Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a ~55 minute talk on the topic of the "Multiscale Human" (https://humanatlas.io/events/2024-24h/). I cover the topics of "what are we", "implications for biomedicine", and "future beyond human repair" from the perspectives of diverse intelligence at different scales of our bodies and at scales of evolution, development, and cognition.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Introduction and strange plasticity

(08:42) Multi-scale minds and individuation

(17:48) Bioelectricity and anatomical programming

(25:09) Cognitive glue and morphology

(34:36) Bioelectric control of health

(42:45) Anthrobots, morphoceuticals and synthbiosis

(50:48) Redefining humanity and summary

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/46 · 00m:00s

My group is a mix of multidisciplinary people. On our best day, we span the gamut from very conceptual, almost philosophical questions to quantitative theory and computer simulations to wet lab experiments that give rise to pre-clinical and hopefully someday actual biomedical applications.

You can see all of the primary stuff here: the papers, the data sets, the software, everything is here.

This blog contains my personal ideas on what I think all of these things mean.

Slide 2/46 · 00m:39s

Let's start today's overview of the multi-scale human with this. This is a very famous piece of art called "Adam Names the Animals in the Garden of Eden." There's something very interesting about this, something that's fundamentally wrong and something else that's extremely important.

One interesting thing about this story is that it was up to Adam to name the animals. God couldn't do it, the angels couldn't do it. It had to be Adam that names the animals.

What's interesting is that in these ancient traditions, naming something means that you've discovered its true nature. By giving something a name, or finding out its true name, you've really understood what this is. The thing about this that we're going to have to change is the idea that there is a fixed set of natural kinds, that we all know what these different animals are, and Adam is a natural kind, and he's in fact different from all of these. So as I'll show you today, all of that has to go. But this idea that we are going to have to do the hard work of understanding the true nature of some very unconventional beings with whom we will have to share our world, that is profound and will affect all of us going forward.

Slide 3/46 · 01m:53s

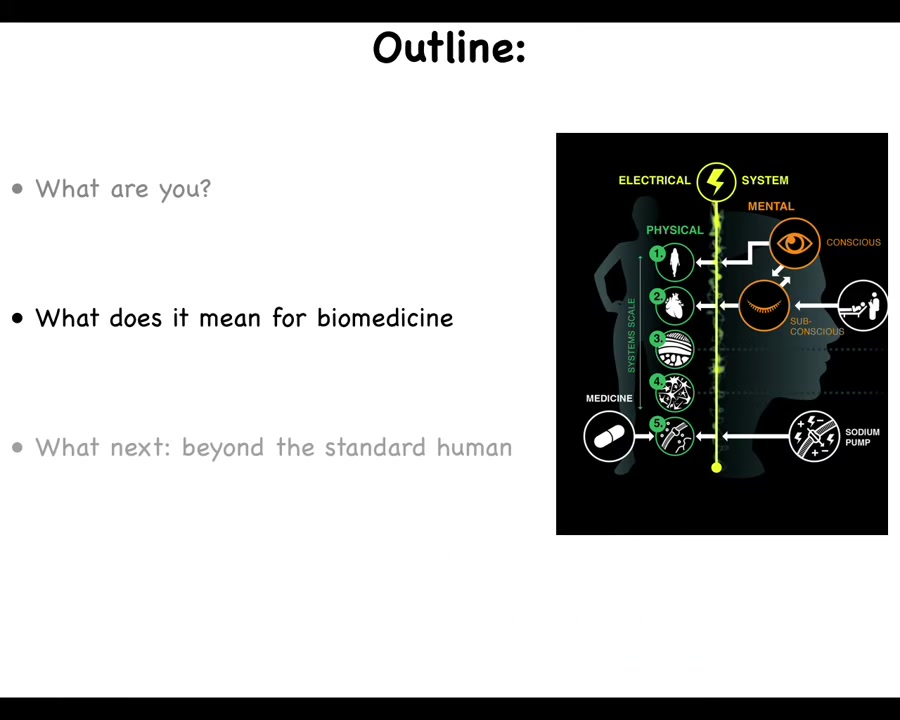

Today I would like to do three things. I would like to talk about what we are, and then what that means for biomedicine; some of the facts around our multi-scale nature and what that means for regenerative kinds of applications going forward; and a little bit at the end about what I think this means beyond repair of the standard human anatomy.

One of the most important things is that we are in continuity with a lot of fascinating biology of other creatures. I want to show you what some of your kin are capable of so that we get an idea of how plastic and rich biology is beyond what we typically think of as models of health and disease.

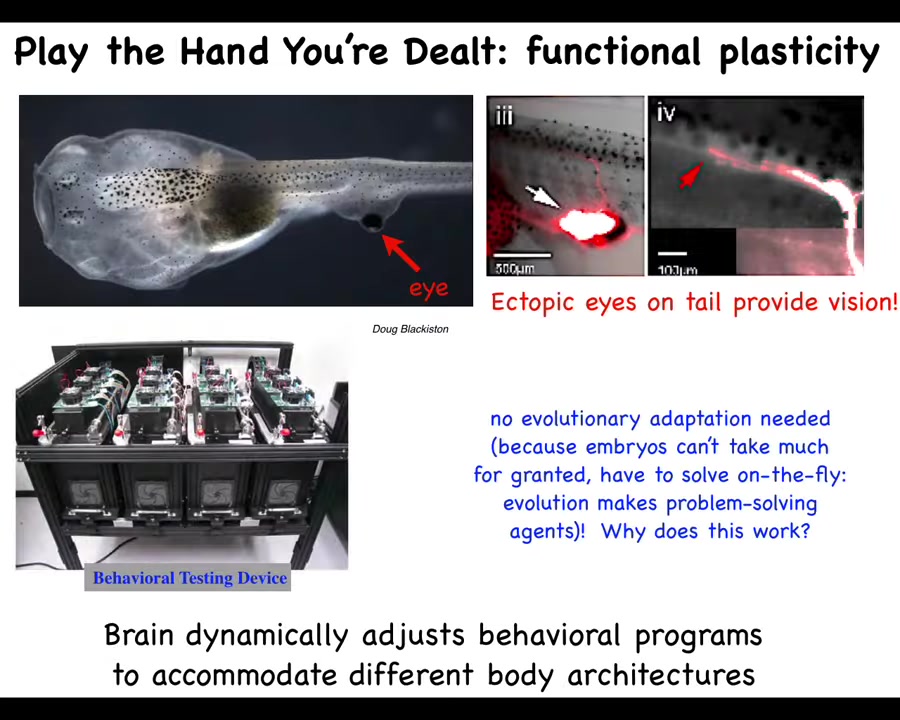

Slide 4/46 · 02m:35s

This here is a tadpole of the frog Xenopus laevis. You've got the nostrils here, here's the mouth, here's the brain, the spinal cord, and the tail. This is the gut. You'll notice two interesting things. One is that there are no primary eyes here. We've prevented those from forming, but we did form an eye on the tail. When the eye forms, it does put out an optic nerve. The optic nerve sometimes synapses onto the spinal cord here. Sometimes it goes to the gut, sometimes nowhere at all, but it never goes to the brain.

Yet, when we built this machine to test these animals for behavioral learning in the visual assay with different light stimuli, we find that they learn perfectly well. These animals can see out of these eyes. Isn't it remarkable that an animal with a radically different sensory motor architecture with an eye on its tail that does not connect to the brain can use it with vision in its behavior. We didn't need extra rounds of evolution: no mutation, no selection, no adaptation. This works out-of-the-box. Why does it work out-of-the-box? I'll show you some of these things. You start to get the idea that there's some very interesting plasticity here that goes beyond simply making a reliable body every time during embryonic development.

Slide 5/46 · 03m:50s

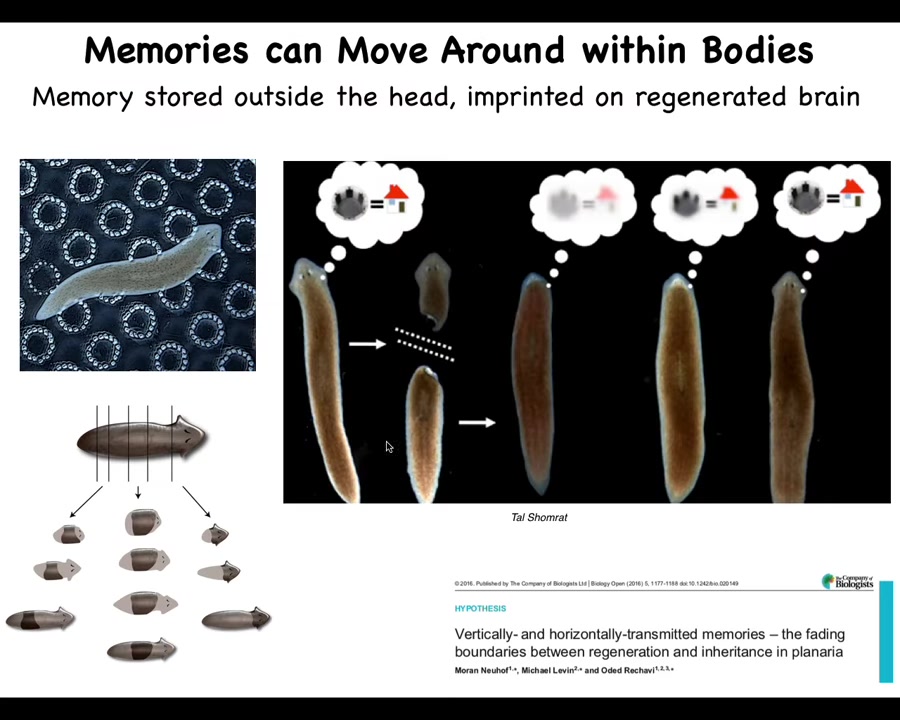

Here's another interesting thing. This animal is a planarian, a flatworm. They have a true brain, bilateral symmetry. They're similar to our direct bilaterian ancestor. One of their fascinating properties is that you can cut them into pieces. When you do cut them into pieces, every piece regrows the rest of the worm. Every piece knows exactly what a planarian is supposed to look like. So they're highly regenerative. But they're also smart. You can train them for place conditioning. You can feed them on these little bumpy surfaces, and they learn to look for food in this location. Then you can cut their head off containing their brain. The tail has no behavior. It sits there doing nothing until it grows back a new brain. When it does grow back a new brain, you find out that it still remembers where to find the food. Not only is the information apparently stored outside the brain, but it's also imprinted onto the new brain so that the correct behavior can take place when the brain is developed.

So as information moves throughout the body, we start to think, what will happen in human patients when we deal with degenerative brain disease by, for example, implanting naive stem cells into the brain of a patient with many decades of memories and personality traits? At least in some model systems, we see that memories can colonize new hardware that appears. We don't know if this will work in humans, but it's interesting to watch behavioral memories move around through tissues.

Slide 6/46 · 05m:21s

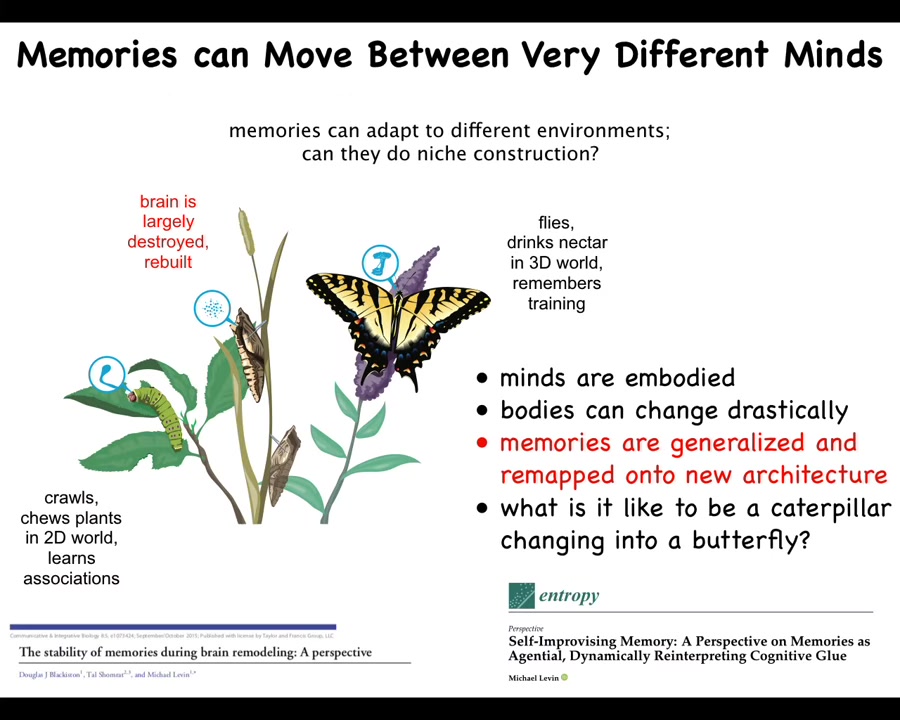

It gets even weirder because some creatures like this undergo a metamorphosis where this soft-bodied being that crawls around in a two-dimensional world and eats leaves has to tear up its brain, start from scratch, rebuild a new body and a new brain to become this three-dimensional world dweller that flies and drinks nectar.

What has been shown is that if you train this caterpillar to look for leaves in a particular color cue, the butterfly still remembers this information. It is remarkable that the information persists through a completely refactored brain.

So how does it stay intact is one question. But an even more profound question is that it's not enough for it to just persist, because butterflies don't care about leaves and they don't crawl the way these caterpillars do. They fly.

So the exact memories of the caterpillar are of no use to the butterfly. What the butterfly can use are the generalized lessons that the caterpillar learned. Then it has to remap that information onto a new body with a completely different controller for its motion. So it has to generalize, it has to remap, and all of this happens on the fly. In other words, during the lifetime of this agent, it becomes a completely different being with remapped and generalized memories.

