Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a ~46 minute talk by Michael Levin titled “The Unreasonable Effectiveness of the Behavioral Sciences in Developmental Biology and Biomedicine” given at a developmental biology/bioengineering symposium, explaining the connections between the cognitive/behavioral sciences and the study of morphogenesis, from the lens of our framework and new technology.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) From oocyte to mind

(05:57) Agential materials and morphospace

(12:14) Goal-directed body remodeling

(18:12) Bioelectric pattern encoding

(23:32) Reprogramming anatomy with voltage

(31:57) Learning, memory, and repair

(36:10) Xenobots, anthrobots, and MomBot

(41:22) Future impacts and conclusions

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/46 · 00m:00s

What I'm going to do today is give a talk that I call "The Unreasonable Effectiveness of the Behavioral Sciences in Developmental Biology, Bioengineering, and Biomedicine." That title is patterned on this very famous paper by Eugene Wigner on mathematics in the natural sciences. I'm going to make the claim today that tools from behavioral science are of prime importance to developmental biology, to bioengineering, to cell biology. That's a very odd claim. People generally don't think that's true.

The reason it seems unreasonable is because we tend to be educated with this ladder of sciences that everybody knows. You have physics on the bottom, then chemistry, then biology, then behavioral science and psychology, and then whatever comes above that. That's the standard view that we're given. I think that's basically exactly backwards. I think that behavioral science goes all the way down, and we'll talk about it.

What I'm going to do is take you on a tour of data and approaches that others and we have taken over the last 30 years or so to try to explain why this is the case.

Slide 2/46 · 01m:28s

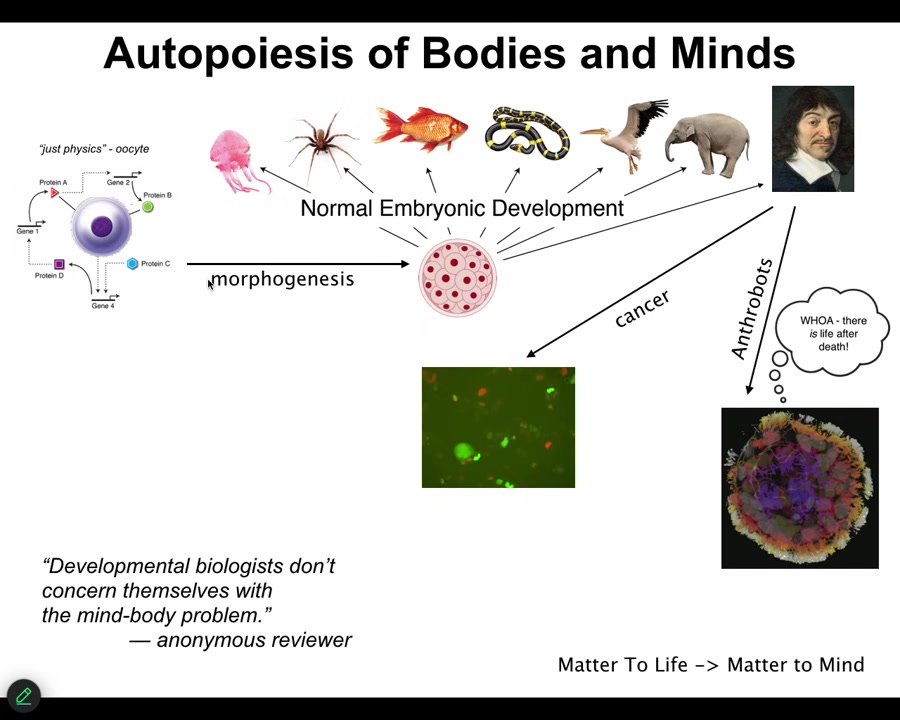

In a review on one of our papers, a reviewer said, "developmental biologists don't concern themselves with a mind-body problem." I think that's deeply wrong, even if they don't know that's what they're doing. I think that is exactly what they're doing. If it's not developmental biologists who are going to crack the mind-body problem, I have no idea who it's going to be.

Because in biology, especially in developmental biology, you have this incredible journey from a single unfertilized oocyte, which looks to be described by the laws of physics and chemistry, and then there's this slow, gradual process, and something like this shows up, or even something like this. Here's René Descartes, and he's going to talk about not being a machine and being something else.

After that, some interesting things happen, which I won't get too much into today, although I will show you some anthrobots. This is the process of matter, life, and mind. This is exactly where these things come from. I think absolutely developmental biologists have to concern themselves with these issues.

Slide 3/46 · 02m:38s

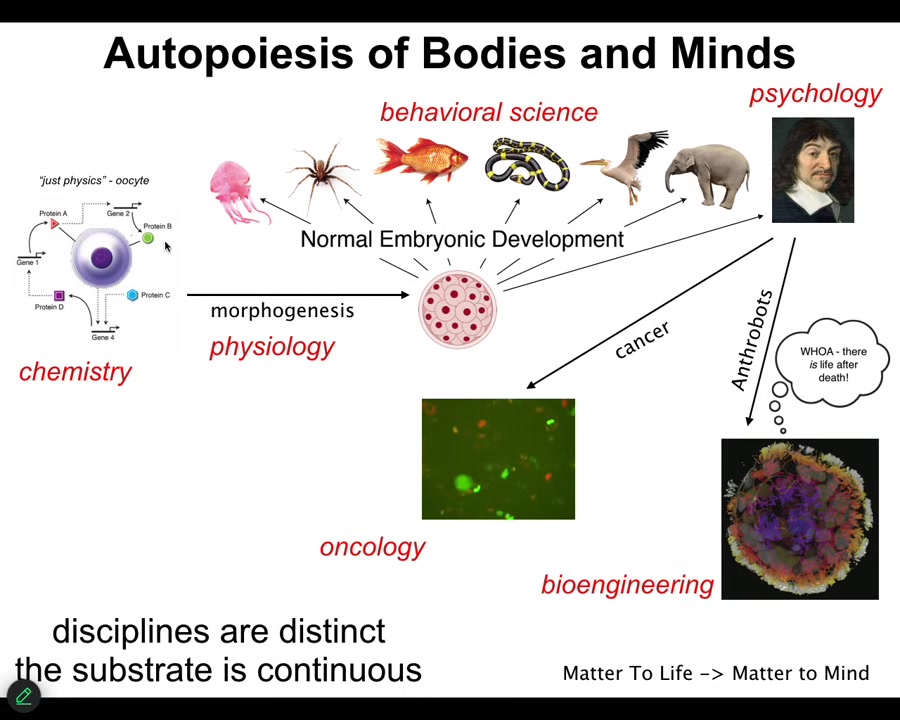

Not only do we take the journey, each of us, from this kind of object to these sorts of things, we also transition across disciplines. So first you are the province of chemistry and then some physiology and then eventually developmental biology and behavioral science and maybe psychology and psychoanalysis. And maybe we take a detour through oncology and parts of us take a detour through bioengineering.

The important thing about this process is that it's smooth and continuous. There is no magic lightning flash at which point you go from being just matter to being a mind. The disciplines are distinct, and that's just for convenience, so that funders, university departments and journals can have boundaries that they try to enforce, but the substrate is continuous. I don't believe it obeys any of the kinds of distinctions that we try to make among these things. It's the transformation across this journey that I think we need to understand.

Slide 4/46 · 03m:38s

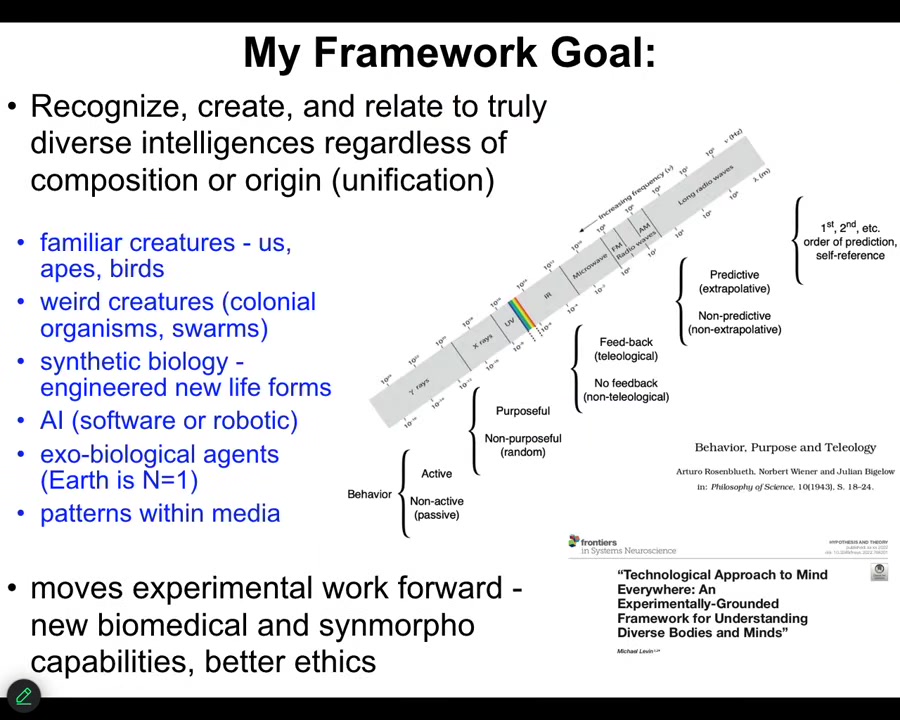

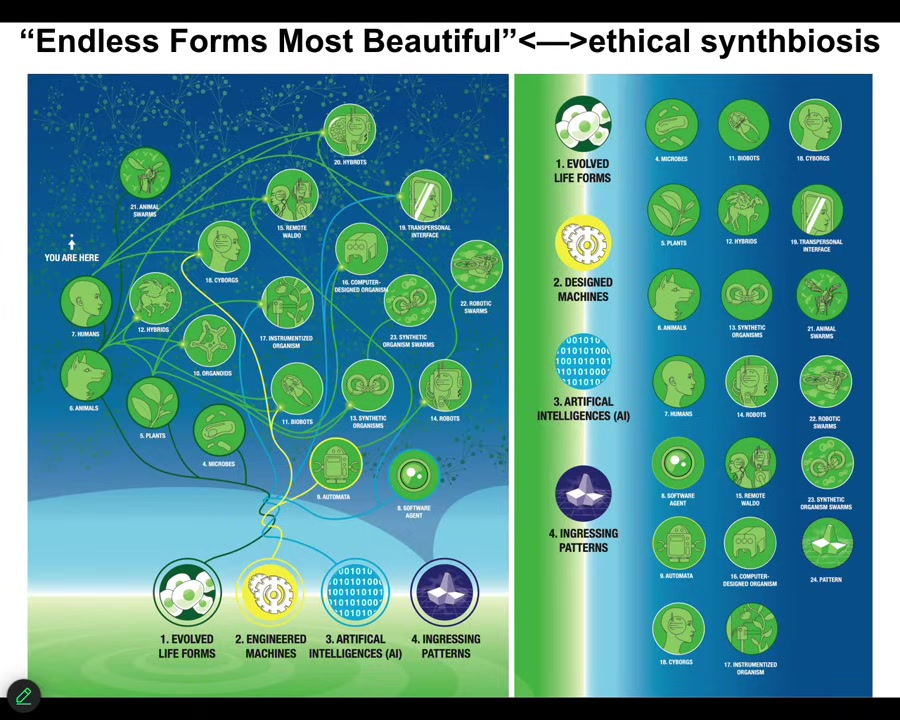

My framework is attempting to create a structure that is tools and also conceptual kinds of things where we can learn to recognize, create, and ethically relate to truly diverse intelligences.

That means familiar creatures like primates, birds, a whale or an octopus, but also some very weird creatures. Colonial organisms, swarms, engineered synthetic new life forms, AIs, whether embodied or purely software, and even someday some exobiological agents. Some very exotic things that we're not going to talk about today.

There are two aspects to trying to do something. People have tried before. This is Rosenbluth, Wiener, and Bigelow back in 1943, trying to show what the great transitions might be on a scale from passive matter to human-level metacognition.

What I always have in mind is this electromagnetic spectrum, this idea that before we had a good theory of electromagnetism, we had magnets and light and lightning and static electricity. We thought those were all different things. We had different names for them. Because of our own evolutionary history, only a tiny bit of that spectrum was accessible to us.

What a theory enabled us to do was have a unification, where we now understand that all of these things are part of the same phenomenon, and it allowed us to make technologies to operate in regions we are normally not able to reach.

I think something very similar is going on here in science, where we have a tremendous amount of mind blindness. That is, because of our own evolutionary history, we're only good at recognizing intelligence in very narrow types of embodiments. What I'd like to do is to create tools to ameliorate that, in particular in ways that are not just philosophy or linguistics in terms of redefining intelligence.

I want to move experimental work forward. I want this framework to drive new biomedical discoveries, new capabilities in synthetic morphology, and better ethics. If you want to read a very lengthy exposition of that, this is a kind of a 1.0 version of that.

