Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

A talk by Michael Levin (with Q&A at the end) given at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory Colloquium given in November 2023 (not May as the title screen says).

CHAPTERS:

(00:06) Colloquium intro and bio

(01:42) Collective intelligence and morphogenesis

(01:02:35) Plants, AI, and goals

(01:08:08) Cancer and regeneration Q&A

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/83 · 00m:00s

Good afternoon, everyone, and welcome to today's colloquium. Our guest today is Michael Levin.

Michael is the Vannevar Bush Distinguished Professor of Biology at Tufts University and associate faculty at Harvard's Wyss Institute. He serves as director of the Allen Discovery Center at Tufts and co-director of the Institute for Computationally Designed Organisms at Tufts and UVM.

He's published over 400 peer-reviewed publications across developmental biology, computer science, and philosophy of mind. Dr. Levin received dual BS degrees in computer science and biology, followed by a PhD from Harvard. His graduate work on the molecular basis of left-right asymmetry was chosen by the journal Nature as a milestone in developmental biology in the last century.

He did postdoctoral training at Harvard School of Medicine in cell biology and started his independent lab in 2000, developing the first molecular tools to read and write bioelectric pre-patterns in non-neural tissue.

Slide 2/83 · 01m:28s

His group at Tufts works to understand information processing and problem-solving across scales, in a range of naturally evolved, synthetically engineered, and hybrid living systems. With that, over to you, Michael. Thank you so much.

Slide 3/83 · 01m:45s

Really appreciate the opportunity to share some thoughts with you. Hopefully you can see my slides. If anyone's interested in finding the primary papers, the data, the software, everything is at this site.

Slide 4/83 · 02m:00s

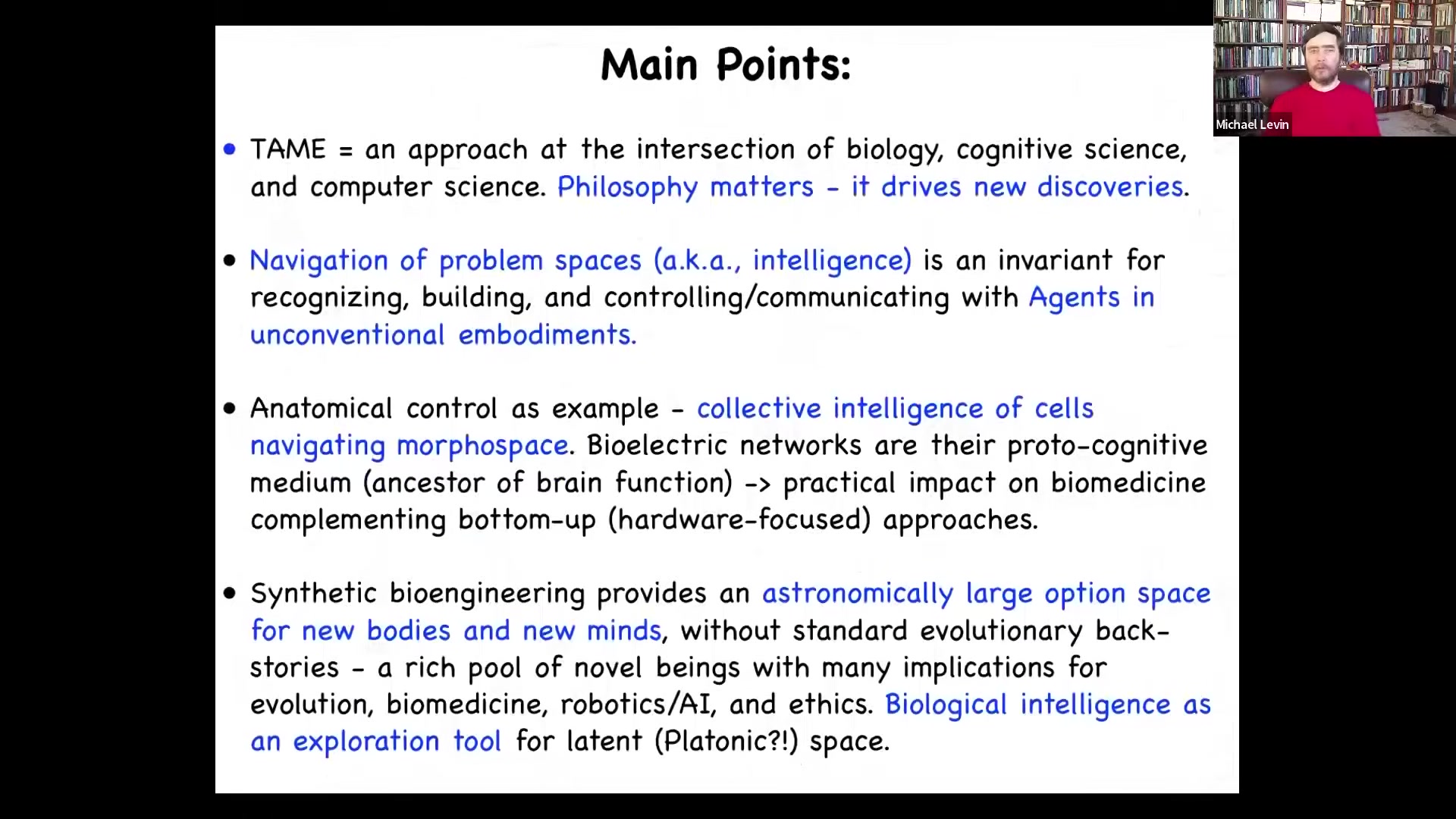

What I'm going to try to transmit is a few main points. First, our approach at the intersection of several disciplines that drives specific new discoveries. It's a way of thinking about agency, about memory, in a way that drives new capabilities.

I'm going to talk about this notion of navigating arbitrary problem spaces and the idea of that being an invariant that helps us to recognize, build, and communicate with some very unconventional agents in different embodiments. I'm going to use the collective intelligence of cells navigating anatomical morphospace. I'm going to talk about how electrical networks in particular are a kind of proto-cognitive medium which allows this collective to have problem-solving capacities in anatomical space. This has many applications in biomedicine and bioengineering.

At the end, I'll talk about some synthetic living beings that we created to at least begin to understand where novel goals for these agents can come from. The first part of the talk will be to set a kind of philosophical foundation and to go over some examples that help us stretch our thinking about some of these topics. This is a well-known painting.

Slide 5/83 · 03m:20s

It's Adam naming the animals in the Garden of Eden. The thing about the worldview that supports this kind of picture is that all the animals here are quite discrete. So it's very obvious which one is Adam. It's very obvious that there's a discrete set of other beings with different properties.

Interestingly enough, according to this tradition, it was up to Adam to name the animals, not God, not the angels. It was Adam that had to assign them names. Or another way to say it is to really understand their true nature. I think that part's right on the money. We're going to talk about that.

Slide 6/83 · 04m:02s

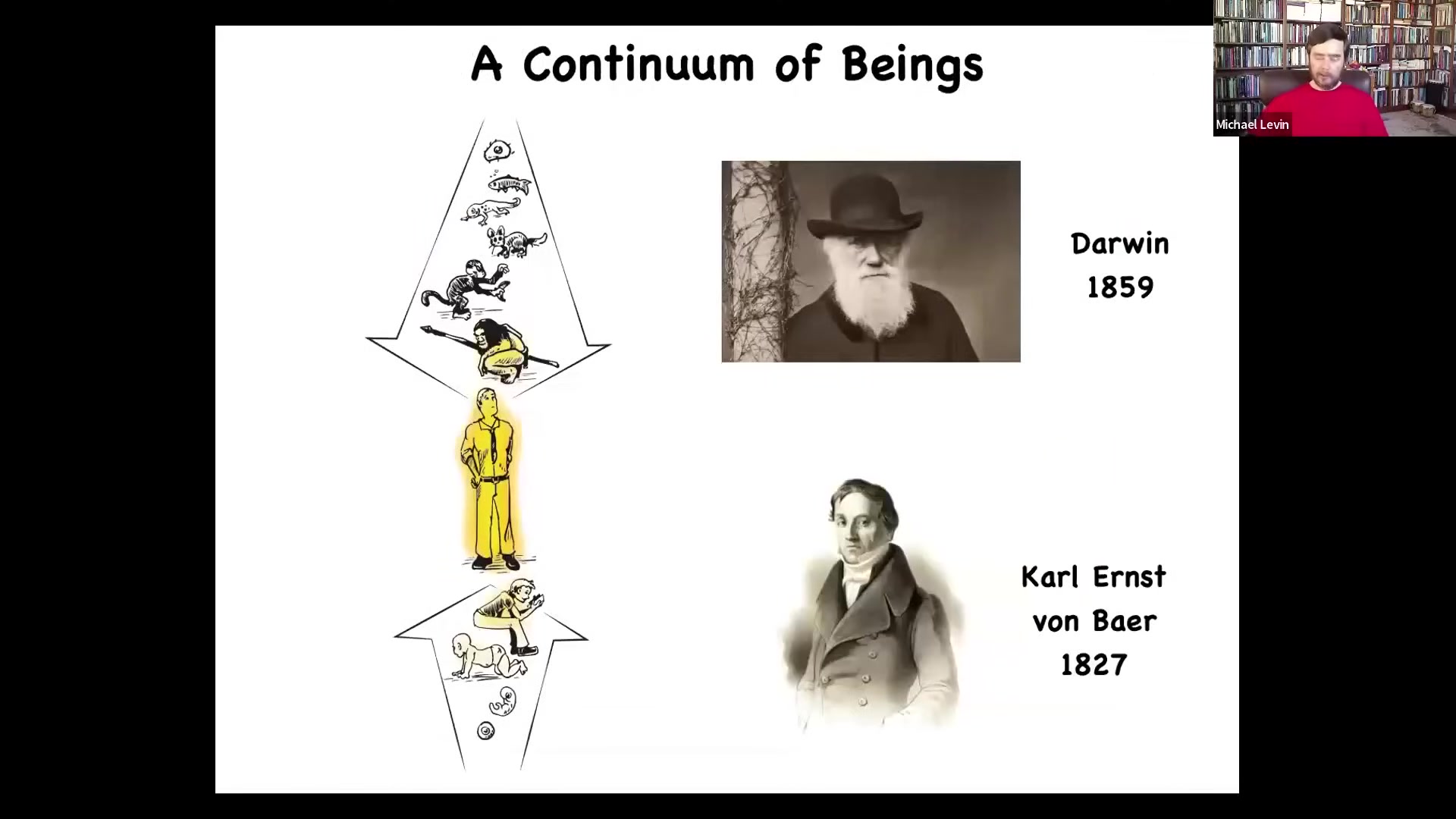

In this worldview, there are some discrete natural kinds here, but we've discovered since Darwin showed us that this form here that most thinking in philosophy says—the human and the human mind—is a single point on a very rich continuum going all the way back to single cells. Developmental biology shows us that this is true even on the scale of a single animal; we all arise from one cell.

There's this continuum. We're at the center of a very rich, smooth continuum of other forms, some of which may, to different degrees, have the kind of human-level agency, intelligence, and other properties that we typically think of as the modern human having.

It's even more interesting than that, because with both biotechnology and all kinds of engineering, we see that there's a whole other axis here where we can start to make both biological and technological hybrids, chimeras, and various alterations, providing a whole new access to this continuum where it becomes really hard to say at what point you lose or gain certain properties that we used to think were obvious between humans and animals.

That's because at every level of organization, we can mix in new materials, new information, new policies, and create all kinds of novel beings.

Slide 7/83 · 05m:30s

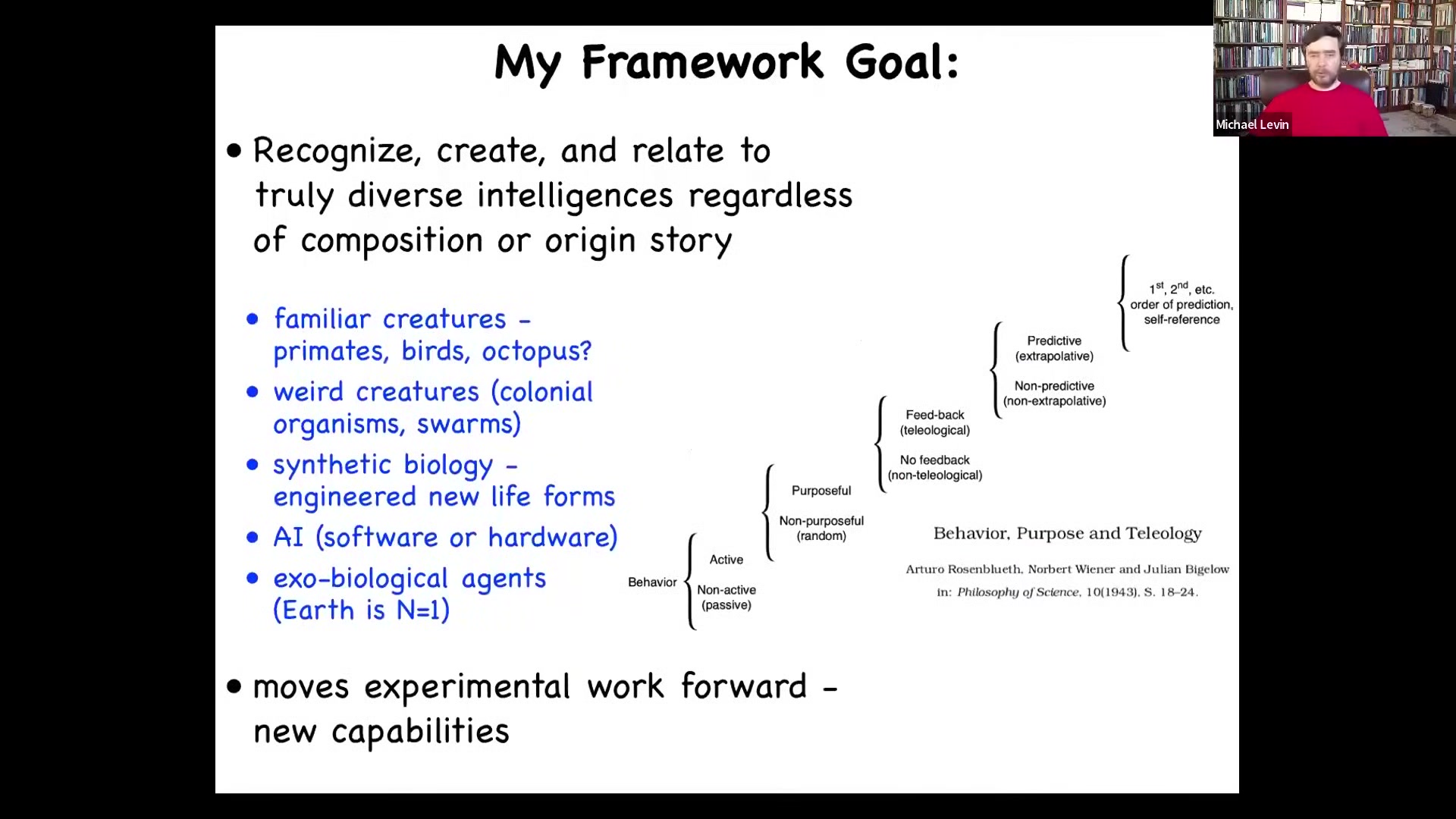

It becomes increasingly important to develop a framework that will allow us to simultaneously think about all sorts of unconventional agents.

Beyond primates, birds, an octopus or a whale, but also weird colonial organisms, swarms, synthetic new life forms that are engineered. Artificial intelligence is either purely software or hardware robotics, and exobiological alien agents.

The idea is that we need a framework that allows us to think about all of this. I'm not the first person to suggest this.

Here's Rosenbluth, Wiener, and Bigelow with a cybernetic scale going from passive matter up to human-level metacognition. They were trying to show how there is a continuum of all these capacities.

What's important about this framework is that it has to move experimental work forward towards new capabilities. It can't just be philosophy.

Slide 8/83 · 06m:30s

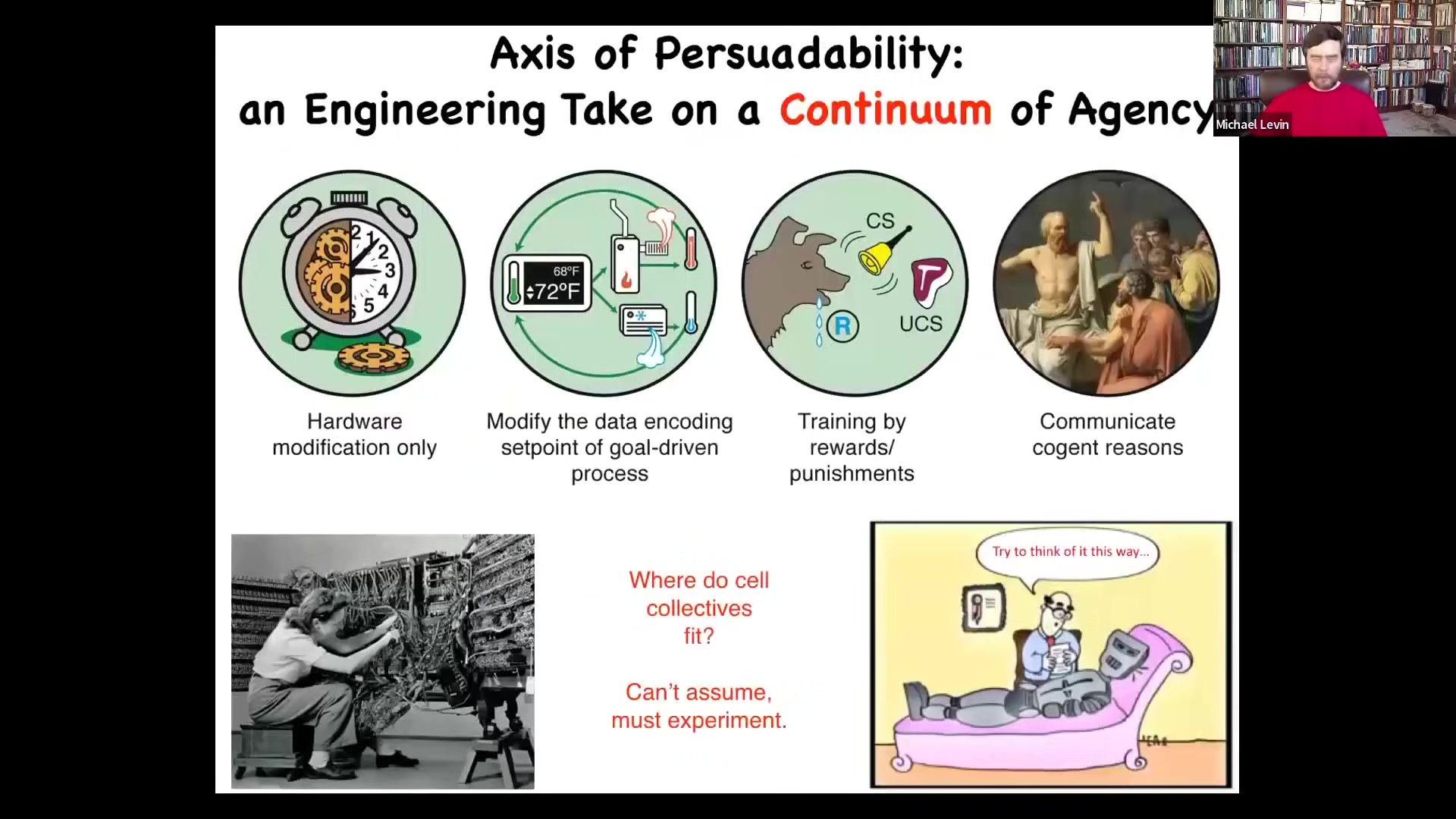

In my framework, there's this notion of a continuum of persuadability, meaning focusing from an engineering perspective on what are the tools and approaches that one takes to modify what a system does. You can imagine that along this continuum, and this is just four waypoints, there are many very simple systems which you can only modify by hardware rewiring.

Then there are some cybernetic systems where you can change the set point and it will do something different. You really don't have to know everything about how it works. You just have to know how to rewrite that set point. Then you've got these other beings that have this marvelous interface that allows us to alter their set points without actually digging in and physically changing them at all, meaning by experiences and stimuli. This is why humans could train dogs and horses for thousands of years before we knew any neuroscience whatsoever, because they offer up this amazing interface that allows us to do that without this kind of rewiring. Then even more complex systems where you can communicate with reasons and arguments.

The key is that when you're faced with a novel system, you really can't make assumptions about where it's going to be. Many people do. They have philosophical pre-commitments to where, let's say, cells and tissues would fit on here. Modern molecular medicine says they've got to be somewhere up here. We think it's an empirical question that actually needs to be answered by experiment. This is what we do. Let's think about where it is that we actually come from.

Slide 9/83 · 08m:00s

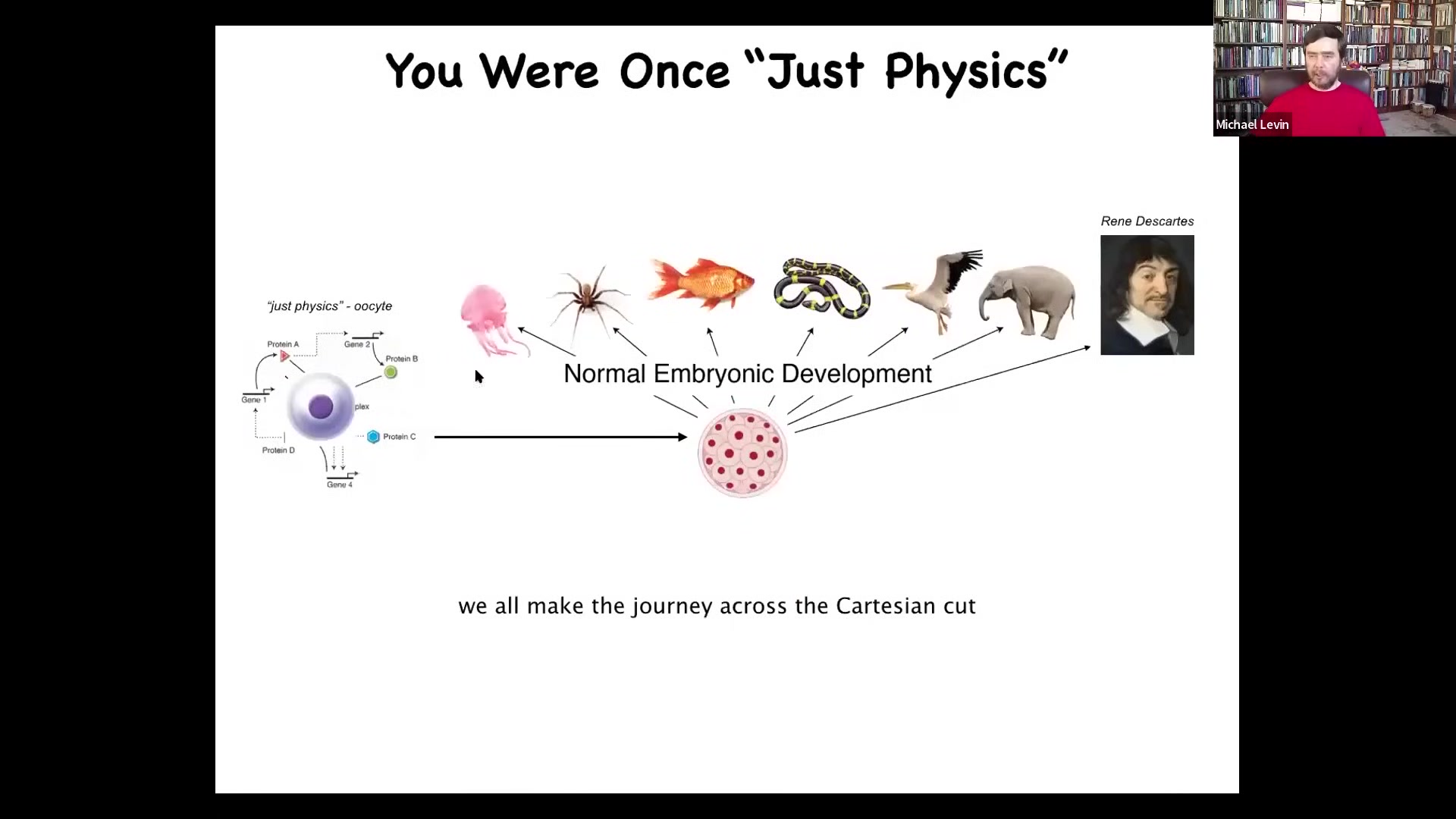

We originate as a single unfertilized oocyte, this little quiescent cell. And that is the sort of thing about which people say, "that's just physics." I really dislike that term, but it really is a piece of chemistry. Eventually, through this incredibly remarkable process of development, we end up being one of these things, or even something like this, a human that's going to make statements about not being a machine and so on.

What's important is that the process is smooth and continuous. There is no place here that developmental biology offers where you can draw a sharp line and say, "everything up till now was chemistry and physics." Then from here on, you have a mind. There is no spot like that. So we have to go from systems that are pretty well described by basic chemistry and physics to ones that are routinely dealt with by the psychological and other kinds of techniques.

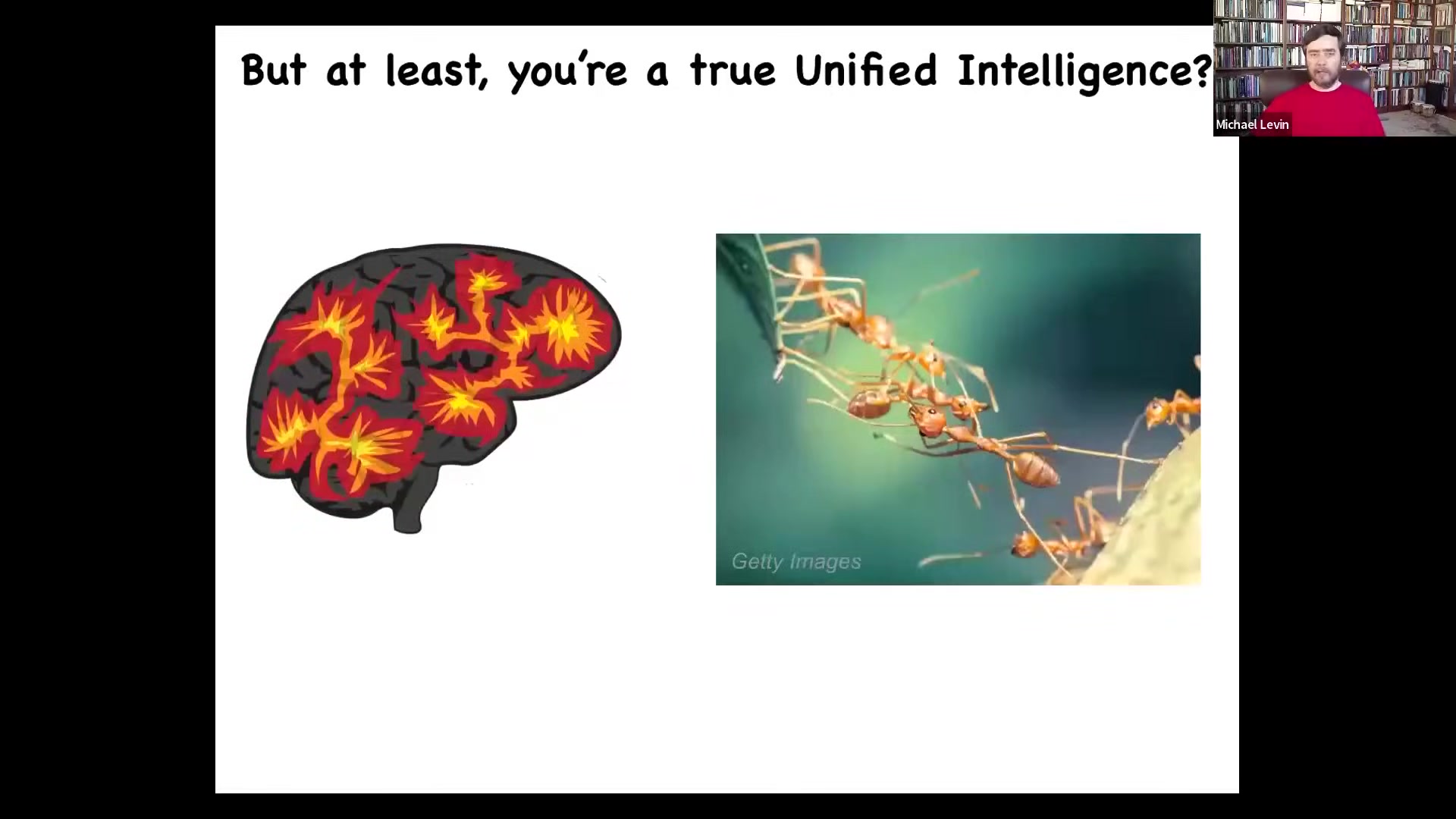

We have this one complex issue: we're the product of this slow, gradual development, but at least we're a unified intelligence, right?

Slide 10/83 · 09m:05s

We all feel like a centralized single being. And we think that when people say ant colonies and beehives are collective intelligences, maybe they're a kind of intelligence, but they're not like us. They're a distributed thing. It's not real like us.

