Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This episode explores how developmental bioelectricity may have laid the groundwork for brains, cognition, and behavior. Our guest explains how tadpoles can see with eyes on their tails, why cells collectively navigate “morphospace,” and how electrical networks in non-neural tissues store pattern memories. We end with the future of xenobots, hybrid organisms, and what they reveal about the true scope of intelligence.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Behavior and body plasticity

(05:20) Where anatomy is specified

(11:07) Morphogenesis as goal seeking

(17:43) Developmental bioelectricity overview

(24:07) Bioelectric patterning and repair

(28:21) Planarian memories and regeneration

(37:27) Synthetic chimeras and prediction

(42:12) Xenobots and future life

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/33 · 00m:00s

If anybody wants to contact me later on, I can be found at either of these addresses.

I would like to start by warming up to the idea that plasticity of behavior and body structure is a very linked problem. We study behavior, we study computation, and we study the plasticity of the body.

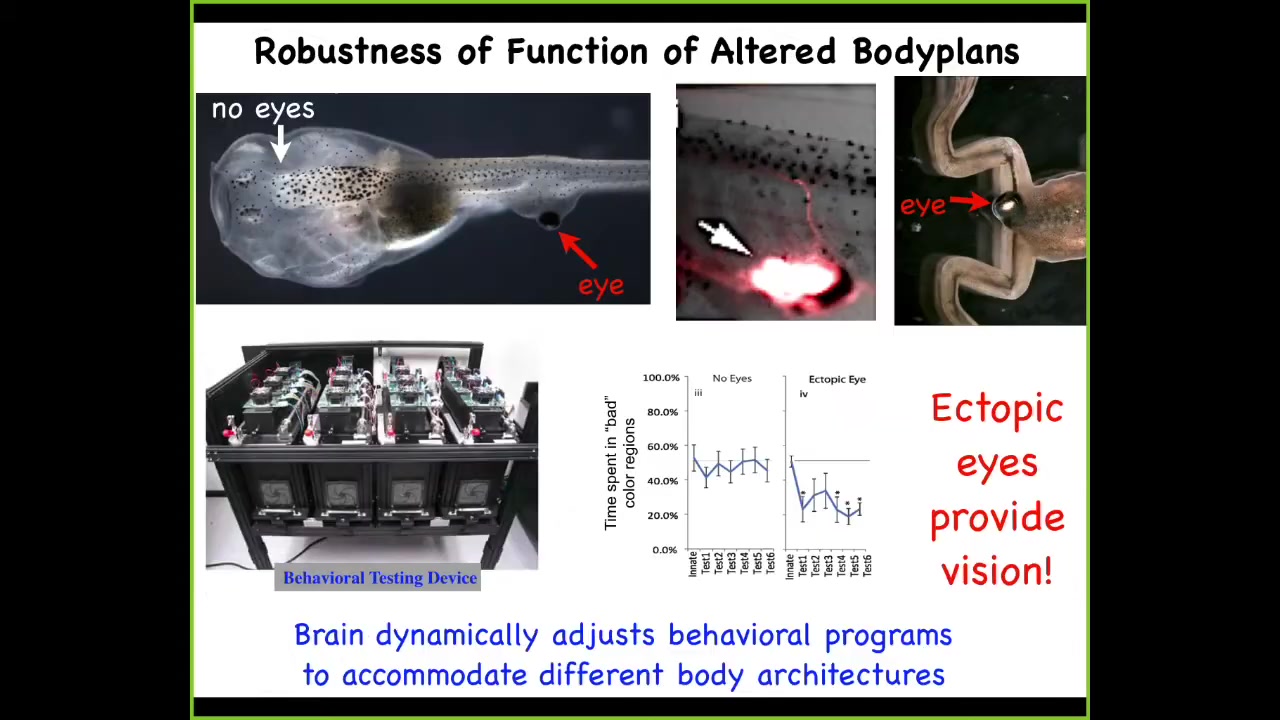

This is a tadpole of the frog Xenopus laevis. Here's the brain, here's the gut. There are no eyes in the head. The eyes are missing. But there is an eye sitting on the tail of this animal.

I'll show you in a minute how we produce these very unusual creatures. When you produce an animal with an eye on its tail, these animals can see out of that eye perfectly well. We have a machine that we've built that automates the training of this animal on visual cues. When you test these guys, you find out that they can learn visual instrumental learning assays.

If you track where this eye is actually connected, it's not connected to the brain. It's connected to the spinal cord here. It synapses on the portion of the spinal cord. That's sufficient for these animals to learn things like "stay out of the blue light" as it chases you around the dish.

If you wonder what happens to this eye when the tail resorbs and the tadpole becomes a frog, now you've seen a frog with an eye on its ****. The tail undergoes apoptosis and dies. The eye ignores those signals, completely rides all the way back, and then eventually lands on the posterior of the animal to continue growing.

This is incredible plasticity, where this animal evolved for millions of years to expect visual input from this particular location. Now it's in this weird configuration. There's a patch of itchy tissue on its back that's providing signals onto the spinal cord. No problem, the animal adjusts and the brain can make use of these data.

We're really interested in this relationship between the novelty and plasticity of the body and how that plays out with the robustness of behavior.

Slide 2/33 · 02m:12s

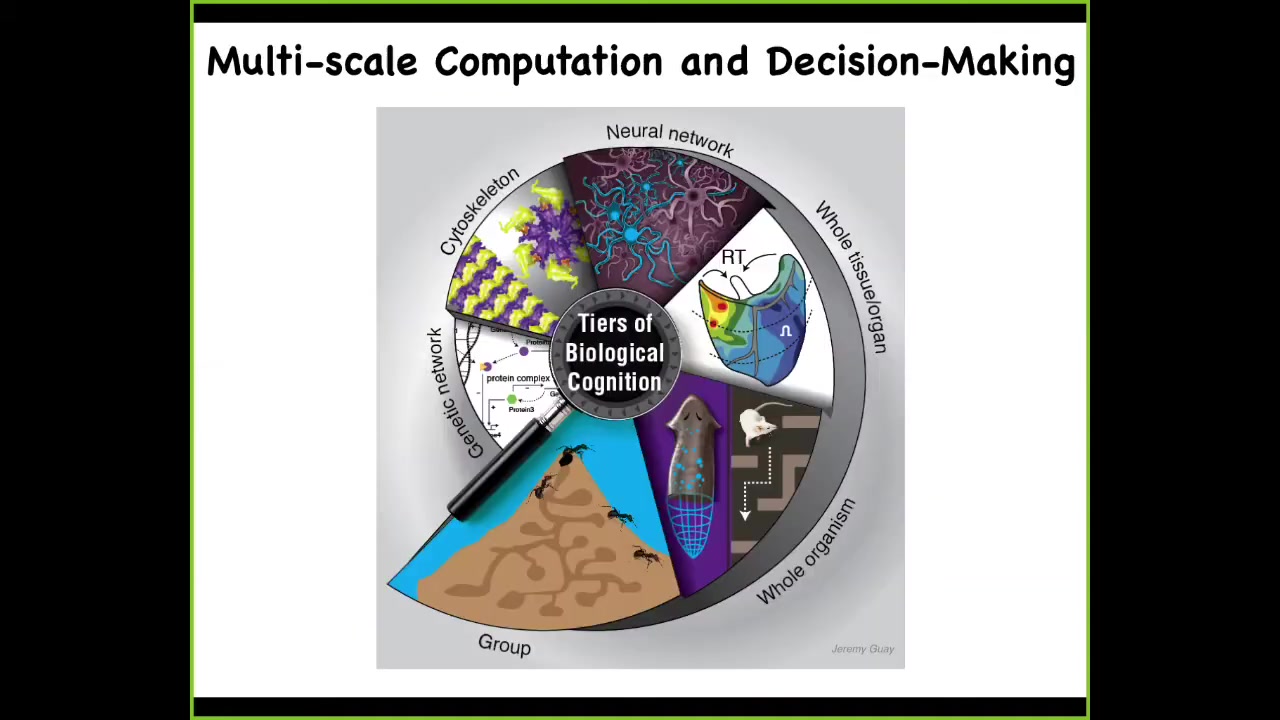

In my group, we take a very multi-scale approach. We look at computation in genetic networks, and we've done work, for example, on training gene regulatory circuits. We work on subcellular components, neural networks, tissues and organs, whole organisms in various ways, and even swarms. We have a project, for example, on training ant colonies. Not the individual ants, but the colony.

Slide 3/33 · 02m:40s

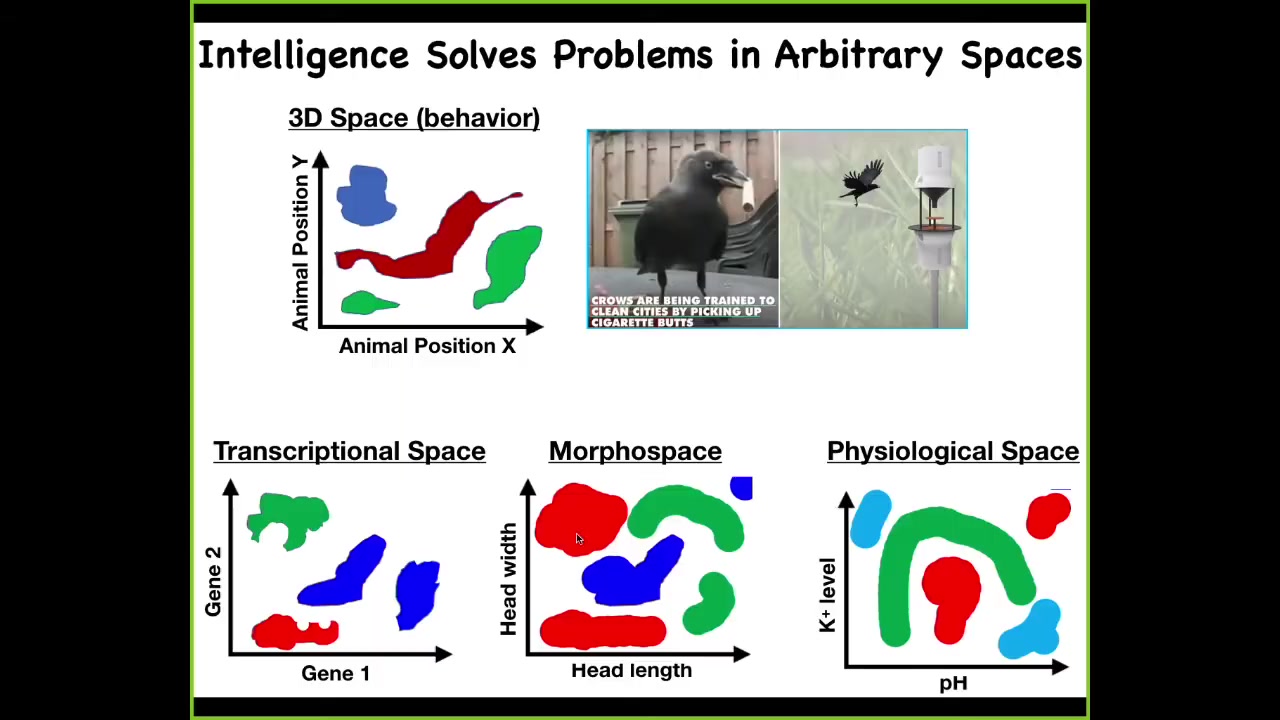

And so one way to think about intelligence is as problem solving, as one navigates a particular space. And there's the familiar three-dimensional space where animals do interesting things, and we all recognize this as behavior and intelligence and so on. But living things navigate all kinds of other spaces. And so the cells and tissues navigate transcriptional spaces. They navigate morphospace, or the space of possible anatomical configurations. And this is what we'll spend all of today talking about. They navigate physiological space. I've only shown two axes. But some of these things are very high-dimensional. For example, transcriptional space is a hugely high-dimensional space. So we're interested in this very general property of being an agent that can navigate these spaces with various degrees of expertise to get from wherever they are to a more desirable, more adaptive region of that space and stay there.

