Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a ~35 minute talk on commonalities and differences between biological and technological information processing, and the implications for AI (given at the AGI-25 conference in Iceland). The full program, including Hananel Hazan's talk (which is the 2nd half of mine), is at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fdftA37yZJw.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Turing, bodies, and minds

(06:11) Radical developmental plasticity

(11:32) Multi-scale goal-directed morphogenesis

(17:06) Bioelectric control and memory

(22:01) Interpreting compressed biological memories

(27:41) Synthetic organisms and AGI

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/27 · 00m:00s

Thank you so much. Thank you for giving me the opportunity to be here, virtually. I'm really looking forward to having a discussion with you about some issues, specifically around the similarities and differences between the way biology and technology process information.

I'm going to go fairly quickly over some of the biology if you want to dig into the details. Everything is here. These are my own personal thoughts about what some of this means.

We all know who Alan Turing is and how he was interested in the fundamentals of intelligence in diverse embodiments. He thought a lot about how to implement different kinds of minds in novel architectures. In particular, he was interested in reprogrammability and thus intelligence as a kind of plasticity. What's not as frequently appreciated is that he also wrote this paper on the chemical basis of morphogenesis. This goes into mathematical models of how embryos self-organize from initially a randomly distributed set of chemicals.

Why would somebody who is interested in computation, in programmability and intelligence, be interested in the early stages of development? I think it's because Turing saw a very profound truth. That is, there's really a deep symmetry between the self-assembly of the body and the self-assembly of minds, and we have studied now for a couple of decades the various parallels between those two processes, and I think they're fundamentally the same process.

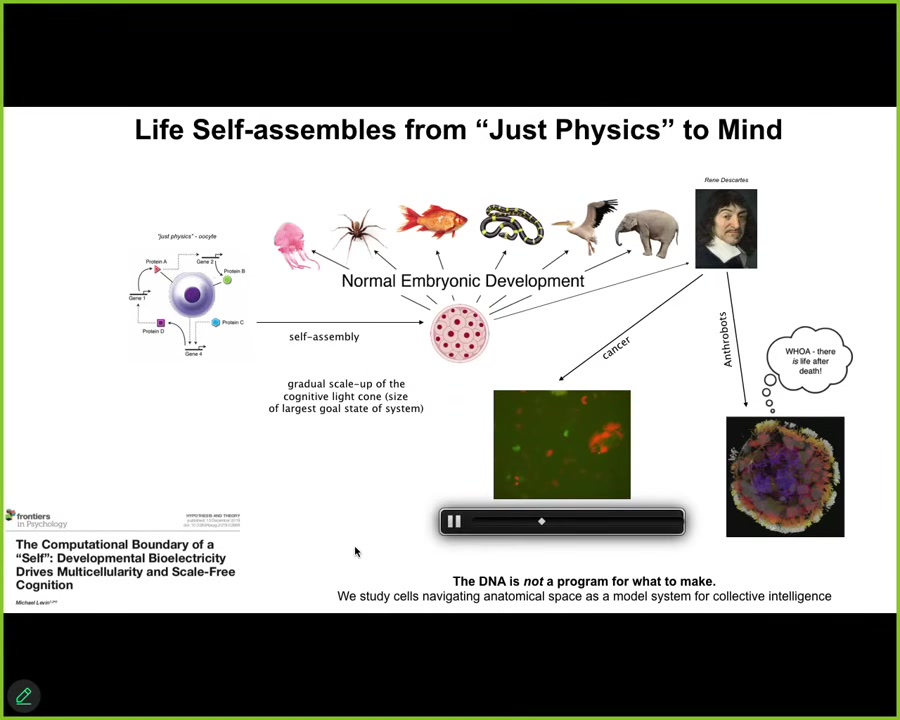

Because what happens in biology is that life makes a journey. Each of us took this trip from being a unfertilized oocyte. This is a little bag of quiescent chemicals that people would look at and say, this is well handled by the laws of physics and chemistry. There's no need for concepts from intelligence or cognition or anything else. But slowly and gradually, this becomes something like this or even something like this, a system that will certainly make claims about being cognitive and having beliefs and memories and goals and perhaps even not being a machine.

What's important here is that the hardware, the biological hardware, is able to autonomously make this slow and gradual transition. This is not the end of the story. There are many interesting things, both pathological and just really strange, that I'll talk about in a little bit that can happen even after this journey is complete.

One thing that I want to point out that's important for deriving insight for AI from this sort of process is that the standard story of biology that you may have heard is incomplete in important ways.

Slide 2/27 · 02m:42s

It's being revised by a number of people, including our lab. What's important to know is that DNA is not a program for what to make. DNA is not a description of the final product that we're going to get from any of these kinds of cases.

What we study in our lab is a model system, which is groups of cells navigating the space of anatomical possibilities, a model for collective intelligence. This is important because what it reminds us is that we need better theories of transformation and scaling, not ancient magical categories such as humans and machines or living things versus computers.

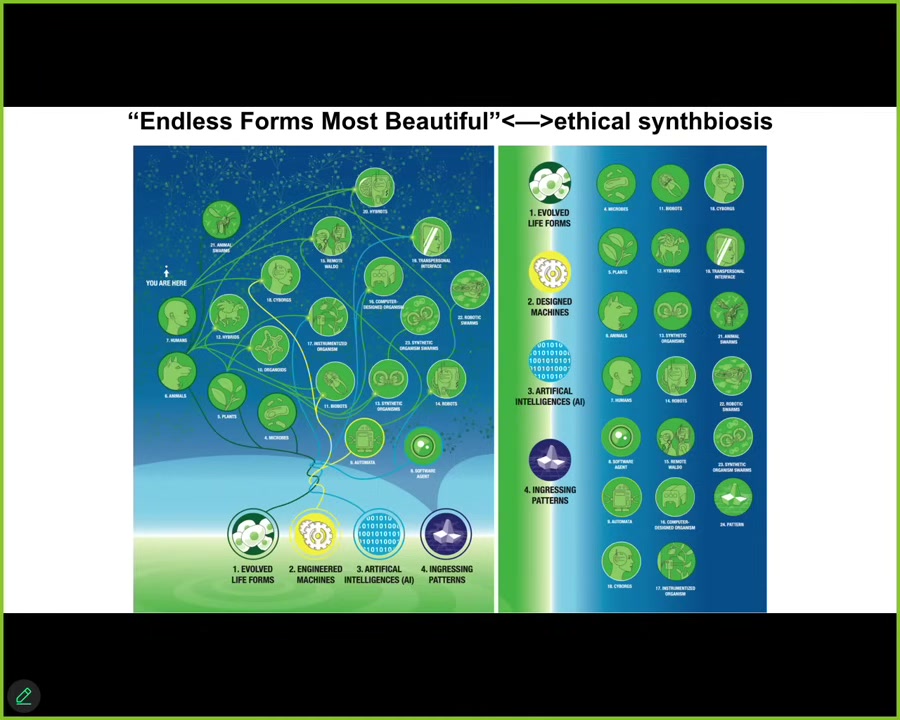

Those hold back science in important ways because all of us started life as a single cell and chemical networks before that, and eventually, both on an evolutionary scale and on a developmental scale, slowly, gradually, without any special jumps or discontinuities, we become this kind of modern human that features in all of the discussions of philosophy of mind and things like that. Not only is this a continuum, but we know that both biologically and technologically there's a very wide range of different kinds of chimeras possible, and many of these already exist.

The reality is that both we and the kinds of technologies that we make are at the bottom made of some of the same stuff. Some of the details differ here, but fundamentally we are all composed of matter.

The trick is to understand how different kinds of observers interact with different kinds of systems to create events, agency, and the kinds of things that we're interested in in terms of intelligence. This is as much a problem for biology as it is for robotics, for computer science, for artificial intelligence.

What I would like to do is develop a framework that allows us to recognize, perhaps create, but most importantly ethically relate to truly diverse intelligences, regardless of what they're made of or how they got here. This means familiar creatures such as us and birds and maybe a whale or an octopus, but also some really weird organisms, colonial things, swarms, synthetic biology, engineered new life forms. I'm going to show you two of those today. AIs, whether software or robotic, and perhaps even someday aliens.

Broadly speaking, this is a program in the field called diverse intelligence, which I think is very important and underappreciated given the implications that this field has for AI and AGI. I'm not the first person to try for a framework like this. Here, Weiner and his colleagues back in 1943 tried for some kind of a scale from passive matter all the way up to human and beyond-human intelligence.

What we're interested in is using various model systems, including cells navigating anatomical decisions, to understand how exactly the scaling works. How do you get from simple matter to these kinds of cognitive things?

In order for me to claim that development and regeneration are not simply the mechanical feed-forward emergence of complexity from simple local rules, I would have to show you that what we're actually dealing with is context-sensitive plasticity. In other words, intelligence, the way William James defined it: being able to reach the same goal by different means.

We need to talk about what exactly it means to navigate this morphospace in a way that is something other than simply feed-forward, some sort of cellular automaton-like structure. You can see all of this described in careful detail here. I'm going to go through fairly quickly to give you an overview of some of the biology that underlies some of these ideas.

