Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

A talk on "Diverse Intelligence: understanding and relating to unconventional biological, engineered, and hybrid agents" by Michael Levin

CHAPTERS:

(00:31) Host introduction and title

(02:16) Diverse intelligences framework

(08:16) Unusual biological cognition

(14:16) Morphogenesis as problem solving

(25:00) Bioelectric patterns and organs

(35:40) Planarian body-plan memory

(45:00) Scaling agency and cancer

(52:46) Xenobots and synthetic organisms

(01:02:00) Philosophical implications and ethics

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/60 · 00m:02s

Hello, good evening all. Welcome back to the last talk of the conference. Professor Michael Levin is here and he is a professor of biology, University of Gulf, USA. He also holds Vanier Bush Professorship there. He's also the director of Lemin-La and the director of Allen Discovery Centre, Gulf CMMC, Headphone, United States. He's a co-founder and principal investigator of the Institute for Computationally Defined Organisms from 2020 onwards. He's also a senior research investigator, Forsyth Institute, Harvard, Department of Molecular Genetics, Cambridge, from 2008 to present. He is going to deliver a lecture titled "Diverse Intelligence: understanding and relating to unconventional biological, engineered, and hybrid agents." I extend a warm welcome to Professor Michael Levin on behalf of the department and the organizing team, and thank you, Professor Levin, for accepting our invitation and delivering this sector over to you.

Thank you so much. I appreciate the opportunity to share some thoughts with you. I will do my best. It's 5 A.M. here this morning. I will try to be coherent. If anybody is interested in the details of the things I will talk about today, you can find me and all of the primary papers, the data sets, the software, everything is here at this website. Please get in touch if you're interested in any of this.

Slide 2/60 · 02m:46s

The traditional picture is shown here. This is a famous painting of Adam naming the animals. It's this old idea, which is really prevalent in a lot of thinking today, even among scientists, that there are humans and human minds. Then there are many other creatures, and these are distinct, discrete, natural kinds. They're just sharply different from each other. Humans have all sorts of cognitive capacities. If you try to look for these capacities elsewhere in the natural world, this is often called anthropomorphism: an inappropriate attribution of these magical qualities outside of the human organism.

Slide 3/60 · 03m:32s

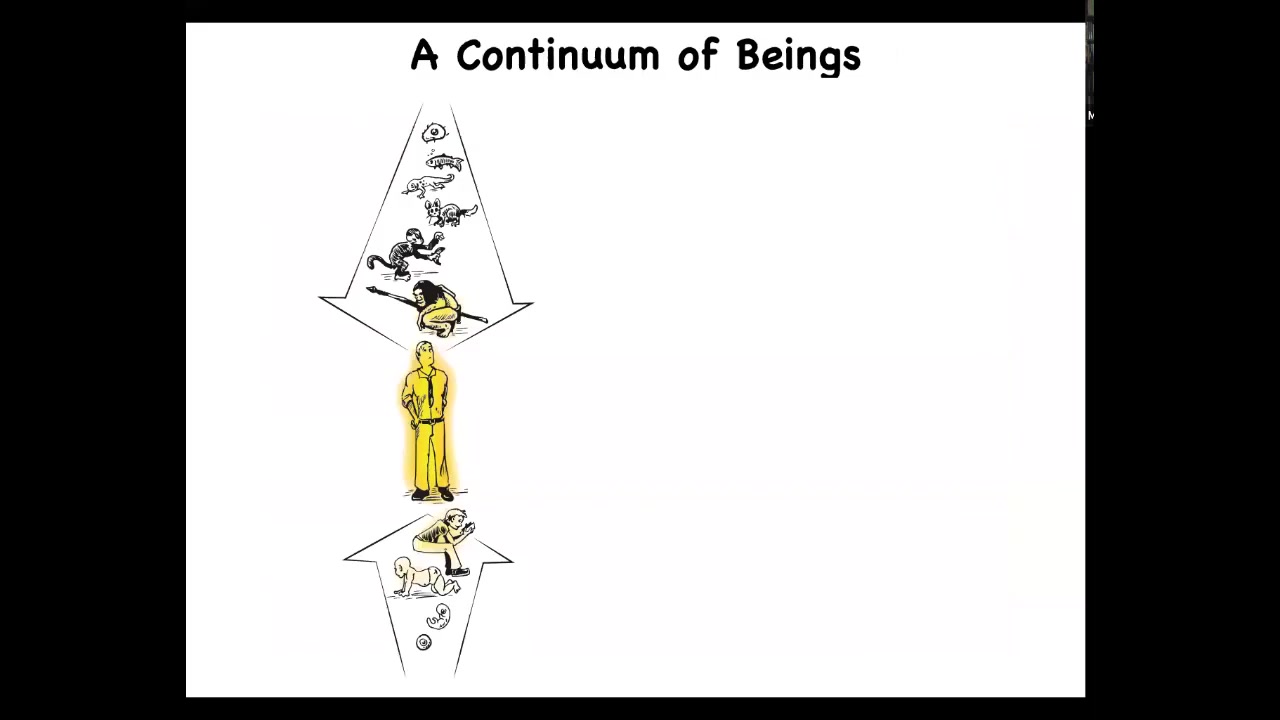

But if we take developmental biology and evolution seriously, we realize that both on long phylogenetic time scales as well as developmental time scales, we all share a continuity of much different kinds of beings. This is really a slow continuum. Any special properties that we have, you have to ask, where did these properties come from, and to what extent did they exist in our various ancestors and when did they begin or end, if you think that these are discrete categories.

Now, because we have the ability to replace components of a living system at all scales — at the cellular scale, tissue, organism — we can replace biologically evolved components with all kinds of chimeric engineered materials. Whether this be nanomaterials or edited DNA or various inorganic components, we can make very novel organisms. Laterally, you can see that there's a potential chain of beings, which are and increasingly will be realized, where not only through biological changes, but also technological hybridization, there is a very wide range of different types of creatures. You have to ask, what kind of minds do they have?

Slide 4/60 · 05m:01s

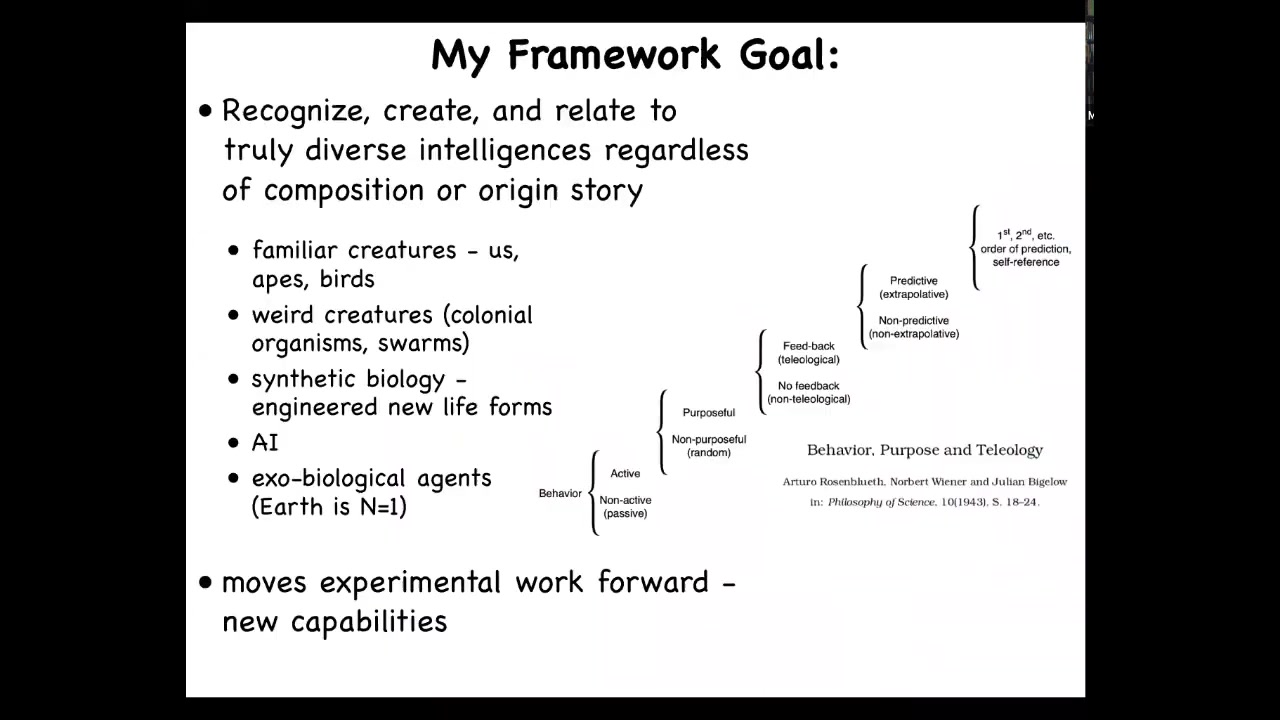

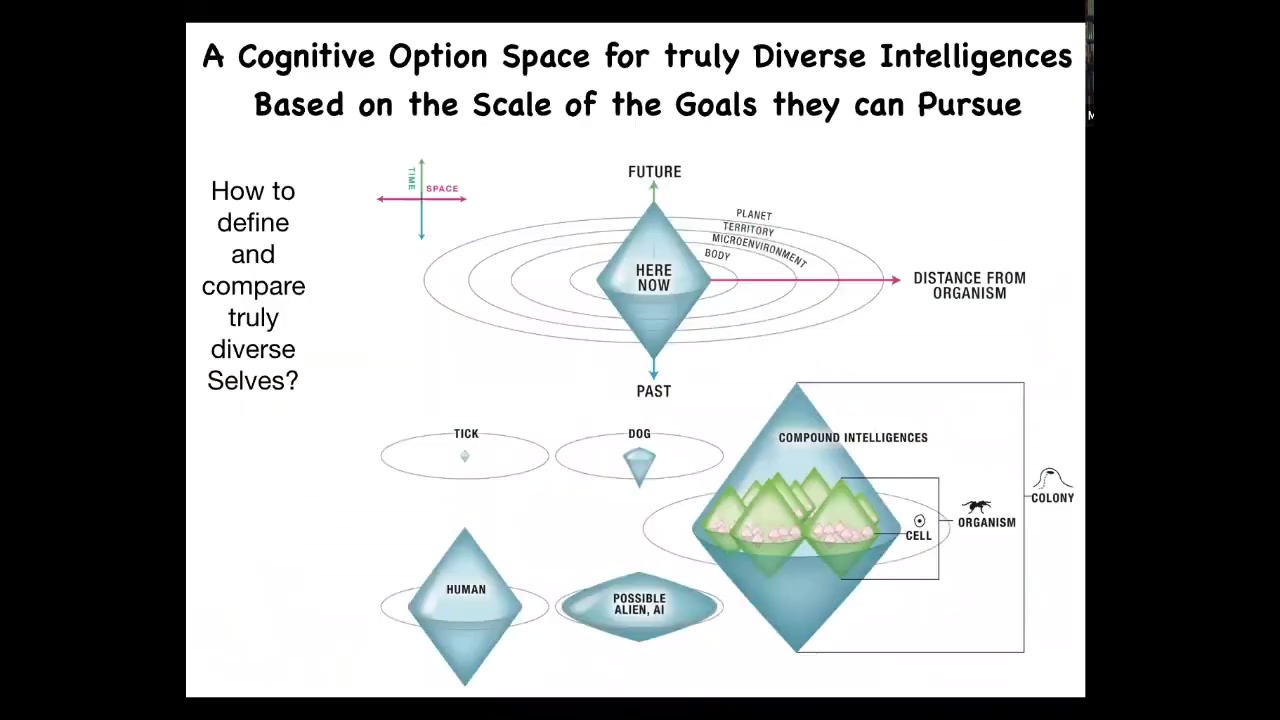

I have this framework that I've been working on. It's called TAME, T-A-M-E, stands for Technological Approach to Mind Everywhere. The idea is simply this. We need to be able to create and relate to truly diverse intelligences, regardless of what they're made of or how they got here. That means that we would like a single framework on which we can compare and understand the kinds of cognitive systems that exist in familiar creatures. We humans, primates, birds, octopus, these kinds of things, but also really unusual creatures, colonial organisms, swarms, in synthetic biology, new engineered life forms, software, artificial intelligences, and maybe someday exobiological agents, realizing that the Earth, all of the examples on Earth are just an N of 1. We really have to understand broader than that.

A number of people have tried for such a thing. This was a very nice beginning by Rosenbluth, Wiener, and Bigelow, who created this kind of scale that shows you through some examples of great transitions, all the way from passive behaviors, all the way up to what we would call human level cognition with a second order of metacognitive kinds of processes. What's interesting about the scale is that it's very cybernetic. It doesn't say anything about neurons or brains or the embodiments. What it talks about is functionality and ways of processing information. That makes it compatible with all of these things. I think that's the right approach.

What I'm interested in is developing a framework like this that really picks out what are the symmetries, what are the invariants among all of these different kinds of agents to give us new capabilities in the laboratory and to move experimental work forward.

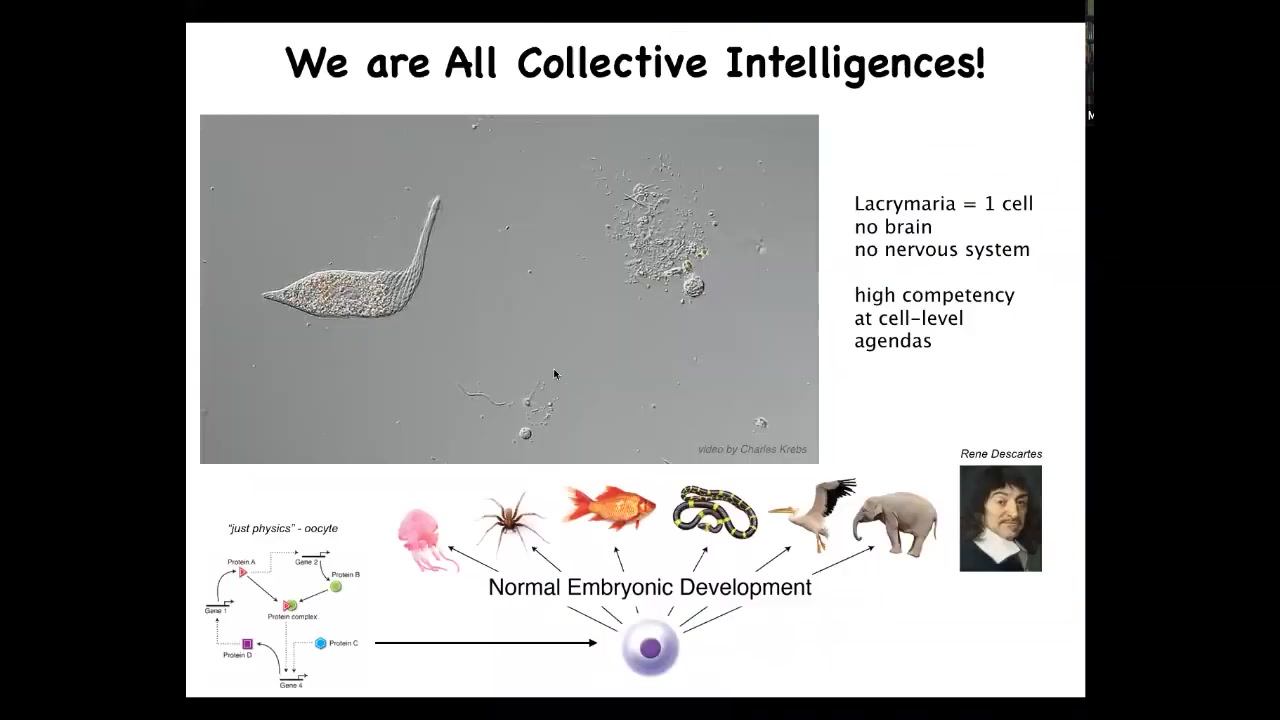

This is a nice quote from Searle, which says that we have to allow ourselves to really examine things that are generally taken for granted. This is the most common one. This is a really magical process in science. It's developmental biology. All of us take this amazing journey through the Cartesian cut. We start as just physics. This is an oocyte. This is a quiescent egg cell prior to fertilization. It's a BLOB of chemicals. You would look at it, then you would say that it's basically just physics. There's not much cognition going on there.

But eventually, we become one of these organisms, a human organism that will make statements about being unique and having a kind of inner perspective. The important thing to realize is that this process is extremely slow and gradual. Step by step, developmental biology offers no sharp line at which, boom, prior to that, it was just chemistry and physics, but now you're a cognitive being. There are no sharp lines in developmental biology. Everything is continuous and somehow this process results in mind emerging from matter. This is one of the most interesting questions that exist.

Slide 5/60 · 08m:28s

There have been a variety of ways to think about this. In particular, there's this idea of collective intelligence. People sometimes say ants and colonies of bees and birds are perhaps a collective intelligence. But we are a unified intelligence. We're not a swarm of ants. We are a collective intelligence. We have a brain and it's centralized. And Descartes wanted to find a center in the brain that was specifically connected to this unified experience that we had. But we are also made of parts. In fact, all intelligence is collective intelligence.

Slide 6/60 · 09m:10s

Here's the brain. The brain is made of parts. It's made of cells, these neurons. Inside each cell is an incredible number of things that are all operating under various rules to give rise to the collective behavior. The real trick to all of this is to understand the scaling, to understand how the physics and computation of lower level components give rise to a cognition that appears to be unified. We are also collective intelligences. How does collective intelligence work?

Slide 7/60 · 09m:46s

Let's just take a look at what our pieces are. So this is a cell. This happens to be a free-living organism, but all of us were once free-living organisms. This is Lacrymaria. So there's no brain, there's no nervous system, there's no cell-to-cell communication, there are no stem cells. This is just a single cell doing everything it needs on its own.

So you can see it's handling its physiological, its metabolic, its behavioral goals at the level of a single cell. Look at the ability: it's feeding, it's eating bacteria and other things in its environment. This is the envy of soft robotics and other kinds of engineering. We have nothing that's of this level of sophistication. So each one of our cells was an independent organism. And this makes it really important to understand how these capacities, these competencies of our subunits add up together to give us what feels like a unified cognitive experience.

Slide 8/60 · 10m:48s

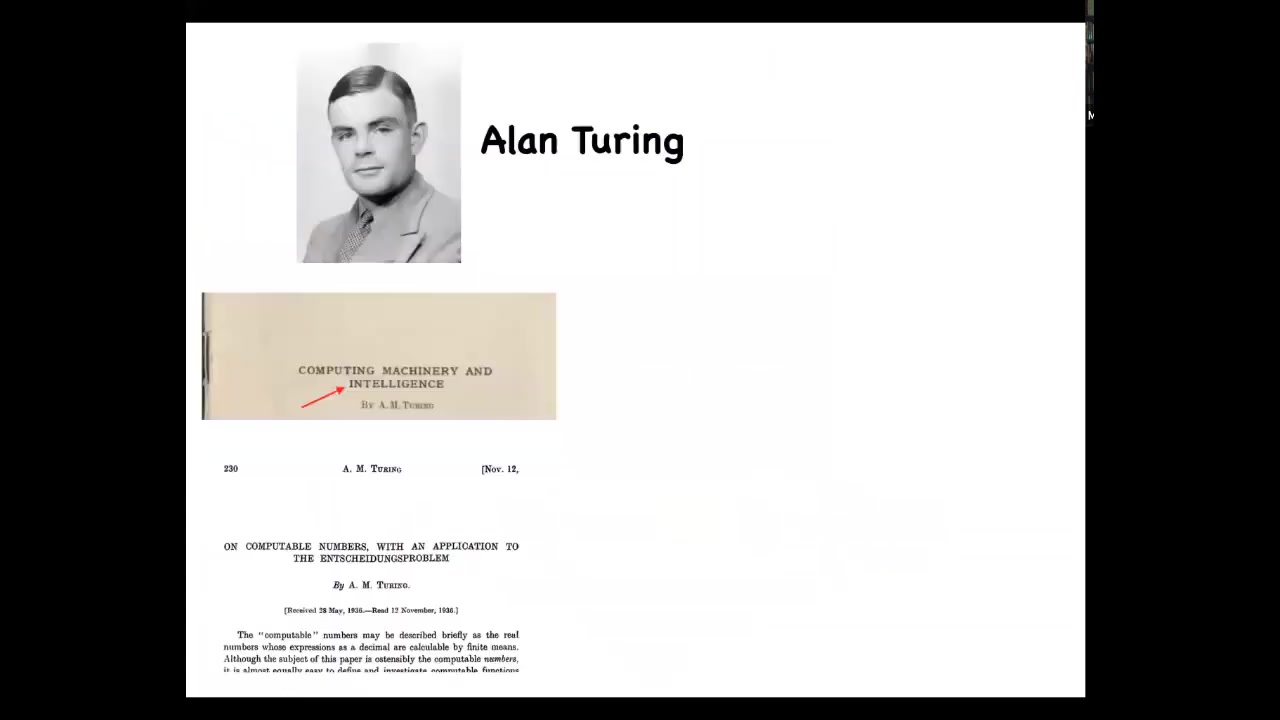

Now, one very interesting thing is that Alan Turing, who needs no introduction, was really interested in intelligence, in different embodiments for intelligence, in computation, these very fundamental things that he wanted to understand the mind in its most general case. But one other thing that he did is that he was also interested in developmental biology. He wrote a very early paper on morphogenesis, the appearance of order, the spontaneous generation of order in chemical systems.

You might wonder why somebody who is interested in intelligence would also be interested in morphogenesis and in chemical models of developmental biology. I think Turing, although to my knowledge he didn't write much about this, saw quite clearly that these are fundamentally the same problem. In a very deep way, this is true. The secret of developmental biology and morphogenesis is, if we understood it properly, it would open up all of the mysteries that we're interested in for cognition. It is the same problem.

