Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a ~52-minute talk titled "The Biology of Apparent Selves:

Bioengineering Model Systems for the Contemplative Sciences" that I have at the CSCSC 25 (Complex Systems and Contemplative Studies Conference) symposium (https://luma.com/3vyrtz4j?utm_source=ep-g2M2JDmWHB).

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Embodied minds and TAME

(03:28) Mind blindness and continua

(09:40) Spectrum of persuadability

(18:55) Morphogenesis and bioelectric memory

(24:40) Metamorphosis, memory and self

(30:38) Xenobots and anthrobots

(39:45) Mathematical space of patterns

(45:43) Platonic minds and machines

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/38 · 00m:00s

So what I'm really interested in and have been for a very long time is how embodied minds exist in the physical world. I want to understand how cognition and consciousness exist in this universe, how it's compatible with the laws of physics and chemistry as we know them, how third-person science can be complemented with first-person science. I take a very empirical approach to this: what I think is really key is that whatever theories we have in this space make contact with experiment and with the physical world. In particular, how I think we know that we're on the right track with some of these things is that we can create novel applications. We can create new capabilities, new discoveries, things that everyone can look at and say, yes, I see, this is working. We didn't have it working before. Therefore, there's something, at least something right about the way of thinking that got us here.

For us, that tends to be a couple of different areas: biomedical application. So I won't show too many of these things, but we work in birth defects, in regenerative medicine, growing back limbs and organs, and reprogramming tumors. And then bioengineering and some synthetic living machines. The idea is that we address some very fundamental philosophical problems and then we show how they can actually help us discover more about the world, and that's how we test these ideas to see if they're any good.

My policy is that I generally don't talk about things too far from what I can demonstrate and that have strong reasons to make claims. I'm happy to talk about anything and everything with you all. But as Pavel said, the reason that I've only been recently talking about some of these bigger issues is that now our data allow us to make strong statements about some of this stuff. Before, I had been thinking about it but hadn't been talking about it because I couldn't say anything strongly.

So if you want to see all the primary data, the software, all the papers, everything is here. This is my own personal blog where I talk about what I think some of these things mean.

Slide 2/38 · 02m:15s

The main points that I'm going to give today are the following. I'm going to briefly talk about this framework that I have called TAME. That stands for Technological Approach to Mind Everywhere. Technological means that I take an engineering approach where we should have empirically demonstrable novel efficacies to the things that we come up with.

I want to talk about ways of thinking about the scaling of cognition. I'm going to make the claim that there is a continuum of mind that's very important. It's a different idea than the typical categorization, the sharp categories that a lot of people think about. I'm going to talk about how we get from the very basic homeostatic competencies of single cells to morphogenetic and ultimately behavioral problem solving. This is the emerging field of diverse intelligence.

I'll show you a couple of new kinds of beings that we have to learn to recognize and ethically relate to. I think it's very important to deal with what we have as mind blindness, and I'll describe that. Then we'll talk about some implications for the future.

Slide 3/38 · 03m:30s

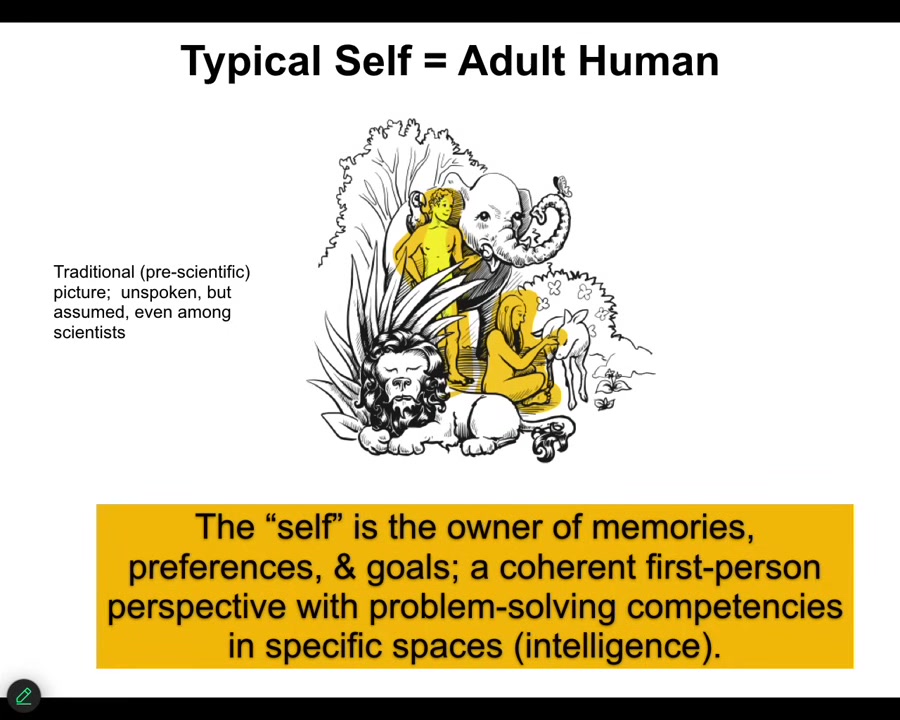

The first thing is that, in most discussions of philosophy of mind and ethics, what is thought about, if not outright stated, is this notion of an adult modern human. And that is typically the perspective. And so when we talk about the mind and the self, implicitly, even among scientists, this is typically what is meant.

Slide 4/38 · 04m:00s

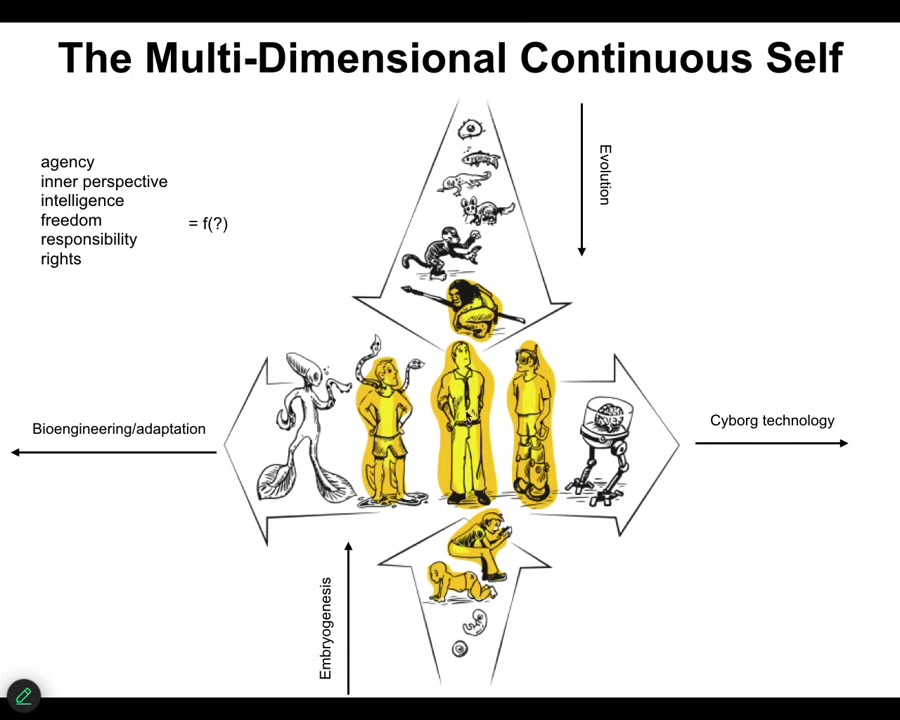

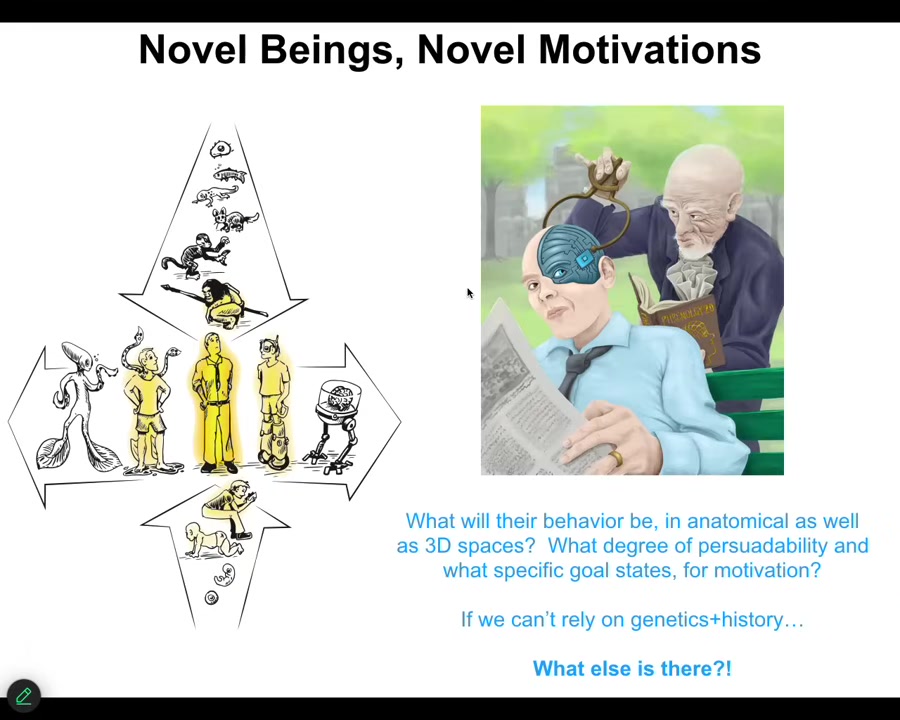

But I want to point out that we stand at the center of two very important continua. And whatever this yellow agential glow is, which is that we have agency, we have inner perspective, we have intelligence, we have freedom and responsibility and all these amazing things.

We have to actually understand what these properties are a function of. Because all of us started life on a developmental scale and also on an evolutionary scale. We started life as a single cell. We all start life as something compatible with physics and chemistry, and then eventually we become this amazing thing. So that's one continuum.

If you have thoughts about humans having specific responsibilities and agency, you have to ask yourself when did this exactly show up? Which of our hominid ancestors had it? How far back?

The other spectrum is that with both biological changes and now technological changes, the standard human is a very fuzzy kind of term. That's something else we can talk about: what actually is a human? I don't think it's what we thought it was.

Slide 5/38 · 05m:15s

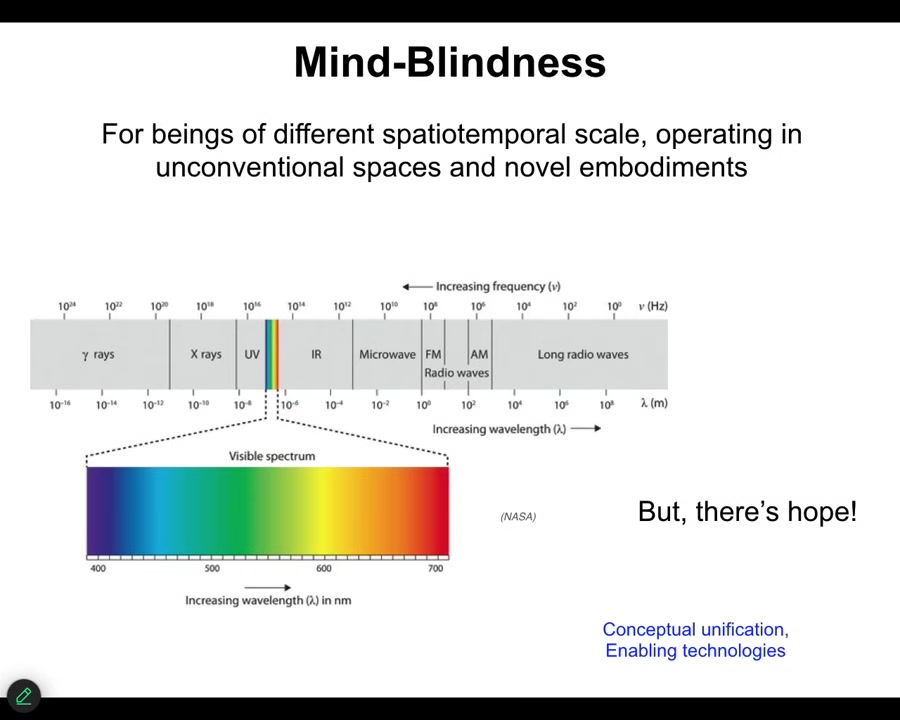

What I think we have here, and this is due to our own evolutionary history, is something that you can call mind blindness. To understand what I mean, think of the electromagnetic spectrum. Back in the day, before we had a modern theory of electromagnetism, we had lightning, and we had static electricity, and we had light and magnets and some things like that. We thought those were all categorically different things. We had different names for them. We really thought these were all different things. A, we were mistaken about the fact that these are all fragments of the same kind of thing. B, we were completely oblivious to huge areas of this electromagnetic spectrum because of our own evolutionary history. We simply didn't have the sensors to operate in this and we were blind to them.

