Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

Michael Levin explores cancer as a breakdown in electrical communication among cells that normally cooperate to build and maintain complex body structures. He explains how somatic tissues form decision-making electrical networks and how computational models can guide “electroceutical” ion channel therapies to normalize growth. The episode looks ahead to noninvasive diagnostics and reprogramming cancer by restoring the body’s bioelectric code.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Why anything but cancer

(05:14) Regeneration and anatomical control

(11:41) Bioelectric codes in tissues

(19:00) Electrically triggering regeneration

(25:31) Bioelectric predictions for cancer

(29:50) Inducing metastasis via voltage

(35:07) Reprogramming and long-range control

(40:45) Electroceutical strategies and outlook

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/44 · 00m:00s

First, I'm not a clinician. I'm a basic scientist, in fact, originally a computer scientist and more recently a biologist. What I'm going to say today are things that are one perspective on the cancer problem. I'm not claiming this is the only perspective. Many other things are important, but this is one thing I think we should be paying attention to. If you want to contact me or want any of the primary data that goes with all of the things that I'm going to go over today, you can reach me at these two websites and everything is there.

Slide 2/44 · 00m:33s

So the summary of today's talk is the following. The first is that I'd like to focus on the question of why is there anything ever other than cancer? Why is there an alternative? Because I think that's a deep question. I'm going to argue that one important way to look at cancer is as a disruption of networks of cells cooperating towards large-scale goals. What are these goals? These are goals of organogenesis, of histogenesis, of keeping up anatomical structure. When these processes, which are central to multicellularity, are disrupted, we see the kinds of things that we call cancer. I'm going to show you that much of the cellular communication that's required to do this is in fact electrical, much like in the brain, but it's in all of the tissues of the body. And now we're entering an era where we can target this system for control of this collective decision making, which has many applications in regenerative medicine, cancer medicine, and bioengineering.

Slide 3/44 · 01m:39s

In two sentences, the whole talk boils down to this: as it turns out, like the brain, somatic tissues form electrical networks that make decisions. These are decisions about growth and form. Computational modeling of these network dynamics enables us to design ion channel modulation strategies, which we call electroceuticals, to reinforce morphogenesis and reprogram cancer. That's the claim.

Slide 4/44 · 02m:04s

The first question is, what is the alternative to cancer? This is a single-celled organism known as a lacrimaria. This is one cell. You can see it's very competent in handling the goals of a one-celled organism. Morphologically, behaviorally, physiologically, it does everything it needs. Here it is hunting in its environment. There is no brain, no nervous system, no cell-to-cell communications.

Slide 5/44 · 02m:44s

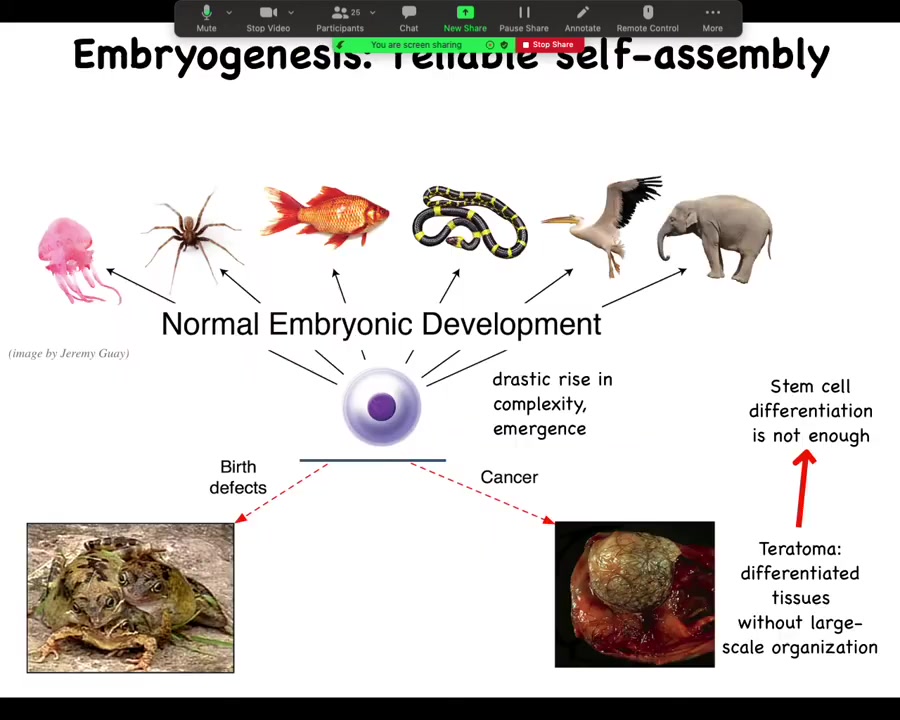

And so the amazing thing then is that creatures like this can actually get together and pursue very much larger scale goals because we know that we start life as a single cell and then through an amazing process of self-assembly, many of these really complex anatomies appear.

And we know that this is not just a stem cell differentiation problem because the key is not simply to get the right collection of tissues as you might have in a teratoma, skin and nerve and hair and bone. What's different here is that the three-dimensional structure is missing. So simply getting your cell types isn't enough. You have to know where the cell types go. This is the beginning of the many, many decisions that the cellular collectives have to make.

Slide 6/44 · 03m:25s

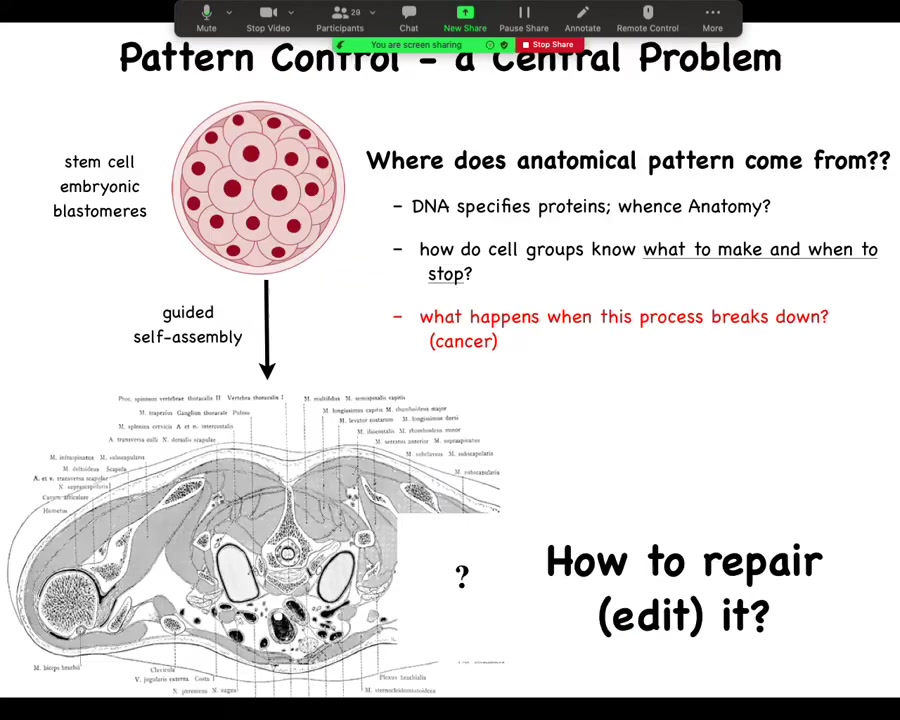

In particular, then we can take a cross-section through a human torso. Here it is, this incredibly complex arrangement of organs and tissues, everything most of the time in the right place, right size, shape, orientation, position relative to each other. We can ask the question, where does this pattern come from? Because we all start as a set of embryonic blastomeres and then something this incredibly complex shows up.

Well, often people are tempted to say DNA, but we can read genomes now and we know that nothing like this is in the genome. What's in the genome are protein sequences: descriptions of the very smallest pieces of hardware that the cells can deploy to do signaling and various other things. But then the cellular collective has to operate a kind of software using these pieces of hardware, these protein and other types of signaling pathways to arrange themselves in this invariant pattern.

We would like to know, how do these collectives know what to make and when to stop growing? In regenerative medicine, we'd like to know, if a piece is missing, how do we repair it? How do we cause these cells to rebuild what they once built? For this audience, what happens when this process breaks down?

Pattern control in this large global vision of how do we control what it is that cells build is huge. It's a central problem. If we had control over this, we would be able to deal with birth defects, traumatic injury, cancer, degenerative disease, synthetic bioengineering. All of these things would be solved if we could answer one question, which is, how do groups of cells know what they should be building?

Slide 7/44 · 05m:10s

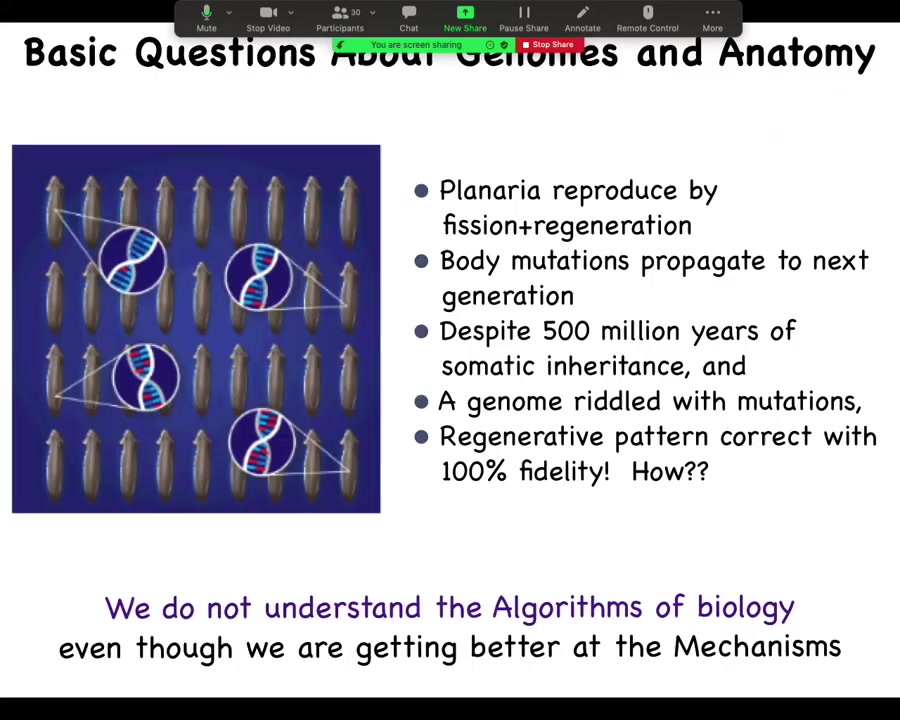

There are very fundamental areas of ignorance still in the field. This is a creature known as a planarian. You'll see lots more of this momentarily. The interesting thing about these flatworms is that they reproduce by fission and regeneration. So they tear themselves in half. The front half makes a new tail. The back end makes a new head. Now you have two worms. That's how they regenerate.

That means that they don't have Weisman's barrier. It means that any mutation that doesn't kill the stem cell that it hits is propagated into the next generation. For several hundred million years, these things have been accumulating mutations. You can see this in their genome. Their genomes are an incredible mess. In fact, each animal is mixoploid. We don't even have a proper assembly because you don't know what you're sequencing. Every cell, rather, has a different number of chromosomes. So the genome is an incredible mess.

And yet, when you cut these animals, they regenerate to a perfectly correct planarian anatomy 100% of the time. Incredible anatomical fidelity, lots of noise down at the genetic level. How is that possible? How do these things maintain such incredibly tight anatomical constraints when the genome can vary widely? We don't understand these kinds of algorithms.

Slide 8/44 · 06m:28s

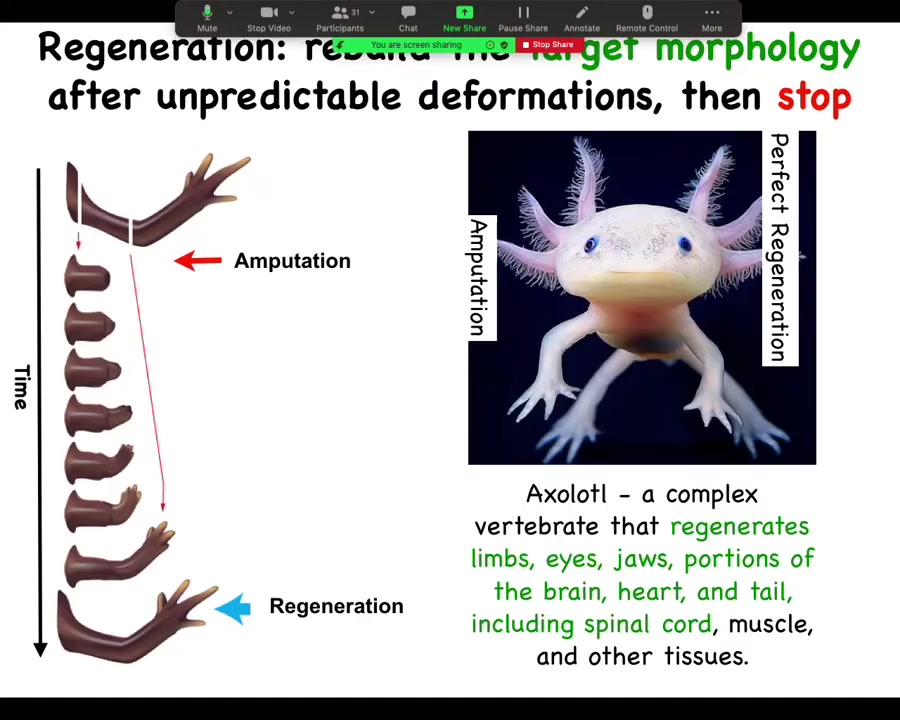

In general, the issue of regeneration is really important. This is an axolotl, a Mexican salamander. These creatures regenerate their eyes, their jaws, their limbs, their spinal cords, portions of the brain and the heart.