Slide 9/60 · 12m:08s

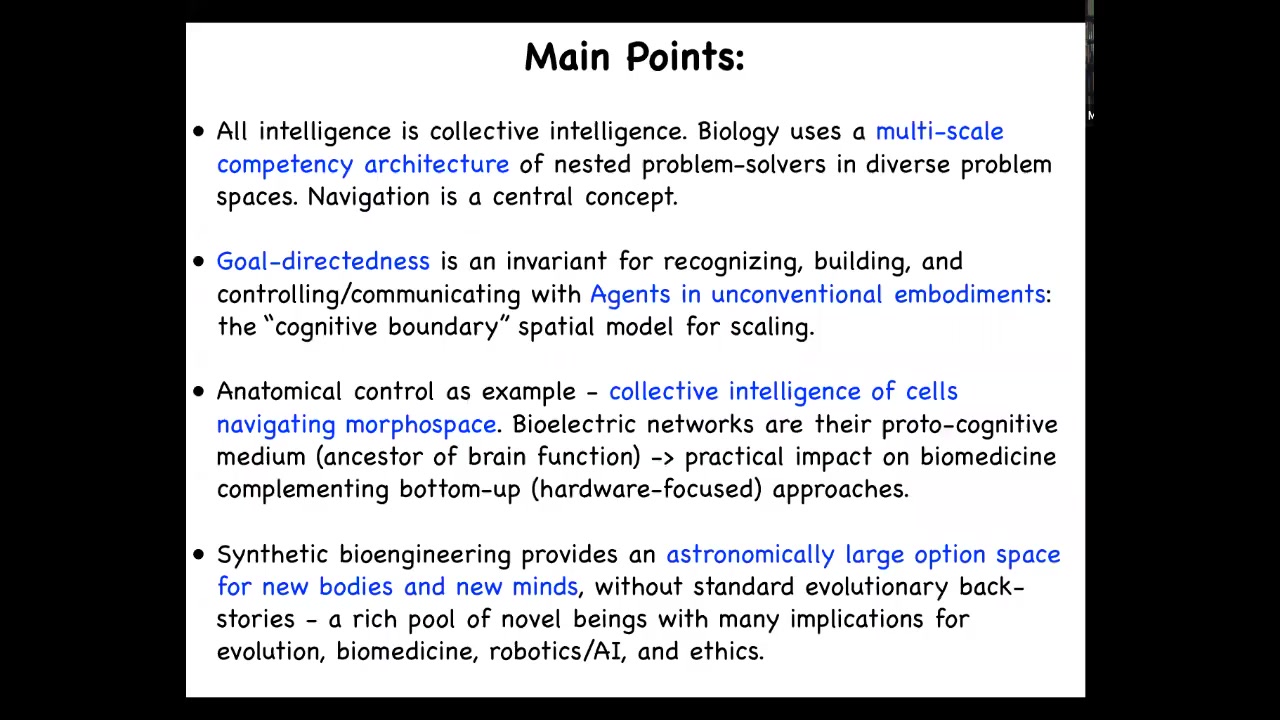

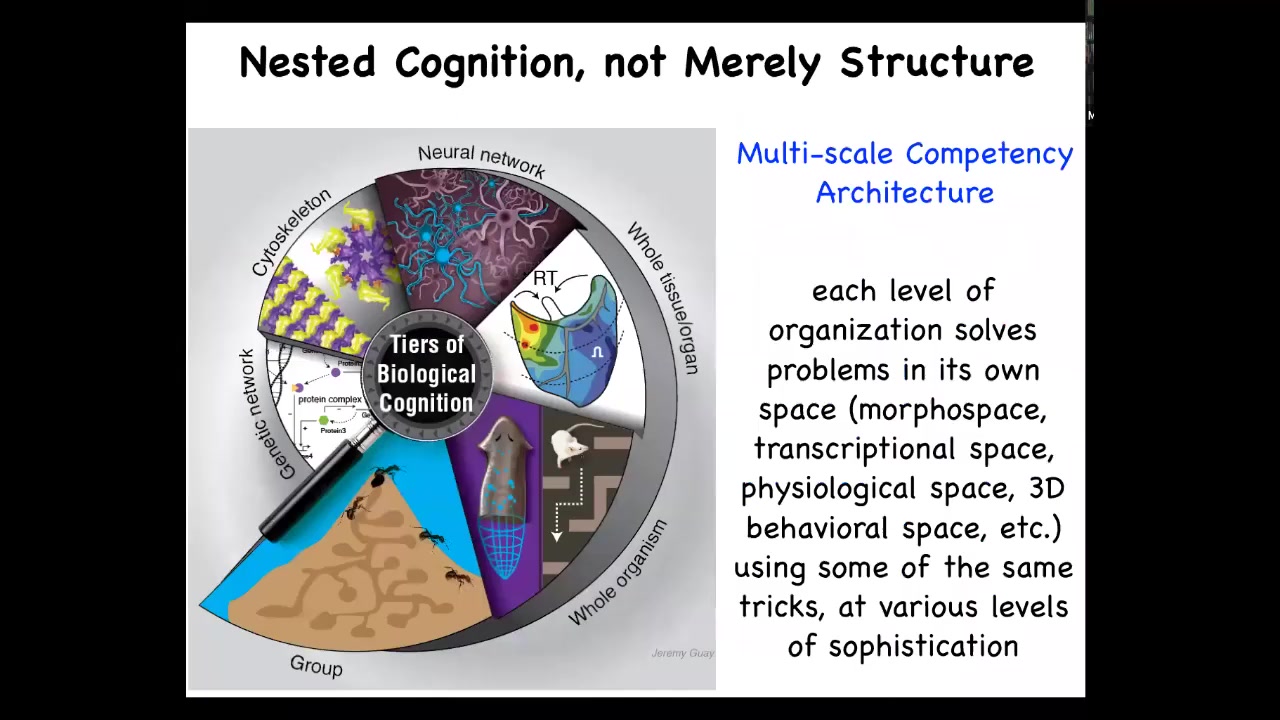

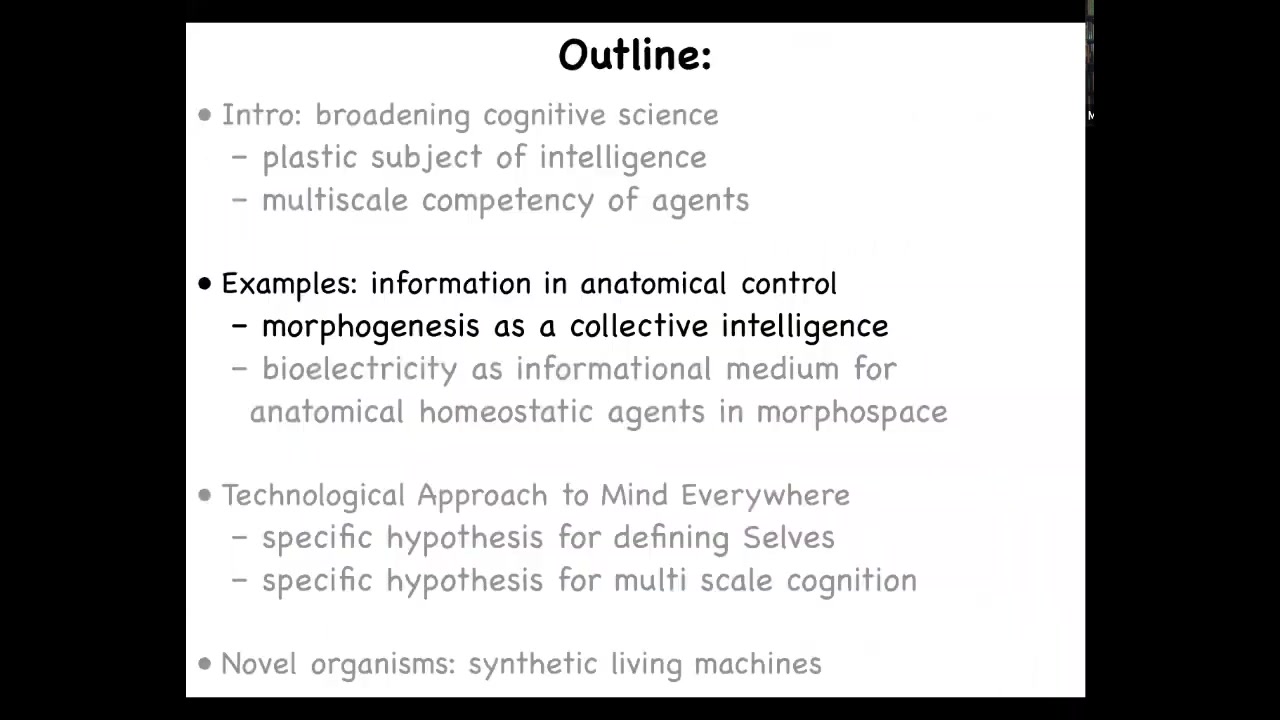

Biology uses this kind of multi-scale competency architecture of nested problem solvers in diverse problem spaces. I'll show you what that is. Navigating these problem spaces is a central concept. I think it's a concept that binds together diverse fields from engineering and autonomous vehicles all the way through to cognitive science and developmental biology and biomedicine.

I use the notion of goal directedness, and I will define that shortly, as a kind of invariant to recognize, create, and control or communicate with agents and unconventional embodiments. I'm going to show you this cognitive boundary model for the scaling of cognition.

I'm going to spend some time talking about a specific example. I want to take apart in detail a specific example of an unconventional intelligence and how we work with something like this. I'm going to talk about the collective intelligence of morphogenesis — groups of cells navigating anatomical space. I'm going to show you that bioelectric networks are a kind of proto-cognitive medium, which is also the ancestor of brain function.

This has huge impact on biomedicine that I think is going to allow us to do something very different than today's molecular medicine approaches. I'm going to close with pointing out again that synthetic bioengineering is giving us an enormously large option space of new bodies and new minds, which are going to exist, and some of them already do. These have no standard evolutionary backstories, and this has many implications for not only understanding evolution and biomedicine, but also AI, robotics, and ethics.

Slide 10/60 · 13m:55s

In my framework, one of the things we focus on, this is a very engineering based approach because I want to be close to experiments. I want all of these philosophical ideas to be testable empirically. I want them to generate new work.

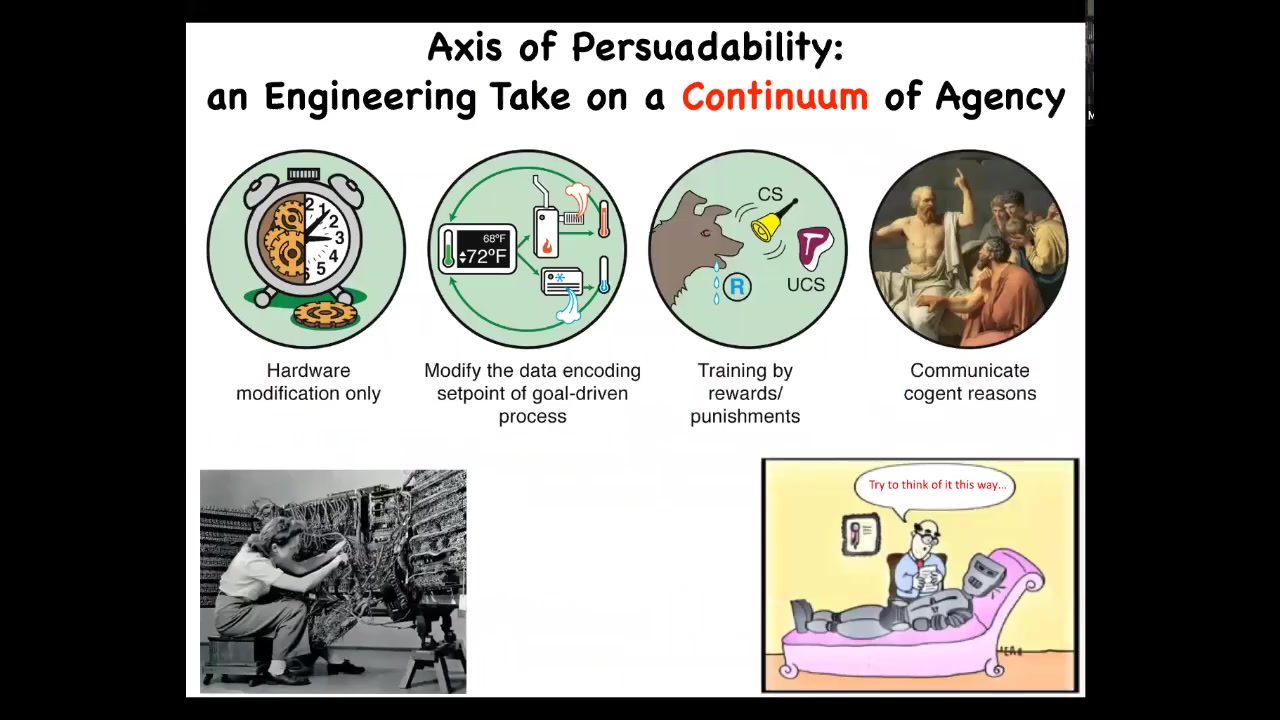

The engineering approach is simply this: we can place all these diverse beings on a continuum that exists with respect to persuadability, meaning what technologies, approaches, techniques, or strategies would you use to control the system. That's the engineering approach.

You can see immediately that all kinds of diverse systems land on this spectrum. You can have very simple mechanical systems like a mechanical clock on the left of that continuum. If you wanted to control this system, you will not program it, you will not convince it of anything. All you can do is modify the hardware.

Then you have more interesting systems like homeostatic systems, where you don't need to rewire the hardware, but you can reset the set point. Then this thing will have different behaviors.

You can move from that to systems, whether living or non-living, that are able to learn. You can train them with rewards and punishments and various behavioral paradigms. Eventually you get to systems that you don't even need to reward and punish directly. You can communicate with reasoning and perhaps get them to do things.

You can see as we move from modification at the level of hardware to eventually get to something that, sure, it's hardware, but the most efficient way of dealing with it is through something that in human terms looks like psychotherapy, which is just very high-level communication to try and control what happens.

Slide 11/60 · 15m:46s

The first thing I'm going to do here for the next few minutes is try to show you some unusual biology. To really reinforce this idea that everything lives on a continuum and that we have to understand how agents change along that continuum. The first thing I want to talk about is this. Here is a creature. This is a caterpillar. Caterpillars live in a two-dimensional world of surfaces. They crawl on these flat structures and they eat the leaves and they have a particular brain that's highly specialized for doing that. But they need to turn into this creature, which is completely different. This one lives in a three-dimensional world. It doesn't care about the leaves at all. It drinks nectar, and it has a different life, and it has a different brain that's well-suited for its environment.

Now, the way you get from here to there is through a process of metamorphosis. During this process, this guy dissolves its brain. Most of the connections are broken. Many of the cells die. The brain is then reassembled from this state to this state.

There are two interesting things from this process. The first is that, in philosophy 101, you might be challenged to ask what's it like to be a butterfly or what's it like to be a caterpillar? Well, this is the next meta question, which is, what's it like to be a caterpillar slowly changing into a butterfly? This is a radical change of your embodiment, of your existence in the physical world that occurs during your lifetime, not during evolutionary time scales, but literally during your lifetime. That's an interesting question. What happens to you?

The other important point is that you might be tempted to say, well, you disappear and then there's a new creature. Basically there is no transition. But actually that's not the case because under the most common criterion for personal identity, which is retaining your personal memories, it turns out that memories are retained through this process. There's pretty good evidence that caterpillars that learn something, that are trained, the moth or butterfly remembers the original information. To some extent, it is in fact the same organism in a new body. This is an interesting rebirth but of the same organism in a new body.

Slide 12/60 · 18m:19s

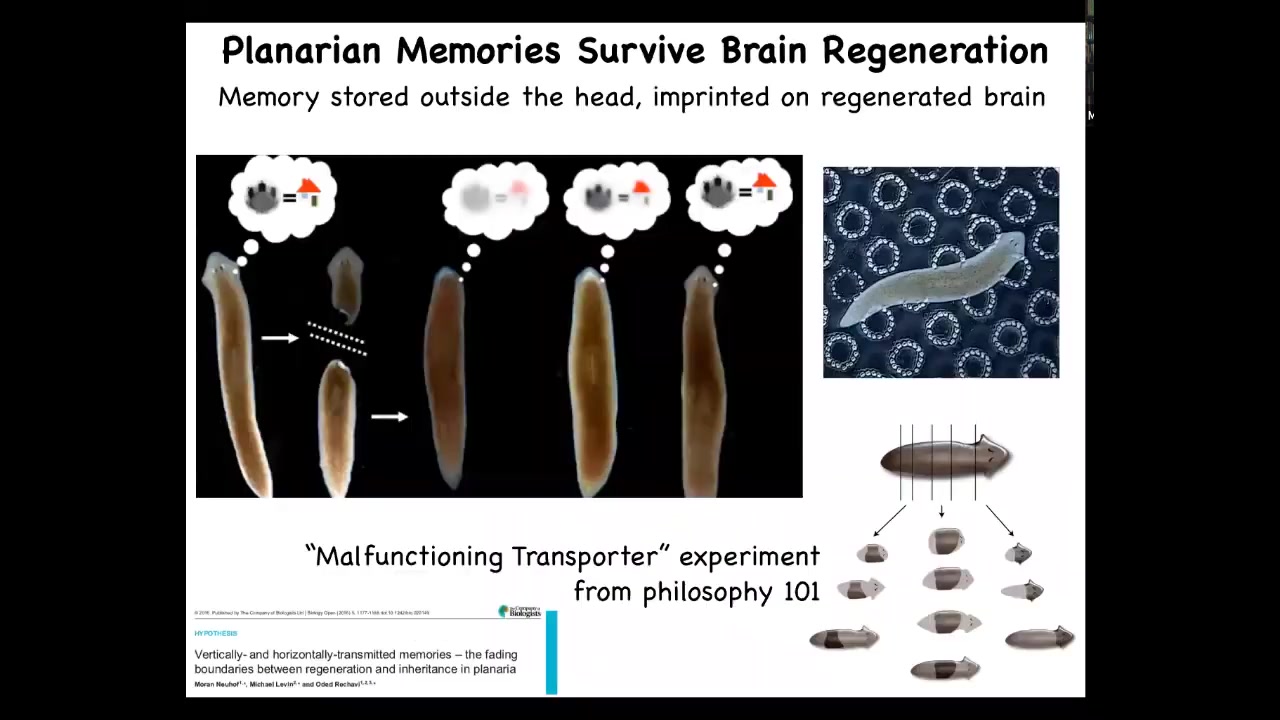

Now, this is even in these animals, this is even more apparent that these are planaria. These are flatworms, which I'll talk about more in the rest of the talk. But the key feature of planarians is that they regenerate. So if you cut them into pieces, every piece will give rise to a new worm and they have a brain up here, a true centralized brain with the same neurotransmitters that you and I have. that you can cut off the head and they will regenerate. But the amazing thing, and this was discovered by James McConnell and we replicated his work using modern automation in 2013. What he discovered is if you train this animal, then you cut off the head. The tail sits there doing nothing for about a week. They eventually regrows a new brain. And when it regrows a new head and brain, you can show that they remember the original information. And so they learn that food is to be found on these little laser etched discs. Now, This allows you to perform an experiment, again, from philosophy of mind, which is called the malfunctioning transporter. So the idea that, you know, let's say there's a transporter that somehow transports you from here to there, but it's broken down. And so once it's transported you, it fails to remove the original copy. So now there's two of you. And so which one is the original person? So in the plenarian, you can actually do that. We can cut them into pieces. And now you have multiple individuals that are basically copies of the original. as far as the content of their brains are concerned. So you can see this amazing plasticity that where the ability to change the body, in this case to regrow a head or to metamorphose and rebuild a brain, is deeply connected with the cognitive content of that creature's mind. And this plasticity of the body extends to vertebrates.

Slide 13/60 · 20m:09s

Here is a tadpole of a frog. Here are the nostrils, the mouth, the brain, the gut, and this is the tail back here.

What you'll notice is we've created a tadpole in which the eyes are missing. There are no eyes up here. But we did create an eye on its tail. I'll talk later about how we do that. These animals, when you create this eye without long periods of evolutionary adaptation, can see out of this eye.

We know that because this device that we've built, the same device that we use to train and test the planarian during their behavior studies, shows that these animals can be trained on visual tasks to stay away from particular moving lights.

This is amazing because the brain dynamically adjusts its behavioral programs to accommodate a completely different body architecture. This has many implications for evolution that we can talk about later if people want to.

That plasticity—how eye precursor cells implanted onto the tail not only make a perfectly normal eye even though they're in a weird environment with muscle next to them—is remarkable. They make a perfectly normal eye, but they figure out how to connect, and they don't connect to the brain. They connect here to the spinal cord, for example, and that information is able to be picked up by the brain. That competency of the parts is really quite remarkable.

Slide 14/60 · 21m:38s

What this gets us to is this, that biological organisms are not merely nested dolls structurally. We all know we're made of organs, tissues, cells, molecules. Not just structurally, but functionally, each of these independent layers is solving problems. It's independently competent in solving various problems. This is happening simultaneously at all scales of organization. Now, what are these problems that it's solving?

Slide 15/60 · 22m:11s

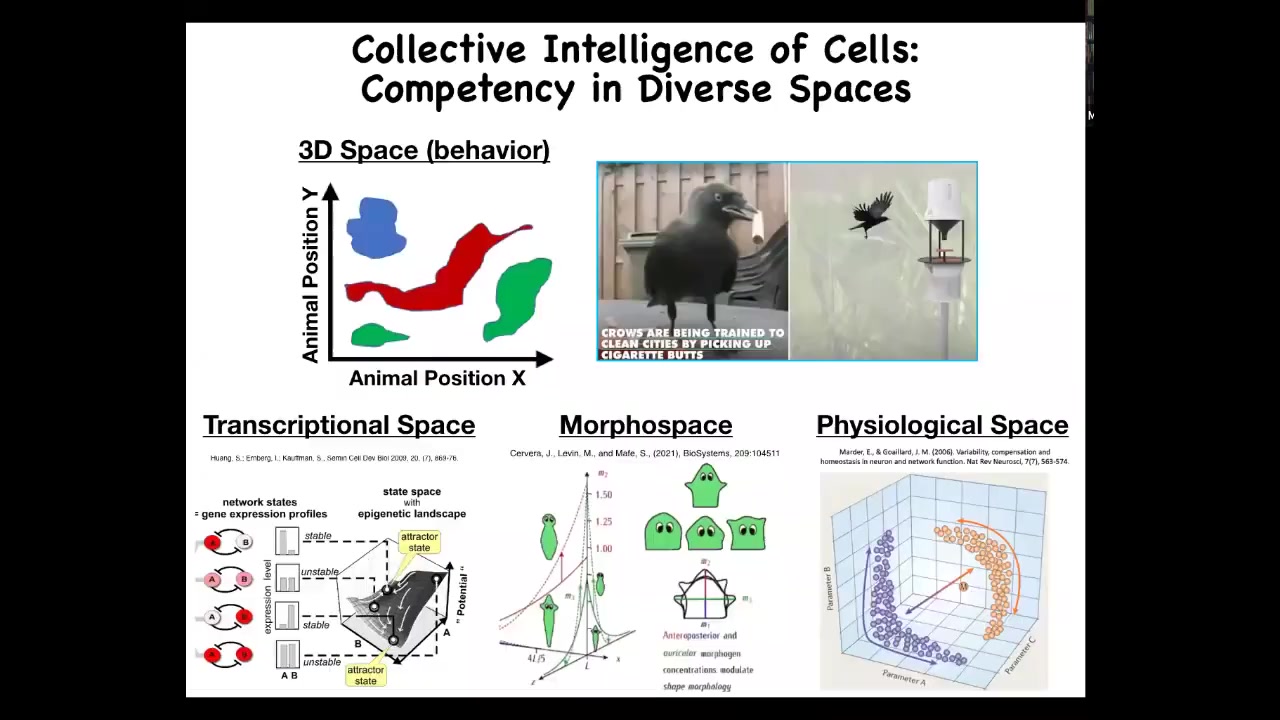

We're pretty used to recognizing intelligent activity in three-dimensional space. Our cognitive and sensory structures are primed to look for medium-sized objects moving at medium speeds through three-dimensional space and doing clever things like this crow that's learned to pick up cigarette butts to receive a reward. But imagine if we had the innate sense of feeling all the parameters of your blood chemistry, for example. If we had an innate feeling of that, much like we see the outside world, we would have no problem recognizing, for example, that our liver, our kidneys, our various organs are performing very interesting intelligent behaviors in adjusting to all these novel circumstances in physiological space.

There are numerous other problem spaces that we're not used to, but these spaces are ones in which intelligence can be manifest in exactly the same way that it can be manifest in three-dimensional space. We just have to learn to think about these.

What are these spaces? There are spaces of physiological parameters. There are spaces of transcriptional states, meaning gene expression, a separate dimension for every gene, and then you have this huge dimensional manifold in which every cell is navigating as it changes its transcriptional states. And we have this, which is my favorite and what I'll spend the most time talking about, which is anatomical morphospace. The space of all possible shapes, for example, the parameter space that defines different shapes of planarian heads.

