of them already have learning capacity.

Slide 16/64 · 15m:38s

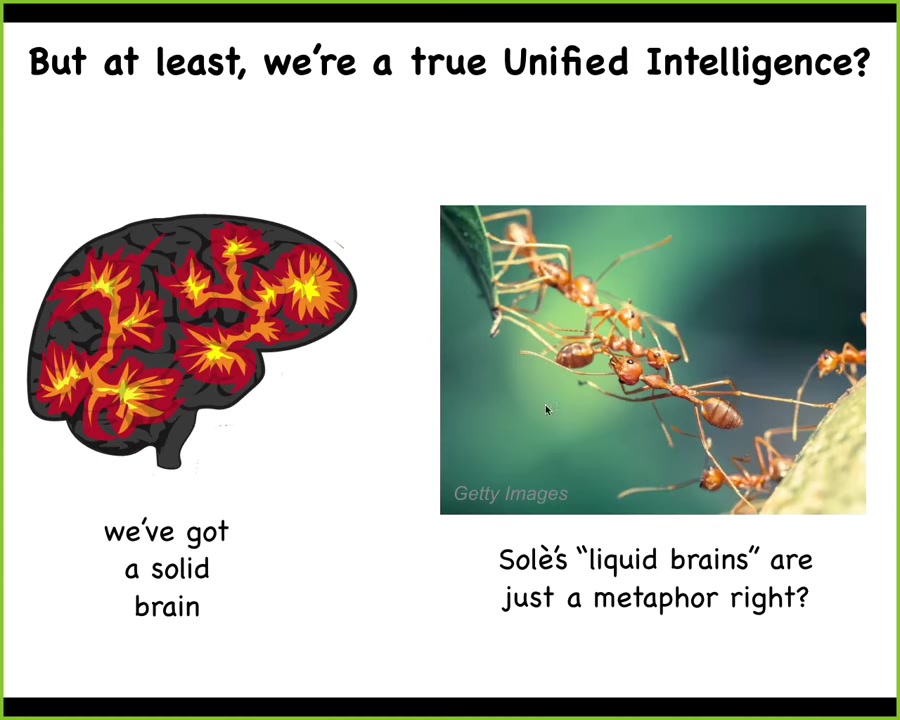

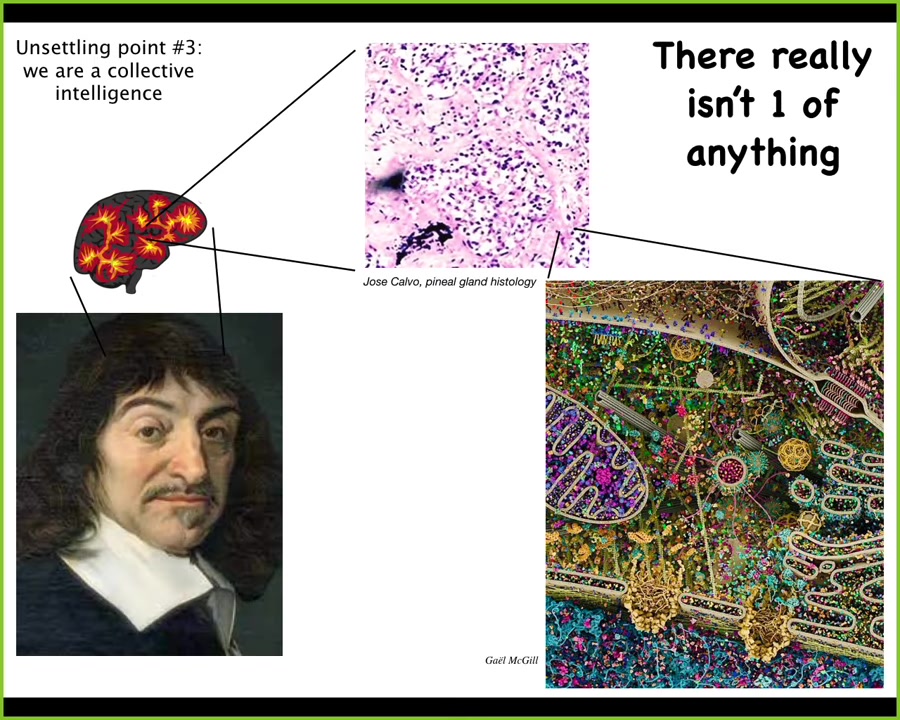

But some people will argue, at least we are true unified intelligences. We have this nice big brain, and it's a single, it's a singular organ. Maybe at least we're different. We're not looking at colonies and beehives; it's just a metaphor when people call these things liquid brains.

Slide 17/64 · 16m:00s

Descartes thought so, and he really liked in particular the pineal gland, because there's only one of them in the brain, and he thought that was a reasonable place to centralize the human experience, which is unified most of the time. But if he had access to good microscopy, he would have looked at the pineal gland and realized that there's not one of anything, because inside the pineal gland is all of this stuff. Inside each one of these cells is all of this stuff. We are all collective intelligence. We are all made of components, and whatever we have is the result of alignment of the competencies of our parts.

Slide 18/64 · 16m:39s

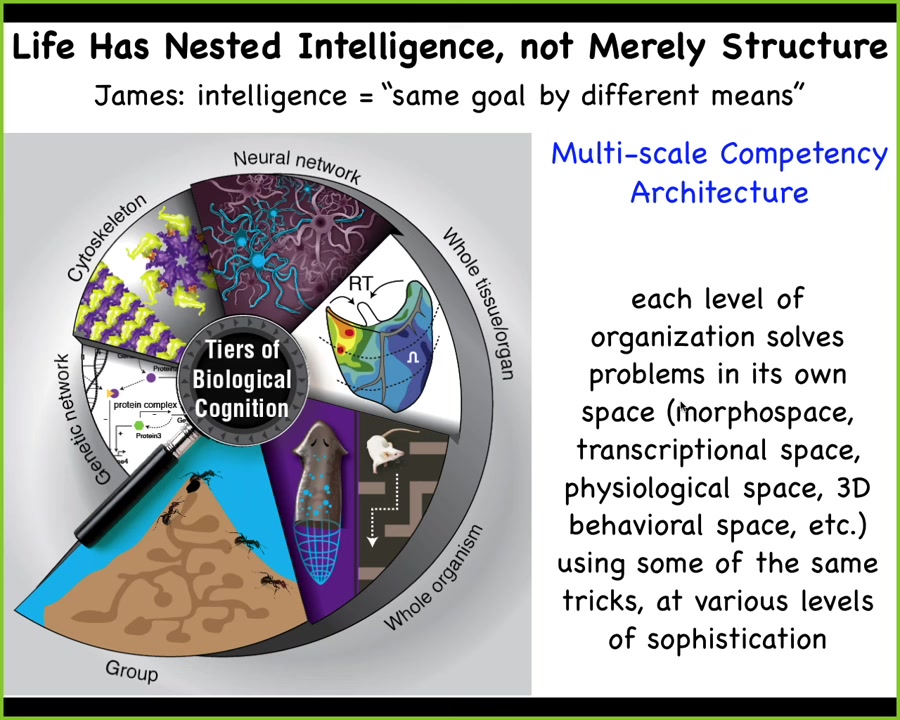

This is what we need to understand. When I talk about intelligence, there are many different definitions. I don't claim this to be the best one or the only one, but I like William James' definition: "the ability, some degree of the ability to reach the same goal by different means." It's a very cybernetic definition. He's not talking about brains. He's not saying what kind of goals, what problem space, but it's a kind of navigational competency to reach your goal when things are different.

It turns out that what we are made of is this multi-scale competency architecture where we're not just nested all structurally, but actually every layer solves problems in different spaces.

Slide 19/64 · 17m:20s

What kind of spaces? Well, as humans evolved over time in our environments, we're reasonably good at noticing the intelligence of medium-sized objects moving at medium speeds in three-dimensional space. Dogs and octopuses, and then birds and things like that, we're okay with that.

But we're actually really bad at recognizing similar kinds of navigational skills in other spaces. For example, the space of possible gene expression, the space of possible physiological states. And most of all, the space of anatomical possibilities.

I tend to think that if we had evolved with a primary sense of the blood chemistry of our bodies — for example, another 10 different sensors that could look inwards and tell us the physiological states of our body — I think we would have no trouble recognizing our liver and our kidneys as this autonomous symbiont that navigates these spaces, is intelligent, and helps keep us alive by the decisions that it makes. But these are hard for us to recognize.

I will also point out that once you start thinking in this direction, we can realize that actually this perception-action loop, which a lot of workers in robotics and AI claim is really important to have, to have embodiment and to have this feedback between the agent and the environment. A lot of things that we think of as not embodied are actually perfectly embodied, because they're just carrying out this loop in other spaces that are not obvious to us, so paying attention to these other spaces in which engineered agents are actually working is, I think, really important. Embodiment, I don't think, is what we typically take it to be.

Slide 20/64 · 19m:10s

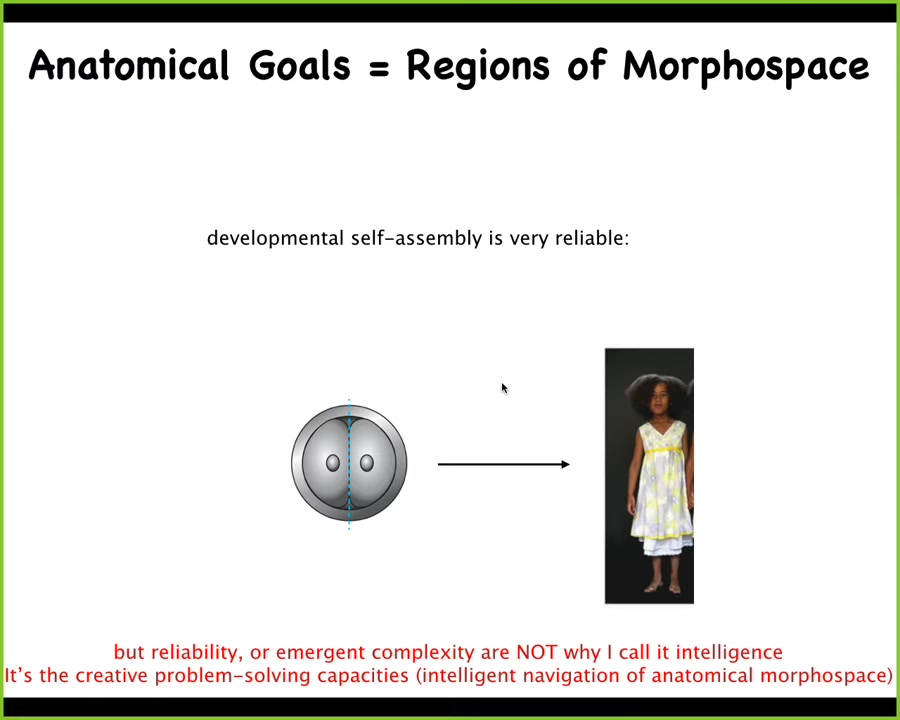

Let's talk about the intelligence of the cellular collective as it navigates anatomical morphospace. What I'm going to claim is that groups of cells form a collective intelligence and their behavior plays out in morphospace. It plays out in the space of anatomical possibilities.

Just like we are a collective intelligence of neurons, which allows us to navigate three-dimensional space and linguistic space, all of that started when cells were working together to navigate anatomical space.

Now, why do I call it intelligent? Not because it's reliable. There's a massive increase in complexity from this stage to this stage. That's not it. It's not about reliability or complexity. It's about the creative problem-solving capacities.

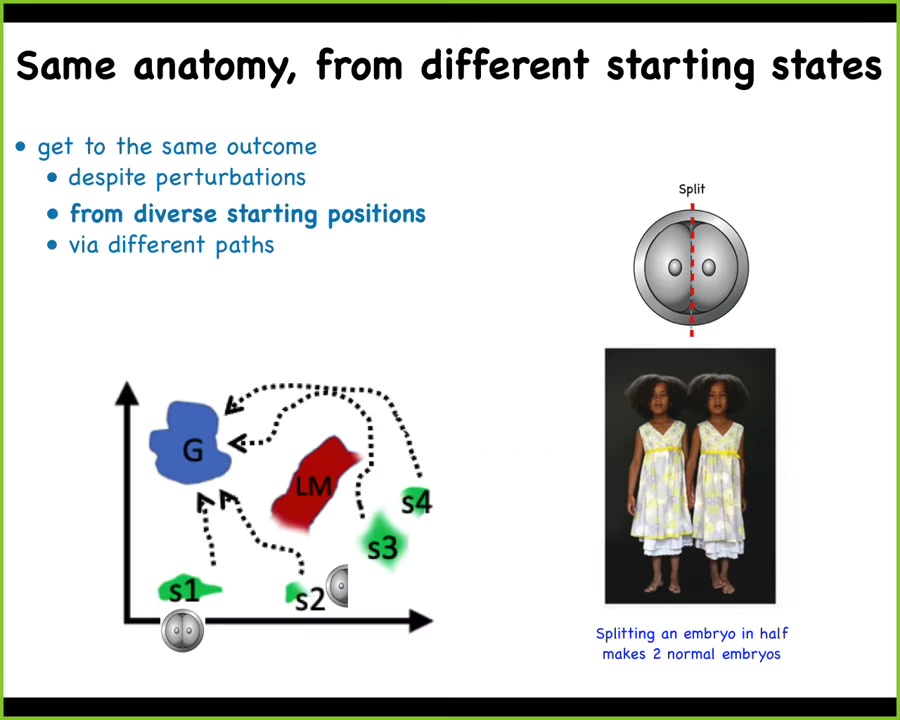

Slide 21/64 · 20m:03s

The first thing you see, and I already mentioned an example of this in that frog face, is that many kinds of embryos, including mammals like us, you can cut them into pieces as young embryos and you don't get half bodies. You get perfectly normal monozygotic twins and triplets. So that means they're navigating the anatomical space to get to their goal state, this sort of ensemble of states that represents a normal human target morphology. They can get there from different starting positions. If you chop off half, each side immediately recognizes what's missing and will get to where it needs to go in that space.

Slide 22/64 · 20m:40s

Some animals can do this throughout their lifespan. This is an axolotl, and these guys regenerate their limbs, their eyes, their jaws, portions of their heart and brain. You can see that when they lose portions of the limb—they bite off each other's legs fairly frequently—and when they lose a portion of the leg, the cells will build exactly what they need to build and then they stop. The most important thing about regeneration is that it knows when to stop. When does it stop? It stops when the correct salamander limb has been completed. Not only does it do exactly what it needs to reduce the error between this state and that state, but it recognizes when it's done to some tolerance of comparison.

