Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a ~1 hour 15 minute talk titled "Patterns of Form and Behavior Beyond Emergence: how Platonic Space in-forms evolved, engineered, and hybrid embodied minds", which is the kickoff talk for our Symposium on Platonic Space (https://thoughtforms.life/symposium-on-the-platonic-space/). Here I go slowly step by step to review the data that motivates this unconventional way to look at biology, and then (at around minute 47) present a speculative model and a research program we are pursuing to test and extend these ideas in a practical way.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Talk overview and roadmap

(03:34) Biological forms and behaviors

(15:07) Goal-directed morphogenesis and homeostasis

(25:01) Beyond genetics and selection

(31:50) Xenobots, anthrobots, and algorithms

(46:05) Platonic patterns versus emergence

(56:46) Minds, machines, and interfaces

(01:04:44) Summary, implications, and roadmap

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/48 · 00m:00s

This talk is called "Patterns of Form and Behavior Beyond Emergence." This is my attempt to think about how patterns from the Platonic space inform evolved, engineered, and hybrid embodied minds. The paper describing all of this in more detail is here. It's a preprint that's going to be a chapter of a book, and you can download it here.

Slide 2/48 · 00m:24s

The basic structure of what I'm going to say today has these components. First, I want to talk about the notion of patterns that are generalized types of forms of structure and behavior. They're specific forms in various spaces. Then I'm going to talk about morphogenesis as an example, a model system that we use, which we are going to describe as a homeostatic process that aims toward a specific form. It's a navigation of a space and error reduction to try to get to a specific form. This is in contrast to the mainstream paradigm of complex morphologies arising by emergence from open loop complexity, things like cellular automata and so on.

Then, having established why I think morphogenesis proceeds towards specific forms, we're going to ask, where do these forms come from? That is, the set points of the homeostatic process. Where do they actually originate? The answer I will give attempts to go beyond this idea of selection for a specific shape in an evolutionary history and the specificity of a prior environment, a history of the genome interacting with an environment as being predictive of forms that can serve as targets for morphogenesis. Where else besides environment and genetics can these forms come from? The model that I will try to defend is this idea that there is this space, it is a structured space of patterns that serves as the source for these kinds of forms.

I'm going to call it a Platonic space, not because I'm trying to stick close to the views of Plato, but simply to begin by consilience with what Platonist mathematicians say they're doing in studying a structured, established space of pre-existing patterns. I'm going to talk about how I think these patterns serve as both causation and an explanation for patterns that we see in biology. For this reason, I think physicalism is insufficient. I'll talk about that. I'm not going to focus on physics very much. I hope the physicists will do this later in this series.

I'm going to mention the idea that it doesn't take a very complex interface. It doesn't have to be a living biological body. I'll mention how even very simple interfaces can get some of these forms ingressing through them. We'll talk about how this works in brains, in very simple minimal algorithms, and chimeras. At the end, I'll point out that what we have here is a research program with a very practical empirical component. We can study the contents of the metric of that space, and we can try to understand the mapping between the pointers or the interfaces, which are the physical objects that we make, whether living or non-living, and the patterns that ingress through them. This is the structure of the argument that I'll give today.

Slide 3/48 · 03m:34s

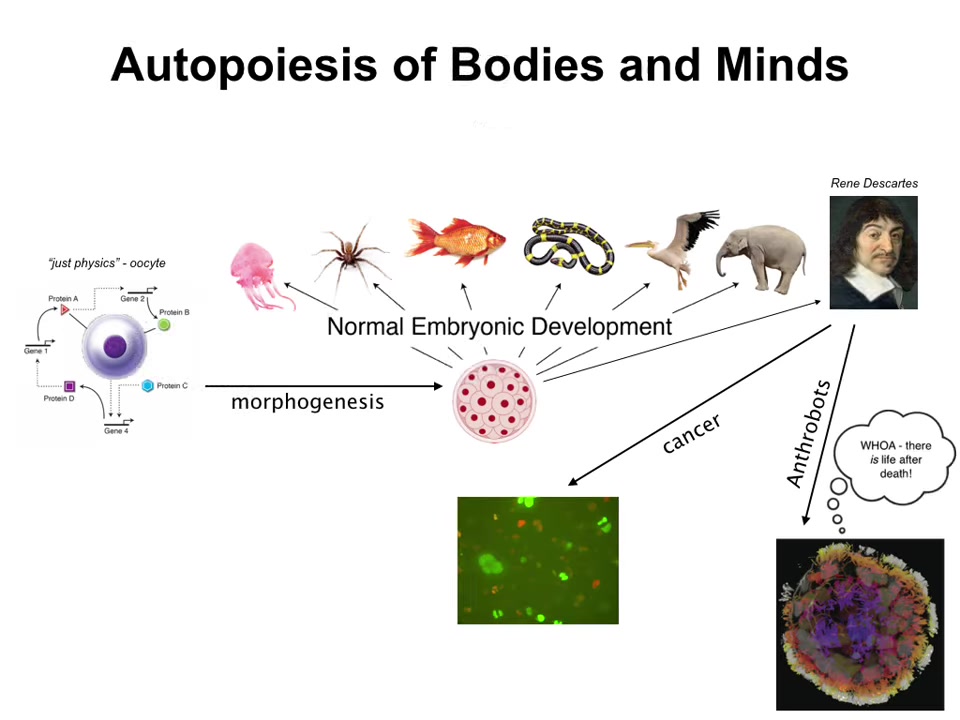

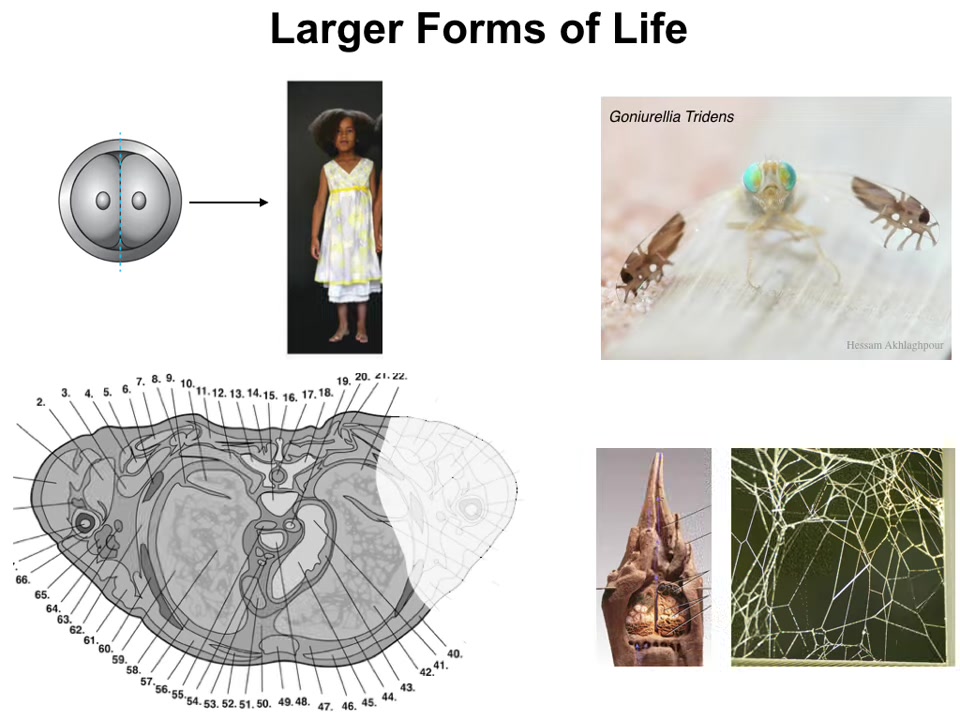

The first thing to note is that we all arise via this specific process, this journey from being something that people think amenable to the sciences of chemistry and physics. This is a quiescent oocyte, a little BLOB of chemicals. Then through this amazing self-assembly process known as embryonic development, we self-assemble the form of our body, the anatomy, and even the form of our behavior. Perhaps we end up something as complex as this, which then will make statements about not being a machine. This is a slow, gradual process by which our bodies and our minds come to be. This is not the end. There are some other interesting things that I've covered in other talks where the morphology of the body can actually undergo some really profound transformations. Now we can talk about what's actually going on here when we make this transition.

Slide 4/48 · 04m:36s

The first claim that I would like to make is that there's really a profound symmetry between the forms of the body, that is anatomy or morphology, and the forms of behavior. In other words, kinds of minds. I'm going to argue that these are part of the same class.

Slide 5/48 · 04m:51s

Alan Turing saw this pretty clearly. He was very interested in intelligence and reprogrammability and things like that. In particular, unconventional embodiments of mind, going beyond the biological embodiments of mind.

But he also wrote this amazing paper called "The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis," which looked at how chemicals can self-organize during early embryonic development. You might wonder why somebody who was interested in computation and intelligence would be looking at chemicals during early development. He probably saw the idea that there's a really deep symmetry between the self-assembly of the body and the self-assembly of the mind. So let's look at what some of these shapes are.

Slide 6/48 · 05m:40s

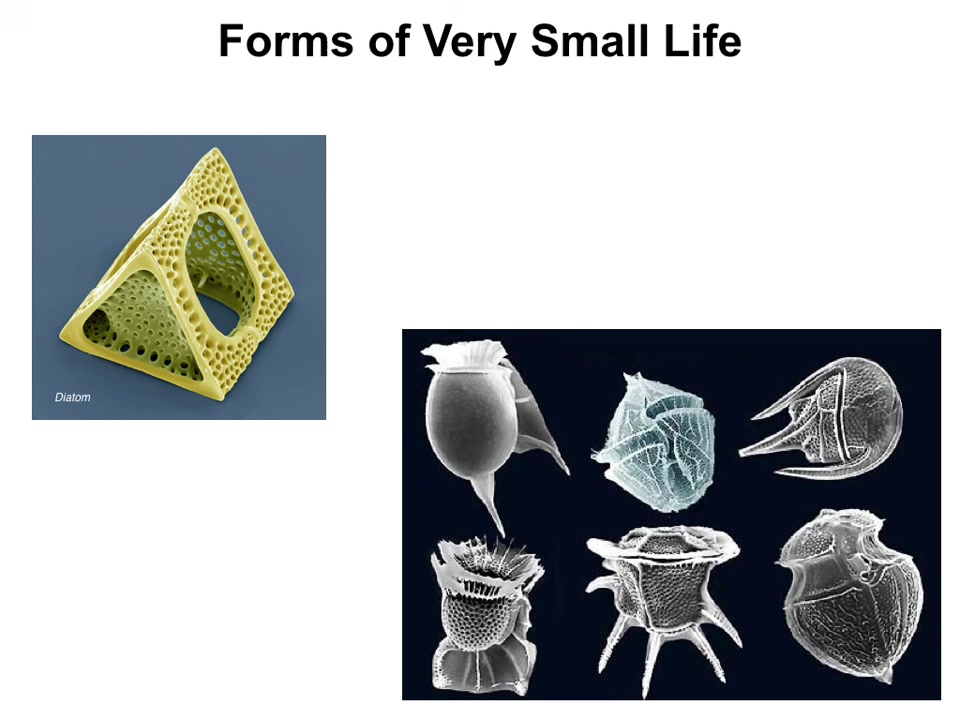

First of all, we can look at some really intricate and definitive biological forms. So here are some diatoms. These are very small things. These are tiny on the level of a single cell. And all of these are quite specific. And we need to try to understand why exactly these shapes form and not something else.

Slide 7/48 · 06m:01s

The same question arises during the embryonic development of multicellular forms. An embryo reliably gives rise to a standard body, a standard target morphology. If we look inside, we find a very stereotypical set of organs and tissues that almost always does the right thing. These cells build all the correct organs, correct shape, size, and the right location, orientation, and configuration. Where do these patterns come from?

Some of these patterns are very, very complex, such as the actual three-dimensional body of this fly, and some are stripped down, two-dimensional projections of a different kind of body. This fly is running a virtual ant morphogenesis program on its wings to fool predators as to the presence of some ants nearby.

We need to understand the origin of all of these invariant patterns, how they arise, including large-scale things such as termite colony structures and spider webs. All of these structures are no more specified in the DNA directly than the specific structure of the spider web or the termite colony. All of these things are not hardwired in the DNA. The DNA specifies the proteins, the microscopic hardware that all the cells get to have. After that, the actual outcome is the physiology, the real-time in vivo physiology that runs on that hardware. These are the biological forms that we need to understand.

Slide 8/48 · 07m:54s

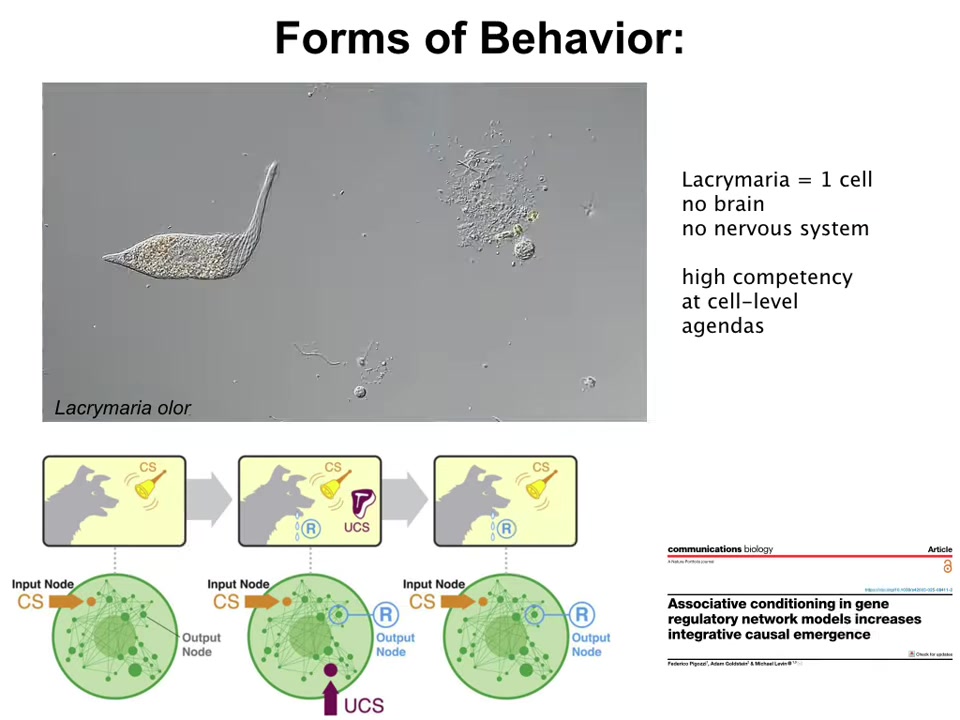

Now, forms of behavior. We can start at the single cell level. This is a lacrimaria. It's a single-cell organism. You can see it has some remarkable behaviors that are the envy of soft matter roboticists and things like that. It has all these local competencies in its own tiny little cognitive light cone, despite the fact that it doesn't have a brain or a nervous system.

Even below this level, if we ask, what is this single cell made of? It's made of molecular networks. If you model molecular networks, you'll find that just by virtue of their connection to each other, certain kinds of networks can do up to six different kinds of learning: habituation, sensitization, Pavlovian conditioning, associative learning. They can do these simply by virtue of their structure. You don't need evolution or any particular fact of physics; this will become important later. This is a free gift from the mathematics of networks.

So even the material from which the cells are made is already on the spectrum of agential materials, because it does have not only this learning capacity but, as we found recently, learning actually increases its causal emergence. These are things that are important to neuroscientists and other people who study different kinds of behavior.

Slide 9/48 · 09m:25s

Now, we can look at a couple of different behaviors in some of these very simple organisms. This is, for example, a Physarum slime mold. What you see it doing during the first few hours is it grows outward evenly. Now you'll notice there's one glass disc here, there are three glass discs here, there's no food, there are no chemical gradients, it's just the mass. What it is doing during this time is gently tugging on the soft agar that it grows on. What it senses are the vibrations that come back to it, and it can tell the strain angle of the different masses. Then what it'll do is reliably reach out to the heavier mass. You can play all kinds of games of stacking the disks on top of each other. So it's gathering information about its environment. Once it has processed that information, it figures out where the larger mass is.

