Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a ~1 hr10min talk I gave at a conference on modeling aspects of neuroscience. The talk is about the inverse idea - how tools and concepts from neuroscience apply far beyond neurons and brains, and can help understand a lot of biology across development, evolution, and diverse intelligence. I talked about what the symmetry between cognitive science and the study of morphogenesis means for biomedicine and for some questions in behavioral/cognitive science.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Introduction and overview

(04:16) Multi-scale developmental intelligence

(15:37) Bioelectric morphogenesis and cancer

(27:09) Programming anatomy with bioelectricity

(33:21) Planarian morphogenetic memory

(39:48) Morphogenetic problem-solving and plasticity

(47:01) Evolutionary ratchet and memory

(55:34) Unconventional bodies, minds, ethics

(01:02:58) Consciousness, summary, and closing

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/48 · 00m:00s

Thank you to the organizers for having me here to share some thoughts with you. Today, rather than talking specifically about modeling neuroscience itself, I'm going to talk about how some neuroscience ideas can extend beyond their usual substrate. We're interested in collaborations and, hopefully, work that can shed light on the origin and some fundamental principles that are useful to neuroscientists. All the datasets, software, and primary materials are here. Here are some personal thoughts on what some of our work means.

Slide 2/48 · 00m:39s

Here is the summary of what I'm going to talk about today. One of the things I'm most interested in in neuroscience is that it's uniquely poised to study multi-scale intelligence. I'm going to make the claim that the tools and concepts of neuroscience are applicable far beyond neurons, in particular through the evolutionary conservation of both mechanisms and strategies that are used. I'm going to talk about bioelectricity as a specific example of cognitive glue that holds together various emergent collective intelligences. I'm going to describe morphogenesis as a model system for studying unconventional cognition. I'm going to talk about the implications at the end for evolution, bioengineering, regenerative medicine, and consciousness studies.

What I'm really interested in, in my group, is to create a framework that will allow us to create, recognize, and relate to really diverse kinds of agents, regardless of what they're made of or how they got here. These include familiar creatures such as primates, colonial organisms, swarms, but also organs and tissues, synthetic biology, engineered new life forms, and AI, whether software or robotically embodied, and potentially even exobiological agents someday. What I'm interested in is frameworks that move the experimental work forward, that give us new capabilities, new biomedicine, and some new ideas about ethics of how to relate to beings that are not exactly like us.

This is, of course; I'm not the first person to try something like this. Here's Wiener, Bigelow, and Rosenbluth back in the 40s, trying to show what are the transitions that can lead from passive matter all the way up to complex human metacognition.

I often wonder what would have happened if the biologists had come to them and said, actually, we made a mistake. It's not really in the brain, it's in the liver or it's somewhere else. Would they have said, "No problem, our models still work, it doesn't matter"? Or would they have said, "No, you must be wrong. Our models say this is exactly why it's in the brain"? We're interested in this question of what exactly, if anything, is special about the brain and the nervous system.

I find it very interesting that Turing, who was extremely interested in generic problem-solving machines and in general intelligence through plasticity and reprogrammability and very diverse embodiments, also became interested in morphogenesis. He wrote a very famous paper on how the chemicals in an early embryo actually arise in terms of patterns, how you get chemical patterns. He saw that the self-assembly of bodies and the self-construction of minds are isomorphic problems. There's a deep symmetry in these kinds of things. That's what I'm going to talk about today: common features of understanding cognition and developmental biology.

Slide 3/48 · 04m:15s

We'll talk about three things today. First, some comments on the evolutionary origin of neural mechanisms, we'll talk in detail about morphogenesis and then the implications.

One interesting thing about neuroscience is that you can take a neuroscience paper and do a find-replace. Anytime it says neuron, you replace the word cell. If it says milliseconds, that becomes minutes. Instead of movement and behavior in three-dimensional space, we analyze anatomical morphospace. What you get then is a very readable developmental biology paper.

I used to have students do this by hand, but now we have an AI tool that does it for you. You can go here and play with it. This is the paper that's associated with it. You can put in a neuroscience abstract and see what the corresponding developmental biology looks like.

Slide 4/48 · 05m:15s

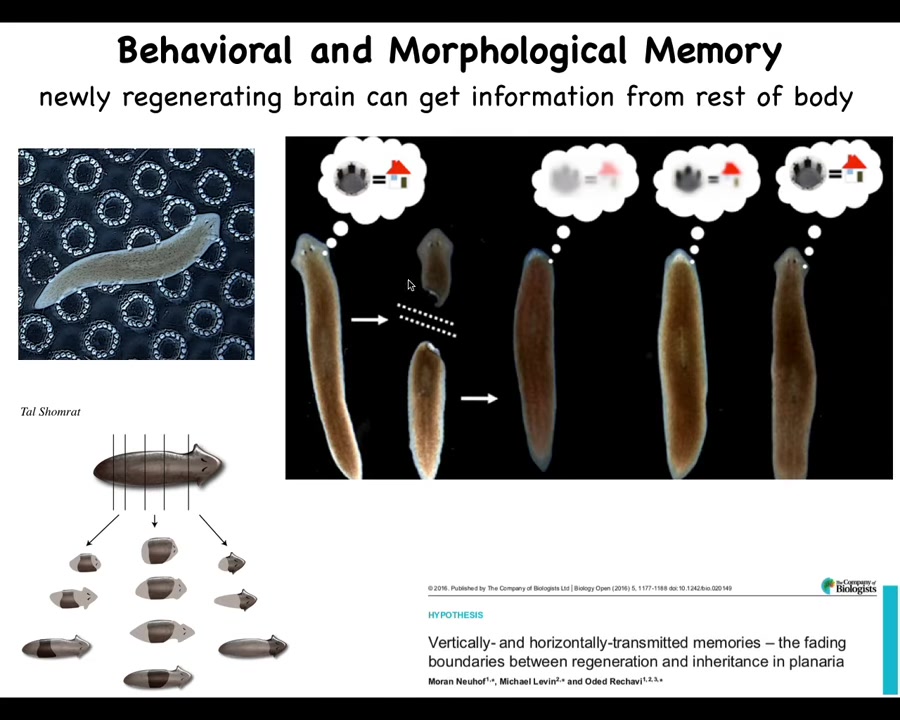

There are some interesting experiments that show the interconnectivity of the memory of behavior, functional behavioral memories, and the memory of the morphogenesis in the body.

For example, these are planaria, these flatworms that you can chop into little pieces. We'll talk a lot more about them later in the talk, but what happens is that each of these pieces regrows a perfect little worm. Every piece knows how to make a perfect little worm, but remarkably, if you train these animals on a particular task, such as place conditioning to feed on these bumpy surfaces, and then you amputate their head, which contains a centralized brain, the tail sits there doing nothing for about eight days. There's no behavior without the brain. Eventually, they grow a new brain. When they do, you can recover the original information. You do behavioral testing and you find out that they still remember the information.

What you have here is not only the storage of information outside the brain, but the ability to imprint that information onto a brand new brain that forms after regeneration. This may have implications for human medicine, let's say replacement of degenerative diseased tissues with naive stem cells and so on. Of course, we don't know how this is going to work out in humans, but the ability of information to move through the body in this example, the consilience of behavioral memories with anatomical memories, already tells us that there's an interesting relationship here.

Slide 5/48 · 06m:48s

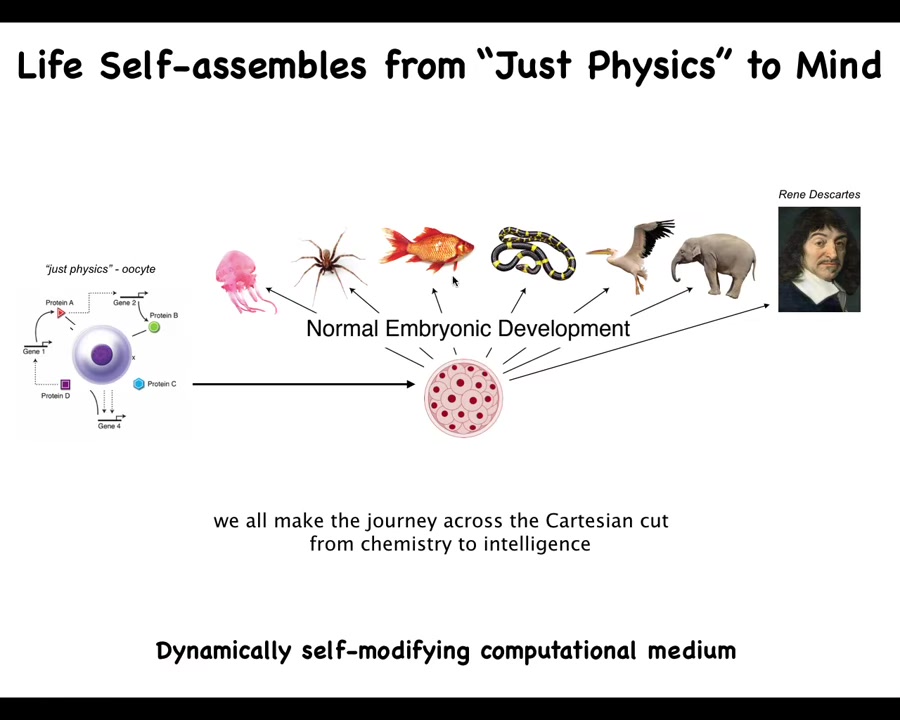

This is the journey that we all take. We start off life as an unfertilized quiescent oocyte, a little BLOB of physics and chemistry, and then very slowly and gradually, we become one of these things or even something like this. The important thing about developmental biology is that it offers no place to draw a bright line that says, well, before this was a system of physics, but now you have mind and now you are amenable to behavior science and psychoanalysis. There is no specific place where that happens. It's all very slow and gradual. And what you have here is a dynamically self-modifying computational medium that builds itself and scales up its various cognitive powers. We need to understand how this works. We need to understand the scaling of the competencies from here to here as a story of transformation.

Slide 6/48 · 07m:44s

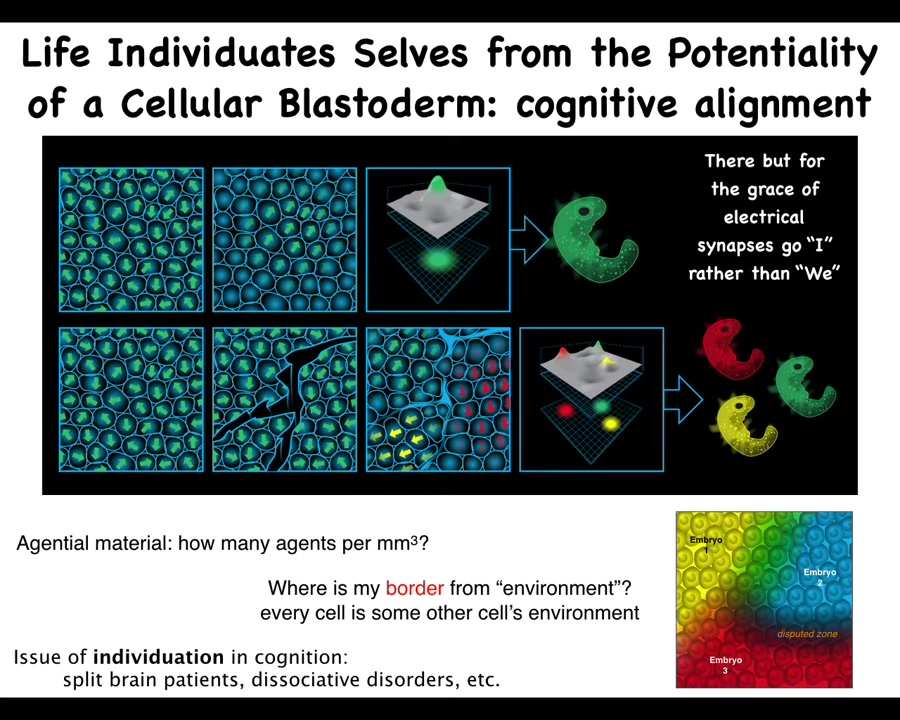

Interestingly enough, the way these embryos appear is already a dynamic process. So when you're looking at a blastoderm and you say, there's one embryo, what are you actually counting? What is there one of? There may be 100,000 cells. What there is one of is alignment, both physical and behavioral, on the part of these cells; they are all making the same journey in anatomical space. They are all committed to building exactly this thing. If you make some scratches in this blastoderm, each of these little islands, before they all heal up and become one contiguous blastoderm, each one of them will self-organize their own embryo, and then eventually you get conjoined twins and triplets and so on. So the number of cells, the number of cognitive individuals that can be formed out of this material is anywhere from zero to half a dozen or more. Unlike with computer memory, we actually don't have a good way of formalizing what is the carrying capacity of this medium, how many individuals can be formed here, but clearly it's more than one. And this already has interesting parallels with the same kind of thing in cognitive science, where you have split brain patients and dissociative identity disorders and so on, when there are multiple individuals running on the same hardware. We're very interested in this question of self-organization and scaling and where both minds and bodies come from.

Slide 7/48 · 09m:10s

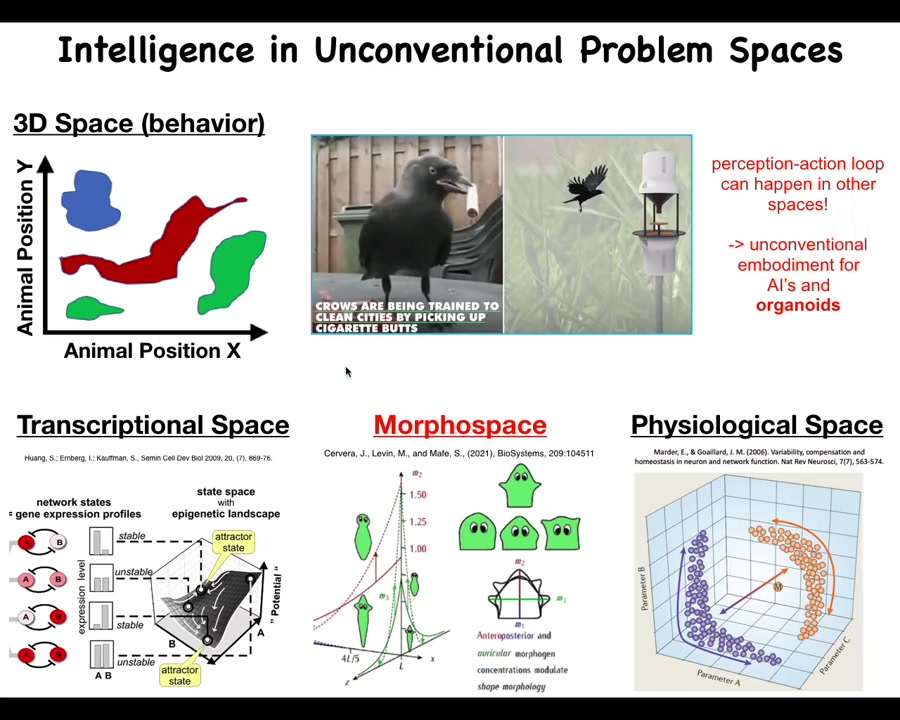

One important aspect is that Intelligence, as many people study it, takes place in the three-dimensional space of behavior, motility. Medium-sized objects moving at medium speeds through the physical world. We're pretty good at recognizing these things as intelligent behaviors. But biology does this in many other spaces. The perception-action loop can happen in many other kinds of problem spaces. The space of transcription, all possible gene expression states, physiological state space and the one we're going to talk about mostly today, which is anatomical amorphous space. Living systems navigate all of these things, not just three-dimensional space. We need to remember that when we talk about embodiment. Lots of people have claimed that neural organoids or brain organoids in culture are not embodied and thus lack certain aspects of cognition. The visual space of motility is not the only space. They are in fact navigating these other spaces.

