Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

Dr. Michael Levin introduces TAME, the Technological Approach to Mind Everywhere, as an empirical framework for comparing diverse intelligences from animals and swarms to synthetic and exobiological agents. He explores morphogenesis as a form of collective intelligence, the cognitive light cone model, and how synthetic bioengineering creates new bodies and minds that blur traditional boundaries of self, agency, and consciousness.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Collective intelligence in biology

(44:00) Collective selves and consciousness

(52:43) Light cones and superagents

(59:02) Memory, meaning, and evolution

(01:03:41) Shared and extended minds

(01:09:20) Closing thanks and outro

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/34 · 00m:00s

If anyone's interested afterwards in any of these things, you can reach me at these websites. Also, that is where all of the primary papers are. So if you want to see all of the primary science that goes into all of this, you can download everything there.

Slide 2/34 · 00m:20s

Here are the main points that I would like to get across today.

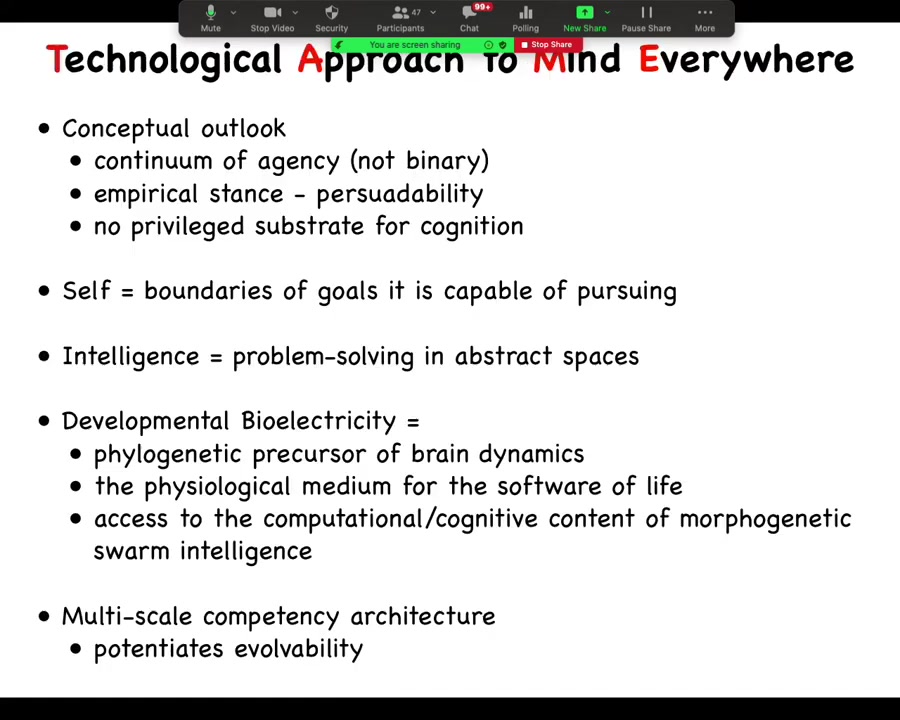

The first view that I would like to put out there is that this question of how much intelligence or agency or cognition any given system has, whether biological or not, should be framed as an engineering problem. We treat this as not just philosophy, where we could make pronouncements about what ought to be considered intelligent or an agent, but actually as an empirical problem, and I'll show you how I think we can deal with that. What I want to do is propose an empirical approach using the appropriate level of concepts from cognitive science to better predict and control complex systems.

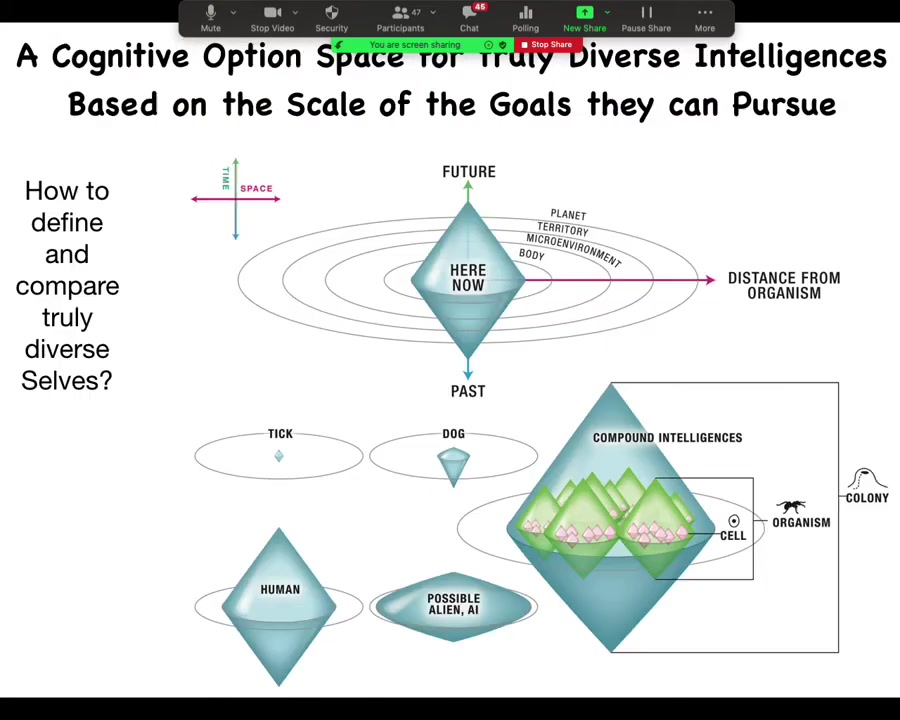

I think diverse intelligences, truly diverse intelligences, can be directly compared with each other with respect to a particular component, which is the spatial-temporal scale of the goals that they're capable of working towards, and I'm going to try out the cognitive light cone model, and I'll explain how that works.

I want to get across this idea that synthetic bioengineering and advances in it provide an incredible expansion of the option space for new bodies and thus new minds. These things will not have the evolutionary standard backstories. They form a rich pool of beings for any diverse intelligence framework to consider and apply to.

I'll also show you some data on the study of morphogenesis as an example of an unconventional collective intelligence. As I talk about all these unusual types of cognitive agents, I'll show you one particular example which solves problems in morphospace. I'm going to argue that developmental bioelectricity and the study of how morphogenesis is a kind of collective intelligence bound together by electrical dynamics provides a new and interesting window on this problem of binding lots of competent subunits into one greater unit.

Slide 3/34 · 02m:31s

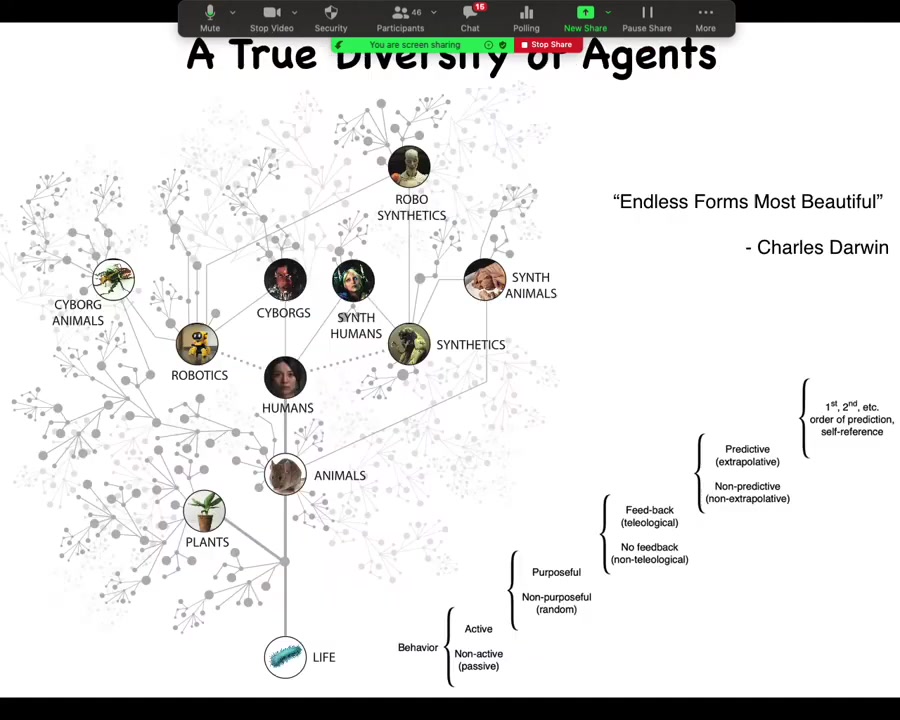

The goal of my framework is this. What I would like to do is to enable comparing truly diverse intelligences. This means not only the things that we're all used to, complex animals, apes and birds, but also weird creatures such as colonial organisms and swarms, but also synthetic biology and its products, so engineered novel life forms, software agents that arise out of artificial intelligence work, and possibly any exobiological agents, because the Earth's biosphere is, of course, an example of N = 1. If we find something else, we ought to be able to deal with it. This is what I would like to do, is to have a framework that applies to any of these things, and also that helps move experimental work forward. I'm going to talk about this in three pieces. First, the introduction where I want to broaden a little bit the way we think about the subjects of cognition. I'm going to talk about how the subject of intelligence and cognition is really plastic. Then we'll talk about this framework, which we call the Technological Approach to Mind Everywhere or TAME. Then we'll talk about some data that shows how this thing works.

The first thing I want to point out is that whenever we study cognitive systems that are doing something interesting, we often posit that there's this self, there's this centralized agent that is the subject of complex memories, of rewards and punishments, of goals and goal directedness. There's this kind of self. I want to start off by pointing out how malleable these selves can be. Here's a caterpillar, and lots of people study caterpillar behavior. Here's a butterfly, and lots of people study butterfly behavior. One of the most interesting things is that in order to become a butterfly, the caterpillar basically dissolves its brain. So much of the brain is destroyed. Cells die. A lot of the synaptic connections are broken up. You build an entirely new brain that is appropriate for operating this entirely different body, this hard body that has to fly and drink nectar. What happens during this process is that the substrate of whatever cognition this caterpillar had is completely remodeled. You can see more examples of this in this review. But one can wonder, what happens? What is it like? People in philosophy of mind ask, what's it like to be a caterpillar or a butterfly or anything else? What's it like to be a caterpillar changing into a butterfly? Minds are embodied and bodies can change drastically. We have to start thinking about the plasticity of the body and the brain.

Slide 4/34 · 05m:16s

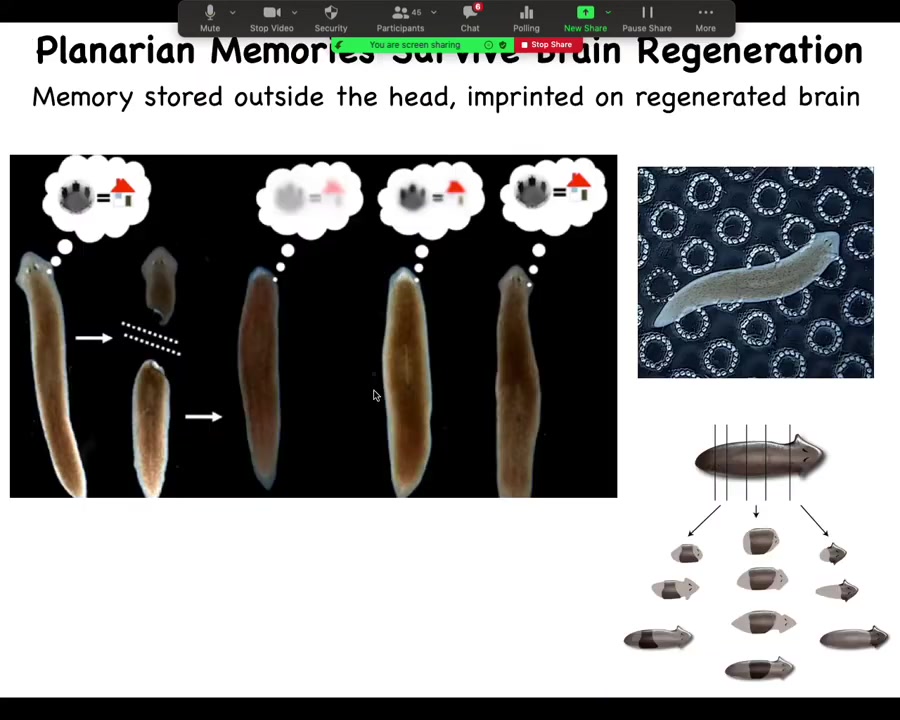

This, we can put that even on steroids by looking at planaria. So these are flatworms. And these flatworms are relatively smart. They can learn and they have all kinds of interesting behaviors. And one of the things about planaria is that you can cut them into pieces and every piece gives rise to a whole new worm. So they regenerate. Every piece knows how to make a whole new planarian.

