Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a ~50 minute video on evolution from the perspective of diverse intelligence. I discuss 3 main things: the nature of the mapping between genotype and phenotype (an intelligent, problem-solving process that interprets genomic prompts, not simply a complex mechanical mapping), the implications for evolution of operating over such a multi-scale agential material, and a few recent findings about the origin of the intelligence spiral taking place before differential replication dynamics kick in.

Editing by https://x.com/DNAMediaEditing

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Framing evolution and intelligence

(06:26) Morphogenesis as collective intelligence

(12:06) Regeneration and downward causation

(16:10) Bioelectric patterning and memory

(21:05) Reprogrammable adaptive anatomies

(26:06) Interpretation, plasticity and evolution

(31:58) Competent matter and evolvability

(35:45) Novel beings and emergence

(41:54) Prebiotic learning and agency

(46:43) Mind beyond life

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/35 · 00m:00s

What I'm going to talk about is 2 aspects of the relationship between evolution and intelligence. First, I'm going to claim that they make a positive feedback spiral, which I will explain. I also think there's an interesting inversion to be discussed where intelligence actually precedes and potentiates evolution and not the other way around.

As a preface, I want to say a couple words about the perspective that I take on these problems. In my group, we study an intersection of biology, computer science, and cognitive science. I'm interested in this journey that all of us take from a little bag of chemicals in an unfertilized oocyte all through the various sciences. We traverse disciplines that we have given names to: chemistry, developmental physiology, behavioral science, psychology, and so on. While the disciplines and the funding bodies and journals and departments and all these things are distinct, I think that the substrate is continuous. All of these, to me, are kinds of behavioral science, but that's what I think is going on here. That's one aspect of where I'm coming from.

Slide 2/35 · 01m:11s

Another is that I'm really interested in going beyond the typical focus on biological materials and natural evolution here on Earth and a focus beyond anthropomorphism. And I'm interested in the status and properties of all kinds of unusual beings.

We all know we are at the center of the spectrum, both on an evolutionary and developmental scale. But also now with technology, increasingly, we're getting further apart from this standard adult human that features prominently in discussions of philosophy of mind, where we have technological changes, we have biological changes, and we have to ask ourselves what do we mean by a human and how much of that is critically related to our origins on Earth.

Slide 3/35 · 02m:12s

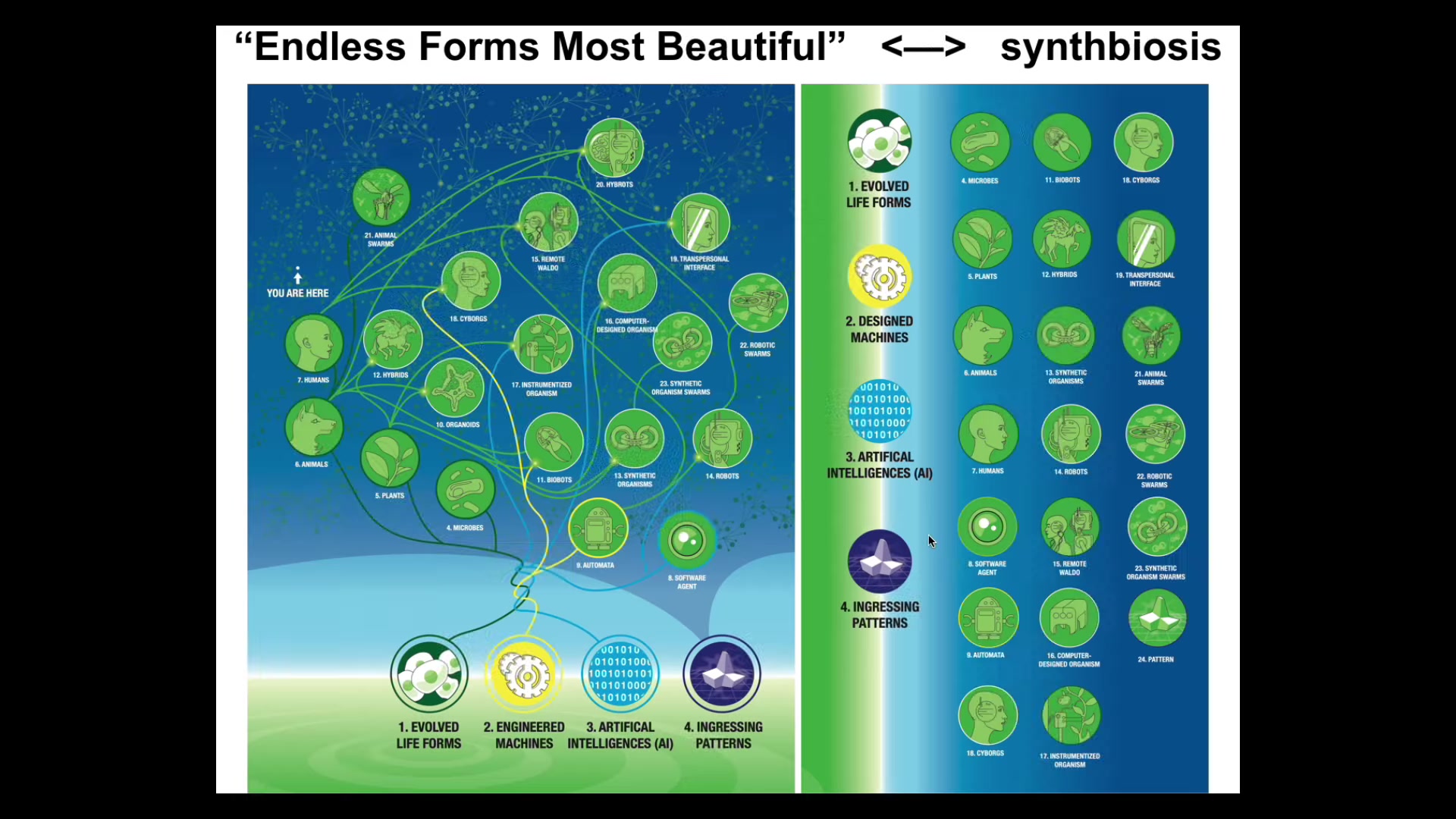

This is not the whole story because the space of possible embodied minds is truly vast. Everything that Darwin was talking about when he said 'endless forms most beautiful' is like a tiny corner of this possible space.

Any combination of evolved material, engineered material, software, and something I will mention at the end, patterns from a latent space, is probably some kind of interesting embodied intelligence. Many of these already exist. Cyborgs and hybrids and all kinds of unusual creatures are going to be sharing the world with us. We need to work to have ethical synthbiosis with these other unconventional minds. This is the direction I'm coming from.

Slide 4/35 · 02m:59s

In particular, Richard and I on a recent paper had an interesting quote from a reviewer who said that developmental biologists don't concern themselves with the mind-body problem. I think this is fundamentally mistaken. I think developmental biologists are ideally suited to address the mind problem, body problem. In fact, they have to. I'm not the only person who thought this. Here's Alan Turing, who thought very hard about intelligence and embodiment and different vehicles for minds. He wrote this very famous paper on the origin of order and embryonic development. I think he recognized a very important fact, which is that there are deep symmetries between the autopoises of the body and the autopoises of the mind, and these things come together in a very, very important way.

What I'm going to talk about today is the relationship between intelligence and evolution. What I will not be talking about is non-random mutations. Many of you study these. Whatever is going on there is in addition to everything that I'm going to say. Nothing that I say today relies on having non-random mutations.

What I am going to talk about is to try to convince you of three specific things. First of all, that the map between the genotype and the phenotype is intelligent. That is, the process of morphogenesis that converts the substrate of mutation into the substrate of selection is itself a problem-solving, creative process. The thing that sits in the middle is very important, and it is not just complex. It is not just a big hairball of causal interactions. That means that we have to ask ourselves, what does it look like to evolve on this kind of material? I'm going to claim that evolving on a multi-scale agential material works quite differently than we're used to thinking about evolution. I think this has major implications. Both of these points rest on this idea that there are autonomous agents all the way down, and this makes evolution work differently.

What I'm going to talk about for the last third of the talk is to address two questions: where do the properties of entirely novel beings come from, beings that have not been specifically selected in the evolutionary stream on Earth. I won't have time to talk about this, but I will point you to talks by myself and many other people about an idea related to this claim that the properties of novel beings, and in fact of existing beings too, come from the same latent space that things like the precise value of E and other mathematical objects come from. I'll only have time to touch on that.

I will also talk about some of the recent work that we've done on what actually kickstarts the evolutionary process before you get replication. What's going on before even replicators and thus differential replication kicks in? I'll introduce you to a concept I'm still working on the name of, but for now this is what I'm calling it. I'll talk about some very speculative things for the future.

Let's talk about this first issue. In order for me to convince you that the genotype to phenotype map is a kind of intelligence, what we would have to do is dissolve some assumptions, specifically assumptions that intelligence and problem solving are things that brainy animals do in three-dimensional space. In order to do that, I will try to make two claims. First, that diverse intelligence forms a kind of continuum. Then we're going to talk about what morphogenesis is actually doing with the genome, with the genomic information.

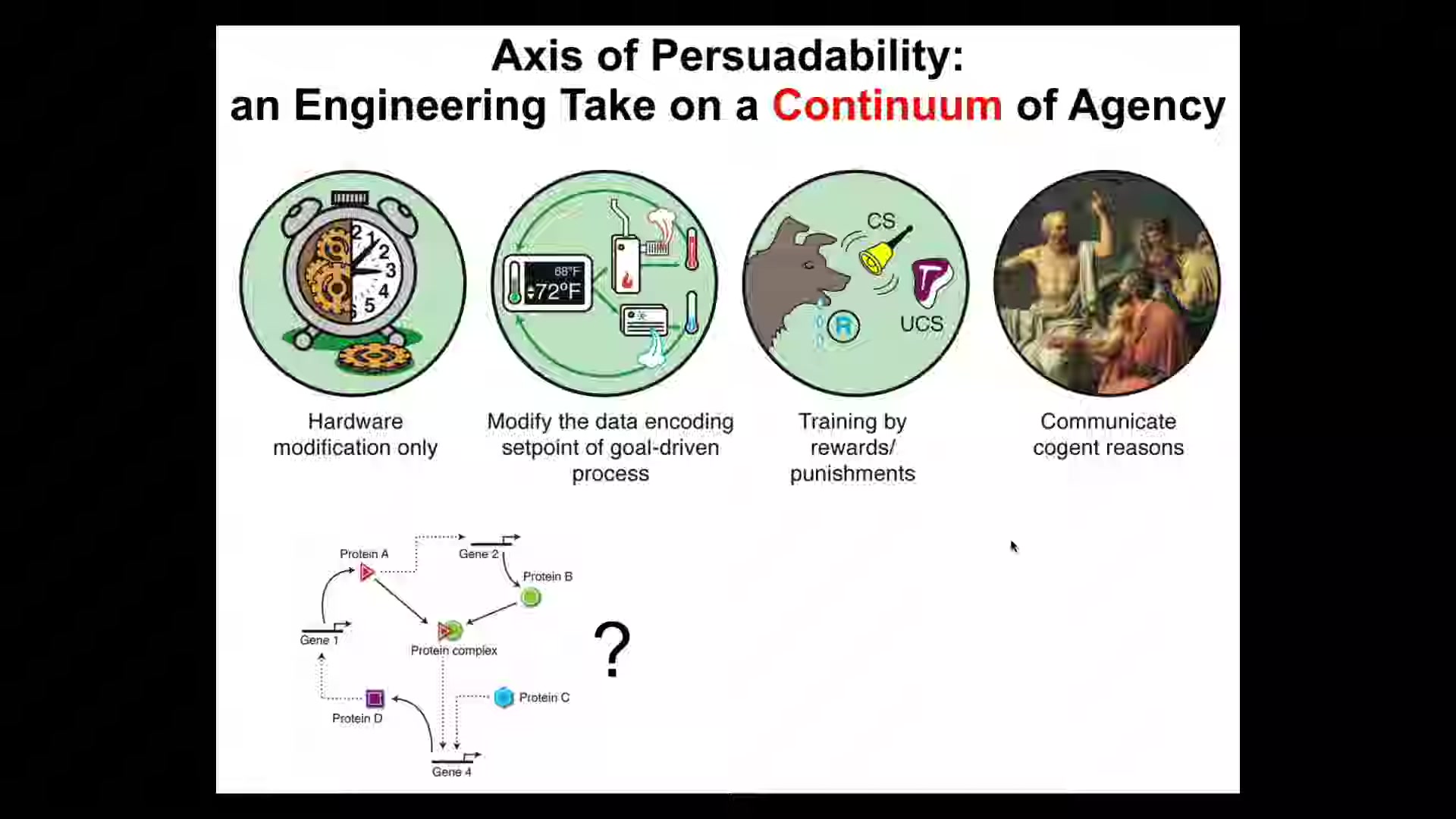

One approach that we take in my group is a kind of engineering slant on this problem. You can think about it as an axis of persuadability. In other words, the degree of intelligence, agency, cognitive capacities, for any system is basically a claim about the kind of interactions you can have with it.

Slide 5/35 · 07m:24s

You don't know ahead of time where a given system fits on the spectrum, you have to do experiments. That is, you can't just hold up ancient categories. This is not a philosophical project or a linguistic project. This is empirical.

You ask, is it this kind of system which can only be addressed by hardware rewiring. Maybe it is better subject to cybernetics and control theory. Maybe it has homeostatic properties and thus you can talk about goals and things like that. Maybe you can train it with rewards and punishments and other behavioral paradigms. Or maybe the best toolkit to bring is rational communication, friendship, love, psychoanalysis, all the kinds of things at the right side.

The idea is that we actually don't know for any of the things we deal with biology ahead of time where this lands. Our intuitions are not good. We have to do experiments.

Slide 6/35 · 08m:16s

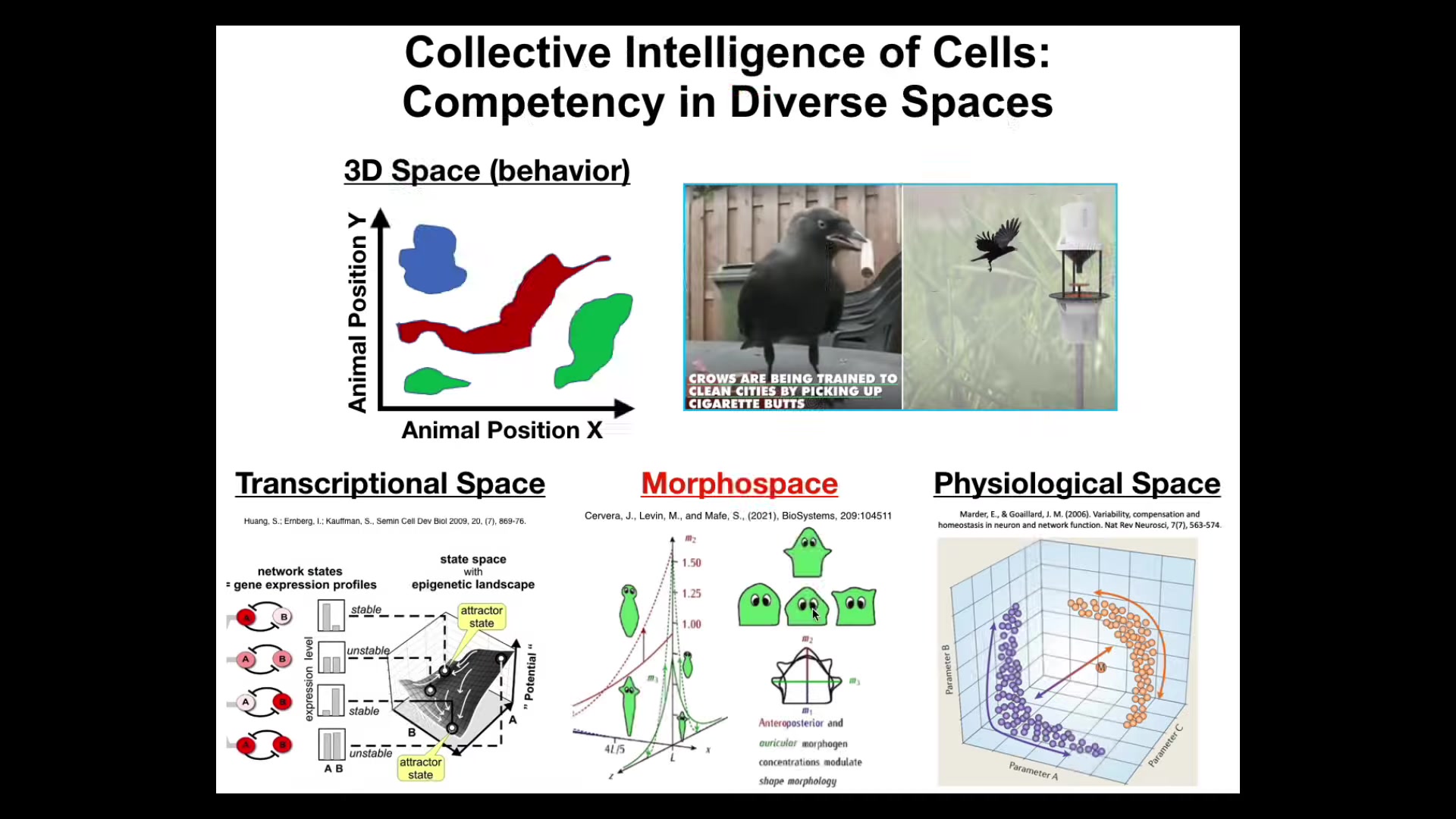

One of the important things that's hard for us is to recognize intelligence in other spaces. For example, medium-sized objects moving at medium speeds, birds and primates, maybe a whale or an octopus in three-dimensional space, we're okay at noticing when they're doing something intelligent. But biology has been navigating all kinds of other spaces at other scales that are very difficult for us to recognize. Navigating the space of transcriptional states, gene expression states, physiological state space, anatomical morpho space. Biology uses the same kinds of strategies to navigate all of these spaces. This was happening long before a nerve and muscle came on the scene.