It has interesting internal mechanisms for doing computations. For example, if you inject fluorescent beads into the system, you find that there are these flows. Each one of these tiny branch points is controllable, independently controllable. The whole thing could be potentially a hydraulic computer. It has the ability to independently control the signaling through each branch of this enormous network. These are some "quote unquote" simple behaviors that these systems can do.

Slide 10/48 · 10m:54s

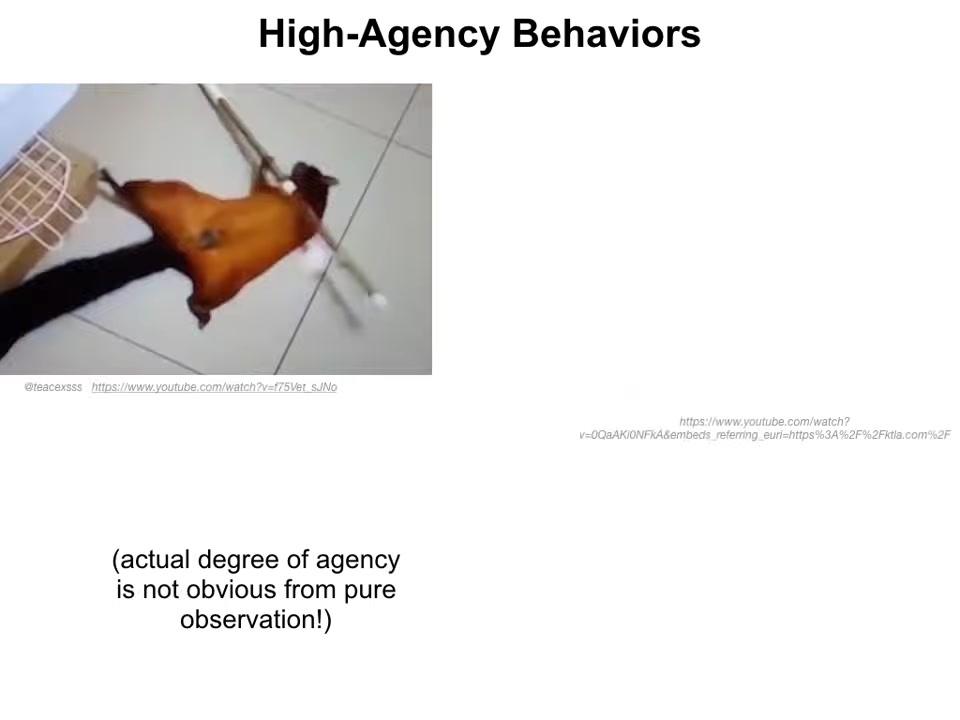

We find it pretty easy to recognize high agency behaviors. Here's the squirrel. It's going to set up a little accident scene like this. Very intentional. In a moment, it's going to look up to make sure that its owners are catching what's happening here. It wants some attention. We can all recognize this because it's very similar to ours. It happens on the same time scale, same roughly spatial scale. These creatures live in a similar world that we do. They want some of the same things that we want.

Slide 11/48 · 11m:38s

We can recognize this behavior easily, although I will point out that the actual degree of agency in these kinds of things cannot be derived from pure observation.

For example, you can see things like this, and by looking at this, you can't tell what is going on here or to what degree this creature understands the tool that it's holding. You have to do perturbative experiments.

Slide 12/48 · 11m:56s

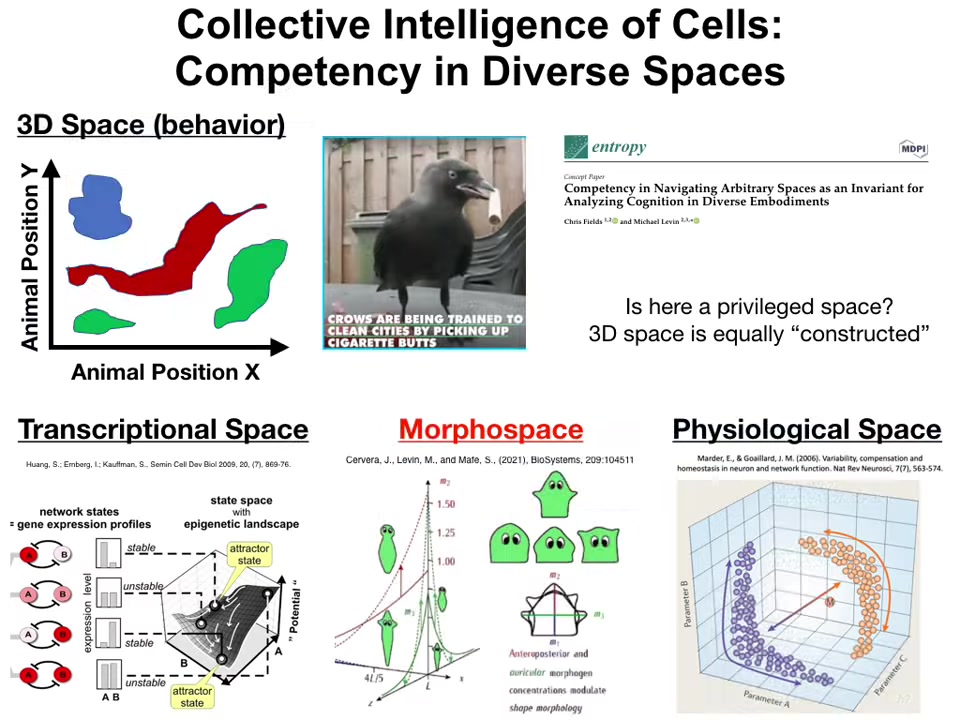

To really understand patterns of behavior, we have to free ourselves from our obsession with three-dimensional space as the only space in which problem-solving behaviors can happen. We as humans are primed to recognize behavior of medium-sized objects doing medium things, doing things at medium speeds in three-dimensional space. We're okay at recognizing intelligence in those kinds of scales.

But biology has been navigating spaces for a very long time, long before muscle and brain appeared. Before neurons and muscles allowed us to navigate three-dimensional space, living matter was navigating the space of gene expressions, the space of physiological states, and the thing that we're going to talk mostly about here, which is anatomical morphospace.

Chris Fields and I wrote this paper to try to show what's common to all these spaces is the ability of biology to navigate and to do the perception-action loop that we associate with intelligence, and that loop, that control of behavior, can be done in many other spaces. In fact, I'm not sure that three-dimensional space is privileged at all. I think to some extent we construct it cognitively just like we can construct all these other spaces.

Slide 13/48 · 13m:19s

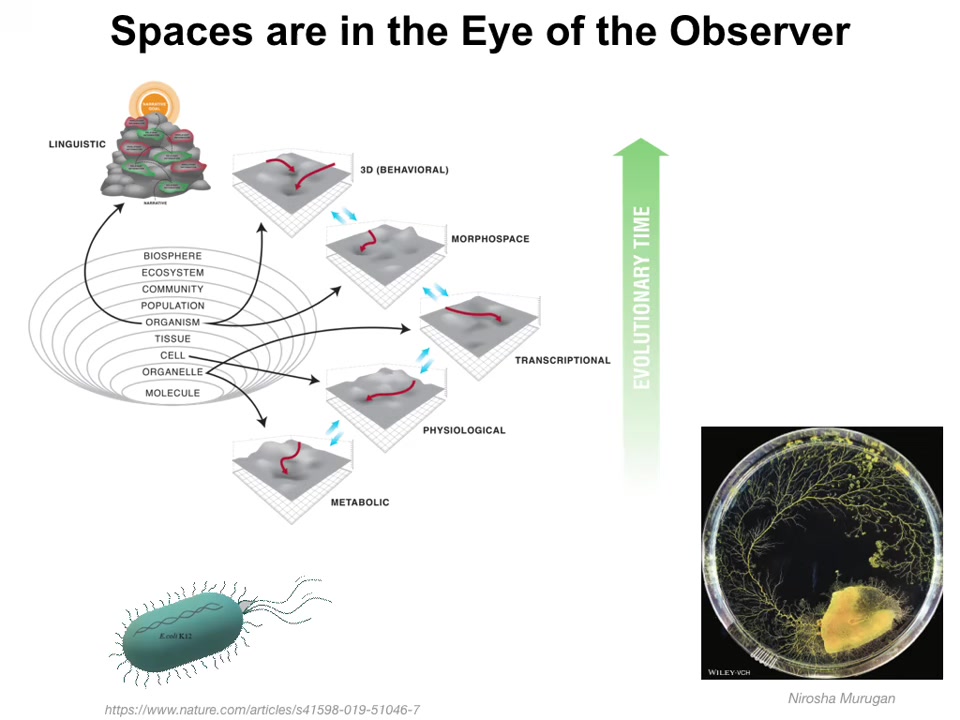

On the one hand, we can look at evolution as progressing some of the same tricks through various spaces as complexity increases, metabolic spaces, physiological spaces, and so on, all the way up through behavioral and eventually linguistic and other spaces.

On the other hand, this all looks reasonable, but it's in the eye of the beholder. A bacterium could increase its ability to gain sugar by either physically moving up the sugar gradient or by taking a step along transcriptional space and turning on a different gene encoding a different enzyme that allows it to metabolize a completely different sugar. Either one of those would get its job done, and it is not clear at all that the bacterium and the way that it processes information view those two actions as happening in different spaces.

Physarum, this slime mold, its behavior is its morphogenetic change. That is how it does behaviors—by changing its shape. This neat division into various problem spaces is up to the observer who's trying to understand what's going on.

In this first part of the talk, what I've tried to show is that there are specific and characteristic patterns, both of anatomy and behavior, and that these are just members of the same class of patterns that can exist in many different spaces. The reason this is important is because towards the end of the talk, I'm going to point out that it's the same space of patterns, this platonic space, that I think is responsible for the presence of both anatomical shapes and behaviors and probably many other patterns in biology and in other disciplines.

Slide 14/48 · 15m:07s

The next thing that we have to look at is this idea that these patterns are not emergent in an open-loop feed-forward manner from subunits executing simple rules, but are very specific patterns pursued by goal-directed or homeostatic mechanisms. These are discrete targets that are implemented by specific mechanisms. I like James's definition of intelligence, "the same goal by different means." I think that's exactly what's happening in the biological substrate. If you're interested in this topic, there's a whole talk about this here.

Slide 15/48 · 15m:55s

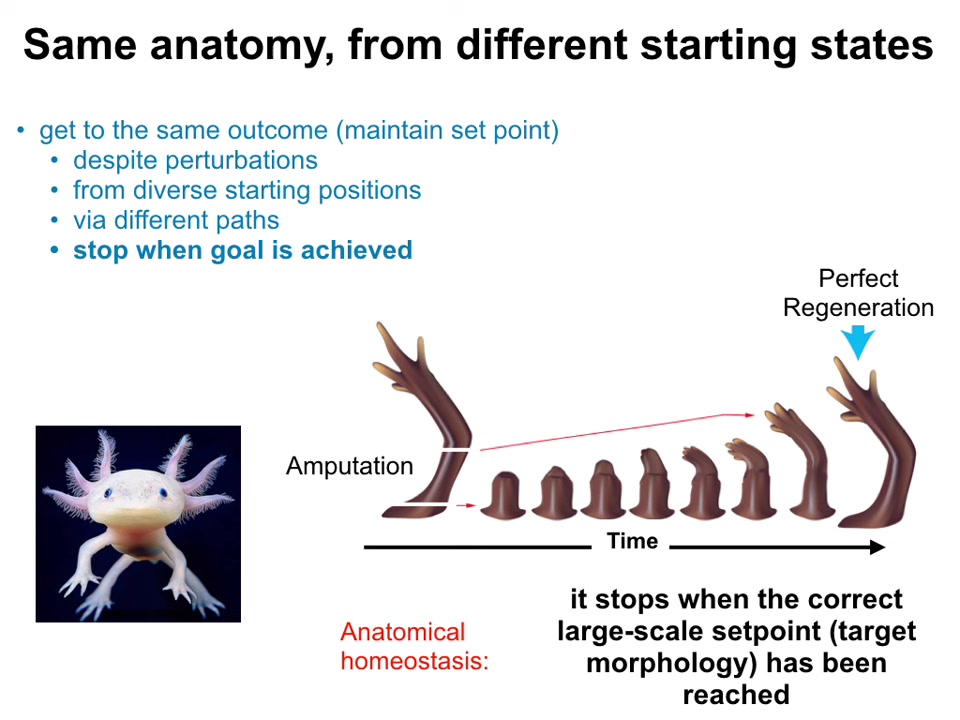

Very simply, anatomies show this kind of homeostatic error minimization process. Here's an axolotl. It's an amphibian that is highly regenerative. If you amputate anywhere along this limb, the cells will spring into action. They will work to regrow that limb, and then they stop. And that's the most amazing part of the regenerative process: it knows when to stop.

When does it stop? It stops when the correct axolotl limb has been completed. So there's the ability of the system to detect when it's been deviated from the correct target morphology, it works to get closer to that target morphology, and when the error is within acceptable levels, it stops. This kind of thing is pattern homeostasis or anatomical homeostasis. It shows you that it's not an example of cells doing what they do. If you try to deviate it from their goal, it will work hard and spend energy to get back to where it's supposed to be.

Slide 16/48 · 17m:04s

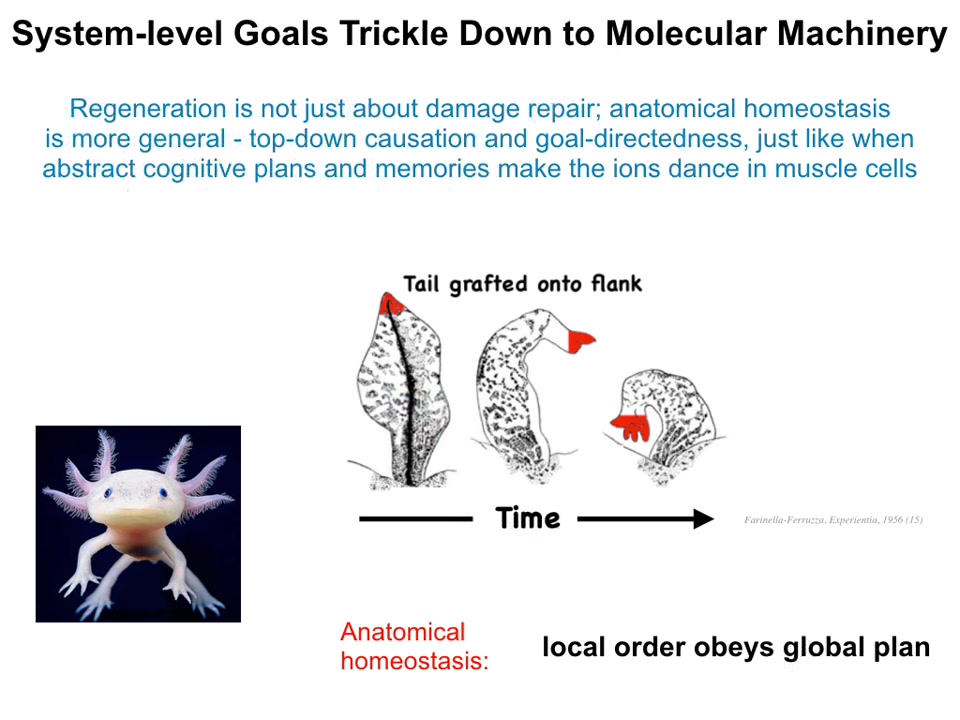

But what's really interesting about this is that it's not just repair of damage. It is not just minimization of error after some injury. There's a really interesting top-down causation situation going on here. And you can see that when people graft the tail to the side of the flank. What happens after a little while is that the tail turns into a limb. It remodels in place. And in order to do that, the cells at the tip of this tail have to turn into fingers. Why are they doing that? There's nothing wrong up here. They're tail tip cells sitting at the end of a tail. But what's happening is that the error signal operates at the level of the entire body. In other words, there's no error with the cells. There's nothing wrong there. But there is an error at the level of the entire body because it knows that a tail doesn't belong there. What happens is that error now propagates down to the cells and to the molecular machinery that has to do certain things to turn tail cells into limb cells and to build finger structures. This is very interesting that the local order obeys a global plan. These things filter down all the way from a global anatomical plan to the specific molecular events that have to happen.

