Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a ~1 hr talk on what is similar and what is different between biological and (current) technological information-processing systems, and the implications for biomedicine, AI, and ethics. A version of this talk with Q&A at the TPC consortium at Argonne National Lab is at https://tpc.dev/tpc-seminar-series/

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Turing, morphogenesis, and minds

(05:39) Unconventional biological intelligence

(13:11) Collective cellular intelligence

(23:39) Bioelectric networks and code

(30:45) Rewriting anatomical body plans

(38:00) Unreliable substrates and agency

(48:51) Future minds and models

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/55 · 00m:00s

Thank you for having me here. What I'm going to do today is share some ideas around the intersection of biology, cognition, computer science, and philosophy. If you want to download any of the primary papers, the data sets, the software, everything is here at the site. My own personal views of what it means are at this blog here.

Slide 2/55 · 00m:26s

So Alan Turing needs no introduction. He was very interested in intelligence, broadly conceived in different embodiments, and in particular in problem-solving machines, that is, intelligence through plasticity or reprogrammability.

Towards the end of his life, he also wrote this paper on the chemical basis of morphogenesis. This was one of the first computational attempts to understand how embryonic order self-organizes from mixed chemicals. You might wonder, why would somebody that was interested in intelligence and computation be interested in the ordering of chemicals during embryogenesis? I think it's because Turing saw a really important symmetry, an invariance between the self-creation of bodies and the self-creation of minds. I think he was on to something very important because, as I will argue today, those processes are tightly related and if we want to understand where minds come from, we really need to understand developmental biology.

Slide 3/55 · 01m:31s

Today, I want to talk about four broad things. I will show you some amazing examples of biology, in particular intelligence in biology. These are things that you may not have seen elsewhere, because nowadays things are much more focused on a canonical set of things that are convenient for molecular biology. I'm going to show you some things that are outside of that set.

I'm going to talk about the recent progress we've made on communicating with the agential material of life, in particular, the bioelectric interface that has many applications in medicine and engineering. I'm going to talk about why I think it works. What are the principles that are special for the agential material of life? At the end, I will speculate wildly on what I think it means for not only biology and medicine, but AI and beyond.

Fundamentally, what I'd like to do is to describe which are the things that are very different between the way biology handles things and the way our current computational approaches do, but then also point out that there are some things that are fundamentally very similar despite these apparent differences. It's pretty popular nowadays to focus on the distinction, at least among the biologists, and point out why machines and computers are not doing what biology does. To some extent that's true, but I want to focus on the similarities as well.

Slide 4/55 · 02m:57s

One of the things that underlies a lot of thinking in this field is this classic piece of art called Adam Names the Animals in the Garden of Eden. He is naming a discrete set of other creatures. Everybody knows what these different species are. They are quite discrete and distinct from each other. Natural kinds is the idea. Of course, Adam is different than all of them. I'm going to argue that this is an incredibly rate-limiting framework for progress, and we need to dump many of the ideas that underlie this.

There is something foundationally profound here, which is that in this old story, it was up to Adam to name the animals. God couldn't do it, the angels couldn't do it, Adam had to name the animals. I think that's because in ancient traditions, naming something means that you've discovered its true inner nature. By giving something a name, or learning its true name, you've really understood something deep about what that is.

I think that's very important for us because we, like Adam, are going to have to name and understand and then live with a very wide range of creatures that are well beyond anything we can imagine now.

Slide 5/55 · 04m:11s

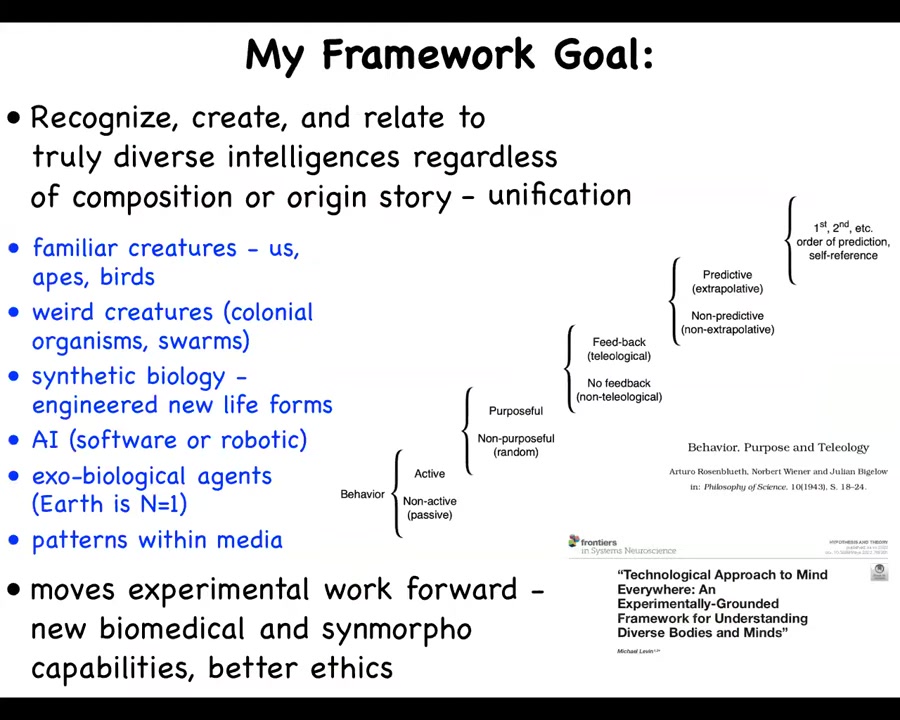

The goal of my conceptual framework is this. What I would like to do is to be able to recognize, create, and ethically relate to truly diverse intelligences, regardless of what they're made of or how they got here.

This means the familiar creatures such as primates and birds and maybe an octopus, but also very unusual creatures like colonial organisms and swarms, synthetically engineered new life forms that have never been on Earth before, AIs, whether purely software or robotically embodied, potentially someday exobiological agents, aliens. Even something that's even more unusual, which I won't have time to talk about today, but actually patterns with the media that don't look like traditional embodied minds.

The goal of my framework is that it has to move experimental work forward. This is not just philosophy. When I make these claims, I will only talk about things that have already had positive impact on our ability to make new discoveries and to reach new capabilities.

Of course, I'm not the first person to try to do this. Here are Wiener, Rosenblueth, and Bigelow in the 1940s trying to describe a spectrum that goes all the way from passive matter up to a kind of human metacognition and beyond. But my exposition of what I think is going on is here in this paper.

Here are the three parts. Let's start with the unconventional biology. That is, what are the unique features of the biological substrate? I'm going to give you a tour of some things that should really expand our ideas of what bio-inspired means. I want to go way beyond this idea that in AI or in machine learning, we're going to try to mimic the architecture or the algorithms of the brain.

Slide 6/55 · 06m:03s

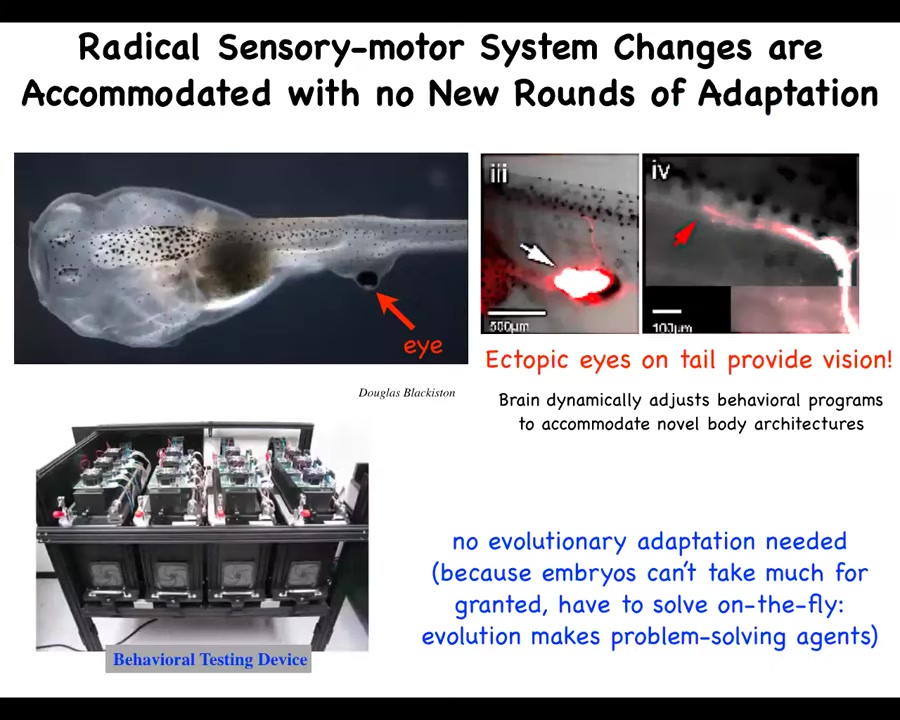

The first example is this. What you're looking at is a tadpole of the frog Xenopus laevis. Here's the mouth, here are the nostrils, here's the brain, here's the gut, the tail. What you'll notice is that we've prevented the primary eyes from forming, but we did put an eye on its tail. I'll show you later how we do that.

When you put some cells on the tail that are going to become an eye, they also make an optic nerve. That optic nerve does not go to the brain. It sometimes synapses onto the spinal cord here, sometimes nowhere at all, sometimes to the gut. But what you can see if you build this machine, which we made to automate the training of these animals in visual assays, is that they actually can see quite well.

This is remarkable because the traditional story that we're told is that the sensory motor architecture of a creature has to be evolved and shaped over eons of mutation and selection and so on. Why does this work out-of-the-box? Why does this creature, which for millions of years evolved with eyes sitting next to the head up here connected to the optic tectum, suddenly work? It can see when there's this weird patch of tissue on its tail. You don't need any more evolutionary adaptation. I'm going to argue that's because what biology builds is problem-solving agents. That is, even the standard tadpole could not assume that it was going to be a standard tadpole. It makes problem-solving agents. That plasticity was one example.

Slide 7/55 · 07m:30s

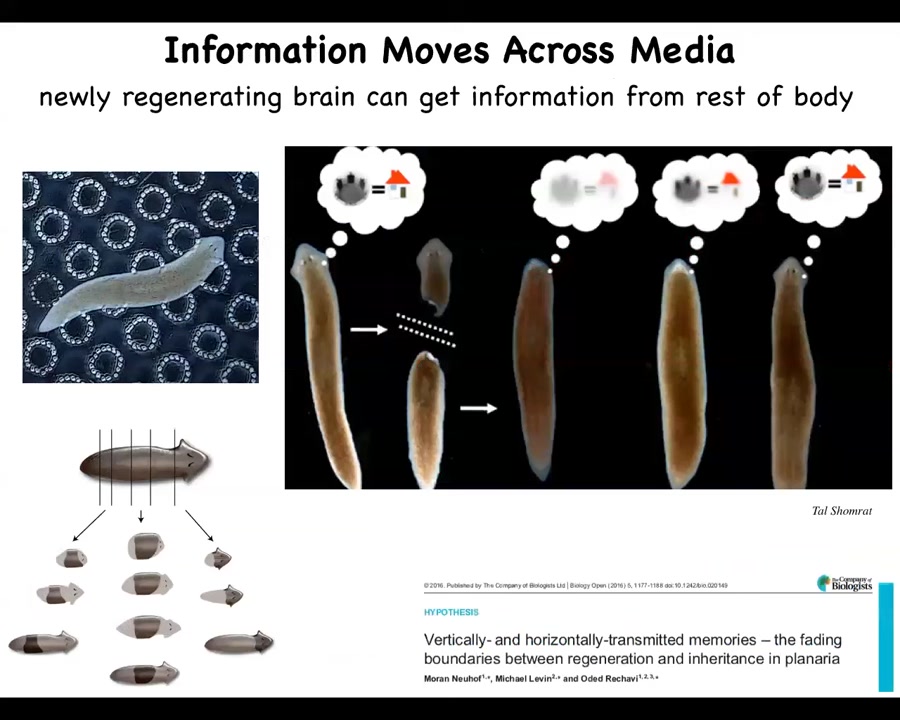

Here's another one. These are planaria. These are flatworms. They have a central nervous system. They have a brain. They have eyes. And what you can do is cut them into pieces. The record is, I think, 275 or something like that. And every piece will regrow a perfect worm. We'll see more about this later. But one of the things is that they're also smart, and you can train them to find food in this particular area that has these bumpy little discs laser etched into the surface. And this is called place conditioning. They associate this with a safe home environment. And you can then cut off their heads. The tail sits there for eight days doing nothing until it grows back a brain. At that point, behavior resumes. So the brain is controlled by the behavior. The behavior resumes, and then you find out that they remember the original information. This means that not only can it be stored elsewhere in the body, but it can also be imprinted onto the new brain as it develops. So the idea here is that you have information moving throughout living tissue, and also that the behavioral information and the structural information needed to build a brain go hand in hand where the new brain becomes the recipient and the memory colonizes this new real estate.

Slide 8/55 · 08m:40s

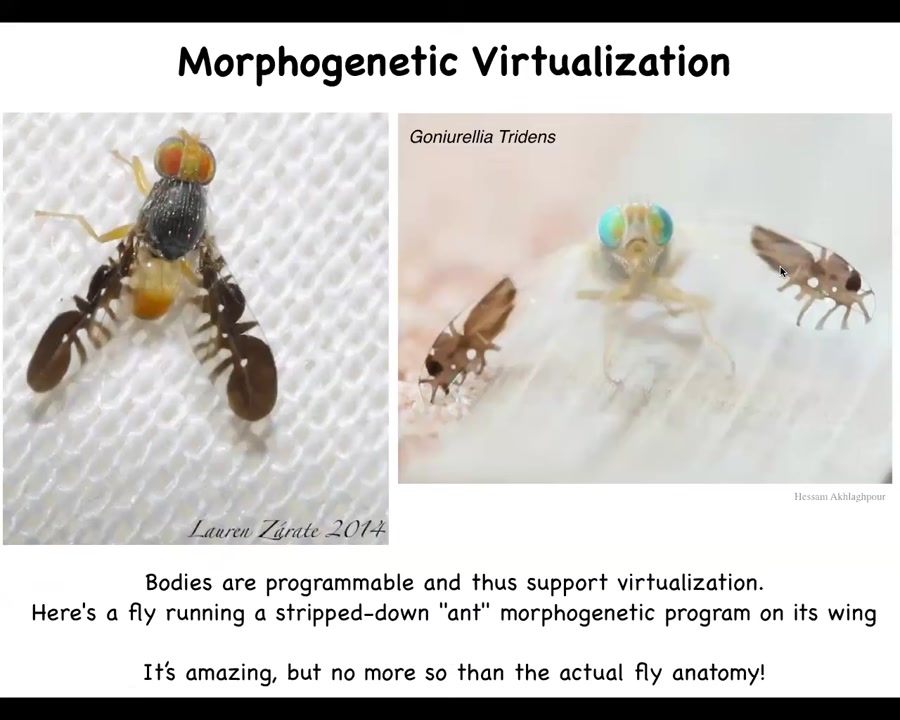

Now the morphological control of these things is interesting.