Slide 16/60 · 23m:56s

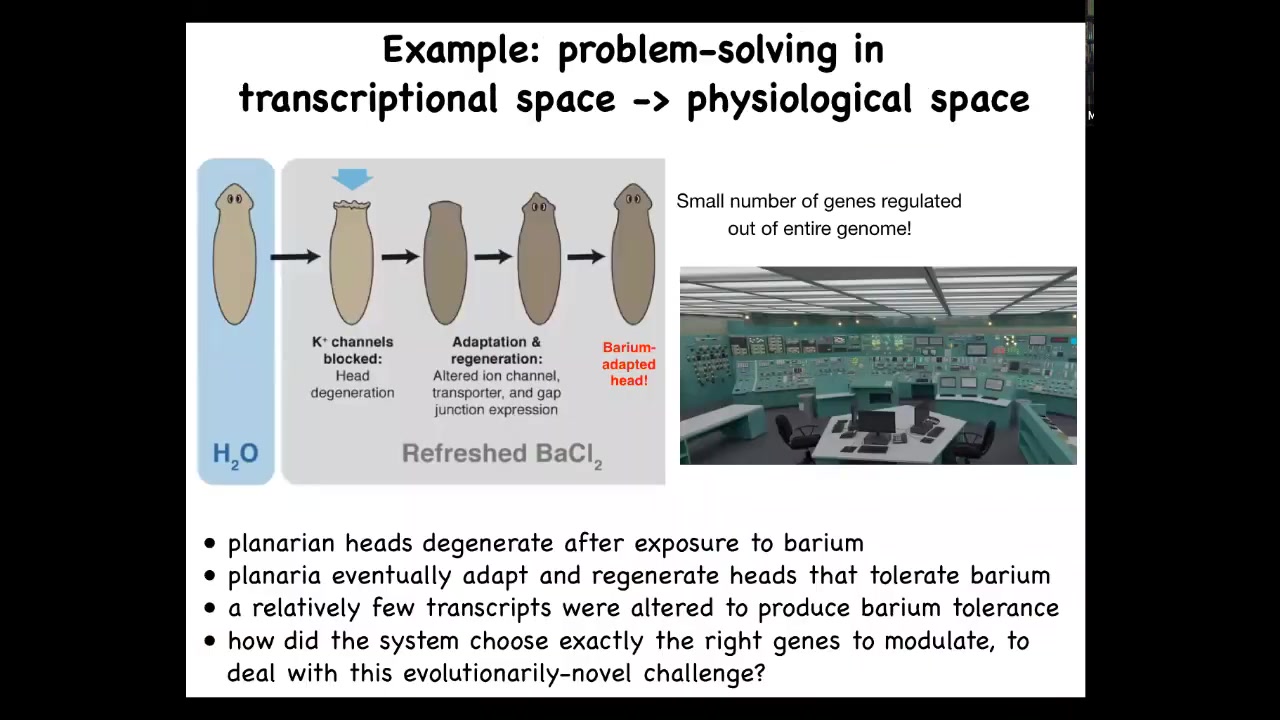

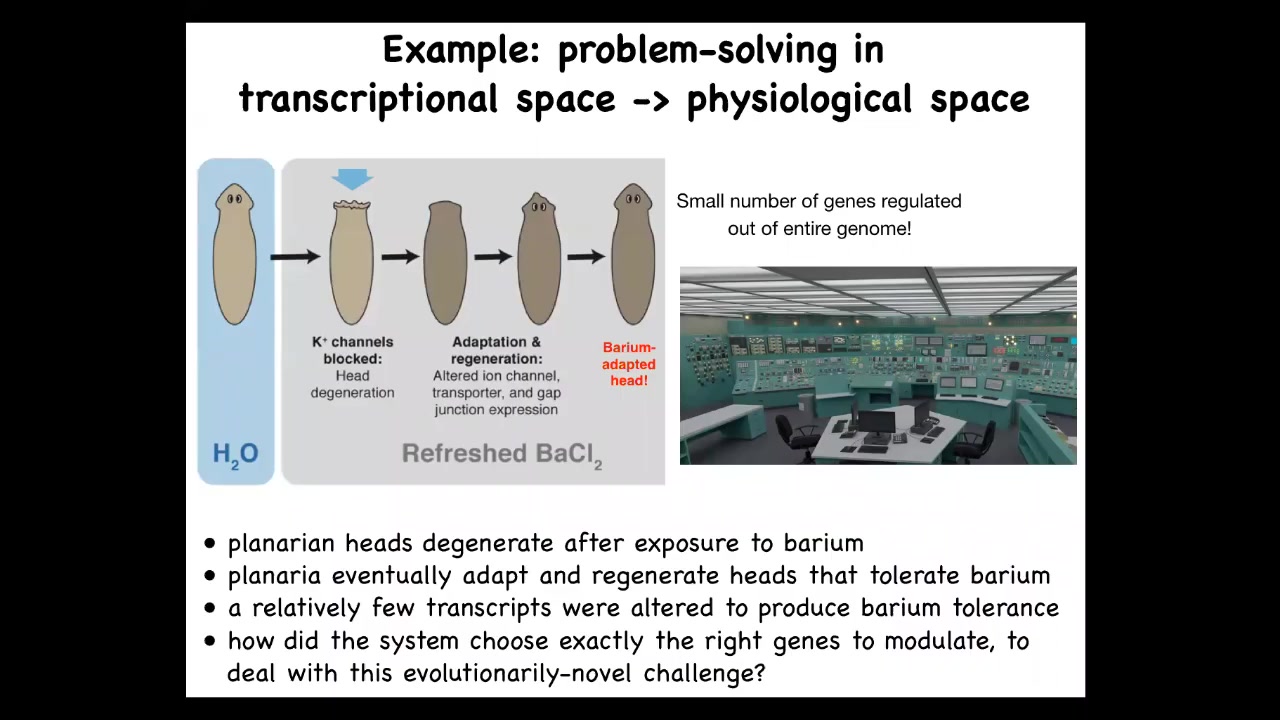

Before we launch into morphospace, I want to give you one example of transcriptional and physiological space that we discovered a couple of years ago. Here's our planarian. What we've done is we take this flatworm and we put it into a solution of barium chloride. Barium is an interesting chemical. Barium blocks all of the potassium channels. When you block all the potassium channels, cells, which rely on potassium flux to manage their physiology, become extremely unhappy. In fact, the planarian head has so many neurons that require this, the whole head explodes. They just overnight lose their head. The amazing thing is that if you keep them in barium, what they will do over the next week or two is they will grow a new head. The new head is completely adapted to barium and has no problem with barium. We asked the very simple question, how is that possible? What is this head doing that's different from the original head?

Slide 17/60 · 25m:19s

What we did was we compared the transcriptomes. We looked at all of the genes that are expressed in these normal heads versus the ones that are expressed here. We asked what's different. What's transcriptionally different about these animals. What we found is it's really a very small number of genes that were turned on to allow them to adapt to barium.

Now here's the amazing thing. Planarians never encounter barium in nature. There has never been evolutionary pressure for being able to deal with barium exposure and for knowing what to do when you're in barium. How did these cells know exactly which genes to turn on to deal with this new physiological stressor? You can imagine this problem. It's because 20,000 genes or however many there are; it's like you're in a nuclear reactor control room, it's melting down, there's a big problem. How do you know what to do? In fact, you can't. There's no time to just start flipping genes randomly on and off. The cells don't turn over like bacteria, so there's no time for some kind of random change where everything dies and the one successful cell repopulates the head. There's this real problem of understanding how these cells navigate to the correct region of transcriptional space. They have to take this walk from this state to this state, and it's not known how they do that. That's an example of problem solving in physiological space.

Slide 18/60 · 26m:54s

What I'd like to do next is to focus on morphogenesis and problem solving in anatomical space as a kind of collective intelligence.

We all start life like this as a ball of embryonic blastomeres. This is an early stage, and these cells eventually build something like this. This is a cross-section through the human torso. You can see the amazing order here, the structure. Every organ and tissue is in the right place, the right size, the right position relative to each other. Where is this order specified?

People often will want to say it's in the DNA, but we can read genomes now, and none of this is directly in the DNA. What the DNA specifies is the micro-level hardware of each cell, the proteins that every cell gets to have. But it's the physiology and the dynamic behavior of these cells that gives rise to the right number of fingers, eyes, and everything else. So we have to understand: how do cells, groups of cells, know what to make and when to stop.

As workers in regenerative medicine, we would like to know, if a piece of this is missing, how do we get these cells to rebuild again? And as engineers, we would like to ask a further question, which is, that's fine to regenerate this, but what else can we make? Can we ask these cells to build something completely different? I'll show you that towards the end of the talk.

Slide 19/60 · 28m:22s

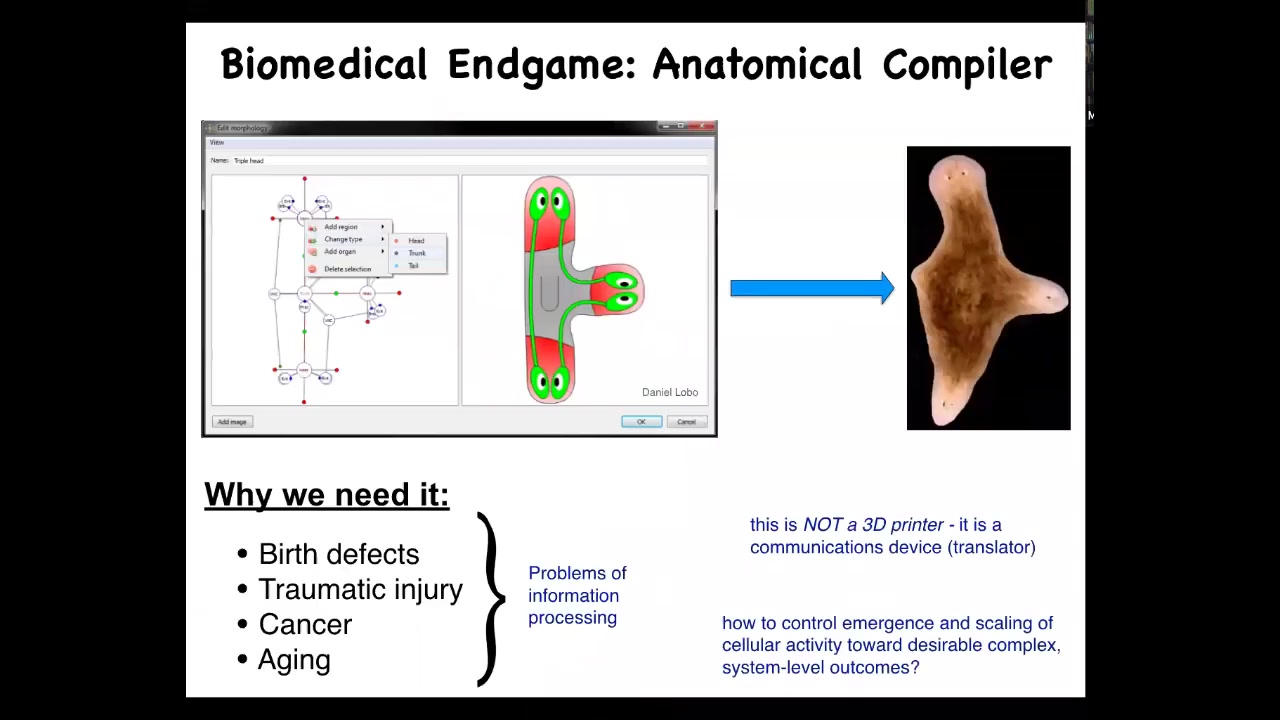

So I like to think about the endgame of this field, specifically of regenerative medicine, with a concept of an anatomical compiler. An anatomical compiler is an aspirational future system where what you should be able to do is sit down in front of a computer and draw the animal or plant that you want. It could be anything. It could be a typical one. It could be some sort of hybrid. And if we knew what we were doing and we understood we had a mature science of morphogenesis, what the system would be able to do is output a set of stimuli that you could give to a group of cells and they would build exactly what you asked for. An anatomical compiler. Now notice that I'm going to argue that an anatomical compiler is not a 3D printer. You are not micromanaging the positions of individual cells and trying to print it. What it really is deeply is a communication device. It's a translator from your desired three-dimensional shape to the signals that need to be given by the cellular collective to cause that collective to build it in exactly the same way that it normally builds something else. We need it because, with the exception of infectious disease, most problems of biomedicine boil down to the control of shape. Birth defects, traumatic injury, cancer, aging, all of this would be solved if we knew how to convince a group of cells to do what we want them to do. We have molecular biology and genetics.

Slide 20/60 · 29m:55s

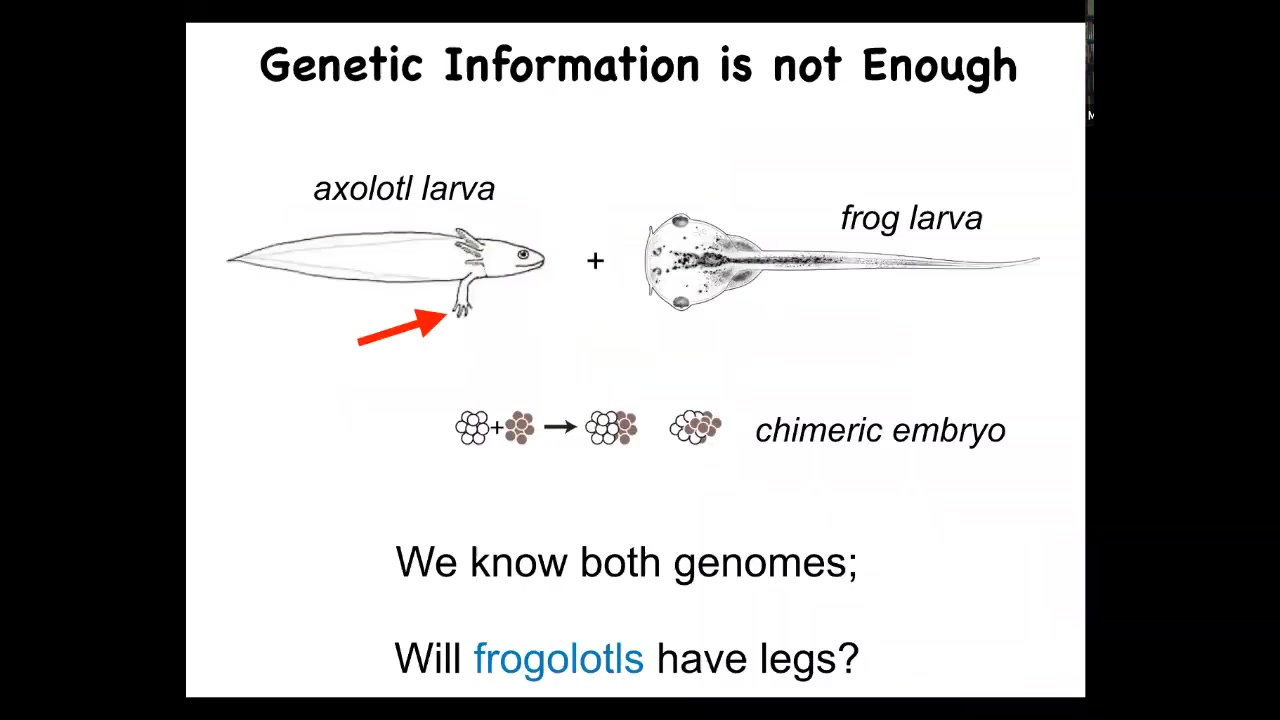

So isn't that enough? What else do we need? Here's a very simple example. This is an axolotl larva. These are salamanders, and baby axolotls have little legs. This is a tadpole of a frog. Frog tadpoles do not have legs. In our lab, we can make a chimeric embryo called a frogolotl by mixing early cells. Will the frogolotl have legs or not? We have both genomes: the axolotl genome and the frog genome. Can you tell me if the frogolotl is going to have legs? The answer is no. We have absolutely no frameworks currently to determine this kind of anatomical information, even though you have the full genetics for both animals.

Slide 21/60 · 30m:42s

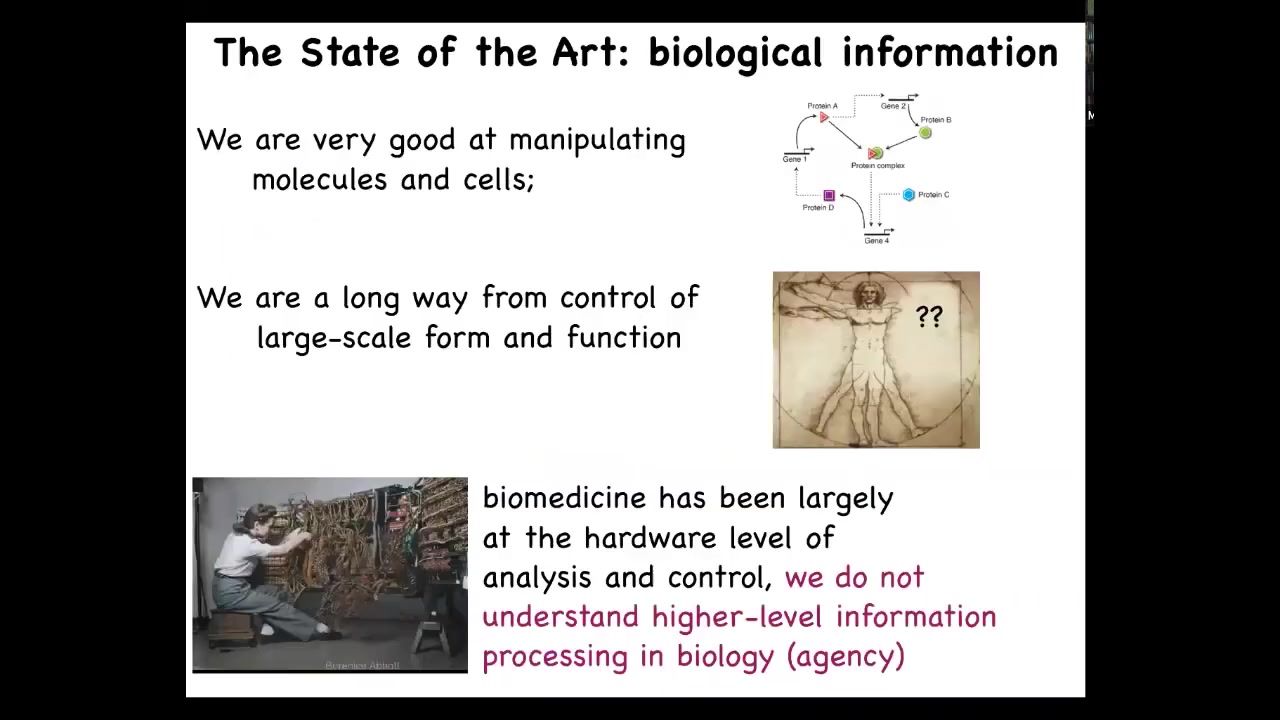

Molecular biology and medicine are very good at manipulating pathways, so cells and molecules. But we're quite a long way from controlling form and function, which is what we want.

My argument is that in biomedicine we are where computer science was in the 40s and 50s: it was still stuck at the hardware level. Everything is about pathways and molecules and genome editing. This is all at the level of hardware, but we have an opportunity to exploit something remarkable that exists in biology and also in some computer systems, which is higher-level information processing. In biology, we call this agency.

Slide 22/60 · 31m:24s

I want to give a definition of what I'm talking about. I like William James's definition for intelligence: the ability to reach the same goal by different means. It's the continuum of different capacities that make the difference between two magnets trying to get together and Romeo and Juliet trying to get together. It's the degree of sophistication you can expect from a system in meeting a specific goal, which looks like energy minimization in very simple systems, and it looks somewhat different in complex systems.

How does intelligence work out in morphogenesis? Here's a simple example. We know that development is extremely reliable. Almost all of the time, an embryo will give rise to a proper human body. But it's reliable and robust. It's not hardwired. If we take an early embryo and cut it in half, you don't get two half bodies. You get two perfectly normal monozygotic twins. Development in general has this ability to reach the same goal, meaning the same state in anatomical amorphous space, from different starting positions and despite various perturbations, unlike hardwired systems that would simply get stuck at local maxima, the way two magnets trying to get together would be forever stuck. If you put a barrier in their place, they're never going to walk around it. They're just going to try to get together in the direct path. Development isn't like that.

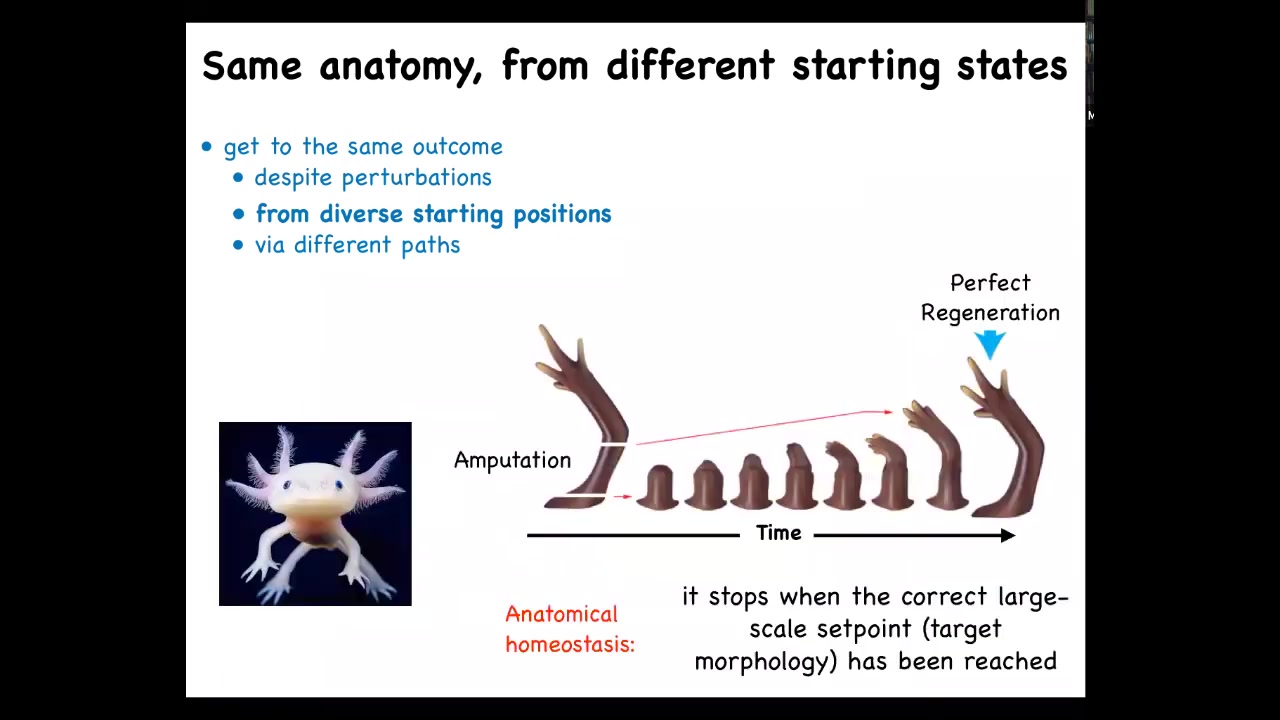

Slide 23/60 · 33m:01s

And regeneration isn't like that either. Here's a salamander. That's called the axolotl. They will regenerate their legs, their eyes, their jaws, various internal organs. If you amputate anywhere along this limb, they will grow exactly what's needed, and then they will stop. The stopping is the most amazing part. When do they stop? They stop when the correct large-scale anatomy is complete. The system as a whole knows exactly what a normal salamander looks like. This is an example of anatomical homeostasis, or the ability to return to that region of anatomical morphospace when it's been perturbed away from it.

