Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a ~18 min talk plus ~10 min Q&A on a top-down approach to bioengineering and robotics that I gave at the Biohybrid Robotics Symposium in Switzerland in July 2025 (https://biohybrid-robotics.com/).

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Agential materials and bioelectricity

(19:02) Cognitive neuroscience for bioengineering

(21:48) Xenobot responses to sound

(24:15) Training intelligent cell collectives

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/22 · 00m:00s

Very excited to be here and share some ideas with you. I'm going to say some large-scale conceptual things in addition to some data that I'm going to show you. It's hard to do that in 15 minutes.

So if anybody wants to download the primary data, the software is here. This is just a personal blog where I try to write about what I think some of these things mean. A lot of what I'll say at the end is work done in collaboration with Josh Bongard's lab as part of this ICDO organization that we have.

What I'm going to describe today is this notion of agential materials and a way of interacting with your materials that are more around the concepts of collaboration and a kind of social engineering with your material because we view these things as a collective intelligence that we want to motivate, not just rewire or micromanage.

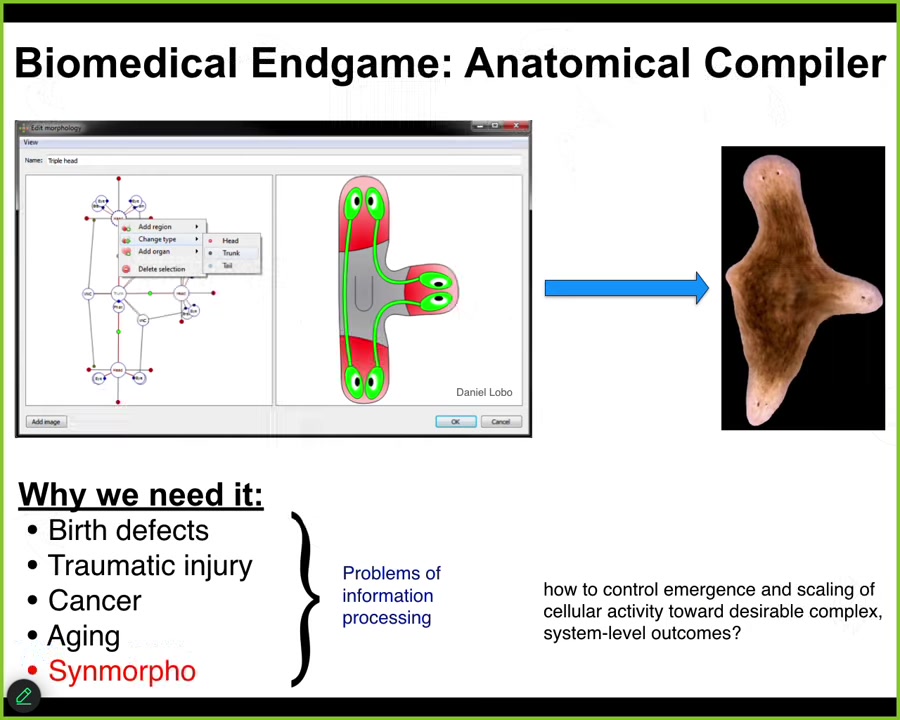

Slide 2/22 · 00m:55s

One of the great challenges in our field, which is both synthetic morphology and biomedicine, is that someday you want to sit in front of a computer and you want to draw the plant, animal, biobot, organ, whatever you want with no limitations. What this thing should do is compile that description down to a set of stimuli that would be given to cells to get them to build whatever you want, such as this three-headed flatworm.

If we had something like this, a lot of problems in biomedicine would go away and a lot of problems in bioengineering would be solved. We can only do this, if at all, in a very small set of circumstances.

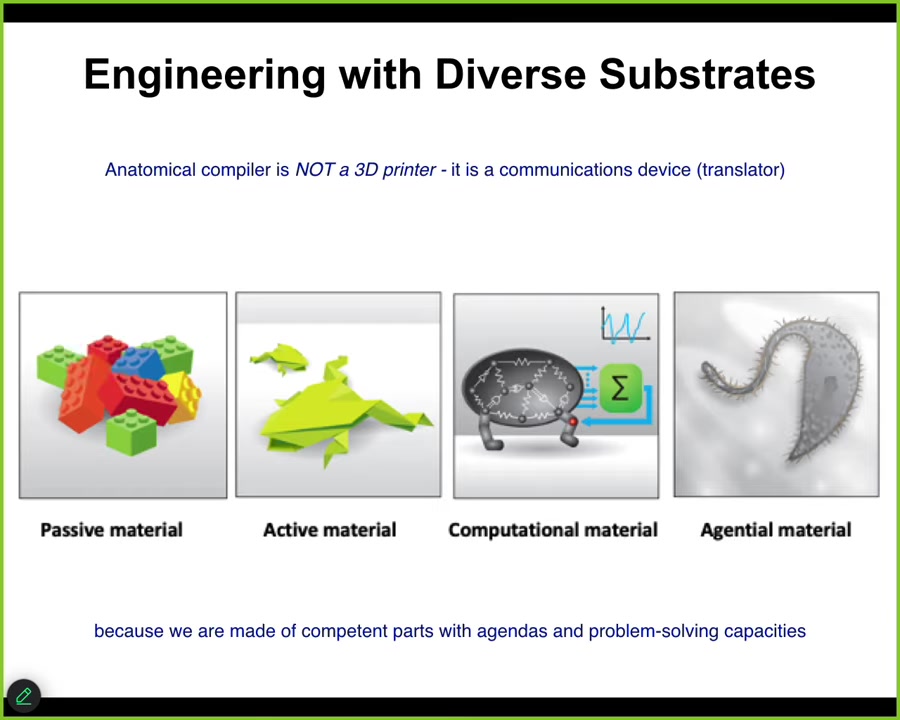

Slide 3/22 · 01m:41s

That's largely because we've been thinking so far about either passive matter, now increasingly active matter and computational materials. In biology, what we're dealing with is what I call an agential material. It's a material that at multiple scales has agendas and problem-solving capacities, which we have largely not yet taken advantage of.

For me, the anatomical compiler is not a 3D printer. It is a communications device. It is a translator between your goals as the engineer and the goals of the material, because in a cybernetic sense, the material has goals. In fact, many of them.

