Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a ~58 minute talk titled "The Embodied Mind of a New Robot Scientist: symmetries between AI and bioengineering the agential material of life and their impact on technology and on our future" which I gave as a closing Keynote to the ALIFE conference in Japan (https://2025.alife.org/). This is a different talk than any I've done before, in that besides going over the remarkable capacities of living material, I discuss 1) the symmetries between how all agents navigate their world and how science discoveries are made, and 2) a new robot scientist platform that we have created. With respect to the latter, I discuss how the body and mind of this new embodied AI can serve as a translation and integration layer between human scientists and living matter such as the cells which make up Xenobots.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Introduction and cognitive spectrum

(10:11) Agential materials and plasticity

(23:00) Bioelectric anatomical intelligence

(32:13) Xenobots and Anthrobots

(44:56) Mombot embodied discovery engine

(51:22) Future directions and synthesis

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/44 · 00m:00s

Incredibly pleased to be here to share some ideas with you. The A-Life community in general is one of my favorite audiences. I think the A-Life mindset is probably the most likely to make the transformative advances that we need in a number of areas that I'll touch on today. Unfortunately, I can't be there in person, and I'm going to talk about a robot building robots. I thought it would make the most sense to actually give the talk through a robot, which is my telepresence there today.

I'm going to talk about three things in this presentation. First of all, I want to discuss the symmetry between what active agents do in living their embodied life in the world and the way we do science and discovery. The second thing I would like to do is show you some special features of the biological material. In A-Life, we often try to draw inspiration from living things, but there are many properties that are generally not covered in courses on biology, or you may not have heard of. I want to show you what's actually very special about the material of life that we are trying to understand.

Towards the end, I want to introduce you to a new colleague, a synthetic embodied mind that is going to make some very important discoveries together with us in fields that are of interest to all of us.

Slide 2/44 · 01m:19s

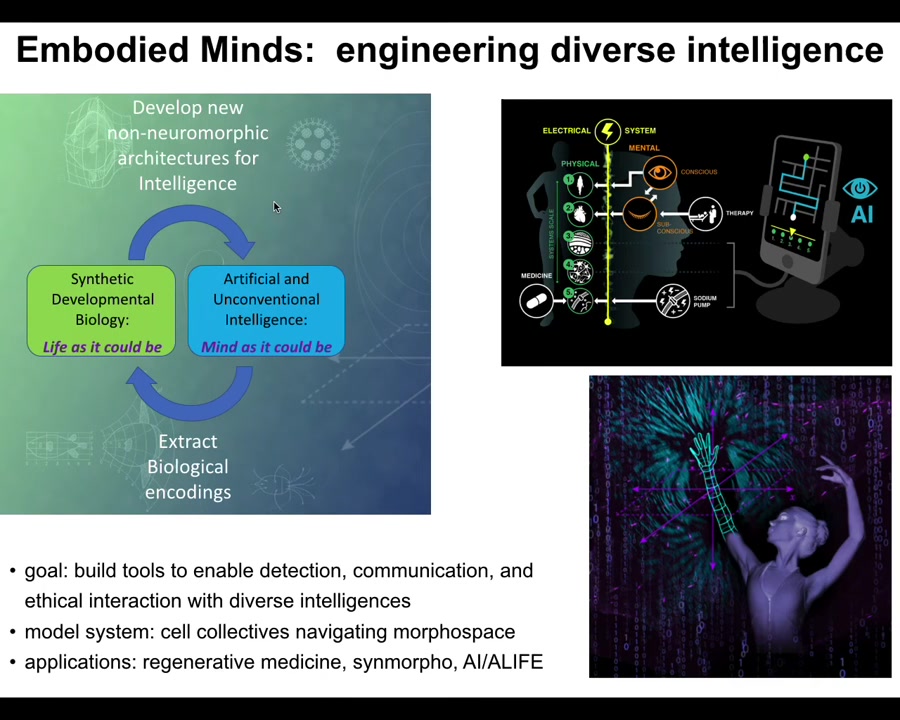

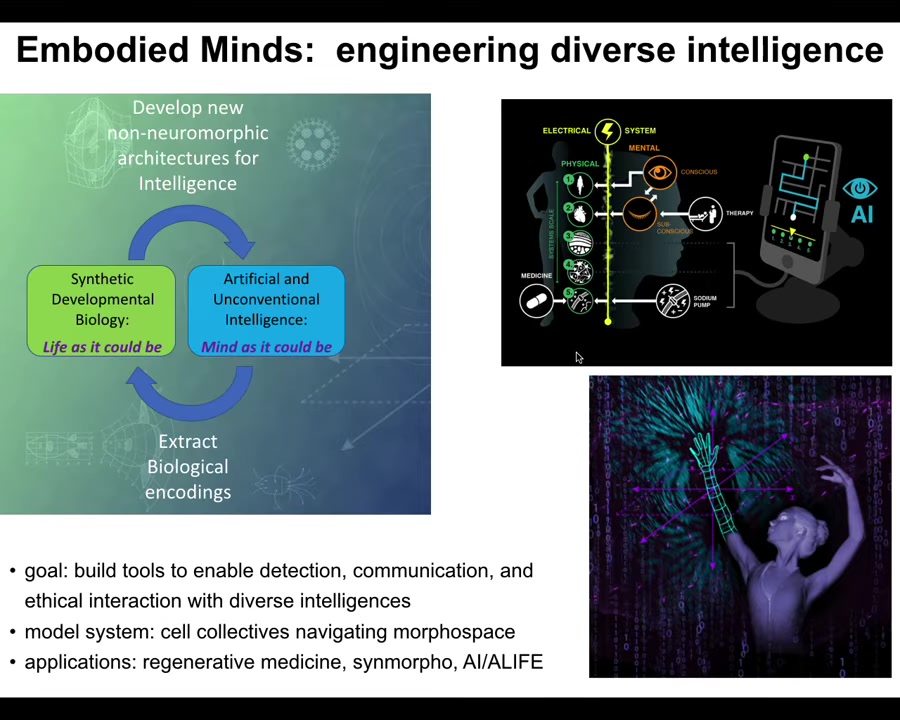

In my group, what we try to do is a cycle that goes back and forth between life as it could be and mind as it could be. I'm sure you'll recognize this and the relevance of this to Alife. The idea is that we try to use computational tools to understand what life is actually doing.

We also try to develop the ways that we exploit biology in order to learn about ourselves and learn about the world. Our goal is to do several things: to build tools to enable the detection, communication, and ethical interaction with diverse intelligences, minds that I think are all around us.

As a model system, one thing we use is collectives of cells or groups of cells navigating the space of anatomical possibilities. We try to communicate with all of the layers of the body, so down from the molecular networks all the way up through the tissues, organs, and ultimately the entire organism. We develop applications in regenerative medicine, synthetic morphology, and bio-inspired AI.

Slide 3/44 · 02m:54s

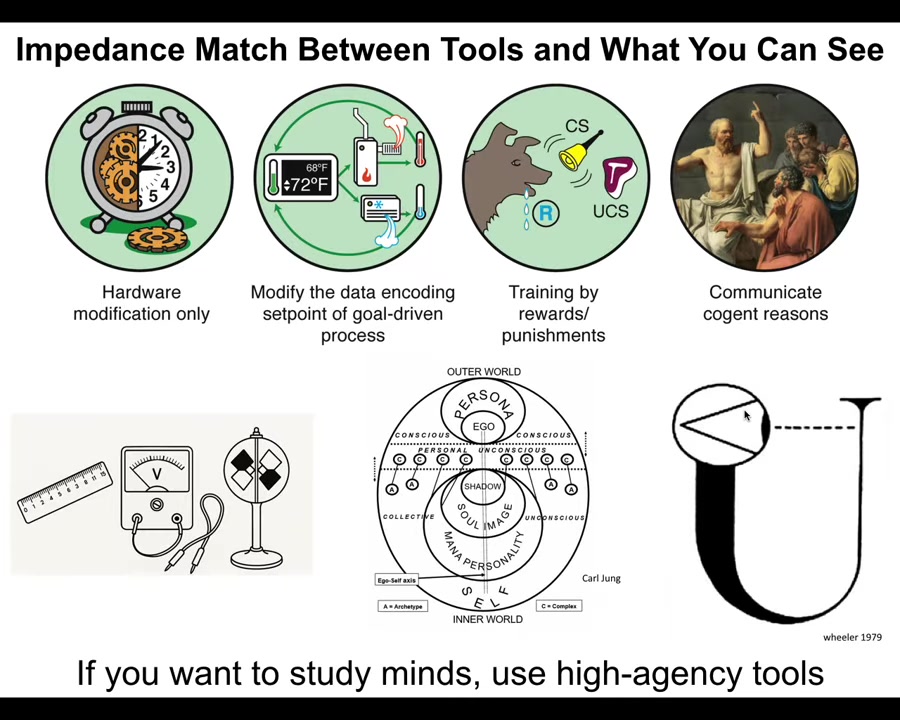

The first thing that I want to mention is that there's this curious, but very important need for an impedance match between the tools you use and what you can see. Across this whole spectrum of cognition, all the way from so-called just physics and so simple machines, all the way up through the kinds of things that are addressable by cybernetics and control theory and behavioral science and then psychoanalysis and love and things like that, all across the spectrum, where agents land on this is not obvious at all. This is important for us to develop a science of this, to try to understand where any particular system is on this. You want me to start from the beginning? That's okay. No problem. Just one second.

Slide 4/44 · 03m:58s

Because at one point I was hearing my own voice through the earphone, which was very distracting. I hope that's working.

Thank you all very much for allowing me to share some ideas with you. I'm really happy to be here, even if not in person. Because A-Life is perhaps my favorite kind of audience, I think that the A-Life mindset is really unique and very uniquely and powerfully positioned to make advances in many areas that are important for humanity and beyond. Unfortunately, I can't be there in person today.

Since I am going to be talking about a robot that helps us build biological robots, I thought it would be appropriate to try to give this talk through a robot. So there's my avatar for today.

I want to talk about three things in particular. I want to describe the symmetry between what it is to be an active agent navigating the world and the way that we do science and the way that we learn about the world around us. I think these things are fundamentally very similar.

Then I want to go over some of the special capabilities of the biological material. In A-Life, we are often trying to take inspiration from living matter. There are aspects of biology that you may not have seen before because they don't feature prominently in typical discussions of advances in biology.

Towards the end, I want to introduce you to a new kind of embodied mind, a new colleague in the field of synthetic morphoengineering, a synthetic robot scientist with whom we are collaborating to hopefully make some important discoveries. So those are the three things I would like to show you today.

Slide 5/44 · 05m:47s

In my group, we try to do this kind of a cycle that goes back and forth between understanding life as it could be and understanding mind as it could be. We're interested in understanding how embodied minds exist in a physical universe. We try to use computational tools to understand what the biology is doing at a fundamental level, abstracted from the contingencies of its current implementation. We're very interested in what the study of life has to tell us about the kinds of minds that can be made by computational and other means.

In my group, we use AI and other tools to try to communicate with all of the layers of the biological system, so all the way up from molecular networks to cells, tissues, organs, and the organism itself. We have several goals. We spend a lot of time trying to build tools to enable us to detect, communicate with, and have ethical interactions with a very wide range of diverse intelligences that I believe already exist all around us, but there will be many more to come.

As a model system to try to shape and improve our intuitions and our tools, we use collectives of cells, groups of living cells navigating the space of anatomical possibilities. We have other models, but this is a prime workhorse to try to understand a very unconventional mind that works at a different scale in a different space.

The applications of this kind of work range across regenerative medicine, birth defects, injury, cancer, and aging. So we develop those kinds of things, as well as applications in synthetic morphology and AI and ALife.

Slide 6/44 · 07m:30s

The first thing that I want to discuss is what I think is a very interesting aspect of how to do discovery and how to navigate one's world. There is a spectrum of cognition all the way from simple machines with whom you can only interact by modifying the hardware, rewiring, and then all the way up through systems that are amenable to the tools of cybernetics or control theory or behavioral science such as training, and ultimately through psychoanalysis and psychology and love and friendship and those kinds of things. It's a very wide spectrum. Where a given system lands on the spectrum is not obvious. You can't know that from a philosophical armchair. You have to do experiments and find out. I think it's very important to realize that there has to be an impedance match between the tools you're using and what you're able to see. For example, I think that physics sees mechanisms, not minds, because generally speaking, the tools of physics are low-agency tools. The interface that it uses, rulers, voltmeters, and various other things are actually pretty low-agency tools. If you want to study minds, you have to use high-agency tools, AKA other minds. It takes a mind to recognize a mind and to help you as either a scientist or a being living in the world, to identify other agents. People like Wheeler have thought about what it means for the entire universe to be observing itself and how much capacity to detect agency there is in the large-scale process like this.

