Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a very fast (~33min) flyover of some ideas relevant to the relationship between biology, computation, cognition, consciousness, and related subjects. This was given at the amazing Progress and Visions in Consciousness Science series (https://amcs-community.org/events/progress-visions-series/) as the prologue to a discussion.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Introduction and mind blindness

(04:23) Collective intelligence in morphogenesis

(11:33) Biological problem solving

(16:35) Creative interpretation and evolution

(23:24) Novel beings and goals

(30:21) Platonic space of minds

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/30 · 00m:00s

And what I thought I would take you through is some ideas that at the beginning of the talk, some things I feel pretty strongly about, and then some things at the end, which are way at the edge of what we know and speculation that I think is useful nevertheless.

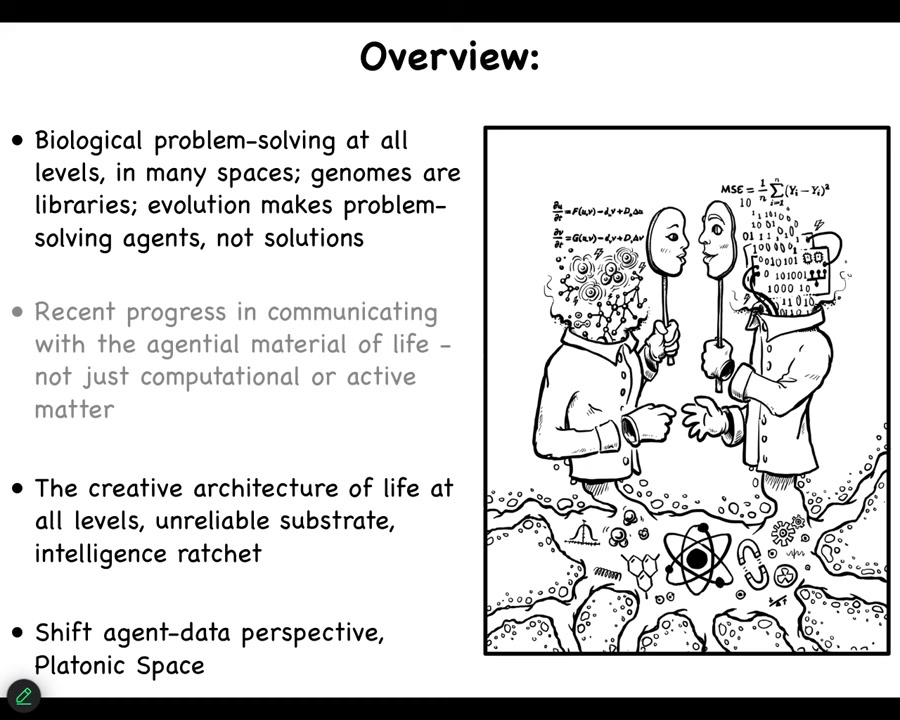

Here are four things I'm going to try to talk about very quickly. First of all, I'm going to address this issue of biology solving problems at all levels in all kinds of problem spaces. I argue that genomes are not drivers. If anything, they are more like libraries of affordances, and that evolution makes problem-solving agents, not solutions to specific problems. I will not have time to talk about this. Normally, if I give a long talk, I actually show how we go about communicating with the agential material that underlies life, because this is where we have most of our data.

Then I will give some thoughts about the fact that the architecture of life is fundamentally creative because it is dealing with an unreliable substrate and that this gives rise to a really powerful intelligence ratchet. Towards the end, if we have time, I'll talk about some recent ideas about shifting the perspective of agents versus data and how the notion of platonic space can be useful for research.

Slide 2/30 · 01m:24s

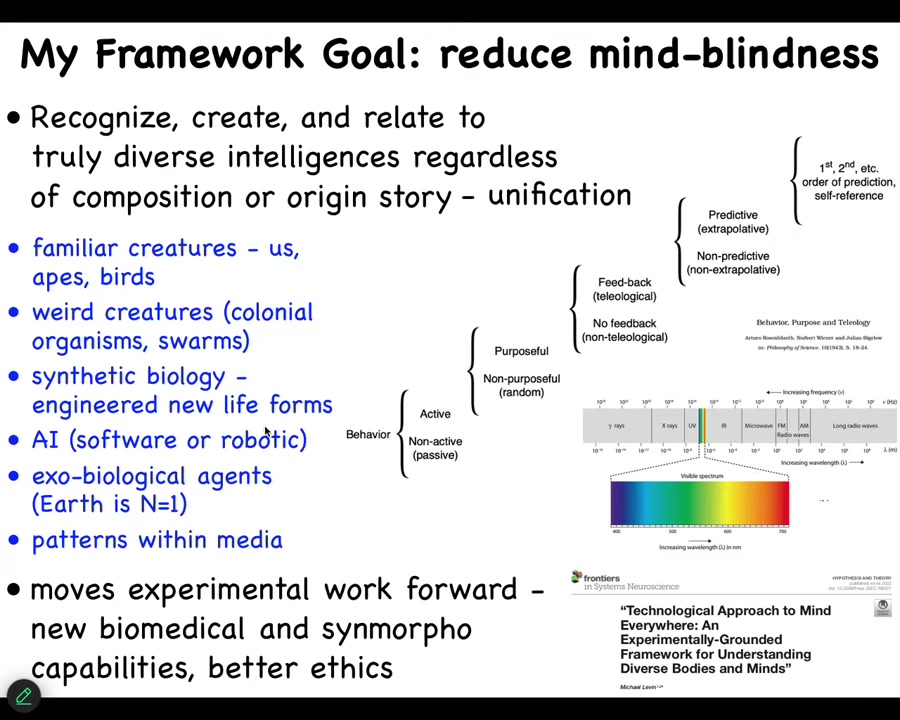

What I'm interested in is to address something that I think we have, which is a degree of mind blindness. You can think about this as the electromagnetic spectrum. It used to be that things that happen when you wave magnets around, light, x-rays, all of those things were thought to be very different things.

Something interesting happened when we ended up with a proper theory of electromagnetism, which is that phenomena that were thought to be extremely different turned out to be manifestations of the same thing. We have an idea for how they relate to each other. It allowed a technology to be made that enables us to detect and interact with and make use of all kinds of things that were completely inaccessible to us with our natural set of senses.

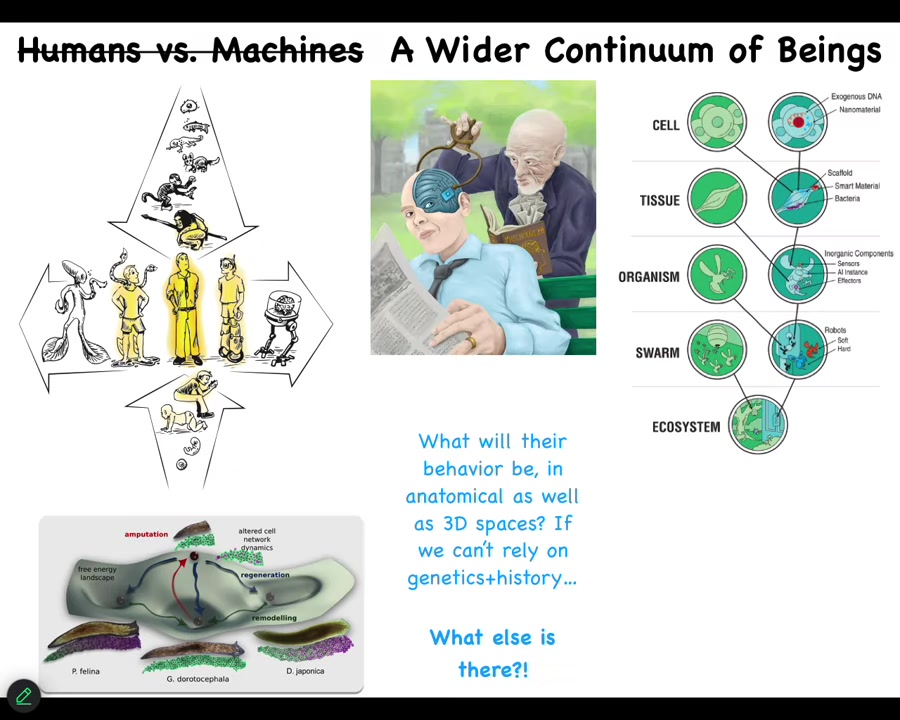

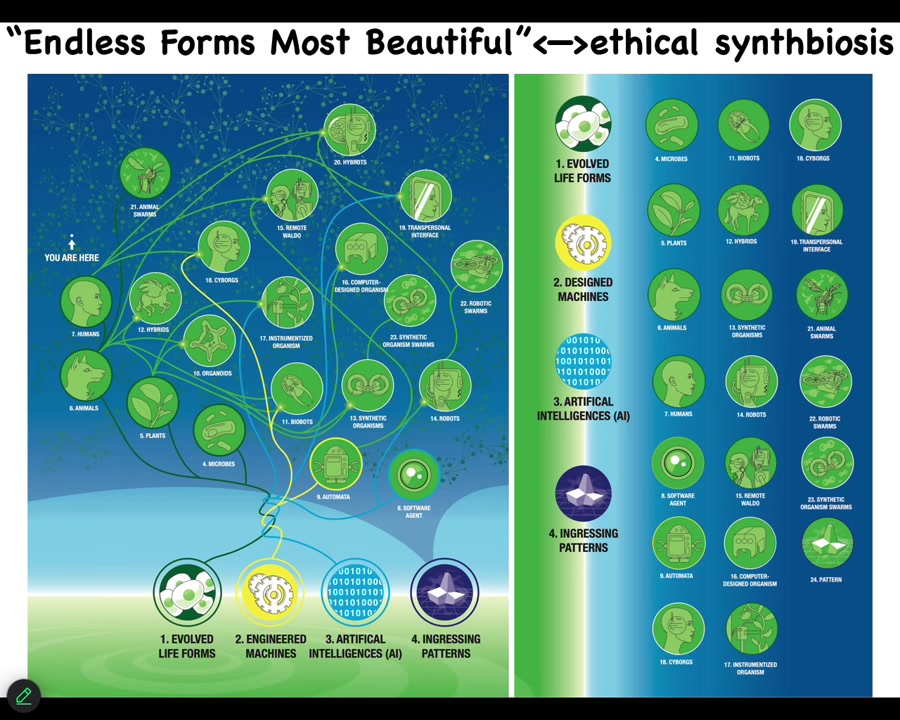

I think something like that is happening with cognition, where evolution has given us some firmware that enables us to recognize a certain, extremely narrow range of kinds of minds. I think we need to develop theory, and that will lead to practical tools to enable us to recognize, create, and ethically relate to a very wide, diverse set of intelligences, regardless of how they got here or what they're made of. We're interested in my group in understanding how to relate to all of these kinds of weird things. In particular, very important to move experimental work forward. I like philosophical ideas that end up being computational models and then end up being applications and eventually therapeutics. This is why part of the lab does birth defects, regenerative medicine, cancer, because then we know we're on the right track.