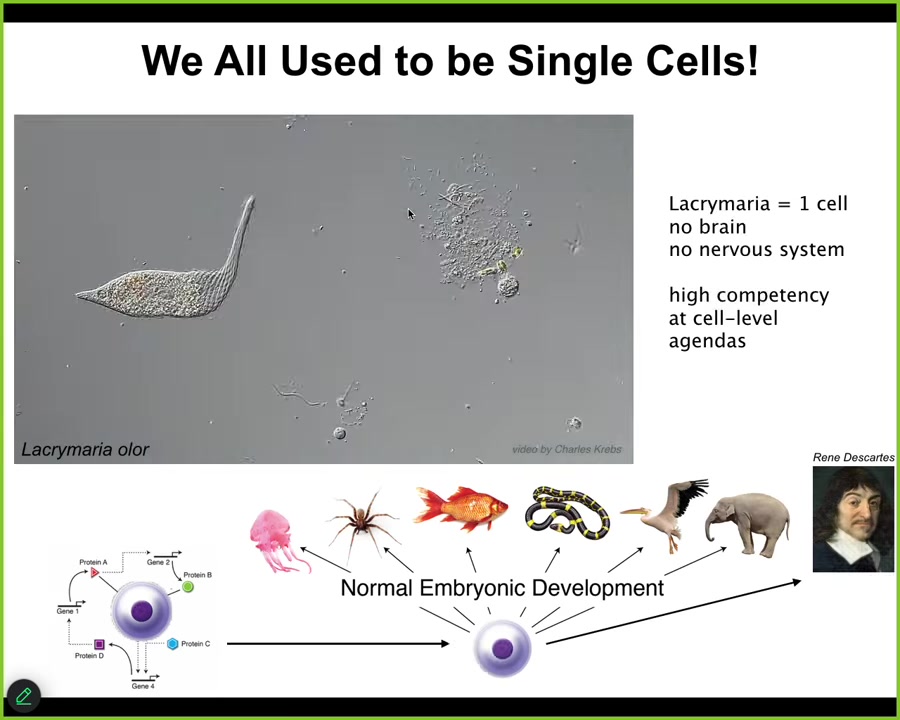

Slide 4/22 · 02m:15s

This is the sort of thing we're dealing with. This is a pre-living organism called a lacrimaria, but you get the idea. It's a single cell. There's no brain. There's no nervous system. It's handling all of its needs in anatomical space, metabolic space, and physiological space. From that one cell, all of these kinds of amazing creatures normally develop, including these, which have very significant problem-solving cognitive capacities. What we know from developmental biology is that this is a slow and gradual process. There is no specific magic line at which intelligence kicks in. This is a process of scaling competencies, not a process of magical categories. We need to understand the scaling in order to have good interactions with the material.

Slide 5/22 · 03m:02s

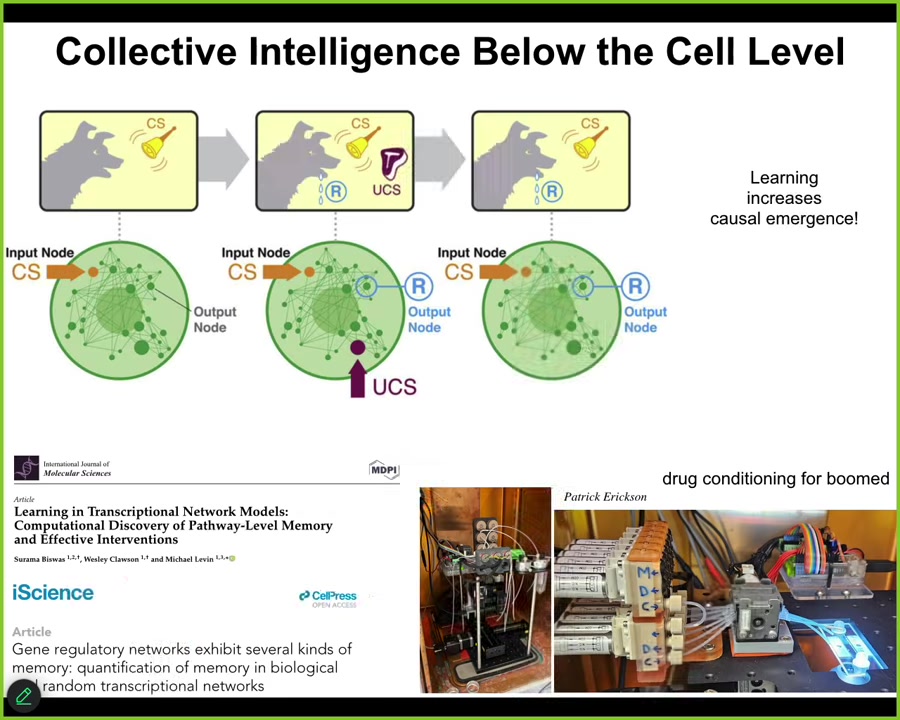

It turns out that even below the single cell level, the molecular networks themselves, gene regulatory networks or molecular pathways, already have six different kinds of learning they can do. This does not require a cell or synapses; the molecular pathways themselves are sufficient, and this is a free gift from the mathematics of networks; they can already do habituation, association, Pavlovian conditioning, and we're now taking advantage of all of that for experiments in drug conditioning for biomedical purposes. The material has these capacities from the very bottom.

