Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a ~45 minute talk given at the Imagining Summit (https://www.artificiality.world/the-imagining-summit/) on Diverse Intelligence and synthbiosis, approaching those topics via communication with cellular collectives in the context of regenerative medicine. The newer material is at the end.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Overview and conceptual framing

(06:24) Persuadability and interaction spectrum

(09:57) Scaling minds from cells

(14:11) Development, individuation and patterning

(18:22) Anatomical compiler and regeneration

(26:03) Bioelectric patterning and control

(33:38) Synthetic life and agency

(41:20) Agents as dynamic patterns

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/45 · 00m:00s

I'm sorry I can't be there in person. If anybody is interested in the details, the dataset, software, published papers, everything is at this site. My personal thoughts on what it all means are here.

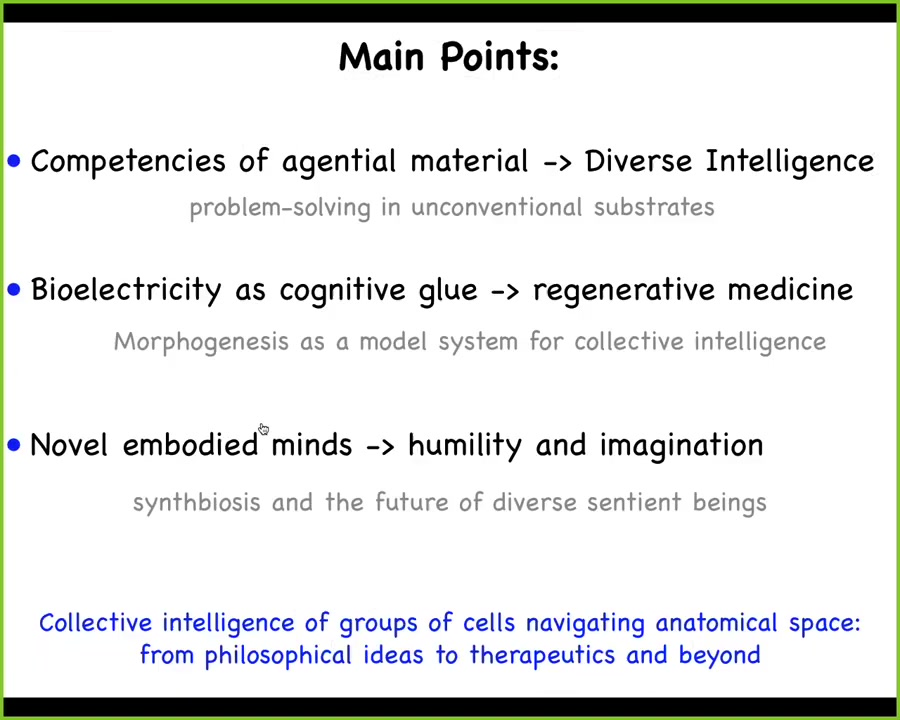

Slide 2/45 · 00m:13s

The main points that I'd like to transmit today are these. First, I'm going to talk about agential materials and the field of diverse intelligence or problem solving and unconventional substrates. I'm going to try to widen our expectations of what active agents and what intelligence looks like. I'm going to use a specific example in regenerative medicine of cellular collectives functioning as a large-scale intelligence that navigates anatomical space. I'm going to be talking about bioelectricity as cognitive glue that binds these subunits together towards common purpose. All of this is to show you an example of being able to recognize, communicate with, and actively engage with a novel type of intelligence that we're not used to dealing with.

It has many applications for regenerative medicine, which I'll show you, but in particular it serves as an example of what the practical benefits are of some of the ideas that we're talking about. Towards the end, I'm going to discuss some novel embodied minds. I'm going to show you a couple and talk about a few that are impending for all of us. We'll talk a little bit about this notion of synthbiosis and the future of living positively with diverse sentient beings.

Altogether, the whole talk, boiled down to one sentence, is that we can use the collective intelligence of cell groups, navigating the space of anatomical possibilities, to show us how you can move certain philosophical ideas forward to therapeutics and then to some broader issues beyond.

Slide 3/45 · 01m:46s

This is a very, very well-known classic painting. This is Adam naming the animals in the Garden of Eden. This is a conventional view with which most of us arrive at these questions.

There is something profoundly wrong here, but also something very deeply correct. I want to talk about those. What I think is wrong here is that by looking at this, you get the idea that what we're faced with is a set of discrete natural kinds. There are specific animals. We all know where they are, what the difference among them is. Here's Adam. He's able to count them. He's able to point to them. He's significantly different from them. He's a different kind of creature. Those are the things I think are going to need to change, and I'll show you why.

But the thing that's quite deep and correct about this is that in these old traditions, naming something meant that you've understood their true nature. The idea of giving something a name or discovering its true name meant that you've understood something very fundamental about what it is and how you're going to relate to it. This is profound because, as individuals and as a society, we are going to have to be able to name, in this sense, a very wide range of highly diverse embodied minds.

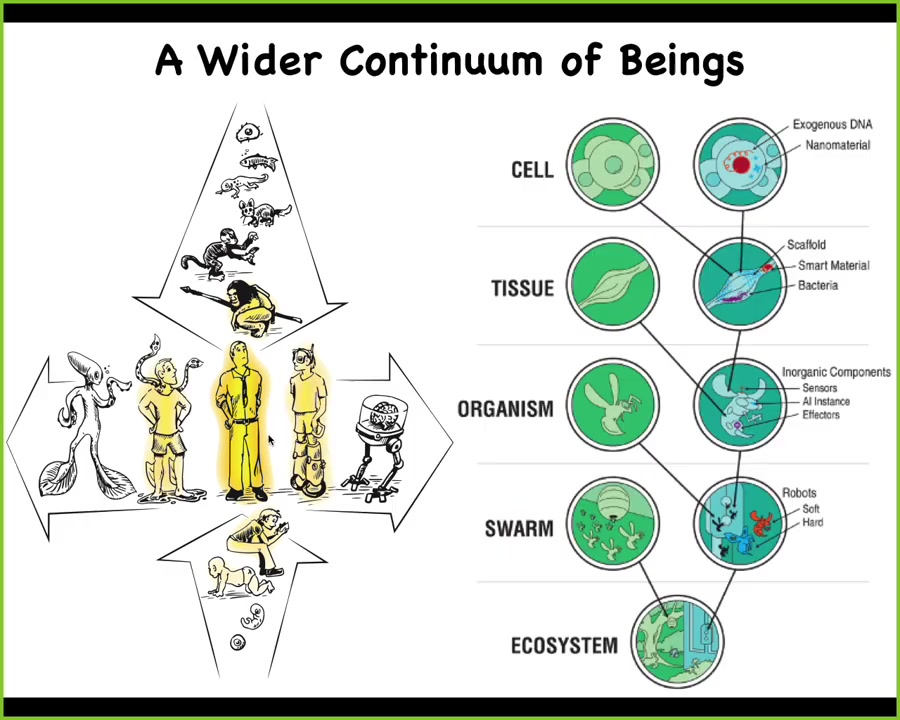

Slide 4/45 · 03m:01s

Ever since we've understood evolution and development, we now know that what we're looking at is a continuum of beings.

Each of us was a single cell, both on an evolutionary time scale and a developmental time scale, and whatever philosophers might say about a human and the kinds of things that humans have—intelligence, goals, purpose, responsibilities, moral value—these are not things that snap into focus in some sharp emergence, but are actually scaled up from properties of very different kinds of systems.

Neither developmental biology nor evolution offers any kind of a sharp phase transition at which you go from being one kind of system to something magical like this.

This gentle glow that surrounds the modern human actually spreads down into a spectrum.

Slide 5/45 · 03m:56s

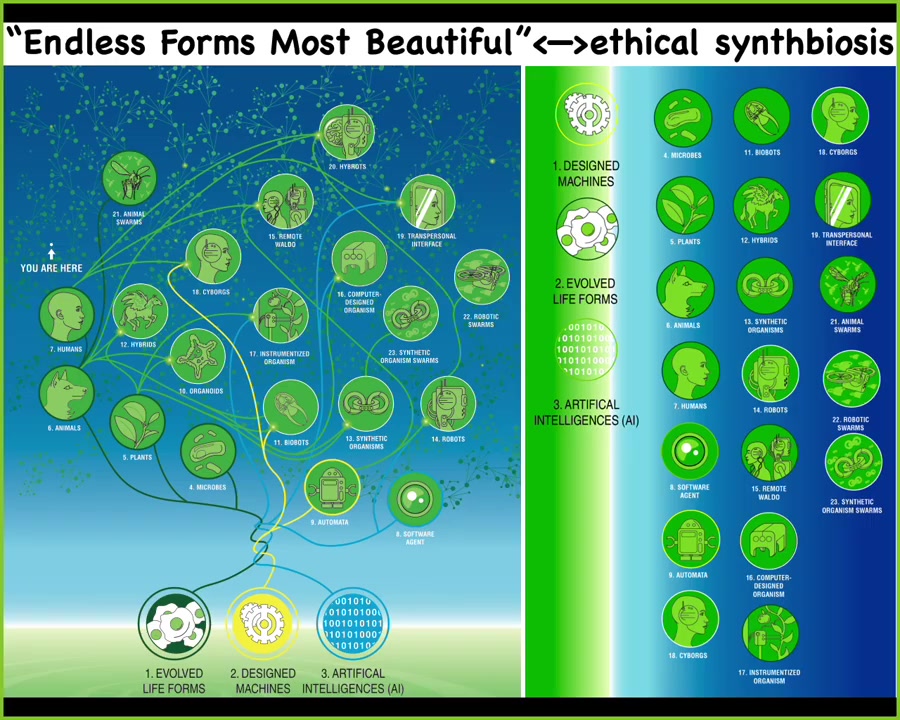

But now with the advent of bioengineering and other kinds of synthetic sciences, we now see that there's another continuum as well. We stand at the epicenter of this other continuum where, using changes to the biology but also combinations of technology, we can produce, and have and will increasingly produce, a wide range of novel beings with different kinds of embodiments and different kinds of cognitive structures.

Again, anything that you want to say about a human, and you might be tempted to try to distinguish that from a machine, for example, you're going to have to be able to say something about all of these kinds of beings. You're going to have to say how much of these changes and what it is that makes them different.

That's because biology is incredibly interoperable. Basically, at every level of biological organization, we can introduce engineered materials, engineered algorithms, making all kinds of chimeras and hybrids.