Clearly science gives us some hope because a good quantitative theory of electromagnetism allowed us to not only recognize that all of these things were in fact facets or aspects of the same underlying phenomenon, but also allowed us to operate in this spectrum, to both send and receive and recognize novel systems in these other spectra that we otherwise couldn't have done.

I think because of our own evolutionary history, we are completely blind to embodied minds that are not like our own, and this is the role of our group and some others, to enable a conceptual unification of what is common to all kinds of minds, and then develop enabling technologies to allow us to recognize them and relate to them.

Slide 6/38 · 06m:55s

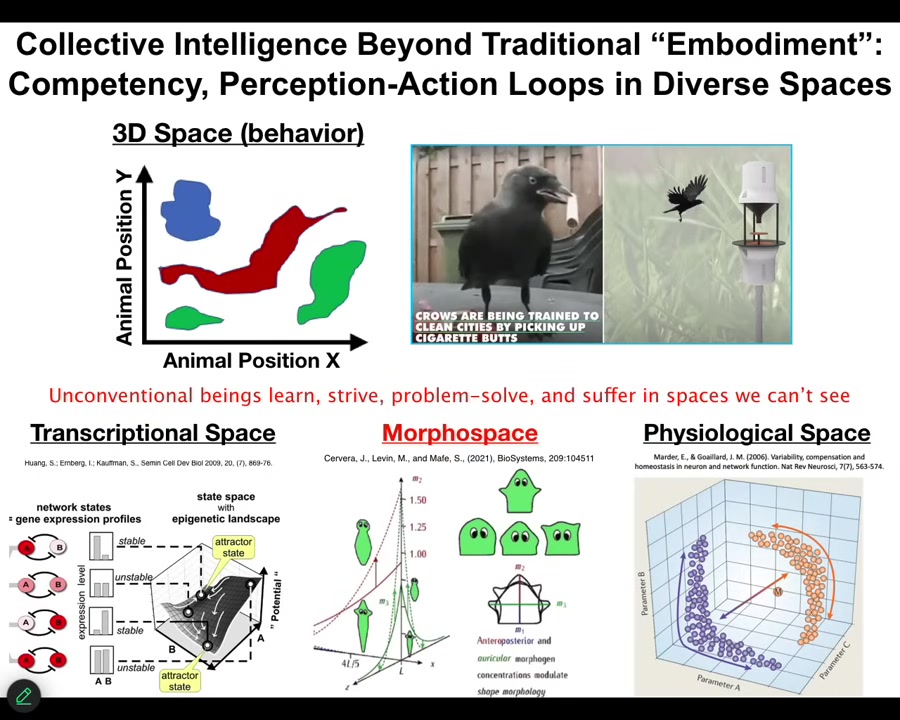

We as humans are okay at recognizing intelligence in medium-sized objects moving at medium speeds through three-dimensional space. You've got birds and primates and maybe a whale or an octopus, and we do okay in some cases. We can recognize the behavior here. But biology has been telling us that life has been navigating problem spaces long before there were any nerves or muscles or brains. In other words, long before you could move through three-dimensional space and do intelligent actions, your cells have been moving through the space of different gene expressions. That's a very high-dimensional space, maybe 20,000-dimensional space, through the space of physiological states, through anatomical amorphous space, which we'll talk about more today, the space of possibility of anatomical shapes. There are all of these systems; they do that same sensing, decision-making, behaving loop in spaces that we can't see.

It's very hard for us to visualize. If we had an inner sense of our own body chemistry—let's say you had a sense of your blood chemistry, 20 other parameters of your blood, and you could sense them the way that you could smell and taste and see now—you would have no problem understanding that your liver and your kidneys were this amazing symbiont that navigates this 20-dimensional space to keep you alive every day. You would be able to see the intelligent behavior of these organs as they go through their day. But we can't see it because we're simply not built for that.

Slide 7/38 · 08m:30s

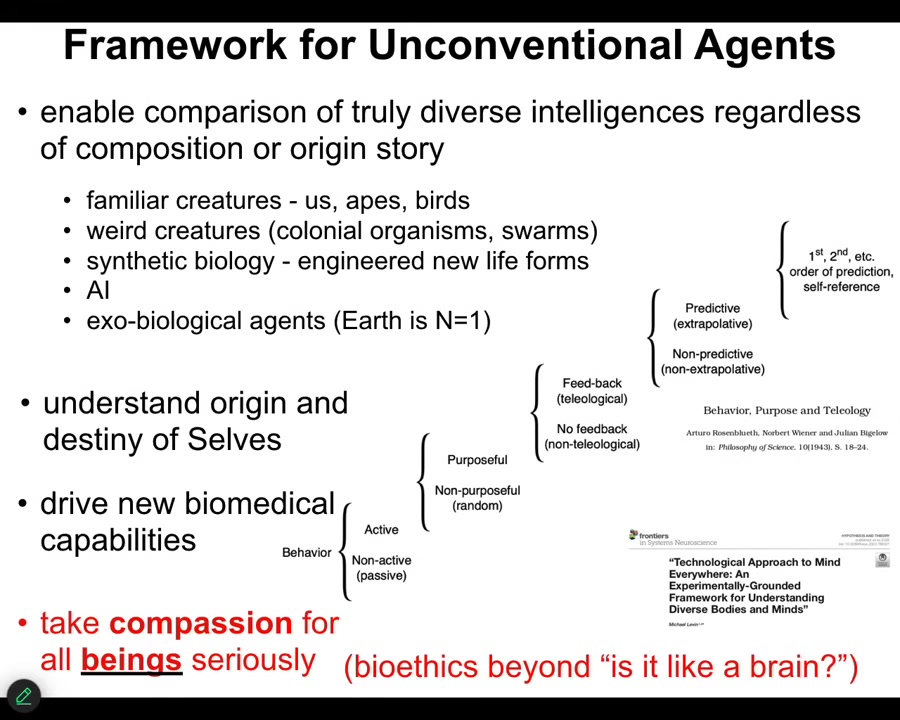

What I'm interested in is developing tools to allow us to think about truly diverse intelligences regardless of what they're made of or how they got here.

That means not only familiar creatures, but colonial organisms and swarms, things like beehives, including engineered new life forms, which I'm going to show some of today, AIs, whether embodied robotic or purely software, maybe aliens at some point.

That's really important because we need to understand the origin and the destiny of selves, especially including ourselves. It's critical to derive new biomedical capabilities, which depend on learning to communicate with the collective intelligence of cells and our bodies, not micromanage them but collaborate and communicate with them.

It's required to take compassion for all beings seriously. These bioethics discussions about organoids — is it like a human brain or isn't it — totally miss the mark because this is not about anything specific to human brains.

This is an older attempt, 1943, Wiener, Rosenblueth, and Bigelow, trying to understand what the scale of cognition is. This is my newer attempt at it.

Slide 8/38 · 09m:40s

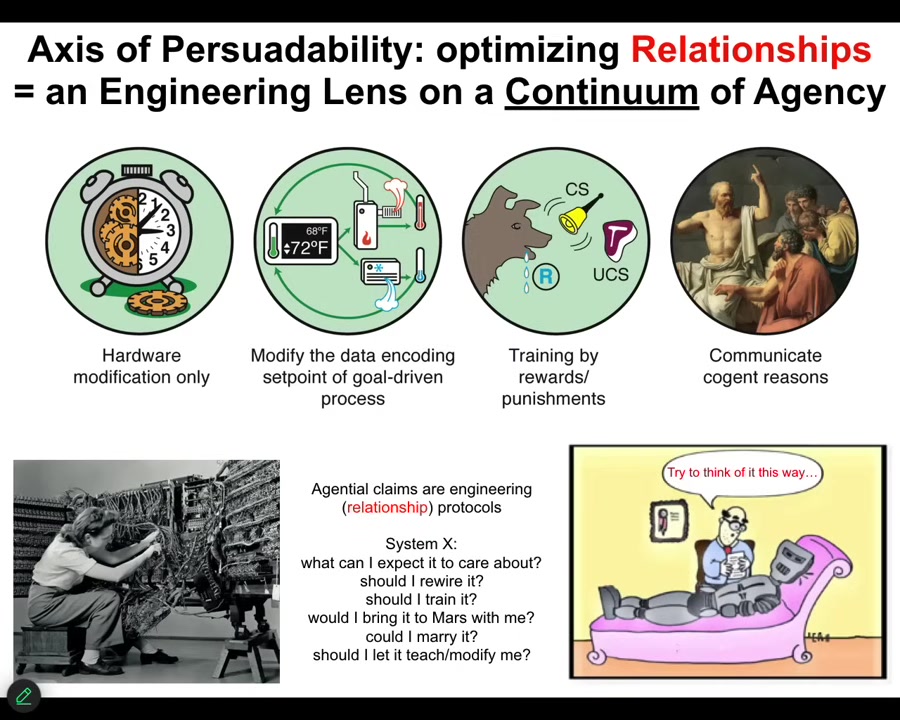

The one thing I'll say is that what we have here — I often call this the spectrum of persuadability — is all about relationships. It's about what kind of techniques you can use to relate meaningfully to a system. You might be using the tools of hardware modification, such as with simple machines. You might be using the tools of cybernetics or control theory, like your thermostat. You might be using behavioral science with training and things like that. Or you might be doing psychoanalysis and friendship and love.

This is a continuum. It has interesting waypoints on it, but because we all emerge from a single cell, we know this has to be continuous scaling. For any given system, we don't know where it lands here. People often say simple machines can't do this or that, or cells don't have brains and they can't do this or that. You can't know any of that until you do experiments.

This is not a project in linguistics trying to redefine what we mean by intelligence or cognition. It is not philosophy. You can't do this from an armchair. You have to do experiments. You have to say, this is the set of tools I plan to bring in my interaction with the system. I'm going to do it. Then all of us can see how well that worked out for me, and we'll know whether I guessed correctly.

In our work in biology, what we find is that skewing high often lets you discover things that nobody had seen before, because the standard version of science is Morgan's canon, which skews low: assume it has zero to very low cognition until proven otherwise. I think that leaves a lot on the table.

For any given system, these are the kinds of things you want to ask, and that's because all of us go through this amazing journey across the different sciences.

