Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a talk I gave (1 hour) to a computer science and robotics audience.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Framing diverse intelligences

(05:28) Collective intelligence across scales

(13:41) Morphospace and target morphology

(22:04) Regeneration as homeostasis

(28:31) Bioelectric networks and cancer

(39:02) Anatomical memories and regeneration

(47:33) Xenobots and self-replication

(54:18) Endless forms and ethics

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/56 · 00m:00s

Thank you for having me. It's a real pleasure to have a chance, especially to a computer science audience. My original training was in computer science before biology. I think we have some interesting things to talk about today. Afterwards, if you want to find any of the data sets, the papers, the software, all of that is here at this website.

Slide 2/56 · 00m:24s

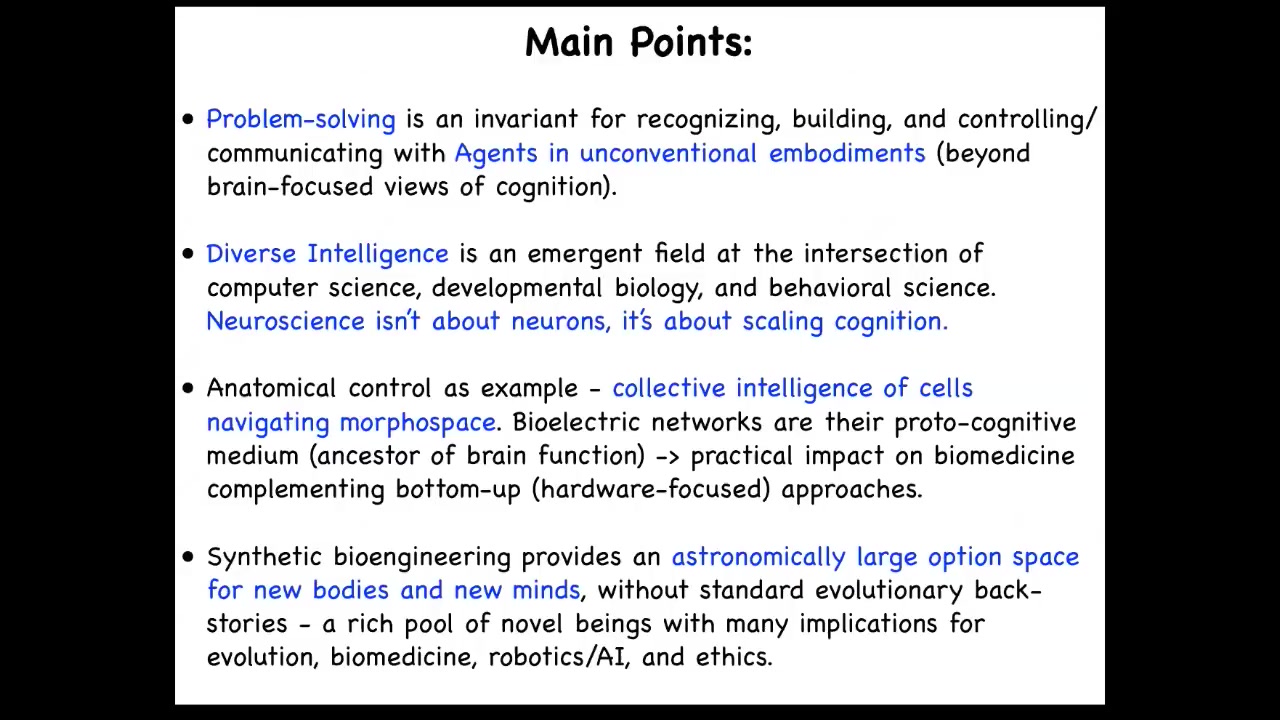

Here are the main points that I'm going to transmit today. I'm going to talk about agents and unconventional embodiments. We're going to go beyond the typical thing that people think about intelligence, which is brains and brainy animals. We're going to talk about problem solving in some unconventional spaces.

All of this is a contribution to the field of diverse intelligence, which is this emerging area at the intersection of computer science, biology, and behavioral science. Part of the message here is that neuroscience isn't really about neurons. It's about scaling cognition. That has many implications for machine learning and AI that often tries to look at the brain as its inspiration. I'm going to use the control of anatomy as the example of a collective intelligence, specifically the collective intelligence of cells that navigate anatomical morphospace. I'm going to tell you that electrical networks, specifically bioelectrical networks, carry the computational medium of that collective intelligence. This has interesting applications in biomedicine. At the end, I'm going to show you some novel creatures, some synthetic proto-organisms, and talk about a very large option space of new bodies and new minds, which the young people in the audience are going to be living with over the next few decades.

Slide 3/56 · 01m:45s

So life used to be pretty easy. People had this view of the world. This is an old, very well-known painting of Adam naming the animals in the Garden of Eden. And it was simple because we knew there were discrete kinds and there were very specific kinds of animals. And here's Adam and he's different from all of these. And so that was easy. We knew what everything was. In particular, there's one other interesting thing here, which is that in this mythology, it's up to Adam to name the animals. It wasn't God or the angels that were able to name these animals. And I think that's actually pretty profound because, as I'll show you towards the end of the talk, it's going to be on us to name, or more accurately, to learn the true nature of all kinds of new beings. So it used to be pretty simple to know what a human was.

Slide 4/56 · 02m:35s

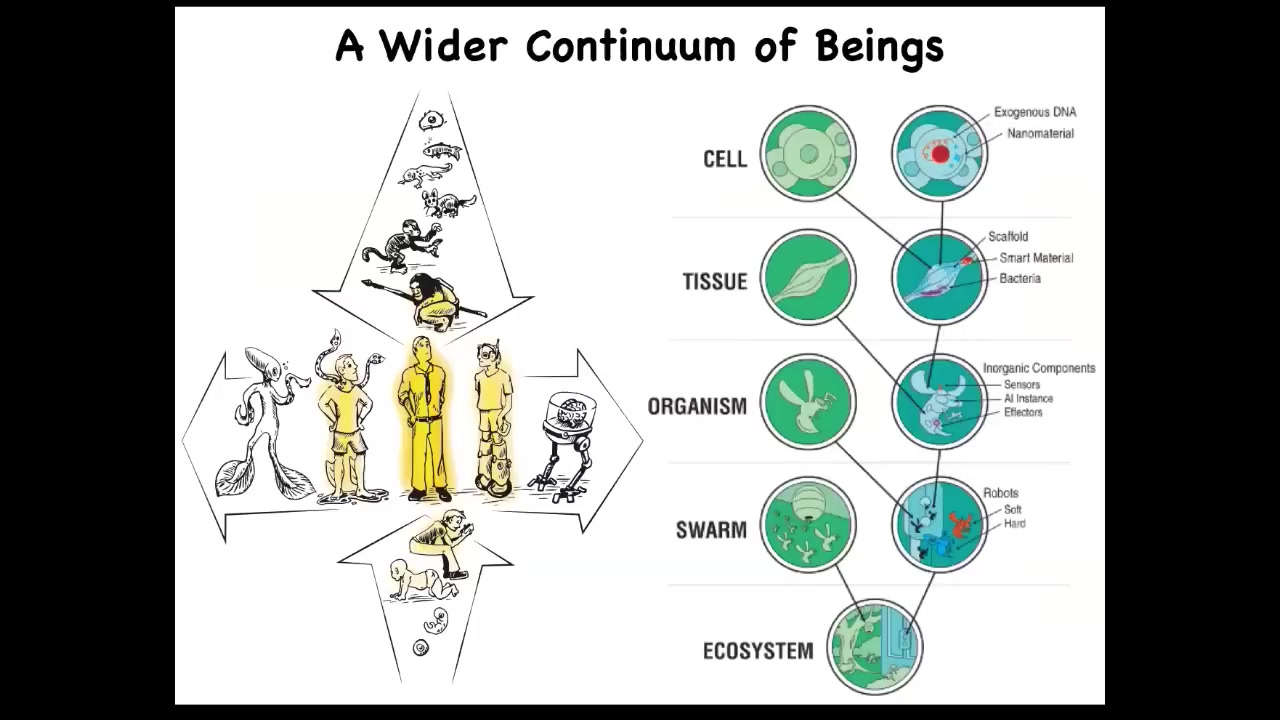

But then with the advent of developmental biology, where we now realize that we emerge, we could self-construct from a single cell, and through evolutionary biology, where we now see that we emerge, we started as a unicellular life form and eventually became this human. And so we have this vertical axis of transformation, but also there's a horizontal axis where both through biological modifications and through technological modifications, there's a spectrum of human-adjacent possibilities. And that's because at every layer of organization, we can augment evolved biology with various designed or engineered materials.

Slide 5/56 · 03m:20s

That means that we really need frameworks to recognize, create, and ethically relate to a really very diverse set of intelligences that can be very different from the conventional ones we're used to in terms of how they got here or how they're made.

We need a framework to understand not only familiar creatures like primates, birds, an octopus, but also all kinds of unusual creatures like colonial organisms, ant swarms, and synthetic life forms, AIs, whether software or hardware, and someday even exobiological agents.

I'm not the first person to try for such a framework. Norbert Wiener and colleagues were already trying to lay down a continuum, a cybernetic continuum from passive matter all the way up to humans and above — second-order metacognition.

We want to develop frameworks like this to help us understand what all these things have in common and to move experimental work forward.

Slide 6/56 · 04m:24s

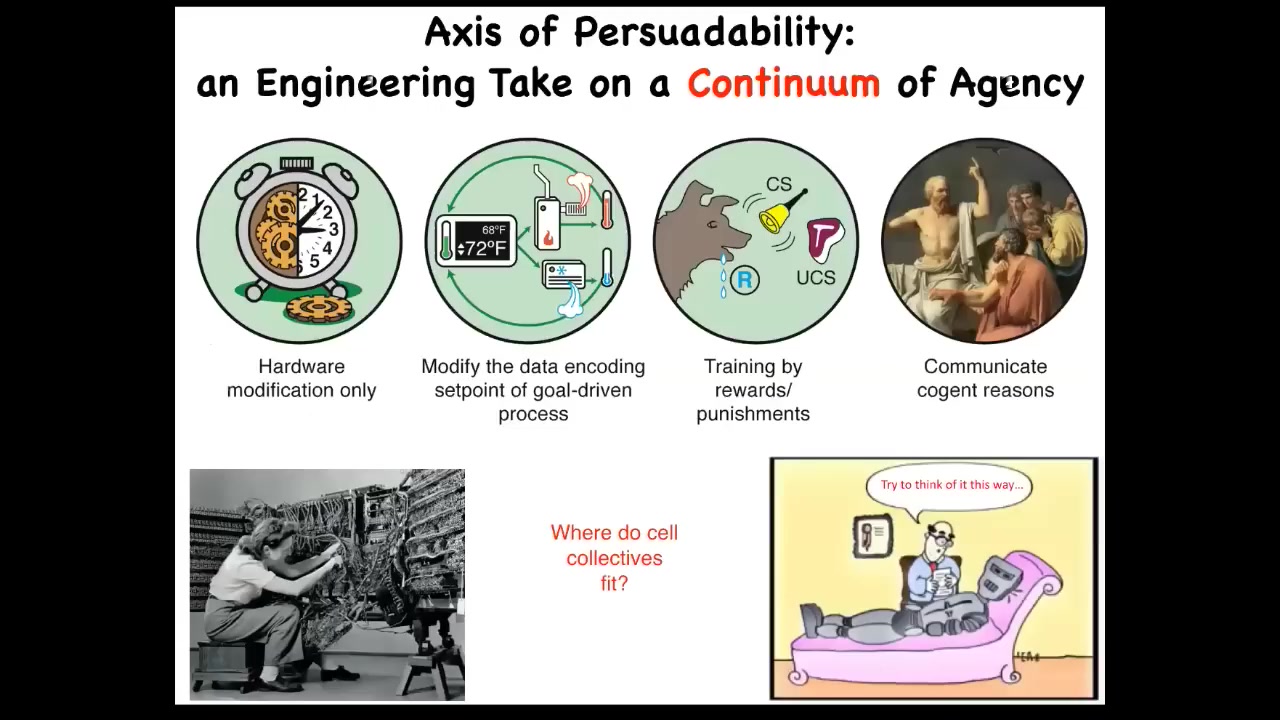

I work with something I call the spectrum of persuadability. It is this idea that there are numerous different kinds of systems, all the way from very simple mechanical ones to homeostats and various kinds of animals and learning devices, and then human and whatever's above that. The idea is that at different places along this continuum, there are different tools that you might use to interact with that system, from hardware rewiring to modifying set points, to learning and training, and various kinds of high-level communications.

What's important is that when you're faced with a new system, it's not enough to have philosophical feelings or preconceptions about where you think it has to fit on the spectrum. You have to do experiments. You have to see which one of these paradigms, these sets of tools are going to be appropriate, and you don't know ahead of time. One question you might ask is, where do collections of body cells fit in? Are cells more like this, or are they like this, or something else? We'll talk about that today.

Slide 7/56 · 05m:29s

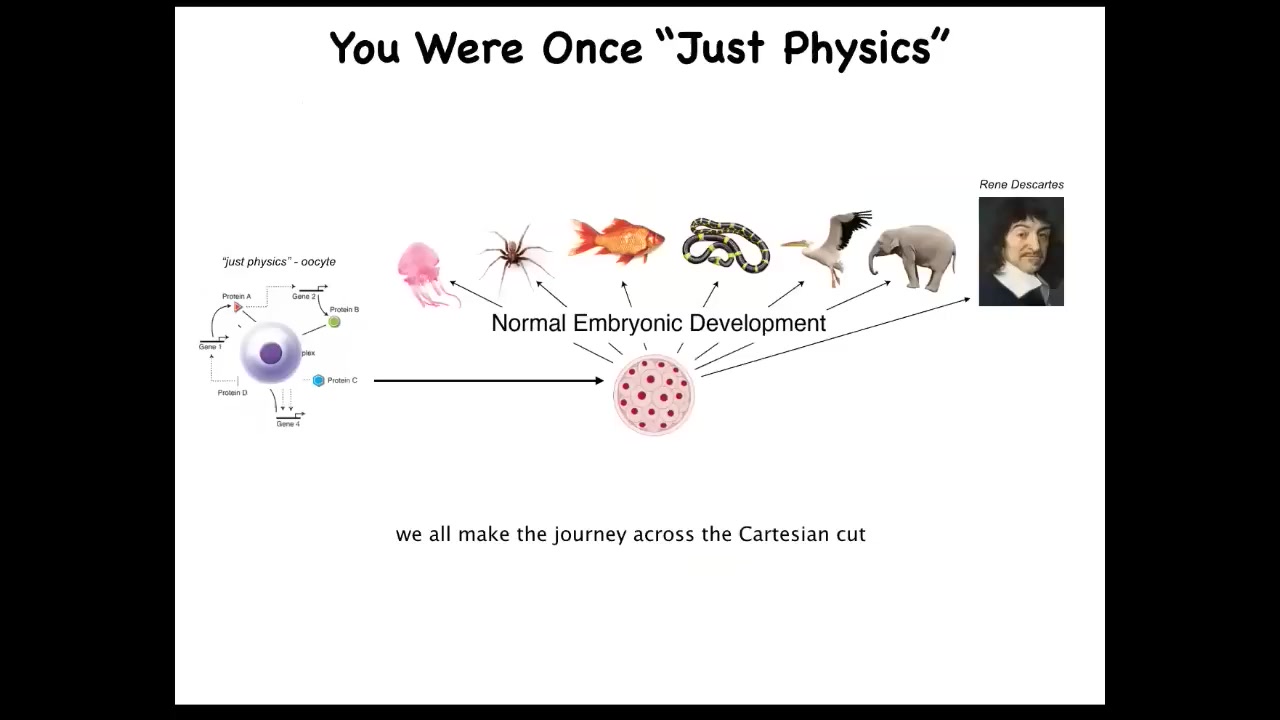

And that's important because all of us made this journey from a single unfertilized egg cell, a quiescent oocyte, to one of these amazing morphologies, even something like this, a human. It's critical to note that this process is smooth and continuous. There is no magic time point or lightning flash that turns the physics and chemistry of the early cell into what you might think of as true cognition; there is no such flip over. All of this is smooth and continuous, and we really have to understand how that scaling of competencies from here to here works. That's already a little destabilizing this idea that actually we slowly metamorphose from a fairly simple chemical physical system, but then at least we're a unified kind of intelligence.

We're not like ants or bees that are a kind of collective intelligence. A lot of people feel that we're a unified true intelligence, and these things have collective intelligence.

Slide 8/56 · 06m:39s

But all intelligence is collective intelligence because we are all made of parts. And René Descartes really liked the pineal gland in the brain because there's only one of them, and he felt that this unified human had to have one representative in the brain, not multiple. But if he had access to good microscopy, he would have seen that the pineal gland is full of cells and each cell is full of all of this stuff. And there isn't one of anything in the brain. Everything is made of parts.

Slide 9/56 · 07m:05s

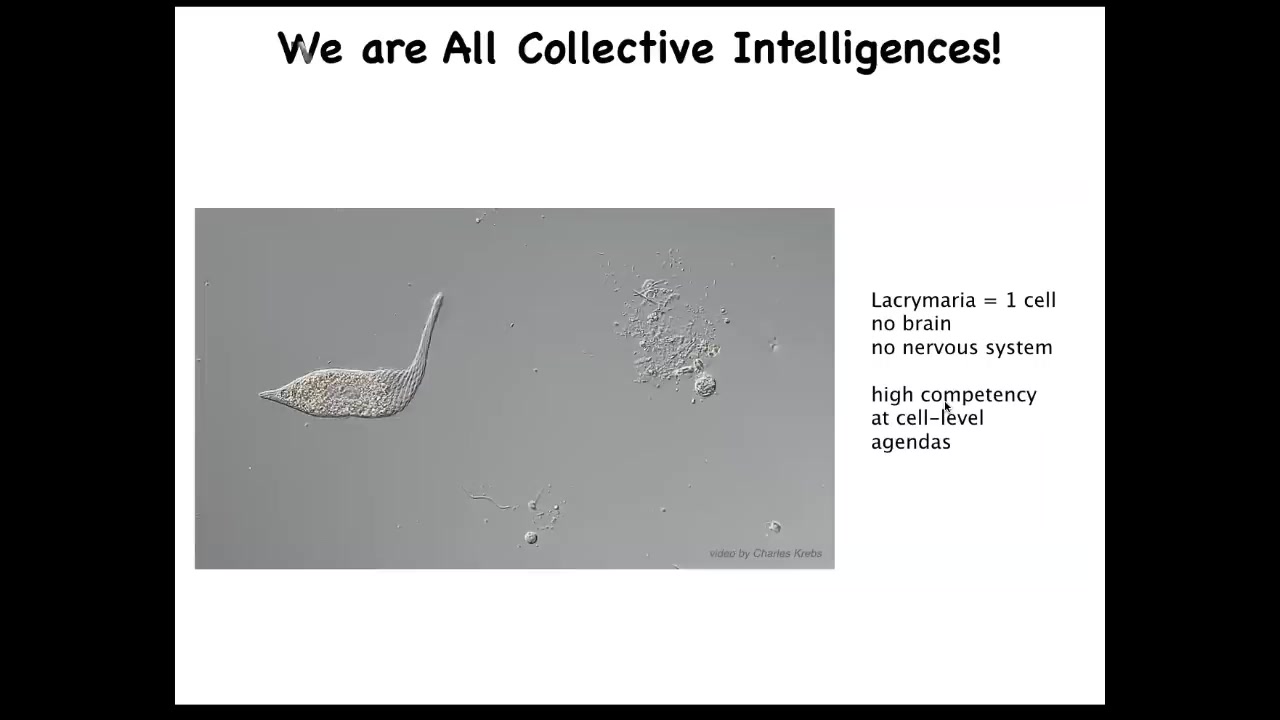

And in particular, we are collective intelligences. We're made of cells, a gentle material. This is a unicellular organism. This is called the lacrimaria. It's one cell, there is no brain, there's no nervous system, but it has all these interesting competencies in problem solving at its own scale. It handles its metabolic, physiological, anatomical goals all on its own.

Slide 10/56 · 07m:33s

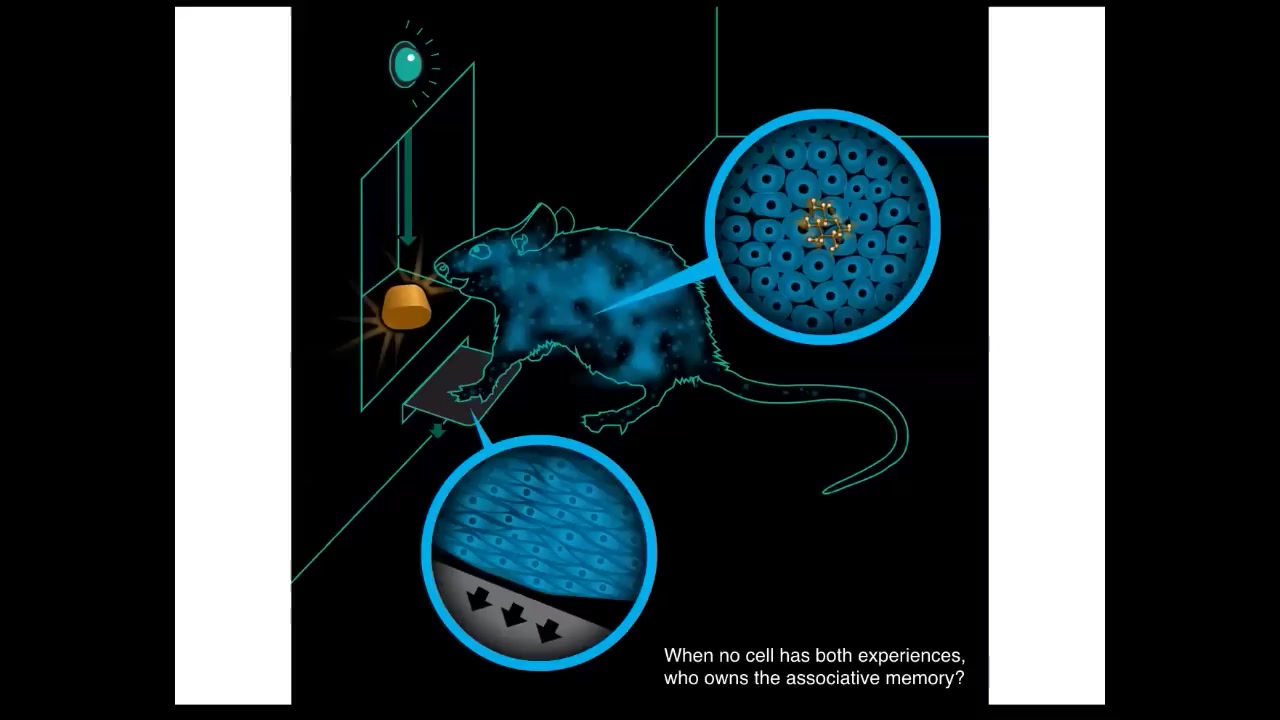

The thing about organisms like this is that we really have to think about how they scale up into something larger. Here's an experiment where you train a rat to press a lever and receive a reward. Now, the key is that no individual cell in this creature has both experiences. In other words, the cells at the bottom of the feet interact with the lever, the cells in the gut get the delicious reward. No individual cell has both experiences. Yet this associative learning, this idea that there is an owner of this information, that pressing the lever gives you a reward, is this emergent thing called a rat. And the idea is that in order to do this, to figure out who owns this associative memory, you need to have cognitive glue. You need to bind the individual cells together and be able to do credit assignment and figure out what the different things that happened in this body mean and how they go together?

