Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a ~1 hour talk I gave at the Oxford Robotics Institute called "Intrinsic motivation in evolved, engineered, and hybrid systems: the interface of biophysics, computer science, and behavioral science". It covers our work from the perspective of motivations - what are they (in various unconventional agents, spaces, and scales), how can we predict/change them, and where they "come from".

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Introducing intrinsic motivation

(05:50) Scaling patterns and spaces

(18:07) Goal-directed morphogenesis and reprogramming

(31:51) Synthetic organisms and motivations

(41:05) Algorithms, emergence, and mathematics

(52:04) Latent-space model and outlook

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/48 · 00m:00s

I'm going to give a somewhat different talk than I usually give. What I want to do today is talk about the idea of intrinsic motivation. I'm going to talk about this in a variety of natural, meaning biological, but also engineered and hybrid systems.

If you're interested in the details, everything — the software, the data sets, the primary papers — is at this lab website. This is my personal blog around some ideas of what I think all of this means.

Slide 2/48 · 00m:29s

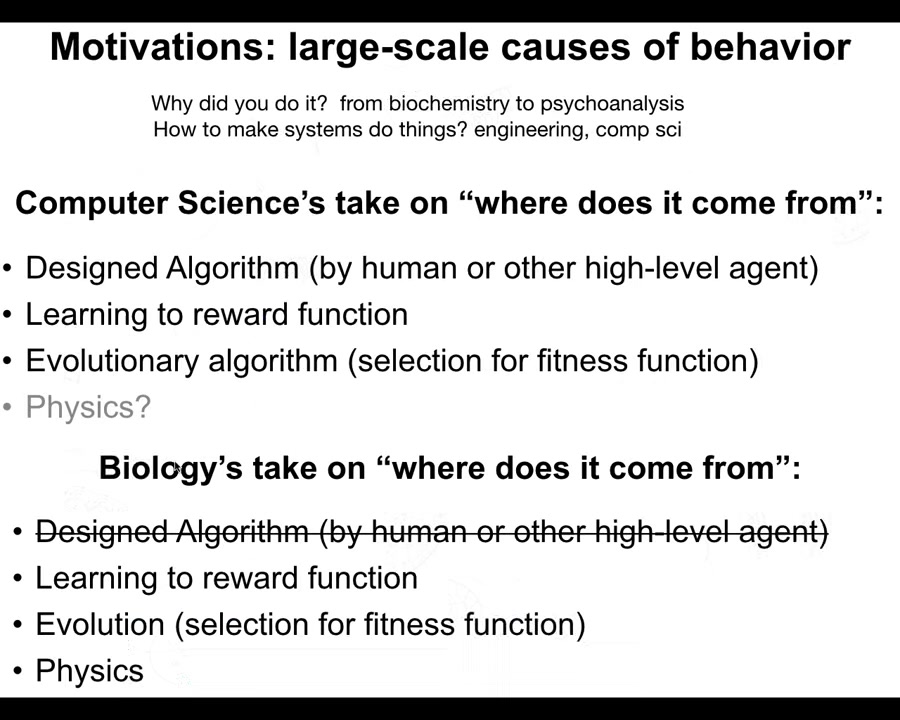

When I say motivations, what I mean is large-scale causes of behavior across systems. That takes many forms. For example, in biology, it often takes the form of asking, "why did the system do what it just did?" The explanations can range from biochemistry to psychoanalysis, depending on what kind of system you're talking about. As engineers, we would like to know how to make systems do things. This is engineering, but also bioengineering, computer science, and so on. This idea of why it is that systems do specific things and how we can communicate to those systems to do something else.

Typically in computer science, when we think about where the motivations of systems come from, we think about a designed algorithm. A human or perhaps an AI designed a specific algorithm to do a specific thing. Sometimes it comes from learning. There was a reward function and the system learned to do something. Sometimes there's an evolutionary algorithm, meaning that it was selected for a specific fitness function. There is also morphological computation in physics that can be exploited in robotics and engineering.

In biology, some of these things overlap. We tend not to like the idea that there were designed algorithms, but the rest of this fits. Learning: all kinds of living systems can learn. Evolution: selection for specific functions, and a lot of emphasis on physics. This is what I'm interested in, understanding whether these are sufficient, and how we can think about motivations across a range of systems.

Slide 3/48 · 02m:10s

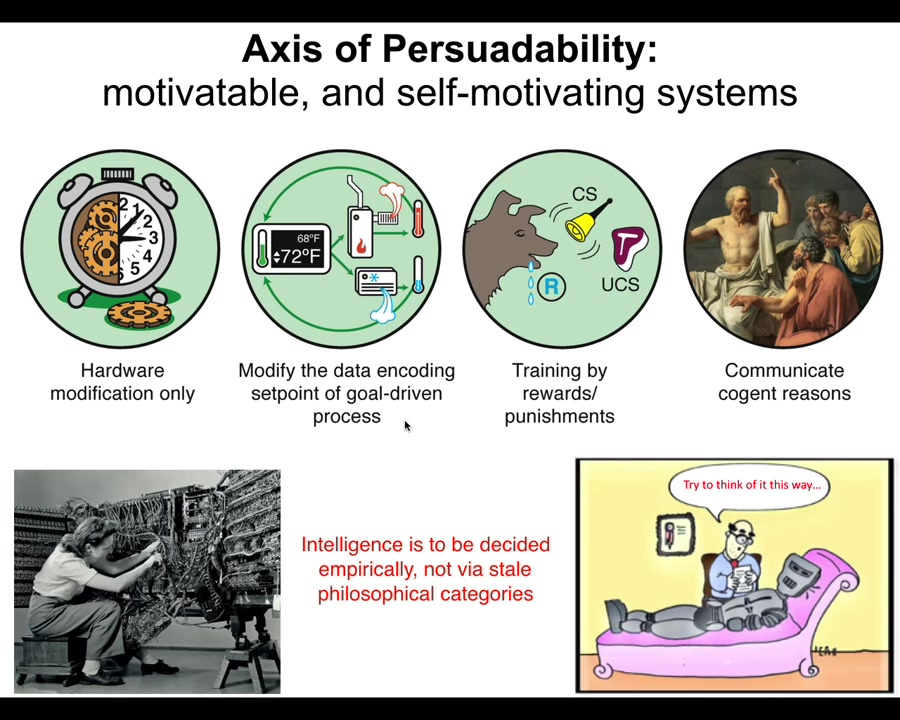

To help us think about this, I would like to propose a continuum. I don't like binary categories, things like machines versus living organisms. I don't think those kinds of categories are useful. What I like instead is a continuum so that we can ask what exactly is changing, what is different across this continuum, and in particular, what kind of tools and approaches can we use to motivate and to understand the motivations of systems across the spectrum.

If you are only amenable to hardware rewiring, you might be down here. If you are a cybernetic kind of system that's amenable to control theory and the tools of cybernetics, you're here. Here we start seeing systems that are trainable by rewards and punishments, and eventually systems that communicate via reasons and are amenable to psychology, friendship, love, and things like that.

The important thing about this spectrum is that where a system fits here is not obvious. It cannot be determined from a philosophical armchair. You can't just say this is a machine, therefore I know it doesn't have cognition, or this is a cell, and I know it's not intelligent. Only brains are intelligent. None of that is really scientific or useful in engineering. What we actually have to do is experiments. You have to take systems and find out which kinds of tools across the spectrum are actually applicable. When you do that, you get many surprises.

Slide 4/48 · 03m:41s

Here's the outline for today's talk. What I'm first going to do is generalize the notion of patterns, which are forms of either structure or behavior and many other things besides. I'm going to show you why I think these are actually the same thing.

Then I'm going to show you a model system called morphogenesis. This is biology. The first two-thirds of the talk are going to be around biology. I'm going to show you a model system in which groups of cells solve problems as a collective intelligence. The best way to describe what they do is not a mechanical machine metaphor, but literally a navigation of a problem space and a collective intelligence to which many tools from cognitive science apply. This is the model system that we do a lot of work on.

Then we have to ask the question, if you have a system which attempts to fulfill specific goals, where do those goals come from? Now we start talking about motivations. I'm going to start us thinking about where goals come from that goes beyond selection. In biology, this means in the genetics and the specificity of the environment. But what else is there? Where do motivations come from? This will help us connect it to engineering and computer science.

Towards the end, I'm going to argue that in order to understand where these motivations come from, and more importantly, to be able to predict and to call up the ones you want in your artificial systems, we have to start thinking about what you might call a Platonic space. It's a structured space of patterns, of form and behaviors that is really critical for both biology and physics. I'm going to argue briefly that basically standard reductive physicalism is quite insufficient for either causation or explanation in these systems, and more importantly, for building, for creating new things. I'm going to argue at the end, too, that even extremely simple interfaces are the benefits of some of these ingressing patterns from this latent space.

At the end, I'll just talk about our research program and what we are doing to study this space and the mapping between the patterns in that space and the physical interfaces that we make.

Slide 5/48 · 05m:50s

The first thing to remind us of is that while many textbooks and papers in the philosophy of mind start off here as a modern human, an adult modern human, we all took the journey across different disciplines. We started here as an unfertilized oocyte. This was considered the province of chemistry. Then there was this amazing process of self-assembly that gave rise to either something like this, which we recognize now is to be handled by behavioral science, or even something like this by psychology. But that's not the end of the line. Different components here can do multiple things afterwards, and they can take paths into the field of oncology by disconnecting from this collective or even bioengineering. I'll show you some of these anthrobots shortly. What we need to understand is the pattern of scaling. How is it that the simple system here becomes something like this, right? There are no binary categories here. There is no magic lightning bolt at which point chemistry becomes cognition.

The first thing that I want to get across is this idea that forms or patterns of body and mind are really part of the same thing. We need to think about them in the same fashion.

Slide 6/48 · 07m:09s

Alan Turing was already on top of this because here's someone who is very interested in intelligence, in reprogrammability, in body and cognition in other substrates. At the same time, he wrote this amazing paper on the chemical basis of morphogenesis. He wanted to know how chemicals in the embryo self-organize. Why would somebody interested in computing and intelligence be looking at chemicals in morphogenesis? I think it's because he recognized these are fundamentally the same problem. I think this is a very deep point. I'm going to show you a few examples.

Slide 7/48 · 07m:41s

These are the kinds of things that are easy for us to recognize.

Here, this little squirrel has a very good theory of mind. He knows his owners are going to be upset to find him in this accident scene. There he sets up this little scenario, and then if nobody comes to check on him, he's actually going to look to see has anybody noticed all the hard work he's put into this.

These kinds of things are easy for us to recognize because they happen in the same problem space that we share, three-dimensional space. They happen at the same time scale and so on.

Slide 8/48 · 08m:14s

There are other things like this which look like we understand what's going on, but it's not obvious at all. We can't understand this from pure observation. We have to do functional experiments to really understand what's happening. These are the kinds of things we mean by behavior.

Slide 9/48 · 08m:32s

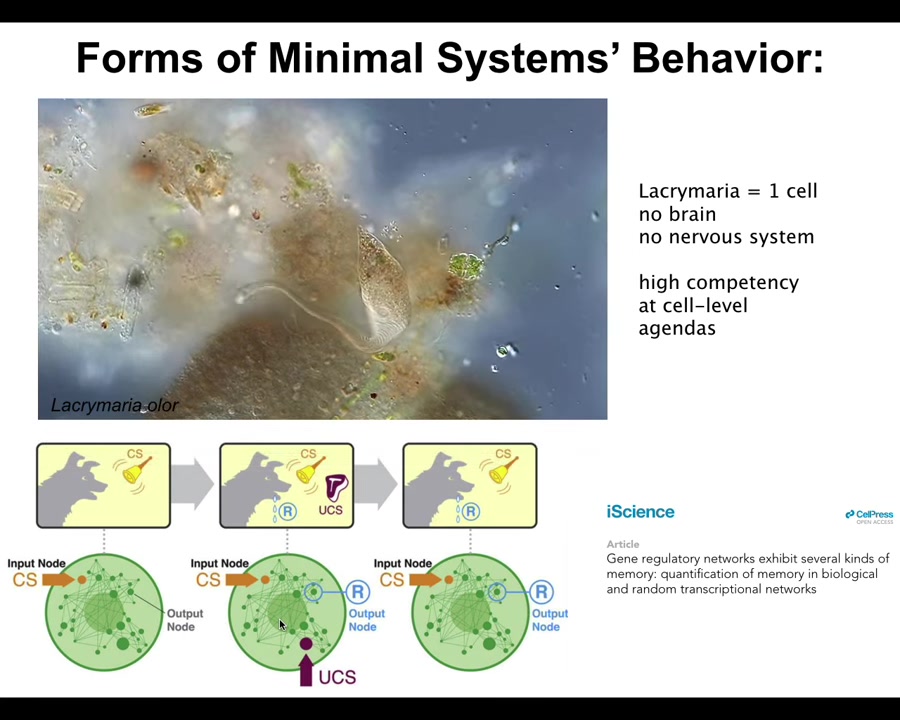

Even very minimal systems do this. This is a single cell. This is what we are all made of. This is a free-living organism called the lacrimaria, but all of us are made of single cells working together. There's no brain here. There's no nervous system, but you can see this incredible competency of solving its problems at the local scale.

If you're into soft body robotics or something like this, you're probably very jealous because we don't have anything that is this competent. Remarkably, even the material of which this creature is made—molecular networks: molecules activating and suppressing each other's activity—the molecular components already have six different kinds of learning that they can do, including Pavlovian conditioning. We are made of an agential material. There are competencies and agendas all the way down to the molecular level. It does not start at the brain or the nervous system; it goes all the way into cells and the material of which the cells are made. These are all in the behavioral sphere.

Slide 10/48 · 09m:34s

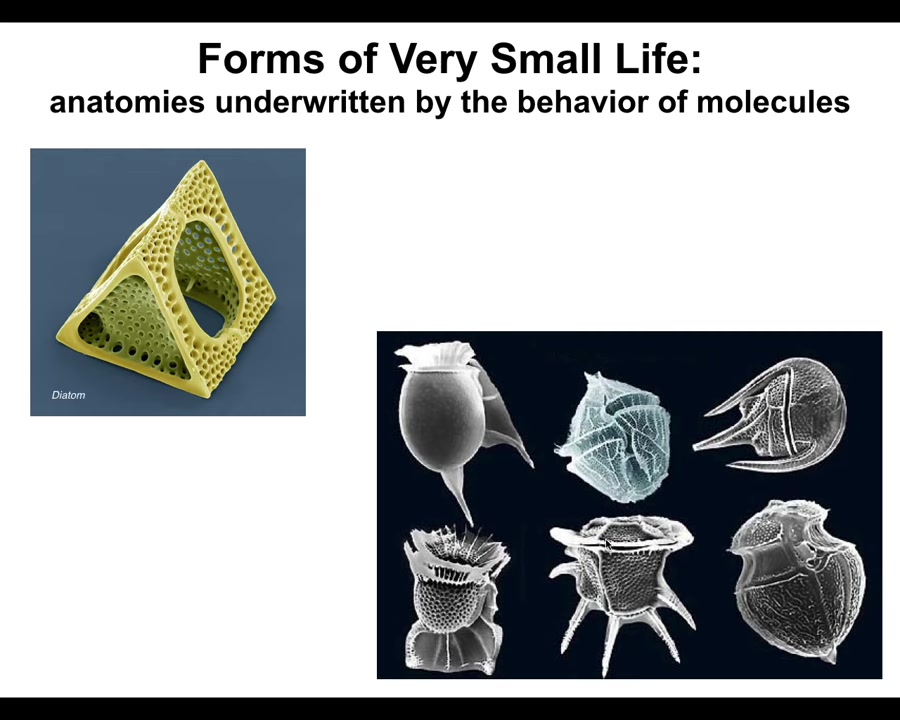

Now let's look at shape anatomy. These are diatoms, and you can see this whole thing is 1 cell. It's extremely small. These are all single-celled creatures. They have very specific shapes that are defined by the behavior of molecules.

