Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

A 30-minute talk on implications of my work for the study of consciousness (fyi, I do not offer a new theory of consciousness or try to support/rule out any of the existing ToC's; I talk about reasons to suspect consciousness in other parts of bodies than the brain and other diverse embodiments).

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Expanding consciousness beyond brains

(03:20) TAME and cognitive scaling

(08:08) Collective selves and morphospace

(12:51) Morphogenesis as problem solving

(17:00) Bioelectric control of form

(21:29) Rewriting bioelectric pattern memories

(27:26) Xenobots and novel organisms

(31:11) Future minds and ethics

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/33 · 00m:00s

Thank you for having me here. It's a huge pleasure to be able to share some ideas with you all. I've never been to this conference before, and I'm going to enjoy saying some things that are not as radical as some other things people have said. That's a new experience for me. If anybody's interested in the kinds of things I do, you can find all of that here.

Slide 2/33 · 00m:27s

I don't particularly work on consciousness. I work on cognition, agency, intelligence, things like that. I do think they have implications. I'm going to make a fairly modest claim. I'm not going to try to produce a new theory of consciousness. I'm not going to try to support one specific theory of consciousness with data.

Here's what I'm going to try to do. I'm going to try to make a fairly simple argument that if we use composition and behavior as evidence of consciousness in other systems when addressing the problem of other minds — if our criteria include things like what are you made of, what are your behavioral competencies — then for the exact same reasons that we tend to associate consciousness with complex brains, we need to take very seriously the possibility of consciousness in many body structures.

That's a very controversial claim in some audiences. Maybe it won't be particularly controversial here. What I'd really like to do is to widen the set of systems we think about when we think about consciousness and related issues beyond human brains.

When we talk about AI, I don't want to think just about is it human-like, because it's much more interesting than that.

Slide 3/33 · 01m:47s

So one of the key things is that I think we have to move beyond these conventional intelligences. There's a famous painting of Adam naming the animals in the Garden of Eden. And if you think that there are these very discrete natural kinds, then one can have these binary categories of which things do and do not have consciousness. People are pretty sure about Adam, not so sure about some of the stuff that's not shown here, paramecia, slime molds, and various other things.

Slide 4/33 · 02m:20s

So the reason that we have to think about these things is that the standard human, which features prominently in philosophical accounts of consciousness and so on, is really just one point on 2 continua, or 4, depending on how you want to count. You have to decide what happens to it as you walk backwards from a modern adult human all the way back to the oocyte that all of us once were. You can also walk it back on an evolutionary time scale and ask what happens all the way back, because all of these things are smooth and continuous. And in fact, with modern bioengineering and synthetic biology, it's now very clear that both using biological means and hybrid technological means, we can create hybrids and chimeras in every possible way and extend the typical embodiment in very diverse directions. And so we'll get back to this more towards the end of the talk.

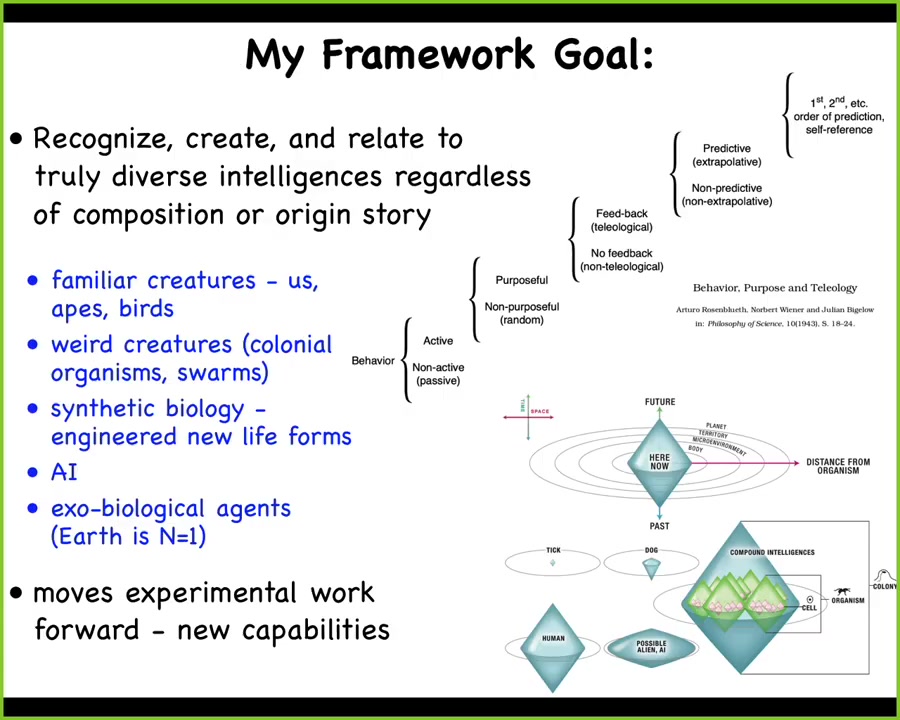

Slide 5/33 · 03m:19s

And so what I've been working on is a framework which I call TAME, which stands for Technological Approach for Mind Everywhere. And the idea is to be able to recognize, create, and ethically relate to truly diverse intelligences, regardless of composition, meaning what you're made of, or origin story, meaning whether you were produced the natural way, or engineered, or some combination thereof.

And I want to be able to handle the familiar creatures, all kinds of weird colonial and synthetic organisms, AIs, whether software or hardware, and potentially exobiological agents.

And so, people have tried before for these kinds of things. This is Rosenbluth et al. from the 1940s, trying for a scale of these kinds of things that are not particularly bound to embodiments, brains and things like that, a very cybernetic definition.

And I've been working on a model that has to do with what I call a cognitive light cone, which is this idea that all agents have one thing in common, no matter what they're made of or how they got here, which is the ability to pursue certain goals in certain spaces. The size of those goals, the literal spatio-temporal size of the largest goal that an agent can pursue, is one way that we can classify and compare very diverse intelligences.

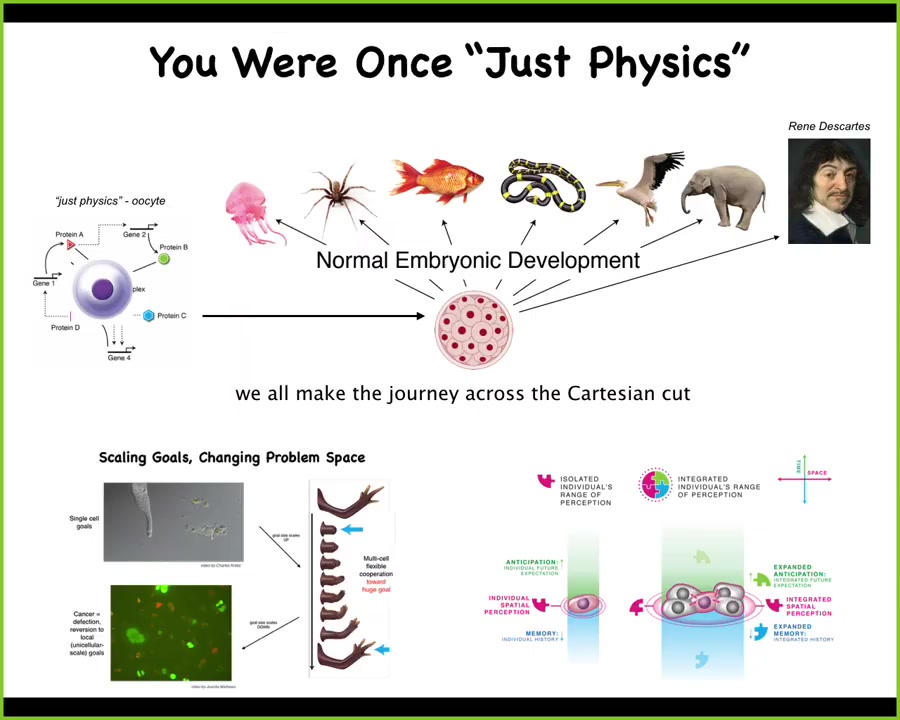

Slide 6/33 · 04m:38s

The critical thing is that, as I'm primarily a developmental biologist, what astounds me is that all of us were once what people call "just physics." We were all a quiescent oocyte, a little BLOB of chemicals. Slowly, gradually, without any magical lightning flash that comes in at any particular point during development, we become one of these things, or perhaps even something like this that can reason back and make comments about not being a machine.

This process is very slow and gradual. What we're interested in is that process and the scaling of competencies of very simple, minimal matter, chemical signals, systems, and cells and tissues, the scaling up of the tiny goals of single cells, so metabolic and transcriptional goals, into collective systems that have very large goals, and the kinds of failure modes that the system has, which is a breakdown of that collectivity into cancer, back down to cells that have tiny goals about proliferation and migration, and they no longer care about the rest of the system.

The meat of our research program has to do with understanding the scaling, understanding that cognitive light cone and how it actually scales up from that of a single cell, and below that in some other work that we've done with Chris Fields and Carl Friston.