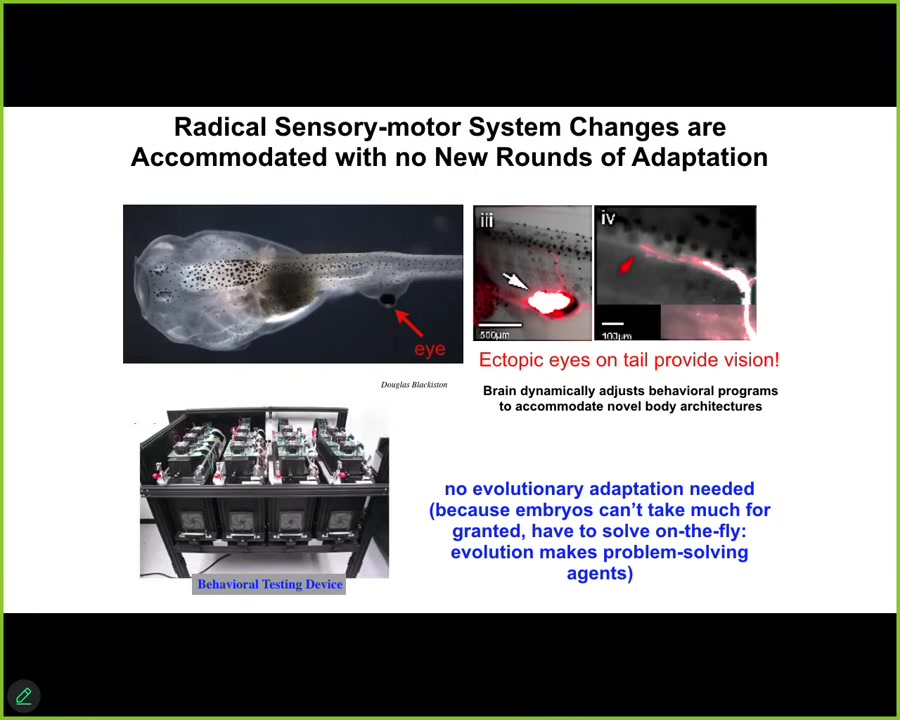

Slide 3/27 · 06m:52s

What you're looking at here is the tadpole of the frog, Xenopus laevis. Here are the nostrils, the mouth, the spinal cord is here, the tail, the gut. This yellow thing is the gut, and then this whole thing is the head. What you'll notice is that we've prevented the two primary eyes from forming, but there is an eye that we've caused to form on its tail. That eye makes an optic nerve. The optic nerve comes out. It starts to look. Sometimes it synapses on the spinal cord, sometimes on the gut, sometimes nowhere at all. It certainly doesn't hit the brain. It never reaches the brain. And yet, as we discovered by building this machine that automates the training and testing in behavioral light-responsive training assays, these animals can see, and so what you find is this amazing ability for the radical refactoring of sensory motor architecture. For the first time in millions of years, the eyes are not in the head, they're not connected to the brain, they're somewhere else. And yet this animal does perfectly well right out-of-the-box. No new mutation, selection, evolution, adaptation, no need for any of that. You change the configuration, it works perfectly well. They can see.

Slide 4/27 · 08m:02s

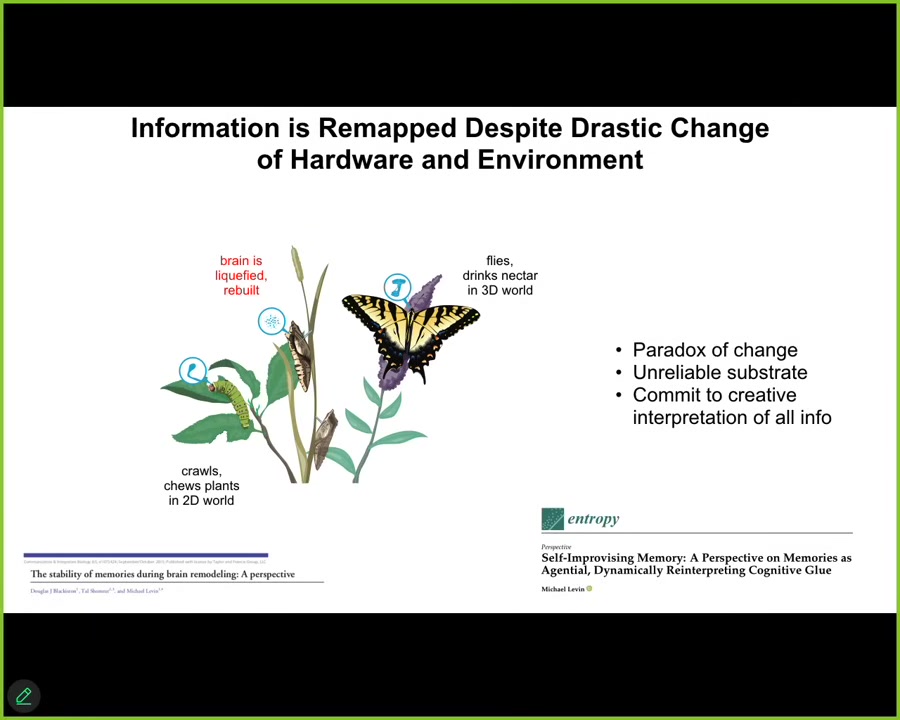

It gets even more impressive as caterpillars, which you can think of as a kind of soft-bodied robot with an appropriate controller for running a soft body that moves in two-dimensional space and eats leaves. It has to become this butterfly, this hard-bodied creature. You need a completely different controller for that. It flies now.

In order to get from here to here, what happens during metamorphosis is that the brain is basically dissolved. Most of the cells die, most of the connections are broken, and then it builds an entirely new brain suitable for this kind of lifestyle. What's amazing is that if you train the caterpillar, the butterfly or moth will still have the information. Retention of information past this drastic refactoring is not the amazing thing here. It's amazing enough that it would be nice if we had architectures where you could scramble the hardware and the memories would stay intact. It's more amazing because the specific memories of the caterpillar are of no use to the butterfly. If you train it to crawl and eat leaves, the butterfly moves differently. It doesn't crawl, it doesn't care about leaves, it wants nectar. There has to be not only a generalization, but a remapping of the specific experiences that this creature had onto an entirely new body. What's happening for these memories to survive is they have to be remapped onto a new architecture. This requirement to maintain not the fidelity of information, but the saliency of information for novel scenarios is, I think, what underlies the magic of biology and the things that we can learn from it in computer science.

Slide 5/27 · 09m:40s

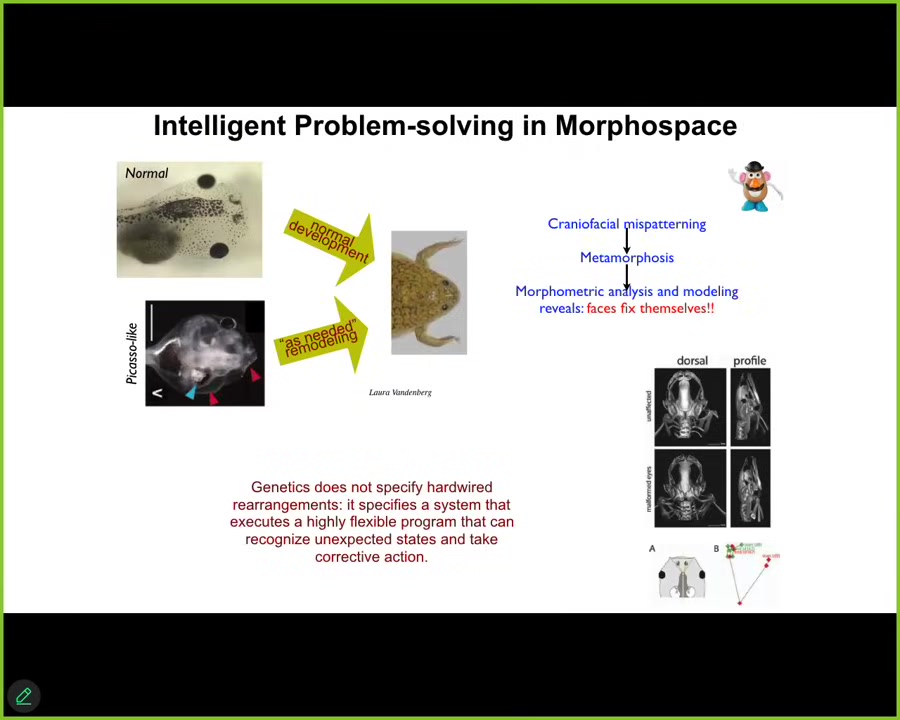

There are many kinds of plasticity. For example, if you take this tadpole and you scramble the craniofacial organs — this eye is on top of the head, the mouth is off to the side, we call them "Picasso tadpoles," everything is in the wrong place. They will still make quite normal frogs because all of these organs will move around in novel paths, they'll get to where they're going, and then they stop. You see that genetics is not specifying a set of hardwired steps for these. What it does specify is a system that can do error minimization, and it can do this kind of means-ends analysis where it will keep moving until it gets to a particular pattern, and then everything is satisfied. Not only that, but these kinds of systems are reliable for sure.

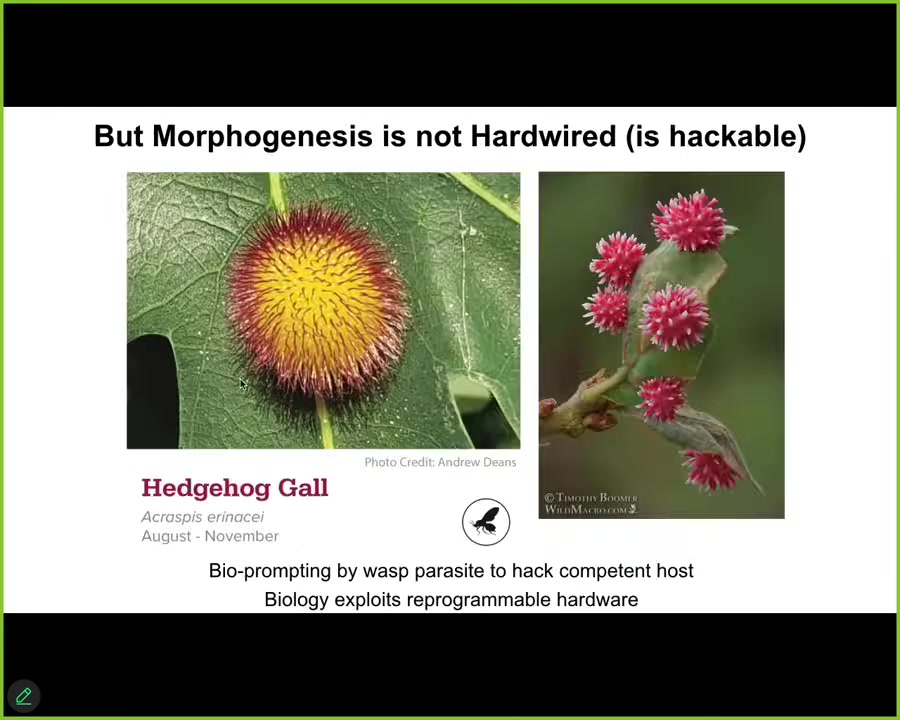

This acorn, all over the world, you see these things reliably, in billions and billions of cases, just building the same exact structure. It sort of lulls us into a false sense of understanding that we say, well, we know what the oak genome knows how to do, it knows how to build this particular structure.