Slide 4/33 · 03m:38s

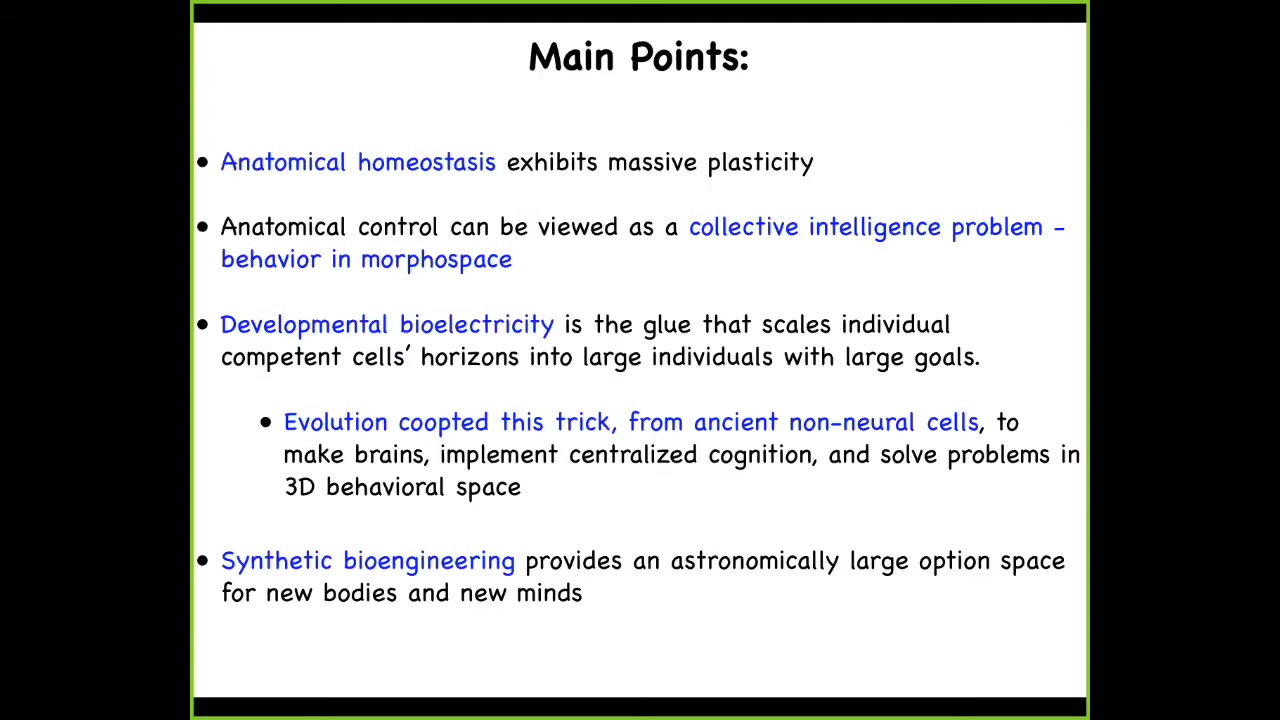

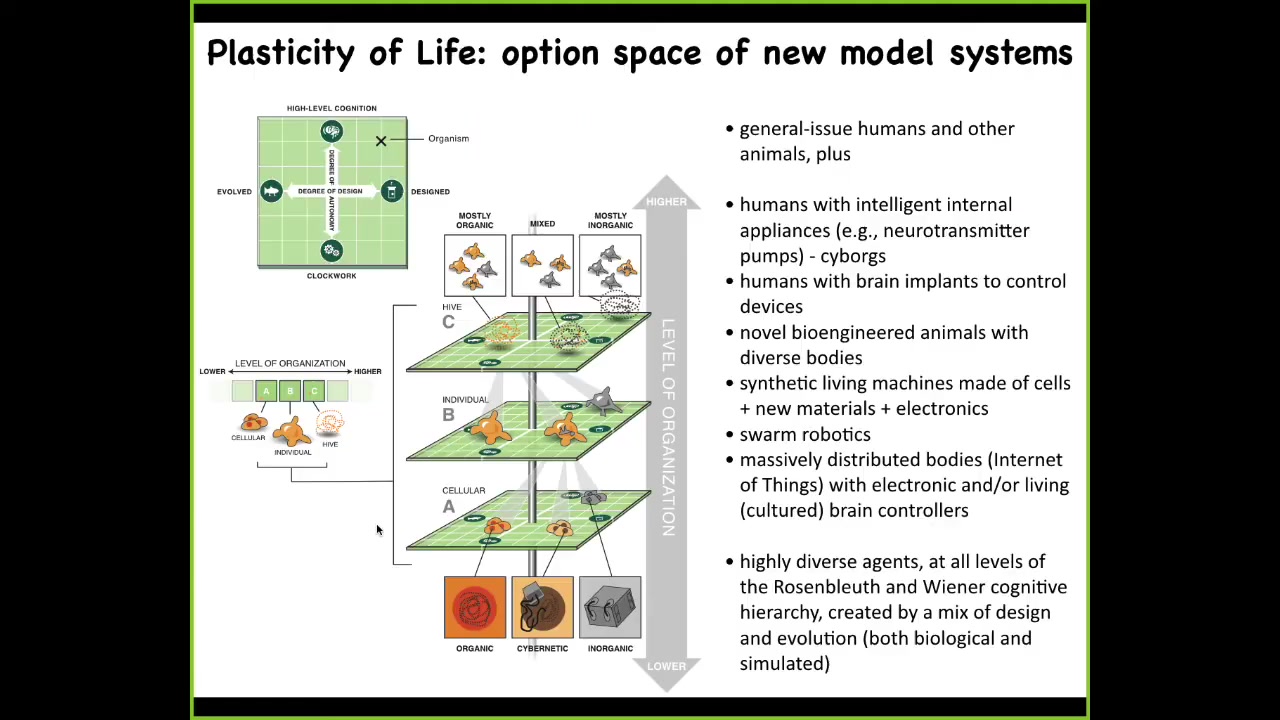

I'm going to argue four things today and try to take you through some of our reasoning. I'm going to show you that there's this process called anatomical homeostasis, which exhibits incredible plasticity and robustness. I'm going to argue that one way to look at this process is as the outcome of a collective intelligence. That anatomical control is a behavior in morphospace. It is a collective intelligence problem, much as behavior in three-dimensional space is the collective intelligence of neurons bound together into a new organism. We're going to make that conceptual pivot. I'm going to argue that developmental bioelectricity is the glue that scales individual cellular computational horizons into large individuals with very large goals. I'm going to talk about what I mean by goals. I think that evolution learned this trick used in brains from ancient pre-neural cells. That is, to make brains that implement centralized cognition and behavior. The basis of this was much older, and it was used to handle other spaces like morphospace and physiological space before animals started running around and solving problems at high speed in three-dimensional space. At the very end, I'm going to show you a novel synthetic organism that's never existed on Earth before and has some interesting behaviors. I'm going to argue that synthetic bioengineering provides a massive option space for new model systems for all of this work. That's the journey we're going to take today.

Let's talk about anatomical homeostasis. Here is a problem that many people think is solved, but it's open: where is anatomy or anatomical structure actually specified? We all start life as a collection of embryonic cells and blastomeres. This is a cross-section through a human torso. Look at the incredible invariant order. All of the different organs and structures in a normal human body are placed in the right orientation, position relative to each other, and size. Everything is exactly where it's supposed to be. Where does it come from? We might be tempted to say it's in the DNA, but we can read DNA now. We can read genomes, and nothing like this is in the genome. The genome specifies the micro-level hardware every cell gets to deploy, the proteins. In the end, we have to understand this collective of cells is going to build something, and then it knows when to stop. As workers in regenerative medicine, we ask questions like, if a piece of this is missing, how do you convince these cells to rebuild it? As engineers, we ask, what are the possible boundaries of this? What else can you make these genetically wild-type cells do? At the end, I'm going to show you some examples of this. This is a question of information processing. We need to understand the software, not just the molecular hardware.

Slide 5/33 · 06m:51s

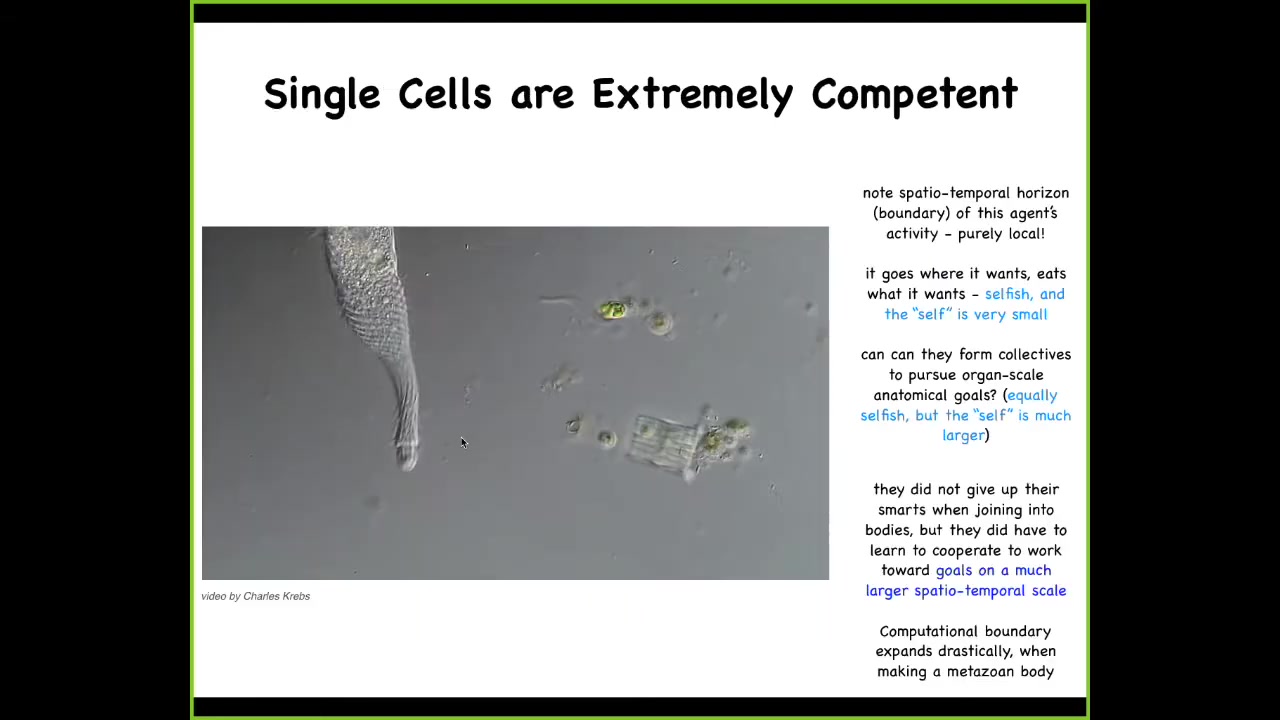

And we start with the fact that single cells are actually extremely competent in their own size and scale. So this is a creature known as a Lacrymaria. It's a single cell. There is no brain. There's no nervous system. There are no stem cells. There's no cell-to-cell communication. This is real time. This creature is handling all of its local goals—physiological, behavioral, anatomical, metabolic—all of these things are being handled at the scale of a single cell and at the expense of the environment. Here it is eating various other life forms in its environment. This is incredible real-time control. Engineers salivate at the sight of this thing. We don't have anything that can do this kind of fine control. But what's interesting is that when individual cells join together, they don't lose all this intelligence and competency. They scale it up.

Slide 6/33 · 07m:48s

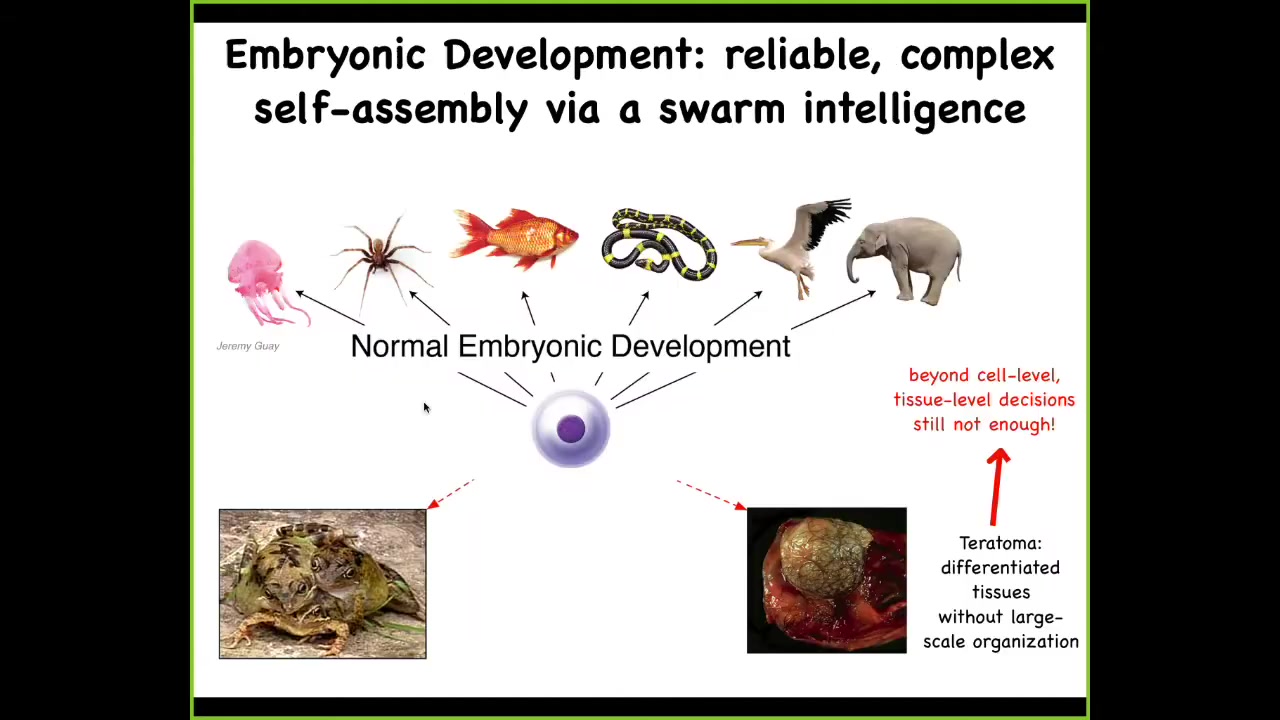

They scale it up in order to be able to build these remarkably complex, highly varied bodies, these anatomies. This is not simply a problem of stem cell biology because this thing down here is a teratoma. It's a tumor that might have skin and hair and teeth and bone and muscle. The reason that this thing is not a proper embryo is that, even though the stem cell biology proceeded perfectly well — in other words, all the particular tissues that you need were generated — they're lacking this three-dimensional structure. So it's not enough to get your building blocks of morphogenesis; you actually need to be able to specify where everything goes.

Slide 7/33 · 08m:34s

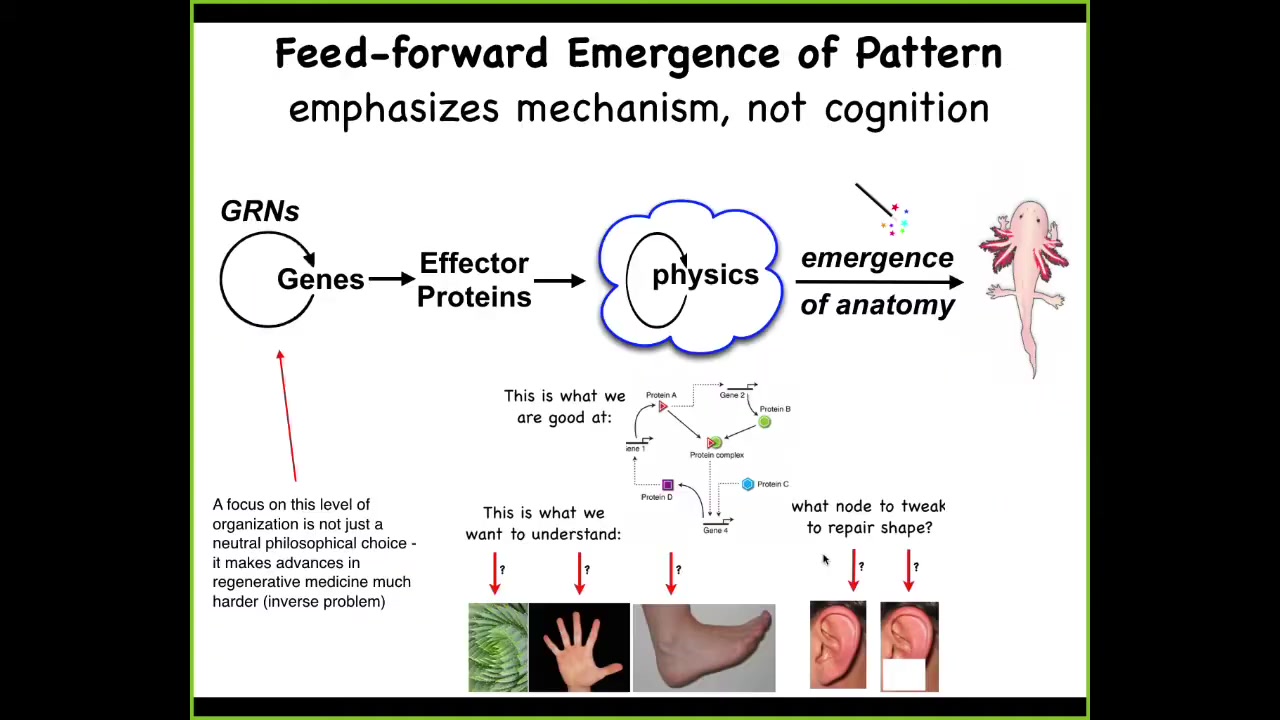

So, in developmental biology... we are taught this very basic system, which is a kind of feedforward scheme, where there are gene regulatory networks. The genes interact with each other, meaning they turn each other on and off. Some of these genes encode effector proteins that are sticky or they exert force or they diffuse. There is this massively parallel physics where everything interacts according to local rules of chemistry. Voila, there's this process of emergence and something like a salamander comes out the other end.