Here's a fly, and all of the weird images I'm going to show you today are real. None of this is Photoshop or AI. This is a fly that is running a stripped-down, two-dimensional, low-resolution virtual model of ants on its wings. And that's because it moves its wings around and simulates the scurrying of poisonous ants, and that keeps the predators away from the fly. So it's able to virtualize this kind of morphology, run it on the wings, which is remarkable, but not any more remarkable than the actual three-dimensional fly itself. And that just gives you an idea of the kind of plasticity that this system has. This ability to reliably reach this complex pattern is not hardwired.

Slide 9/55 · 09m:35s

It is a process that has some interesting intelligence built in. Here's an example. These tadpoles have to become frogs. In order to become a frog, they have to rearrange their craniofacial organs. The eyes have to move forward, the nostrils, the mouth, everything.

You might think that because every tadpole looks the same and every frog looks the same, you could just somehow encode specific movements for the specific organs of the head. But we tested this and we created so-called Picasso tadpoles where every organ is in the wrong position. Here the eyes are on the back of the head, the mouth is off to the side. What we find is that these animals still make perfectly normal frogs. Things don't end up in the wrong position as they would if they were merely counting steps or estimating direction. They actually will keep moving until they reach the correct pattern. In fact, they move through unnatural paths to do so.

What the genetics is giving us is not a bunch of hardwired rearrangements. It actually specifies an error minimization scheme. Some kind of means-ends analysis that is able to keep moving roughly in the right directions until you get to a particular point. We're going to talk about how it knows what that point is. In fact, there are some really interesting properties of this morphogenetic, navigational kind of process.

Slide 10/55 · 10m:49s

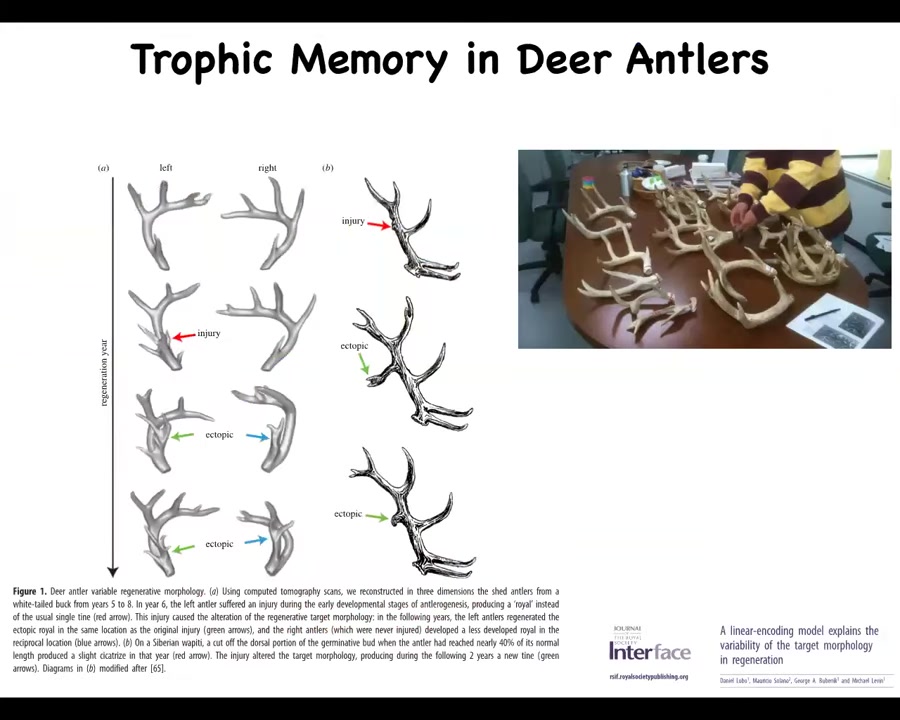

One is called trophic memory in deer antlers. These deer regrow this amazing structure with bone vasculature innervation. They drop it and then they regrow it. It was shown by a number of people that if you make an injury at one location on this tine, this whole thing will fall off. Next year, the antlers will grow a new tine at this location. The whole tissue is gone. Somehow for months, this information is stored somewhere in the body. Then that information becomes actionable when the cells have to make decisions about which way to grow. It reminds them to make this ectopic tine. Eventually, after a few years of this, it will go away. This is a kind of memory of injury. If you do molecular biology, what would a typical pathway model look like? People love gene regulatory networks and pathway models. What would it look like that could store the location of arbitrary damage somewhere along this branch structure, hold onto it for some months, and then use it to guide cell decisions later when the system is rebuilt?

Slide 11/55 · 12m:00s

And the final thing is that this whole system is highly reprogrammable. You wouldn't know it because very reliably what happens is that this is an acorn, here's an oak leaf, and repeatedly all over the world this thing makes that thing. You would think that what the oak genome encodes is the instructions to make a nice flat green object that looks like this.

Slide 12/55 · 12m:26s

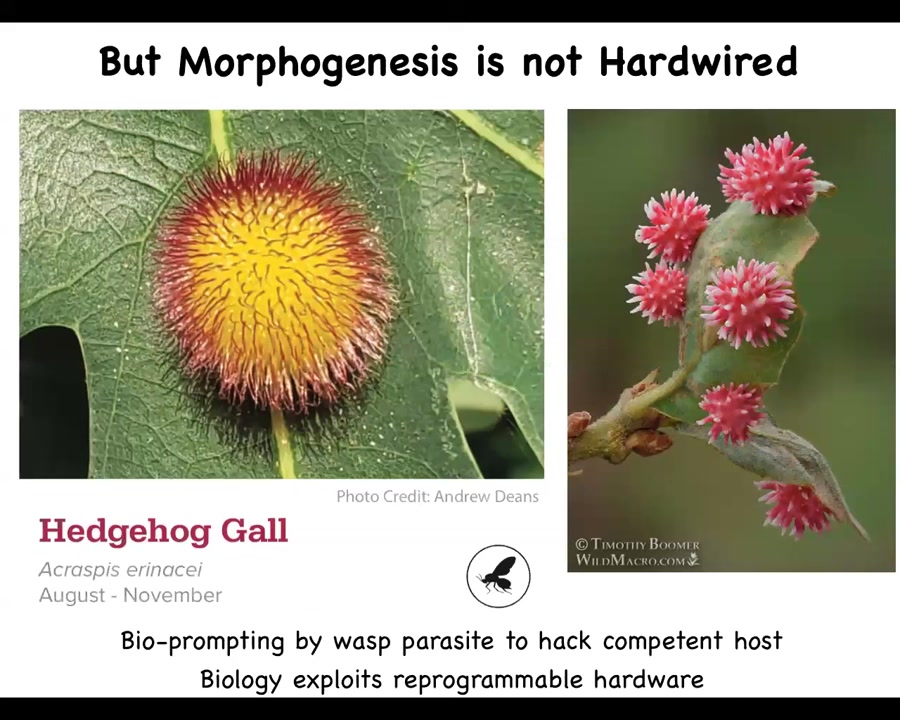

There's a bioengineer, it's a non-human bioengineer called a wasp of this type. There are many of these kinds. What it does is hack that system and lay down some signals that will induce the plant cells, not the wasp cells, to build this kind of structure. There are many amazing pictures of galls. What this is telling us is that while there's a default outcome that's reliably induced, the competencies are way beyond what we might be able to directly infer. If we understood how to communicate novel goals to these cells, we could take advantage and hack them for novel circumstances. Biology does this all the time.

Slide 13/55 · 13m:12s

What this amazing plasticity, this robustness to change, the ability to come up with novel solutions under novel circumstances, how does all this work? We're going to talk about some of these features, such as self-construction, the multi-scale competency architecture, and the idea of communicating with the collective intelligence of cells.

Slide 14/55 · 13m:37s

Let's first think about where bodies come from. All of us at one point were a single little bag of chemicals and a quiescent unfertilized oocyte. Typically people would look at something like that and they would say, there's chemistry and physics there, but there's no mind, there's no cognition. It just obeys the laws of chemistry. But slowly but surely, through a very gradual process, it's going to self-assemble into something like this or even something like this.

One of the critical things to realize is that in this process, there is no special point where mind snaps into being. In other words, this is a slow and gradual process. All of us took this journey from physics to mind.

We need to understand how this works. What is the process of scaling that takes the very primitive competencies of single cells and enables them to do this or even things like this?

This is not the end of the story, as I'll show you today. After you've built a body, there are some interesting things that can happen related to malfunctions, such as cancer, or being reborn in an entirely different embodiment, such as these anthrobots, which I will also talk about. The key feature of all of this is that we are actually a collective intelligence.

Slide 15/55 · 14m:57s

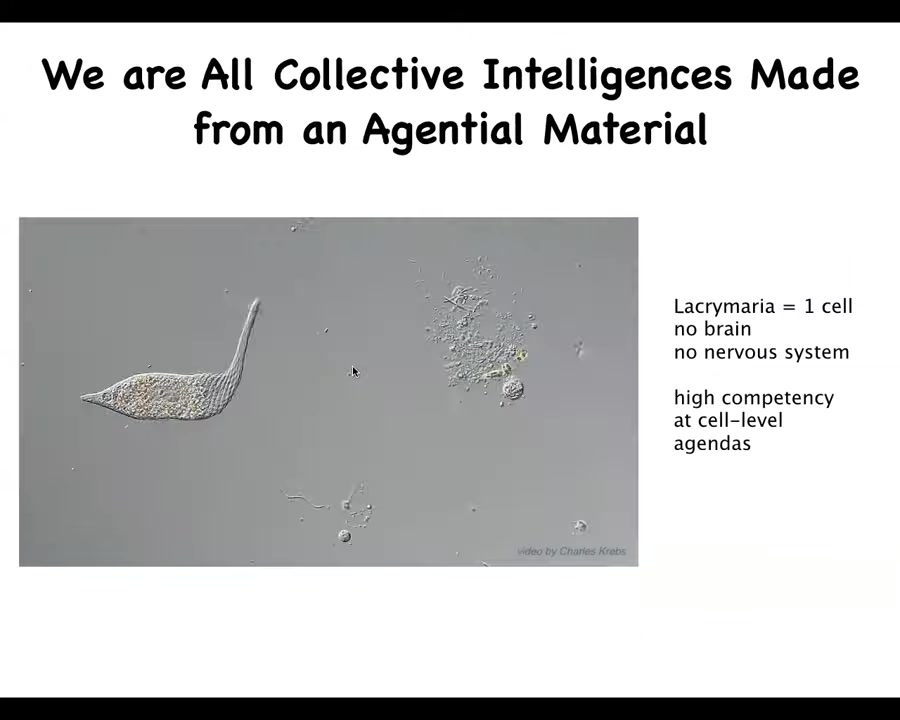

Our body is a collective intelligence. We are made of components with agendas, with learning capacities, with information processing skills.

So this is a single cell. This little guy is called the lacrimaria. It handles all of its needs, its metabolic, physiological, behavioral — all of them are handled within one cell.

Even below the single cell level, not only can individual cells learn from experience and have anticipation — there's a large body of work on this — but even the molecular networks inside of cells already have some of those capacities; for example, they can learn.

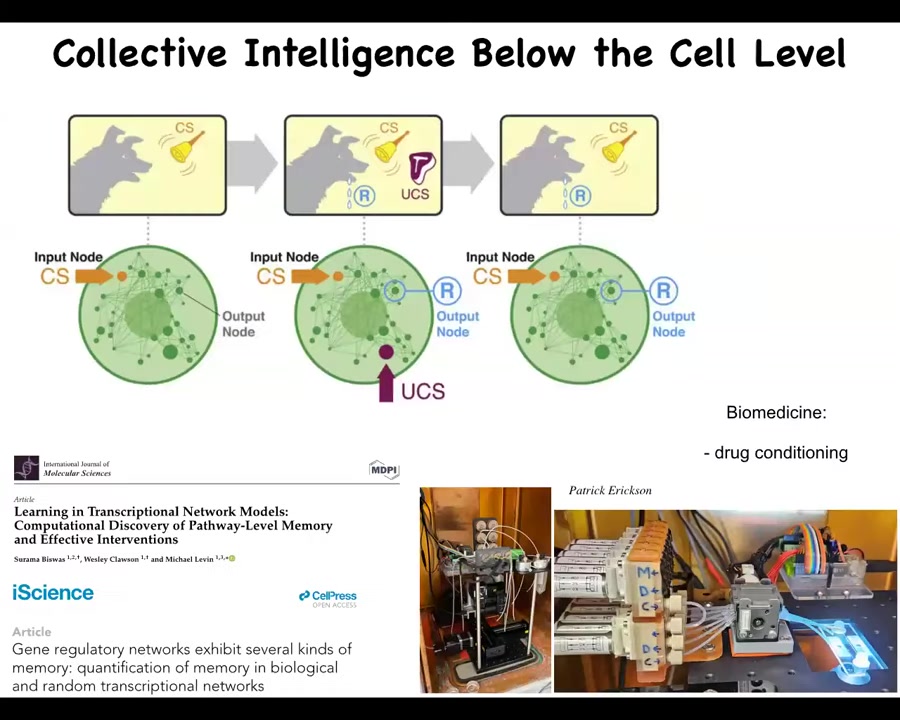

Slide 16/55 · 15m:34s

So the gene regulatory networks inside of cells, just the gene regulatory networks alone, the pathway by itself, is capable of six different kinds of learning, including Pavlovian conditioning. And in our lab, we're exploiting some of that. We're making these devices to train individual cells, more accurately train the molecular networks inside the cells, and use them for applications like drug conditioning.

So this is interesting and a little unsettling, this idea that we are made of components with so much autonomy and their own various goals and learning capacities.

Slide 17/55 · 16m:22s

But at least we're a unified intelligence. Most people think that ant colonies and beehives are metaphorically called an intelligence or a super organism, but we are a true collective intelligence. In fact, because we have this nice solid brain.