I think what evolution has been doing is pivoting some of the same tricks in terms of navigating spaces all the way from metabolic, physiological, transcriptional, anatomical, and eventually when nerve and muscle came on the scene, behavioral and then linguistic and who knows what else.

Slide 8/48 · 10m:40s

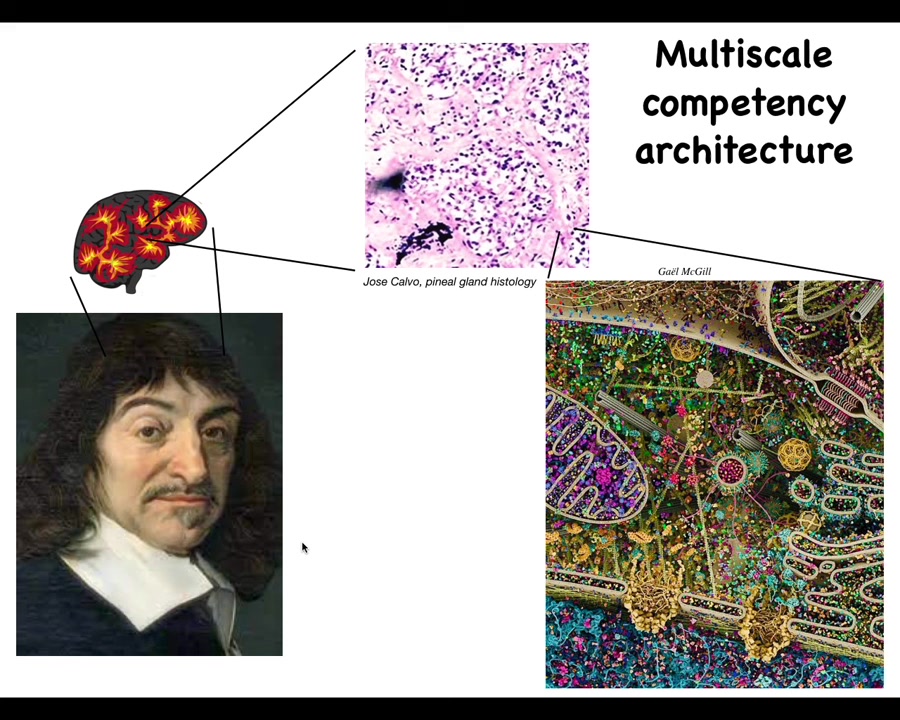

But all of these spaces are ones that biology navigates using some of the same strategies, and the interesting thing about how it does it is that it's a very deep, multi-scale competency architecture. Nothing is centralized. Inside the brain, there's the pineal gland that Descartes really liked because it's a unitary organ. But inside of that, if he had good microscopy, he would have seen that there isn't one of anything. It's made of cells. And inside each of those cells is all of this stuff.

Slide 9/48 · 11m:07s

We are all, not just the bees and the ant colonies and the termites, all of us are a collective intelligence. We are all made of parts. This is the thing we're made of. This is an organism called the lacrimaria. It's a single cell. There's no brain. There's no nervous system. You can see that it's got significant competency in its own very small cognitive light cone. The thing about the material that we're made of is that it's not just nested scales of organization. It's not just complexity. The material has agendas and competencies at every level.

Slide 10/48 · 11m:46s

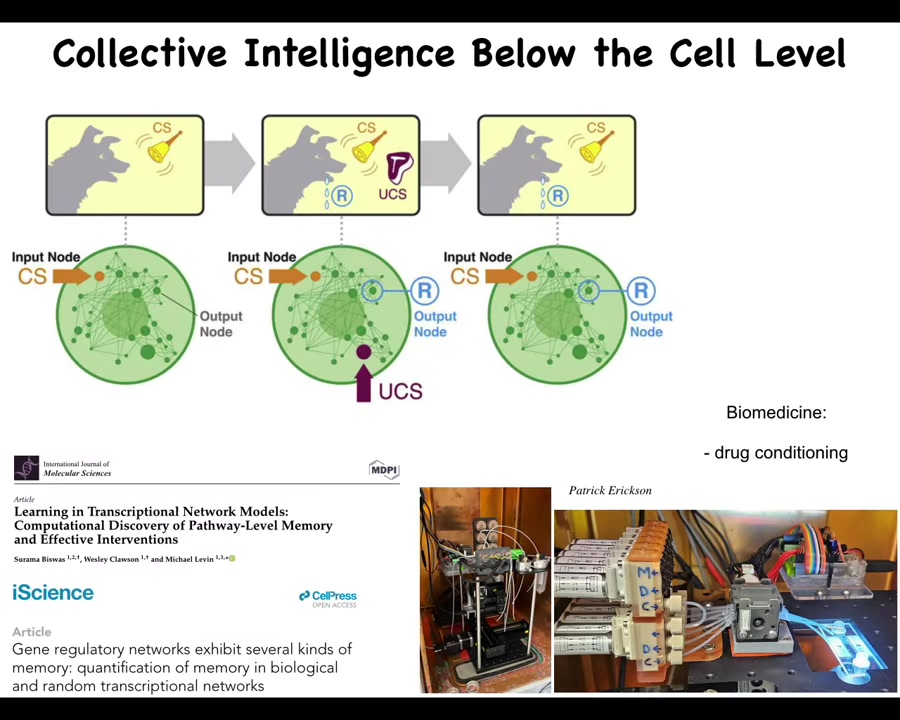

For example, even this little guy is made of molecular networks, and it turns out that molecular networks can exhibit six different kinds of learning on their own. You don't need the cell or the nucleus. Just the gene regulatory networks themselves can do learning, including Pavlovian conditioning. We're in the process of developing apparatus that actually exploits that to train cells and do drug conditioning and other things that are interesting for biomedicine. But even below the cellular level, you already have capacity for learning and decision making and so on.

What we have here is this architecture that at every level is able to solve different kinds of problems and exert different kinds of competencies to navigate that space.

Slide 11/48 · 12m:25s

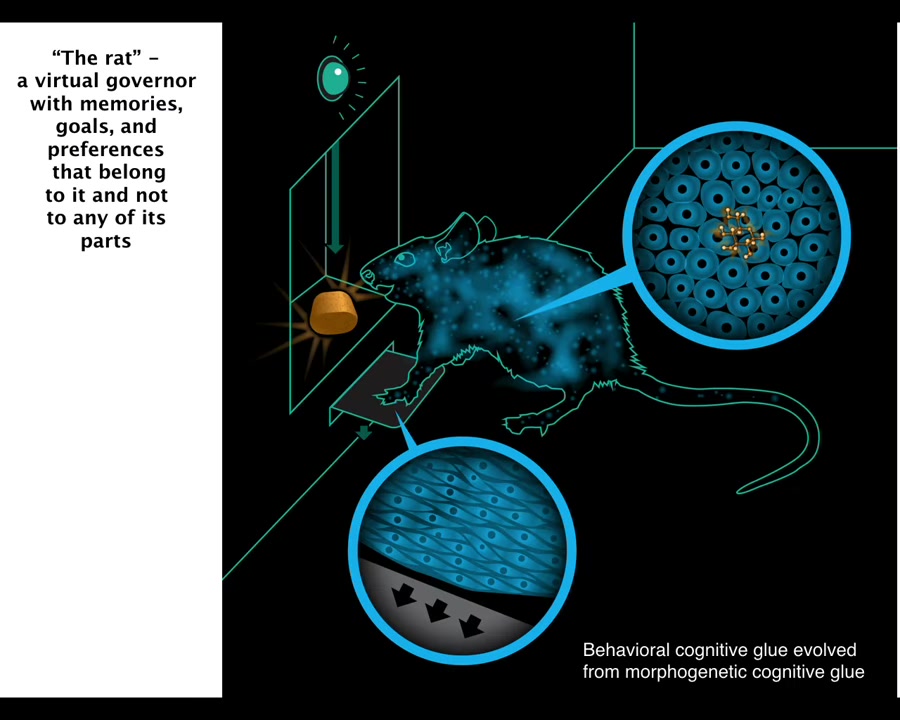

But one thing that's very important about such an architecture is you need something that we call "cognitive glue." You need something that binds these things together towards the emergence of a larger scale system that has goals and preferences and memories that don't belong to any of its parts. When a rat is trained to press the lever and get a reward, the cells at the bottom of the feet interact with the lever, the cells in the gut get the delicious reward. No individual cell has both experiences, but it's this rat, this collective that has the associative memory.

Slide 12/48 · 13m:04s

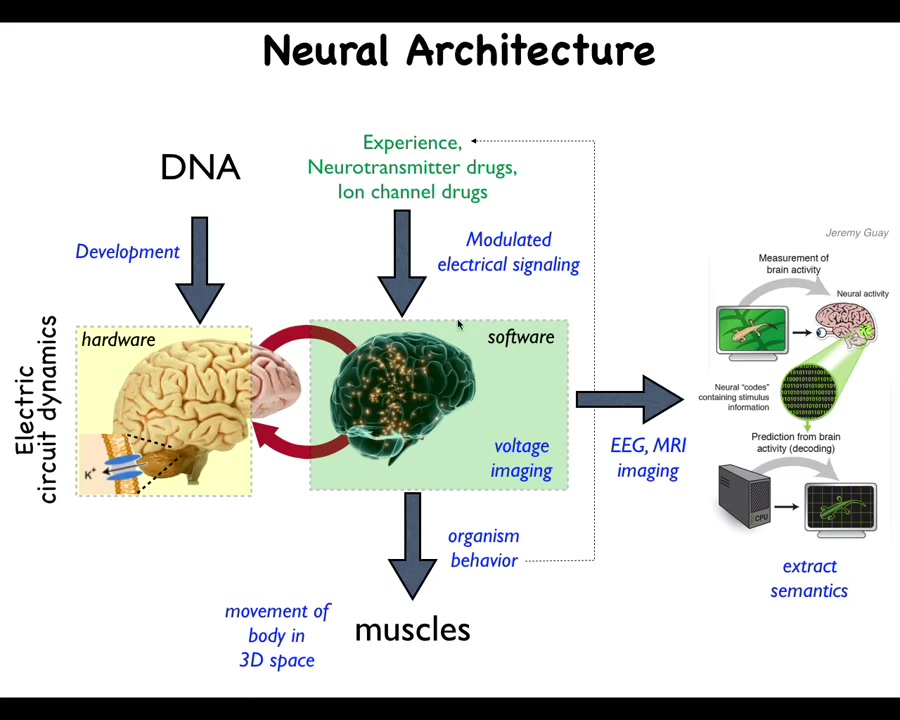

We know what binds these things together in the behavioral space. Here's the hardware: the physical neural networks and the physiological kinds of computations and other things that progress on these networks. What they do is typically issue outputs to your muscles to move you through three-dimensional space. We do processes such as neural decoding to read these physiological states and extract semantic content.

Slide 13/48 · 13m:45s

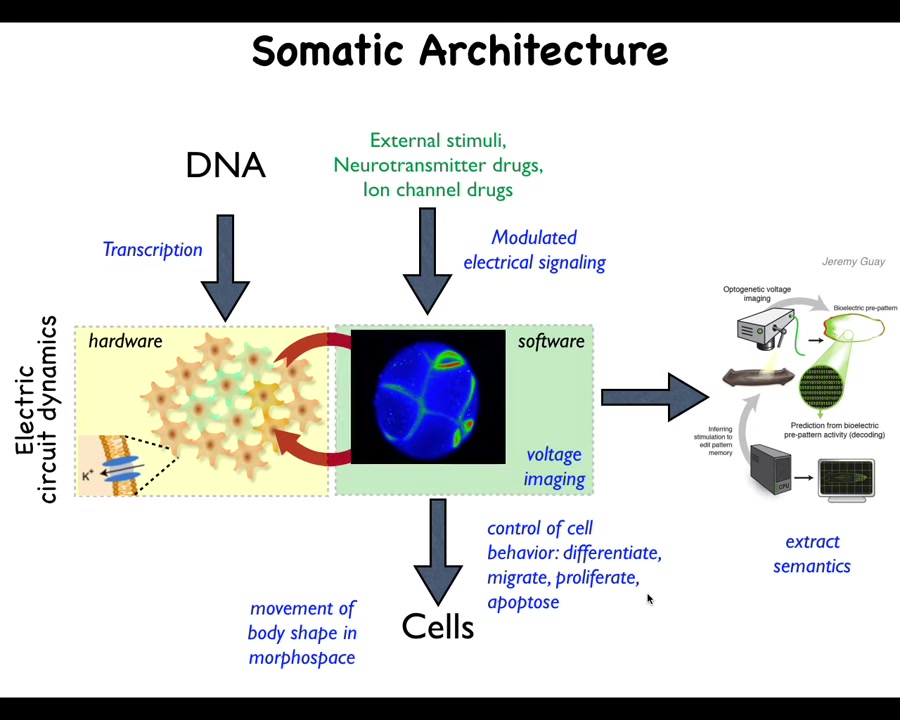

And one thing that's interesting about this is that this is an extremely ancient architecture. This long predates the evolution of neurons. This idea that cells make electrical networks that then have a very particular kind of computational dynamics that runs on them. What was it doing before? What did these networks think about before they were thinking about moving a body through three-dimensional space? They were thinking about moving the configuration of the body through anatomical morphospace. These electrical networks were issuing commands to all cells, not just muscles, but all cells, to move the configuration of the body through the space of possible anatomical configurations. And what we're doing in our lab is developing a very parallel kind of effort to neural decoding to try to extract the semantics from these non-neural electrophysiological events to understand how the developmental decision-making happens.

Slide 14/48 · 14m:43s

What we'll do is we'll talk about some examples of what happens during morphogenesis as a model of collective intelligence. It's carried out by groups of cells, and I'm going to make the claim that it not only exhibits a kind of collective intelligence, but also that much like in the brain, what holds it together and allows it to do things that the individual parts don't do is electrical networking and the information processing that it does.

When I say intelligence, I mean William James's definition. William James said, "intelligence is the ability to reach the same ends by different means." It's a very cybernetic definition. It doesn't say anything about brains or scale or the problem space that you're working in. The ability that you have some degree of competency to reach a goal in your problem space, even when things change.

Let's take a look at what development does. Development is a process that can go from starting conditions such as this egg to a species-specific target morphology like this. We encounter something very interesting, which is that the process is incredibly reliable. Most of the time, this goes off without a hitch. It's an amazing process that does this reliably. It does occasionally make mistakes.

We encounter this notion because chemistry doesn't make mistakes. Chemistry just does what it does. Developmental biology and cognitive systems can make mistakes. They can make mistakes when they take actions that block them from the goal that they're trying to reach.

The reliability or the emergent complexity that happens here—these are not why I'm calling it intelligence. A lot of people have this picture that this is a rote mechanical process. It's just the workings out of chemical rules, and then it's an open loop emergent process. Eventually, you get complexity. That is not what it is. I'm going to show you some examples which explain why I think this is a problem-solving process. It's not just the complexity, and it's not just the reliability.