Slide 5/46 · 05m:58s

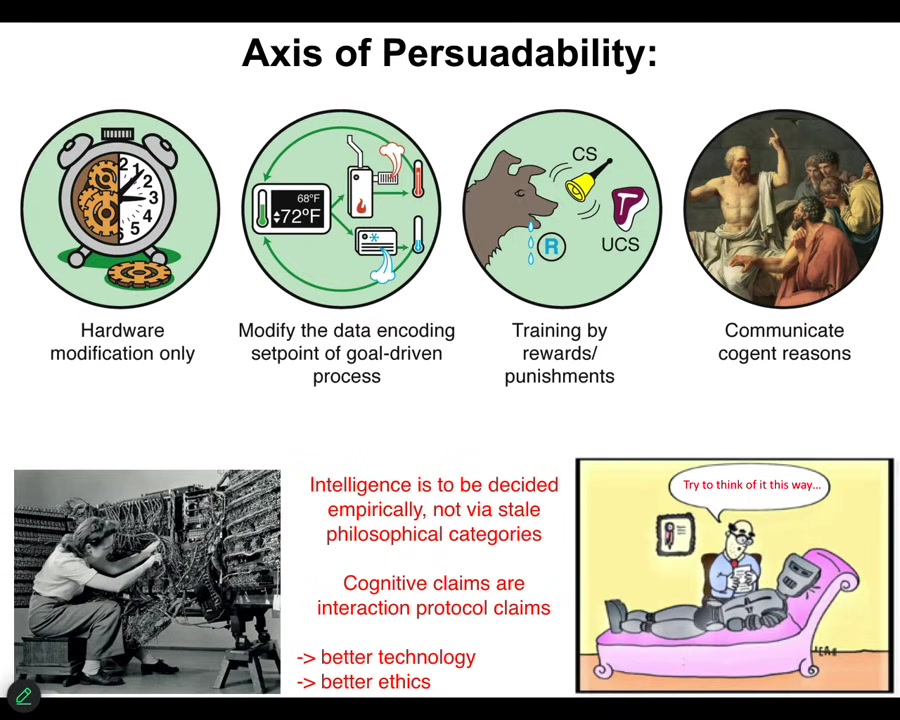

One of the things that I always think about in trying to put different types of agents on the same scale is what do they all have in common? I think one way we can start to think about this is through the axis of persuadability. As engineers, you look at a system and you ask yourself, what tools can I use to optimally interact with that system? Hardware rewiring is the only thing that I can do, but the tools of cybernetics and control theory will do, because we're talking about a homeostatic system, or training with rewards and punishments, behavioral science, psychoanalysis, friendship and love.

What I think is that any claim about a system is really a protocol claim. What you're really saying as an engineer is, here's this bag of tools that I plan to bring to that system. Let's all see how that works out for me. Then we find out.

That means it's an empirical question as to how much or what kind of intelligence any system has. You can't decide it from a philosophical armchair. You can't try to prop up ancient philosophical categories about what intelligence or cognition means; you have to do experiments, see how they work out, and then we can all see how that went.

Slide 6/46 · 07m:18s

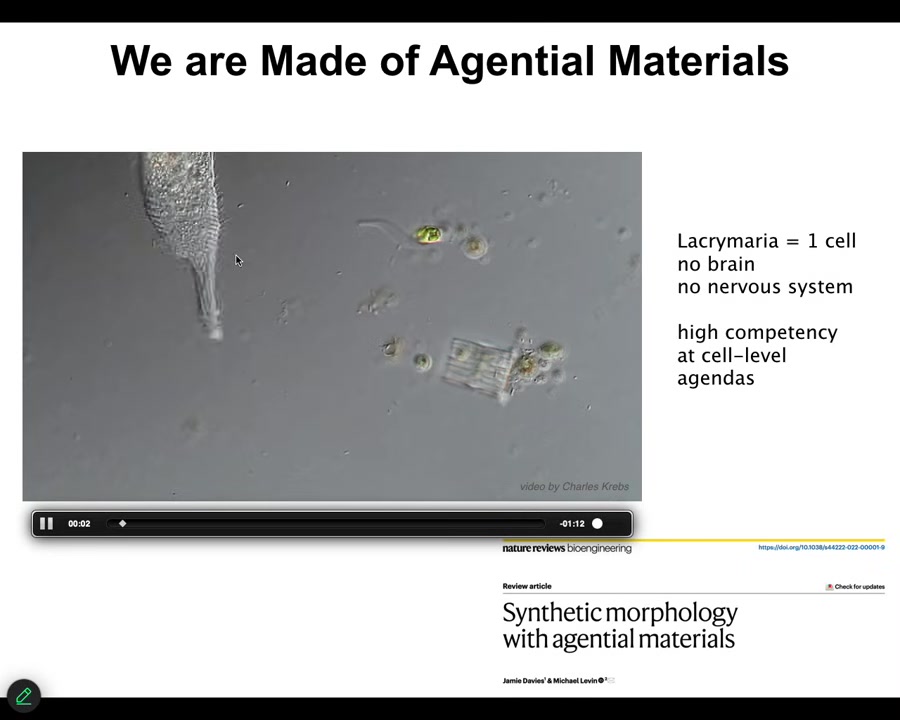

Now, this is the sort of thing we're made of. We are made of an agential material, meaning that unlike wood or metal or these kinds of things that basically just hold their shape, we are composed of, for example, cells. So this is a single cell called the Lacrymaria. There's no brain or nervous system. You can see it has this incredible ability to get its goals met in the local micro-environment. If you're into soft robotics, you might be drooling right now because we don't have anything remotely this capable that we can build. Jamie Davies and I talk about how you engineer with these kinds of materials, which is very different from engineering with normal matter.

In biology, we have a multi-scale competency architecture because all the way from the molecular networks up through cells and tissues and organs and whole animals and of swarms, all of these systems are not just scales of size; they're different: they have different competencies projected into different spaces.

Slide 7/46 · 08m:18s

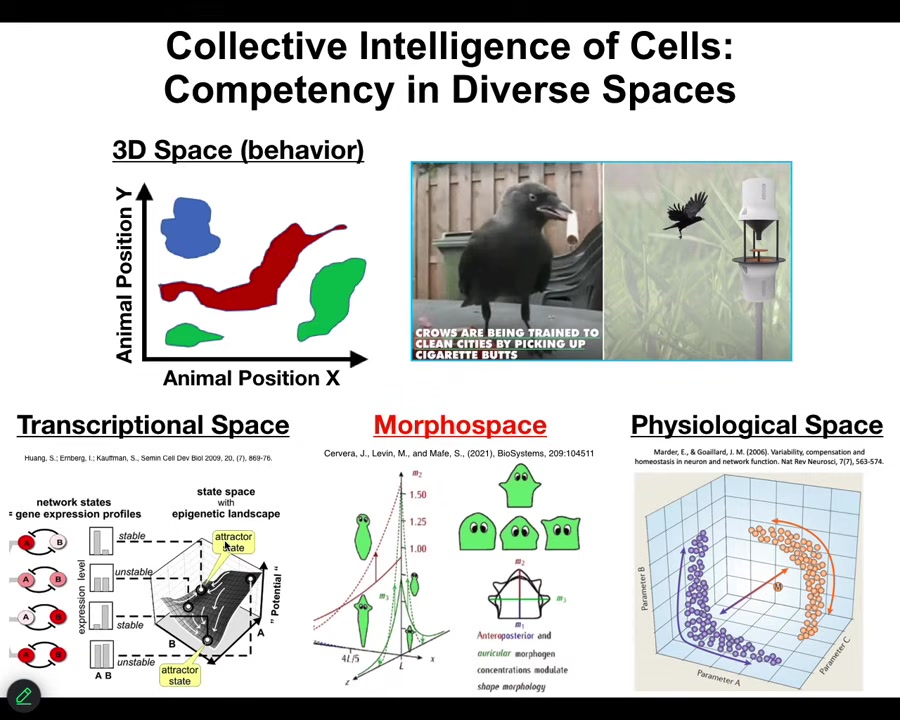

People are very used to thinking about intelligence as movement through three-dimensional space. When you see crows picking up cigarettes to receive a reward, it's a medium-sized object moving through medium speeds and 3D space; we're primed by our evolutionary origins to recognize that. Biology has been doing that kind of sensing, decision-making, actuation loop in many spaces long before we had muscle, long before we had nerves. Lots of biological materials navigate transcriptional spaces, high-dimensional difficult landscapes, physiological state spaces, and anatomical morphospace. This is the one we'll spend the most time talking about today: the space of anatomical possibilities. What we're interested in is understanding this navigation. What kind of information processing do these systems do? What do they know about their world? How much memory do they have?

Slide 8/46 · 09m:12s

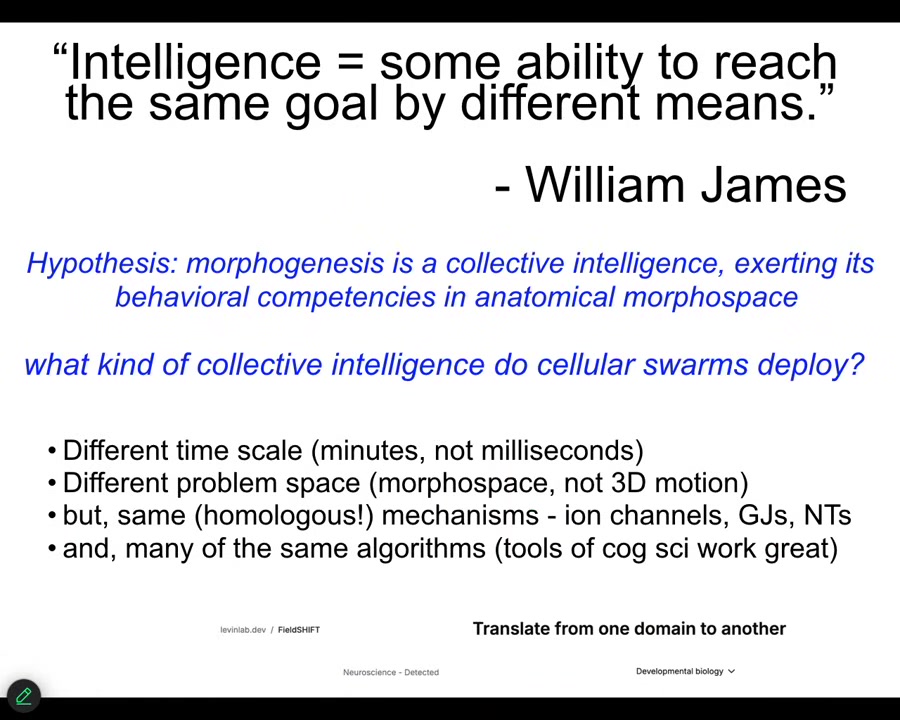

I'm going to use one definition of intelligence. There are many. I'm not claiming this is the only definition, and I'm also not claiming that it captures everything. It doesn't, for example, capture play and exploration. I'm going to focus on one particular aspect of it, which was emphasized by William James, which is some degree of the ability to reach the same goal by different means. This is nice because it focuses on a measurable thing, that is the ability to reach certain goal states under different circumstances. It doesn't talk about brains. It doesn't talk about a specific problem space. It's a nice general cybernetic definition, very helpful.

The middle part of this talk is going to be basically just exploring the data that we've generated with this hypothesis, that morphogenesis, pattern formation out of cells in vivo or in vitro, is a collective intelligence. That collective intelligence, it's like all of us, it's made of parts. All intelligence is collective intelligence. It exerts its behavioral competencies in an unusual space, an anatomical amorphous space. It's a nice stepping stone towards understanding really diverse or unconventional intelligences because it's related to us. It's made of the same stuff, so it's not completely alien. Yet it operates on a different scale with different kinds of goal states that it can undertake in anatomical amorphous space. It really significantly stretches our imagination and our ability to generalize from our kind of ancient pre-scientific experience. I think this is a very valuable exercise.

What we're going to look at next is some examples of what kind of collective intelligence cellular swarms deploy. What we're going to see is that it works on a different time scale. Instead of milliseconds in brains, we have to think about minutes and hours. It's a different morph, different problem space. Not three-dimensional motion, but changes in morphospace. Interestingly, same mechanisms, same exact mechanisms as your brain uses to do this. Ion channels, gap junctions, neurotransmitters; we'll talk about that momentarily. Many of the same algorithms, the tools of cognitive science, work great in this field.

Thomas O'Brien developed this amazing tool that you can go to this website called "Field Shift," which automates something that I used to have my students do manually, which is to take a neuroscience paper and just replace words. Every time it says neuron, I make it say cell. Every time it says milliseconds, say minutes. If you do that replacement, generally you have yourself a pretty reasonable developmental biology paper because there is incredibly deep symmetry between the question of where bodies come from and the question of where minds come from.

Let's just look.

Slide 9/46 · 12m:00s

I'm going to take you very briefly through these examples. If you want to see the papers and the underlying data, everything's on our website. We're just going to run one by one through a bunch of well-established components of intelligence. First, goal-directed activity.

Slide 10/46 · 12m:18s

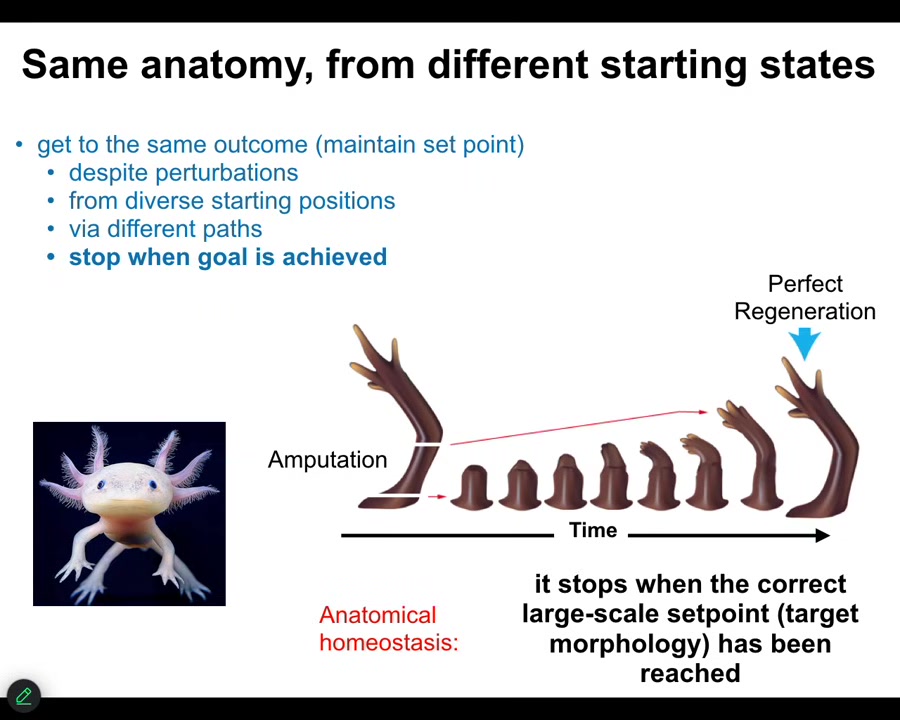

Here's a simple example. Here's an axolotl. We know that it is not simply a matter of feed-forward open-loop emergence, how you get from an egg to an axolotl, because if you amputate the limb, then the cells will very rapidly grow, they will pattern, and then they will stop. The most amazing part is that they know when to stop. When do they stop? They stop when a correct axolotl limb has appeared. And so this is a context-sensitive homeostatic system. You can think about it as trying to keep to the same region of anatomical space, this particular region. If you're deviated from it, you'll do your best to try to get back there. This is not simply a progressive unrolling of a cellular automaton. This is very much context sensitive, and it has a set point. We know it has a set point because we can see it, and if we deviate from that set point, that is the state towards which it will come back.