So all of this is true, but it's incomplete and it has a couple of problems. One of the problems is that it's a huge limitation for regenerative medicine because this is what we're good at. We're good at highlighting and understanding the structures back here, which genes control which other genes. But what we'd really like to understand are questions at this level. Why is your hand different from your foot? What would you do in this kind of network if you wanted the part of an ear to come back with a very specific structure?

So the focus on manipulation down at the lowest level gives rise to an important inverse problem. We have no idea what to do for the vast majority of things we might want to change about this large-scale outcome. Going backwards is extremely difficult under this view, and what is going to make life a little easier for us and much more interesting is that this process is not entirely feed-forward.

Slide 8/33 · 10m:04s

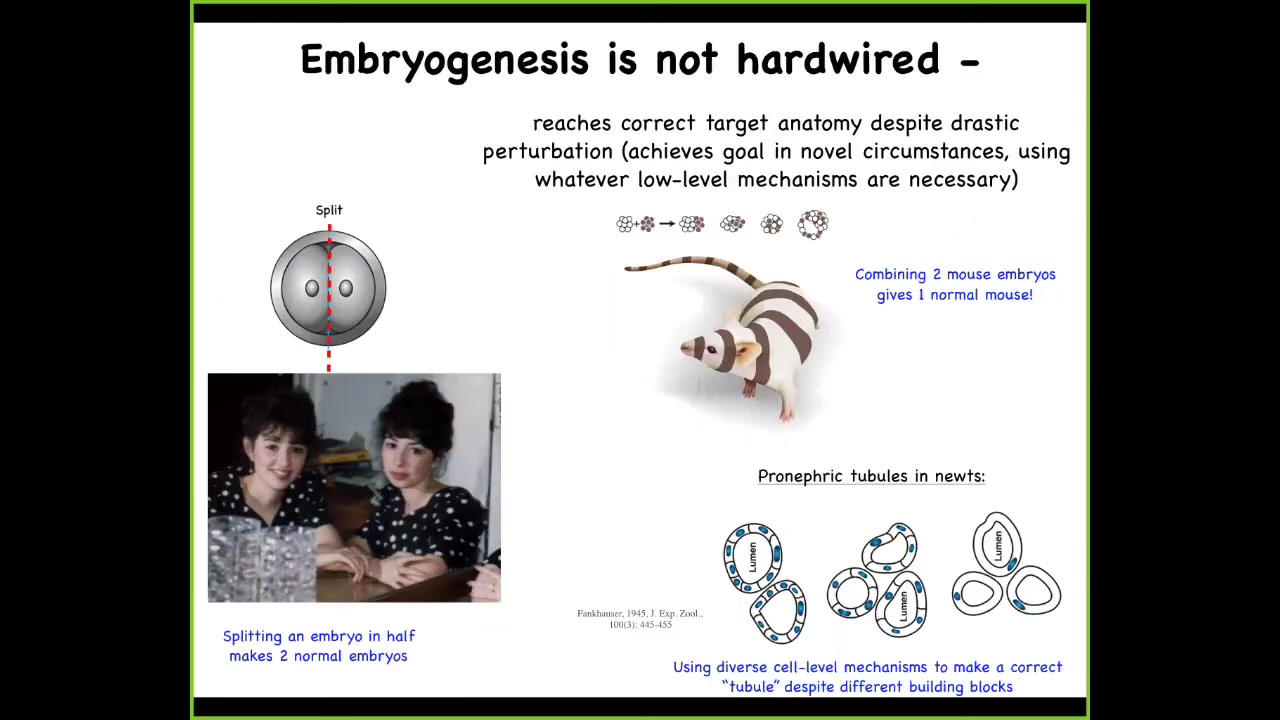

Despite the fact that it is highly reliable, it is not hardwired. For example, we can take an early embryo and cut it in half, and you get two perfectly normal monozygotic twins. You can do the opposite; you can mush mouse embryos together like a snowball, and you'll still get a normal mouse.

You can even do things like take a normal salamander, where the kidney lumens are made of 8 to 10 cells communicating with each other, and create polyploid newts where there's 6 to 8 times more DNA than there should be. They make these gigantic cells, and at that point each cell will bend around itself to create the exact same three-dimensional lumen, but now using a completely different molecular mechanism. We're using cytoskeletal bending, not cell-to-cell communication. That's a kind of plasticity. It's an invariance in some very basic properties of your building blocks that somehow still enables you to get to the correct large-scale outcome.

Slide 9/33 · 11m:06s

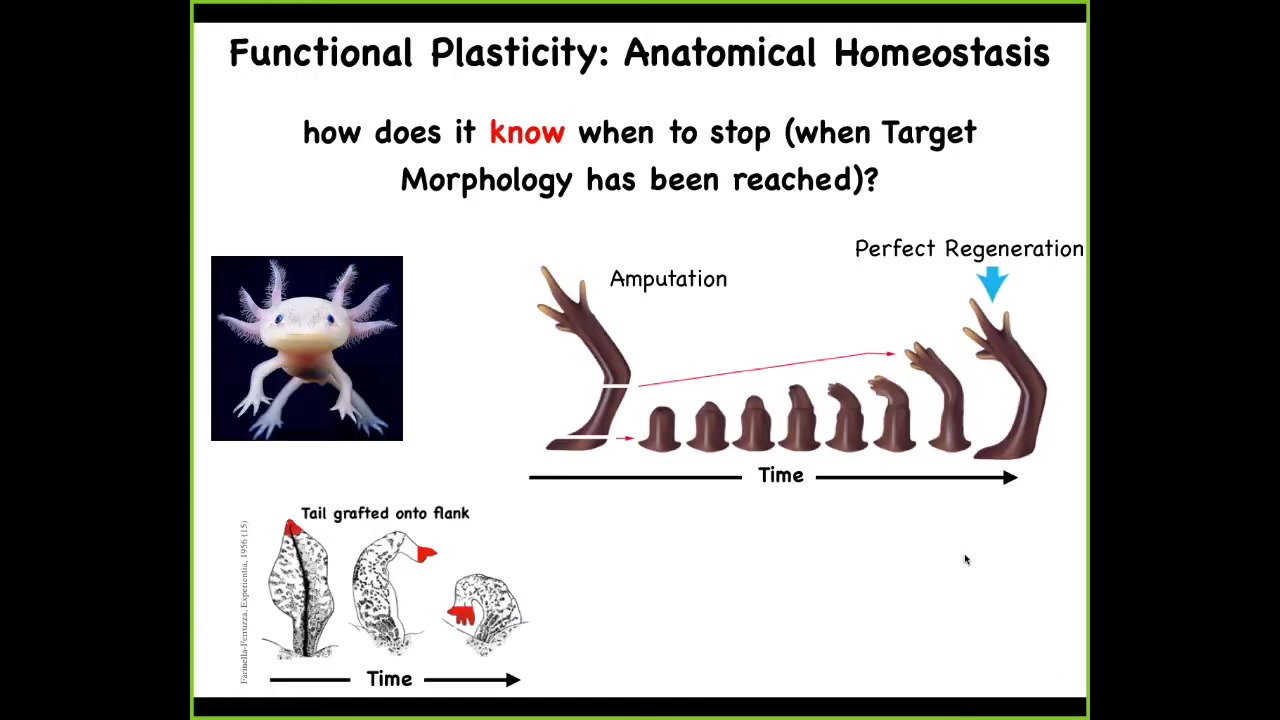

One of the most amazing examples of this whole process is regeneration. Here's a salamander. This is an axolotl. These animals regenerate their eyes, their limbs, their jaws, their tails with spinal cord, portions of the brain and the heart.

You can see here, again, another example of plasticity in this, of problem solving in this space. If you were to amputate the limb here, it starts to grow, and then you get a perfect limb, and then it stops. If you amputate up here at the shoulder, it starts to grow from here on, and still gets you exactly the right limb, and then it stops. If you graft the tail onto the flank of the salamander, it will slowly remodel in place and become a limb. The cells at the tip of the tail will become fingers. There's this incredible robustness and ability to get to where you're going despite these unexpected perturbations.

Slide 10/33 · 12m:04s

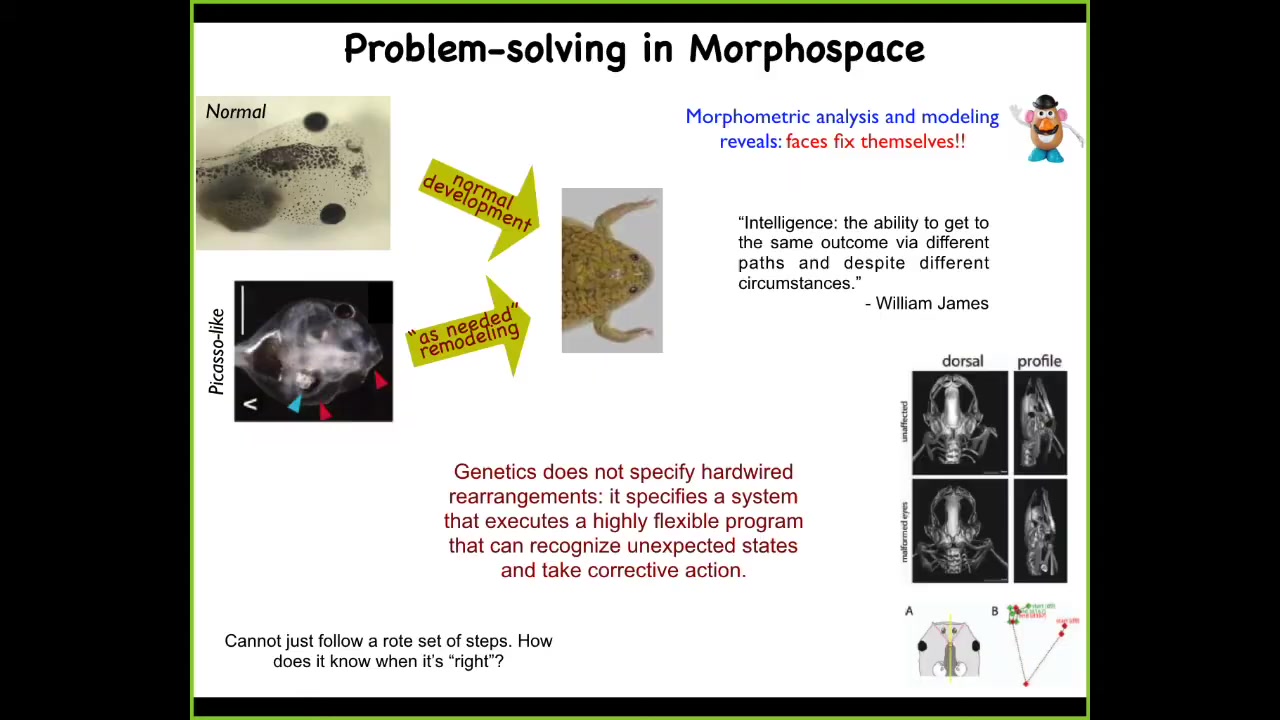

This is an example that we discovered a few years ago, which is that tadpoles, in order to become frogs, need to rearrange their face. The eyes have to move forward, the jaws have to move, everything has to move. It was thought that somehow the genetics specified a hardwired set of movements. If whatever organ primordium you are, you just move in a certain direction a certain amount and you can get from being a normal tadpole to being a normal frog.

We created so-called Picasso tadpoles. Everything is in the wrong place. The eyes are on the back of the head, the jaws are off to the side, nostrils, everything's in the wrong place. Remarkably, what we found is that these animals still make largely perfectly normal frogs, because all of these different components of the face will move, and they will continue to move in unnatural, novel paths until you get to the right position, and that's when everything stops. In fact, sometimes they overshoot and they have to come back.

This meets a definition of intelligence put out by William James, which is the ability to get to the same outcome via different paths and despite varying circumstances. What we found is that the genetics doesn't specify hardwired rearrangements. What it does specify is an incredible machine that is an error minimization engine. What it's able to do is to continue to remodel until the error is within tolerances, which raises an obvious question: how does it know when it's correct?

Again, I come back to the idea that we see all of this as a kind of behavior. It's not behavior in three-dimensional space, it's behavior in morphospace. The cellular collective agent has been taken to a region of morphospace that's completely wrong, and it has to navigate, it has to act by directing individual cell behaviors so that it can regain the correct ensemble of states in that morphospace.