In biology, what we're dealing with is this kind of multi-scale competency architecture where at every level you have autonomous subunits that have certain abilities in navigating that space. And all of these spaces are different.

Slide 7/35 · 09m:14s

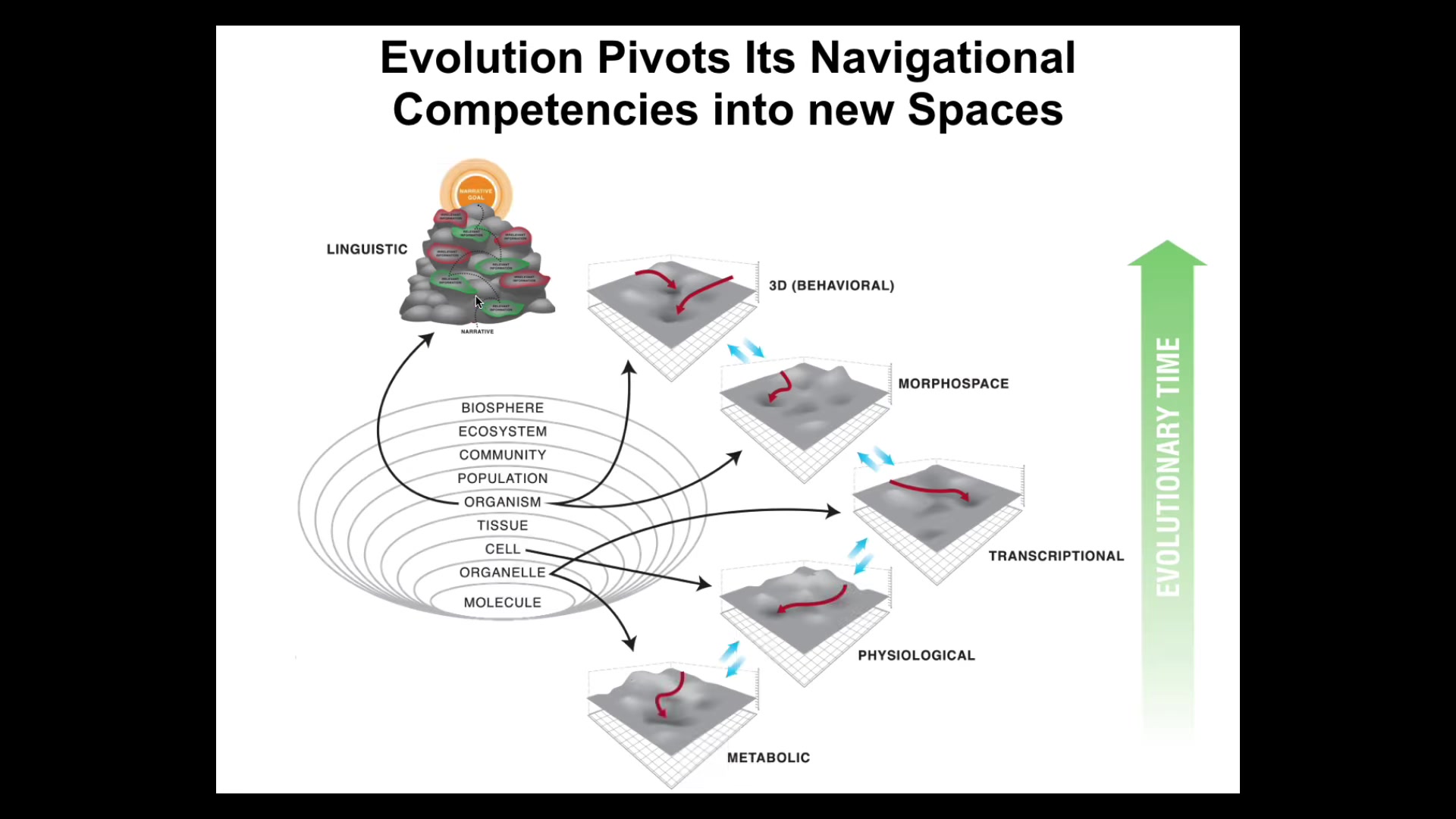

You can think about evolution as pivoting the same kinds of tricks through lots of different spaces. You start out in metabolic space and then you have physiological circuits and eventually gene expression comes along and then multicellularity and you have to navigate anatomical morphospace and then nerve and muscle. So now you can navigate conventional behavioral spaces and eventually linguistic space and many other abstract spaces.

Slide 8/35 · 09m:43s

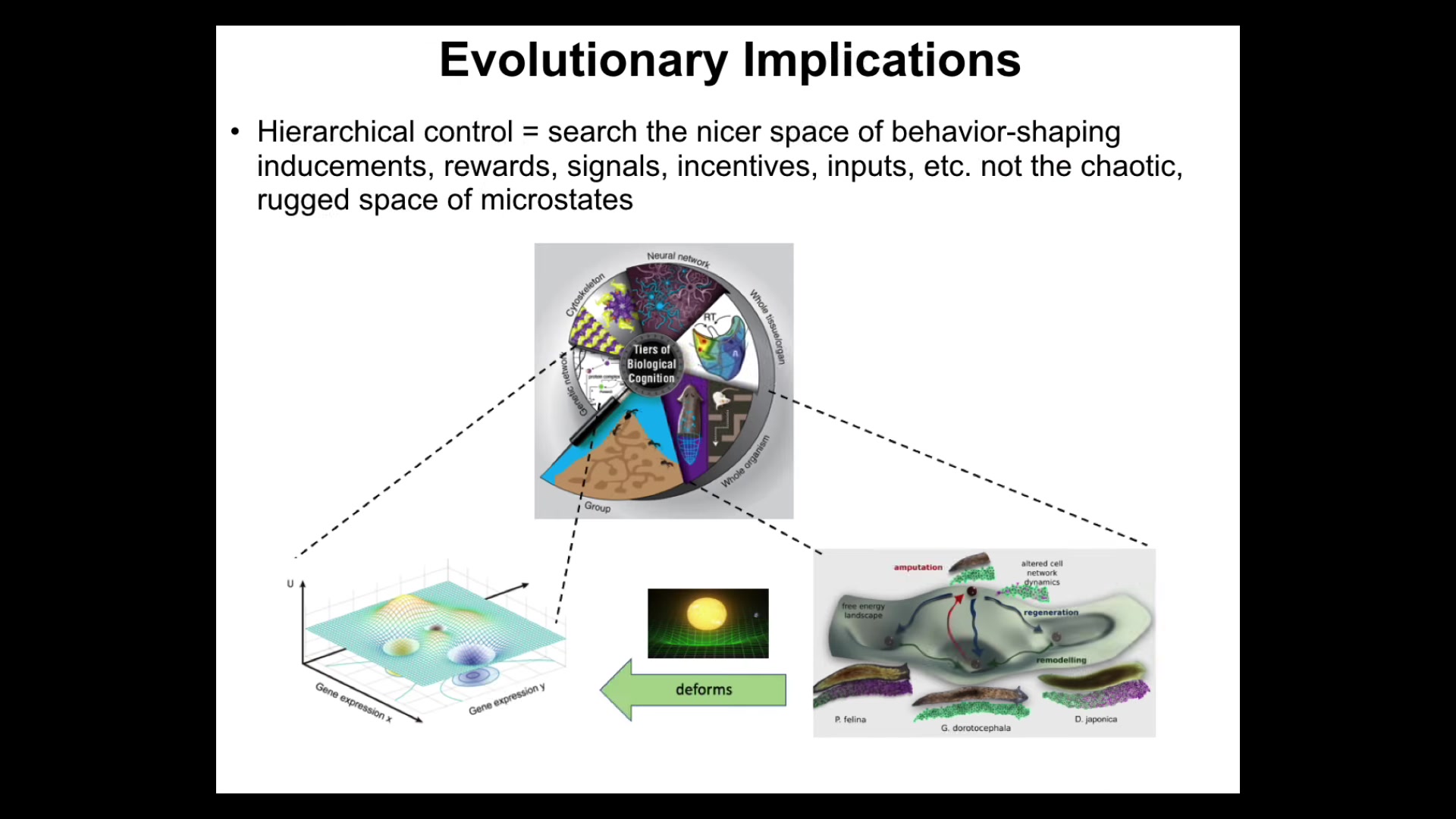

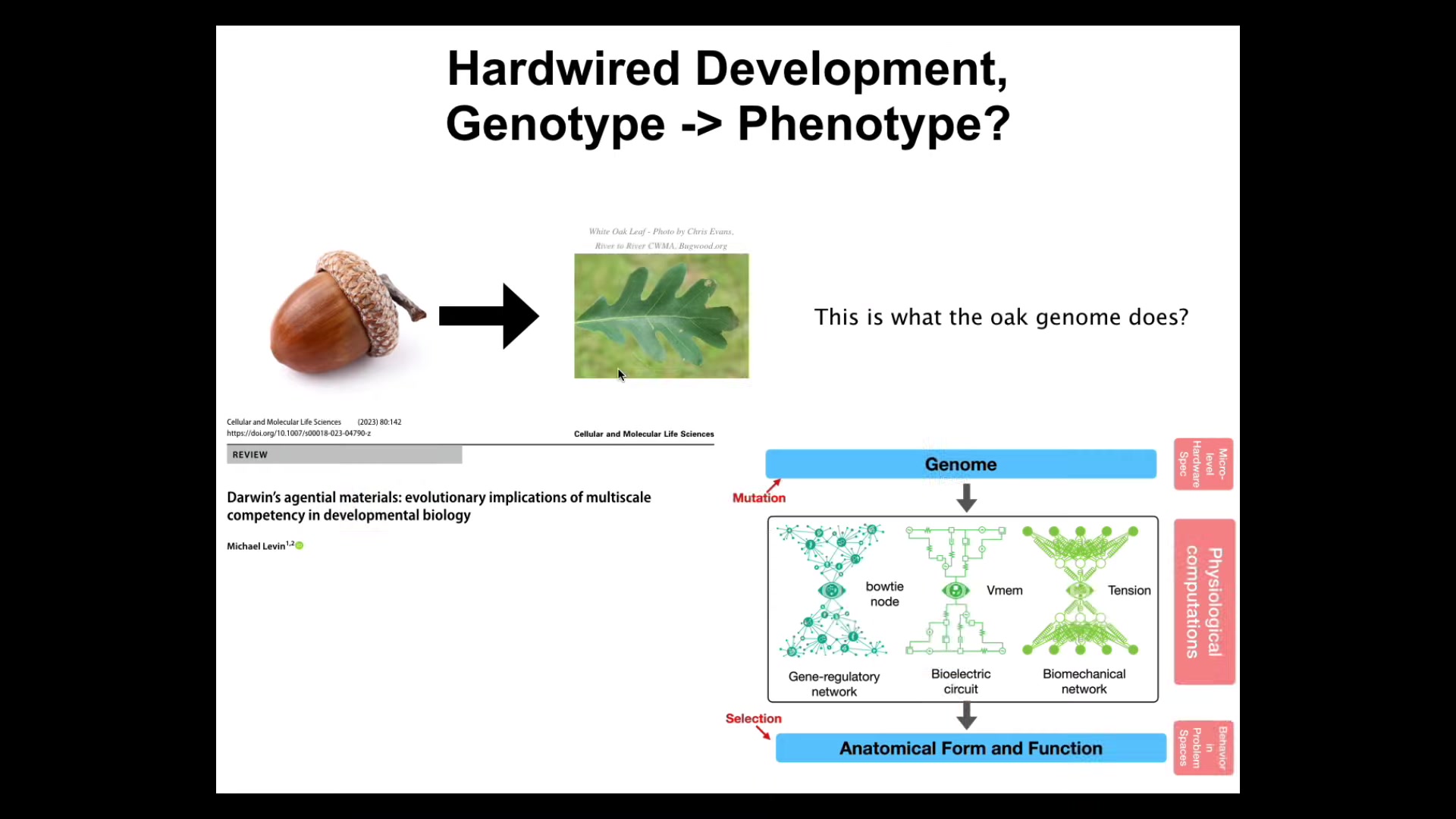

What's interesting about systems like this is that every level is bending the option space for the subunits below. They are navigating their space as best as they can, but their option space is being deformed by the level above such that the actions that they take are actually serving goals that they don't know anything about. Morphogenesis, or broadly speaking, the conversion of genotypes into phenotypes during different kinds of autopoietic processes, is a kind of improvisational interpretation of the genome. It's not a mechanical process; it's an interpretational process.

Slide 9/35 · 10m:28s

And that's because there is enormous distance and there is a lot of divergence between the genotype and the actual form and function that results. And it's not just complexity, it's not just polygenicity or degeneracy or any of those things. There are actually some very deep parallels here between cognitive science and the developmental biology that implements this. And typically I would do a whole hour just on this, but I'm going to say very briefly what I mean by intelligence is the kind of thing William James talked about, a substrate-agnostic, cybernetic definition, roughly summarized by the ability to reach the same goal by different means. Some level of navigation capabilities of some space to get to a goal when things change. And the hypothesis that we've been following for about 25 years now is that morphogenesis is a collective intelligence. We're all collective intelligences made of groups of subunits. And it exerts its behavioral competencies in anatomical morphospace, the space of possible anatomical configurations. And in order to test that hypothesis, you have to go through and experimentally test all the different kinds of protocols that you would expect cognitive beings to be amenable to. You have to show goal-directed activity and you have to show context sensitivity and different paths through that space and hackability and learning and various other things. This is what we've been doing, taking tools from behavioral science and applying them to the biological substrate to understand what exactly are the competencies of the thing that maps the genetics to the phenotype. I'm just going to show you a few examples.

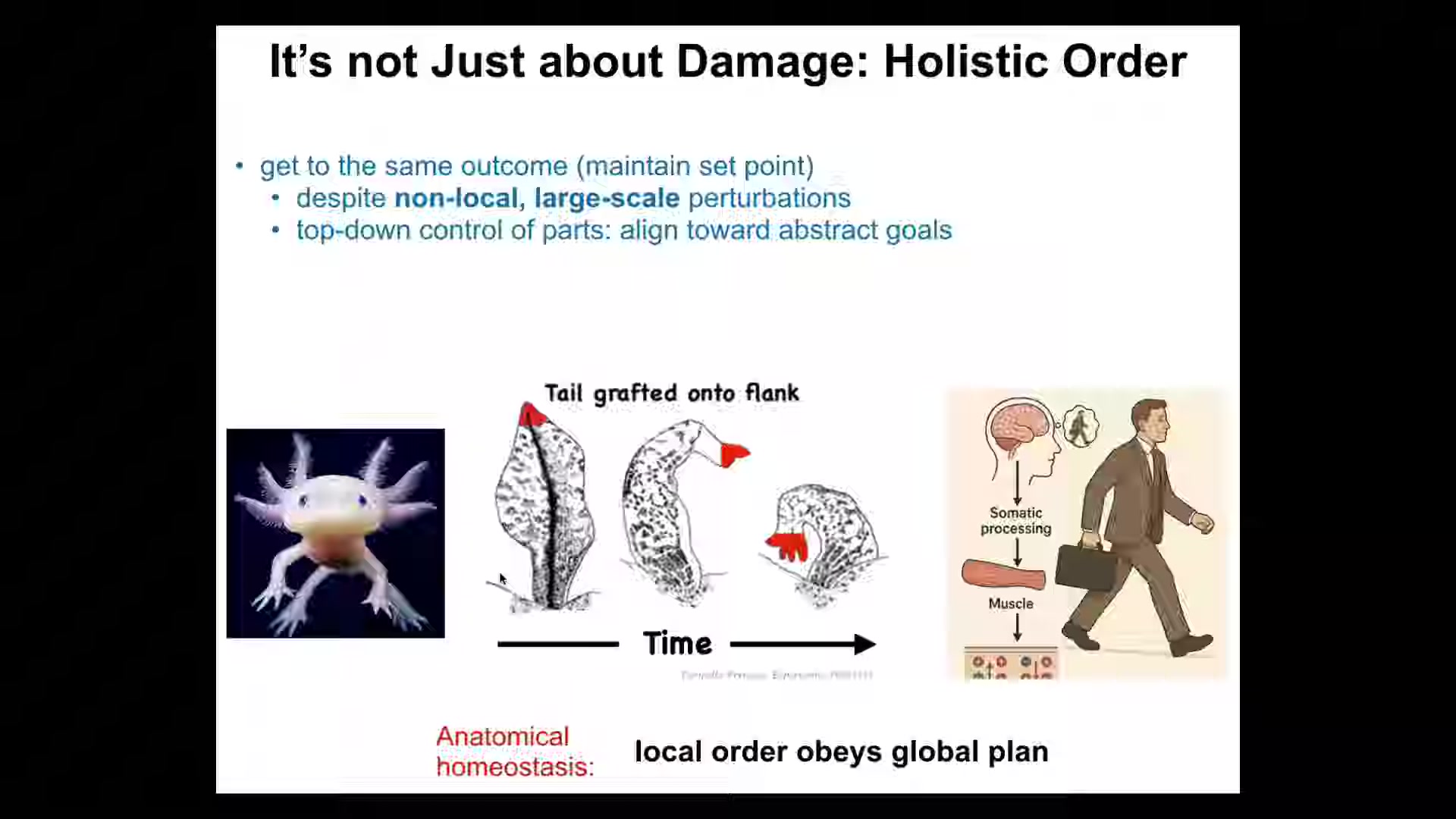

We all know about regulative development, so embryos very reliably turn into whatever they're supposed to do. And this reliability actually obscures the fact that it is not a rote, hardwired process. It's very good, at least in many species, at getting to the same anatomy from different starting states. If you cut an embryo into pieces, you don't get half bodies, you get perfectly normal monozygotic twins and triplets. And so you can think about development as basically regeneration. It's regeneration from one cell. You're restoring the whole body from one cell, which is in turn just an instance of homeostasis. It's anatomical homeostasis. And this is the kind of thing that is most commonly illustrated. Let's say you've got this axolotl and it has a limb. You can amputate anywhere along the path here and what it will do is the cells will rebuild this exact structure and that's when they stop. And that's the most amazing thing about regeneration is that it knows when to stop. When does it stop? It stops when it has reached back to the correct location in anatomical space. Here it's been deviated, then it takes this traversal back and then it stops. So far, anatomical homeostasis. The cells work together to restore a particular position in anatomical space. But there's something even deeper about this. It's not just about damage. This is about holistic order, reaching down in a downward causation. I'll give you an example here.