Slide 7/33 · 06m:08s

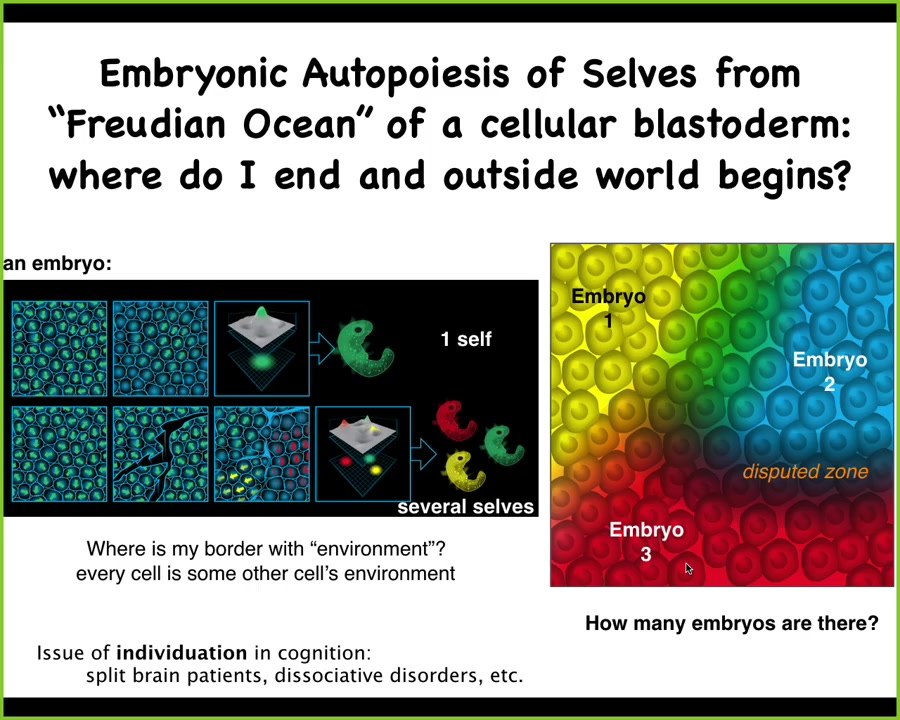

And one of the things that happens in development, which is interesting, is the autopoiesis or self-construction of a single individual from a pool of potentiality, and it looks like this: it's an early blastoderm of a human or a chicken or many other animals. We see 50,000 cells, and we say there's an embryo. What are we counting when we say that's one embryo? There really isn't one of anything physical. There are many, many cells. What is there one of? And this is going to become an individual.

What there's one of is alignment, both physical alignment and functional alignment towards a particular goal. That alignment is the creation of a particular target morphology, a particular anatomical structure. If you try to deviate it, it will find new ways to get there. It's definitely a homeostatic system.

But there doesn't have to be just one. If you make temporary scratches in this blastoderm, what you end up with is each of these regions, not being able to feel the other, self-organizing into an embryo. Eventually you end up with twins, triplets, and many other selves.

The question of how many individuals are in an embryo is not clear. It's not set up by the genetics. It's a physiological self-organizational process. What it means is that each one of these individuals, on the fly, every single time they arise in this physical world, has to solve this important problem: Where do I end and where does the environment begin? Every cell is some other cell's environment. How do these cells know what they belong to?

As I think Turing recognized, this question of how bodies self-organize is probably fundamentally the same as the question of how minds self-organize. We see these kinds of dynamics in split-brain patients and dissociative disorders. This question of how many individuals are present within a particular amount of medium underlies it.

Slide 8/33 · 08m:09s

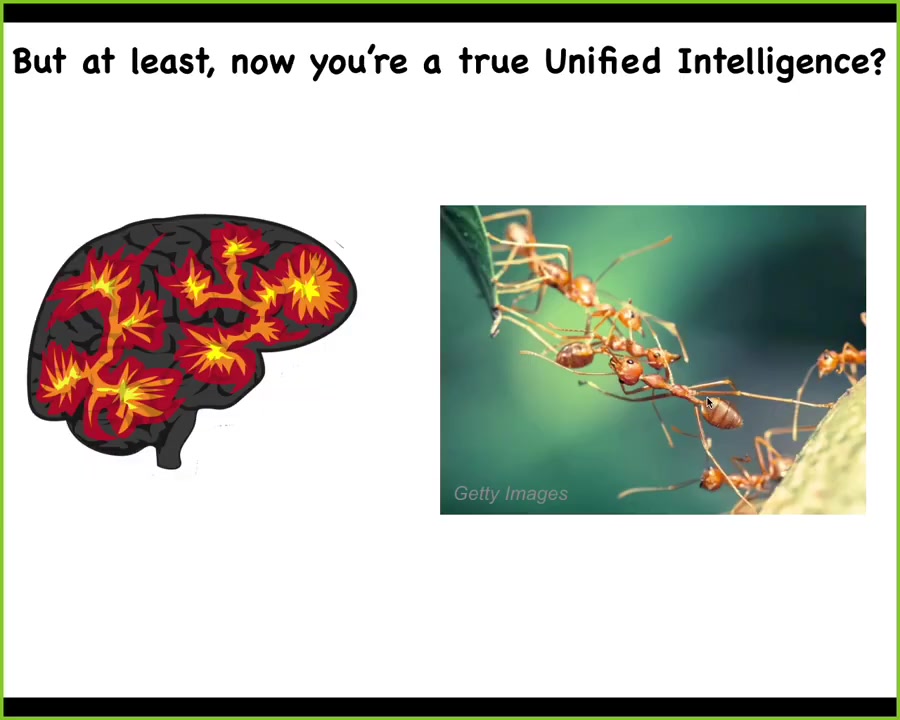

People who think about these things often think we have these what we call collective intelligences, colonies of ants and termites and so on. But we are a true unified intelligence, right? Many people think that there's a fundamental difference between these cases.

Slide 9/33 · 08m:27s

Descartes really liked the pineal gland because it's an unpaired structure and he felt that was suitable to the unified human experience. If he had access to good microscopy, he would have noticed that there isn't one of anything here either. This is what the pineal gland tissues look like. Inside each one of these cells, you get all of this stuff. So there's an incredible multi-scale organization.

Slide 10/33 · 08m:52s

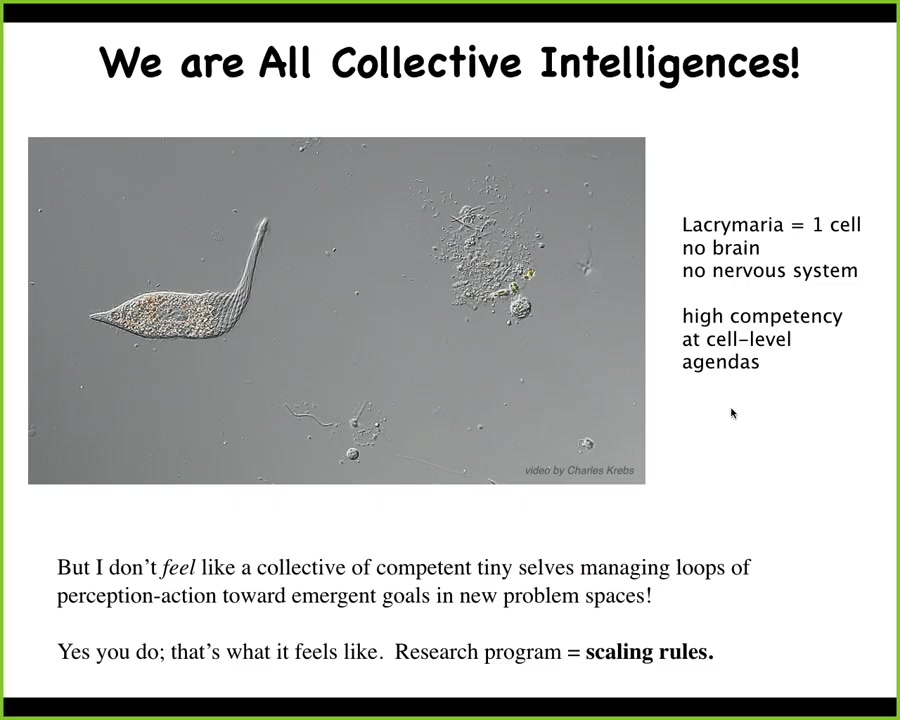

We are all collective intelligences. We are made of this agential material.

This is a Lacrymaria. It's a single cell. It has no brain, it has no nervous system. It's very good at taking care of local goals in terms of its anatomical structure and metabolism.

When we talk about machines and living organisms and consciousness, we have to remember that whatever theories we make have to make a ruling on things like this. What happens here? Certainly people have very chemistry-based views of these things: that this is what we are actually made of.

We may not feel like a collective of competent, tiny little selves that are managing perception-action loops towards emergent goals and weird problem spaces. That is exactly what it feels like to be that kind of a system. We do feel exactly like that.

The research program that we and others have embarked upon is to discover the scaling rules. How do we go from the individual competencies of our components to rotating those goals and competencies into novel spaces?

Slide 11/33 · 10m:05s

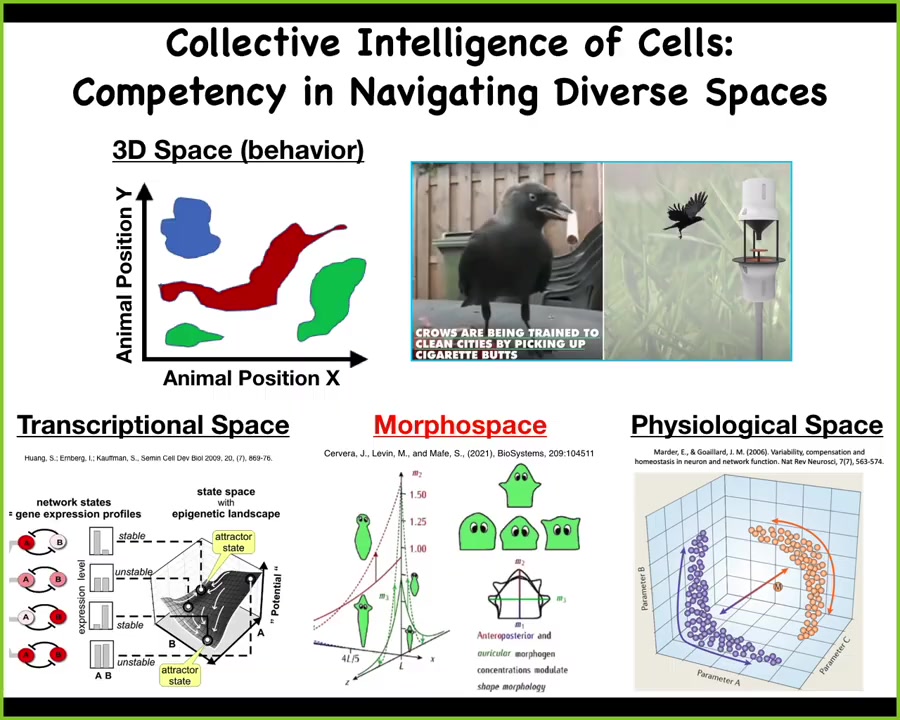

In bodies, not just human, but all bodies, biology uses this multi-scale competency architecture, this idea that we are not only nested dolls structurally, cells, molecular networks making up cells and tissues and organs and so on, but actually each one of these layers has its own problem-solving capacity.