If a limb is amputated, whether it's amputated up here at the shoulder or here at the elbow, they will grow exactly what's needed, no more, no less. Then the process stops. This is the most profound mystery. Lots of people are working on kick-starting regeneration, but the most profound mystery is how does it stop? When does it stop? It stops when a correct salamander arm has been completed. How does the system know what a correct salamander arm looks like? This is still very much an open question.

Slide 9/44 · 07m:18s

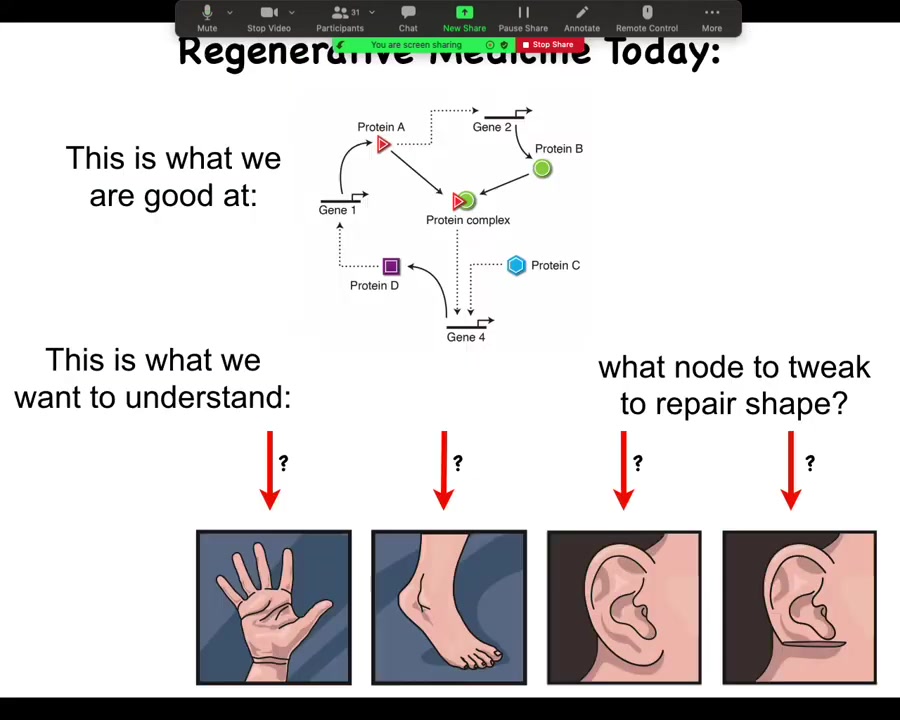

What we're good at in regenerative and molecular medicine today is identifying pathways like this, at the hardware level. What we would like to understand is the system-level anatomical outcomes. Why does your hand not look like your foot? They have the same cell types. What would we need to tweak in a big network like this to get a particular structure to reform, let's say a part of the ear or some organ? We still don't know. That gap is what we're trying to fill.

Slide 10/44 · 07m:50s

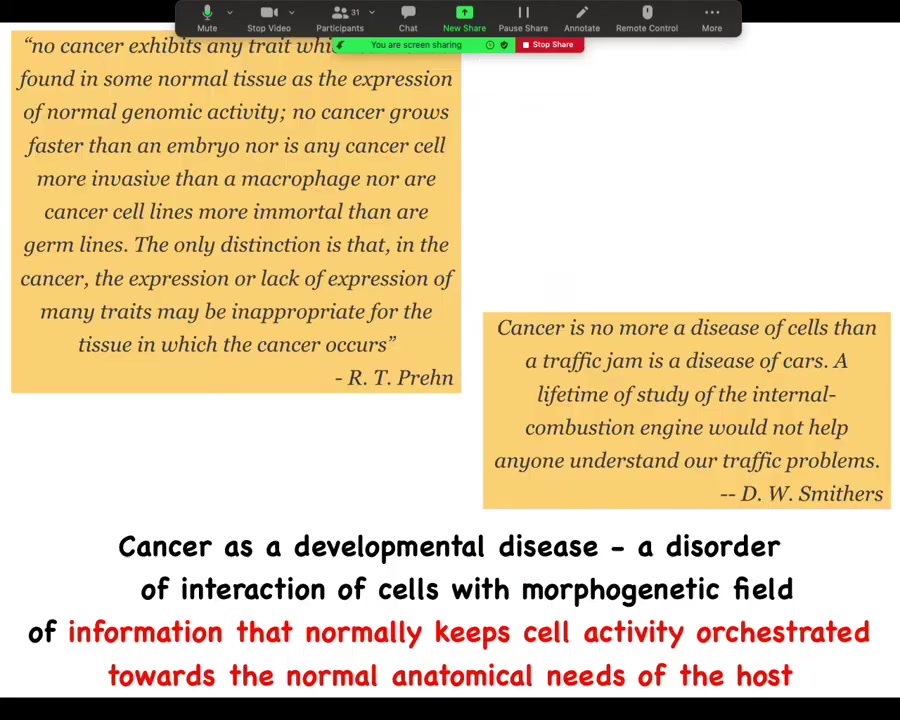

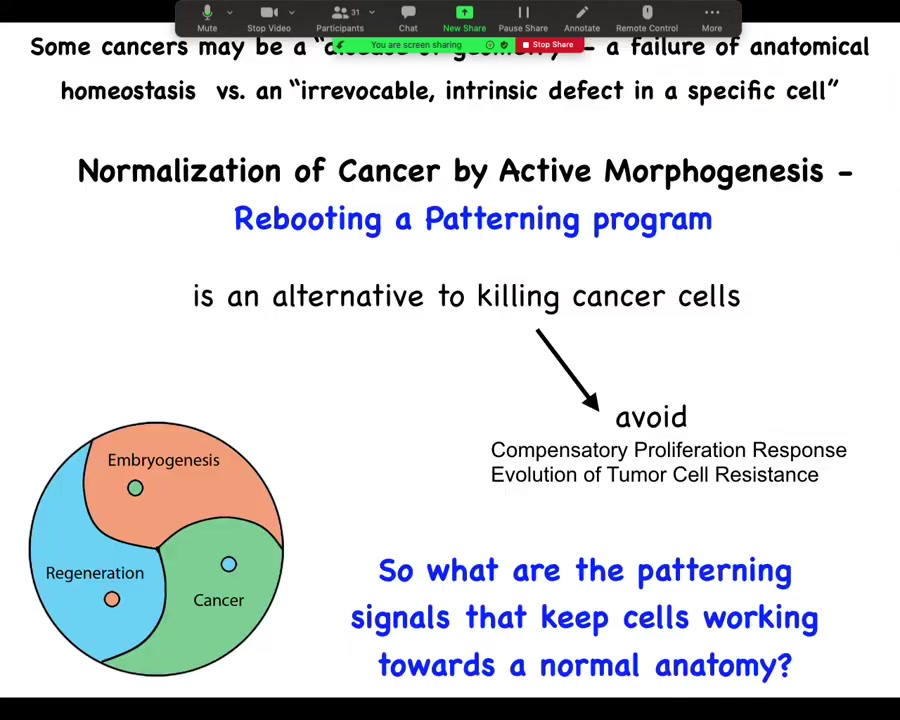

Cancer is not so much necessarily a disorder of the molecular hardware. It certainly can be caused that way, but it's fundamentally a large-scale problem in the scope of the geometric goals that are trying to be implemented by the biological system. Single-cell optimization versus large-scale cooperation towards morphogenesis. One way to look at this is that it's a developmental disease, which is a disorder of the interaction of cells with a field of information that normally keeps them bound together towards the anatomical needs of the larger host body.

Slide 11/44 · 08m:39s

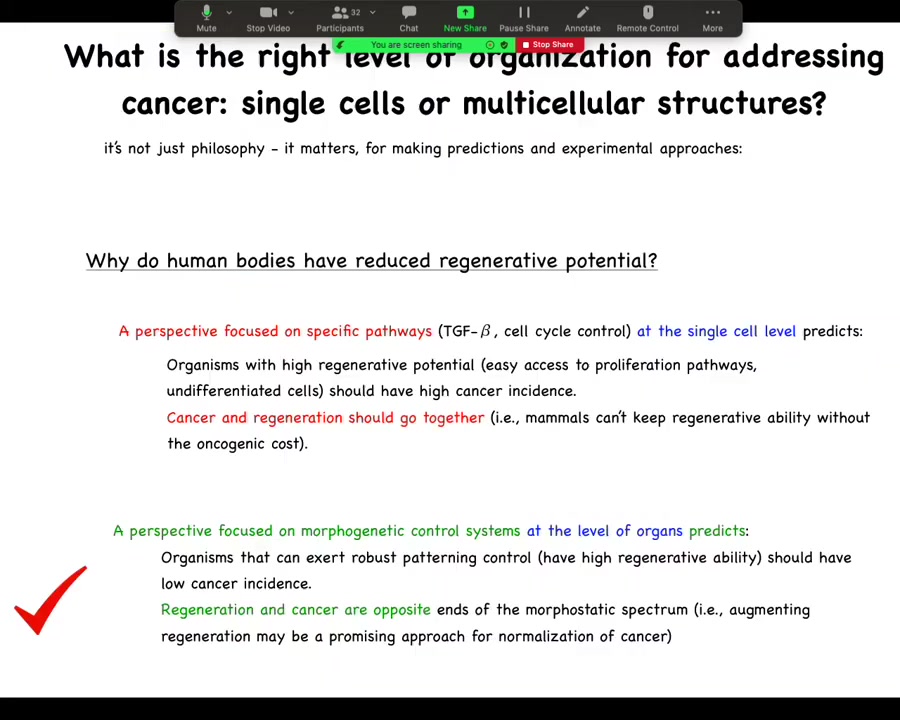

And this kind of thinking is not just philosophy, it has very practical implications. Let's look at just one prediction here. If we ask the question, why do human bodies have reduced regenerative potential? Why are we not like salamanders? If you have a perspective focused on very specific pathway, single cell level control, cell cycle, things like this, you would say that organisms with high regenerative potential, and thus easy access to proliferation pathways and undifferentiated plastic cells and so on, should have a high cancer incidence, meaning that cancer and regenerative capacity should go together. The idea is mammals couldn't keep regenerative ability without an oncogenic cost. But the opposite version of this would say that if you have a perspective focused on the morphogenetic control system, you would say that no, organisms that can exert robust patterning control, meaning have high regenerative capacity, should have a lower cancer incidence because they're better at harnessing cells towards these large scale goals. You would then predict that regeneration and cancer are opposite ends of the morphostatic spectrum. In fact, this is correct. Organisms that are highly regenerative tend to be very resistant to cancer.

If you do manage to induce a tumor on one of these organisms, you amputate through the tumor, they will regenerate the limb, they will hijack the remaining cancer cells, bring them under control, and now you have a healthy tissue. Planaria do this as well. There are lots of interesting scenarios like this that illustrate the importance of large-scale patterning control with respect to cancer.

Slide 12/44 · 10m:24s

What we want to do is pursue normalization strategies that reboot the ability of cells to participate in patterning. This is an alternative to trying to kill them. We'd like to avoid compensatory proliferation and the evolution of tumor cell resistance. We're not trying to kill off the susceptible ones. We're trying to get everybody back into a network that works towards normal tissue structure.

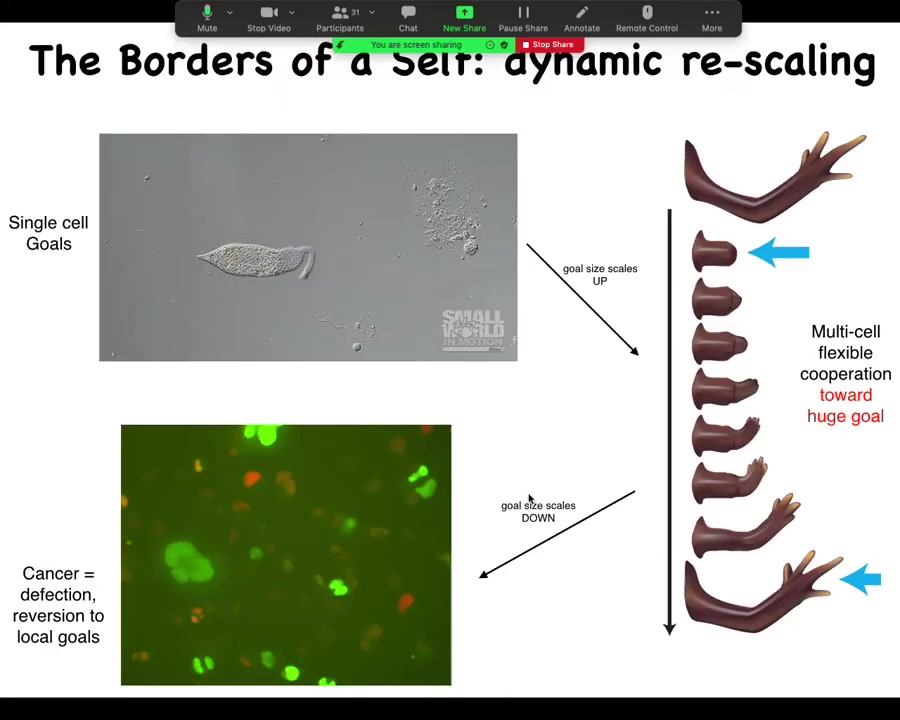

Slide 13/44 · 10m:54s

This is how we think about this as the change in the scaling of the homeostatic activity, where we start off as individual cells that can scale up towards a large-scale goal, such as making limbs, but then it can also scale back down.