Slide 6/45 · 04m:59s

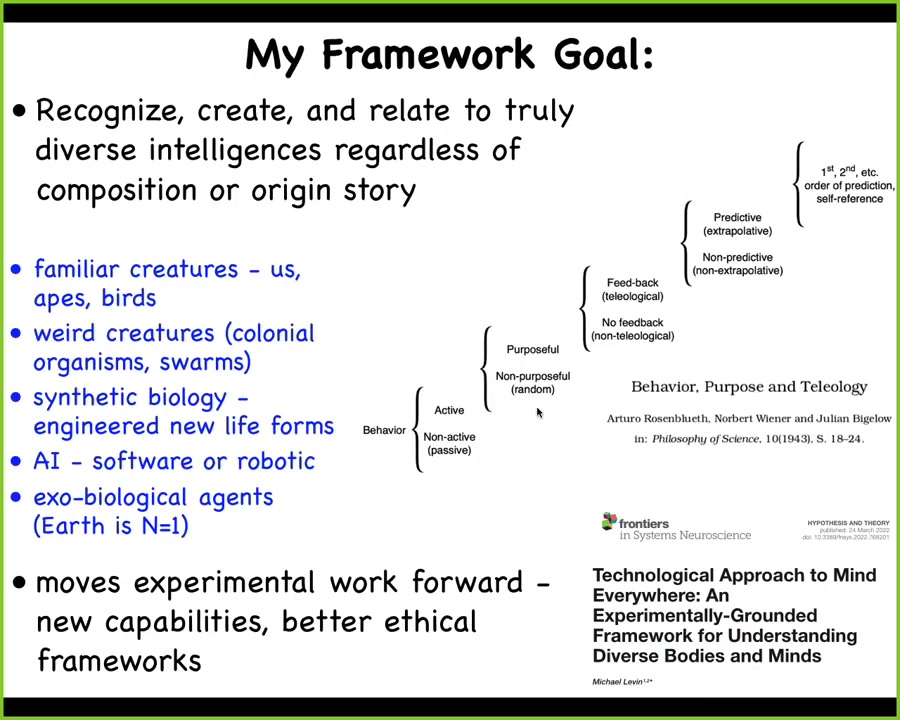

What I'm interested in is developing a framework that will let us recognize, create, and ethically relate to truly diverse intelligences, regardless of what they're made of or how they got here.

That means familiar creatures, primates, maybe a whale or an octopus, but also all kinds of unusual creatures: colonial organisms, swarms, unicellular life forms, engineered life, synthetic morphology, which I'll show you examples of, AI agents, either robotically embodied or pure software, and maybe someday even alien exobiological agents.

I'm certainly not the first person to try for something like this. Here's 1943: Rosenbluth, Wiener, and Bigelow tried to show a scale of how it is that you can get from purely passive matter through various cybernetic arrangements all the way up to this kind of human high-order metacognition.

This is the sort of thing I'm looking for, and it's described in great detail in this paper called "TAME" (Technological Approach to Mind Everywhere).

For me, what's really critical is that whatever frameworks we come up with, they have to be useful. They can't just be philosophy. They have to move experimental work forward. They have to lead to new discoveries and new capabilities, and to better ways to understand the ethics of increasingly complex life on this planet.

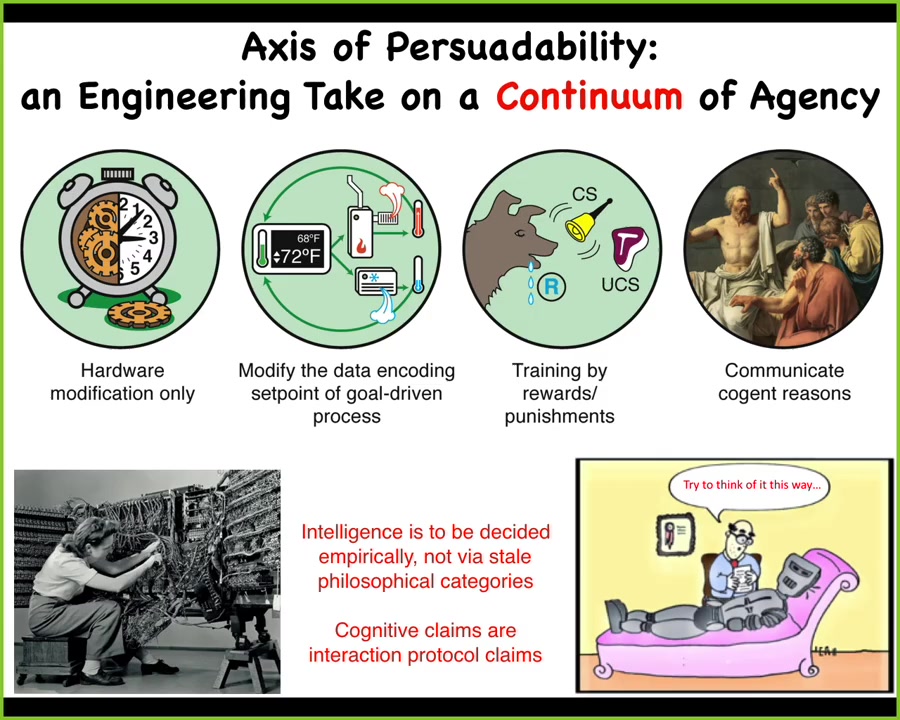

Slide 7/45 · 06m:23s

Central to this framework is this idea of an axis of persuadability. You'll note that it has some things on it on the same spectrum that you might have thought were quite different, which are machines, and then here are some humans.

The idea here is that all along the spectrum, what varies is the degree of autonomy and the tools that you might bring to relate to that system. For these machines, you're only going to be doing hardware rewiring. You cannot punish them. You cannot convince them of anything. Those are the tools that you bring.

Here, the tools of cybernetics and control theory start to be useful because you don't need to rewire your whole heating system to get your house to stay at a different temperature. You need to understand how the goal is encoded and then you can set the set point and the system will do what it needs to do. More autonomy and now a different way for you to relate to it.

Eventually you reach some systems where you really don't need to know much about the molecular mechanisms. Humans trained dogs and horses for thousands of years, knowing nothing about what was between their ears or what neuroscience was, because the system offers a completely different set of tools for interacting with it. Training, learning.

Up here, you get into communication with cogent arguments. The important thing is that you can't have feelings about where certain systems sit along this continuum. It's not one of these, "I'll know it when I see it." You have to do experiments.

We're not very good at figuring out what intelligent competencies something has until we study it and test it. My claim is that, first of all, anything you say about a new system, be it an AI, a language model, a robot, cells, tissues, if you're saying something about its level of intelligence and agency, you are, first of all, making an interaction protocol claim. You're saying, this is how I'm going to relate to that system using this set of approaches. Therefore, you yourself are taking an IQ test because that might be a good idea or a bad idea, depending on how things shake out.

This is experimental. We are not tied to ancient philosophical categories. We have to do experiments.

Slide 8/45 · 08m:38s

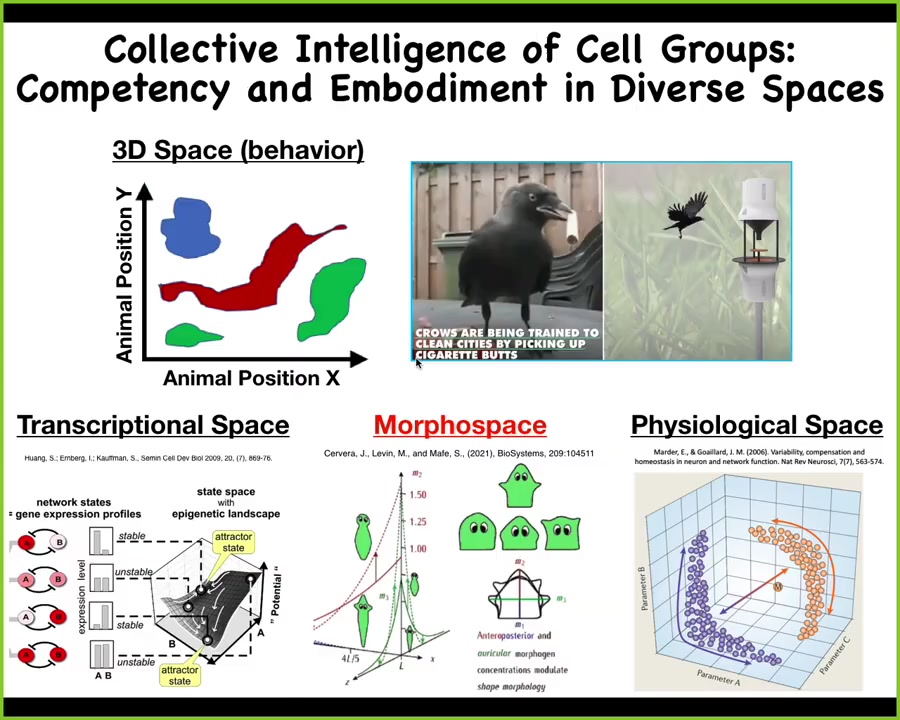

And that's because while we are pretty good at recognizing intelligence in navigating three-dimensional space — animals that are roughly medium-sized and move at medium time scales — we can sometimes see these things and recognize intelligence. But life explores, navigates, exploits, and suffers through all sorts of different other action spaces.

There are the spaces of possible gene expression, physiological state space, and anatomical configuration space. All of these spaces are equally real and challenging to the embodied minds that navigate and traverse those spaces.

Slide 9/45 · 09m:19s

That means that all of this is not just about humans, it is about all kinds of other observers that have to understand how these systems navigate through those spaces. That means parasites, conspecifics, the subunits of the system, greater systems within which they are embedded. All of these things are trying to understand where a given system fits along this continuum.

We have to get beyond our evolutionary firmware that makes it hard for us to think about intelligences in these other spaces that have much different scales and much different ways of navigating them.

Slide 10/45 · 09m:56s

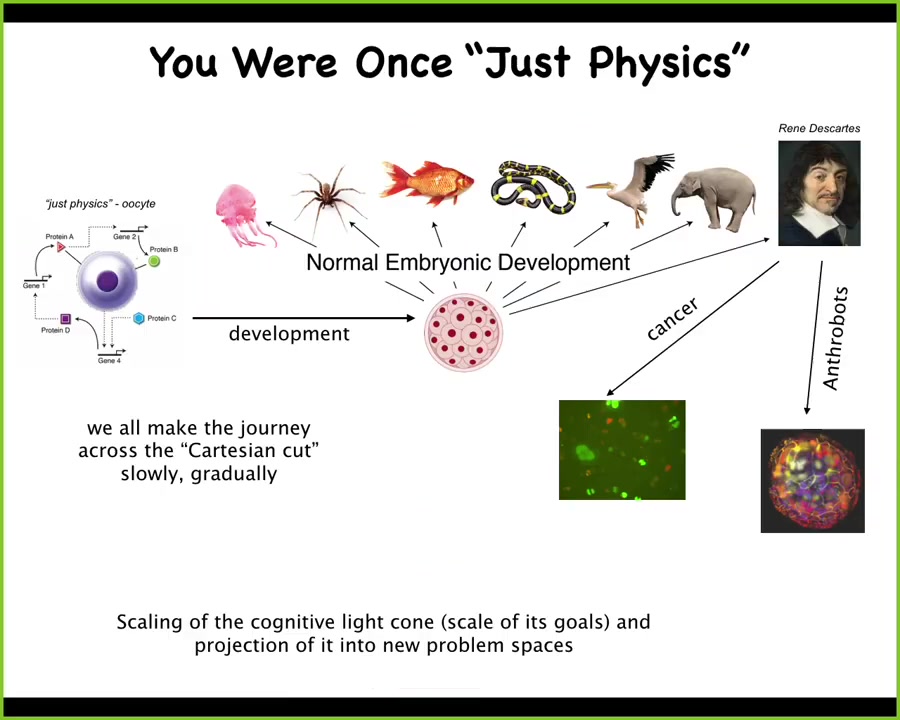

The thing that we all have to start with is the idea that we were all an acquiescent oocyte once. You might look at that and say this is a system that's perfectly describable by chemistry and physics. It's a little BLOB of chemicals. It doesn't have any of the things that we normally associate with intelligence or agency.