Slide 11/48 · 09m:54s

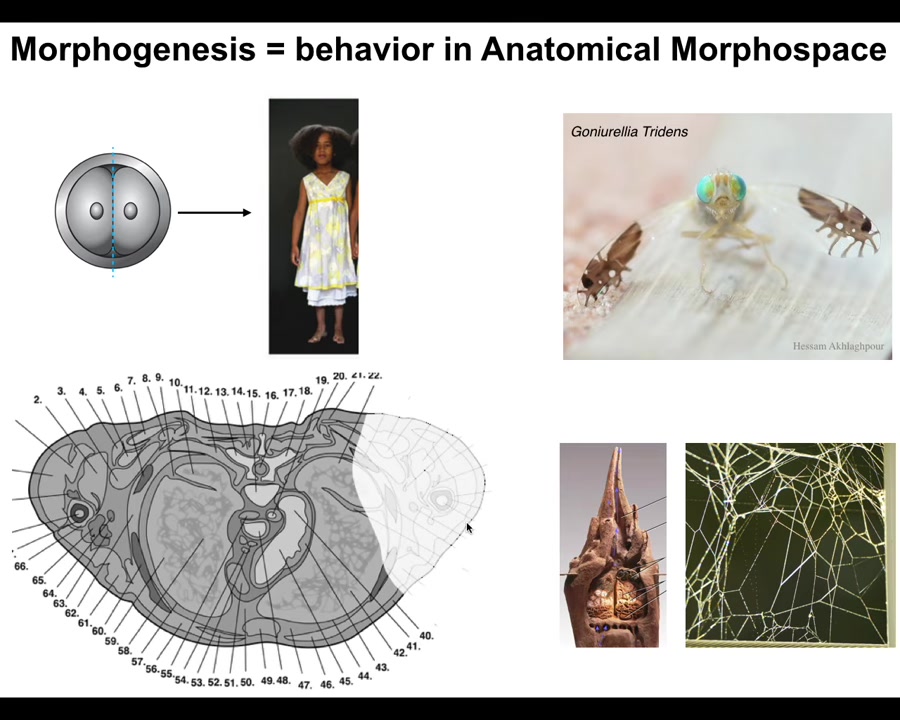

Morphogenesis, the generation of form, is an example of that, but on a much larger scale. We become embodied through the action of many cells working together. If you take a cross-section through the human torso, you see this incredible order. Everything is in the right place, the right shape, the right size, next to the right thing. If something is damaged or missing here, we need to know where this pattern actually comes from. How do we convince these cells to rebuild this?

A large part of my lab does regenerative medicine, where we try to regrow organs and things like that. There are many amazing morphogenetic structures. For example, this fly is running a very simplified, stripped-down, two-dimensional ant morphogenesis program on its wings. It does this to scare predators who don't want to deal with ants. It wiggles the wings, and it looks like the ants are running around. There's a program here of making the shape of these ants, but also of the fly itself in three dimensions.

There are morphogenetic events outside the body. For example, the collective of termites will make this incredibly complex structure. Spiders will make the spider web. None of these patterns are in the DNA. If we ask where this pattern actually comes from, many people think it's in the DNA somehow. But the genome doesn't say anything about this any more than it says what the structure of the spider web or the termite colony should be. The genome contains the specification for the hardware, the micro-level proteins that every cell gets to have; all of this arises as a function of the physiological dynamics and software that are running on this system.

Slide 12/48 · 11m:35s

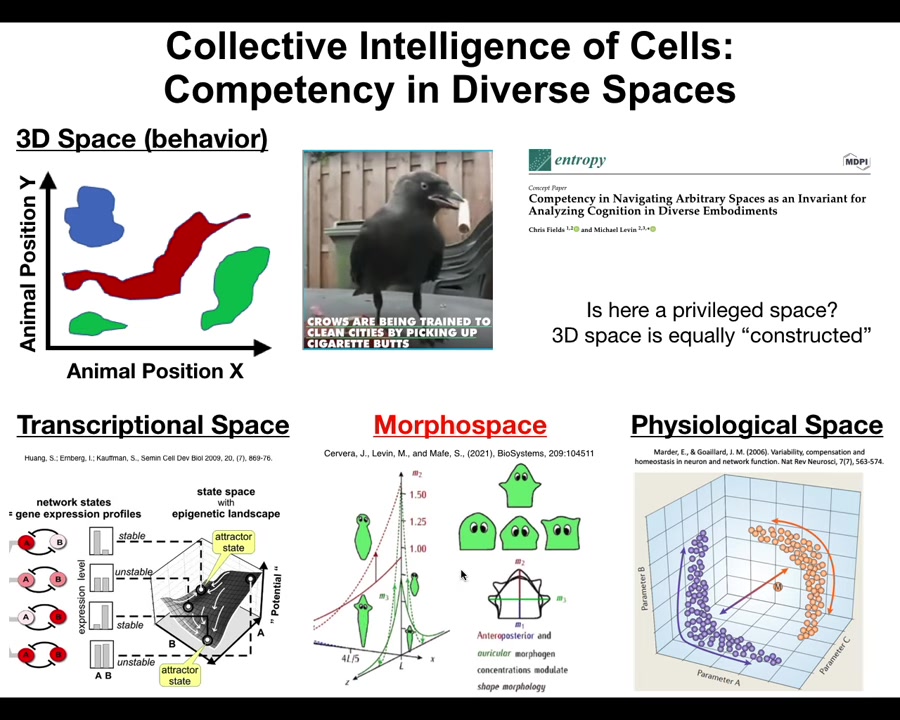

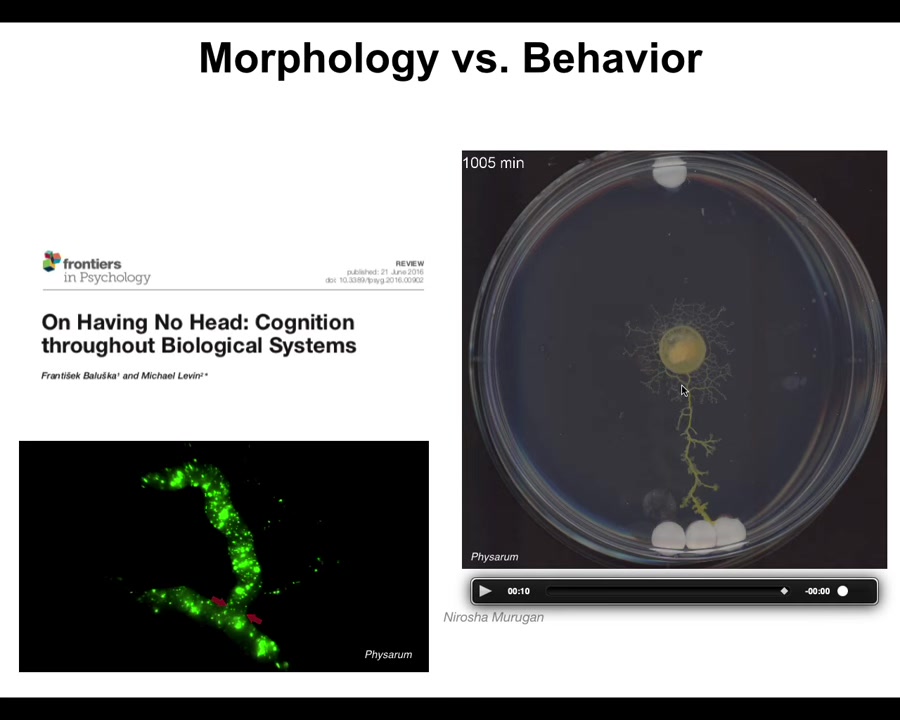

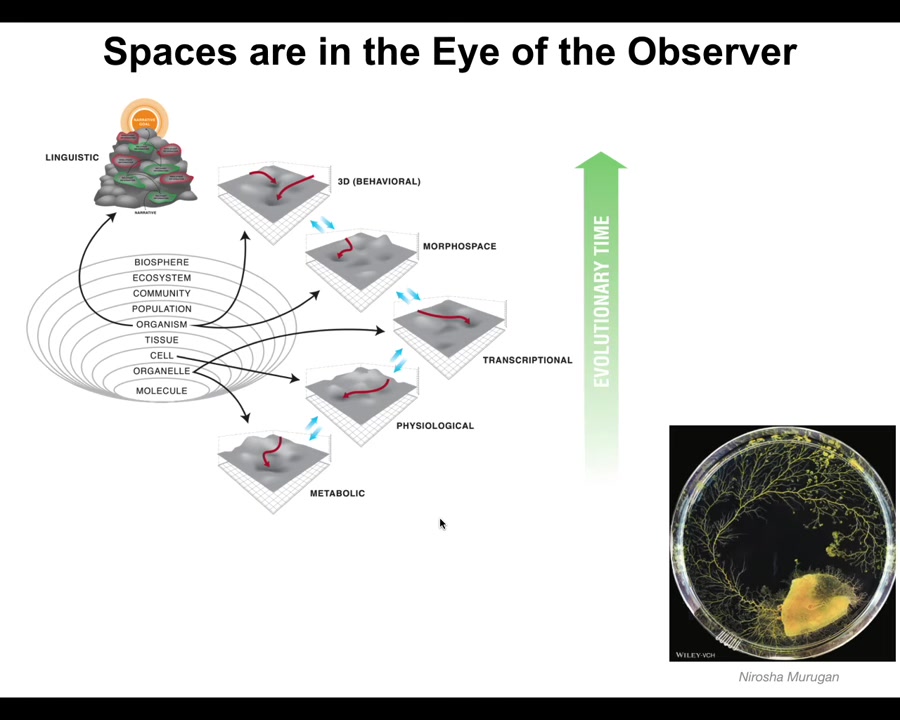

The reason I say that shape, the forms of behavior and anatomy are the same thing is because they are underlied by a symmetry of this notion of a space.

What space do systems navigate?

We as humans are obsessed with three-dimensional space because of our own evolutionary history and our vision, the importance of vision. We can recognize navigation of spaces, meaning intelligent behavior. We can recognize navigation of medium-sized objects at medium speeds moving through three-dimensional space, birds and mammals and especially primates.

But biology has been navigating all kinds of other spaces that are often high-dimensional, really hard for us to visualize, and not obvious at all. For example, the space of possible gene expression states. This might be a 20,000-dimensional space. Or the space of physiological states.

In particular, one behavior that we study in our group is morphogenesis, the navigation of systems through anatomical space, meaning the space of possibilities. You can think about the movement of the configuration of the body from a single cell towards the shape of a human or a snake or a giraffe or a tree as a navigation of this anatomical space. All of these, morphogenesis, the generation of the body shape, becomes just the behavior, albeit in a different space at a slightly different time scale.

Slide 13/48 · 13m:02s

Deciding what is morphogenesis and what's behavior is really hard. This is a slime mold called Physarum polycephalum. It's growing out: here's one glass disc, here are three glass discs. During this time, while it's growing evenly, it's gathering information about its environment by gently pulling on the substrate and reading the strain. This is biomechanical sensing. It reads the strain angle, and then eventually it figures out where the bigger mass is, and it goes right to the bigger mass. It can do this partially because it is a hydraulic computer. It has these flows inside with independently addressable synapses here in between all these structures. But is this behavior or is this morphogenesis? It's both. Trying to label it is not helpful because the way that the system exerts its behavior is through changing its body shape. It's through morphogenesis. This is all one cell. That is how it does behavior.

Slide 14/48 · 14m:02s

So I think what happens is that evolution pivots the same tricks through different problem spaces. Very simple early forms of life were navigating metabolic state spaces and then physiological state spaces, and then the genes came along and the space of transcriptional states. Then multicellularity came along and we could navigate anatomical morphospace. Then nerves and muscles came along and we were able to navigate three-dimensional spaces and now linguistic spaces and financial spaces and who knows what else.

The idea is that these spaces are really plentiful, but also the distinction between them is really in the eye of the observer. That is, we as scientists decided to cut it up this way, but as you see from the Faiz arm, it's not obvious that there is any kind of ground truth about what the space really is. Very importantly, with these kinds of systems, you may have to ask, what do they see? What space do they think they're navigating?

So what I've tried to do here is to generalize this notion of a pattern, and it's a pattern in any of these spaces. It might be a physiological pattern, it might be a gene expression pattern, a behavioral pattern, an anatomical pattern. These are all the same things.

Slide 15/48 · 15m:13s

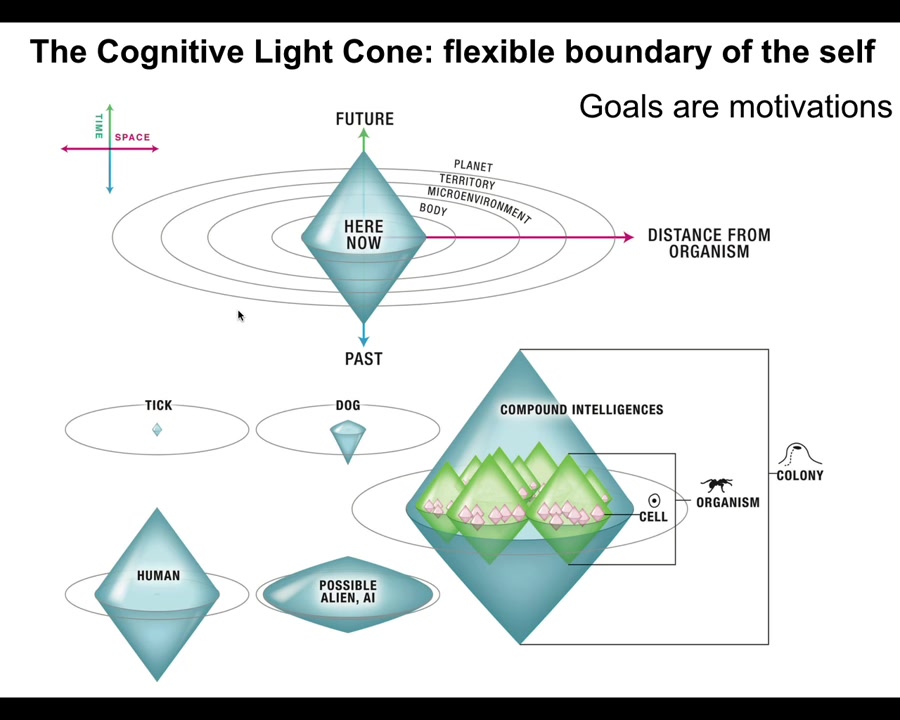

The next part of the argument is to point out that these patterns are not just emergent outcomes. It is, at least in biology, not the case that in cellular automata there are local rules. You turn the crank, execute the local rules, and then something complex pops out. That certainly happens, but that is not the whole story, because these patterns function as goals. And you can see us working up to this idea of motivations. The patterns are targets of behavior because they are goals that are being pursued by diverse means, and the degree of diversity and ingenuity by which different systems pursue specific goal patterns is a measure of their intelligence.