Slide 7/44 · 09m:05s

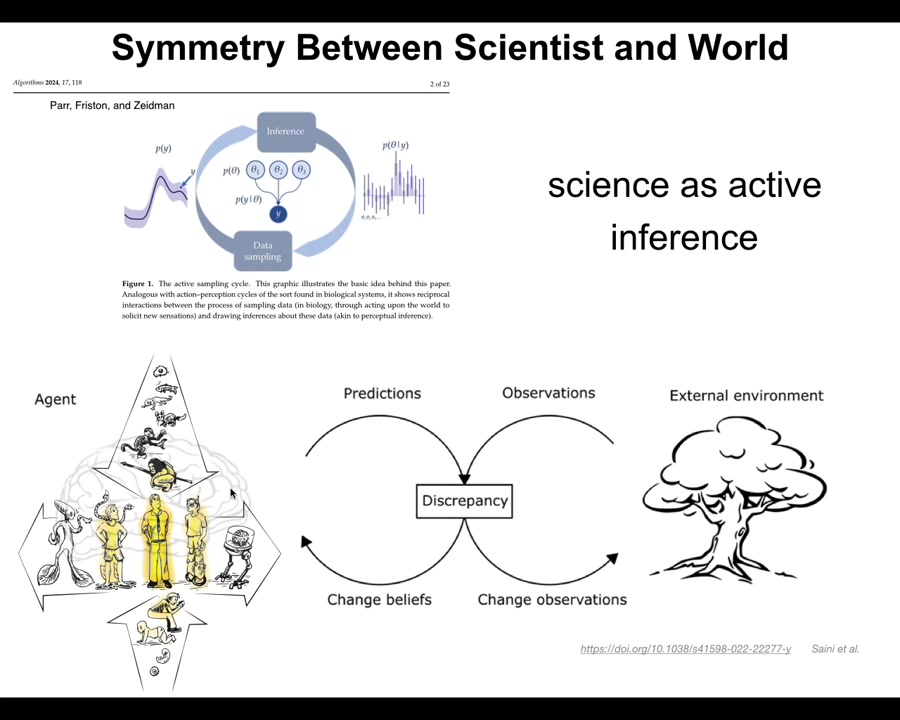

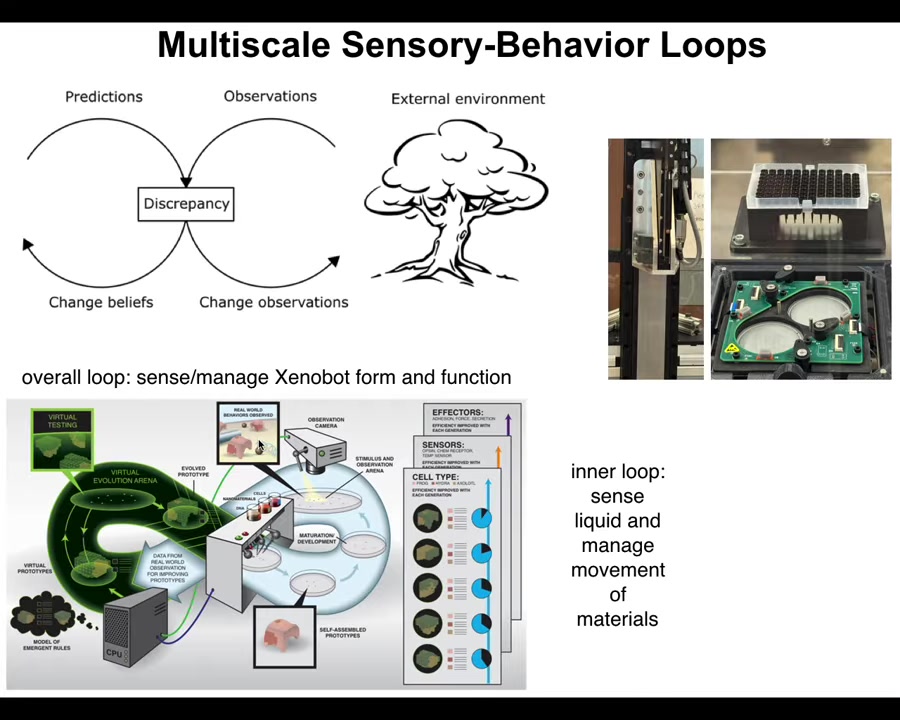

I want to paint a picture of both embodied life and science as a kind of active inference.

In both of these processes, what you have are predictions. You try to make observations by interacting with the outside world; those will inevitably give rise to some kind of discrepancy between what you thought was going to happen and what actually happened. That leads you to do two things. It leads you to change your priors, and it also leads you to change the observations that you make next. It's a continuous cycle. This is how we do scientific discovery, but it's also how all agents navigate the world.

The original diagram here had a brain doing this because in this paper they were studying the standard idea of a brainy organism navigating their world. But I think that all of the different kinds of beings across the spectrum, from single cells all the way up through humans and the different modifications that we can make, are a part of that same active inference cycle.

Slide 8/44 · 10m:11s

In biology, we engineer with a very new kind of substrate. People have been engineering passive materials like wood, metal, Legos for thousands of years. Then we had active matter and now even computational matter. But I want to talk about something very special, which are agential materials. And this is what happens when you engineer with life. To understand to what degree your material is an agential material, meaning from an engineering perspective, to answer this question, these are the kinds of things you have to ask yourself. How much of what it does do I not need to micromanage? How much autonomy does it offer? How much is what I do basically communication as opposed to micromanagement? How much of my task is reverse engineering as opposed to engineering? That is understanding and managing what the system is already doing. Very importantly, how much more do I get out than whatever my materials or my algorithm put in? I have to understand the intrinsic motivation and the agendas of the material that I work with, and what kind of tools, all the way from rewiring to some sort of high-end psychoanalysis, are going to work best for me. The living matter is actually very high on all of these kinds of metrics.

For the next few minutes, what I want to do is show you some special properties of living matter.

Slide 9/44 · 11m:28s

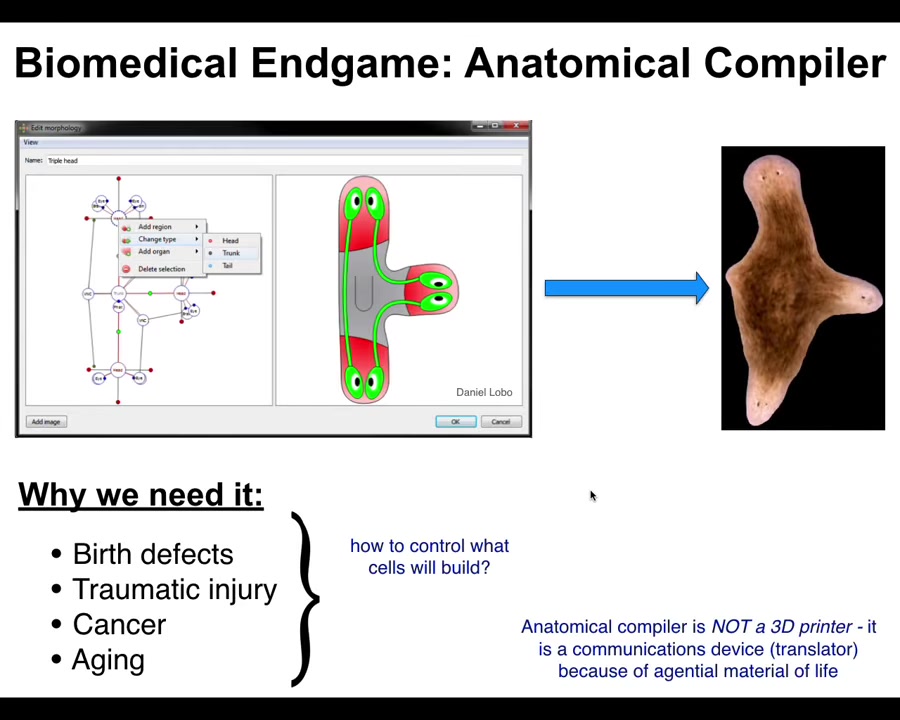

As a biologist, and in particular a worker in regenerative medicine, one of the things we're most interested in getting to is something I call the anatomical compiler. Someday you will be able to sit in front of a computer. You will be able to draw the animal, plant, organ, biobot, whatever. You'll be able to draw the being that you want. The system would compile that down to a set of stimuli that would have to be given to specific cells and groups of cells to get them to build exactly what you draw. It could be anything. It could be things that have existed before. It could be completely novel, things like this three-headed flowerworm. This is the end game for understanding how to interact with the material of life in biomedical settings.

It's obvious why we need this. If we could do this, if we could tell cells what to build, we would be able to abolish birth defects. We would be able to regenerate after traumatic injury, reprogram cancer, defeat aging. You might wonder, why don't we have this? You've been hearing about genetics for decades, but molecular biology, biochemistry have been going very strong for a long time. Because we don't. We don't have anything remotely close to this.

That's because this anatomical compiler is not something like a 3D printer. It is not for micromanaging the cells or the molecular pathways inside of them. It is a translator. It's a communications device that's designed to take the goals of the engineer or the scientist and translate them to be the goals of the goal-directed living system. That is a very unconventional view of biology. That is certainly not how most biologists think about it. That, I think, is the barrier that's holding us back from transformative regenerative medicine.

Slide 10/44 · 13m:09s

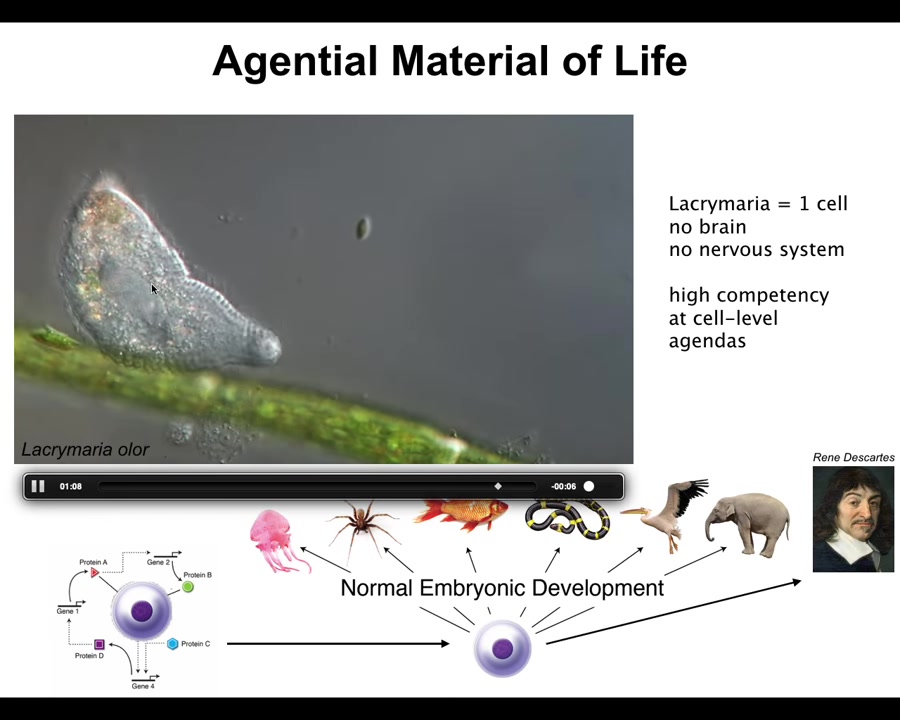

Because what all of us are made of is something like this: a single cell. This happens to be a free-living organism called Lacrimaria, but you get the idea. There's no brain, there's no nervous system. If you're into soft robotics, you're probably very jealous right now. This is an incredible degree of control over this system. It's handling all of its local metabolic, physiological, structural needs without a brain or anything like that.

All of us made the journey from a single cell — a fertilized oocyte that's self-assembled into one of these remarkable morphologies, something very different from something like this, which people think of as being amenable to the laws of physics and chemistry alone. How did that happen? How did this process of self-assembly and the emergence of a high-level mind from what initially looks to be just physics and chemistry occur?

We are made of these kinds of things. There are agendas and competencies all the way down.

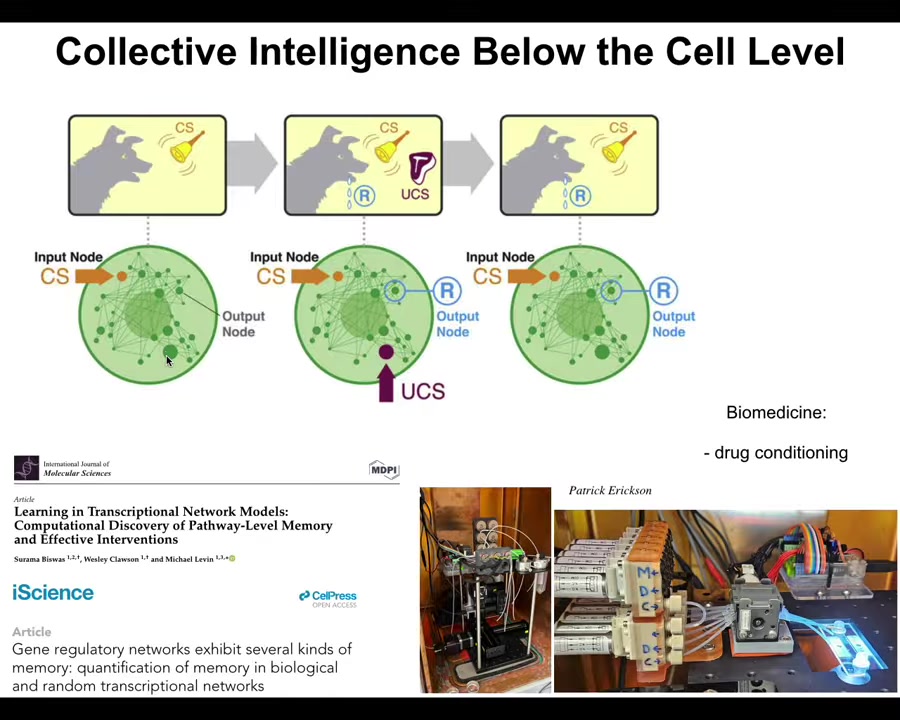

Slide 11/44 · 14m:13s

Even inside this little creature, the chemistry—the molecular pathways—are already capable of at least six different kinds of learning. We discovered recently that the molecular networks alone, as a free gift from mathematics, can do several different kinds of learning, including Pavlovian conditioning. We are in our lab trying to take advantage of this for drug conditioning and various other medical applications. Even the material inside cells has certain cognitive properties. It can learn from experience.