Slide 11/83 · 09m:25s

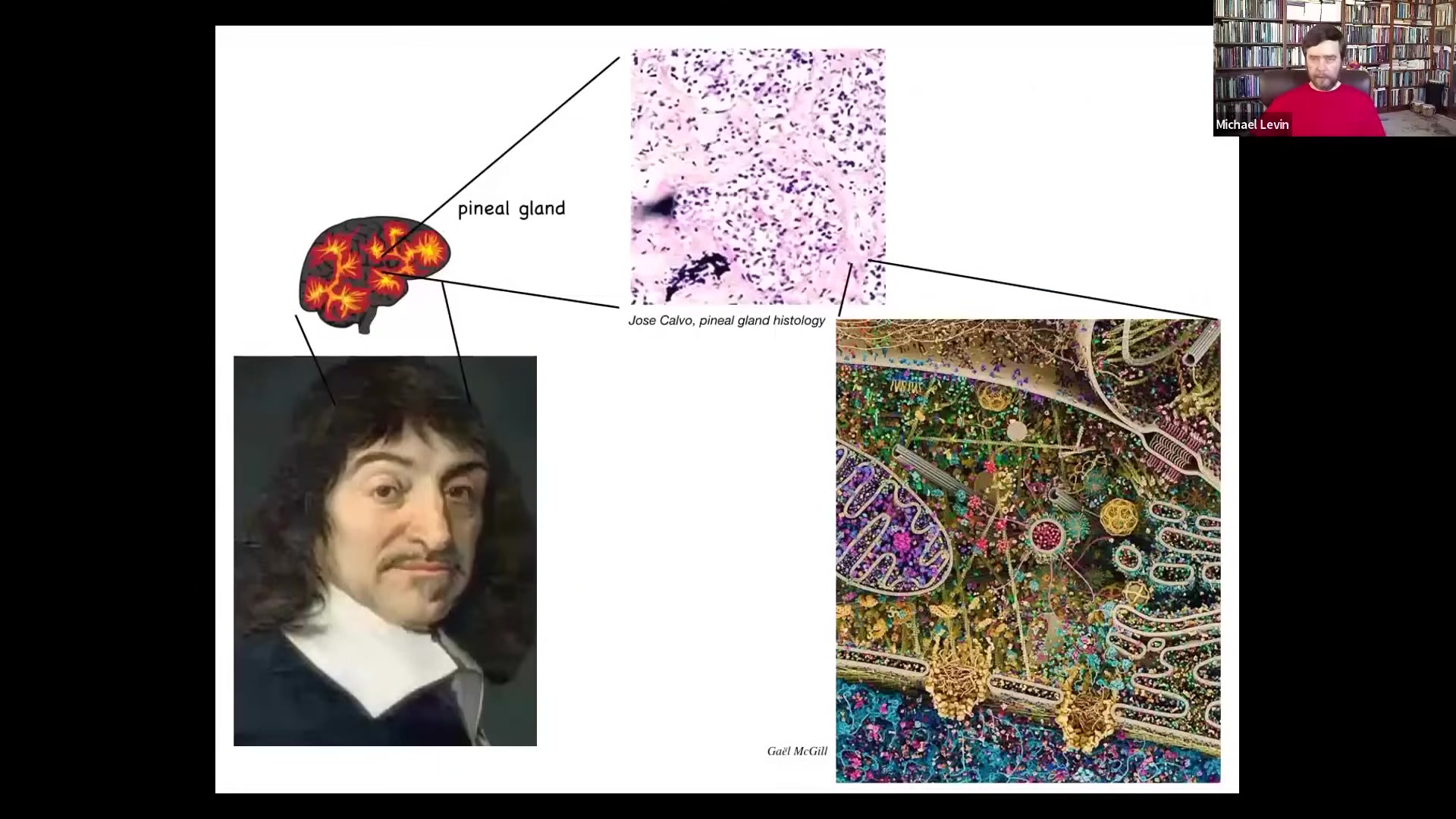

Descartes really liked the pineal gland because there's only one of them in the brain, and he felt that was really the seat of human consciousness because the unified feeling that we have really has to have only one structural representation. But if he had access to good microscopy, he would have looked inside the pineal gland and he would have seen that there's not one of anything. It's made of thousands upon thousands of cells. Each one of those cells has all of this stuff inside. So there really isn't one of anything. And so the fact is that we are all collective intelligences.

We are all built of parts.

Slide 12/83 · 10m:02s

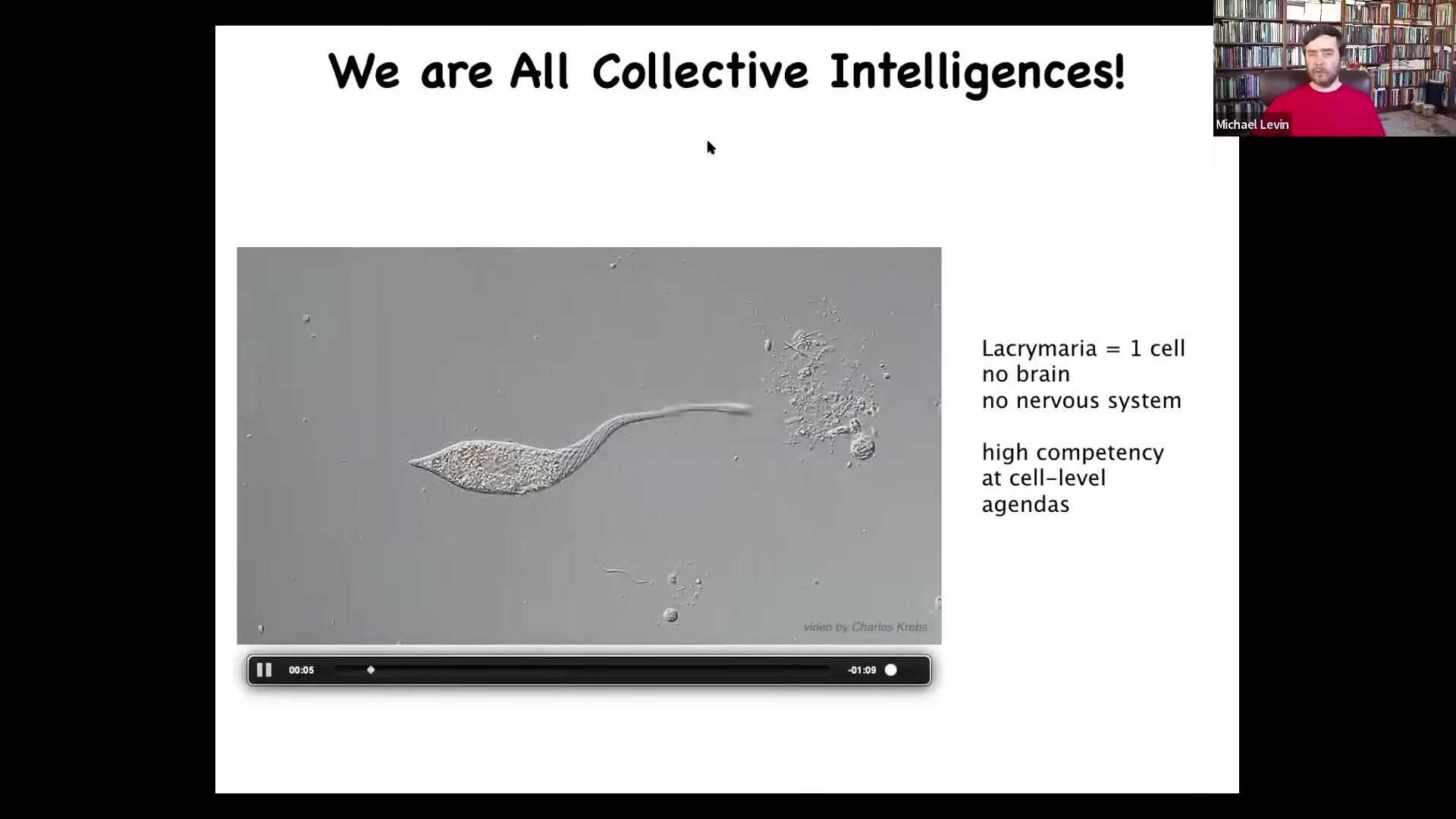

The research program that is suggested by this is to understand how those parts scale up to a larger emergent individual.

So this is the kind of thing we're made of. We're made of an agential material, not passive matter, not even active matter, but matter with agendas.

This is a single cell. You can see there's no brain, there's no nervous system, and yet it handles all of its physiological, anatomical, metabolic, and other needs at the scale of this single cell, quite competent. The reality that our biology uses this architecture means that we can even have fascinating cases like this.

Slide 13/83 · 10m:40s

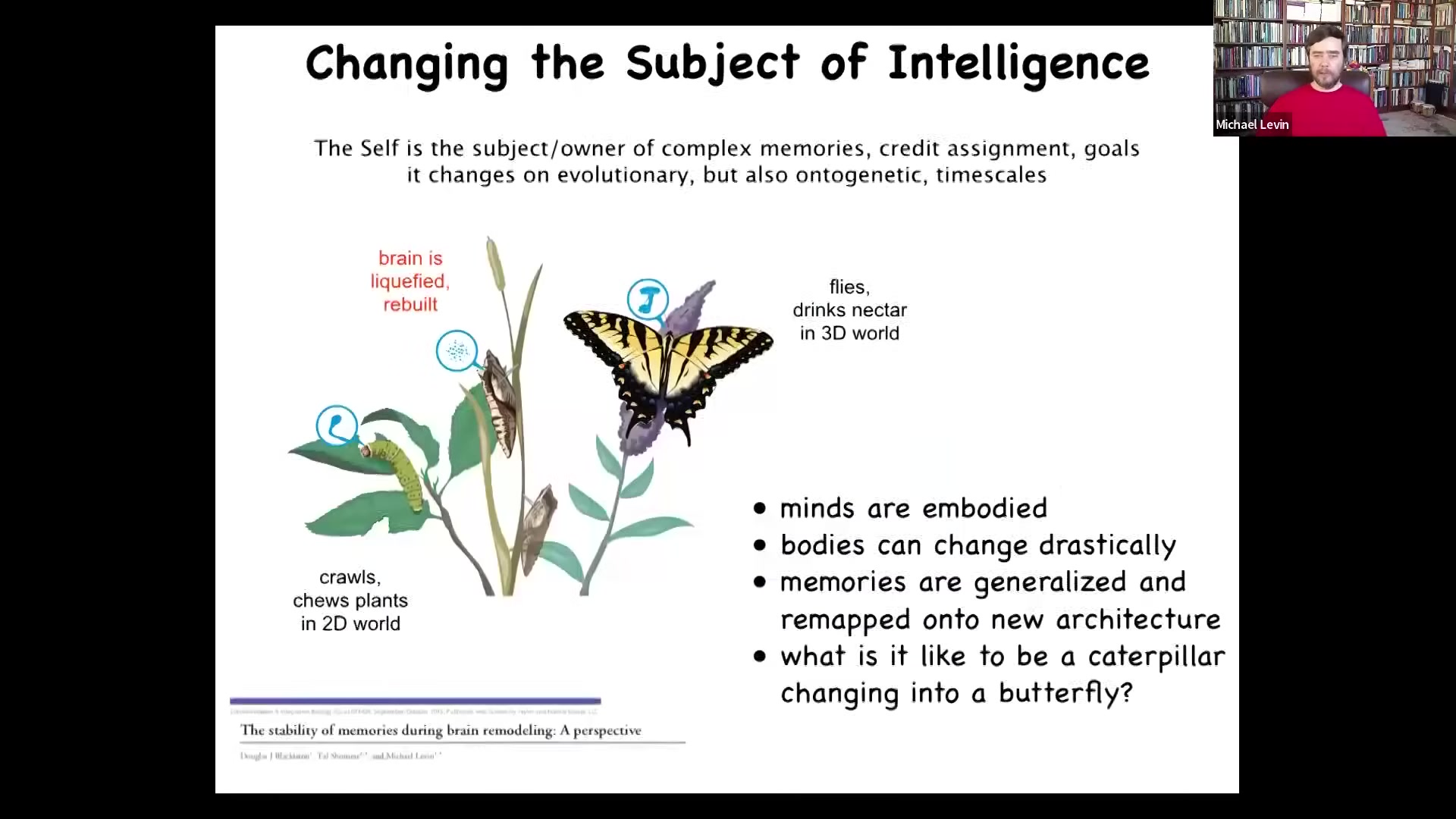

This is a caterpillar. It's a soft-bodied creature, so it has a particular controller made for a body with no hard elements; there's nothing you can push on. Everything is pneumatically operated. It has a brain suitable for driving that kind of body in a two-dimensional world of leaves.

But it has to turn into this. It's a hard-bodied creature now that has to live in a three-dimensional world and drink nectar. It doesn't care about leaves. In order to change from here to there, all of the cells are rearranging. Most of the brain is dissolved. The connections are broken. Most of the cells are in fact killed off, and you build a new brain. But the remarkable thing is that the moth or butterfly still shows recall of memories that are formed in the caterpillar. You can train the caterpillar and get memory recall out the other end.

We're starting to see that not only can we have change on the evolutionary scale, but even within the lifetime of an individual, radical changes to the body structure occur while some memories remain. And so this gives rise to all kinds of interesting philosophical questions. What's it like to be a butterfly? What's it like to be a caterpillar changing into a butterfly? It makes the changes of human puberty seem absolutely minor compared to this. And the ability to store information in this robust medium that remains after the medium is refactored.

Slide 14/83 · 12m:12s

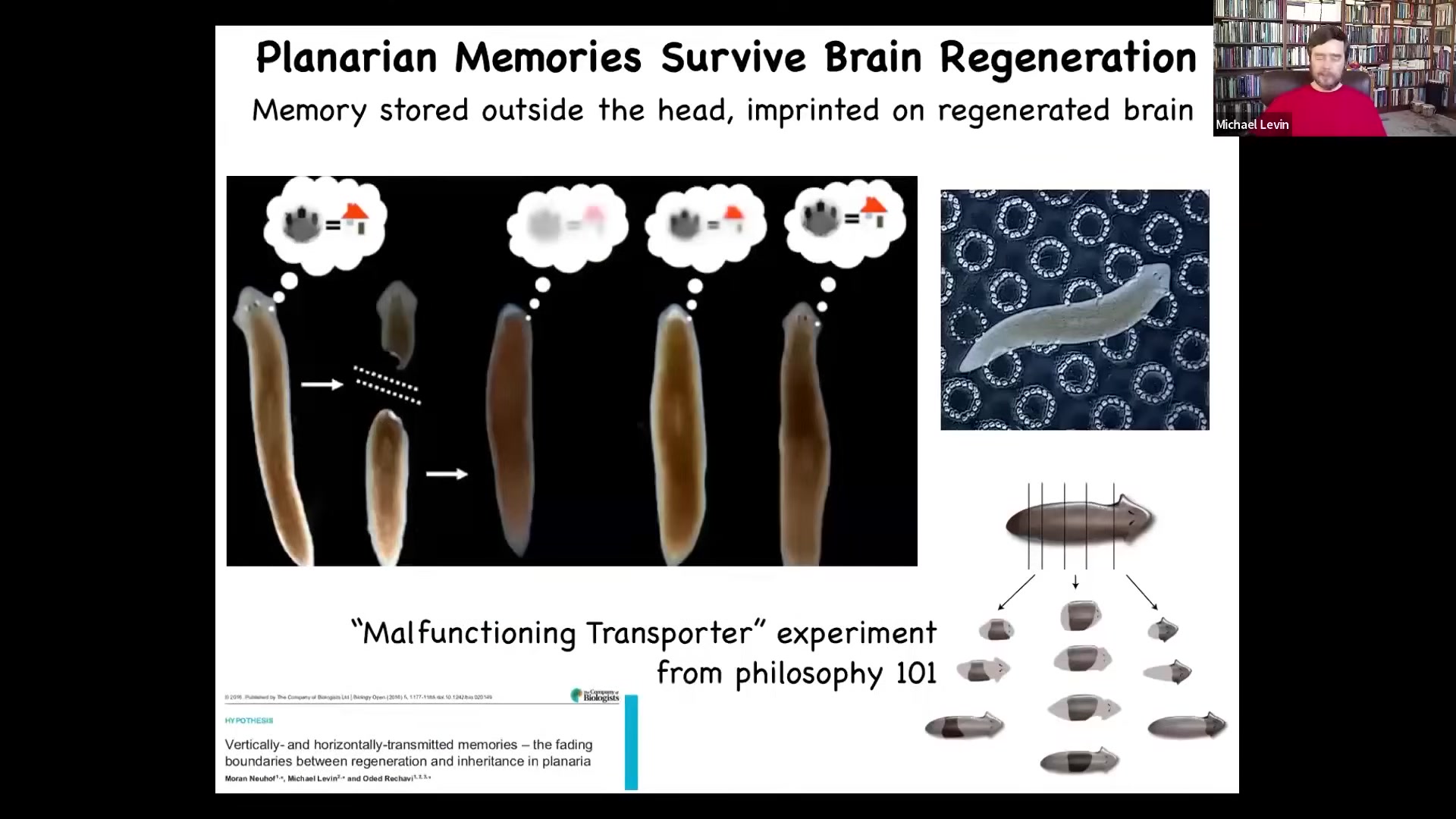

These are planaria. They have a true brain and you can train them to expect food in this particular location with these little bumpy circles. Then you cut off their head and the tail sits there for about a week. It doesn't do anything. It grows back a new brain. When the new brain has grown back, you find that they now spend their time looking for food at the correct location. This is called place conditioning. The rest of the body seems to store that information and imprint it onto the new brain.

You can cut them into many pieces and then ask thorny philosophical questions about which one is the original creature or all of them. This amazing feedback between the plasticity of the body and the cognitive content is fundamentally because we are built on a multi-scale competency architecture.

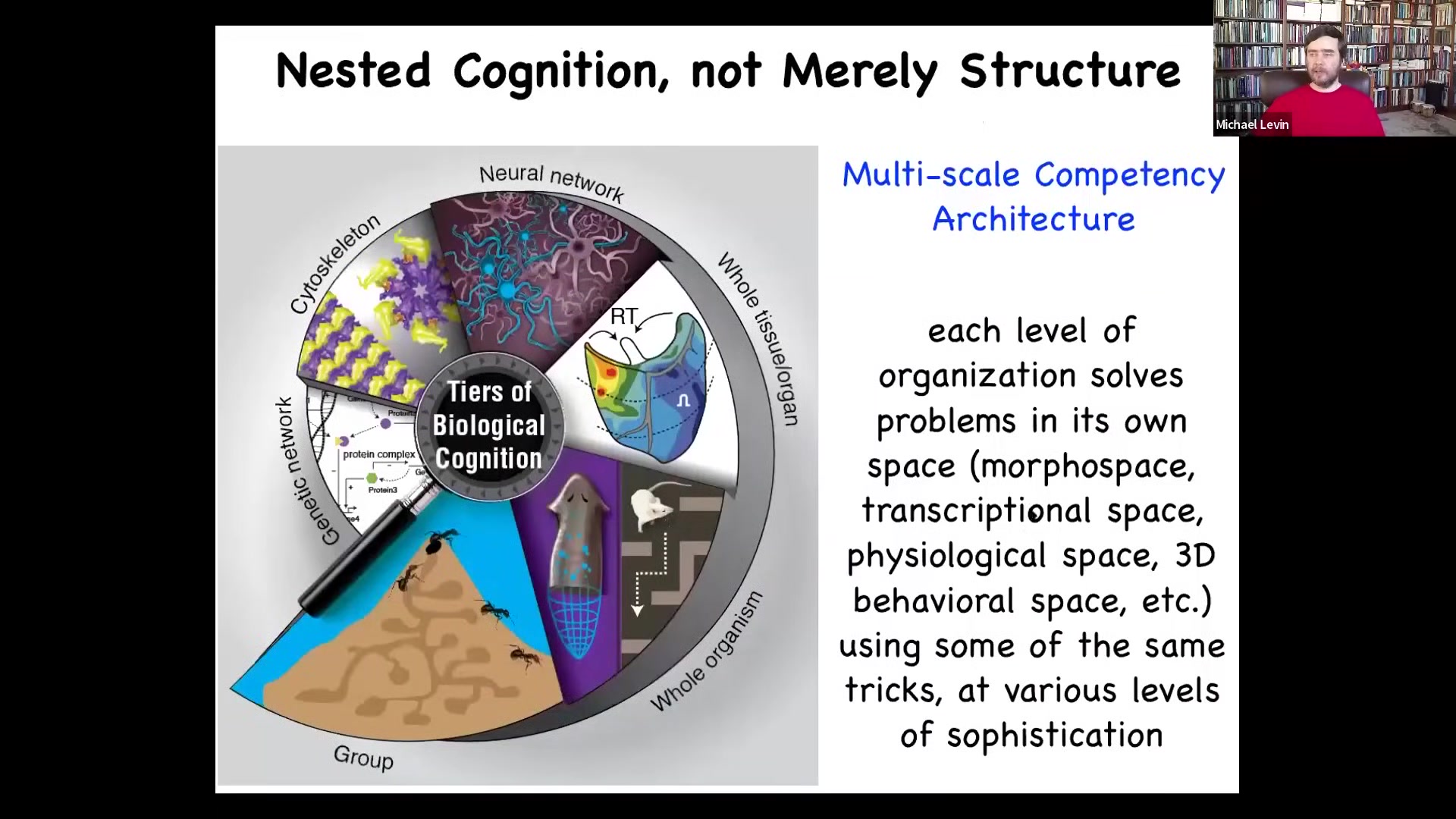

Slide 15/83 · 13m:05s

Every layer going all the way back through the body and the various organs and the tissues and the subcellular components. It's not just structural, it's functional. It solves problems in various spaces. There's a competency at all levels.

Slide 16/83 · 13m:25s

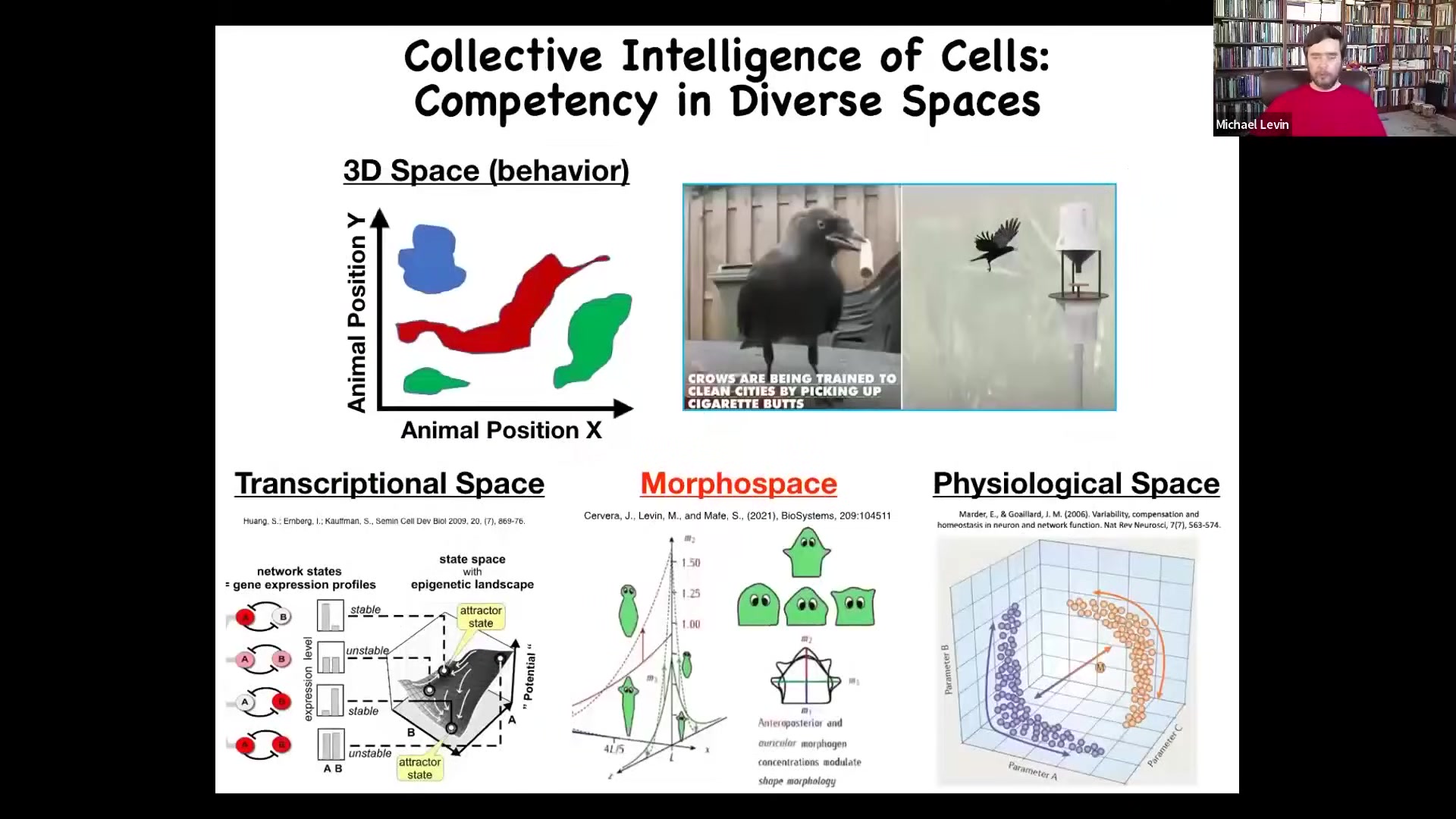

We humans are okay at recognizing intelligence and problem solving in medium-sized objects moving at medium speeds in three-dimensional space. That's our familiar; all our sense organs point outwards that way.

Imagine if we had a direct sense of our blood chemistry and we had a sensor inside that was able to give 20 different measurements of our blood physiology. I think we'd have no problem having a direct perception of living in a 23-dimensional world where our liver and our kidneys were intelligent agents that navigate that physiological space on a daily basis.

We deal with biological competencies in transcriptional space. That is the space of possible gene expressions, anatomical morphospace, which is what we'll spend most of today talking about, and the space of physiological states. All of these spaces have agents in them which strive and solve problems and succeed or fail, much like the obvious ones do in three-dimensional behavioral space.

You can even think about evolution as pivoting some of the same tricks. All of these tricks are around this notion of navigation, this goal-directed navigation, pivoting some of the same tricks through different spaces. Early life in metabolic space, then physiological space, eventually the genes come along and it's transcriptional space. Then morphology and multicellular organisms, then brains and muscles develop and you can do three-dimensional behavior.

Eventually even linguistic navigation. Navigation is keeping the thread of a story or an argument through linguistic space.

We start to get an idea that things are not so simple as Adam in the Garden of Eden. It's not just about three-dimensional space. It's not just about a fixed natural kind. Many things are extremely plastic and exhibit competencies in different spaces.

Slide 17/83 · 15m:18s

The bulk of today's talk, I want to talk about one particular example of all of this, although we studied many examples, but the one I want to talk about is the agent that lives in anatomical morphospace. And that is a collective intelligence made of your body cells.

It's interesting that Alan Turing needs no introduction. He was very interested in intelligence broadly conceived, in thinking in machine substrates, in fact all kinds of substrates for computation. He was interested specifically in intelligence through plasticity or reprogrammability.

One thing that is sometimes noted is that he also wrote this interesting paper about morphogenesis, about a model of order arising in well-mixed chemical media that could be an example of how order can arise during embryonic development.

You might wonder why somebody who is interested in computation and intelligence would be thinking about the origins of order in chemical systems. I think that's because he saw a very profound symmetry between these two fields. The formation of the body and the formation of a mind are, I think, very tightly linked. In fact, the same problem, just in different spaces. We're going to talk about problem-solving living machines and how reprogrammable they are.

Slide 18/83 · 16m:48s

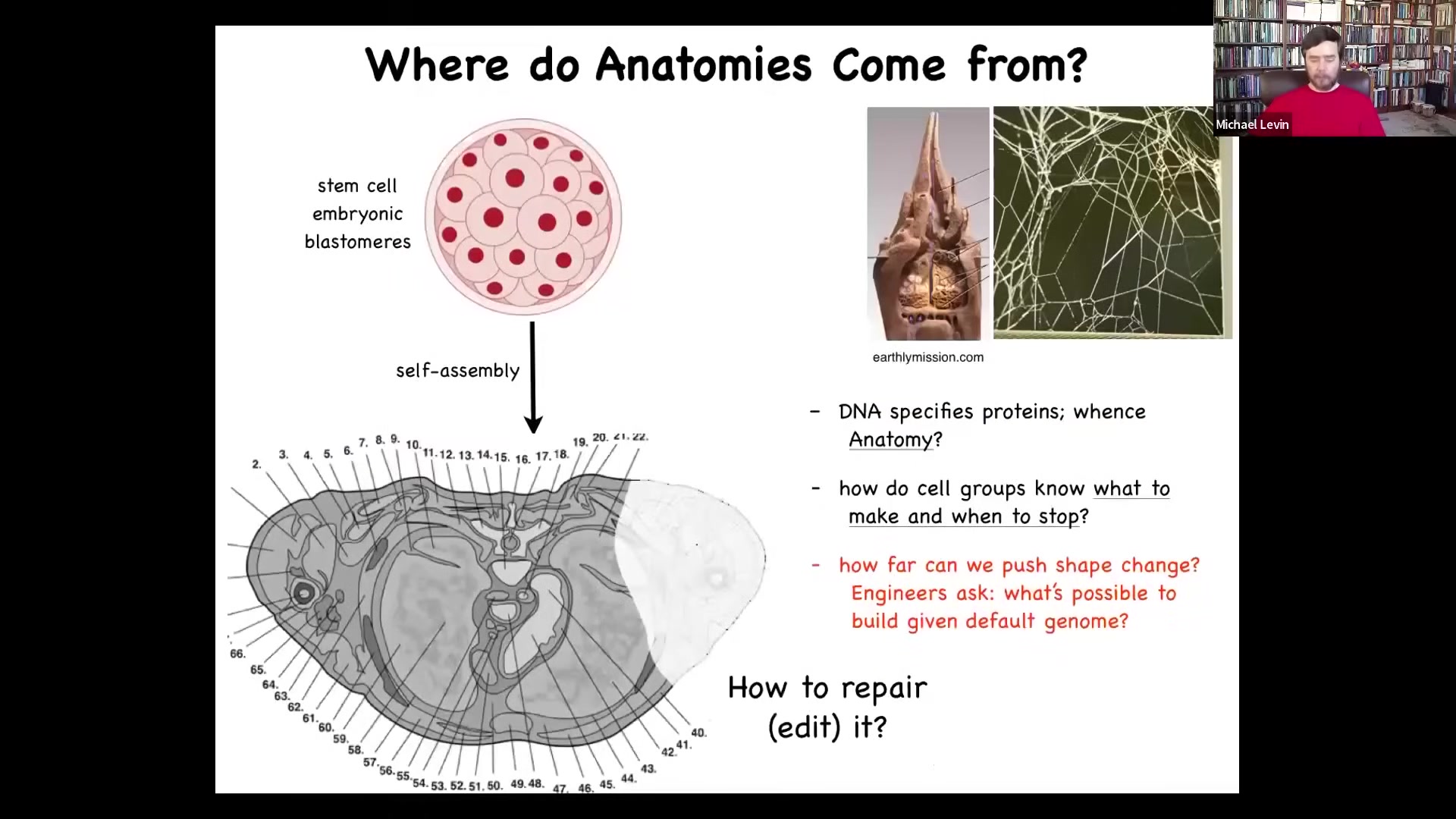

So let's think about what anatomical space really looks like. Here is a cross-section of a human torso. You can see this amazing order. All the cells, the tissues, the organs, everything is in the right place, the right size, oriented correctly relative to each other. And it comes from this, from a collection of embryonic blastomeres. This is how we start. Where is this pattern actually encoded? Where is this pattern determined?

People will reflexively say it's the DNA. It's in the genome. But we can read genomes now, and we know what's in the genome. What's in the genome are descriptions of the tiniest level hardware that every cell gets to have, the protein sequences. There's nothing directly about any of this in the genome. The genome doesn't have a blueprint of any of this. And so what this then boils down to is the problem of asking about the software. How do large numbers of cells, given particular computational machinery, end up working together to build something very specific? This pattern is not in the genome any more than the structure of a termite nest or the shape of a particular spider web is in the genome of the termite or the spider. This all emerges from physiology.

So we need to understand how cell groups know what to make and when to stop. As workers in regenerative medicine, we need to know if a part is missing, how do we convince the cells to rebuild it? As engineers, we would also like to ask, what else is possible? Given the hardware that you have, what else could you build? Could the exact same cells build something completely different?