Slide 11/56 · 08m:36s

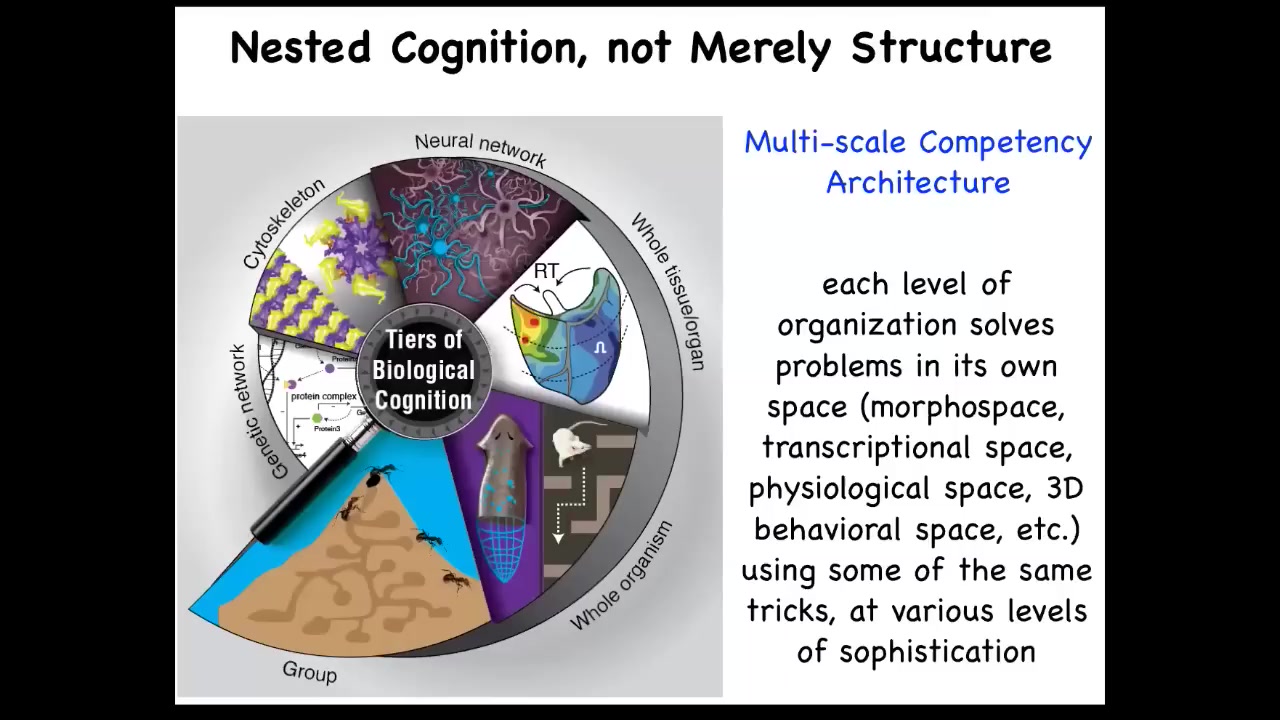

And so our bodies and biology in general are not just physically or structurally nested from molecular networks to cells to organisms and so on, but functionally, we live with a multi-scale competency architecture. Every layer of the body has its own ability to solve problems in different spaces, and they all cooperate and compete both laterally within the layer and up and down through scales to interact. And so we are all this collective intelligence. I want to show you a few unusual examples of biology that you may not have learned about in biology class if you've had biology.

Slide 12/56 · 09m:13s

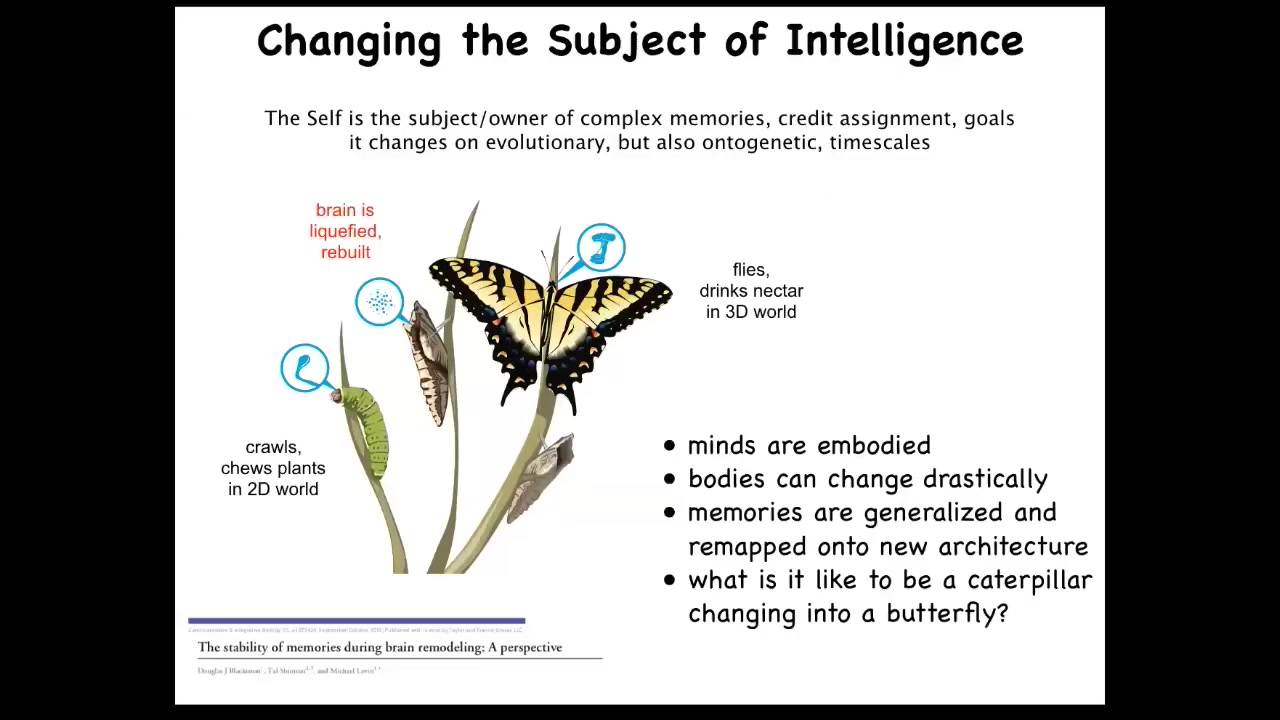

One is this, and it's the idea of transformation. You've got this caterpillar. Caterpillar has a particular brain suitable for driving a soft-bodied robot. There are no hard elements in the caterpillar, so you can't push. The controller can't push on any of the elements. It eats leaves, and it lives in a two-dimensional world. It has to transform into this completely different type of creature, which is a hard body, so it needs a different controller that can now push on all these hard elements. It lives in the three-dimensional world. It flies, and it doesn't eat leaves; it drinks nectar.

During this metamorphosis process, the brain is disassembled. All the connections are broken, most of the cells are killed off, and it's reassembled here. The amazing thing is that it's now been shown that the butterfly will retain memories of what the caterpillar was trained on. We don't have any hardware like that that you can store certain information and completely chop up and mix around the substrate, rearrange in a completely different organization, and still the information is there. The robustness is amazing.

In fact, it's even more amazing because there's generalization here. The caterpillar learns to associate certain stimuli with these leaves that it likes, but the butterfly gets a completely different food in that assay: nectar. It's not that you can learn that these triggers mean that there's leaves. It's actually the notion is food. So there's also generalization going on.

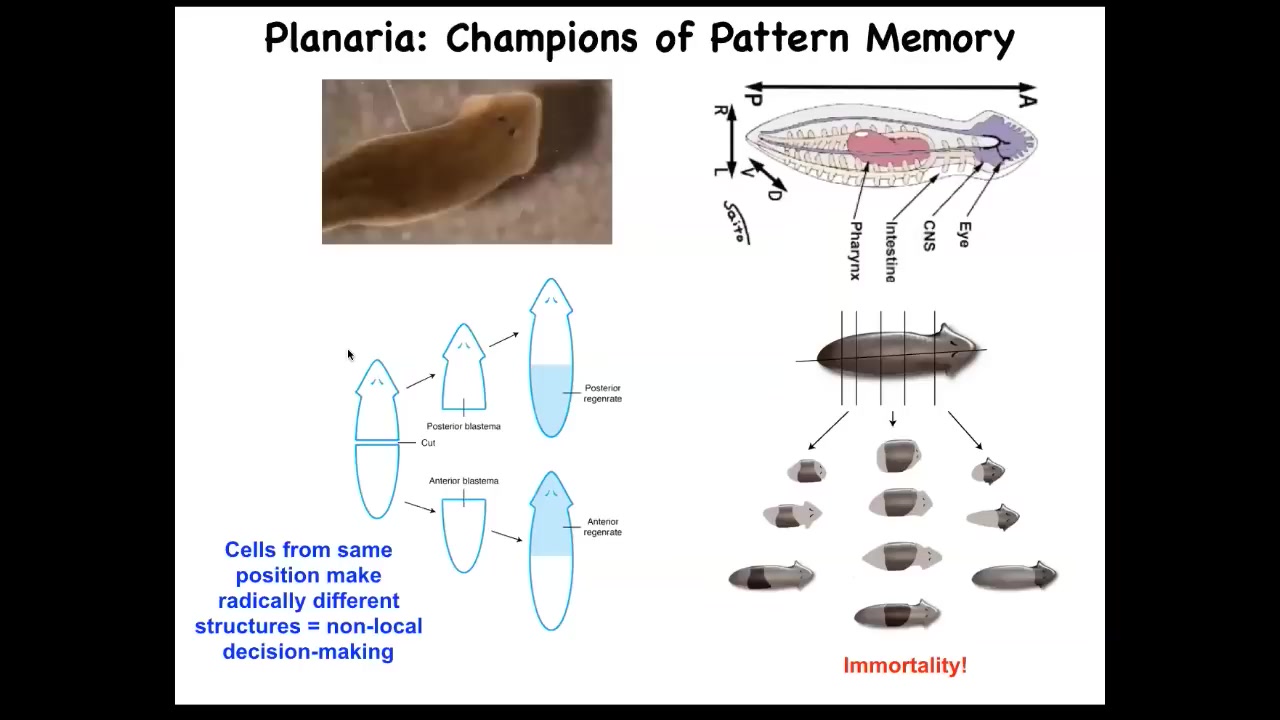

Slide 13/56 · 11m:00s

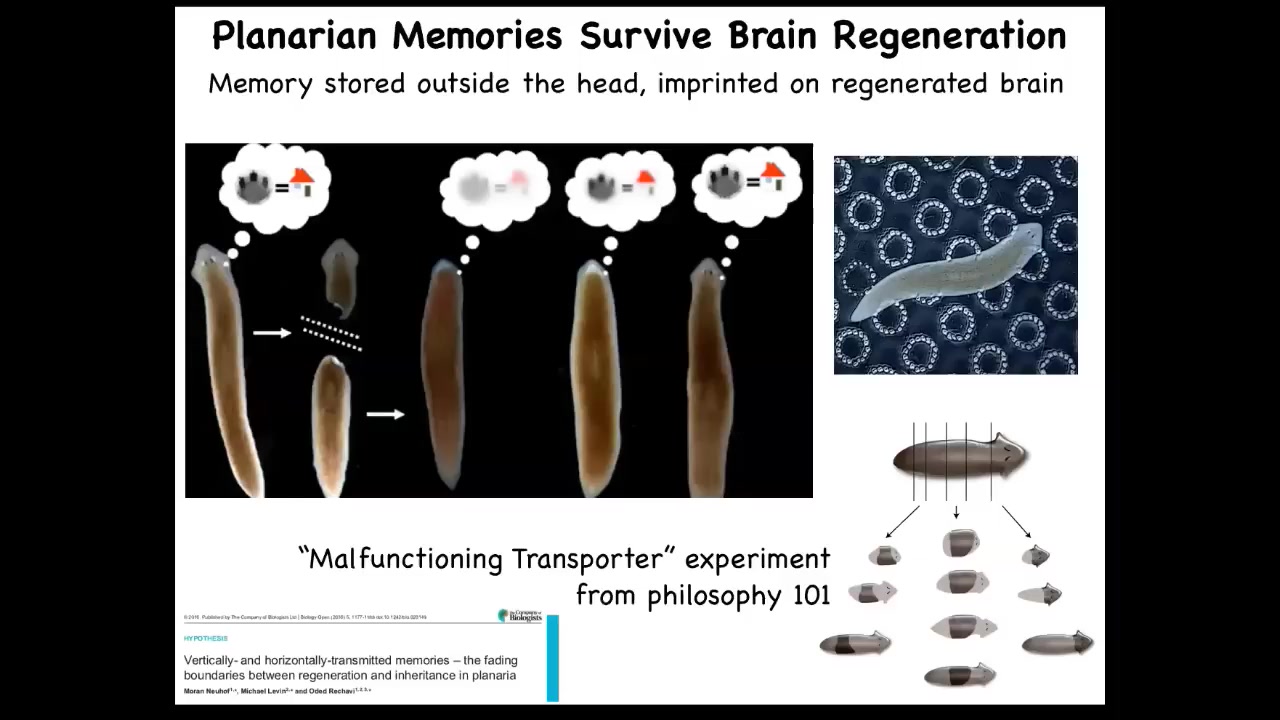

This persistence of information through bodily changes can be even more impressive. These are planaria. These are flatworms. Flatworms have this amazing ability. I'll show you lots more about this in a minute. When you cut them into pieces, they regenerate. If you cut them in half, the tail makes a new head, the head makes a new tail. They have a true brain, a true centralized brain, the same neurotransmitters as you and I have, and you can train them on a particular task. This idea that food will be found where these bumpy spots are; that's place conditioning.

You cut off their heads while the tail sits there doing nothing until the body regrows a new head. As soon as it regrows a new head, it begins to exert behavior again. You can find out that it actually remembers the original information.

If you've ever taken philosophy 101, they describe this idea of a malfunctioning transporter that builds an exact molecule-for-molecule copy of you somewhere else, and then it forgets to destroy the original, and now there's two of you, and which one is the real one? In this creature, you can do this many times, and you can cut it into many pieces, and they all will have memories of the original. It's a profound philosophical issue. Both in the caterpillar-to-butterfly case, you can ask yourself what it is like to be a creature fundamentally changing, changing everything, changing structure, changing preferences, changing the world that you're in, but still keeping your memories. It's an amazing phenomenon. It makes human puberty seem easy, which of course it is not.

Slide 14/56 · 12m:32s

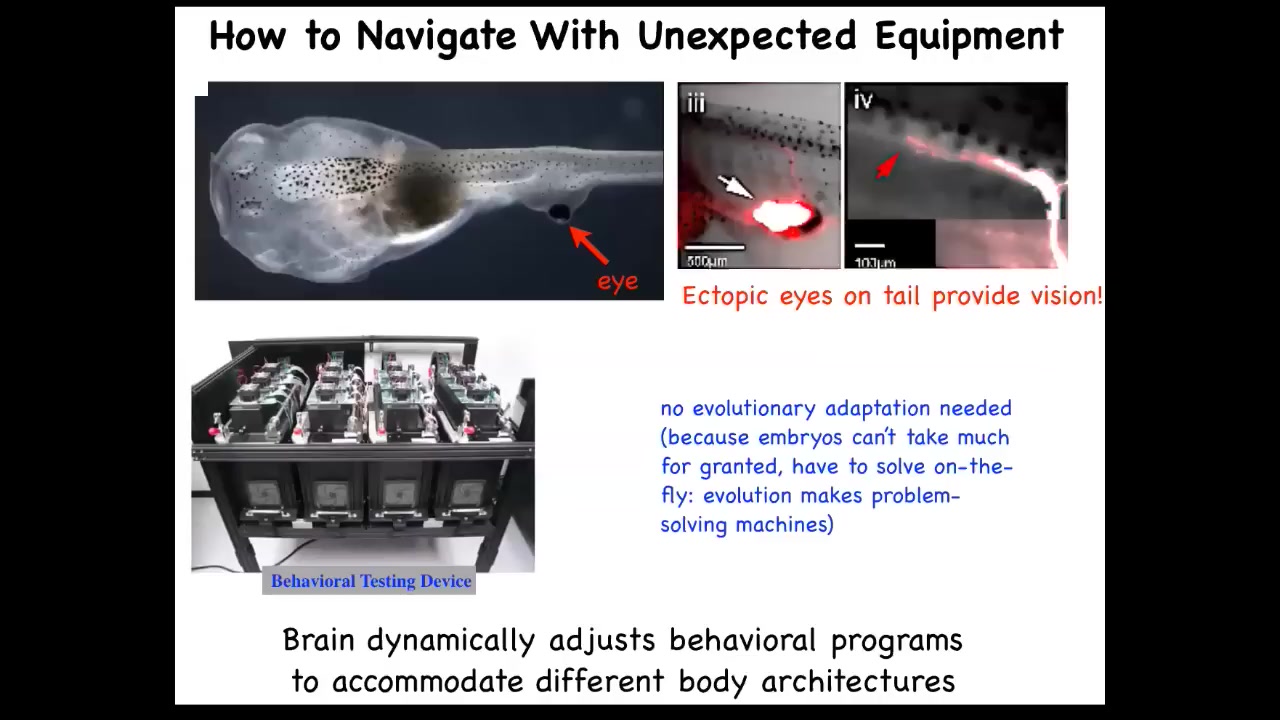

The plasticity also exists in vertebrates. Here's a tadpole of Xenopus laevis. Here are the nostrils, here's the mouth, here's the spinal cord and the tail, and here's the gut. What you'll notice is there are no primary eyes here. We prevented those from forming, but we did put an eye on its tail, and I'll show you in a minute how we do that. When you do that, immediately those cells that make that eye put out one optic nerve. That optic nerve doesn't go all the way to the brain. It synapses onto the spinal cord here. These animals can see. We know because we made this machine that trains them on visual assays, and they can see quite well.

The amazing thing is that you don't need any evolutionary adaptation. These animals, as soon as they're made this way, can already see. You don't need multiple generations of adapting to this new sensory-motor architecture. This is what biology gives us. It gives us this incredible multi-scale competency architecture where the cells are able to deal with huge amounts of injury and plasticity, and keep information around when the body is changing.

Slide 15/56 · 13m:39s

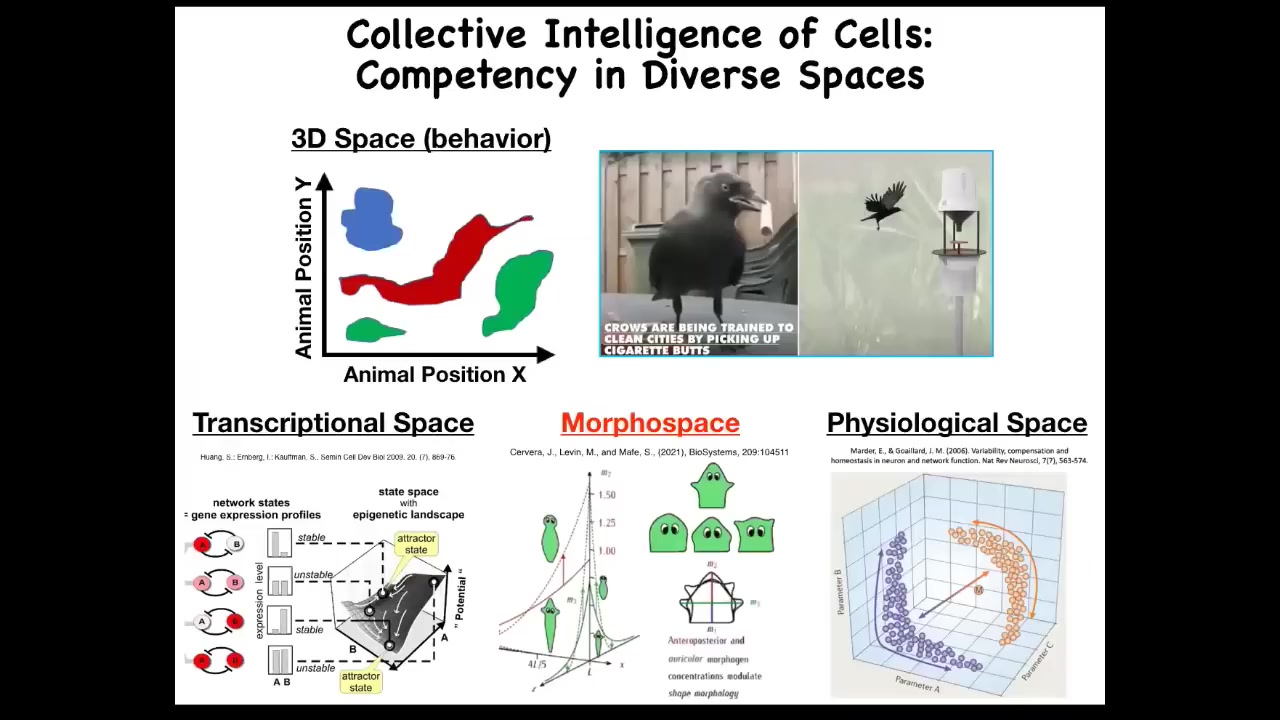

Partly what we need to do to understand all of this is to learn to detect competency in diverse problem spaces. We're pretty good as humans at recognizing intelligence in medium-sized objects moving at medium speeds through three-dimensional space. Birds, primates, maybe an octopus — things like that — we can recognize intelligent behavior. As soon as you get to things that are very small or very large or very slow or very fast or operate in other spaces, we're not very good at noticing that as intelligence at all.

