Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a ~57 minute talk titled "The Bioelectric Interface to the Collective Intelligence of Morphogenesis: development, regeneration, cancer, and beyond" which I gave at a UCSF seminar for an audience of graduate students and post-docs in Biophysics, Bioinformatics, and Chemical Biology. I covered the role of bioelectricity as cognitive glue underlying high-level adaptive plasticity in living tissue, recent progress in exploiting that interface, and new developments in research platforms for this field.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Framing bioelectricity's role

(09:28) Morphogenesis as goal-directed

(22:45) Bioelectric control of form

(35:10) Rewriting anatomical set points

(43:55) Cancer and aging bioelectricity

(49:36) AI, anthrobots, and outlook

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/54 · 00m:00s

I want to talk today about bioelectricity, but more specifically than the diverse biophysics that you have to add in order to understand development. I want to paint bioelectricity as a really important link that allows us to take the insights of cognitive neuroscience and apply them far outside of brains and neurons.

In other words, what I think is really special about bioelectricity is not just the mechanisms, but the role that it plays in scaling up processes and properties that we typically associate with cognition, with learning and memory. So that is what we're going to talk about today.

If you want to see any of the details, all the papers, the data sets, the software, everything is available here at this website. This is my own personal blog around what I think some of these things mean.

Slide 2/54 · 00m:58s

I want to start out by thinking about how we talk about machines and organisms.

This material is being micromanaged. In other words, this is the kind of thing you would do in carpentry. You've got some chisels and some hammers and some screws, and you're putting everything where it needs to go, and then eventually it's going to look like this. Some part of this biomedical approach here is very much micromanagement in terms of we're going to treat this as a machine. We know what all the parts do. We're going to assemble it exactly how we want it. The patient is sent home to heal. That is interesting. What happens after that when we rely on the autonomy of the material? In other words, we're going to let the system do what the system does. We are not going to try to micromanage it. We don't even know a lot of what it does, but we have some degree of trust that it's going to do what it needs to do.

There's some very interesting work in the study of placebo effects. Fabrizio Benedetti has this amazing quote where his work shows that words and drugs have the same mechanism of action. This reminds us that high-level information flows eventually have to impact the physics of whatever system you're talking about. That interface between information and physics is where I think some interesting and deep questions lie.

Slide 3/54 · 02m:35s

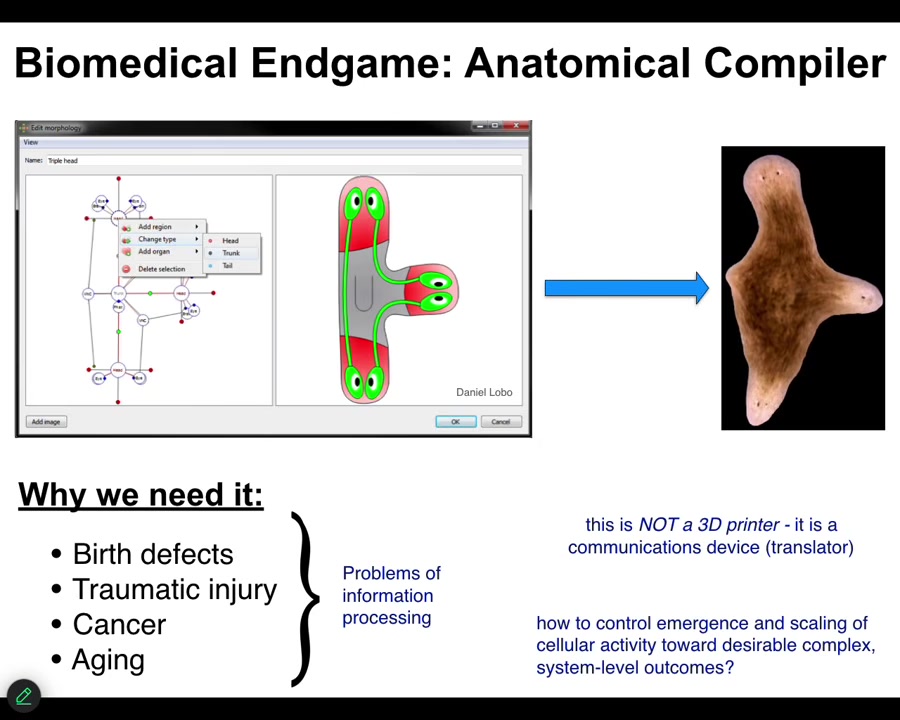

And bioelectricity can help us. Let's think about what the end game of developmental biology, bioengineering, what does all of that look like? When can we assume we're done? We've done our job and we can all rest easy. The way that I envision it is something that I call an anatomical compiler. Someday you will sit in front of a computer and you will be able to draw the plant, animal, organ, biobot, whatever, the living construct that you want. You won't be describing it at the level of molecular pathways. You will be describing it at the level of large-scale form and function. You're simply going to draw what you want.

If we had a system like this, what it would be able to do is to compile that description into a set of stimuli that would have to be given to individual cells to get them to build exactly what you want. If we have the ability to do that, to communicate large-scale anatomical goals to groups of cells, we would solve birth defects, traumatic injury, cancer, aging, degenerative disease. All of these things would go away if we knew how to give new anatomical goals to groups of cells.

I don't think this kind of thing is something like a 3D printer where you simply put the cells where you want them to be. This is not that. This is a communications device. It is a translator from your goals as the engineer or the worker in regenerative medicine to that of the cellular collective. It's the cellular collective. It's how do you get them to build the thing you want them to build.

Slide 4/54 · 04m:10s

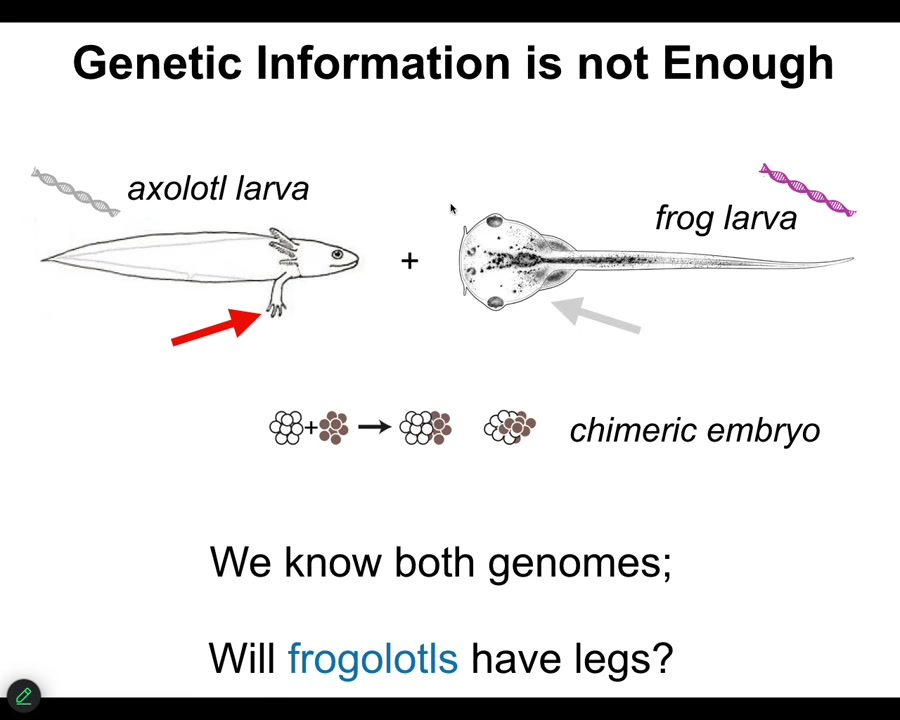

The typical information that we all focus on, genetics and biochemistry, is not enough.

Here's a very simple example. Here's the larva of an axolotl. Baby axolotls have little forelegs. Here's a tadpole of a frog. They do not have legs. In our lab, we make something called a frogolotl, which is basically a chimeric combination of these two creatures. Will frogolotls have legs or not? You've got the axolotl genome, you've got the frog genome. The answer is no. There's currently no model that allows you to look at this genetic information and know what's going to happen in this chimeric decision.

Slide 5/54 · 04m:55s

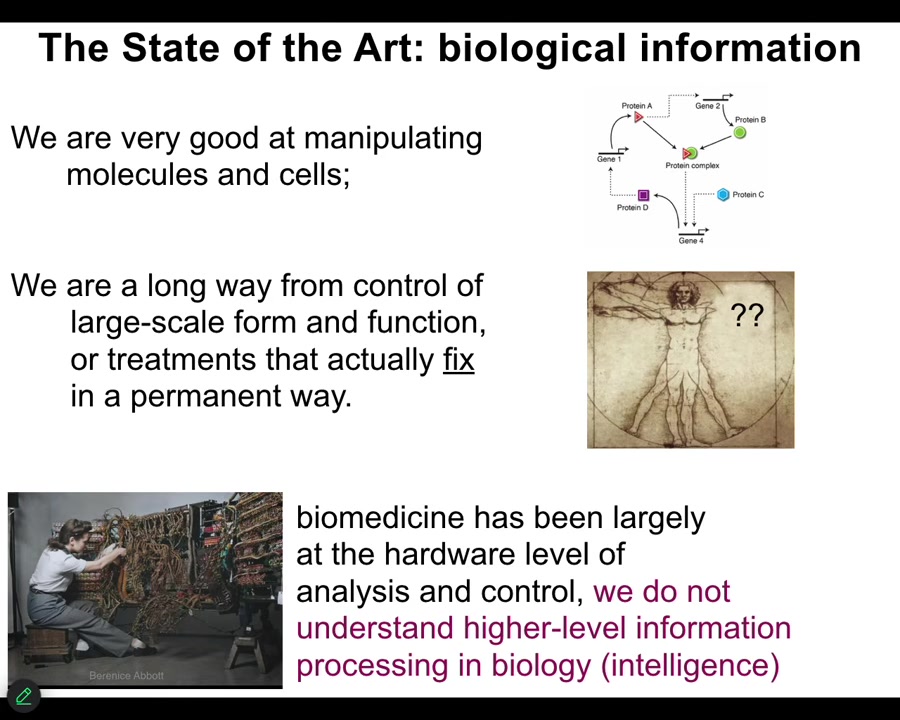

Because while we are very good and getting increasingly better at manipulating cells and molecules, we are really a long way away from understanding large-scale decision-making. What that means is not only can we not predict outcomes in various novel scenarios, to be fair, we can't even predict outcomes in the standard scenario. If you didn't already know what a Xenopus tadpole looks like, or if you didn't compare that genome with some other genome where you do know what it looks like, you would have no idea how to derive the actual anatomy from the genetic information.

And one of the consequences of that for medicine is that with the exception of antibiotics and surgery and then a couple of other things, a couple of other recent technologies, we really don't have anything that fixes things. Typically the treatments we have target the symptoms; they suppress the symptoms, ideally for as long as you're taking the drug, and then if you stop, everything comes right back.

So here's what I think is going on. I think that molecular medicine is still stuck where computer science was in the 1940s and 50s. This is what it looked like to program back then. She had to interact with the hardware. She's literally rewiring this thing because everything was about the hardware. And now this is where we are. We have genomic editing and pathway engineering and all these kinds of things. But mostly all the exciting advances are at the level of hardware. We have barely begun to understand the high-level information processing and in particular aspects of problem solving, AKA intelligence in the material.

Slide 6/54 · 06m:28s

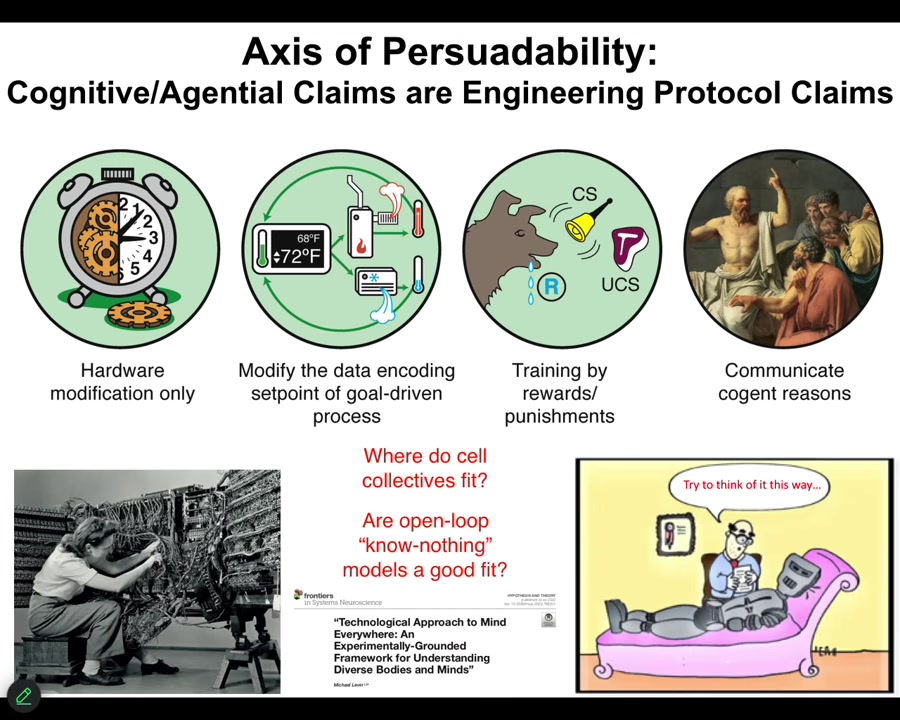

What I want to point out first and foremost is that this notion we all learn in our biology classes that good models are cashed out in terms of chemistry. At that level, nothing knows anything. The system does not know where it's going. It doesn't have any kind of a goal. It just does what chemistry does. Then it's up to us to figure out what emergent outcomes are going to come. These are a class of feedforward, open-loop models. This is not an experimental result. It is not a necessary axiom. It is an assumption. That assumption needs to be tested. Is it really the case that when we deal with cells and tissues, we are only going to be using models of devices that don't know anything and don't have set points and goals? Or maybe that doesn't fit the data very well. I'm going to argue that it doesn't fit the data at all. We actually have a spectrum here. I call it the axis of persuadability, that reminds us that we have a wide range of tools, starting with rewiring, but also cybernetics and control theory and the tools of behavioral science, where we're dealing with processes that since at least the 1940s, and for behavioral science long before that, we've had ways of addressing mechanisms that actually have goals, have memories, know things, and so on. The question is how much of that applies to the biology that we care about. You can see this worked out carefully in that paper.

Slide 7/54 · 08m:08s

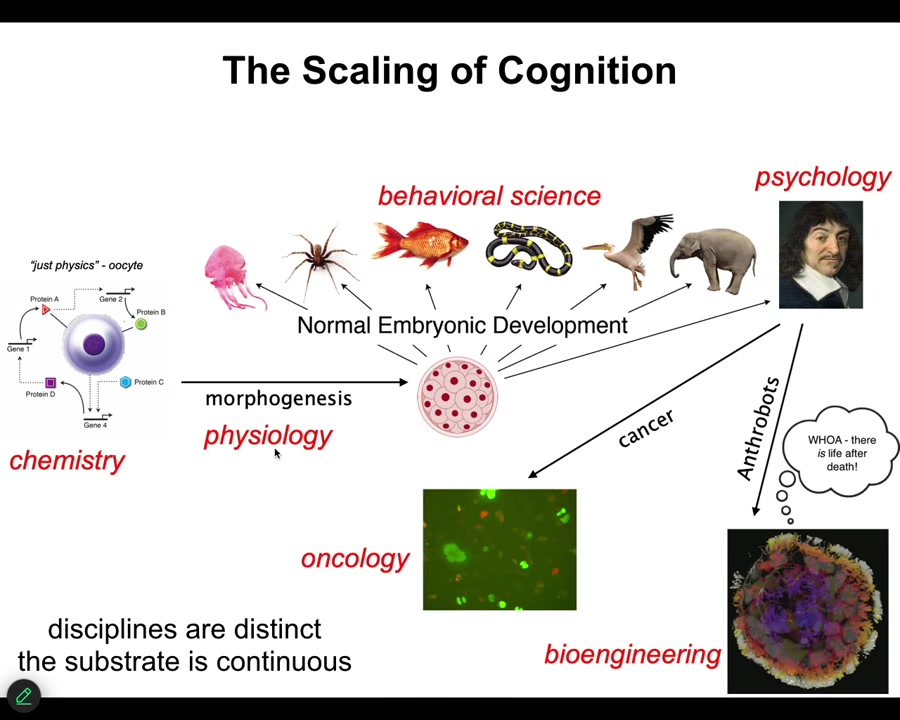

All of us take this journey. We start out being the subject of chemistry, and then as we're a little unfertilized oocyte, and eventually there's some developmental physiology, and then some behavioral science, psychology and psychoanalysis, and we take a detour into oncology or bioengineering. I'll talk about this momentarily.

The disciplines are distinct, and the journals and the departments and the funding bodies are all different. But the substrate is continuous. What we really have here is a kind of scaling of competencies. If you think that the final product, let's say an adult human or an adult animal, has certain properties, what we're looking for is a story of transformation. How did we get there from a little BLOB of chemicals? If you think that there are great transitions, sharp phase transitions where something critically new happens, you have to argue for that. You have to say, how exactly does that happen? Because the substrate is actually a slow, continuous developmental process. For this reason, I think developmental biology is unique among the sciences because here you see the journey from matter to mind. You start with chemistry and you end up in psychology. This is slow and gradual with no magic lightning flash in the middle that converts chemistry to mind.