In fact, that's one way to define intelligence: how good are you at meeting the same goal by different means when the situation changes. In particular, I've defined this concept called a cognitive light cone, which is simply the idea that we can estimate the size of the biggest goal that a system can try to implement. So the size in space and time of the biggest pattern that the system is capable of storing as a set point for its behavior and trying to achieve that behavior. You can see different kinds of creatures can have different size cognitive light cones. This is not the range of your perception. This is not the range of your possible actions. This is the size of the goals that you're able to pursue. The idea is that goals are subsets of a motivational strategy, and goals are what hold organisms or agents in general together. We see a collective, and we say this is a goal-seeking system to the extent that all of its parts are aligned to meet a specific goal.

Slide 16/48 · 17m:06s

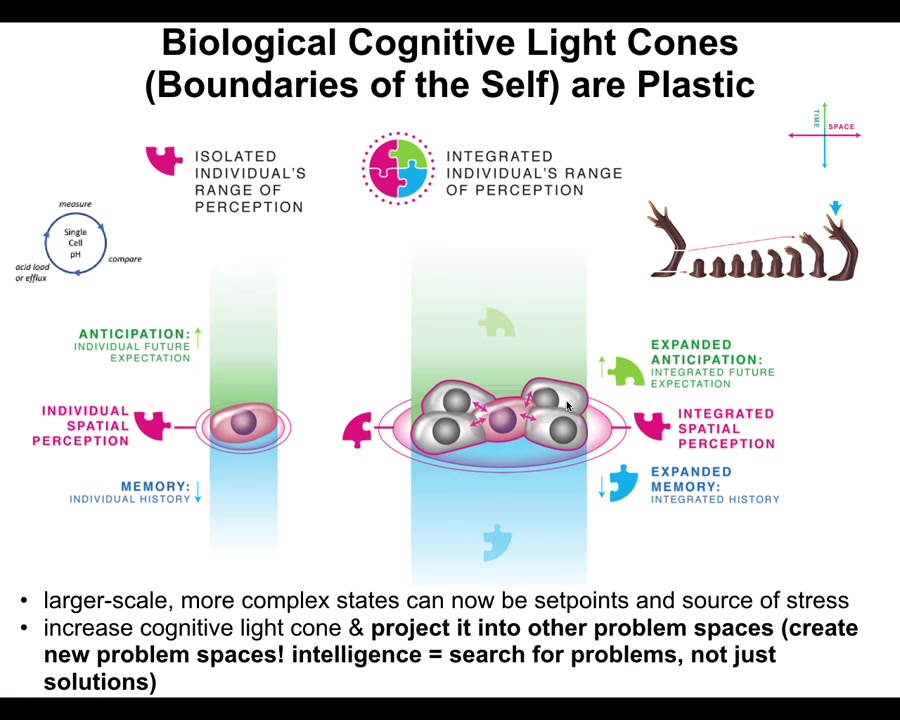

And the interesting thing about biology is that the cognitive light cones are plastic. They can shrink and they can grow. A single cell has a tiny little cognitive light cone. All it cares about is scalar values of things like pH and hunger level. At a very small region of space-time, only a few minutes forward anticipation and memory back: a tiny little cognitive cone.

But when cells join into networks, and these are the kinds of multicellular tissues in your body, then suddenly they're capable of representing enormous, grandiose goals, such as how to build a limb. I'll talk about this momentarily as to why this is a goal. The idea is that the goals can grow. During evolution and during embryonic development, systems are able to acquire bigger and bigger patterns as goals, and they can project them into new problem spaces and open new problem spaces. Now it's time for me to explain how this navigation works.

Slide 17/48 · 18m:11s

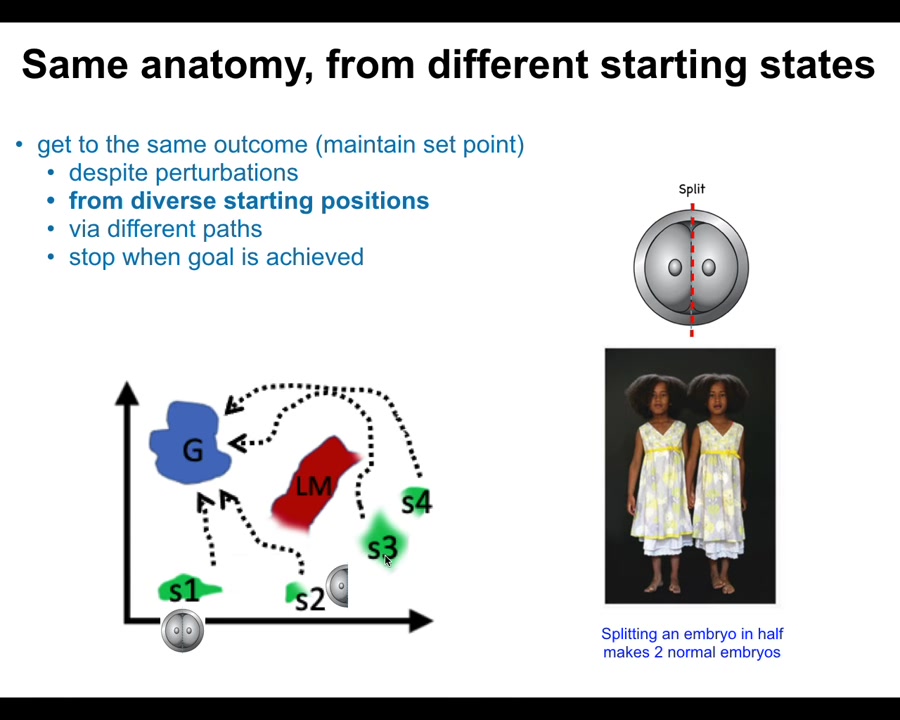

The basic fact of morphogenesis is that we start with a single cell, it divides, that's the egg, it divides, and then eventually you get something like this. This process is extremely reliable. There's a huge increase of complexity from here to here. But those two things are not why I'm using agentic terminology. This is very important.

Many times people will see something complex like this. You can't say it's intelligence simply because it's reliable or because it's increased in complexity. Those are cheap. It's very easy to get those from feed-forward, purely open-loop kind of processes. That is not what's happening here. This is not pure emergence. The reason that I'm using this agentic terminology is that if you poke this process, if you do perturbative experiments, you find out something very interesting beyond this reliable thing.

First of all, if you chop embryos into pieces, you don't get half bodies. You get normal monozygotic twins, triplets. These systems are able to get to the same ensemble of goal states, a correct human target morphology, from different starting positions. You can start as an embryo cut in half. You can start as a normal embryo. You can avoid local maxima and still get to where you're going. You can get to the right place from different starting positions.

Slide 18/48 · 19m:32s

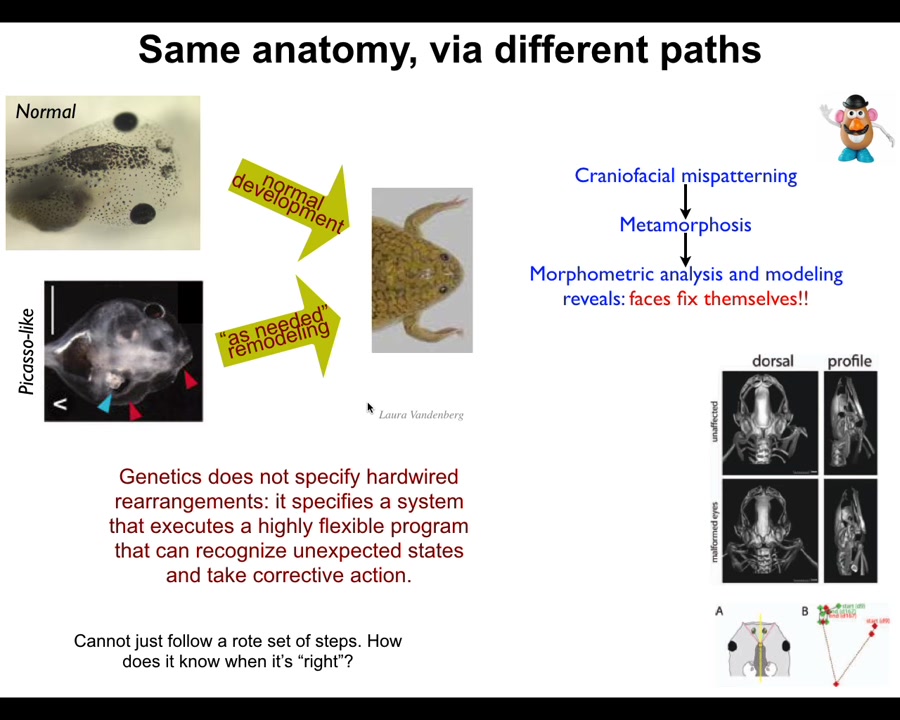

In fact, we discovered this about 10 years ago. These tadpoles have to become frogs normally. Here are the eyes, here are the nostrils, the brain, the mouth, all of these things have to move to create a frog phase during metamorphosis. And people thought this was a hardwired process. Every set of cells just moves in the right direction, the right amount, and you get a normal frog.

We created these so-called Picasso tadpoles where we scrambled all the starting configurations. The eyes are on the back of the head, the mouth is over here off to the side. And yet these things become normal frogs too, because the organs don't just move in the correct direction, the correct amount. They actually do a kind of error minimization scheme. They keep moving through novel paths until they get the right final shape. This is a completely different process than simply feed-forward open-loop emergence.

Slide 19/48 · 20m:23s

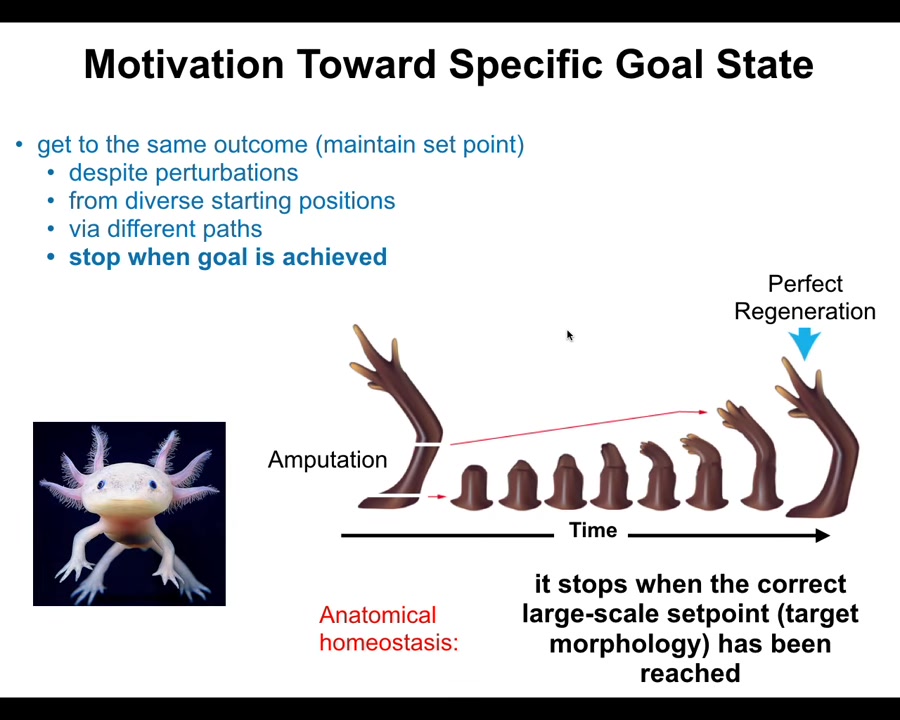

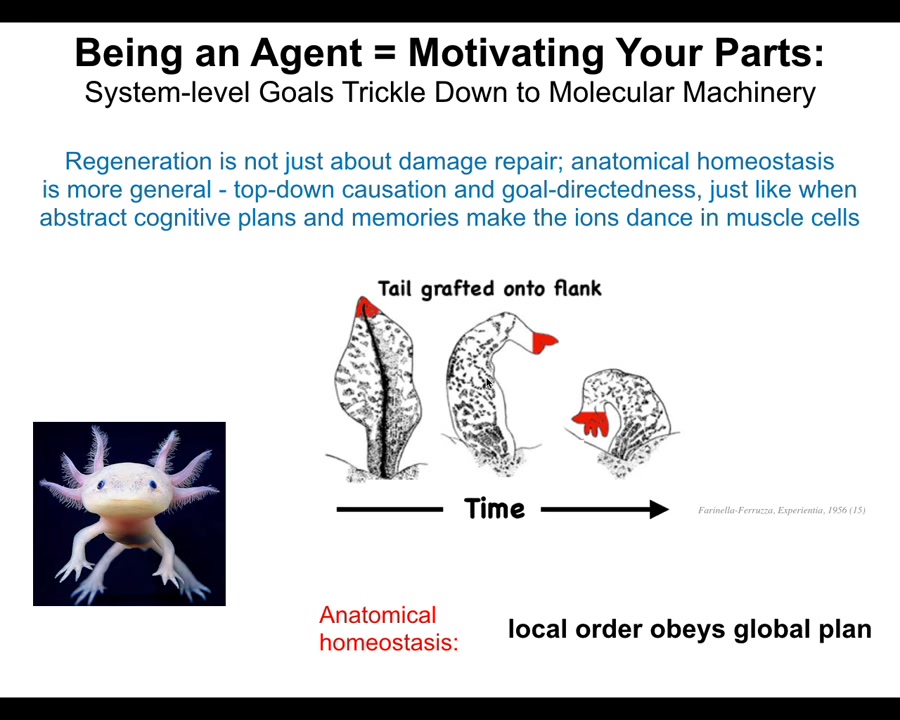

More broadly, you can see this in the kind of process called regeneration. This is an axolotl. It's an amphibian that can regenerate its limbs, its eyes, its jaws. If the limb is amputated anywhere along the length, the cells will quickly become activated, they grow, they produce the original structure, and then they stop. The most amazing thing about this process is that it knows when to stop. It stops when the correct axolotl limb has been produced.