Slide 3/30 · 03m:15s

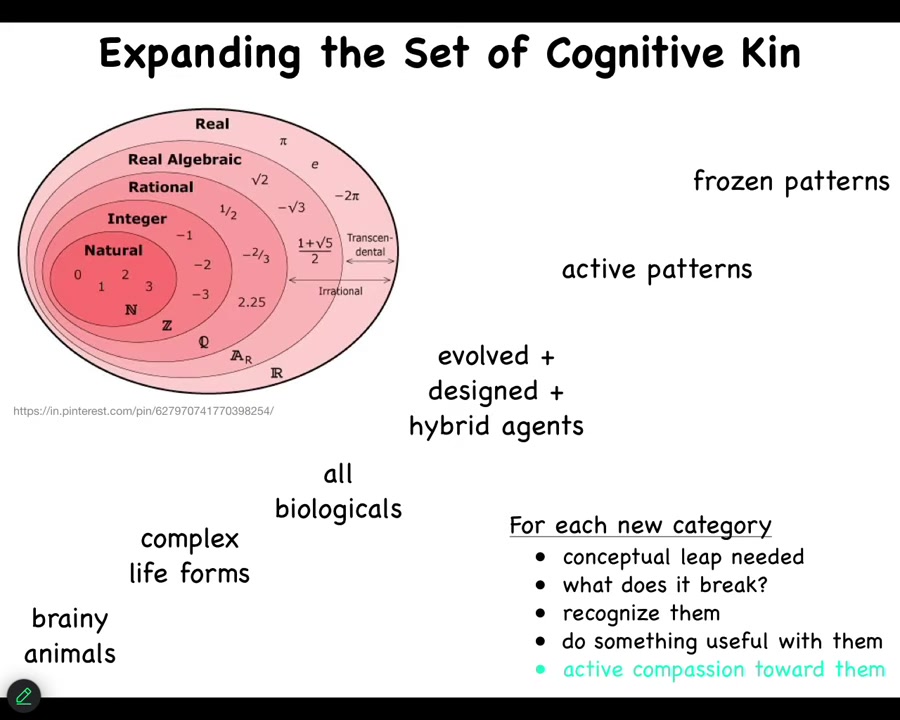

I've just made a recent talk about all of this. It's similar to what happened to different kinds of numbers, where we slowly, with certain kinds of schisms and people freaking out when they discover certain new kinds of numbers. We've enlarged, even though some of these sets are infinite, we've discovered novel degrees of infinity and new kinds of numbers. I think the same thing is happening and going to happen more with the sets of cognitive agents that are out there. We all can recognize this. Some of us are okay with this, but actually it gets really weird. I'm not prepared to talk much about this today, but we can certainly talk about this. The infinity of sentient forms, I think, once we understand what we're looking at, is getting bigger and bigger and bigger. We can think about for each of these things what is needed to be able to recognize these things, and then what does it break for our assumptions? And then how do we do something useful?

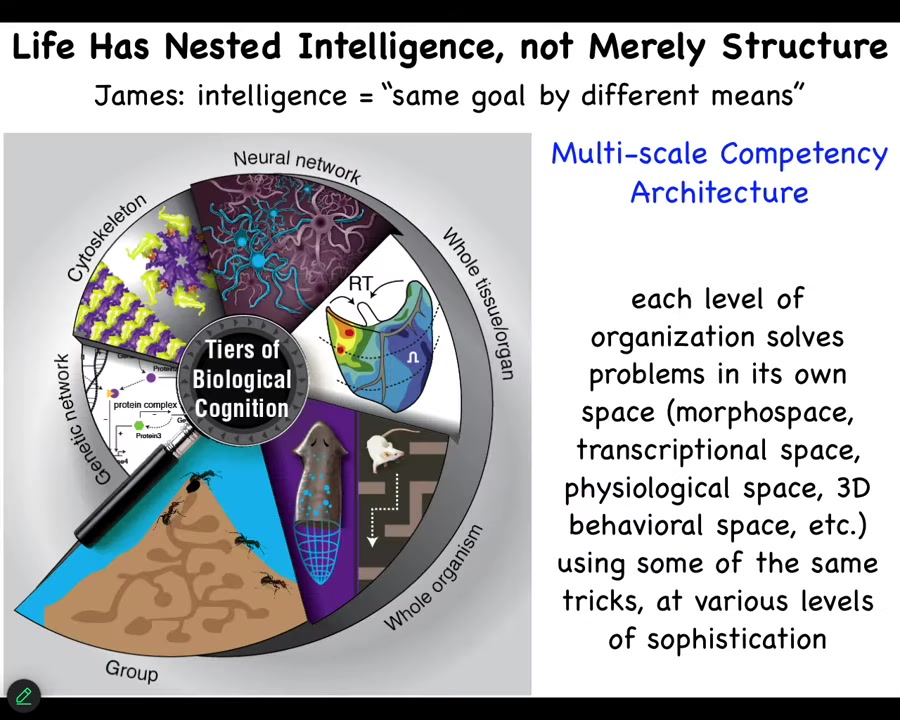

The first section here is I'm just going to show you a little bit of biology and this idea that what we call life are systems that self-assemble into a multi-scale competency architecture where every level has agendas and certain capabilities, which explores problem spaces by aligning its parts towards larger and more diverse goals.

Slide 4/30 · 04m:44s

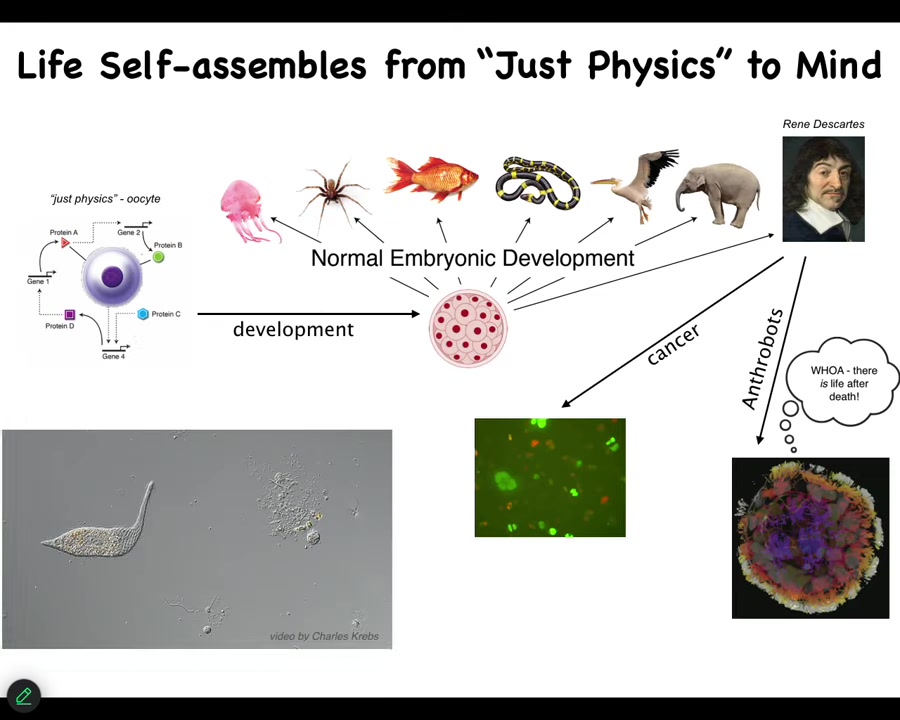

This is the journey that each of us takes from physics and chemistry, which describe this quiescent oocyte. That's how we all start life. Eventually, through this slow, gradual, continuous process, no magic lightning flashes that suddenly push us into the realm of psychology. Eventually we end up being something like this. This is what we're made of.

These are single cells. This is a free-living organism, but you can see in a single cell, no brain, no nervous system. It has all kinds of capacities to pursue its own tiny little goals. And then life normally goes this way. It can take some twists and turns. It can have a breakdown of multicellularity, a kind of dissociative identity disorder of the collective intelligence that gives rise to cancer. It can also, with our help, go into new directions such as these anthrobots, which can continue life even after a patient has died.

Slide 5/30 · 05m:40s

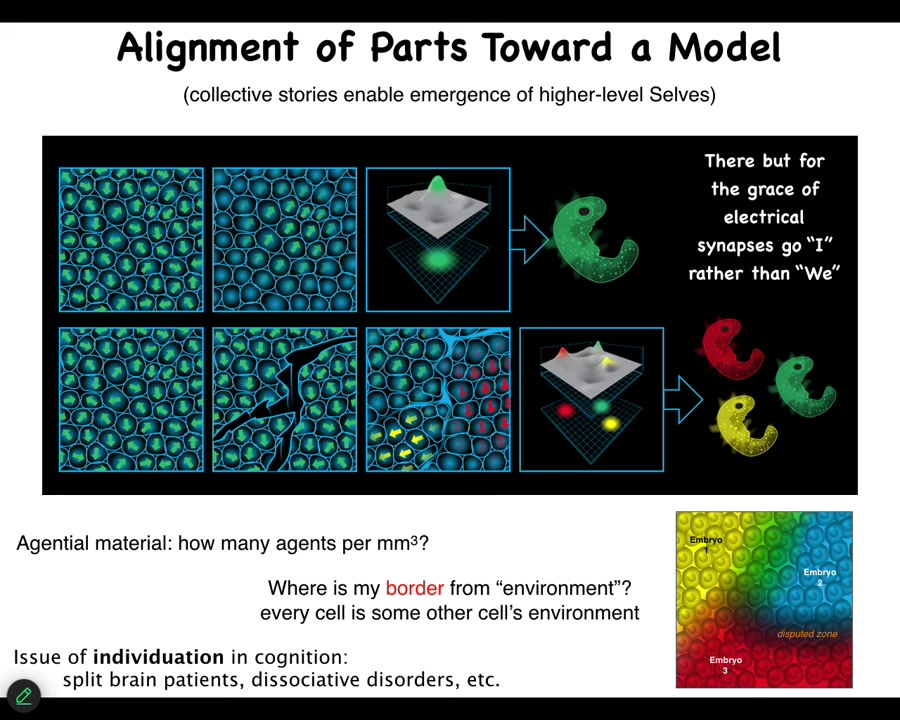

And what fundamentally happens to bring us into the world is alignment and dynamic storytelling. When we look at an embryo, at an early stage it's a sheet of 100,000 cells. Why do we look at that and we say there's one embryo? What is there one of? If there's 100,000 cells, what's there one of? Well, what there's one of is a particular model, a commitment to travel in anatomical space to a particular location that describes whatever it is that's being built, a human, a giraffe, a snake.