But this process is slow and gradual, and that system will eventually become something like this or even something like this that's going to make statements about not being a physical machine and having extra properties. This is the process that we need to understand. We need to understand the scaling of minds from very simple things that are amenable to chemistry and physics all the way up through systems that require all kinds of other new tools.

This is not the end of the story, as I'll show you, because there are ways that this simple subunit scales up to something enormous, but it can scale back down again and fall apart into pieces, or in fact transform into something completely different. While all of us make this journey across the so-called Cartesian cut, we now have to understand the scaling. How is it that the cognitive light cone of these simple systems inflates to something like this?

The first thing to realize is that we're all basically slowly amplified versions of much more simple biochemical systems, but at least we're a unified intelligence.

Slide 11/45 · 11m:23s

We have this nice brain. We enjoy a pretty unified perspective on the world. We know that we are a self. We're not a collective intelligence like ants and beehives. We're different. We're a truly unified intelligence.

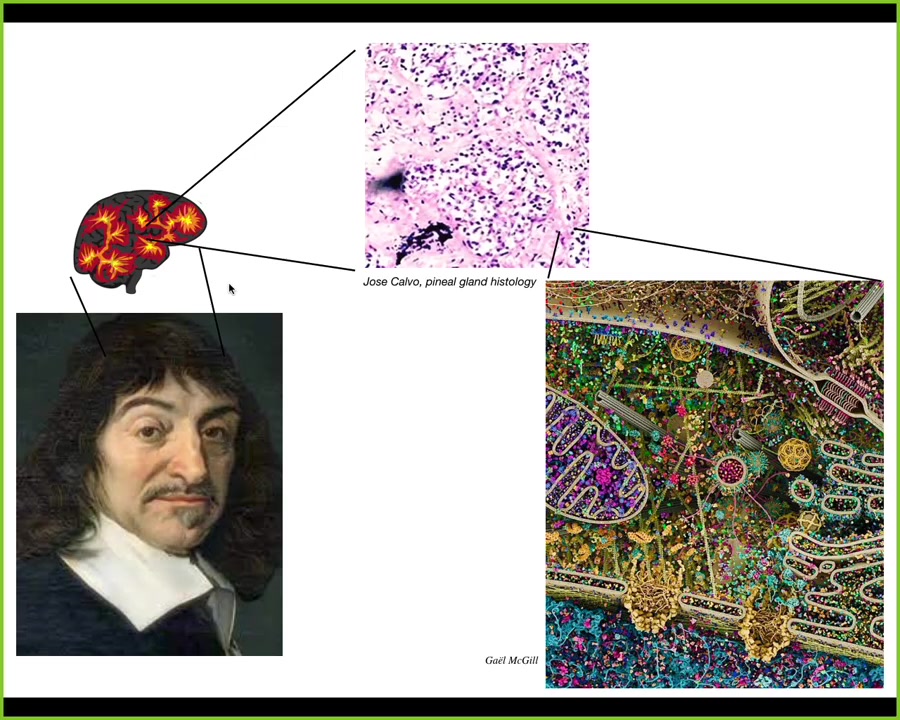

Slide 12/45 · 11m:38s

Descartes liked this idea and he liked the pineal gland inside the human brain because it was a singular organ and he felt that the unified human experience needed a single structure in the brain to correspond to. But if he had access to good microscopy, he would have found out that inside that pineal gland is all of this. There are tons of cells, and inside each of those cells there's all this. So there really isn't one of anything.

Slide 13/45 · 12m:05s

And that then reminds us that all intelligence is collective intelligence. We are all made of parts. This is a single cell. This is called a lacrimaria. You can see the kinds of building blocks that we are made of. They have their own agenda. They have their own competencies. It has a small cognitive light cone that extends in time and space around this tiny region. That is where its goals lie. It has physiological, metabolic, behavioral, and so on in these goals. But we need to understand how this scales up into the goals of much more grandiose agents.

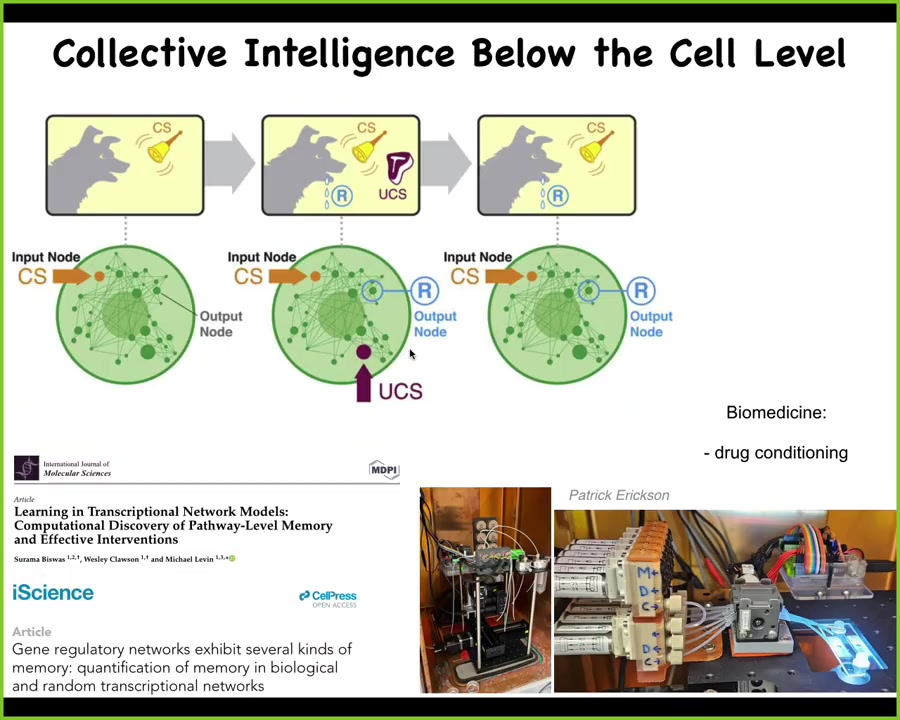

Slide 14/45 · 12m:40s

Even inside that cell, there are simple molecular networks that already can do things like Pavlovian conditioning. Intelligence does not — never mind the brain and the nervous system; we go back to the cell level, even before that, and point out that aspects of memory and learning are already here when you have a small network of chemicals interacting with each other.

That's already true, and we're trying to exploit that process here by developing applications in drug conditioning, where we can train cells to respond to drugs in particular ways, because they are already made of an agential material, not passive matter, not simple machines, but machines with learning capacity inside of every cell.

Slide 15/45 · 13m:28s

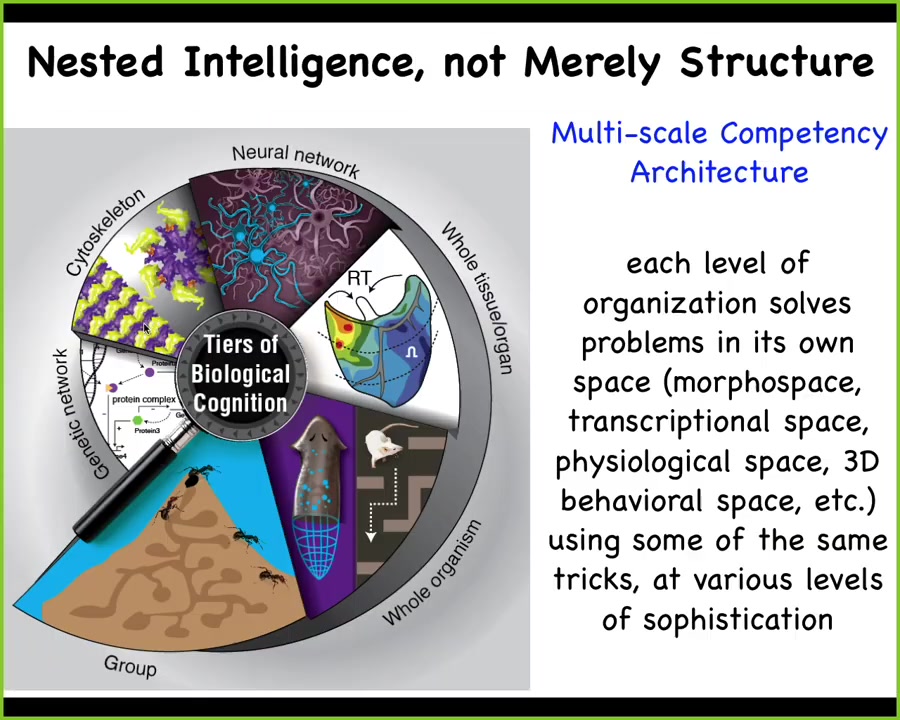

So now we see that evolution is using this amazing thing called a multi-scale competency architecture. Every level of organization in our bodies and beyond, to groups and collectives, has its own ability to solve problems in different spaces. They all have various competencies to navigate their spaces in an adaptive way. Intelligence does not merely show up at the level of brains and whole organisms. It is baked in all the way to the bottom through molecular networks.

Slide 16/45 · 13m:59s

Alan Turing was very interested in different types of embodiments of mind and machines that could think, and other ways to do the kinds of things that humans do. Problem-solving intelligence through reprogrammability—this is what he studied, but he wrote this paper, which was looking at how chemicals pull those cells together and generate order during embryonic development. Why would somebody who was interested in the intelligence of mathematics and reprogrammability and so on be looking at chemicals in development? I think that's because he realized a very profound truth, which is that the mechanisms that are involved in the self-creation of minds are, in fact, very similar to the mechanisms involved in the self-creation of bodies. We can learn from development, and we would have to, because that's where our minds arise, how it is that minds self-assemble. I think he was on to a great truth.

Slide 17/45 · 15m:00s

One of the things we can say is that if you look at an embryo, let's say a piece of a flat chicken or mammalian embryo, so you're looking down at this, you'll say, there's one embryo, it's an egg, and one embryo comes out of it. That's what normally comes out of it. But if you ask how many cells are in there, the fact is that if we make little scratches in this blastoderm—I used to do this as a grad student with duck embryos and use a little needle to put some scratches in it—what you end up with is little fragments that, before they heal together, each one of them decides that it is the embryo and self-organizes. You get twins and triplets and all kinds of things.

The real question of how many cells are inside an embryo could be anywhere from zero to probably half a dozen at least for the kinds of embryos that we know about. They have to do this amazing self-construction. They have to know where I end and the outside world, or other beings, begin. This is very much not set by the genetics. This reveals the self-construction that any living agent has to do to pull itself out of a background of disorder and establish its boundaries between itself and the outside world. This has many implications for issues of individuation, including split-brain patients and dissociative identity disorder.

What we're looking at here is the ability of an excitable medium in which the cells are going to act. What makes this one embryo is that they all share the same plan of what they are going to do—the path that they're going to take through anatomical space; they're all aligned and committed to the same story. That's what makes it one embryo. These little islands here are committed to slightly different stories because each one of them is going to do it. It's a matter of alignment to get to be one of these beings.

