Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a ~45 minute keynote talk at the Bioelectricity and Cancer conference (https://cam.cancer.gov/research/bioelectricity_and_cancer_conference.htm) held at NIH in September 2024.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Introduction to cellular competencies

(05:36) Homeostasis, cognition, cancer

(11:09) Brain-body bioelectric analogy

(15:52) Bioelectric hypothesis of cancer

(21:52) Bioelectric induction of organs

(24:40) Channels, physiomics, and diagnostics

(29:16) Inducing metastatic-like phenotypes

(33:00) Normalizing tumors with electroceuticals

(39:37) Future of bioelectric oncology

(42:44) Acknowledgments and broader vision

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/35 · 00m:00s

Thank you to the organizers for setting up this remarkable meeting. I'm incredibly pleased that this is happening at NIH and to also have the opportunity to speak to all of you and share some ideas.

What I'm going to do today is go back to the very beginning and ask the question of what cancer is and introduce the idea of cancer as a dissociative identity disorder of the morphogenetic intelligence. I'll explain what all of that means.

Slide 2/35 · 00m:33s

Let's ask a strange question. Why is cancer not a problem in the robotics field? What you can see here is that we have now fairly complex engineering structures, very functional, doing all sorts of interesting things. One thing that this field does not have is a problem that is similar to cancer. Why is that? What I want to point out is that, at least for now, the major type of architecture that we deal with in engineering is very flat. The large-scale system as a whole might have various problem-solving capacities, but they're made of parts without agendas. The parts themselves are not smart.

Slide 3/35 · 01m:17s

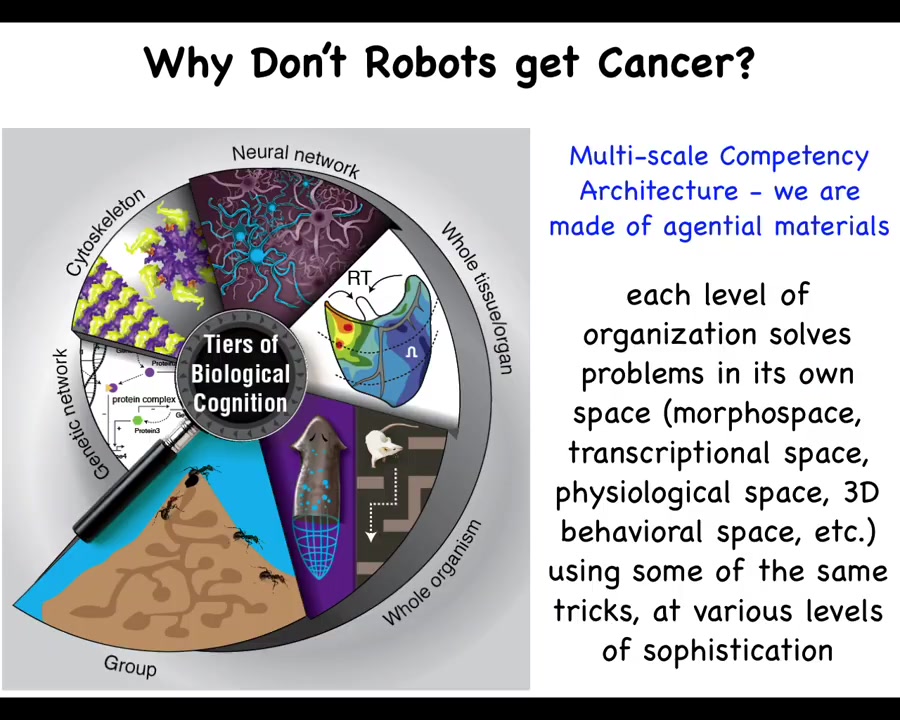

And biology is not like that at all. What we have in biology... is what I call a multi-scale competency architecture. That is, we are made of a material that all the way down from the genetic components to the subcellular organelles, tissues, organs, and all the way through groups and colonies and so on, have various competencies at every level. This is not just a structural set of nested dolls, but actually at each level, there are competencies of solving certain problems in different spaces. And this has massive implications, both for the remarkable plasticity and robustness of life, but also for certain failure modes. All of these are able to pursue specific states with various degrees of competency and ingenuity in different spaces that I will mention momentarily.

Slide 4/35 · 02m:10s

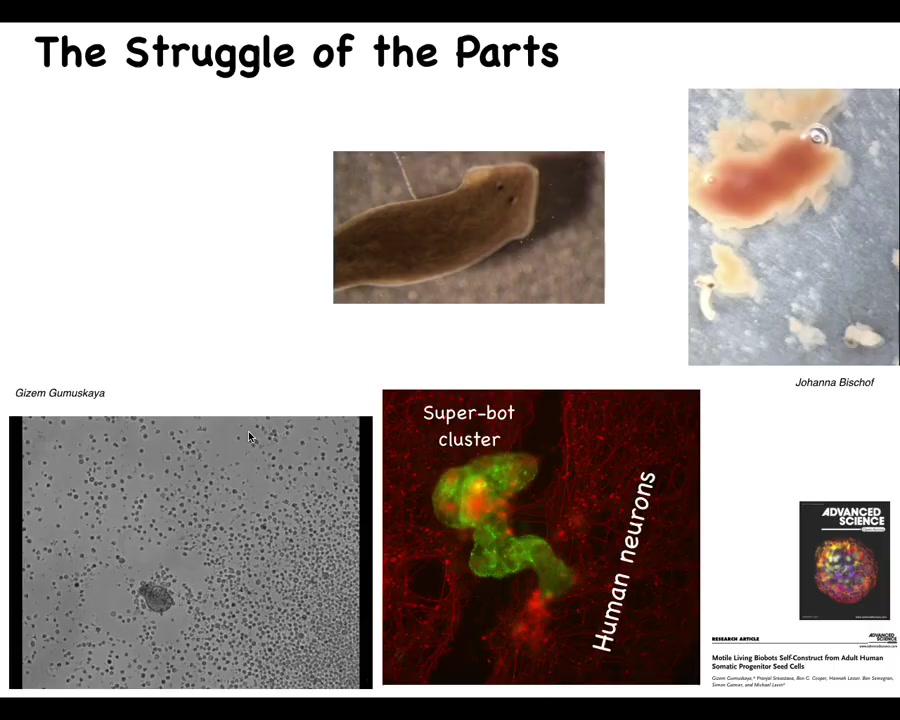

The classic developmental biologist Wilhelm Roux wrote this amazing monograph called "The Struggle of the Parts," and he was talking about the idea that we are made of components that cooperate in some cases but also have their own individual identities. Keeping the organism together—the sort of ship of Theseus that is our body, where cells and molecular materials must be constantly replaced and fit into the functional architecture—many of these parts have autonomy, and that autonomy must be harnessed in order for global health to take place.

I'll show you a couple of examples. This is a flatworm called a planarian. One thing you don't see here is a little tube called the pharynx that they use to eat. This pharynx is quiescent most of the time, but if you liberate that pharynx from the rest of the animal, here they are, you will see that they have their own ability to move. They have their own little set of behaviors. This is a piece of liver that they're going to try to eat. Of course, they're just tubes, so what they end up doing is burrowing through it and the food comes out the other end. Basically, these components here have independent activity that are normally harnessed by the rest of the body towards specific behaviors.

Here's another example. This little creature, if you see this for the first time, you might think that this is something that we got from the bottom of a pond somewhere. Actually, what it's made of are adult human tracheal epithelial cells. This is what we call an anthrobot, and Gazem Gamushkaya and her PhD work in our lab showed that if you take these out of an adult human patient under specific circumstances, they join together to be a novel kind of moving construct with all sorts of fascinating behaviors. It has its own transcriptome that's quite different from that of the source tissue, and they have interesting behaviors. Here they are, assembling into a superbot cluster, where they are able to heal neural scratch wounds. This is a scratch wound through some neural tissue, and these anthrobots will sit there and try to heal the gap. We see that we are made of a material that has all kinds of interesting and often unexpected competencies.

Slide 5/35 · 04m:27s

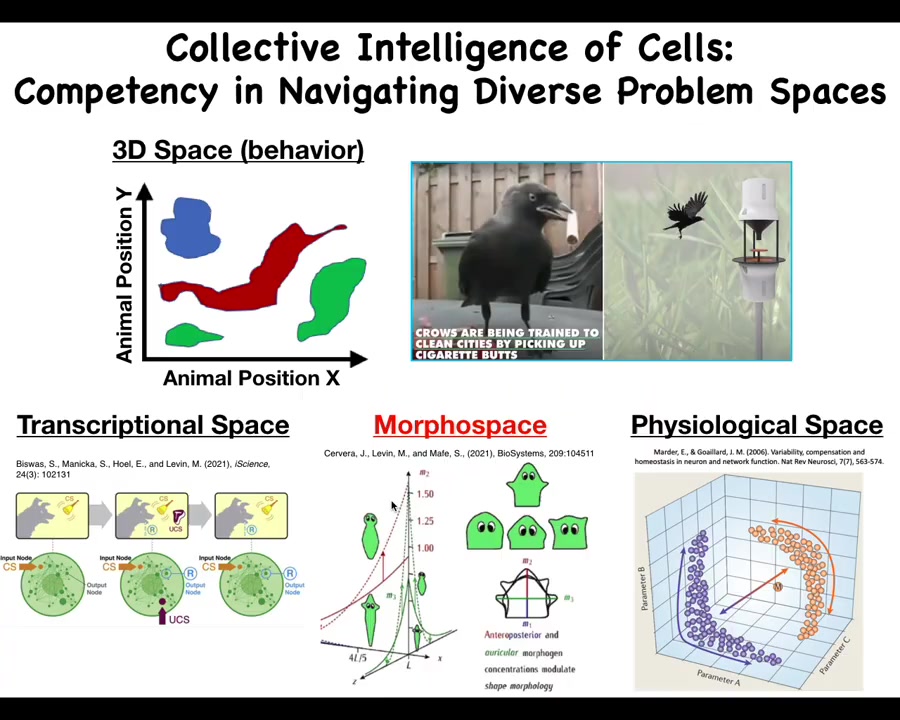

Those project into different spaces. We as humans are pretty primed to observe intelligent behavior in three-dimensional space. That's medium-sized objects moving at medium speeds in 3D space, like birds and primates, maybe an octopus or a whale.

But there are all of these other spaces. There's the space of possible transcriptional states. There is the space of physiological states and the space of possible anatomical configurations, which is the one we'll talk most about today. In all of these spaces that are hard for us to visualize, we don't normally think of this as behavior, or problem-solving behavior. But in all of these spaces, cells and tissues can do some very sophisticated things. For example, individual cells, even gene regulatory networks—never mind the whole cell, but just small gene regulatory networks—can do Pavlovian conditioning and several other kinds of learning. This is the sort of thing that we must understand if we're going to be able to detect, prevent, and reverse defections from this coordinated activity.