This is human glioblastoma. One of my postdocs, Juanita Matthews, works on this, and there's a video of human glioblastoma cells. You can see that this inflation of the goal space of these systems is not permanent. During the lifetime of the body, it can also revert back to a kind of unicellular defection where, in effect, these cells will simply treat the rest of the body as the external environment. They don't consider themselves part of the whole anymore.

Slide 14/44 · 11m:41s

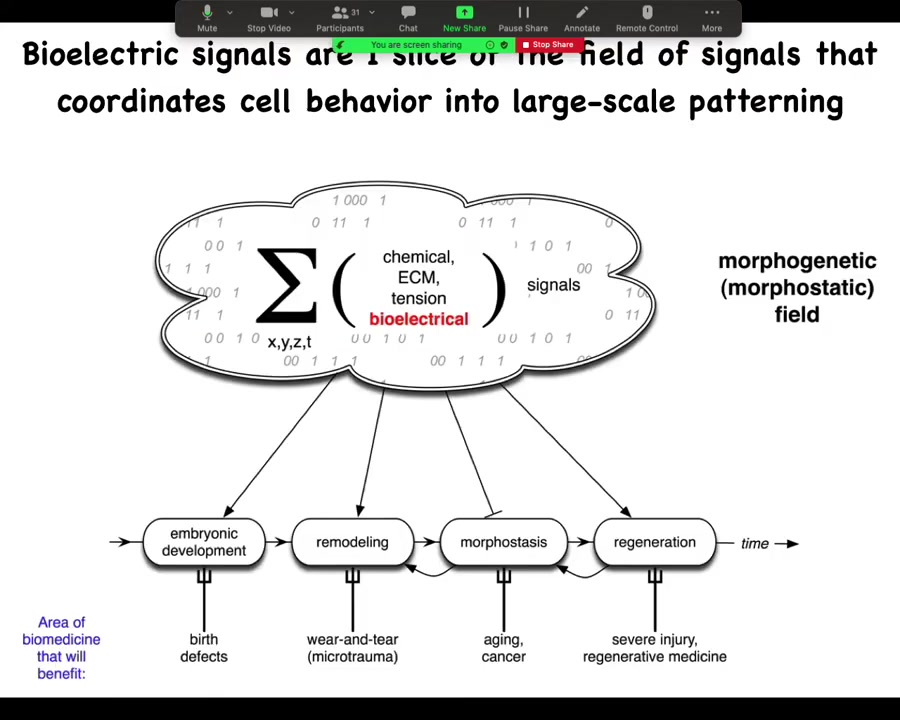

In order to make any practical use of this, we ask, what are these information signals that allow cells to join into networks to make limbs and eyes and livers and so on? There are lots of different components of this morphogenetic field. I'm going to focus on my favorite, which is bioelectricity. That's not to say that bioelectricity does everything. Of course, matrix is important and chemical gradients and oxygen gradients and extracellular tensions and stresses. All of these things are valuable. But I'm going to talk about one particular layer, the bioelectric layer.

Slide 15/44 · 12m:22s

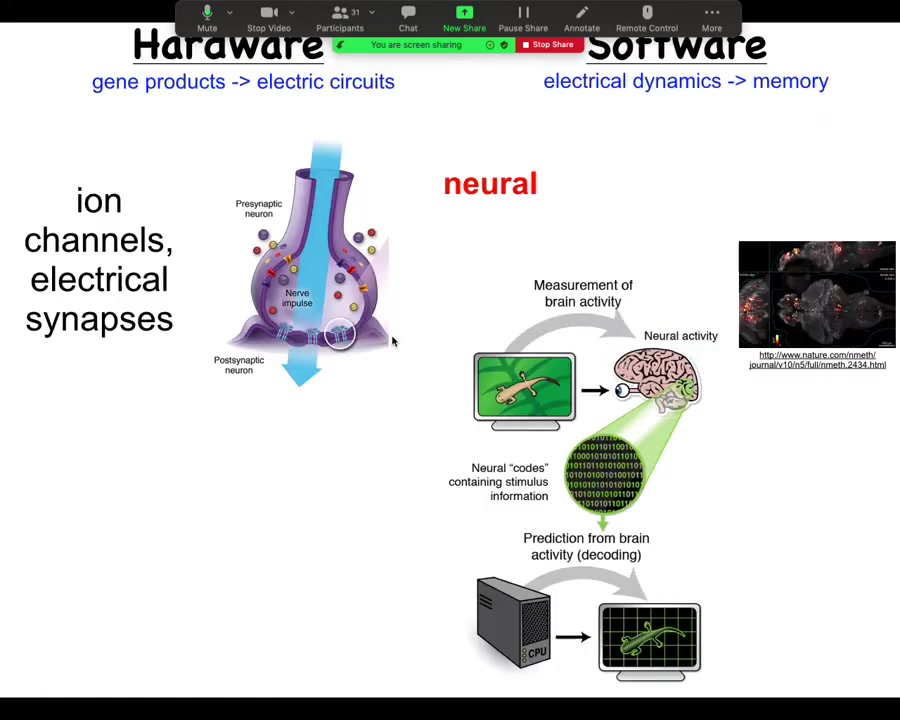

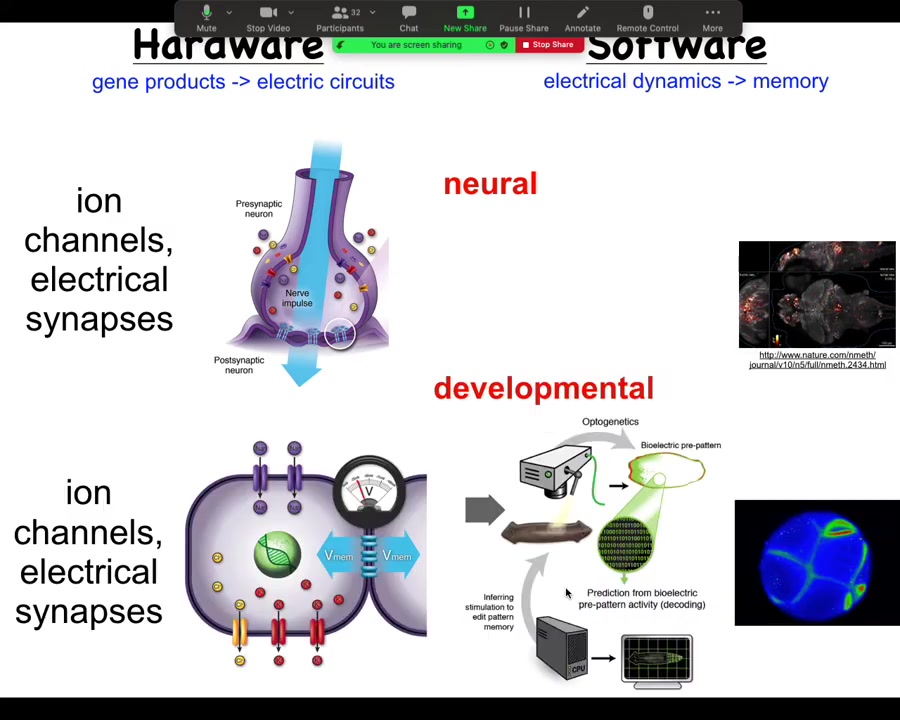

To start thinking about this, let's think about how it works in the brain, because that's the most familiar system. So in the brain, we have a connection, a collection of cells. Each cell has ion channels in their membrane; these ion channels pass things like chloride and sodium and potassium and protons, which go in and out, and the combined imbalance between positive and negative charges on either side of the membrane give the cell a resting potential. This resting potential can change as a function of time. It can propagate to the neighbors through electrical synapses known as gap junctions. We're not going to worry about chemical synapses for now. There's a large network. The electrical activity propagates through these things. Both the channels and the gap junctions are themselves voltage sensitive, which means that they are a voltage-gated current conductance, which is in effect a transistor. All of these electrical propagation dynamics can be pretty complex. You can't just estimate them in your head. You have to do modeling. All of this is an amazing system for running a certain kind of software.

Now, in the brain, this plays out as behavior. This is imaging that was done by this group on a living zebrafish brain, as the zebrafish is thinking about whatever it is that zebrafish think about. There's the idea of neural decoding, which is if we knew how to interpret these electrical signals, we should be able to take a reading of the living brain and extract from it, using various information processing tools, the cognitive content. We should know what the animal is planning, remembering, thinking, what it is going to do next, and so on. We believe that the dynamic activity of the system, the information flow, is encoded in these electrical signals. This is the commitment of neuroscience.

Slide 16/44 · 14m:25s

Turns out all cells in your body do exactly the same thing. Every cell has ion channels. Most cells have gap junctions. What we are trying to do is use electrical voltage imaging.

Here you see this is not a model or a simulation. This is a real frog embryo using a voltage-sensitive dye to reveal, much like here in the brain, the dynamic electrical communication that exists between these cells.

I'm going to argue that this is not just a pretty readout of what the cells happen to be doing. It's actually the information processing that enables these cells to go from being a ball of blastomeres to an incredibly complex tadpole.

Slide 17/44 · 15m:12s

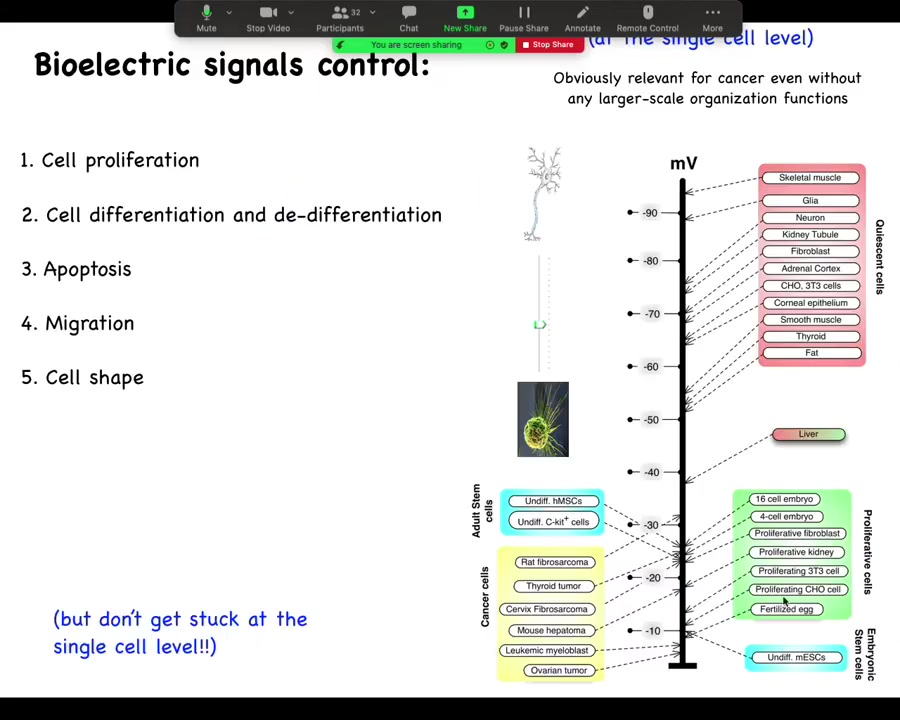

One thing I want to show you. One thing that's been known for a really long time is that if you track individual cell voltage, you'll see this really interesting relationship where very active proliferating cells, embryonic cells, stem cells, cancer cells tend to be very depolarized. They have a very low resting potential, whereas your terminally differentiated adult mature cells tend to be up here, hyperpolarized. And in fact, this is not just a readout. You can drag cells from this state to this state, for example, take mature neurons and get them to reenter the cell cycle by depolarizing them for several days. Conversely, you can take cells from this state and get them to lose their plasticity. Then you have interesting outliers like liver, which hangs out in between, which is interesting because it's an adult tissue with lots of regenerative potential.

The reason that I go back and forth on showing the slide is because people tend to really like this and then they focus on voltage as a single cell parameter. They say if we just address the voltage level of individual cells, we could target cancer. And that's part of the story. But I think a much more important part of the story is that the key decisions are not made at the individual cell level. They are network or tissue level decisions.