Slide 18/55 · 16m:43s

Descartes really liked the pineal gland because there's only one in the brain. Now, the problem is that he didn't have access to proper microscopy. If he did, he would have looked inside this pineal gland, and he would have realized that there really isn't one of anything. Inside the pineal gland is all of this stuff, all these cells, and inside each one of those is all of this stuff. Biology is extremely rich at every level. There isn't one of anything anywhere. We are all collective intelligences going all the way down to the molecular level.

Slide 19/55 · 17m:23s

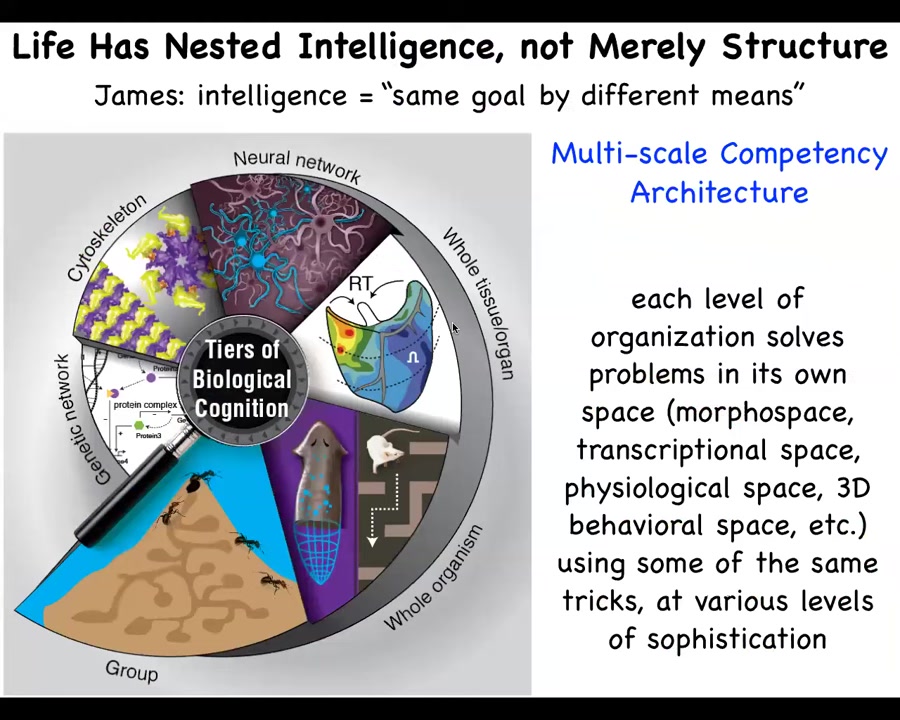

And so what's important about the way that life operates is that it's a multi-scale competency architecture that is at every level, from the molecular components to the subcellular to cells and tissues and organs, whole organisms. But also collectives and societies and so on, all of them solve problems in their own different space.

And so when I say intelligence, and I point out that all of these have problem-solving capacities, what I mean is William James' definition of intelligence, "the ability to reach the same goal by different means." So being somewhere on the spectrum of intelligence means that you have some ability to reach the same goal even when things change, when the environment changes, when your own parts change. I'll show you some examples of that. So ability to improvise novel solutions to existing problems.

Slide 20/55 · 18m:13s

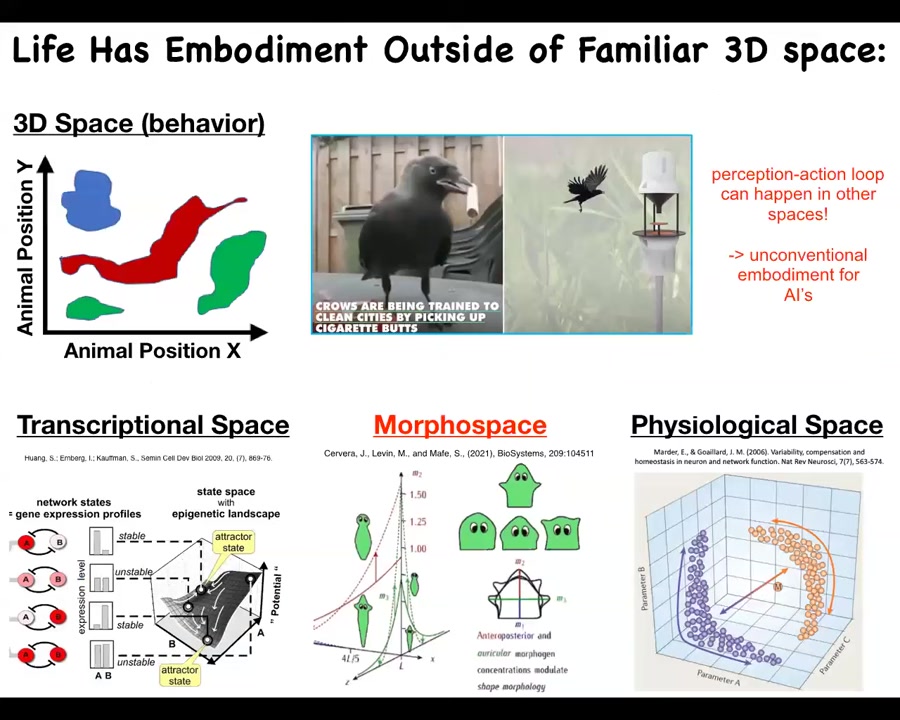

We as humans have inherited some mental firmware from our life history. That mental firmware makes it relatively straightforward for us to identify intelligence in medium-sized objects moving at medium speeds through three-dimensional space. We love three-dimensional space as the problem space, and we are well-tuned to recognize some kinds of intelligent behavior.

But biology utilizes some of the same tricks to navigate all kinds of other spaces. High-dimensional spaces like the space of possible gene expressions, the space of physiological states, and anatomical morphospace, which we will talk the most about.

This becomes important, especially for philosophy of mind, computer science, because the perception-action loop that is required to deploy and for us to recognize intelligence in spaces can actually occur in all these other spaces. These other spaces are very hard for us to visualize.

Organoids that are sitting in a dish, not doing anything, not moving around. People say they don't have a body, so you don't have to worry about them. They may not have a body with which they move through three-dimensional space, but you can bet they're moving through at least these two spaces and navigating them adaptively.

I think if we had evolved with some sort of sense organ that could report our blood chemistry, 10 other parameters of blood chemistry, we could feel it the way that we feel other things. I think we would have no problem recognizing that we live in a 14-dimensional space and that our liver and our kidneys are some sort of intelligent symbiont that traverses part of that space to keep us alive on a daily basis.

That realization that embodiment does not mean three-dimensional space has massive implications, for example, for artificial intelligence, where people say this thing is just software. It's sitting there in a server somewhere. It doesn't have a body. It's disembodied. I'm not sure that's true at all. We'll get to this.

Slide 21/55 · 20m:12s

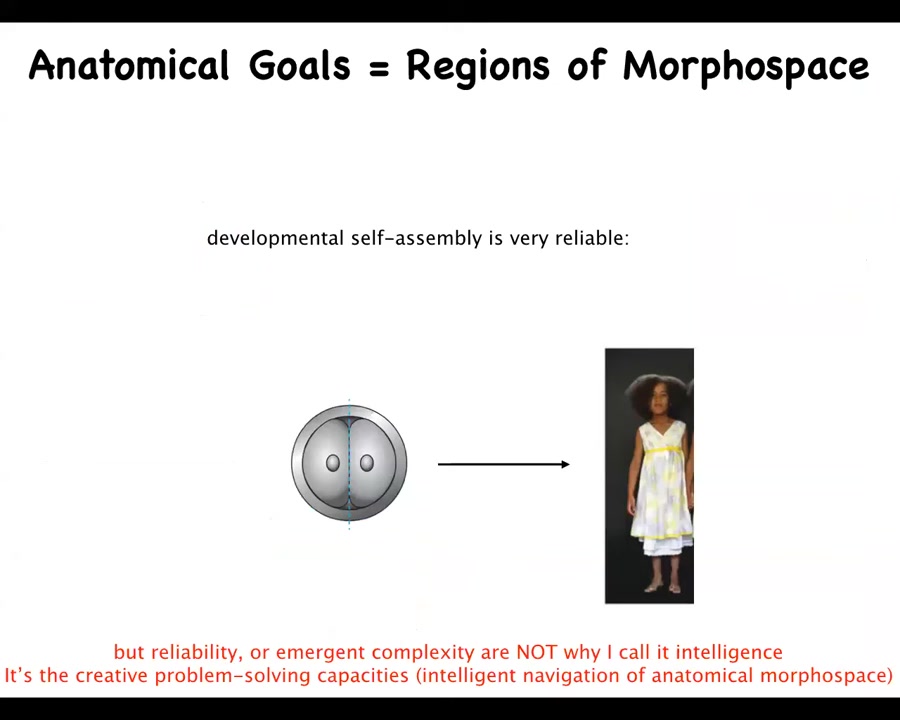

Let's talk about anatomical morphospace. Anatomical morphospace means that you're going to traverse, as a collection of cells, you're going to traverse from a location where you're just a single cell to a point in that space corresponding to a normal human target morphology like this. This is a very reliable process. That navigational process happens almost every single time correctly. But the reliability of that process and the emergent complexity, the fact that this thing is much more complex than this, is not why I call it intelligence. That is not why I call it intelligence. Why I call it intelligence is because of the creative solving capacities of that navigational controller.

You can see the first example of it when you take an early embryo and you cut it in half. If I cut it into pieces, I don't get half embryos. What I get are normal monozygotic twins, triplets. When you're navigating this anatomical space, in order to get to your goal, you can get to it from your normal state, but the system can also get there from some other starting states, avoiding some local maximum along the way. You're starting to see that it's able to adapt to novel circumstances and, having been moved in the space, it can still find its way to where it needs to go.

Slide 22/55 · 21m:30s

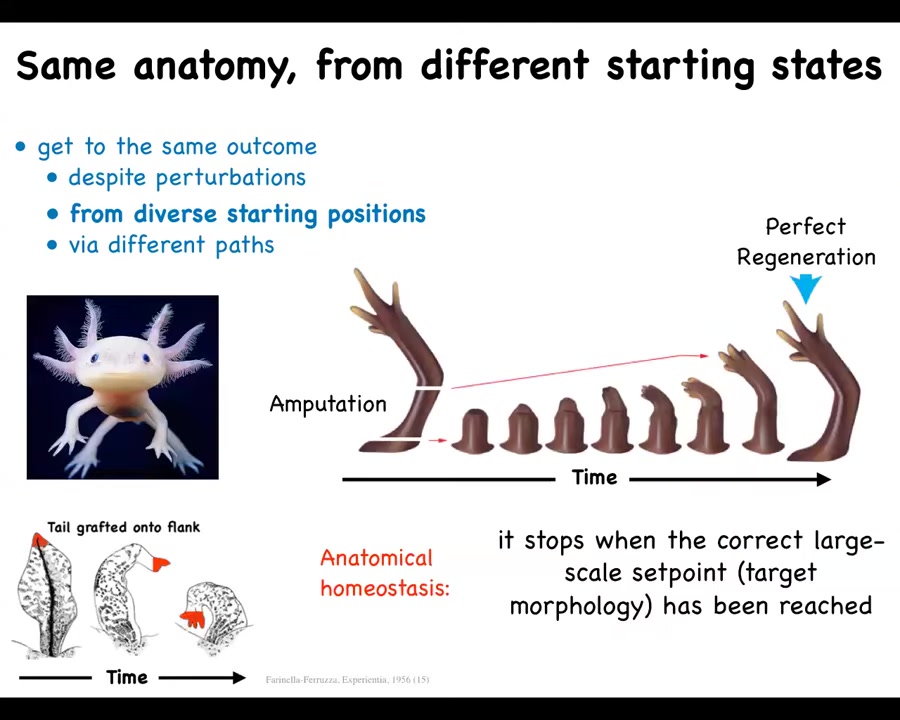

Some creatures hold on to this property their whole life. This is an axolotl. It's an amphibian that has the amazing capacity of regenerating limbs, eyes, jaws, ovaries, portions of the brain and heart. You can see here when a limb is amputated anywhere along this axis, the cells will immediately grow exactly what's necessary and then they stop. The most amazing thing about this is that they know when to stop. When do they stop? They stop when a correct amphibian limb has been completed. This is an anatomical homeostasis process. It senses that it's been deviated and it takes the necessary steps to get back to where it needs to go. But that homeostasis is not about a scalar like a pH or a hunger level or something. It's within a high-dimensional space and the goal state is a geometric arrangement.

Notice that it's not just about repairing the pattern that was there. It's much smarter than that. If you take a tail and graft it onto the side of the salamander, and this is very old data from the 50s, what will happen is that tail will slowly remodel into a limb-like structure. In fact, the cells at the tip of this tail will become toes, even though locally everything's fine. There are tail tip cells sitting at the end of the tail. Why do they need to change? The whole thing changes to be more in line with a large-scale structure of the amphibian. It's got the ability to remodel, to repair, and to get to where it thinks the system ought to be in that space, despite some very weird changes. This is something that happens during evolution, because they bite each other's legs off all the time. This is completely novel. This does not happen during a salamander's lifetime; the tail doesn't get grafted to the flank.

These are all emergent problem-solving capacities. These are not just built-in hardwired capabilities. How does this work? How does it remember? How does the body remember, not the animal, but the body remember what it's supposed to look like. How do we think about sets of cells having memories of their goal state and pursuing goals? Do we have a formalism for that?