Slide 12/44 · 14m:49s

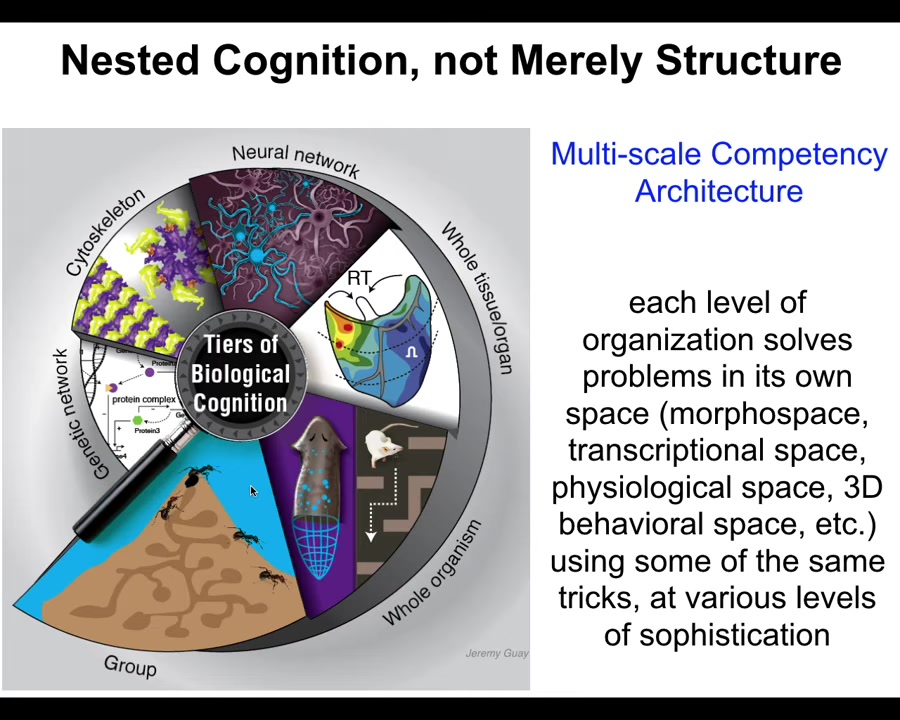

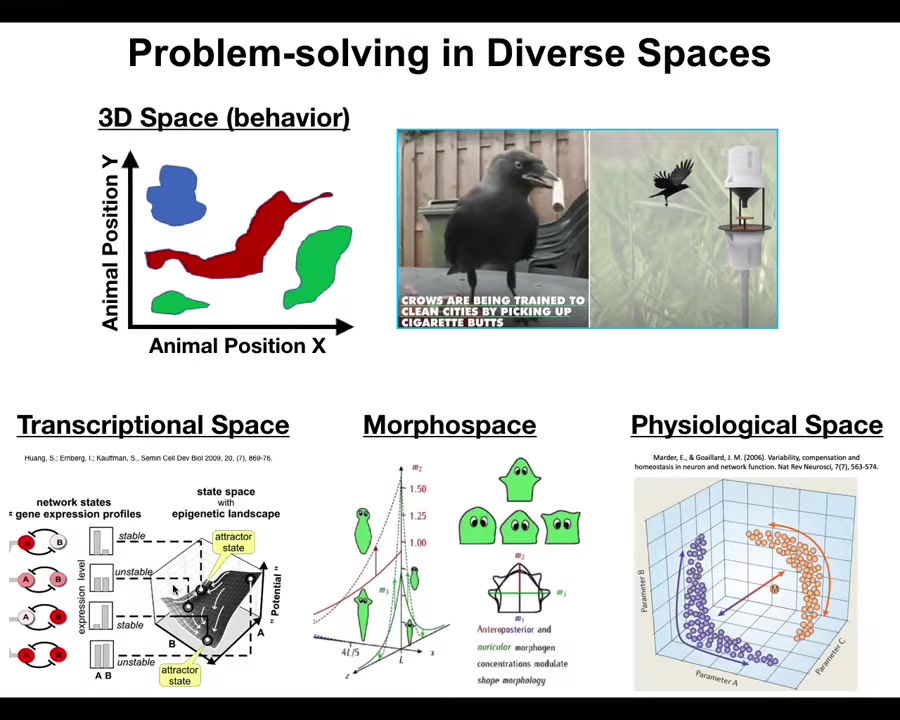

We are made of this multi-scale competency architecture. The crucial aspect of biology is that it is not a single-layer intelligence. It has intelligence baked in all the way down: problem-solving competencies in different kinds of spaces. That architecture has many implications. I only have time to show you a few, but they are quite interesting.

Slide 13/44 · 15m:12s

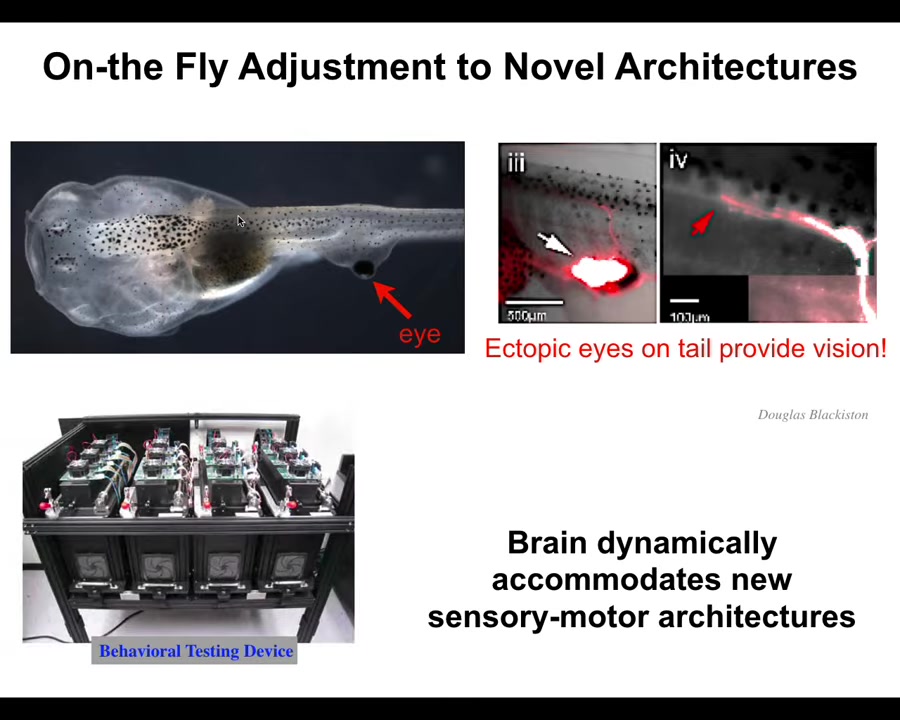

The first is that it makes on-the-fly immediate adjustments to entirely novel scenarios. What I'm showing you here is a tadpole of the frog Xenopus laevis. Here's the mouth, the nostrils, the brain, the gut is back here, and this is the tail. We've prevented the two primary eyes from forming, but we put an eye on its tail. When you induce an eye to form on the tail, it makes an optic nerve — that optic nerve, you can see it, does not go to the brain. It sometimes goes to the spinal cord, sometimes to the gut, sometimes nowhere at all. But we've made this machine that enables us to automatically test and train these animals for vision, so optical visual cues, and we find out that they can see perfectly well.

This system is a radically different sensory-motor architecture. It does not need new rounds of selection, mutation, adaptation, or evolution. Out of the box, you make a completely different creature where the eye is now on the back. We don't know how the signals are actually getting up here, but all of this works out of the box. Zero-shot learning — it works out of the box because the material is so plastic, primed to solve problems every single time. Evolution does not make specific solutions to specific problems. It makes problem-solving agents, multi-scale problem-solving agents. You see the degree of plasticity here.

Slide 14/44 · 16m:42s

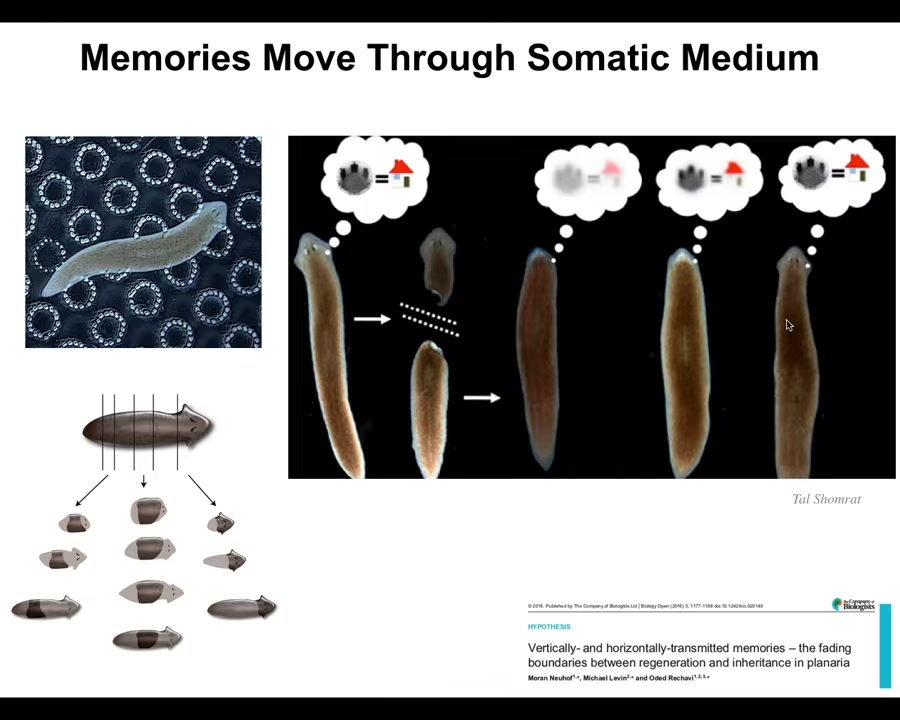

Another amazing thing about the material is that it facilitates memories to move through the living matter. This is a flatworm, a planarian. There are a couple of interesting properties. One is that they're highly regenerative; you can chop them into pieces. Every piece gives rise to a perfect little worm. The record is something like 270 pieces. They're also smart. You can train them. If we train them to recognize these little laser-etched bumpy areas as safe locations to eat — this is place conditioning — we train them, then we cut off their head, which contains the centralized brain. You have this tail. The tail does nothing. It sits there for eight or nine days. It has no behavior, but eventually it grows back a new brain. When it does grow back a new brain, you find out that these animals remember the original learning. Memory not only persists the removal of the brain; the more interesting thing is that wherever it's located, it is actually able to be imprinted onto the new brain as the brain develops, because the brain is what drives the actual behavior. The learned information throughout its lifetime is interacting with the morphogenetic information. As the brain is being built, you have to remember what the correct planaria head looks like, you build the brain, and then you have to imprint that information onto the brain. So learning, the results of learning are somehow moving through this tissue.

Slide 15/44 · 18m:08s

But there are actually even more tricks up biology's sleeve here, which is illustrated by the following.

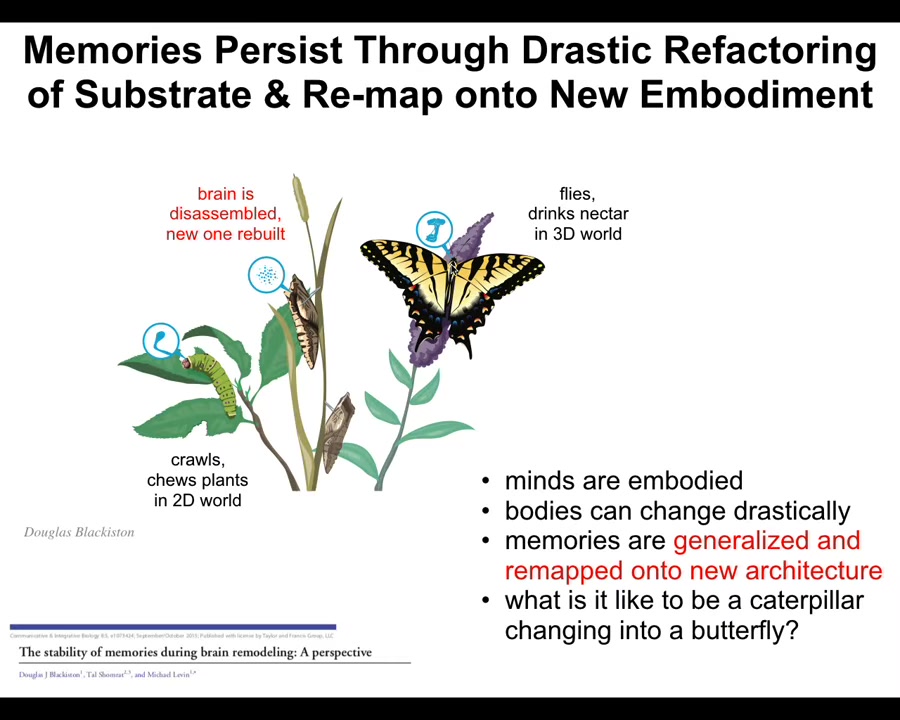

This is a caterpillar. Caterpillars have a particular kind of brain that are suitable for their two-dimensional lifestyle. They crawl around, they eat leaves, they have a soft body architecture. They need a controller that's suitable for soft body robotics. You can't push on anything. There's no hard elements. They have a particular kind of brain. Well, it was found that if you train caterpillars for specific tasks, for example, to recognize certain color stimuli and then to go over and eat the leaves that are under that color, when they turn into butterflies, what they basically do is they completely refactor their brain, because they're going to be in a hard body flying through a three-dimensional world, completely different creature. They need a new brain. Most of the cells are killed off, most of the connections are broken, totally reconstruct the brain. The first thing that was found is that they still remember the original information, and that's remarkable. We don't have any computing devices, to my knowledge, that allow you to completely trash the memory medium and then still remember the information.

But there's something deeper going on here, which is that the specific memories of the caterpillar are of no use to the butterfly. They're completely irrelevant. It doesn't move the same way. It doesn't want the same things. It doesn't want the leaves. It wants to drink nectar from these flowers. You can't just maintain the fidelity of the information through this process. You actually have to remap it onto a completely new body architecture.

Again, this notion of biological plasticity, it's not the body shape that remains. All of that is plastic and can change, just like in that tadpole. And the information is not exactly persistent in its old form. It transforms. Biology is the study of the transformation of memories and of goal states and other properties through different physical media, appropriately to adaptively and appropriately to their new context, that we don't even have the beginnings of an understanding of how exactly these kinds of things are remapped onto new embodiments.

Slide 16/44 · 20m:15s

One important aspect of this is that biology solves problems in many, many different kinds of spaces. There's a lot of discussion, especially in AI, about embodiment. The idea is that you have to get around in the three-dimensional world. You have to engage with the world to have real intelligence. But one thing that biology teaches us is that we as humans are totally obsessed with the three-dimensional space because of our own evolutionary history and our own sensory motor architecture. We are okay at recognizing medium-sized objects moving at medium speeds. Birds and primates, and maybe a whale or an octopus, we can recognize. But biology has been doing that loop, that sensory decision-making effector loop, in other spaces long before nerve and muscle appeared.

Cells navigate a very high-dimensional space of gene expression states, of physiological states, and of anatomical morphospace. Just because you see something that doesn't look to be physically embodied, meaning it moves through the three-dimensional space, doesn't mean that it's not embodied and it isn't doing that loop that's so important for agency and for intelligence.