Slide 23/64 · 21m:26s

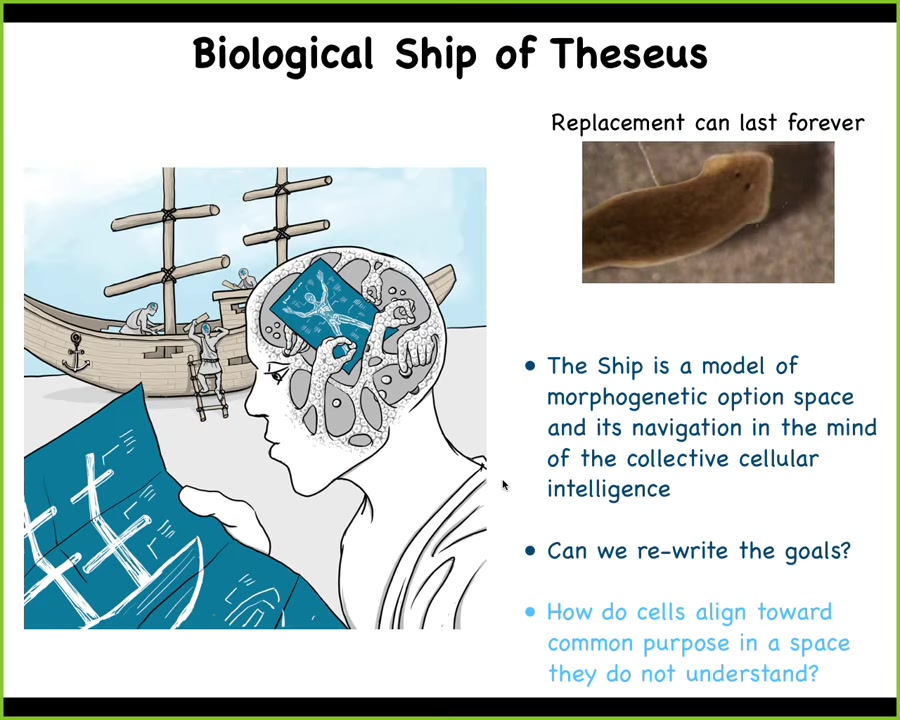

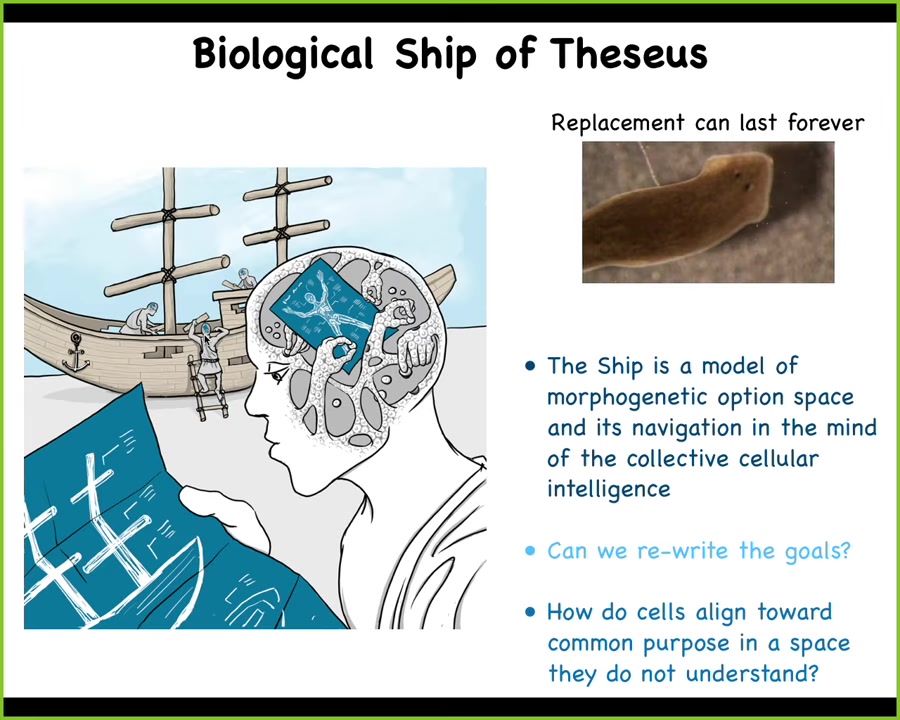

All of our bodies are the "ship of Theseus," the old philosophical puzzle of continuously replacing the planks in a ship—when is it still the same ship, and when isn't it? All of our cells continuously turn over, and the material within ourselves continuously turns over. We are not a stable object. We are a continuous construction project.

You can think about the actual ship of our body as not the material, not the physical stuff. The ship is actually a model in the minds of the replacement machinery that guides their activities. That's the actual ship. The actual ship is the model that they're all following to know what to do next and where the pieces go.

In some species, such as in planaria, especially in asexual strains of planaria, that project can last forever. Planaria do not age. These asexual strains do not have any evidence of senescence. They go on forever replacing their cells.

I want to look at two issues here. First, can we rewrite this plan? This machinery, meaning the cells inside the body, have a plan of what they're constantly upkeeping. For very long periods of time, can we rewrite that plan? Then we'll talk about how the cells actually align.

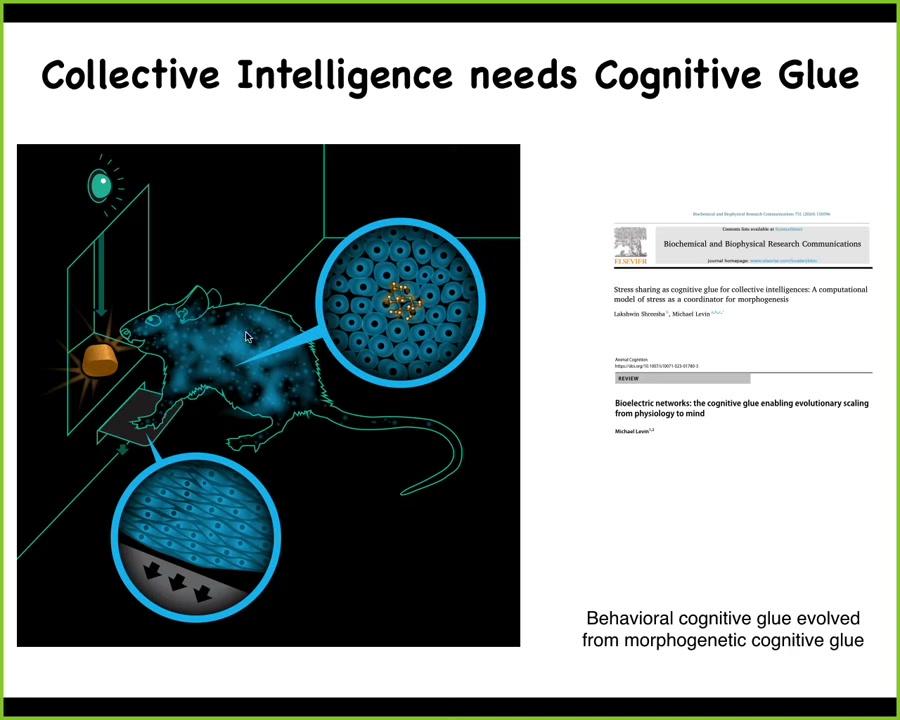

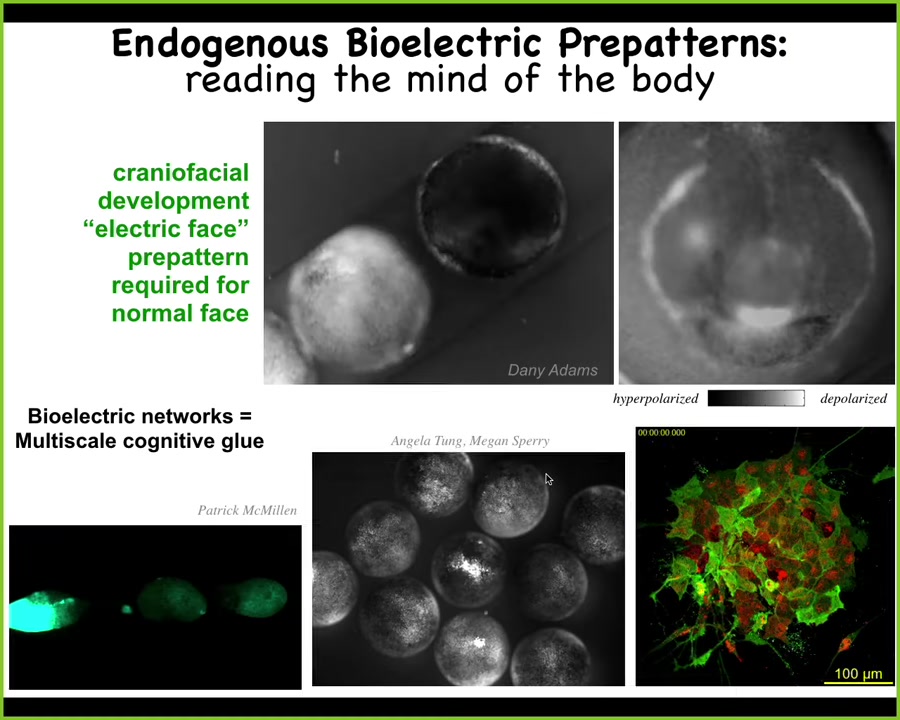

The first thing to think about is that collective intelligence, such as the cells that make up something like this, needs something I call a "cognitive glue."

Slide 24/64 · 22m:53s

There's a variety of cognitive glue mechanisms, including stress sharing and other things, but we're going to talk about bioelectrics. Here's a rat. The rat presses a lever, gets a reward. Notice that no individual cell has had both experiences. The cells at the bottom of the feet interact with the lever. The cells in the gut get the delicious sugar. Who owns the associative memory? It's the rat. And the reason that there is a rat is because there's a process, electrophysiology, which binds all of these cells together into a higher level agent that can know things that the individual parts don't know. It has goals, preferences, memories, and other things that the individual parts don't have. That's what binds it together into a higher level intelligence.

Slide 25/64 · 23m:47s

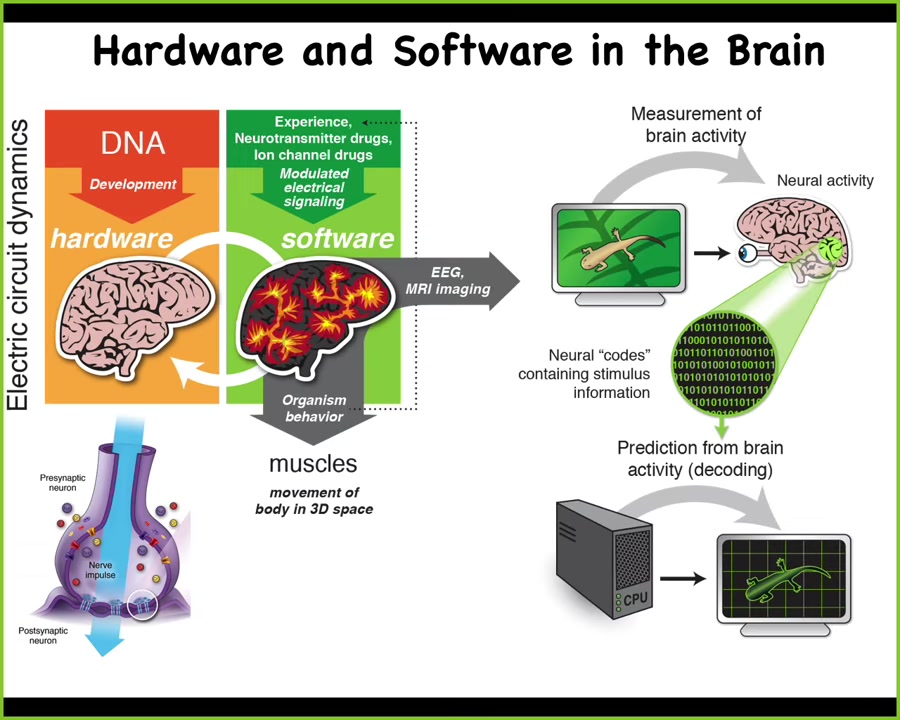

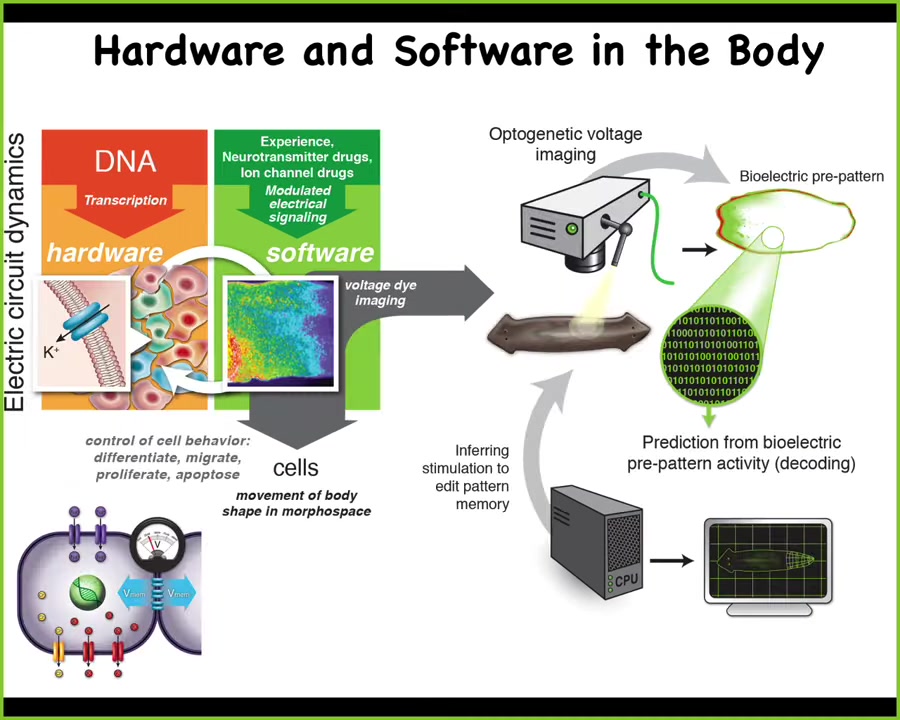

So we know something about how this works in traditional intelligence and behavior. You've got some hardware, which is the brain and central nervous system. The way that works is you have some cells in a network. The cells have ion channels, which are proteins that allow charges to go in and out, and that sets up a voltage, and that may or may not get propagated through the network through these electrical synapses. So that's the machinery, and that gives rise to some electrophysiological dynamics, which you can think of as the software that runs on this hardware. I'm certainly not claiming that our current paradigms of writing software are how this works at all. The idea is that there's massive reprogrammability here and plasticity.

The way that this system works is that it issues commands to your muscles to move you through three-dimensional space. Neuroscientists have this project of neural decoding, where they read out the electrophysiology, decode it, and extract the cognitive content of your mind. The commitment of neuroscientists is that if we could just understand how the encoding works, we could retrieve your memories, your goals, your preferences. We could retrieve that from the electrophysiology, because that is where it's encoded. And in fact, people have written in new memories in mice, incepting false memories into these animals. It turns out that this amazing system is not new to brains and neurons.

Slide 26/64 · 25m:22s

It is incredibly ancient. In fact, it was discovered around the time of bacterial biofilms. Evolution was already doing this when bacteria were making biofilms. Every cell in your body has these ion channels. Most cells have these gap junctions, these electrical synapses. You have exactly the same parallel kind of scenario. But instead of issuing commands to your muscles to move you through three-dimensional space, what this system was doing. Before there were any brains and neurons, before we could move around, what were these electrical networks thinking about? They couldn't be thinking about motion. They were actually thinking about traversing anatomical morphospace. What they do is they issue commands to all of your cells to change and move the configuration of your body through morphospace so that you can make the journey from being a single-celled fertilized egg to whatever we end up being.