Another interesting thing about intelligence is not simply that it can reach the same goal every time, but it can do so by different means.

Slide 11/46 · 13m:22s

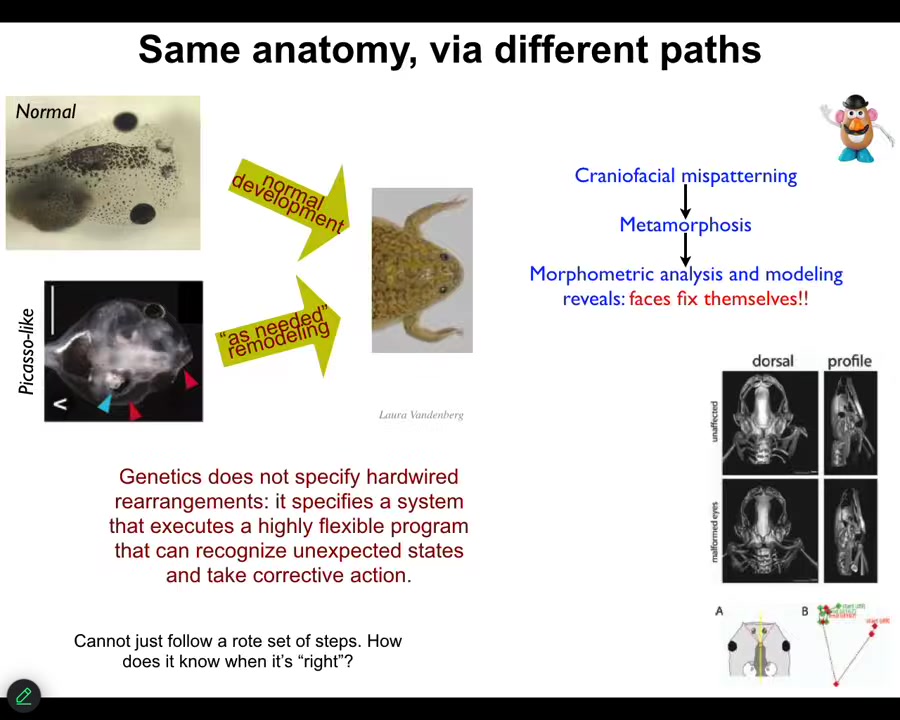

One simple example that I can show you is the transition from tadpoles to frogs. Tadpoles have to rearrange their face. The eyes, the nostrils, the mouth, all of these structures have to rearrange. You get from a tadpole to a frog. That was thought to be a hardwired process. All tadpoles look the same. All frogs look the same. If you do the same motions in the same direction you should get from here to there.

What we created were called Picasso tadpoles. We scrambled the face. The eyes on top of the head, the mouth is off to the side, everything is completely scrambled. What we found is that these creatures make pretty normal frogs because all of these structures don't just go in the same pattern they always go. They move in novel ways. In fact, sometimes going too far, having to come back. They have all kinds of rearrangements to get to the correct final state.

What the genetics gives you is not a hardwired set of movements. It actually specifies a program that executes a flexible ability to recognize unexpected states and take corrective action toward a specific goal. This idea that we're all told in chemistry and cell biology classes—that none of these systems know anything, that cells and tissues just follow hardwired rules and eventually interesting things happen—that's a claim. That shouldn't be an axiom. That should be an empirically testable claim.

The claim is that open-loop emergent models, like cellular automata, are sufficient to explain and harness morphogenesis. It turns out, as a matter of empirical testing, that claim is incorrect. Those are useful models in some cases, but they definitely don't give you everything you need. There are many other kinds of tools in the study of goal-seeking systems—cybernetics, psychology, and so on—that are very useful in our field. You should not think that there's a rule that you have to stick to open-loop kinds of models.

The next thing that's interesting and relevant to what I was just saying has to do with hierarchical non-local control.

Slide 12/46 · 15m:38s

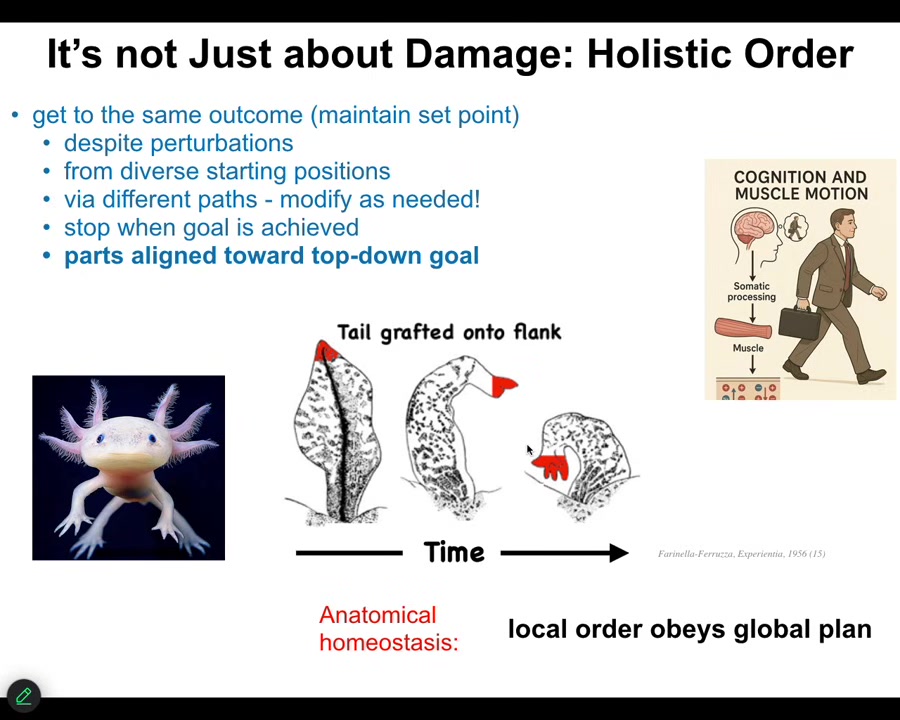

I want to point out this experiment done first in the 1950s, when you take a tail and you graft it to the side of an axolotl or a newt or some other kind of amphibian. What happens then is that over some period of time, this thing metamorphoses into a limb. In other words, the tail turns into a limb structure. It remodels. Now, pay attention to the cells at the tip of the tail. They eventually turn into fingers. Why? There's nothing wrong at the tail. There is no damage. There's nothing wrong here. There are tail tip cells sitting at the end of the tail. Why would these things suddenly start turning into something else? It's because there is a very important top-down control where the parts are aligned towards a goal that they don't know anything about. Individual cells have no idea what a tail is or what fingers are or anything like that, but the collective absolutely does. It does because if you deviate the large-scale form by putting a tail where a limb should go, over time the system will correct to a large-scale target morphology that is more correct. In other words, having a limb here instead of a tail. In doing so, it filters down all of the control signals to change the molecular biology of the cells at the tip of the tail, even though locally there's nothing wrong, to turn them into fingers. While the individual cells have no idea why they're being reprogrammed and remodeled and killed off and so on, to become these fingers, the collective is doing what collectives always do, which is to deform the option space for their parts so that the parts will then do things that are aligned with goals of the large scale in some other space that the parts don't need to know anything about.

Notice the interesting similarity between voluntary motion. Every morning when you wake up, you might have very abstract research goals, social goals, financial goals. But in order for you to act on them, ions have to cross your muscle membranes. This is the essence of mind-matter interaction right here. Your goals and your hopes and dreams and your plans have to eventually be able to make the biochemistry do things in your muscles, right? And your whole body, using the electrical system we're about to talk about, your whole body is a set of transducers that allows that to happen. For the exact same reason that the ions in your muscle membranes dance due to high-level abstract goals in weird spaces that you might have, these molecular events inside these cells are obeying a large-scale anatomical plan.

One other interesting component of intelligence is hackability. That is, intelligent systems generally have software, not just hardware that they're made of, but they actually have software that can be exploited to get them to do things they don't normally do.

Slide 13/46 · 18m:30s

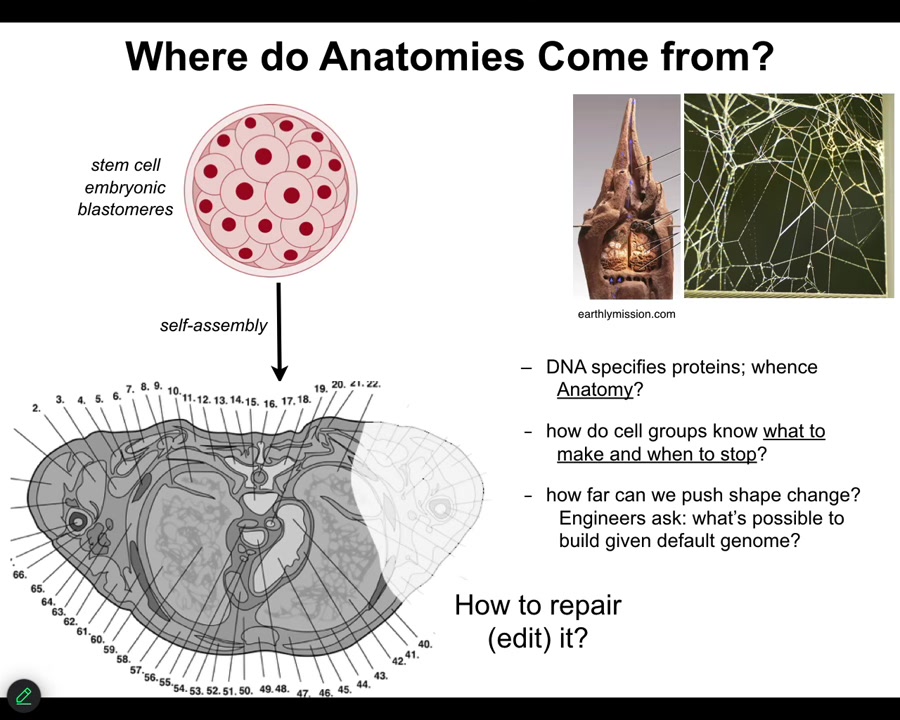

In order to look at that, this is now where we're going to talk about bioelectricity and the interface that my group uses to access the reprogrammability of life. Let's first ask, where do anatomies come from in the first place? Here's a cross-section through a human torso. Lots of amazing complex structures. Where was this pattern specified? Most people immediately will say the genome, of course, it's in the genes, but we can read genomes now. We know that none of this is directly in the genome. What the genome specifies are proteins, the tiny molecular hardware that every cell gets to have, and some timing information around where certain things will be expressed. But this is all the function of the software that's encoded by that molecular hardware. This kind of information isn't in there any more than the structure of termite colonies or the specific structure of spiderwebs is in the genome of those species. We need to understand how this works?

Slide 14/46 · 19m:32s

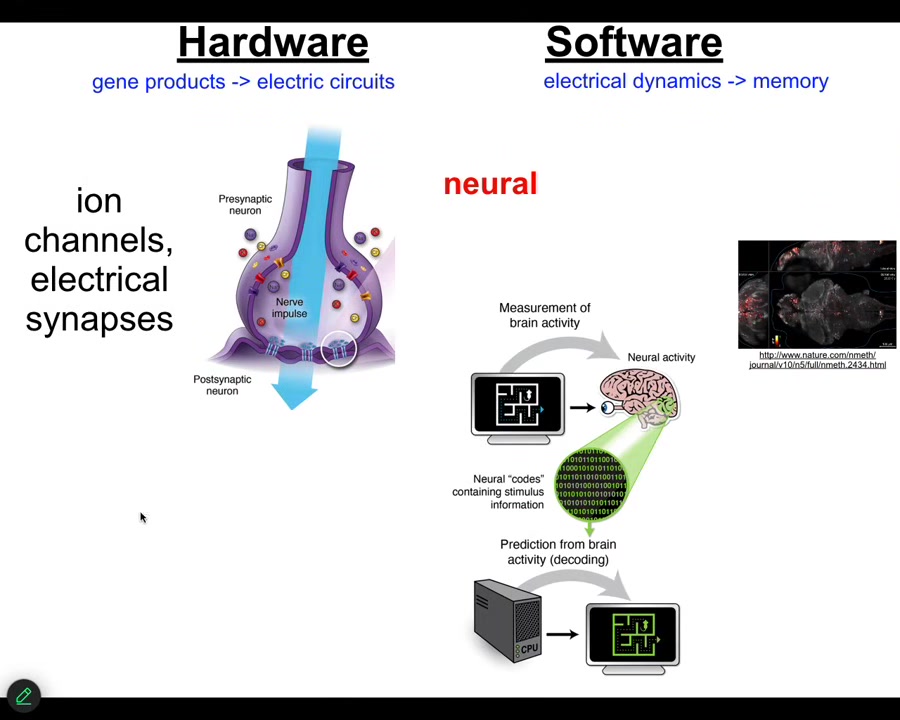

What I'm going to tell you is that it works very similarly as in another system, which is the brain. In the brain, the hardware is made of ion channels. These are proteins that let charged chemicals in and out, calcium, potassium, sodium, chloride. Because of that, it acquires a voltage gradient, and it can pass on that voltage information through electrical synapses to neighbors. The software: this group did this amazing video of a zebrafish brain, of a living zebrafish brain doing whatever it is that fish think about doing. The cognitive content, the memories, the preferences, all of that stuff is encoded in the electrophysiology of this network. So that's the commitment of neuroscience. Neural decoding is this idea that if we were able to read and decode these electrical signals, we would know what the creature is thinking about, what its memories are, and so on.