Slide 18/44 · 16m:35s

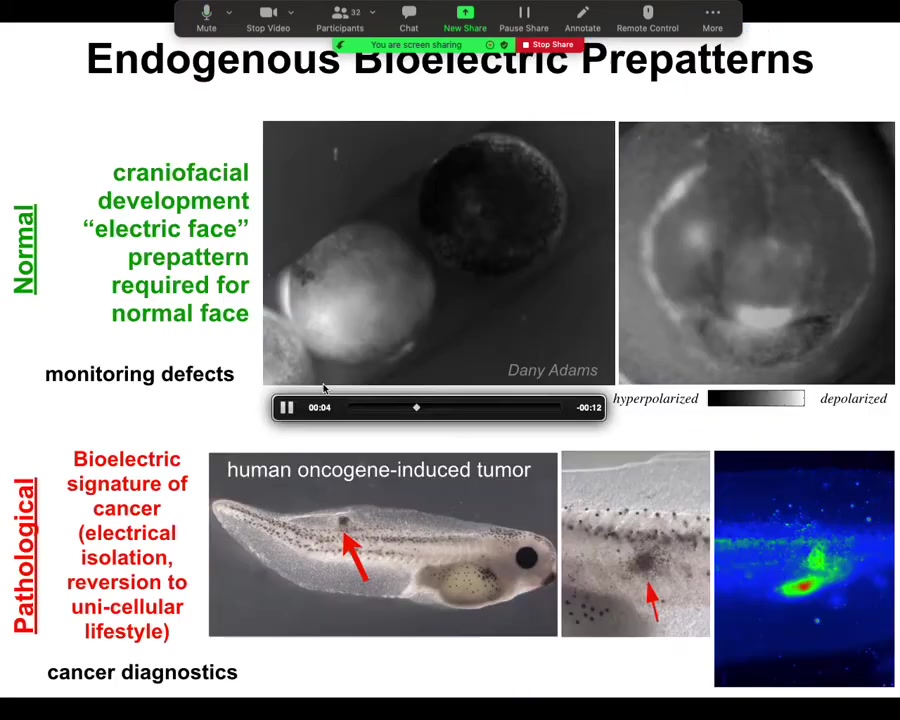

What happens in the normal embryo, for example, is shown in grayscale — a different way of visualizing the color values or the voltage. What you see is the embryo putting its face together. What you will see is something that my colleague Danny Adams identified when we were doing this some years back, looking at the bioelectrics of face patterning. Here's one frame out of that image. What you see is that here's where the eye is going to be, here's where the mouth is going to be, here where the placodes are going to be.

The layout of the future face, and in particular the gene expressions that are going to be required — frizzled and wints and all these things that are going to be required to do this — are shown in advance by the bioelectric pre-pattern that tells all of these domains where they're supposed to go. It's not just an image: if we artificially move this — if we wipe off this voltage spot and reintroduce it somewhere else — guess where the eye is going to be. This is instructive for face. In fact, human channelopathies which have craniofacial birth defects often have these kinds of ion channel mutations that alter this electrical face pattern. This is a native endogenous pattern that is required for normal face morphogenesis.

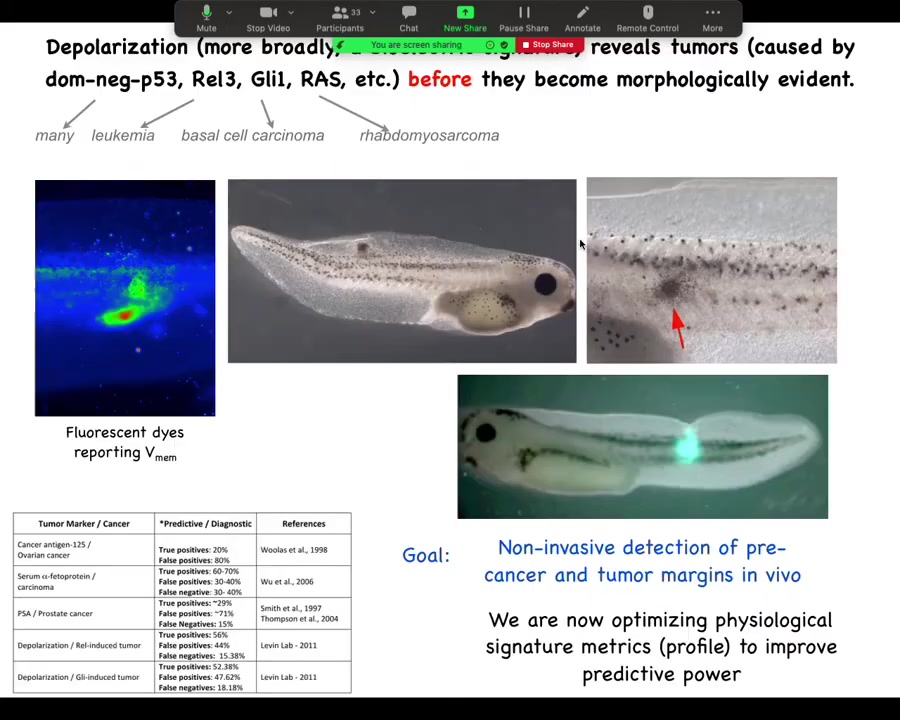

Here's the pathological pattern that Thea was just asking about. If we introduce an oncogene into this tadpole, it will eventually make tumors. Here it is. It's starting to spread. Even before that tumor is histologically or anatomically apparent, you can already see from the voltage map where it's going to be. Here's the epicenter of it, and then here's some other stuff around it that you may not catch later on. This has straightforward implications for cancer diagnostics. I have some ideas for a goggle system that you can use either at home to screen your skin or during surgery to see tumor margins. You can use these voltage reporter dyes to identify these aberrant cells.

There needs to be some interpretation because the other thing you're going to catch is some stem cells. There needs to be some work done to be able to distinguish those two. You can find things like this that are nascent tumors.

Slide 19/44 · 18m:54s

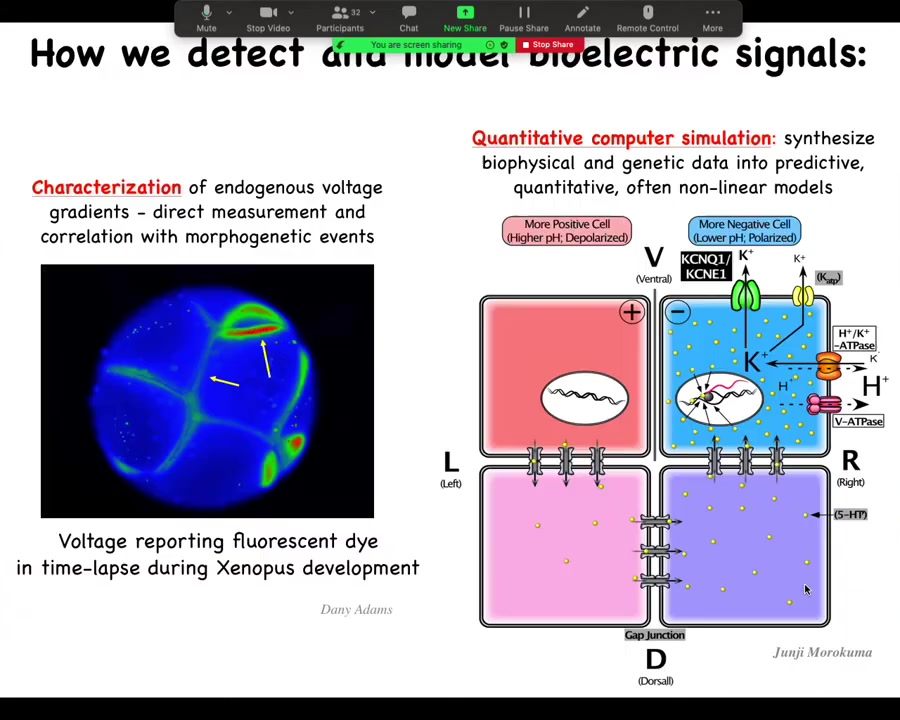

Here are the techniques we've developed because it's important to know how we do this. Voltage-sensitive fluorescent dyes — there are a variety, although we still need some development of these. Lots of computational modeling: taking expression levels of different channels and pumps and gap junctions and putting them together in a quantitative model that explains why the pattern is this as opposed to some other pattern.

Slide 20/44 · 19m:22s

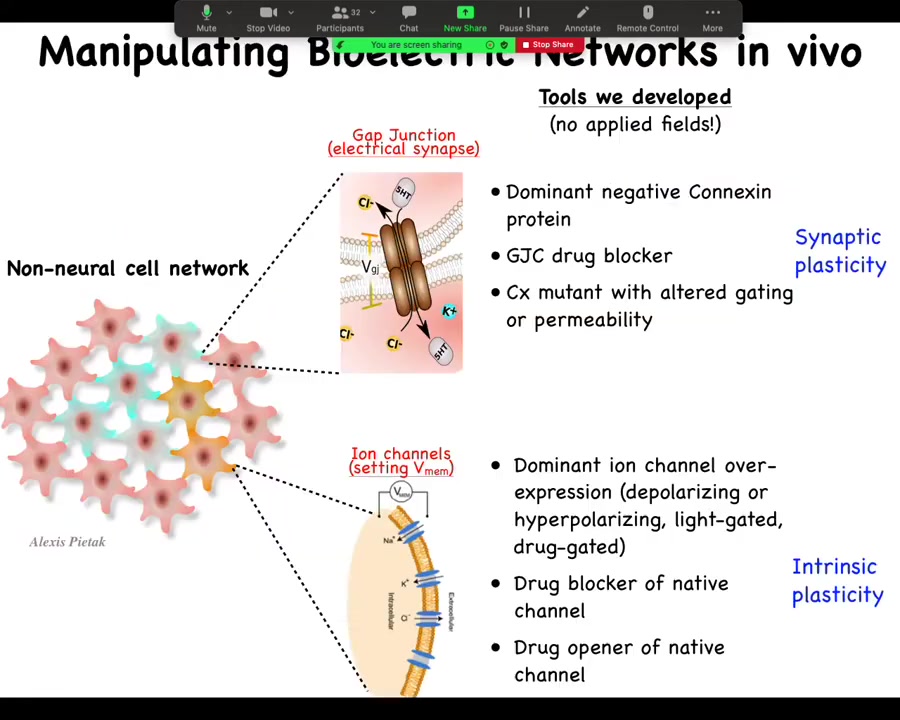

And the most important part is the functional tools. So this is really critical. In perturbing these electrical networks, we do not use external electric fields. There is no magnetic component. We don't use waves. We don't use electrodes. We don't apply fields or currents. This is all molecular physiology. We manipulate the endogenous channels and gap junctions that give rise to these electrical computations.

So what we might do is go in and control which cells talk to each other via gap junctions. So we change the topology of the network. This is equivalent to synaptic plasticity if we were neuroscientists. So you go in and you can mutate the gap junction to another form or you can block it with drugs. And with ion channels, we can manipulate the voltage of individual cells. And so again, you can mutate the ion channels; there is a huge pharmacological library of compounds to open them or close them. You can use optogenetics. You can use light to open and close certain channels. And this would be the equivalence of intrinsic plasticity.

So why is this interesting? Why would you want to do something like this? I'll say that when we first started, the standard assumption was that voltage was just a housekeeping property of the cell, and if you mess with it, you're going to get uninterpretable cell death, and that wasn't going to be it. And I'm going to show you that is not the case.

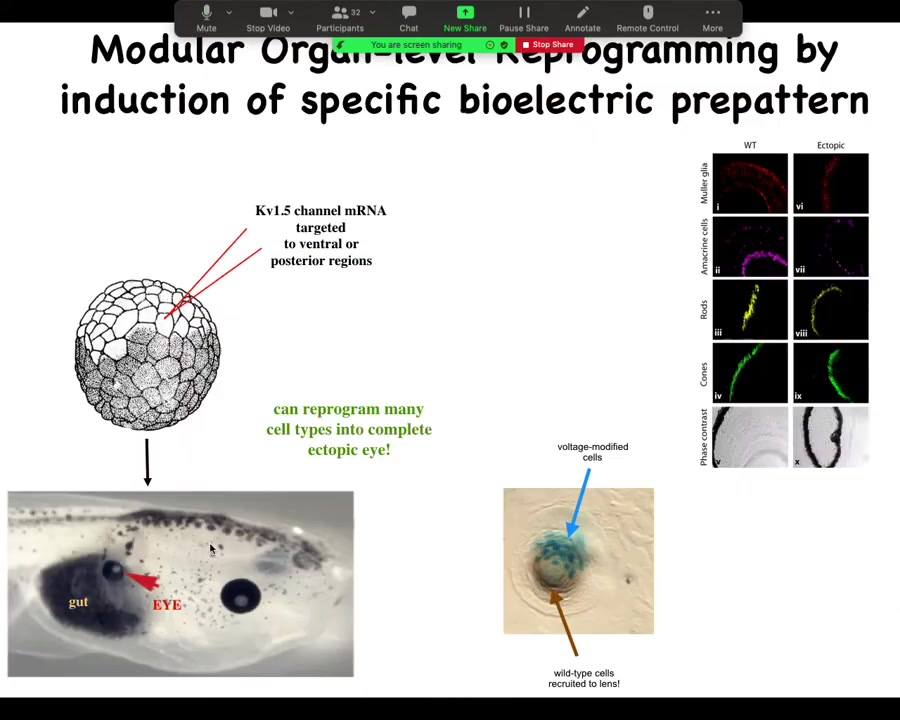

Slide 21/44 · 20m:44s

One of the things you can do is you can trigger organ-level morphogenesis. What I can do is take some cells in this tadpole that normally are fated to be gut, endoderm, and I can inject one ion channel, let's say KV 1.5 RNA, and what happens when I inject that ion channel is that it sets the voltage potential to a particular state. In particular, it creates a spot that's a pattern that looks like that eye spot in the electric face.

When you do this, what you're saying to the cells by putting down that pattern is, make an eye here. It's a trigger. That bioelectric pattern serves as a kind of subroutine call to the rest of the cells that say, you are now pressed into the following anatomical goal. You're going to express a bunch of eye-related genes, and then you're going to make an eye. Sure enough, they do on the gut.