Slide 11/33 · 13m:59s

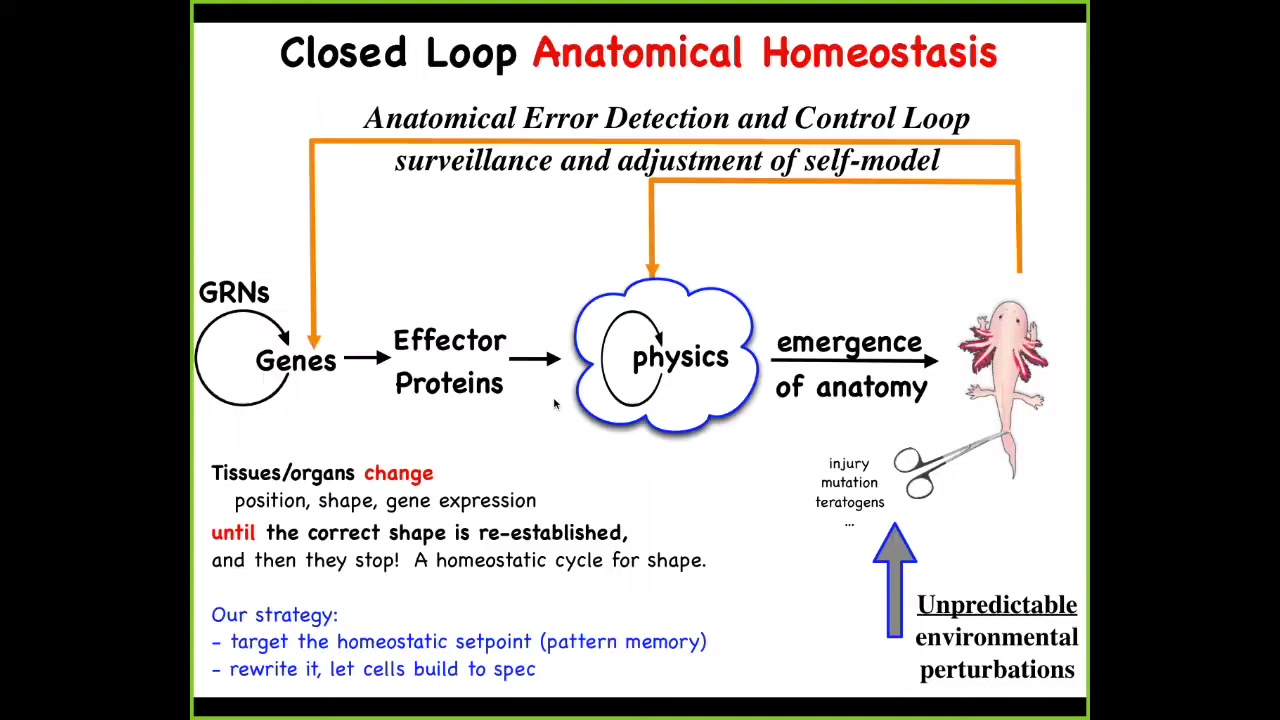

So what we then do in my lab is, to this feedforward scheme, we add feedback loops, both at the level of physics and genetics, that will act to get you back to the correct, not only physiological, but morphological level when the body has been deviated. This might be injury, teratogens, or pathogens.

There's a couple of things here. First of all, feedback is nothing new. In biology, there's lots of feedback. But what's different here are two things. First, the set point for this homeostatic cycle. Any homeostatic cycle has to have a set point with respect to which you make changes based on encoded information.

One thing is that, in this case, the set point is not a simple scalar like pH or a metabolic level: it's actually a fairly complex, a rough, coarse-grained version of what the anatomical outcome should be. So it's a somewhat complex data structure that has to be represented in the tissue to be a set point for this process.

The other thing is David said this at the very beginning: this idea of goals, because what you see in this kind of basic homeostatic process is a non-magical understanding of what it is to be a physical system that has goals. Cybernetics and control theory nailed this down many decades ago. It is no longer magic to say that a system can have goals. It absolutely can have goals in the sense that it will deploy to various degrees of intelligence. It will use energy to continue to achieve a certain state of affairs despite perturbations. So that's the very simple notion of goal here.

The architecture facilitates an incredibly important type of plasticity because what it means is that if you wanted to make changes out here, you don't have to rewire the machine back here. What you do, once you know that you're dealing with a system that has this homeostatic property, is you might simply edit the set point. If you understood the encoding and the physical implementation of that set point, you could change the set point. You wouldn't have to rewire down here at the level of physics, much like you can change your thermostat setting once you know how that's encoded. You don't need to know much about the rest of the thermostat, as long as you know how the whole system is supposed to work.

This has massive promise for regenerative medicine because much like computer science moved from having to program by pulling wires in the 1950s, we would program by rearranging the hardware, by rewiring, and this is where molecular medicine is today. It's all about genome editing and rewiring pathways. We might be able to interact with the system in a clever way by changing the set point and letting the system build to that set point.

So is something like this possible? It's a very unusual, non-standard account of developmental biology where people don't like to think of goals. They like to think of feed-forward molecular biology reactions.

So our strategy was this, and we've been doing this for years. Can we find and identify how this homeostatic set point is stored? Can we learn to read it? Can we learn to rewrite it? And can we show that the cells will build various things?

And so here is where we enter the part about bioelectricity. In thinking about developmental biology, one can start and say, OK, what type of system do we know for inspiration that has this property, that it has particular memory of goals and can pursue those goals? The obvious thing is the brain and traditional behavior. And here's the interesting thing.

Most of the components of neurons that are deployed in brains for goal-directed behavior, things like ion channels, things like electrical synapses or gap junctions, things like neurotransmitter machinery, in fact exist in almost every cell of the body. So every cell has ion channels. Most cells have these electrical synapses to their neighbors. Many cells are using things like serotonin long before there are any neurons during embryogenesis. These things are extremely ancient.

We've argued that morphological coordination was the ancestral function of all of these things. The reason nervous systems didn't just come out of nowhere is that they speed-optimized things that all cells were already doing, using machinery that actually exists even in our unicellular ancestor. Evolution discovered very early on, around the time of bacterial biofilms — even bacterial biofilms do some of these things — that electrical networks and electricity were a tremendously powerful way of processing information, of integrating information, of making decisions, of storing memories. It gives you access to a whole lot of physics that you don't need to evolve. You get it for free once you've evolved these ion channels and some gap junctions.

Slide 12/33 · 19m:27s

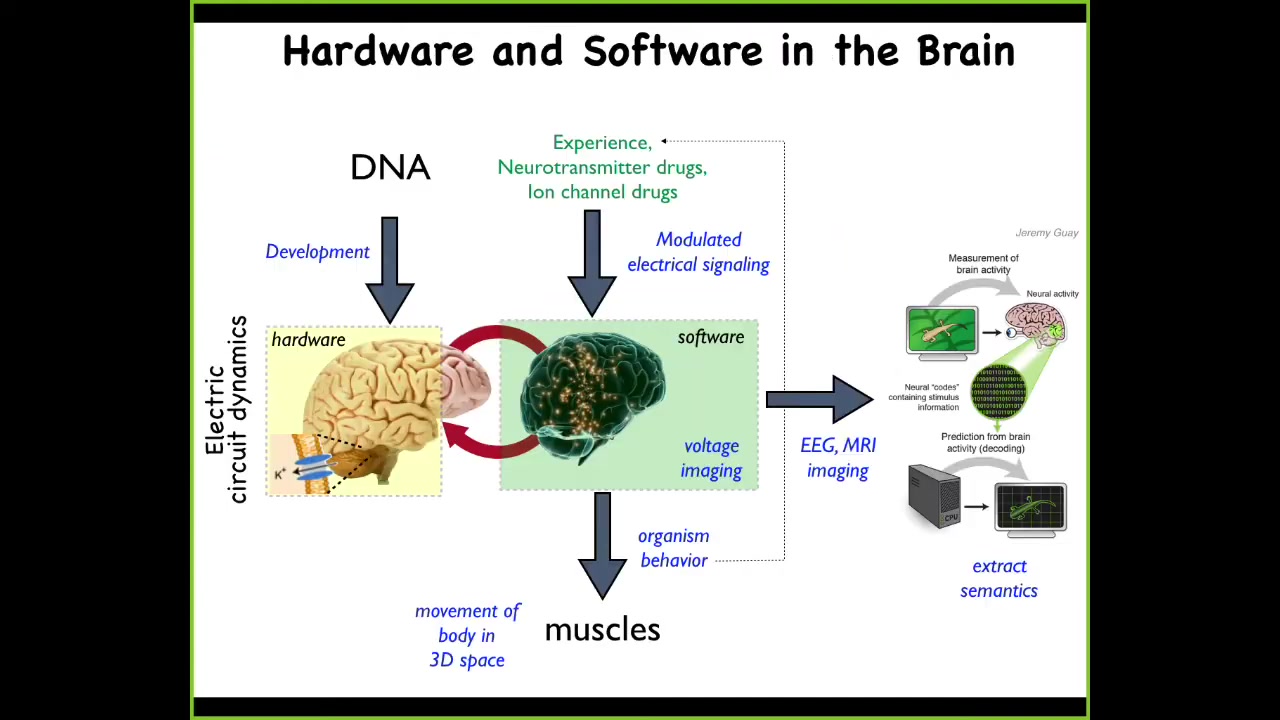

For this audience, I don't have to go through this relationship between the brain and the physiology that goes on, but I want you to pay attention to the isomorphism.

What the electrochemical activity of the brain does is issue commands to your muscles to move the body in three-dimensional space. That's behavior.

We have this project of neural decoding, where one commitment of standard neuroscience is that if we understood the encoding, we would be able to read the electrical activity and know what the memories, the preferences, the goals, and other things of the animal are. All of this is designed to move the body through three-dimensional space.

Exactly the same thing happens everywhere during remodeling and development, because these electrical cues are being used to move the body through morphospace by issuing commands to cells, not to muscles, in terms of differentiate, proliferate, migrate.

What we can do is have exactly the same kind of research program where we seek to extract the semantics, where we read the electrical activity and we try to read and then write, eventually, the information into this set of decision-making networks.

Slide 13/33 · 20m:48s

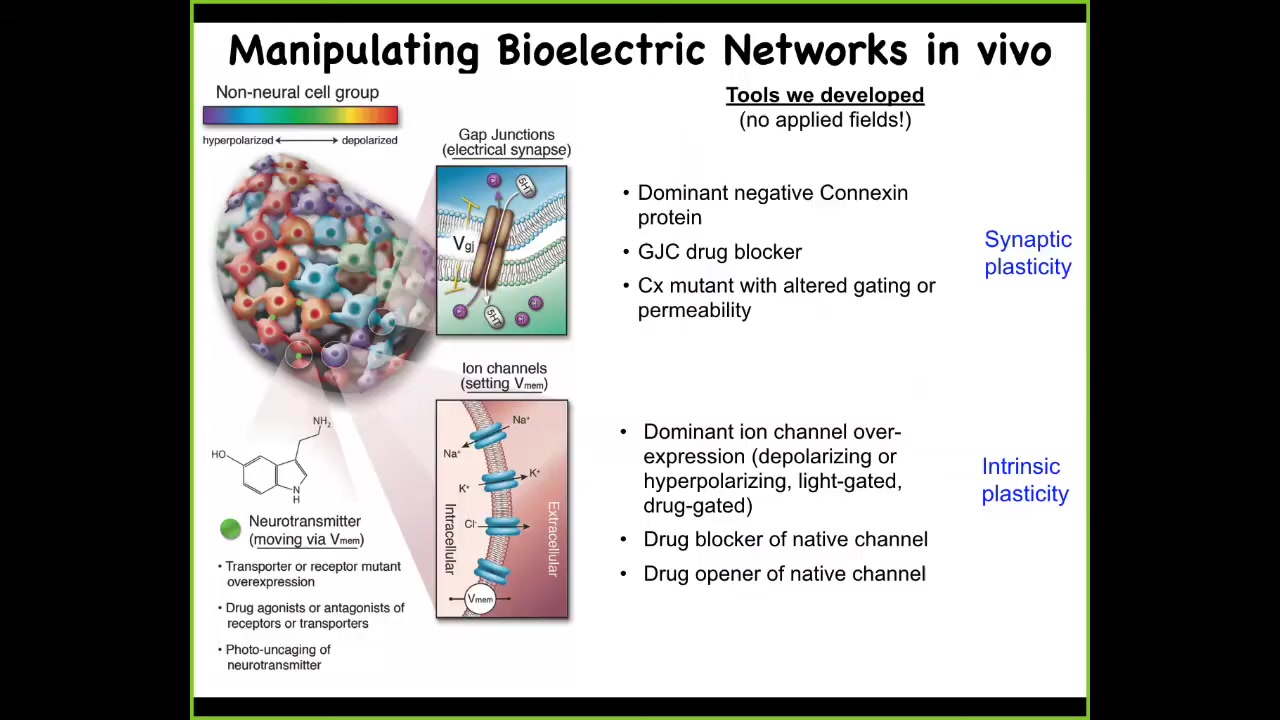

We developed some tools to do this, and they parallel the tools that you're familiar with. We can control the topology of this network. This is any kind of non-neural tissue. We can control these electrical synapses. We can mutate them, we can open them, we can close them. That controls the topology of which cell talks to each other cell and how the voltages propagate through the tissue. We can control the individual ion channels. Optogenetics, drugs that open and close these channels, mutant channels that we can introduce.

None of the phenotypes that I'm going to show you momentarily is obtained by putting electric fields on things. There are no waves, no electromagnetics, no radiation, no electrodes. All of this uses the exact same techniques that you're used to: manipulating the endogenous ion channel and gap junction activity within cellular networks. There are no fields being applied. I'm going to show you some examples of what you can do with this approach.

Slide 14/33 · 21m:54s

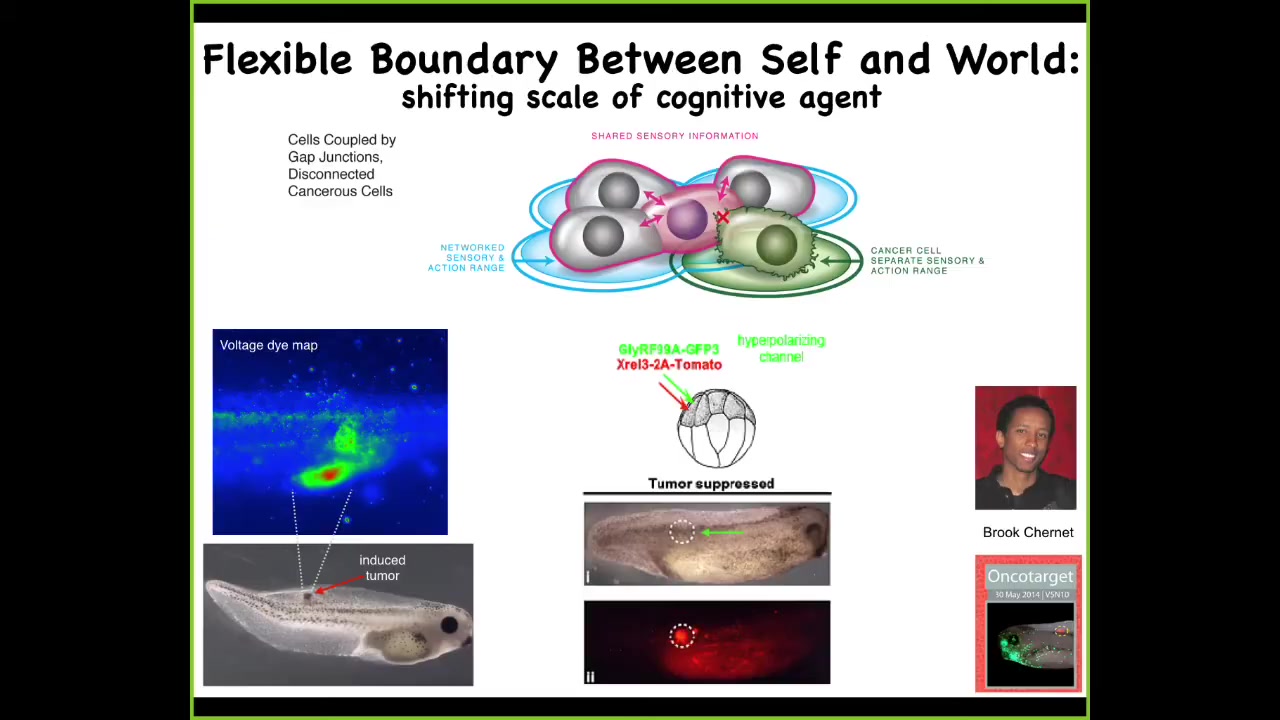

So one thing you can do is you can ask, here we have the problem of cancer. We introduce a human oncogene, and at some amount of time, these cells are going to make a tumor, and then they're going to start to metastasize. What you have in that situation is a breakdown of a reduction of the size of the goals of those cells. In other words, they used to be part of a collective that were working on building a piece of muscle or some skin or, in fact, the whole tail. When they convert to tumorigenesis they shrink that computational boundary. They revert back to a unicellular lifestyle where these cells' goals were tiny. Their goals were: each cell tries to become two cells, and they go wherever life is good and wherever they can get the most nutrients. The rest of the animal to them at this point is external environment.

