Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

Biology hacking itself, Xenobots, and morphogenesis

CHAPTERS:

(00:03) Host introduction and bio

(01:15) Xenobots and multi-scale minds

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/40 · 00m:01s

Okay, good morning everyone. I think we can start. Our 4th and plenary talk will be given this morning by Michael Levin. Michael Levin is a professor of biology and biomedical engineering at Tufts University in the US. Like many of you, I first got to know Michael's work through his papers on the Xenobots, a collaboration with Josh Baumgart. But it was after I caught his interview on Lex Fritzman's podcast that I became intrigued by the possibilities of his work. Michael is a very accomplished academic. He has the Vannevar Bush Distinguished Professorship. He is the founding director of the Allen Discovery Center at Tufts and the co-director of the Institute for Computer Design Robotics. His work is at the intersection of developmental biophysics, cognitive science, and computer science. I am very excited about this talk. Without further ado, let's welcome Michael.

Thank you so much. I'm really pleased to be able to share some ideas with you today. I appreciate the invitation. I will try a completely new way of giving this talk today. This is a very different way to tell these stories than I've ever done in the past. It goes along with John Searle's comment that you have to allow yourself to be astounded by things that any sane person takes for granted. We're going to go over some of these things today.

Slide 2/40 · 01m:46s

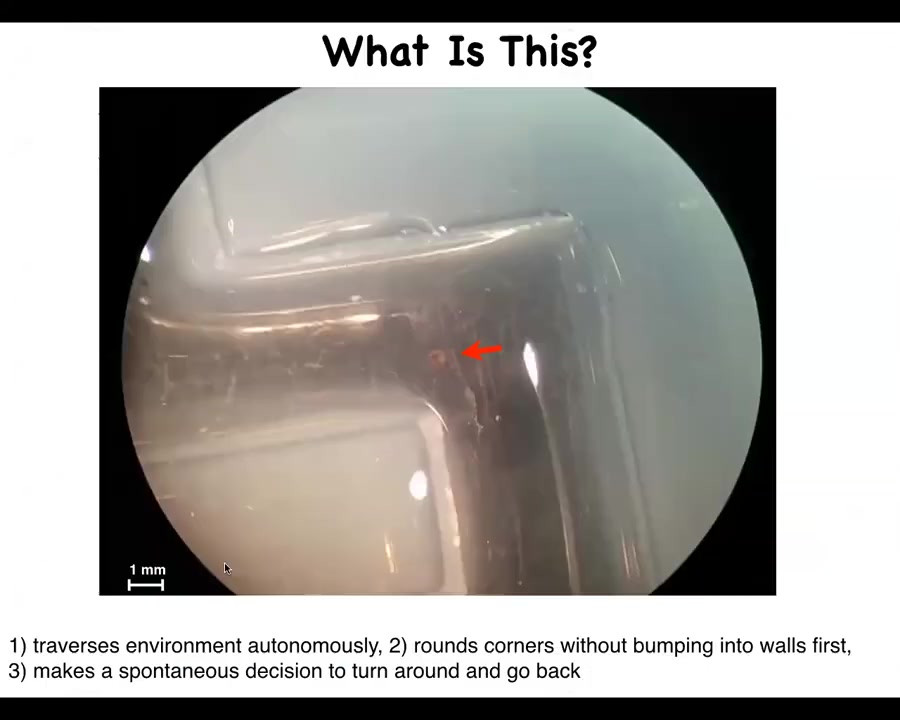

I want to start by asking what this is. This is a small biological that seems to traverse an aqueous path. This is filled with water. It moves down the path on its own. You'll see here it's completely self-driven. It moves down the path. It takes the corner without bumping into the opposite wall. Then spontaneously, it turns around and goes back where it came from. What is this?

Slide 3/40 · 02m:13s

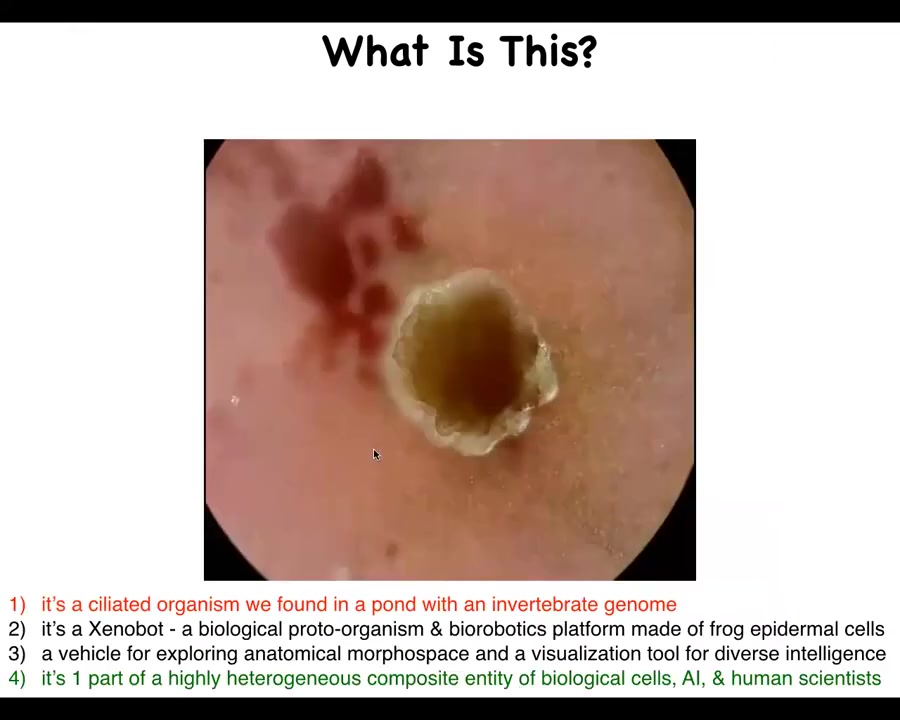

One thing you might think is that this is a ciliated organism that you might have found in a pond somewhere, and it would have an invertebrate genome. And that's definitely not correct. It's a Xenobot. This is a biological proto-organism and a bio-robotics platform that's made of frog epidermal cells. And this is true. It's also a vehicle for exploring anatomical morphospace and a visualization tool for diverse intelligence research. And I think that would be deeper and closer to the truth. Today I'm going to talk about another way of thinking about this, which is that it's just one part of a very heterogeneous composite entity, which consists of biological cells, artificial intelligence in a computer, and human scientists.

Slide 4/40 · 03m:01s

So to understand this composite entity, I want to first show you a few unconventional examples of biology. We're going to talk about a multi-scale competency architecture, which is related to a concept of polycomputing that Josh Bongard and I have been working on. I'm going to show you that functionality in living systems is often cryptic, often hidden by reliable, robust outcomes, and it has to be uncovered. I'm going to tell you that in biology every part is constantly hacking all of the other parts, and I'll show you some examples of this. We'll talk about plasticity, virtualization, and using a hardware-software lens to understand what these biological systems are doing.

Slide 5/40 · 03m:45s

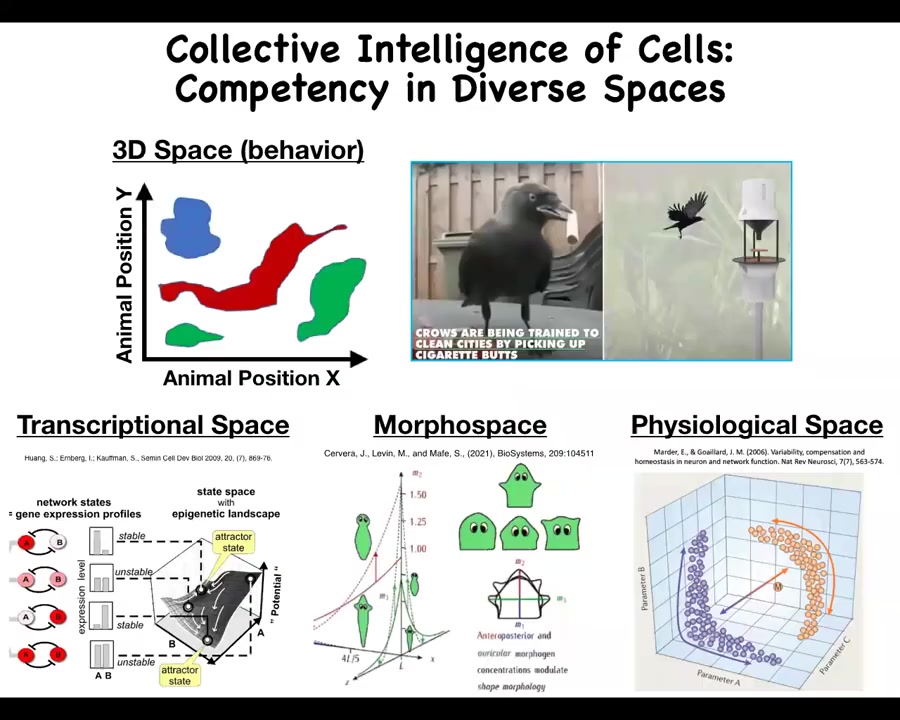

While we're very comfortable detecting intelligence of medium-sized objects moving at medium speeds in three-dimensional space, such as birds and primates, biological intelligence actually exists in many diverse spaces that are very hard for us to recognize.

For example, living systems routinely solve problems in navigating gene expression spaces, the space of physiological states, and the space of possible anatomical configurations, or anatomical morphospace. There are remarkable examples, of which I'll only have time to show a few, of problem solving in all of these spaces.

Slide 6/40 · 04m:31s

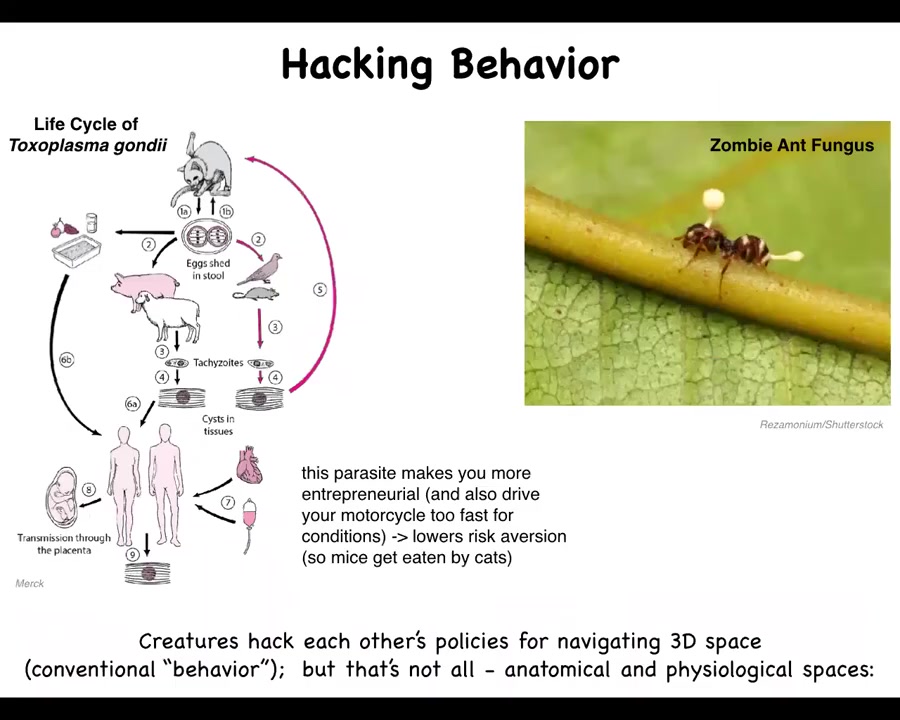

One of the things that we want to talk about is how organisms hack each other or control each other's behavior. You've probably all heard of this zombie ant fungus, which infects these ants and causes them to do a certain behavior, which is to crawl up on these leaves and freeze and later be eaten. There's another parasite which has this complex life cycle where it spends part of its time in certain animals, part of its time in other animals that eat the former animals. One of the things that this parasite does in order to make sure that the host gets eaten by the next one is that it reduces its risk aversion. If it finds itself in a rodent, for example, these rodents will lose fear of cats and they will come out in the open; they'll get eaten by the cat and the parasite goes there.

