Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

How can we engineer with living, “agential” materials that solve problems on their own? This episode explores bioelectric networks, cellular collective intelligence, and the vision of an anatomical compiler that communicates target shapes to cells. We also discuss xenobots, kinematic self-replication, and what these systems mean for future biomedicine and bioethics.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Introduction and anatomical compiler

(04:25) Basal cognition in cells

(14:18) Morphogenesis and anatomical homeostasis

(29:36) Bioelectric networks as software

(40:05) Planarian memory and morphospace

(47:01) Modeling bioelectricity and cancer

(52:56) Xenobots and emergent agency

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/52 · 00m:00s

Thank you so much for the opportunity to visit with you all virtually and share some thoughts with you.

If anybody wants to get in touch with me or download the software or the primary data, everything is here at this website.

Today I want to talk about this notion of agential materials and how we are going to engineer with such materials.

Slide 2/52 · 00m:27s

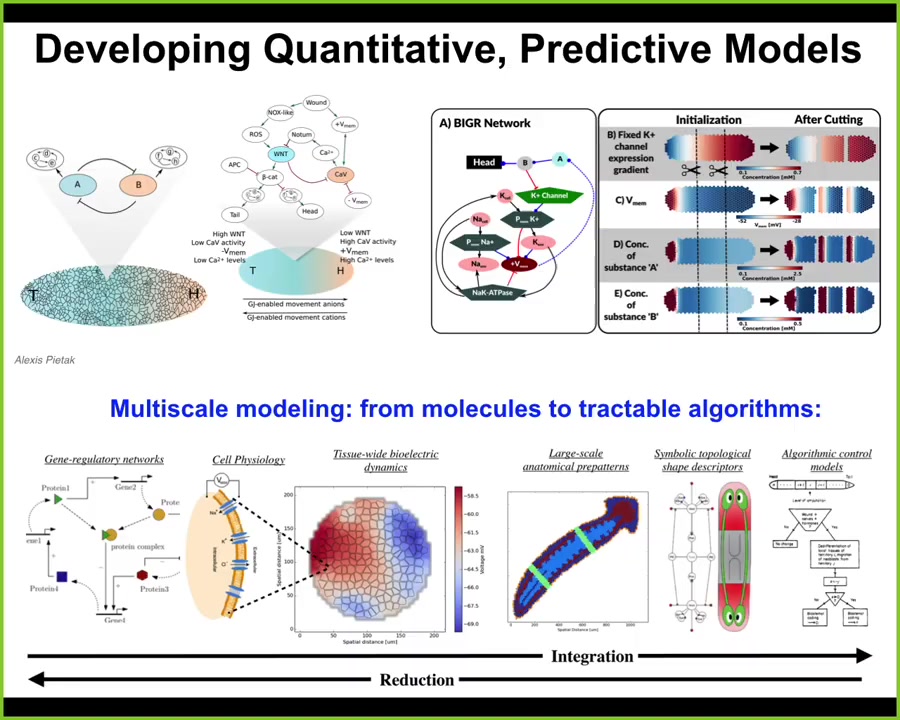

These are the main points I would like to transmit today. First, that most problems in biomedicine and also in synthetic bioengineering boil down to the control of morphogenesis. I'm going to frame this problem as the behavior of a collective intelligence of a cellular swarm in a particular problem space we call anatomical morphospace. I'm going to emphasize that biology uses a multi-scale competency architecture, which consists of hierarchical problem solvers in various problem spaces, and we, evolution, and various parasites can exploit this architecture and the interface that cells and tissues use to shape each other's behavior. In particular, bioelectrical networks are a large part of the medium through which this collective agent processes information. They're basically the ancestor of the nervous system and brain function. I'm going to tell you that tools now exist that we have created to read and write memories into this software layer that sits between the genome on the one hand and the anatomy and function on the other hand. There are many applications here in birth defects, regeneration, cancer, and synthetic bioengineering.

Slide 3/52 · 01m:45s

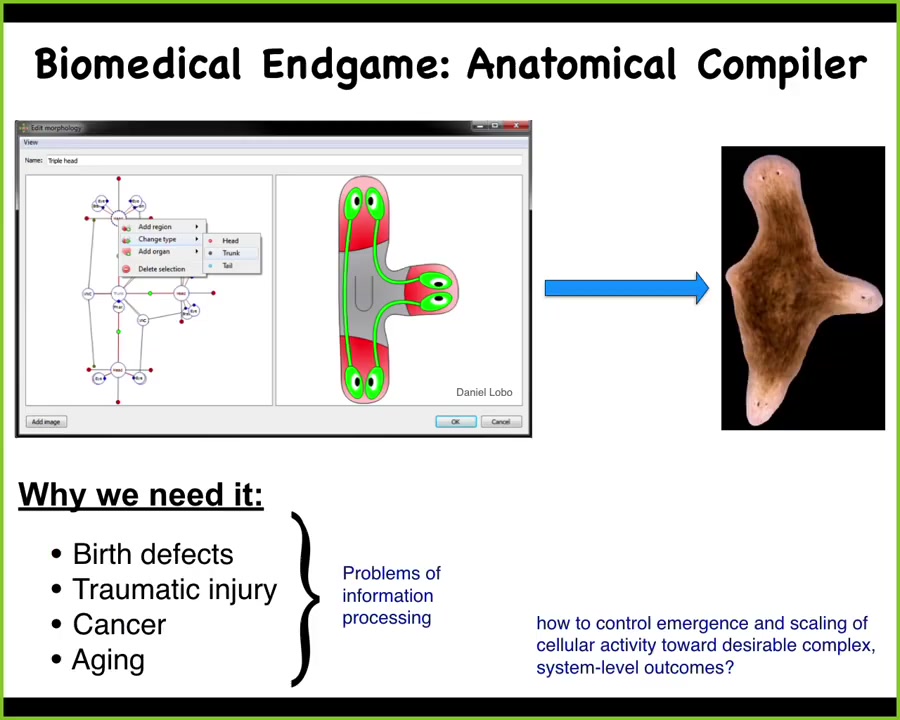

I want to start with this idea. Most of the problems of biomedicine, we're talking about birth defects, traumatic injury, cancer, aging, degenerative disease, they all have one fundamental thing in common, which is that if we understood how to convince a collection of cells to build a particular structure, these problems would be solved. I see the end game of our field as something I call the anatomical compiler. Let's have a vision of what success for us would look like. Success means that if we knew what we were doing, we could have a system where you sit down at a computer and you draw the animal or plant that you want to have at the level of anatomy. Then what the system would do is compile that description down into a set of stimuli that would have to be given to some kind of source of cellular material to get it to build exactly what you want. In this case, you might draw this three-headed planarian, and there it would create that. This is the crux of our problem: how do we control the emergence and scaling of cellular activities towards your desired complex three-dimensional outcome? We don't have anything remotely like this. We have very few examples where we can control shape in this way.

Slide 4/52 · 03m:09s

And part of that is because we are still largely thinking about engineering in this way. Now we're moving from this position where, for thousands of years, we've engineered with passive materials. What's important about this kind of spectrum is that the question of what can you expect the material to do when you are not around to micromanage it.

So this traditional material, pretty much the only thing it does is it maintains its shape. That's the autonomous feature it has. Once you've created it, you put it in place and it maintains.

More recently, there has been a lot of exciting work on active matter and computational materials. Today we're going to talk about what I call agential materials, which is what happens when you come to living cells. And that's why this anatomical compiler idea is not a 3D printer. The idea isn't to micromanage and place every cell where you want it to go, but it's a communications device. It's a way to transmit your desired target morphology to the computational agent that is this collective of cells. Now that's a weird way of thinking about this problem, so let me try to explain how we got there.

Slide 5/52 · 04m:24s

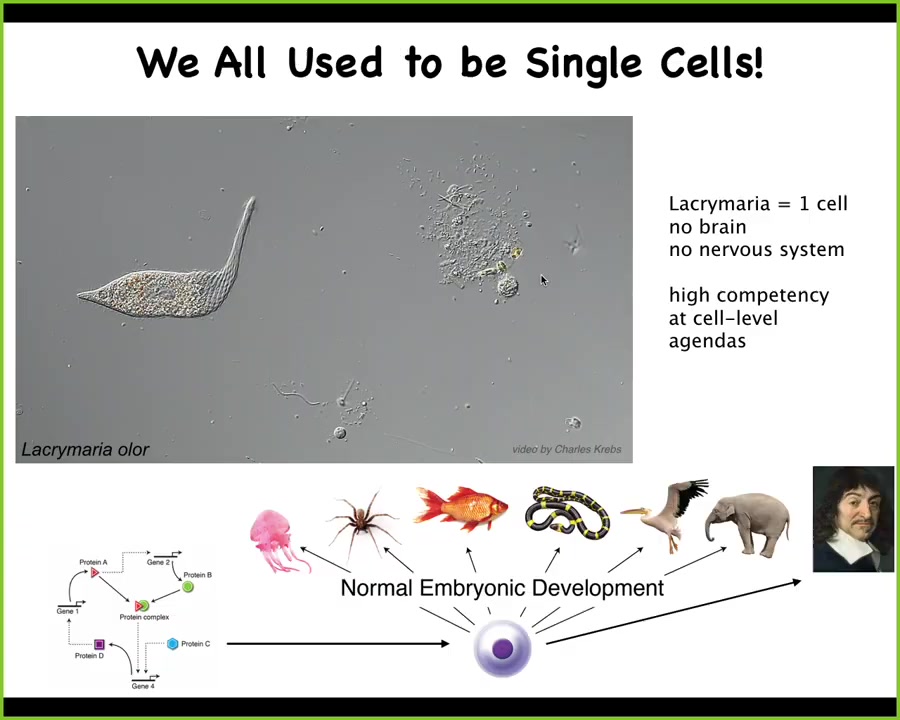

This is a single cell. This is a lacrimaria. What you can see, if you're into soft robotics or active matter, is the incredible control that this little guy has over his body shape. It manages to solve all of its local goals, metabolic needs, physiological needs, at the level of a single cell. There's no brain, there's no nervous system. Everything is done within this one cell.

Each of us has taken this incredible journey from being an unfertilized oocyte, a little collection of quiescent chemicals, to being something like this, or perhaps even something like this, a metacognitive human that's going to make statements about how distinct humans are from mere matter that was here. What developmental biology shows us is that this process is extremely continuous. It's slow and gradual. There's no magical bright line that you can draw at which you stop being a physical dynamical system and you start being a cognitive system. This is a slow process.

That means that certain capacities that we recognize up here, which are very common, we need to ask where they came from and what other unconventional systems might have those properties. This is the field of basal cognition, which seeks to understand that.

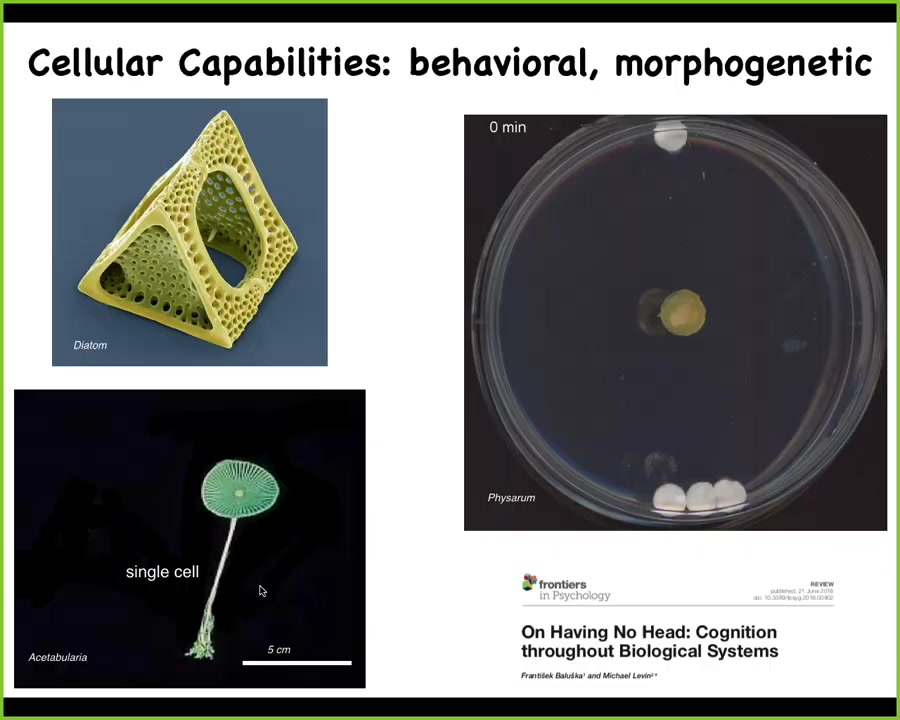

Slide 6/52 · 05m:47s

Cells do many interesting things. This is a cell. Cells have these interesting morphological capabilities. This is also a cell. This thing can be up to 10 centimeters tall. This is an acetabularia. It has a stalk. It has some roots down here. It has a cap. The whole thing is 1 cell. It has one nucleus. As you think about morphogenesis and this idea of differentiation and different cell types, you can actually do all of this quite large in one cell.

This here also is 1 cell. This is a Physarum polycephalum slime mold. The whole thing is 1 cell. This is the work of Nirosha Murugan in my group. What she's done is to place one glass disc here, 3 glass discs here. They're just glass. They're completely inert. There are no chemicals, there's no food gradient, nothing like that. For the first few hours, it grows in all directions, and you think it might keep growing. But what it's actually doing during this time is using biomechanics to pull on the medium that it sits on and receive back the mechanical signals that allow it to measure strain angle. Even though these glass discs are extremely tiny and light, what it will do is reliably realize that there's more of them here than there is here. This is quite a reliable process. All of this time is spent acquiring information from the outside world, making a decision. At this point, right here is where you see that it's already decided what it's going to do. You can play all kinds of interesting games about stacking these on top of each other and tilting it and do various things.

Even very primitive single-cell organisms have these amazing morphological and behavioral capacities. In fact, here your behavior is the change of morphology. This animal, this creature straddles those two problem spaces.

Slide 7/52 · 07m:37s

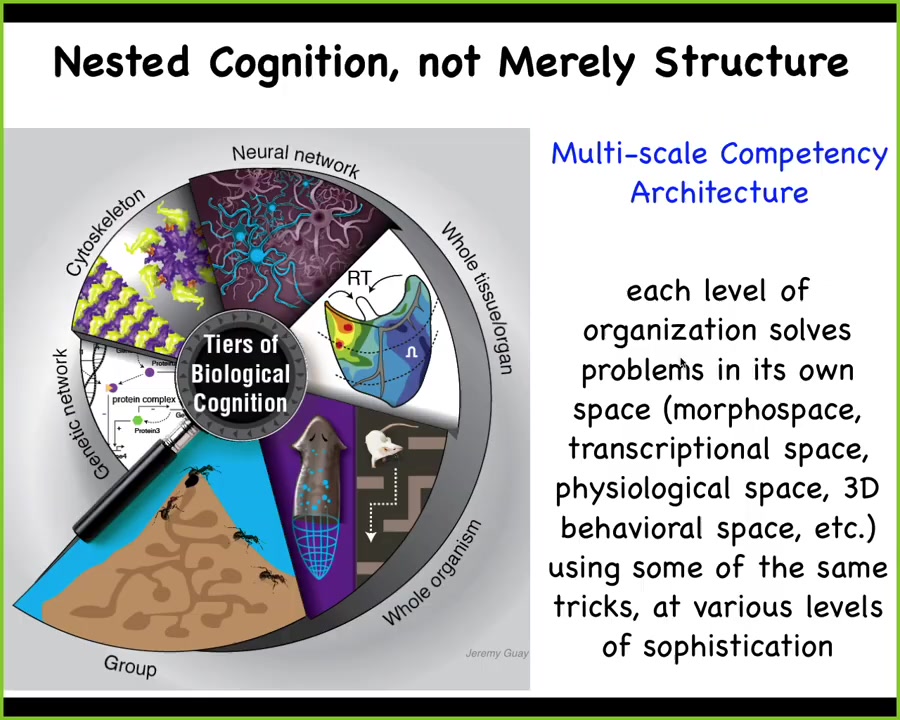

Here's what we're looking at in biology. We're looking at a multi-scale competency architecture where every layer is not just the nested doll of structure, but it's actually a set of nested problem solvers that are able to have various capabilities, not passive materials, including down to the level of protein networks that solve problems in anatomical space, transcriptional space, physiological space. This enables some amazing capabilities. I want to run through with you some of the things that life is capable of that we don't hear a lot about in our standard textbooks.