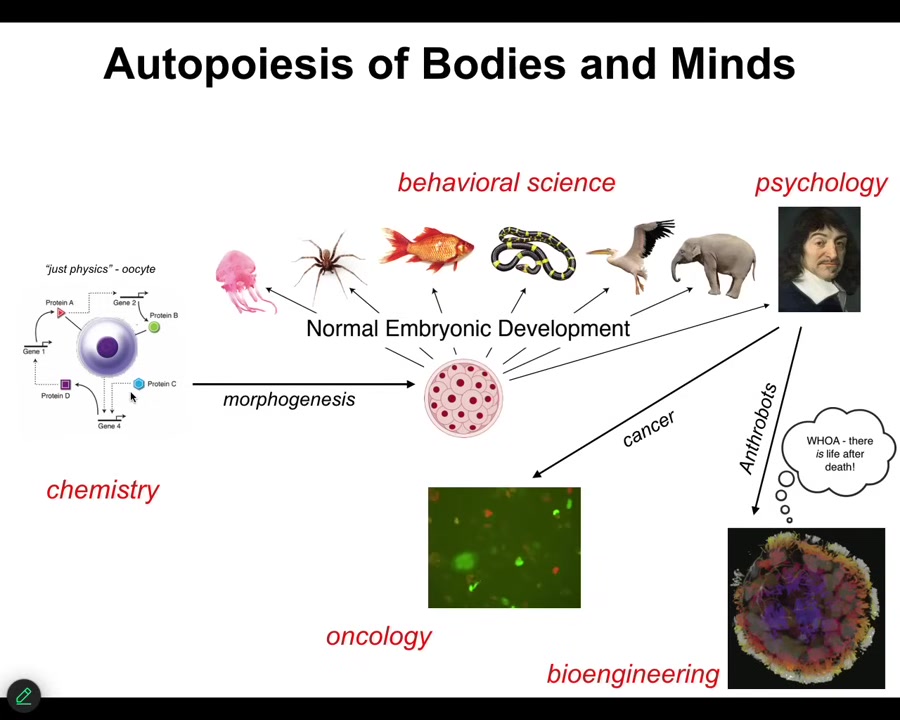

Slide 9/38 · 11m:38s

We start out as the province of chemistry, as an unfertilized oocyte, then slowly and gradually we become something like this, or even something like this. There is no magic lightning flash during the developmental processes. You were just chemistry and physics before, but now you're a real mind. That doesn't happen. This is slow and gradual.

Even that's not the end of the story because there are breakdowns of collective intelligence that manifest as cancer. There are alternative lives that your body cells can have, and you may or may not be around to see it. I'll show you some of these anthrobots. All of this is a journey of transformation.

We have to understand the scaling of minds. Where do they come from and where do they go and how do they scale?

Slide 10/38 · 12m:30s

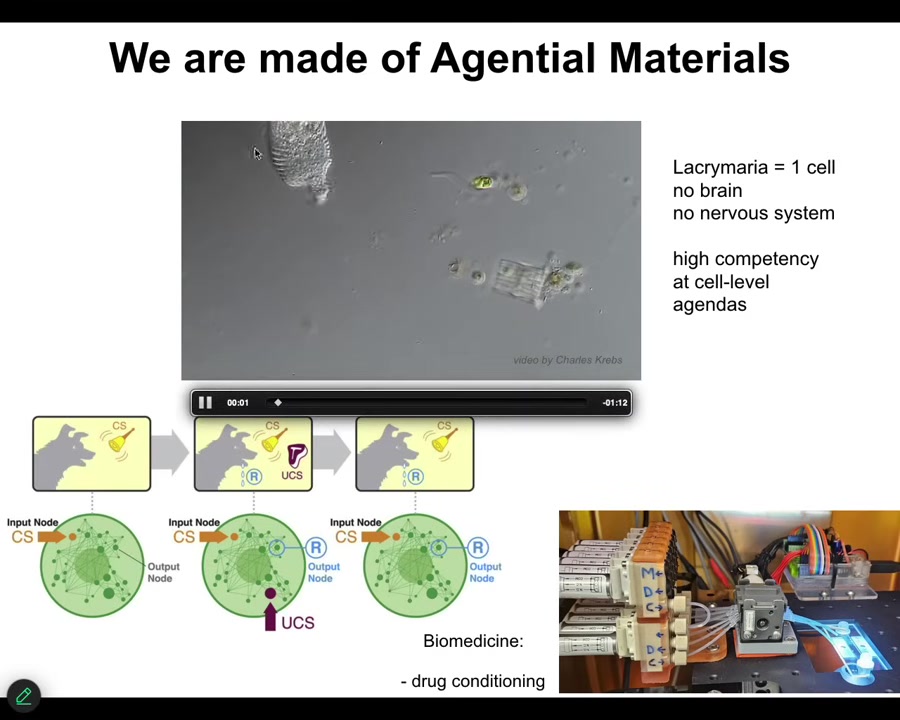

That's because all of us are made of agential materials. In other words, unlike wood and Legos and metal and things we've been engineering with for thousands of years, this is the kind of stuff we're made of. This is a single cell. It's a Lacrymaria. The cells in our body were like this once. There's no brain here. There's no nervous system. This creature is incredibly competent in its own little environment. Even the material it is made of—the chemical reactions inside this creature—have a learning capacity, at least six different kinds of learning, including Pavlovian conditioning.

We're taking advantage of that in our lab for drug conditioning and other medical applications.

Slide 11/38 · 13m:15s

If you wonder what it means to have valence and to be subject to reward and punishment, with a rat you can give it positive and negative reinforcement. You look at something like this and say I'm pretty sure we could also give this little guy positive and negative reinforcement. That's clear.

If I ask you, "Can I punish a chemical network?" you might say no, chemical networks are just machines. They don't have a valence or first-person perspective. I would point out, what do you think is inside of this? It's these chemical networks. We really have to develop a story of scaling. Here's how we develop.

Slide 12/38 · 13m:50s

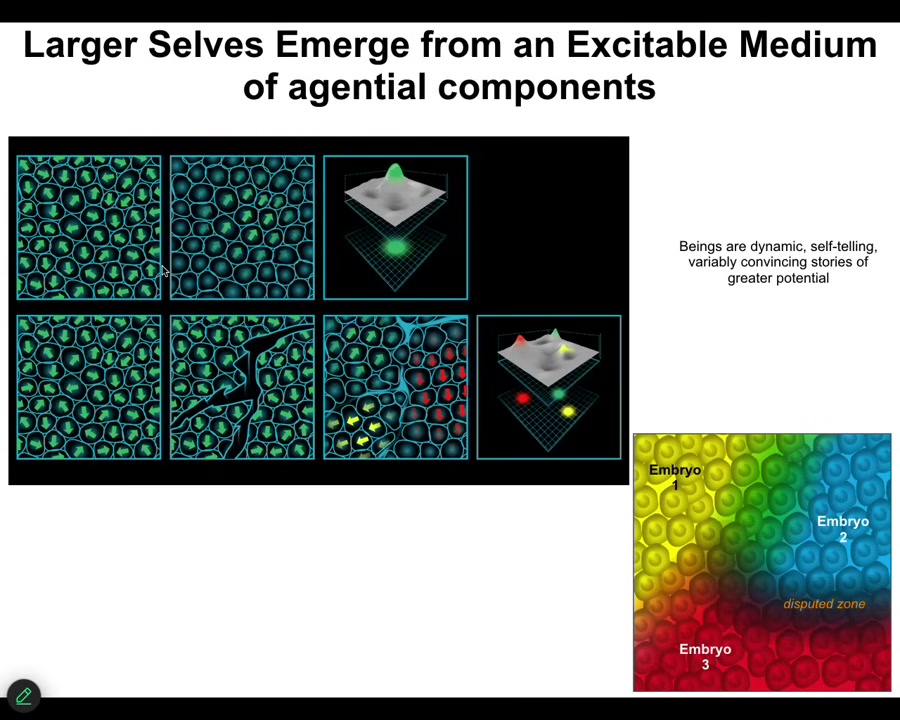

Because I do think that the facts around the bigger questions of inner perspective and mind and all that really have to be compatible with the facts of how our bodies develop and where we come from. So imagine an early embryonic blastoderm. There's 100,000 cells. We look at that and we say, there's an embryo. What are we counting when we say it's one embryo? What is there one of? There's hundreds of thousands or millions of cells. What is there one of? What there's one of is alignment. There's one story that all of these cells are committed to as far as where they're going to go in anatomical morphospace. Are they going to make a snake, a tree, a human, an octopus, whatever.

That is what binds all of these individual, very competent subunits to the same cooperative outcome because of a coherent self-model that the collective has. As a grad student, I did this in duck embryos: you can take a little needle and put some scratches in this blastoderm, and every fragment here, every island, until they heal back up, doesn't feel the presence of the others. They develop into a new embryo, and then that's how you get twins and triplets.

So what we have here is the number of beings, the number of cells inside an embryo is not fixed by genetics, it's not determined by physics. It is developed in real time as a result of the physiology of the cells trying to decide what am I and what am I going to be. And the number of individuals that can arise from a single egg is anywhere from zero to typically one, but often two, three, up to dozens in some cases. So how many different individuals are packed into this little case? Very, very important. We have similar problems in cognition where you can ask, how much brain real estate does an actual human personality take? And we now know from dissociative identity disorders and split brain patients that is not an obvious question.

Slide 13/38 · 15m:55s

One of the most interesting things about this architecture, the fact that we're made of cognitive subunits, is that there's this mind-matter interaction, which is very interesting. If I were to tell you that with the power of my mind alone, I can change the voltage state of 20 to 30% of my body cells. You might say that's either crazy or that's some sort of special yoga, long-term mind-matter skill. But this is ubiquitous voluntary motion.

So when you wake up in the morning and you have social goals, research goals, financial goals, whatever the abstract, extremely high level, very abstract goals you may have, in order for you to get up out of bed and execute on those goals, ions have to cross muscle cell membranes. In other words, the chemistry has to obey these larger scale of very abstract goals.

What your body does is an amazing process of transducing these incredibly, incredibly high level goal states in weird spaces that your cells and certainly the molecules inside them have no comprehension of, has to transduce them to literally make the chemistry dance to the tune of your mental state. It's ubiquitous, it happens all the time, and it is one of those examples of everyday magic.

And in our group we're trying to learn to communicate using various tools to communicate with all of the different layers of the body, because that's the road to transformative regenerative medicine.

Slide 14/38 · 17m:25s

What I just told you, at least for a modern-day story, is very unusual; it sounds very dualistic. It sounds like you've got these abstract mental goal states, and then eventually they have to make the chemistry literally change what it was doing before. There's got to be some mind-matter interaction.

This Cartesian model has been very unpopular in modern science. One of the things people say is, if you want to think about that kind of structure, you have to tell us where the interaction is. Where in the body does it tick over from being a mind to being just physics or physiology or chemistry? My point is, when does it tick over? Never, because it's cognition all the way down.

The issue here is that it is different degrees and kinds of intelligence all the way down. What you're looking at is not an interaction where a very smart, non-physical, ghostly substance tells dumb matter how to move. My point is, and I'm going to expand on this shortly, there is no dumb matter. You have communication and transduction of behavior-shaping signals all the way down from the large scale to the small and back up. The trick is to understand communication and the scaling of goals.

Slide 15/38 · 18m:50s

I'm going to show you what the biology of this kind of scaling of goals looks like.

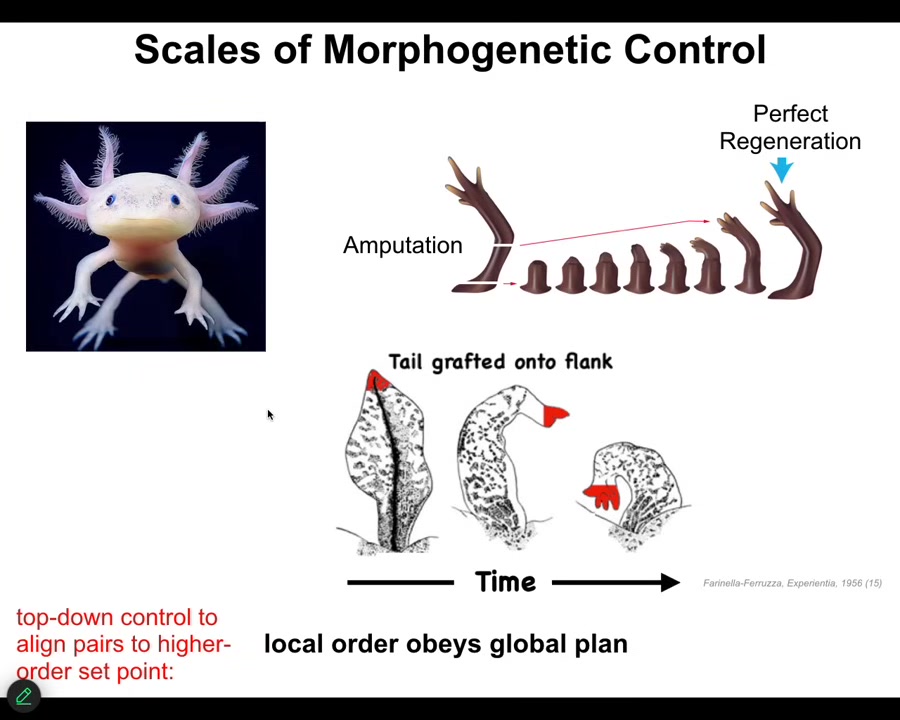

First, let's look at this creature. This is an axolotl. It's an amphibian. These guys are amazing. They regenerate their limbs, their eyes, their jaws, lots of different organs. What you see is that if, for example, they lose their limb anywhere along this line, the cells will very rapidly regrow exactly what's missing, and then they stop. No individual cell knows what a finger is or how many fingers you're supposed to have, but the collective absolutely knows. We know it's a goal state, because if you deviate it from that goal state, it will work hard to regain it, and then it stops. That's the definition of homeostasis, and homeostatic systems store a representation of the target state. Even your thermostat knows one simple thing: it knows what the temperature range is supposed to be.