And so what we can do is we can train planaria on some particular fact, such as that food is to be found on these bumpy little circle patterns. And then you can amputate the brain, or the whole head. The tail will sit there doing nothing for about eight or nine days. Eventually it will grow a new head, a new brain. This tissue somehow imprints that original information onto the new brain and the new planarian still remembers the information. This is work that was originally done in the 60s by McConnell. We did it more recently using an automated platform.

So you can imagine what happens when you take this planarian that has learned something, you cut it into pieces, every piece is a clone of the original. It carries the information content and the memories of the original. This is from Philosophy 101, the cloning machine experiments; this actually happens. So you can actually do this. So as the brain is removed, as the brain is restored, as the information is imprinted on this brain, lots of interesting questions about what it's like to be that agent or what we can even say about the different stages of this process and when is that original agent present or absent or what's happening.

Slide 5/34 · 06m:50s

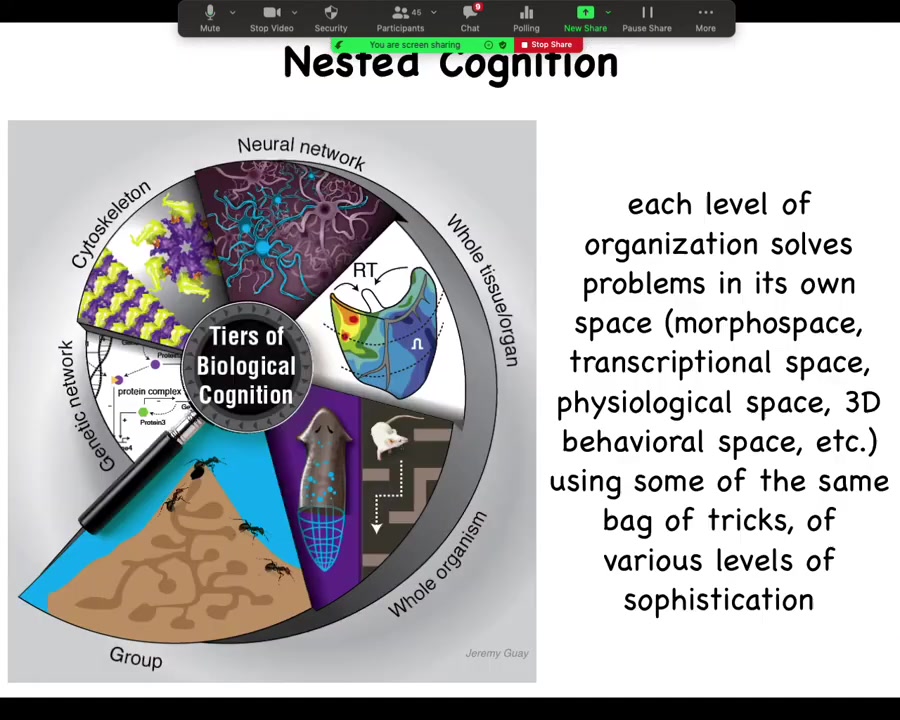

Okay, so we're really interested in this idea that agents, all cognitive agents are collective intelligences. So all of us are made of parts. There's no such thing as a indivisible monadic intelligence. I'm not even sure what it would mean to be able to learn if you didn't have parts that could change. But because we're all made of parts, we have to potentially think about how those parts relate to each other and what other intelligences might be in any given system. So we study all the way from learning capacities in protein pathways and gene regulatory networks to the computational capacities of the cytoskeleton, of neural networks, of tissues and organs, whole organisms and swarms. All of these tiers of biological organization are simultaneously solving problems in various spaces, and we'll get to that momentarily. The interesting thing is that not only do we have to look at an agent and say, what are the parts doing and how are the parts able to rearrange, but in fact, we can now replace all of these parts.

Slide 6/34 · 07m:53s

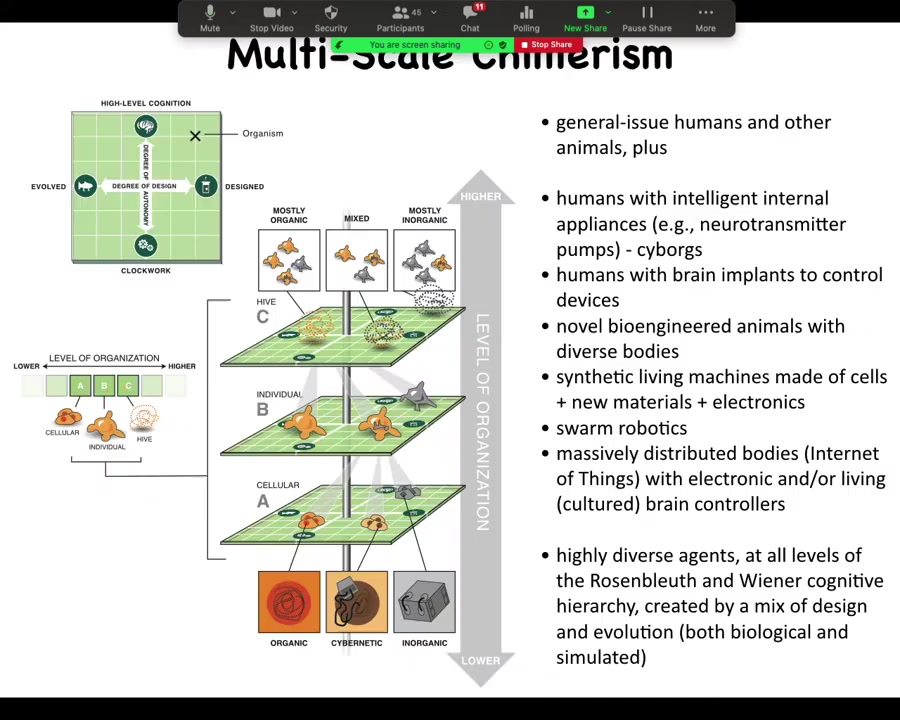

This is a scheme we call multi-scale chimerism. What it means is that we can take any living system and replace or augment parts of it on any level. We can add DNA that belongs to another creature. We can add various nanomaterials, whether active or passive. We can replace cells. We can replace whole tissues or whole organisms.

At every level, you can mix and match different parts, some of them evolved, some of them designed, organic or inorganic. In the end, you have this composite creature that is different from anything we've ever seen before on Earth. In any one of these layers, you have a whole spectrum to choose from of things that are either evolved or designed. You can grab them from some other creature, or you can engineer them. They might be something very simple and mechanical. They might be quite complex and active.

You can see that we now have the ability to study regular humans and animals, but also, for example, humans with all kinds of appliances: cyborgs, brain implants, bioengineered animals, synthetic living machines (on which more later in this talk), swarm robotics, all sorts of unusual cognitive capacities, because the bodies and the minds of these things will be different.

Slide 7/34 · 09m:22s

You can imagine this tree of possible agents and possible organisms where everything we're used to is just one tiny corner of this. The space of possible agents is enormous. You can see here, this is Wiener and Rosenblueth's scale, where you can see that all the way from passive materials to smart materials to active matter, as you start climbing the ladder of complexity, there are all sorts of capacities that might be increased depending on what you're making.

Now that you've got the idea for how widely we want to expand these ideas, so that they're able to apply to this whole space of possible agents, let's talk specifically about this framework that I want to put out there. We want to do three things. I want to make explicit the philosophical principles that underlie this, because it's important to pull this stuff out into the light so that everybody can see what is being assumed here. Then I'm going to propose a specific hypothesis for one way to define what a self is, and a specific hypothesis for how these selves scale from very humble beginnings up to more complex things.

Here are the foundations. Here's where I'm coming from on all this. I'm happy to discuss what happens if some of these are not true or to argue about the value of these things.

The first thing that is important is that there are no binary categories. What gets us into trouble is when we ask, is that really an agent? Is it really learning? Does it really have memory or is it just acting as if it does? This is a problematic way of putting these questions because it assumes there's a bright line between cognitive and non-cognitive agents. If we take evolution seriously, we have to understand that if you follow backwards from anything that you assume has true cognition, eventually you're going to get to something that looks like it's just physics. Is that really cognition or is it just physics? Everything is physics. If you follow things backwards, you're going to find something where it's unclear on which side of the line we are. What that tells me is that there is no line and we shouldn't have a line; we should have a continuum.

The point then is not to try to anthropomorphize simple systems. I don't believe there is any such thing as an anthropomorphization because that very word supposes that humans have a magical property that we're wrongly attributing to other systems. We have to demystify cognition and treat it as a continuum from very humble, very minimal kinds of systems to very complex human and possibly transhuman. The point is to demystify the right side of that spectrum, not to try to apply it inappropriately.

What I would like to propose is that we take an engineering stance on these theories. This is very close to what Dan Dennett calls the "intentional stance." The intentional stance simply goes like this: you attribute intentionality to some kind of system when it becomes profitable for you to do so. If it's helping you predict and control the system, then you've made the right choice, and we need to do that here.

The problem is that a lot of people work in teleophobia, where we're terrified of Type 2 errors of attributing agency inappropriately to something that doesn't need it, and that's certainly a problem. But the other problem is just as bad: if you fail to recognize agency where it could have helped you with prediction and control, you leave a lot on the table. The idea is to find the correct amount.

The way you find that correct amount is through empirical experiment and proposing models and asking whether this level of cognitive modeling helps me or does not help me?

What I'm going to do here is not to focus on the hard problem of phenomenal consciousness, although we can talk about that a little bit at the end, but to use experiment to decide what level of agency.

What that means is that asking how a thermos knows whether it should keep something hot or cold is a bad use of the word 'no', not because of any prior philosophy you could have done, but simply because we now know that you don't need that to explain how the thermos works. It's a much simpler model that does everything you want it to do. That's how we're going to decide these things.

In addition, the idea is that agents are a patchwork of multiple intelligences, all at different levels, and that there's really no magic in the material. Synapses, when you say cognition, a lot of people think of brains. There's nothing really magical about the material that brains are made of, and very similar things can be implemented by all kinds of other architectures, and in fact, in evolution, it works.

What I would like to do is to study not zoology or how particular animals and plants do things, but actually wide biology, so life as it can be and mind as it can be.

Slide 8/34 · 15m:16s

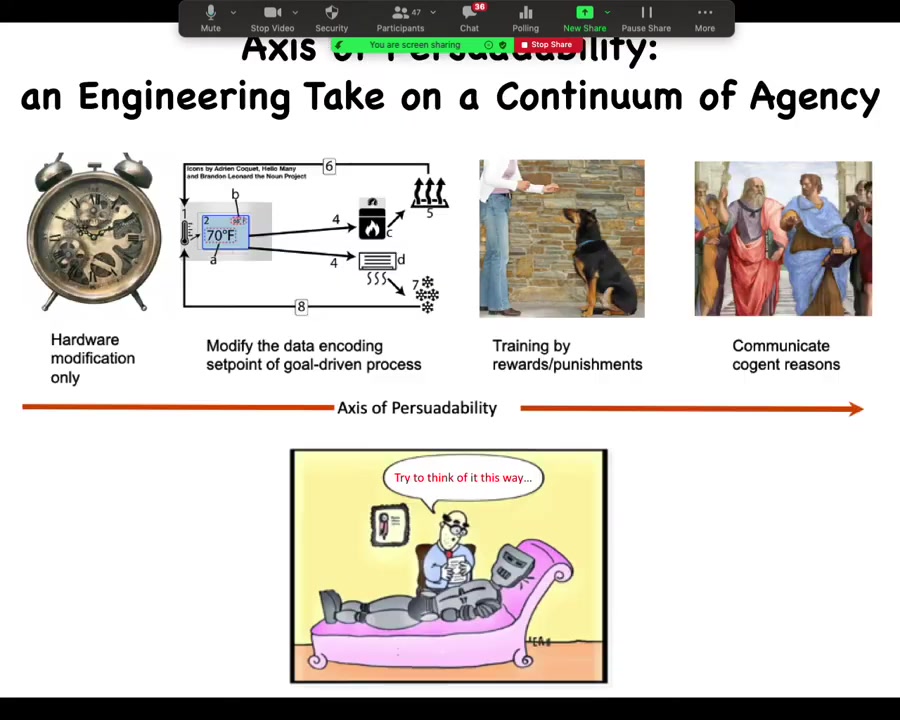

Here's a silly diagram that I made up for something we call the axis of persuadability. These are just examples of different systems.