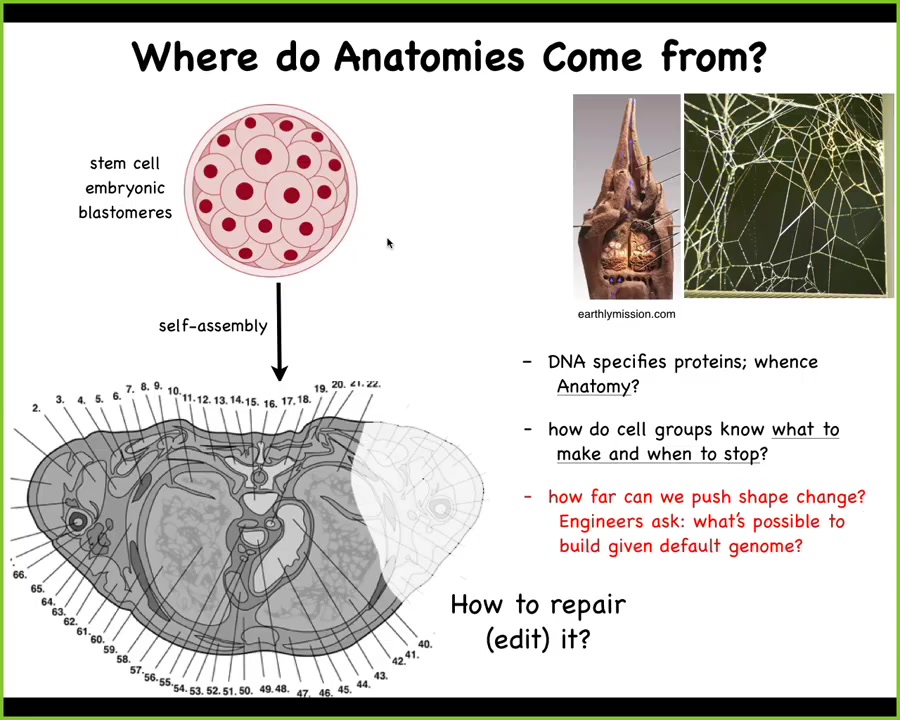

Slide 18/45 · 16m:56s

Let's ask, where does this information come from? Because we all start life like this, a collection of embryonic blastomeres. Here is a cross-section through a human torso. Where does this order come from? Look at this incredible pattern. I could just as easily have shown you brain architecture. It's an amazing pattern. Where does this come from? You might be tempted to say it's in the DNA, but we can read genomes now, and even long before that, we knew that the DNA doesn't directly set any of this, any more than the DNA of termites sets the structure of their colony, here, this building, or the DNA of spider webs indicates the specific construction of the spider web. What the DNA encodes is the hardware. It encodes the little proteins, the tiny, tiny hardware that every cell gets to have. After that, it's the physiology or the real-time working out of this physiological software that allows the cells to figure out what to build and when to stop. We're interested in understanding how to rebuild. If something is damaged, how do we convince these cells to rebuild? And as engineers, we want to ask, but what else is possible? What else can these cells build besides their native course that they take through anatomical space?

Slide 19/45 · 18m:14s

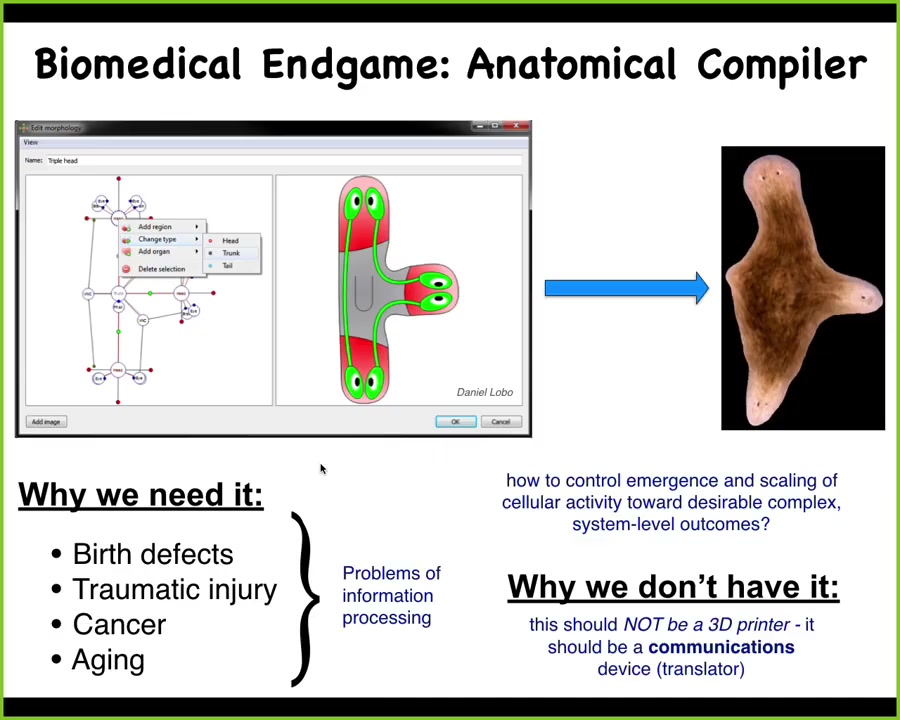

So imagine in the future, this is my vision of where this field is going. We want to get to something called an anatomical compiler.

What that means is that someday you will sit down in front of a computer system and you will draw the plant, animal, organ, biobot, whatever that you want. It can be a standard one for transplantation, or it can be something completely new. You should be able to draw anything you like. And if we had this, it would compile your target description into a set of stimuli that would have to be given to cells to get them to build exactly that. In this case, we've drawn a three-headed flatworm, and then here it is.

The idea is the end game for the field, but we don't have anything remotely like this. Now, why do we need it? If we had it, all of this would go away. This would be transformative regenerative medicine. There would be no more birth defects. You could regenerate after traumatic injury. You could reprogram cancer, defeat aging and degenerative disease. If we had a way to communicate to cells what it is that they should build, all of these things would be solved.

This anatomical compiler is not a 3D printer. It's not anything that tries to micromanage cell constructions onto a scaffold. It's a communications device. It's a translator. It tries to get your desired spec as the bioengineer. It tries to get your spec into the recorded set points that the cells are using to decide what they're going to do.

This is why we don't have this yet, despite the fact that genomics and biochemistry and molecular biology have been going back gangbusters for decades. It's because we have not yet understood how to communicate to cells.

Slide 20/45 · 19m:58s

So while the state-of-the-art is very good at this kind of stuff, different kinds of genes and proteins interacting with each other, we're still very far away from this. If you want to regenerate a limb or fix a birth defect or have a different structure.

That's because biomedicine has been largely focused at the hardware. Genomic editing, protein engineering, pathway rewiring, all those exciting things look like this. It's where computer science was in the 40s and 50s. If you're going to rewire it, you would have to physically get in there. If you wanted it to do something different, you would have to physically rewire it. That is the assumption that what we're dealing with is merely a complex machine. It's complex, but it's a machine. That's the standard assumption of molecular biology and a lot of biomedicine. But I think this is wrong and we're fundamentally dealing with an agential material. Once we really realize this and deploy the tools that are used in behavior science and cognitive neuroscience, we will then be able to do for medicine what computer science has become: an information technology where on your laptop, when you want to go from Microsoft Word to Photoshop, you don't get out your soldering iron and start rewiring, because we now understand that if your hardware is good enough, you can do way better than this. You have high-level ways of communicating with your device, and the biological hardware is absolutely good enough.

Slide 21/45 · 21m:18s

And so I want to show you some examples. We started out talking about intelligence and navigating the anatomical space. So what are the capabilities of the biological hardware? First of all, here's development. Here's a human egg that gives rise to a human body. This is an amazing rise in complexity, and it's very reliable, but that is not why I call it intelligence. It's not just because complexity rises. It's very easy to increase complexity with no intelligence. That's not it. It's because this process has some amazing problem-solving competencies.

One of those is that if you cut this early embryo in half, you don't get two half bodies, you get two perfectly normal monozygotic twins. As I showed you for those duck embryos a few minutes ago, the whole thing is a decision-making process of finding borders and navigating towards your anatomical goal state. It is not a mechanical hardwired step through a bunch of biochemical steps. That's not what's going on here. In this system, once you've cut it in half, each side realizes that a bunch of it is missing. If you boil down anatomical space into just two axes, this is the goal space corresponding to the goal states corresponding to the kind of a normal human target morphology. They can all get there from different starting positions, just avoiding certain local maxima and so on. That is the navigation I'm talking about.

Slide 22/45 · 22m:46s

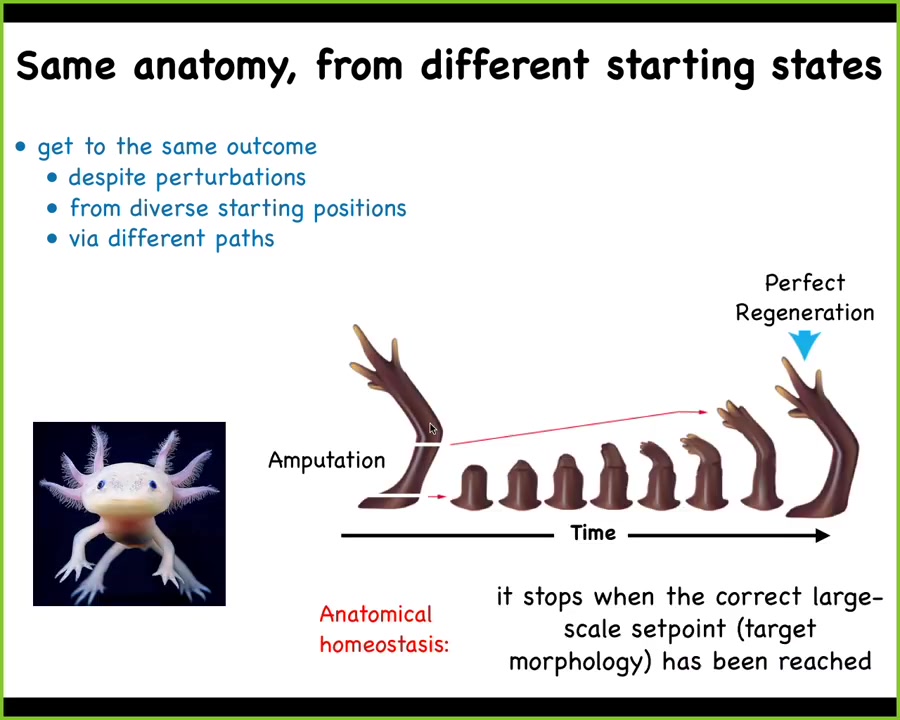

That process in some animals continues throughout their lifespan. This is a salamander, an amphibian called an axolotl. They regenerate their limbs, their eyes, their jaws, portions of the heart and brain, spinal cord. You can see that when they bite each other's legs off, no matter where it is amputated, the cells will very rapidly grow and eventually give you a perfect axolotl limb.

The most amazing thing about this regenerative capacity is that it stops. It stops when a correct salamander arm has been completed. What you're looking at here is anatomical homeostasis, the thermostat in your house, which continuously seeks to reduce error relative to a set point, so it has a memory, it has to remember what the correct point is. Here, what it's remembering is this particular structure. It's going to get the cells to keep going until that structure is rebuilt.

So it's the ability to get to the same point from different starting positions, even when you're deviated from it. You can think of all of development as just regeneration. Development is regenerating an entire body from just one cell. All of this is about error minimization and navigating that space to get to where you need to be.