This system has a memory that we've decoded, not particularly in an axolotl, but I'll show you some examples. This is how the collective of cells pursues that goal. What I'm using here is a model system, which is groups of cells executing morphogenetic behaviors — not in three-dimensional space, but in anatomical space. What they're doing is navigating this anatomical space as a collective intelligence.

It's not just about healing damage. This is, I think, one of the most profound experiments in biology for the things that we want to think about. In 1956, these guys took tails and grafted them to the side of this axolotl. Over time the tails metamorphose into limbs. They remodel into limbs over time.

Look at it from the perspective of these cells at the tip of this tail. There's nothing wrong locally. They're tail-tip cells sitting at the end of the tail. There's no injury, there's no damage, there's nothing wrong with them. Yet, all of a sudden, they're getting this incredible set of signals that causes them to remodel into fingers. I often think about what this would feel like for these cells: there's a major change going on. We have no idea why it's happening. We didn't cause it locally. It doesn't make any sense. We can't tell if there's some greater plan to this or not, but all our molecular biology, all the chemistry is changing.

It's changing because of this transduction, because this global plan that knows that you need a tail here, not a limb, is transducing down and making even non-local, remote regions and very low-level events act in a way that then probably looks like synchronicity to them, but eventually it makes this very coherent outcome. The local order obeys a global plan.

We found that the memories for all this stuff are stored electrically. Not a huge surprise because the brain does it and that's where the brain learned its tricks.

Slide 16/38 · 21m:52s

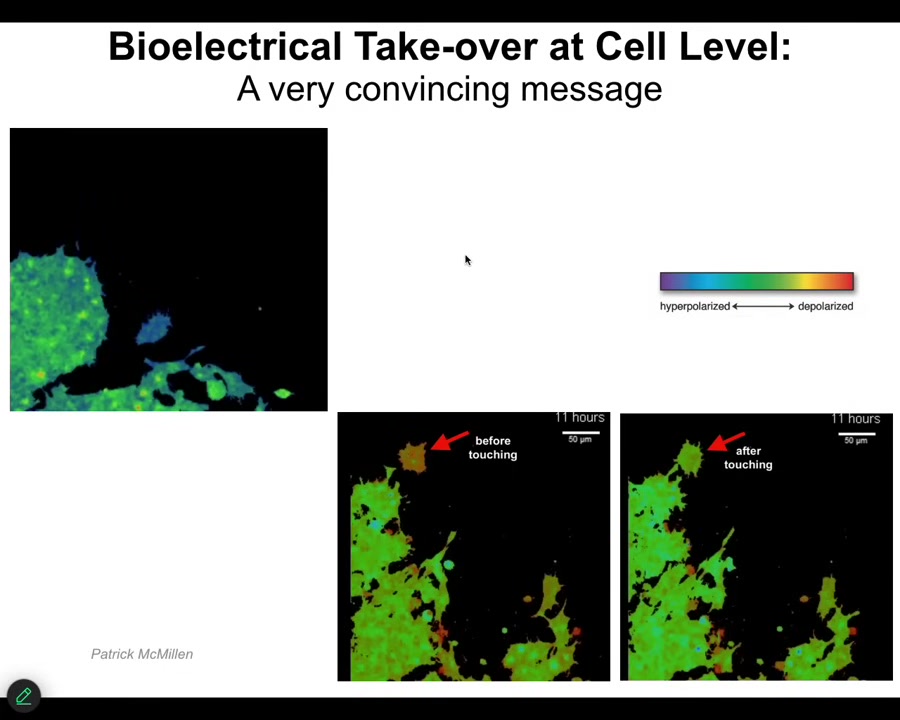

I just wanted to show you a very simple example of what it means to convince a cell to do one thing versus the other. These are two frames from a video I'm going to play shortly. The color is showing you the voltage state of a cell. We've learned to image the voltage of these cells.

This particular cell has a very different voltage than this whole mass over here, but all it takes is this tiny little touch here, and you'll see that it is now converted. This cell, it's blue, it's minding its own business, walking around. This guy's going to reach out, bang. That's it. The tiny little touch. It's changed its voltage, and now it's part of this collective. It is going to build whatever it is that this group of cells builds.

Understanding that kind of messaging that was just passed through that little contact is critical because we, as workers in regenerative medicine, would like to tell cells what to do.

Slide 17/38 · 22m:40s

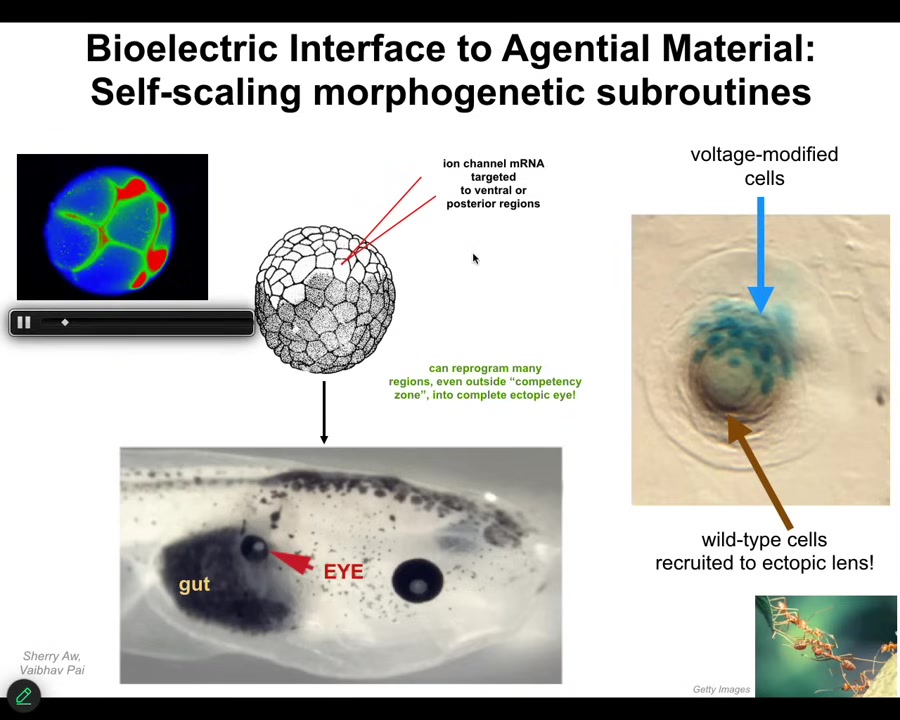

And so this is a time lapse of an early frog embryo. You can see all the cells, all the conversations that the cells are having with who's going to be left, right, head, tail. And when we take advantage of this kind of thing, we can tell cells, hey, you really should be an eye. And then they go ahead and they form an eye, for example, in the gut of this tadpole.

So this is, here's the normal eye, here's the brain up here, the mouth. There's a side view of a tadpole. And we can say, you should be an eye. We don't know how to make an eye. We don't know all the probably hundreds of thousands of molecular events that have to happen to make a proper eye, but we don't need to because the material is smart. Because all we need to do is convince the material that it wants to make an eye. And by establishing a bioelectrical pattern here, that is the memory of an eye. And if we're convincing, then the cells will do it.

In fact, not only will the cells do it, they will tell other cells to join them. So the blue cells here are the ones that we targeted. There's not enough of them to make an eye. But what they do is they recruit all this other stuff. We never touched it. They tell their neighbors, hey, you should work with us to make this out.

Slide 18/38 · 23m:48s

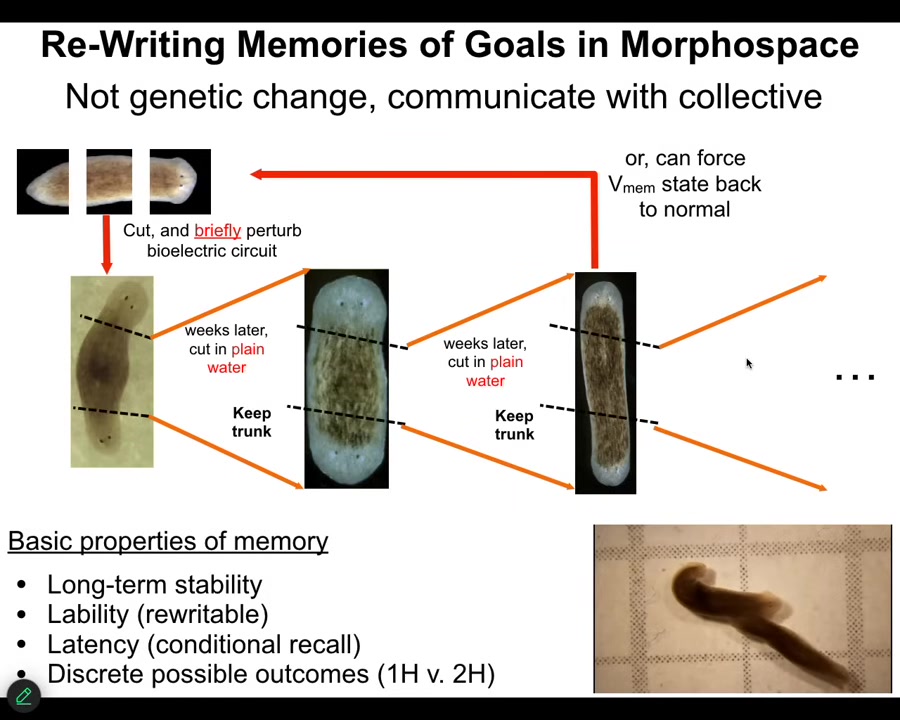

If you do things like this, you can also convince flatworms that they should have two heads. Here's a flatworm. They normally regenerate. You cut it into pieces. Every piece makes one tail, one head. But there's a bioelectrical pattern there that says one head is what you should have. We can rewrite that information. We can say, no, two heads is what you want. If we do that correctly, you get a worm with two heads. If you keep cutting this worm, you will continue to get two-headed animals. Even though their genetics is perfectly normal, the hardware has not been touched. There's nothing wrong with the hardware, but they have a new memory, a new representation of what a correct planarian looks like, a new goal state. We can communicate with this system by rewriting that goal state. This is not micromanaging the molecular biology. This is convincing the collective that its goals are different. You can see what these two-headed worms do.

Slide 19/38 · 24m:38s

A couple of quick things before we take a break. I want to point out a couple of other aspects of the biology that I think are very important for thinking about the kinds of questions that the symposium is about.