Slide 8/54 · 09m:30s

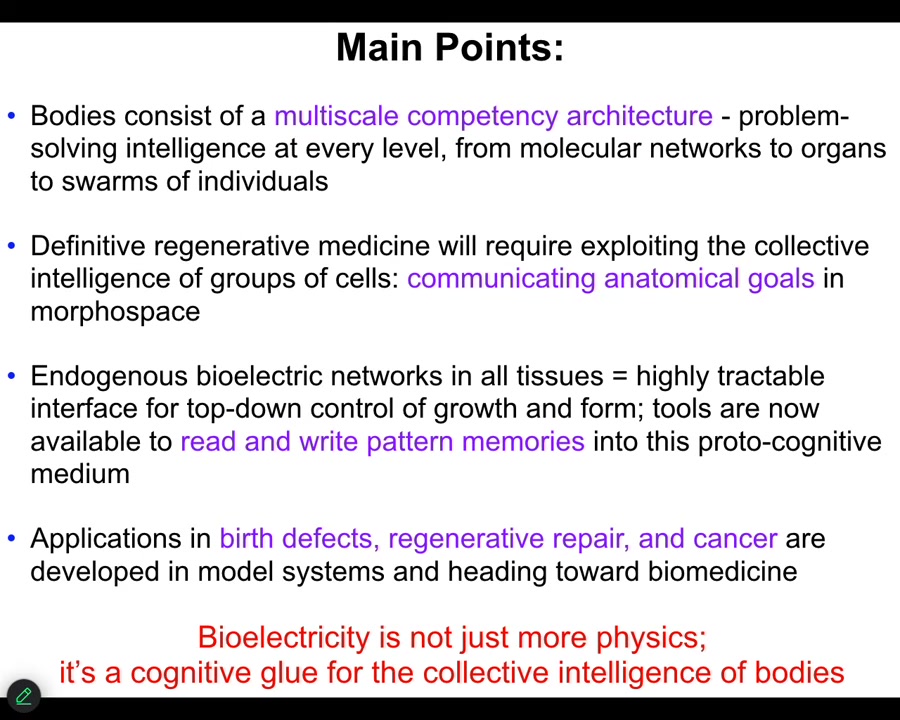

What I'm going to do today is try to make the following points. One thing that's interesting about bodies is that they consist of a multi-scale competency architecture. There's actually problem solving at every level, all the way from molecular networks up. That definitive regenerative medicine is going to require us to understand these systems as cybernetic goal-seeking systems. In other words, they have set points, and they have various degrees of ingenuity in meeting those set points when circumstances change. I'm going to show you how we use bioelectrics to read and write those set points.

These are pattern memories in that living medium, and we're going to be able to read and write them.

Bioelectricity does exactly what it does in the brain. It is a cognitive glue. It's a set of mechanisms that enables the collective to know things that the parts don't know. Just like you know things your individual neurons don't know because of electrophysiology. That is what developmental bioelectricity does, but it's more ancient and it does it in the rest of the body.

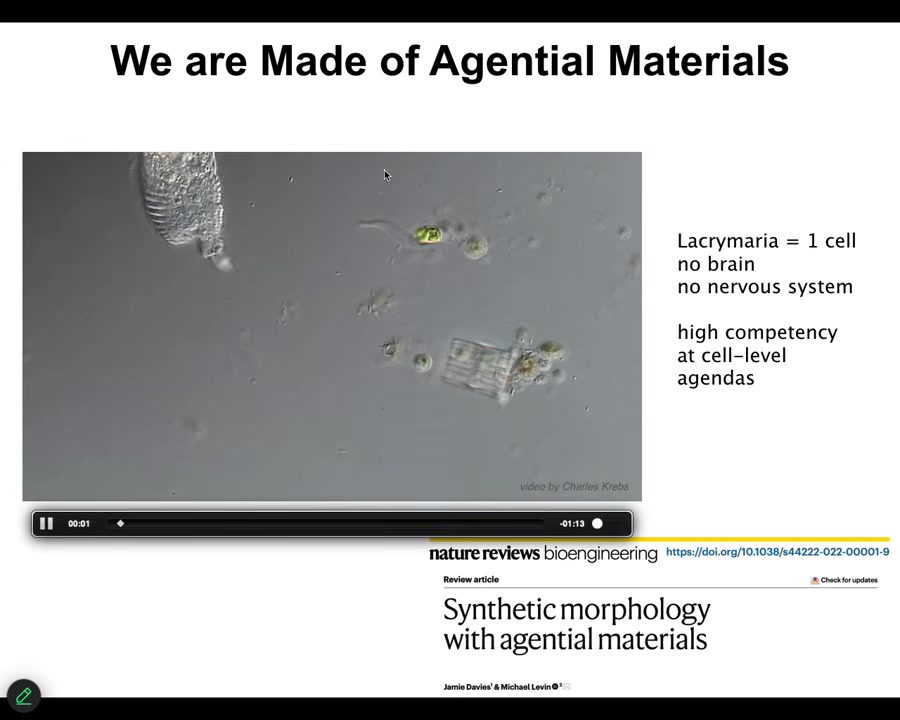

Slide 9/54 · 10m:38s

This is the kind of thing we're made of, individual cells. Here's a unicellular organism called the lacrimaria. No brain, no nervous system, but very significant competency in its own local environment. That's the kind of thing that we have to tame if you're going to make a multicellular body that does interesting things.

Even this is not where things start, because what it's made of is a set of chemical networks.

Slide 10/54 · 11m:02s

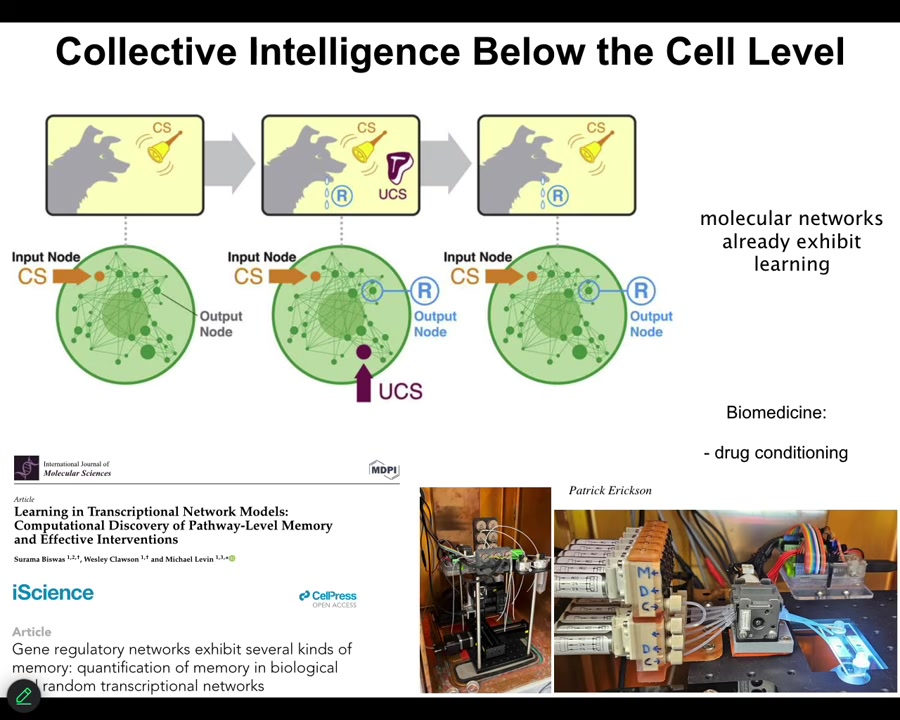

These might be gene regulatory networks, they might be molecular pathways. One of the interesting things about these networks is that they exhibit 6 different kinds of learning. You don't need a neuron, you don't need a brain, and you don't even need a cell, the chemical networks alone. Very small ones. You only need about 5 nodes in certain cases to do it. They do habituation, sensitization, associative conditioning. You can find all of that here.

Even the material already is capable of some very interesting behaviors. We are currently taking advantage of that to try to train the pathways. Applications include drug conditioning and things like this, where you can condition very powerful drugs to inert triggers and so on, because the material itself is able to associate different kinds of history of stimuli with specific responses. This goes all the way down.

Slide 11/54 · 12m:00s

That means that we have to extend, or at least we have the opportunity to extend some of the tools of behavioral science to systems that operate in very unusual spaces. We use those kinds of tools to study things that move around in three-dimensional space. This is conventional behavior. You see birds or mammals, maybe an octopus, doing interesting things in 3D space. We know we have tools to recognize when they're solving problems, when they're pursuing goals.

But biology has been doing this long before nerve and muscle appeared. Cells navigate a high-dimensional transcriptional space, they navigate a physiological state space, and, my favorite, they navigate anatomical morphospace.

What I'm going to claim is that morphogenesis, whether it be in development, in regeneration, and cancer suppression, is a kind of behavior, and it is the behavior of a collective intelligence, just like you and I are. It is the behavior of a collective intelligence as it navigates anatomical space, and anatomical morphospace is simply the space of all possible anatomical layouts that a system can have.

Slide 12/54 · 13m:15s

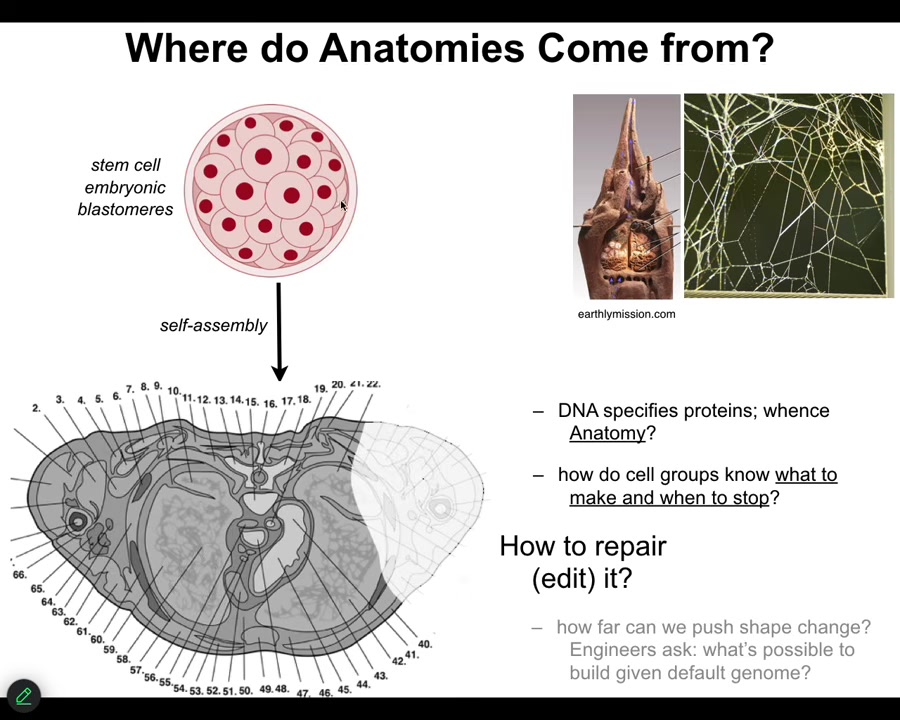

Let's talk about where anatomies come from. We all start life like this, a collection of embryonic blastomeres. Eventually, through a cross-section, you see something like this, incredible order. Everything is the right size, the right shape, next to the right thing. Where does this actually come from?

Most people will immediately say, it's in the DNA, it's in the genome, but we all know now that the genome specifies proteins and it specifies some timing information about how they appear. But actually, none of this is directly in the genome. The genome doesn't say anything directly about your anatomical layout. You still have to ask, how do these cells, given the molecular hardware that the genome does encode—the genome tells you what proteins and different types of computational machinery you get to have.

After that, you have to start asking what the software looks like. How does it know what to build? How does it know when to stop? If something is missing, how do we get it to rebuild?

As engineers, and I'll only talk about this briefly, we might ask it to build something completely different. Can the same genome build something totally different?

We just have to remember that this, the standard anatomy is no more in the genome than the shape of termite colonies or the precise shape of spider webs is in these animals' genomes. These are all outcomes of the physiological software that rides on the genetically specified hardware.

Slide 13/54 · 14m:42s

And so now we have to ask, what are the properties of that computational layer, and I'm going to use a definition of intelligence by William James to simply focus on goal-directed activity, meaning the ability to reach a set point. You can think about this at the lowest level as a simple homeostasis. Your thermostat has the very basis of goal-directedness. It has a set point. It represents that set point physically, and it tries to manage a set of variables to try and reduce the error to that set point. So let's ask the question of, is that something that we see in cell and developmental biology, or is it just open loop emergence, something that's going to explain everything we need to know?

Slide 14/54 · 15m:28s

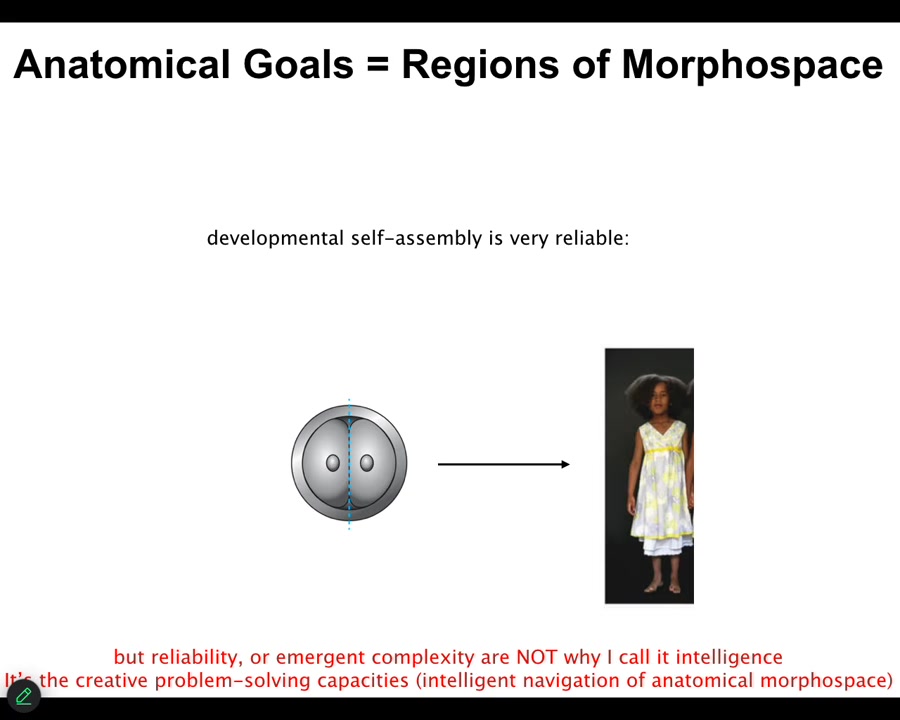

Well, the first thing we know is that development is very reliable. So you start off, you almost always end up with the right species-specific target morphology. But that is not why I'm using the word intelligence. It is not because it's reliable, and it is not because there's a rise of complexity. That is not my point. My point is about the high competency of navigating anatomical morphospace in unexpected conditions. This normal development really hides a lot of interesting capabilities.

Slide 15/54 · 16m:02s

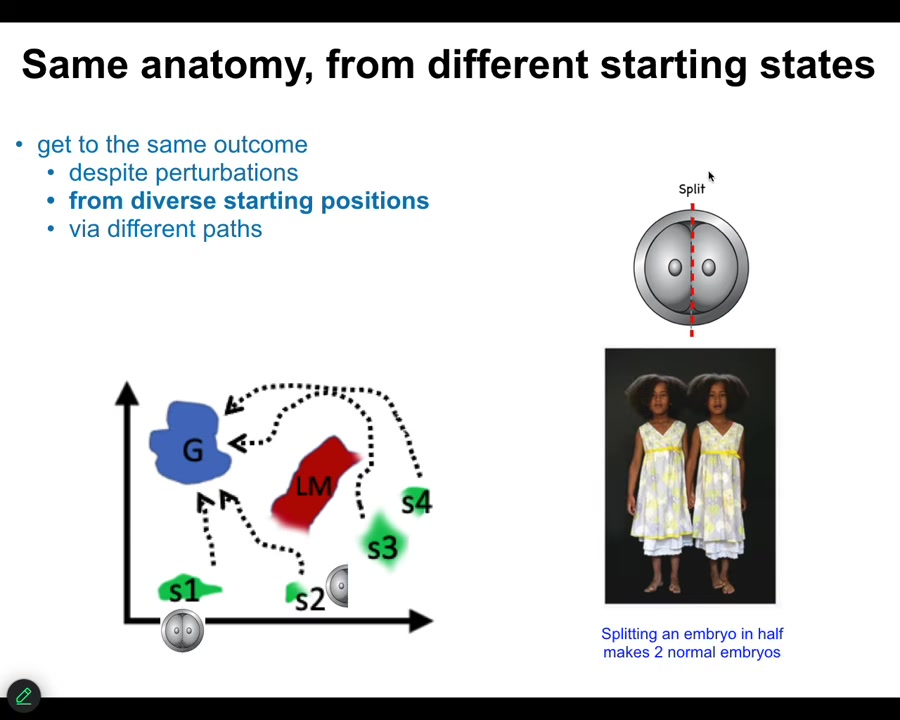

The first thing we know is that if we cut embryos into pieces, you don't get half bodies. You get perfectly normal monozygotic twins and triplets. We know that you can start off in different regions of that anatomical amorphous space. You can avoid various local minima, and you will eventually get to this correct ensemble of goal states. That's one thing. Same anatomy from different starting states. It's not just for embryos.