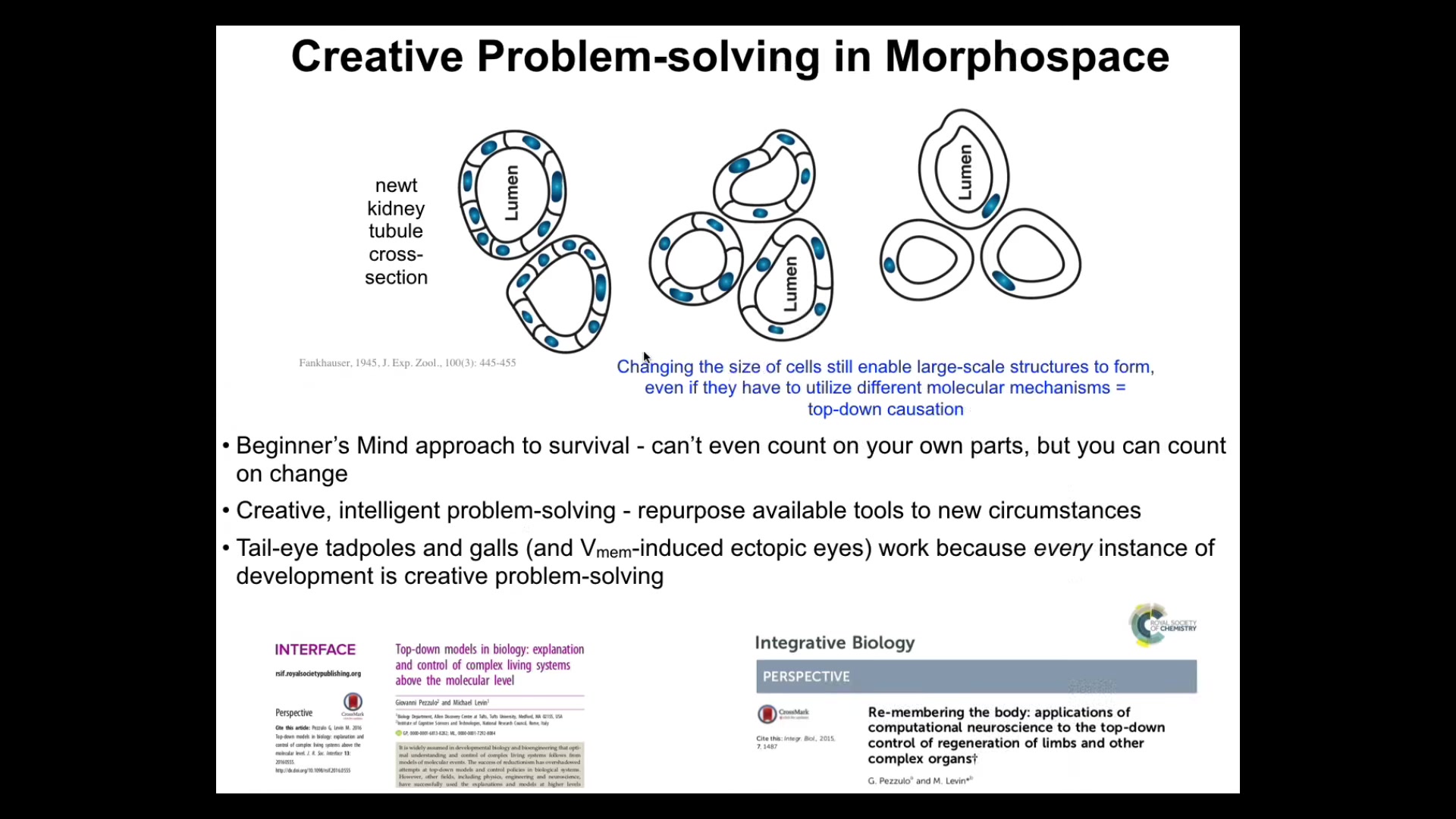

Another thing that you can do with these organisms is take a tail and graft it to the middle of the flank. You take the tail, graft it to the middle. What will happen over time is that this tail turns into a limb. Pay attention to the cells at the tip of the tail here. There's no injury, there's no damage, there's nothing locally wrong. Why are they turning into fingers? Why am I being turned into fingers? Everything was fine. We were tail tip cells sitting at the end of the tail. And what's happening here is that there is a global delta between what the body plan should look like and what it looks like here. No individual cell knows what a finger is or how many fingers you're supposed to have or anything like that. But the collective absolutely does.

Slide 10/35 · 14m:33s

What happens is that when you have this inappropriate structure in the middle of the organism, it tries to regulate back to a more appropriate body plan. And what that involves is filtering down from this very abstract space of the body plan and organ positions to the molecular biology to make these terminal structures undergo a kind of metamorphosis to get back to where it needs to go.

Now, this idea of large-scale abstract goal states filtering down to make the chemistry behave is something we've seen before. We've seen it in voluntary motion. So when you wake up in the morning and you have very abstract goals — these may be social goals, research goals, financial goals — in order for you to get up and walk and execute on those goals, those highly abstract kinds of structures have to eventually make the ions move across your muscle cell membranes. Literally in our bodies, we have this amazing transduction machinery that allows very abstract goals in all kinds of spaces to change what the chemistry is doing. It's not some strange mind-body interaction. It's not some yoga practice. It's everyday voluntary motion.

Both in our standard behavior in the cognitive science of voluntary motion and in morphogenesis, we have examples of large-scale, high-level goal states propagating down to make the chemistry do new things that it otherwise wouldn't do. I think that's very important.

Slide 11/35 · 16m:13s

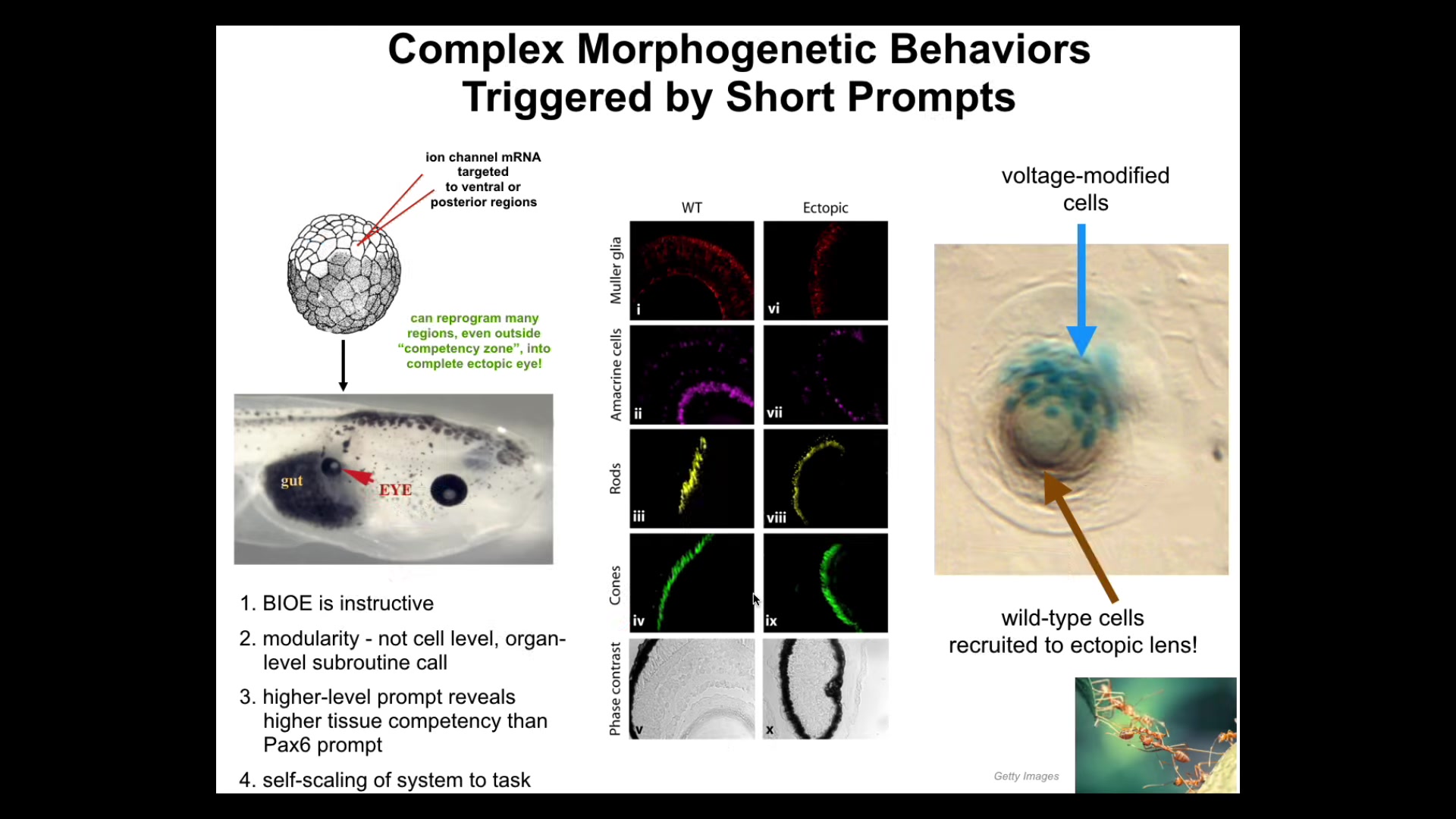

You can try to turn on and off genes and things like that, but you can also communicate with the higher levels. Just as I'm communicating with you, I don't need to worry about where the synaptic proteins are going to go in your brain. You're going to handle all of that. All I need to do is give you high level prompts. If I do a good job, your brain will do all of the necessary chemistry to make sure that you remember these things.

Here's one example in which we can communicate with these higher level control structures. For example, here's a side view of a tadpole. You've got the gut here, here's the animal's right eye, here's the brain up here, the mouth is here, the ventral body is down there. What we've done is inject some ion channels that provide a specific bioelectrical signal. This is something I would normally talk for hours about: the role of bioelectricity as cognitive glue, just like in our brains. The reason you know things that your neurons don't know or that none of your individual neurons know is because of the electrophysiology that binds them into a particular network. That's true in every part of the body. We've exploited that interface to be able to send through various ion channel manipulation techniques, optogenetics, those kinds of things. We can send specific signals that mean something to the surrounding tissue, and we can talk about organs, not individual gene expression, not stem cell biology, but we can say build an eye here. It's a very simple, high-level prompt. When we say build an eye here, that's what the cells do. They build an eye. The eye is the right shape, the right components. It has these sections. It has lens, retina, optic nerve. We can communicate; we don't have any idea how to micromanage it any more than I know how to tweak your synaptic proteins to facilitate our conversation. We know how to send prompts and that's okay because the material is competent.

If we only get a few of the cells here, this is a cross-section of that, the blue cells are the ones that we injected. If our message is convincing, and that's not easy because the neighboring cells are actually trying to prevent them from doing it as a cancer suppression mechanism, there's a tug of war of possible futures here. If we're convincing, what these cells do is instruct all of their neighbors to participate in this eye formation. That's secondary instruction. We didn't teach them to do that. They already know how to do that. This is the kind of material that you're evolving on.