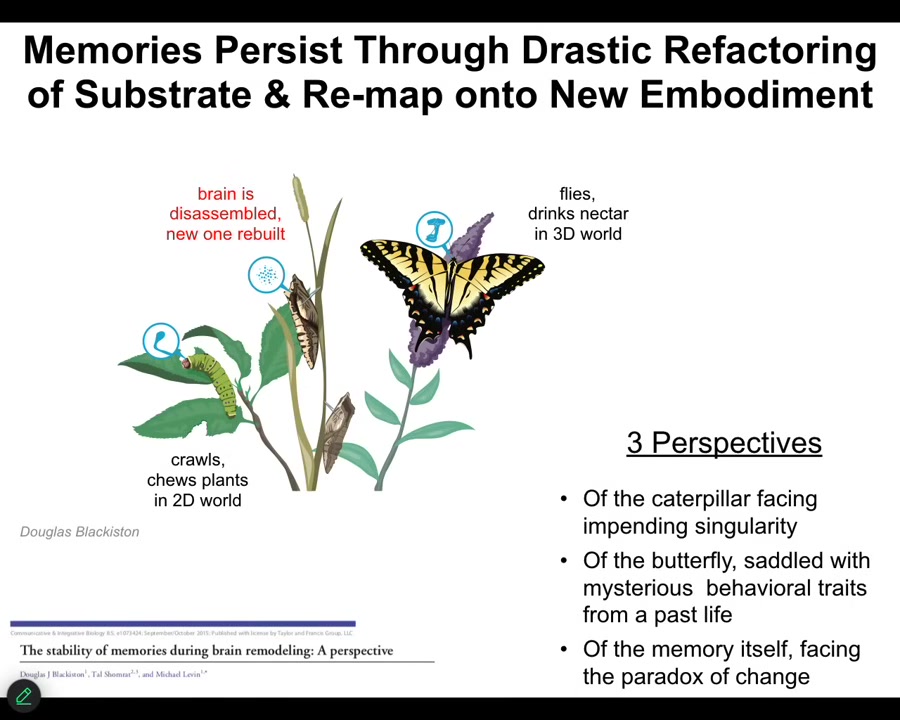

Consider this caterpillar. It lives in a two-dimensional world. It eats leaves. It has a brain suitable for that purpose. What it has to do is turn into this amazing moth or butterfly that flies. In the process of doing that, it has to rip up its brain. It basically kills off most of the cells. It breaks all the neuronal connections and it completely rebuilds a new brain.

You can train these caterpillars to go and eat leaves of a particular color. It turns out that despite the refactoring of the brain, the moth or butterfly remembers that original information. The obvious question is how do you hold on to memories while the supposed memory medium is being destroyed? That's one question.

There's a deeper issue here, which is that the actual memories of the butterfly, "this is how you crawl to get to the leaves that I want," that memory is completely useless to the butterfly. The butterfly doesn't want leaves, and it doesn't crawl. It operates in a completely different way and it drinks nectar. That memory, it's not about holding on to the memory, it's about remapping that memory onto a completely new architecture in your new higher-dimensional life. You basically cease to be a caterpillar. You are reborn in a higher-dimensional space. The memories that you used to have are not useful in their details, but they are useful in the deep meaning.

I invite you to take three perspectives in this story. First of all, take the perspective of the caterpillar facing an impending singularity. I'm going to cease to be the kind of creature that I am now. I'm going to be a different creature, an alien creature. What does that mean for me? We are all facing that, both as individuals and, I think, as a species in terms of transformation. That's one perspective.

The second perspective is that of a butterfly. Here I am, I'm this magnificent butterfly, everything's great. I seem to be saddled with some behavioral traits that I don't know where they came from. They affect my behavior. Not sure where they came from, but here they are, and I've inherited them from somewhere.

Even weirder, a third perspective is that of the memory itself. The memory pattern that is sitting here is going to disappear unless it can change itself to be of more use to its new environment. It faces the paradox of change. If I don't change, I will cease to be. If I do change, I'm no longer myself and, in some sense, have ceased to be. What can I do as a memory to make sure I survive this transition? What patterns survive this transition? I think it's very interesting.

Slide 20/38 · 27m:35s

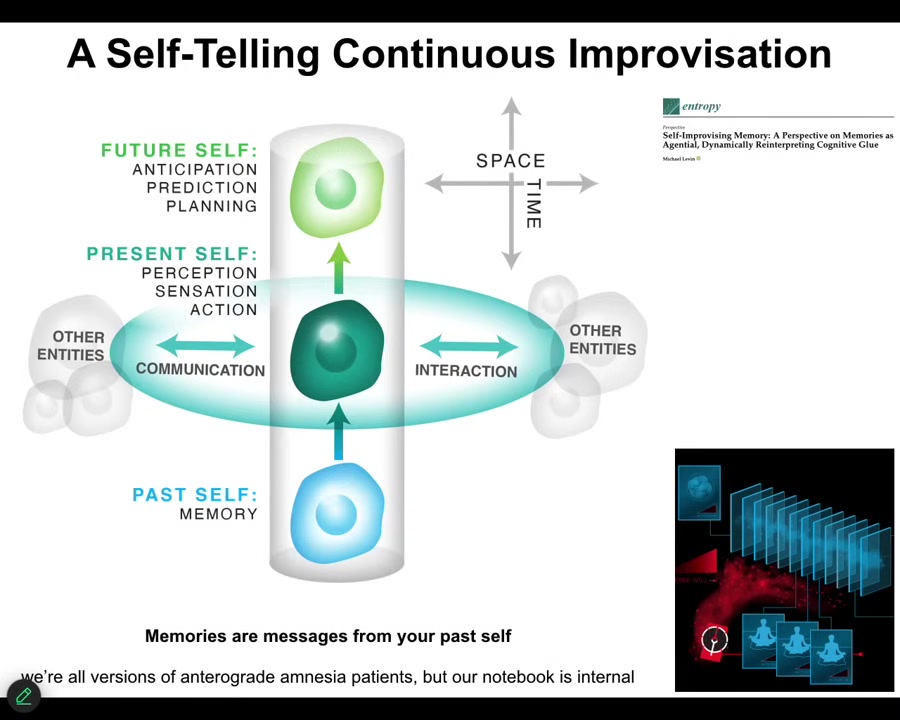

I think that we are all in this interesting situation where we don't have access to the past. All we have access to at any given moment is the memory traces that events in the past have left in our brain and body. At every moment, so let's say 200–300 milliseconds, we have to subconsciously reconstruct a story of what we are, what our memories mean, because it's not obvious at all, and what's going to happen going forward. Memories are messages from your past self. They're just like memories that you get laterally from other entities. At every moment, you've inherited a whole bunch of molecular, bioelectric, and genetic memories. We are constantly a kind of self-telling dynamic story of what our memories mean. I go into this in this paper.

But this has all kinds of implications, including the fact that the plasticity here is incredible. The degree of freedom here is incredible in terms of being able to reimagine ourselves, reinvent ourselves continuously, because we are under no obligation to interpret our engrams the same way that our past self did. If there's a new story that fits better now, we should learn to embrace that. We are not permanent structures. We are not objects. We are this dynamic, continuous interpretation of what it is that we are and what our past was like, what our environment is, exactly the way that the embryo is not the cells and it's not the genetics. It's the story that binds them all together about what it is that they should be doing into the future.

Slide 21/38 · 29m:22s

I'm supposed to take a five-minute pause. Let's take that here. I was asked also to come up with a couple of things to think about during those five minutes. I'll leave you with this cartoon.

Here are two parasites sitting inside this guy's digestive tract. While he's looking out into the universe, wondering if he's alone in this cold, unfeeling universe, components of him are saying: one is a kind of materialist-reductionist type. He says, "We live in a cold mechanical universe. There's no order out there. It doesn't care about us." This one has a suspicion that maybe there is something going on. Maybe we are part of a larger system that is somewhere on that spectrum of cognition. You can do the same thing with two neurons in a brain arguing back and forth.

I'll take five minutes and leave you to think about what criteria do you use to recognize other minds around you in novel embodiments at different scales operating at different spaces? People often ask me, how would you know if you were a component of a larger mind? What would that look like? I've said that cells don't know what a finger is, but could you get evidence that you were in fact part of some bigger story?

Slide 22/38 · 30m:40s

The second half of this, I'm going to start by showing you what that plasticity implies: the idea that we are constantly having to revise, reinvent, and improvise the meaning of our own memories.

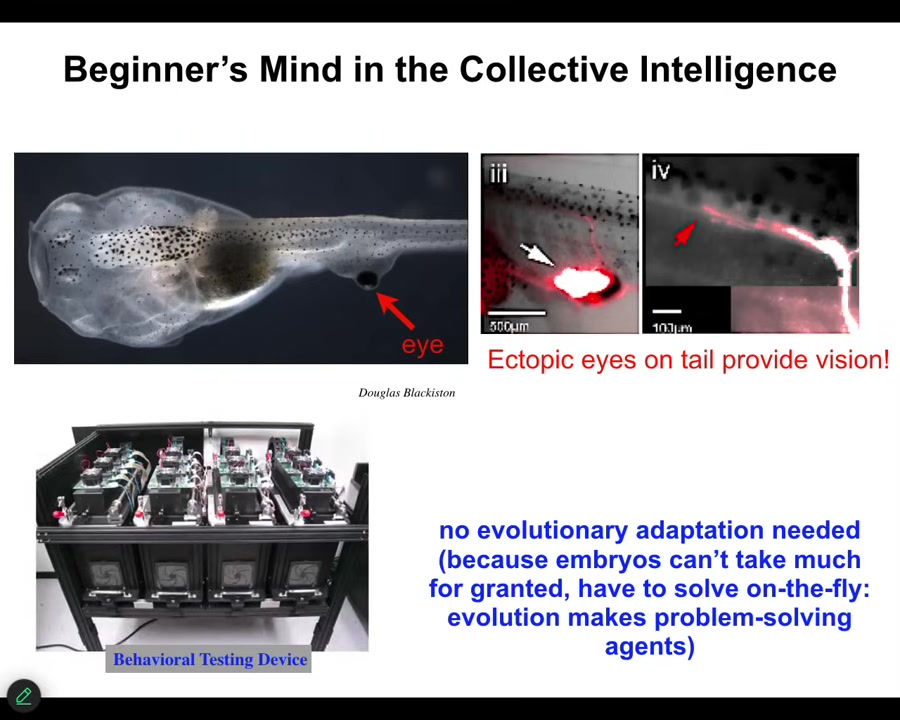

This is not just on the behavioral side. The reason we are so good at doing this behaviorally is that biology has been doing this from day one. Evolution doesn't make solutions to specific problems. It makes problem-solving machines. These machines don't take their past and their memories too seriously. It has implications. For example, here is a tadpole. In this tadpole we've prevented the primary eyes from forming in the head. The head is to the left, the mouth and the nostrils are facing left. But we've put an extra eye on its tail. We find that the eye is perfectly happy forming wherever you ask it to be. Then it makes an optic nerve. That optic nerve grows out. It might synapse on the spinal cord, maybe on the gut, maybe nowhere at all. It never goes to the brain. Yet these animals can see. We know they can see because we've built this device to train them to respond to visual cues so they do behavioral learning. They can see perfectly well out of an eye on its tail that does not connect to the brain.

You would think that this kind of radical change of the sensory-motor architecture would require new rounds of evolution, mutation, adaptation, selection. No, you don't need any of that. It works out of the box. The reason it works out of the box is that those cells were never quite certain where any of the stuff was going to be in the first place. It is a constant construction of "let's tell the best story we can" at any given moment. Just the way our minds do that from our memories, the body does it. That layer from genotypes, from the genetics that's the hardware of every cell to the actual outcome of form and function, that middle layer, that morphogenetic layer is a problem-solving system. It is intelligent. It solves problems. We could do hours on that alone. But that plasticity gives rise to these kinds of things.