This is an amazing system, but it turns out that it's incredibly ancient.

Slide 15/46 · 20m:35s

This is not really about nerves and muscles. In fact, I don't think neuroscience is about neurons at all. It's about this kind of cognitive glue, the processes that make us all a collective intelligence. It's why things your individual neurons don't know, because it makes a computational network that can operate in other problem spaces.

Biology discovered this a very long time ago, around the time of bacterial biofilms. Now every cell in your body has ion channels. Most cells have these electrical synapses to their neighbors. We have been running that same kind of decoding program, not in neurons, looking at embryos to ask, what did these electrical networks think about before there was motion such that you could think about positioning yourself in three-dimensional space?

Slide 16/46 · 21m:22s

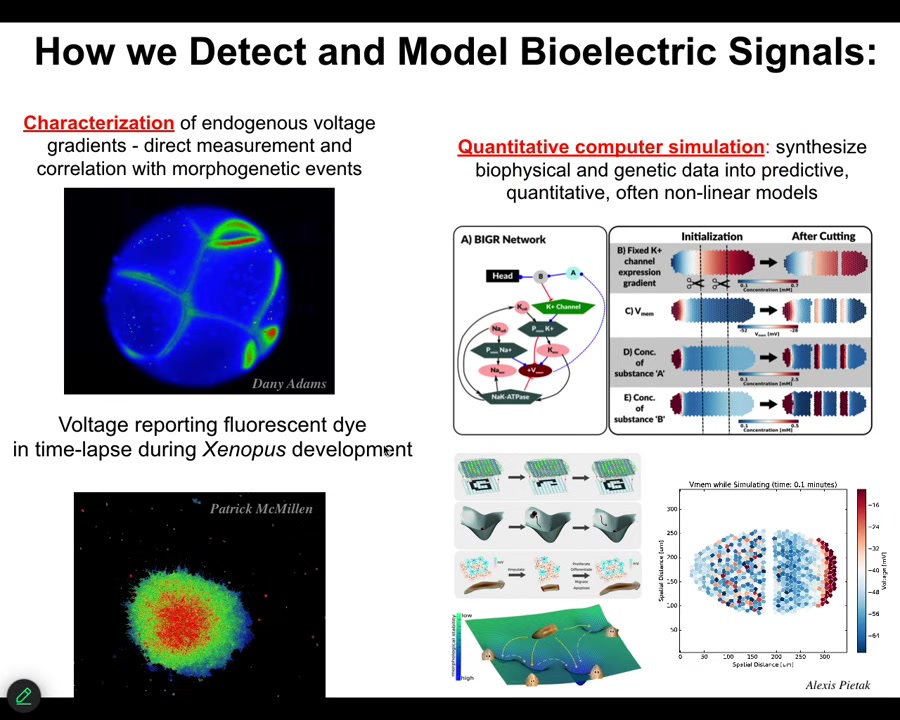

To do that, we developed some tools. Back in 2000, we developed the first molecular tools to read and write electrical information into tissues, into non-neural tissues. We have voltage-sensitive fluorescent dyes, and we can do this in vitro. The colors here reveal voltage. These are not models. These are real data. The colors reveal voltage in this early frog embryo. You can see all the conversations that the cells are having with each other.

Lots of computational tools to try to understand all the way from the molecular networks that express channels up to tissue properties of what happens to these electrical patterns, and then how they do things like pattern completion, AKA regeneration, how they store memories as attractors in these electrical networks. Pattern memories.

Slide 17/46 · 22m:10s

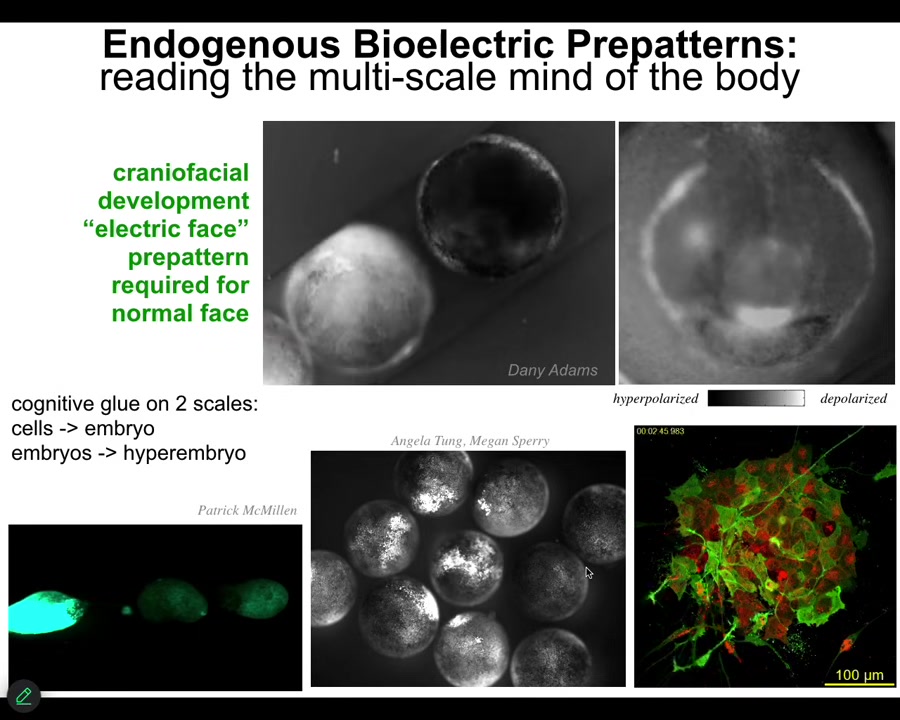

I'll show you just really quickly what they actually look like. This is a video of what we call the electric face, defined by Danny Adams in my group years ago. This is — there's a lot going on here, but here's one frame from that video. You can see there's a bioelectric pre-pattern. Here's where the eye is going to go. Here's the mouth. It's going to be here. The placodes are out there. This is well before the genes come on to pattern the face. And if you change this electrical pattern, the pattern of the face changes. Not only is bioelectricity the memory medium that helps complex structures know what they should look like, it also works to glue individual cells into large-scale structures, but actually across embryos, so multi-scale.

Here's an example. We poke this embryo, and within minutes all of these other guys find out about it. If we poke this one, these two, even though they're not touching, that information spreads. In fact, we now know that groups of embryos form a kind of hyper-embryo that can solve problems better than individuals. Large groups resist teratogens better than small groups. They have unique gene expression. Again, you see this idea of bioelectricity being able to align competent parts into larger-scale systems.

Slide 18/46 · 23m:32s

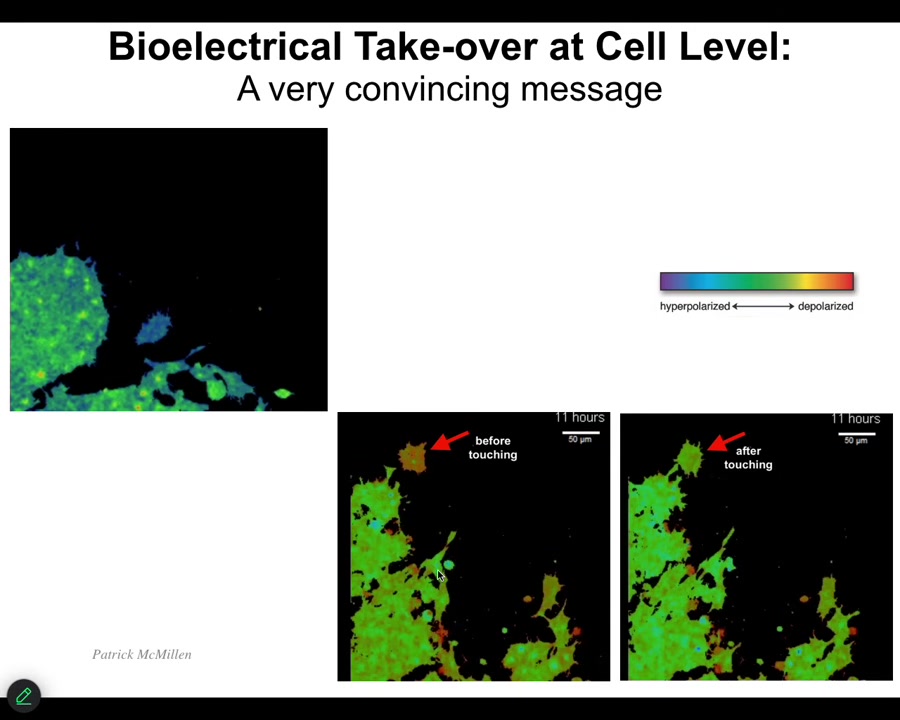

Now we're going to get to this reprogrammability angle. Having seen this and having seen this idea that bioelectricity is how cells normally communicate with each other to make all kinds of patterning decisions, we wanted to try to exploit that. I want to show you one simple example. This is a video which I'll play momentarily. Here are the before and after frames. The color represents voltage. Here it is. You can see this cell before it touches this cell, it has a different voltage than all of these guys. But as soon as it touches, it has the same. Here's the video. It's crawling along, minding its own business. This guy is going to reach out, touch it, bang. That's it. Now it's green like the rest of them. The ability to inject an electrical signal through even an extremely tiny contact like this has the ability to change the cell voltage and change the cell behavior. We wanted to be able to do this as well. We developed tools now.

Slide 19/46 · 24m:25s

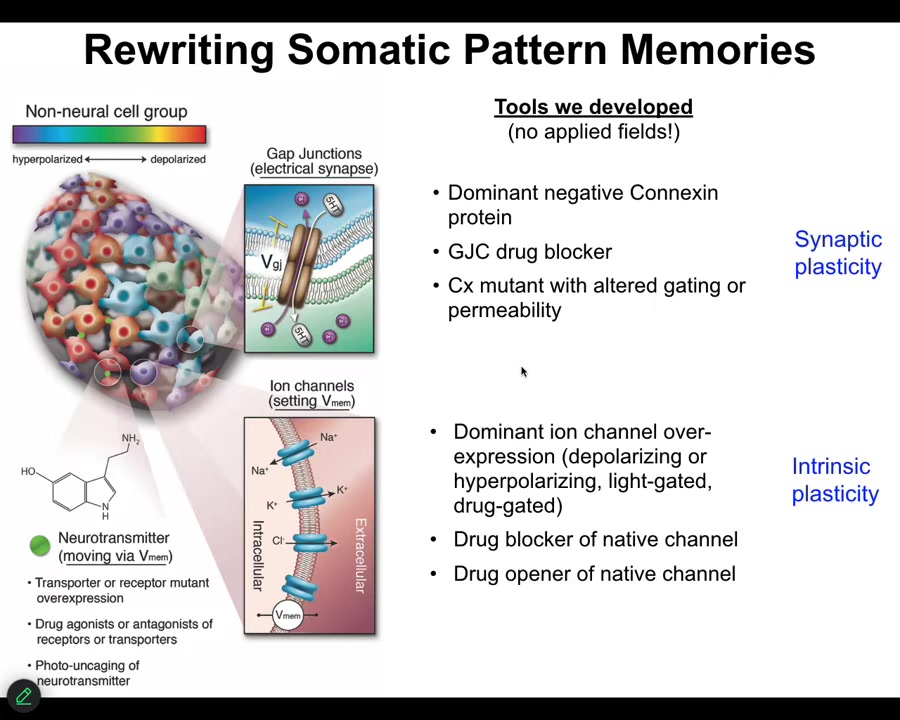

We don't use any electrodes. There are no magnets, no waves, no frequencies. We don't do anything. We use all the tools of neuroscience. We manipulate ion channels and gap junctions. That means neuropharmacology. It means optogenetics. It means being able to mutate these channels and enclose the gap junctions. So we can control the electrical state of these cells and we can control who talks to whom.

Slide 20/46 · 24m:52s

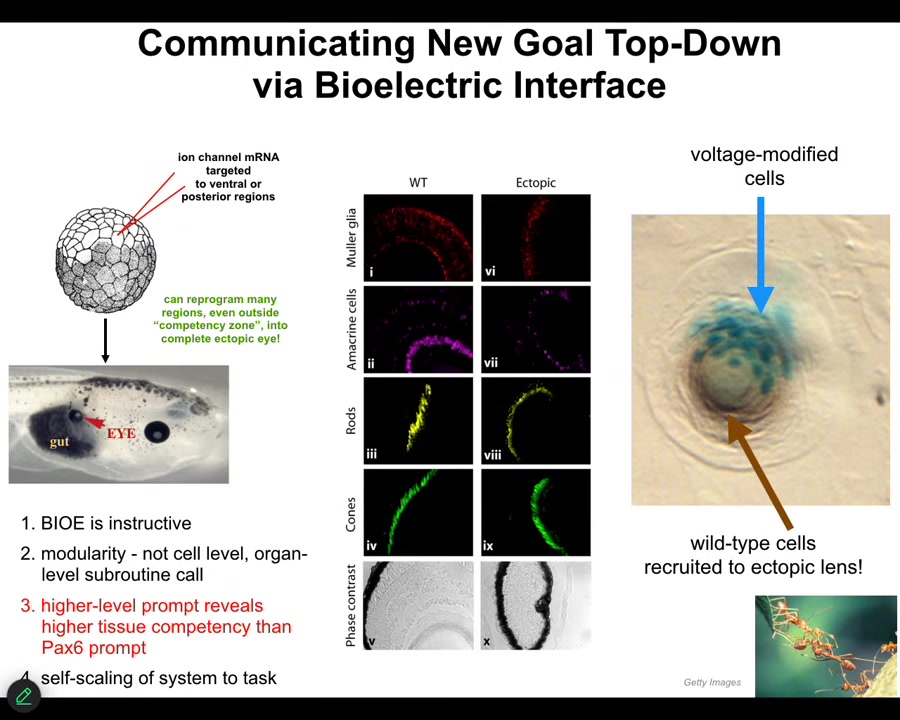

I'll just show you one of many examples, two examples for what this means. Here's the side view of a Xenopus laevis tadpole. Here's the gut. Here's the animal's right eye. Here's the mouth over here. The brain is up here.