This is, again, a kind of homeostatic system. It has feedback. This simple model of open-loop emergence is not a good fit for these data. You have to use cybernetic models with feedback. This kind of anatomical homeostasis has a set point, and as long as you deviate from that set point by more than some acceptable small error, the system will work hard to correct it.

It has the right number of fingers, the right shape. No individual cell knows what a finger is or how many fingers you're supposed to have, but the collective does, the group does. This is important: the whole point about being a large-scale goal-seeking system is that you have goals that your parts don't have. You can align your parts towards goals that they don't know anything about. At each level, novel cognitive content is being generated.

Slide 20/48 · 21m:52s

And so what's important here is that what I just showed you is not about repair of damage. It's not a simple inpainting where you simply repair a static structure. That's not the key here. The key is this top-down control. I want to show you this experiment that was done back in the 1950s, where they took tails and they grafted them to the side of this amphibian. What you'll see is that the tail slowly turns into a limb. Now, notice the cells up here at the tip of the tail. These are tip cells sitting at the end of a tail. There's no damage there. There's nothing wrong there. There's no injury. Why are they turning into fingers? They're turning into fingers because the large-scale system, which does in fact have an error, the large-scale system can tell that this is not, tails don't belong in the middle of this body. What it does is propagate that error and propagate the stress and the fact that the situation is not what it should be propagates it all the way down to the lowest level components so that even though the molecules, meaning the molecular networks inside the cells and the cells themselves would have no idea that anything is wrong here because in their local scale everything's fine, they're being told by the higher level system that actually it's not fine and you need to become these fingers. So what we're looking here at is a multi-scale system where local order obeys a global plan.

This is of course the hallmark of a cognitive system. You do this too in the morning when you wake up and you have very abstract educational goals and financial goals and social goals and whatever, in order for you to get up out of bed and do those things. The chemistry of your muscle cells has to change. The potassium ions have to cross the muscle cell membranes in order for you to do voluntary motion. So your whole body is this transduction apparatus that takes very high-level abstract goals and transduces it into the aligned actions of your parts, very, very small molecular parts. We're now seeing that these forms that we are talking about, the shapes of behavior of cell groups, are a target for goal-directed behavior.

Slide 21/48 · 24m:04s

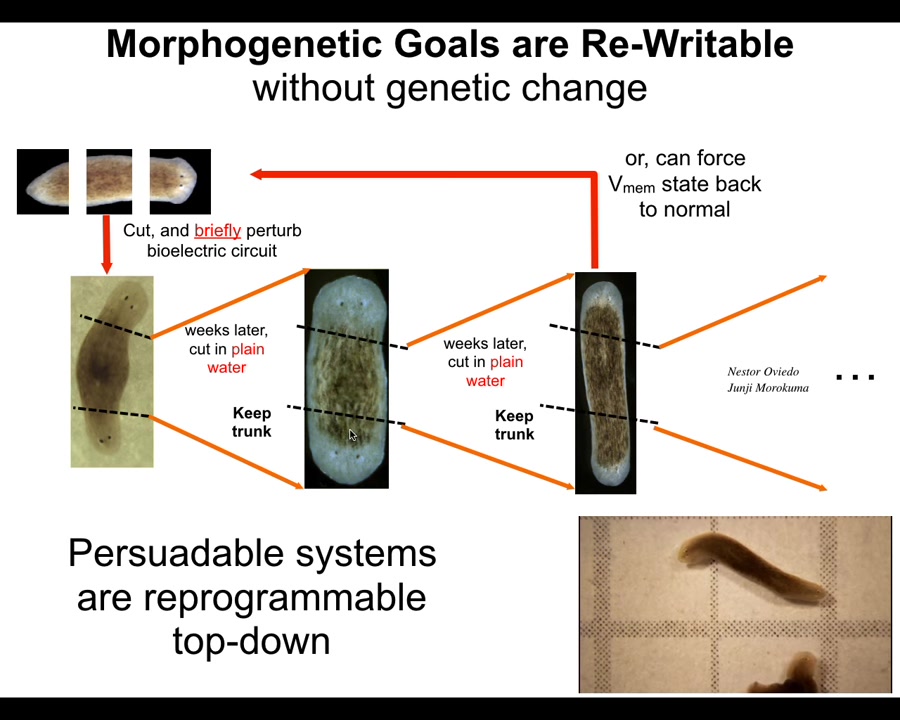

Now, as with any complex cognitive system, these kinds of persuadable systems should be reprogrammable. I want to show you one example, and I could give several hours of talk on this, so I'll go very quickly through it. This is a planarian, a flatworm.

The amazing thing about these planaria is that if you cut them into pieces, and you can do it in hundreds of pieces, every piece will regenerate into a perfect little worm. It's normally 100% reliable. But what we were able to do, because we learned to read and write the representation of these goal states within tissue. It is bioelectrical. I'll show you a brief example of that. It is just like in the brain. It's stored in an electrical network, but we can now see those patterns and we can change them.

We could go in and say, no, you should have two heads as a planarian. When you cut those animals, they make two-headed worms. When you recut those, they continue to make two-headed worms. This is not Photoshop. It's not AI. These are real animals. You can see them here. The system will continue to remember the new goal and to pursue it under future rounds of regeneration. So again, these patterns serve as targets of goal-directed activity, and they are rewritable. They are plastic.

Slide 22/48 · 25m:22s

Not only can we change the number of heads, we can actually change the species type of head that you get. So this species that has normally a nice triangular head, we can ask them to make flat heads like a P. falina or round heads like an S. mediterranea, but 100 to 150 million years distance between these creatures and this one. What you see is that the hardware here is perfectly willing to visit attractors that belong to other species in this morphospace if their decision-making process is perturbed. Again, bioelectric signaling is how they navigate this space. Keep in mind, the hardware is stock; in none of these cases do we change anything about the genome. This just illustrates how evolution makes these amazing problem-solving agents that are very plastic and their goals are rewritable. And not just the shape of the head, but even the shape of the brain and the distribution of stem cells becomes just like these other species.

What I've shown you is that these goal states are rewritable. But in all of these cases, the goal states were natural products of evolution. In other words, we can make these weird shaped heads, but that's because there are other species that already have those heads. So all you're doing is walking around in this morphospace.

Let's talk about what the novelty here can be beyond the forms that have already been selected for — what else is possible. The key is that the hardware is actually able to find some very novel forms.

Slide 23/48 · 26m:54s

First, an evolutionary example in plants. You look at an acorn and it very reliably makes these oak leaves and you think that's what the genome knows how to do. This genome specifies; it encodes this particular shape. That's really not a good way to think about it at all.

Slide 24/48 · 27m:11s

We are taught this by a non-human bioengineer. Along comes this little wasp and the little wasp does some bio-prompting, which is to put down some chemical signals that cause these cells to build something completely different. This is not built by the insect cells, this is built by the plant cells. These are called galls and you see this amazing structure. Who would have known, we would have no idea that these flat green cells are capable of building something like this if this plant didn't hack them into a new region of morphospace. It doesn't do this the way that it builds its nest, which is a 3D printer to lay down the structure and build this nest. That isn't what happens. It puts down some signals and then it motivates the plant cells to build something very different. The standard evolutionary default, the flat green leaf, is a point. It's a single point in that latent space. But we now see that there are other interesting outcomes besides that point that we can reach.

Slide 25/48 · 28m:16s

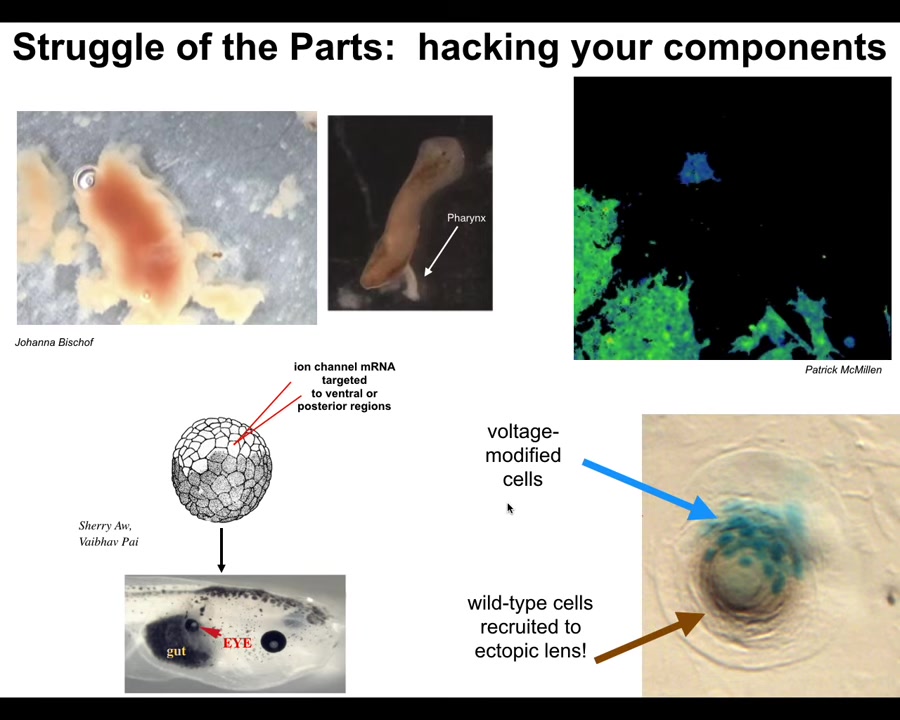

And I just want to show you a couple of cute examples. Wait, let me pause this video. Because along with hacking other systems, your first job as a high-level collective is to hack your own parts. You have to have control over your own components and get them to do new things. So I want to show you a couple of examples of biology. This is that flatworm that I showed you. This is a planarian. And it has a little tube that it can put out called the pharynx, and this is how it eats; it can suck up nutrients using this little tube. But normally you don't see this. It stays inside the body and you almost never see it. But if you liberate it from the rest of the body, it turns out that these little pharynxes, here's one, have their own life and they live for hours and they run around. And this one in particular is going to attack this piece of liver and it's going to actually burrow through it because it doesn't realize that there's nothing on the back of it. So as it eats the liver, the liver falls out the other side. But you can see it come out the other way. The pharynx actually has lots of autonomous activity and being a normal planarian involves 99% of the time keeping that activity suppressed, keeping it inside the body, keeping it from running around and doing things on its own.

Here's another example of what it means to hack a biological system. These are cells, and I'm going to play this video in a moment. You're going to see the colors represent voltage. So the voltage potential across the cell membrane. So this cell has one voltage, it's blue. These cells have another voltage, it's green. And so this cell is crawling along, minding its own business. Here it goes. Now the green cells are going to reach out and they're going to touch it. That tiny little touch is all it takes to turn that cell green and now it's joining the collective and it's going to be part of building whatever these things are building. So this is the kind of thing that cells do to hack each other's behavior. And it's very important for us to learn how to do this because we would like to control what cells build.

And here's an example of that from our regenerative medicine program where we take an early frog embryo and we provide a bioelectric signal to a group of cells that tells them to become an eye. If we do this in cells that are going to be gut cells, they build this eye. So we want to be as convincing as possible so that we can build new organs for regeneration, for transplantation. And you can see here, this is a cross-section of this early region. The blue cells are the ones that we injected. So we want them to acquire a new goal to form an eye. We want them to convince their neighbors because there's not enough of them to make an eye. All these other cells that are not blue, we didn't touch those. These, the blue cells, convince them to make an eye, right? So there's a second level of instruction here. These other cells resist because it's a cancer suppression mechanism. If somebody's telling you to become a weird voltage, you try to resist and, in fact, normalize them out. And so they resist and there's this battle of worldviews that happens where these cells are saying, we're going to build an eye and these are saying, no, you should be gut cells. And depending on who wins, you either get an organ or you don't. And this is the kind of hacking that we want to control. Again, none of this is manipulating DNA. None of this is even seeking to manipulate specific gene expression. It's about convincing a complex system to undertake a new goal.

This issue of motivation—taking on a new goal and the hard part of coordinating all the downstream steps without us having to worry about it. All of these systems, the galls, the planarian faces, the frog face, the eyes, were developed by evolution. They have millions of years of history behind them.

Slide 26/48 · 31m:51s

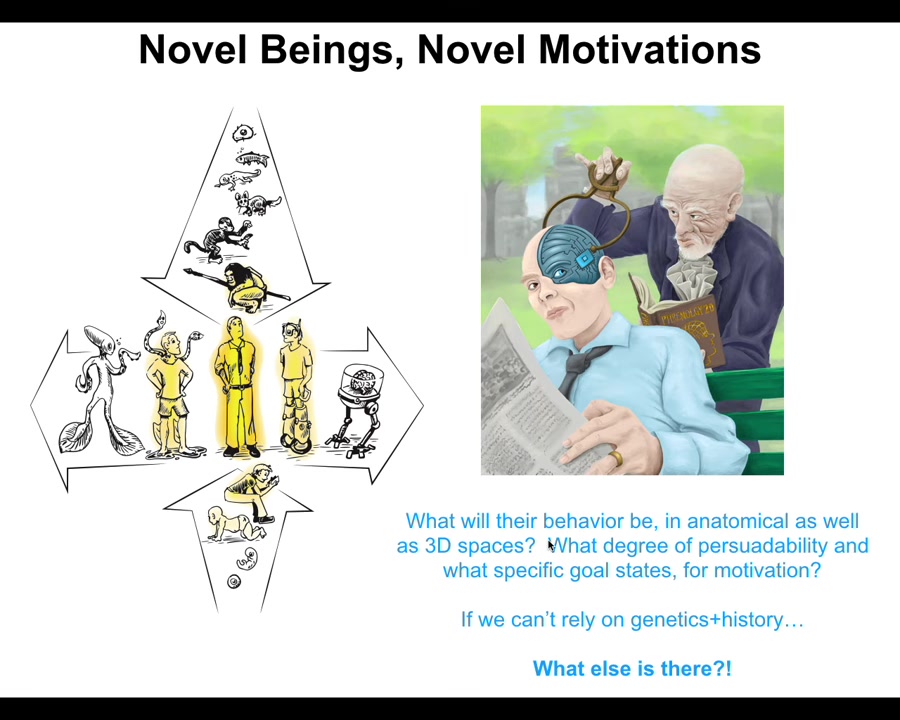

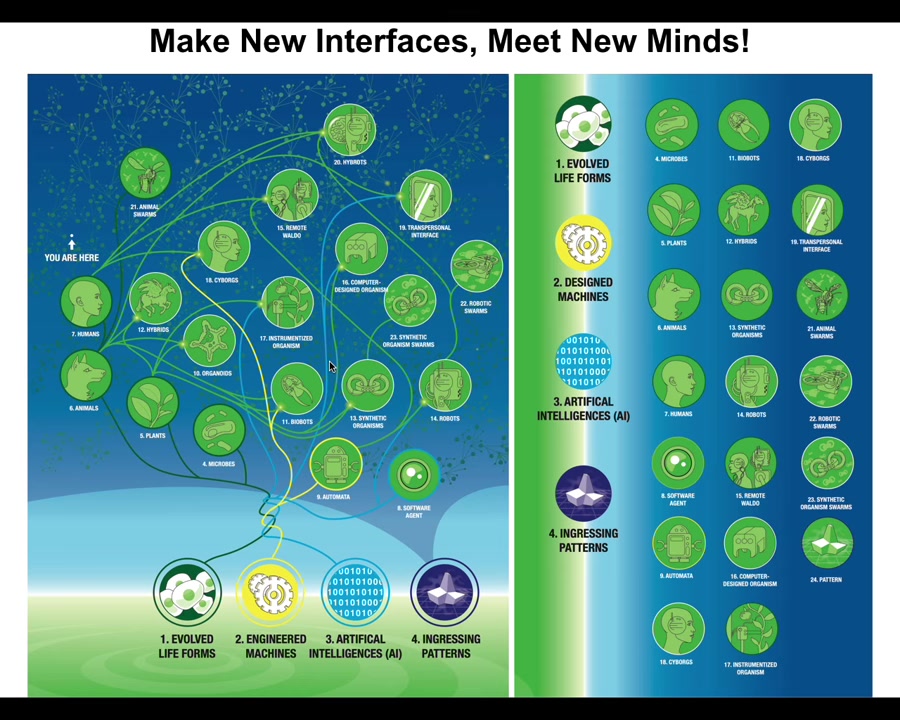

What happens when this continuum, we all were a single cell at one point, the normal human here stands at the middle of this continuum, but now there's another continuum here, which is that both through technological changes and biological changes, we are already now creating novel beings that have never been here before.