Slide 8/52 · 08m:09s

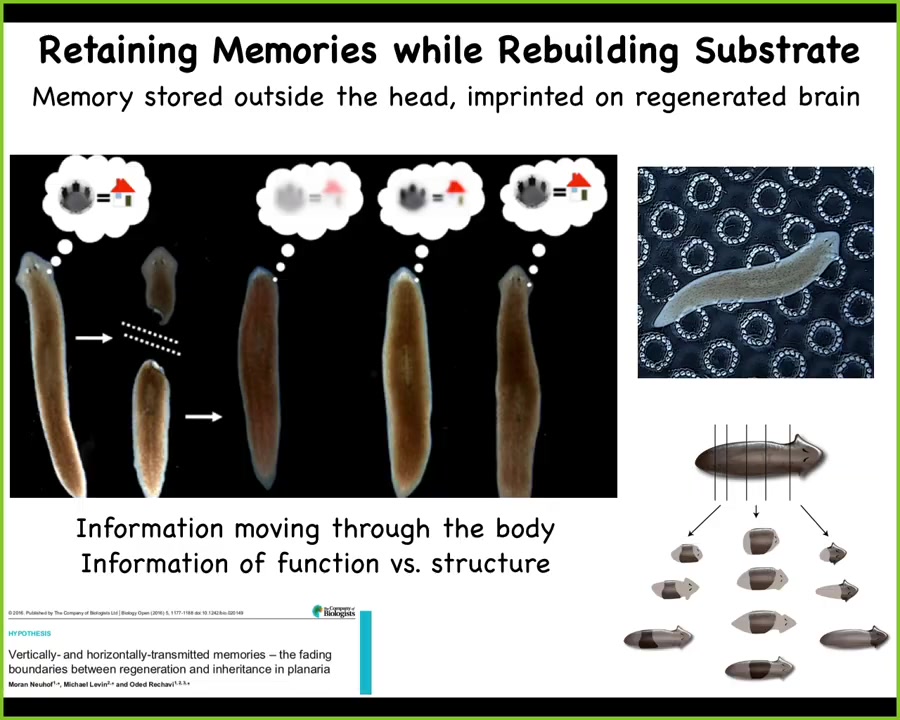

So this is a flatworm, a planarian. The amazing thing about planaria is they have a true brain and all the neurotransmitters that you and I have. What you can do with these planaria is cut them into pieces. Every piece will give rise to an entire perfect worm. They regenerate.

What McConnell learned in the 60s was that if you train this animal to recognize a specific stimulus and then cut off the head, the tail sits there doing nothing for about 8 to 10 days. Eventually it grows a brand new brain, and then you find out that this animal remembers the original training. What you have here is the ability to store behavioral memories somewhere outside the brain and then to imprint that information onto the new brain as it develops. This is the movement of information throughout the body and a tight integration of morphological information.

In other words, how do we create this new head with behavioral information? What was the content of the mind that this primitive animal had? This plasticity, this amazing plasticity both of behavior and of morphology is not just for invertebrates.

Slide 9/52 · 09m:27s

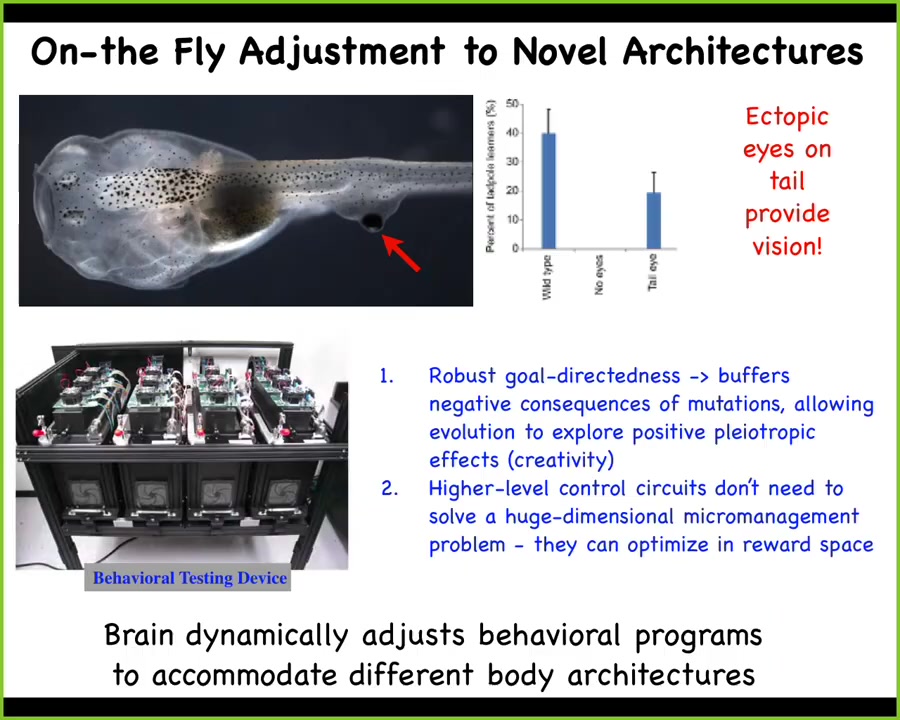

Here's something that Doug Blackiston in my group did years ago. He created this tadpole which has no primary eye. This is the tadpole of the frogs, Xenopus laevis. Here's the mouth, the nostrils, the brain, the gut. You'll see there are no eyes, but what he did do was to put some eye cells on the tail.

These eye cells had no trouble becoming an eye, even though they were sitting next to muscle instead of where they belong next to the brain. What we found out, having built a machine to automate the training and testing of these animals, is that they can see quite well. This eye confers vision. It doesn't connect to the brain. In some cases, it connects up here to the spinal cord, and you can trace the optic nerve.

This animal, which had a very particular sensory motor architecture for evolutionary time periods, all of a sudden in one generation has a totally different architecture. There's this weird itchy patch of tissue on its back that gives some kind of electrical signals. This brain has no trouble recognizing that this is visual data and behaving accordingly. That ability to adjust to novel scenarios on the fly without needing eons of evolutionary selection for it has massive implications. It has massive implications for evolution itself, for biomedicine, and for our ability to use cells and tissues in engineering, because they are not passive elements. They are little problem-solving engines.

Slide 10/52 · 10m:59s

Now that probably sounds very strange to many people in the audience, because we, as many animals, are very good at recognizing intelligent behavior in the three-dimensional world. Our sense organs, our cognitive apparatus, are really tuned to pick up a gentle behavior from middle-sized objects moving at medium speeds in three-dimensional space. When birds and mammals do clever things, it's very easy for us to know that.

But there are other spaces, including transcriptional spaces, morphological spaces, and physiological spaces, where biological systems execute very similar kinds of intelligent behaviors. If you had an innate sense of your blood chemistry the way that we do with vision and smell, if you could feel the different components of your blood chemistry, you would have no trouble recognizing your liver and your kidneys as intelligent agents that were navigating that space with all kinds of interesting competencies.

Slide 11/52 · 12m:02s

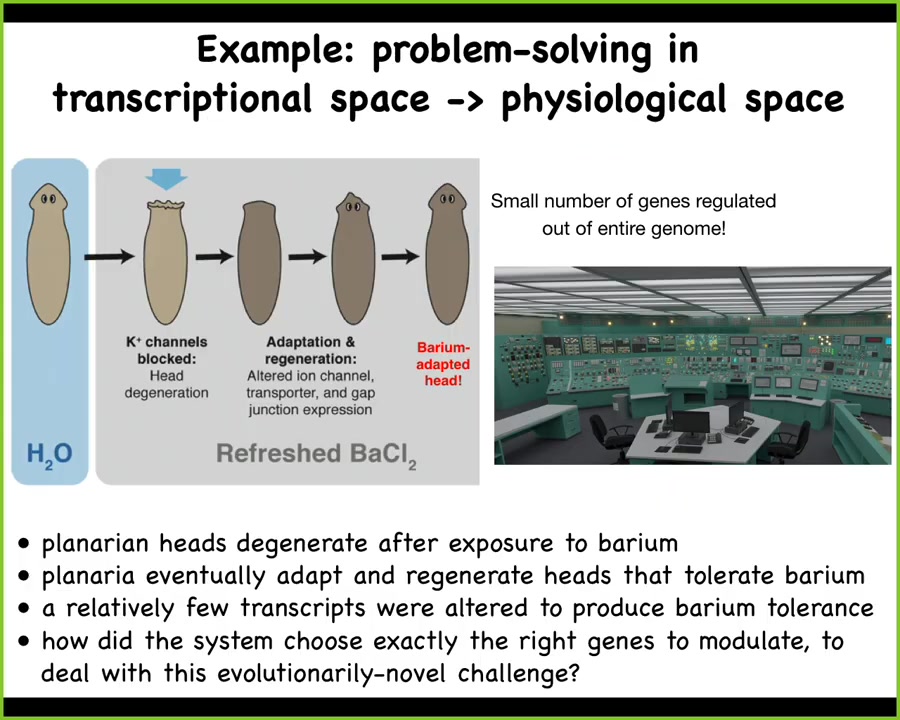

I'll give you a simple example. This is the work of Maya Emmons-Bell and Angela Tung in our lab.

What they did was to take planaria and put them in a solution of barium. Barium is a nonspecific potassium channel blocker. What it does is it makes it impossible for the cells in the head to exchange potassium. That makes these cells extremely unhappy, especially the neurons, and their heads explode. Just overnight, their heads are gone. If you leave these planaria in barium, refreshing the barium as needed, they will soon build a brand new head and the new head is completely barium-insensitive.

That seemed very strange to us. How could that be? We did a very simple experiment, which was to compare the gene expression of barium-adapted heads with normal heads. We found that only a small number of genes are different. Out of the whole genome, tens of thousands of genes, they found exactly the right transcripts to up- and down-regulate in order to make up for this drastic environmental stressor.

Here's the most amazing part: planaria never encounter barium in the wild. There is no evolutionary pressure to know what to do when you encounter barium. So what we're looking at here is an amazing ability to navigate the very large dimensional space of gene expression to find exactly the ones you need to solve your problem.

I often envision this as being stuck in a nuclear reactor control room with the things melting down. You have 20,000 different buttons. How do you know what to do if you've never seen the stressor before? The key is that you don't have time to simply start turning genes on and off to see what happens. Most of that would make things worse, not better.

They have this incredible ability, which we still don't understand, although I have a hypothesis about what's going on here, that allows them to navigate competently this kind of space. This is a problem-solving example. They are able to adapt to a new stressor that they've never seen before.

Slide 12/52 · 14m:22s

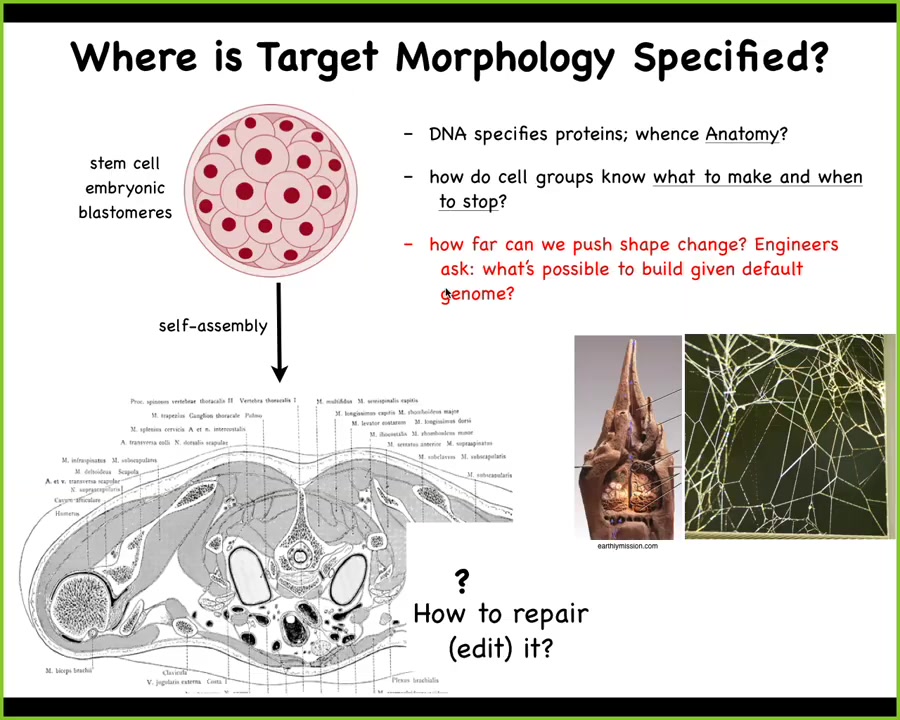

Now, this is transcriptional and there are many such examples that I could give you, but I want next to focus on morphogenetic space, problem-solving in anatomical morphospace.

We start life like this: a collection of embryonic blastomeres, and then eventually, we get to something like this: a cross-section through a human torso. Look at the amazing order. Look at all the organs, the structures. Everything is in the right place, the right shape and size relative to each other.

So you might ask, where is this pattern encoded? It's got to be somewhere. One is tempted to say DNA, but we can read genomes now. We know what's in the DNA. What's in the DNA is the descriptions of the micro-level hardware that every cell gets to have, the proteins. The genome doesn't say anything directly about what the layout here is, what kind of symmetry it has, whether it's regenerative, how many fingers. The DNA doesn't say anything like that any more than the DNA directly specifies the shape of termite colony nests or spider webs. These are all the results of a physiological software layer that sits between the genome and the anatomy.

So what we would like to understand is a few things. How do these cell groups know what to make and when to stop? How, if something is missing, do we repair it? As engineers — and this will be the last part of the talk — how far can we push this? What else can you build given a default genome? Does it have to be this or can you build something else? Now, you might think that this problem really should have been solved a long time ago. We have all kinds of genetic information, molecular biology, genomics.