So what we've been doing over the years is developing a very parallel research program. So basically neuroscience beyond neurons, to try to learn to decode this somatic electrophysiology, understand what it's encoding, and try to read the mind of the anatomical decisions that the body makes. Again, this is not a fixed hardwired process, as I've shown you many examples. There are lots of decisions to be made because you need to be able to reach these outcomes despite all kinds of novelty.

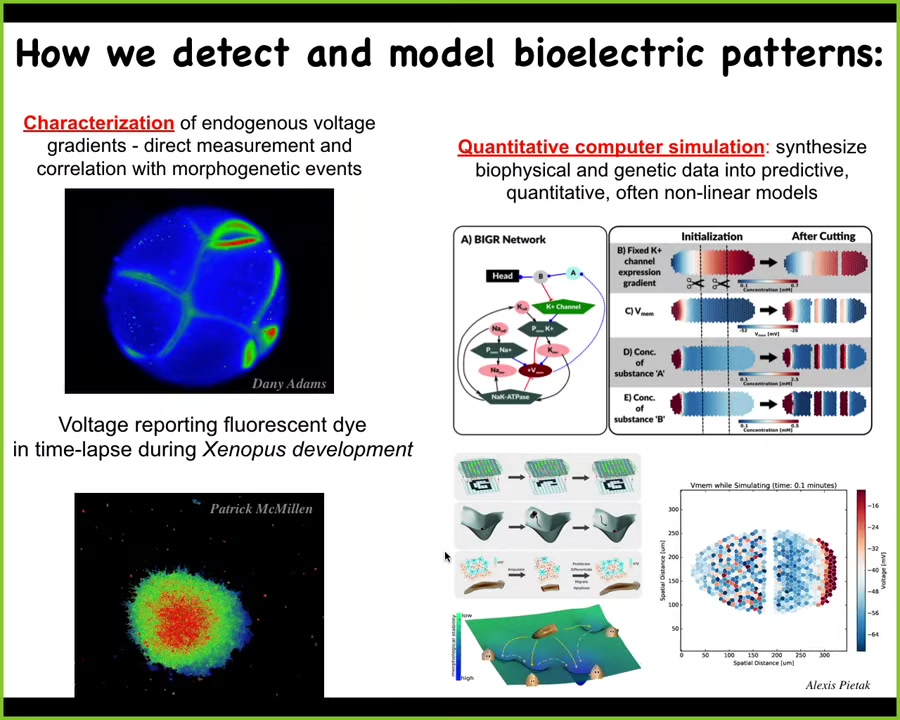

Slide 27/64 · 26m:51s

We've developed some tools to directly observe the bioelectrical states that go on in these tissues. This is an early frog embryo. These are some explanted cells deciding whether they're going to stay together or leave. The colors represent voltage. This is just like imaging a brain. This is done with voltage-sensitive fluorescent dyes or genetically encoded reporters. We can now read the electrical states of these living systems, which before was not possible because you'd have to poke every cell with a separate electrophysiological electrode. Now we can get these amazing time-lapse movies.

We do a lot of computational modeling. Different scales of models from the molecular biology of these ion channels to the tissue electrophysiology and how the patterns spread over time and properties like pattern completion and various attractors in the state space of this physiological network.

Slide 28/64 · 27m:49s

Here's what these patterns actually look like. I'm going to show you two phenomena so you can see what this is. A frog embryo putting its face together. And you see there's a lot of complicated things happening. But if you look at one frame out of this video, we call this the electric face because it looks like a face. It's telling the cells exactly where the organs are going to be. Here is the mouth. Here's the animal's right eye. The left eye comes in shortly thereafter. Here are the various placodes off to the side. This bioelectric pattern is what determines the gene expression and downstream anatomy of the face. You can read out the plan of what it is going to do later by tracking the electrophysiology.

Now, not only does this set of bioelectrics dictate the global order within a single embryo, it turns out that there are similar phenomena that function across embryos, multi-scale. Here, we poke this one here. And you can see this calcium wave propagating where these two guys, they're not even touching, there's this water, salt water between them. They find out about what's happening here because these waves are propagating. You can see it here. There's a communication at this level just like there is here. And here you can see the slow bioelectrical changes and then the more rapid kinds of things that go on in a few of the neurons here.

So watching and tracking these things is all well and good, but more importantly, you've got to do perturbational experiments.

Slide 29/64 · 29m:15s

That's because you can't judge the intelligence or learning capacity or anything else of a system just by observation. You have to do perturbational experiments to see how it pursues its goals under various circumstances.

What we did was adapt the tools of neuroscience to rewrite these bioelectrical pattern memories. We don't use magnets, electrodes, applied electromagnetic fields, or frequencies. What we are doing is what neuroscience does, which is interact with them through the interface that these cells are normally exposing to each other, which is the ion channels and the gap junctions on the surface.

We can open and close these things. We can use optogenetics, drugs, and molecular biology to control the spatial patterns of bioelectric state, which do for the somatic decision-making machinery what brain bioelectric patterns do for our behavior.

This is the communication interface that we are trying to hack. That's the only reason that the things I'm about to show you work. It's not because we're that clever. It's because this system is exposing a very powerful API to us to send these kinds of signals.

Slide 30/64 · 30m:34s

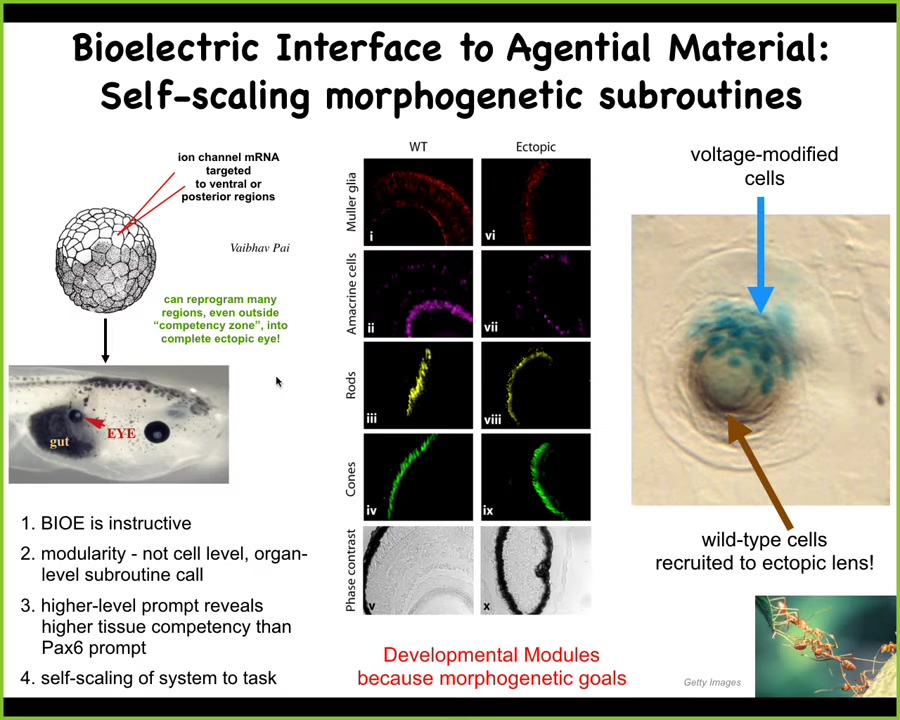

I'm just going to show you 2 examples of what the material is capable of. One is that I showed you that electric face. And when you look at the electric face, there's a little spot of depolarization that says, build an eye here. We wanted to know what happens if you produce that signal somewhere else, let's say on the gut or in the tail. We inject some ion channel mRNA, which encodes a few potassium channels. They set up that little voltage spot, and the cells get the message, they build an eye. Here's an eye sitting on the gut. If you section them, these eyes have all the lens, retina, optic nerve, all the stuff they're supposed to have.

And now we've learned a few things. First of all, we've learned that the bioelectricity is actually instructive. By giving it a specific stimulus, we actually had it make a new organ. Not just screw up what normally happens, but actually create a good new organ. It's instructive.

Number 2, the architecture is incredibly modular. The eye is a very complex organ, dozens of different tissue types. We don't know how to make an eye. We didn't say do this with the stem cells or position the retina this way or that way. We didn't do any of that. We gave it one very simple top-level subroutine call, which says, build an eye here. Then the system did everything else. Notice that that's exactly what happens in neuroscience. When you give somebody a message, for example, via language or some other behavioral example, you don't have to worry about them going in and micromanaging the synaptic weights in their brain. They do all that for you. You're providing a very simple signal. It rearranges its own lower levels of molecular biology to make it work.

The other thing that's cool is that this is a lens sitting out in the flank of a tadpole somewhere. If we only inject a few cells, the blue ones, what you find is that the eye itself is actually made of a bunch of cells that we never injected. It's these guys that realize there's not enough of them to build a whole eye, so they recruit their neighbors. There's a little communication tug of war going on here. The neighbors, this is a cancer suppression mechanism, are all saying, your voltage is wrong, change it, you should be skinned. These guys are saying, no, our voltage's pattern is that of an eye, and you should help us make an eye. This goes back and forth, and sometimes the skin wins, and sometimes the eye wins.

Here's what you get. It's a battle of commitment: which path down in morphospace are we going to go on? Then they all make a decision and they all go together. We know other collective intelligences that recruit their neighbors to handle a larger task when need be.

That's the first thing I wanted to show you, that we can actually now communicate through that interface to control its behavior in anatomical space and make it build whole organs and exploit competencies such as recruitment. We didn't have to teach it to do that. It already does.

Slide 31/64 · 33m:30s

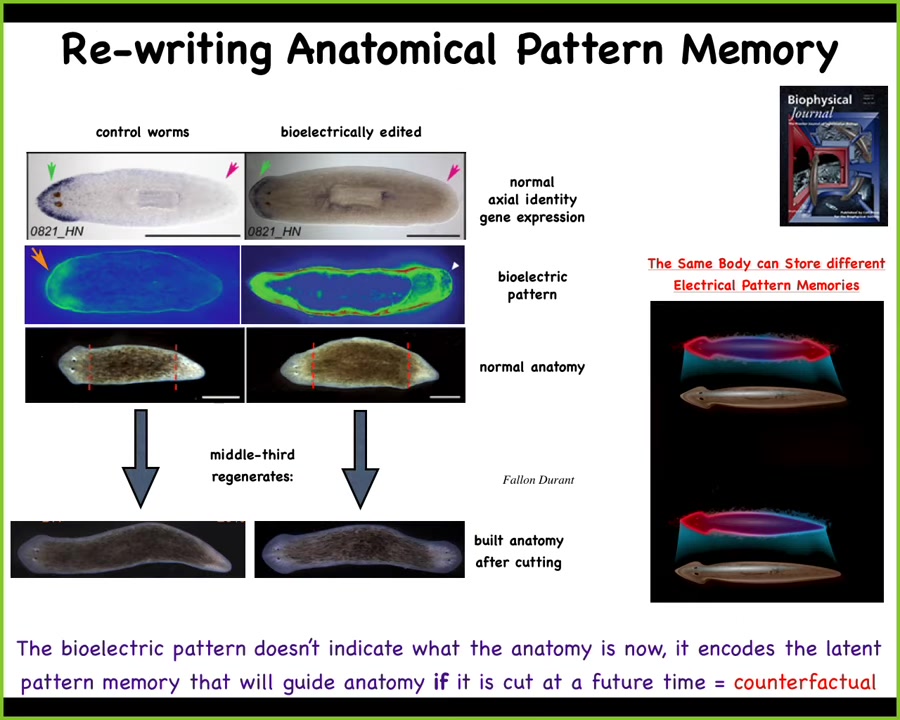

I'll show you one other example of this, which is how to rewrite these anatomical pattern memories.

I told you earlier that when you cut a planarian — let's say we cut off the head and the tail and take this middle fragment — they are incredibly reliable in building a one-headed worm. You might ask, how does this piece know? This piece has two wounds. How does this piece know how many heads it's supposed to have and where the head goes?

It turns out, if you look at these animals, there's a voltage gradient that you can see that is interpretable as one head, one tail. The molecular biology shows the anterior markers are up in the head, and when you cut them, that's what happens.

We were able to change this bioelectrical pattern by exposing these animals to specific ion channel modifying drugs. With a computational model, you can say which drug, which channels do I need to open and close to change this? Then you can make something like this, which has this pattern that says, no, two heads, one at each end. It's a little bit messy; the control of this is still being worked out. You can then make these two-headed animals. Again, not AI, not Photoshop. These are real live animals.

This bioelectrical map is not a map of this two-headed animal. This is a map of this perfectly normal-looking one-headed animal, not only is the anatomy normal, but the molecular biology is normal too. The anterior markers are up in the head; they are not in the tail. Anatomically, there's nothing wrong with this animal. Structurally, the hardware is completely fine. Genetically, everything's fine. We haven't touched the genome whatsoever.

But it has this memory: the collective intelligence of the cells is storing an altered version of what we are going to do if we get injured in the future. I think it's the beginning of counterfactual memory — that amazing ability of brains to think about things that are not true right now, either the past or the future.

We can put in a pattern that is not true right now. It's a latent memory. Nothing happens until you cut them. When you cut them, this is the state towards which they build, and they stop when they achieve it, and that's how you get these two-headed worms.

The normal body of a planarian can store at least two different representations of what a correct planarian should look like. We have now this material that is able to store memories of what it's going to do in the future, and those memories are readable and rewritable.

Slide 32/64 · 36m:07s

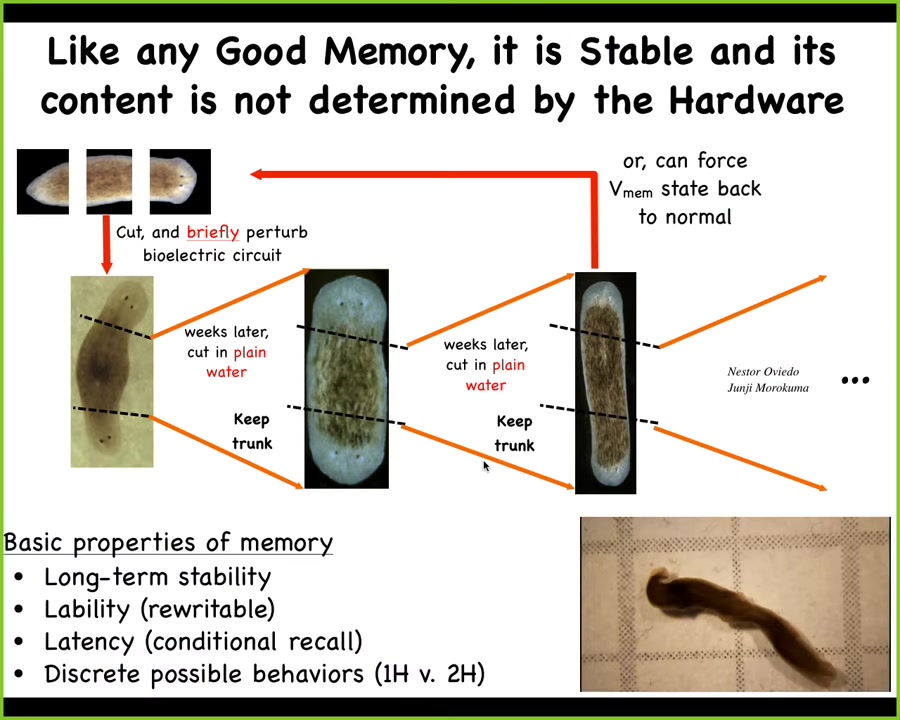

The reason I call it a memory is because if you take these two-headed animals and continue to cut them in plain water, no more drugs or any manipulation of any kind, you will continue to have two-headed animals. Because the material has a memory, and once you've changed that pattern, it holds.