What happens in humans who spend time hanging out with cats when they get infected is that it makes you more entrepreneurial and it also makes you drive your motorcycle too fast for conditions. What it does is it lowers risk aversion. It's been found that people who have crashes, for example motorcycle crashes, and various captains of industry tend to have high rates of being infected by this parasite. It literally hacks high-level behaviors.

What's interesting is that in order to understand this creature, it is not enough to just study the creature itself. You have to understand the whole cycle. You have to understand what else it's doing, what is affecting the creature's behavior, and it might be an entirely different living organism.

This theme is that it's not enough to just look at the organism to understand what it's doing; you have to understand all of the aspects of its environment, some of which are agential organisms themselves. Not only do creatures hack each other's policies for navigating three-dimensional space of conventional behavior, but they also do it in anatomical and physiological spaces.

Slide 7/40 · 06m:34s

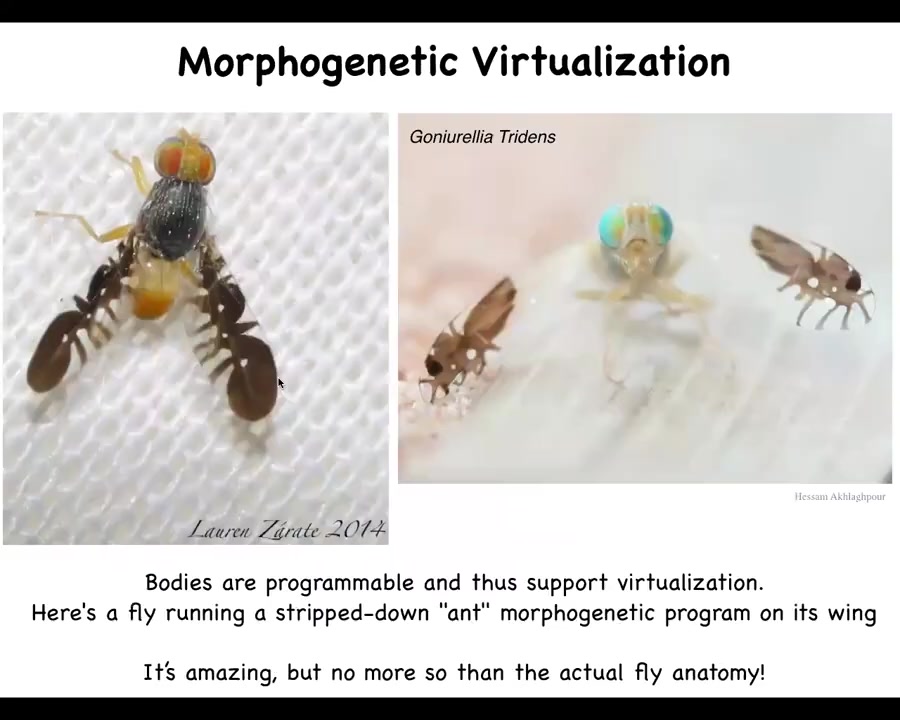

So here, and this is not Photoshop, this is real. There's this insect called Gonierella tridens, and what it has is an image of ants on its wings. When threatened, it flaps its wings in a particular pattern that looks to predators as ants scurrying around, and then nobody wants to mess with these ants. It uses them to scare off predators.

This is remarkable. This creature is running a stripped-down, two-dimensional, low-resolution morphogenetic program of these sand shapes. The first time I saw this I was floored until I realized that this is amazing, but not more so than the actual fly anatomy. The fact that these cells can make something that looks like this, and even more impressively, the actual host is a much more complex creature. But this is a virtualization. These cells are able to make various different shapes.

Slide 8/40 · 07m:43s

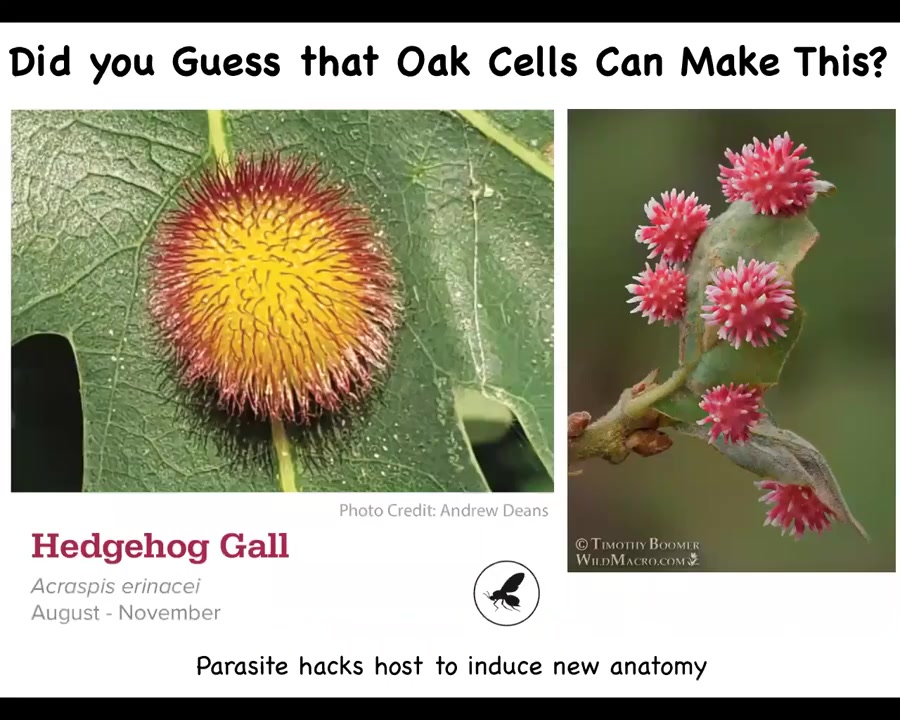

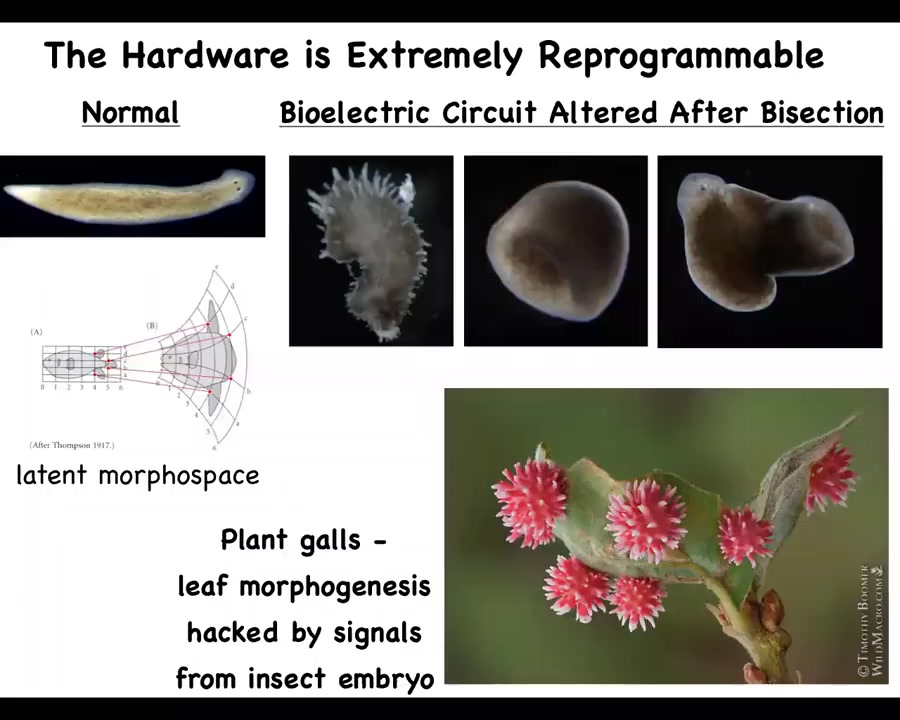

We are generally not drawn to these kinds of ideas because we think of development as reliable. Development is very reliable and robust. After all, acorns always give rise to oak trees, and we think that this sort of thing is what a genome does. The oak genome that comes from the acorn is able to make this nice flat green structure.

Slide 9/40 · 08m:09s

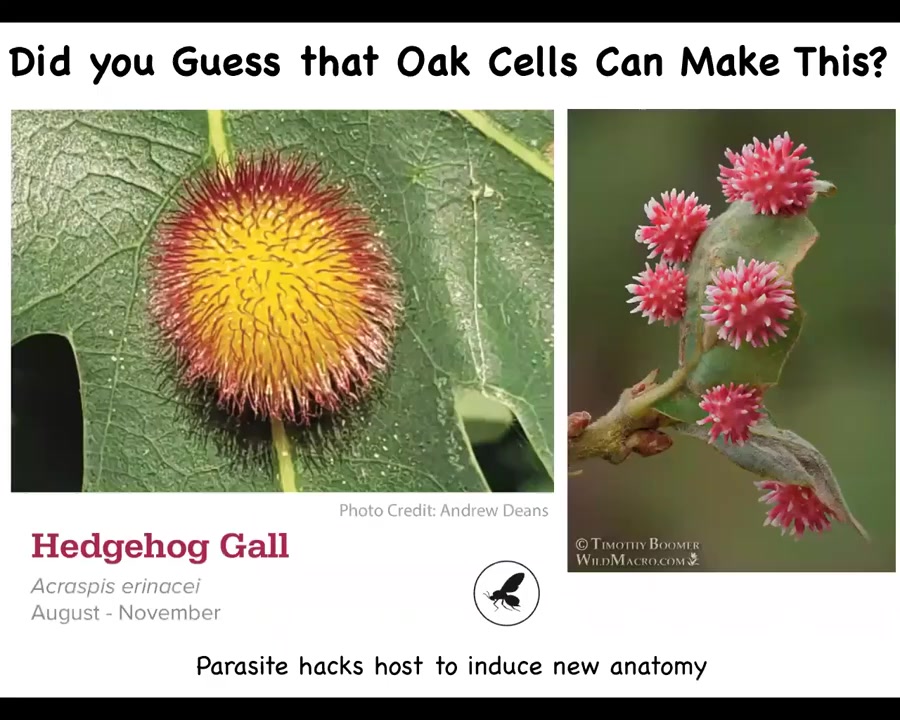

But what you might never guess is that it can make these structures. These structures, which are called galls, are made of the plant cells themselves. They are induced by a parasite, a particular wasp, hacking these plant cells, releasing certain signals that get these cells to build these unconventional structures.

Slide 10/40 · 08m:31s

This is incredibly reliable and robust. You would have no idea that these cells are capable of making something completely different.

Slide 11/40 · 08m:39s

Instead of a flat green leaf, they make this round, spiky, colorful structure. There's a very wide range of these gall structures.

We're getting a couple of concepts. One is that these cells are capable of much more diversity than what they normally do when they're impacted by other agents. The other is that because of this, you have to understand more broadly the outer world in which these things live in order to understand what they are capable of.