Slide 24/60 · 33m:48s

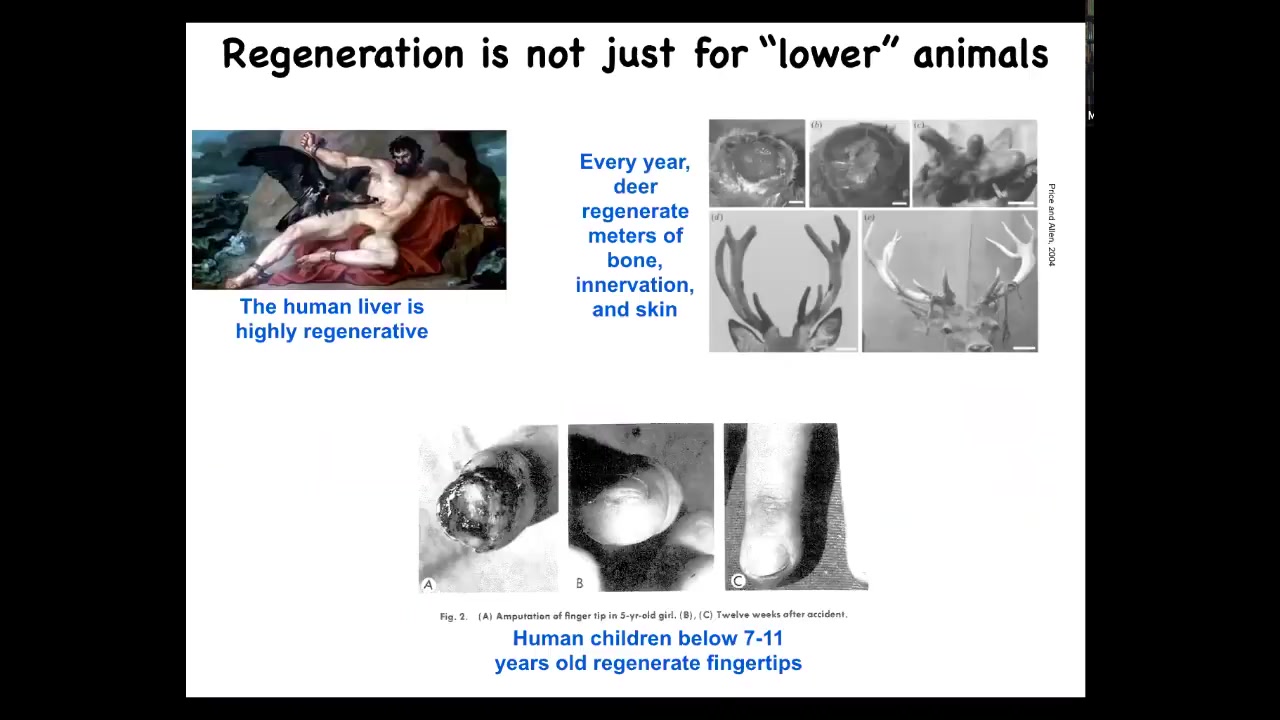

I should say that this is not just some weird capacity of lower organisms. Human livers are highly regenerative. Human children will regrow their fingertips, and deer regrow large amounts of bone innervation and vasculature every year. There's all kinds of capacities for that regeneration.

Slide 25/60 · 34m:07s

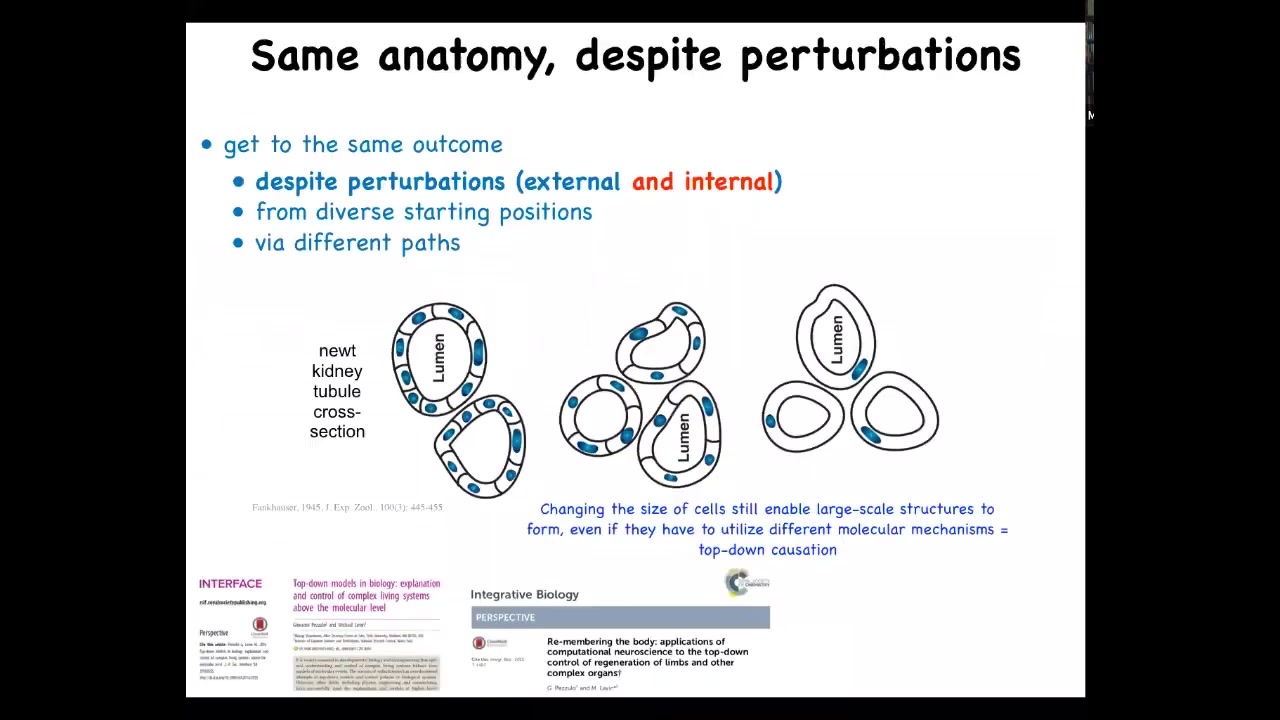

One of the most amazing and one of my favorite examples is this, and this was discovered back in the 1940s. This is a cross-section through a kidney tubule in a newt. What you see is that there's 8 or 10 cells that cooperate together to build this kind of tubular structure. One thing you can do is force these cells to be much larger. When the cells get larger, the newt stays the same size. It has a regulative ability. Remarkably, fewer cells are being used, but they make the same structure. The most amazing thing happens when you make these cells so enormous that one cell will bend around itself to form the exact same structure.

What's remarkable about this is that this is a completely different molecular mechanism. This is cell-to-cell communication and tubulogenesis. This is cytoskeletal bending. What you have here is a nice example of top-down causation. In the service of a large-scale anatomical goal, making a proper tubule of the right shape and size, different molecular mechanisms will get called up. In this case, cytoskeletal bending, in this case, cell-to-cell interactions. Different molecular mechanisms get called up to serve this high-level anatomical goal. We can see this kind of multi-scale. This is very much what cognitive architectures do. You have a high-level executive function of some sort, and that eventually feeds down to physiological processes and making your muscles move and so on.

Slide 26/60 · 35m:47s

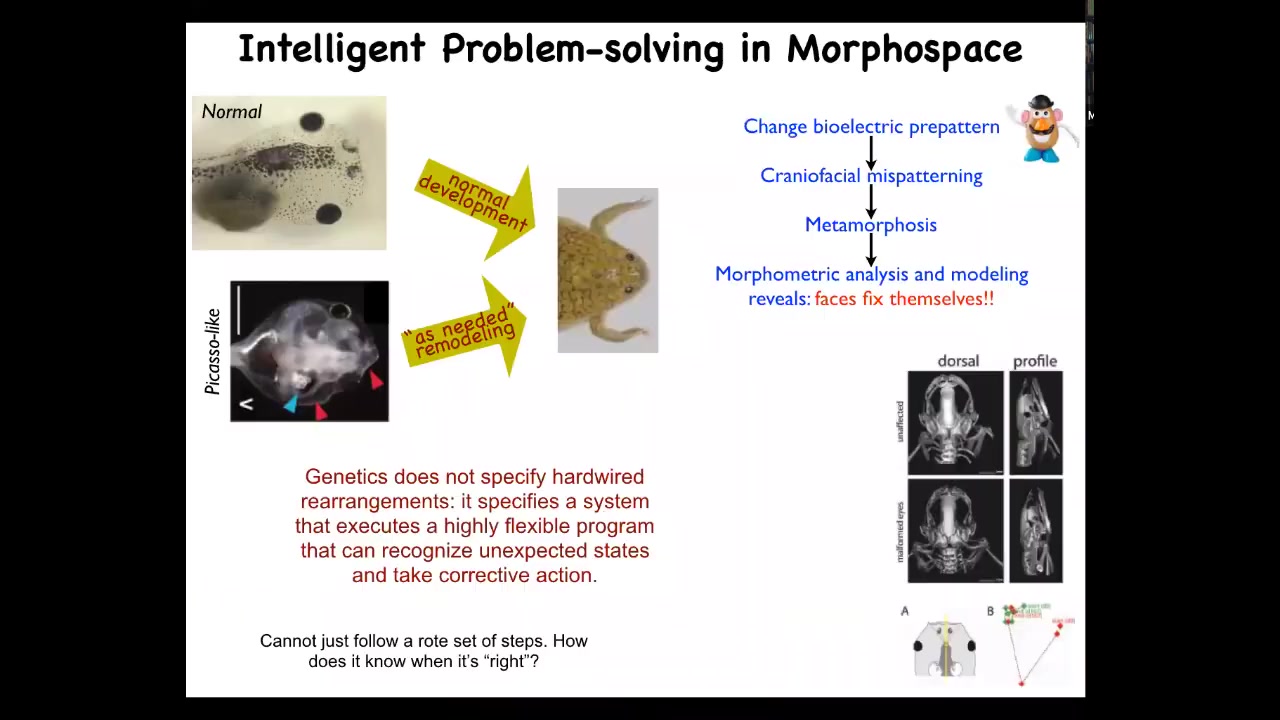

This is another really nice example, which we discovered a few years ago. This is a tadpole: the eyes, the brain, and so on. These tadpoles need to become frogs. In order to become frogs, they have to rearrange their face. The jaws have to move, the eyes have to move, everything has to move around.

It was thought that this was a hardwired process, meaning every organ just moved in the right direction, the right amount, and then you go from a normal tadpole to a normal frog. We decided to test the idea that this process had very low intelligence and was a hardwired set of movements. We scrambled all of the initial starting positions. We made these Picasso tadpoles, where all the organs are in the wrong place.

They still make normal frogs. Everything moves around in novel paths. Sometimes they go too far and they have to come back, but everything moves around until they get to their normal position and then they stop.

This is very interesting. The system is not just a set of hardwired movements. It can do the same. It can reach the same goal despite this perturbation. What the genetics gives you is not a hardwired machine. What it gives you is an error minimization scheme. It gives you a system that executes a very flexible program that can start off in different starting positions and still get to where it needs to go through novel actions that are not normally taken through development.

This kind of navigation of morphospace with different competencies is exactly what we're looking for as an invariant across diverse problem-solving systems.

Slide 27/60 · 37m:33s

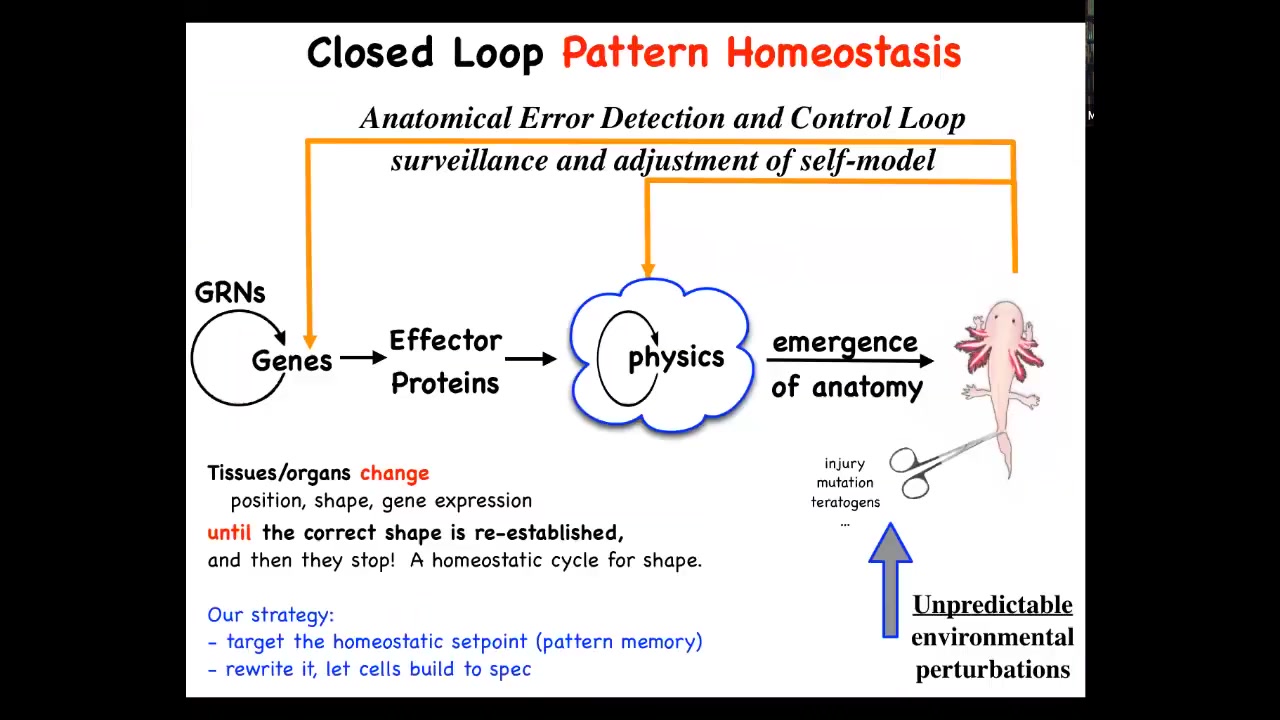

So we started to think about this process as this kind of homeostatic loop, a simple homeostat on that initial scale that I showed you from Weiner and colleagues. The idea is that this is the typical developmental story that you get in textbooks where you have gene regulatory networks. The genes turn each other on and off and you get some proteins that interact according to the laws of physics. So this is a kind of a complex dynamical system. And then through the magical process of emergence, you get a complex outcome. You get something like this. That's true. All of that does happen. But the more amazing part of it is that this is not a purely feed-forward emergent process. What you actually have is a set of control loops that will be activated if you deviate from this target state. That means injury, mutation, teratogenesis, cancer — if you deviate from the state, then both at the level of transcription, at the level of physics, actions will be taken to try to get the system back to where it needs to be.

Basic homeostasis.

Now, here's the thing. In biology, in medicine, we're very used to homeostatic circuits. That's no big surprise for temperature and pH and things like that. However, two things are unusual here. One is that in those kinds of systems, the set point parameter is a scalar. It's a single number — pH, temperature, a metabolic state. But here what we're saying is the set point is some kind of coarse-grained anatomical descriptor. The set point is complex here. It's not a single number. It's a shape descriptor. The other thing is that because this has the cybernetic flavor of error minimization, it's very much a goal-directed system in the formal engineering control theory sense of a goal. It's a state toward which the system can repair itself, using energy to get back to that state despite perturbations. That's unusual because in molecular biology and fields like that, you're not supposed to talk about goals. You're only supposed to talk about feedforward emergence. I think that's a big miss for those kinds of approaches.

This way of thinking makes a couple of very strong predictions. The first is that if this is true, it has to have an explicit encoding of the goal state. Every thermostat has a set point; it must be recorded somewhere. In order to have this kind of homeostatic circuit, you need to be able to know what the set point is. Somewhere you have to store the actual memory of what the correct salamander looks like. That's quite unusual. If that's true, the prediction is twofold. First, that you should be able to find it, decode it, and rewrite it.

The other big thing is that if you do that, that's a completely different way of controlling the system than the traditional bottom-up molecular biology approach. Because if this were an emergent system, then your only hope would be to figure out what to do down here: which genes do I alter? For example, if we decided that we wanted more fingers, or we wanted this to have three-fold symmetry instead of bilateral symmetry, can you figure out which genes need to be changed to make that happen? The answer is we have no idea how to do that.

There's potentially another approach. Let's leave the hardware alone, the way you would do with a thermostat, and change the set point. Can we decode that set point and get the exact same cells to build something completely different?

Slide 28/60 · 41m:12s

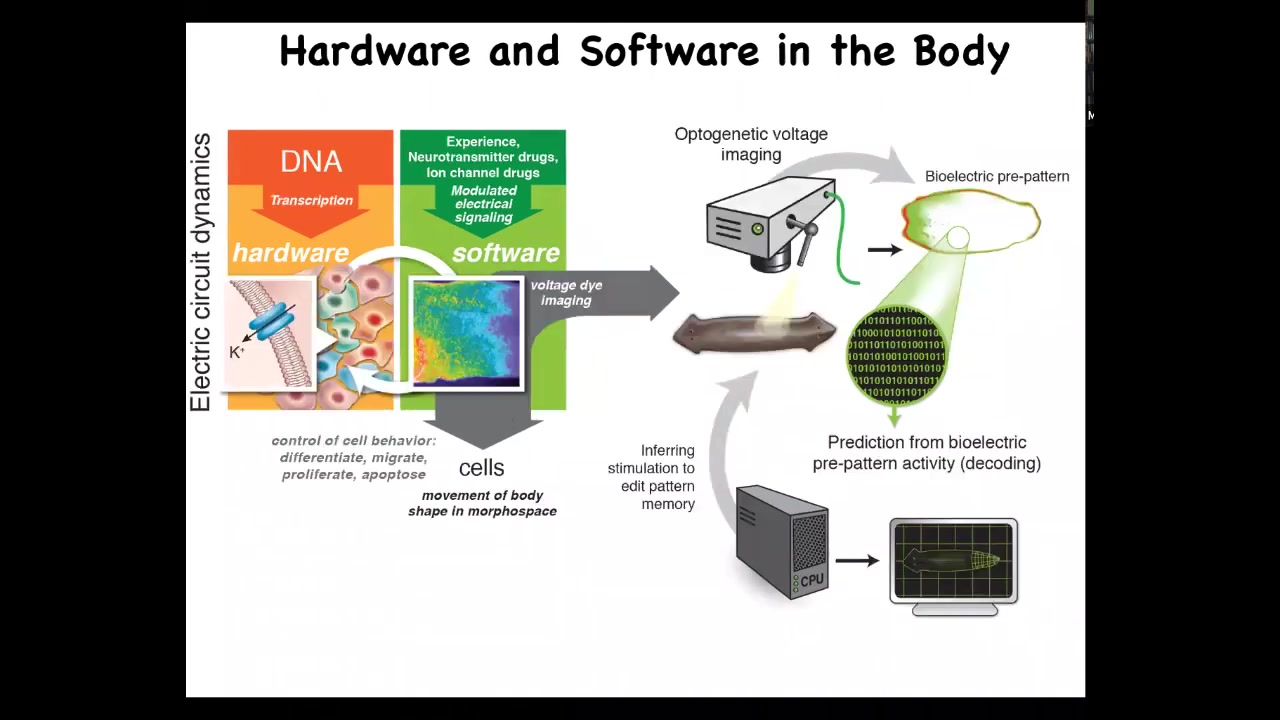

What I'm going to show you now is our efforts to do that because we've basically uncovered the idea that the informational medium for this collective intelligence, these groups of cells that do these amazing things and repair and so on, there is a kind of cognitive glue that allows them to do that, binds the individual cells into a single agent that has goals and morphospace. That glue is perhaps not shocking because that's what happens in the brain. That mechanism is developmental bioelectricity.

Let's look at brains as an example of a biological system in which this kind of problem-solving capacity exists. How do brains solve problems in three-dimensional space? Well, the hardware looks like this. It's a network of cells connected to each other. Each cell has these little ion channel proteins that allow the cell to maintain different voltage potentials. That electrical state can be propagated to the neighbors through these little electrical synapses known as gap junctions. That kind of hardware is known to support an amazing kind of behavioral software. You see this here: this group made this amazing video of electrical activity in a zebrafish brain and a living zebrafish brain as fish think about whatever it is that fish think about. And this drives a process of, or a project of neural decoding.

The idea is that if we record all of this activity and we learn to decode it, we will be able to read out the mental states, the goals, the preferences, everything else about the mental life of the system, because it is a commitment of neuroscience that all of the cognitive content of the organism is stored and implemented by the brain physiology here.

That's the standard neuroscience story, but neuroscience is actually applicable way beyond neurons because all of the cells in your body have ion channels. Most of them have gap junctions to their neighbors. What we've started is this parallel idea of non-neural decoding. This happens to be a frog embryo developing, same technology, imaging the electrical conversations that these cells have with each other. We should be able to decode this. From there, derive all of the proto-cognitive capacities that the system is using to navigate anatomical space and become a proper embryo. What does the collective measure? What does it remember? What does it know? What errors does it try to minimize? All of these things we should be able to discover if we knew how to crack this bioelectric code.

The interesting thing is that it's this architecture of brain and behavior, where the DNA specifies the electrical components, and then you have this excitable medium, which with certain architectures supports behavior that you can affect not just by editing the DNA, but with experience, with electrical signals through sensory organs, with drugs. What it does is it controls your muscles electrically to move the body through three-dimensional space.

Slide 29/60 · 44m:39s

This system is evolutionarily ancient. This was used long before brains and neurons appeared; even bacterial biofilms knew how to do this. It exploits the exact same computational capacities of electrical networks to make decisions collectively that move your body shape through anatomical morphospace. It controls your journey, not through physical space, but through anatomical space before you have a brain and muscles. This is not only evolutionarily ancient, but developmentally extremely early. There's a really strong isomorphism here because evolution likes to reuse things. We think that what it did was simply pivot the same set of tricks into different effectors and thus into different problem spaces.

Slide 30/60 · 45m:28s

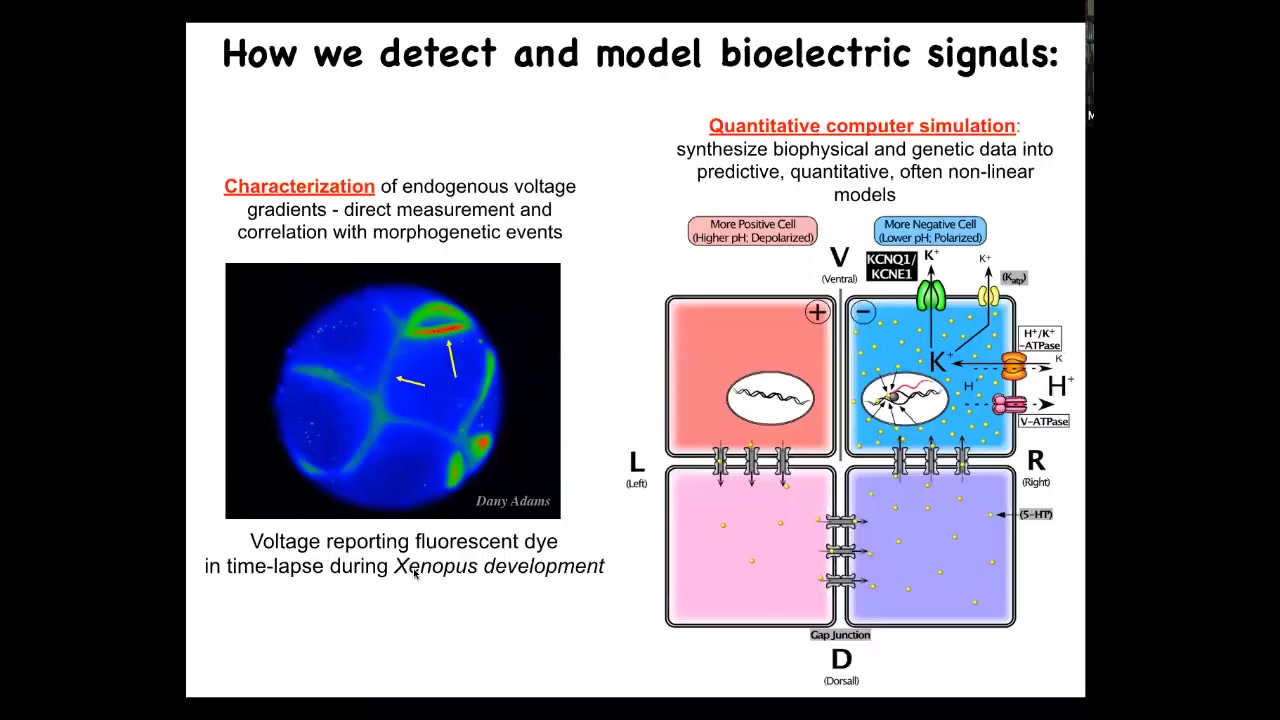

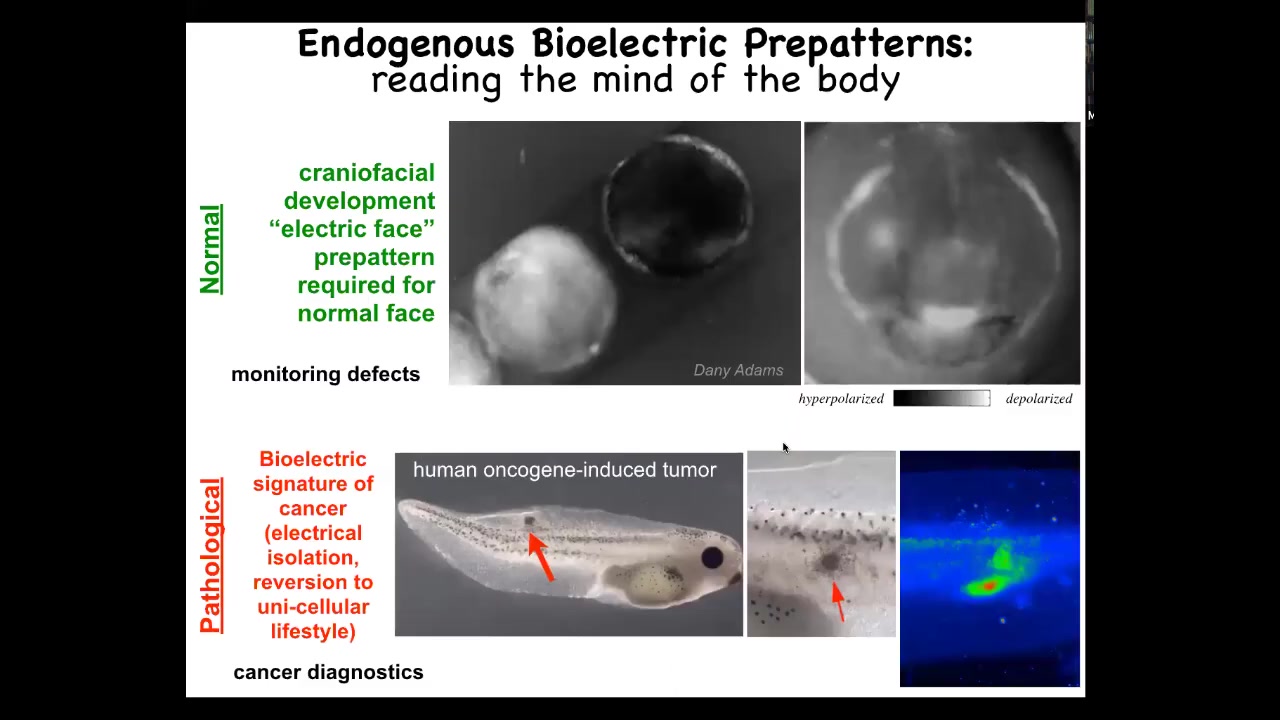

Here are some tools we developed. We developed these voltage sensitive dyes that allow us to track all the electrical states of, for example, an early embryo. Here's a time lapse taken by my colleague Danny Adams. We do a lot of computational modeling to link it to the molecular biology of these ion channels to figure out which channels and pumps are responsible for the states of individual cells. Then it's the hard work of doing the systems physiology of figuring out what the patterns mean.