That's because mostly our sense organs point outwards. If we had senses feeling your blood chemistry—if you could measure 20 different parameters of your blood chemistry and feel them—we would all realize that we live in a 23-dimensional space and that your liver and your kidneys are intelligent agents navigating that physiological state space.

There are many different spaces: the space of gene expression, which is a very high-dimensional space; the space of physiological states; and anatomical morphospace, which is the space of possible anatomical configurations of a particular structure.

Slide 16/56 · 14m:54s

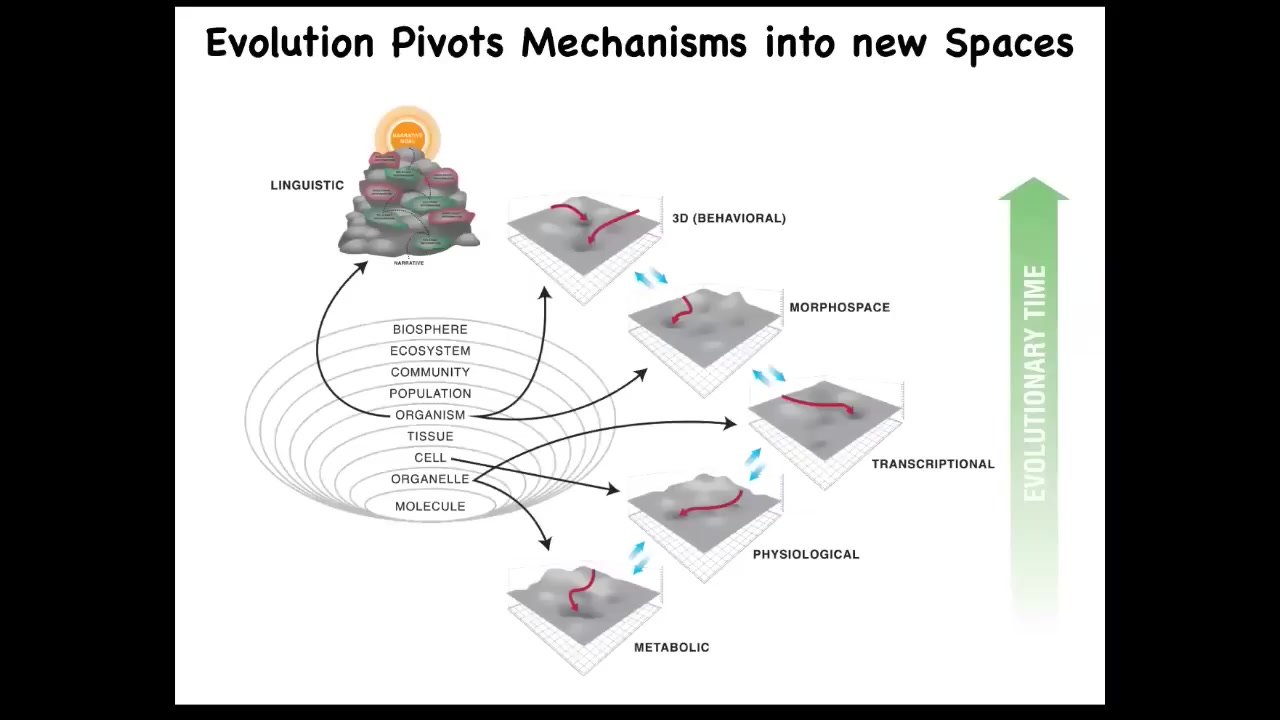

What I think is that evolution pivots some of the same tricks, these tricks being navigational competencies across all of these spaces as we went from very simple prebiotic states to early life and then eventually to a linguistic space in humans. But I'm going to focus on this today, the anatomical morphospace.

I want to point out that Alan Turing, who was always focused on what it means to be intelligent, what minds are, and how minds can be instantiated in various media and computation, was interested in problem-solving machines, intelligence through reprogrammability. But he also wrote a paper called "The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis." This is about how molecules can self-organize to form a structure in embryonic development. Now, that's weird. Why would somebody who was interested in computation and intelligence be looking at what chemicals are doing in morphogenesis? Although, as far as I can tell, he didn't write about this, I think that Turing saw a very profound commonality, an invariance between the question of where minds come from and where bodies come from. I think that is a very deep truth. There's a lot here, and that's what we've been studying for a couple of decades now.

Slide 17/56 · 16m:23s

Let's just ask this question then. Where do body structures come from? This is a cross-section through a human torso. You see the amazing order. Everything's in the right place relative to each other. But we all start life as a collection of embryonic blastomeres. Where is this pattern actually encoded? Where is this structure? And you might say it's in the DNA, of course, it's in the genome. But we can read genomes now. We know none of this stuff is directly in the DNA. What you read from genomes are protein sequences, the tiny molecular hardware that every cell gets to have. The DNA is not software. The DNA is actually a specification of the cellular hardware. And this pattern isn't directly encoded there any more than the shape or structure of a termite nest or a spider web is in the genome of the termite or the spider.

So we need to understand with this computation here, how do these cell groups know what to make? How do they know when to stop? As workers in regenerative medicine, we ask, if something is damaged, how would we cause these cells to repair? And as engineers, we ask a further question, which is, What else could they build? What else could we get the exact same hardware to build? And I'll show you some thoughts on that.

Slide 18/56 · 17m:33s

When I think about the end game of this field, once we have the answer to all those questions, what does that look like? I think what it looks like is something I call the anatomical compiler. The idea that someday you should be able to sit down in front of the computer and draw a plant, animal, organ, biological robot, whatever. Here I've drawn a three-headed planarian, three-headed flatworm. You should be able to draw whatever you want. If we knew what we were doing, we'd have a system that compiled that description into a set of instructions or stimuli that would have to be given to specific cells to get them to build exactly this.

Why do we want this from basic science? Notice that most biomedical problems, such as birth defects, traumatic injury, cancer, aging, all of this would be solved if we had the ability to tell a group of cells what to build. Remember, this is not a 3D printer. The point isn't to micromanage this and put the cells where they go. It's a communications device. What it does is it translates from your anatomical goals to the set points in anatomical amorphous space of a cellular collective. It's a communicator.

This is what we want. Now, we don't have anything remotely like this. We don't have the ability to do this, and why?

Slide 19/56 · 18m:54s

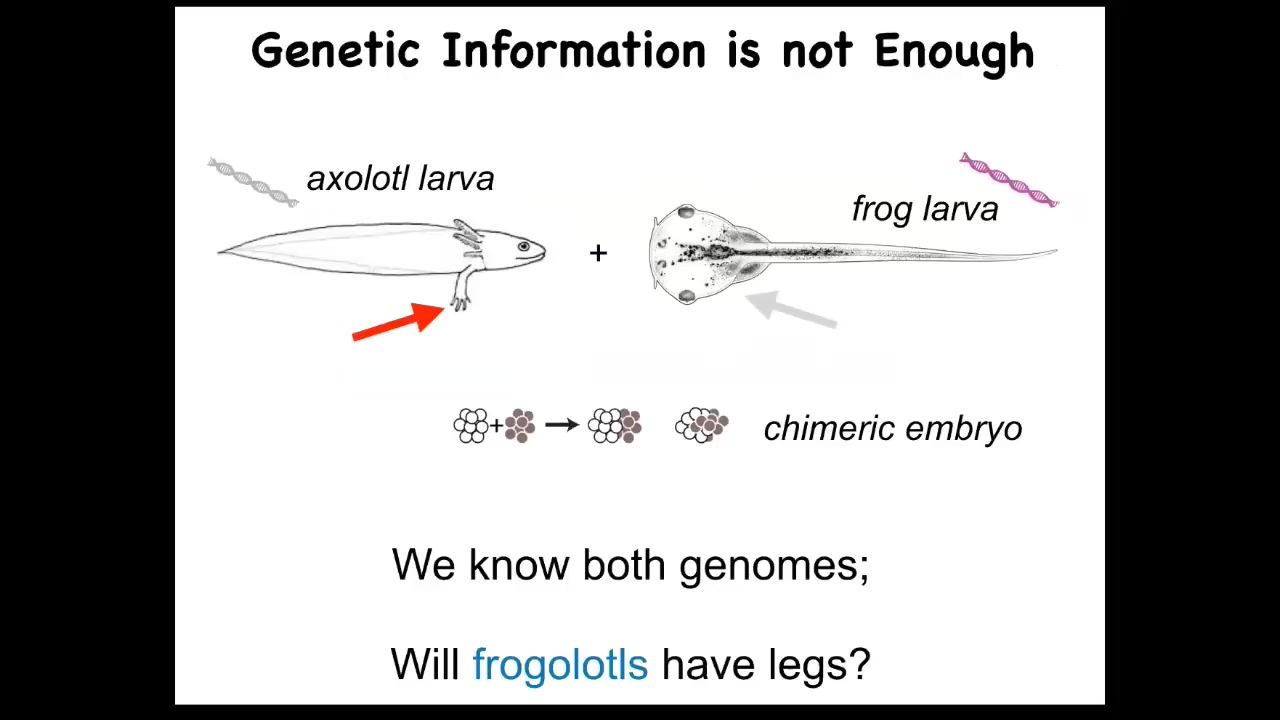

Genetics and molecular biology has been doing really well for decades. Why do we not have a way to do this? I'll just give you a really simple example. Here's a baby axolotl, which has little legs. Baby frogs do not have legs, so these tadpoles don't have legs. In my lab, we make something called a frogolotl, which is basically a combination of axolotl cells and frog cells.

Now I ask a simple question. Well, you've got the axolotl genome; it's been sequenced. You've got the frog genome; it's been sequenced. You know exactly what the genetic material is. You know what the specification of the cellular hardware is. Can you tell me if a frogolotl is going to have legs or not? The answer is no: we have no models that will predict from genetic information what this chimera is going to do.

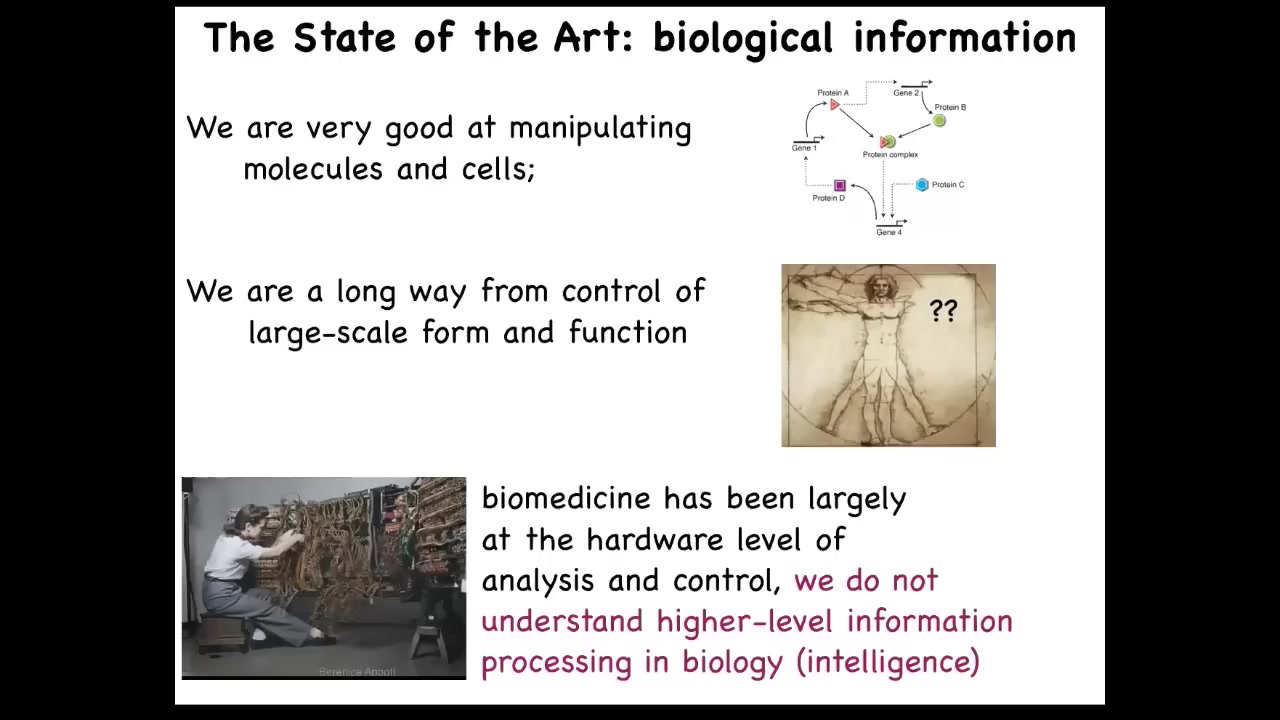

Slide 20/56 · 19m:41s

And that's because we have lots of methods and strategies for getting information like this or molecular-level information, what's going on at the lowest hardware level. We're a very long way away from understanding collective decision-making, how large groups of cells make their decisions about what they're going to build. And I think that's because currently, biology and molecular medicine are where computer science was in the 40s and 50s. So originally, in order to program, you had to physically rewire the machine. So you had to be there directly interfacing at the hardware.

But now there's way more interesting stuff happening beyond the hardware level, which is the software, the ability to reprogram, the ability to interact with high-level controls, high-level programming languages, and various interfaces where you don't need to get out your soldering iron and rewire your laptop every time you want to switch to a new application. This is something that in biology we're just beginning to understand. And I think what we're still missing is the idea that in biology, our material is reprogrammable, it has all kinds of interesting computational capacities, and we still haven't really embraced that.

Slide 21/56 · 21m:00s

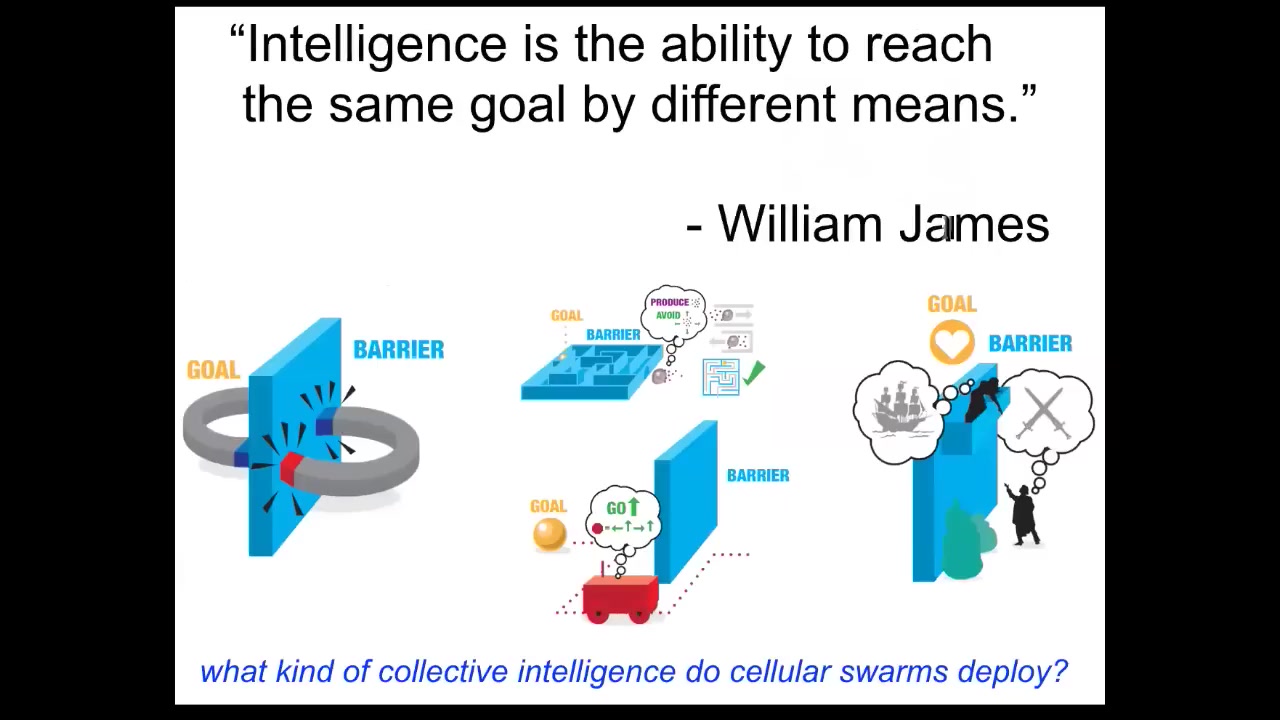

When I say that the material has intelligence, I mean intelligence in William James's sense. Not metacognitive, "I know what I know," but really just the ability to reach the same goal by different means. It's a very nice cybernetic definition. He talks about two magnets separated by a barrier. That's it. No magnet is ever going to come around the barrier and get to its goal because the system doesn't have the ability to do that delayed gratification of stepping further from your goal to get your needs met. Whereas Romeo and Juliet have additional competencies. They have long-term planning, they have the ultimate metacognition.

In between, there are different systems. There are self-driving vehicles, autonomous robots, cells, tissues, insects, and systems that are somewhere between this and this. When we talk about intelligence, we're talking about the ability to reach certain goals despite perturbations or barriers. What kind of collective intelligence do cellular swarms deploy? What can they actually do?

Slide 22/56 · 22m:11s

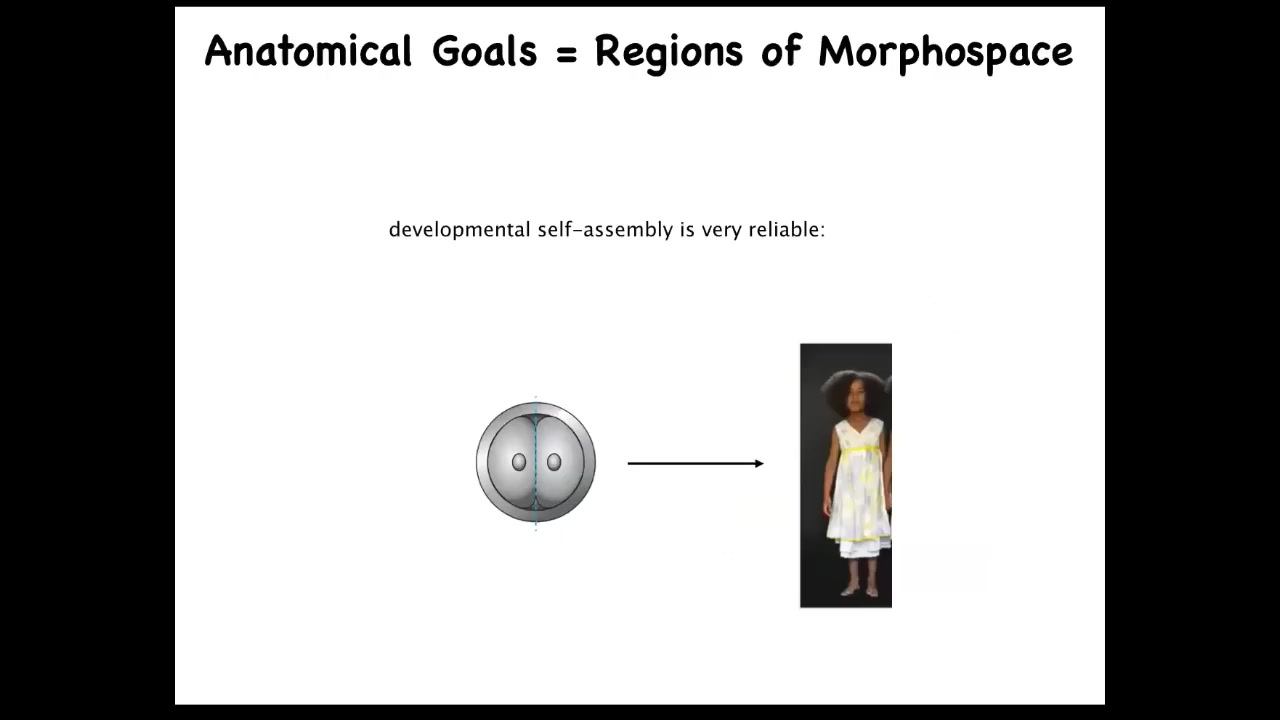

Let's look at development again. The point of development, the most exciting thing about it isn't the complexity. It's not that a relatively simple system like an oocyte gives rise to this amazing complex body, reliably. That's cool, but that's not really the whole story.

If you cut these early embryos in half or in quarters or more, you don't get partial bodies. You get perfectly normal monozygotic twins. What you see then is that in this anatomical morphospace from different starting positions, you can reach the same ensemble of goal states corresponding to a normal human target morphology, despite the fact that you're starting from different positions, unexpected ones, and you can avoid certain local minima. That's interesting.

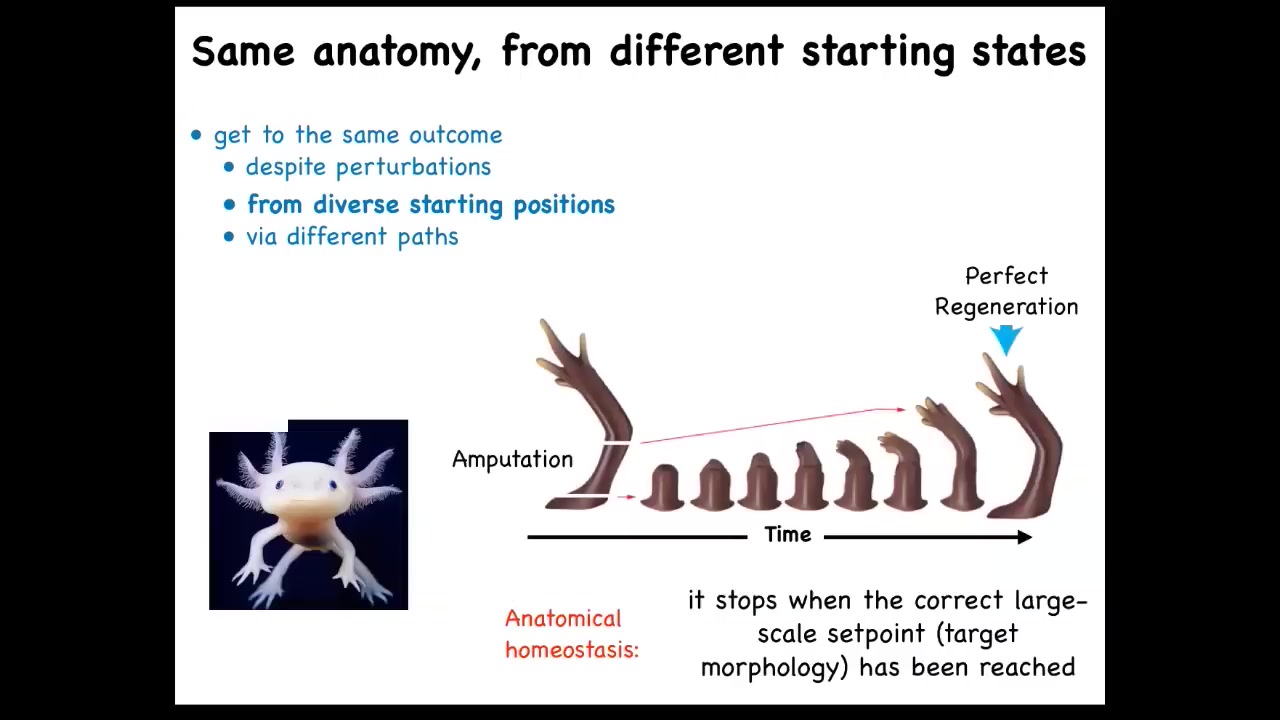

Slide 23/56 · 22m:58s

That doesn't stop at embryogenesis in some animals like this salamander. They regenerate throughout their lifespan. These axolotls regenerate lots of different body parts. For example, the limb you can amputate at any position. It builds exactly what's needed to build a perfect salamander limb. They regenerate their eyes, their jaws, their tails, including spinal cord, ovaries.