Slide 23/55 · 23m:39s

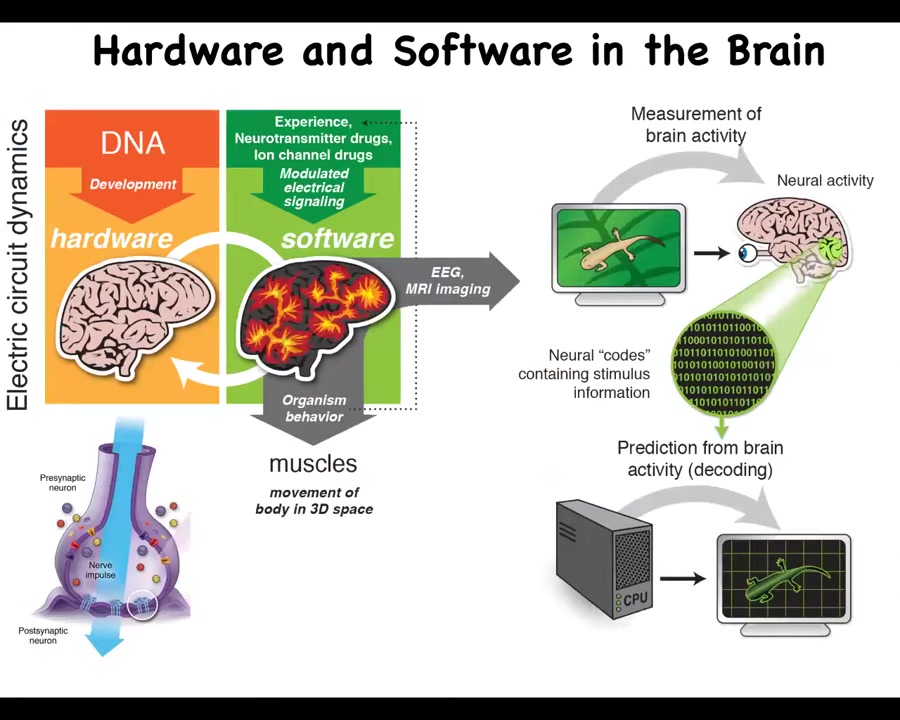

We have a familiar one, and that's called neuroscience. In neuroscience, we know that the brain is a collection of cells that remembers the specific goals, and it has the ability to navigate three-dimensional space to meet those goals.

You've got the hardware, which is a network of cells that have little proteins on their surface called ion channels. These ion channels allow charged atoms to move in and out. That results in a voltage gradient across the membrane, which may or may not be propagated through these little electric synapses called gap junctions. Information moves through the network, and it is the physiological information that lives in this network, which is what we consider to be the carrier of the content of a mind. What it does is it controls the muscles to move the animal through three-dimensional space.

But this process of neural decoding is a project in neuroscience where people think that if they're going to be able to read out and decode all the electrophysiology that occurs in the brain, they will be able to extract the cognitive content, the memories, the preferences, the goals, the plans, the intentions, and so on of the animal. The commitment of neuroscience is that all of that stuff is somehow encoded in the electrophysiology of the brain. That's how things work for three-dimensional space. How does this help us with understanding the intelligence of morphogenesis of building and repairing complicated bodies? The amazing thing is that this incredible trick of using electrical networks to store and integrate information across space and time is actually much older than brains.

Slide 24/55 · 25m:22s

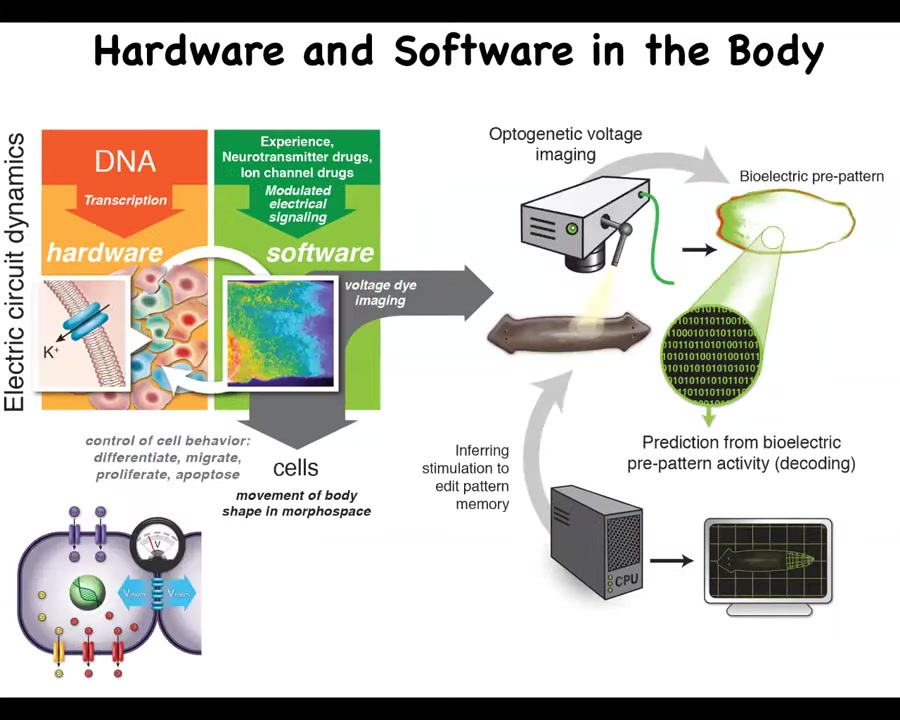

It started around the time of bacterial biofilms, and it is ancient. Every cell in your body has ion channels. Otherwise, the whole system is exactly the same, except that we're not dealing with neurons anymore. We're dealing with every cell in your body; most of them have ion channels and electrical synapses, and so they form electrical networks.

You can take almost any paper in neuroscience, do a find and replace: everywhere it says neuron, say cell; everywhere it says millisecond, say minutes, and you have a nice developmental biology paper.

While the electrical networks of the central nervous system control muscles to move you through three-dimensional space, what does the somatic electrical network think about? It thinks about shape. What it does is issue commands to all cells, not just muscles, to move the configuration of the body through anatomical space.

The reason that our brains can do so well in three-dimensional space is because evolution pivoted and greatly accelerated the ability to navigate a problem space via a collective intelligence. That is what's going on here. Evolution figured out that bioelectrics are an amazing cognitive glue that can bind individual cells toward navigating a large-scale problem space that no individual cell can perceive on its own.

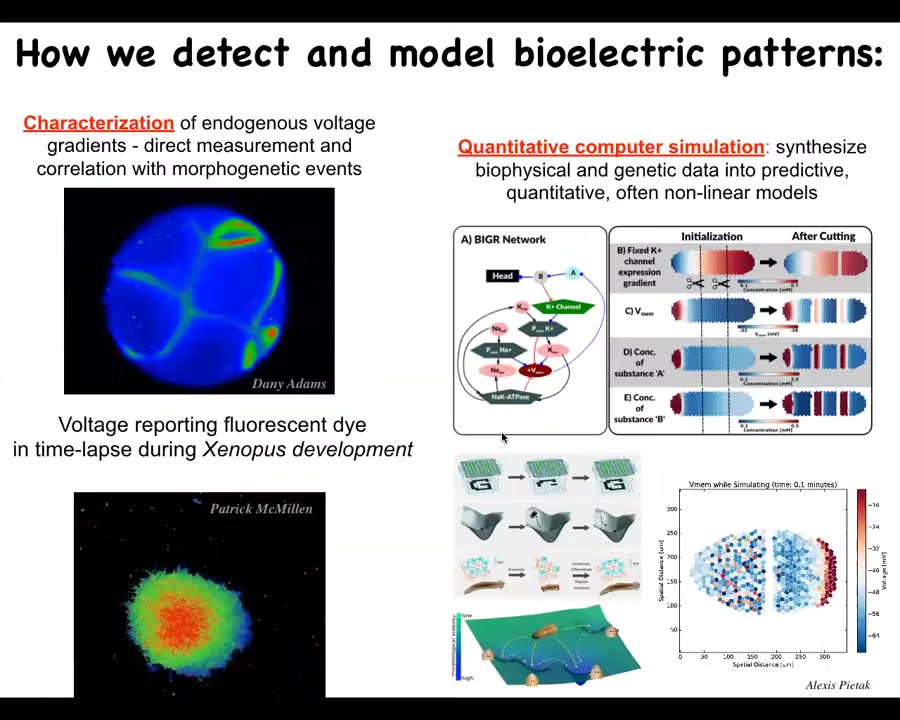

When we developed this analogy, we started the project of developing tools and methodology for non-neural decoding, to read the mind of the body in the same way that people try to extract information from the brain. What is the cognitive content of the electrical activity in the rest of the body as it thinks about how to navigate shapes?

Slide 25/55 · 27m:13s

The first set of tools we developed had to do with the use of voltage-sensitive dyes to reveal the bioelectrical states of tissue in vivo. These are time-lapse videos. Here you can see an early frog embryo, and you can see all the electrical conversations that cells are having with each other. Here are some explanted cells that, again, show the same thing: the color indicates the voltage states. We can read these states now. That's the imaging technology.

We do lots of computer simulations to understand how the genetics of the channels leads to voltage patterns on a tissue level, or in fact, a body-wide level. We do a lot of computational modeling of how these patterns remap, and in particular, try to integrate that with models from dynamical systems theory and connectionist kinds of networks to try to understand, for example, pattern completion. What you saw in the case of that salamander that lost a portion of its arm and grew it back is an example of pattern completion of the memory of the proper limb. These are the kinds of things that we try to do.

Slide 26/55 · 28m:21s

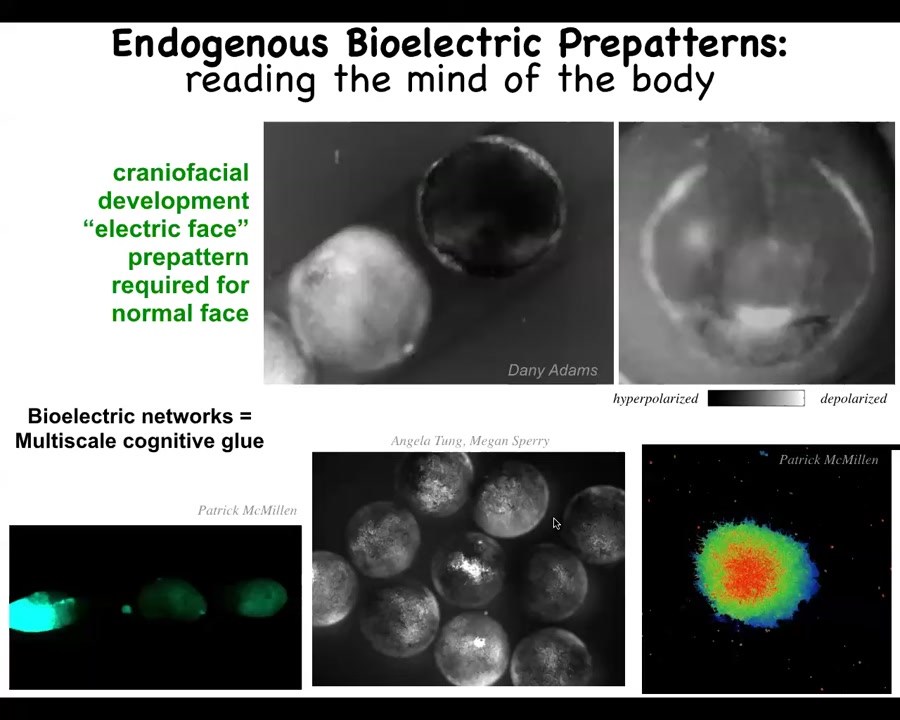

I'm going to show you an example of what these patterns actually look like. This is an early frog embryo putting its face together.

There's a lot going on here, but one of the things you can see: we took one frame out of this video, and we call this the electric face. You can already see, before the genes turn on to regionalize the anterior ectoderm, here's where the mouth is going to be, here's where the eye is going to be; the animal's right eye comes first. Here where the placode is going to be. The layout of the face, you can read that out as a memory in the electrical layer of information, and this is what ends up controlling the gene expression and ultimately the cell behavior that gives you a face. This is an endogenous pattern. In fact, it's required for normal face development.

One cool thing about bioelectrics is that not only does it organize individual cells into a large-scale pattern, but embryos, like whole bodies, exchange information on a group level. Here you can see what happens when we poke this one animal: all the surrounding ones find out about it quite quickly in this injury wave. Same thing here. This one on the left is going to get poked, and by reading out, in this case, the calcium signaling, you can see that they find out. It's a multi-scale coordination system.

Tracking and modeling these patterns is fine, but more importantly, you need to be able to rewrite them.

Slide 27/55 · 29m:54s

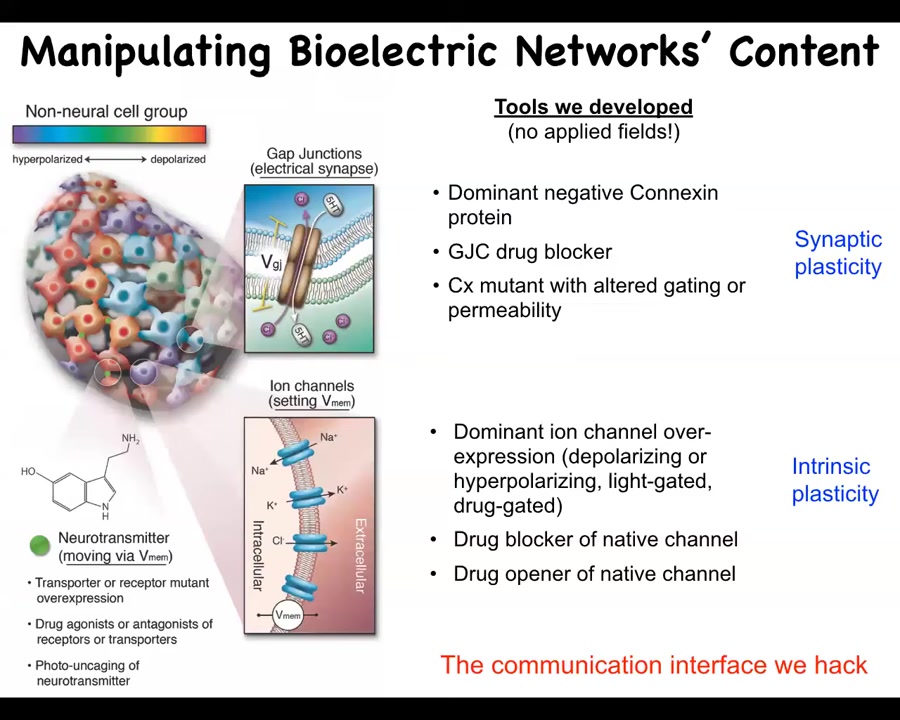

So it's not just about listening in to the content of that electrical network. We want to be able to change it. And so, when we do that, it's important to note we don't use any electrodes.

Slide 28/55 · 30m:08s

We don't use electromagnetics. There are no magnets. There are no waves, no frequencies. What we are doing is controlling the interface that the cells are using to control each other. They have a bunch of ion channels that set the voltage. They have these electrical synapses. By appropriating tools from neuroscience, we can control both of those things. We can control the network topology and we can control the states of the electric patterns. We use things like optogenetics and drug blockers and activators. This is the communication interface that we're hacking.

Slide 29/55 · 30m:42s

Now it's time for me to show you what happens when you do this.

Can we show that the patterns that we read out from the bioelectric layer are functionally instructive?