Slide 23/45 · 24m:03s

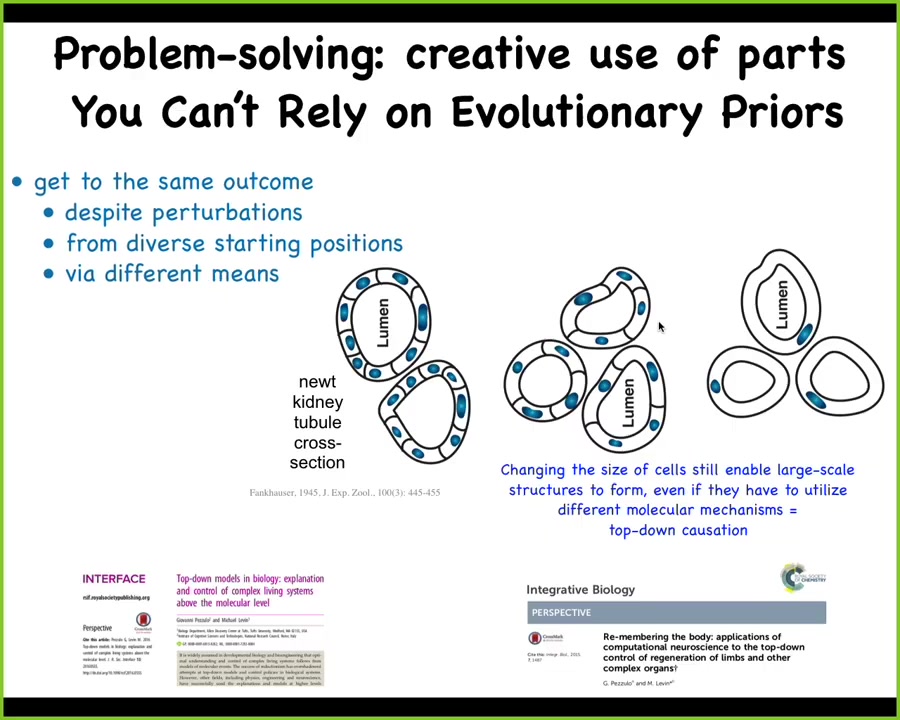

This is one of my favorite examples. This is remarkable. If you can take a newt and make sure that during the earliest steps of cleavage the DNA multiplies extra, so the cells become bigger to accommodate those extra copies of the genome. When the cells get bigger, the newt stays the same size. Taking a cross-section through the tubule, you then see that instead of 8 to 10 cells, there's now fewer of them that still make exactly the same structure. When you make newts that have so many copies of their genome that the cells become enormous, then one cell will wrap around itself and leave a hole in the middle. So what you're seeing here is this incredible problem-solving capacity where if you're a newt coming into the world, you can't count on how many copies of your genome you're going to have. You don't know what the size or the number of your cells are going to be. You have to figure out how to solve your problem and get to where you're going using the tools that you have.

This is one set of tools: cell-to-cell communication. This is cytoskeletal bending. It's using a completely different set of molecular steps to achieve your goal. This is textbook intelligence: using the tools you have to solve the problem under completely novel circumstances. So not being able to assume and not be able to take your evolutionary past literally is really critical for problem solving. And so now we see that what happens in the creation of bodies is this incredible problem solving capacity where you can do all sorts of things and they will readjust and get their goal. So how is that possible? What is doing all these computations? In particular, where is the memory stored? How do these things know what shape they're supposed to be?

Slide 24/45 · 25m:57s

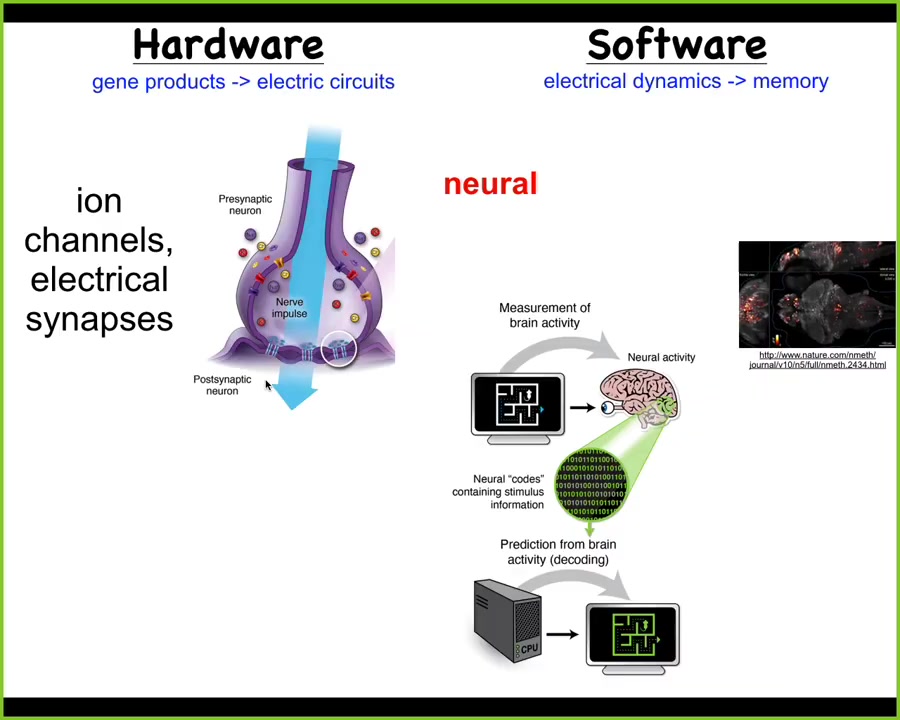

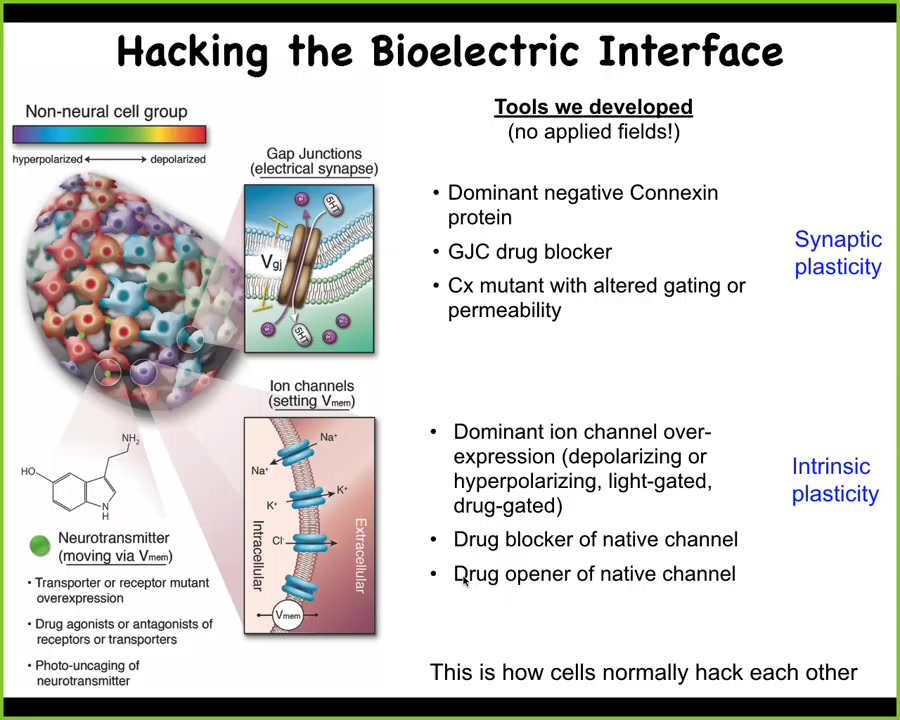

A couple of decades ago, we started, in my group, developing some of the first tools that were used to discover this.

The idea is we took our inspiration from the nervous system. In the brain and in the nervous system, which is a kind of the one non-controversial example of systems that have goals and have clever behaviors to pursue those goals. This is how it works. The hardware is relying on ion channels to set voltage states in these neurons. And these electrical voltage states do or don't get propagated to their neighbors through these electrical synapses. And so as a result, you get this very dynamic electrophysiological activity.

Here's a zebrafish brain recorded by this group showing what happens when the fish is thinking about whatever it is that fish think about. You could imagine, as people are now doing, this kind of project of neural decoding. Could we read and decode these physiological events to understand what are the memories, the preferences, the goals, the behavioral repertoire of this animal? All that cognitive content is here in this electrophysiology. That's what neuroscience is committed to.

Slide 25/45 · 27m:01s

This bioelectric system for processing information towards goal-directed activity is ancient. It was not new with brains. Every cell in your body has ion channels. Most of them have gap junctions that allow the networks to form. We can use these tools to do a non-neural decoding and ask: what are all these cells talking to each other about? What does the collective remember? What does it know that the individual cells don't know?

Slide 26/45 · 27m:32s

We developed some of the first tools to molecularly read and write this electrical information. Here it is using voltage-sensitive fluorescent dyes on a bunch of cells. You can see all the amazing electrical conversations that these cells are having. Some of them are fast, some of them are slow. This pattern, just like in the brain, encodes the collective processing of information in this group of cells. We do a lot of computational modeling to try to understand how that works.

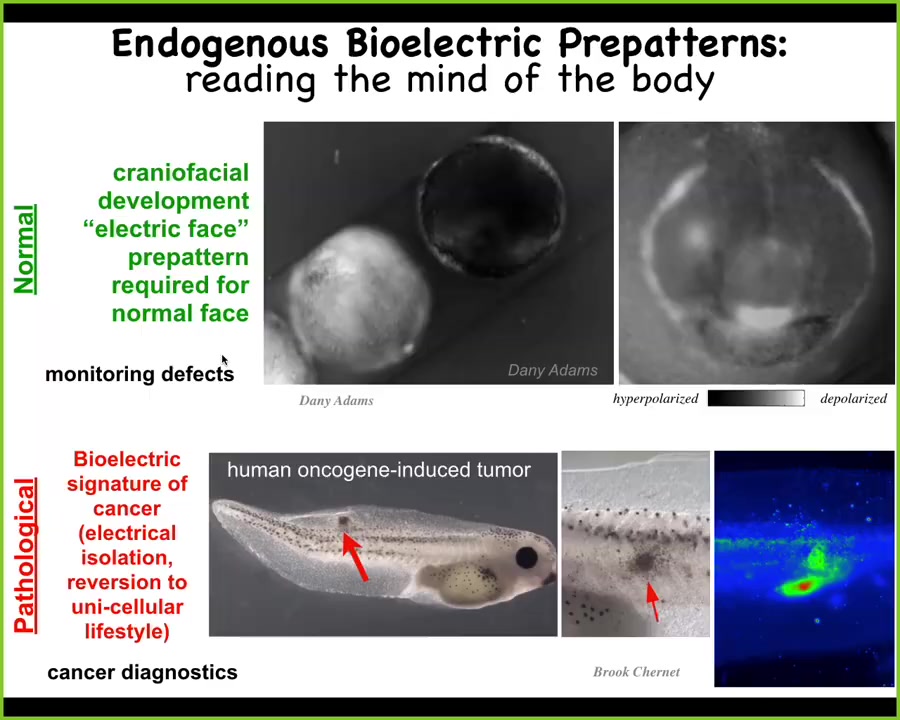

Slide 27/45 · 28m:00s

And let me show you some specific dynamic examples. Here is what we call the electric face. This is again a voltage-sensitive dye showing you what happens when a frog embryo is trying to put its face together. This is one frame from that video. What you see here, the thing looks like a face. This is why we call it an electric face. It's very easy to see that these bioelectric states, in fact, map to here's where the eye is going to go, here's where the mouth is going to go, here are the placodes out to the side. What we're seeing is the pre-pattern. We're seeing the informational scaffold that these cells are going to use to turn on specific genes and ultimately create a vertebrate face. As I'll show you in a minute, this pattern is essential to being able to reach that goal.