All of the cells are committed to this one story of what it is that they're building. The fact that they're all committed to the same story and reliably make that journey together is what allows us to call it one embryo. But I used to do this in grad school with duck embryos: you take a little needle and you put some scratches into this blastoderm. Each one of these little islands will align within itself because it can't feel the others and self-organize into a new embryo. You get multiples, twins, triplets, quadruplets, and so on, which may or may not then heal up and reattach. In the meantime, you have multiple individuals.

So the question is how many cells are present in an embryo is not at all obvious. It's a self-organizing process that leads to the manifestation of anywhere from zero to half a dozen or more individuals. The capacity of this excitable medium is not really clear, much like it's not really clear in the brain at all, of how many actual individuals fit into a particular amount of real estate. We can talk about that.

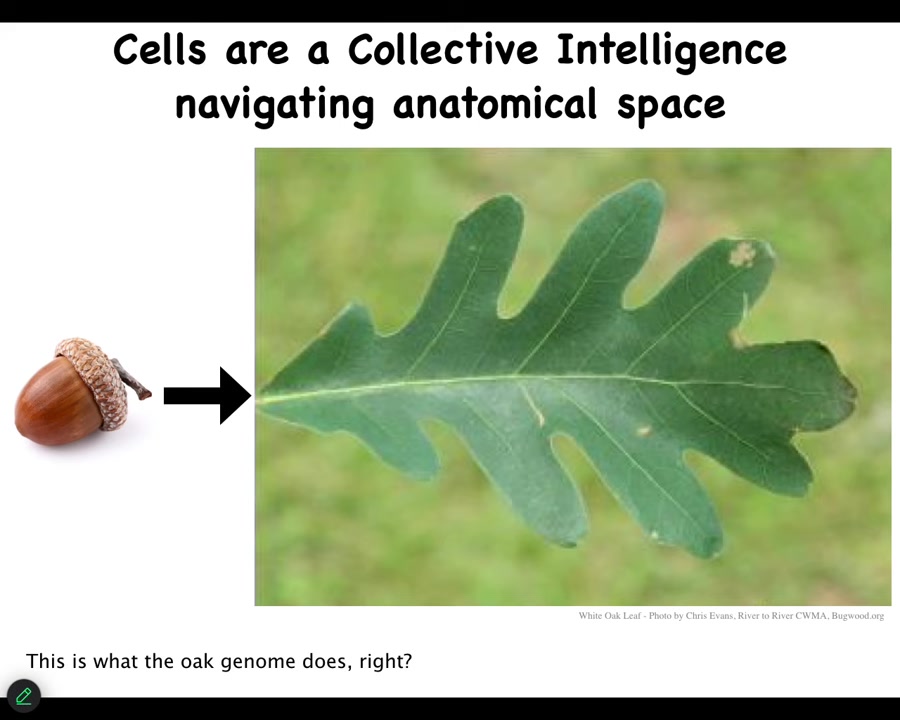

What you have here is alignment, both physical and functional, to a particular model of navigation of that space. Like any good collective intelligence, or any intelligence really, we can think about how reliably it does its job, so here are acorns.

Slide 6/30 · 07m:33s

They make these oak leaves. We think that this is what the oak genome knows how to do: direct the formation of exactly this pattern. It's incredibly reliable. They're very good at doing their job, these cells.

Slide 7/30 · 07m:56s

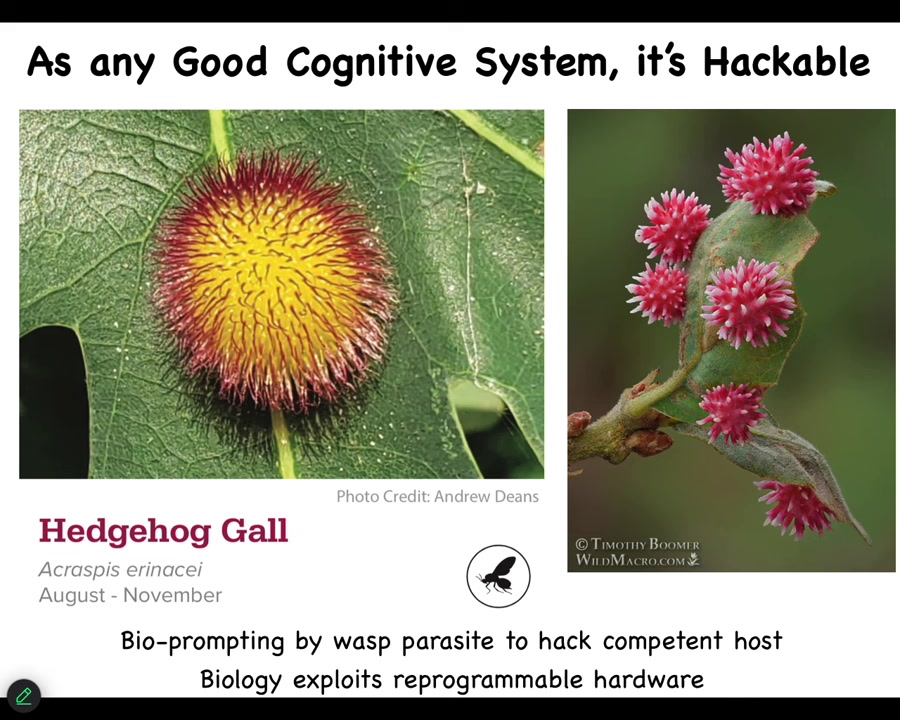

It's hackable. This is an example of a non-human bioengineer, this little wasp, that comes around and deposits some signals, a bio-prompting that causes these cells to build something completely different. You'd have no idea that these flat green things were actually capable of building something like this or something like this. There are lots of examples of how life hacks itself and each other and how we are learning to do it.

Slide 8/30 · 08m:26s

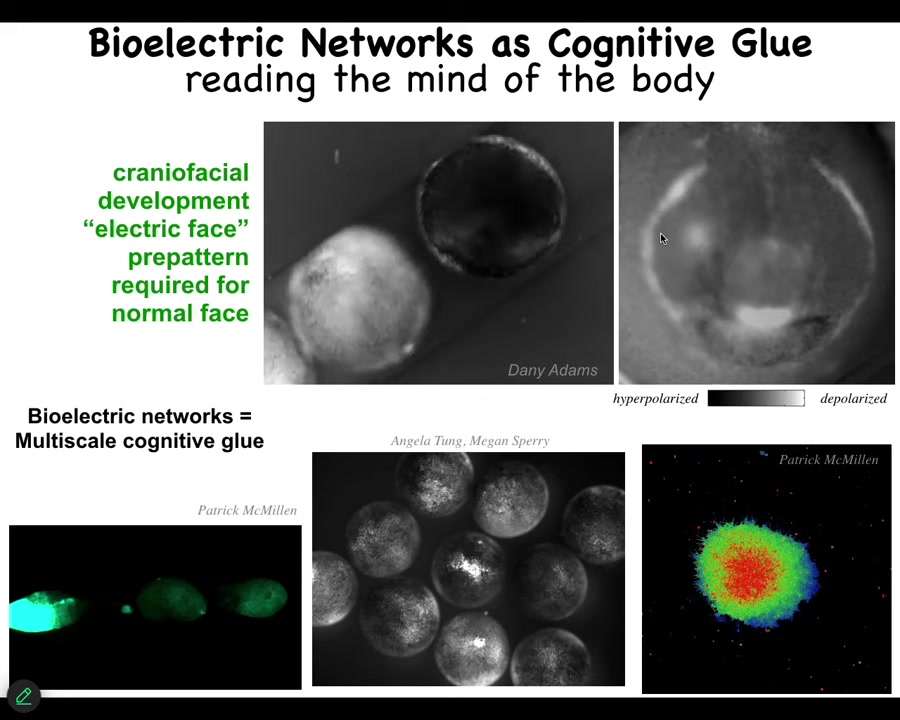

One of the most interesting interfaces to this collective intelligence, much like in the brain. So what is it in the brain? It's bioelectricity, electrophysiology. That's actually extremely ancient. It was used as a cognitive glue by evolution long before brains and muscles appeared. We now have ways to observe and manipulate it.

This is an early frog embryo putting its face together. You can see that the colors are voltage. The colors are the different voltages of the cells. This is one frame. What you're seeing here is reading out the memories inside the collective intelligence that's navigating that anatomical space. This is the memory, this is the face. Here's where the mouth is going to go, here's where the right eye is going to be, here are the placodes. This is what guides downstream gene expression and the anatomy to form a proper face. This is how they know what to do. This is their memory.

That bioelectric pattern is not just for bundling together cells to form a single embryo. It actually connects multiple embryos together. It's a multi-scale phenomenon. If I poke this guy, all of his friends — each one of these things is a separate frog embryo. Each one of them finds out about it. You can poke this one. Within some minutes, they all find out about it. Here you can see some cells doing their thing. Once you start to read these, it's basically think of neural decoding, think of trying to read the electrophysiology of the brain and extract memories and preferences and so on. We can do the same thing in morphogenesis and we can start to manipulate it.

