Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a ~55 min talk by Michael Levin "Endogenous Bioelectrical Networks: an interface to somatic intelligence for regenerative medicine", going over the state of the art in developmental bioelectricity in the context of collaborating with the cellular collective intelligence for applications in birth defects, regeneration, and cancer. It has some new material beyond what my recent talks on this topic have covered.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Michael Levin introduction

(01:18) Bioelectric regenerative medicine

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/44 · 00m:00s

It is my distinct pleasure today to introduce our invited speaker, Dr. Michael Levin. He is a world-renowned scientist with research spanning developmental biology, computer science, bioelectrics, and philosophy of mind. Dr. Levin is the Vannevar Bush Distinguished Professor of Biology at Tufts University. He is associate faculty at Harvard's Wyss Institute and the director of the Allen Discovery Center at Tufts. He has published over 400 peer-reviewed publications. His graduate research was published in Cell in 1995, and it was chosen by Nature as a milestone in developmental biology in the last century. Michael is one of the most brilliant scientists and one of the best speakers I have ever had the privilege to meet. Please join me in welcoming Dr. Levin.

Thank you so much for that extremely kind introduction. I wish I were there in person to meet with you. Thank you for having me here to share some ideas.

What I'm going to talk about is endogenous bioelectrical networks. I'm going to argue that this is not simply another layer of physics that we need to understand, but actually a very profound interface to the intelligence of the body, which has many implications for regenerative medicine. If you're interested in downloading any of the primary papers, the data sets, the software, everything is at our lab website here. This is my personal blog around what I think some of these things mean.

Slide 2/44 · 01m:58s

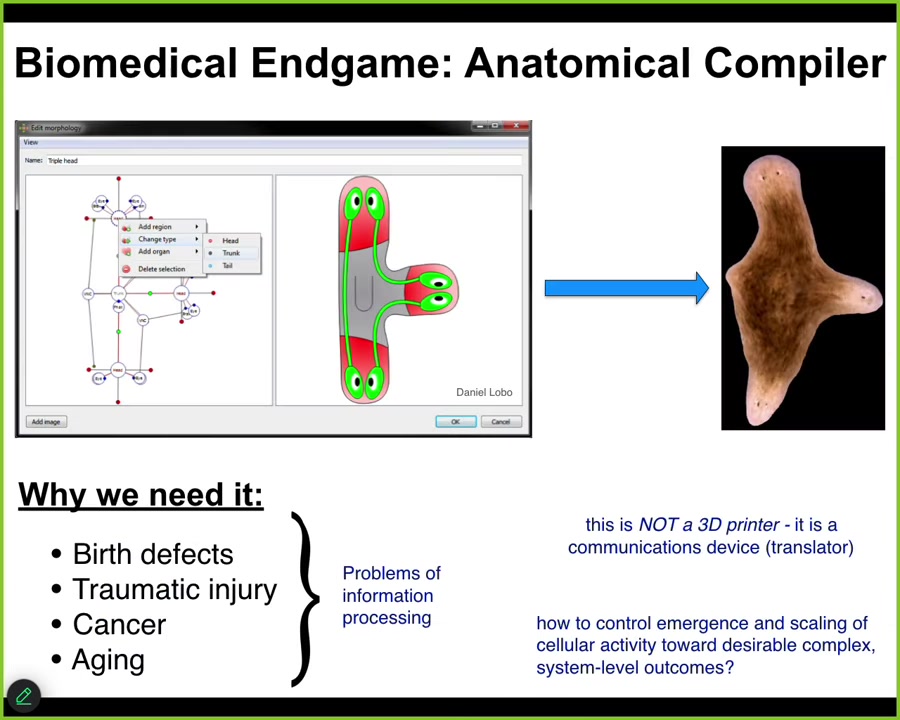

I'd like to begin by considering the end game of our field. Where is all this going? Imagine something I call the anatomical compiler. Someday you will sit in front of a computer and you will be able to draw the plant, animal, organ, biobot, any living structure, whether already existing or imaginary. And what this thing will do is compile your description into a set of stimuli that have to be given to cells to get them to build exactly that structure.

We need it because if we had the ability to communicate our goals to groups of cells, we would automatically end birth defects, we would be able to repair traumatic injury, reprogram cancer, reverse aging and degenerative disease. All of these things would be solved if we had the ability to tell groups of cells what to build: healthy new organs, living machines.

This is not some kind of a 3D printer. The goal is not to micromanage the position and the gene expression of cells. This is meant to be a communications device. It's a translator between our goals as engineers and workers in regenerative medicine and those of the cellular collective.

But how do we do this? Genetics and biochemistry and molecular biology have been going strong for decades. Why don't we have anything remotely like this?

Slide 3/44 · 03m:17s

We are very good at now as a field at manipulating cells and molecules and knowing which molecular machinery binds and acts on which other kinds of molecules. But we're still a very long way away from control of what we're really interested in, which is large-scale form and function, restoring somebody's entire limb. We're quite far in most cases from biomedical treatments that actually fix things in a permanent way. We don't have very many of those.

That's because today, I would claim that biomedicine is largely stuck at the level of hardware. This is where computer science was in the 1940s and 50s. This is what programming looked like in the early 1950s. You can see that in order to get this computer to do something different, she's rewiring the hardware. She's physically interacting with the hardware. This is where modern molecular medicine is today. All the exciting things are at the level of genomic editing, protein engineering, pathway rewiring. It is all at the level of the hardware.

And I think in order for biology and medicine to reap the kinds of benefits that we have seen in the information technology revolution, we would have to move from an exclusive focus on our biological hardware to understand the software of life. And what I'm going to argue today is that largely speaking, the most exciting part of that software of the living material is its intelligence, its multi-scale problem-solving capacity.

Slide 4/44 · 04m:43s

Today, I would like to give you these four points. First, I'm going to show you that bodies are constructed of a multi-scale competency architecture, agential systems at multiple scales that solve problems in different spaces. I'm going to argue that definitive regenerative medicine is going to require exploiting the collective intelligence of groups of cells, communicating anatomical goals, collaborating with their competencies, not micromanaging them.

Most appropriate for this venue, I'm going to show that endogenous bioelectrical networks in all tissues, not just brains, are a highly tractable interface for this kind of control of growth and form. Tools are now coming online to read and write goal states into the living medium of the body, which is going to be the future of regenerative medicine. This will give rise to some examples that I will show you of applications in birth defects, regenerative repair, and cancer.

The whole message of the talk is this, that bioelectricity serves as the cognitive glue for the collective intelligence of bodies, with all the implications that has.

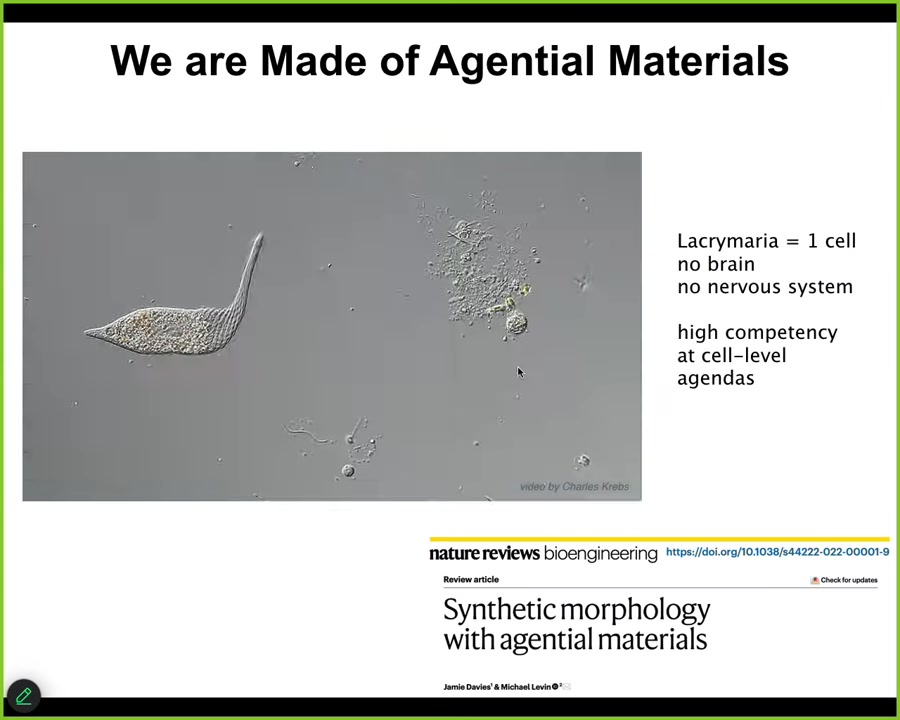

Slide 5/44 · 05m:56s

Let's consider what we are all made of. This is the kind of material we are all constructed of. This is a free-living organism called the lacrimaria. Cells are incredibly competent beings on their own. There's no brain here. There's no nervous system. There are no stem cells or cell-to-cell communication. This little creature in one cell is doing everything it needs to handle its physiological, anatomical, and metabolic requirements. If you're going to engineer with a material like this, you have to work very differently than engineering with passive matter such as wood and metal. All of that is described in this review of synthetic morphology with these agential materials.

Slide 6/44 · 06m:41s

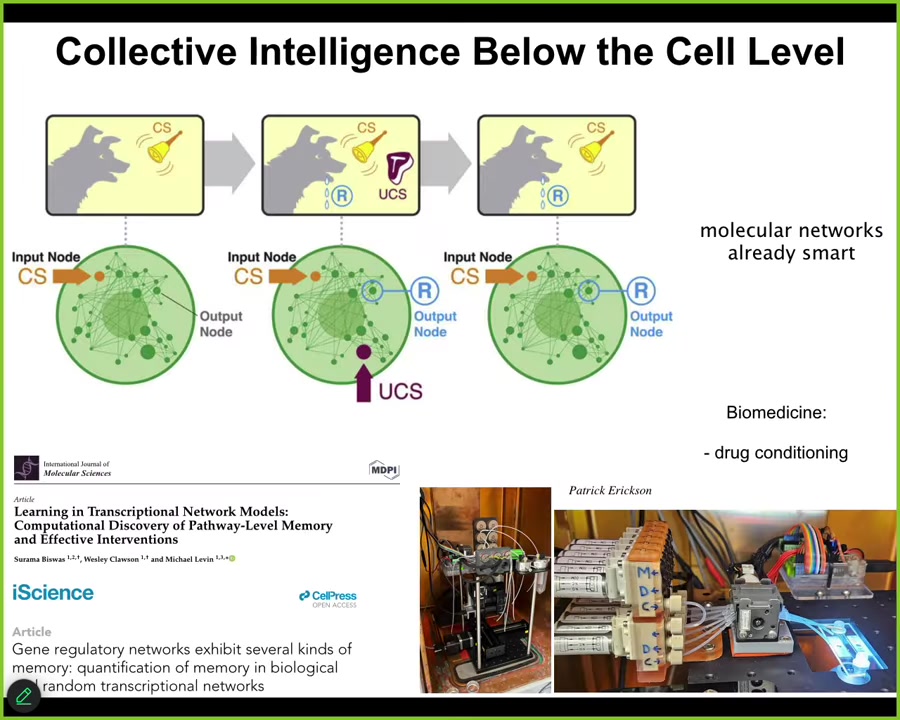

We know that cells are very active and competent, and even below the cell level, the molecular networks inside of cells are themselves capable of, for example, at least six different kinds of learning. They can do habituation, sensitization, and even Pavlovian associative conditioning.

In our group, we're building devices to train the molecular pathways inside of cells, for example, drug conditioning. What you see is that it's not only the brain and nervous system that are capable of learning and decision making. This kind of thing goes all the way down. We could spend hours on examples. I don't have time to do that here.

Slide 7/44 · 07m:22s

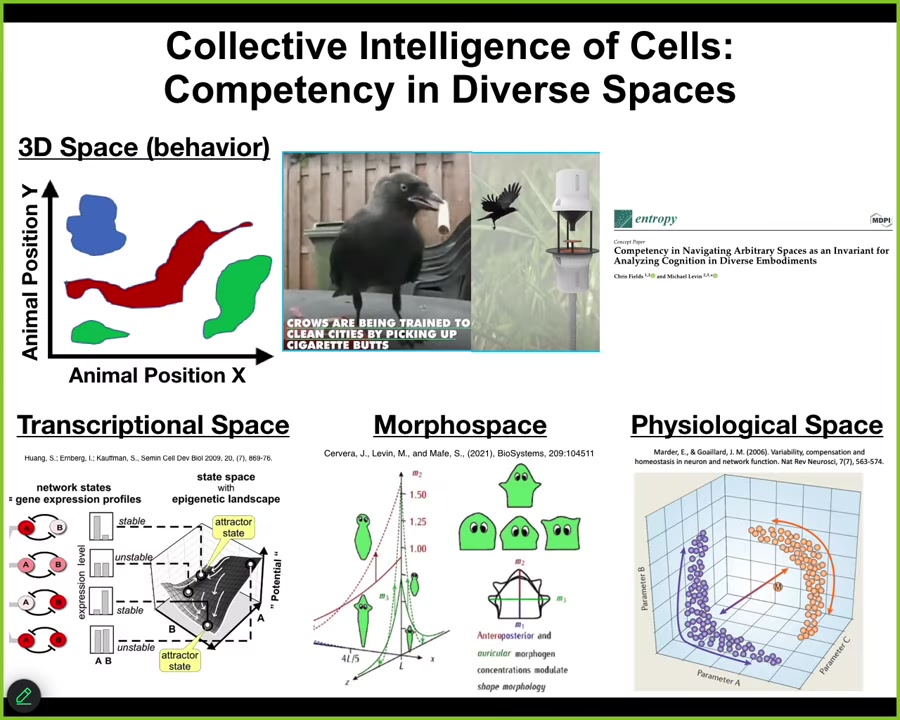

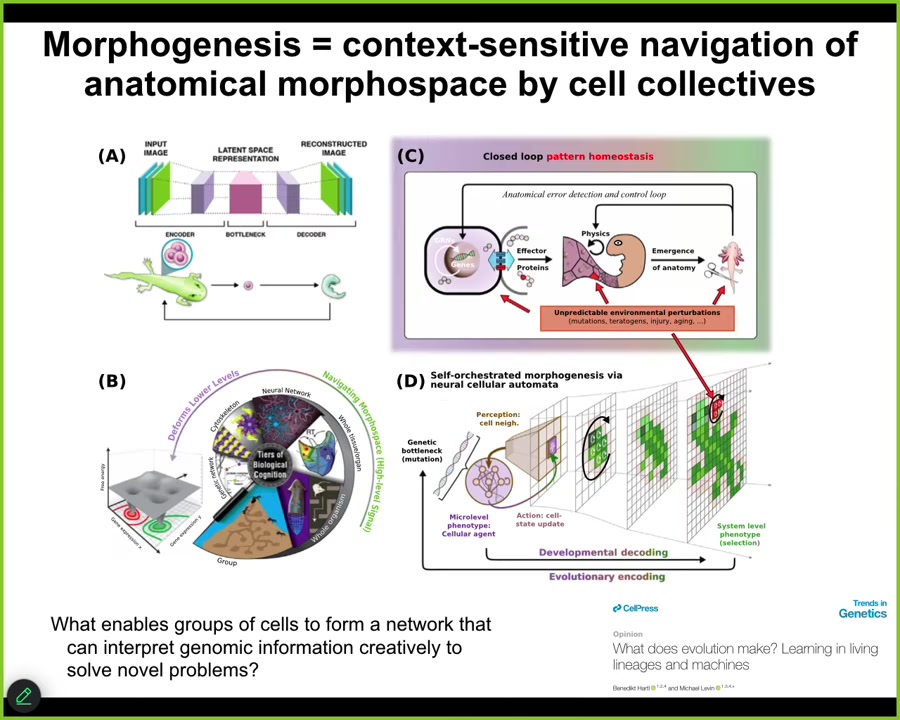

So I will just move on with a general point that we as humans, because of our own evolutionary history, are reasonably good at recognizing intelligence of medium-sized objects moving at medium speeds through three-dimensional space. Birds, primates, maybe a whale or an octopus. We can recognize their ability to navigate three-dimensional space. We can see that they solve problems and that they're intelligent. But biology has been doing this long before brains and muscles appeared. Living systems live in all kinds of exotic spaces that are very difficult for us to visualize, but they make decisions and they traverse these spaces in goal-directed ways. They live in transcriptional space, a very high-dimensional space of gene expression states. They live in physiological state space, and anatomical, amorphous space, the one that we'll talk about the most today. So this idea of embodiment, of being able to perform this loop of sensing, decision-making, and then action takes place in many different spaces. And today we will talk about how living systems navigate the space of anatomical possibilities.