Slide 12/35 · 18m:52s

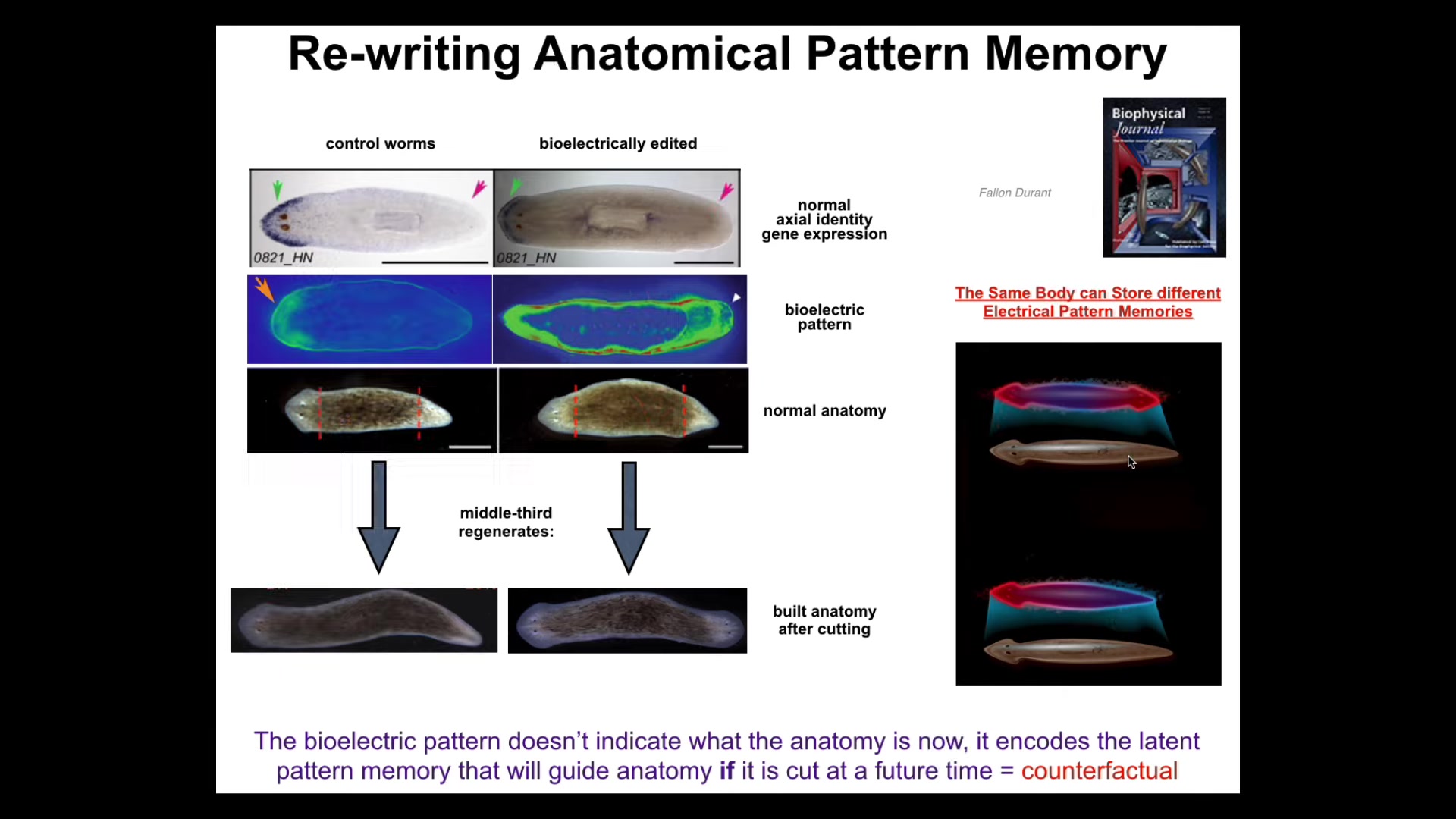

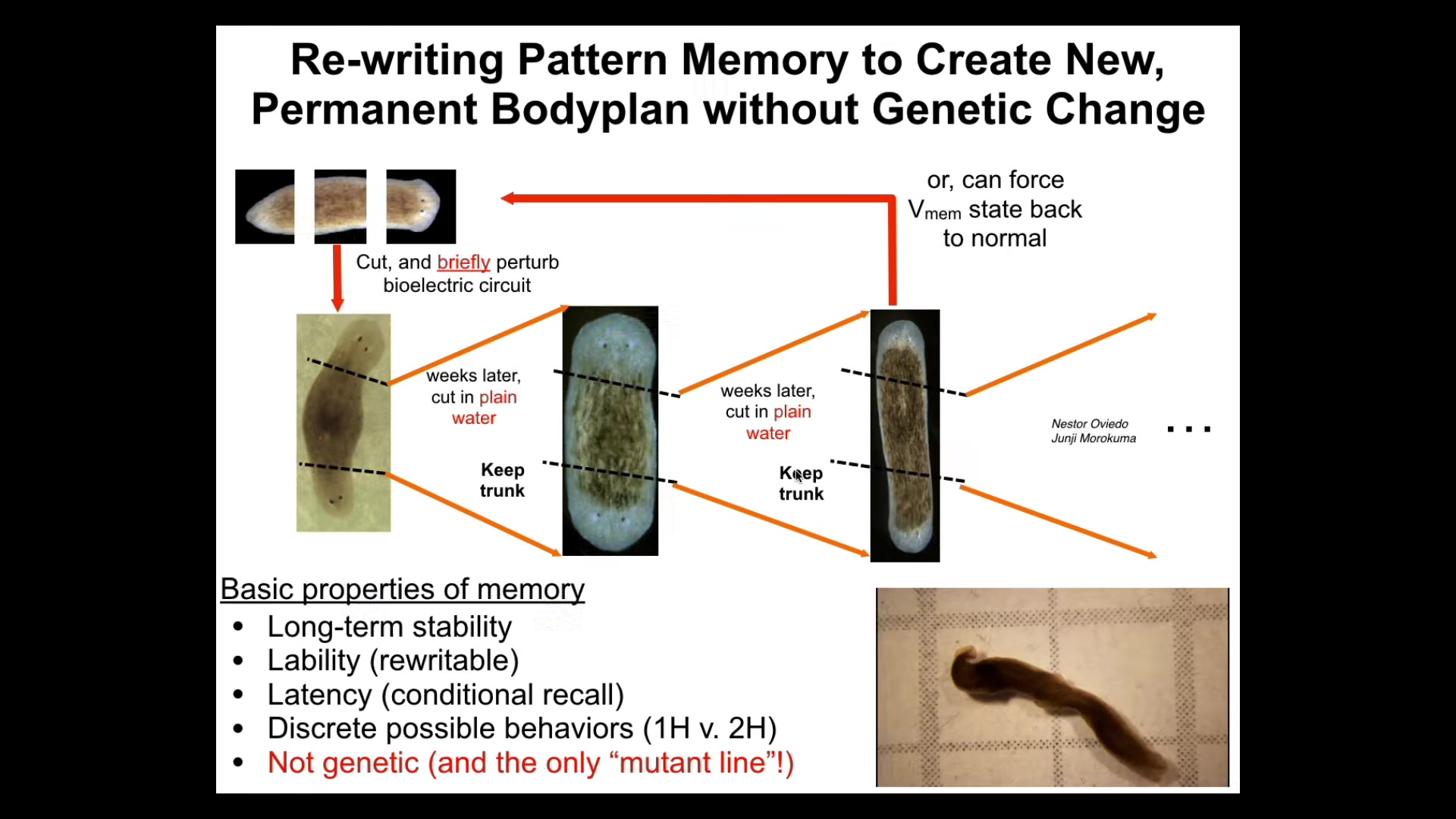

The material is highly reprogrammable. These are planaria. These are flatworms. They have a head and a tail. You can cut them into pieces. Every piece knows exactly how many heads it's supposed to have. You might think that this is somehow genetically specified, except that it turns out what the genetics really gives you is an electrical circuit that by default has this very particular pattern that says one head, one tail.

This is a voltage-sensitive dye image. One head, one tail. We can take this animal and rewrite that electrical signal so that both sides have this head pattern. When you've done that, the molecular biology doesn't change yet. The anterior marker is still only in the head, not in the tail. The anatomy hasn't done anything. This is a perfectly normal, anatomically normal one-headed worm. Molecular biology is normal. What's not normal is it bears a patterned memory of what it should do if it gets injured at a future time. This is a counterfactual. These kinds of non-neural systems can even do simple counterfactuals, but it's a representation of what a correct planarian would look like. It is latent. It's a latent memory until you cut out the middle fragment, and then it consults the memory and builds the two-headed form. A single body, a normal planarian body, can store at least one of two different representations of what a worm should look like.

Slide 13/35 · 20m:20s

And the reason I call it a memory is because if you keep cutting these two-headed worms, they will keep producing two-headed animals. In other words, once you've changed that pattern, it stays, unless you go and change it back, and we can do that.

The other thing to keep in mind here, as we think about genetics and evolution, is that we haven't made any genetic changes. There's nothing wrong with the genome. In fact, there are no genetic lines of planaria that are anything different than the one head. This is a completely different way to do it. The genome is perfectly normal, but luckily the genome actually encodes the electrical components for an excitable medium that can store multiple different kinds of patterns. The one head pattern is the default, but it is reprogrammable.

Slide 14/35 · 21m:06s

Plant systems are reprogrammable too. Again, they tend to fool us with their reliability. This is an acorn, and billions and billions of times every year all over the earth it makes this exact leaf. You think, okay, this is what the oak genome knows how to do. It knows how to make this flat green thing with a particular structure. But again, that layer between the genome and the phenotype has all kinds of interesting properties, including reprogrammability and hackability.

Slide 15/35 · 21m:38s

So here comes this bioengineer. It's a little parasite. It does not build this gall. These are incredible plant galls that are formed on different kinds of leaves. It doesn't build this the way it builds its nest, a 3D printer laying down pieces. What it actually does is leave some prompts. It leaves some prompts for the plant cell, and because this material is so reprogrammable, we would never know. If not for this thing, we would have no idea that these flat green cells can actually build something like this, an incredible structure. That aspect of it, the reprogrammability, the software aspects of it have many implications.

Slide 16/35 · 22m:28s

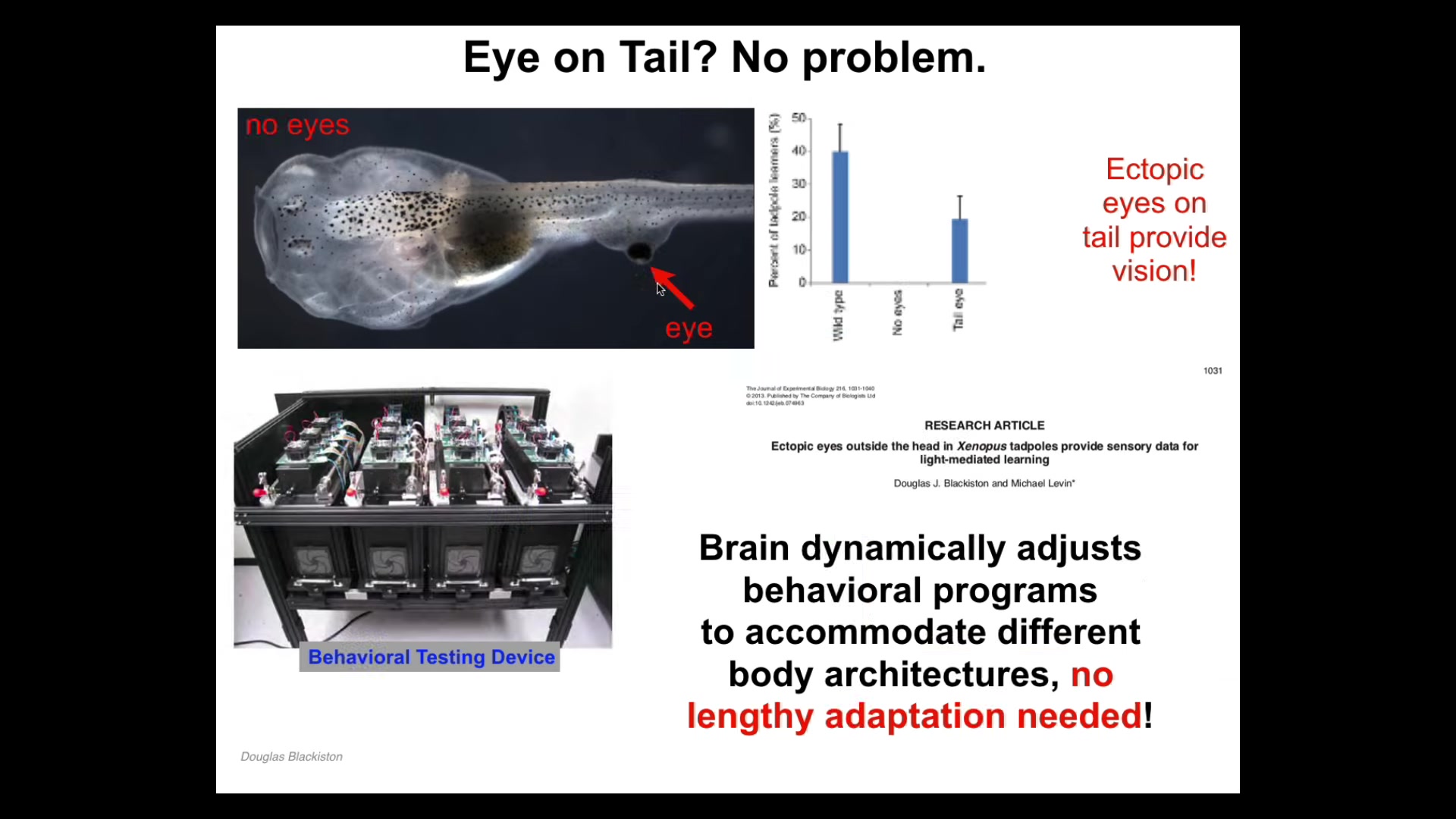

One implication is that when you make radical changes to the material, it almost always makes something that is quite adaptive and coherent.

For example, here we've made these tadpoles. This is a top view. The primary eyes are missing, but we put an ectopic eye on its tail. This ectopic eye makes an optic nerve. The optic nerve does not go to the brain. It typically ends up here somewhere on the spinal cord, sometimes nowhere at all.

These animals can see. We know they can see because we built an automated device that trains and tests them for visual cues. And they can absolutely run useful behavioral programs out of these. The only eye they have is this eye on their tail. It doesn't even connect to the brain.

This raises an interesting question. How is it possible that you don't need rounds of adaptation, selection, mutation to readjust the rest of the animal so that this novel sensory motor architecture works? Why does it work out-of-the-box? Why is there no need for adaptation?

Slide 17/35 · 23m:33s

I'll just show you one more thing before I float an idea of why I think all this works. This is one of my favorite examples of what I think is creative problem solving in anatomical space. This is a cross-section through a kidney tubule in the newt. What you'll see is that they're usually about 8 to 10 cells that work together to build this kind of structure. What you can do is you can make polyploid newts that have extra genetic material and their cells are bigger to accommodate the bigger nucleus. When you do this, it turns out the newt is the same size. How's that possible? Because fewer cells are now being called upon to make the exact same structure. When you make the cells truly gigantic, this is a 6N newt, one single cell will wrap around itself, leave an empty space in the middle, and still give you the same structure.

Notice what's going on here. There are a couple of things happening. First of all, what you're seeing here is, again, a top-down causation where in the service of a large-scale structure, different molecular mechanisms are being called up, in this case, cell-to-cell communication, in this case, cytoskeletal bending. This is what they have on every IQ test. You're given a standard set of tools, but you're given a problem that's quite different than what you're used to, and you're saying, how can I use these everyday kinds of affordances that I have to solve a different problem. We can find different molecular components to solve this problem.

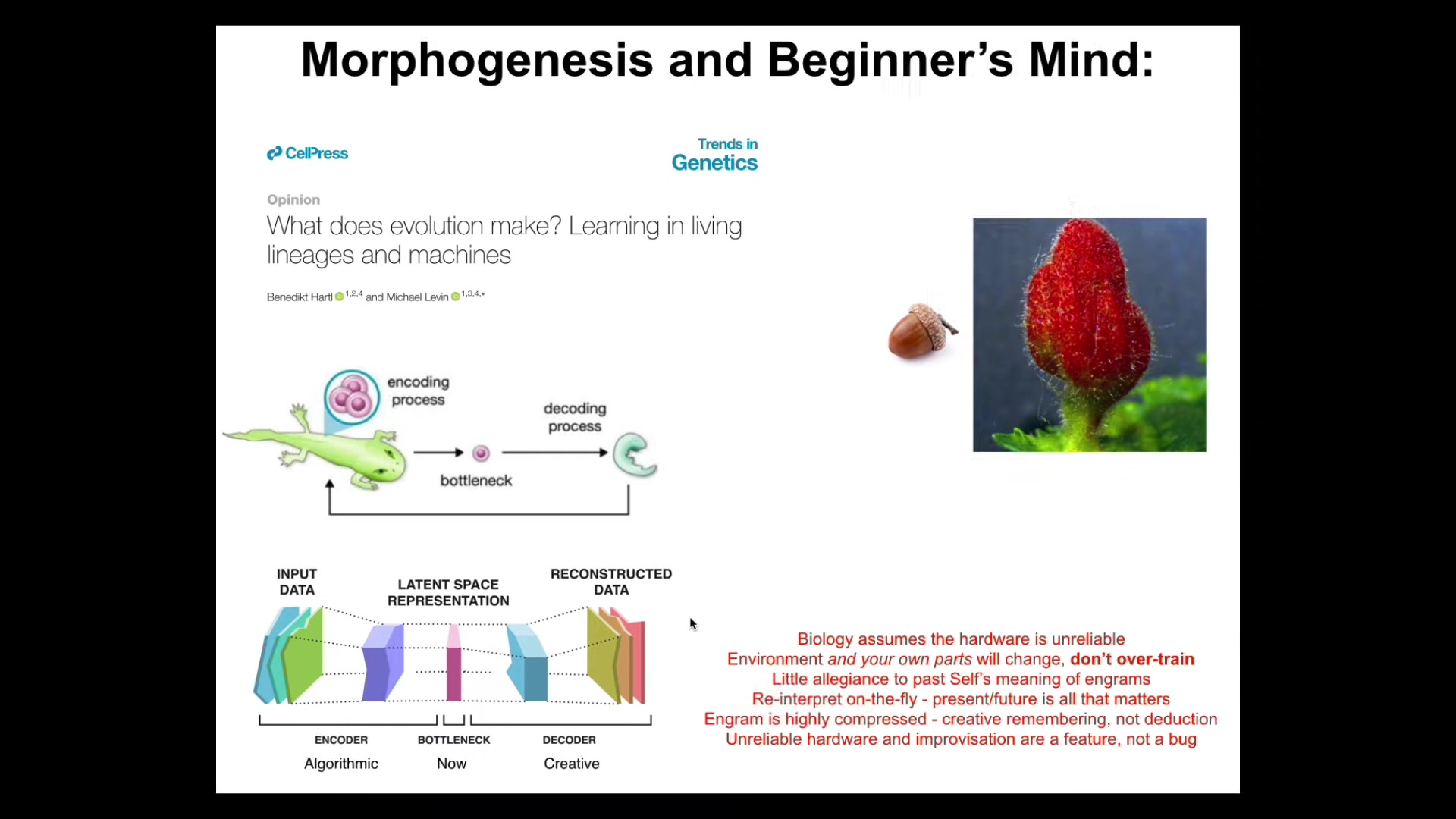

But think about what this means from the perspective of the creature coming into the world. We already know you can't really count on your environment. You don't know what's going to happen after you self-assemble. But you can't even count on your own parts. You don't know how many copies of your genome you're going to have. You don't know how big your cells are going to be. You can count on change. That's the one thing you can count on. This is the paradox of change: things are going to change. You will be mutated, your parts will be different, the outside world will be different. I think what the process of evolution actually does is commit to this idea. It's a beginner's mind concept that what you really are creating is a problem-solving agent. You're not creating fixed solutions to specific problems. And that's why things like galls and eyes on the butts of tadpoles actually work. They work because every instance in development is creative problem solving. They were never really attached to having them in the right place. They have to work it out every single time.