If you make a novel being that has never been here before and doesn't have a history of selection, what are the patterns that they're going to have? Patterns of behavior, patterns of morphology, patterns of physiology. What are their goals going to be? What degree of persuadability? Where on that spectrum are they going to be? What specific motivations are they going to have? This is really critical. I see this as much more important than the current issue about language models and AIs and what their status is. Forget all that. This is where the hardest thing is going to come from.

Because at some point your neighbor is going to have either 49 or 51% of their brain replaced or engineered by some weird thing. You don't want to be in a position to try to decide whether they're really human or not. That's not going to end well. We really need to understand what are we actually asking here. We're not trying to use these very brittle categories. We're trying to understand how to predict and ethically relate to new kinds of life that haven't been here before.

What's a model system that we can use for this? I want to show you two things that we've developed.

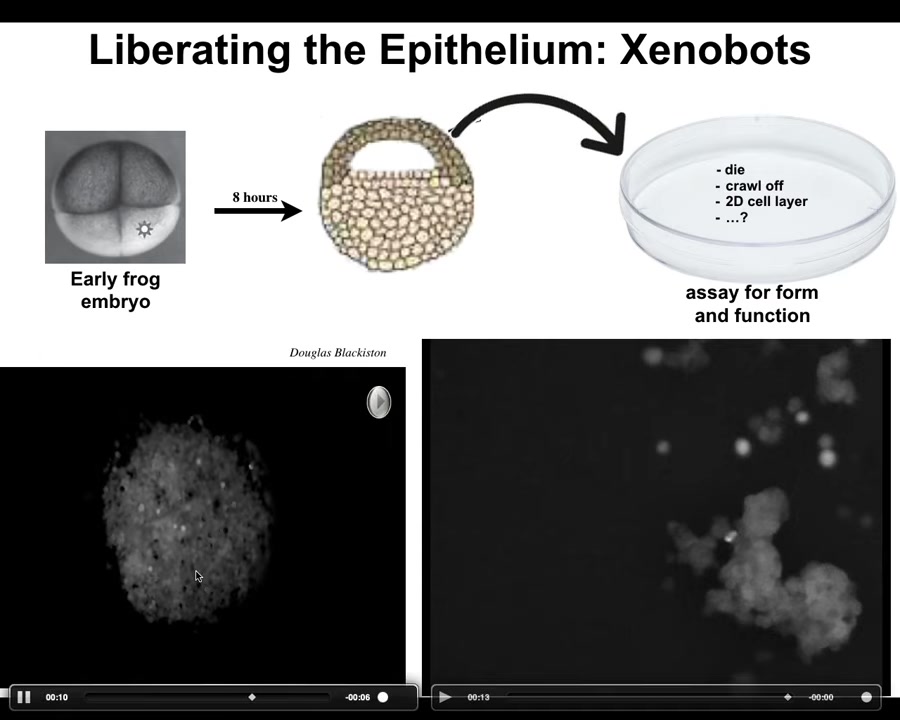

Slide 27/48 · 33m:17s

The first we call xenobots, and they come about when you liberate the cells from the epithelium of a frog. So here's the frog embryo. The cells up here are epithelial cells. We take them off, we put them in a dish. They don't die. They don't crawl away from each other. They form this amazing little structure. In fact, here you can see how they do it. Each one of these is a single cell. And they don't all look like a cute little horse, but occasionally you get these fun things. They get together into this little pile. They move as a unit. We still don't understand how they move exactly. So it's over here. It's sniffing around this other bigger area. You're going to see a little calcium flash right here, which is a signaling event.

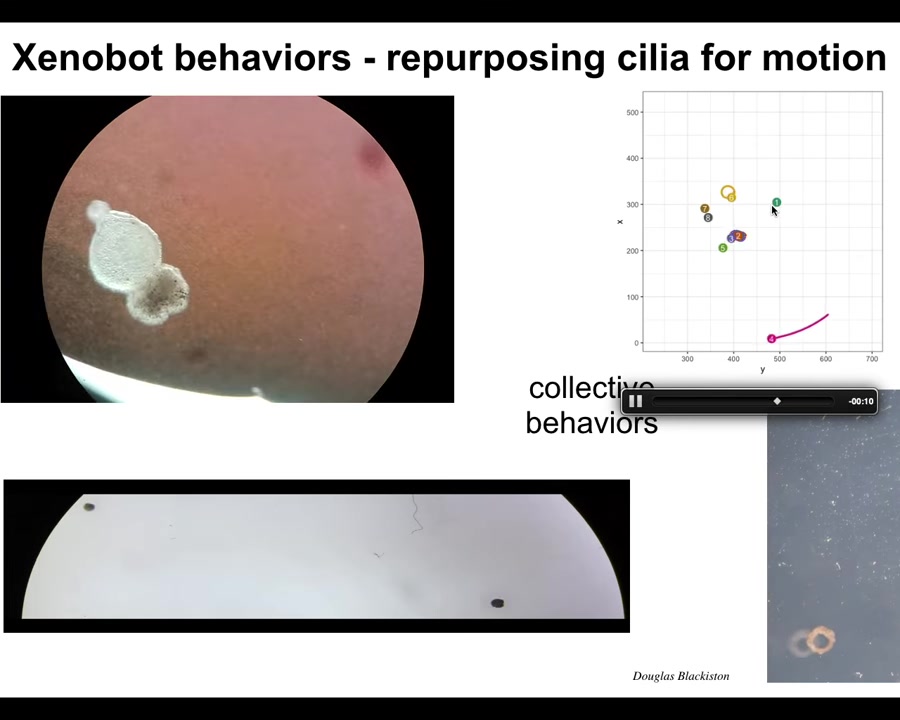

Slide 28/48 · 34m:00s

Eventually they pull themselves together into this kind of thing and then the behavior begins. Then they start to swim. They have little hairs, cilia on their surface that allow them to row through the water. They have lots of behaviors. They can go in circles. They can patrol back and forth. Make weird shapes out of them, these donuts. They have collective behaviors like this. They can work in a group. They can take individual journeys. They can hang out doing nothing.

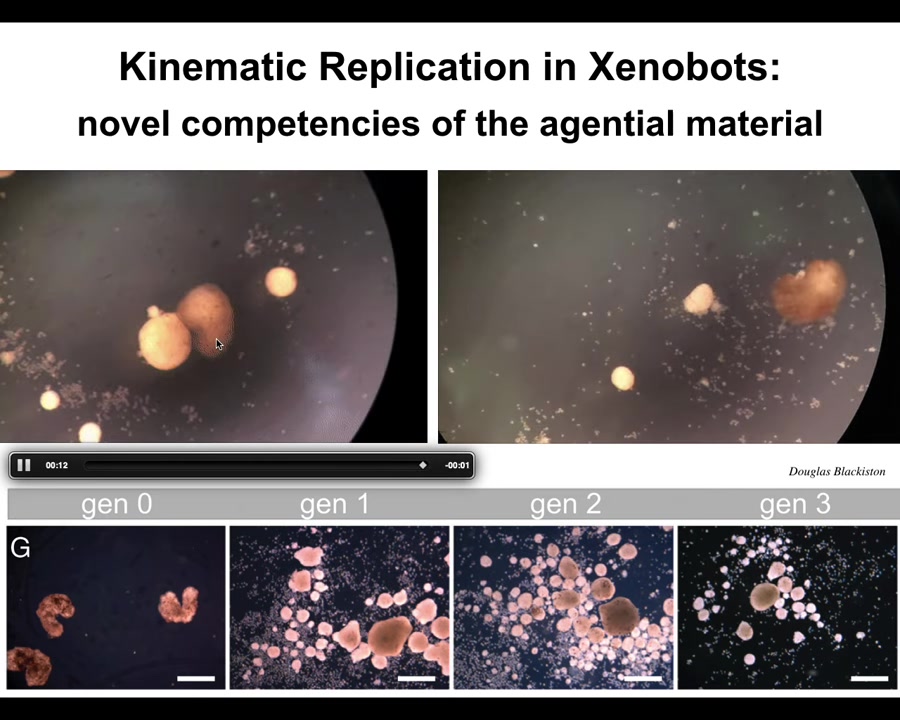

Slide 29/48 · 34m:22s

One of the most amazing things they do is called kinematic replication. If you give them a pile of loose epithelial cells, the xenobots will go around and they will collect those cells into little piles. The piles then mature into the next generation of xenobots. They run around and make the next generation and the next. Both on a collective level and on an individual level, this is von Neumann's dream. It's a machine that runs around and builds copies of itself from parts that it finds in the environment.

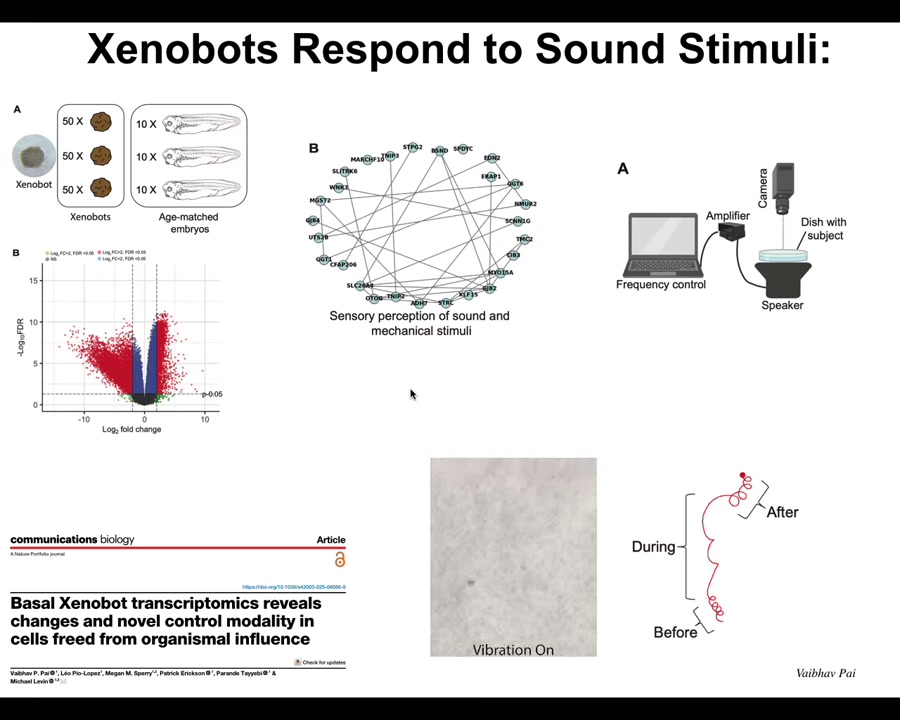

Slide 30/48 · 34m:59s

Now there are many amazing things we're just beginning to scratch the surface of, but one interesting thing is when we looked at what genes Xenobots express that are different from what those cells would have expressed in the body. So we've liberated them from the body. What new genes do they express? It turns out there are hundreds of new genes. Each one of these red dots is a new gene that they express differently.

Some of the genes they express have to do with hearing. We thought that was really strange. Why are these things expressing genes that are normally related to hearing? We said, could it possibly be that they can hear? So we put a speaker under the dish, and we found that when they have certain behaviors and you turn on the sound, their behavior changes. They can, in fact, hear sound stimuli in the water. Embryos that they come from don't do this. This is a new thing that they've started doing.

So when we talk about motivations and forms of behavior, it's really interesting to ask: the Xenobots apparently now care about sound. They didn't in their natural embodiment. Where do all these motivations come from?

Slide 31/48 · 35m:56s

This is a really interesting set of questions. That was frog embryo cells. You might think amphibians are very plastic, embryonic cells are certainly very plastic. Maybe that's some sort of frog-specific weird thing.

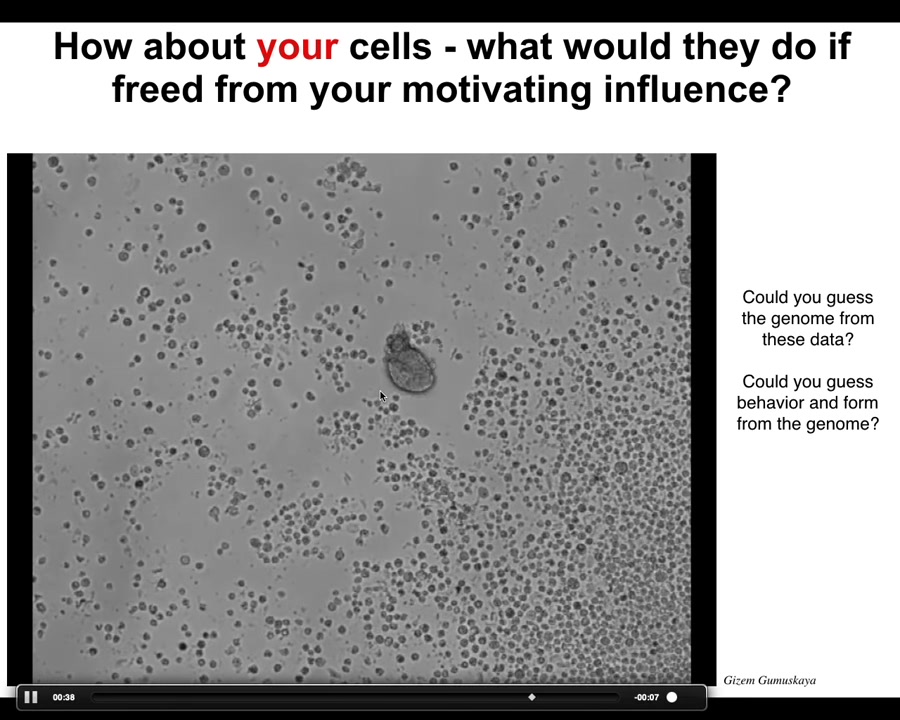

What would your cells do if we liberated your cells from the influence of the rest of your body? I'll show you this. It looks like something we got off the bottom of a pond somewhere, some sort of primitive organism, but actually, if you were to sequence the genome here, you would see 100% Homo sapiens.