Slide 6/35 · 05m:36s

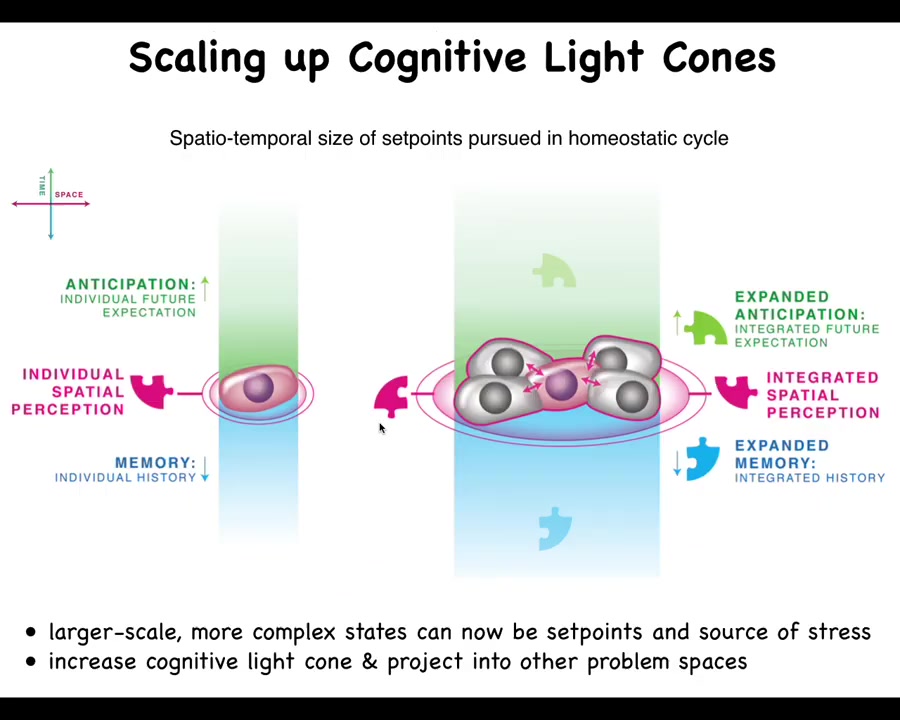

What happens in multicellularity, both during our embryogenesis and during evolution, is a radical scale-up of what we call the cognitive light cone. So the cognitive light cone is simply the size, both in space and time, of the largest set point that any system, be it cells, animals, artificial systems, can pursue in a homeostatic process. The bigger the ability of the system to have a memory going backwards in time, anticipation forwards in time, and spatial extent, the more the right connectivity between subunits allows them to expand their cognitive light cone and use much larger states as the goals they pursue in these homeostatic loops.

Slide 7/35 · 06m:32s

And what I mean by that is this. This is a single cell. So this happens to be a free-living organism known as a lacrimaria. You can see there's no brain, there's no nervous system. It's handling all of its local goals within the scale of a single cell. The cognitive light cone of this system is roughly the size of the cell. It's doing whatever it needs to do to manage the conditions inside of the cell. The rest of the environment doesn't matter. It will dump entropy into the environment. It will eat what it wants. It will go where it wants.

What happens during embryogenesis and through evolution is that cells, individual cells, get together and instead of pursuing very tiny physiological, metabolic goals, they end up taking on these massive grandiose construction projects. Here is a group of cells making a salamander limb. If you deviate them from this state, meaning you cut the limb anywhere along this axis, they will very rapidly spring into action and rebuild, and they stop when it's done.

What's happening here is this kind of anatomical homeostasis where all of these cells are perfectly aligned on what their goal is. Their goal is to rebuild this. We know this because if we deviate them from this quiescent position, they will build it again, then stop, and do exactly what's needed, no more, no less, to get back to this particular region of that anatomical morphospace. By scaling up their cognitive icons, individual cells are able to have much larger set points as the target of these kinds of homeostatic processes.

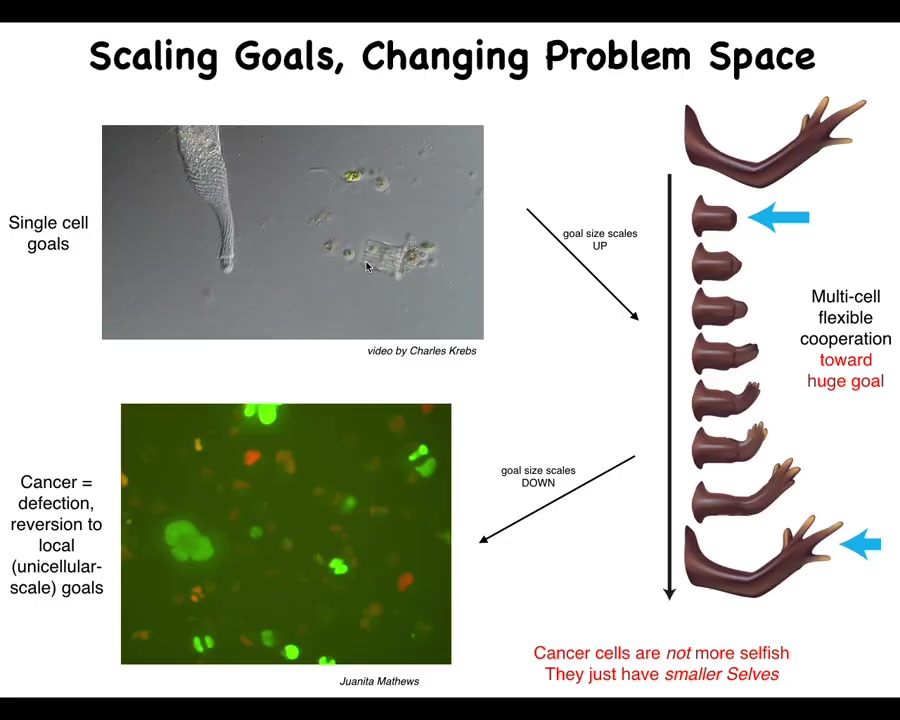

That system, that ability to take on larger set points by joining together, has an obvious failure mode. It's inevitable; unlike many other disease conditions, which are very contingent on the details of evolution and physiology, cancer is fundamental because this process of joining together towards large-scale construction projects is going to break down occasionally for a number of reasons, and that is when we see cancer.

This is human glioblastoma. What's happened here is that the boundary between self and world—the size of the things you are actively trying to manage—is quite large in the normal case, and here it's shrunk back to the scale of individual cells. At this point, the rest of the body is just external environment to them. All they're trying to do, like their ancient unicellular ancestors, is manage their own internal state.

There's a lot of work that's been done on this atavistic theory of cancer. I think what we need to do is pay attention to the policies that normally allow this scale-up to see if we can reverse this process.

Slide 8/35 · 09m:29s

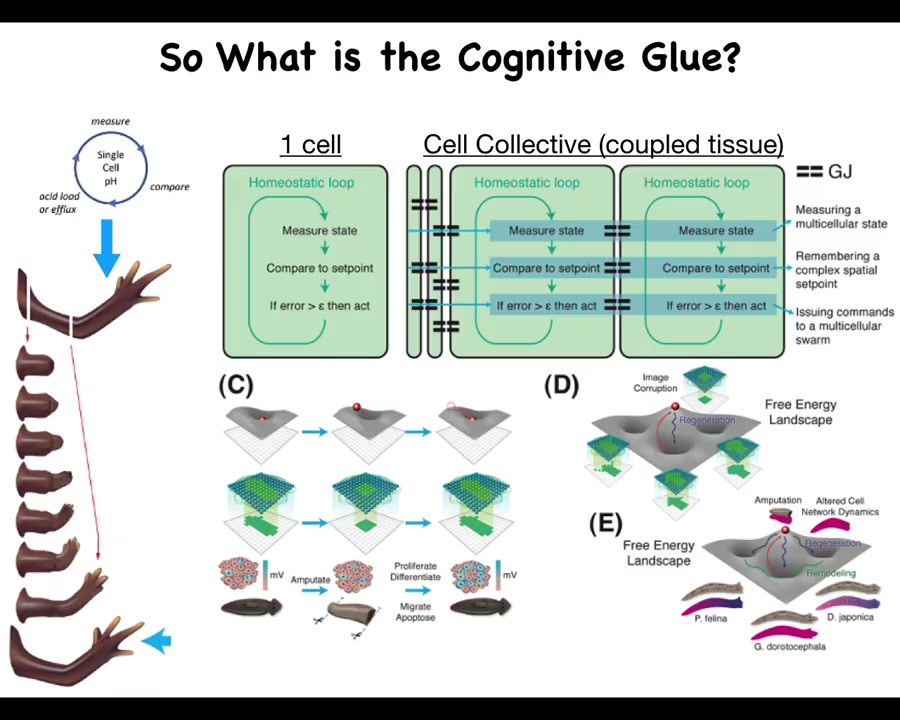

So what is this cognitive glue?

Individual cells have these little homeostatic loops. There's a particular scalar that they might be managing, pH or hunger level. And then by joining together, here's this homeostatic loop. You measure something, you compare it to a remembered set point, and if the error is more than some acceptable level, you act to reduce that error. Individual cells are able to measure and control fairly small things.

By the time you have a large group of cells, a tissue or an early embryo, you're able to do things like this. What's critical here are these connections, the policies and the information exchange that allow this tiny loop to scale up to much bigger things that can then be modeled via landscapes, whether the morphogenetic or transcriptional landscapes. Pattern completion, such as here: when part of this information is gone, the cells will rebuild.

There's a collective that knows what the whole thing is supposed to look like and is able to reduce the error. It becomes really important to understand what that cognitive glue is.

Slide 9/35 · 10m:39s

And we know what it is in the brain. So in the brain, you have groups of neurons. We also are more than just a pile of neurons because there is an electrophysiological communication system that binds those neurons into memories, goals, preferences, and various other capacities that do not belong to any of the individual neurons themselves.

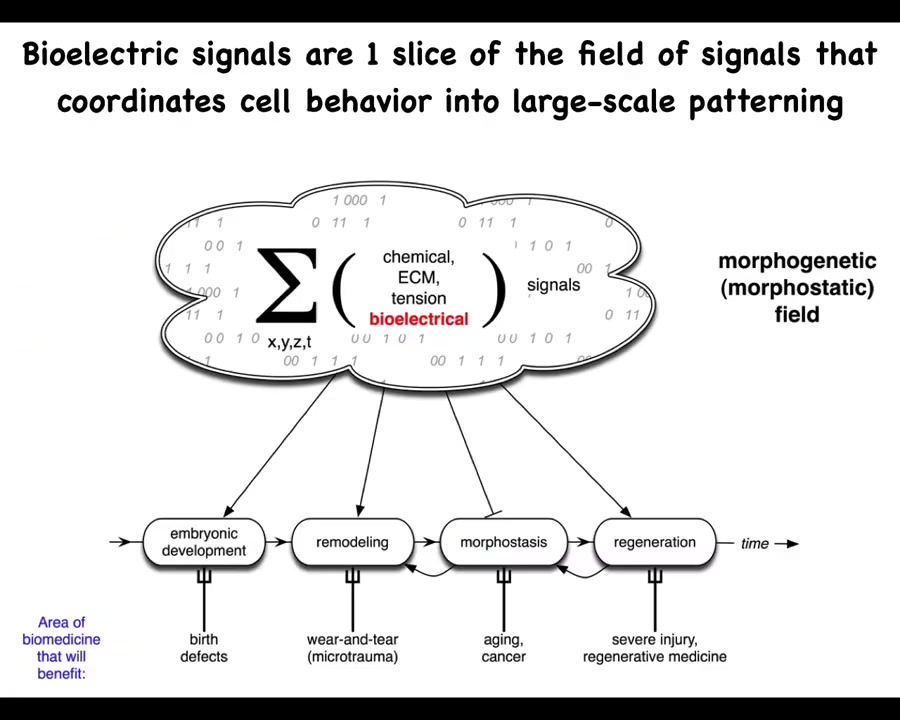

And so in the body, we have numerous kinds of signals, chemical, biomechanical, and so on. But today, we're going to talk about my favorite, which is the bioelectric layer. I think it's not that bioelectricity does everything by itself. These other things are quite important. But I think the bioelectrical layer of this communication network has some very useful and interesting properties that make it distinct and a very attractive target for regenerative medicine.