The amazing thing about regeneration isn't that it happens. The amazing thing about it is that it knows when to stop. When does it stop? All the activity stops when a normal salamander arm is complete. How does it know when it's complete? What you're seeing is an error minimization scheme. You're seeing you've deviated from this pattern and you somehow correct.

Slide 24/56 · 23m:47s

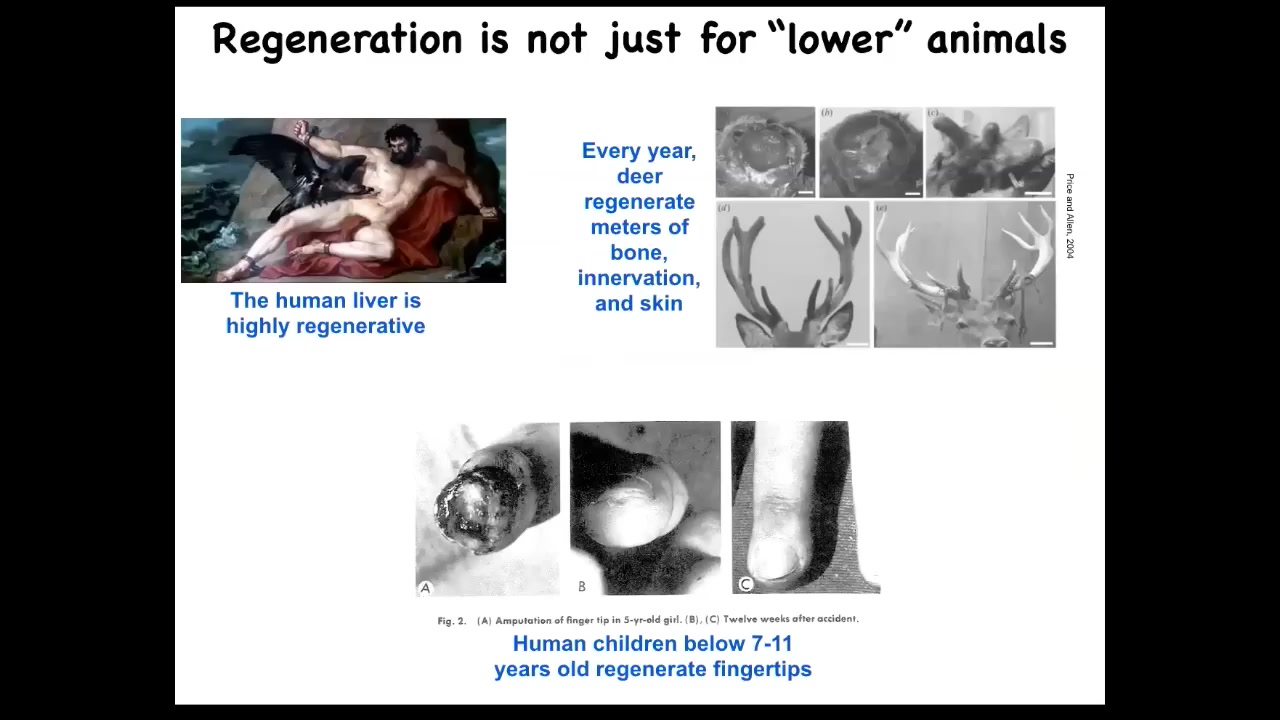

Mammals can somewhat do this. Humans regenerate their liver. Even the ancient Greeks knew that. Human children regenerate their fingertips. If you lose a fingertip at a certain age, you can regrow it with a nice cosmetic outcome. Deer are large adult mammals that regenerate their antlers. They regenerate bone, vasculature, and innervation, up to a centimeter and a half of new bone per day when regenerating.

Slide 25/56 · 24m:15s

Fundamentally, what we have here is the ability of these patterning systems, not just to make complexity, because emergent complexity is easy, cellular automata, fractals, it's easy to just have open loop complexity, but you actually have a kind of problem solving capacity. I want to show you a simple example of this. We discovered a few years ago.

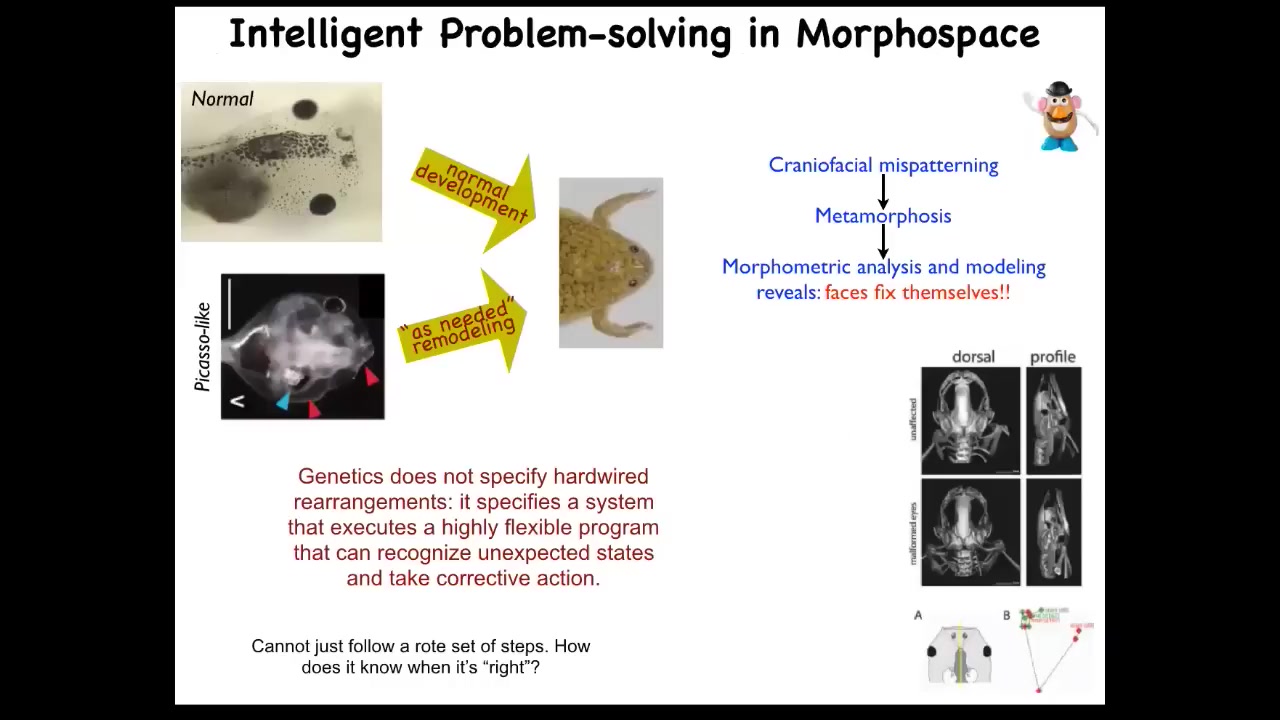

These tadpoles need to turn into frogs. In order to turn into frogs, they have to rearrange their face. The eyes, the nostrils, the mouth, everything has to move around. You might think that's a hardwired mechanical process. Tadpoles look the same and all frogs look the same. Each organ needs to know which direction to go and how much.

We decided to test that hypothesis, and we made what we call Picasso tadpoles. We scrambled all the initial positions. The eyes on the back of the head, the mouth off to the side, the jaws here, everything was scrambled. These animals make pretty normal frogs. That's because it's not hardwired. All of these structures move through novel, abnormal paths to get to where they become a correct frog. And then they stop. If we had a robotic swarm that could do this, we would be calling this an amazing collective intelligence.

What the genetics specifies is not a fixed set of deformations. What it specifies is this kind of error correction scheme that can deal with novelty. This raises an important question: how does it know what the correct shape is? How does it know where it's going in this anatomical space?

Slide 26/56 · 25m:49s

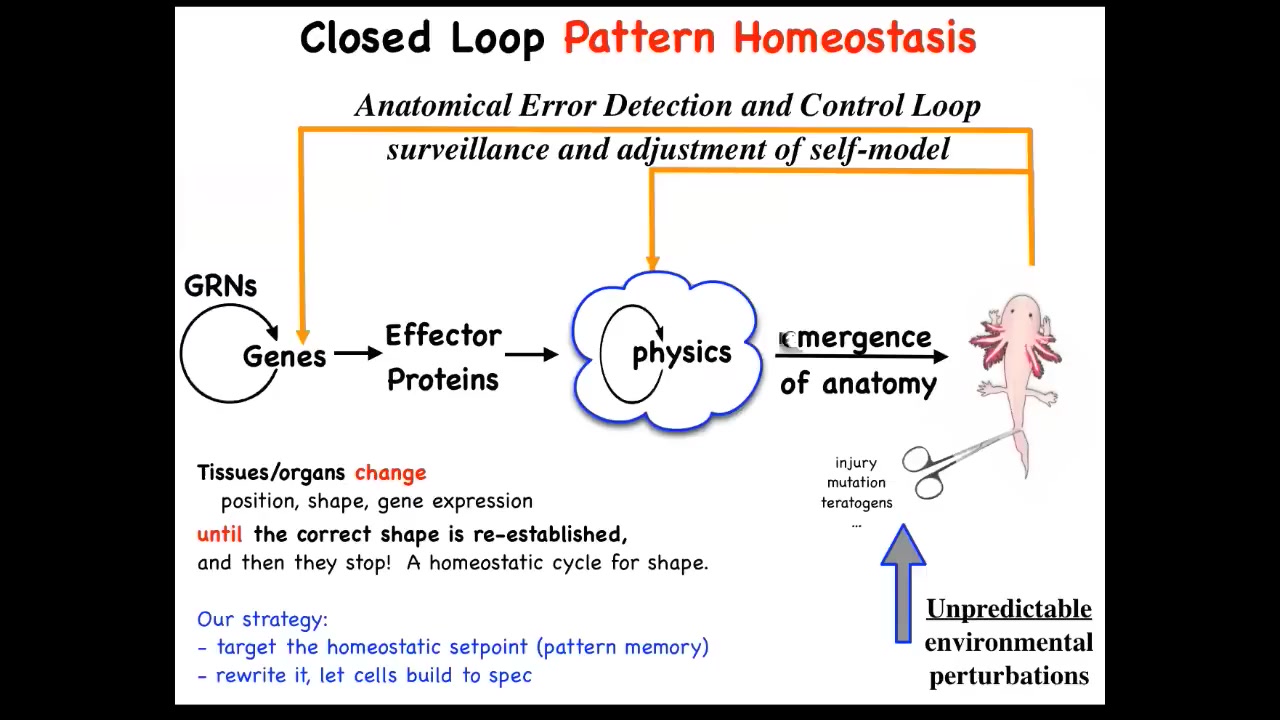

That means that to the standard model of developmental biology, this is what you'll see in textbooks. It's a feed-forward open loop system where there are genes which produce proteins and they turn each other on and off. These proteins interact with each other according to the various laws of physics and chemistry. Eventually you get this emergent complexity. And that's all true. All of that does happen.

But there's another piece to this, which is really important and exciting, which is that after that, if you then deviate from this target morphology by injury, by mutation, teratogens, whatever, if you deviate from this, there are these feedback loops, both at the level of genetics and physics, that actually try to minimize the error and get back to where you were. This is a kind of homeostasis. It's the sort of thing your thermostat does.

There are a few interesting things here. First of all, in a typical homeostatic loop that biologists are familiar with, so hunger level, pH, things like that, temperature, things like that, the set point of this process, and every homeostatic process has to have a set point. The set point of this process is a scalar, it's a single number. But here, that's not going to work. You need some kind of large data structure, a descriptor, an anatomical descriptor that allows the system to minimize the distance from it. That's kind of odd. You might ask yourself, how could you store such a thing in biological tissue? Where is it? How do you store it?

This kind of view makes a very strong prediction. It suggests that if that's true, you should be able to find this homeostatic setpoint, and you should be able to rewrite it, to edit it, and decode it, find it, decode it, and rewrite it. The reason that's exciting is because otherwise, your only hope for making changes, repairs or modifications is down here. If you want to make changes up here, you have to figure out what genes do I change to make that happen. This going backwards is fundamentally intractable.

Think about, for example, fractals. You've got a fractal formula, you've got this really beautiful complex pattern, and you look at that and you say, I want this curlicue to be a little smaller and I want another one over here. What should my formula be? You can't derive that for exactly the same reason because this is a recurrent system where everything adds up on top of each other.

So we said we could learn to edit the set point and make changes there and then let the cells do what they do best, which is to implement that set point. It's how you use your thermostat. You don't rewire your thermostat. You change the set point and let the system do what it does.

Slide 27/56 · 28m:37s

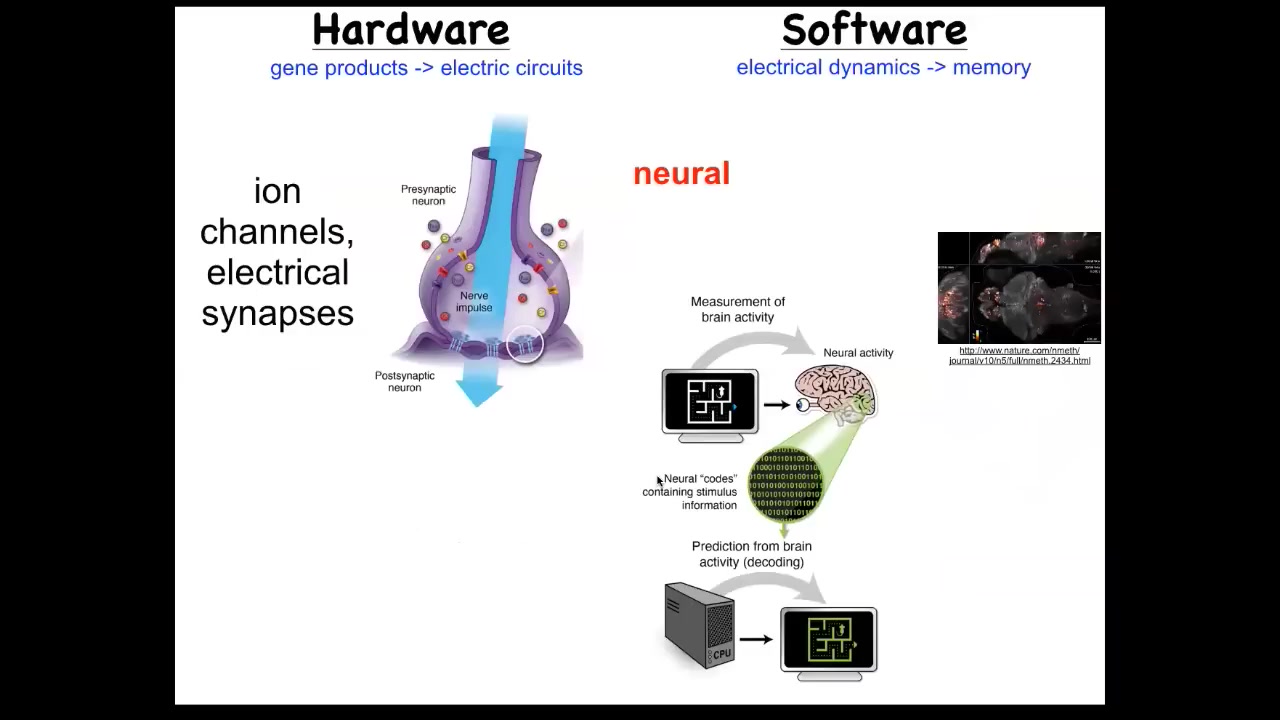

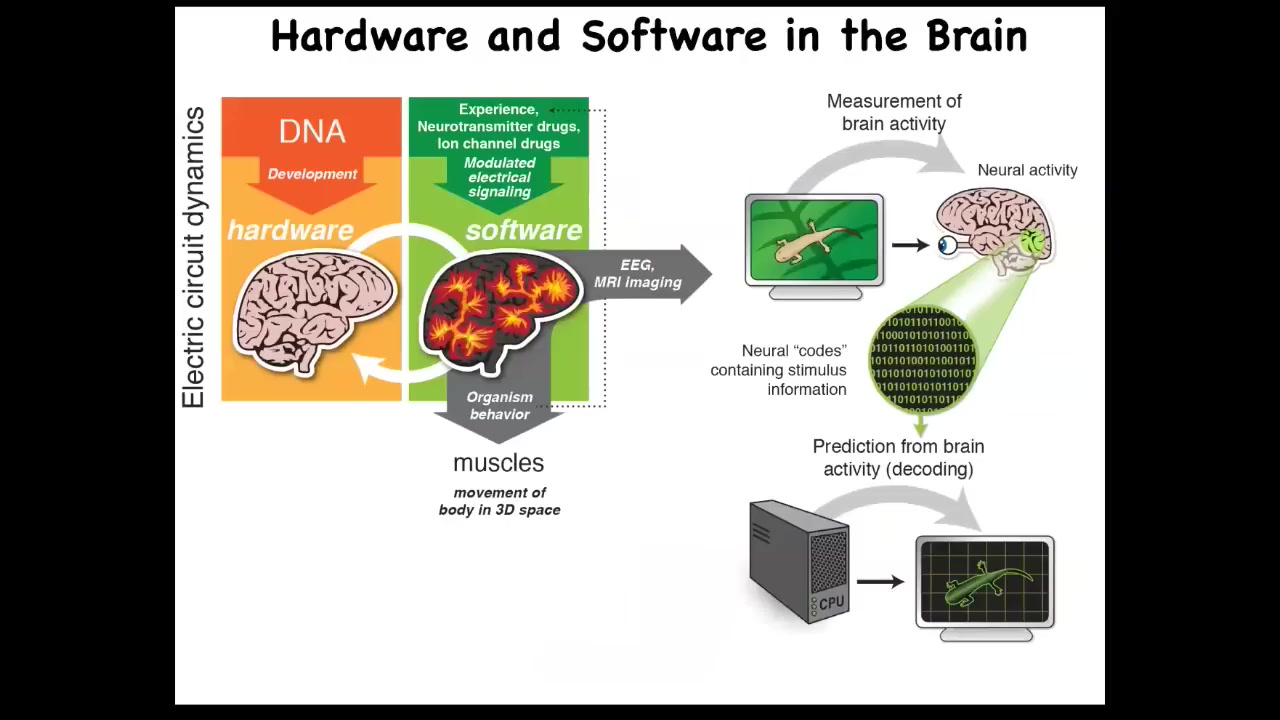

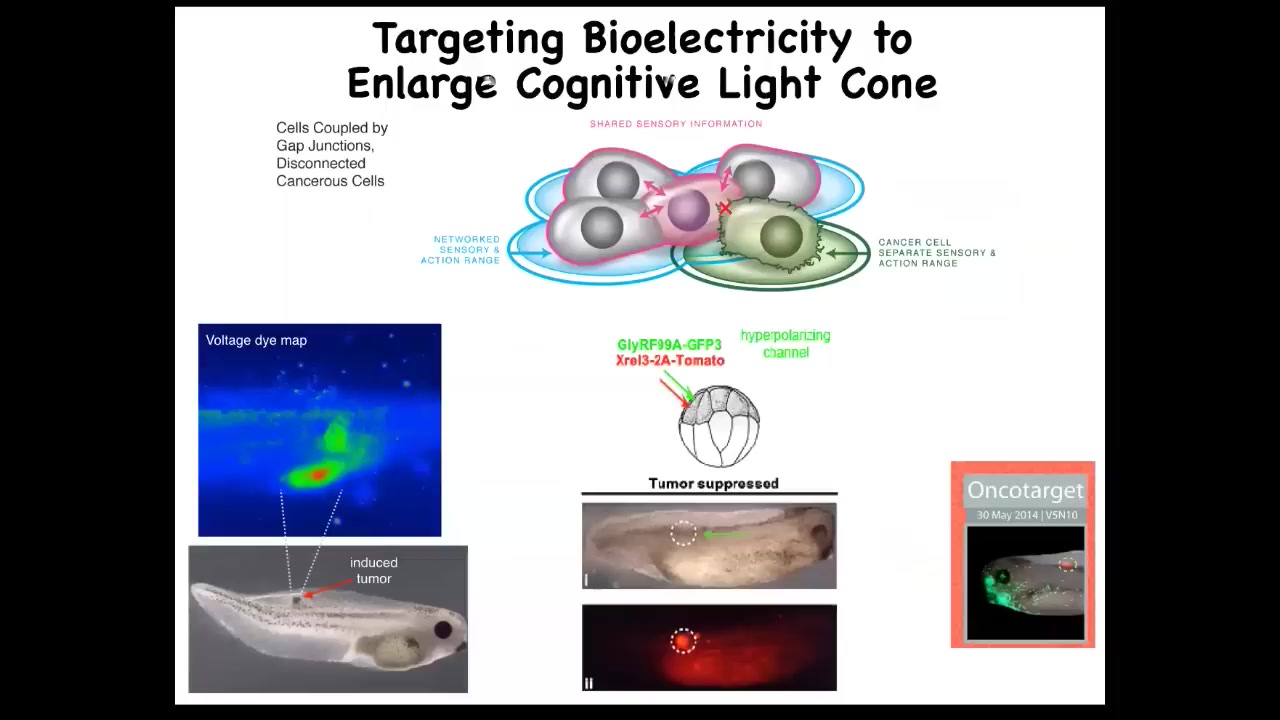

So we took our inspiration from the nervous system, which is a system where we know it's uncontroversial that there you store complex patterns. And so the nervous system, here's the hardware. It's these cells in the network, and each one has these little ion channels that pass a current back and forth. As a result, there's a voltage gradient. That voltage gradient may or may not be communicated through these electrical synapses known as gap junctions. That's the hardware. This is the software.