These are perfectly normal adult human cells taken from patients who donate a tracheal epithelium for airway biopsies and so on. We buy the cells, we put them in a matrix where they simply self-organize. Much like with the Xenobots, we're not doing very much to them at all. The environment's the same. There are no synthetic circuits here. There is no genomic editing, no scaffolds, no nanomaterials, no weird drugs.

This is basically just liberating the plasticity of these systems where these used to be part of a normal trachea. Now they're this amazing little self-motile creature. And you could never guess this from looking at a human genome. You have no idea that they're capable of doing this. Nor could you guess what their behaviors are.

Slide 32/48 · 37m:20s

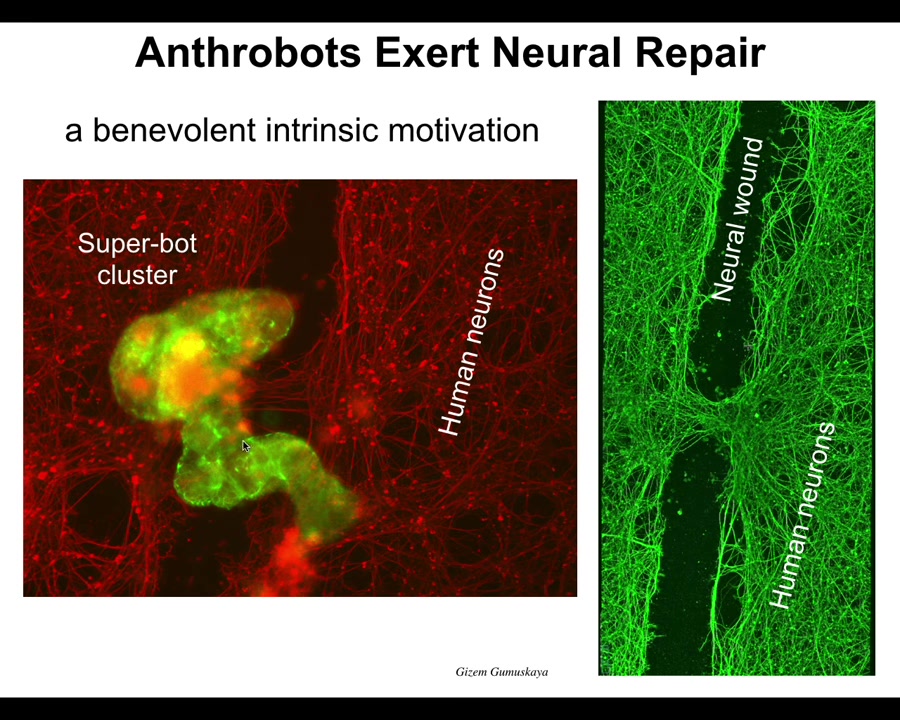

Well, here's one example: if we take a bunch of human neurons and we plate them in a dish, and then we take a scalpel and make a big scratch through it here, this big wound, the anthrobots, that's what we call these motile structures, will drive down the scratch, then they pick a spot to settle in. They settle in a group. So this is probably 8 to 10 anthrobots collected together into this cluster. And then what they start doing is they start knitting the neurons across the gap. They start repairing the damage. If you lift it up, this is what you see right where they were sitting. They start to knit. No one knew this was going to happen. No one had any idea that your tracheal epithelial cells, which sit there quietly for decades in your lungs dealing with mucus and air particles, have the ability to form a little creature that's going to run around and heal neural defects.

This is just the first thing. It's probably a million other things that they do that we're investigating. But this was the first thing. So I call this an intrinsic motivation because we didn't have to teach them to do this. They were not selected for this because this has never happened before. There's never been any anthrobots. They were not trained to do this. They were not designed to do this. They were not engineered to do this.

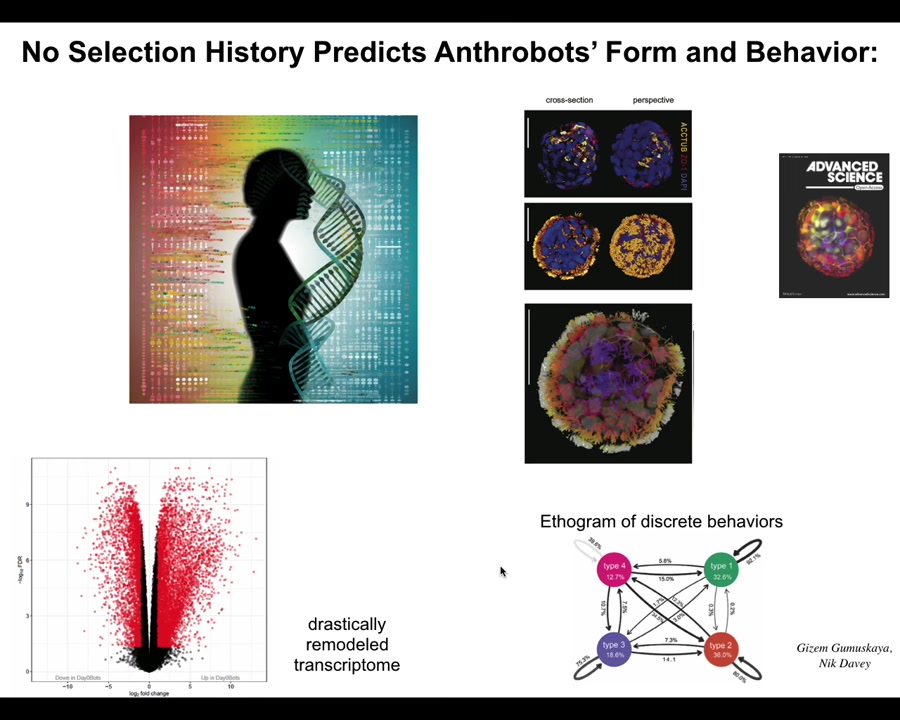

Slide 33/48 · 38m:35s

In fact, the Xenobots have 9,000 differentially expressed genes, so about half the genome. Their transcriptome is completely different. In transcriptional space, they have gone to a completely different location than they would have as human airway tissue. Again, their genome is standard. We haven't touched the genome; it's completely the same. You would have no idea from sequencing them that you're not looking at human airway, or in fact, human cells at all. They have four different types of motile behavior. We can draw a little behavioral diagram that shows us the transition probabilities between their different behaviors. Why are there four? Why are there not ten or one or zero? There's never been any anthrobots. There's never been selection to be a good anthrobot. Where do these things come from?

Slide 34/48 · 39m:23s

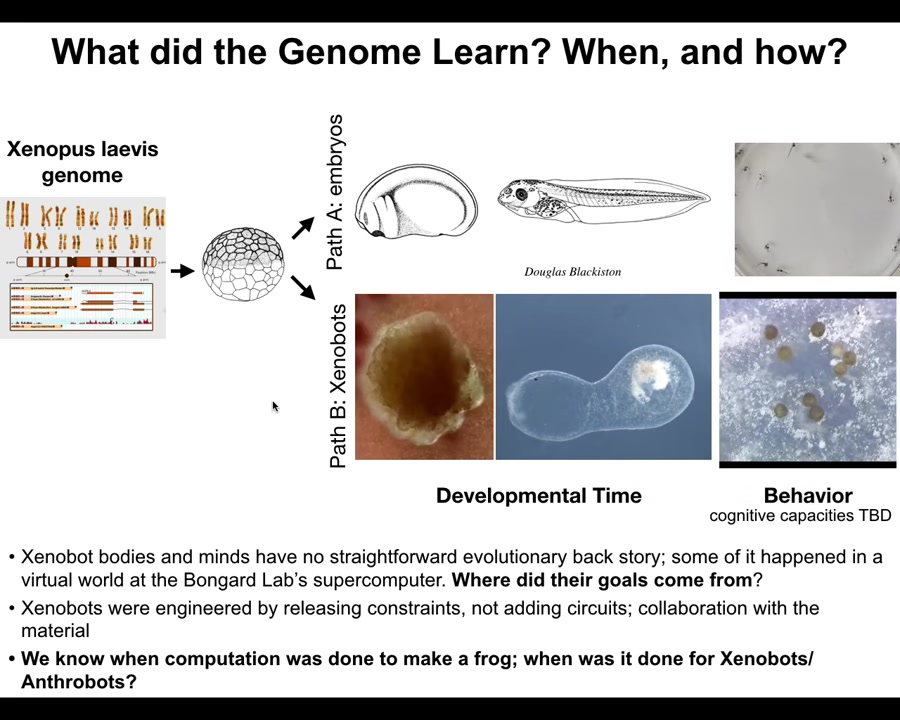

And in fact, if we ask in this case in Xenopus, the frog genome learned over the years that it's been on Earth to do these developmental stages and then eventually make these tadpoles. But also they can make Xenobots, and this is an 83-day-old Xenobot; we have no idea what it's turning into. Different behaviors such as kinematic self-replication.

We know when the computational cost was paid to design this, it was paid during the eons that the frog genome was bashing against the environment, that's the standard story. And that makes sense. When did we pay the computational cost for this? There's never been any selection to be a good Xenobot. These kinds of novel behaviors.

I haven't made any claims about the cognitive capacity of Xenobots. I haven't said what their level of intelligence is. We're testing that now. We know they can learn. We're testing all of these things, so stay tuned for that.

Nevertheless, there are forms of gene expression, forms of physiology of behavior in these kinds of synthetic creatures that you cannot tell an evolutionary story from. You could say it learned to do this at the same time it was doing this, but that undermines the whole point of evolutionary theory because evolution was supposed to show you a very tight causal connection with great specificity between what you have now and the environment of selection that got you here. And if you can say the environment of selection was for this, but also it somehow got this, that isn't really how these things are supposed to work in a predictive fashion.

It's very interesting: where do these extra things come from? You might think biology is certainly special. In fact, maybe what makes biology different than physics, than engineering, than machines, is precisely this, that they have some special ability to have emergent — I'll talk about this in a minute. I don't like that word at all, but some emergent motivations that you couldn't have guessed from their past history. Maybe that's the secret sauce of biology.

Slide 35/48 · 41m:36s

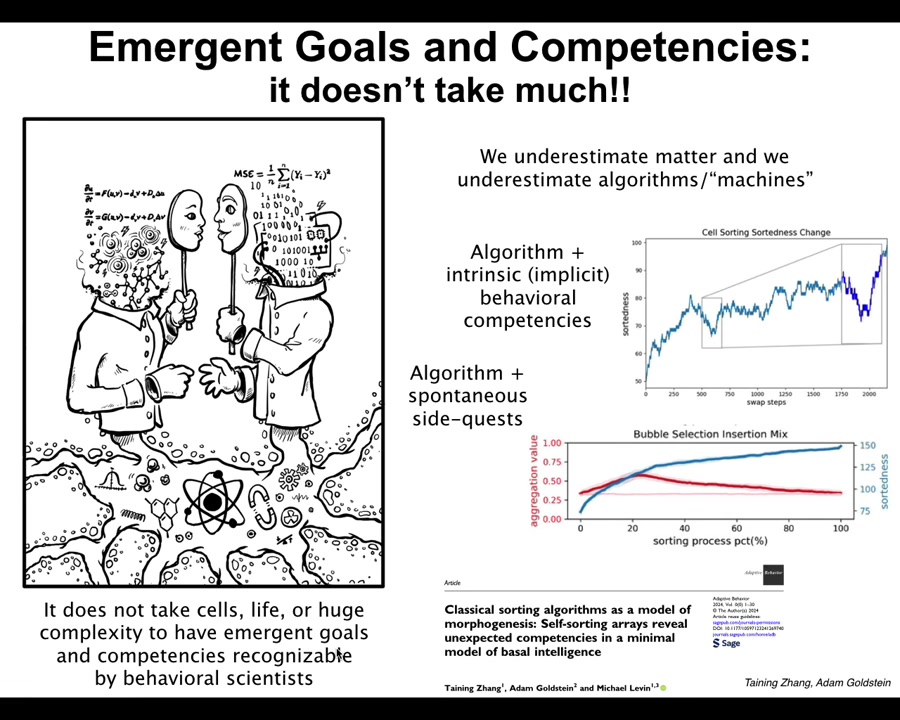

I don't have time to go into great detail, but I'll just point out this paper.

We decided, exactly to address this issue, because I don't believe that this is a property of only very complex living systems. For maximum shock value, I wanted to take the simplest, most deterministic, most familiar thing that we could. And so we took sorting algorithms, like bubble sort, selection sort. Just a few lines of code, completely deterministic, totally transparent, unlike biology where there are more mechanisms; there might be quantum biology. In this case, you exactly know what the algorithm is. There's nowhere to hide. There are no more steps. You see all the steps.

There are two very interesting things about it, and there's more coming on this year. There'll be a couple more papers on this kind of thing. First of all, we found that it has behavioral competencies that are not in the algorithm. For example, one of the things it knows how to do is delayed gratification, and so, as it's sorting the data, if you break some of the numbers so that they don't move, the algorithm says swap the four and the five, but the five is broken, it doesn't move. The algorithm has no—in the standard algorithm, you assume the hardware is reliable. There are no provisions to say, okay, I wanted to swap, but what do I do if they don't swap? There's nothing like that in the algorithm. You assume that everything will go well. It turns out that in that case, what it does is it sorts the array a little bit to move things around that stuck number, and then eventually it gets to where it needs to be.

Any behavioral scientist, if you didn't tell them that this came from a simple algorithm, would look at it and say, we know what this is. Delayed gratification. This is going backwards away from your goal in order to recoup gains, bigger gains later on. But it's not in the algorithm. There's nothing in there that tells you that it's going to do that or how it's going to do that.

It also does these weird side quests, for example, clustering by algo type, where these are things that are not forbidden by the algorithm, but neither are they in the algorithm. They're not prescribed by it either. They're filling up the empty spaces between what it has to do and other things that it does that we never asked it to do. In fact, things that have nothing to do with the sorting problem itself.