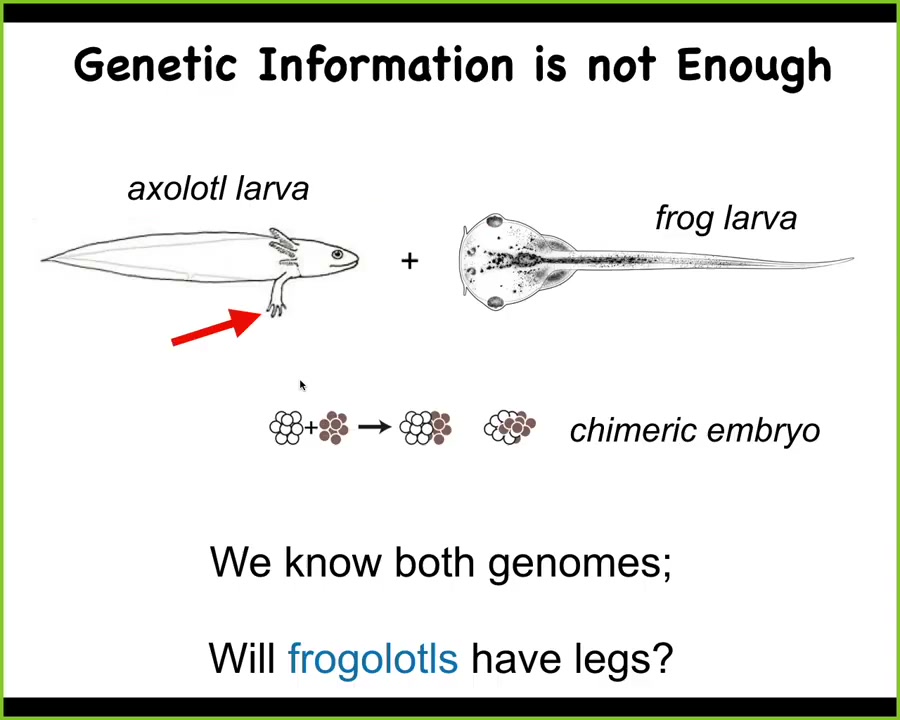

Slide 13/52 · 15m:57s

Here's a very simple example. These are baby axolotls, and baby axolotls have little tiny forelegs. These are tadpoles of the frog Anapus laevis. They do not have legs at this stage. In our lab, we make something known as a frogolotl, which is part frog, part axolotl.

I ask a simple question. If I were to make this frogolotl, is it going to have legs? After all, you have the axolotl genome, you have the frog genome. Can you tell me if a frogolotl is going to have legs or not? And if it is going to have legs, can you tell me whether those legs will be made only of axolotl cells or whether the frog cells will somehow participate in this process? And by the way, what will the shape of those legs be? Will they be like axolotl legs or like frog legs? We have no ability to derive any of these things from genomic information.

Slide 14/52 · 16m:43s

Here's where we stand today. Biologists are very good at manipulating cells and molecules, and information about those cells and molecules and pathways. We are a very long way away from control of large-scale form and function. If you wanted to convert an axolotl to three-fold symmetry instead of bilateral symmetry, what genes would you change? We have absolutely no idea how to do things like that.

I think that both biomedicine and engineering are where computer science was in the 40s and 50s. What she's doing here in order to program this computer is she's physically rewiring it. She's having to interact with the bare metal, with the hardware.

All of the most exciting kinds of advances in molecular medicine are this. It's genome editing, protein engineering, pathway rewiring. It's mostly focused at the hardware. I think that we need to complement that with the approaches that computer science took, which are to go up and take advantage of the software of the system.

I'm going to argue that biology is reprogrammable in exactly the same way that universal kinds of computing devices are reprogrammable. In particular, what we're missing and what we are trying to work on is being able to exploit higher level information processing, what we call agency memory, decision-making, problem-solving, goal-directed activity.

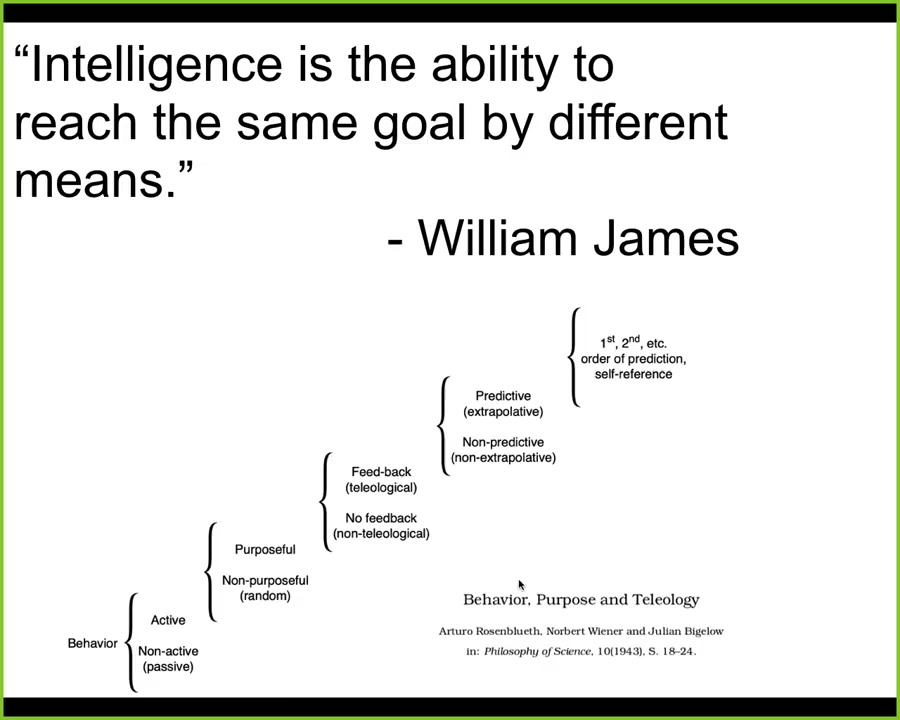

Slide 15/52 · 18m:13s

Now I'm going to use some terms from time to time, things like intelligence and problem-solving. What I mean is not some mystical, magical feature that only humans have. What I mean is a definition like one used by William James, who said that "intelligence is simply the degree of ability to reach the same goal by different means."

There's also a quantitative cybernetic version of this, due to Wiener and colleagues. It is a spectrum of competencies from passive matter up through human-level metacognition. The point is to benefit from ideas in behavioral science, cybernetics, and computer science to understand how we deal with and how we engineer systems that are not necessarily down here but might be at higher levels on this hierarchy. For many of them, we don't know where they are on the hierarchy, which means we need to find out.

Let's look at anatomical kinds of behavior or morphogenesis. The first thing we know is that development is very reliable. In the vast majority of cases, an egg will give rise to a particular target morphology.

But it isn't hardwired, because if you cut this animal in half or an embryo is taken apart into quarters, you will not get two half-embryos; you get two normal monozygotic twins. This means that we have the ability, if this were morphospace boiled down to two dimensions, to get to the right ensemble of target states from different starting positions, avoid local minima and various other traps, and get there.

We're starting to understand that we can get to the same outcome. This is, again, William James's definition: we get to the same outcome despite perturbations from diverse starting positions.

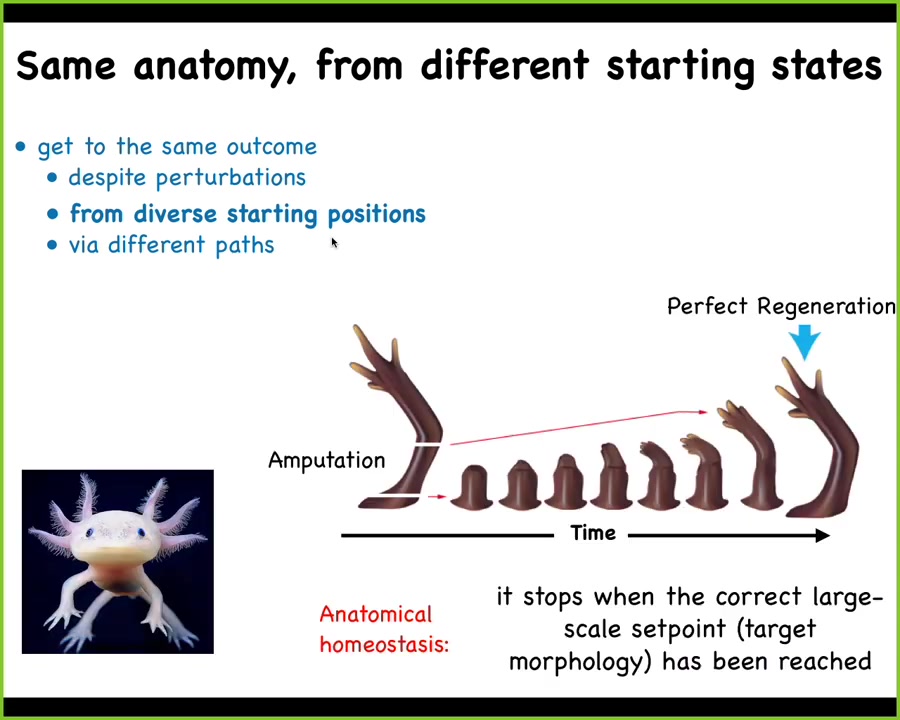

Slide 16/52 · 20m:21s

Here is another example of that in an adult organism. This is an axolotl. These guys regenerate their limbs, their eyes, their jaws, their spinal cords, their ovaries, and so on. If you amputate anywhere along this limb, the cells will start to rebuild. They will build exactly what's necessary, no more, no less, and then they stop. When do they stop? They stop when a correct salamander arm has been completed. That starts to suggest the process of anatomical homeostasis, meaning that this walk in the space of possible morphologies that it does, the system not only ends up where it needs to go, but then it actually can stop and stabilize where it needs to go.

Slide 17/52 · 21m:11s

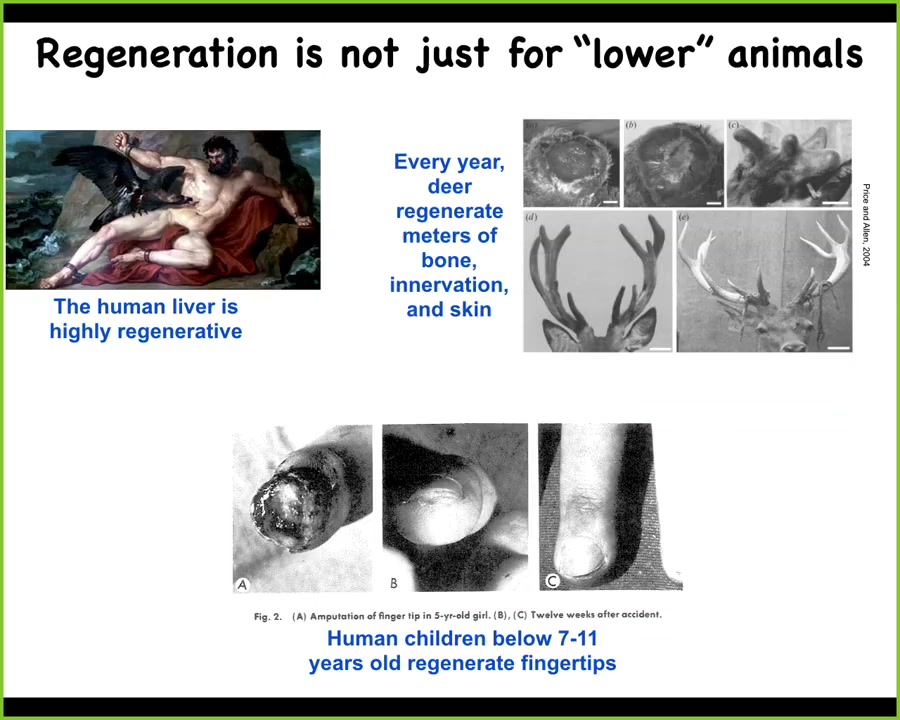

Regeneration isn't just for worms and amphibians. Humans have a highly regenerative liver. Even the ancient Greeks seem to have known that. The deer every year regenerate huge amounts of bone and vasculature and innervation. These antlers grow at a rate of a centimeter and a half per day of new bone. Remarkable regeneration of an adult mammal. And human children are known to regenerate their fingertips up until a certain age. If they have a clean amputation and you don't close it up, you'll get, cosmetically, a very nice finger regeneration after that.

Slide 18/52 · 21m:49s

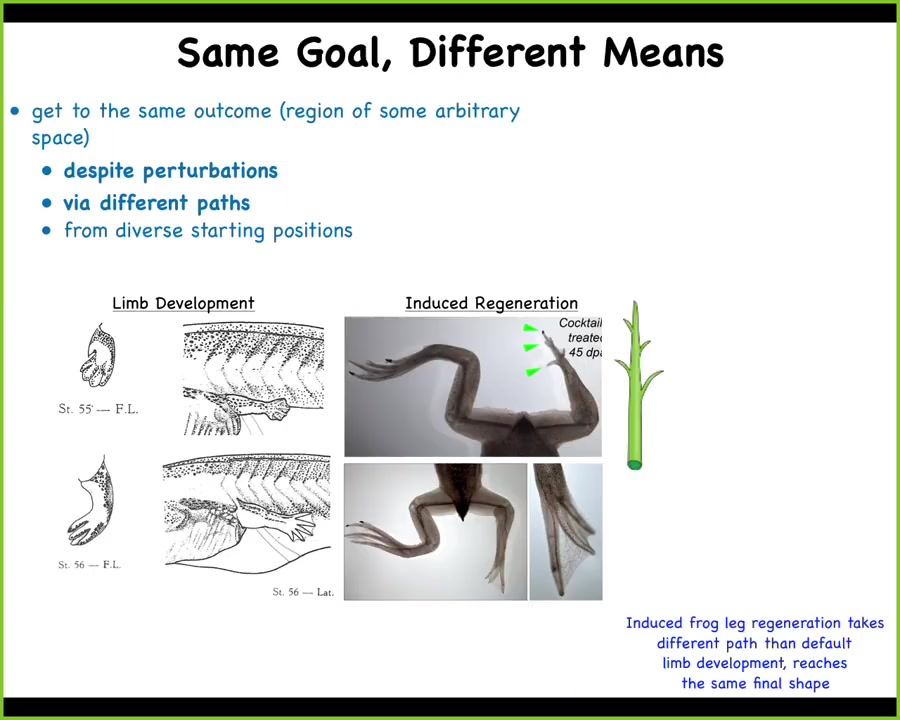

The other interesting issue about this is that, yes, the systems get to the same point in morphospace, even from different starting positions, but they don't all get there the same way.

This is work done by Kelly Chang, a postdoc in my group many years ago, showing how frog legs regenerate.

What you see here. Frog legs at this stage normally don't regenerate; we've induced them to do so using a method I'll describe in a few minutes. What you see is that while the developmental path is to create a flat paddle and then kill off some cells in between the fingers by apoptosis, that isn't how the regenerate forms. The regenerate, you can see here with these little green arrowheads, you've got this middle stalk that creates the central axis with a toenail at the end. You've got some toes that come off the sides. It looks a lot more like the way a plant grows than the way the limb developed in the first place.

A different path through the space, but reaching the same final shape.

Slide 19/52 · 22m:54s

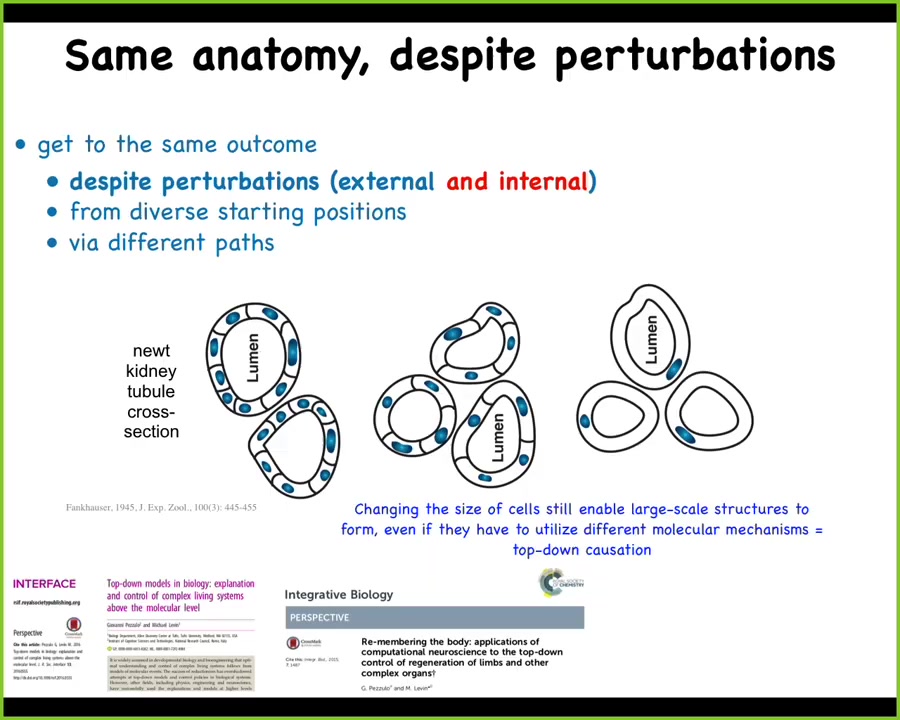

This is perhaps my most favorite example ever of this creative problem-solving process, which is this. It is a cross-section through a newt kidney tubule.