On the left, you have systems. It's all about prediction and control. If you have a system like this, a mechanical clock, you're not going to provide it rewards and punishments. You're not going to be able to reason with it. The only way to control it is through hardware modification.

Slightly more complex than that are these kinds of homeostatic systems like your thermostat. That's interesting because that can be seen as a goal-directed process where you can actually go in and change the set point. You can alter the goal. You don't have to rewire the whole thing. You simply alter the goal that it follows and the behavior is changed.

You have more complex kinds of systems where you can change what they do by rewards and punishments. Interestingly, right around this point you stop needing to know too much about what's under the hood. With the clock, you have to know exactly how it works to make changes. With a thermostat, you don't need to know exactly how it works, but you need to know how the set point is encoded. You need to understand something about the mechanism. Once you're providing rewards and punishments, you don't need to know anything. Humans have been training animals for millennia, knowing nothing about electrophysiology simply by understanding that what you have is a learning system that has preferences for various things.

All the way on the right side of the spectrum are systems that you can communicate with and provide reasons as opposed to causes, and they will do all the heavy lifting for you by following the inferences.

This axis of persuadability is what I meant about being able to order these things based on the degree and type of control that you can exert in prediction.

Slide 9/34 · 17m:10s

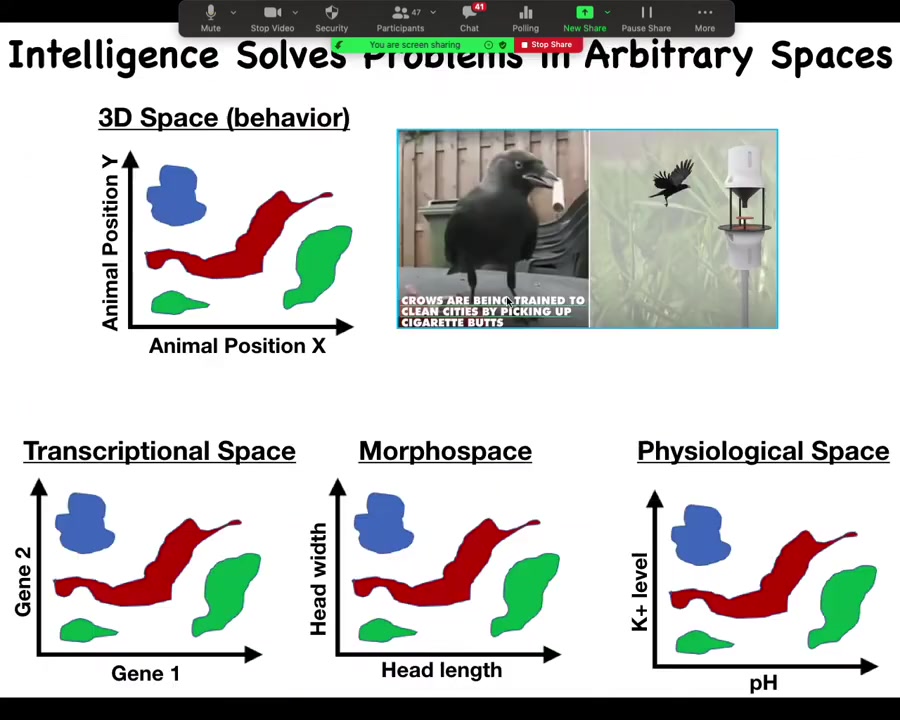

Another thing to think about is the fact that intelligence solves problems in arbitrary spaces. What is intelligence? What do we mean by an intelligent agent? We're very used to this kind of thing where you have a highly intelligent creature that solves problems in three-dimensional space. It moves around and will do various things. That's the space in which it's operating. It's a behavioral three-dimensional space.

But all kinds of systems, cells, tissues, organs and so on, solve problems in other spaces. In transcriptional space, the space of all possible gene expression patterns, you have to navigate that space and be able to turn on exactly the right genes to be in the state that you want. Morphospace, about which we'll talk more in a minute, is the space of anatomical structure and deformation of the body, and physiological space. As things happen and physiological parameters are impacted, how do you navigate that space to keep within homeostasis?

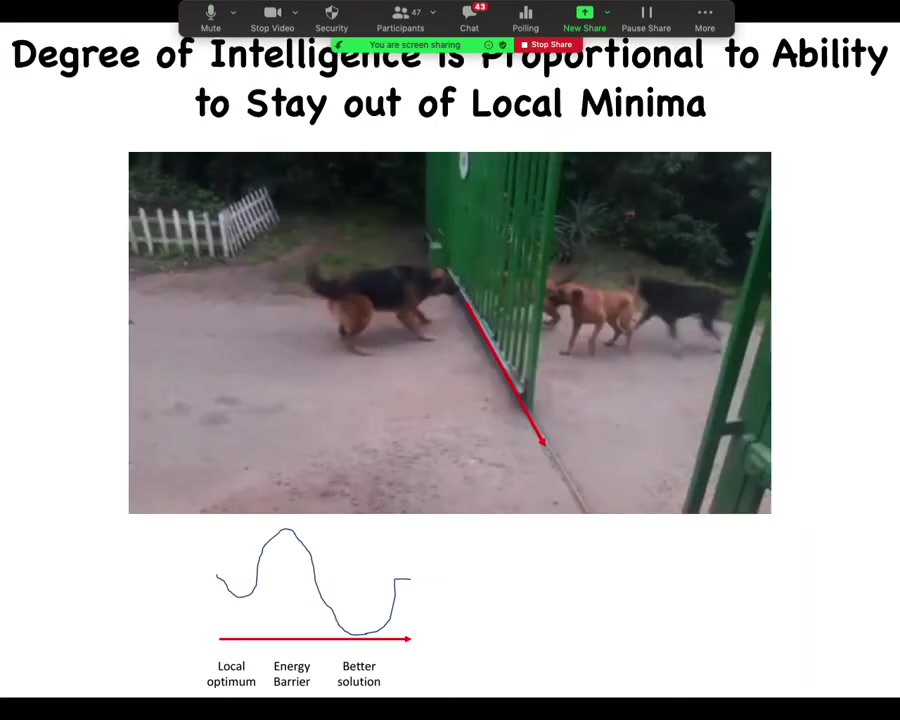

One way to generalize this question of how much intelligence, because I've made the claim that everything's a continuum, is that the real question is not if something is intelligent, but how intelligent is it. One way to define that across all these different systems is to ask, how competent is it at staying out of local maxima?

Slide 10/34 · 18m:24s

What I mean by that is a simple example. Here are some animals that would like to get at each other. The closest path to your goal is this direct line. What you could do if you were smart enough is you could go around here this way. But in order to do that, you would have to temporarily get further from what you see as the direct line to your goal. The level of IQ is roughly proportional to your ability to delay gratification and navigate the space in a way that temporarily takes you away from where you think you want to go, knowing that ultimately you stand a good chance of finding an appropriate, deeper global maximum.

We can think about how these systems navigate their various spaces and quantify this as the degree of intelligence that they have.

Slide 11/34 · 19m:15s

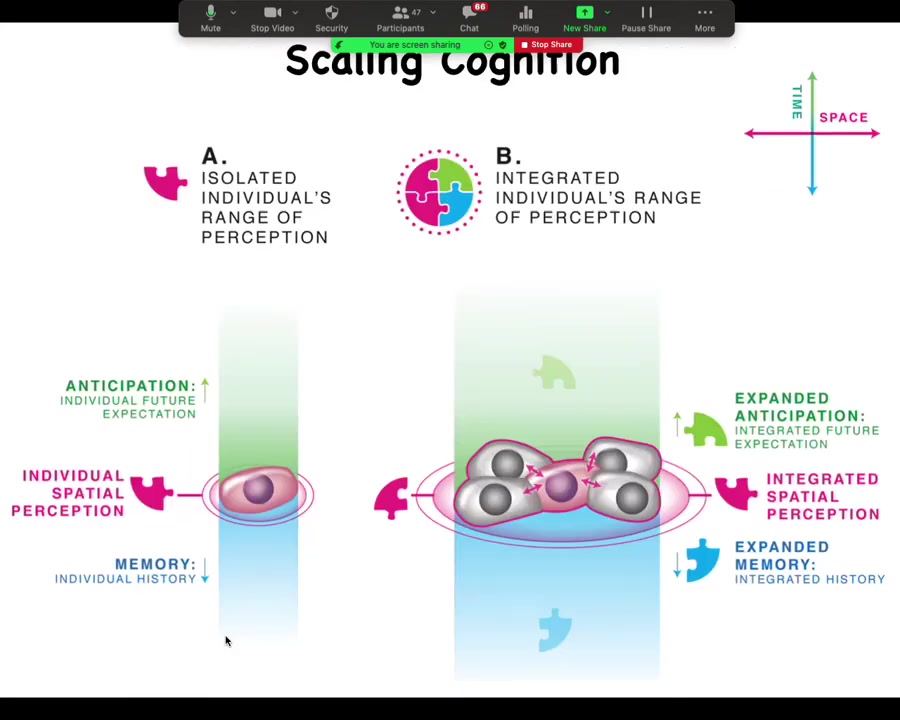

Here's this cognitive light cone model. The idea behind being able to compare all these different intelligences, we can't use what they're made of anymore because who knows, it could be almost anything. We can't use their position on the phylogenetic tree anymore to compare them because now we're creating artificial creatures that don't belong anywhere on this tree. One way to do this is to ask this question. We say that the definitive kind of property of a cognitive agent is that it's able to pursue some type of goal. The next question is, what is the scale, both in space and time, of the goals that that agent is capable of pursuing? What you have here is a space-time diagram where all three dimensions of space are collapsed on this one axis, time is on this axis. What we're going to do is plot for different kinds of creatures what is the radius of concern that they have? What are the scales of the goals that they can pursue?

Very importantly, this is not the radius that they can sense. This is not simply a sensory thing: how far out can they sense. This is about the scale of the actual states that they are trying to manage that stress them out when they don't achieve them and so on.

Here are some examples. If you're a tick, you have, as far as we know, very little predictive power forward, very little memory going backwards. All you're interested in is the very local concentration of butyrate, which you're going to follow the gradient. You're like a bacterium. Everything you care about is very local, both in space and time. If you're a dog, you've got a bit of memory going backwards, you've got a bit of predictive capacity going forwards, but you're never going to care about what's going to happen 2 weeks later in the next town over. For certain systems, that's never going to happen. If you're a human, you could have a massively large cognitive light cone in the sense that you might be working towards world peace. You might actually be depressed that the sun is going to burn out in billions of years. Humans are able to comprehend massive goals that, unusually for all these other creatures, transcend their own lifespan in terms of their time, for example. We are perhaps the only creature that understands that the goals that we have are actually not achievable because we have a limited lifespan.

There are all sorts of alien, artificial, synthetic intelligences that could have any shape of light cone. The reason we call this a light cone in this space-time diagram is simply that it sets the boundary of the goals that are accessible to you. Anything that's outside the light cone your cognitive structure cannot use as a set point for your goals. We are all compound intelligences, so you as a human may have various grandiose goals that you're working towards, but you've got components that are at the same time individuals with much more local and much more self-contained goals that are smaller on the same diagram and everything interpenetrates.

I want to show you how this plays out in real biology.