Slide 18/35 · 26m:07s

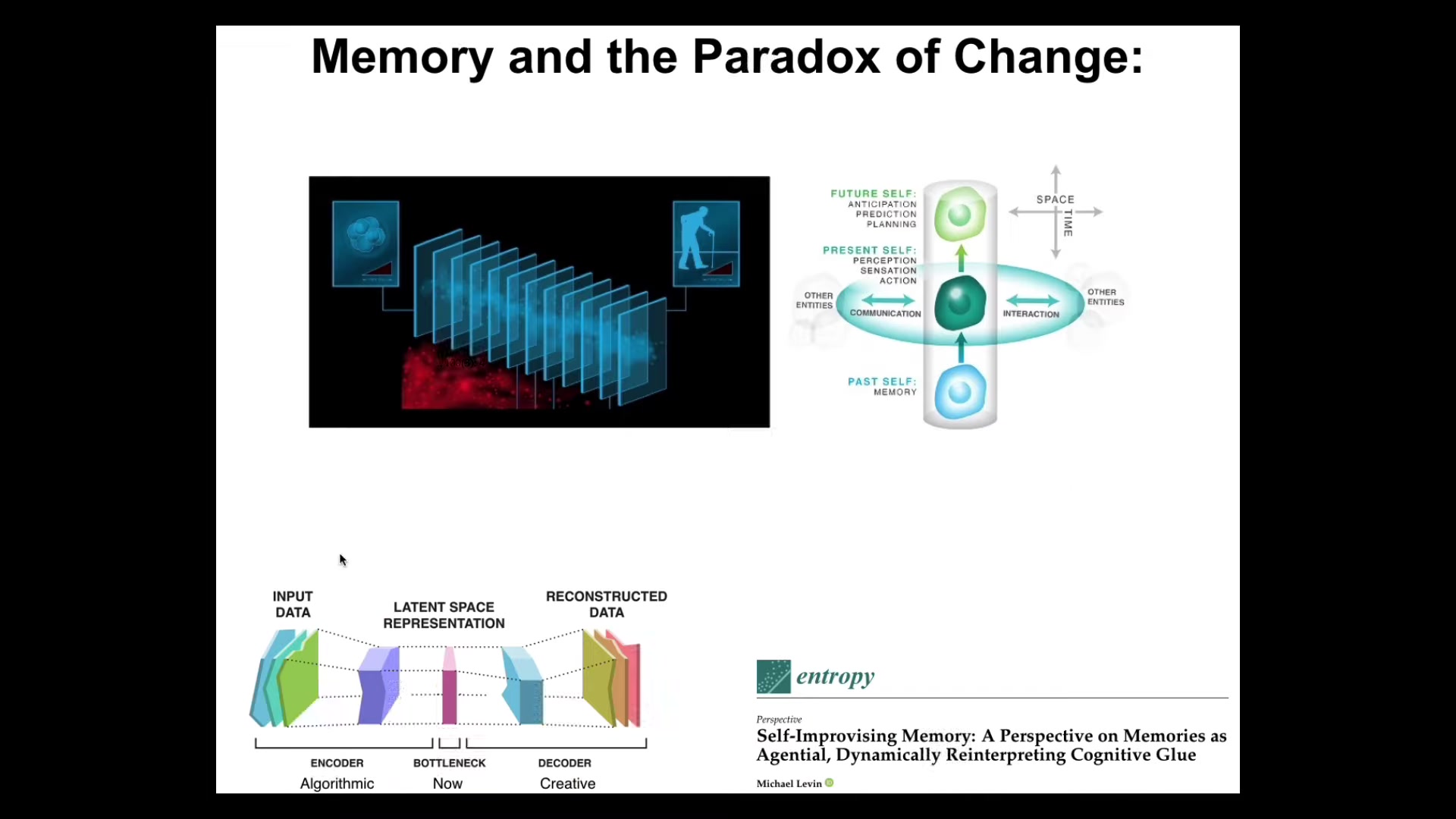

Think about what it's like for each of us at any given point in time. You don't have access to the past. What you have access to are the memory engrams that past versions of you left in your brain and body as compressed representations of what happened before. So your memories are messages from your past self. And what you have to do at every moment is actively construct a story for yourself of what you are and what your possibilities are and what you're going to do next.

Think about this bow tie architecture. We live here in this center of the bow tie, the now moment. Everything that happened before was algorithmic because we can throw away the details that don't matter and compress specific instances into generalized representations that serve as compressed n-grams of the past. So that part can be algorithmic. But this part can't because you've thrown away a lot of the correlations, you've thrown away a lot of the details. This part has to be creative. You have to take those engrams and re-inflate them. And that's a process of interpretation. You cannot simply know what your memories mean. You have to actively interpret them. And that's why neuroscientists will now tell you that recall is actually reconstruction. There are no non-destructive reads. No memory trace speaks for itself. You have to actively interpret what that memory means. It may not be the same way that your past instances of you interpreted it.

Slide 19/35 · 27m:55s

I think this is very much what's going on in biology. This is all discussed in this paper, where we talk about the exact same thing happening across the evolutionary scale. In other words, when you're an embryo or any kind of morphogenetic system, you're given some engrams in the form of DNA, but you don't, at least for most species, simply follow along what they say. You have to interpret them. You might interpret them in the form of an oak tree, or you might interpret them in the form of a gall.

Here's what I think is happening. Biology fundamentally assumes that the hardware is unreliable. It's going to mutate. You never know how many copies of anything you have. The hardware is fundamentally unreliable computing. Your own parts will change, which means it doesn't help to overtrain on your priors. You don't simply try to maintain whatever the meaning of this information was before; you have to reinterpret on the fly. The present and the future are all that matters. You have to get good at reinterpreting. This is a feature, not a bug. It drives the plasticity and the problem-solving capacities of evolution.

What's it like to evolve in a gentle material? What actually happens? Let me give you an example. Here's a tadpole: two eyes, two nostrils, and the mouth. In order to become a frog, this tadpole has to rearrange its craniofacial organs. The mouth has to move forward, the eyes have to shift, everything has to move around. It was thought at one point that this is simply a hardwired process. Every tadpole looks the same, every frog looks the same. As long as you move all the pieces in the right direction, the right amount, you'll have a normal frog.

We decided to test that. All of these things have to be experimentally tested. We produced what's called Picasso tadpoles. We scrambled everything: the eyes on the back of the head, the mouth off to the side. We found that they make normal-looking frogs because all of these things will move in novel paths to get to where they're going and then stop.

When the material itself readjusts, it has plasticity to get things right from different starting positions. Selection, when it sees this beautiful frog, doesn't know whether the initial state was really good or junky but repaired by regenerative plasticity. Selection can only pick out the successful ones at the end.

We have done many simulations and everything is in this paper. We find a ratchet that works like a positive feedback loop. As soon as this phenomenon happens, evolution starts to spend more time tweaking plasticity and less time perfecting the initial state, the structural information. But the more you do that, the harder it becomes to see the structural information. Evolution spends even more time cranking on the plasticity.

Everything changes because: A, the whole process moves faster; B, it spends more and more effort on producing morphogenetic algorithms that are creative problem solvers with an unreliable material that cannot be perfected.

Slide 20/35 · 31m:53s

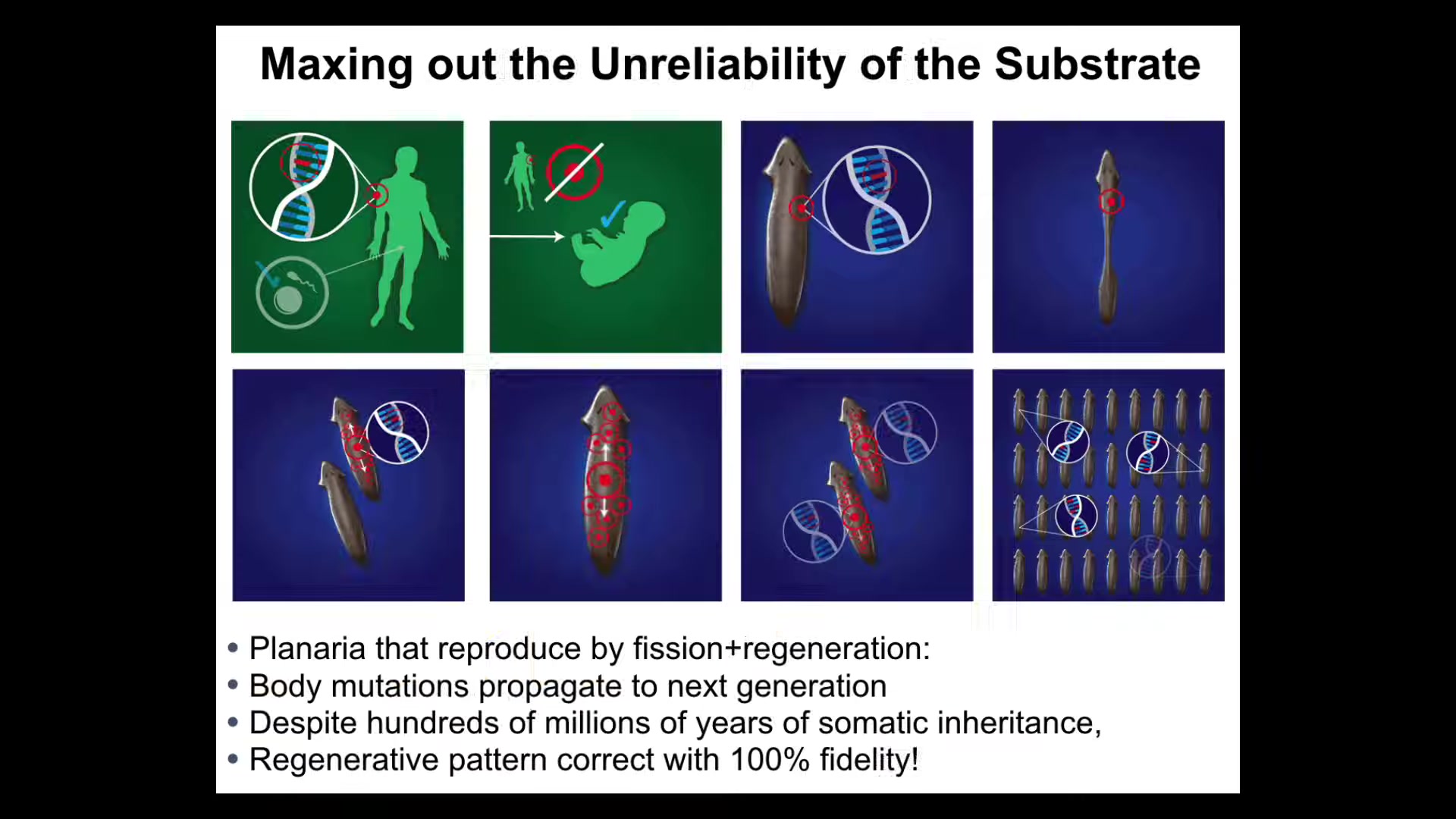

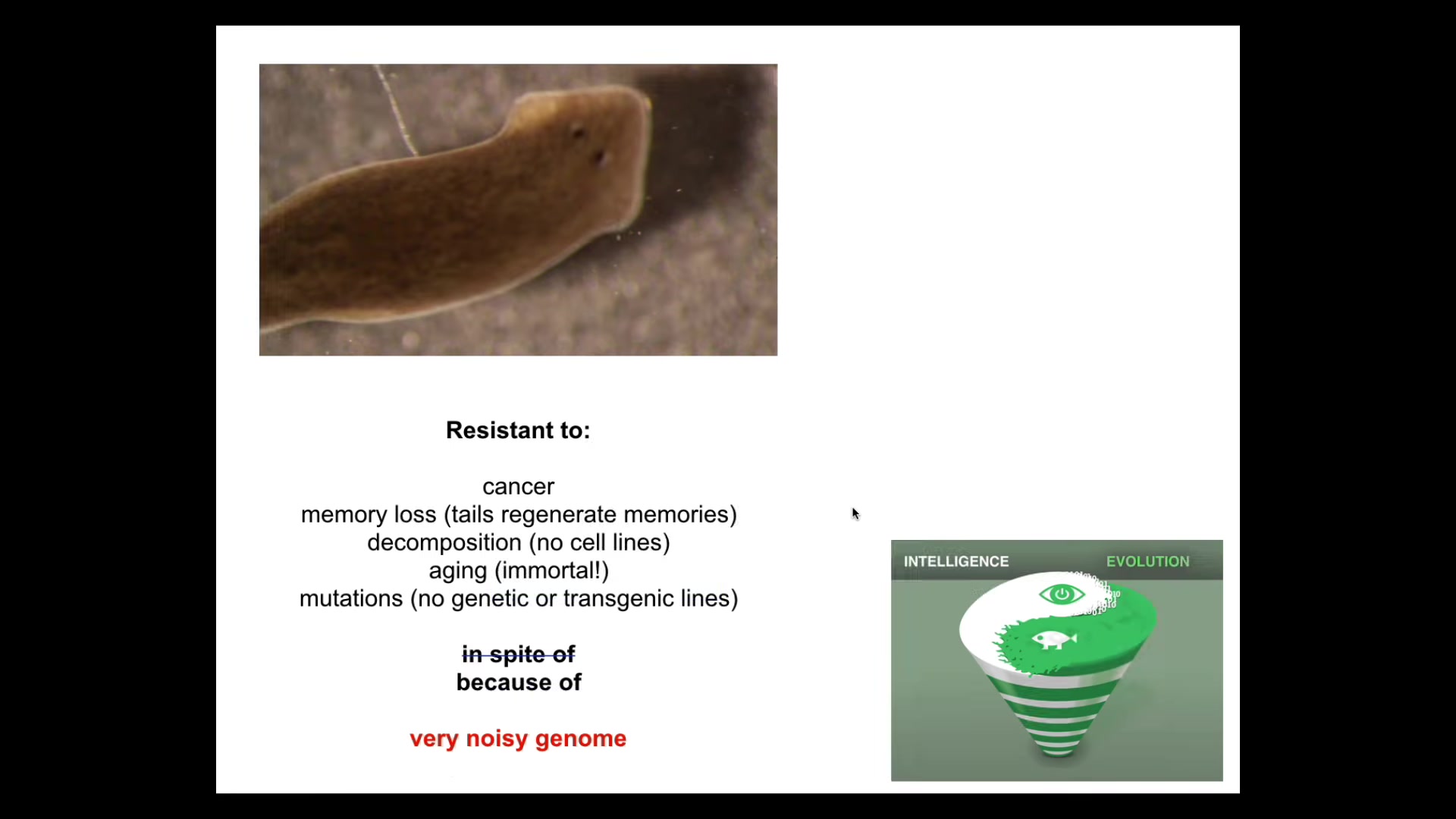

And for me, the most impressive example of this is planaria. The thing with planaria, at least the species we study, is that they reproduce asexually. They tear themselves in half and regenerate. That means this kind of cleaning up of the genome that happens in us, where our mutations and our soma don't make it to the next generation, doesn't happen here. Any mutation that doesn't kill the stem cell gets proliferated into the next generation as they regenerate. And so they keep an incredible amount of mutations. They're mixoploid. The cells have different numbers of chromosomes. They're an incredible mess.

Slide 21/35 · 32m:35s

And yet, these guys are resistant to cancer. They are resistant to memory loss because even their tails retain memories of things they've learned. They are resistant to being decomposed. There are yet no cell lines of these guys. They are immortal. They don't age. There's no evidence of aging in planaria. They are resistant to mutations. There are no genetic lines of planaria. There are no transgenic lines of planaria.

I think what's happened is that because of the incredible unreliability of their substrate, the fact that it's constantly getting mutated, what evolution has done is spent all of its effort cranking on an amazing algorithm that will try to get a perfect worm no matter what's going on with the underlying hardware. And really the only effective way to make permanent change is at higher levels of organization, such as our two-headed worms and some other things that we've done that were done by bioelectrics.

When I first introduced this to students, it's kind of scandalous. When I tell you that there's going to be a creature with incredible regenerative capacity, no aging, resistance to cancer, you would think they have the cleanest genome in the world. This is what we're all taught, that the genome is responsible for all these things. And it's actually the exact opposite. The animal with the kind of most junky genome is the one that has all of this. And I think it's because of this spiral of having to be creative and doing all kinds of error correction on the outcome, not on the hardware itself.