Now normally what you'll see is that there's 8 to 10 cells that cooperate together to build this kind of structure. One thing you can do is make polyploid newts that have multiple times the amount of genetic material of a normal cell. The first amazing thing is that if you do that, these newts up to 6N or 8N are still perfectly normal animals. Having multiple copies of your genome doesn't apparently hurt anything here. So that's amazing.

Second amazing thing is that the cells enlarge in proportion to the amount of DNA they have.

The third thing is that when that happens, the cells scale their number to the task, meaning that with bigger cells, fewer of them will come together to build the same size structure.

The most amazing thing of all is that when you make the cells so gigantic—these are the 6N newts—that they simply cannot fit with others to do this, one cell will bend around itself and form the exact same anatomical structure.

What's crazy about this is that this is a different molecular mechanism. This is cell-to-cell communication and tubulogenesis. This is cytoskeletal bending. What you have here is an example of top-down causation. In the service of maintaining a specific anatomical structure, in order to reach that region of anatomical space, you can call up different low-level mechanisms.

This is something we see in neuroscience all the time. When an animal has a certain goal in behavioral space, it will often execute different specific behaviors; different low-level modules will be activated to get to the final state. Development is no different in the morphogenesis process.

Slide 20/52 · 24m:56s

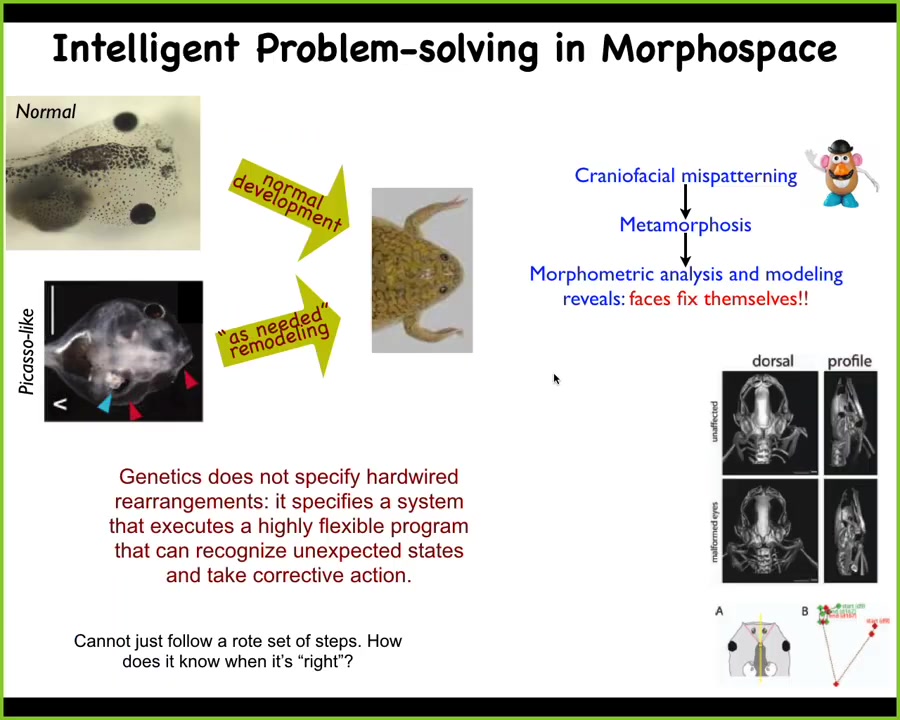

The final example of this before we go on and look at the mechanism is something we discovered a few years ago that a normal tadpole becomes a normal frog by rearranging its face.

The eyes have to move, the jaws have to move, the nostrils and so on. This used to be thought of as a hardwired process. Every organ just moves in the right direction, the right amount, and there you have your frog. We decided to test that, and what we created was these so-called Picasso tadpoles. Everything is in the wrong position. The eye might be off to the side, the mouth might be on top of the head. Everything is scrambled.

We found out these animals give rise to normal frogs, because each of these components doesn't just move in the same position that's default for development. It will move in new ways. If it goes too far, it'll move backwards in order to give you the right frog face, and then they stop.

What the genetics does is not specify, even if it could, some specific motion. What it instead does is give you an error minimization machine. It gives you a system that can flexibly take action to minimize an error parameter. In this case, the error parameter is morphological distance from this target.

Slide 21/52 · 26m:11s

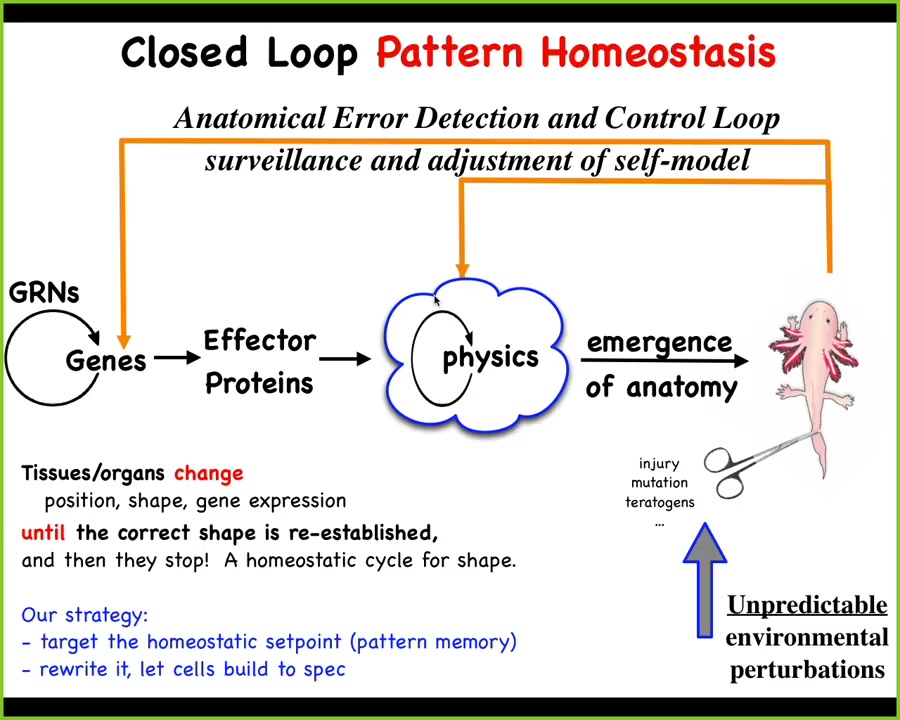

The mainstream story of morphogenesis is that you have some gene regulatory networks, some of them make proteins that do things, they diffuse or they're sticky or they exert force or something. You have this process of emergence. This is the dominant idea in this field. The idea is that when individual components act according to local simple rules, out will come complex outcomes. So the idea is that this notion of emergence plus complexity science will be able to explain these kinds of things. This is true. There are many simple systems in which following local rules, even though the rules are simple, give you something quite complex at the end. This is all true.

There's a big problem here. There's a huge component missing. The thing that's missing here is that this is a feed-forward, open-loop kind of process, which means that if you want to make changes down here, let's say convert this guy to three-fold symmetry or make some other kind of change, this process is not reversible. It is in general impossible to know which genes you're going to tweak to do that. This greatly limits the opportunities for CRISPR, genomic editing, because beyond some low-hanging fruit, we're not going to have any idea of what genes to tweak to get a particular outcome. This is an inverse problem that is generally not solvable.

We think biology doesn't work like this either. What exists on top of this emergent dynamic is a set of feedback loops, which, if this system is deviated from the correct shape — through injury, mutation, teratogens — kick in both at the level of physics, which is what I'm going to show you next, and the level of transcription to try to get back to the correct state.

Biologists know all about feedback loops, and there are many examples of homeostatic cycles. There's something weird here, which is that in this case, the set point of the homeostatic process is not a single number the way it would be for pH or some metabolite level. The set point here is some kind of anatomical descriptor. It's a complex data structure. It's not a scalar.

This scheme makes a very strong prediction. The prediction is that if this is true, then your opportunity to make changes is not limited to down here. What you could do is take advantage of what's great about this architecture; think about your thermostat. The amazing thing about your thermostat is that you can change the temperature if you understand where the set point is encoded, and you don't need to rewire the machine. In fact, you don't have to understand everything about how your thermostat works. The only thing you have to do is recognize that it is a homeostat, and you have to know how to decode and encode the set points. The system takes care of it.

If this is all true, what we ought to be able to do is find, decode, and rewrite anatomical set points, and let the same standard wild-type cells do what they do best. We don't need to rewire the hardware. Is this possible? If so, we spent the last couple of decades looking for this. We started thinking about this: if this is a goal-seeking error minimization system, what inspirations for that do we have?

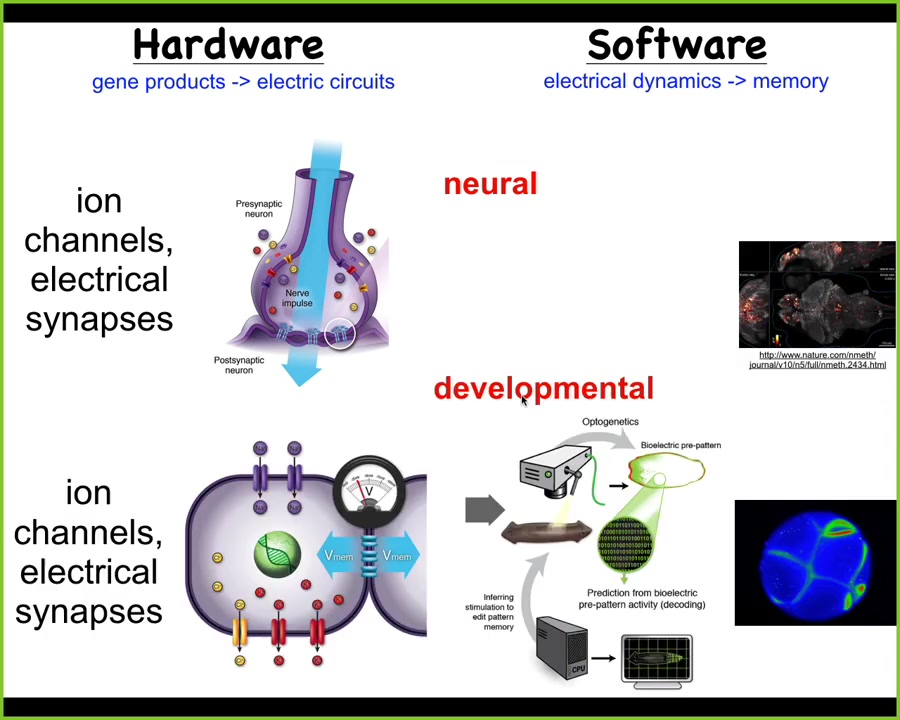

Slide 22/52 · 29m:46s

And the obvious one is the brain. What we have is a collection of cells which work together to allow flexible problem-solving towards specific goals. How do we do that? There's this hardware, which is a network of these neurons that have ion channels on their surface. They thus have a voltage state, and that voltage state is communicated to the neighboring cells. And that hardware underlies the cognitive software.

This is a zebrafish brain. You're seeing all the electrical activity as this fish is thinking about whatever fish think about. The commitment of neuroscience is that if we understood how to decode these physiological events, we could literally know what the animal was thinking, what memories it had, what preferences it has, what behavioral repertoires it has. Everything is actually encoded in this electrical activity. It's a very profound and bold claim.

Slide 23/52 · 30m:46s

It turns out that every cell has this. Every cell has ion channels. Most cells have gap junctions, these electrical synapses with their neighbors. This system is way older than neurons and brains. This was actually invented around the time of bacterial biofilms. Evolution discovered this. Could we port from neuroscience all of the tools and concepts to do the neural decoding that people do in the brain and do it during morphogenesis to ask, what is the collective intelligence? What people are doing is asking, how does this electrophysiology help us understand what the collective intelligence of these cells is doing? How is the electrophysiology of morphogenesis helping us to understand how that collective behaves in morphospace?

There is a very strong invariant between these two fields. The results of these electrical networks control your muscles to move the animal through three-dimensional space.

Exactly the same system was the ancestral form, and what it used to do was make computations to control cells to move your body configuration through morphospace. What evolution did was simply pivot this thing from one space into the other, but all the mechanisms are the same, and many of the algorithms are the same, although it's much slower.

You have to make a couple of changes, including speed, but otherwise, we think that neurons and synapses just speed-optimized some things that cellular networks were doing long before behavior showed up.

Slide 24/52 · 32m:34s

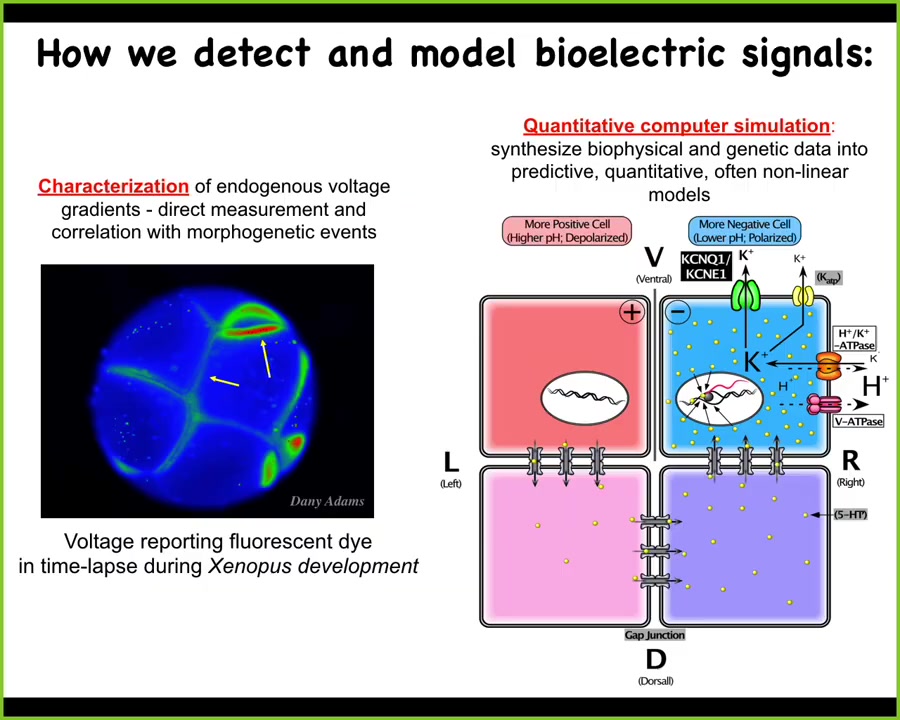

We developed some tools to try to read and write this information into the collective computations of cells. First, voltage-sensitive dyes. This is a voltage-sensitive reporter dye that helps you image what all the electrical states are in this early frog embryo. This is a time-lapse here. Then we do biophysical modeling to understand how these gradients arise from different channels and pumps that all of these cells have.