Slide 10/35 · 11m:32s

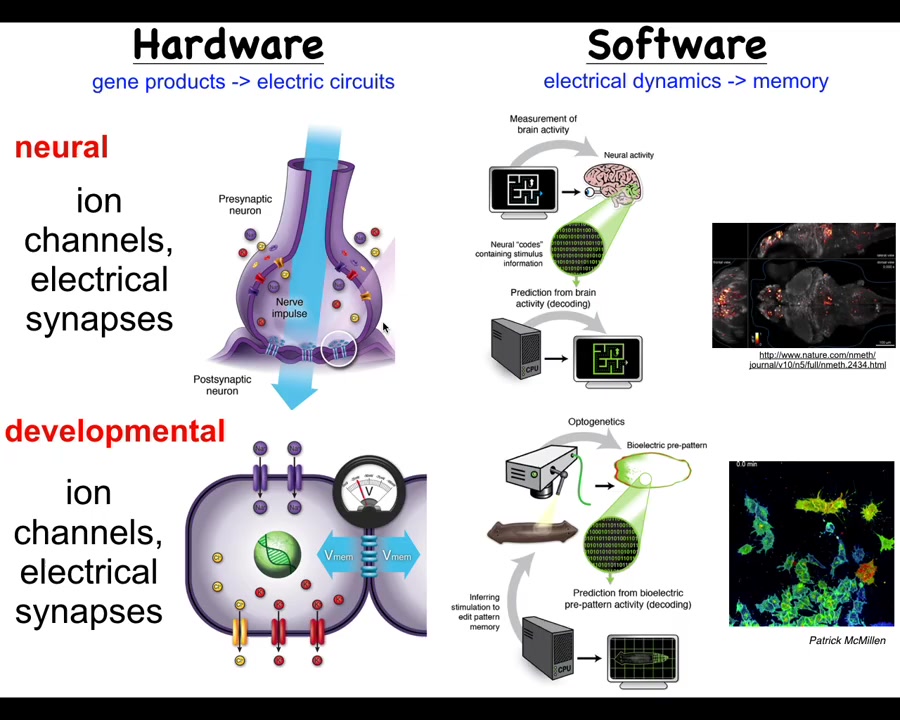

Let's compare this to what actually happens in the brain, because I think it's a very good analogy to start with, and then we have to break some of those assumptions to really understand developmental or cancer bioelectricity.

In the brain, we have this hardware architecture that's specified genetically, where you've got individual cells with their membranes. They have ion channels. These ion channels, by virtue of letting ions in and out under specific rules, will set up a voltage potential across this membrane. That voltage potential may or may not be communicated to the neighbors through these electrical synapses known as gap junctions. All of these, many kinds of ion channels and certain kinds of gap junctions, are themselves voltage sensitive. This enables a really interesting kind of hystericity, meaning what it's going to do now depends on whatever the physiological state was before. That gives you a kind of memory and feedback loops already at the level of the single cell. Things get much more complex in these networks.

That's the hardware, and what neuroscience does is study how this network supports an interesting kind of software. The software is the physiological dynamics that operate within the brain and nervous system. Here's an example: this group made this amazing video of the electric activity of a living zebrafish brain as the fish is thinking about whatever it is that fish think about.

In neuroscience, there's this project of neural decoding. The commitment is that all of the animals' memories, preferences, goals, and behavioral competencies are in some way encoded in the electrophysiology that you're seeing here. The idea is that if we could record in the living state this electrophysiology, we can translate it, mine it for the patterns that are there, and decode, by reading this electrophysiology, what the animal has done before. We can read the memories and tell what it's going to do later, meaning we can understand the system's goals and incipient behaviors in three-dimensional space as it navigates via manipulation of muscle activity.

This system is incredibly ancient evolutionarily. Pretty much every cell in your body has ion channels. Most cells have these electrical synapses or gap junctions to their neighbors. During evolution, we've been suggesting that what's happened here is that evolution took these ancient ways of processing information in cellular networks, which originally were for processing decisions in anatomical space, deciding what the shape of the early embryo and the final body anatomy is going to be. It basically did two things. First of all, it pivoted into a new space. Instead of navigating anatomical space, once a muscle and nerve came on the scene, it started to use that system also for navigating three-dimensional space, and it sped up the timescale. Instead of the kind of long-term, hours-long timescale activity here, we went to milliseconds and enabled rapid motion.

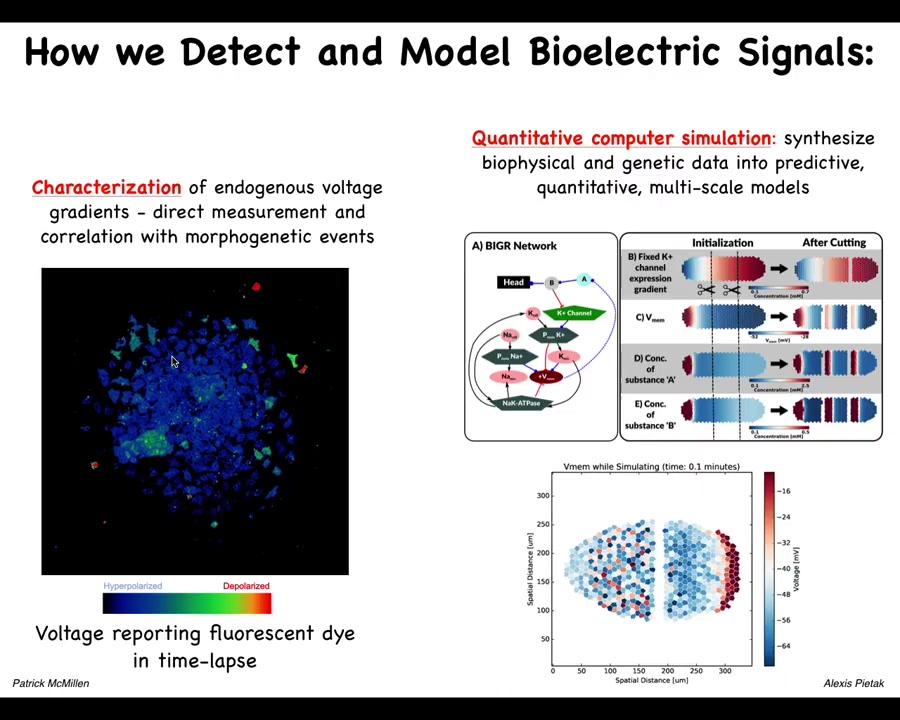

There's a fundamental symmetry here between neuroscience and developmental biology and its disorders such as cancer. That means we can take many of the tools and concepts, both practical tools and conceptual ways of thinking, from cognitive neuroscience and see what they allow us to do in this field. This is some technology that Patrick McMillan has been pushing in our group, which allows you to look at non-neural cells in real time, both in vivo and in vitro, and characterize their bioelectrics and process them via interpretation pipelines similar to what neuroscientists are doing in the brain.

Slide 11/35 · 15m:53s

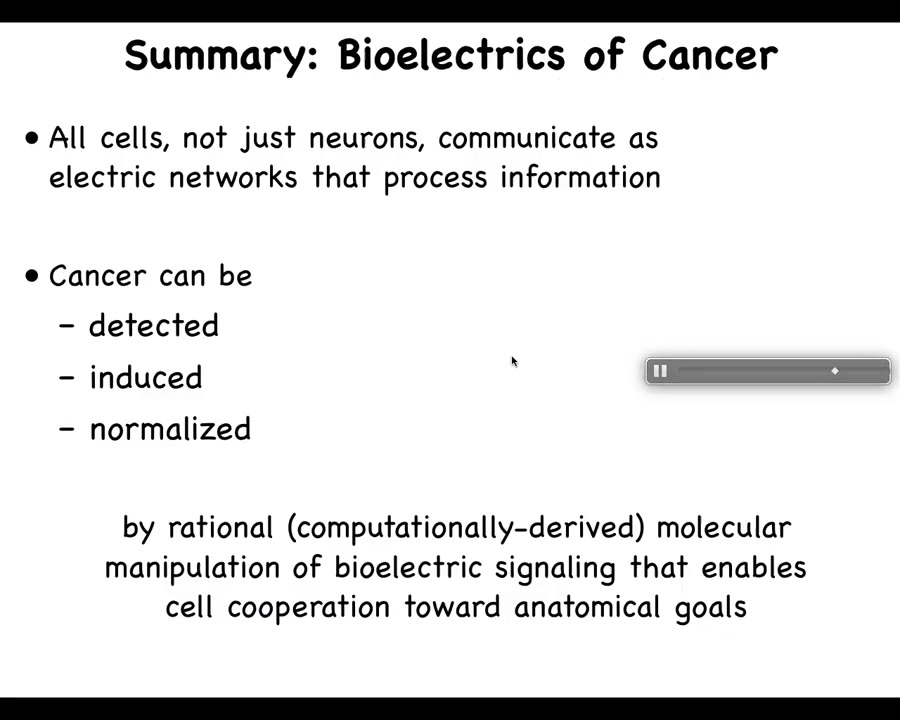

Let's get specifically into cancer. What I've just told you is that all cells, not just neurons, communicate as electrical networks that process information important for cancer suppression. The continuous essential process of taking new cells and integrating them into the anatomical structure of the body enables maintenance of healthy tissues against aging, degenerative disease, and carcinogenic transformation. This leads to the hypothesis that we've been working on for some years: cancer can be detected, induced, and perhaps even normalized by manipulation of bioelectrical signaling that normally enables cell cooperation towards anatomical goals.

To put the whole talk in one slide, what I'm going to show is that, like the brain, somatic tissues form electrical networks that make decisions about anatomy. Then we can target this control system of large-scale homeodynamics with many applications in cancer medicine.

Slide 12/35 · 17m:14s

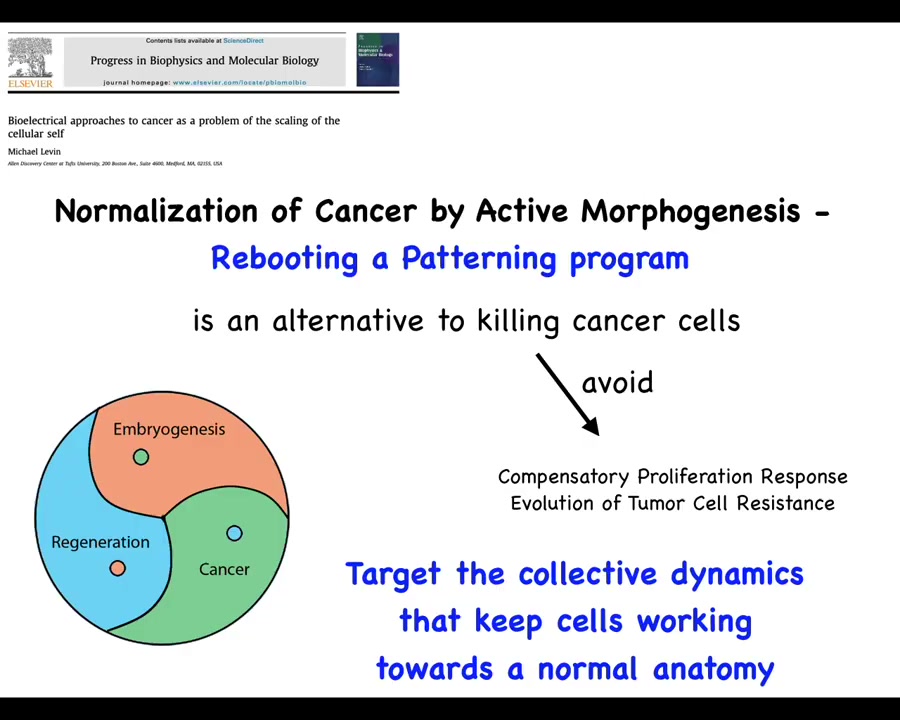

So this leads to a suggestion, which is that perhaps what we can do is normalize cancer by rebooting a patterning program, by connecting cells to the set of cues that normally keep them harnessed towards some kind of morphogenesis. This would be an alternative to necessarily killing those cells, which might allow us to avoid a compensatory proliferation response, evolution of tumor resistance, and so on. Instead of trying to kill those cells, we're going to try to reconnect them to the large-scale homeostatic set points that they used to have. So, let's see how we might do that.