Slide 12/40 · 09m:17s

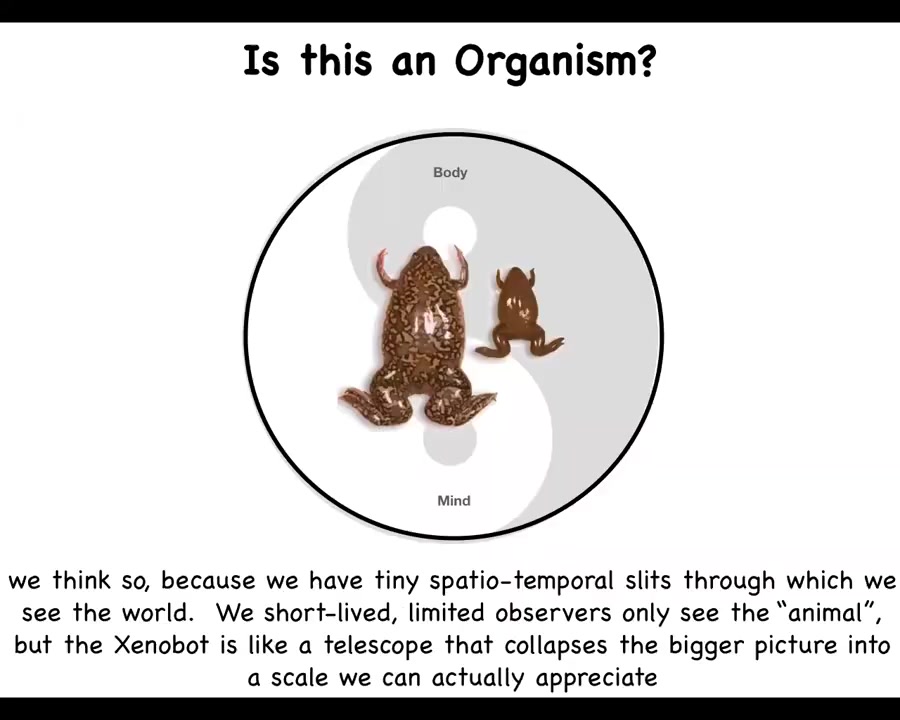

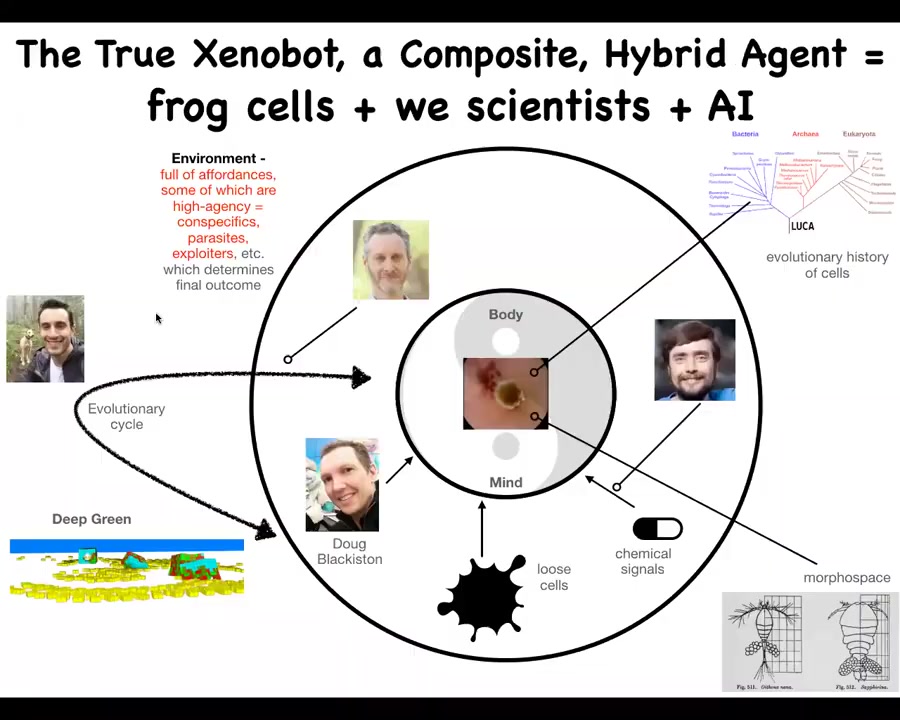

And so we can ask ourselves, as we look at this frog and it has a certain body and it has a certain cognitive structure with behavior. And so we say, okay, here is the organism. This frog is an organism. But I'm going to argue that we think this is an organism because we have really fairly tiny spatiotemporal portals through which we see the world. We don't see the whole evolutionary cycle. And I think that something like a Xenobot is an amazing device that collapses this much bigger picture into a scale that we can actually appreciate.

Whereas this is the simplistic view, what really is an organism is the physical body, but also its relationships with various aspects of the environment. All of the affordances, which may be high or low agency. So there may be other creatures ranging from scientists to microbes that are there to manipulate this thing. There are physical, chemical features of the environment. There's an evolutionary cycle that's wrapped around all of this. There are parasites, there are exploiters, there are conspecifics. All of this is actually what we need to understand to understand this organism, because we need to know what all of these things can do and how the hardware responds to this in order to be able to predict, control, understand, really rebuild, and create and relate to these kind of complex structures.

So as we think about a Xenobot, this is the story I want to tell in the first half of the talk. What really is a Xenobot?

Well, this is a project done in collaboration with Josh Bongard's lab.

Slide 13/40 · 11m:07s

The other people involved are Douglas Blackiston, who's a scientist in my group, and Sam Kriegman, who did all the programming. Doug did all the biology.

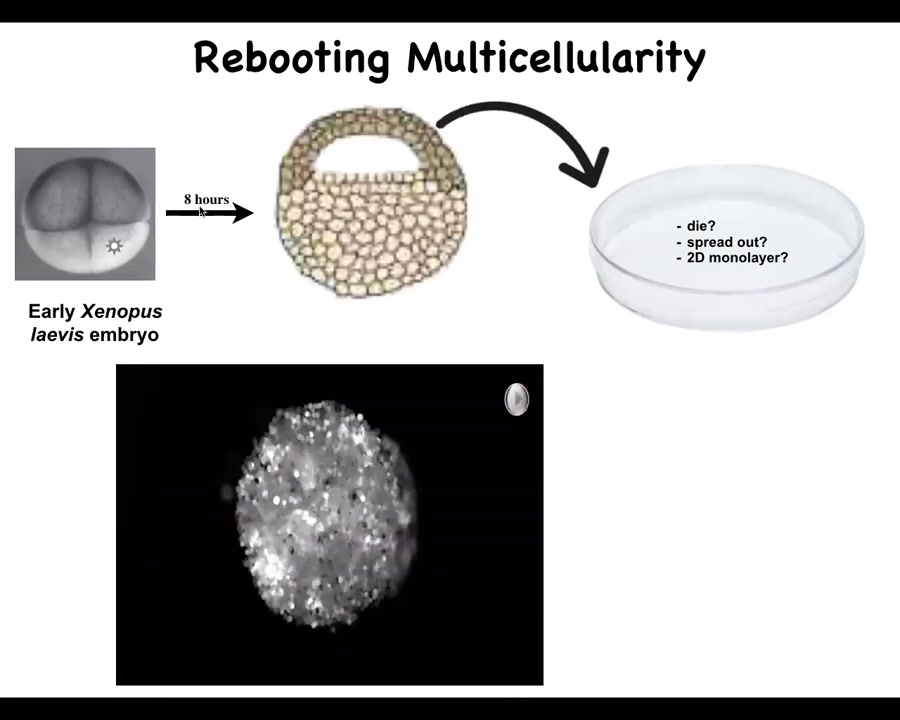

What we decided to do was to ask this question: What would somatic cells, perfectly normal, genetically normal cells, do in a different context? Would they be able to reboot their multicellularity?

This is the embryo of the frog, Xenopus laevis. In about 8 hours, the cross-section looks like this. These cells up here are fated to be epidermal or skin cells.

What Doug does is take off these cells, dissociate them, and put them in a separate environment away from all these other cells. They could have done many things. They could have died. They could have spread out and moved away from each other. They could have made a two-dimensional monolayer cell culture. Instead, this is what they do. When you dissociate the cells and plate them in this little hole, overnight, they coalesce.

They make this round little structure.

Slide 14/40 · 12m:12s

What the structure does is it begins to swim because it has little hairs. The skin, a tadpole skin, has little hairs called cilia on it. The hairs rotate, and the normal function is to move the mucus down the body of the frog to keep the pathogens and everything else flowing away and prevent it from catching cold. But in this configuration, what it can do is use those same cilia. It can repurpose that hardware for a different functionality. You can use them to swim.

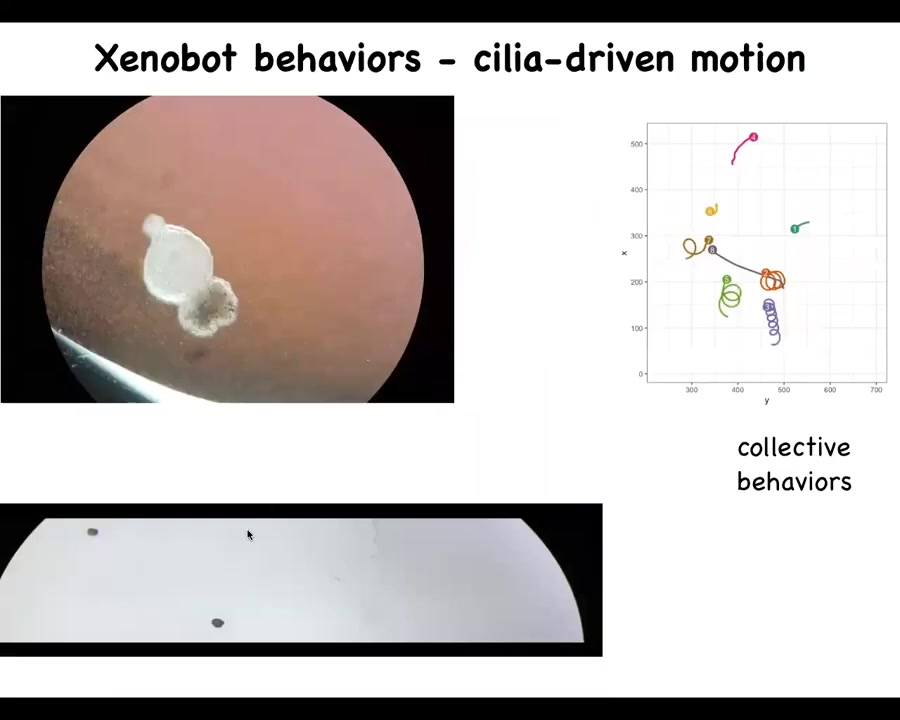

Slide 15/40 · 12m:43s

What you can see here is a single one swimming. Here is some collective behavior. This one is going on a long journey. Some of them are doing nothing, sitting there. These two are interacting with each other.

Slide 16/40 · 12m:58s

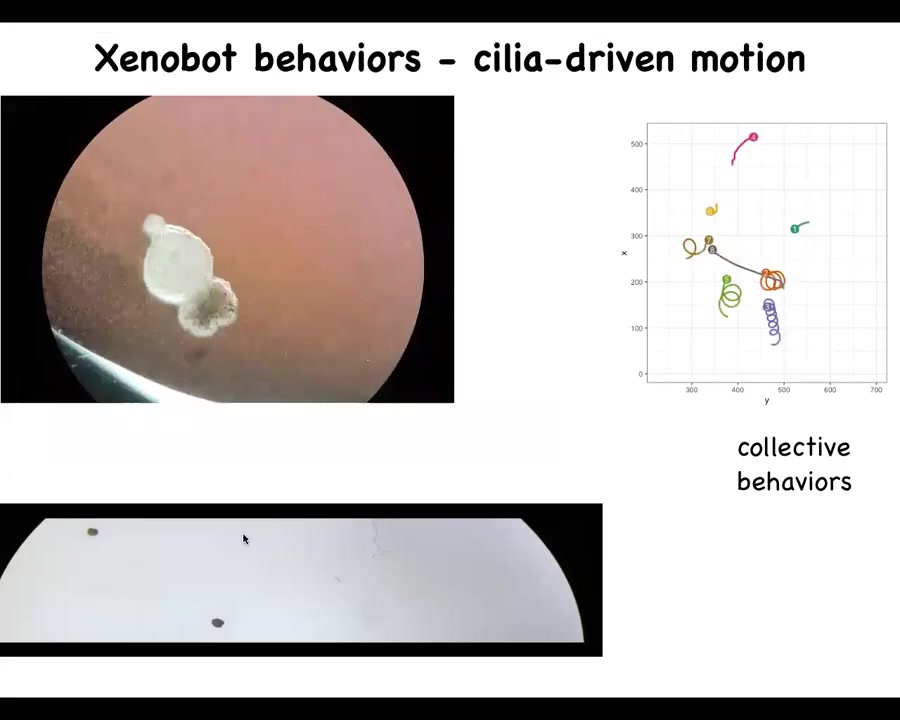

There are all kinds of shapes that you can make. Here, Doug made this donut shape which swims along. There are others that have this motion. This one was made by Pi in my group. They have all sorts of different shapes and motions. Remember, this is just skin.