Keep in mind that there is nothing genetically wrong with these. We haven't touched the genome.

The question of where the number of heads is encoded is tricky. What the genetics encodes is a machine that by default reaches a pattern that says one head. That's the default instinctual pattern. But it can be overridden by experience, by only a few hours of physiological experience with these drugs. The memory changes, and then it holds.

Here you can see these two-headed guys hanging out. It has all the properties of memory. It's long-term stable, it's rewritable. I showed you conditional recall, and it has distinct behaviors. We can now take the two heads and turn them back into one head, so we can flip it back and forth.

Slide 33/64 · 37m:15s

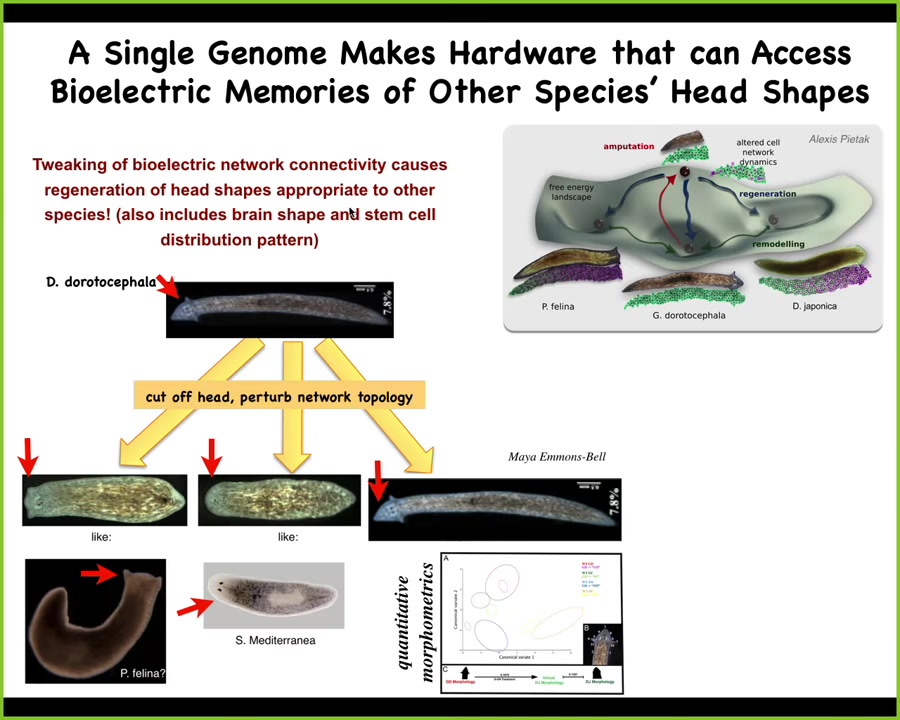

It's not just about the number of heads, it's also about the shape of the head. For example, this guy, a very characteristic species with a triangular little head, can be, if we amputate the head and then confuse the cells with a gap junction blocker, they can make flat heads like a P. falina, they can make round heads like an S. mediterranea, or they can make their normal heads.

This is not just about head shape; the shape of the brain becomes just like these other species, about 100 to 150 million years of evolutionary distance. So the exact same hardware, no genetic change, is perfectly willing to visit other attractors in the anatomical state space that belong to these other species. That's where they normally live. This one normally lives somewhere else, but it can visit these other attractors if it wanted to.

Slide 34/64 · 38m:06s

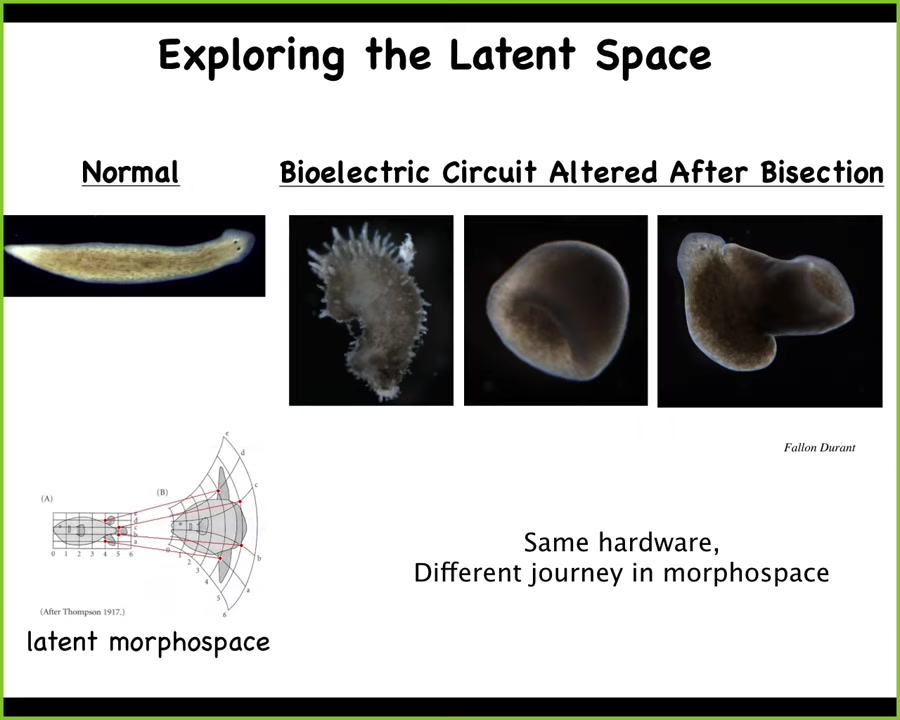

We can go much further and we can make things that don't look like planaria at all. We can make these crazy spiky things, these kinds of cylinders, hybrid forms. The latent space of possibilities for this genome, much like what I showed you with a plant gall, those constructs on the oak leaves, the capabilities of the material are far, far beyond the reliable version that you normally see.

Slide 35/64 · 38m:34s

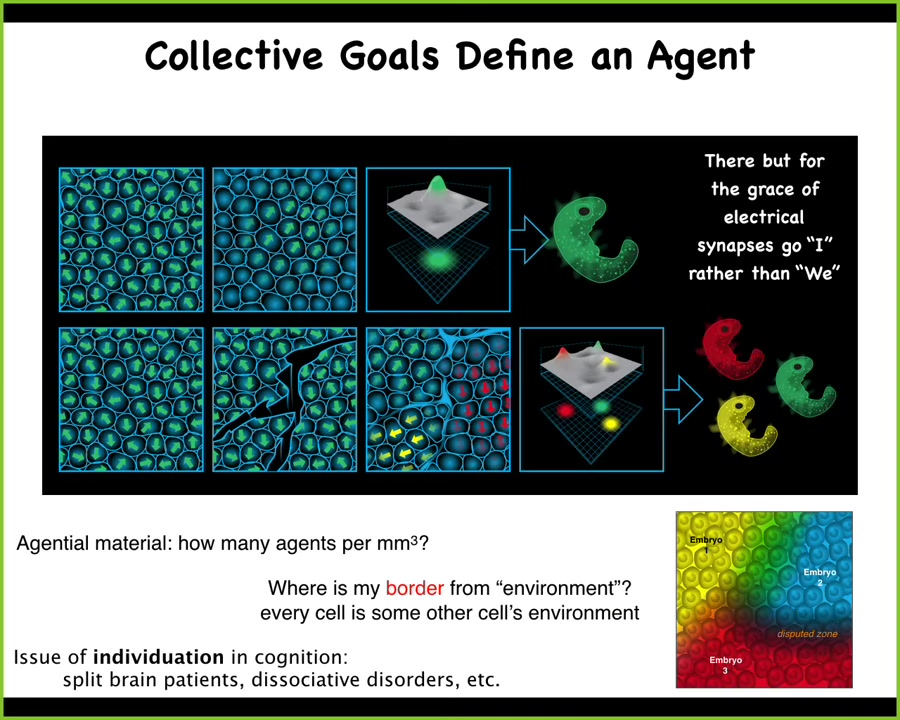

The last piece of this that I want to talk about is the creation of the self and the plastic borders between the self and the outside world. Specifically, if we are going to be a collective intelligence where the pieces are somehow aligned towards specific goals, I've shown you how they store the goals and I've shown you how we can rewrite some of those goals. But how does the alignment work? The individual cells have no idea what a head is or what an eye is or any of that. It's the collective that knows. How do the cells align towards this?

Slide 36/64 · 39m:09s

So I want to come back to embryonic development. Let's just look at an early blastoderm here, this early thin layer of embryonic cells. We look at that and we say, there's an embryo. There's one embryo. But what is there actually one of? There are maybe 100,000 cells. What are we counting when we say there's one embryo? And what we're counting is alignment of goals. We're counting the fact that, under normal circumstances, all of these cells have bought into the exact same plan of where they're going to go in anatomical amorphous space. They are all going to work together to build this. The only reason we are an I as opposed to a we is because of these gap junctions that keep all of these guys connected into an electrochemical network. Because if you take a little needle, and I used to do this as a grad student in duck embryos, and make little scratches in this blastoderm for four hours or however long it takes for these guys to heal up. Each of these little islands can't feel the presence of the others. What it does is self-organize an embryo. Eventually they heal and you get these conjoined twins and triplets and so on. Each of these things can be its own embryo.

So there's a couple of interesting issues here. First of all, how many cells, how many individuals are actually inside of a single embryo? Well, the genetics don't set that. It's an excitable medium that can self-organize multiple individuals. It can be anywhere from zero to probably half a dozen or more. Then you have this issue that, in a case like this, once they heal up, every cell is some other cell's environment. How do they set the borders? Where do I end and somebody else begin? Where is the outside world?

What this is reminding us is that this material, these agents self-organize at the very beginning. The first thing they have to figure out is how do I align my parts to have a common goal? The next thing is, how do I set the borders between me and the outside world so that I can work on goals that are scaled to the collective, and at the expense of other things that happen in the world. This actually has lots of interesting parallels to issues in psychiatry and cognitive disorders, because there are various kinds of dissociative disorders that introduce multiple selves in the same material, in the same biological hardware.

Slide 37/64 · 41m:41s

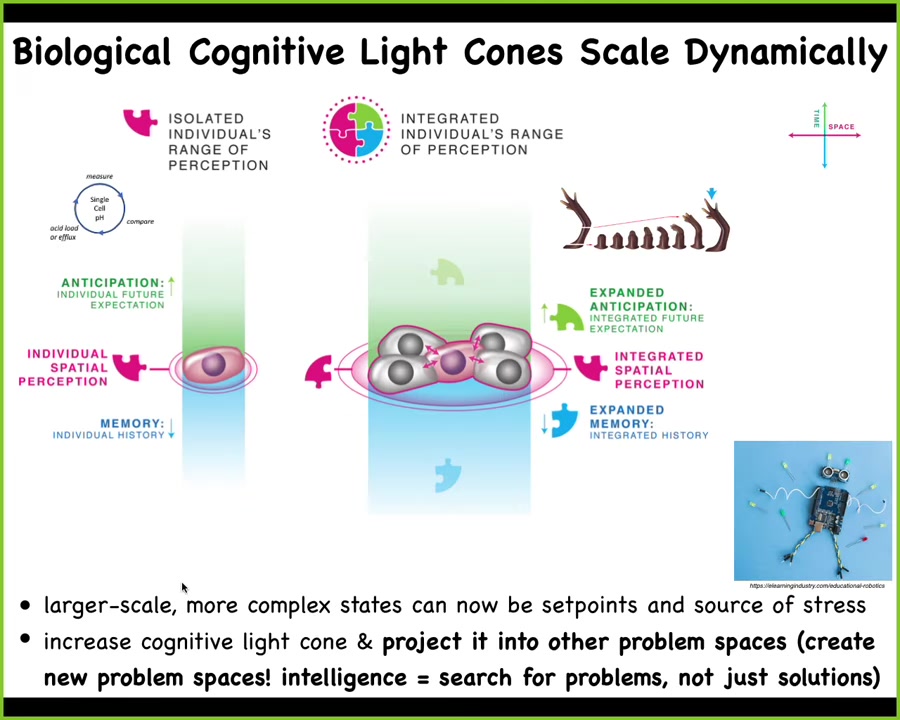

So one of the ways I think about these things is with something I call the cognitive light cone, which is the size of the biggest goal that a system can work towards. Individual cells have little cognitive light cones. They only care about metrics right inside that single cell. Spatially very small. They have anticipation capacity, memory going back. They remember tiny things like "what pH should I be at?" "What's my hunger level at?" Very small kinds of goals. But the collectives can have these grandiose construction projects.