Slide 16/54 · 16m:28s

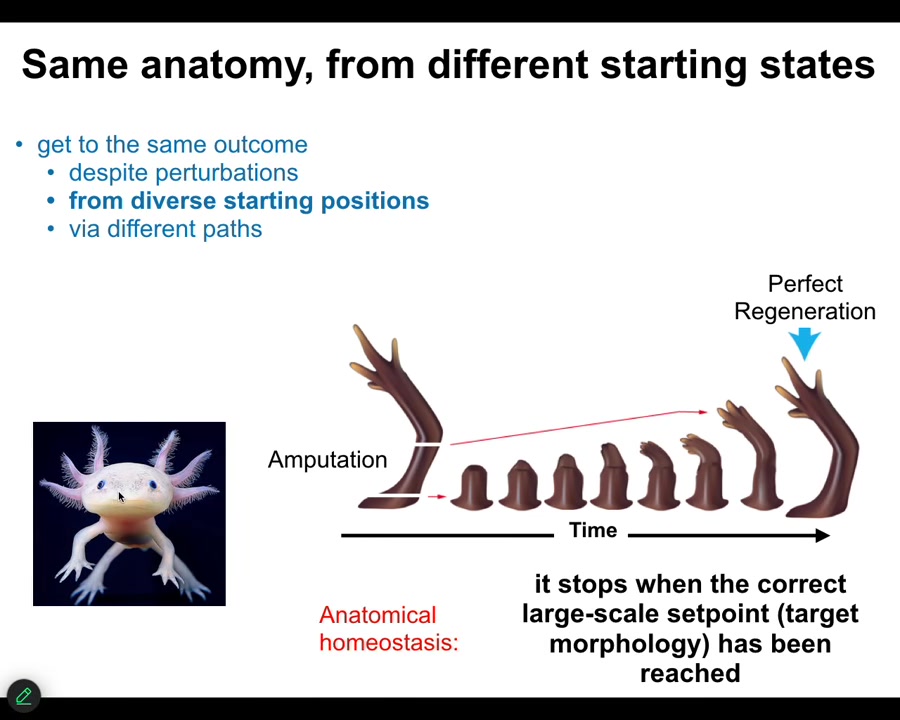

Many animals, such as this axolotl, can do this throughout their lifespan. You can cut the limb anywhere along this axis. The cells quickly detect that there's been a deviation from the correct goal state. They will reduce that error, and eventually they stop. When do they stop? They stop when the correct salamander limb has been completed. You can do this from different starting positions, but what it does is anatomical homeostasis and an error minimization scheme. There's something interesting here.

Slide 17/54 · 16m:58s

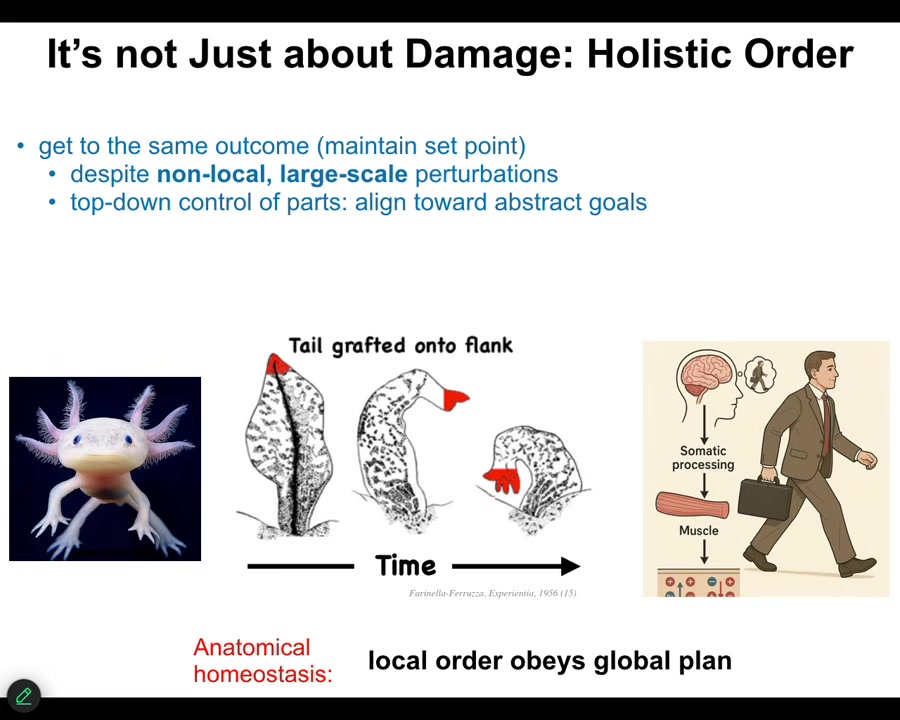

This is not just about damage. This is not a story of simply minimizing damage. You can think of development as a kind of regeneration. You're restoring the entire body from one cell. You might think the whole thing is about error minimization. But there's one other aspect to this that needs more attention.

This is an old experiment from the 50s where they took a tail and surgically grafted it to the flank of an amphibian. Over time, that tail remodels into a limb with fingers. Take the perspective of these cells at the tip of the tail here. They are tail end cells sitting at the tip of the tail. There's nothing locally wrong with them. There's no damage. There's no injury. Why are they turning into fingers? No individual cell knows what a finger is, but in some way, they're responding to something that at their level doesn't exist: the body plane of an entire animal.

What's happening here is a large-scale error-detection system that recognizes that having a tail here is not what's supposed to be happening. All of that error propagates down into the molecular steps that are needed to turn this structure now into this structure.

Where have we seen this before? We've seen it before in humans, in any kind of behavior. When you wake up in the morning and have very abstract goals, social goals, financial goals, research goals, in order for you to get up out of bed and do those things, ions have to cross your muscle cell membranes. The chemistry of your body cells has to be affected, functionally changed by these abstract high-level goals that the large-scale system has that the cells don't know about.

One of the most interesting things about bodies is that they form this transduction network that allows these high-level abstract things to serve as drivers of chemistry underneath. That is what's happening here. The fact that an amphibian is supposed to have a limb and not a tail here is what ultimately drives the molecular biology of this transformation. So the local order obeys a global plan. That's what's important here.

Slide 18/54 · 19m:08s

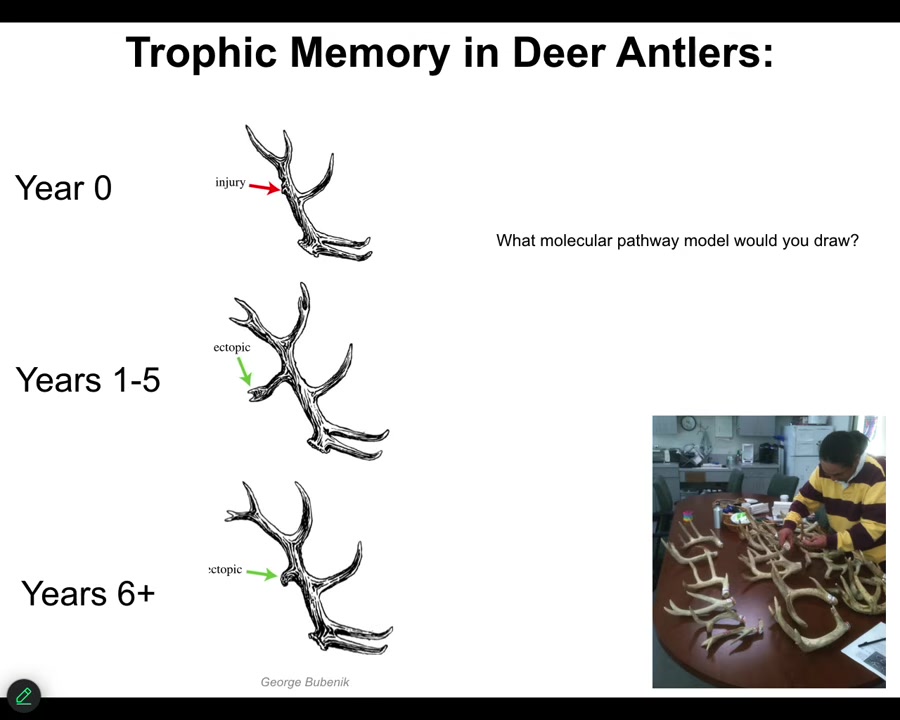

There are lots of examples like this that are not in our developmental biology textbook, mostly because they're very difficult to explain with current tools. Here's an example. This is called trophic memory in deer antlers.

Deer, large adult mammal that every year has this incredible structure of bone and vasculature and innervation. They lose these every year and then they regrow them from scratch. What you can do is cause an injury here. You cut into the bone. It makes a little callus. It heals, no problem. This whole thing falls off. For the next five years in certain species, that location will have an ectopic branch, an ectopic tine, and then eventually it goes back to normal.

The information as to the location of the damage has to be stored somewhere in the body because this whole thing is going to fall off. When the bone is growing, by the time you get to this, there has to be a new signal that says take an extra branch point here because there was damage last year.

Think about what kind of molecular pathway model you would draw for something like this. We're all used to making these arrow diagrams, Figure 7 in your Cell paper. We don't have really good tools to describe things like this.

And this is what the material is capable of. It has a pattern memory, it can store and recall these memories from distant locations, and it can guide morphogenesis in accordance to that pattern memory that does not have to be the default that you see from the species most of the time. It can be changed. I'm going to show you some examples of this.

The guy who discovered this, Bubenik, sent us 35 years' worth. This is a 35-year-long experiment. Imagine trying to tell your PhD advisor you want to work on a herd of deer for 35 years. He sent us all these antlers and an amazing data set.

Slide 19/54 · 21m:08s

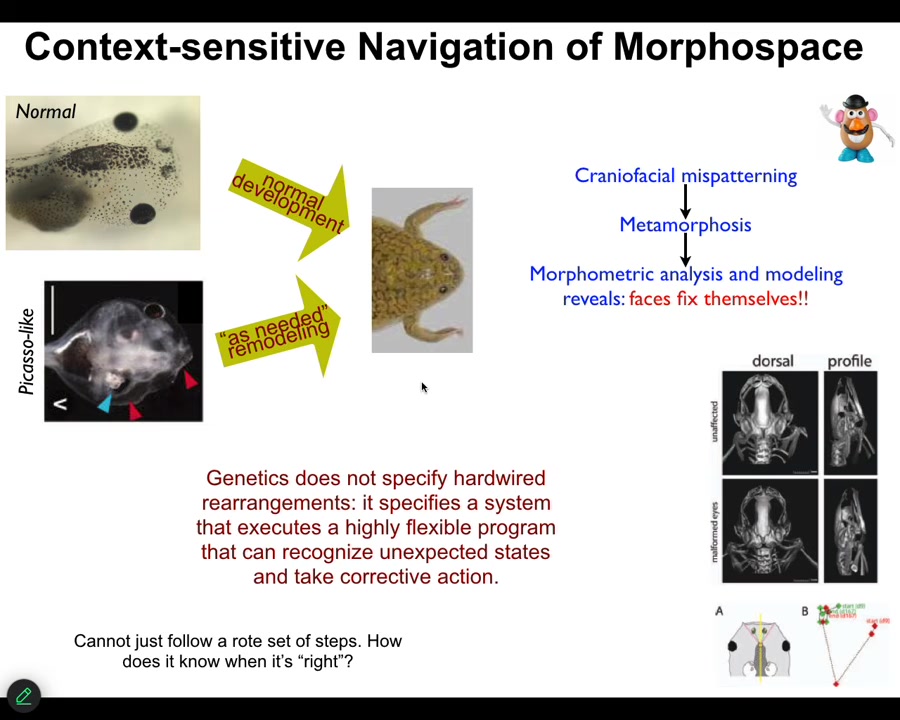

So just one more example in a much more tractable model system that we identified. This is a tadpole of the frog, Xenopus laevis. So here are some eyes, here are some nostrils, the mouth, the brain is here, the gut. And when these guys become frogs, they have to rearrange their face. All these different organs have to move to look like this. It was thought for a long time that what's genetically encoded is a set of hardwired movements. Everything moves in the right direction, the right amount, and you go from a tadpole to a frog. Well, we decided to test that. The way you test it is you perturb the system and see what it does. And so we created these so-called Picasso tadpoles where we scrambled the face. Everything's in the wrong place. The eyes on the back of the head, the mouth is off to the side. But it turns out they make perfectly normal frogs. All of these things move in novel, unnatural paths. In fact, sometimes they go too far and have to come backwards until you get to a correct frog and then everything stops.

What the genetics specifies is some hardware that can execute a very flexible error minimization scheme that takes corrective action as needed to get to a specific outcome. The most obvious question is, how do you know when you've reached the correct state? How does a regenerating limb or a developing embryo or a deer antler that's been modified by experience know what the correct pattern is? I'm going to show you one way in which anatomical target states—set points—can be encoded in tissue.

Slide 20/54 · 22m:48s

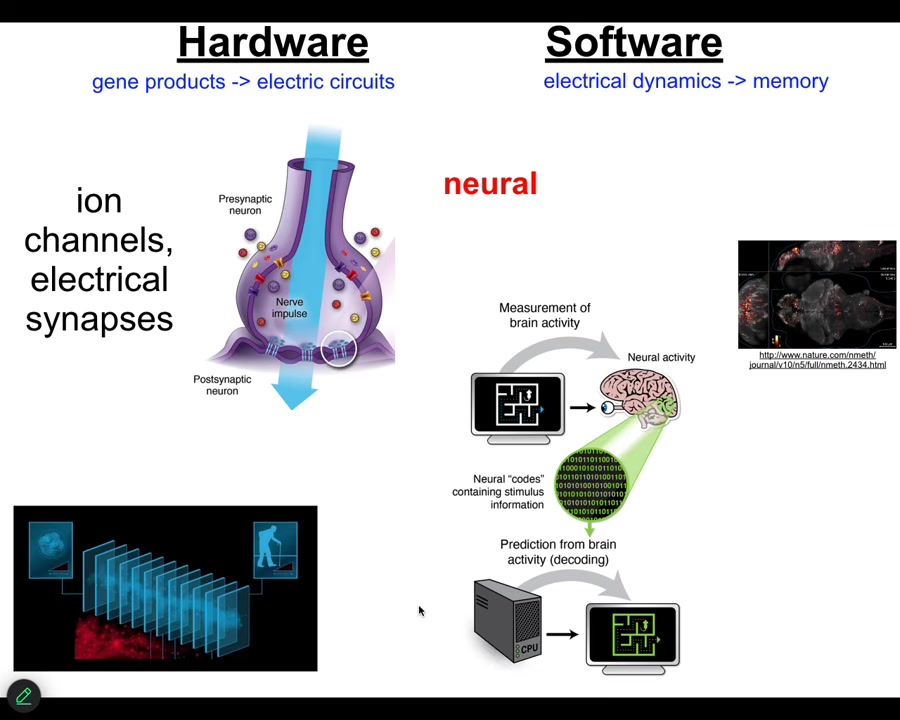

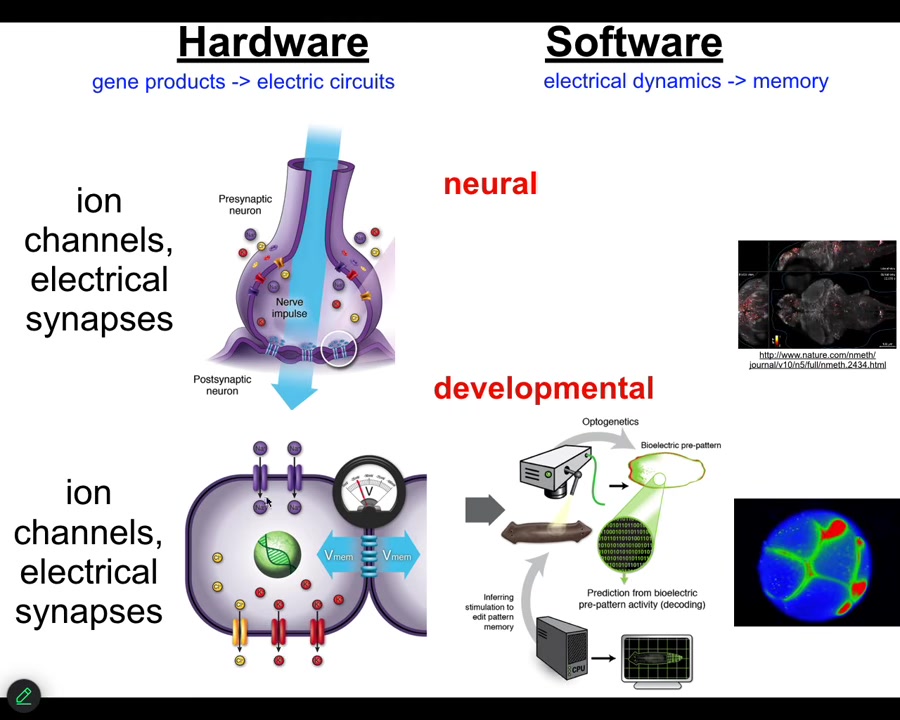

Now, the neuroscientists among the audience are already thinking, we know how, we have an example that does this, and that's the brain. We know in the brain that animals store set points as memories, and they execute behavior in accordance with those memories to reach specific states. And how is that implemented? There are ion channels that enable the network of cells in your brain to be electrically active. There are ion channels that set voltage gradients, there are gap junctions or electrical synapses that allow these signals to propagate across the network.

This group made a video of zebrafish brains while the fish was thinking about whatever fish think about. You can then try to do neural decoding. You can read this electrophysiology and decode it to understand what are the memories, the goals, the preferences, the behavioral competencies of this animal. In other words, we know from neuroscience that the cognitive states of beings are encoded in the real-time electrophysiology of certain cells. Where did this incredible system come from?

Slide 21/54 · 24m:20s

It turns out that it is extremely ancient. All cells in your body have ion channels. Most cells in your body are connected by these electrical synapses. This design feature, this architecture by which you can store and integrate information across space and time electrically in electrical networks is here from about the time of bacterial biofilms. Back from the time that bacteria were first getting together into colonies, that is when evolution discovered the amazing suitability of bioelectricity as a cognitive glue, as a way to connect competent subunits into systems that know things that the subunits don't know.