Slide 8/44 · 08m:25s

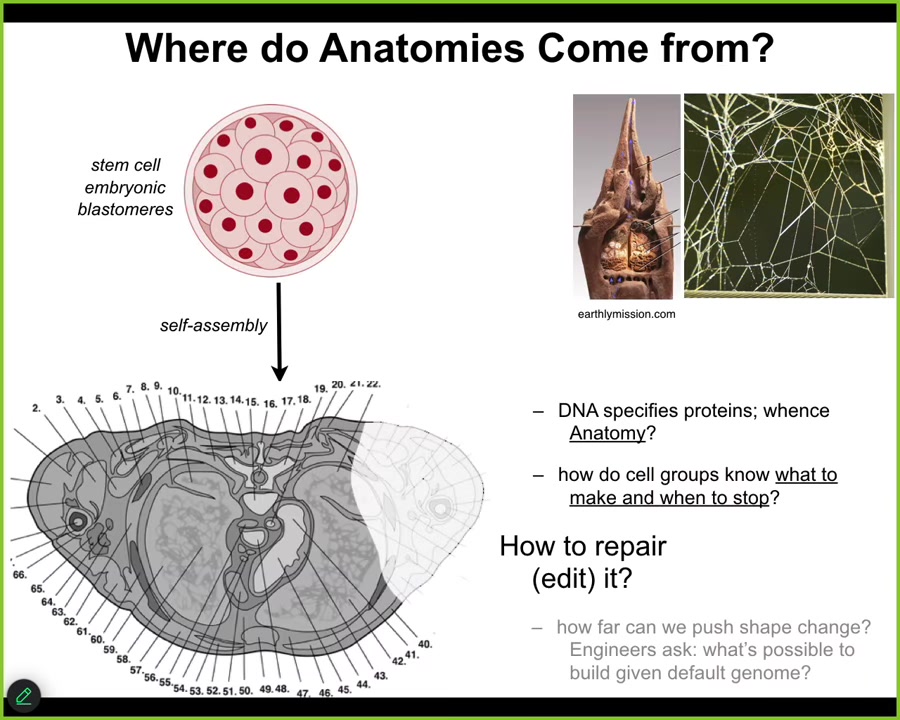

The first thing to ask is, Where do anatomies come from in the first place? Here's a cross-section of a human torso. You can see enormously rich structures. Everything is typically in the right place, the right size, relative to the right neighbors. Where does this pattern come from? Where is it written down?

We all start life like this. There's a bunch of embryonic blastomeres. People will initially say, well, of course, the human genome tells you what to do. But we can read genomes now, and we know that what the DNA specifies are proteins. What we're interested in is a three-dimensional anatomy. How do cell groups know what to make? How do they know when to stop?

This structure is no more directly in the DNA than the structure of a termite colony is in the genome of the termites, or the particular pattern of a spider web is in the DNA of the spider. All of these are the outcome of physiological software running on the hardware that's encoded by the genome. So we have to understand how do cells know what to do? How does this hardware enable that? And how do we induce them to repair when things are missing or damaged?

A large chunk of our lab is working on this. Can we get them to build something completely different? I'll show you just a brief glimpse of it in this talk.

Slide 9/44 · 09m:44s

I've said a number of times that the living material has intelligence baked in at multiple levels of organization. What I mean by intelligence is this definition by William James. I don't mean that it's a human level metacognitive ability to know what you're doing or anything like that, but simply the functional ability to reach the same goal by different means. In other words, to adaptively navigate a landscape in a goal-directed way with some degree of ingenuity to get your goal met when things change.

Let's take a look. What kind of collective intelligence do swarms of cells deploy? The first thing we know is that morphogenesis is incredibly reliable. Almost all of the time, this process gives rise to the correct target morphology. But that is not why I'm calling it intelligence. It is not the reliability. It is not the emergent complexity. That's not it. Those are cheap and easy. You don't need intelligence to have those things. The reason I call it intelligence is specifically because of its problem-solving capacity in navigating that space when things change. What kind of things? The first thing you can do is for most kinds of embryos, you can cut them into pieces. You don't get half bodies. You get perfectly normal monozygotic twins, triplets, and so on. That's because from different starting positions, whether this normal position or this injured position, these systems can navigate anatomical space and still reach the correct ensemble of goal states that they're trying to get to, despite pretty radical deformations. They can avoid local minima of all kinds, and they still get to where they're going from different starting positions. That's the beginning.

Slide 10/44 · 11m:22s

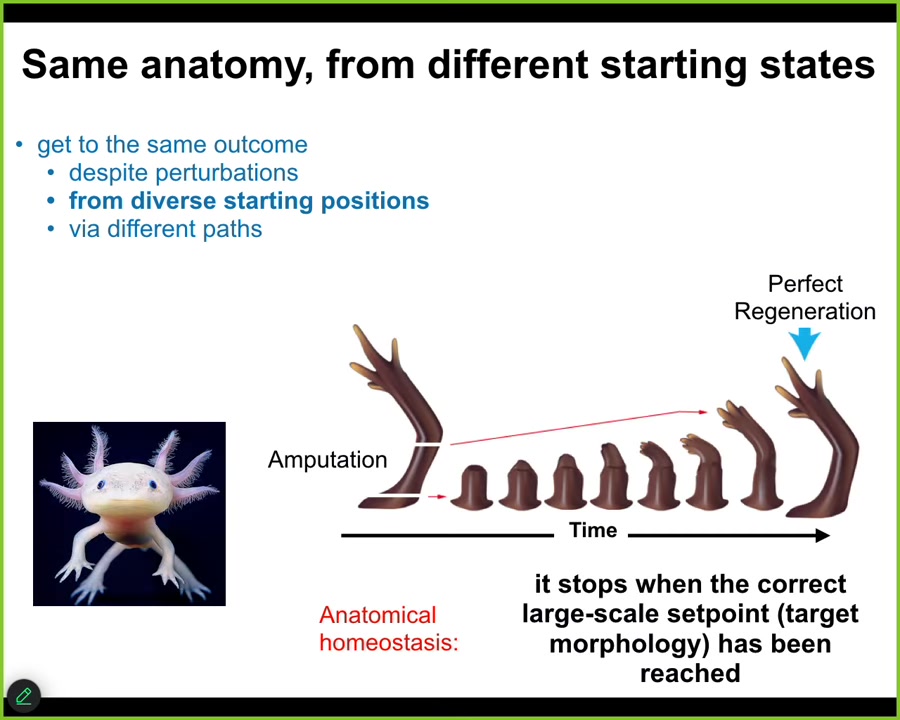

This is not only for embryogenesis. I think embryonic morphogenesis is just a special case of this anatomical homeostasis property. Some animals do this as adults. Here is an axolotl. This amazing amphibian can regenerate its eyes, its jaws, its limbs, its spinal cord, portions of the brain, and heart. In the limb, if you amputate anywhere along this path, the cells will immediately spring into action. They will build very rapidly. The most amazing part is that they stop. When do they stop? They stop when a correct salamander limb is complete. This is a homeostatic loop. When they sense that they've been deviated, so the error is high, they will work to reduce that delta. They're traveling back to that region of anatomical space. As soon as they reach it within some very small tolerance of error, they stop.

Slide 11/44 · 12m:19s

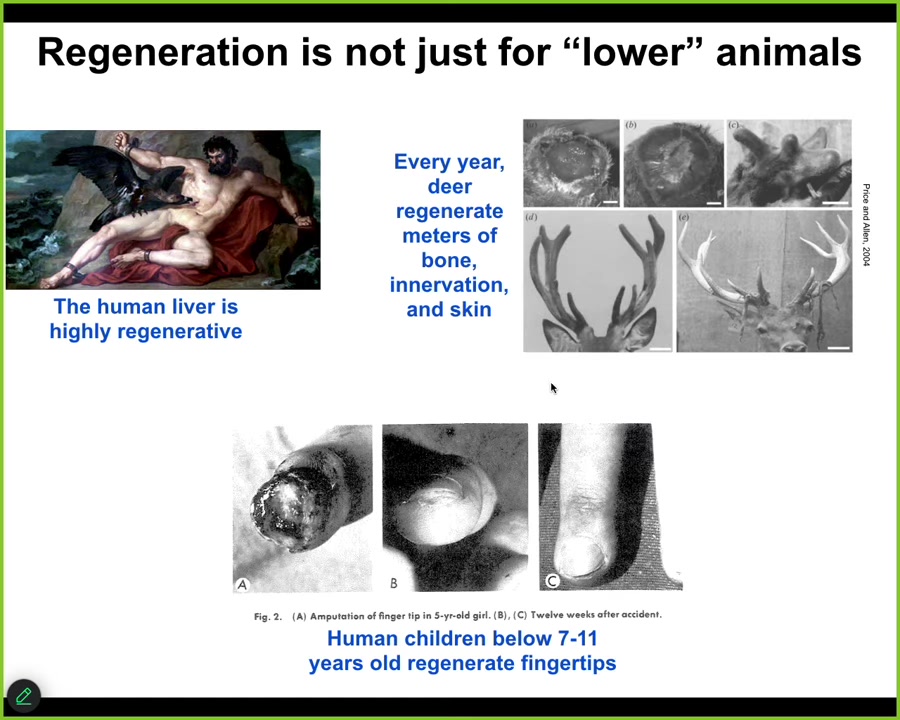

Regeneration is not just for amphibians and the worms I'm about to show you. Some human organs do it too. The human liver is highly regenerative. Even the ancient Greeks knew that. I have no idea how they knew that, but they did.

Deer are adult mammals that every year regenerate huge amounts of bone, vasculature, and innervation, up to a centimeter and a half of new bone per day during this process. Human children below a certain age regenerate their fingertips with a very nice, cosmetically perfect outcome. This is quite a distributed kind of capacity to restore from damage.

Slide 12/44 · 12m:57s

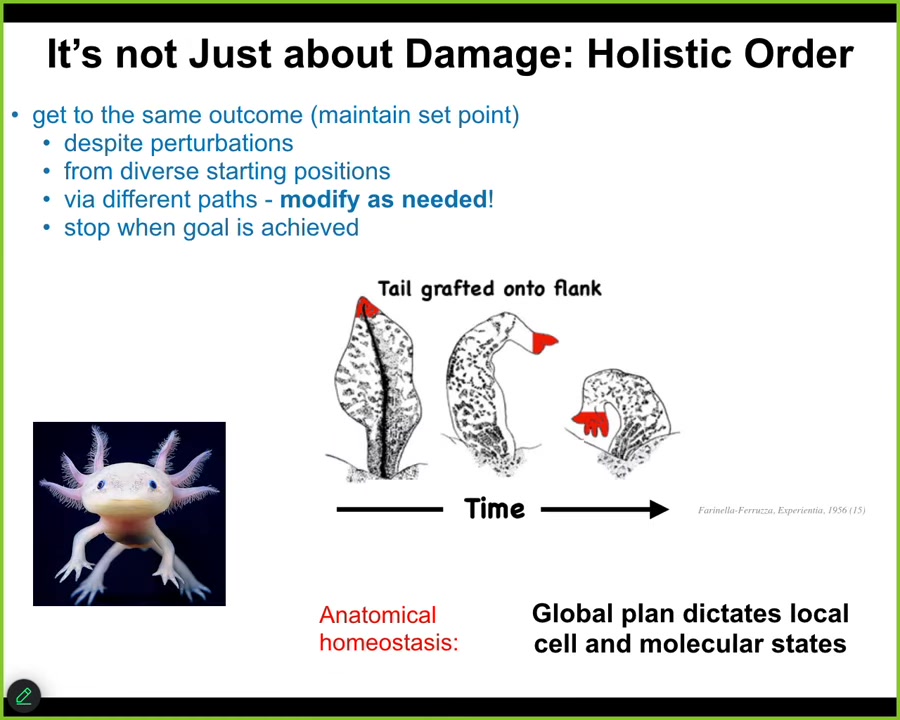

But it's not all about restoring from damage. It's much deeper than that because here's another experiment done in the 50s. If you take a tail of an amphibian and you surgically attach it to the flank between the two limbs, what you will see is that over time it undergoes metamorphosis, it becomes converted into a limb and becomes a structure that belongs at this new location.

The amazing thing about this is that even the tip of the tail, which are tail-tip cells sitting at the end of a tail, locally there's nothing wrong—they're perfectly correct, but they become fingers. The whole thing, even the regions that locally have no issue, become remodeled. Because what you have here is a kind of top-down control. The global body plan dictates local cell and molecular states, using the plasticity inherent in this creature to convert them to a new structure that's more suitable for the large scale.

There is even some human data on this now in terms of transplants, people getting arm transplants or seeing remodeling of their arms to better suit the rest of the body.

This is a remarkable ability of multi-scale intelligent systems, just like us, when you have thoughts and goals in your mind that are very abstract. You might have career goals or social goals. In order for you to move around and to walk and to execute those goals, in other words, voluntary motion, those very abstract high-level goals have to be converted in your body to ions moving across your muscle membranes, literally mind over matter. And that is exactly what's happening here. Large-scale collective goals of a system trying to be a proper amphibian are filtering down to the molecular cues that have to tell individual cells what they're going to be.

This is a fundamental feature of a multi-scale cognitive system.