Slide 17/40 · 13m:16s

There's nothing there other than skin cells. In fact, if you do some calcium imaging, this is the same kind of imaging that one would do on a brain for looking at physiological signaling activity in brains. What you'll see in these Xenobots is something similar. You see lots of activity, and you can imagine all of the tools of information theory being applied to ask how much integration there is within the bot, how much communication might there be between bots, and so on. The cognitive capacities are being studied now, so I'm not going to talk much about that. Stay tuned for that. We have all kinds of experiments asking what can they learn, what do they sense, what are their preferences, all of that is to come.

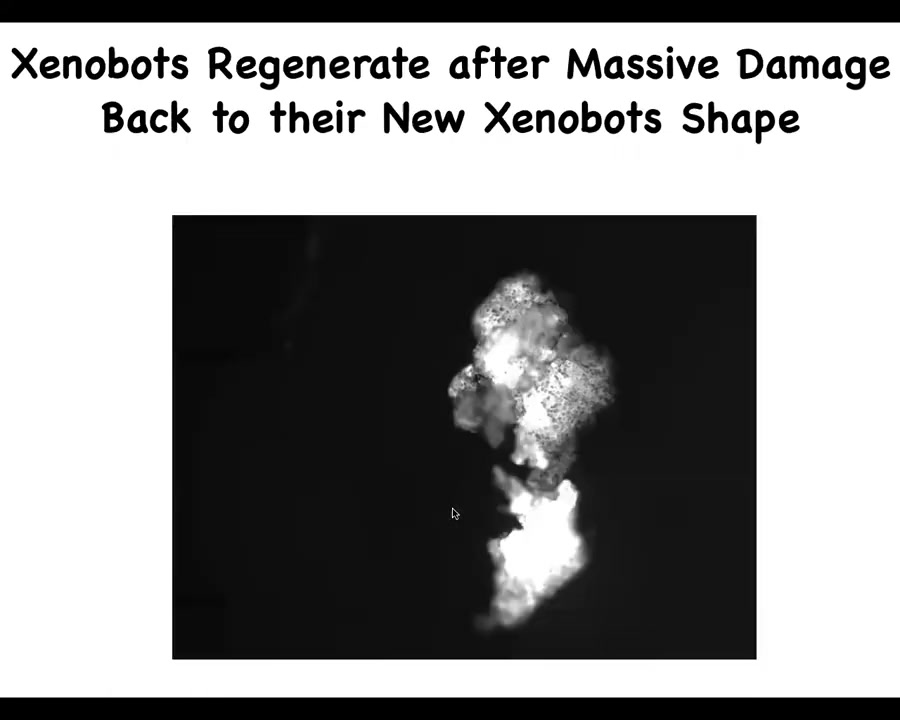

Slide 18/40 · 13m:58s

They can also regenerate after damage. If you cut them almost in half, look at that hinge and how much force it takes to squeeze the whole thing through that 180-degree hinge back up into the new Xenobot shape. They have many unexpected behaviors for a bunch of skin cells.

Slide 19/40 · 14m:22s

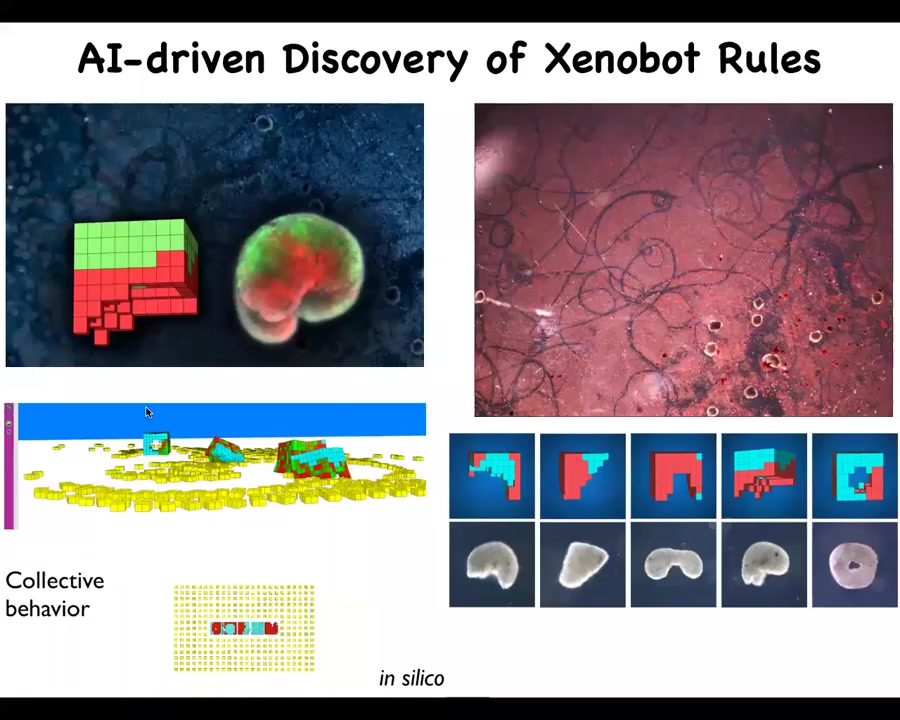

But one of the most amazing behaviors was discovered by AI. What Josh's lab did was to create a simulation environment where they could test out different shapes of these spots and different activities, and also look at what the predicted behaviors would be if they were put in an environment where there was loose material in the vicinity. This material can be passive particles such as this, or it can be other cells.

Slide 20/40 · 14m:55s

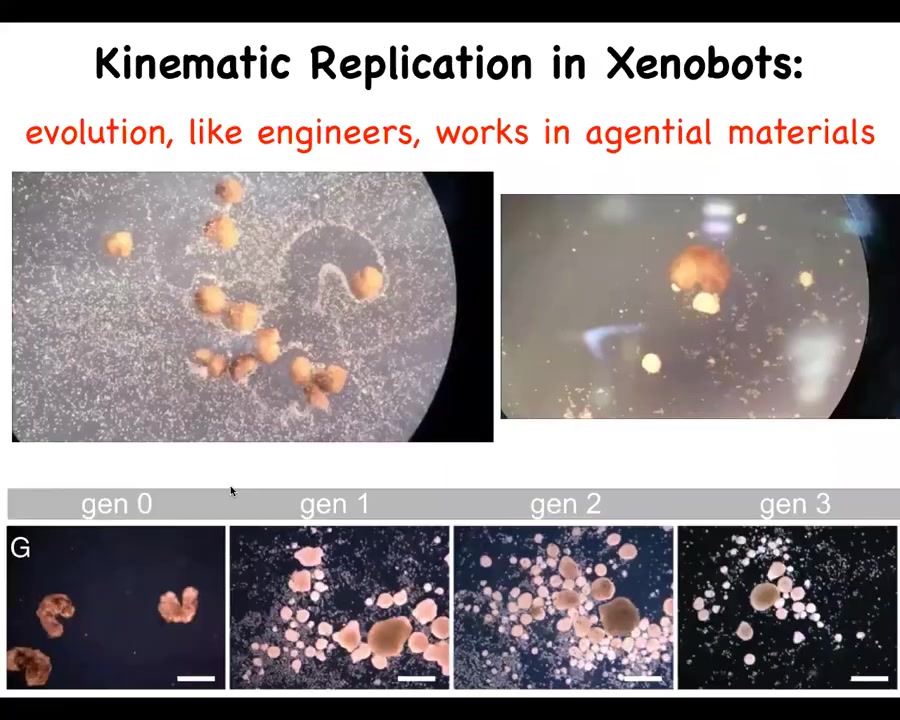

And if you provide them with cells, it turns out that what happens is that they implement von Neumann's dream of a robot that goes around and builds copies of itself from materials it finds in the environment. So these white flecks here are individual cells. What the bots do is they run around and they collect the material into little piles. They both collectively and individually shape the cells into smooth little piles.

And because they're working with an agential material, meaning these are cells that have competencies and tendencies for certain kinds of behaviors, what ends up happening is that these kinds of balls that they make mature into the next generation of Xenobots. So you have the first generation, the second, the third, and so on. You'll notice the first one has this interesting Pac-Man shape. What the AI discovered through simulated evolution is that this shape would be very efficient at building these things. Doug was able to make them. You can see them here. Much like us as bioengineers, the reason this worked in the first place is because we are working with an agential material. These cells, they're not passive particles.

Slide 21/40 · 16m:12s

I'd like to propose the idea that what the Zenobot really is. The Zenobot is actually all of this. There are multiple components to what actually makes up a Zenobot. It's a composite system consisting of Doug, who physically manipulates the cells, and myself, and Josh and Sam, who implement the evolutionary cycle, set up the particular environment that allows this thing to explore morphospace, the space of possible anatomical and behavioral configurations, and do things that these skin cells otherwise would never do.

The cells themselves have an evolutionary history, down to our last common ancestor. But the proto-organism that they make is completely different than what normally happens.

There's this composite entity of the AI that did the evolutionary simulations to figure out what the manipulations should be to get the cells to do this. The other features of the environment, particularly the four of us, are features of the Xenobots environment that are hacking it in exactly the same way that I showed you the other biology hacks.

One of the key parts of this is that we are not hacking it by putting in synthetic biology circuits. There is no genetic change here. There are no novel transcriptional circuits. There are no nanomaterials. What we're doing is providing signals that take advantage of the competencies of the creature, as in those galls that I showed you and in the various other examples.

This is a strange entity that's a distributed being that consists of biological parts and some fairly high-agency manipulators and some AI and so on. But the reality is, altogether, this kind of thing is a strange, unconventional collective intelligence.

Slide 22/40 · 18m:18s

But we are, because it's important to remember that not just ants and termites and beehives and things like this, not just they are collective intelligences, but we are. In fact, all intelligence is collective intelligence. There's no such thing as an indivisible, unified diamond of intelligence that doesn't have any parts.

Slide 23/40 · 18m:39s

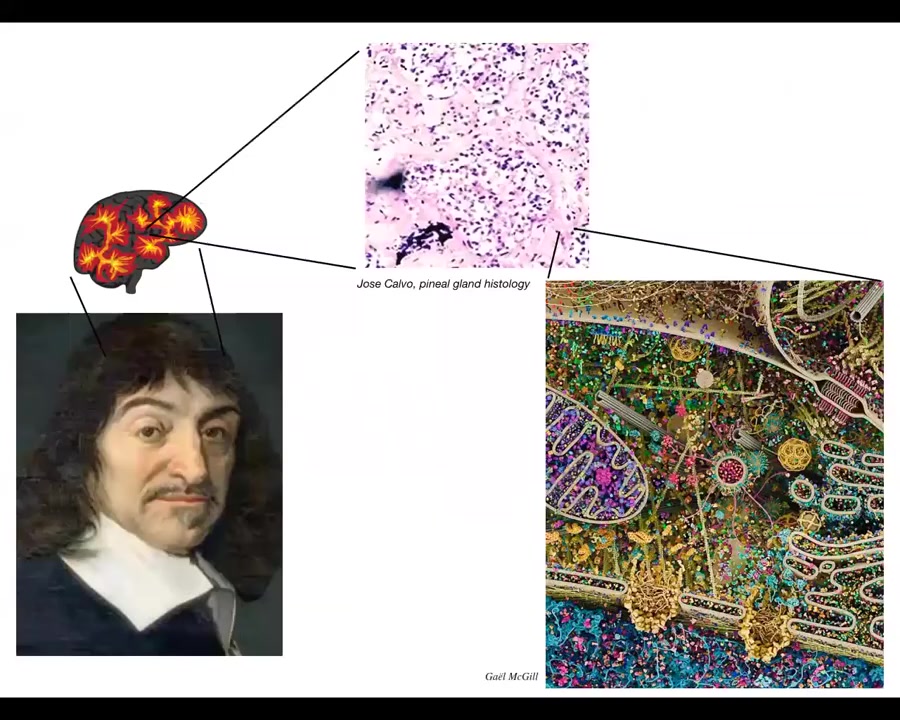

In fact, Rene Descartes was really interested in where in the brain one could attach this unified intelligence that we feel, the unified experience of humans. And he really liked the pineal gland because he said that there was only one of them in the brain. So that fit this idea that there should be one place where the unified cognition of the human resides. But if he had access to good microscopy, what he would have seen is that there isn't one of anything. Inside that pineal gland is this. So lots and lots of little cells. And inside each one of those cells is this stuff. Look at this amazing structure. All of this is what works together to result in the competencies of single cells and all of them together, for example in the brain, but also in the body, working together, result in emergent competencies and cognitive systems of higher types of creatures.