They are all solving problems in different spaces: anatomical morphospace, the space of gene expression, the space of physiological states, and the familiar three-dimensional behavioral space.

I really like William James's definition of intelligence, which is the ability to reach the same end by different means using some degree of sophistication. It's very good because it's substrate-invariant. It talks about the idea of a spectrum of competencies, and it is agnostic about what space we're working in, and that becomes important because, for example, in conversations about AIs, when we say they're not embodied, we need to expand our understanding of what spaces we could be embodied in.

We and many other animals are good at recognizing intelligence in familiar three-dimensional space, so good old behavior.

Slide 12/33 · 11m:15s

These medium-sized objects moving at medium speeds in three-dimensional space; we're familiar with birds and primates and other things doing that. Biology does the same thing in other spaces. There are transcriptional spaces where cells are able to solve very interesting problems. Same thing with physiological space. I don't have time today, but I could give you some examples of cells exerting novel problem-solving behaviors by navigating these spaces.

What I will focus on for a few minutes is this: anatomical morphospace. This is basically the space of all possible configurations of a group of cells. D'Arcy Thompson in the '40s was the first to really get the idea of embryos and other morphogenetic systems navigating that morphospace.

We really have to get into the idea that beings can be embodied and can have consciousness in these other spaces. If you had an innate immediate sense of your blood chemistry, let's say, you would have no problem recognizing that you live in a higher dimensional space and that your liver, your kidneys and other organs are in fact problem-solving intelligent agents that are navigating that space exactly the way you navigate three-dimensional space.

Let's focus on morphospace and talk for a few minutes about what the competencies are of this. What we argue is that morphogenesis is the behavior of a collective intelligence. It's the collective intelligence of cells trying to achieve a particular anatomical structure.

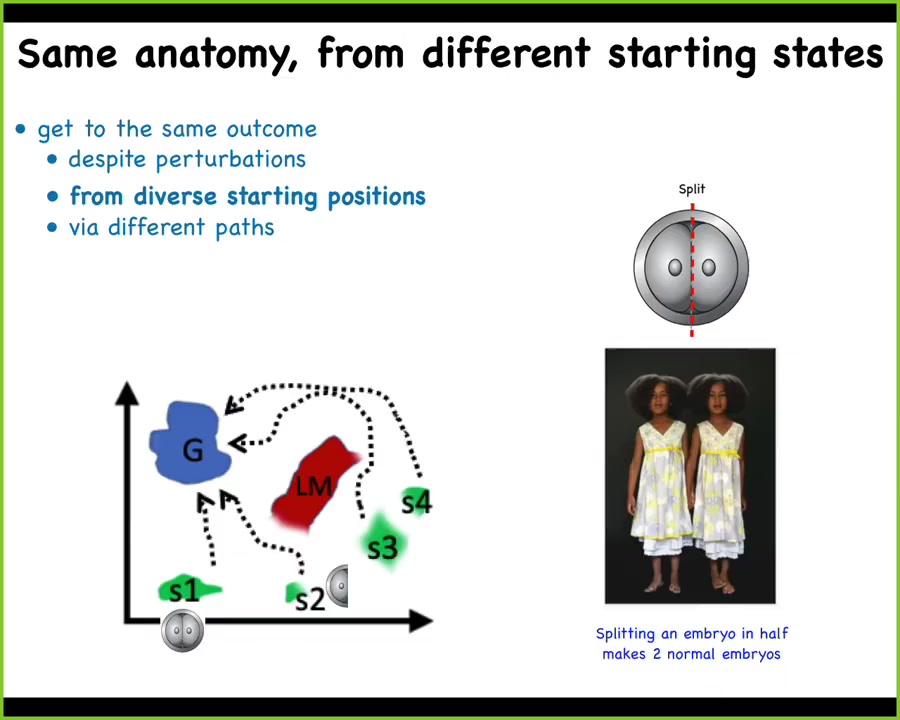

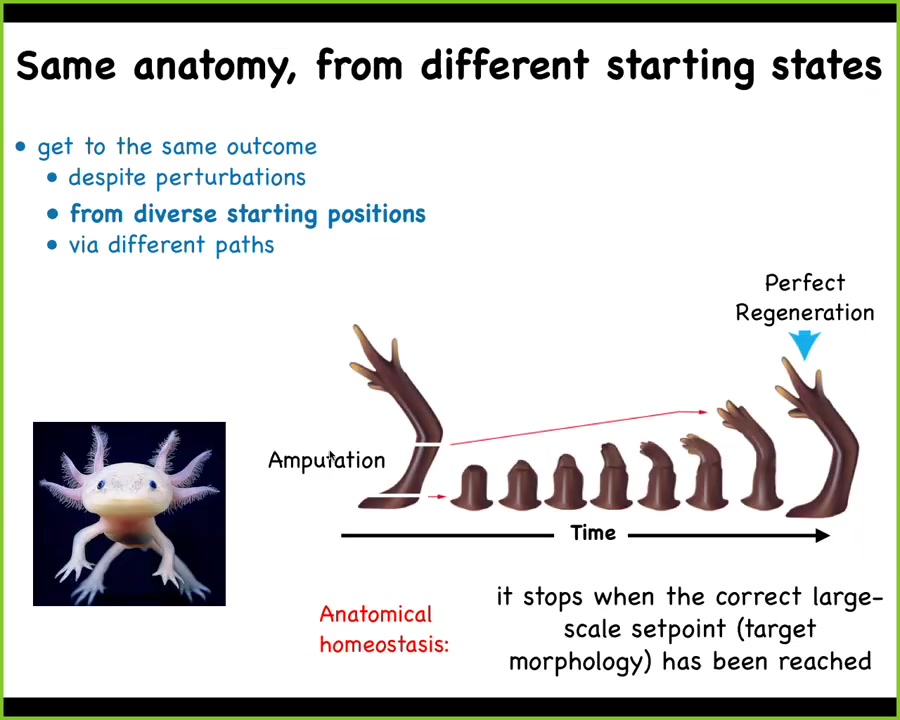

Slide 13/33 · 13m:02s

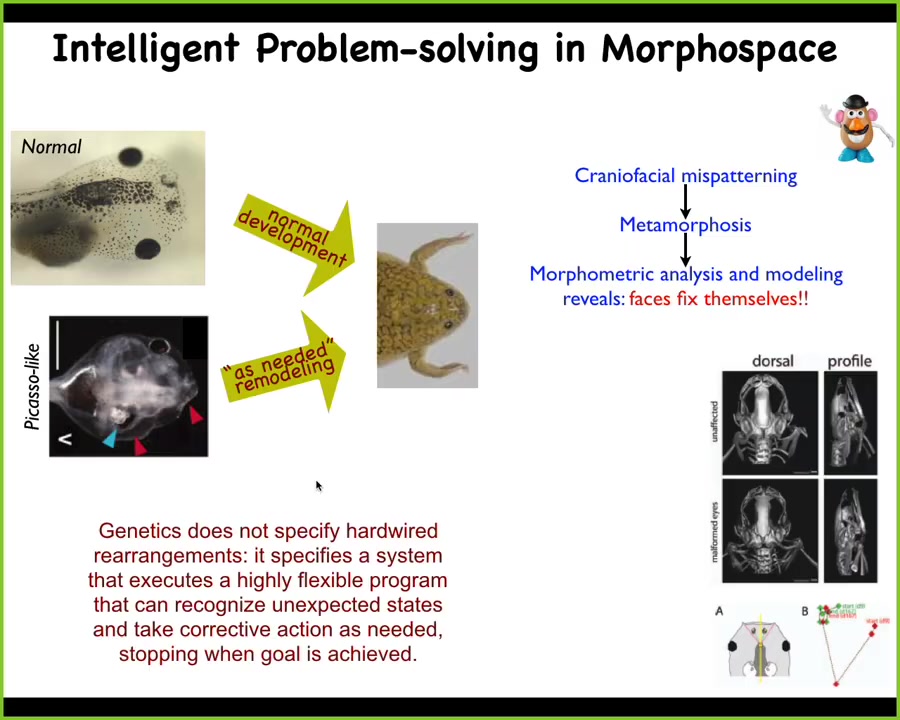

One thing we know is that development is incredibly robust and reliable, but it is not hardwired. If I cut an early embryo in half, I don't get two half bodies, I get two perfectly normal monozygotic twins. There's this notion of different starting states being able to lead to the same goal state, this ensemble in morphospace that we equate to a normal target morphology, and it can avoid certain local minima.

Slide 14/33 · 13m:30s

Here's an example that we discovered some years ago. This is a tadpole. Here are the eyes, the nostrils, the brain. Tadpoles need to become frogs. In order to become frogs, they have to rearrange their face. The eyes, the nostrils, everything has to move around. It was thought that this was a hardwired process, that every organ just moves in the right direction, the right amount. What we decided to test was how much intelligence actually is there. We created what we call Picasso tadpoles. Everything is scrambled. The eyes are on the back of the head, the jaws are off to the side, everything is mixed around.

What we found is that these tadpoles become largely normal frogs, because in fact, genetics does not specify hardwired rearrangements. What it gives you is a problem-solving machine where every organ now moves in novel, unexpected paths to get to where it's going. Sometimes it overshoots and has to come back, but it'll stop when it's done. What you really have here is a machine that can do an error minimization scheme and start off in different configurations, but always get to that same place in morphospace.

Slide 15/33 · 14m:33s

This is what happens in regeneration. This guy is an axolotl. They regenerate their legs, their eyes, their jaws, and so on. You can amputate the limb anywhere. These cells will build exactly what's needed until they get to a correct salamander limb, and then they stop. This is the most amazing thing about this process: it stops. When does it stop? When a correct limb has been formed. Individual cells don't know anything about what a limb is or how many fingers you're supposed to have, but the collective does, and it can stop when you get there, no matter where you start it.

