Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a ~40 minute talk on the future of medicine from my perspective given remotely to students at the University of Bologna, Italy.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Mind, body, and bioelectricity

(05:19) From genes to goals

(11:19) Anatomy as problem solving

(17:47) Decoding bioelectric patterning

(23:36) Bioelectric organ regeneration

(29:03) Bioelectric repair and cancer

(35:24) Anthrobots and future medicine

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/36 · 00m:00s

Thank you to all of you for having me here to exchange some thoughts with you.

If you're interested in following the details of any of this work for the papers, the software, the data sets, everything is here. Here are some personal takes on what I think it all means.

Slide 2/36 · 00m:20s

Let's think about our bodies and some of the magic that actually happens every day. If I told you that with the power of my mind alone, I could depolarize 30% of the cells in the body, you might think that I'm talking about some yoga practice or unusual mind-body medicine. But actually, this is exactly what happens every day during voluntary motion. When you wake up in the morning, you may have very high-level executive goals, social goals, career goals. In order for you to execute behavior that implements those goals, this intent must move ions across the cell membrane in your muscle cells. So this ability of high-level intelligence and its goals to control the chemistry of the body is not a rare and unusual phenomenon. It is the everyday miracle that is implemented by the electrical system of the body. There's a scientist, Fabrizio Benedetti, who has this beautiful phrase from his work on the placebo effect. He says, "words and drugs have the same mechanism of action." This is because the intelligence of the mind and the mechanisms that drive the physiology and the morphology of the body are really part of the same system, and this is very important for the future of medicine. This is what I will talk about today.

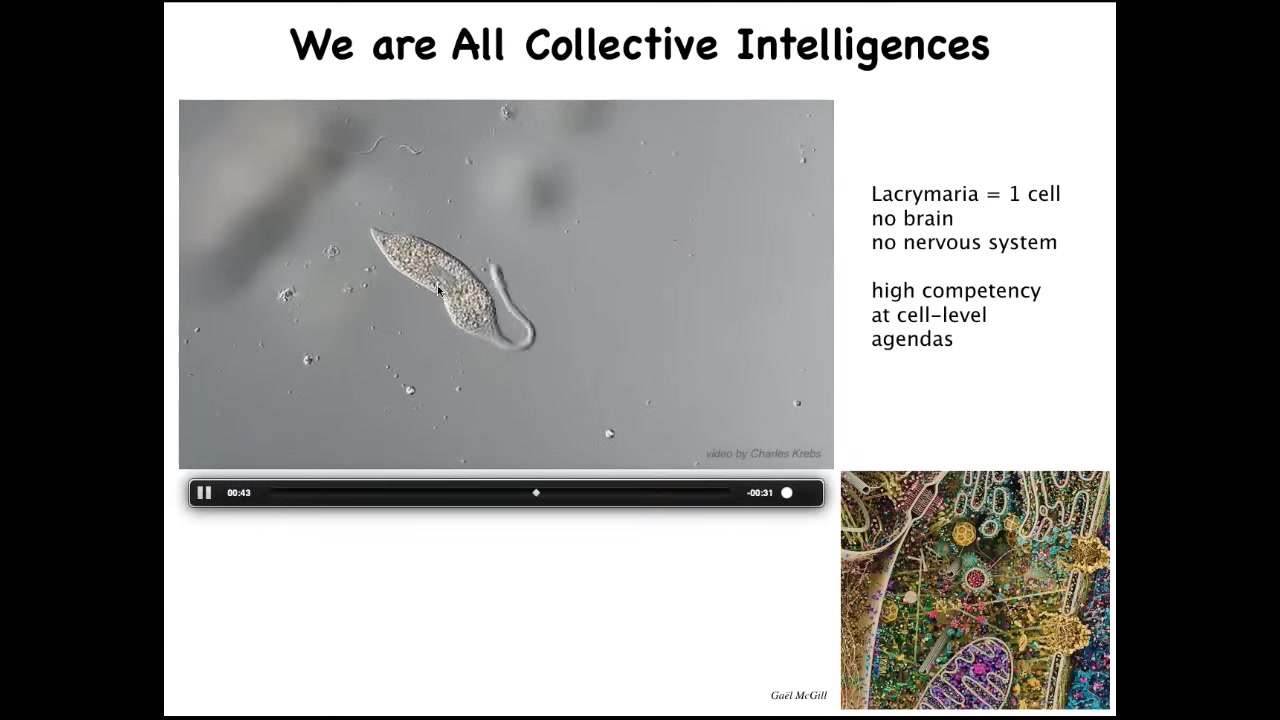

The first thing to realize is that all of us are, in an important sense, collective intelligences, not just ants and termites and bird flocks, because we are made of a very interesting agential material.

Slide 3/36 · 02m:02s

This is a single cell. This is called the lacrimaria. It's a free-living organism, but it's a single cell. It has no brain, it has no nervous system, and yet it has these amazingly competent behaviors to solve all of its local single-cell level problems.

If you look inside the cell there's also all of this stuff.

So all of us are really collective intelligences made of many components. These components are not only complex, but they also have agendas.

Slide 4/36 · 02m:30s

They also have, as I will point out, a kind of intelligence. Within the cell that I just showed you are some molecular networks. You might think that in order to have memory, to have learning, to have intelligent problem solving, you would need many of these cells. You might think they need neurons or a brain.

But what we have found, and other people have found as well, is that even within single cells, the molecular networks, so gene regulatory networks, protein pathways, already exhibit many different kinds of learning, including Pavlovian conditioning. You can find that in the details in these papers. In these molecular networks, if you stimulate various nodes by providing agonists to turn on specific elements in this pathway, and you trace what happens to certain output nodes, you will find that you can see dynamics of habituation, sensitization, associative conditioning, and probably much more. We're looking for many other things now. So the ability to learn and to solve problems is baked into the very bottom of the substrate of which we are all made.

Slide 5/36 · 03m:45s

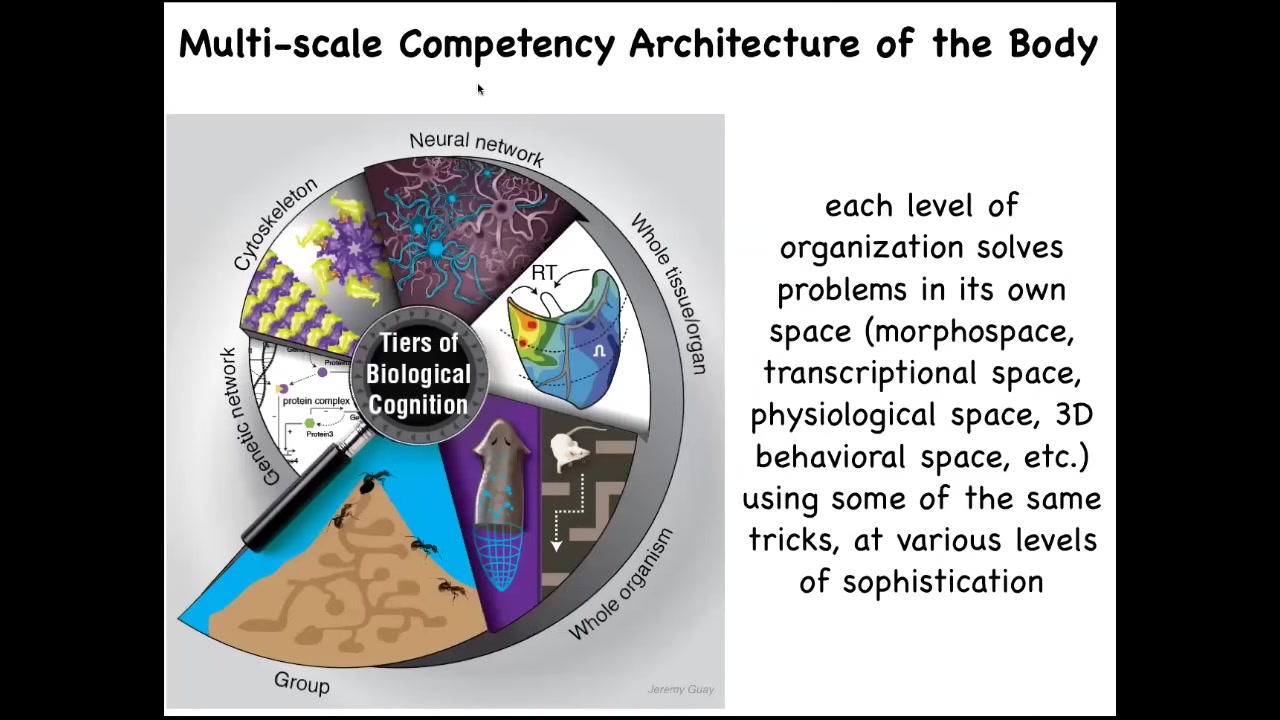

In fact, the whole body functions as something we call a multi-scale competency architecture, where from the bottom, the molecular networks, the subcellular organelles, the cells, the tissues, the organs, and through groups and colonies, you see that each level of organization solves problems. It is not just a structurally nested set of dolls one within the other, but it is a set of diverse intelligences which solve problems in different kinds of spaces. And I will talk about how that works.

Slide 6/36 · 04m:18s

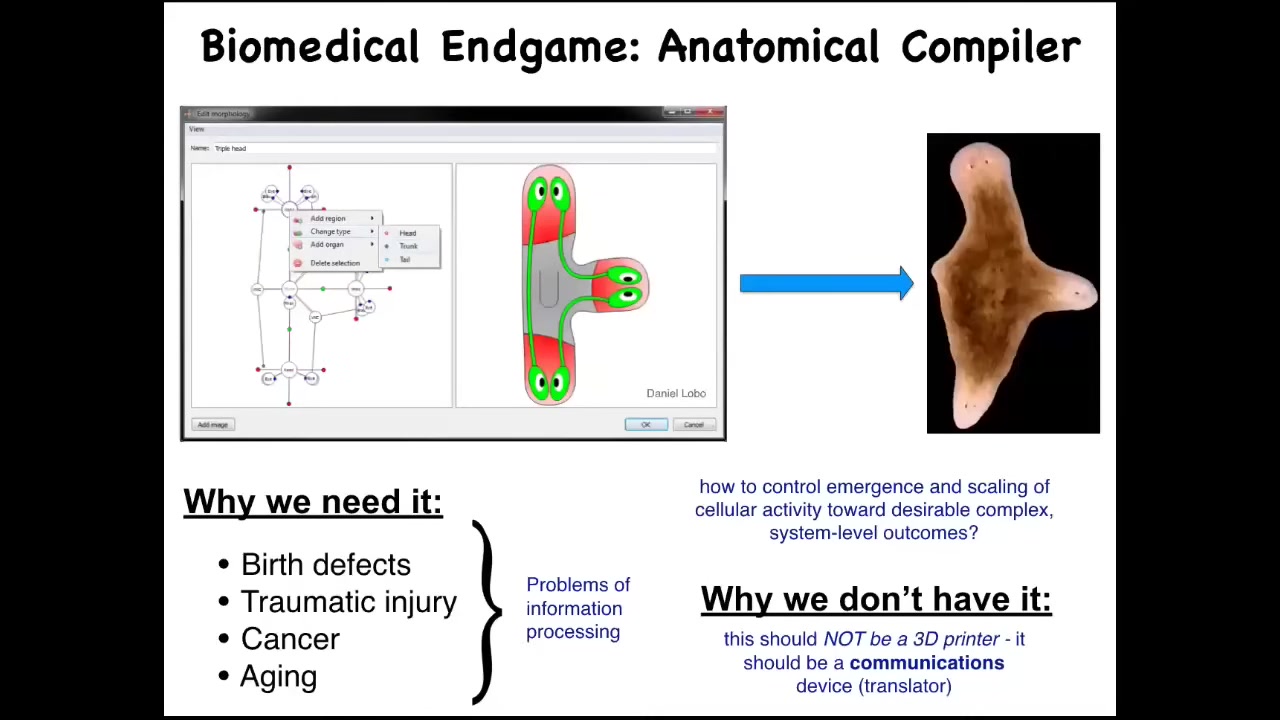

Let's think about the end game of medicine. What are we really looking for? I think that in the future, you will be able to sit in front of a computer and draw the anatomy of the plant, animal, organ, or biobot that you want, whatever it is. You can draw anything you like, any anatomical structure whatsoever. If we have this anatomical compiler, it will convert that description into a set of stimuli that have to be given to cells to get them to build exactly this. In this case, this nice three-headed flatworm.

Why we need something like this is clear. If we had the ability to convey our goals to groups of cells, then all of this would be solved. There would be no more birth defects, traumatic injury, cancer, aging, degenerative disease.

Why don't we have this? Molecular biology and biochemistry have been advancing wonderfully over the decades. I think that's because we've been thinking about this problem in the wrong way. Many people, when they see this, think, this is a 3D printer, something to control gene expression, something to put the cells where they need to go to form whatever structure you want.

I want to propose the idea that we should be thinking about this differently. This is not a 3D printer. This is not about micromanaging the cells. This is supposed to be a communications device. It's supposed to translate your goals into those of the cellular collective.

Slide 7/36 · 05m:58s

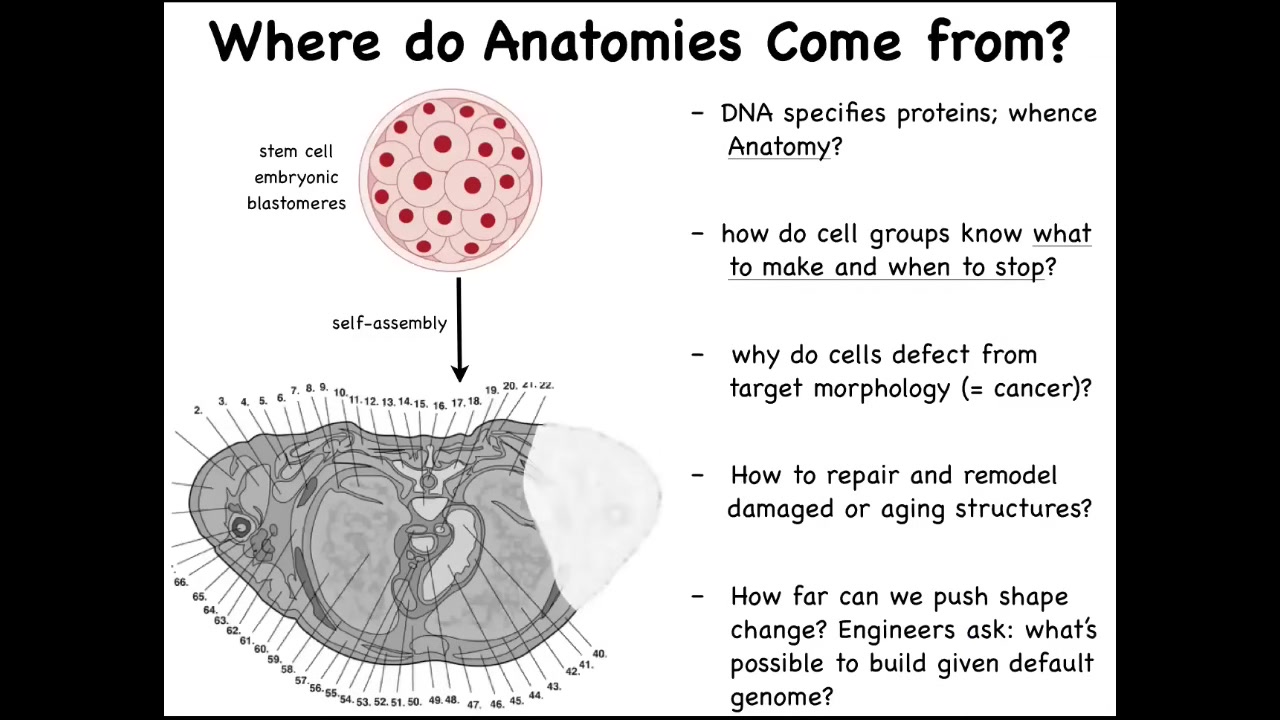

In order to understand what I mean, let's ask, where does the body come from in the first place? Here is a cross-section through the human torso. You can see incredibly complicated organs, everything is in the right place. But we all start life like this as a collection of embryonic blastomeres. Where does this pattern actually come from? You might be tempted to say that it's in the DNA, the human genome. But we can now read genomes. Long before that, we knew that genomes don't really code for any of these patterns. What genomes code for are proteins. They directly encode the hardware that every cell gets to have. Once you have that hardware, you still have to figure out how the physiological software grows a particular structure. How does it know when to stop? What happens if cells decide to do something different in the case of cancer, for example? If something is missing or damaged, how do we induce them to repair and to rebuild it again?