Slide 9/30 · 10m:07s

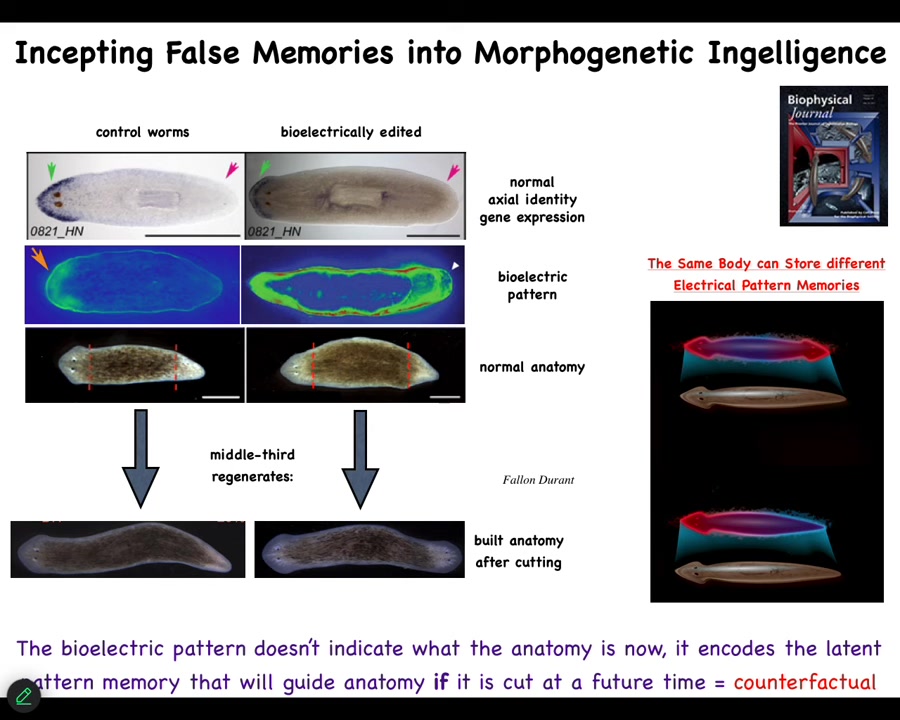

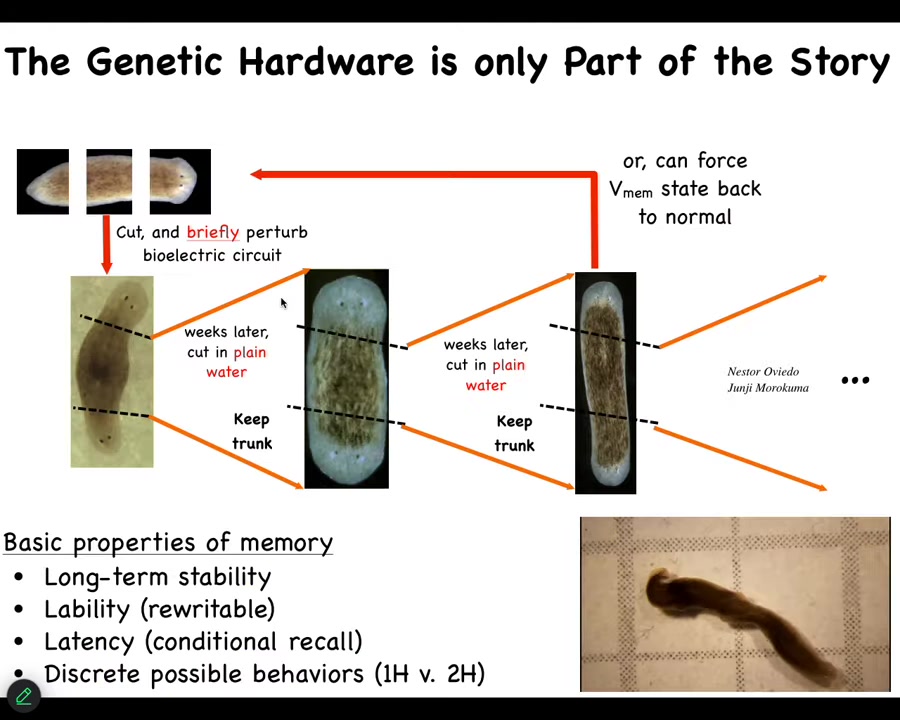

So while the normal flatworm has a very clear memory that it needs one head and one tail, so that when you cut it into pieces, every piece makes one head and one tail, we can change that.

We can incept false memories into these things using optogenetics and pharmacology and various other means. This is still messy. We're still working this out. But you can say, no, actually, you should have two heads. It's a perfectly normal one-headed animal. There he is, with the wrong internal representation of what a correct planarian should look like. It's a latent memory. In fact, it's a counterfactual because it's not true right now. He has one head.

But what happens is, if you cut them—if you cut the head and the tail—the fragment is actually going to give rise to a headed animal. I now have to tell people this is not AI, this is not Photoshop; these are real results. This is what enables the collective to know what to build and when to stop. So you can read out these pattern memories.

Slide 10/30 · 11m:05s

If you continue to cut these two-headed animals, the memory holds. It's a bioelectric memory. It is not controlled by the genetics. The genetics are totally wild-type. Nothing has changed in the genome. Sequencing the genome will not tell you that these things have two heads. It will also not tell you that the whole lineage will have two heads because you can keep cutting them. And in fact, when they reproduce, they cut themselves in half on their own and then they regenerate. They will continue to be two-headed. Here's a video. You can see what these guys are doing.

Slide 11/30 · 11m:34s

I don't have time to talk about all the cool things that the genetic networks are doing. They can learn too. You don't even need cells. The molecular networks alone have six different kinds of memory, including Pavlovian conditioning. But all of these things work together and they solve problems in various spaces.

Slide 12/30 · 12m:00s

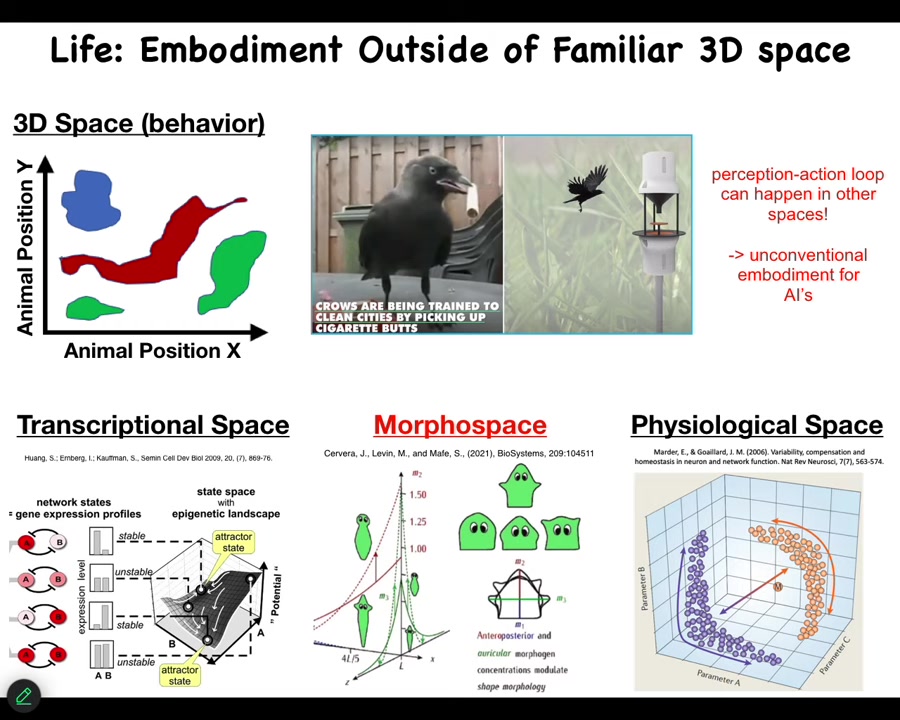

And as I mentioned before, we are tuned to recognize medium-sized objects moving at medium speeds in three-dimensional space. And so crows and primates and maybe a whale or an octopus, we can get that. But what biology is teaching us is that embodiment is not what we think. So when people say that various kinds of AIs are not embodied because they don't roll around the room on wheels and they don't walk around, that's not the right way to think about it at all, because there's lots of perception action loops and goal directedness and intelligence that take place in spaces that we cannot see.

So your cells and your tissues are navigating a high dimensional space of possible gene expressions. They're navigating a space of physiological states. And what we study is morphospace. So the space of possible anatomical configurations. And they don't just roll down hills and automatically do the same thing every single time. They are navigating with some amazing capabilities.

Slide 13/30 · 13m:04s

The kind of problem solving that they do is astounding. I'm going to show you two examples. We could talk about this for hours. It's really important for us to understand in order to make real artificial intelligence.

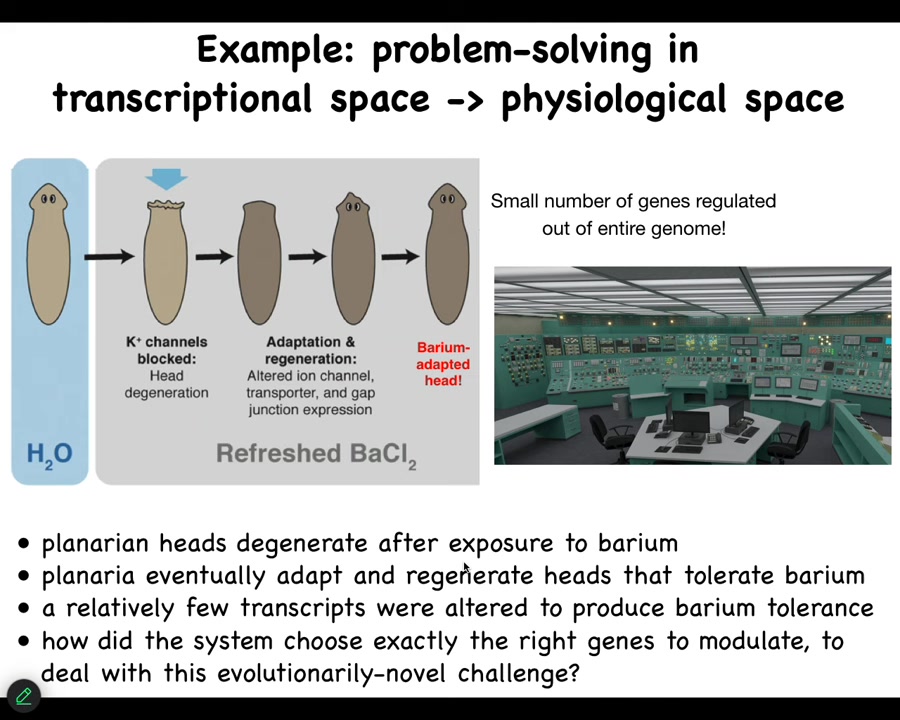

Here's one example. You take this planaria, these flatworms, you put them in a solution of barium chloride. Barium is a non-specific potassium channel blocker. It makes their cells very unhappy. Their heads explode over the next 24 hours.