Slide 25/52 · 33m:00s

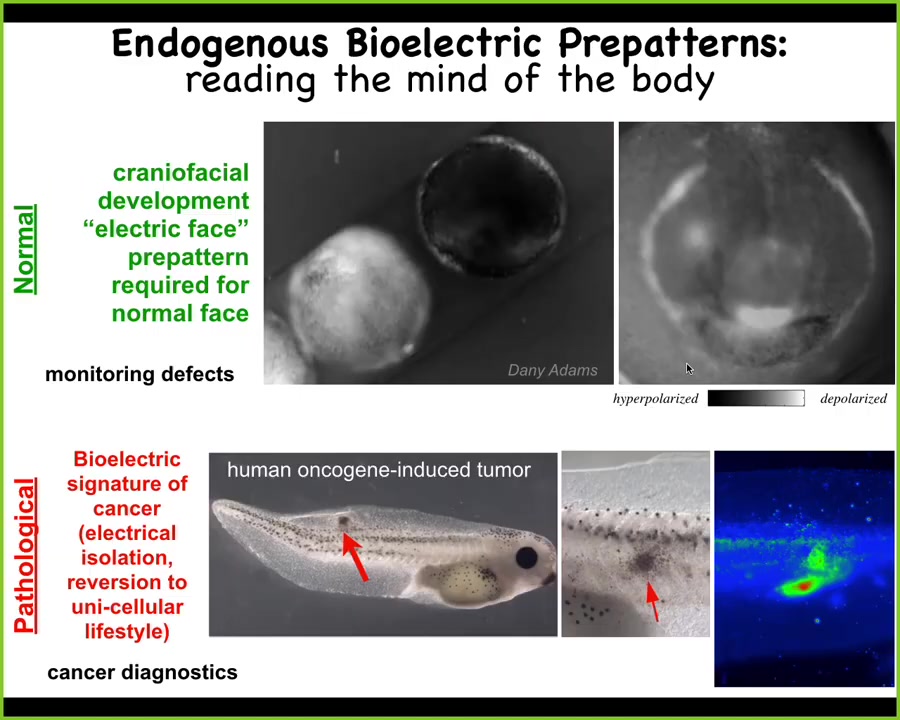

I want to show you two quick examples. This is the work of Danny Adams in our group. What she did was make this video of this frog embryo that is putting its face together. These are the early steps of craniofacial formation. We're using this voltage-sensitive dye. The light colors are depolarized, the dark are hyperpolarized.

Prior to the gene expression that regionalizes the face, you already see: here's where the eye is going to go, here's where the mouth is going to go, here are the lateral structures. This tissue already has a pre-pattern, an energetic pre-pattern of where the different organs are going to go. We know this is instructive because if you alter this pre-pattern, then the shape of the face is changed accordingly. I'll show you that momentarily. This is a natural pre-pattern that is required for normal morphogenesis.

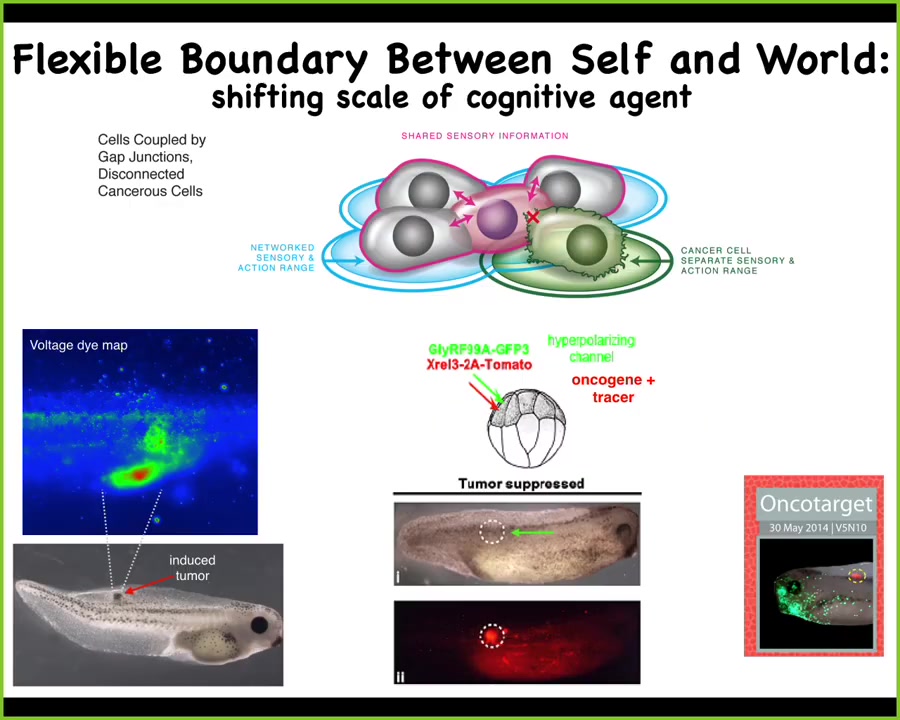

This is a pathological pattern where we can inject a human oncogene into these tadpoles. What the oncogene does is cause them electrically to disconnect from their neighbors and to depolarize; at that point they just become amoebas. The boundary between self and world shifts. They scale down to the kinds of things individual cells know how to do as opposed to large cellular networks, they become a tumor, they metastasize, and they treat the rest of the animal as just external environment. This is how we trace and track these communications.

Slide 26/52 · 34m:30s

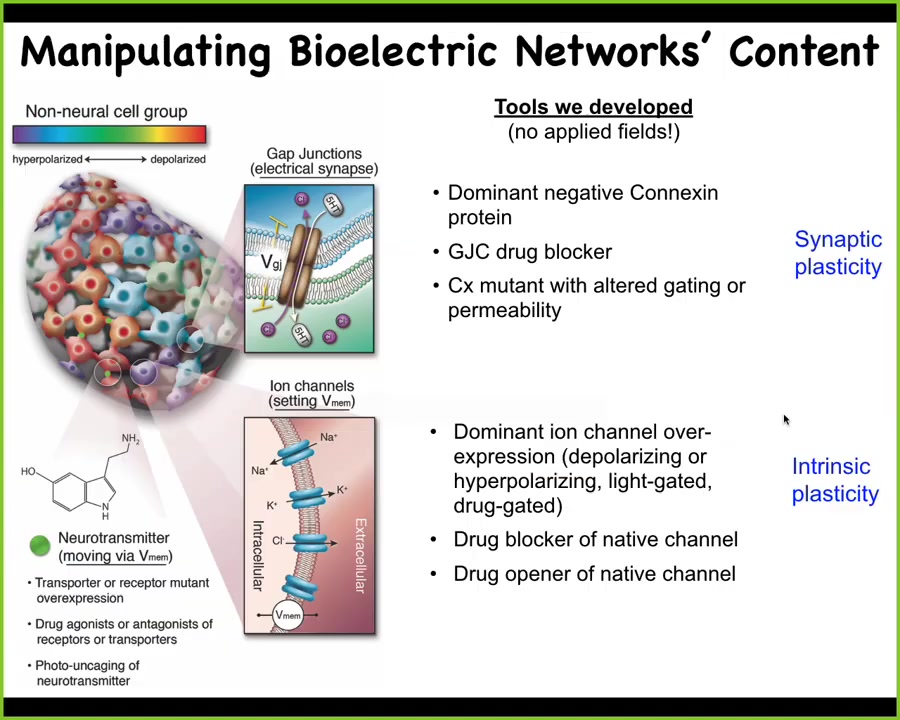

Now, the more important thing is the functional tools. What we do is we steal everything from neuroscience. We don't use any applied electromagnetic fields. We don't use electrodes. What we do is we target using molecular tools such as pharmacology and optogenetics. We use molecular tools to target the natural interface that these cells offer to us and to each other. That interface is the gap junctions that determine the connectivity of the network and the ion channels that determine their electric state at any moment in time. So we can open and close these things with drugs. We can use light in the case of light-gated ion channels. We can use neurotransmitter signaling directly. All of the same tools that work in neuroscience work in every other tissue of the body.

Slide 27/52 · 35m:21s

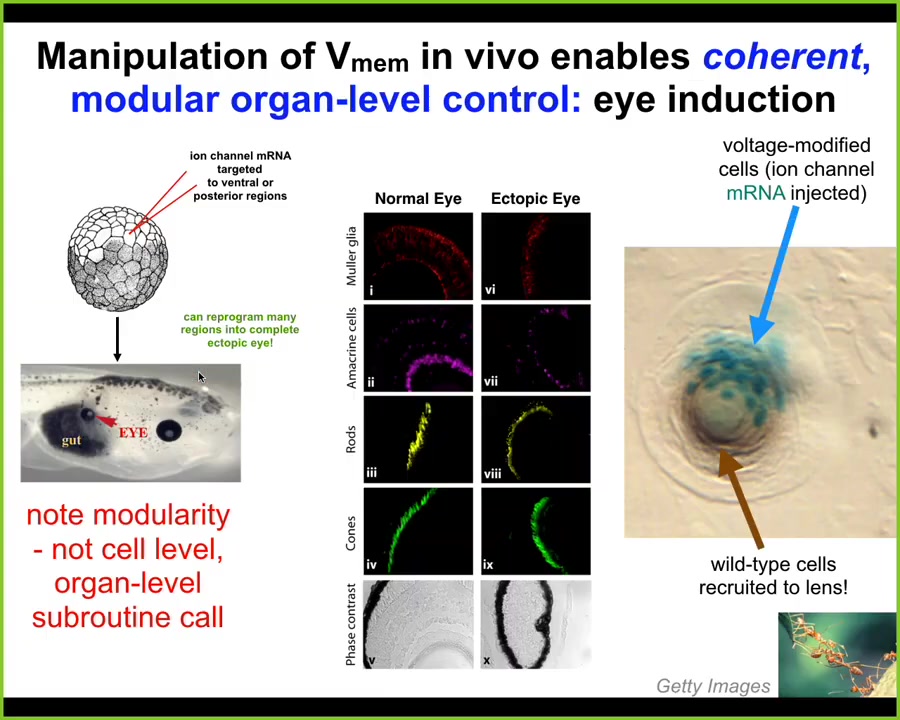

Here are some examples of interesting things that you can get that way. I showed you a special bioelectrical pattern that indicates where the eye is going to go. We decided to reproduce that pattern somewhere else. This is the work of a graduate student at the time, Sherry Au, in my lab, and Vipav Pai, who's a staff scientist. What they did was introduce an RNA encoding a particular potassium channel into some cells that are going to be the various other parts of the embryo, for example, the gut. What you find is that even in tissues that were, according to the textbook, not competent to become eye, you can still form an eye if you first establish this particular bioelectrical pattern that says, build an eye here.

Notice a couple of critical things. First of all, these eyes have the same sort of internal components that normal eyes are supposed to have: lens, retina, optic nerve. But we didn't give them enough information to specify any of that complexity. All we did was specify a very informationally poor stimulus that didn't include all the details. This means it's a modular, almost subroutine call. It's a trigger. The cleverness isn't in what we put in. That's just a simple trigger. All the intelligence is in the rest of the tissue, which can see that simple signal and interpret that at the scale of organs. We're not telling individual cells that this stem cell should become a retinal cell. The information is an organ-level modular trigger.

The second amazing thing is this. Look here: this is a lens, an ectopic lens sitting out in the tail of a tadpole somewhere. These blue cells, which are labeled with a beta-galactosidase lineage label, are the ones that we injected with the potassium channel. But there's not enough of them to make a proper lens. What do they do? They do exactly what another familiar kind of collective intelligence does, which is ants: they get their neighbors, they recruit their neighbors to participate. While there's not enough of these cells to build a proper lens, they take cells that are perfectly wild type that were never directly modified by us, and they recruit them into this project to build a lens of the right size and shape.

Not only the ability to specify organs at a high level, but the ability to take care of all the morphogenesis and, in fact, the recruitment, the scaling of agents to your task is done in an automatic way that we do not have to micromanage. This is great for engineering, for bioregenerative medicine. These things have all kinds of interesting capacities that we do not need to micromanage. We can take advantage of them.

Slide 28/52 · 38m:09s

What else can you do this way? We can ask for ectopic otocysts or inner ear organs. We can make extra hearts. We can make extra forebrains, extra limbs. There's our six-legged frog. Or we can make fins. That's weird. Tadpoles aren't supposed to have fins. That's more of a fish thing. We'll get to that momentarily.

Slide 29/52 · 38m:31s

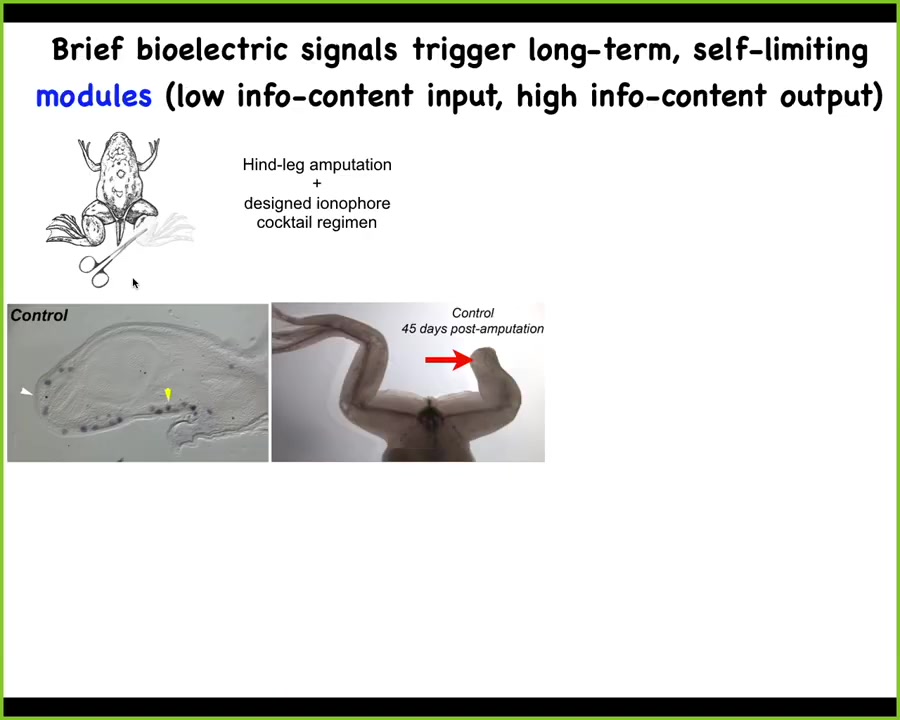

This is potentially very useful for regenerative medicine. Adult frogs at this stage do not regenerate their legs. We came up with a bioelectric cocktail that triggers a "build a leg here" cascade.

After 24 hours of exposure to this bioelectric stimulus, the MSX1 blastema markers are turned on. You've got this blastema forming and it makes a leg within about 45 days; you get this nice leg and eventually you get a pretty respectable leg out of it.