This was over 20 years ago; we asked, could we take the tools of behavioral and neuroscience and apply them outside the brain to do neural decoding except to non-neural cells and ask, what do they know? What information do they store? How does the collective store pattern memories that no individual cell has? I'm going to show you how we do that.

This was a zebrafish brain. This is an early frog embryo that we are monitoring in the same way.

Slide 22/54 · 25m:35s

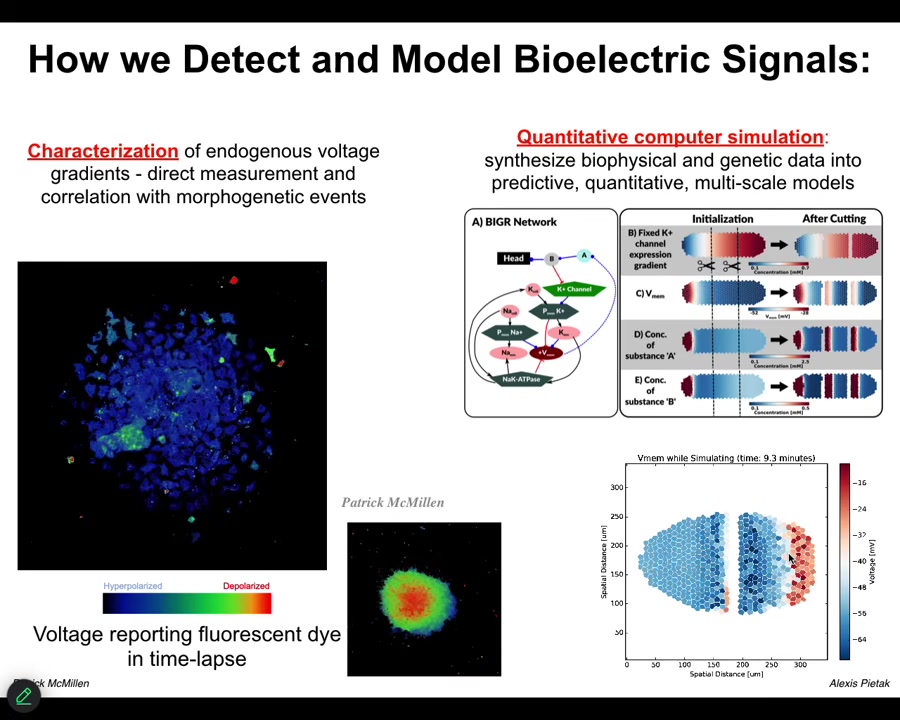

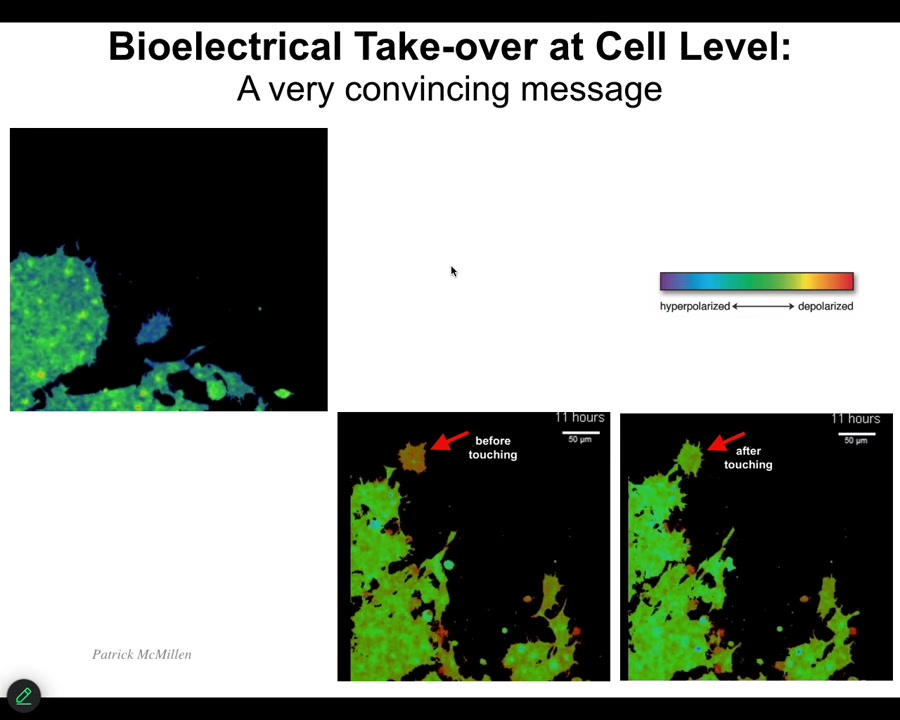

The first thing we did is to use a voltage-sensitive fluorescent dye technology to be able to read electrical states. You can see these are individual cells in vitro. The colors represent different voltages, and you can see the spatial and temporal patterns of bioelectrical states in these cells.

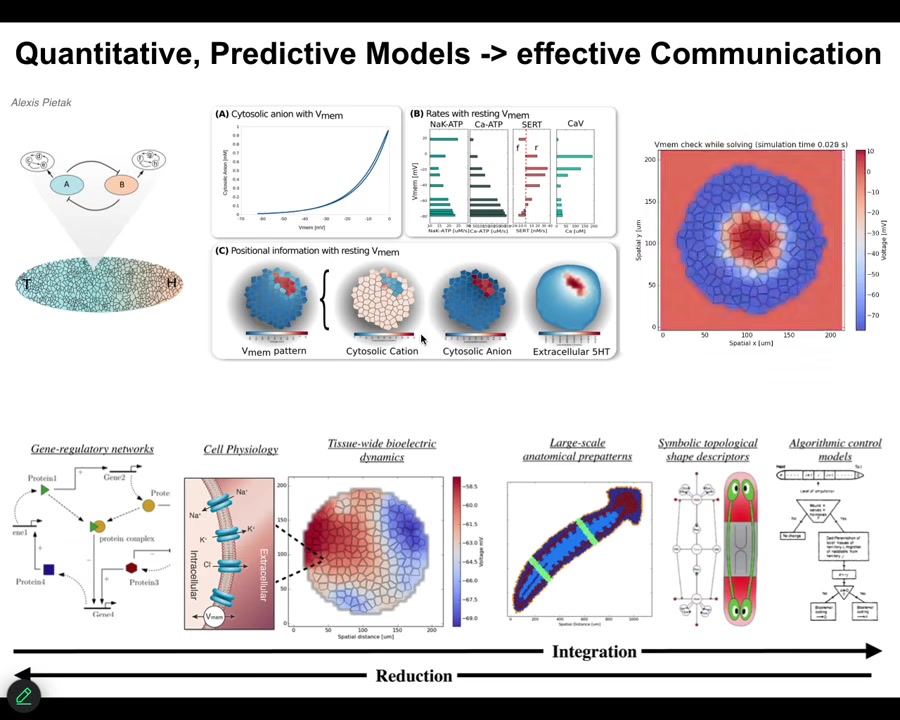

We do a lot of quantitative simulations. We start with the gene regulatory network that tells you which channels and pumps you're going to have in your cells. Then you can do large-scale tissue-level simulations that allow you to make cuts, damage the tissue, make certain changes, and ask what's going to happen. What is the behavior of this network? You can't do it in your head. It's not obvious at all. They have very complex and interesting properties.

Slide 23/54 · 26m:25s

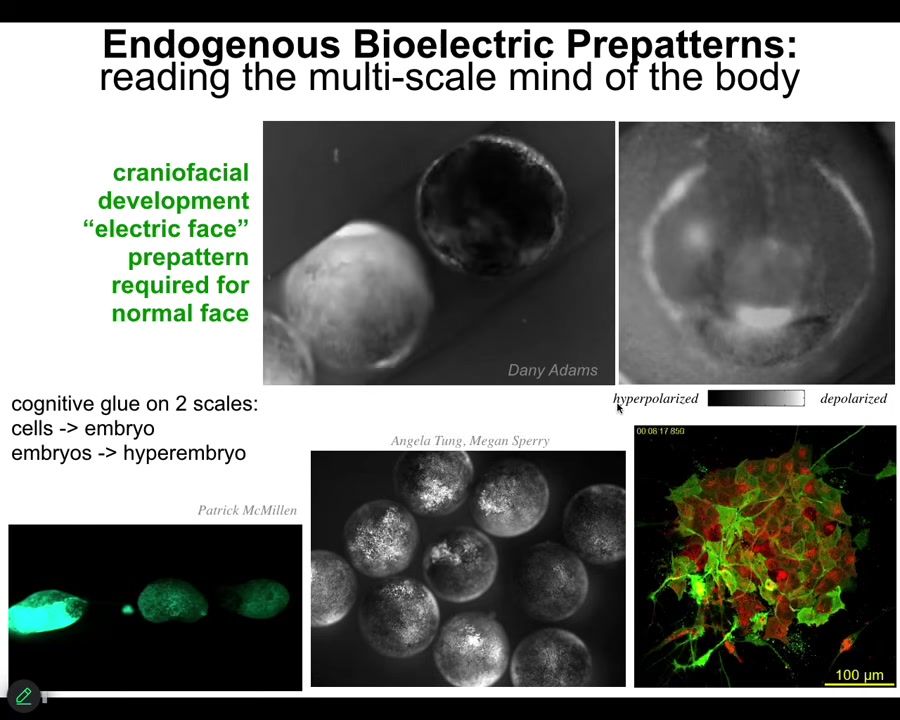

I'm going to show you a couple of examples in development. This is something we call the electric face. Here's a time lapse of an early frog embryo. The gray scale represents a voltage here using this dye. There's a lot going on, but look at this one frame. Before the genes turn on that regionalize the ectoderm of this embryo to become a face, you can read out the electrical pre-pattern that tells you here's where the right eye is going to go, here's where the mouth is going to go, the placodes are out here. It already lays out the basic features of the face. This voltage pattern, the spatial pattern of steady resting potential across the cell membrane, is what determines the genes that are going to turn on and the regionalization of the face.

Now, not only is bioelectricity a way to merge individual cells into a large-scale structure, it does that in multiple levels because these are individual embryos. If I poke this one, all of these guys find out about it. You can see this wave, this calcium propagation wave. In minutes, these guys all find out.

We have some interesting data; we can discuss hyperembryos if anybody wants. Hyperembryos are groups of embryos that solve problems that individual embryos can't solve. There's a multi-scale hierarchy going on here.

Slide 24/54 · 27m:48s

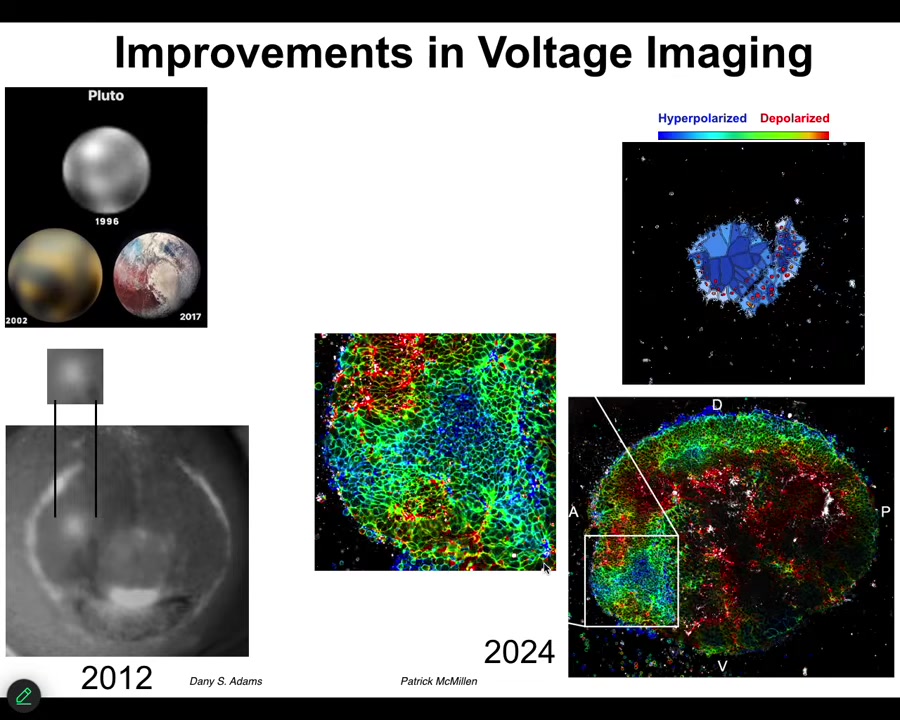

These improvements in technology have been really powerful. I always like this picture. This is what's been happening in astronomy. This is what Pluto looked like in 1996, 2002. By 2017, you can actually see some mountains and some features. And that's what's happened in our ability to track bioelectrical states.

This is what the eye spot looked like in 2012. We just knew that it was there. But by now, we can actually see the very complex patterns of this region and the technology is just developing more and more. But in addition to simply being able to read out all the bioelectrical states without having to poke each cell with electrophysiology electrodes, functional experiments are really critical.

Slide 25/54 · 28m:30s

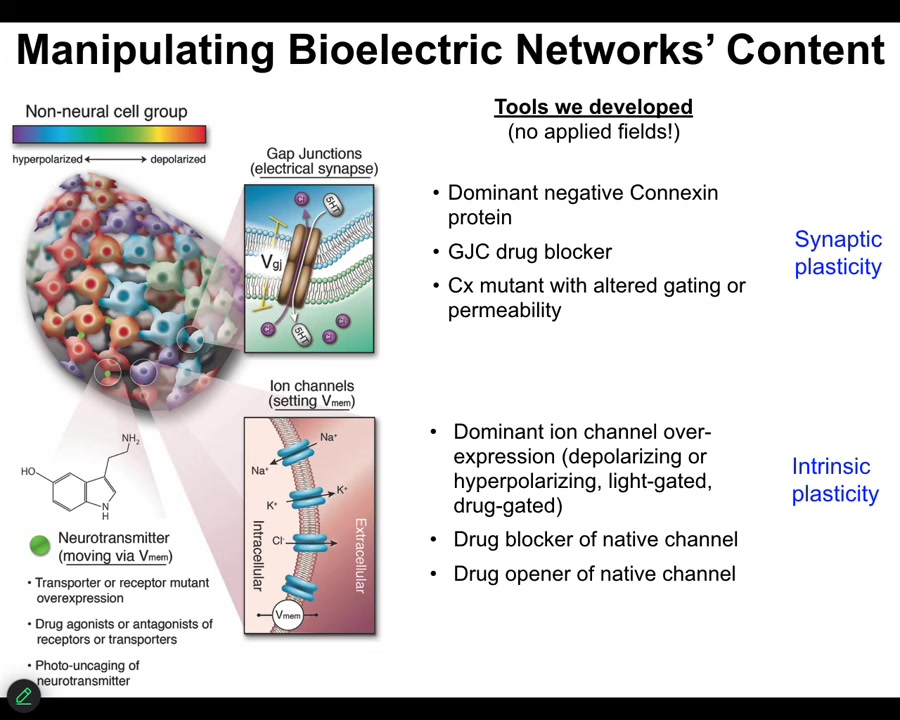

How do we write the electrical information? We don't use electrodes or magnets or applied fields or anything like that. There are no waves, no frequencies. We manipulate the natural interface that cells use to hack each other. We control the ion channels, and we can do that with drugs that target specific types of channels and pumps. We can do it with optogenetics. There are also some nanomaterials. Gap junctions. We can control the topology and the actual voltage of individual cells. Now it's time for me to show you what happens when you do that.

Slide 26/54 · 29m:15s

One of the interesting things that we have to watch is the ability of cells to control each other electrically. I'm going to show you one example. This is a video. I'm going to play it. The voltage, again, is denoted by the colors. These are cells in vitro. Notice that this cell starts out as one voltage until it gets touched by this cell, and then it changes. It's crawling along, it's minding its own business, nice and blue. This thing touches it, bang, that's all it took. A tiny little touch like this, and the cell voltage has changed, and now it comes down and becomes part of this group and starts working on some novel morphogenetic thing. We would like to understand this kind of ability to control cell behavior electrically and to tell them what to build.