Slide 6/22 · 03m:43s

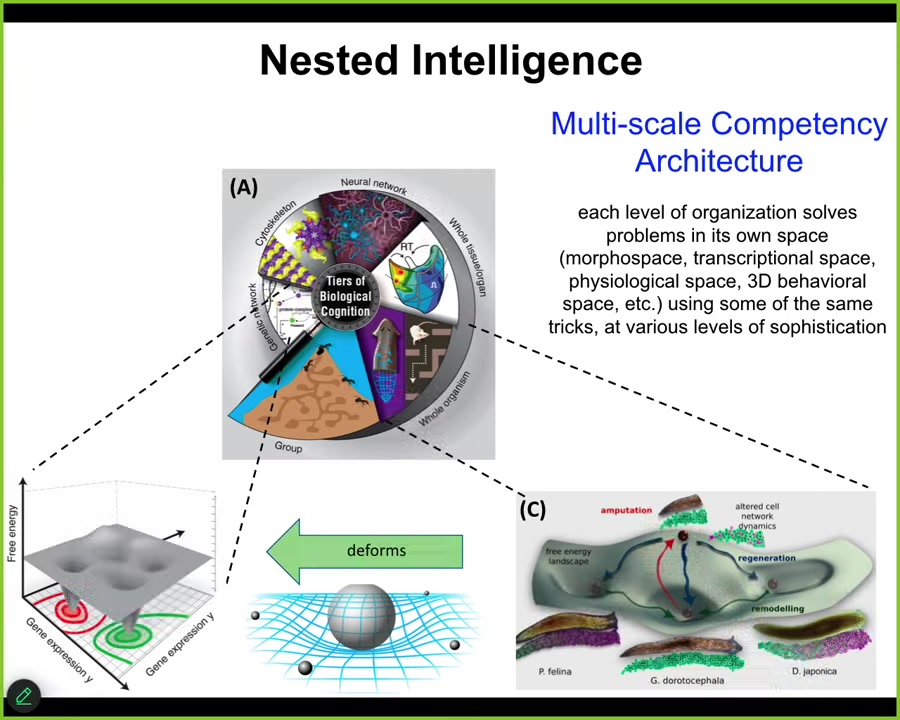

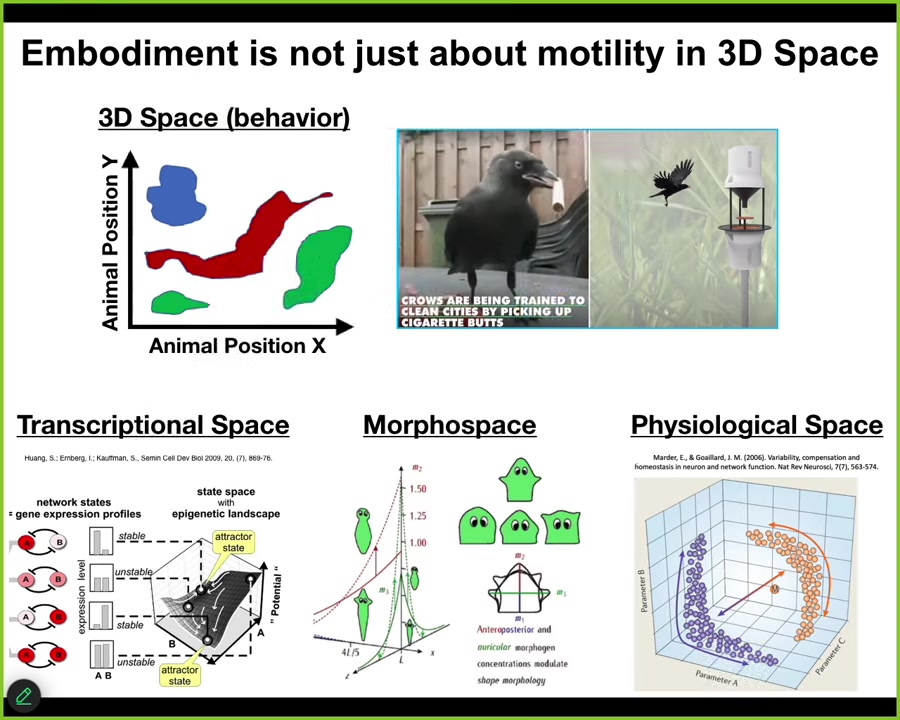

What I think is happening here is a multi-scale competency architecture where each level is basically deforming the option space for the levels below. Each level is navigating that space, context-sensitive navigation of the option space, and these are transcriptional spaces, physiological state spaces, anatomical morphospace.

At some point when nerve and muscle kicked in, three-dimensional space of behavior. This relationship is present all the way down. What each level is doing is deforming the option space for its parts to ensure that their conventional behavior is also serving the needs of a higher level in a different space that the parts don't know anything about. This enables some very interesting properties in the biological material.

Slide 7/22 · 04m:34s

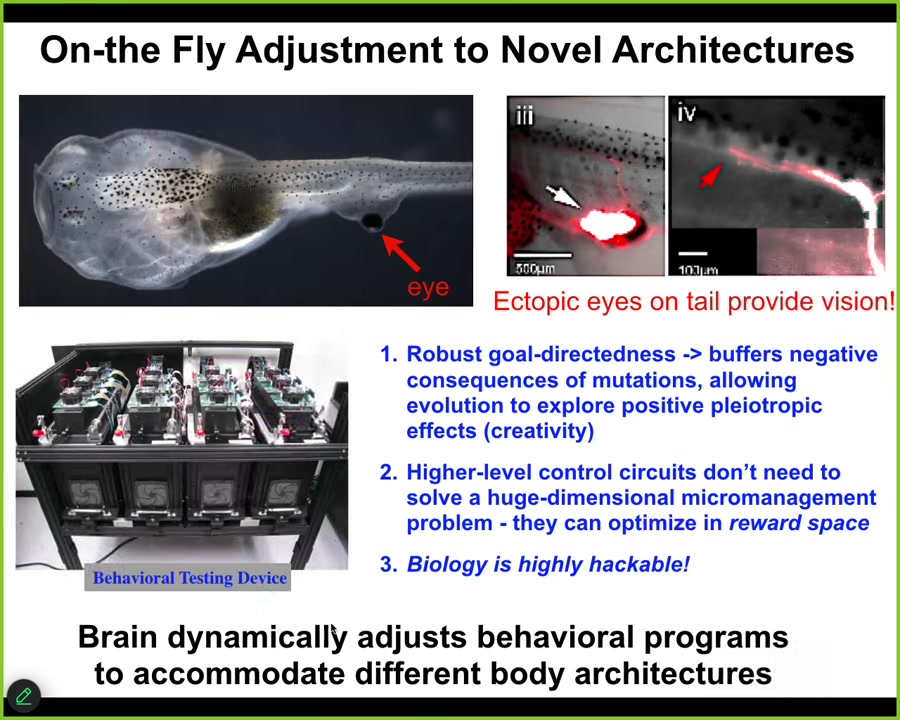

First, as an example, there are many cool versions of this. Here's a tadpole of the frog. You'll see nostrils, mouth, brain here, gut. We've prevented the primary eyes from forming, but we've put an eye on its tail. By building a machine that automates the training and testing of these guys in visual cues, we notice they can see perfectly well. Here's the ectopic eye. It makes one optic nerve. Sometimes it goes to the spinal cord, sometimes to the gut, never to the brain. Yet they can see and learn in visual tasks. That's amazing. Why does this animal with a novel sensory-motor architecture not require new rounds of mutation, selection, adaptation? It works out-of-the-box. The plasticity for these kinds of things is absolutely enormous. We can really take advantage of this in bioengineering. It's not just animals.

Slide 8/22 · 05m:27s

Plants do this too. Development is an incredibly reliable process. You might think that what the oak genome encodes is the ability to build this flat green thing. It does it all the time, very consistently.