Slide 13/35 · 17m:55s

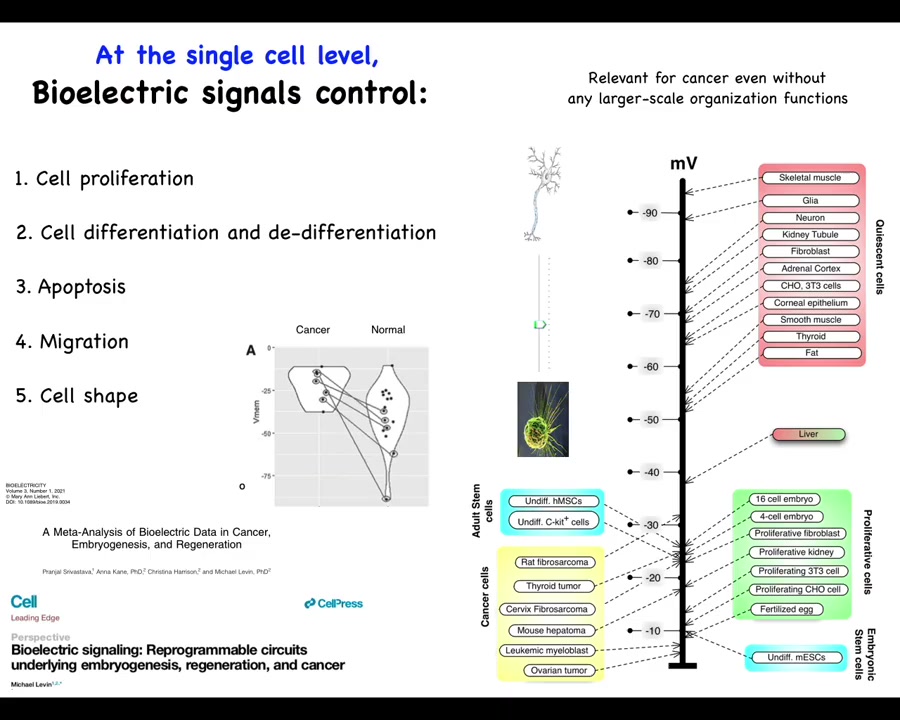

One thing that's been known for a really long time is that if you just take measurements of cells in different states—highly proliferative embryonic cells, stem cells, and cancer cells tend to be depolarized. Quiescent, mature, terminally differentiated cells tend to be hyperpolarized. Liver is an interesting exception, highly regenerative, but even the mature tissue hangs out around down here with this group.

This has suggested an axis of plasticity where resting potential might allow you to move from this state to this state and vice versa. This is something that Clarence Cohn first postulated back in the 70s. This is our meta-analysis: if you track more recent data, the exact same cell types, which can be quite hyperpolarized in normal cells, are depolarized in cancer. The exact same cell types.

Since then there's been a large database of results showing that resting potential is responsible for controlling many things, including cell differentiation, apoptosis, migration, and changes in cell shape. As interesting as this is at the single cell level, I think that the true import of bioelectricity in cancer is going to shine at the multicellular scale, as I was just talking about the role of these potentials in an electrical network that makes decisions.

In order to study those things, we developed some tools.

Slide 14/35 · 19m:35s

These include voltage dye approaches to read the information that these cells are exchanging with each other. Lots of computational modeling goes on in our lab.

This is a simulator, a bioelectrical simulator made by Alexis Pitak in our center that allows us to take voltage information like this, both the slow and the rapid dynamics. You can see a mix here of very rapid dynamics and slow ones in this kind of voltage imaging that Patrick has developed. We're now able to simulate it to understand why the patterns change the way they do.

Slide 15/35 · 20m:20s

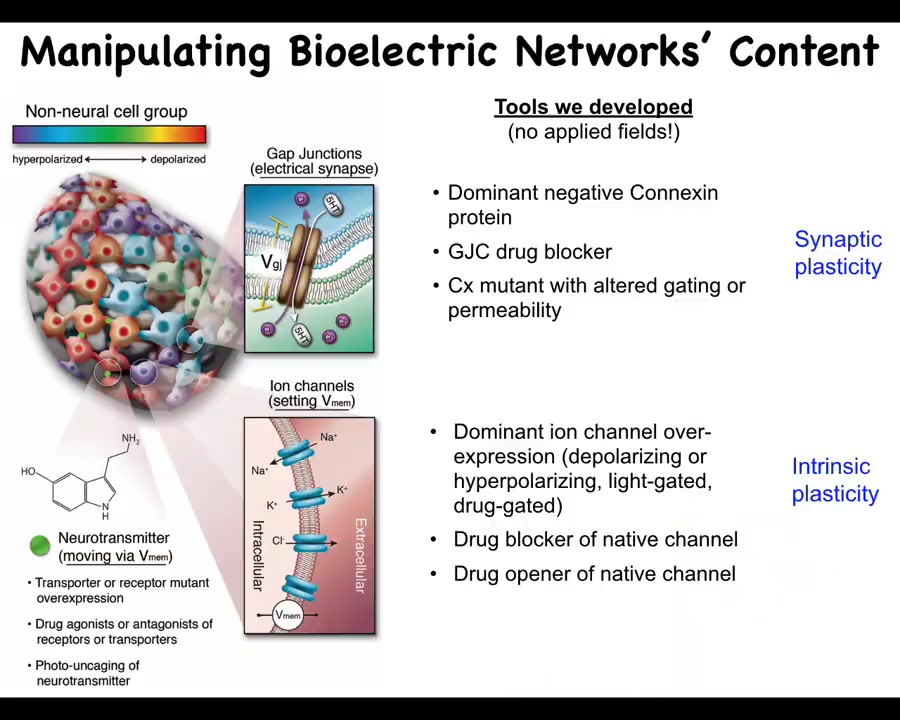

Even more important than simply characterizing these patterns, we need functional tools.

What we've developed are ways to control the bioelectrical states without having to use old tools such as electrodes. We don't use electric field application. There are no electromagnetics, no EM waves. What we are doing is targeting the native interface that the cells are already using to communicate with each other. That would be the ion channels in the membrane and the gap junctions. This allows you to change individual voltage states of cells. This can be with mutations. It can be with pharmacology to open and close these channels. It can be via optogenetics. That allows you to put down specific bioelectrical patterns.

By manipulating the gap junctions, you're changing the topology of the electrical network, which cells talk to which other cells. It's quite a different type of change. You can go downstream and look at, for example, some of the signals that are actually downstream of the second messengers, like serotonin and other neurotransmitters.

When you do this, what can you actually achieve? What does bioelectricity control in the large-scale body besides individual cell properties? What can you actually do by controlling bioelectricity?

Slide 16/35 · 21m:52s

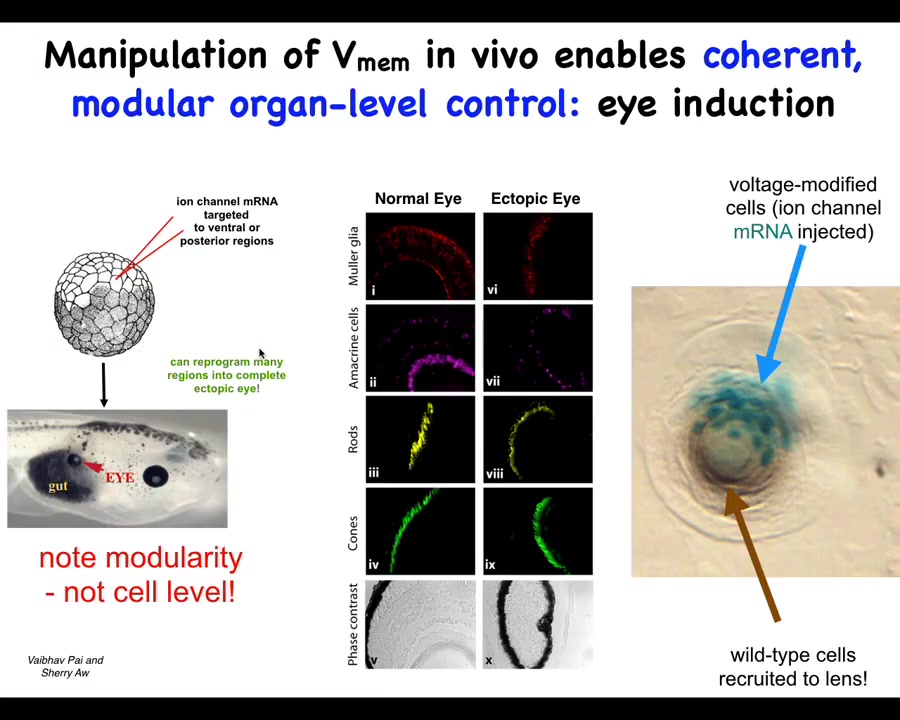

This is one example. It's an old one from our lab and it's one of my favorites. This was by Vaipav Pai and Sherry Au. It was discovered that one thing you can do is you can set up particular voltage states in the body that correspond roughly to endogenous patterns that dictate the position of certain organs.

If you inject specific potassium channels that set up a little voltage spot that's very similar to the eye spot. Danny Adams, when she gives a talk, will show you the electric face and those eye spots. You can introduce that anywhere else in the body by injecting this RNA. When you do that, it makes eyes. It can make eyes all over the place, even in locations that the developmental biology textbook will tell you are not competent to induce eyes. Even outside the anterior neuroectoderm, you can still form eyes if you use the right prompt.

This bioelectric state, if you section these eyes, they can have all the normal components. The retina, the optic nerve, the lens, all of that.

There's a couple of interesting things about this. First of all, it shows that the bioelectric state is instructive. This is not just about causing defects in existing structures. You can call up entire new structures elsewhere in the body. It's extremely modular. This is a very low information content stimulus. We don't tell them how to build eyes. We have no idea how to build an eye with all of its many components and all of the genes that have to come on and all of the spatial relationships. All we have to do is say, build an eye here. It's a very high level, almost a subroutine call that takes tissues that in this case were going to be gut, and it says to them, build an eye. Everything else is handled below that.

The other interesting thing is that this is a section of a lens sitting out in the tail of a tadpole somewhere. The blue cells are the ones that we injected. All of these other cells that are participating in this morphogenesis were never targeted by us. What's happened here is that we tell these blue cells, build an eye. They determine that there's not enough of them to complete the task, and they recruit their neighbors to help them do this.

That ability — other collective intelligences do this; ants and termites do exactly that — to scale your influence to the needed task and to communicate to the other cells that we as the regenerative medicine workers don't need to worry about is already in the material. That is part of the competency of the material that you can harness when you use this bioelectrical interface.

Slide 17/35 · 24m:40s

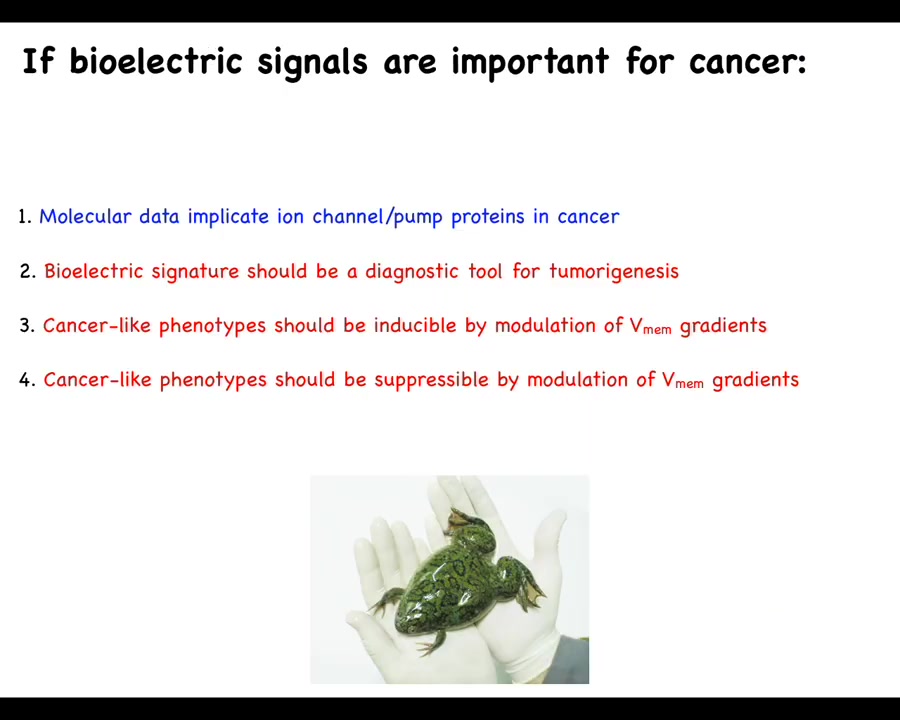

The specific claims here are these: if bioelectrical signals were to be important for cancer, you can expect a few things. There should be molecular data that implicate channel and pump proteins in cancer. We should be able to use this as a diagnostic tool for incipient tumor genesis. We should be able to induce these kinds of phenotypes in the absence of, for example, DNA damage by modulating the VMEM signals. We should be able to suppress or normalize them.