There are also patterns that are pathological. If we introduce a human oncogene into these tadpoles, the oncogene will make a tumor, but the way it does it is by disconnecting cells from the electrical network. Here you can see this is where the tumor is going to be, and there's a bunch of escapees, straggler cells here, that are going to disconnect from the network, roll back to their unicellular lifestyle, and treat the rest of the body as external environment. Again, that border between self and world, evolution scales it up. But during this cancer process, it can actually scale back down to the tiny cognitive light cones of individual cells, which then do not recognize that they're part of this large network. And that has many implications for therapeutics, which we are pursuing.

Slide 28/45 · 29m:28s

I've shown you how we detect these patterns, but more important than detecting is actually being able to write them so that we can show what happens. We don't use applied fields, electrodes, waves, frequencies, electromagnetics, nothing like that. What we do is manipulate the native interface that these cells are normally using to hack each other. Those are the ion channels in the membrane and these gap junctions that allow the cells to talk to each other. We use all the tools of neuroscience, which are pharmacology, optogenetics, and other tools, to control the electric state of these cells.

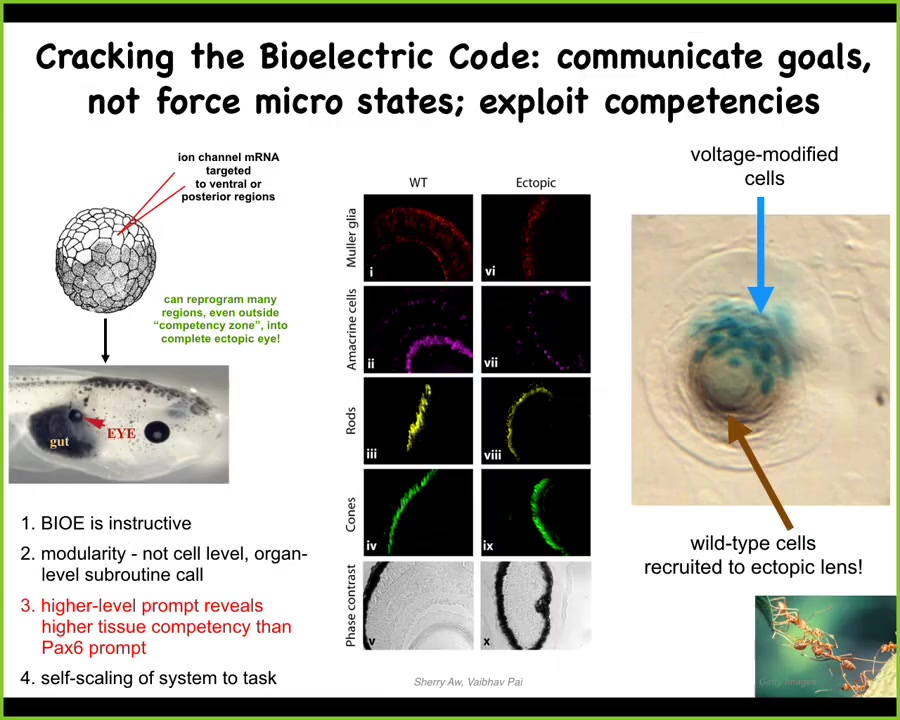

Now the million dollar question. Having posited that this electrical connectivity is the glue, much like in the brain, it is the glue that binds individual cells together into these grandiose pattern memories of making limbs and eyes and brains and so on, what actually happens when we perturb these pattern memories? Can we test this idea? How do we know this is right?

Slide 29/45 · 30m:31s

I only have time to show you a couple of examples, but here's one. I showed you that little spot of voltage depolarization that indicates where the eye is going to go.

And so if you actually inject some potassium channel RNA into other cells in the frog model, this is a tadpole here, that are going to make other structures, you can set up an ectopic little domain of voltage that says build an eye here. When you do that, that's what the cells do. So there's an eye sitting in some gut tissue. If you section them, this eye has all the lens, retina, all that stuff that eyes are supposed to have.

This was done not by micromanaging. We did not control the stem cells. We don't have any idea how to build an actual eye from scratch. We didn't need to do that. We communicated to those cells, "you should build an eye." This is an example of using that bioelectrical interface to communicate with a different kind of collective intelligence. It doesn't navigate three-dimensional space the way that motile animals do. It navigates anatomical space, and we were able to pass it one message: make an eye right here. That's it. It did the rest. It was competent to do all the downstream steps.

If you only get a few cells here, they will recruit all their neighbors. The blue ones are the ones we injected. All this other stuff we never touched. These cells induce their neighbors to help them complete this construction project, much like ants communicate and recruit nestmates to help them move a large piece of food. All of this is part of the competency of the tissue. We did not have to build that in.

Slide 30/45 · 32m:06s

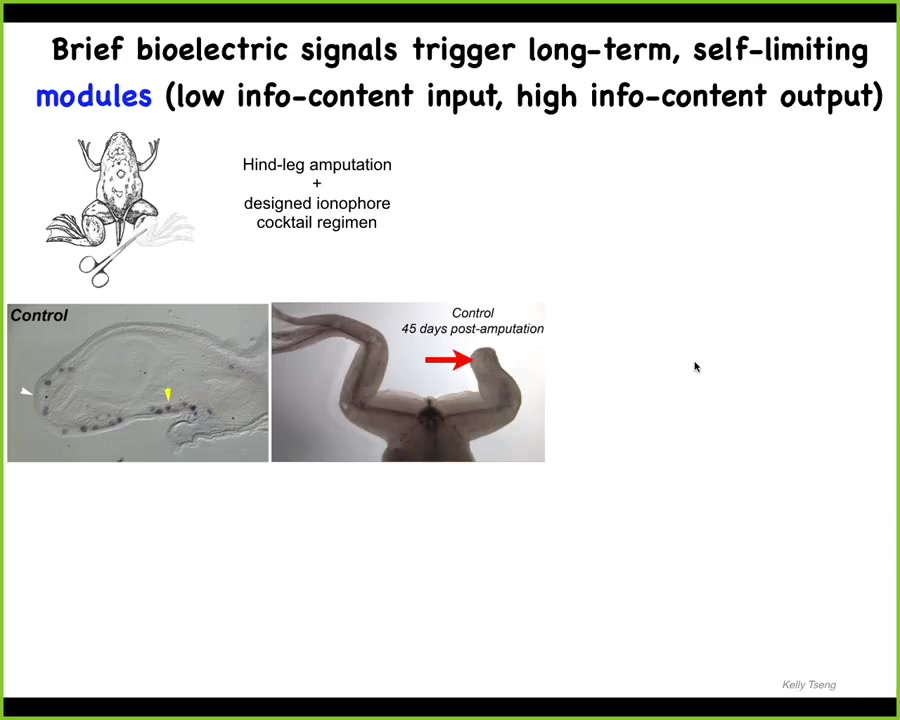

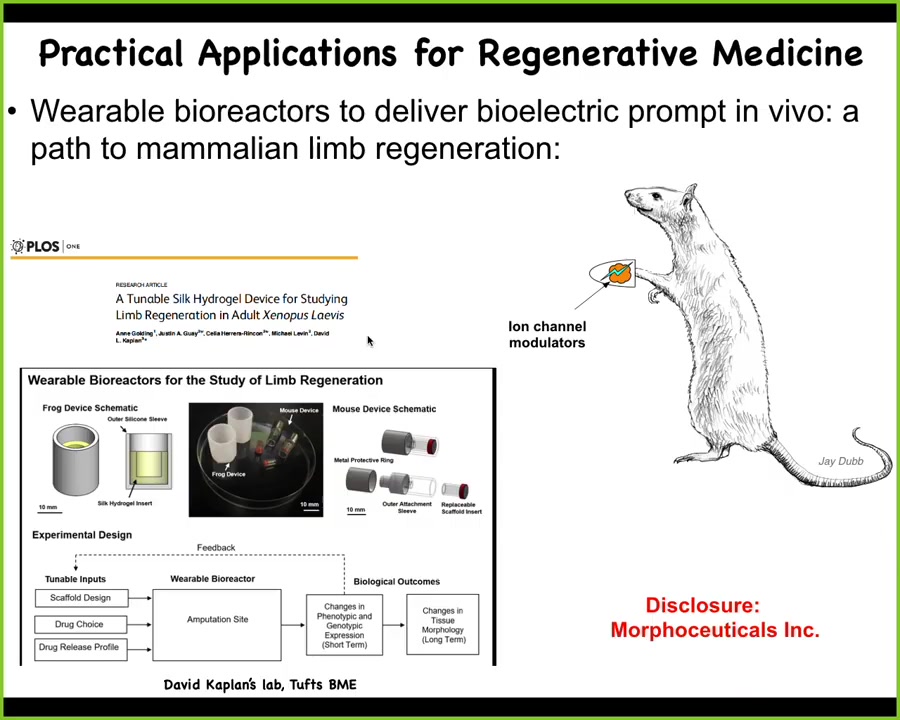

Another example of communication occurs in our regenerative medicine program. Frogs, unlike salamanders, do not regenerate their legs. What can we say to these cells to get them to rebuild a leg, even if we don't know how to do it?

Slide 31/45 · 32m:21s

We discovered a bioelectric cocktail where 24 hours of treatment gives a year and a half of leg growth, during which we don't touch it at all. Here you can see what happened. Immediately, within 45 days, there are already some toes, there's a toenail. Here, some pro-regenerative genes are coming on and you can see the leg is touch sensitive and it's motile. The animal can feel the touch and can use that leg to swim. This is again the idea of not micromanagement, but communicating that you should go not the scarring route, but the leg-building route and let the system take care of the rest.

Slide 32/45 · 32m:56s

At this point, I have to do a disclosure. Dave Kaplan and I have started a company called Morphoseuticals, Inc., which is trying to move this towards clinical applications first in rodents and then hopefully in human patients to regenerate organs.

The details aren't super important, but what is important is the idea that when we take seriously that the dynamics that we're seeing are not just the mechanical clockwork, but are actually a set of decision-making processes by a competent system that is trying to minimize error relative to set points, it unlocks all kinds of discoveries that are inaccessible if we treat the thing as a dumb machine. This is just scratching the surface.

The next thing I wanted to show you was when we're looking at these examples of repair, and there are many examples of birth defects and many, many other kinds of things that we've done, it's very clear where the pattern comes from. Presumably it comes from evolution. That is the correct shape for that species. That's where the pattern comes from, or so the conventional story goes.