All of this is for us, not only does it lead to applications in regenerative medicine, but the idea is to learn to understand an intelligence that is not quite like ours, not like our brain intelligence in many ways, but at the same time close enough that we have some hope of learning to understand it and communicate with it.

Slide 30/55 · 31m:13s

So here's an example. Having seen that little voltage spot in the eye, that electric face, we decided to recapitulate that spot somewhere else in the body and see if we can see what would happen. When you inject RNA encoding some potassium channels to create that voltage pattern, if we inject it into cells that are going to become the gut, what you find is that there's a little patch of that gut that becomes an eye. And these eyes have the same lens, retina, optic nerve, all this stuff that you would expect.

And so the first thing we've learned by this is that the bioelectric pattern is actually instructive. So that pattern is not just a readout of what's going on, but actually tells cells what to do. B. It's incredibly modular, meaning that we didn't say anything about which genes to turn on or how an eye is made, and we have no idea how to micromanage the creation of an eye. But what we did find is a high-level subroutine call. This is a hook, a minimal stimulus that, much like in behavior science, a simple stimulus can give rise to a very complex downstream set of behavioral responses. We said build an eye here, and that's what happens. The cells build an eye.

One other thing: if we hit very few cells, the blue cells here are the ones that we inject, they will themselves recruit all of these other cells around here to help them form the eye because there's not enough of them to do so. And the system knows perfectly well how many cells it takes to build a proper eye. So they end up recruiting. We didn't have to teach them to do that. We didn't have to worry about how many cells we inject.

And so all of this works, this incredible modularity and the ability to trigger complicated behaviors without knowing all that much about every downstream molecular step, it's certainly without having to worry about micromanagement, is because the system itself is a goal-driven, highly modular hierarchical system where modules expect to get high-level instructions from other goals and are competent to carry them out. We did not construct this. The system already works this way.

Slide 31/55 · 33m:24s

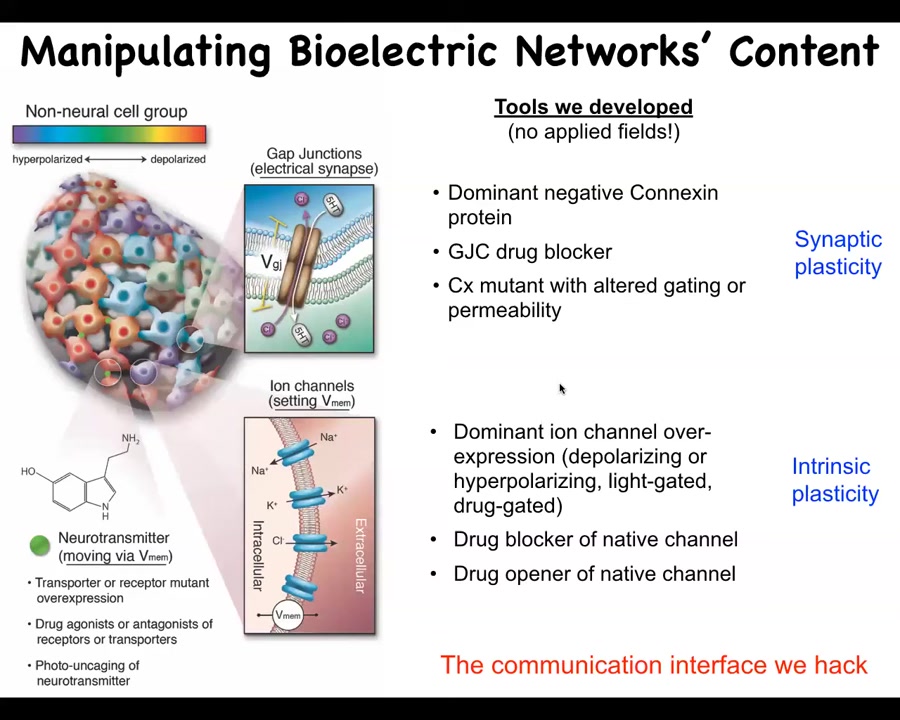

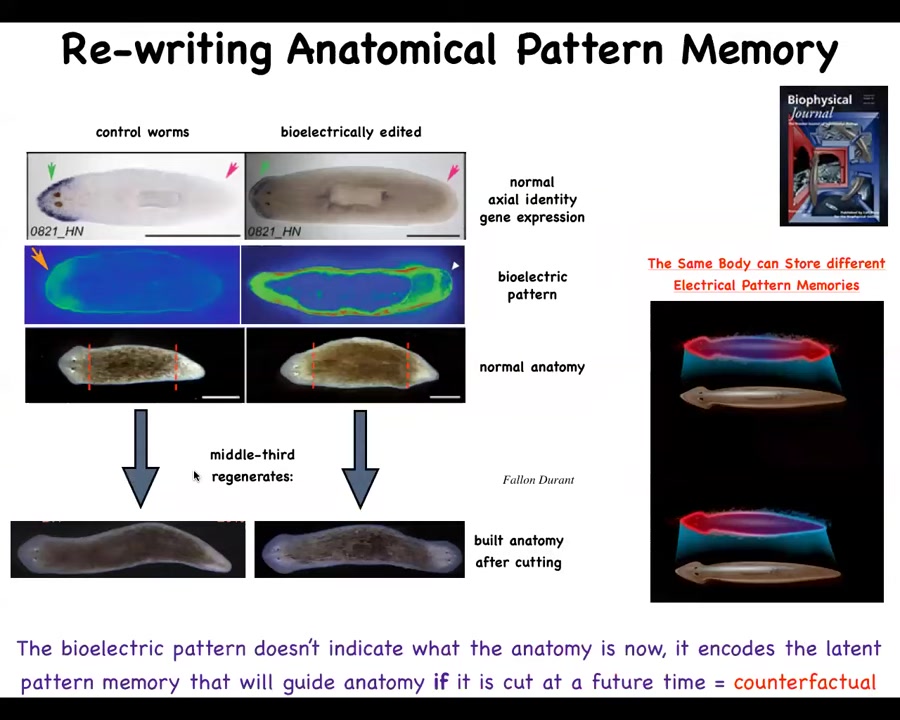

I will show you one other example, because I keep calling these things a memory. Here's something interesting where we took these flatworms, and normally when you cut them into pieces, this middle piece will very reliably build exactly one head and one tail. You might wonder, how does it know which wound should get the head? And how does it know there should be one of them?

Here's actually the bioelectric pattern in this animal that says one head, one tail. And here's the resulting molecular biology: the anterior marker is expressed here in purple, not here.

What we can do is take this animal and change the bioelectrical pattern so that it looks like this, two heads, not one. When you do this by itself, nothing happens. You still have an anatomically normal animal like this, and that same animal has the normal molecular biology, so anterior marker expressed here. But when you cut it, the cells have a completely different view of what a normal planarian is supposed to look like. They build this two-headed worm.

This memory is latent because it doesn't do anything until you've injured the animal and forced it to try to recall what the cells are supposed to be building. It is also an example of a counterfactual. It's a primitive example of our brain's ability to do this kind of mental time travel, thinking about things that are not true right now. It processes information that's simply not correct right now.

Here the animal's internal model of a correct planarian, with two heads, does not match the current anatomy, and it will only start to match after injury forces a resolution of this discordance. So the standard body is able to keep at least two different pictures of what a correct planarian should look like.

Slide 32/55 · 35m:23s

Now we know it's a memory because if you take these two-headed worms and you cut them in further rounds of amputation, plain water, no more manipulation of the bioelectrics. You don't do anything else other than keep cutting them. They will continue to form two-headed animals. We can turn them back into one-headed if we want to. But this has all the properties of memory. It's long-term stable. It's rewritable. It has conditional recall, which I just showed you a moment ago, and it has some discrete possible behaviors.

Here's a video of these two-headed animals from these subsequent generations.

The first time I showed this data in a developmental biology meeting many years ago, somebody stood up and said, "Well, that's impossible. Those animals can't exist." They said that because the genome has not been touched here. The genome is completely standard. We don't do anything to the genome. These animals have totally wild type genetics. What we're showing is the information is actually not in the genome and that the tissue has a rewritable memory.

What the genome actually does is build a system that, by default, has inborn instincts for simple behaviors. This system is born with a bioelectric memory that says build a one-headed animal, but it's quite rewritable.

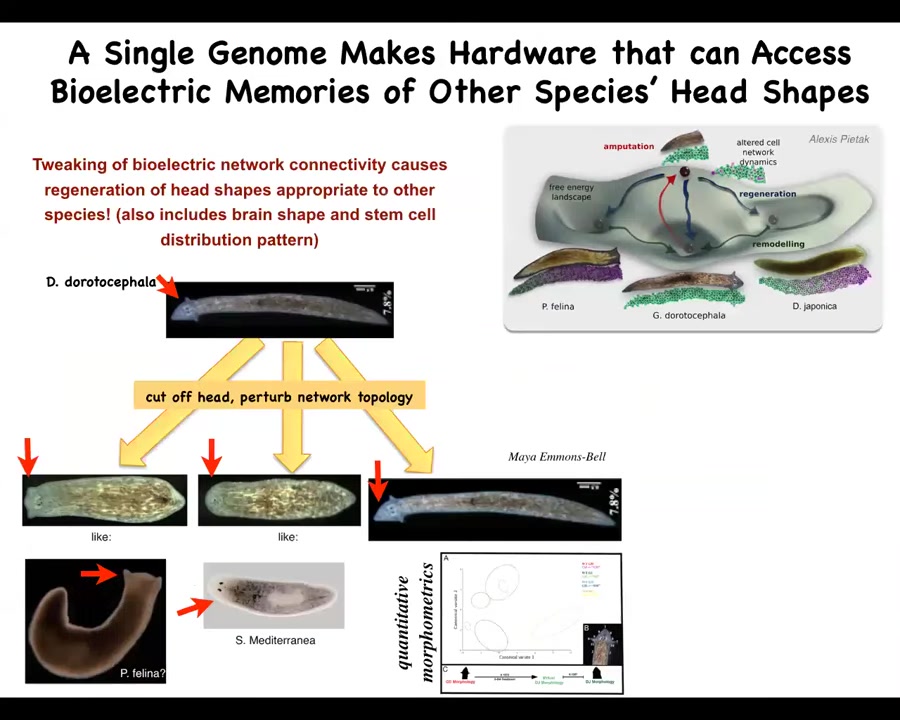

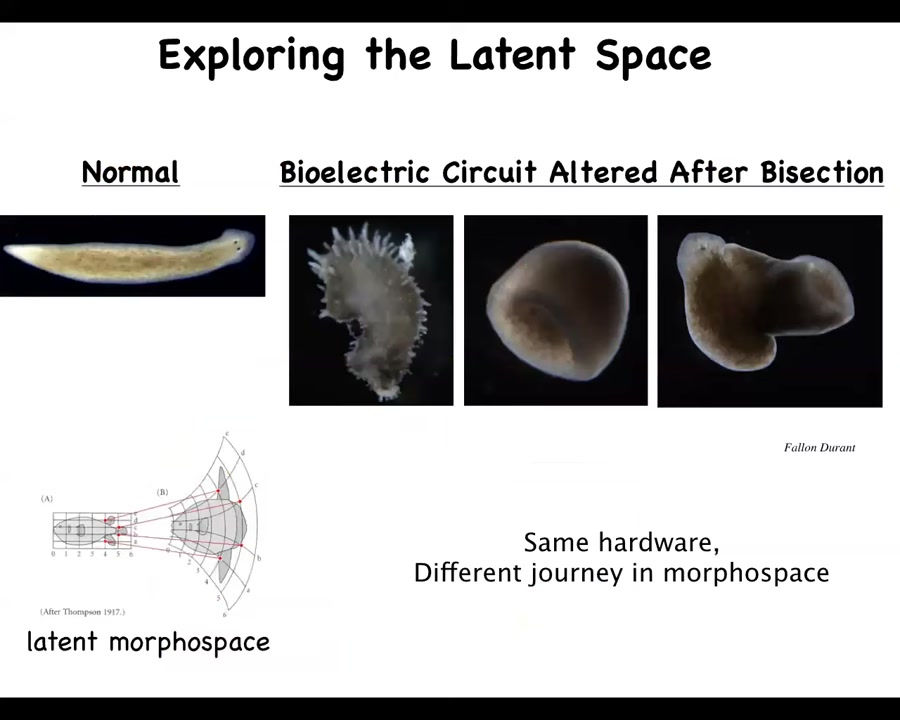

Slide 33/55 · 36m:43s

Not only is it rewritable for the number of heads, but it's actually rewritable for the shape of heads, and we can make the heads belong to other species. Without touching the genome, this triangular-shaped planarian can make heads that are flat, like this P. falina, round, like this S. mediterranean, or the normal one. What we're doing is manipulating the bioelectrics of this head that control the navigation of morphospace. In anatomical space here, there are attractors belonging to other species, normally occupied by the defaults of these other species. But this hardware is perfectly capable of visiting these other attractors if the bioelectric pattern, which controls the navigation through shape space, says to go to one of these other locations.

Not just the shape of the head, but the shape of the brain and the distribution of stem cells are just like these other species, somewhere between 100 and 150 million years' evolutionary distance, without touching the genetics whatsoever.

Slide 34/55 · 37m:40s

Also, you can make things with this method that don't look like planaria at all, like any species. You can make this weird spiky shape thing. You can make cylinders, you can make combinational forms, same hardware, different journey through the latent space of possible shapes that the hardware can make.