As engineers, we have a lot of work asking, what else can these cells build? Can we get them to build something completely different that is not what their native outcome is at all? In order to solve this problem, genetic information is not enough. There's a lot of excitement about genomics and CRISPR. The deep and fundamental problem here: this is a baby axolotl. At this juvenile stage they have four little legs. This is a tadpole of a frog. They do not have legs at this stage. In my lab, we make something called a frogolotl. It's a hybrid. It's a combination. It has some cells from the axolotl, some cells from the frog, and we make a chimeric embryo. Will frogolotls have legs or not? We have the genomes. You have the axolotl genome. You have the frog genome. Could you tell me if the frogolotl is going to have legs? If it is going to have legs, will those legs be made entirely of axolotl cells or will they be made of some frog cells? We currently have no ability to predict this from the genomes.

This is because while molecular medicine is very good at this low-level description— which proteins interact with which other proteins— we are really a long way away from large-scale form and function. What we want in biomedicine is when somebody comes to you and they're missing an arm, or they had a birth defect or a tumor, and they want you to grow them a new one, or perhaps even change the one they have into a different shape. We are still at the very beginning with this.

Biology today is where computer science was in the 1940s and 1950s. This is what programming used to look like. What she's doing here is she's reprogramming this thing by physically moving the wires in and out. She's rewiring the hardware. On your laptop, when you want to switch from PowerPoint to Microsoft Word, you don't get out your soldering iron and begin to rewire your laptop because computer science has learned something very important: if your hardware is good enough, and the biological hardware is absolutely good enough, then instead of trying to force everything bottom up at the level of the hardware, you can take advantage of reprogrammability and other competencies of the machine.

We've only just begun to understand the high-level information processing that exists in the amazing agential material of which we are all made. This is what we need to focus on: reprogrammability and the problem-solving capacity of our substrate.

When I say intelligence and problem-solving, I mean this. William James gave this definition of intelligence: it's the ability to reach the same goal by different means. I'm not talking about human-level intelligence.

I'm not talking about what it feels like to solve problems or consciousness. I'm talking about a very objective, third-person competency to navigate some problem space and reach your goal when new things are happening. And this requires problem solving and it requires a lot of plasticity. It means that you can't just do the same thing every time. You can't rely on your genome to instruct you on exactly what to do, you have to have a problem-solving capacity.

So let's talk about this. We as humans and as scientists are reasonably good at detecting intelligence in three-dimensional space. So we see birds or primates, maybe a whale or an octopus, and we see medium-sized objects moving through three-dimensional space at medium speeds and we can notice intelligence. But I want to stress that in biology, there are many other spaces in which intelligences navigate and make decisions and solve problems and feel stress.

There is a transcriptional space, so the space of all possible gene expression levels. There is physiological state space, and this one we'll talk more about today, anatomical morphospace, or the space of possible anatomical configurations. In all of these spaces, they are very hard for us to visualize. We don't consider these kinds of actions as behavior. But if you look carefully and use the tools of computational neuroscience and behavior science, you can find phenomena that bridge these two worlds. All of the things that we study in physiology and molecular biology are really behavior of unconventional intelligences. I want to show you a couple of examples of problem solving.

Slide 8/36 · 11m:30s

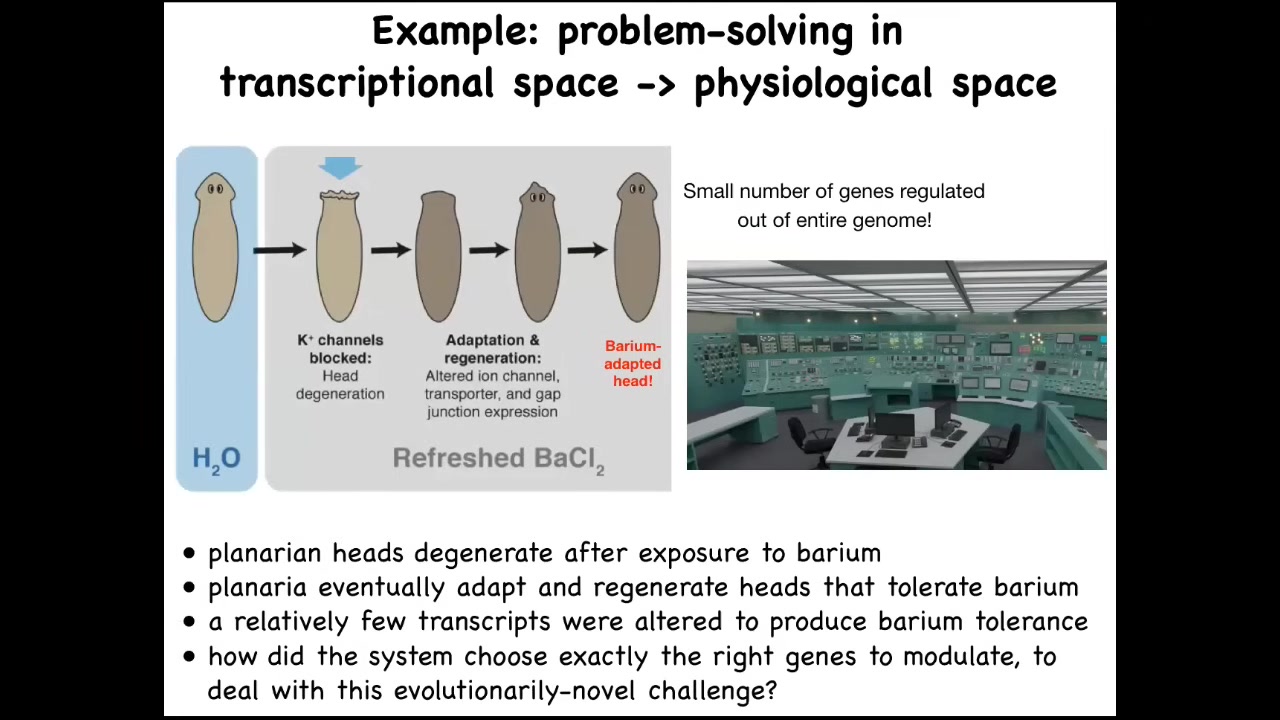

Here is a planarian, this flatworm, and we discovered a few years ago that if you put these planaria in a solution of barium — barium chloride blocks all the potassium channels — the first thing that happens is their heads explode. Literally overnight, their heads explode because these cells cannot continue functioning without the ability to exchange potassium with the outside medium.

If you hold on to these tails, something interesting happens. Over a couple of weeks' time, these tails will regenerate a new head while kept in barium, and the new head is completely barium-adapted. We asked the simple question: how is that possible? We looked at the genes expressed in these barium-adapted heads compared to the genes in the normal head, and we found that really, there's only about a dozen or so transcripts that are different.

Think about what's going on here. I always visualize this as being in a nuclear reactor control room and the thing is melting down. There are all these buttons. What do you do? This is a completely novel stressor. These planaria have never seen barium before. You have a very strong physiological problem. You need to figure out which of your genes you're going to turn on or off to solve this problem. You can't do it randomly because there's no time to look through all the astronomical combinations of possible gene expressions through a 1,000–20,000-dimensional state space. If you start randomly changing genes, you're most likely to kill the cells anyway.

How do you find what you should do for this novel problem? We've seen this many times. Cells have a remarkable ability to find solutions to novel problems. We as workers in medicine should be looking for a translator interface to ask them how they do it. We should be able to ask the cell, for a given stressor, what kinds of homeostatic adjustments would you do? They can do many things that we have no idea how to do.

Let's move beyond this kind of single-cell survival and talk about anatomy and where the body comes from.

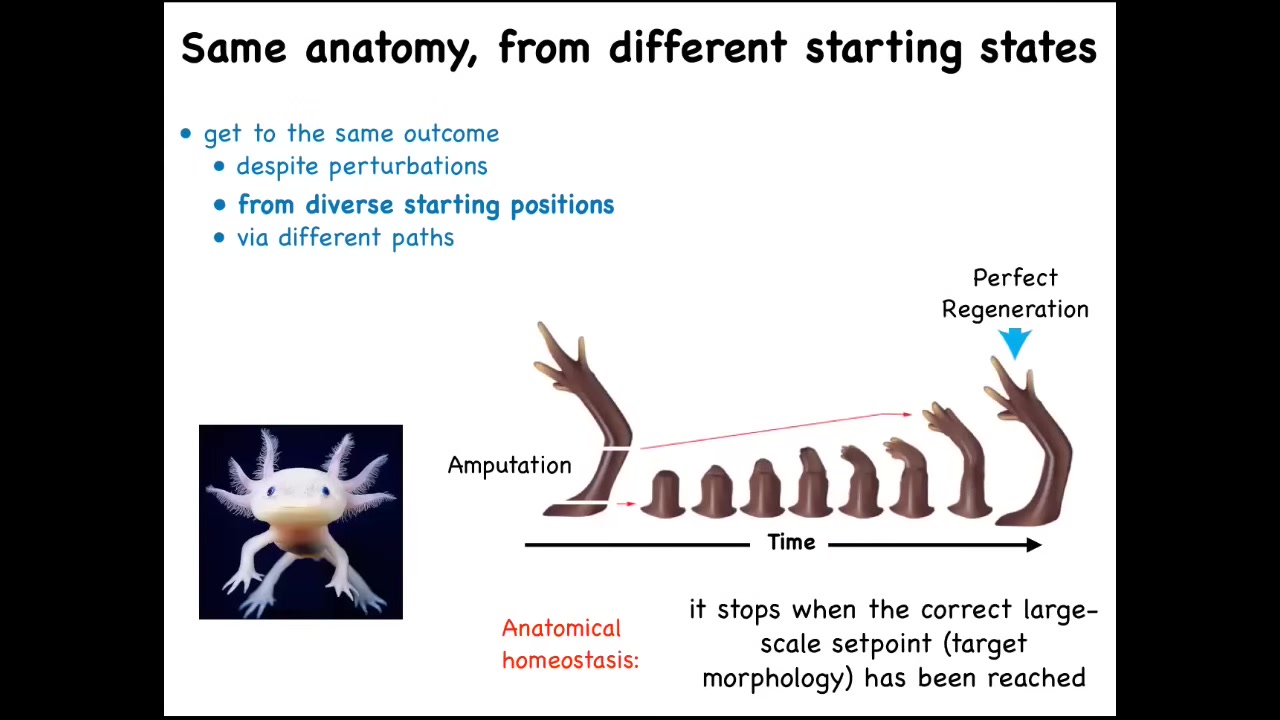

Slide 9/36 · 13m:40s

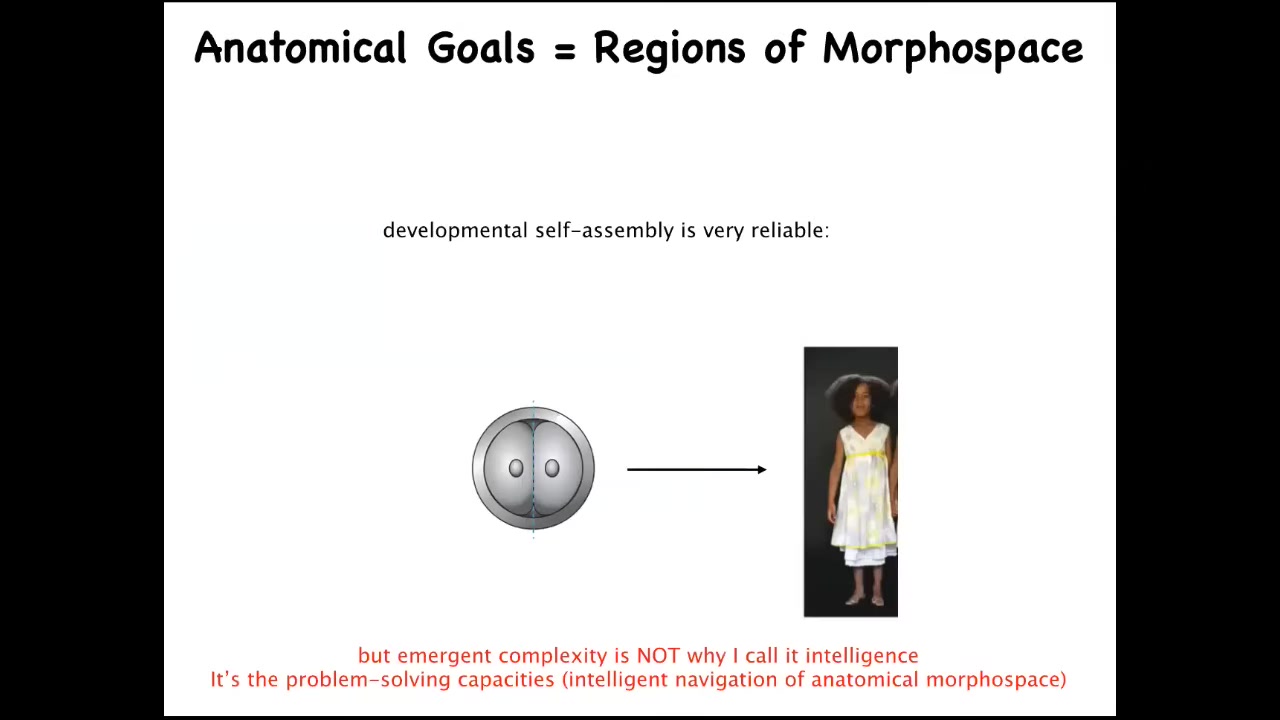

Now, we know that development is incredibly reliable. These eggs reliably will give rise to a normal target morphology. We also know that there's a huge rise in complexity from this state to this state, anatomically, complexity rises. But the reason I'm calling this intelligence is not because it becomes more complex or because it is reliable. That's not sufficient for intelligence. What I'm talking about is problem-solving. Specifically, the idea that if you take these early mammalian embryos, for example, and you cut them into pieces, you don't get half bodies. What you get are perfectly normal monozygotic twins and triplets. And that's because this process can reach the goal state in anatomical space, being something like a normal human morphology, from different starting positions. They will in fact avoid local minima and get to where they're going through novel paths. Regulative development does an amazing job at this. Some animals can do this throughout their lifespan.