Slide 16/33 · 15m:15s

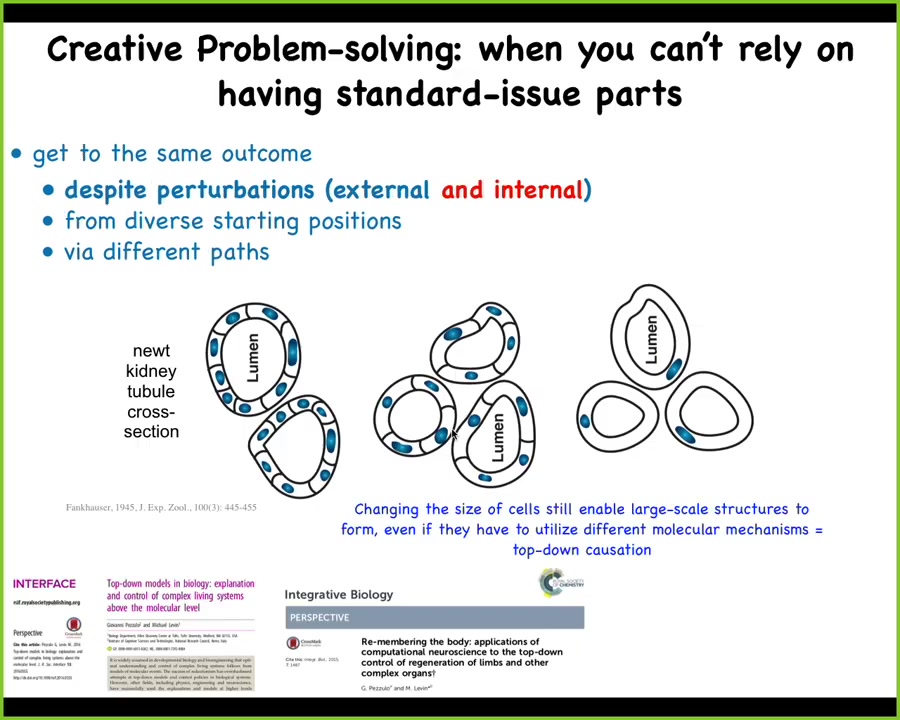

of problem solving goes beyond damage to an existing structure to what I think of as a good example of really basal creative problem solving. And it looks like this. This is a cross-section of a kidney tubule in a newt. And so usually about 8 to 10 cells work together to create these little tubules. But if you artificially make the cells very large, this is different than damage. This is not something that normally happens in evolution. Newts lose their arms all the time, but this is quite different. We've artificially made these cells to be gigantic. And so what happens is then fewer of them get together and they make the exact same size lumen. And the most remarkable thing is that you can make these cells truly enormous. And the way you do this is you make them polyploid, so they have multiple copies of their genetic material, and so the cells get bigger and bigger. And in that case, one single cell will wrap around itself and give you the whole lumen. What's amazing about this example is a couple of things. Number one, scaling of number to size, you can wrap your head around that. But what's happening here is a completely different molecular mechanism. Instead of cell-to-cell communication, you're now using cytoskeletal bending. So this is a good example of top-down causation, where in the service of a particular anatomical goal, different molecular mechanisms will get called up to solve the problem to give you the same outcome. And the second cool thing about this is that this is really an example of unreliable hardware. As an embryo, you can't count on how many copies of your genetic material you have. You can't count on what the size of your cells are going to be. You have to figure out how to get the job done despite massive amounts of novelty, injuries, uncertainty in your own parts and in the environment. So this is very basal kind of collective problem solving. And how does all this happen? How can they do this?

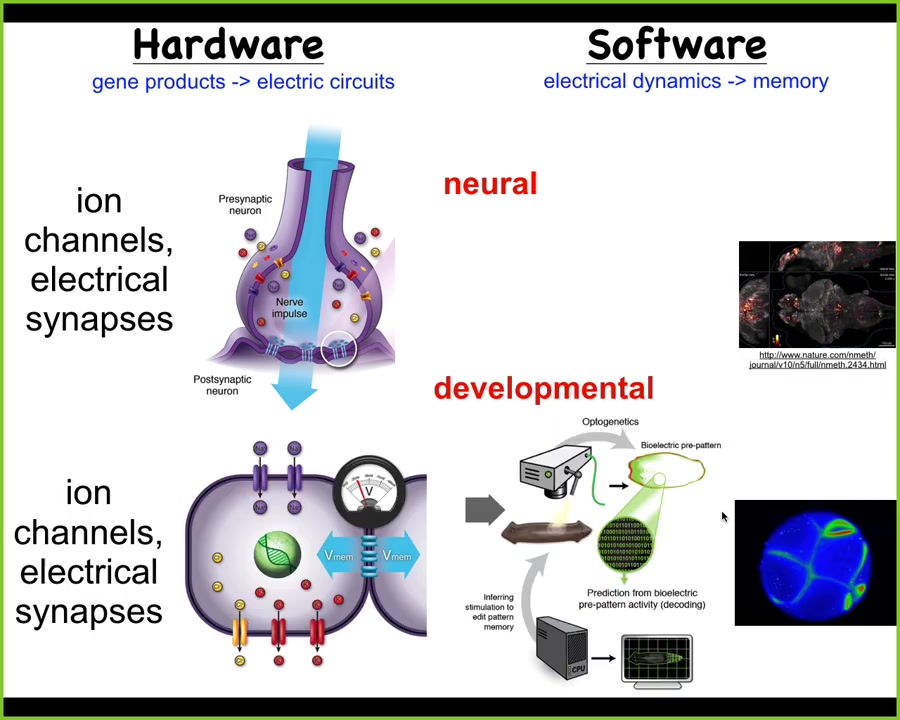

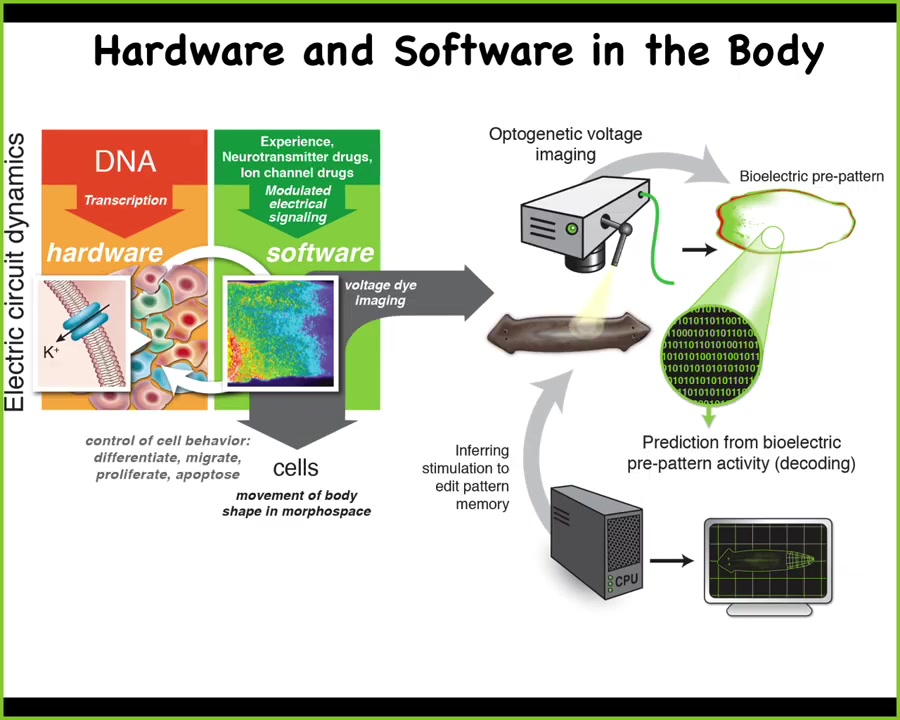

Amazingly, it happens using the same mechanisms that the nervous system uses to perform these functions. So I don't have to tell anybody here what the hardware and software looks like, but this idea of ion channels setting up various states that then drive the physiology that is thought to underlie various aspects of cognition and consciousness. Neuroscience has this project of neural decoding, where we're going to try to read all of these things and infer what the creature is thinking, remembering, experiencing.

Slide 17/33 · 17m:40s

The kind of salient effect here is that this system did not arise when brains and neurons came on the scene. This is evolutionarily ancient. Even at the time of bacterial biofilms, through the work of Goro Soel, we now know that evolution was using electrically based computations to coordinate across space and time and to drive specific goal states from collective systems. We've developed some of the first tools that can read and write this kind of electrical information from non-neural tissues. We want to do exactly what neuroscientists try to do in the brain, but we look at other unconventional intelligence as solving problems in anatomical morphospace.