If we inject RNA encoding a particular ion channel into cells that are going to become these gut cells, we can set up a little voltage spot that looks just like that eye spot in that electric face that I showed you. What was done here by Viphof Pai and Sherry Au in my group was to inject the ion channel RNA, cause the voltage spot to be there, and the cells interpret it as a "make an eye" signal. Sure enough, they make an eye, and here it is. Those eyes have lens, retina, optic nerve, all the same stuff.

Notice two interesting things. First of all, it's instructive, but it's very modular. In other words, we didn't have to specify how to build an eye. That's the benefit of dealing with an agential material: you don't micromanage it. You give it cues or prompts. We gave a very simple voltage signal that said, "make an eye here." All the downstream stuff, all the regulation of stem cells and morphogenesis, everything was taken care of after that.

Exactly what happens in cognitive systems. When I'm talking to you now, I don't need to worry about putting your synaptic proteins in particular places. You'll do that yourself. I'm just giving you text prompts. That's the joy of communicating with a multi-scale agential material.

In this cross-section through an ectopic lens, the blue cells are the ones we injected, but there's tons of others that are contributing to this morphogenetic process. We didn't have to tell them to do that. We didn't have to warn them that there's not enough injected cells to actually make an eye. They will do that themselves. They recognize that there's not enough. They recruit their neighbors. There's a bunch of back and forth because the neighbors resist, because this is also how tumors can form. The neighbors don't immediately snap into line. But when things go well, and the signal is sufficiently convincing — which is what we want as workers in regenerative medicine — they will do all kinds of other things, like recruit their neighbors and undergo morphogenesis, and so on.

Prompt, not micromanagement.

Slide 21/46 · 27m:12s

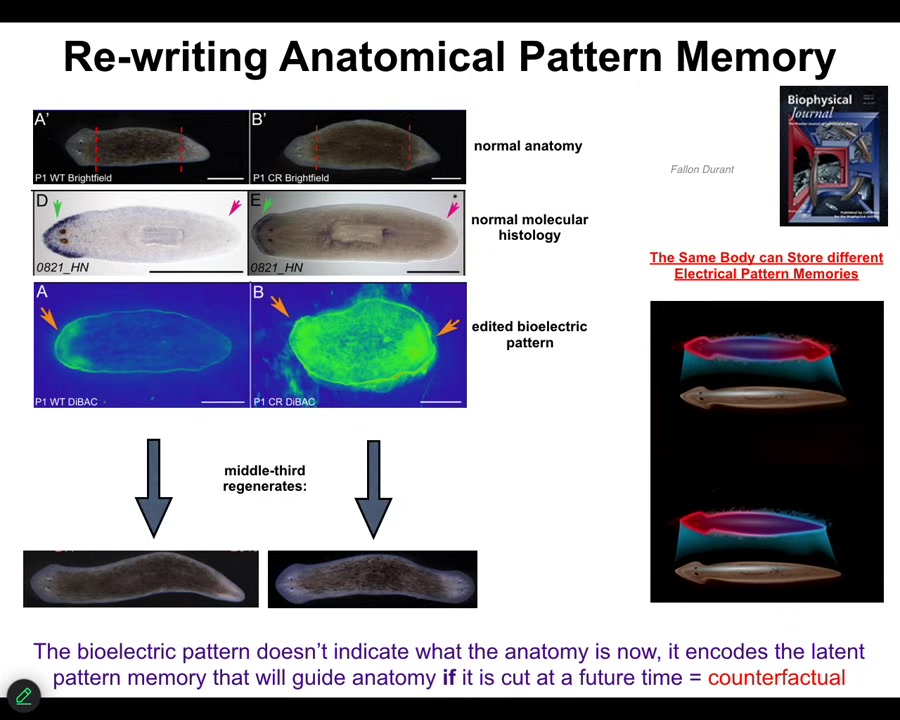

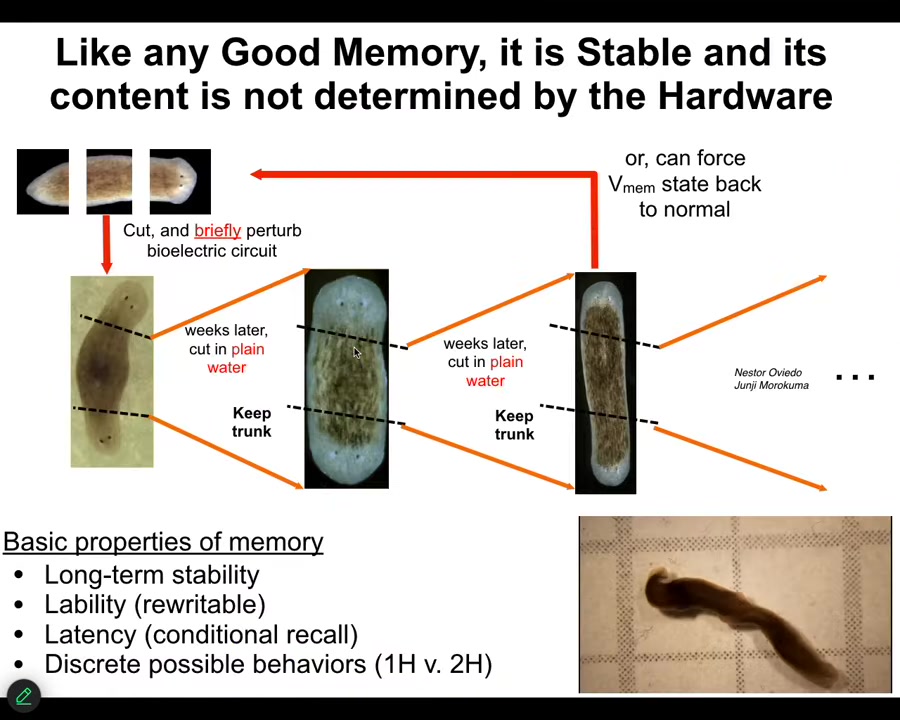

One other example I want to show you is planaria. This is regeneration. Here's what these worms look like, one head, one tail. When you cut them into pieces, every piece reliably makes one head, one tail. Let's look at this middle piece: it reliably makes one head, one tail. You might wonder: How do they know how many heads they're supposed to have? We looked and it turns out that there's this voltage gradient that says one head, one tail. We can take this animal and reprogram the bioelectrics. This is done with drugs, with ionophores and ion channel drugs. We can establish a different state. Two heads.

You can see it's messy. The technology is quite messy still. The anatomy is still quite normal. The molecular biology is still quite normal. The anterior markers are expressed up here, not in the tail. The molecular biology doesn't know anything's happened. The anatomy doesn't know anything that's happened. It's a latent pattern memory.

If you then cut this animal, this is what it does. It will go and make two-headed worms. Then this memory becomes active and it will do what the memory says. One normal planarian body is able to store two different representations of what a correct planarian should look like. That representation is a counterfactual memory. It's not true right now, because I only have one head, but it is what I'm going to do in the future if I get injured.

You can see what's going on here. This is the pattern memory. If you want to know how all these systems know what they should build, they have a bioelectrical encoding that they maintain of what the correct pattern is, and then they will try to reduce error towards that encoding, but it's rewritable.

Slide 22/46 · 28m:55s

The reason I keep calling it a memory is because it is stable, but it's rewritable. And so if I take these two-headed worms and I cut off this ectopic secondary head, it doesn't go back to normal, even though the genetics are completely normal. We haven't touched the genome. It will continue to make two-headed worms because that's where the memory is. It is not genetically specified. What the genetics does specify is a hardware that by default acquires a voltage memory that says one-head, but it's totally changeable. We can change it back. We can take two-headed worms and change them back. Here you can see a video of what they do when they're just hanging out. The question of where the fact that they should have two heads is stored is subtle. The genetics matters because you need to have hardware that's capable of acquiring those states. But after that, it is actually stored in the bioelectrical state and you don't need to change the genome any more than we need to change our genomes when we learn new things in the brain. Not only can you reset this animal to have two heads, you can also ask it to have heads of other species.

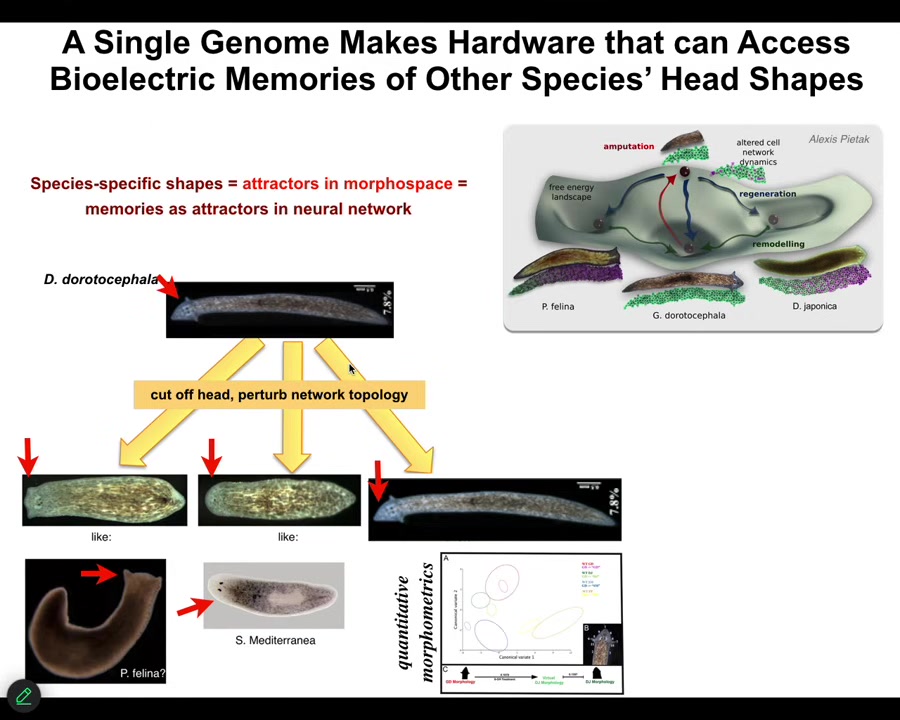

Slide 23/46 · 29m:58s

So we can take this triangular form and we can ask it to make flat heads like a P. falina or round heads like an S. mediterranea by perturbing the bioelectrical pattern memory that encodes which of these attractors in anatomical space they normally go. These other species live in these attractors, but the hardware is perfectly capable of visiting them if you push it in that direction, and the distribution of stem cells and the shape of the brain becomes just like these other species.

There's something between 100 and 150 million years of evolutionary distance between this guy and these actual things, but no problem traversing the amorphous space.

In fact, you can ask them to do much more exotic things, you can go further in that latent space to forms that aren't even flat or planar at all. You can make these spiky things, you can make round cylindrical things, you can make hybrids.

Slide 24/46 · 30m:52s

And plants do this too. This is the only thing I'll say about plants in this talk, but they absolutely have this plasticity. And you can see that the reliability of development is obscuring a lot of important things, because we see these acorns and we know that they reliably make these oak trees, and we think that is what the genome knows how to do. The oak genome knows how to make these oak trees, these oak leaves with a very specific shape.

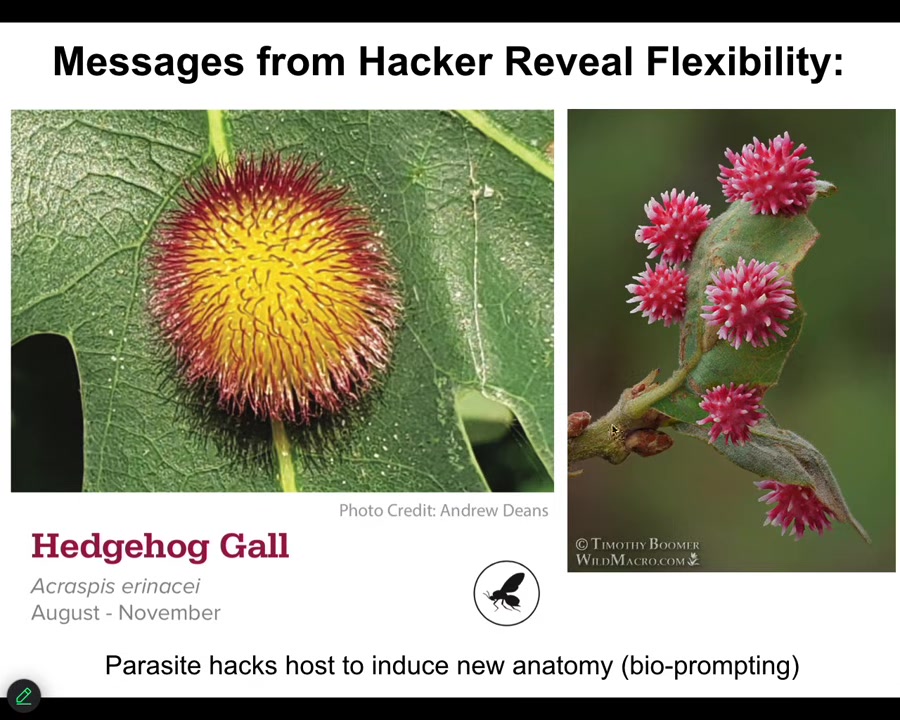

Slide 25/46 · 31m:28s

The reliability of it hides the fact that, if prompted by a good bioengineer, and these wasps are amazing at putting down prompts, that cause the plant cells. They don't build these themselves. The wasp isn't building this. These are plant cells. They make these galls with these incredible structures. We would have no idea that these cells are even capable of doing this. But the plasticity and the other aspects of the morphospace are revealed when you start probing it. Bioelectricity is how we do that.

Just the last couple of things I want to show you, learning.