Slide 24/40 · 19m:36s

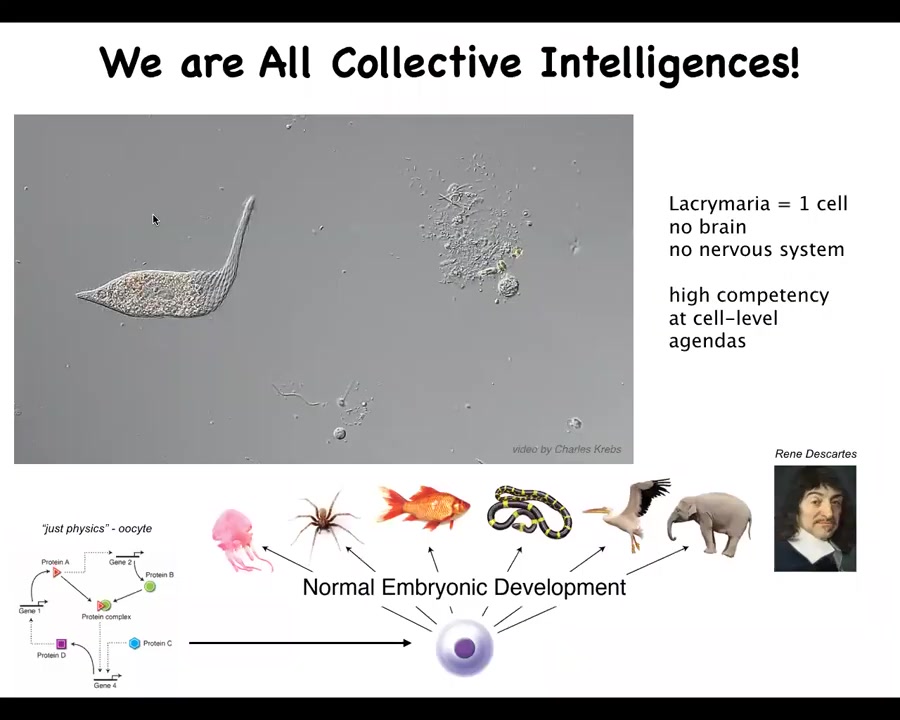

Now, we are all made of cells. We all take this amazing journey across the Cartesian cut, starting off as just physics, a little pile of chemicals in an unfertilized oocyte. Then slowly and gradually through this process of embryonic development, we become something like this, or maybe even something like that. This is really key. This process is very slow and gradual. There is no specific special point in embryonic development where you go from physics to mind. It's all a gradual thing. And this is what our components are made of.

Now, this happens to be a free-living cell, but all of our cells used to be free-living organisms at one point. This is called Lacrymaria. Notice a few things. There's no brain. There's no nervous system. The control over morphology is real time. The control over morphology is unbelievable. If you're into soft body robotics, you should be drooling right now. This is an incredible level of control. All of it is handled in one cell. All of its local physiological, anatomical, and metabolic needs are handled here at the level of a single cell as it feeds in its environment. If you cut off this little portion of the cell, this head, it will simply reform.

Slide 25/40 · 20m:52s

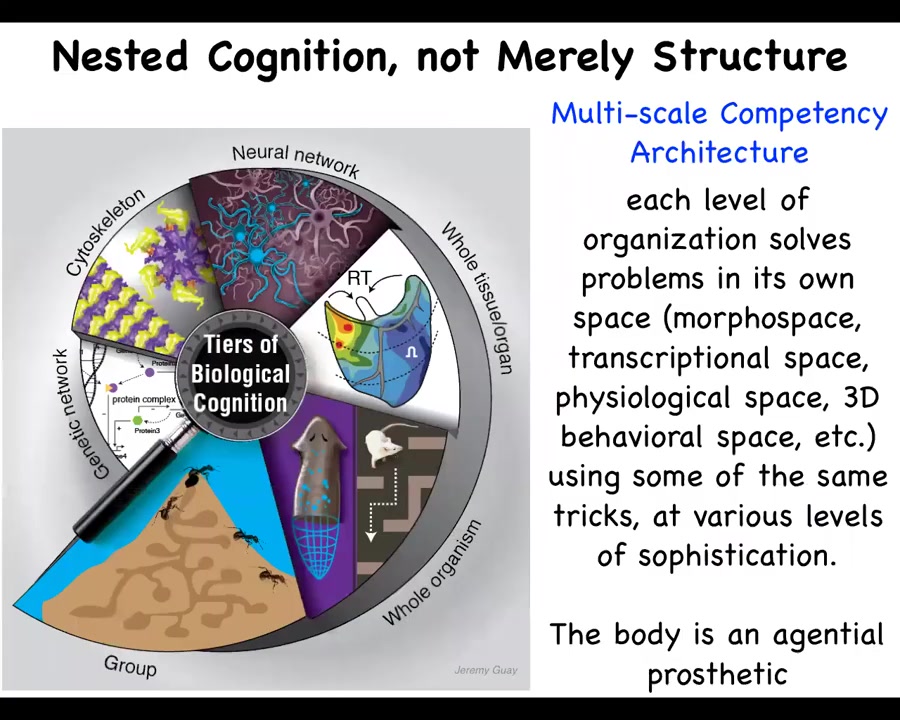

And so what we have in biology is this idea that we are not just structurally nested, that is, made of organs, tissues, cells, and molecular networks, but actually each of these layers is competent to solve various problems in its own space. So this is a multi-scale competency architecture. The molecular networks, the cellular networks, the organs, the whole bodies, and swarms all solve problems in various spaces: the space of morphogenesis, the transcriptional space, the physiological space, and then, in our case, linguistic and social spaces as well.

Because all of the parts of the body have their own competencies, their own abilities to solve problems, you can think of the brain-body connection as an agential prosthetic. The idea is that we not only have various effectors that we can use in Andy Clark's sense of the expanded mind, but also other types of sensors and effectors that your mind can use. But actually, these are agential prosthetics. They're ones that have agendas of their own. And so together, they form a more global, integrated, high-level system. Now, that allows for some amazing types of robust problem-solving. I'll show you a few examples.

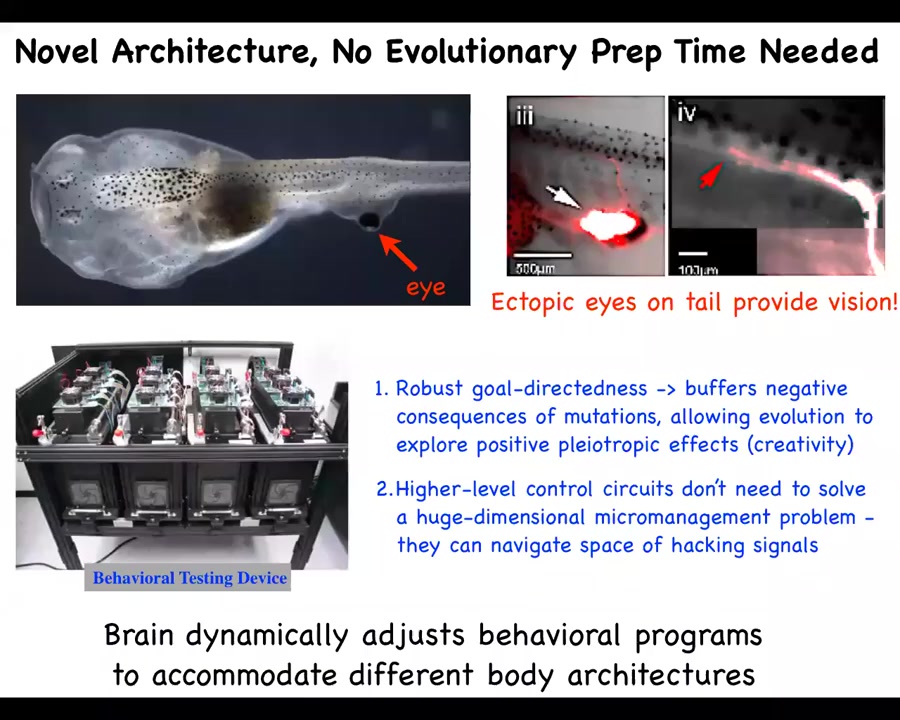

Slide 26/40 · 22m:18s

This is a tadpole of the same frog that we were talking about before. Here's the mouth, here are the nostrils, here's the brain, the spinal cord, and here's the gut. What you'll notice is that there are no eyes here, but there is an eye on its tail. Doug Blackiston took some cells from the early embryo that are going to make an eye, removed them from their primary location, so there are no eyes here in the head, and stuck them in the tail. Not only do they form a perfectly good eye. Even though they're in a weird location next to a bunch of muscle instead of being next to the brain where they belong, they put out one optic nerve. That optic nerve comes out and synapses here. You can see where it ends. It synapses on the spinal cord, does not go all the way up to the brain. What we found by building a machine that automates the training and testing of visual learning behavior in these animals is that these eyes can see perfectly well. The brain for millions of years was used to having visual input from these locations. Now you've got this weird, itchy patch of tissue on the back that provides some kind of stimulation onto the spinal cord. How does the animal even know that's visual data? They do perfectly well in visual learning tasks.

This has many interesting consequences. For example, this robust ability to deal with large-scale changes to the structure of the organism, the fact that these cells are perfectly happy to build an eye wherever, they will find some interesting place to connect to and so on, during evolution, this massively buffers the negative consequences of mutations. If your eye happens to be moved somewhere else, no problem, your fitness is not zero after that. You still have quite a degree of behavioral success. This allows evolution to explore positive pleiotropic effects of various mutations, in effect, a kind of creativity. And it also means that this kind of evolutionary process doesn't need to solve a huge dimensional micromanagement problem of how to direct every cell. What it actually could search and navigate is the space of hacking signals, signals that get various cells to do various things. And we think that that's a much more tractable space.

Slide 27/40 · 24m:37s

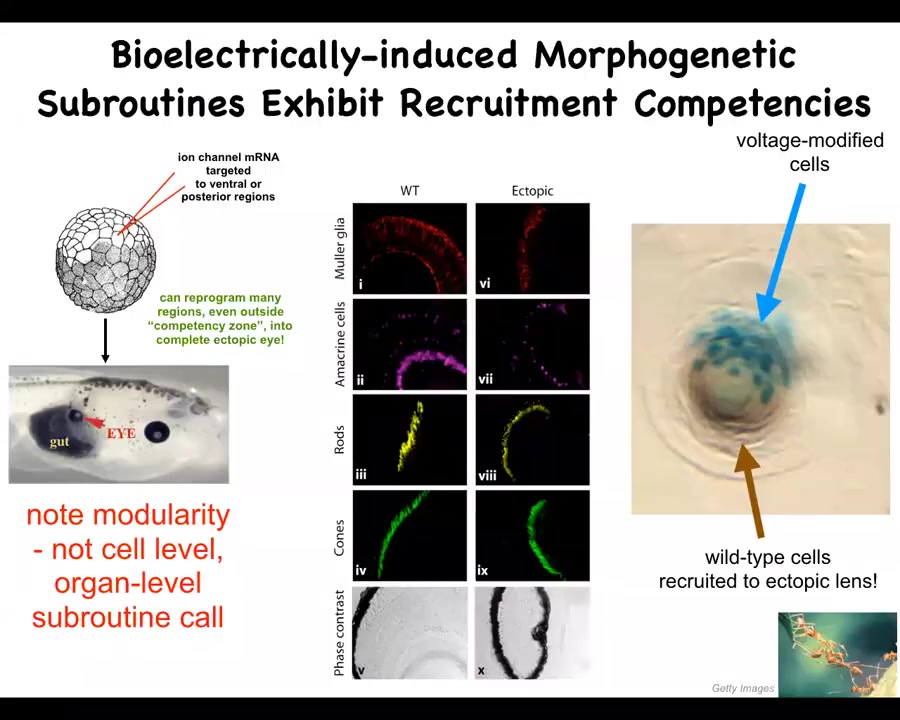

Now, in this case, what we've done is something quite different. We, in my group, study bioelectrical signaling. This is voltage-based signaling between all cells, not just neurons, but all cells exchange these electrical signals. One of the things we've learned is a kind of bioelectric subroutine call that says build an eye at this location. We can make many different organs. We can make brains and limbs and hearts and inner ear organs and so on. But I'm going to show you an example of an eye.