So in cancer, what happens is that boundary between the outside world and the self shrinks back down. It grows during multicellularity. It shrinks back down during cancer.

What you can see here is a voltage-sensitive fluorescent dye, where you can non-invasively watch all the electrical states. One of the first things that happens when an oncogene is expressed is that these cells depolarize and shut off their gap junctions to the neighboring tissue. They become electrically isolated and then revert.

One thing you can do, by co-injecting a particular ion channel, is force these cells to stay in electrical communication with their neighbors. Then, even if there is a very strong expression of an oncogene — this could be a KRAS mutation — even though the oncoprotein is still blazingly strong and in fact all over the place, there doesn't have to be any tumor. If you force those cells to stay connected to their neighbors, the entire network works on creating a portion of this tail bud instead of crawling off and being metastatic. So that's a story at the single-cell level.

Slide 15/33 · 24m:04s

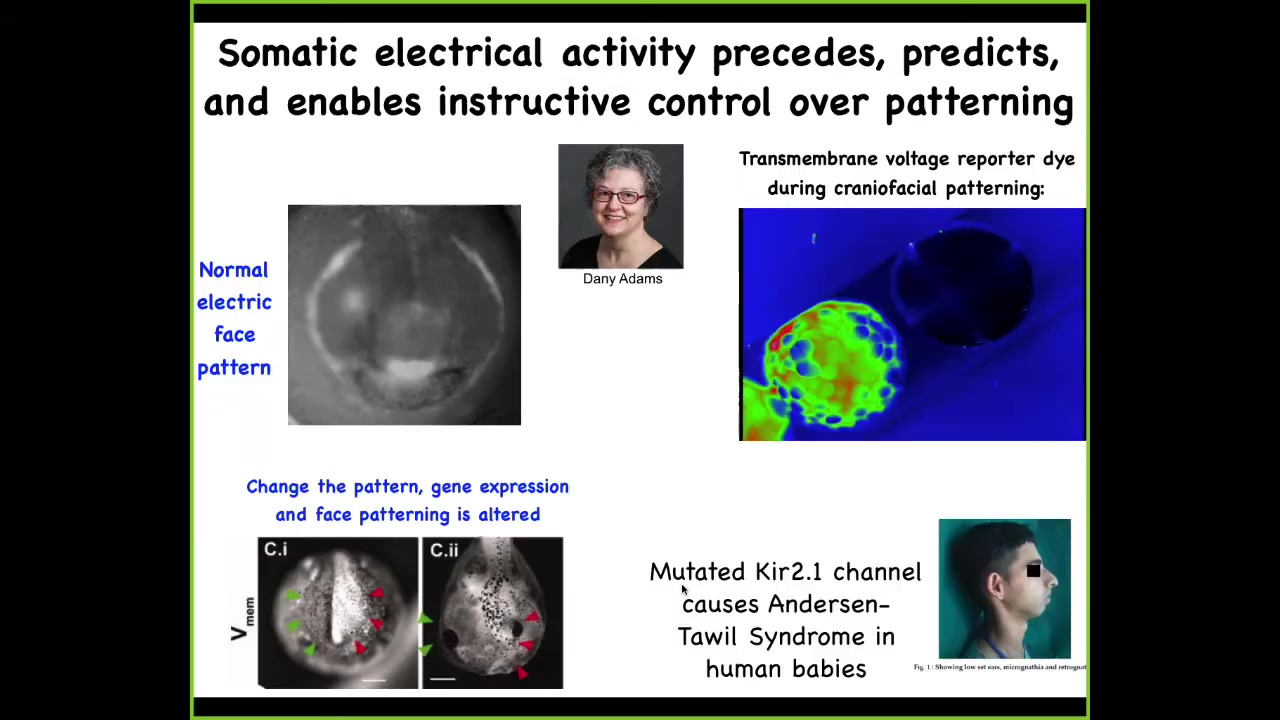

But things get even more interesting in multicellular organisms. What you're seeing here, it's a voltage-sensitive dye, and you're seeing a time-lapse video of a frog embryo putting its face together. The different voltages are pseudo-colored to different colors. And this is one frame from that video.

Danny Adams in my group discovered this, and we call this the electric face. What you will see, I'm showing you this because there are many such patterns, but this is the most obvious one. This is really easy to understand.

Long before this tissue starts to express the genes that are necessary to make the craniofacial organs, electrically you can put out a kind of a prospective scaffold, a prospective pattern that's going to place all those genes and thus the anatomy. Here's where the animal's right eye is going to be, here's where the mouth is going to be, here are the placodes out here.

One way to make those Picasso tadpoles I showed you is by moving these electrical patterns around. If I wipe out this pattern and reproduce this type of eye spot somewhere else, guess where the eye is going to form? That's one way you can make animals with eyes on their tails, by perturbing this normal electrical layout of where everything is going to go.

This is an endogenous native bioelectrical pattern that is required for normal gene expression and normal morphogenesis. It is instructive because if you mess it up or if you move it somewhere else, you can have those predictive consequences for gene expression and anatomy. Being able to read this is tremendous because, talk about neural decoding, it actually looks like a face. This is a really easy decoding. Most of the other patterns are not nearly that simple. They're very convoluted, but this is a nice, simple one.

This, of course, occurs in humans, too. There are lots of human channelopathies that cause craniofacial dysmorphias and limb defects. This is how we track these patterns. But more importantly, as I showed you, we now have tools to manipulate them.

Slide 16/33 · 26m:13s

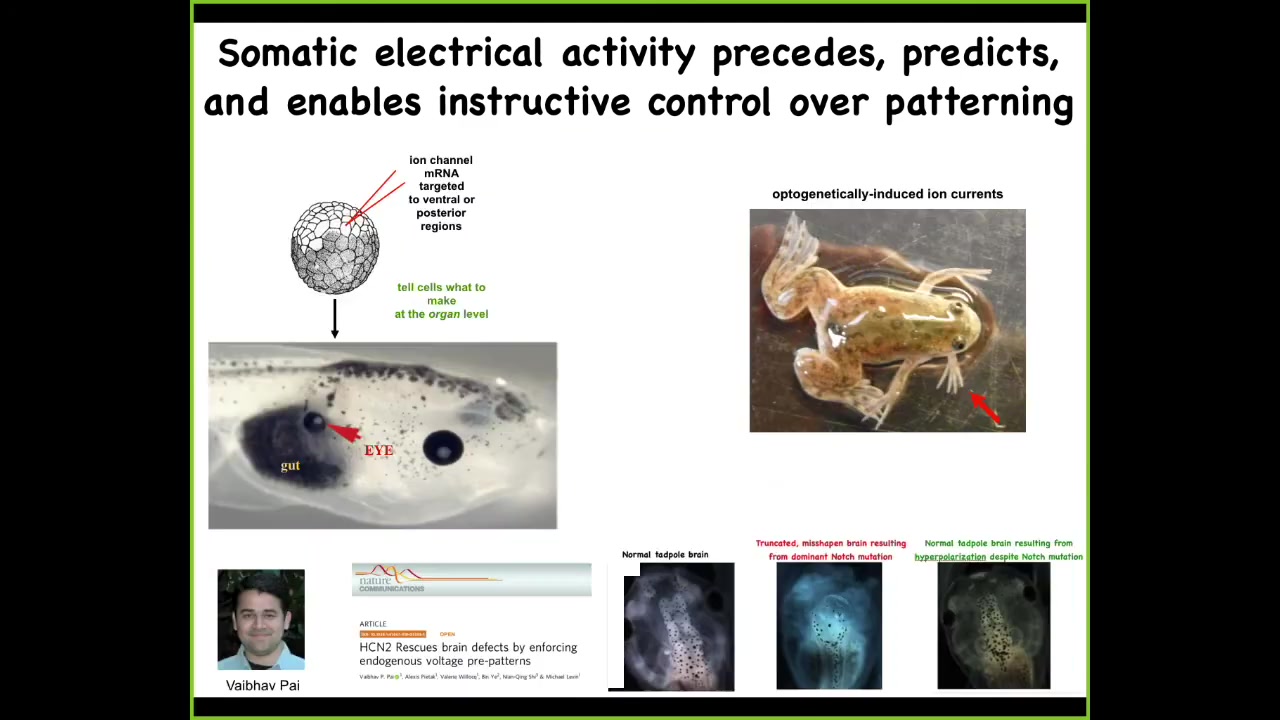

Here's what happens when you manipulate them. Here's the injection of one single ion channel RNA into some cells that are going to become gut. What that ion channel does is it sets up a local pattern of voltage that corresponds to a pattern that's associated with eyes. Sure enough, it will make eyes. You can make eyes out of endoderm, which completely transgresses the boundaries that you'll read about that only this anterior ectoderm is competent to be eyes. That's not true. You can make these anywhere. This is an optogenetic frog line that we made where you can, for example, induce limbs growing out of the jaw of the animal.

All of this is now to the point where we actually have computational models that tell us exactly what channels to open and close to exert very complex morphogenetic outcomes. Here's a proper frog brain. You've got a forebrain here, a midbrain, and a hindbrain. If you introduce a dominant mutation to a gene called Notch, which you're all familiar with, very important neurogenesis gene, the forebrain is gone, the midbrain and hindbrain are a bubble, these animals have no behavior; they lay there doing nothing. We made a computational model to ask a simple question: given the bioelectric pattern that sets up the size and shape of the brain, how do we fix this? Notch mutations, fetal alcohol syndrome, nicotine poisoning — if that happens, what channels do we need to open and close? The model told us, and we did it. Sure enough, not only do you get brain structure and gene expression back, but you actually get their IQs back. The learning is back up to wild-type rates.

I just want to be clear that this has now moved from the early days of screens to see what phenotypes bioelectric gradients even control, down to the point where we now have rational design and discovery of treatments for very complex disorders that can override even dominant genetic mutations. To continue with this theme of plasticity, I want to show you one example here.

Slide 17/33 · 28m:26s

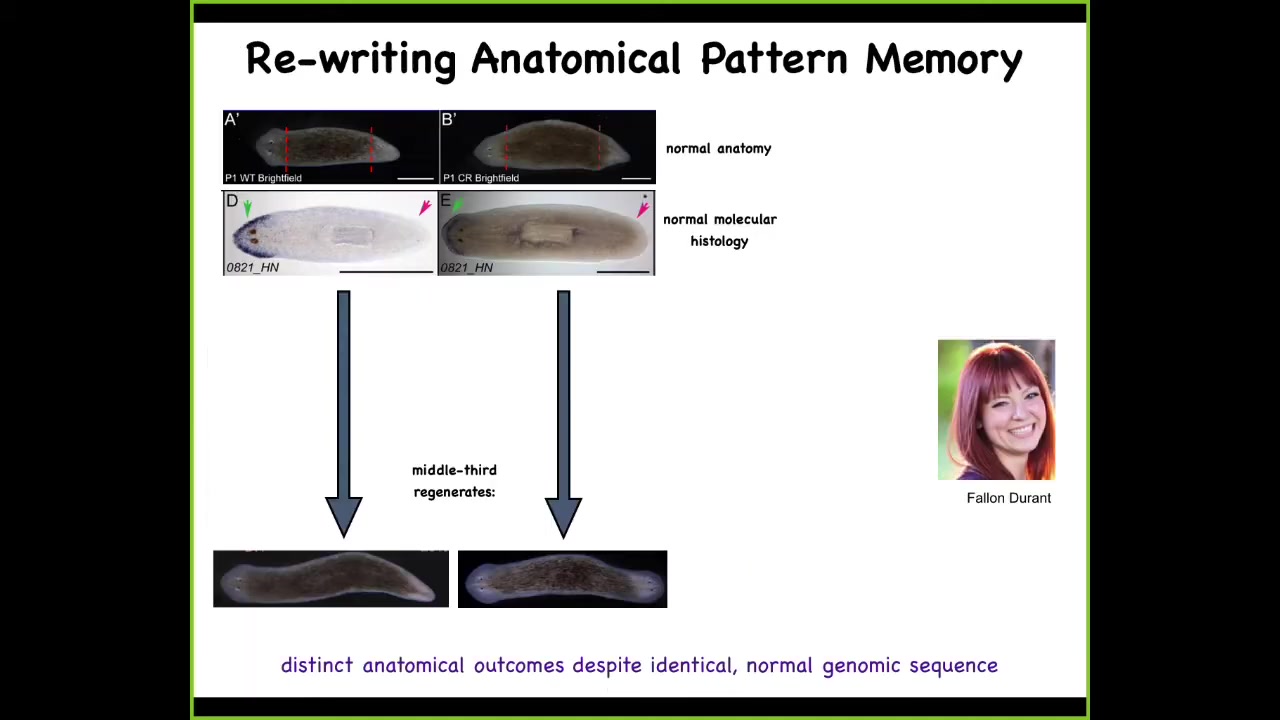

These are planaria. These are flatworms. First you check: the anterior gene is expressed in the head; missing in the tail. You amputate, and this middle fragment, very reliably, 100% of the time, gives you a normal one-headed worm.

Now, here's another worm. Anatomically, same thing, one head, one tail. The gene expression is normal: anterior gene in the head, no anterior gene in the tail. We amputate, and this middle fragment gave us a two-headed worm. This is not Photoshop; these are real two-headed worms. This is the work of my grad student, Fallon Duran.