Slide 10/36 · 14m:38s

For example, here's a salamander. This vertebrate can regenerate its eyes, its jaws, its limbs, portions of the heart and the brain, its spinal cord, and its ovaries. Think of how amazing it would be for evolution, for regenerative medicine if we understood how this worked.

What happens here is that if you deviate, here the cells have reached their target morphology: here's a perfect limb. If you amputate anywhere along this length, the cells will quickly start to build this structure and then they stop when they're finished. The most amazing thing about regeneration is that it stops when it's done. Because if you deviate from the correct position in anatomical space, it can tell that that's happened, and it will work hard to get back to its goal. This is a kind of homeostasis. This is a kind of anatomical homeostasis.

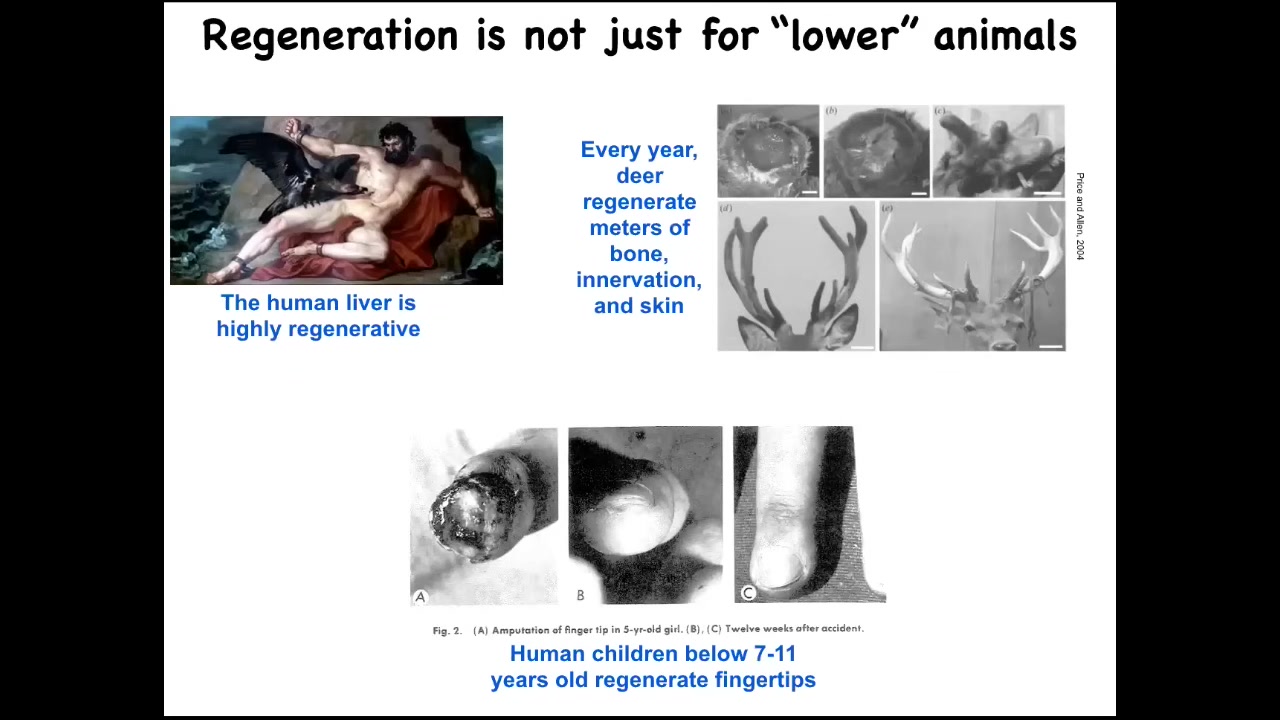

Slide 11/36 · 15m:30s

This regeneration is not just for the so-called lower animals. The human liver is highly regenerative. Deer regenerate huge amounts of bone and vasculature and innervation every year. They grow about a centimeter and a half of bone per day when they're doing this. It's remarkable. Human children, below a certain age, have been known to regenerate their fingertips. We have some regenerative capacity, not as good as a salamander.

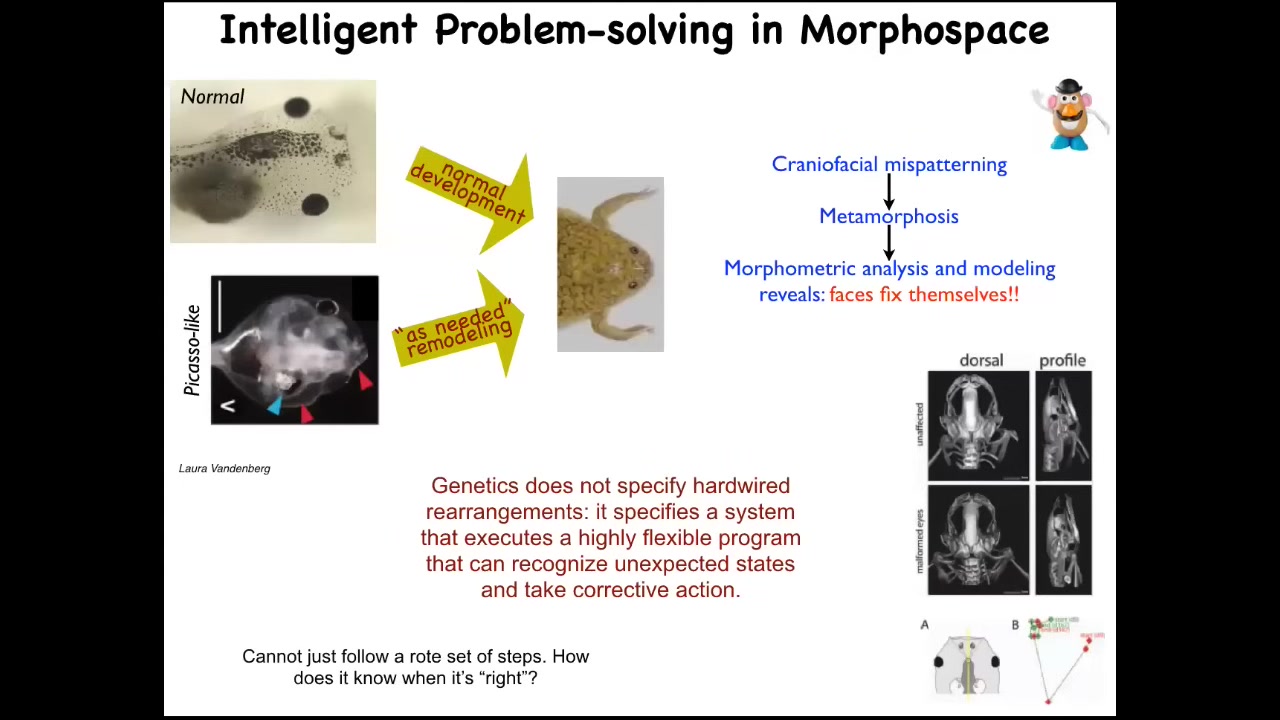

Slide 12/36 · 15m:58s

But the most interesting part of this is the ability to accommodate novel scenarios. We discovered that if you take this tadpole, which is supposed to become a frog, and in order to become a frog, it has to rearrange its face. The eyes, the jaws, the nostrils, everything must move. All of this stuff has to rearrange. People thought that this was just a hardwired set of processes. Every organ moves in the right direction, the right amount, and eventually you go from a normal tadpole to a normal frog.

We decided to test that. To see the intelligence of these materials, you need to challenge them with problems. You need to do perturbations, functional perturbations. We created the "Picasso-like" tadpoles. What's happening here is the eyes on the back of the head, the mouth is off to the side, the whole thing is scrambled. Everything is rearranged. We found they still make remarkably normal frogs because all of these organs move through novel paths. Sometimes they go too far and they must come back. They go through novel paths until they get to where they're going and then they stop. We can track all of this with CT scans.

It turns out that the genetics does not specify a hardwired set of movements. What it gives you is a system that executes an error minimization scheme. It is able to detect that it's in the wrong position, it's able to move in the correct direction, and then it stops when it's done. This idea of homeostasis.

But now we have to ask some very basic questions. First of all, how does it know what the correct position is? How does it know what a normal frog face looks like? And #2, how does it do the computations that take it from the abnormal position and get it closer? How does it navigate that anatomical morphospace? What kind of competencies does it have for navigation? And how does it work?

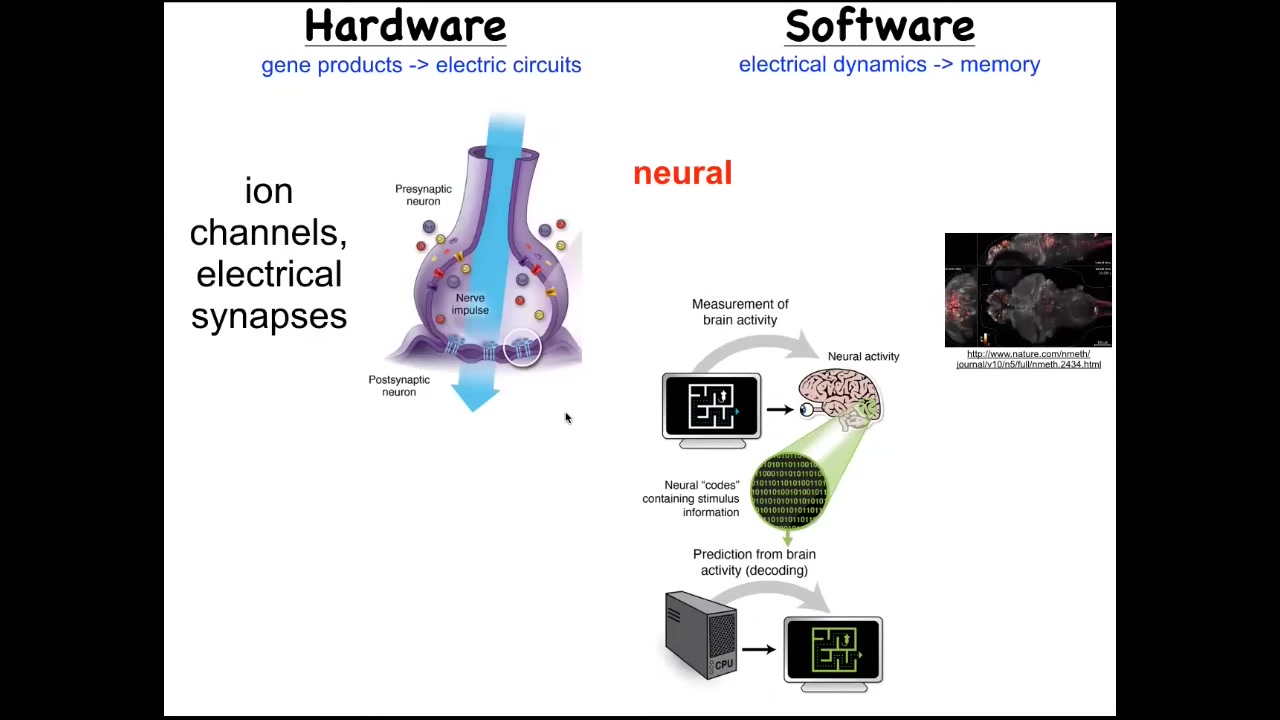

Slide 13/36 · 17m:55s

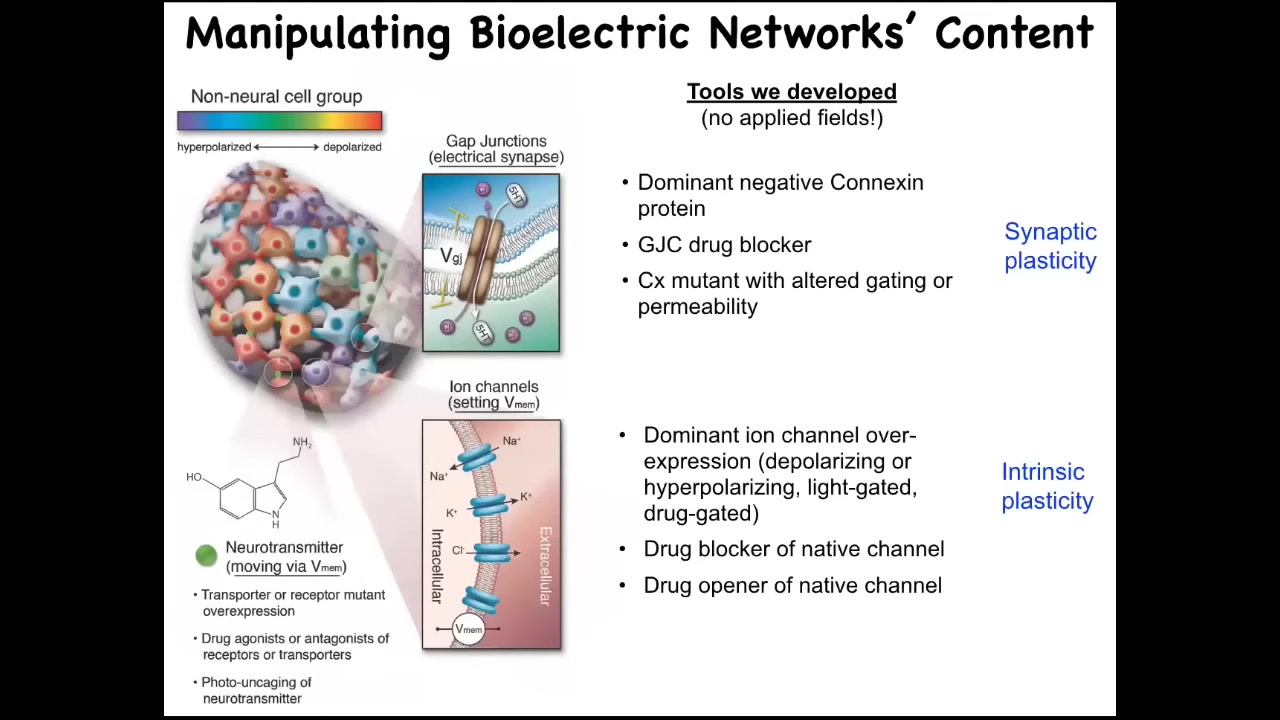

We took our inspiration from another system where we know what sorts of mechanisms lead from high-level goals in some kind of problem space to the actuation of movement in that space. The most familiar is the nervous system. The hardware in the nervous system looks like this. You have neurons that have ion channels in their membrane. These ion channels produce a voltage gradient, which may or may not be propagated through electrical synapse to their neighbors. The movement of this electrical information through the network is what underlies the thing that I talked about at the beginning of the talk, which is the ability to pursue goals in a problem space, to process information, to remember what your goal is, and then to act in order to get closer to that goal. It is the commitment of neuroscience that electrophysiology is what underlies the software of the mind.

This is a real-time zebrafish brain. You can see all the signaling in the zebrafish brain. The idea is that if we knew how to decode this, we would be able to read out the memories, the preferences, the goals, the behavioral repertoire of this animal, that all of its cognitive features are encoded in the electrophysiology of these cells. This is our inspiration for asking how does a group of cells know what the goal is and how does it try to get there?

It turns out that this idea, the use of electrophysiological networks to process information to link and align information across distance and across time from the past to the future, was discovered by evolution very early. It did not wait for neurons and muscles and brains to evolve. It actually evolved around the time of bacterial biofilms. Every cell in your body has these ion channels. All the cells in your body are electrically active, not like nerves. They don't spike necessarily, but they're all electrically active. Many of them have these electrical gap junctions and they form networks.