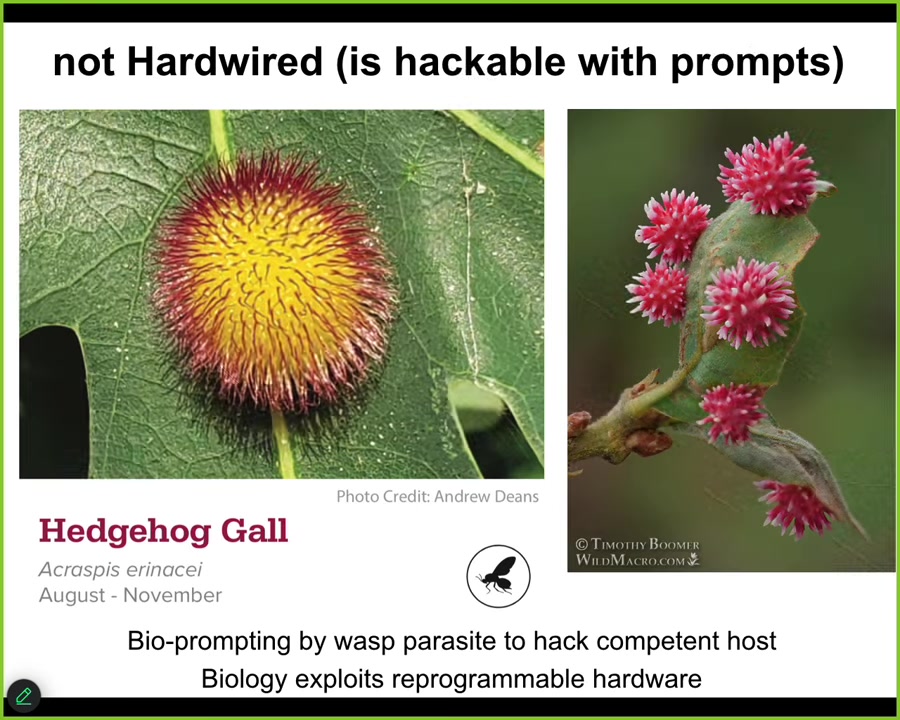

Slide 9/22 · 05m:40s

Except that along comes a non-human bioengineer, this wasp. And it puts down some prompts that cause these cells to build something completely different.

So here's this round spiky red and orange thing. Here's another one. They're called galls. There's an amazing variety of them. And they're not made from insect cells, they're made from plant cells. And they're not built the way that wasps build their nests, which is basically a 3D printing approach where it goes around and builds it piece by piece. It lays down some signals, and it basically hacks the morphogenetic competency of these plants, which we would have had no idea they're even capable of if we hadn't had this example. And that opens the question: what does the latent space look like? What else are they capable of building?

Slide 10/22 · 06m:23s

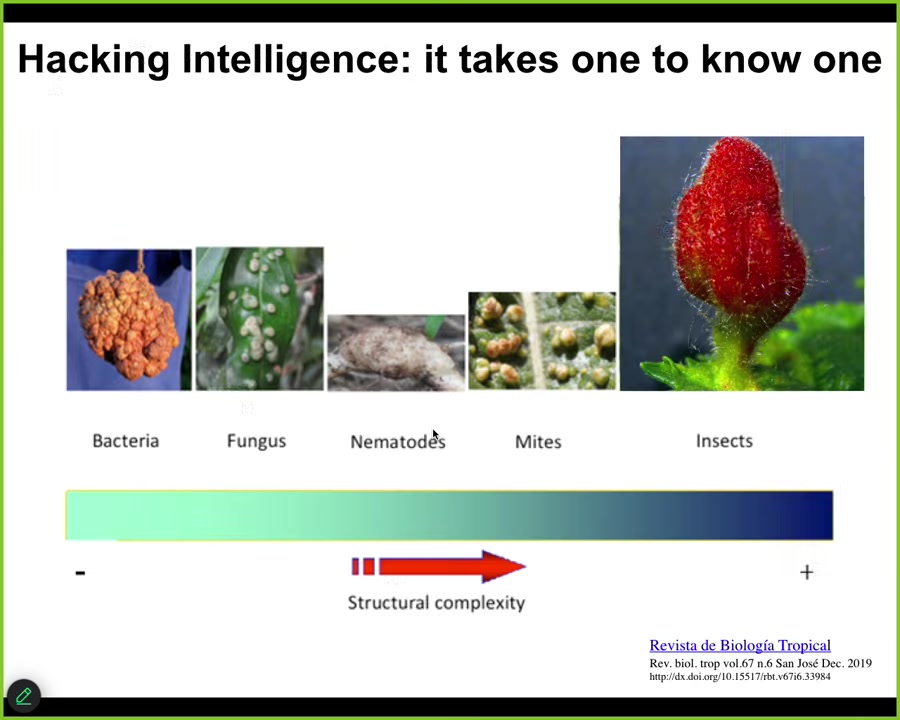

In order to find out what they're capable of building, we are going to have to ratchet up our own intelligence. You can see there's a cool relationship between the sophistication of the hacker and the complexity of what it actually builds. Bacteria induce galls that are featureless lumps, fungi do the same. Nematodes and mites make something that has a shape, but by the time you get to insects, you get this beautiful structure. There's a bi-directional relationship between how smart we are as hackers and what we can get the material to do.

Slide 11/22 · 06m:55s

As I pointed out, we as humans, because of our own evolutionary history, are obsessed with three-dimensional space. We are okay at recognizing intelligence of medium-sized objects moving at medium speeds through the three-dimensional space that we're used to. But biology has been navigating all these other spaces, and doing the sensing, decision-making, actuation loop in all kinds of other spaces, high-dimensional weird spaces that are hard for us to visualize, transcriptional space, anatomical morph space, which is what we study, physiological state space.

So embodiment is really not just about motility in three-dimensional space. When we build these things that navigate spaces in ways that we would like them to do, we have to think beyond just motion in three-dimensional space. All of these other spaces, and many that we can't even visualize, are fair game for this.