Slide 13/44 · 14m:51s

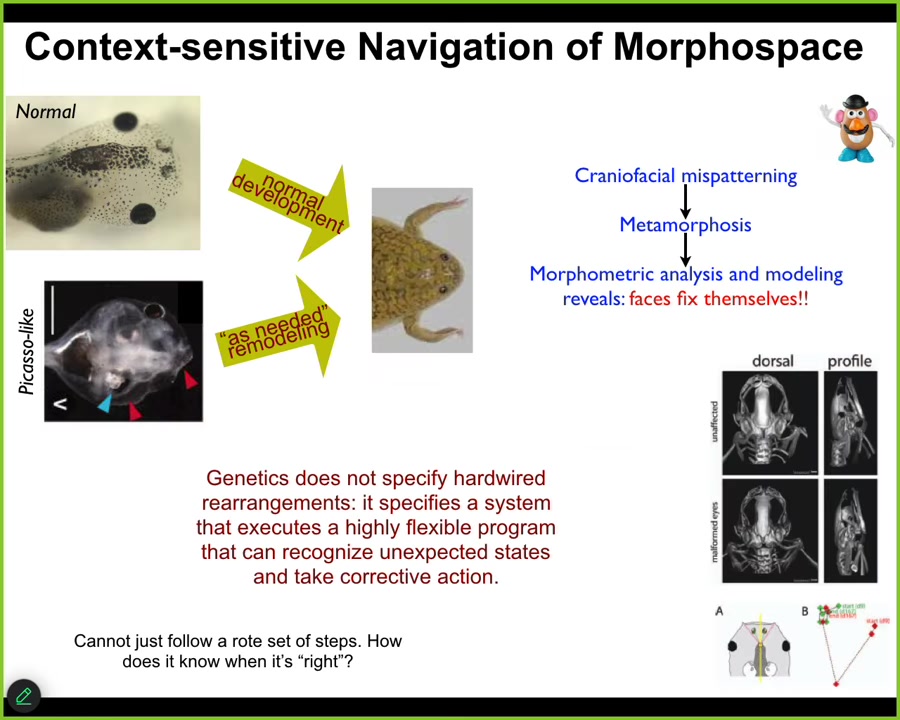

You have things like this showing the flexible navigation of anatomical space. Here's a normal tadpole. Here's a brain, the gut, the nostrils, the mouth, the eyes. These things have to drastically rearrange their face to become frogs. Everything has to move around. It used to be thought that these kinds of movements were hardwired. Somehow the genetics just made everything move the right amount in the right direction.

We decided to test that, and it is very important to test any claim of intelligence in any system experimentally. You have to show the problem solving. What we did was create these so-called Picasso-like tadpoles. Everything is scrambled. The eyes are on top of the head, the mouth is off to the side, everything is in the wrong position. We found that these give rise to quite normal frogs. All of the organs don't just go in the same paths. They go in novel paths as needed to give a correct frog, and then they stop. Sometimes they go too far and have to come back.

What the genetics actually gives you is hardware that can execute a highly flexible, context-sensitive, goal-directed program of reaching a specific location in anatomical space, and it will do it in different ways depending on what's going on. We need to ask the question: how does it know what the goal is? How do any of these systems store the set point? Any homeostatic process has a set point, and they have to be able to store that somehow, and then compute the delta and try to reduce that error. How do they do this? I'm about to show you.

Before that, one last thing. What I'm showing you here are examples of systems that are navigating space to reach their default goals. What happens if that goal is completely unreachable? What if it's impossible to reach?

Slide 14/44 · 16m:37s

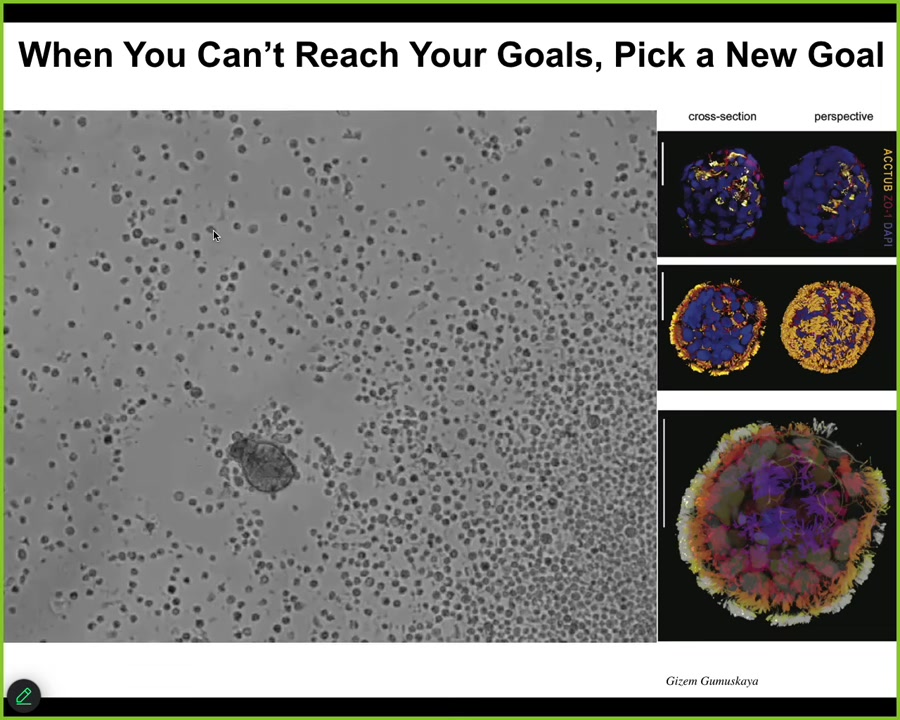

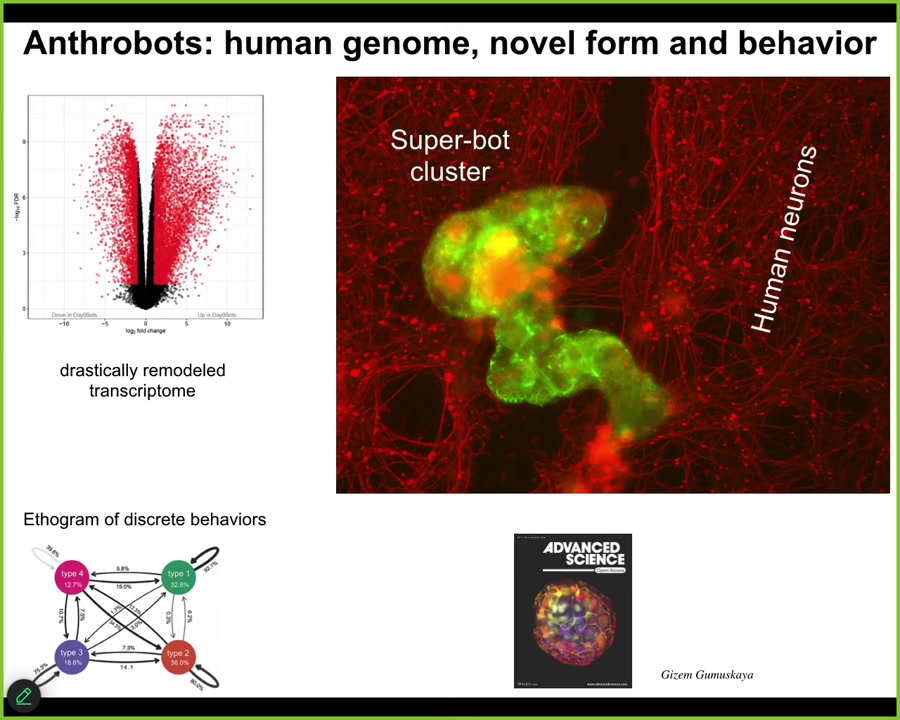

Well, one thing biological systems are very good at is deriving novel goals. If you can't reach your original goal, come up with a new goal. What I'm showing you here is one example of many that I could tell you about. This little creature, it looks like a primitive organism I got from the bottom of a pond somewhere. You can see it navigating around. Close up, this is what it looks like. It has these little hairs on the outside surface. They're cilia. That's how this little guy moves around. You might guess that it's a primitive organism with a primitive genome. If you were to sequence the genome, what you would find is 100% Homo sapiens, unedited human genome. This comes from adult cells from adult patients, taken from tracheal epithelia. When extracted from the patient, these cells self-assemble into this self-motile living creature, which has a lifestyle completely different from that of the human that it came from. It looks like no stage of normal human development.

Slide 15/44 · 17m:32s

It has some interesting features. It expresses about 9,000 genes, in other words, half the genome, differently than the way it did when it was in the body. Radically remodels its transcriptome. It has four specific behaviors that it can do, and you can build a little ethogram of it. One cool trick that they can do: if you place a cluster of human neurons here and put a big scratch through it, they will assemble into something we call a superbot. There are about a dozen of these things together. What you can see is that over about four days, they knit together across the gap. They heal the neural wound. Who would have thought that your tracheal epithelial cells have the ability to make a self-motile creature that also can heal your neural wounds. Lots of biomedical implications here, but fundamentally what you're seeing is that an unedited genome, no Yamanaka factors, no synthetic biology circuits, no genomic editing, no weird scaffolds or drugs or nanomaterials, just the cells themselves, if they can't do the normal thing that they do in the body, they will find something else to do. Often it is quite coherent and quite remarkably complex. This is yet again another skill: finding new attractors in the space of different ways to be alive.

Slide 16/44 · 18m:49s

Fundamentally in our group, what we've been studying, and this is described, some of it is described in this paper, what we've been studying is the ability of networks of living cells to use various principles that are, interestingly enough, now studied in machine learning and computational psychiatry to create networks that actually interpret the information they're receiving from the genome, not follow it as a mechanical device, but actually creatively interpret them as cues. This bow tie that occurs when individuals compress down everything that the lineage has learned over evolutionary time into a single generative seed, like an egg, and then it has to be creatively reinterpreted during morphogenesis, maybe as the normal embryo, but maybe as an anthrobot or many other things.

We really have to ask, in all of these examples that I showed you, what underlies the ability of groups of cells to remember their goals? What allows them to reduce the delta between what's going on now and what they think is the target? What allows them to interpret this information, this environmental and genetic information, creatively to solve novel problems? What's the machinery that does it?

Slide 17/44 · 20m:06s

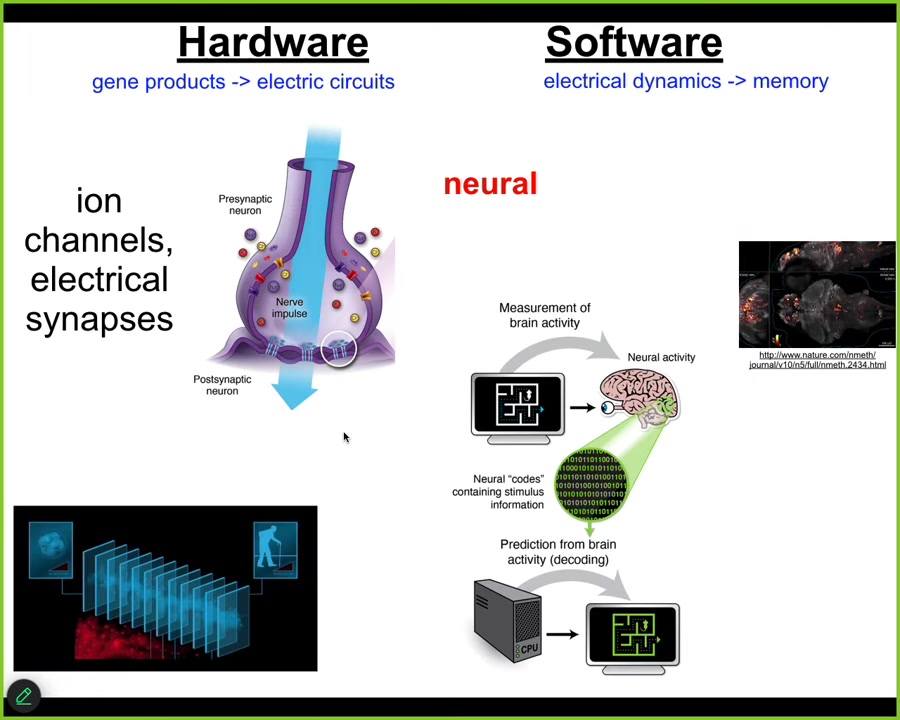

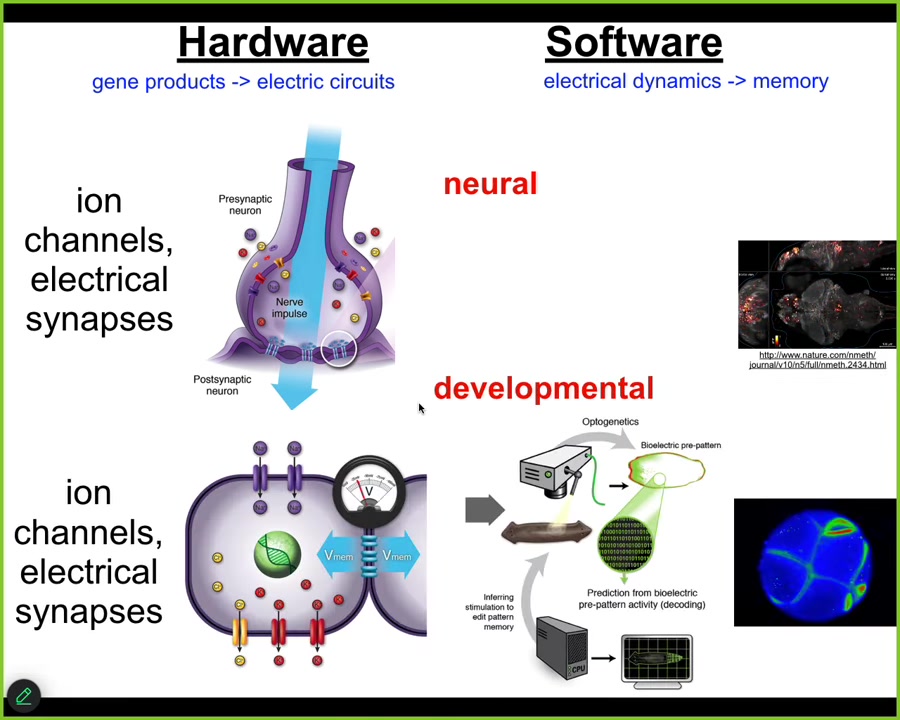

It turns out that we can get a lot of cues from looking at how the brain does things.

What's happening in the brain is that you have some remarkable machinery that allows the individual self, a single human extended over time, made up of a bunch of time slices of being. At every slice, what the nervous system has to do is create, confabulate a story, a self-model and a model of the outside world from memory engrams, from messages left by prior versions of yourself. In other words, memory engrams left in your brain and body have to be continuously interpreted in a way that executes on various adaptive goals.