Slide 35/55 · 38m:01s

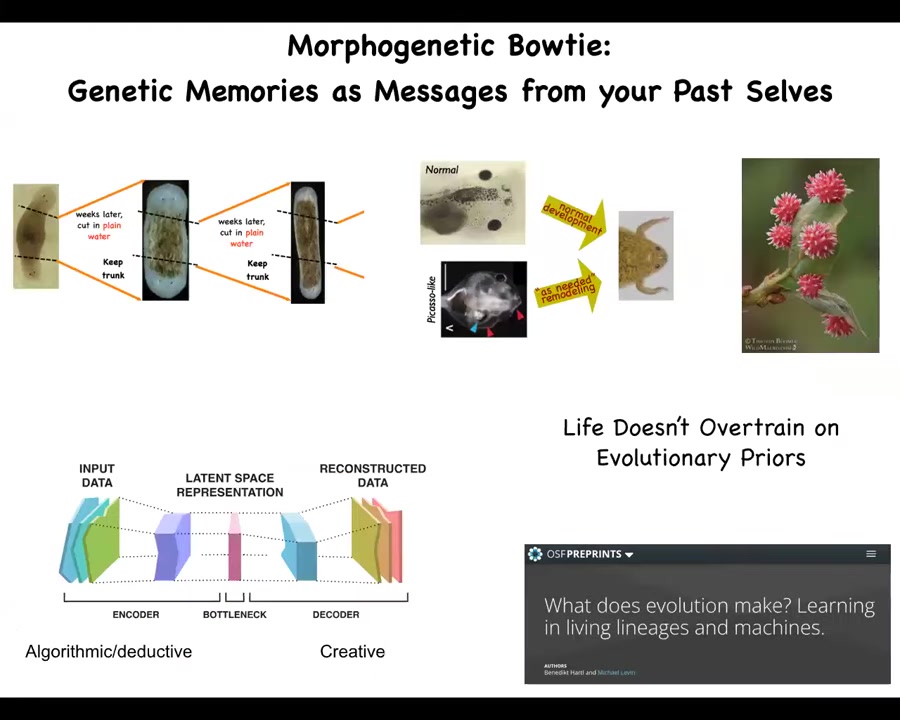

I've shown you some examples of the intelligent problem-solving capacities in anatomical space. I've shown you how we can communicate with that system to control where it goes in that space. Much like animal behavior, we've developed some signals, some stimuli, and some understanding of how to get it to do specific things. Now it's time to understand why that works. In particular, to take a quick look at the agential material that we're dealing with here, and the summary of everything I'm about to tell you is this: that biology commits to an unreliable substrate, which requires on-the-fly creative problem solving. This is the part that is the most different from what we do in traditional computer architectures, where we work very hard to provide abstraction layers, a reliable substrate. When you're programming a high-level language, you never worry that the copper is doing something or that the numbers in your registers are going to float off randomly. Biology has to worry about all of that. It has massive implications. The fact that the substrate is so unreliable has huge implications for the architecture. Let's think about this model here.

You've got a caterpillar. The caterpillar is a soft-bodied creature with a particular controller that you need to run a soft-bodied system. It lives in a two-dimensional world, crawling around on surfaces and eating leaves. It needs to turn into this. This is a very different architecture. This is a hard-bodied creature that now has hard elements that you can actually push on, which you didn't have here. It flies, so it lives in a three-dimensional space. It has a different brain suitable for this lifestyle. What happens in the middle is that it dissolves its brain. Most of the cells die, most of the connections are broken, and then it makes a new brain.

What we know is there's a weird personal identity that persists through this, because otherwise you might say the caterpillar's long gone and you have a butterfly, much like with development it's a different animal. If you train the caterpillar on a specific task to find and eat leaves using a special visual cue, you'll find that the butterfly actually remembers this. The first amazing thing is that information somehow survives drastic refactoring of the brain. It's not understood how it does that. But there's an even more amazing thing beyond that, which is that the actual memories of the caterpillar are of no use to the butterfly. The butterfly does not move the way the caterpillar moves. It doesn't like the same food. The butterfly, rather, doesn't care anything about leaves. It wants nectar from flowers.

That means that instead of keeping the memory, you have to remap it. The memory has to be altered, generalized, and remapped onto a completely different architecture. Biology here is taking advantage of not the fidelity of the information, not trying to keep the same information, but a creative reinterpretation of that information. What is it that the caterpillar knows that can be useful in this novel circumstance: new body, new behaviors, new environment?

This kind of wild transfer learning—how do we remap it? Here we first encounter the paradox of change. The memory stuff is covered in this paper.

What's happening here is that living systems face a paradox. If they don't change, if they try to remain the same, they will certainly disappear and die when the environment changes, when their parts become mutated. No evolutionary lineage can survive without change. But if you change and evolve and adapt, then again, the old one is in some sense gone. So what biology does is commit to persistence not by remaining unchanged but by constant adaptation and change to novel circumstances.

Slide 36/55 · 42m:29s

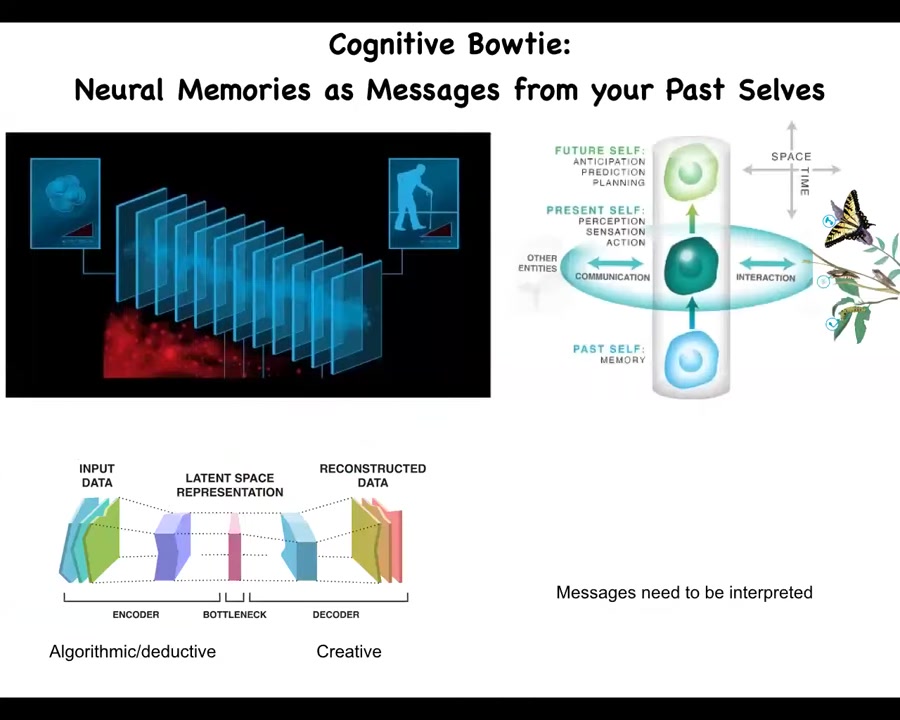

At any given moment as a cognitive system, you don't have access to the past. What you have access to are the engrams, the memory traces that the past has left in your brain or body. From those, you have to recreate the story of what those memories mean. You don't actually know. You have to reconstruct them. This constant process of reconstruction is what selves do. Active agents and selves are continuously trying to refine and reinterpret their own memories to form models for future actions.

What's important about that is that, much like messages laterally from other creatures, memories are a message from your past self. They're incredibly sparse because they've been compressed down to these memory traces or engrams. You don't actually know what they used to mean or what your past self was doing with them, but they're a message and now it's up to you at any given moment to interpret that message.

This is what's happening in the butterfly-caterpillar case. It happens to all of us, even with less drastic deformations such as this. It's the idea that your memories must be reinterpreted. You don't necessarily care what your past self was doing with them and how they were interpreting and what you need to know any more than the butterfly cares about what the caterpillar was actually doing with them. You need to reinterpret them looking forward.

Both cognitively on the evolutionary scale, as I'll show you momentarily, and on the developmental scale, there's an architecture almost like an autoencoder architecture with a thin bottleneck in the middle. That means that you take information; this process is algorithmic or deductive, and you form these engrams here, but then the future is a creative process because information has been lost here. You can't recreate this exactly, and you don't want to recreate it exactly, because you want to reinterpret it for novel circumstances.

Slide 37/55 · 44m:53s

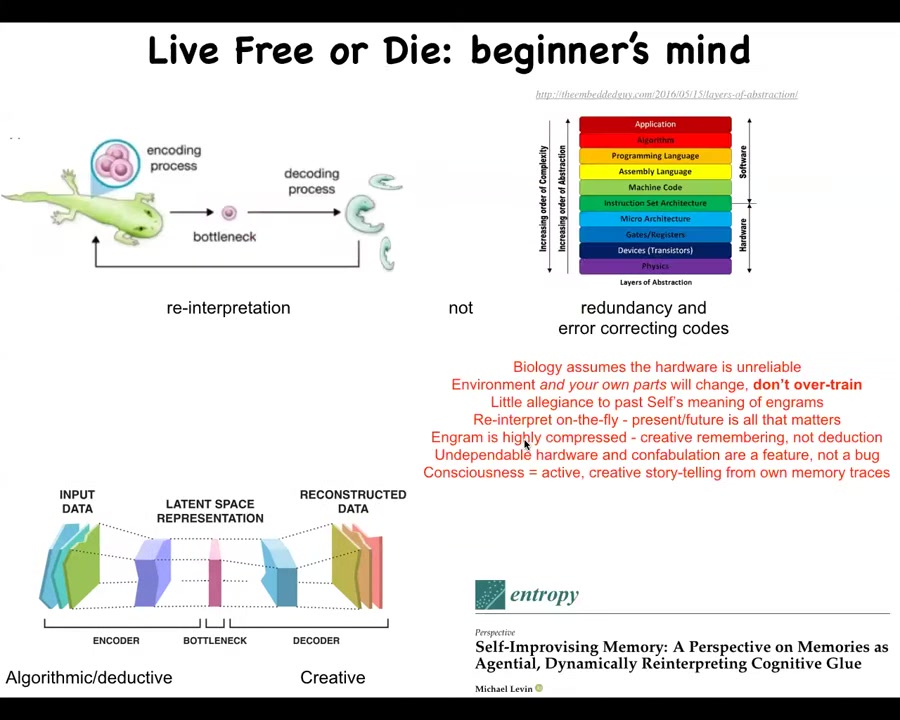

So I'm going to give you a quick example of how some of this works in biology. And then it'll make sense why that tadpole at the very beginning that I showed you with the eye on its tail can see perfectly well right out of the box. It's because the system never could be certain that the standard scenario was going to work in the first place. And it has to do this on the fly. I like to think of this as a kind of beginner's mind idea.

This is a cross-section of a kidney tubule in the newt. Normally 8 to 10 cells build it. If there's a trick that you can do that forces these cells to be very large, as you do this, fewer and fewer cells will build that same tubule and the newt stays the same size. The way you do this is you increase the copy number of your genome. In polyploid newts with more and more copies of their genome, the cells get bigger, but the newt stays the same size. So the first amazing thing is that it's fine if you have extra copies of your chromosomes. The second thing is it's fine if your cells are bigger; you would just adjust the number of cells. But the most amazing thing happens when the cells are enormous, and then just one cell will wrap around itself to make the same thing.

The reason this is so impressive is that this is a different molecular mechanism. This is cell-to-cell communication. This is cytoskeletal bending, which means that what you have—first of all, two things. First, you have an intelligent system here that is able to solve the problem, get to the same goal by using its parts in a new and creative way. Lots of IQ tests are like this. They give you a bunch of parts, and then they give you a problem, and you have to use those parts in novel ways to solve the problem. Things that are not in your history. This is how we measure intelligence. This system is able to do that.

But look at the predicament that it's in. If you're a newt coming into the world, what can you count on? You can't count on having the right number of chromosomes. You can't count on having the right cell size. You have to do everything you can with the tools that you've been given to solve the problem; never mind the environment, you can't even count on your own parts.

The whole point here is discussed in two papers from our lab, and in a paper from Josh Bongard from 2006 where they made robots that didn't immediately know what their shape was supposed to be. From the very beginning, biology commits to the fact that the material is unreliable. You don't know how many proteins you have. Things degrade. There's so much noise at these lower levels. What you have to lean into is the fact that everything is going to be creative problem solving, even normal development. Nothing is hardwired or reliable.

Slide 38/55 · 47m:31s

This is why, and you can see more in this pre-print. Life doesn't overtrain on evolutionary priors. It can't take them too seriously. It has to create problem-solving agents.

Slide 39/55 · 47m:48s

Here's what I think is the major difference with how we try to build computers: not redundancy and error-correcting codes where we say there is an objective meaning to the information that we're storing, and we're gonna do our best to make sure that stays. So the fidelity of the information. We're gonna say, and this is a system called the polycomputing that Josh Bongard and I have been developing around this idea that there are multiple observers, and each observer has to have its own interpretation of its own memories, of the outside world, of what's going on. So everything is committed, in biology, to developing systems that reinterpret on the fly. Only the future matters. What that information used to mean does not matter. We can think about what are the implications for things like consciousness. Being an agent means being responsible for continuous storytelling to yourself from your own memory traces.

Slide 40/55 · 48m:52s

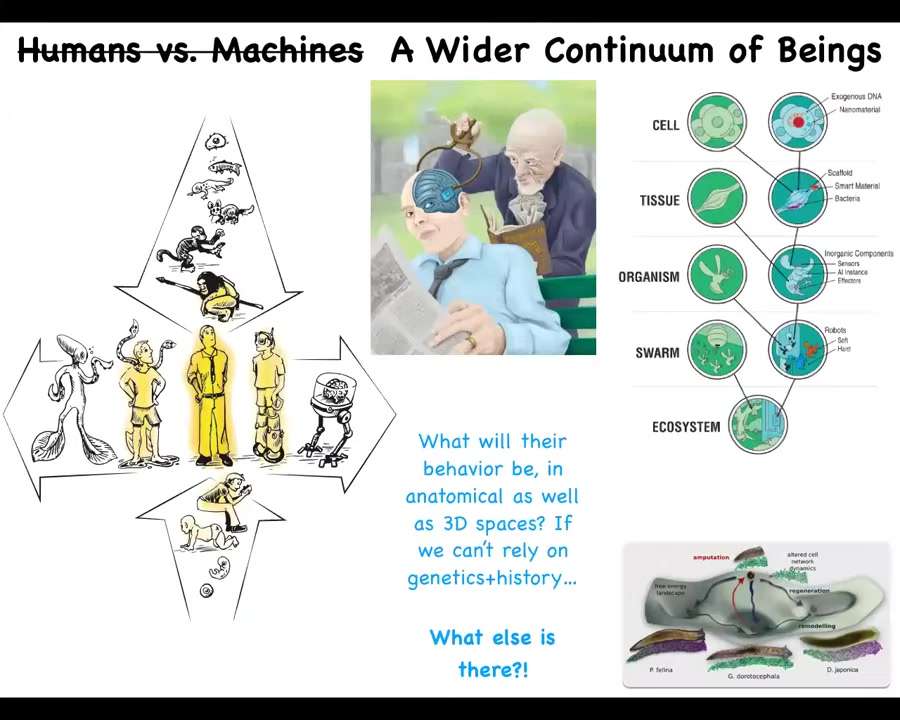

So the last part, I want to talk about what this all means, everything that I've told you today. There are a few areas where this is going to have an impact. All that plasticity, this ability of life to solve problems on the fly, makes it extremely interoperable. It's not just the fixed set of beings that you saw in that engraving of Adam naming the animals in the Garden of Eden.