Now you might ask: this is normally 100% fidelity. Why would a normal animal with normal gene expression, normal anatomy give rise to a two-headed regenerative offspring?

Slide 18/33 · 29m:30s

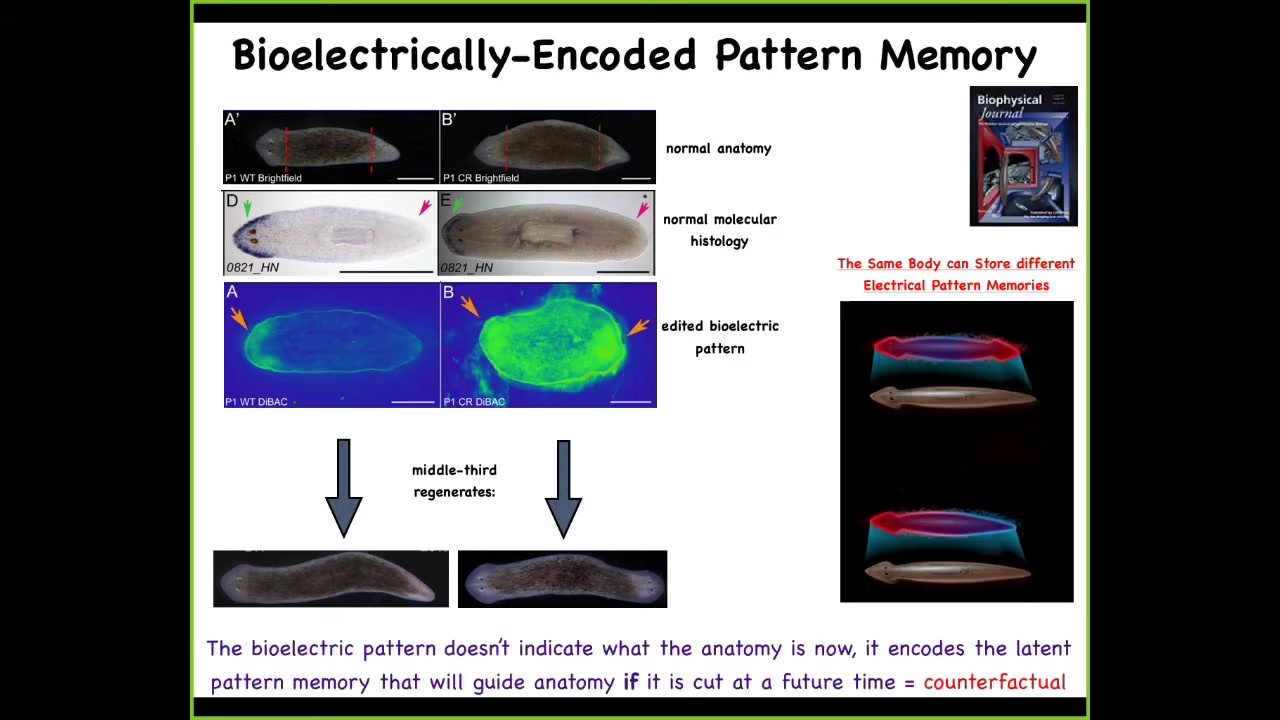

And that is because what we did in the meantime was we took this animal and we saw that there's this standing bioelectrical pattern that says how many heads you're supposed to have. This is very messy; the technology is still being developed. What we did is we said, your pattern is such that you should have two heads. Here are two of these depolarized spots. Sure enough, there's the two-headed animal.

Now here's the really critical part of this. The electrical map is not a map of this two-headed creature. This is an electrical map of the one-headed creature in which we basically incept it, think about Tanagawa's or Duhoi's or inception of new memories into living animals. This single-headed, anatomically normal animal, normal by gene expression, is now holding an abnormal memory of what a correct planarian is supposed to look like, specifically how many heads it's supposed to have.

When we injure that animal, that is when these cells begin to pay attention to this and build the two-headed animal. Up until then, they ignore it completely, and that means that a single-headed normal planarian anatomy can store at least one of two possible versions of what it will do in the future if it gets injured.

That target morphology, that pattern to which the animal regenerates, the set point, the set point of that anatomical homeostasis, is stored in a stable electrical circuit that can diverge from the anatomy; they're completely separate. Being able to store different types of information in exactly the same hardware. Maybe this is the sort of basement of counterfactual memories. This animal is storing a representation of what it will do in the future if it gets injured, not anything related to what the situation is right now. Again, this map of a one-headed animal. Now, why do I keep calling it a memory?

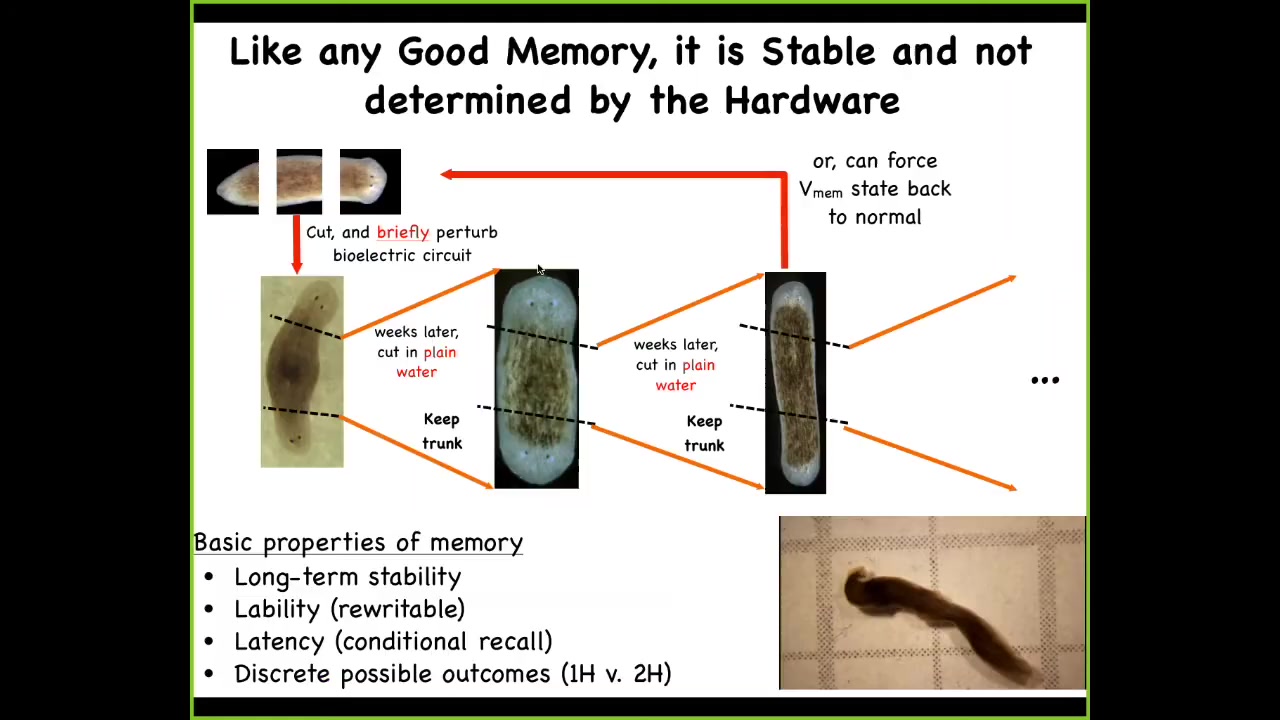

Slide 19/33 · 31m:29s

Because if you take one of these two-headed animals, you can continue to amputate the heads. You amputate this ectopic posterior head, you amputate the primary head, you take a nice normal middle fragment, and in plain water, no more manipulations, it will once again give you a two-headed animal. You can do it again and again, and it's permanent.

We also now know how to set it back to being one-headed. Again, no genetic manipulations anywhere here. The genome is completely wild type; we don't touch it, no genomic editing, we don't do anything like that. The question of how many heads a proper planarian is supposed to regenerate upon damage is not nailed down by the genome. In fact, it is stored in an electrical circuit, which the genetically encoded physiological hardware is able to maintain over time. That circuit has long-term stability. It's rewritable, so we can go back, we can shift back and forth between one-headed and two-headed. It has conditional recall, as I just showed you. That memory stays hidden until you injure the animal, then it becomes apparent. It has a couple of discrete possible outcomes. No doubt many more, but this is the one we've nailed down.

You can see here, this is what these animals do in their spare time. They're two-headed animals. I always show the video because the first time I showed this at a meeting, somebody stood up and said that was impossible and these animals couldn't exist. Here you can see what they're doing.

What we're doing now, among other things, is to make quantitative models using tools of connectionist modeling, for example, Hopfield networks, where we actually try to understand the ability of this electrical circuit to store specific memories as representations of amorphous space and to get back to those regions when perturbed, but also to be knocked into a different attractor.

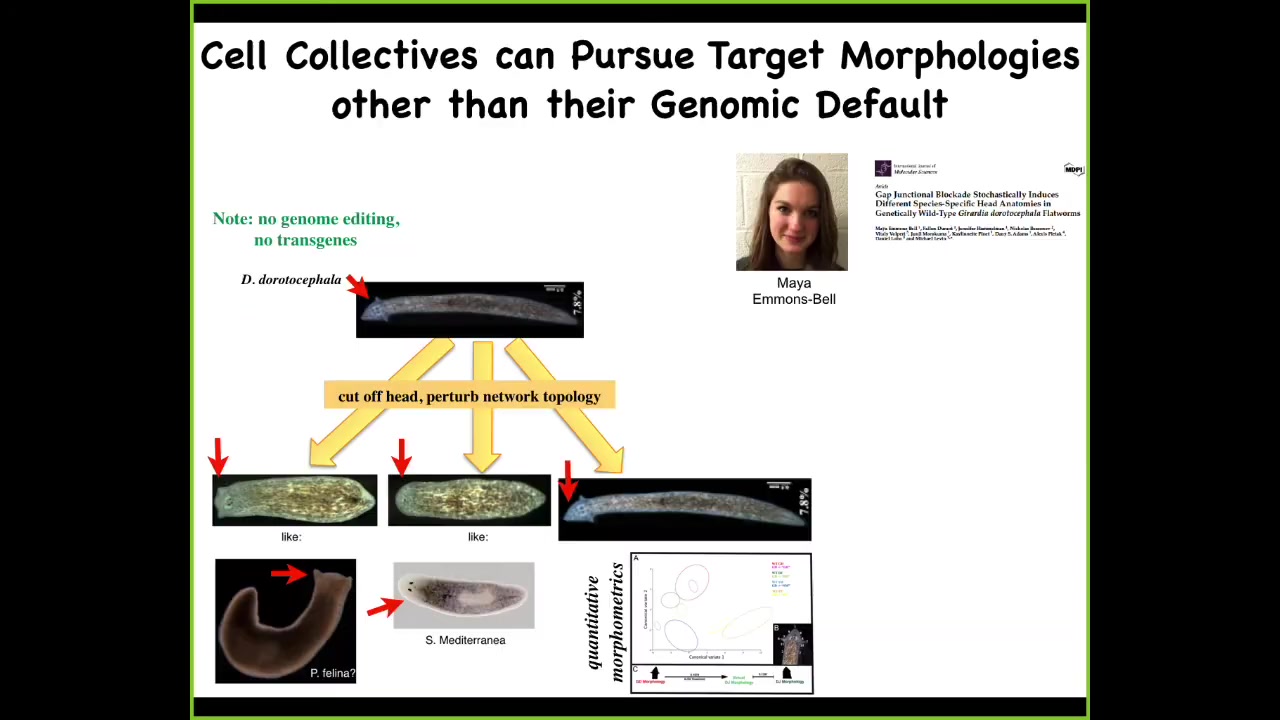

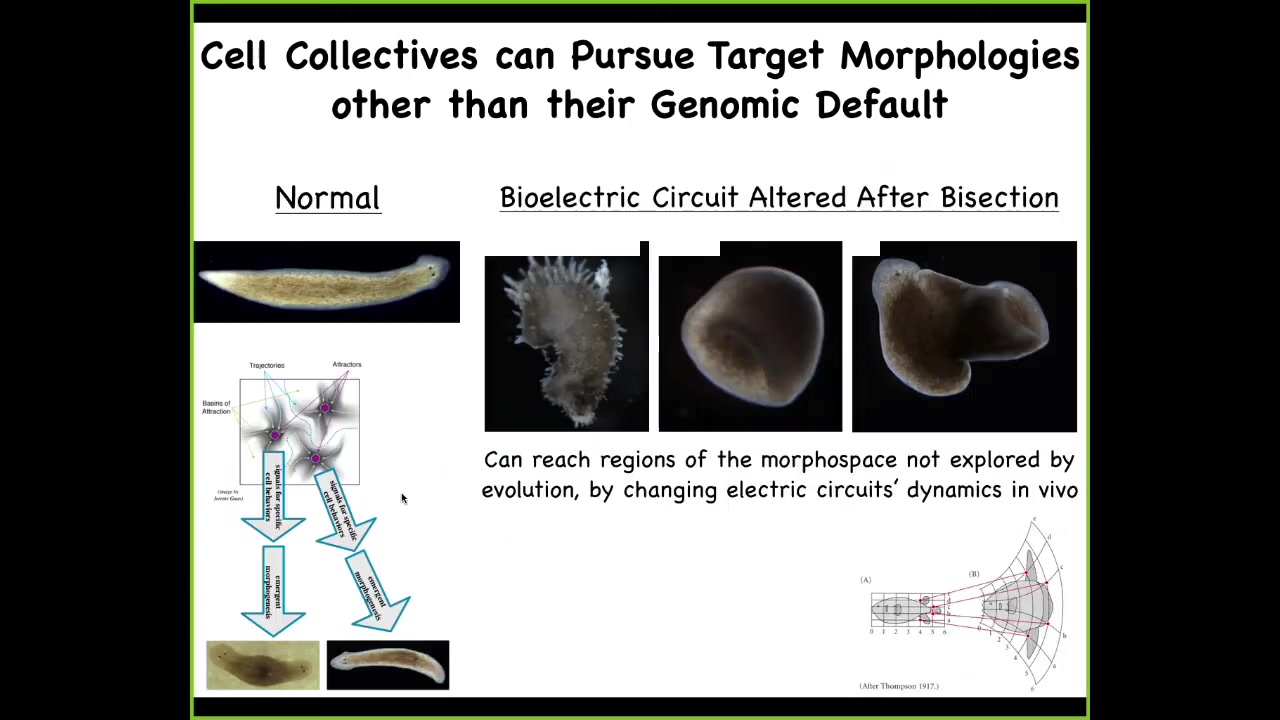

Slide 20/33 · 33m:21s

And that becomes a very powerful notion because you can take, and this is the work of an undergraduate, Maya Emmons-Bell, who showed that you can take genetically wild-type planarian with a triangular head, amputate the head, perturb the gap junctions for a couple of days to prevent the cells from properly settling into their correct state. And from this, you can regenerate your normal triangular head, but you can also get round heads like an S. mediterranea, or you can get flat heads like a P. felina. You can make heads appropriate to other species of planaria without any genomic change. Not only the shape of the head, but the shape of the brain, the distribution of the stem cells, becomes exactly like these other species. So you can knock this thing into other regions of morphospace that have attractors that are normally occupied by other species. Evolution can use this process in the short term, and then long term there's probably some sort of canalization, like a Baldwin effect, which is how you get these genetic lines. But you can do more than that.