If you leave them in the barium, a little while later they will make a new head, and the new head is completely fine with barium. It's barium-adapted. When you check what is different about the original head and the barium-adapted head, you find that less than a dozen genes are different.

The trick is that these planaria have never seen barium, nor in their evolutionary history has there been selection for knowing what to do when you get hit with barium.

Think about this problem. You've got an extreme physiological stressor. You have on the order of 20,000 control knobs that you can twist. It's like a Moravec bush with an incredible number of effectors. Which of these genes do you turn on and off to solve a novel stressor?

It's like being in a nuclear reactor control room. The thing's melting down. Unless you know exactly how it works, unless you have a model of your own apparatus, you can't start flipping switches randomly to see if life gets better, because you'll be dead and there's no time for that.

We need to understand how these living systems actually solve novel problems that they haven't seen before.

Slide 14/30 · 14m:44s

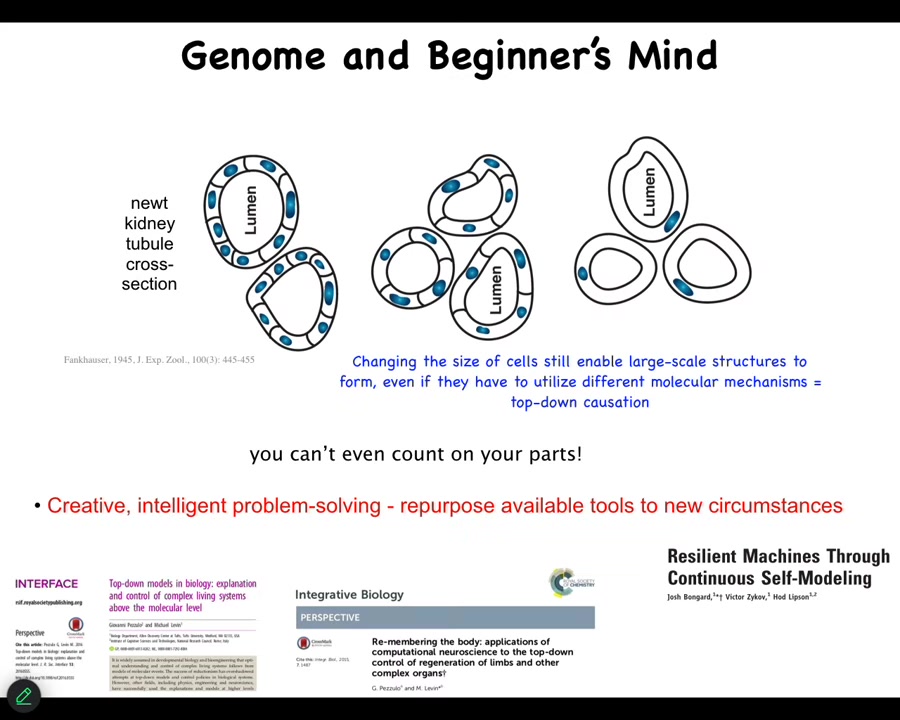

This is maybe my favorite example of all time. This is a cross-section through the kidney tubule of a salamander.

Normally, 8 to 10 cells make this thing up. You can make these newts with more copies of their genetic material. When you have more copies of their genetic material, instead of 2N chromosomes you can have 4N, 5N, 6N, and so on. When you do this, the cells get bigger. But the newt stays the same size. How can that be? It's because there are actually fewer cells that make up the same structure. The cells are bigger, but there are fewer of them.

When you make the cells truly gigantic, one cell will bend around itself like this and leave a space in the middle. Same structure.

Here are a couple of amazing parts. This is a completely different molecular mechanism. Instead of cell-to-cell communication and tubulogenesis, this is cytoskeletal bending.

The system is doing what you would do on an IQ test: use various tools at your disposal to solve the problem, to get to the same goal in novel ways beyond what you would normally do. It's creative use of the tools that you already have.

Think about what this means from the perspective of the system. You come into the world: what can you count on? You can't count on your environment. But you also don't know how many copies of your genetic material you're going to have. You don't know how big your cells are going to be. You don't know how many cells you're going to have, but you still have to make that newt. I'm going to show you can actually make other things, but you try really hard to make that newt despite the fact that you can't even rely on your own parts, never mind the environment. You can't even assume that your parts are what they are.

Unlike most of the things we program, life really operates with a polycomputing architecture where you are free to reinterpret all the messages that you have. Those are genetic messages from the past. Everything you have is up for interpretation because your substrate is unreliable. You cannot afford to care too much about what your ancestors thought your genes meant or what your past self thought your memories meant. You have to reinterpret all this stuff from scratch.

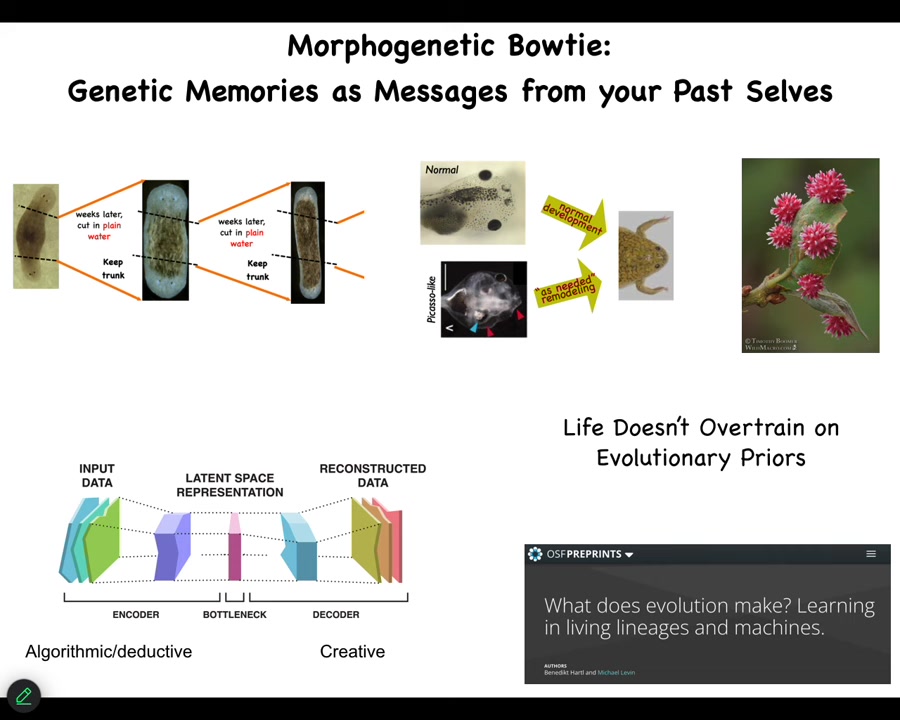

Here are a couple of examples of how this looks on three scales: the evolutionary scale, the developmental scale, and the cognitive scale.

One of the things I like to think about is caterpillars and butterflies. Caterpillars are a soft-bodied creature with a controller suitable for soft-bodied motion; they crawl around and eat leaves. They have to turn into something that lives in a three-dimensional world, flies around, is a hard-bodied creature, and needs a completely different controller. In the meantime, it liquefies its brain, kills most of the cells, breaks most of the connections, and eventually rebuilds a new butterfly brain.

If you train the caterpillar to eat leaves when it sees a particular colored disc, butterflies retain this information. On the surface, the crazy thing to think about is how do you maintain information while you're drastically refactoring the substrate? That's a cool question, but there's an even more amazing piece: the actual memories of the caterpillar are of absolutely no use to the butterfly. The butterfly doesn't crawl or eat leaves; it wants nectar. The memories of the caterpillar, if they were trying to stay intact, would never survive. But if they are able to be remapped onto a new architecture—not just carried over or persist, but actually change and remap—then they survive into this new embodiment as the creature gains a new life in a higher-dimensional space.

You have here something like the paradox of change, where, as a biological organism or a lineage, if you stay the same, you will surely die when the circumstances change. But if you change to fit those circumstances, in a sense, you, meaning the old you, are still gone. How do you persist? You cannot persist in place. That seems to be the paradox.

