Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a ~55 minute talk titled "Novel Bodies, Unconventional Minds: a diverse intelligence perspective on a continuum of cognition (and consciousness)" by Michael Levin given at the CIFAR (https://cifar.ca/next-generation/cifar-neuroscience-of-consciousness-winter-school/) Neuroscience of Consciousness Winter School, + about 20 min of Q&A. My lab doesn't normally work on consciousness per se, but we do a lot of things that are relevant to questions in the philosophy of mind so in this talk I actually focus on the intersections between our experimental and conceptual work and questions of consciousness science.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Intro and continuity framework

(10:30) Unusual biology of cognition

(21:00) Bioelectric morphogenetic intelligence

(32:00) Editing morphogenetic setpoints

(43:00) Platonic space and biobots

(53:23) Conditioning and genetic resources

(57:59) Clarifying Platonic latent space

(01:03:03) Distinguishing tuning from learning

(01:09:51) Phase transitions and continuity

(01:14:37) Mathematical structure and kinds

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/50 · 00m:00s

Thank you for that very kind introduction, and thank you for having us out here. The talk is going to be me first, and then Wes Claussen towards the end. You might know that my lab doesn't really work on consciousness per se, but we work on a lot of things that are related to this. I usually don't mention it in my talks because, for this audience, I'm going to say some very speculative things that do bear on consciousness. Let's see what we can do. If you're interested in any of the primary data, the data sets, the software, the papers, all of that stuff is here. This is my own personal take on what I think some of these things mean.

Slide 2/50 · 00m:44s

Right out of the gate, I'm going to say, first of all, what I do not claim. I do not claim to have a new theory of consciousness, nor do I have any data that specifically supports one theory over another. What I am going to claim today, among a few other, even more speculative things, is that if we use cellular mechanisms and problem-solving behavior as evidence of consciousness in addressing the problem of other minds, then for the exact same reasons that we tend to associate consciousness with complex brains, we need to take seriously the possibility of it occurring in many different body structures and some even more unusual types of architectures.

I feel strongly that issues around AI and many ethical problems are not going to be resolved if we keep a focus on humans, on 3D space as a definition of embodiment, and on the brain as privileged. Towards the end, I'm going to get to a very out there idea, which is that I don't actually think we make minds. I think we make pointers into a platonic space. For the same reason that biochemistry, and below that quantum foam, don't tell the story of the human mind, I think that algorithms and the materials of which machines are made don't tell the story of machines either. We'll get to that at the very end.

Slide 3/50 · 02m:08s

I want to do four things. I want to peek under the hood of some biology that you may or may not have seen before to expand our understanding of the one natural set of minds that we have here on Earth. I want to show you a model system, which is a collective intelligence of cells behaving in anatomical space. It's as close as we get to a really unconventional intelligence.

I will then show you some new model systems. These are novel beings that are partially outside of the evolutionary stream. Towards the end, I'm going to say some really strange things about the very minimal end of the spectrum. We need to use these things as fodder for really hard questions and shake up some conventional assumptions.

First, let's look at some biology.

Slide 4/50 · 03m:04s

This is a traditional view. This well-known depiction of Adam naming the animals in the Garden of Eden has something that I think is profoundly wrong. The thing that it gets wrong is that it gives you the idea that there are these natural kinds. There are very distinct animals here. We know what they are. Adam is also distinct, different from the other animals. I think this is fundamentally problematic and I'll explain why.

One interesting thing it gets right is that in this old story, it was on Adam to name the animals. God couldn't do it, the angels couldn't do it. It was Adam whose job was to name the animals. In some of these ancient traditions, naming something means that you've discovered its true inner nature. I think that part is very deep. I think we're going to have to discover the inner nature of a whole number of novel beings with whom we are going to have to share our world.

What's wrong with this picture of natural kinds?

Slide 5/50 · 04m:01s

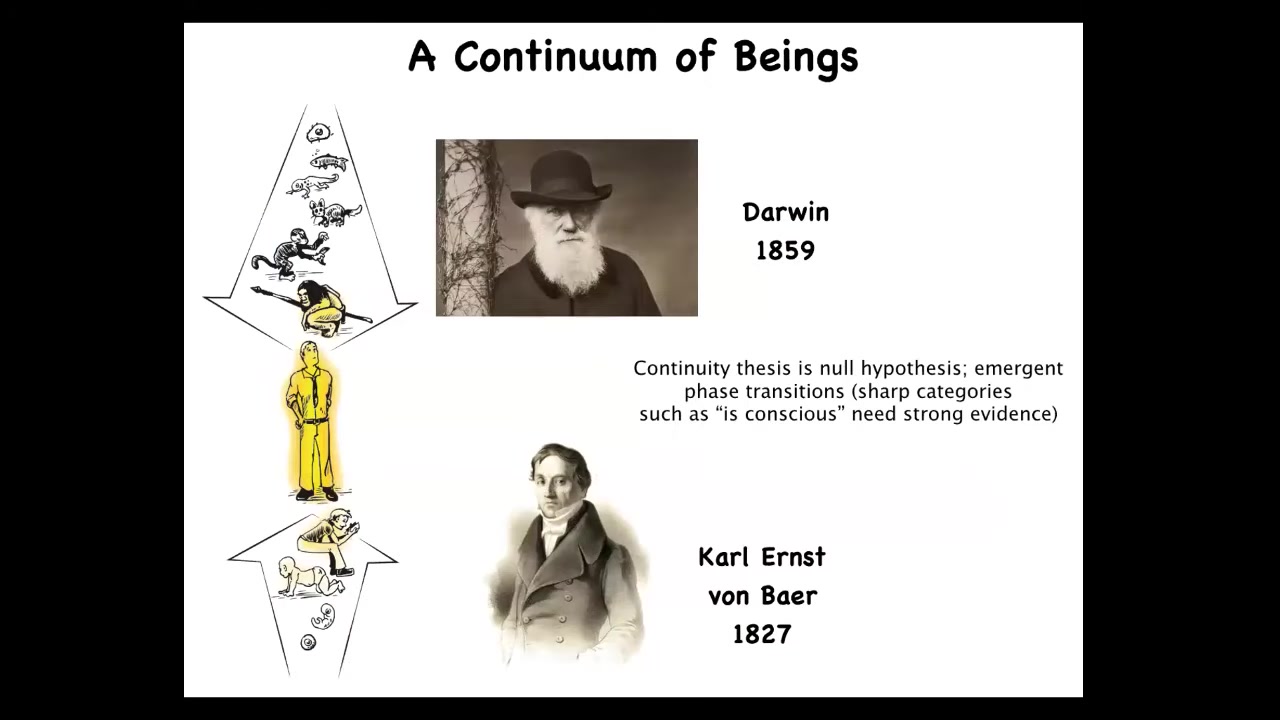

If we take evolutionary theory and developmental biology seriously, then the continuity thesis becomes the null hypothesis. It is not that somebody has to argue that the human is continuous with other beings and that there's a whole graded set of steps as far as cognition, intelligence. We have to start asking where, when, and how much these things showed up.

Sharp categories that people use all the time, such as "is it conscious or isn't it," "does it have this or doesn't it," need really strong evidence. We need really strong evidence for sharp emergent phase transitions or anything like it. I'm going to argue, because of the facts of biology, the baseline is a continuity thesis.

Slide 6/50 · 05m:01s

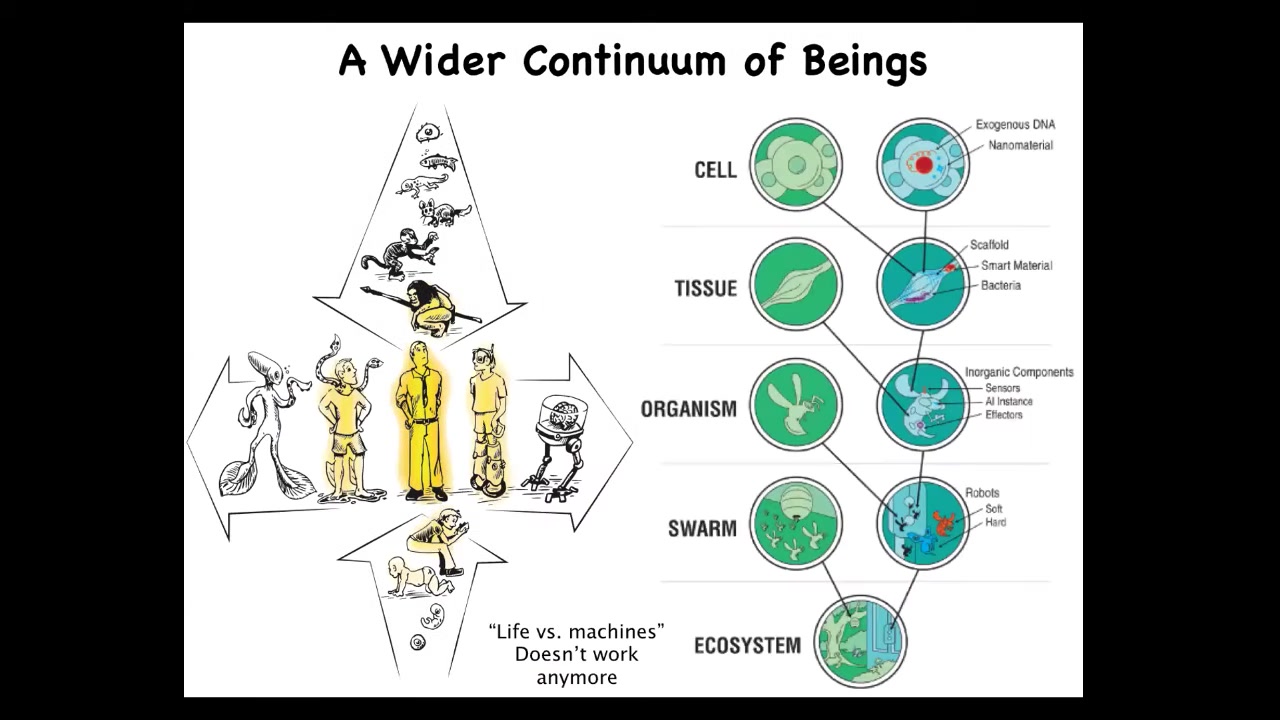

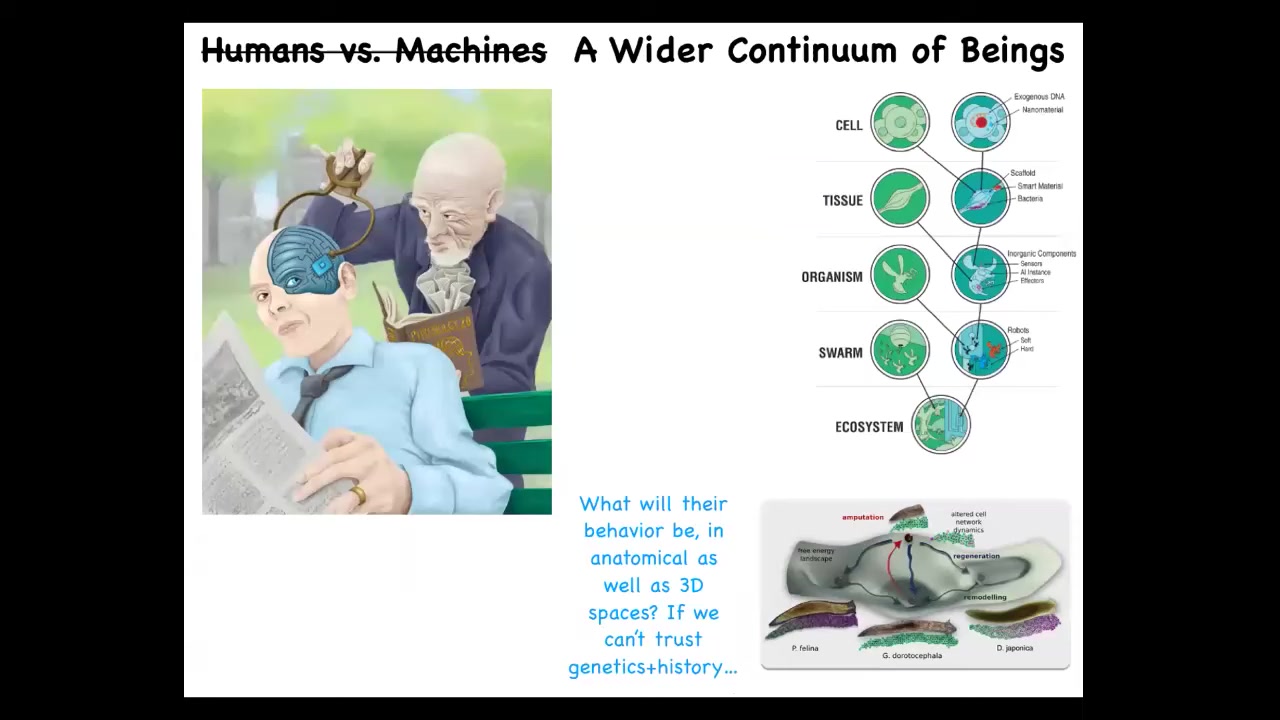

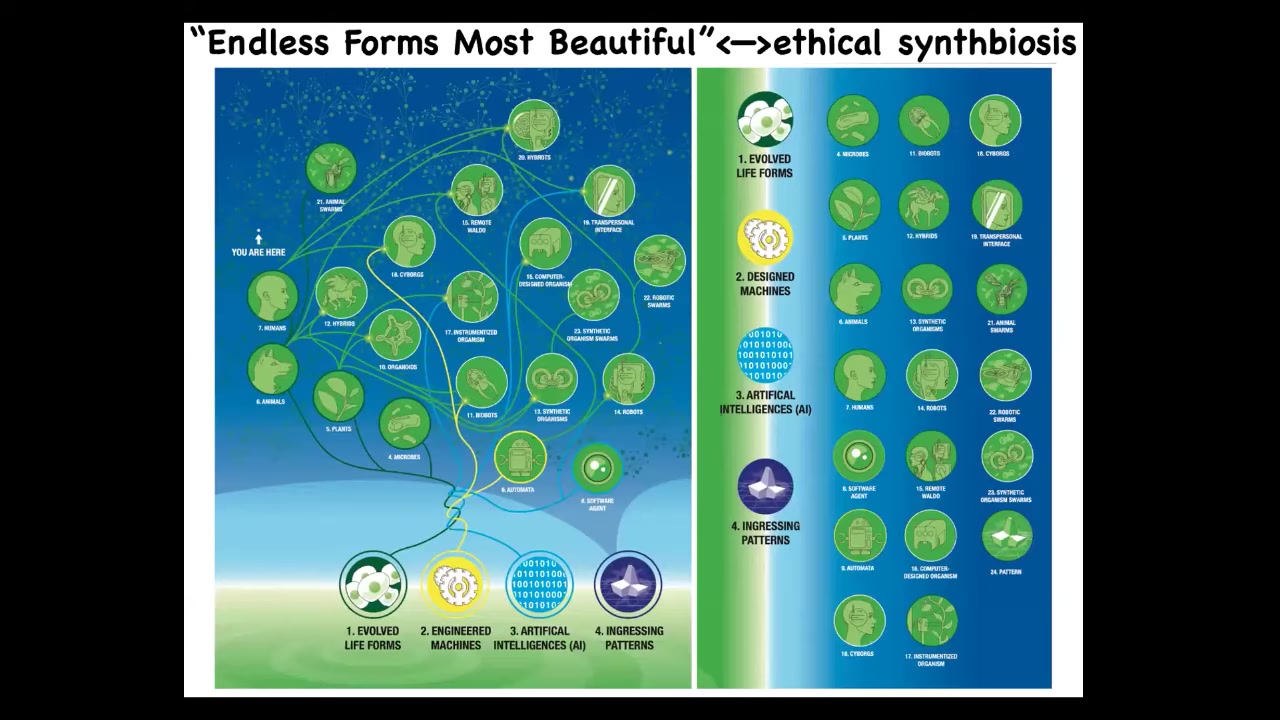

Furthermore, there is a whole other axis here, which is the fact that because biology is incredibly interoperable, and I'll show you why that is in terms of its plasticity, there's another axis where you can start to make slow and gradual changes, both in the technological space and in the biological space.

And again, you have this idea that this is not a magical distinct category of human, but you can start to ask questions about all these other different kinds of things. Because of the interoperability of life at every level, the old categories of life versus machine just don't do us any good anymore. We have to have much more nuanced categories because none of these things can be sharply delineated.

So my framework is to attempt to recognize, create, and ethically relate to truly diverse kinds of agents. And this means the familiar creatures such as primates and birds and maybe an octopus. What is it like to be a creature that has some autonomous parts, such as its tentacles? But we should note, we are all octopuses in an important sense. We are all chock full of organs that are taking autonomous action all the time, only partially under our control, in some cases, not at all under our conscious control, in various spaces that are hard for us to see. And so all of us are in this position; octopus isn't unique in that sense. But not only those creatures, but also colonies and swarms and synthetic new life forms and AIs, whether purely software or robotic, and maybe someday exobiological agents.

I'm not the first person to try for something like this. In 1943, Rosenbluth, Wiener, and Bigelow tried to map out some of the great transitions to go from passive matter all the way up to human level metacognition and so on.

So I'm trying to develop this kind of framework, and the rules are simple. I wanted to move experimental work forward. In other words, I don't want something that's just a philosophy. It needs to lead to not only new experiments, but new discoveries, new capabilities. And for our lab, that's mostly biomedicine, but also a little bit of robotics. I would like it to enable some better ethical frameworks where we can try to understand how we're going to relate to some of these unusual creatures.

Slide 7/50 · 07m:35s

So the first thing that I'm going to take you through is just some unusual biology that as we think about the very kind of simple thought experiments in cognitive science and philosophy 101, philosophy of mind, I want us to keep in mind some of these unusual things.

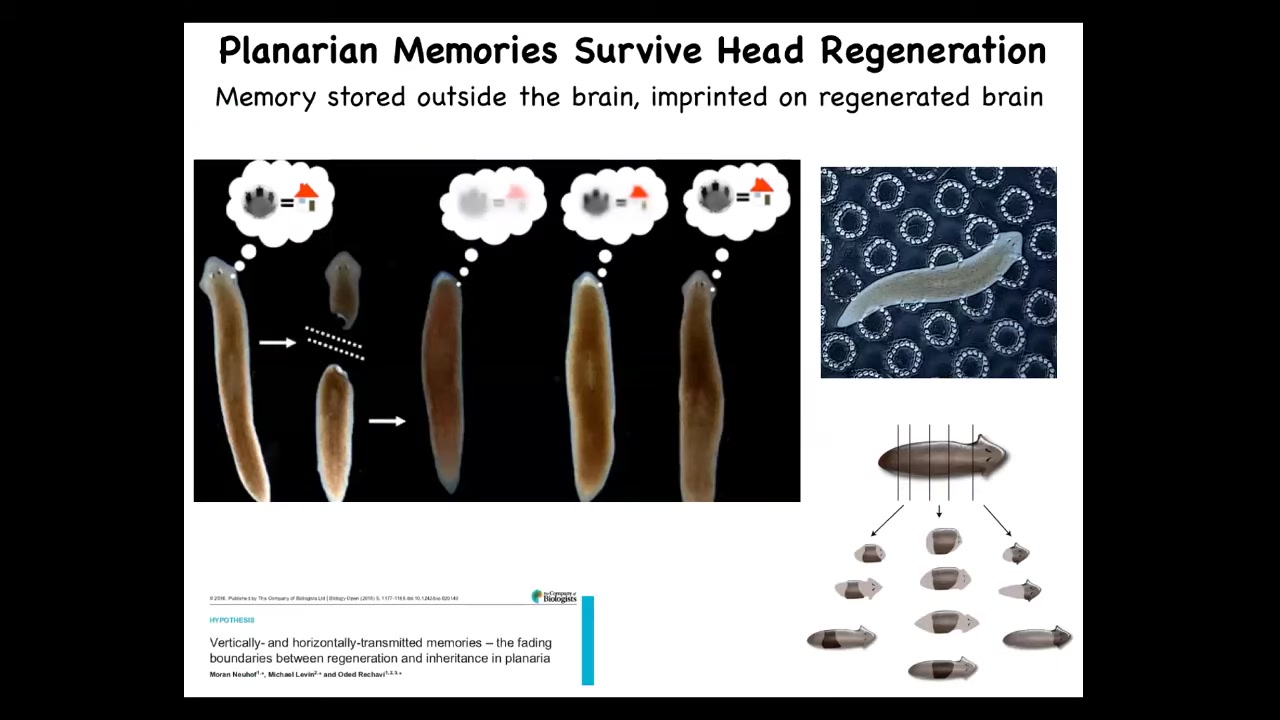

So first of all, these are planaria. These are flatworms. They have a true brain, central nervous system, similar to our direct ancestor. You can cut them into pieces, and every piece regenerates a new worm. That's interesting for many reasons. The other interesting thing is that they're smart. You can train them. It's pretty much the only animal where you can do regeneration and learning in the same animal.