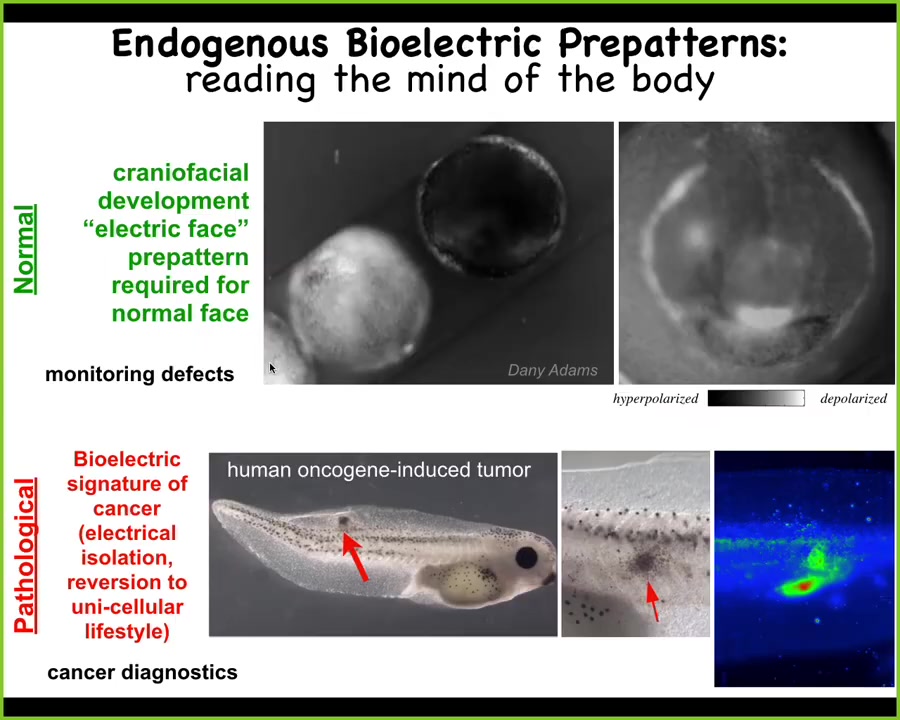

This is a voltage map of a time-lapse of a frog embryo organizing its primary axes. We can, using these voltage-sensitive dyes, see, interpret, and modify the integrated information and the communication that goes on to enable it to reach collective goals.

It's a parallel system, very much the way that the bioelectrical events in the brain are controlling muscles to move you through three-dimensional space.

Slide 18/33 · 19m:01s

This more ancient system is using bioelectrical events elsewhere in the body, from the moment of fertilization, to control all of the cells to move the configuration of the body through morphospace. It's the same thing. And what we think evolution does is pivot the same set of tricks across various spaces.

Slide 19/33 · 19m:18s

What we can do is image this. These are voltage-sensitive fluorescent dyes. This is a video of a frog embryo putting its face together, and this is one frame. Long before the genes and the anatomical rearrangements of the cells begin to form the frog face, you can already read out this pre-pattern. I'm showing you this one because it's the easiest one to decode. We have others that are a real bear to make sense of. This one is pretty obvious. Here's the animal's right eye, here's the mouth, here are the placodes. You can already read the pattern memory in this tissue that is going to guide the collective activity of the cells to reach that normal frog target morphology. This is the normal pattern. This pattern is required for development. If I perturb this memory, I'll show you in a minute what you get.

This is a pathological example. This is a human oncogene that's going to cause the cells ultimately to electrically disconnect from their neighbors, roll back to a unicellular lifestyle, and their cognitive niche shrinks from that of a large organ down to individual cells. As far as they're concerned, the rest of the body is just external environment. They're no longer part of this collective, and that's tumorigenesis and metastasis. You can detect this shift quite readily. You can see it happening.

Slide 20/33 · 20m:44s

The way we manipulate these things, we don't use any electrodes or applied magnetic fields. We use the native interface that the cells are normally using to control each other's behavior and link up into this larger scale intelligence that's able to move in morphospace and other spaces.

What that means is we can target these gap junctions, these electrical synapses, we can control the voltage states directly using optogenetics, using drugs that open and close these channels. We can control the neurotransmitter movement through these networks. All the same familiar tools of neuroscience do not distinguish between neural tissue and other tissues. Everything works. Everything is readily portable. That's what we do.

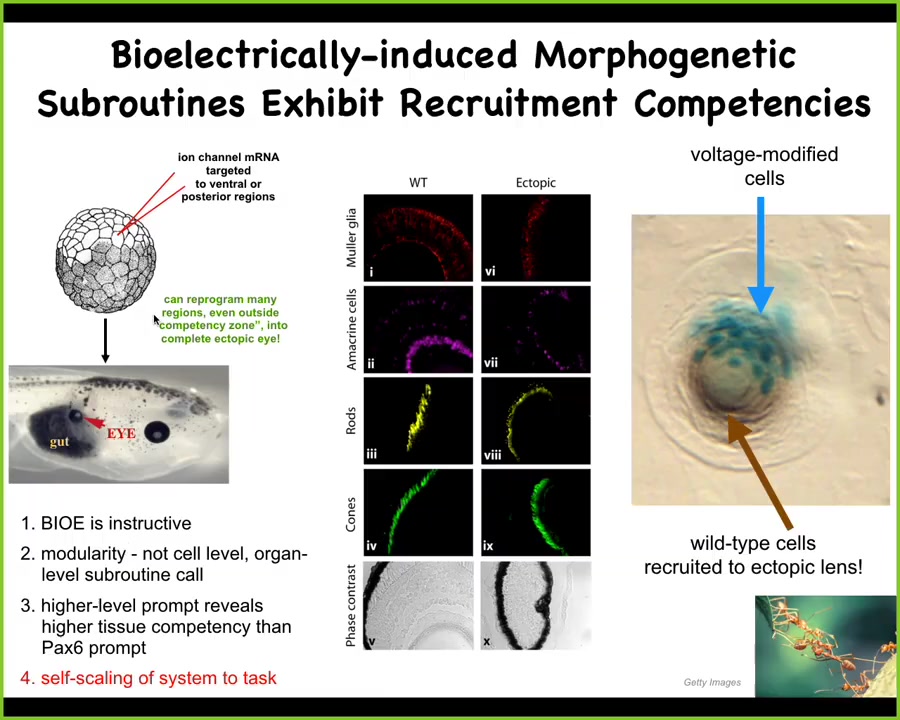

Slide 21/33 · 21m:30s

I want to show you an example. This is one of many examples of what happens. I showed you that electric face picture and one of the things there was an eye spot. It was a particular pattern of voltage that corresponds to an eye. We said, what happens if we recreate that same pattern memory somewhere else in the body? We injected ion channel RNA encoding a potassium channel that sets that particular voltage state. We encoded it; we stuck it in some cells that are normally going to be gut here. So this is endoderm. When you do that, those cells make an eye. This eye has all the right lens and retina and optic nerve and all of that stuff. Many things we could say about that.

One of the most interesting things about it is that, very much like the scaling that you see in other collective intelligences, it has the following property. This is a lens sitting out in the tail of a tadpole somewhere. The blue cells are the ones that we actually injected, but there's not enough of them to make a proper eye. They know this. What they've done is recruit a bunch of their neighbors, these unmarked cells, because they were not directly modified by us, to participate in this eye-building project.

What's happening here is these are all native competencies of the tissue. We didn't have to do size control. We didn't have to tell them how to build an eye, what all the different gene expressions and cell types are. We didn't have to do any of that. We put in a very simple prompt or stimulus, "build an eye here," and all the stuff that's downstream of that, including the way ants recruit their neighbors when they have a task that's too big for them, all of that works. We're starting to see some of these properties and how to interface with them in the body.

Slide 22/33 · 23m:09s

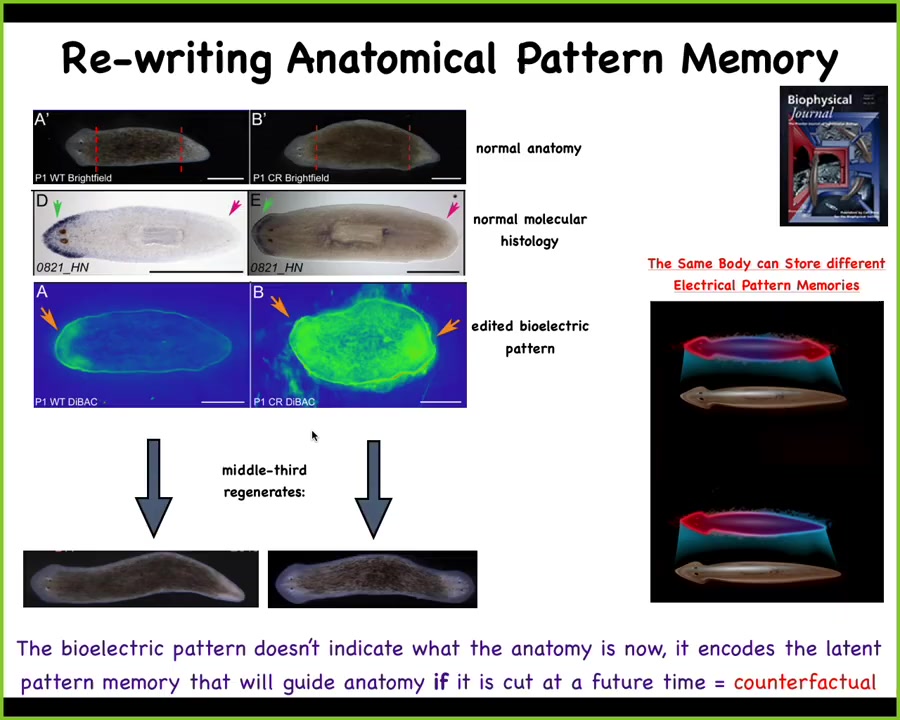

And one of the most important things is the ability to literally rewrite these pattern memories. So this is a planarian, these flatworms. The most amazing thing about them is that you can cut them into pieces. If I cut off the head and the tail, this middle fragment 100% of the time regenerates into a nice one-headed worm. You can ask the question, how does it know how many heads it's supposed to have? If you look at the bioelectrical pattern, you see this pattern that says one head, one tail.

What we can do now is we can rewrite that pattern. This is messy. The technology is still being worked on. But you can see what we've done is we've set two heads. If you cut this animal, now you get a two-headed worm. This is not Photoshop. These are real animals.

This bioelectrical map is the map of this perfectly normal anatomical structure, a one-headed creature. The gene expression is in the right place, the anatomy is in the right place. What we've changed is the internal representation of what a correct planarian looks like, and they stay normal until you injure them. If you injure them, then all the cells consult this pattern and they end up building this different pattern.

That question that I asked at the very beginning, how do the regenerating cells know what to make? They literally store a memory of where in morphospace they're supposed to go. That memory is rewritable. You can think of this as a very primitive precursor to our amazing time travel, mental time travel capacities, being able to imagine things that haven't happened yet and remember things that are not happening now, because this bioelectrical pattern is not a map of this two-headed creature. This is a map of this perfectly normal one-headed animal. So a single planarian body is able to store at least two different representations of what a correct planarian is supposed to look like. And I'm sure there's lots more, but this is the one we've nailed down. So it's a very primitive example of a counterfactual memory. What would I build if I were to be cut at a future time? Not what's going on right now. What's going on right now is this, one head, one tail.