What do these networks think about? If this network thinks about moving you through three-dimensional space, this network thinks about how to build and maintain the complex anatomy of your body. The cellular collective uses bioelectricity to navigate anatomical space, first to build it during embryonic development and then to defend it against cancer and against aging throughout the lifespan.

We've started the same kind of project, neural decoding, but not in neurons, to see if we can interpret these. This is all the electrical conversations that an early frog embryo is conducting. You can see the colors correspond to different voltage levels. You can see all the cells having these little interactions with each other to determine who's going to be head, tail, left, right. Could we learn to decode this? Could we understand what are the memories? What are the plans that this morphogenetic collective intelligence has?

Slide 14/36 · 20m:50s

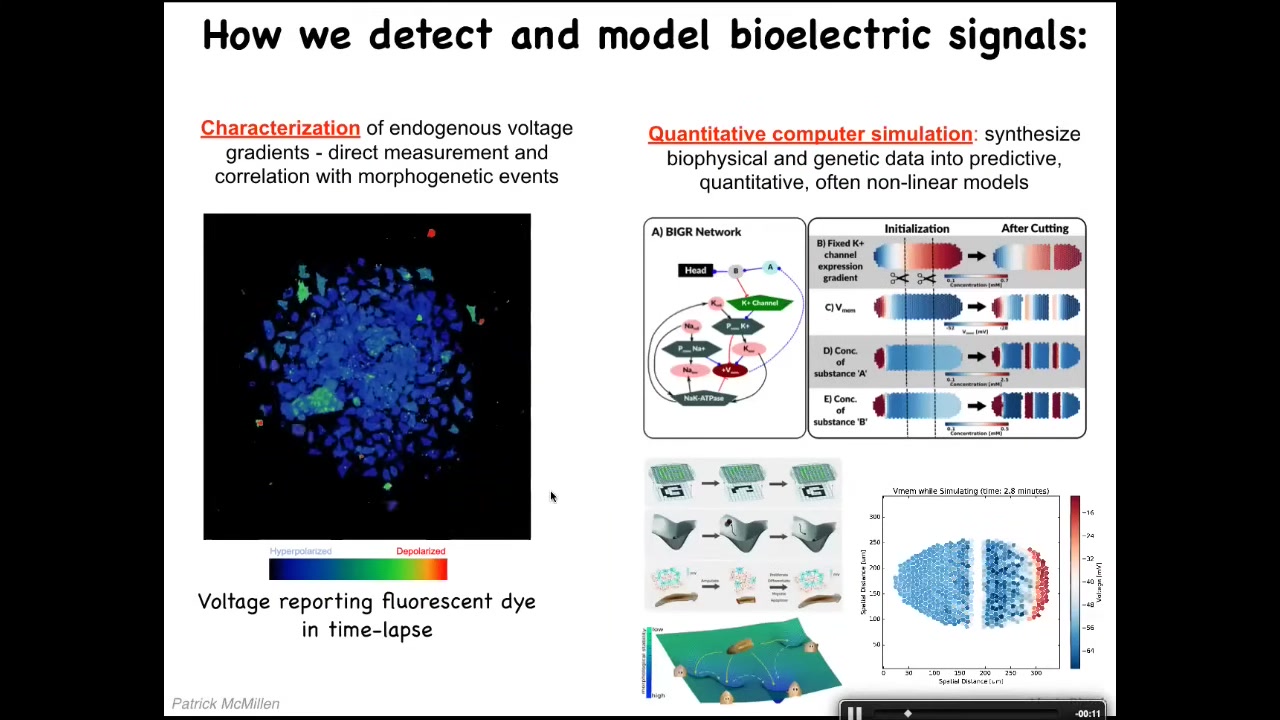

We developed the first tools to read and write the electrical information of the non-neural tissues. First, we use voltage-sensitive fluorescent dyes. There are some rapid changes, but there are also some quite slow changes. There are all kinds of patterns. These cells are doing lots of things. We do a lot of computer simulations to tie the electrophysiology to the gene expression and to understand its properties. For example, how does it change over time? How does it spread over distance? I want to show you two interesting patterns.

Slide 15/36 · 21m:22s

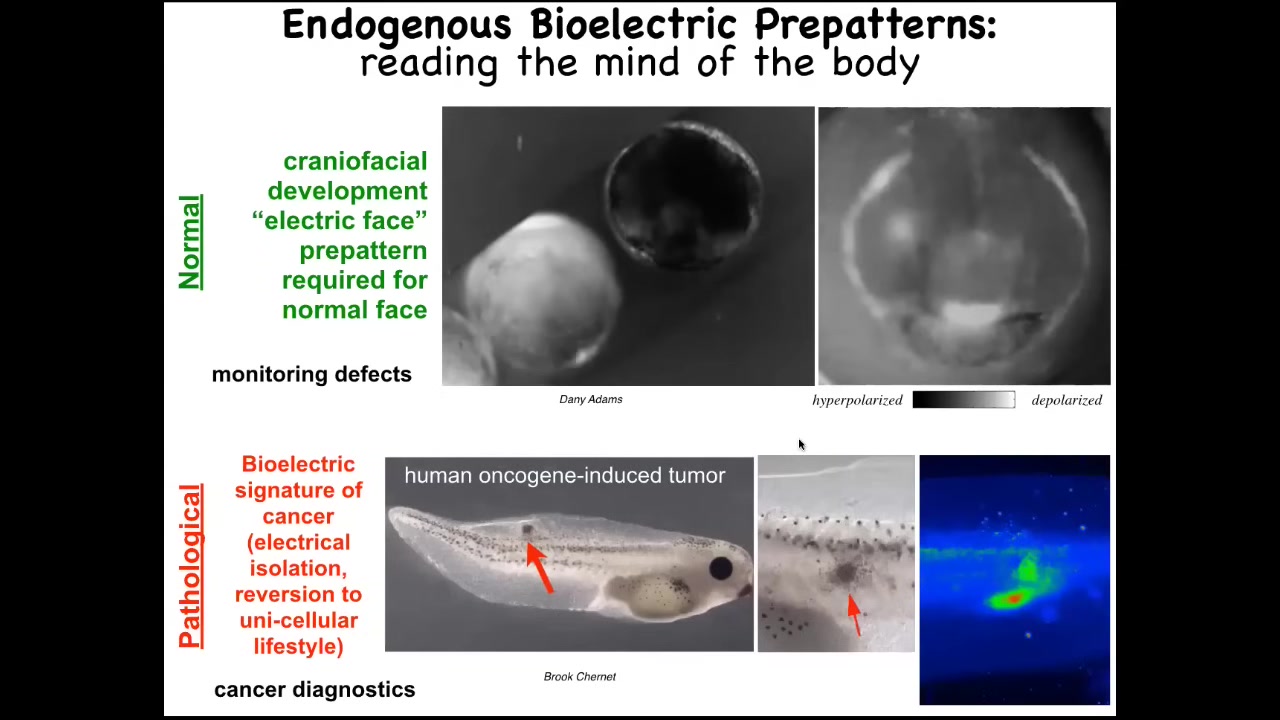

This is a time lapse of the frog embryo putting its face together. This is a grayscale color map of the voltage. This is 1 frame from that video. In this one frame, we call this the electric face. This was first found by Danny Adams in my group. What happens is that long before the genes come on, and the cells are starting to build a face, these bioelectric patterns are already regionalizing the tissue and they are telling the cells where all the organs are going to be. This is where the animal's right eye is going to be. Here's the mouth, here are the placodes. If you manipulate this electrical data structure, you will see that the gene expression changes and the anatomy changes. I'll show you that in a minute. This is a critical, natural component of normal embryogenesis. We are reading the bioelectrical pre-pattern, the memory that these cells are going to use in order to plan and then build the face.

Here's a pathological structure. Human oncogenes have been injected into this tadpole. They're going to make a tumor. The tumor is going to metastasize here. Long before that happens, you can use these voltage dyes to read the electric state of these cells and see that there's a region here which is aberrant. It's highly depolarized. It's very different than the rest. Here's where the tumor is going to be, and then here are some straggler cells.

We built these tools to read the electrical information, but much more important than that is to be able to modify and to do functional experiments and write the information.

Slide 16/36 · 22m:58s

And so here's how we do it. We do not use any electrodes. There are no fields, there are no waves, there are no frequencies, no electromagnetics. We do exactly what neuroscience does: control the interface that these cells are using to control each other. That means we can change the open-close state of the gap junctions, we can open or shut them and control which cells talk to which other cells, and we can directly control these different ion channels. This means with pharmacology, with mutant channels, with optogenetics, all the tools of neuroscience we can deploy here.

The critical question is: what can you do with this? When you change these voltage patterns, what actually happens? How do we know that the cells care about this at all?

Slide 17/36 · 23m:48s

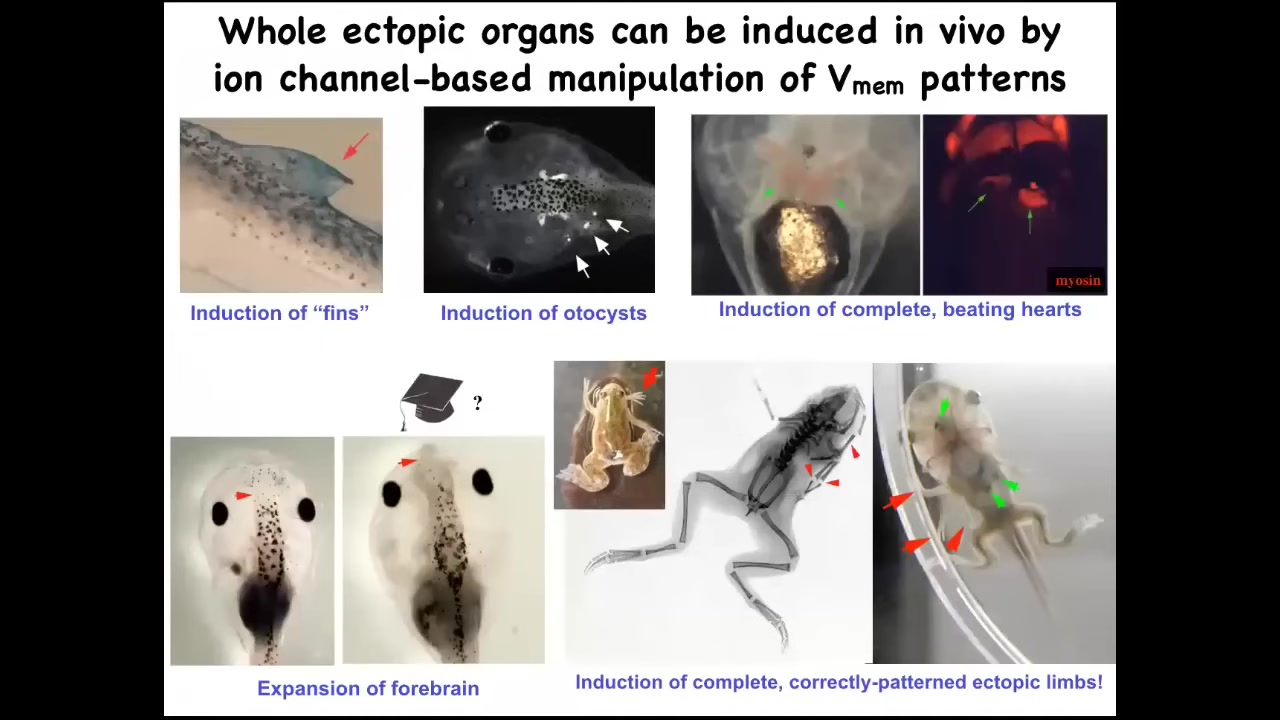

One thing that you can do is call up new organs this way. I'll show you one in particular, but you can make ectopic inner ear structures. Here are some otocysts. You can make ectopic hearts. You can make extra forebrain. Here's where the normal forebrain stops. You can make this extra large forebrain. We can call up extra limbs. Here's our six-legged frog.

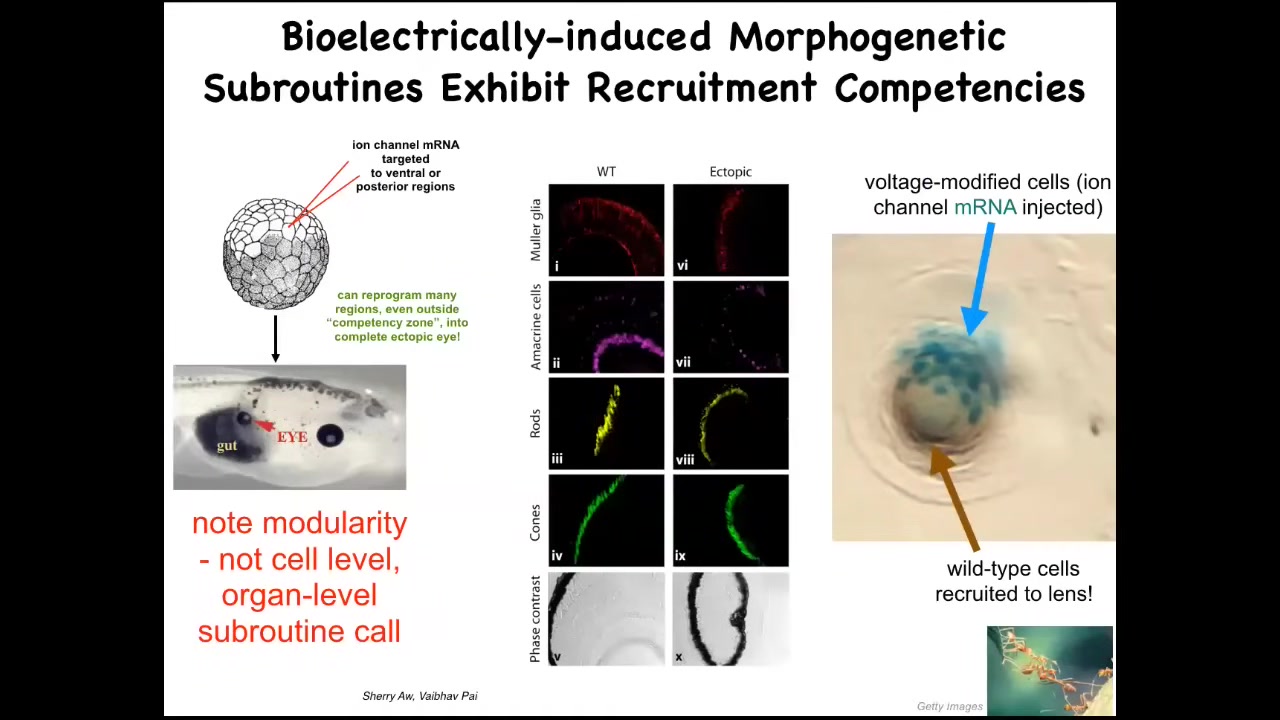

Slide 18/36 · 24m:12s

And one particular example I want to show you in a little bit of detail is the induction of ectopic eyes. The developmental biology textbook will tell you that only the cells here in the anterior neorectoderm are capable of forming eyes. That's because they use this so-called master eye gene PAX6 to try to induce eyes. It's true: if you use PAX6, it only forms up here. But it turns out that if you use potassium channels, ion channel mRNA for specific potassium channels, and you inject them into regions of the embryo where they will set up that little spot, that little voltage pattern that I showed you in the electric face, if you set up that pattern somewhere else, it convinces cells to build an eye.