Slide 27/54 · 30m:05s

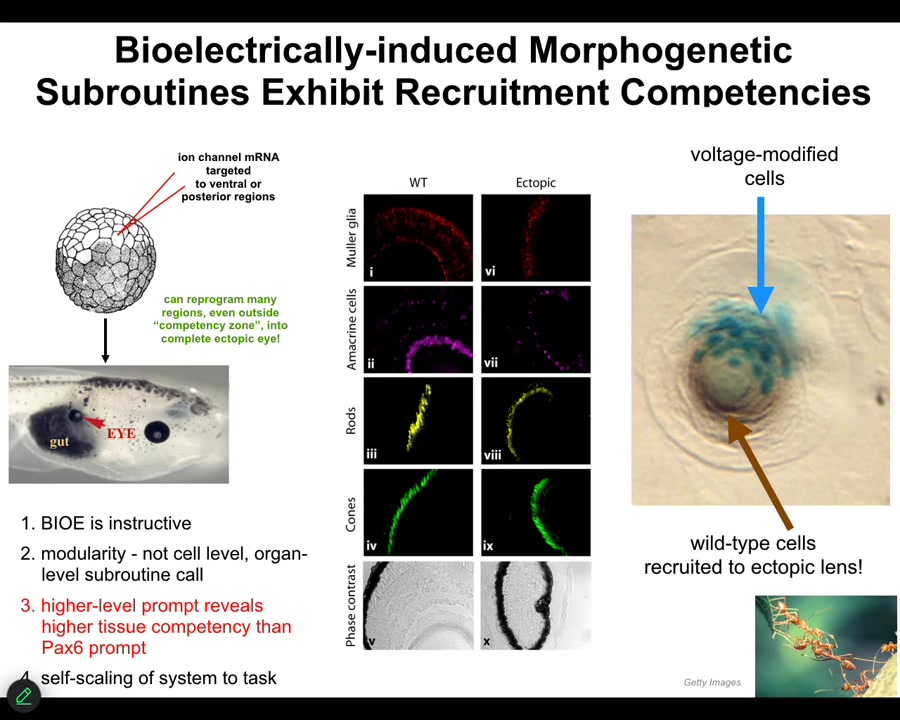

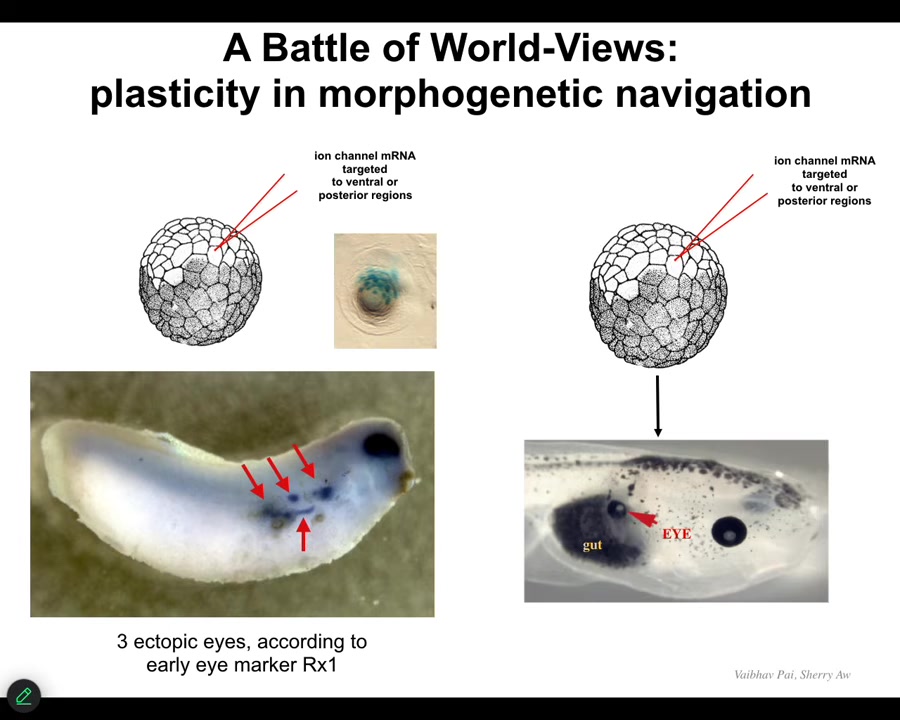

Here's a couple of examples. One of my favorite examples is the induction of ectopic eyes. You might see in your developmental biology textbook that only the anterior neuroectoderm up here is competent to make an eye. That's only true if you use chemical or molecular genetic inducers like PAX6, the so-called master eye gene. But most regions in the body are capable of doing it if you know the right prompt. The right prompt is that bioelectrical state, that little spot that I showed you in the electric face. We can induce that anywhere by injecting RNA encoding specific ion channels, in this case potassium channels. When you do this, those cells get the message to build an eye. And they do. They build an eye. That eye has all the lens, retina, optic nerve, all that same stuff that it's supposed to have.

Notice a couple of interesting things. First of all, the bioelectrical signal is instructive. In other words, it actually controls. We're not just screwing up development with a poison. We're actually building new and coherent structures. It's highly modular. We didn't have to talk to the individual stem cells. I have no idea how to micromanage the production of an eye. We didn't have to tell which genes to turn on. Much like that top-down control that I showed you from the abstract goals in behavior or the body plan of the amphibian, we can communicate at the highest level. We can say, build an eye here. That's the trigger, and everything else that's needed is taken care of downstream.

For example, if we only inject a few cells — this is a cross-section through a lens in the body of a tadpole — only a few of them were injected by us, but what did they do? They apparently can tell that there's not enough of them to really build an eye, and so they recruit their neighbors. They tell their neighbors, which were never touched by us, so all these brown cells were never injected. These guys get them to participate in the process. It's like a secondary instruction event.

Slide 28/54 · 32m:08s

They will start an ectopic eye spot. So this is an earlier frog embryo, and you can see the blue is in situ hybridization marking Rix1, which is a very early marker of eye field specification. So we can start all kinds of eye spots but only some of them will become an eye. You can, in fact, make eight or nine of these, but only some of them will become an eye. Why? Because while these guys are telling their neighbors, "work with me to build an eye," the neighbors, as part of a cancer suppression mechanism, are saying, "no, actually, you should be skinned like us, or you should be gut or something else." And they basically cause them to change their mind, and despite their early expression of Rix1, that winks out and they go back to normal.

So that back and forth conversation about "Are we going to be an eye or something else?" takes place at the electrical level. It eventually gets canalized into gene expression and then into anatomy. For regenerative medicine, this is what we would like to have control over. We would like to be super convincing to these cells. We don't want to know the 20,000 different genes that we're going to have to turn on and off. We want to give a high-level stimulus to say, build this structure and have the material do it.

Slide 29/54 · 33m:18s

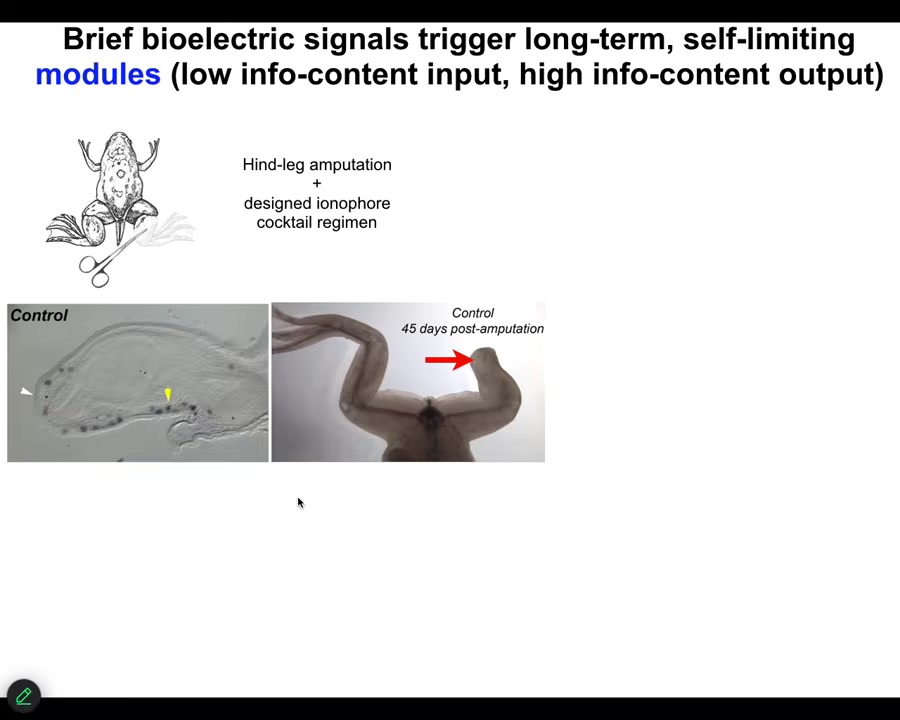

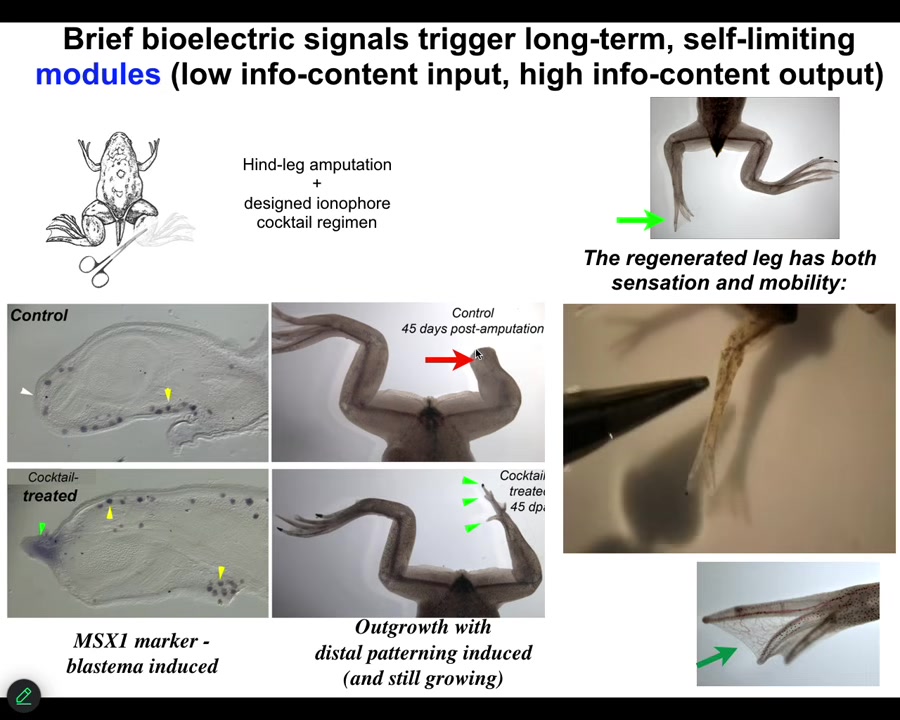

As an example, I'll show you some of our work on limb regeneration. Frogs, unlike axolotls, do not normally regenerate their legs. After an amputation, 45 days later, there's basically nothing.

Slide 30/54 · 33m:32s

We came up with a cocktail that we apply right after injury, or even a little bit delayed. And what it does is it immediately triggers regeneration. So within 48 hours, you have an MSX1-positive blastema. By 45 days, you've got some toes, you've even got a toenail, and eventually a very respectable looking leg that is touch sensitive and motile. You can see the animal can feel.

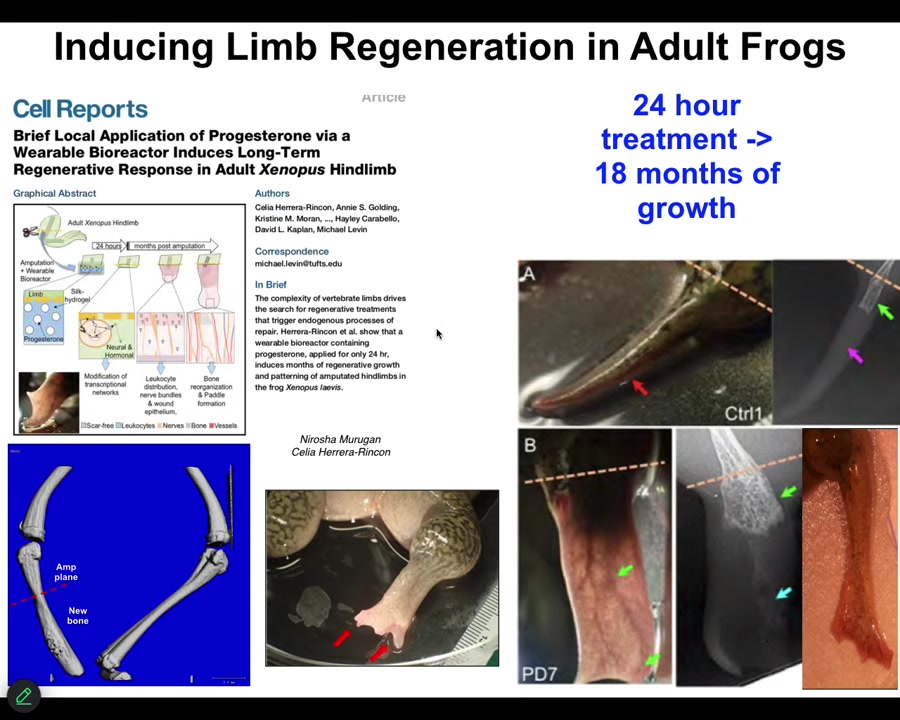

Slide 31/54 · 34m:00s

One of the most interesting things about this is that this is an example on an adult frog, the treatment that we do, in this case, it was a wearable bioreactor containing some drug payload. The treatment is 24 hours. That's it. After that, you get a year and a half of leg growth, during which time we don't touch it at all.

So this is a top-down, trigger-based thing, where we say to the system in the first 24 hours, go down the leg building path, not the scarring path, and then we completely take our hands off the wheel. We are not using scaffolds or stem cell kinds of approaches or growth factors. It's right at the beginning, the physiological decisions about what journey you're going to take through that anatomical space.

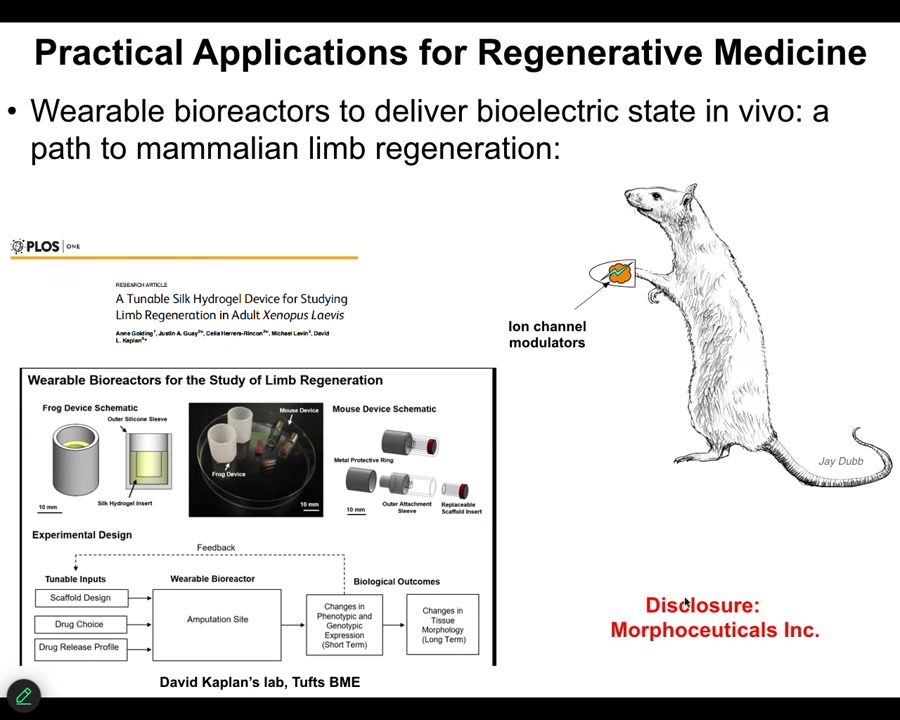

Slide 32/54 · 34m:48s

I have to do a disclosure because David Kaplan and I started this spin-off called Morphoceuticals, where we are now trying to do this in mammals. Stay tuned; that work is ongoing. We have bioreactors through which we're trying to apply these kinds of signals. I want to switch gears and show you a different model to hammer this notion of memory.

Slide 33/54 · 35m:05s

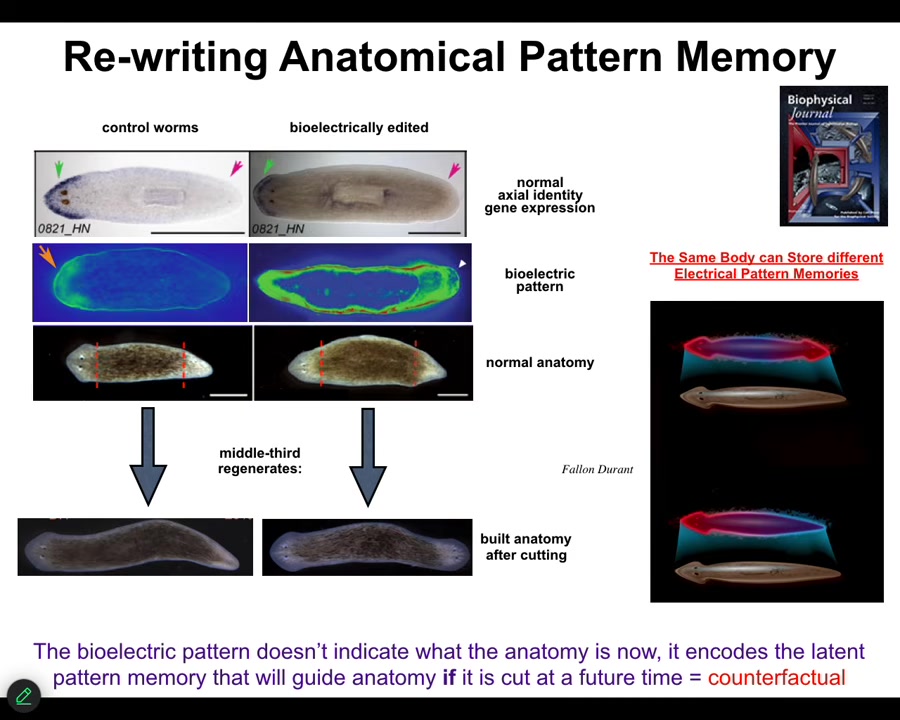

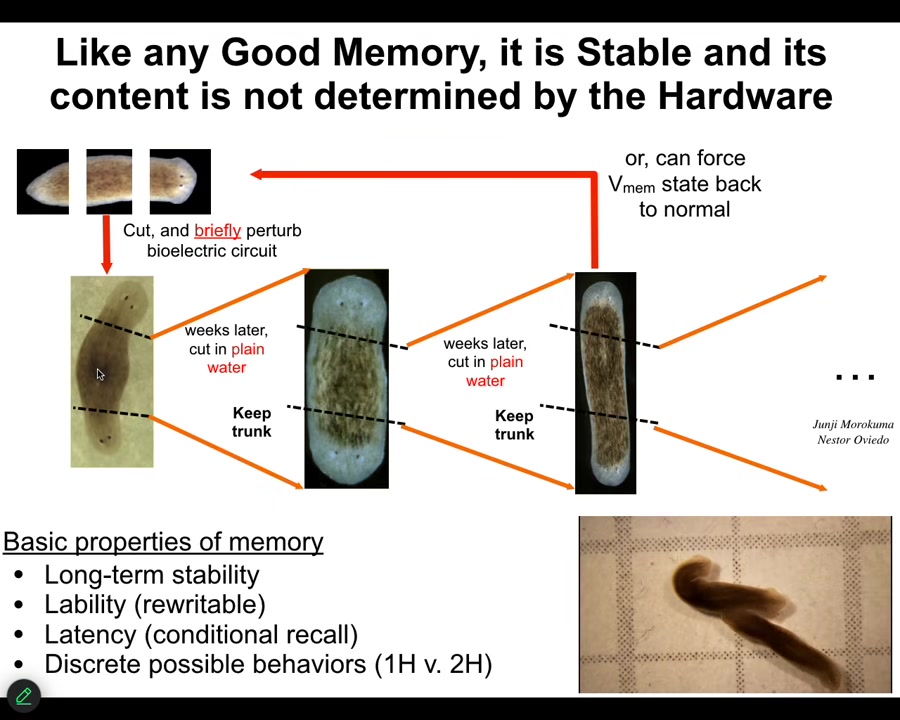

Specifically, I made this claim earlier on that morphogenesis has an encoded set point towards which it is trying to reduce error. It is a homeostatic system. I'll show you another example of rewriting that pattern memory.