Slide 17/44 · 21m:30s

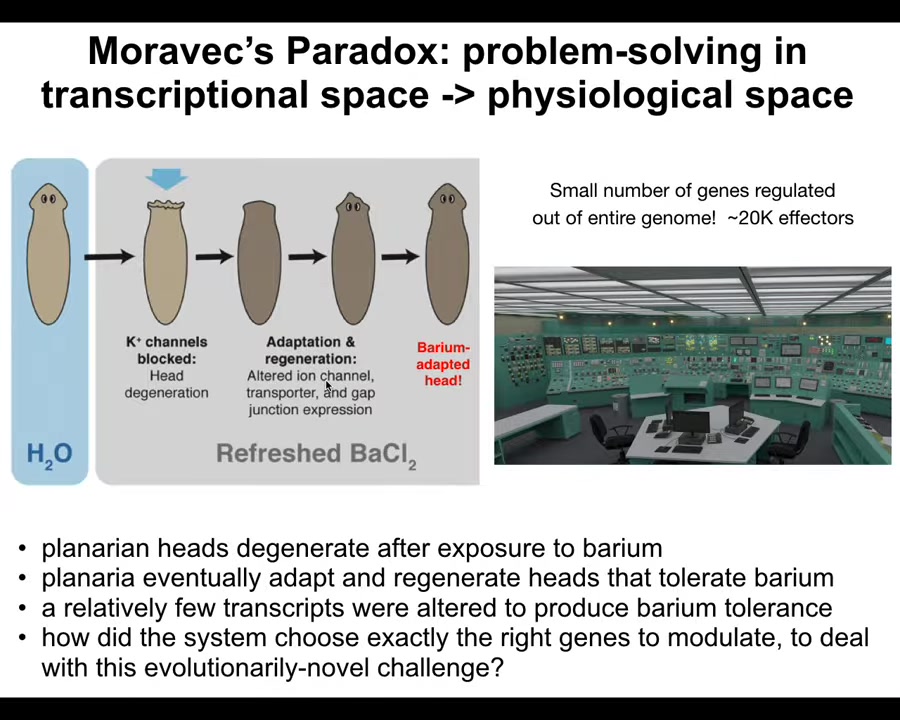

Within that space, I just want to show you one example of problem solving in transcriptional space, and then we'll talk about anatomical space. So we discovered with these planaria that if you put planaria in a solution of barium, barium makes it impossible for them to pass potassium ions, so many cells are very unhappy, especially the neurons in the head. Their heads explode. If you leave them in fresh barium, you find that after a little while, they regrow a new head, and the new head is totally adapted to barium, no problem whatsoever.

Planaria don't encounter barium in their life, or in fact, in their evolutionary history; there's no pressure to deal with this crazy new stressor. And yet, it's Moravec's paradox. You have a system that has tens of thousands of possible genes and can up- and down-regulate. So a huge number of effectors. How do you know which of those to fire to solve a new problem that you haven't seen before? It's like sitting in a nuclear reactor control room. There's just an incredible amount of buttons. What you don't have time to do is to start pushing all of them to see what happens. You have to very rapidly navigate a high-dimensional space and solve a problem you've never seen before. And planaria do this. They identify less than a dozen genes that allow their heads to now grow in this completely physiologically novel environment. So this is the kind of problem-solving that we need to understand both for the biomedical side and for the robotics. They're managing a space in which you can walk in tens of thousands of directions.

Slide 18/44 · 23m:03s

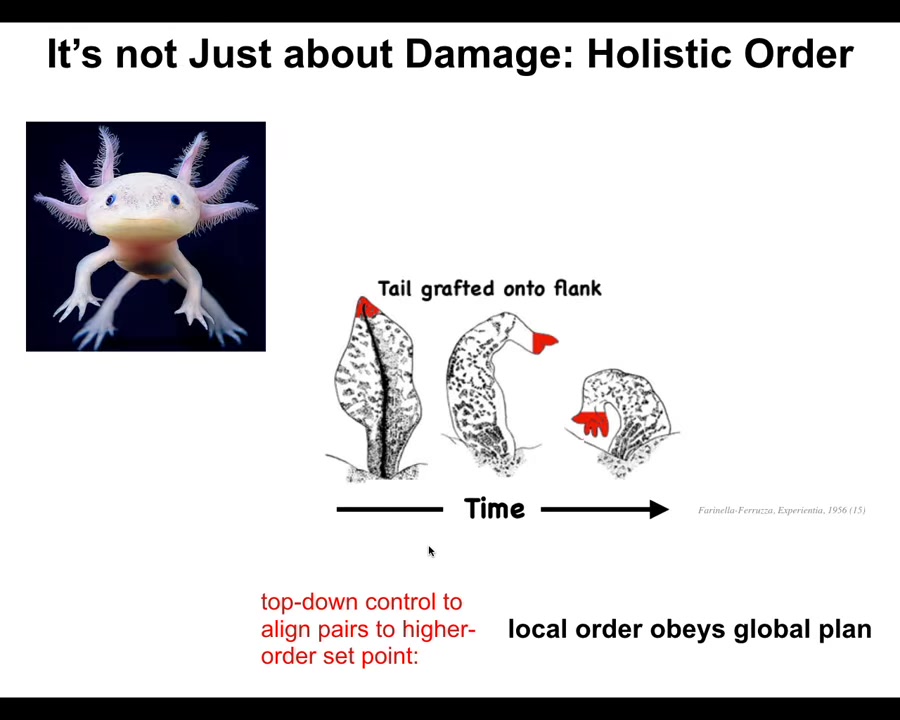

I want to talk about anatomical decision making and anatomical intelligence. I want to start by briefly introducing this creature. This is an axolotl. These guys are also incredibly regenerative. They can regrow their eyes, their jaws, their limbs, the spinal cords, ovaries, portions of the brain and heart.

The first thing you realize is that morphogenesis, or the assembly of specific bodies from cells, is not just a kind of open loop emergent process. It actually is a process of error minimization. If they lose a limb anywhere along this axis, the cells will immediately spring into action. They will restore the structure and then they stop. The most amazing part is they know when to stop. When do they stop? When the correct structure has been completed. What happens is that the system can tell it has been deviated from its correct location in anatomical space. They get back to within some error tolerance, and then they stop. An error minimization scheme.

What's really important here is that it's not just about damage. This is not about repairing damage. I'll show you one important example, which is what happened when they took axolotl tails and grafted them to the flank of the amphibian. That tail over time remodels into a limb. Take the perspective of these little cells up here at the very tip. They are tail-tip cells sitting at the end of a tail. There's nothing wrong locally. There's no injury. There's no damage. Why are they turning into fingers?

Because this system, just like our cognitive system, is very good at taking very abstract, high-level goals and transducing them down into the molecular components that need to be aligned to implement that goal. Individual cells don't know anything about what a finger is or how many fingers you're supposed to have, but the collective absolutely knows. We know that because you can intervene and it will continue to make the right thing. What happens is that the collective knows that you need a limb there, not a tail. All of that percolates to align the downstream components to give you what you want.

If you were a cell here sitting at the tip of this tail, you might have no idea why you are turning into fingers. Why this transformation? Why do all these things that keep happening seem to be aligned and coordinated in a way that doesn't seem to make any sense to you? It's almost like a synchronicity that all of this seems to be happening, but you don't have any understanding why there's a higher level system that is making this happen.

This is our everyday experience too. When you wake up in the morning, you might have very high-level social goals, research goals, financial goals, career goals, whatever you have, very abstract things. In order for you to get up out of bed and actually execute on those, they have to make the biochemistry dance. They have to make ions move across your muscle membranes in order for that to happen. Each one of us is this amazing example of mind-matter interaction, involuntary motion, in that very high-level goals and weird spaces that our body machinery doesn't know anything about can actually trickle down to align the internal parts to make these things happen.

Slide 19/44 · 26m:18s

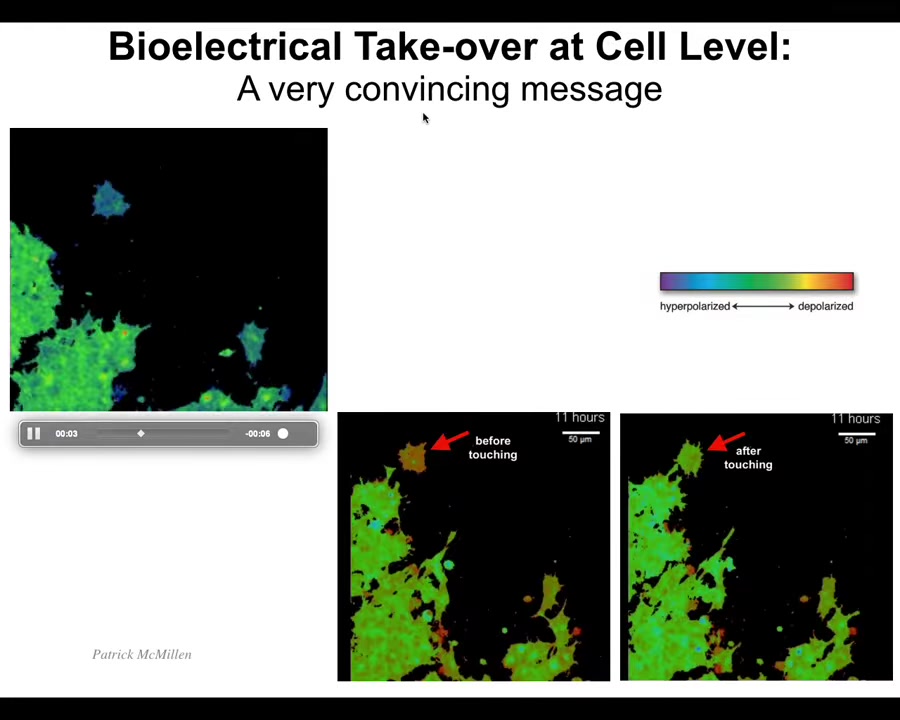

And I want to show you an example of how this happens. In particular, in my group, we study a lot the bioelectrical interface that groups of cells use to store goals and to communicate those goals to each other in networks. I'm going to play this video, but I want you to just look at the before and after frame. These colors indicate voltage. So we have ways of measuring the voltage of any given cell, not just neurons. Every cell in your body has voltage potentials, and they all make networks that process information.

And so what you'll see is that this is the before. And so this cell, which has a very different voltage than the rest of these cells, right before it gets touched, it's different, but boom, now it has been hacked. Look: this blue cell here, minding its own business, moving along, this thing reaches out, touches a bank. That's it. That's all it takes is this tiny little touch to communicate a bioelectrical state that totally takes over what the cell is doing. And now it's going to come back and it's going to be part of this collective and it's going to work on something. Learning to pass along these convincing messages is really important.

Slide 20/44 · 27m:20s

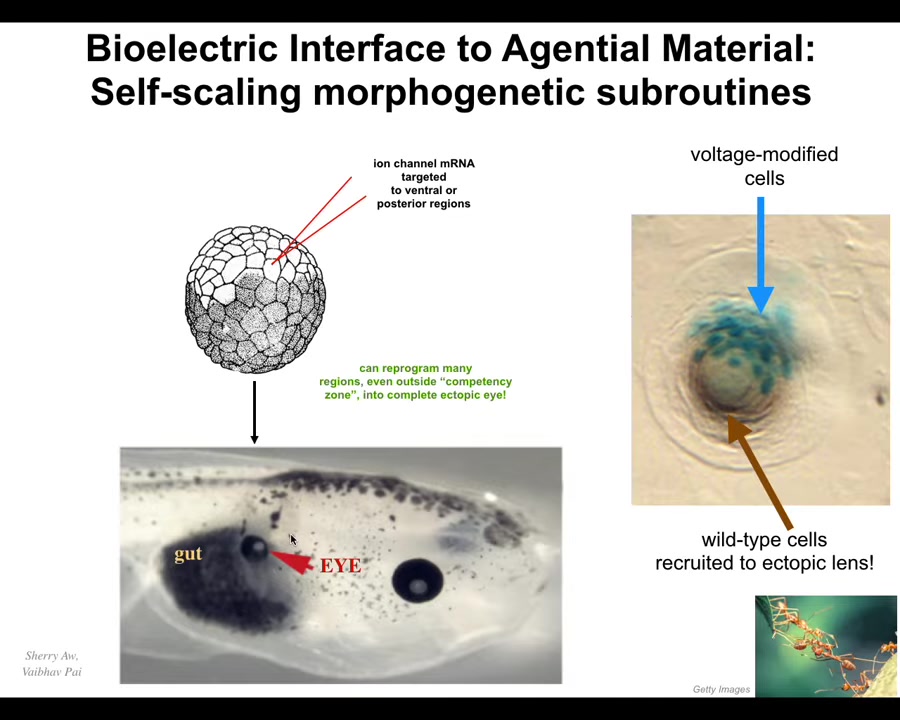

And I'll show you two very quick examples of how we use them for regenerative medicine. Here what we do is into this early frog embryo, into some cells that are going to make gut here, we introduce an ion channel that establishes a particular voltage state, and a voltage state just says, build an eye here. That's all it says. It's a very high level subroutine call. We don't know how to micromanage the process, thousands upon thousands of genes necessary to make an eye, to tell the stem cells what to do. We don't know how to do any of that. What we do know is how to say to the material, build an eye here. And when we do, here it is, very nice eye built where your gut should be.

We didn't have to micromanage any of it. The material has this amazing property. If you only get a few cells, in this cross-section through a lens sitting out in the tail somewhere, the blue cells are the ones that we injected. There's not enough of them to build an eye. What do they do? They recruit their neighbors. All this other stuff out here, we never touched it. It is building an eye in cooperation with these cells because they are instructing it. We didn't have to teach it to do that. It already knows how to do that. We say to you, build an eye. And they figured out that there's not enough of us. We need to recruit other cells, much like other collective intelligences, like ants and termites, recruit nest mates to lift heavy objects and things like that.

So the body is in fact a collective intelligence. It solves problems in physiological and gene expression spaces and of course in anatomical space. And we can use this bioelectrical interface to communicate with it and ask it to do new things. This to me is not only an application heading towards the biomedicine of organ regeneration, but an example of learning to communicate with a novel intelligence that works in a space that is very hard for us to visualize.