Slide 19/83 · 18m:18s

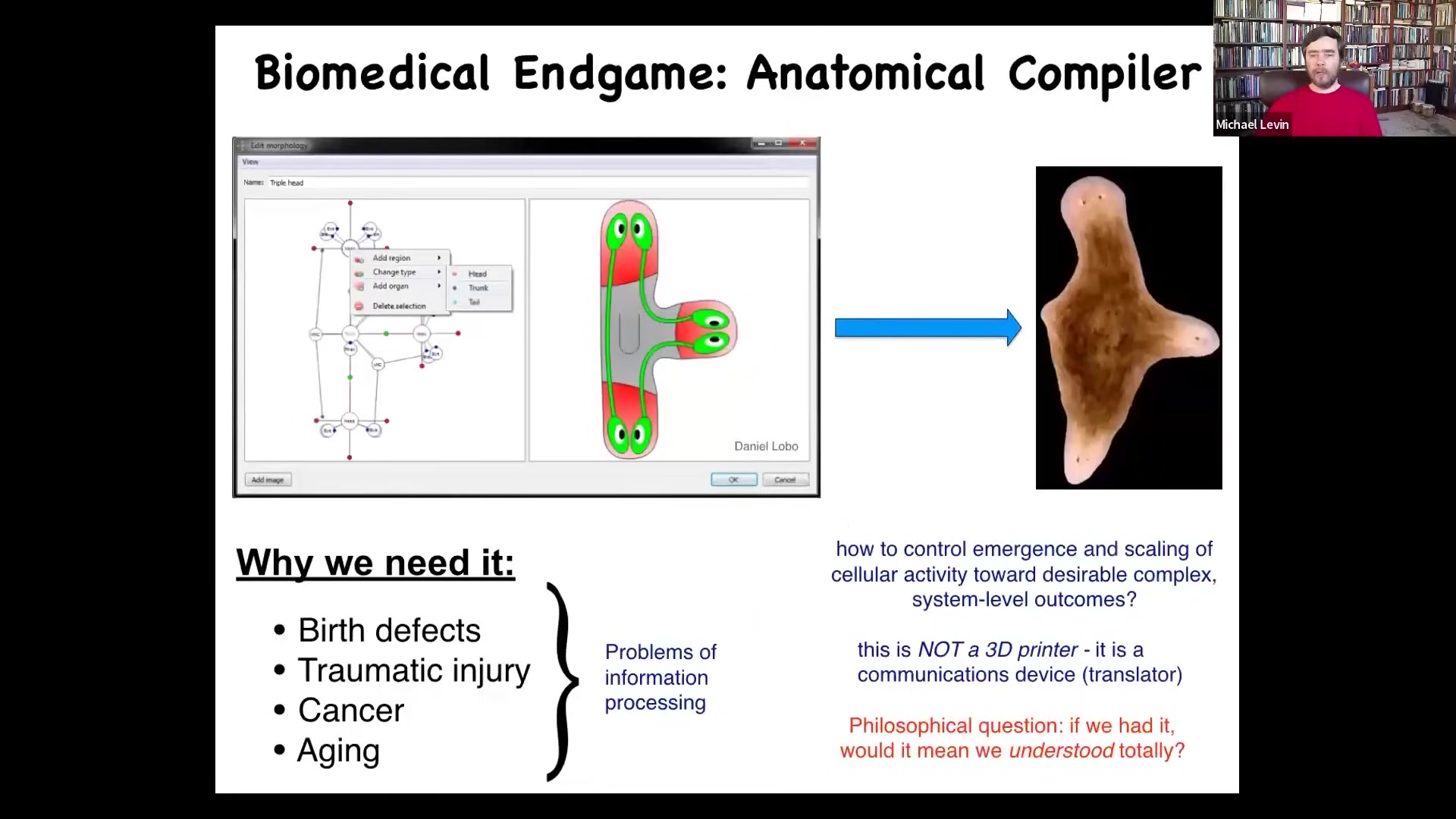

And as we think about the end game of this field, at what point did we consider ourselves done? I think of something we call the anatomical compiler. So the idea is that someday you should be able to sit in front of a computer, draw the plant or animal that you want, or maybe an organ, or maybe some biological robot, whatever shape you want. And the system, if we knew what we were doing, would compile this description down into a set of stimuli that would have to be given to cells to get them to build exactly this.

Why do we want it? In addition to very basic questions about evolution and cellular controls, this is the key to most problems in medicine. So if we had the ability to tell groups of cells what to build, we would be done with birth defects, with traumatic injury, meaning we'd have regeneration, we could reprogram cancer, aging, degenerative disease. All of these things would go away if we could communicate our goals to a set of cells. And so this anatomical compiler fundamentally is not a 3D printer. It's not about micromanaging the positions of cells where you want them. It's about communicating. It's a translator, really. It's about communicating your anatomical goals to the mechanisms guiding the set points of the cellular morphogen.

Slide 20/83 · 19m:32s

Why don't we have this? We have nowhere near that kind of capability. Why not? I'll give a very simple example.

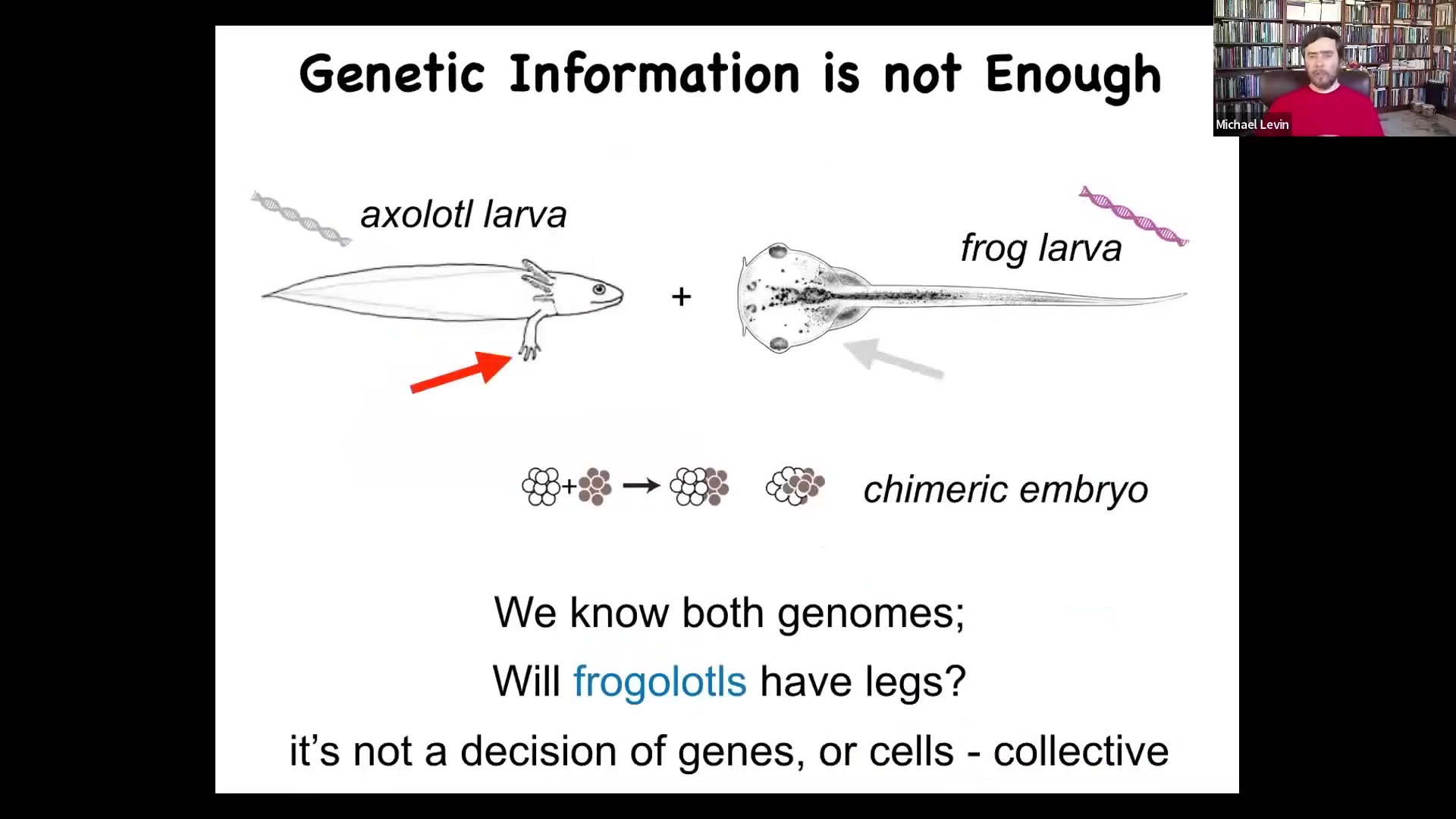

Here's a baby axolotl. It's a salamander. The babies have little legs. Here's a tadpole of a frog, Xenopus laevis. They do not have legs in this stage. In my lab, we make a chimeric construct called a frogolotl. So we take a bunch of cells from Xenopus and a bunch of cells from axolotl and we make a frogolotl.

Can anybody tell me whether the frogolotl is going to have legs or not? The answer is no. We have absolutely no formalism, no models that will make a prediction on this. That's because this kind of thing is not a decision made at the level of molecules or genes, and it's not made at the level of individual cells. It is a collective decision, and we still do not have a good understanding of how cellular collectives make decisions.

Slide 21/83 · 20m:35s

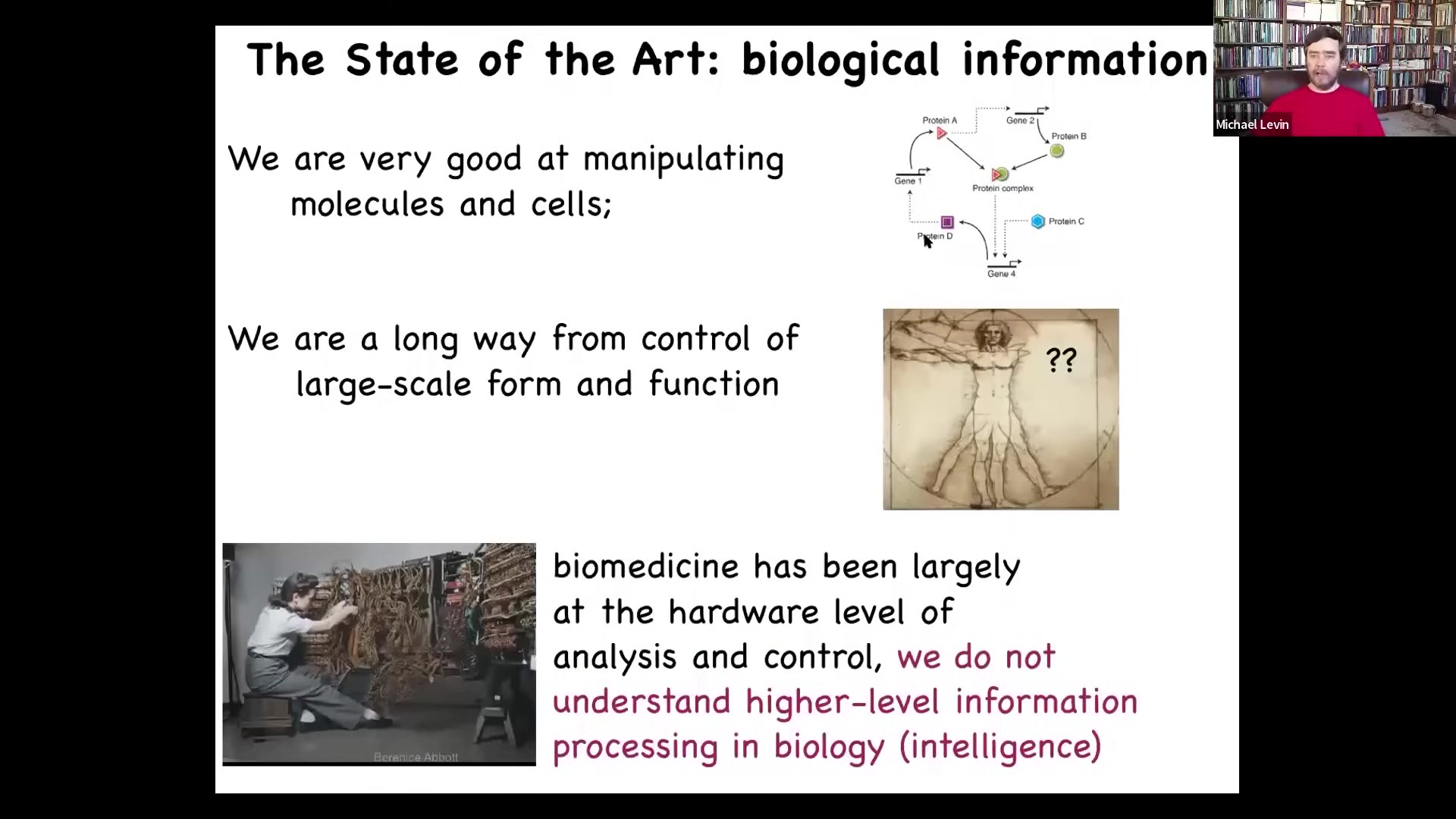

We're very good at manipulating information like this, which cells, which molecules talk to which other molecules, but we're a long way away from control of large-scale form and function. And the reason I think is, because molecular medicine is still stuck where information technology was in the 40s and 50s. This is how you program the computer in the 40s and 50s. You physically had to rewire the machine. You were down at the hardware level. And this is where modern biology is.

All the excitement is around DNA editing, pathway rewiring, protein engineering — all of these things are directly single-molecule approaches. And what we're still leaving on the table is really the software of life, specifically the competencies, the intelligence, and the problem-solving capacity of the material, which is very different from all of the passive matter that we've been engineering with for millennia.

Slide 22/83 · 21m:35s

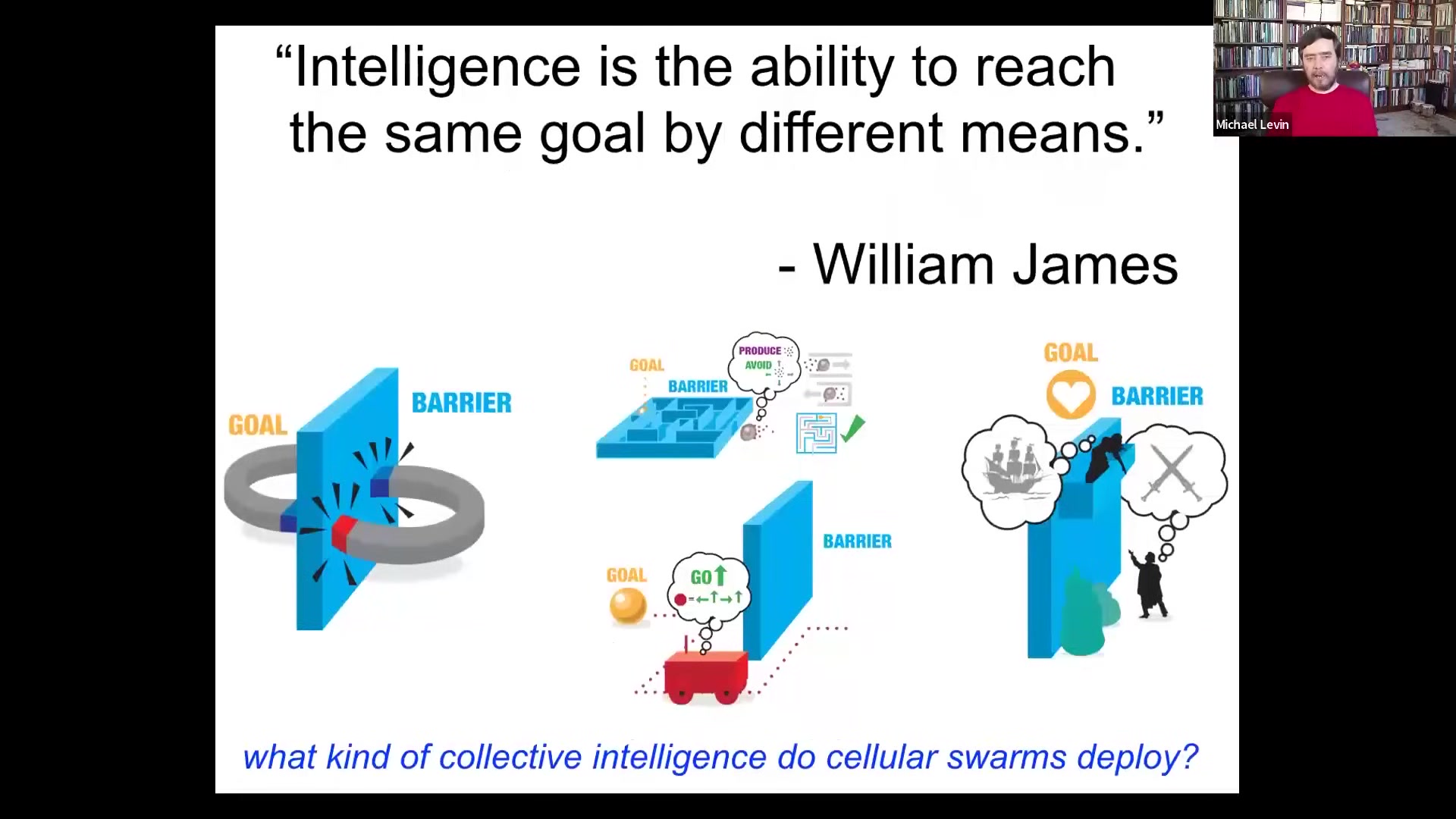

When I talk about intelligence, I do not mean a human-level metacognitive ability to know that you're smart and to know what your goals are. I mean something much more basic and fundamental. This is William James's definition. It is the ability to reach the same goal by different means.

What we have here is a continuum, and James actually talks about the continuum between two magnets trying to get together and Romeo and Juliet. The difference being that these magnets, if separated by a barrier, are never going to go around and meet each other because they do not have the ability for delayed gratification. They cannot go further away from their goal in order to later do better. Romeo and Juliet have the ability to plan.

In between, you have lots of different systems, cells and animals and autonomous vehicles and robotics that have different degrees of competency to reach their goal when confronted by a barrier.

The idea is that you have to force them to use different means. You cannot do this from observational data. You have to do perturbative experiments to put a problem between them and their goal. Then you have to see what level of competency they can muster.

What kind of collective intelligence do we see in cellular swarms?

Slide 23/83 · 22m:52s

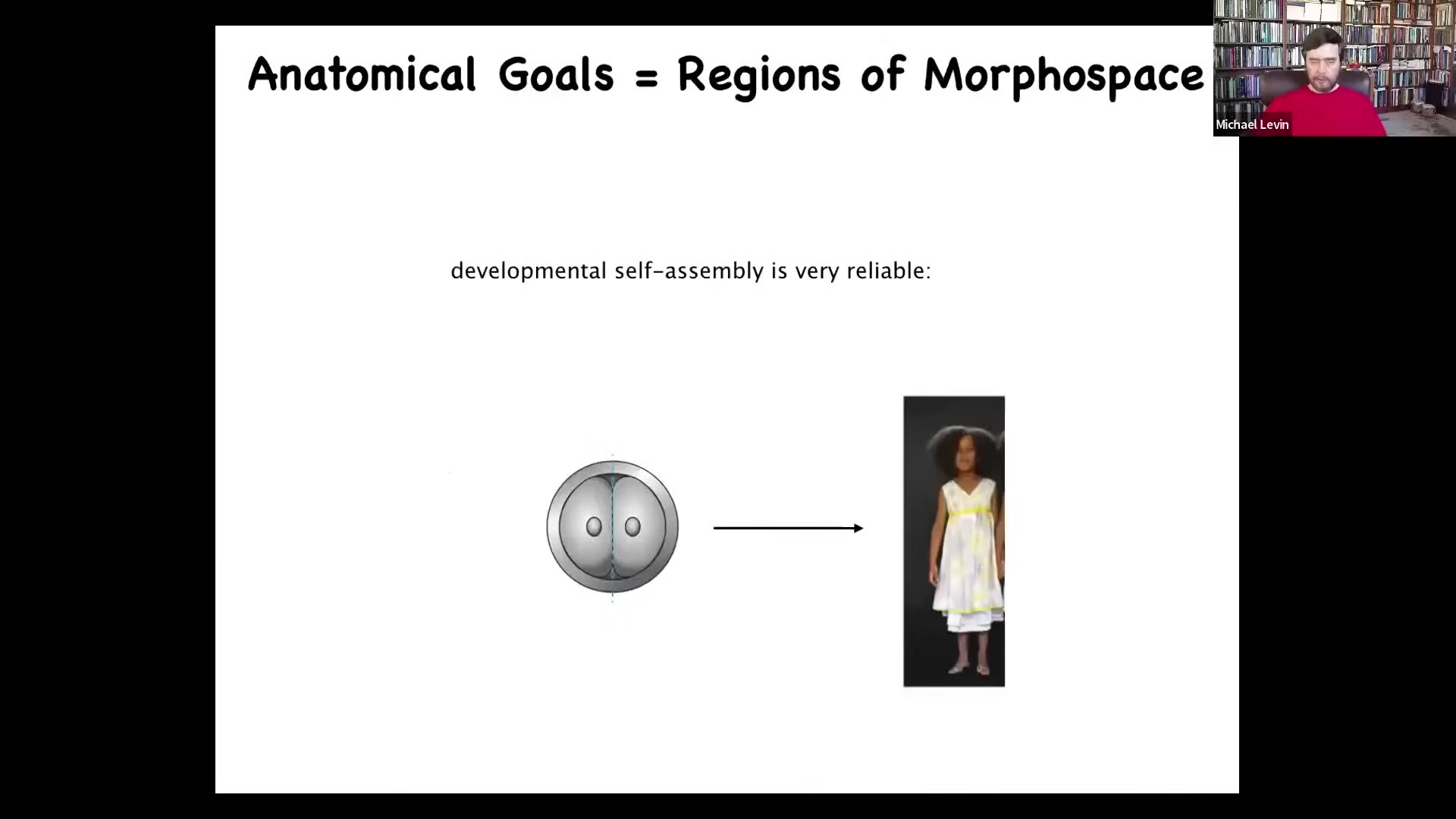

Development is quite robust. It's quite reliable, and that's great. Most of the time, a normal early embryo will have a normal human morphology.

Slide 24/83 · 23m:05s

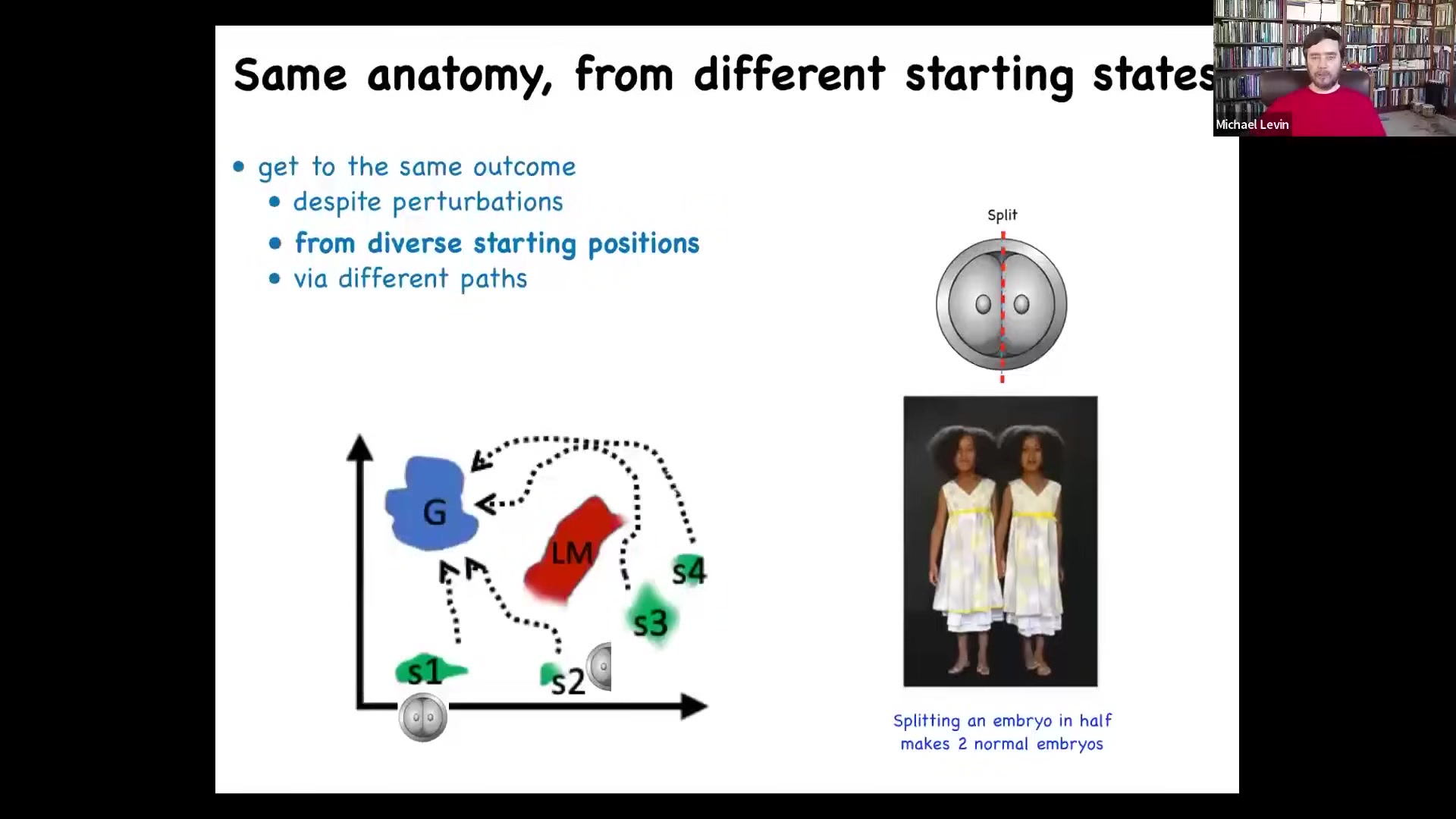

But the amazing thing is that actually it's not hardwired because you can cut early embryos into pieces. You can cut them into halves, quarters, eights, and so on. And you don't get a half body. Each piece will give rise to perfectly normal monozygotic twins. And so if this is anatomical amorphous space boiled down to two axes, you can have this ensemble of states associated with a normal human target morphology, this goal state here, and you can get there from fairly diverse starting positions, maybe avoiding some local minima along the way, but you still get there. So that's interesting. Development, regulative development is able to get to the same goal by different paths. Different means to the same goal.

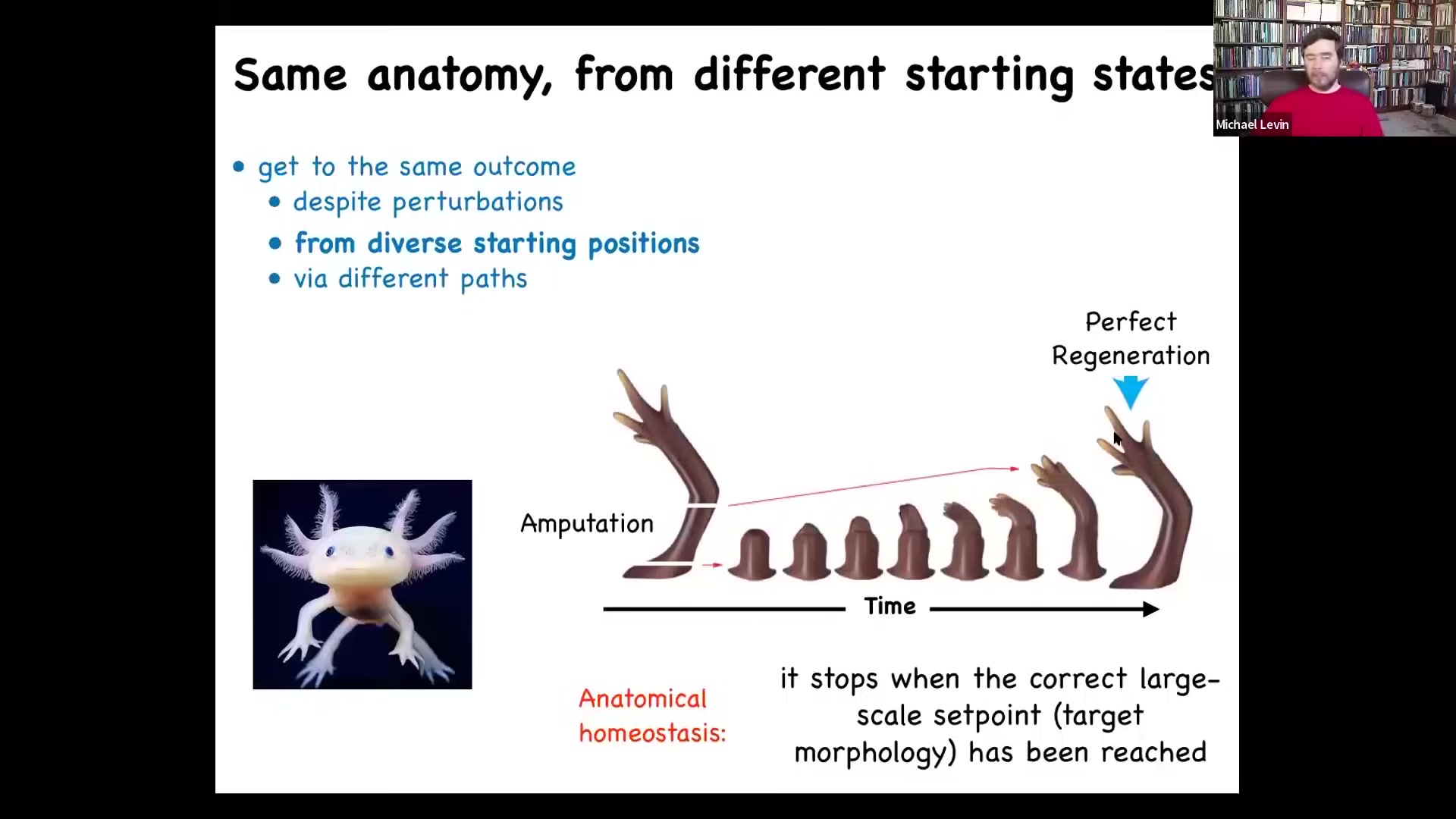

This is not just for embryos. Some animals, like the salamander, can do it throughout its lifespan. Amputate the arm anywhere along. In fact, they also regenerate their eyes, their jaws, their spinal cords, and so on. And you amputate anywhere here, and this thing will grow exactly what's needed, no more, no less, to give you a perfect limb, and that's when they stop.