Slide 7/46 · 06m:45s

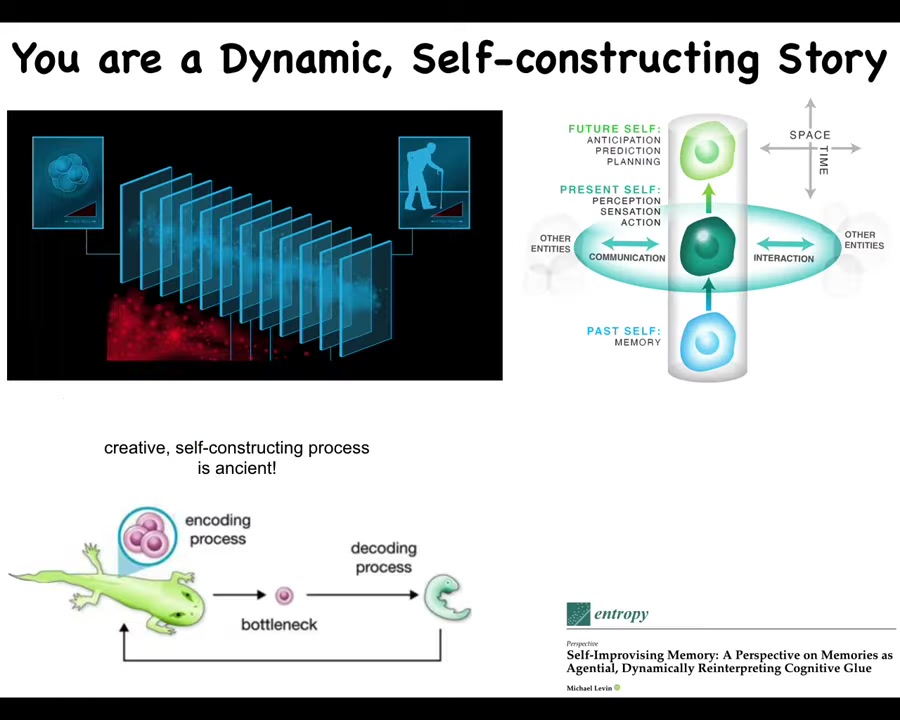

Now, you might think that this is an unusual case. We don't metamorphose in this drastic way. But the reality is that none of us, cognitive beings, have access to the past. At any given moment, what you have access to is the engrams, the memory traces that the past has left in your body or brain.

So, in effect, we are these continuous slices, and at any one moment in this slice, all you have to go on in order to decide what you are, who you are, and what to do next is a reconstruction of your past, the dynamic reconstruction of your past from the memory traces that have been left in your body by a learning process.

So you can think about your memories as messages. Who are they from? They're from your past self. And like any other kind of message, they need to be interpreted. You don't just automatically know what they mean. You must interpret them.

And not only is this true for this kind of cognitive process that we all undergo, but in fact, on the developmental and evolutionary time scale, you have the same thing. You have lessons learned by an evolutionary lineage. These are compressed and squeezed down into a very small representation, which is an egg. Most creatures don't create copies of themselves; they actually create an egg, which is a very narrow, compressed representation of all the wisdom of past generations, and then the embryo has to deflate this process to reconstruct and to decode what actually was there before.

But what's really important and what I will show you momentarily is that this process is creative. It doesn't actually just literally build exactly what was there before. It uses the information, but it uses it creatively in new ways. And so you're starting to see these unusual aspects of the biology that aren't emphasized in typical biomedical settings.

Slide 8/46 · 08m:43s

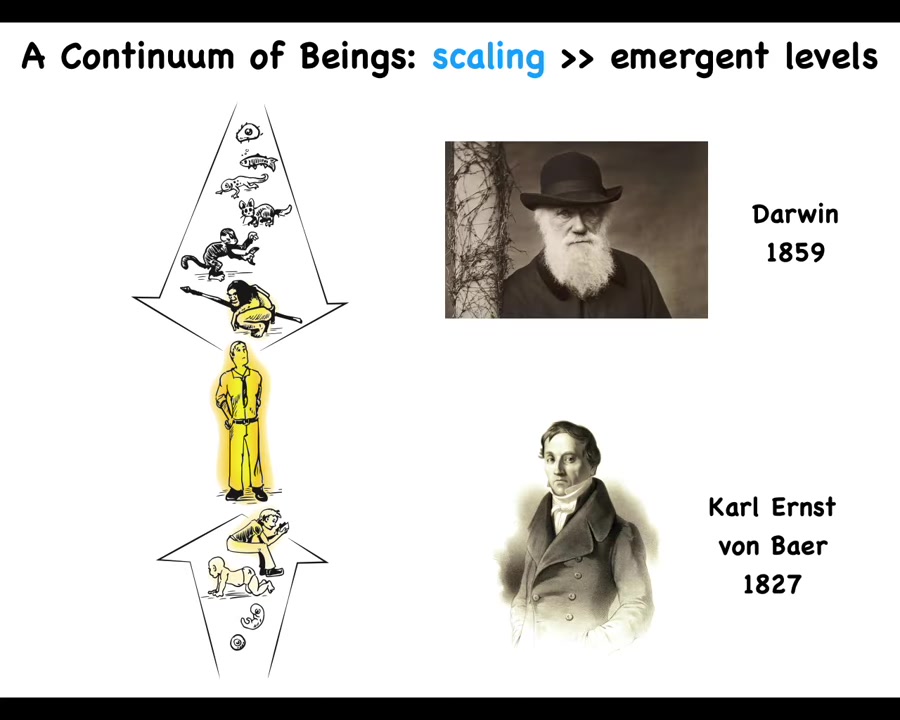

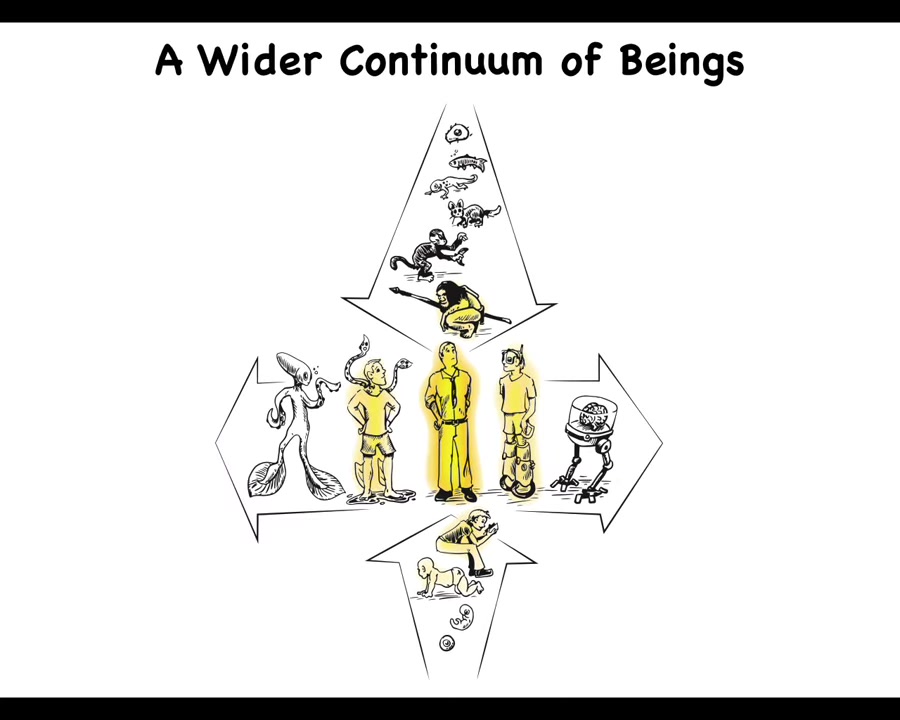

Now it's important to remember that whatever properties we have—philosophy of mind talks about the capabilities, the moral responsibilities, and so on of the human mind. But we are at the center of a continuum. We are a continuum evolutionarily, and we're a continuum developmentally, and in both cases we develop smoothly from a single cell. So whatever you think we are, we have to have a story of scaling, not of categorical differences, but how that emerged and scaled up from our very humble single-cell origins.

Slide 9/46 · 09m:21s

We're actually at the center of two continua, because not only are we spread out according to our history, but now with bioengineering and other tools, we can make changes. We can make changes both biologically and technologically. Therefore, it becomes very difficult to say what an actual human is, because where these different properties start and stop on these continua are not at all trivial to say.

One of the things my group does is work on a framework that I've developed that tries to allow us to think about all kinds of agents. This means the familiar creatures like primates and birds and maybe an octopus and a whale, but also swarms and engineered new life forms and AIs, whether robotic or purely software, and maybe someday alien kinds of beings. The idea for this framework is that it has to move experiments forward. It has to give us new capabilities in biomedicine and engineering and hopefully better ethical frameworks for dealing with these kinds of unusual creatures. All of that is described here. I'm not the first person to try something like this. Here's Rosenbluth, Wiener and Bigelow trying to understand how passive matter eventually becomes second-order metacognition such as we have.

This is all of our journey. We all start life as a single cell, a BLOB of chemistry and physics, and then eventually we become something like this, or maybe even something like this. I really hate this phrase. People will look at mechanisms and say, that's just physics. All of us were just physics once. The one thing we know from developmental biology is that there is no sharp line where a magic lightning flash says, you used to be physics, but now you have a true mind, true cognition. There's nothing like that. The appearance of what we take to be central to being a human is scaled up from the properties of the biochemistry and the physics of an oocyte. We need to understand how that process works.

Slide 10/46 · 11m:27s

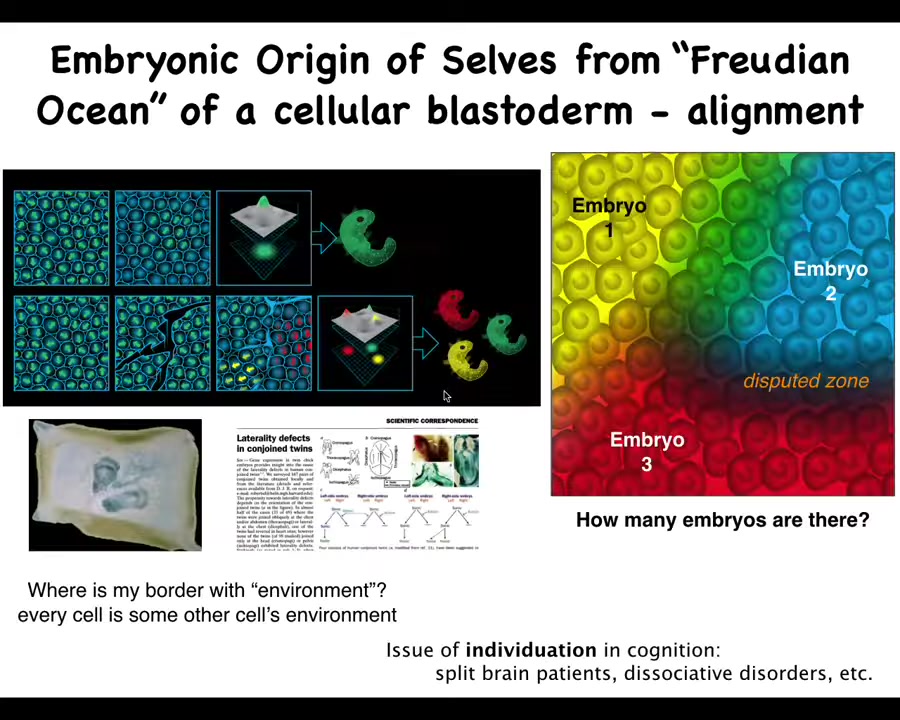

To really dig into this, take a look at the blastoderm of an early embryo. There's maybe at an early stage a flat disk of 50,000 cells, and we look at that and we say, there's an embryo. But what are we counting when we say there's one embryo? What is there one of? There are thousands and thousands of cells. What is there one of? Well, what there's one of is alignment. It's alignment between all the cells, both physically—they literally get aligned—but also teleologically; they get aligned towards the same journey that they're going to take in anatomical space. They are aligned with respect to their model of themselves and the outside world and the shape that they are building. They're all together collaborating on building one very specific thing.

One thing you can do, and I used to do this with duck embryos as a grad student, is take a little needle and make some scratches in this blastoderm. When you do this, it's about four to six hours before they heal up, but before then each of these islands does not feel the presence of the other, so it self-organizes into an embryo. When it heals up, what you end up with is twins and triplets and things like this. There's something very interesting here. The tissue that we call one embryo could actually be anywhere from zero to probably half a dozen individuals. How many cells, be that ducks or humans in a blastoderm, is not set by the genetics. It is not obvious. It is determined by these kinds of individuation processes that take place within this blastoderm, and how many beings are in there is set dynamically.

This question of where do I end and somebody else begin, or the outside world, has a lot in common with questions of cognitive science in terms of split brain patients and dissociative identity disorders and so on, when there are multiple individuals sharing the same brain hardware. What we are is not only scaled-up beings from single cells, but also a kind of geometric individuation of a potential, of a medium with pretty large potential for how many beings can come out of it. That's already disruptive to our view of ourselves as monolithic agents.

Slide 11/46 · 13m:51s

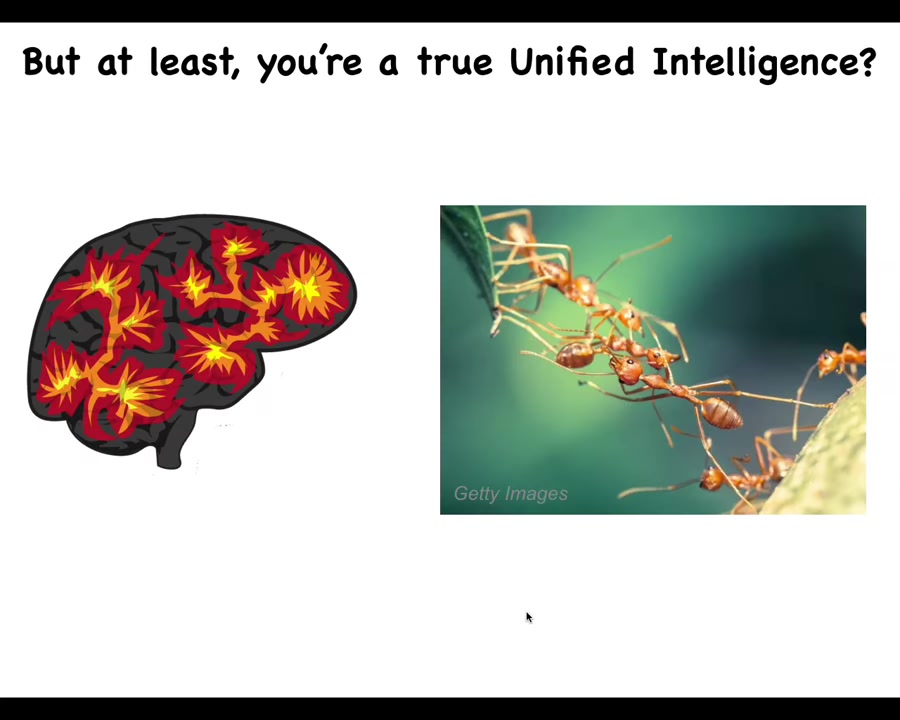

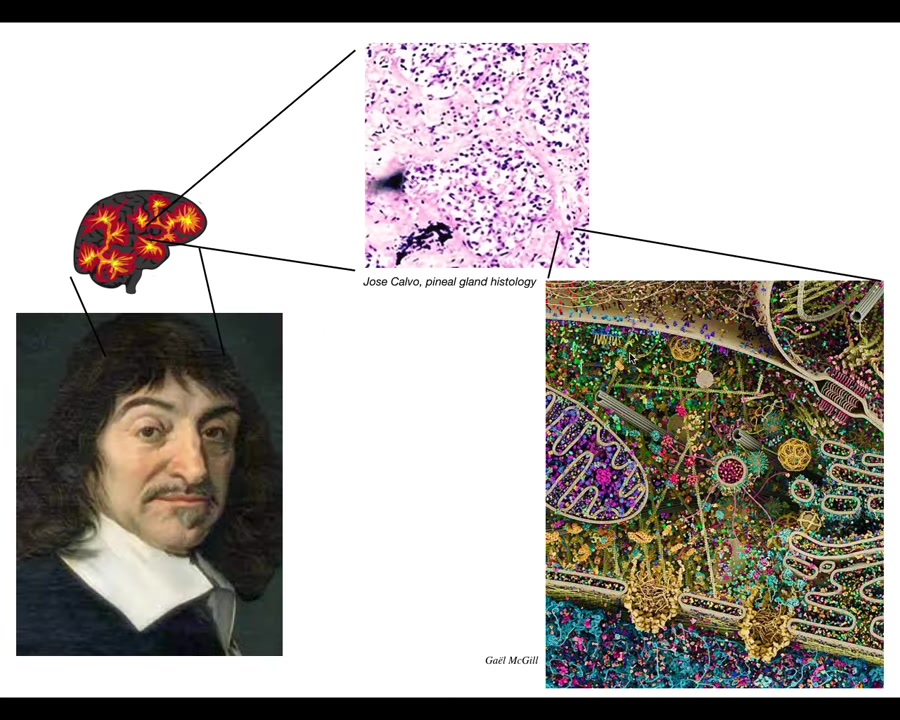

But at least we're a true unified intelligence. We have a brain, we have a centralized brain. We're not like ants and termite colonies and bees and so on that other people call collective intelligence. We're a real unified intelligence.