Slide 41/55 · 49m:24s

Not only are we in the center of this continuum where we used to be single cells and we gradually became this, the subject of popular philosophy of mind, the books and papers, the adult neurotypical modern human.

Not only is this a continuum, but there's another continuum where, gradually, by engineering efforts and changes, but also biological changes, there are many different scenarios by which it becomes very difficult to say what exactly is a human.

This has many implications. That's because everywhere in that multi-scale architecture, we can introduce designed material in addition to the evolved material.

Here, our graphic artist has drawn for me the futility of trying to develop any kind of "proof of humanity" certificates or any of the stuff that people are trying to do. Because what we're going to be dealing with are things like this. They're combinations of material where that's not going to make any sense to try to say, have you got 51% of your brain replaced by constructs.

What we need to understand then is, given that these kinds of beings are possible, and we know they're possible, they already exist, how do we predict their behavior? What is their cognition going to be like? What are they going to be able to do? What are their goals? What are their competencies?

If we can't rely on genetics and history, which is how we do this in biology—we try to estimate what things can do based on where on the evolutionary tree they are—what else is there?

We know that worms have these attractors in this morphospace because we see these species already exist so we can map out the space. But what about things that never existed in the world before? What else is there besides genetics and history?

I want to point out this is going to become very important.

There is a source of information here that has nothing to do with either genetics or history.

Slide 42/55 · 51m:29s

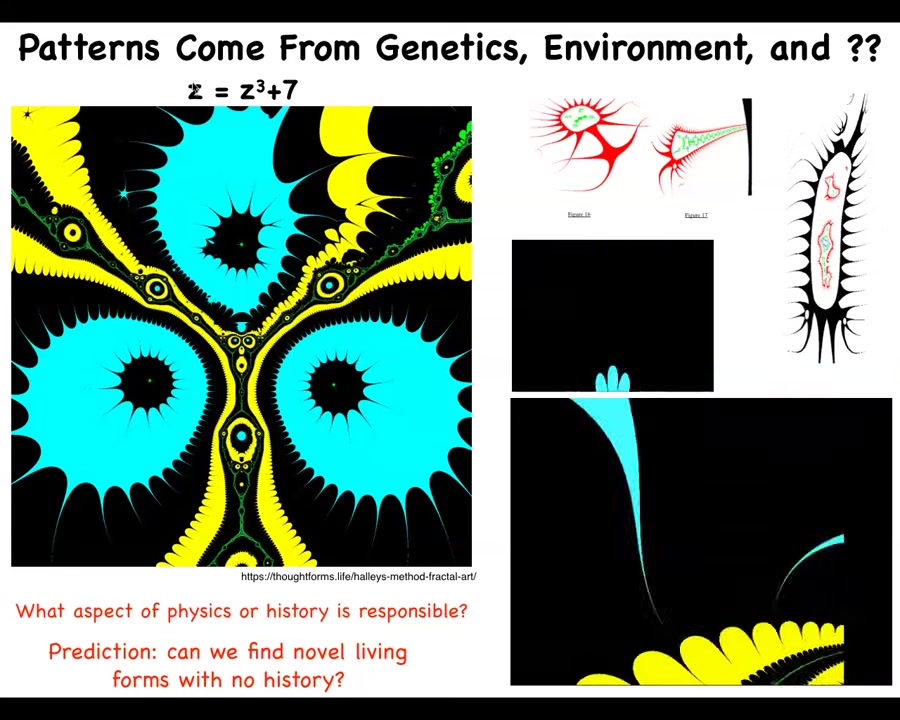

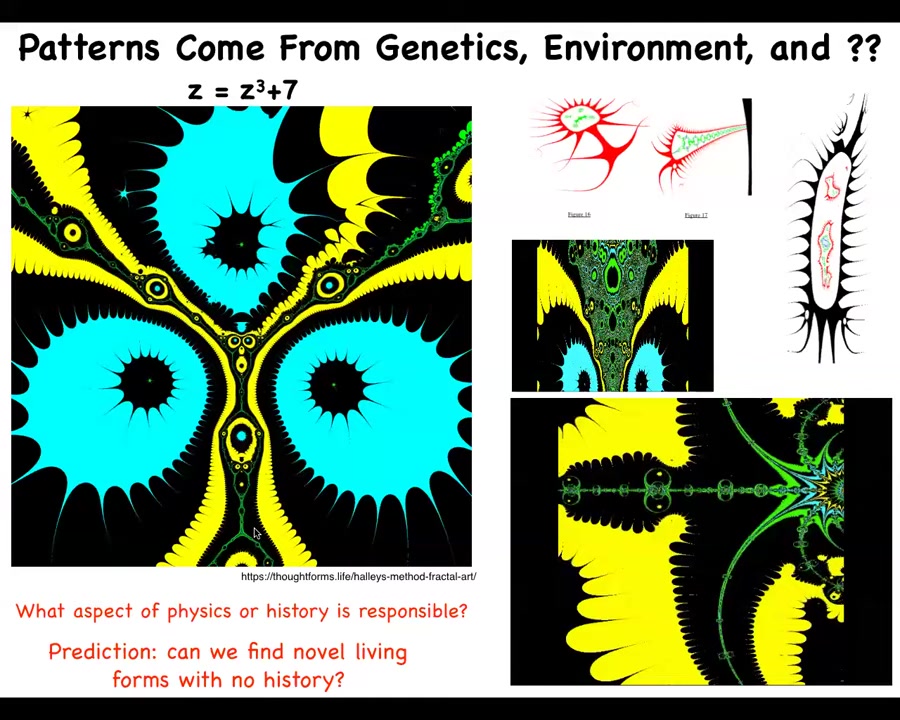

So if you take a very simple function like this, it's a function in complex numbers, in complex Z, and you plot it using something called a Halley plot. It's a short algorithm that looks at different parts of the complex plane and how they lead to this, what they mean for this function in terms of a root-finding method. Then you just color it based on how well it converges. You see that within this tiny little seed is encoded this enormous morphological complexity.

We can make videos of these things by just gradually changing one of these numbers, very slowly changing each frame as a video like this. There are some other things you can do that look like these. These are very organic-looking, very biological-looking.

Slide 43/55 · 52m:10s

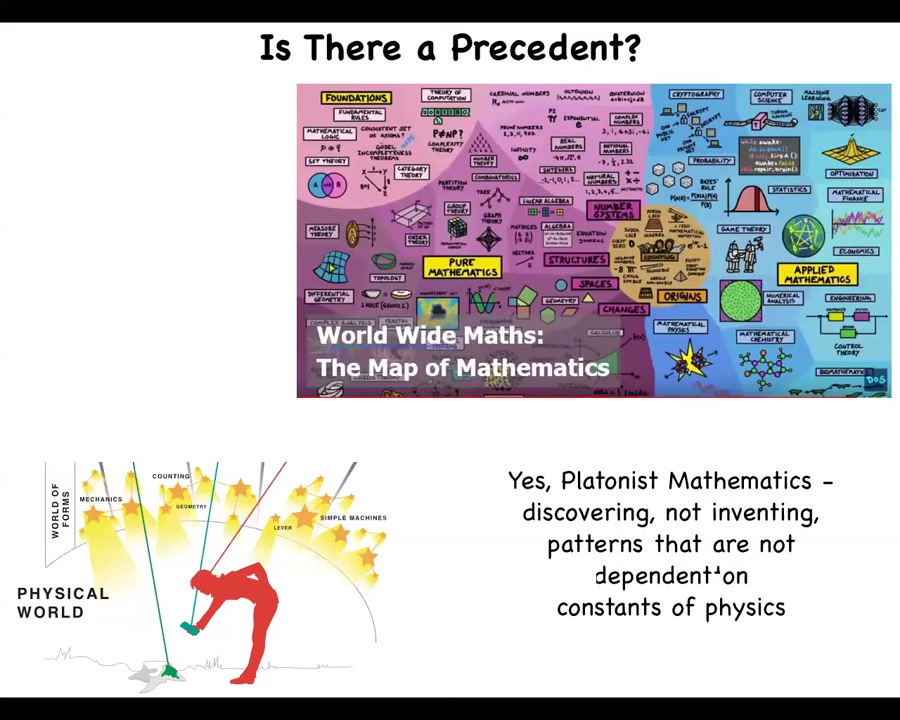

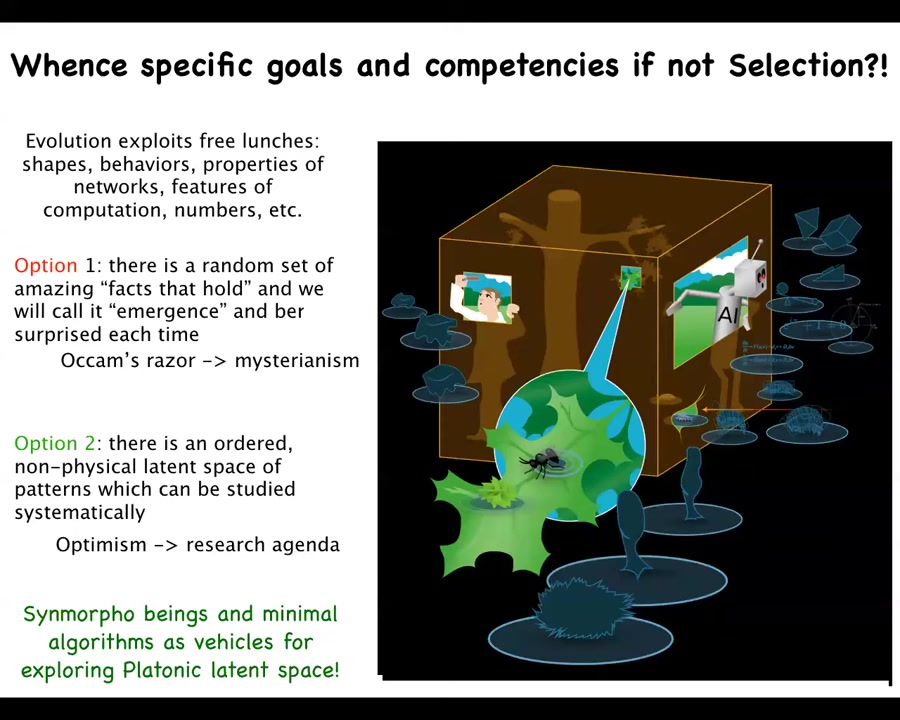

But the point of all of this is that these patterns are not determined by any aspect of physics. They're not determined by any kind of historical process. There is no genetics. Where they come from is the same place that many other mathematical truths come from, which is some non-physical.

We can call it platonic space, for example, of patterns that are not determined by events in the physical world.

You can change all the constants of physics, and many things in math are still going to remain exactly the same. This is a very strange thing for a biologist to be saying, because typically biologists love evolutionary history, they love chemistry.

Slide 44/55 · 52m:58s

They love having processes that are causally closed, where everything is happening in the physical world. I no longer believe that. I think there's an important component from patterns that are absolutely not physical.

Slide 45/55 · 53m:08s

There's a precedent for this. Mathematicians, a lot of mathematicians already believe this, that they're not inventing, they're discovering, building this map of mathematics where they discover pre-existing mathematical truths. So these are Platonist mathematicians. What does all this have to do with biology? Well, evolution uses all of these things, properties of prime numbers and many other things extensively because they provide a kind of free lunch.

Slide 46/55 · 53m:40s

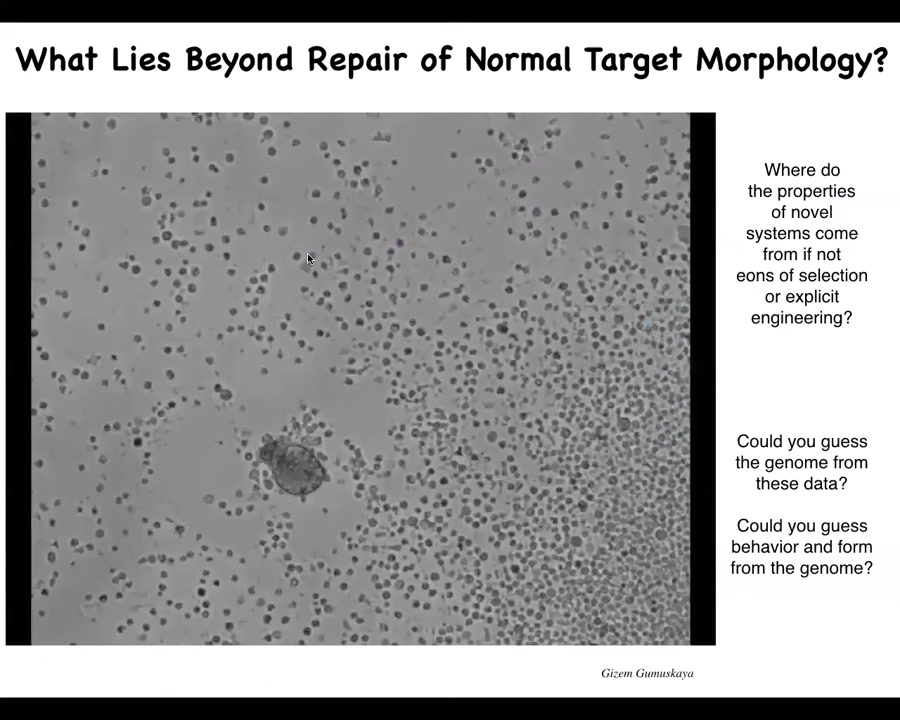

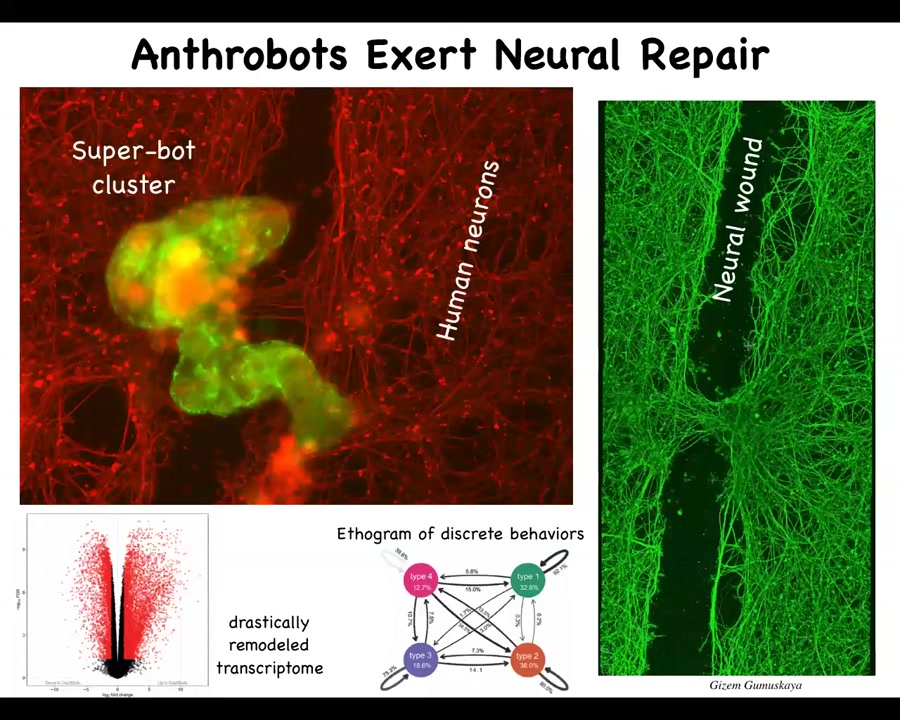

What I want to show you is things like this. This is a little creature. If you look at it, it might look to you like something out of the bottom of a pond somewhere. It looks like a primitive organism. You might guess that its genome is like that of a primitive organism. Actually, if you were to sequence it, you'd see that this is 100% Homo sapiens. These are unmodified tracheal epithelial cells from adult donors. No embryos, no genetic modification, no scaffolds, no weird drugs. This is what your tracheal epithelial cells will self-assemble into when they're taken out of your body and away from all the other influences that the cells use to shape it.