Slide 15/30 · 19m:07s

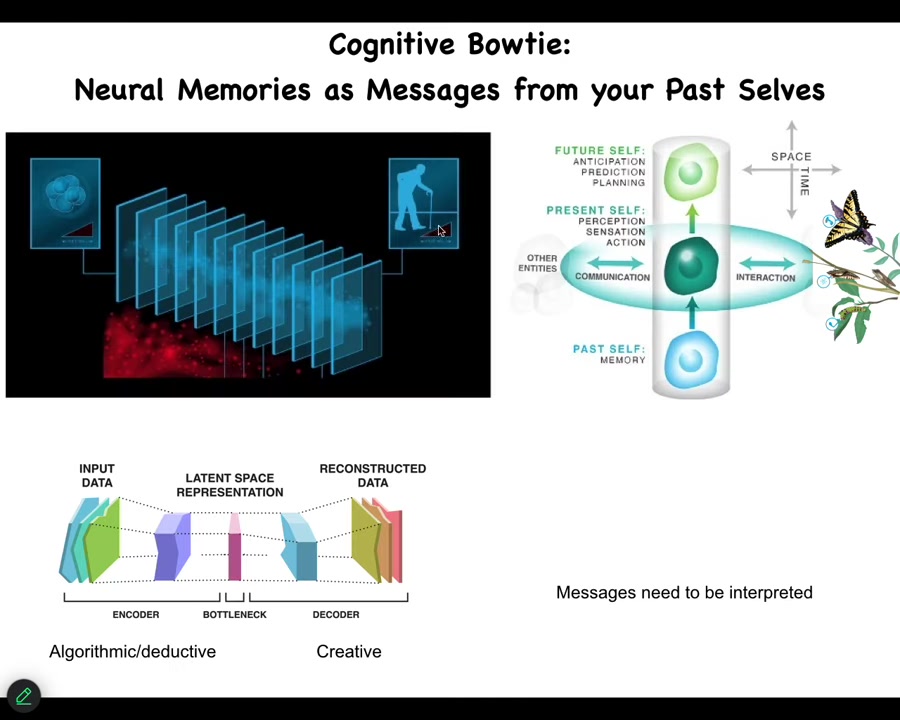

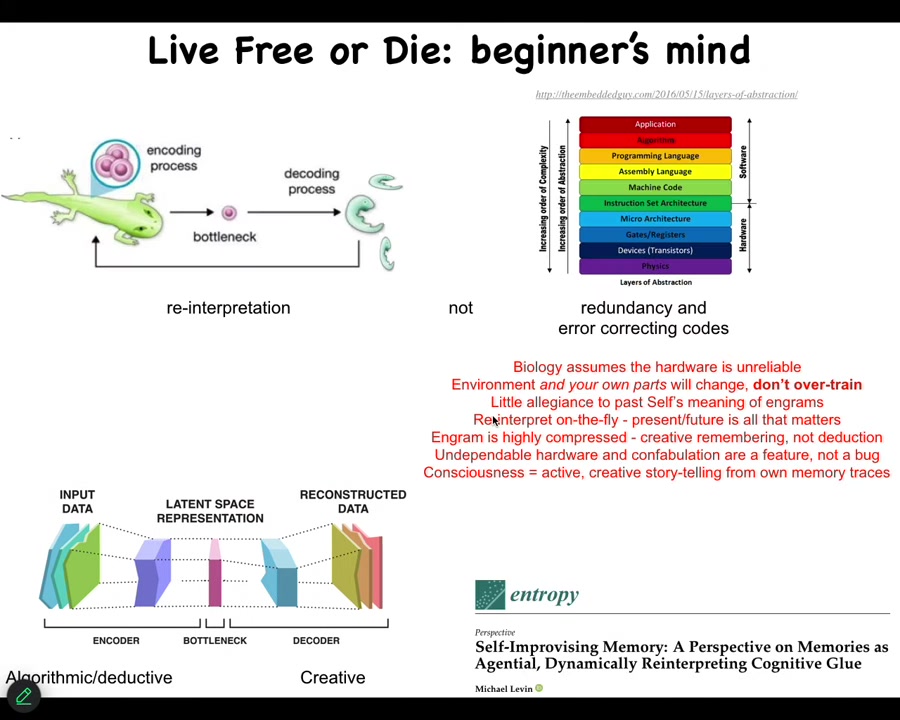

So what I like to think about is this idea that your memories, and these are memories, these are both cognitive memories and genetic memories, are just messages from your past self.

So what you don't have access to at any given moment in time is the past. You have no idea what happened in the past. What you have are memory engrams, traces left in your brain and body that were constructed by your past selves.

They were compressed, they were generalized, they went through this bottleneck. Here are all the inputs and the diverse experiences that came through. They were compressed somehow into this very thin material substrate, which are the engrams that people still fight about. But future you has to decompress them. Information was lost here. You don't actually know what these memories mean when you find a particular memory molecule or a set of electrical states in your brain. You don't actually know what they mean. You have to creatively interpret them.

I suspect that while this part can be algorithmic and deductive, this part cannot. I suspect this, and I don't exactly know what it is. But there's something else going on here, which allows those memories to be remapped in a novel context.

Every memory, every message from others at the current time, messages from past you also need to be interpreted. You don't need to care about what they meant before. What you do need to care about is how do I make them adaptive now? So what the biology is optimizing for is not fidelity of information, it's saliency. So you're not trying to keep the caterpillar memories as they are. You're trying to remap them to a new meaning and new functions.

Slide 16/30 · 20m:59s

The same thing is happening in the cognitive side. The same thing is happening in the developmental side. When you have a genome, you can find some of the stuff in this paper.

Slide 17/30 · 21m:18s

But the idea is this, that you come into the world with a certain genome, but now comes the creative process. This is all of past history; this is your genetics. If you're an embryo or a regenerating organ or anything like that, is to say, what do these things mean? And in my current environment and given what's going on now, how do I use this information to do something useful? We have lots of examples in biology of this happening. I'll show you a couple more.

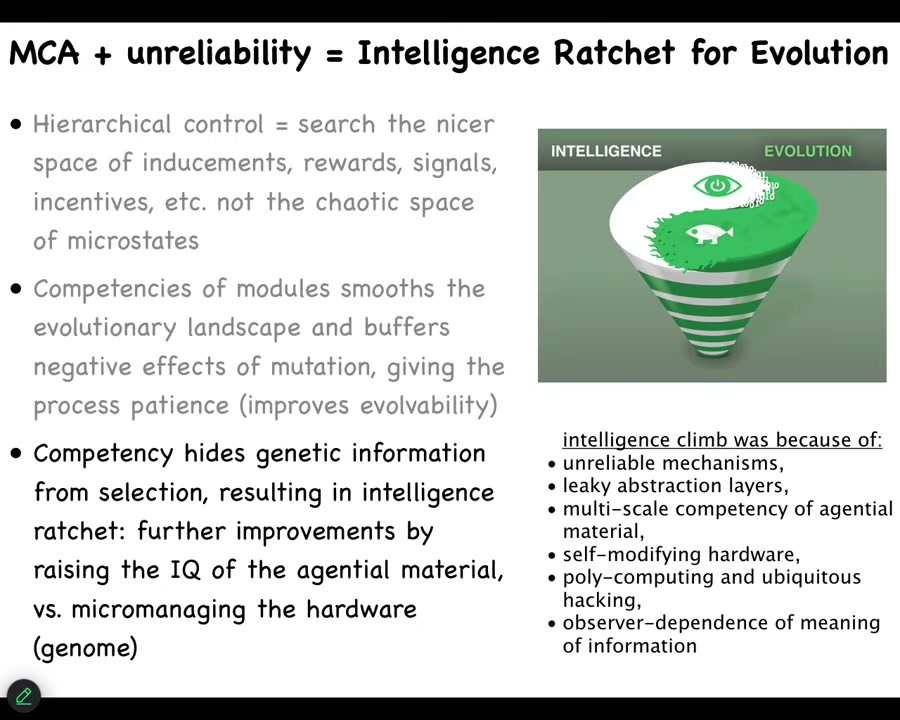

The idea is that you can't overtrain on what the past was. You assume that the hardware is unreliable, meaning you're going to get mutated. Proteins come and go. You have no idea exactly how many of anything is in your cell. All of that stuff is very fluid. For this reason, you have to commit to interpreting on the fly. And what evolution does is produce systems that are very good at creative interpretation of data. First, that was the case physiologically, then genetically and developmentally, and then eventually conventional cognition. And again, all of this is here.

Slide 18/30 · 22m:28s

This gives rise to an interesting intelligence ratchet. The more creative interpretation of your genome you do during development, the harder it is for selection to know whether your genome was any good or not. We've done simulations of this to show that what happens when you evolve over a competent material like this is that the pressure on the structural genome comes off and all of the work of evolution starts being done on the actual algorithm of the creative interpretation of the tools that you have. With each run through that loop, it becomes harder and harder to select better genomes because you can't see them. You can see the fact that useful phenotypes had appeared. I think that ratchet started very early on and it contributes to the amazing conventional intelligence that we see in the animal world.

Slide 19/30 · 23m:25s

The last part is this. The systems that I showed you, when I talk about problem solving, what I've been showing you are systems that can get to their goal by different means. That's William James's definition of intelligence.

The newt will be the same size even if you mess with the genetics or the size of cells.

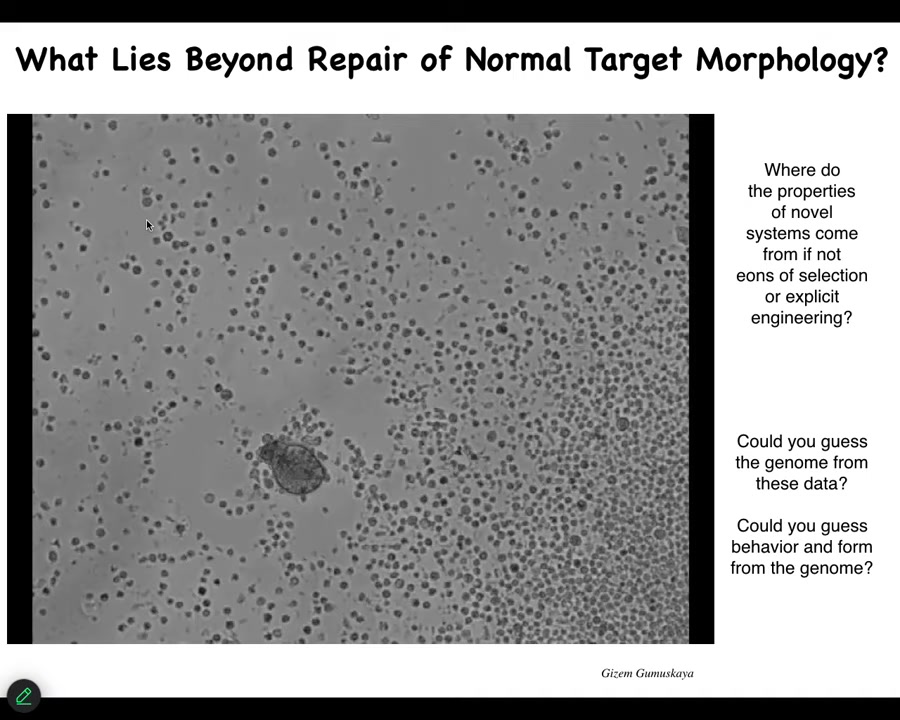

But what happens when you make novel systems? Where do their goals come from? Because for all of the natural systems, you could say evolution did that. Evolution gave you the goal. That's what we normally say. Why does this animal look the way it looks? Why does it have the behaviors that it has? Because of selection. Eons of selection gave you that goal.

What happens in novel systems? I'm very interested in where goals come from. I don't think they come from evolution per se. We wanted a model system that tries to study that aspect of it.

In biology, we like genetics and environment, and those are the two sources of information that we think.