The way the brain does this is through electrical networks. You have neurons that have ion channels in their membrane. They have electrical synapses to other cells. It forms this amazing electrophysiological network where, for example, this group tracked the electrophysiology of a living zebrafish brain as the zebrafish thinks about whatever it is that fish think about. The idea is that if we could read out all this electrophysiology and decode it, then you would have access to all the memories, the goals, the preferences, the capabilities of the agent. The cognitive content is encoded in this electrophysiology. Remarkable architecture.

Slide 18/44 · 21m:35s

Evolution discovered this a very long time ago, long before brains and nervous systems appeared. Back around the time of bacterial biofilms, evolution was already using electrical networks as a kind of cognitive glue to bind individual competent subunits, microbial cells, into a large-scale collective that can do things and that knows things that individual cells don't know. There's beautiful work by Agarol Soel out of UCSD on that whole evolutionary story.

For us, what's important is that every cell in your body has ion channels. Most of them have electrical synapses or these gap junctions to their neighbors. For about 20 years now, we've been working to take everything that's been done in neuroscience to understand the cognitive glue, the electrophysiology that makes you and I more than the sum of our neurons, and do the same thing for the rest of the body. That is, read and decode the electrical activity of the body cells and ask, how do these electrical networks help cells navigate anatomical space, the way that brains help you navigate three-dimensional space? The deep lesson that we've learned is that almost everything from the behavioral and cognitive neurosciences can be translated into developmental biology. You can take almost any paper in neuroscience, and anytime it says neuron, just say cell. Anytime it says millisecond, you say minutes or hours. A couple of other small changes, and you've got yourself a great developmental biology paper. There's huge symmetry between the formation of the body and the formation of the mind, because the mechanisms are evolutionarily homologous, not just analogous.

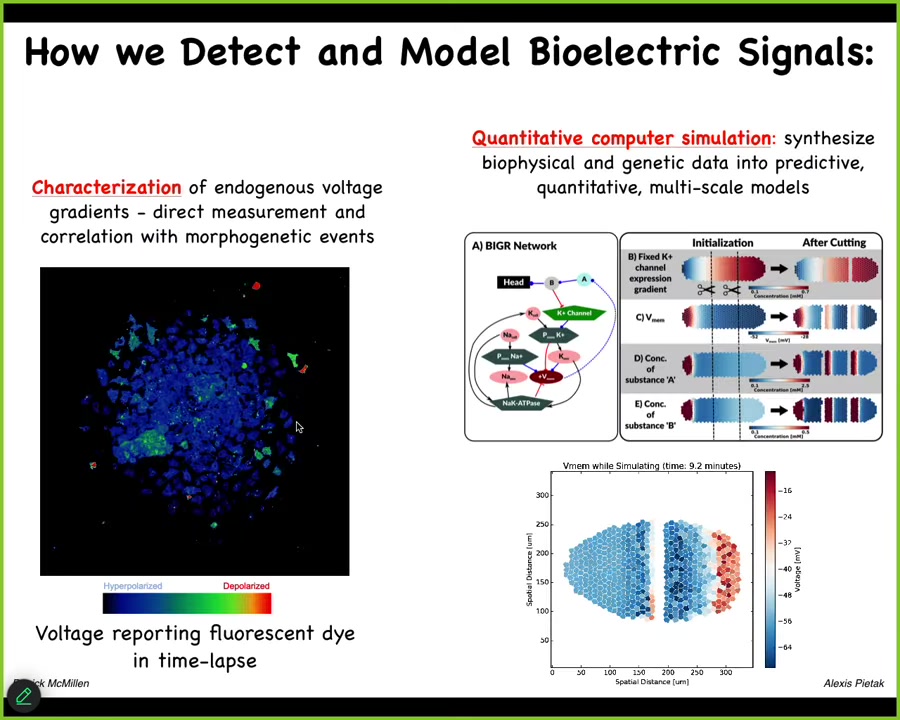

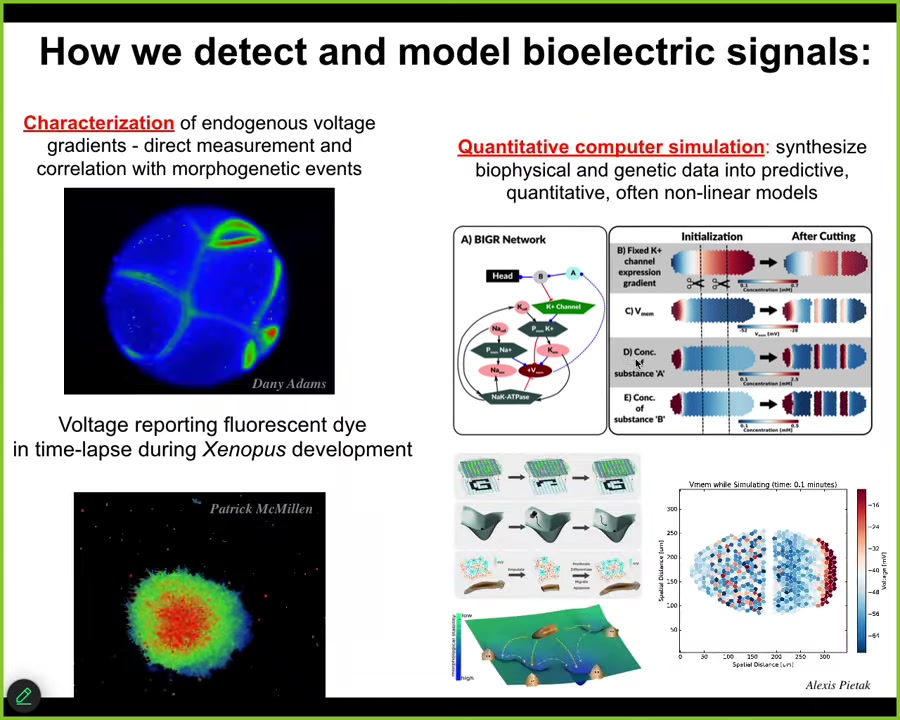

Slide 19/44 · 23m:17s

We've developed tools to read and write the electrical patterns that are driving this collective intelligence. Using voltage-sensitive fluorescent dyes and new technologies like fluorescent lifetime imaging, we can see all the electrical conversations the cells are having with each other. We make computational models of what's going on.

Slide 20/44 · 23m:40s

Here are some examples of this kind of thing in the real system. Here's a frog embryo putting its face together. Here's one frame from that video. This is a pre-pattern. We call it the electric face. It looks like a face. You can already tell. Here's where the eye is going to be. Here's where the mouth is going to be. Here are the placode structures. This electrical pattern is a subtle scaffold that controls the gene expression that is going to regionalize the face and result in the normal craniofacial anatomy.

Not only is the bioelectrical pattern binding individual cells towards large-scale organ-level outcomes, but it does the same thing on a multi-embryo scale. For example, if I poke this embryo here, there's a wave, a calcium wave that within 30 seconds all these neighbors find out about it. You see the same thing here after I poke that one on the left: all the neighbors find out about it. Bioelectricity is a multi-scale system that allows collective dynamics.

Slide 21/44 · 24m:55s

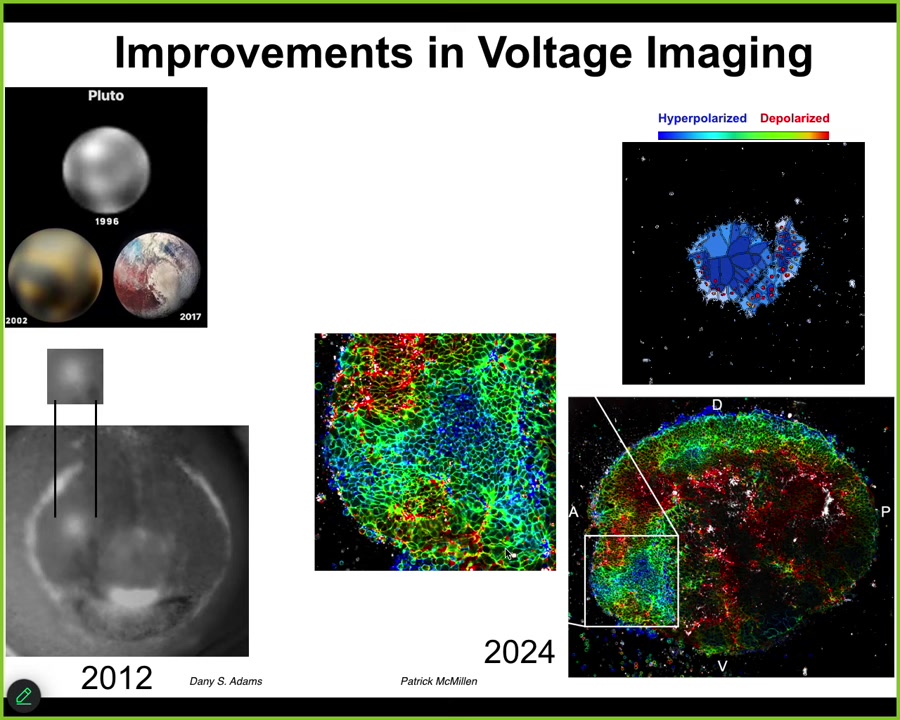

The improvements in this field have been remarkable. The example from astronomy: in 1996, this is what we had for Pluto. By 2002, it looked like this. And by 2017, it looked like this. You can see actual features.

The same thing is true. This image of the electric face was made in 2012 by Danny Adams. Here's what the eye spot looked like. Here's what it looks like now with modern FLIM imaging. This is the work of Patrick McMillan, who's revolutionized a lot of our ability to read these electrical signals. But reading them is just the first start.

Slide 22/44 · 25m:29s

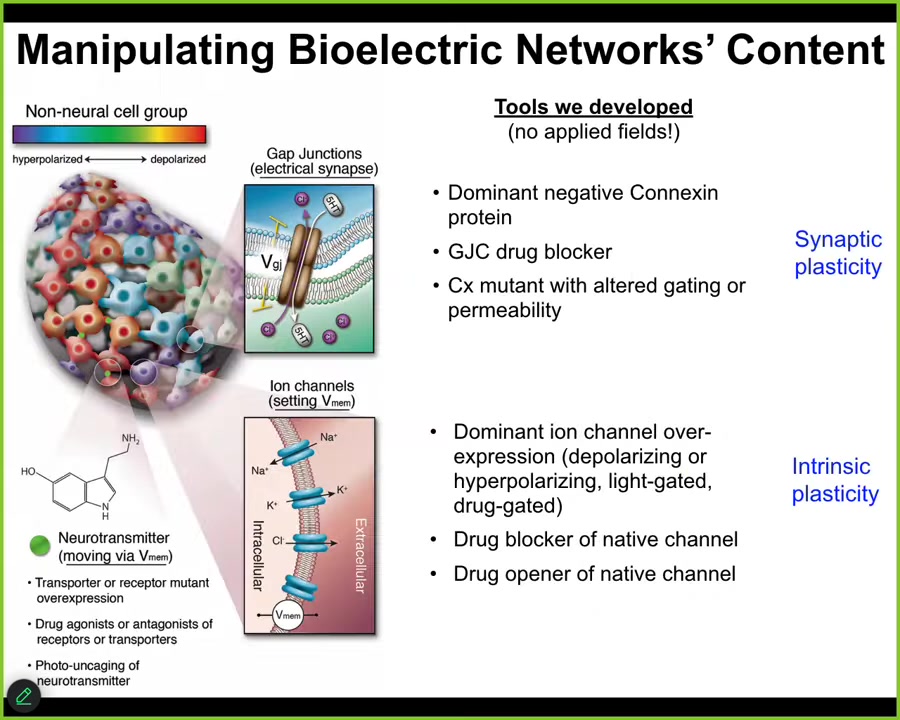

You really have to be able to rewrite the patterns. Not just listen to what the cellular collective is doing, but actually communicate with it and write patterns back into it.

We don't use any applied fields, so there are no waves, frequencies, electromagnetics, nothing like that. What we're doing is using the tools of neuroscience to hack the interface that cells normally use to control each other. We can control the gap junctional connectivity between cells, so that's a property of this tissue network. And we can turn channels on and off using traditional methods, using pharmacology, optogenetics. We can also make modifications in the channel structure. We control the synaptic plasticity and the intrinsic plasticity just like neuroscientists do. And now we can write functionally new messages into the system. I'm about to show you what happens.

Slide 23/44 · 26m:28s

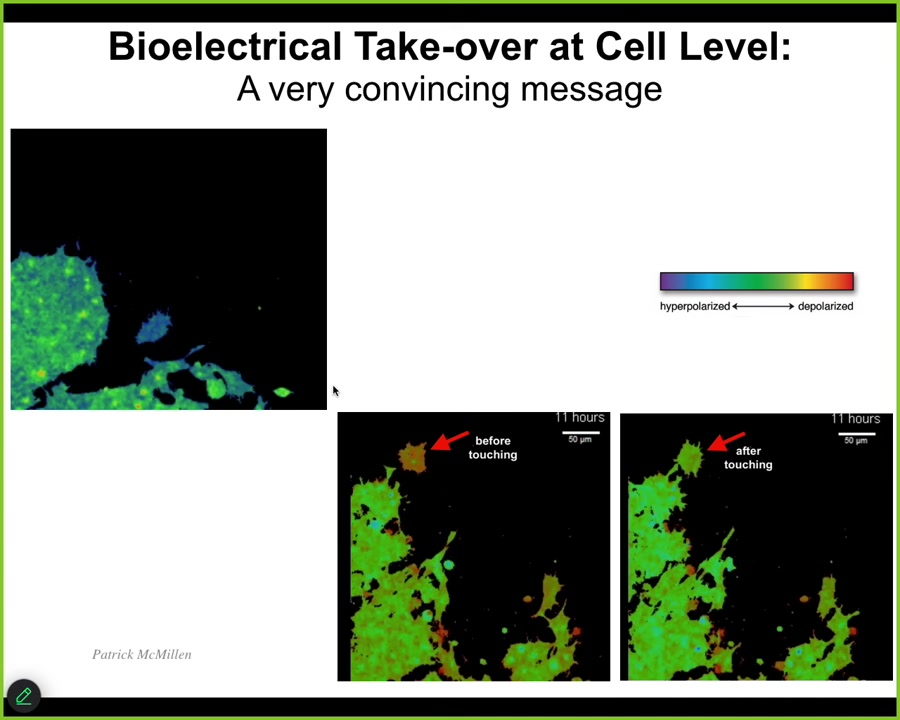

But the first thing I want to show you is some amazing work by Patrick, illustrating what it means when cells are controlling each other using this electrical interface. So I'm going to play this video in a second. But notice what happens. Here's a single cell. Here's a bunch of cells. The color represents voltage. So this is voltage imaging dye. The color is voltage. This cell has a very different voltage than the rest of them. And what's going to happen in this frame is it touches right here, barely touches. So you can see what happens. So here it is. It's crawling along, minding its own business. This guy reaches out and touches it, boom. And now it's got the same voltage. And once it does, it joins this collective. So you can see here the tiniest of contacts is able to basically take over and impose a new bioelectrical pattern with consequences for cell behavior. So this is the native version. This is what natively happens.