Slide 25/83 · 24m:08s

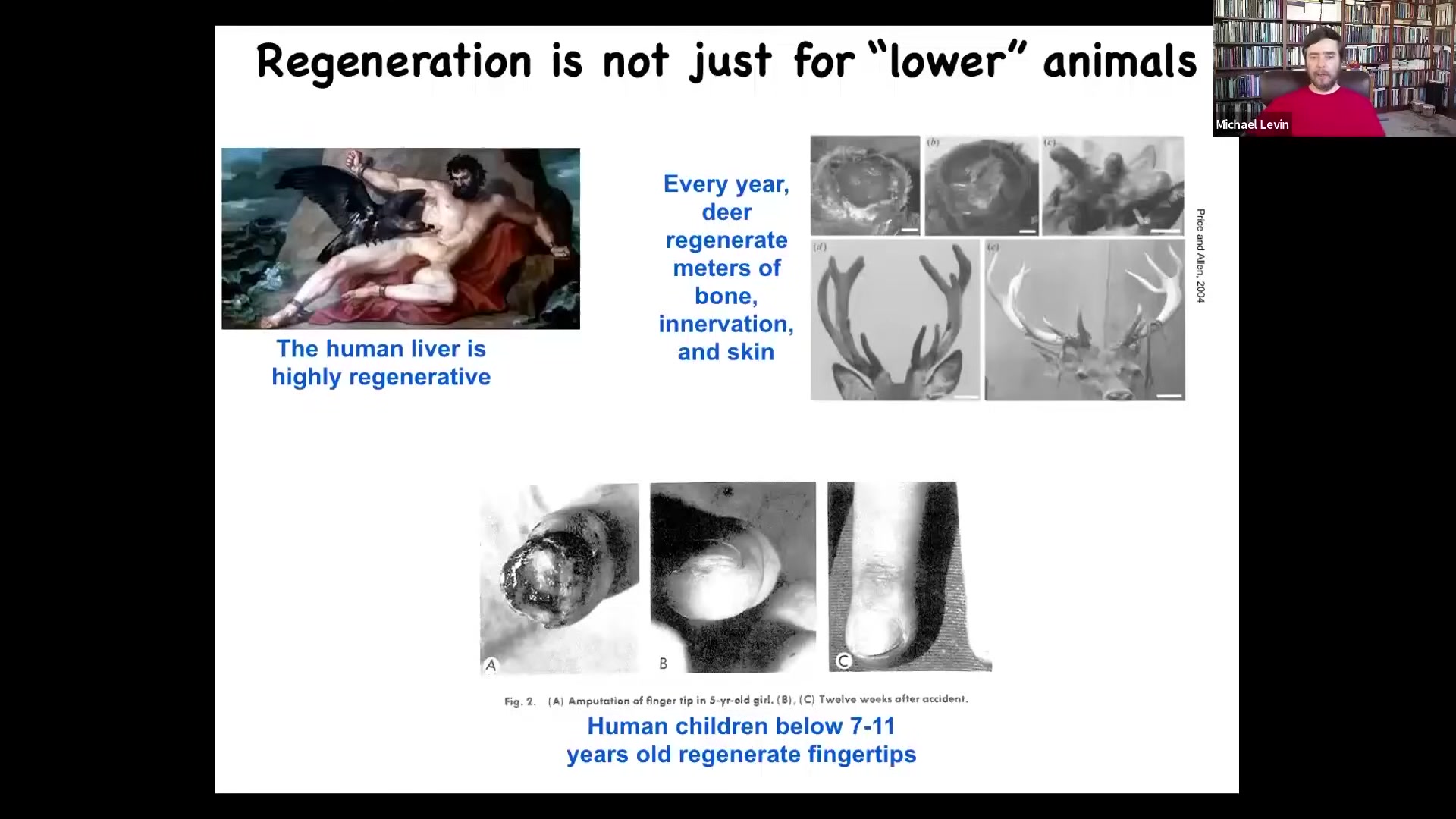

So that's the most amazing thing about regeneration, is that it knows when to stop. When does it stop? It stops when the correct salamander arm has been completed. This is a means-ends analysis; it's an error minimization scheme because the collective — no individual cell knows what a finger is or how many fingers you're supposed to have, but the collective absolutely does because if you deviate it from that state, it will do its best to come back to where it needs to be, and then it stops. This isn't just for worms and amphibians.

Slide 26/83 · 24m:35s

Humans can do this somewhat, and mammals can do it. So we regenerate our livers, human children regenerate their fingertips, and antlers in deer, which are a large adult mammal, grow back every year at a rate of a centimeter and a half of new bone. This kind of ability is not something that mammals couldn't do.

Slide 27/83 · 25m:00s

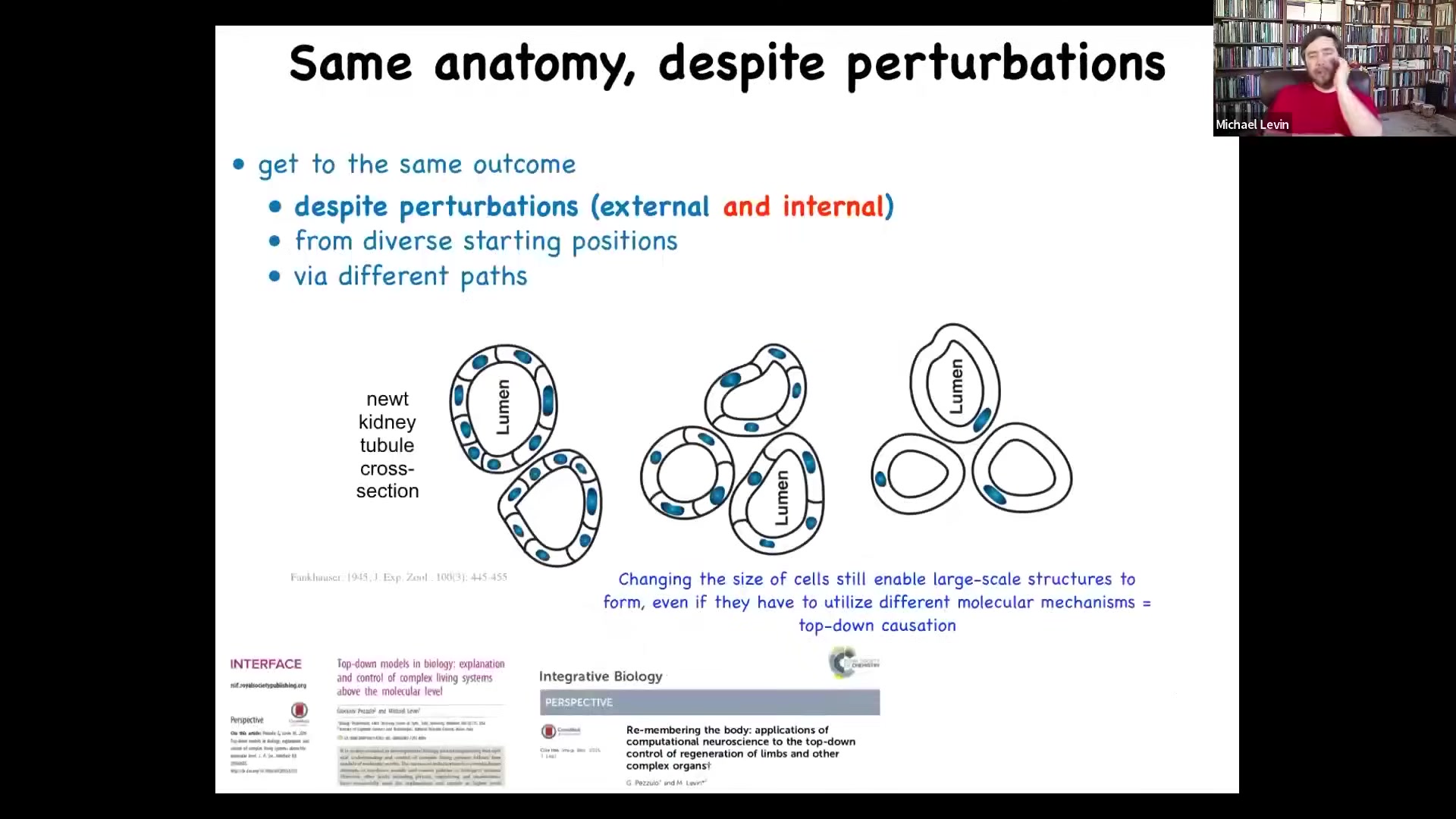

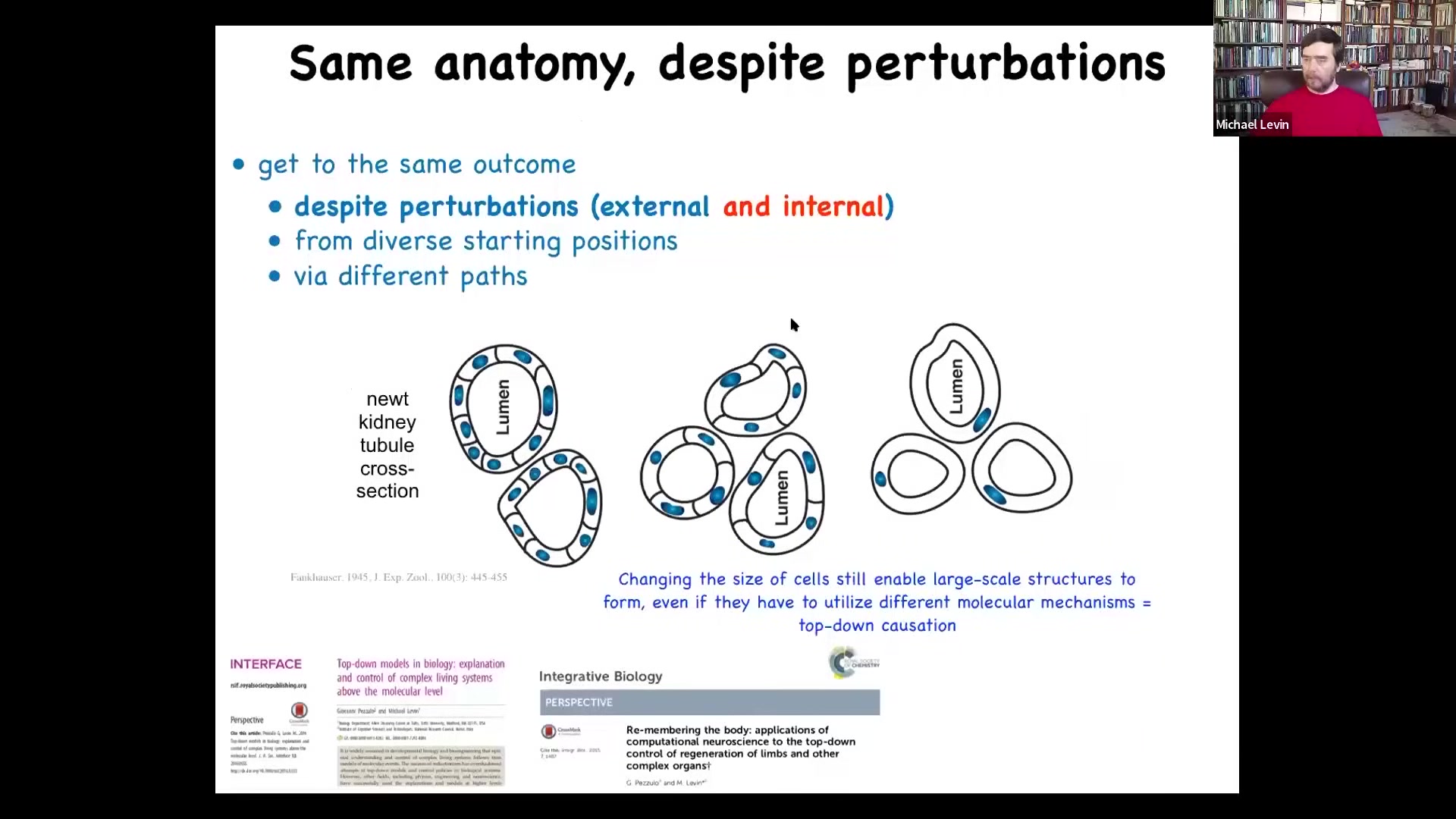

I want to give you another example because everything up until now has been about external perturbation, injury, and the ability of regulative morphogenesis to overcome injury. But there's an even more interesting example.

This is a cross-section of a kidney tubule in the newt, and this was discovered back in the 1940s. If you take a cross-section, you see that the normal lumen is within about 8 to 10 cells that work together to form this kind of tubule.

You can make sure that the early divisions end up with cells that have more genetic material than normal. Instead of 2N, you can have 4N, 5N, 6N, and so on.

The first amazing thing is that if you do that, you still get a perfectly normal newt. You can have multiple copies of your genome. That's fine.

Slide 28/83 · 25m:52s

Then what you find is that the cells actually get bigger to accommodate that genetic material, but the nuclei stay the same size. And this means that fewer of these larger cells get together to form exactly the same lumen. That's also pretty amazing. The cells adjust their number to their size. And then the most remarkable thing of all: if you make truly gigantic cells, one single cell will bend around itself, leaving a space in the middle to give you that same lumen. What's wild about that is that this is a different molecular mechanism. This is cytoskeletal bending. This is cell-to-cell communication. And so that means that it's an example of top-down causation.

In the service of a large-scale anatomical goal, different molecular mechanisms are being called up to execute. And just think about what that means for a newt coming into the world. Evolution had to produce not just a solution to a problem of a noisy environment, but actually a problem-solving machine, a second-order machine, where you can't count on how much genetic material you're going to have, how many copies of each gene. You can't count on the size or the number of your cells. You can't count on not being separated by a scientist during embryonic development. You can't count on any of that. You have to be able to complete morphogenesis despite a wide range of not only external deviations, but changes in your own parts. We don't have anything remotely like this in our technology that can tolerate not only injury, but changes in its own composition and still get the job done. So this is what I mean by anatomical intelligence. It's a problem solving capacity, which we still do not understand.

And so the idea here is that this process is not simply complexity. It's not just feed-forward emergence. This idea that, and this is what's in all the textbooks, is that there are gene regulatory networks, they make some proteins, and then you get this process of emergence and complexity where simple rules get activated and eventually something complex happens. And here you go, you've got this structure. Of course, all this does occur. There are many ways to get complexity out of simple rules. But there's something much more interesting here, which is that it's not just complexity. It's the fact that if you deviate the system from this particular outcome, there are these loops that kick in both at the level of physics and genetics that will try to get you close back to where you were, navigate back to that region of morphospace, and in fact, take different paths and do different things to get there. So it's not just a feedforward system. You might think about this as anatomical homeostasis.

Now, on the one hand, biologists know all about feedback loops, and so that's obvious, but there's some stuff that's quite different here. First of all, typical feedback loops have a scalar as a set point. It's temperature or hunger level or pH or something like that. But that's not going to work. In this case, you need a descriptor. It's a shape descriptor. It has to have more information to it than that, even if it's not down to the single cell level. But also, we're really not encouraged, especially in molecular biology, to think about goals. We're not encouraged to think about processes that have an end point that they are trying to reach. That's considered unwelcome anthropomorphic talk. And we're really just supposed to think about emergence and how the simple rules will give rise to whatever it is that they give rise to. Since the 40s, we've had cybernetics. So I think we can talk about systems with goals now that isn't magic and it's not scary.

And what this does is make some very strong predictions. It predicts that if something like this is true and it has what every homeostatic system has to have, which is a set point encoded somewhere, if it has a biophysical mechanism that encodes the set point, we should be able to do something interesting. We should be able to change the set point without rewiring the machine.

So you cannot make changes down here, which are actually extremely hard to know what to do. This process is not reversible. And so if you wanted to make a change up here, in general, we have no idea what to change down here. That's what's going to limit all the genetic editing, CRISPR and all that stuff; it's going to reach a ceiling after some low-hanging fruit of single gene diseases, because it's in general impossible to invert this.

But if we could change the set point, then maybe the system would just do what it does best and implement that set point. So this means that we should be able to find the encoding of the set point, we should be able to decode it, and we should be able to rewrite it. And that's what I'm going to show you now.

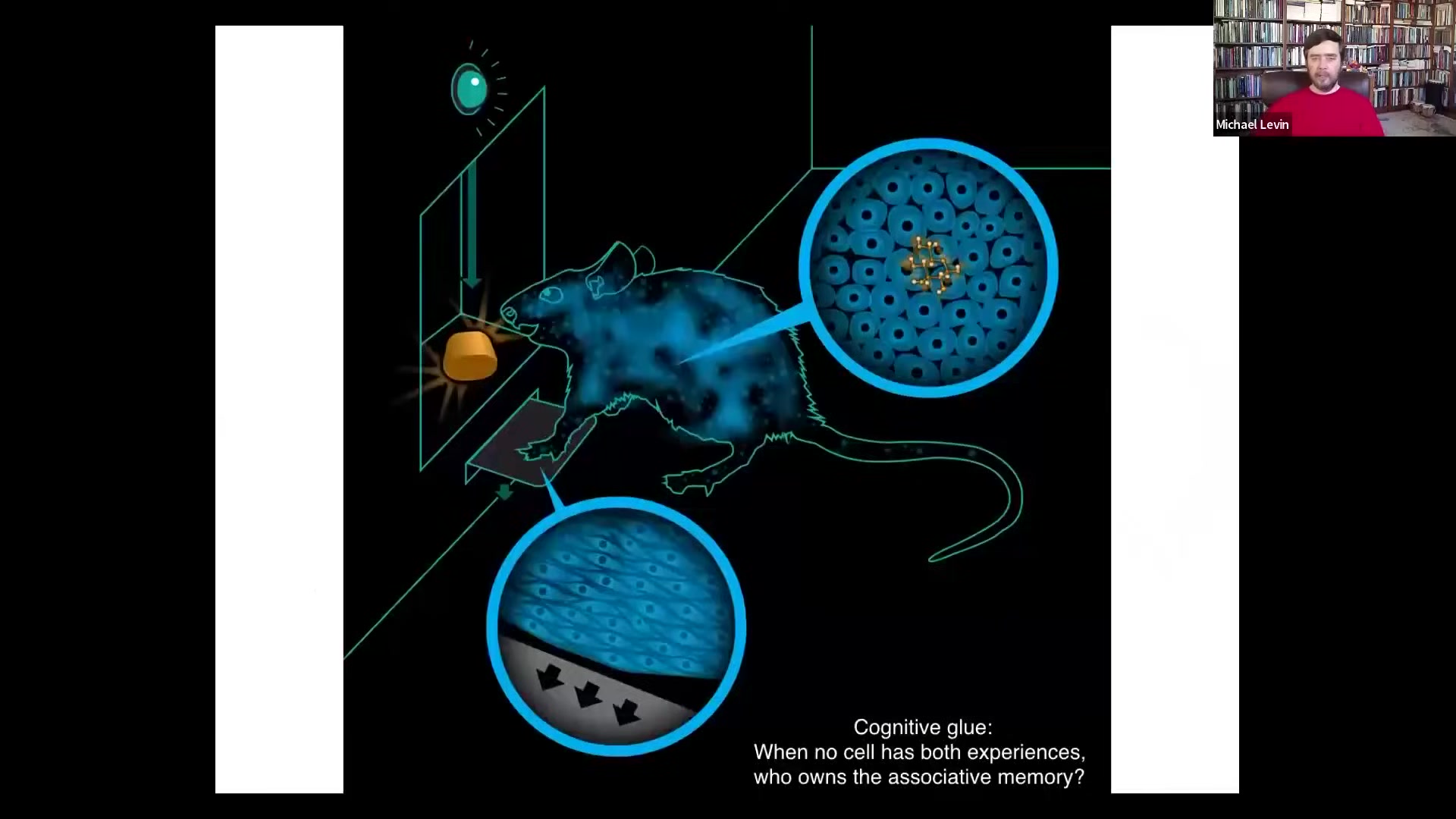

Interestingly, we start to think about how it is possible that cells and tissues store a memory, a pattern memory of what it is that they're trying to build. How could that possibly work? Well, we have to note that in order to have memories about large-scale states of affairs, you need a kind of cognitive glue that binds together the components.

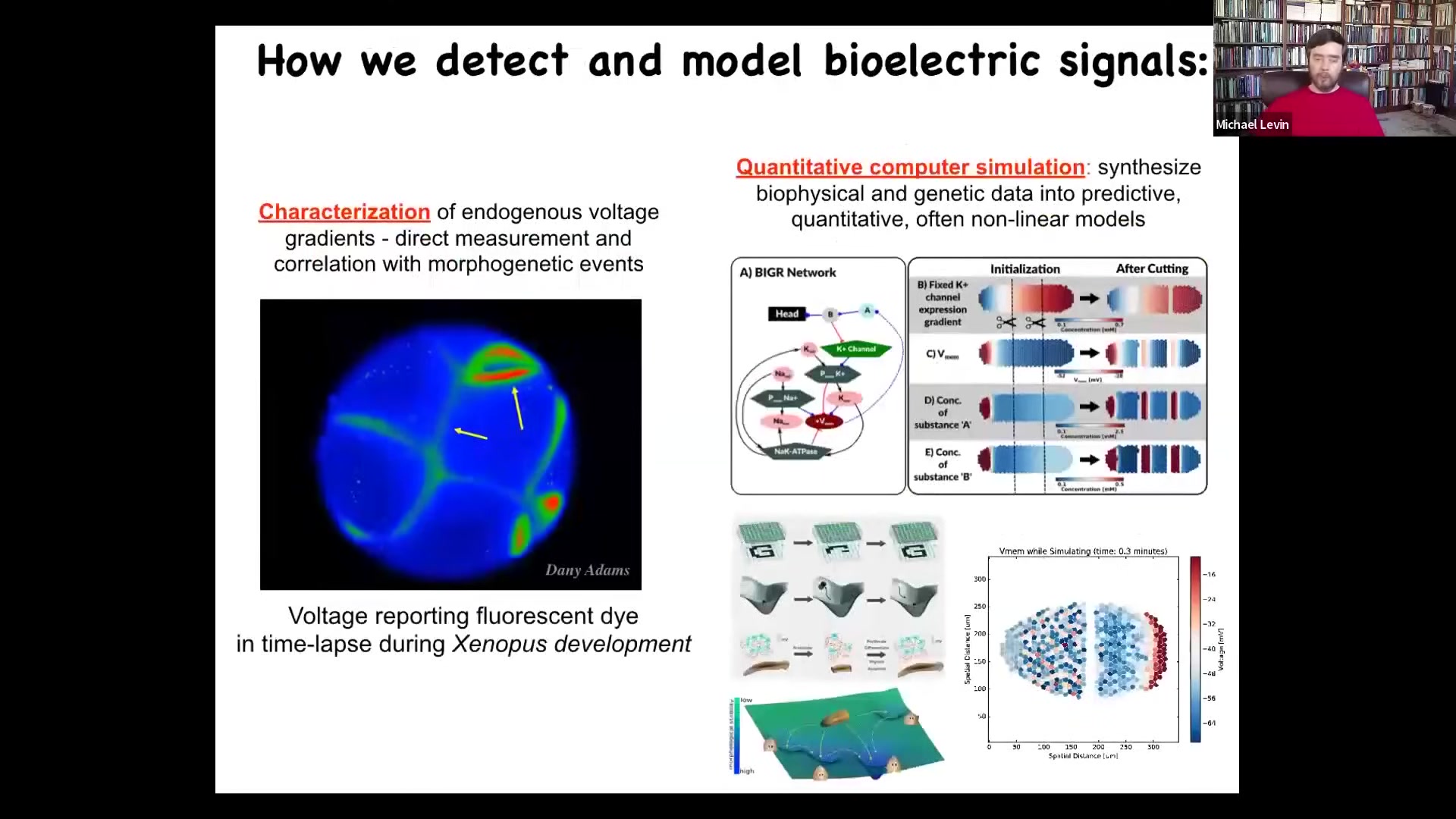

Slide 29/83 · 30m:55s

We have an example of this from neuroscience.

Here's an animal that learns to press the lever and get a delicious reward. No individual cell has both experiences to form that associative memory. The cells at the bottoms of the feet interact with the lever. The cells in the gut are going to get this, the sugar that comes from it. No cell has had both experiences. Who owns this associative memory? In order to own that associative memory, you have to bind all of these cells together into one collective agent that has memories, goals, preferences that none of the components do. We don't know how it works, but we know the architecture in neuroscience, and that's bioelectricity.

Slide 30/83 · 31m:38s

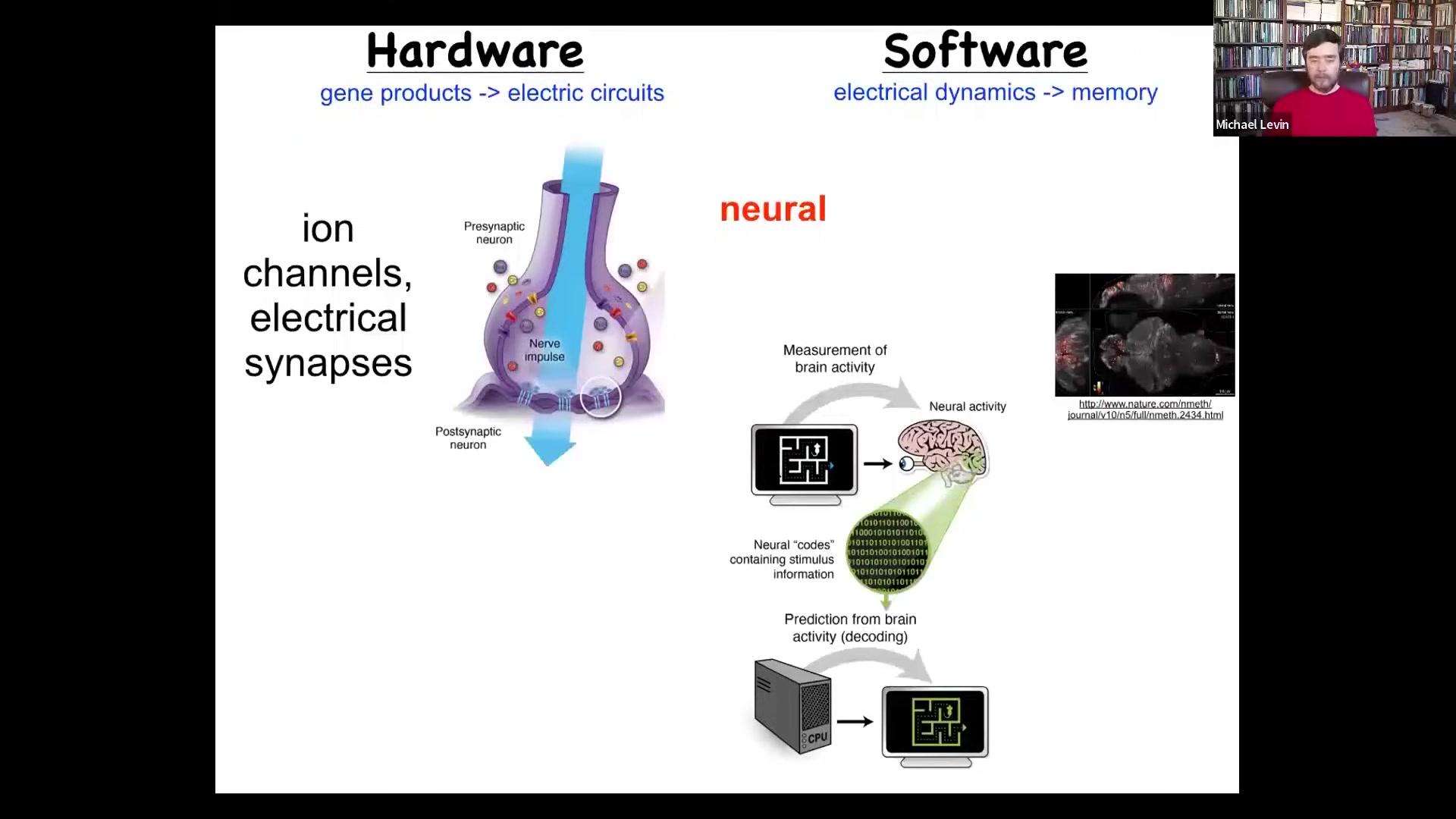

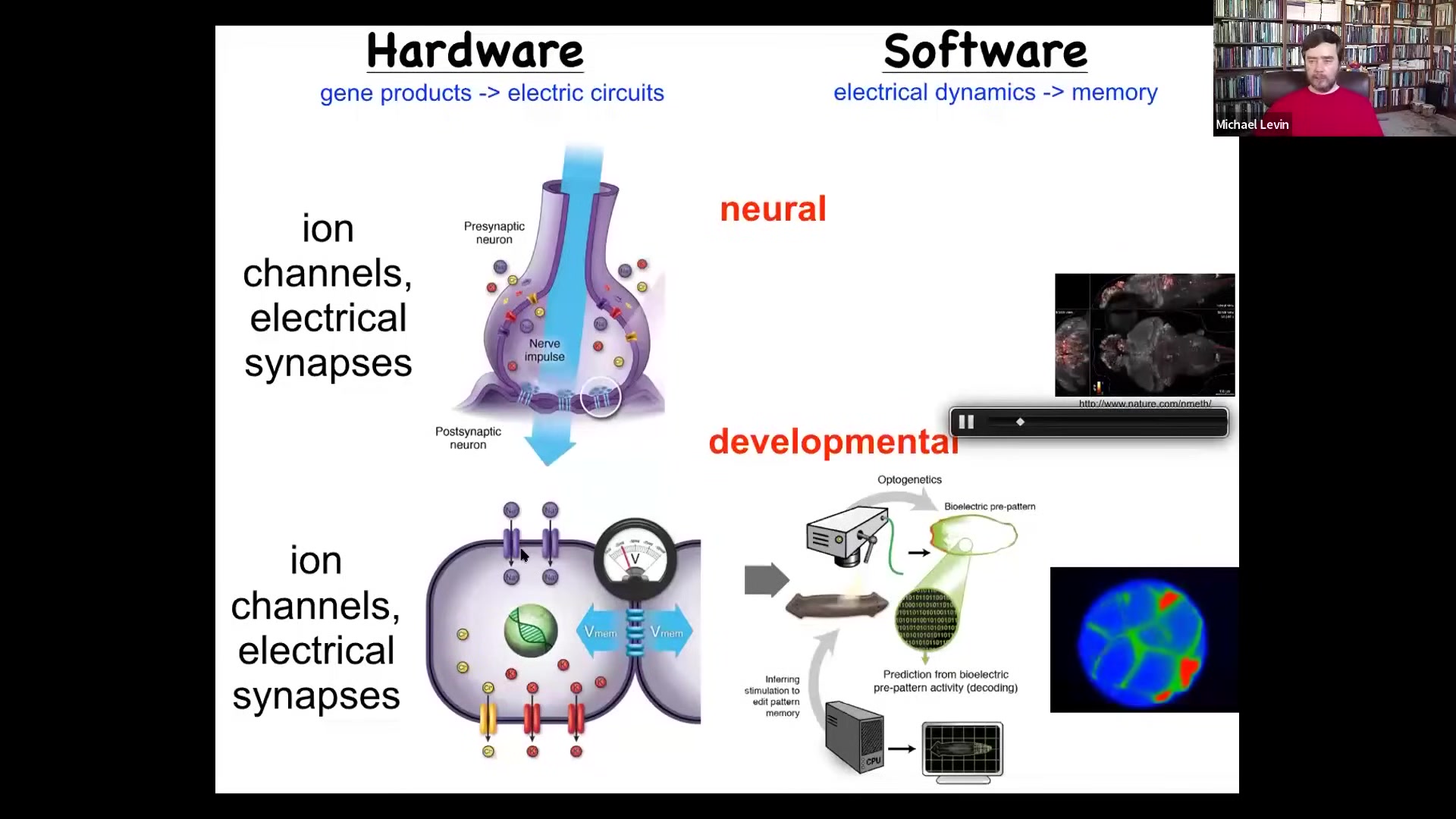

The thing that binds the neurons in your nervous system together to make up an organism that has goals and preferences in other spaces, what we have is some hardware. These are ion channels that sit on the outside of these neurons, and they set a voltage gradient, and that voltage gradient may or may not propagate to their neighbors. Now you have a network, you have an excitable medium, and it can do computation because information propagates in a very complex and regulatable way through that network.