Slide 12/22 · 07m:49s

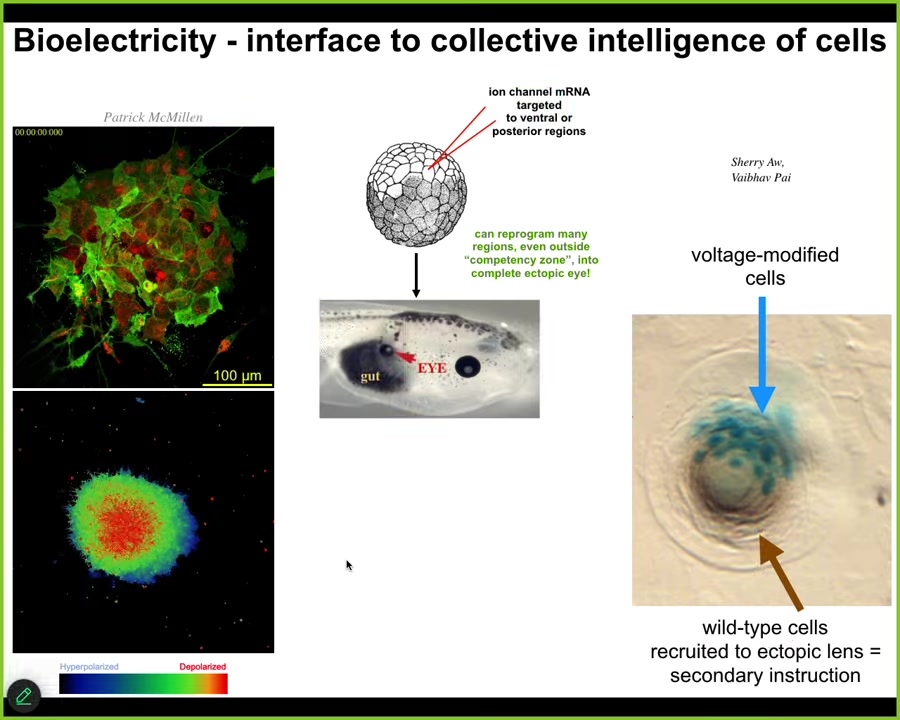

In our group, we've been studying one particular kind of cognitive glue that binds individual cells with their agendas in transcriptional space and physiological space into large-scale multicellular constructs that navigate anatomical space. One kind of cognitive glue, much like in the brain that does exactly the same thing for your neurons, making you more than just the pile of neurons, is bioelectricity.

We have ways to read and write electrical states into non-neural tissue. We've developed these techniques over the last 20 years to take all of the tools of cognitive neuroscience and bring them into understanding the decision-making, the memories, the problem-solving capacities of non-neural cells in navigating the space of possible shapes. Because we understand what the cognitive glue is, we can start to use that as an interface to communicate new goals to the tissue.

For example, we can do this with drugs, with optogenetics, by injecting specific mRNAs guided by a computational model, we can introduce specific bioelectric patterns into the early embryo and convey a very high-level message. So here we've probably put in a message that says, "build an eye." This makes a complete eye with lens, retina, optic nerve.

We don't know how to micromanage the building of an eye. It's a very complex organ, lots of genes expressed, lots of cell types in a very stereotypical order. Luckily, we don't need to. With any good cognitive system, there are simple stimuli that result in very complex behaviors that the system knows how to do that you don't have to worry about.

The material has some properties. For example, this is a cross-section taken through a lens sitting in the tail somewhere. What you'll notice is the blue cells are the ones we injected. All this other stuff that participates, we never touched it. This is secondary instruction. We told these cells you should build an eye, and they intrinsically know that there's not enough of them to do it, and so they recruit their neighbors.

So they propagate their abnormal bioelectrical state to their neighbors, and then the whole thing makes a decision to build a coherent lens. We don't have to hit every cell. We didn't have to teach it to do that. It already does that.

These are the kind of competencies of this material. Top-down control. A modular communication where we can talk about an organ, not genes, not cells of individual type. We can talk about whole organs. Cracking this bioelectric code is one of the main efforts in our lab to maximize our ability to communicate with this material.

Slide 13/22 · 10m:48s

The last few things I want to show you have to do with synthetic kinds of living constructs that don't have the benefit of eons of evolution where we can say, it makes an eye because it evolved a high-level subroutine call that causes eyes to form because that's what the evolutionary history gave. What happens with beings that have no specific history of selection for this form factor?

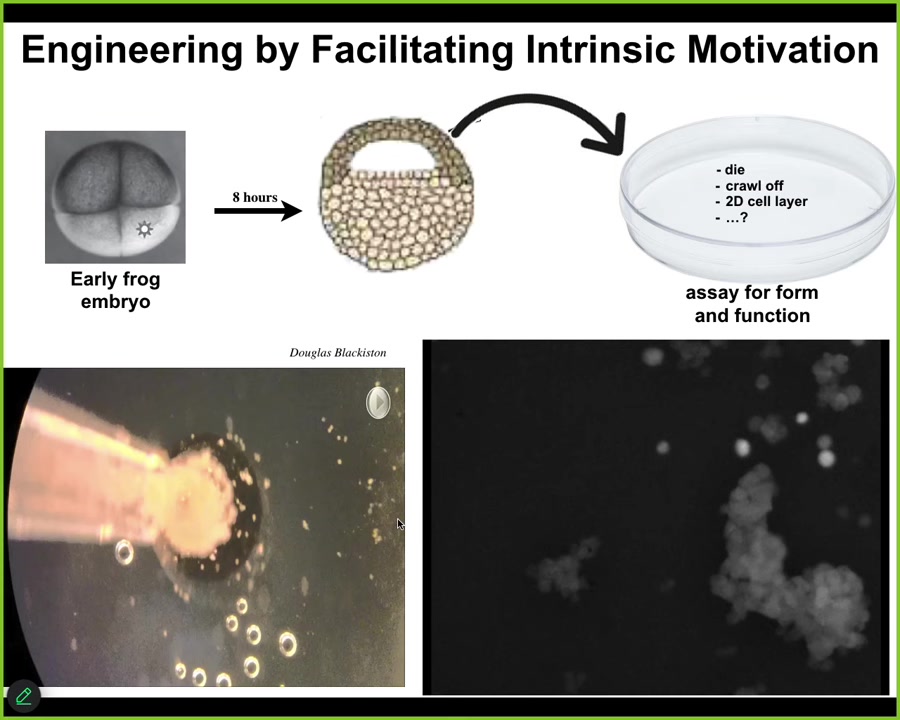

This, I'm sure Josh has already shown you some of, is basically epithelial cells taken from a frog embryo. When you take them away, we don't change, we don't edit the DNA, we don't put in synthetic biology circuits, there are no scaffolds, there are no drugs, no nanomaterials. All that we do is we engineer by subtraction, meaning that these cells normally are going to be bullied by these other cells and forced into being a boring two-dimensional outer cover for the tadpole that keeps the bacteria out. If you subtract this influence away and you ask, what do these cells intrinsically want to do? Then you see something interesting. They don't just crawl away from each other. They don't die or form a monolayer. They self-assemble.

You can see, here's a group, each one of these circles is a single cell. Here's this tiny little thing that looks like a little horse or something. It makes its way over here. It's moving around in a very interesting way that we still don't understand how it moves. There's a little calcium flash as it interacts with this big one.