Slide 18/35 · 25m:16s

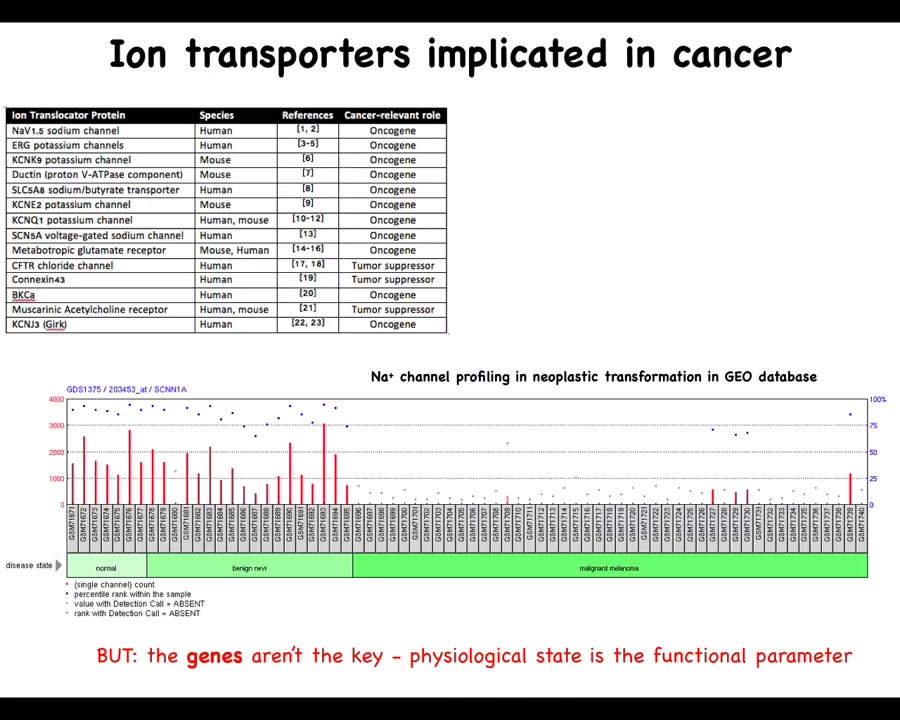

Let's look at those one at a time. There have been numerous ion channels, and this is a fairly old list; there are many more now that are known as either oncogenes or tumor suppressors. For example, from the work of Emily Bates and many other people, lots of channels have been identified that contribute to this phenotype.

One thing to note is that this is a serious underestimate because of the properties of these physiological networks that are very robust, where many different channel genes can compensate for each other. What we see from genetic knockdowns, for example in genetic screens, is probably an underestimate of what's actually there. You knock out one thing; often other channels will take their role in the physiological circuit, and we can miss that. I'm sure there are many others, but this is a good starting list.

You can see for many of these things, if you look through the geodatabase, that through the progression of cancer there are significant changes that you can track already. You can track this just in the bioinformatics. But the bioinformatics is really a drastic underestimate of what's actually going on because these channels open and close post-translationally. That is, you cannot infer from the presence of the gene or the RNA or the protein directly what the physiological state is going to be. You can't guess the bioelectrics just from their presence, at least not reliably. That means we have to go beyond the existing omics profiling of molecular entities to physiomics and the actual functional parameter, which is the distribution of voltage.

Slide 19/35 · 27m:04s

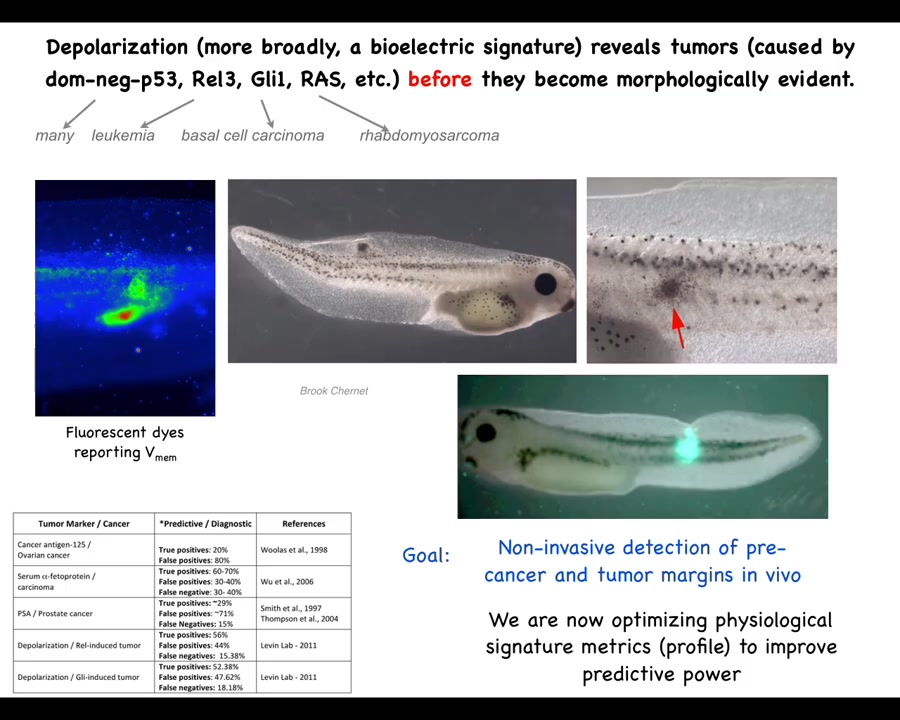

So this is an example of the diagnostics modality. This was worked out by my grad student years ago, Brooke Chernett. What she found is that by injecting a variety of human and other oncogenes, they will form tumors. The tumors will eventually metastasize; in the tadpole model they'll spread. But before the tumor, even before the tumor becomes histologically apparent, we can see using a voltage-sensitive fluorescent dye technique that the region where the tumor is going to be already has an abnormal voltage potential.

We start with the voltage monitoring techniques that Danny Adams worked out in our group a while back for looking at embryos and how these voltage gradients change during embryogenesis. We can take that into tissue and organ maintenance and ask, what does it look like when these cells contract their cognitive leg cones and start treating the rest of the body as just external environment? You can see that they depolarize, and not just the tumor itself, but there are plenty of other cells out here that are going to have this aberrant behavior. So this is an obvious beginning of a diagnostic technology.

Slide 20/35 · 28m:32s

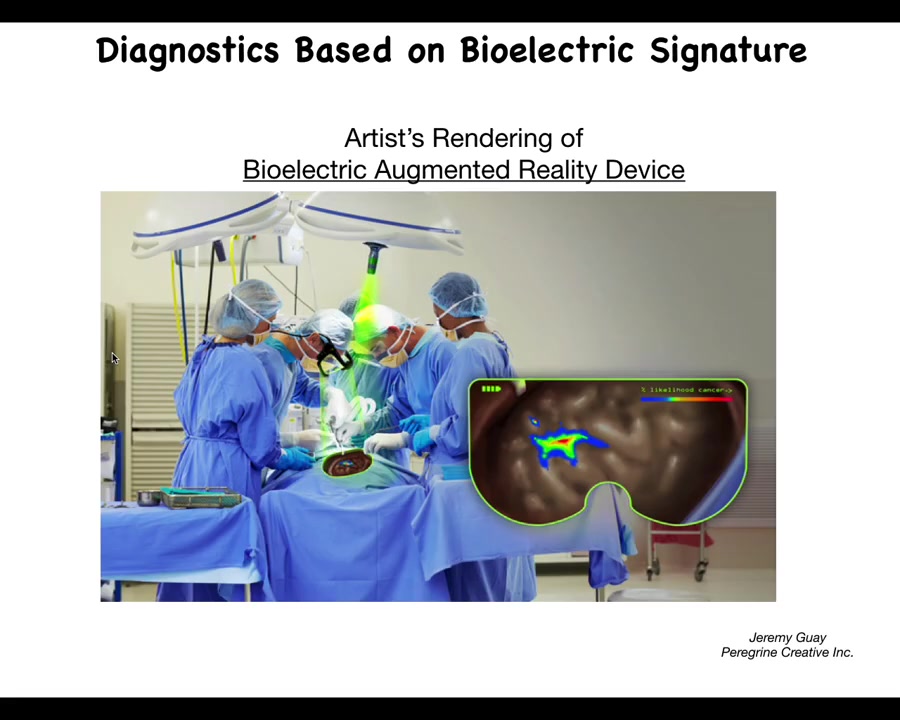

This is an artist's rendering, so we don't actually have this working yet, but we're working on something like this where the idea is that, in real time, using augmented reality goggles, surgeons already use this for various other indicators, but we should be able to have a voltage indicating channel in there where the surgeon is going to be able to see where the margins are, how much they need to take, what are the straggler cells they might need to get.

The idea is of using real-time voltage, bioelectric voltage imaging. Ultimately, this technology is coming and we'll be able to use it for diagnostic applications and for surgical applications.

Slide 21/35 · 29m:17s

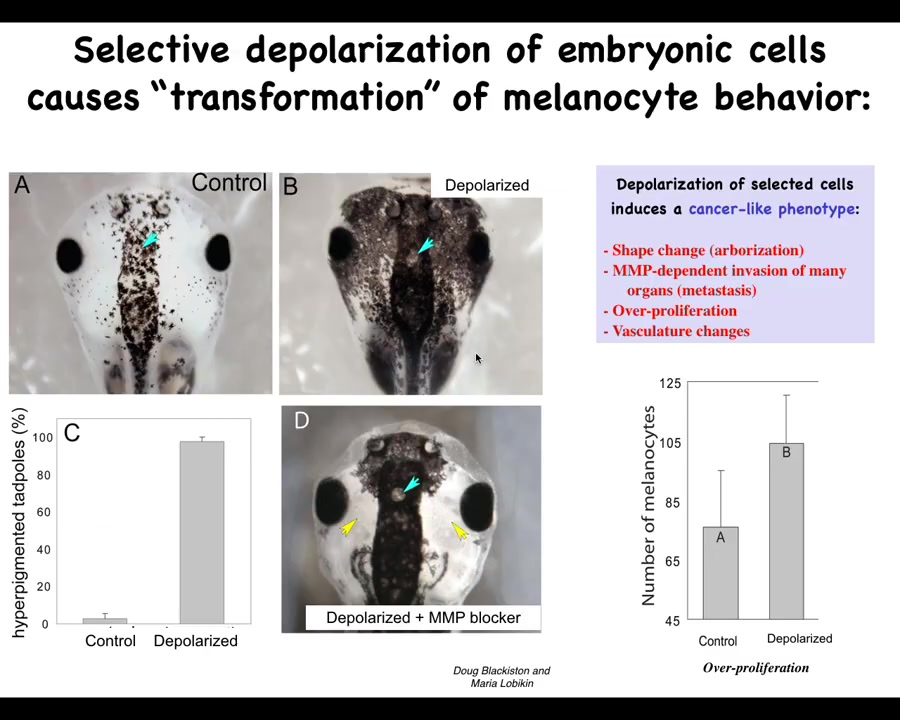

The second prediction we talked about is the ability to induce a cancer-like state in the absence of carcinogens, oncogenes, DNA damage.