The software looks something like this: it is the physiology. This group made this amazing video of a zebrafish brain active as the fish thinks about whatever it is that fish normally think about.

There's this project of neural decoding, the idea that if we were to read out all of this physiology and decode it, then we would have access to the memories, the preferences, all of the kinds of cognitive content of this mind. The commitment of neuroscience is that all of that stuff is literally in the physiology. The amazing thing is actually that every cell in your body does this. All cells have ion channels.

Slide 31/83 · 32m:48s

Most of them have these electrical connections to their neighbors. This is evolutionarily where the tricks of the brain come from. It comes from this much older system that evolved around the time of bacterial biofilms.

So we started to wonder, could we not port all of the things that are important about neuroscience, which is not the details of neurons, but the multi-scale cognitive scaling, to decode the collective intelligence of the body? Could we read and interpret this information and see what it's thinking about? Could we read out these goal states?

So the mapping that I'm asking you to consider is this: the traditional story is that in the brain, these electrical networks are giving commands to muscles to move your body through three-dimensional space. All of this can be read out and analyzed.

Slide 32/83 · 33m:48s

But that system comes from an older system, which otherwise works exactly the same, using the same mechanisms as well as the same algorithms. Where these electrical networks are giving commands to all of the cells to move the configuration of your body through morphous space. As an embryo develops, as regenerative organs repair themselves, it's just an evolutionary pivot. Instead of working in three-dimensional space, you're working in anatomical morphous space. There's a different time scale. You're not talking milliseconds, you're talking hours. Otherwise, it's a very similar thing. We've been able to import lots of different techniques from neuroscience.

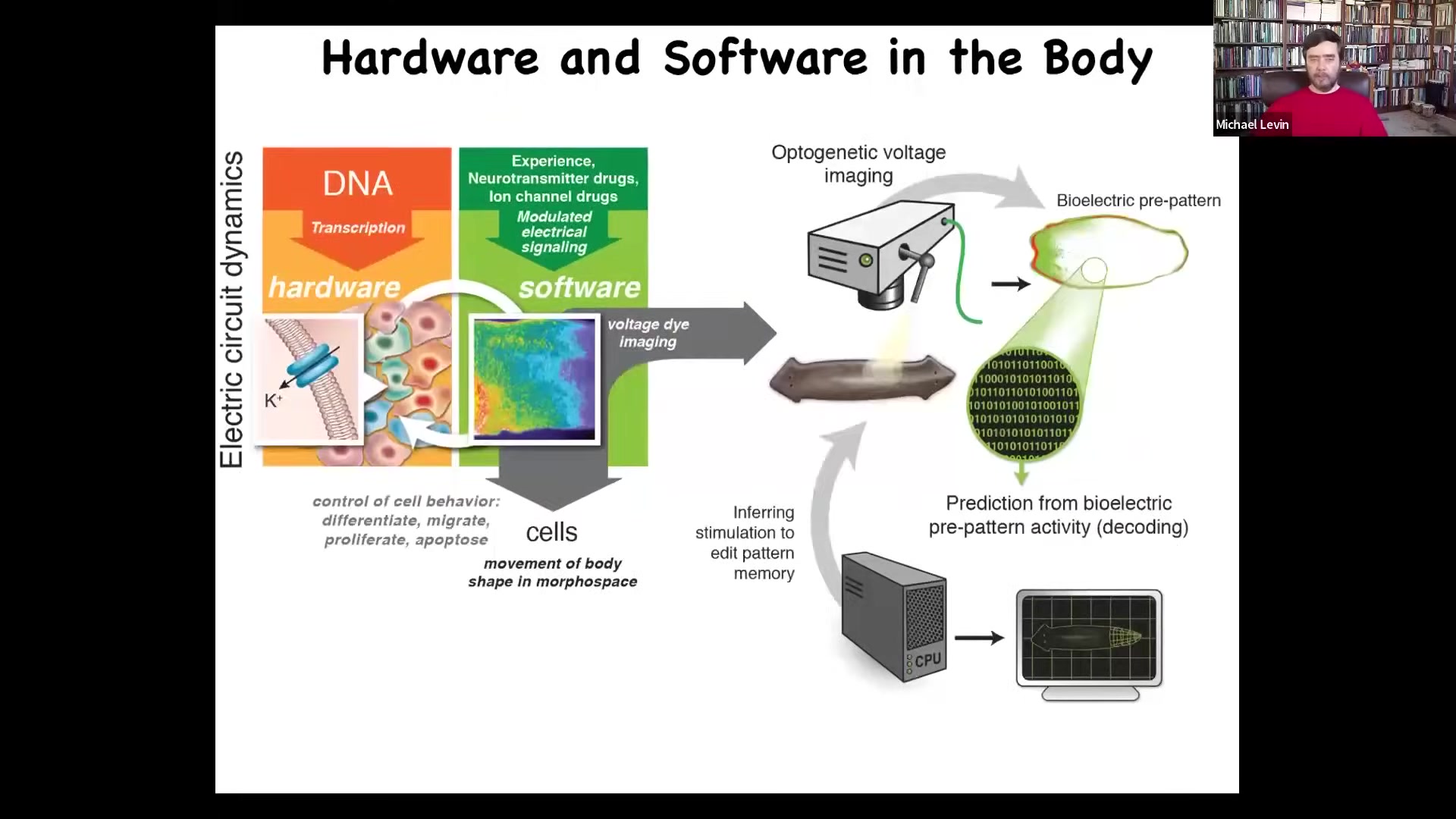

Slide 33/83 · 34m:25s

One thing we've developed is the first use of voltage-reporting fluorescent dyes to characterize all the electrical conversations that cells have with each other. There's a time lapse, and the colors give us a map of the voltage. We do a lot of quantitative simulation to ask where these patterns come from, knowing the channels and pumps that are expressed here. We have these simulators that allow us to understand what the collective dynamics are going to be once the tissues have set up all these different states. I want to show you a couple of examples of these patterns.

Slide 34/83 · 35m:08s

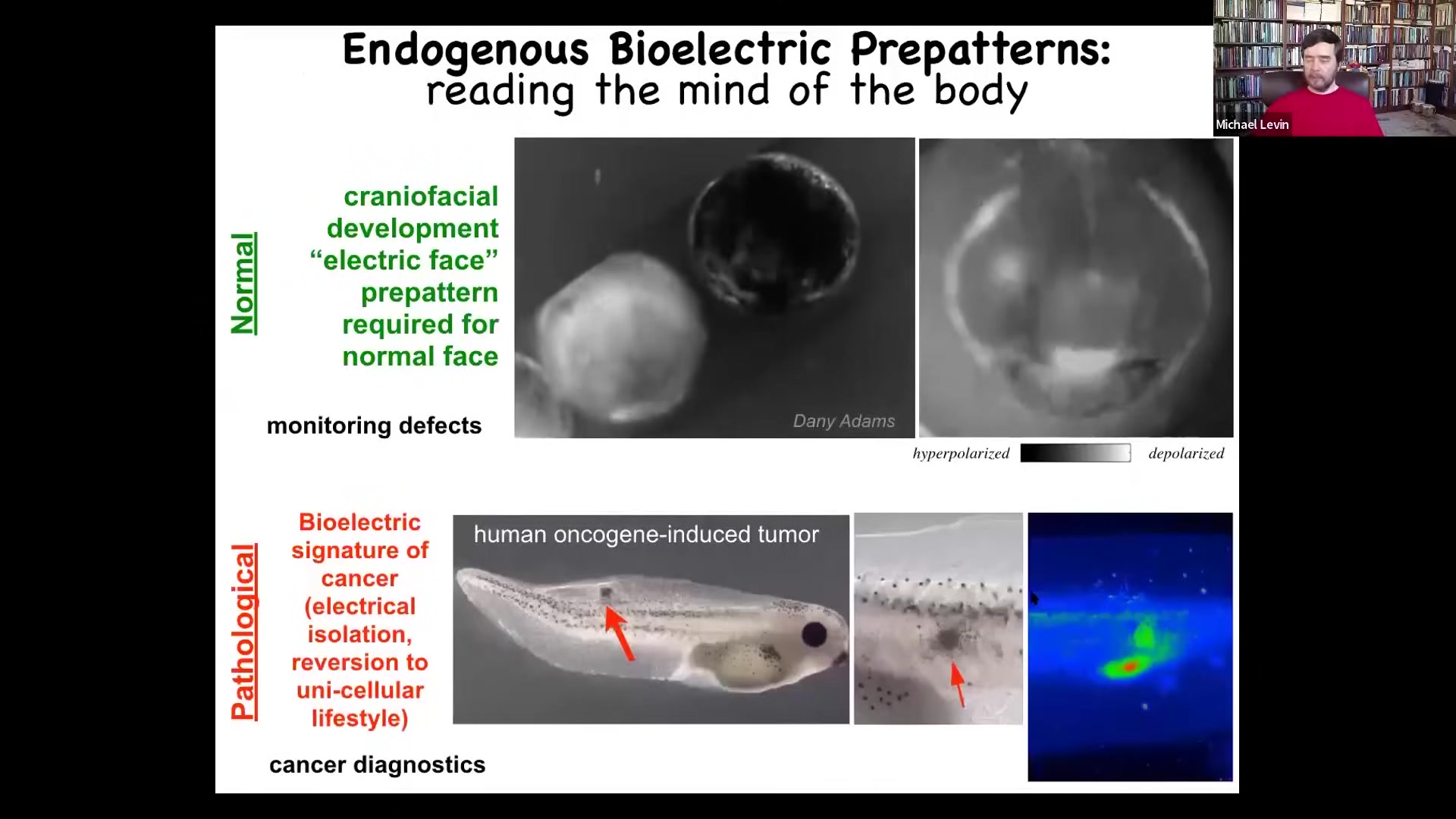

The first example is what we call the electric face.

This is a time lapse, this time in grayscale, of a frog embryo putting its face together. What you'll see is one frame out of that movie. At one point, you can read out a pre-pattern of where all the organs are going to go. Here's where the eye is going to be, here's where the mouth is going to be, here are the placodes. Actually, the animal's left eye comes in slightly later. You can already see that long before the genes turn on and the anatomy of the face is nailed down, there is an electrical pre-pattern that you can read that shows that there is a representation of the thing it's aiming for.

I'm showing you this one because it's one of the easiest to decode. We have many others that we have not yet decoded, but this is pretty easy because it looks like the face. I'll show you in a minute what happens when you interfere with that pattern. This is an endogenous pattern that is absolutely required to form a normal face. Because if you change any of these electrical states, the gene expression will change and the anatomy will change. This is required for normal development.

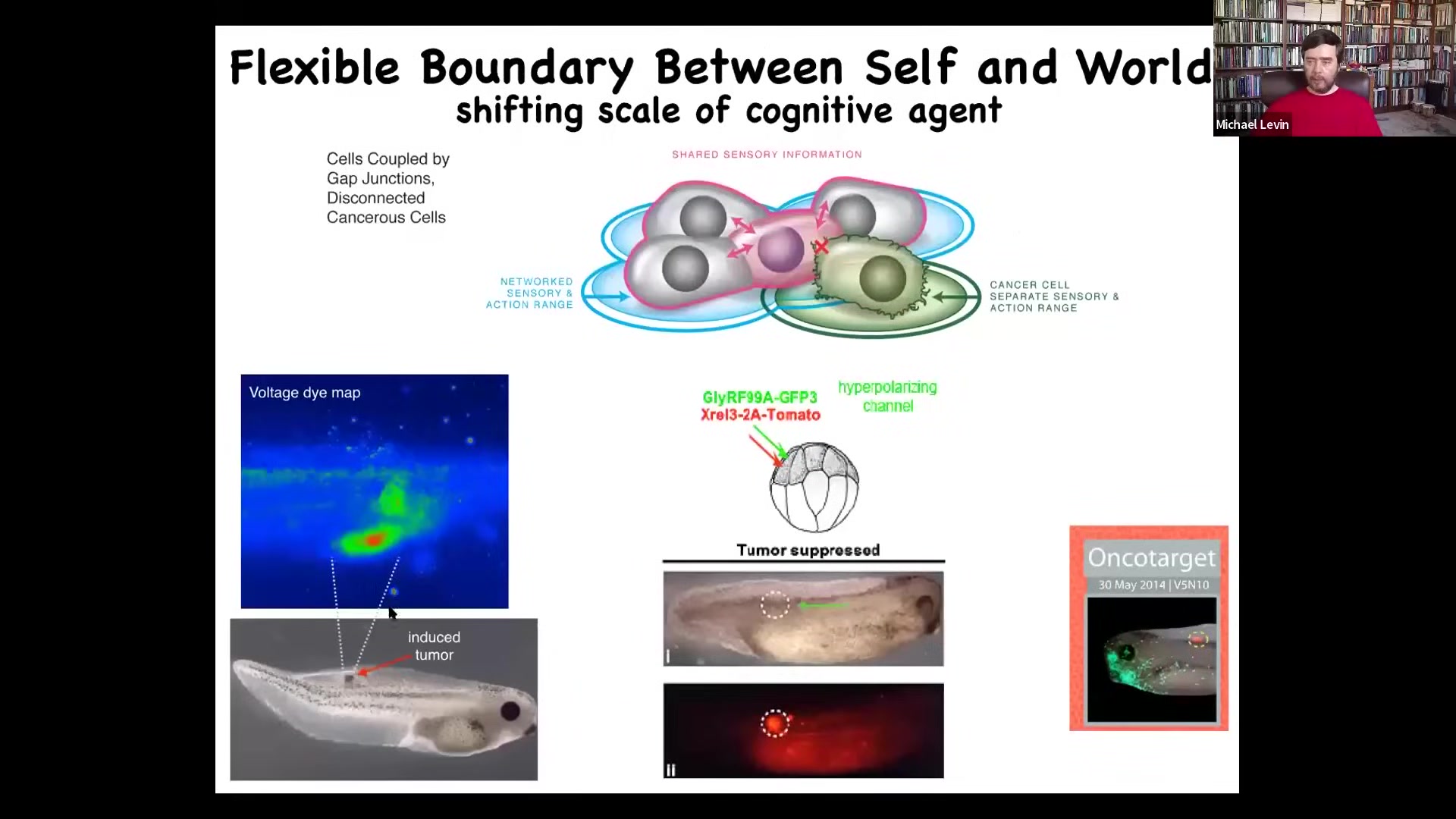

This, on the other hand, is a pathological pattern induced by injecting oncogenes into the embryo. They will eventually make a tumor which metastasizes. At early stages, you can see that what happens is the way you get tumors is these cells detach electrically from their neighbors. They acquire a different depolarized voltage potential. At that point, they're amoebas again, they're not connected to anything, and the rest of the body might as well be external environment to them.

These are imaging technologies, and this is how you can read the mind of the body.

Slide 35/83 · 36m:48s

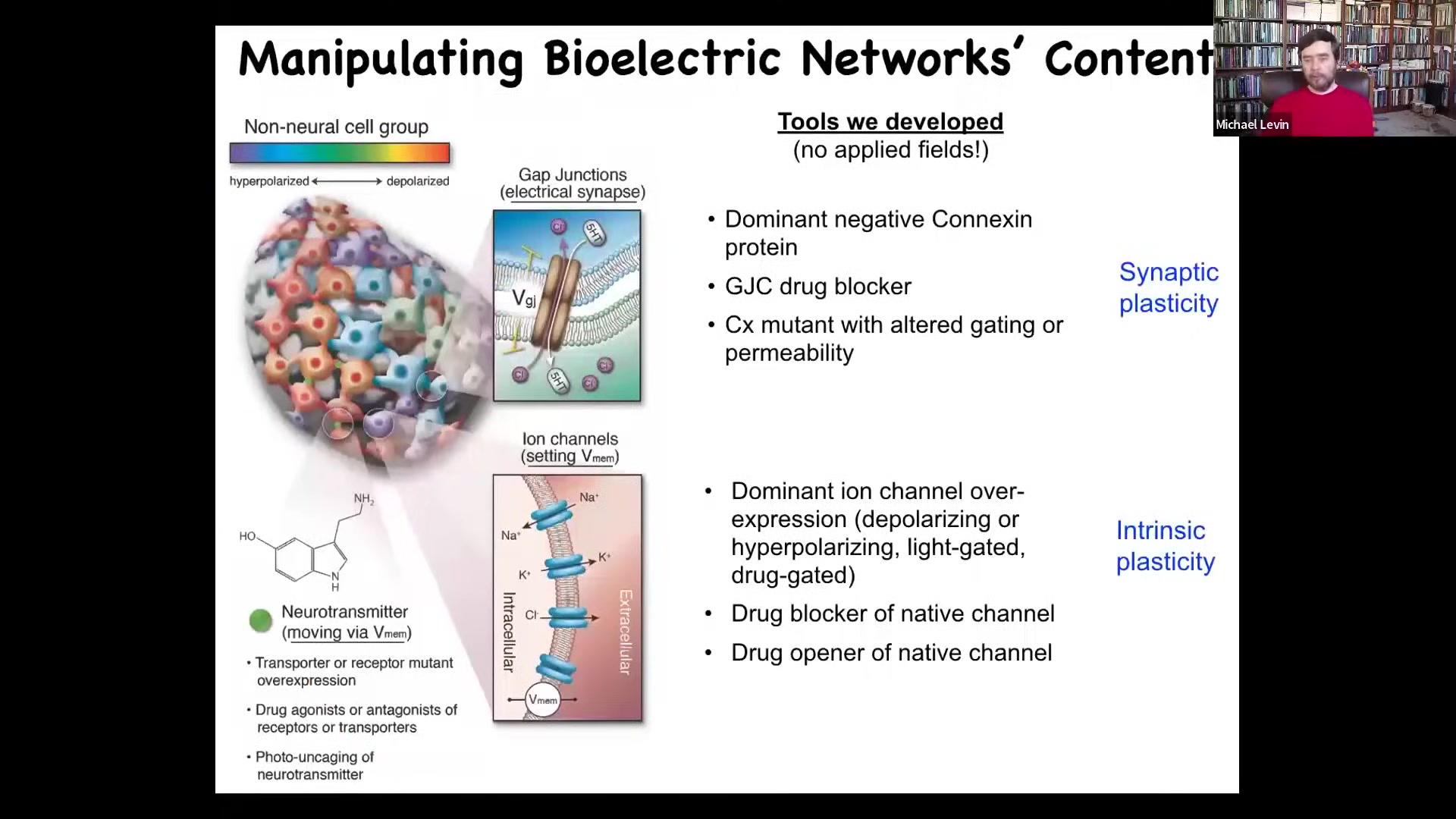

Also critical, you need to be able to rewrite it. I promised you that we were going to be able to find the medium in which these set points are encoded. We were going to be able to read and translate them, and then we're going to be able to change them, rewrite them. How do we do that? We do not use any applied fields. There are no magnets. There are no electromagnetic waves. There are no frequencies. There are no electrodes.

What we're doing is modulating the native interface that cells expose to each other. This is how cells normally hack each other by exposing this beautiful ion channel keyboard, which is a bunch of different ways to control the resting potential of any cell. We can now hijack this. We can open and close these channels. We can use drugs. We can use optogenetics or light to open and close them. We can mutate some of these channels.

The same thing applies to the gap junctions. We have control of the topology and the electrical states of the network. Again, no electrodes, no applied fields of any kind, opening and closing the control machinery that normally processes this electrical information. This is all taken directly from neuroscience where people do this for synaptic plasticity and intrinsic plasticity.

I have to show you what happens when you do this. In other words, if I'm telling you that these bioelectrical states are not just a readout, but they're actually the set points that determine where in anatomical morphospace this collective agent is going to go. Remember, my central claim is that groups of cells are a kind of collective intelligence navigating anatomical morphospace. What binds them together and gives them the ability to reach goals despite the various perturbations is this electrical medium, exactly like in the brain. What happens when we change it?

When I was first doing this in 2000 or so, the standard expectation was that voltage is a housekeeping parameter: if you mess with it, you'll get uninterpretable toxicity and death, and nothing was possible this way. I want to show you that is not correct.

Slide 36/83 · 38m:55s

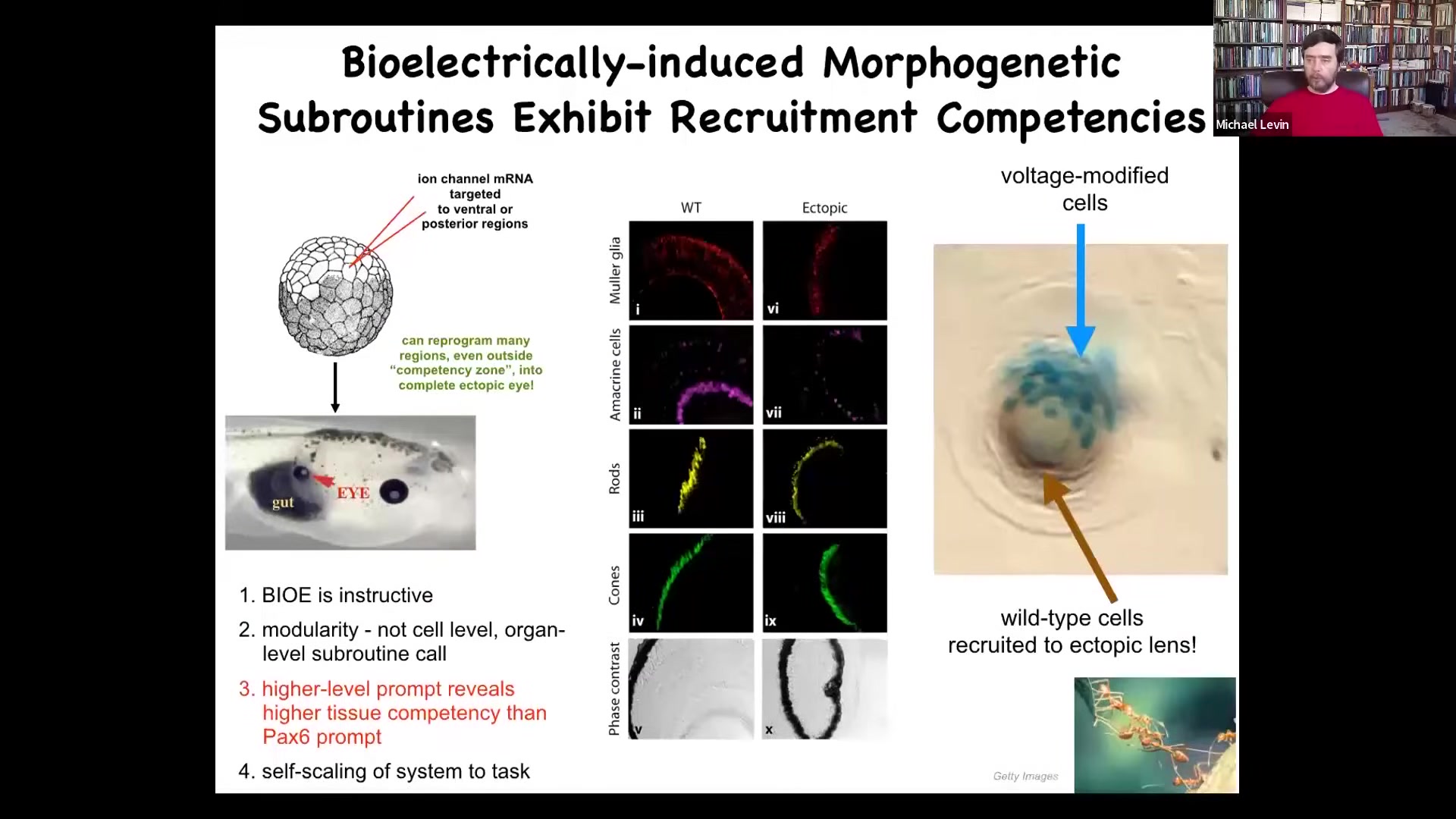

Here's one example. Remember I showed you in that electric face, there's one particular spot that is going to be where the eye forms. We asked the simple question: could we reproduce that voltage spot somewhere else? Could we get some other region to think that it should make an eye? The way we do that is we inject mRNA encoding a particular set of potassium channels. We inject that, say, here in a region that's normally going to be gut. Here's this tadpole. There's the mouth, the nostrils, the brain is up here, and here are the eyes. This whole thing is gut, and it has an eye on its gut. Because we injected some ion channels that told this particular region to acquire a voltage pattern, a pre-pattern memory that says build an eye here. If you cut these eyes open, you'll see all the same lens, retina, optic nerve, all the stuff that they should have.

Here are the important lessons from this set of experiments. First of all, the bioelectricity is instructive. It's not just toxicity. You can actually call up different organs. In fact, there are many organs that you can call up this way. It determines what happens. It's not just an epiphenomenal readout.

Second, it's extremely modular. Any system with good competency, you don't micromanage it. You give it signals. All we gave it was a very low-information-content input. We just said, make an eye here. We didn't give it all the information needed about how to make an eye. We didn't talk to the stem cells and tell them where to go or any of that. All we said was, make an eye here, and then the system takes care of the rest. That's a hallmark of a good vertical architecture of competency.

In the developmental biology textbook, it will tell you that only the tissues up here in the anterior neurectoderm — that's a developmental biology term — are competent to make eyes. That's because people probed it with what they call the master eye gene called Pax6. And indeed, Pax6 only makes eyes up here.

When we make a claim of competency about any system, what we're really doing is taking an IQ test ourselves. All we're saying is that as an observer, this is what we figured out. It turns out that if you use a better trigger, so bioelectrics instead of Pax6, in fact any cell we've seen eyes in, in every region of the body, all of them can make eyes, but you wouldn't know that if you didn't stimulate them with the right prompt. I really think this is an example of bio-prompting in the same sense that people use this in machine learning.

Finally, the system also has the ability to scale itself to the task. This is a lens sitting out in the tail of a tadpole somewhere. These blue cells are the ones that we injected, but there's not enough of them to make a good lens. All these other cells are recruited by them, even though we didn't touch them. It's a second-level instruction. We instruct these cells to make an eye. These cells instruct the others: "Hey, help us. There's not enough of us. All of you need to participate to make this eye." We know many collective intelligences that do exactly this. For example, ants and termites: if a couple of scouts come across something that they can't lift, they will recruit a bunch of their neighbors. We already know collective intelligences are very good at doing that. We didn't have to tell the cells how to do that. This is all built in. This is the competency of the material that we as engineers and evolution are dealing with. It's completely different from a passive, simple machine.

Slide 37/83 · 42m:25s

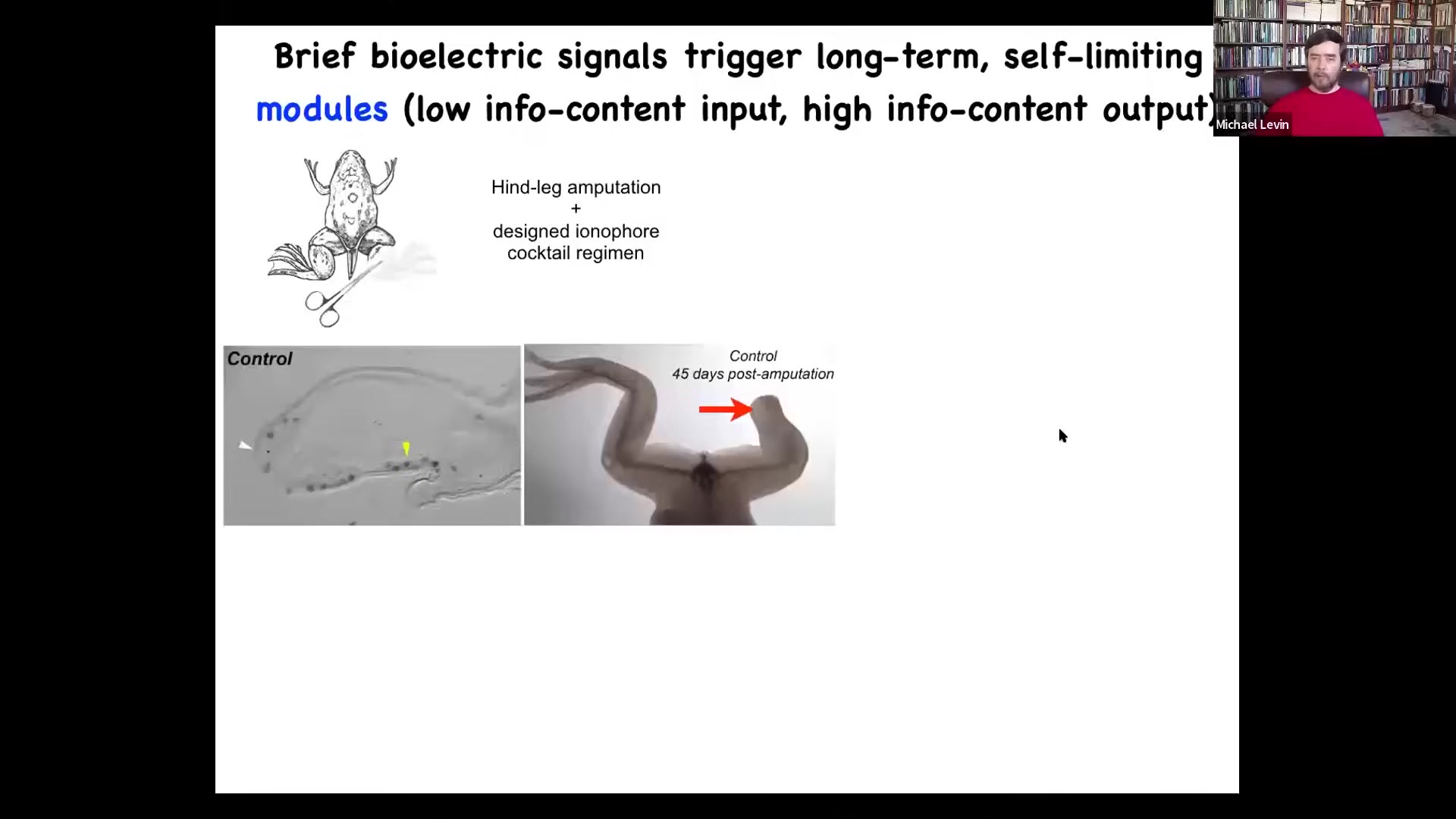

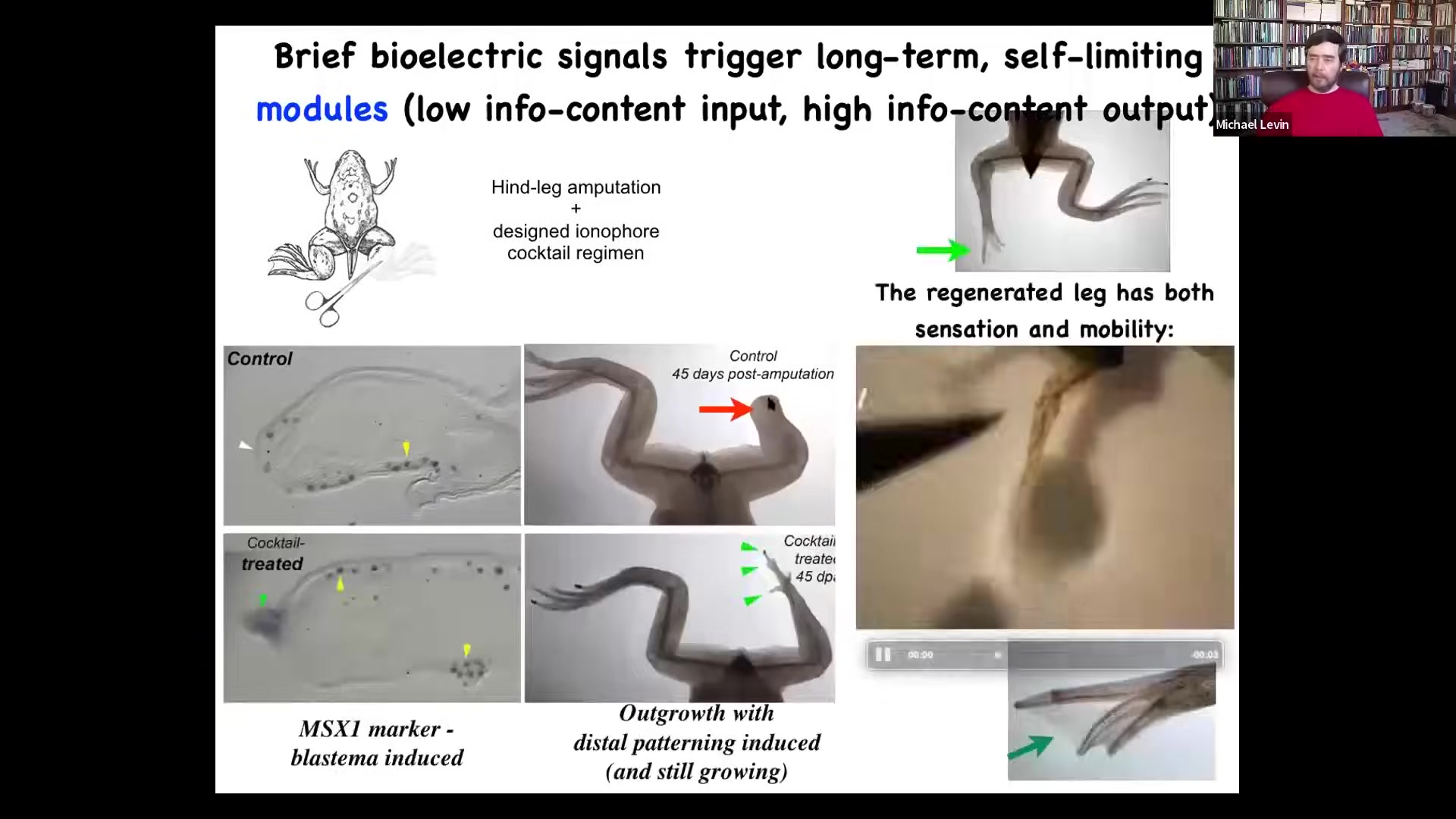

We've been using these approaches, this idea of triggers, to drive a regenerative medicine program. So here are frogs that normally do not regenerate their legs. 45 days later after amputation, there's nothing.