Now, your developmental biology textbook might say that gut cells are not competent to be eyes, that only happens in the anterior neorectoderm. That's true if you stick with molecular biology master regulators like PAX-6, but it is not true if you go up the causal chain and address the bioelectric states that tell every tissue what it should and shouldn't be.

We can induce these eyes on the tail, in the gut, in the flank, wherever. It has a very interesting non-local property: what you see over here is a lens sitting out in the flank of a tadpole induced this way. The blue cells, marked with beta-gal, are the ones that got the channel. They are the ones that have been directly modified. But all these other cells down here have been induced by them to participate together in making this perfectly round lens. These cells down here were never directly modified by us.

What you see is that you're not micromanaging the spatial structure. Once you get enough cells committed to the fact that we're making an eye, you trigger instructive interactions whereby you don't have to micromanage these details. You don't have to tell them how many cells make up a lens. They figured that out on their own. Your goal is to identify the trigger that convinces the whole region that that's what they should be doing. You can do this with only partial cell coverage.

What would you call this—an emergent event?

I would call it an emergent event in the sense that the information you're providing is very, very low information content relative to what comes out. We don't have any clue about how to make a whole eye. There are all kinds of different cell types, tons of genes that would have to be turned on and off. If we tried to do this manually, at the lowest level, just programmed directly with some sort of stem cell strategy, to program directly the creation of an eye, that's not going to happen in our lifetime. You just pull the trigger.

It is absolutely emerging because what we've identified by treating the rest of the tissue not as a clockwork machine of the simplest type, but actually as a programmable, information-processing agent that has subroutines, is that we can now ask the question, what subroutines exist and what are the triggers? Here's a trigger that the embryo natively uses. It's not one that we created. We're just hijacking what's already there. It already uses this voltage trigger to make eyes in the first place, and the cells are happy enough to do it again and again. Here you can see they have the lens and retina and optic nerve and all the stuff they're supposed to have.

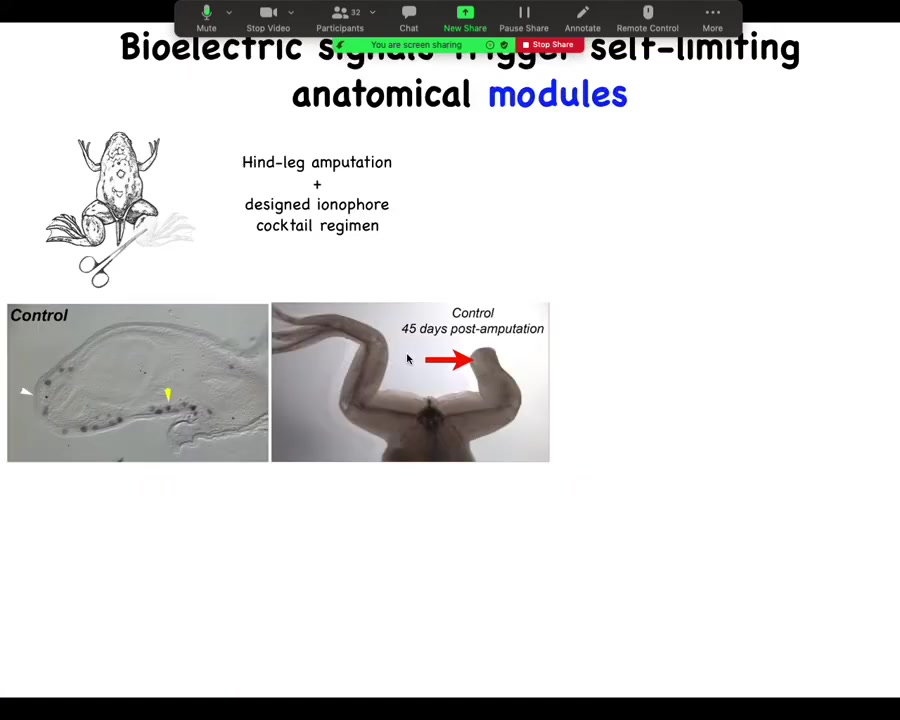

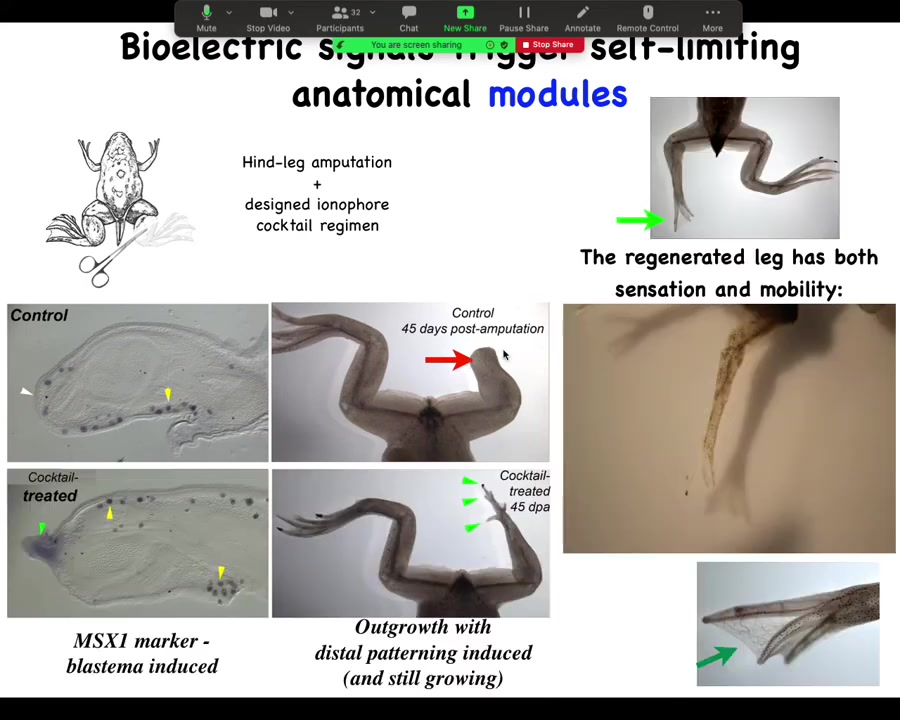

Slide 22/44 · 24m:31s

For further regenerative medicine, we're moving forward into, for example, limb regeneration. So here is a frog. Frogs, unlike salamanders, normally do not regenerate their legs. 45 days later, there's nothing after amputation, but we have a cocktail that triggers a bioelectric state that then kickstarts this whole cascade.

Slide 23/44 · 24m:49s

It turns on pro-regenerative genes such as MSX1. It starts to grow with the leg, with the toes and the toenail, and eventually the leg is quite respectable. You can see that it's both touch sensitive and motile. The animal can feel that and use the leg to get away. It's a pretty good leg.

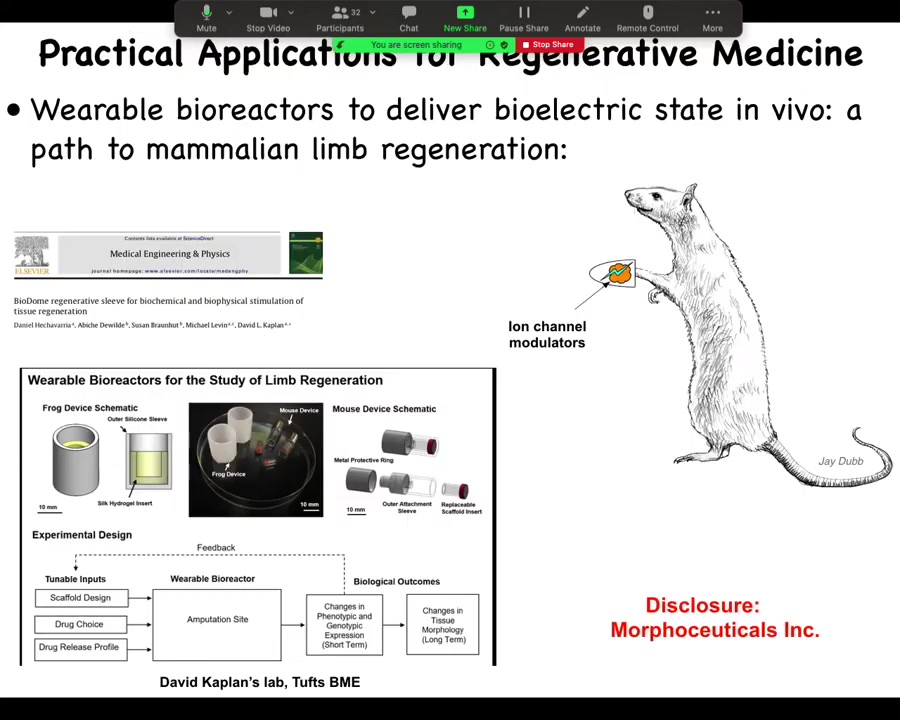

Slide 24/44 · 25m:14s

Now we are moving this into mammals. We're trying this in mice. This is where I have to do a disclosure. We have a company called Morphoseuticals, Inc., which David Kaplan and I founded to use this technology for limb regeneration. That's an industry disclosure. What I've shown you so far is that these bioelectrical signals are important determinants of large-scale anatomical structures.

Slide 25/44 · 25m:41s

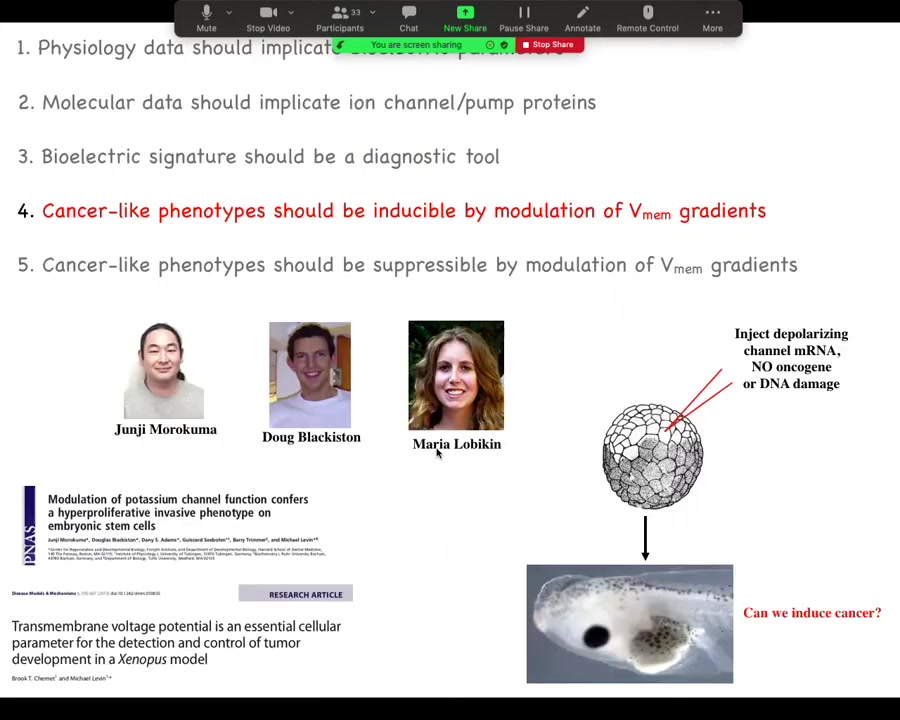

What do they have to do with cancer? We can make 5 predictions. The first is that the physiology data should implicate electrical parameters in cancer. The molecular data should implicate ion channel and pump proteins in cancer. The bioelectric signature could be a tool, a diagnostic tool for tumorigenesis.

This interesting suggestion is that cancer could be inducible by modulation of voltage gradients in the absence of genetic damage or carcinogens or anything like that. Better yet, this is the one we're all hoping for: cancer could be suppressible by modulation of these V-mem gradients. Let's just run down these and see what's true.

Slide 26/44 · 26m:30s

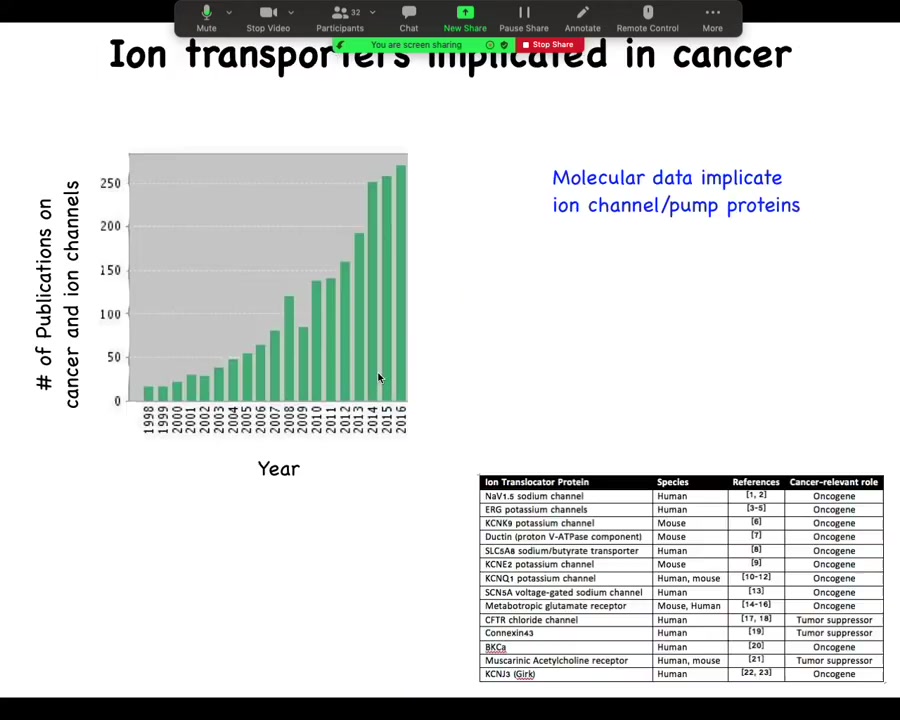

This is now quite old. I'm realizing 2016. But if you look at the number of publications that deal with cancer and ion channels, it's started shooting up in the last 20 years, and now there are way more. I need to update this. In fact, there are about a dozen channel and pump genes known as either oncogenes or tumor suppressors. So that's interesting.