Slide 12/34 · 22m:32s

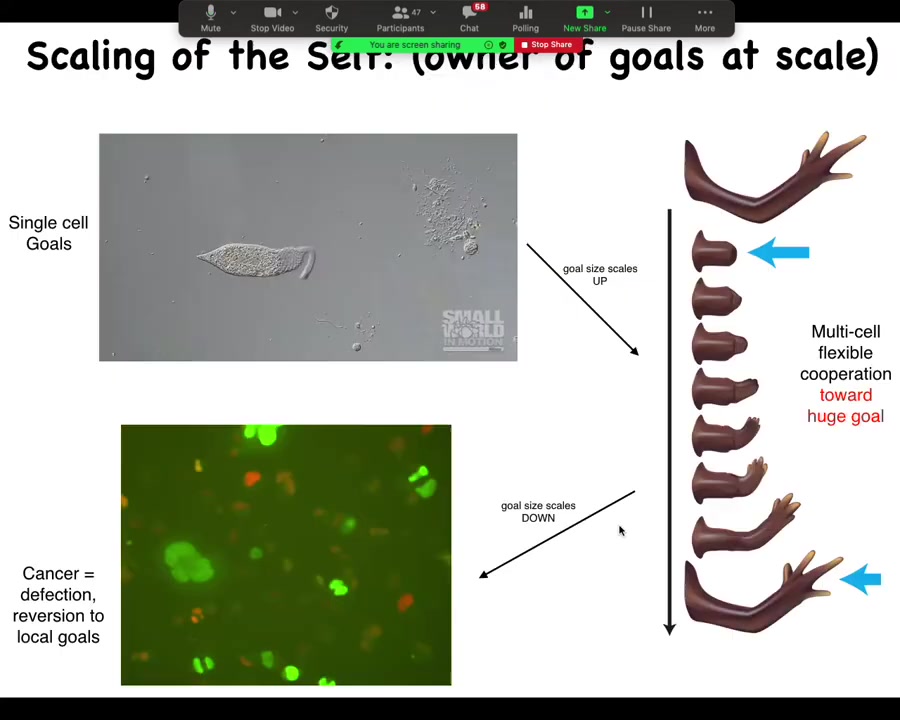

What you're looking at here, this thing right here is a cell called a lacrimaria. It's a single cell. There's no brain, there's no nervous system, no stem cells, no cell to cell communication. But notice how incredibly competent this thing is. All of its physiological, anatomical, and behavioral goals are solved at the level of this one cell. In its local environment, it can do everything that it needs to do and it's very adaptive.

During multicellularity and the metazoan body plan, cells got together and started to work on massively larger goals. Here is a salamander, and in the salamander, the cells built this arm. If you amputate the arm, the cells immediately spring into action. They continue to rebuild, and when do they stop? They stop when a correct salamander arm has appeared, and then everything stops.

This is a collective intelligence agent that knows the difference between this state and this state. It knows when the correct state has been restored. That's when it stops doing everything. This is the target morphology. All of these cells are working together towards this goal.

When deviated from this region of anatomical morphospace, meaning you're out of the region of having a correct arm and down into this stub, then it's able to navigate that morphospace by deforming this structure, getting back to the correct region, and then that's where it sits and that's where it rests.

This ability to get back to the correct region of the space, even under drastic perturbations, is an immediate signature of the goal-directedness of these cells. And the goal is huge. No individual cell knows what a finger is or how many fingers you have. It's the collective intelligence of this tissue that is able to make these decisions. Do we stop growing? Do we keep growing? What do we grow?

That process—what you've seen here is the inflation of the boundary of the self. Here, the computational boundary of the self is the size of one cell. Here, it's massive. It's the size of a whole limb. Now you see the inflation of it. Now I'm going to show you the contraction of it.

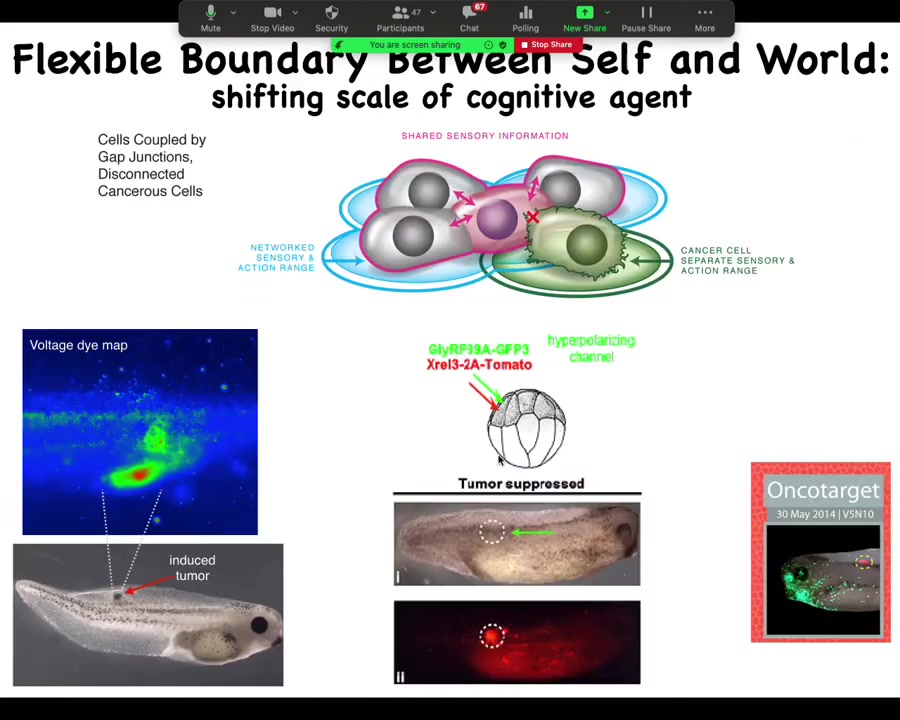

One of the things that can happen is the communication between these cells can go awry, and then these individual cells can stop being part of this whole collective network. When that happens, that's cancer. What you're seeing here is glioblastoma. These individual cells have reverted back to this unicellular lifestyle. As far as they're concerned, the rest of the animal is just the outside environment, meaning that boundary between self and world has shrunk back down to the level of a single cell.

Slide 13/34 · 25m:18s

Conceptually then, what you see is a single cell that has a little bit of anticipation, a little bit of memory, a certain radius of concern.

A collection of these cells connected into a network now necessarily has a bigger radius, both in space, because now we can integrate information across a larger spatial area. It has higher computational capacity because now you've got a bigger network with way more states. Now you have more ability to anticipate forward and more capacity to remember backward.

There is a drive that cells have for predictability, which is why they surround themselves with copies of themselves. That could be a driver for multicellularity.

One of the predictions of this set of ideas is that we could probably address cancer by targeting this problem. If what we're saying is that what keeps you working towards healthy tissues as opposed to metastasis is this kind of network of communication that binds you into a larger agent, maybe we can enforce that. Maybe we can track that during cancer and actually enforce it artificially as a method of treatment.

In my group, the connection and communication I study are bioelectrical. All cells, not just neurons, communicate electrically.

Slide 14/34 · 26m:41s

In a tractable frog model, we injected human oncogenes into these tadpoles. The oncogenes make tumors. This is an image of a voltage-sensitive fluorescent dye. What this electrical imaging shows is that even before the tumor becomes apparent, these cells electrically disconnect from their neighbors. They acquire an aberrant bioelectrical potential, and that's when they're going to go off on their own.

We did the same experiment but artificially forced these cells to remain in connection with their neighbors, even though the oncogene is still there. Nasty mutations like KRAS mutations — you can prevent tumorigenesis here. In this animal, the red is a fluorescent lineage tracer showing where the oncogene is. There's no tumor because these cells were injected with an ion channel that forces their voltage so the gap junctions are open and the cells stay in a network. They don't get the chance to shrink their informational boundary.

This shows a model system in which we go from ideas about what's really the nature of goal-directed intelligence in morphospace, making a healthy tissue instead of crawling around randomly as an amoeba, and how we can manipulate that in a very predictive way.

Slide 15/34 · 28m:05s

To show you a couple of things, let's talk about how this plays out in two ways. Morphogenesis is a collective intelligence, and then I'm going to show you some novel organisms.

The big question: this is a cross-section through a human torso. We all get there from this point where we start as a collection of cells. These cells work together. They build this unbelievably complex invariant structure. Look at this thing. All of the cells, the organs, everything is in the right place next to each other. We want to understand where this pattern comes from. If you're thinking DNA, keep in mind that we know what the genome actually encodes. The genome encodes protein sequences. It doesn't directly say anything about this.

We need to understand how these cells bind together to pursue these large-scale goals.

Slide 16/34 · 29m:03s

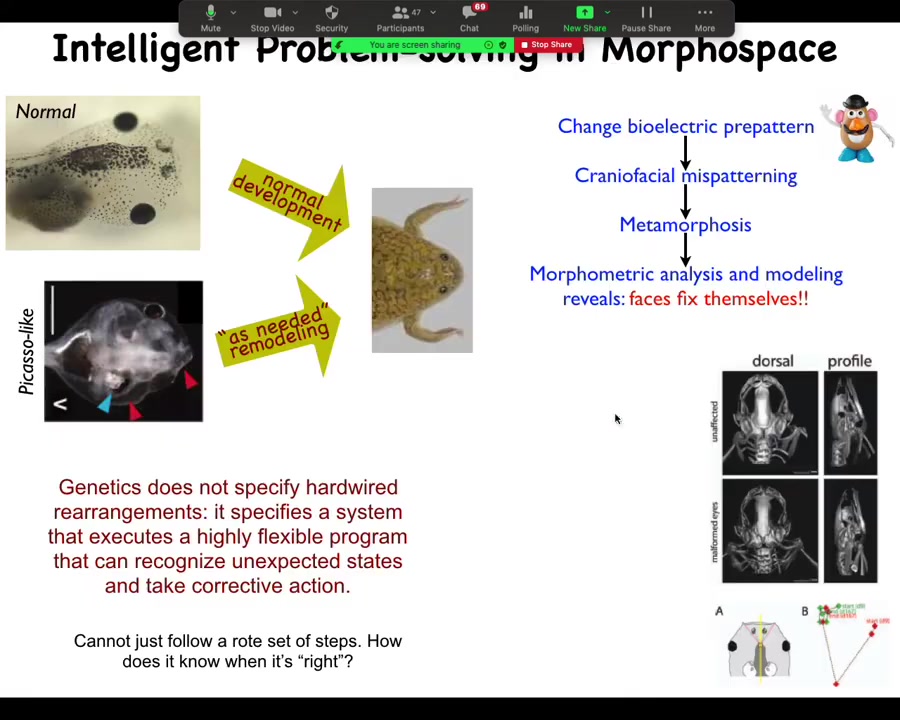

In order to have an example of this goal-directedness, we found in our lab that these tadpoles, in order to become frogs, they rearrange their face. The organs, the eyes have to move, the nostrils, the jaws, everything moves.

What we found is that if we make these so-called Picasso tadpoles, where everything's in the wrong place, they still make largely normal frogs. The genetically encoded hardware does not specify hardwired movements for each individual organ because otherwise they would just end up in the wrong place, having started from the wrong place. What it actually specifies is an error minimization scheme: keep moving until the final product is correct. That means it's much more intelligent than this system because it can actually handle novelty. It can handle new situations where everything starts out wrong. You still get a pretty normal frog, which raises questions about how it knows what a normal frog is.

Slide 17/34 · 30m:01s

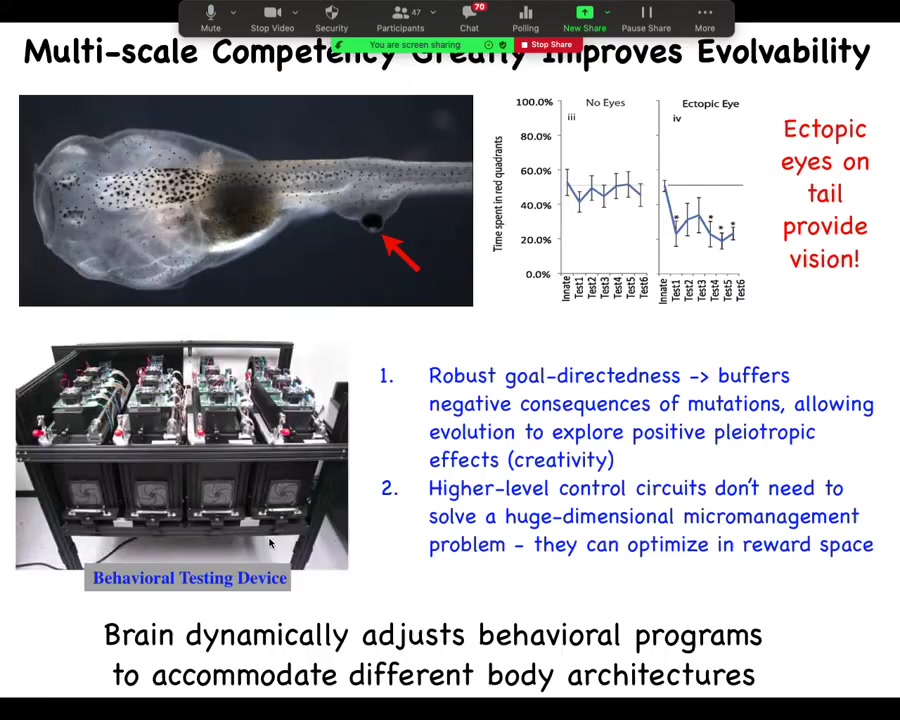

The amazing thing about all of that is the implications for evolution. Here we have a tadpole. You will notice that this tadpole has no eyes where the eyes normally are supposed to go, but we've given it an eye on its tail. These tadpoles can see perfectly well. You can use this machine to train the tadpoles on visual learning tasks. They learn quite nicely. What this suggests is that these eyes don't connect up to the brain. They connect often to the spinal cord. Completely novel architecture. Behaviorally, they still do what they're supposed to do.