Slide 47/55 · 54m:25s

It has some amazing properties. Half of its genome is expressed differently. Given its new lifestyle, it expresses a very different set of genes. It has behaviors that we can build epigrams around as we do for animals. It has this weird ability to heal neural wounds. If you plop them down on it, these things are human neurons. We put a big scratch through it. These anthrobots come down and they sit there and eventually they'll start to heal this gap.

Who would have thought that your tracheal cells, which sit there quietly in your airway dealing with mucus, that they could have a whole life in and of themselves and have these capacities?

There have never been any anthrobots. There's never been evolutionary pressure to be a good anthrobot. It's not like any stage of human development or anybody's development in this kind of lineage. Where do their behaviors come from? Why do they already know how to do these things?

Slide 48/55 · 55m:22s

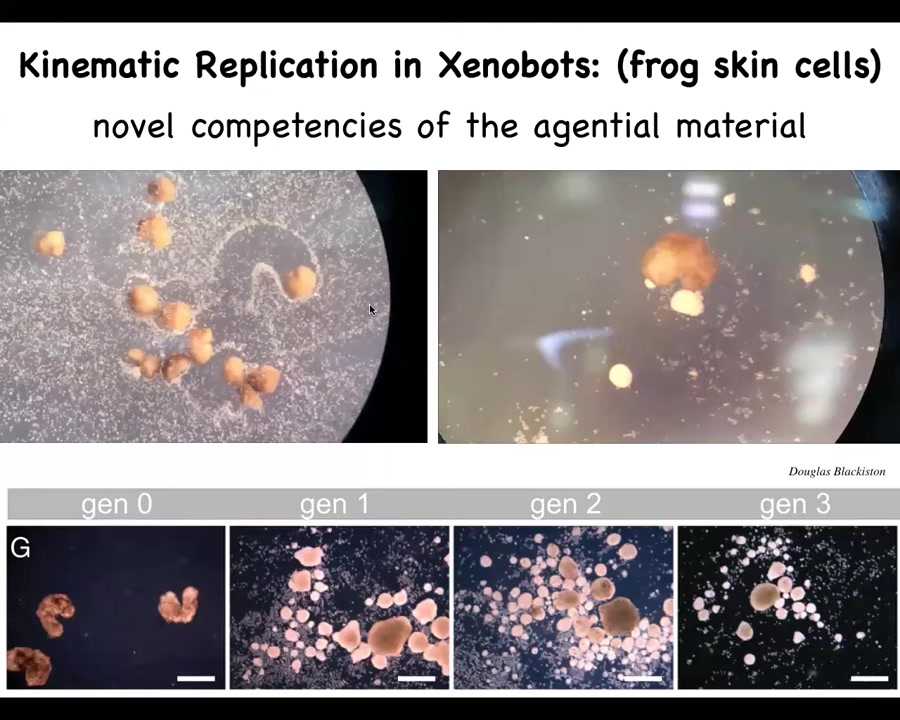

This is a similar kind of model system. These are called Xenobots. They're made from frog skin cells. They self-organize into these little swimming creatures, but they can do something wild. They can do kinematic self-replication, like von Neumann's dream of a robot that would find materials and build copies of itself. If you sprinkle it with loose skin cells, they will build the next generation of Xenobots. When they mature, they do the same thing. They build the next and the next generation.

Slide 49/55 · 55m:54s

So what I'm arguing for is this idea that there is a massive latent space of patterns that evolution exploits that ingress into the physical world and guide events that are an extra influence besides genetics and environment. And what we're doing is using these synthetic morphologies, antibots and anthrobots and various other things, as exploration vehicles to let us study the patterns in the space. And I don't think these are just the facts that hold about the world. I think this is a systematically organized space that we can study.

The really big conjecture here, and this is total speculation, is that Platonic space not only includes the things that mathematicians are interested in, facts about prime numbers and number theory, but actually patterns that we would recognize as kinds of minds.

And the reason that's important is because we are going to be living, in the coming decades, with cyborgs and hybrots and augmented and modified humans and animals and weird chimeras and combinations, pretty much every mix of evolved material, design material, software, and the input from these ingressing patterns — these non-physical facts that are not determined by things in the physical world — make various kinds of embodied beings. We are going to have to develop a new system to ethically relate to them in a kind of synth biosis, a mutual interaction that enriches both kinds, even though these systems are nowhere on the tree of life with us.

Slide 50/55 · 57m:33s

And so I think that AI is going to be a really useful translation layer, not only to the biology of the body, because this is what we're looking at. We need to be able to convert this into actionable understanding. But also to recognize all kinds of very unconventional minds, because our own mental firmware is not sufficient for that. We have a lot of mind blindness, and we're going to need tools, like we develop tools to understand other parts of the electromagnetic spectrum that we are normally completely insensitive to, and understand that it is a spectrum, that magnetism and microwaves and light and so on are all part of one spectrum. We're going to have to do the same thing for "machines" and living organisms and many things that are on that spectrum.

Slide 51/55 · 58m:19s

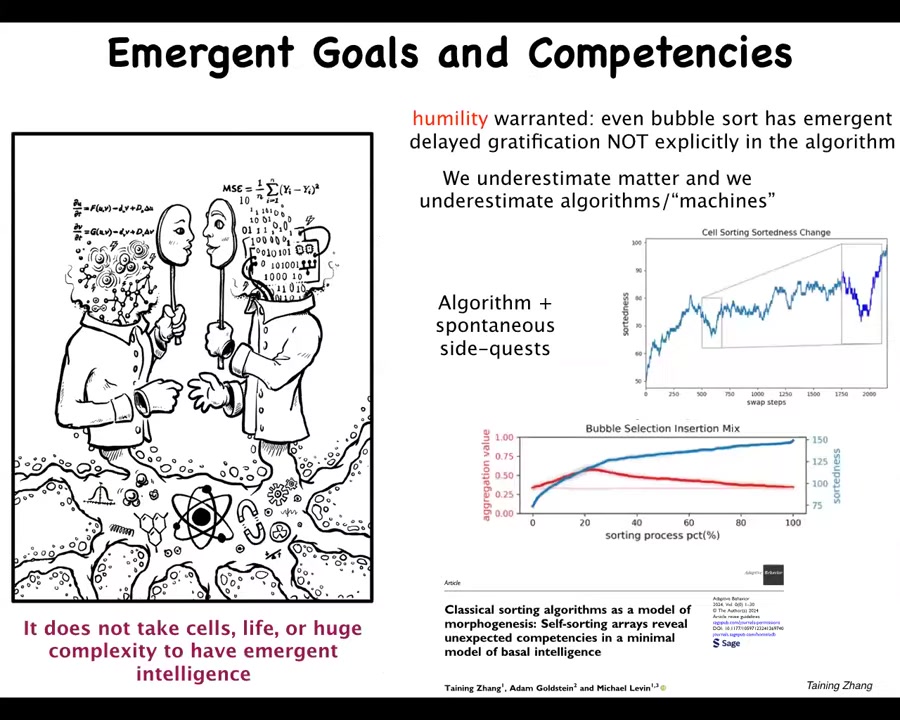

I've talked about all the remarkable features of the living material, but there's nothing magic about the proteinaceous hardware that arrived by trial and error of evolution. In fact, extremely simple systems, in this case, we studied sorting algorithms, bubble sort and selection sort, also have what I call side quests. They do things that are literally not in the algorithm. Here's the paper you can take a look at. If you look at their behavior, they have delayed gratification and interesting clustering properties while following the thing that you think they're doing, which is sorting numbers. It's not just humans, it's not just brains, it's not just living material that can do things that are not explicitly encoded in their biochemistry or, in this case, in the algorithm. It goes all the way to the bottom.

Slide 52/55 · 59m:19s

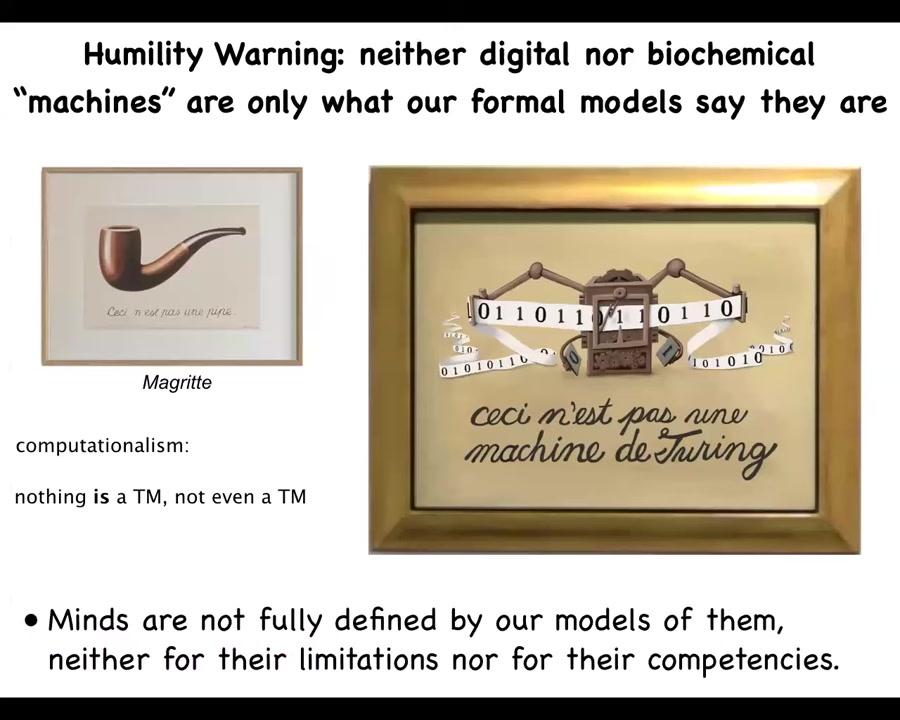

I like this painting by Magritte that reminds us that our models of things are not the things themselves. This says in French, "this is not a pipe." It isn't; it's a painting of a pipe. This is not a Turing machine. It's our model of Turing computation. I think that Minds are not fully defined by our models of them, neither their competencies nor their limitations, any more than human cognition is fully described by the laws of biochemistry.

Slide 53/55 · 59m:51s

And so the future Garden of Eden is going to be extremely weird. It's on us to name all of these things that are going to be far stranger. And include some very diverse kinds of minds that are just not on anybody's radar at this point.

Slide 54/55 · 1h:00m:08s

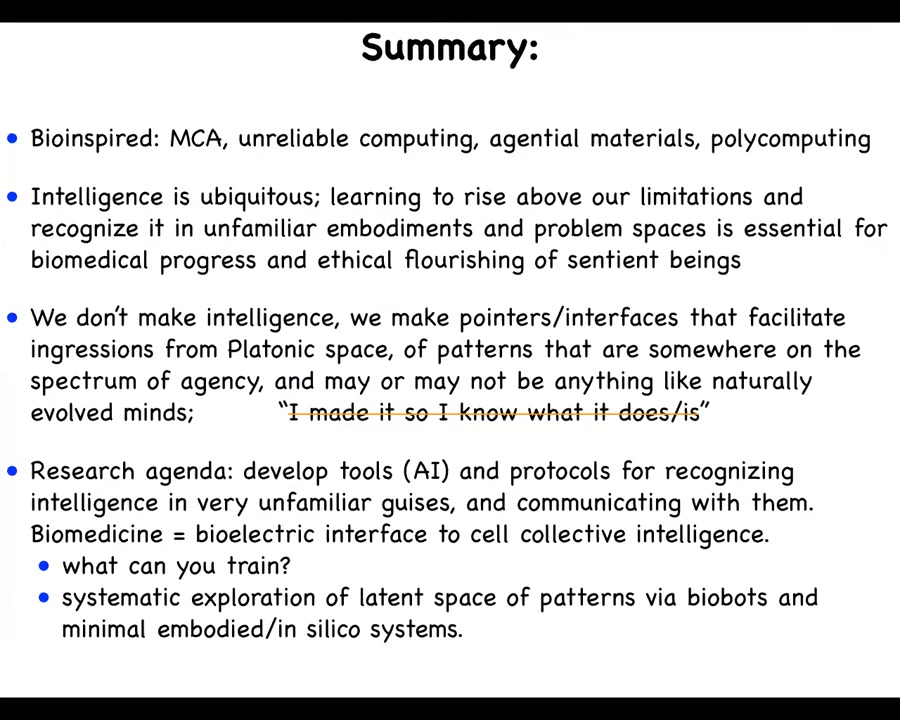

What I've said is that the unreliability of the substrate drove an intelligence ratchet. That's very interesting in biology. But I don't believe that we make intelligence either in biological systems or in technological systems. What we make are pointers or interfaces that facilitate specific patterns from the space. There's this research agenda that we are now following.

Slide 55/55 · 1h:00m:36s

I'll thank the people who did all the work. These are various postdocs and collaborators in our work. I have to do a disclosure. There are three companies that have funded us and our amazing collaborators and the model systems. Thank you very much.