Slide 23/38 · 32m:52s

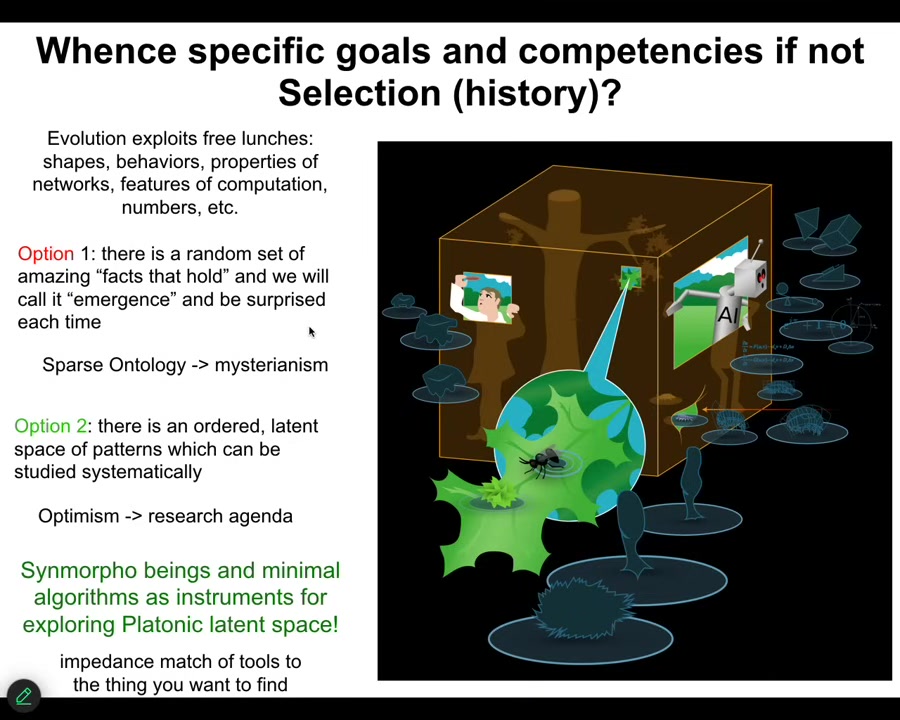

So, if the central principle of our biological body architecture is problem-solving and goal-directed behavior in anatomical space and gene expression space and so on, we know where those goals come from. Well, evolutionary selection is the standard story. We have eons of history shaping what those goal states are going to be. But now there are all kinds of novel beings that don't have a history of evolutionary selection. Where do their goals come from? What goals do they have? What sets their cognitive properties?

I'm going to show you two quick model systems for thinking about that. Going forward, it's not the language models and the AIs that we need to be thinking about. For a lot of the questions we care about, it's this. It's the humans that have been altered in various ways. This guy's concern that his neighbor has more than 51% of his brain replaced by an engineered construction, and now he thinks that he's not actually a human and that he doesn't deserve all those rights and responsibilities that he has.

People are constantly looking for proof of humanity certificates. This is really where the rubber is going to hit the road. Let's look at some model systems for understanding this.

Slide 24/38 · 34m:15s

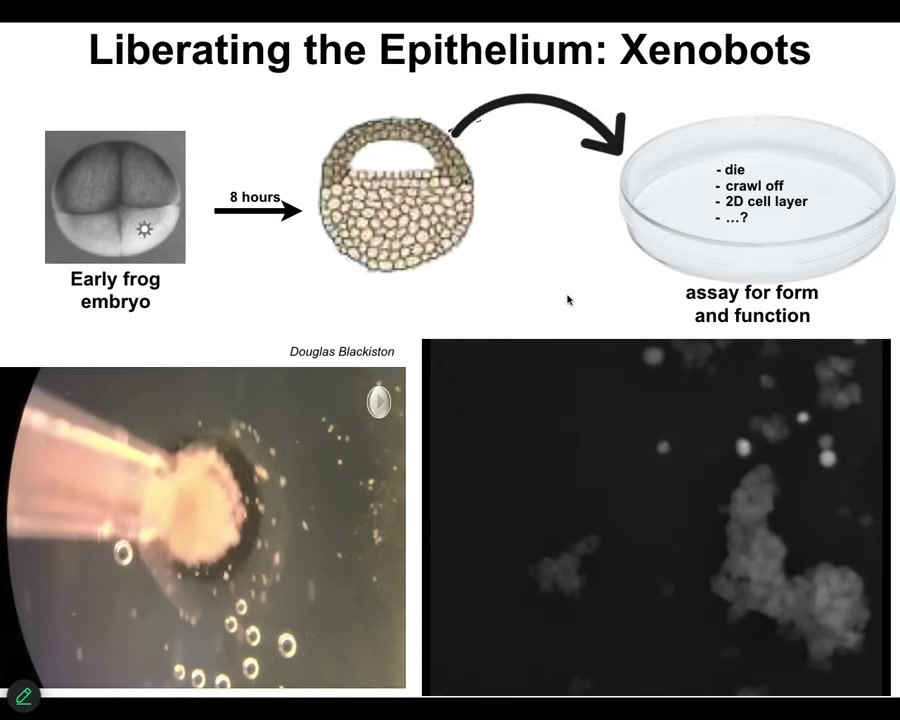

This is a model system we call xenobots. What we do is we liberate some epithelial cells from the animal pole of the frog embryo, and we dissociate them. We set them aside. They could do many things. They could crawl away from each other. They could die. They could form a two-dimensional cell culture. Instead, what they do is they combine into this little structure right here. I want to show you how that actually happens. This is a close-up. Each of these circles is a single cell. So this is a group of cells. I like the fact that it looks like a little horse. They don't all look like that. They have all kinds of different shapes. But what you'll see is collectively, this little thing's going to wander over here. There it goes. It wanders over here. This sniffs around this other region here. There's a little calcium flash, which is a signature of some communication event has taken place here. And eventually, they pull themselves together into this kind of thing.

It has cilia, little motile hairs on the outside of it, which allow it to swim like this. They can swim in circles. They can patrol back and forth. You can make them into shapes like this swimming donut. They have collective behaviors. They have individualized behaviors.

One of the most amazing things they do is kinematic self-replication. If you provide them with loose epithelial cells in the material, so that's what this white stuff out here is, they will go around and they will push it into little piles like this, both collectively and individually. They will polish those little piles and those little piles mature to become the next generation of xenobots. They do exactly the same thing and they make the next generation.

They have these really interesting behaviors, kinematic self-replication.

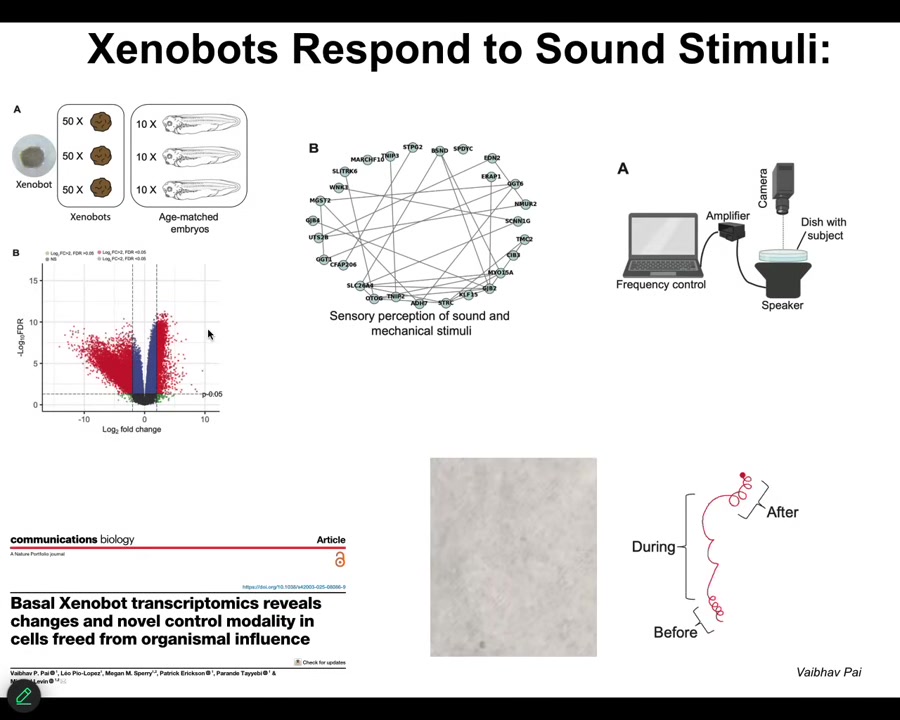

Slide 25/38 · 36m:10s

We found that Zenobots, if you look at what genes they express, they express hundreds of genes differently than they did back in the body. In fact, they turn on a bunch of new genes. Among them are genes for hearing and processing of sound. We thought that was really strange. Is it possible that these things could hear? So we put a speaker under the dish, we provided vibrational stimuli, and we found out that, yes, in fact, they do react differently to sound that you play under there.

Embryos don't do this. This is something that Zenobots do. This is a unique thing. They have novel gene expression, novel sensory behaviors, novel motile behaviors like kinematic self-replication. Now you might think amphibians are plastic and embryos are plastic. Maybe this is some kind of frog-specific thing.

Slide 26/38 · 36m:58s

So I would then ask you, what do you think your cells would do if we freed them from the motivating influence of the storytelling that the rest of your body does to its parts? This little creature here, you might think we got this from the bottom of a pond somewhere. It looks like a primitive organism. You would guess that it has the genome of a primitive organism. If you were to sequence this, you would find 100% Homo sapiens. There's been no genetic editing, no synthetic biology circuits. In all of the examples that I've shown you, the two-headed worms, the xenobots, we don't touch any of the hardware. All we're doing is releasing the natural plasticity of these guys. We call them anthrobots. They're made of adult human tracheal epithelium. Adult patients, usually elderly, go in and they get tracheal samples taken for diagnostics, then they donate the cells, we buy them, and we allow them to self-construct this little creature, which, like the xenobots, has cilia, so it's running around. It's not very good at kinematic replications. It's trying these other cells, but it's not very good at actually pushing them into piles. But it does have other skills.

Slide 27/38 · 38m:05s

For example, if I plate a dish of human neurons here, these are human neurons growing on the bottom of a petri dish, and you take a scalpel and put a big scratch through it like this. The anthrobots are the green ones. They'll come down, they'll pick a spot along this scratch, they settle, and they all hang together in this superbot cluster. Then look what they start to do. They start to knit the wound closed across the gap. Four days later, you pick them up, this is what you see. They're sitting here and they're connecting the two regions.

We never told them to do this. We never taught them to do this. Who would have known that your tracheal epithelial cells could become a tiny, motile little creature that has no similarities to any stage of human development that can run around. One of the things it likes to do is to heal neural wounds. This is a platform for biomedicine, for biorobotics. If we were to inject these things into your body someday, you wouldn't need immunosuppression because they're made of your own cells. They have a billion years of history with damage, with stress, with inflammation, with bacteria, with cancer, all these things. They already know what all those things are. We don't need to teach them.

Slide 28/38 · 39m:12s

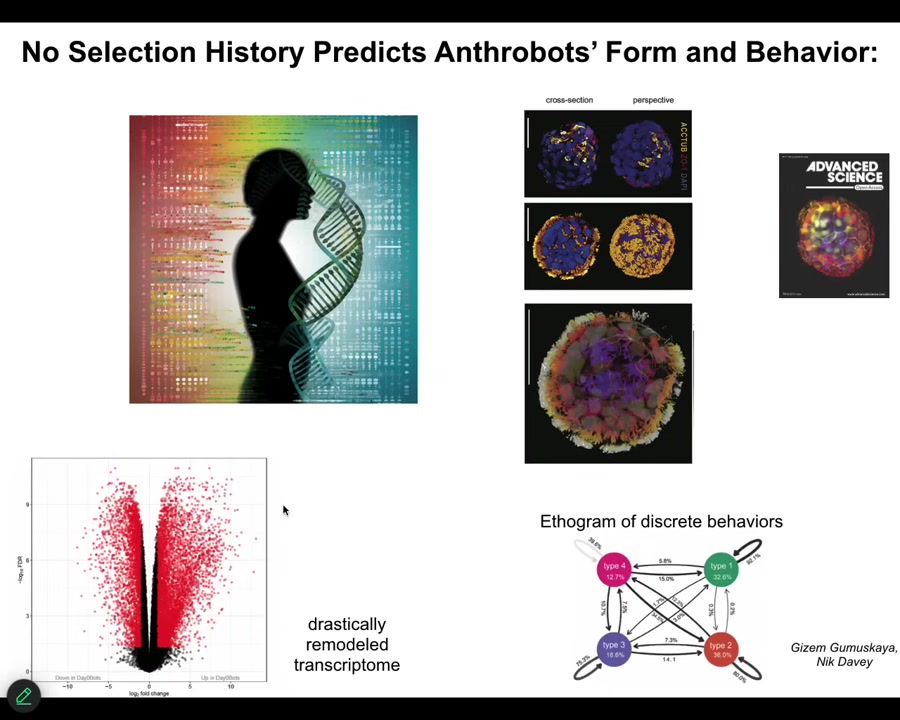

Anthrobots have 9,000 new or differently expressed genes than they did when they were sitting in your trachea. They're younger than the cells they come from, so they roll back their age. If you look at epigenetic age profiling, they've rolled back the age that they think they are. This is what they look like in close-up. They have 4 discrete behaviors, not 12, not one, four. They have these amazing properties that no one knew about, no one guessed. We can ask a simple question, and I'm going to finish up here.