Slide 12/46 · 14m:06s

Rene Descartes loved the pineal gland, because in the brain there's only one of them, and he felt that was the ideal place for the unified, centralized human experience to be located. But Descartes didn't have access to good microscopes. If he had good microscopy, he would have looked inside the pineal gland and realized that there isn't actually one of anything. There are tons of cells inside the pineal gland. It's not a monolithic construct. Inside each of those cells there's all this stuff. So there really isn't one of anything.

Slide 13/46 · 14m:45s

We are all collective intelligences. We are all made of parts, even those of us with brains. This is the thing we're made of. This happens to be a free-living organism called the lacrimaria, but this shows you what cells are capable of. This is one cell. And here he is leading its life, hunting in its environment. There is no brain. There are no stem cells. This is incredible competency at its little single-cell tasks.

And so what we as scientists and philosophers owe are stories of scaling. Where do large-scale minds come from? How do they self-assemble from these components, which themselves are active and agential? We are built of an agential medium. We're not passive matter, not even active matter, but in a gentle medium where all the components have their own goals and competencies.

Slide 14/46 · 15m:37s

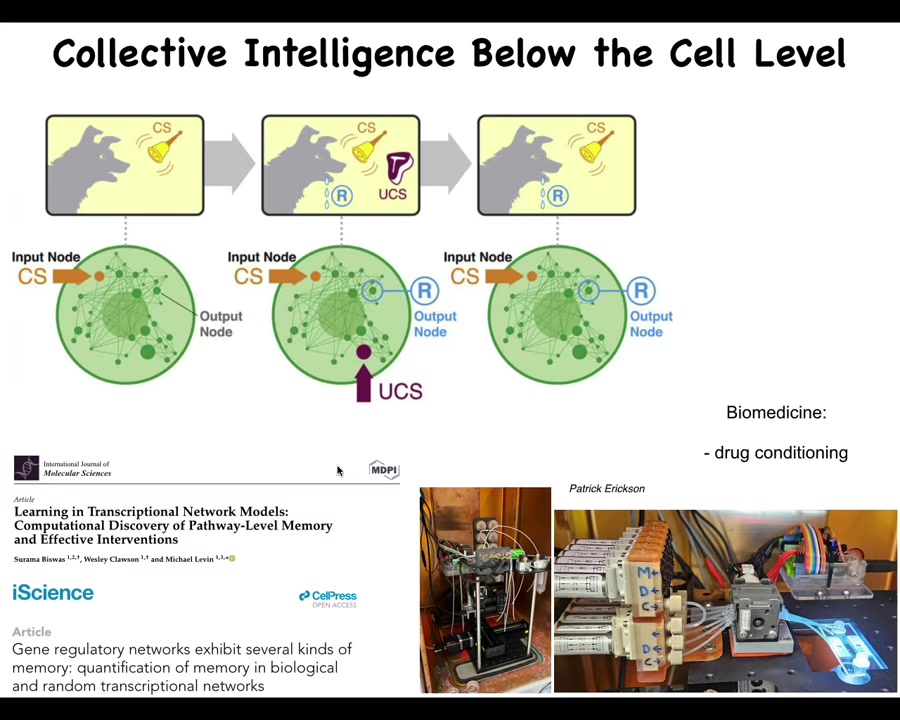

Inside of that lacroom area are a bunch of biochemical networks. What we've shown is that if you model these networks, for example, gene regulatory networks or pathways, what you can find is that even the networks themselves, just a few, literally a half dozen chemicals turning each other on and off are already sufficient for six different kinds of learning, including Pavlovian conditioning. The chemical networks inside your cells can learn. This has massive implications. Here we're working on developing tools to train these pathways inside cells for drug conditioning and some other applications in regenerative medicine.

We are a kind of self-assembling, multi-scale competency architecture.

Slide 15/46 · 16m:36s

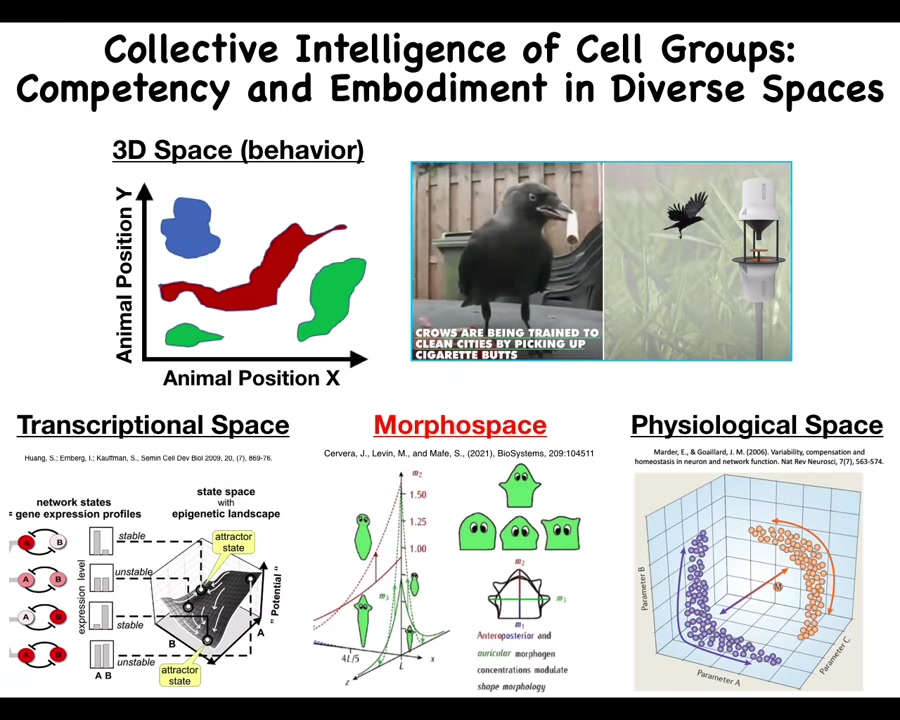

Every level of organization, from the molecular networks up, is solving problems in their own space. As humans, we're reasonably well primed to recognize intelligence in three-dimensional space, medium-sized objects moving at medium speeds in 3D, dogs and crows and things. But we're actually very bad at noticing intelligent behavior in other spaces. For example, the space of all possible gene expression, transcriptional space, physiological state space, and what we'll talk mostly about today is anatomical morphospace, the space of all possible shapes that you could acquire.

I think that if we had, for example, sense organs that looked inwards to, let's say, measure 10 different kinds of parameters of your blood physiology, if you could directly sense the physiological parameters in your bloodstream, I think you would have absolutely no trouble recognizing that your liver and your kidneys are intelligent symbionts that traverse physiological states navigated every day, dealing with all the things that happen, and they help keep you alive, but we're just not very good at noticing that.

This idea of intelligent navigation of these spaces is what I'm gonna describe next, and the reason I'm gonna focus on it is because I think it has massive implications for biomedicine.

Slide 16/46 · 17m:42s

One of the things that evolution has used in our bodies is an electrical system that spans all of these scales. Just imagine if I told you that with the power of my mind alone I can make ions move across cell membranes, and I can depolarize up to 1/3 of my body just with the power of my mind alone. Now you might think that I'm either lying or this is a yoga or mind-body medicine. It's a biofeedback thing. The reality is all of us can do this. It's called voluntary motion.

When you wake up in the morning and you have all sorts of very high-level goals, so executive-level kinds of cognitive goals, things about your career and things you're going to do during the day, all of those high-level cognitive goals have to be transduced into the motion of potassium and calcium and other ions across your cell membrane. Your high-level mental content makes the ions dance in the membranes of your cells. The reason that works is because of an electrical system that captures that cognitive activity and transduces it down to the smallest level of biochemistry. It's an amazing system, and that's what we're going to talk about.

Slide 17/46 · 19m:07s

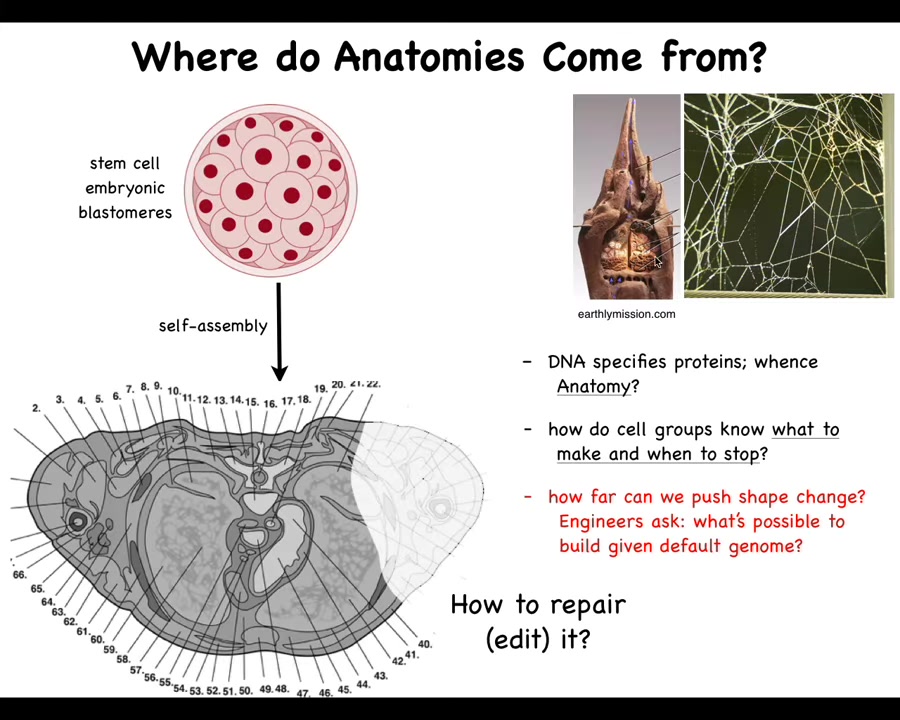

Let's first take a step back and ask, where does our anatomy come from? We all make this journey from a single-cell egg to some kind of species-specific correct anatomy. There's our navigation of space. How do the cells know where to go? We all start life as a collection of these blastomeres. Eventually, they make this incredibly complicated thing in the case of a human. Look at all the organs. They're in the right place, the right size, the right shape, relative to each other. Amazing order. Where is this actually specified?

You might be tempted to say it's in the DNA, but we can read DNA now, and we know it's not any of this that's there. It's a specification of proteins, the tiny molecular hardware that every cell gets to have. The DNA doesn't directly say anything about shape, size, organs, or any of that. We need to understand how that hardware makes decisions in order to form something like this. This is the outcome of the physiology and the computations that the hardware does, and the outcome isn't in the DNA any more than the structure of the termite mound or the precise structure of the spider web is in the genome of these animals. It's the result of the activities of all of these active agents.

We want to understand how they knew what to build. How do they know when to stop? If something is missing, how do we get them to repair, to edit it? As engineers, we'd also like to ask, what else is possible? Could we get these cells to build something completely different? Or is this the only thing they know how to build?

Slide 18/46 · 20m:38s

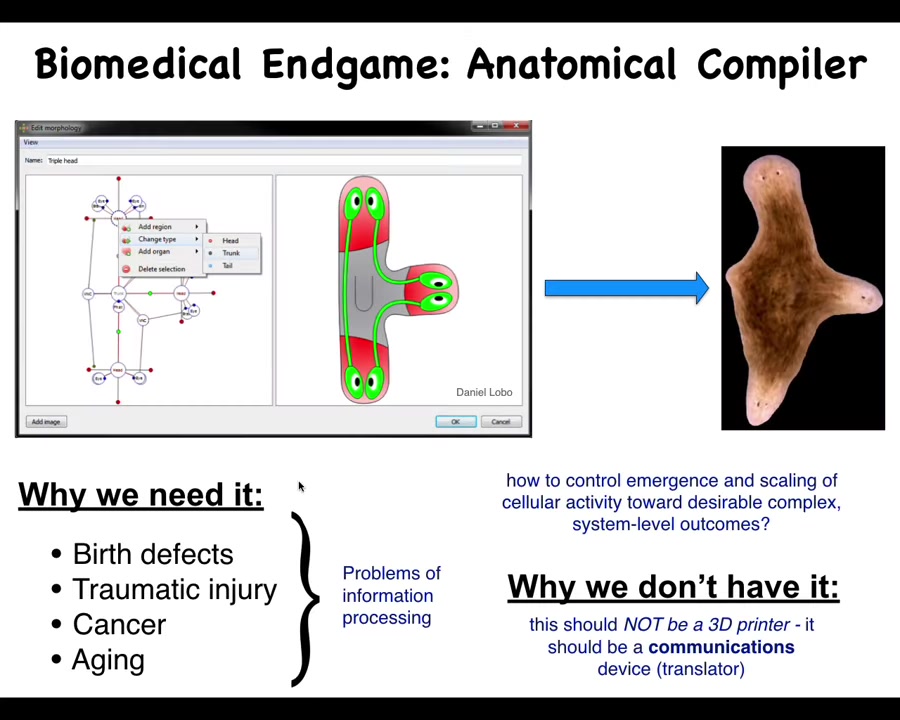

I visualize the end game of that whole field as the anatomical compiler. Just imagine, someday you'll be able to sit in front of a system, you'd be able to draw the plant, animal, biobot, organ, whatever you want, at the level of the anatomy, not in terms of any molecular properties, but at the exact anatomy that you actually want. What this system would do is compile that description down to a set of stimuli that would have to be given to cells to get them to build exactly that.