Back in the '60s, this guy named McConnell, and we later replicated some of his work with modern tools. He was absolutely right, despite all the flak that he got at the time. The fact is that if you train these worms on a test — place conditioning — they learn to collect liver treats in this little bumpy area. You can cut off their head. The tail sits there doing nothing. You need the brain in order to have behavior. But then it grows back a new head, and when it does grow back a new head, you can test these animals and find evidence of recall of the training.

This tells you, first of all, that the memory isn't entirely in the brain. Interestingly, it can be imprinted onto the new brain as the new brain develops. We are now looking at information moving throughout the body. Now you've got this amazing property of beh

Slide 8/50 · 09m:25s

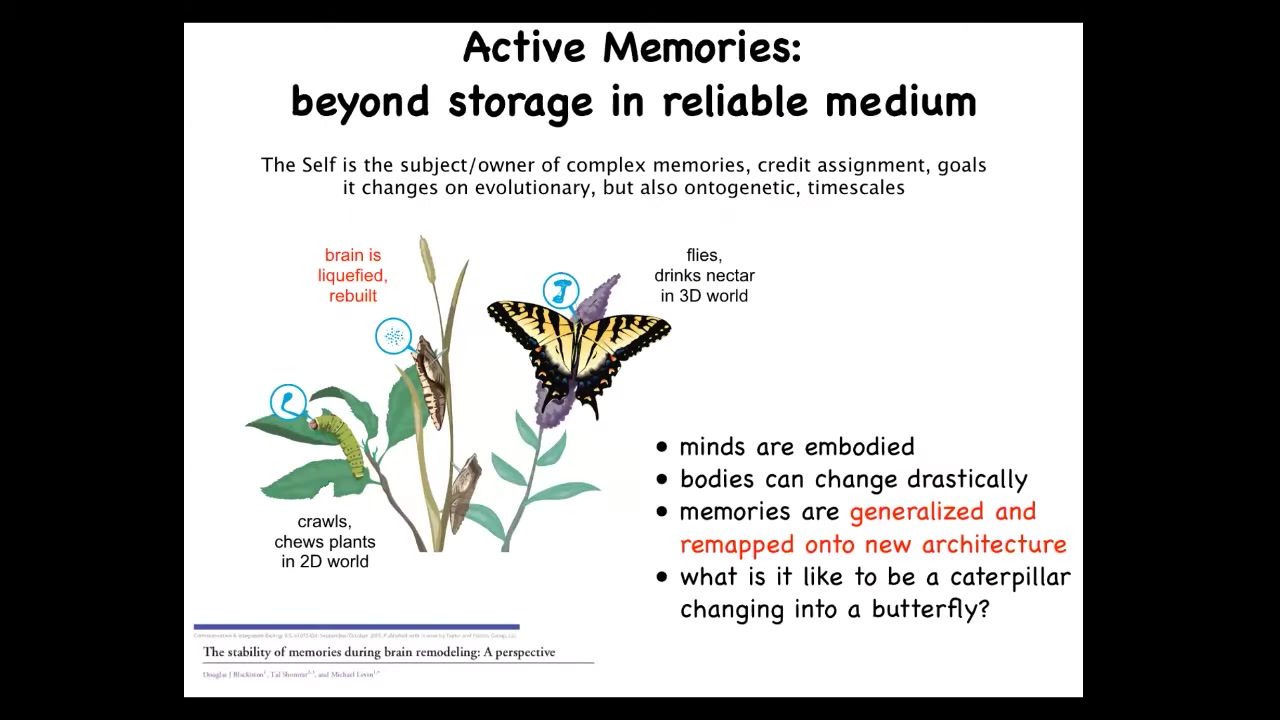

Now there's an even more interesting example, which is the caterpillar to butterfly transition. What happens here is that this creature basically dissolves most of its brain, a radical reconstruction and refactoring of its body and brain. You can train these caterpillars and then show that after all that happens the butterfly or moth remembers the original information.

One question is where is the information and how does it survive the refactoring of the brain? Even more interesting is that the information the caterpillars have is of no use to the butterfly directly. The butterfly doesn't move the way this two-dimensional creature crawls; butterflies fly with muscles, and the food that it learned to find over certain color stimuli is of no use to the butterfly because the butterfly doesn't like leaves, it likes nectar. So what has to happen here is not just mere preservation of the information; that's not sufficient. You have to remap the information across a drastic change of body architecture. The information has to be generalized, it has to be remapped into a behavioral repertoire that makes sense here, and it's quite different. So it's not just about holding on to the information. If you're interested in philosophy of mind, what might it be like to be a creature that has this incredible reconstruction and wakes up in a new higher dimensional world than it went into.

Slide 9/50 · 10m:51s

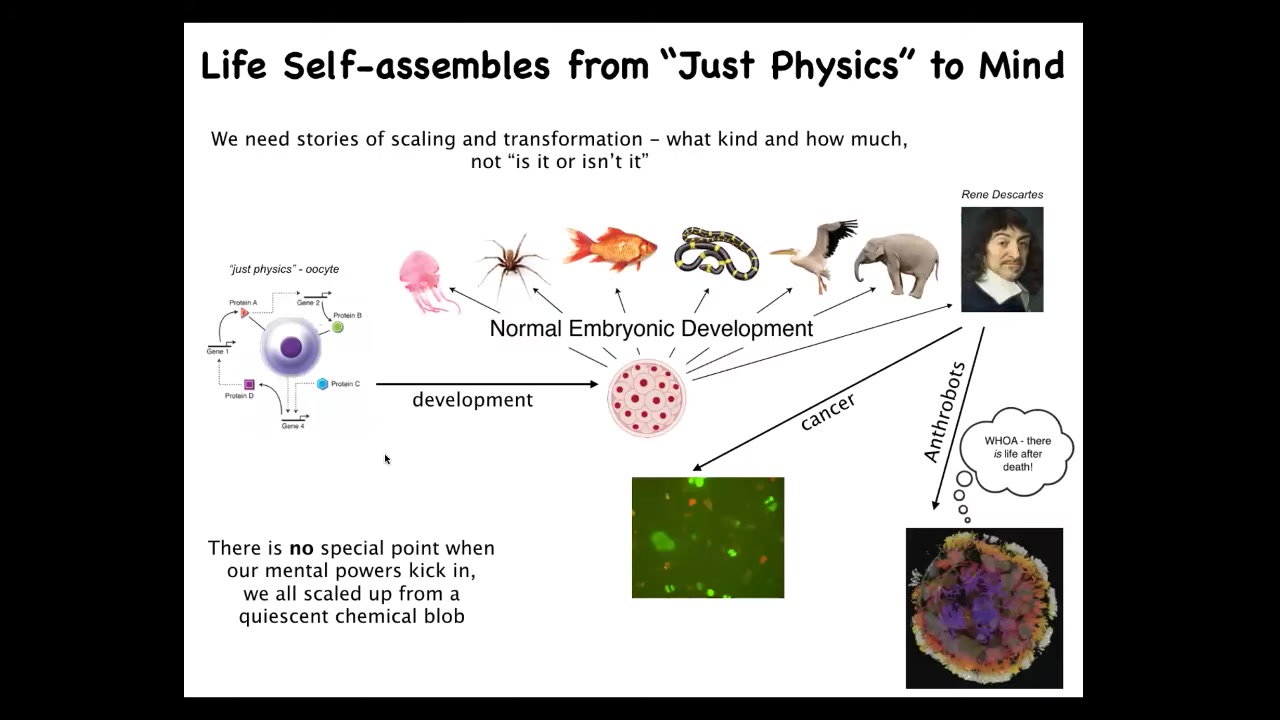

So that's some interesting biology, but perhaps the most fundamental piece is this, that all of us start life as a single cell. Whatever is true of this ends up here: how to scale up and how to undergo a process of transformation from a single cell. And developmental biology offers no support for the idea that there's some special bright lightning flash that happens. Everything is slow and gradual and it takes a long time. We all made this journey from a quiescent BLOB that presumably is well handled by the science of biochemistry and physics. Eventually we're here in the land of psychiatry and psychoanalysis and things like this. This happens slowly and gradually. Even that's not the end of the story because the cells that make up this amazing creature can disconnect from the collective and give up on their large scale goals that they have and become cancer. As I'll show you in a minute, there is a weird kind of life after death possible via this AnthroBot platform. Now, this is a little bit disturbing because it's pretty clear that we were all single cells. This journey from physics to mind is something that we all have to take. I would argue that this is emphasizing models of scaling and transformation, not whether something is cognitive, because you're not going to find any bright lines here.

Slide 10/50 · 12m:20s

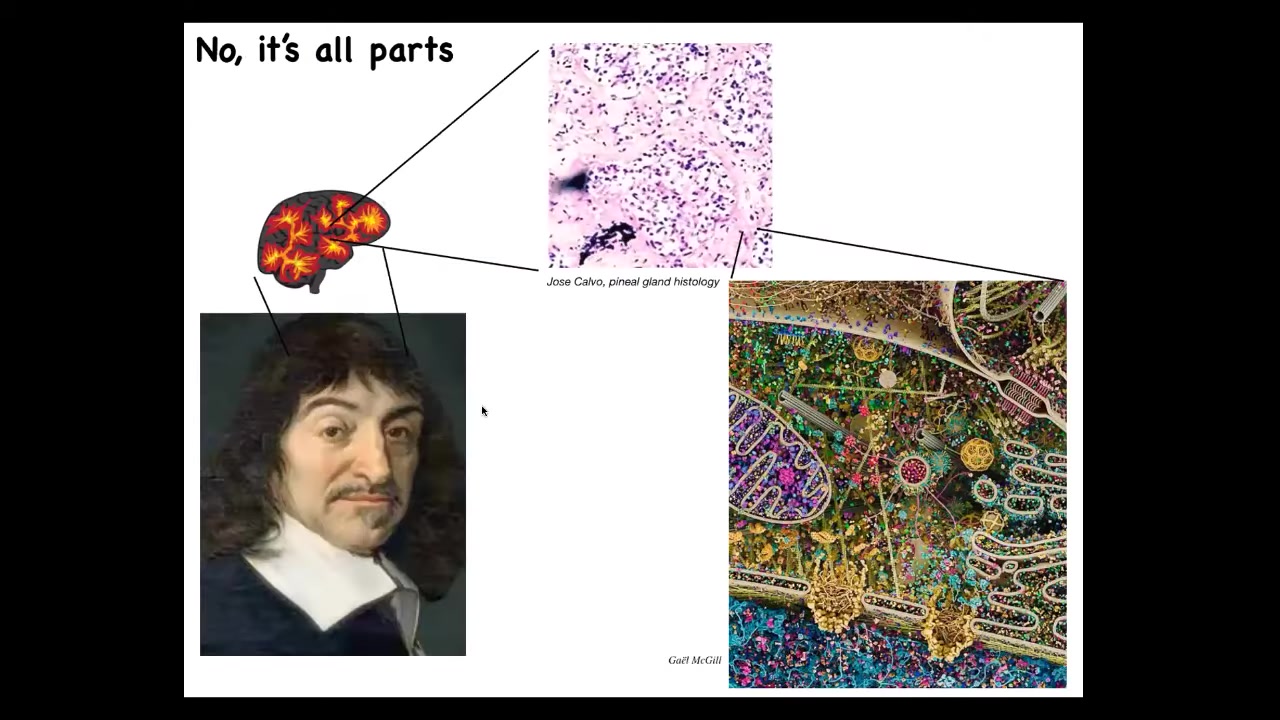

At least some people think we have a nice centralized brain, so we must be at least a centralized intelligence. Descartes really liked the pineal gland because there's only one of them in the brain. But if he had access to good microscopy, he would have said that we don't; there isn't one of anything. Inside the pineal gland is all of this stuff, and inside of each one of these cells is all of this stuff. So all of it is parts.

Slide 11/50 · 12m:44s

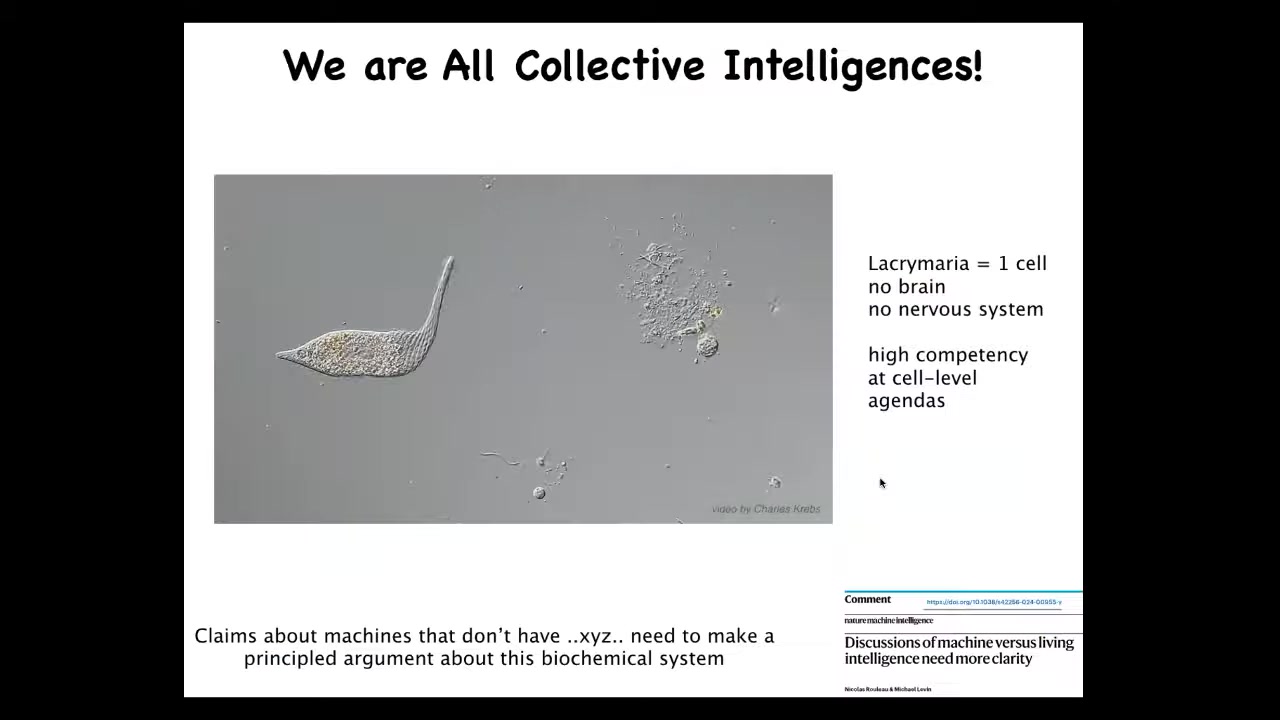

All of it is collective intelligence. I claim that all intelligence really is collective intelligence. This is the sort of thing that we're made of.

This is a free-living organism named Lacrimaria. This shows you what individual cells can do. This is a single cell. There's no brain. There's no nervous system. It handles all of its local needs here. This video is in real time. The soft body roboticists drool when they start to see this. We don't have anything that has this degree of plasticity. It's really important that any claims about machines can do this versus organisms can do that, and what real life has in terms of valence and preferences and so on. We have to be able to make claims about a system like this.

This is a single cellular biochemical system. And whatever your theory of consciousness or any of that, you have to be able to say what you think about this. It is pretty close to a molecular machine, if there is such a thing. And we have to be able to know what we're going to say about it. And in fact, even below this level, what is it made of?

Slide 12/50 · 13m:51s

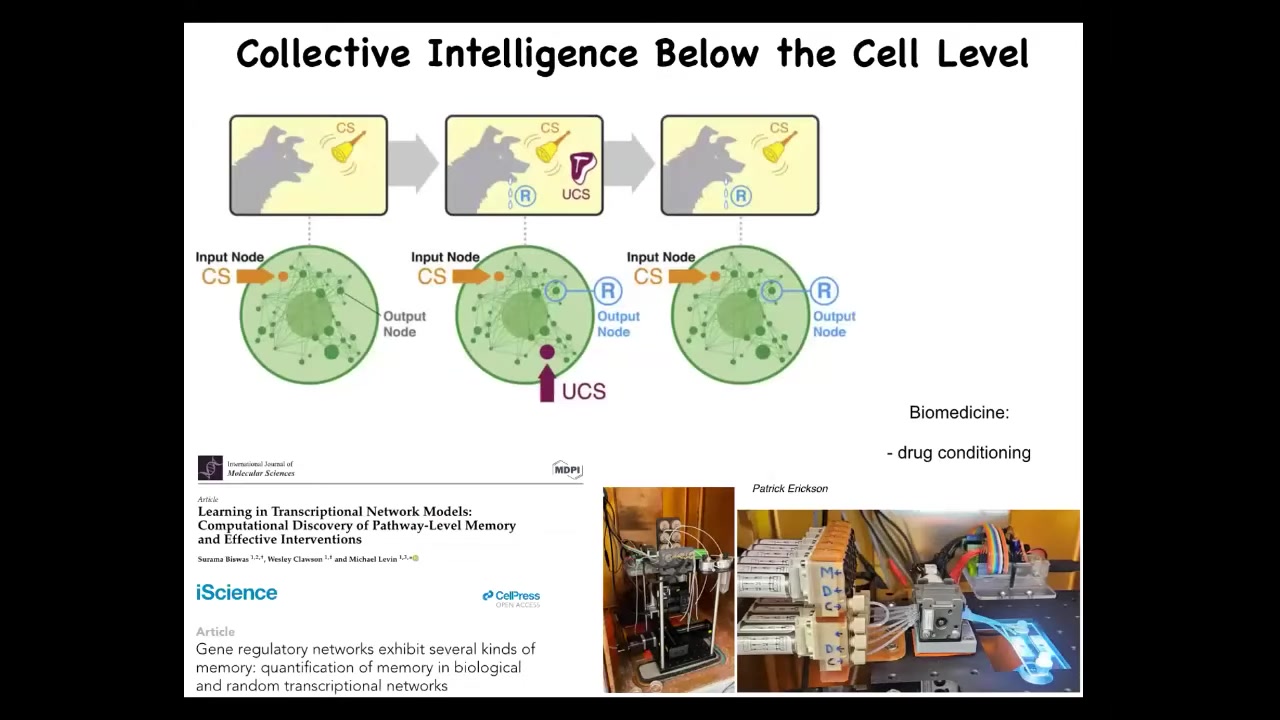

It's made of molecular networks like this. We now know that even these molecular networks, never mind the cell, the nucleus, all the other stuff that creature had, are a small set of molecules turning each other on and off. A chemical cycle, a gene regulatory network — that alone is capable of six different kinds of learning, including Pavlovian conditioning. You can take a look at the data here. The idea is that it falls out of the math. There are no complex extra mechanisms that you need. The kinds of materials that individual cells are made of at the very bottom are capable of memory and learning. We're using this in the lab to try to train cells and do things like drug conditioning because the molecular networks are competent in this task.