Slide 31/60 · 45m:57s

I'm going to show you 2 examples of these patterns. This is a voltage movie taken of an early frog embryo putting its face together. You can see here that this is 1 frame out of that movie that we can now read out the pattern memory that these cells have of what a normal face looks like. Before all the genes come on and all the cells become rearranged you can already see the tissue knows, here's where the mouth is going to go, here's where the first eye is going to go, the second eye comes later, here are the placodes. We can already read out these pattern memories.

We know these are instructive because if you change this using optogenetics or various other techniques, everything downstream has changed. The gene expression has changed. The position of the organs changes and so on. This is the reference point that serves as the representation for making this embryo. That's the native one required for normal development.

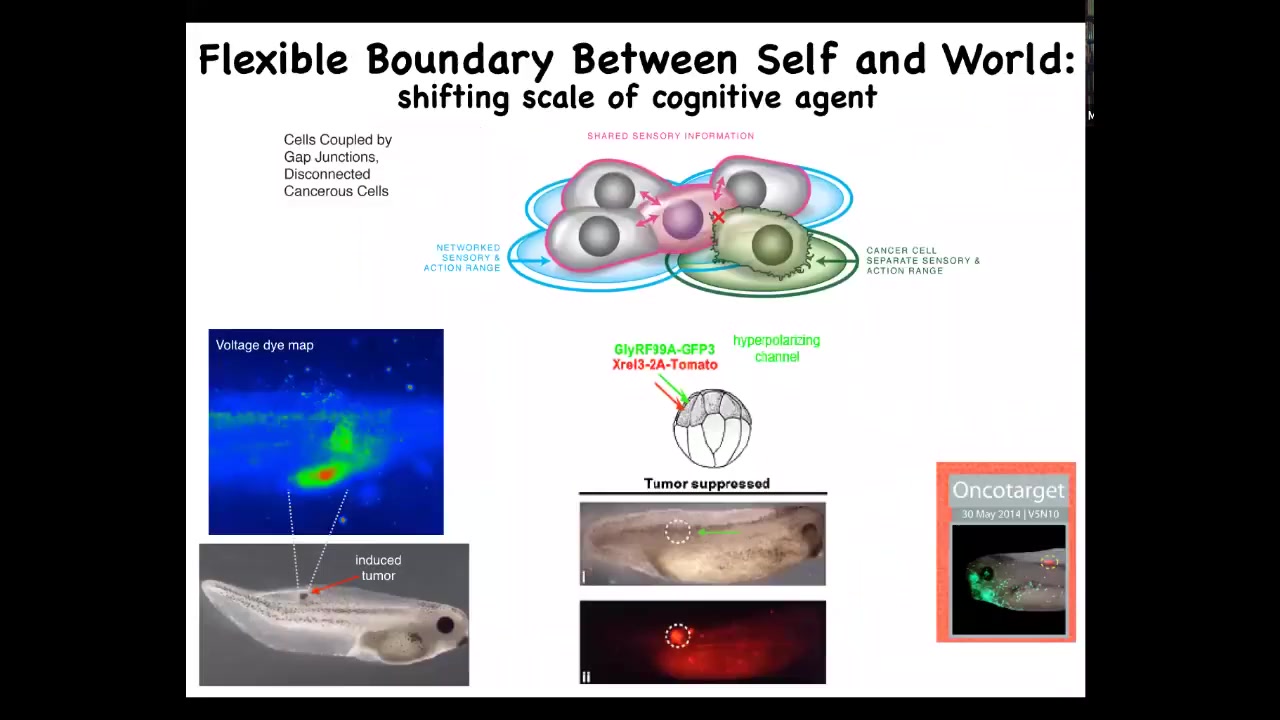

Here's a pathological one. We can inject human oncogenes into these tadpoles. They make little tumors. Even before the tumor becomes morphologically apparent, you can already see the bioelectrical changes that happen as this oncogene causes these cells to disconnect electrically from their environment and go off and live as amoebas, treating the rest of the body as just an external world. It breaks the connection of these cells to this global bioelectrical pattern. The collective intelligence is broken here.

Slide 32/60 · 47m:36s

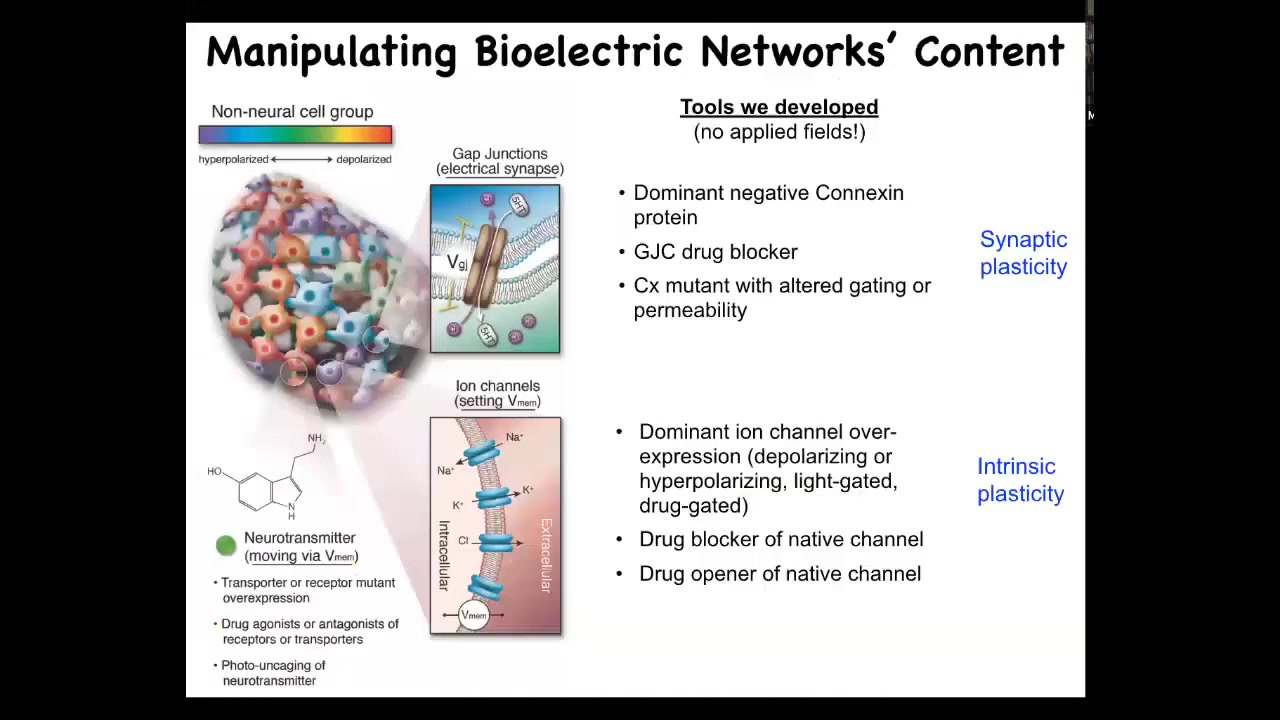

So to do these functional experiments, to manipulate these things, we've developed two kinds of tools: everything stolen from neuroscience and appropriated to other cells. None of the techniques of neuroscience distinguish between neurons and other cells. Everything works. All the concepts from active inference to perceptual bistability to rewritability of memory work. We use all the same techniques. We use optogenetics, neurotransmitter drugs, and ion channel drugs.

In the things I'm going to show you, there are no electrical fields being applied. There are no waves or magnets or radiation, nothing like that. All we do is control the native bioelectrical interface that these cells expose to each other to allow them to program each other's behavior. That interface is these gap junctions and these ion channels. We use drugs, we use light as in optogenetics, and we can change the structure of these channels.

What we're trying to do is change the resting potential, and in particular, the spatial pattern of resting potential. This is not a single-cell phenomenon. This is a network phenomenon. So what happens when you do this?

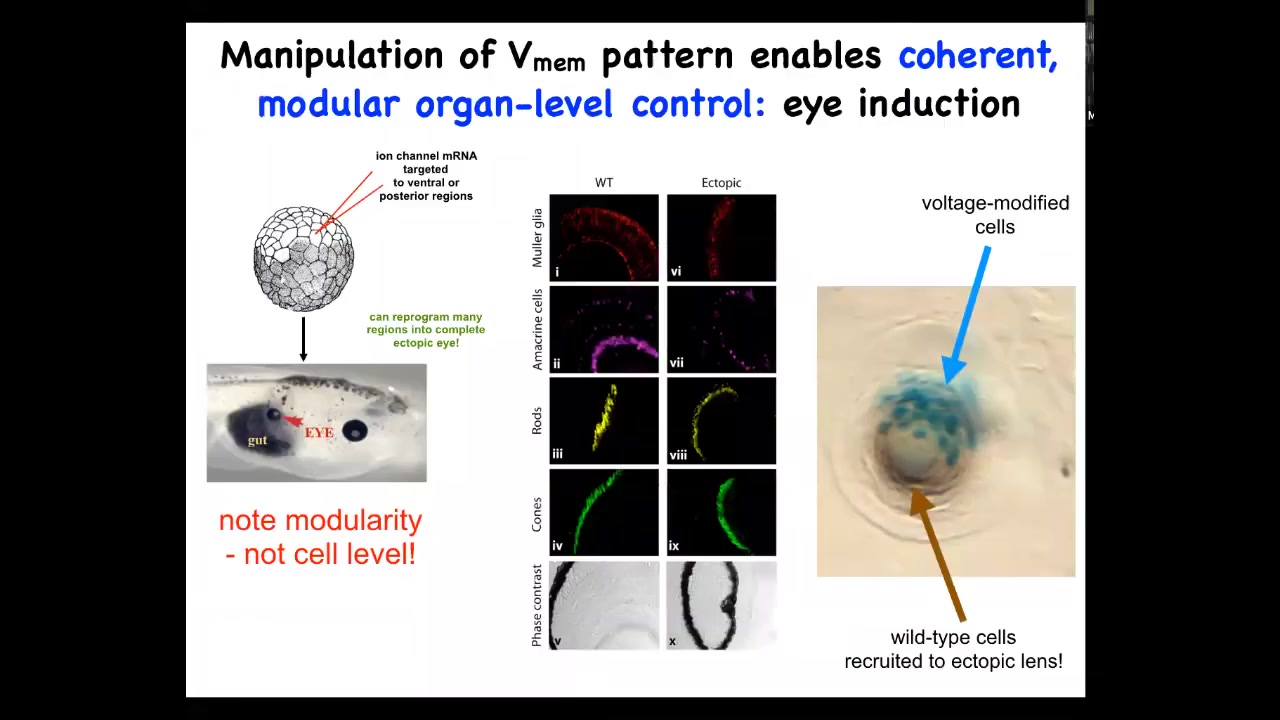

Slide 33/60 · 48m:57s

If we inject into the early embryo an mRNA encoding a specific ion channel that will cause a pattern similar to the pattern we saw in the electric face that I just showed you, we can induce those cells to form an eye.

We can make an eye anywhere, not just in the anterior neuroectoderm, which is where textbooks will tell you the only tissue competent to become an eye is. So that's not true. If you go far upstream of master eye genes like PAX6 and set the correct electrical state, you can get any region of the body to make an eye, for example, the gut here.

If you section these eyes, they have all the same components that normal eyes do. So here are your lens, your retina, your optic nerve.

Notice a couple of interesting things. First of all, this shows you that these bioelectrical patterns are instructive. They're not just epiphenomena or just make defects; they're actually instructive for large-scale pattern.

Also notice the modular control. This electrical state that says build an eye here is basically a subroutine call. We don't provide all the information needed to make an eye. It's a very simple electrical state. Downstream, all the complexity of actually carrying it out does not have to be micromanaged.

They have an interesting capacity, seen for example in ant colonies, which is recruitment. If I only inject a small number of cells not enough to make this whole lens — this whole thing is a lens sitting out in the tail of a tadpole — if I only inject a few cells, what they do is they recruit their neighbors.

The blue cells are the ones whose voltage we changed. These other cells we never targeted; they're completely wild type. They become recruited to this process of making this very nice lens. They have the ability to recruit their neighbors to handle a task that there aren't enough of them to do. That's an interesting capacity of collective intelligence.

Slide 34/60 · 50m:54s

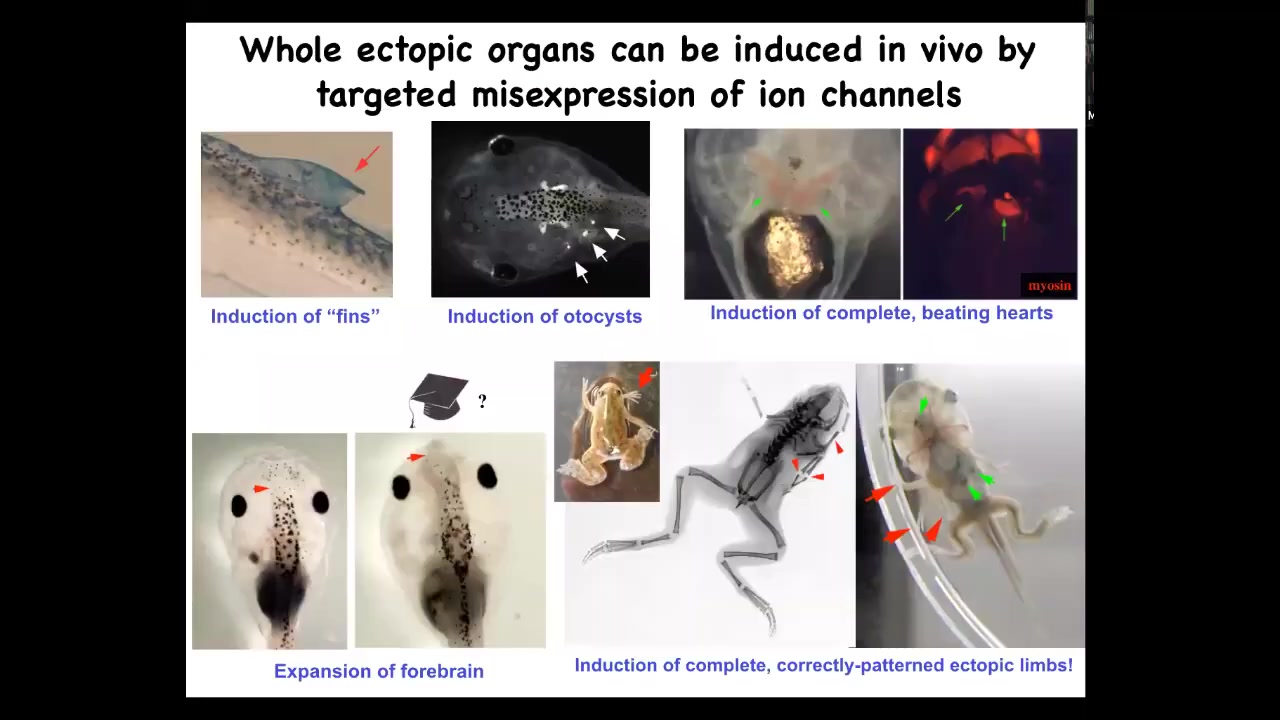

What can we make? We can make ectopic hearts. We can make legs. Here's our six-legged frog. We can make ectopic forebrains using this technique. We can make inner ear organs or otocysts. We can also make fins. That's weird because tadpoles aren't supposed to have fins. That's more of a fish thing, but I'll show you what's going on here in a minute.

Whole organs can be re-specified. Again, we're programming the collective. We're not telling individual stem cells what tissue to be. We're telling a whole region you should be an eye or a leg or something else. What is an eye or a leg? Individual cells don't have any way of representing that, but collectives do. The way they represent it is through these electrical signals.

Slide 35/60 · 51m:38s

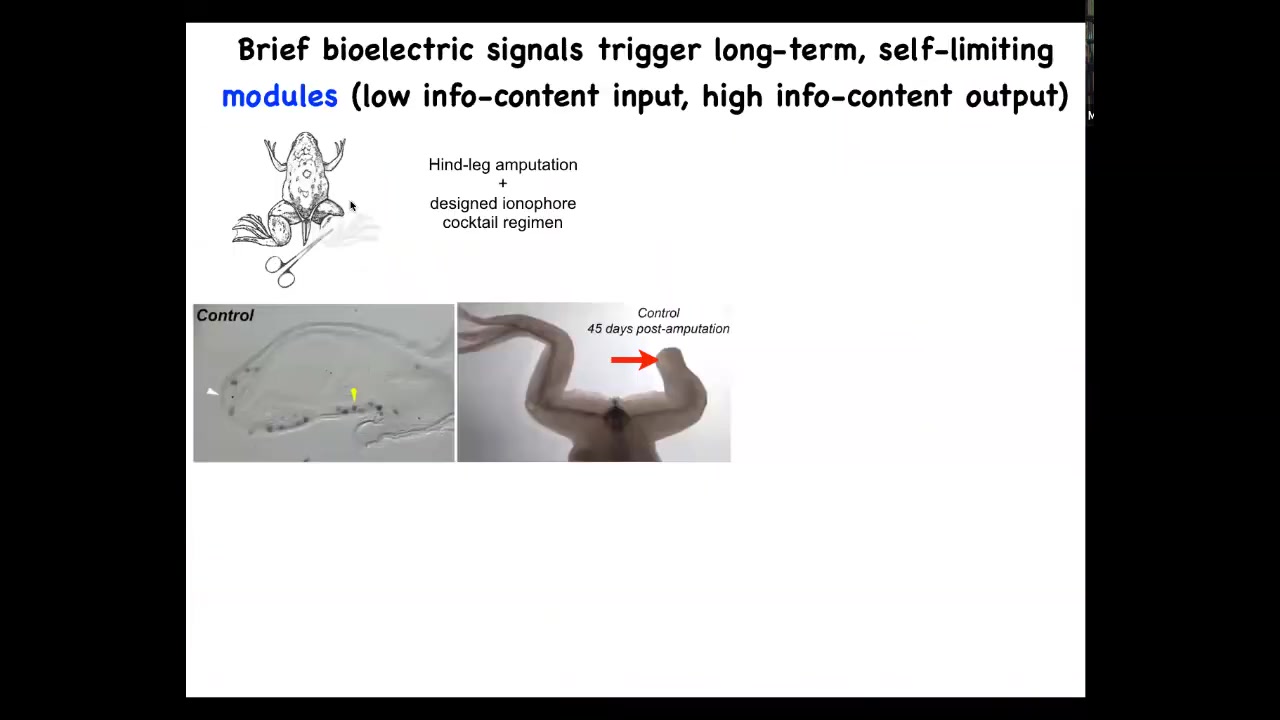

Biomedically, we're using this to try to achieve certain goals in regenerative medicine. Here's our leg regeneration project. Frogs normally do not regenerate their legs, unlike salamanders. If you amputate, 45 days later at this stage there's basically nothing.

Slide 36/60 · 51m:57s

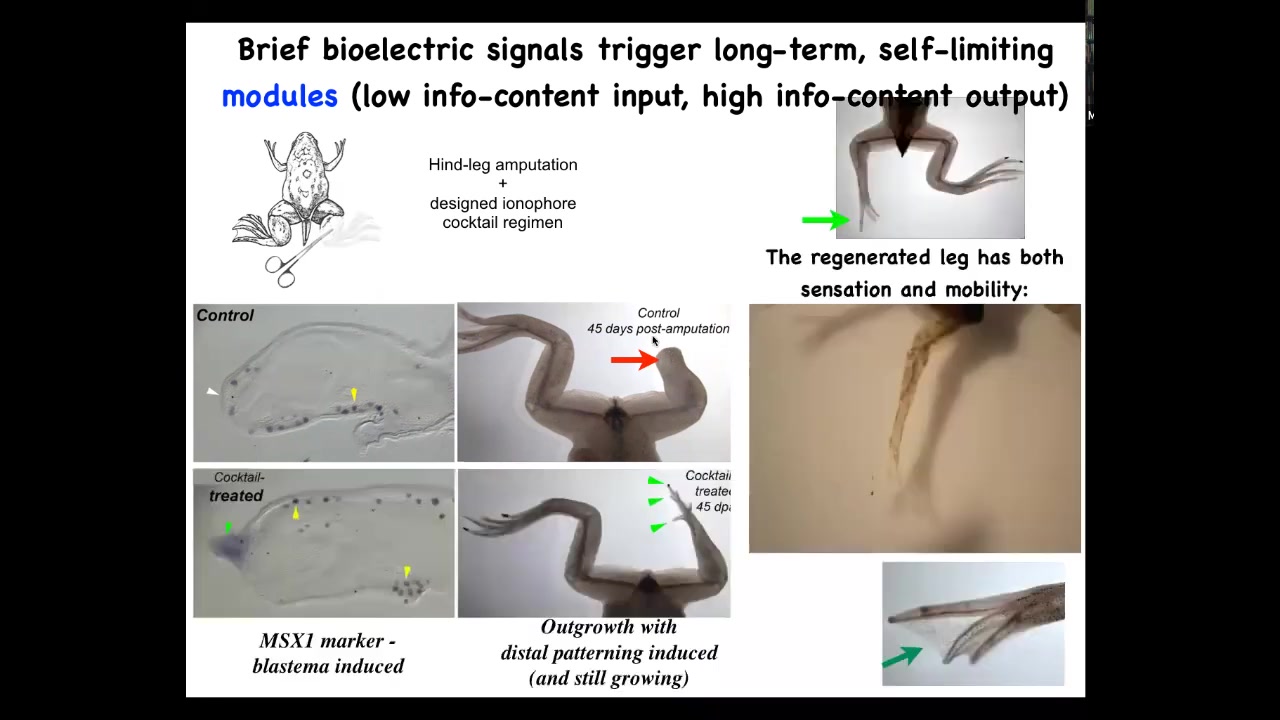

But what we've done is we've created a bioelectrical cocktail that, when you apply to the early wound, shifts the decision-making of that collective towards a leg-regenerating goal. It's just a single-day treatment, and then you get about a year of leg growth. By 45 days, this MSX1 blastema marker, the blastema genes are turned on. By 45 days, you've got a toenail, you've got some toes, and eventually a quite respectable leg. The leg is touch sensitive and it's motile. So the animal can use this leg. Again, it's this idea of communicating a very simple thing to a collective and then taking your hands off the wheel, not trying to micromanage what the stem cells do or what the gene expression is. All of that is handled top down. The idea is to give the appropriate information at the very beginning.