Slide 38/83 · 42m:42s

We came up with a bioelectric cocktail that immediately triggers after just a day of stimulation, it triggers a pro-regenerative blastema, and then eventually a leg with some toes, here's a toenail, and eventually a very respectable leg with touch sensitivity and motility. This idea that we don't micromanage, in fact, in our most extreme example, 24-hour stimulation followed by 18 months of leg growth, during which time we don't touch it at all, meaning that we're not trying to tell it how to build a leg. This is communicating right at the very beginning to the cells: you should go towards the leg building part of anatomical space, not the scarring.

I have to do a disclosure because Dave Kaplan and I started this company, Morphaceuticals, whose job it is to push all of this technology into mammals and hopefully eventually to humans using a combination of a wearable bioreactor, which David's lab makes, and the payload, which we're trying to design to convince the cells that that's what they should be doing.

Slide 39/83 · 43m:48s

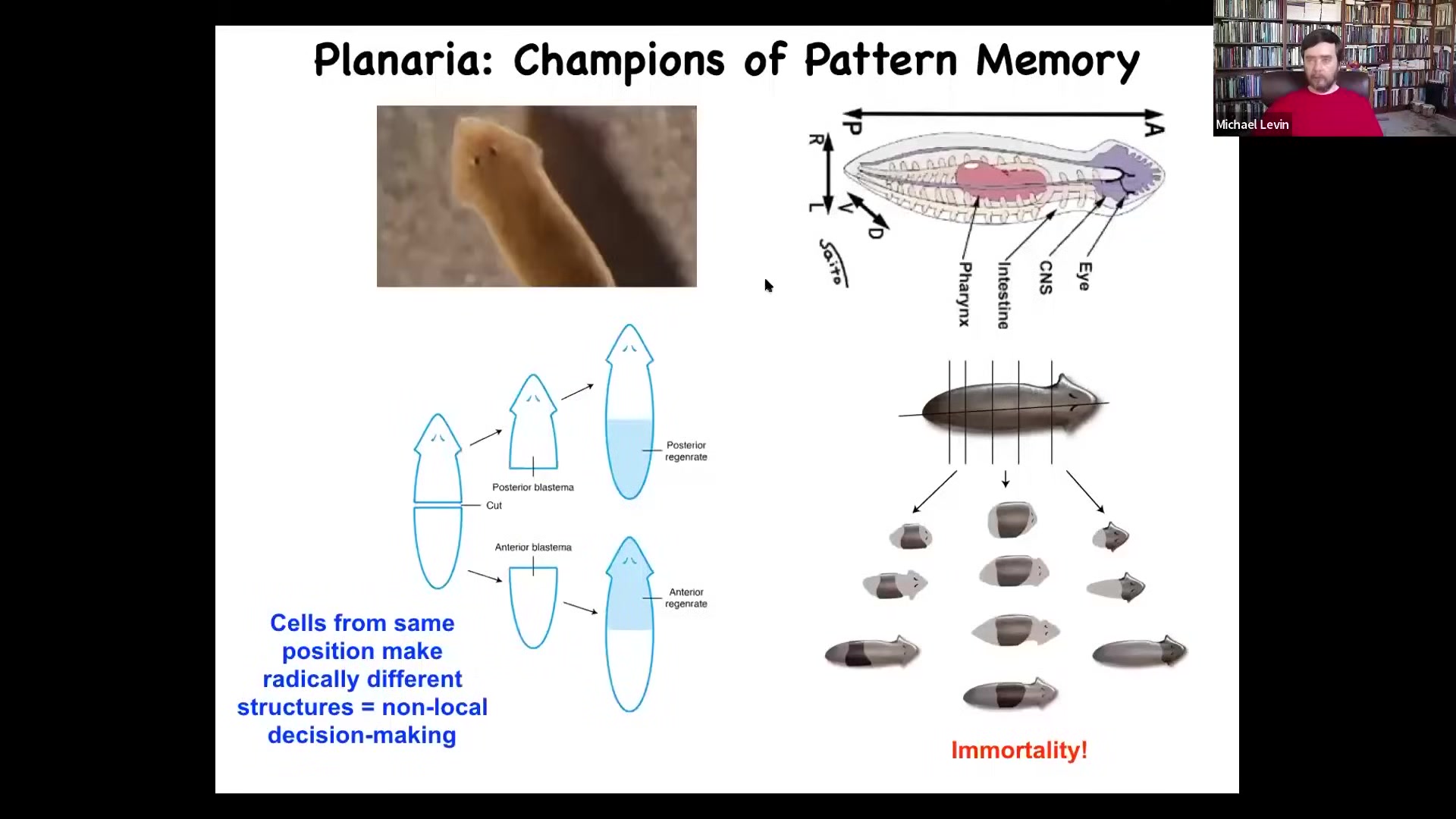

What I want to do now is talk about planaria again to reinforce the idea that these bioelectrical patterns are pattern memories. They are the encoded set point of an anatomical homeostasis process in the primitive yet competent mind of a collective intelligence of cells.

The amazing thing about these animals is that they are robust regenerators. You can cut them into many pieces. The record is 276. They're also immortal. They also have an extremely noisy genome. If anybody wants to talk about that at the end, we can. There's something profound here: why the animal with the noisiest genome is the one that's immortal, cancer resistant, and incredibly regenerative. We can talk about that at the end.

Slide 40/83 · 44m:30s

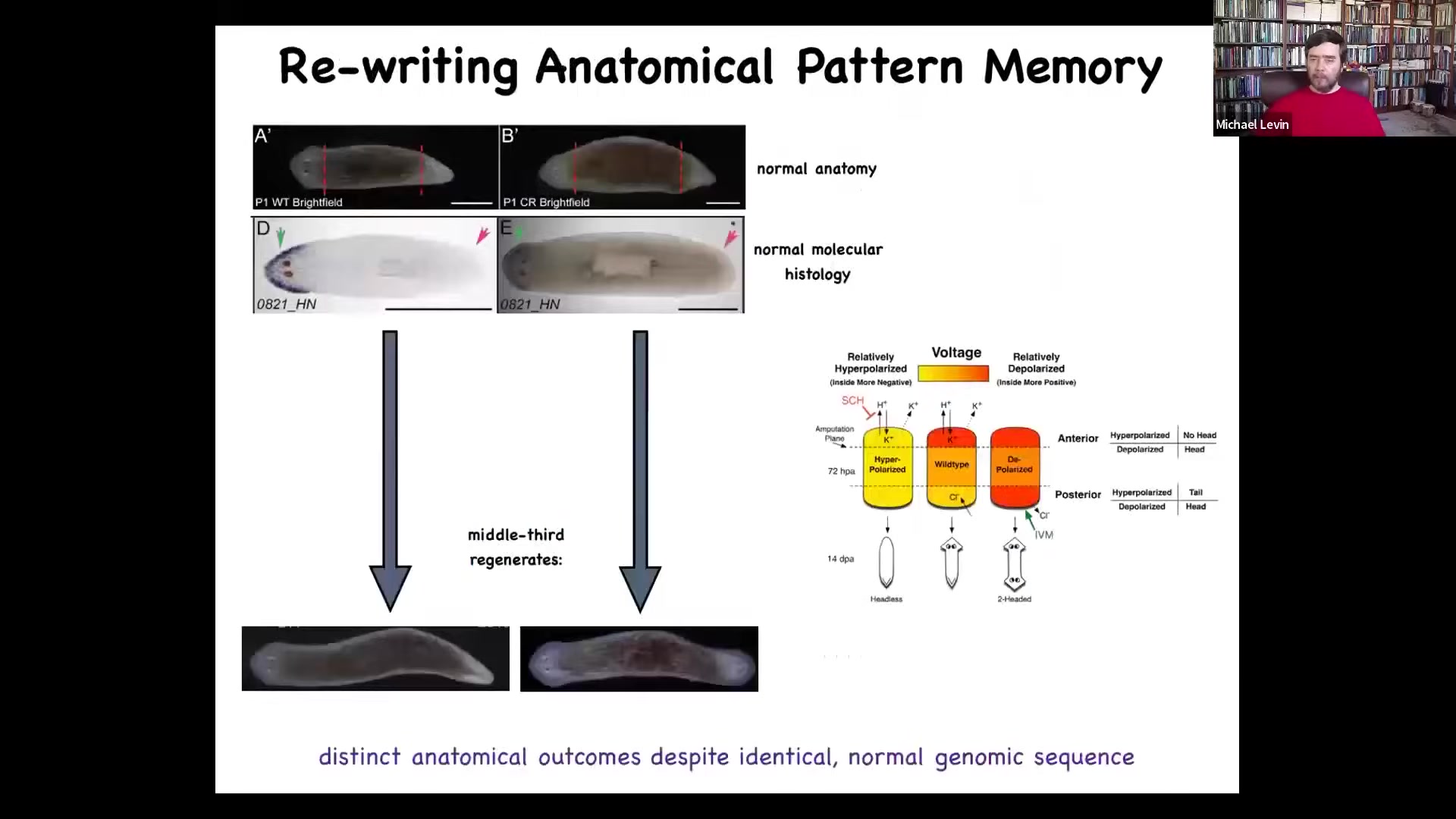

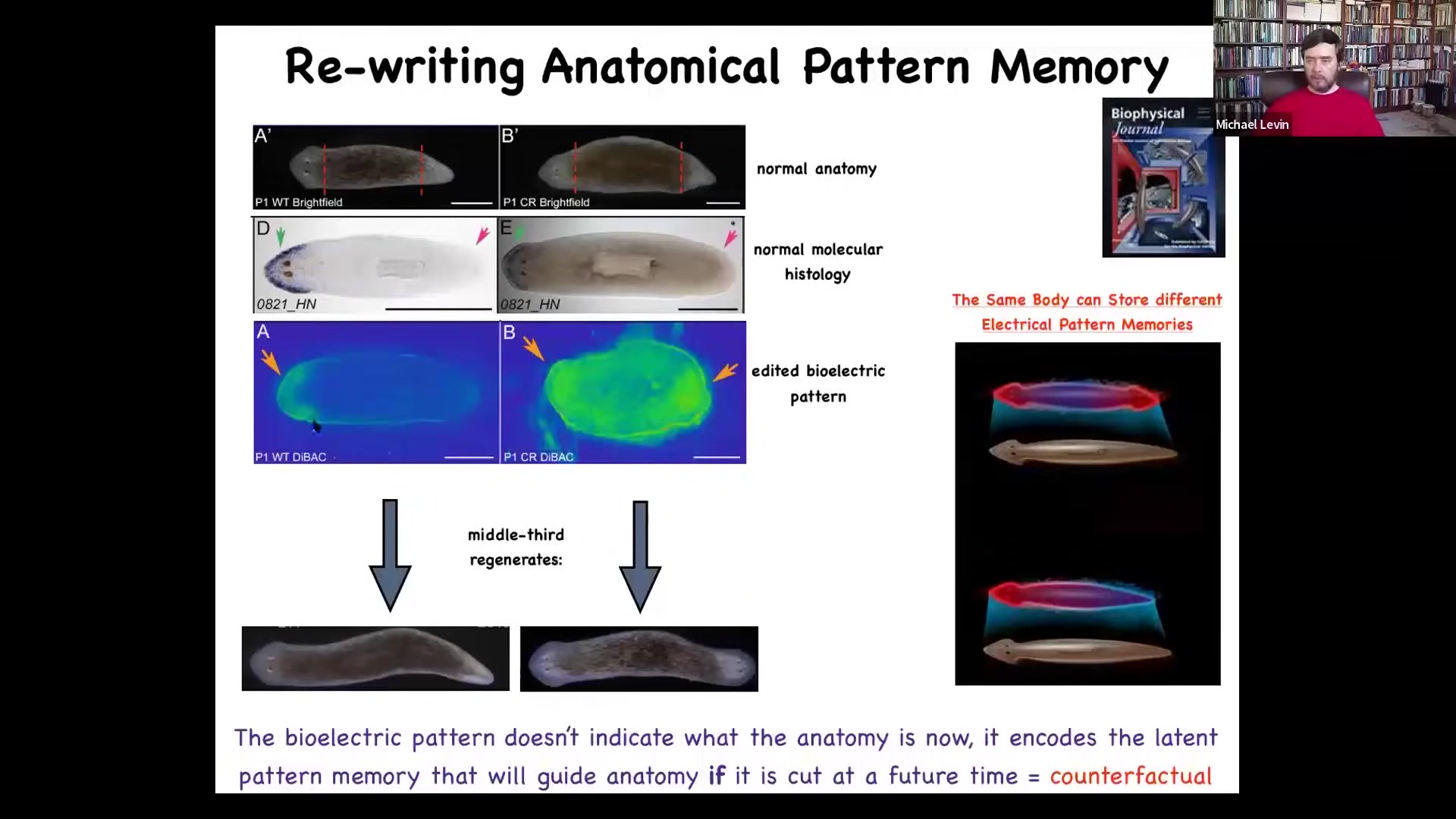

We asked the simple question, when you cut a planarian like this, you cut off the head and the tail, here's the middle fragment. How does this fragment know how many heads to have? Because reliably, 100% of the time, it makes one head, one tail. It turns out there's an electrical circuit that we identified that controls how many heads you're supposed to have. If you target that circuit, you can make these two-headed animals.

Slide 41/83 · 44m:58s

The way you do it is here is the bioelectrical pre-pattern of this animal, and it says, one head, and the molecular biology says one head, here's the head marker, and sure enough, one head. What you can do is you can take this animal and rewrite this bioelectrical pattern. This is still messy, the technology is still very in its infancy, but you can do it. You can give it a pattern of two heads, and then this animal will in fact make a two-headed animal. This isn't Photoshop. These are real animals.

What's amazing is that this bioelectrical pattern is not a map of this animal. This is not a readout of a two-headed animal. This is a readout of this anatomically normal one-headed animal. The anatomy is normal. The gene expression is normal. The bioelectric pattern memory has been edited, but nothing here has changed until you injure him. Once you injure him, these cells consult this pattern and produce what the pattern says. This is their reference point. They don't know any better. Of course, they're just going to do this. The cells have no way of knowing that this is defective in any way.

What I think is interesting here is that this is a really primitive counterfactual. One amazing thing about our brains is this ability of mental time travel, that we can think about states that are not true right now, that either have been true in the past or might be true in the future. This is a counterfactual memory in the mind of the collective intelligence. This is not true right now. And that's fine. It deviates from the anatomy. A single body can store at least two different representations of what you are going to do in the future if you get injured. All of this can be stored in one anatomically normal body. This is a simple counterfactual.

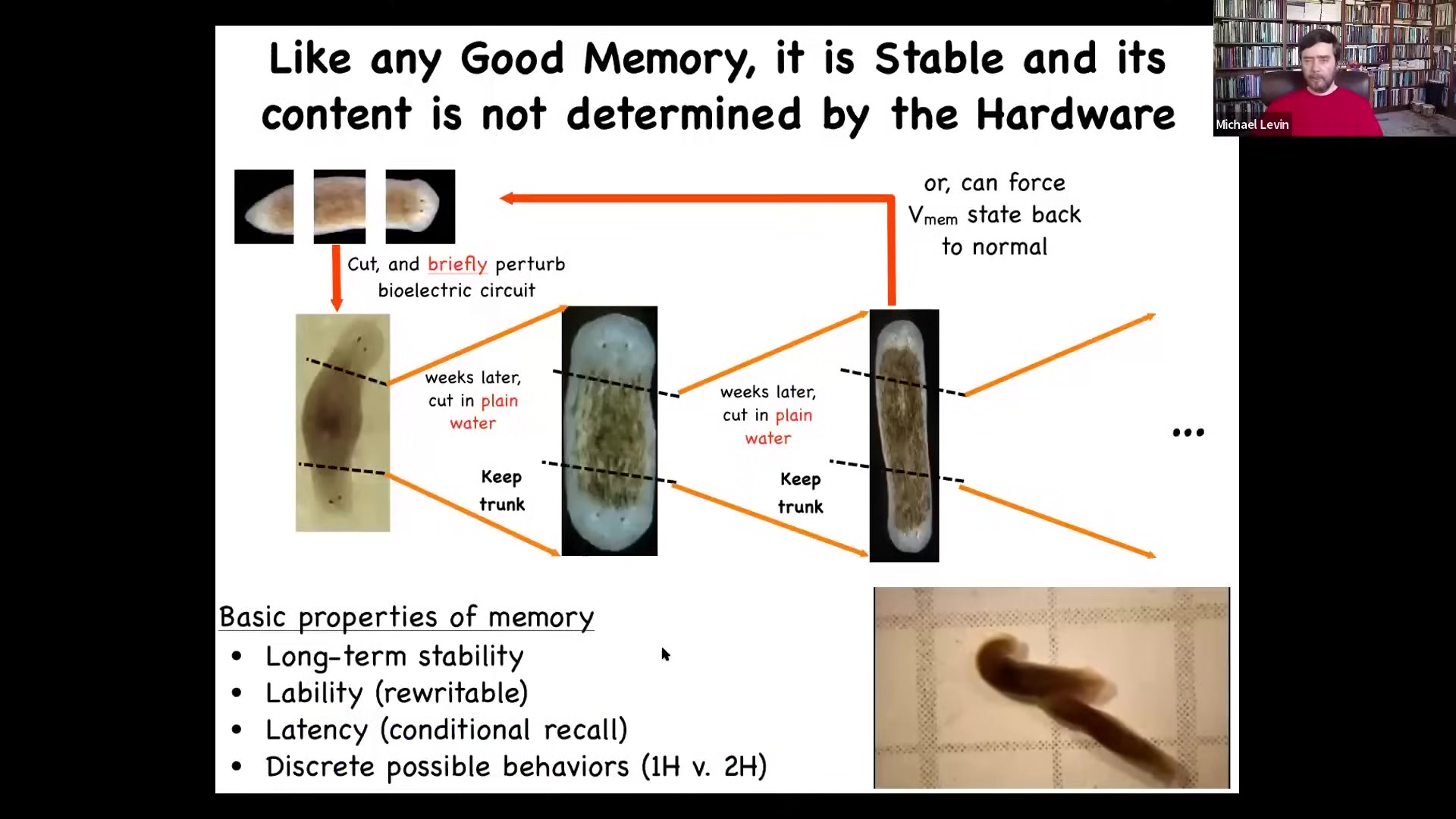

Slide 42/83 · 46m:45s

And the reason I call it a memory is because if you ask what happens to these two-headed animals, once you recut them in plain water, no more manipulations, you recut them. The traditional approach says we haven't touched the genome. The genetics are still wild type. You cut off this ectopic secondary head, you get rid of the primary head. It's going to go back to normal and give you a normal one-headed animal. That's the way of thinking; it's the reason why two-headed worms were first seen in 1903 or so. From 1903 to 2009 nobody recut these two-headed worms. That's because it was considered completely obvious what would happen. The genetics are normal. They'll go back to normal. But that is not what happens. If you cut them, they continue to be two-headed in perpetuity.

I call it a memory because it has all the properties of memory. It's long-term stable, it's rewritable, it has a conditional recall, and it has two discrete behaviors. Here are some videos of these animals moving around.

This is one of those examples where we're thinking about these things with a different framing. Not as a molecular biology machine that is going to do whatever the genome says, but as a proto-cognitive kind of agent that has to navigate morphospace and whose memories could be rewritten. It suggests new experiments that had not been done.

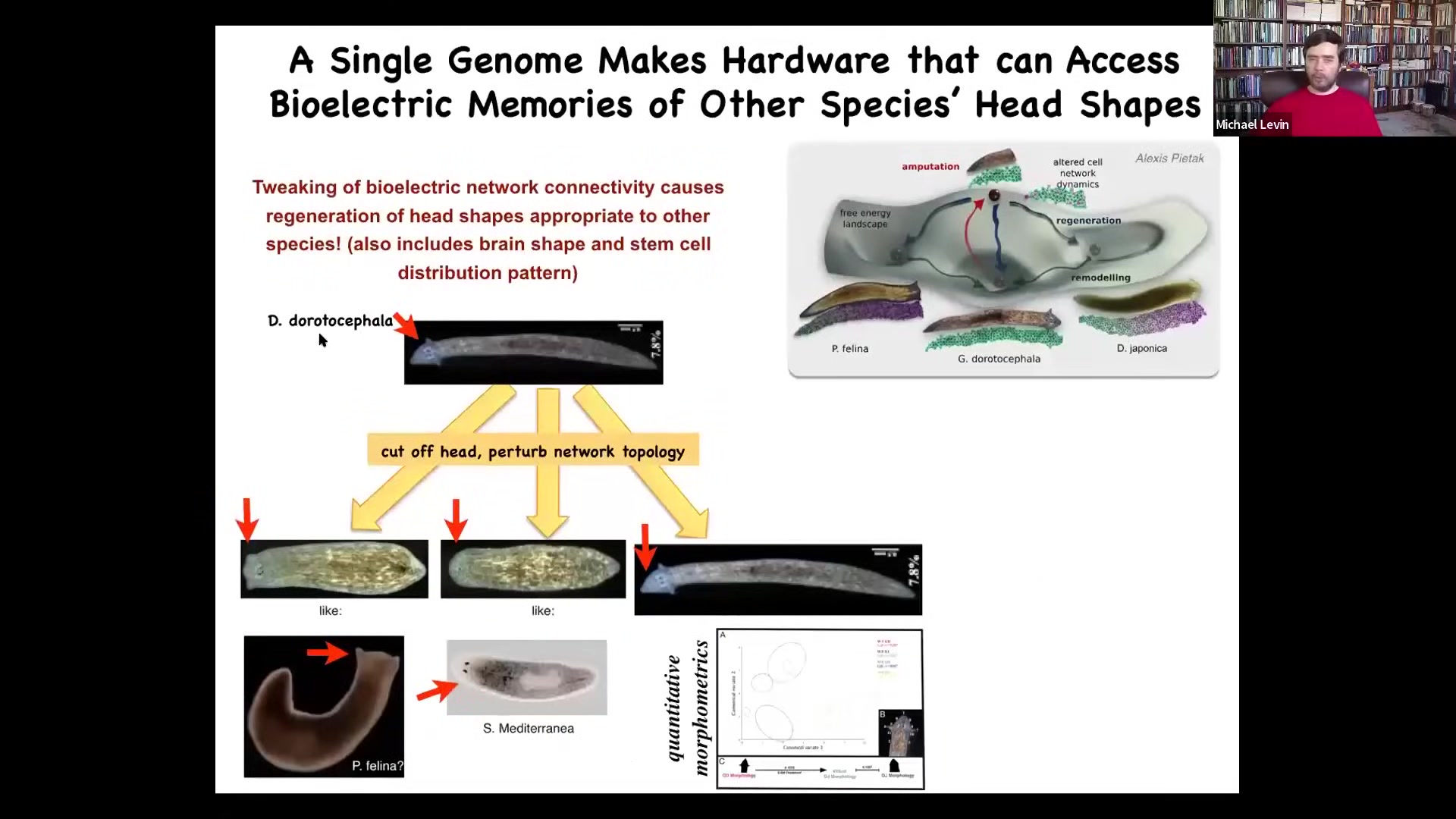

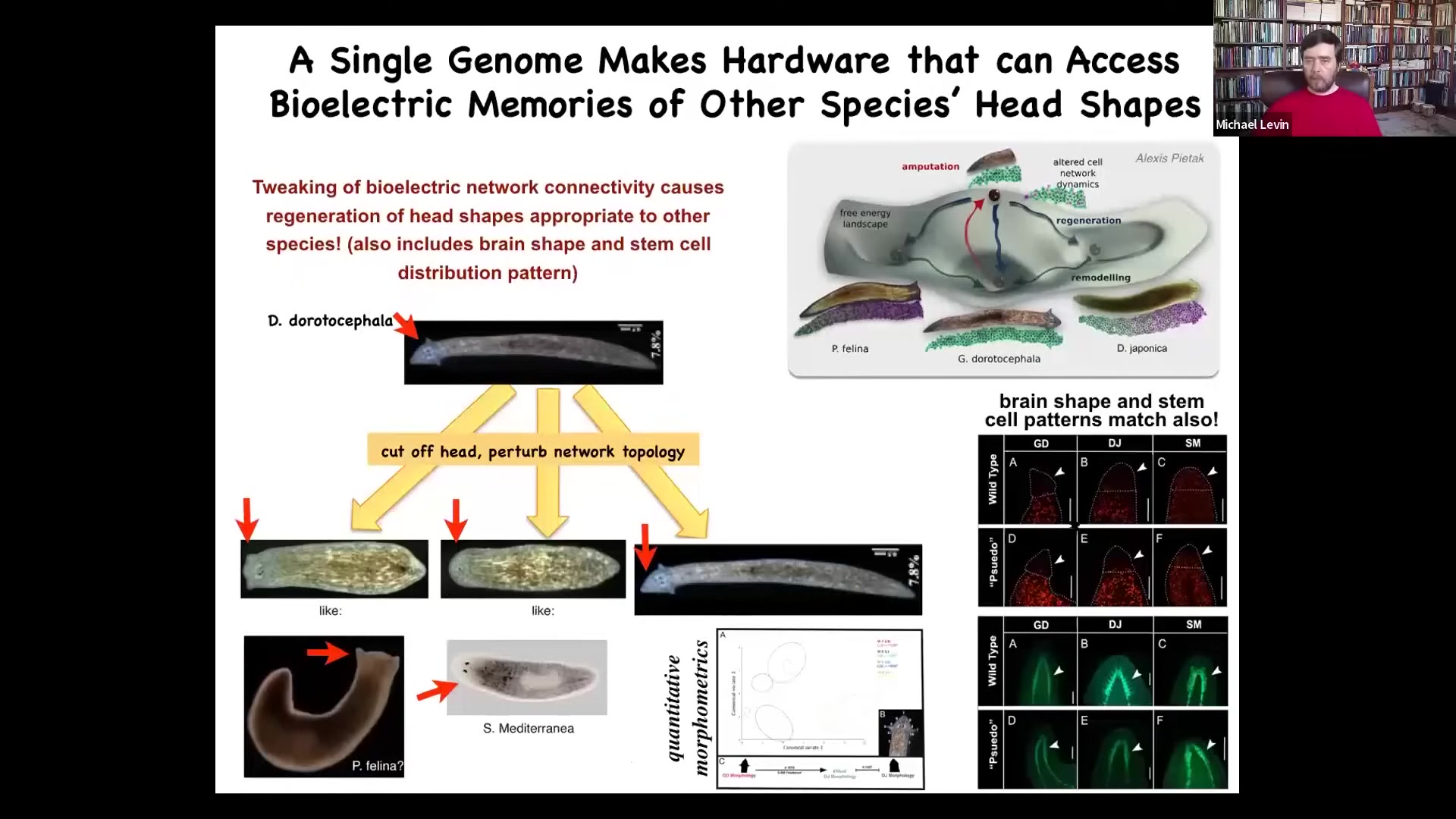

We're doing a lot of computational modeling to unify the picture of the bioelectrical circuit and its state space with some ideas in connectionist machine learning and dynamical systems to understand how these electrical networks can restore from partial inputs and store memories as attractors. Interestingly, it's not just about head number. It also controls head shape.

Slide 43/83 · 48m:35s

So here's a nice triangular headed species. If you cut off that head and you confuse that bilecular network for a while, it takes about 48 hours, they will end up making flat heads like a P. falina or round heads like an S. mediterranean in addition to its normal head.

Slide 44/83 · 48m:55s

Not only the head shape, but actually the distribution of the stem cells, the brain shape will be like these other species.