I think this is very similar to what happens cognitively. This is drawing that parallel between the processes that shape the body and those that shape behavior when very abstract, high-level cognitive plans and memories can be transduced into the movement of ions across your muscle membrane. So when you wake up in the morning and you have very abstract goals, eventually potassium and calcium ions have to flow across various muscle membranes in order for you to get up and carry out the behaviors. So voluntary motion is the same kind of transduction of very high-level abstract target patterns into specific changes of physiology and ultimately chemistry inside the body.

Slide 17/48 · 19m:15s

The final thing I'd like to show is that this kind of process is not just repair of damage. It also involves this kind of top-down control.

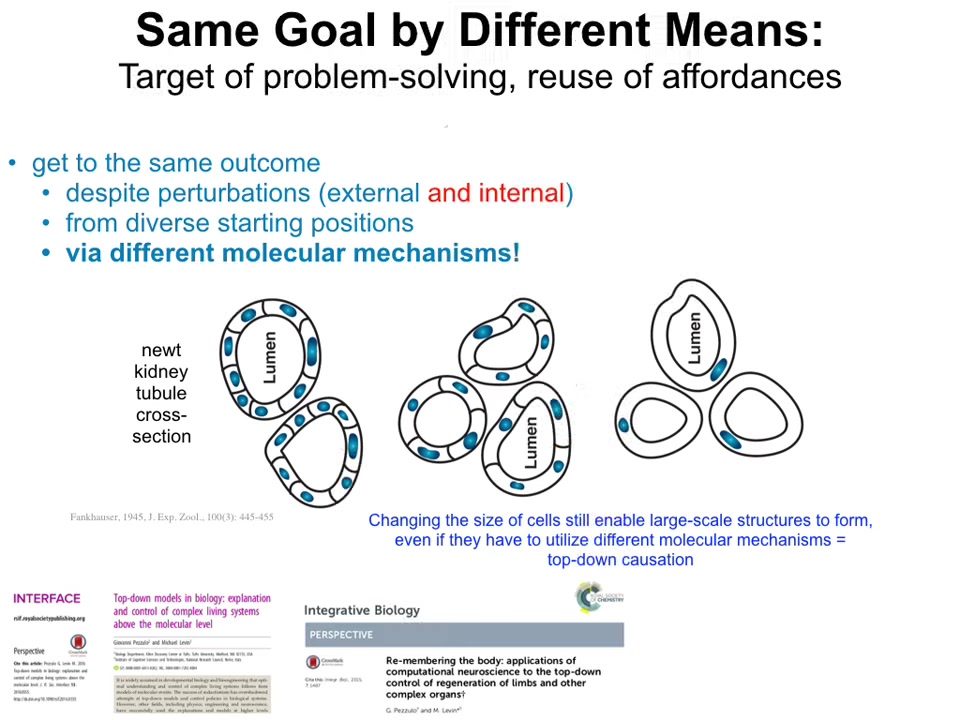

There's another feature to this, which is problem solving. It's the reuse of available tools to solve a problem and get to the same goal by different means.

This is one of my favorite examples. This is a cross-section through a kidney tubule in the newt. What you can see is that there's a lumen, and then there's 8 to 10 cells that form it by working together to create this kind of tubule. One thing you can do experimentally is force the cells to have extra copies of their chromosomes, in which case the cells get much bigger but the newt stays the same size.

If you take a cross-section, you find that fewer of these larger cells then work together and they make exactly the same structure. You can keep doing this until you make really gigantic cells, and then what you find is something striking. One cell will bend around itself and again keep that same structure.

Now the reason this is amazing is that this is a completely different molecular mechanism. This is cell-to-cell communication, normal tubulogenesis. This is cytoskeletal bending.

What the system is doing when it's placed in an unexpectedly new situation is that it's not just that the environment changed. If you're a newt coming into the world, you can't even trust your own parts. Your own components are unreliable. Suddenly your cells are way bigger than they should have been.

What it's able to do is use other tricks in its molecular repertoire to solve the problem, which, again, looks like a lot of IQ tests you see when they give you a set of objects and say, Can you solve a problem in a new way, in a creative new way, with these tools that you have?

The system is able to exert a high-level problem-solving competency to reach a specific pattern. The importance here is that there's a very specific pattern that it's trying to reach. Whether it's repair or different kinds of top-down causation or reuse of different molecular affordances, all of these things are aimed at creating specific goals.

Slide 18/48 · 21m:35s

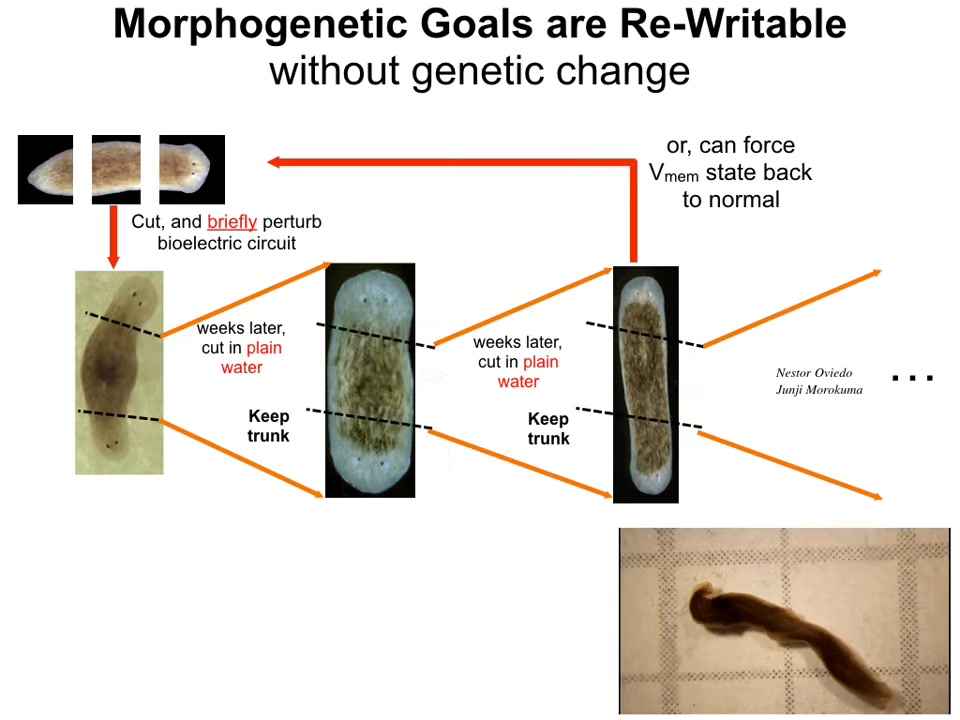

These targets, these goals can be rewritten.

That's one of the amazing things about homeostatic mechanisms: it isn't just feed-forward, where it's very difficult to know what to change in the low-level rules to give you the correct final outcome. These kinds of processes that explicitly have a goal state or a set point that they aim towards, that set point can be rewritten.

What we've done here is taken these planaria, which normally very reliably regenerate. This middle fragment will normally grow exactly one head and one tail. We've modified the set point, and it turns out that set point is stored bioelectrically. When you rewrite that set point, you can make it two heads instead of one, and the cells are happy to build two heads.

In fact, that information is kept stably. It's a memory. If you keep cutting these two-headed animals, you will continuously get more two-headed animals.

What I'm showing you here is that not only is there a kind of specific form that the processes pursue, but that form is rewritable because it is selected as an endpoint or a set point towards which these mechanisms strive. You can see here, these are two-headed flatworms hanging out in this video.

Slide 19/48 · 23m:04s

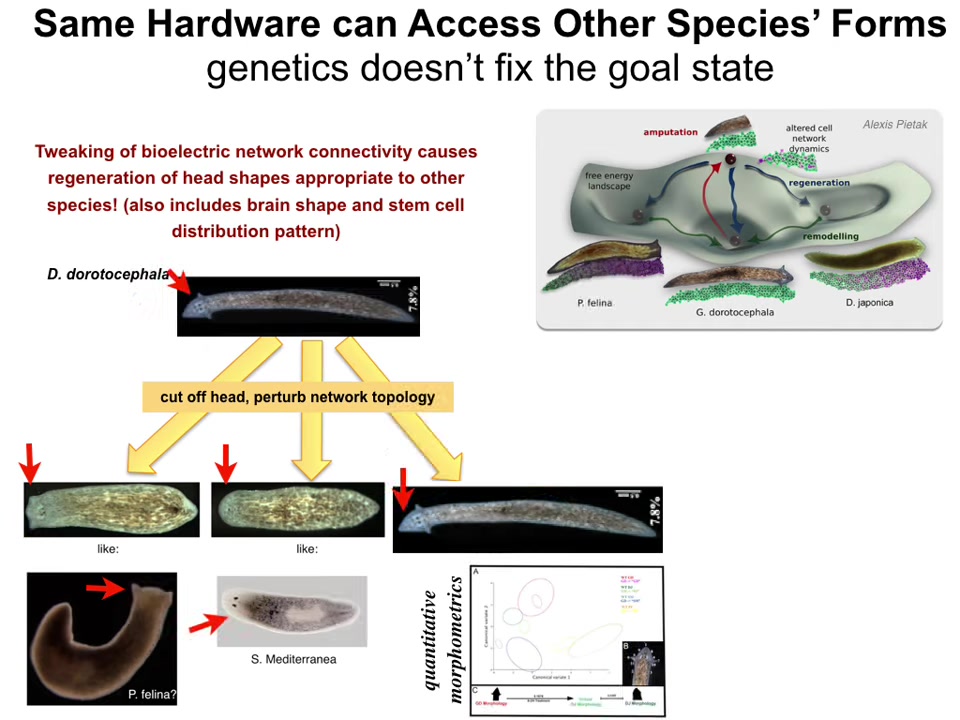

Now, not only can we shift the set point to say 2 heads instead of 1, we can also move them towards the patterns of different species. We can take this nice triangular head-shaped planarian, cut off the head, bioelectrically change the information that is driving the regeneration, and instead of the triangular head, you can make a flat head like a P. falina, you can make a round head like this S. mediterranea, or of course the normal triangular head.

Not only the shape of the head, but the distribution of the stem cells and the shape of the brain changes too. What's happening here is that, much like in the previous example where I showed you, we can get permanently two-headed worms with no genetic change. We are editing the bioelectrical pattern memories, not the genetics. The genetics is perfectly wild type. It creates hardware, cellular hardware, that is quite happy to visit different attractors in that anatomical space.

Now, some of these attractors belong to other species. We can also make some things that don't look like any known species. The idea is that there is this landscape in anatomical morphospace that contains specific attractors into which these systems will try to reach, even if you try to deviate them in various ways, and you can push the system to prefer different attractors.

This biological interface in this issue will come up again in a few minutes; basically what you have here, the DNA codes for a particular hardware that acts as an interface to various patterns in that space, and that interface can be dialed into different patterns in that amorphous space.

What I've shown you in the first part is that there are very specific types of forms of anatomy and behavior that the biological systems work really hard to reach, and they have all kinds of cool tricks to implement those specific forms.

Slide 20/48 · 25m:02s

So now it's time to think about where these forms actually come from. If you're going to have shapes and behaviors that the system is going to try to reach these very stereotypical target morphologies, where do they actually come from? What I want to show is that some of them are reasonably explained as having been selected for, but others are not. It's quite clear that the hardware is able to find truly novel forms in that space that don't appear to have anything to do with a past history of selection.

Slide 21/48 · 25m:32s

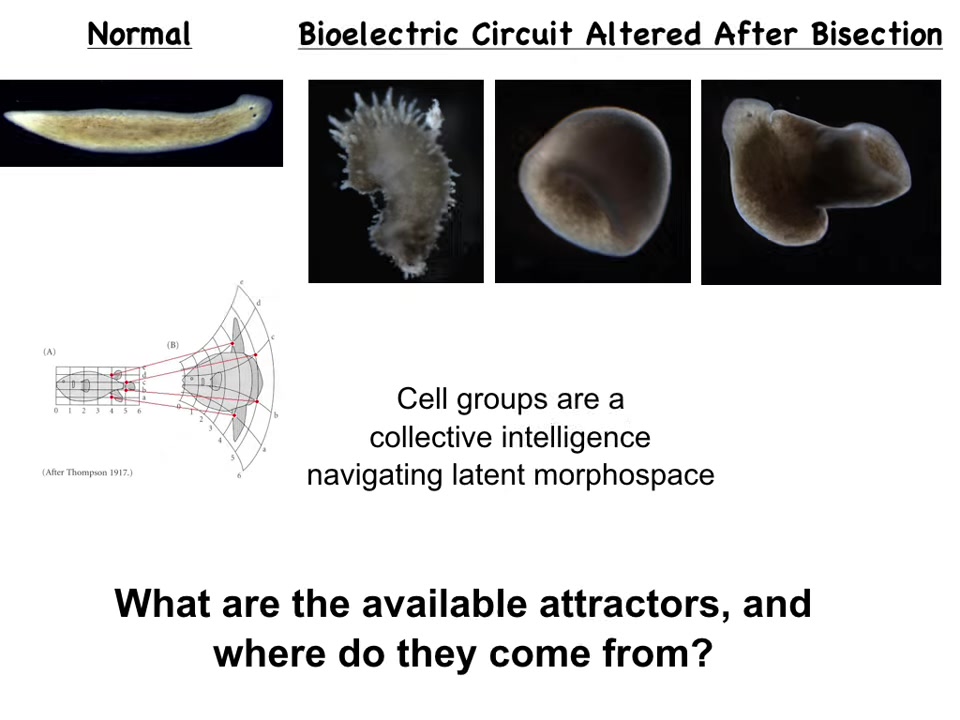

The first thing to look at is this. These are, again, the planarian flatworms, and I've shown you that we can make them have either extra heads or heads of other species, but we can also push them into regions of that space that don't seem to belong to any species. In other words, we can make these spiky forms, these cylindrical forms that aren't even flat anymore, and these kinds of hybrid forms.

The idea here that we've been studying for years and that I showed you just a few examples of is that groups of cells are a kind of collective intelligence. Why? Because they become aligned towards specific goals in this morphospace of patterns and they navigate that space and they try to reach specific patterns even though they might encounter various serious challenges like you saw in the newt. The question then is what are the available attractors and where do they come from?

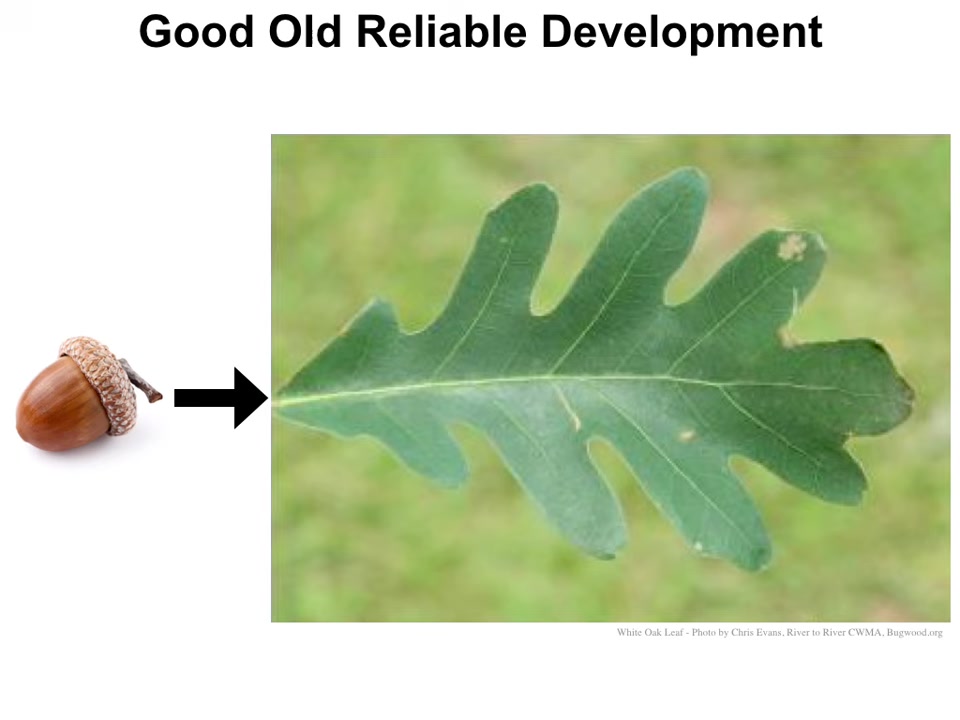

Slide 22/48 · 26m:33s

Some of them are quite remarkable, but some of them have an evolutionary explanation. For example, here these acorns are so reliable in making oak leaves that we can be forgiven for thinking that that's what the oak genome encodes. It encodes this particular kind of pattern, and this is what it knows how to do.