Here's an eye made out of cells that were going to be gut here. If you section that eye, you have lens, retina, optic nerve, all the same kinds of things that should be in an eye. Notice a couple of interesting things. First of all, the bioelectric pattern is clearly instructive. By rearranging that pattern somewhere else, you can call up whole organs. It's clearly functionally determinative of what happens. It's not an epiphenomenon.

The second thing is that it is incredibly modular, meaning that we didn't have to tell these cells how to build an eye. We didn't say anything about stem cells, about gene expression, about the geometry of all the different tissues inside the eye. We didn't say any of that. All we provided was a very high-level subroutine call that says, build an eye here. This is great for regenerative medicine because that means we can call up complex downstream outcomes without having to or knowing how to micromanage the details.

To point out another interesting competency of the material, this is a cross-section through an eye in the flank of an embryo somewhere. The blue cells are the ones that we actually targeted with our ion channel RNA. They realized there's not enough of them to make a good eye, so they recruited all these other natural cells to work with them to make this eye. Much like ants and termites, a different kind of collective intelligence recruits its friends from the colony to help move heavy objects. We didn't have to teach the cells to do that. They already do it. As soon as these cells learn that they must make an eye, they take on the next step of instructing all these other cells that they have to help, and here's how we make an eye.

All of these are things that we have to take advantage of, and this is not available from the bottom-up level of genes or proteins or anything like that. We have to understand the decision-making and the collective competencies of our material.

Slide 19/36 · 26m:45s

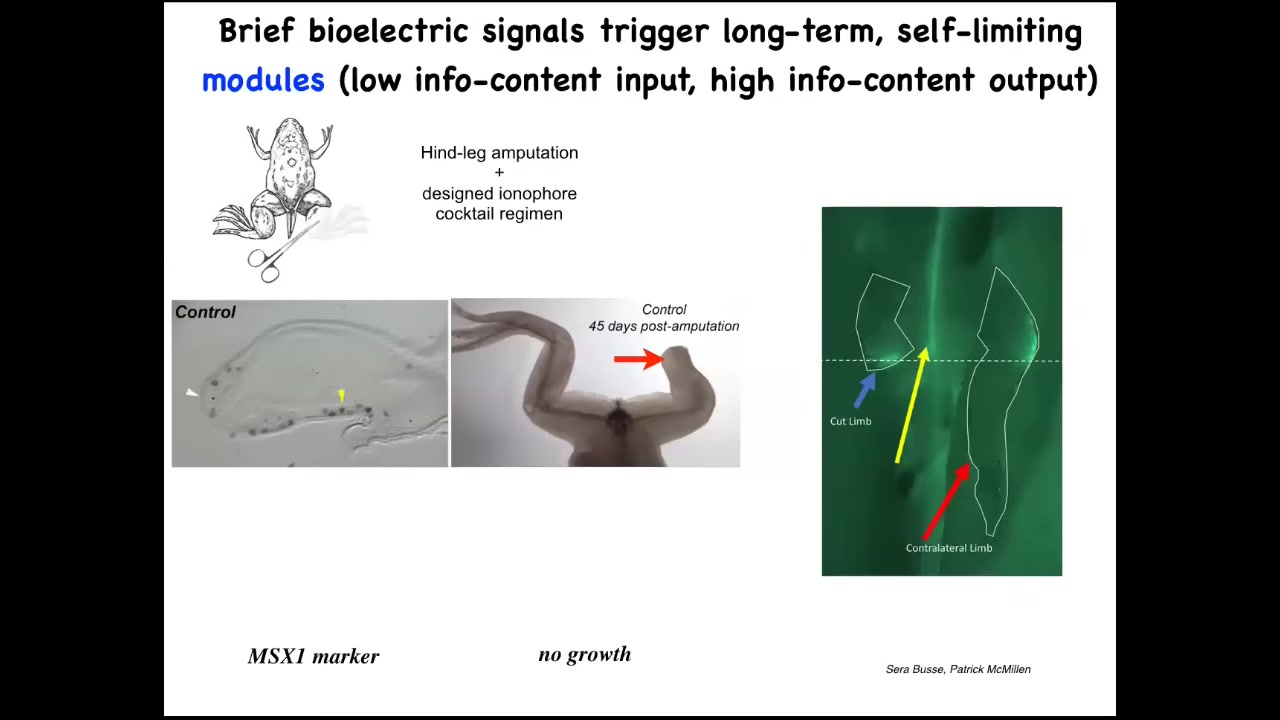

I want to show you another story about limb regeneration. Normally in frogs, if you amputate the limb, unlike salamanders, frogs do not regenerate their legs at this adult stage. What you do see is something quite interesting. We call it injury mirroring. The cut leg will show you a bioelectric signal here at the wound, but so will the uncut leg. Within 30 seconds, the information passes to the leg that was never touched, and that leg lights up at exactly the same location where the wound happened on the opposite side. It is not neurally mediated. You can remove the spinal cord. It still works fine. That information is spread across. We know bioelectrical networks are really good at spreading information.

So now, those of you interested in medicine can start to think: what kind of information about disease and injury is available at a distance on the opposite side of the body that we could read and have some kind of surrogate site diagnostics where you don't have to measure the tissue you're talking about, what other tissues are picking up damage information like that?

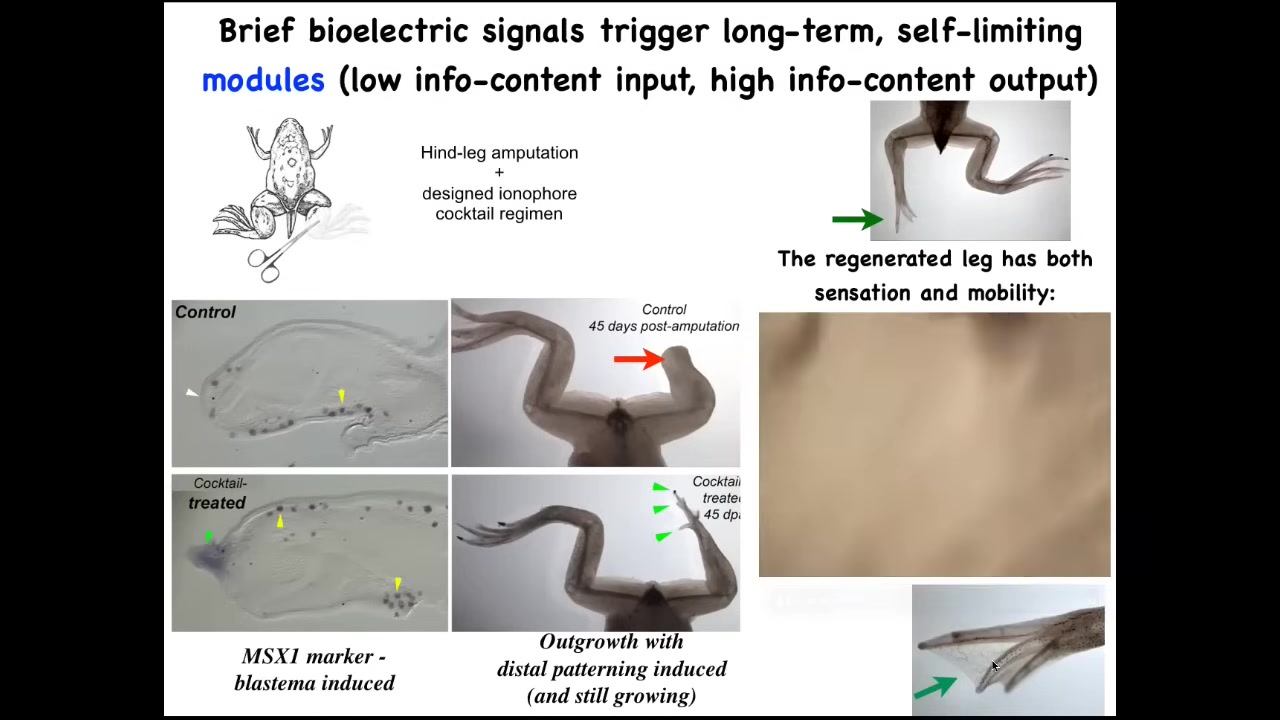

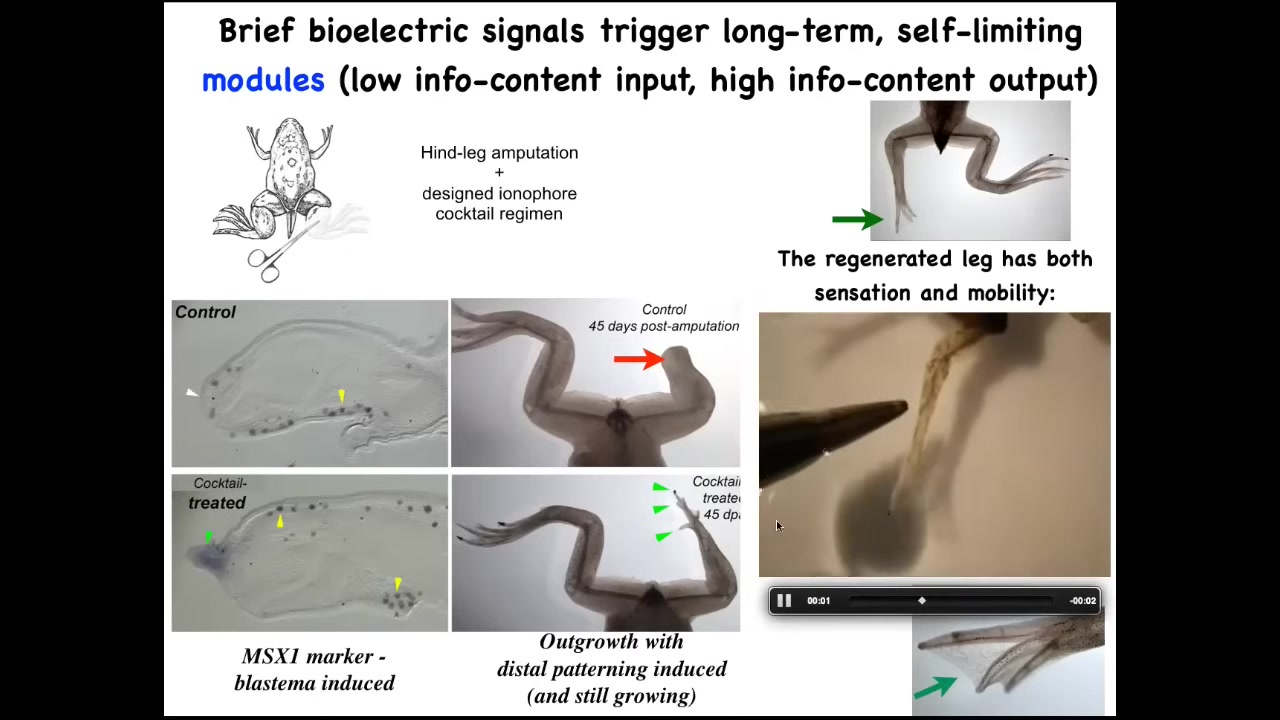

Going beyond that, we decided to test if we could tell these cells to go to the regeneration area, not in the morphospace, not the scarring area.

We developed a cocktail of ionophores that triggers regeneration.

Immediately you start to get toes, you get a toenail; eventually you get a quite nice leg that keeps growing.

The leg is touch sensitive, it is motile, patterned, fairly respectable.

Slide 20/36 · 28m:12s

We don't know how to build a leg. All we tell the cells is we communicate the goal. We say, build a leg, and then we don't touch it. A one-day intervention with our cocktail results in a year and a half of leg growth, during which time we don't touch it at all.

Slide 21/36 · 28m:30s

Once you've communicated to the cells, they do the rest.

I have to do a disclosure: there's a company called Morphozeuticals, which was started by David Kaplan and me. We are now moving that technology through the use of wearable bioreactors into mammals and, eventually, we hope, into human patients to be able to use these stimuli, these triggers of complex organ regeneration. We're aiming with Morphozeuticals for limb regeneration, hopefully eventually in patients.

Slide 22/36 · 29m:05s

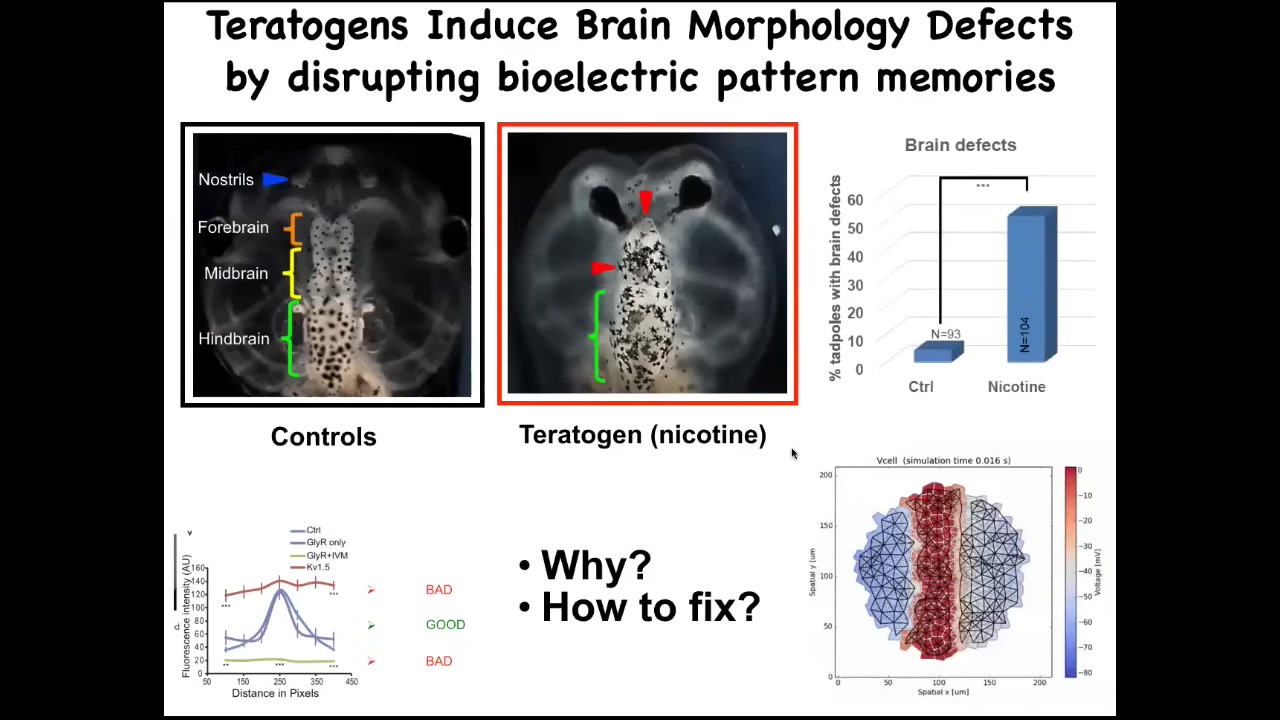

Okay, the next story I want to tell you about is birth defects. Once again, these bioelectrical patterns are critical for the organs to know what shape they should be.

Here’s the brain of a tadpole. Here’s the forebrain, the midbrain, the hindbrain. If these embryos are exposed to a teratogen, for example, nicotine, alcohol, or many other things, you can see there’s a defect. The forebrain is greatly damaged. The eyes are connected to the brain. It doesn’t have the right shape. Everything is problematic here.

We decided to ask, what can we do about this? Could we fix this somehow? We made a computational model that linked the changes in the bioelectrics with the final outcome.