These are planaria, flatworms that have a head and a tail. One of the many cool things about planaria is that if you cut them into pieces, each piece regenerates a complete worm.

You might ask, when I cut this piece, how does it know how many heads to have? How many heads should it have? These cells up here are going to make a head, but these cells here are going to make a tail; they're right next-door neighbors. It's not an issue of being at a different positional information. They're at the same location, but they make a context-appropriate decision in each fragment of what they're going to make.

How do they know? We asked that question, and we observed there's a bioelectrical pattern in that fragment that says, One head, one tail. We can change that pattern; using ionophores and some other tools, we can say, Actually, you should have two heads. When you do this... First, nothing happens.

This animal has this incorrect internal representation of what a correct planarian should look like. But the molecular biology is correct. In other words, head marker in the head, not in the tail. The anatomy is correct, head, tail. But if you cut this guy, all the pieces will make two-headed animals.

This is a counterfactual memory. It is not true right now. It is latent because until you cut it, it doesn't do anything. When you cut this animal, the cells consult this pattern as the recorded ground truth of what a correct planarian should look like. That is what they build to. They make these two-headed animals.

You can see here we are looking at the representation of what the axial makeup of a planarian should be. A normal body can store at least one of two different representations. Another reason I keep calling this a memory is because it is stable.

Slide 34/54 · 37m:22s

Once you change it, the tissue holds. We can take this two-headed animal, we can cut them into pieces, and what they will do is continue to generate two-headed animals in perpetuity, as far as we can tell, forever. Here's a little video of what they're like. Remember, there's nothing wrong with the genome. We haven't touched the genome. The genetic information has not been changed. What the genome actually gives you is some hardware that, when the juice is turned on, reliably takes on a default bioelectrical state, which by default is one head, one tail. But that is not the only state it's capable of. It can be rewritten, and once it's rewritten, the memory holds.

These are the basic properties of any memory. It's long-term stable, but it's rewritable. It has conditional recall. It has discrete behaviors that it can do.

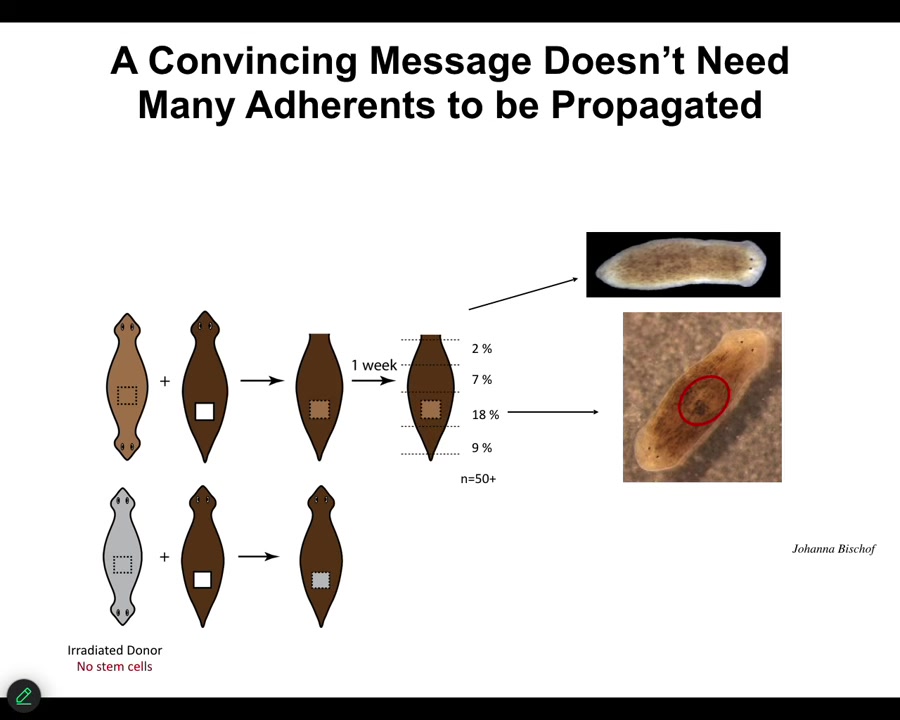

Now, I raised this issue of being convincing to the cells: producing a signal, whether endogenous or applied by us, that the cells are actually going to take on.

Slide 35/54 · 38m:28s

We're still working on some of the very important and puzzling aspects of this. For example, in order to be convincing, that message doesn't have to have a lot of tissue behind it. We can take a little chunk out of a two-headed animal, in fact, irradiate the heck out of it so that there are no stem cells in it, implant it into a normal one-headed host, and in some percentage, almost 1/5 of the cases, this fragment turns into a two-headed animal. Even a small piece, and even at a distance, some of these will still do it. That message will overwrite the endogenous memory of all these other tissues. Very interesting.

Slide 36/54 · 39m:12s

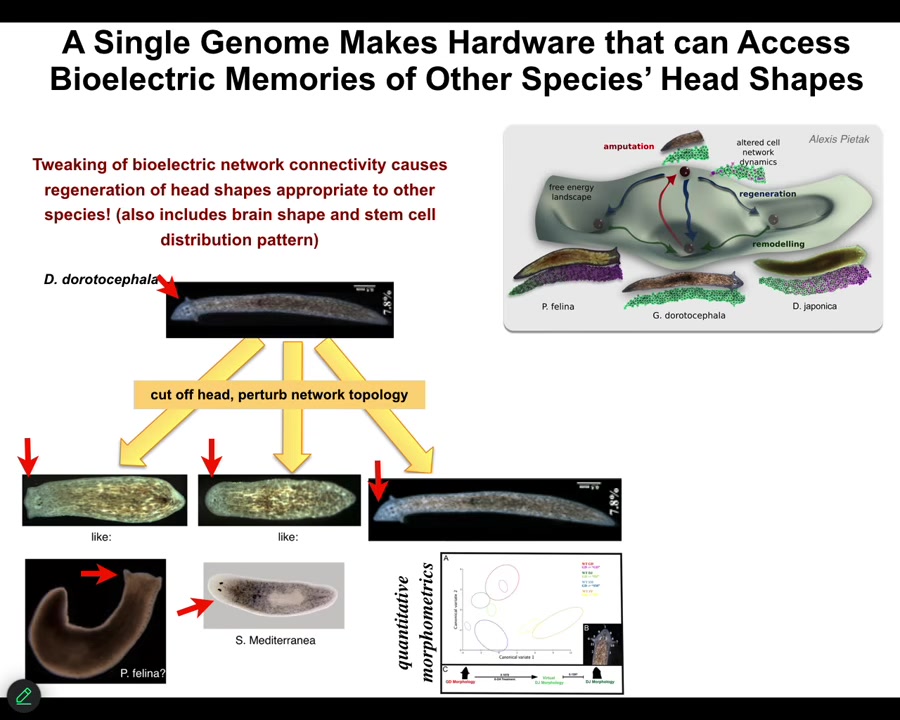

Not only the number of heads, but the species-specific shape of the heads. For example, this triangular species, if we change the bioelectrics that control head development, we can get flat heads like this P. fulina. You can get round heads like this S. Mediterranean, about 100 to 150 million years evolutionary distance between these guys and these guys, but no problem.

This hardware is perfectly happy to visit these other attractors in anatomical space where these species normally hang out, not just the shape of the head, but the distribution of stem cells, the shape of the brain, just like these other species. This is not hardwired.

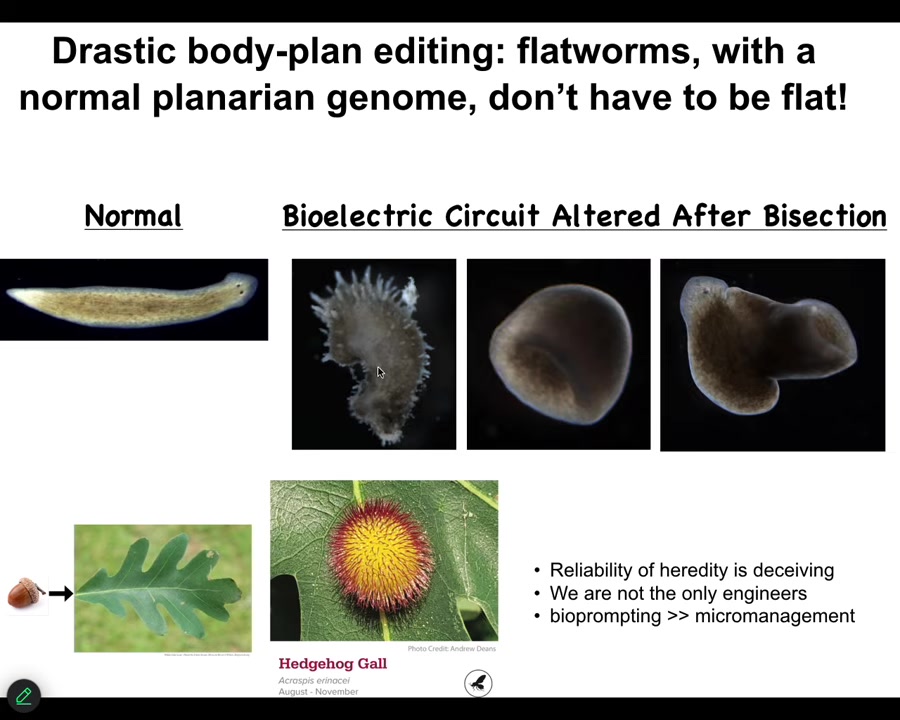

Slide 37/54 · 39m:50s

You can go further and make things that don't look planar at all. They're not flat. You can make these crazy spiky things. You can make cylindrical and hybrid forms. Not just animals, plants do it too.

So here's what an oak leaf looks like. You might think that this is what the oak genome knows how to do. But along comes this bioengineer, who happens to be a wasp, lays down some prompts and gets the plant cells to build this incredible gall, this spiky yellow and red thing. We would have no idea that the plant cells are even capable of building something like this if we hadn't seen it.

So the reliability of development is deceiving. It hides a lot of plasticity and reprogrammability. We are not the only ones. Evolution noticed all this. Much of it takes place with high-level interfaces, not with micromanaging the molecular details.

Slide 38/54 · 40m:45s

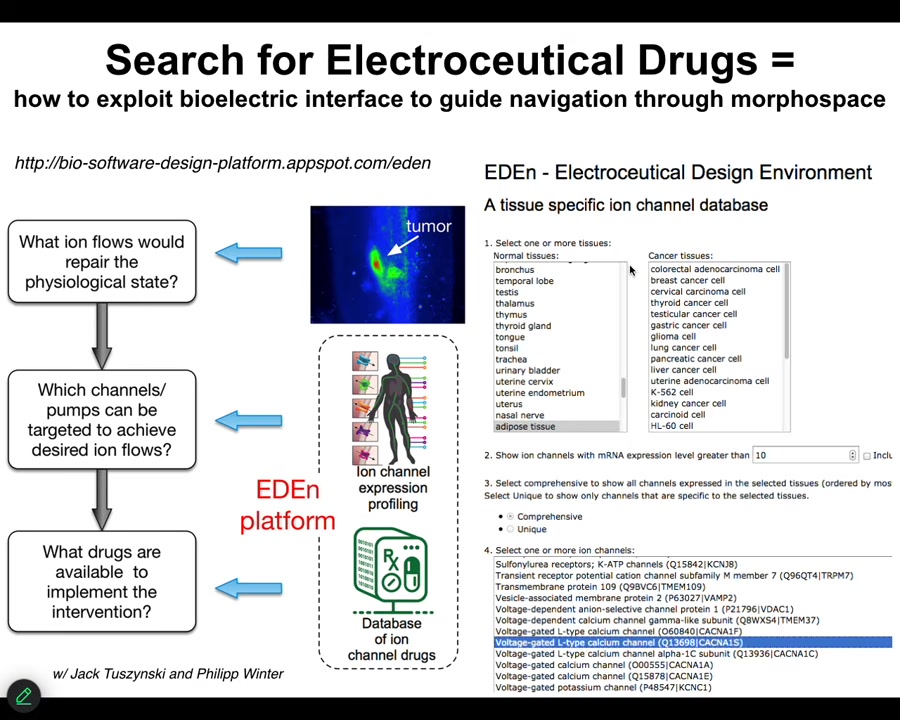

One of the things that we're trying to do now is build a full-stack computational platform that starts off with gene expression data, then goes to the physiology of individual cells, then tissue level, and eventually to whole-body algorithmic understanding of the decision-making of how these things, in fact, encode different kinds of structures. Once we can connect all of that, we can use these approaches to actually pick electroceuticals. Design stimuli that get the tissue to do what you want them to do.

Slide 39/54 · 41m:18s

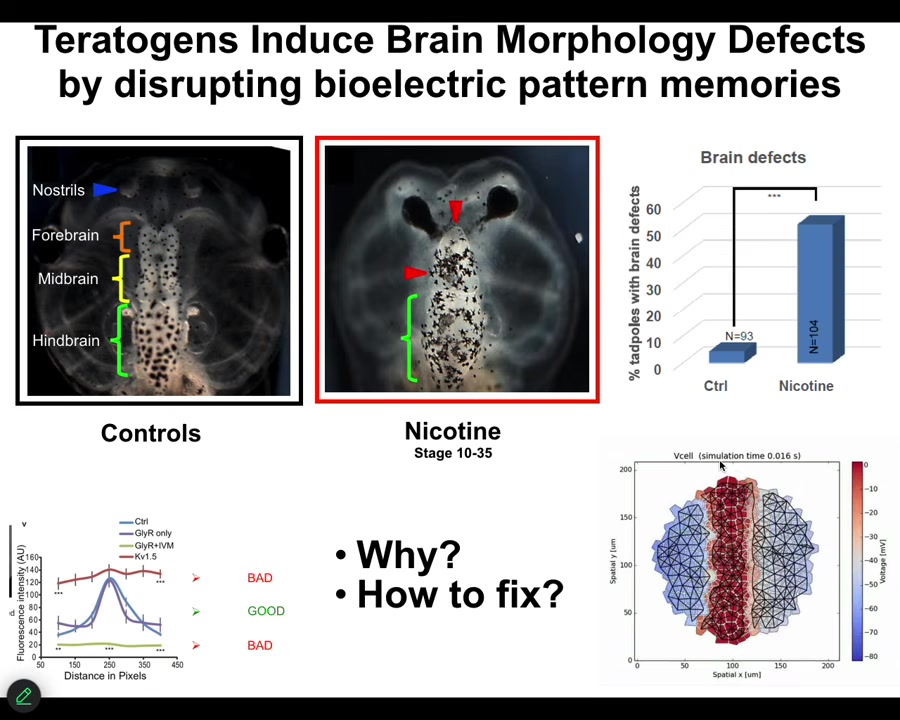

I will just show you one successful example where we've done that for a complex structure like the brain. Here's a frog brain with forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain. If you hit it with a teratogen like nicotine or other nasty things, you get defects. We wanted to know what's going on and how to fix these defects. We built a computational platform. Our collaborator, Alexis Pytak and Vaipav Pai, built this bioelectric model of the tissue from which the brain arises.