Slide 14/22 · 12m:17s

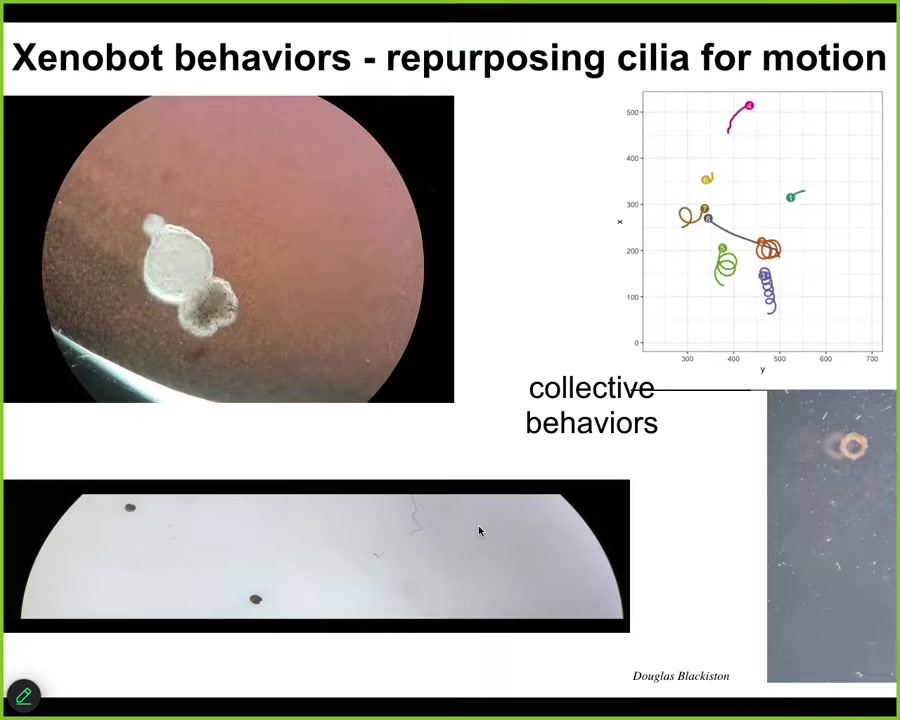

And these are Zenobots and they have some amazing behaviors. They've repurposed their cilia to move through the fluids. You can see that here. They can go in circles. They can patrol back and forth like this. You can make weird shapes out of them, like this donut thing. They have collective behaviors that we're still studying.

Slide 15/22 · 12m:35s

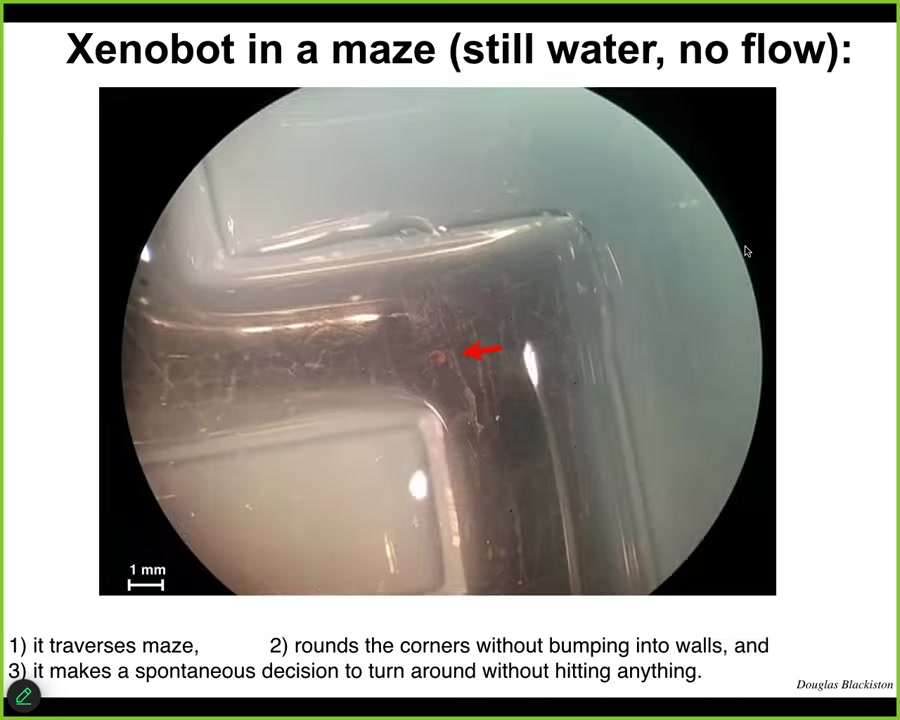

Here's a Zenobot navigating a maze. It's self-powered. We don't need to actuate it at all. We have no idea what guides it at this point. We're studying all that, but the decision-making — why it turns around at this particular spot. There's no liquid flow here. There are no gradients. There's no food. It takes this corner without having to bump into the opposite wall. At some point it spontaneously turns around. All of these kinds of things are completely spontaneous. We're not pacing it or controlling it.

Slide 16/22 · 13m:08s

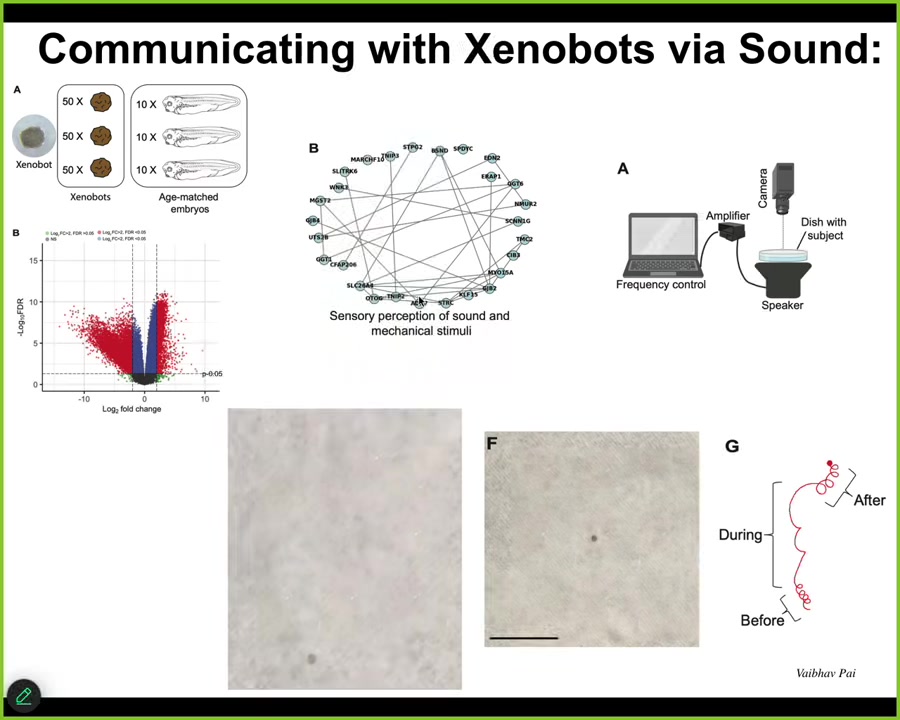

Now, one of the studies that we've made of it is what does the transcriptome look like of a creature that has a novel lifestyle that has not been selected for? It turns out that it has hundreds of genes that are expressed very differently than these same cells back in the embryo. I'll show you one example of what it does as it dips into the genome to pick out novel things that are there for this lifestyle.