Slide 23/36 · 29m:42s

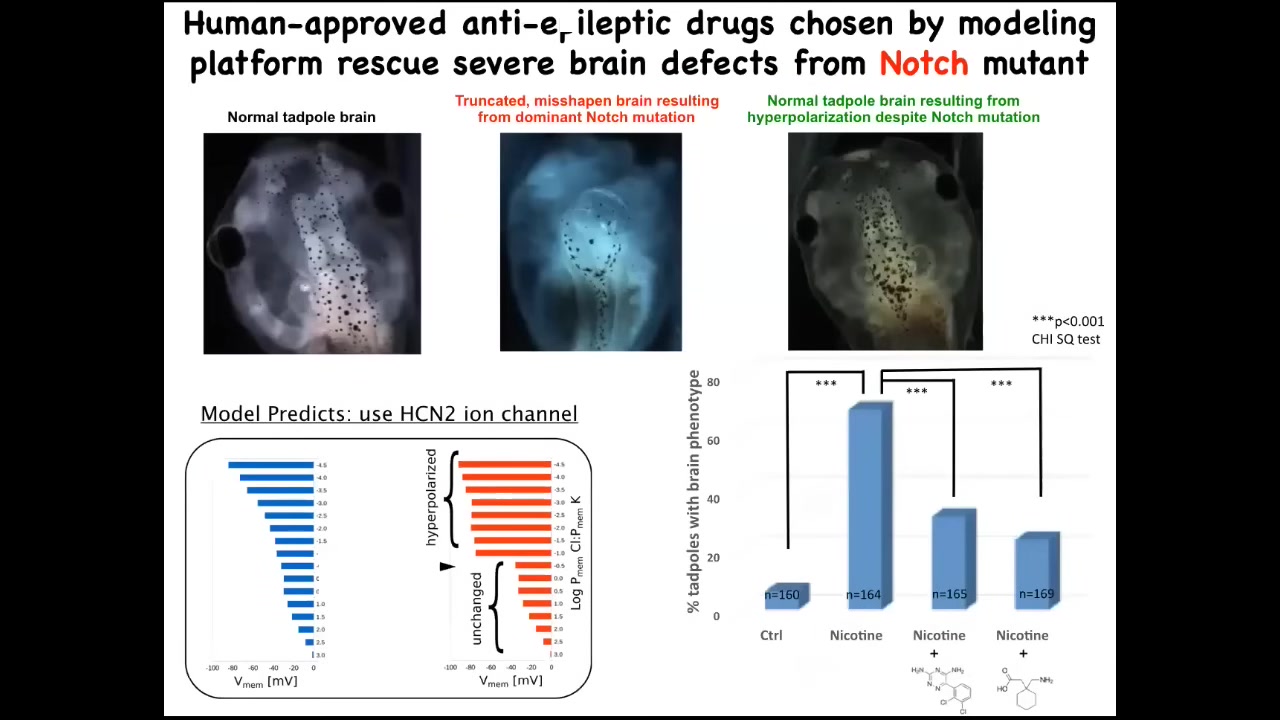

And that model was good enough that we could ask it a simple question. If the brain is incorrectly shaped, what kind of ion channel could we open or close in order to repair that?

Here's again a normal brain. This is a brain of an embryo with a mutation in a gene called Notch. Notch is a very important neurogenesis gene. With its dominant Notch mutation, the forebrain is basically gone. The midbrain and hindbrain are just bubbles. These animals have no behavior. They're profoundly affected. This is a radical birth defect.

Now we asked this model, how could we fix this? The model pointed us to one specific ion channel called HCN2, and it suggested that if we turn on HCN2, the sharpness of the pattern that is ruined here — basically what's happening here is that the pattern has become blurry or fuzzy. The brain doesn't know where the edges are. We used the opening of HCN2 to sharpen that pattern. You can do that with drugs that open native HCN2 channels, or you can introduce novel HCN2 RNA. In either case, you're back to a normal-shaped brain, normal gene expression in the brain. In fact, their IQ comes back to normal.

These animals have a dominant Notch mutation, but you couldn't tell that from their behavior or from the anatomy or from the gene expression. They're all fixed. At least in some cases, and I'm not saying this will be true in all cases, certain hardware defects can be fixed in software by communicating the correct pattern to the cells, regardless of what's underneath and what would have happened normally with the hardware. This is our roadmap for birth defect repair.

Slide 24/36 · 31m:35s

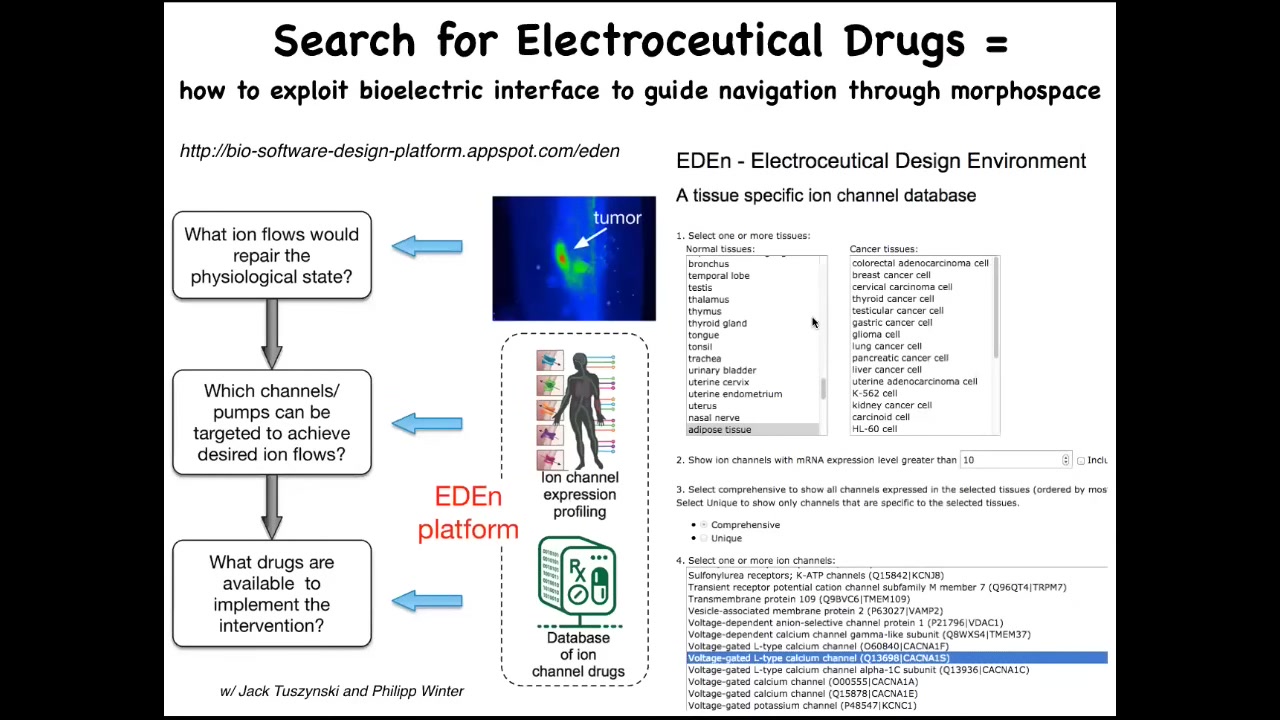

And so what we're doing now is creating this system, we call it EDEN, the electroceutical design environment, where the electric state is incorrect that you're trying to fix. If we do enough physiomics to get the data so that the correct pattern is known, then you can ask the computational system which ion channel targets are the ones that are going to get you from the wrong state to the correct state. And so you can already play with this. It is online at this link. Anybody can look at different tissues, both normal and transformed. And it will tell you which are the ion channels that are your potential targets. And that makes it easy for you to pick electroceuticals. Now we can pick drugs. Something like 20% of all drugs are ion channel drugs. And so there's this enormous toolkit that allows us to do these kinds of things once the computational model tells you what to do. So the final thing I want to show you has to do with cancer.

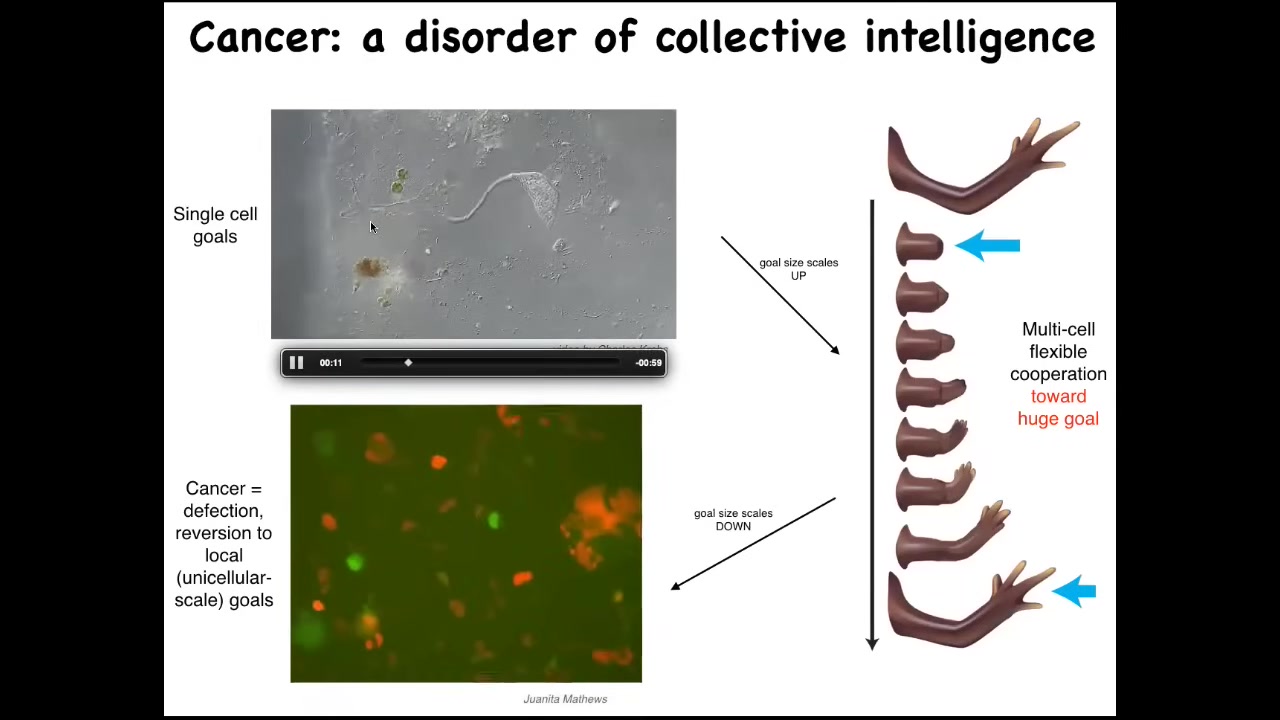

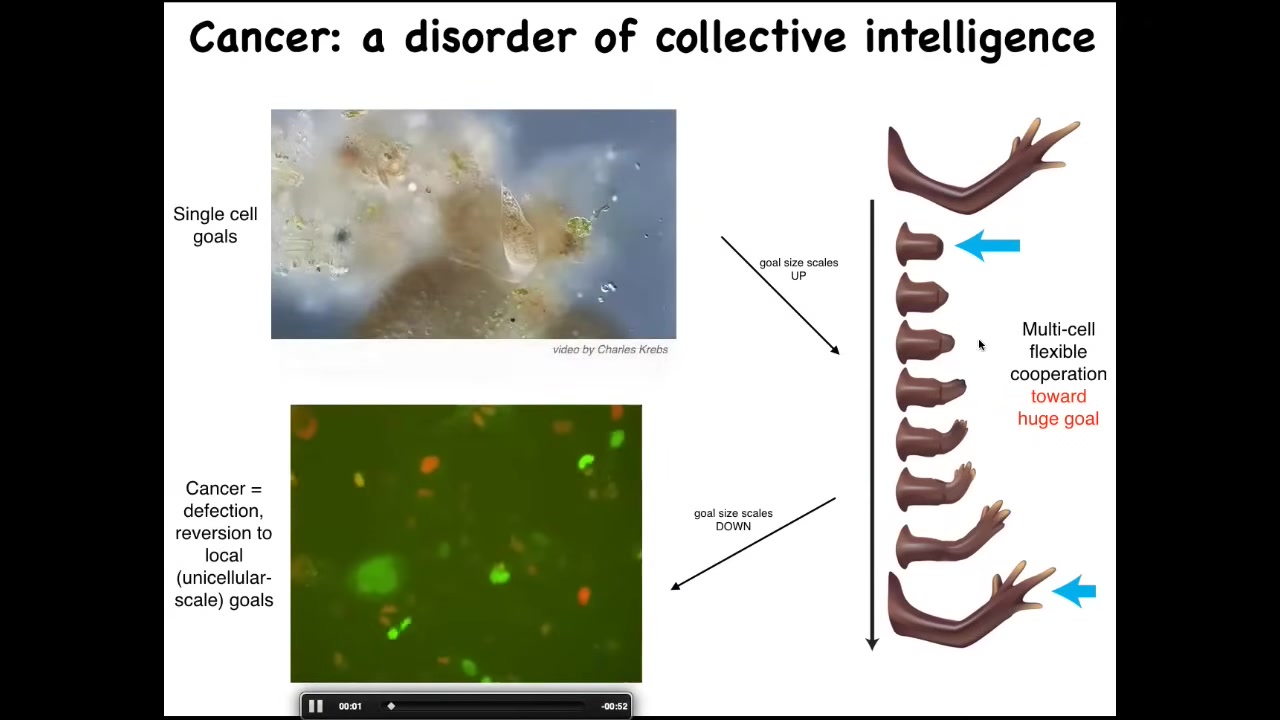

So our cells are extremely good at solving little tiny problems. They have very small goals.

Slide 25/36 · 32m:40s

Their goals are around metabolic state, about the pH level, these little tiny goals at the level of a single cell. But look at this homeostatic system. This huge collective has enormous grandiose goals of building a limb. And when they're deviated from that, they work hard to get back there. So evolution and development has allowed the scaling of the goals to rise during the lifetime. There's a failure mode to this process, and that's cancer. So this is human glioblastoma. What's happening here is that these cells are disconnecting from the electrical network. When they disconnect, they can no longer remember this giant thing they're working on. They're back to their ancient unicellular, tiny little cognitive light cone. These cells are not more selfish than normal cells.