If we had something like this, birth defects, traumatic injury, cancer and aging, degenerative disease, all of this would go away. All of these issues boil down to our inability to tell a bunch of cells what they should be building.

Why don't we have something like this? Molecular biology and genetics have been going gangbusters for decades. Why don't we already have this? We don't have anything remotely like this. Why not? I think that's because it's very important to understand what this is. This is not some kind of 3D printer. This is not about micromanaging molecular biology states or gene expression or scaffolds or anything like that. It's a communications device. It's supposed to translate your needs as an engineer or a worker in regenerative medicine into the goals of the cells so that they build it.

Slide 19/46 · 21m:57s

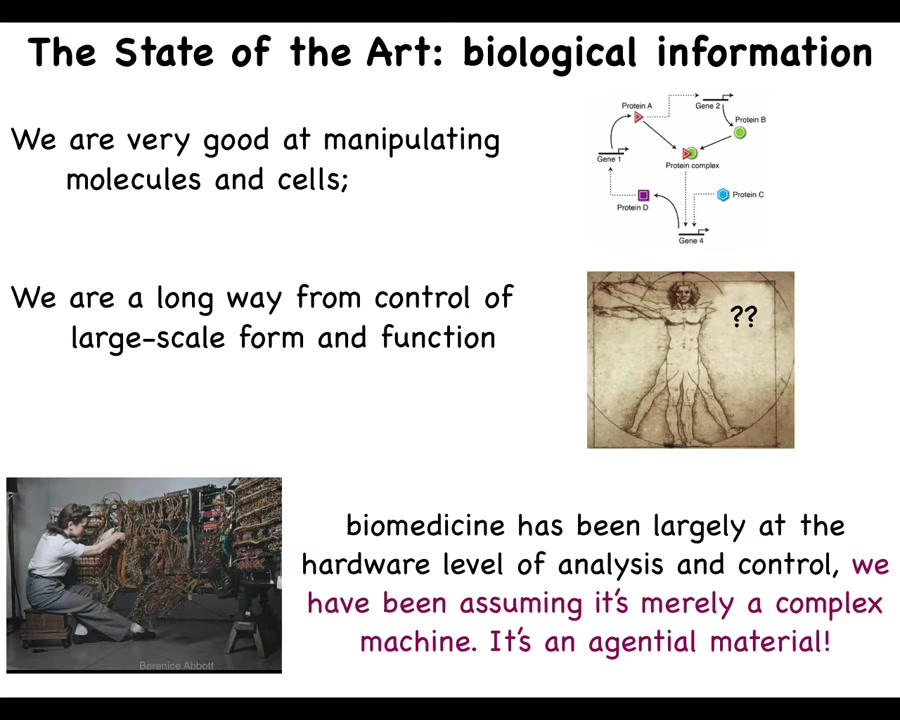

Why don't we have something like this? Here's where we are today. This is what programming looked like in the 1940s and 50s. In order to program this computer, she had to interact with the hardware, physically rewire the thing.

The reason that today, when you're on your laptop and you want to go from Photoshop to Microsoft PowerPoint, you don't get out your soldering iron and start soldering your laptop is that computer engineers have figured out that if your hardware is good enough, if you make reprogrammable hardware, then amazing things are possible by communicating with it with signals, not by rewiring the hardware, but taking advantage of its various computational competencies.

Where biomedicine is today is at this stage. All the exciting advances—genomic editing, CRISPR, pathway rewiring, protein engineering—are about the hardware of life. So we're very good at manipulating which cells and which molecules talk to which other cells and molecules. We're a long way away from what we want, which is control of large-scale form and function. That's because we've been assuming that what we're dealing with is merely a complex machine. What it really is is an agential material.

Slide 20/46 · 23m:14s

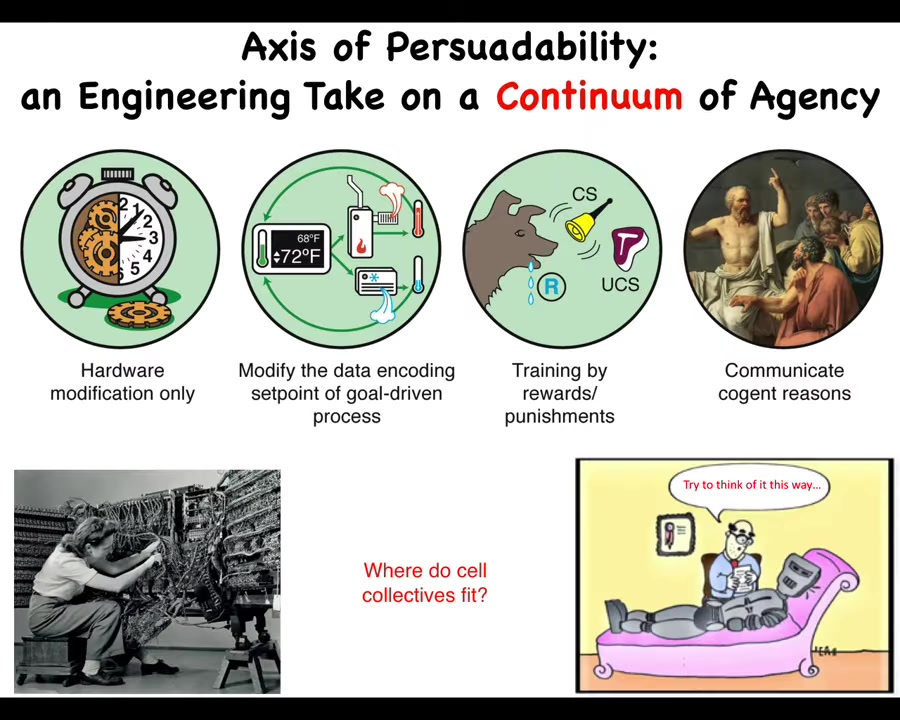

In order to think about how we engineer with different kinds of materials, it's useful to think about an axis of persuadability. The point of this axis is that different systems are at different places on this continuum. The idea is that depending on where you are, you're amenable to different sets of tools.

Down here, it's just rewiring. You're not going to convince it or reward it or punish it.

Then you have some cybernetic systems, which are interesting. You can reset the set point, as in your thermostat, and you don't need to rewire the whole system. You just change the set point, and it will keep the temperature. In fact, you don't even need to know how the rest of it works. You just need to know what the encoding is. Then you have these systems, which are incredibly complex, but they hide all that complexity under an interface of learning. As long as you know what the reward and punishment currency is, you can train them, and they handle all the difficulty of tweaking all the synaptic potentials. You have very complex agents that you can convince to do things with cogent reasons.

There are sets of tools, all kinds of hardware things, control theory and cybernetics, behavioral science, psychology and psychoanalysis.

Now we can ask a simple question: where do cellular collectives fit here? You can't simply guess and you can't have philosophical pre-commitments to saying that cells are chemical machines and they have to be here and maybe here. You actually can't assume any of that. You have to do experiments. You have to test which of these many types of tools are actually amenable.

What I'm going to do next is talk about the kind of cellular intelligence, specifically the ability to reach their goals by different means in novel circumstances that cell collectives are able to exhibit.

Slide 21/46 · 25m:09s

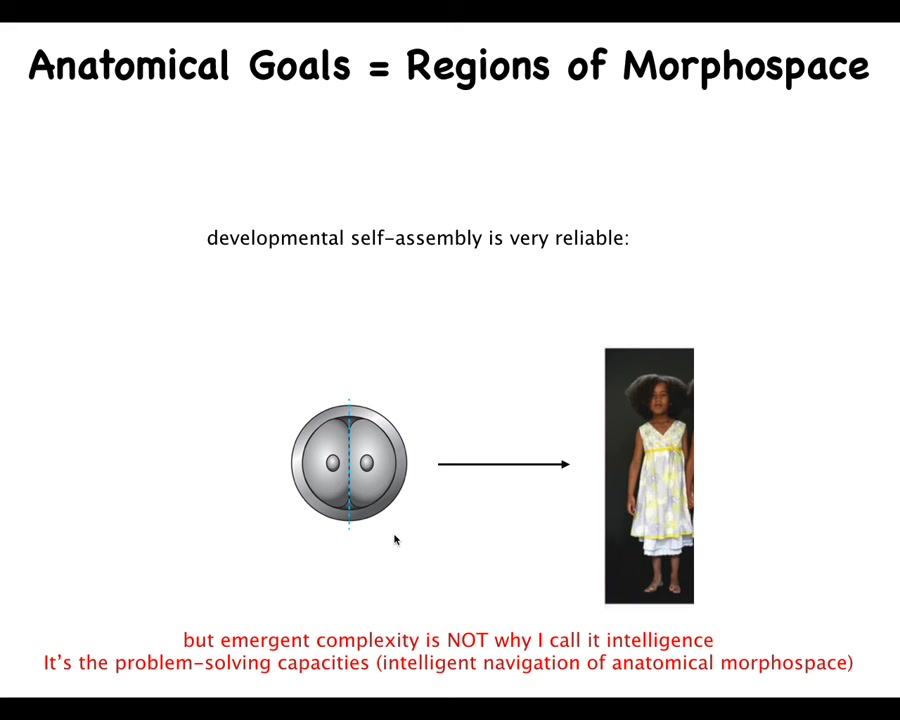

The first thing I will point out is that development is very reliable. It happens correctly most of the time. But the reliability and the emergent complexity, the fact that the final product is more complex than this, are not why I'm calling it intelligence. It's not about emergent complexity. It's not about reliability. It's about navigation of anatomical space that is very, very plastic.

For example, if we cut early embryos into pieces, you don't get half bodies, you get monozygotic twins, triplets. That's because the system can get to where it's going in anatomical space from different starting positions. That's interesting, but it gets better.

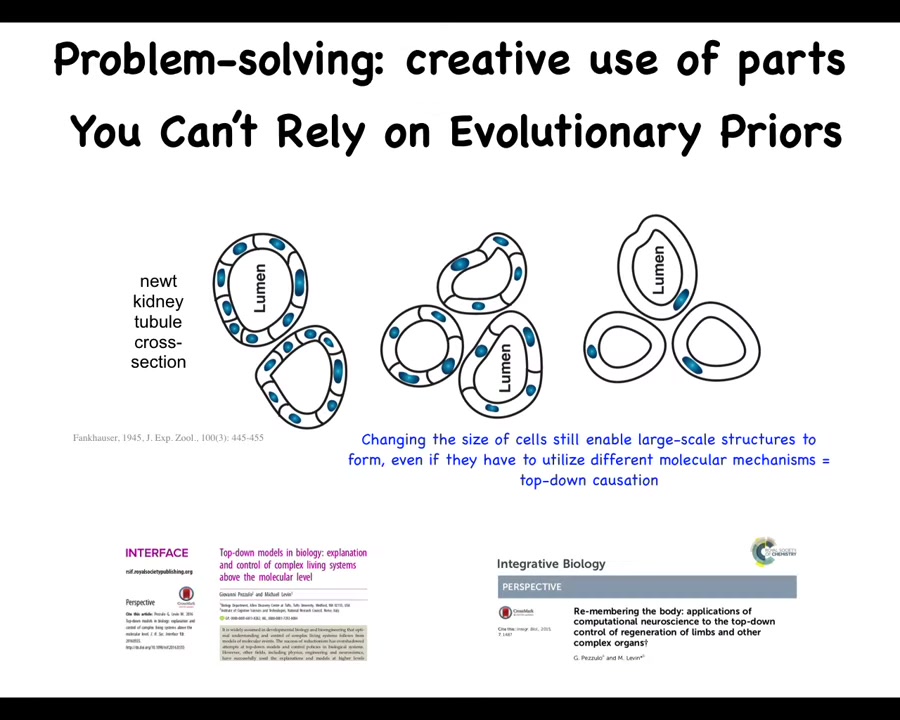

Slide 22/46 · 25m:50s

This is one of my favorite examples. This is a cross-section through the tubule of a kidney in a newt. You can see there's about 8 to 10 cells that normally form this structure. One thing you can do is create polyploid newts that have extra copies of their chromosomes. When you do this, the cells get bigger. Not only do you still get a normal newt — it doesn't matter how many copies of your chromosomes you have — but the number of cells scales to the cell size. When the cell size gets bigger, fewer cells are able to do exactly the same structure. That's amazing, but it gets really remarkable when you make these newts very highly polyploid: the cells get so big that one cell bends around itself to give you that same structure.

Look at what's happening here. First, this is a kind of top-down causation. In the service of this final outcome, the cells are using different molecular mechanisms. They're using different tools to solve a problem they've not seen before to reach the same outcome. In this case, cell communication, in this case, cytoskeletal bending. So they use different molecular tools to get their job done.

But more broadly, think about what this means for a newt. This is what I meant by the creative interpretation of your genome, that every creature that's born doesn't do exactly what its predecessors did, but it can use the tools that they've left for them. Coming into the world as a newt, what can you be sure of? You can't be sure of how many copies of your DNA you're going to have. You can't be sure of the cell size that you're going to have. From some other work I haven't shown you, it also works if you take away a bunch of cells or add a bunch of cells. So you can't be sure of your cell number. It doesn't matter. Under all those circumstances, you have to be able to get the job done. That is the creative problem solving that these cells are doing. You have to navigate that anatomical space with the tools you have, even when circumstances change. Not just the external environment, but you can't even count on your own parts.

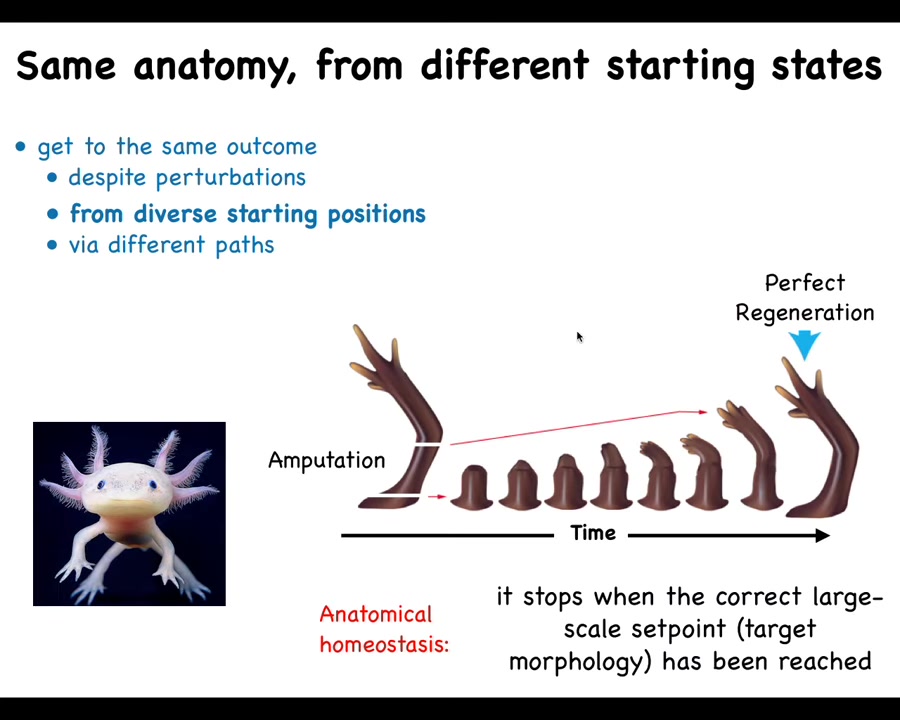

Slide 23/46 · 27m:47s

That kind of problem solving is what drives regeneration. Some creatures, like this axolotl, are able to regenerate their limbs, their tails, their eyes, their jaws, portions of the heart and brain, incredibly regenerative. What happens here is that if they lose part of the arm and they're always biting off each other's legs, so they will inevitably lose part of the leg, it will regrow and it will grow exactly the correct structure and then it stops. The most amazing thing about regeneration is that it knows when to stop. This is basically a homeostatic process. When you deviate from your correct path in anatomical space, you work really hard to try to get back there. When you get back there, you're back there, so you stop. That process, any kind of a homeostatic process, needs to remember the set point. It needs to know where it's going in anatomical space. How does it know when it's created the correct shape? Moreover, all of the individual cells need to be working together to achieve this purpose. How do they do that?