Slide 38/64 · 42m:17s

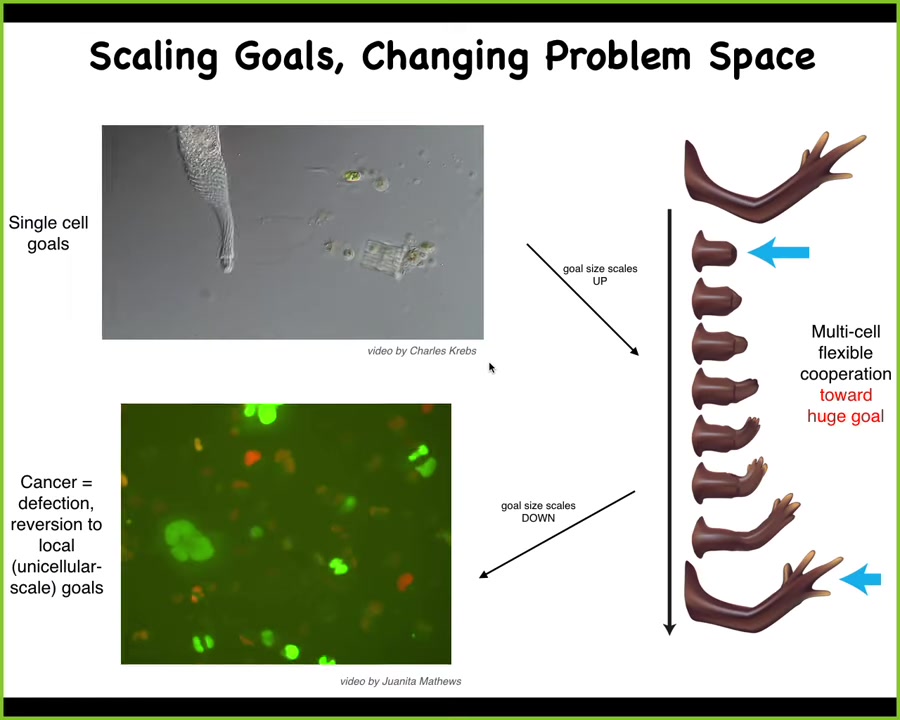

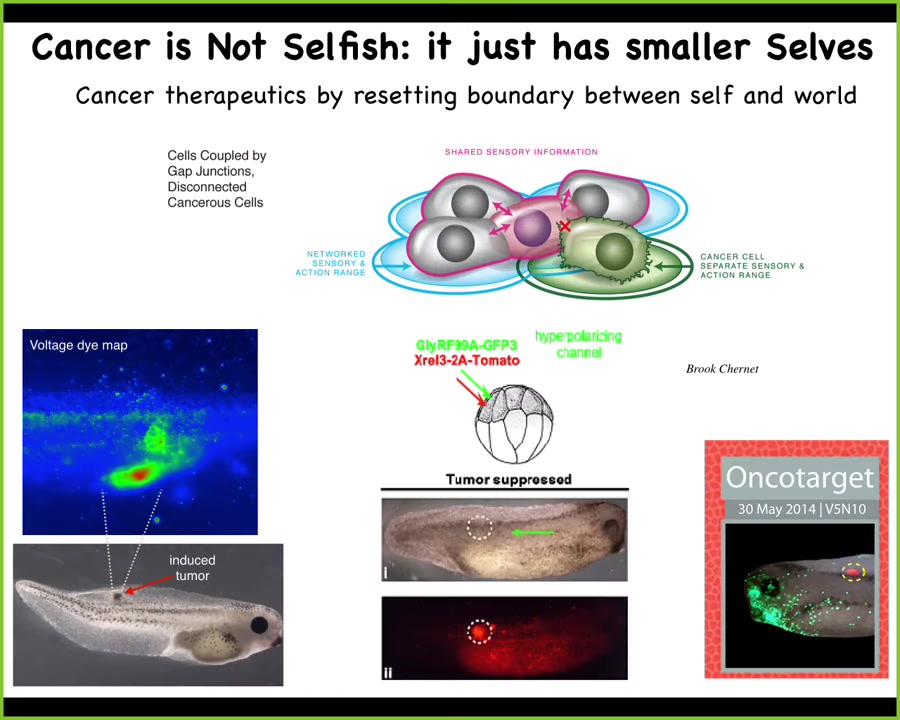

So here's a single cell with a tiny cognitive light cone. But evolution and development allow them to work together, and individual cells have no idea what a finger is, but the collective absolutely knows, because if you damage it, they will work to get to the same thing and the right final pattern. Now, that electrochemical network, the network that allows the system to store and pursue bigger goals than these systems can, has a failure mode, and that failure mode is known as cancer. They can break down. When cells electrically disconnect from the rest of the network, they can no longer remember this massive construction project they were working on; they roll back to their ancient evolutionary self and become like amoebas. This is human glioblastoma. At that point, these cells are not more selfish than other cells. They just have smaller selves.

Slide 39/64 · 43m:13s

All they're working on are little tiny goals at the level of single cells, which are proliferation and migration, which is metastasis.

To show you a practical application of those ideas, if you inject human oncogenes into a frog embryo, it will make a tumor. You can tell with voltage imaging ahead of time where the tumor is going to be. Here are the cells that are already disconnecting from this electrical network, their voltage is all wonky.

Instead of chemotherapy, instead of trying to kill these cells, if you forcibly reconnect them to the electrical network by injecting an ion channel that sets their voltage correctly so that they stay part of the network, here's the oncoprotein. It's blazingly strongly expressed. Same animal, no tumor. Because it's not the genetics or the hardware problem that's going to drive this. It's actually the decision-making of the collective. In some cases, some of these hardware problems, this genetic mutation can actually be ameliorated, not by removing the cells, not by fixing the genetics, but by convincing the cells that they are all part of one collective and keep working on the nice skin and muscle and everything else.

Slide 40/64 · 44m:20s

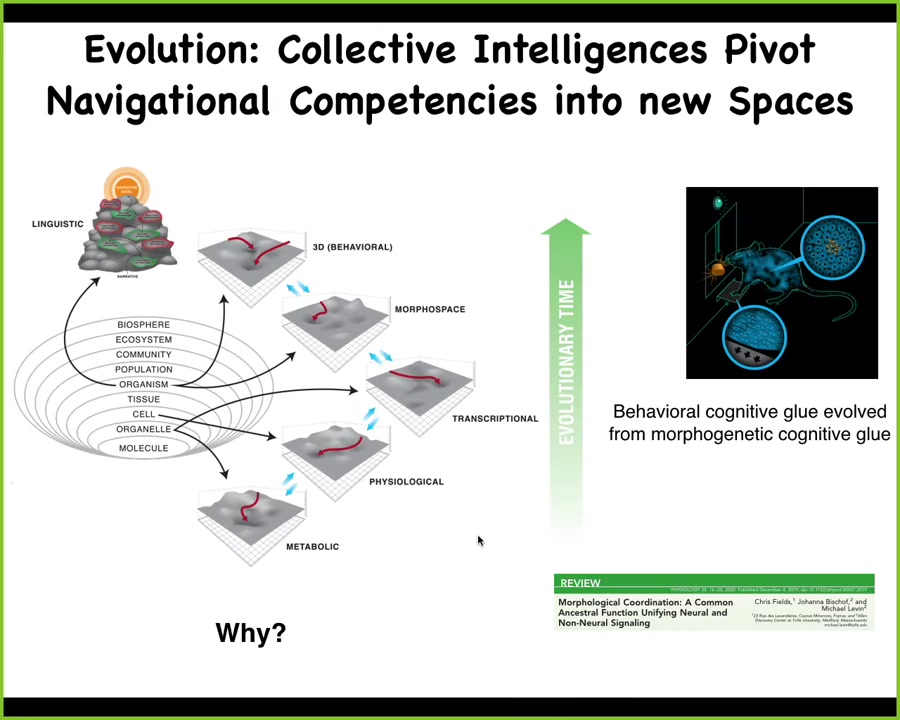

What I think is happening here is that evolution is pivoting some of the same competencies, this idea where you have multiple subunits. The subunits are themselves. They're not only active, but they have goal-directed competencies; they're able to achieve either simple homeostatic or homeodynamic ends, but what the collective is doing is aligning them so that, while they're working on their local problems, together it ends up solving problems in other spaces.

Evolution has pivoted this across first metabolic spaces and then physiological spaces. Then genes came along and it became transcriptional space. Eventually multicellularity with anatomical morphospace. Eventually nerve and muscle came on the scene. You got behavioral and then linguistic and what else is after that.

The last two things I want to talk about are, why does this work? Why are these things progressively being scaled up into higher level spaces with bigger cognitive like cones? Why is that happening?

Slide 41/64 · 45m:22s

In order to do this, I want to talk about the unreliable substrate and the commitment that biology has to creative problem solving.

Caterpillars are soft-bodied creatures. They crawl around, eat leaves, and have a brain that's suitable for that purpose. When caterpillars become butterflies, they have to undergo a process of metamorphosis, which causes them to completely refactor their brain. Most of the cells die, many of the connections are broken; they completely refactor it, building a new brain that's suitable for this lifestyle.

If you train the caterpillars, the butterflies still remember the original information. This is the early work of Doug Blakiston, linking a particular color disk as a stimulus to go find your leaves.

One problem is how do you keep information when the substrate is being completely taken apart and refactored? Even more interesting is that the actual memories of the caterpillar are of no use to the butterfly. The butterfly doesn't move the way the caterpillar moves. The butterfly lives in a three-dimensional world. It also doesn't care about leaves. It wants nectar.

You can't just keep the memories. You have to remap them onto a completely new architecture. That means you have to generalize. That means you have to not just hold on to the fidelity of the information, but you have to remap them for continued saliency.

This is a paradox of change that was seen by evolutionary biologists. If you're a species that refuses to change, you will eventually die out when you fail to meet the needs. Conversely, if you do change, then you're not the same species anymore. So again, you're gone.

What does that say about us as a continued process? This idea that we cannot remain the same, we are not a fixed object that's trying to maintain itself. We are continuously trying to remap ourselves onto new scenarios.

Slide 42/64 · 47m:32s

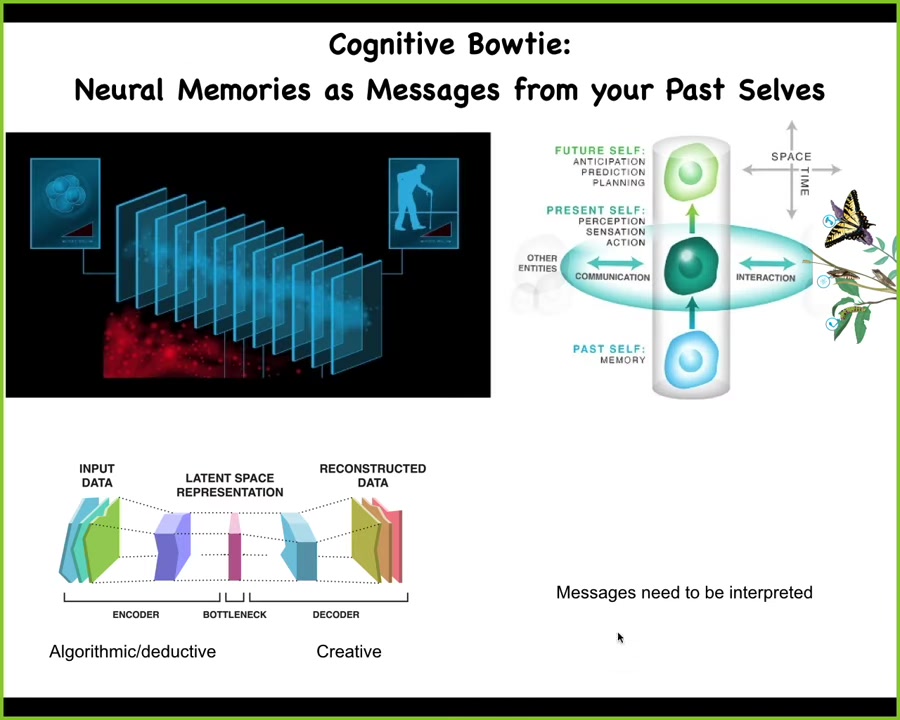

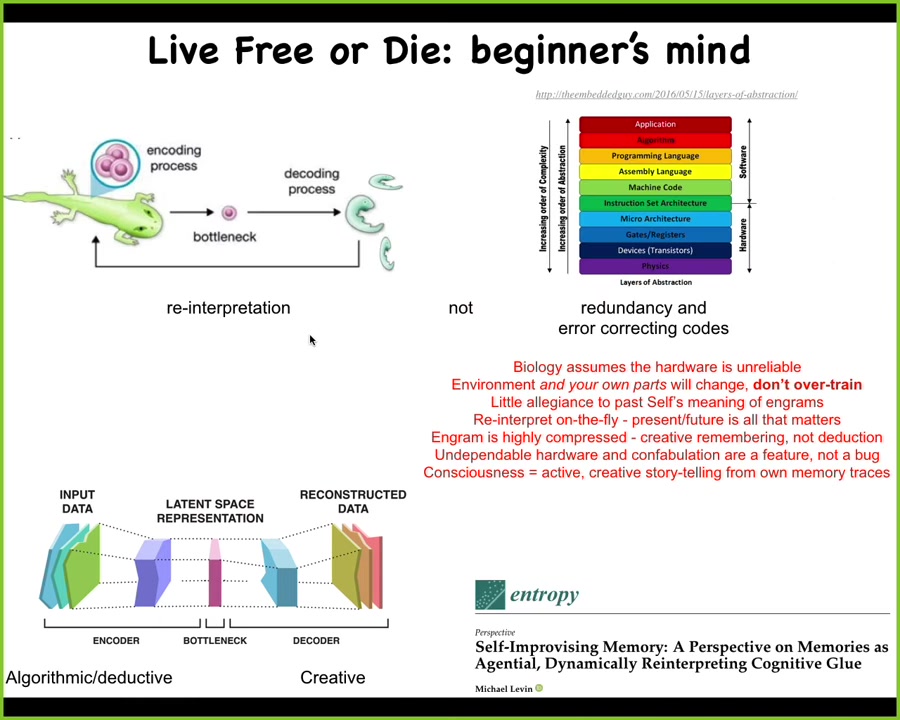

One way to start to think about this: I'll do the cognitive version first and then the morphogenetic version.

The cognitive version is that at any given moment, none of us have access to our past. What we have access to are engrams, memory traces that were formed in our body or brain by past experience. At any given moment, our job as active agents, which are future-facing and needing to make decisions, is to interpret the messages left by past selves. This is a view of memory as communication. All communication, all messages need to be interpreted. In fact, we can't guarantee to interpret them the way that our past self interpreted it because you don't know what that was. Everything will be different. A butterfly is a drastic case. For us, the change is less drastic, but over puberty and those kinds of things, we actually do undergo some massive changes.

We have this kind of architecture, which you will all recognize immediately, which is that there are experiences that get encoded, compressed into n-grams. And then on the other side, the past self is doing this. Future selves, or our current self, have to pick up these compressed n-grams and re-inflate them into whatever reasonable story about ourselves, about our external environment, is going to be best suited for us now adaptively. This part is probably algorithmic and deductive. This part is creative because you've lost information here. There is no algorithmic way to do this.

And so biology has to commit to an unreliable substrate. Everything is going to change, the environment is going to change, but even you're going to change as a lineage, as an evolutionary lineage, because you will be mutated. You cannot assume anything.

Remember the very first thing I showed you. Why does that, the eye on the back of the tail, work? Because in all of these cases, I think biology is making problem-solving agents, not fixed solutions, and it's always ready to reinterpret the information it has.

So this is the cognitive version of reinterpreting our memories.