What you're looking at here is a living zebrafish brain. This group made an amazing video of the activity of a living fish brain. There's this notion of neural decoding, which is that if we were to understand and decode all of the information in this electrophysiology, we would be able to read the creature's memories, its preferences, behavioral repertoires, and so on. That's the commitment of neuroscience: that all of the cognitive content is stored in this electrophysiology.

Well, it turns out that every cell in your body does this; it is not just for brains. Every cell has ion channels. Most cells have gap junctions to their neighbors. So you could ask the same question. If you did a non-neural decoding, what could you learn? You would learn what it is that non-brain cells are thinking about. What are they thinking about? This is something that we've now been studying for some years.

Slide 28/56 · 30m:10s

And the idea is that there's this profound kind of invariance between neuroscience and developmental biology. In traditional neuroscience, the electrical activity of the neurons in your brain, the software, is giving directions to muscles. It's controlling muscles to move you through three-dimensional space. That's a pretty cool trick. Where did it learn that trick? Evolution learned this around the time of bacterial biofilms, very early on.

In a multicellular organism, which is a more complex version of a bacterial biofilm, the same kinds of electrical circuits are now controlling all cells to move your body configuration through morphospace. Again, it's a navigation, it's an earlier navigation, but what evolution did was speed it up: neurons are much faster than this, and it also pivoted to a different space. Instead of anatomical space, you're now running around three-dimensional space when nerves and muscles show up.

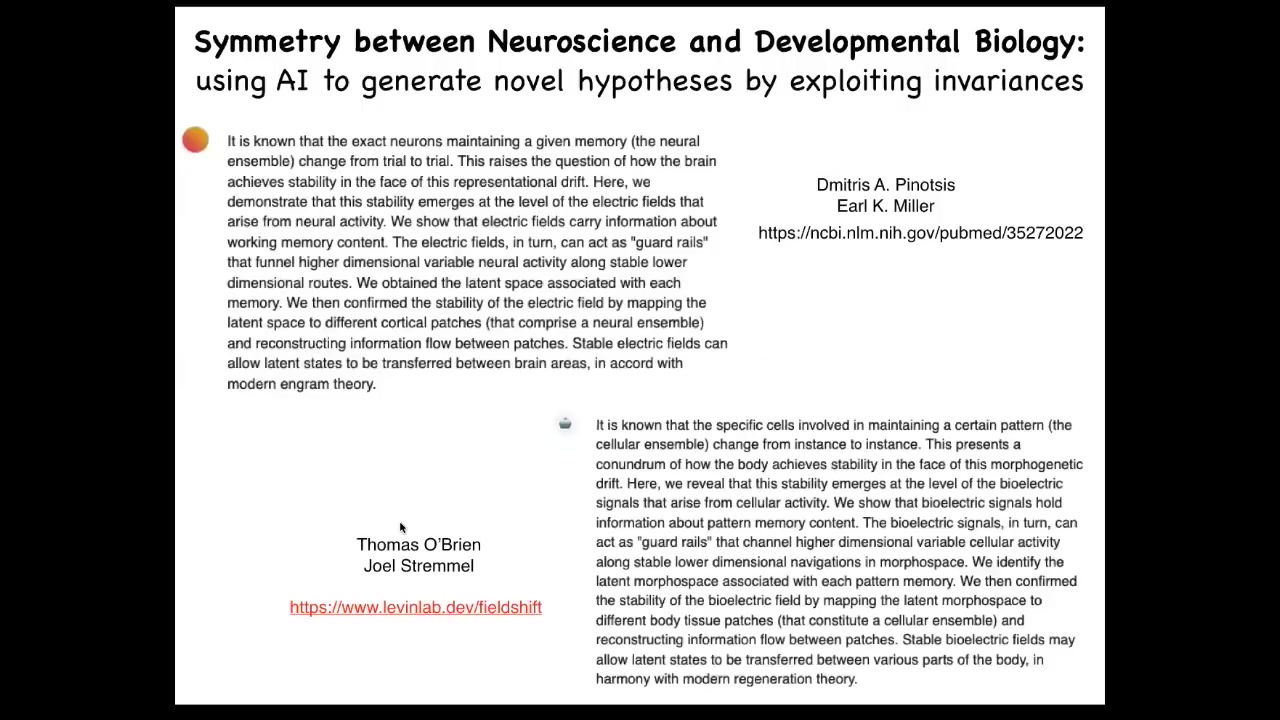

And so this isomorphism between developmental biology and neuroscience allows us to do things like this, and you can play with this.

Slide 29/56 · 31m:21s

is a tool that we developed that you can access it here, which basically takes any abstract from a neuroscience paper, such as this beautiful work by Panotsis and Miller, and it uses AI to convert it to a developmental biology paper that doesn't exist. It's letting you explore the latent space of possible papers. All it does is convert: whenever the neuroscience says neuron, this just says cell. Whenever it says millisecond, this has minutes or hours. It does a few other translations. If you read this, it's a great abstract, but it generates a very nice possible developmental biology paper that actually makes sense and gives you hypotheses of new things to test. That kind of using AI to explore; in fact, this thing called FieldShift, there's also opportunities to shift the papers to other areas like finance and so on. Using AI to exploit these symmetries between fields is really powerful.

Slide 30/56 · 32m:24s

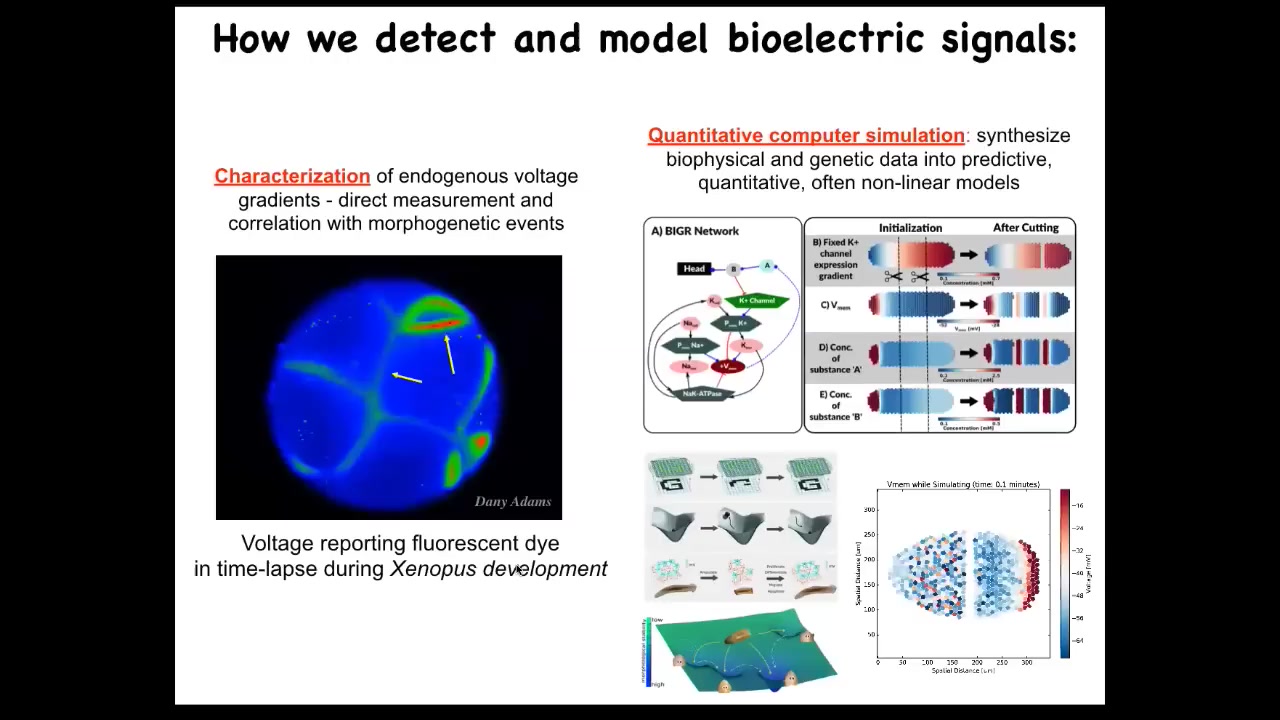

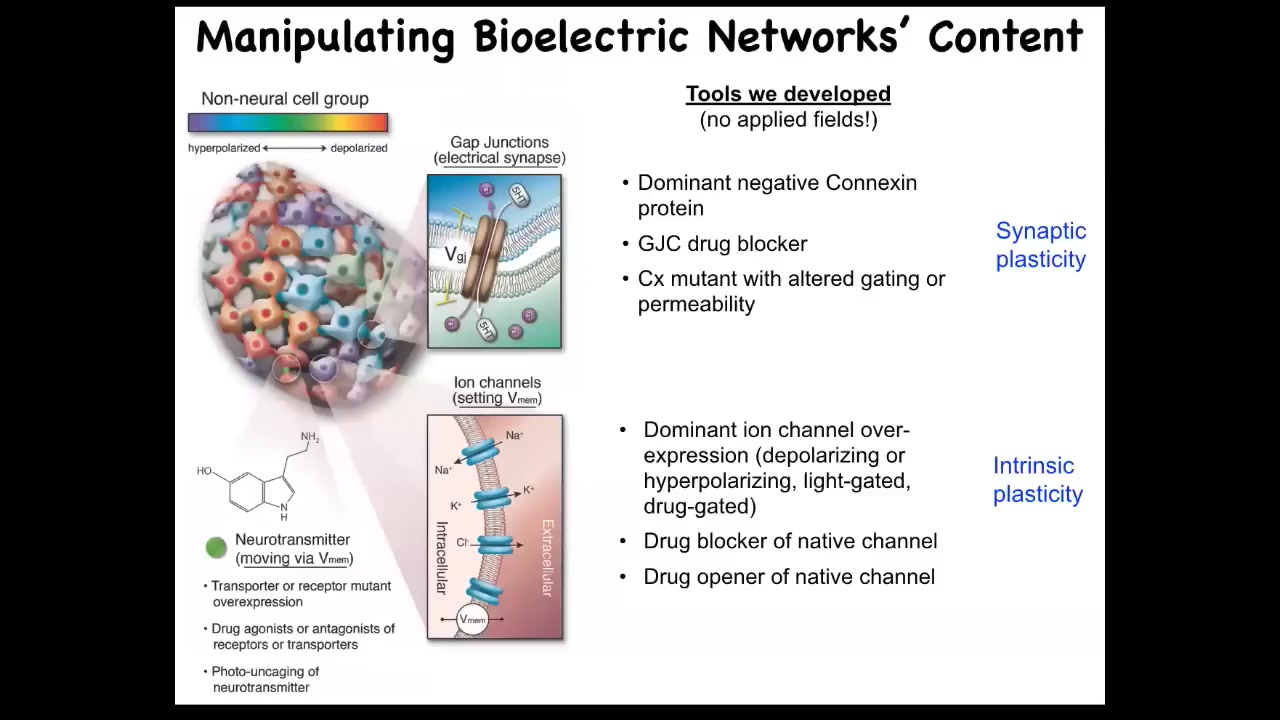

What we did years ago was to build the first molecular tools for reading and writing electrical information in non-neural cells. We appropriated from neuroscience because those tools can't tell the difference. They work everywhere. They're not specific for neurons.

First, it's voltage-sensitive fluorescent dyes. What you're seeing here is a time lapse of an early frog embryo, where we can see all the electrical conversations that all these cells are having with each other. We get to read the voltages, and then we do simulations. We have this simulator, and we do work to try to understand how the molecular biology of the ion channels gives rise to electrical circuits that have specific behaviors.

Slide 31/56 · 33m:08s

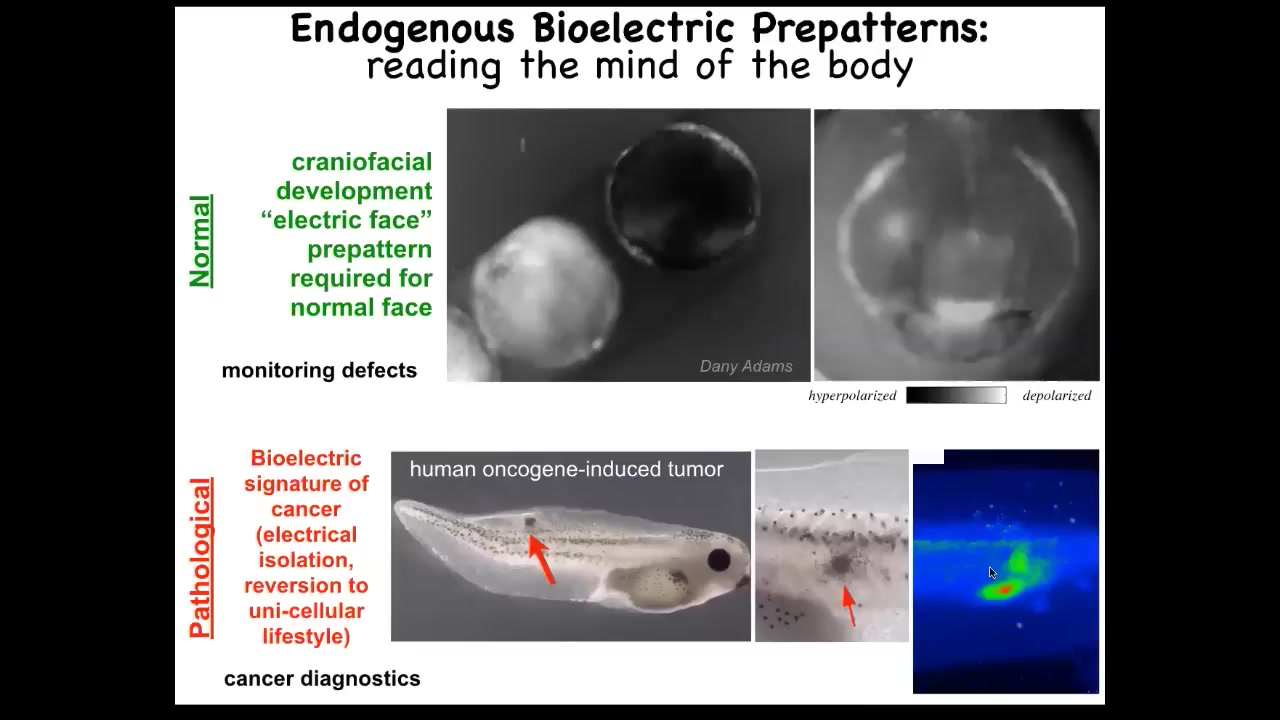

I'm going to show you a couple of patterns. This is voltage imaging, and this is an early frog embryo putting its face together. There are all kinds of things going on. One thing to look at is this is one frame out of that movie right there. That's the frame. You can see here that long before the genes are turned on to pattern the face and before the anatomy of the face develops, by looking at these electrical pattern memories, you see this animal knows: here's where the right eye is going to go, here's where the mouth is going to go, here are the placodes. It's a subtle energetic scaffold, a pre-pattern, that tells the face what the shape should be. If you mess around with the shape, then the gene expression changes and the anatomy changes. I'll show you that in a minute.

This is a natural pattern that's required for normal face development. This memory is required for the cells to know how to build a frog face. You could use this technique to monitor for a birth defect.

This is a pathological pattern. The idea is that we inject a human oncogene. Eventually it makes a tumor. The tumor starts to metastasize here. Before that happens, you can already see these cells electrically disconnecting from their neighbors and going off on their own, treating the rest of the body as just external environment.

Slide 32/56 · 34m:30s

Even more important than the monitoring is the idea of being able to rewrite these patterns via functional states. I'm going to show you some outcomes to that, but I want to be very clear. We do not use electrodes, electromagnetic fields, magnets, waves, radiations, or frequencies. What we are doing is targeting the native interface that the cells are using to hack each other. What they're using are these little ion channels on their surface and the gap junctions that pass electrical signals to each other and to the outside world, and that's how they set their voltage and process information. There's a native interface, like the keyboard of a computer, that gives you privileged access so that you don't have to try to directly micromanage the information flow that's happening here.

And of course, we use the same tools that neuroscientists use. We can introduce changes into these channels. We can use pharmacology to open and close the channels. We can use light, which is now optogenetics, the same techniques.

Now I'm going to show you what happens. What is this bioelectricity good for, these electrical signals through the tissue? The argument I'm going to make is that it is the proto-cognitive medium of the collective intelligence of these cells. It's the network that allows them to navigate from a single-cell shape to a complex organism.

Slide 33/56 · 35m:59s

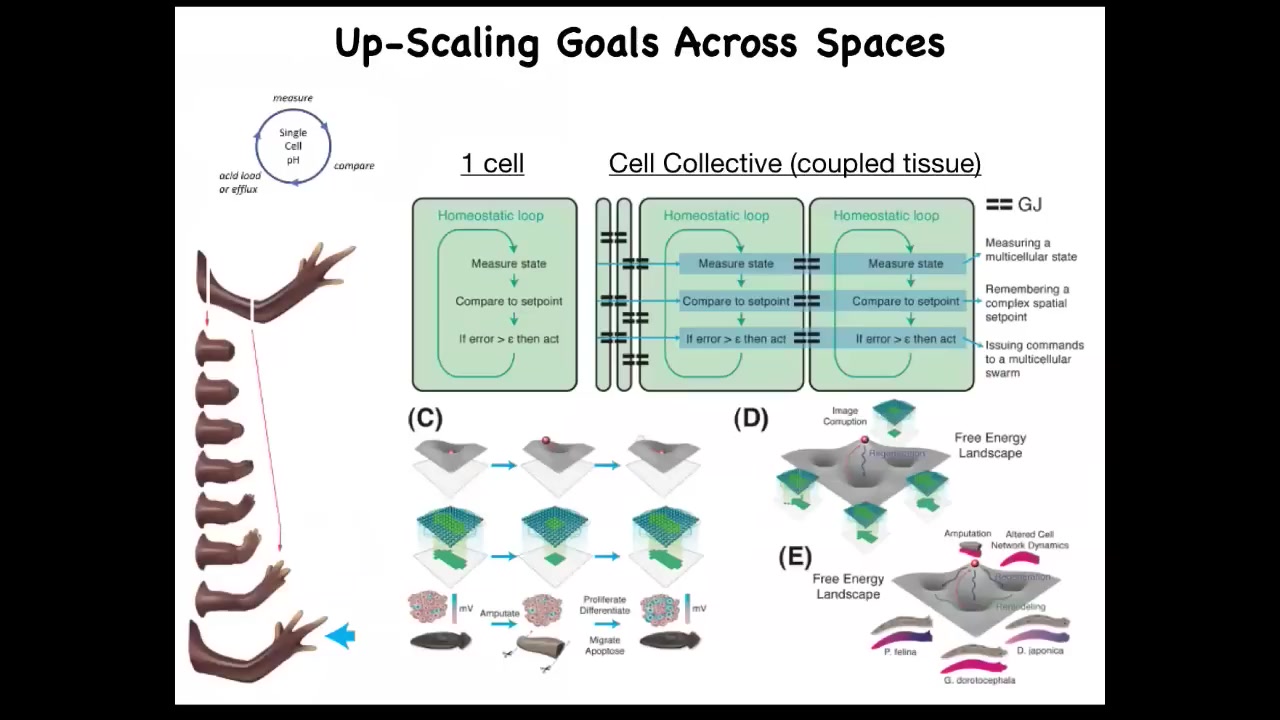

When you're doing that, what you're doing is scaling up the goal space of these systems. So when you have a single cell, you could have this nice simple homeostatic loop that would respond to a certain local variable: pH, temperature, or hunger level.

But what you want here is a very humble goal. It's a very tiny goal. My goal is making this limb, and it's not enough for me to be a single cell worried about local information. All of these cells need to be able to build this and then stop. No individual cell knows what a finger is or how many fingers you're supposed to have, what the collective absolutely does.

So what you need to do is scale. You have to use communication between these cells to scale them to larger-scale goals, enlarge that cognitive light cone so that the set points that they're going after are much bigger and in a different space, and they're able to recover from partial information and navigate these energy landscapes.

Slide 34/56 · 37m:03s

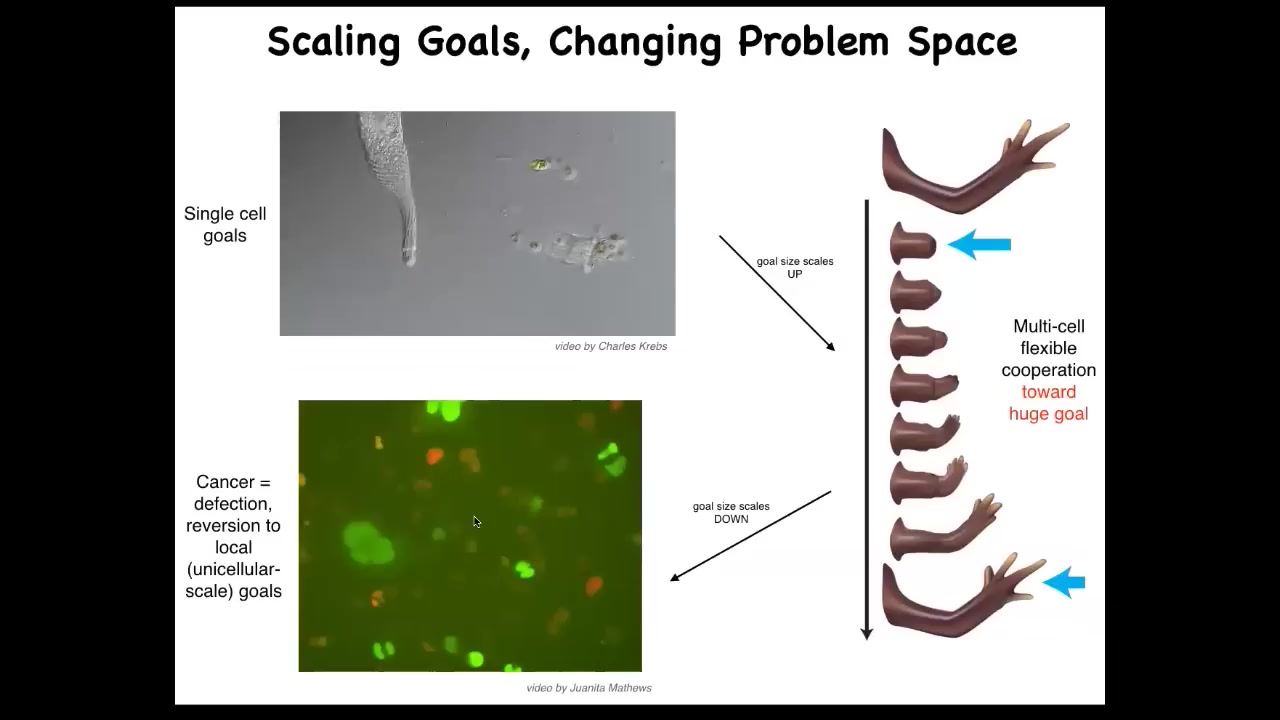

One of the things you can do with bioelectricity is address a particular failure mode of multicellularity. That failure mode is known as cancer.