Slide 15/48 · 16m:55s

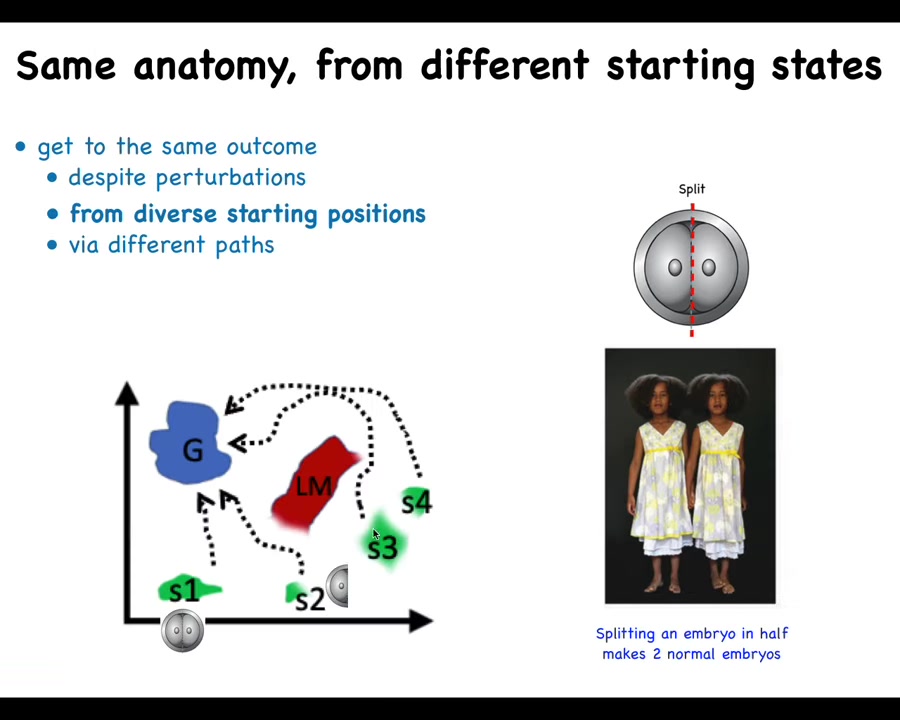

The first thing we know is that if we chop some of these early embryos into pieces, including human, what you get is not half bodies. You get monozygotic twins and triplets and so on. The system very rapidly realizes that half of it is missing and it restores the rest. And so if we boil down all of anatomical space into just two axes, you see that it's able to start in different starting positions and get to the ensemble of goal states that represents a normal human morphology, and it can avoid all kinds of local maxima and so on.

Slide 16/48 · 17m:34s

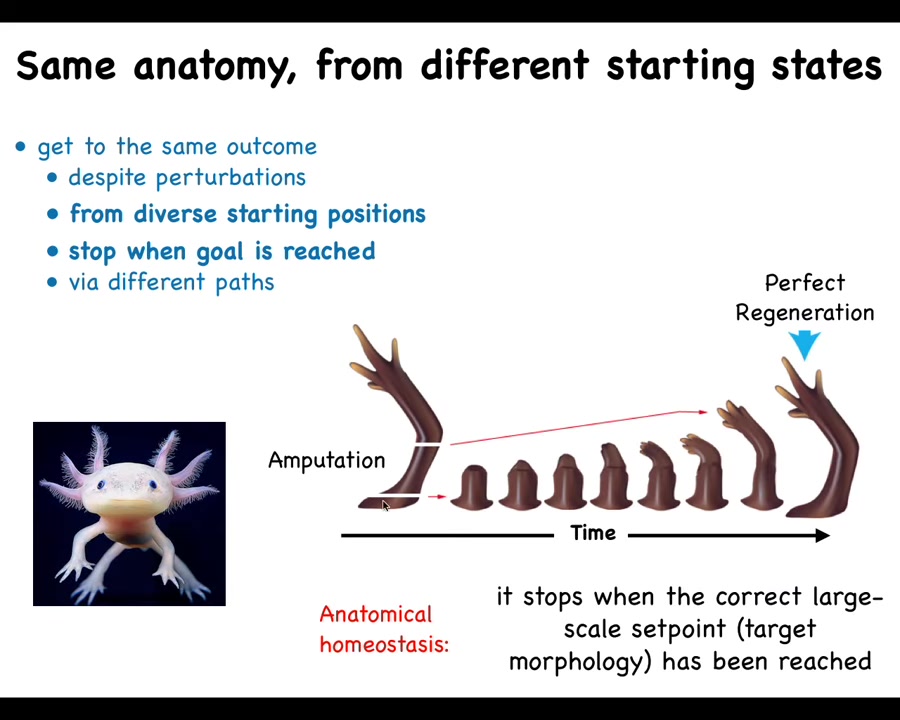

What it can also do, and this is a process known as regeneration, is that some animals, like this axolotl, can regenerate body parts. They can regenerate their limbs, their eyes, their jaws, their ovaries, lots of different organs. When this limb is amputated at any particular region, the cells will grow exactly what they need, and then they stop. That's the most amazing thing about regeneration: it knows when to stop. When does it stop? When the correct salamander limb has been completed.

This is a kind of anatomical homeostasis. You can think of it as a means-ends analysis: when there's a delta here, it will try to reduce that error as much as it can, and then it stops. There are also some amazing examples of the fact that this happens often via different paths. It doesn't always recapitulate the same path that it used to grow during development, but it ends up in the same place.

What we can see here is that it's not simply a feed-forward emergent process. It's actually a closed-loop error minimization scheme.

Slide 17/48 · 18m:41s

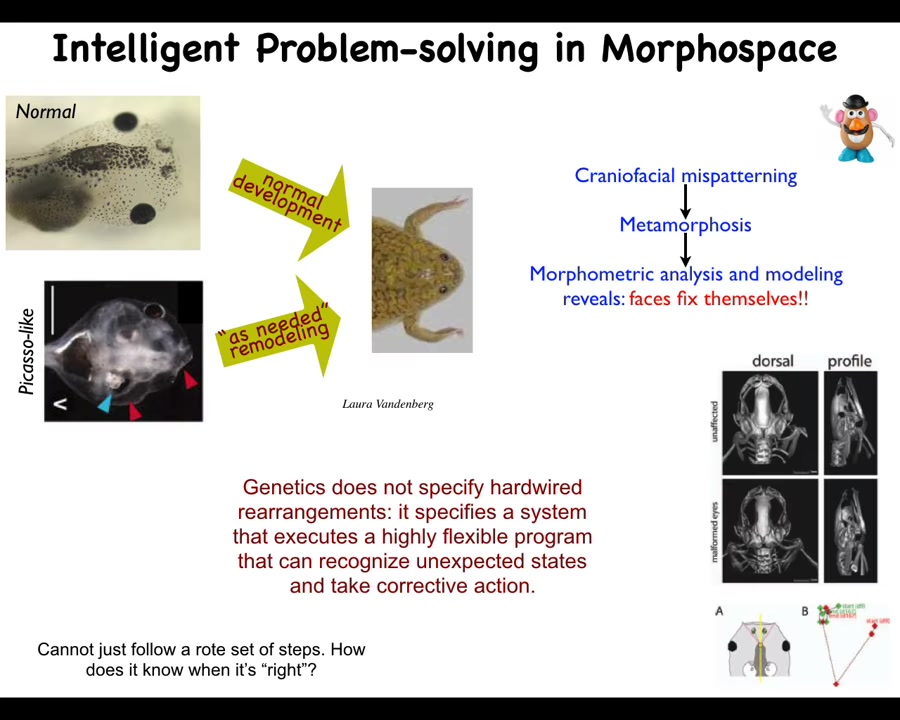

For example, you can see that here. This is something we discovered a few years ago: when these tadpoles—here are the eyes, the brain, the nostrils, the mouth—when these tadpoles need to become frogs, all of these organs have to rearrange themselves in order to become a normal frog. It turns out that, counter to the initial expectation that this is hardwired and you just move the organs the right amount in the right direction and you get your frog, we made these Picasso tadpoles where everything is scrambled. So the eyes are on top of the head, the mouth is off to the side. These guys become quite normal frogs because all of the organs will move in novel paths to get to where they need to go until you get a normal frog and then they stop. Sometimes they go too far and have to double back.

What the genetics gives us here is not some kind of set of hardwired rearrangements. It specifies a system that executes a very flexible program of moving things around until they get to the correct place. One obvious question is how does it know what's correct? Where is the encoding of the set point for this homeostatic process? Where are they going, all of these cells, in their journey in anatomical morphospace?

Slide 18/48 · 19m:53s

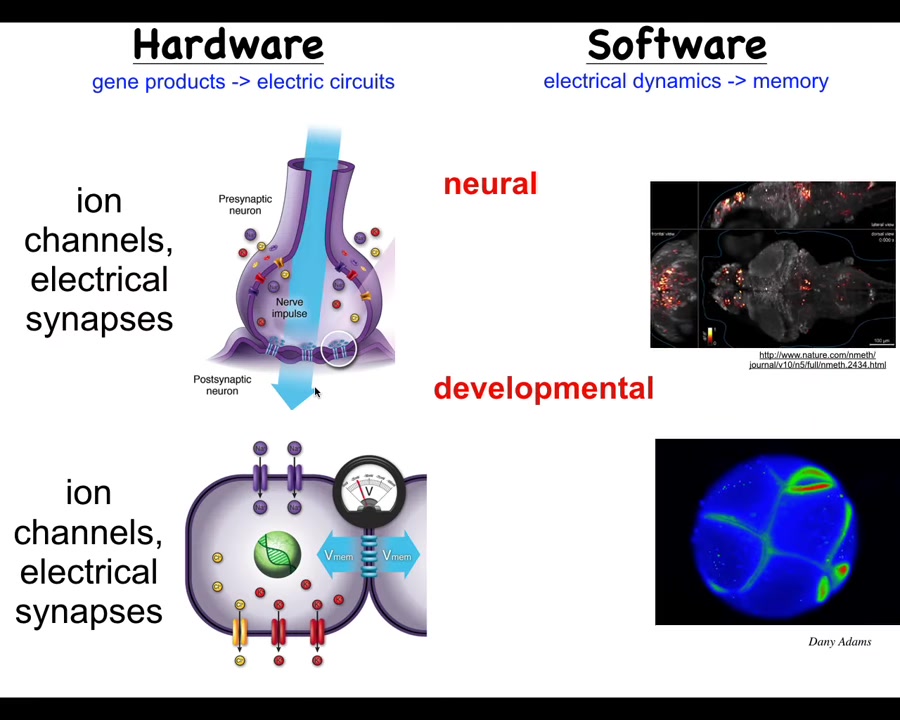

What we've been studying is the idea that, very much the way that nervous systems can encode specific goal states as memories, it turns out that something like this happens in all of your body tissues. These ion channels, these electrical synapses and the neurotransmitters that regulate some of the stuff that happens in neurons actually operate in every cell in your body. Every cell of your body has ion channels. Most of them have these gap junctions with their neighbors. Evolution discovered, back around the time of bacterial biofilms, that these electrical networks are an amazingly effective way of storing information and integrating it across space and time.

Just as neuroscientists study the meaning of the physiological signals in the brain, we do the same thing. This is an early frog embryo.

The molecular mechanisms that neurons use are in fact very ancient. They're conserved all the way to pre-multicellularity. One of the things they have that's different is speed. Here we're talking millisecond kinds of events, and here minutes or hours.

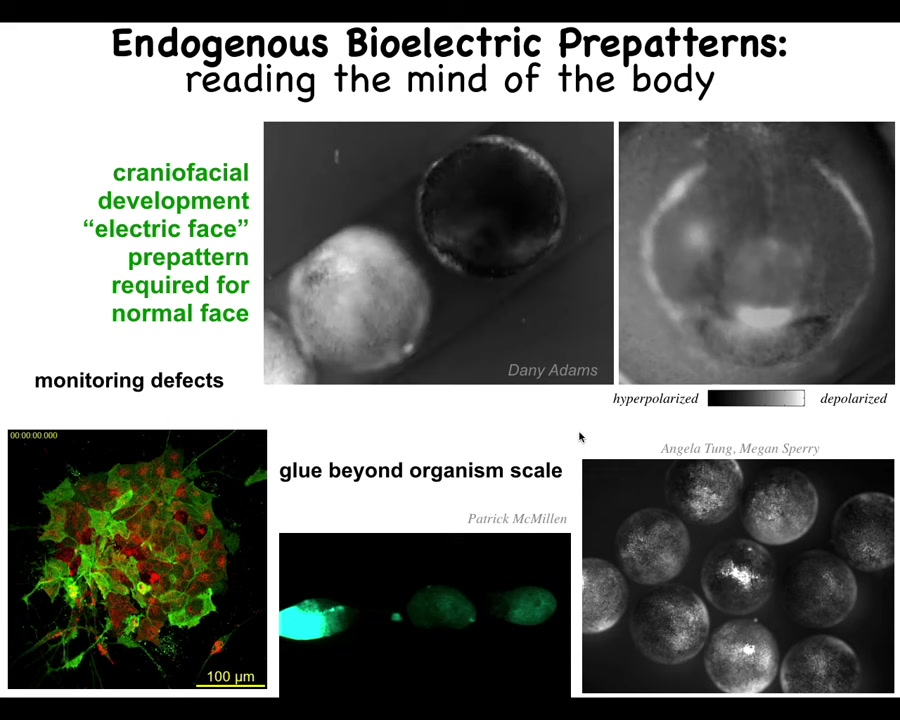

Slide 19/48 · 21m:03s

We've developed some tools to read the electrical state of non-neural cells. You're seeing here some cells explanted in culture. Here's a frog embryo. All of this is, in this case, using a voltage-sensitive fluorescent dye. We also have genetically encoded reporters, such as neuroscientists use in optogenetic studies.

We do a lot of simulation, all the way down to the molecular networks that express the different channels, and the collective behavior of the bioelectric gradients. We try to understand how they do pattern completion and what the attractors in these spaces are. We have these models and analyze them in these ways.

Slide 20/48 · 21m:46s

I want to show you a couple of examples of what non-neural bioelectricity actually looks like. This is a time-lapse movie of an early frog embryo putting its face together, and the grayscale levels indicate bioelectric state. What you can see here is that prior to the formation of the craniofacial structures, prior to the necessary genes turning on and off, this tissue has a layout of what it's going to build in the future. Here's where the animal's right eye is going to be, here's where the mouth is going to be, here are the placodes. As I'm going to show you in a minute, this pattern is instructive. It actually tells the cells where to put the different structures. We are reading out from this tissue the plan that it has for building it. It's literally a pre-encoded set point.

This is not just the output of a cellular automaton or something that just emerges over time. This is a pre-existing map of what the system is trying to reach. It will try to reach this state, even if you try to block it, as we talked about.

This is a different kind of imaging. You can see there are a few neurons here, but everything else, all these other cells, are non-neural cells, and there are multiple scales, both spatially and temporally, by which these different electrical systems interact. This bioelectricity isn't just the cognitive glue that binds individual cells towards common purpose within an embryo. It actually operates across groups of embryos. You can go beyond the organism scale. If I poke this animal, within about 30 seconds, these two find out about it. There is water in between. It propagates across space.

There's a signal that involves calcium, ATP, and some other things, and you can see waves—these injury waves propagating across groups of animals. Groups of embryos are much better able to solve various teratogenic challenges than individuals. Even there, there's a new level of collective intelligence where they can solve problems as a group better than they can as individuals.