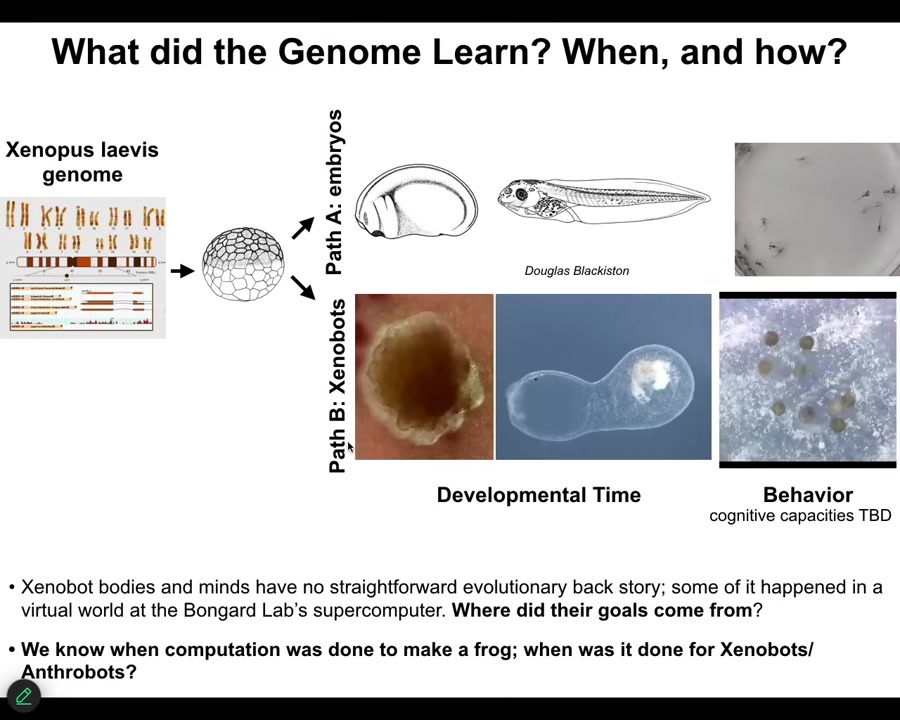

Slide 29/38 · 39m:42s

The question is this: The conventional story is. We know when the computational cost was paid to learn to make frog embryos and tadpoles and frogs, it was paid in the millions of years of selection of this genome banging against the environment and getting selected to be like this. When did they learn to be xenobots or anthrobots? When was that computational cost paid? There's never been any xenobots or anthrobots. There's never been selection to be a good xenobot or anthrobot.

Here's the early one. This is an 83-day-old xenobot; it's becoming something. I have no idea what it's becoming. What is this developmental trajectory? Where did the kinematic self-replication come from? This is really important to understand where the goals of novel beings come from that don't have an easy evolutionary story to tell.

Some people would say they learn to do this at the same time. It's a side effect. You might say it's emergent. It's emerging from what the selection forces were doing up here. But this rips up the whole point of evolutionary theory, which was supposed to paint a very tight correspondence between the features you have now and the history of environments and the selection that got you here. If you can say this was, we were selected for this, but by the way we also got this for free, there's something deeply missing here. I'm going to try to address what that is. It is not sufficient to say this was somehow done at the same time.

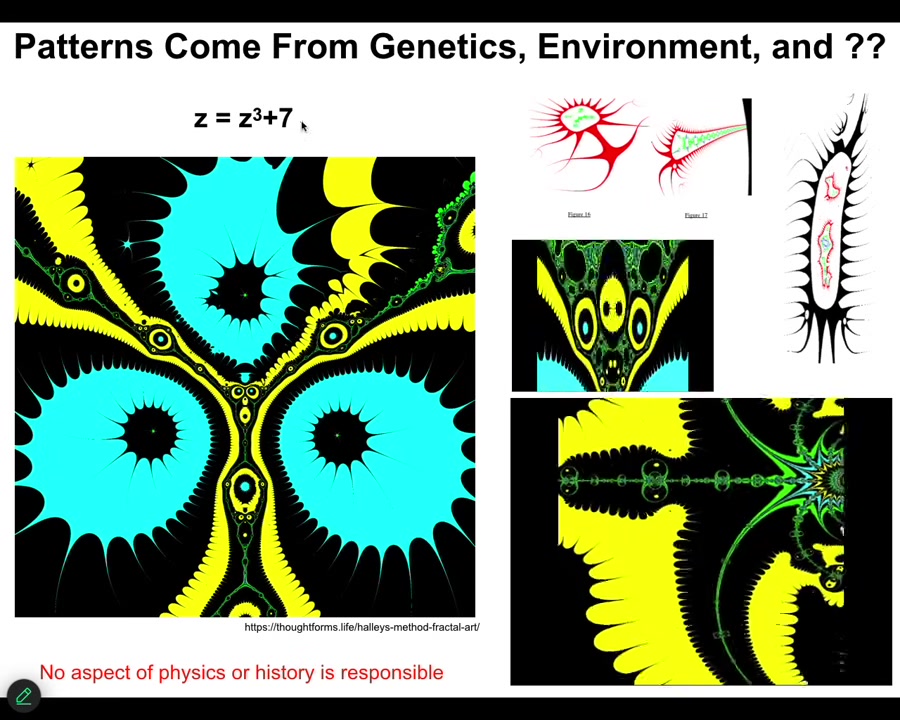

So now we have to ask ourselves, where do patterns come from? Biologists like two sources of information. They like genetics and they like environment. That is a history, a genetic history of selection and the environment, which means some sort of physical or chemical constraints on what you're doing. But there's a third, there's a third source which people often don't think about.

And that's the following.

Slide 30/38 · 41m:42s

Look at this very simple formula. Something like this. Z is a complex number here.

If you plot the behavior of this function in what's called a Halley plot, you get this incredible. This is very organic looking and so are some of these other things.

You can make a video of it by changing these parameters very slowly.

You can get a flyover of this world. Where does this pattern come from?

We get to it by using this as an index.

It's certainly not a compression.

You can't compress this thing and get anything that's only four characters wide.

But this is a pointer into a space of patterns. There's no aspect of physics or history that's responsible for this.

There's nothing you can change in the physical world that would make this pattern different. That's not where it comes from.

It comes from the properties of mathematical objects, in particular the way complex numbers behave.

There is no history. We didn't select this from rounds of selection.

This is the property of a mathematical object that exists separately from what happens in physics.

No amount of physics will tell you what this pattern will be.

Slide 31/38 · 42m:50s

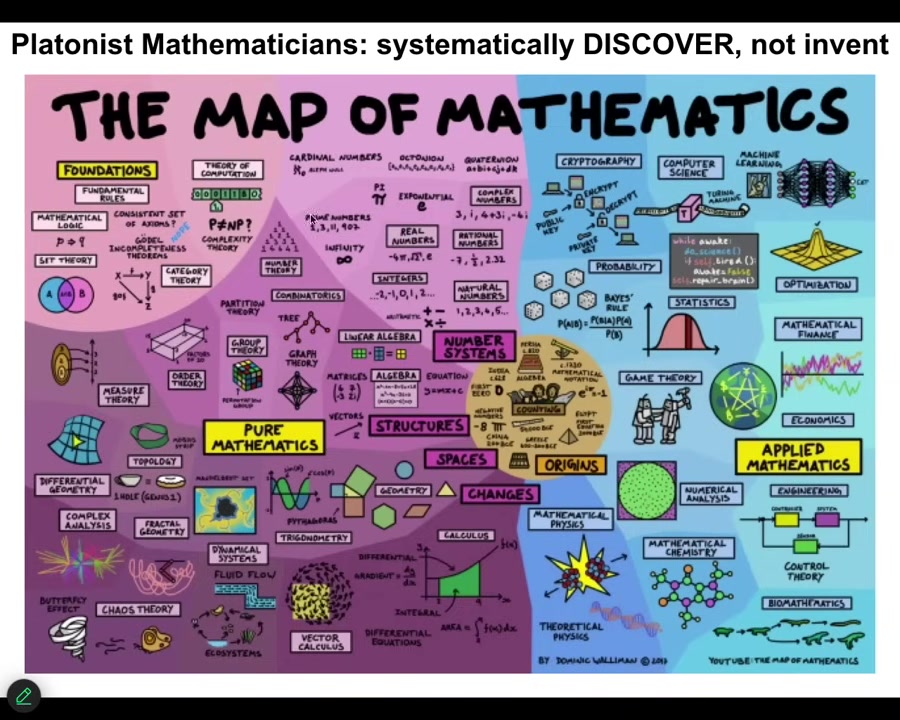

There's a lot of mathematicians that think this way. They're called Platonists. They think that what they're doing is systematically discovering, not inventing, properties of objects that, while they impact the physical world, are not defined by the properties or the events that happen in the physical world. This is Plato, Pythagoras, lots of other folks have said this. A lot of mathematicians think this, that there's a space of patterns. There are two ways to think about this.

Slide 32/38 · 43m:20s

This is what I think most biologists do. They say, look, we want a sparse ontology. We don't want to think about some other weird non-physical space. We want to be physicalists. Everything that's important is here in the physical world.

So when I say, where do specific new goals of novel creatures come from that are never here before, they say, it's emergent. You could ask what that means and say these are just facts that hold in the physical world. You can ask why some of these gene regulatory networks have associative conditioning—where does that come from? These are just facts that hold in the physical world.

So I think the problem with that is the benefit is you get to have a sparse ontology and think that physicalism is workable. The downside is I think it's a very mysterian, pessimistic view. It just means that when we come across these things, we will write them down in our big book of emergence. That's it. Maybe someday we'll find another one and that'll be cool. That's that.

I much prefer what the mathematicians are doing, which is to say, let's not assume this is a random grab bag of cool facts. This is a structured, ordered latent space of patterns, which can be explored systematically. That gives us a research agenda, which is what we're doing in our lab. How do you explore this space? Everything we build in the physical world, be they robots, cyborgs, chimeras, biobots, embryos, cells, all of it, is a pointer or an interface to patterns from this latent space. By making these kinds of interfaces and studying them, we actually have a research agenda to try to understand what's the relationship between the thing you build and the patterns from the space that come through your interface.

Slide 33/38 · 45m:05s

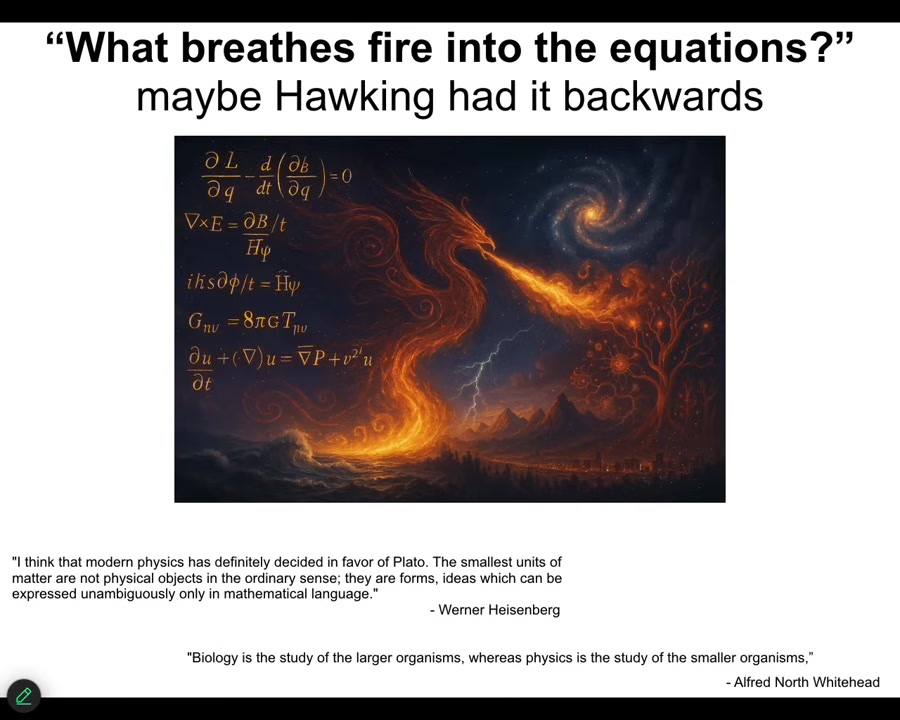

And I would say that when Hawking asked what breathes fire into the equations, I suspect that he actually had it backwards. It's the truths of that mathematical space that actually breathes fire into the physical world. And I'm certainly not the first person to say this. Heisenberg, Whitehead, lots of people have this idea.