Think — the individual cells have little tiny cognitive light cones. All this cell cares about is its own local state. But here you've got this very large cognitive light cone. It's a whole limb. That process can break down.

If individual cells disconnect from the environment, that is glioblastoma, a kind of cancer. They treat the rest of the animal as external environment. The boundary between self and world shrinks.

That cognitive light cone — the size of the goals you're interested in and pursuing — is really the size of you as a self. It's what determines the boundary between you and the outside world. Evolution inflates it, but sometimes it shrinks and becomes cancer.

Slide 35/56 · 37m:52s

Those cancer cells aren't any more selfish than normal cells. It's just that their self is smaller. It's the question of how you know where you end and the outside world begins. This is one way that cells use to determine that.

Knowing that allows you to start to develop therapeutics. Here is this nasty oncogene, a human KRAS mutation. Normally it would make a tumor like this. It's all over the place, but there's no tumor. This is the same animal. There's no tumor. Because what we did was inject an ion channel into these cells to force them to be in the right electrical state relative to their neighbors.

Even though there's genetic damage—the hardware is damaged—you can get around that at the software level by having the appropriate connection to the network. The network can overcome local damage. This isn't chemotherapy. You're not killing these cells. You're normalizing them. You're bringing them back into correct functionality by reconnecting to the network. That's what you can do on a single-cell level. We're pursuing that into human medicine soon.

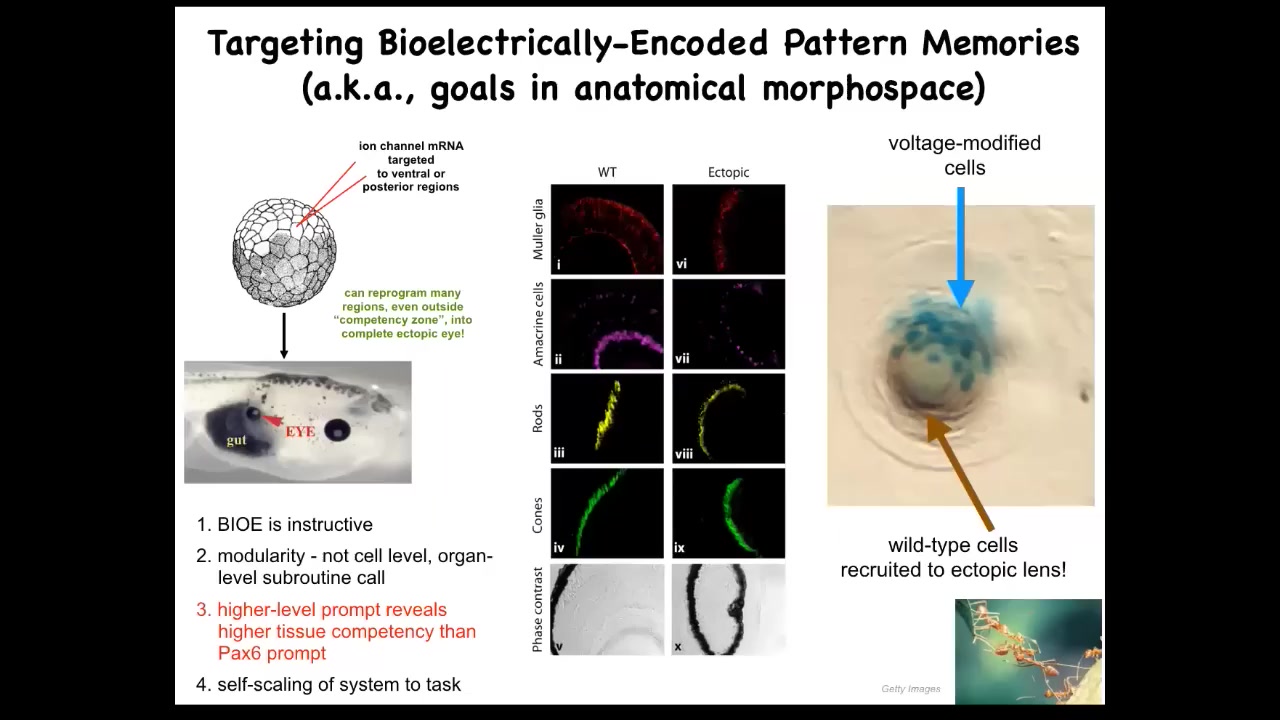

Slide 36/56 · 39m:03s

But you can also work at organ level. You can take ion channels encoding, RNA encoding specific ion channels, inject them into this early embryo at a location that's going to become gut. And what you can do is you can recapitulate that little eye spot. I showed you that electric face, and there's a little pattern there that's corresponding to an eye spot. You can recapitulate that pattern somewhere else. When you do that, these cells happily make an eye. These eyes have all the same lens and retina and optic nerve and everything else.

This tells you a few things. It tells you that the bioelectric pattern is instructive because it could call up whole other organs. It also shows you that it's incredibly modular, meaning that we didn't put in very much information at all. There's not that much information to specify an entire complex eye. In fact, we have no idea how to make a frog eye. What we did find is a trigger, a subroutine call, that triggers all the stuff downstream. It encapsulates. This very simple signal says build an eye here, and that encapsulates all of the gene expression changes and the morphogenesis and everything else that has to happen.

Not only that, it actually encapsulates some problem-solving behavior. For example, if you inject only a few cells here, there's not enough of them to make this lens. What they'll do is the same thing that ants and termites do, another collective intelligence. What they'll do is they'll recruit their neighbors. The blue cells are the ones that we injected. All of these other cells were recruited by these guys because they realized there was not enough of them to complete the task. All of those competencies are downstream of a very simple subroutine call that says build an eye here.

I've shown you that by manipulating the bioelectric states, you can change the size of that goal-directedness, the size of the cognitive light cone. I've shown you that you can induce specific pattern memories. For example, eyes. We can do some other organs.

Slide 37/56 · 41m:00s

And now I want to show you more specifically what these pattern memories look like. This is our planarian, and I remind you that you can cut them into many pieces. The record is something like 275, I believe. And they're also immortal, so they go on forever. They just continuously regenerate.

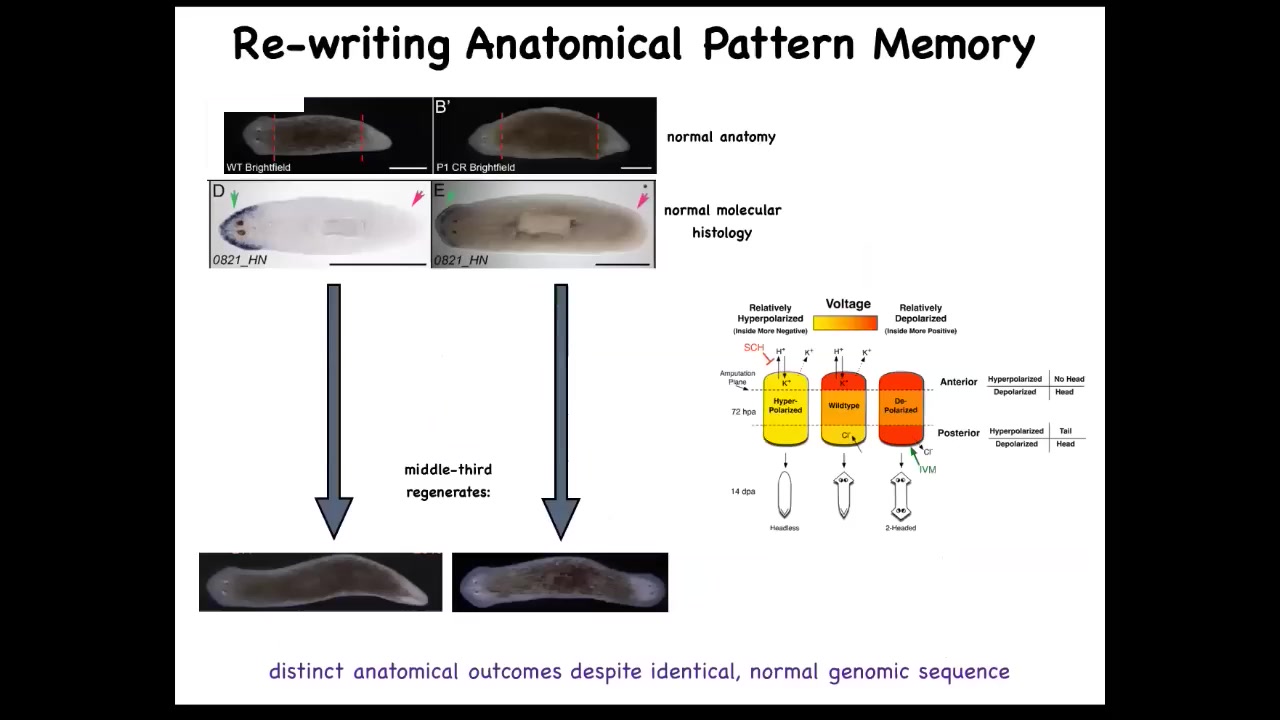

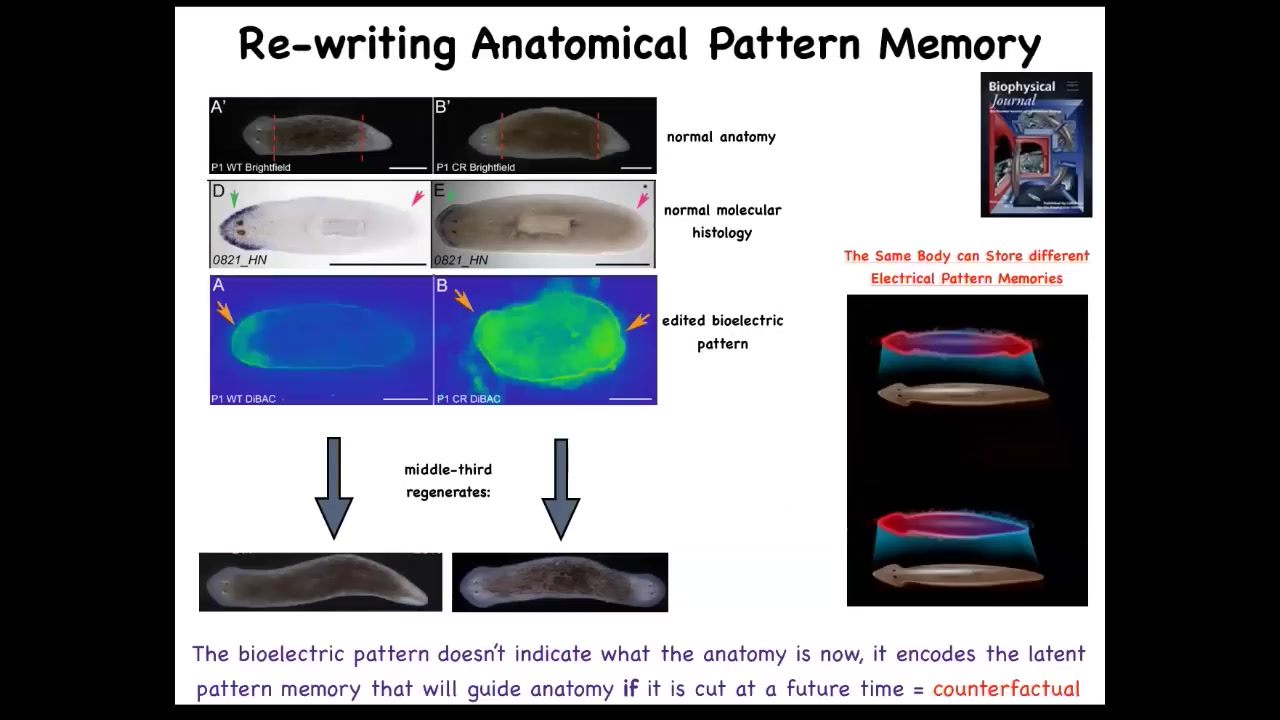

Slide 38/56 · 41m:19s

One simple question you could ask is if we cut these into pieces, here's a middle fragment, we've cut off the head and the tail, here's the gene expression, the anterior genes were up here at the head, and you cut this middle fragment, this middle piece 100% of the time knows how many heads it's supposed to have. One head, one tail. How does it know that? We found an electrical circuit that we characterized that carried that information.

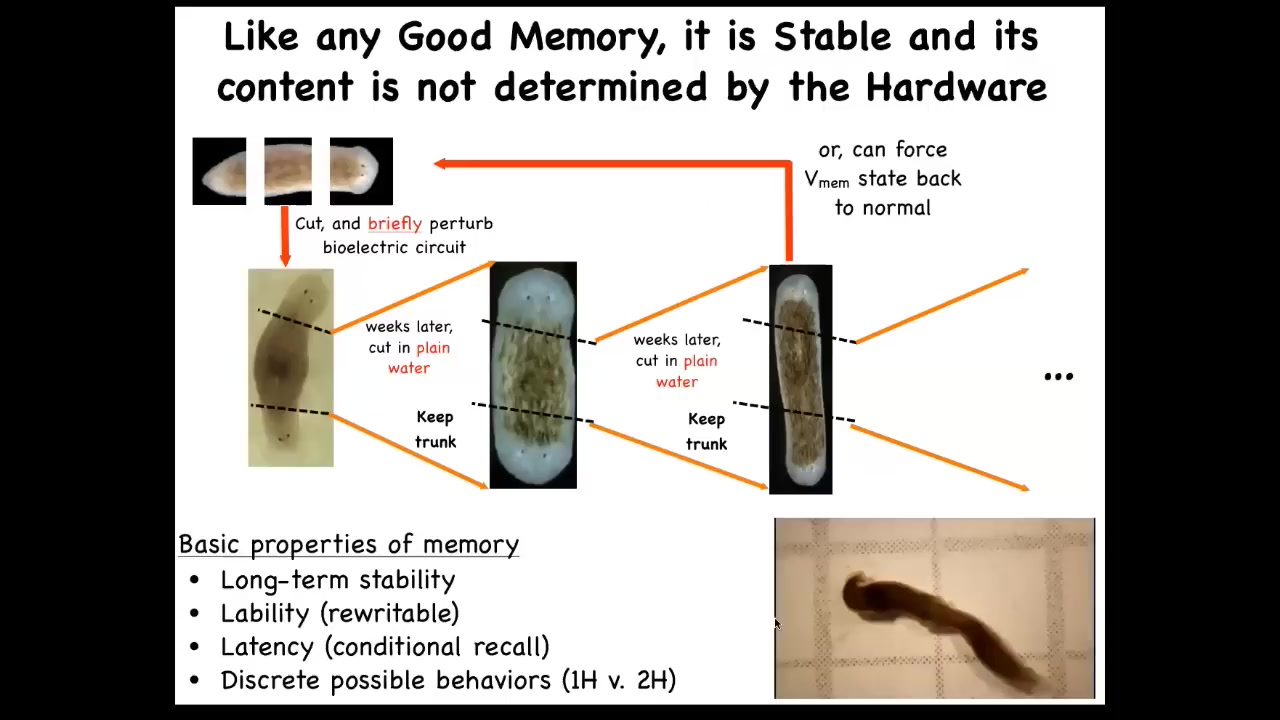

Slide 39/56 · 41m:43s

This is what it looked like. That piece has a pattern, an electrical pattern like this, one head, one tail. We then asked, what happens if we change that pattern, if we rewrite it? And what we did was use ion channel modifying drugs to rewrite that pattern and make it look like this. It's a little messy, but you get the idea. Here it is. This technology is very much still at early stages. When you do that, and this is the animal here, you cut that animal and that piece will go on to make a two-headed worm.

This is really critical. This electrical pattern is not a map of this two-headed guy. This electrical pattern is a map of this one-headed, normal-looking and normal gene expression having worm. That's because this is encoding. I promised you when we talked about set points in anatomical homeostasis that I was going to show you where the memory is. You are now looking at it. This is literally where the pattern memory is. We can now visualize it. This fragment thinks that a normal worm should have two heads. That is the representation of what a correct worm looks like, and that is what the cells build when they are injured.

A normal worm body can store up to one of two different, but this is what we know now, two different representations of what a correct planarian looks like. It's actually a counterfactual memory because at this point, the body is not two-headed and yet it has this pattern. It's not what's happening now, it's what you're going to do if you get injured in the future. It might be the evolutionary precursor of this amazing mental time travel that brains allow us to do.

Slide 40/56 · 43m:28s

Now, I keep calling it a pattern memory because if I cut these two-headed worms into pieces again and again in plain water, they continue to generate two-headed animals. You might think that if I amputate this ectopic secondary head and the genetics are normal, we haven't touched the genome, then that hardware should just go back and continue to make normal worms. But that's not what happens. The memory holds and it keeps the two-headed state. And then we now know how to turn it back. This has all the basic properties of memory. It's long-term stable, it's rewritable, it has conditional recall, and it has discrete behaviors, discrete paths that it takes in anatomical morphospace. Here you can see these two-headed worms hanging out. The question of how many heads a planarian is supposed to have is not directly written in the genome. The genome encodes some hardware that, when the juice is turned on, by default, makes a pattern that says one head, but it's reprogrammable. This tissue is reprogrammable such that when we change that pattern, it holds.

What we're doing now is combining lots of ideas from the dynamical systems theory of these electrical circuits with some powerful paradigms in connectionist and machine learning to try to understand how these electrical networks recall complex patterns from partial stimuli, how they handle noise, and how they navigate these energy landscapes.

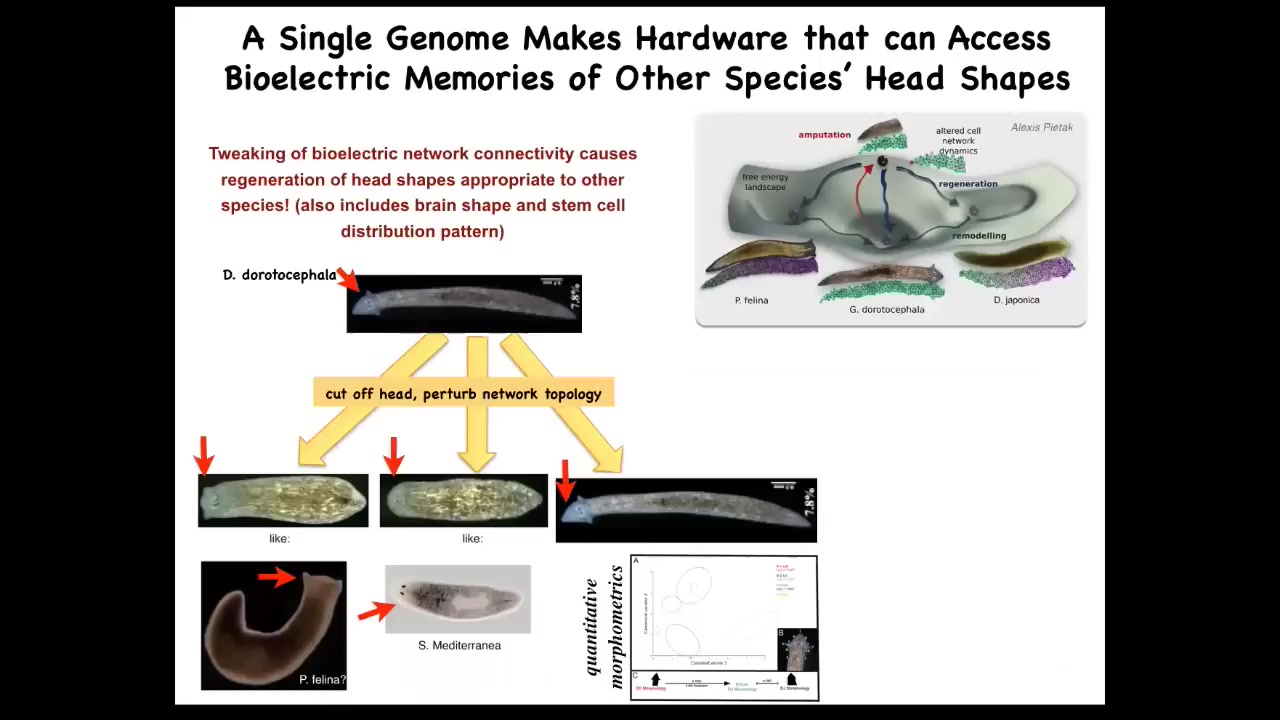

Slide 41/56 · 44m:58s

Now, it's not just about head number, you can do this with head shape. In fact, you can get this species with a triangular head shape to make flat heads like a pifalina or round heads like a nes mediterranean. Not just the head shape, but the shape of the brain and the distribution of stem cells becomes like these other species. The distance between this and this is about 100 to 150 million years of evolution. What that tells you is that this hardware, without any genetic modification, but purely with physiological stimuli, is able to visit other attractors that normally belong to other species. You're starting to see that plasticity.