Slide 13/50 · 14m:43s

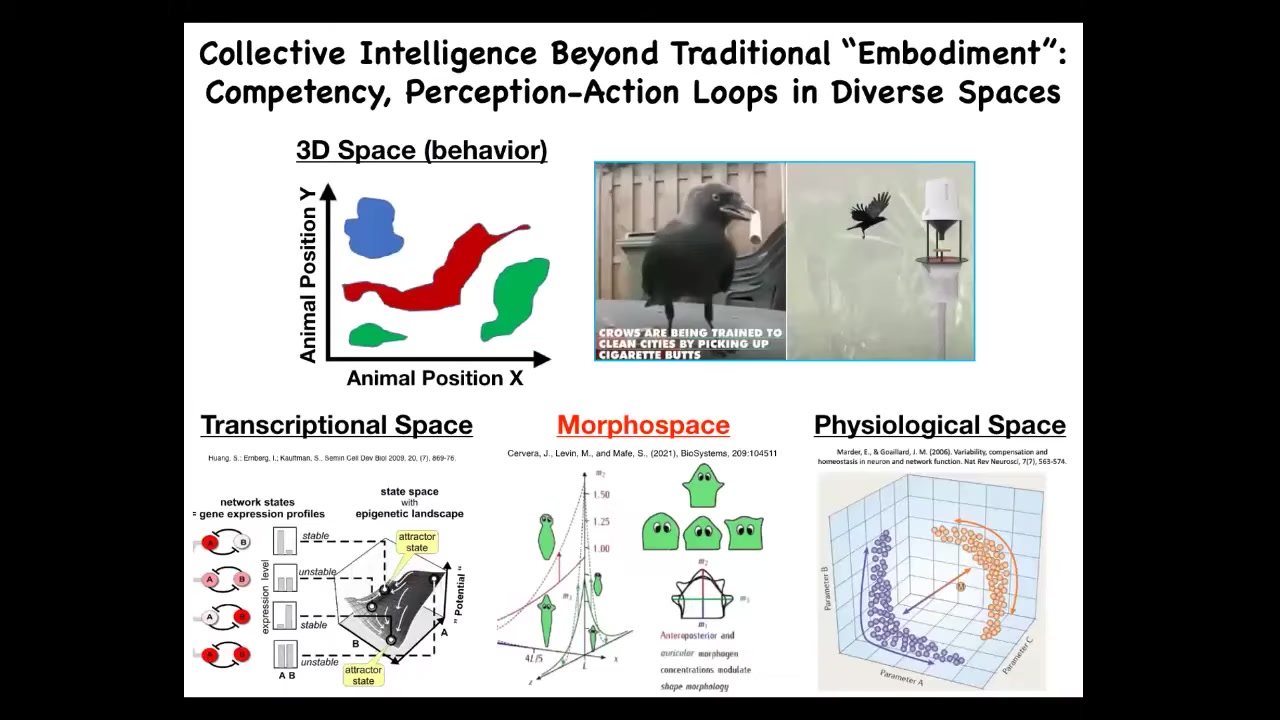

We have to go beyond traditional embodiment. Humans are okay at noticing intelligence of medium-sized objects moving at medium speeds in three-dimensional space. But biology uses these same tricks in all sorts of other spaces. There's the space of possible gene expressions. There's the space of anatomical states, which is what we'll talk about most. You have physiological states, lots of other spaces. And life is doing problem solving and these perception-action loops and everything else in all of these spaces, all the time. It's hard for us to notice.

If we had direct primary perception of our blood chemistry—if we had some kind of taste receptor looking inside at our body physiology—we would have no trouble recognizing our liver and our kidneys as some sort of a competent symbiont that navigates physiological space to keep you alive on a daily basis. But our sense organs aren't built for that. So we need a lot of help to visualize what intelligence looks like in these other spaces.

Slide 14/50 · 15m:51s

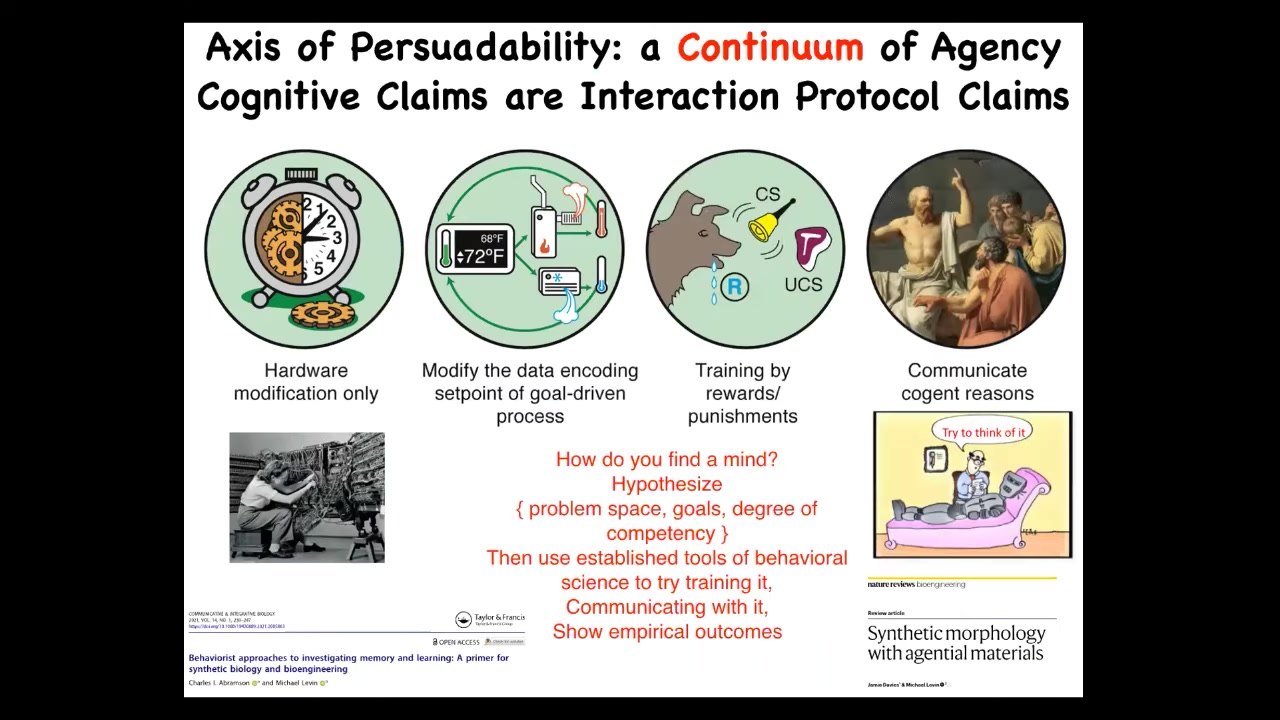

In my framework, I tend to use a spectrum like this. This is an axis of persuadability because what it's doing is putting the emphasis on the interaction protocol. It's a very engineering approach. I think cognitive claims are primarily interaction protocol claims as far as what bag of tools are you going to use with a given system. You've got physical hardware rewiring and you've got the control theory in cybernetics and behavior science and many other things.

The idea then, and I've provided lots of examples of how you do this in these other papers, is that where something fits along this continuum has to be an empirical question. You can't do this from an armchair and just decide that only certain kinds of creatures do this or that. You have to do experiments, knowing that we have to be more creative in what space and what goals we're looking at. We have to hypothesize some problem space, some goals that the system might be trying to reach, and then some degree of competency.

Then we use tools. We use the established tools of perturbational behavioral science to try training it, try communicating with it, and then we look at the empirical outcomes. What does that let you do? The idea around using agency talk with systems that are not normally thought to be fodder for that is simply the empirical question: does porting the tools from other disciplines, for example, cognitive and behavioral science, give you a better interaction with that system? That's how you know if you've got it right.

Slide 15/50 · 17m:26s

Using those strategies, the next thing I want to look at is an example of the collective intelligence of morphogenesis. What does it mean to say that this system has collective intelligence and how does that help us at all beyond the standard molecular biology paradigm, which typically assumes that that's not the right question to ask?

I find it very interesting that Turing, who was interested in intelligence, diverse embodiments, and different machine minds, also wrote a paper on the chemical basis of morphogenesis. He was asking, how do embryos organize themselves? He saw an incredibly profound symmetry between the way that minds come to be and the way that bodies come to be, and the processes through which they self-organize were very deep. I want to show you some examples of what I mean by intelligence in the case of cells and morphogenesis.

Slide 16/50 · 18m:23s

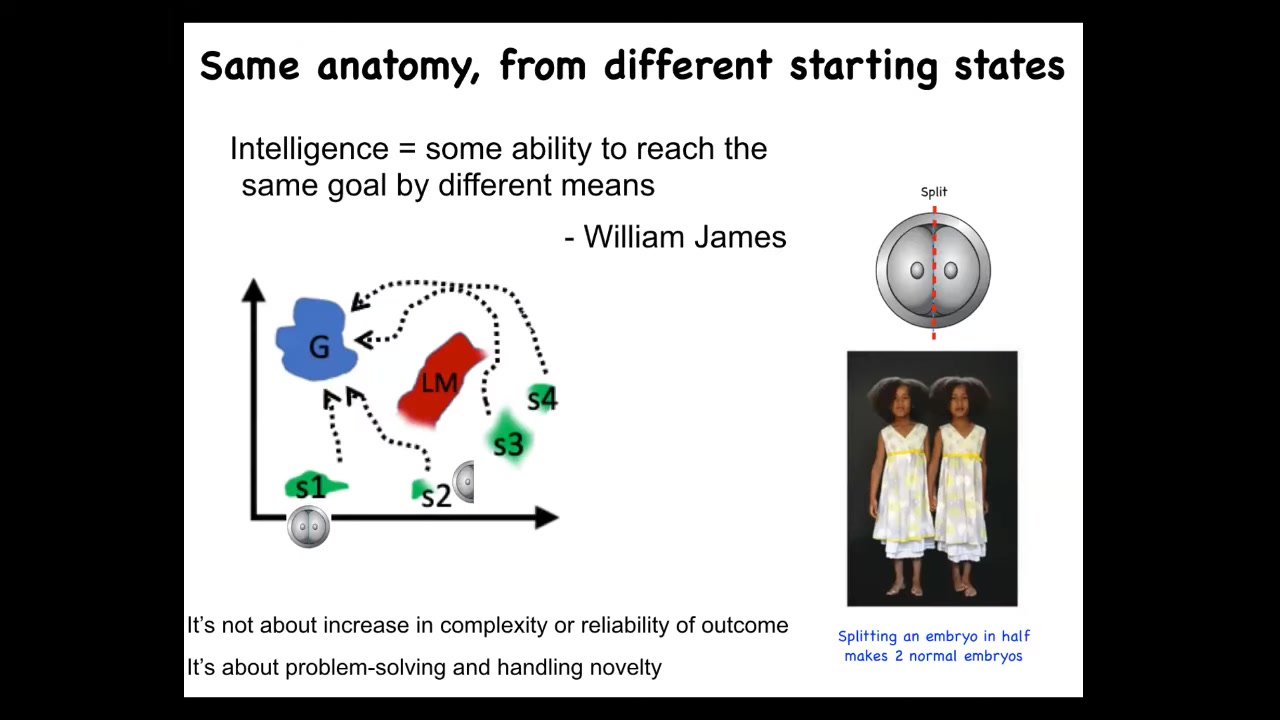

Intelligence, as William James put it, is an ability to reach the same goal by different means. How much ingenuity does a system have in a given problem space to reach its goals despite various things that go wrong?

The first thing that we know is that if you cut early embryos into pieces, you don't get half embryos, you get perfectly normal monozygotic twins, triplets, and so on. The reason I mention it is not because there's an increase in complexity, that's not intelligence. It's not because it's reliable, even that's not intelligence. It's about problem solving and the ability to handle novelty. That's what's impressive about this example. You can start off in many different starting positions.

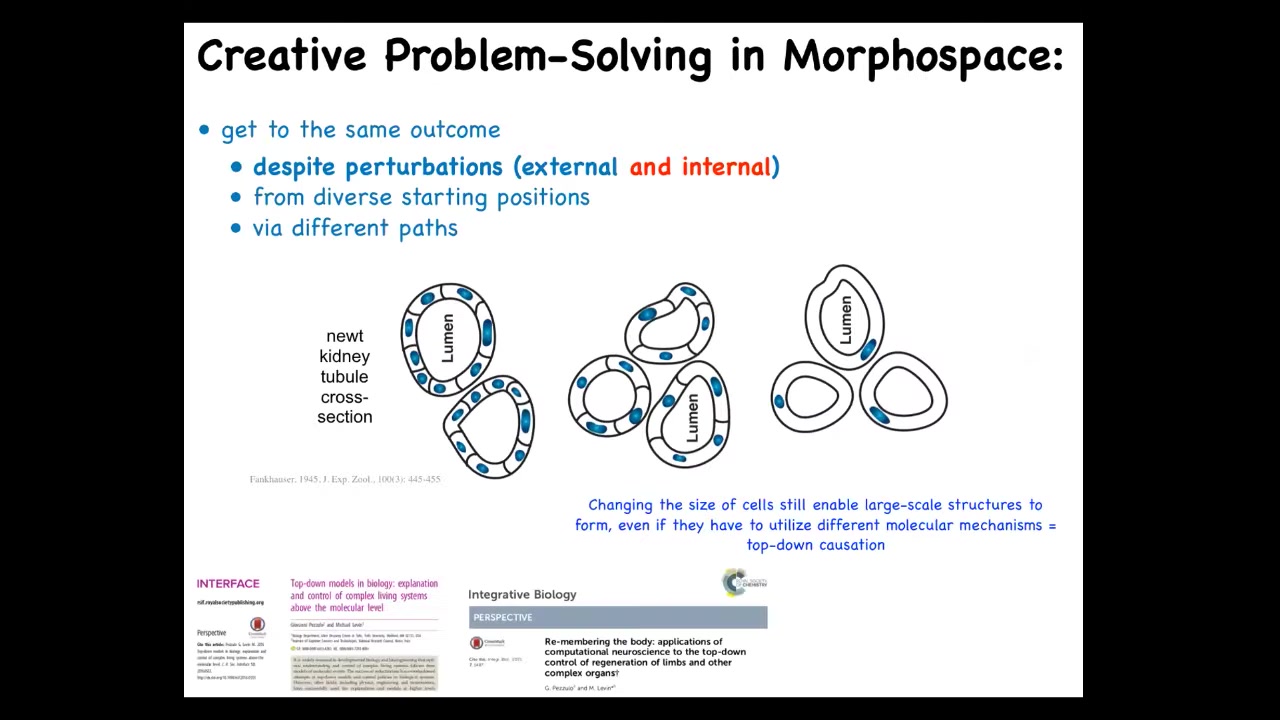

Slide 17/50 · 19m:14s

I just want to show you one example that I think is instructive. This is a cross-section through a kidney tubule in a newt, and there's about 8 to 10 cells that normally work together to form this little tube, and then there's a lumen in the middle.

Now, one thing you can do with these embryos is prevent them from dividing early on such that the DNA keeps dividing, but the cell stays the same. So you end up with polyploid newts that have multiple copies of the chromosome complement. When you do this, the first thing you find out is that it works and you get a living newt. It doesn't actually matter how many copies of your genetic material you have, you can still get a newt.

Second thing you find out is that the cells scale proportionally to the amount of DNA you have and they get bigger. Then you find out that the newt is exactly the same size. That's because fewer cells are now building the exact same structure, but they're bigger, so fewer of them get to do this.

By the time you get to 5N or 6N newts, the cells get so gigantic that one single cell bends around itself to give you the same structure. What's interesting about this is that this is a completely different molecular mechanism. This is cell-to-cell communication. This is cytoskeletal bending. What you have here is a system that can use different molecular affordances that it has, different mechanisms, in the service of a large-scale goal in anatomical space. It's trying to traverse from that egg to that proper newt target morphology, and it will use different mechanisms when you do really strange things like make its cells much bigger.

Think about what this means. If you're a newt coming into this world, what can you rely on? We already knew you can't really rely on the outside world. Things change all the time. But you can't even rely on your own parts. You don't know how many copies of your genetic material you're going to have. You don't know the size of your cells. You don't know how many cells you're going to have. You have to get your job done regardless in creative ways given the problem that you have.

This is the thing that we're interested in, not just the reliability of development, which starts to look like a mechanical feed-forward process. That isn't it at all. It's this ability to use the tools you have to reach your goal despite all kinds of weird things happening. We've been studying these kinds of systems for a long time.

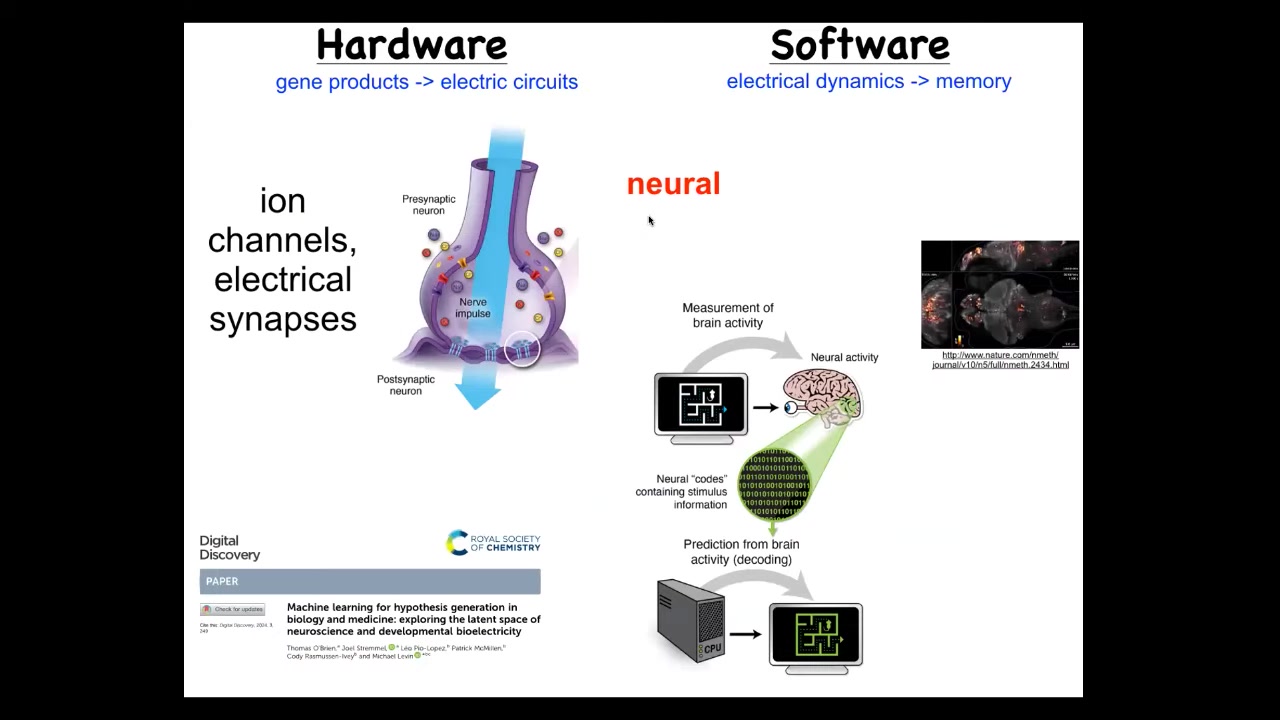

Slide 18/50 · 21m:38s

We took our inspiration from the one uncontroversial example where systems can store some record of, some representation of a goal, and then they can work to achieve it. The same kind of neural decoding strategy that neuroscientists do when they try to understand how the cognitive content of a mind maps onto the electrophysiology that they're measuring here, that system is incredibly ancient. Every cell in your body has ion channels. Most of them have electrical synapses with their neighbors. This idea of having electrical networks integrate information over space and time was invented around the time of bacterial biofilms. It certainly didn't wait around until neurons and muscle came on the scene. It is very old. Even bacterial biofilms coordinate their activity via these electrical networks.

That same kind of idea: could we decode this electrical activity and try to understand what problems is it solving? What space is it working in? If your brain is usually thinking about moving you through three-dimensional space, what are your somatic networks thinking about? What did your body cell electrical networks think about before there was a brain, and given that they can't move through three-dimensional space? It turns out that what they were thinking about is anatomy. They were thinking about shape. And so what I'm going to argue is that most of the tricks that we see happening in brains, with possibly a few exceptions, are really old kinds of things that were simply pivoted from other problem spaces into a familiar 3D space of behavior. In order to actually do this, we have to develop some tools.