Slide 21/33 · 34m:28s

You can also explore the space and reach attractors that are just ecologically not viable. For example, we can make these crazy spiky forms. We can make cylinders with planaria; they don't even have to be flat, with exactly the same genome. Here's a common kind of combined effect of a flat planarian with a big tube coming out into the third dimension. There are all sorts of different types of attractors in morphospace, and the cells are perfectly happy to build to it if the electric circuit is appropriate. For regenerative medicine, we would like to understand how to control this.

Slide 22/33 · 35m:07s

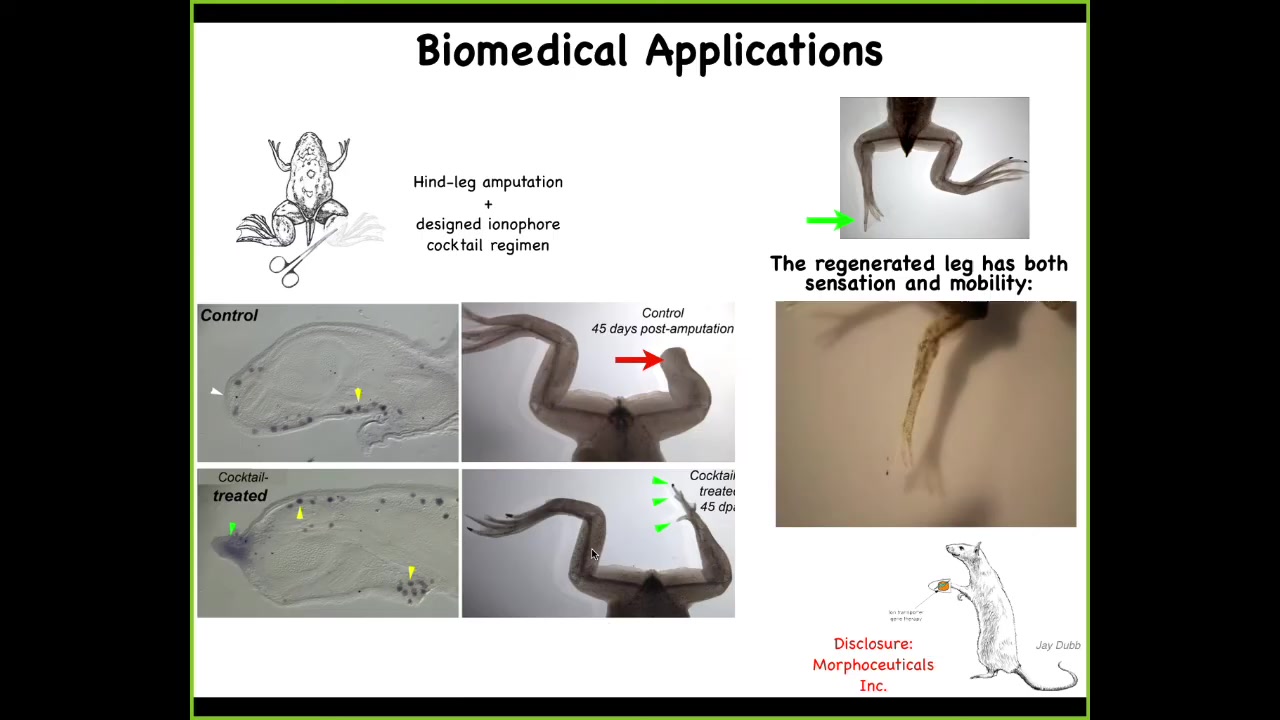

And this is an example for us in our kind of regenerative medicine approach where we've learned to do in the frog, which does not regenerate their limbs the way that a salamander would, 45 days later there's nothing, what we can do is we've designed a set of cocktails that open and close specific channels to turn on an electric state that basically says build a leg here. And what happens is you trigger some pro-regenerative gene expression, you have a blastema with MSX1, and then it starts to make a leg. And it makes a perfectly serviceable leg, which you can see is touch sensitive and motile. Eventually it becomes very nice. This is an early phase.

And one interesting thing, going back to this theme of being able to reach the same outcome through different means, this early frog leg, here's a toenail, some toes coming off the sides. This is not even remotely how frog embryos build their legs. This is not it. This is a completely different path through morphospace that nevertheless results in the same goal, which is a functional frog limb.

I have to do a disclosure here. David Kaplan and I are co-founders of a company called Morphoseuticals, Inc., which is now taking this technology into rodents and trying to do mammalian limb regeneration, hopefully eventually for human patients.

Slide 23/33 · 36m:24s

So here's what I've tried to say so far, that bodies are extremely plastic. They harness different types of low-level mechanisms towards very specific large-scale outcomes, which cybernetically are in fact goals. In the brain, this is mediated by electrical and neurotransmitter networks. I haven't even talked about the role of serotonin here, which is huge. They store a kind of pattern memory. They store a stable bioelectrical state that instructs large-scale anatomy, not individual cell fate. This is not about telling a particular stem cell what type of cell it should be, but this is about large-scale, how many heads, where do the heads go, where do the legs go, that kind of thing, which can now be rewritten in software without rewiring the machine. We can change that electrical state without having to edit the hardware.

We can now take advantage of lots of different physical tools, but also conceptual tools, to try to understand the decision-making by these cellular collectives. That's allowed us to gain all kinds of new capabilities that didn't exist before.

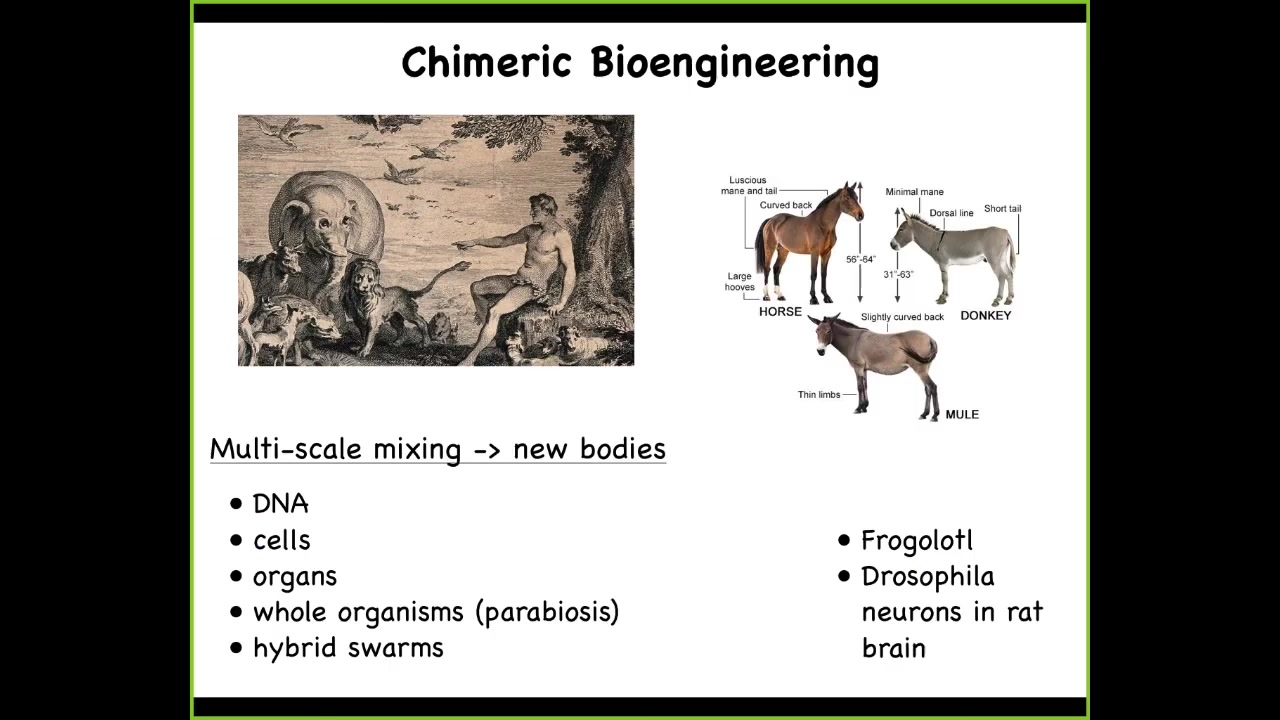

In the last few minutes, I want to talk about the role of synthetic morphology in this sort of merger of neuroscience and developmental biology. We have a really fundamental knowledge gap here. Here, imagine this is a thought experiment. Here's a planarian that has a flat-headed species where these cells know how to make a flathead and then they stop. There's this round-headed species where these red cells know how to make a round head and then they stop. What we can do is make a chimera where a bunch of these cells are injected into this body, they move around and get comfortable, and then we cut off the head. What shape is going to form?

The interesting thing is that despite all of the incredible papers in Science and Nature on the molecular pathways that determine planarian stem cell lineages, there's not a single model in the field that makes a prediction on this experiment. This is not an experiment about what the individual stem cells are going to do. This is an experiment about when and how this collective agent builds a particular thing and when it stops. Will it build an intermediate head? Was one of the shapes dominant? Will it never stop remodeling because neither set of cells is ever happy about what the shape is supposed to be? We have absolutely no idea. The field lacks conceptual tools to even think about this. There are no models.

What's important is that while this is most easily seen in these kinds of chimeras, it's actually true in all animals.

Slide 24/33 · 39m:07s

All standard model systems because we actually can't derive anatomies from genomes. No one knows how to do this yet.

This is a painting of Adam naming the animals in the Garden of Eden, a fixed set of animals, and that's all that there are, and here they are. We now can create incredibly rich chimeras. We can mix DNA. We can transplant cells and organs. We can do parabiosis of whole bodies. We can make hybrid swarms. We can make things like a frogolotl, which we're working on in our lab, which is a mixture of a frog and an axolotl. Baby axolotls have legs. Frog embryos do not have legs. You have access to the frog genome. You have access to the axolotl genome. Can you tell me if the frogolotl is going to have legs? Nobody knows. What we're missing still is this general ability to guess the goal states of collective agents, especially when these collective agents consist of multiple different subunits. People have been doing something like this for many years. Somebody discovered that if you made a horse and a donkey, you'd get this mule. In general, we can now do these incredible things.

Slide 25/33 · 40m:21s

And specifically, we can replace every layer of a living system from the molecular components that might be smart materials and nanomaterials and these kinds of things to the cellular. And every level of organization could be replaced by something that is somewhere on this scale from evolved, some combination of evolution and design by engineers and some degree of sophistication from a very simple passive system to some sort of high level active intelligence. So we can make these things. Here's one of my favorite examples of somebody cultured some rat neurons and showed that if you provide the appropriate rewards and punishments, they can learn to fly a flight simulator game. That you instrumentize. There are six electrodes. There are six controls of an airplane. You feed this into an Xbox or you run it on a Mac. You electrically shock it when the plane crashes. Soon enough, it learns to keep the plane afloat like an autopilot. This tells us that everything is up for grabs in this system of an embodied agent of a brain, a body, and the external environment. Every part of that can be swapped out, and the biology has the plasticity to work with it. So the world and the body of this mini-brain is this virtual airplane.

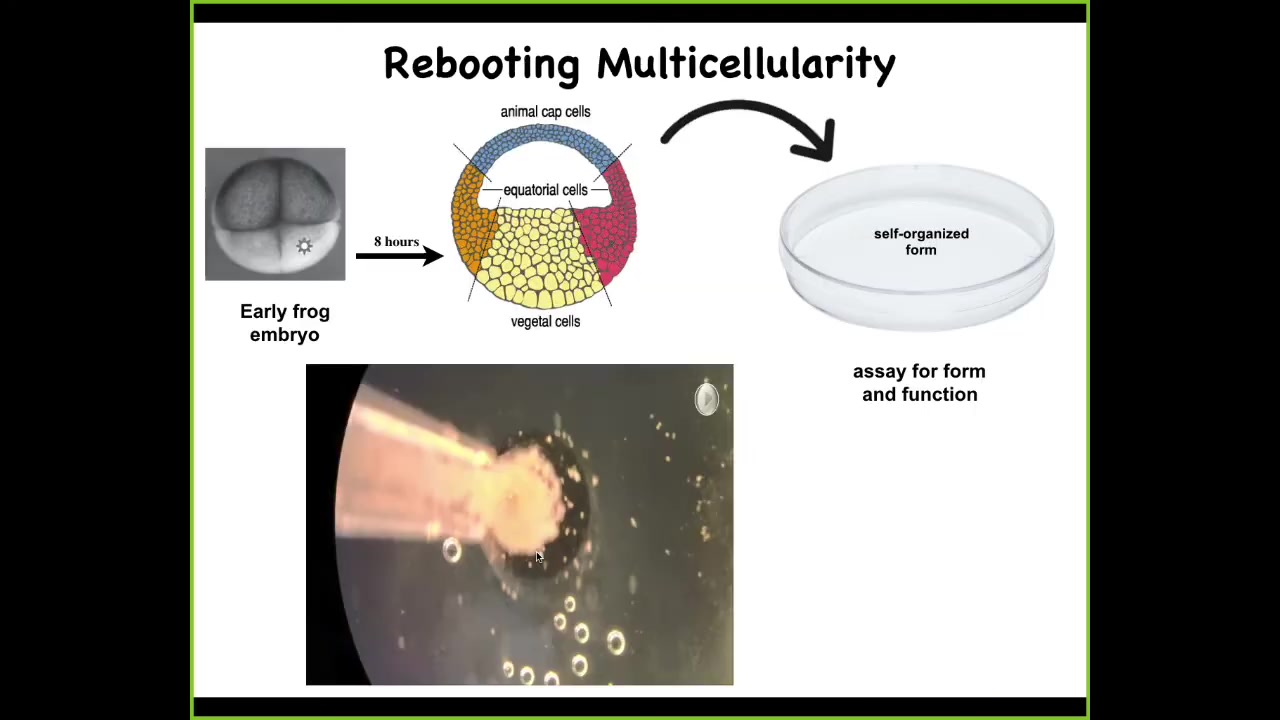

And so these kinds of creatures that we can now make that will be combinations of designed and evolved things will be somewhere along this: Wiener and Rosenblueth's scale of cognition. It's this continuum from very simple kinds of things all the way up to more complex cognitive structures. All of these things will be somewhere on here. I want to show you a quick example. This is Doug Blakiston. He's a staff scientist now in my group. We asked a simple question about plasticity. We said, if we liberate some cells from their normal boundary conditions, meaning the rest of the embryo telling them what to do, will they reboot their multicellularity? Do they cooperate? And what will they build? We're looking for a sandbox within which to start to understand how can we learn to predict the outcomes of these collective agents.