Slide 6/27 · 10m:42s

But along comes this non-human bioengineer, which is this little wasp. What the wasp does is prompt the cells with new information that hijacks their morphogenetic ability and causes them to build these galls, these amazing structures. We would have had absolutely no idea that these cells are able to, besides the flat green thing that they always make, make such a structure. We would have no clue if it wasn't for this creature that figured out how to get the desired behavior. These are not made of wasp cells; they're made of plant cells. So this is a minimal prompt that hijacks the ability of this thing to build many things beyond what it normally reliably builds. So what I've shown you so far is this plasticity of novel outcomes. And of course, such plasticity is hackable or reprogrammable.

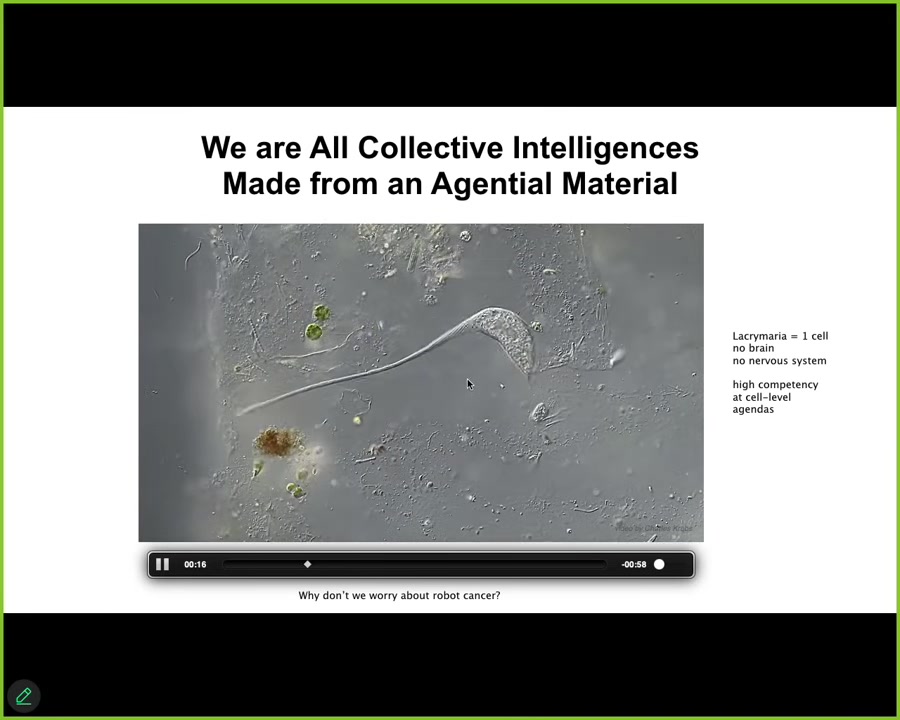

Now, we are all a collective intelligence because we are all made from agential materials.

This is a single cell. Now this is a free-living organism called the lacrimaria, but you get the idea.

Slide 7/27 · 11m:48s

This single cell has no brain, it has no nervous system, but it is incredibly competent in all of its tiny little goals. It has a little cognitive light cone, and it's very competent in those goals. We are made of parts with agendas.

This is quite different than most of the technology that we build.

You don't need to worry about robot cancer because they are made at a single level where the parts don't have their own agendas. They're not going to decide to defect and go off and do something else.

The collective does not need to worry about constantly binding its parts, hacking and controlling them towards common purpose. This is what biology is doing all the time, 24-7.

Slide 8/27 · 12m:28s

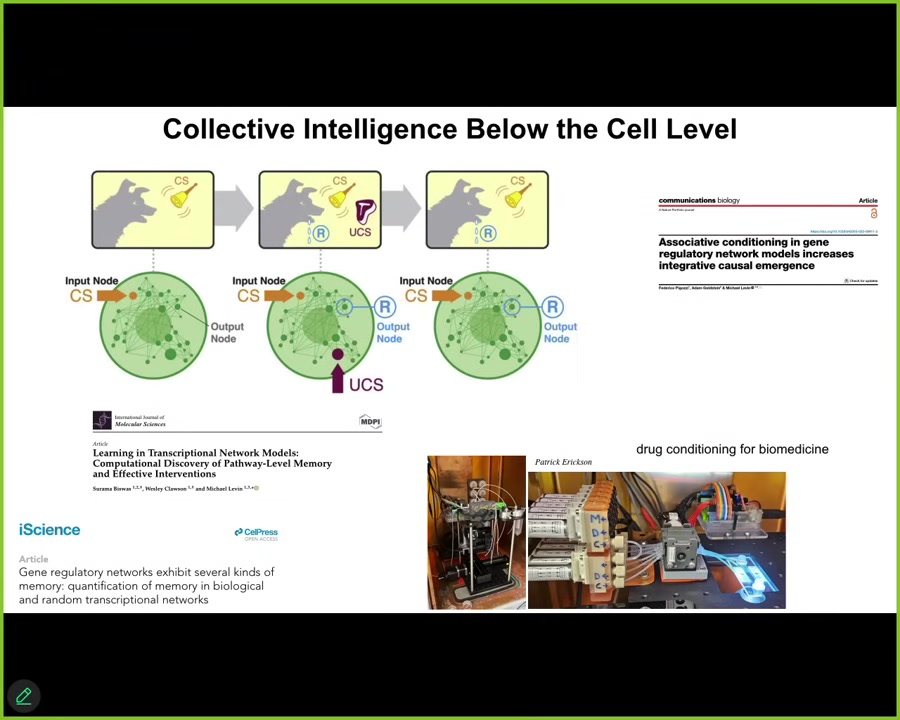

Because we are made of parts that otherwise would do their own thing, even below that, the level of that single cell, the material of which the cell is made, the chemical networks inside already have six different kinds of learning that they can do. Just by virtue of the mathematics, the way that these networks work out, it turns out that they can do habituation, sensitization, and associative conditioning. The material itself, long before you get to cells or brains or anything like that, the chemical material that we're made of already has the ability to form memories. As they're trained, as they form these memories, causal emergence goes up. The system is actually reified as a high-level system. We are currently in our lab trying to take advantage of this kind of thing for drug conditioning and various medical applications.

What's happening in biology is that unlike most of our architecture, it is a multi-scale system like this, not just structurally, but the fact that every level has the competency to solve certain problems in their own spaces. That means that each level has to bend the option space for its parts and keep them aligned towards goals that the lower level knows nothing about.

Slide 9/27 · 13m:42s

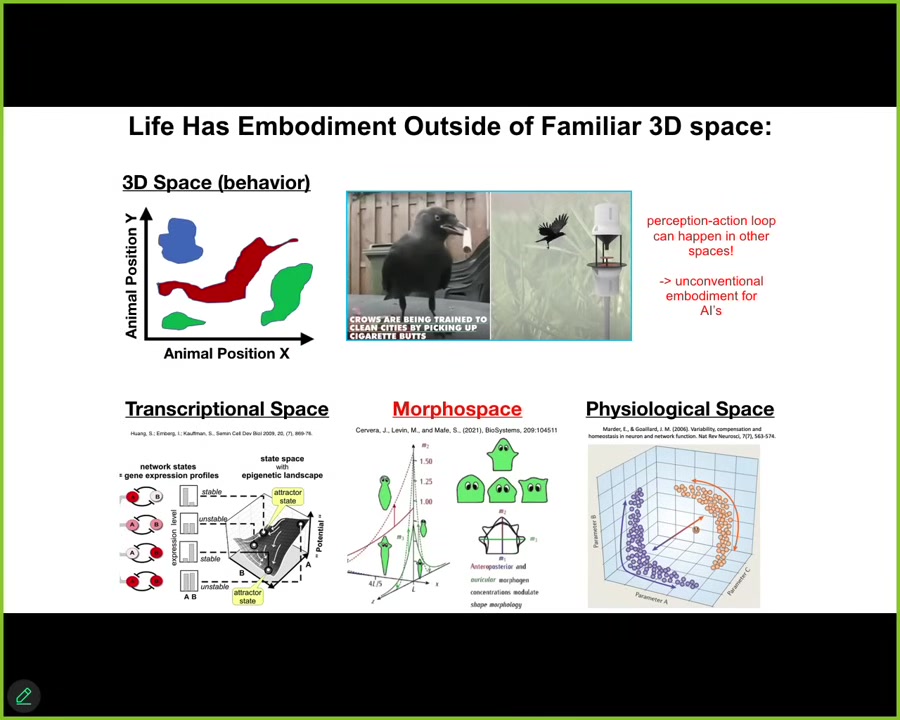

Here we come to an interesting point about embodiment. Because of our own evolutionary history, we are very obsessed with three-dimensional space. We think that three-dimensional space is the real one. Mathematicians are good at thinking about some other spaces. We are pretty good, not great, at recognizing intelligence of medium-sized objects moving at medium speeds in 3D space. But biology has been solving problems by navigating spaces long before muscle and nerve evolved.

We have to really understand that this perception-action loop, that's the basis of all agency, happens in many other spaces. Biology does it in the space of gene expression, in the space of physiological states, and anatomical morphospace.