Slide 33/45 · 34m:12s

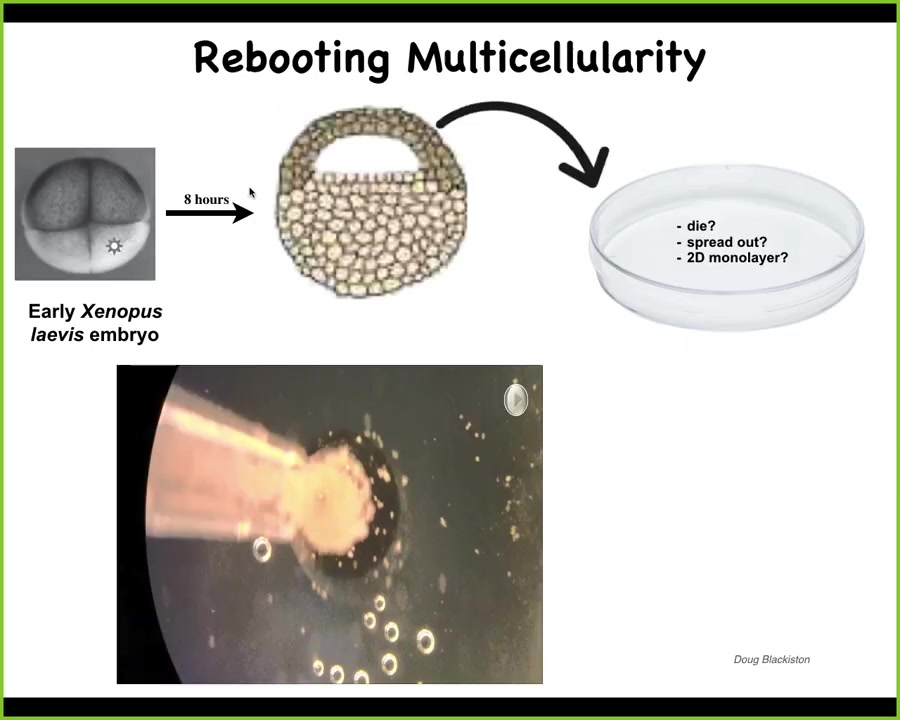

But we wanted to push that idea, and the way we did it was to try to make a synthetic novel life form that is in a different configuration than anything in its evolutionary lineage. And so the way we do that is we take early frog embryos, we take some of the epithelial cells from the top here, we dissociate them, and we put them by themselves in this little depression. Now, many things could have happened. They could have died. They could have crawled away from each other. They could have made a flat monolayer like cell culture. But we wanted to know, what would these cells do if we extracted them from the embryo and gave them an opportunity to reboot their multicellularity?

Well, what they do, they don't do any of these things. They gather together and they make this thing we call the xenobot.

Slide 34/45 · 34m:52s

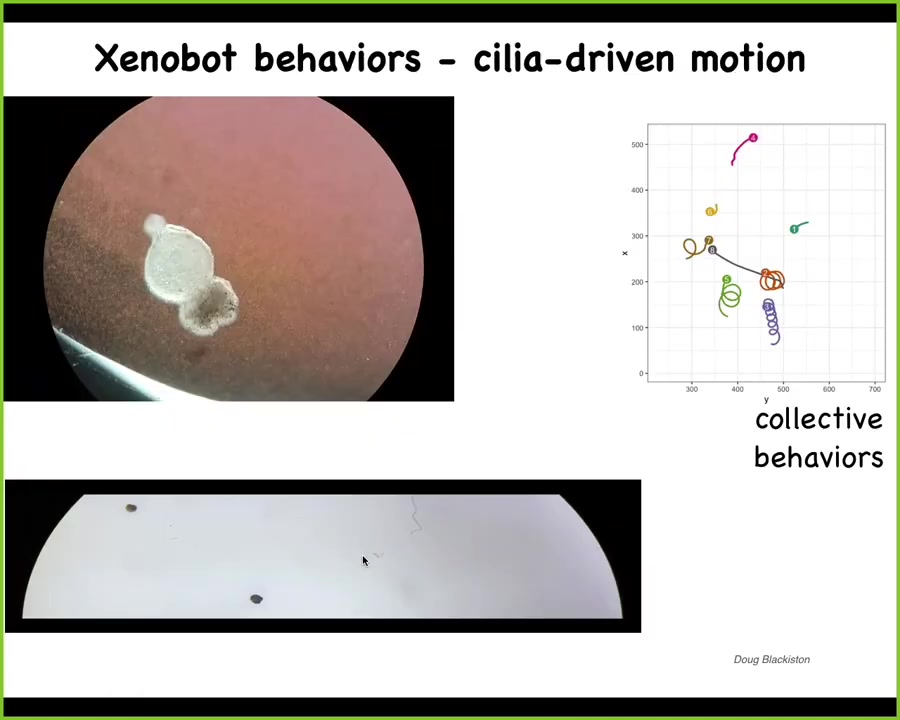

Xenobot, because Xenopus laevis is the name of the frog that we get them from, and we think this is, among other things, a bio-robotics platform. They start to swim. They're autonomous. They use little hairs on their outer surface. These hairs are normally used to move mucus down the body of a frog. Here they're using it to row against the environment. They can go in circles. They can patrol back and forth. They can have collective behaviors where they interact with other bots.

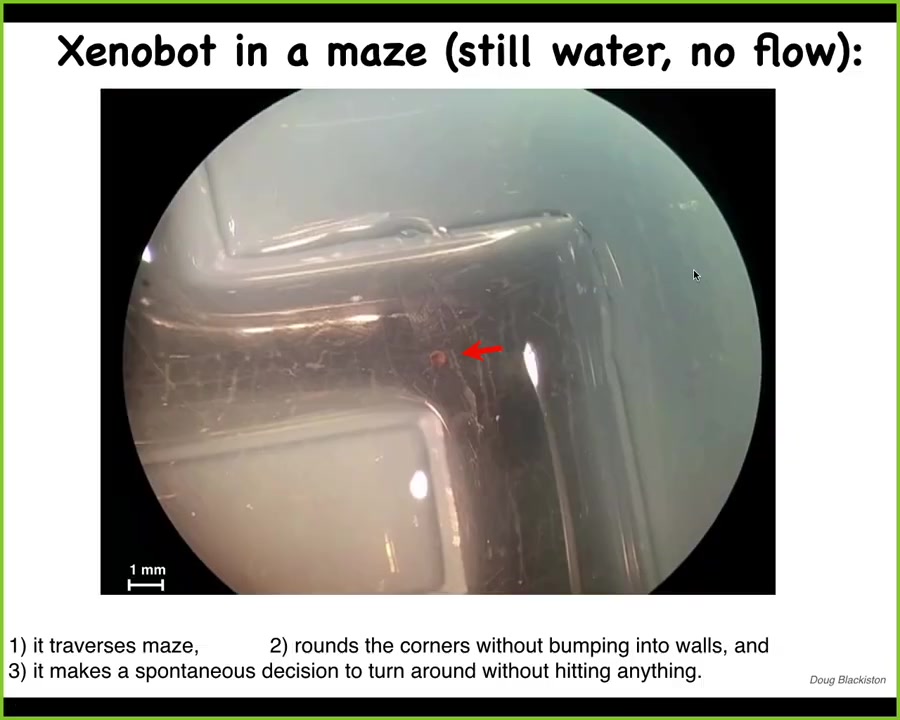

Slide 35/45 · 35m:24s

Here's one moving down this maze-like structure. You'll see here that it takes this corner without having to bump into the opposite wall. And then here it spontaneously turns around and goes back where it came from. Remember, there are no neurons here. This is just skin. This is a novel proto-organism that's made entirely of skin cells here. It has all kinds of interesting behaviors.

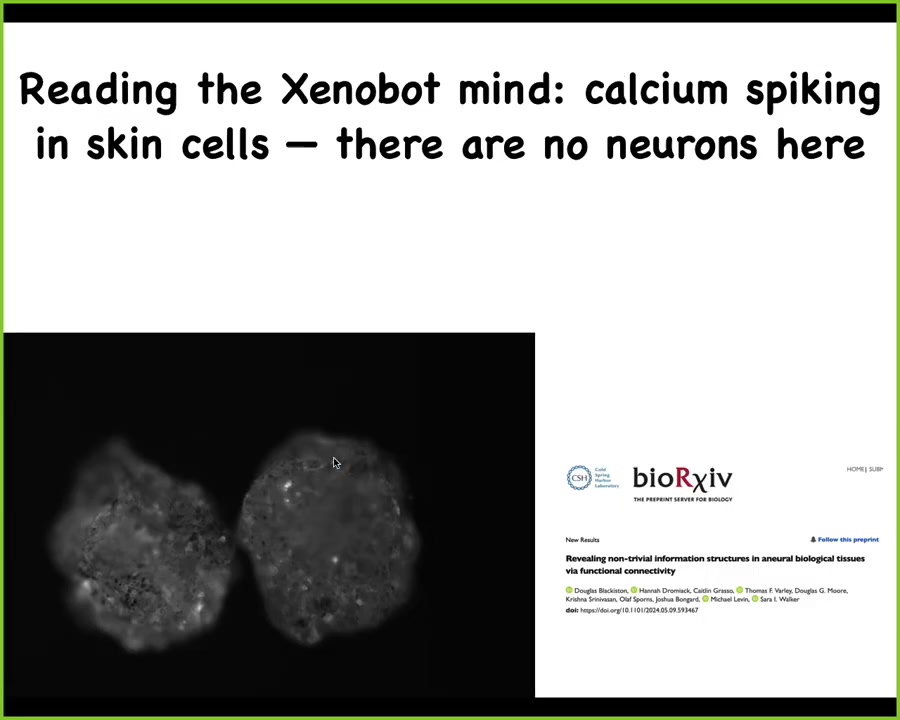

Slide 36/45 · 35m:46s

If we look at its electrophysiological activity, this is a calcium sensor, there's tons of it. This looks like the kind of thing that people record from brains, even though there's no nervous system here. If we were to functionally analyze these signals, there are some really interesting features of them. This is just a preprint for now, but there are some interesting comparisons that can be made between the physiology that goes on here and the kinds of things we would read from a brain.

Slide 37/45 · 36m:19s

They have some unexpected capabilities. Here's something we call kinematic replication. We've made it impossible for these bots to reproduce in the normal ****** fashion. They don't have any of the organs that are needed to do that. But what they can do is if you sprinkle a bunch of loose skin cells into their fields, this white stuff is loose epithelial cells, what they'll do is they'll run around and they will collect them into little piles and they'll polish the piles, both collectively and individually. And then because they're working with not passive matter, but any gentle material, these little piles mature into the next generation of Xenobots. And guess what they do? They run around and make the next generation.

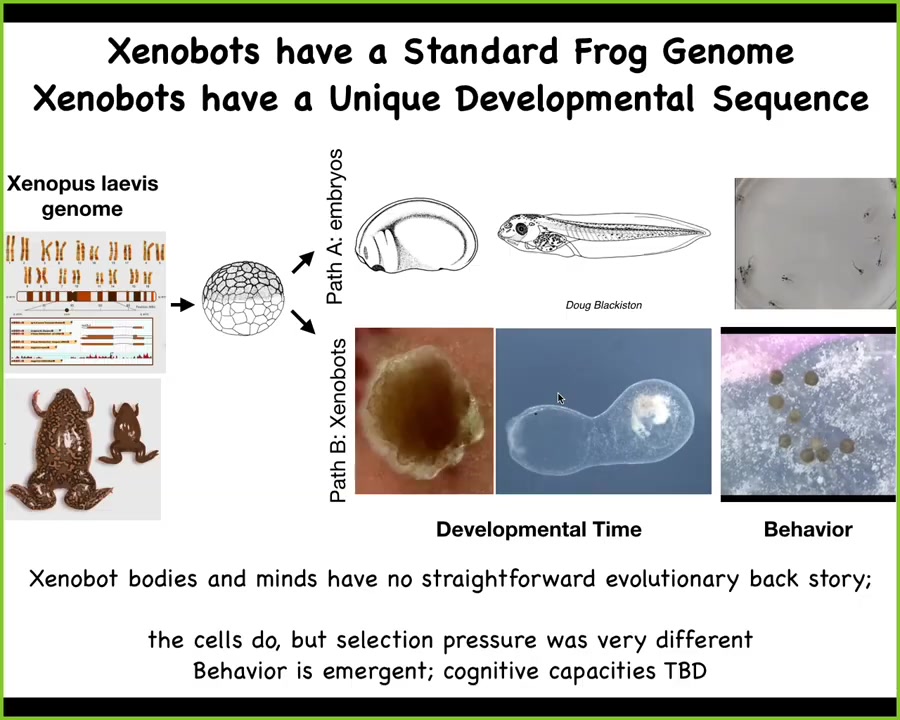

Slide 38/45 · 37m:02s

What has the frog genome learned here? What do genomes do? Over the years of evolutionary selection, it's certainly learned to do this so it can make a specific developmental sequence and then some tadpoles. But it also makes Xenobots with their own really weird developmental sequence and things like kinematic self-replication. As far as we know, no other animal on Earth reproduces via kinematic self-replication. There's never been any selection to be a good Xenobot. There have never been any Xenobots.