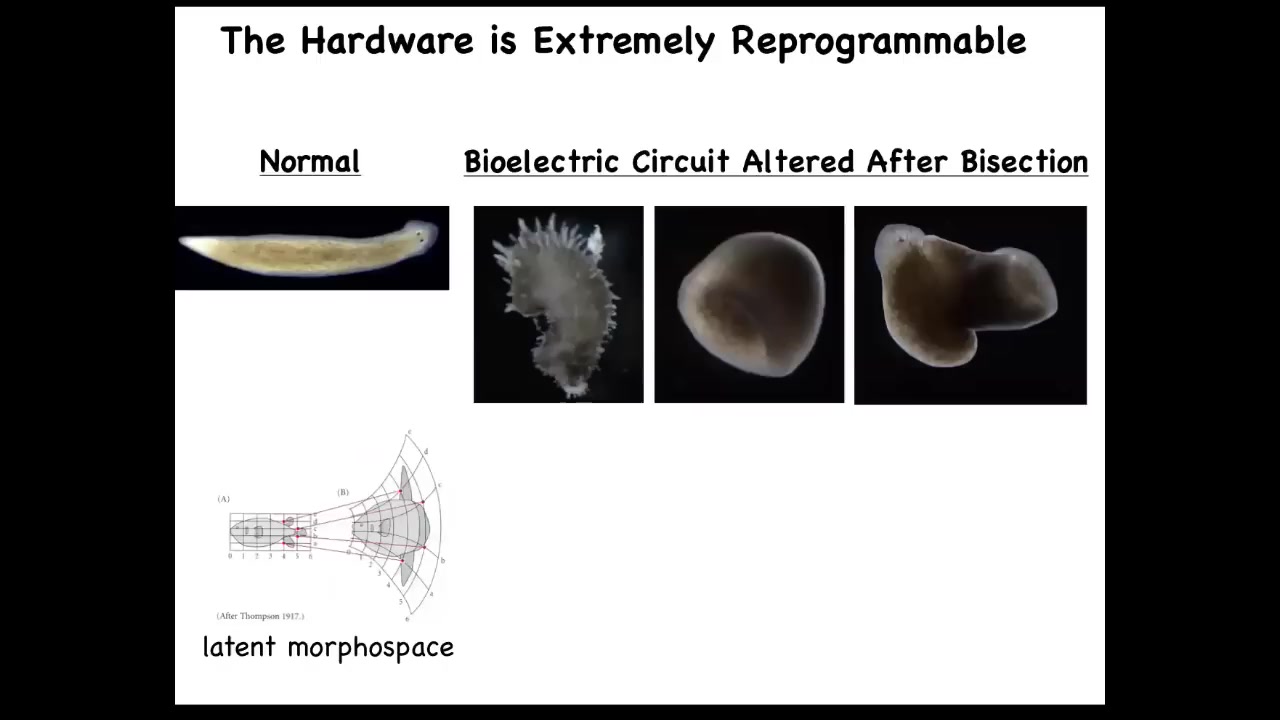

Slide 42/56 · 45m:35s

In fact, you can get them to make shapes, crazy shapes that don't look like a planarian at all. That's because there's a huge latent morphospace around the normal physiological behavior of that system. You can push it to explore other areas of that morphospace.

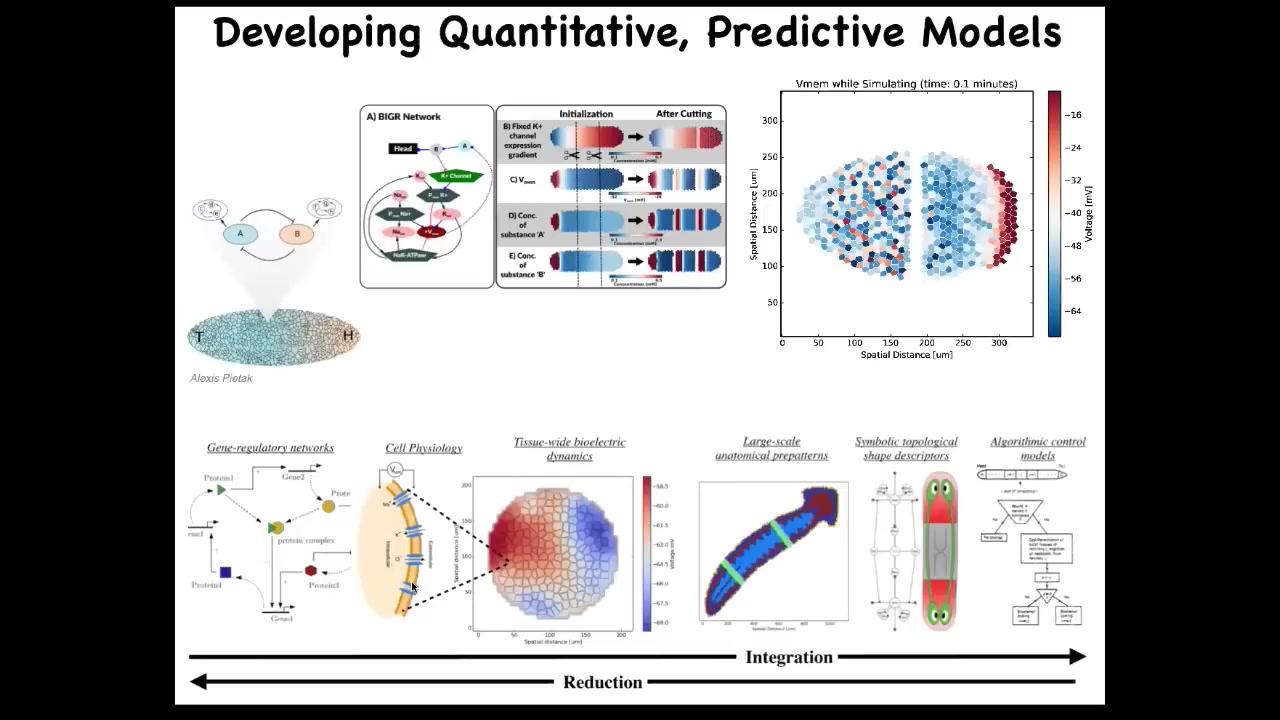

Slide 43/56 · 45m:53s

One of the things we're doing now is trying to make a full-stack model all the way from the molecular biology of ion channels to the simulation of the electrical circuits to the large-scale body-wide patterns that appear, and then ultimately in the kind of algorithmic view of this decision-making so that you can have a human-understandable set of algorithms. We want to be able to integrate the whole thing. Partly why we want to do that is for regenerative medicine applications.

Here's an example.

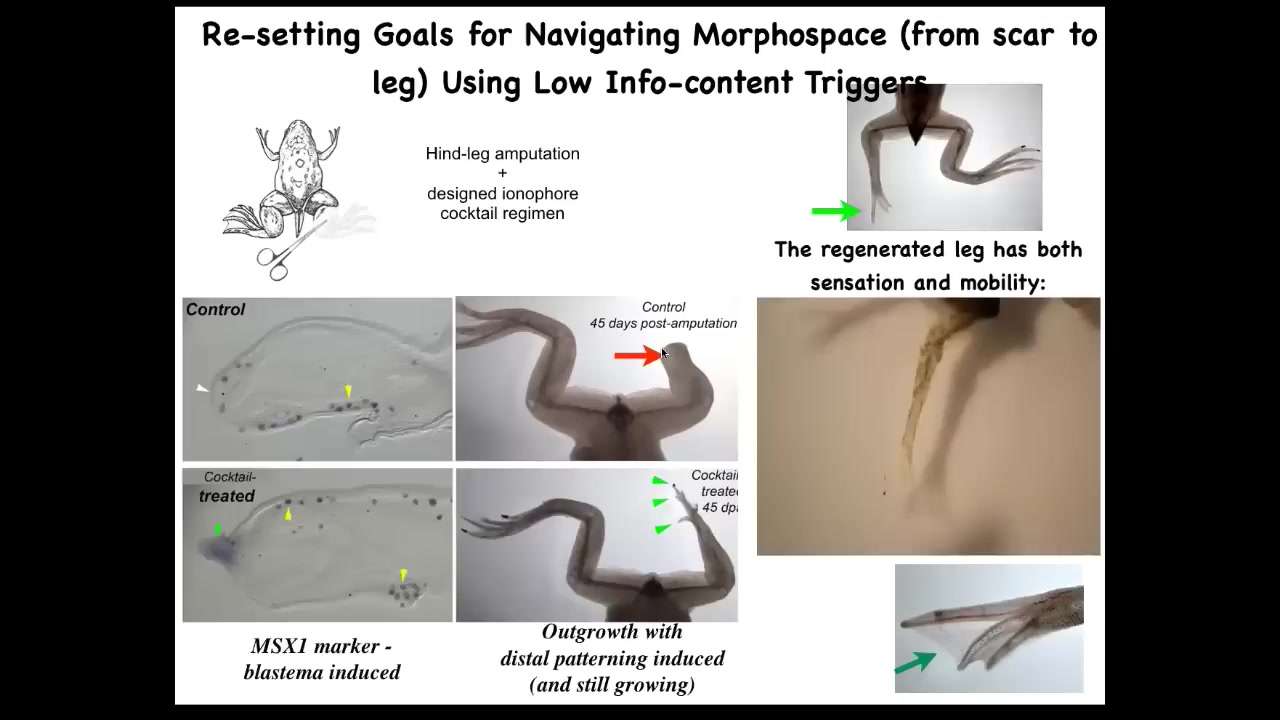

Slide 44/56 · 46m:34s

Frogs, unlike salamanders, do not regenerate their legs. Normally after 45 days, you get nothing, but we made a bioelectric cocktail that triggers leg regeneration within 45 days; you already have some toes, you've got a toenail, eventually a pretty respectable leg that's touch sensitive and motile.

The idea is that we're not micromanaging the process. We're not telling the stem cells what to do. We're not 3D printing anything. We're telling the cells in the first 24 hours after amputation you should go down the leg building path, not the scarring path.

After that, we don't touch the animal at all. We leave them alone for a year and a half. This whole thing will grow for 18 months after only a 24-hour application.

Because we're not trying to micromanage the process, we're looking for subroutine calls. We're looking for hooks into the native software of the morphogenetic agent.

Slide 45/56 · 47m:20s

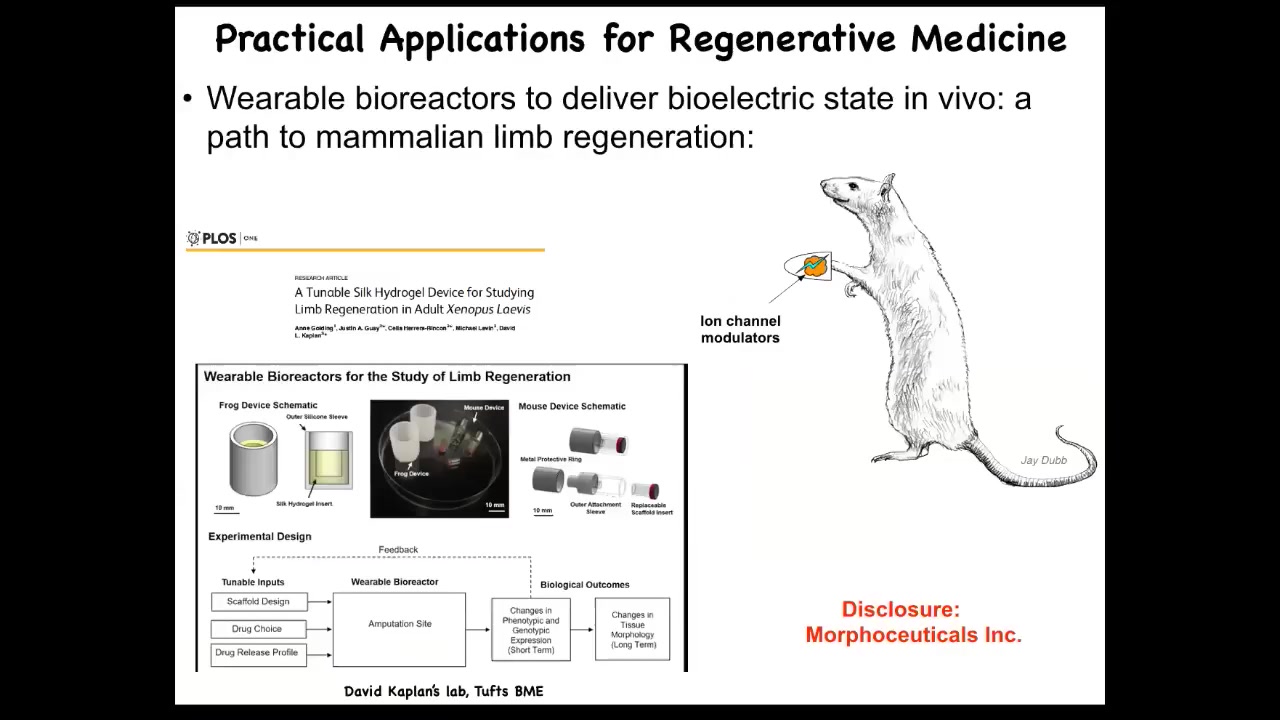

Having done this, we are in the process of trying to do this in mammals. We have to do a disclosure here. Morphoseuticals is a company that Dave Kaplan and I started to take some of this technology and push it into mammals.

The last thing I want to show you today is a set of novel beings, because I've told you that these biological systems are exhibiting problem-solving capabilities in anatomical space. When you ask, where do the set points come from? How does it know what shape it should be? Typically, the answer is evolution, selection. In other words, if you're going to be a frog living in a ****** environment, there's really only a small set of forms and functions that will survive there and everything else died out. That's why it takes eons of selection.

What we decided to do was to make novel organisms that never existed before. We decided to ask, can we make this from scratch? How much plasticity is there? What are cells going to do when you reboot their multicellularity? Where do novel goals come from? I'll also do a disclosure here because this is work with Josh Bongard at the University of Vermont, and we have a company called Fauna Systems. Doug Blackiston is the biologist in my lab who does all of this work.

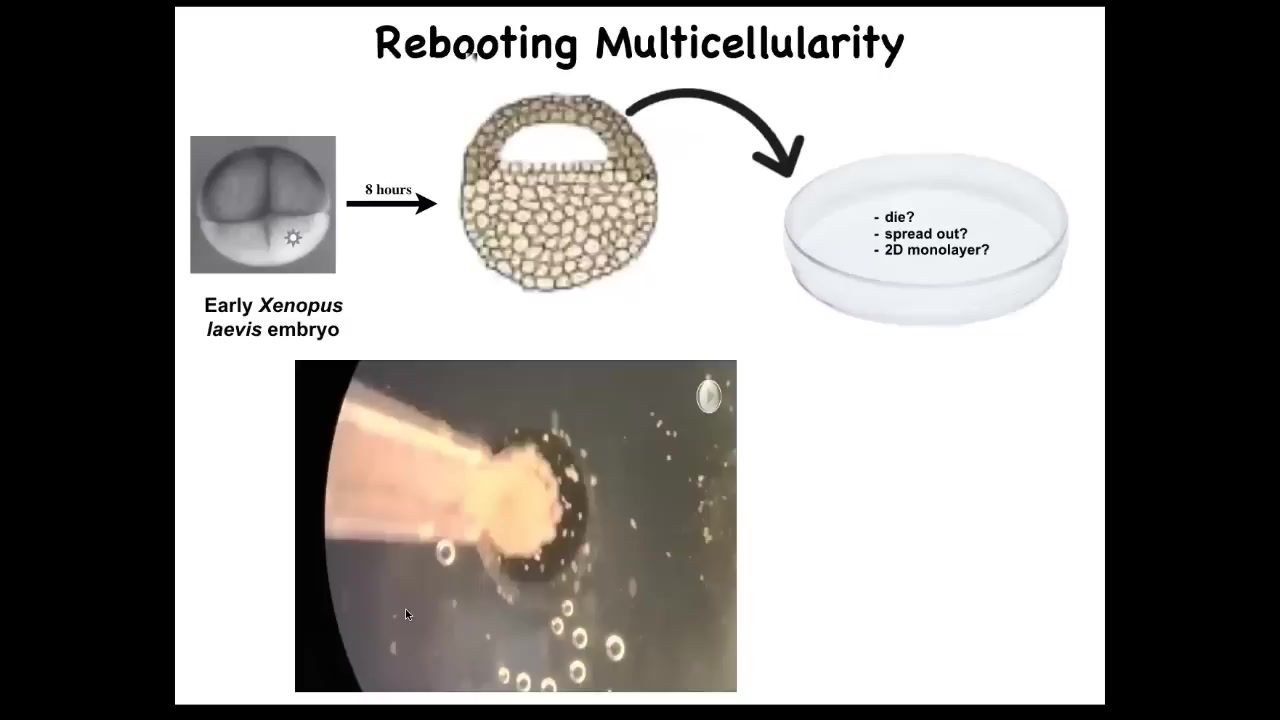

Slide 46/56 · 48m:39s

And what we did was take the skin cells, these skin cells off the top of an early frog embryo, and we set them aside. We dissociated them. What will happen? Well, they could just die. They could spread out, crawl away from each other. They could do nothing. They could form a nice flat two-dimensional monolayer like cell culture.

In fact, what they do is if you dissociate these cells and pipette them here, what they'll actually do overnight is they coalesce into this little ball and the flashes that you're seeing are calcium signaling.

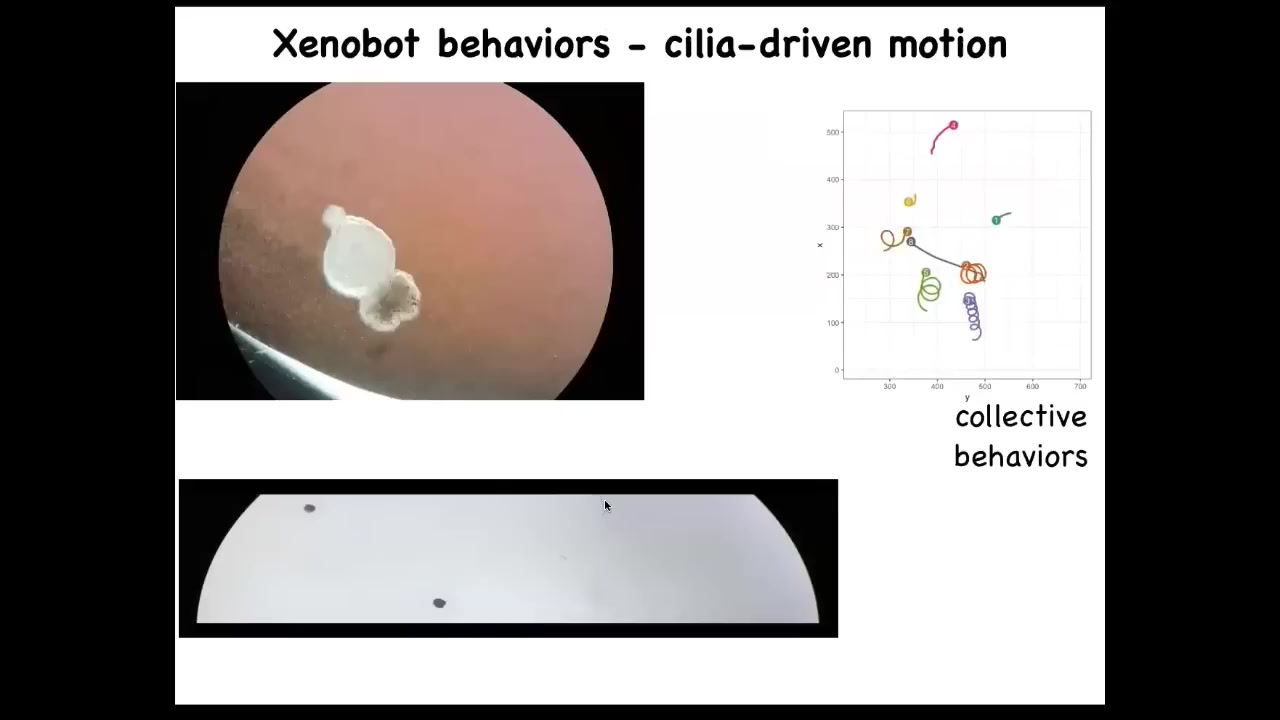

Slide 47/56 · 49m:20s

This little ball starts to swim. We call these Xenobots because Xenopus laevis is the name of the frog, and we call them biobots. We think it's a bio-robotics platform. They have little hairs on their surface that they wave, and they row against the water. The hairs are normally used to move mucus down the side of the frog, but these guys have used it for swimming. They can go in circles. They can patrol back and forth. They have all kinds of group behaviors. These guys are interacting with each other. These ones are taking a rest. This was one who was going on a long journey.

Slide 48/56 · 49m:55s

Here's 1 navigating a maze. You can see it swims down here. It's going to take this corner without hitting the opposite wall. For some reason, it turns around and goes back where it came from.

Slide 49/56 · 50m:10s

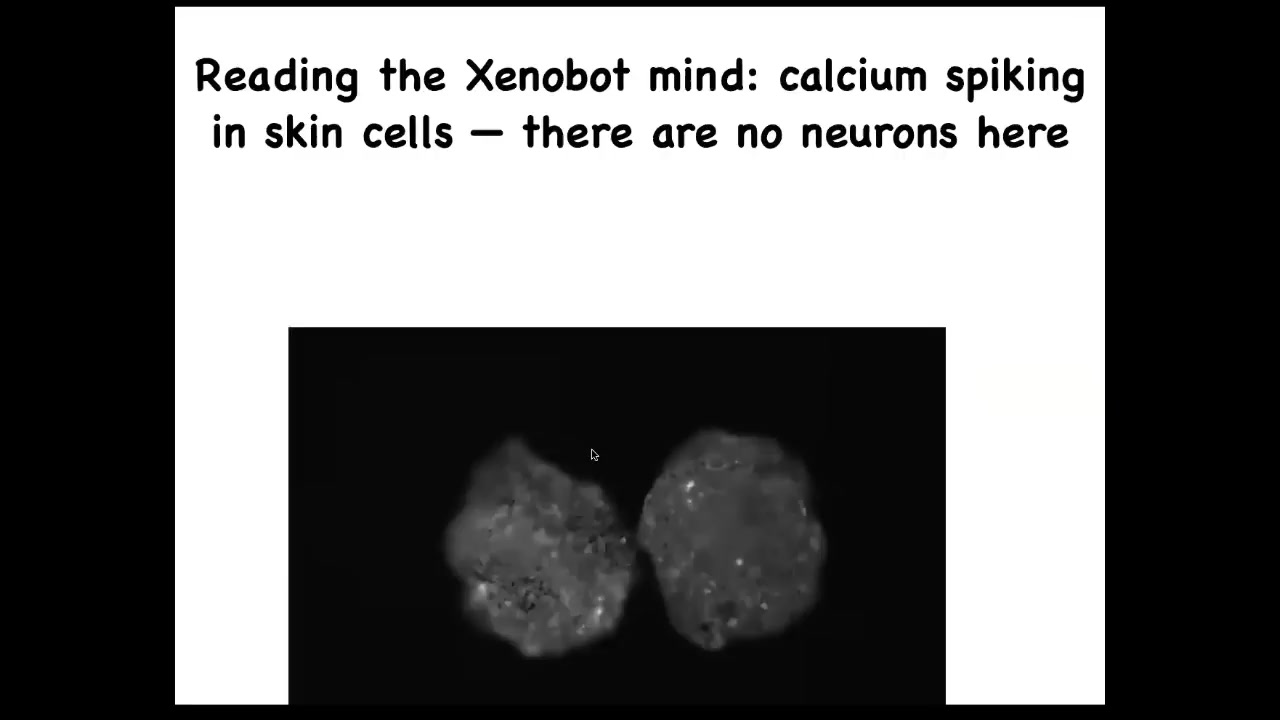

They have no neurons, but if you image their calcium signaling, which calcium is basically a readout of cellular computations, you will see that there's tons of activity and you can apply all kinds of information theory metrics to ask, are the cells talking to each other? Are these two bots talking to each other? What's the information processing that's going on here? But there's no neurons, they're just skin.