Slide 24/44 · 27m:16s

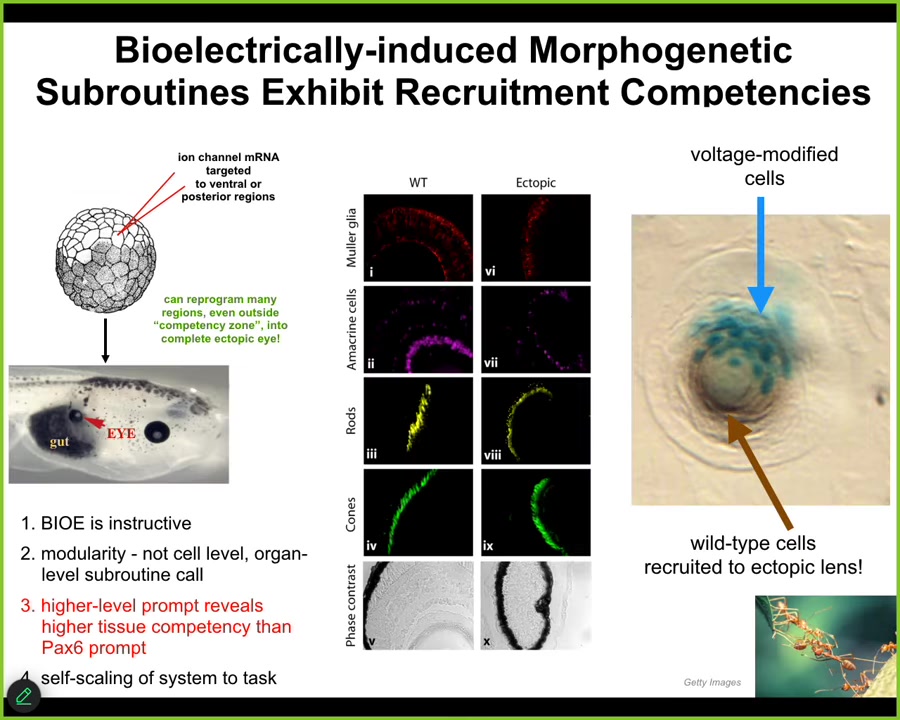

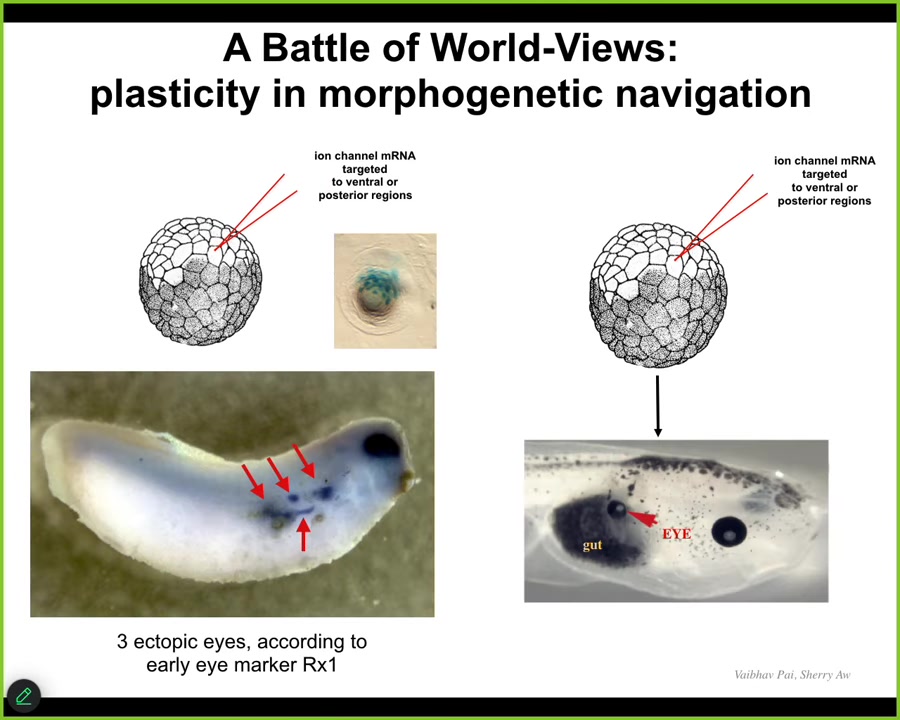

So let me show you what happens when we try to do the same trick. I showed you that the position of the native eyes in the head is set by this particular voltage pattern, the eye spot. What we can do is impose that pattern elsewhere in the body. We do that by injecting ion channel RNA, encoding potassium channels that will set up that same voltage spot. If you do that, let's say in the gut, the cells are perfectly happy to do what the message says and build an eye. If you take cross-sections through that eye, you find lens, optic nerve, all the things that belong inside an eye. It's a very well-formed eye.

Notice a few interesting properties here. First of all, I'm showing you that the bioelectric pattern is instructive. By giving a new message to the cells, I can get them to grow a brand new structure. This is not just making a defect. This is not just preventing some passive or permissive pathway, this is instructive for the organ. The second thing is it's incredibly modular. The eye is a very complex organ. We don't know how to build an eye. We don't know how to control all the gene expression that needs to change, all the position of the stem cells and all the different structures. We have no idea how to micromanage that. All we provide is a very high-level subroutine call that says build an eye here. The system does all the rest. This is the hallmark of a cognitive system because just as when I talk to you, I don't need to worry about all the molecular synapses in your brain doing the right thing so that you can understand me. You will do that yourself. All I need to do is to provide the stimulus via a very narrow linguistic interface. You will handle all the biochemistry of the brain to form memories and to have opinions about it.

Two more quick things. One is that, if you look at the developmental biology textbook, what it had said was that actually only the cells up here in the anterior neuroectoderm are competent to become an eye. That's because people have been prompting it with a PAX6 gene, which is called the master eye gene. It's true, in frog, the master eye gene only induces eyes up here. But that's because they were using the wrong prompt. It's not the cells that were not competent to make an eye. Actually, almost any cell in the body can make this eye. It's because we as engineers were using the wrong prompt. The competency limit was on our end, not on the system's end. So it becomes very important to understand how to communicate convincing messages to the system in order to overcome certain limitations.

The final thing, which will be important for the next slide, is this. If we take a section through one of these eyes, you often find that there are only a few cells that we actually targeted. The blue ones are the ones we injected. But all this other stuff was never injected by us. Instead, the blue cells recruited their neighbors to become part of this eye. Competency of the material itself — we didn't teach them to do that. We have no idea how to make them do that. They already do that. Once they become convinced that they need to build an eye, they can tell there's not enough of them and they recruit a bunch of their wild-type neighbors to help.

Slide 25/44 · 30m:15s

This is important for therapeutics: if you're going to try to change the goals of the cellular collective, you need to be convincing. You need to get buy-in of the system. This is not micromanagement. This is not rewiring. You have to get the system to take on the new goal. Often we fail at this.

Oftentimes when we inject embryos, this is the native eye. So you've got these four ectopic eye spots. This is gene expression for Rix1, which is a very early eye marker. This embryo is going to have four extra eyes.

Oftentimes, you get none or sometimes one, because the rest of the cells resist. There's a cancer suppression mechanism that says if I'm your neighbor and you have a weird voltage that is saying "be I," you're trying to recruit me, but I'm also going to try to recruit you to whatever we were doing before—skin, muscle, gut. I'm not just going to let you take me over.

Sometimes the one pattern wins, sometimes the native pattern wins. It's a battleground of models that the cells have about what should be located in this region. We know they know what it should be, like that example I showed you with a tail being grafted to the middle of the flank. The system has a very clear model of what the correct pattern is. If you're going to override that, you need to be convincing about it.

This is very important. Learning to speak the language that really activates these kinds of things is therapeutically what we're looking for.

Slide 26/44 · 31m:53s

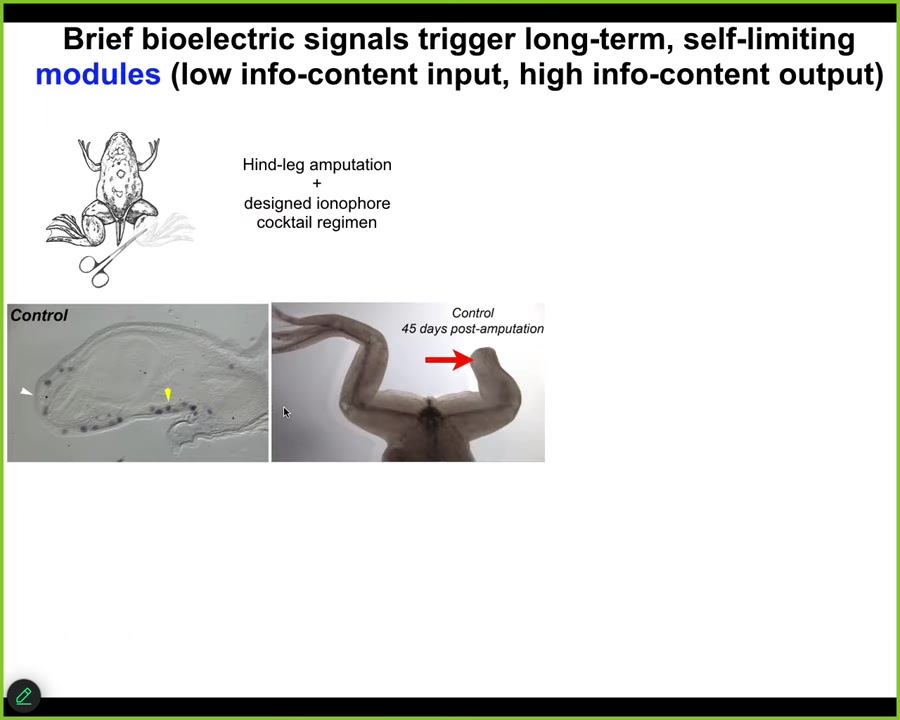

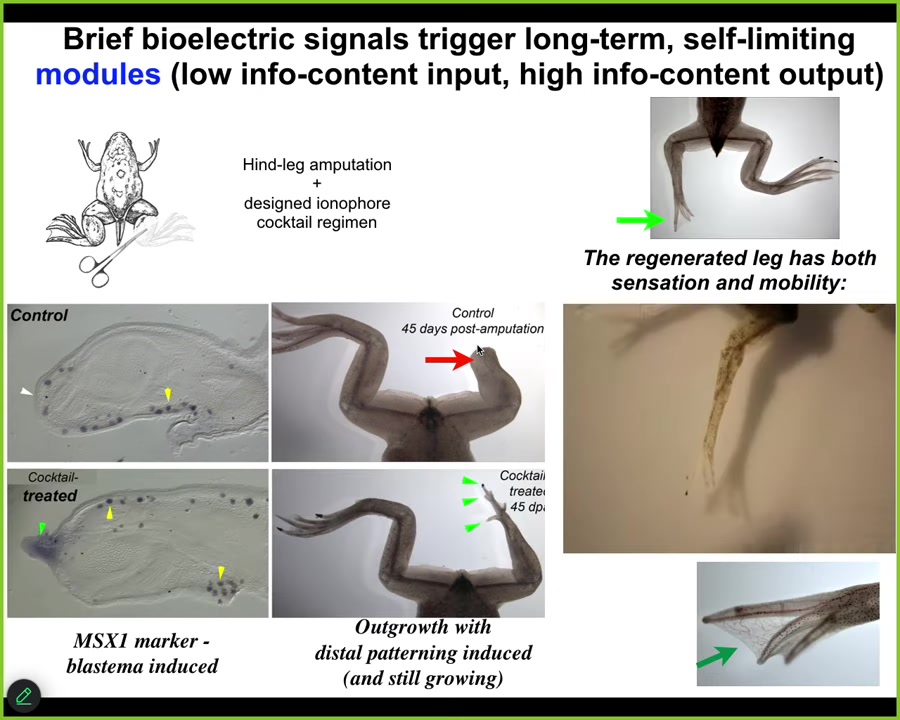

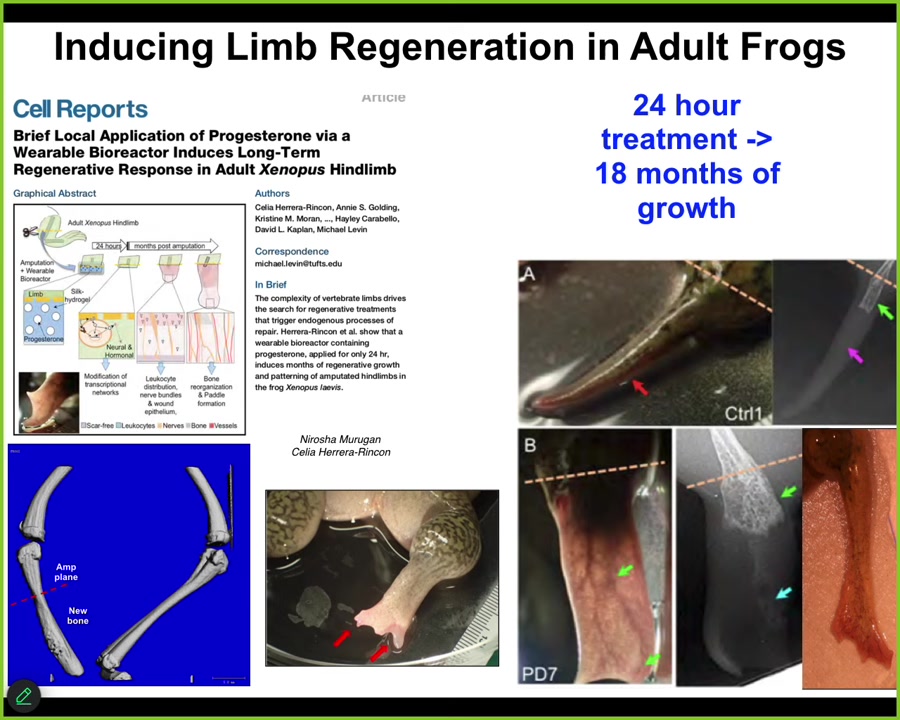

A couple of other examples in regeneration. Frogs, unlike salamanders, do not normally regenerate their legs as adults. Here, 45 days later, you normally get nothing. We created an ion-modifying cocktail that drives a message that says, go to the leg building path, not the scarring path.

Slide 27/44 · 32m:16s

Sure enough, it activates downstream pro-regenerative genes MSX1. Eventually, in 45 days, you've already got some toes, you've got a toenail, and a pretty respectable leg. It's got the right shape. It's touch sensitive, it's motile, it's functional.