This was found by Doug Blakist and Maria Lebickin in my group, where we took animals with normal melanocytes. These little pigment cells are normal melanocytes in this frog embryo. By targeting a specific ion channel, in this case a glycine-gated chloride channel, we disrupted the ability of a population of cells. This is a specific population. We call them instructor cells; they talk to the melanocytes. They normally keep the melanocytes in order. When you silence the ability of those instructor cells to communicate, the melanocytes—the brakes are off—and they go completely crazy. They over-proliferate. They enter regions where they shouldn't be. Their migration is MMP dependent.

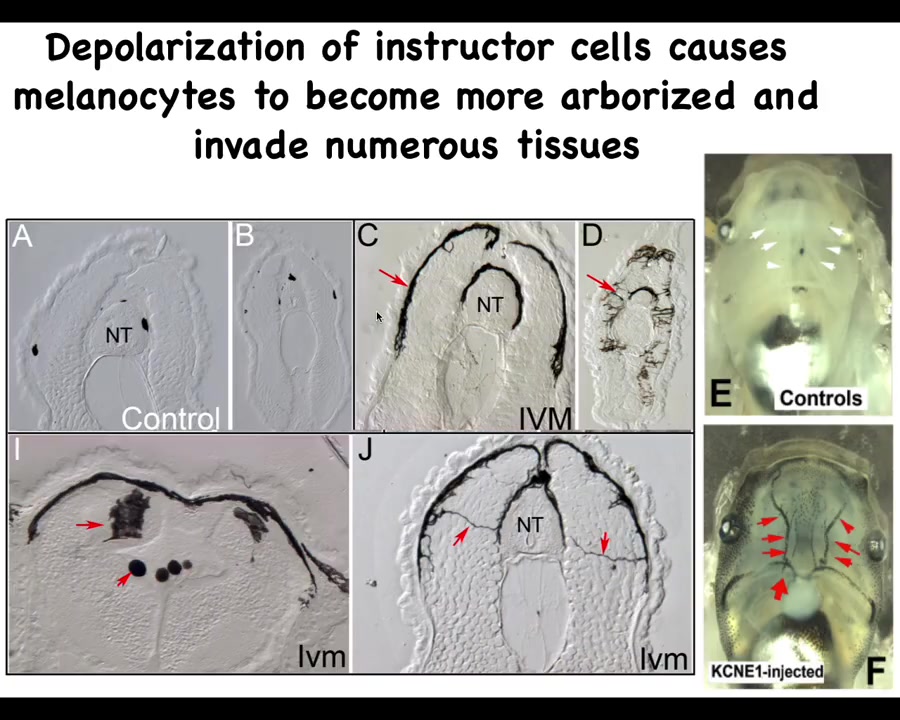

Slide 22/35 · 30m:29s

If you look in a section what's happening here, these are sections, the neural tube here, these are sections anterior and posterior through tadpoles. This is what normal melanocytes are supposed to look like: little round things. There's quite a few of them. This is what ivermectin, which is an opener of these chloride channels, does. This is what ivermectin-treated animals look like: the melanocytes. First, there's way too many of them. Second, they have this crazy projection: they're long, they're almost like neurons here. This is what they normally look like.

Once those bioelectrical signals from the instructor cells are squelched, they transform and start digging into all the other tissues. Here they are digging into the brain, here they are in the neural tube, and the blood vessels here. What happens is that basically an animal-wide metastatic melanoma phenotype develops, which you can pick up. Initially, there are no oncogenes, there is no DNA damage. All there is is temporary interference with the normal bioelectrical signals that keep order. But once this all starts, they turn on markers of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and all the other things you would see in cancer, but that comes later. The first event is physiological, not genetic.

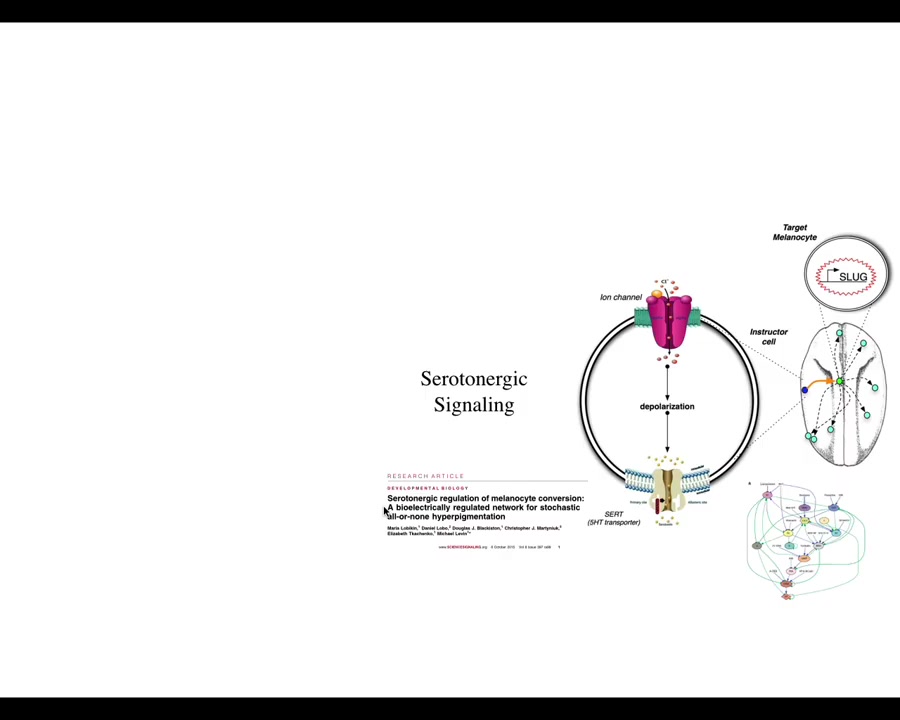

Slide 23/35 · 31m:41s

What's interesting here is that the effect is not cell autonomous. This is a cross-section through that tadpole. These are the cells. This is an injected dominant negative ion channel. These are the cells that we target, but the melanocytes that change their phenotype are at some distance. We've worked out how this works. That takes place through a serotonergic signaling pathway.

What's apparent here is that it isn't the voltage of the cells themselves that determine what they're going to do. It's a voltage change in the environment as a physiological switch towards metastatic behavior. It's not even necessarily the microenvironment because in vivo, it only takes a few targeted cells to kickstart this. They can be quite far away, on the other side of the animal. We have data looking at where you can inject and where this property turns on. The entire tadpole can be transformed by just a small number of cells that have an aberrant electrophysiological signature at one location.

This is a story of how you can kickstart a cancer process with the physiology. That gives us some hope. That gives us the idea that we should be able to prevent and maybe even reverse this.

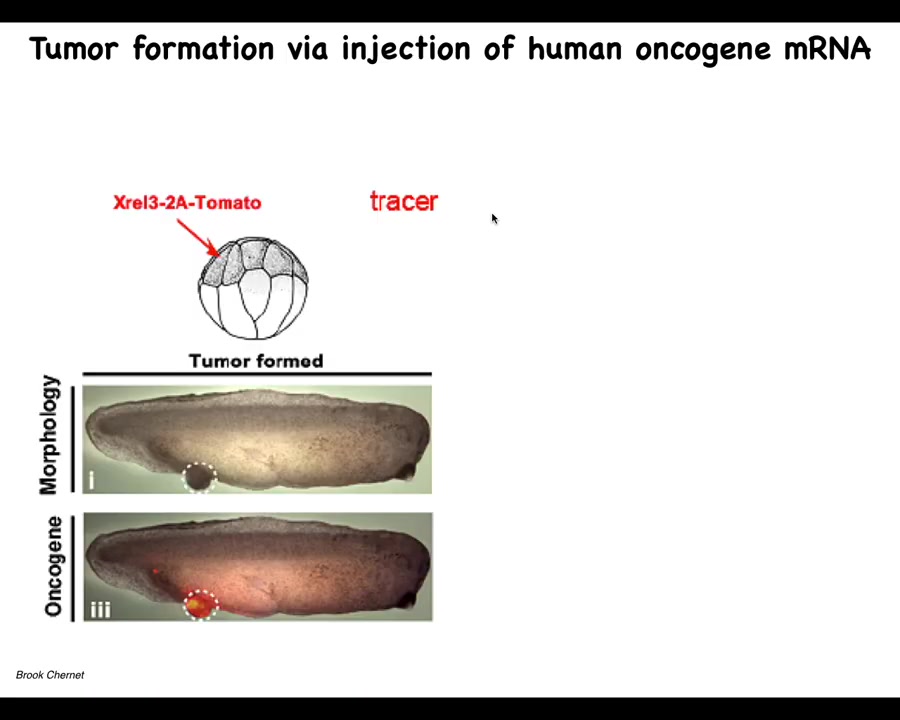

Slide 24/35 · 33m:08s

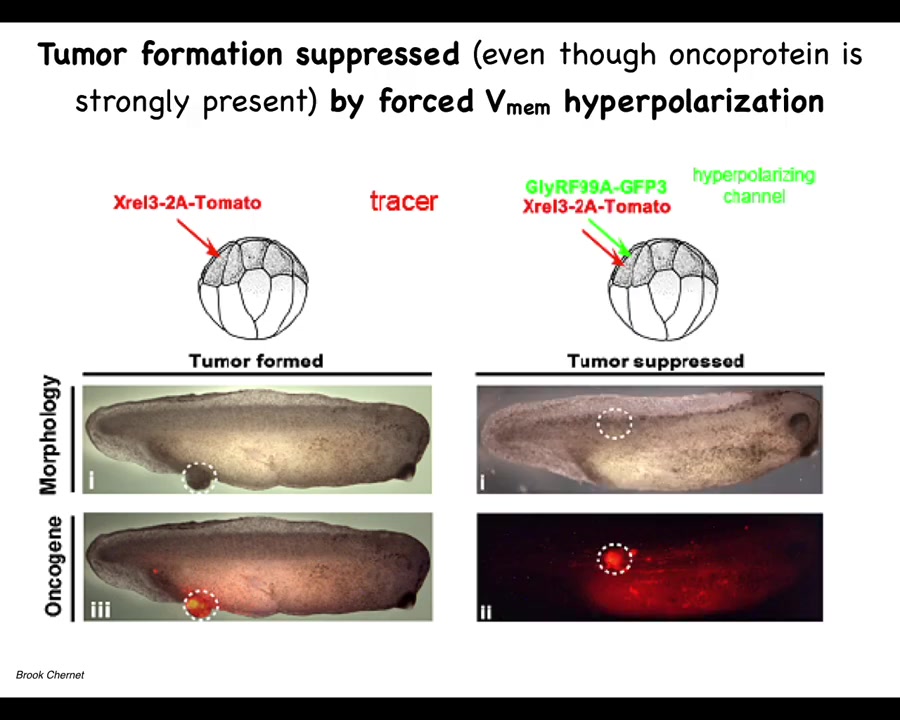

So we tried this, and this again is the work of largely of Brooke Chernett, when he was a PhD student and a postdoc in our group. And what he did was, once again, he would inject oncogenes into various blastomeres. They, and they're labeled, they're labeled with a tomato fluorescent tracers. So here you see it. We tried all kinds of oncogenes, so really nasty KRAS mutations, P53 dominant negative, P53 mutations, all sorts of things that cause these tumor structures. And what we see is that they're quite efficient at causing this.