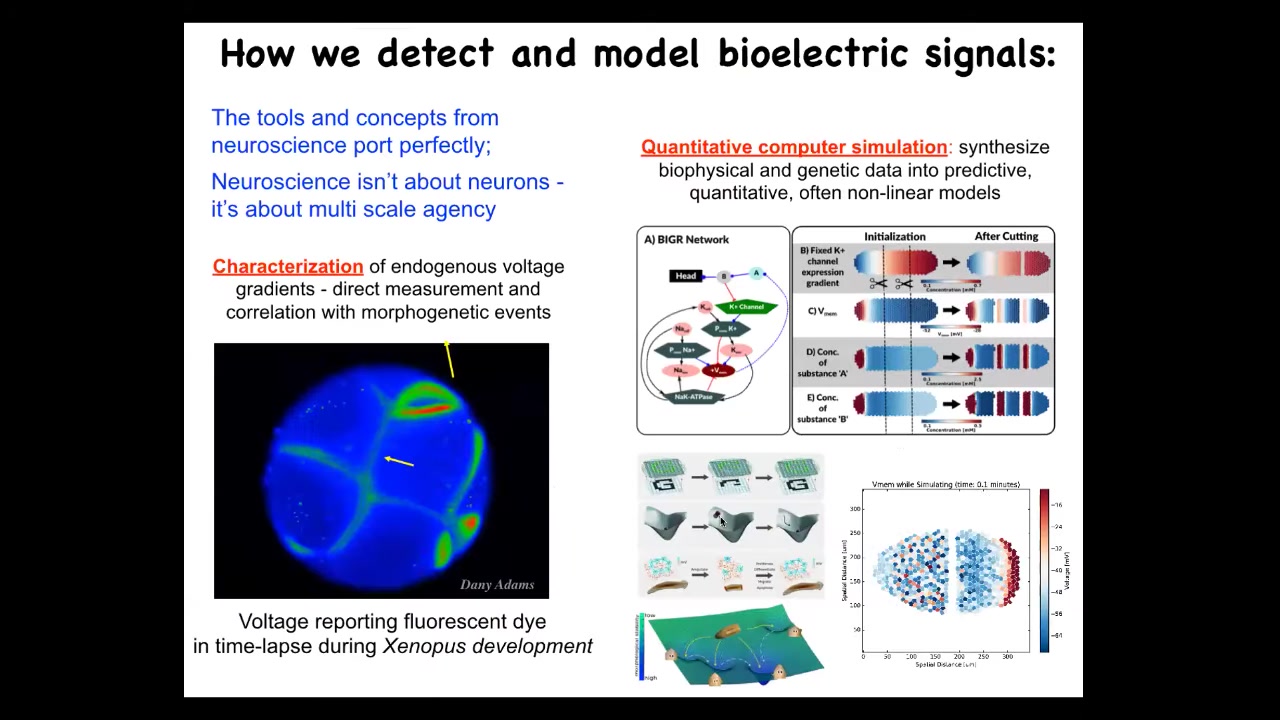

Slide 19/50 · 23m:34s

The first thing we developed were ways to visualize the electrical activity in non-neural cell groups. We do this using voltage-sensitive fluorescent dyes. This is like a scan of brain activity, except this is an early frog embryo. There is no brain yet. You can watch all of the cells communicating to try to figure out who's going to be head, tail, how many eyes.

We do a lot of quantitative simulation, and we do everything from the molecular biology of these ion channels through tissue level, and then large-scale things like pattern completion during regeneration and so on. The idea is that the tools and concepts from neuroscience port perfectly. Lots of the ways in which computational neuroscience studies decision making and memory and visual illusions and various disorders. Those things actually don't distinguish between neurons and non-neural networks. We've ported most of these things and they're really useful and they work really well.

That leads me to conjecture that neuroscience really isn't about neurons at all. What it's about is scaling multi-level agency from very humble, low-level mechanisms up through very, very high-level goals. We even have an AI tool that we created to mimic something that I always used to have my students do, which is to take a neuroscience paper, do a find-replace, and every time it says neuron, replace that with cell, and every time it says milliseconds, say hour, and you have yourself a developmental biology paper. It's fun to play with.

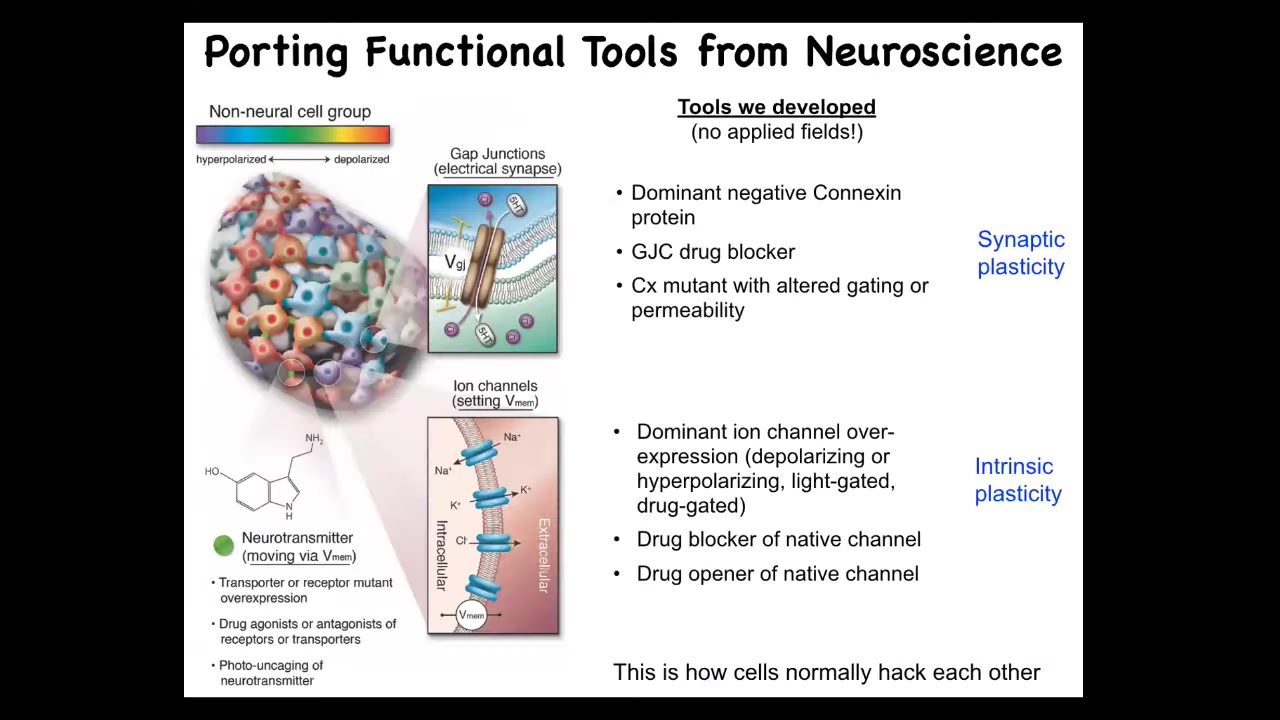

Slide 20/50 · 25m:15s

The next thing we developed were the functional tools. How do we actually change the bioelectric content of these networks? We do it exactly how neuroscience does it. No magnets, waves, frequencies, fields. We target the ion channels and the gap junctions, the topology of these electrical networks. We can do this with optogenetics, with pharmacology, we can replace the channels, all the same tools. This is how cells normally hack each other.

Now it's time for me to show you what happens when you do this. If we go in and we do non-neural decoding and inception of false memories into this electrical network, we try to communicate with it. What can we tell it to do?

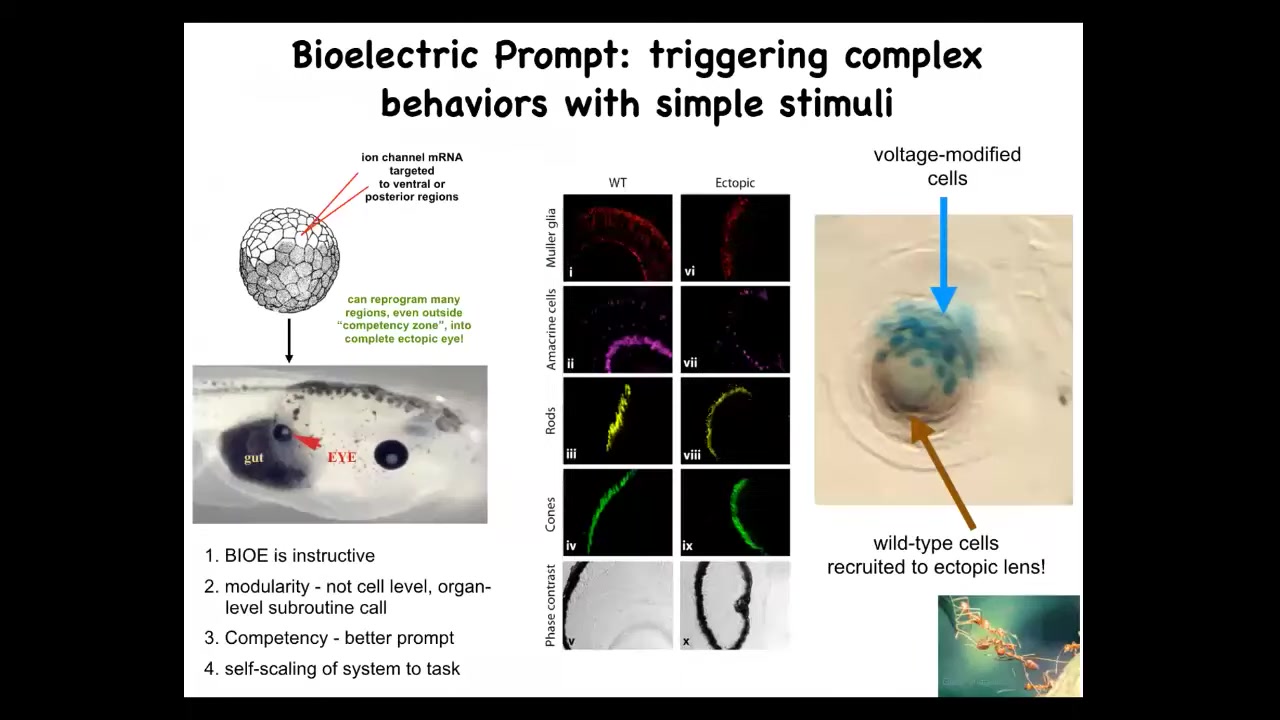

Slide 21/50 · 25m:58s

Here's an interesting prompt. We can take a certain bioelectrical state that occurs during normal face development that tells the cells where the eyes are supposed to go. We take that bioelectrical pattern and we can introduce it elsewhere in the body. We do that by injecting RNA for specific ion channels. If we inject it here in a region that's going to be gut, what these cells end up doing is making a perfectly nice eye. These eyes have lens, retina, optic nerve.

From here, you learn a couple of things. First of all, these bioelectrical patterns, just like in the brain, are instructive for behavior, in this case, more for genetic behavior. We were able to prompt the system to build an eye. The second thing is it's incredibly modular. We didn't have to tell it how to build an eye, any more than when you train a dog or a horse you have to tell it what to do with all the synaptic machinery and everything else. The system takes care of all that. You provide a high level of communication. If you know what you're doing, you can convince the system to do very complicated things on the molecular level, and that's what happens.

Something else that's interesting and a reminder about humility in this whole thing: in the developmental biology textbook, it says that only the cells up here in the neurectoderm are competent to become eye. That's because traditionally people prompt them with the PAX6 master eye, so-called master eye gene. If you do that, indeed, only the cells up here can become eye. But the competency wasn't the problem with the cells. It was a problem with us, the scientists, because if you have a better prompt, in this case the bioelectric one, it turns out that pretty much any region in the animal can do it. That reminds us, when your system looks like it's limited and isn't able to do specific things, the question may be, do we really understand how to prompt it to do so? Do we know how to communicate with it?

It also does many other interesting things like scale itself to the task. This is a lens sitting out in the tail of a tadpole. These blue cells are the ones that we injected, but there's not enough of them to make this organ. What do they do? They recruit all their neighbors to help them finish the task. It's a self-scaling thing, like many other collective intelligences do.

Slide 22/50 · 28m:05s

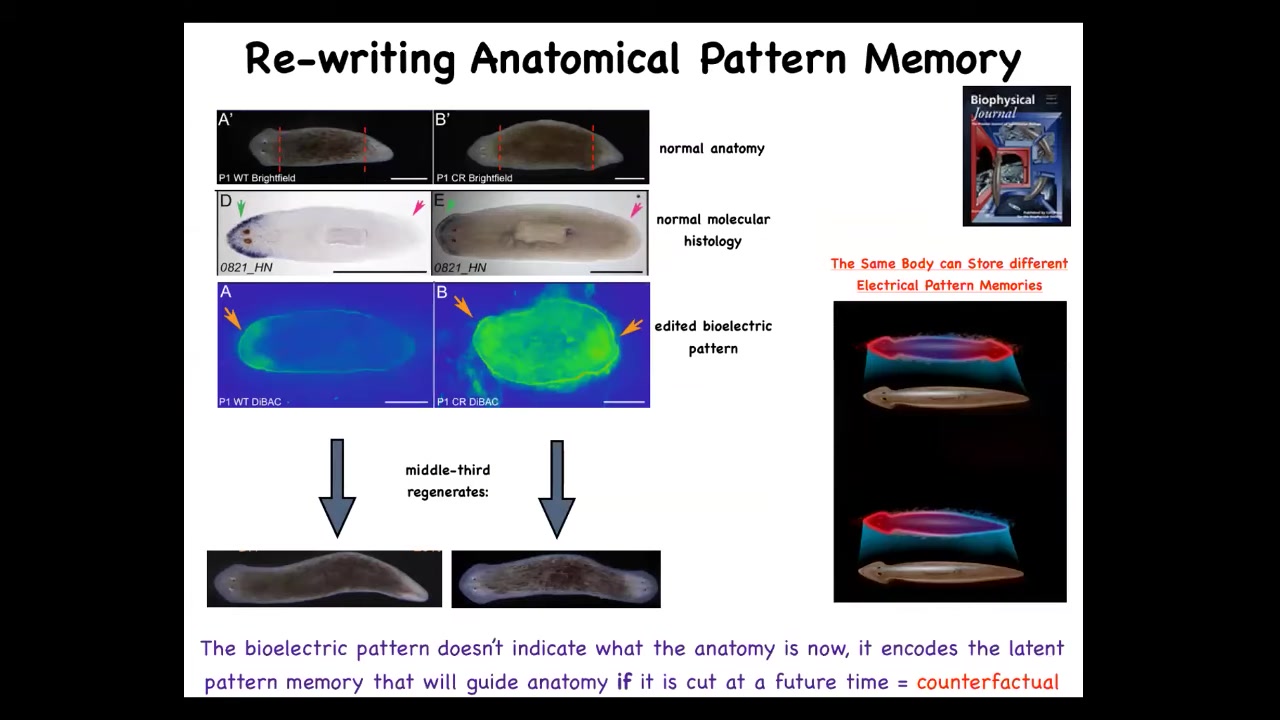

I want to switch from this into a different model, which are now planaria. The idea there is, remember, you chop them into pieces. The piece knows exactly how many heads it's supposed to have. It turns out that one way it remembers how many heads it's supposed to have is by this bioelectrical pattern, which says one head, one tail.

This is very robust, but we can rewrite that. Using drugs that open and close ion channels as guided by a computational model, we can say, nope, you should have two heads. When you do this and then you cut the animal, there you go. It builds a two-headed animal. This is not Photoshop or AI. These are real animals.

Something very important and interesting here is that this bioelectrical map is not a map of this two-headed animal. This is a map of this perfectly normal animal anatomically and molecularly. The head markers are here, not in the tail. This memory is latent. It is not expressed until the animal is injured. In fact, it disagrees. The memory it has disagrees with what the situation is right now, because right now it has one head.

I think it's a very primitive counterfactual. I think it's an example in this unconventional system of the kind of mental time travel that we all enjoy, the ability to represent states that are not true right now, either from the past or from the future. A normal body of a planarian can represent at least two different representations of what it's going to do if it gets injured at a future time.

Slide 23/50 · 29m:41s

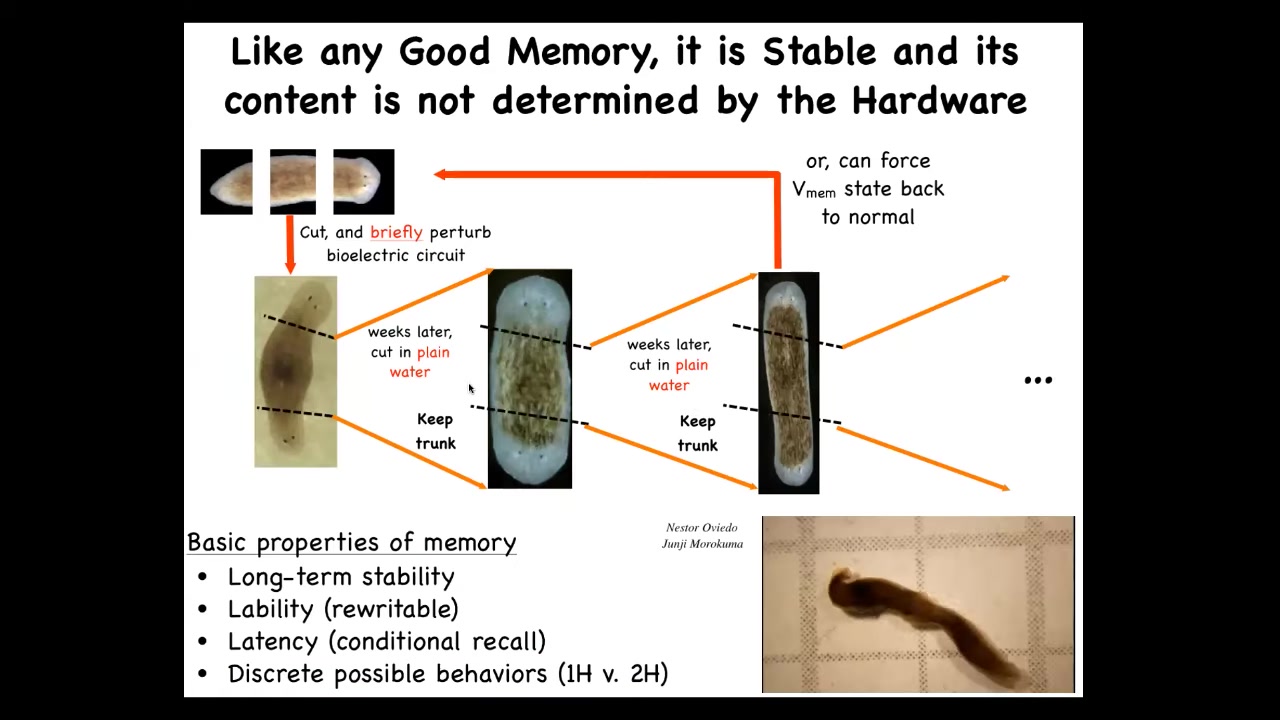

One reason I keep calling this thing a memory is because it has all the properties of memory. In fact, if I take these two-headed worms and cut them into pieces, the fragments will continue to build two-headed animals in perpetuity.

There's nothing wrong with the genetics here. The genome—we haven't touched the genome. The genome is unchanged. The question of how many heads you're supposed to have is in fact not really nailed down in the genome.

But much like with the cognitive systems that you're used to in brains, you can learn things that don't need to make it back into the DNA, and they are stored stably, but we can rewrite them in either direction, like any good memory.

Here they are. There's lots of interesting behavioral science that we can do with animals with multiple heads in the same body.

Slide 24/50 · 30m:27s

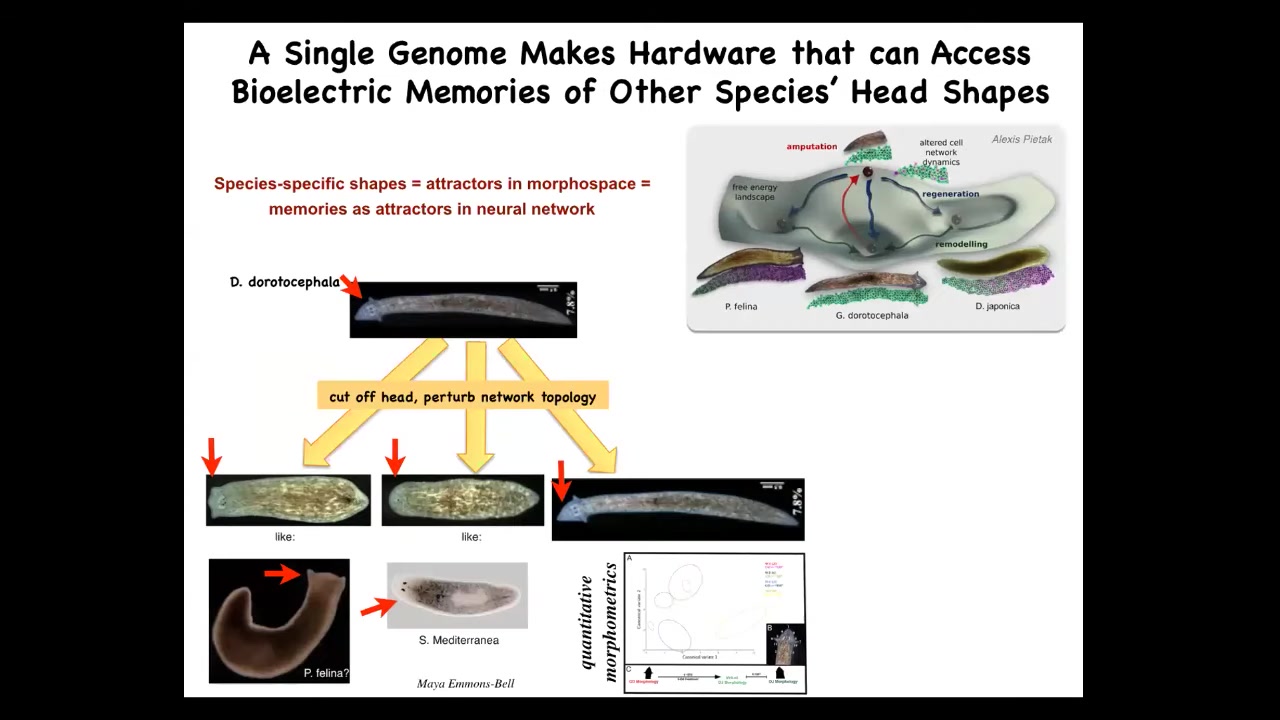

Interestingly enough, it's not just the number of heads that you can build, but actually even the type of head. We can ask this guy with a triangle head to build heads like these other species, 100 to 150 million years of evolutionary distance. No changes in the genome, just alter the bioelectrical pattern memory. You can get flatheads like a P. felina, roundheads like an S. mediterranean. The shape of the brain changes, the distribution of stem cells changes, just like these other guys. The hardware is perfectly capable to visit these other attractors in the morphogenetic landscape that normally belong to these other species, but you can visit there if you change the content of the bioelectric memory.