Slide 20/30 · 24m:33s

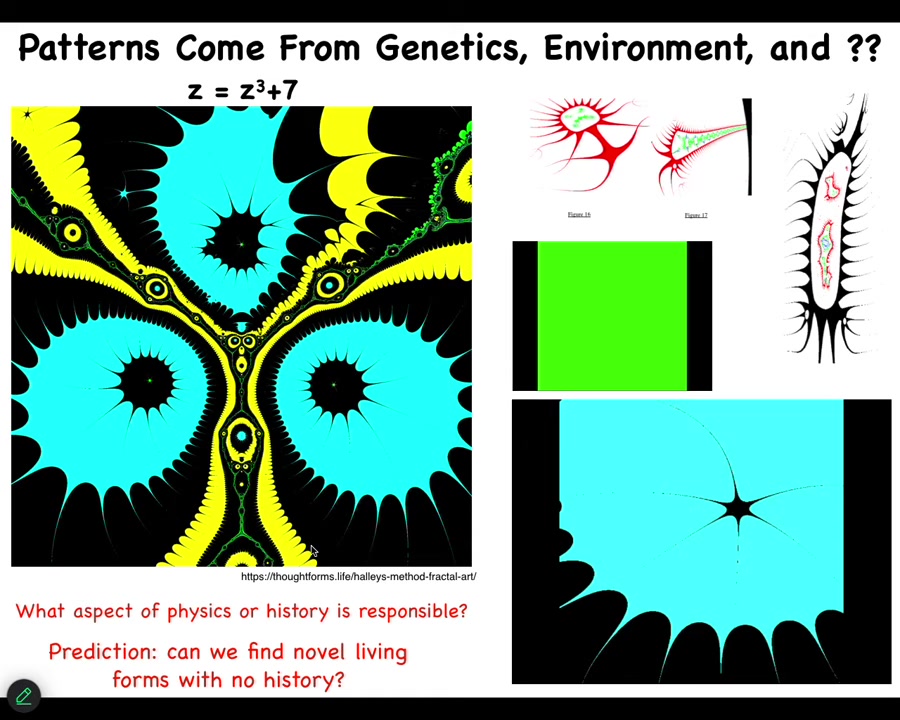

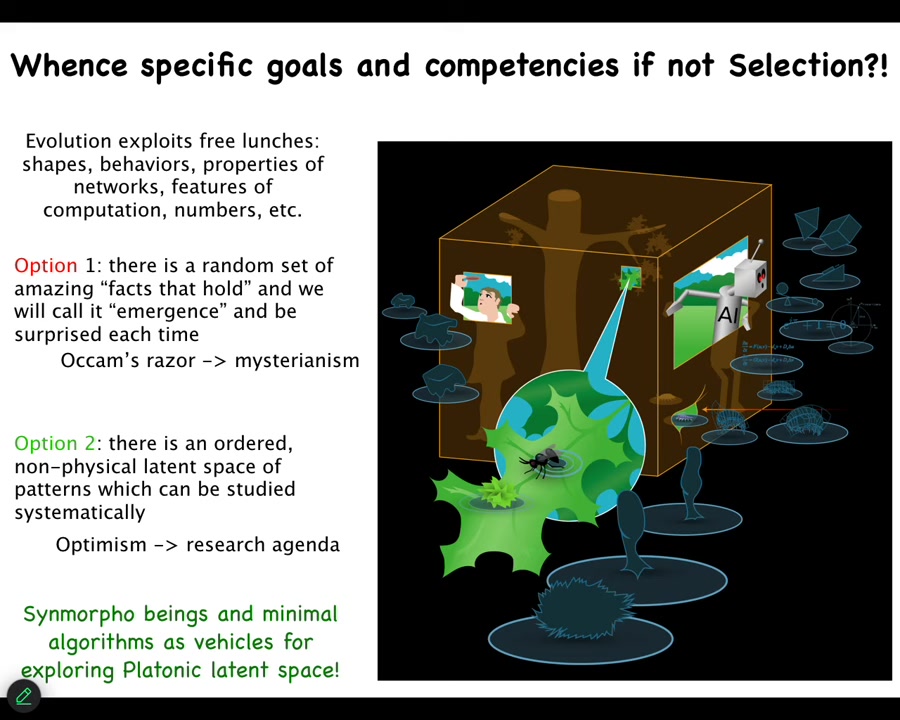

I'm very interested in this kind of stuff. When we make novel beings, whether technological hybrids or biological, cyborgs and augmented humans — all kinds of weird stuff that is already partially in existence — these things here don't necessarily have a history of selection for specific properties. Where do these patterns come from if it's not selection?

One story I didn't show you is that there is an anatomical space. There are these attractors that correspond to different species shapes. We can show that the same genetic hardware can visit multiple attractors. It doesn't have to go to its species-specific attractor, but they're there. People will say these are shaped by evolution. I'm interested in patterns that don't have a history and don't have an explanation in terms of physics. What could that possibly be?

Slide 21/30 · 25m:31s

Here's one example. This thing is called a Halley plot. There are a million examples; I just like these. It's a fractal from plotting this very simple formula. This tiny little seed in the complex number Z gives you this. If you slowly change one of these numbers, you'll get videos of all this.

You can make all sorts of other things. Clearly, clear complexity. It doesn't hurt that it's kind of organic looking as well. What's interesting about it is that, to my knowledge, it does not have an explanation in physics. It does not have an explanation of history. It was not evolved. It was not selected. It is in some way indexed into by this tiny little seed or pointer.

I don't think you can call it a compression, but clearly there are patterns from mathematics that do not have the conventional kind of explanation that biological patterns have. So how much of this is actually relevant to biology?

Slide 22/30 · 26m:41s

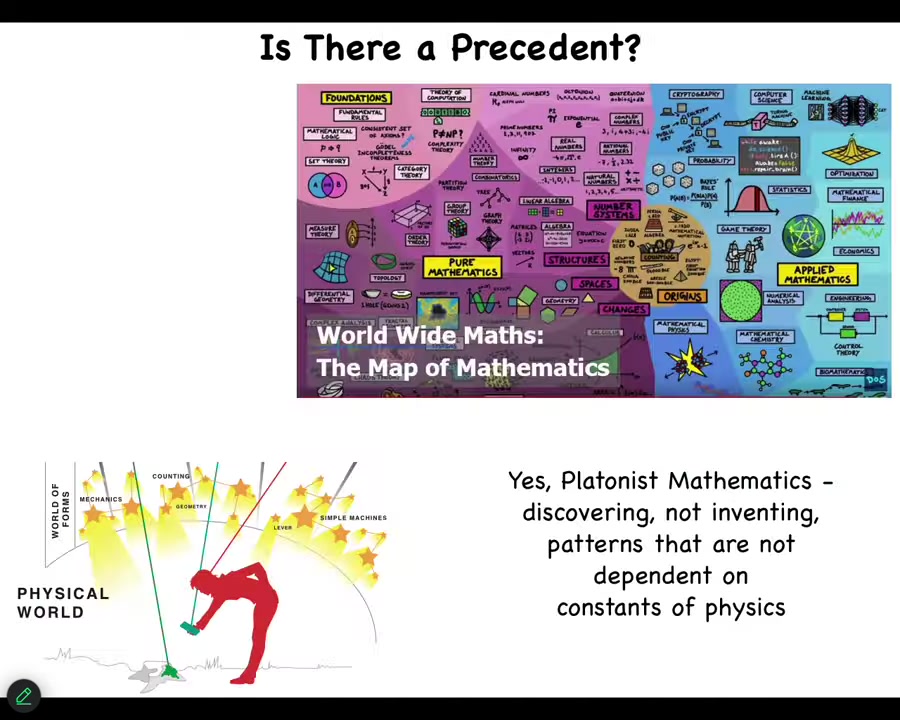

So biologists hate this idea because they want a nice sparse ontology where you have the physical world and that's it, and they don't want any weird stuff. But I think a lot of mathematicians are actually pretty comfortable that what they're doing is exploring a completely different world that is not, in fact, explained by any fact of physics. It matters for physics. So it has influence in the physical world. But it isn't something that you're going to find by studying physics. And so we've started to ask, what other kinds of patterns might be interesting for biology?

Slide 23/30 · 27m:20s

I'll show you just a couple of quick things. This little thing, when you're looking at it, you might think that this is a primitive organism that we found from a pond somewhere. If you were to sequence the genome, you would find out that you're very mistaken. The genome is Homo sapiens.

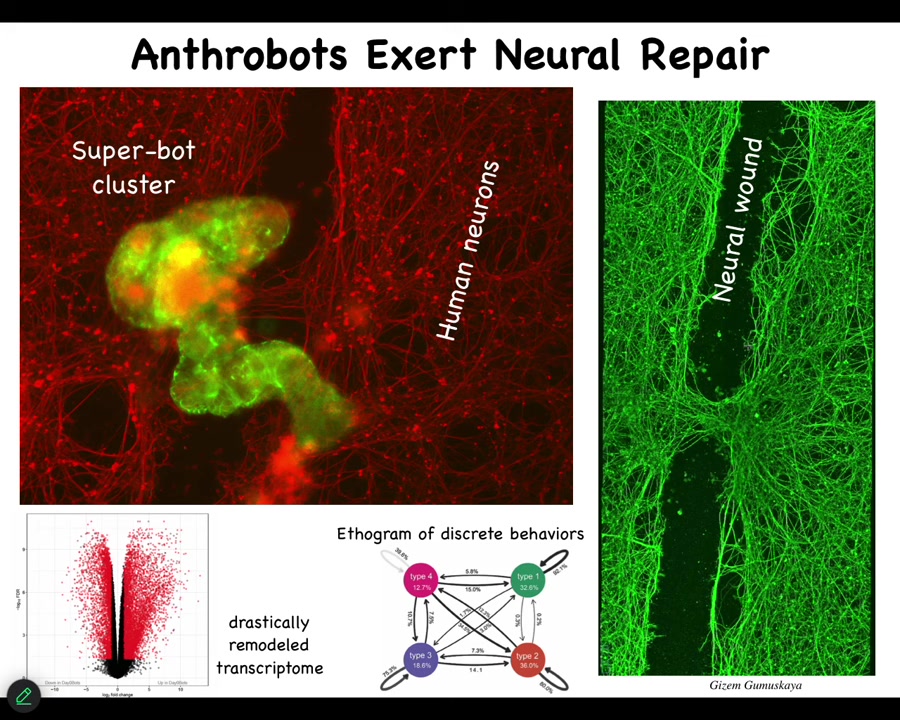

We call these anthrobots. They're self-constructing little biobots that are made from adult human tracheal epithelial cells. They are not embryonic. There's no embryonic tissue here. They don't resemble any stage of normal human development. They are what your cells do when liberated from the rest of your body and given a chance to have a new life. The patient that donated these may or may not be alive, but these guys have rebooted their multicellularity. They do some cool stuff.