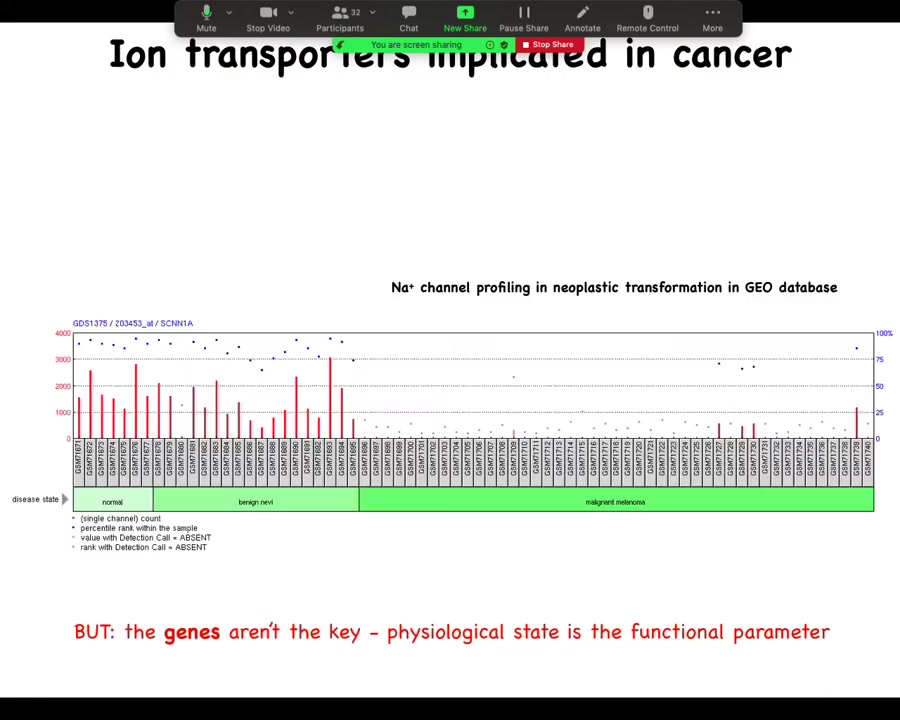

Slide 27/44 · 26m:58s

You can mine all sorts of databases, such as this one, where you can see during the progression there are important changes in the expression of specific channels, but this is really critical: the genes are not the key here. All this is a rough guide of where to look, but this is not the driver. The driver is not the gene expression; the driver is the physiological state, and the reason that's really important is that these channels, because they are information processing hardware, open and close post-translationally.

You cannot, using any kind of profiling, not transcriptomic, not proteomic, tell what the electric state of a cell is by looking at what's expressed, because you don't know if the channels are open or closed, because that's driven by the physiological history of the cell. So this kind of profiling can give you a hint of what might be the important players in terms of control knobs that you can use. What are the channels that might be useful to you?

But you cannot extract a bioelectric state from profiling dead cells. All of the important bioelectric parameters disappear as soon as you fix the cell. And then if you take, you fractionate it into protein and RNA, all of that goes away. So physiological profiling is really key.

Slide 28/44 · 28m:18s

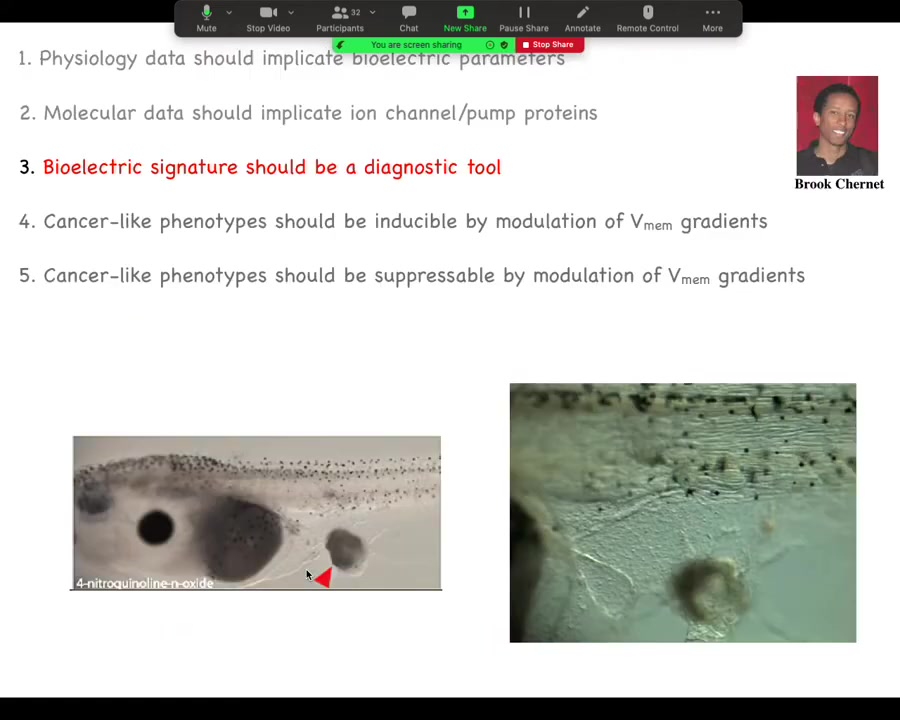

There's a whole effort in treating, looking for ion channel drugs as cancer drugs. What holds back that whole subfield is this idea that what people do is they treat ion channels as oncogenes and they see it upregulated in some tumor and they go, we need to block it and then life will be good. And that is maybe how you would do it if it were a transcription factor or some biochemical thing. But bioelectricity does not work like that. And it's really important to keep track that it's the physiological state that's critical. And this is largely the work of my PhD student, Brooke Chernan, from a few years back.

Slide 29/44 · 28m:58s

The first is diagnostics. We can inject various oncogenes from human patients into embryos. This is not a claim that oncogenes are always what start tumors. I'm just using these as a tool because they do happen to trigger tumor genesis to some extent in tadpoles.

We can use that to gauge the false positives and false negatives against other tests. Ultimately, the signature is going to be a combination of dyes and some interesting formula of how much aberrant potassium flow versus voltage versus other things. We've done work on this as a diagnostic, and you can tell exactly where the tumor is going to form.

Slide 30/44 · 29m:50s

We had a heck of a time initially with reviewers on this, because what we show here is that you can do something very interesting. Here are two of the main papers on this, and this was driven by these folks in my group. We said if we artificially disrupt this electrical communication, could we trigger cancer without any damage to the genome, without any oncogenes, no carcinogens? Could we trigger this because that's a strong prediction of our model?

Slide 31/44 · 30m:21s

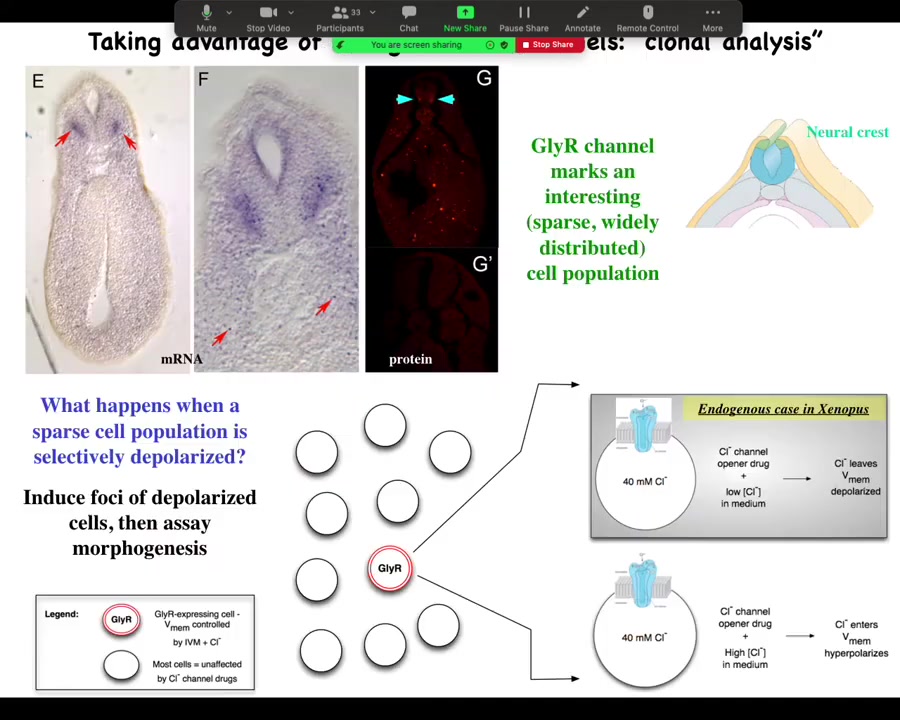

And the way we did it was we identified an interesting and sparse cell population here. You can see them here. The marker for this is the GlyR channel, the glycine-gated chloride channel. The reason we like this is because chloride is cool.

Here's one of these cells. It has a chloride channel in the membrane. If you use a drug like ivermectin to lock this channel in an open position, then what you can do is add various amounts of chloride externally and use that to dial the cell voltage up or down, because the inside, at least in a tadpole, is about 40 millimolar. If there's more outside, it'll go in, and now you've hyperpolarized the cell because you drive a bunch of negative charges into the cell. If, on the other hand, you're in a medium where there's less chloride, this chloride will tend to come out. And so you can use it as a convenient control knob on the voltage.

We said, here's this rare cell population. Nobody had described it before. What happens when you mess with its voltage?

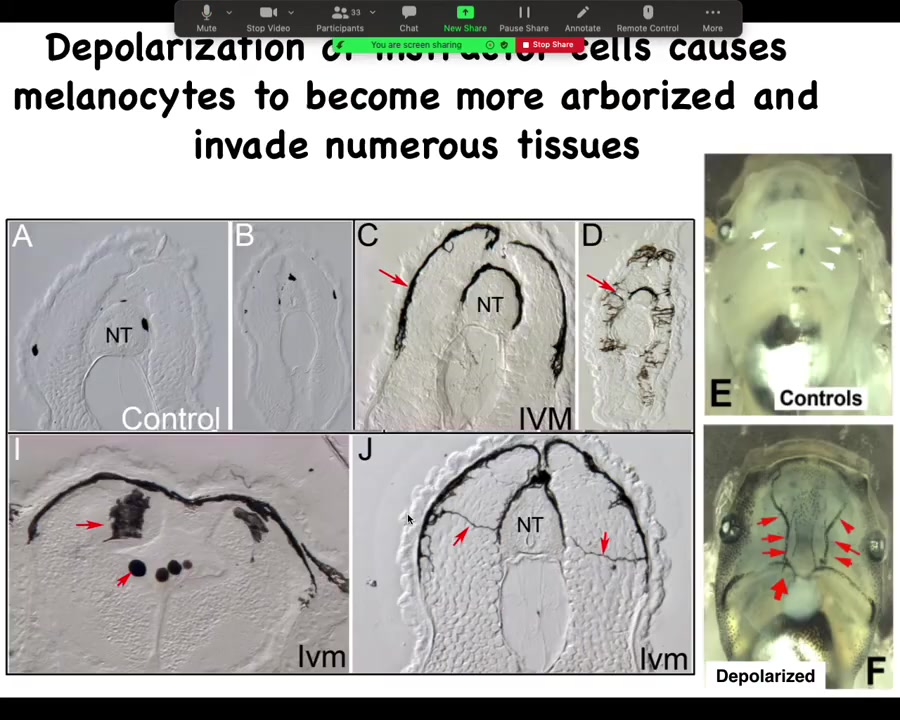

Slide 32/44 · 31m:25s

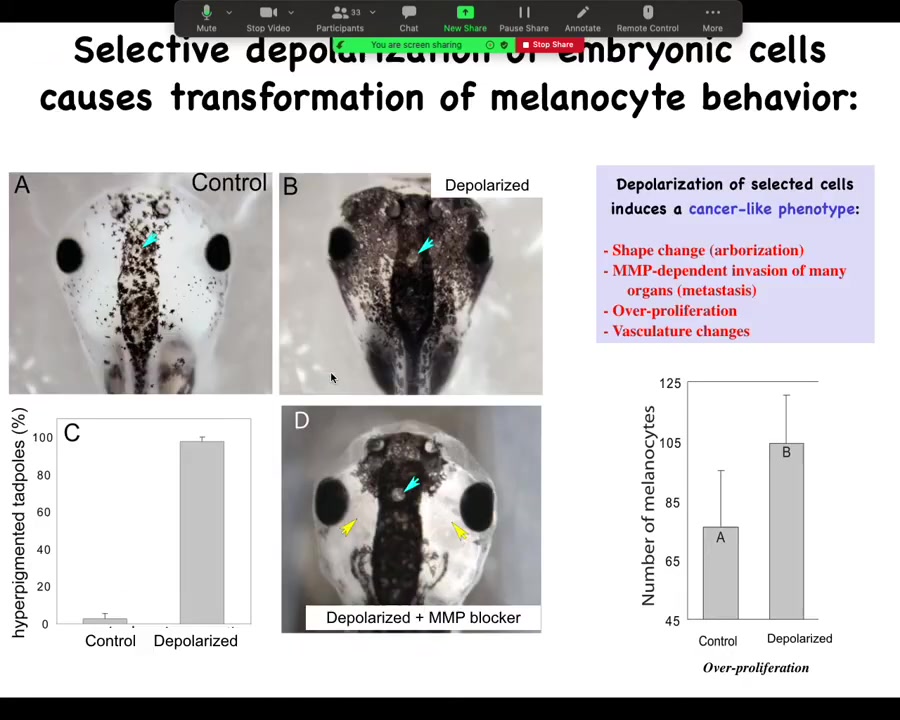

The embryos end up with metastatic melanoma. These are normal melanocytes. These are pigment cells. You can see there's usually a variety of them up here in the neural tube. This is a tadpole. Here are some nostrils. These are the eyes. Here's the brain and here's the gut back here. Normally it's this.