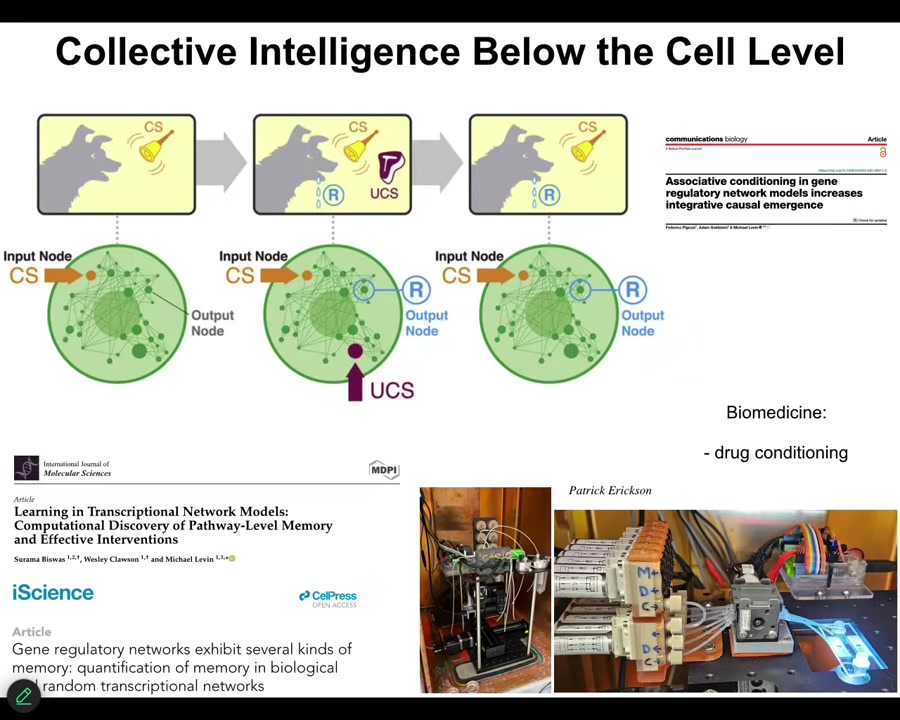

Slide 26/46 · 32m:02s

Even molecular networks inside of cells are capable of six different kinds of learning. Association, associative conditioning, habituation, sensitization, just from the network itself. You don't need special proteins for this. It's just the properties of all kinds of networks that do this. We're taking advantage of this for drug conditioning and other applications. Large-scale memory.

Slide 27/46 · 32m:30s

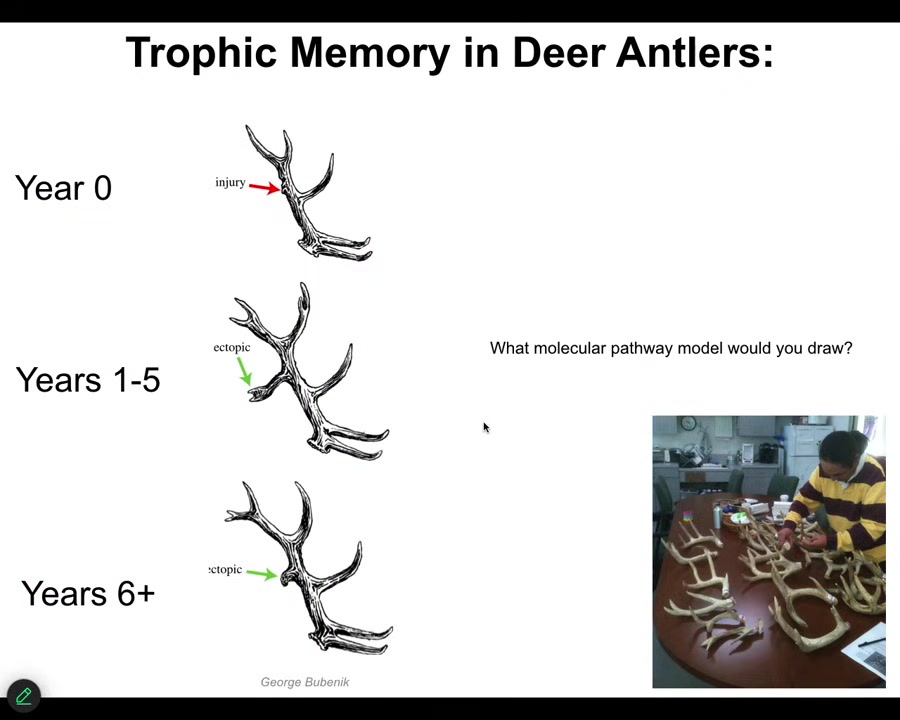

This is an amazing phenomenon called trophic memory in deer antlers. This was discovered by Bubenik: in one year, if you make an injury, you get a little callous, and then this whole thing falls off. Next year they grow a new rack, but it has an ectopic tine at the location of last year's injury.

The system has to remember where the damage was, store the information in the stem cells, and then when it rebuilds the bony structure, take a detour in that same location. Try to think about what molecular pathway model you could possibly draw for something like this. These are the kinds of arrow diagrams that we have in all our cell biology papers. It's incredible. We don't have good tools yet for dealing with things like this. There are aspects of creative problem solving. Sometimes you can't get to the goal, the target state, by your normal means.

Slide 28/46 · 33m:25s

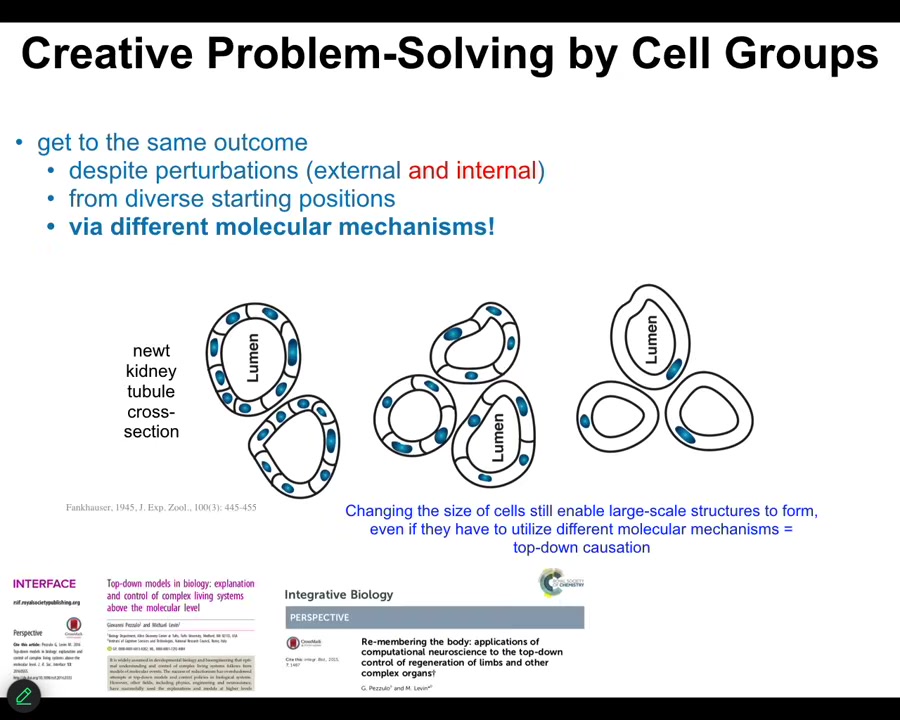

This is the kind of example where if a kidney tubule is normally built by a large number of small cells working together, if you make the cells gigantic, no problem, it will reduce the number of cells, but eventually one single cell will bend around itself and still give you that same large scale structure, different molecular mechanisms.

This is cell-to-cell communication. This is cytoskeletal bending. Use the tools you have to solve the problem in a novel circumstance. My cells are too big. I have tools that I can use to get here. That's the component of every IQ test.

We use these kinds of insights to address birth defects.

Slide 29/46 · 34m:02s

Here's a really severe brain defect in a tadpole caused by a mutation of the Notch gene. But we have a computational platform that told us how to give them the appropriate bioelectrical pattern memories to get them to rebuild a correct brain, even though the Notch gene is still mutated. Some hardware defects are fixable in software; if you understand the pattern that is here and what the cells are doing, you can then ask them to build new structures, very complex structures, without micromanagement.

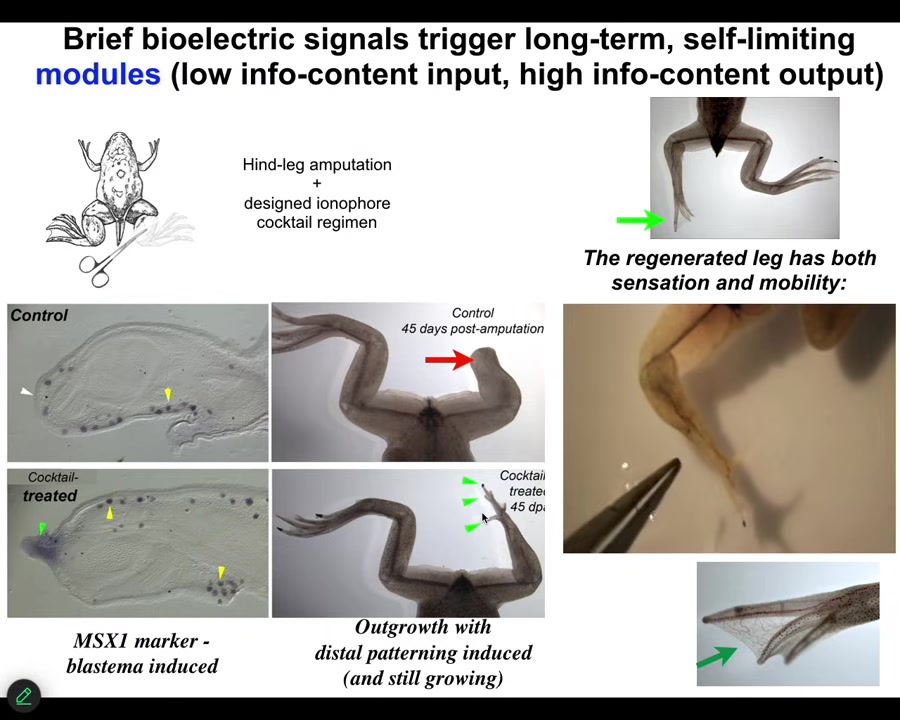

In the same vein, we have a program on regeneration. Frogs, unlike axolotls, do not regenerate their legs.

Slide 30/46 · 34m:48s

But what we were able to do is to provide a bioreactor with a bioelectric payload that triggers pro-regenerative genes and growth cascades. By 45 days, you've got some toes, you've got a toenail here. Eventually, a pretty respectable leg.

Our intervention is 24 hours. After that, the legs can grow for a year and a half, and we don't touch it during that time. That's because we're not trying to micromanage cell or molecular events. We're trying to signal to the system to commit it to the leg building path instead of the scarring path at the beginning.

Slide 31/46 · 35m:20s

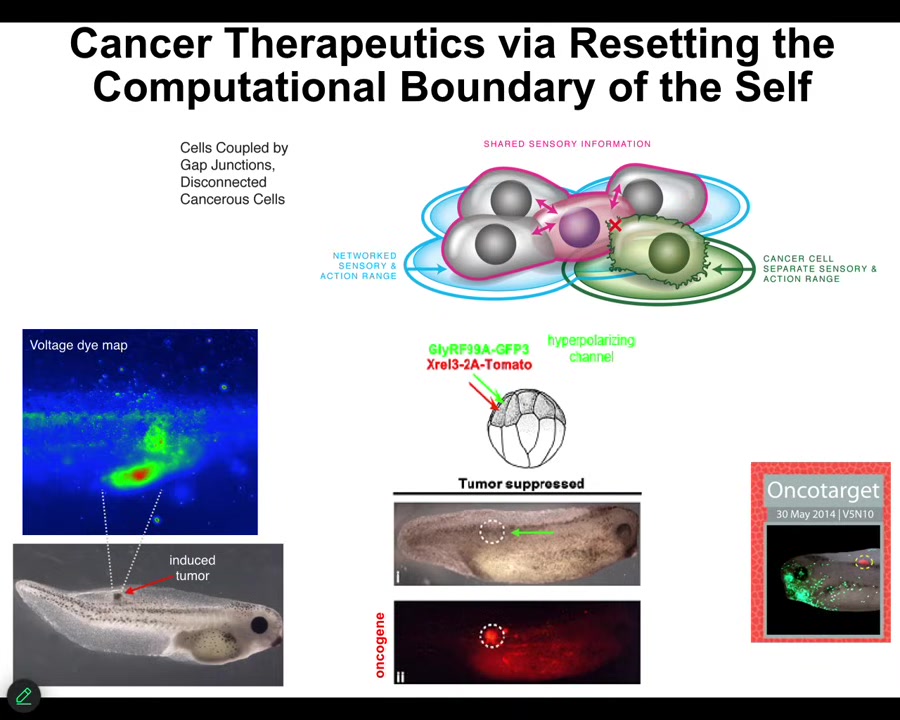

The final thing I'll show you is this: our work on cancer. The idea is that when cells disconnect electrically from these pattern memories, they roll back to their evolutionary precursors and they become like unicellular creatures. The rest of the body is just external environment to them. They go where they want, they reproduce as much as they want, and we can detect this non-invasively with the bioelectrical imaging. You can see before that's going to happen, and if you artificially force them to remain in connection with the other cells, you don't fix the oncogene, you don't kill the cells, no chemotherapy, but you control the bioelectrics, then even though the oncoprotein is blazingly expressed here — it's all over the place — this is the same animal. There's no tumor. And that's because the outcome is not directly a matter of the genetics. The outcome is a matter of the physiological decision-making that happens.

Slide 32/46 · 36m:10s

The final thing I want to show you is this notion of novel beings. Everything that I've shown you so far is creating evolutionarily provided structures. Normal frog eyes, normal frog legs, frog brains, all of that. What happens when we move to novelty?