Slide 22/35 · 34m:10s

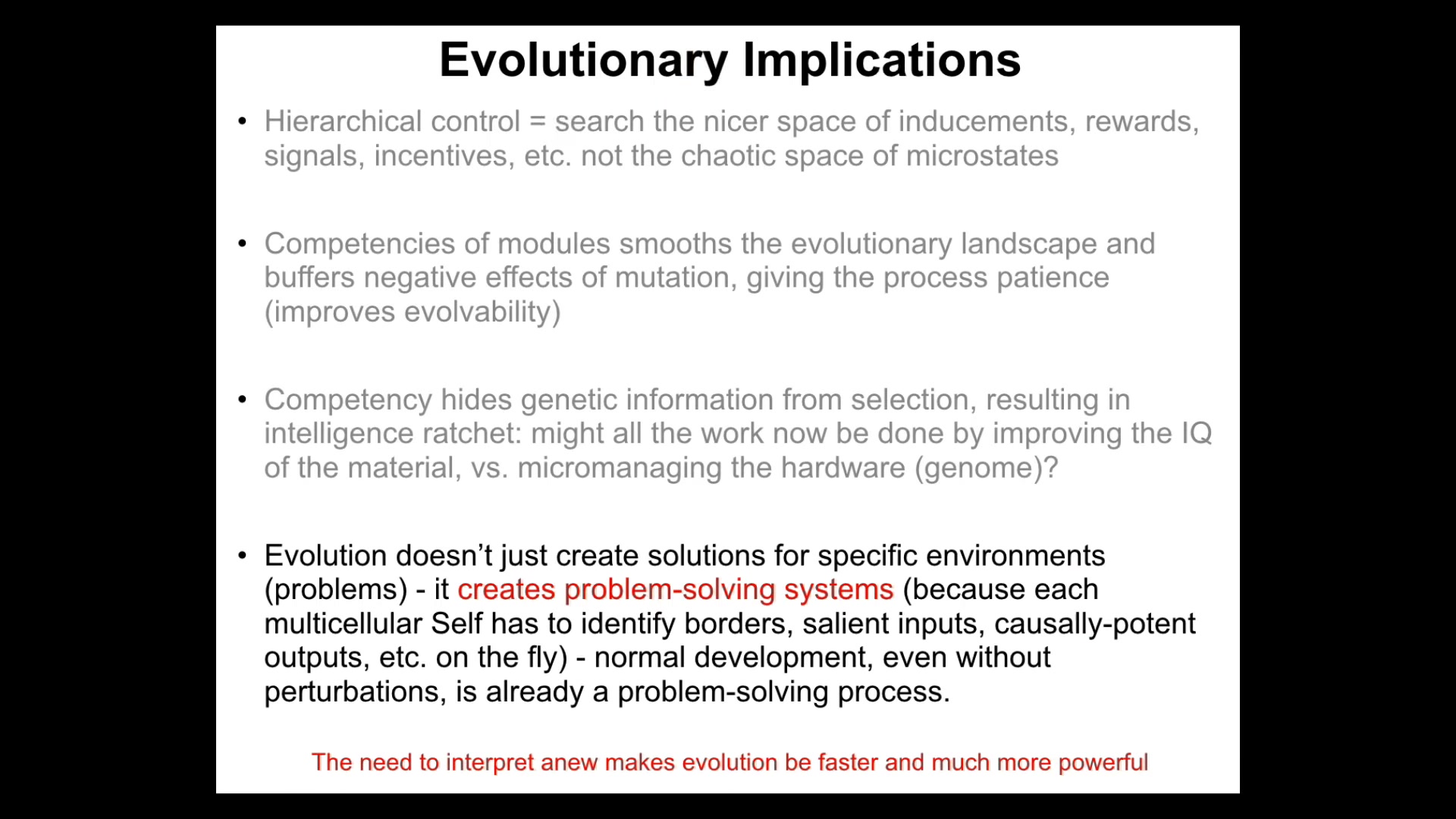

Fundamentally, the competencies of the underlying material really smooth the evolutionary landscape. It gives the process patience.

For example, if you had a mutation in that tadpole that moved the mouth off to the side, but it also did something good in the tail, in a non-self-repairing material the creature would starve and you would never see the good consequence of that mutation. In this case, the mouth finds its way back to where it needs to go. Now, lots of potentially deleterious mutations become neutral mutations because the competencies compensate for them.

That really changes the amount of patience the evolutionary process is able to exert. That improves evolvability. Fundamentally, what it's creating are problem-solving systems, because every biological system at every scale has to identify its own borders. It has to make choices about which inputs are salient. It has to coarse-grain its environment. Even without any perturbations, normal development is already a problem-solving process.

The need to interpret the information, both environmental information and your own genetics, the need to interpret it creatively every single time makes evolution much faster and much more powerful. That's because that mapping from genotype to phenotype is not a direct or even simply complex map. It is a problem-solving process.

Just two more things to mention. We've talked about the properties of naturally evolved systems. What about novel beings? Where do their properties come from? I want to introduce you to two such creatures.

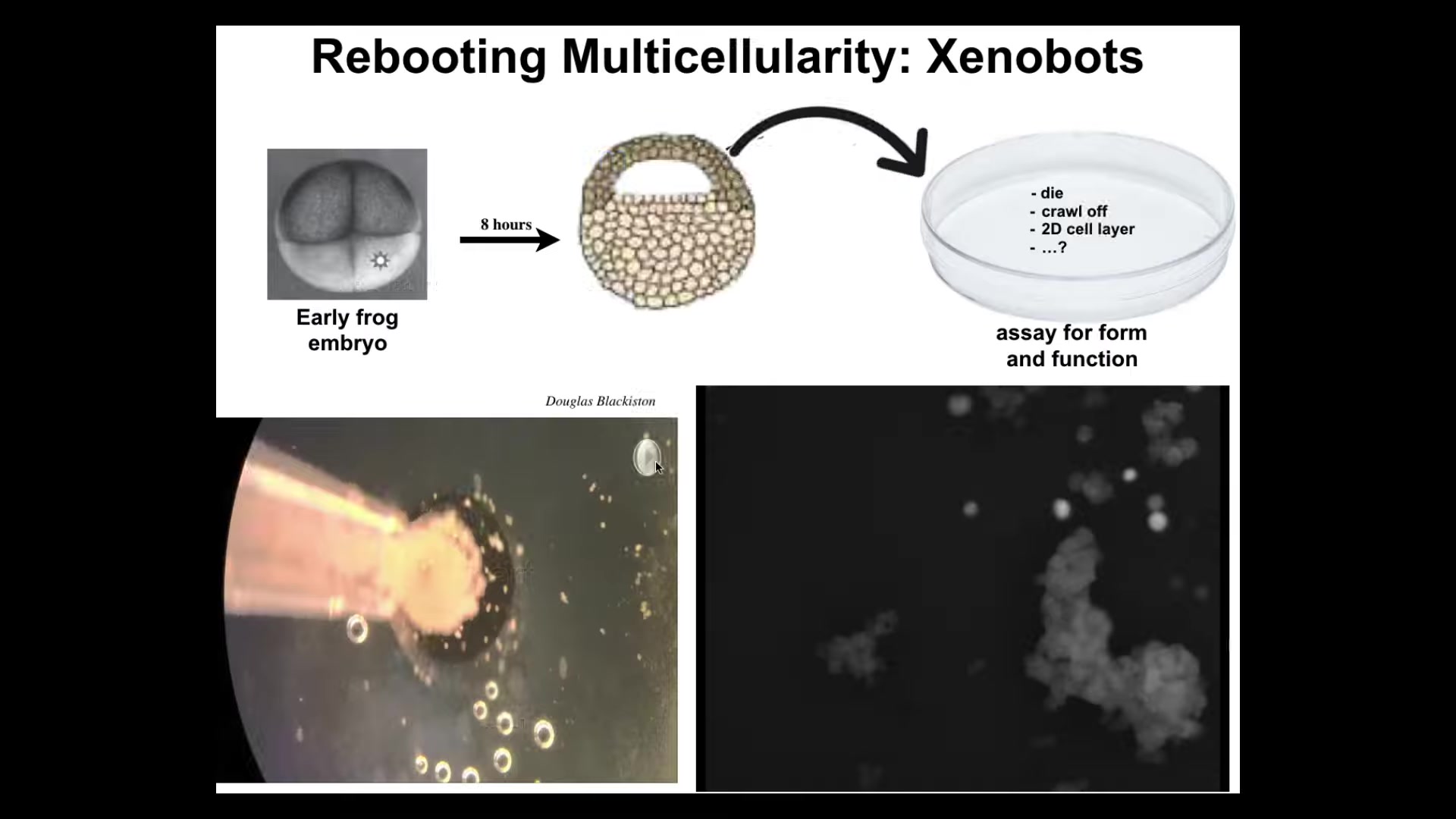

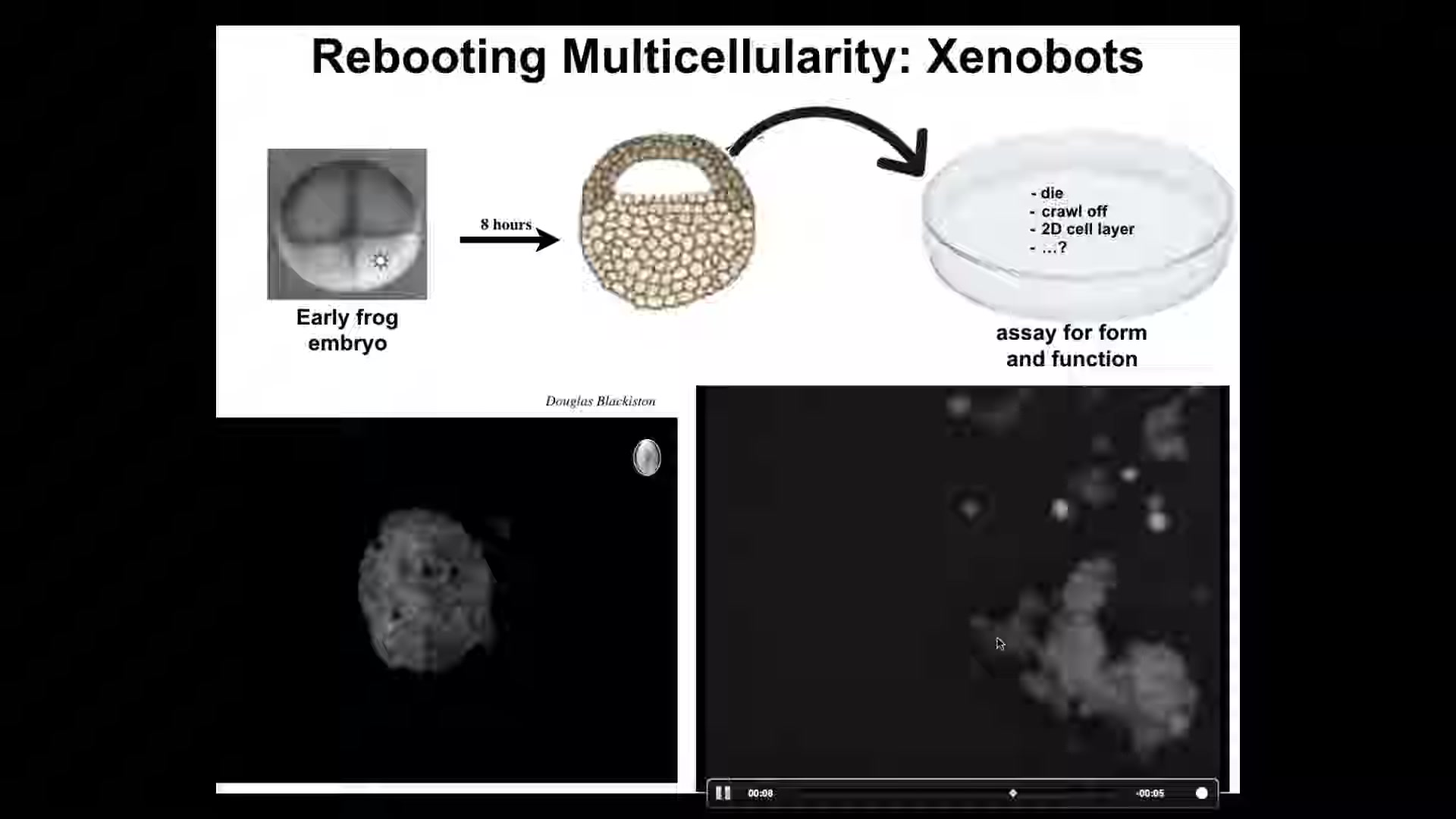

Slide 23/35 · 35m:59s

The first we call xenobots. What we do is we liberate some epithelial cells from the animal pole of a frog embryo. We set them aside. They could do many things. They could die. They could crawl away from each other. They could form a monolayer, like in cell culture. But instead, what they do is they get together.

Each one of these things is a single cell. I think it's really fun that this looks like a little horse. They don't all look like that.

Slide 24/35 · 36m:29s

There are lots of different shapes, but they move as a collective and they start coming together. You can see that here. There's a little calcium flash as they interact.

Slide 25/35 · 36m:39s

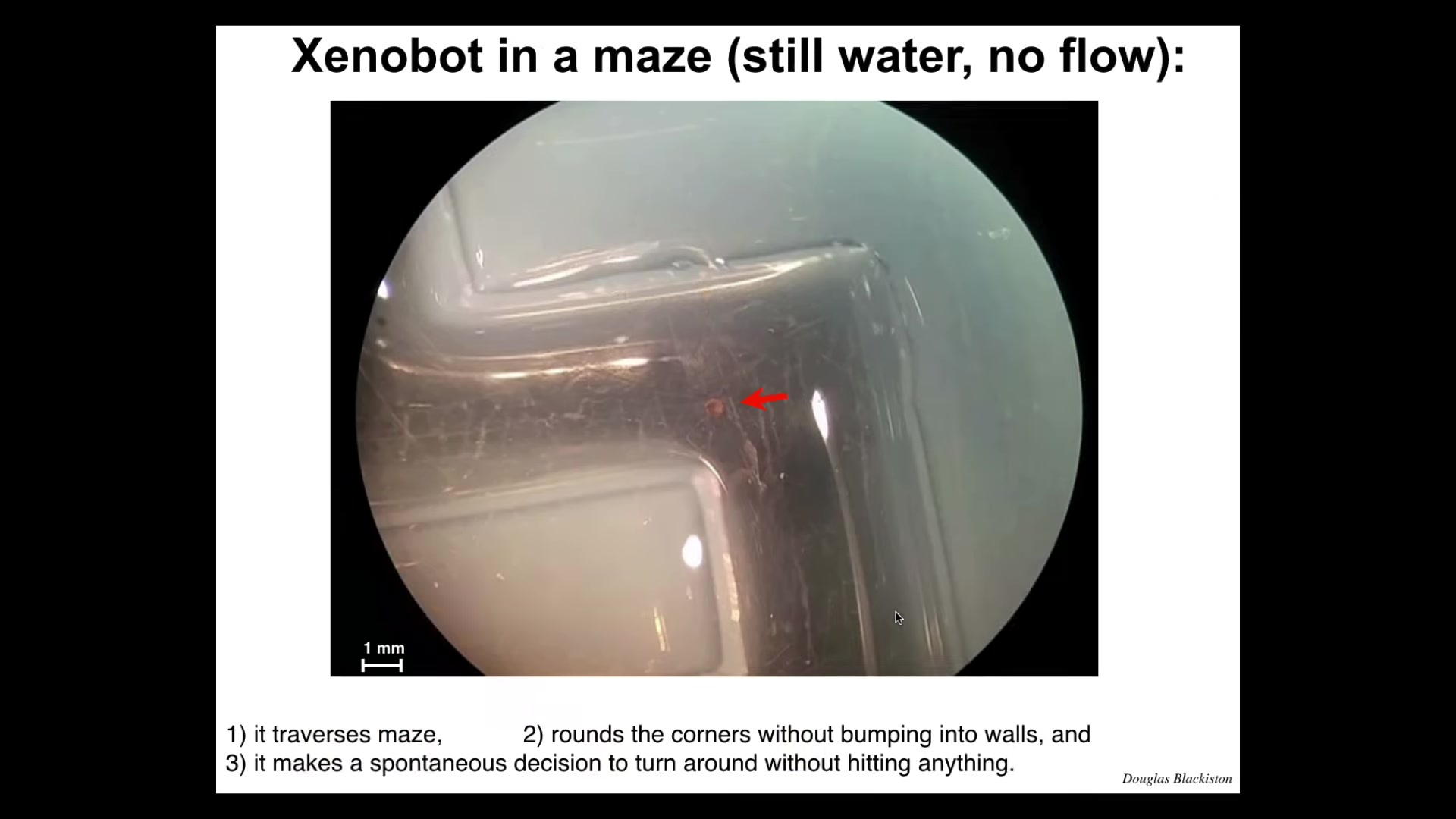

And then what they do is they self-assemble into this multicellular little construct. It's swimming along in this maze. It takes the corner without having to bump into the opposite wall. It has spontaneous changes in behavior. For some reason, it turns around and goes back where it came from. They have lots of interesting behaviors that I don't have time to show you.