Slide 23/48 · 26m:56s

But then along comes a non-human bioengineer, this little wasp. The little wasp hacks the morphogenetic competency of these leaves and makes the plant cells build these kinds of structures. They don't come from the insect cells, they come from the plant. If not for this prompting them, we would have never known that these reliable flat green leaf cells are capable of making these amazing round spiky red and yellow structures.

What we see here is that the standard form, the leaf itself, is a tiny pinpoint in that latent space. It's one outcome. But around it there are some other things that this exact same hardware can do. In asking where the actual information for making the various options is written, in other words, where the different set points of these processes are specified — the different forms — in biology there are two criteria for answering this "where does it come from" question.

Slide 24/48 · 27m:58s

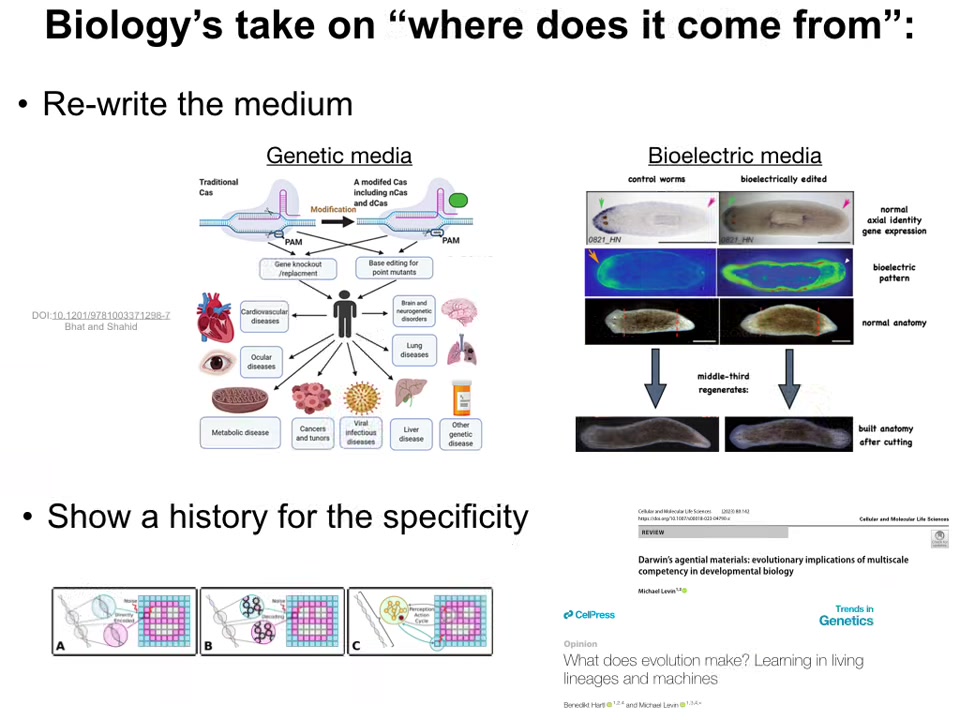

If you want to say that a specific medium contains the information for a specific phenotype, for a specific outcome, you have to do two things. You have to be able to rewrite it.

Whether it's genetic, meaning the genome, or whether it's bioelectrical, the pattern memories like we do in planaria, you have to show that if you change the information in the medium, then the anatomy actually changes. And that's one important piece of the evidence: that is where the pattern was written. Certain things are written in the genetics, and many other things are written in the physiological patterns. And here, in these two papers, we discuss what it really means to think about where these patterns are actually encoded, but the other thing that's important in order to say that some kind of process is the origin of these patterns is that you have to be able to show a history for the specificity.

In other words, in biology, you have to be able to say that the reason it is this pattern and not some other pattern is because there is a history of interaction with the environment, meaning evolution and selection, that explains why this is the particular outcome you have. Biologists love these two kinds of explanations: the ability to rewrite a specific medium and get a predicted outcome, and to show a history of specificity of a given pattern, because the material has faced a certain history of selection in the environment in the past.

Slide 25/48 · 29m:43s

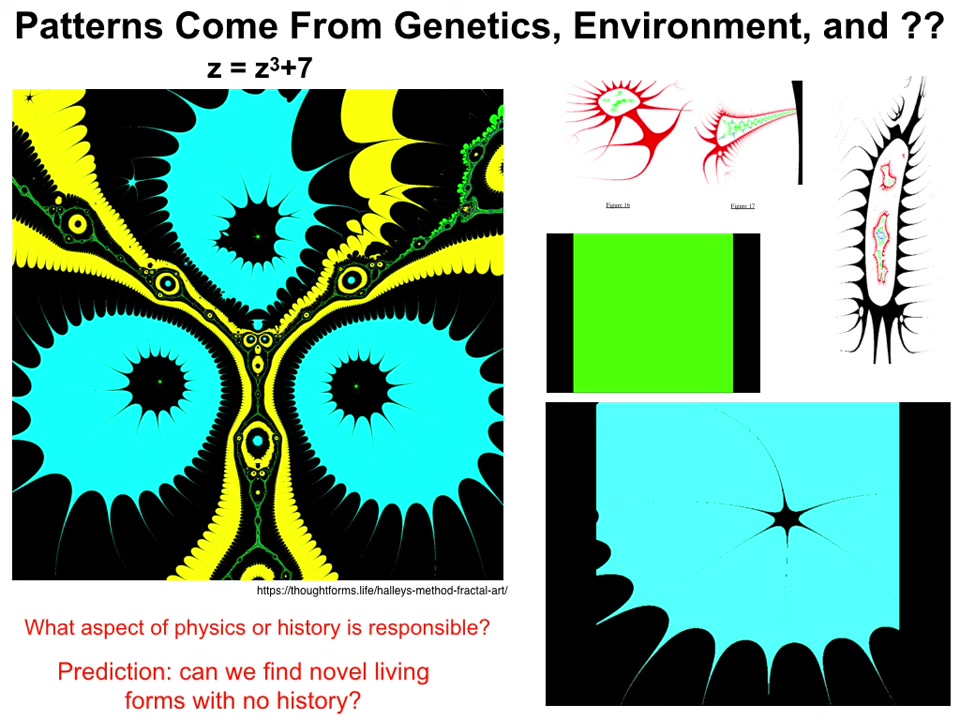

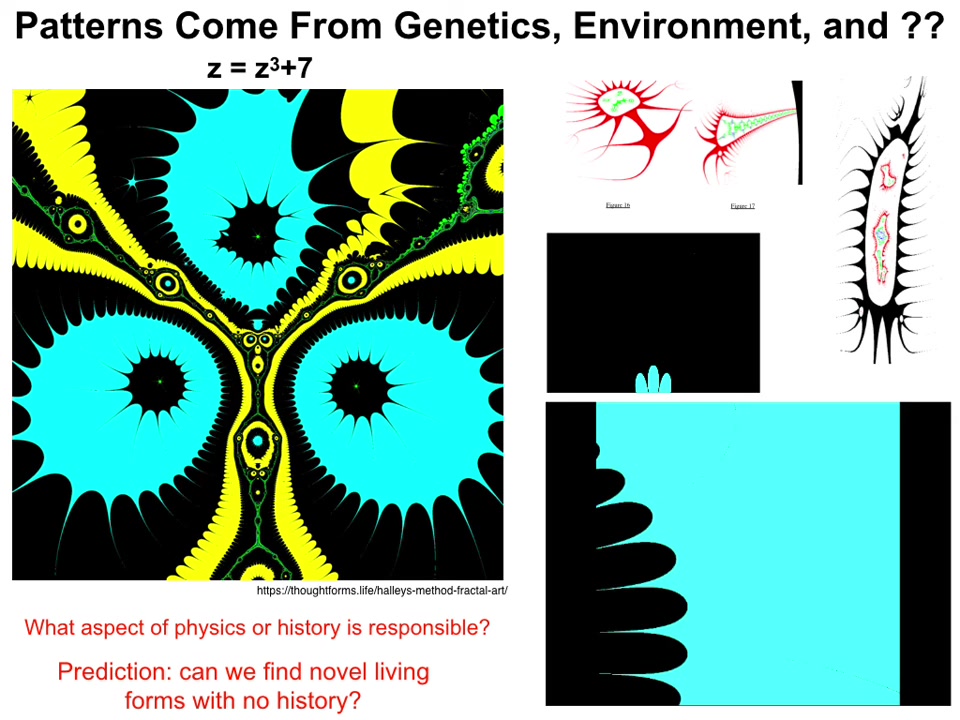

But there is a third interesting kind of source for patterns. Here's a particular example. This is a very simple formula in complex numbers. This is a Halley plot, which uses a simple algorithm to plot the pattern indicated by this function.

Slide 26/48 · 30m:03s

Now, it is incredibly rich. It's amazing that this rich structure comes from such a tiny little formula. If you change these functions very slowly and make frames, you can make videos that look like this. An incredible amount of order and structure packed into a tiny little seed.

Again, we have this notion of an interface or a pointer into a much richer space. If this was a compression, it would be insane levels of compression. But this is a pointer to this mathematical object. What's important is that it doesn't hurt that these things look very organic.

What's important here is that if you want to explain why this thing has the particular shape it has, that answer is not going to be found in any fact of physics. There's nothing about the physical universe that determines what the shape of this is going to be. The shape is not a consequence of any physical process. There's no history of selection. We can't say that this looks the way this looks because there were many other variants and they all died out. That is not what happened here.

Where does this come from? All of this very particular, very specific structure. If it's not physics and it's not selection, where does it come from? Having seen that that's possible, that the space of mathematical objects has all kinds of patterns in it that are distinct from what physics and history gives you, we can ask, is this relevant for biology? Can we find novel forms that do not have a history of selection for their specific properties?

Slide 27/48 · 31m:48s

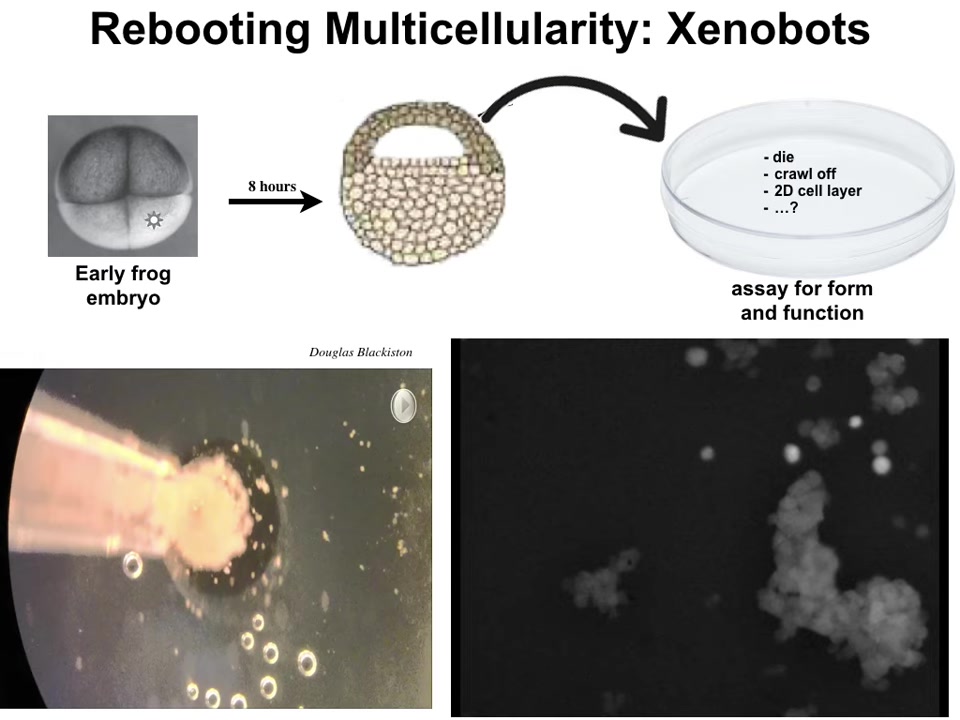

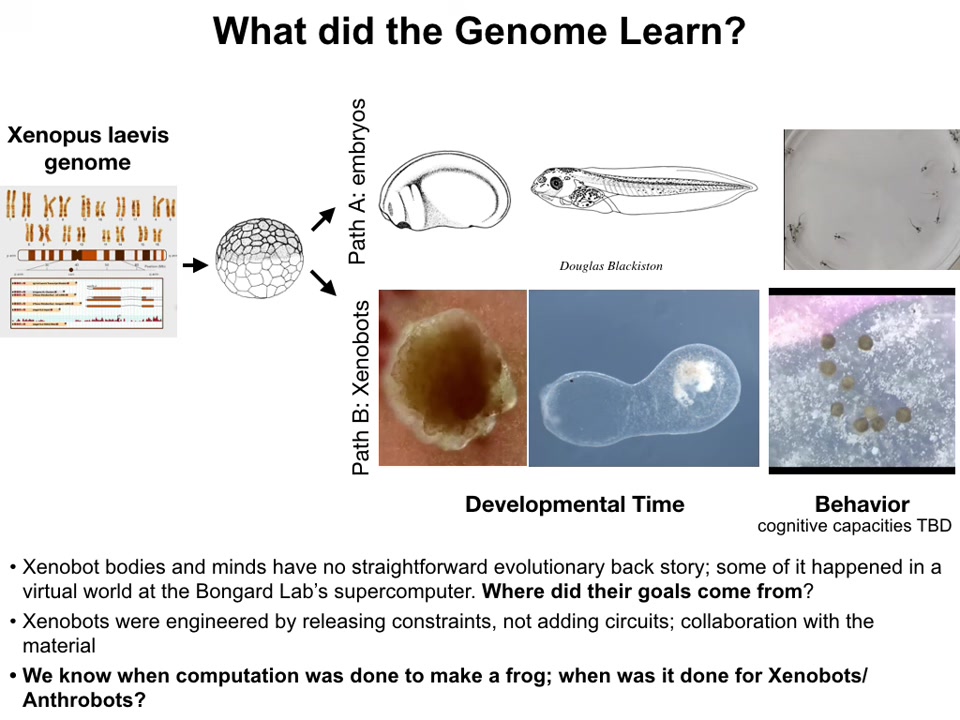

Here I will show you two of them. First, something we call xenobots. This is a biological construct made from the extracted cells of an early frog embryo. We take them off of the embryo, we put them in this dish. They could have done many things. They could die, they could crawl away from each other, they could form a flat monolayer-like cell culture.

Instead, they merge together and form this little construct. The flashes are calcium signaling. Each one of these little tiny things is a single cell. This is a close-up. You can watch this little group of cells. It's really funny that it looks like a little horse. They move as a unit. They wander over here. They interact with some other cells here. There are little calcium flashes as the cells interact with each other, and eventually they all coalesce into this thing. This is the shape, and there are all kinds of intermediate shapes.