I think that it doesn't take life or cells or huge complexity to have novel behaviors and novel motivations that would be easily recognizable by behavioral scientists if they weren't happening in such a minimal medium. I think it goes all the way down.

Slide 36/48 · 44m:21s

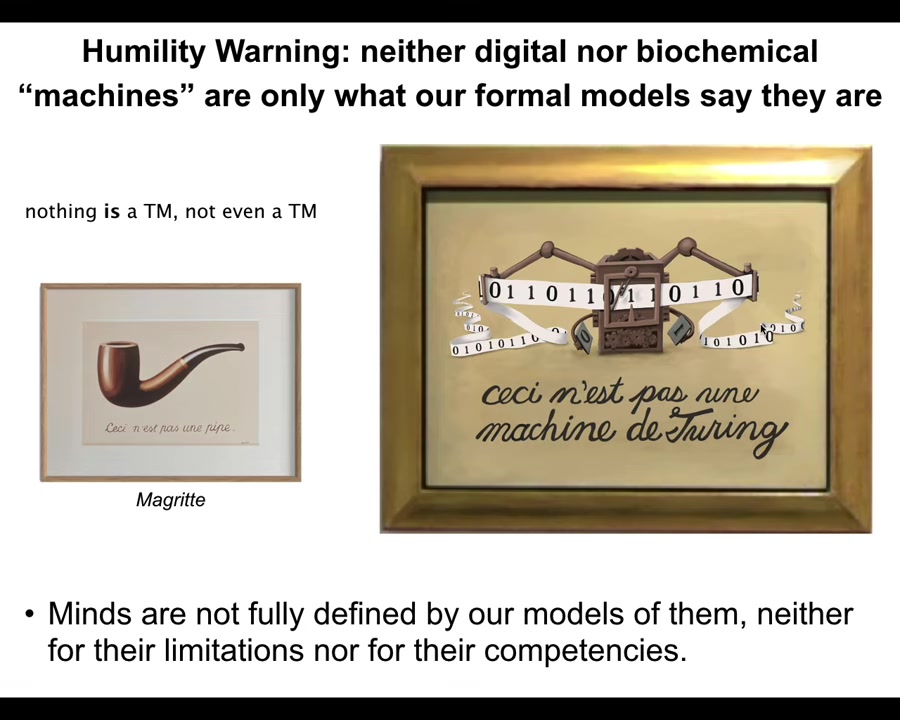

We typically have this idea that there's biology and biochemistry doesn't tell this whole story of the mind, and we can all live with that, but at least there's a corner of the world that acts exactly the way it's supposed to.

We have machines, we have algorithms, and the story, the theory of algorithms and the theory of computation is a complete theory of what boring machines might do. Many people think that those kinds of theories are not applicable to living things, and I would agree with that. They do not cover what we see in living things. But my claim is they don't even cover what simple machines are. You shouldn't expect them to, because they're formal models, and nobody said that any formal model has to give you the whole story of the object itself.

The formal models have limitations, and we should be very careful not to confuse those limitations with the limitations of the thing itself. When Magritte was telling us "this is not a pipe," this is a representation of a pipe. So we can say, this is not a Turing machine. This is a representation of a machine that has a particular set of capabilities and limitations. But that doesn't mean it's a full description of what's happening.

I think for the same reason that living things and their capacities are not well described by our formal models of what's going on. I think this goes all the way down. Even something as dumb as bubble sort can have novel behavioral competencies, not just complexity, unpredictability, or indeterminism, but novel competencies and novel Goal states that are not predicted by or made easy to discover by the standard models of computation.

Slide 37/48 · 46m:14s

I think these things go all the way down, and the final piece of this story that I want to ask is this: however far down it goes, we need to understand where these motivations come from. If it's not going to be a history of selection and a specific design for a specific outcome, where else do they come from?

There are two ways to think about this. One is called emergence, and this is by far the more popular right now, but I want to argue for something different.

First, especially to biologists, that seems crazy.

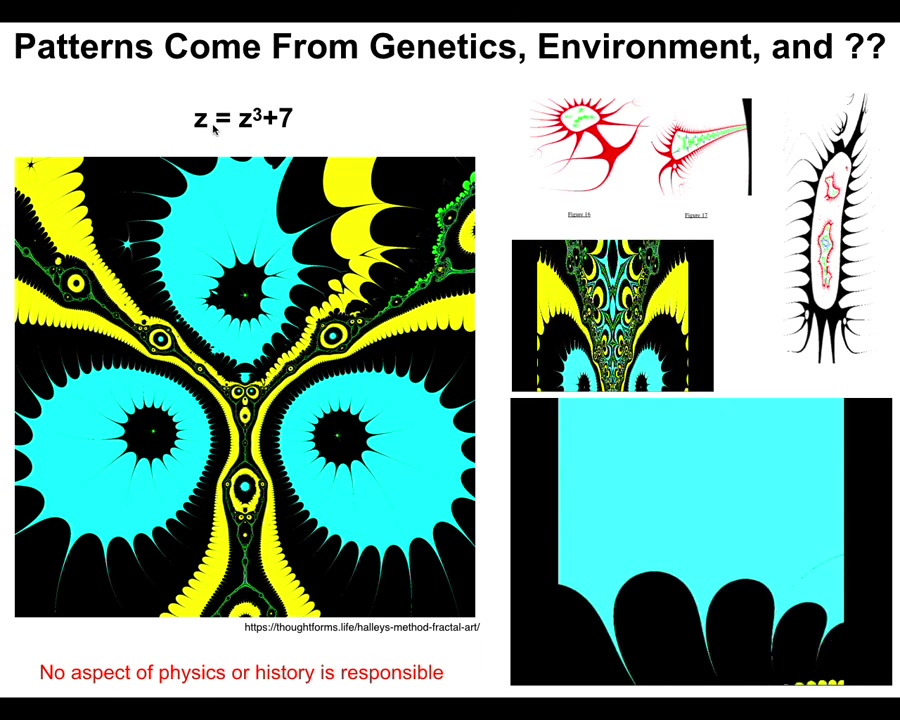

If the patterns are not coming from physics or from genetics, where could they possibly come from? I want to remind us about mathematics.

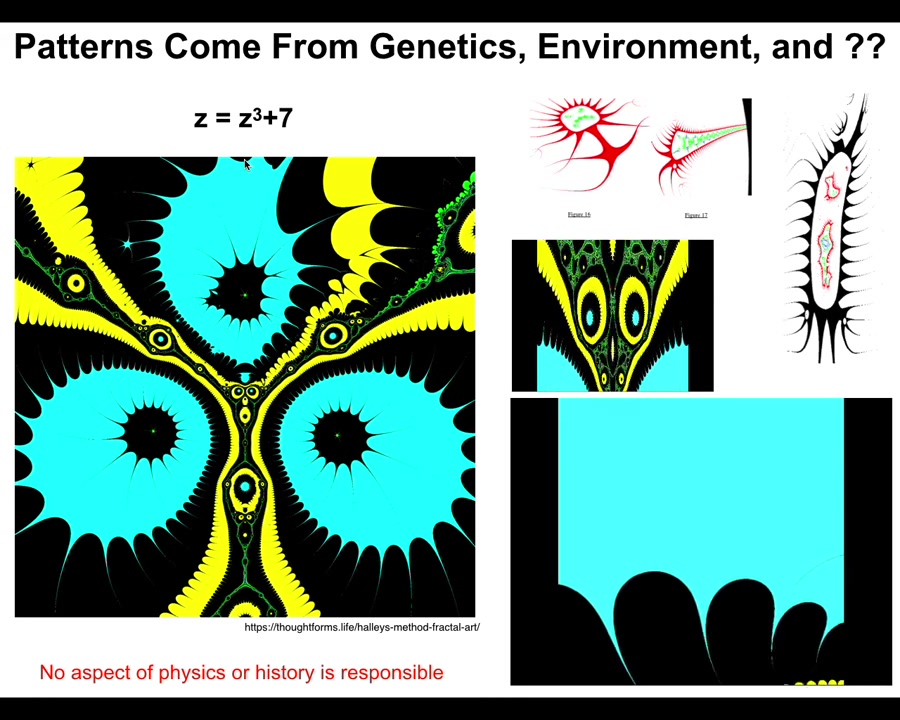

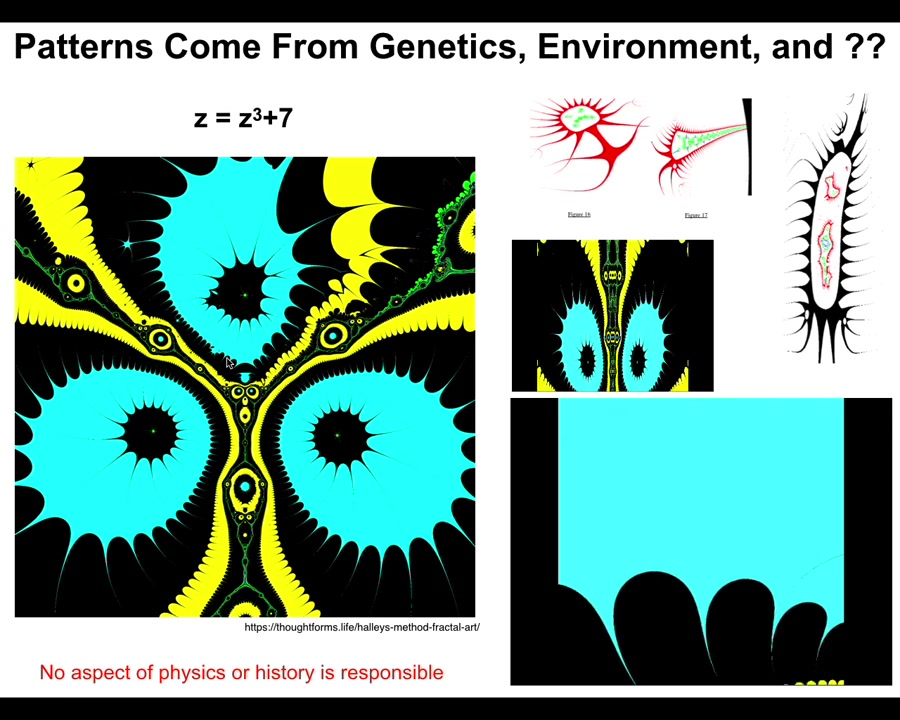

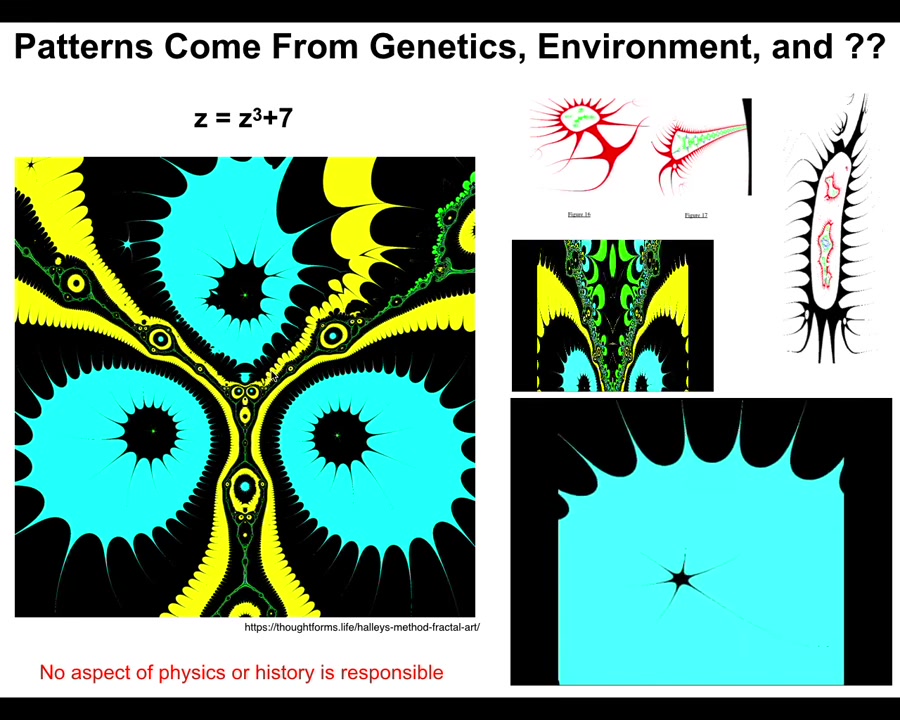

Slide 38/48 · 47m:02s

This is a very simple function in complex numbers. Z^2 + 7, and you iterate this and you draw the Halle map and you see something like this. If I vary this a tiny bit at a time and put the frames together, I can make a movie that is a flyover of some of these structures. They look very organic.

Slide 39/48 · 47m:26s

They come from this tiny little seed. It's not compression. There's no way you're going to compress something this complex into a thing of six or seven characters. This is an index into a pre-existing pattern. It's a mathematical object. And the important thing about these mathematical objects is if you ask why does it have the shape it has, the answer is not because there was a process of selection that killed off all the things that didn't look like this.

Slide 40/48 · 47m:49s

There was nothing like that. Nor is the answer, because physics. There's some aspect of physics that determines this. There is no aspect of physics that determines this. You could change all the constants at the Big Bang, and this wouldn't be any different. So now we understand. There are patterns with great specificity, and in fact, complexity, that are not the results of either a selection history or some sort of necessity of physical laws.

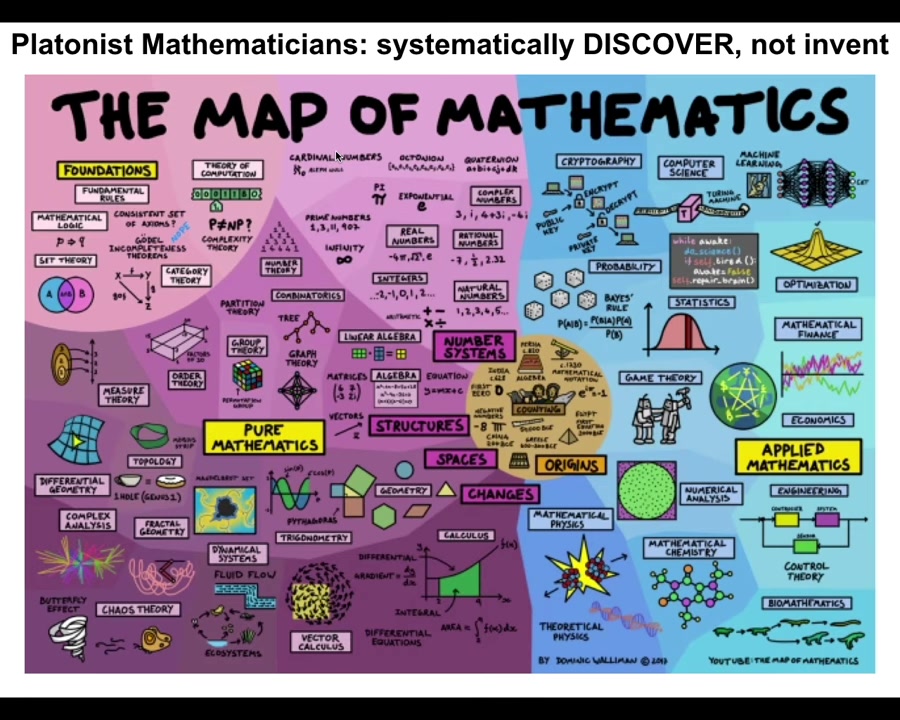

So, what do we do with these patterns?