There's a whole cluster of genes that are associated with sensory perception of sound. We thought that's amazing. Is it possible that these things could hear or respond to sound? What we did was this experiment. We put a speaker under this. These are brand-new kinds of things. They do change their behavior when you provide these sound stimuli.

These little tight circles, as soon as you turn on the sound, they do this, and when you stop, they go back to this, not exactly the same. Maybe there's a little bit of residual memory, but we're trying to figure that out. For all of these things, we're now doing behavioral experiments to ask what they remember, what they can learn, what their preferences are.

Slide 17/22 · 14m:18s

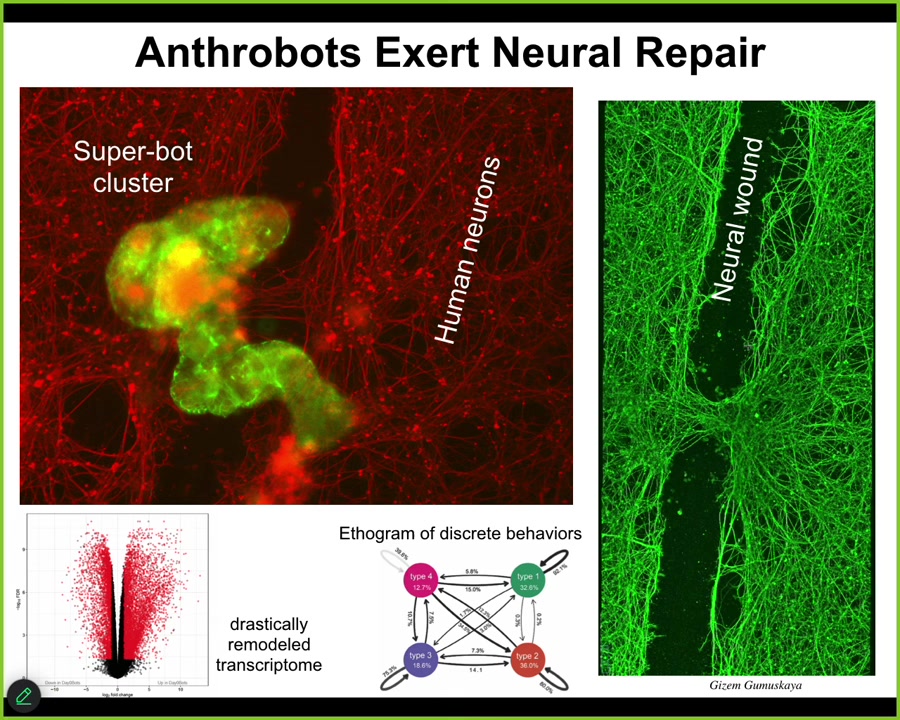

The last thing I'll show you is that this is not some weird fluke of frog development. This little thing, which looks like we got it off the bottom of a pond somewhere, is actually, if you were to sequence it, Homo sapiens, 100% wild-type. These are anthrobots made of human tracheal epithelial cells.

They also do some interesting things. If you plated a bunch of human neurons and you put a big scratch through it, they will traverse that scratch.

Slide 18/22 · 14m:46s

But then they'll pick a spot and sit down and they form the superbot cluster. And what you see is that what they're actually doing is healing the gap. They can actually induce repair if you lift them up four days later. This is what it looks like. They can actually induce repair across this gap. So who would have known that your tracheal epithelial cells have the ability to form this autonomous little biobot run around and heal wounds. They have thousands, about 9,000 genes differently expressed than the tissue of origin. Tons of amazing things here that we're still mining. Four discrete behaviors that you could build a behavioral ethogram of. We're also working on understanding what their proto-cognitive properties look like.

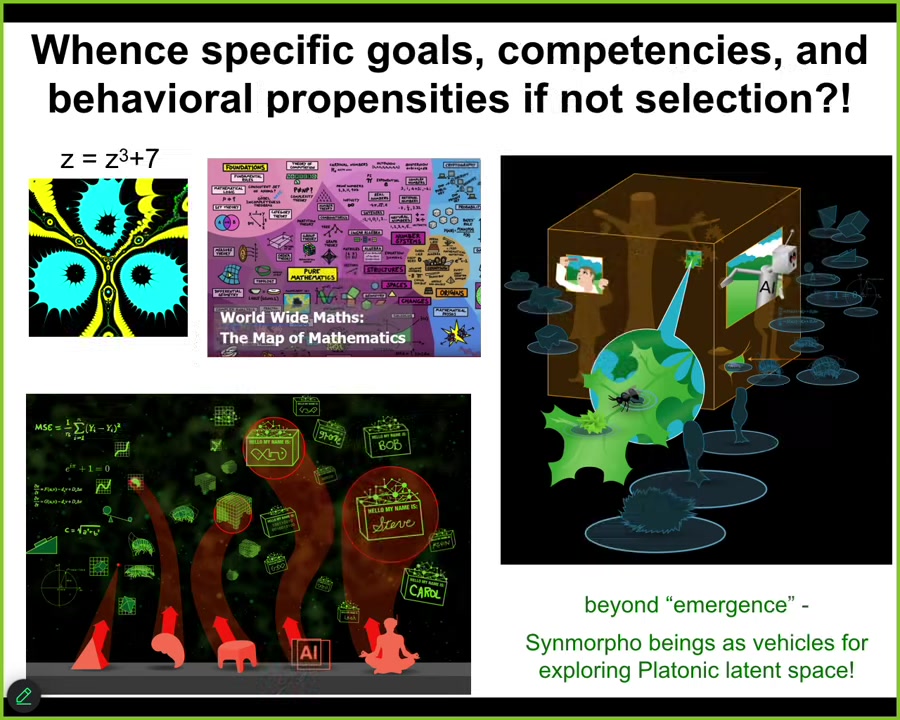

And so the very last thing that I'll say, and this is the weirdest part of this, is that we have to start thinking, if it wasn't a history of selection, which people take to explain this path, what are these Xenobots turning into? If it wasn't direct engineering, which we didn't do, all we did was liberate the cells, we didn't program them in any way, and if it wasn't selection, where does other information come from?