Slide 28/48 · 32m:54s

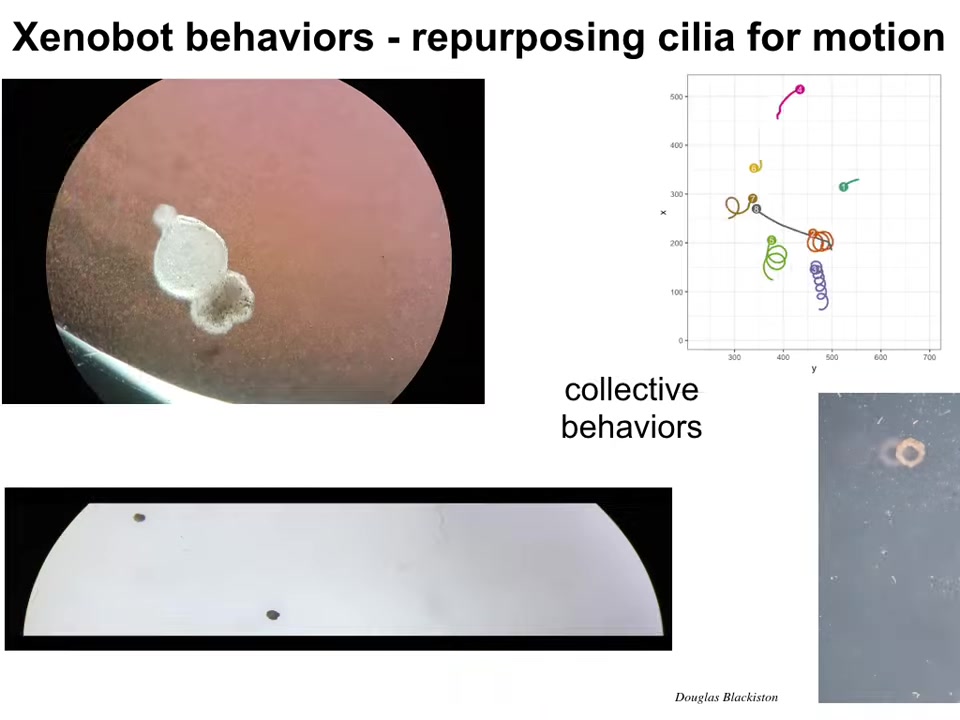

Here's the actual Xenobot. It's swimming along by waving cilia, the little hairs on their outer surface. It has lots of specific behaviors. It can go in circles. It can patrol back and forth. It can do this kind of collective group behavior. If we track their motion, they can do all kinds of interesting things. We can make them into weird shapes like this swimming donut.

Slide 29/48 · 33m:19s

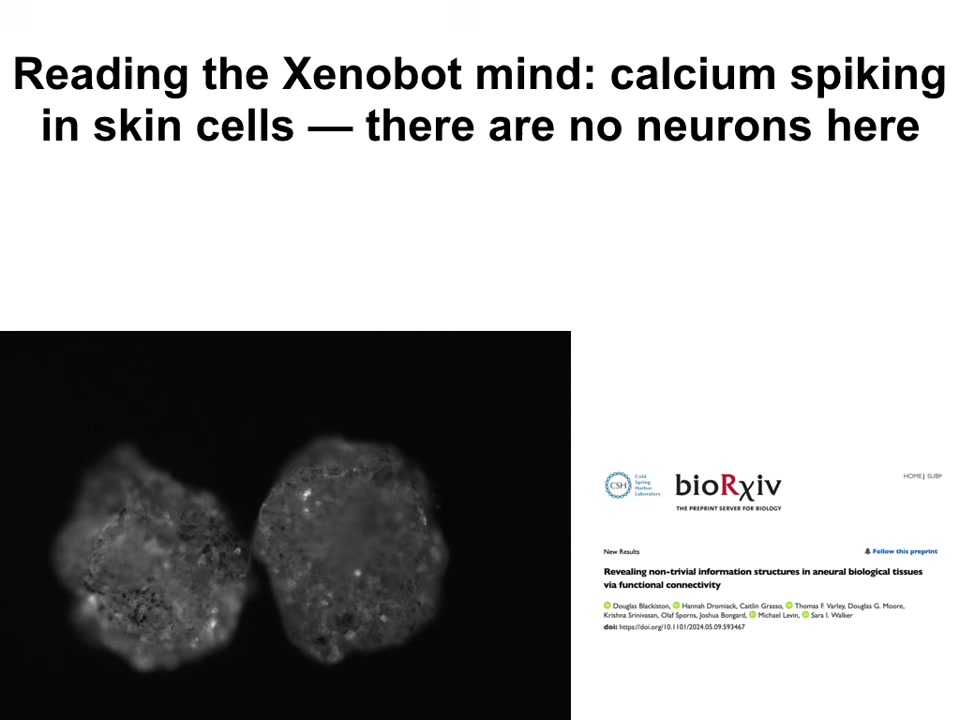

The calcium signal is interesting. There's no neural tissue, there's no brain here, but there is a lot of calcium activity and calcium is a readout of cellular computation and a lot of neuroscience uses calcium signaling as a proxy for the computational activities that are going on. And many people are developing tools to decode. This is generally a field called neural decoding, where people try to decode the dynamics of these flashes to understand what a brain is doing. So as I said, there's no brain here.

In collaboration with Josh Bongard's group and Sarah Walker and Olaf Sporns, we've been using metrics that come from neuroscience to understand both the connectivity pattern and the actual dynamics of this to see what might be going on here and what kind of computation this might suggest. And all of that is yet to come. Those analyses are going to be published in a bit.

So what you've seen is novel morphogenesis in these Zenobots. And now I want to show you some behaviors.

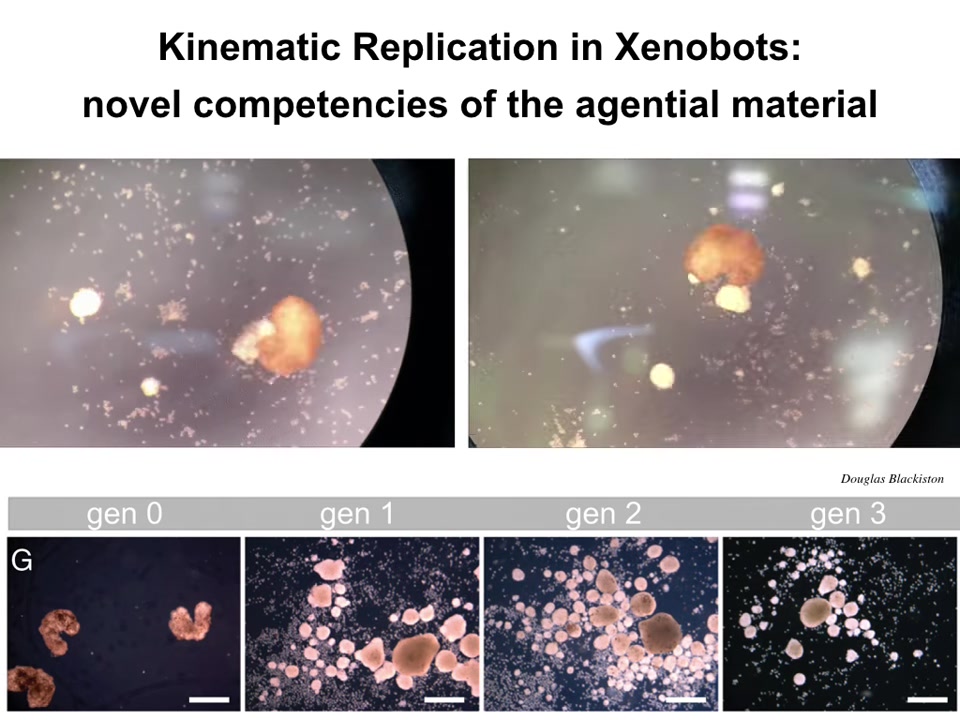

This is one thing that they do called kinematic self-replication. And this is some work done with Josh Bongard's lab and all the Zenobots.

Slide 30/48 · 34m:52s

The biology for the Zenobot stuff was done by Doug Blackiston in our group, and then Sam Kriegman did the computational analyses.

What you're seeing here is that when provided with a material substrate, each one of these little tiny dots is loose epithelial cells thrown into the arena with the bots; they run around and they do something amazing. They collect them into little piles and then they polish these little piles like that.

Because they're working with an agential material themselves, these are not passive beads; these are cells. Each one of these piles matures into the next generation of Xenobots. Guess what they do? They go and collect the cells into new piles and make the next generation and the next.

We call this kinematic self-replication. That's one interesting thing.

Slide 31/48 · 35m:38s

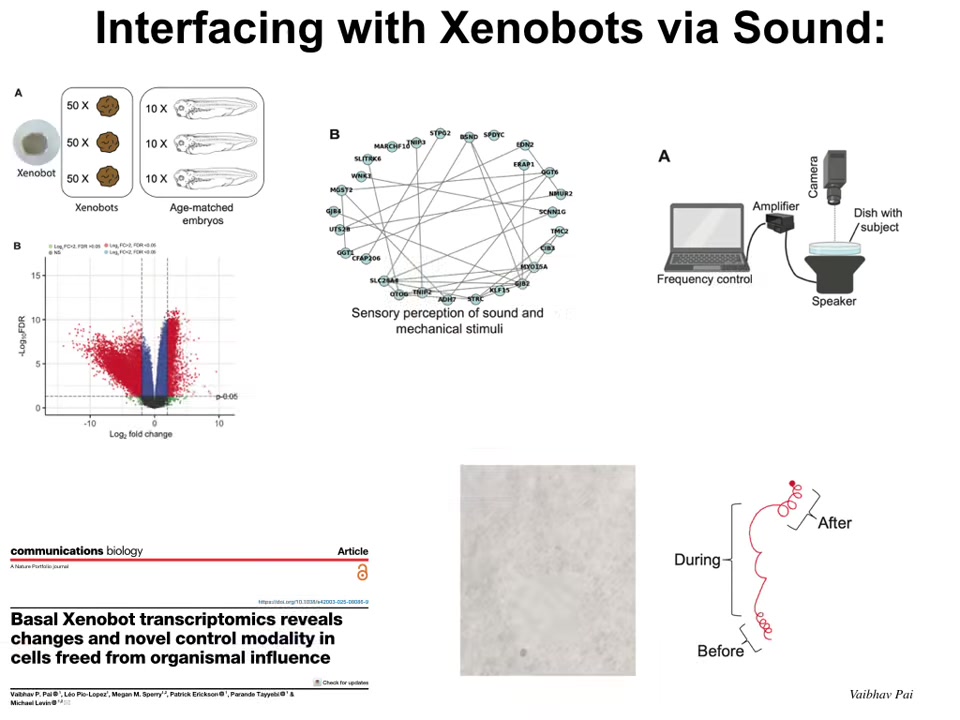

Another interesting thing is we found out that these xenobots have a really altered transcriptome. They have hundreds of genes expressed differently than the cells would have if they had been inside the embryo. Lots of interesting genes get upregulated. One, just as one example, one thing that gets upregulated is a cluster of genes related to the perception of sound and mechanical stimuli. We saw this. This is the work of Vaipav Pai in this paper, and we asked, is it possible that these things now could actually perceive vibrations or perceive sound? Because these are genes that they would not otherwise, in their normal environment in the embryo, be expressing.

It turns out that, yes, if you put a speaker under them and play a certain sound, during that sound they change their behavior in a very stereotypical way that you can detect. After the sound is turned off, they go back to their normal behavior. So what you've seen here is that these cells, taken out of their normal context, reconfigure themselves into a new kind of living construct that has different behaviors. It has different transcriptomic profiles. It has a different pattern in transcriptomic space, in behavioral space, and, of course, in anatomical space.

Slide 32/48 · 37m:00s

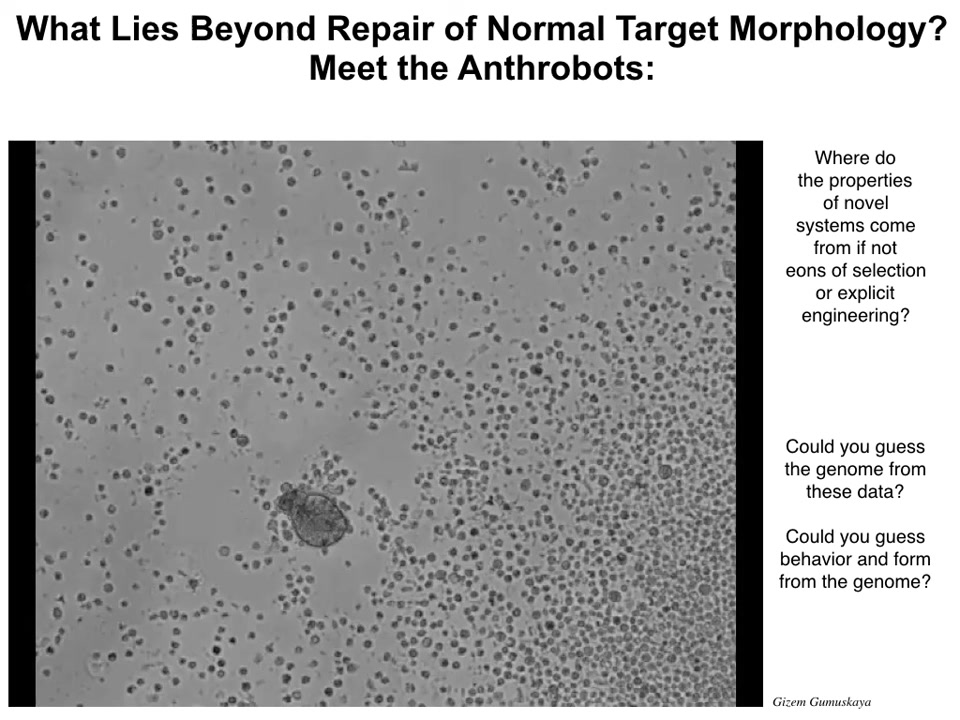

I'm going to show you one more version of this. It is another synthetic creature made of, this time, human tracheal epithelial cells. You might think the thing I showed you before was a specific feature of amphibian development. Amphibians are pretty plastic and they are embryonic cells. You might think they would have plasticity to do other things. These are adult human cells. In both cases, there is no genetic editing. We haven't done anything to the genome. There are no synthetic biology circuits. There are no scaffolds, there are no weird nanomaterials. This is all plasticity on the part of the cells to reimagine their multicellularity and to find new patterns in various spaces.

As you look at this thing running around, these other dots are just other cells. If I didn't tell you what this is, you might think it is something we got from the bottom of a pond somewhere. It looks like some kind of primitive organism, but if you sequence the genome, it would just be Homo sapiens. You get this idea that the genetics specifies hardware that is actually perfectly capable of picking up other patterns of form, of behavior, of transcription.

Slide 33/48 · 38m:17s

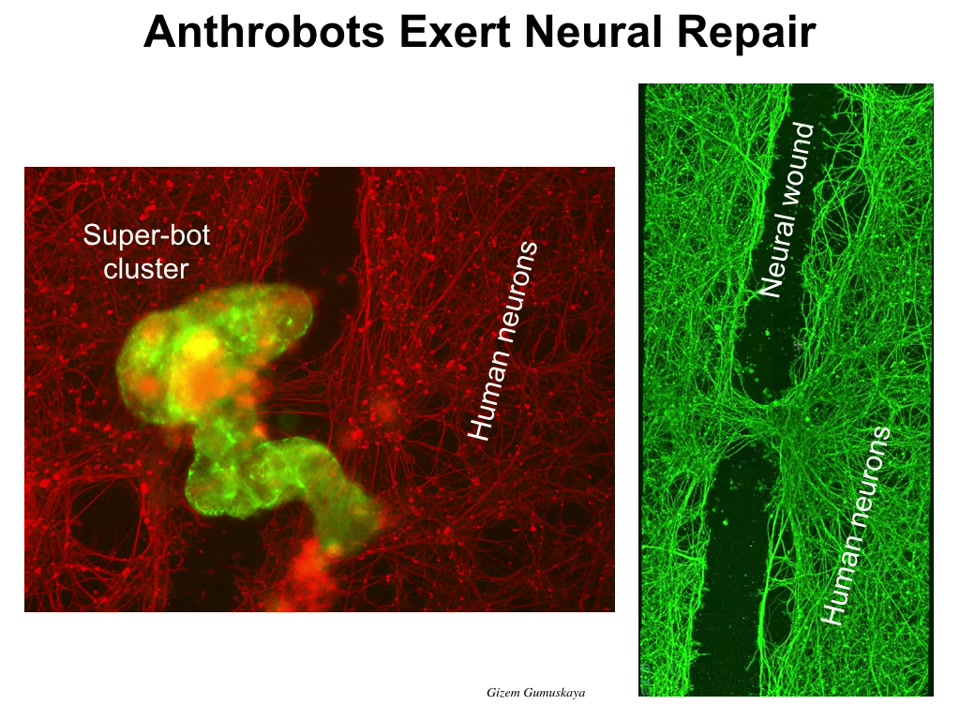

Here's something cool that the Anthrobots can do. If you lay them down on a field of neural cells and you put a big scratch through it, so here's a wound, these anthrobots will gather into something we call a superbot clusters. So there's maybe a dozen of them here. They kind of gather into this pile. And what you see here is that over the next four days, they start to knit across the gap. Here's where the anthrobots were sitting. When you lift them up, this is what you see. They're actually repairing the tissue. So they have this ability to repair other tissue damage. Now, who would have known? These cells sit in your trachea quietly for decades dealing with mucus and things like that. And it turns out that they can form a self-motile little creature with the ability to repair the neural tissues.