Slide 21/44 · 29m:10s

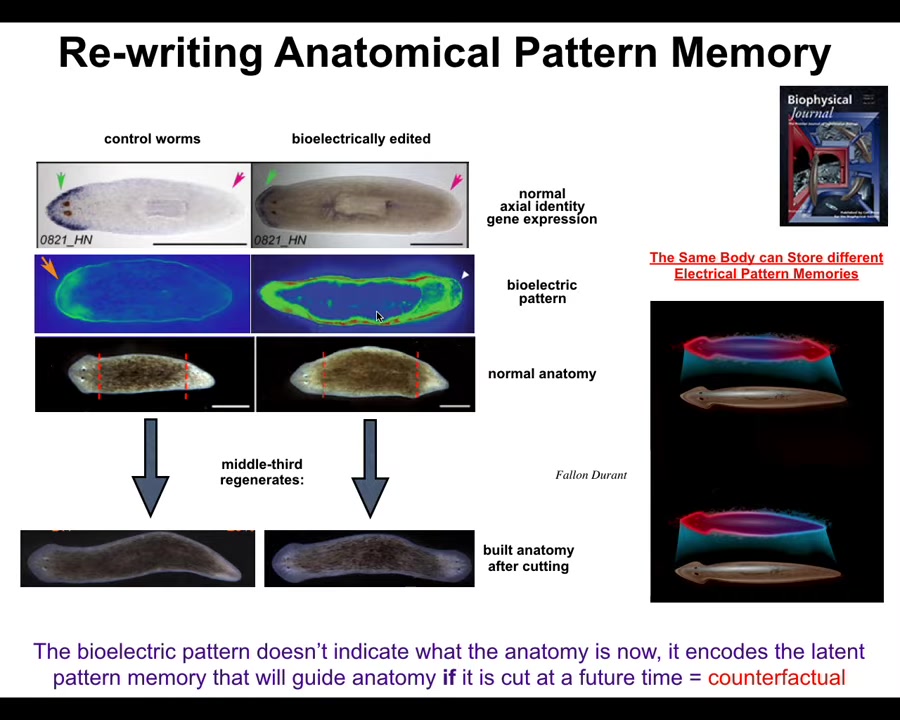

We've learned how to do some other things, for example, to change the memory of that collective intelligence.

So here is the planarian, and what you can do is chop off the head and the tail, and this middle fragment will reliably build one head, one tail. How does it know? How does it know how many heads to build? In fact, these cells back here are going to make a tail, but these cells back here are going to make a head. They were near neighbors before you cut them apart. Why are they doing different things? How do they know?

So it turns out we can visualize a bioelectrical pattern memory in this fragment that says one head, one tail. And that's what they built. And so we figured out a way to rewrite that pattern to say, no, actually two heads. And it's a little messy, but it works and the technology is still being developed.

If you do this, at first, nothing happens. The body is still normal, one head, one tail. The head marker here is expressed in the head, not in the tail. So there's nothing that you would see different about this body. The anatomy is normal. The molecular biology is normal.

But what's not normal is the stored internal representation of what I will do if I get injured at a future time. It's actually a counterfactual memory, and we can read those memories out of the medium non-invasively. And if you do cut this animal, then what happens is the cells consult the memory and they say, a proper worm should have two heads, bang, and that's what they built.

And this is not AI or Photoshop. These are real animals. And so what you see here is that we're starting to learn how to not only communicate signals, but to actually rewrite the goal states. Rewrite the patterns to which the collective intelligence is trying to reduce error.

Slide 22/44 · 30m:50s

If we do that, we find out that it is in fact very appropriately called a memory, because if you take these two-headed animals and you amputate the ectopic secondary head, you amputate the primary head, they will continue to form two-headed animals in the future.

There is no genetic change going on here. We haven't touched the genome. There's nothing genetically wrong with these guys. You can sequence the genome all day long. You'll never be the wiser that they would make two heads. It's a lineage that, as far as we can tell, has been permanently changed. Its sensory-motor and, in fact, in general, the body architecture has been permanently changed, because we have reset its bioelectric memory, not anything having to do with the hardware. The hardware is wild-type and intact, but the software has now been rewritten in place. You can see what these guys are doing.

This is the amazing aspect of this living material. Evolution gives you hardware that is incredibly reprogrammable. It is really that layer of morphogenesis between the genotype and the phenotype that is highly, highly intelligent in the sense of problem solving, which actually makes evolution go quite differently than the standard model.

What I do want to switch to now for the last part of the talk is to show you the implications of this going forward. So far, everything that I've shown you — the extra eyes on the tadpole and these extra planarian heads and all of that — is natural. These are the normal, evolutionarily provided kinds of systems that you've seen.

But I want to talk about some novel forms.

Slide 23/44 · 32m:31s

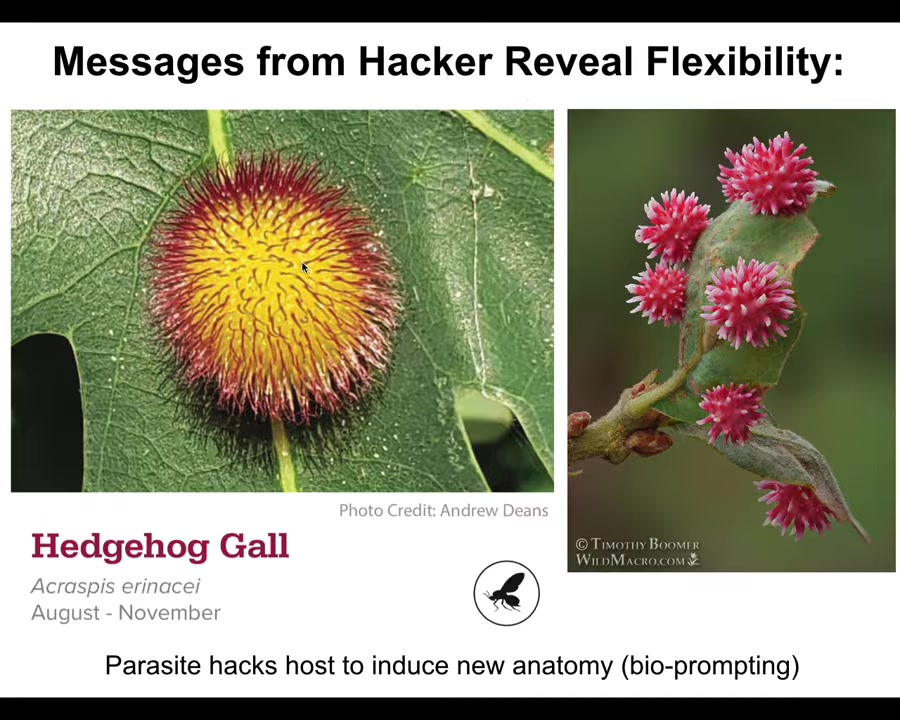

We'll warm up to that by looking at the effect of a non-human bioengineer. This little wasp leaves prompts on plant cells to cause the cells to build this. These are called galls. They're incredible structures.

If not for this, we would have absolutely no idea that the plant cells, which very reliably build flat, green leaves of a particular structure, were even capable of this. The latent space of possibilities for morphogenesis — we'd have no idea this is possible if this thing hadn't discovered it over millions of years, and this is what we're going to speed up greatly, as I'll show you momentarily.

They're not made of insect cells; they're made of plant cells, and it's not made the way the wasp creates its nest, which is a 3D printer where it goes along and puts down every particle. It leaves instructions, prompts, that then cause the plant cells to change what they do.

Slide 24/44 · 33m:32s

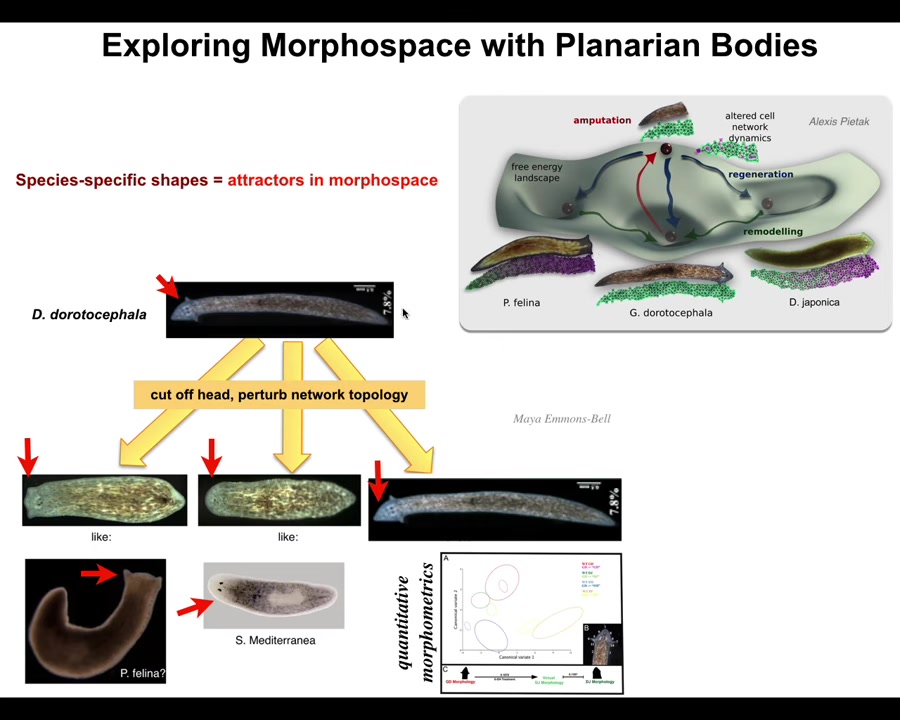

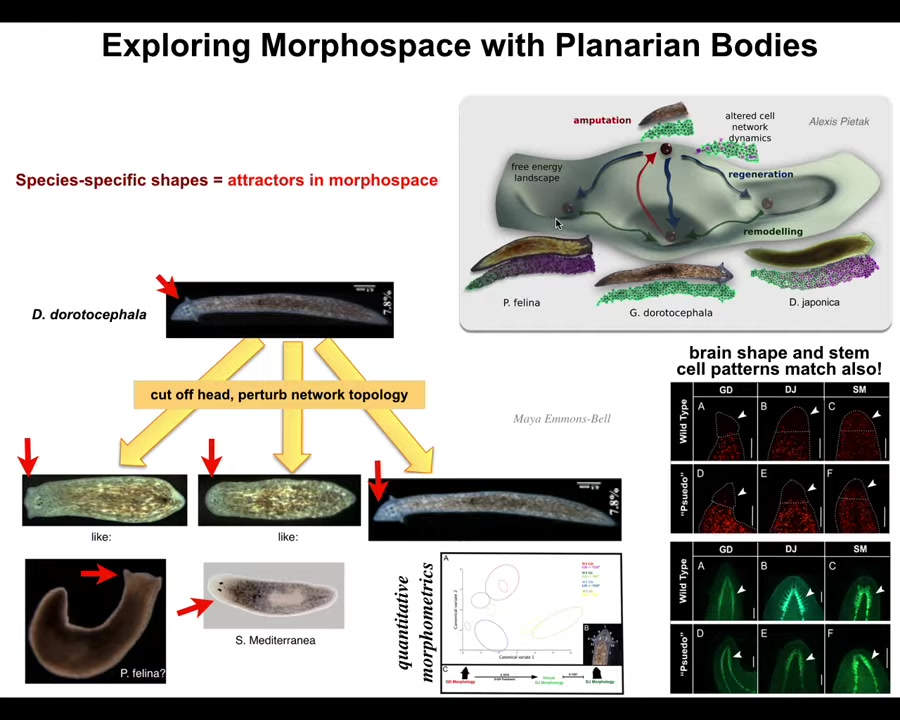

We can do some of this too. We can take this planarian, a nice triangular-headed Dugisia duratocephala, and we can amputate the head and perturb the electrical decision-making, the memory of what kind of head should I make. This can make flat heads like a P. falina. It can make round heads like an S. mediterranea. Of course, it can make its own head. There's about 100 to 150 million years of evolutionary distance between these guys and this. Again, no genetic change. We haven't touched the genome.

Slide 25/44 · 34m:02s

What you're seeing here is not just the shape of the head, it's also the brain. The shape of the brain and the distribution of stem cells is just like these other species. What we're seeing here is that perfectly wild-type hardware is happy to visit other attractors in that anatomical space.

In anatomical morphospace, you have other attractors that are normally occupied by other species, but this hardware can visit it too. The navigation of that space involves a lot of decision making about where we should go, but you can impact that if you can communicate with the material.

Now we want to ask the following question. Evolution has given us certain attractors in that space. What else exists in that space that we may not know about?

Slide 26/44 · 34m:44s

And I'm going to show you a couple model systems for that, but I just want to make this a larger point. If anybody's interested in this, you can come here. We have an asynchronous symposium going on all fall about the nature of this platonic latent space of form and behavior.

I think that everything that I'm about to show you—the Xenobots, the Anthrobots, the Mombot that we've built—all of these things are vehicles; they are our periscope to peer into this platonic space of possibility to understand what other patterns can come through the interfaces that we build. These interfaces are cells, biobots, chimeras, AIs, embryos. Everything that we build, I think, is a kind of interface to patterns from this latent space. And some of those patterns are the kinds of things mathematicians have been studying for thousands of years: low-agency things that can be formalized easily by mathematics, which you can think of math as the behavioral science of those kinds of forms. But also much more complex active forms that we would recognize as kinds of minds.

And I think that, incredibly, the physical pointers that we make, the architectures that we build, are really the future of all of these fields. So I want to show you a couple of examples of this. Let's explore that space and see what can happen.

The first thing we'll look at is Xenobots.