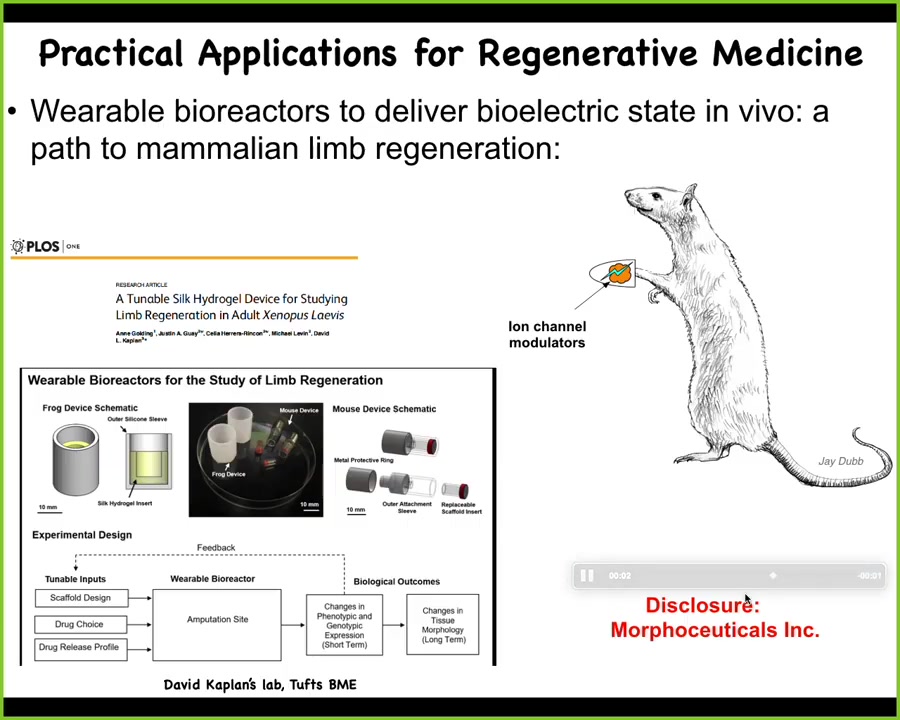

Slide 30/52 · 39m:11s

At this point, I have to do a disclosure. Dave Kaplan and I are co-founders of a company called Morphoceuticals, Inc., because we're now taking the same thing into mammals. The idea is using David's bioreactor, wearable bioreactor technology to stimulate the wound and try to get back some regeneration after injury. Remember, we are not micromanaging this process. We're not putting in stem cells. We are not directing differentiation over that time period. 24 hours of stimulation gives a year and a half of leg growth in the frog. It is not controlling that process. It is convincing those cells right at the beginning, when they're trying to make a decision between scarring and growth, which way they're going to go. After that, we take our hands off. That's a key strategy from the perspective of engineering that you want to exploit the autonomous capacities of your material. You do not want to try to have to micromanage it.

Slide 31/52 · 40m:08s

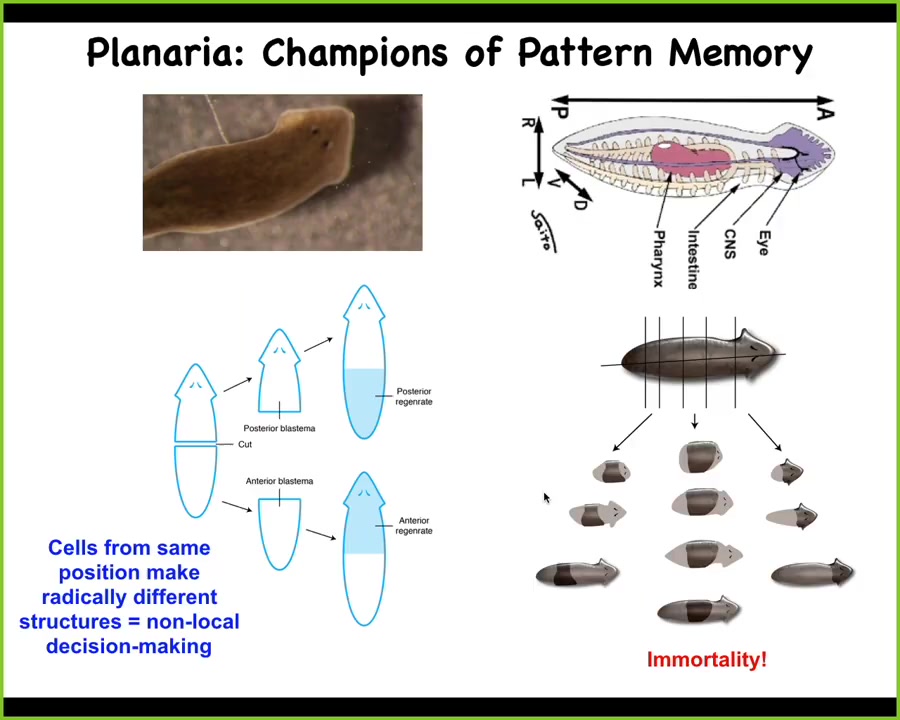

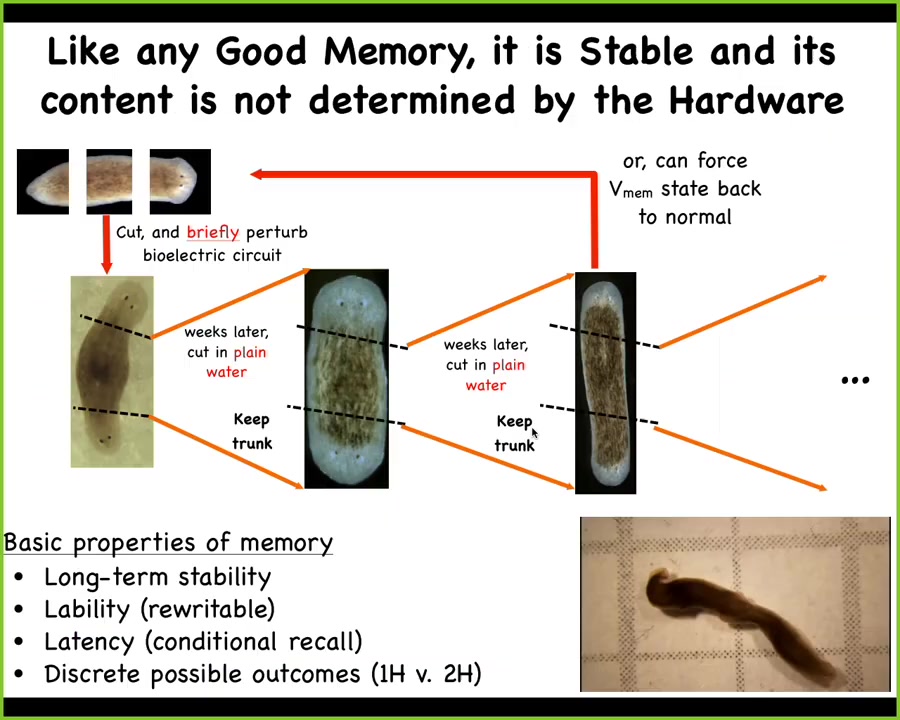

I want to shift gears to this organism and think again about this notion of memory and goal-directedness in morphogenesis.

These planaria are immortal. They do not age. They're such great regenerators that they regenerate everything continuously.

Slide 32/52 · 40m:28s

One thing you can do in these planaria is this amazing experiment. Here's one head, one tail. If I cut off the head and the tail, this middle fragment reliably, 100% of the time gives me a normal worm.

Now, what we discovered was this. How does this piece know how many heads it's supposed to have? We discovered that this is the work of Wendy Bean in my group, that there's an electric circuit that tells these cells how many heads are supposed to be built.

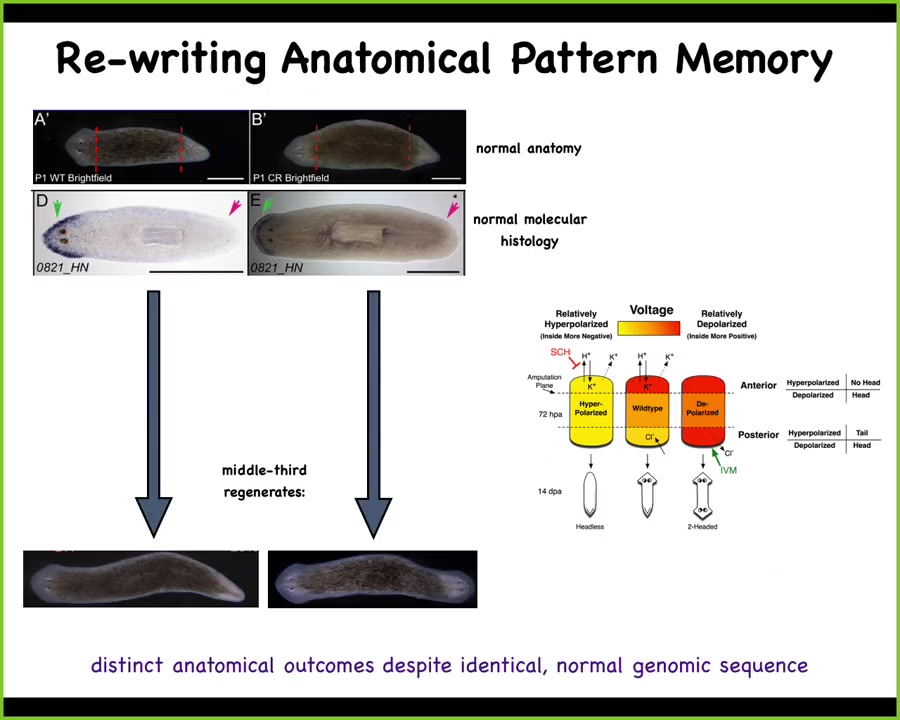

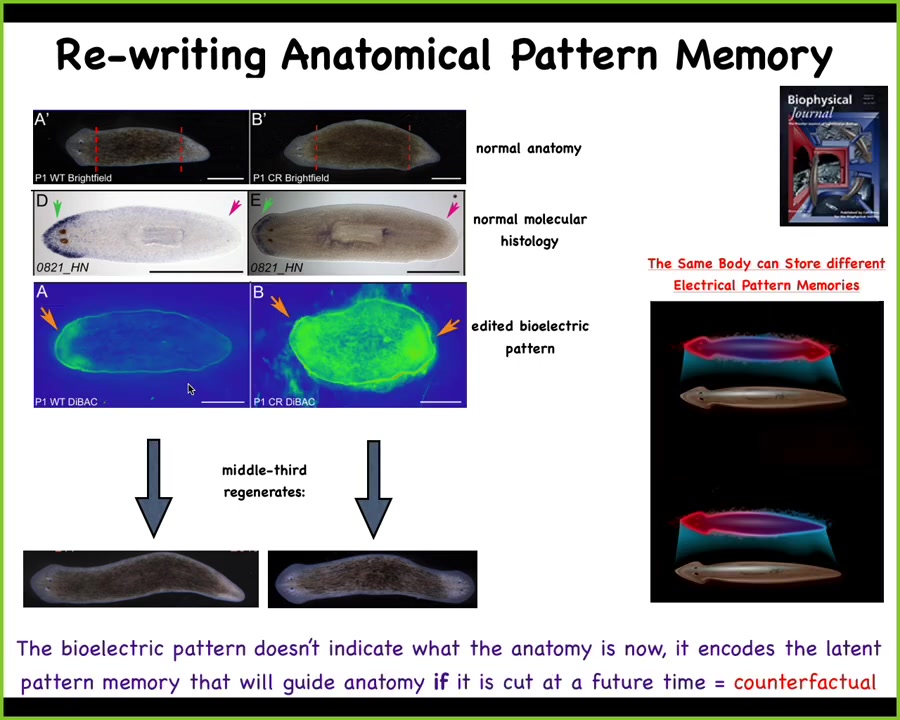

Slide 33/52 · 40m:57s

What we can do is, here's the voltage pattern that represents their memory of what a correct planarian looks like. And what we can do is we can go ahead and edit that by targeting specific ion channels to look like this. It's messy, the technology is still being worked out, but you have clearly this pattern says 2 heads instead of 1. When you do this, you get a two-headed worm. This is not Photoshop. These are real animals.

Not only is this electrical pattern instructive for how many heads you're supposed to have, this pattern is the readout of this animal. A single-headed body with normal gene expression, anterior genes in the head, no anterior genes in the back, can have two different representations of what to do if it gets injured. In other words, I claim that morphogenesis is a homeostat because it stores an explicit target morphology. It stores the information on what the correct pattern is going to be. This is one of those cases where we've decoded it, and I can show you that this is that pattern. This is the pattern that determines it, and it's there long before the situation actually comes up.

In a way, this is an interesting example of a counterfactual memory. This is not what's going on right now. This is a stored data structure about what you're going to do if you get injured in the future. That's a really primitive version of something that brains do very well, which is this kind of mental time travel where you remember what happened before, you can predict what happens next. It doesn't have to be happening right now.

Slide 34/52 · 42m:38s

Why do I keep calling this a memory? This is the work of Nestor Oviedo. What we did was we took these two-headed planaria and we simply recut them again in plain water, no more manipulation of any kind.

We found that the genomics are wild type. We didn't do any genetic editing here. There's nothing wrong with the genome. If we get rid of the ectopic primary head and the ectopic secondary head, and this middle gut fragment that has normal genetics, surely it should go on to be a normal worm. That's not what happens. What happens is if you keep cutting these guys, this middle fragment will continue to generate two-headed worms, and you can see them here.

So this fulfills the basic criteria of memory in anatomical space. It's long-term stable. It's rewritable because we can set it from here to here. We now also know how to take a two-headed worm and get it back to a one-headed state. It has latency and conditional recall.

The question of what determines how many heads this animal has is important from the engineering perspective. If you want to engineer your life, you need to know what the determinants are.

It's really interesting. It's the genetics only insofar as the genetics create the hardware where the default behavior of that circuit is to specify an electrical pattern that says one head. That's the default pattern that happens when you turn on the juice of this electrical circuit. But the cool thing about this circuit is it's actually reprogrammable. Experience in physiological space, not genetic change, will convert it to store a new piece of information, and that new piece of information is stable. It will keep until you reset it.

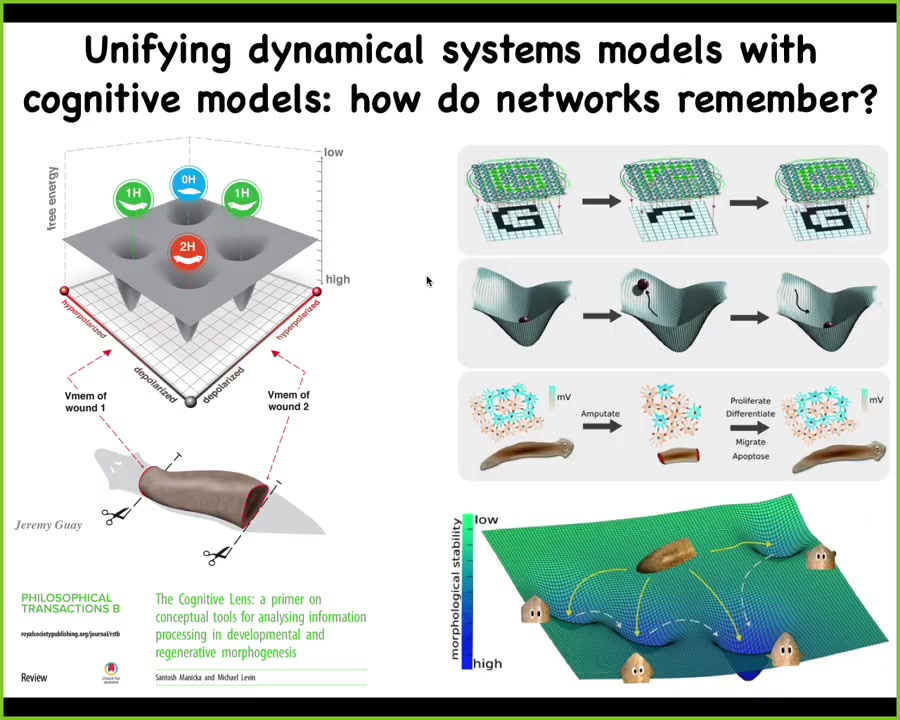

Slide 35/52 · 44m:18s

What we're doing now is trying to refine these computational models that merge the state space of the electrical circuit that maintains this information with existing thought in connectionist architectures.

People are now working on understanding how electrical networks store and encode information in a way that allows them to regain that information when pieces of the material are gone.

There's lots of work being done on this in computer science and machine learning.

Now it gets even more interesting because that's what this is all about, the number of heads.