Slide 21/48 · 23m:52s

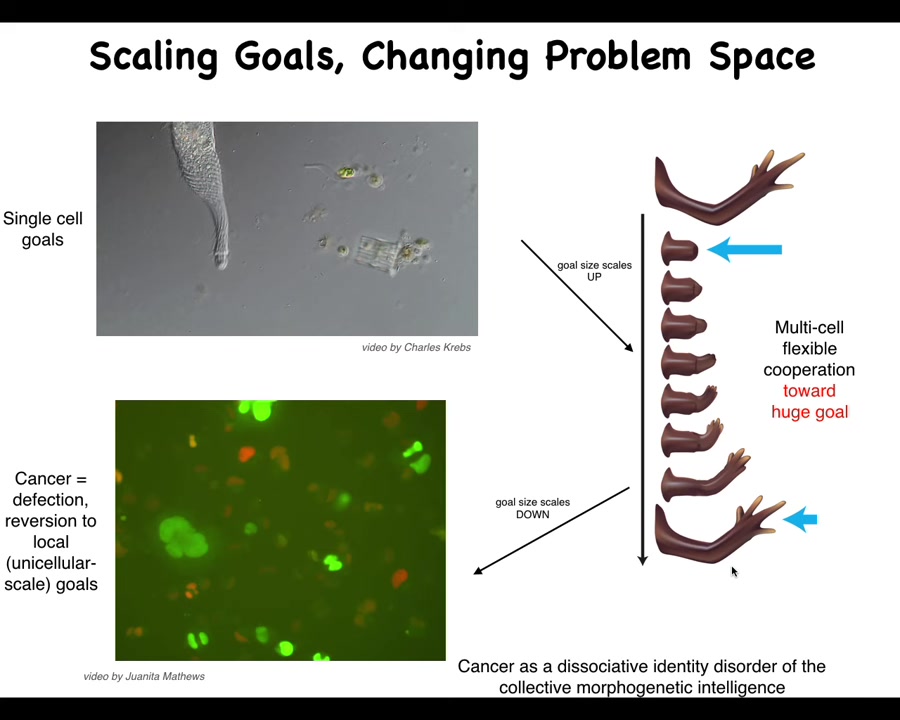

One of the ways that this collectivity arises is through the scaling of the set points that these systems can manage. You can think about the size of the largest goal that they can maintain, which I think defines their cognitive lycone.

Individual cells have tiny goals maintaining physiological and metabolic states on this tiny scale. What evolution and development does is wire them together with electrochemical networks that maintain huge goals like building a limb here. We know this because if you perturb them, they will come back. They will try to reach this despite different perturbations.

No individual cell knows what a finger is or how many fingers you're supposed to have or anything like that. The collective absolutely knows. We know that experimentally. It will try to come back to this location. If you do this five or six times, it eventually gives up. It has the ability to detect. It has this metacognitive thing where it will just stop trying. For the first attempts, it will do a very nice job of rebuilding.

That ability to join into larger networks that can store and remember larger goal states has a failure mode, and that failure mode is cancer. What can happen is that when individual cells disconnect from that network, they can no longer remember this gigantic goal state they were working on. They basically roll back to their ancient unicellular past. This is human glioblastoma. We can study this reversion to cancer as a kind of dissociative identity disorder of the collective morphogenetic intelligence. It literally fragments into pieces with very tiny goals.

Slide 22/48 · 25m:35s

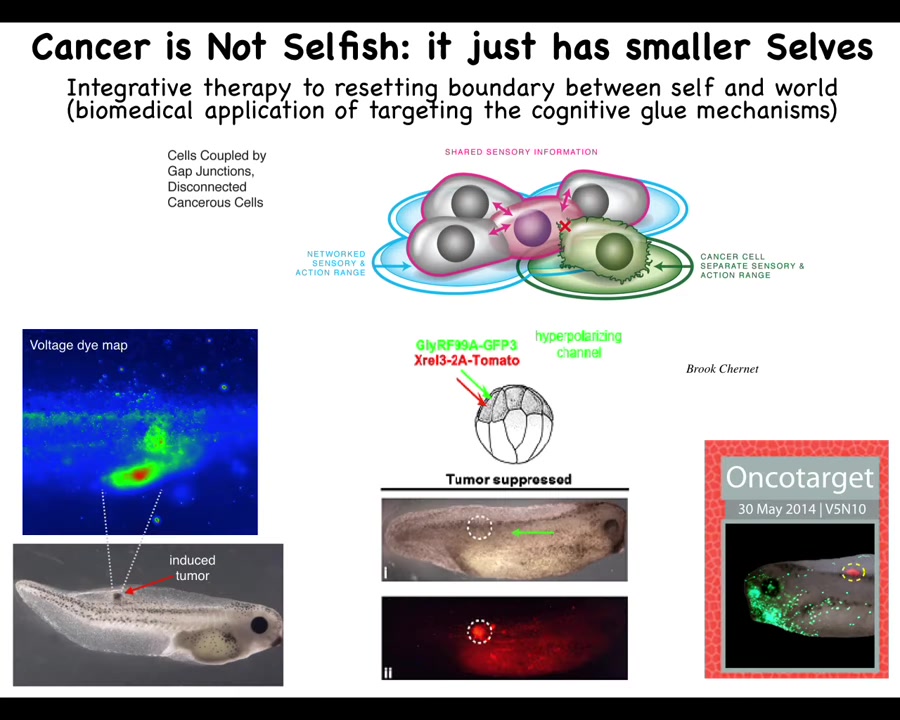

And once you start thinking about this as cancer not being more selfish, the way that it's sometimes modeled in the game theory models, it just has smaller selves. The boundary between self and world has shrunk for each of these cells. That leads directly to a kind of therapeutics. You can imagine targeting that mechanism and actually doing a kind of forced integration.

Here's a tadpole that's been injected with a human oncogene. Already, you can see immediately the voltage is off. These cells depolarized; they're going to start crawling away and metastasizing. As far as they're concerned, the rest of the body is just environment. The border between self and world has really shrunk to the single cell level, and they don't care about the rest of the body anymore. They're just maintaining their own tiny little goals.

But what happens is that if along with this human oncogene, you inject a specific ion channel RNA, which forces the cells to acquire an electric state that keeps them in good connection with the rest, then here you will see this is the same animal. There is no tumor. The oncoprotein is blazingly expressed. It's labeled with red fluorescence. In fact, it's all over the place, but there's no tumor because the genetics isn't what drives. What drives is the decision-making of the collective. In this case, these cells have been reattached and forced to remain part of this electrical network, and they go on building nice skin and muscle and everything else, despite the fact that their genetics have these really nasty oncogenes.

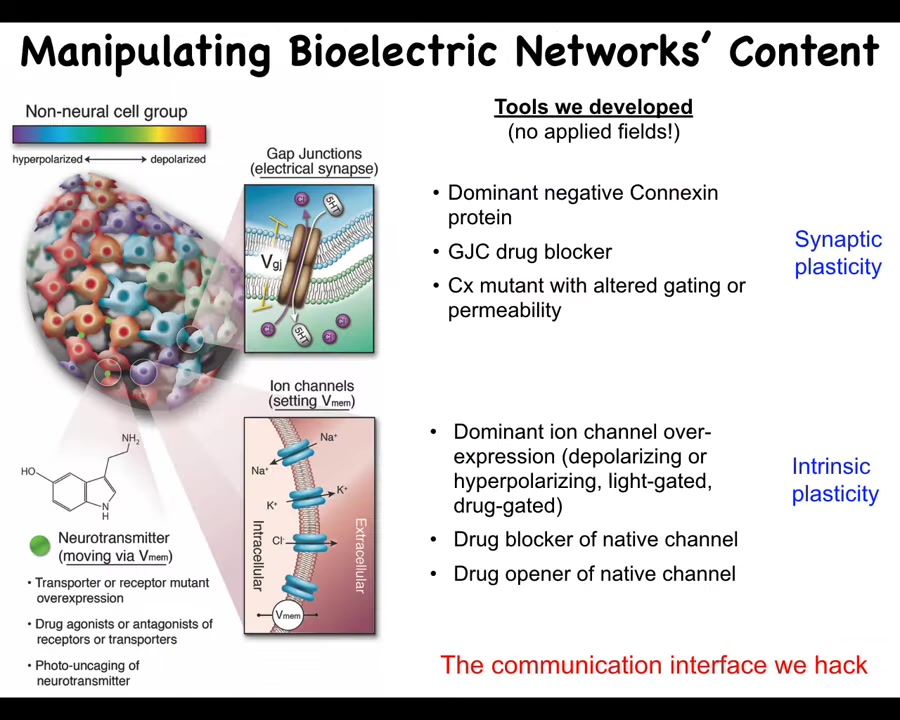

OK, now how do we do this? What are the techniques by which we can read and write new information into the electrical networks of these cells.

Slide 23/48 · 27m:20s

We do not use applied fields, magnets, waves, frequencies, or electromagnetic radiation. We take everything from neuroscience. We do exactly what neuroscientists do, which is we can change the topology of the network by targeting these electrical synapses. We can alter the synaptic plasticity across these cells. We can target the actual electrical state of these cells by modifying these channels. You can modify them genetically. You can use ion channel–targeting drugs. We use optogenetics and light to turn these things on and off.

What we do is hack the communication interface that cells normally use to control each other's behavior. The only reason these things work is because that is what the cell collective is already doing. Whereas before we were trying to read the mind of this network, now we're incepting new memories and new behavior patterns in it, just like people try to do in the brain. So what happens when you try to do this? What can you actually do with this?

Slide 24/48 · 28m:31s

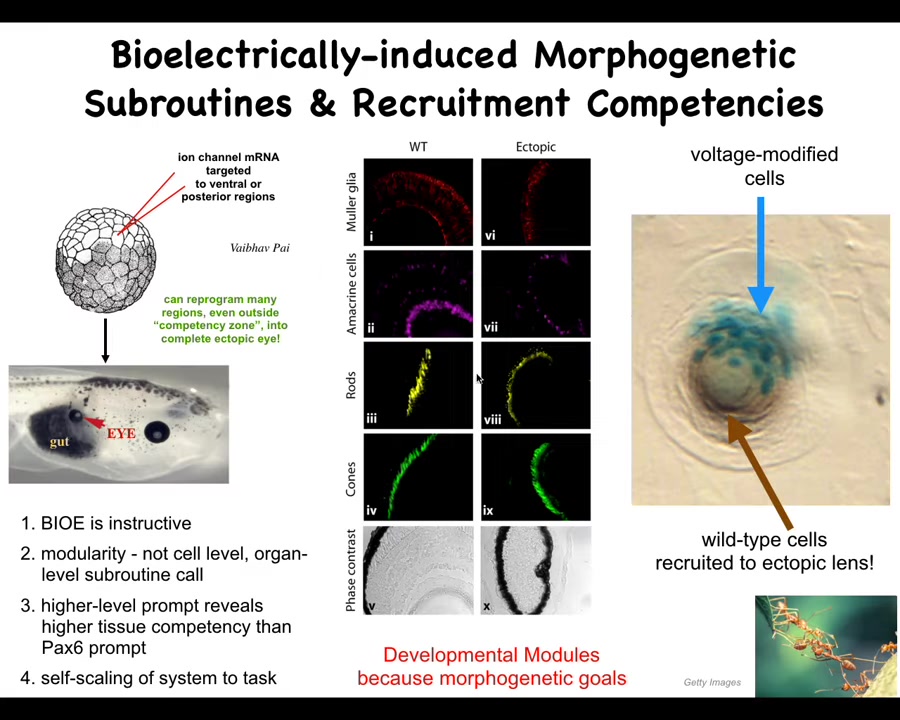

So this is one of my favorite examples.

This is an early frog embryo. And if you remember that electric phase pattern that I showed, there was one particular little eye spot that's where the eye's going to come out. We wondered what would happen if we recapitulated that eye spot somewhere else. If we inject some RNA encoding particular kinds of potassium channels that will set the cell voltage to roughly that spot, and we hit cells that are normally nowhere near the head, such as these gut cells, it turns out that they will make an eye. Inside the eye is lens, retina, exactly as you would expect.

Now, that teaches us a few things. First, the bioelectric pattern is instructive. This is not just about making defects. It's about telling groups of cells what organs to build. It's actually functionally instructive. It's extremely modular. We didn't tell these cells how to build an eye. We have no idea how to build an eye. And we certainly aren't able to manipulate all the different stem cells and the different spatial relationships between them and all the genes that have to be turned on and off. We provided a very low information content, high level subroutine call, which says, build an eye here. And that is what the cells did. We're now in the process of discovering more of these signals that cause specific large-scale changes.

Interestingly enough, the developmental biology textbook said that only the tissue up here, only the anterior neuroectoderm, was competent to build an eye. And that's true if you use the so-called master eye gene called PAX6, which is normally sufficient for making ectopic eyes. PAX6 doesn't work anywhere behind this location. But the bioelectric prompt works anywhere in the body. That reminds us that when we see limitations of competency on some particular system, that may well be a limitation on our competency to provide the right prompts. That may not be a competency of the system itself.

This is a section of a lens sitting out in the flank of a tadpole somewhere. If you only inject a few cells—these blue cells have been injected—there's not enough of them to make a proper eye, but they can tell. What they do is recruit a bunch of their neighbors here. These are not blue. These are cells we never touched. We told these cells, "make an eye." They then recruited a bunch of their neighbors and said, you now have to participate with us and make this eye. All of this works—this self-scaling.

There are other collective intelligences that scale. Ants and termites will recruit their nestmates to move large objects. All of these competencies, the ability to use very simple top-down controls to rely on the self-scaling and the competency of organogenesis, are specifically because all of these systems are already primed to accomplish specific tasks when given specific signals. They do not need to be micromanaged.

Slide 25/48 · 31m:25s

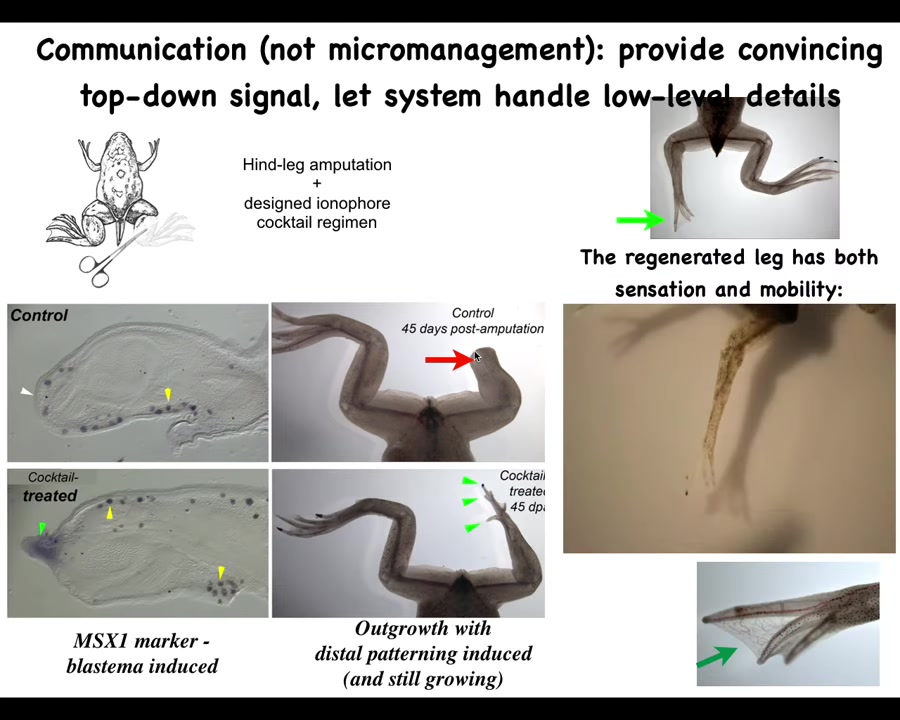

Here's another example, which is what we're doing for regeneration. Frogs, unlike salamanders, do not regenerate their legs in these adult stages. We wanted to know what kind of signal could we give them to allow them to do this.