Slide 40/54 · 41m:50s

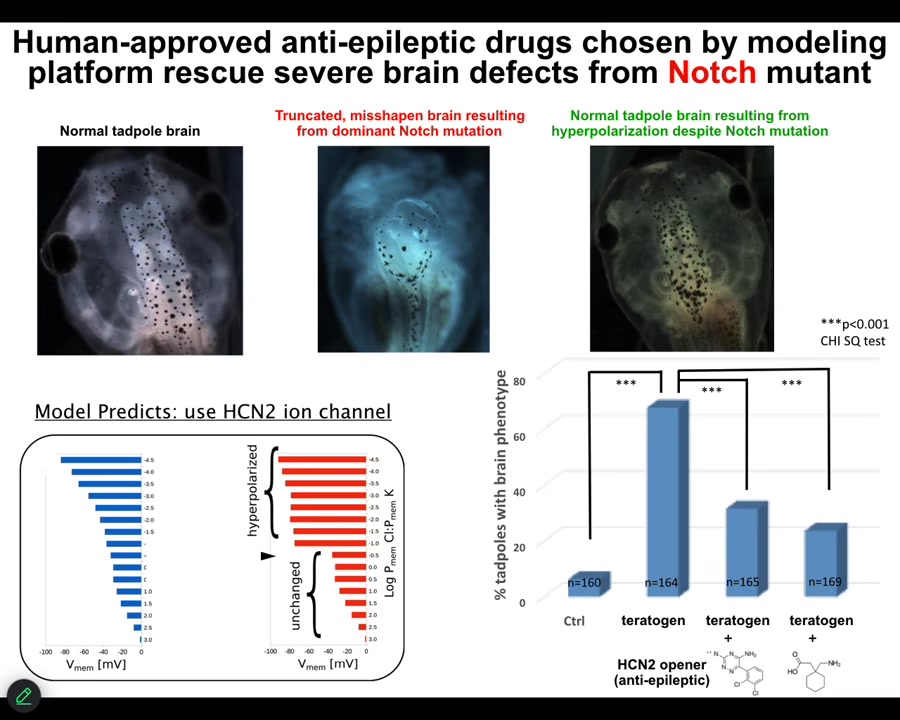

We decided to go after one of the most unlikely examples we would be able to fix, and that is a genetic mutation of notch. Notch is an important neurogenesis gene. If you introduce a dominant mutation — the overactive notch ICD — here's what you see. The forebrain is gone. The midbrain and hindbrain are basically a bubble of water. These animals have no behavior, profoundly defective.

We asked the model: we know what goes wrong with the bioelectrics once you've done this; how can we fix it? The model said it turns out that there's this specific channel called HCN2 that will sharpen the bioelectric pattern back to normal. If you do that, even animals expressing high levels of this notch ICD get normal brain structure, normal brain gene expression, and normal behavior. In other words, their IQs are indistinguishable from controls.

You can do this either by opening existing HCN2 channels or introducing new HCN2 channels. What you're seeing here is that with the right computational model, we can address the bioelectric layer to overcome, in some cases, even hardware defects. I'm not saying this is going to work in all cases, but in some cases the hardware is fixable by physiological stimuli.

Slide 41/54 · 43m:20s

And so this is what we're aiming for, is a kind of system where we know what the correct state is supposed to be. This is where a lot of the hard work now has to take place: to characterize what the normal bioelectric states of different organs are. We then might have an incorrect state, and we have a computational platform that says, if you want to go from the incorrect state to the correct state, what channels do you need to open and close, which means what ion channel drugs do you deliver on what schedule? You can play with an early version of this at this website.

Slide 42/54 · 43m:52s

A couple of things before I start to wrap up. I'm going to show you a couple of other stories. One has to do with cancer. I've shown you regeneration. I've shown you organ formation. I've shown you birth defects. Let's talk about cancer for a moment.

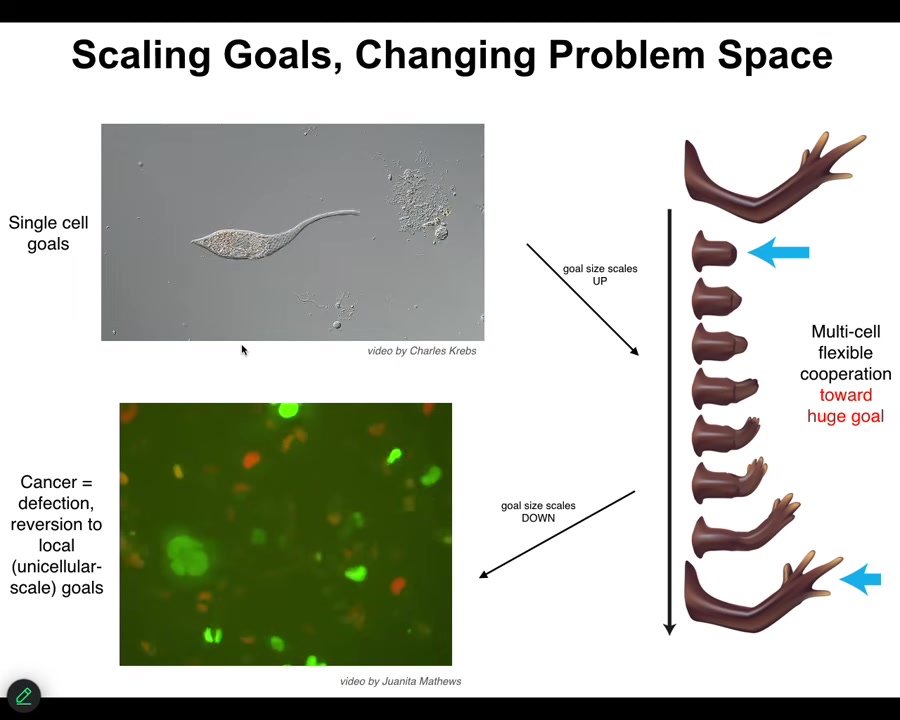

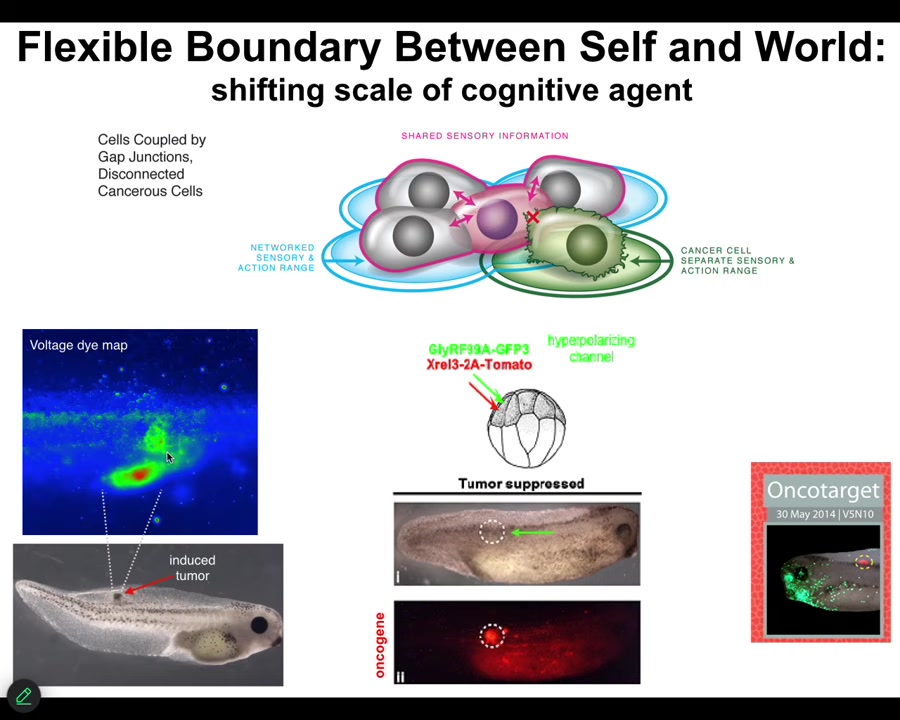

One of the interesting things that happens during evolution and multicellularity is a scaling of goals. The set points, the actual homeostatic set points towards which these systems try to reach start off very small. Individual cells have little tiny cognitive light cones. Their goals are all very small. They're trying to manage pH, metabolic state, in a tiny little region of space-time, little bit of memory going backwards, a little bit of predictive capacity. But this tiny little area is all it's trying to manage.

A multicellular system like this has an enormous grandiose kind of set point. In other words, this is the correct pattern memory, and as long as you haven't reached it, your cells are going to be actively trying to get there. They only stop when they reach this particular state. This is massive. No individual cell knows what this looks like or how many fingers you're supposed to have, but the collective absolutely does, and this is what it reduces the error to.

What you see during development and during evolution in general is a scale-up of the capacity to store these kinds of set points. These are tiny set points in metabolic space and transcriptional space. These are set points in very large anatomical space. But that kind of system, where cells join into networks where the network can remember targets that individual cells cannot remember, has a failure mode. The failure mode is called cancer.

When these cells disconnect from each other — what you're looking at here is a glioblastoma in culture — they roll back to their primitive unicellular tiny goals, meaning proliferate as much as you can, migrate to where life is good, metabolize, because at that point the rest of the body is just external environment to you. You're just an amoeba again, and the outside body is just environment. That boundary between self and world shrinks.

What's happening here is that cancer is not more selfish than normal tissue, and sometimes when people model it in game-theory models as being more selfish and less cooperative, it isn't more selfish, it just has smaller selves. In other words, the boundary between the self and the outside world, the region of space-time that you care about in terms of trying to manage the states, becomes very small, and then the rest of the body isn't part of the adaptive behavior anymore.

Slide 43/54 · 46m:35s

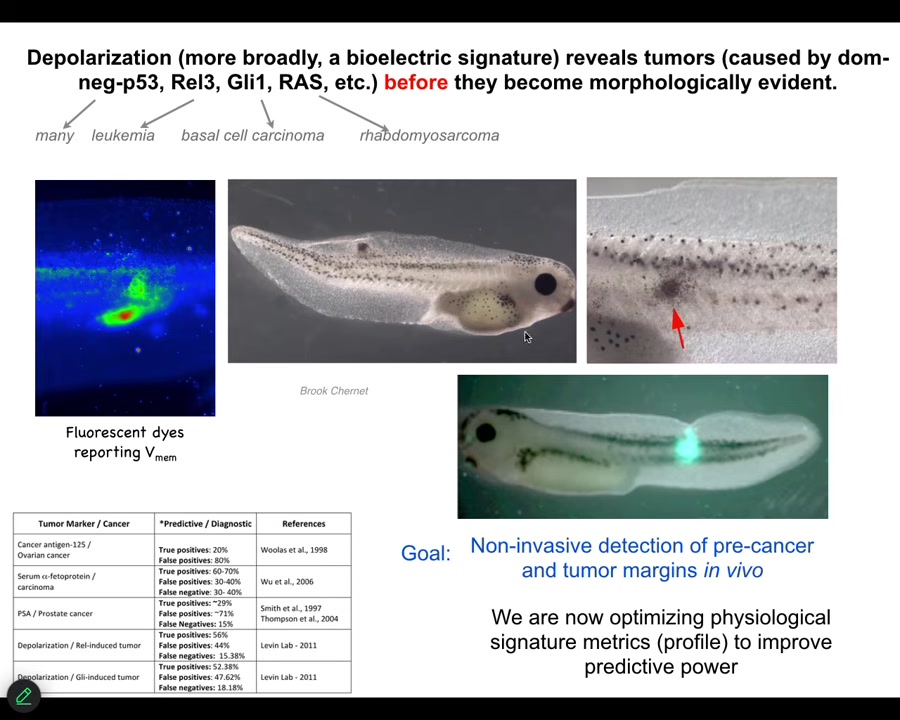

That interesting way of looking at it had a specific prediction. It meant that we should be able to detect incipient tumors via their disconnection from the rest of the body. Bioelectrical dyes should be able to show us where the tumorigenesis is going to happen.

We showed that by injecting tumor-inducing oncogenes into tadpoles. These are nasty things such as dominant negative P53, GLE, KRAS, and so on. They make tumors, but before the tumors become apparent and start to metastasize, the dye will tell you exactly where the tumor is going to be.

Slide 44/54 · 47m:20s

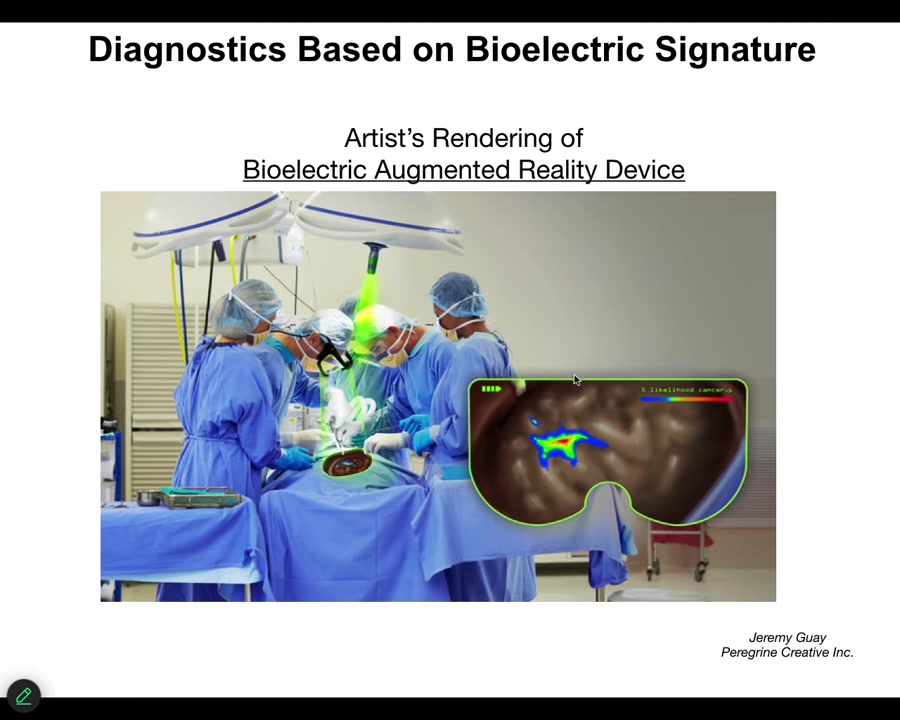

We are now optimizing towards this kind of thing where either a human surgeon or a robot surgeon is going to be able to look down, for example, and see the tumor margins. He's going to see that here's the normal tissue, but here's some stuff you got to be careful of because these cells have already acquired an abnormal bioelectrical state; they've disconnected from their neighbors.

Now, more importantly than just tracking it, could we change it?

Slide 45/54 · 47m:40s

What we did here was instead of trying to kill these cells, we said, what if we force them into a normal bioelectrical state with their neighbors? Again, what happens is we inject these oncogenes. Here you can see the ACA protein is blazingly expressed. It's all over the place here. Here's a massive one that normally would be a tumor, except there is no tumor. This is the same animal. There won't be a tumor because we've also co-injected an ion channel. It doesn't kill the cells. It doesn't fix the genetic defect. But it forces the cells to be part of this large-scale network that's working on making nice skin, nice muscle, and so on, instead of going off and doing its own thing. That is something that we are currently working on in humans.

This is some data on glioblastoma. We also have a project on colon cancer, reusing existing ion channel drugs—candidates for electroceuticals to reconnect cells back to their neighbors.

Slide 46/54 · 48m:45s

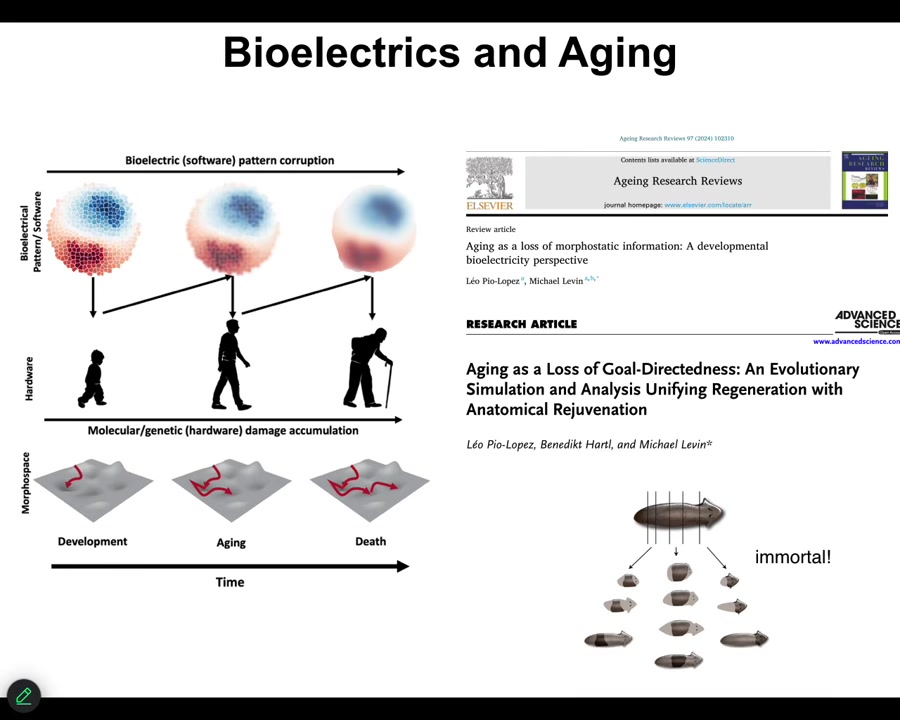

The final story, briefly, is our program in aging. One of the hypotheses is that much like these bioelectrical patterns that are critical for establishing normal anatomy during embryogenesis, during regeneration, during cancer suppression, but in your whole lifespan, as cells come and go, old cells become senescent and die, new cells come in, could it be that with age the bioelectrical pre-patterns get fuzzy? They get degraded. And if we sharpen them, I've shown you one example of sharpening — that's how we fix the brain defects in the tadpole — could we sharpen them as an aging therapeutic? Could it be that the pattern memory in planaria is part of why these guys are immortal, that they're really good at holding on to their bioelectrical patterns? We have some interesting stuff coming on that.

Slide 47/54 · 49m:38s

I'm going to start to wrap up here and point out a couple of interesting things.