You throw them into some ivermectin with low external chloride, and the animals start to turn black. All these melanocytes go crazy. They over-proliferate. They cover these areas that are normally kept clear. One area they never cover is this little moon roof on top of the pineal gland. It's unknown why they refuse to cover that, but they respect this boundary. It's wild.

They do this in an MMP-dependent fashion. If you block MMPs, they can't get out here, but they still over-proliferate.

Slide 33/44 · 32m:22s

Here's what it looks like internally. These are cross-sections through that tadpole. Normally these black spots are the melanocytes. NT stands for neural tube. Here's the neural tube. You should see one, two, three, four, five of these small, round pigment cells. Here it is up at the anterior of the animal, and here's the tail; it's a little squished, but here's where it is.

The ones that are transformed by our ion channel drug—this is what they look like. The melanocytes have gone completely crazy. Look at these projections. Instead of being these little round things, they form these long, ridiculous projections. The projections are all over the place, and they start to invade. They invade the neural tube, the brain. They dive into the spinal cord, into the lumen of the neural tube, and they just completely start to take over. They are filling up the blood vessels. These are the two major blood vessels, which should be nice and clear normally. They're just completely going crazy. The longer you let these animals live, they get completely filled with these melanocytes that just go nuts and they change. Everything about them changes.

Not just the melanocytes, but the vasculature changes. You start to induce these abnormal vascular paths.

Slide 34/44 · 33m:46s

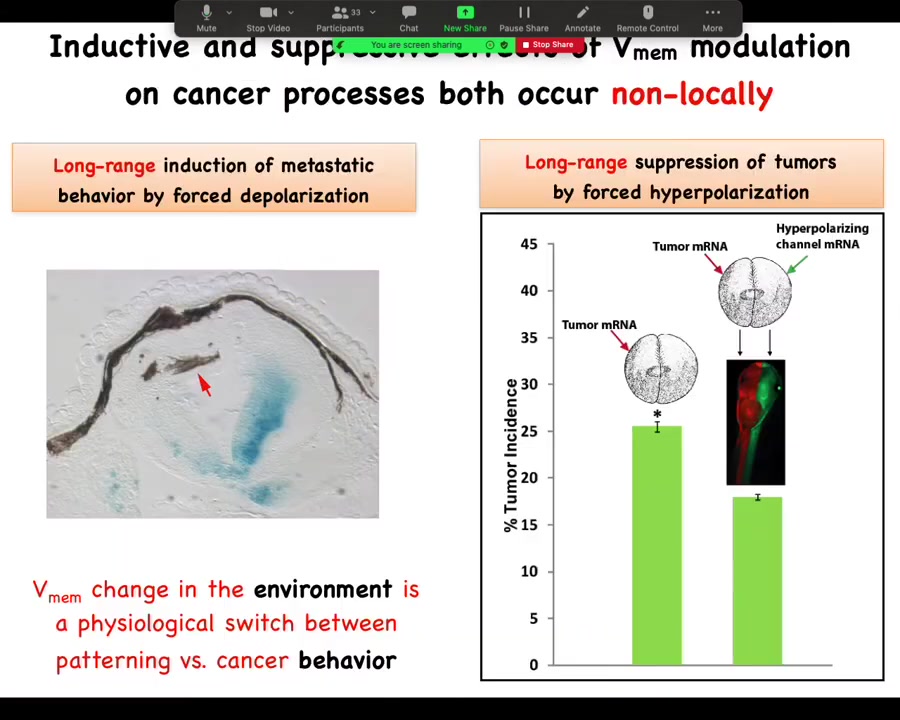

One thing that's really interesting about this is that the cells that transform are not the cells that we depolarized, and you can see that in this experiment: the blue region is where we put a depolarizing channel. This is with a drug; you can't really do spatially specific experiments, so we use the depolarizing channel here, and the blue cells are the ones that we depolarized.

The melanocytes that went crazy are up here at a considerable distance, and this is going to become important momentarily: this is not a cell-autonomous phenotype. It's the voltage change in the environment that is the physiological switch towards metastatic behavior. I won't take the time here unless somebody asks afterwards, but we took apart the whole process.

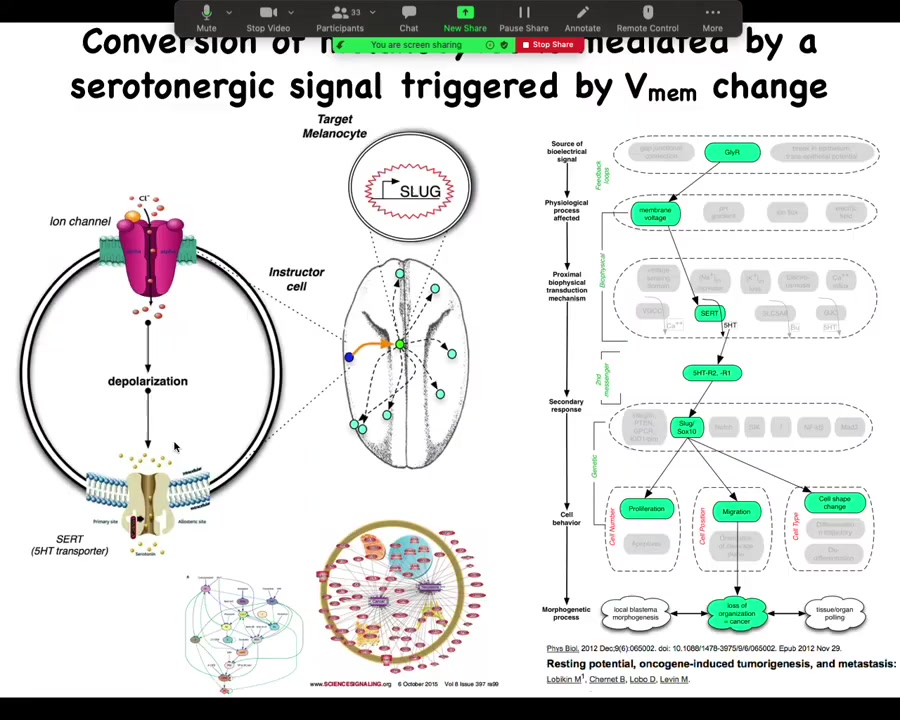

Slide 35/44 · 34m:37s

It's serotonergically mediated. Those cells communicate to the melanocytes via serotonin, and we've done all kinds of profiling of the transcriptional responses.

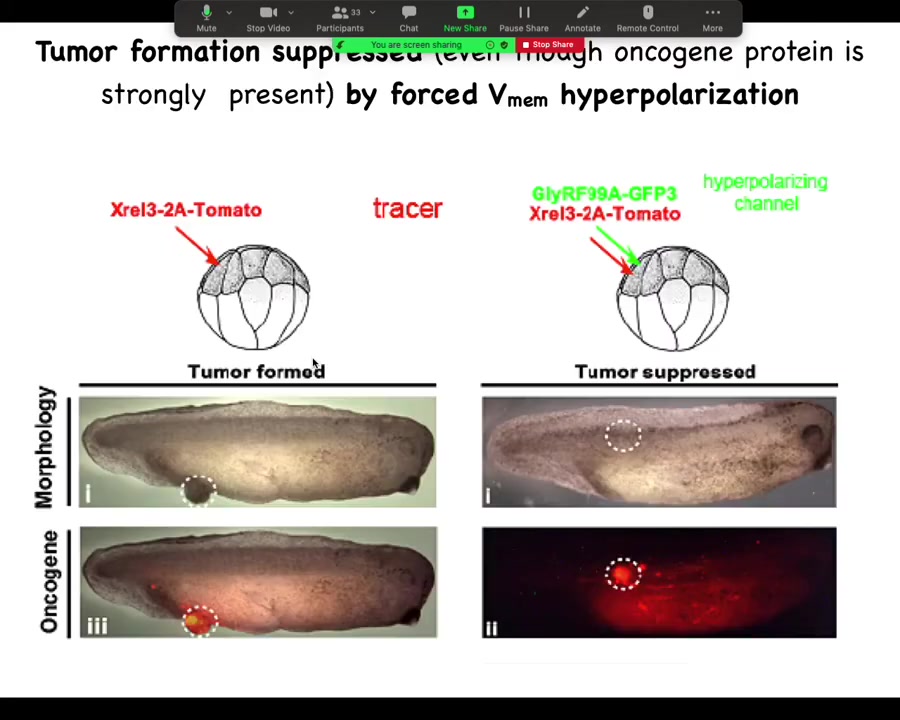

Back to Brooke's work: can we suppress this? Now that we know we can induce this phenotype, can we suppress this?

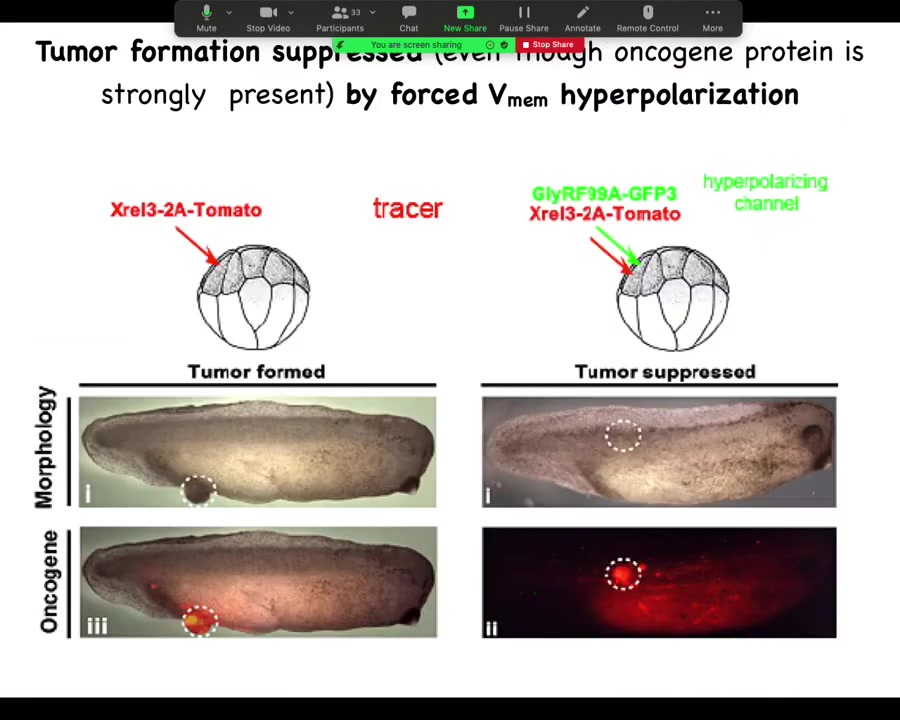

Slide 36/44 · 35m:13s

He did a very simple experiment: inject your various oncogenes, and the oncogene itself is labeled with a red fluorescent protein, so you can see it. Here it is, and it makes a tumor, and all the tissue that got injected is bright red, and here there's some escapees that are leaving and colonizing.

What he found is that if you co-inject into these cells an ion channel that will prevent that cell from depolarizing and closing its electrical connections to their neighbors. One of the first things that gap junctions do is they cause cells to depolarize and lose gap junctional connections. That's been known since the 80s.

When you put in this RNA for this ion channel, even though the oncogene is blazingly strongly expressed, it's all over the place here. There's no tumor here because the channel, the oncogene says depolarize and leave and go off and start migrating and do your amoeba-like life. The ion channel says, nope, you're part of a network. You're going to undergo normal histogenesis like the rest of your neighbors. That tends to be dominant.