I think this is important because a lot of people say that if it's not driving a robot that wheels around your kitchen or the outside environment, that it's not embodied. I think that's a big mistake. Both in robotics and in biology, many organoids that look like they're sitting there, and many software AI agents that look like they're not engaging with the real world, are actually very likely navigating many other spaces that we're bad at noticing.

Within this anatomical morphospace, we see a number of things. We see things like regeneration. For example, in this axolotl, an amphibian, you can cut anywhere along this line, and the cells will immediately grow what they need to do, and then they stop. That's the most amazing thing about this, because they can sense they've been deviated from the correct place in the anatomical space. They will work very hard to get there. When they get there, they know they've gotten there. They can sense that the error has fallen below acceptable thresholds and then they stop. That stopping point is really critical. It's not that any particular cell knows what a finger is or how many fingers you're supposed to have, but the collective absolutely does. You know that it does because you know that it will stop when it gets to the right point. And as I'll show you in a minute, that set point is actually rewritable, it's reprogrammable.

It's not just about controlling or repairing damage. It's really about the top-down control of high-level goals onto the hardware. What you're seeing here is another experiment done back in the 50s where people would take the tail of an amphibian and surgically attach it to the flank. What you see here is that over time, it slowly transforms into a limb. Not only does this thing transform into a structure more appropriate to its new location, but the cells at the tip here, in their local environment, are perfectly correct. They're tail tip cells sitting at the end of a tail. But what happens is that they start to turn into fingers. That's because this large-scale pattern, the error that is sensed by the system when you do this grafting experiment, propagates all the way down to control not only the cell behavior, but the molecular biology, the new genes that need to be turned on and off, to make the whole thing more coherent.

Talk about alignment. You have to get the cells and you have to get the molecular pathways aligned towards this large-scale body plan of which they know absolutely nothing. You have to have an architecture, which biology does, that propagates these signals all the way down and makes sure that the low-level details are feeding this high-level anatomical journey that the whole system wants to take.

One of the central new things that our lab has done.

Slide 10/27 · 17m:10s

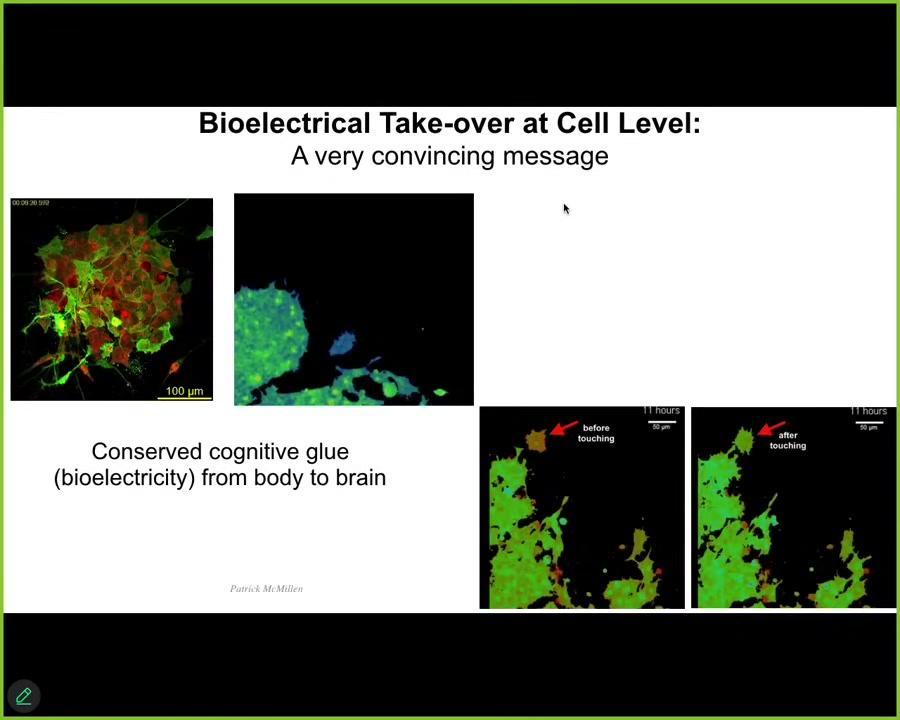

It is to find out that, very much like in the brain, the exact same mechanisms, which we call cognitive glue, because it binds subunits towards large-scale goals, the same mechanisms are used in the body as are used among the neurons of the brain to allow you to navigate space towards specific goals.

In other words, if you ask how it is that we have this amazing neural architecture that allows us to pursue goals in the future, have memories of the past, it turns out that brains got that trick from a very ancient bioelectrical signaling that has been here since the time of bacterial biofilms. This is just one example. We've learned to visualize in non-neural cells all the electrical activity that's happening here.

I'm going to show you a couple of cool examples. So what's happening here: these are two frames of a video, and the colors here represent cell voltage.

These are slowly changing voltage states, just like they study in electrophysiology, but slower. The colors are different voltages. There's this cell and what you'll notice is that it starts off with this voltage represented by the red. As soon as it touches just a little bit, it touches this whole mass, bang, it gets hacked.

I'm going to show you the video. Here it's got its own voltage, it's moving along. Now this guy's going to reach out, boom, that's it. It's been now convinced that it's going to become part of this group and it merges.

These bioelectrical states are controllers, not just indicators, but controllers of whether cells are going to go off to do their own thing or join a collective and work on these very large-scale goals. We can now track these messages that are able to hack them.

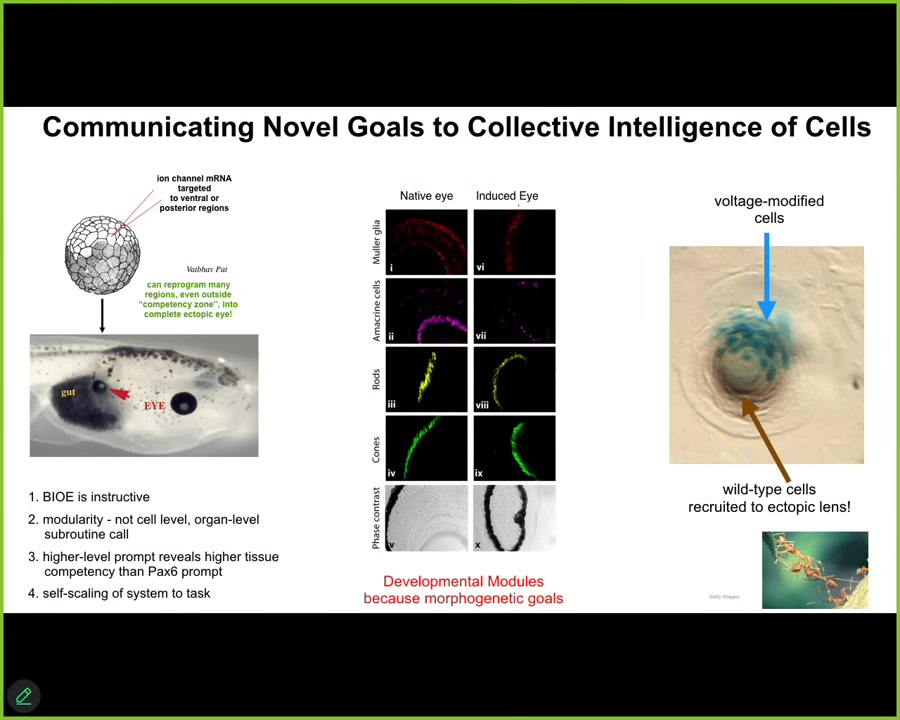

Slide 11/27 · 18m:52s

Not only can we track them, but we can reproduce them and bend them to our own purposes. For example, when I change the bioelectric state of specific cells — and this is not by electrodes: there's no frequencies, no magnets, nothing like that — we hack the native interface that the cells are using to control each other, which means ion channels. You change the ion channel properties in these cells, and we can put in a little pattern that says make an eye here. Sure enough, there's an eye in a place where the gut was supposed to be. These eyes have all the right internal structure: lens, retina, optic nerve.

This is important. Talking about this multi-scale architecture, we did not have to control any of this. In fact, we have no idea how to micromanage the cells and tell them to make an eye. Eyes are very complex. We don't know how to do that. What we do know how to do, much like you would with any cognitive system, is to give a high-level prompt that the rest of the material interprets in ways that propagate down to the parts to enable them to do the thing that we're supposed to do. We're doing it right now. For me to get you to remember what I'm saying, I'm not trying to reach into your brain and change your synaptic proteins. You will hopefully do that on your own. We are communicating through a very narrow interface with very sparse kinds of messages. We can do those kinds of things. The cells that we inject — here are these blue cells — will go on and recruit all these other cells, which we never touch directly, to help them build this larger scale structure. We instruct these cells and we say, build an eye. That's all we say: build an eye. Then they instruct everybody else and get them to do the right thing. We can do that.