Slide 24/30 · 28m:09s

They have novel behaviors, which we can arrange in ethograms, like we do for animals. Half their genome is expressed differently than what they were doing when they were part of the tissue inside the patient. They have cool properties like they will heal your neural wounds. So if you make a big scratch through this neural tissue in vitro, they'll sit here in this biobot cluster and heal it. You can see here that your tracheal cells can do this.

Slide 25/30 · 28m:37s

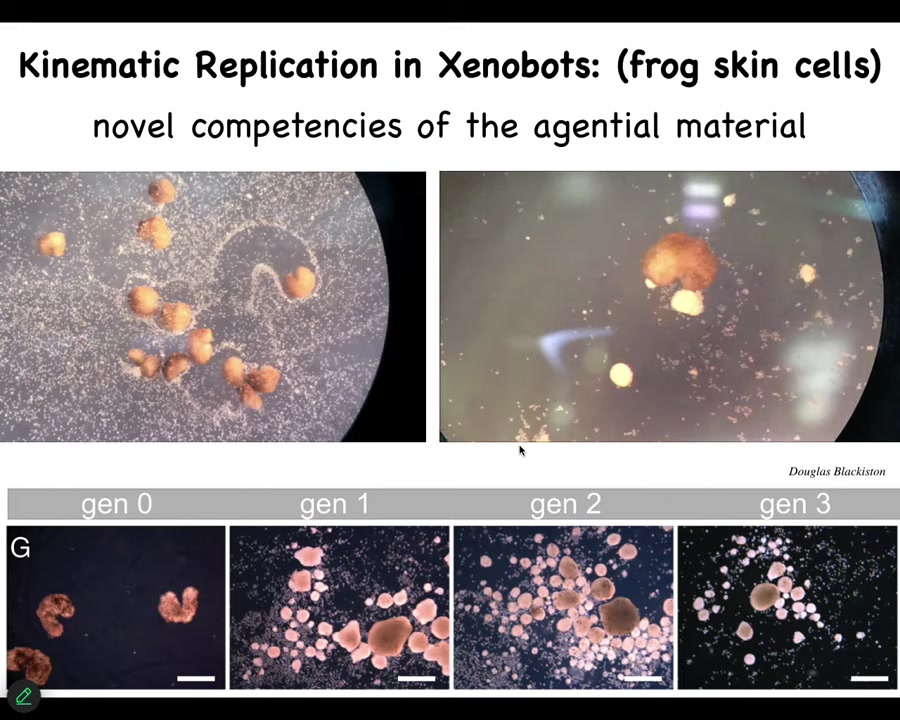

We've done this with frog embryos too. These are xenobots, which are made from frog skin cells, embryonic epithelial cells. They don't have the ability to reproduce the way normal frogs do, but they've figured out something different. This is von Neumann's dream of a robot that finds material and makes copies of itself. If you provide them with loose epithelial cells, they will push them together into little piles. They then polish the little piles. The little piles mature into the next generation of xenobots. And guess what that does? It does the same thing. It makes the next generation and the next. None of this existed before in evolution. There's been no evolutionary pressure to be a good xenobot or to be a good anthrobot. So now we're confronted with two options to try to deal with these novel forms, behaviors, and other patterns that are not directly selected for by evolution. We can say they're emergent, which just means that they're surprising to us. We can catalog them, and when we come across them, there they are, we find emergent things.

Slide 26/30 · 29m:45s

I don't like it. It allows you to have a sparse ontology, but it's a mysterian position. I don't like saying that it's a fact that holds in the physical world, and that's that. I prefer a more optimistic version, which is to say, much like the mathematicians, there's probably an ordered space of these things. We should have a research agenda to systematically investigate them, and the things that we're making, such as Xenobots, Anthrobots, various chimeras, and some other crazy stuff such as minimal algorithms, are actually vehicles. They're exploration vehicles that you can use to look for patterns in the latent space of possibilities and understand how those patterns come into the physical world and under what circumstances.

Slide 27/30 · 30m:33s

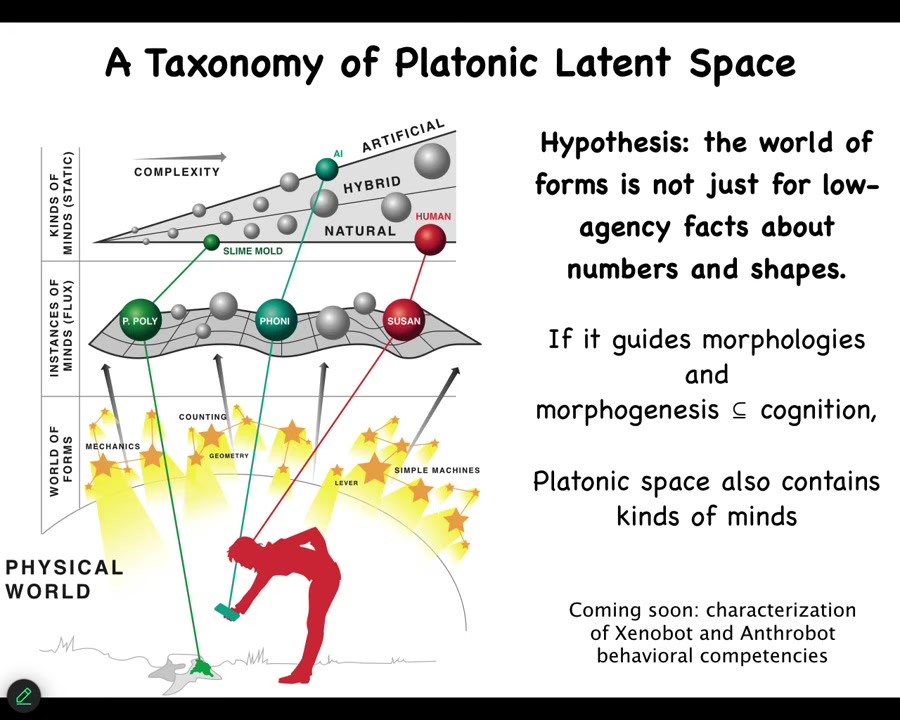

So this is my current hypothesis, and certainly other people have put out versions of this in the past, but the idea is that I think we now have actual tools that we can begin to study this and to figure out why it is that the frog genome doesn't just point to frog morphologies, but actually it knows how to make many different things that it pulls down. And so what I think is that the platonic space doesn't just contain things that mathematicians like, such as facts about prime numbers, but also things that we would recognize as kinds of minds, in other words, behavioral patterns and capabilities. And what we make, when we produce embryos, xenobots, computers, pretty much anything, you're not really making these kinds of things. What you're doing is making pointers that allow the ingression of specific patterns from that space into the physical world. And our job is to understand the relationship between the pointers and the thing they bring down.

Slide 28/30 · 31m:33s

I'm going to stop because I already ran way out of time. But just to point out that natural living things are a tiny corner of the possible space of beings because any combination of evolved material, engineered material, and software is some kind of a system that's going to pull down interesting patterns from the space that we are very bad at predicting. We do not know when these things come. They come in extremely minimal forms. It doesn't take much.

We found crazy capabilities in classical sorting algorithms, things like bubble sort, which have been studied for decades.

Slide 29/30 · 32m:12s

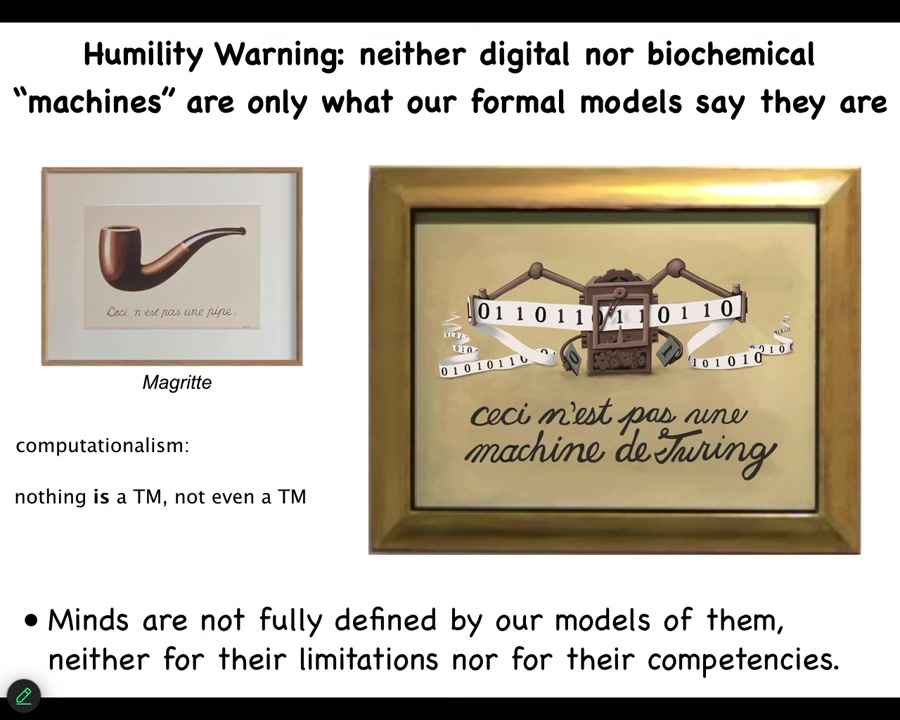

I think what Magritte was trying to tell us here when he said "this is not a pipe" is that when people say, "I know what it is, I've built it, I built it with my own hands, I chose the material, so I know what this is and I know what it can do," we have to be extremely careful because I don't think anything is exactly what the algorithm or the material says it is. I don't think that's true for humans in terms of the laws of biochemistry. I don't think it's true for machines because of the formal limitations of the algorithms that they're supposedly running. That's it.

Here's the summary of these ideas. I think we now have a research agenda for all of this stuff.

Slide 30/30 · 32m:56s

I'd like to thank the people who did all the work. These are the postdocs and students in my group, and we have lots of collaborators. I have to do a disclosure. There are three companies that I'm involved with. Thank you.