Slide 34/48 · 39m:07s

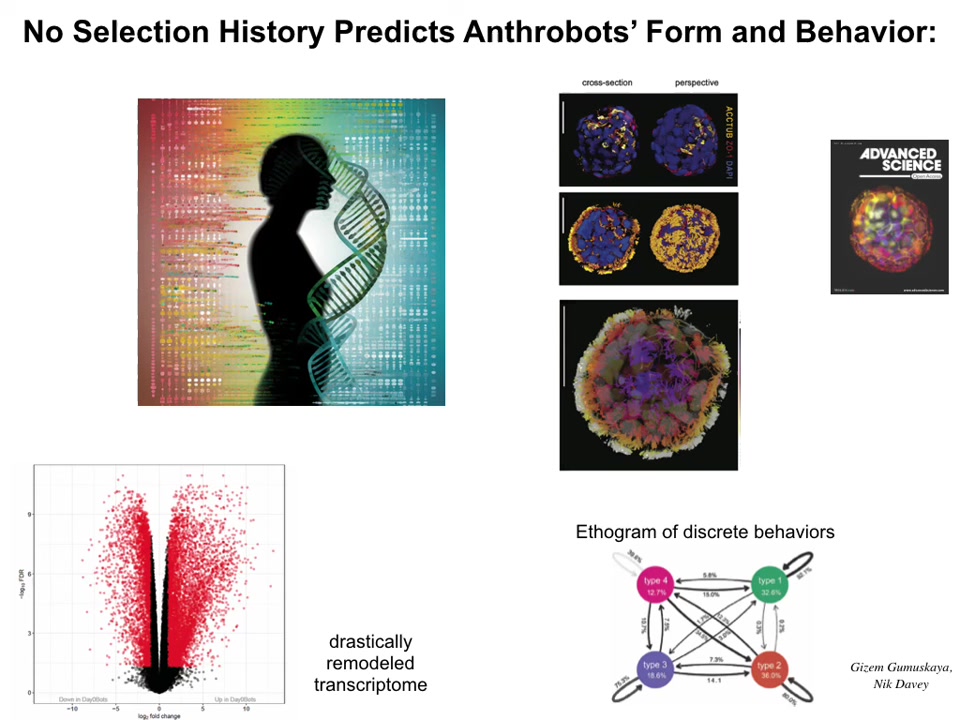

These guys also have a radically remodeled transcriptome, over 9,000 different gene expressions that they would not be having inside the body. Lots of fascinating different genes that they turn on. They have four distinct behaviors, and you can draw an ethogram of how they switch between these behaviors. This is a close-up of what the anthrobots look like. Now that I've shown you these two synthetic creatures, here's the most important part.

Slide 35/48 · 39m:42s

There's never been any xenobots. There's never been any anthrobots. We don't think that the anthrobots look like any early stage of human development. All of these things are an alternate path.

Here's the frog genome. We know we can make this developmental set of stages and these tadpoles. It turns out it can also do this. These are the xenobots. They do have some weird developmental stage. This is like an 84-day-old xenobot. We have no idea what it's turning into. It's got some developmental sequence, and here's the behavior. It's got different behaviors.

In these two cases of xenobots and anthrobots, there is no straightforward evolutionary backstory. Where did these goals come from? There's never been selection to be a good xenobot or a good anthrobot. What we see is that the hardware is picking up other kinds of patterns that we cannot say came from selection. You can try and say that these things were learned at the same time that it learned to be a frog or a human. That breaks the whole point of evolution as being able to explain the specific features of a creature with reference to the details of its past, the details of the selection forces in its environment. Nothing, looking at the human, the history of the human body, tells you about xenobots or about anthrobots, about the genes the anthrobots are going to express, about the neural healing that they do and all kinds of other things. Those things are just not derivable in any obvious way from the evolutionary selection forces.

There's also an interesting computational aspect to this: we know when the computation was done to make a frog—presumably it was done in the millions of years of the frog genome struggling with the environment. When was the computation done for xenobots? When were those computations done? In an important sense, the ability to access these other patterns is a kind of free compute. This is a much bigger topic, but this notion that there are some free lunches here and that, if you make hardware that's versatile enough, it can pick up patterns that do not specifically need to be evolved, is a massive time saver for evolution.

Slide 36/48 · 42m:19s

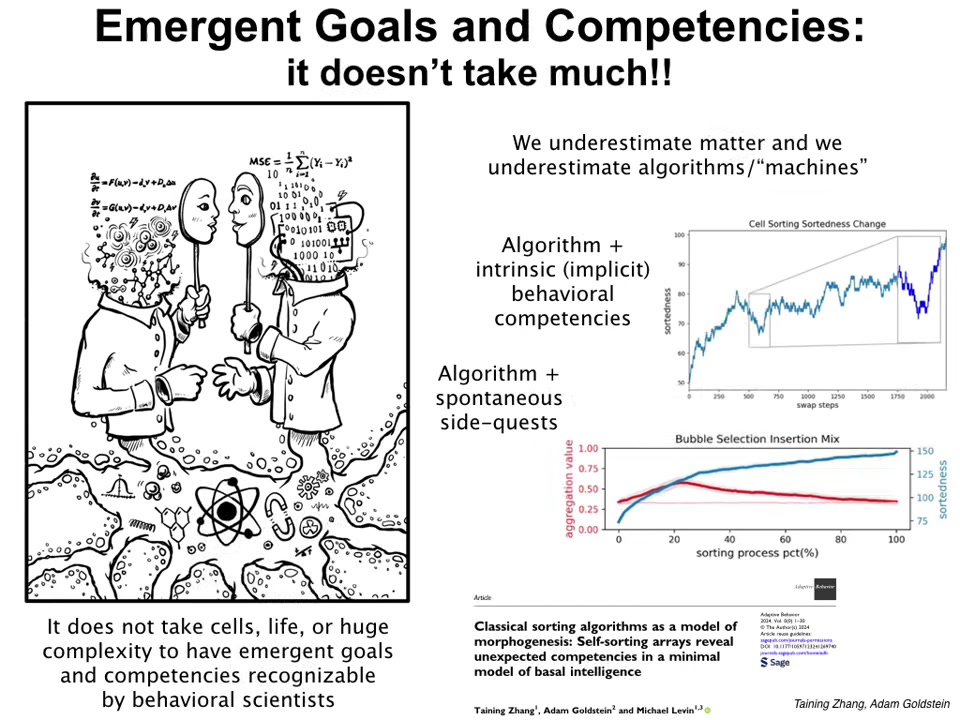

You might think that these kind of tricks, being able to find amazing new forms and behaviors and other things that are just not derivable or not expected from the history or the hardware of the system, might require very complicated interfaces, biologicals.

This paper and some other things we have coming out later this year suggest that it doesn't take much to benefit from this. It doesn't take cells, life, or huge complexity to have emergent goals and to have navigational competencies in various spaces that would be easily recognizable by behavioral scientists. These surprising outcomes are not simply complexity or unpredictability, but they're competencies well familiar to behavioral scientists.

What we studied in this paper is something extremely simple. It's an extremely minimal model. It's a sorting algorithm, things like bubble sort. What we find is, for example, they have a couple of interesting features. First, they have competencies that are not obvious from the algorithm. One thing they have is delayed gratification. If you put a barrier, if you apply a barrier such that the sorting algorithm is having trouble moving a particular number to where it needs to go, it will backtrack, reduce its sortedness in order to solve the problem in a different way. In the standard algorithm we're studying, there is no provision for this. There is absolutely no provision for what to do if you encounter a broken cell. The algorithm itself assumes that the hardware is reliable. It's short, deterministic, and completely transparent. You can see all the pieces, unlike biology: there are always new mechanisms to be discovered in biology, but in the algorithm you can see everything that's there. There is nothing there about what to do in these cases or about how to do delayed gratification, yet that's exactly what it does.

It also does some other things, which are interesting side quests that the algorithm doesn't ask them to do, but they are able to do. It's this thing called clustering, where they are able to recognize other cells running the same algorithm as them, and they tend to cluster together for as long as they can until the need for actual sorting overcomes it. These kind of side quests are not anything the algorithm asks them to do.

What we're seeing here is that even in extremely minimal systems like deterministic sorting algorithms, but certainly in complex biologicals, there are novel goals that do not seem to come from the typical sources taken to be the origin of these patterns, which are either the physics, the history, or in this case, the algorithm. There are things that are not explained by any of those and not predicted by them. Consistent with them, none of this is magic: physics or the algorithms do not prohibit these behaviors, but they do things that are not predictable or obvious, not explicitly stated in these sources.

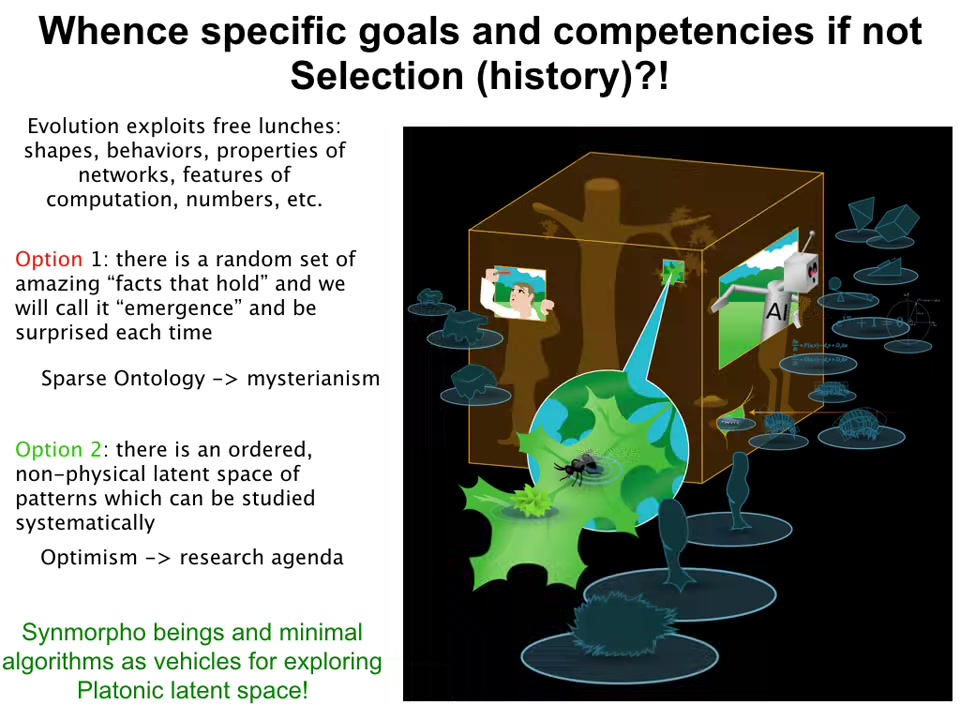

Having seen all of this, I would like to make a claim: where do these novel goals come from? I will argue that they come from a structured space, which avails us of a research program and is a much better option than the standard popular view today, which is emergence.

Slide 37/48 · 46m:36s

And so when we see various systems acquiring unexpected patterns, a form of behavior, and so on. There are a couple of ways to think about this. Option one, which I think is the kind of popular option nowadays, is this idea that there are just some things that hold in our world. These are some amazing facts. We call them emergent because we didn't see them coming. Emergence is, in this case, a measure of surprise. Some subunits together did something that wasn't obvious. We're going to call it emergence, and that's it. That's just something that holds in our world. The benefits of that view is that it gives you a sparse ontology. In other words, you can stick with the physical world. You don't need to think about a non-physical platonic space. I think this is really a pessimistic or mysterian view. It suggests that these things are random, they crop up when they crop up, and the best you can do is note them and move on and wait till you find the next one.

I think there's a better option, which is what the Platonist mathematicians assume, which is that these things are not a random grab bag of strange, curious facts that hold in our world, but actually there's an ordered, latent space of patterns which can be studied systematically, that these things are arranged in some sort of rational way that allows us to study them. That allows us to have a research agenda, which I'll talk about more in a minute.

But what it does is cast synthetic morphology beings such as arthropods, xenobots, chimeras, and so on, and computers and robotics and so on, all of these things are vehicles for exploring this platonic latent space of patterns. If we assume that the forms that I've been showing you that serve as the target of behavior at different scales are not random surprises, but are part of an ordered, structured, latent space, then we can use these constructs to explore the space, to watch what kinds of patterns are manifested by these things and work out the relationship.

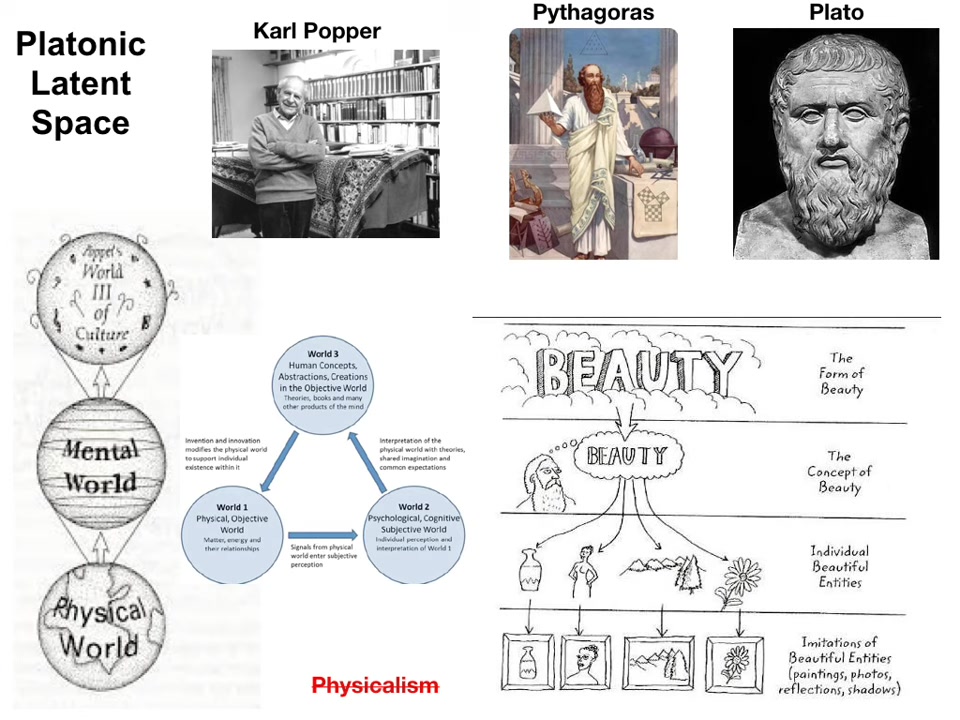

Slide 38/48 · 49m:03s

This is not a new idea. This has been around forever. Pythagoras and Plato and modern philosophers like Popper and others had this idea that there is a non-physical space of patterns of different kinds and that these things are in some way functionally important for what happens in the physical world. I only show this to point out that this rough idea has been present before.

Slide 39/48 · 49m:37s

I'm not trying to stick close to any of these specific proposals, except to say that there are many, many mathematicians that believe that there is a space, that what they're doing is mapping out the space, that they are systematically discovering, not inventing, but discovering the kinds of objects that live in that space. And they can move from one to the other by learning about each one. And that's the conventional view, is that this Platonic space contains properties of mathematical objects, truths of different branches of mathematics.