Slide 25/50 · 31m:10s

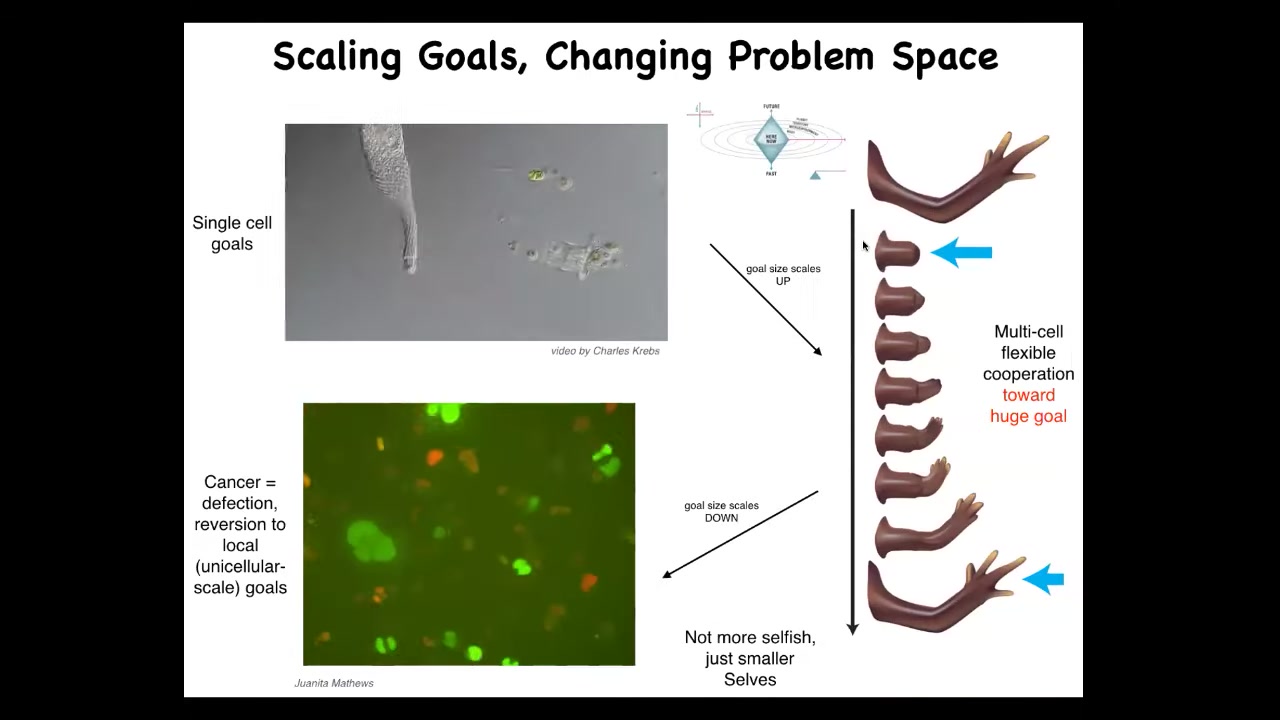

And then the final example of this that I want to show you is what happens when you change the size of the self. This, our concept of the cognitive light cone, which is basically the size of the biggest goals that a system actively pursues, the individual cells are very small cognitive light cones. All it cares about is this, both in time and space, a very small region here, maintaining physiology and metabolism. But what happens during both evolution and development is that they join it to networks, and then their cognitive light cone becomes very large. They're cooperating now towards a huge goal. How do we know it's a goal? Because in this case, making a salamander limb, if you amputate anywhere along this axis, the cells will work very hard to rebuild it, and then they stop. It's a clear homeostatic process where they can tell when they've been deviated from their set point, and they'll work hard and get there, and then they stop. So these things work on very small goals. The collective works on these grandiose construction projects, creating them, maintaining them, detecting deviations. But that process has a failure mode, and that failure mode is cancer. Because when individual cells disconnect from this electrical network, they no longer have access to these enormous set points that they were trying to reach. Everything is back to their ancient unicellular metabolism and proliferation. This is human glioblastoma. What's happening here is that these cells are not any more selfish than these cells. A lot of game theory of cancer focuses on cells being uncooperative. I don't think they're any more selfish. They just have smaller selves. What's happened here is a scale up and then a scale down of the dynamic border between self and world. The size of your goals determines the size of yourself and the kind of cognitive capacity that you're capable of reaching, but it can change. It's plastic. It can change during the lifetime of an individual.

Slide 26/50 · 33m:12s

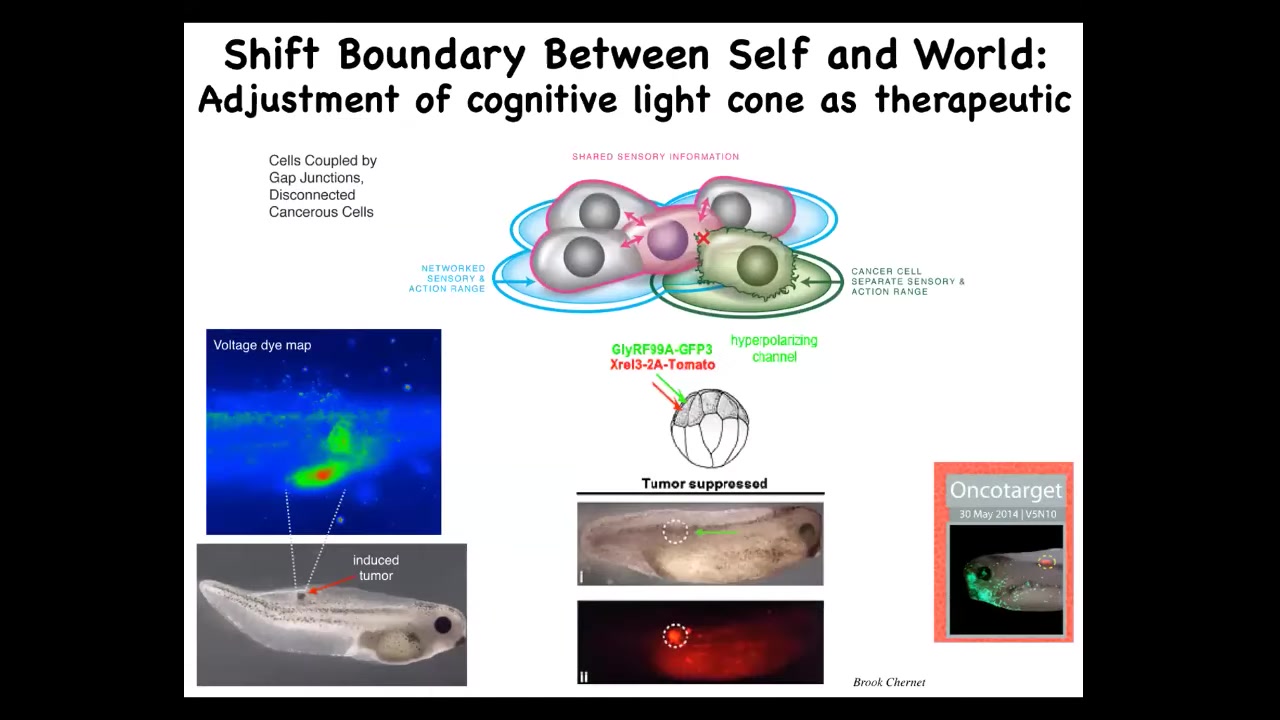

And that kind of weird way of thinking about it leads directly to therapeutics. As the previous stuff I showed you with the bioelectrics, we have lots of regenerative medicine coming along those lines to try to regenerate organs and so on. I haven't shown you any of that. But this is a simple example of how this leads to therapeutic approaches in cancer. When oncogenes are injected into these animals, the cells are bioelectrically decoupling from the rest of the network. And what you can do, you don't kill them, you don't repair the DNA, you leave the hardware intact. But what you do is you force them to reconnect to the rest of the cells. You inject an ion channel that keeps the voltage such that they're going to be connected to the rest of the cells. And then this is the same animal. Here's the ONCA protein blazingly expressed. There's no tumor, because what drives it is not the genetic hardware. What drives are the physiological decisions and the scale of the cell. The individual cells would like to crawl off and be amoebas and go where they like and eat what they want. But the collective is working on making nice skin, nice muscles and so on. That's an example of how we test some of these ideas and make sure that there's some utility in these kinds of models.

Slide 27/50 · 34m:25s

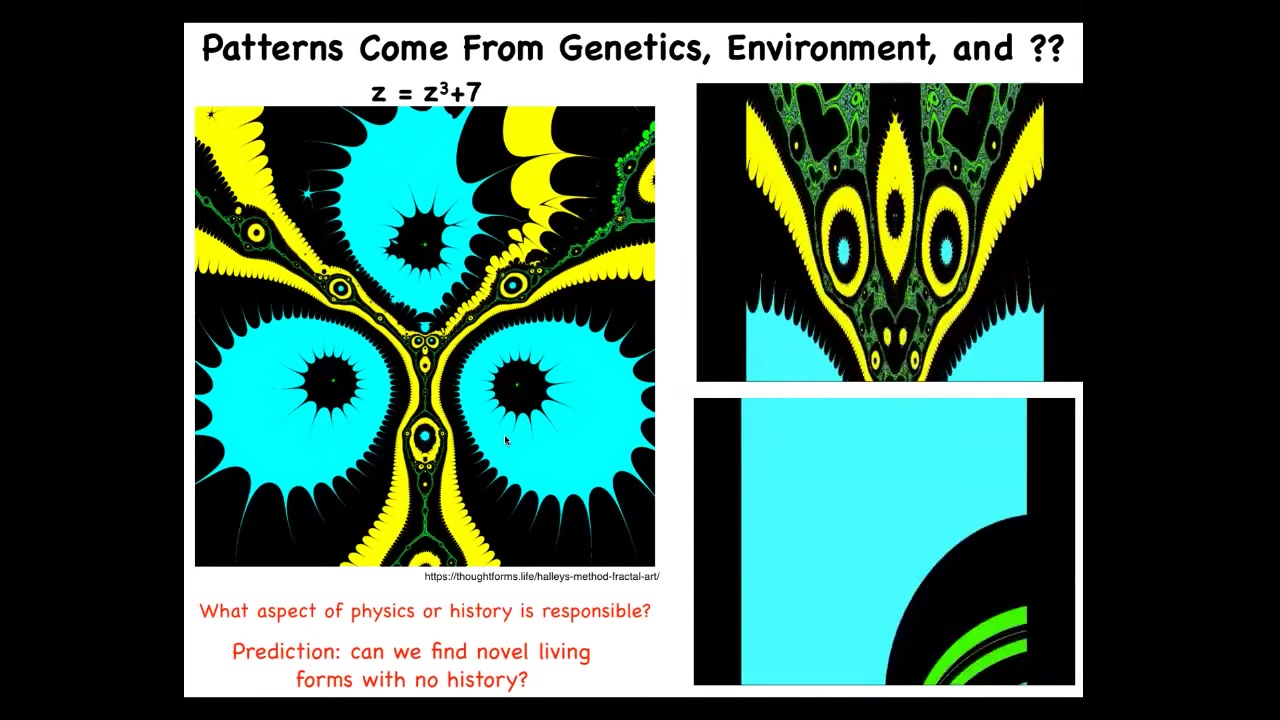

The next question I want to address is this issue of where do these patterns come from? What I showed you is the ability of groups of cells forming a collective intelligence that navigates anatomical space to reach specific patterns, specific anatomical structures. Now we want to ask, where do these come from?

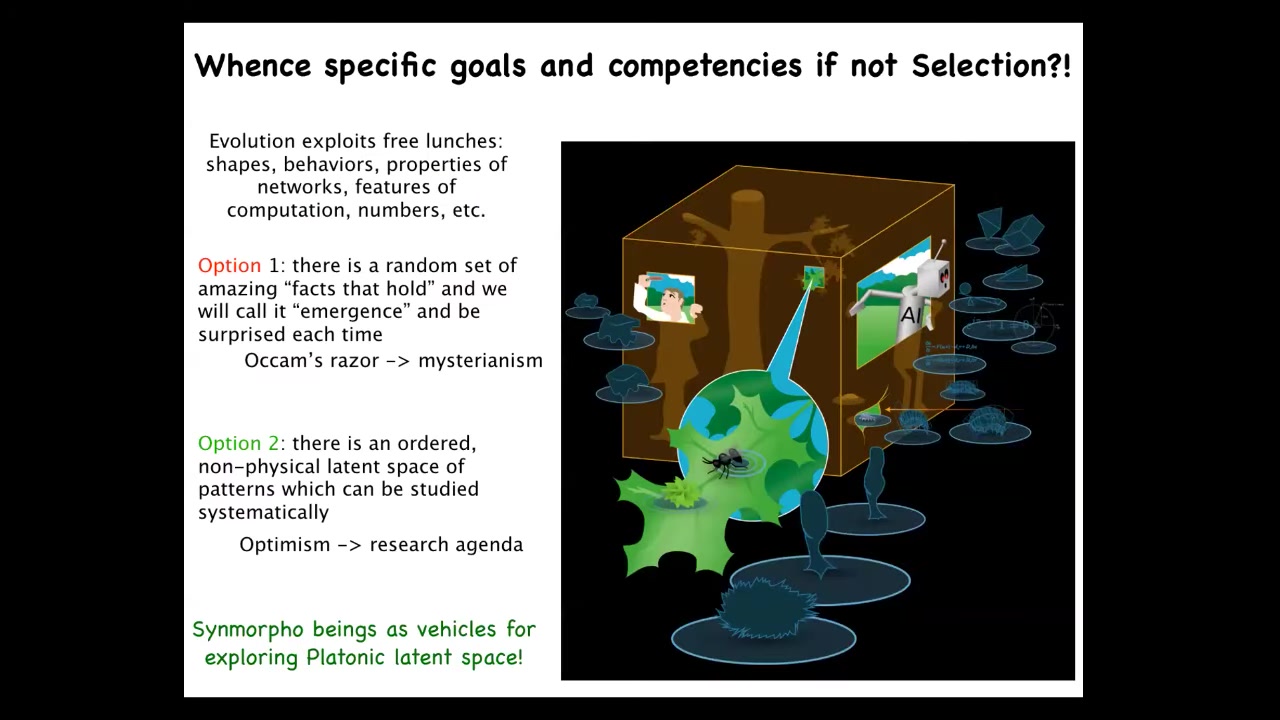

The obvious answer is evolution. Evolution shapes the anatomical amorphous space. It rewards certain attractors. It wipes out certain other attractors. But what else is there? In particular, we are interested in asking, what happens when there's a new agent that has a lifestyle that has never faced selection? We are interested in the plasticity of self-assembly. The first thing I want to talk about is this idea of where do things come from?

What kind of answers do we want to the question of where things come from?

We're used to saying, some of them come from genetics, some of them come from environment.

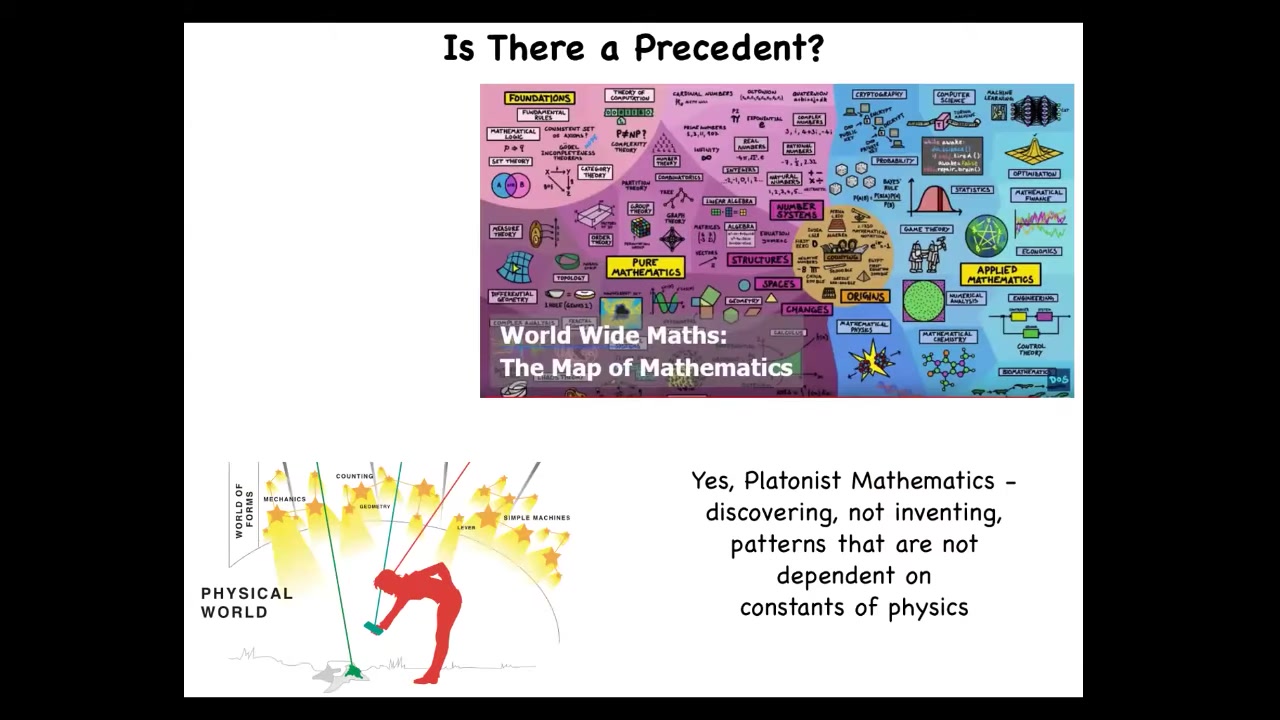

There is a mathematical space that provides a really important third kind of input into this whole system.

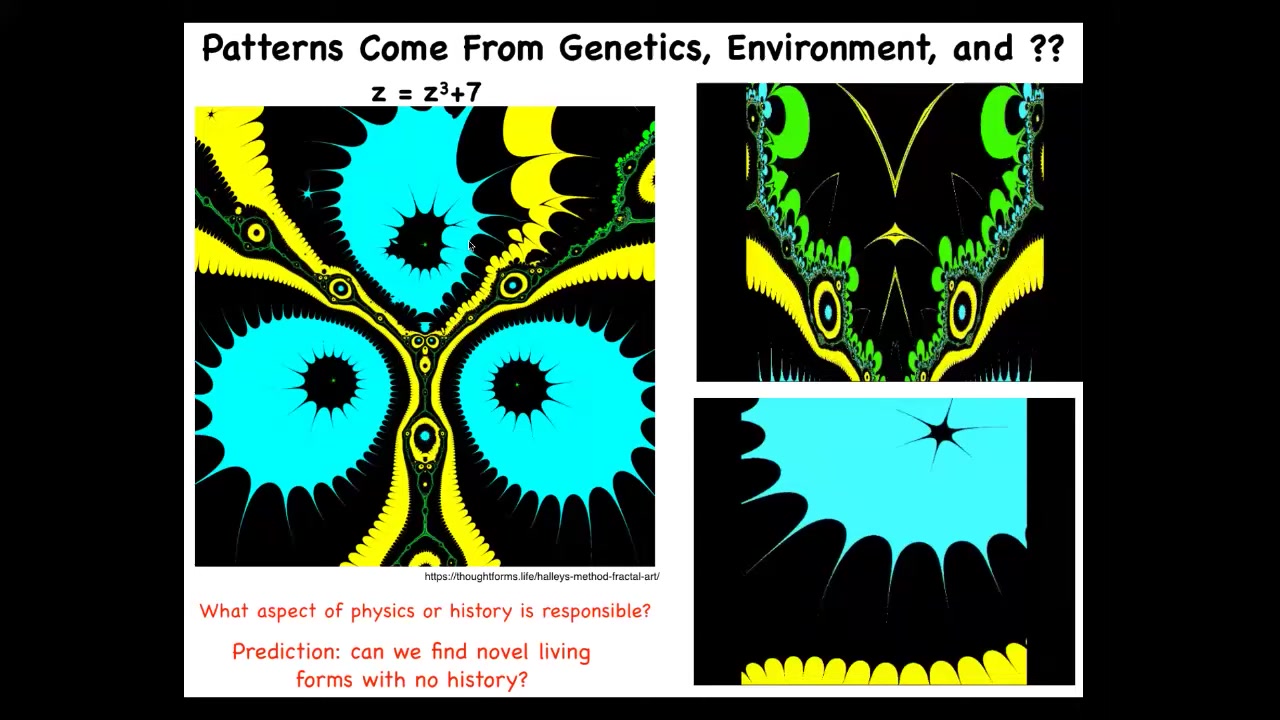

This is called a Halley plot. It's a very simple way of graphing equations and complex numbers.