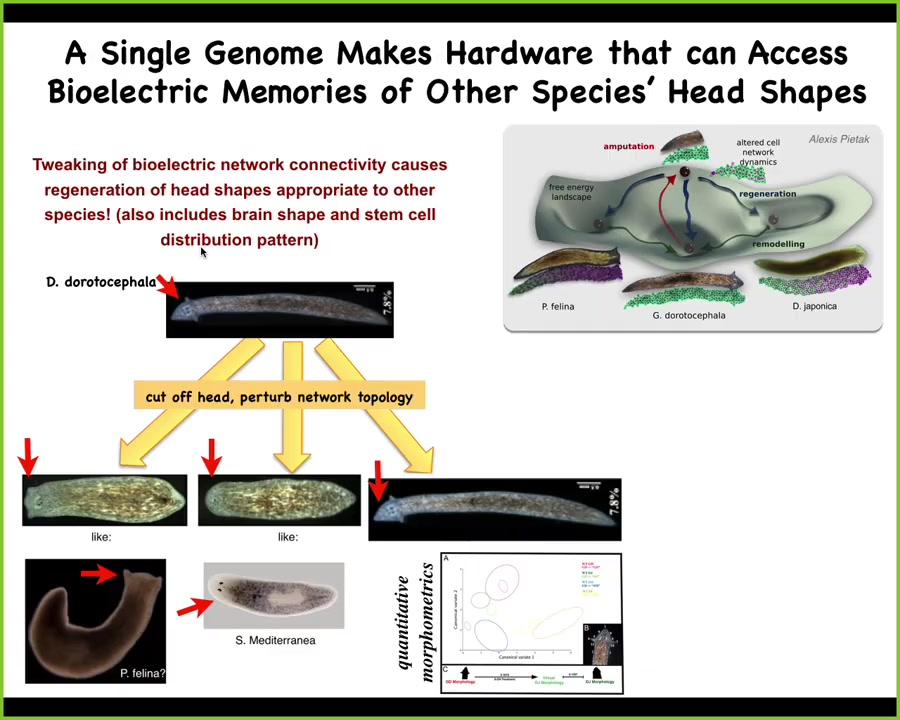

Slide 36/52 · 44m:58s

It's more interesting than that. It's also about head shape. You can take this triangular-shaped planarian, amputate the head, and perturb the electrical connectivity of the rest of the cells as they are trying to figure out where the electric circuit should settle. Here's the normal attractor. It gets confused, and sometimes you get these flat-headed piphalinas, and sometimes you get round-headed S. mediterranea. It's not just the shape of the head, but it's also the distribution of the stem cells and the shape of the brain that's the same as these other species.

These other species are about 150 to 100 million years distant from this. So without genetic change, what you can do physiologically is to explore the different attractors that are the standard outcome for other species, but you can explore them with exactly the same hardware.

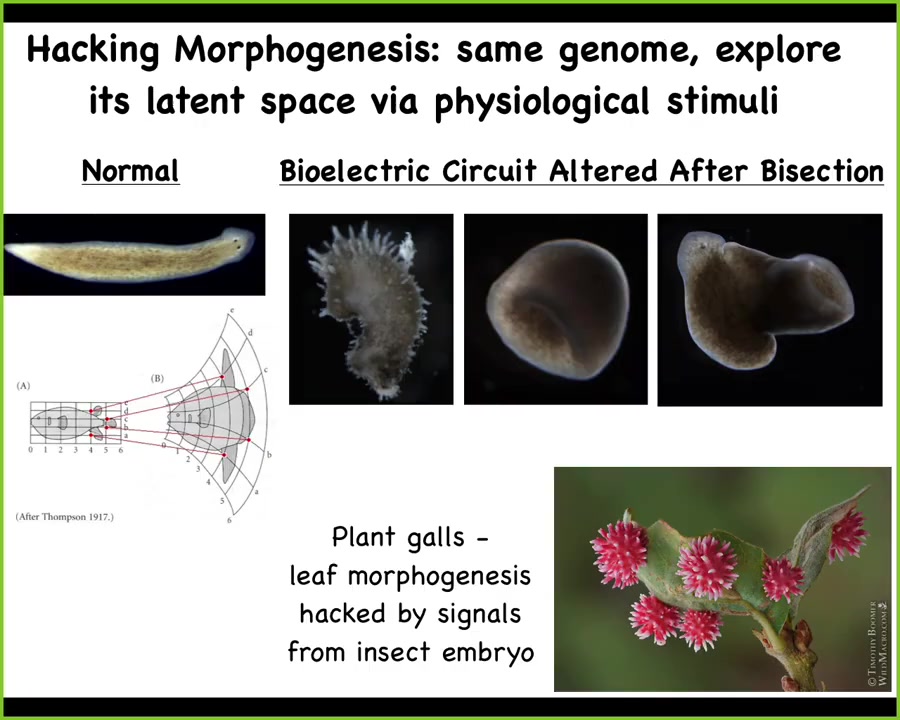

Slide 37/52 · 45m:48s

Not only can you explore those attractors, there's a huge latent space of possible shapes that you can make. These are all wild-type planarian cells. This is a crazy spiky haired, spiky shape form. You can change the symmetry type, you can make composite forms like this. This is not some weird feature of planaria. This is ubiquitous.

Look at this example from the plant kingdom. These are galls. This bizarre looking thing is formed out of the plant's own cells because it's being hacked by signals from a wasp embryo that's in there. These are not created from wasp cells. The wasp is putting out signals that hijack the normal morphogenetic machinery of these cells that normally make a nice, flat, green architecture. Instead, they make this round, red, spiky thing. That's because morphogenesis from the beginning is reprogrammable. It is amenable to being hacked because the cells are normally doing that to each other to get them to undergo complex morphogenesis.

Slide 38/52 · 46m:53s

I'll show you some examples of that in a minute. A couple of quick medical things, then we'll get to the Xenobots.

I just want to say that the key to all of this is getting a nice multi-scale view, a full stack model of what's going on from the molecular networks that express ion channels. Here's where your hardware is determined. Then to understand the physiology that gives you the bioelectric gradients. We have a simulator that allows us to do all this, written by Alexis PITAC. To understand the logic and eventually get it down into an algorithmic model of how regions make decisions about what they're going to be.

To scale up the decision-making progressively from the hardware all the way to anatomical-level decision-making where the discovery of regenerative interventions is the easiest.

Slide 39/52 · 47m:43s

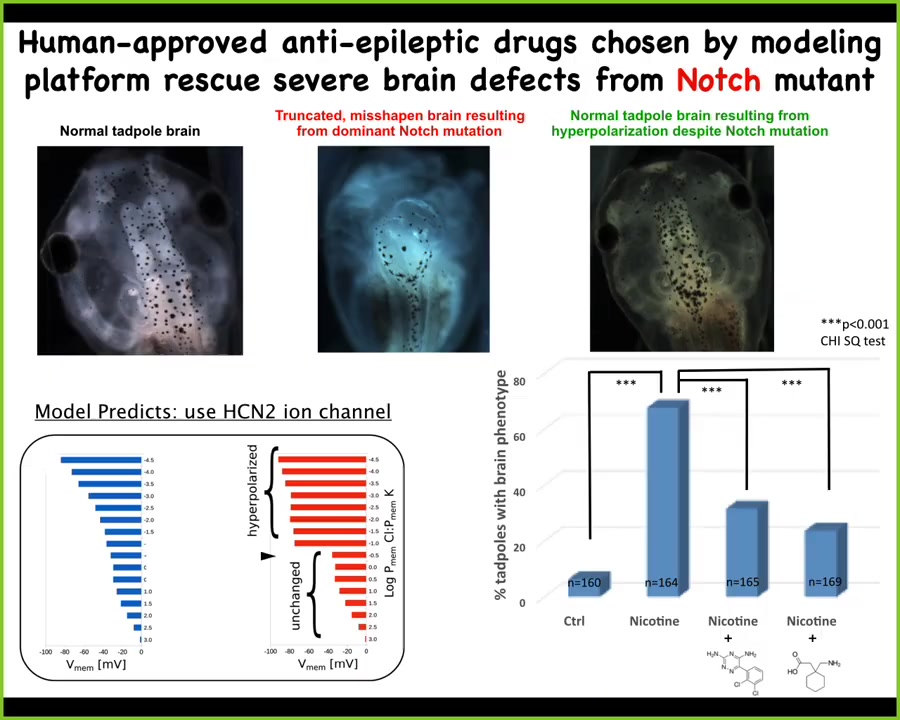

This is a quick example of how we did that, to show you that it's positive, that this whole thing is possible. Here's a normal frog brain. Here's a forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain. When these guys are exposed to various teratogens, nicotine, alcohol, or even mutations, the brain has all kinds of defects. What we wanted to do was to build a model that would help us find repair interventions. As engineers, we want to know what's the easiest thing we can do to get this thing back to normal. We make this computational model that explains how the bioelectrics of the early ectodermal cells dictate the shape and size of your brain. Then we do this.

Slide 40/52 · 48m:25s

We ask the model in a scenario where that bioelectric shape is wrong. This is the hardest case. This is a mutation in a gene called Notch. Notch is a really critical neurogenesis gene. With a dominant Notch mutation, the forebrain is gone. The midbrain and hindbrain are a big bubble. These animals have no behaviors. It's a radical defect.

We asked the model something very simple. Which channel could we open and close to get the bioelectric state back to normal? The model knows nothing about the pathways that are downstream of the bioelectrics or about gene expression. All we asked was how do we get back to the correct high-level pattern that tells these cells what a normal brain looks like?

The model said that under those conditions, this is a good channel to open. This is the HCN2 ion channel. Then we did something very simple. We either introduced extra HCN2 channels, or we used two known drugs to open the existing HCN2 channels. Lo and behold, they get their brains back. They get brain structure back, they get gene expression, and they get their behaviors back. Their IQs become indistinguishable from controls, even though they're still bearing this really nasty Notch mutation.

This is an example, and I'm not saying this will work in every case, but this is an example of fixing a really drastic hardware defect in software. Despite the fact that you've got some broken signaling machinery, if you override it with a top-level signal that says this is what your brain should look like, you can rescue a very drastic fundamental kind of defect.

Slide 41/52 · 50m:00s

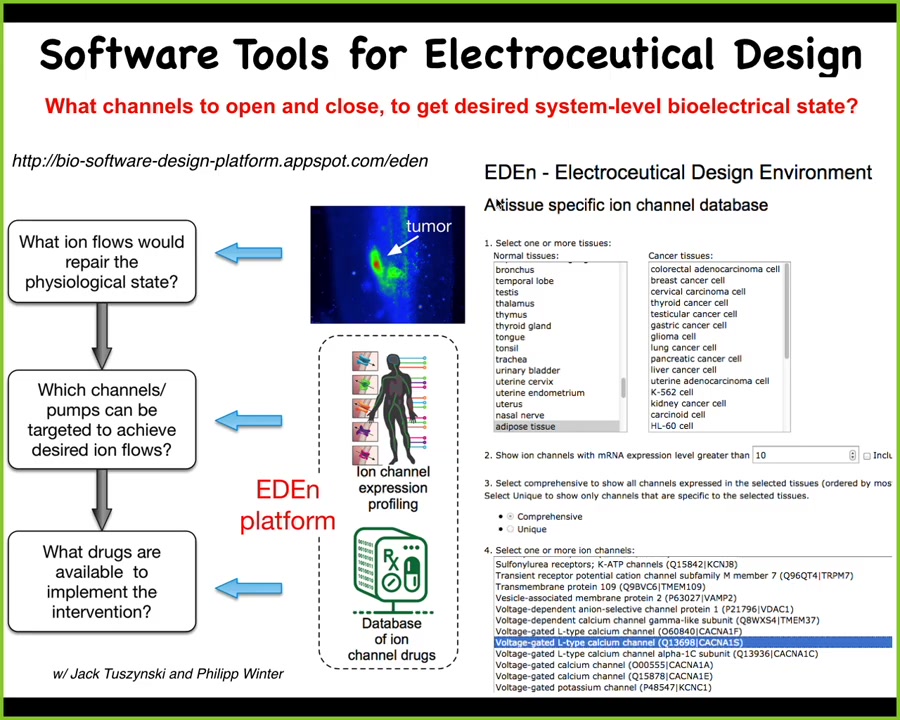

And so what we're working towards is this kind of computational environment for designing electroceuticals. You should know what your desired electrical state is, what your disease state is. You use the simulator to say, how do I turn the disease state into the healthy state? And then you go to the drug bank and you pick out an existing ion channel drug, many of them already approved for human use, and then you do some filtering to make sure you don't hit the cardiac rhythm circuit.

Slide 42/52 · 50m:33s

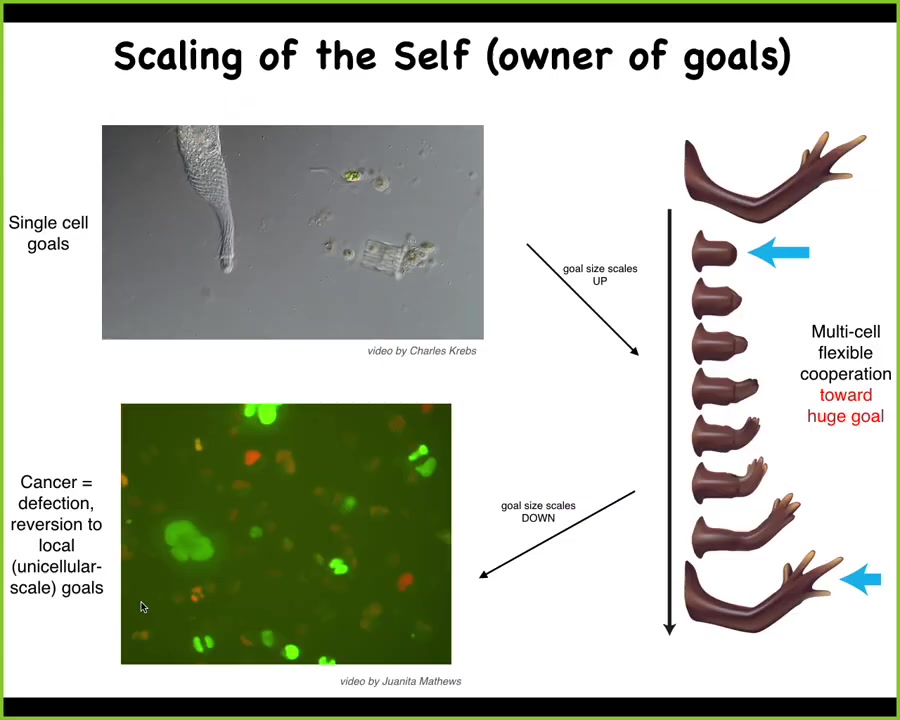

What we see in evolution is this amazing process of scaling up of goals. Individual cells have very local homeostatic set points that they can pursue, such as metabolics and various other things. What evolution did is allow them to form electrical networks that communicate, that merge these little homeostats into something that can pursue a much larger goal. They can pursue navigation policies and anatomical morphospace, something that the individual cells cannot do.

But this has a failure mode. This is human glioblastoma. When this process breaks down, the cells revert back to their unicellular goals, which is, every cell wants to become two cells and eat as much as it can and go wherever life is good. That's metastasis.

If you have this unusual view of cancer as a problem of a shrinking computational boundary between self and world, the idea is that when cells connect to each other, they have a bigger perceptual, cognitive light cone that allows them to hold on to bigger goals, bigger homeostatic set points.

Slide 43/52 · 51m:44s

You can think about engineering a therapeutic like this. We put in the human oncogene. Normally it makes a tumor. But what we'll do is co-inject a specific ion channel to keep these cells connected to their neighbors. This works for nasty KRAS mutants, P53, and so on. You can see the oncogene is labeled in red. It's still strongly expressed, but there's no tumor. This is the same animal. There's no tumor. Because what drives it is not the genetics. What drives it is the physiology, in particular the scale at which these cells make decisions.