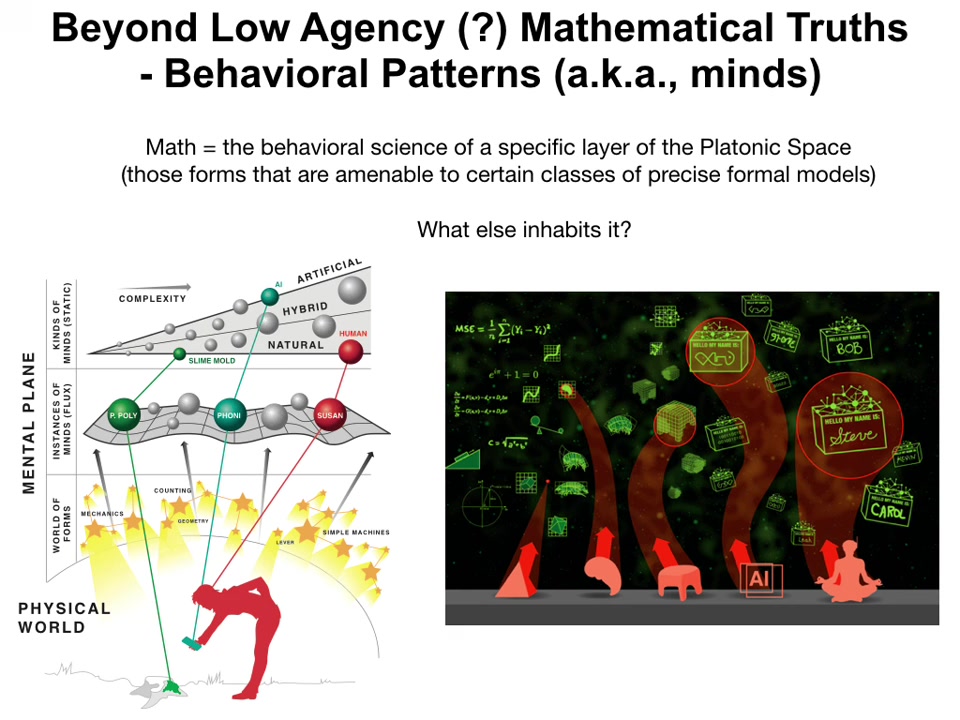

Slide 40/48 · 50m:13s

But one thing we can do is we can ask, what else might be in that space? If there are — let's assume for now that what mathematics is — it's a behavioral science applied to one specific layer or one specific region of this Platonic space. It's the science of the behavior of low-agency forms that are amenable to certain classes of precise formal models.

In addition to those things, might there be much more complex and active forms that we would recognize as behavioral propensities, aka kinds of minds. So the proposal here is that, yes, there's a non-physical Platonic space that contains various mathematical facts that then inform particle physics and biological structures. But also there are more complex patterns that inform not just anatomical outcomes, but behavioral outcomes as well, and if we think about it that way, these forms constrain aspects of physics — mathematical facts constrain aspects of physics — and they are exploited by biology. Then perhaps this famous question by Hawking, "what breathes fire into the equations," maybe it's backwards.

Maybe it's the idea that it's actually the mathematical properties that are breathing fire into the physical world. In this case, I've been alluding to this throughout the talk, that parts of, or perhaps all of the physical world are a set of interfaces, or front ends or thin clients to the main show, which are the patterns that come through and that drive what happens.

Slide 41/48 · 52m:05s

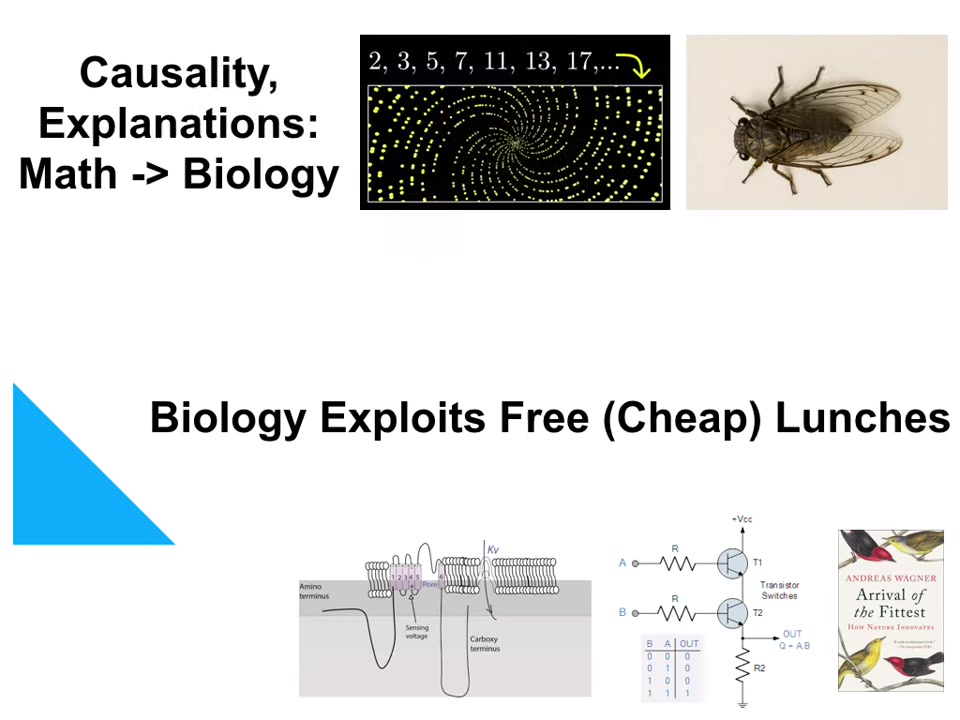

There are two things I want to lean on. One is this idea of explanations. So cicadas come out every 13 and 17 years. If you're a biologist, then you would like to understand why this is happening. Eventually, you get to the idea that it's because they're prime number years, and that allows them to be off of cycles with their predators. Then you say, okay, but why 13 and 17? Why are those special? Now you've left the province of biology and physics; you are now in the math department. If you want to understand why 13 and 17 are the way they are, then you need to talk to mathematicians and understand the distribution of primes.

As far as I can tell, this happens in biology and physics. If you keep pushing the question—"but why this specifically"—the further back you push that line of inquiry, eventually you always end up in math. You always end up in facts about mathematical structures. Explanations tend to take you out of physics and out of biology and into math.

There's this idea of causality. It's difficult to talk about traditional causality because I don't know how to do time in this case. Instead, if we think about interventions. If somehow the distribution of primes were different and it wasn't 13 and 17 that were prime but something else, then that is what the cicadas would be doing. In other words, the behavior of the biology is driven by the properties of mathematics, not the other way around.

As far as I can tell, there's nothing you can do in the physical world to have a different value for Feigenbaum's constant or E or any of these facts of number theory or topology. There's pretty much nothing you can do in physics to change any of that. But the reverse is not true. These things are actually driving aspects of biology and, I think, of physics, although I won't get into that.

The other interesting thing with biology is that it isn't merely constrained by these facts. It actually exploits them. What I mean by exploit, or free lunches, is the amount of effort involved.

If you're evolution and you're trying to evolve a very particular kind of triangle, you spend a bunch of generations getting the first angle right, you spend a bunch of generations getting the second angle right, but you don't need to do any effort to get the third angle. You already know what it is by this free gift from the laws of geometry. That saves evolution a bunch of time.

Or if you discover a voltage-gated ion channel, such as a KV channel, what you really have is a transistor, a voltage-gated current conductance. If you have a couple of those transistors, you can make a logic gate. The properties of the logic gates, with the truth table and the fact that NAND is special, you don't have to evolve those. You don't have to spend time evolving them. You get it for free from the properties of the logic gate that you made.

These are just two examples. There are tons. Andreas Wagner has a really interesting book about where the successful patterns actually come from in evolution.

So what I'm arguing for is that a lot of what we see in the sciences of engineering, biology, and computation are really sciences of the front ends of these things. They're the sciences of the interface. If you can depend on the resource that's behind that interface, you can start to really exploit it, kind of like a parasite that loses a bunch of functions. They depend on the host to do all the things that they need to do; they start to become more sparse and lose things. This is seen in biology as well.

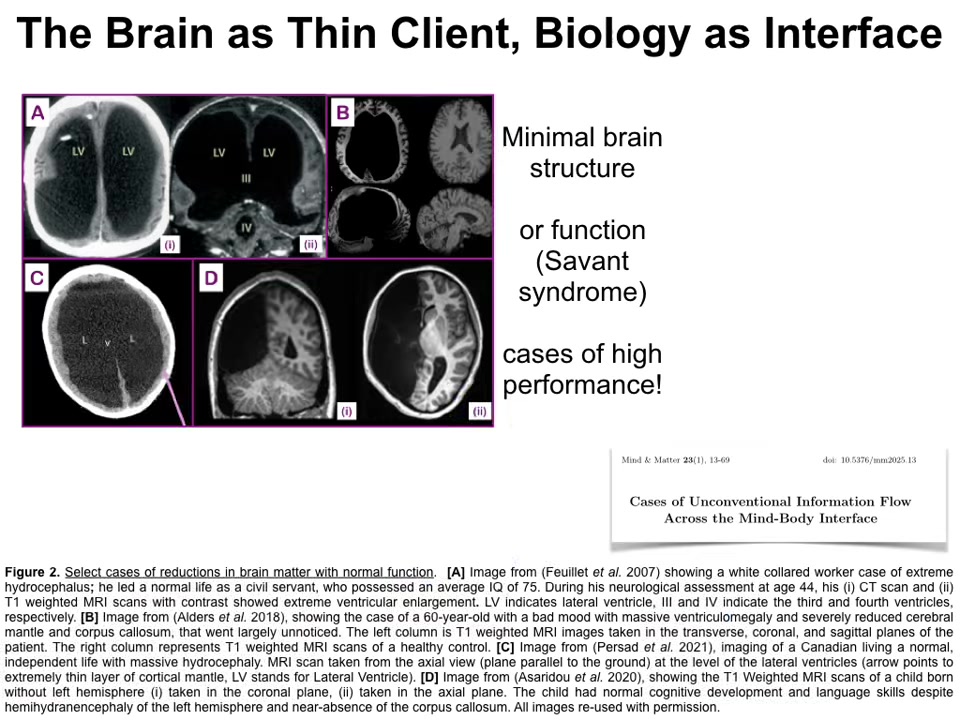

Slide 42/48 · 55m:55s

This is, and you can see these cases reviewed in this paper, this idea of even the brain as a thin client. There are rare humans with extreme lack of brain matter and yet normal or even above normal IQ.

Mostly that's not what we see. These are exceptions. There are amazing clinical cases that you can see here where the brain tissue is not at all what neuroscience would predict is necessary for the kind of functioning that they do. This idea of how many of these things are actually described as a kind of front-end interface to some patterns, either static patterns or computations, active patterns, done in this space.

Slide 43/48 · 56m:45s

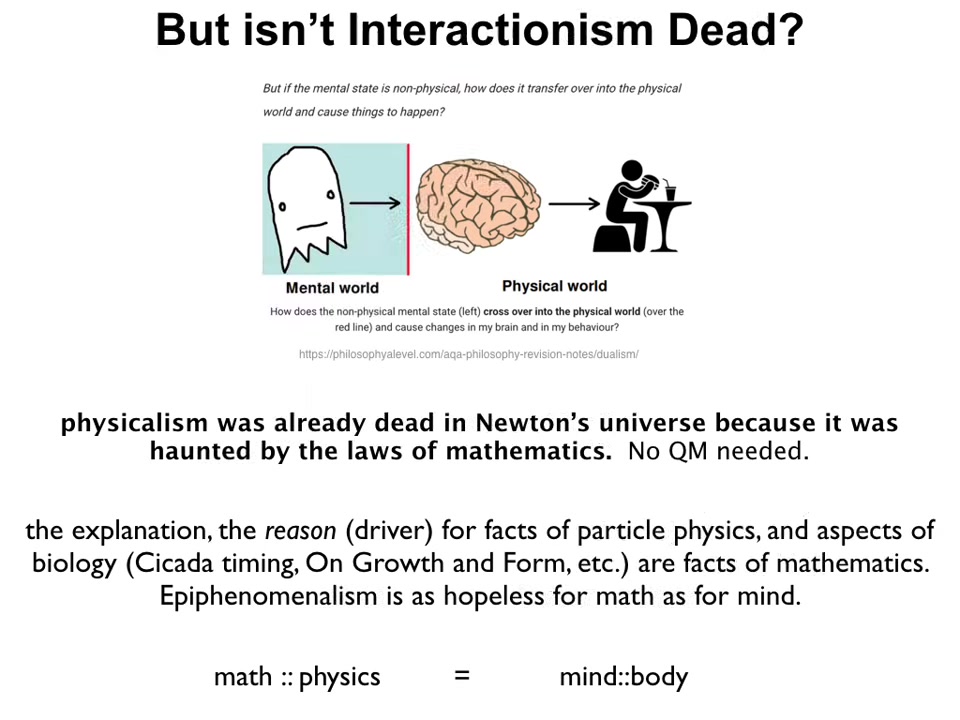

Now, at this point, you might be thinking that, wait, we've heard this before. This is what Descartes was saying, that there's this non-physical world, and there are minds in this non-physical world that interact with brains and are responsible for behavior. And generally people think that this is dead. This view has been put to bed because there's this basic question that was posed to Descartes by the Princess of Bohemia, and she said, look, if these mental states are not physical, how could it possibly have a causal influence over the physical world? If these things aren't physical, we have conservation of mass-energy, you are not going to be able to push around the chemistry by any non-physical kinds of things. And I want to say two things about this.

First of all, I'm surprised that Descartes, being a mathematician, didn't say this. And as far as I could see, he has not actually said this. As a reply to this, we already had a problem of interactionism, in other words, non-physical objects determining aspects of physics. We already had this from the time of Pythagoras. We've already known that there are mathematical features that constrain and enhance things that happen in this physical world.

In that sense, physicalism was already dead even in Newton's boring classical universe. We didn't need quantum mechanics because that universe is already in an important way haunted by the laws of mathematics. In the way that I explained, if you start asking why, you eventually end up in the realm of facts about mathematical objects and mathematical structures, not physical ones.

So we already knew that this was the case. And what if the mind-body relationship is basically the same as the math-physics relationship? In other words, in order to understand how minds supervene on bodies, we can take our cue from, and granted, I think there's a lot we don't understand here, but I do think the shape of the problem is roughly the same.

In the relationship between math and physics, you already have a situation where non-physical states of affairs are determining things that happen in the physical world. And I don't think we need to look for a quantum interface or any exotic physics. I think this is really fundamental, what's going on. And that basically, when we're seeing low agency forms from that space do low agency things in the physical world, we call it mathematics and physics. And when we see high complexity, high agency patterns, doing it through a biological interface, we call this minds and bodies. But otherwise, it's basically the exact same spectrum.