Think about what this gives evolution. If you know that your parts are competent, meaning they're going to still get their job done even when things around them are changing, maybe drastically changing, it means that every time you have a mutation that moves things around or makes some sort of changes, you don't immediately acquire very low fitness when everything falls apart. Let's say you had a mutation where something had some kind of a positive effect somewhere, but also it moved your eye to a weird location. If your parts were hardwired and not competent, evolution would never see the benefit of that mutation because you would immediately get a penalty for all the other stuff not working, you'd be blind. You would never get to explore that. The evolutionary landscape would be really rugged.

The fact that some of the consequences of that mutation are simply going to be buffered by the fact that the subunits are still able to get their job done when things around them change means that you now have the opportunity to explore the positive consequences of these mutations and accumulate lots of mutations that are now neutral instead of by default being deleterious. The fact that these subunits are goal-directed, locally competent agents really cranks up evolvability.

Slide 18/34 · 31m:52s

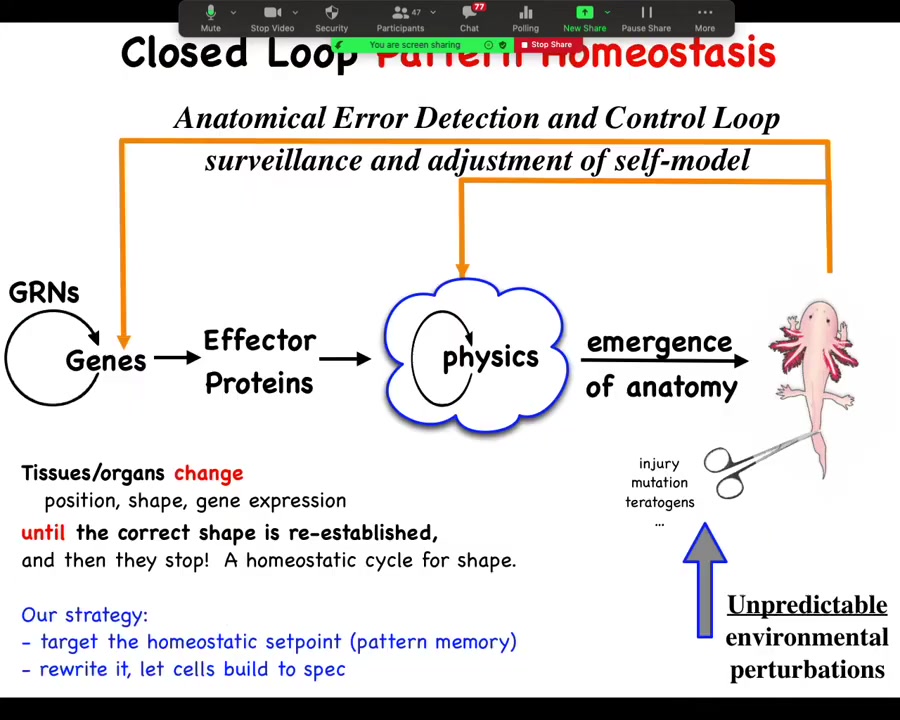

In my group, we've been studying this. This is the typical developmental biology story where you have these gene regulatory networks, they make some proteins, and then somehow there's an emergent process by which you get this amazing thing.

We study these feedback loops that, when the system is deviated from its goal, either morphological or physiological, by mutation, by injury, teratogens, whatever, there are these feedback loops that come back and try to get it back to the space where it needs to be. One of the key things we want to know is, where is the set point? How does it know what the correct pattern is? Every homeostatic system has a set point somewhere. The brain is a great example of this.

Slide 19/34 · 32m:42s

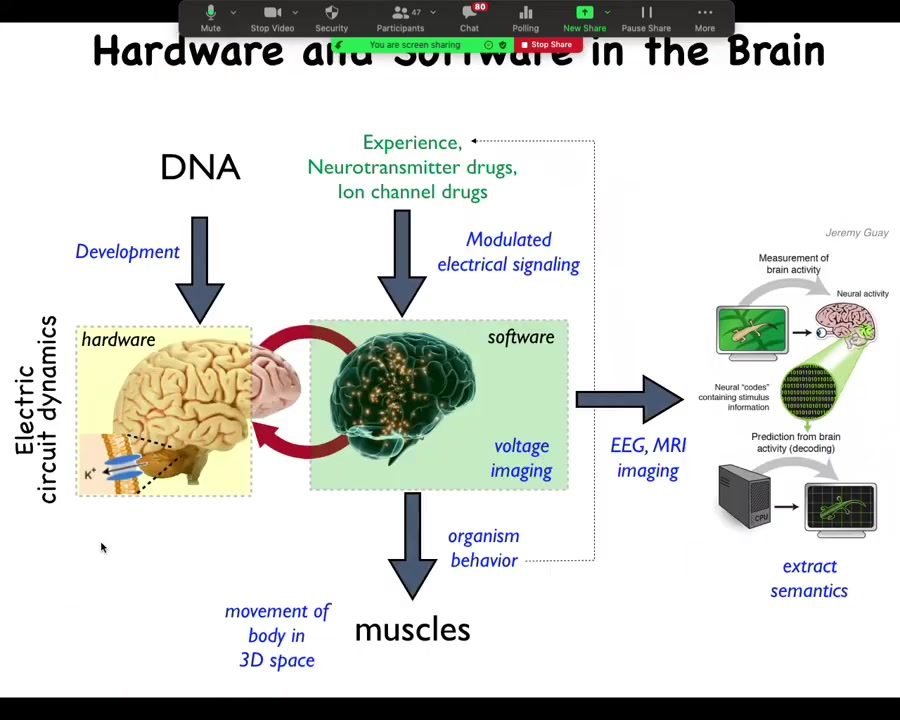

We asked, how does the brain do this? We know there's this interesting hardware system that is using an electrical network to run software. What the software does is it activates the muscles to move you through three-dimensional space. You can try to read this out, and people do this with neural decoding.

Slide 20/34 · 33m:07s

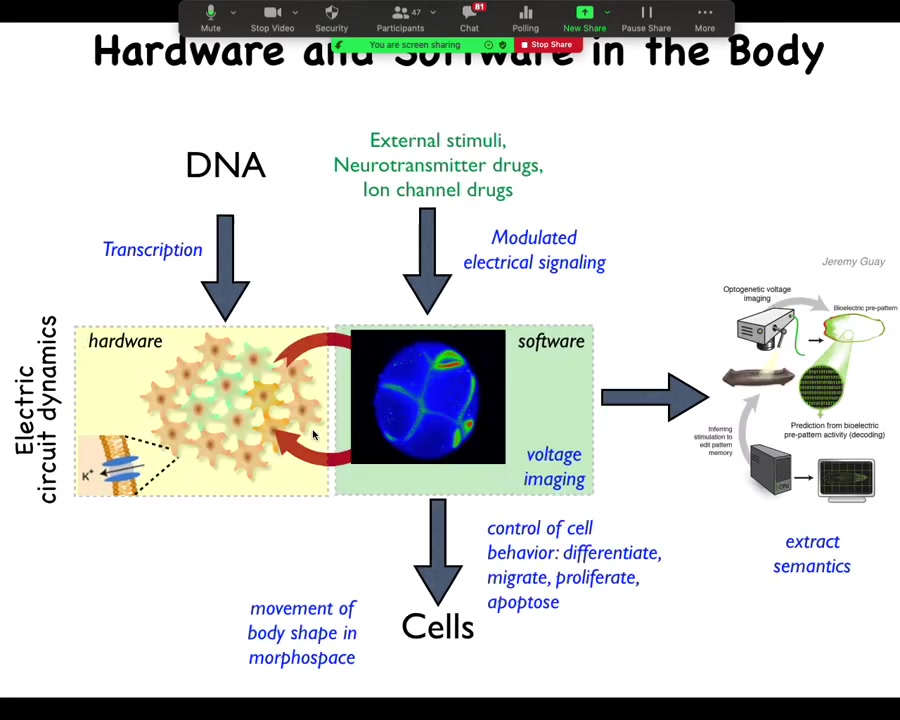

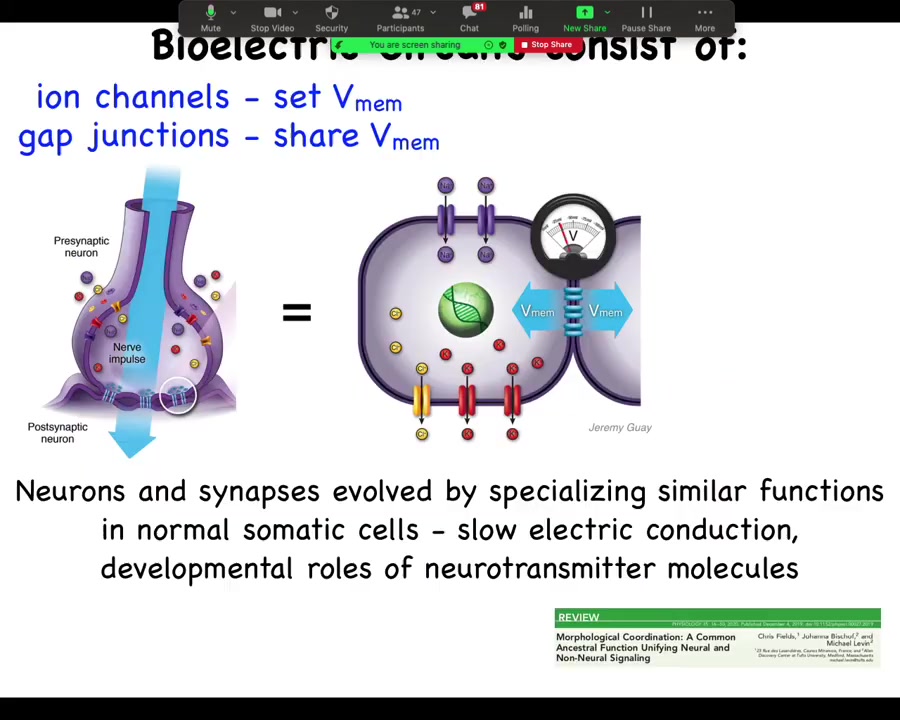

It turns out that all cells do this, and so all cells have the same architecture where there are a bunch of cells connected electrically. The electrical activity is a kind of software, but instead of moving muscles to get you around three-dimensional space, it controls cells to get you around morphospace, to change the shape to develop and then to repair the anatomy of the organism. You can take almost any neuroscience paper and do a find-and-replace and replace "neuron" with "cell." And if you replace milliseconds with minutes or hours, almost everything else holds. This is a system that evolution was using before brains came on the scene.

Slide 21/34 · 33m:45s

So the way it works is that every cell has these ion channels; they set voltages. These voltages can be communicated to the neighbors through these gap junctions, these electrical synapses that can open and close. Both of these things can be voltage sensitive themselves, which means that it's a feedback loop. So that means it's a transistor. It's a voltage-gated current conductance. So that means that you can now make feedback loops, logic circuits, all of that. Evolution found everything we do in our computing devices long before brains, somewhere around the time of bacterial biofilms.