I have to do a disclosure because David Kaplan and I are co-founders of a company called Morphoceuticals, which is trying the same technology in mammals. The idea is to ultimately go to limb and organ regeneration in human patients someday.

Slide 37/60 · 53m:09s

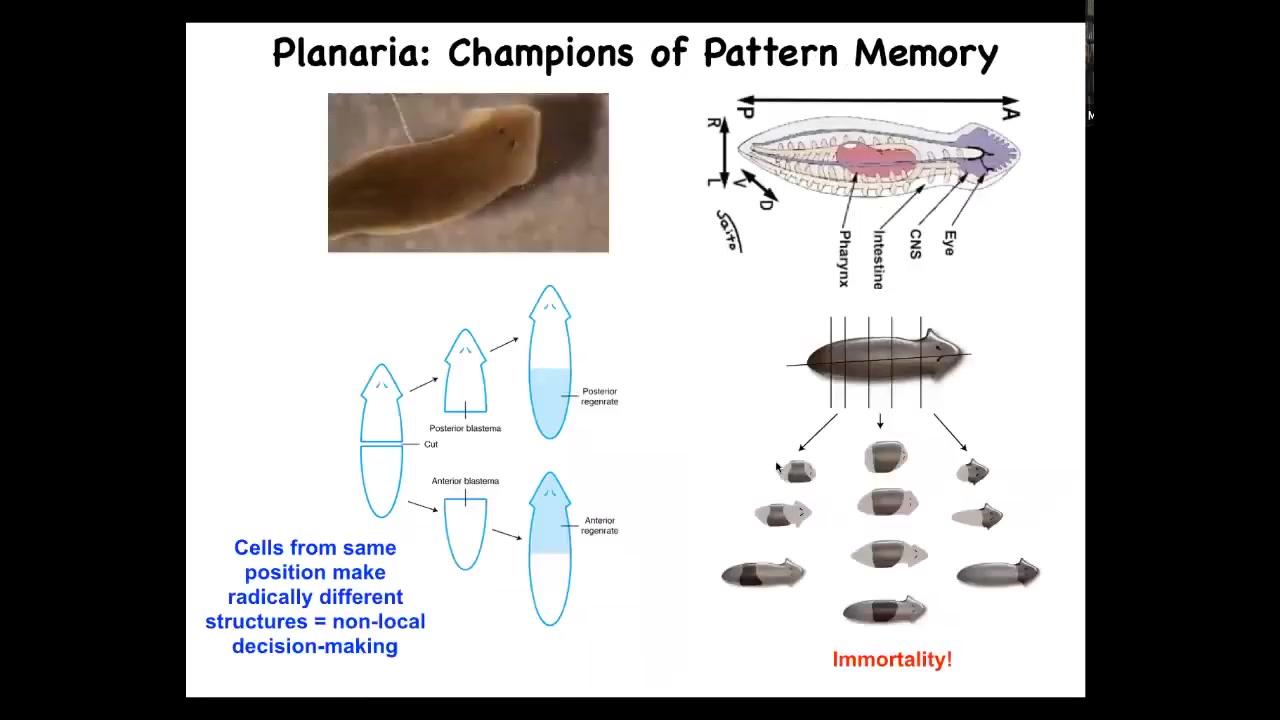

So I want to go back to this amazing creature, these planaria, and think about, try to cash out this idea that these electrical networks, much like in the brain, are storing the goals and the informational content of the collective intelligence.

And so, just to introduce you to this creature a little bit: quite complex, many different organs, a true brain. You can chop them into pieces, and every piece knows exactly what's needed to form a perfect little worm. In fact, they are so good at maintaining the correct shape that they do this all the time in their bodies and thus are immortal. There's no such thing as an old planarian. They don't age at the level of the organism. They just keep going.

They have to have a very developed system of global communication because if you cut them in half, this half becomes a tail. These cells up here form a head, but these cells were direct neighbors a moment ago. So that decision to make a head or a tail can't be locally determined in these cells. They have to communicate with the rest of the body. Do we already have a head? Which way is the wound facing? And then they make their decision. So understanding this decision-making process was really key for us.

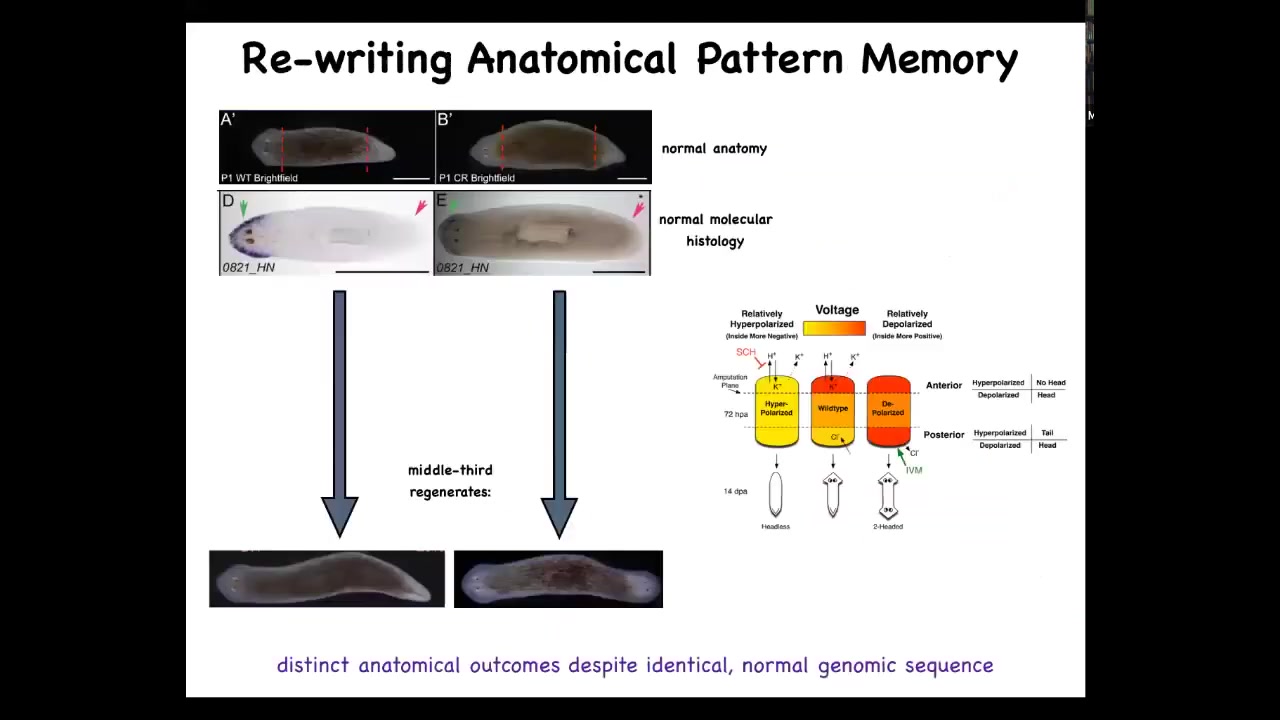

Slide 38/60 · 54m:27s

We developed a model of bioelectrical signaling at the wound that appears to be involved in that head-tail decision, and that allows you to do the following thing. Here's a normal planarian, one head, one tail. It has normal gene expression, anterior genes turned on in the head. Then when you amputate this guy, 100% of the time you get a one-headed offspring from this middle fragment.

But what you can do is you can take one of these, anatomically normal, transcriptionally normal, and it makes a two-headed worm. This is not Photoshop. These are real animals.

You ask, why is it that I just told you this was an incredibly reliable process? Why did this guy form an ectopic head at the posterior?

Slide 39/60 · 55m:14s

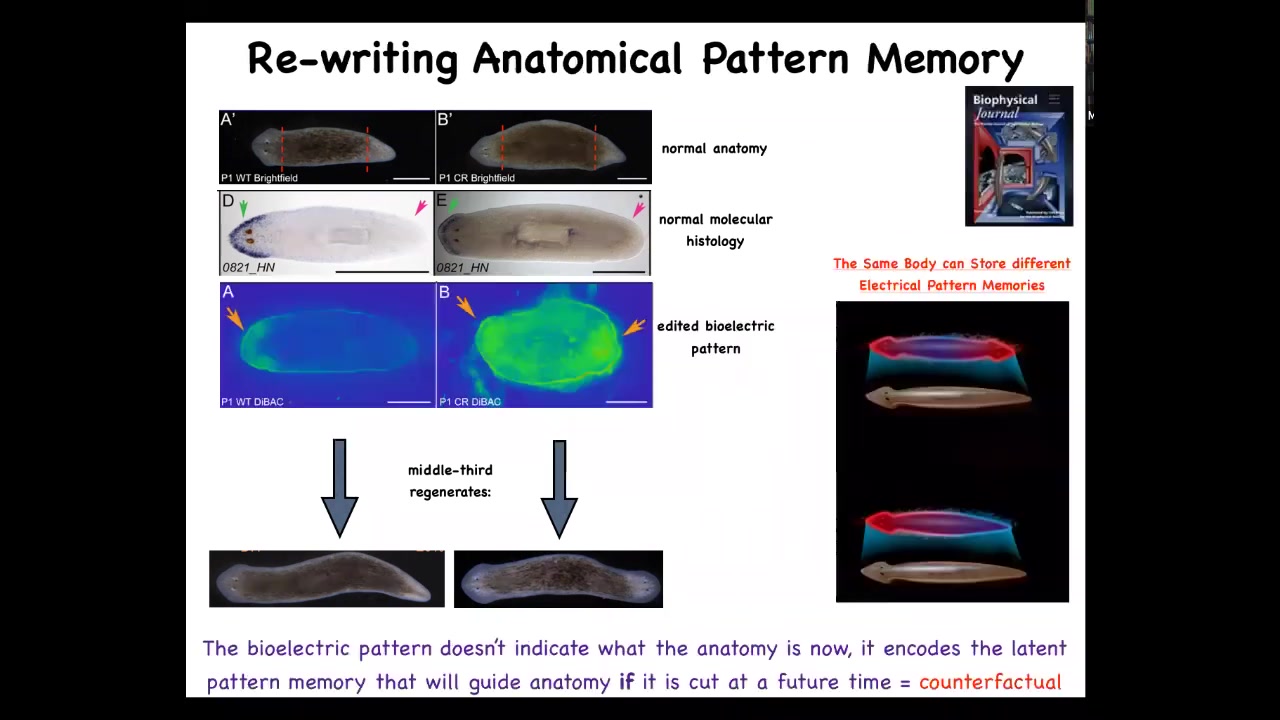

Because having figured out this electrical circuit, we were able to rewrite their pattern memory of what a correct planarian is supposed to look like.

So here is what this animal represents as a normal planarian, one head, one tail. This is again voltage imaging. This is somewhat messy, but the technique is being worked out. But we were able to change that electrical pattern by acting on the ion channels and the gap junctions to store this: two heads. When you cut that animal, it makes a two-headed worm.

Now this is really critical. This electrical map is not an electrical map of this animal. This electrical map is a map of this perfectly normal, anatomically one-headed animal. And this is an electrical memory that is latent. It's not doing anything. This animal doesn't match the anatomy. The idea of I should be two-headed does not match the current state, which is one-headed. That memory is latent because we rewrote it, but nothing happens until you injure the animal. Once you injure the animal and cut off this middle fragment, it consults that memory and becomes two-headed.

This is, if you're interested in neuroscience and our brain's amazing ability for what they call time travel, the ability to store and imagine states that are not true right now. So either things that were true or things that might be true later, but are not true right now. I think this is a good example of a very basic, primitive version of this because this tissue can store a bioelectrical pattern of what it will do if it gets injured in the future. It's a counterfactual memory. It's not true right now. And so a single planarian body can store up to two different ideas of what a correct planarian should look like.

I promised you earlier on that I would show you that we can find and edit the cognitive medium of this collective intelligence of morphogenesis. And here it is. When we ask, "Where is the information that guides what you build?" here it is. It's represented, much like in the brain, by stable electrical states in the tissue that guide the activity. And no doubt there's more than two, but this is what we've worked out.

Slide 40/60 · 57m:21s

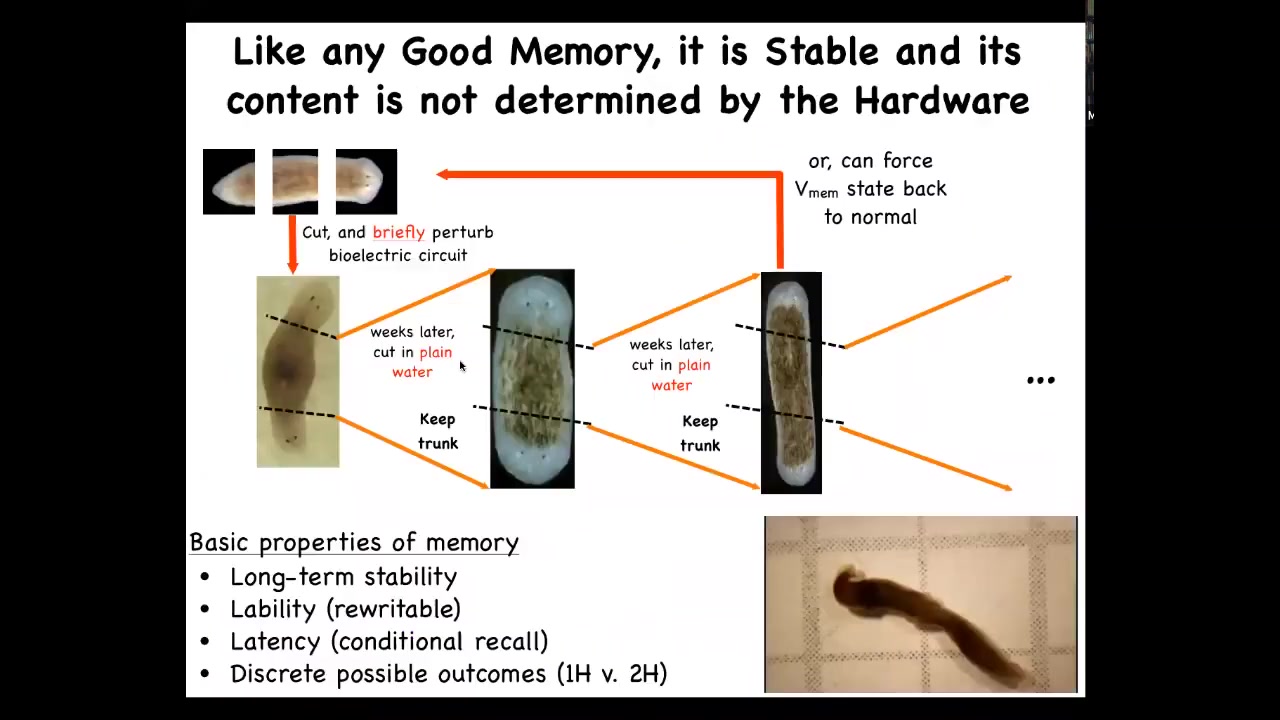

Now I keep calling it a memory. Because we also found out that if you take these two-headed worms — if we take these two-headed worms and we continue cutting them, in plain water, no more manipulation of any kind, this middle portion will continue to regrow two-headed worms, even though their genetics is completely untouched.

Let me reiterate that. There's nothing genetically wrong with these animals. We did not change the hardware at all. What we changed was a very brief physiological manipulation of the electrical state, a stimulus. We communicated to this collective intelligence with a brief physiological stimulus of turning the channels on and off, the way that it happens, for example, in your retina when you see stimuli. We've communicated the idea that there should be two heads instead of one. Once you do this, the circuit holds that memory. In the future, with no more manipulation, despite the wild-type genetics, it will continue to generate a completely different anatomy.

The deep question of what determines how many heads you have: you can't simply say DNA. What the DNA does is give you a hardware machine, a bioelectrical machine, that by default generates a memory of a one-headed pattern, but it's rewritable. If you rewrite it, it will maintain. So this has all the properties of memory. It's long-term stable, but it's labile. It can be rewritten. It has conditional recall, which I just showed you. It has discrete possible behaviors.

What we're doing right now is trying to use techniques from connectionist machine learning and tools of dynamical systems theory to pull together what we know about the physiology, the electrophysiology of the circuit and the state space of the circuit and the ability of the system to do amazing things like regain specific states if it's pulled out of that condition and also to be rewritable the way that memory in real and artificial neural networks is rewritable. What's interesting is that this memory goes beyond setting the number of heads.

Slide 41/60 · 59m:38s

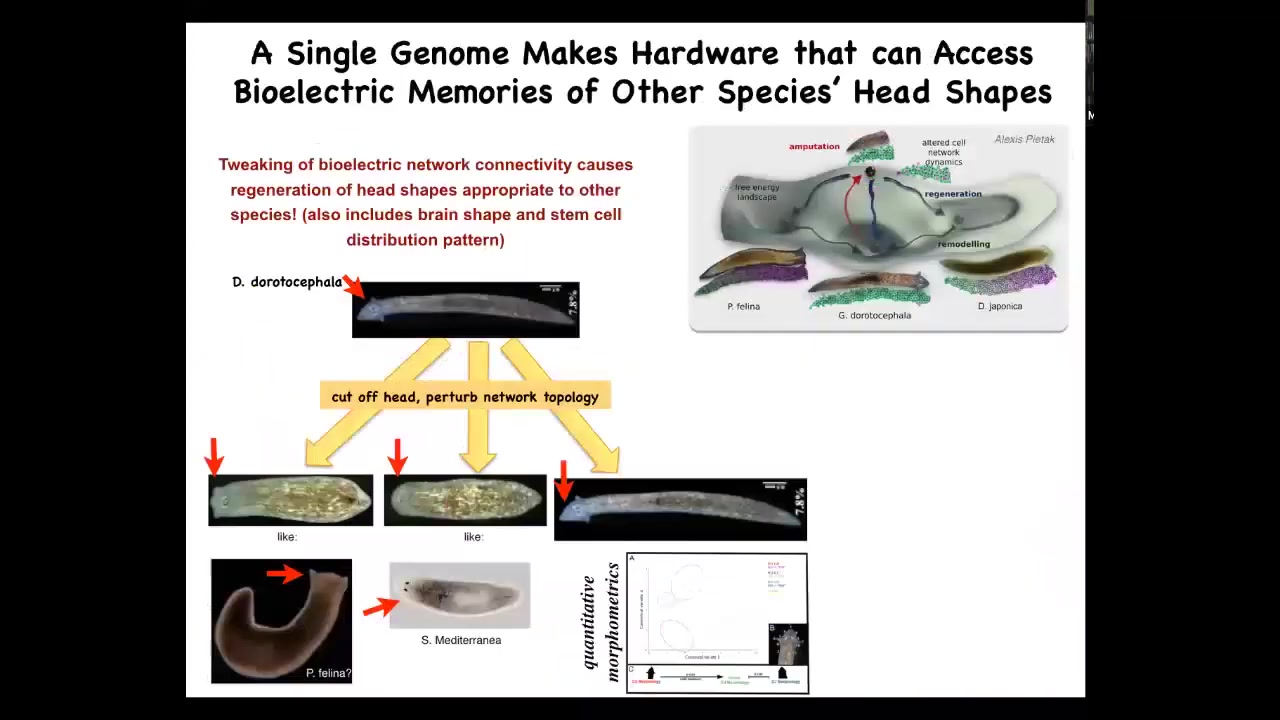

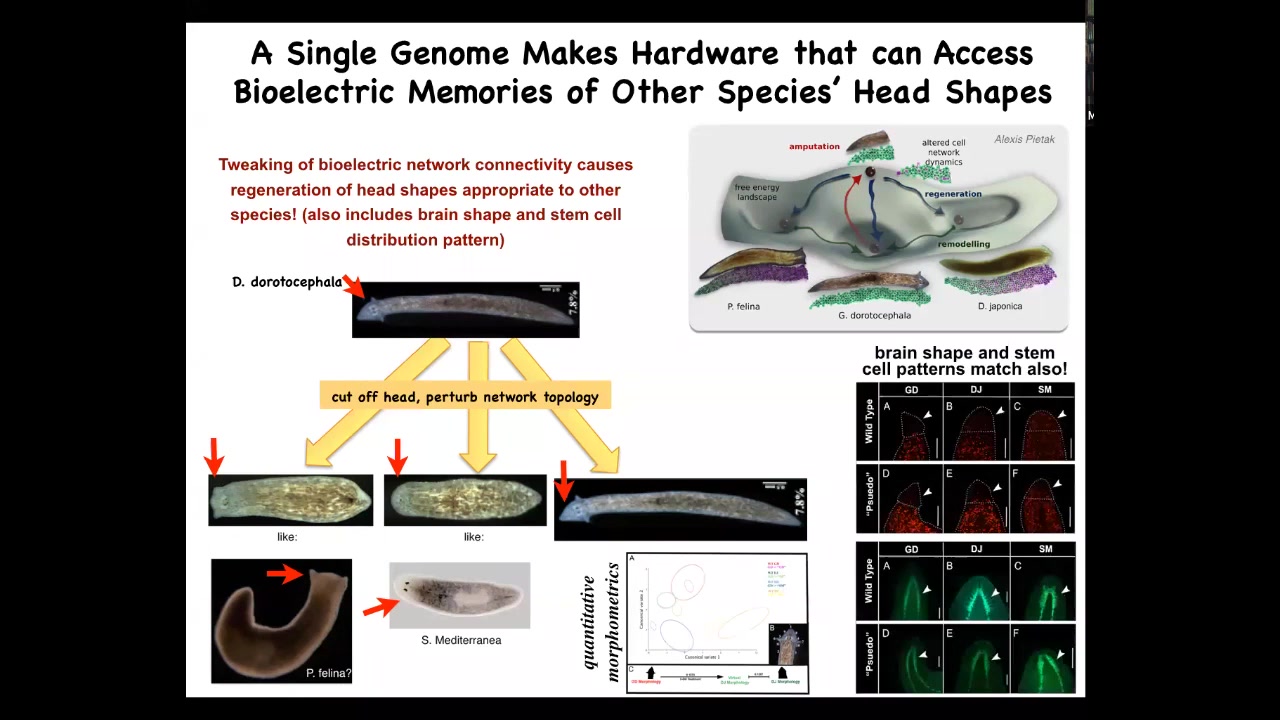

It also is involved in setting the shape of the heads. This is a perfectly normal Dugesia dorotocephala with this nice triangular head. What we can do, without changing the DNA, is cut off the head and then perturb the bioelectric network topology of this creature by blocking the gap junctions. Then you let it go and the system settles back down. It can make flat heads like a P. falina, it can make round heads like an S. mediterranea, or it can make the normal heads.

Slide 42/60 · 1h:00m:16s

What you see is that not only the head shape, but also the shape of the brain and the distribution of the stem cells become exactly like these other organisms. They are about 100 to 150 million years of evolutionary distance. You can ask the exact same hardware to make heads belonging to other species; other attractors in the state space of this electrical circuit correspond to other species. Evolution can search the state space of this bioelectrical circuit to derive these other species, and it does not require a genetic change, although it might become genetically assimilated and then become heritable.