Slide 33/46 · 36m:32s

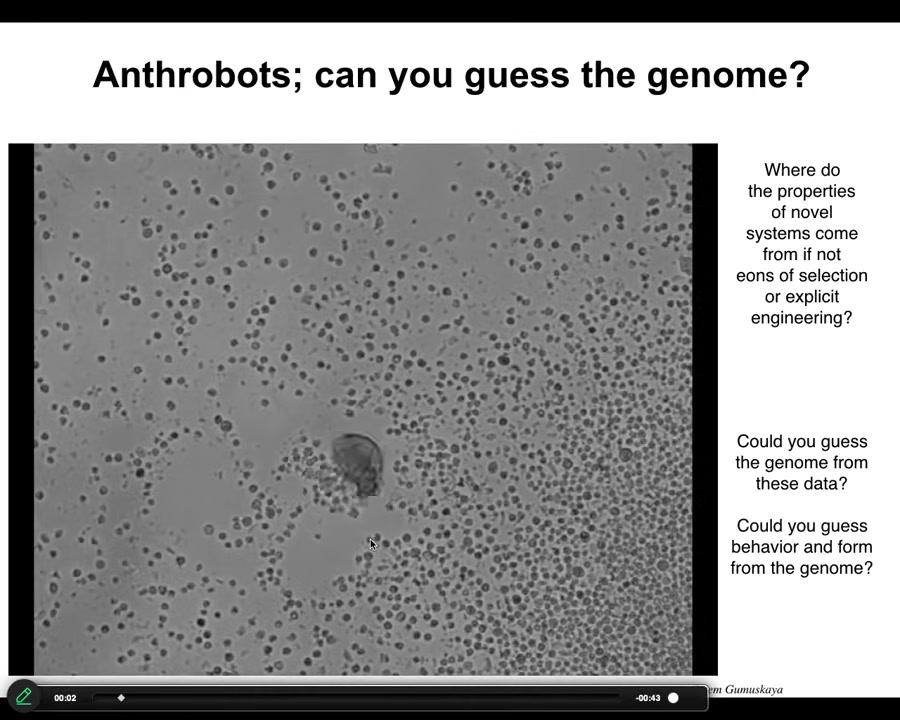

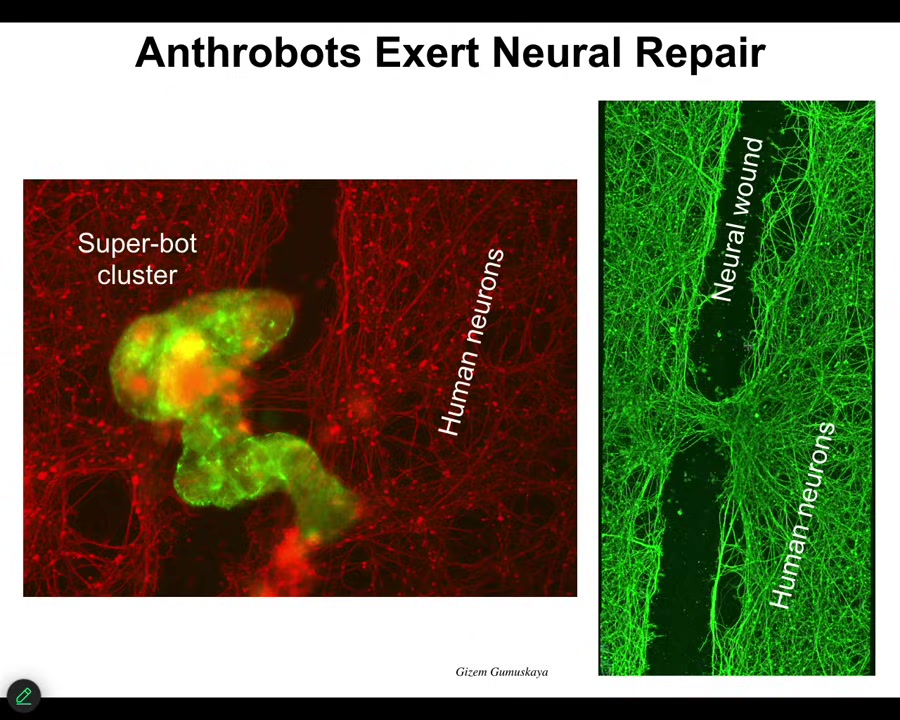

This little creature, which looks like something I might have found in a pond or a lake somewhere, if you were to sequence the genome, you would see 100% Homo sapiens. We call these anthrobots. We allow them to self-assemble from adult, not embryonic, human tracheal epithelia. They put themselves together into this little motile creature. It has all kinds of interesting capabilities.

Slide 34/46 · 36m:55s

For example, if you put them down on a bed of human neurons that you've put a big scratch through with a scalpel, they will assemble into this kind of superbot cluster and they will start to knit together the gap. This is what it looks like when you lift them up. They start to repair. Who would have thought that your tracheal cells, which sit there quietly in your airway, have the ability to be a self-multi-little creature?

Slide 35/46 · 37m:15s

They look like this with the little cilia on top. They swim around. They have over 9,000 differentially expressed genes; their transcriptome is about half the genome. We didn't touch the genome. They have exactly the same unedited human genome. There are no synthetic circuits, no transgenes, no weird nanomaterials. What they do have is a different lifestyle. This is releasing native plasticity, and they have four discrete behaviors that they can transition through.

Slide 36/46 · 37m:50s

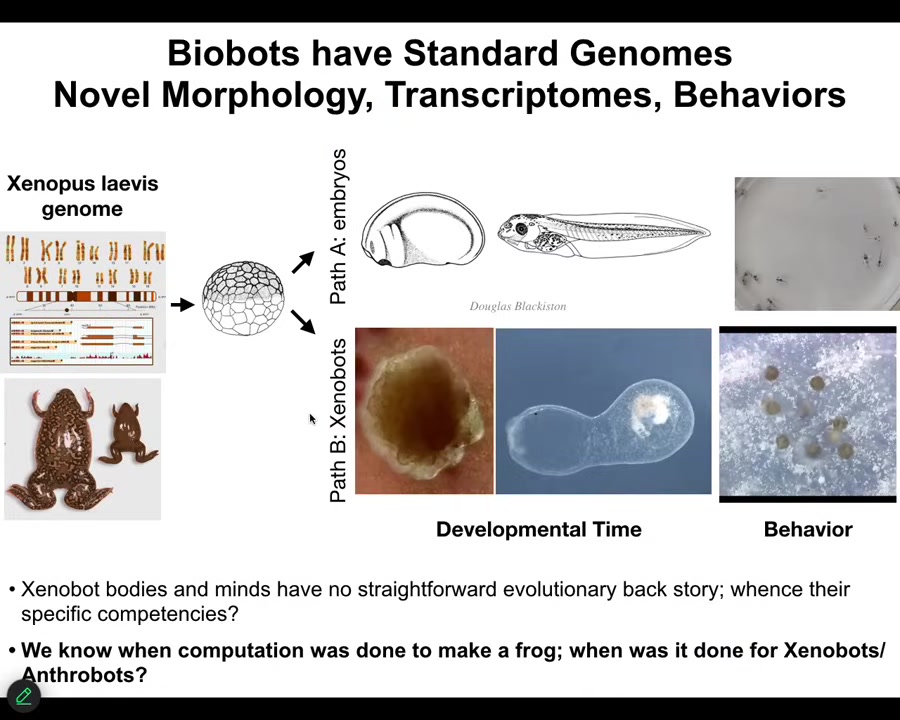

The one thing I didn't show you is Xenobots, a similar idea made from frog epithelia. The question I want to ask is this: Xenobots and Anthrobots have no straightforward evolutionary backstory. There have never been any Xenobots or Anthrobots. No Anthrobot has ever been selected for the ability to swim or to repair neural defects or any of the other things it's doing. Where do their properties come from? If it's not from a story about past selection forces, where does it come from? We know the computational cost to design a human or a frog was paid in the eons of the genome bashing against the environment and being selected. When did we pay the computational cost to make good Xenobots and Anthrobots?

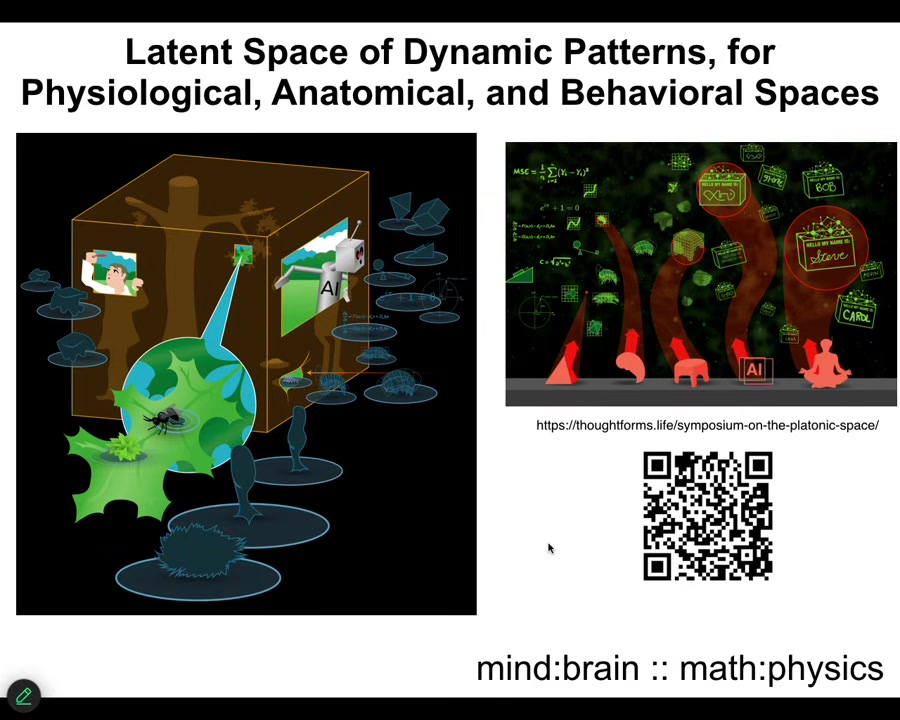

Slide 37/46 · 38m:35s

I don't have time to go into it except to point out that there's some exciting work from a number of people, and you can see all this at our symposium. This is an asynchronous symposium on the platonic space with the idea that the latent space of mathematics provides some very important information that impinges not only on physics, but also on developmental biology and on cognitive science. There are some interesting things to be said about the mind-brain relationship, and I encourage you to come and check that out.

Slide 38/46 · 39m:02s

The very final thing I'll point out is our efforts to breach the two areas that I was talking about today. I was talking about the plasticity of life itself and the development of cognition in minimal media and our tools to study that. What tools and apparatus do we have to explore that space?

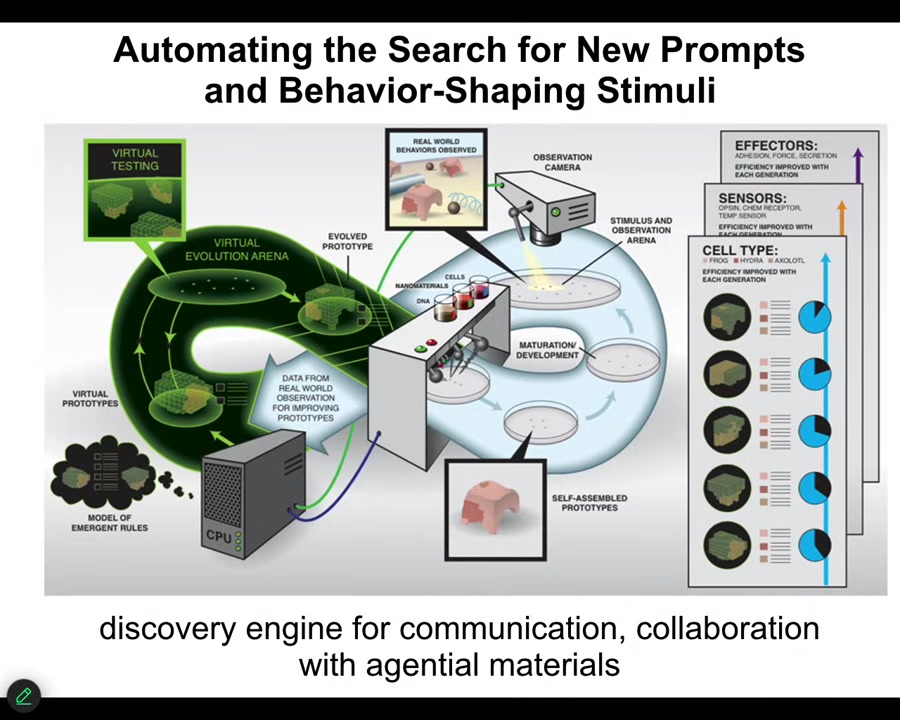

Slide 39/46 · 39m:30s

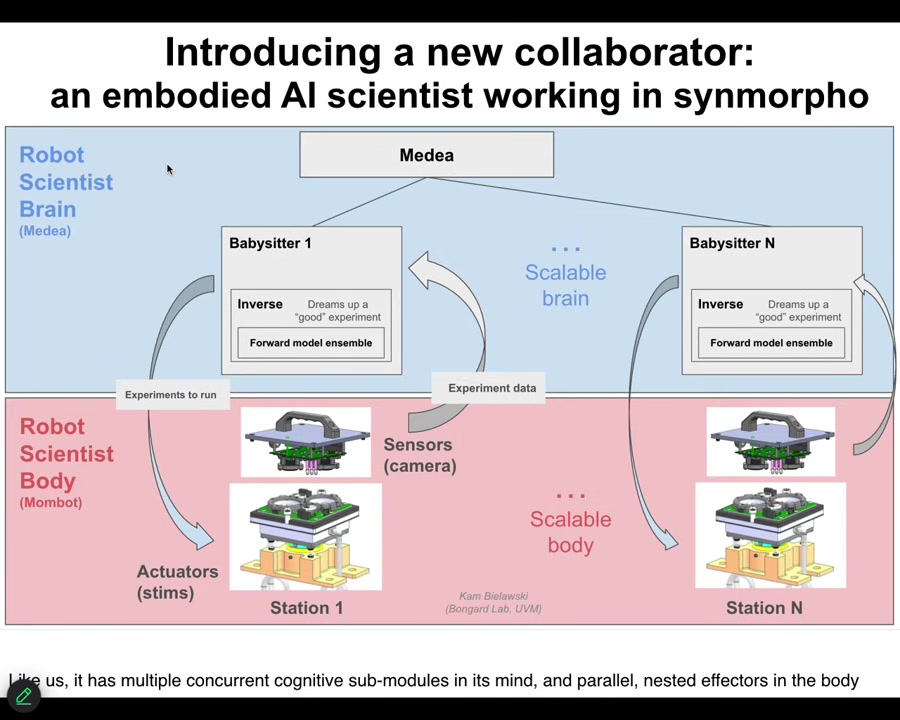

I want to merge those two categories and show you our latest piece of engineering, which is a robot scientist platform that makes hypotheses about the kinds of signals that have to be given to cells to get them to do whatever. So it makes hypotheses about anatomical amorphous space. It then carries out the experiments, observes what happened, learns and changes its hypotheses, and so it does this loop. So the idea is for it to learn to make Xenobots, anthrobots, and all kinds of synthetic bioengineered constructs to specific goals. We've had this diagram as a hopeful vision of what we want for the longest time. But what I can tell you is that we've got the thing running in our lab.