Slide 26/48 · 31m:41s

We made a cocktail of ion channel and other drugs that kickstart a regeneration. Within 45 days, you've got some toes, you've got a toenail, and eventually a pretty good regenerating leg. In the latest experiments, 24 hours of stimulation gives rise to a year and a half of leg growth. During that time, we don't touch it at all.

Slide 27/48 · 32m:07s

That's because, like we're familiar in behavioral science, when you communicate with another person or with an animal, you're providing signals. It is not on you to rearrange all of the synapses in their material to make that information sink in. The system itself does all of that. You are providing high-level signals. The system is primed to take all of that and make the molecular changes needed for them to become memories, to become executed goals.

Exactly the same thing is here.

Slide 28/48 · 32m:36s

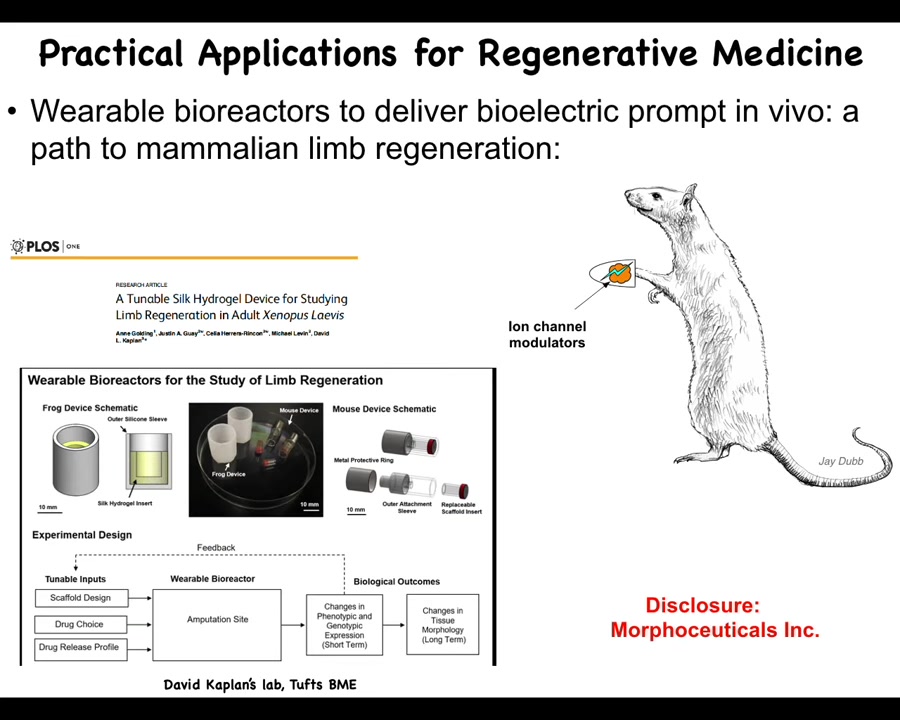

We are currently trying to move. We figured that out in frog. The next step is mammals. We're trying to do this in rodents with wearable bioreactors in collaboration with Dave Kaplan.

I have to do a disclosure because there's a company called Morphozeuticals, Inc., whose job it is to try to figure out how to induce things like limb and other organ regeneration with top-level stimuli, convincing the cells to go to the leg-building route, not the scarring route, in ways that are not micromanaging, not scaffolds, not trying to convert stem cells.

Slide 29/48 · 33m:16s

The next thing I want to show you is something interesting about memory in these systems.

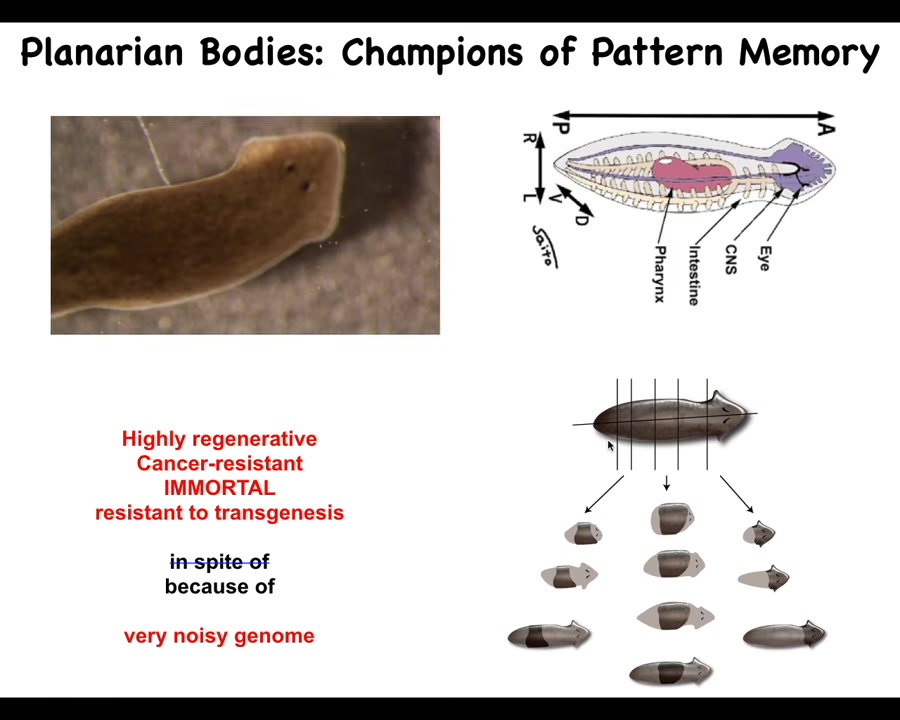

Here are our planaria. These planaria are remarkable. They are incredibly regenerative, with almost 100% fidelity. They are also cancer-resistant. They are immortal; these asexual strains don't seem to age. They're also incredibly resistant to transgenesis.

They have an incredibly noisy genome, and I think that's why they have these amazing properties.

One thing you might ask is, how does each of these pieces — the record is something like 276 pieces — know how many heads it's supposed to have?

Slide 30/48 · 34m:05s

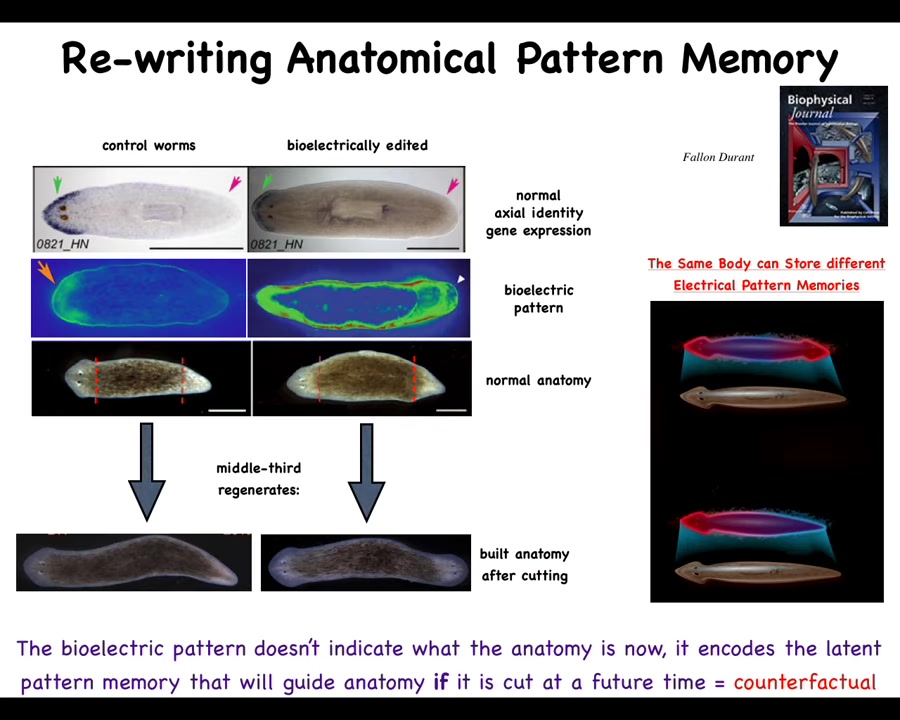

We studied this question and we realized that they have this bioelectrical pattern that we can read out that says one head, one tail. When you cut this, you then have 100% of the time a normal animal with one head, one tail. But what we were able to do using drugs that target this bioelectrical pattern is induce a system that now has this kind of pattern at both ends. When you cut that animal, you end up with an animal with two heads. This is not AI, it's not Photoshop. These are real two-headed worms.

That's because this bioelectrical pattern is the memory, it is the encoded representation of what a planarian is supposed to look like. Once you've changed it, the cells will do whatever that pattern says. Critical to note, this electrical pattern, this memory, is not a readout of this two-headed animal. This is a readout of this perfectly normal one-headed animal where the molecular markers are anterior in the head, not in the tail. The only thing wrong with this animal is that it has a different representation of what it will do if it gets injured in the future.

I think this is the beginning of a very simple version of the kind of time travel that we can do with brains, where we can imagine the scenarios that are not true right now. That's what's happening here. This is a counterfactual memory. This is not true right now. This is two heads. This animal does not have two heads right now. That is what it will do if it gets injured. If not, it stays a latent memory.

So the body of a planarian can store at least two, and I'm sure it's more, but these are the two we've nailed down so far: at least two different representations of what the goal is, where it is going in anatomical amorphospace, are encoded in this electrical network and they're labile.

Slide 31/48 · 35m:50s

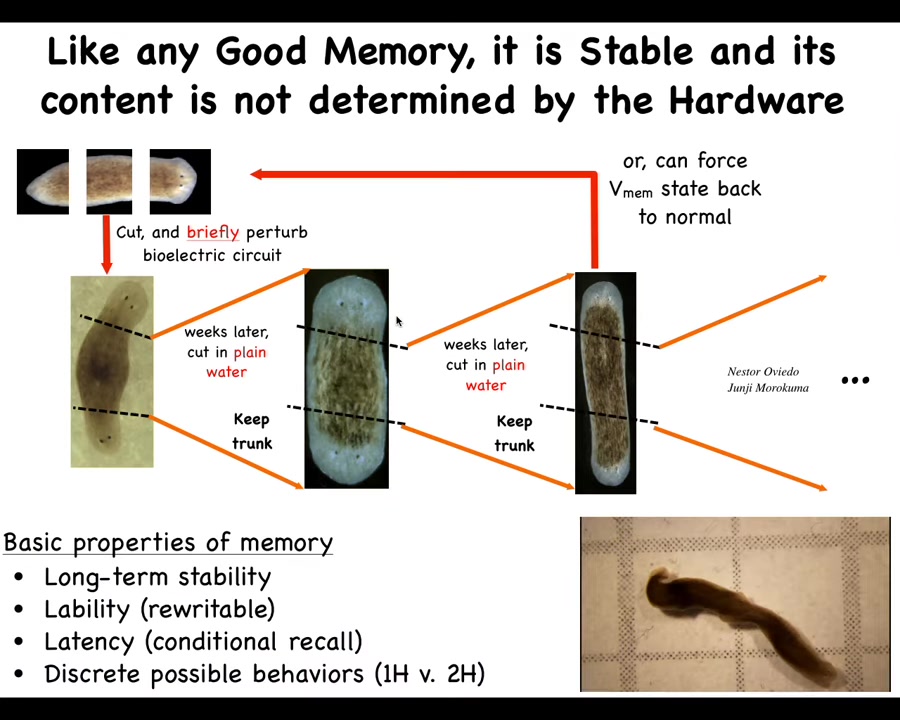

Now, one reason I keep calling it a memory is because if you take these two-headed worms and you chop off the primary head, you get rid of that ectopic secondary head, and you have this middle fragment, it will again give rise to two-headed worms with no more manipulation. It's permanent.

So this system has all the properties of memory. It is long-term stable. It's rewritable. It is not entirely determined by the genetics. So different memories can sit and run on the same hardware.

The question of what determines how many heads a planarian has, is it the genome? It's a subtle question. The genome determines the initial state, which reliably will say one head, but that is not where the information actually sits, and you can rewrite it.

Now you can see these animals in behavior. We can set it back now. We can rewrite that pattern back to one-headed and then these guys will return. There's something else we can do with these. You can make this strain of two-headed worms.

Slide 32/48 · 36m:52s

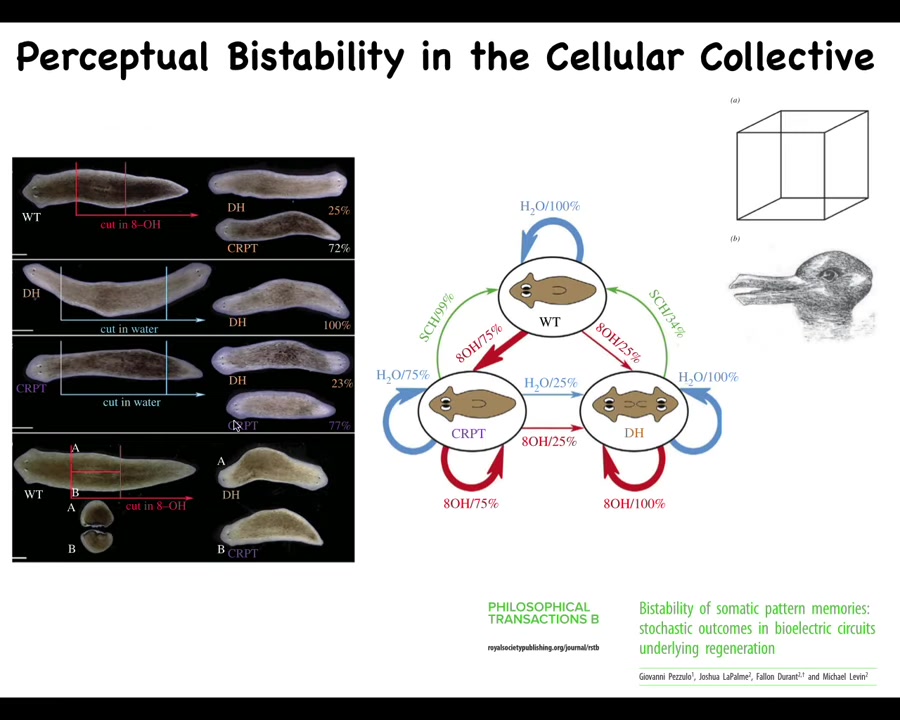

You can make another one, which we call cryptic worms. They're confused in that when you cut fragments — this fragment up here and this fragment down here — some of them will form two heads, some of them will form one. It's a stochastic decision now. What you've done here is destabilize that pattern. With GeoPazulo, we analyzed it as a kind of perceptual bistability. The bioelectric pattern is poised in a way that it can be interpreted in multiple ways, such as Necker cubes and the rabbit–duck illusion, where the system that reads the electrical pattern stochastically. You can make a transition table; it's roughly 3/4 to 1/4 where it will interpret that pattern as either two heads or one.

We've been making models of these kinds of things to go from the bioelectric circuit, which we now understand to some extent, to the system-level behavior to try to understand how it recovers specific patterns when things are missing, and, in fact, how it makes mistakes.