Slide 24/46 · 28m:49s

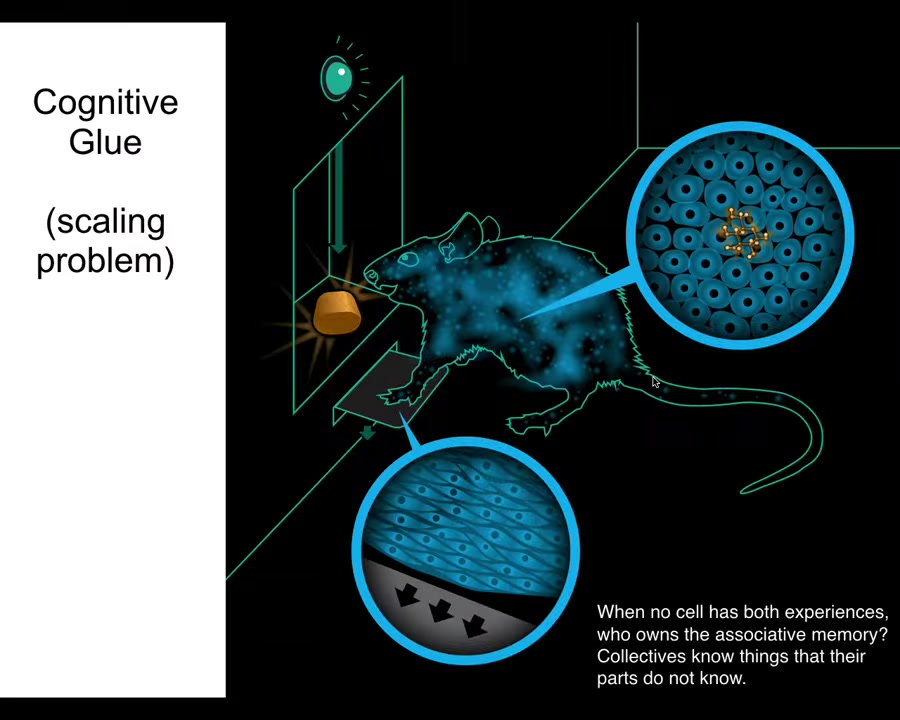

There's an interesting concept that I call cognitive glue, which is basically the set of policies that bind subunits together into a larger scale collective. We know how this works in behavior.

Here's a rat. The rat has learned to associate pressing the lever to get a delicious reward. But notice that the cells at the bottom of the feet touch the lever. The cells in the gut get the delicious reward. No individual cell had both experiences. Who owns the associative memory of these two things being associated? It's not an individual cell. It's the rat. The collective, known as the rat, is able to keep this associative memory among its different parts.

It does that because it has an important kind of cognitive glue within its central nervous system. It has neurons that are bound together, which allows it to learn, have goals, and execute behavior to achieve those goals.

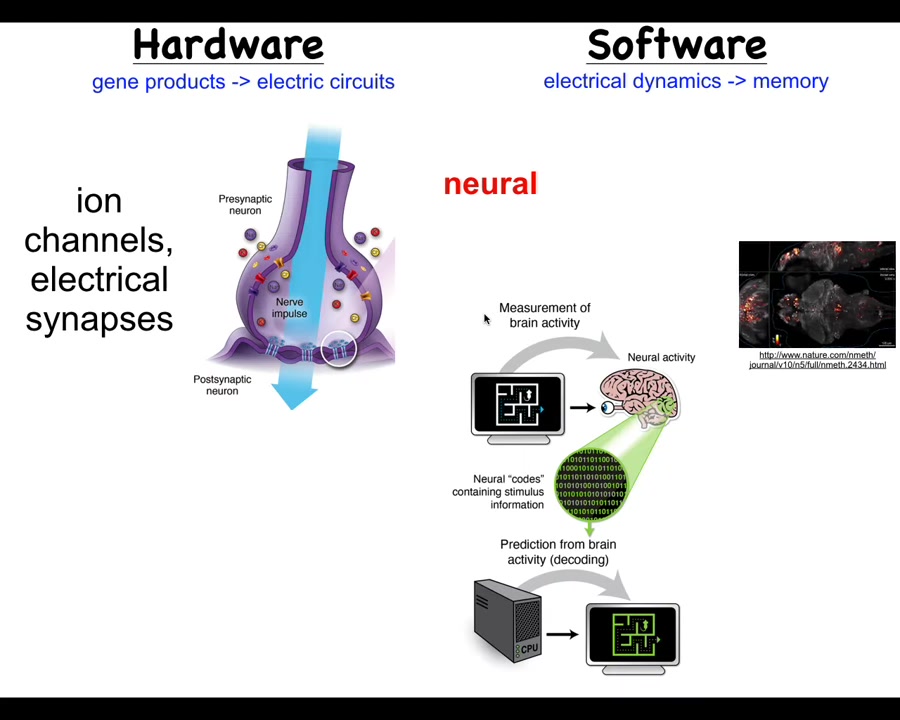

Slide 25/46 · 29m:40s

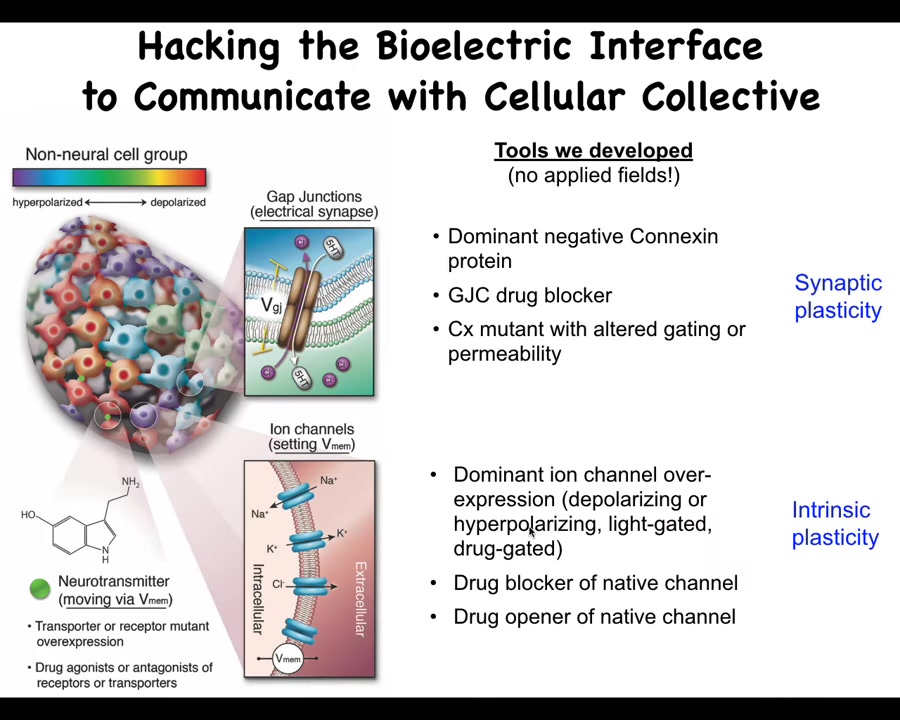

Now, the way this works is that it has these neurons which have ion channels here that enable them to achieve voltage potentials. Those voltage potentials may or may not propagate to their neighbors through these electrical synapses called gap junctions. By propagating these electrical signals through that network, it's able to process information. It's able to integrate what's happening across space and time across a large body such as a rat. And it's the commitment of neuroscience that if we track the physiological activity of these neurons, here is a zebrafish brain tract for its electrical activity, then we should be able to decode it. All of the cognitive content, the memories, the goals, the preferences, everything that is in the mind of this animal should be contained within these electrophysiological signals. And we should be able to do what's called neural decoding to get them out.

Slide 26/46 · 30m:35s

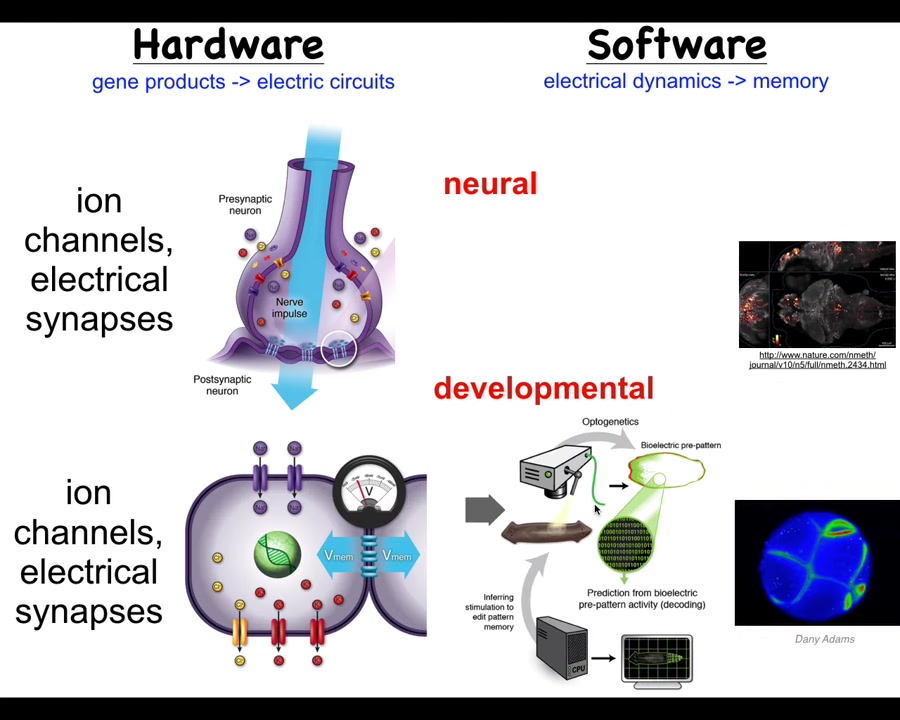

It turns out that idea, the use of electricity and electrical networks to integrate information across space and time, is incredibly ancient. Neurons did not invent this trick. It actually showed up around the time of bacterial biofilms. All the cells in your body have ion channels. Most of them have electrical synapses and form networks. We can actually do the same kind of strategy as the neuroscientists did. One of my claims is that neuroscience actually isn't about neurons at all. It's about the use of information-processing networks to integrate competent subunits into a greater collective, an emergent being with a mind, such as a rat or a frog or a human. We can do exactly the same kind of strategy. In fact, we can port all of the tools from neuroscience — all of the tools of neuroscience can be used outside the nervous system.

Now we can ask: we know what the brain thinks about. Brains think about moving you through three-dimensional space, and then later maybe through linguistic space and things like that. What do the rest of the body cells think about? It turns out they think about shape. From the very earliest moment of fertilization, the cells make networks that think about shape.

Slide 27/46 · 31m:47s

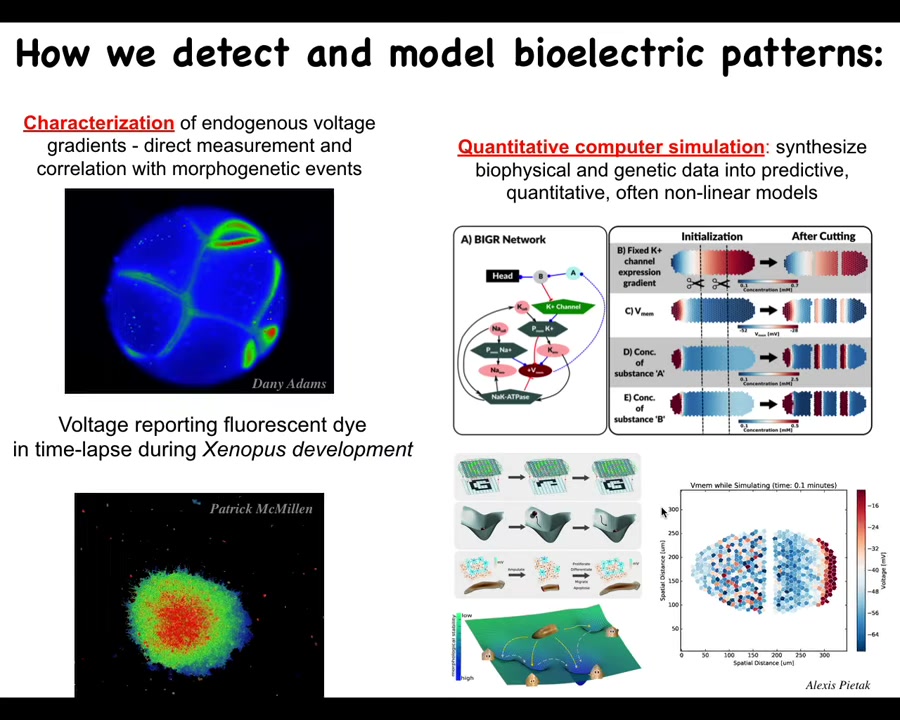

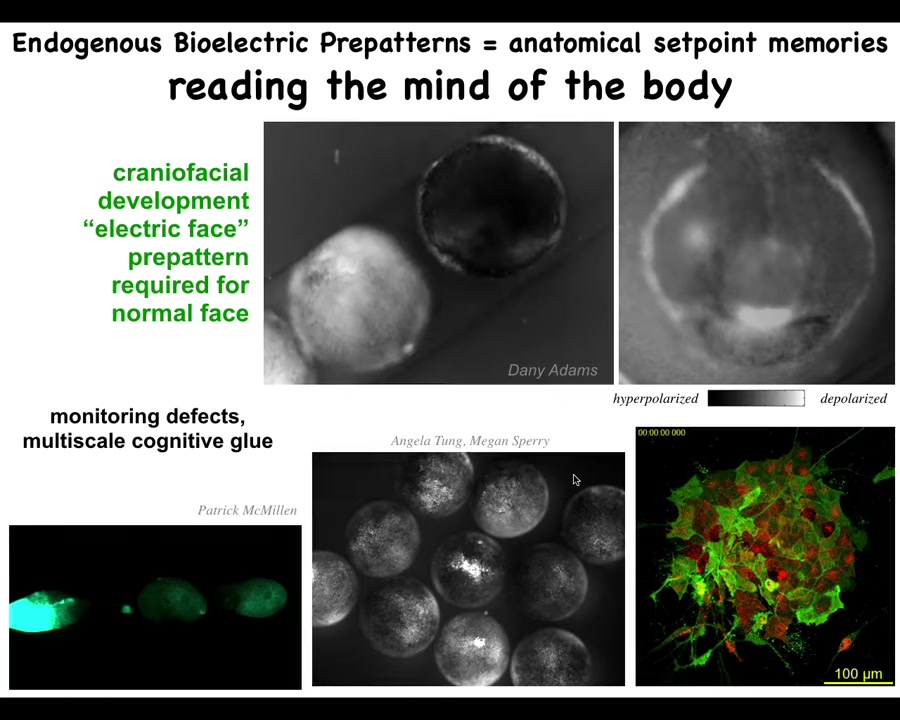

In order to discover this, we had to develop some tools. First, we developed voltage-sensitive fluorescent dye methods that allow us to read all the electrical activities. Here's an early frog embryo where the cells are sorting out who's going to be left, right, front, back, and so on. Then here are some cells in culture. Now we have the ability to read these electrical states without having to poke cells with electrodes. We can get a map of the whole tissue.