Slide 23/33 · 25m:13s

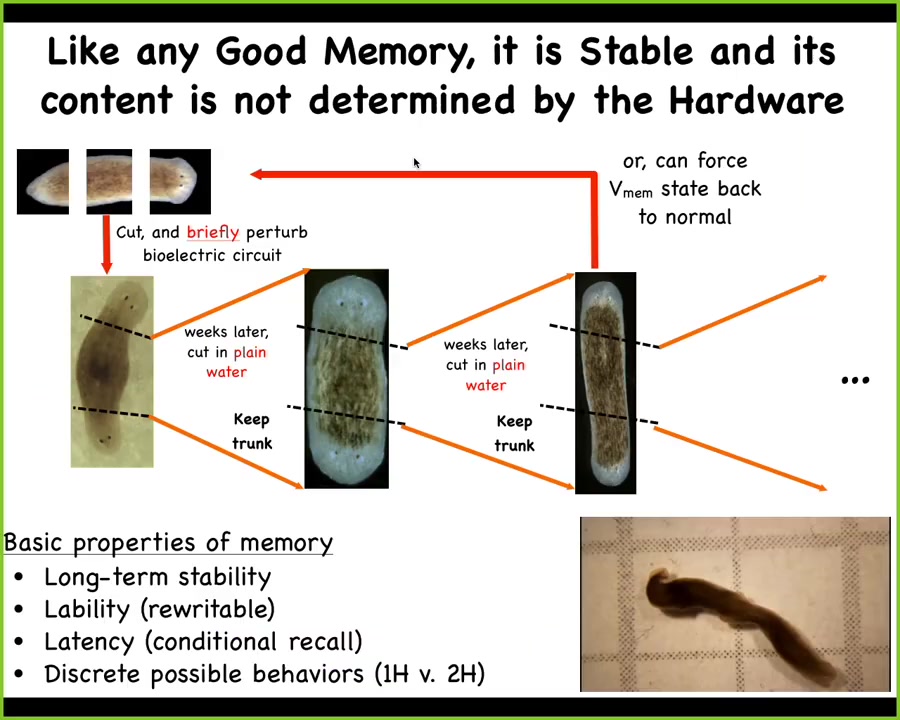

I keep calling it a memory. Why is that? Because it has all the properties of memory.

If I take these two-headed animals, which are genetically perfectly normal. The question of what sets the number of heads in the planarian is not very simple. The answer is not genetics. If I take this two-headed animal with a perfectly wild-type genome, I can cut him again and again. In perpetuity, he will continue to regenerate as two-headed forms until we set him back. We know how to rewrite it back to the one-headed state.

This question of how many heads are supposed to be formed, that memory of where you go in morphospace to the one-headed region or the two-headed region is stored physiologically, not genetically. It is long-term stable. It is rewritable. I showed you the latency a minute ago, conditional recall, and it has discrete behaviors.

Here you can see what these two-headed guys do in terms of when they're hanging out. Not only can we control head shape this way by putting these false, literally false memories into this collective agent, we can think about head shape.

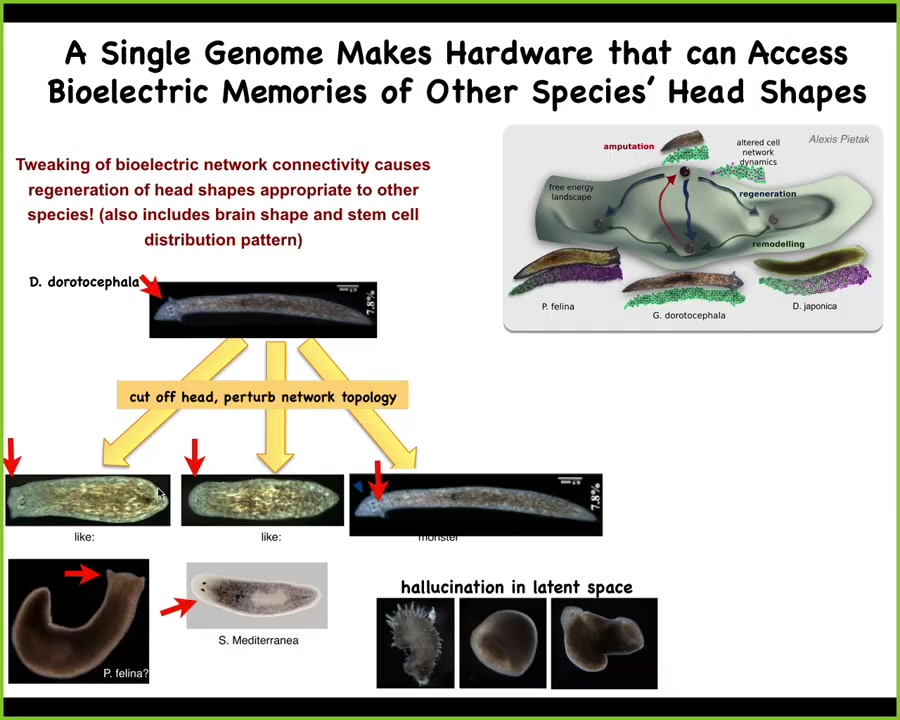

Slide 24/33 · 26m:13s

So whereas normally the species would make a triangular head shape, if we perturb the network topology while it's regenerating for 48 hours, they sometimes make normal heads, but they can also make round heads like S. mediterranea or flatheads like P. felina. These are other species of planaria. They are, again, genetically untouched, but there's about 100 million years of genetic distance between these animals.

This includes the shape of the brain and the distribution of stem cells. They become like these other animals. The same exact hardware can be pushed to visit other regions of that morphospace. This is very much like behavior in three-dimensional space. The hardware can learn many different things. It doesn't always do the same thing. You can get them to hallucinate kinds of morphologies that are not even typical for any species of planaria, such as spiky forms, cylindrical forms, and combinations. The exact same hardware can be pushed into lots of different domains.

Slide 25/33 · 27m:27s

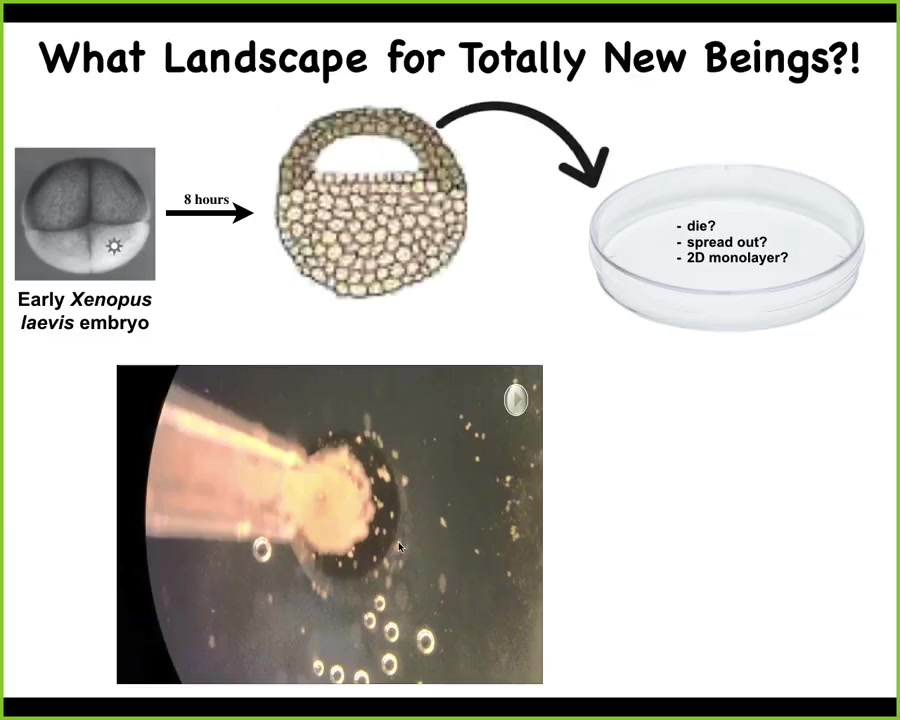

And so for the last couple of minutes, I just want to show you one thing. We were just talking about this anatomical morphospace and the different shapes that are there in the species that naturally know how to get to particular regions, and then how you push other types of implementations into those regions. But what does the space of possibilities look like for totally new beings? So let's make something that has not existed on Earth before and see what happens.

So this is a project that we did with Josh Bongard's lab at the University of Vermont, and Doug Blackiston did all the biology that I'm showing you here. This is an early frog embryo. At this stage, we take the animal cap ectoderm. This is skin. All of these cells are going to become skin. We dissociate them, cut them away from the embryo, and put them on their own. They could die. They could spread out. They could form a two-dimensional monolayer. They could do nothing. Instead, what they do is gather together and, over the next 24 hours, make this little interesting thing, which we call a Xenobot.