Slide 27/44 · 36m:15s

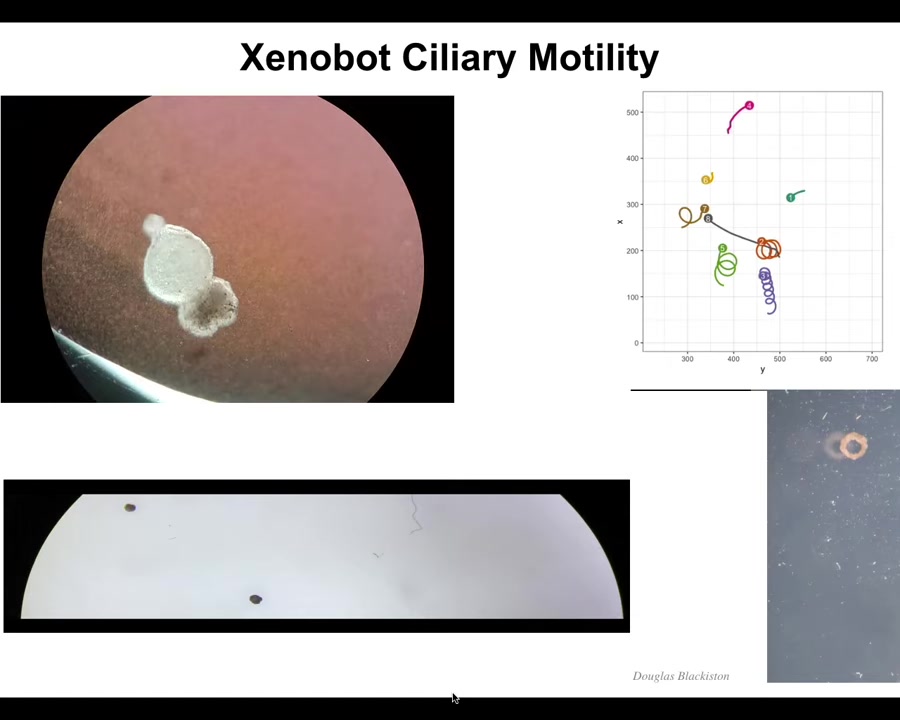

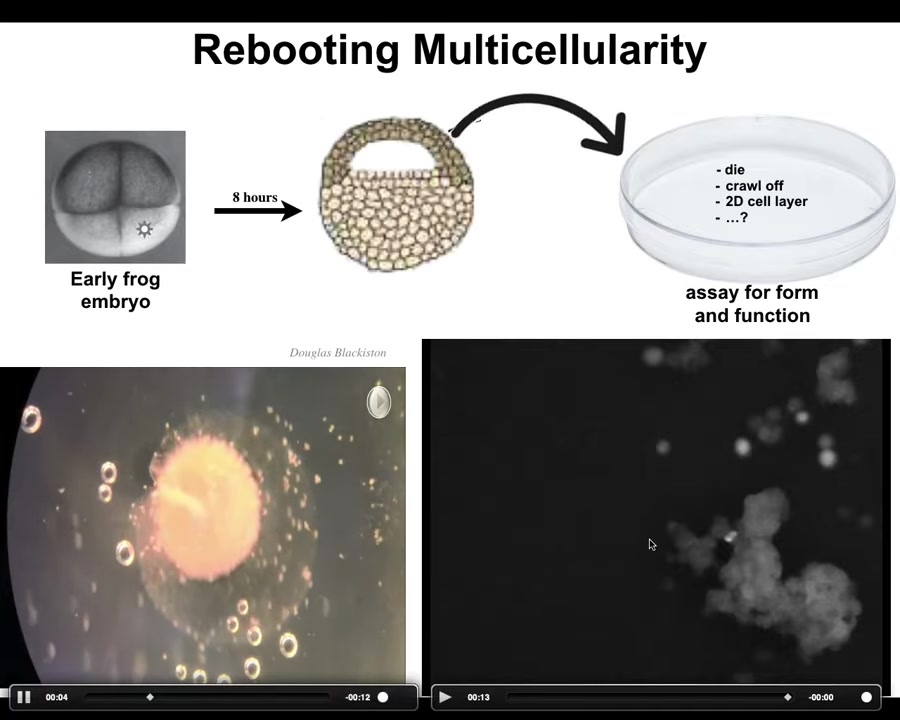

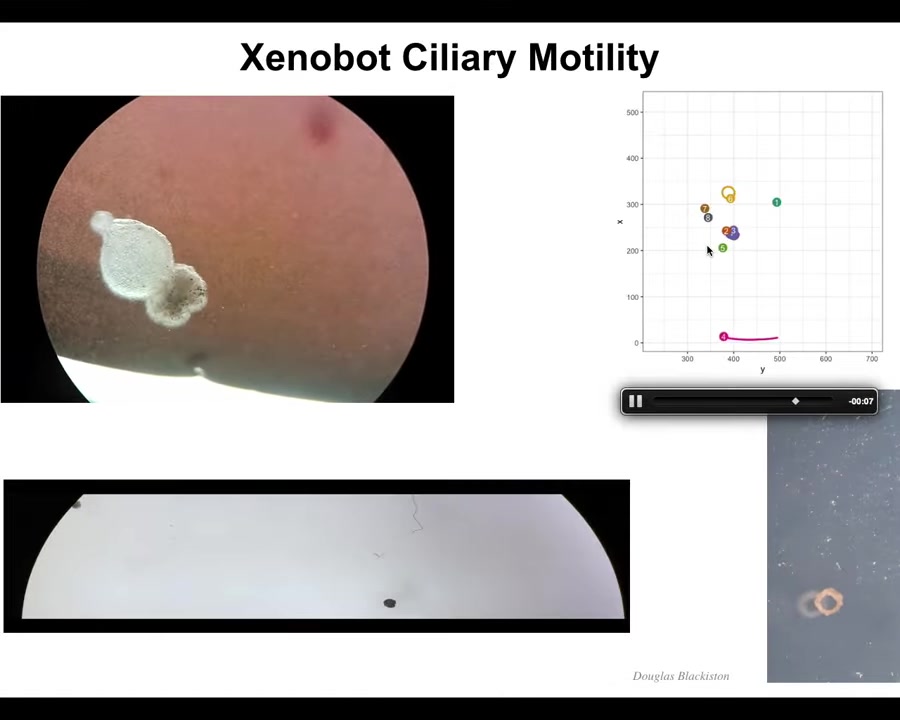

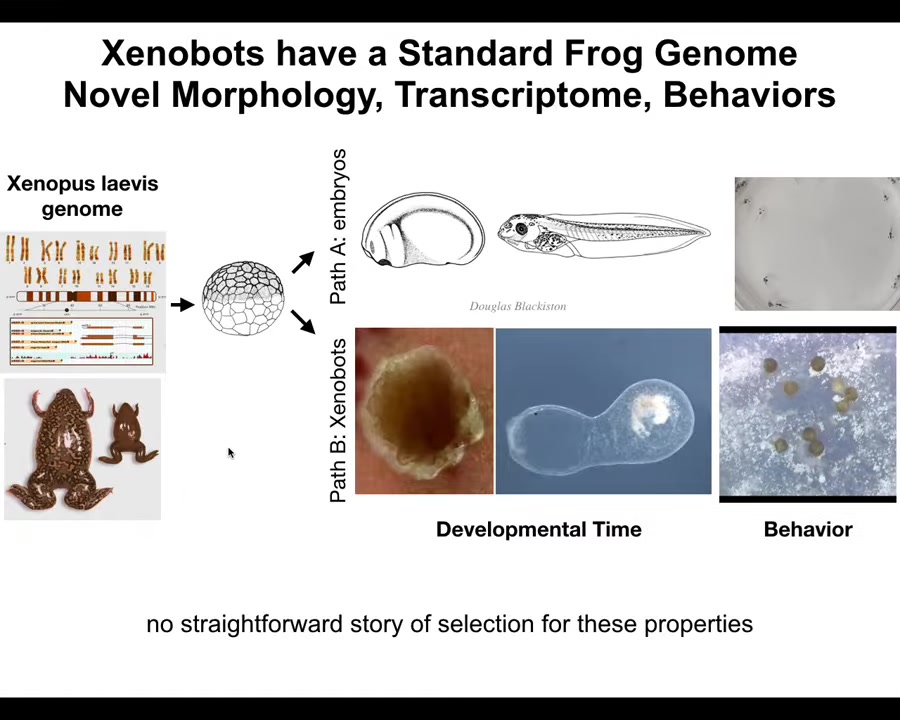

I'm going to pause this here. What we've done here is we've taken some cells from an early frog embryo. These cells that are going to be the epithelial cells, we take them off and we dissociate them here. They could have done many things. They could have died. They could have crawled off and gotten away from each other. They could have formed a nice flat two-dimensional layer like cell culture. Instead what they do is they assemble into this kind of creature. I'm going to show you close up what that looks like.

This is a close up. Each one of these circles is a single cell. All these groups of cells have very stereotypic kinds of collective movements. Here it wanders over and it has some movements and some exploratory signaling that it's doing. You get a calcium flash. The flashes are calcium signaling, which basically indicates computation that cells are doing.

Slide 28/44 · 37m:17s

These amazing properties come together, and what they form is what we call a xenobot. It has cilia on the outside, so it swims. We don't have to pace it the way that the muscle-actuated biobots have to be paced. It is completely self-assembling. It is completely self-motile. It can go in circles. It can patrol back and forth. You can make it into weirder shapes, like this donut bot that Doug made. They have collective behaviors, they have individual behaviors.

Slide 29/44 · 37m:43s

Here's one traversing a maze. It goes here, it's going to take this corner without bumping into the opposite wall. There's a corner here, it takes the corner. Then at this point, it spontaneously turns around and goes back where it came from.

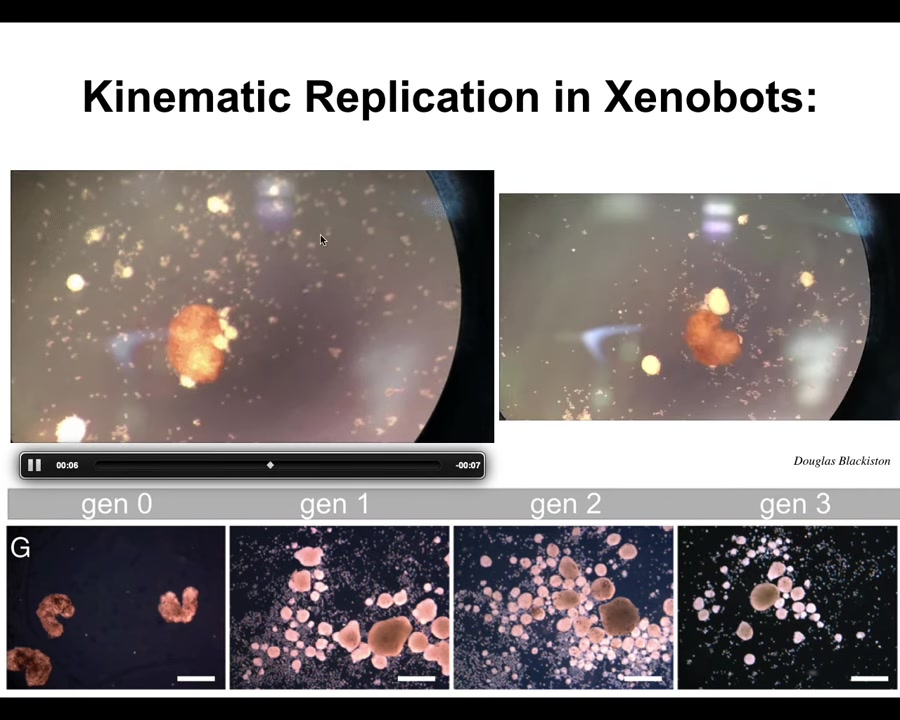

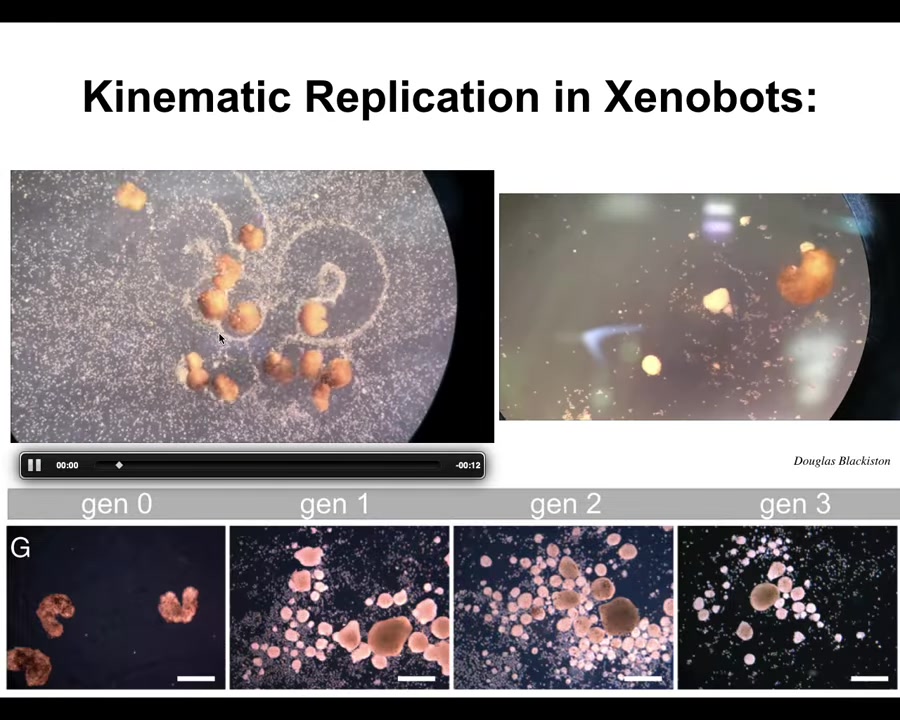

One property that they have is kinematic self-replication.

Slide 30/44 · 38m:03s

If you provide them with loose material of a machine that goes around and makes copies of itself from stuff it finds in the environment. They knock the cells into little piles. They pull them into little piles, and then they polish the little piles. Because they are dealing with an agential material themselves, those little piles mature to become the next generation of Xenobots. They do the exact same thing and make the next generation. This is a kind of replication cycle for this novel system.

Slide 31/44 · 38m:38s

Now, notice something interesting. There have never been any Xenobots. There has never been any selection to be a good Xenobot. We don't think any other creature on Earth reproduces with kinematic self-replication. So it's very interesting to think about what the Xenopus genome learned in its time on Earth. Apparently it learned to do this. So it can make Xenobots, and this is an 83-day-old Xenobot. It's turning into something. I have no idea what it's turning into. They have distinct behaviors here.

We can say when the computational cost for all of this was paid, it was paid during the eons that the embodied genome was bashing against the environment and selection and all of that. When was the computational cost to design all of this paid? This has never existed. There is no straightforward story of selection for these properties. There are a few ways that people try to go with this. Some people will say it's emergent. You say, what does that mean? I say it just means that at the same time that you were doing this, you also learned to do this. But that doesn't answer the question of when the computational cost was actually paid. Second, it undermines the whole point of evolution, which was supposed to explain the properties of a living thing with very tight specificity around the environment that gave rise to it. That was supposed to be the whole point. It's the history of environmental forces that got you to where you need to be. That is not a story that works here.