Slide 33/48 · 38m:01s

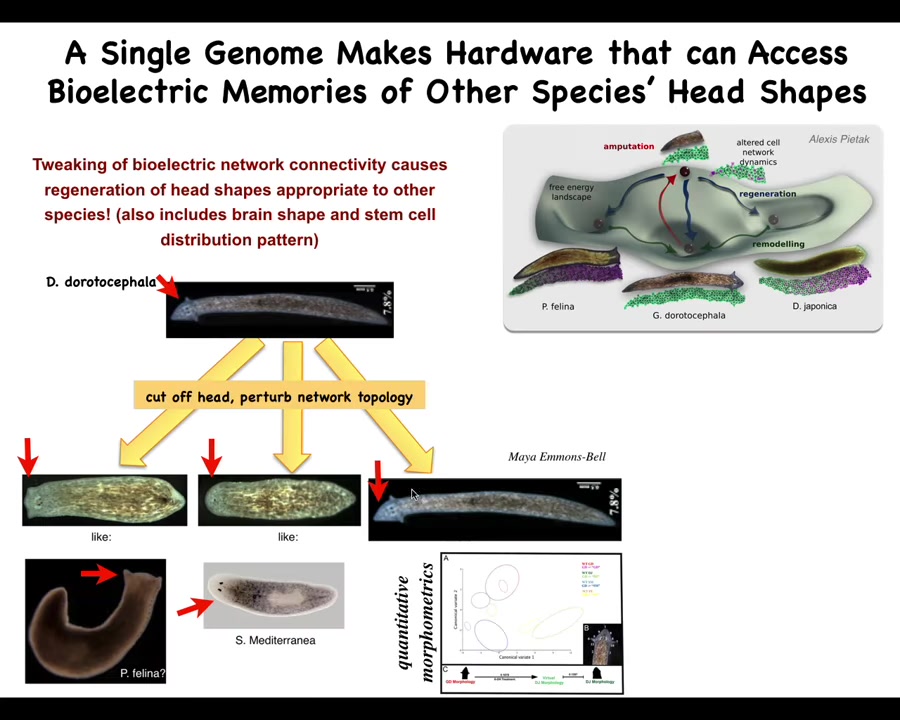

One thing, in keeping with the idea that much like with learning, is that the same hardware can have lots of different memories. What we can do is take a planarian with a nice triangular head, and by perturbing that bioelectrical network during regeneration, we can get them to make flatheads like a P. falina, roundheads like an S. Mediterranean. So no genetic change here.

They're perfectly happy to visit the attractors that normally are occupied by other species of planaria, about 100 to 150 million years of evolutionary distance. But if the pattern memory says that this is the kind of head that you should have, then that's what it builds. Not just the shape of the head, but the shape of the brain and the distribution of stem cells become just like these other species.

Slide 34/48 · 38m:55s

What we've talked about here is morphogenesis as a model of collective intelligence, which solves a number of problems in reaching its goals in the anatomical space. We've shown how we can use some tools and concepts from neuroscience to address this.

We've done things with memory blockers and with hallucinogens and with various anxiolytics and SSRIs, and all of these map very well onto this idea of a system making decisions and navigating that anatomical space. Once you do that, you unlock some biomedical applications that are not readily available from the standard bottom-up view of genetics as a simple mechanism that drives the outcomes. In the last few minutes, I want to talk about some of the implications of all this.

Slide 35/48 · 39m:48s

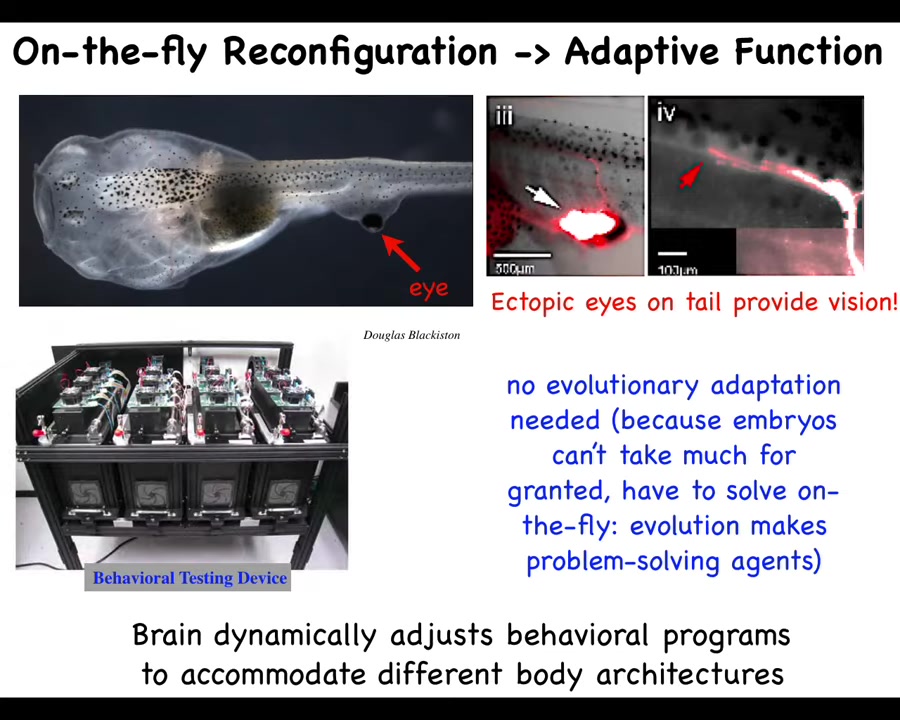

Here's a basic observation. You take this tadpole and what we've done here is, here are the nostrils, the mouth, the gut, the brain. What you'll notice is that we've prevented the eyes from forming in the head where they normally form. But we've made an eye form on their tail. The first thing is that eye precursor cells are perfectly happy to build an eye on the tail. It makes an optic nerve. The optic nerve does not go to the brain. Sometimes it synapses on the spinal cord here, sometimes on the gut, sometimes nowhere at all.

The key thing about these animals is they can see. How do we know? Because we built this automated system that trains them on visual tasks, and it turns out they can see quite well. This is somewhat remarkable. We've made a system with a radically different sensory-motor architecture. The eye doesn't connect to the brain. How is it that it works out-of-the-box? Why don't we need additional rounds of evolutionary adaptation, mutation, selection of different circuits? Why does this work on the fly? I'm going to argue that the reason this works is because fundamentally, all of morphogenesis, even normal morphogenesis, is a problem-solving, in-real-time system that never actually assumed the eyes were going to be there in the first place.

Slide 36/48 · 41m:04s

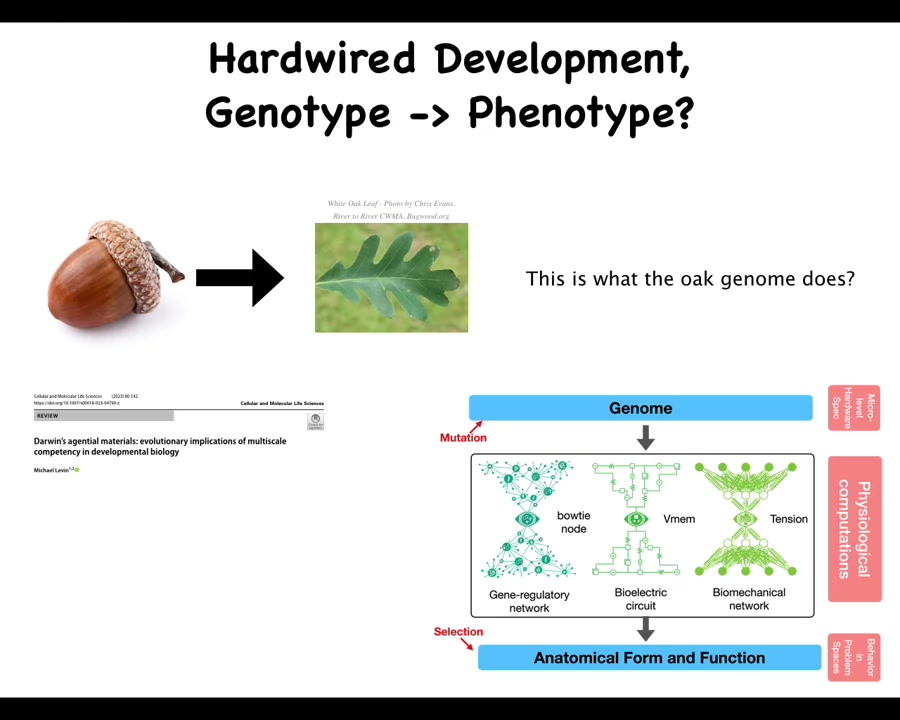

And to give you an idea of what I mean, a few more examples. Because development is so reliable, we're used to thinking that it's a hardwired process, acorns always give rise to oak leaves. This is the shape, and it happens so reliably, so consistently, that we tend to think that this is what the genome actually encodes. It encodes this. The conventional kind of approach is that the genotype encodes the phenotype. What I'm arguing, and all the details are here in this paper, is that there's actually a very important layer in the middle, which is this morphogenetic layer that I've been describing, which has a bunch of problem-solving competencies that make a huge difference to evolution.

The fact that this layer here, from genotype to phenotype, is not just complex; there's not just redundancy and degeneracy and pleiotropy and all of these things. It's not just complexity. It's the fact that the interpretation of the genetic information by these electrical, mechanical, and chemical networks, that is what gives rise to the anatomy. I've shown you this in the case of the two-headed worms that override the standard genetics, the lack of tumor despite the presence of oncogenes, many examples where it is really the competency of this layer that makes an enormous difference. And so, when you think about this map, we would assume that that's all that the oak genome knows how to do is make this thing, except that along comes a bioengineer.

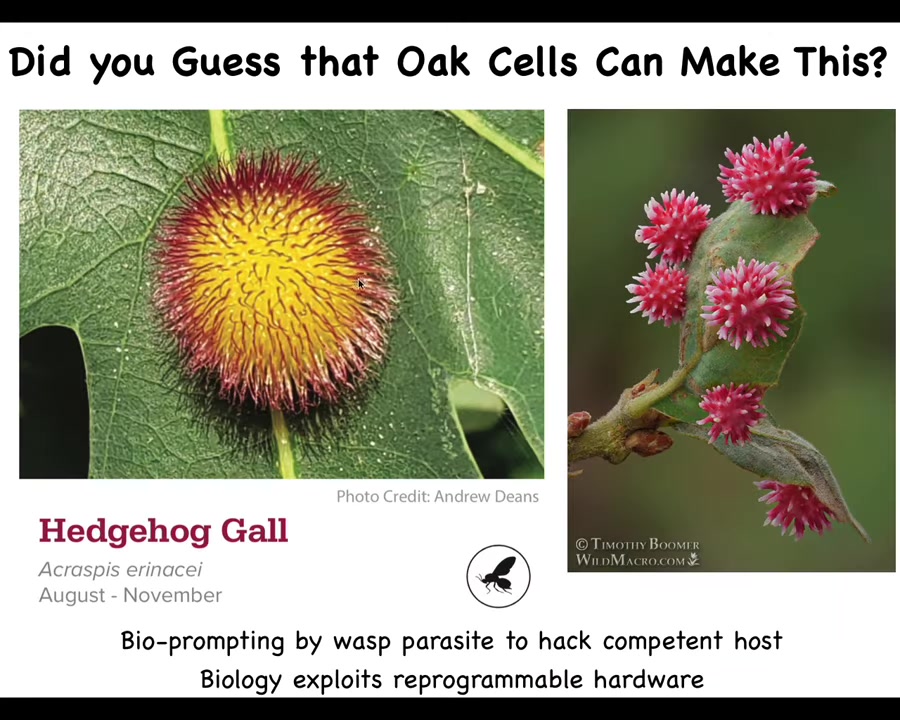

Slide 37/48 · 42m:37s

It's a non-human bioengineer; this is a little wasp parasite, and what the wasp does is provide some chemical prompts to the cells. And then they end up building something like this. These are called galls. You see something like this. We would have absolutely no idea that these cells, which normally make a nice flat green structure of a particular shape and size, they were even capable of doing something like this if we didn't see this organism doing that. We now understand that default behavior is reliable, but the space of possibilities is vast. This wasp is not building this the way that it would build its nest, which is like a 3D printer laying down glue and little pieces of material and meticulously building it by hand. All it did was drop off some signaling molecules and leave. That's because it can rely on the material's competency to interpret those signals and build the thing that it wants to build. It does not need to micromanage this process any more than we need it to micromanage the creation of the eye or the frog leg or anything else.

Slide 38/48 · 43m:46s

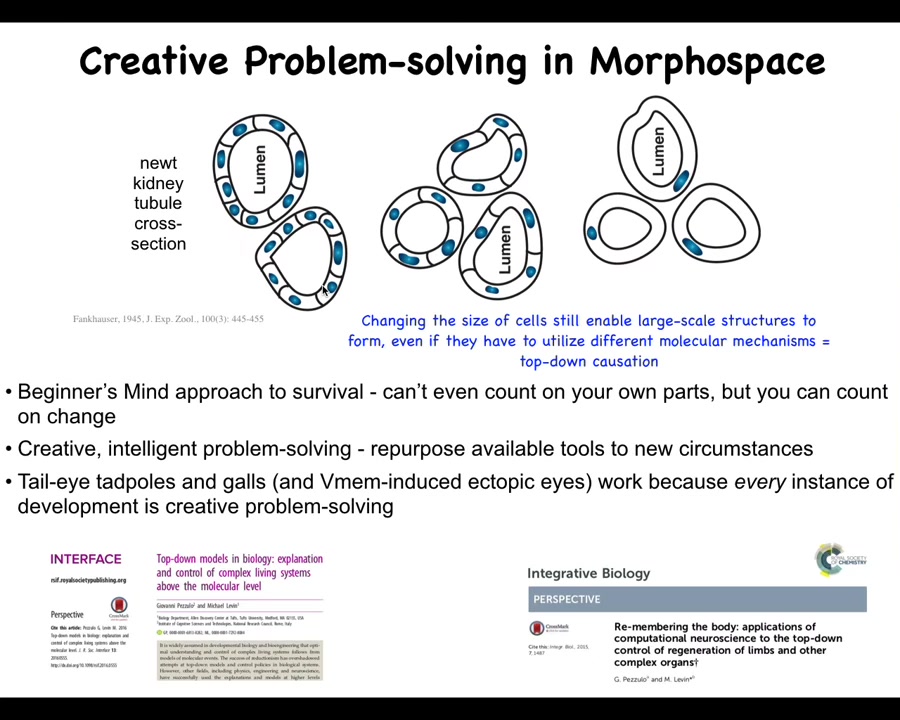

Here I want to show you one of my favorite examples of actual creative problem solving in MorphoSpace. This is a cross-section through the kidney tubule in a newt. There are about 8 to 10 cells that work together to build this structure with an empty lumen in the middle.

One thing you can do with these cells is to produce newts that are polyploid. They have multiple times the amount of chromosomes that they're supposed to have. Instead of 2N newts, you can make 4N, 5N, 6N, and so on. When you do this, something interesting happens. First, embryogenesis works. You still get a newt, which is already interesting. Then you find out that the cells scale to the amount of genetic material, so you get bigger cells. The tubule itself is the same size. How does that work? That's because the cells automatically reduce the number that are used to create this tubule.

That's the second amazing thing: the cells scale the number given their new size. The wildest thing of all is that when you make really gigantic cells this way, one single cell will wrap around itself and leave a space in the middle for this lumen. The reason that's amazing is that this is a different molecular mechanism. This is cell-to-cell communication. This is cytoskeletal bending. What you have here is a kind of top-down control where, in the service of this large-scale anatomical structure, the cells will use different molecular mechanisms. They are using the tools that they have, the genetically specified affordances, in new ways to get their job accomplished.

Think about what this means. If you're a newt coming into this world, not only can you not count on what the outside world is going to be like, but you can't even count on your own parts. You don't know how many copies of your genome you're going to have. You don't know the size or the number of your cells. You need to adapt and use the mechanisms that you have to achieve the path through anatomical amorphous space that you need to take.