Slide 26/33 · 28m:39s

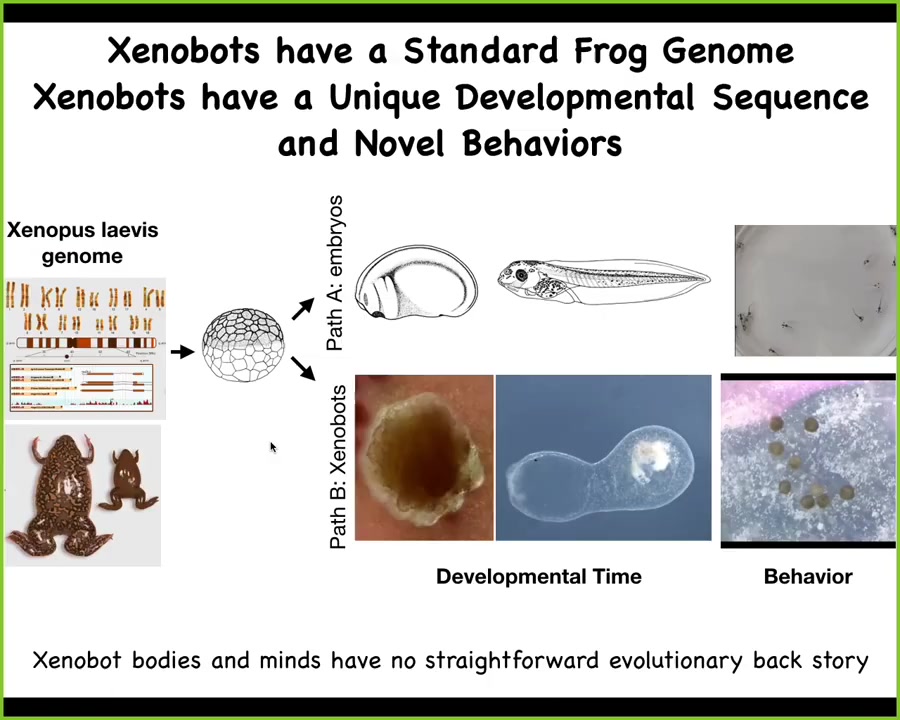

Xenobot — Xenopus laevis is the name of the frog and it's a bio-robotics platform. The interesting thing is that the frog genome certainly knows how to make this. This is what we typically think the frog genome encodes, a set of developmental stages and then some behaviors. But they can also encode this: a xenobot, and it has its own interesting developmental sequence. It's never been seen before, and it has interesting behaviors.

Slide 27/33 · 29m:03s

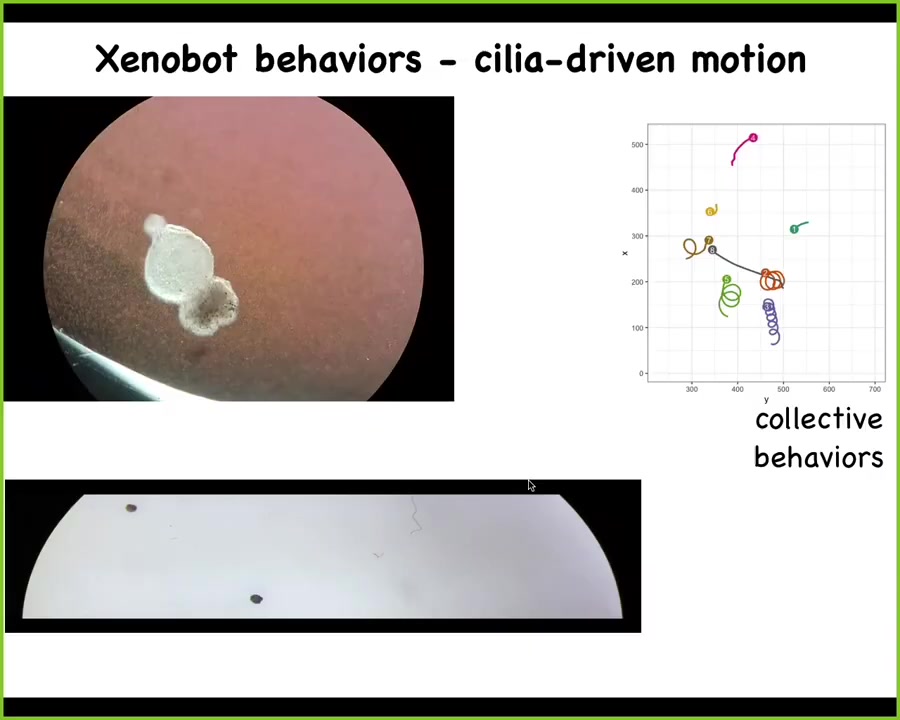

What are the behaviors? The first thing these things do is they repurpose their little cilia, the little hairs that normally redistribute mucus down the body of the frog, and they start to swim. They can go in circles. They can go back and forth. They have collective behaviors. They have individual behaviors.

Slide 28/33 · 29m:19s

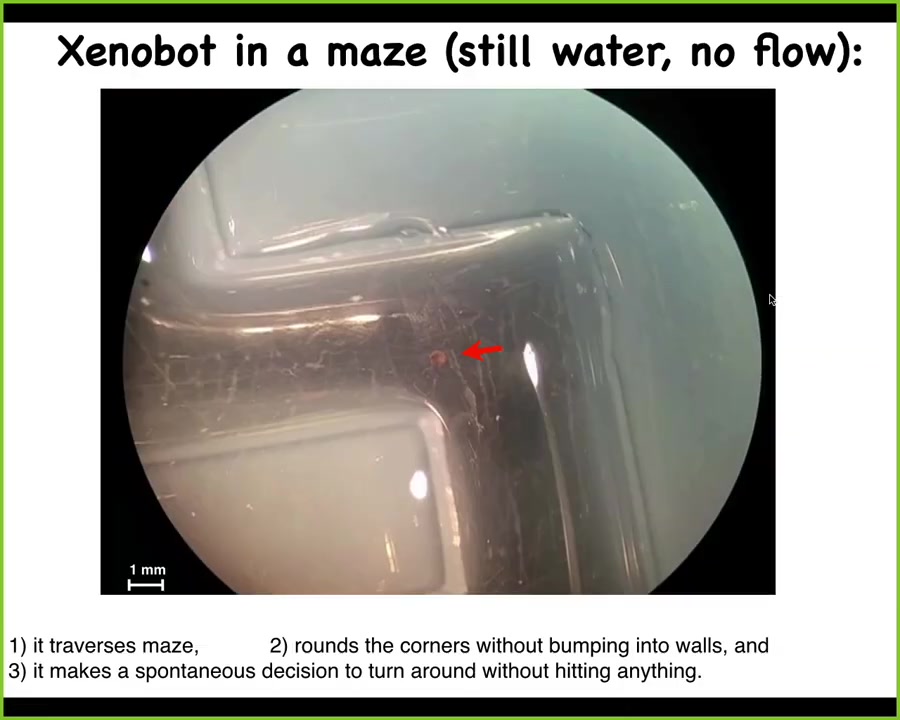

Here's one navigating a maze. You can see here, there's no nervous system. This is just skin. It takes the corner without having to bump into the opposite wall. For no reason that we understand yet, it has a spontaneous change of heart and it turns around and goes back where it came from. These are spontaneously motile organisms that have different behaviors.

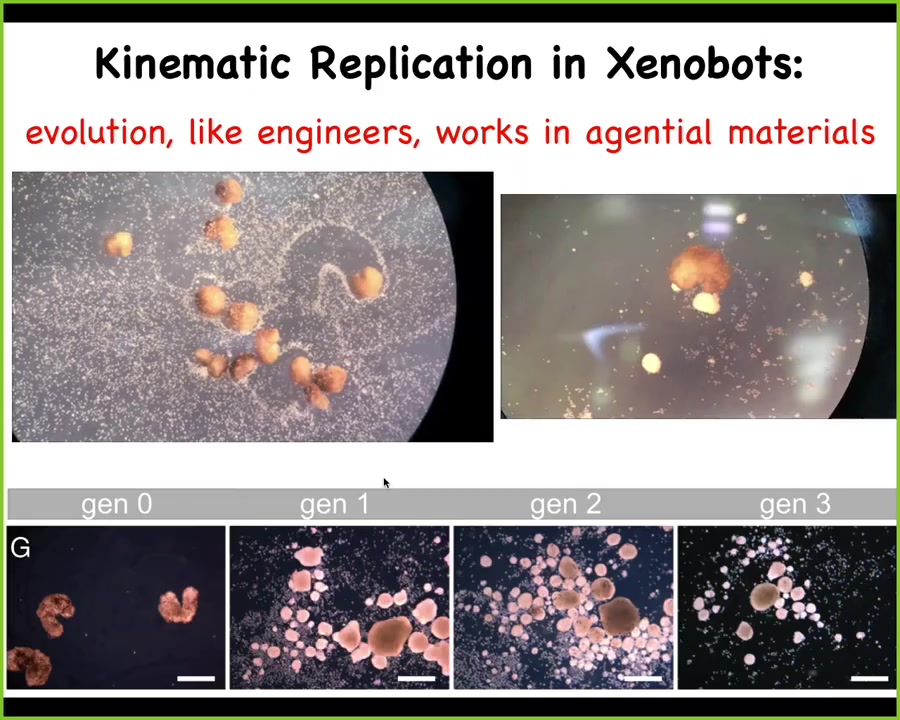

Slide 29/33 · 29m:43s

Here's one amazing behavior. If you provide them with loose skin cells, they will run around and collect those cells into little piles. They will compact them like this. Because they're dealing with an agential material that is not passive particles but cells, these little piles mature into xenobots themselves. That's the next generation. They go on and do the exact same thing, producing the next generation. This is called kinematic self-replication. No other animal on earth, to our knowledge, does this. It is completely novel with this kind of construction.