What we do is early on in embryogenesis, we inject here a kind of ion channel RNA. There are no electrodes, there's no waves or fields or anything like that. We inject RNA to control the interface that these cells are using to communicate with each other, which is voltage across the membrane. When we put the appropriate potassium channel RNAs, that sets a voltage pattern that causes any cells in the body to make an eye. In this case, the gut is making this eye. Here are all the layers that they have. Retina, optic nerve, everything's fine.

There are a couple of interesting things here. First of all, what we see here is the incredible high-level control. We don't provide all the information needed to make an eye. Eyes are incredibly complex. We provide a very simple piece of information that's a high-level subroutine call that says, build an eye here. Everything else is folded within that, and the system takes care of all of it, the size control, the different structures relative to each other, and so on. All of this is discovered. We didn't program this. The system does most of the heavy lifting here. There are many remarkable competencies to be discovered in these multi-scale systems.

For example, this round thing is a lens sitting out in the tail of a tadpole somewhere. The blue cells are the ones that we injected with this ion channel RNA. So the blue cells are the ones that we tell, "you should make an eye." But there's not enough of them. So what they do is recruit their neighbors. All the brown and clear cells were never targeted by us. What these cells do is recruit their neighbors to participate in this morphogenetic event because they can tell there's not enough of them to do it by themselves.

This is a common property of these kinds of distributed intelligences like ants and termites. When there's a task to be done, they recruit their buddies to scale up to the task at hand. That's what happened here. There are two levels of instruction. Here's us instructing these cells that there should be an eye here. Then these cells take care of everything else, including redirecting and behavior-shaping a bunch of their neighbors so that they will go and help, and instead of making skin and everything else that belongs in the tail, will help them to make this eye. So these kinds of competencies are there to be discovered in these multi-scale systems.

Slide 28/40 · 27m:28s

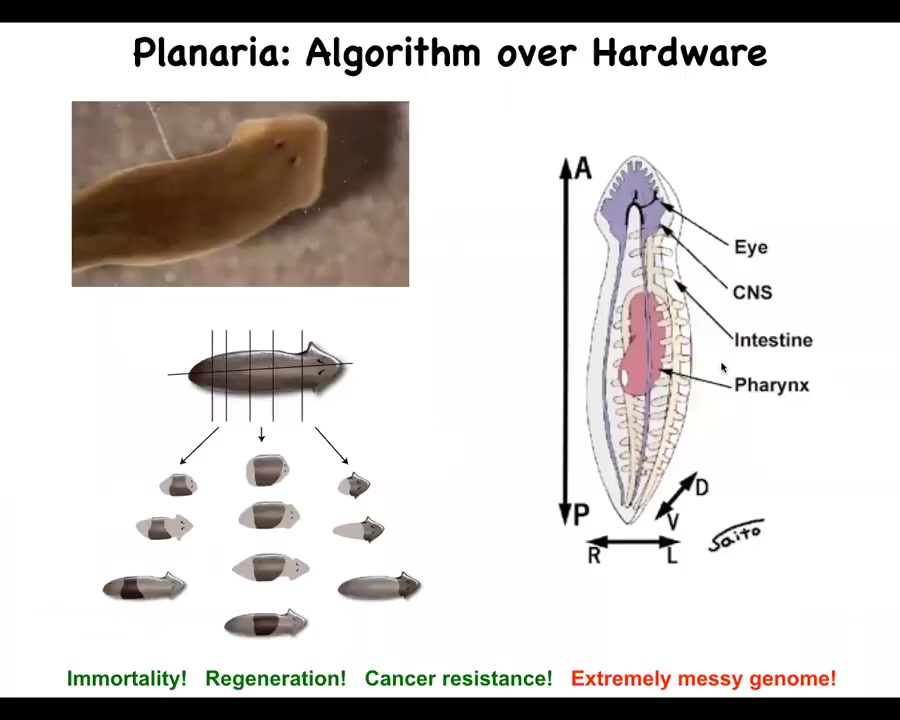

I want to show you another example in this animal. This is called a planarian. It's a flatworm. It has a true brain, a central nervous system, lots of different organs, quite an interesting creature, fairly complex.

It has a number of remarkable properties. It's highly regenerative. You can cut this guy into pieces. The record is something like 276. Every piece will grow exactly what's needed, no more, no less, and give you a perfect tiny little worm. Because of this regenerability, they are also immortal. There's no such thing as an old planarian. They regenerate any senescent cells, and so they just continue to rebuild themselves, as far as we can tell, forever. They're also very cancer resistant.

All of this takes place in the presence of an extremely messy genome because the way these guys often reproduce is they just tear themselves in half and each side regenerates and now you've got two worms. This means that, unlike the rest of us, who do not pass on mutations that we get in our body to our children, in these guys they keep every mutation that doesn't kill the cell. It's propagated into the new body after they regenerate and rebuild larger bodies. And so they accumulate mutations.

What happens in these guys is that they've basically perfected the algorithm that evolution isn't expecting the hardware to be robust. The hardware is assumed to be highly variable and faulty. Every cell in these guys can have a different number of chromosomes. They're mixoploid. So you really can't count on the hardware very much. What you have to have is an algorithm that builds a perfect worm no matter what's underneath. And that's why they're resistant to disorders of aging and cancer. In fact, of transgenesis: they don't even have transgenic planaria or lines of mutant worms. Those don't exist because these guys will build a perfect worm under a huge range of conditions.

But one thing you can do is you can target that morphogenetic machinery. How do they know how many heads, how many tails they're supposed to have? If all of this is happening, all this unreliable hardware is underneath, how do they remember what's going on here?

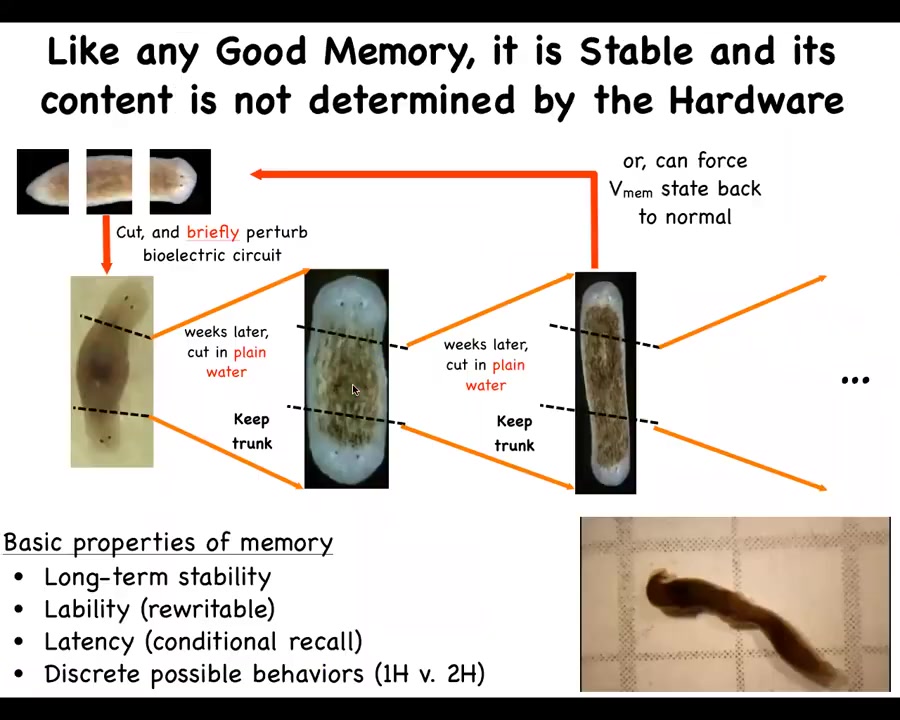

Slide 29/40 · 29m:44s

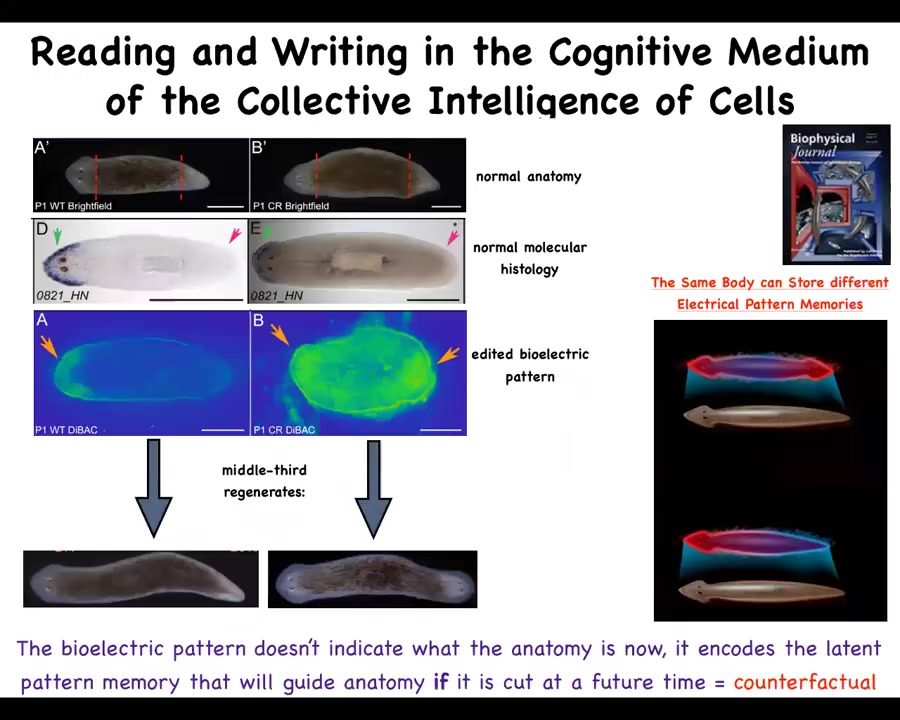

We studied this process and tracked using voltage-sensitive fluorescent dyes; we did a kind of imaging. It's akin to neural decoding, except it's not for neurons, it's for the rest of the body. We're interested in decoding the memories of the collective intelligence that makes up this morphogenetic process of rebuilding.

What we found is that there's a voltage pattern that literally tells the animal how many heads to have. This is the wild type pattern that says one head, one tail. When you cut an animal like this, you get one head, one tail.

We were able to take this animal, a perfectly normal one-headed worm, with gene expression just like the normal one, meaning the anterior genes are on in the head, they're off in the tail. What we've been able to do using ion channel targeting drugs is to rewrite this pattern so that instead of 1 head, it says 2 heads. It's messy, but the technology is still being worked out.

What you have here is this idea that a single planarian body can store at least one of two different representations of what a correct planarian will look like. That representation is used as the set point of a homeostatic remodeling process so that when you cut this animal, this is what it builds. Not Photoshop; these are real two-headed animals.

This bioelectric pattern is a map of this one-headed body, not of this one. It's even a counterfactual memory. It doesn't do anything until you cut off the head and the tail. That information is used to drive morphogenesis.

We now, much like neuroscientists, are able to do some neural decoding and try to understand what the electrical patterns in the living brain entail about the memories, the preferences, the goal states of the human or animal subject. We can do this with the collective intelligence of the body, read out the pattern memories, understand what it's going to build if it gets injured, and rewrite them.