Slide 28/50 · 35m:45s

This is what you get when you plot something like this. There's about 6 characters here. The compression is insane. Inside of this is hiding all of this.

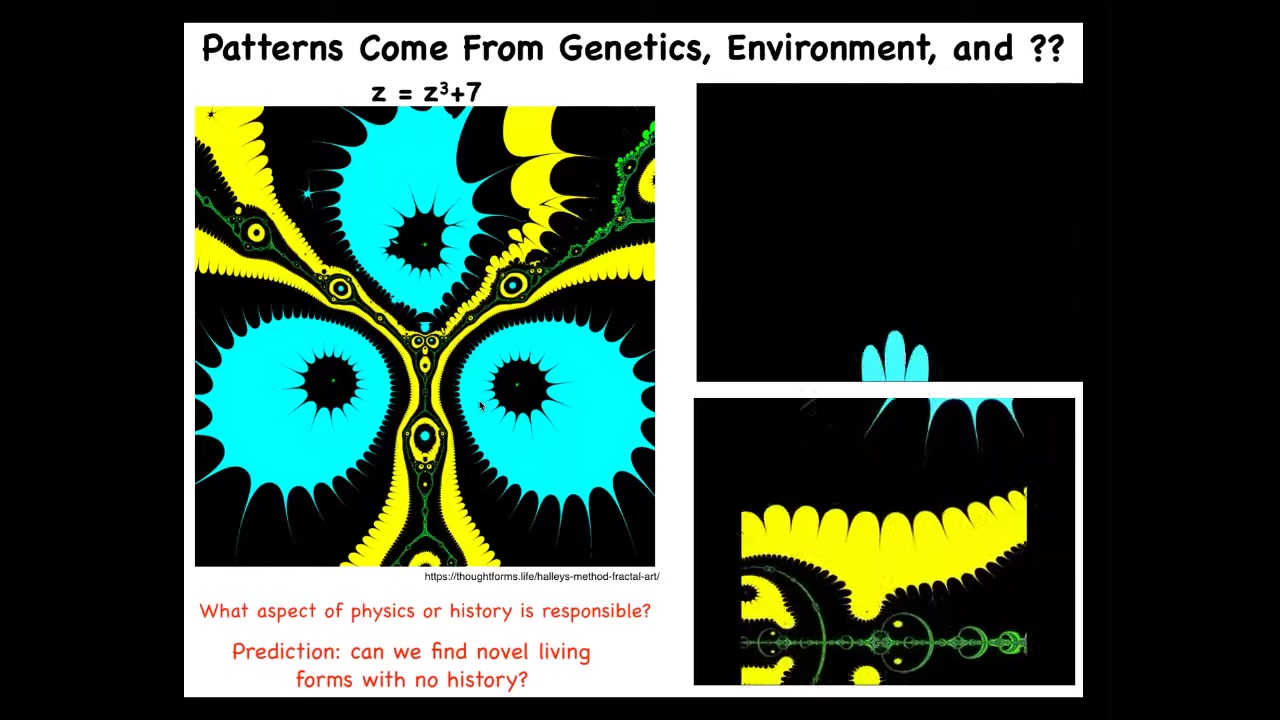

Slide 29/50 · 35m:54s

These are just videos that you can make by changing the formula slightly and making the frames. It doesn't hurt that it also looks biological. Where does this pattern come from? You're not going to find anything in the laws of physics.

Slide 30/50 · 36m:10s

You're not going to find anything in the history of life or of the universe that tells you why it is that this pattern is the way it is. What evolution is doing is exploiting free lunches that you get from a kind of platonic space of mathematics and computation and some other things. And what evolution actually makes are pointers into that space that pull down patterns that are not to be directly found in the physical world. So how do we test this? Could we find some novel life forms with no history?

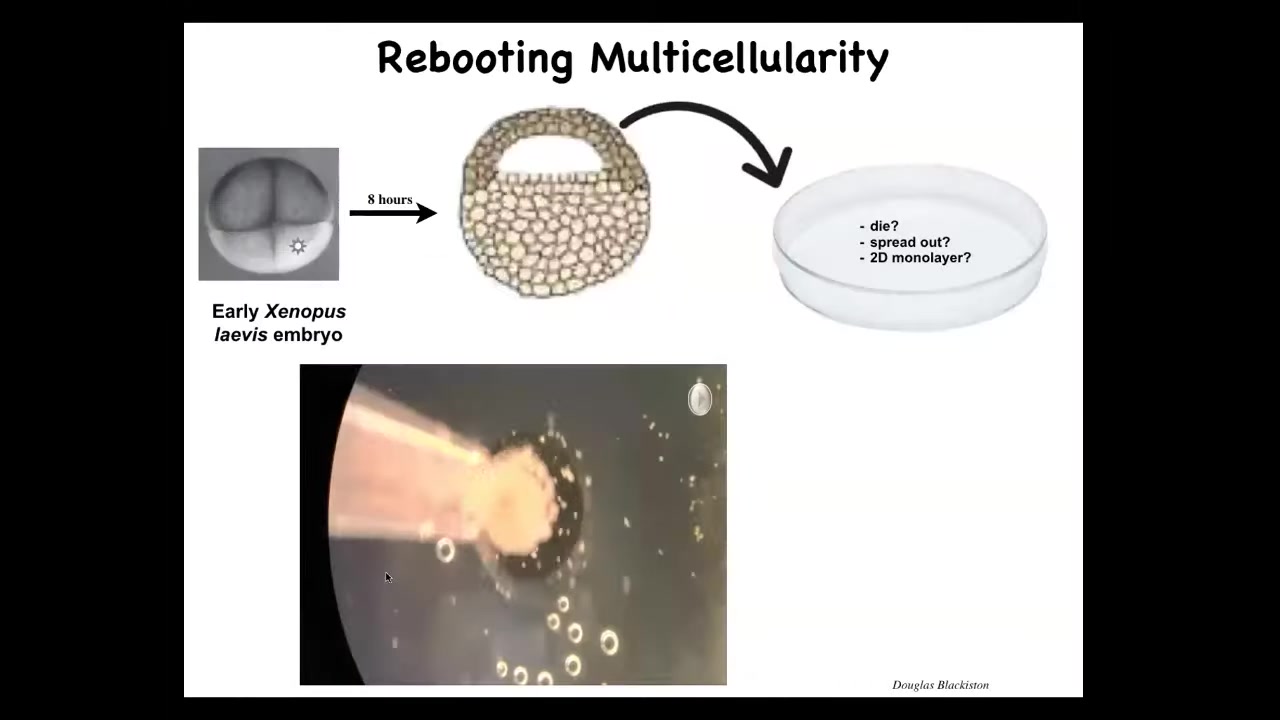

Slide 31/50 · 36m:46s

No history is hard on earth, but no selection for the new pattern is possible. Here are some epithelial cells from the top of a frog embryo. We liberate them from the rest of the animal. We put them in a petri dish. They could do a lot of things. They could die. They could crawl away from each other. They could spread into a 2D monolayer.

Slide 32/50 · 37m:15s

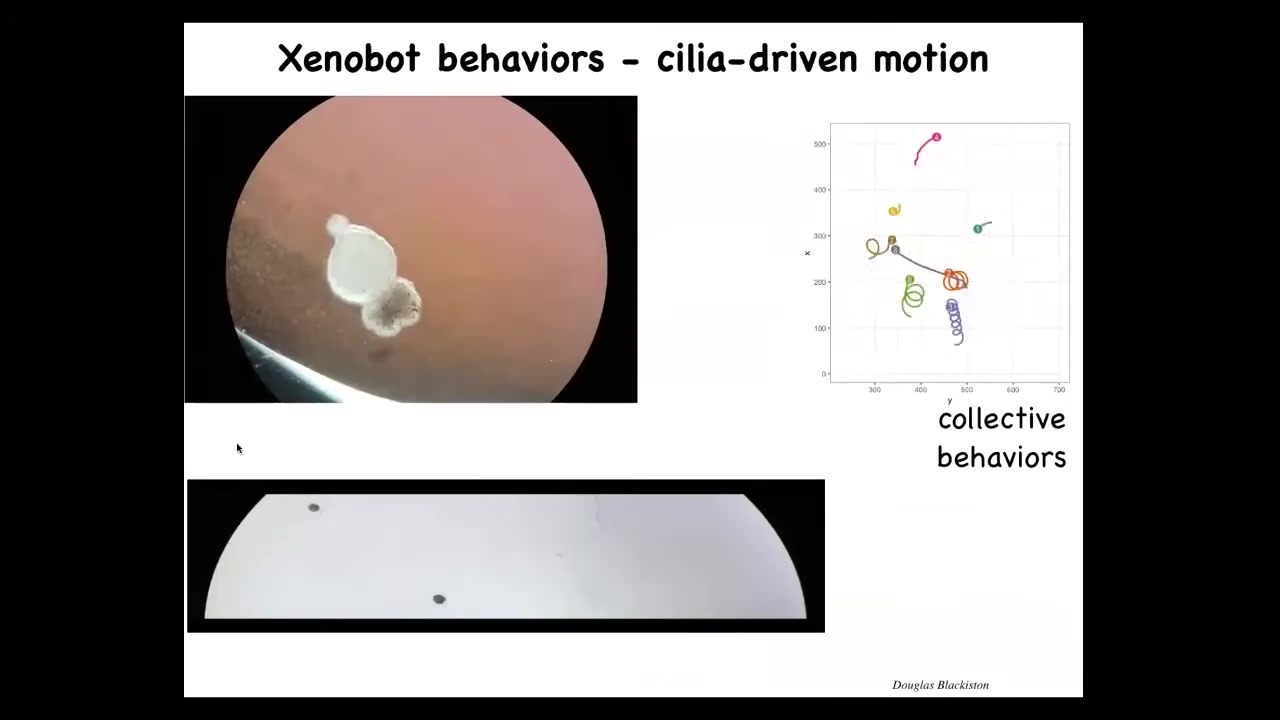

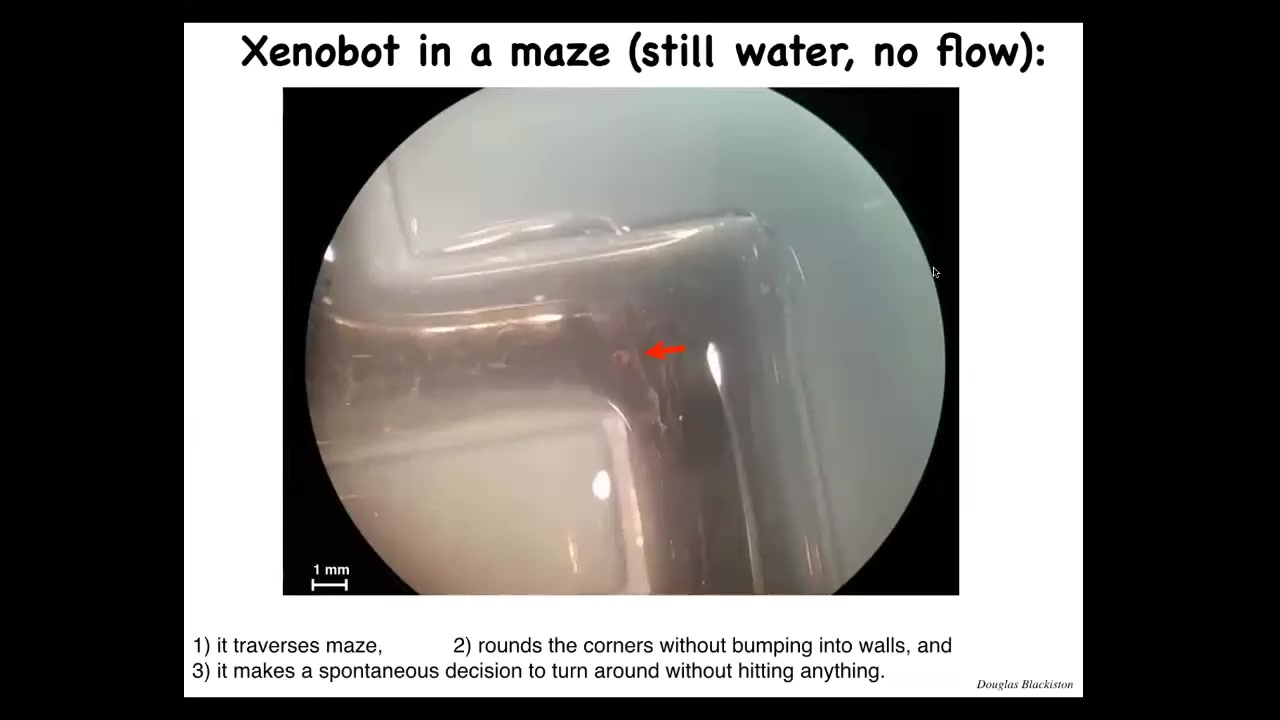

Xenobot, because Xenopus laevis is the name of the frog, is a biorobotics platform. You can see what's happening here. It's using the little cilia, the little hairs on its surface to swim. It coordinates them, and it can go in circles. It can patrol back and forth. It has collective behaviors. Here's one traversing a maze.

Slide 33/50 · 37m:34s

It's going to go down here. It's going to take a corner without bumping into the opposite wall. It takes this corner. Then here, for some spontaneous reason that no one knows, it turns around and goes back where it came from. It's fully self-motile. We're not pacing it. We're not activating it. It's doing its own thing. It has various behaviors.

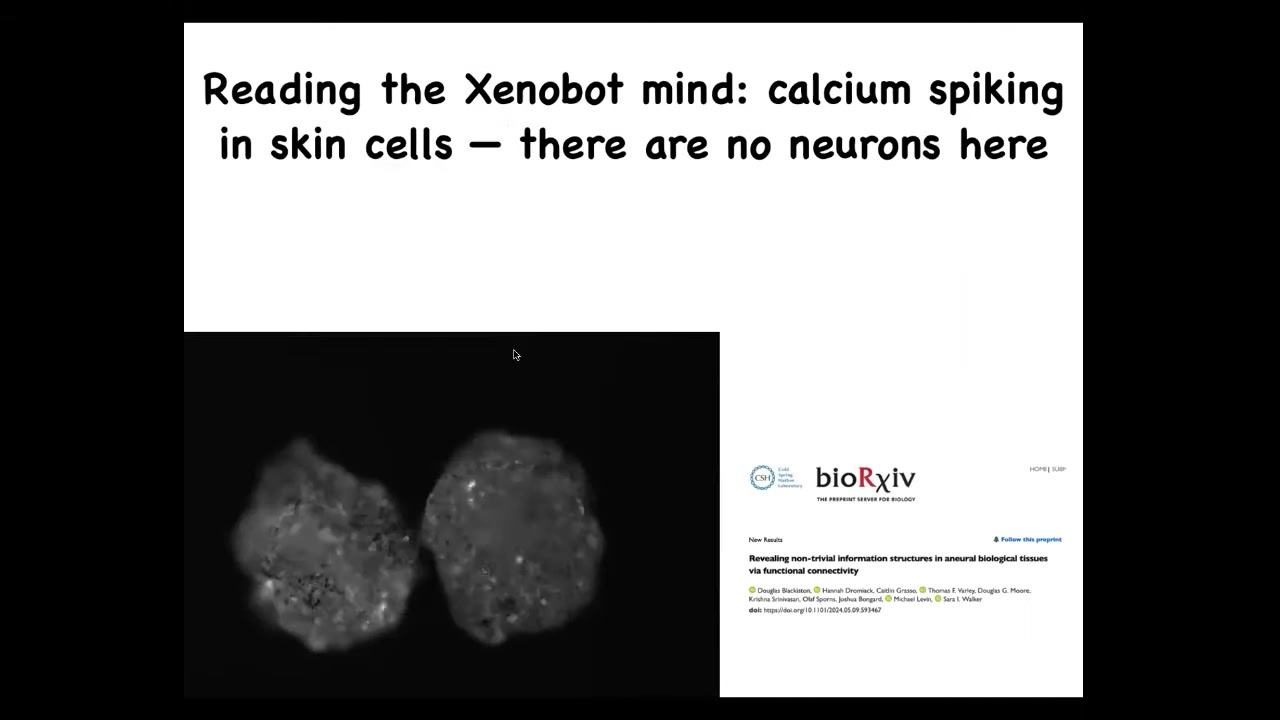

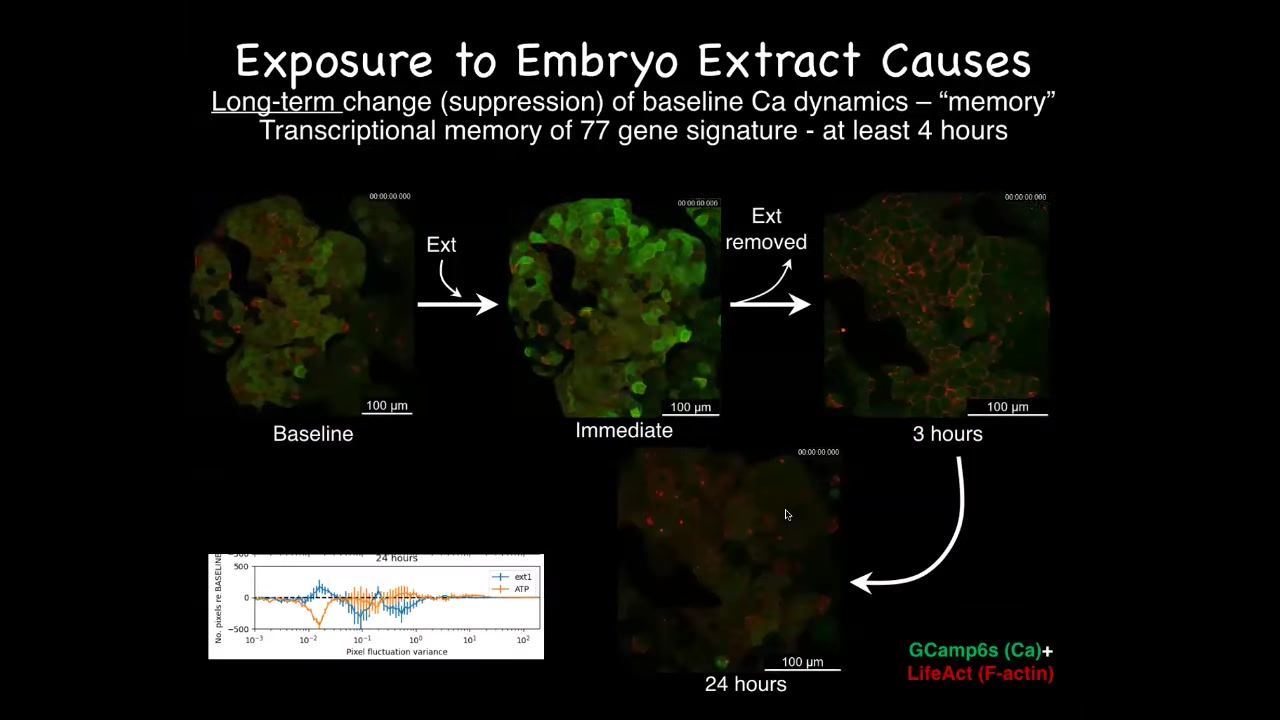

Slide 34/50 · 37m:55s

If we study the calcium signaling here, it looks very interesting. Remember, there's no neurons here. This is just skin. These are just epithelial cells. But you can imagine deploying all sorts of interesting connectivity mathematics on it. We've already done some of that. Various other tool information metrics — we've done all of that. So that will be forthcoming. You can ask that question: what would we say about this? If these were neurons, what would we say about some of these patterns both within and between bots? There's something else that I can show you about these bots.