Slide 26/36 · 33m:22s

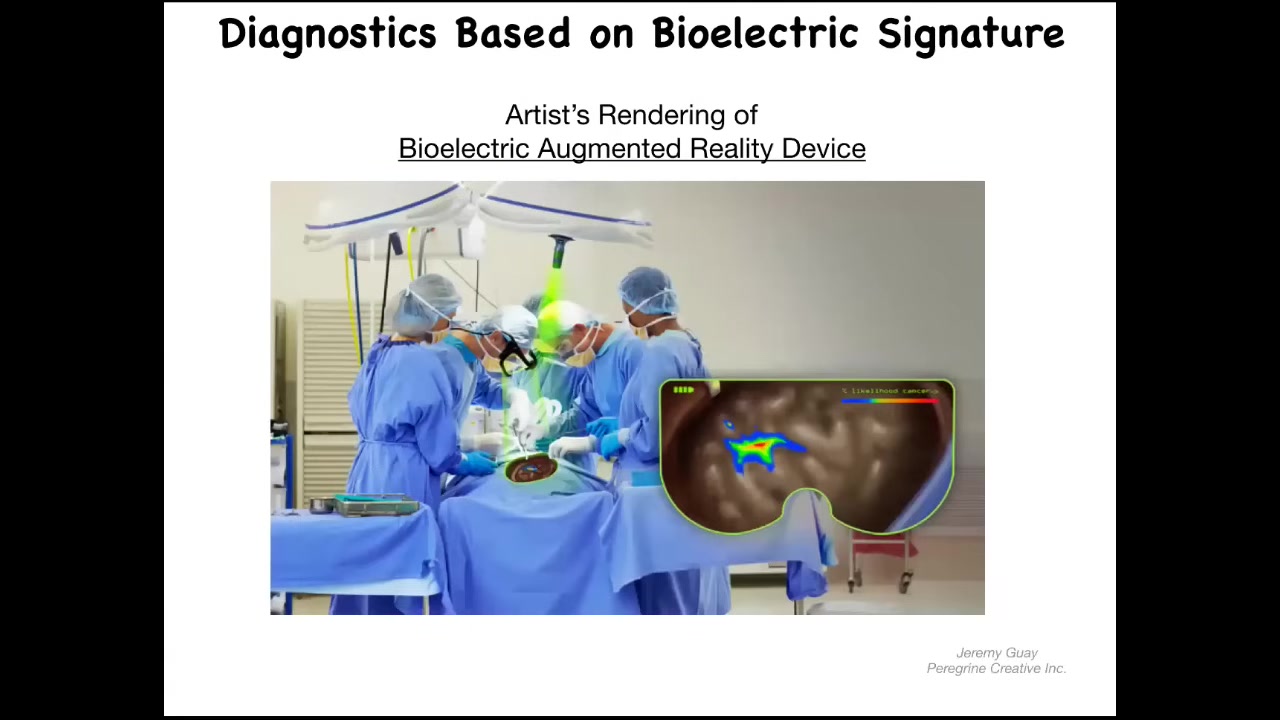

They have smaller cells. Cancer is a dissociative identity disorder of the cellular collective intelligence. These cells are only working on little tiny single-cell goals. This means two things. First, we can watch for this electrical change.

Slide 27/36 · 33m:40s

We can envision. This has not been created yet. This is an artist's rendition of what we're working on. The idea is to have augmented-reality goggles along with a voltage-sensitive dye so that surgeons or even people at home with these dyes can look and see pre-cancer. They can see cells that are about to disconnect from the network and the margins of the tumor. This is where the aberrant electrical states are. We're hoping to create something like that.

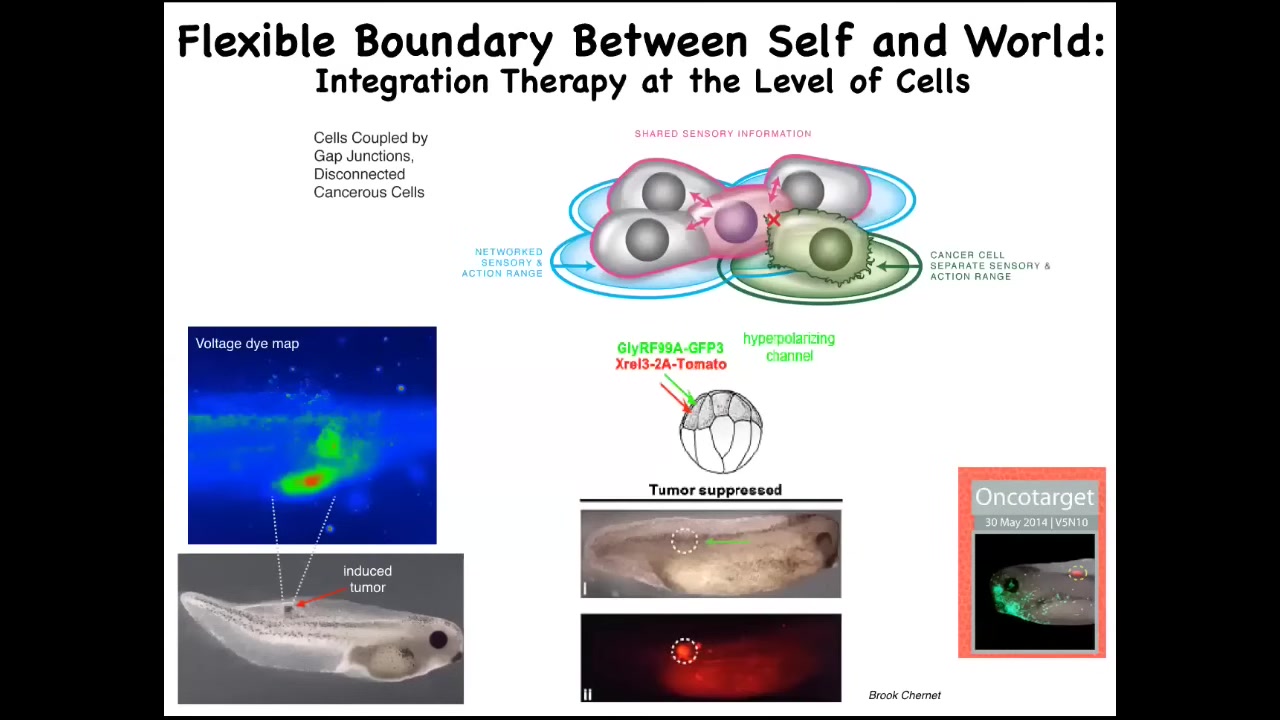

Slide 28/36 · 34m:10s

But even more importantly than just detecting it, you can imagine what if we forcibly reconnected these cells to their neighbors, not kill them with toxic chemotherapy, but just reconnect them. Here is an animal injected with a nasty oncogene. We've done KRAS mutations, dominant negative p53, all those kinds of things. What you'll see is that the oncoprotein is still blazingly expressed here. It's very strong, but there is no tumor; this is the same animal because we co-injected an ion channel that forces, it doesn't kill the cells, it doesn't remove the oncoprotein, but what it does do is force the cells into an electrical network that will work towards large-scale goals, building nice skin, nice muscle, and so on.

We think this tumor reprogramming or normalization approach is not at the genetic level. Here's another example where the physiological state drives the outcome, not the genetic state, but the physiological information drives the outcome.

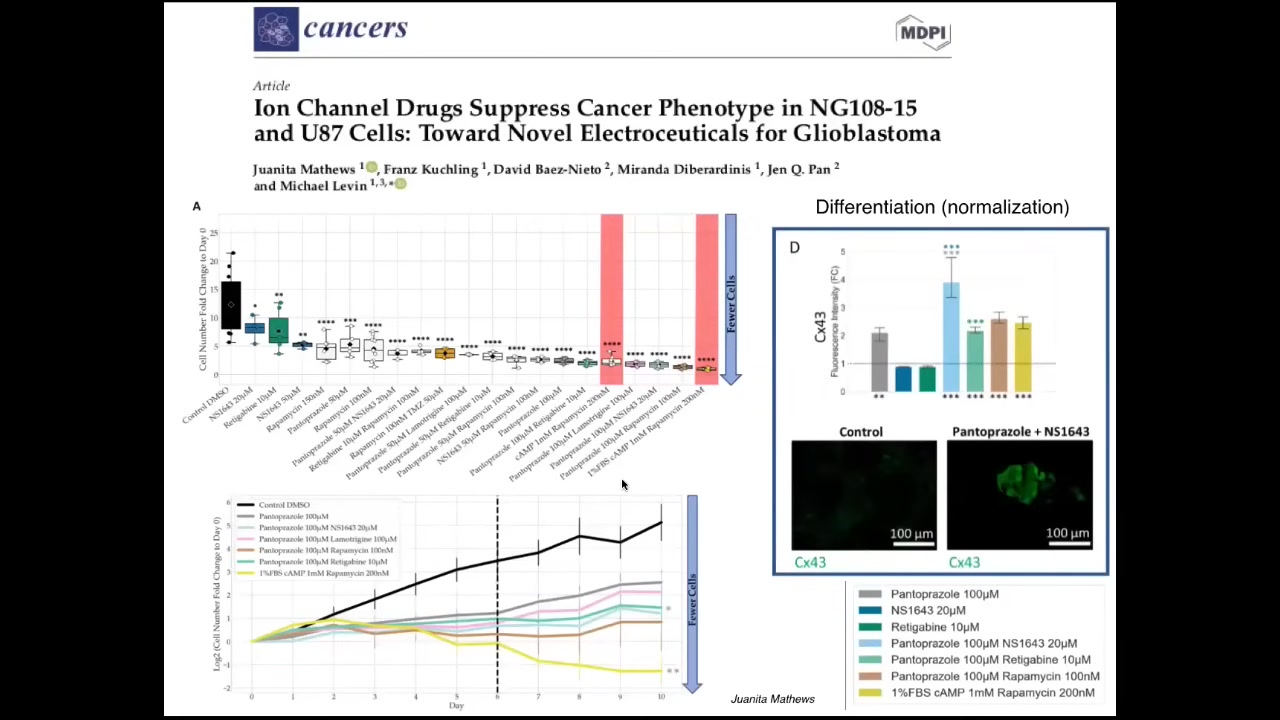

Slide 29/36 · 35m:08s

We've now started moving from the frog model into the human model. This is recent work—Juanita Matthews' work in human glioblastoma, looking for ion channel drug combinations that normalize these cells and make them stop proliferating and be more neuro-like. The very last thing I want to show you is this.

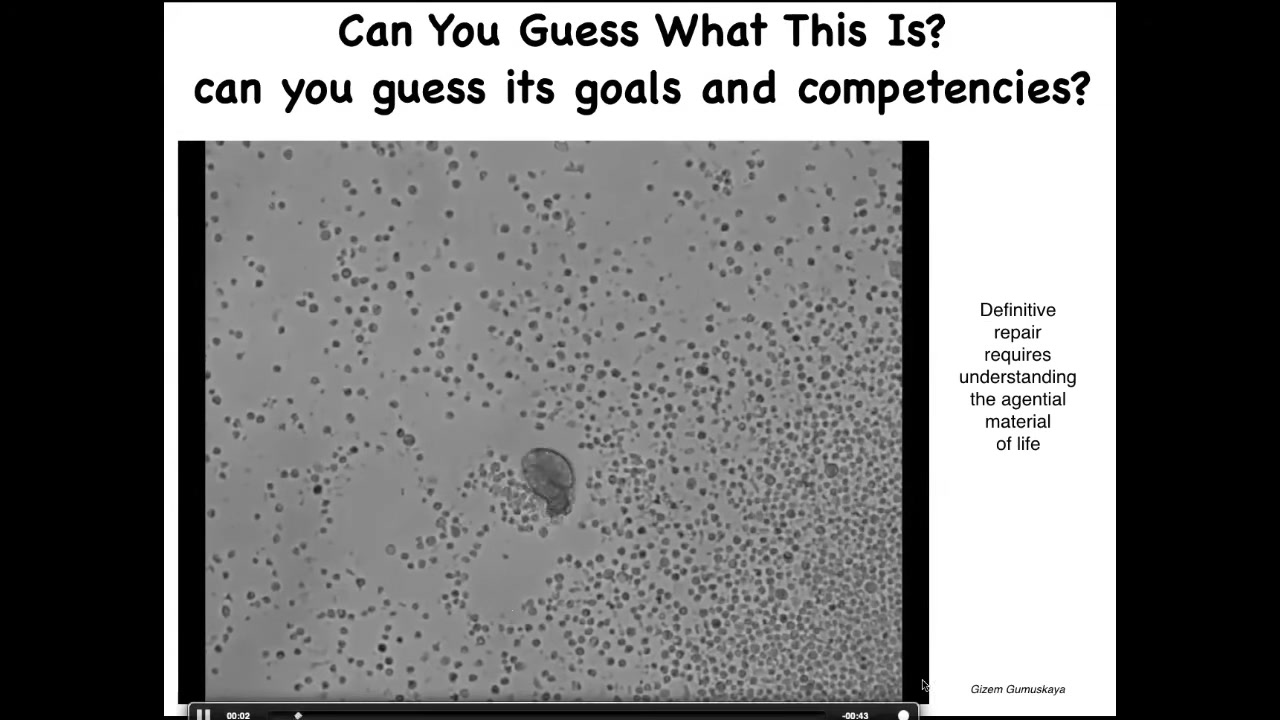

Slide 30/36 · 35m:28s

Take a look at this little creature. If I asked you what this was, you might guess that it's some simple life form that we found on the bottom of a lake somewhere. If you thought about its competencies, you might think that the conventional kinds of things that simple aquatic animals make.

But it's important to understand for definitive regenerative medicine. It's important to understand our material. If you were to sequence this, what you would see is 100% Homo sapiens. These are adult human cells.

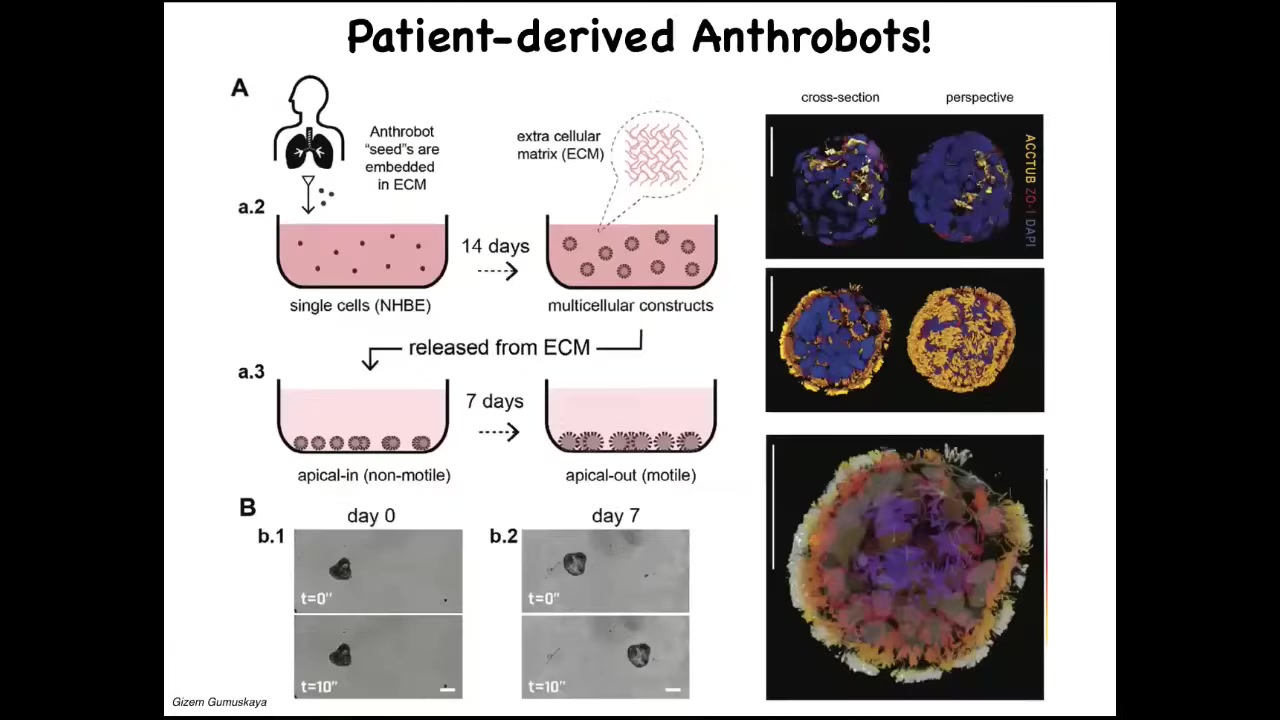

Slide 31/36 · 36m:05s

We call them anthrobots because these are biobots made from adult patient-donated tracheal epithelium. These cells, in a special environment, self-assemble into this kind of multiple little things that you just saw. This is what they look like when we stain them. They have little hairs on their surface; these are little cilia that they use to swim around. They have some interesting competencies. I can only show you one today.