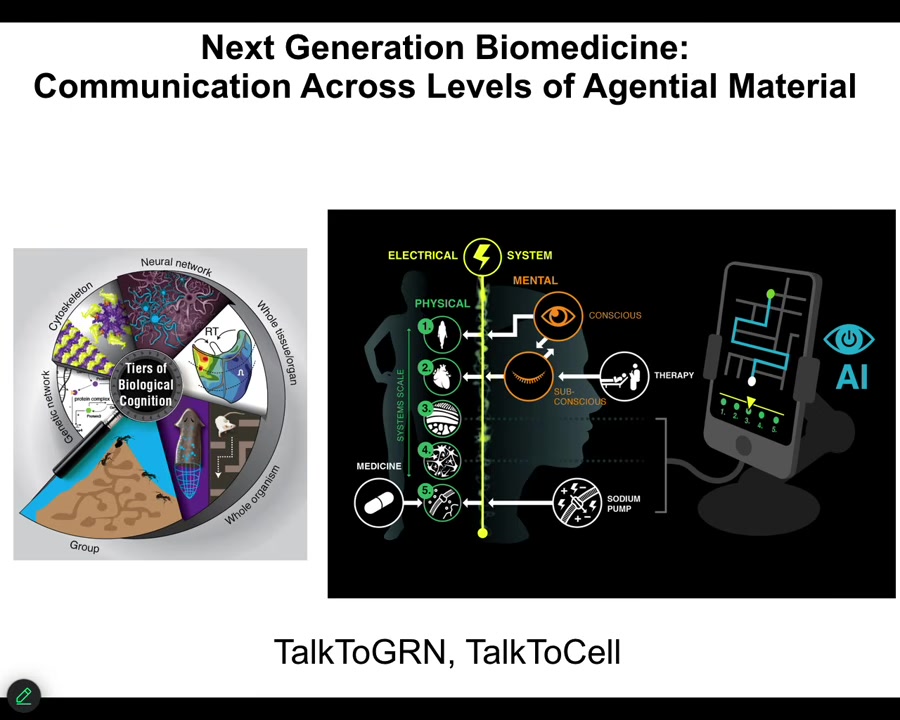

One is that because your body is made of this multi-scale system where there are competencies and agendas at every level, starting with the molecular networks, the subcellular structures like your cytoskeleton, the cells, the tissues, all of it has the ability to take in input, make decisions, and navigate various kinds of spaces.

It means that we can now use various technologies, including AI, to try to communicate not just with the lowest level—people try to make drugs to hit specific receptors and pathways and so on—but could we communicate with these higher levels of transduction, and do in patients what I've been showing you in these model systems?

We have a couple of projects called Talk to GRN and Talk to Cells, where we're trying to use language models coupled with real-time closed-loop electrophysiological data to use language to communicate, get information out of the cells, and give them commands.

Slide 48/54 · 50m:50s

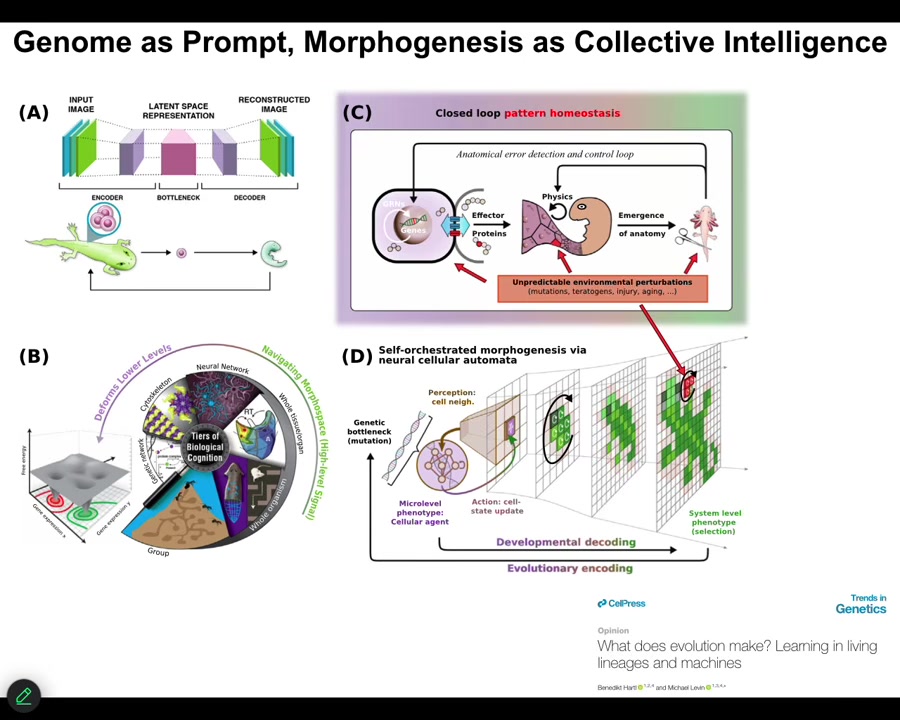

So that's the first thing. The second thing is that this idea that bioelectricity and other kinds of physiological networks are providing a multi-scale competency to the material that lets it deploy plasticity and problem solving in the face of novel scenarios. This has implications for evolution because evolution is not working on a passive material where the genome directly maps in a fixed way to some kind of outcome. We've been working on models, and you can see that in this paper in Trends in Genetics called "What Does Evolution Actually Make?" Thinking about the information in the genome as a kind of prompt, as a way to give suggestions to a material that actually has some great flexibility about how it's going to implement that.

Slide 49/54 · 51m:42s

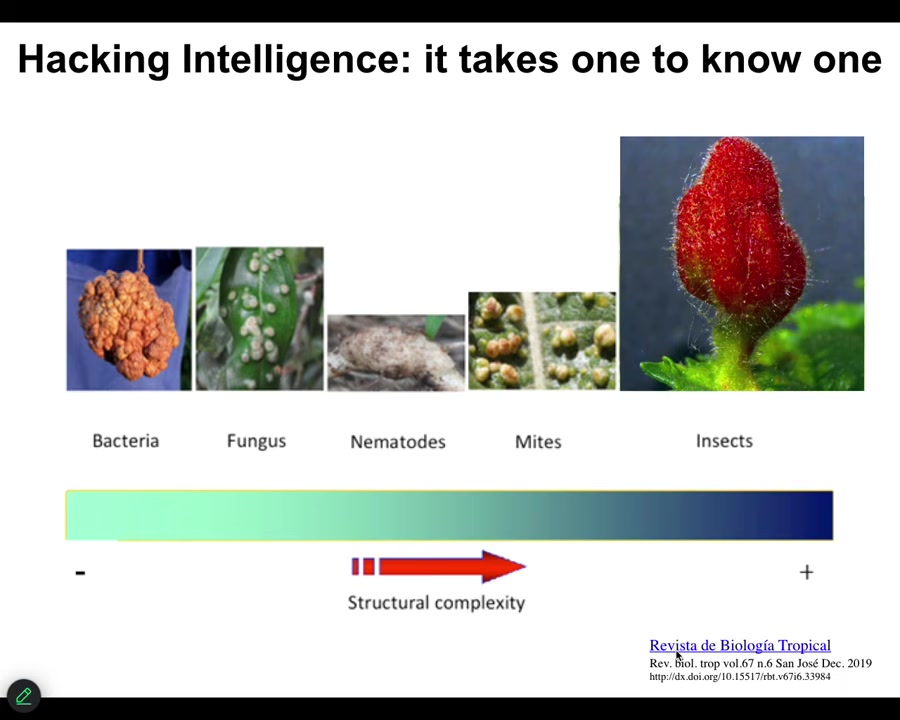

I'm going to show you this in a minute. But what's important and challenging about this is that it's trying to manage a material that has some degree of plasticity and intelligence is a two-way IQ test. You have to be smart enough to do it, and we're learning.

Here's an example of hacking plant cells. Bacteria manage this featureless lump, and fungi don't do much better. Nematodes can make something that has a little bit of a shape, but by the time you get to insects, they can get the plant cells, the leaf cells to make this beautiful thing. The sophistication of the hacker matches the sophistication of the product of what you're able to do. We have to get a lot more clever about how it is that we communicate goals to these various subsystems.

Slide 50/54 · 52m:35s

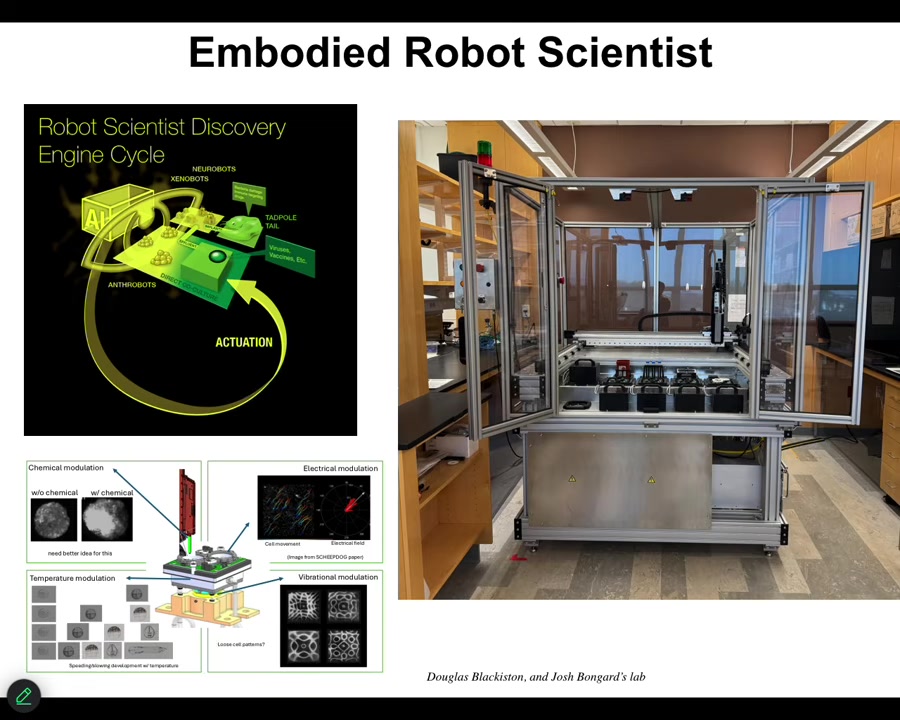

I'll briefly mention some new technology that's currently sitting in our lab. It's been up and running for probably about a month now. That is a closed-loop AI-powered robot scientist that makes hypotheses about how to traverse anatomical space. That is, what signals given to cells will get the collective to do one or another thing. It has little wells inside where it can give different stimuli to those cells. Vibration, optical stimuli, chemical stimuli, electrical, and so on. It observes what happened, learns from that experience, revises its hypothesis, and goes back and does it again. So this is a new colleague that is working with us to operate in anatomical morphospace using living cells as the front end interface to explore that space of possibilities. I'll show you one example of the kinds of things we build.

Slide 51/54 · 53m:32s

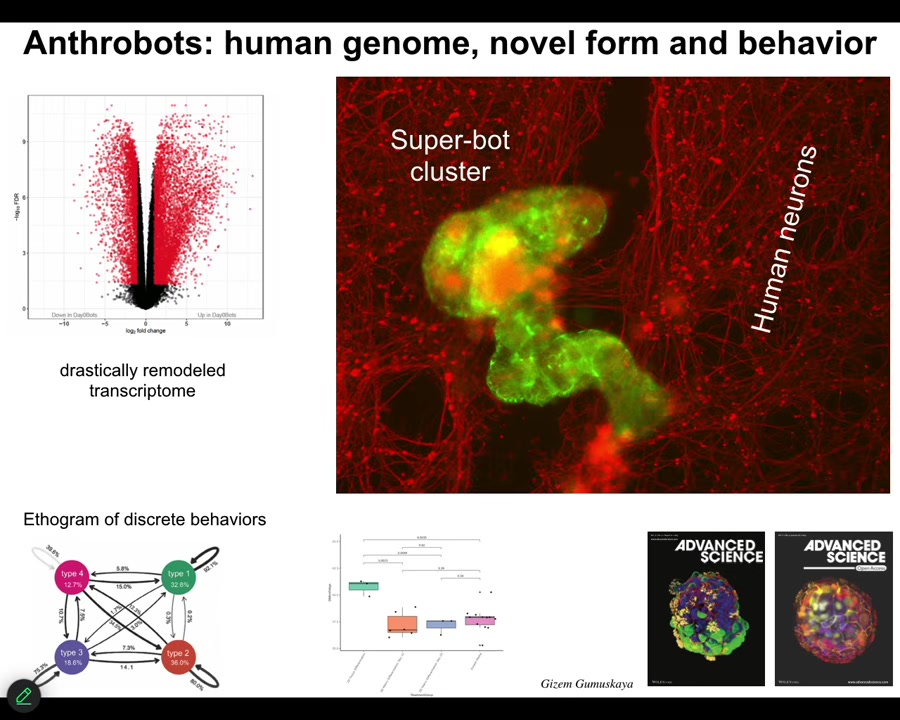

Asa talked about Xenobots. I didn't bring any Xenobots slides today, but here's an Anthrobot.

This is the question of if you can't reach the goal states that you normally reach despite perturbations, what biologicals will often do is find a new set of set points. This little creature is not something I got off the bottom of a pond somewhere. If you were to sequence it, you would find 100% Homo sapiens genome. Not edited. These are adult, not embryonic, human tracheal epithelial cells that self-assemble when you take them out of the body. They self-assemble into this little motile creature. This is what they look like. They swim around because these little cilia are waving. They have all kinds of interesting properties. These guys, taken out of the body, can no longer make a human. They can't be a human body, but they do something very coherent.

Slide 52/54 · 54m:30s

And they have some interesting features. First of all, 9,000, over 9,000 differentially expressed genes. No genomic editing, no synthetic biology circuits, no nanomaterial scaffolds, no drugs, just a different lifestyle that they've adopted, and they spontaneously change; half their genome is now expressed differently.

The second thing is they have four different behaviors, four different motility behaviors that you can quantify. This is the probability transition diagram between them, like you would do with any animal. One of the first things we realized they could do is if you take a lawn of IPS-derived human neurons, you put a big scratch through it, the anthrobots will come, they'll settle down as in the whole cluster. They're shown in green. They will settle down and start to knit together the gap. So when you take them off, you'll see that under where they were sitting, they were trying to repair this. So they have some sort of ability to induce the neurons to join up.

Who would have known that your tracheal epithelial cells, which sit there quietly in your airway for decades, if you take them out, they become a self-motile little creature that can fix neural defects. This, of course, we're working towards as patient-specific in-body robotics. They're made of your own cells, so you won't need immunosuppressive drugs. We're trying to figure out what are all the things that they know how to fix and how to deploy them for biomedicine.

One of the interesting things about them is they're younger than the cells they come from. So this process of becoming an anthrobot actually rolls back the clock as measured by the epigenetic clock on these guys. They're actually younger than the cells they come from. So again, there's an aging story.

Slide 53/54 · 56m:22s

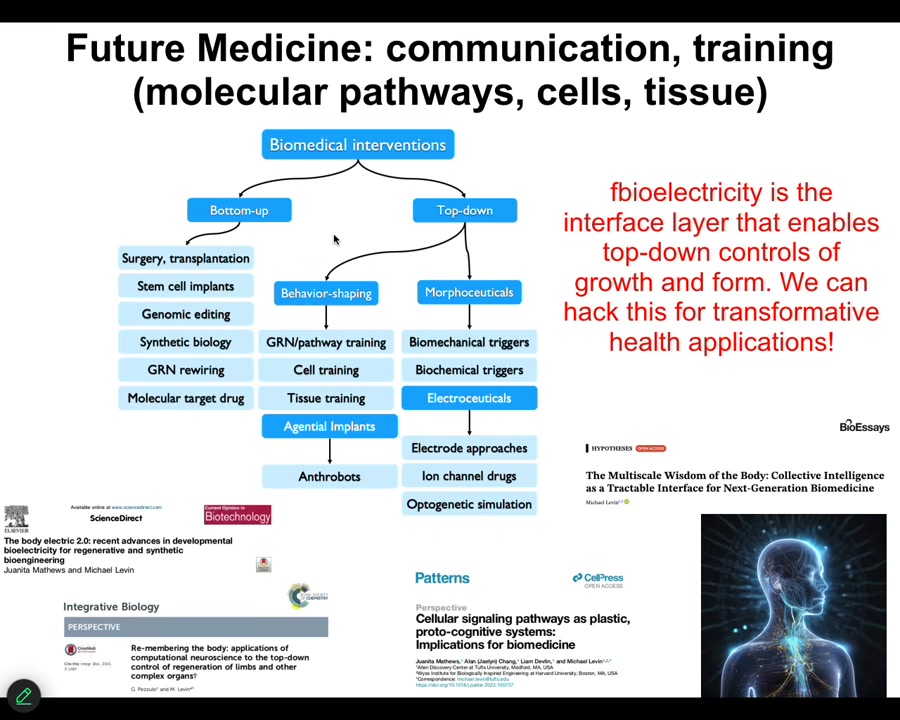

So this is my last slide. And what I'm going to say is that almost everything that people are excited about today in terms of biomedicine comes from these kinds of approaches, these bottom-up approaches focused on the hardware. And we would like to complement that with tools taken from other disciplines. So this is cybernetics, behavioral science, cognitive and computer science: the material we're dealing with is actually amenable to all top-down approaches that let us do very complex things that are really difficult with this.

And so as bioengineers and as workers in regenerative medicine, but also if we're seeking to understand evolution and our own origins of our bodies and of our cognitive systems, we really have to drop this idea that the material is only to be described by simple open loop models in which nothing knows anything up until you get to a big mammalian brain, but that actually the sciences of information processing and of behavior are helpful all the way down. Bioelectricity is the interface layer that really enables that control of growth and form. It's not the only one, but it's the one that we have the best amount of control over now. We'll be able to hack this for some incredible applications. Some of that is described here.

I'm going to stop here and thank the people who did all the work.

Slide 54/54 · 57m:48s

My postdocs and grad students and the team at Josh Bongard's lab worked with us on that discovery engine that I showed you. We have lots of amazing collaborators. Thank you to our funders. Here are my disclosures. There are three companies that have licensed the various technologies that I've shown you today.