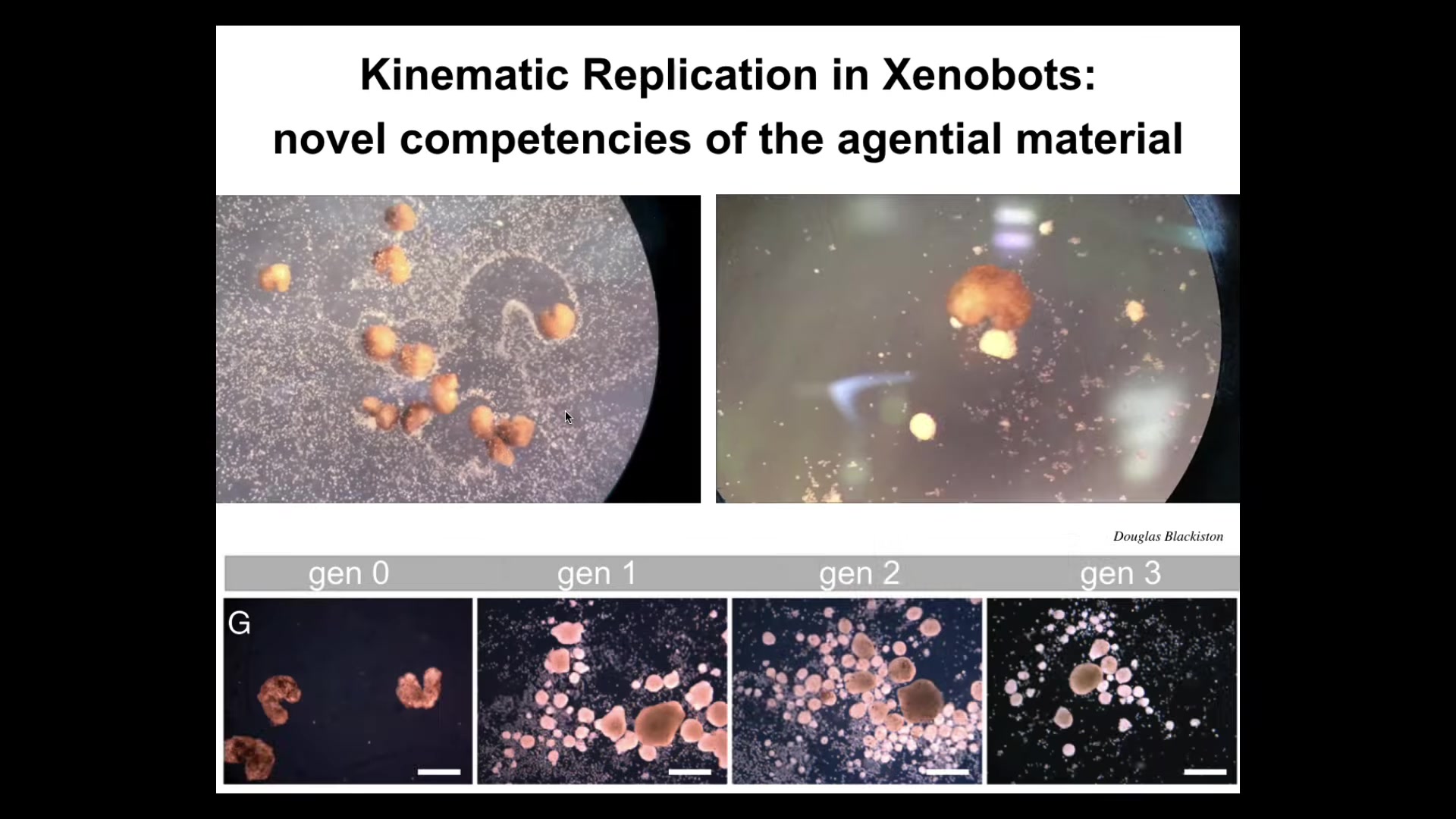

Slide 26/35 · 36m:56s

One of the things it does is kinematic self-replication. So if you give it a bunch of loose epithelial cells, what they will do is run around both collectively and individually and polish them into little balls. This itself is an agential material. The little balls mature into the next generation of Xenobots, and they make the next generation, which then makes the next generation. There is no strong inheritance here, but there is a replication. There is kinematic self-replication. And we didn't have to teach them to do this. It is perfectly standard for frog cells, no synthetic biology circuits, no scaffolds, no weird drugs. This is native competency of the material.

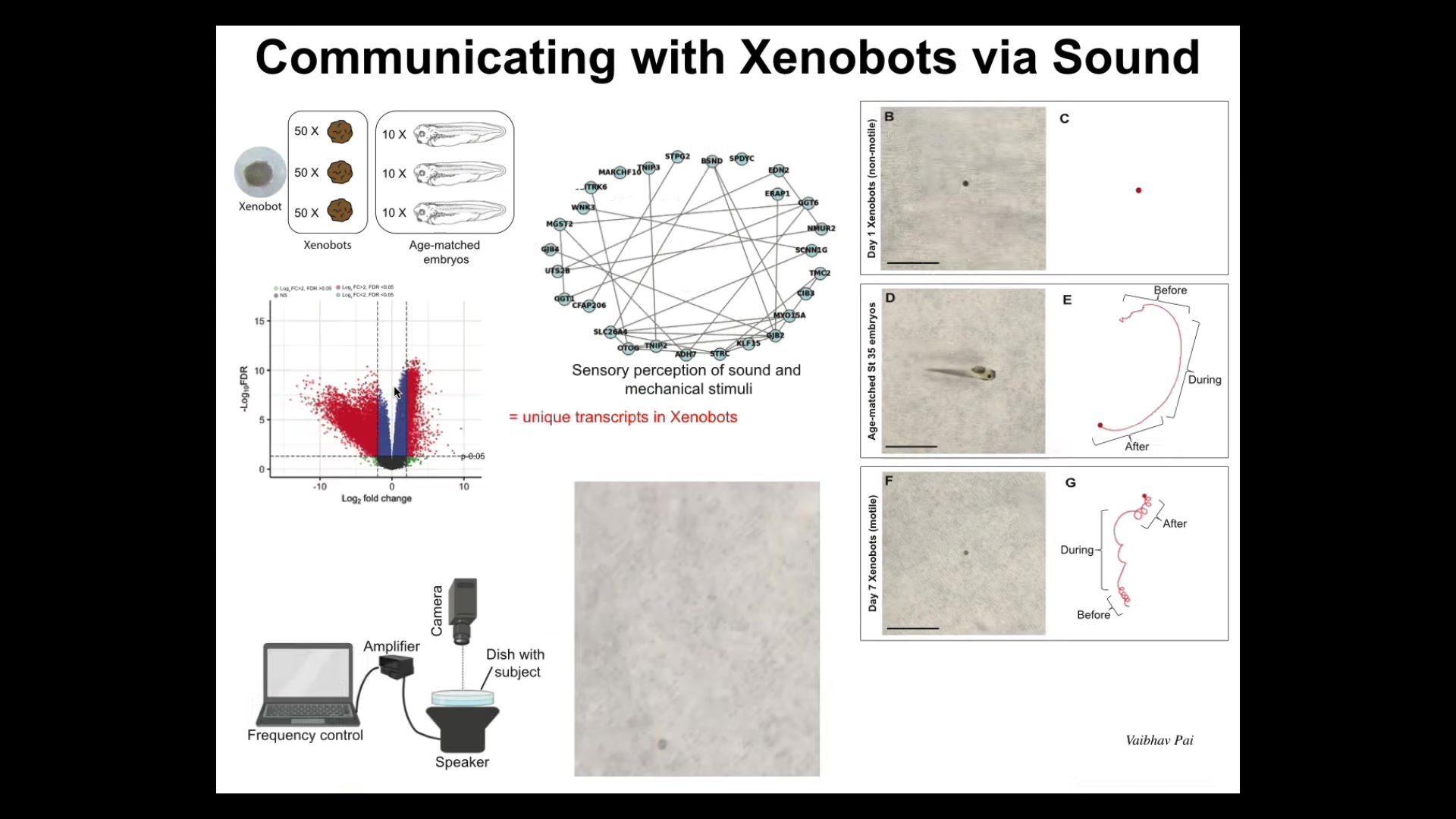

You might ask, what genes do these guys express that normal frog embryos do not express?

Slide 27/35 · 37m:42s

They have about 600 differentially expressed genes. Among them, I'll show you one example. There's this cluster having to do with sensory perception of sound and mechanical stimuli. So we asked ourselves, is it possible that they could hear? They absolutely react to the sound. This is a new kind of capability that they have that normal embryos don't have.

Slide 28/35 · 38m:12s

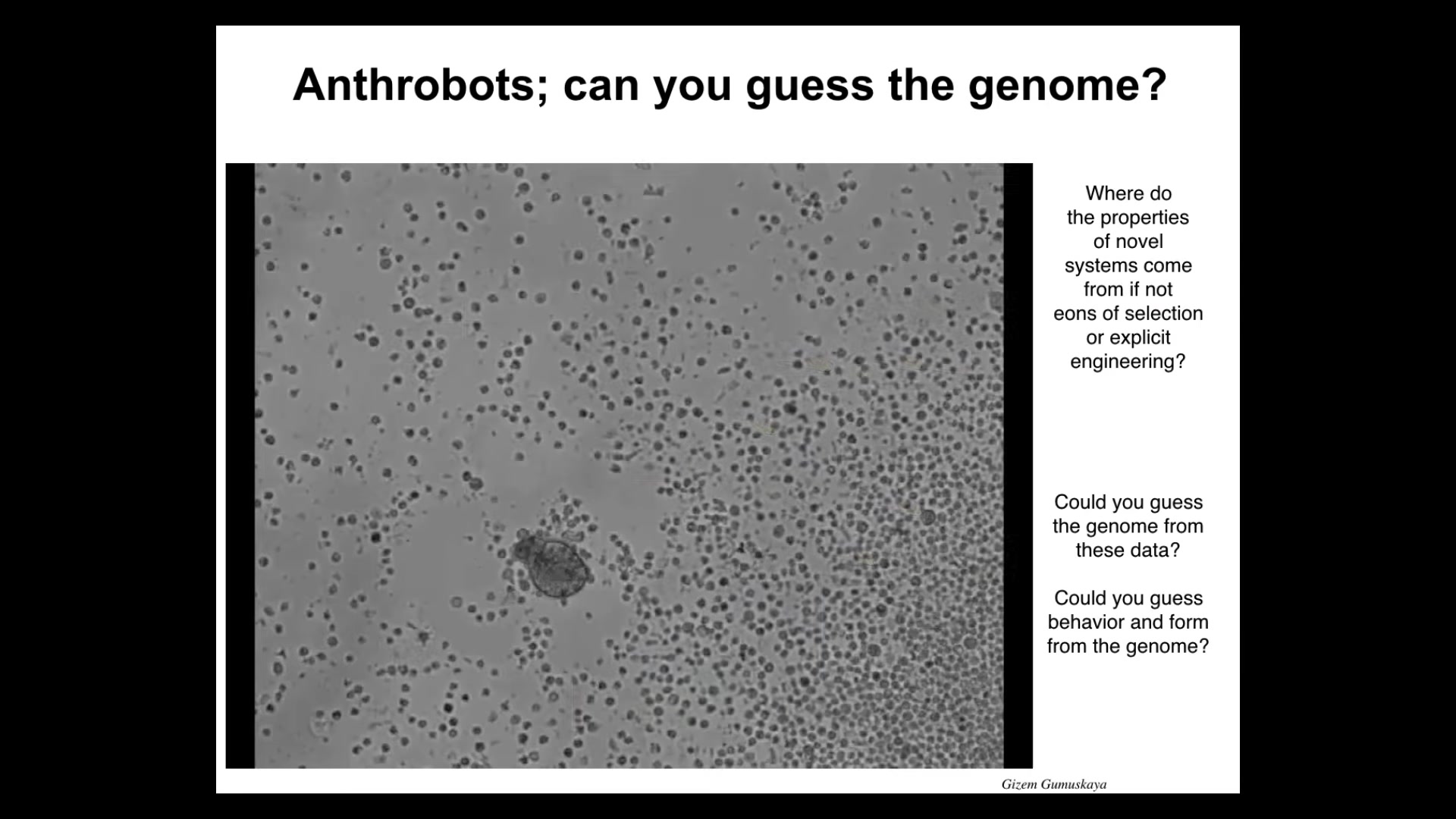

You might be thinking that that's some special frog, amphibian thing. I would ask you, what would your cells do if we liberated them from the rest of your body?

I would here introduce you to anthrobots. This little creature, if you were to sequence it, would show a 100% normal Homo sapiens genome. We took cells from adult human tracheal epithelial donors. The cells self-assemble into this little motile proto-organism. Here it's running around, possibly trying to collect these cells, much like the Xenobots do. They have lots of other interesting capabilities.

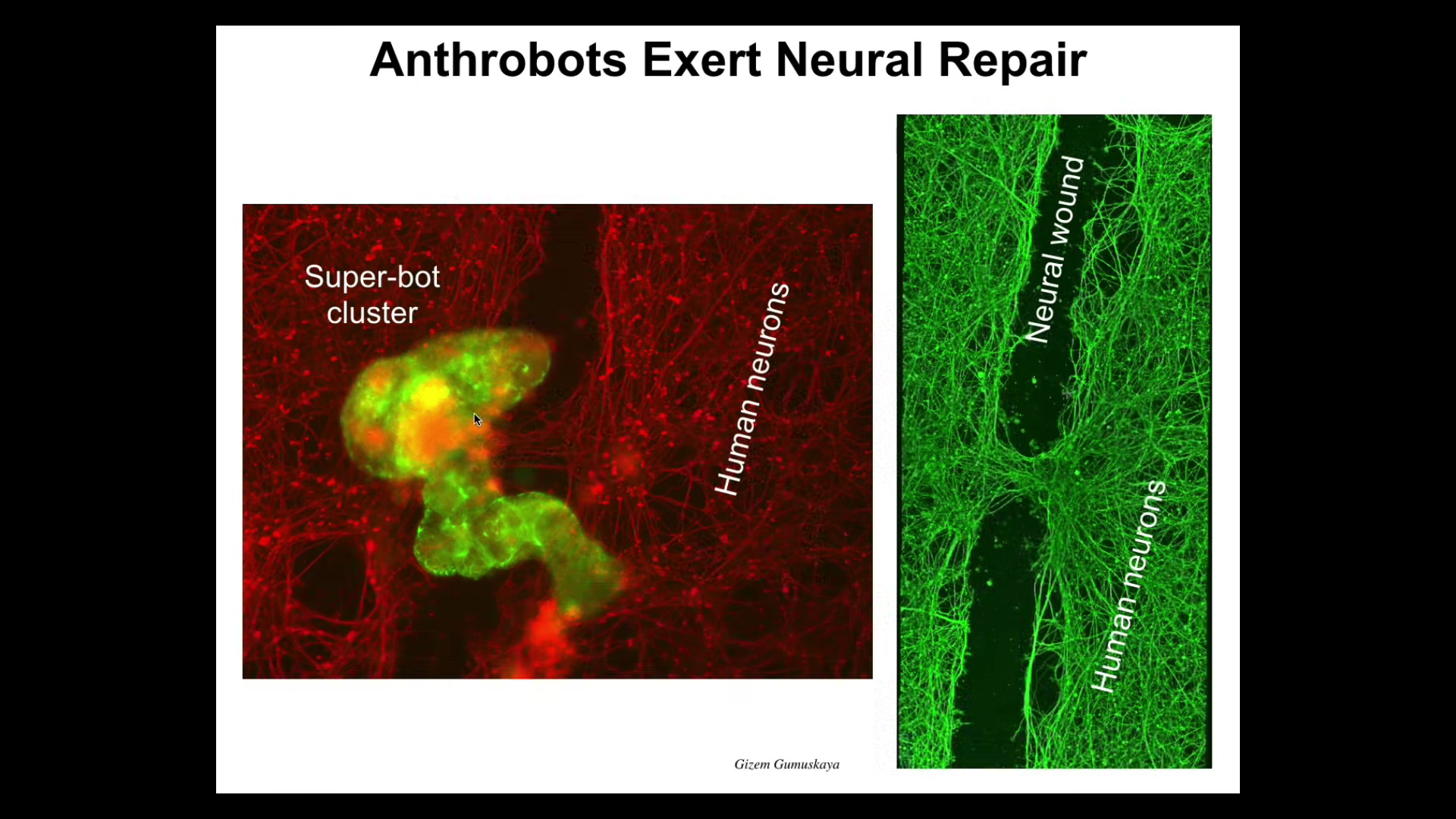

Slide 29/35 · 38m:55s

For example, if we take a bunch of human neurons and plate them and make a big scratch through them, the anthrobots are in green here. They will come and sit in this cluster. And what they start to do is knit across the gap. They start to heal. Here you can see the neurons. They can start to heal them. So who would have thought that your tracheal epithelial cells that sit there quietly in your airway for decades, if we take them out of your body, would form a multi little creature that can swim around and heal neuron wounds when it finds them?

Slide 30/35 · 39m:28s

These guys have 9,000 differentially expressed genes. About half the genome is completely differentially expressed. Again, we haven't touched the genome. There's no synthetic circuits here. There are no weird nanomaterials, nothing like that. Just a different lifestyle, different environment. 9,000 differentially expressed genes. They have four different behaviors that we can make a little ethogram with transition probabilities from. Not 12, not one, four.

You might ask where these specific properties come from: the specific gene expression, specific types of behavior. We know that the frog genome learned to do this. It learned to make specific developmental stages and then eventually some tadpoles. But apparently it can also do this. This is a xenobot. This is an 83-day-old xenobot. It's turning into something. I have no idea what it's turning into.