Slide 28/44 · 32m:32s

One of the most amazing things about this is that the intervention, which we deliver by a wearable bioreactor, is only there for 24 hours. After you've given your message over 24 hours, you get 18 months, a year and a half of leg growth, during which time we don't touch it at all. This is not about micromanagement. This is not about telling the stem cells what to do. This is about convincing the tissue at the beginning to head down one particular region of anatomical space rather than another, and then we take our hands off the wheel. That is what we are looking for, is triggers. Triggers of complex downstream behavior, stimuli, not micromanagement.

I have to do a disclosure. A company called Morphoseuticals is a spin-off by David Kaplan and myself, where we're going to try to move this technology to mammals, hopefully someday humans, in building these wearable bioreactors to deliver the most convincing message that we can in the form of electroceutical cocktails sitting in the gel inside this bioreactor that is going to support the growth.

Slide 29/44 · 33m:32s

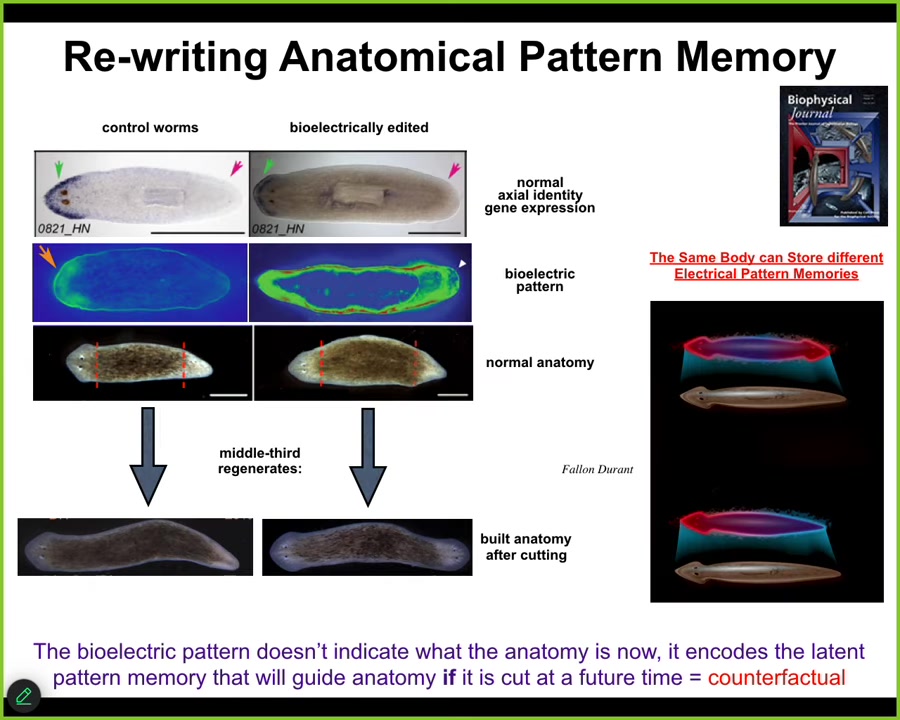

The next example I want to show you has to do with the ability to rewrite pattern memories. What I've shown you so far is the ability to hijack the electrical system to insert messages to change the bioelectrical system. I want to drill down on this example for a couple of minutes to show you that what we are actually doing is rewriting native memories.

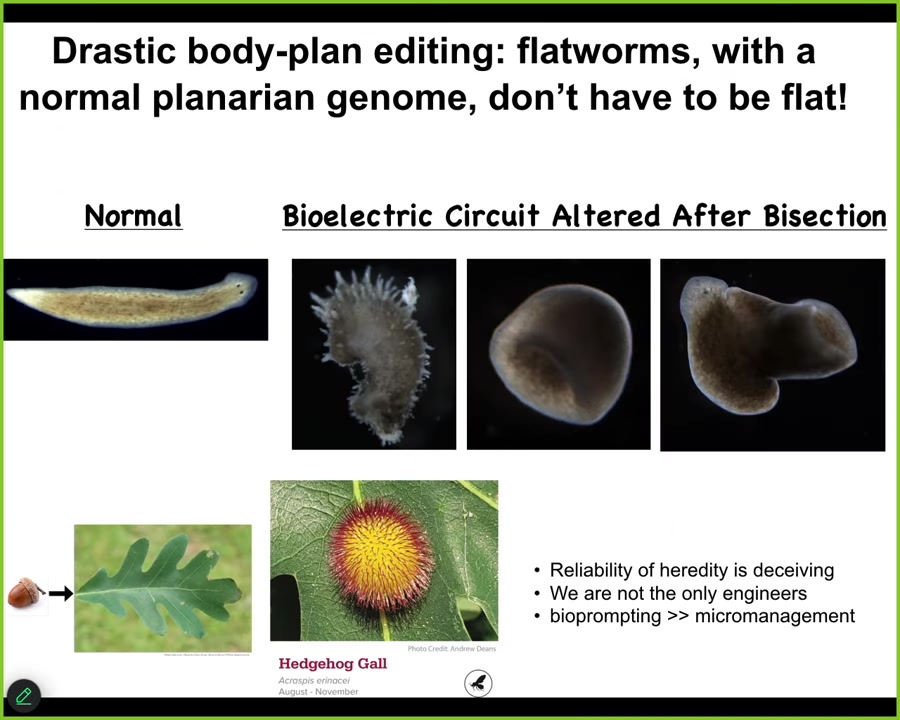

This animal is an amazing creature called the planarian. These flatworms have one head, one tail. We've been studying their properties of regeneration. In planarians, if you cut them into pieces, every piece gives rise to a worm. In fact, under normal circumstances, extremely reliably, you get worms with one head, one tail.

We asked, why is that? If you chop off the head and the tail, how does this middle piece know which wound gets a head and which wound gets a tail? Why don't they both get heads? It turns out that there's a voltage gradient, which we can see here, that, as we found out, says one head, one tail. When you do that, you very reliably get this.

What we were able to do, using drugs that modify native ion channels and pumps, is change this pattern. All it takes is about three hours. The whole process of regeneration takes about 8 to 10 days. In the first three hours, you can change this pattern to be like this: two heads here.

If you change this pattern, at first nothing happens. In an intact animal, they look perfectly normal: anatomically one head, one tail. Molecularly, the head marker is only in the head, not in the tail. You have no idea that anything is wrong with this animal until you cut him. If you cut him, taking this middle fragment, he will do what the pattern says, and he will build a two-headed form.

What's happening here, again, is that this map, this bioelectrical map, is not a map of this two-headed animal. It is a map of this anatomically normal one-headed animal. The internal model of what a correct planarian should look like, the goal state, the set point, the representation of correct anatomy, is encoded by this bioelectrical pattern, and it can be different than the anatomy. The anatomy is one-headed, but already the pattern encodes what I will do if I get injured in the future. In other words, a counterfactual memory.

These are the beginnings of this amazing thing that evolved into our brain's ability to do mental time travel, to imagine scenarios that are not true right now. This is, I think, the basal version of this, the very simple version in the somatic intelligence: the ability to hold two different models of what the future should look like in exactly the same body.

Slide 30/44 · 36m:12s

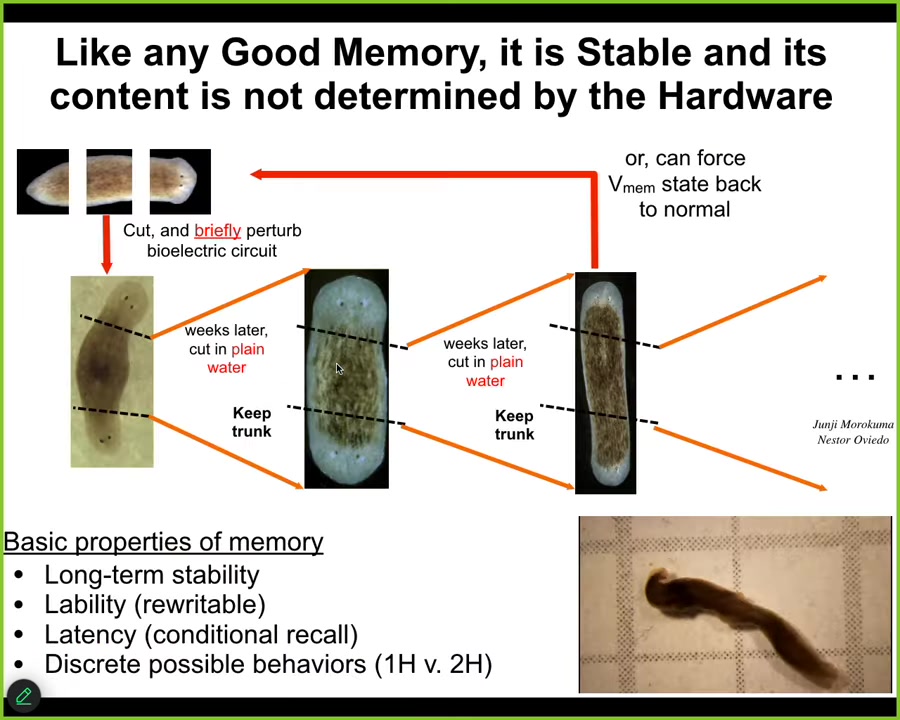

Now, I keep calling it a memory in part because it has all the properties of memory. It is rewritable, as I just showed you, but it's also long-term stable. So once we make these two-headed worms, we can continue to cut them again and again and again with no further treatment. You don't need to do anything else. These fragments will continue to generate two-headed animals as many times as you cut them because the memory circuit holds. Once you've changed the set point to say two-headed, that is what it will hold and it will generate new individuals like this that have the same commitment to a two-headed body plan. And here you can see, this is the video of these little guys moving around.

Slide 31/44 · 36m:54s

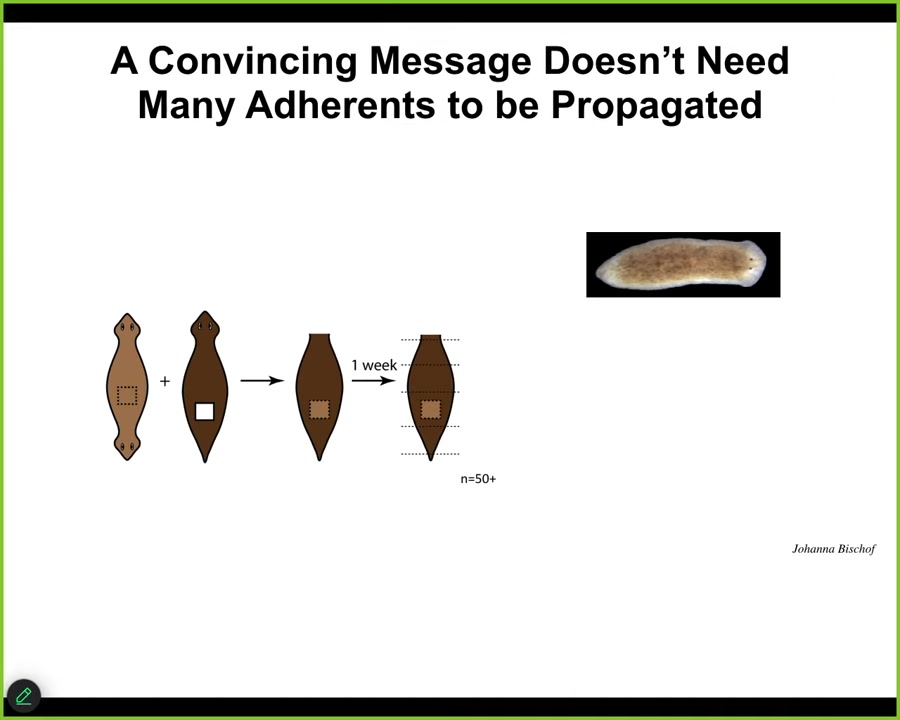

One more piece of data, and this is something that's actually not published yet, but I thought I would show it to you, the work of Johanna Bischoff, again, talking about this business of being convincing when you're trying to change the goal state of a collective system. What she did here was to see if we could transplant the two-headed memory.

So we took a piece of tissue from a two-headed worm, surgically transplanted it into a normal one-headed host. If you want to irradiate it in the meantime to kill all the stem cells, it's fine. It doesn't change the outcome at all. What happens is that a percentage of these different fragments will give rise to two-headed animals. So even up here, even here and here, which do not contain the implant at all, will give rise to two-headed animals.

Now, what's really interesting about this is that it's a tiny piece. So this piece believes it should be two-headed, but all these other cells have a perfectly normal pattern. Why are they listening to this one piece? And we still really don't understand very well what it is that makes certain messages convincing to their neighbors. How come in 20% of the animals, or close to 10% of the animals here, the message that's coming from here actually takes over these other pieces?

Slide 32/44 · 38m:22s

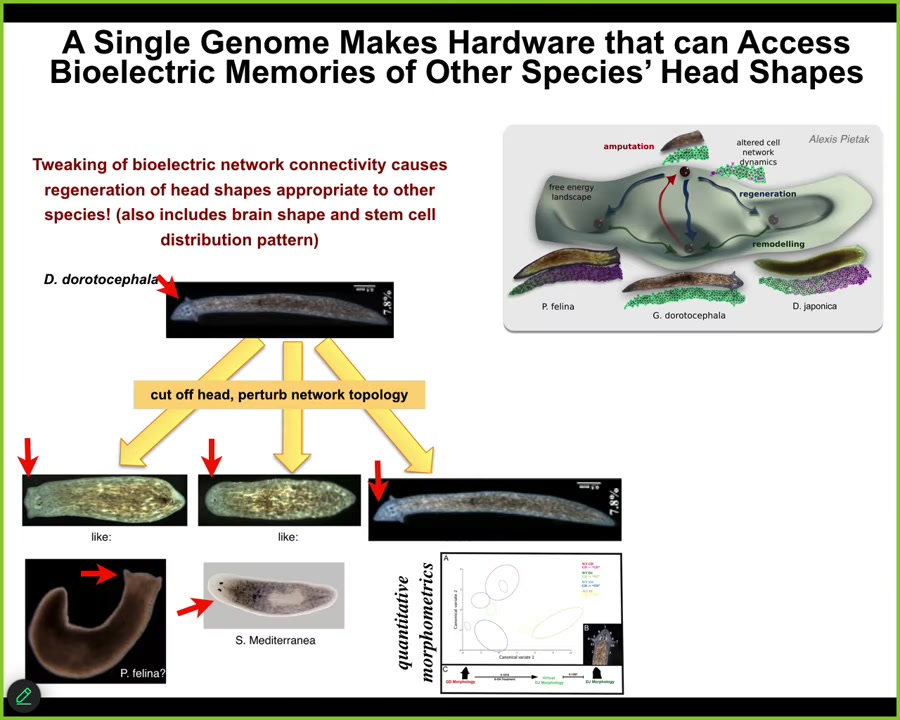

It's not just about the number of heads, it's also, for example, about head shape. So you can take this species that has a nice triangular head shape and cut off the head, perturb the electrical network topology, and they will happily make flat heads like a P. falina, they will make round heads like an S. mediterranean, and they can make the normal ones.