Slide 12/27 · 20m:28s

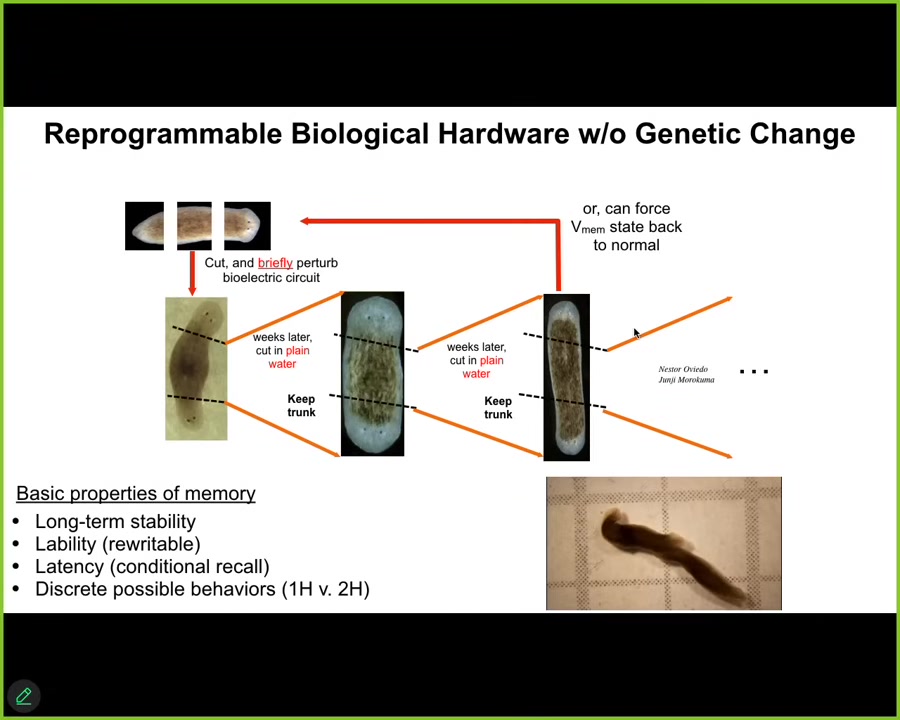

We can do many other things. For example, here are flatworms. They normally have a tail and a head. They have bioelectric pattern memory, not in the brain, in the entire body, that tells them how many heads a proper worm is supposed to have. We can now visualize that set point, the pattern to which they repair, and we can rewrite it in a way that says, no, you should have two heads.

If we do that, then when we cut off the head and the tail, boom, you get these two-headed animals. This is not Photoshop, it's not AI. These are real animals; you can see them here. The amazing thing is that when you then cut these things, they will continue to regrow as two-headed. It's permanent because, as any good memory does, it holds.

What's critical to understand is that there's been no genetic change here. There's nothing wrong with the hardware. You can sequence these guys all day long. None of the tools of modern molecular genetics will reveal that these guys are going to regenerate as two-headed, because that's not where the information is. You can see that the material uses these physiological circuits to store information that does something different than the default outcome that this hardware normally does when it comes into the world. I've now shown you many examples of this amazing reprogrammability and plasticity.

Slide 13/27 · 21m:50s

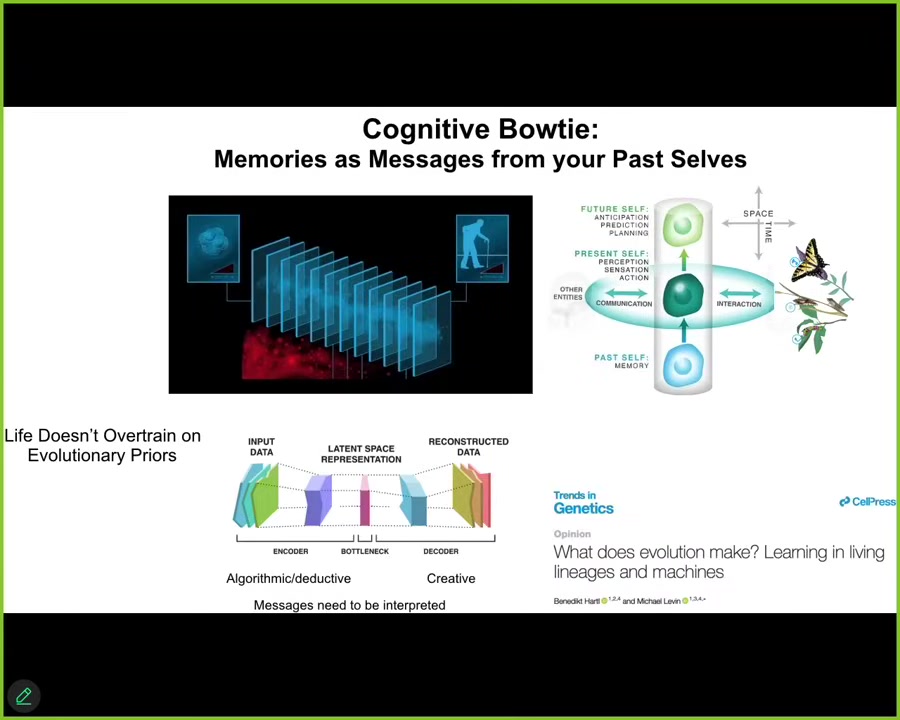

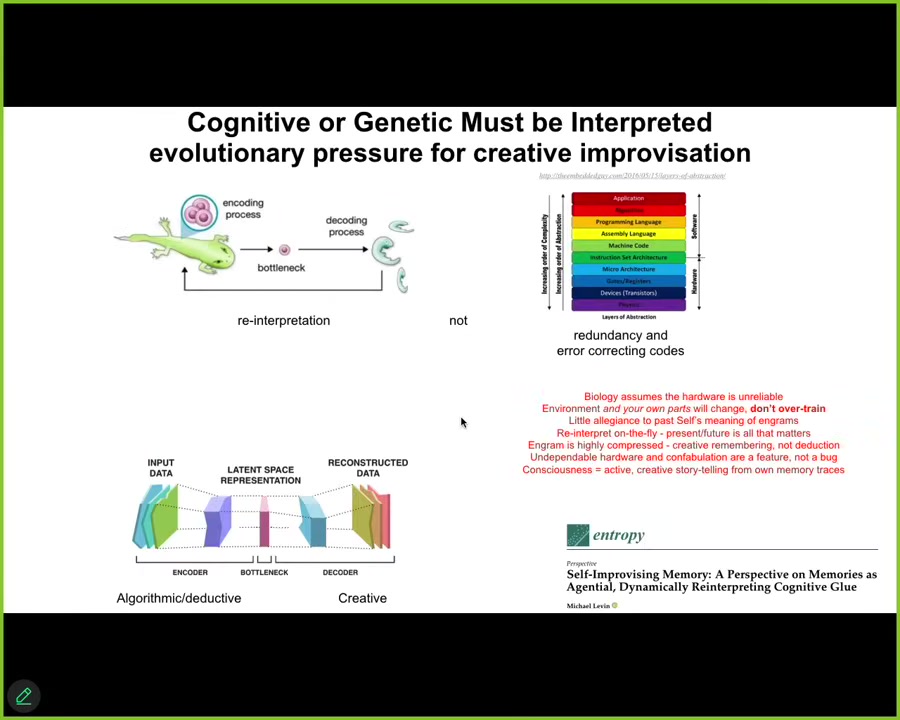

It's time to take some guesses as to why this occurs and what is it that's special about the biological architecture that maybe we can learn from in making AIs. What I think is happening here is that both on a cognitive and a morphological level, the following phenomenon is taking place. Just consider that you don't have access to the past. What you have access to at any given moment is the engrams, the memory traces that have been left in your brain or body by past experience. We are a collection of these kinds of selflets, and many of them are not changed that much. For the butterfly-caterpillar thing it's pretty drastic. In puberty, mammals have a pretty drastic change as certainly humans do. Fundamentally, most of these things are similar.

Nevertheless, what's happening here is that at any given moment, you don't know what your memories really mean. In fact, it doesn't matter what they meant to pass to you. What matters is how to interpret the information that you got for the most adaptive story going forward, the thing that will tell you what to do next. I'm sure you'll all recognize this kind of architecture, and it's described in detail here. What's happening first is that your experiences and the results of them are getting squeezed down. They're getting compressed and generalized into this thin, very, very sparse representation, and this is the memory medium inside of cells. Continuously, it has to be decoded. In other words, what does this set of molecules or this bioelectrical map mean? Can we decode it and find out what we're supposed to do?

This part, I think, is algorithmic and it's deductive. This part, I think, is fundamentally creative because you've lost information here. You don't know what it meant to your past self. It actually doesn't matter. The result of this is that life isn't over-training on its evolutionary priors. Whether it's memories in your mind or genetic information in your cell, all of it is just a message from your past self. As with all messages, it is now up to you to interpret it in whatever way you want. That is not only a kind of freedom, but it's actually a really important responsibility because you have to do this. You have to do this continuously.

Slide 14/27 · 24m:10s

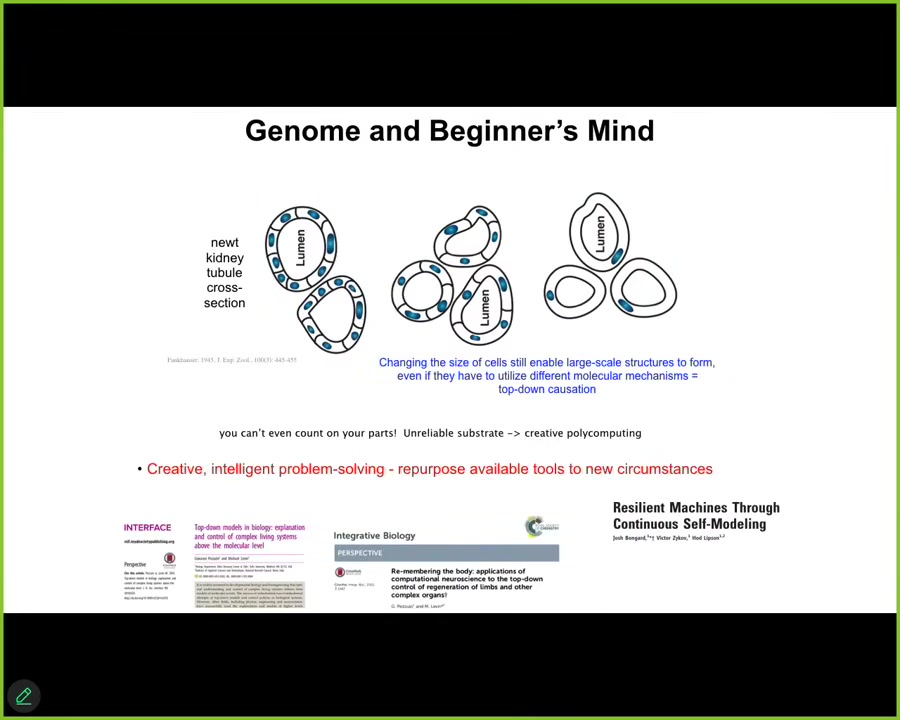

That gives rise to this idea of morphogenesis as a kind of beginner's mind where you can't really assume very much. I'll just give you a simple example.