Slide 30/40 · 31m:44s

And so when you do rewrite them, the reason I call this a pattern memory is because once you do this, if we change it to a two-headed state, that electric circuit that sets up that pattern actually has a memory to it. When you change it, it holds. And so these two-headed animals, if you keep cutting off the heads, they will continue to rebuild as two-headed forever. Here's what they look like.

So this has all the properties of memory. It's long-term stable. It's rewritable. It has conditional recall. I just showed you that. And it has two discrete possible behaviors.

Now notice that in planaria, there are no mutant lines. There are no transgenic worms; people have been trying for many decades. When you change the genetics, nothing happens because these animals are already built. The algorithm assumes that the structural genome is unreliable. But what you can do is you can produce permanent lines of aberrant two-headed worms. This is a permanent line, but it's not genetic. It's done by rewriting at the software level.

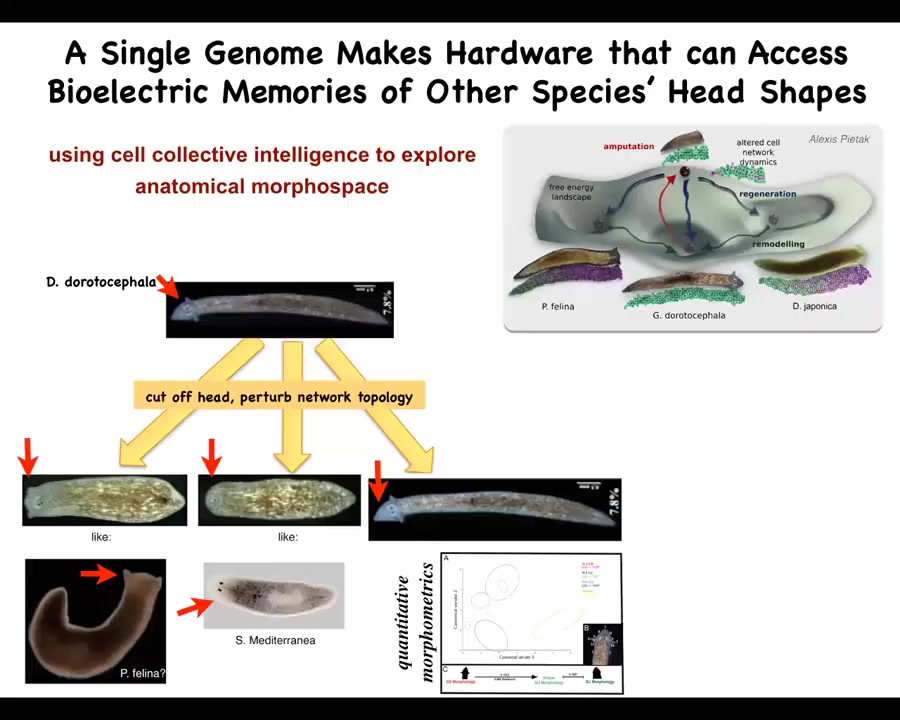

Now, not only can we make worms with the wrong number of heads, we can make worms with the wrong species shape of head.

Slide 31/40 · 32m:52s

You can take this triangular species, Dugisia duradocephala, cut off the head, treat them with a drug that confuses the bioelectrical circuit, and as a result, they will make flat heads like this P. felina, round heads like this S. mediterranea, or their normal heads.

Not only the shape of the head, but actually the shape of the brain and the distribution of stem cells becomes just like these other species, about 100 to 150 million years of evolutionary distance.

So what you see is that the exact same hardware can visit attractors in this anatomical morphospace that normally belongs to other species. Normally, this other genetically specified hardware is what lives there, but you can prompt this group of cells to visit them as well if the appropriate information is there in the physiological control circuits. So head shape, head number, you can go well beyond that.

Slide 32/40 · 33m:50s

We can make planaria with shapes that don't look like flatworms at all. You can explore really diverse regions of this latent morphous space. You can make these spiky worms, this kind of cylindrical thing, and these hybrid forms. The idea is that you can get cells to visit really far regions of that anatomical morphous space given the right set of signals.

The DNA here, in all of these examples, is exactly the same. We haven't changed it. Similar to here, the DNA in these guys is exactly the same as in the rest of the leaf.

The next slide is a little gory. It's a picture of a surgery. If you're squeamish, you might not want to look at the next slide.

I want to talk about this idea of hacking and how we and other creatures manipulate each other as part of this relationship.

Slide 33/40 · 34m:52s

This is an example of a surgery where you can see whether living things are machines or not. There are a number of approaches. This is a very machine-like approach. Here's what it ends up being, the surgery, there's an integration of living material and a very low-agency passive material, which all it does is hold its shape. But this is not the only game in town as far as manipulating living matter, because after we do this, we rely on the body to, quote unquote, heal. All of the things that happen after this are things that we don't have much control over. In molecular medicine, the only successful interventions, permanent interventions, are things that work against the low-agency invaders of the body, such as microbes, cancer. Antibiotics, chemotherapy, those things work well.

Slide 34/40 · 35m:52s

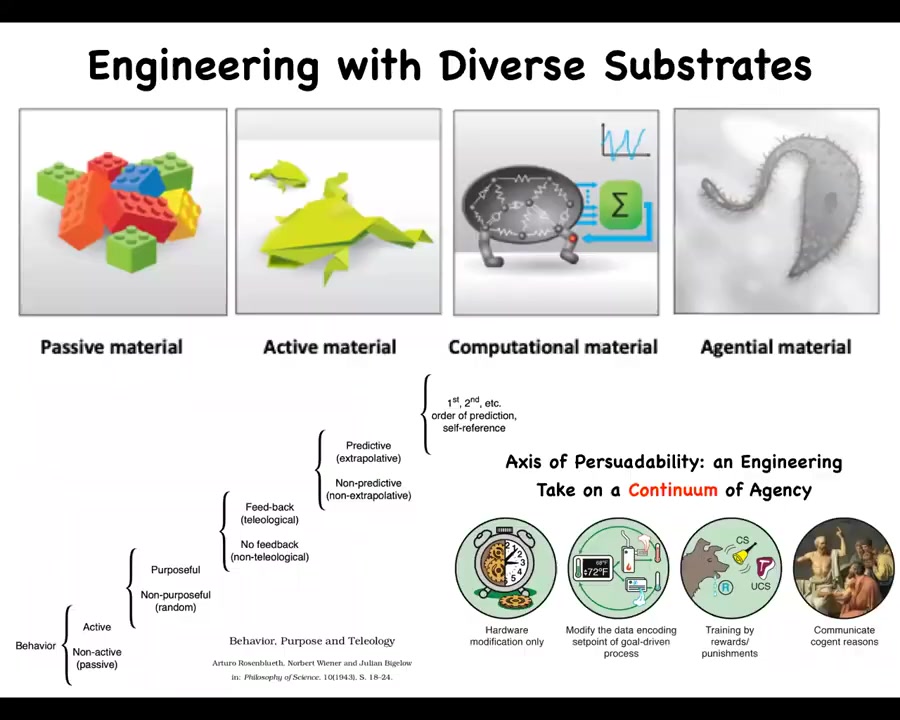

But actually, in biomedicine, we have very few things that treat the body itself in a permanent way, not just target symptoms.

That's because we are still groping for ways to interact with truly agential materials, which living bodies are. We've been engineering with passive materials for thousands of years. Now we're coming into some active materials and even active matter and some computational materials.

Bodies are all the way to the right of this continuum; I call it an axis of persuadability as far as different types of technologies that you need to optimally relate to these different systems. Even molecular networks have six different kinds of learning that they can do. All up and down this scale of different levels of sophistication by Wiener et al., we start to find different ways to relate to these systems to try to change their function.

Slide 35/40 · 36m:57s

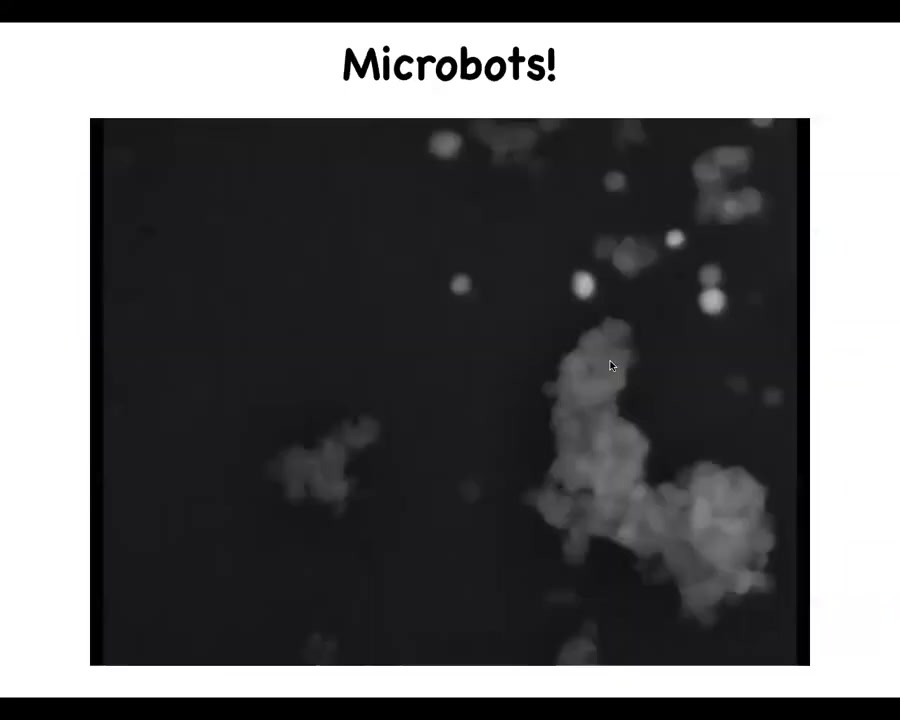

These are the individual cells of which Xenobots are made. So you can see here; we call it the little tiny horse. These are just loose skin cells, and you can see they move as a collective. There's all kinds of interesting behaviors. The lightning flash is calcium.

Those cells have individual behaviors. They have collective behaviors on a scale much smaller than even the xenobots.

Slide 36/40 · 37m:27s

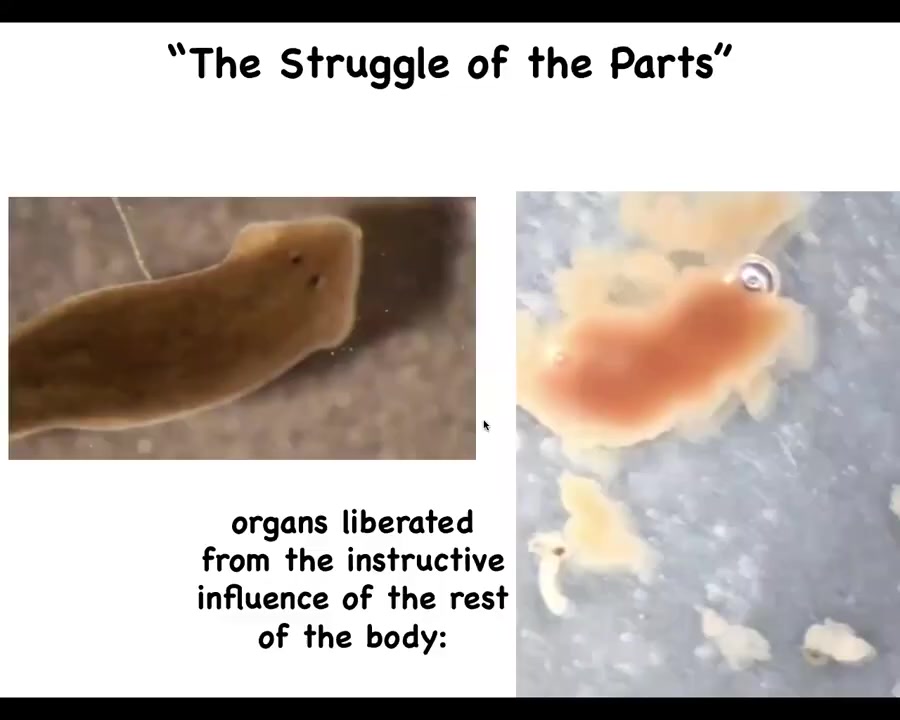

At a larger scale, here's our planarian. One of the things that you don't see in this planarian is the pharynx. The pharynx is this muscular tube that it uses to pick up food. It's sitting quietly, passively inside the animal. But much like with the Xenobot, where we released the skin cells from the instructive influence of the other cells, when you remove the pharynx from the rest of the body, here is what happens.