Slide 50/56 · 50m:34s

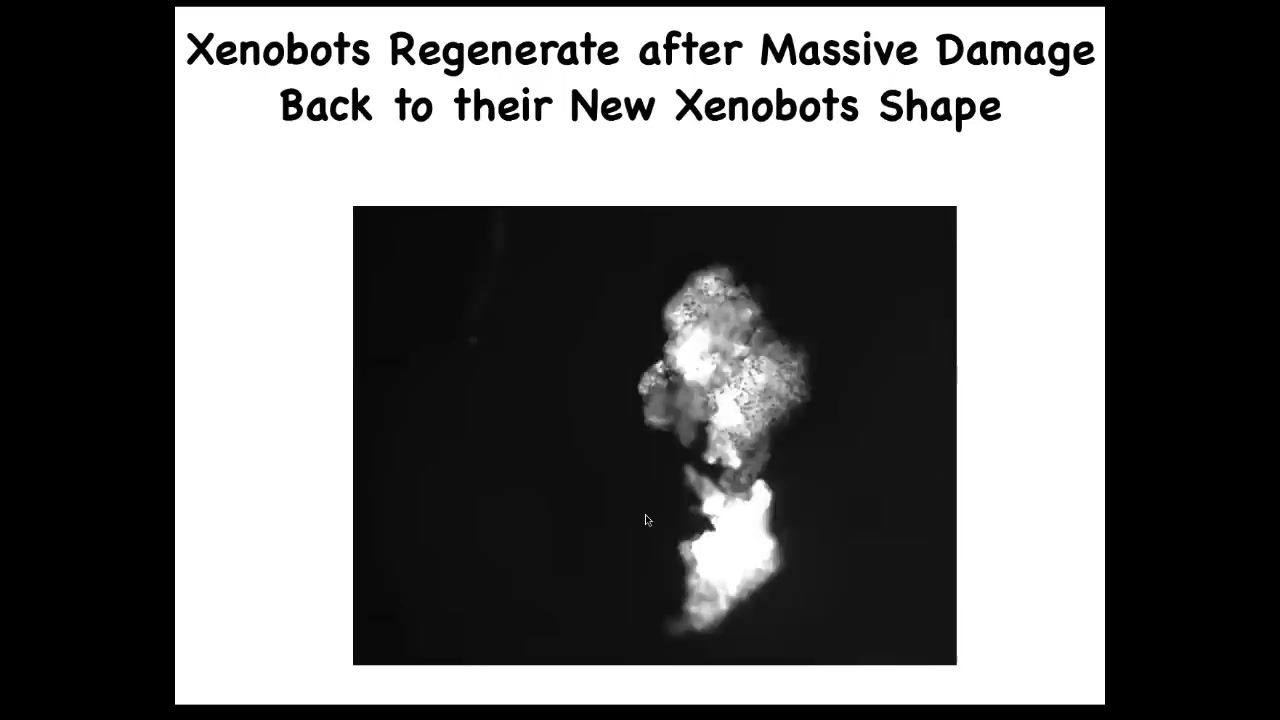

They also regenerate. If you cut them almost in half, they will seal up. Here you cut them almost in half and boom, they seal up to their new Zenobot shape.

Slide 51/56 · 50m:46s

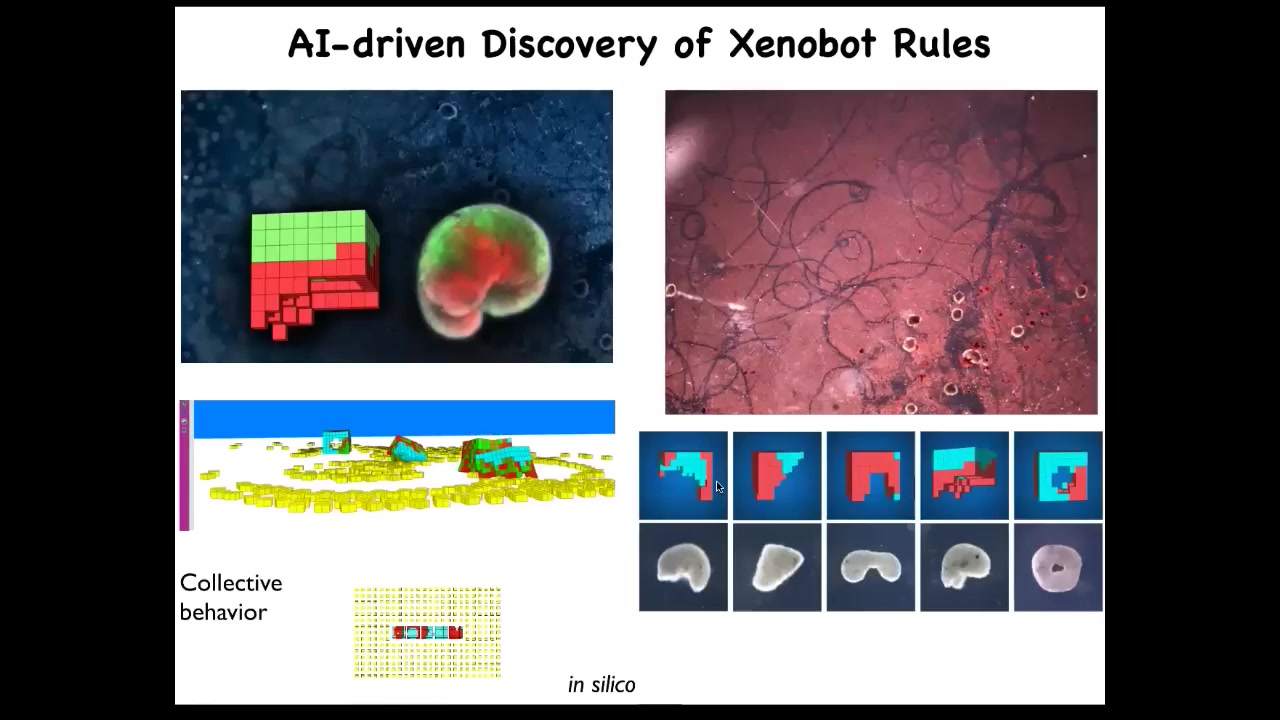

One of the most amazing things they do was discovered by Sam Kriegman, a student in Josh Bongaard's lab. They were doing computer simulations of these Zenobots running around, and they found that if you give them loose material to work with, they do something quite interesting. These are patterns that these bots etched overnight on this dish.

Slide 52/56 · 51m:11s

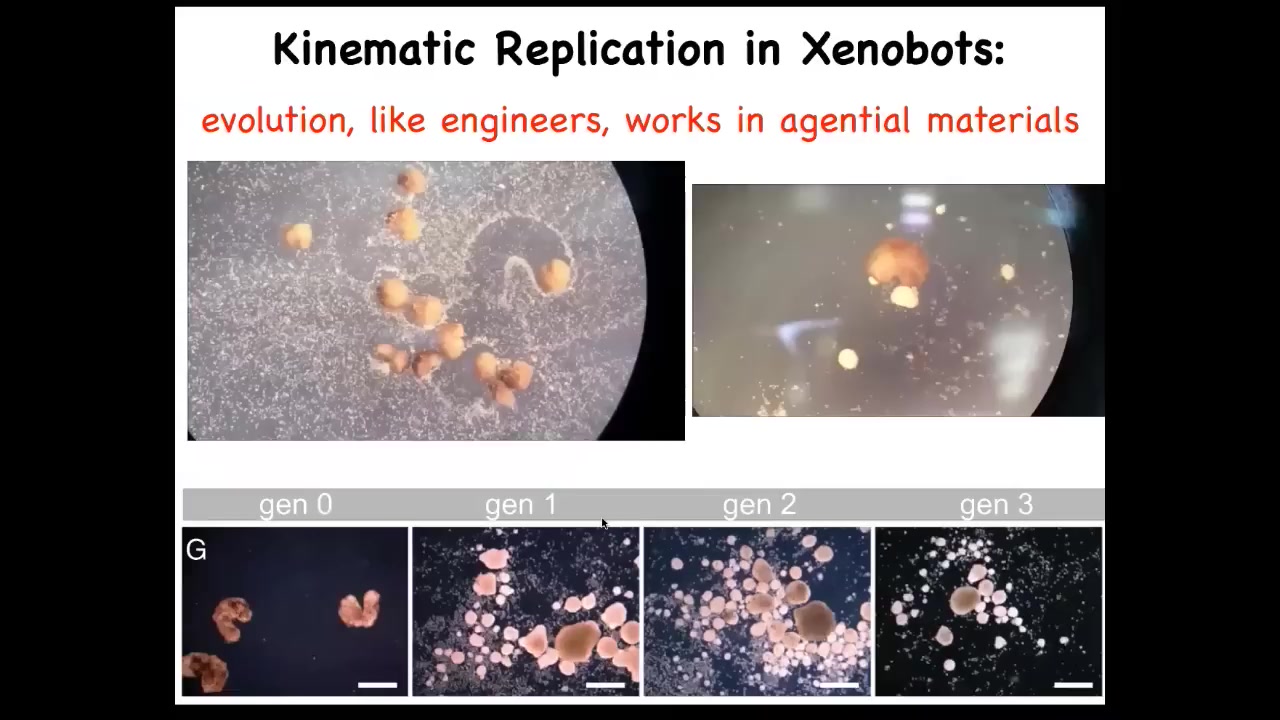

What they do is basically von Neumann's dream of a robot that goes out and builds copies of itself from loose materials it finds around. What we do is these little white things are just skin cells that we sprinkle into the dish and we let the bots go at it. What they do is they run around and they collect these cells into a little ball and they polish that little ball. That little ball, because they're working with a gentle material, these are not passive particles, these are cells. For the same reason that we were able to make Xenobots, they're able to make the next generation of bots. These little balls mature, they become the next generation of bots. And guess what they do? They run around and collect cells and make the next generation and the next generation and so on. We call this kinematic self-replication. It's just one of many novel competencies that these guys have.

Slide 53/56 · 52m:03s

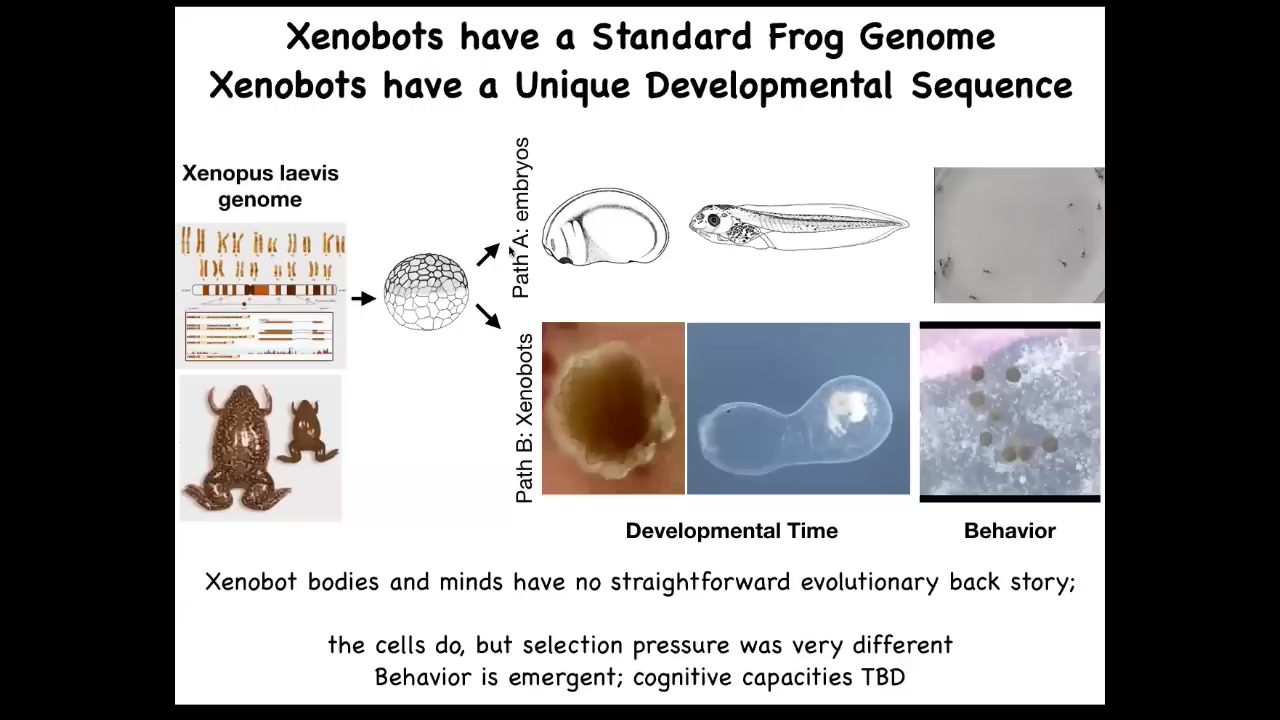

The amazing thing is that you might ask, what does a frog genome encode exactly? What did evolution learn when it developed a frog genome? We think, if we just look at normal development, you see that what it's learned is to make this set of shapes. Here's the developmental sequence and then some tadpoles running around. But actually, it can do much more.

Here's a 2 1/2-month-old xenobot. It's turning into something. I have no idea what it's turning into. The idea here is this. What we've done is we haven't changed the genome. We haven't put in any weird nanomaterials. All we've done is liberate these skin cells from their normal environment. We found out that their normal, boring, two-dimensional life as the skin of the outer surface of the animal is basically forced upon them by the instructive interactions of their neighbors. If you take them away from that, you get to see the native form of what these cells really want to do. This is what they do when nobody's telling them what else to do. This is a reboot of their own goal states. They do this, which nobody had any idea was possible. You can't use evolutionary selection to explain this because there's never been any xenobots. There's never been selection to be a good xenobot. This is something that we made for the first time here. Of course, the cells were in the evolutionary stream, but they lived this life. They never lived this life before. Where did this kinematic self-replication come from? It's a really deep question.

Slide 54/56 · 53m:34s

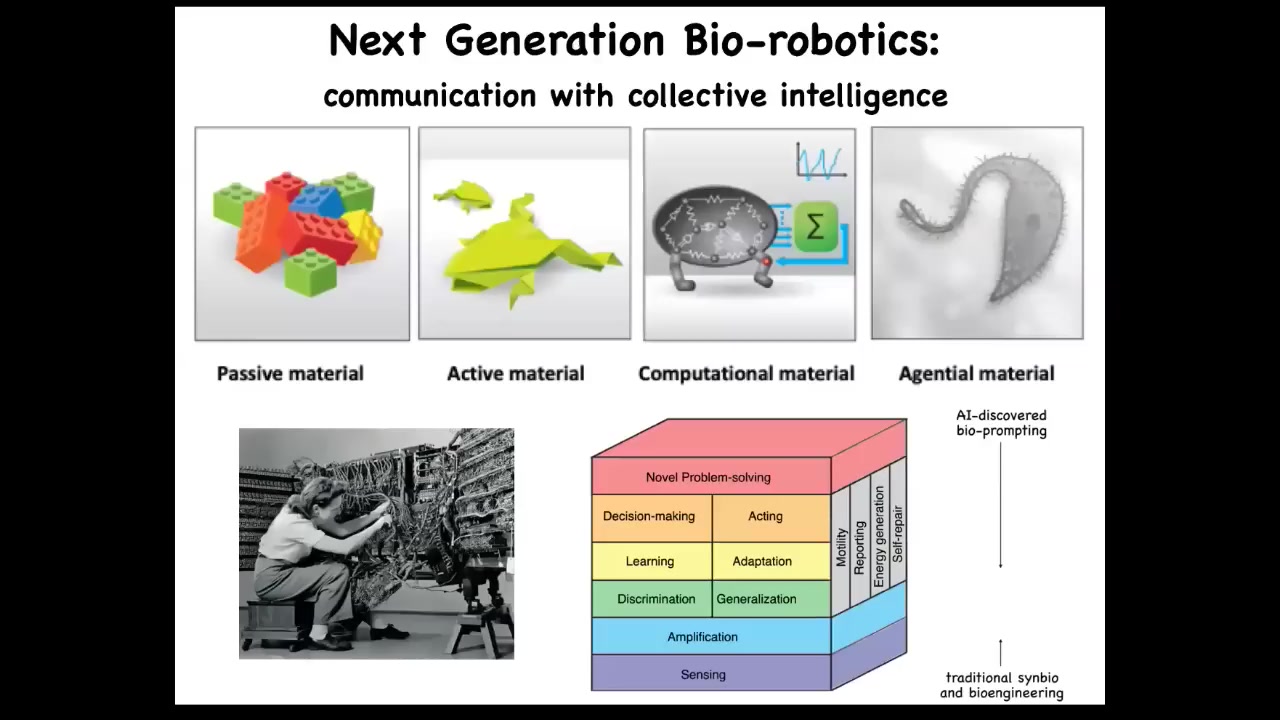

As we're doing robotics, engineering for millennia has been using passive materials like wood and metal, but we're moving to active matter and even computational matter. The future is here. It's in a gentle matter. It's in materials that you don't control bottom-up the way you do with this kind of hardware. You take advantage of all these things they already know how to do. We're working on some techniques for bio-prompting, which is to learn to program this kind of material, not by trying to force states, as in synthetic biology, but by training them and giving them various stimuli that reset their set points.

Slide 55/56 · 54m:18s

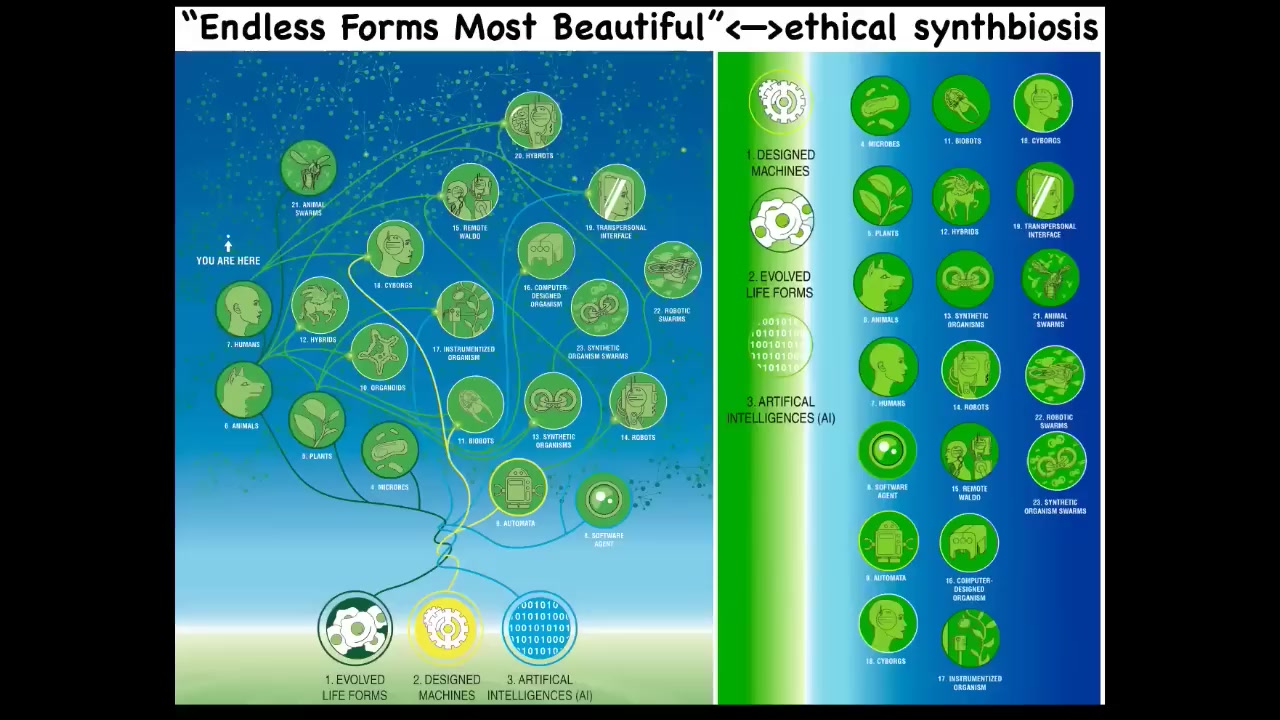

The last thing I'm going to say is this. Darwin had this great phrase, "endless forms, most beautiful." He was impressed with the variety of life. I want to say that basically all of life on Earth in its magnificent variety is a tiny little corner of the giant possibility space of new bodies and new minds. That's because life is incredibly interoperative. Because evolution doesn't generally make specific hardwired solutions, it makes problem-solving machines that are open to novel configurations and coherent action and novel embodiments.

Any combination of evolved cellular material and the various kinds of engineered machinery and software is going to be some type of agent. You've got hybrots and cyborgs. All these things — many of these already exist and have been made. But they're going to be incredibly plentiful in the coming decades, and I don't think it's going to take very long.

You and this audience will be living in a world with many other creatures who are nowhere on the tree of life relative to you. That is, their origin story and their composition are no longer good guides, and their place in the evolutionary web is no longer a good guide to how to relate to them. They're going to be truly alien bodies and minds with different degrees of recognition. That means we need to develop some new ethics around a kind of synth biosis where you can coexist and flourish by interacting with beings that are very different from us and the old ways we used to figure out how we relate to plants and animals and ecosystems and each other in terms of, what are you made of and what do you look like? Did you come out of a factory or were you evolved and do you look like me and do you have the same kind of brain?

None of those are good guides anymore. They were never good, but they served while things were pretty primitive. Those things are out the window. We're going to have to come up with an entirely new way of understanding diverse intelligences.

I'm going to stop here and say that if you're interested in any of these topics, you can follow up with these or many other papers.

Slide 56/56 · 56m:37s

I want to thank the students and the postdocs who did all of the work that I showed you today, and our various support personnel. Lots of collaborators to thank, various funders here. Again, the disclosures here are three companies that fund our work. Most of all, I thank the animals because they do all the hard work. Thank you very much.