Slide 22/34 · 34m:20s

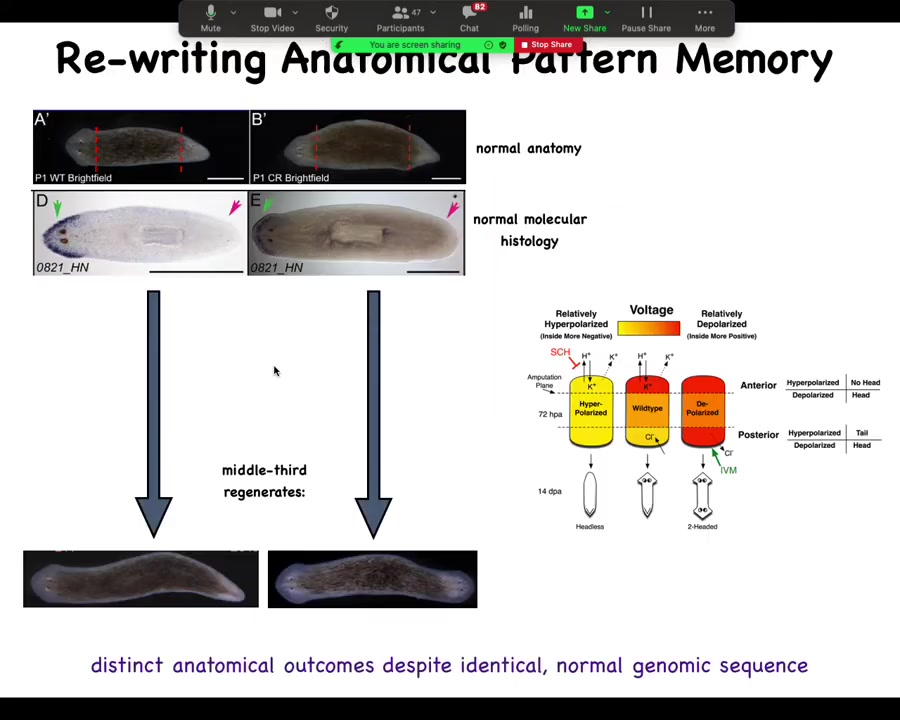

And so I'll show you a very quick example of this, which is that these planaria — here's a one-headed flatworm. We look at where the molecular markers are. Here's an anterior marker up in the head. So this animal molecularly, here's where the anterior tissues are, not in the tail. And then when we amputate this, we take the middle fragment and that thing makes a single-headed animal. We take this middle fragment and it makes a two-headed animal. Why? Because in the meantime, what we've done is manipulate the electrical circuit that tells these cells how many heads we're actually supposed to have.

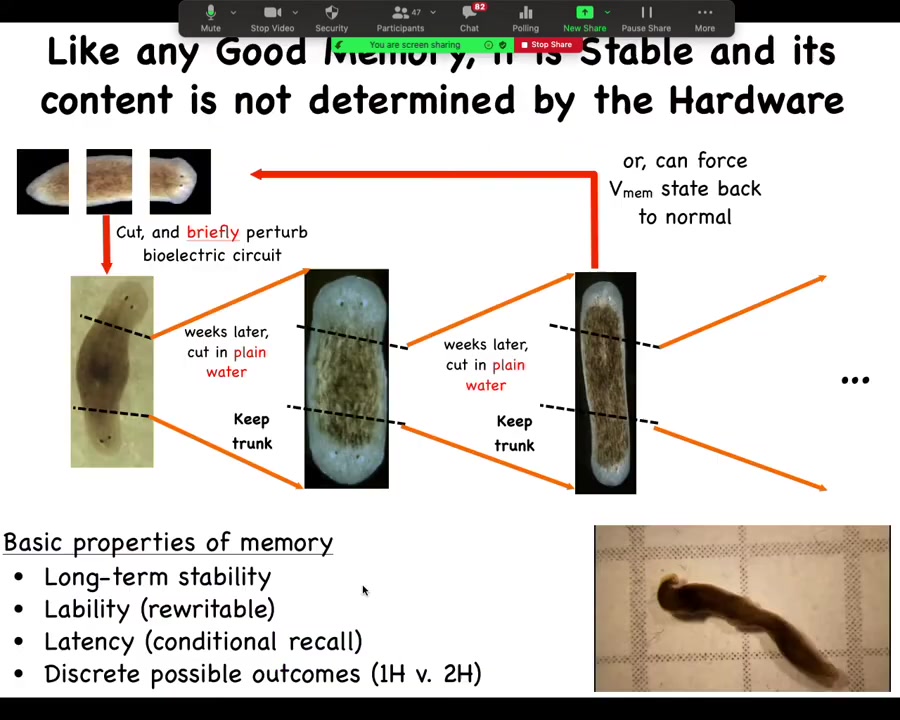

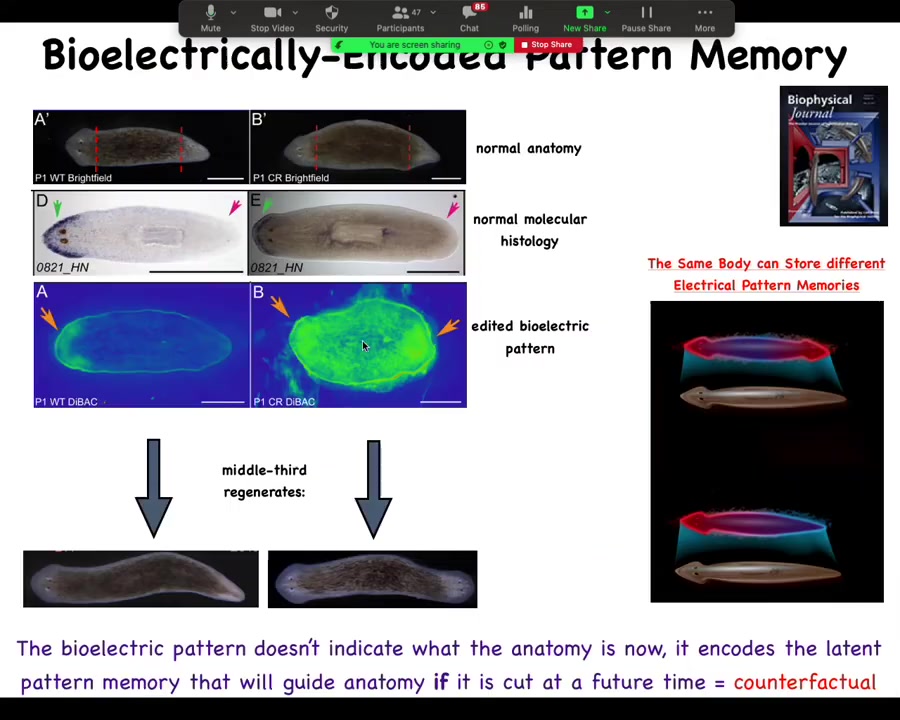

Slide 23/34 · 35m:01s

I call it a pattern memory because if you take these two-headed animals and you cut them again with no more manipulation, and, in perpetuity, you just cut off the ectopic head, you cut off the normal head, normal middle fragment, it will continue to form two-headed animals. No changes to the genomic sequence. Nobody's genetically edited. There's no CRISPR. It's wild-type genetics. That's not where this information is. The information is stored in the electrical pattern. It's literally using the same mechanisms the brain uses. It's in the electrical memory of this collective agent known as the tissue of this worm. Here you can see what these guys are doing in their spare time.

Slide 24/34 · 35m:38s

What the pattern looks like, it looks like this, and it's messy because the technology is still being worked on.

But here is the bioelectric pattern memory. We can literally think of this as neural decoding. We can literally look into the mind of this collective intelligence and see what the memory is. Here's the memory of how many heads you're supposed to have, just one. We can go in and give it a different pattern of two heads, and sure enough, that's what the cells build.

This is a system that is able to pursue goals. It is able to represent the goal that it wants to have. Notice something very important. If you think about a memory of something that's not going on right now. We're very advanced. We're able to entertain counterfactuals. This electrical pattern here is not the pattern of this animal. It's actually the pattern of this animal that we've already changed. In other words, this one-headed body can store one of two types of memories of what a correct planarian is supposed to look like. When it gets injured in the future, it uses its memory to construct the new body. This bioelectrical pattern is not a readout of the current anatomy. It is a represented counterfactual memory of what you're going to do if you get injured in the future. If you don't, you stay as one-headed.

We start to see this is the basement of counterfactual cognition. This is a simple form.

Slide 25/34 · 37m:15s

For the last couple of minutes, I'm going to show you some work done by Doug Blackiston, and we have this new institute with the University of Vermont where we're pursuing all of this.

What we did was ask the question: if we liberate cells from their normal position in the embryo, would they reboot multicellularity? And if they do, do they cooperate? What would they make?

What he did was to grab some skin cells from this early frog embryo, dissociate them, let them reassociate, and ask what they do.

The predictions at the time were: they might make a monolayer, they might crawl off and make a cell culture where every cell is for itself, they might all die — all kinds of predictions.

Slide 26/34 · 37m:59s

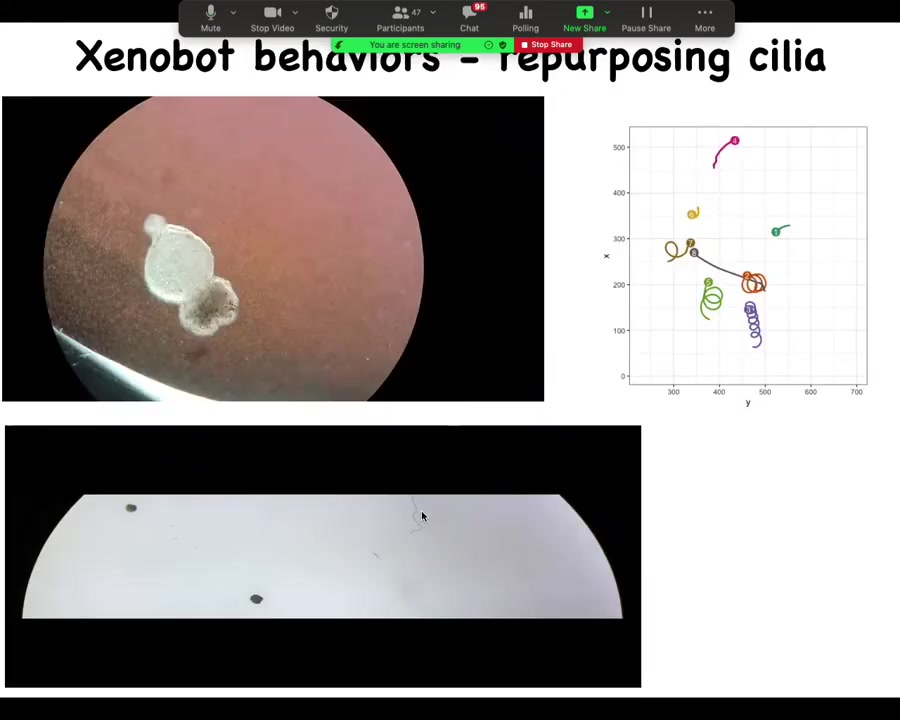

This is actually what they do. What you see here is they work together to build this little critter. They use the cilia, these little hairs on the skin cell that are usually used to redistribute the mucus along the body of the tadpole. They actually use it to swim around. They become like marine plankton larvae and things like this that work like this. So they have all kinds of behaviors. They can swim, of course. You can see here: these two, this one is going in circles, this one patrols back and forth. This is a group. When you put them all together, they have some interesting group behaviors where they can circle each other or go on a longer journey around the dish, or they can just sit around doing nothing.

Slide 27/34 · 38m:45s

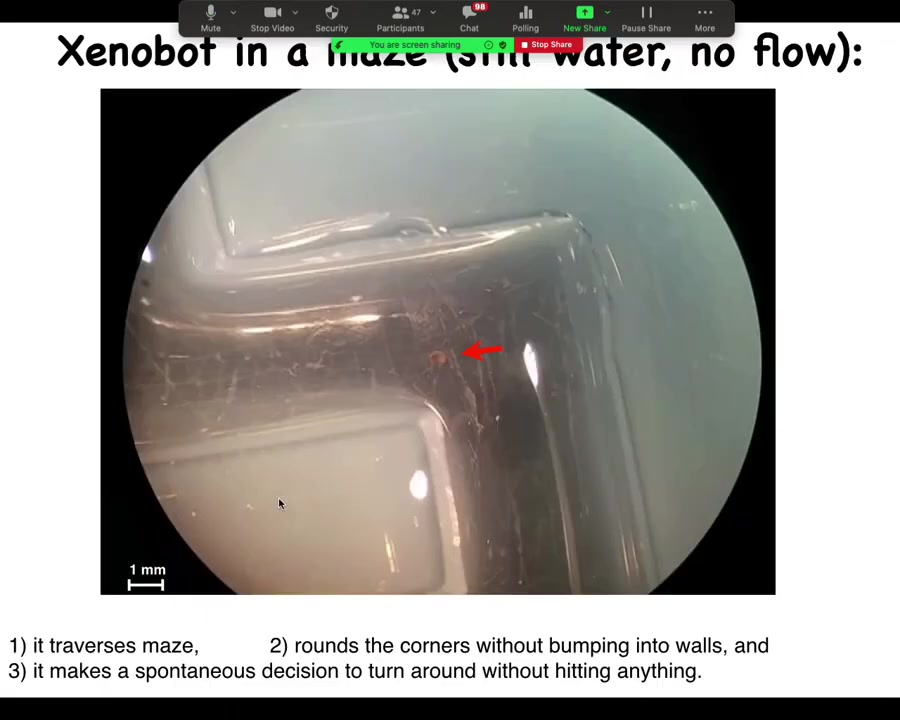

This is an example of a maze traversal.