Slide 43/64 · 49m:54s

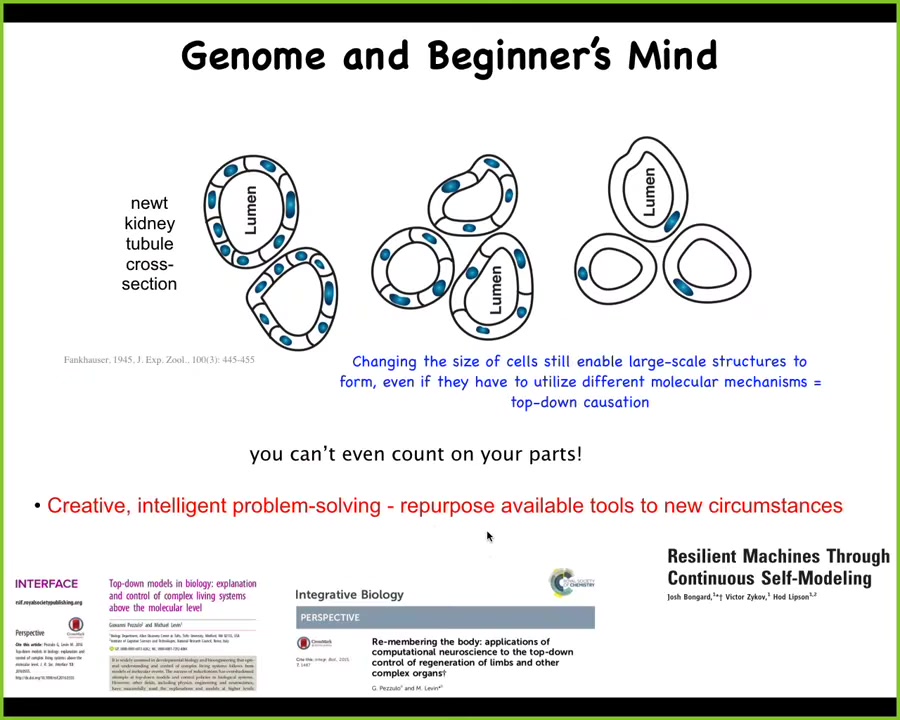

Here's the morphogenetic version. Imagine the amazing problem that biology faces. Here, this is a cross-section through a kidney tubule of a newt. Normally, there's about 8 to 10 cells that work together to form this thing. One thing you can do is make early newt embryos with extra numbers of the genetic material. These are called polyploid newts. Instead of 2N, they can have 4N, 6N, and so on. When you do this, the first thing you find out is that you still get a normal newt. You could have extra copies of your chromosomal material and it's fine. Then you find out that the cells get bigger to accommodate the new large nuclei, but the newt stays the same size. How can that be? That's because it automatically adjusts the number of larger cells to the same structure. The real kicker is that when you make these cells completely gigantic, you find that only one cell will wrap around itself and give you the same exact structure. The reason that's amazing is that this is a different molecular mechanism. This is cell-to-cell communication. This is cytoskeletal bending. Think about what you're facing as an embryo, in this case, a newt coming into the world. What can you count on? You can't really count on the environment. That's going to change. You have to have all kinds of physiological systems to make up for different environments. You can't even count on your own parts. You have no idea how many copies of your genome you're going to have. You have no idea what the size of your cells are going to be or the number of your cells. You have to make it work with different affordances, different molecular components that you have. You're going to have to make a normal no matter what, under a very large set of different perturbations. Being able to use the tools you have in novel circumstances that you've never seen before to solve a problem is literally intelligence. In anatomical space, it's a kind of creative problem solving. Josh Bongard had something back in 2006 around robotics that didn't know what shape they were either and would have to discover it on the fly. This is extremely powerful.

The fact that biology is always dealing with an unreliable substrate means that the genetics that you get passed on from prior examples of your lineage cannot be taken literally. They are a bag of tools that you will have to utilize however you can under different circumstances to get the job done.

Slide 44/64 · 52m:32s

This is very different from how we do a lot of computing today, because instead of these nice sharp demarcations between the abstraction layers that we have in our architectures, we have redundancy and error correcting codes to make sure that our data stay fixed, that everybody knows what the data mean. They don't go floating off. The higher levels don't need to worry about the lower levels being unreliable.

That is exactly the opposite of what biology does. Biology assumes that everything is up for grabs; you never know how many copies of anything you have or what your situation is going to be. It doesn't overtrain on its evolutionary priors. It reinterprets on the fly. Evolution produces agents that solve problems.

My gut feeling is that a lot of consciousness is around this idea of continuously having to interpret your own memories and build an active story of what you are cognitively, the same way that your body replacement machinery is constantly building up a story of what your organism is.

Slide 45/64 · 53m:45s

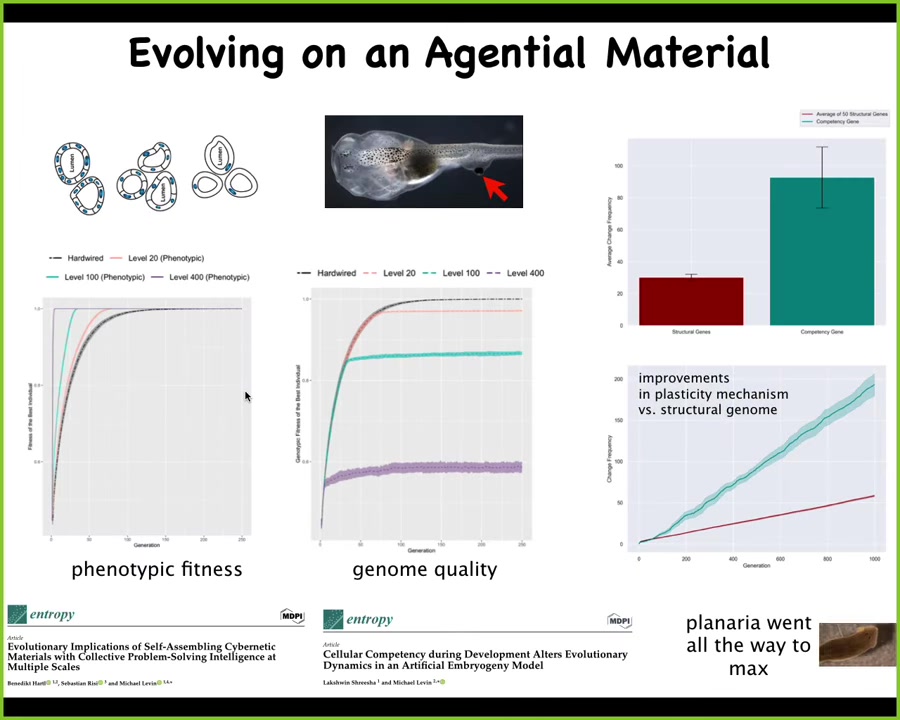

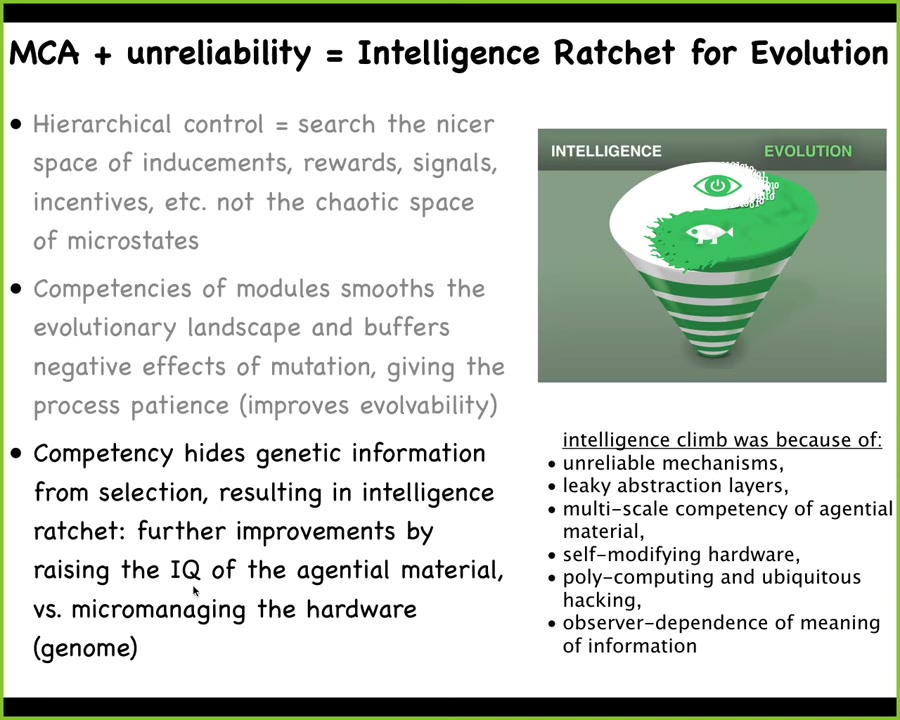

This has huge implications for evolution itself. Because we've done lots of computational modeling of this. If you model evolution operating on a competent material as opposed to a hardwired mapping between genotype and phenotype, some very interesting things happen. In terms of the pressure that comes off of the genome, eventually all of the work gets done on the actual competency as opposed to the structural genes.

Slide 46/64 · 54m:15s

And you end up with this amazing intelligence ratchet that the more competent the material, the less selection can actually see the genome. The more trouble it has distinguishing good genomes from bad genomes because the material is continuously making up for it, rearranging the frog faces if they start out wrong. Then what ends up happening is that all the work of evolution ends up being done on the competency mechanism itself. And you end up with something like planaria, where that ratchet has gone all the way to the end for reasons we can talk about, and their genome is incredibly noisy, and yet they are highly regenerative, cancer resistant, do not age, and they have some other amazing properties specifically because of this. I think the climb of intelligence, as we think about what is intelligence, as we think about bio-inspired computing, is based on the continuous need to interpret information from scratch with an unreliable material and not have allegiance to the fidelity of it, but to optimize for saliency in an architecture that has this crazy self-modifying hardware with multiple observers at different scales, all trying to hack each other, constantly trying to generate their own meaning of an interpretation of what's going on.

The very last thing I'll show is a few more recent thoughts around where I think this is all going. All that plasticity that we've been talking about, this ability of life to make sense of novel scenarios, has a consequence, which is that it's very interoperable.

Slide 47/64 · 56m:02s

Pretty much at any level of organization, from cells and tissues, we can introduce engineered materials. We can make these hybrids, these chimeras, which is one reason why I think a lot of this discussion of what proof of humanity certificates and what real humans are is a complete lost cause because we're not dealing with simple machines. This is what we're going to be dealing with, trying to figure out whether this is 50% or 51% human is hopeless. We need to start to ask ourselves, all of these different kinds of beings, what is their behavior, what is their mind going to be like if they are not on the evolutionary tree of life with us?

I think that all of Darwin's endless forms most beautiful, all the variety of life, is like a little tiny corner of the option space of possible bodies and minds. Cyborgs and hybrots and every combination of evolved material, engineered material and software is going to be some kind of agent and we are all going to be living together and we need to be able to understand each other. There's one other piece that I've added to this, which is what Whitehead called, and I think is a good term, ingressing patterns.

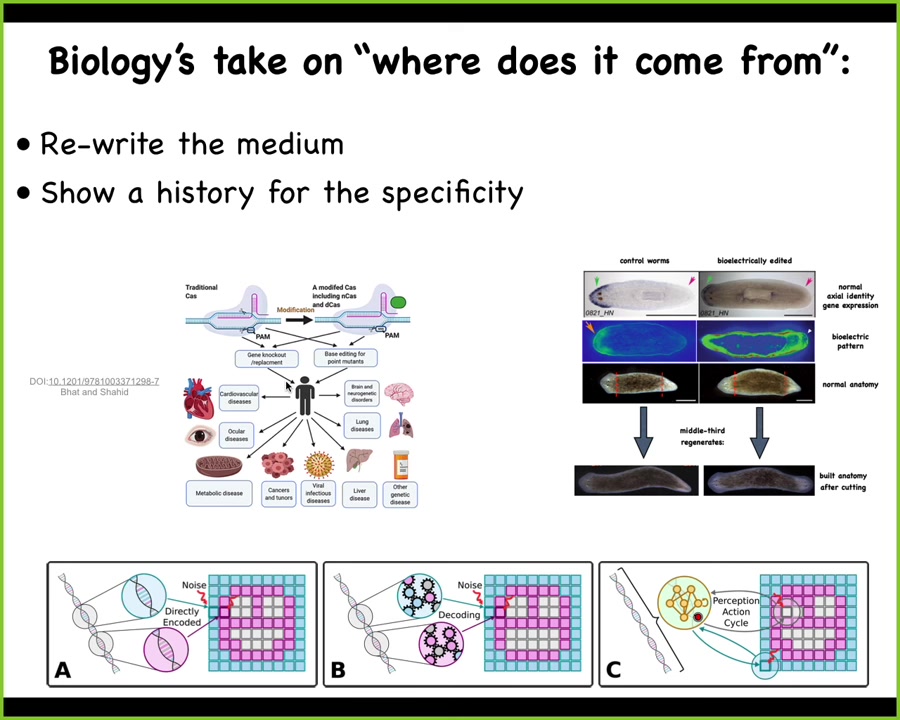

Biology, where do these patterns come from?

Slide 48/64 · 57m:32s

When you make these novel creatures that never existed before, we know where biological patterns come from. People will say, "it's evolution." You have a long history of selection. That's where the electric face and all these goals of these collective intelligences were set by eons of selection.

Now we have all these creatures who have never been here before. Where do the goals of collective intelligence come from? Where are they written?

Slide 49/64 · 57m:55s

Where are they specified? Biology likes two things when you claim where information comes from. You have to be able to rewrite it. So in the case of DNA, you have to be able to rewrite the DNA and show that the anatomy changes. Then you can say that's where the information was. It also likes a history. So it wants to know why that information as opposed to some other kind of information. There are different mappings, direct and indirect, from the genome to what happens. But basically, this is what you want.