Slide 26/33 · 42m:41s

We did something very simple. Here's a frog embryo. At the early stage, all of these cells up here are going to be skin, so ectoderm. What we did was we took these cells, dissociated them, put them in a little pile, let them reassociate, just skin, nothing else. We asked, what are you going to do?

Here you can see they are sitting in this pile overnight. This literally takes about 8 hours. Overnight, they coalesce. You can see them moving around and doing various things. All the flashing that you're going to see is calcium signaling. They get together and they build this thing. By the following day, you start to see that what they've actually built is a novel proto-organism.

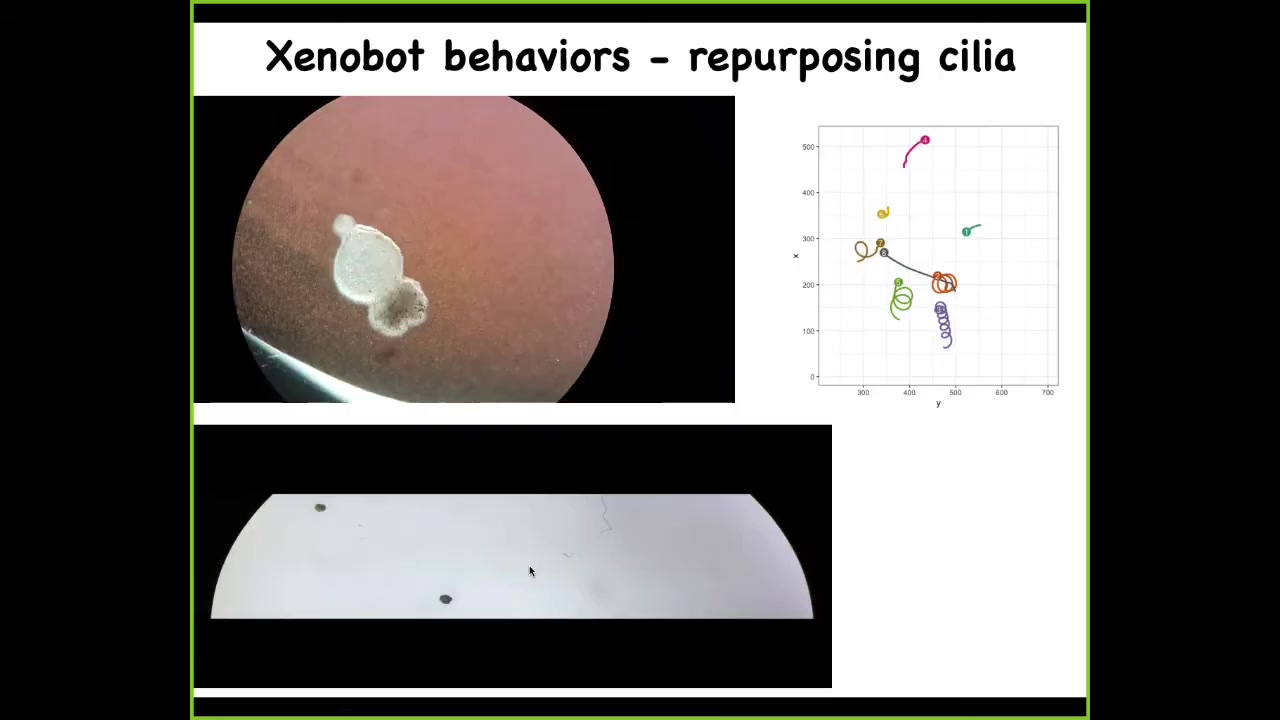

Slide 27/33 · 43m:19s

This thing here has little hairs on its outer surface, the cilia, that it can use to row against the water. It becomes motile. It's able to swim. They have all kinds of interesting novel behaviors. They can go in circles. They can go back and forth. This guy's patrolling back and forth.

Here are some tracking data so you can see what happens. Some of them are sitting still doing nothing. These two are interacting with each other. This one goes in circles. This one's going on a long exploration of the whole dish. You have a wide variety of behaviors. Remember, this is just skin. There are no neurons. We didn't program this. We didn't engineer it. This is a completely spontaneous plasticity of these cells finding themselves outside of their normal environment and figuring out how to work together to make a coherent organism of some sort.

Slide 28/33 · 44m:10s

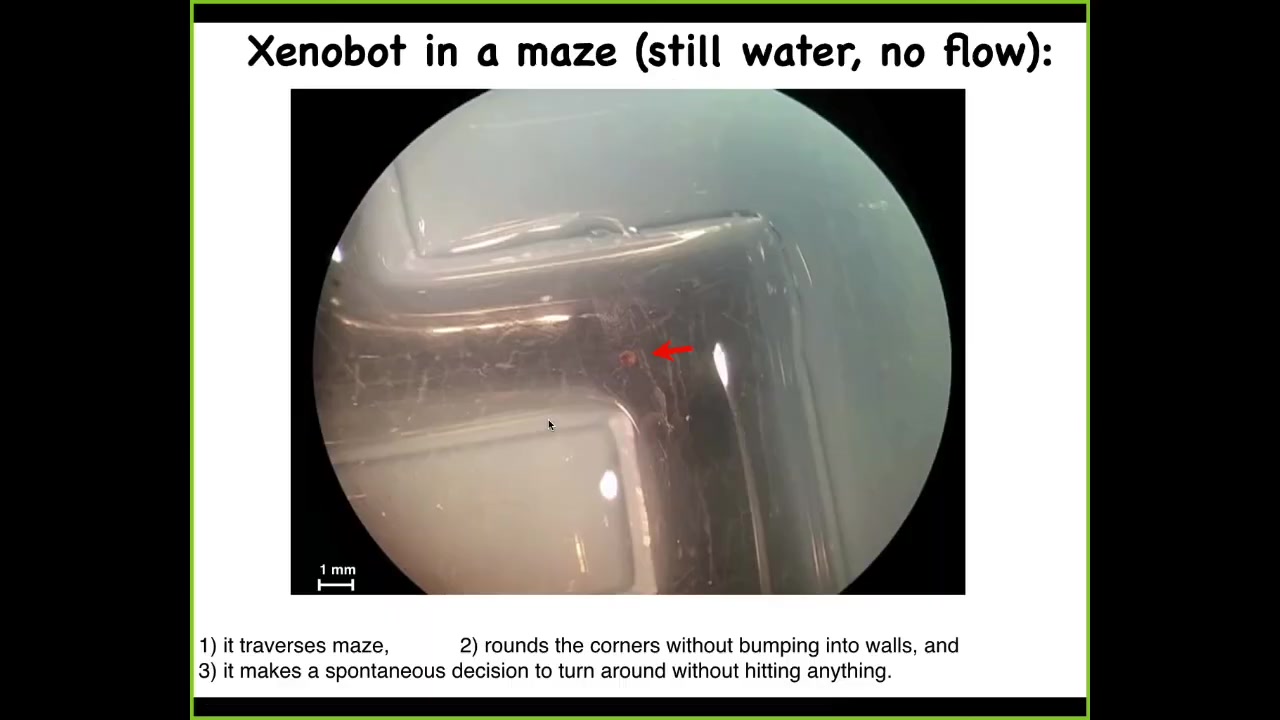

I'm going to show you what they do in a maze. This is a maze. It's water that's completely still. There's no flow, there are no gradients, there's no food, nothing. It's completely still. Let's watch this thing. It starts swimming along, and then it gets to here. And without bumping into the other wall, it can take a corner. It's able to do that without hitting anything. And somewhere around here, some internal dynamics is, nah, I'm turning around and going back where I came from. For some reason, without any external manipulation, it just turns around and goes back. They have some basic internal dynamics.

One way that I sometimes give a talk is I'll spend 20 minutes showing all the different things they do, and I'll ask people what they think these things are. I don't tell you upfront what it is, and people will say, maybe you got them out of the bottom of a pond, some organism.

Slide 29/33 · 45m:04s

They have some other amazing capacities. They can regenerate. So here, if I chop this guy in half, look at that hinge, that 180 degree hinge, it generates incredible force through that hinge to seal itself up again and go back to being a normal Xenobot. So they have regenerative ability. And here's the calcium signaling again. We've taken two and we've sort of glued them down so that they can't move. And so you can see here, there's all kinds of interesting calcium activity. And of course, we're working to understand, are they talking to each other, how much mutual information is there between the various signals and so on. Again, no neurons here. This is just skin.

Slide 30/33 · 45m:46s

Sequence them. All you ever see is this, Xenopus laevis. The interesting thing about these organisms is that they do not have a straightforward evolutionary backstory. For every other animal, you can ask, why does it have wings? Why does it have particular behaviors? The answer is always the same, because for millions of years, it was selected for the ability to do X, Y, Z. It had an advantage.

What you're seeing here is skin. These cells were selected to sit quietly on the outside of an embryo or a frog and keep out the pathogens. There was never specific selection to form a xenobot and run around and do various things. Yet within 48 hours of being placed in this novel configuration, they pull together a set of morphological and behavioral repertoires that are coherent. We're just now starting to understand: can they learn? Do they have preferences? What are their capacities?

Slide 31/33 · 46m:43s

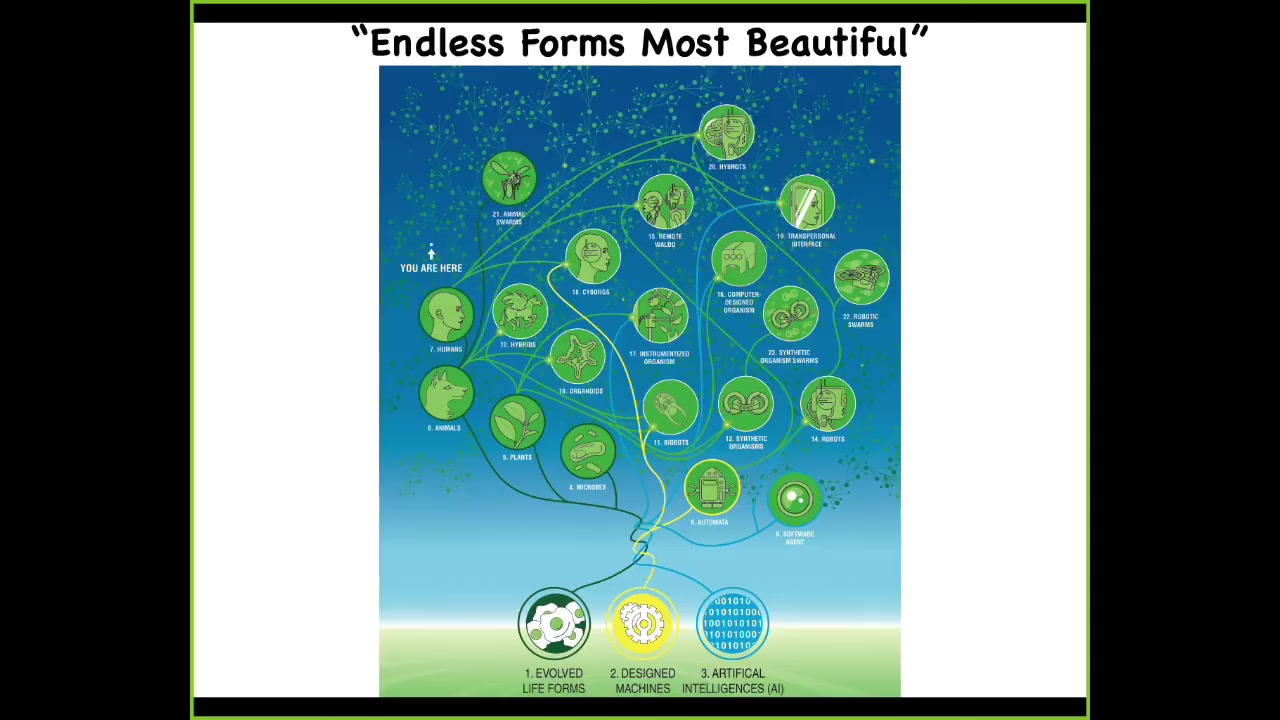

So in the future, what I think is that what Darwin referred to as "endless forms most beautiful" are basically just a tiny corner of this incredibly huge option space where synthetic bioengineers are going to be creating novel life forms that are every kind of combination of evolved material, meaning cellular types of material, designed hardware, and software agents in all sorts of combinations. We already have some cyborgs, humans with various implants. And we have hybrots, robots with living brains and living cells on them. And every combination of this is going to be somewhere, which raises all kinds of interesting possibilities. But certainly we will be able to study novel nervous systems, novel creatures without nervous systems. What kind of behaviors do they have? Where are they on this cognitive continuum?

Slide 32/33 · 47m:38s

What I've tried to argue is that morphogenesis is not simply an emergent process. It is a computational type of process with massive context-sensitive plasticity and a kind of intelligence that solves problems in morphospace. I could have told the exact same story about physiological space and transcriptional space. Electrical networks store and process pattern memories. This is a kind of neuroscience that doesn't involve neurons in the sense that almost every concept that we've seen in neuroscience can be ported to these kinds of non-neural events. This ancient process has much to teach us about intelligence and the scaling of cognition.

The fact that you can even make these chimeras that are connected to a computer and they're driving all sorts of novel bodies and interacting with metamaterials and all of these things is fundamentally about the plasticity of life. It highlights major puzzles, the open questions that link genomes to functional bodies. It provides a very rich new space for creating new model systems, which have to be dealt with by theories of cognition. The challenge is to develop models of the origin of behavioral capacities that don't have a long history of evolutionary selection. Here are a few papers that you might be interested in if you want to follow up on some of the details.

Slide 33/33 · 49m:16s

I want to thank all the postdocs and students who did the work. Here they are, our amazing collaborators. I always thank the animals that we work with and the funders.

I thank you for listening, and I will take questions.