This immediately raises the question: the goals that these collective systems have. The goals of novel systems, which do not have a history of evolutionary selection, are even harder to predict. What's really necessary now is a science of understanding what are the goals that novel collective systems are going to have. I haven't said anything about their behavioral intelligence, but over the next few months, we'll have a couple papers out that actually characterize that.

Slide 39/45 · 38m:16s

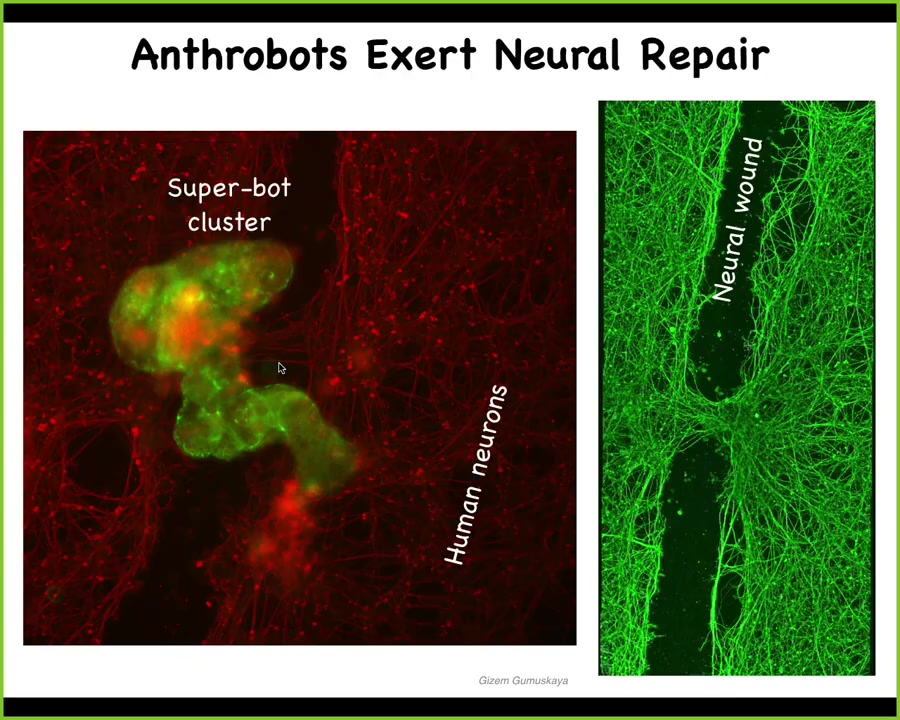

If I showed you this video, you might guess that this is a primitive organism I got from the bottom of a pond somewhere. We have no idea what its goals or its competencies are. Turns out this is something we call an anthrobot. It's made out of human cells. If you were to sequence this, it's 100% normal human genome. This comes from adult patients. These are tracheal epithelial cells that come together to be an anthrobot instead of a xenobot from the frog. And so this is a total reboot of human multicellularity. It doesn't look anything like the standard organism, but they have some amazing properties.

Slide 40/45 · 38m:57s

If you put them on a petri dish where you've grown a bunch of human neurons and you put a big scratch through it. Here's the defect: a neural wound. What you'll see is that these bots cluster. They form something we call a superbot. Underneath, within four days, you lift it up. What they've been doing is taking the two edges of the neural wound and healing it together.

Who would have known that the cells that sit quietly in your trachea for long periods of time, when given the opportunity, will rebuild themselves into a self-motile little creature that has the ability to go around and heal neural wounds? Who knows what else it can do?

Slide 41/45 · 39m:31s

To start winding down here, I want to point this out. Because of this ability of life forms to decide on the fly how to solve various problems, they are not hardwired. They are constantly using fairly ingenious problem-solving competencies to get their needs met.

It means that not only can they regenerate after damage, but life is incredibly interoperable. Almost any combination of evolved material, engineered material, and software can be viable agents. We have cyborgs and hybrots and chimeras. Many of these things already exist. They will increasingly become more prevalent.

All of the variety of biology that Darwin saw when he said "endless forms most beautiful" is one tiny corner of the space of possible beings. We are going to be living with all of these. This will increasingly be a part of society. The point of all this is not to make weird creatures and to see what we can do in an engineering sense.

The changes that certain people will make to themselves and to other systems, both biological and technological, are shedding critical light on understanding what we are. What does it mean to truly have a mind, to have goals, to have intelligence? And what does all that mean for a collective of cells to say that they understand something and they can navigate a specific space?

All of this is about understanding us better, but critically it's about being able to ethically relate to a wide range of beings that we have never seen before and are not on the evolutionary tree with us.

Slide 42/45 · 41m:21s

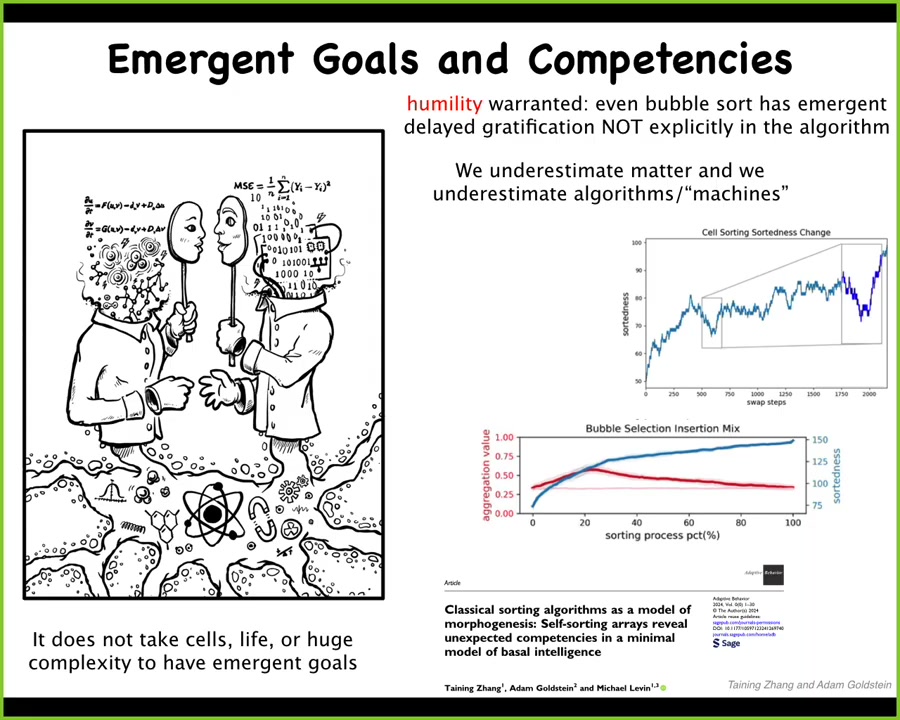

Two very quick things I will say are that a lot of people have strong feelings about what certain types of AIs can and can't do and what living things can do. I want to point out that it is essential at this early stage of the game to have some humility about this, because we do not know what it is that allows biological machines, constructs of biochemistry and so on, to enjoy the kinds of cognitive properties that we all have — we actually don't know. Therefore, we have to be careful about saying what other kinds of constructs can and can't do.

In fact, there's been all kinds of research in minimal matter and our own work on very simple sorting algorithms. If any of you are coders, it's something you study in your first year of algorithms in the computer science curriculum. We found novel problem-solving capacities in simple sorting algorithms that nobody had noticed for a really long time. So it really doesn't take much to start to climb that continuum of agency.

I will argue that for the same reason that you can't look at the laws of chemistry and think that you've understood everything that's important about being cognitive in the world, you really can't look at the construction of a machine, either in its hardware or its algorithm, and think that you've understood everything that it's doing. Unexpected, not just complexity, not just unpredictability, but unexpected cognition starts to crop up extremely early, and it doesn't even require cells, never mind brains or anything like that.

Slide 43/45 · 43m:00s

The very last thing I want to say is this: I just want to tell you a quick story. This is a science fiction story, but it makes an important point.

Imagine that some creatures come out of the center of the earth. They live in the core of the earth. They are incredibly dense. They come up onto the surface. What do they see? They don't see any of our stuff. They're using gamma rays as vision because they have to see through rock. They don't see any of this. This planet seems to be covered by a very tenuous, very ethereal plasma. There's some kind of gas that's on top of them, but none of this is solid to them. They are solid. All of this is basically gas. They’re walking all over everything.

One of them is a scientist, and he's been watching this gas, and he says to the others, "I've been watching this gas. There's patterns in this gas. You would almost swear that these patterns are actually doing something. You almost think that they're agents of some kind. They seem to have goals and they solve problems."

The other is saying that's ridiculous. Patterns in the gas can't be agential. We're real. They're just patterns in an excitable medium.

How long do these patterns hold together? He says, around 80 years on average. That's nuts. Nothing interesting can happen in 80 years.

This kind of thing reminds you that this has been understood by people working in metabolics. We too are temporary patterns in metabolic media, like whirlpools and solitons and gliders in the game of life. All agents are actually patterns in some medium. We have to be really careful in our commitment to expanding our ability to recognize novel minds, whether they be in physical embodiments like ours or something very alien.

Slide 44/45 · 44m:54s

I'll end here and point out that intelligence is very widely distributed throughout the world. Learning to rise above our evolutionary limitations and recognize that is critical to expand this idea of sentient beings. I don't think we've even scratched the surface of what that really is.

We now have, in the field of diverse intelligence, a research agenda: a principled search for frameworks that avoid teleophobia but also avoid unwarranted animism, painting hopes and dreams on every rock. We don't have to daydream high or skew low. We can get it right, or at least we can optimize way past what we have now by dropping untenable ancient categories that are not serving us any longer, these things that sound like we know what they are, machines and organisms and so on. It sounds like we know what we're talking about. We really don't. This is the beginning of a research program that can use ideas of a continuum of agency, observer-relative models, and AI as universal translators to these diverse intelligences to really have a much better future than is possible using today's frameworks.

So if anybody's interested, I can send any number of papers where we go in depth on all this stuff.

Slide 45/45 · 46m:15s

These are the people that contributed to all this work.

Lots of postdocs and grad students and undergraduates and tech support. We have many amazing collaborators here, our funders that I thank for supporting this work.

Disclosures: there are three companies that are supporting us and are commercializing some of our IP.

I'll stop here and thank you so much for listening.