We do a lot of computer simulations, starting with the molecular networks that transcribe the different channels, then tissue-level bioelectrics, and then eventually symbolic things where we try to understand pattern completion and memory properties of these circuits.

Slide 28/46 · 32m:32s

Let me show you what some of these fields look like, these patterns. This is a voltage dye time lapse of an early frog embryo putting its face together. Instead of the colors, this is grayscale, but it's the same idea. The brightness indicates the voltage level.

What you'll see — there's a lot going on — but here's one frame from that video. What you're seeing here is that prior to the appearance of the organs and prior to the gene transcription that is necessary to make these organs, we call this the electric face: you already see here's where the animal's right eye is going to be, here's where the mouth is going to be, the placodes are out here. The tissue already has a pre-pattern that is going to become the anatomy. As I'll show you in a minute, this pre-pattern is essential to forming the face correctly.

We can now read out the plans that this collective intelligence of the body has for making the different organs. The reason I'm calling it a collective intelligence is because we are using the tools of neuroscience to understand how collectives exhibit problem-solving behavior in anatomical space instead of a three-dimensional space such as conventional behavior. We're looking at the cellular collective doing behaviors and solving problems in anatomical space — problems such as injury, having the wrong number and the wrong size of cells.

This bioelectric pattern we can read. It doesn't just hold individual cells together into an embryo. This cognitive glue is multi-scale because here, if we poke this one embryo, these others find out about it, and the same thing happens here when you poke this guy: within a few seconds all of these find out about it. It works across scales to integrate active subunits into larger collectives.

We've done work showing that groups of embryos are better able to solve problems, for example, exposure to teratogens, than singleton embryos are. There's a collective intelligence within the tissue and there is one across multiple animals.

Slide 29/46 · 34m:36s

Now, not only do we know how to read these patterns, the more important thing is to be able to rewrite them, because that's the only way we know that the patterns are actually functionally important. We don't use any applied fields. There are no electrodes, waves, frequencies, radiations, no magnets, nothing like that. What we do is use the tools of neuroscience to control the bioelectric interface that cells are normally using to hack each other, which means we open and close their ion channels on the cell surface, and we open and close these gap junctions to control the topography. We can do this with drugs, and we can do this with optogenetics, all the typical kinds of tools. Now it's time for me to show you what happens when we do this. What actually happens when we rewrite the electric pattern memories of the body?

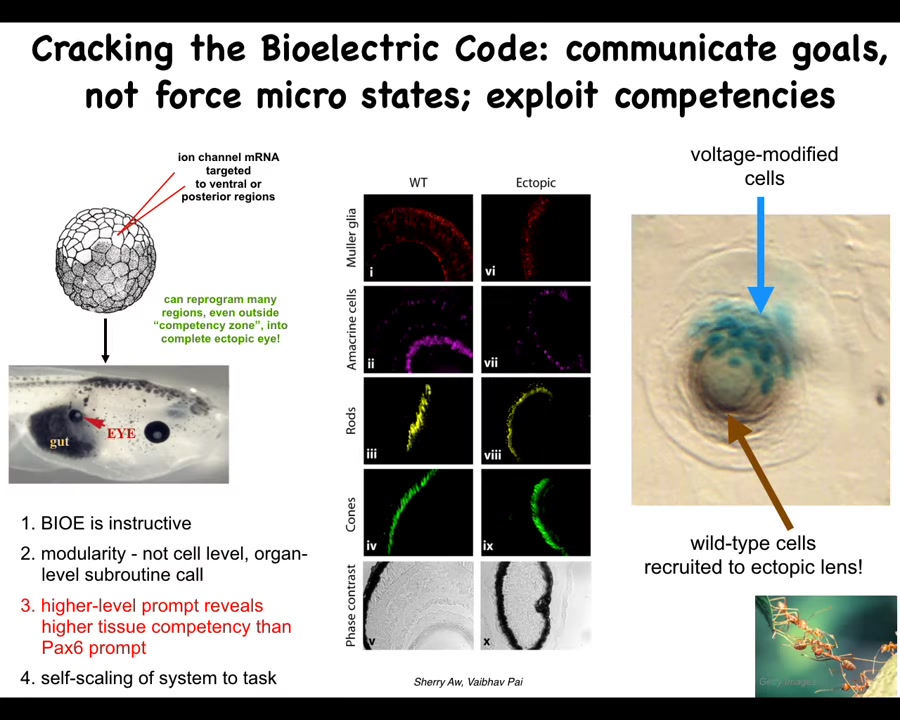

Slide 30/46 · 35m:22s

I only have time to show you a couple of examples, but here are a few of my favorites. You saw that little eye spot in the electric face picture that I showed you. One question you might ask is, if we introduce that voltage pattern somewhere else in the body, what's going to happen? You can do that. We can take some ion channel RNA encoding specific kinds of potassium channels. We inject it into cells that are going to become, in this case, the gut. What you see is that those cells are perfectly happy to build an eye. In this frog embryo, there's the gut, there's the eye. If you section this eye, you've got lens, retina, optic nerve, all the typical things.

Here we learn a few things. First of all, the bioelectric pattern is instructive. It called up an entire organ. Second, it's extremely modular. We didn't have to tell it how to build an eye. Frankly, we don't know how to build an eye. There are so many different cell types, so many genes that have to come on and off. We have no idea how to control any of that. What we did find is a high-level subroutine call that says to the tissue, build an eye here, and they take care of all the rest. All the molecular steps are taken care of.

In the developmental biology textbook, it says that only the cells up here are competent to become an eye. That's true when you prod them with the master eye gene called PAX6. Only these cells up here will obey and make an eye. If you use a better prompt, such as this bioelectric state, it turns out that all the regions of the body are capable of doing it. When we talk about competency and the lack of it, we have to understand: is that the competency of the material or the competency of us as the engineers who don't yet understand how to communicate our goals to it.

We also found out that if you only inject a few cells here, the system knows there's not enough of them to make an eye. These cells recruit their neighbors. All this other stuff up here was never touched by us. It's a kind of a secondary instruction, just the way that ants and termites recruit each other to help them do certain tasks. All of these are competencies of the material. We did not have to teach them to do that. They already do it.

Slide 31/46 · 37m:32s

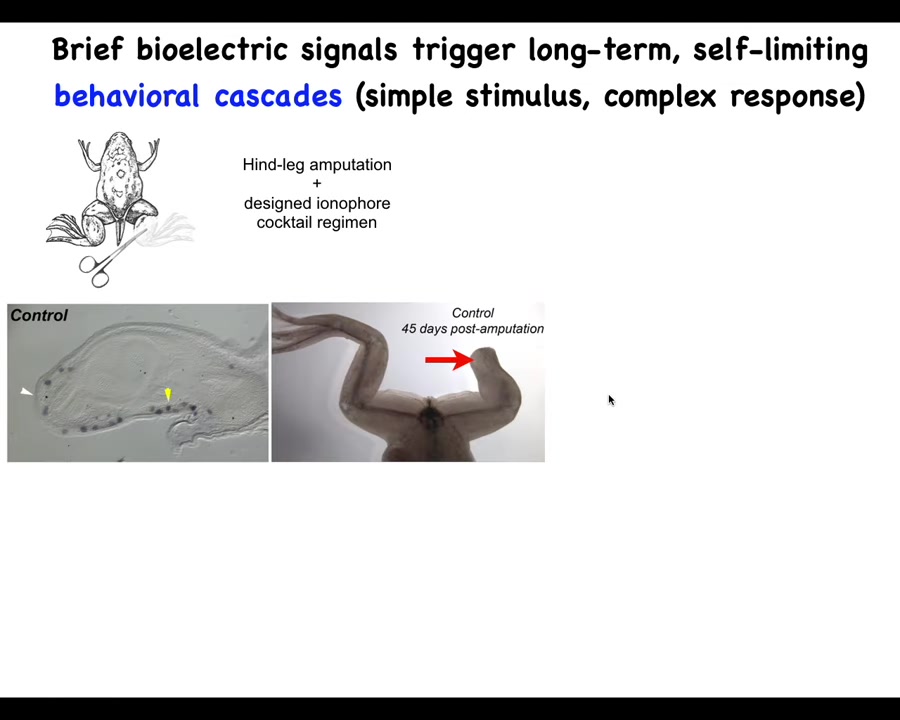

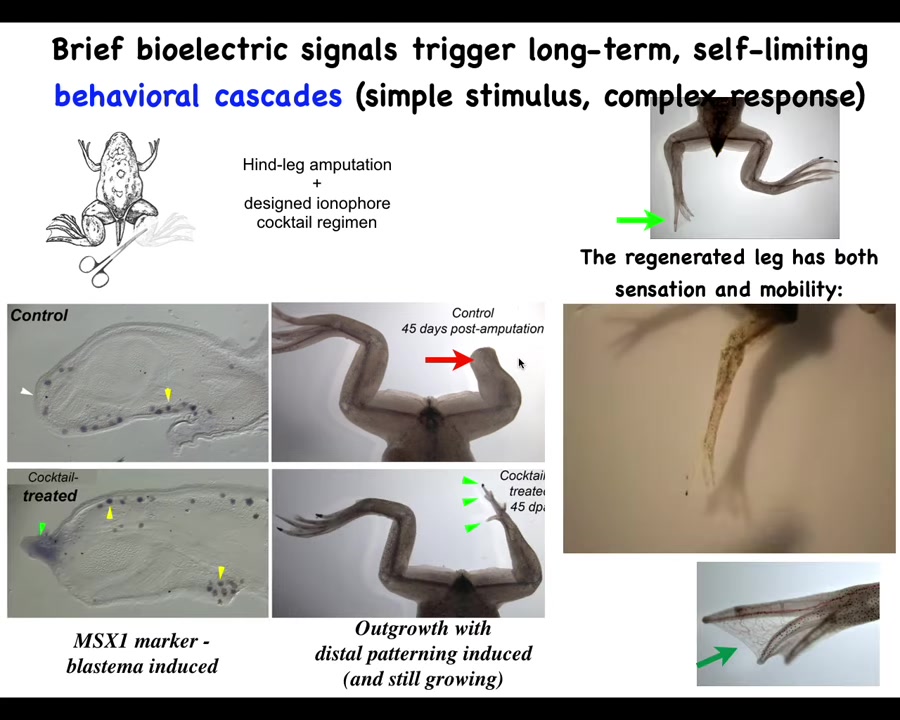

We've used this kind of thing for a regenerative medicine program having to do with limb repair. Frogs, unlike salamanders, do not regenerate their legs. If they lose a limb, 45 days later, there's nothing.

Slide 32/46 · 37m:46s

What we did was work out a cocktail of ion channel modifying compounds that immediately trigger this kind of MSX1-positive blastema. Within 45 days, you've got some toes, you've got a toenail, and eventually a very nice leg that is touch-sensitive and motile.

In our latest experiments, 24 hours of stimulation with this cocktail leads to a year and a half of leg growth. During that time, we don't touch it at all. No scaffolds, no 3D printing, no talking to the stem cells.

Just in that first 24 hours, you communicate that they have to go to the leg-building path, not the scarring path. Then you take your hands off the wheel.

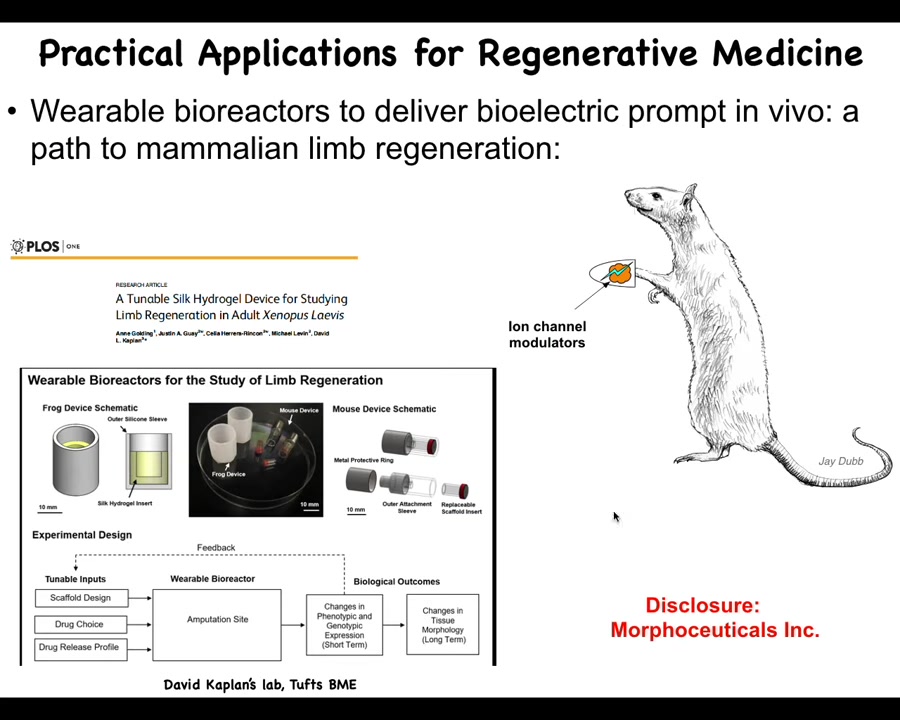

Slide 33/46 · 38m:27s

At this point, I have to do a disclosure. David Kaplan and I are scientific co-founders of a company called Morphoseuticals, which is now pushing this towards mammals and hopefully someday towards patients. We build these bioreactors, which are a delivery method. It's a wearable bioreactor that delivers the ion channel drug payload to the wound and then protects it while it tries to regenerate. Stay tuned for these kinds of things in the future.