Slide 35/50 · 38m:28s

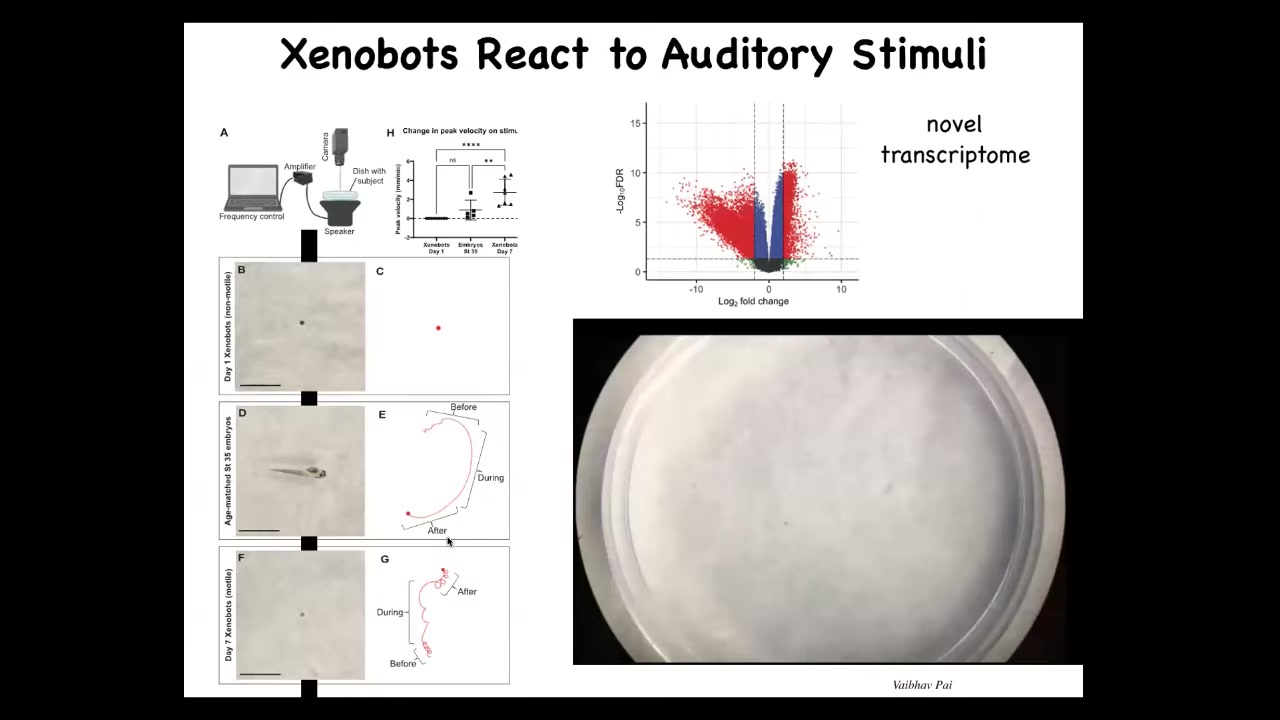

One thing that we did was study the transcriptome of xenobots compared to the tissue that they normally come from, compared to the embryo. Now, remember, these are made without any new synthetic biology circuits. There's no mutation. There is no new DNA added or changed. What is their transcriptome like? It turns out that, of course, they're missing a lot of transcripts that embryos have because they're missing a lot of endoderm and mesodermal structures and so on. But they actually have hundreds and hundreds of new upregulated genes. They upregulate in their novel lifestyle just by removing the other cells and liberating these guys into their novel lifestyle. They turn on hundreds of genes. Some of these are extremely interesting.

One of the things we found was a cluster of genes involved in hearing. Genes that, again, are not very much upregulated over what happens in normal embryos, these xenobots are expressing a cluster of genes for hearing. We thought, that's weird. What could that possibly mean? We decided to test it.

Here, we are tracking this little bot. So what it normally does, this particular one, is it kind of spins in circles. Then we turn on a speaker that's underneath the dish to provide it some sound. You can see the track of what it's doing, and then you'll see what happens when the vibration goes off and it's back to going in a circle.

By analyzing some things that these guys are doing differently, we start to gain insight into some ways to interact with them, some ways to provide signals and to change their behaviors. Embryos do not do this. This is just a xenobot thing.

Slide 36/50 · 40m:22s

So the other thing that they do is this fascinating thing called kinematic replication. The xenobots can't reproduce in the normal fashion. They don't have any of those organs. But if you provide them with a bunch of loose skin cells, then what you see is that they run around, they collect them into little balls, they polish the little balls, and because they're working with an agential material—these are not passive pellets, these are cells themselves—the little balls mature into the next generation of xenobots. And guess what they do? They run around and make the next generation of xenobots and the next. So in this system, to our knowledge, there is no strong heredity. In other words, these are all basically alike, not more like their parents than other individuals. But it is a new kind of self-replication. It doesn't exist anywhere in the world. There is no other animal that reproduces this way. It looks a little bit like von Neumann's dream of a robot that builds copies of itself by finding parts in the environment.

Slide 37/50 · 41m:21s

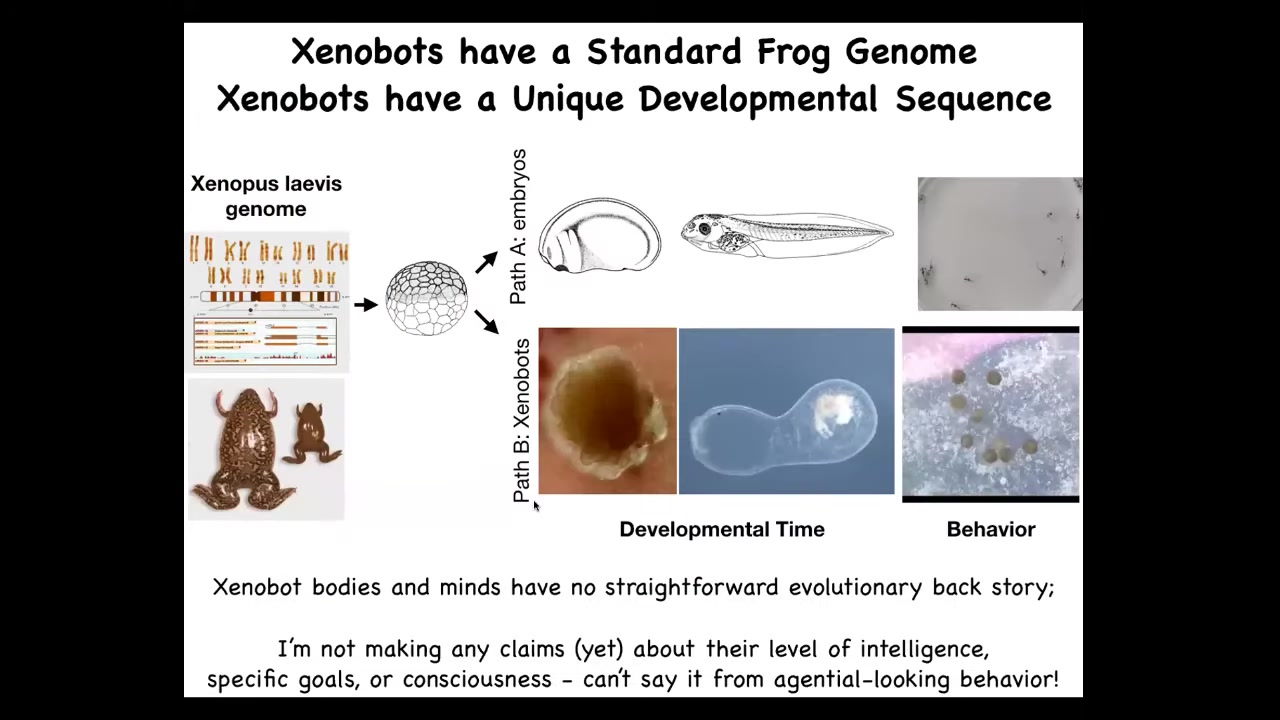

So now we can ask, what did evolution learn during the process of evolving frogs? Well, it certainly learned how to do this. So this is a standard developmental sequence, and then here are some tadpoles. But apparently, it also learned this, although there's never been any Zenobots, there's never been any selection to be a good Zenobot. We're not yet making any claims about their level of intelligence, although we've done a bunch of experiments on memory and things like that, which we will be reporting soon. I'm not saying anything about what specific goals they have. I'm not saying anything about their consciousness, because you actually can't tell any of that from just reading behavior. You have to do perturbative experiments, which we're doing, but they're not ready yet. But what you have here is an interesting model system in which to try to ask where do behavioral, not just morphological, but behavioral patterns come from. If they weren't under specific evolutionary selection in this novel circumstance, where did they actually come from? And one thing you might think is that this is something very, very frog specific. Embryos and amphibians are both plastic. This is frog specific thing. But I want to point out how general this is.

Slide 38/50 · 42m:33s

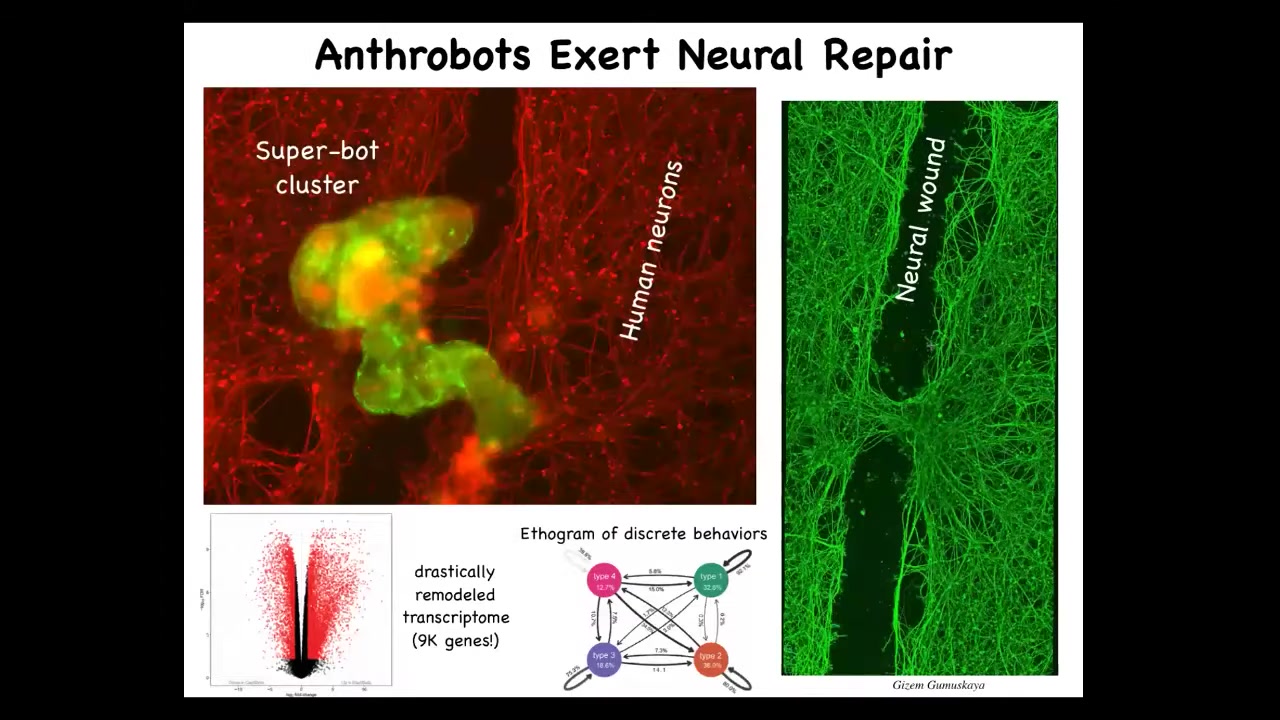

I'll show you this and I'll ask, what do you think this is? What sort of thing is this? You might think it's something we got out of the bottom of a pond somewhere. You could try to guess the genome. If you guessed something primitive, you would be wrong. This is 100% Homo sapiens. These are what we call anthropots. They're made of human adult tracheal epithelial cells. There's nothing embryonic about this. They don't look like any stage of human embryonic development, but they do have these little cilia. There's this little motile creature that does interesting things. What does it do?

One thing it does is, if you put it on a dish of human neurons with a big scratch through it, it can move down the scratch and then eventually it will settle down.

Slide 39/50 · 43m:18s

If it settles down, a bunch of them together will form this thing we call a superbot. If you lift it up four days later, you'll see that what that superbot was doing was trying to knit the two sides of the wound together. Now, who would have thought that your tracheal epithelial cells that sit there quietly in your airway have the ability to form this self-motile little creature with weird abilities such as healing neural wounds. This was the first thing we tried. This isn't experiment 800 out of 1000 things we tried.

So you can imagine how many other things these things are doing that we have no idea. They express about 9,000 genes differently than their tissue of origin. Their transcriptome is completely redone. About half the genome is altered. They have 4 distinct behaviors that you can build an ethogram out of in terms of the transition probabilities between these behaviors.

Now we see that there's the default kinds of form and function that we expect, but there are also some really interesting things that you might call emergent that we need to discover by interacting and prompting these things and trying to guess what level of cognitive sophistication they have.

Slide 40/50 · 44m:29s

What I'm interested in is this idea of a much wider continuum of beings. I don't think we should be trying to maintain sharp categories that lead us, when we're confronted by all sorts of novel beings, to ask, is it really human? Is it 51%? We have to try to understand the space of possible bodies and minds, because if we can't rely just on the genetics and the environment and the history, what do we have?

Slide 41/50 · 45m:02s

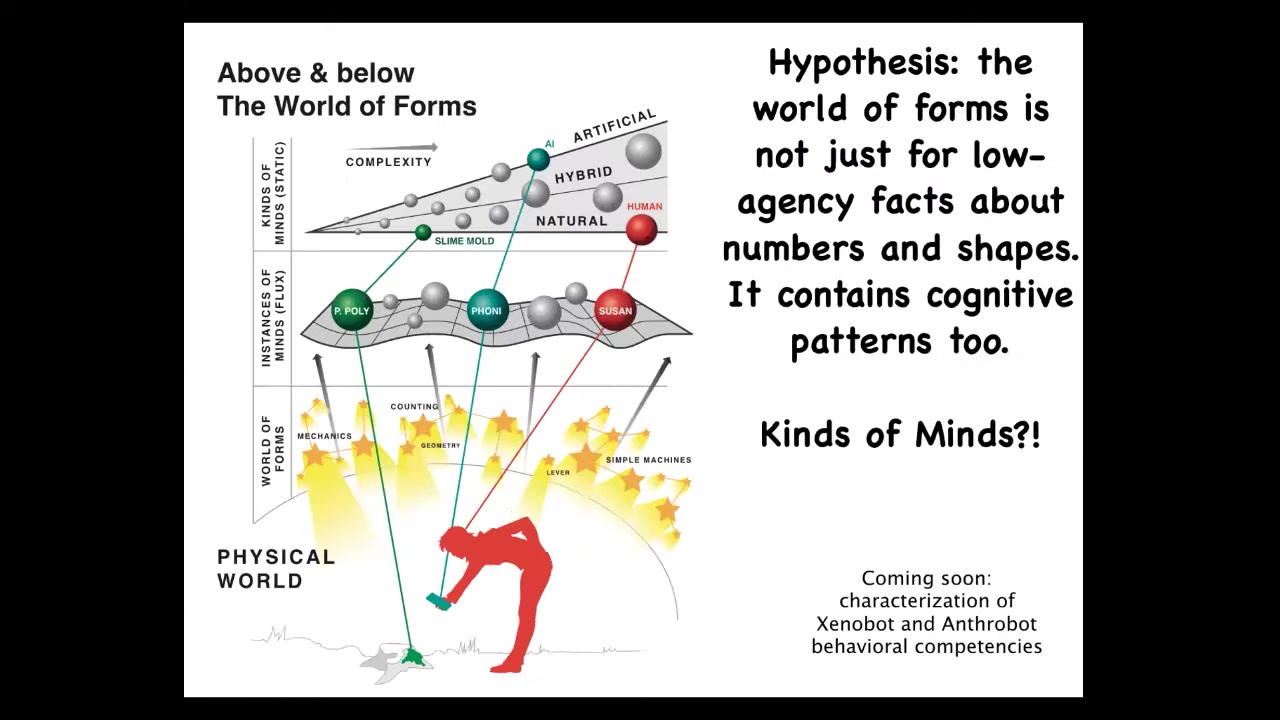

So my weird claim is that in the same way that evolution exploits patterns in geometry, in computation, all the different kinds of things that mathematicians study, in the Platonic space, the other things that exist in this Platonic space are structures that regulate different kinds of minds.

I think that what these xenobots and anthropots are, among other things, are exploration vehicles for an enormous Platonic space of form and cognition.

There are two ways that you can think about this. The conventional way is that there are some facts that hold. These are truths about network properties, numbers, and computation. These are amazing facts that hold. When we find them, we write it down and it's surprising and it's great. The good news is that it's minimal. The bad news is I think this is a mysterian outlook. If we want to find surprising things that emerge, I think that's giving up on what's the best thing about science, which is the hypothesis that there's an order to the world that we can study.

I think Option 2 is better, which is the assumption that there is an ordered, non-physical latent space of patterns. These are very boring, low-agency patterns — facts about triangles — and also some much higher-agency patterns that can be studied systematically. That's the research agenda: to figure out how we can use anthropots and xenobots and frogilotls and all this weird stuff that we make as pointers into this space to see what is actually there.

That's what I think these synthetic morphology beings are. Is there a precedent for this? There is.

Slide 42/50 · 46m:53s

Most mathematicians don't think that they are finding a grab bag of random facts. They're working on a map of mathematics. These things have a structure to them. They think they're discovering it, not inventing it.

Slide 43/50 · 47m:12s

I think we could develop a model like this where all of the layers of the biology that we see are using all sorts of different things from this kind of space. What's found there is not just facts about the body, but different kinds of mind. That's my hypothesis.

Slide 44/50 · 47m:33s

What I think we're looking at here, because life is so incredibly interoperable, the ability of problem solving at every level of organization allows it to form pretty much any combination of evolved material, engineered material, and software is some kind of possible agent. All of them take advantage of this incredible space of, as Whitehead said, "patterns that ingress into the physical world." Everything that Darwin said, "endless forms most beautiful," is like a tiny little corner of this incredible space of bodies and minds.

Many of these already exist: high brats and cyborgs. You're going to hear from Wes a cool story about his high brat. A lot of these things already exist. I think in the coming decades, there will be more and more of them. I think we need to start working on frameworks for an ethical synthbiosis. This is a word that GPT came up with when I asked it to come up with a simple word that enables visualizing a symbiosis with all of these novel creatures that are coming and to understand what it means to be in a beneficial relationship with beings that are nowhere on the tree of life with us, that are completely radical, that are pulling down very different patterns from the space of possible minds.

Slide 45/50 · 49m:01s

I'm going to give you a couple of quick things and then I'll stop. My main conclusion about many of these things is that we really need a lot of humility about the idea that we know what we have once we've made it. That's because when we make things, in an important sense, we get out more than we put in. By building pointers, these living or non-living pointers into this space of patterns, we pull down things that we did not know we were going to get.

We've done studies of extremely simple systems. These are minimal kinds of things, sorting algorithms, bubble sort, that it turns out, if you look at them the right way, have interesting problem-solving behaviors that nobody had noticed before. I can answer questions about it. They do these weird side quests, have delayed gratification, and do things that are not anywhere in the algorithm.

Based on this and other work in minimal matter, I think that it doesn't take cells, it doesn't take life or large complexity to have emergent goal-directed competencies that are very hard to predict—not just complexity, not just unpredictability, but emergent cognitive patterns that we did not know about. We have to be very careful. If we don't even know what bubble sort can do, we have to be careful about thinking that we know what certain kinds of AIs can do, what linear algebra can do when used on large data. I think we really don't know. For this reason, I really like this kind of thing.