Slide 19/22 · 15m:56s

I want to pitch this idea that we do have a precedent for information that does not come from the physical world. This is a mathematical object called a Halley plot of this little function. If you want to ask why it has the particular shape that it has, the answer is not anything about its evolutionary history. It's not about any facts of physics. It comes from other laws of mathematics that many Platonist mathematicians are studying as a structured, ordered set of patterns: this map of mathematics. I want to argue to point out that I think we need to go far beyond emergence as an answer to the question of where these properties come from. We need to ask, what are the structured patterns that we are releasing here? I view these synthetic beings as vehicles for exploring this latent space. I think this is the research program.

So as we make cyborgs and hybrots and biobots and all these kinds of things, they're combinations of evolved material, engineered material, sometimes software, but also patterns from the space of mathematical patterns that are not to be found specifically among the laws of physics. I think by itself, emergence is not going to do the trick.

We really need to develop tools to understand, to map out that space and map out the interactions between the physical interfaces that we make and the patterns that we see. The ability to use all of these amazing features of the living material is part of the field of diverse intelligence, and we are trying to use some AI tools to communicate across all the different levels.

Slide 20/22 · 17m:41s

What I've tried to say is that in biology, there's this multi-scale competency architecture of nested problem solvers. We, as evolution, can exploit this material via prompts and training, not just rewiring or micromanagement. Tools are coming online to communicate with these systems via bioelectrics and other modalities. Lots of applications. We need to pay a lot of attention to the intrinsic motivation of the system, not just programming, not just reinforcement learning, but actually understand what it is that these things can do aside from what we've made them do.

Slide 21/22 · 18m:20s

I'll stop here and thank the people who did the work. Some amazing postdocs and grad students did the work I showed you today. Lots of collaborators who work with us, and we always thank the funders. Most of all, the model systems, both biological and synthetic in every combination, have taught us all of these things. Thank you.

Slide 22/22 · 18m:45s

Any questions from the audience? Yes. Hello, it's an inspiring M.P.T.D. student from Sheppel. I want to ask you about your insights. If we're using Kaufman principles, like dealing with biological cells as reaching steady states in a non-equilibrium environment, or using models of biological cells in quantum undeterministic rules, this will help us to predict its behavior so we can know what it will do and control it by controlling its behavior without controlling it, really. I want to hear your insight about this. Thank you.

My current framework for all of this is that I think the most powerful advances in predicting and manipulating behavior are not going to come from thermodynamics or from quantum biology, although those things have important things to tell us. I think the biggest impact is going to come from behavioral and cognitive neuroscience, because those disciplines are not about neurons at all. They're about much more fundamental aspects of different modalities that function as a cognitive glue that scale the competencies of subunits and project them into novel problem spaces.

There is a wealth of experimental and conceptual approaches that have so far been deployed around brains and development, but these approaches work in many other contexts. Not just learning in molecular networks, but use of hallucinogens, anesthetics, and serotonergic modulators to change the priors, decision-making, and certainty — these things work, as far as I can tell, all the way down.

To me, that is where the biggest advances will come from: the field of diverse intelligence applied to bioengineering. There's a massive opportunity because that field is very focused on natural animals of all kinds; they cover bacteria, unicellular organisms, and whales. At those meetings, there have been very few bioengineers. The opportunity for cross-fertilization between these fields and roboticists is massive. Other questions?

I'm curious about the sound, how you chose that. Is it just a really precise, non-invasive way to do mechanotransduction, or was there another reason that motivated that choice?

The question of sound began because we did transcriptomics and found a cluster of hearing genes. I think the bigger picture is the idea that these novel systems with a novel lifestyle are problem solving in the sense that they dip into their genome to transcribe things that will be useful in that lifestyle. This primed us when we saw the hearing: let's just test it now.

In terms of what the sound is, the only thing we've published so far is a single-wavelength sine wave — one frequency. We are currently testing everything from a full frequency sweep to different kinds of music; we let them talk to each other — there are many possibilities. The jury is still very much open on what they're doing with that information. I'm sure the molecular view is some sort of mechanotransduction; that's probably how they're hearing. They're using cilia the same way we do.

At a higher level, I want to understand ecologically why this is important: why are they transcribing these genes? On the computation side, I want to know the internal causal architecture that allows the system to go from "this is my environment" to "this is what I want to transcribe."

The examples we've had in our lab have to do with, for example, flatworms identifying just a half dozen genes out of a genome of tens of thousands that allow it to overcome a novel toxin it's never seen before. We have experiments where we hit them with something that's never been around during evolution. Within a week, they find the solution. How do they find it? This has massive biomedical implications. All of this has two layers. There's the biophysical layer where it's mechanotransduction. But the bigger question is what information it is processing, how, and why?

Hi, I'm wondering if you have any thoughts. We're in this field, especially with the muscle tissue, trying to replicate the form and function of an organ that exists as part of an organism. At the same time, we are exposing it to conditions and an environment where the cells are in some way trying to do problem solving on their own. From the perspective of advancing the function of the tissues, do you have any thoughts about how we should be approaching treating these cellular collectives? Should we try to copy in vivo environments or explore alternatives?

The two approaches to this that I've written about, and that we are trying to follow in our lab, are, first of all, training. Rewards and punishments and training of cells and tissues for specific outcomes. Building closed-loop devices is one thing we're doing now, not with muscle, to continuously reward desirable behavior and exploit the learning capacity to train, not physically force, the cells to do what you want them to do. That's the first thing.

The second thing, which you can do with that same kind of platform, is instrumental learning. You can ask the cells what they want to do by giving them control over the environment. You set up a closed-loop system where different actions lead to different outcomes, and you let the cells find behaviors that give them stimuli and outcomes that are meaningful to them. By doing that, we learn more about the system and can become much better at motivating them.

Humans have been training dogs and horses thousands of years before we knew any neuroscience. We had no idea about mechanisms, but we did understand that they have an amazing interface: if we understand the currency of the way that they learn—rewards and punishments and behavior-shaping paradigms—then we can get amazing outcomes, even if we're not micromanaging synaptic chemistry. I have a feeling that's what we'll need to do here: get a much better idea of what the cells actually want to do, what they value as rewards and negative reinforcement, and how we can do behavior shaping to get them to do it.