These are individual pharynxes. They're actually very active. They have a life of their own. This one is going to try to eat a piece of liver. It's just a tube, so the liver comes out the other end. All it ends up doing is burrowing through. They have their own independent life, and they live for quite some time, differently than what they do inside.

Wilhelm Ruh called it "the struggle of the parts" back in the early days of developmental biology, the idea that because we are multi-scale competent systems, all the parts have to be controlling each other all the time in order for our emergent selves to appear.

Slide 37/40 · 38m:34s

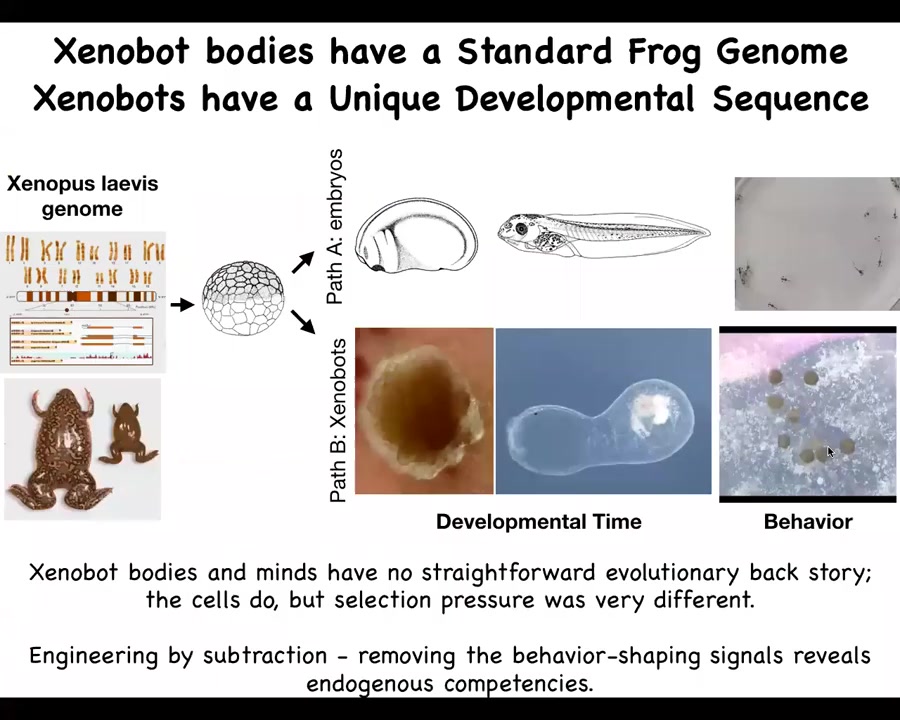

When we think about going back to this idea of Xenobots, what did evolution actually learn in producing the Xenopus laevis frog?

Here's the genome. Most of the time what it does is this, it makes these embryos with a standard developmental sequence that they end up being tadpoles with a standard set of behaviors. If one just looks at the natural course of things, this is what you think evolution has learned. It has evolved a frog. It's highly adaptive, very fit, very nice.

But it turns out that in a different scenario, these exact same cells with this exact same genome can make a xenobot. These xenobots have different shapes. They have different developmental sequence. This is a xenobot about a month old. It's turned from this into something like this. They have a completely different set of behaviors. This provides us with an interesting challenge. Typically, when you ask for any given animal where does its shape and behavior come from? The answer is evolutionary selection. For eons, it's been sculpted by evolutionary forces and selection to have certain properties. But there's never been any Xenobots. There's never been any selection to be a good xenobot. All of this is completely emergent. The cells, of course, evolved in the frog lineage, but the evolutionary pressures on them were completely different.

Everything, including this kinematic self-replication — this idea of the ability to make copies of themselves when all of the normal frog reproductive machinery is removed — emerges. This is just skin. They don't have the ability to reproduce the normal way. They come up with a different way. That, to our knowledge, has never existed in evolution before.

What's happening here is engineering by subtraction. What we did was we removed the other cells that normally bully these skin cells into having a boring two-dimensional life on the surface of the animal. In the absence of those signals, you get to see what the cells want to do, which is the default behavior of those cells when they're not being acted on and influenced by their neighbors. This is what they're going to do. All of these competencies are non-obvious, and they allow us to have these model systems with which we can start to develop a science of predicting the goals, the behavioral repertoire of complex multi-scale systems from knowing the properties of the parts, which we still don't know very well.

Slide 38/40 · 41m:10s

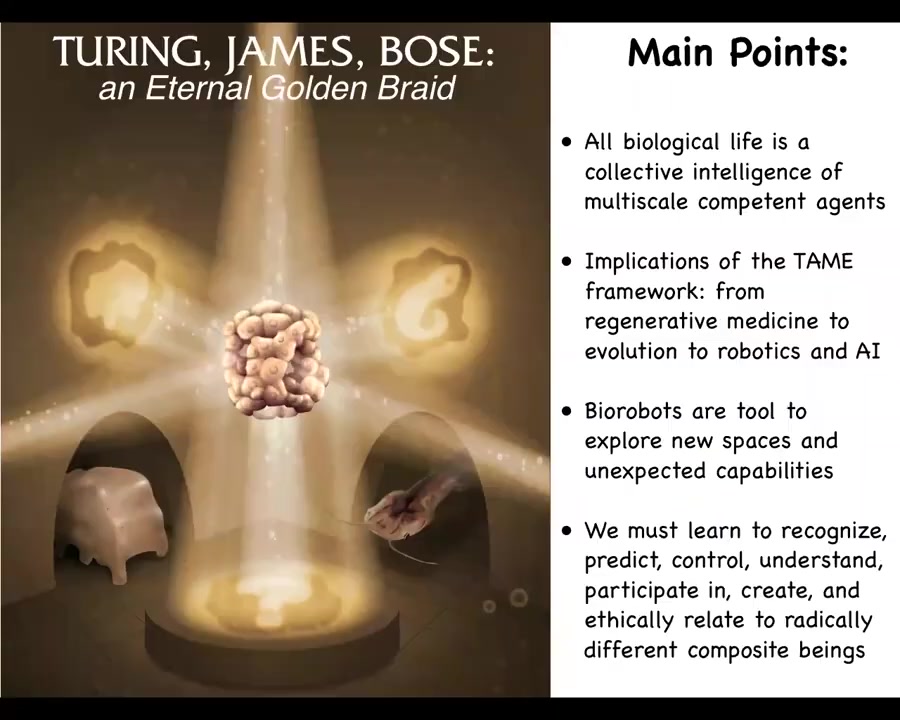

I'm going to summarize what we have here, and this is an obvious homage to Doug Hofstadter's classic book, the idea that what you have in the Xenopus genome is the ability, under various circumstances, to produce different kinds of creatures. And in fact, we don't know what else it's capable of doing.

This hardware, I want to float the idea that biological evolution doesn't just produce solutions to specific problems, but it actually makes problem-solving machines. It makes very versatile hardware that can solve problems in multiple spaces and has different, very surprising behavior, and collaboration with AI and with human scientists is what's allowing us to start to catch a glimpse of what else is possible.

The main points that I tried to transmit today are that all biological life is a kind of collective intelligence of multi-scale competent agents.

The implications of this — I call this the TAME framework, T-A-M-E, for technological approach to mind everywhere — have many applications from regenerative medicine to understanding evolution to novel robotics and AI to really start to take on board the deep lessons of biology in terms of how the hardware and the software relate to each other and how they implement novel ability to solve novel problems.

These biological robots are really exploration tools. They're a kind of device that we can use to explore new spaces, to explore morphospace, to find these unexpected capabilities.

It is now on us to learn to recognize, predict, control, understand, participate in, because Josh and Doug and Sam and I are part of this novel Zen about creation, to create and to ethically relate to radically different composite beings.

Slide 39/40 · 43m:13s

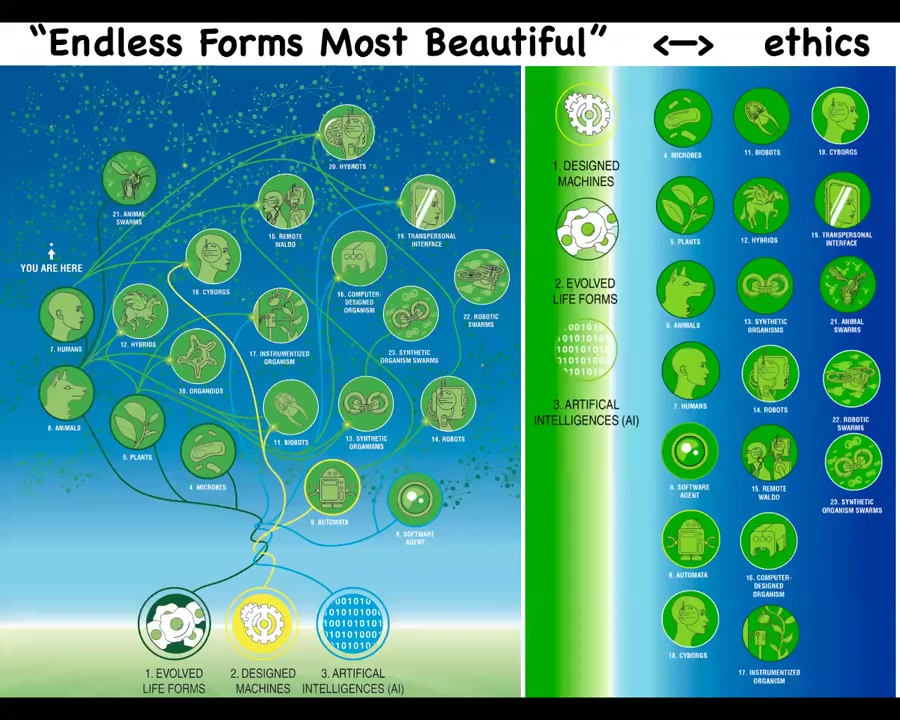

I also think that when Darwin had this famous phrase, "endless forms, most beautiful," he was really impressed at the wide variety of living forms that he saw. Everything that he saw, that end of one example of the tree of life on Earth, is a tiny corner of this massive option space of possible beings, possible bodies, and possible minds. Because biology is so highly interoperable, because biological systems will find a coherent way to exist even when mixed at every level with foreign DNA and nanomaterials. And so every combination of evolved material, designed material, and software is some kind of plausible agent. So we have cyborgs and hybrids and chimeras. Many of these already exist. They will increasingly exist. And this has huge implications for ethics because the old way of figuring out how you're going to relate to something, which is where did it come from, meaning was it evolved or designed? And what does it look like? What's inside? Is it a human brain? Is it soft and squishy? Is it made of metal? Those kinds of criteria are basic, they were never any good really, but they served okay in prior ages. They're not going to survive the next couple of decades. It's a completely different game looking into the future where we're going to have to find ways to relate to beings that are nowhere on the tree of life relative to us and that are completely different in terms of their provenance and their structure and behavior. And so we're going to have to figure out a way to relate to them.

If you want to see more, there are a couple of interesting papers here. This one with Josh, some stuff on machines, some stuff on engineering with agential materials.

Slide 40/40 · 45m:02s

I want to thank the people who did all the work. This is the Zenobot team, Doug Blackiston, Sam Kriegman, and Josh Bongard. I have to do a disclosure because Fauna Systems is a spin-off company that was formed around the whole Zenobot technology.

Pai and Sherry did the eye work that I showed you. This was our worm team. Our various collaborators, our funders. Jeremy Gay did all the amazing diagrams, and always the animals: they do all the heavy lifting, they teach us everything of importance.

Thank you for listening and I'll take questions.