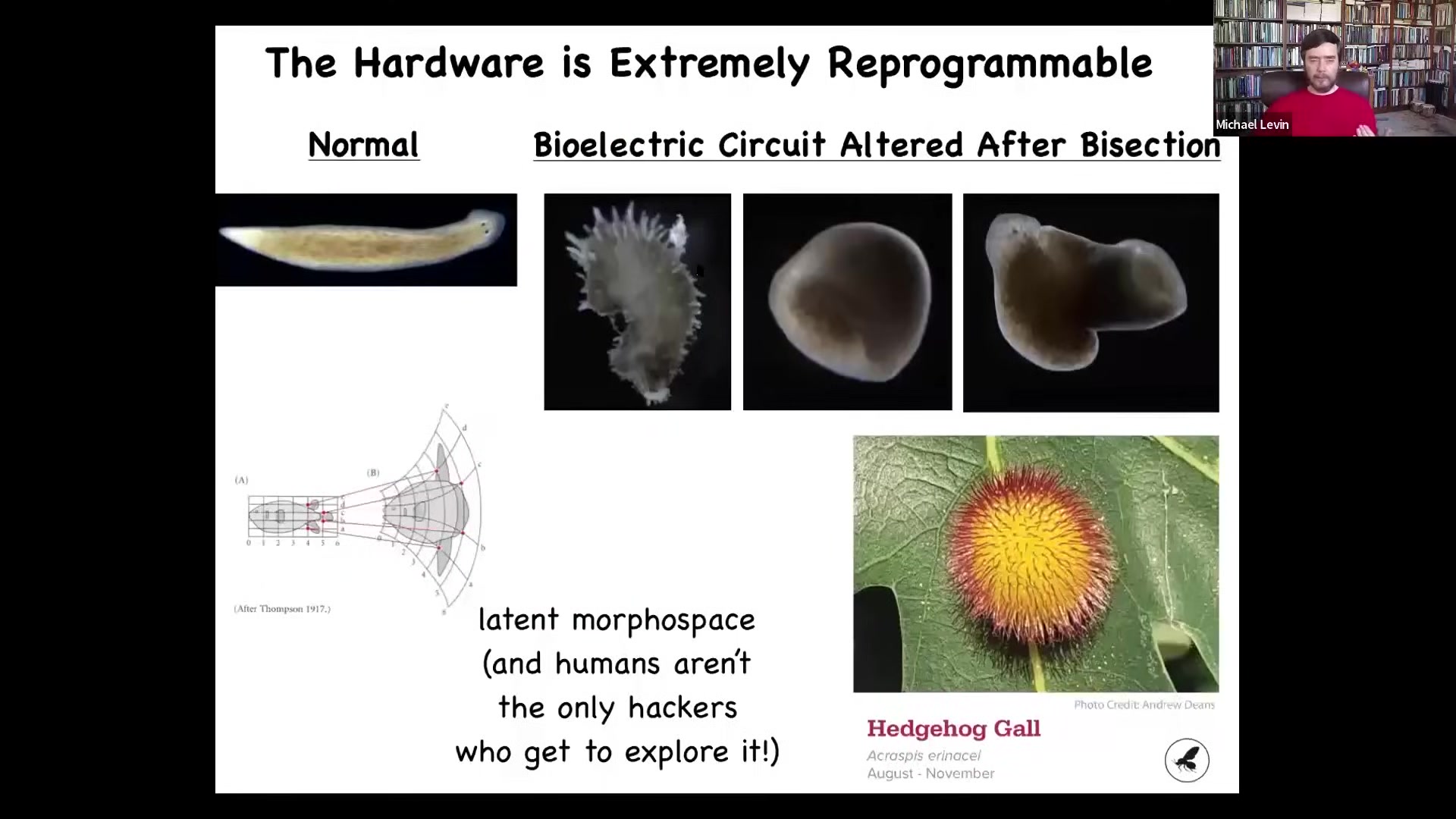

These other species are between 100 and 150 million years distant from this guy. In morphospace, there are lots of attractors. They're normally occupied by these particular species, but this hardware has no problem going there if the electrical state says so. They will visit these attractors and you can get a different species anatomy from the same cells. You can go further and explore the latent morphospace.

Slide 45/83 · 49m:28s

And you can make planaria this way that don't look like worms at all. They can have a different type of symmetry. They can be hybrid forms like this. They can be these crazy spiking things. You can do all of this with genetically normal cells. It's cool that humans aren't the only ones that know how to hack these cells to explore the latent morphospace of possibilities.

In fact, other biology hacks each other all the time. This is a gall formed on an oak leaf by signals from a parasite from a wasp embryo. This thing is not made of wasp cells, it's made of leaf cells. So that wasp has produced some signals that hack the morphogenetic competencies of these cells and get it to build this. We would have had absolutely no clue. We don't have anything in our arsenal yet that would allow us to look at the genome of the oak and the thing it normally makes and say that most of the time it's flat and green, it's also capable of forming this round spherical red spiky thing. We have no ability to guess that. So this exploration of morphospace is a challenge for the coming decades, I think.

Slide 46/83 · 50m:35s

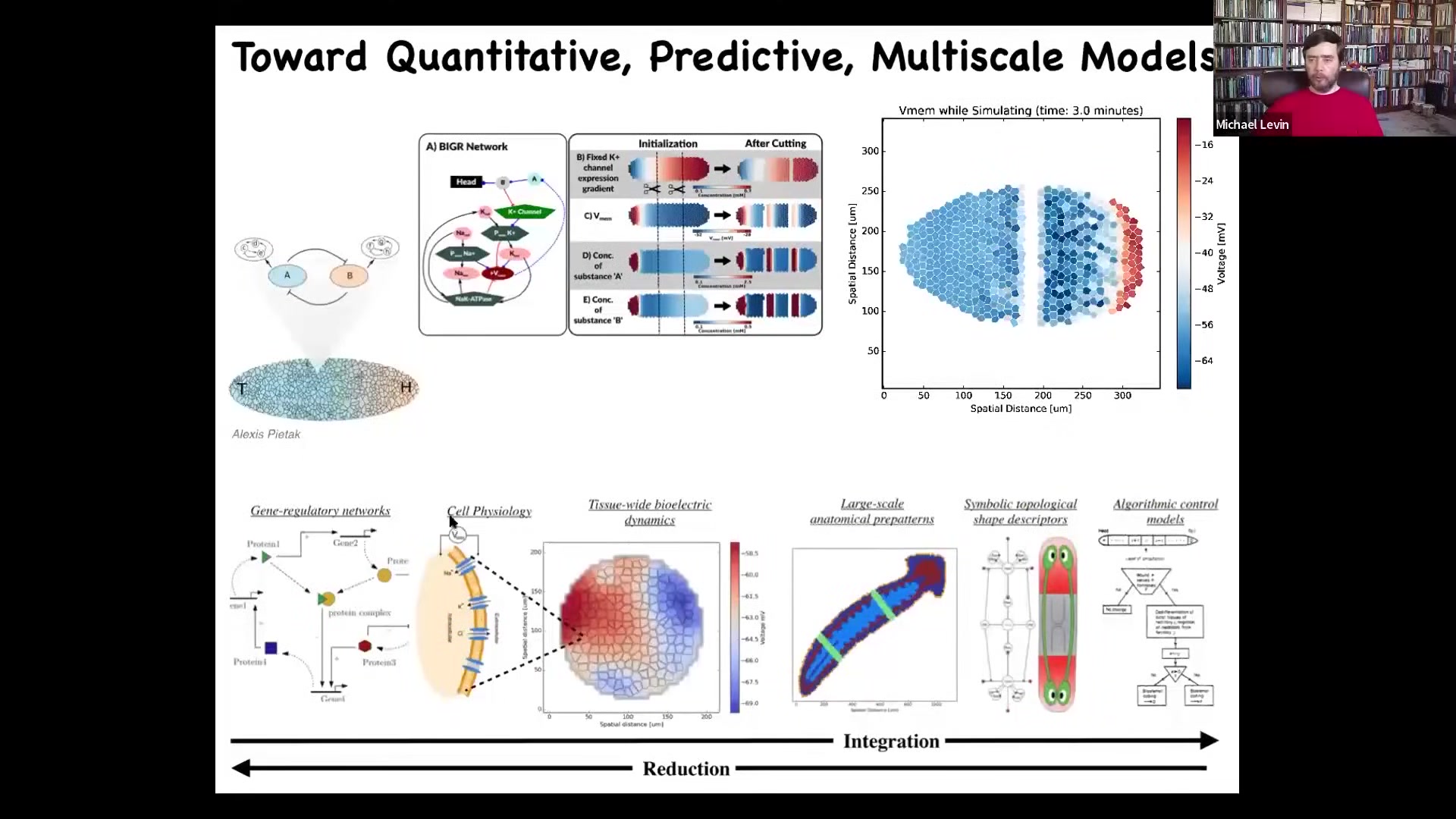

In order to do this, we're trying to do a full stack framework where you go from the expression of the different hardware components, so channels and pumps, all the way up through the physiological, multi-scale physiological dynamics, the organ-level patterns, and then eventually a body-wide algorithmic description of what's going on.

Full integrative information so that you can actually read out human-understandable rules at this end. Looking at this and the idea that there are all these problem-solving competencies, there are memories, there's learning capacity, both at the molecular and at the cellular level, suggests to us that there is a complement to this conventional biomedical approach, which is that these things are bottom-up ways to try to force the hardware to take on specific states.

Slide 47/83 · 51m:18s

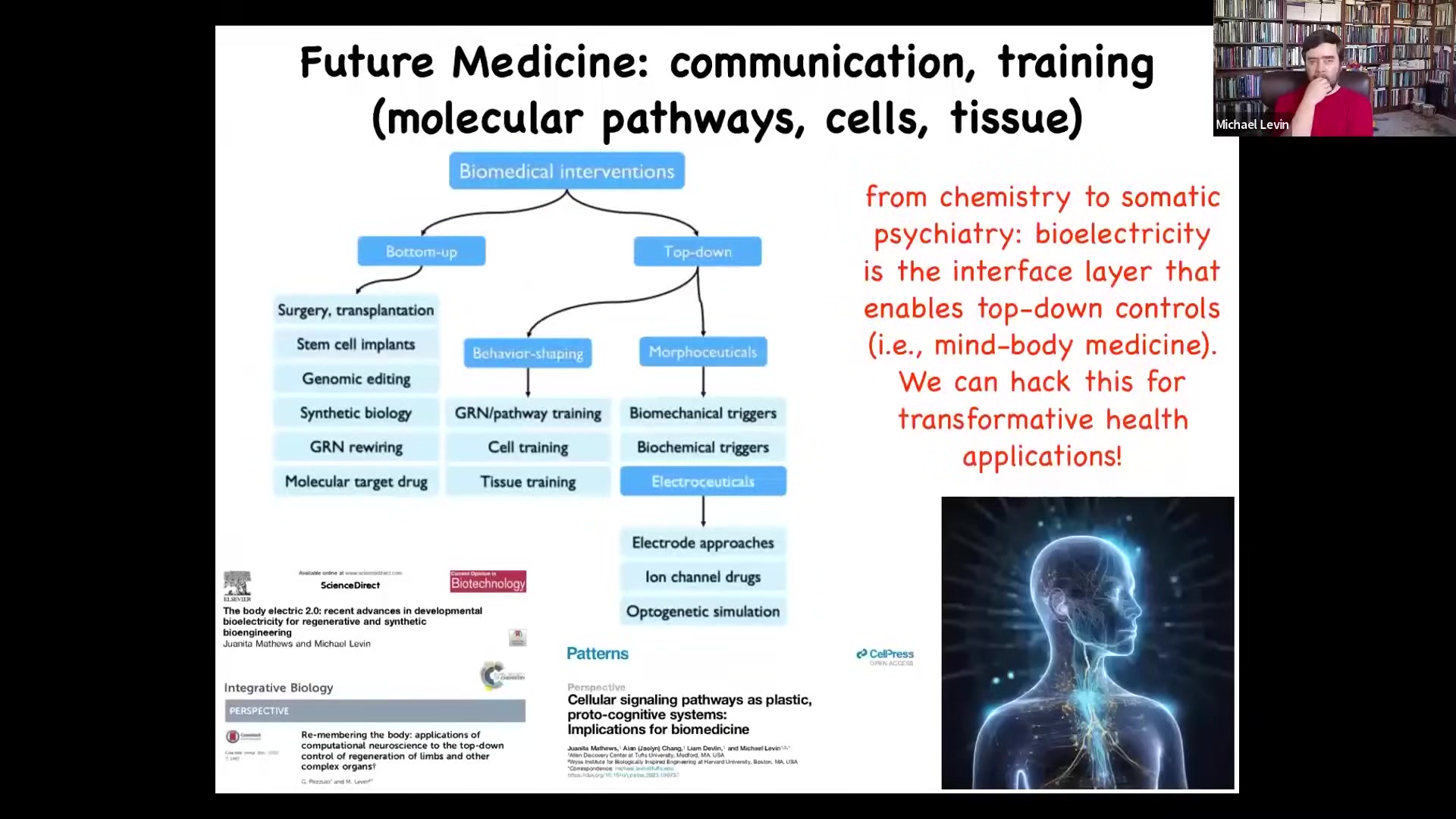

But there's a wealth of techniques from behavioral science and from computer science and so on that could take advantage of some of the top-down controls that are possible to reach states that are way too complex for us to micromanage.

All of that is described here and the implications for biomedicine. But all that is to put out this very controversial idea that I think the future of medicine is going to look less like chemistry and a lot more like somatic psychiatry. It's going to be all about communicating and resetting the goals of the cellular collectives.

Slide 48/83 · 52m:08s

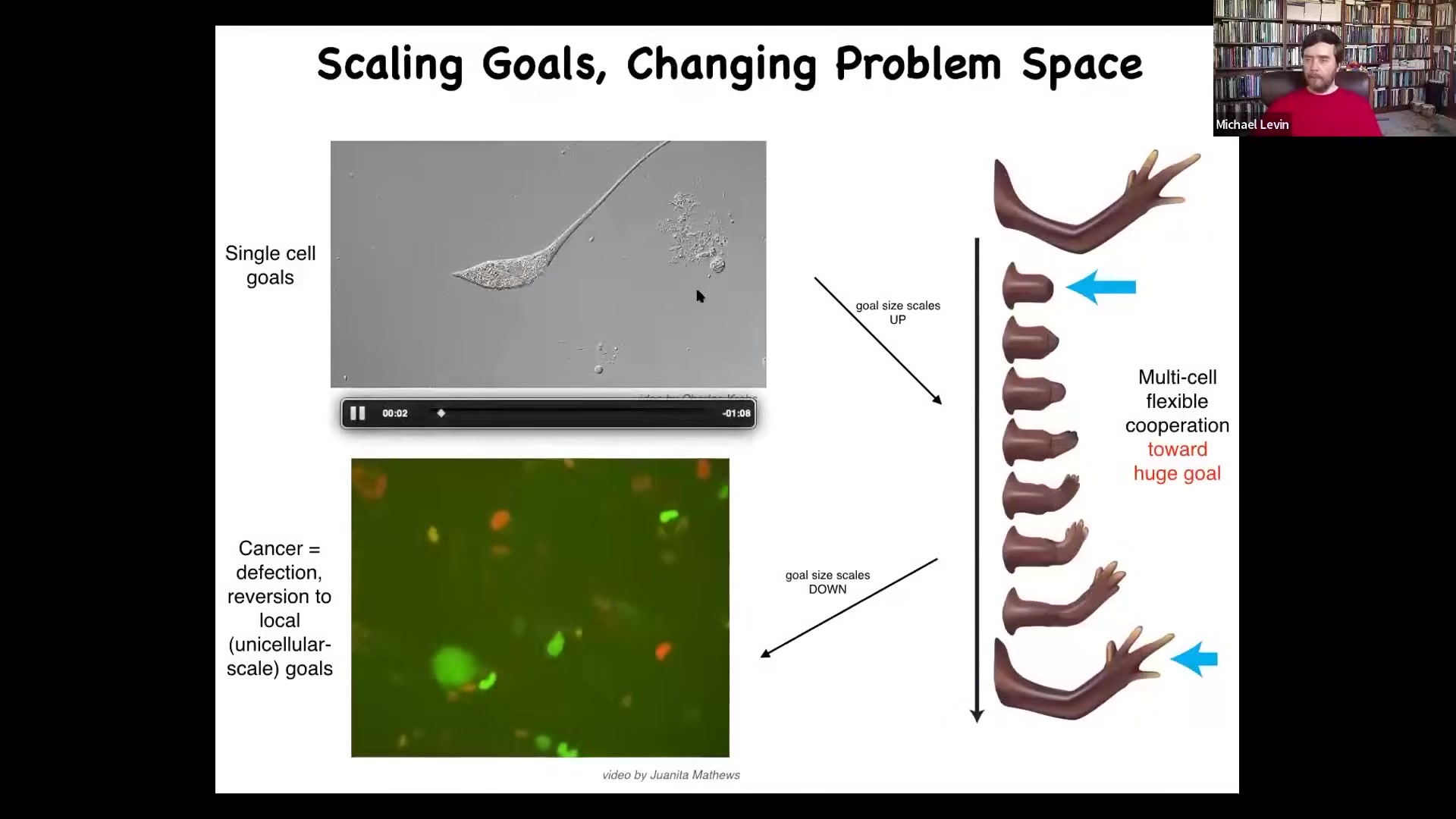

At the very last thing I want to show you for a couple of minutes is this. We talked about these kinds of systems having various goals that they try to reach. Where do these goals come from? Typically, if you want to think about anatomical goals, such as target morphologies that embryos make, or repair to, or even physiological states, the typical answer is evolution. They're set by evolution. So everything that had the goals that are not fit in a particular environment has died out. And so now this is what you have. We want to explore that idea. The first thing that I'm going to show you is this important notion that the scale of goals can change radically, not just on an evolutionary time scale, but on the time scale of a single individual, and this has real implications.

I use this concept of a cognitive light cone. The cognitive light cone — these diagrams are stolen from some of the physics space-time diagrams, where we can try to imagine the size of the biggest goal that a given system can follow. Creatures like ticks, bacteria have little goals. Everything they're doing is to keep within a tiny region of space-time in a particular physiological state. Some creatures can have bigger goals. Your dog can certainly have some planning and some spatial awareness. It's never going to care about what happens three weeks from now, two towns over. Humans actually can have extremely large cognitive light cones. There are people working towards world peace and what the financial markets are going to do one hundred years from now. We are composed of many agents cooperating and competing with each other that all have different-sized cognitive cones in different spaces.

Here's the practical end of it.

Slide 49/83 · 53m:58s

Biology, during evolution, went from having little tiny goals to much bigger goals such as this. All of these cells are a single agent pursuing this target in anatomical space and doing a very nice job of being able to reach it. You have a scale up. During evolution, you have an inflation of this cognitive icon. But that process has a failure mode. That failure mode is cancer. What happens is that when cells disconnect from the electrical network that allows them to remember these grandiose goals, they revert to being amoebas.

Slide 50/83 · 54m:35s

And this is what I showed you a few minutes ago, that these cancer cells disconnect and treat the rest of the body as environment. They're not any more selfish. They have smaller selves. Some game theory approaches model cancer cells as being fundamentally more selfish. I just think they have smaller selves. I think it's a shrinking of the boundary between self and world. As far as they're concerned, the rest of the body is external to them. That way of thinking about cancer, which is quite unconventional, makes a strong prediction.

It suggests that you don't have to kill cancer cells. If you convince them to reconnect to the rest of the electrical network, they will simply meld their tiny little goals into the major goal of the collective and go back to making nice organs and so on. That's exactly what we showed. In the frog, if you inject an oncogene here, the oncoprotein is blazingly strong. It's in fact all over the place, but there's no tumor. There's no tumor because we co-injected an ion channel that forces these cells into electrical communication. It doesn't get rid of the genetic damage, doesn't kill the cells, but they are now back as part of the network and doing what they're supposed to do, which is to make nice, smooth muscle and skin and so on.

And so again, you see this idea of thinking about what a self is and how it sets boundaries between itself and the outside world and how collective-scale goals lead directly to a kind of biomedical approach, which we're now pushing all this into human cells, in particular glioblastoma. This is a biomedical research strategy.

Slide 51/83 · 56m:10s

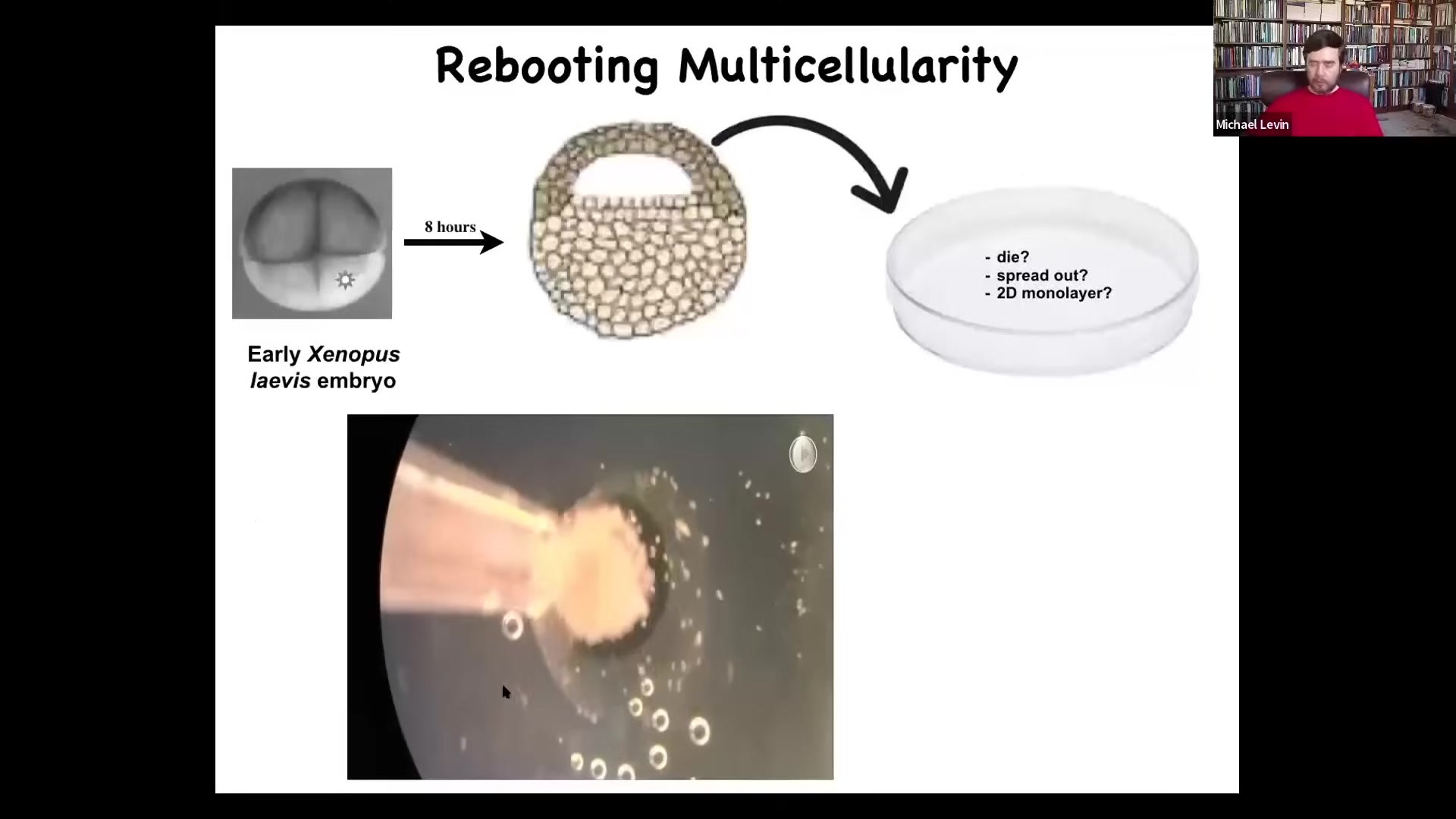

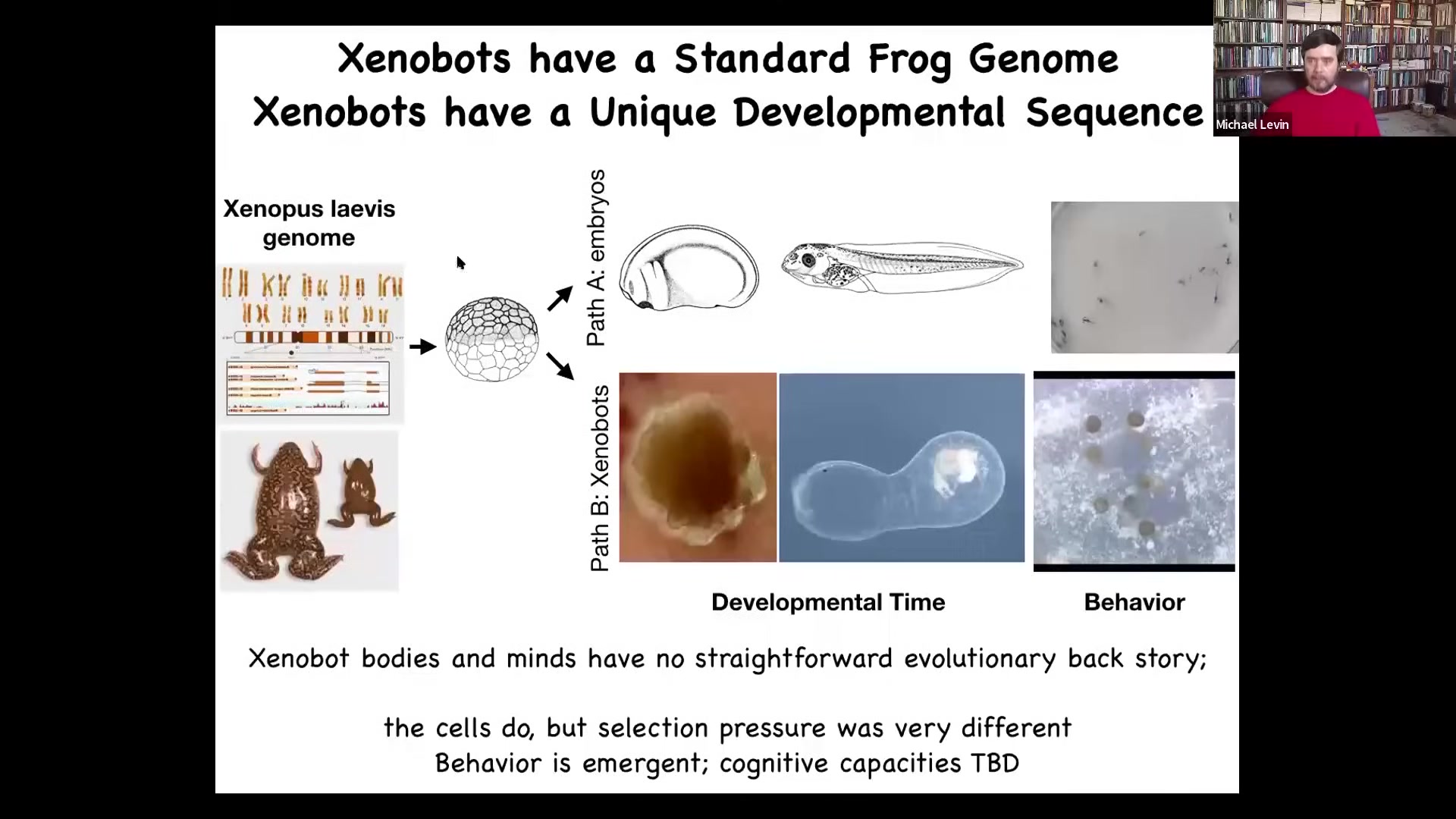

The very last thing that I want to point out is that in addition to that cognitive light cone being able to change in our lifetime, so the size of the goals can change, but also, where do these goals come from? This is work done with Josh Bongard's lab at UVM, and Douglas Blackiston is the biologist who did everything I'm about to show you. I have to do a disclosure: Josh and I have started a company around some of these ideas. We asked: what will cells do if they're liberated from their normal boundary conditions and asked to reboot their multicellularity? Would they have different goals? If so, where do they come from?

Slide 52/83 · 56m:48s

Here's what we did. Very simple experiment. Here's a frog embryo. This is a cross-section. You take a bunch of skin cells from up here and you put them in a little Petri dish. As you do this, you've dissociated all these cells, just a cloud of cells. They could do many things. They could die. They could move away from each other. They could do nothing. They could spread out like a two-dimensional monolayer. Instead, they coalesce to form this amazing little thing, which we call a Xenobot.