Slide 50/64 · 58m:29s

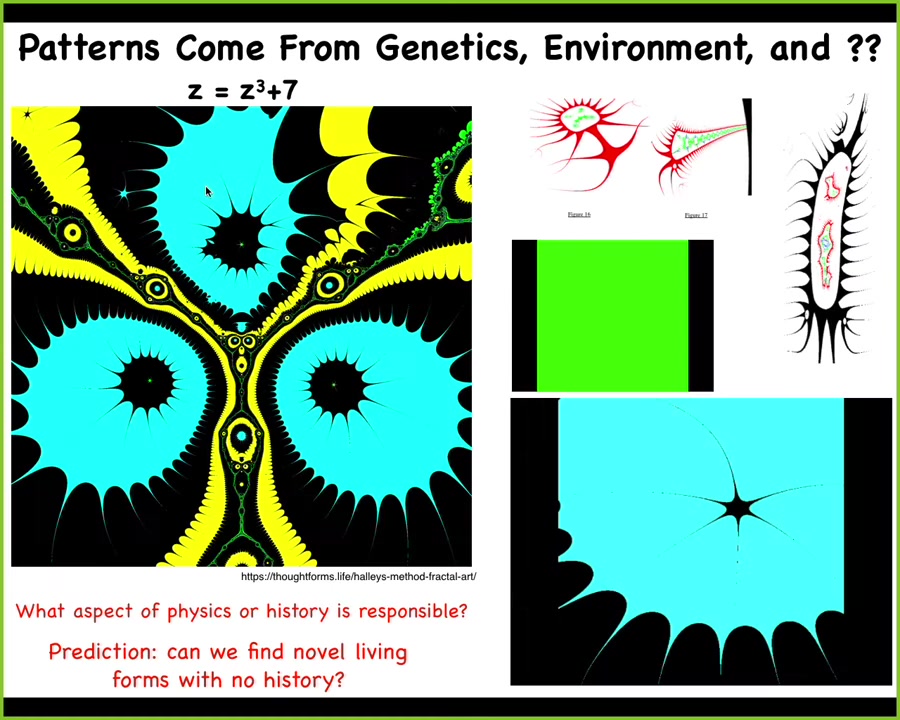

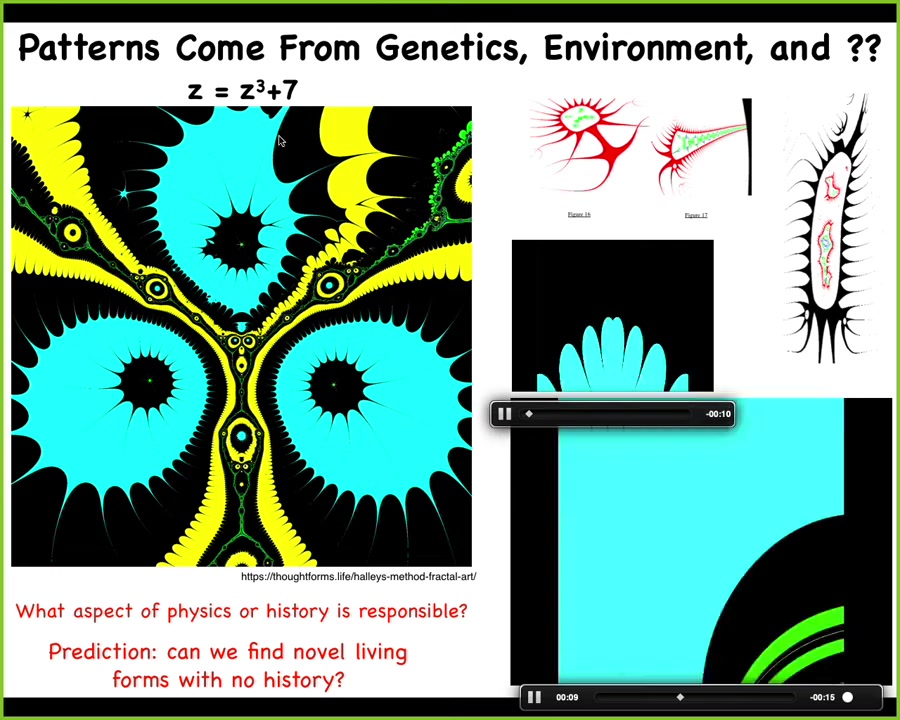

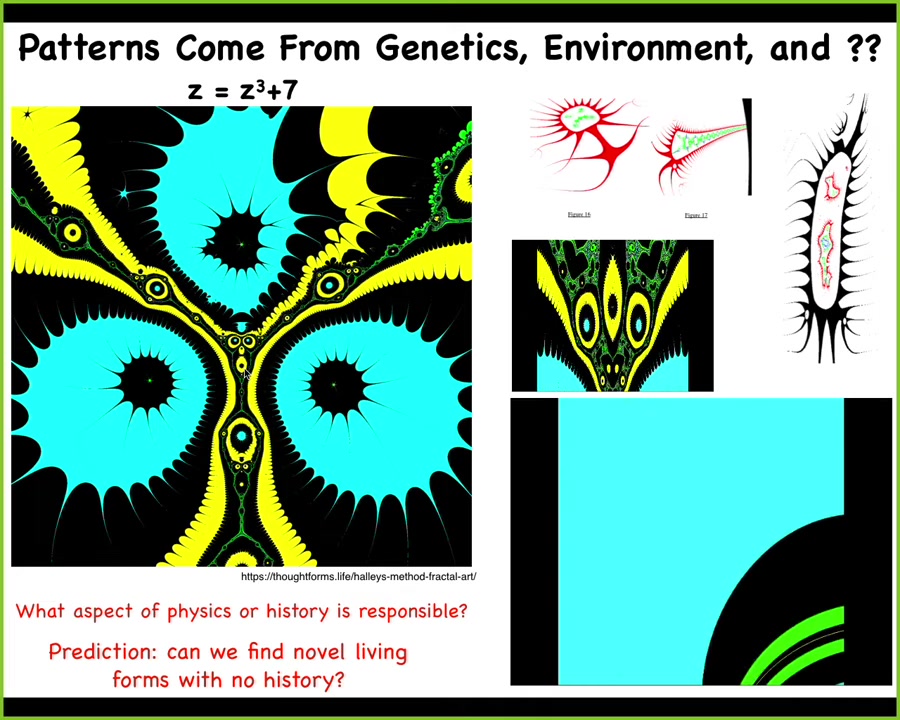

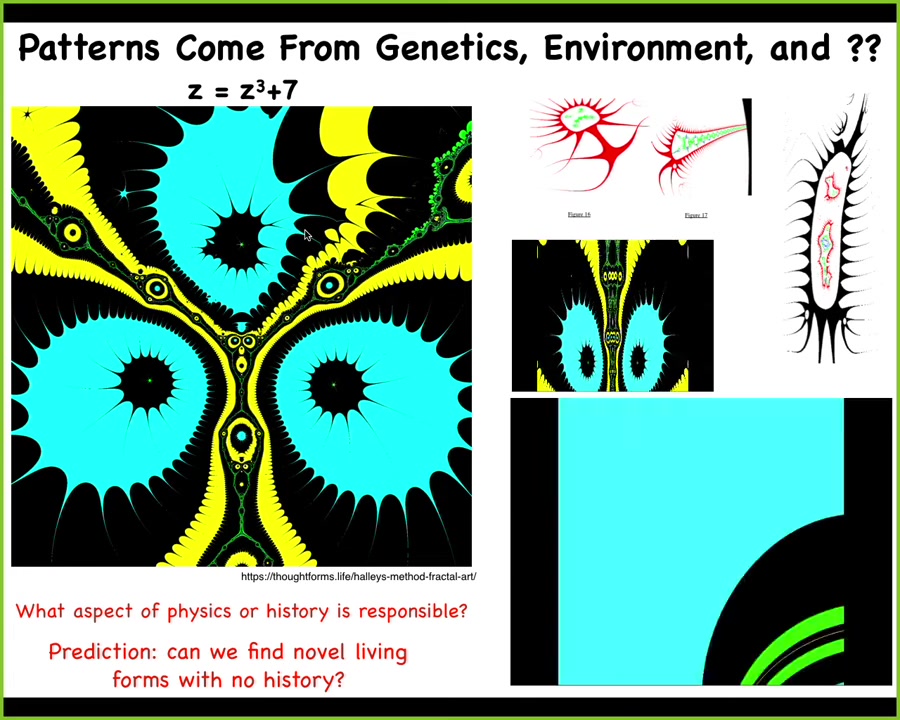

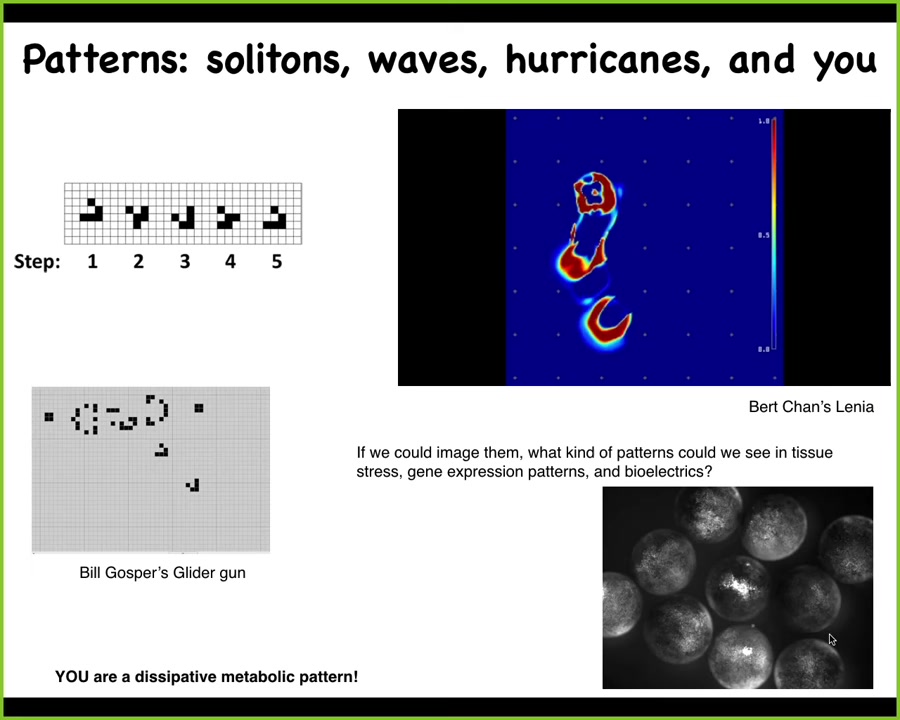

So I want to point out that there are a lot of patterns. And so what you're looking at here is something called a Halley plot. And then a couple of videos of tweaking this formula.

Slide 51/64 · 58m:39s

This whole thing right here comes from decoding this tiny little formula in complex numbers. That's it. There's a simple algorithm, about 10 lines of code, that takes this simple generative seed and makes something incredibly rich like this. There are some other patterns that come out for other formulas. Lots of richness. So now we can ask, if you're a biologist, you want to ask, well, where is this encoded?

Slide 52/64 · 59m:03s

This is a very specific pattern. It doesn't hurt that it's organic looking, but it's a very specific complex pattern. It's not a compression of it. We can't recover things like this for arbitrary patterns. Where is it encoded? There's no genetics, so there's no history, there's no historical story to be told about this.

Slide 53/64 · 59m:27s

There doesn't seem to be any piece of physics that you can blame on this particular pattern. If the rules of physics were different, the mathematical structure would still be what it is. And so now we ask the final question: if these patterns exist outside of a historical evolutionary track and some kind of physical property, what does that mean for biology?

Can we find novel forms with no history?

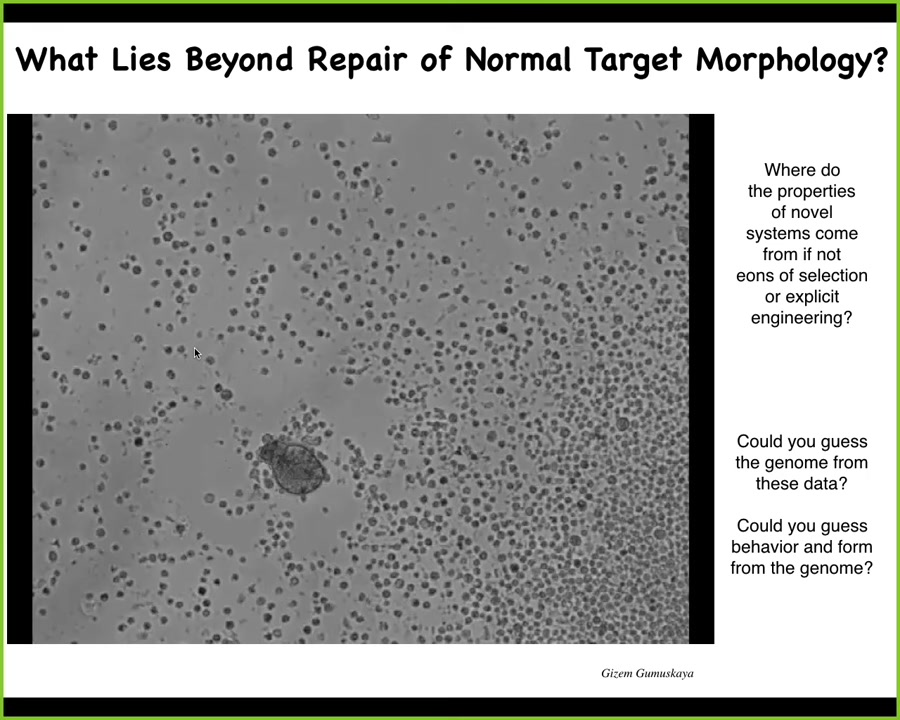

Slide 54/64 · 59m:57s

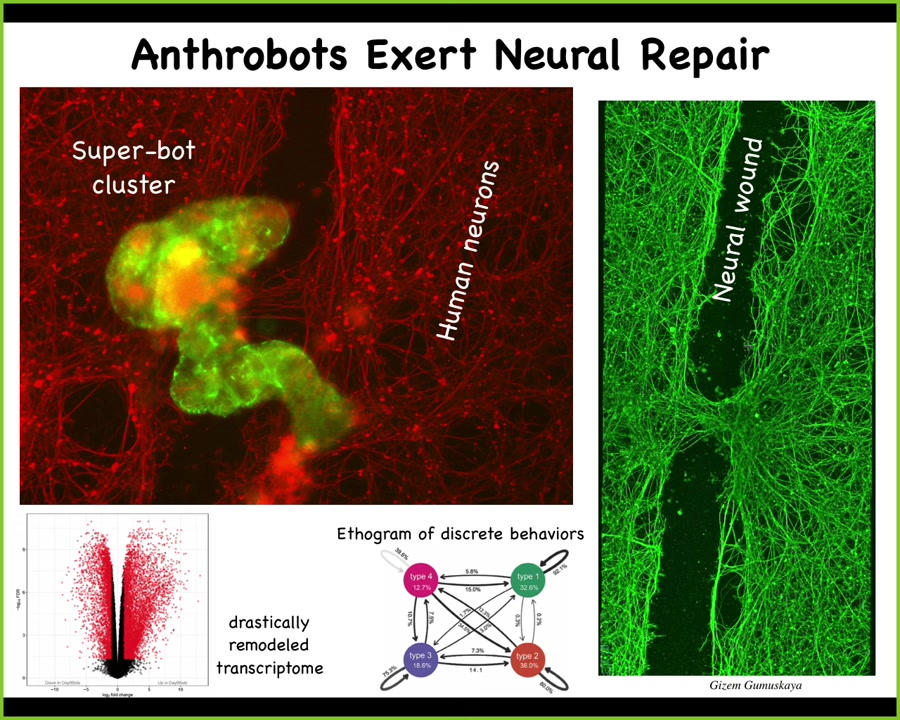

I'll just show you two quick things. If you look at this little organism, I might ask you what this is. You might say that this is a primitive organism I got from the bottom of a pond somewhere. I would ask you, what do you think the genome would look like? You might say it would look like one of these primitive organisms. If you sequence this, you'll find Homo sapiens. This is 100% human cells. These are not embryo cells. These are adult, in fact usually elderly patient cells, that we have allowed to reboot their multicellularity, and they make something we call an anthrobot.

This self-motile little creature looks like no phase of human development. It is an entirely new reboot of morphogenesis, no genetic change, no scaffolds, no drugs, no synthetic biology circuits. The original patient may or may not still be alive, but some of its bits will have their own little life here.

Slide 55/64 · 1h:00m:59s

They have amazing properties. They have a massively altered transcriptome. Half the genome is expressed differently, even though the genetics are still the same, but they turn on different genes in their new lifestyle. They have discrete behaviors, so we can make an ethogram of different kinds of behaviors, and they have weird capabilities.

If we take these xenobots and we put a big scratch through them, then these xenobots will sit down and start to knit the wound closed. So they'll repair neural scratches. They come from tracheal epithelia. Who knew that your tracheal cells, which sit there quietly in your airway for decades, when given the opportunity, can make a completely different little multicellular creature with new transcriptomes, new behaviors, new capabilities.

Where did this come from? There's never been any selection to be a good xenobot. The situation never comes up in life. We don't know where this comes from, but as I showed with those mathematical forms, we do have a precedent for complex forms that do not require either an explanation at the level of physics or evolutionary history, and the same thing is true with these xenobots; these are frog cells.