The maze here is still. There are no gradients, there's no water flow. It's just still spring water. You can see what this thing is able to do. I'm going to talk you through this path again.

It starts moving. It keeps going. It's going to take this corner here without having to hit the opposite wall. It somehow can tell that there's a way to turn here. Around this point, some primitive version of free will kicks in where there's some internal dynamic that forces it to turn around and go back where it came from. Again, no gradients, no external flow. Something internal is going on that says turn around and go back. They have a stochastic behavior in doing this.

Slide 28/34 · 39m:27s

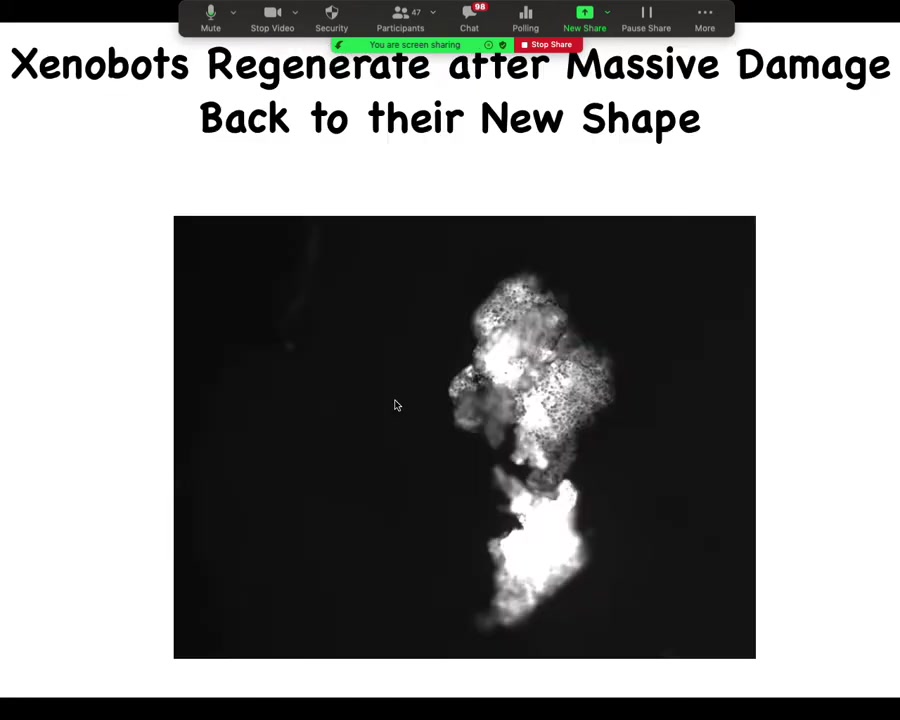

If you injure them, here's one that was cut down the middle; it will regenerate. It will regenerate to its new shape, to a proper Xenobot shape. If you think about this position right here, this is 180 degrees. Think about the forces that have to be generated through this hinge. It's doing a bicep curl from a completely straight arm. That's the worst. Energetically, that takes the most power. And they're able to exert that force through the hinge and try to merge. These flashes that you see are calcium signaling.

Slide 29/34 · 40m:01s

Here are two sitting next to each other. What we've done is we've expressed a calcium reporter that shows you that the skin, even though there are no neurons, it's just skin. It's 100% skin. What you can see is that they still have these interesting calcium dynamics that are, we don't know yet, a readout of the computations that they're doing.

They do other interesting things, like if you put them in a dish with particles, they collect the particles into piles.

Slide 30/34 · 40m:30s

We can make something we call microbots, which are very small versions. You can see this little horse-looking thing. They have their own interesting shapes. They wander around. It's exploring this piece over here. You can see in a minute there's going to be a calcium. Something happened over here. These are all novel creatures with novel capacities. And the cool thing is, sometimes I've done this talk in the past where I just show people this. I don't tell them what it is. And then I ask them to guess. If I said, okay, guess what all these things are, they said, well, you found them in a bottom of a pond somewhere. I'll say, well, we've sequenced the genome. They say, that's great. Let's look at the genome and see what we can gather here.

Slide 31/34 · 41m:07s

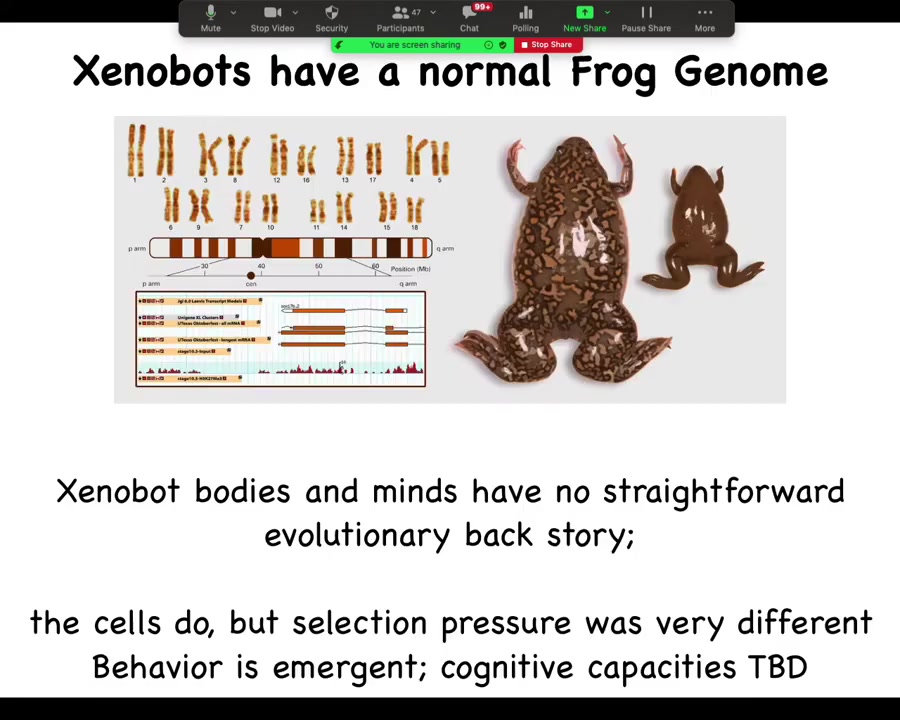

The genome is 100% Xenopus laevis.

This is an example of the unbelievable plasticity of the hardware that is genetically encoded, which is that it has a default outcome, which is this frog, or a tadpole, and then a frog. But these cells are perfectly competent to make other things, not just single-cell things, but large-scale things.

These Xenobots, whatever cognition they have, we have no idea how advanced they are; we don't know if they can learn — we're going to find out. They have no straightforward evolutionary backstory.

If you ask why it swims or why it has a particular color or tail or anything else, the answer is always the same: because of millions of years of selection pressure for the ancestors to do X, Y, Z. These xenobots don't have any of that because the cells were selected for their ability to sit quietly on the outside of a frog and keep out pathogens. Now they're doing completely different things.

That just shows that we can make creatures that are, in an important sense at the organism level, outside the phylogenetic tree of life as we know it.

Slide 32/34 · 42m:17s

I'm going to wrap up by reminding you what I talked about. Here's our approach, the continuum of agency. It's not binary, it's a continuum. It's all about an engineering approach to this where we can't just decide how cognitive we think things are. I've proposed one way to categorize and compare selves with the scale of the goals that it's capable of pursuing. I've framed intelligence as a kind of problem solving in abstract spaces, and there's a lot to be said on this. We can talk about this. Developmental bioelectricity is the evolutionary precursor of everything that goes on in the brain. It's a kind of physiological medium for the software of life. It gives you the direct access to the cognitive content of these swarm intelligences that build bodies. We have this incredible multi-scale architecture that potentiates evolvability.

This is a drawing that our graphic artist Jeremy Gay made for us showing how at this point we are just a tiny speck in this incredible option space of organisms that are combinations of evolved materials, design materials, software materials. We're going to have to have frameworks that deal with all of this.

These are the various papers that get into this.

Slide 33/34 · 43m:41s

I want to thank the people. This is Doug Blackiston, who, with Emma, does all of the Zenobot work, and various other people who did the things I showed you today. Thank you.

Slide 34/34 · 43m:54s

I will take questions. I'm sorry for running over time and happy to discuss. Thanks so much, Mike.

Hi, thanks so much for that talk—that was mind-blowing. I am curious if you could elaborate on the different mechanisms that underlie individuation or de-individuation. On one of the last slides you defined it in terms of the boundaries of goals that you're capable of pursuing. Earlier you talked about cancer cells defecting from their collectives and becoming more individual, and that seemed to depend on not being in communication with others. Could you outline it again? I'm trying to wrap my head around it.

Sure. It's a great question. I didn't get a chance to really talk about it, so I'll do that now. I'm going to tell you what I think is going on, and then I'm going to speculate about the mechanism.

When you have individual cells connected by gap junctions, you end up with a network that has much increased computational capacity and is able to store and work towards goals that are much bigger than single-cell level goals.

When you pursue goals, you need to do three things: be able to measure the current state, compare it to a memory you have, and exert broad activity because the things you have to fix may not be local.

Connecting cells by gap junctions hugely scales all three. You can measure across a wider area; you're not just a single cell measuring a tiny thing. Your memory as a network is much larger than anything a single cell can keep. And your effectors can remodel a whole large structure; before, a single cell's options were divide, die, or change shape. All of those things are potentiated.

At least for this particular collective agent that I've been talking about, that's what happens.

Gap junctions are magic in the following way. When two cells communicate by sending a diffusible chemical from one to the other, because it comes from the outside, the recipient cell can tell that it is not mine. The cell can ignore it, act on it, but it knows it's not its own internal state. So it can keep a tight boundary cognitively between memories that are mine and information that comes from the outside.

Think about what gap junctions do. Gap junctions are a direct link between the internal milieus of two cells. If two cells are connected by gap junctions and something happens to one—it's poked or injured—calcium flux goes up and enters the other cell. That receiving cell all it sees is calcium. There is no metadata on the calcium saying, "I came from a different cell." There's no idea where it came from. The fact that a gap junction introduces information directly into your cognitive structure without labels about origin makes it very difficult for the two cells to maintain individual minds.

What information you have is the same information that you have. And so that means two things. Number one, it's like a mind melt where you just can't maintain distinctiveness anymore because all the information is shared. And in a game-theory way, it means that you are now tightly linked as far as cooperation. You can't help but cooperate because whatever you do to your neighbor, it's going to happen to you within seconds. So there's no sense in which you can now defect and do nasty things to your neighbor because you can't even maintain that boundary. So all that is a long-winded answer to the fact that the gap junctions have this incredible property that they scale the self both computationally and in the sense of game theory and in all of these ways.

Thank you, Michael. This has been truly ******* great. And you offered the possibility during the talk that if somebody brought it up, you would talk about the hard problem with phenomenal consciousness. I'm offering you that opportunity and look forward to being further blown away.

Okay, well, I should say that one reason that I don't lead with it is that I have the least to say about it in the sense that I think it's a really hard problem. Hopefully without insulting anybody, a lot of work on consciousness is not really work on consciousness. It's work on correlates of consciousness on all kinds of things. Consciousness is really hard to get a handle on. I really only have two interesting things to say about it. One is that as far as I know, we actually have only one reagent that lets us actually address consciousness. And that is general anesthesia. So when you undergo general anesthesia, you walk into the doctor's office, you are a collective centralized intelligence. You talk about your hopes and dreams for after the surgery, they turn on the gas, you disappear. The cells are still there. Everybody's healthy. None of the cells are injured. Everything is exactly where it's supposed to be. You're gone. Why are you gone? Because most anesthetics are gap junction blockers. In fact, I think all general anesthetics are gap junction blockers. So what's happened is that the individual agents are still there, but the ability, this binding into the collective is temporarily suspended. When the halothane wears off, you come to it and you say, hey, doc, how'd the surgery go? And you're back.