In this case, they're making individual cell decisions of what's good for them. They're not more selfish than other cells. Their cells are much smaller. The rest of the embryo is external environment to them. In this case, they're making collective decisions, and the collective is looking to make a nice muscle, nice skin. It's navigating this different space that the individual cells can't.

When we start to think of it this way, we can ask where the goals of these collectives come from. Furthermore, what kind of goals are they capable of pursuing, and where do the specific set points come from?

Slide 44/52 · 52m:55s

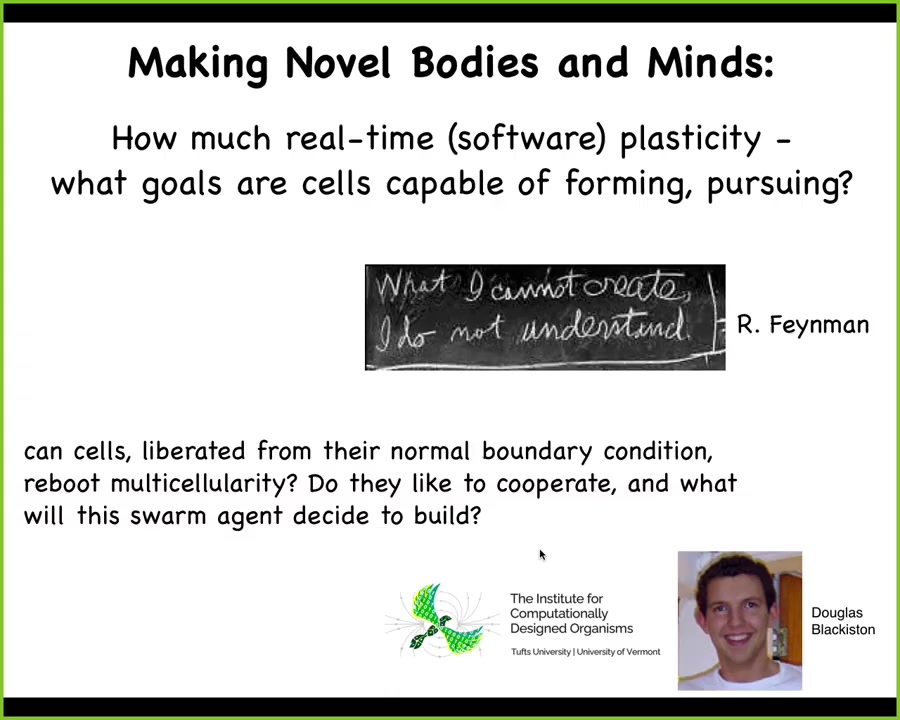

This is the work of Doug Blakiston, who did all the biology; Sam Kriegman did the computer science, and this is a project with Josh Bongard at the University of Vermont, with whom we've started this institute. We asked the simple question. If we were to liberate cells from the normal boundary condition, could they reboot their multicellularity? Do they like to cooperate fundamentally? What would they build if they were out of their normal environment?

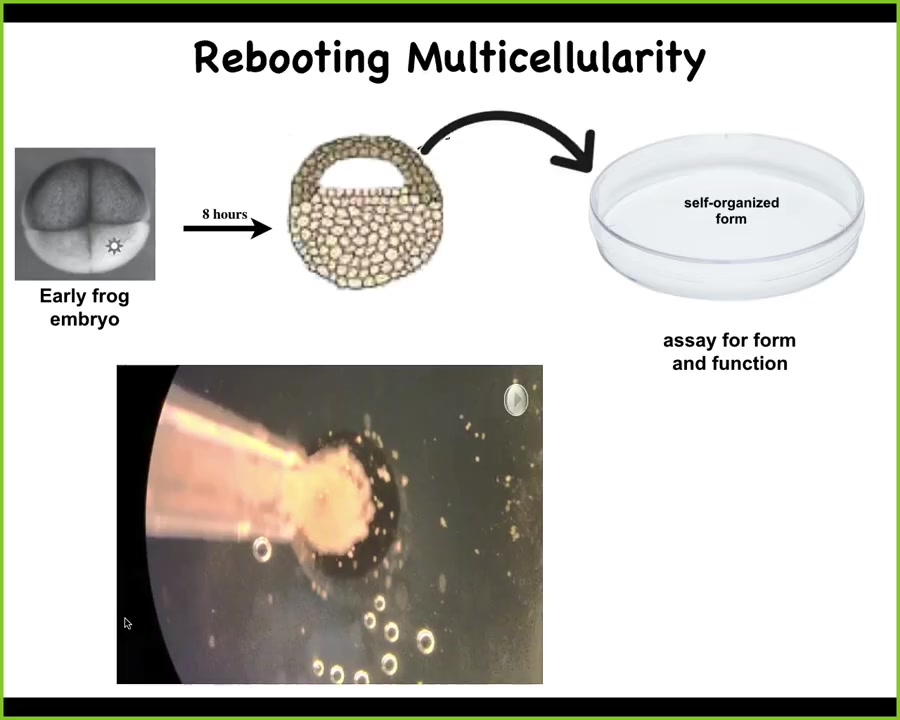

Slide 45/52 · 53m:22s

So what we did here is this. This is an early frog embryo. We take some cells up here that are going to be epidermis, so skin. We dissociate these cells. We put them in a little pile and get rid of everything else, so just skin. Now, what could they do? They could do a number of things. They could crawl away from each other, they could die, they could do nothing, they could form a two-dimensional monolayer.

Instead, here's what they do. They coalesce together into this little fragment, and they become this compact little round thing. The flashes you see are calcium signaling.

Slide 46/52 · 54m:07s

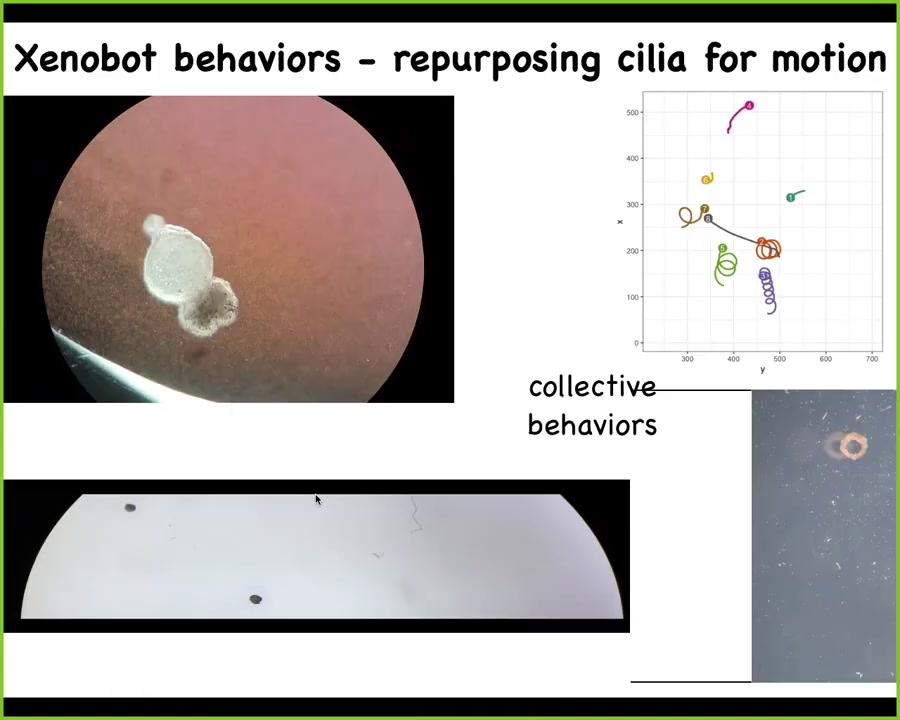

And what it does is this: it becomes a xenobot. Xenopus laevis is the name of the frog, biobots, so we call them xenobots. They're using the little hairs that they normally have for pulling mucus down their bodies. They use them to swim. The ones on this side row to the left, the ones on this side row to the right, and this little patch of skin starts moving around. They can go in circles, they can go back and forth. We can track collective motion like this, where they interact with each other when they take various long journeys; we can make them into various shapes. Doug does all this. Under the directions of this AI program that Josh and Sam have written, he can make various shapes.

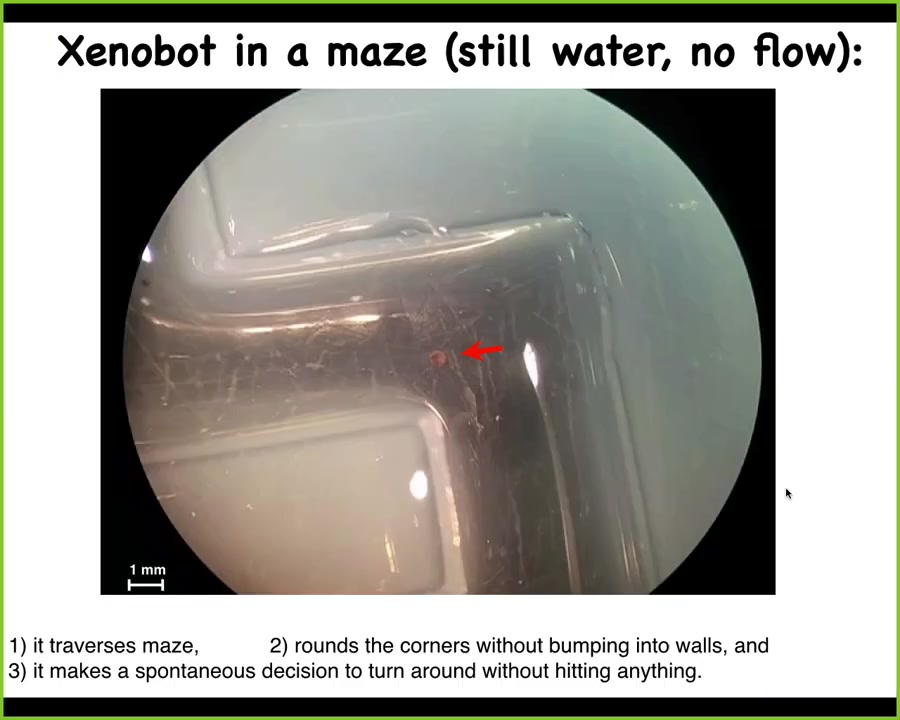

Slide 47/52 · 54m:50s

Here's a Xenobot doing a maze. Still water, no water movement; it takes the corner without having to bump into anything. At this point, it spontaneously turns around and goes back where it came from. All of this is skin. There are no neurons here. There's no brain, just skin. You're starting to see the novel behaviors and capabilities, both morphogenetic and behavioral, that are in this tissue.

It regenerates. If you cut it in half, about here, look at this 180-degree hinge — boom, it folds up like this.

They have some interesting calcium signaling that we are in the process of analyzing to see if there's evidence of mutual information and how many of the tools from neuroscience will fit here. I'll end with this.

Slide 48/52 · 55m:40s

is the most amazing part of all. We have made it impossible for these animals to, for these creatures to reproduce the normal ****** fashion because they're just skin. So turns out that if you provide them with loose skin cells, what they do is they run around and they collect these skin cells and they shape them into little balls. And because they are working with an agential material, just like us, we were working with these skin cells and so are they.

Slide 49/52 · 56m:14s

Because of that, these little balls become xenobots. Overnight, they mature to become the next generation of xenobots. They run around and repeat the cycle and do exactly the same thing. This is kinematic self-replication. This is von Neumann's dream of a robot that goes around, finds parts in its environment, and makes a copy of itself. This is extremely primitive. There are many things missing. There's no hard heredity, meaning that the offspring don't particularly look like their parents. They all look like the same thing. But it is kinematic replication.

Slide 50/52 · 56m:45s

Here's the most amazing piece of this: what did the Xenopus laevis genome actually learn during evolution? You might think that it learned to make this. It learned through eons of shaping, through selection. It makes this developmental sequence, then it makes tadpoles.

But actually, under this scenario, the skin cells have an invariant outcome. They have this boring two-dimensional life as the outer layer of the embryo. But that's not the only thing they know how to do. If you take away all of the other cells — we don't engineer by adding different transgenes or circuits; all we do is take away the other instructive influences that bully these cells into being this boring two-dimensional layer — you then find out that in the absence of that behavior shaping, this is what those cells actually know how to do, and this is what they do by default. This is what they want to do, which is to form a xenobot with its own bizarre developmental sequence. This is several weeks of development. What this is, nobody knows.

This never existed before. There's never been evolutionary pressure to be a good xenobot, to do kinematic replication. All of this is completely emergent in the latent space of behaviors from the machine that this genome encodes. I would argue that in some cases, evolution is not creating specific solutions to specific problems. It makes general-purpose problem-solving machines that are able to navigate different kinds of spaces in new ways. And as engineers, this is what we need to learn to manipulate.

Slide 51/52 · 58m:23s

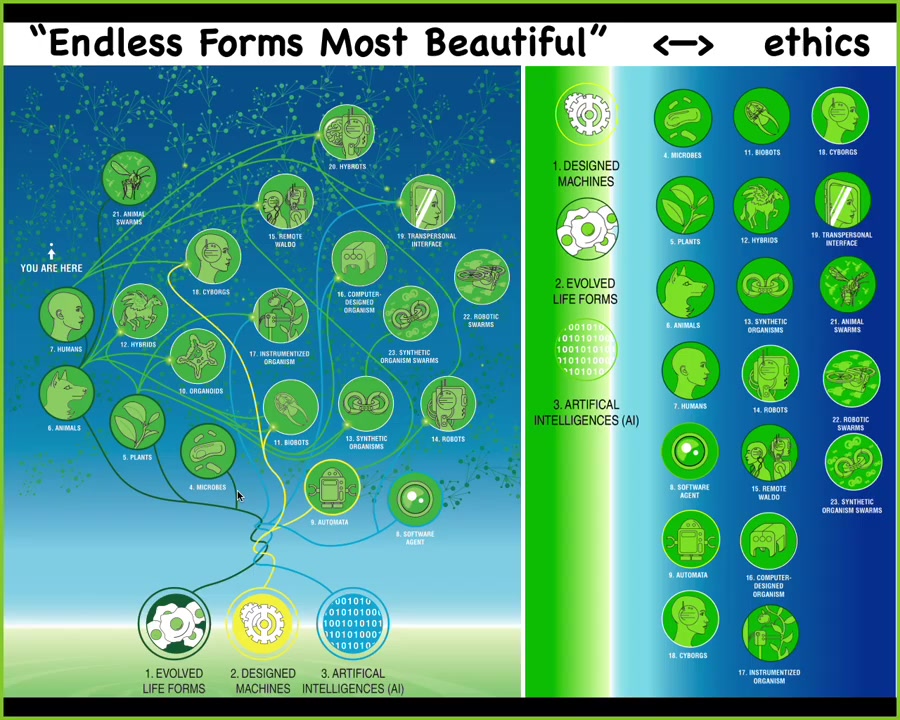

I think because of this, biology is incredibly interoperable. So every combination of evolved material, meaning genetic sequences, cells, tissues, organs, whatever, and some kind of designed matter and some kind of software, every combination is going to be some kind of viable creature on this enormous option space. So all of Darwin's "endless forms most beautiful"—the natural forms on earth are here. And all of these hybrids, cyborgs, every kind of combination of these things is here somewhere and that has huge implications for trying to develop not only a science but an ethics of relating to organisms that do not share any path on the evolutionary tree with us and have potentially radically different embodiments and thus minds.

I'll stop here. If anybody's interested in this stuff, here are a variety of papers that you can take a look at.

Slide 52/52 · 59m:23s

I want to thank the postdocs and the students who did all the work that I showed you today, our funders here, all the illustrations by Jerry McGay, and the two company disclosures. Most of the credit goes to the model systems because they do all the heavy lifting. I'll stop here and thank you for listening.