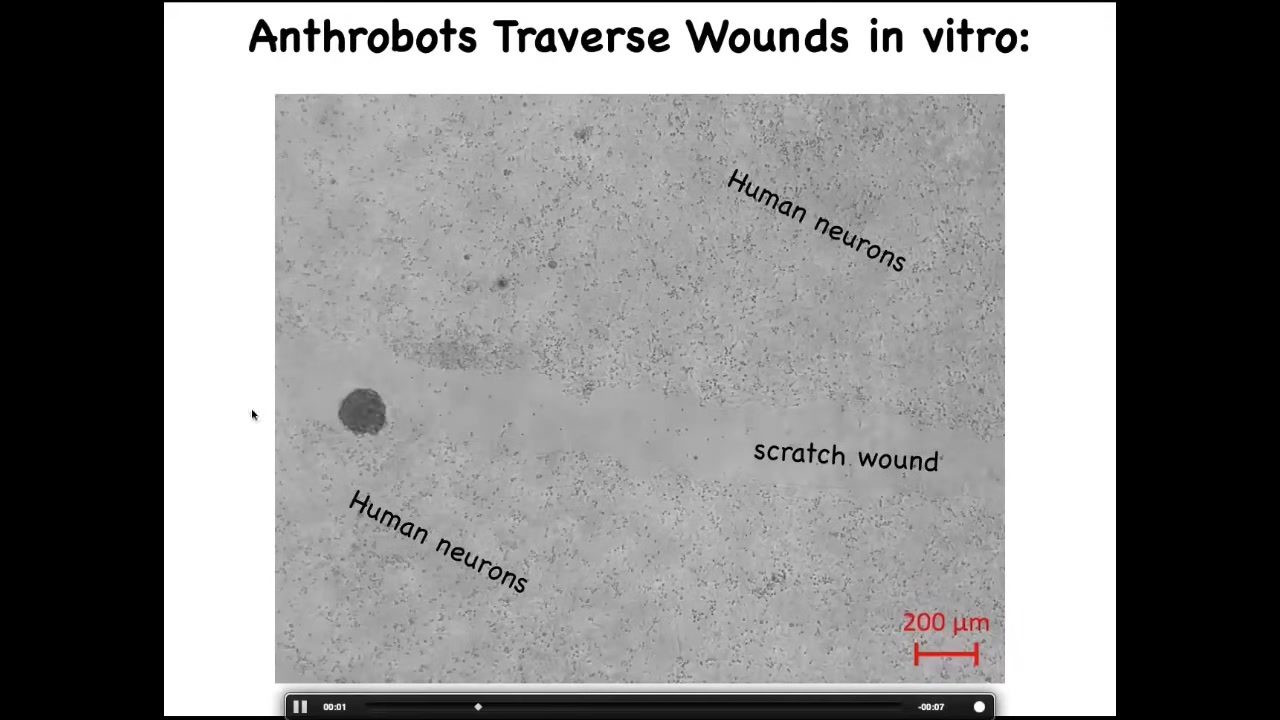

Slide 32/36 · 36m:28s

Here's one. These are human neurons plated in a dish here and here. We've made a scratch wound. They traverse them. They can settle there and they form these superbot clusters.

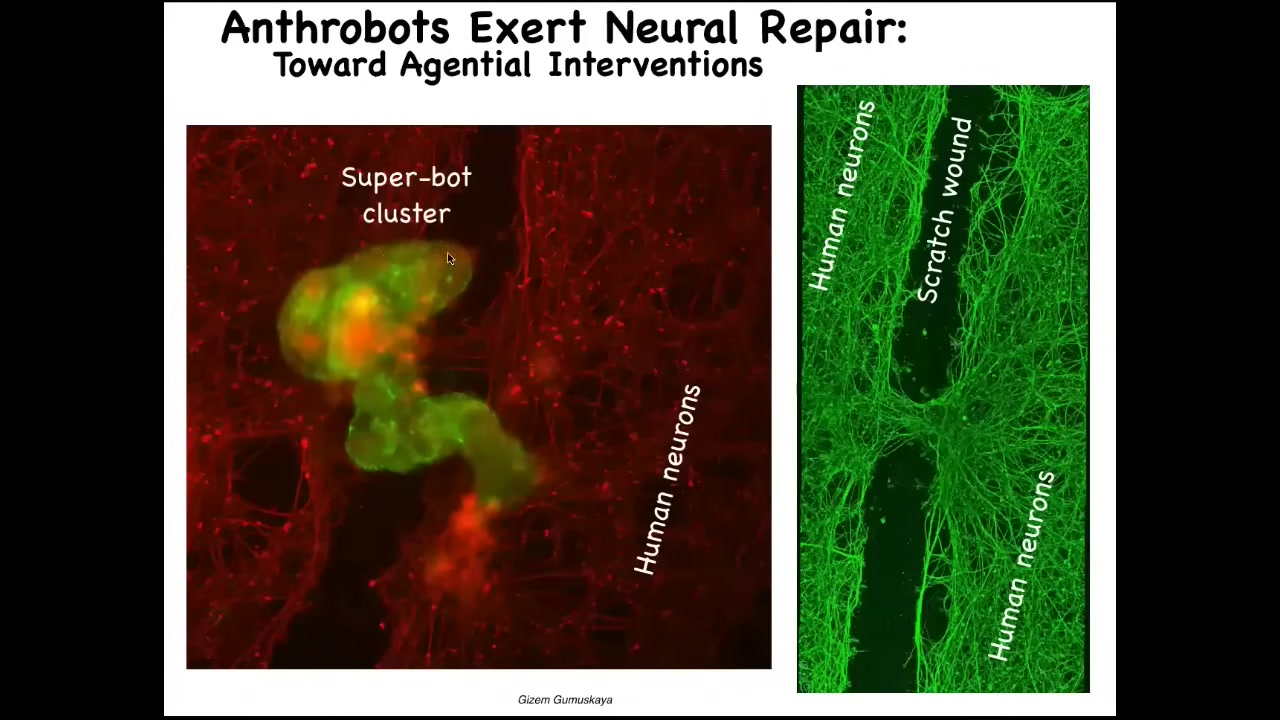

Slide 33/36 · 36m:42s

This is probably around 10 of these anthrobots. They form this cluster. What they're doing here is they're knitting together the two sides of the neural wound. When you lift them up four days later, you find that underneath they were healing the gap between this injury. These are IPS neurons, peripheral innervation.

Who would have thought that your tracheal cells, which sit quietly for decades in your airway, have the ability to form a multi-little creature that looks nothing like a standard human or any human developmental sequence? They express thousands of genes differently than the native human tissue, almost like a different life form. Yet, they have this amazing capacity to heal your body.

This is the beginning of what we call agential interventions. Drugs are very simple. They're mechanical. They just do what they do. Wouldn't it be amazing to deploy biobots made of your own cells, so you don't need immunosuppression? They're made of the patient's own cells. They go into your body. They have healing properties like this natively, or maybe we've taught them to do other things. Eventually they biodegrade, but they are your own cells, and they already know what health, disease, stress, inflammation, and cancer are. We don't need to manufacture this from scratch, such as mechanical nanobots.

Slide 34/36 · 38m:10s

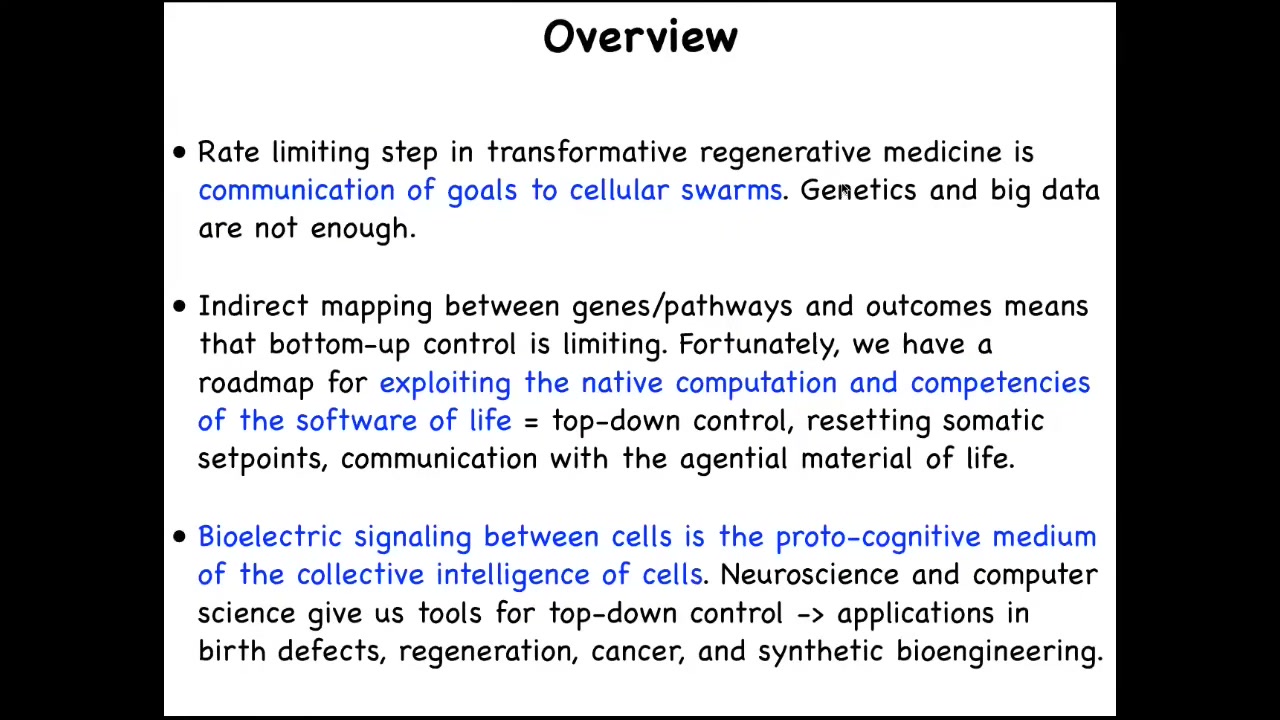

I'll stop here and just summarize what I've tried to say. I think the rate-limiting step in truly transformative regenerative medicine is our ability to communicate goals to cellular swarms, to view them not as complex machines, but agents, problem-solving agents with goals and preferences and agendas that we need to communicate and collaborate with. Genetics and big data are not sufficient for this. CRISPR, the biggest problem is going to be what genes do you CRISPR? What genes do you edit? This kind of bottom-up approach for complex problems is not going to be sufficient.

Fortunately, we have a roadmap for this, and it comes from behavioral science and neuroscience, and we can exploit the native computation competencies of the software of life. Top-down control, resetting their goals, resetting their set points, not trying to micromanage them molecularly. Specifically, the bioelectric interface. There's a lot of different kinds of intelligence in cell groups, but bioelectricity is a very nice interface to that intelligence, much like it is in the nervous system. And we now have the beginning of tools, both computational tools and practical benchtop tools, to use that interface to make applications in birth defects, regeneration, cancer, and synthetic engineering.

Slide 35/36 · 39m:35s

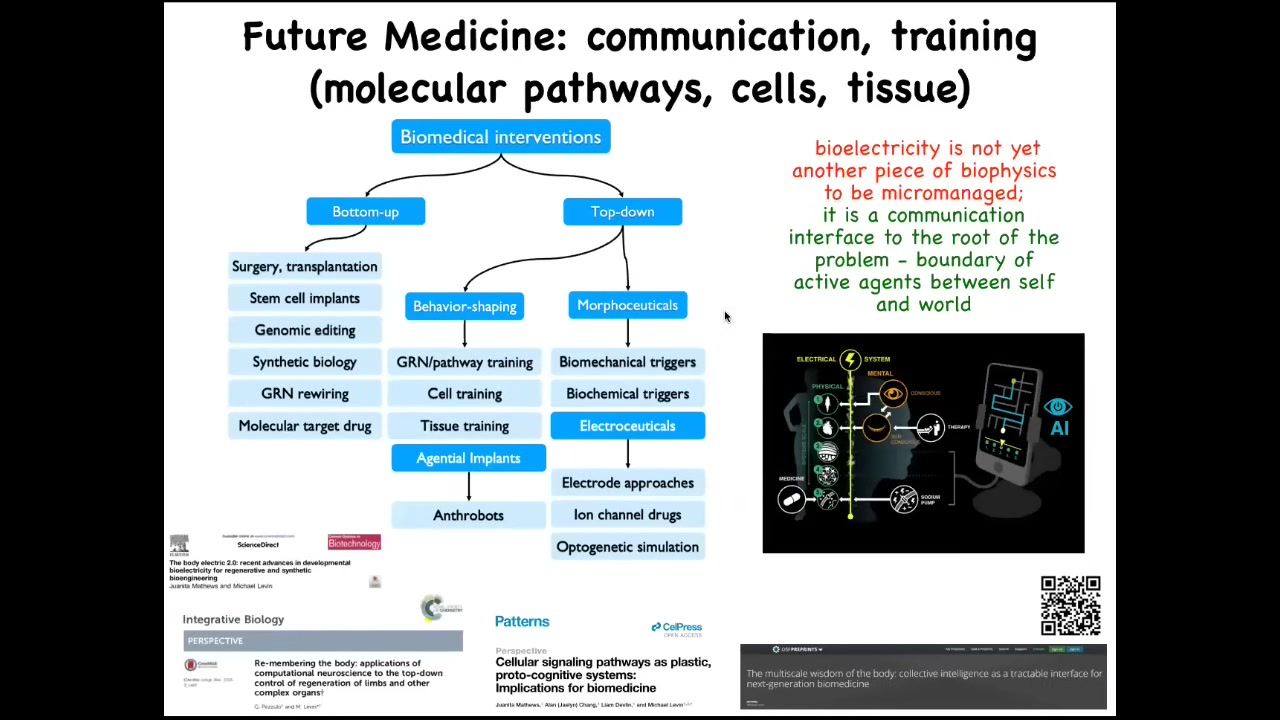

The way I see biomedicine developing in the future is that you have all these bottom-up interventions, and this is where all the attention has been focused, and there's some incredible advances here. But there's now this whole new frontier of top-down interventions. I haven't even talked about our work in training cells and tissue, behavior-shaping them. Here are the agential implants that I talked about, the electroceuticals. All of this is discussed in great detail here in these papers.

The idea is that the bioelectrical system that pervades our bodies is an interface to the intelligence that exists at different levels. Now, especially with AI tools, we have the ability to not only communicate, as we do now with drugs and surgery and so on, at the very lowest level, but we can communicate with some of these higher levels and take advantage of the idea of complex, goal-driven outcomes propagated down through the intelligence of the tissue, not simply micromanaged.

Slide 36/36 · 40m:35s

I'll end here. I want to thank the people who did all the work. These are the postdocs and the graduate students who did all the work that I showed you today. We have lots of amazing collaborators. Here are the funders that have supported some of this work. For disclosures: three companies have supported this work. Thank you very much for listening.