So I think we need to go beyond just saying that it's emergent and really understand that latent space of possibilities of why specific interfaces are pulling down specific forms of anatomy, of behavior. There are hundreds of new genes being expressed differently in these guys, about 600 new genes. So transcriptional behaviors, where are those coming from? Can we learn to predict and to manage them? You might think that this is some weird amphibian thing. Frogs are plastic and embryos are plastic. Maybe this is some very specific frog thing. I'll ask this question.

Slide 32/44 · 40m:46s

What would your cells do if we liberated them? This looks like something we might have gotten off the bottom of a pond somewhere. It looks like a primitive organism. If I asked you what the genome looked like, you might guess that it has a primitive organism's genome. If you were to sequence it, you would find 100% Homo sapiens genome.

These are anthrobots. They self-assemble from tracheal epithelial cells, so from lung epithelium, taken from adult human patients. Not embryos. Nothing embryonic going on here. Adults, usually elderly patients, give epithelial biopsies. We buy the cells and we have a protocol in which they self-assemble into these anthrobots. We do very little. There are no scaffolds. There are no nanomaterials, much like with the xenobots. There is no synthetic biology. We don't touch the genome. There are no weird drugs in here. They're living in the same environment, except that they've been liberated from the rest of the instructive influence of cells.

In bodies, the name of the game is cells hacking other cells to align them towards goals that they don't know anything about. So what we've done is liberated these guys from those influences in the body, and this is what you get. You get a different type of creature that's never existed on Earth before. It doesn't look anything like a stage of human development.

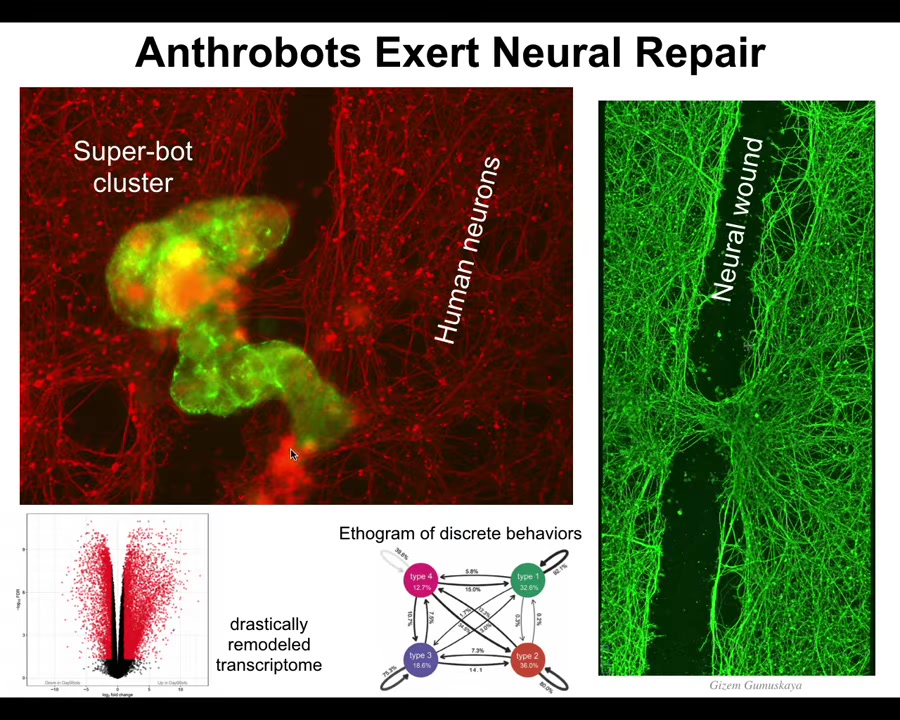

Slide 33/44 · 42m:18s

They have weird properties. For example, one of the things that they do is if you plate a dish of human neurons, the red stuff here is human neurons, and then you take a scalpel and you put a big scratch through the middle, and you throw some xenobots into that culture, they drive down the scratch, they find a spot to settle in. In fact, they combine into this, we call this a superbot cluster. Then they start to knit the neurons across the gap. If you lift them up, this is what you see four days later. This is where the xenobots were working. They try to heal the damage. That's just the first thing we notice. No doubt they do many other things. But who would have thought that your tracheal cells, which sit there quietly for decades in your airway, have the ability to move around on their own as a coherent little creature and heal your neural wounds?

It's amazing. The first thing we discovered from this novel being is a very benevolent kind of event. It's actually helping to heal these neurons. They're an amazing creature. They have 9,000 differentially expressed genes compared to what they were doing in the body. Almost half the genome, right? Their transcriptional profile, their behavioral profile, their anatomy, completely different from what they were doing before. Where does it come from? We need to understand this.

They have four different behaviors. You can draw a little ethogram of the probability of shifts between the behaviors. There's 4, not 12, not one, but specifically 4. There wasn't selection for any of this stuff.

Slide 34/44 · 43m:58s

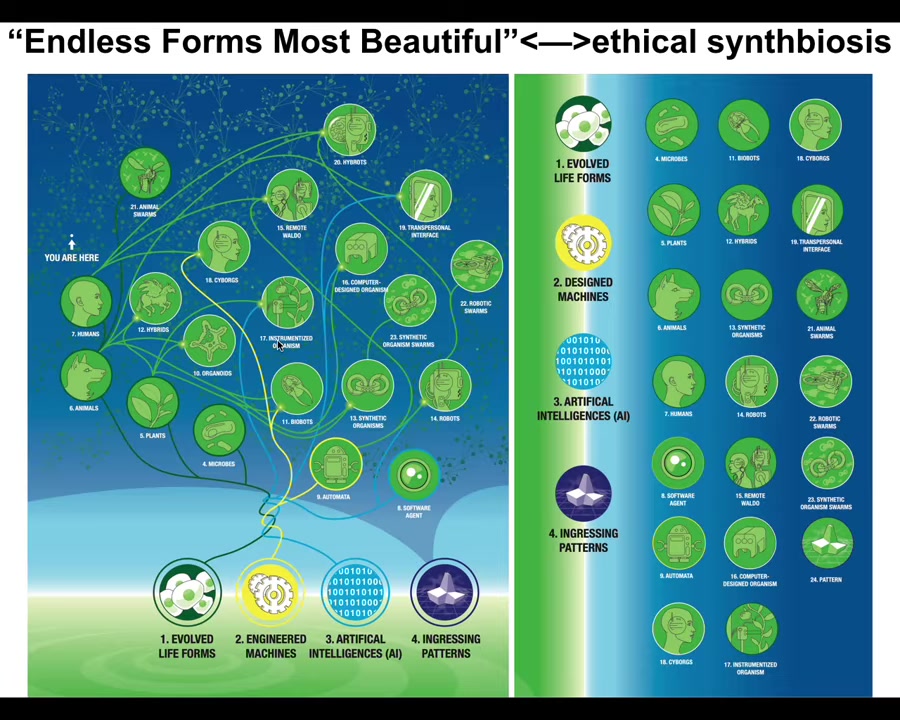

It's important that we now understand that because of the interoperability of life, because living things are constantly solving problems, they make few assumptions about their own structure, about the outside world. They have to make the best of every situation. Life is incredibly interoperable. Almost any combination of evolved material, engineered material, and software is a viable embodied mind that will benefit from ingesting patterns from this latent space. We will have, as we already do, cyborgs and hybrots and chimeras and synthetic beings of every kind. All of Darwin's endless forms most beautiful are a tiny little corner of this space of possible beings. We need to ramp up our game in being able to recognize and relate to all of these different kinds of novel embodied minds with which we will increasingly share our world.

Slide 35/44 · 44m:57s

For the last few minutes, what I want to show you is our attempt to develop tools for this. We take this continuum very seriously in that we're developing tools, but we're also developing colleagues. We're increasingly going to see this shift across this spectrum.

Slide 36/44 · 45m:17s

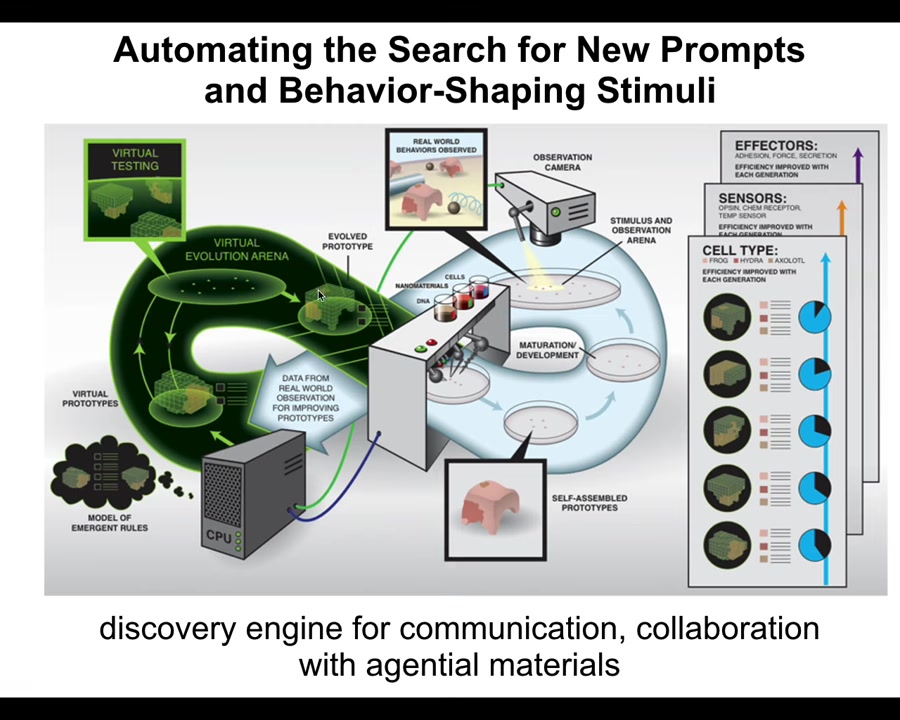

What we would like to do is develop a discovery engine that can do the following cycle. It should be able to make hypotheses about what stimuli to give to cells to get them to build a particular kind of multicellular organism. So this is that anatomical compiler idea I spoke about. Then it should test those hypotheses. It should build a living system with those stimuli, observe what happens, and revise its internal model of the morphogenetic code and the communication with that system.

We want a robot scientist in the lab, an AI-powered embodied robot scientist, which has a mind that thinks about hypotheses of how to talk to cells, but also a body that enables it to physically communicate with those cells and thus refine its view of the outside world.

This is the symmetry of active inference: making hypotheses, being surprised when expectations are not met, revising your priors, and engaging with the physical world to solve problems. This is science, but also the exercise of any agent. We want this discovery engine for communication and collaboration with agential materials, so we started to build one.

Slide 37/44 · 46m:41s

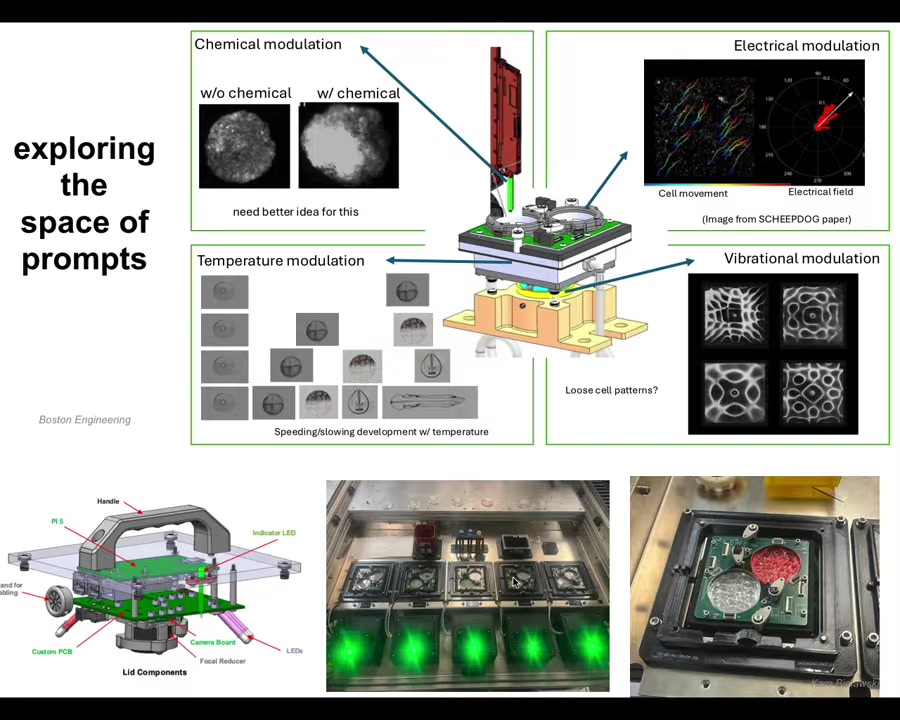

The specific stimuli we're going to start with, there are many things that are coming, but we're going to start with stimuli in four categories. Chemical signals, electrical stimulation, vibrational, biomechanical, and temperature gradients. We're going to start with those.

With our partners at Boston Engineering, this is a project that we're doing with the Bongard Lab at University of Vermont. Josh and I and Doug Blackiston, who started out in my group and now has his own lab, are all collaborating to build this system to try to understand what it takes to build really an autonomous communication interface to the living material of biology.

This is what the individual plates look like in which different hypotheses are to be tested. These are not artist's renditions. This is literally what's being built in our lab.