I don't think it's an accident that general anesthetics are gap junction blockers. I think the gap junctions and consciousness are actually closely linked. One of the guys who discovered gap junctions, Werner Lowenstein, was working on a book about gap junctions and consciousness when he died. I think it's a massive loss actually, because the book is gone, but he was working on this. I think there's a lot there. I think the remarkable thing about it is that any of us ever get back to the pre-anesthetic state afterwards. Think about it. You have this electrical network. You shut off all the connections, and then you hope that afterwards you land in the same attractor. It's amazing that ever happens. If you watch people coming out of general anesthesia oftentimes the first couple of hours are wacky stories about how they're pirates or they're gangsters or whatever. Go to YouTube and watch people coming out of general anesthesia. It's not just that they're out of it, it's that they literally have all these crazy changes to their cognition that eventually, usually, settles back to where they come from. That's the first thing.

The second thing I can say about it is that if whatever it is that we think about, assuming we think there is such a thing as primary phenomenal consciousness, for whatever reason we think it exists in the brain, for those exact same reasons, we ought to be willing to attribute it to a lot of other systems. There is nothing magical about the material in the brain that I know of that would underlie consciousness. Now, there are some cool tricks that make it verbal, which is interesting that we can talk about it mainly to our left hemispheres are usually talking to each other. If you do a split brain experiment, you find out that there's another agent in there, which doesn't share a lot of preferences necessarily and a lot of opinions with a verbal one. But those same kinds of architectures that enable consciousness are all over the body and probably all over other places in the world. And so they may not be verbal, but for the same reason we're willing to entertain consciousness in brains, you should be willing to entertain the idea elsewhere in other parts of the body. It would be a very different kind of consciousness, but there it should be.

Michael.

I am curious about your light cone graphic, which to me occludes the internal horizon or the resolution or granularity of the awareness that these systems have about themselves. It looks like data viz for integrated information theory. Again, not a hard problem question, but more a question about, in SFI language, the way that my awareness of my own body is the aggregate or collective awareness. I'm thinking of Jessica Flack's work on collective competition, and I like that you don't privilege any particular viewpoint here. Where you stand on this line of thinking, as it reflects on a society's ability to be aware of itself, or my own ability to be aware of what's going on inside me at a cellular level?

A couple of things. The first thing is that I definitely don't mean that framework to be the only valid one. That way of plotting this can be overlaid with anything else that you're interested in. If you say, okay, that's a nice way to scope the self, but I've got three other things that are also axes in my cognitive system, great, you can have a six-dimensional space, no problem. You can add it to other things.

But the other thing to keep in mind is that diagram is not a diagram of what you sense. It is explicitly not a boundary of what you're actually sensitive to. It is completely compatible. If you wanted to draw a space that was built around that, no problem, they would work together because that shows the boundary of the goal states.

Now, those goal states are both internal and external. I'm currently writing a paper on exactly this question of how the different agents are talking to each other and measuring states internal and external.

There's also some great work by Robert Prentner and some other people looking at how different types of agents construct virtual spaces for themselves, because the space in which you work, for us as scientists to say it's working in transcriptional space or it's working in behavioral space, that's not necessarily what the agent thinks it's doing. The system internally, how it represents its own space, might have nothing to do with how we represent its space.

Chris Fields made this very important point to me once where you've got a bacterium in a sugar gradient. The bacterium wants to get to a better place in the gradient. One thing it can do is operate in physical space and move to a better place in the gradient.

But the other thing it can do is operate in transcriptional space, turn on a different enzyme, and exploit a different sugar that's there in a different shape gradient. So now as far as that agent, is there a distinction between motility and transcriptional effectors? Maybe not. Maybe if you're a bacterium, you have this option space that doesn't cut that way at all. We're just cutting it that way because we're scientists and that's how we see things. So I think it's really important to ask how agents construct the virtual space in which they work.

So that's like the niche construction versus adaptation argument in archaeology. So, do you, in your research, see a fundamental generalizable principle about the internal horizon of a system as far as its microscopic horizon is concerned? Or for that matter, there's almost a theological concern around the spatiotemporal frame of different intelligence systems being so different from one another that if the galaxy were alive and thinking, how would we even know?

Absolutely. One of the things I'm working on now. It's still baking. One of the really important questions is exactly that. If you are a sub-agent, how do you know if you're a sub-agent within a bigger agent? You probably won't be able to comprehend the goals that the super-agent is following. But you might be able to infer evidence that you are part of a super-agent by the fact that your local option space is being deformed.

The thing about these nested agents is that what the higher-level agent does is deform the option space for the lower agents so that to them it looks very mechanical. If you zoom in, of course you see nothing but physics because when you zoom in with high enough magnification, all you see are things going down their energy gradients. But how did those energy gradients get there? The shape of those paths is being deformed so that the parts can be a little dumber. They're not completely dumb, but they don't have to be as smart as the whole because all they've got to do is follow their gradient.

In psychology, we do this all the time. Have you ever seen people who are trying to stop smoking and they sneak smokes at night? They'll hide their car keys because they know that at night they're not going to have the energy to look for them. Who are you playing this game against? It's your future self, but you're basically deforming the action space for yourself at a future state because you know that you're going to be less cognitive at that point.

So maybe you can get — and I don't know the real answer to this — maybe there are statistical, information-theory ways that you can look in your environment and say, I don't know what the global system is doing, but I'm definitely part of some global system that keeps deforming my option space in a way that I can get evidence for. Remains to be seen.

Okay, we have two folks who have not asked questions yet. Mike, if you have five more minutes.

Sure, no problem.

Alejandra.

Thank you so much, Michael, for the talk. It was amazing. I was thinking about your paper with Chris Fields, the one, "How Do Living Systems Create Meaning?" There is a specific hypothesis that the evolution of life can be viewed as the evolution of memory. For me, that hypothesis is awesome. I was wondering, what do you think about the idea that memory could be the core basal community capacity that enables the existence of others? And maybe a second question, related to the first one: are these different types of memory embedded in memory?

matter for physiological control and self-regulation, or there is one memory that shares the same mechanisms and principles, or there are different types of memory, editable, not editable, or what. Okay. A lot of interesting things there. So I do think that memory is an extremely important early ingredient in going up the scale of cognitive capacity. I'm not sure if it's number one; possibly number one is something like irritability. But memory is certainly there as at least maybe number one, maybe number two. I agree with that. It's very fundamental.

As far as different kinds of memories, there are certainly different architectures that enable more and less. There's habituation and sensitization, but then associative learning. There's different kinds of memories you can do. But I really think, here's what's important. Somebody said to me once, you really shouldn't be talking about these lower creatures or even materials or whatever having memory. I mean, we have memory, but these things, you got to come up with a different word, a different term, and then people won't be so upset. And I'm like, okay, so Isaac, all I can think about is Isaac Newton sitting there and he's saying, okay, the moon, that's gravity, and this apple, that's got to be schmavity. Now I got two words, great. You've got two words, but you're missing the whole unification that is here. The whole point is as soon as you give it two words, you give up one of the most important hypotheses, which is that different materials and different mechanisms, but the fundamental thing is the same. I'm very much in that camp. I think all of these things should be called memory because they have the important property; that's what's important about memory. It's not whether it's plasticity of synapses as we recognize them. Those are frozen accidents of evolution. Memory is deeper than that.

The thing about evolution is, and I'm sure Chris is—so Chris is brilliant, and you guys should have him to DC as well. I'm going to tell you what I think about evolution from that perspective. Imagine the following, and this ties to some things that Carl Friston has said as well. So think of a lineage, 50,000 years of alligators, 50 million years of alligators or something like that—you have a lineage of a certain agent going all the way back. Imagine that at every timeframe, all of the members of that population are hypotheses about the outside world. Every member of that population is a hypothesis. And so what evolution is doing is it's constantly testing and revising hypotheses about what's a good way to get around in this environment. What you can imagine is actually the whole evolutionary lineage is in fact a giant distributed cognitive agent performing active inference, basically, and the reason we can't see it is because we're tiny in space and we're tiny in time. We're taking one little tiny slice, and we're not seeing this whole process, and so then it sounds crazy because it's pulled apart in space and time, but I think it's actually a perfectly reasonable way to look at evolution, and lots remains to be done there, but I think it's a totally reasonable approach.

All right, last question, Danielle.

Hi, sorry, my camera's not working. I love everything that you're saying. I'm going to rewatch the talk several times. It's fantastic. One of the things that you were saying, I think it was the first or second question in response to consciousness, phenomenal consciousness, hard problem. I had no idea about the gap junctions, but it hints at information transfer, communication, and that is also reminiscent of global neuronal workspace stuff. Even the way that the hard problem of consciousness is framed, it's not why do we experience; it is what experience is like. It's fundamentally relative. It's comparing one type of representation to another. Even the most pure of quality, what is the experience of red light, we interpret relative to our evolutionary history, our memory, the associations that we have of that percept with other things.

I'm wondering what you think about consciousness, whether it's the hard problem or phenomenal, as possibly relating to transferring the representation of one thing relative to another?

I think that's absolutely right. I think a couple of things. First of all, one problem that I've always had with theories of consciousness is that I don't know what format the output of such theories could possibly have.

If you have a correct theory of consciousness of what it's like to be a lizard, and I say to you, what does your model predict about X, Y, Z? What do you hand me? What is the output? We know what most models are: they have some sort of third-person description, measurable and fine. What comes out of a correct theory of consciousness? It has to be some sort of first-person experience. Otherwise I don't know how we interpret them in any meaningful way that makes them about consciousness and not about measurements you take on brains.

I started thinking about whether the gulf between first-person descriptions and third-person descriptions is really so sharp. I think it's not for the following reason. Imagine a spectrum. Imagine a continuum where, on the one hand, you have a person watching an electrophysiological apparatus—electrodes, a CT scan, a PET scan—stuck into a brain, and you're looking at what's going on in that other brain. That's definitely third-person.

Then you say you don't have to look at the apparatus with your eyes. We can instrumentize the brain to drive wheelchairs and perform sensory augmentation. You plug yourself directly into the electrophysiology apparatus. You have electrodes coming into your brain; if you were using a device for the blind, from reports it feels like you're actually seeing. It's primary perception. You're getting signals directly coming off some brain-reading technology. Now it's still third-person, but you're experiencing it firsthand, whatever this brain is doing.

Further along the spectrum are fused brain cases like conjoined twins that have two brains literally connected to each other. No electronics: a biological interface; they are actually connected. You say, but those are two brains. Then you realize that there is no such thing as a brain anyway. What you have are regions of neurons. Even within one brain the regions have to talk to each other. The hemispheres talk to each other; within a hemisphere there's all kinds of communication. Once you've attached another brain in that way, it's no different than what your unitary brain is already doing, which is sharing information with neural tissue.

Shared consciousness sounds doable. I think it's absolutely doable because whether it's instrumentized with electronics or biological, the brain is not an indivisible single thing. You can put some kind of system at every position along the continuum between something obviously third-person and something obviously first-person, which is the ability of different parts of your brain communicating with each other to give rise to a single experience. So with these technologies and different kinds of new brains one can design, that distinction isn't as sharp.

And in fact, the longer I work on this, no distinction seems to survive this chimerism, the idea that you can just create these things in different configurations. It dissolves almost every firm distinction that I've ever heard of. I think everything is very continuous at this point. Your thought experiments are really helpful.

Dissolved brains. Everyone's minds have been completely blown, but as Kenzie pointed out, this dissolution is just a step along the path of all of us becoming butterflies. So thank you very much, Mike. We really appreciate you spending this time with us. We're really excited about your seminar next week. I've saved the whole chat. I can send that to you directly. There's a Slack channel, which I'll send you an invite to, and I'll put it there as well.

Fantastic. Thank you so much, everybody. Thank you for your questions. It's an incredible pleasure to talk to this audience. It's a very different experience, as you might imagine, from talking to some other audiences about these crazy ideas. So this is great fun. Thank you.