Slide 34/46 · 39m:00s

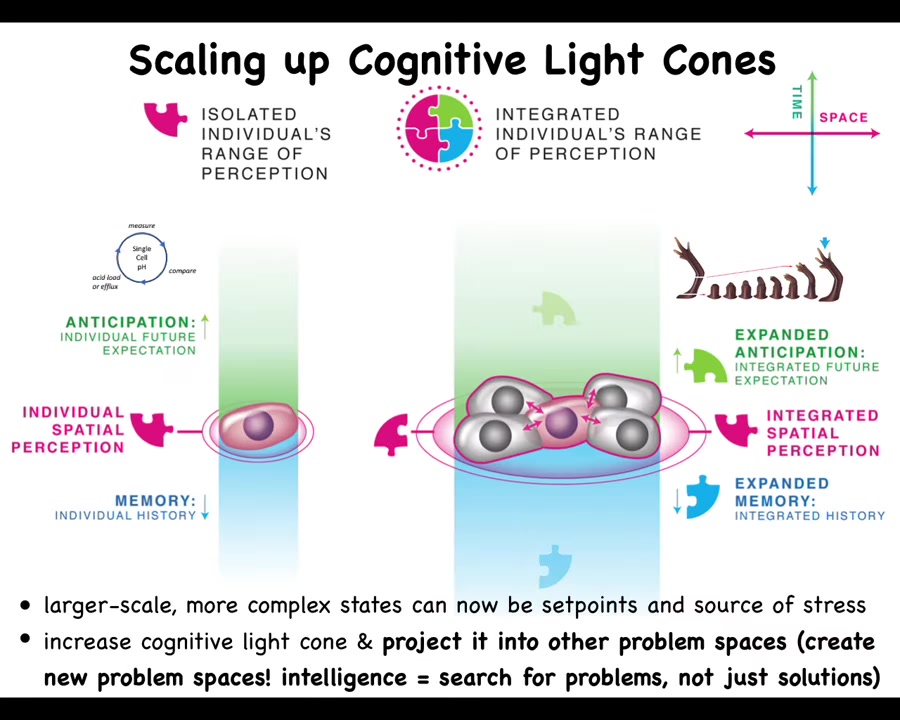

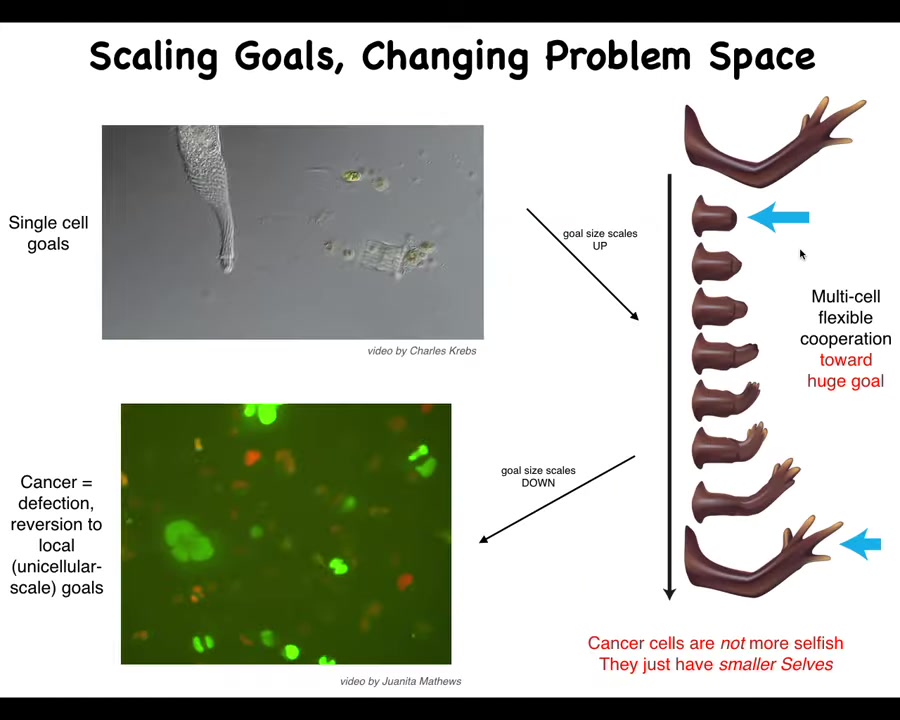

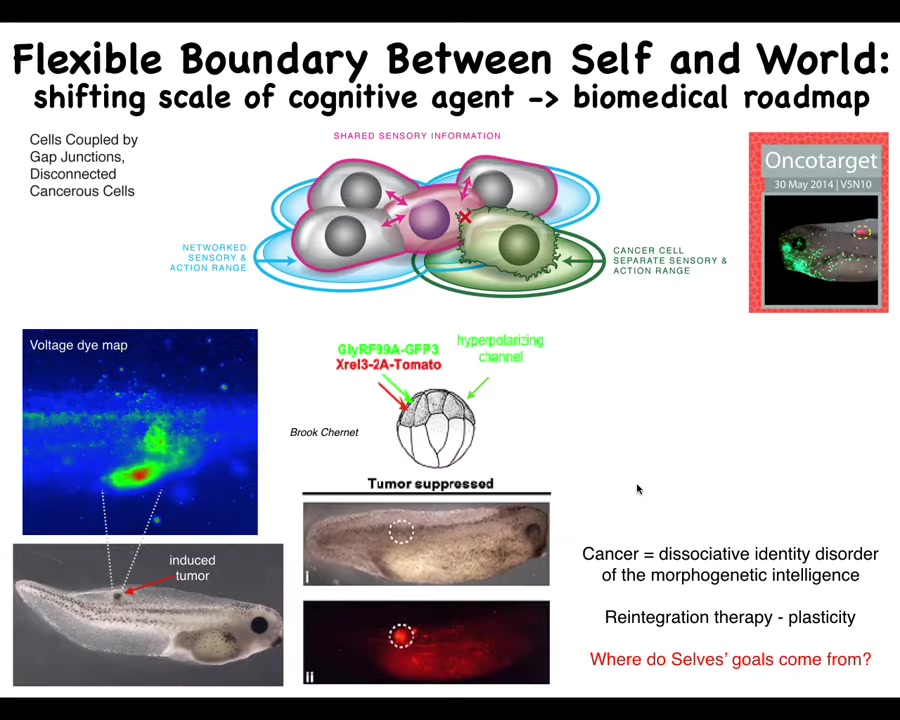

I want to skip now from the regenerative thing to the topic of cancer, because cancer is actually very interesting in terms of this question of what are we and the whole multi-scale human idea. We have this notion of a cognitive light cone. A cognitive light cone is the size of the largest goal that a system can work towards, not the size of how far it perceives or how far it can act. Individual cells have very tiny cognitive light cones and they're very simple things like keeping the pH or the hunger level down at this particular scale. They have a little memory, a little predictive capacity, but everything is about these tiny single-cell goals. But during evolution and during development, when they scale up into these large-scale networks, they can work on grandiose goals, like building these organs. Their memory goes up both spatially and temporally, and they can project their problem-solving competencies into new spaces, from physiological space to anatomical space.

Slide 35/46 · 40m:01s

Here's what's happened. The little tiny goals here, much larger grandiose goals here. No individual cell knows what a finger is or how many fingers you're supposed to have, but the collective absolutely knows. They know because if you remove some, they'll fix it and then they'll stop at the right level.

That process, the ability to connect into a network that remembers these enormous set points, has a failure mode. The failure mode is called cancer. When cells disconnect from that electrical network, they become human glioblastoma. They roll back to the kind of unicellular lifestyle. The boundary between the self and the world shrinks. From this enormous self here that they're building, this giant thing, the borders shrink and now they're just amoebas again. As far as they're concerned, the rest of the body is just external environment.

These cancer cells are not actually more selfish; they just have smaller selves. The boundary between self and world is flexible and it can grow and it can shrink, and it's determined by the size of the goals. Your cognitive light cone is determined by the size of the goals that you are concerned with and actively working towards.

Slide 36/46 · 41m:13s

And so that weird way of thinking about it actually suggests a therapeutic strategy that we explored, which is that if we inject a human oncogene into these tadpoles, they will eventually make a tumor. If you track the bioelectrics, you can see right away where it's going to be. These cells are electrically disconnecting from the rest of the body and acquiring a depolarized potential, and then you'll get metastasis.

What we did was we're not going to try to kill the cells, we're not going to try to fix the oncogene. All we're going to do is reconnect them to the electrical network of the rest of the body. And we'll do that by co-injecting an ion channel RNA that keeps them hyperpolarized so that the gap junctions stay open and they stay connected.

And what you get is this: it's the same animal here. The oncoprotein is labeled in red, and you can see it's all over the place. It's still here. The cells are not dead. The oncoprotein isn't gone, but there's no tumor. There's no tumor because it isn't the genetics that drives the outcome. The genetics sets the hardware. The hardware can do many different things. One of the things that it can do is continue working on this large-scale goal of making nice skin, nice muscle.

So what we're seeing here is that this question of the multi-scale architecture that we have and the ability of each of these levels to determine where the boundary of its concern is is a really critical thing to understand and manipulate for biomedicine. We're now moving from these frog models into human tumor spheroids.

The last thing I'll show you, and then I'll stop here, is that, so far we've looked at the ability of multi-scale cellular systems to reach goals, to do so in surprising circumstances, meaning to solve problems, and to use bioelectrical networks to achieve those goals. One more remaining question: where do these goals come from? And again, we're tempted to say probably evolution. In other words, over the years of the lineage, the specific attractors and all those problem spaces have been fixed by the environment and selection. So I want to show you examples where that thinking breaks down.

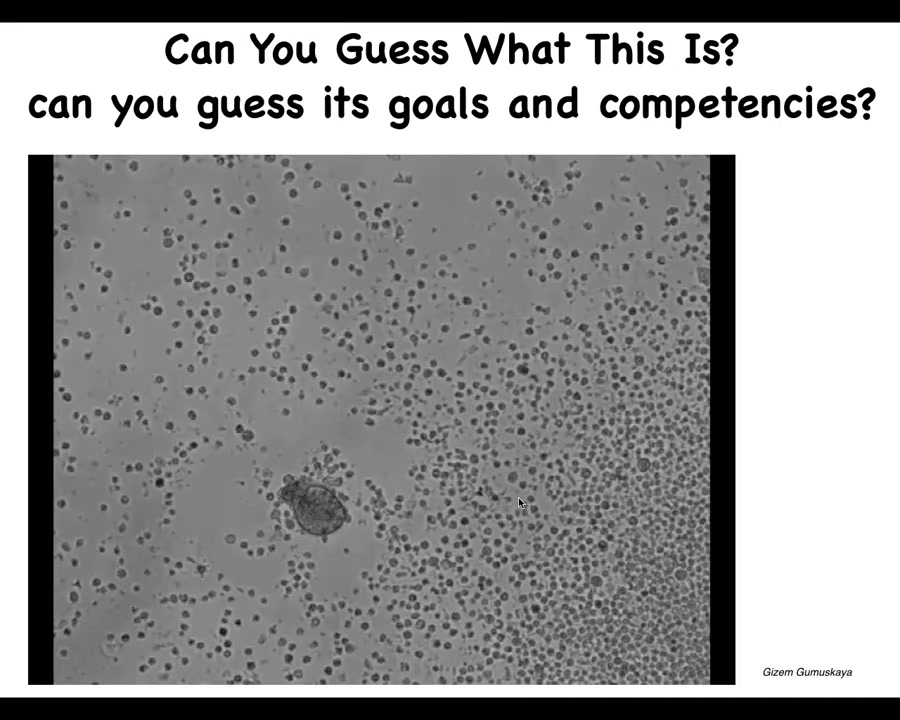

Slide 37/46 · 43m:25s

You look at this and you might say, it looks like something we got out of a pond somewhere. It looks like a primitive organism. If you wanted to guess the genome, you would guess that it's similar to a primitive cellular creature that lives in these aqueous environments. You wouldn't know its goals and competencies. But I can tell you that if you were to sequence this, you would get 100% Homo sapiens DNA. These are human cells. It is made of adult tracheal epithelial cells. If I told you that we were using a human genome, you would not know that. It's capable of building this autonomously moving biobot. This is not like any phase of human development.

Slide 38/46 · 44m:14s

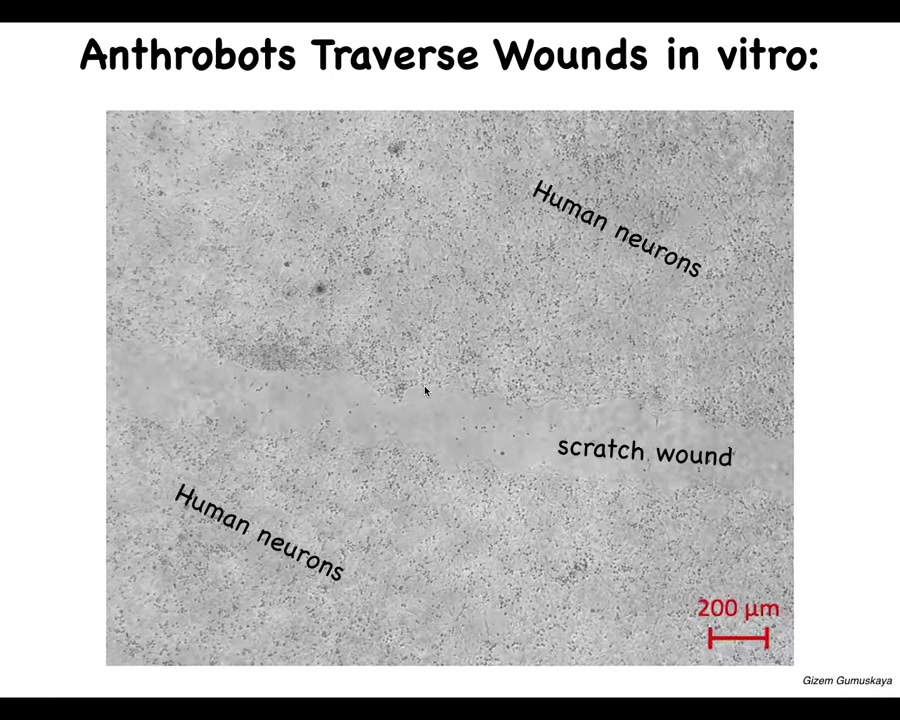

They have some interesting capabilities. One thing they can do is traverse these scratch wounds. This is human neurons, iPS-derived human neurons. We put a big scratch through it.