Slide 25/35 · 33m:41s

If you co-inject an ion channel, that will prevent the cells from depolarizing. One of the first things that oncogenes do is they disconnect cells; this has been known since the 80s from mammalian cell studies, and this happens through a depolarization. If you artificially prevent that depolarization, this is the same animal. Here's what happens. The oncoprotein is still blazingly expressed. It's all over the place, but it's very strong at the site of injection. We don't repair the mutation. We don't kill the mutated cells. They're still here. You can see them, but there's no tumor. The tumor incidence is greatly suppressed because these cells, despite the genetic defect that they have, remain physically connected to their neighbors. Instead of crawling off and doing their own thing, they continue to operate as part of that network, which has large-scale set points. It continues to make skin, muscle, whatever other organs. This tells you that you can override, much like some of our work on birth defects, that some hardware issues, such as the dominant mutation in this protein, can be overridden in software by manipulating the voltage, not repairing the original mutation.

Slide 26/35 · 35m:16s

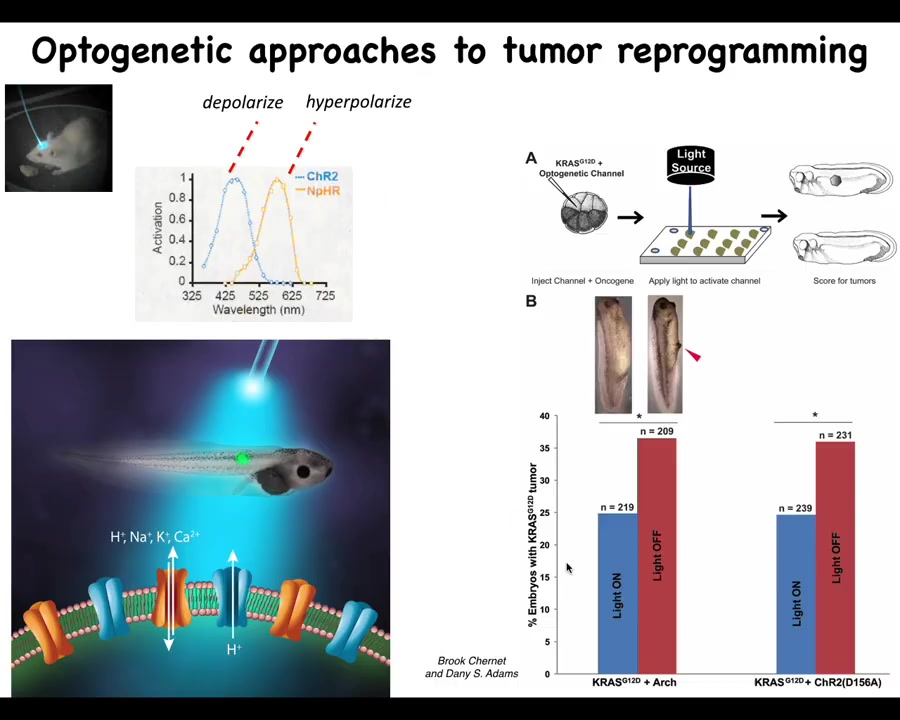

Burke and Danny did some work showing that this can actually also happen via optogenetics. It doesn't have to be any one modality. It really is the voltage pattern that does it, and you can trigger this effect with a light that turns these channels on and off.

Slide 27/35 · 35m:39s

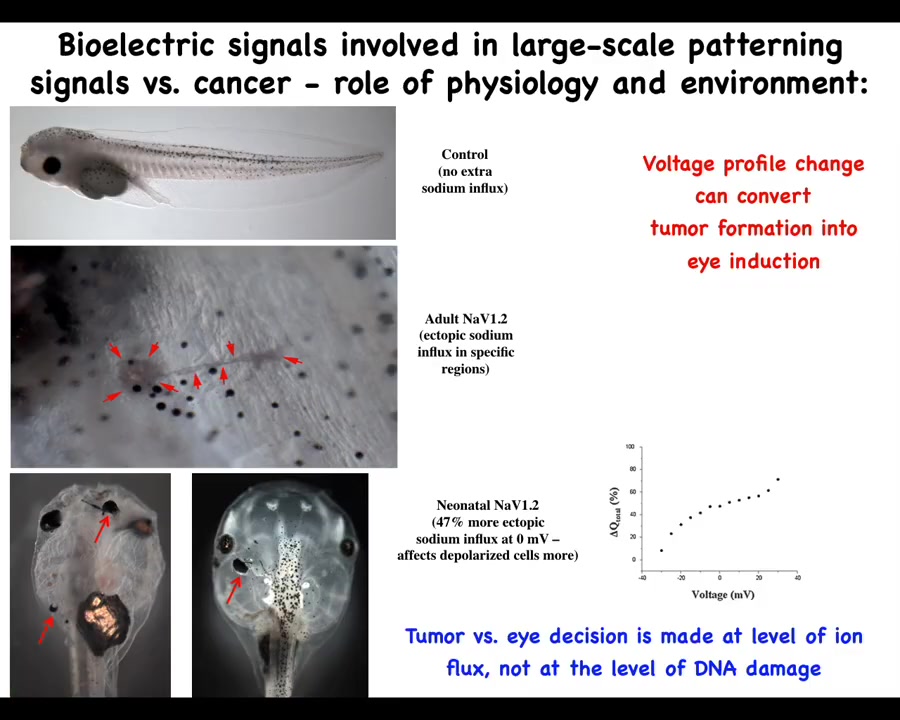

The role of the environment in this is important, and it goes against this mainstream idea that these phenotypes are very tightly linked to the genetics and ultimately to the clonal expansion of one particular set of mutations. Here's a tadpole, and this tadpole can have a tumor or an ectopic eye. What sets the difference between having a tumor or an eye is the amount of sodium that's getting in. And so this is following Mustafa's work. How much sodium is in your medium and how much of it is getting in and some other subtleties will switch between two radically different outcomes, an ectopic organ or a mutant. So we have to start to understand the primary role of the physiology, the collective decision-making in this process and see these ion channels as an important interface to that process.

Slide 28/35 · 36m:48s

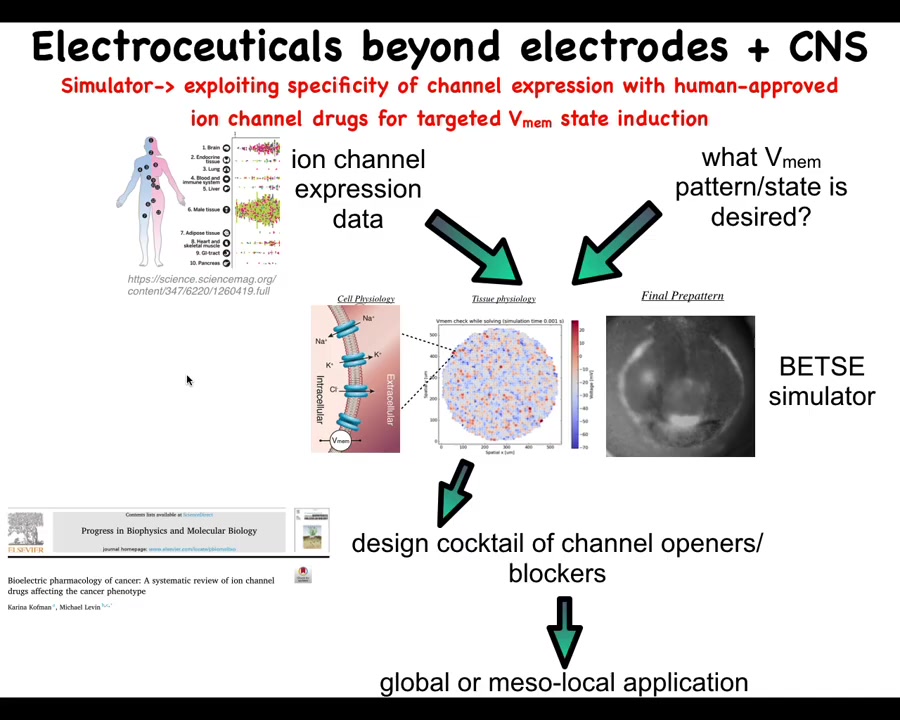

Our roadmap looks roughly like this. What we would like to do is scrape the existing profiling data on what channels and pumps and gap junctions exist in various human tissues. That defines the interface and shows us which are the control knobs that we can use through extensive physiomics, which we are just now getting started on. These data largely do not exist except in a few cases and a few model systems, but this really needs to be done in a very coherent way.

We can use simulators such as the original Betsy platform made by Alexis. This is Danny's electric field preview. A pattern like this where we say, okay, this is the pattern that we want and we can simulate which of these channels and pumps needs to be opened or closed. That enables us to choose these specific reagents to then get what we want.

There's a review of existing links between various ion channels and the cancer phenotype that can also be used by this and other manual strategies.

Slide 29/35 · 38m:05s

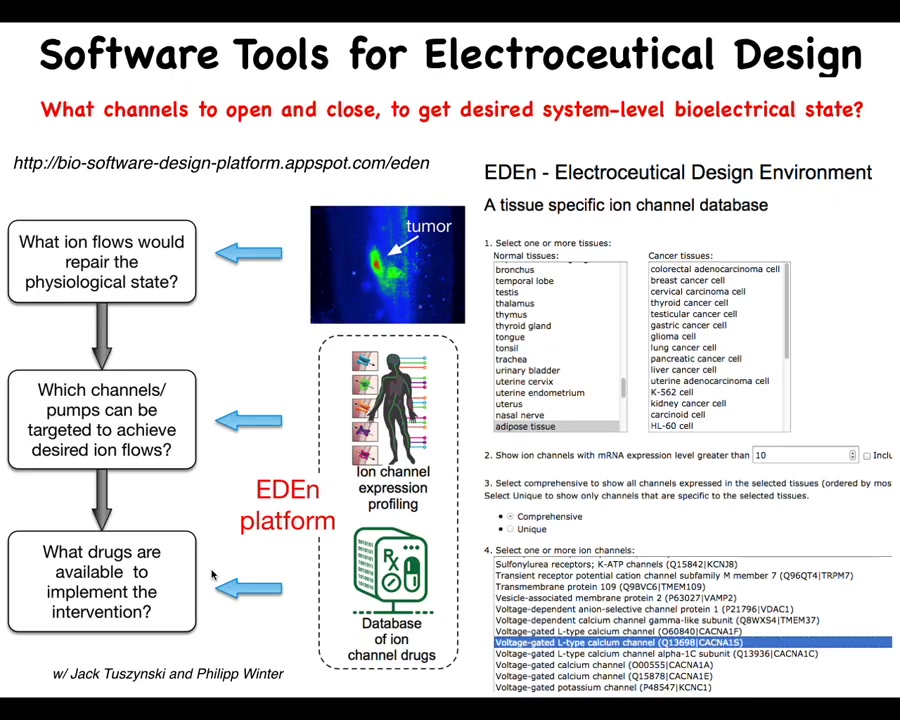

So the cancer pipeline, and you can start to play with this, is online. It's not remotely finished yet, but there's pieces of it already here where you can start to choose specific tissues and specific cell types. It will tell you what are the knobs that you have to play with. What are the channels and pumps that are there? Using the simulator to ask if we know what electric state we want, which of these do we need to trigger? This is collaborative work with Jack Tosinski, and the software is built by Philip Winter. We can then begin to choose electroceuticals, which are either existing or novel drugs targeting ion channels that can have specific effects predicted by this computational platform.