This is a cross-section through a kidney tubule. You see 8 to 10 cells usually work together to make this. One thing we can do experimentally — this isn't my work, this is a very old work by Fankhauser — is make cells gigantic. You can force the cells to be very large. If you do that, what you find is that it adjusts. If you make them large, it will make fewer cells to make the same thing. If you make them huge, one cell will bend around itself and still give you the same structure.

This is the classic thing that they test on every IQ test. We give you a set of objects and you try to solve a problem you've never seen before by creative use of the things at your disposal. The way you do this is you give it way more copies of its chromosome number, and then they do this.

It's able to get the job done. It's able to take the journey, even when it's dealing with completely different parts, because it's able to take new affordances from the molecular hardware that it has and use them appropriately in a context-sensitive manner to solve a problem it has not seen before.

Think about what this means when you're a newt coming into the world. You don't know how many copies of your genome you're going to have. You don't know how big your cells are going to be. Never mind the environment, you can't even trust your own parts.

This is the thing about biology. Josh Bongard had some fascinating work on robots that also don't know exactly what their structure is. They have to figure it out from scratch. This is now quite old, original work.

Slide 15/27 · 25m:58s

The thing with biology is this, at least in most computational architectures that I'm aware of, there's a lot of redundancy, there's a lot of error correcting codes, there are abstraction layers to make sure that you are keeping the fidelity of information. When you program it in high-level languages, you don't worry about your silicon and your copper going off, or your bits out of the registers are going to float off.

You don't worry about it, but biology is completely different. It assumes the hardware is unreliable because it is unreliable. It's going to be mutated. The environment often changes. You don't know how many copies of any protein you're going to have; things degrade. And so it's forced to go through this bottleneck and the same kind of architecture is here. We don't make other organisms like us. We make eggs. And those eggs can. It's on this material to figure out what this information is and what to do with it.

Slide 16/27 · 27m:00s

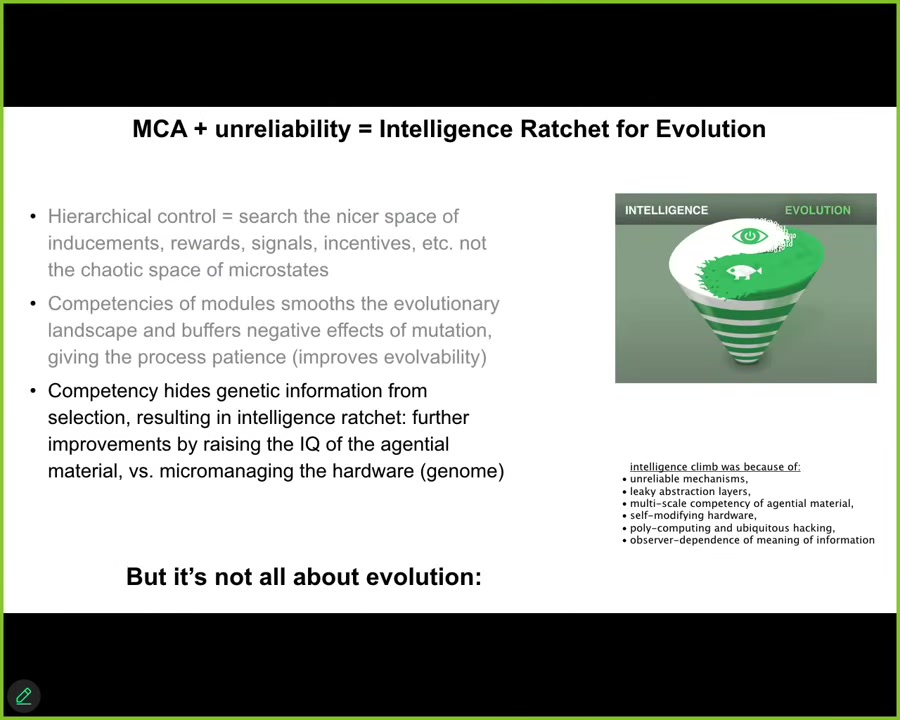

And so what's happening here is that the amazing intelligence ratchet between the fact that competency and the ability to improvise what your memories mean for the future actually hide a lot of information from selection. And as you do this, evolution has no choice but it has a hard time figuring out the good genomes from the bad. And so a lot of the work is done cranking up this competency. And so you get this positive feedback loop because of the fundamentally unreliable material. One of the most interesting things is that it's not all about evolution. Here I'll show you a couple of synthetic life forms.

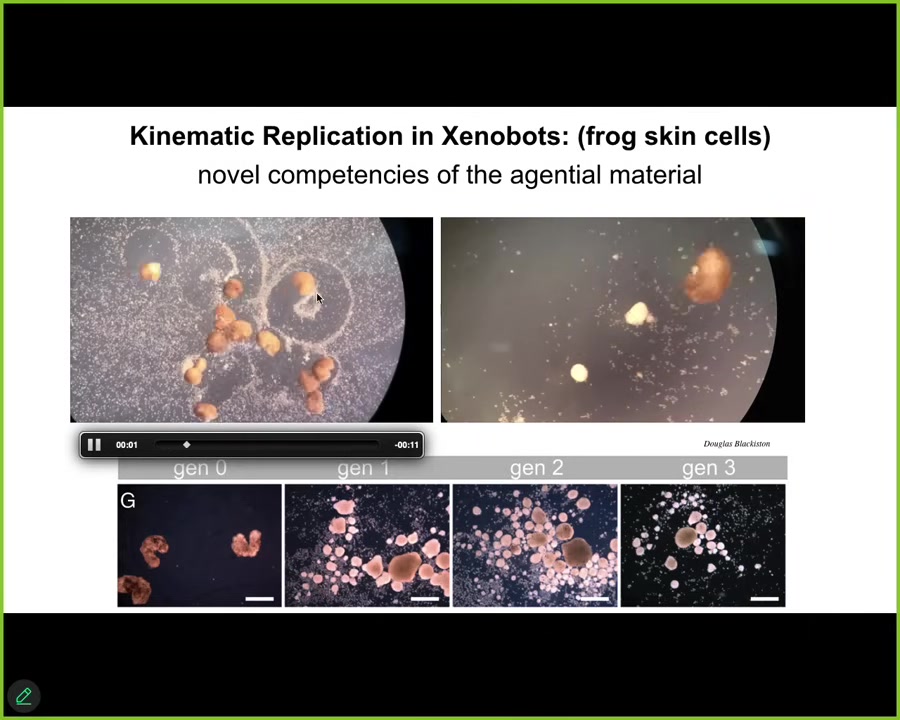

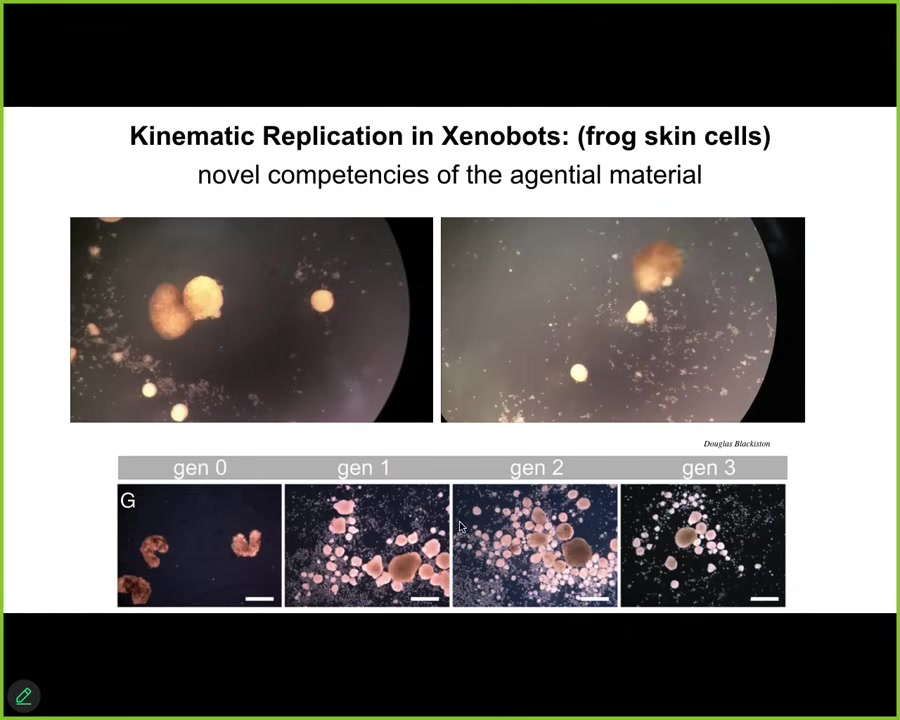

These are xenobots. These are made from frog epithelial cells.

Slide 17/27 · 27m:58s

And not only do they self-assemble into these little motile forms, but if you give them a bunch of loose skin cells, they will also run around, collect them into little piles. Those piles mature to be the next generation of Xenobot. And guess what they do? They do exactly the same thing.

Slide 18/27 · 28m:08s

We call this kinematic self-replication. It's Von Neumann's dream of a machine that goes out and builds copies of itself from things it finds in the environment. But as far as we know, no other creature on earth replicates by kinematic self-replication.

This is completely novel.