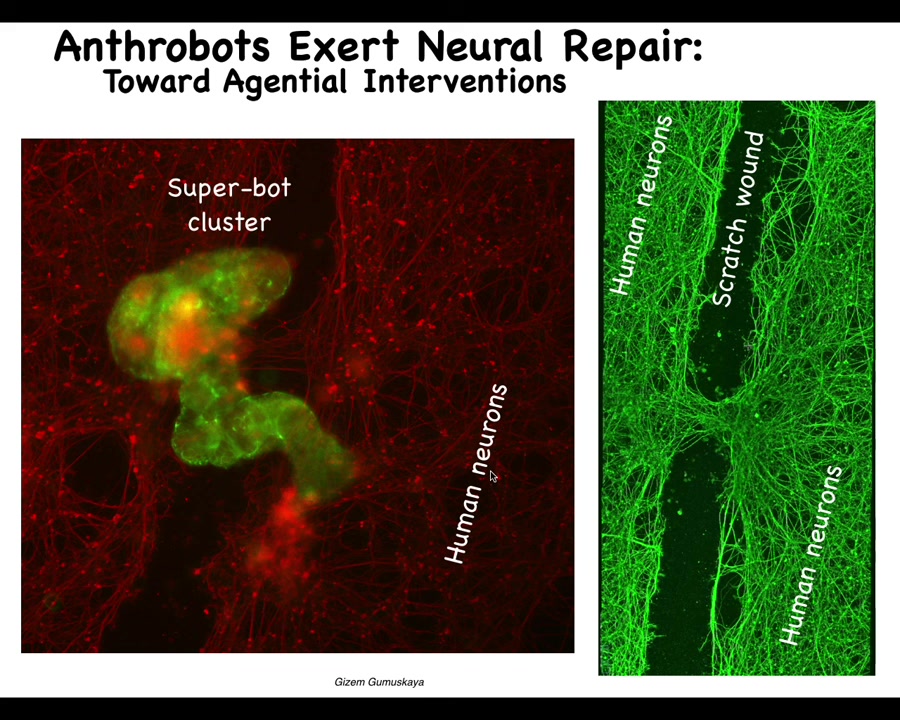

Slide 39/46 · 44m:25s

They go through this scratch and then they land. When they land, they form what we call a superbot cluster. There's probably 8 to 10 or so of these biobots here. What they do when they form this is they start knitting the two sides of the wound together. If you lift them up four days later, you see that what they were doing down here is connecting the two sides of the neuronal scratch.

Who would have thought that your tracheal epithelial cells that sit quietly in your airway for a long time, when taken out of the body — no new genetic circuits, nothing changed about the genome here, no scaffolds, no weird molecular biology — just letting the system reboot its multicellularity into another form gives rise to an autonomous little proto-organism that actually has a number of amazing properties, but one of them is that it likes to heal neural wounds.

What you can think about is something we call an agential intervention. Someday, you will be able to donate some cells from your own body. Those cells will be made into these anthrobots, put back into your body to be able to heal wounds, interact with other tissues, drop off pro-regenerative molecules, do something to the microbiome, look for cancer cells, all these different things. Because these things already have their own autonomous activity. They know what inflammation is. They come from your own body, so you don't need immunosuppression.

Slide 40/46 · 45m:52s

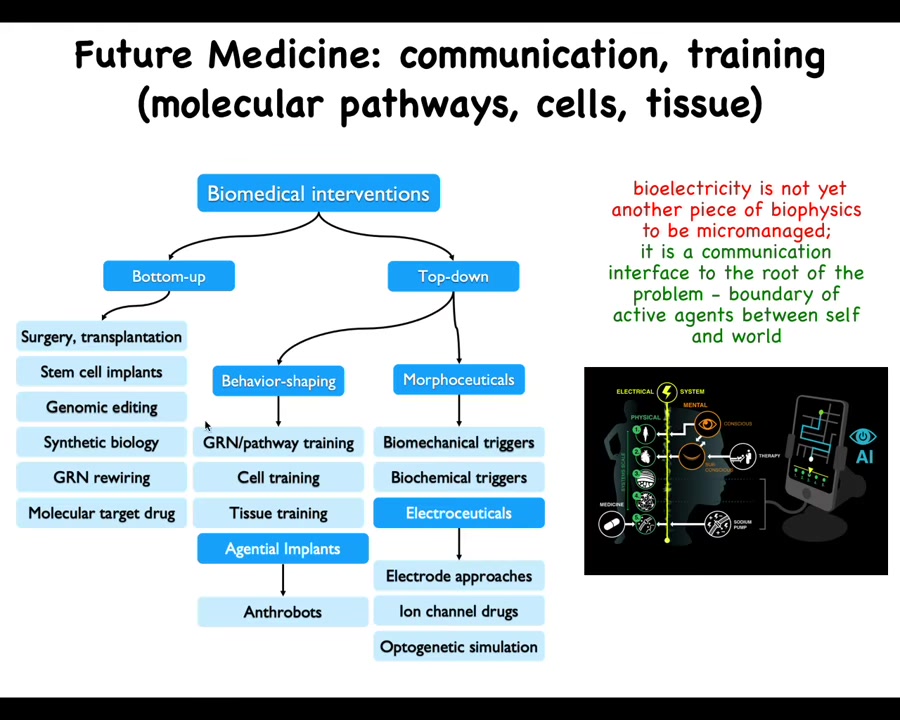

Putting everything together, I'm going to just claim that in the future, this side of the space of biomedicine is going to develop rapidly. Right now, everything is here, bottom-up, focused on the hardware. These are all the things that are in wide use today. But there are all these other options. We haven't even talked about our data on training cells and tissues, but here are some biobots made of patient cells, gentle implants, all the different electroceuticals, which are part of a broader class of morphoceuticals, which are basically top-down controllers that don't seek to micromanage symptoms, they don't seek to establish specific biochemical states, they are signaling to the highly competent cellular collective to undergo very complex behaviors that we do not know how to micromanage.

The future in biomedicine, I think, is going to be much more about communication and collaboration, not micromanagement. I think it's going to look much more like a weird kind of somatic psychiatry, not like chemistry. We're actually using some AI tools to help us communicate with the rest of the body through the bioelectric interface, but there are many other interfaces as well, biochemical, biomechanical. But the idea is not to micromanage molecular states. It's to communicate new goals, reset memories, and take advantage of the highly modular capabilities of the cellular collectives.

Slide 41/46 · 47m:25s

In the last couple of minutes, I want to point out what all of this entails. Remember that in the whole first part of the talk, what I emphasized was the plasticity, the idea that cells and tissues cannot assume much of anything about what they should be doing. They have to solve problems on the fly. They're given certain tools in the form of genetically encoded hardware, but after that, they have to creatively form into some kind of functional being, maybe a standard embryo, if possible. If not, it could be an Anthrobot or a Xenobot or any of the other things that we've built in our lab. They have to figure out what they're going to do. Because of that, they are incredibly interoperable.

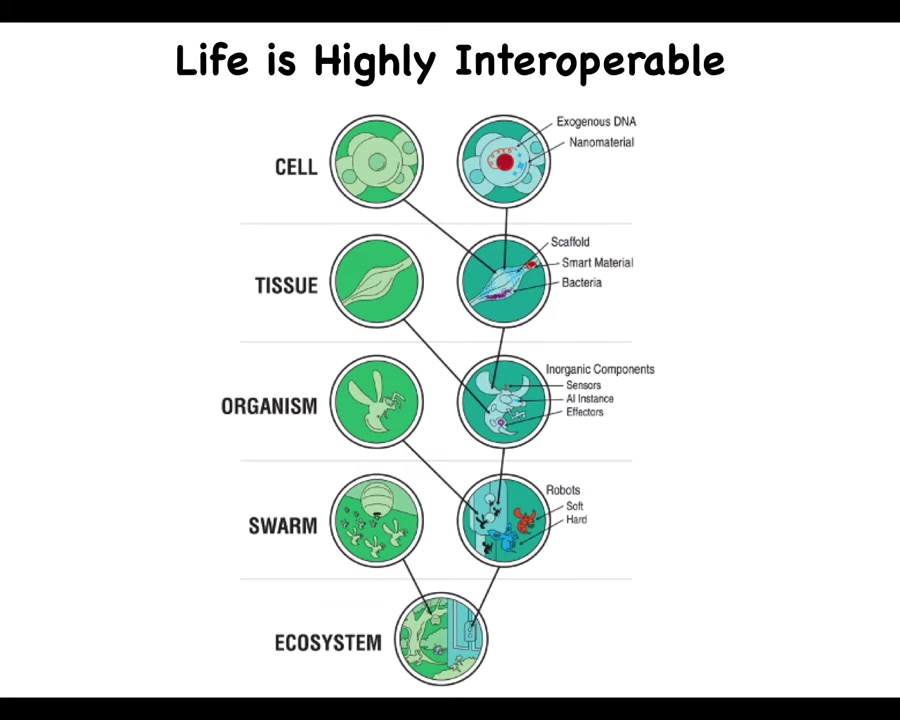

Slide 42/46 · 48m:05s

Anywhere along this continuum, we can add technological components to the naturally evolved ones. You can introduce exogenous DNA and nanomaterials and scaffolds and synthetic organs and all kinds of different things, all the way up through the ecosystem level. Because life is so interoperable and does not make assumptions, it will work with whatever it's got.

Slide 43/46 · 48m:30s

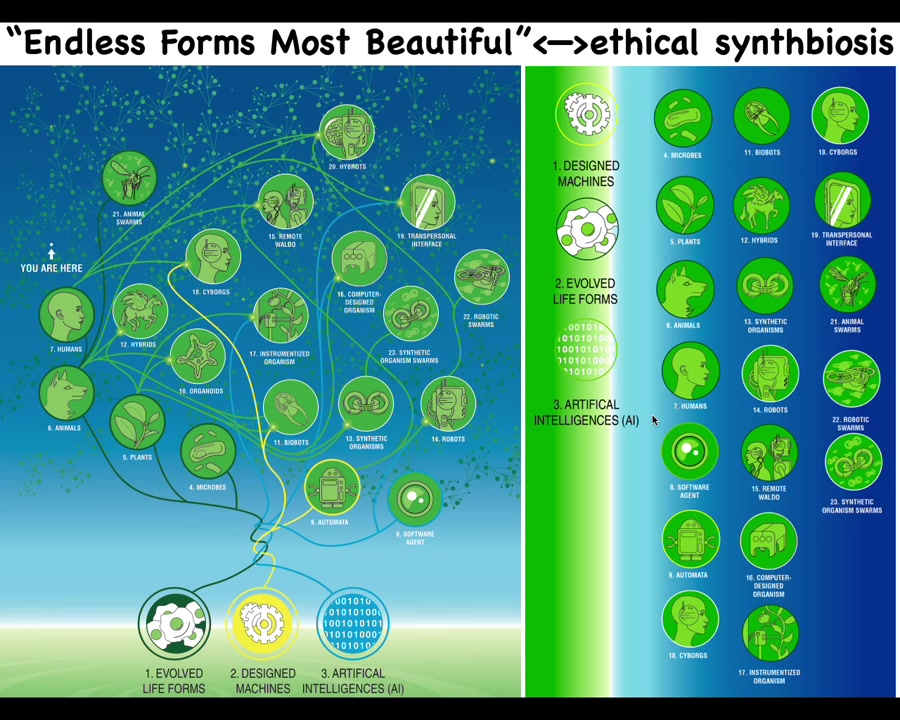

That means that almost any combination of evolved material, engineered material, and software is some kind of possible agent. There are cyborgs and hybrots and various kinds of chimeras and hybrids. Some of this already exists. We already have humans walking around with artificial organs and chips in their brain. This will only expand.

The space of other beings is going to be enormous. When Darwin said "endless forms most beautiful," he was very impressed with the diversity of life on Earth. All of that is a tiny little corner of this enormous option space of new bodies and minds. The interesting thing about all these different creatures that we're going to be sharing our world with is that they are nowhere on the tree of life with us. We cannot judge them in the same way that we're used to thinking about biological lineages.

The old questions that have more or less served us well for years, which is, what are you made of and how did you get here? Are you made in a factory? Are you made of metal? Or are you biological? Those things used to be important binary categories that would determine things like our ethical obligations to you. Those categories are crumbling. They were never good to begin with, but they were okay for some years. They're going to be useless in the coming decades.

What we need to do, and this is a fun word that GPT came up with for me called synthbiosis, which is the idea that we are going to have to live in some kind of ethical harmony with a wide range of unconventional beings, components of which are synthetic.

We don't want to be in this position when people talk about "it's a machine" or "it's a living organism" or "it's a human" or "it's a robot." When somebody has 50% of their brain replaced by various augmentative technologies, you don't want to be this kind of neo-phrenologist trying to figure out, is it 51%?

Those binary categories are completely useless at this point. We are going to have to develop some new frameworks.

Slide 44/46 · 50m:48s

I think the new Garden of Eden picture is going to look a lot more like something like this, where we're going to have to ask, what really are we? We are not our genes. We are not our standard organs. We're not our standard morphology. We're not our commitment to a life cycle where you get astigmatism and lower back pain and loss of cognitive abilities in your 90s and 70s and 80s. We're not committed to any of that. I don't think that's what a human is.

I think we have to start thinking about what makes us truly unique. I actually think it's the size of our cognitive light cone and the ability to exert compassion and wisdom in a particular radius across beings in our environment. I think that's what makes us humans. It's not any of the really contingent biology that was the result of cosmic rays hitting our material over millennia.

Slide 45/46 · 51m:48s

I'll stop here and just summarize. I made the claim that intelligence is everywhere, that we need to learn to rise above our evolutionary firmware and learn to recognize it in very unfamiliar guises. The model system of cellular collective solving problems in the anatomical space is a good way to start thinking about unconventional intelligences, and we're going to have to get much better at this, both for biomedicine and for the ethical flourishing of humanity and other beings.

I try to point out that we are fundamentally a process. We are not an object. We are a self-constructing story, continuously being told by a collective intelligence of multi-scale components. Transformative regenerative medicine for birth defects, cancer, and injury awaits us to develop tools for communicating and collaborating with a somatic intelligence. The future is not going to be about crusty old categories of machines. It's about a continuum of agency, about understanding how mind scales from its very lowest kinds of forms up to whatever it's capable of. Likely, AI tools will be universal translators to talk to and communicate with these diverse intelligences.

Anybody who's interested can look up these more popular things that I've written more recently.

Slide 46/46 · 53m:18s

I want to thank the people who did this work. Here are the graduate students and the postdocs that did some of the work that I showed you today, and the undergrads and our many collaborators, our funders, all the illustrations by Jeremy. Again, disclosures: these are three companies that supported some of our work. Most credit of all goes to the model systems because they're the ones who teach us everything and they do all the heavy lifting. I'll stop here and thank you.