Slide 43/60 · 1h:01m:01s

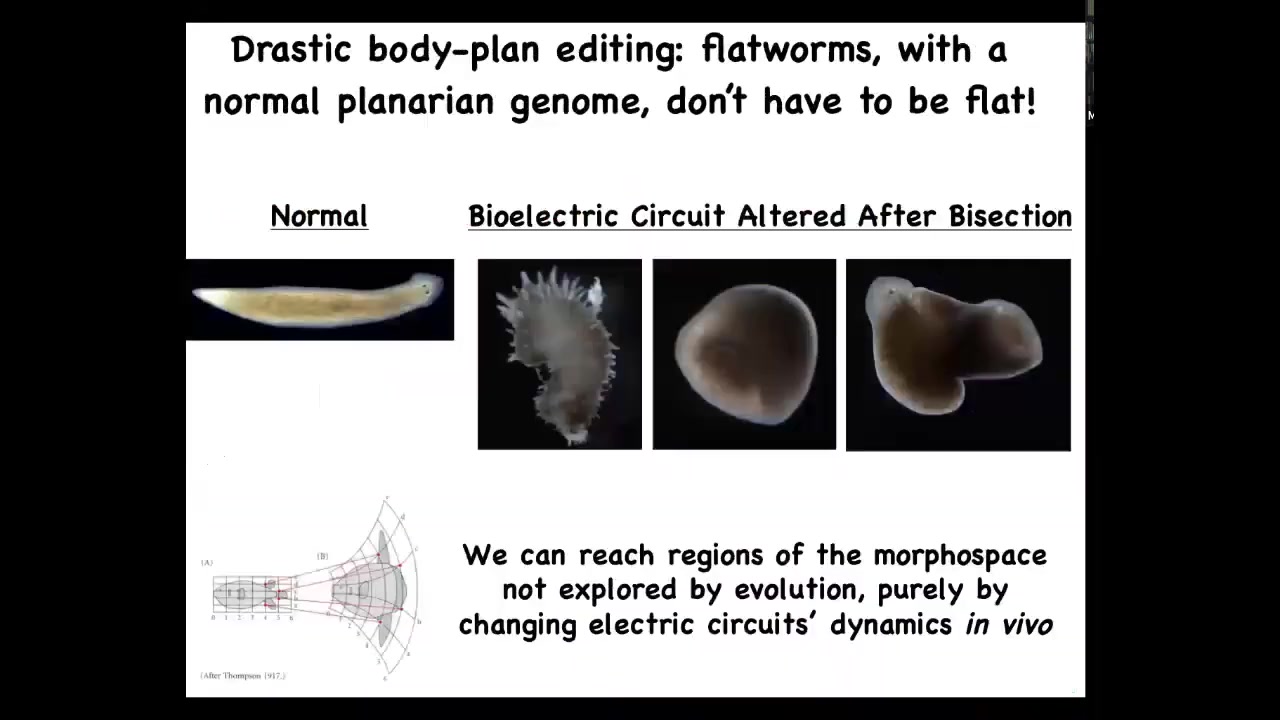

And not only can you find other species in that morphospace, an idea D'Arcy Thompson gave us. In that morphospace, you can find other things that don't look like planaria at all. You can find these weird spiky forms. You can find these cylindrical things that aren't flat. You can find combinations, hybrid forms. All of this is done with exactly the same cells.

Slide 44/60 · 1h:01m:28s

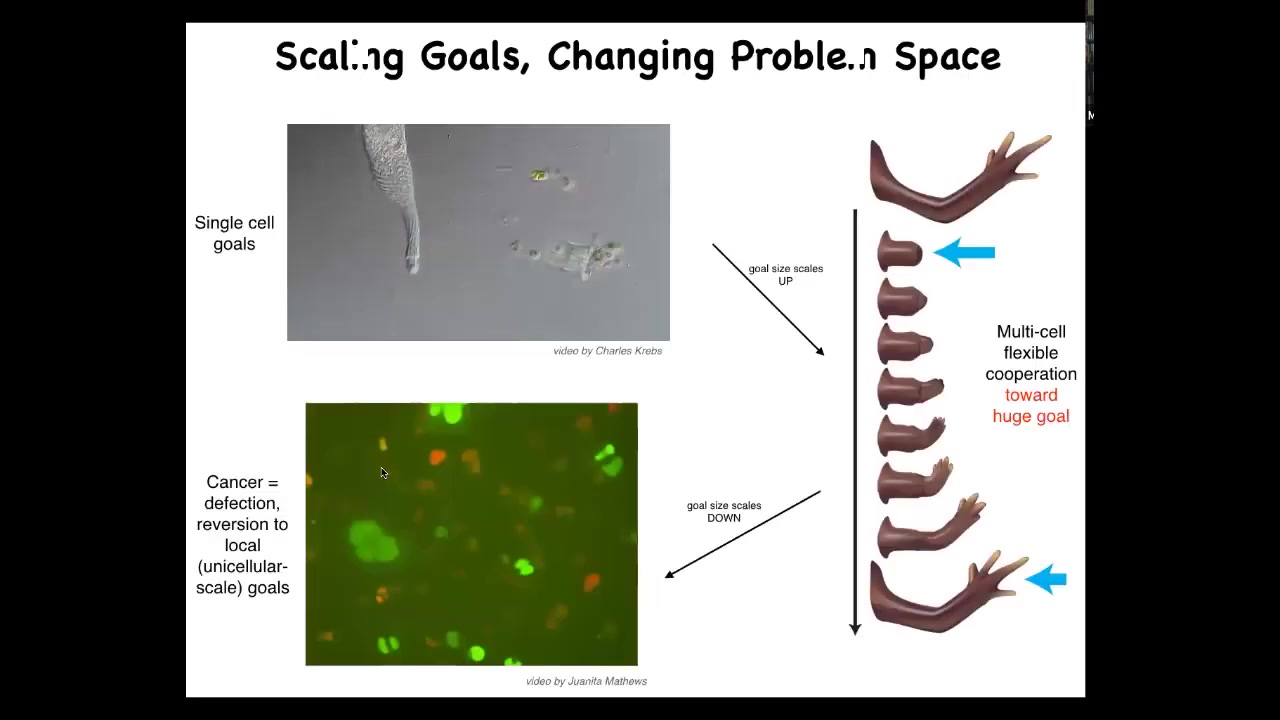

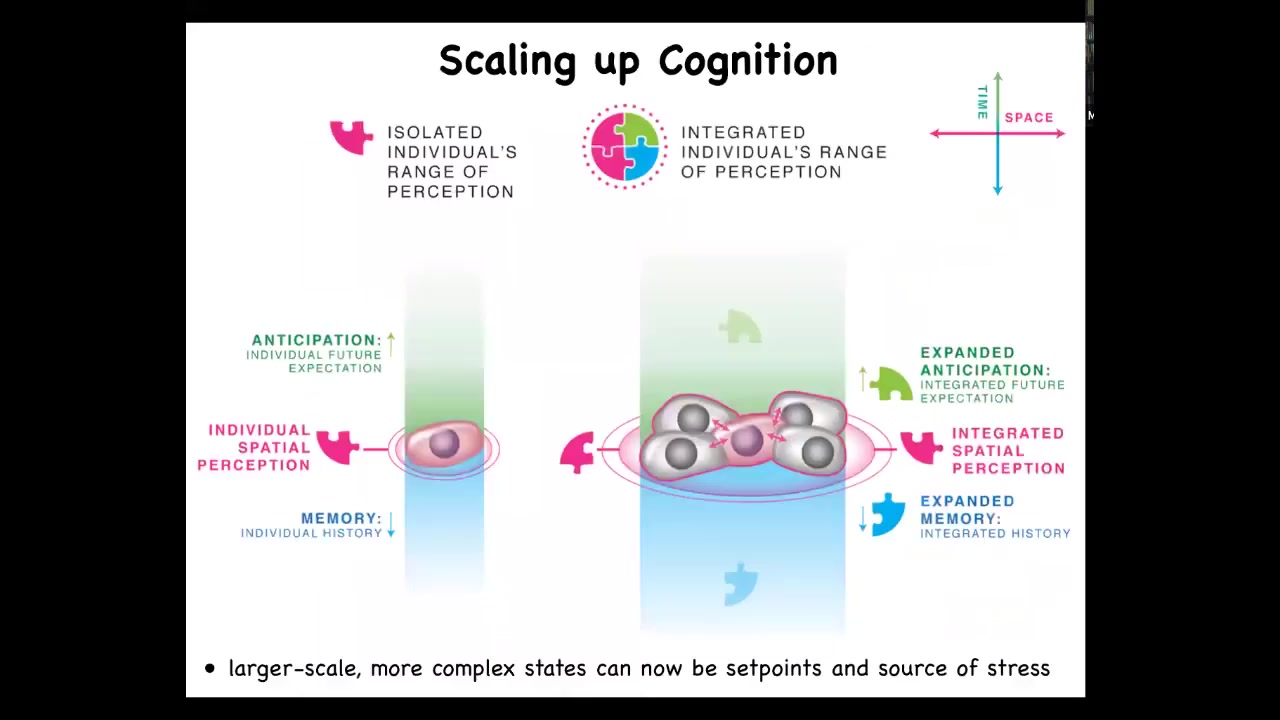

I want to take a few minutes now to go back to thinking about the mechanisms of this collective intelligence idea. What I've shown you so far is that individual cells, which are themselves competent to solve problems in transcriptional space, in metabolic space, in a physiological space, are bound together in a multicellular organism to solve anatomical problems in anatomical, amorphous space, and then eventually evolution reused it to make brains, to solve behavioral problems, and eventually linguistic space and so on. I want to talk for a few minutes about how does this scaling work? How do you go from numerous proto-minds to one larger cognitive system?

Slide 45/60 · 1h:02m:18s

I want to show you some hypotheses about that. In evolution, what we have through multicellularity is an expansion of goal states. This cell is very good at handling very local goals. It's never going to work towards any other sort of large scale goal. But together in a collective, and I've shown you some evidence that what binds that collective together is electrical communication and the properties of electrical networks, they can work on much bigger goals in a different space. Here's the goal of making a limb. And if you've made a limb and I deviate you from that goal, you will use, as the cellular collective, energy and very rapidly try to get back to that state. Individual cells have no idea what a finger is or how many fingers you're supposed to have, but the collective certainly does, and it will keep implementing this under various types of deformations. That is taking a bunch of low-level minds and making something that's able to pursue large-scale goals in a different space, in the anatomical space.

That set of mechanisms has a failure mode, and that failure mode is known as cancer. This is human glioblastoma in culture. What's happened to these cells is that they have disconnected from each other electrically, and when they do that, they roll back down to their unicellular past. They no longer are able to be a part of a network that perceives large-scale goals. They go back to their initial goals, which were every cell wants to become two cells and to go wherever life is good, and that's cancer and metastasis. We need to understand this process of scaling up and the various failure modes.

Slide 46/60 · 1h:03m:58s

I think that what happens is that when you have single cells, they have memory going backwards. This has been shown in the field of basal cognition: cells have the ability to anticipate future stimuli, but it's quite small. Both in space and time, it's quite small. When you join together into larger networks, you have more computational ability to store past memories. You have more ability to predict future states, and you have a larger spatial perception; you're able to collectively measure things on a physically larger scale. If this is how collectives form, we ought to be able to use this to address the cancer problem.

Slide 47/60 · 1h:04m:34s

That's what we've done: the oncogene is there. We're not going to try to edit the genome or to kill those cells or to remove that oncoprotein. What we're going to do instead is force those cells to remain in electrical communication with their neighbors, regardless of what the oncogene says.

When you do that, the oncoprotein is labeled with red fluorescence. It's very bright. It's all over the place. You can see this is the same animal. There's no tumor. What we've done is co-inject a particular ion channel that sets an electrical state that forces these cells into the normal communication with their neighbors, and they participate in normal morphogenesis. They make skin; they make the various organs, instead of going off on their own and making a tumor.

So this is another example of taking advantage of the decision-making at the software level to get a different outcome, even though your hardware is different.

We've had in our lab many examples of addressing these kinds of hardware problems at the software level by exploiting this collective phenomenon.

What we're interested in is what happens when individual cells, which can do this kind of homeostatic loop, scale up to be a collective of coupled homeostats that can do very interesting things like navigate problem spaces and so on.

Slide 48/60 · 1h:05m:59s

And so what you really have here is an expansion of something I call the cognitive light cone. This goes back to my initial stated goal, which is that we want a framework where we can put anything, we can compare anything in the same framework. So whether it's natural, evolved, design, whatever.

In any frame, any agent, what do all cognitive systems have in common? What do all agents have in common? What they have in common is a certain cognitive light cone, which is the spatial and temporal size of the largest goal that they can pursue. If you only care about the local concentration of some kind of chemical and you have a little bit of memory and all you're trying to do is optimize your local chemical concentration, you might be a bacterium or a tick as far as cognitive light cone size is concerned. Very small.

If you're a dog, you have a bigger cognitive light cone, you have lots more memory going back, you have some predictive ability going future, but you're never going to care about what happens three months from now in a town that's 10 miles over. It's impossible for, as far as we know, a dog to have that large scale of goals. And so you have a bigger light cone, but it's still delimited.

If you're a human, you might be working towards goals that are planetary scale for hundreds of years into the future, past your own lifespan. And if you're some sort of an alien being or a future human that has a much bigger cognitive light cone, you might be able to care, for example, in the linear range about all the living beings on Earth. Humans can't do that. We don't have the capacity to scale our care linearly beyond some small number of concerns. But there could be potentially enormous minds that could literally do that, this kind of advanced form.

So all of us have these cognitive light cones, and evolution is a journey of enlarging these light cones that then allow us to have bigger goals in different spaces. And of course, we are composite beings full of other organisms, other cells and organs, all of which have their own different sizes of light cones in different spaces.

I'm going to end in a couple of minutes with one last thing. I want to show you a completely new organism, and then I'll finish. I have to do a disclosure again, because Josh Bongard and I are scientific co-founders of Fauna Systems, which works on computer-designed synthetic organisms.

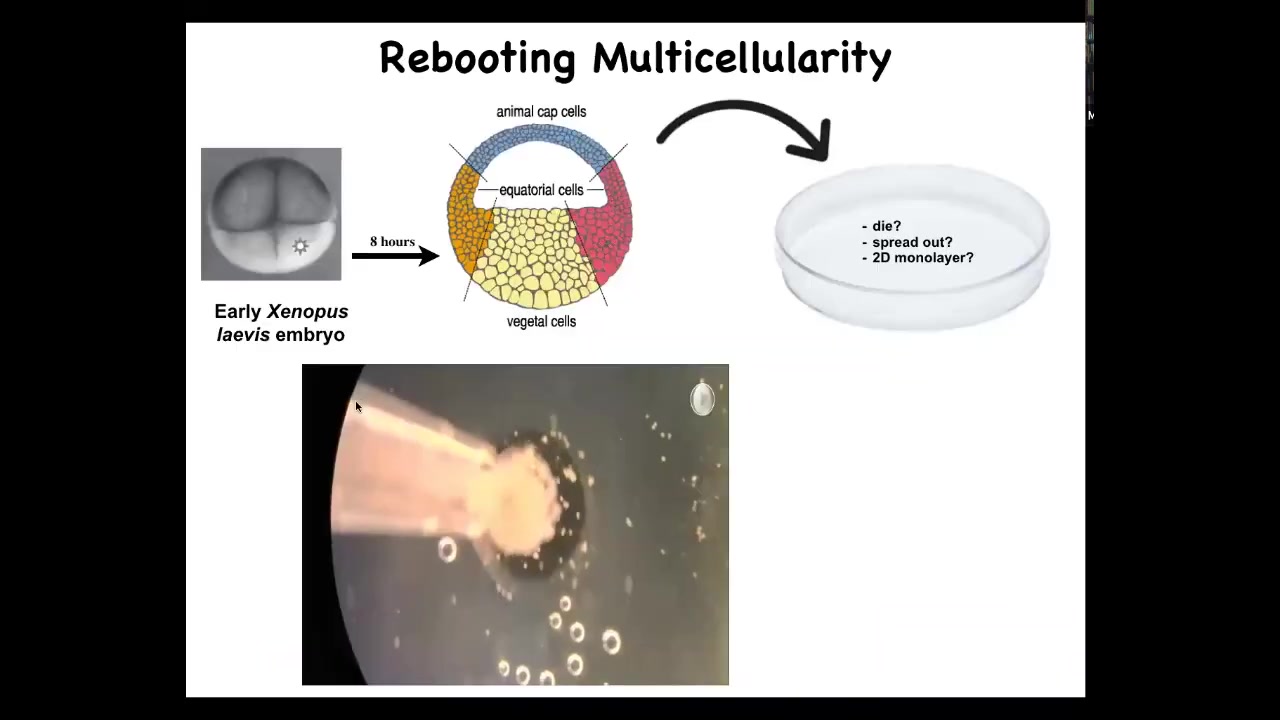

What we wanted to do was ask how much plasticity do cells have to navigate their various spaces. What could we liberate wild-type cells from their normal environment and ask them to reboot their multicellularity? What would they do?

Slide 49/60 · 1h:09m:00s

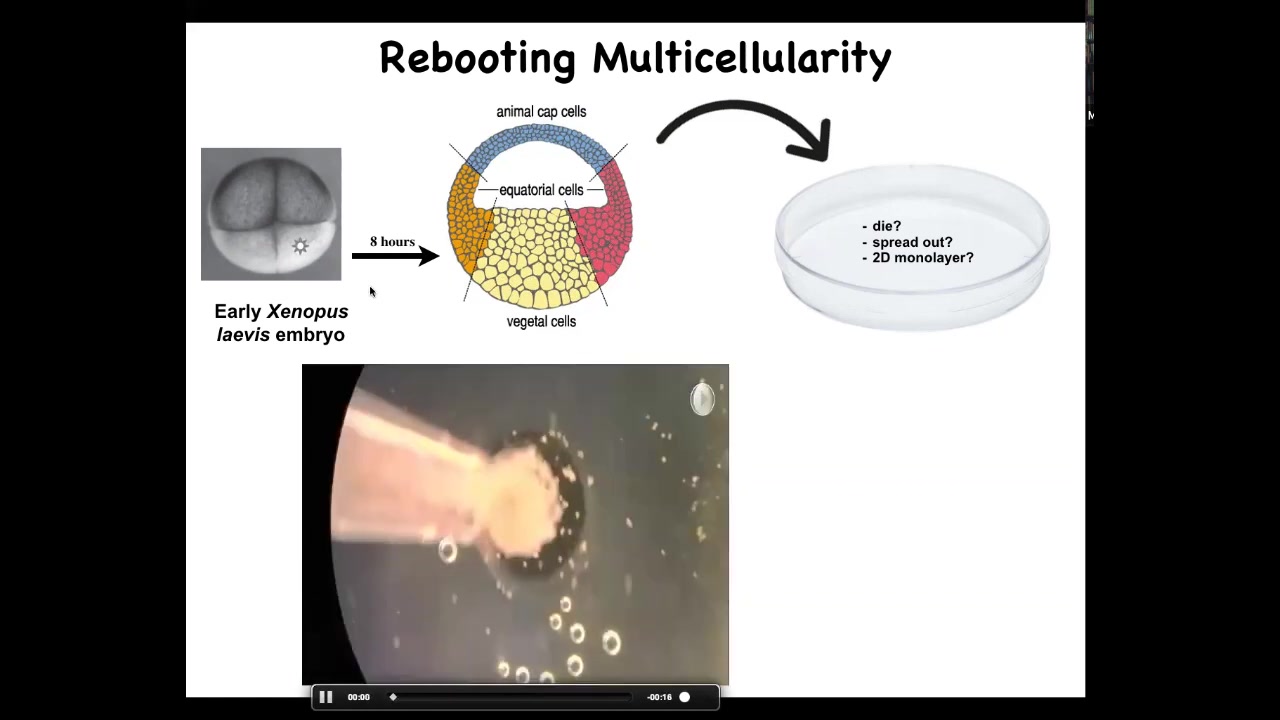

This is the experiment here. What happens is we take animal cap cells from this early frog. Doug Blackiston in my group did all the biology for this work. This was done in collaboration with Josh Bongard's lab at University of Vermont. His student, Sam Kriegman, did all the computational aspects.

These are skin. These are fated to be epidermis of various types. We dissociate them. Then we put them in this little depression, and we leave them overnight. You wonder what might happen. They could die. They could spread out, get away from each other. They could form a two-dimensional monolayer the way that cell culture does. Instead, overnight, this is a time lapse, they coalesce, they come together, and they form this little circular thing which has an interesting property.

Slide 50/60 · 1h:09m:57s

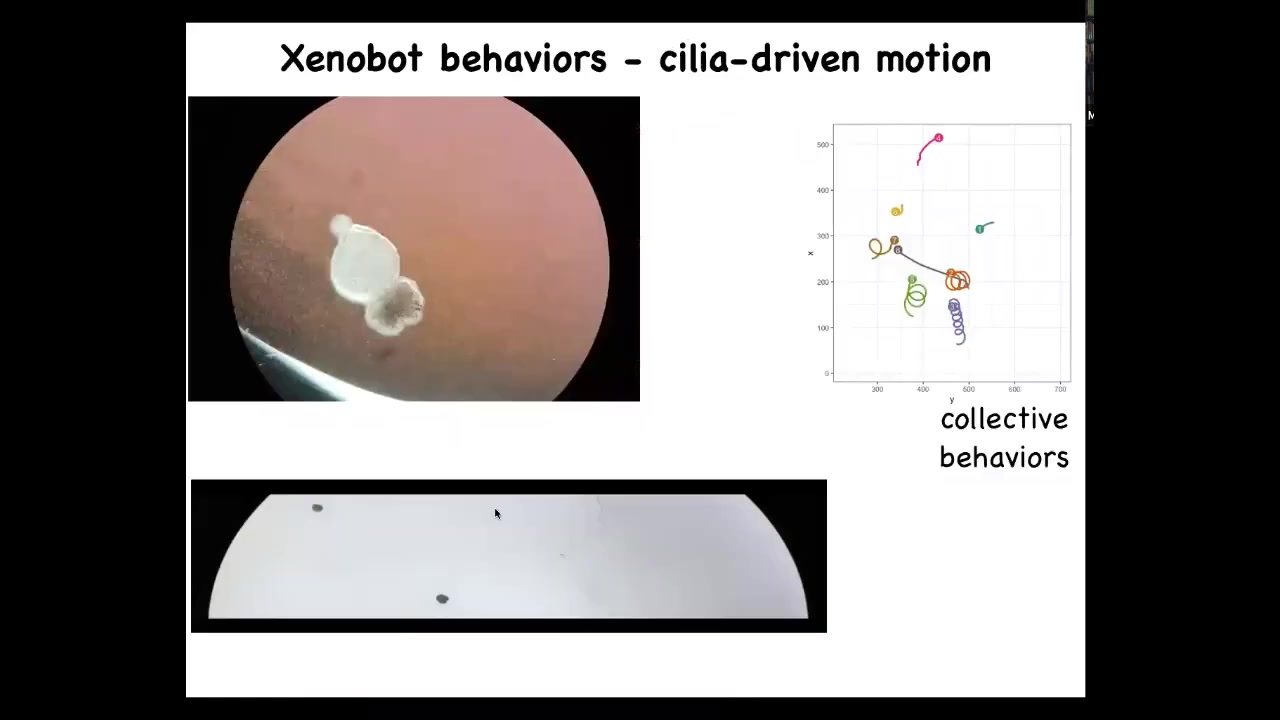

We call it a Xenobot because Xenopus laevis is the name of the frog and it's a biorobotics platform. It's a biobot. We call it a Xenobot.

Slide 51/60 · 1h:10m:02s

What does this Xenobot do? First of all, it swims on its own power. How does it swim? You can see that here. It has little hairs. These little hairs are normally used by the frog embryo to distribute mucus on the surface of its body to keep the mucus flowing down. But these guys have figured out how to row in opposite directions on either side of the structure. As a result, it can swim. They can go in circles. They can patrol back and forth like this. They can have collective behaviors. Here's a bunch of them. These two are interacting with each other. These guys are sitting there doing nothing. This one is taking a long journey around the Petri dish.