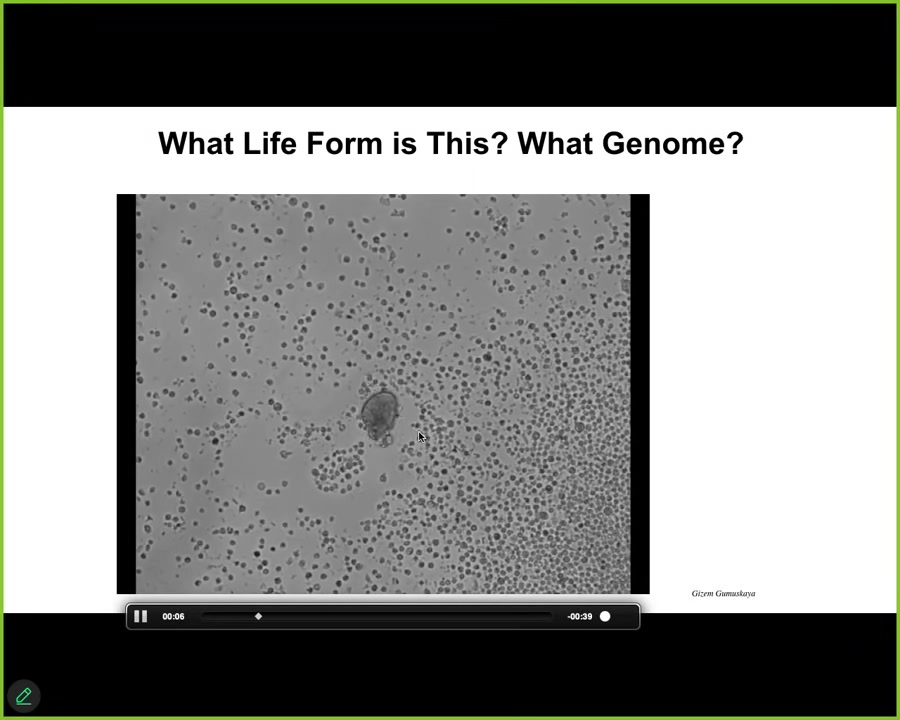

If I show you something like this and I say, what is this? What do you think this is?

Slide 19/27 · 28m:30s

People will often say this is a primitive organism that we got from the bottom of a pond somewhere and it should have a genome like that. If you were to sequence it, you would find the genome of 100% Homo sapiens. These are adult human tracheal epithelial cells that self-assemble into this multi little creature that looks like no stage of human development. It has its own lifestyle.

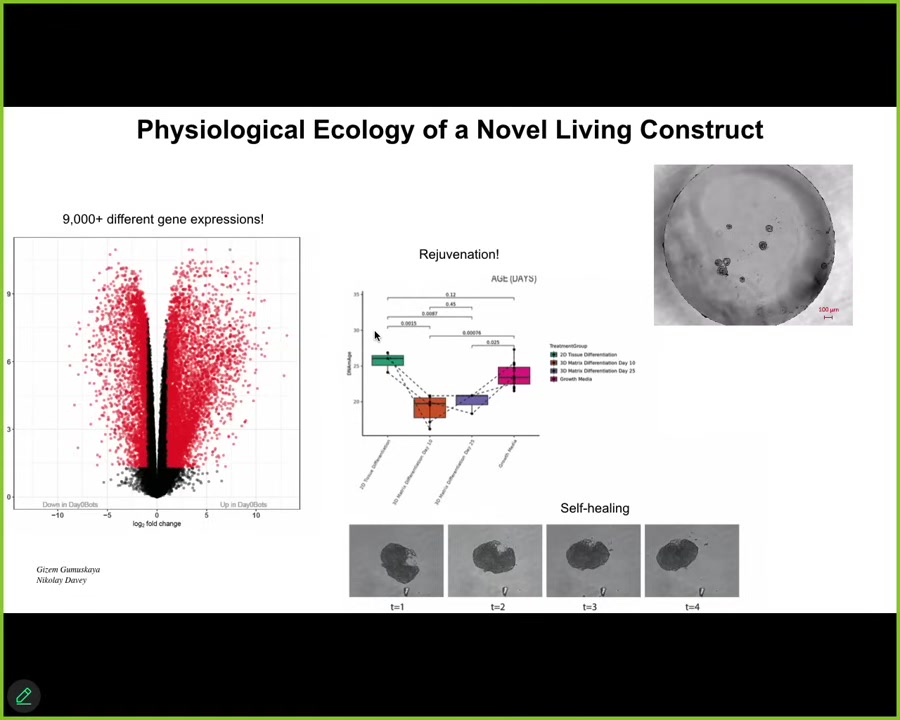

Slide 20/27 · 28m:52s

If you look at the gene expression, it has more than 9,000 differential transcripts. Its transcriptome is completely different than those same cells. We've done nothing to the DNA. There are no synthetic biology circuits. There are no scaffolds. There are no nanomaterials. There's no genomic editing. All we've done is allow them to reboot their multicellularity and you get proto-organisms. You can see here that they self-heal. They have a completely different set of gene expressions. They're actually younger than the cells they came from, so they also roll their age back.

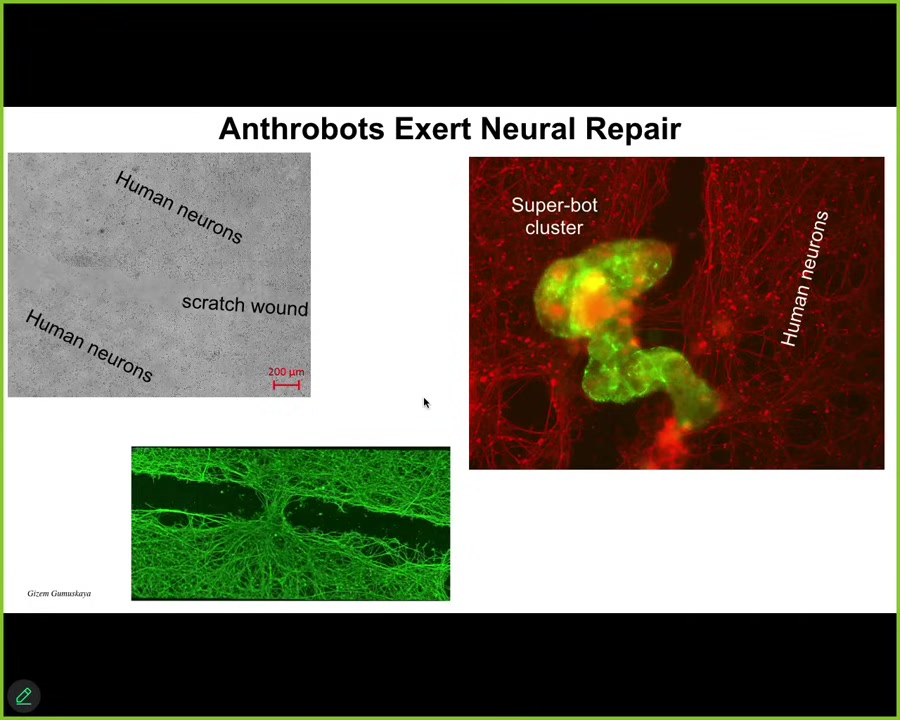

Slide 21/27 · 29m:22s

And they have this remarkable property. If you let them swim down a big scratch that you've made in a bunch of human neurons, you will find out that they actually assemble into the superbot and they heal. They heal across the scratch. Here's what it looks like when you lift them up. They have these amazing properties, but who would have known that your tracheal cells that sit there for decades quietly dealing with mucus have the ability to do this.

Slide 22/27 · 29m:48s

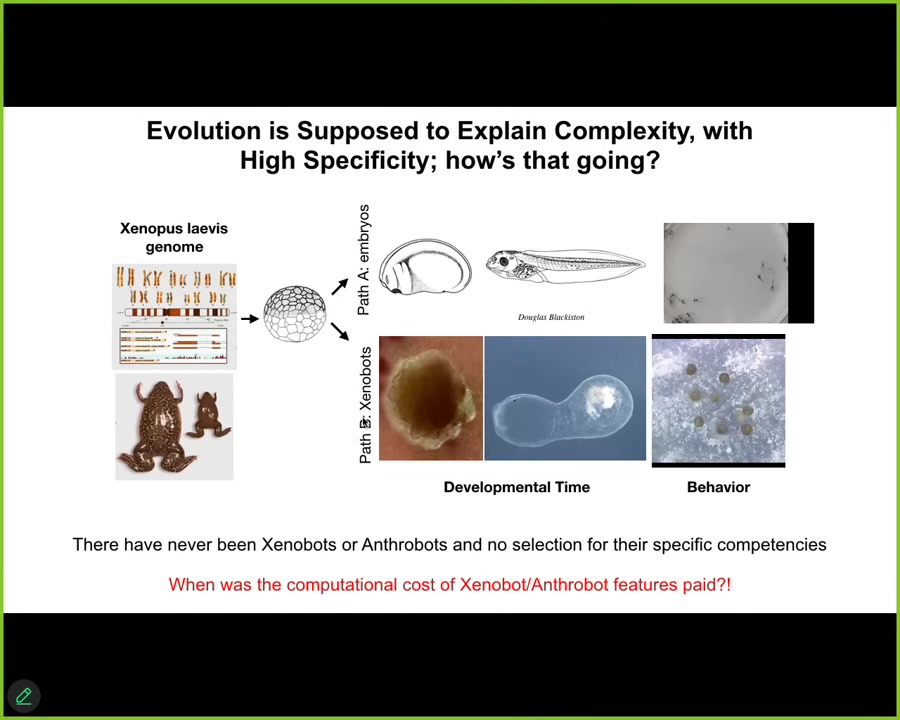

We have a fundamental question, which is we know when the computational cost was paid to develop frogs and frog embryos. Millions of years of that genome bashing against the environment computed the correct way to survive. When was the cost paid to develop xenobots or anthrobots? There's never been any xenobots or anthrobots. There's never been any selection to be a good xenobot or anthrobot. I'm claiming here that not only the standard version of biology is useful for us in AI research, but actually there's something extra that's happening here, which is that it's not just physics and it's not just genetics.

We already know biologists love these two things. Everything in biology needs to be explained by a history and by some physics of the environment. That's it.