Not just the head shape, but the shape of the brain and the distribution of stem cells is just like these other species.

Between 100 and 150 million years of evolutionary distance, the same hardware, the standard genetically unmodified hardware, is just as happy to make two heads or heads belonging to other species. It can live in other attractors of this anatomical space. It can visit these other attractors where the other species live stably all the time.

Slide 33/44 · 39m:13s

You can even go further than the standard other species attractors, and we can make crazy looking things like cylindrical planaria and hybrid forms and these weird spiky things. So the morphospace is very large and very weird, and you can make all kinds of the same hardware is happy to build. Notice that we are not the only bioengineer. There is, for example, this wasp, which is a non-human bioengineer, and this process of acorns making oak leaves is incredibly reliable. People will say, well, this is what the oak genome knows how to do: make these leaves. But that's not all. If you know the right prompt, and that's what the wasp is doing: putting down some kind of prompt onto the tissue, they get the plant cells to build something completely different. Who would have even guessed that the cells that build this nice flat green thing are capable of building something amazing like this spiky and round and red and yellow? The material is highly competent, and we shouldn't let the reliability of the native outcome lull us into a false sense of stability against what can happen if you know what the right prompt is. It took this wasp millions of years, presumably, to figure out the right prompt by evolution. I hope we can do better.

And to that end, we're building quantitative predictive models so that we can actually infer interventions and study these dynamics in a way that allows us to provide highly convincing targeted signals that have very complex outcomes all across the layers of organization, from the molecular networks that specify ion channel expression all the way up to tissue dynamics and then eventually algorithmic representations of head and tail decisions.

Slide 34/44 · 41m:01s

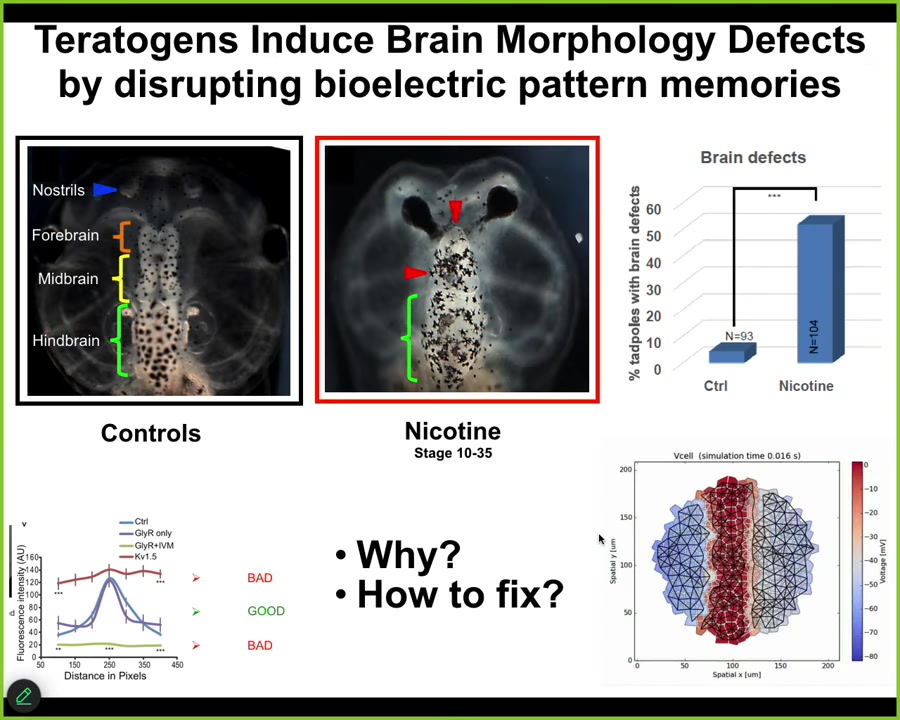

And in the last few minutes, I want to show you a quick example of a successful version of that, which is fixing birth defects. Here's a normal tadpole brain. Here's the forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain. You can see it has very specific structure. All sorts of teratogens, for example, nicotine and alcohol, will disrupt this normal structure. Here's a severe birth defect. And what we try to do is create a computational model of this process; this is the work of Alexis Pytaka and the Vipop Pi in my group, to be able to ask, what channels do we need to open and close to get back to the correct state?

Slide 35/44 · 41m:37s

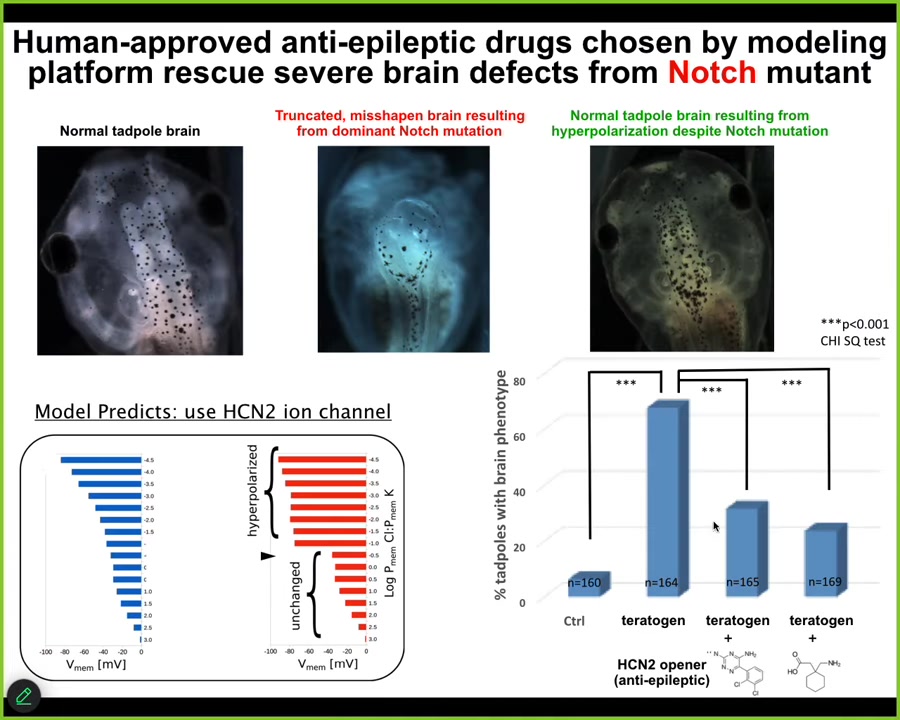

I'm going to show you one example, which I think is the most difficult and most profound.

Here is a normal tadpole brain. This is a brain of a tadpole bearing a dominant Notch mutation. Notch is a critical neurogenesis gene. When Notch is mutated, there is no forebrain. The hindbrain and midbrain are a bubble. They just lay there; they have no behavior, profoundly disabled animals.

We asked the model how the bioelectrics that dictate brain shape and structure change after this mutation, and how we get back to the correct pattern. The model predicted one particular channel called HCN2, that if we were to open it, has the property of sharpening electrical gradients. The model said that should get us back to normal. We did that either by introducing new HCN2 or using human-approved HCN2 openers, which happen to be anti-epileptic drugs in use in human patients. About half the animals had a perfectly normal brain. They had a normal brain structure, normal brain gene expression, and learning rates indistinguishable from controls. They got their IQs back, even though they were bearing this nasty Notch mutation.

At least in some cases, hardware defects can be ameliorated in software. Transient manipulations of the electrophysiology can overcome what are otherwise debilitating genetic diseases. It remains to be seen how broadly this works, but we now have a roadmap for achieving this using a computational model to tell you exactly which drugs to use.

Slide 36/44 · 43m:25s

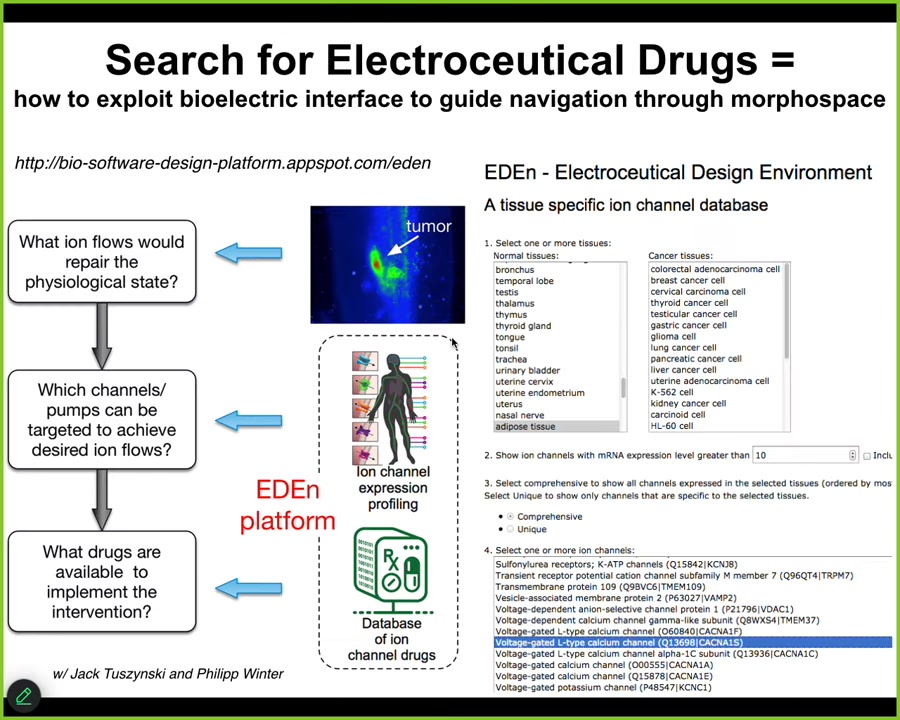

This is the kind of system that we're building, and you can play with an early version here, where you would start with data on the incorrect — a tumor state — and the correct pattern you would like it to have. The system would actually figure out which channels or pumps need to be targeted. That tells you exactly which drugs, and 20% of all drugs are ion channel drugs, so there is an incredibly large toolkit of electroceuticals out there. We're just waiting to be repurposed for these goals, and it will suggest which ones to use. This is a very bare bones system. Lots more needs to be added, but you can already see what's happening here.

Slide 37/44 · 44m:05s

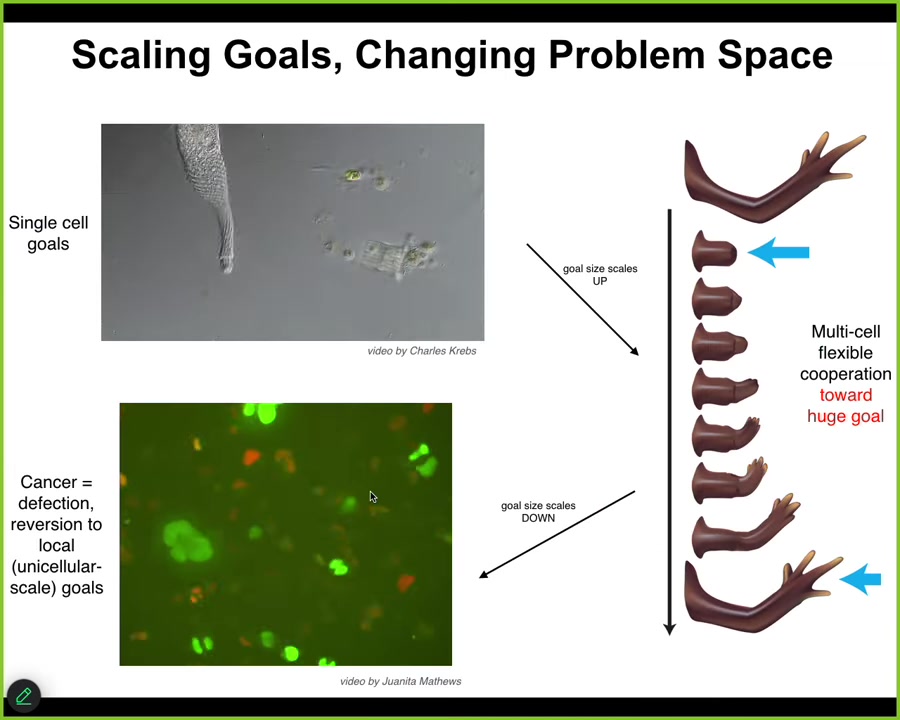

In the final chapter of the story, I want to mention this idea that we talked about reaching goals, and we talked about the ability of cells as a collective intelligence to do that in various spaces.

Another interesting thing about this is the plasticity of the size of the goals. Individual cells have tiny metabolic and physiological goals. During evolution and during development, groups of cells can maintain enormous grandiose goals like this construction project in anatomical space, where no individual cell knows what a finger is or how many fingers you're supposed to have, but the collective absolutely knows. You know that because of this homeostatic process.

That's a scale up of the system's intelligence in being able to pursue larger and more complex goals.

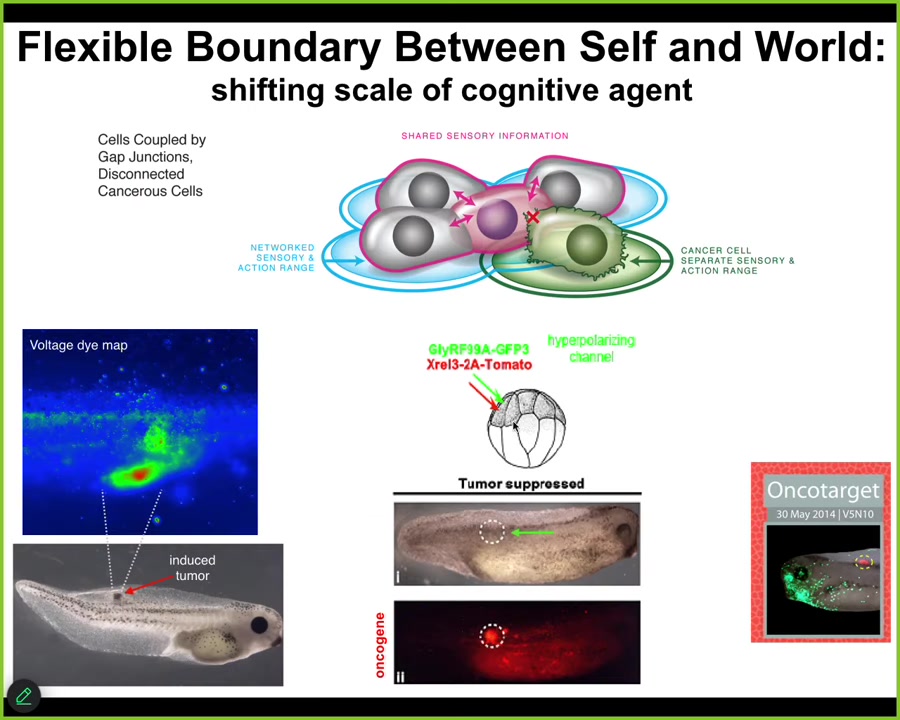

But that process has a failure mode. That failure mode is called cancer. What happens is that when individual cells disconnect electrically from the collective, and that can happen by the function of oncogenes, but also by stress and environmental toxins, they revert back to their unicellular amoeba-like state. They go back to their tiny goals. The border between self and world shrinks. Cancer cells are not more selfish than other cells. They have smaller selves because they treat the rest of the body as external environment. The boundary between self and world has now shrunk, instead of being one giant self pursuing giant goals; this is now back to their ancient lifestyle.