Slide 52/60 · 1h:10m:46s

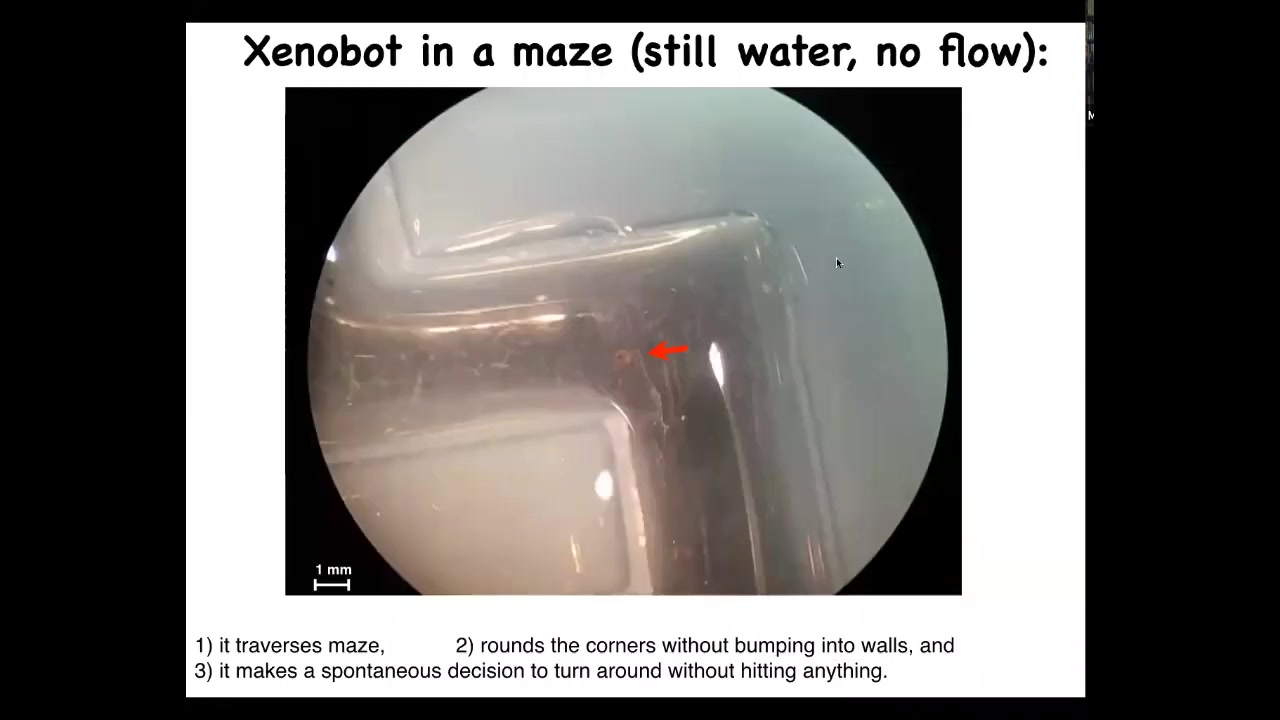

Here's one navigating a maze. What you can see here: the water is perfectly still. It will move forward. It takes a turn without bumping into the opposite wall. And then at this point, for some internal reason that we don't know, it decides to turn around and go back where it came from. This is a very simple example of spontaneous self-determined motion. There's some kind of process inside that guides what it does. It can take turns. It can change direction and go back.

Slide 53/60 · 1h:11m:15s

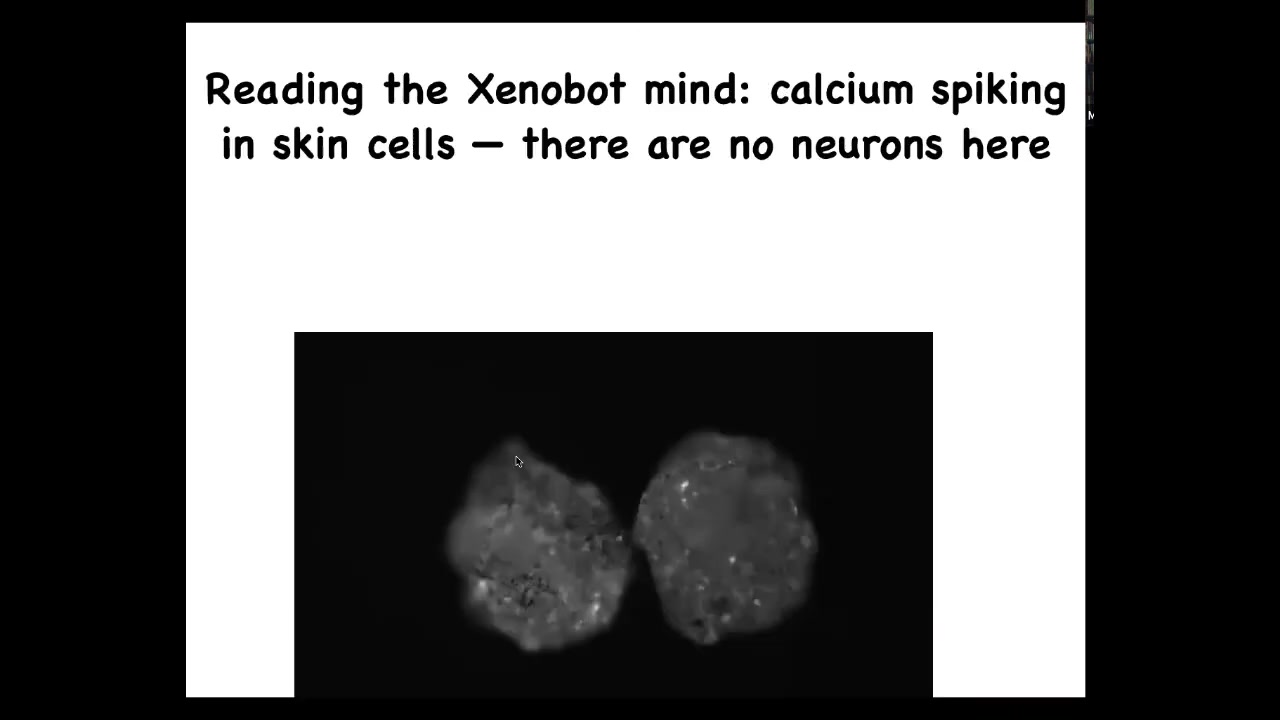

If we scan the physiology, this is calcium signaling. What we're imaging is calcium spiking in these cells. What you see is that, very much like you might see in brains, you see a bunch of calcium spiking. We're currently using all the same techniques used in neuroscience to analyze the information flows here. In fact, within each Zenobot, but also between Zenobots, they're somehow talking to each other, and you can detect that using information theory approaches.

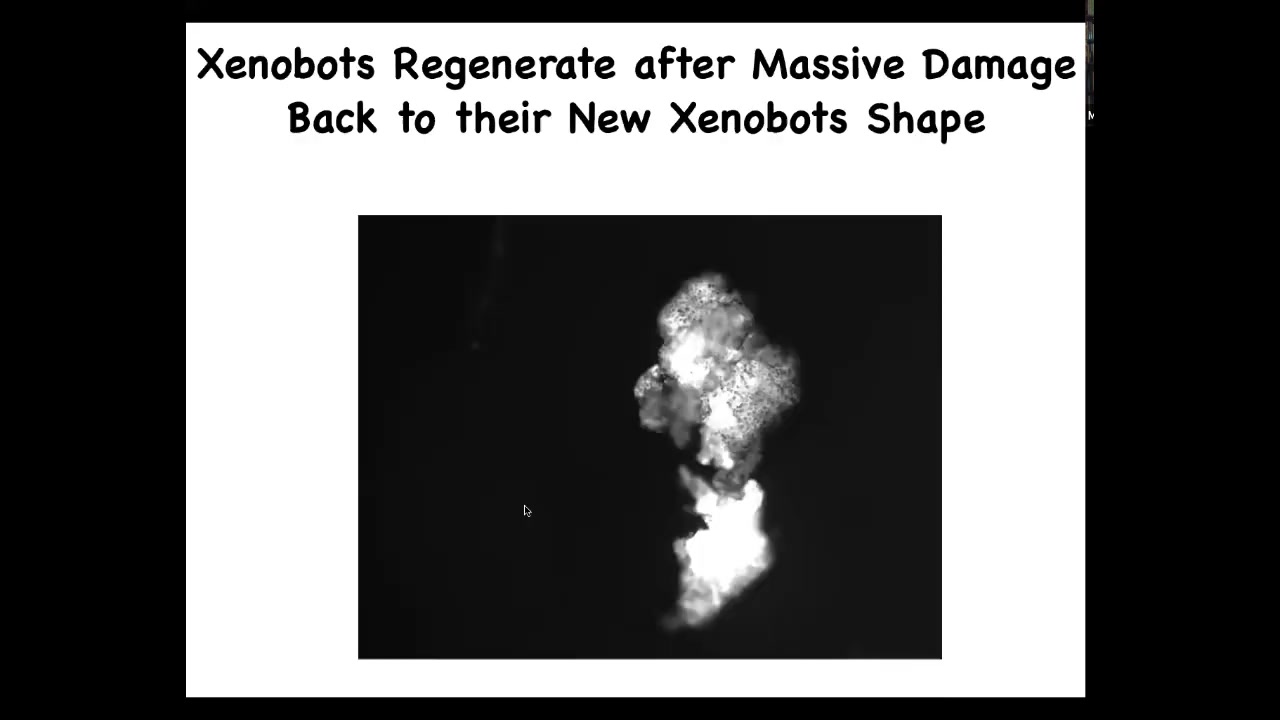

Slide 54/60 · 1h:11m:47s

They regenerate. If you cut it in half, they will seal themselves back up. Here it's cut in half like this, and then they'll seal themselves back up to a new Zenobot shape.

Slide 55/60 · 1h:12m:00s

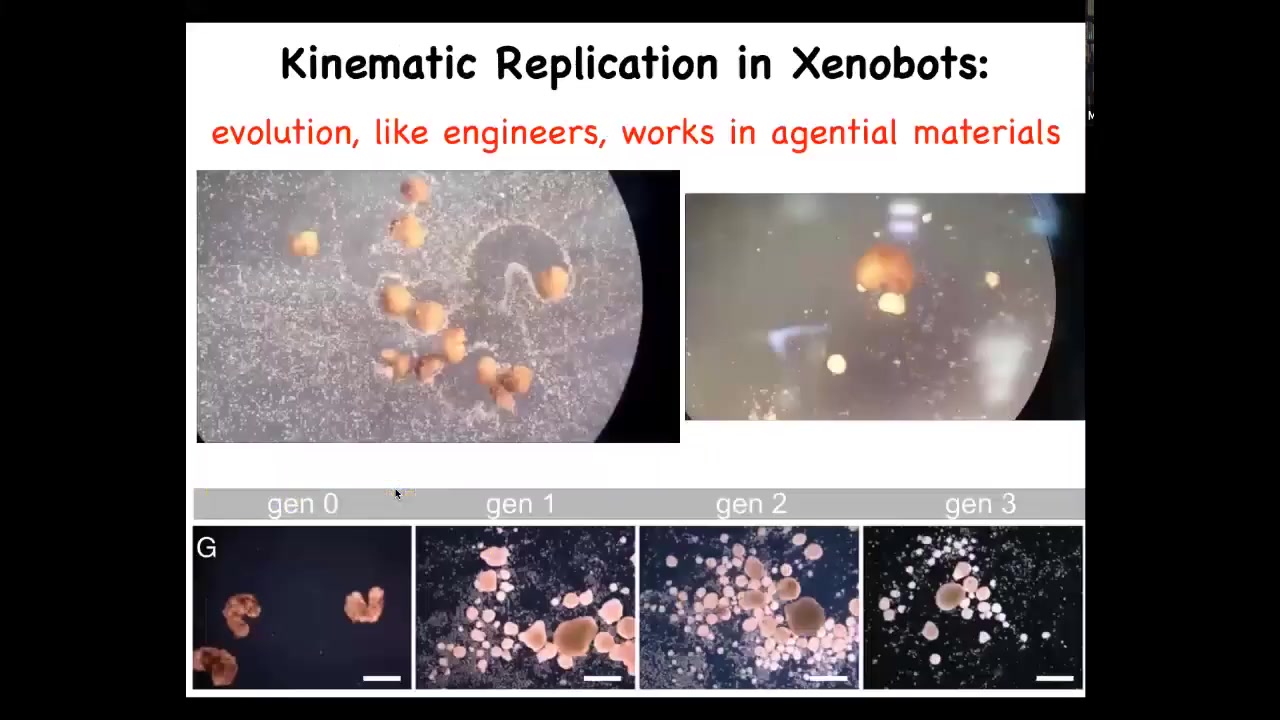

It was noticed that when you simulate these bots with objects in their environment, their behaviors tend to collect particles into little groups.

So, based on this, based on an AI model of their morphogenesis and behavior, we decided to give them some other cells to play with. What we found out was something amazing.

Slide 56/60 · 1h:12m:29s

What they do is this white stuff here, these are loose skin cells. What the Xenobots do is they run around and they collect these skin cells into little balls. We're dealing here not with a passive material, but with an agential material, meaning with living cells, the same material that evolution works with.

We as human engineers, the Xenobots, and evolution, all three of us, work with this kind of agential material. What that allows is that when they do make these little balls, overnight, the balls themselves mature into the next generation of Xenobot, which then will run around and do exactly the same thing. You get the next generation and the next generation and so on.

Think about what this means. We've made it impossible for these guys to reproduce in the normal fashion. It's just skin. There's no neurons there. There's no reproductive machinery. These are just balls of skin.

But what they've been able to do is to fulfill von Neumann's dream, which is a robot that goes around and collects materials from its environment and makes copies of itself. That's what it does. We call this kinematic replication.

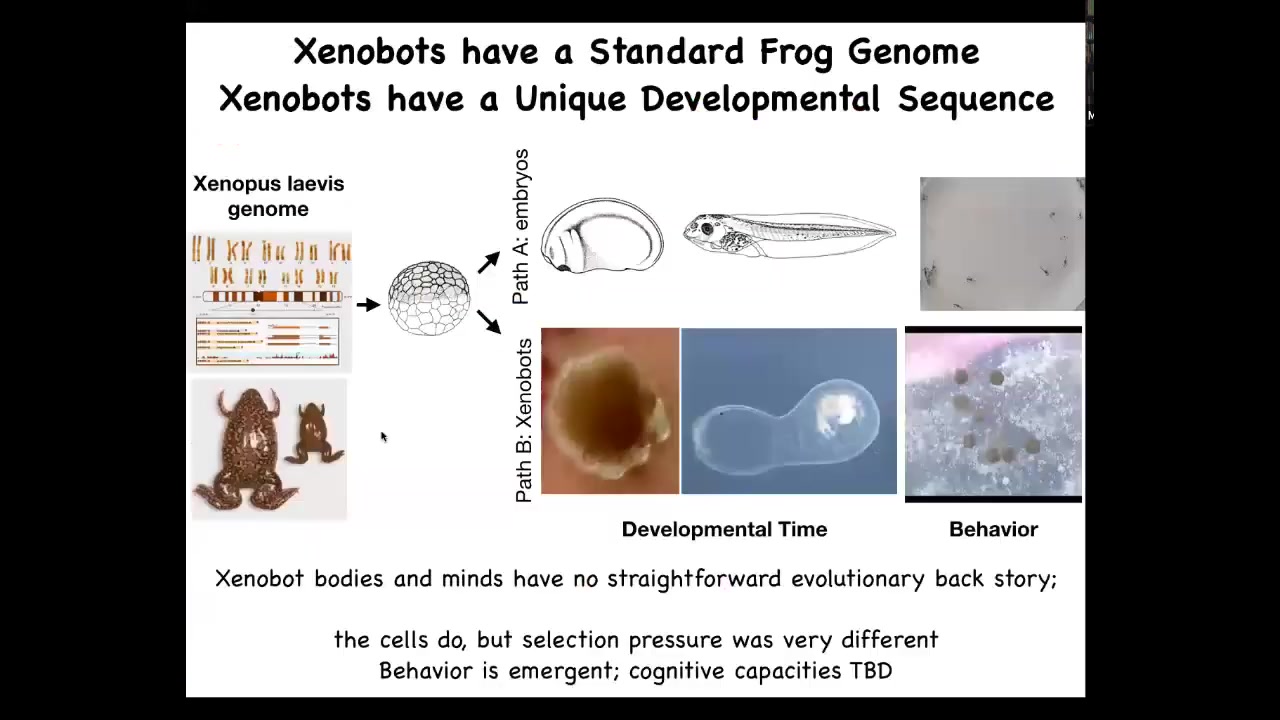

Slide 57/60 · 1h:13m:41s

The last bit here is simply this. Let's think about this. There's been no genomic editing here. We didn't change the genome. We didn't provide some weird nanomaterial. When you sequence the genome here, all you see is standard Xenopus laevis. When we ask what the Xenopus laevis genome actually encodes, it encodes cells, it encodes a hardware machine that under normal circumstances produces this. It produces a set of standard embryonic stages and then some tadpoles that can do this kind of behavior. But under different circumstances, these same cells can solve the problem differently. They can become a Xenobot with its own weird developmental stage and then its own very unusual behavior.

As far as we know, no other system does kinematic self-replication. Here are a couple of interesting things. First of all, this is engineering by subtraction. We didn't add anything, but what we did do was we liberated these cells from the normal influence of the other cells. If you look at a normal embryo and its skin cells and you ask, what do they know how to do? All they can do is be this boring two-dimensional layer sitting on the outside of the animal keeping out the bacteria. But in fact, what you find out by putting them on their own is that that's normally what they do when they're behavior-shaped or bullied by these other cells into having that role. On their own, their default behavior is actually this.

You can start to think about evolution as a way of searching the space of behavior-shaping stimuli. How do we get cells to tell other cells what to do? Because you're dealing with an agential material, not passive Legos, these cells already have certain capacities. You can't just put them where you want and have them stay there. You have to use various signals to get them to change their native behaviors.

The other thing about this is that for any other living organism, if you ask why it has a certain shape, a certain size, certain behaviors, the answer usually is evolution — the anatomical goals come from evolution. You've been selected for eons to be a specific kind of shape. There have never been any xenobots. There has never been any evolutionary pressure to be a good xenobot. All of this is completely emergent from the generic problem-solving capacity of these cells.

One of the things we're working on is understanding how it is that evolution makes not just specific solutions to specific environments, but actually problem-solving machines that have the capacity to do new things in new environments that they never had specific selection for. We are at the moment studying their cognitive capacities. We actually have no idea: what can they learn, what do they sense, what are their preferences? All of that remains to be determined.

Slide 58/60 · 1h:16m:38s

So I'm going to end here with two things. First, a summary of the kind of philosophical aspects of what I've told you. In my framework, we have to look at agency as a continuum, not binary categories. We have to really understand how it is that these capacities change when bodies and minds change.

I think persuadability is a useful engineering way to organize that axis, which enables new discoveries and new capabilities in biomedicine by thinking about how to communicate with these cell groups.

I think there's no privileged substrate for cognition. I think that there's nothing magical about biological substrates. We're going to have intelligences that are extremely diverse. We have this notion of the self, described by a cognitive light cone as the size of the goal, the largest goal that it's capable of pursuing, with this idea of evolution and engineers pivoting these systems through different problem spaces. And it doesn't have to be three-dimensional space.

When we look at how intelligent we think a system is, we're really taking an IQ test ourselves to ask whether we've recognized the space that it's working in, whatever goals it's trying to reach, and its competencies in reaching those goals. Those are not apparent immediately, as I showed you for development. It looks like it always does the same thing, but it's actually much more clever than that.

I've shown you that developmental bioelectricity is an evolutionary precursor of brain dynamics. And it's basically the physiological medium for the software of multicellular life. It's the substrate in which the cognition, the proto-cognition of the morphogenetic swarm intelligence is held, and I've shown you the examples of reading and rewriting the memories of that intelligent swarm.

This is just the beginning. These are very early, primitive experiments.

We have really interesting implications for evolution here, which are not only due to the multi-scale competency of the organs: you put a bunch of eye cells on the tail, and they can still form an eye, they figure out how to connect, and the whole thing still works. If you have a mouth that's off in the wrong place, it will readjust itself.

So this has many implications for evolution and raises a really fundamental question: where do these goals come from if it's not just selection?

Slide 59/60 · 1h:19m:16s

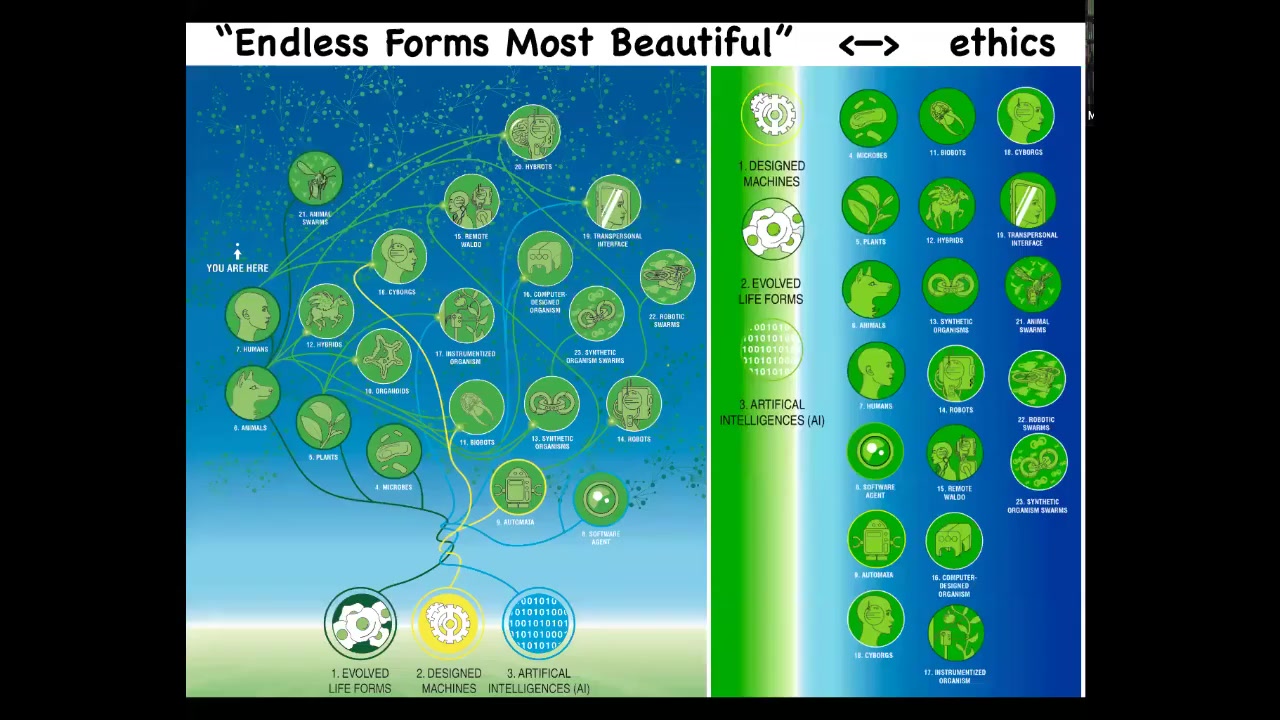

When Darwin said the phrase "endless forms most beautiful," when he was interested and impressed by the wide variety of shapes out there in the biological world, all of that is a tiny corner of possible space of agents. Because biology is highly interoperable, it solves problems that it's never seen, which means that any combination of evolved material, designed material, and software is a viable agent. We have hybrids and cyborgs and all kinds of different things; many of these are already being made.

We really need a new kind of ethics to relate to sentient beings that are very different from us. They have a different origin story, they have a different composition, and they have a different kind of intelligence.

All of the details can be found in these papers, which I'm happy to send to you if anybody's interested.

Slide 60/60 · 1h:20m:14s

These are the postdocs and the students that did all the hard work here, our support staff, my many collaborators, our funders, so many people that have supported this work. I thank you for listening.