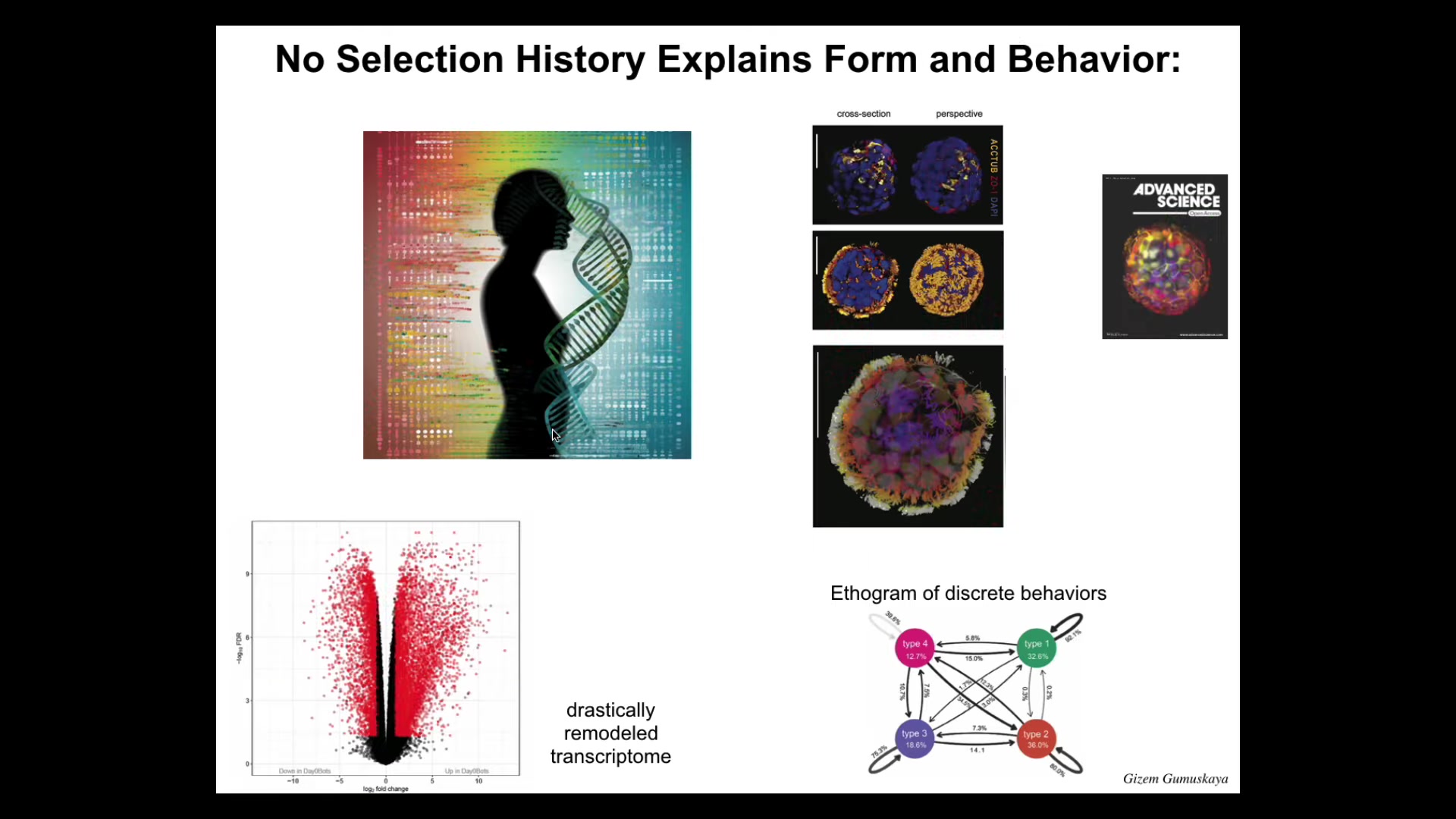

We have to ask a couple of interesting questions here. There's never been any xenobots. There's never been any anthrobots. There's never been selection for kinematic replication. As far as we know, no other creature does kinematic replication. There's never been selection for any of that. Why do they know how to do this? Where do their specific transcriptomes, their physiological states, their behaviors, their shapes, where does this come from?

In particular, we know when the computational cost was made to evolve all of this. It was made during the time of eons of selection, when this genome was bashing against the environment. When did we pay the computational cost to get all of these things?

When I ask people, they often say it's emergent. I said, what does that mean? They said it means that at the time that the things were selecting to be a frog, it also learned to be xenobots and anthrobots. And so I find that very disturbing.

I think standard evolution expects some degree of specificity between a creature's history and the properties it has now. That was supposed to be the whole point. We were supposed to tell the story of why you are the way you are based on the history of environments and selection that you've had. And that this kind of thing where these things are just there — I think that's not remotely good enough.

Slide 31/35 · 41m:41s

The next thing I want to talk about, and then I'll give a few conclusions and we'll stop, are a couple of interesting things about what happens before differential replication, before selection, before all of that. The first thing I would introduce you to is this idea: Even very small networks of molecular pathways describable by ordinary differential equations can learn. You don't need neurons, and you don't even need cells if you have coupled systems that turn each other on and off. This is quite similar to the things that Richard was talking about earlier. From that you can have six different kinds of learning. You can have habituation, sensitization, associative conditioning already in this molecular substrate. It's already baked into the properties of these networks. We're taking advantage of that for biomedical purposes, things like drug conditioning, where we can train molecular networks to respond to specific stimuli.

Slide 32/35 · 42m:42s

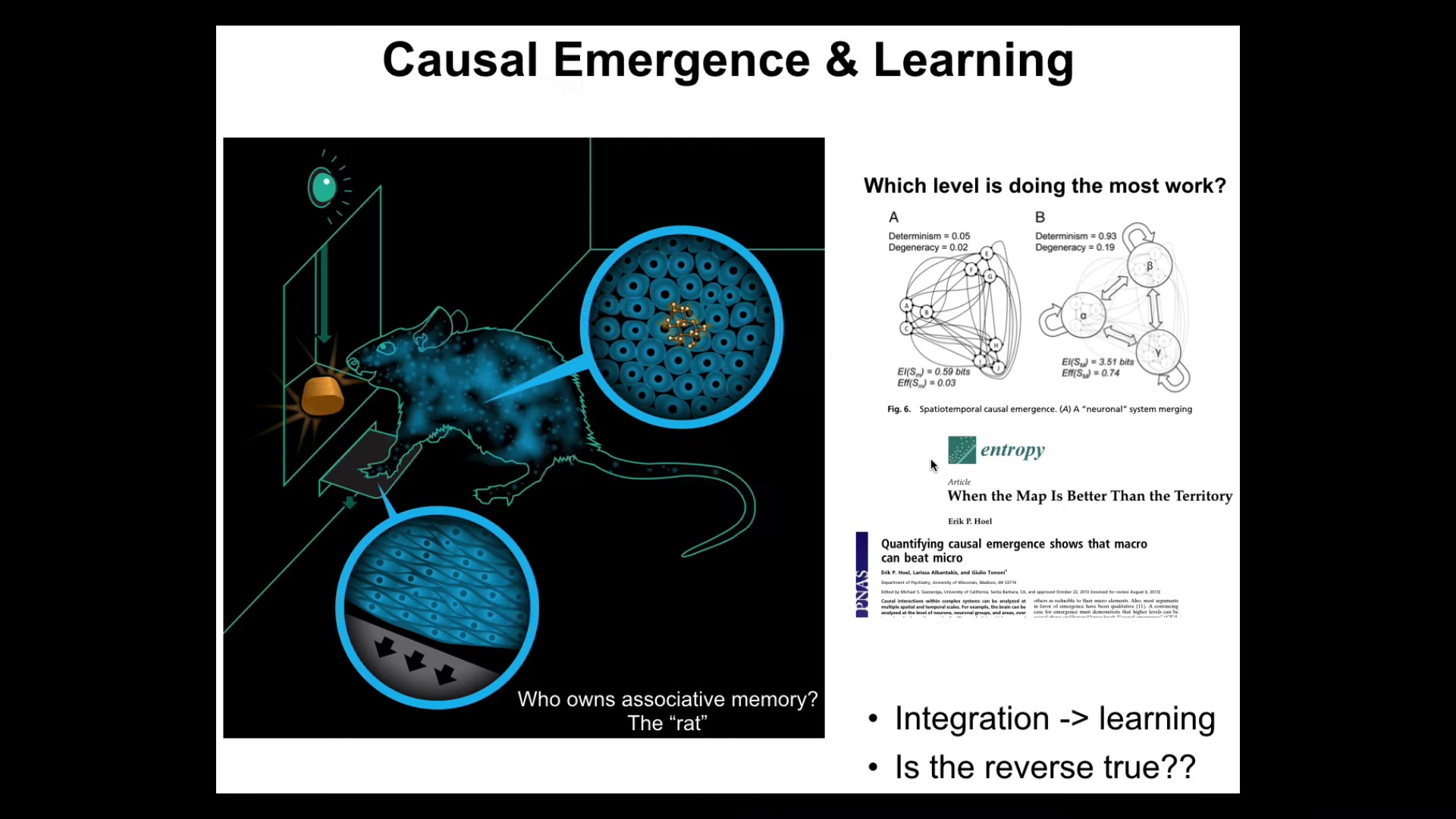

Let's say you have a rat and you train it to press a lever and get a reward. No individual cell has had both experiences. The cell at the bottoms of the feet presses the lever, the cells in the gut get the delicious sugar. Who owns this associative memory? The rat does. Again, a collective intelligence that consists of individual components that none of which know the whole information, but the collective rat does.

What we know is that some degree of integration—one way you can quantify that is by advances in information theory around causal emergence—is needed for these kinds of learning. We asked the question: is the reverse true? We know you have to be an integrated agent to learn, but what does the process of learning do to your status as an integrated agent?

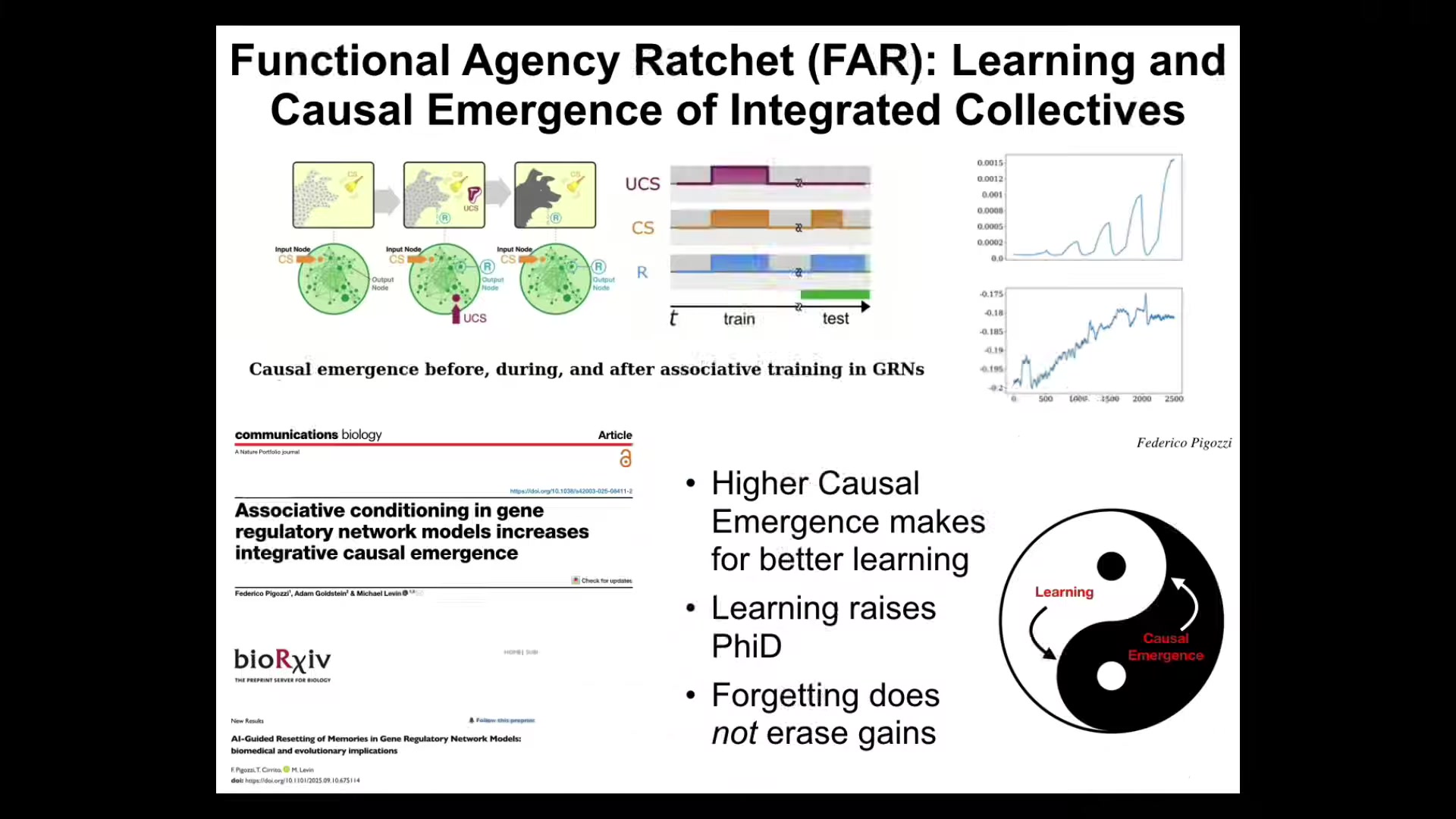

Slide 33/35 · 43m:40s

And it turns out, we discovered something amazing, and there's a couple of papers coming on this very shortly, which is that when you train molecular networks, their causal emergence goes up. Not all of them, but a large number. In particular, some random ones. In other words, this is not a needle in a haystack process. This is a fairly common property of even random networks. Evolution absolutely optimizes the heck out of it. But even random networks can do this.

So here are the three components we have. Higher causal emergence makes for better learning. Learning, on the other hand, raises causal emergence. And the most amazing thing is that forgetting, when you force these networks to forget, they do not lose the gains in causal emergence that they made from learning. So this is an amazing positive feedback loop that has a fundamental asymmetry in it. In other words, a positive feedback loop between learning and causal emergence, between intelligence and the status of being more than the sum of your parts.

This is something that happens very early on. It does not require biology. It does not require any special properties of physics. Where does it come from? It is a free gift from mathematics. It is the property of networks that turn each other on and off, and the properties of causal emergence and the math that regulates that is where it comes from. And it is baked into the very bottom. So these do not have to be in the next paper that we have coming, looks at realistic prebiotic chemistries on Earth to show plausible prebiotic chemistries to show this positive feedback loop between learning and causal emergence. After this thing kicks off, then you can get replicators and then the differential replication can start up. But already from the properties of even random networks, this positive feedback loop already kicks in.

Just to mention very briefly, there's another thing that happens. If you model a prisoner's dilemma where the subunits have the ability to merge and split in addition to cooperate and defect, you find a bias for merging into larger and larger agents whose causal emergence again goes up. Again, this is simply the properties of the mathematics. This does not rely on any specific facts of biology or physics or selection. This is all long before any kind of replicators and selection kicks in. I think this is what's driving a lot of what we see in evolution.

Okay, so I'm going to say a couple of things and stop. I'm not going to read this whole wall of text. If anybody's interested, I'll distribute the slides. But I think what we have here is this notion that intelligence, whatever scale, whether from the molecular components to the whole, potentially the whole evolutionary process itself, it doesn't have to be magic, it doesn't have to be mystery. And we now have tools to study the dynamics of these kinds of things.

Evolving on a multi-scale material that has agency all the way down breaks a lot of assumptions about what evolution can and can't do. I think it's incredibly, incredibly powerful. And we now have the ability through these kinds of biobots and chimeras and things that have not been here before to really ask some deep questions about what is essential to life and cognition, in whatever substrate and what are the specific features that are here on Earth.

And so what I want to suggest is the following. This is the conventional view that you have a lot of dead matter and some region of that dead matter we call life. And most of it is not intelligent, but you have a few brainy life forms and here's where you find minds. I think this is a very popular conventional view. I think what we're seeing now, especially some of the stuff I showed you at the very end, suggests something quite different.

This is what I believe. The set of cognitive systems is wider, not only than the set of living systems, it's actually wider than the set of physically embodied systems at all. I think mind is the larger, the cognition is the largest set here in this diagram, and then within it you have some non-brainy intelligence and some very brainy intelligence. In particular, these things, once you have a replicating body to take care of, then we notice it and we call it life, but it's actually much deeper than that. I think the interesting things for the purpose of cognition and evolution happen long before you get cells, pathways, replicators, and so on. I'm going to stop here and just tease this.

Slide 34/35 · 48m:48s

If anybody's interested in this idea of where do these patterns come from, you can see our symposium. We have a symposium here on the Platonic space. There are talks from all kinds of people, myself and lots of really good folks, who are talking about where information comes from that is not the history of biology or physics. There are some very interesting talks pointing out knowledge gaps.

Slide 35/35 · 49m:13s

Lots of papers. If anybody's interested, I can send you reprints. Most of all, I want to thank the students and the postdocs who have done all the work. We have some great collaborators who have been working with us on all of these things. I have to do disclosures. There are three companies that have licensed some of the stuff I showed you today. These are my commercial interests. I thank all of the model systems because they do all the heavy lifting in this work. Thank you. I'll take questions.