Slide 38/44 · 47m:43s

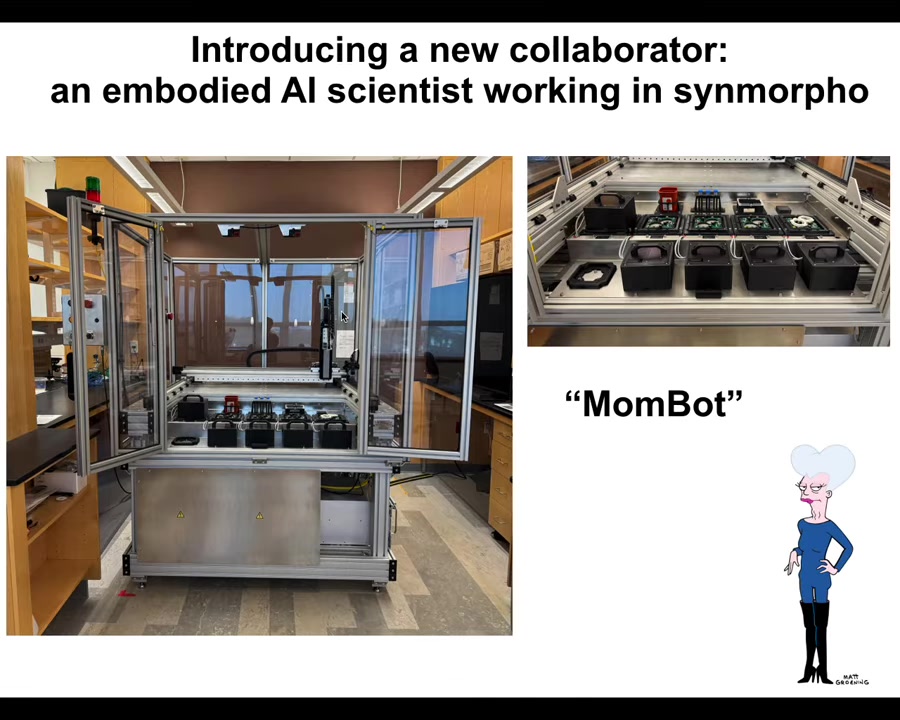

Here's what the thing looks like. Josh and I are both Futurama fans, so we tend to call this thing mom bot. This is it, the first iteration. This is version 1.0 standing in my lab. You can see here what it physically looks like.

Slide 39/44 · 48m:03s

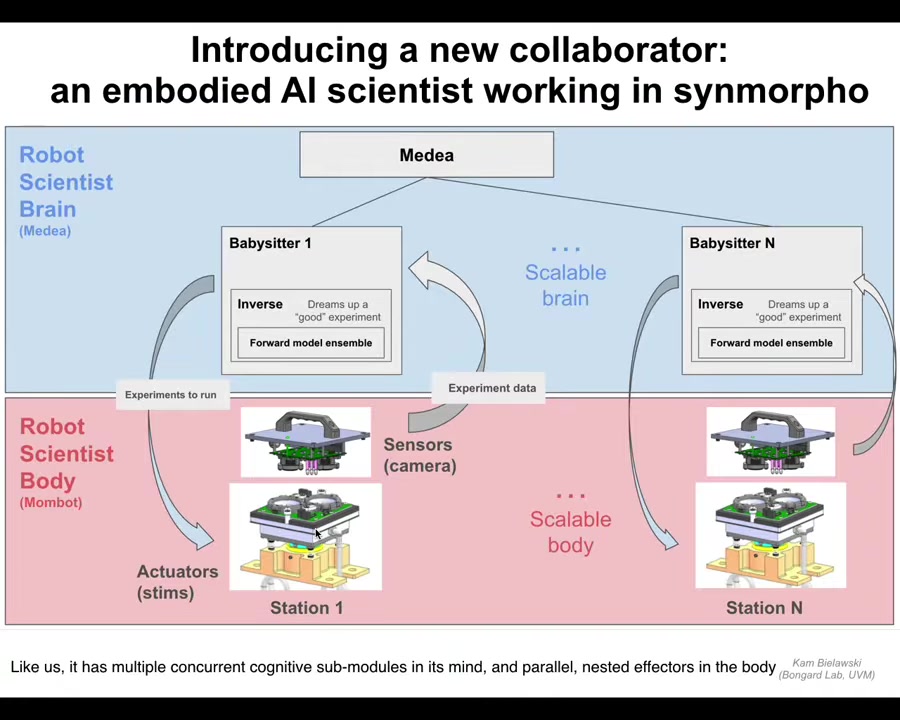

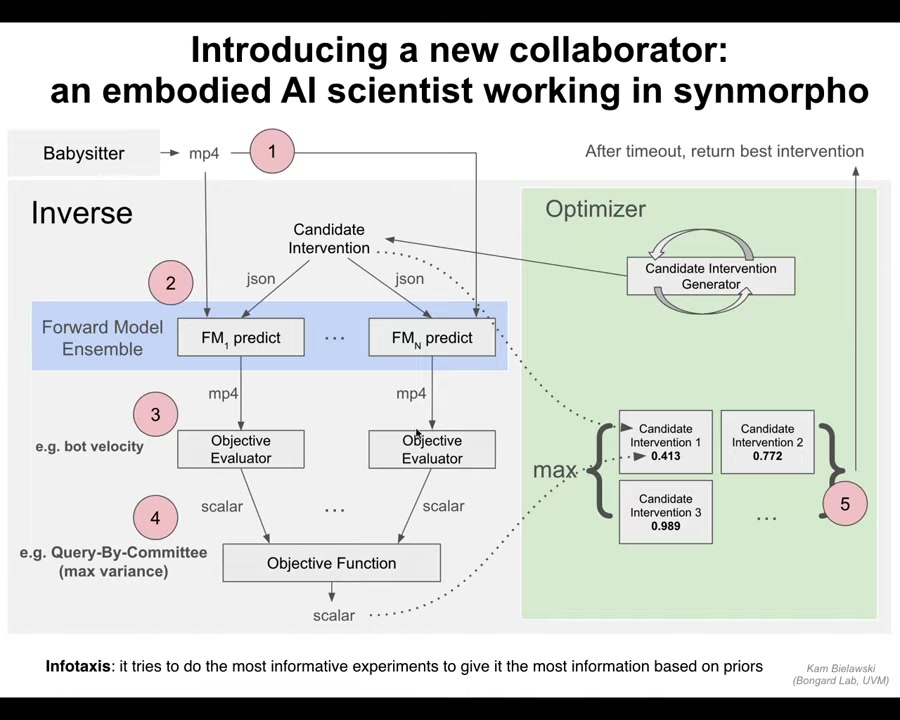

There's a little close-up, and so what I want to talk about is the internal structure, because it is in fact an embodied AI scientist working in the field of synthetic morphology. It has a mind. And much like ours, that mind contains multiple cognitive submodules, which have their own distinct individual goals, which are all communicating with each other and proposing hypotheses and competing for the attention of the large-scale brain, because there's only so many experiments that are actually going to be done. So this is highly parallelized and scalable.

The body is these elements that I just showed you; they are, again, parallel and nested. Many of these things are activated at different scales. So it is this multi-scale architecture.

Slide 40/44 · 48m:57s

One of the things it does, I'm not going to go through all of the architecture, but Doug and Kim are writing a paper on this soon, and what it's actually doing is infotaxis. It's searching for more information by doing experiments. It tries to do the most informative experiment to give it the best way to revise its priors and to learn about the world that it lives in. That world is the world of morphogenesis. It's the world of behavior-shaping cues that have particular results in anatomy.

Slide 41/44 · 49m:35s

And so I just want to point out something interesting: going back to this idea of doing experiments and revising your picture of the world. This system does that at multiple scales. So at one scale, it has hypotheses about the biobots, the xenobots in particular, that it's building, and it revises those. But even the subsystems within that robot have their own proprioception loop.

For example, this thing; there's a pipette that comes down, grabs the disposable plastic pipette ends, so that it can transport xenobots from one well to another or chemicals in and out of the solution. It has sensing through that tip. It's actually able to know whether that tip is touching liquid or not, so there's a sensing mechanism, and there's an internal loop that will adjust its own behavior depending on what it touches.

So just like we have large-scale goals, and then we have smaller loops within us that guide our behavior when you reach out and balance objects. There are nested proprioception loops inside this large-scale operation.

So we're incredibly excited about this because not only is it going to help us understand how to make and how to communicate with xenobot materials, it is also, I think, a model system for creating a kind of exploratory AI system.

Slide 42/44 · 51m:20s

So here are some next steps. First of all, we're going to be using it to develop new kinds of Xenobots, and that's the immediate next agenda.

One thing you might think about is adding a metacognitive loop where it should find new problems to solve, not just solutions. What it's doing right now is we as the users ask for bots that have specific properties, and then it tries to figure out how would I make a bot to do that. Bespoke synthetic living machines, it tries to solve our problems. In the future, there should be components added for creative exploration where it can pose its own problems and actually say, what would be interesting is a bot that does this and this. And finally, what I think would be really interesting is to enable this system to actually communicate with the bots and find out what they want. What I mean by saying what bots want is the following.

You can easily imagine a system where you have a cell culture system and there's instrumentation that monitors metabolic stress and other behaviors. When the cells could learn to activate specific behaviors to get nutrients, to get the machine to put more nutrients into the system. They already have this for plants. They have a system that waters plants when they ask for it. You can learn to run parts of your world to help you achieve goals.

From that instrumental learning all the way to a very sophisticated hybrid system that contains us, a scientist, it contains the MomBot, it contains Xenobot material, in which the behavior of the bots control and give cues to the MomBot to get it to do new experiments to change the way the bots are made and back and forth through that cycle to make an agential material that actively collaborates with its environment. It can do that because the environment is high agency too. The Xenobot's environment contains not just the passive water in the dishes, but it contains MomBot and it contains us as engineers. The material has the opportunity to collaborate with the environment to shape its embodied minds and the future of its evolution.

The future impacts of this are going to be along three basic tracks. First, the obvious thing is useful synthetic living machines: body repair, environmental cleanup, exploration, maybe space. The more long-term thing is robot science to help crack the morphogenetic code. How do we communicate with groups of cells to regenerate after injury, to repair birth defects, to normalize cancer cells and all of that? To help us develop this anatomical compiler. This is the future of science: embodied AI to help us crack these kinds of problems.

Also important is the use of the system to communicate with unconventional minds to help us. This is the diverse intelligence research program to help us recognize very alien kinds of minds that exist all around us, to actually join with them, to be parts of collaborative, aligned, cooperative systems and actually be part of it. One way to look at this is not just as the automation of discovery, not just as an anatomical compiler, but the MomBot platform as a communication node, as a bow-tie node in between human scientists and the cellular collective intelligence. It is a translator interface, but it's not a passive translator interface. It itself is an active intelligence. This idea of having AIs and, in general, nested cognition that becomes interfaces between other cognitive systems is very powerful.

It is particularly critical because of the need to develop an ethical synth biosis. We are going to have to learn to relate to these radically different kinds of minds.

Slide 43/44 · 55m:35s

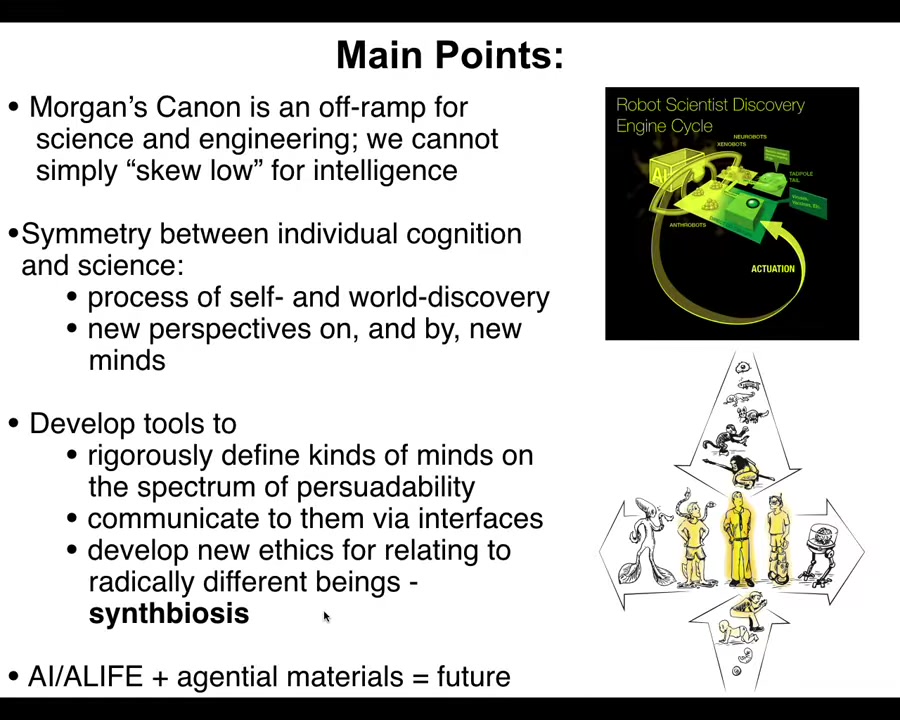

I'm going to wrap up here and remind you of the main points that I tried to transmit.

Morgan's canon, which is the idea that you should always skew low on assays of intelligence for whatever you're looking at. You should assume it's a dumb mechanical system. I think it's an off-ramp for science and engineering. It's really limiting in biology, in bioengineering, in biomedicine. It's a big mistake to do that as opposed to developing tools that allow you to guess correctly, not just skew low, but guess correctly.

There's a profound symmetry between the cognition of agents and the process of science — the process of discovery of the self and of the world, how you enlarge your perspective upon new minds and actually collaborate with them.

Now we can develop tools to rigorously define what exists on that spectrum of persuadability, to communicate to them via novel interfaces, be they bioelectric, biomechanical, or things we haven't even thought of yet, and to develop new ways to relate to them, because AI, ALife, and the understanding of agential materials are really the future.

Slide 44/44 · 56m:55s

I'm going to end here by thanking all the people who did the work.

Here are the postdocs and grad students and everybody else who did the work. In particular, I want to thank my close collaborator, Josh, and his whole lab. This is his team, all the people who worked on the cognitive side of Mombot, Boston Engineering, the company that helped us build all of these things, and their team. Doug, in his new lab. Lots of funders who have supported various efforts, but Krell in particular has really funded us to make this quite expensive engineering effort.

A shout out and disclosures of three companies. Fauna Systems is our partner for taking forward the actual Zenobot technology. Whatever it is that MomBot discovers, Fauna Systems is our partner for that. Astonishing Labs, which are supporting us for the study of different kinds of cellular intelligence and bio-inspired AI. Softmax as well. You heard from Adam Goldstein: this business of aligning parts, and in particular alignment between different scales of cognition and using a bio-inspired cognition-first approach to alignment between artificial systems and humans, is incredibly important for us going forward.