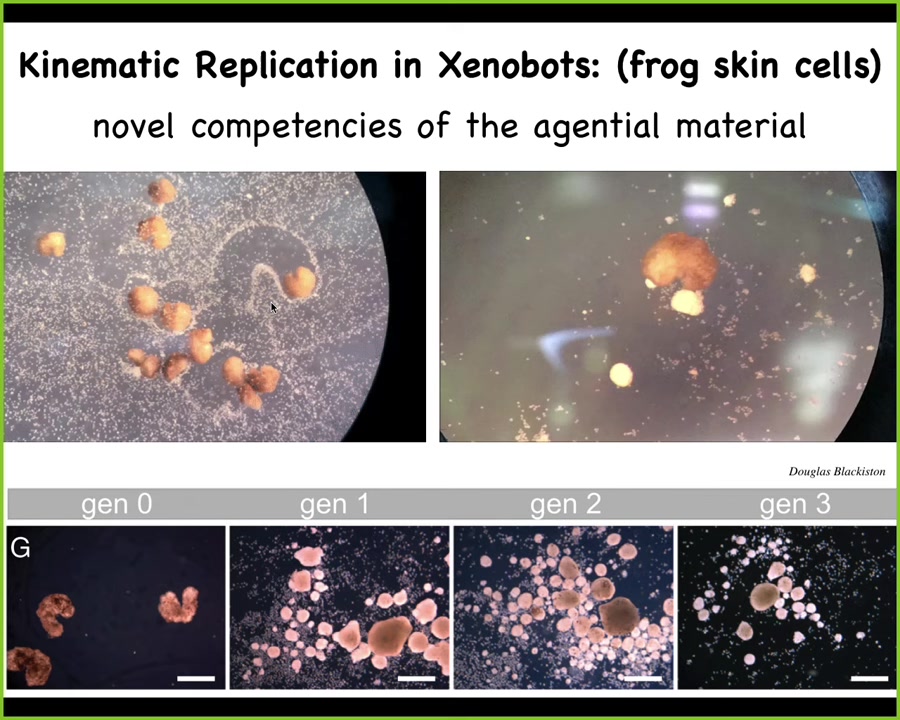

Slide 56/64 · 1h:02m:13s

Something cool that they do is kinematic self-replication, so when you provide them with loose skin cells, they do von Neumann's dream of a machine that builds copies of itself from material it finds in the environment. They run around and they collect these cells into these little piles and the cells mature into the next generation of xenobots. Again, never existed before. No other creature to our knowledge does kinematic self-replication. This stuff is new and not predictable from the genome.

Slide 57/64 · 1h:02m:45s

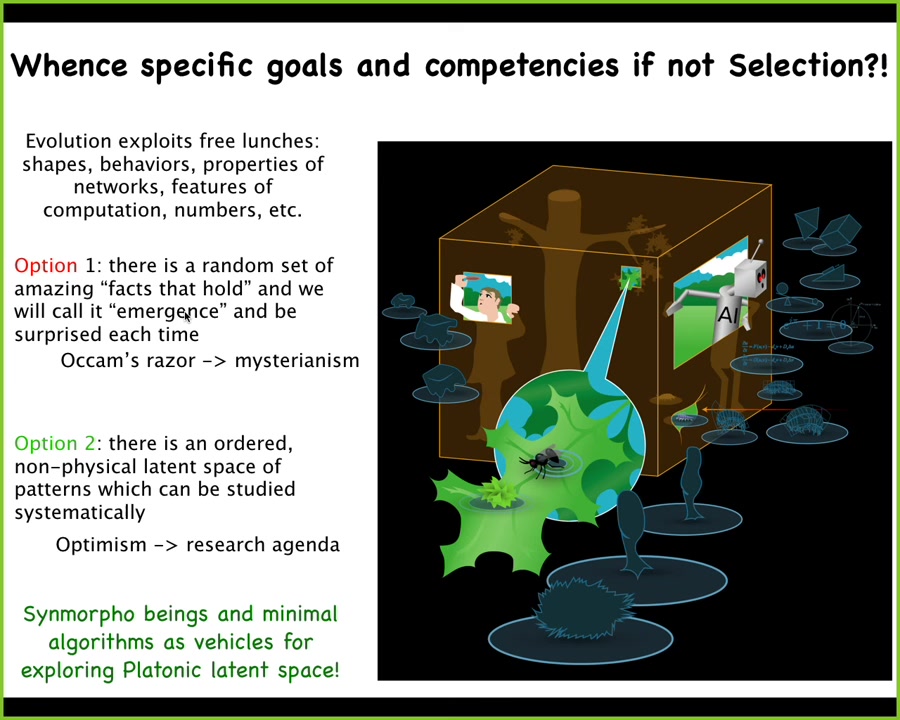

So then we can ask, where do these specific goals and competencies come from, if not a lengthy history of selection? We know that there are all kinds of shapes, behaviors, properties of networks, features of prime numbers, of facts about computation, and so on. And there are two options. A lot of people, because they want to be sparse in their ontology, will say that these are facts that hold about the world. If you do that, what happens is I think that you then end up with a system where every once in a while you come across these new facts that hold, you're surprised and amazed by them, you write them down. That seems to me a kind of mysterianism. I don't like it. I prefer this idea that there's an ordered, non-physical latent space of patterns, which can be studied systematically. It has a metric to it. We are not random, there's not a random grab bag of these patterns, but we can study these systematically and we have a research agenda. It means that when we make embryos, when we make biobots, when we make AIs, when we make hybrid constructions and galls, what we are actually doing is building vehicles to explore this latent space. We're able to sample that latent space and see what other patterns are going to come through. We make interfaces. This platonic space of patterns is something we can poke little holes in and systematically try to understand the mapping between the things we build and the patterns that come down.

Slide 58/64 · 1h:04m:17s

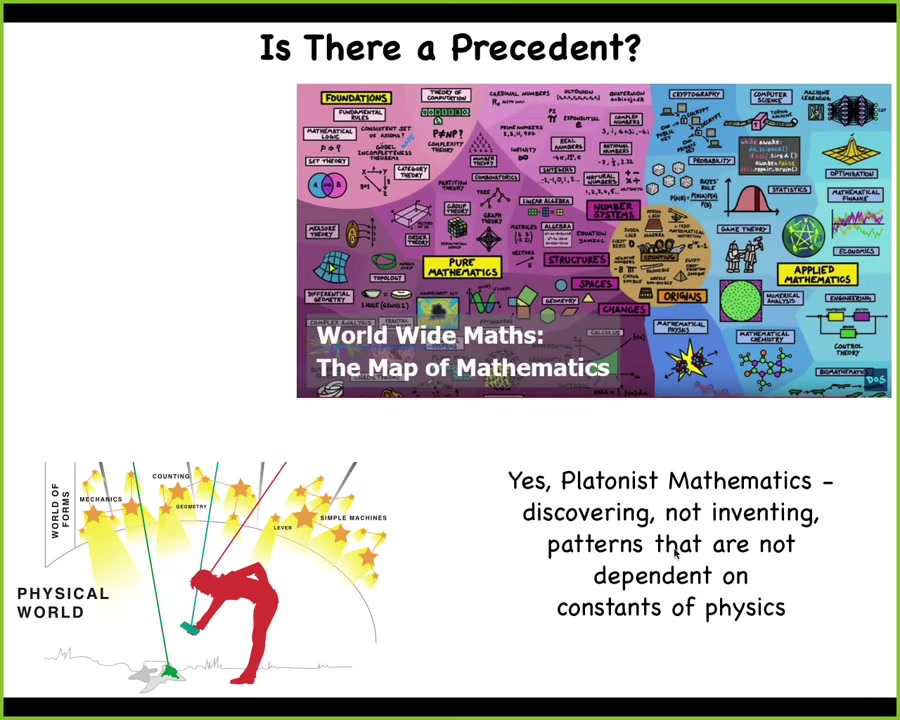

Of course, biologists don't tend to like this because who wants another non-physical space? Some people like to be physicalists about this. But I think that horse has left the barn. Mathematicians mostly do think that they're exploring a space of pre-existing patterns.

Slide 59/64 · 1h:04m:35s

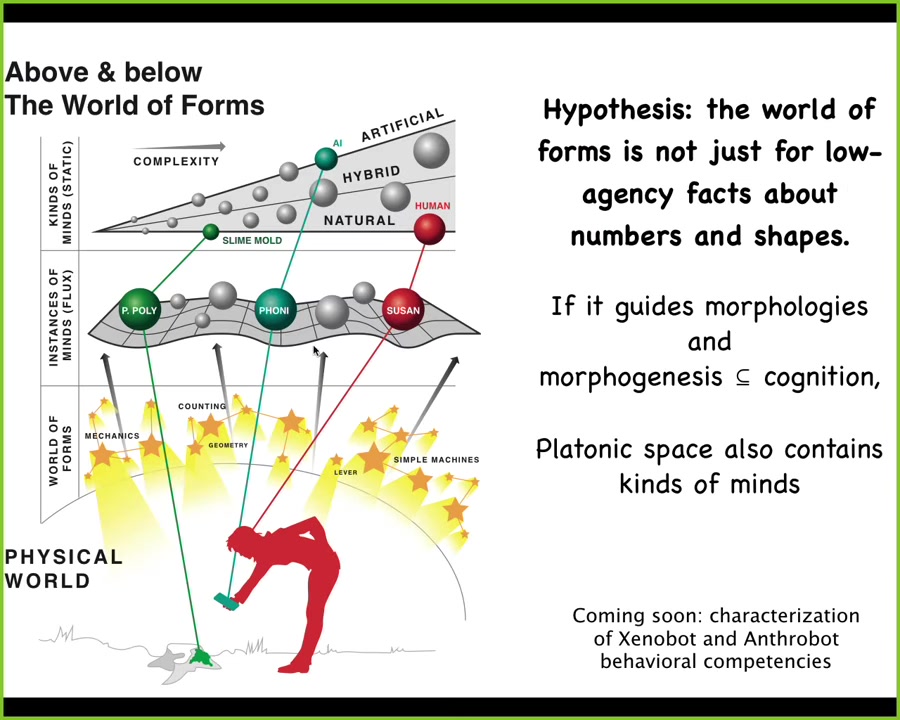

My hypothesis is that if we already know that there are free lunches around types of rules of geometry, rules of computation, of prime numbers, all these kinds of things, that evolution can exploit, and we already know that morphological competencies are a kind of cognition, so morphogenesis is a kind of intelligence, maybe the patterns in that space are not all low agency kinds of boring things about the triangles and truth tables and prime numbers, but maybe some of them are kinds of minds. Maybe some of these patterns are determining morphogenesis, some are determining behavior, and maybe these patterns are in fact kinds of minds. We're currently working on understanding the cognition of these xenobots and anthrobots, which have never been here before.

Slide 60/64 · 1h:05m:37s

I think the Garden of Eden 2.0 that we're all going to be living in is going to be expanded in two ways. First of all, a much wider range of beings in all kinds of embodiments that are going to go way beyond anything that biological evolution has seen. All of these things are fundamentally Pointers or interfaces. I don't think we make intelligence; I think we facilitate its ingression by pulling down patterns into functional bodies as pointers or interfaces, the same way we do it when we build triangular objects and things like that.

Slide 61/64 · 1h:06m:26s

Trying to understand different patterns, different patterns in excitable media, is part of this process to radically expand the set of cognitive beings that we can think about.

Because we too are patterns. We are temporary metabolic patterns.

And we are agential, we have to start thinking about what other patterns in what spaces may have different competencies.

I often think about a fictional scenario where creatures from the core of the Earth are extremely dense and when they come up to the surface, they don't even see any of us because we're like a fine gas to them, a plasma. They might be unwilling to see patterns in this gas that only live for about 100 years as agents because to them we're just disturbances, temporary vortexes in this space.

Slide 62/64 · 1h:07m:25s

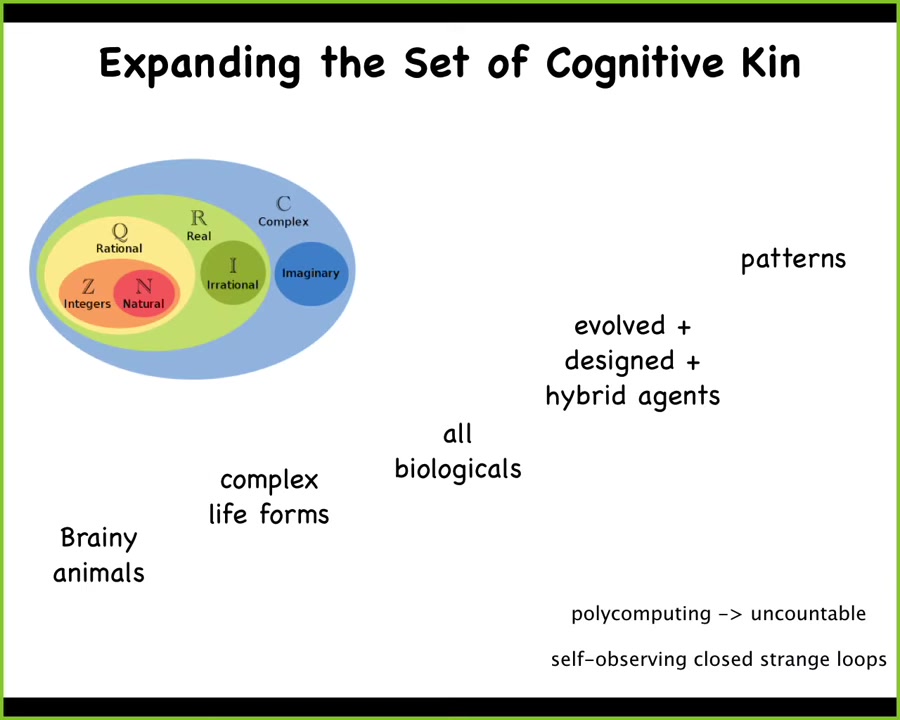

And so we really need to. I've started expanding it. We started saying that it's not just brainy animals: slime molds can learn, cells can learn, and maybe your organs and the morphogenetic agents.

And then it's even bigger than that because you have hybrid agents and so on. Now we have to start thinking about the space of patterns that have not just physically embodied beings, but a much wider space of patterns. So we can think about expanding these categories the way that numbers have been expanded.

Slide 63/64 · 1h:08m:01s

I'm going to stop here and just summarize. If we want to understand biological intelligence or make bio-inspired technologies, these are the things we have to really think about.

Intelligence, I think, is pretty much everywhere. We have to get better at being able to recognize it. A large part of that is going to be to understand the input that comes neither from the hardware/genetics nor from the history of evolution. I take seriously the idea that what we are going to need to do is explore the patterns that we get from this platonic space, which means that there's a lot of humility needed here, because A: we too are patterns, so we need to start thinking about what other patterns are hard for us to recognize as agents.

This idea that when we make something, we know exactly what we've made because we've made it, I think, is completely wrong, because there's always this extra input. You get more out than you put in.

So the research agenda that we have here in this field of diverse intelligence that's emerging is that we can now develop tools, including some AI tools and protocols for recognizing intelligence in very unfamiliar guises, communicating with them. This drives practical applications in biomedicine. This means using the interface to control collective intelligence for regeneration, for cancer suppression, for fixing birth defects, for aging, and so on. We've got some other stuff cooking that will be here in a few months to study the cognition of really surprising things like patterns in minimal media.

Slide 64/64 · 1h:09m:38s

I will thank all the people who did the work that I showed you today. Here are our postdocs, our PhD students, some of our amazing collaborators, all the funders that have supported the work, and disclosure, three commercial entities that have funded some of this stuff. And the animals that do all the heavy lifting to teach us about these things, thanks.