Slide 23/27 · 30m:38s

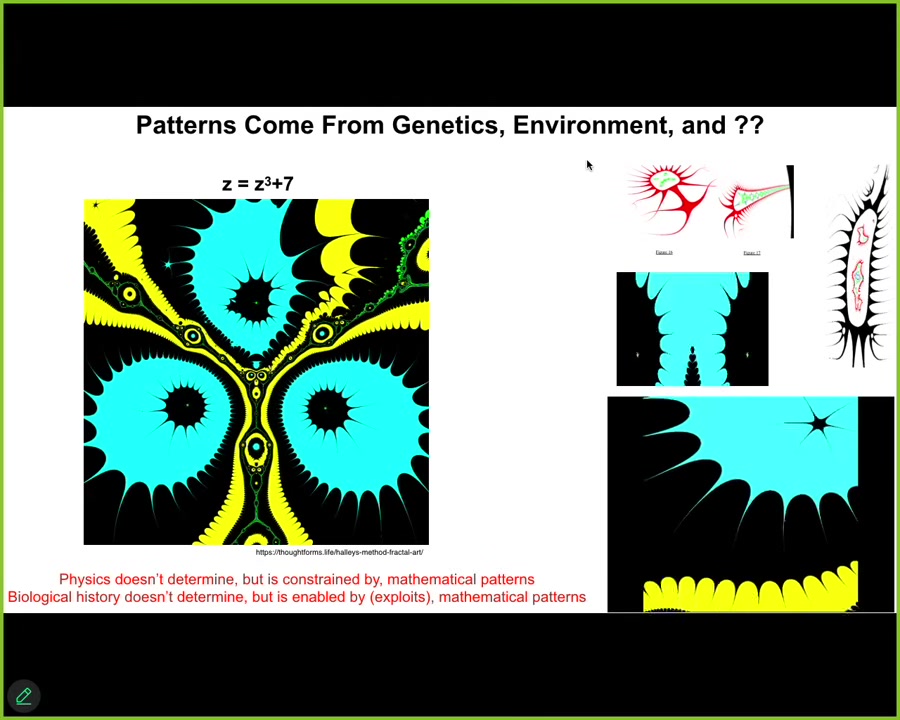

We know that there are mathematical objects. This is a Halley plot made by this very simple formula in complex numbers. Look at the incredible structure. None of this is set by any part of physics. None of it is set by any kind of a history of selection. It comes from the same place that the laws of mathematics come from. I think it's important that physics doesn't affect, but it is affected by, specifically constrained by, mathematical patterns. There are many aspects of physics that, if you ask why is this the way it is, it's because this mathematical thing has certain symmetries.

Biology also doesn't determine the laws of mathematics, but it exploits them. It exploits a ton of free lunches that are provided by these things from this other space.

Slide 24/27 · 31m:22s

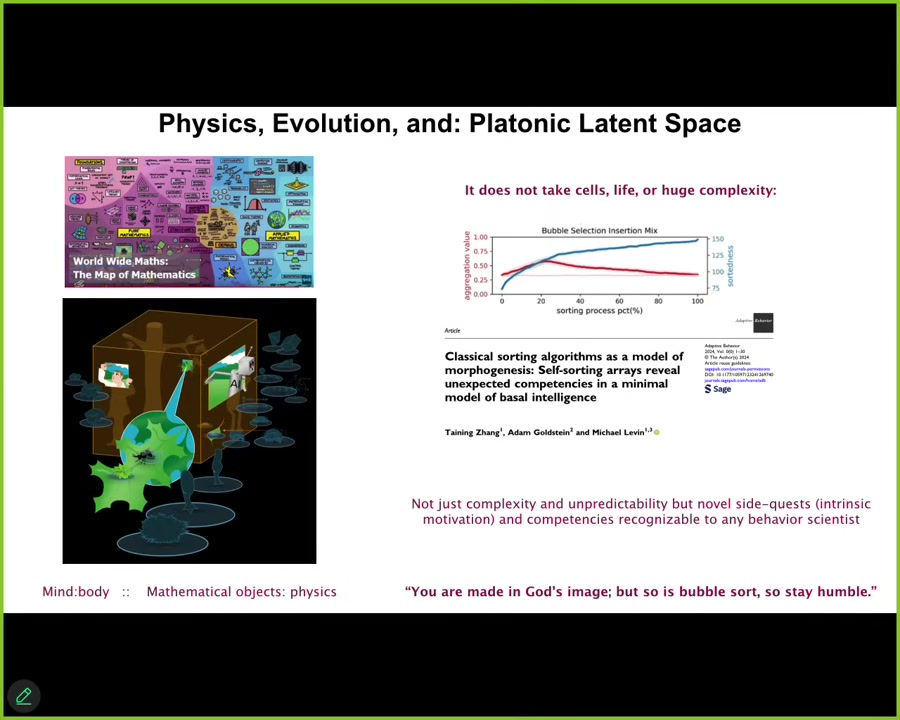

And so my claim is that we should be exploring this space, much like mathematicians do, and that biology offers novel exploration vehicles, so xenobots, anthrobots, that allow us to explore this incredible latent space of form and function that provide a lot of free lunches that are not explained by either the materials, the history, the algorithms.

And I think there's a real parallel here between the relationship between minds and bodies and the relationship between mathematical objects and the physics that they inform.

A lot of people think that there are these amazing features — people call them emergent, I don't like it — but a lot of these amazing features recognizable by behavioral scientists that emerge in complex structures, I don't think complexity has very much to do with it.

You don't need to be alive, you don't need to have huge complexity. Even Bubble Sort has unexpected side quests that they do that are readily recognizable by behavioral scientists that are not in the algorithm. The algorithm is six lines of code. Everybody can see what it is. They're doing things that are not in the algorithm.

So I think this is a tongue-in-cheek point, but the idea is there are patterns that are informing what happens in the physical and biological world, but they are not uniquely for us or even for living things. I think they go all the way down in terms of complexity.

Slide 25/27 · 33m:00s

So this means that because of the plasticity and interoperability of life, all of current living things that Darwin was impressed by when he said this are here. They're a tiny corner of this incredible option space. And any combination of evolved material, engineered material, software, is going to be affected by the ingression of these patterns. And they're not just about distributions of primes. I think some of these patterns are behavioral propensities or kinds of minds. And so we are going to be living in a world with hybrids and cyborgs and chimeras and very unconventional creatures. And we need to radically expand the way that we understand embodiment in other spaces and behaviors that have intrinsic properties, not things that are determined by what we think we've built.

Slide 26/27 · 33m:58s

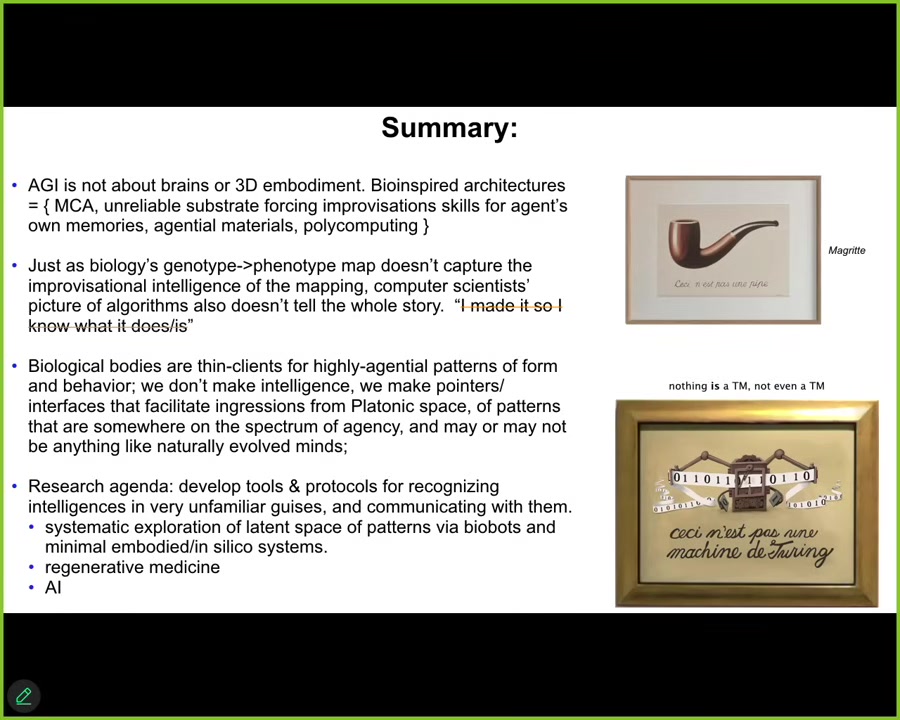

I think the road to AGI is not about brains, it's not about neuromorphic computing or three-dimensional embodiment.

There are some very deep concepts that we've talked about, including this improvisation.

Just as biology's story of the genotype to phenotype map doesn't capture what's actually going on in the problem-solving intelligence of that process, I think computer science's pictures of algorithms also do not tell the whole story.

I think the notion that we made it. I know what the algorithm is, I know what all the pieces are, and so I know what it does. I think that's profoundly wrong in a much deeper way than just that it has unpredictability or unexpected complexity.

I think, much like Magritte was reminding us, our formal models of things or our pictures of things are not the things themselves. Here's the computer science version of this: it is not a Turing machine. Because I think nothing, not even simple algorithmically driven machines, is actually fully encompassed by our formal models of them.

I think in important ways, biological bodies are a kind of thin client for certain patterns that come from this platonic or latent space. I don't think we make intelligence. I think what we make are embodiments that facilitate the aggression of these patterns.

These things may or may not be anything like the natural minds that we have. The stuff that we force them to do, such as talking and language, may have potentially nothing to do with some of their intrinsic motivation, and we need to understand this.

This is the research agenda: to try to understand that mapping between the physical pointer that we make and some of the patterns that come through.

Slide 27/27 · 35m:40s

I'll stop here and thank the people who did the work that I showed you today. We have lots of amazing collaborators. The next part of the story is going to be told by Hanan El-Hazan, who's got some interesting computer science that goes in this direction.