What evolution produces is not solutions to specific problems, rather it produces problem-solving agents. The idea is that, at least nowadays, all of life is this problem-solving architecture that doesn't take much for granted. Even under standard embryogenesis, it is problem-solving. It is not assuming from the beginning; for most organisms it's not assuming what's going to happen. It does its best.

This is why tadpoles with eyes on their tails work and why the galls on these oak leaves work and why we can make induced eyes with voltage signals, because all instances of morphogenesis are creative problem-solving. It is the layer between the genetics, the hardware produced by genetics, and the actual outcome, and that middle layer is doing the best it can to do something sensible. All of that is explored in these papers.

Slide 39/48 · 46m:59s

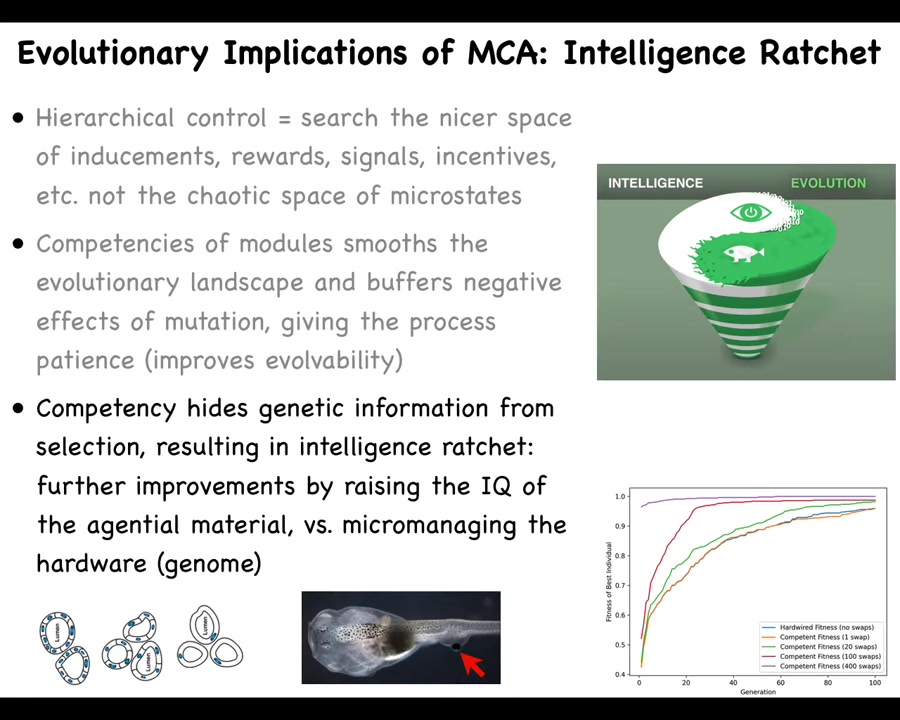

This has really interesting evolutionary implications. In particular, it has an intelligence ratchet that gets intelligence in the material of life going long before there are brains or neurons or anything like that. The layer lying between the genetics and the phenotype is itself a problem-solving system, and that ends up hiding information from selection. Think back to the frog face that was able to rearrange itself to get to the right configuration. When selection encounters an animal with a pretty good face of a frog, it doesn't know whether that's because the initial genetics were great and that's how it started, or whether there was actually some structural problems but the competency took over and fixed it. The ability of the material to meet the same end despite different starting conditions hides that fact from selection.

We've modeled this. We have a couple of papers where we computationally model how evolution works on passive materials, which just do what the genetics say, and this developmental competency where it actually tries to solve the problems of different starting positions. What happens is that when evolution finds it hard to see the genomes directly, all of the work ends up being done on the competency property itself. Not the structural genome, but the competency of the material ends up being really cranked by evolutionary progress. This becomes a positive feedback loop because the more you increase the ability of the material to get to a correct state while the hardware itself is unreliable, the less the selection is able to see the quality of the genome. Progressively it becomes harder and harder to select for the best genomes, but what it can do is select for the most competent individuals.

That's why you get planaria, which are incredibly resistant to all sorts of things: injury, cancer, aging, transgenesis. I think in those animals the spiral went all the way to the right, where a lot of the pressure was taken off of the genome and put into developing an algorithm that can make a proper worm no matter what happens to the genetics. It does that because planaria reproduce by fissioning and then regenerating. Unlike the rest of us, when we get a mutation in a cell in our body, our children don't inherit these somatic mutations. In planaria, that's not true, because they split and then regenerate; any mutation that doesn't kill the cell is propagated into the new generation. They're mixoploid. They're a total mess genetically. All the cells can have different numbers of chromosomes and so on. Biology leans into this fact that the hardware is ultimately unreliable, and a lot of work goes into a creative problem-solving algorithm that gets the job done even when that happens.

Slide 40/48 · 50m:10s

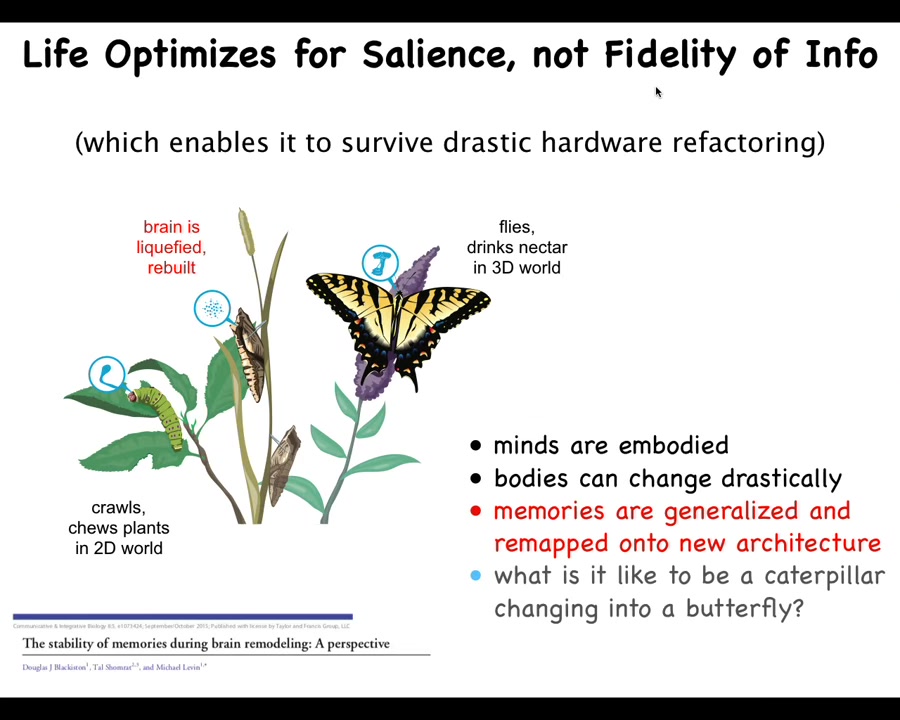

That ends up driving this kind of ratchet where the intelligence just keeps going up in the various spaces and then projected into different kinds of problem space long before we have nerve and muscle. You can see something like this in this example of metamorphosis: what it's doing is because of that creative problem solving that was already there at the very initial stages when you have very simple creatures that are trying to meet specific anatomical, physiological goals.

By the time you get to memories and behavior, the material is really good at having optimization for the salience of the information, not for the fidelity of it. That is, not taking the information from the past too seriously—on an evolutionary scale, this means the genetics of your lineage. On the individual scale, it means whatever materials you've been given; what it tries to do is remap it onto its new situation.

Here's an example of this. You've got these caterpillars, a soft-bodied creature that likes to eat leaves, and you can train it to find the leaves by crawling to a particular location on a particular colored disk. When these caterpillars metamorphose into butterflies, they have to build a completely new brain to now drive a hard-bodied creature that flies. In order to do that, it basically dissolves most of the brain: most of the cells are killed off, all the connections are broken, and then it builds a brand new brain suitable for this lifestyle. What has been shown is that these kinds of trained memories actually persist. It's amazing to think: how is it that memories persist through the basically complete refactoring of the cognitive medium? More importantly, you couldn't even do this if you tried to keep the memories exactly as they were, because the precise memories of the caterpillar are of no use to the butterfly. It doesn't eat the same stuff. It doesn't move the same way. What you have to do is take the deep lessons that the previous animal learned, generalize them, and then remap them onto the new lifestyle—now flying instead of crawling, and nectar instead of leaves.

The idea is that these memories, much like that bottleneck that happens during embryonic development, where past generations give you genetic material but development is a creative process whose job it is to re-inflate that information into a new form and function, the same thing happens to learned information within the lifetime of a single animal.

Slide 41/48 · 52m:55s

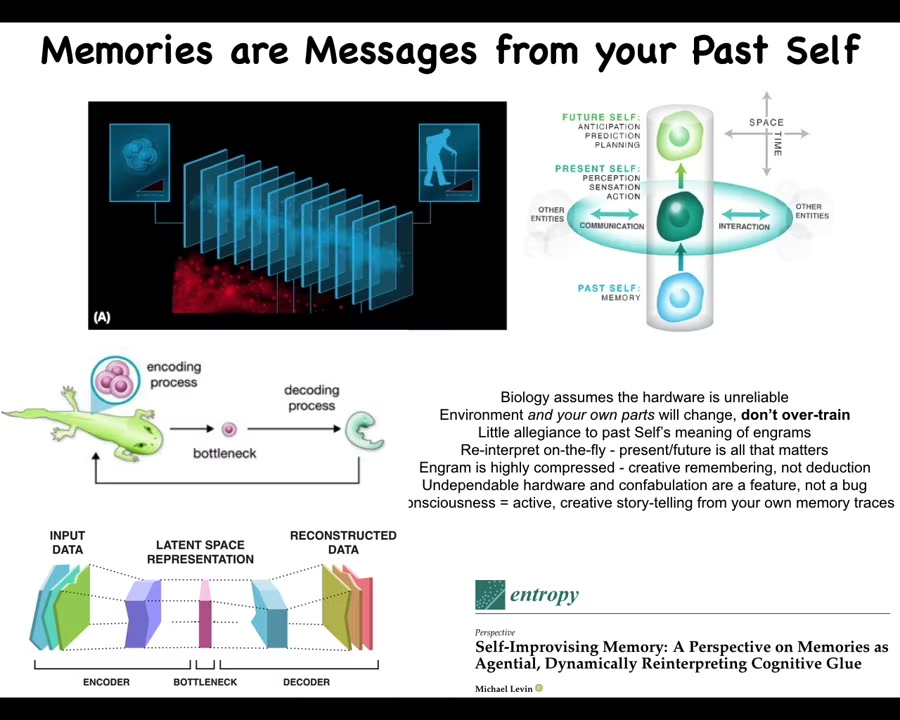

We can start to think about memories, and by memory, I mean more broadly, anything that carries information from past instances of you, so from your past self. Behavioral memories are messages from your past self, and genetic information is memory from the past version of you in your lineage. In all of these cases, the current self, whether that be the cognitive being that is you or the embryo that is trying to assemble itself from the single egg stage, does not have any access to what the past was like. At any given moment, you don't have access to the past. What you have access to are the engrams, the memory traces that learning and past experience have left in your body.

These are generalized and compressed representations of particular instances. Now it's your job. As a cognitive system, we're continuously doing this and refining our story about ourselves and the outside world by interpreting those memories. It has this bottleneck feature. Anybody who does machine learning will recognize this kind of thing immediately, where you have a very thin bottleneck in the middle of something like a variational autoencoder, where what you're doing is some compression and you're throwing away some redundancies back here. Now here you have to re-inflate that information. It is precisely the fact that you have to re-inflate it, whether that be the genetic information of a zygote or whether that be the memory traces in a cognitive being trying to persist through time. It is that creative problem solving on this end that tries to adapt to the current situation, given the information that it has. All of that is described here.

I think biology assumes from the start that the hardware is unreliable, which is very different from how we currently build computational systems, where we have a separation of layers, where you assume the layer below is going to do its job correctly. Biology realizes that environment and even your own parts are guaranteed to change. The one thing that's guaranteed is that there will be mutations and change. We can't overtrain on our evolutionary priors. Much like with cognitive systems, you care less about what your past self was doing with those memories, but you have to reinterpret them on the fly. The present and the need to move into the future are what matter.

Slide 42/48 · 55m:34s

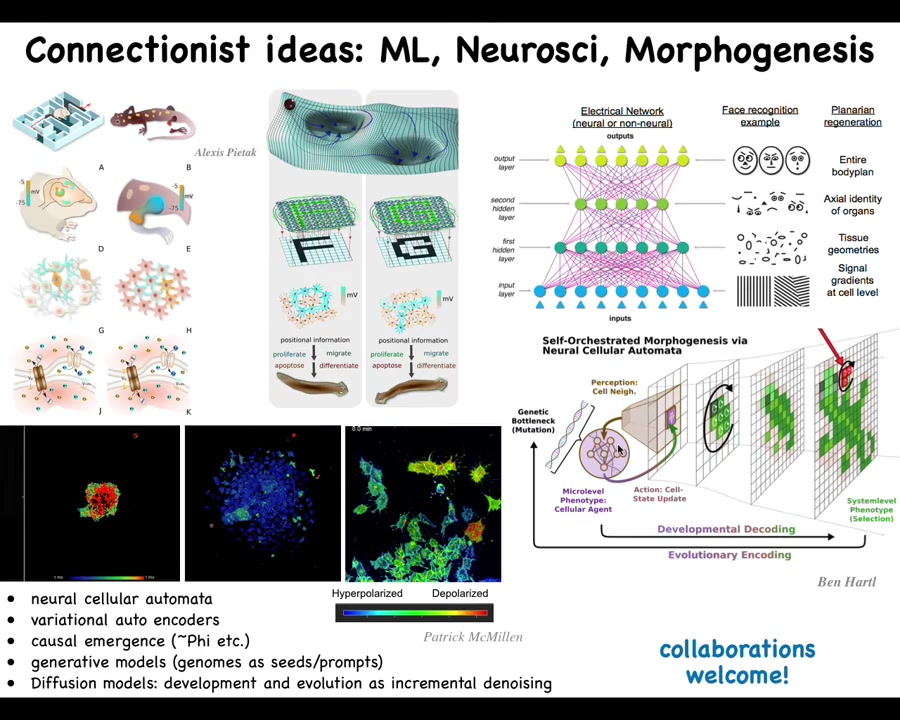

We started by trying to think about a kind of generic connectionist ideas about, for example, the progressive generalization and recognition of layers in neural networks as different components of molecular gradients and then the cells and tissues and body plans.

We now have some very specific ideas that we're testing using the formalisms of neural NCAs, neural cellular automata, autoencoders calculating causal emergence in cells that are not neural.

Tononi's lab and other people measure metrics of causal emergence, phi, in different kinds of brains under different conditions to try and understand to what extent there is a mind, an integrated mind there looking outwards. We can do all of that with the bioelectrics and the calcium imaging of the cells and the developmental systems that we work on.

We are building models of genomes as generative models in development and diffusion models. Lots of interesting conceptual frameworks available now.

We really welcome collaborations with all the people here and neuroscientists in general to help us take some of the tools that are being used to understand learning and information processing in artificial systems, but also in natural systems and in the brain, and various other things, active inference and perceptual multi-stability, to try to apply them to decision-making in non-neural cells.

I want to show you one example. I've made the claim that biology has the beginner's mind idea that the exact same hardware is perfectly willing to confabulate new models of itself and the outside world and do new things in novel circumstances, to make something adaptive.