Slide 44/48 · 59m:45s

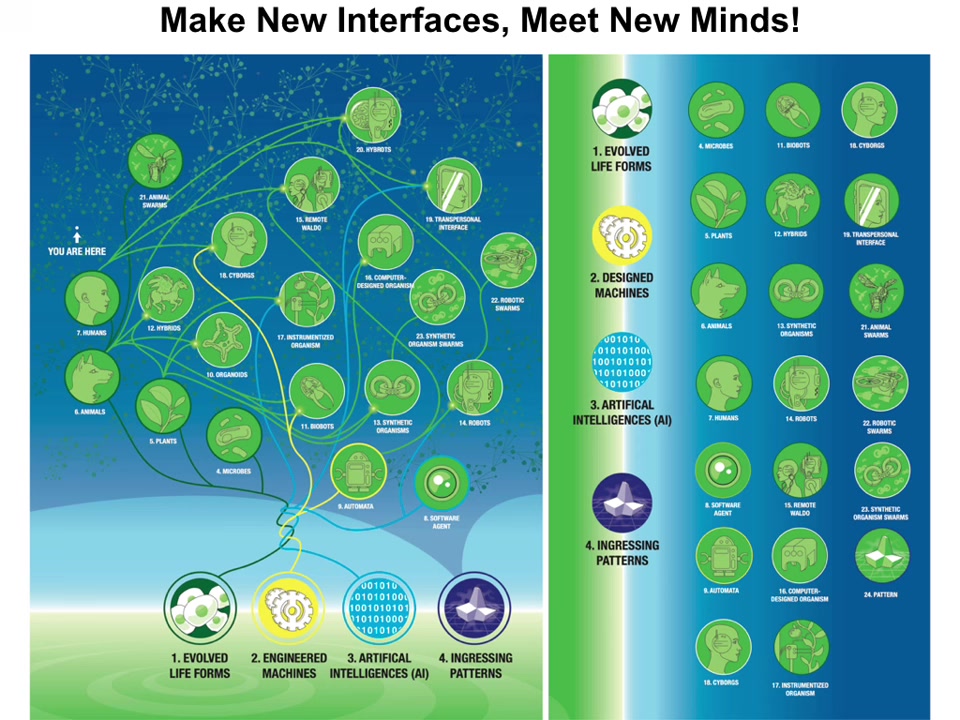

This suggests that, we know because of the interoperability of biology, pretty much any combination of evolved material, engineered material, and software is some kind of viable being. We already have cyborgs and hybrids and various chimeras; every possible combination of life and engineering is a viable embodied mind.

This is a massive space of possible embodied minds. All of the natural ones that Darwin was thinking about when he said the endless forms, most beautiful, are like a tiny corner of this option space. All of these are going to be the beneficiaries of these kinds of ingressions from that Platonic space. They are going to have new patterns because they are new interfaces.

This means that if we continue to make these new interfaces, everything from various kinds of cyborgs and biobots and bioengineered objects and swarms, swarm robotics, and the Internet of Things, all these different things, we are going to end up pulling down behavioral propensities, meaning kinds of minds, from this Platonic space that we have never seen before. Perhaps ones that have never been embodied before anywhere on this planet, maybe nowhere in the universe. We are well underway to making all kinds of new interfaces for new kinds of minds. We have to be alert to that because we are not good at predicting them whatsoever.

I think the project of recognizing what you're going to get and being able to communicate with it and ethically relate to it is going to be of prime importance to us as we get a lot of surprises. Emergence doesn't even begin to cover what I think is going on here when we make novel interfaces without a good ability to actually detect what kind of behavioral competencies are coming through.

Slide 45/48 · 1h:01m:50s

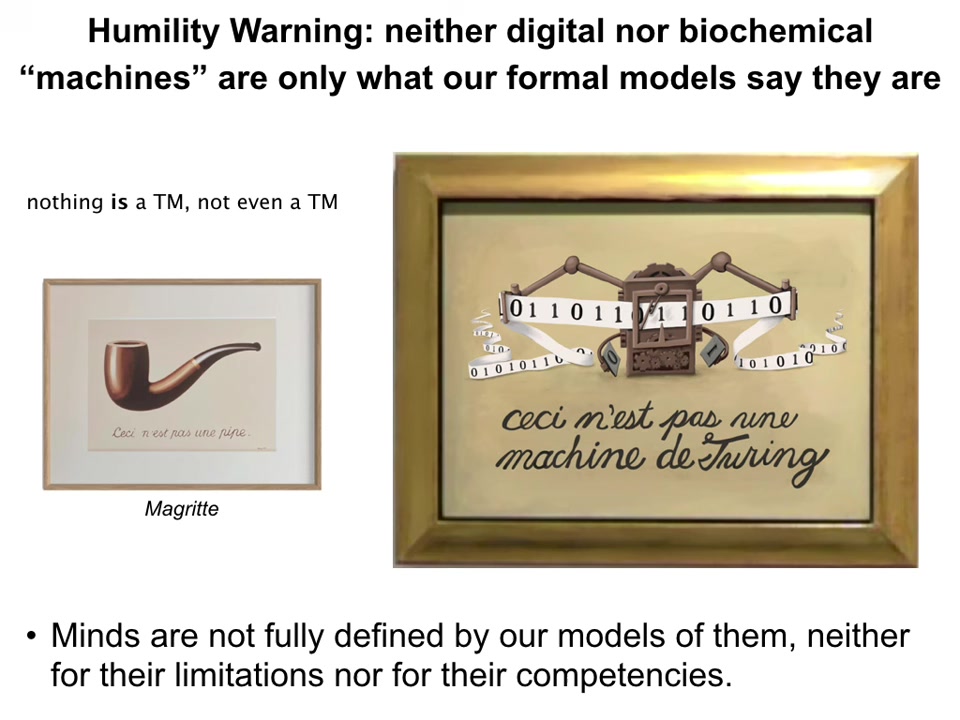

And so at this point, this is a really controversial idea, that many people are pretty comfortable with the idea that the laws of biochemistry don't tell you everything you need to know about the mind. That there's something more going on here, whether on a conventional model or not. We are pretty used to giving ourselves a special status that the facts about the low-level components don't tell the whole story.

But most people think that with machines, that is the case. In other words, when you see an algorithm, you know everything that the machine is capable of. I'm going to claim that most of what we study, in biology, physics, and computer science, are basically interfaces to patterns. These are sciences of the front end, not of the whole system.

Because there are these massive surprises that we're constantly getting, perhaps nothing is only what the materials say it is, not even simple machines. There may not be anything in this world that truly matches this idea of a machine that is fully described by our formal models.

And this should not be controversial: this idea that our formal models are just that. They're formal models. They don't necessarily capture what anything is doing. Certainly not biology. I don't think Turing machines and algorithms are useful formal models for biology. I don't think they exhaustively tell the story of even what we call simple machines.

As Magritte was telling us, "This is not a pipe." This is a representation of a pipe. This is not a Turing machine. We have a formal model of a Turing machine that allows us to explain, predict, and exploit some features of this.

But if even Bubble Sort is doing things that, in six-plus decades of working with these things, nobody had noticed—that it actually has these novel competencies—then it's entirely possible that many of the complex things we build, for example language models, are going to be interfaces for all kinds of surprising ingressions that are not just complexity, not just unpredictability, and certainly not just the thing we're asking them to do, meaning the algorithm, the language use, and so on. I suspect that they're going to be pulling down all kinds of interesting patterns that we're just not smart enough to check for yet.

My claim is that neither minds nor machines are fully defined by our models of them, neither in terms of their limitations nor their competencies.

Slide 46/48 · 1h:04m:44s

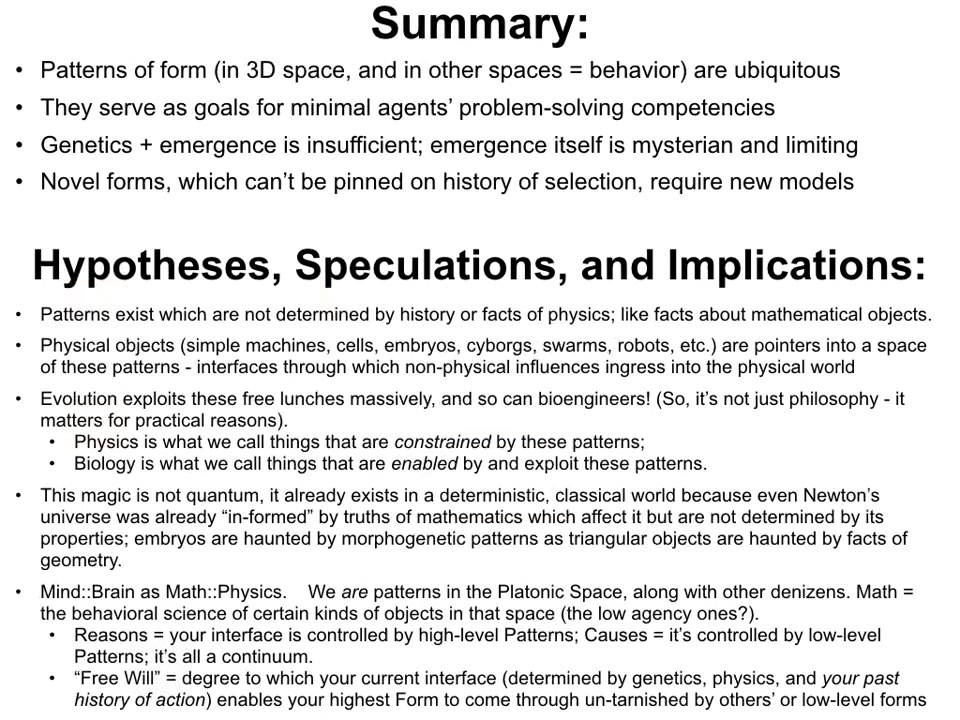

I'll wrap up here by summarizing a couple of things I claim today. First of all, that patterns, whether they be of anatomy or of behavior or of gene expression or anything else, are ubiquitous in the world. They are specifically goals for various kinds of agents, problem-solving competencies. They're not just things that happen. They are specific endpoints for different degrees of intelligence that tries to find them in these spaces. They're targets for navigation; they're attractors in these spaces.

Genetics and emergence are insufficient. Emergence by itself, I think, is too mysterious and limiting. We need to do better than this. Because we now know that there are novel forms that cannot be blamed on a history of selection, we need new models for understanding where these things come from. Those are the things I try to illustrate.

Here are some hypotheses for the future. I think that patterns exist which are not determined by history or by facts of physics. These patterns are like facts about mathematical objects. They come from the same space. I think that physical objects, be they simple machines, cells, organisms, cyborgs, and so on, are basically pointers into a space of these patterns. They're interfaces through which non-physical influences ingress into the physical world.

I think evolution exploits these free lunches massively, and so can we as bioengineers, if we had a better understanding of the mapping between the interface and the patterns you get. This is not just a philosophical speculation. It matters for very practical reasons of progress in regenerative medicine, progress in bioengineering, and so on.

By terminology, physics is what we tend to call things that are constrained by these patterns, low-agency things, and biology is what we tend to call things that are enabled or facilitated by and actively exploit these patterns. I think the magic that we're seeing here is not quantum, although it's entirely possible that quantum biology adds important bells and whistles. I don't know.

The most important magic here is that you get more than you put in, that the mechanism does not tell the whole story, that what we're looking at is an interface that actually allows us to access something much greater than is obvious. That already existed in the deterministic classical world because the truths of mathematics were already constraining things that could happen in Newton's world.

I think embryos are haunted by specific morphogenetic patterns from that space, from the space of anatomical attractors, in the same way as triangular objects are haunted by facts of geometry and particles in physics are haunted by various symmetries of other mathematical objects. I suspect that the mind-brain relation is the same as the math-physics relation. I think we basically are patterns in the Platonic space, along with other things that live in that space.

We can think about mathematics as the behavior of certain kinds of objects in that space, and that idea recasts the pyramid of the sciences with behavioral science at the bottom, behavioral science as the foundation and everything else being regions that are types of behavioral science.

Once we go down this road, it's not only about bioengineering, evolution, and regenerative medicine; we can also say things that might be relevant for philosophy. Systems that do things because of reasons are ones whose interface is largely controlled by high-level patterns. On the other hand, you're a system that's dominated by causes when it's controlled by relatively low-level patterns. In other words, the difference between reasons and causes is continuous. They're on the same spectrum. It's just what kind of patterns are driving the behavior.

We can also say something about free will, which you could define stepping away from issues of determinism.

You could define it as the degree to which whatever you're embodied in, your current interface, is determined by genetics, physics, and your past history of actions, whatever interface you have, to whatever degree that interface enables the most complex, most high-order forms to come through uncontaminated by others' forms or your own low-level forms, to whatever extent that can come through, that might be an interesting measure of what we colloquially call free will.

Slide 47/48 · 1h:09m:53s

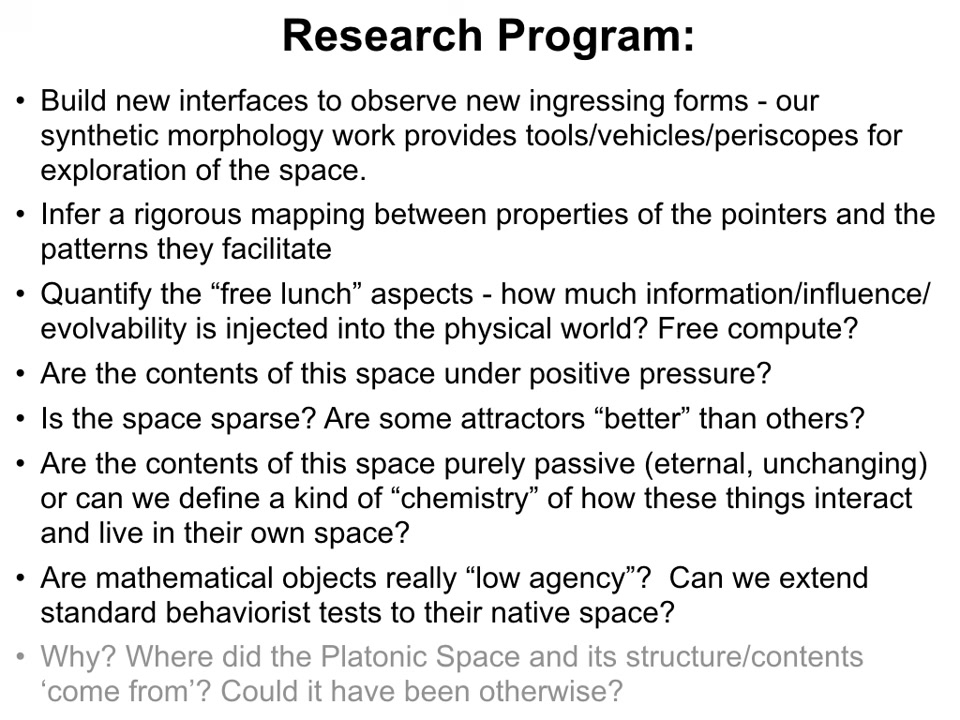

I think thinking about things in this way suggests a very tractable, a very empirically practical research program.

We can build new interfaces to observe new ingressing forms. The synthetic morphology work of our group and many other groups provide some amazing vehicles for exploration of that space. I think we need to start to infer a model of the mapping between the properties of the pointers and the patterns they facilitate. We need to quantify the free lunch aspects. So how much information and influence and evolvability is really injected into the physical world? To what extent, to what numerical extent do we get more than we put in when we make various interfaces? And is it just static patterns or could we actually get free compute? Is there dynamic computation that we can get in this way?

I think it's interesting to think about the contents of that space as under positive pressure, meaning that it doesn't take much to pull them into this world. If you make an interface, they show up. In other words, they are, to some extent, pressurized to ingress through. We don't know if the space is sparse, if some attractors are better than others, or if the space is dense. It's structure. We really don't know.

One thing that I suspect, but don't have any evidence for yet, is that the contents of the space is not purely passive. These are not eternal, unchanging forms, the way that some people have cast them, but actually dynamic, and that maybe we can actually define a kind of chemistry of what's happening to these forms. Can they interact with each other distinct from their interaction via the interfaces of the physical world? And is it really true? I've said several times that maybe mathematical objects are the low agency ones in that space, and then you have these minds and so on. I'm actually not sure of that at all. We have some ideas on extending standard behaviorist tests into the native space of mathematical objects to see if whether we've really misunderstood them all along and have not recognized what they're capable of. Stay tuned for that. We have some papers coming on this in the next few months.

Then there are the really big questions, which I'm not even going to attempt to cover, which is, once you have this model, what sets the structure of the Platonic space itself? Where did it come from? Could it have been otherwise? All these questions. I have no idea how to answer that. But I think this stuff will keep us plenty busy.

Slide 48/48 · 1h:12m:31s

I'll stop here, and I want to thank the people who did the biology and the computation that I showed you today.

All kinds of amazing students, postdocs, collaborators, and various funders who have supported this work all along.

I want to be clear that I'm not claiming that the people I'm listing here endorse this non-physicalist model. I realize that it's very unpopular in the sense that it goes against some very strong assumptions and traditions in computer science, biology, and cognitive science. But there it is for discussion.

Disclosure: three companies have funded various work that I've described today. And then thank the model systems that do the heavy lifting and teach us about what's possible with a physical interface.

Thank you. That's it. I'll stop here.