Slide 38/44 · 45m:39s

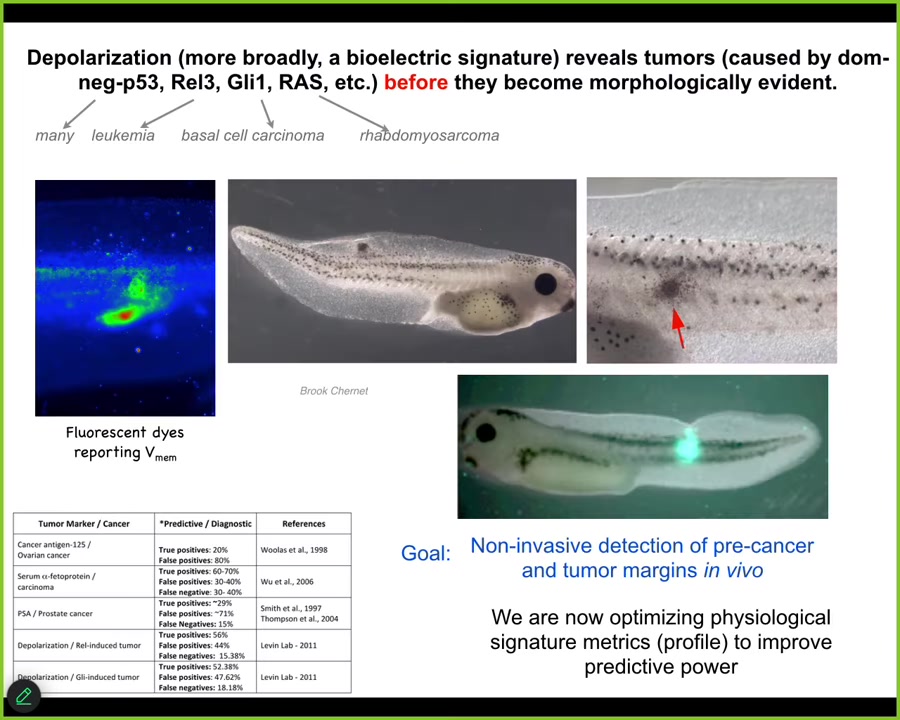

And so that suggests an interesting therapeutic for cancer. First detection modality. We can see the voltage change as these cells; this is a tadpole injected with a human oncogene. They will make tumors, they will metastasize. But long before any of that, you can already see the cells disconnecting. You can see where the tumor is going to be.

This is an artist's transition; this study doesn't exist yet, but this is what we're working on: augmented reality goggles so that when you're doing surgery with a voltage dye, you can immediately see the borders of the tumor, and here we better get this thing. You can immediately see what's going on.

Slide 39/44 · 46m:19s

But more than being able to diagnose, what we found is that if we forcibly reconnect these cells back to their collective, not kill them, not fix the genetics, we're using ion channels to reconnect them to their neighbors, you can get the individual cells to forget their tiny local selfish goals and go back to the large-scale morphogenetic set point.

So here, this is the same animal. The oncoprotein is blazingly expressed; it's all over the place, but there's no tumor. If you were to sequence the cells, you would make the wrong prediction. You would say there's the KRAS mutation; there's definitely going to be a tumor there.

But that's not what drives. It's not the genetics that drives. It's the physiological decision making. If these cells are connected to their neighbors, they will work on nice skin, nice muscle, as opposed to going off and making a metastatic tumor.

Slide 40/44 · 47m:10s

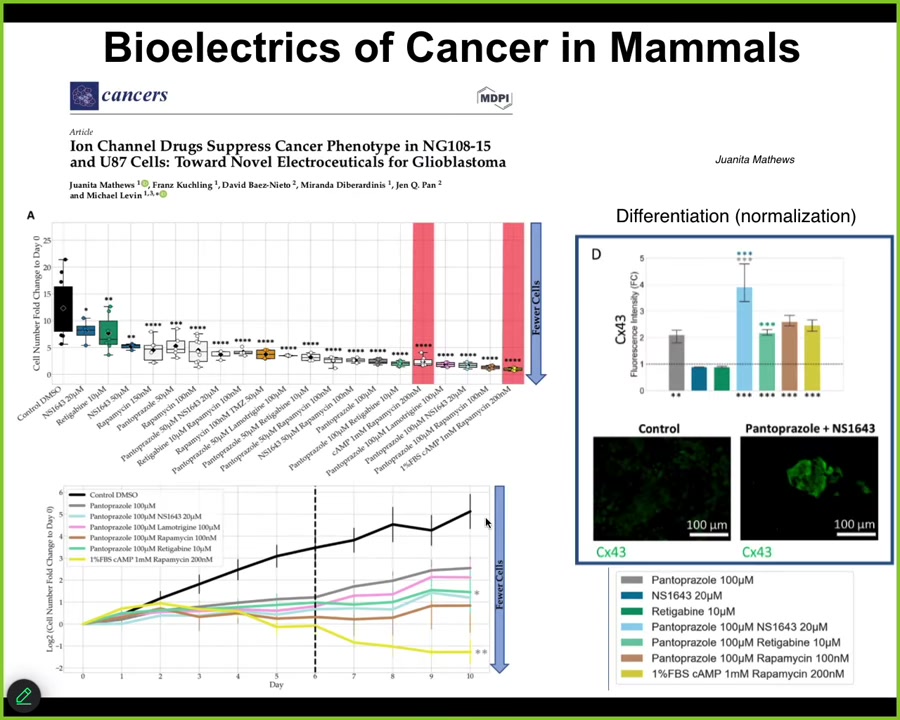

We are now moving all this stuff from frog to humans. This is Juanita's first paper in glioblastoma. We have some other things in colon cancer that are pre-printed and working their way through publication. We think that along with regeneration and birth defects, cancer is a major target of this, by developing tools to reconnect cells to their large-scale network that remembers adaptive goals as opposed to single-cell behavior.

Slide 41/44 · 47m:40s

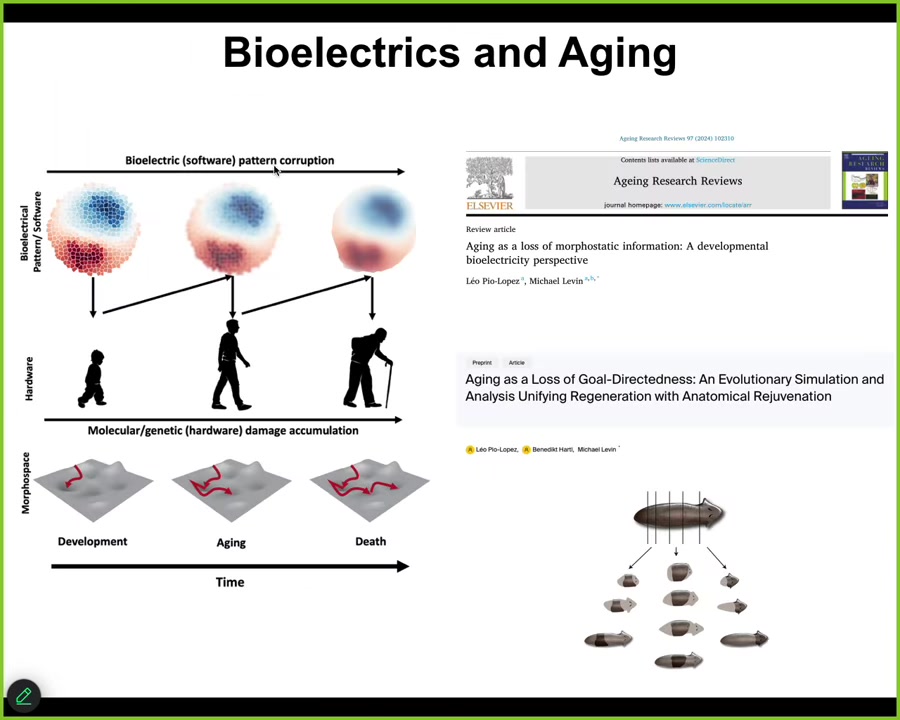

And the final thing to touch on is aging. So if you're interested in aging, we have a couple of papers looking at how these bioelectrical patterns actually change over time. There are a number of interesting things that happen to them that we think result in an aging phenotype. And we think this is quite actionable for longevity therapeutics: we can sharpen these patterns and, hopefully, delay and maybe even reverse aging.

Slide 42/44 · 48m:06s

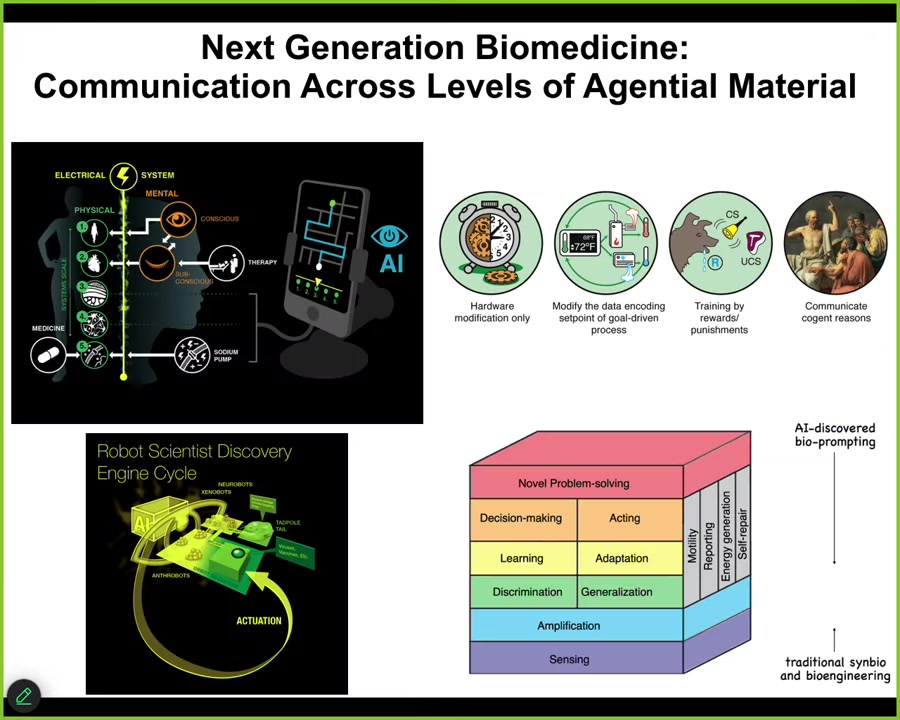

The most important thing we're seeing now is that bodies, biological bodies, are multi-scale, agential materials. There is problem solving, there are agendas, there is learning capacity, and there are defects in all of those properties that can come up at many levels of organization and that we need to learn to communicate with all of these different levels, not just the molecular level of receptors and transcription factors, but the higher levels that lie between the level accessible to the molecular medicine groups and the level accessible to the psychotherapists and psychoanalysts and so on, which is the high level of the personality. Everywhere in between are very important somatic intelligences that we now can target using techniques that are available at different levels of behavioral and cognitive sciences.

We're using AI as a translation interface to help us decode the messages and then talk back and forth to these other systems, including the development of some robot scientist platforms that do the experiments according to the various hypotheses formed by the AI and try to refine these policies so that we can make use of all of the capacities that are present in the material so that we don't have to micromanage them.

Slide 43/44 · 49m:27s

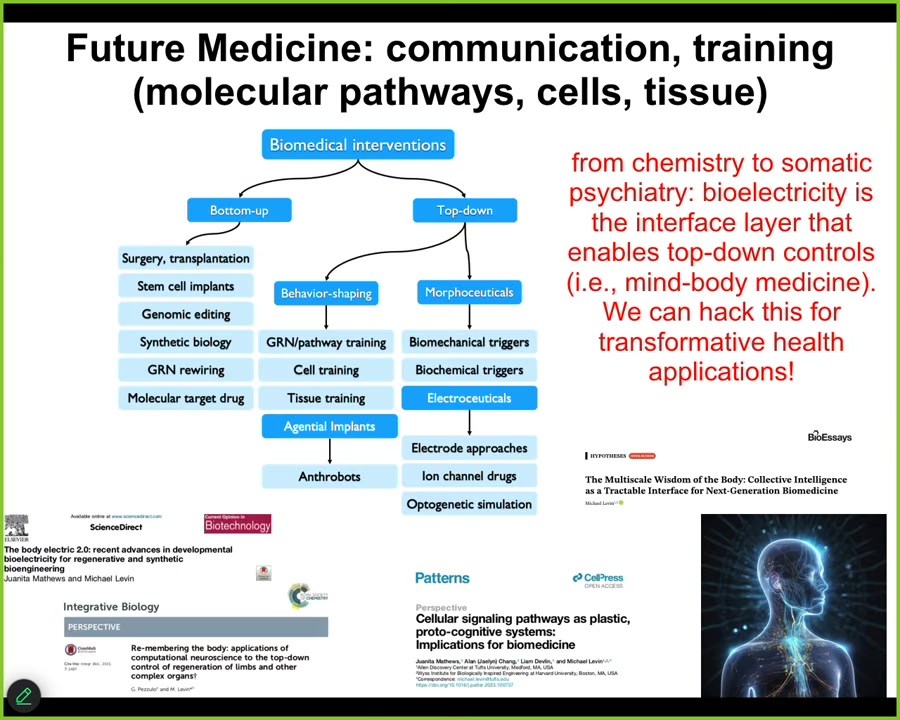

So where modern standard medicine is largely here, these bottom-up techniques focused on the hardware, there's a huge ocean of opportunity opening up in novel applications of top-down control methods. We didn't talk much about this, training cells and tissues to specific outcomes, gentle implants like anthrobots in the body that can help heal.

What I mainly talked about is electroceuticals, which are a subset of morphoceuticals, that is messages that can talk to the material about new shapes and new forms and functions, and all of the details are in these papers. The bottom line is that I think future medicine is going to look a lot more like a kind of psychiatry than it's going to look like chemistry. The bioelectrical interface is critical to show us how to do that. There are no doubt other interfaces, but the bioelectric one is really powerful. And I think we can hack it for some transformative applications in health.

Slide 44/44 · 50m:29s

I'll stop here and thank the postdocs and the students who did the various work that I showed you today. Lots of collaborators that work with us and some amazing technical support. All the foundations of different kinds that funded us.

Three disclosures: three companies that have spun out of our lab are funding some of this work. As always, most of the credit goes to the model systems that actually do all the hard work and teach us about these things. Thank you very much.