Slide 46/50 · 50m:38s

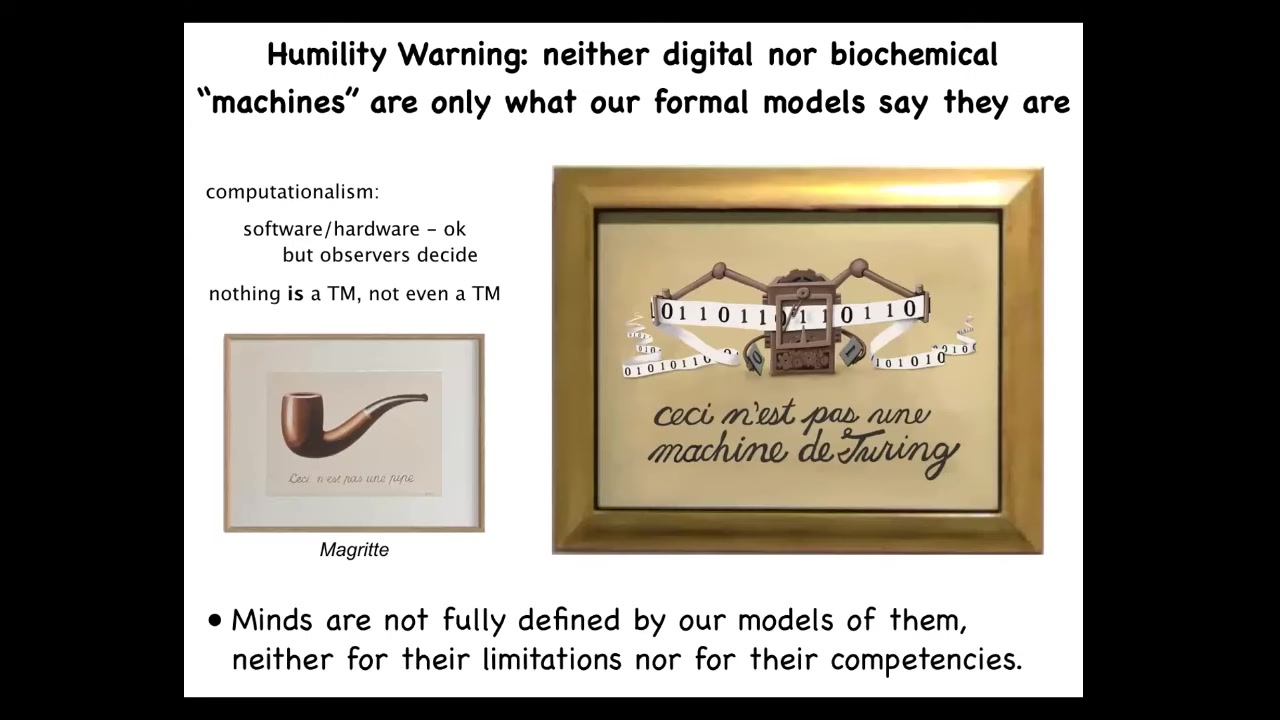

Magritte said, "This is not a pipe." This is a representation of a pipe. I think the same thing is true for computationalism: we have to be really careful. There are many limitations of Turing machine models, and people take those to be the limitations of machines. We have to keep in mind that for the exact same reason that we don't think the story of biochemistry is a sufficient story for a conscious mind, we should not think that what machines do or can do is fully described by our models of what we think they are. The formal models have limitations. The formal models are not the same thing as the actual thing.

Slide 47/50 · 51m:20s

And I think that the new Garden of Eden is going to look something like this. I think we really need to step it up in terms of dissolving some old categories that I think are doing us no practical good whatsoever, and really develop good stories of the scaling and propagation of cognitive behaviors into different problem spaces.

Here are some things I feel relatively confident about: Very little in this field is binary. I think we're talking about scaling and transformation. I don't think it's about brains. I don't think it's about embodiment in three-dimensional space. I think these kinds of properties, and probably consciousness, are all around us, and our formal models do not tell the whole story.

What needs to be worked on, and what we're working on and other people are as well, is what aspects of the architecture manage the different types of perturbations that we get.

Does evolution have any monopoly on making minds? The only reasonable argument for this that I've seen comes from Richard Watson. I used to think definitely not. I'm not so sure now, but this needs much more work.

I think the research program is creating new tools for exploring the space of these minds.

What I have no idea about at this point is how well consciousness tracks intelligence. I'm not sure if there really are any phase transitions or if they are completely smooth and all of the phase transitions are in our minds. I'm not sure how we gain first-person understanding of any minds. They are certainly not exotic minds.

If anybody's interested in following this further, here are some papers where we go through all this in detail. I want to thank the people who did all the work.

Slide 48/50 · 53m:01s

You'll hear from Wes momentarily. Here are all the postdocs and the students that did all the things I showed you today. I always thank our funders. Disclosures. Here are three companies that have supported some of our work, and the model systems get all of the credit. Thank you.

Slide 49/50 · 53m:17s

Thanks very much. Beautiful presentation of some really extraordinary work. I'm the discussant, so I'll just be chairing the discussion session. While people formulate questions, let me kick off with two quick ones of my own.

You show, going back to Mike's talk primarily, but Wes as well, these examples being able to train some of these systems or they start to do things. It's a question of what's trainable. Now, Mike, I think we talked about it before at some point, but there's this really interesting distinction in training animals between trace conditioning and delayed conditioning. Delayed conditioning is where the conditioned stimulus and the unconditioned stimulus are pretty much at the same time; trace conditioning is where there's a tiny delay. This has been associated with awareness of the stimulus and the stimulus contingencies. How far have you been able to push these conditioning paradigms?

The second question: I remember you mentioning at some point the planaria. I'm thinking of the contrast between the planaria and the xenobots and the anthrobots. You talk about in the planaria where they almost don't rely on their genome at all for anything. I imagine that's not the case for the anthrobots or the xenobots. How much does comparing those two model systems tell you about the role of genetics in how you can probe into the space of possible lives?

On the first question, all of those kinds of learning assays are very doable with all of these systems. We talked about collaborating on some of it, so let's do some of that. We've already done some, but we should do way more. We'll find out.

One thing I didn't get a chance to talk about today that's interesting: this is a new preprint that we put up. This is Federico Pigozzi's work for my group, where we've been looking at causal emergence, IIT-style metrics in gene regulatory networks that have been trained. In terms of awareness of what you're learning, it actually, even in GRNs, causal emergence goes up by training. They become more of an integrated agent by virtue of being trained. All of these questions are very tractable in these systems, just like they would be in a neural system.

For the genetics thing, I would say this. If you want, I'll take the time to go through what's up with the planaria; it takes a couple minutes to explain. What I think is most interesting about both xenobots and anthrobots in terms of the genetics is that they are not genetically modified. There are no synthetic biology circuits in them. They are in the same environment they were in before; in one case that's pond water, in another it's cell culture medium. There's nothing informative in the environment. Yet, because of their new independent lifestyle, they upregulate many hundreds, and in the case of anthrobots, thousands, of new genes that they're going to deploy in their new lifestyle.

I think what we're looking at, consistent with the story we've developed in the planaria, is that it's not so much that the DNA is telling you what you're going to be and what you can do, but it's more of a resource book. I realize this is an enormous claim, and I'm not saying that we've proven this in the general case. I think what we're seeing here in this specific example is that, much like all the other molecular mechanisms that NEWT uses, that all of these systems use when we put them in weird scenarios, the genetic information, just like the molecular biology pathways, are tools that these systems can deploy in favor of their new lifestyle — their resources, their affordances.

That's what I think is one of the most interesting things about this, how they deploy all these tools. We'll go Jason, Megan. Maybe you would introduce yourself when you're asking the question, given the direct notes, which would be great. Thanks very much, Michael and Weser. This is Jason Mattingly.

Slide 50/50 · 58m:02s

I'm in Australia at the Queensland Brain Institute. Michael, I'm really interested in this latent non-physical space that you talk about when you talk about ingressing and so on. I just cannot get my head around what that space might look like, how we would go about discovering it. We've talked deeply about this. I wonder if you could say something about what this non-physical space might be.

Sure. I realize this is a wild idea, but it's not as wild as it sounds at first. I'll give you a couple of examples. First of all, mathematicians are already committed to the fact that there is a whole structure: the truths of number theory, facts about certain kinds of logic gates being different in power than others, and so on. All of these things are true no matter what the settings of the various constants of physics are. So at the beginning of the Big Bang, you could have shuffled all the structures. The physics would be different. This is not the only view. There are different views of mathematics that don't believe this.

It is a common view that these things are non-physical in the sense that they do not derive their structure or their reality from any of the things you study in physics. There's nothing you can do in physics to change them.

Imagine that in a certain world, the most fit thing is a certain triangle. You do a bunch of generations and you get the first angle, then more generations and you get the second angle. You don't need to do the same set of generations to get the third angle. You already have the third angle. This is a free gift from the laws of geometry in flat space, where two angles determine the third. Evolution gets to save one third of the time.

That happens all over the place. That's true for geometric facts. That's true for things related to computation. When you evolve an ion channel, which is a voltage-gated current conductance, you get to make a logic gate with a truth table. You don't need to evolve the truth table or the properties of that truth table. It's given to you for free. All of these mathematical things exist and are not determined by features of the physical world. We already know that evolution exploits them.

There's only one extra move I make, which is to say that the platonic space is not just for low-agency things like facts about triangles and computational kinds of things; it also contains what we normally recognize as kinds of minds. That's the most controversial piece of what I just said. The rest of it is pretty regular.

The question is, what is the structure of that space? We know a part of it, which is what mathematicians have been studying. They have a pretty good map of at least some corner of that space. We do not have a map of our space that has to do with cognitive kinds of things. I think we have a very healthy research program now to map out that space by making new kinds of constructs that dip into that space and show us what else is in there.

For example, a standard frog embryo is one point in that space, a well-understood point; everybody's studied it for 100 years. But you don't know what's around it. You can start to make these things that are tools, periscopes to explore that latent space. We can make certain changes, we can make a frogolotl, and now you get to find out what's in the space between a frog and an axolotl.

If you make Xenobots, you are somewhere else in that space that's related, but not really the same. And so all of these things to me are constructions of pointers into that space where we get to find out what comes forward. And then eventually, with enough effort to understand the mapping, we start to build up a map of that space. And the goal is to have rational design. The goal is then, okay, if somebody says to me, I want an organ that looks like this, or I want a biobot that can do this and that, or I want an AI that does this other thing, we have some idea of what it is that we're building to have these things appear. And the final thing I'll say is that with all of these things, I think you get way more than you put in. If simple old bubble sort can do things that we never had any idea about, and it is not obvious at all from the actual six lines of code that is bubble sort, then that space is rich and surprising, but I don't think it's random, and I don't like the mysterian approach that we're just going to assume these are random things that show up from time to time. I think we should be mapping that space. Thank you.

Great. Hi, guys. This is Megan Peters. I'm the UC Irvine Department of Sciences.

My question is about this idea that you have, especially in the anthropots, that you have four different and cognitively sophisticated behaviors that you're talking about, at least a little bit. You mentioned it briefly in passing. Also related to the fear conditioning that Wes was showing with his house system: where do we draw the line between physical tuning of a system and actual learning of cognitive behaviors? How do we make that distinction? Is there a distinction, or is it wrong to think about that as a distinction?

I'm thinking about things like fear conditioning, which in a more complex organism has hallmarks such as extinction and spontaneous reactivation, or that you can actually reactivate it through another cue. Are those the kinds of things that we need to have in order to call this cognition? Otherwise, is it just tuning of a physical system — a physical system that I flicked and it did a very complicated advance in response to me flicking it? How do we distinguish between physical tuning and learning?

Yeah, great. I'll say my piece and then Wes can add to it. First of all, I don't believe in any lines. I don't think any of this is about drawing sharp lines. But I do think that distinctions are very important. It's exactly what you said. I think what we're interested in is to say: here are the tools that are already used to study these things in behavioral science. What we're going to find out is how many of those things usefully port over.

By the way, I did not say that the anthropots have sophisticated behaviors. We don't know, actually. I'm making no claims about that until we figure it out. They have four distinct behaviors that they do. They're not particularly sophisticated. We don't actually know what they can learn, or how many of these criteria they will match. But all of this is predicated on taking specific tools, existing tools from the study of behavioral science, and asking how many of those give you useful discoveries in other models. If it turns out that none of those things — it doesn't do extinction, it doesn't do any of these things — then that is not where the system lands on that spectrum that I showed you. It lands somewhere else. So it's all about being very specific about these categories. I will also say that those categories are not written in stone, and some of them will have to be changed when you apply them to other spaces.

I look forward to developing more of these things and maybe even contributing some of those to behavior science so that people can start looking for new things in classic animals.

The only legitimate use of the terminology is if you've done the experiment and showed that the paradigm actually helps you discover new things in the system.

We know each other from Air Force meetings. The plan now, we've done other experiments and just to say an asterisk on the end of mine, we're also doing some where we reverse these conditions or instead of the reward being no stimulus, we're doing a regular stimulus. We're editing all of that to see how that changes the learning curve.

Similar to the work Mike talked about in genetic regulatory networks, where computationally we explored all the different types of classical conditioning. Could you destroy them? Could they come back? What happens when you break this piece and that piece? Planning on doing all of that in the cultures as well.

We're trying to come up with this suite of tests, treating these cultures as animals. I don't train them for more than an hour a day. They get fatigued. I make sure that when I feed them, I train them at a certain time. I try not to let them get bored. I assume that they are that complex. In the worst case, I'm overcautious. Best case, I learn something new from it.

What's interesting to me is I made it seem simple that these bursts come from the left or the right, but really they come from specific regions. There may be multiple behaviors or things that cause a cascade left or right, or multiple start points that go from right to left.

What's interesting to me is I'm looking for something to steal from other neuroscience—memory and related topics: what does that n-gram look like? Here you have multiple ways to generate the macro-scale behavior that I'm looking for, degeneracy in a sense. If left to right is one behavior, there's multiple ways to get there.

I'm seeing how, when I do this type of training, dependent upon the stimulations that I'm giving, what parts of the network architecture are rearranging themselves. If we can find something in n-gram: can you do extinction? Could you in a different context bring that back up again? Could you switch this learning off and on? In context A, I want you to only do right to left. In context B, I want you to do left to right. Can you go back and forth between those things? What happens when I take the tissue that's been trained and connect it artificially to a tissue that hasn't been trained?

The answer to the question is this: there's a lot of work to do, but the plan is to take all that great stuff, especially at this Air Force meeting. Everyone go ask Megan about it. It's a lot of great work there, and apply all those tools to what we're doing in culture.

One other quick thing I forgot to mention on your point there. In addition to all the different training, in all of these cases we've done anesthetics, hallucinogens, anxiolytics, different ways to perturb perception, memory blockers, nootropics — all of these things that neuroscience uses. You can use them in these other cases and ask: does it let you discover new things about the system? If so, that's great. If not, then it's somewhere else.

Thank you both so much.

We're looking towards the schedule benefit session, but we did start a little late. Because we don't have the pleasure of you being here in person, if it's all right with everyone, we'll just push the schedule a little bit.

Adil and then Tim. That was great.

This is Adil Razi here from the National University in Australia.

So I understand that you're using Maximum, is that true?

We have used that and we have abandoned using it for various reasons. One is expensive and the second is that they don't tell the configurations. They have this proprietary thing. They have got lots of business now; they can give us what we want, but it's still a black box.

So what I'm trying to say is that we have now built our own chip, which I have here. It's 10 times cheaper and you can do a lot of customized stuff. It gives full control, is stable, and is not a black box. We could have a few in person; we can chat about it. It's there if you would like to have a look at it and could be used with your system.

I'm happy to chat later and we can do something. I'll definitely be emailing you. I knew you were going to be there. I was planning on ambushing you at some point in Cancun, but I'll ambush you virtually instead later by e-mail.

I had one question for Mike. On the very last slide you were saying that phase transitions and the continuous spectrum are different, but I don't think these are two different things. I would like to know how you were thinking about this, because to me from ice to water to vapor is a classic example of a phase transition, but it's still a continuous process as well. It seems like you have a different view on this and I would like to know how you see this.

No, I understand. I'm not against phase transitions. I'm certainly not saying that human cognition is indistinguishable from what amoebas do. I mean, there are differences along the spectrum. However, what I find, and this may be less true with professionals in the field but more true with people outside the field, is that the idea of phase transitions, in a subtle but powerful way, gives people license to think that there are sharp categories distinguishing these things. The assumption of sharp categories leads to statements like, "the machines will never do this" and "the humans can do that" — they turn phases along a continuum into a categorical difference.

I think that's profoundly problematic because if you believe in a categorical difference, you don't do the hard work of figuring out what is the scaling parameter that actually turns one into the other, and what the in-between steps are. It gives people license to assume that the scientist or the biologist must have figured this out; we know, here's a human, here's a machine, they're radically different things, and that's that. That's why I emphasize the continuity property. That's why I talk about cyborgs, to remind people that these sharp categories are not as easy as people think.

And you have to do a lot of hard work if you're going to say what the real discontinuity is. I'm not claiming there might not be some, but I've not heard a really good story about some kind of categorical sharp emergence. It's usually once you start to zoom in and talk about in-between cases, then everybody says it's kind of a spectrum. I just go there right off the bat because I don't like what happens when we assume these are radically different natural kinds.

Tim Bain from Monash as well. That was a pair of absolutely wonderful, extremely stimulating talks. Make two comments.

First, relating to the platonic idea you had, Mike, and the idea that the structure of mathematical reality might do real explanatory work here. I think it's a really interesting idea, and it's one that doesn't come naturally to us because it's not part of our ordinary arsenal of causal explanations. I was reading Jim Holt's book, "Why Does the World Exist?" He does a really nice job of pointing out the appeal of mathematical structure in giving explanations. One of the points he makes, I think it's relevant to what you're doing, is he says here's a kind of answer to this question, why does the world exist, which appeals to mathematical structure. Maybe there's something mathematically beautiful about the existence of the world, which you could appeal to as part of a legitimate explanation. Now, again, I'm not saying I buy the story, but he does quite a good job warming you up to this really alien idea that mathematical structure can do causal explanatory work. So it's a great book.

The other thing I wanted to mention relates to the issue that you and Adil were just chatting about with this tradition of natural kinds talk. The way you were talking about it is very much in centralist terms where there are deep, immutable categories, which is what the natural kinds framework will actually want. And that's absolutely a tradition within the natural kinds framework. But I think a lot of philosophers of science still think there's real mileage to be got out of thinking in terms of natural kinds, where you allow transitions, you allow halfway houses, you don't have an essentialist. Philosophers of biology, Paul Griffiths, Peter Godfrey-Smith, I think a lot of those people will say look, there is structure in nature. We're trying to get at it. We're not just imposing the structure. That's the tradition that they're pushing back against by appealing to natural kinds. And I think that's congenial to everything you want to do. So the point is that there's different traditions within this natural kind language. And some of it, I think you're rightly pushing against, and some of it's completely consistent with everything you want to do. I was not aware of the book.

Two things. For the first comment, I fully agree that people are not used to thinking about mathematical truths as a causal input into things. But because biology uses these facts extensively, if we don't accept that these things are a causal input, then we're left with a dead end as far as what is the causal input? I try to illustrate that with that Halley plot. If you don't think that this pattern exists somewhere or you think there's a physical explanation for it, you are not going to find the answer. You could make a catalog and just say that's what it is and that's that.

But what you're not going to have is an explanation for it because the explanation is not to be found in the physical world. So for all of these things, I think if we have a choice between wrapping our heads around an unconventional causal input and no causal input and just people say this to me all the time, oh, that's just that property of networks, that's just the fact that holds about the world. I don't love this idea that we're going to end up with a grab bag of random facts that hold. I think we have to assume first that there's a structure to this and get hold of it.

The other thing, I understand completely about what you said, and you're right, and there is a good story to be told. I do think there are natural patterns, we've talked about some of them. I agree that those exist. But I think we all have to work really hard if we hold subtle views like that. We have to work really hard so that the wider community who are not philosophers of biology understand what the implications of that are. Because with computer scientists, people who work on AI, people who are not scientists at all, lots of different communities, they have a very different understanding of this. And they think that the claim is that there are just radically different things, and they have radically different properties, and we can maintain a nice sharp difference like we used to. In the olden days, it was good. You can knock on something, and if you heard a metallic clangy sound, then you could assume, yes, it came from a factory, it's going to be boring, I can take it apart, it's fine. And if you felt a woolly thud, then you could conclude something else. None of that is going to be any good anymore, and we have to be really careful to transmit what we are really saying when we say there are natural kinds because it isn't what a lot of people think it means.

I think we should wrap up the session. Thanks again so much for taking the time to talk to us. We all recognize Zoom talks were necessary in the pandemic, and none of us really enjoy it, but we really appreciate the time you've taken. Thanks very much. Thank you all so much, and thanks for having us. I would have loved to be there in person. Thank you so much. Great questions. Thank you all. Really appreciate it.