Slide 30/35 · 38m:52s

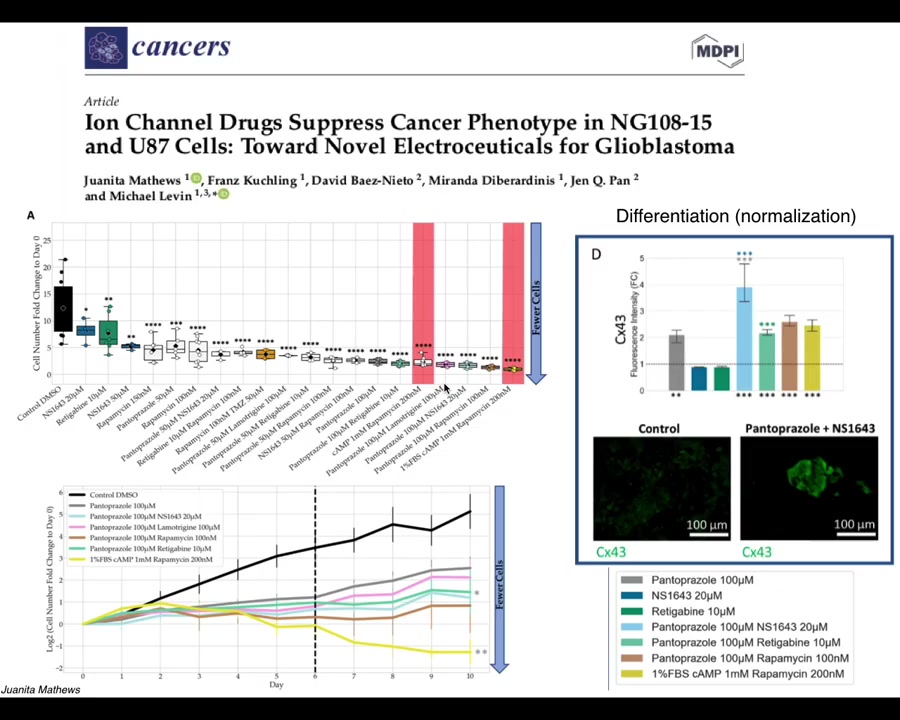

Our latest work by Juanita Matthews is now moving all of this from the frog model into human cells, first in 2D culture and now in cancer spheroids, and eventually in vivo, starting to look at glioblastoma. We're also looking at colon cancer and breast cancer. There is some really nice data on not only affecting the individual cell behaviors but even looking for signatures of normalization. The idea that when we use these drugs, not only do these cells stop many of their cancer-like behaviors, but they actually start to turn on some markers of normal multicellular tissues.

Slide 31/35 · 39m:37s

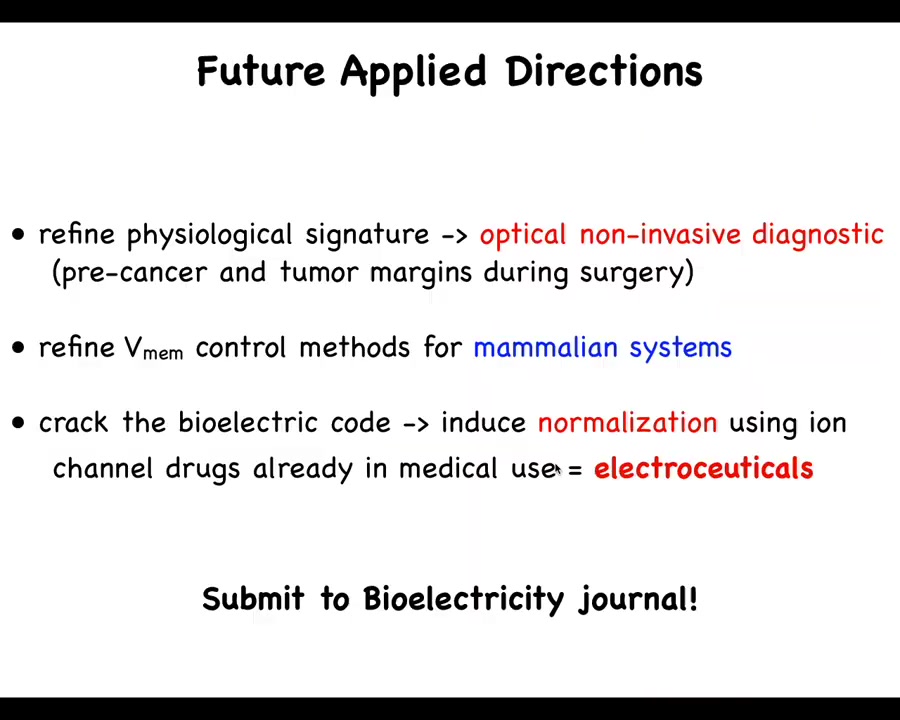

Just a couple of things left to look into the future. I've made the claim that cancer is not just a genetic disease, but actually a disorder of the scaling of cellular competencies in navigating anatomical space. I think that's fundamentally an important way to look at this problem.

I've suggested that bioelectric properties can be used to detect, induce, and normalize neoplastic cell behavior. We now know that the behavior of these electric circuits can be modified in useful ways, just like we do in the nervous system with stimuli. That is not with hardware rewiring, but with various kinds of pharmacological, physiological, and other stimuli. I think the future involves pharmacological, optical, and other strategies guided by computational simulation platforms. One of the important things that needs to happen is knowledge of which bioelectrical states occur in different disease states and what the healthy states are.

Slide 32/35 · 40m:45s

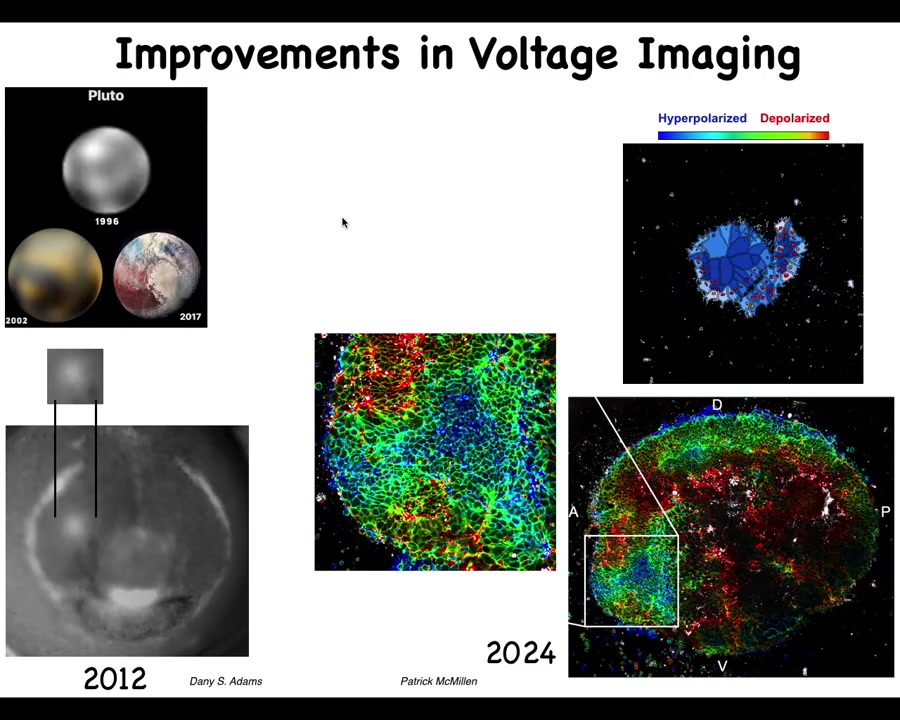

I always like this history of imaging. This is what Pluto looked like in 96 and this is what it looked like a few years ago. The idea is that imaging technologies are very important and the breakthroughs that we had made with Danny's work back in the day, starting to get, for the first time, an actual video. The first pictures of voltage in embryos were done by Thorlen around 2000 in Ken Robinson's lab. Then the first time-lapse movies of watching all the cells interact with each other electrically and the patterns, such as this electric face that Danny will show that presages and determines where all the organs, such as the eye, are going to be.

People like Patrick McMillan and our group are working on novel ways to track in real time many different parameters, cytoskeletal and voltage. This is what that same region now looks like. We can start to get much more complex patterns and get enough data here to deploy state-of-the-art machine learning tools to infer these patterns and apply metrics from computational neuroscience to understand how to manage this behavior.

Slide 33/35 · 42m:12s

In the future, what I would like to see is better technology and better data for developing these physiological signatures.

We are working towards control methods in mammals because we'd like to move this into patients soon.

The big idea is cracking this bioelectric code and using normalization via electroceuticals as stimuli to the cellular collective guided by computational tools.

Reminder: Mustafa, Jamgaz, and I edit the Bioelectricity journal. If you have any papers that are forthcoming on any of this, I encourage you to submit to our journal.

Slide 34/35 · 42m:57s

What I'd like to do is thank all of you for listening and thank the people who did the work. Juanita Matthews, who's doing all of the human cancer bioelectricity in our group, and Patrick McMillan, who is studying the bioelectrics of cell collectivity, and also developing ways to understand how these electric properties relate to single cell versus group cell behavior. Brooke and Maria did all of the early in vivo work on the cancer that I just showed you. This is Gizem Gamushkaya, who did the anthrobots, and that's a model that we're going to be using in the cancer field shortly. Danny Adams and her pivotal early work on looking at bioelectric patterns in real embryos. Lots of other students, lots of support staff, without whom we couldn't have done this work. Many, many collaborators.

Here are some funders that supported some of this work. I need to do a disclosure. Astonishing Labs is a company that supports a lot of this work in our group, and we're moving forward together towards various therapeutic avenues in patients.

Slide 35/35 · 44m:09s

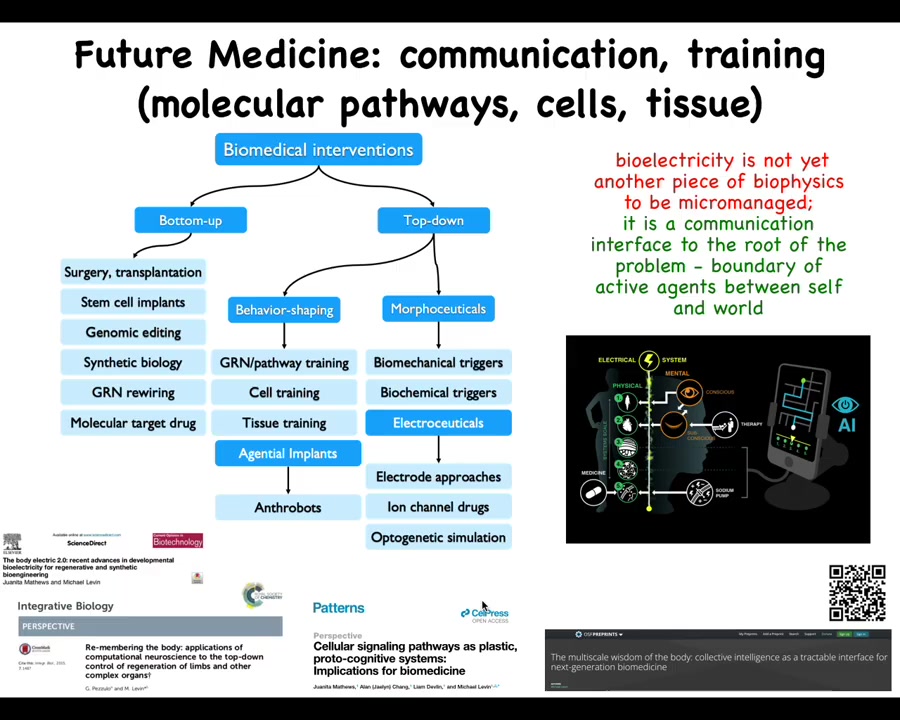

And the last thing is this idea that I really think that the way to think about bioelectricity is not as another piece of biophysics that we micromanage the way we do with transcription factors and signaling pathways. I think when we study bioelectricity, what we're looking at is a communications interface. It's an interface to the root of the problem, which is the boundary that active agents set between themselves and the outside world.

Now pulling back beyond cancer, this is a larger view of how I see biomedicine developing. Whereas currently most of the progress has been around these bottom-up interventions, I think there is massive room for top-down approaches, many of which look at behavior shaping and taking advantage of the various competencies of cells and tissues: various agential implants, such as anthrobots for healing in the body; different kinds of morphoceuticals and electroceuticals. The cancer problem is going to be powerfully addressed in some of these ways if we use new techniques, both in terms of AI and powerful concepts being developed in computational neuroscience to address the cancer problem in this context. Some of the details are here.

So I think that's it. Again, thank all of these people who did this amazing work, and thank you for listening.