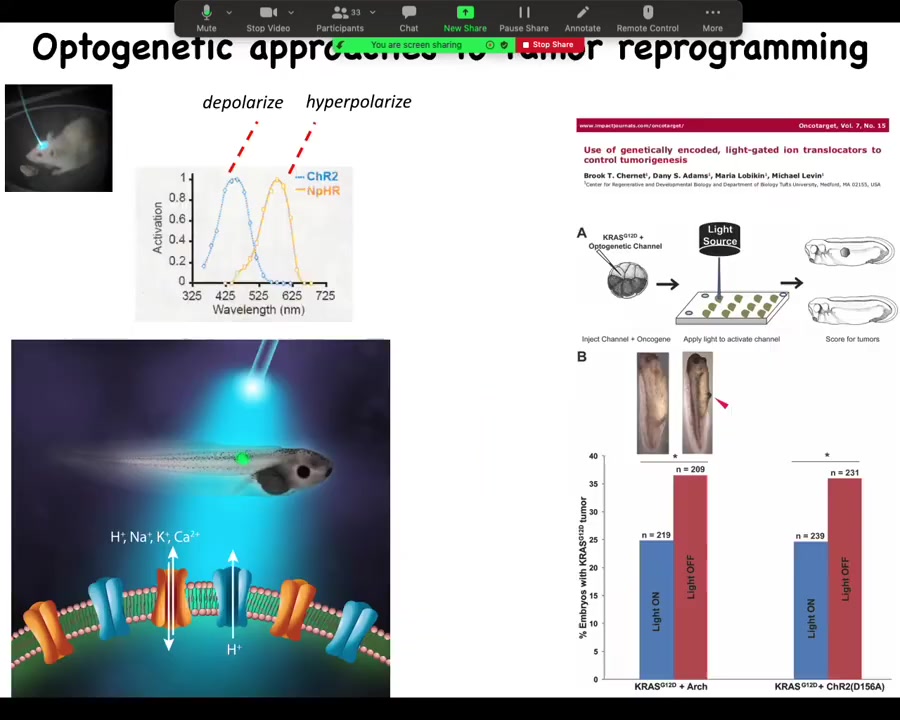

Slide 37/44 · 36m:23s

You have to tighten these things and so on. So the effect is not absolute. But you can see we can even do this with light. In this paper in Oncotarget, we did it with optogenetics. You can use light to turn on ion channels that will prevent oncogenes from inducing tumors.

One of the big issues that reviewers had with the previous story where we induced the phenotype is everybody said, "Where's the primary tumor?" In other words, show me that original broken cell. We said there is no primary tumor. Every melanocyte is converting at once and there's no primary site. None of the cells are broken because that's not what this is. They said if there's no primary tumor, then we don't know what you're looking at. So part of this is a conceptual thing. If you assume right up front that has to be a clonal relationship in a primary tumor site and all this, then this is all something else.

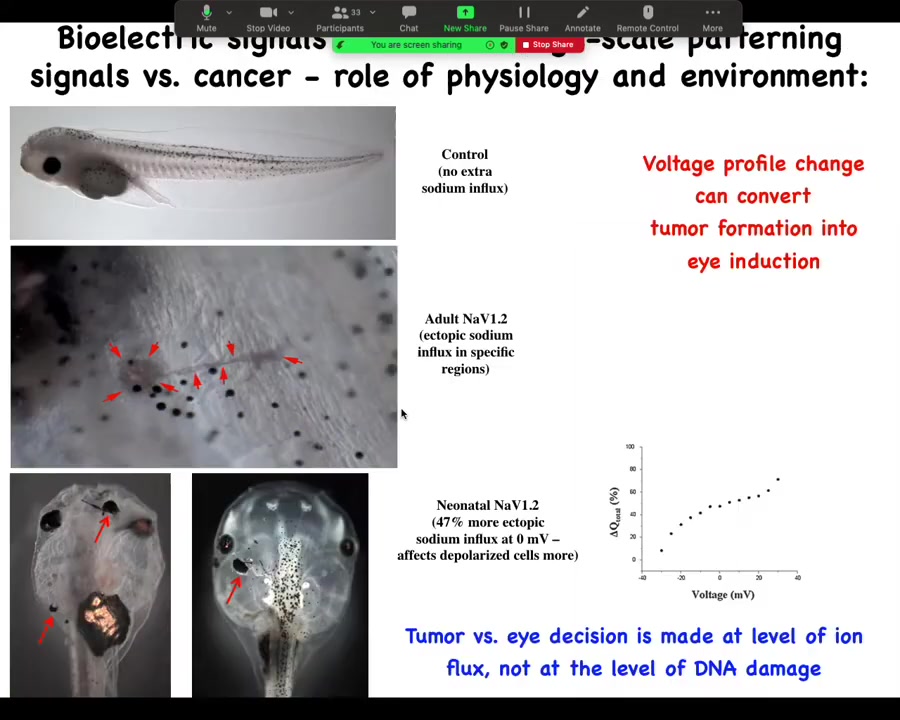

Slide 38/44 · 37m:25s

And in that continuous battle to say that it's not necessarily a problem with your genetics, we developed some of this data. We inject a sodium channel. Depending on the level of sodium outside of the animal, it will either make a tumor that starts to crawl off and invade, or it will make an ectopic eye. And you get to decide, eye or tumor, from exactly the same molecular state, just based on how much sodium is in the medium. And so you can see that these decisions are physiological control, environment, microenvironment, larger environment. It is not just that I've sequenced the mutation and now I can tell you exactly what's going to happen.

Slide 39/44 · 38m:08s

In fact, you can't tell what's going to happen in a case like this. If you were to profile this using any kind of sequencing, you would see this mutation and you would know that that causes a tumor in 80% of the tadpoles and you would be wrong because you cannot catch the bioelectric state that way and you don't know that it would have suppressed it. So in all of these physiological cases, the reality of the bioelectrics can give you a completely different result than anything you can predict from the molecular measurements.

Slide 40/44 · 38m:38s

To emphasize this long-range thing, I showed you before that I can induce this metastatic behavior from a distance.

And the same thing is true with these channels. What Brooke did was he injected the tumor RNA on one side of the animal. He injected the channel all the way on the opposite side. Not together with the oncogene, but on the other side of the animal. We used different color tracers. You can see here exactly where the oncogene went and where the ion channel went. The magnitude of rescue is quite similar. You can do this from a distance as well as in the same cell. Again, not cell autonomous.

Now, this ability to signal across the body to make a difference electrically is not just for cancer.

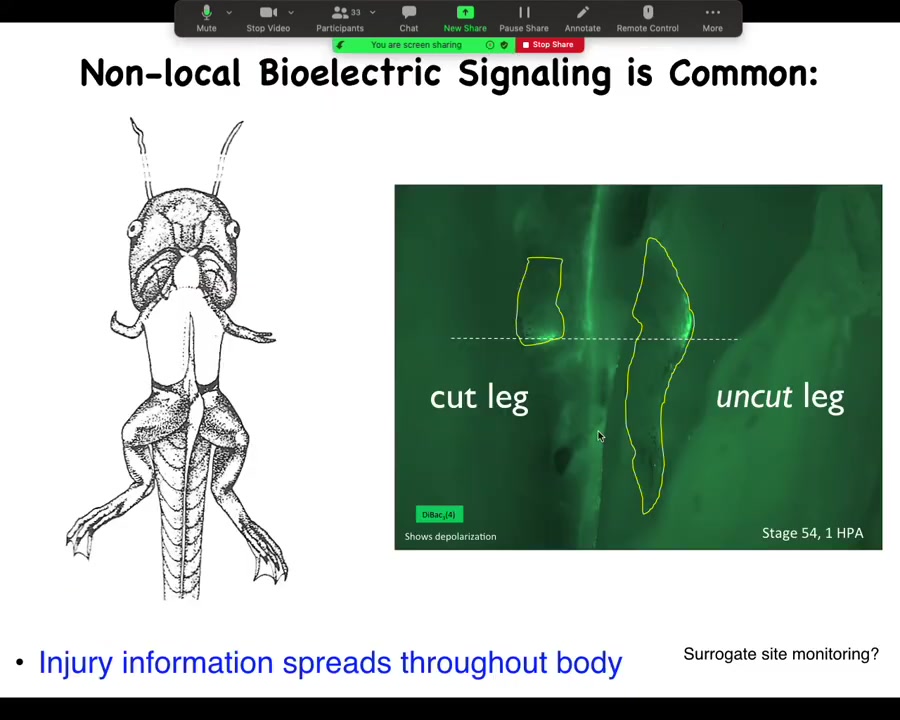

Slide 41/44 · 39m:30s

This is a study we had a couple of years ago showing that here's a froglet. We amputate the leg, and when you amputate the leg, there's a bioelectrical state that comes up, the opposite leg that we never touched, never got injured, lights up within 30 seconds in exactly the same location. And in fact, by tracking this signal, I can tell whether this was an amputation or a puncture wound.

Electrical information about the physiology of what's going on, damage and various other things, is apparent at a long range because that's what electrical signals are really good at. They're good at propagating information. This is not neural because we can take out this whole spinal cord. You just take it out and it works exactly the same way. It doesn't propagate through the neurons.

This actually harkens all the way back to Harold Burr in 1938, who claimed with early voltmeter measurements he could tell which of the rabbits that he was working with had tumors by taking voltage measurements all over the body that he argued for a non-local presence of this information. I think he was probably right because we see this quite clearly.

Slide 42/44 · 40m:46s

Just to summarize, we can look at cancer as a disorder of pattern regulation of signals that bind cellular activity towards tissue and organ level goals. The long-term story is not simply that voltage tells cells whether they should be cancer or not. The bigger picture is that the voltage is a medium in which the decisions of cellular collectives are made in terms of where they're going to go in health and disease.

The actionable discoveries are that bioelectric properties can be used to detect, induce, and reprogram this kind of cell behavior. We know we have tools where these electrical circuit dynamics instruct the outcomes without targeting the genome. Not terribly surprising for anybody who's in neuroscience: we do this all the time through experiences, through rewards and punishments, through drugs; you can affect outcomes and you don't need to rewire pathways or change gene expression directly.

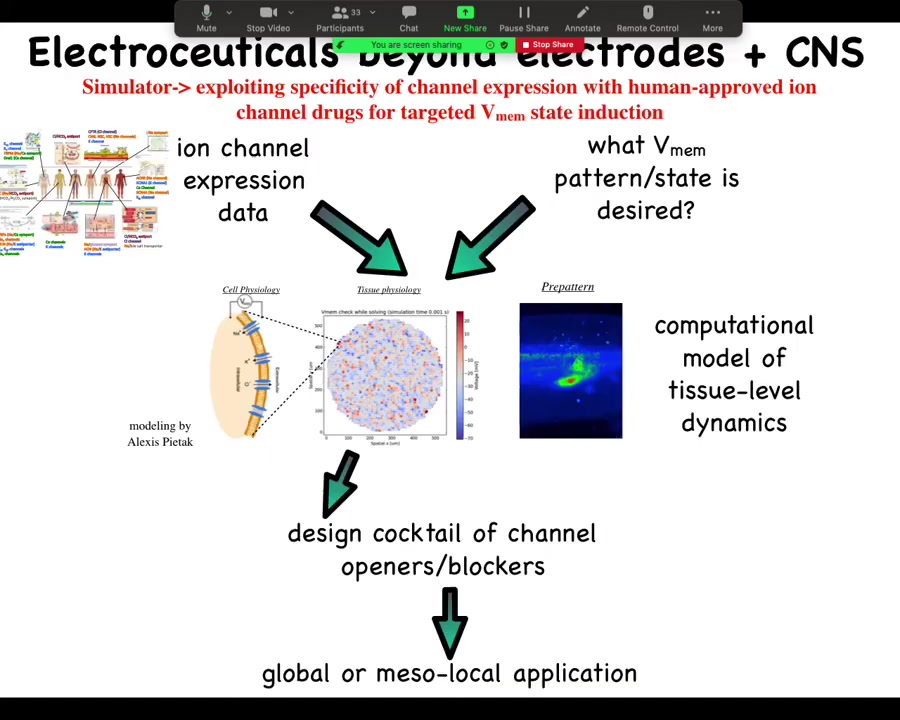

What we're now trying to do is to derive some strategies, if we move this into mammalian systems, for using this stuff as electroceuticals. How would you do that?

Slide 43/44 · 41m:59s

The general workflow looks something like this. We already have from other people's expression profiling, RNA-Seq and things like this, a list of channels that are present in your tissue of interest. Let's say you're working in the liver and you want to know what are my control knobs? What are the channels that I could turn on and off in the liver to make electrical changes? There are profilings and you get that data. Then you have to know what is the correct bioelectrical pattern. What does healthy tissue do? Then you have a question to answer. Which of these channels do I open or close to get to the correct pattern? It's not obvious at all. You need a computational platform, which was built by our collaborator, Alexis Pytak, which is this incredible computational modeling of bioelectrical networks. Once you've built that model, you can invert it and interrogate it to say, here's the electrical pattern I have now. Here's the electrical pattern I would like to have. What channels and pumps do I open or close? It will tell you. Then you go and you say, what drugs exist to target these channels. Something like 20% of all drugs are ion channel drugs, many of them already human tested. People already take this stuff for epilepsy and cardiac disease and so on. Huge pool of electroceuticals for addressing this problem once the computational platform is in place and once we actually know what is the correct state for the various tissues of the human body, because we actually don't know. There's been very little profiling done for most of these. That single slide I showed you with five or six tissues on it, that's about it. Nobody else actually knows what the correct electrical states are. Lots of opportunities here.

We've used machine learning to both make and interrogate these models that link bioelectrical, serotonergic, and molecular components and find that needle in a haystack intervention that will do what you want them to do.

Slide 44/44 · 44m:04s

Here's where we are. We need to refine that physiological signature to get to a non-invasive optical diagnostic, whether it be on excised tissue, during surgery, or at home. We need to refine these control methods for mammalian systems. And bigger picture, long-term, we need to crack this electrical code. We need to understand how to induce normalization, not micromanage cell states, but to really just trigger normalization the way that we trigger eye and leg and brain development. We would love to work with you to do any of this.

And just to thank the people who did all the work I showed you today. There's a review; here's one if you would like to take a look.