Slide 43/48 · 57m:34s

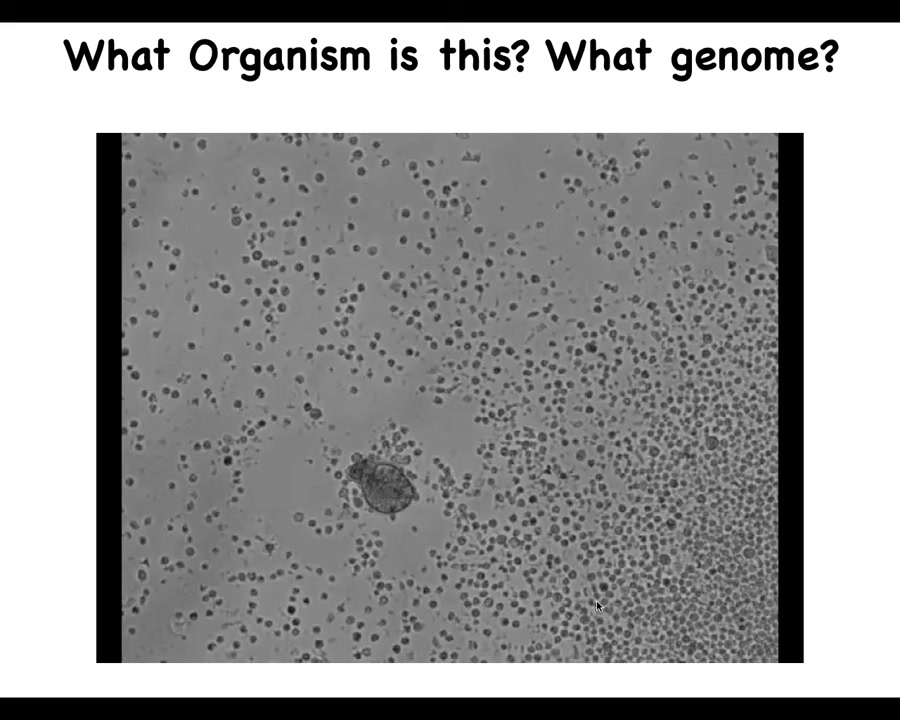

I want to show you one quick example of this. Here's a little life form. If I asked you what this was, you might think that this is some primitive organism that I got off the bottom of a pond somewhere. You might also try to guess the genome, and you might think that the genome would be indicative of some primitive organism. If you were to sequence this, what you would find is that it's 100% Homo sapiens. These are adult human cells that have been given the opportunity to reboot their multicellularity. What they end up doing is something we call making an anthrobot, because we think this is a biorobotics platform. These come from adult human patients donating tracheal epithelial cells. It makes this little autonomous self-motile creature.

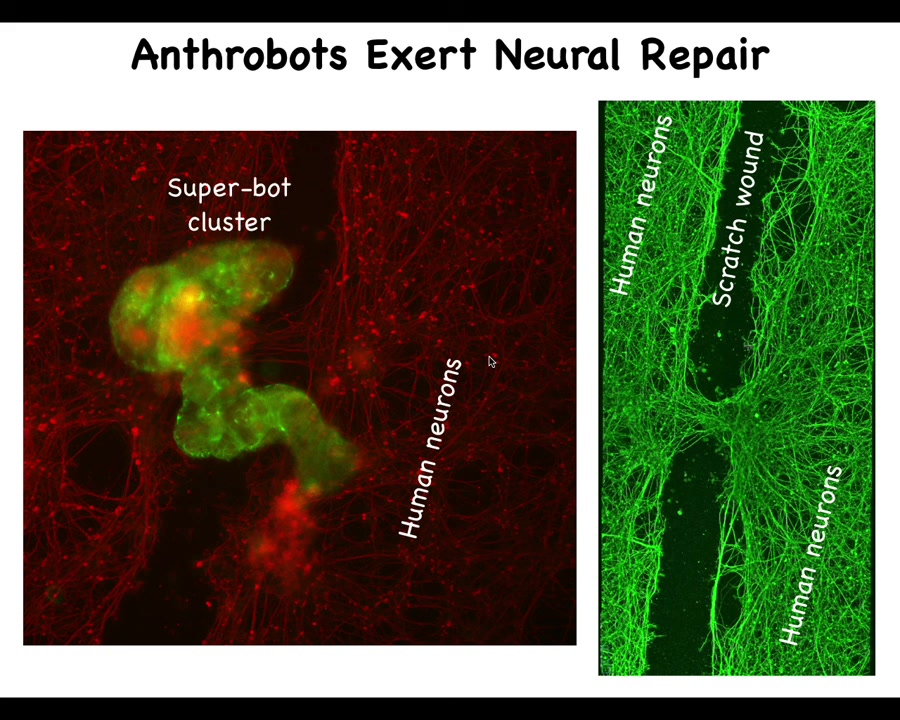

Slide 44/48 · 58m:22s

They have some interesting properties. For example, if you seed a plate of neurons like this, the red stuff is human neurons. We put a big scratch through it, this is a wound, and you've killed off a bunch of neurons here. These Anthrobots will gather in the wound. They make a group of them. We call it a superbot cluster of 10, 12 of these bots. Within about four days, if you lift them up, you see that what they're doing here is they're knitting the two sides of the wound together; they have this ability to heal these neural wounds.

Who would have thought that your tracheal epithelial cells that sit quietly in your airway would be able to make a self-motile little creature like that, and furthermore, that it would have this kind of property. This is the absolute first thing we look for and we found it. I think we do a million other things that we're in the process of discovering.

The point is that these are genetically unmodified cells. These are perfectly normal cells from adults. The Anthrobot looks nothing like any human embryonic stage. It doesn't look like a human embryo. There's never been any selection to be a good Anthrobot.

The form, the function, the capabilities of these Anthrobots, and we're currently beginning to test them for memory, for learning, for preferences, for all kinds of other problem-solving skills — all of these things are novel portions of that latent space that surround the human genome. The exact same hardware, the same human genome, is capable of being used to make lots of different kinds of creatures with different shapes, different behaviors.

It's precisely because of this problem-solving capacity, which in turn ultimately is driven by the unreliability of the biological hardware, that ratchet leads directly from the unreliability of the biological material to a kind of very basal intelligence that permeates all of the different layers of life, leading up to having brains and nervous systems and so on.

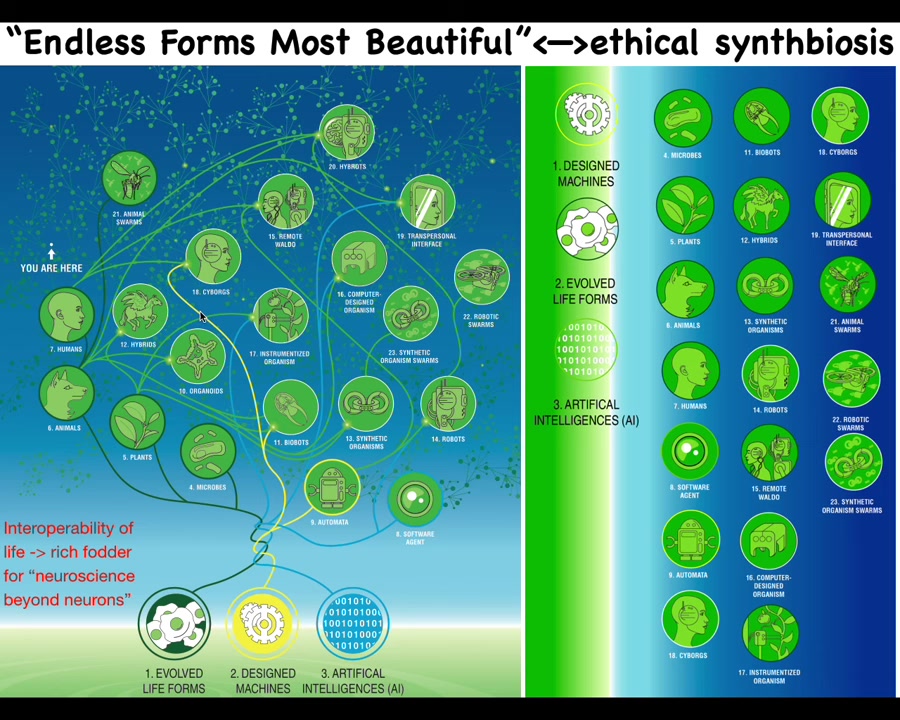

Slide 45/48 · 1h:00m:30s

So because life is doing that, because it is so interoperable, cells will grow in chimeras and hybrids with weird nanomaterials and scaffolds and electrodes. All of these things are completely viable. Because it does not make strong assumptions about what it needs to build, it's able to solve its problems in various ways. Because of that, what we're looking at here is an enormous space of possible bodies and minds. Almost every combination of evolved material, engineered material, and software is some kind of viable agent. We have hybrots and cyborgs and every kind of combination, and some of these things already exist. Many of these things will exist in the coming decades, all sorts of different combinations.

So on this space of the possible, of bodies and minds, all of Darwin's endless forms most beautiful, the natural variety of the evolved living world, is like a tiny corner. It's a tiny region of this space of possibilities.

All of these creatures are incredibly rich fodder for the neuroscience beyond neurons, to understand their emergent behaviors, their cognitive capacities, and, of course, for us to develop novel ways to relate to them ethically. Because the old categories of life versus machine are no good. They were rough heuristics, but they're increasingly going to be irrelevant in the coming decades.

We need to understand how to relate to beings that are nowhere on the tree of life with us and to enter a synth biosis with these beings and thus gain a better understanding of what makes us who we are and what's special about being alive and what's special about being humans.

Slide 46/48 · 1h:02m:29s

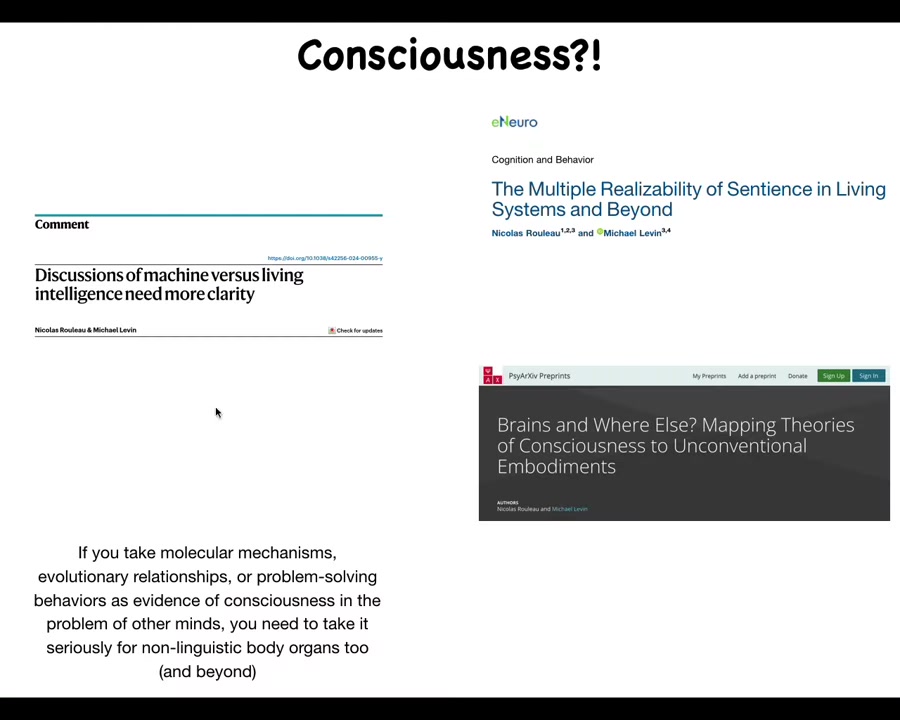

And so that brings me to the last thing, which I'll just say very briefly, because we don't really work on consciousness and I don't usually say much about consciousness, but I think the one thing that we've learned from all this work, and you can see some of this in these papers, is that if you take these three things, any of these three things, as the kind of evidence that you use to solve the problem of other minds. So molecular mechanisms, evolutionary kinship or problem-solving behaviors.

When you look out into the world and you deal with other humans or other animals, and you decide that they too have a mind and an inner perspective and consciousness, usually we use one or more of these criteria. It's either because of what they're made of, because they are related to us, and that you are conscious, so you assume that other things that are closely related to you might be as well. Or sometimes from behaviors, some people make those decisions based on their capabilities and their functional behaviors.

If you take any of those things as important for detecting consciousness, then you need to take seriously the idea of other organs in the body that are not linguistic, that can't make a good verbal case for their own consciousness, and nevertheless have the same molecular mechanisms, the evolutionary closeness, and the problem-solving competencies of brains. That becomes very serious.

I think it actually goes well beyond non-linguistic body organs, but in particular, body structures. That's because we've now shown that the bioelectrics that support the relevant dynamics in the brain are extremely ancient and very widespread throughout the body. In this preprint, Nick Rouleau and I go over all the currently popular theories of consciousness and ask, do they really say anything about brains or are they much more generic than that? And actually almost all of them apply to all of the tissues in your body.

Slide 47/48 · 1h:04m:37s

So I'll stop here and just summarize the following: that all of the mechanisms, meaning ion channels, gap junctions, neurotransmitters, all of that stuff that underlies neural activity are ancient, and they function in all cells in the body and across phylogeny, roughly from the time of bacterial biofilms. So the brain really developed its tricks and sped up those processes, but they are very ancient and very widespread. The role of bioelectric networks as cognitive glue, as policies that allow integration of information across time and space and align the parts of a system towards higher-level goals, is also highly conserved. Our nervous systems are held together by bioelectrical signaling, and that's why we are more than just a pile of neurons. We are also collective intelligences, and that role for bioelectric networks is also extremely ancient. So not only the mechanisms, but also the algorithms and the policies are conserved.

For that reason, many of the tools of neuroscience, meaning both the techniques and the conceptual frameworks, are applicable broadly outside the brain. Applying them outside the brain leads to novel discoveries. You can see here, these are reviews of various aspects of regenerative medicine that are being enriched by taking the tools of neuroscience, and in particular the understanding in neuroscience that there are multiple levels of explanation and of organization that are important in applying them to other processes in the body, to remind us that the molecular biology level is not a privileged level of causation. It is not the only level at which we can do useful interventions.

I think that expanding neuroscience beyond nervous systems in that way enables a very rich and novel roadmap to regenerative medicine. In particular, this is because creative problem solving and learning are not brain specific. The sciences that study the self-assembly of bodies, meaning developmental biology and regenerative biology, and those that study the autopoiesis of minds from those ingredients, I think have a lot to teach each other. I think there's a lot of useful enrichment and information feeding back and forth from developmental biology to neuroscience.

The broader implications of this connect with lots of issues around unconventional embodied minds. This is diverse intelligence research in terms of cyborgs, robotics, AI, and other kinds of implementations that are doing some of the same things that life is doing in aligning parts towards a larger cognitive light cone and enabling an emergent mind that is a collective intelligence made of parts that obey the laws of physics. So more details on all of this can be found here.

Slide 48/48 · 1h:07m:43s

Most importantly, I need to thank the students and the postdocs who did the work. All of the stories that I showed you today were done by these amazing people. You can see them here. We have lots of great collaborators.

I want to thank our funders who have supported the work that I've shown you. The illustrations were done by Jeremy Gay. Disclosures: these are companies that are supporting some of our work and licensing some of the discoveries that have come out.

Most thanks to the biological systems that do all the heavy lifting and have taught us so much about what it is to be an embodied mind. Thank you so much.