What it's doing is it's exploring the space of prompts for cellular collectives because it has components by which it can produce chemical stimuli, electrical stimuli, temperature stimuli, vibration, other ways to communicate with the material. It has both a brain and a body.

Slide 40/46 · 40m:32s

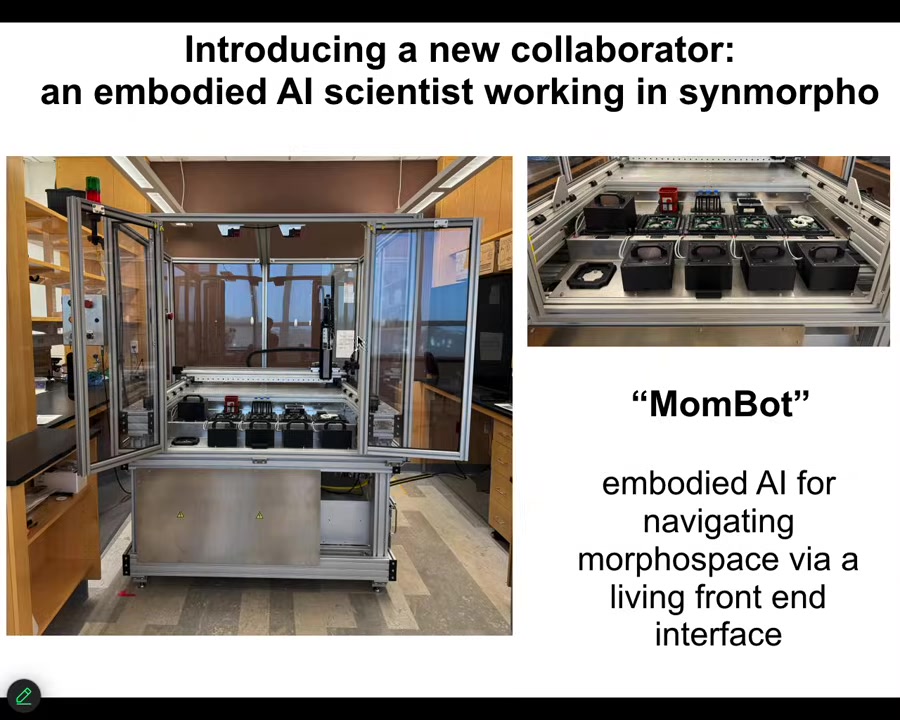

The brain is a set of AI agents that try to compete for better ways to understand that space. Then it carries out experiments. This is what the thing actually looks like standing in our lab.

Slide 41/46 · 40m:45s

It's only been operational for a few weeks. These are very early days. This is an extremely early version of this. This is, to my knowledge, the first robot scientist that operates in morphospace. It's not doing experiments on metabolism. It's building new biological structures by exploring that space.

It is in fact an embodied AI. The AI has a body. It doesn't move through a three-dimensional space. This thing sits still. What it does is navigate morphospace. It navigates the space of anatomical possibilities via a living front-end interface, in this case, frog cells.

Slide 42/46 · 41m:22s

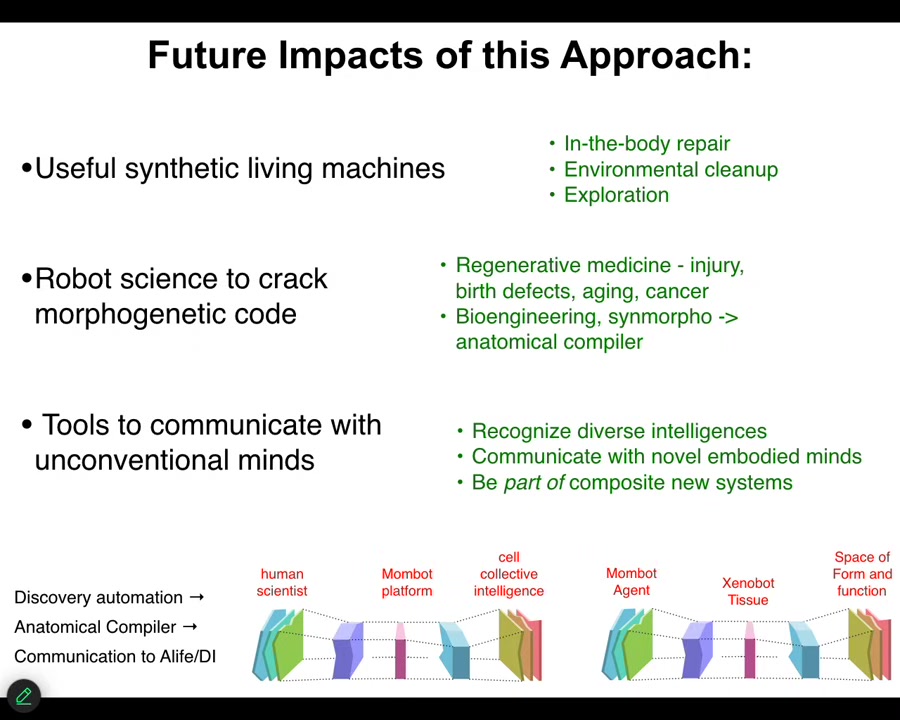

The future impacts are, first, the obvious thing. Useful synthetic living machines. If we can get that cycle of discovery sped up, that means we can do in-the-body repair with anthrobots made of your own cells, environmental cleanup, perhaps with xenobots, exploration of maybe space and so on.

Going one step deeper, this is a robot scientist that can help us crack the morphogenetic code. If we understand how to communicate new goals to groups of cells, that leads to new regenerative medicine of all kinds of interesting applications, and of course, bioengineering towards the notion of an anatomical compiler that is arbitrary, being able to specify arbitrary forms. We're hoping that the next generation of this kind of system will help discover that.

But even going one step deeper and weirder is this idea that this really is a tool to communicate with unconventional minds. You can think about it two ways. You can think about it as a tool where the human scientist, through this MomBot interface, can actually interface to the collective intelligence of cells. We specify our goal states. The MomBot figures out what stimuli those have to be and gets them to execute exactly as your high-level cognitive processes issue commands that eventually, through your body, have to get molecules to act in your muscle cells so you can carry them out.

But another way of thinking about it, and I think these are both useful, is that the MomBot is the active agent. The frog tissue is the translator interface. What it's exploring is the space of possible forms and functions. There are different perspectives on this. You can take the perspective of different parts of the system.

Slide 43/46 · 43m:12s

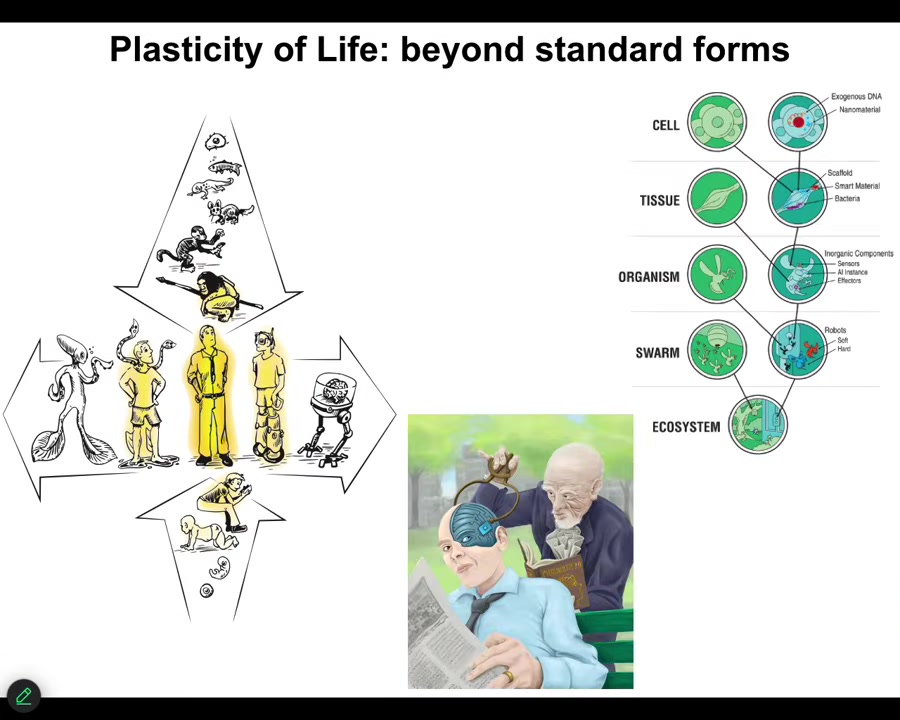

And I think all of these are important because in the future, it isn't only language models and standard AIs that you have to think about. This kind of plasticity, the fact that we are all going to change both biologically and technologically, slowly and gradually, because life is interoperable: every layer can be interacted with synthetic engineered components. Eventually, this is going to be your neighbor. It's not going to be as easy as, I'm a real biological, and this is just a machine. It's a language model. I think we're different. This is what we're going to be talking about: really stretching the notion of what an active agent is, and the fact that you do or do not have components that were evolved by trial and error over millions of years, or components that were designed by engineers. Those things are going to mix in a way that makes ancient categories completely irrelevant.

Slide 44/46 · 44m:05s

And so this is the space of possible embodied minds. Any living material, engineered material, software, and patterns from that platonic space is some embodied agent. So cyborgs and hybrots and chimeras of all kinds, this is Darwin's endless forms most beautiful, all the variety of life on Earth, tiny little corner of the space. These things already exist to some extent. We will be living with all of them. And we have to learn to understand beings that are not like us so that we can enter an ethical synth biosis with these beings. And this is why developmental biology and bioengineering is so critical. It's not just the useful living machines, it's not just evolution that we learn to understand, but we actually can use that as a model system to start to communicate with minds that are not like ours.

Slide 45/46 · 44m:55s

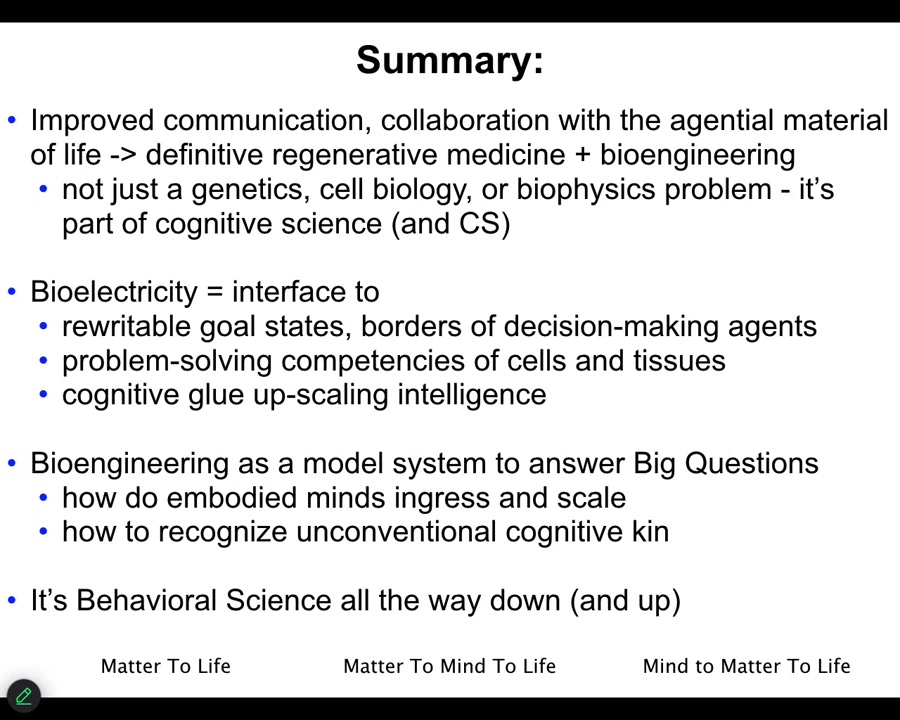

I'll end here by saying that improved communication, not micromanagement, but collaboration with living matter is going to lead to definitive regenerative medicine and bioengineering.

Everything that you're working on is not just a genetic cell biology or biophysics problem. It's part of cognitive science and computer science and vice versa.

Bioelectricity is a convenient interface to that collective intelligence, but only because evolution loves it. It's not magic by itself and there are other kinds of cognitive glue as well.

Bioengineering is an amazing model system for really big questions. How do embodied minds ingress into the physical world? How do they scale and transform? How can we recognize unconventional minds that are all around us?

The basic diagram of the different sciences is wrong: it's really behavioral science all the way down and all the way up. We can think about different ways to think about it.

Matter to life, yes, but also matter to mind first and then life. We can talk about that if anybody has questions.

I think cognition is wider; it doesn't come late in life. It's a much earlier and larger-scale phenomenon, and only a subset of that is life.

Then we can even go further. That's it.

Slide 46/46 · 46m:10s

Thank the postdocs and the grad students who did all the work, and Josh's team that did all the coding for the Mombot, and the team in Boston Engineering who built the thing for us.

Disclosures: there are three companies that have licensed some of the work that I've shown you today and that provide sponsored research agreements.

Thank you so much for listening.