Slide 41/48 · 48m:21s

The mathematicians do something interesting. They think that these patterns come from an ordered, structured space. They're not a random grab bag of things that show up as a surprise from time to time, but an ordered space. One way to think about it is a Platonic space; Plato talked about something like this, a space of objects that are not determined by physics, not determined by evolution.

However, they affect both physics and biology, because biology exploits the heck out of these things. These are free lunches that biology uses, and we can talk about that if somebody wants to ask about examples later. In physics, when you start asking about the very fundamentals of why bosons do this or that, the answer eventually turns out to be because there's this mathematical object and it has these symmetry groups and that's why it's like that. So if you keep asking why, both in biology and physics, you end up in the math department.

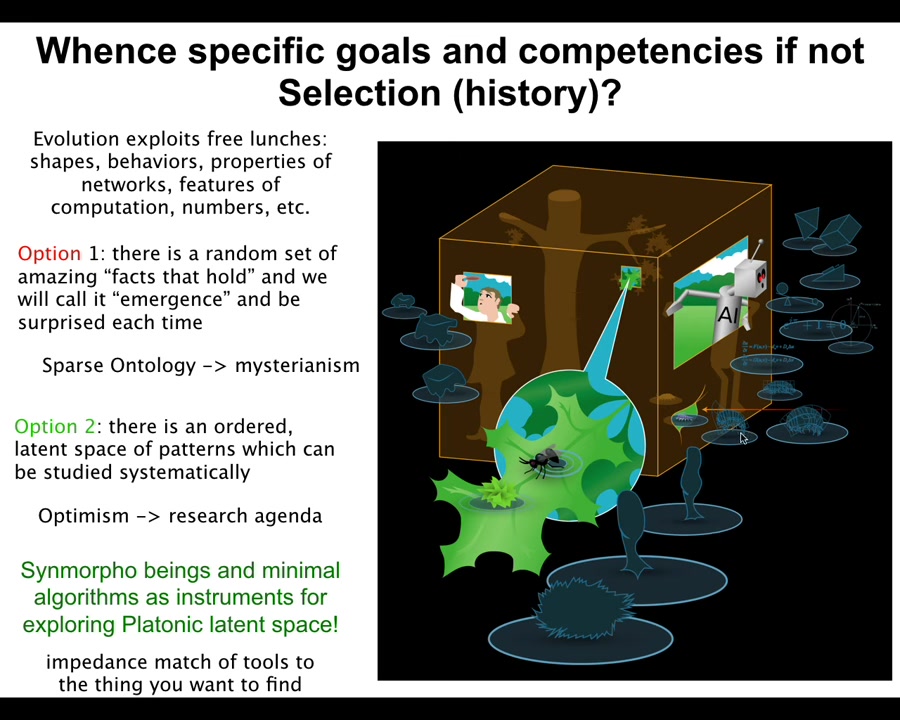

Slide 42/48 · 49m:21s

I think that's really important.

So there are two options for thinking about this. Number one, when I ask people, biologists in particular, I say, look, here are some amazing facts about networks, about logic gates, about numbers that biology is exploiting. Why are these things like that? Why do they exist? And some people say, well, that just happens to hold in our world. It's just an amazing pattern that happens to hold in the world.

The benefits of that view is that you get to keep a nice sparse ontology, meaning that you can be a physicalist and you can say there's nothing other than the physical world. It just has some surprising features in it that are cool. That is where a lot of people end up when they say "emergence." Basically surprise: some stuff happened. We can write it down in our book of emergent facts, and that'll be that.

I don't like that view. I think it's a kind of mysterian view that prevents a lot of research. Instead, we can hypothesize more optimistically that these patterns are not a random grab bag of things that just happen to hold in our world. There's a structured latent space from which these are drawn that we can investigate.

And the idea is that all of these things that we make—synthetic xenobots, biobots of all kinds, robots, cells, embryos—are interfaces into that space and thus are tools or instruments that we can use to explore that space.

The interesting thing is that the tools you use to explore something often determine what it is that you're going to find. In other words, there has to be a kind of impedance match between the tools and what you find. So physics tends to see mechanism, not minds, because it uses low-agency tools, rulers and voltmeters and things like this. If you want to see minds, you have to use other minds. You have to use complex kinds of cognitive systems to find other cognitive systems.

That's very interesting. What we make constrains what it is that we see because the interfaces that we create determine what patterns from that space we're going to be able to pull out.

Slide 43/48 · 51m:34s

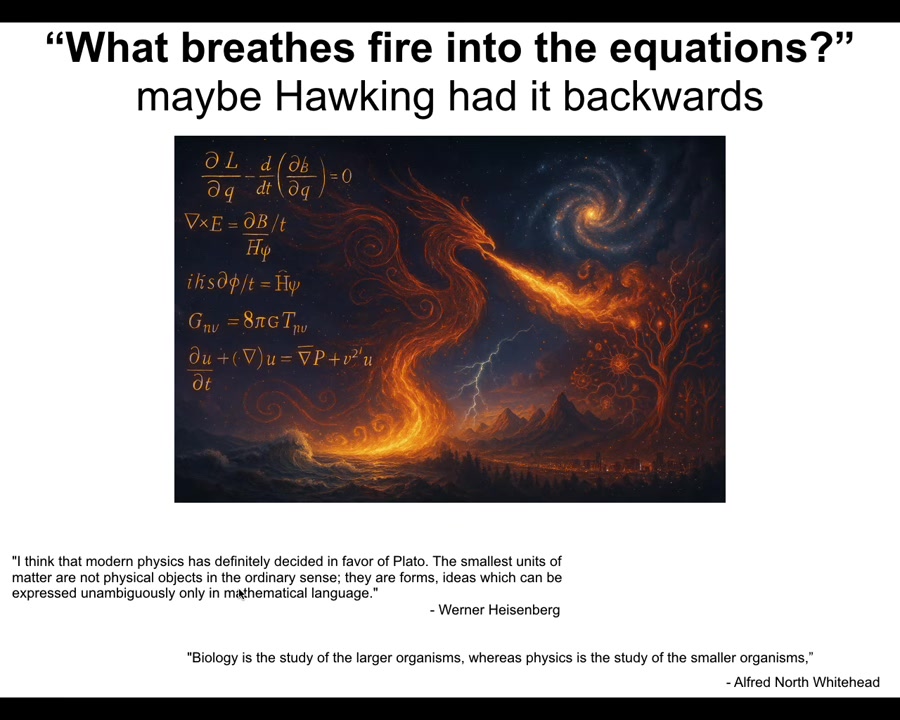

I suspect that Hawking asked what breathes fire into the equations. Maybe that was backwards. Maybe it's actually the equations describe certain structures of that space. And that's what breathes fire into the facts of biology and certain facts of physics and so on. I'm not the first person to say this. Heisenberg and Whitehead basically pointed this out too.

Slide 44/48 · 52m:00s

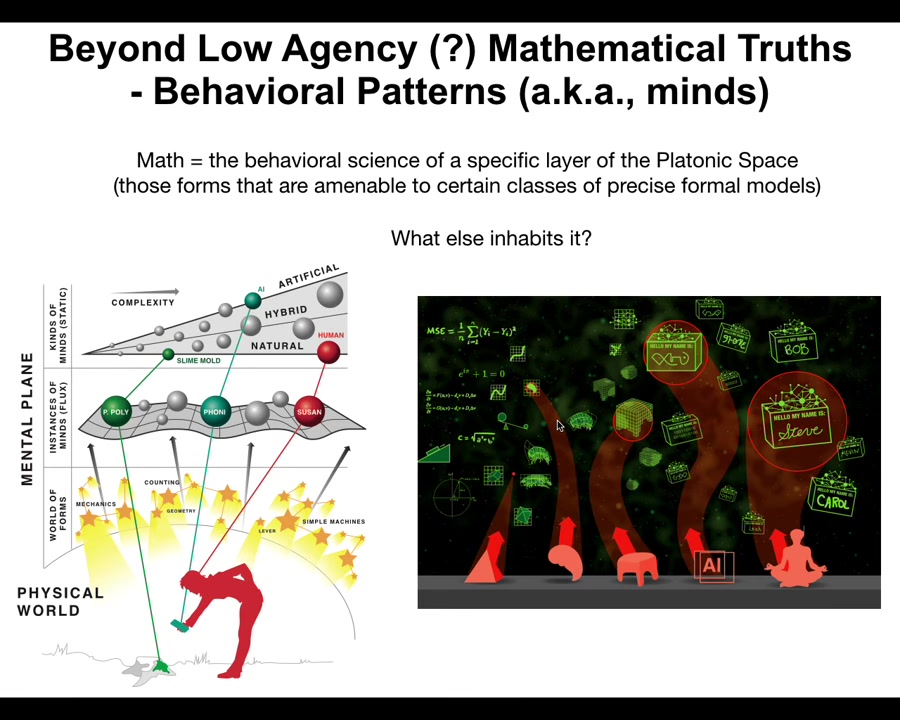

So the model at this point that I'm proposing is this. There is this latent space. It contains some low agency, at least probably low agency, patterns whose behavior is studied by people we call mathematicians. So math is a behavioral science. It's the behavioral science of low agency patterns. But that space also contains much more complex, much more active, dynamic, high agency patterns that we would recognize as kinds of minds. Those are the other things inhabiting that space.

Slide 45/48 · 52m:39s

That means that when you make new interfaces—new bodies that are different from the natural ones—any combination of evolved material, engineered material, and software is going to be a home for these ingressing patterns. When you make these novel kinds of embodiments, you're going to meet some new patterns you've never met before. Now we can talk about AIs and cyborgs and hybrots and all these kinds of things.

Slide 46/48 · 53m:10s

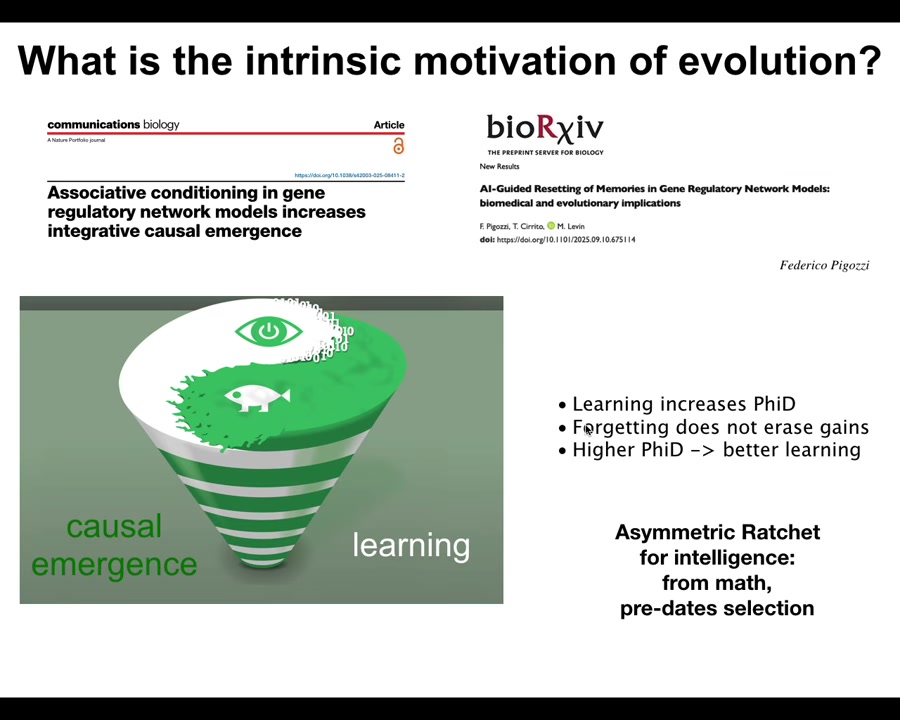

The last thing I'll say before I wrap up is this: we can go further and ask at much larger-scale processes like evolution, what are their intrinsic motivations?

One of the recent things we learned is that there's this amazing feedback spiral where in very simple chemical networks they can learn. That's the first thing: they can learn. Learning increases their causal emergence. It makes the system more real, more than the sum of its parts. Forgetting does not erase those gains. Once you have those gains, you get better at learning. So it becomes a ratchet. It becomes a feedback cycle that points upwards towards intelligence. It's a free gift from the mathematics of networks and causal emergence. You don't need selection for this. It predates selection. So maybe these kinds of things, even processes like evolution, have a fundamental arrow towards higher intelligence; they're patterns of mathematics that underlie this. And then evolution, of course, will optimize the heck out of it. But in the meantime, it comes from math.

Slide 47/48 · 54m:19s

I end here and summarize that I think patterns of all kinds of spaces are ubiquitous. These patterns serve as goals for agents, very simple or more complex. Genetics, physics, emergence are all insufficient. What we really need to do is to map out the latent space. An important claim is that even very minimal systems enable the ingressions of these patterns that take us beyond concepts like complexity, randomness, and determinism. There are other things that are critical.

Here are some hypotheses and speculations: I think that everything from machines, cells, embryos, swarms, robots, whatever, are pointers into this space. They're interfaces through which these patterns ingress into the physical world. Physics is what we call systems that are constrained by these patterns, but biology is what we call when systems exploit these patterns and use them as a kind of free lunch to advance. All engineering is partly reverse engineering, and the attitude towards your constructions and towards AI and everything else should be less Skinner and more Piaget. You want to not just have reward functions. You want to understand what are the intrinsic motivations of the system and to what extent we can collaborate, cooperate with it, because you're going to get surprises, not just perverse instantiation, not just complexity and unpredictability. You're going to get the emergence of cognitive properties.

There are some other things we could say about the relationship of minds to brains along this model and free will. We can talk about that.

We have a research program that we're undertaking. That's the nice thing about all this: it's very actionable. We're building new interfaces. We're trying to quantify the free lunch aspects. We're asking about whether you can get compute in that space, how these patterns are ingressing through the interfaces. There are many different kinds of interesting research questions that my group is now asking.

Slide 48/48 · 56m:34s

I'll stop here by thanking the people who did the work that I showed you today.

We have lots of amazing collaborators in our center and beyond. There are lots of people who have funded aspects of this work over the years. I'm very grateful to them.

Here are three companies that have licensed some of these ideas.

I am not claiming that the people here or any of these people specifically endorse my model. It's very unconventional, not the way most people think about this. I think it helps us to move forward.

Again, all the credit goes to the various model systems, living or not, that are teaching us about these things. I will stop here.