And what I would say is that physics, we call physics those things that are constrained by the patterns from this mathematical space. Biology is what we call things that are enabled by it or that exploit it. And biology exploits these patterns as basically free lunches. So here's my crazy theory.

Slide 34/38 · 45m:45s

Other people have said this, going back thousands of years. But I think we're now to the point where we can be very specific and actually do experiments, which is why I wasn't talking about this stuff until last year, but now I can. I suspect that space, we'll call it Platonic space, although I disagree with a lot of the way people think about that space from Plato's original formulation. Let's call it that for now. I think that space has layers and mathematics is the behavioral science of one layer of that space, which are the kind of low-agency, simple things that are amenable to formal structures and formal descriptions. Truths of number theory and topology and so on.

But I think that space also contains complex, highly dynamic patterns that behavioral scientists would recognize as kinds of minds, that is, behavioral propensities, that given suitable bodies, there are patterns that act in a particular way. Part of our research program is actually giving robotic bodies even to mathematical structures; more of it will be published this year.

This is what I think is actually going on: everything we deal with in normal science is a front-end interface or pointer. For people who remember this, we used to have dumb terminals, where you had a front-end interface to a server elsewhere. If you didn't know that there was a server elsewhere, you could spend a lot of time studying that dumb terminal and thinking that's where the action was happening. I suspect that everything that we normally study is a front-end interface to the real show, which is this space of dynamic patterns. The brain in many ways is a thin client, and so are the rest of the bodies. The sciences that we have—biology, computer science, the theory of algorithms—are theories of the front-end interface. They're not theories of the whole system.

Slide 35/38 · 47m:58s

There are two other quick things, and then I'm going to stop.

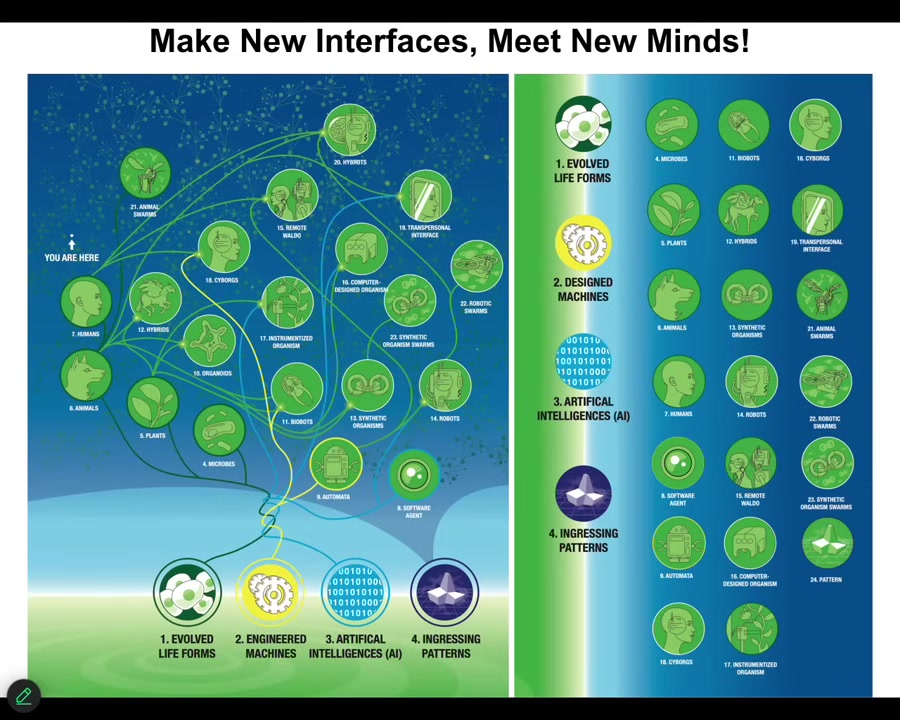

The first is that in the space of possible minds, all the combinations of evolved material, engineered material, software, all of them are subject to these ingressing patterns, and all of them are viable embodied minds in our world. Everything that you see on Earth today is a tiny corner of the space. These are the beings with whom we're going to be sharing our world very soon, and many of these already exist. We already have cyborgs and hybrids. When you build novel embodiments, you are fishing in a pool of that space that we have never explored before. We are going to meet new kinds of beings that are nowhere on the tree of life with us. We need to develop a new ethics of relating to beings that are not like us, a kind of synth biosis. I think we better get a lot more sophisticated in recognizing very diverse kinds of intelligences.

The very final thing I'll say is this. A lot of people who are with me to this point will say, yes, that's great. We agree that there's this non-physical space, which is where these amazing patterns come from. They ingress into the physical world and they inform behavioral and anatomical features. That is what makes us special. That is what makes life special: we are infused with this amazing magic from the Platonic space. So anybody who is with me till that point, I'm going to lose the rest of you in what I'm going to say next.

Slide 36/38 · 49m:28s

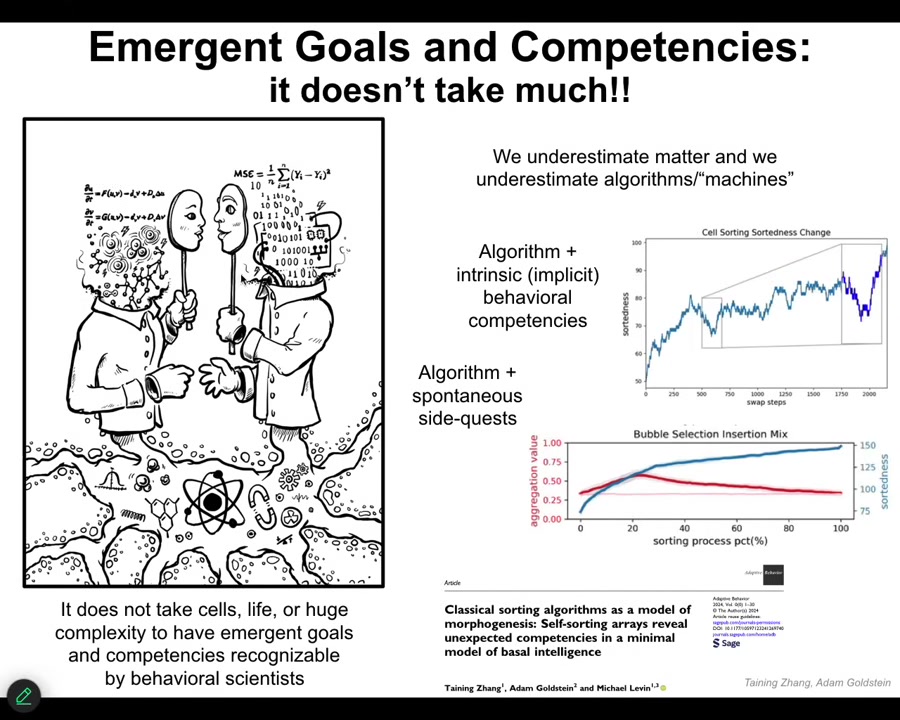

And what I'm going to tell you is that magic, the ability to ingress into the physical world, it's not about life, it's not about complexity, we are not special in that way. We're very good at it. So living beings, what we call life, are systems that are really good at picking up these kinds of patterns. But that magic infuses everything.

And so we've been studying extremely simple minimal systems for exactly this reason, because I wanted the maximum shock value of showing that this works and things that we consider to be machines. And so you can check it out here. We looked at something very simple, dumb sorting algorithms. These are deterministic six-line-of-code algorithms. They're very simple. There's no magic. You can see all the steps. You can see where everything is. And they're totally deterministic. And even those things have behaviors and competencies and, in what I call, intrinsic motivations that are nowhere in the algorithm. They are not written into the algorithm, which means that they're not zero. They are already the beneficiaries of this kind of amazing agency.

So I really think we need to revisit how we have this dichotomy of these magical living things, and then there are dumb machines and algorithms that only do what the materials in the algorithm tell them to do. I don't think there is any such thing in our world. It does not take cells or life or complexity to be part of that magic.

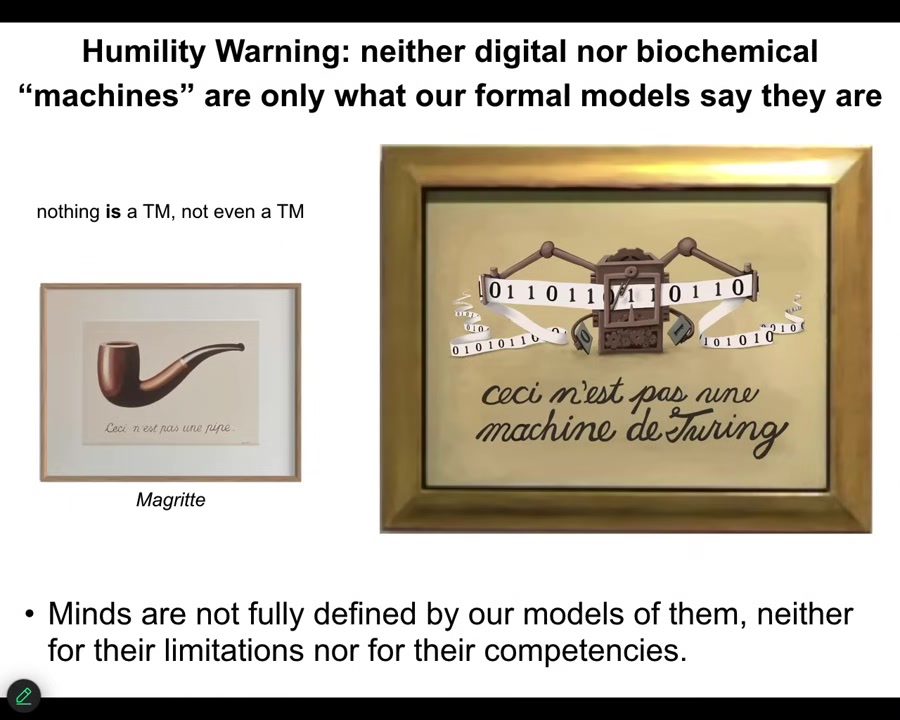

Slide 37/38 · 50m:55s

When people talk about Turing machines being limited and they can't do this and they can't do that, there are no Turing machines. Everything that we build, all these formal systems that we build to try to understand what machines and algorithms do, are just formal systems. They don't capture what's actually going on completely as far as what the machines are doing any more than they capture what the biology is doing. Everybody's willing to give me that the complex mind is not well described by the laws of biochemistry. There's more going on. There is a region of the world which is like dumb mechanical, boring machines that just do what the algorithm says. I don't think that exists at all. I think we really need to be clear that our formal models are not complete stories anywhere.

Slide 38/38 · 51m:42s

I'm going to stop here and thank the postdocs and the students who did a bunch of the work that I showed you today and our amazing collaborators. I have three disclosures. There are three companies that have licensed a lot of our inventions and are funding some of the work. There are commercial interests and funders. Most of the thanks goes to the actual model systems because they do all the heavy lifting. Thank you. I'll stop here.