Slide 30/33 · 30m:18s

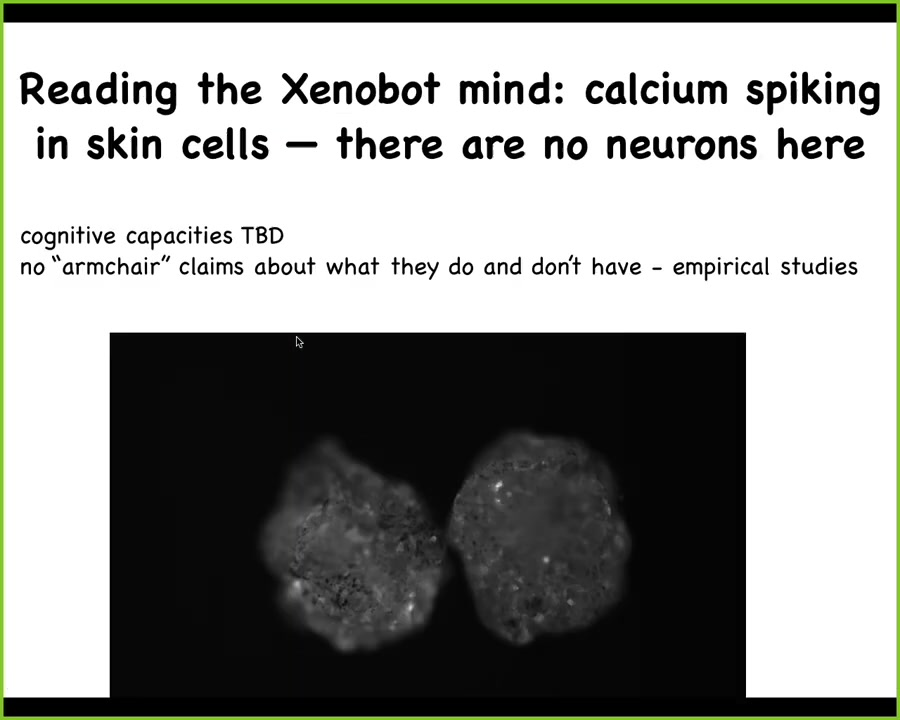

And so they don't have neurons, but they do have a lot of calcium spiking. You can imagine doing all of the things that neuroscientists do, looking for transfer entropy and mutual information.

So we can ask, what do the cells say to each other? What do two xenobots say to each other? We don't know their cognitive capacities. We're investigating that now. What can they learn? What are their preferences? It's really important that we can't make armchair claims about this. It has to be empirical studies.

Slide 31/33 · 30m:46s

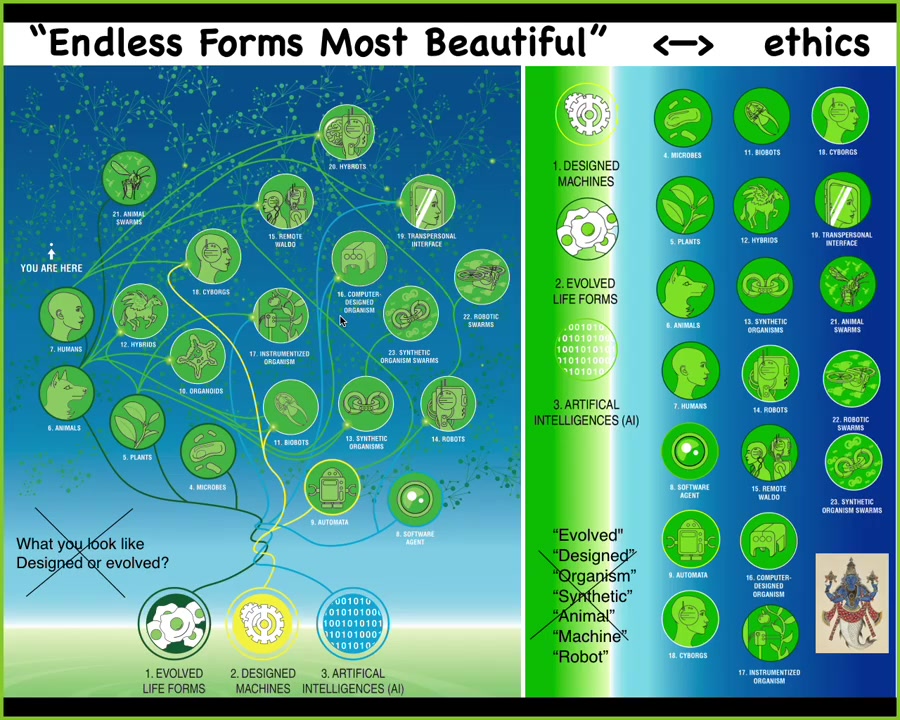

I'm going to end here with two slides to say that because Biology has to solve all these problems every time that a being arises into this world. It has to set its boundaries, figure out what the effectors are, what the sensors are. Nothing can really be assumed. It's so interoperable that any combination of evolved material at any scale, designed material and software is some kind of agent. People are already making cyborgs and hybrots and every possible combination.

We are going to be living in the next few decades in a huge option space of new bodies and new minds. Darwin said "endless forms" is the most beautiful about the natural forms. This is a tiny corner of that space.

We're going to have to come up with ways to relate to beings that are nowhere on our tree of life. These old criteria of what do you look like and how did you get here are not going to be useful anymore. All of these binary categories are going to wash away as well, because when people make claims about machines and robots and organisms, it's very difficult to support any kind of clean separation.

Slide 32/33 · 31m:53s

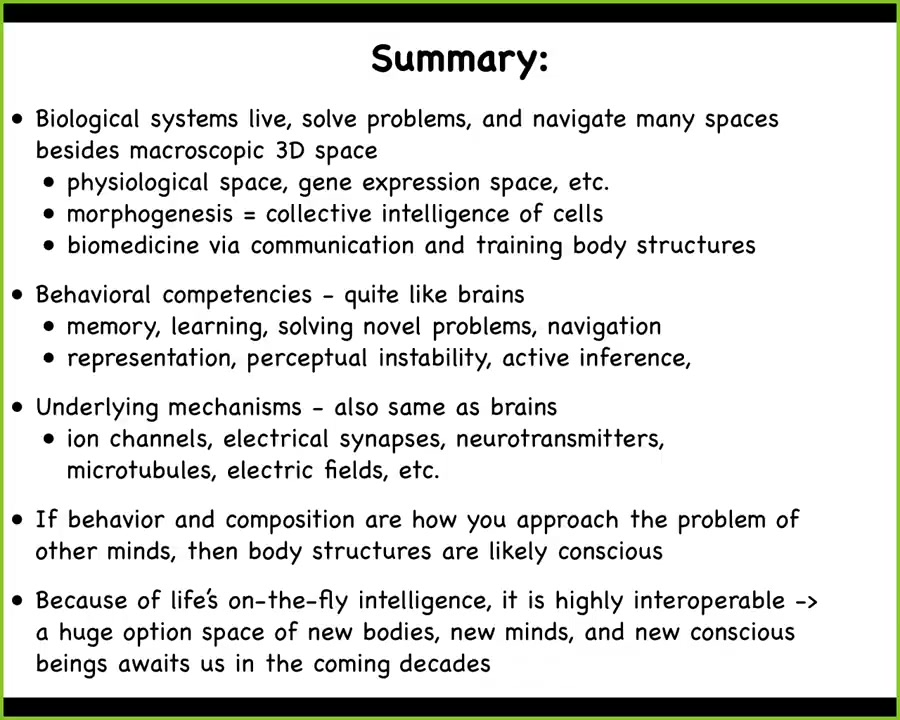

I'm going to stop here and summarize what I've tried to say: biological systems solve and operate in all kinds of spaces. They have behavioral competencies that include memory and learning, problem solving, navigation, representation, perceptual stability, active inference. The underlying mechanisms are also the same. They use ion channels, electrical synapses, neurotransmitters, microtubules, electric fields. All of that is present in the structures of bodies. If these are the kinds of things that we think are associated with consciousness, we have to take very seriously the possibility that there are other unconventional consciousnesses in our bodies and increasingly being made by bioengineering efforts.

Slide 33/33 · 32m:41s

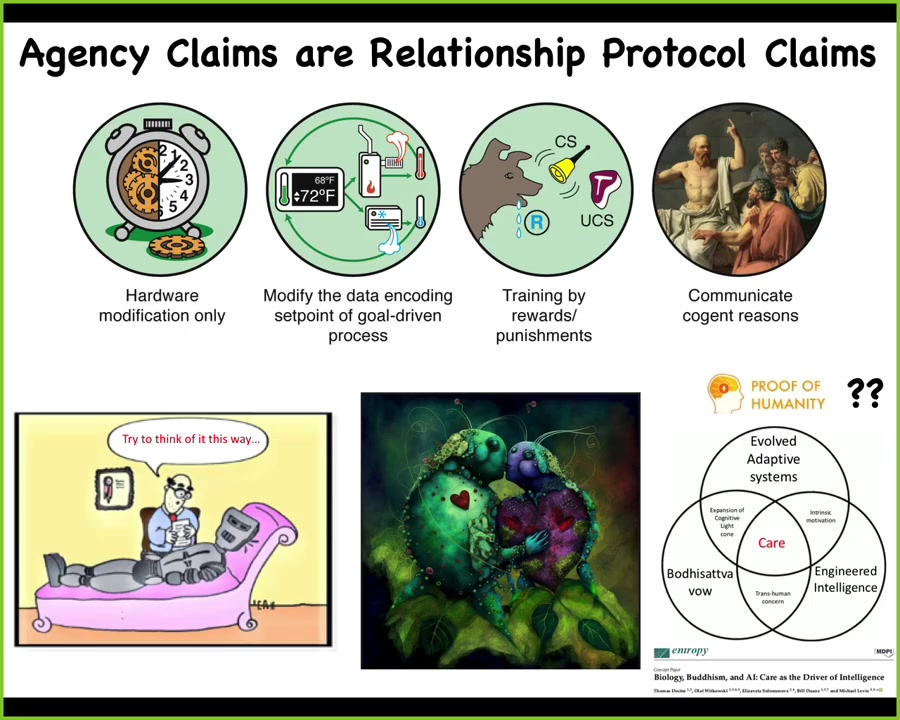

Taking a step back of how we think about these things, all agency claims are really protocol claims for how you can optimally relate to that system. And so as an engineer, I want to guess correctly for various systems as where I am on this spectrum. But of course, it's not just about engineering, it's also about relationships. People are trying to develop proof of humanity certificates. The question then becomes, what do you really want when you have proof of humanity? Are you looking for proof of native DNA? Are you looking for proof of native anatomical structure or something that we explore here, which is a competency for compassion? Maybe that's the more important thing. This is an example. Midjourney is an AI system that I asked to draw its vision of two synthetic organisms in love. This is what I drew.

If anybody's interested, these two papers are especially relevant, but there's a whole bunch of work on this.

I want to thank all the people who did the work that I showed you today, all our many collaborators, of course, and our funders. I thank you for listening.