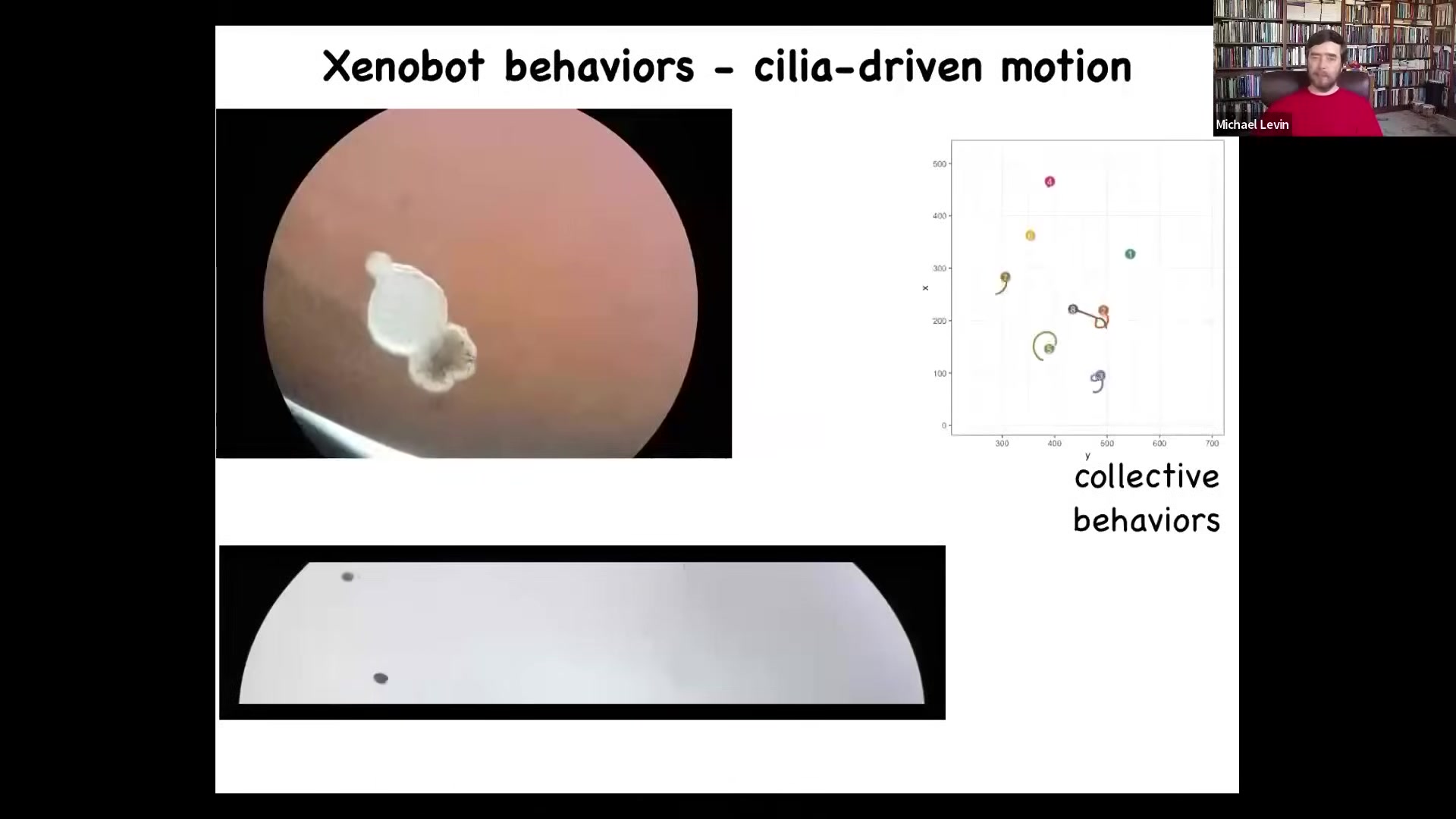

Slide 53/83 · 57m:12s

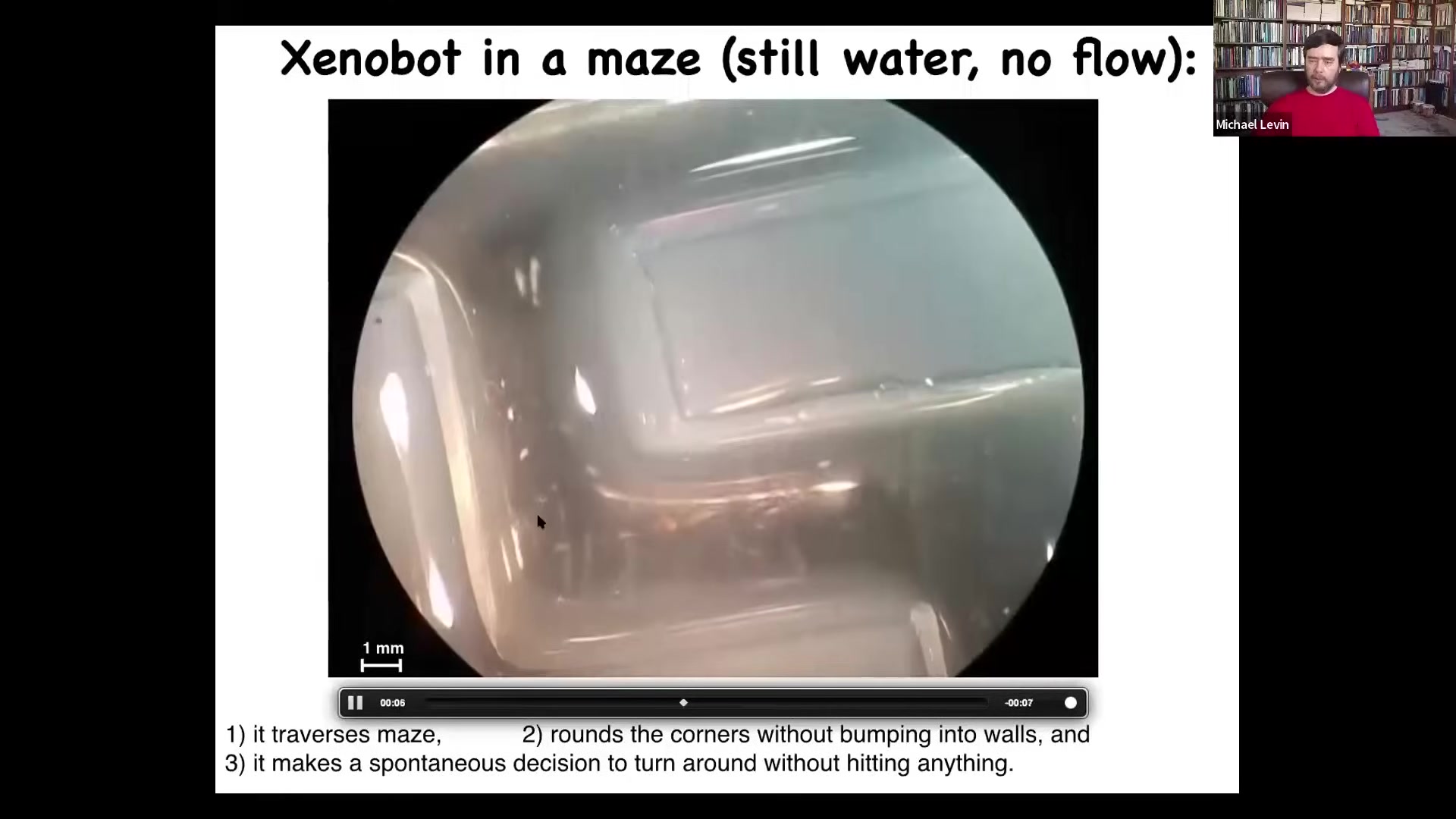

Xenobot because Xenopus laevis is the name of the frog, and it's a biorobotics platform, so we call it a Xenobot. They do a few things. They swim, and they swim by little hairs that they use to row against the medium. Those hairs are normally used to redistribute mucus down the body of the frog, but they've repurposed them to swim. They can go in circles. They can do this patrolling thing back and forth. They have these group collective behaviors and lots of individuality. They're very different behavior patterns. Here's one navigating a maze.

It goes down, it floats down here.

Slide 54/83 · 57m:48s

At this point, it takes the corner without bumping into the opposite wall. It spontaneously turns around.

They have all kinds of spontaneous behaviors too, in addition to being able to react to features of the environment.

Slide 55/83 · 58m:00s

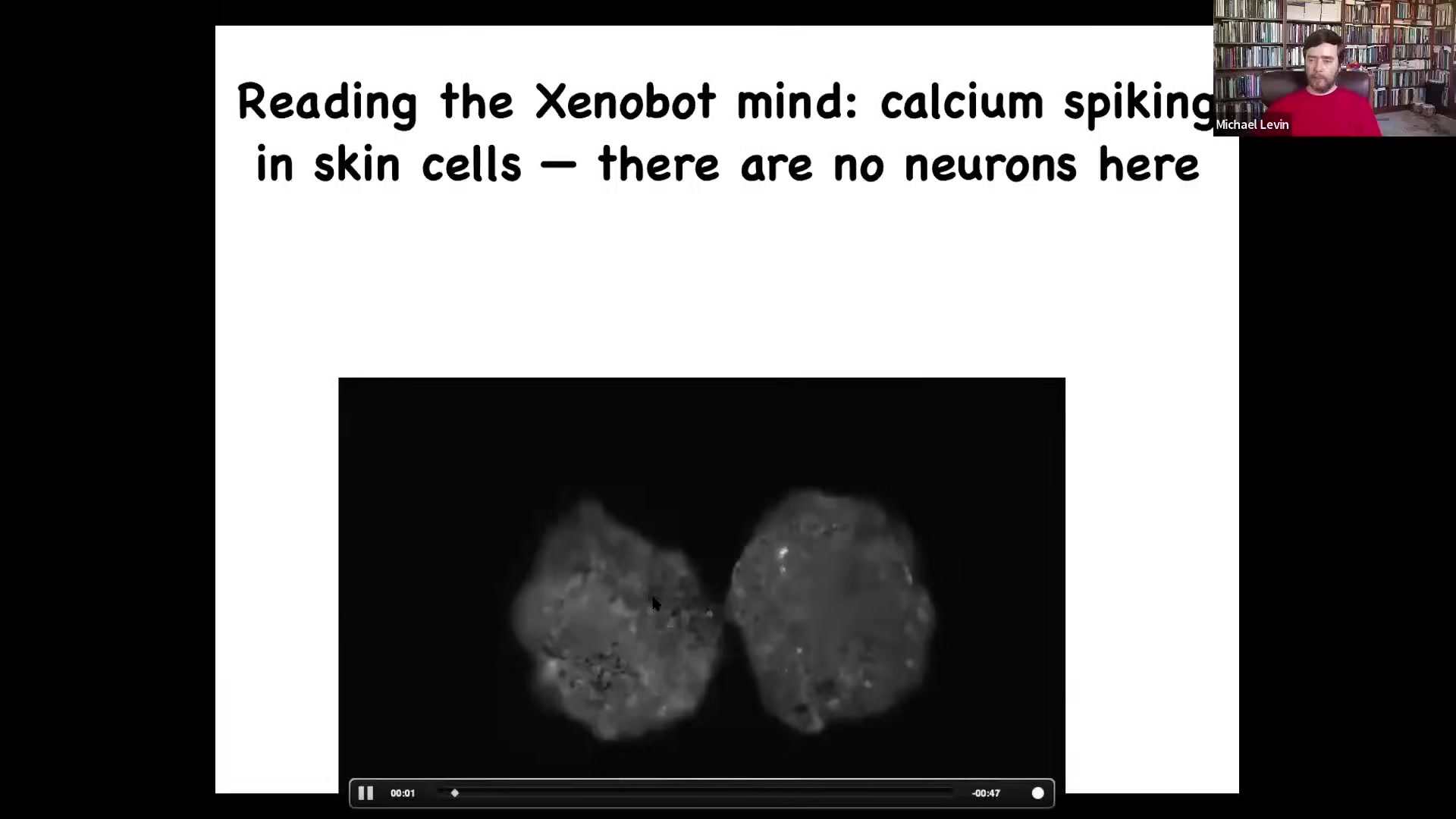

If we do a kind of calcium imaging, which is what people do to read brain activity, you see that they have all sorts of interesting signaling, which we're using information theory now to ask whether they're talking to each other. But there aren't any neurons here. That little creature you saw navigating the maze and turning around whenever it feels like it, that's all skin. There is no nervous system there.

Slide 56/83 · 58m:28s

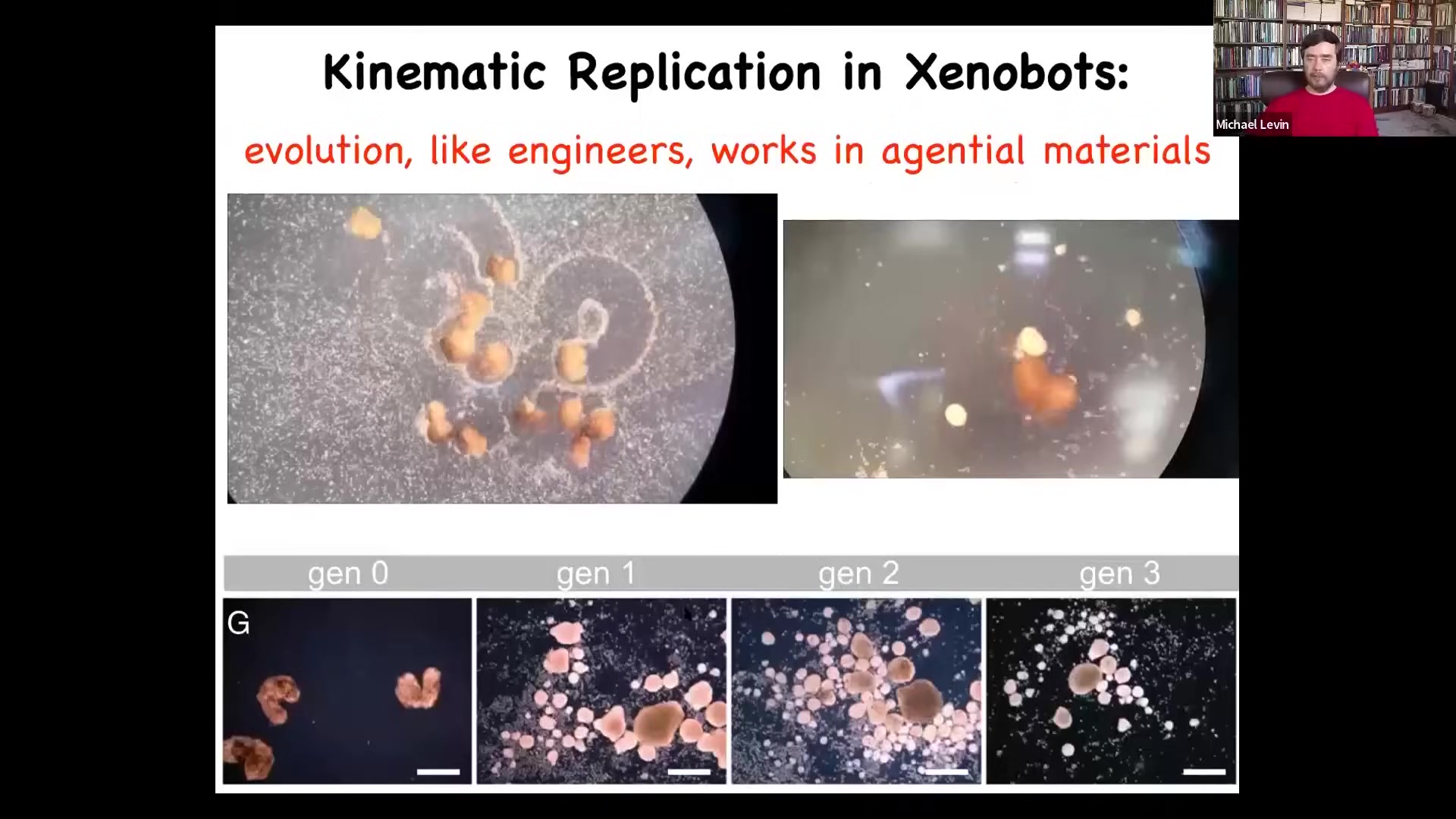

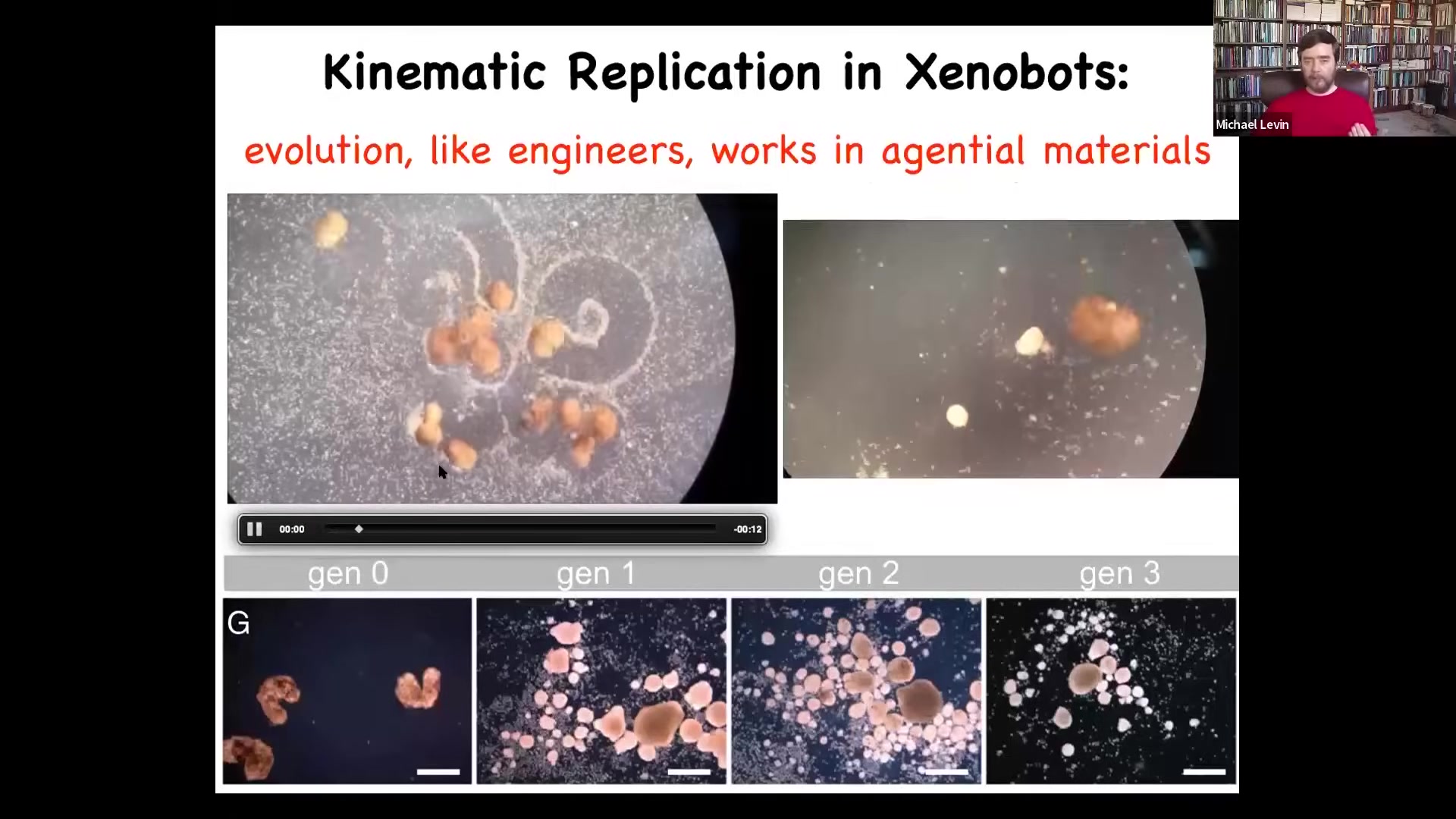

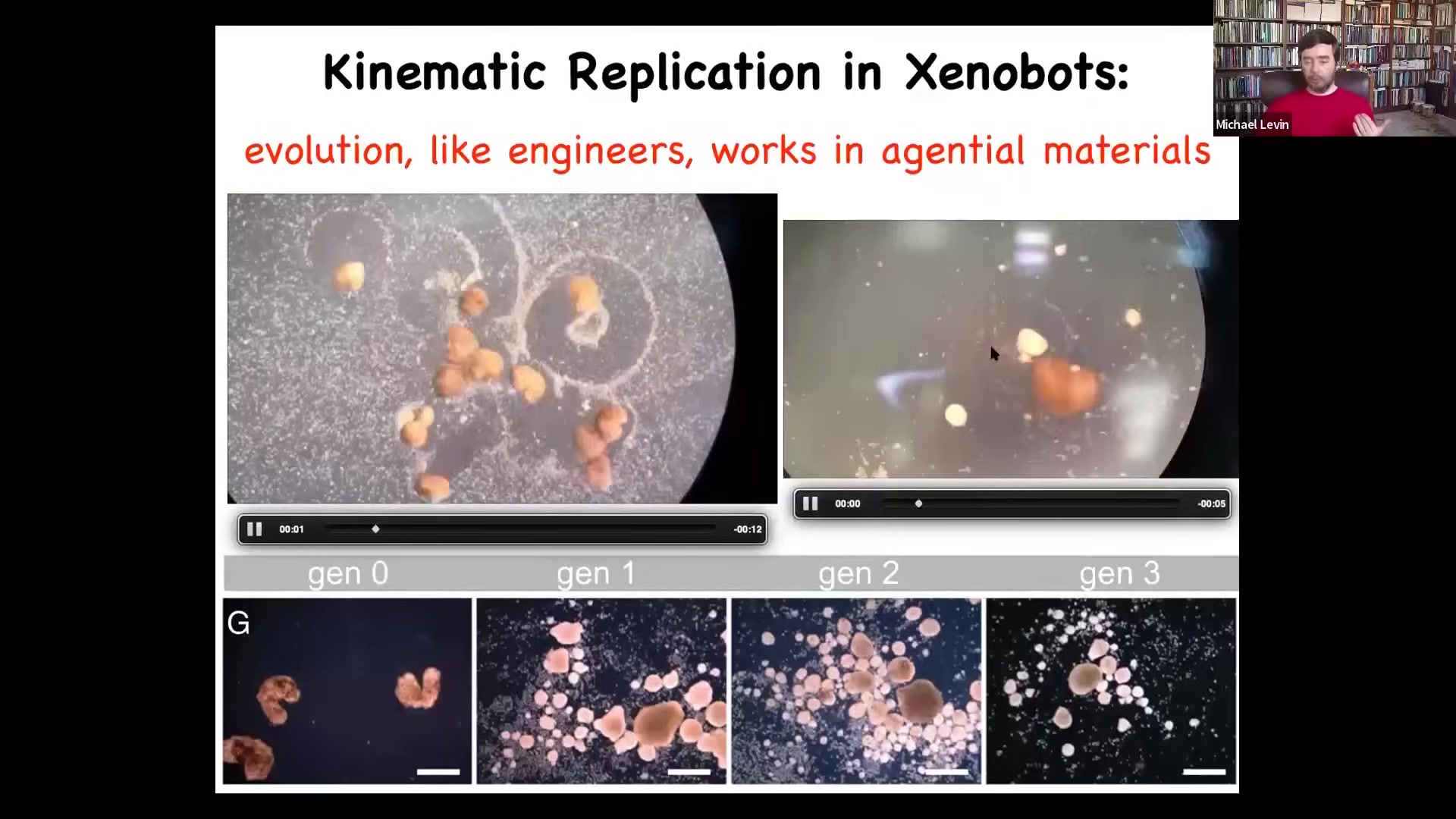

And the most amazing thing they do, they do many things that I don't have time to talk about, but the most amazing thing so far is what we call kinematic self replication. We've made it impossible for these guys to replicate in the normal ****** fashion.

Slide 57/83 · 58m:40s

They're just skin. They don't have any of those organs. What we found is that if you give them skin cells, this white stuff here is just loose skin cells sprinkled in the medium.

What they do is they run around and collect them into little piles.

They polish these little piles and shape them. Those little piles, because these bots are working with an agential material, just like we were when we made the bots, mature into the next generation of Zenobots.

Slide 58/83 · 59m:05s

And what do they do? They go around and they make the next generation and the next generation. So this is an early form of von Neumann's dream.

It's a construct that goes around and makes copies of itself from materials it finds in the world around it.

Slide 59/83 · 59m:25s

You can ask, What did evolution learn with the frog genome over time? Well, it certainly learned how to make these kinds of things. These are the developmental stages, and then you get these tadpoles.

This is an 80-day-old Zenobot. I have no idea what it's becoming, but it's got its own weird developmental trajectory. It has different behaviors, including kinematic self-replication, which has never existed before. There has never been evolutionary pressure to be a good Zenobot. As far as we know, no other creature assembles by kinematic self-replication. It has all kinds of features for which there was never direct selection.

I think that what evolution is doing here is not just making simple single solutions to single environments; it's making problem-solving machines, which is hardware that's actually able to have different kinds of problem-solving capacities and life histories depending on its environment. The fact that there have never been any Zenobots and yet they have a very coherent kind of way of life, including expressing many new genes that normal frog embryos do not express, tells us that the latent space around every genome is actually huge. It's not just the thing we see during normal embryonic development.

Slide 60/83 · 1h:00m:42s

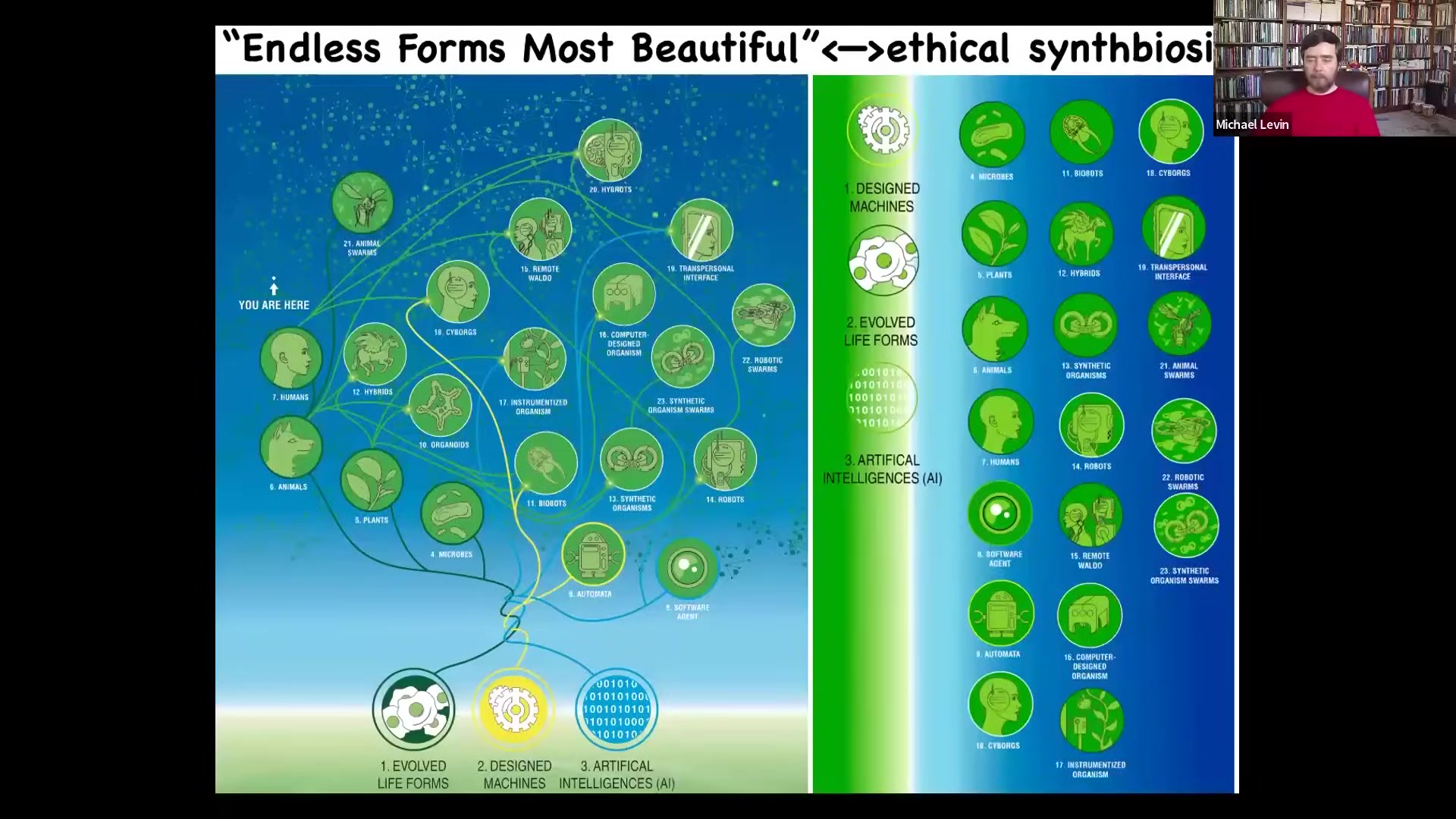

The last thing I'm going to say is this: because of this interoperability, because of life's ability to solve problems at every level and to not overtrain on its past history, it's willing to adopt new ways of being. It's highly interoperable.

Almost any combination of evolved material, designed material, and software is some kind of agent. That's why we already have some of these, but increasingly over the next decades, we're going to see cyborgs, hybrots, chimeras of various types, and biological robots.

When Darwin said "endless forms most beautiful" for the variety of living forms on Earth, all of that is just a tiny speck of this massive option space of new bodies and new minds that are possible and are increasingly going to be with us.

This requires us to not only understand more about how individuals come to be and how cognition scales in the world, but new forms of a kind of ethical synth biosis where you can't use old criteria for deciding how you're going to relate to all these novel creatures. Where you are on the evolutionary tree, what you're made of, did you come out of a factory? None of those things will be reliable guides to the new bodies and minds that will be around us. This will touch every aspect of society ultimately.

I will stop here and say that if anybody wants to dig into any of this stuff, there are many papers like this on our website.

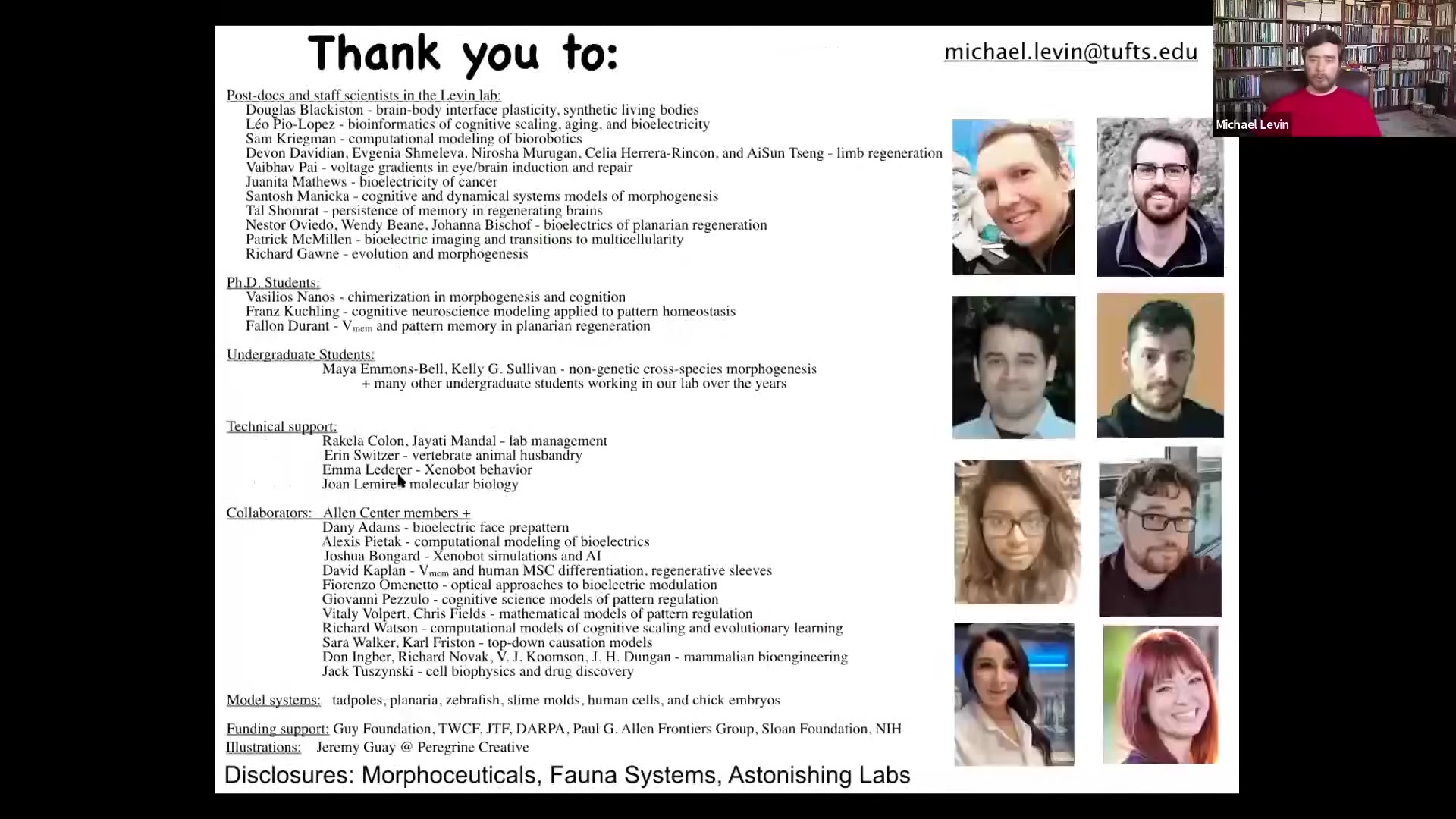

Slide 61/83 · 1h:02m:10s

Most importantly, I want to thank the students and the postdocs who did all the work. Lots of technical support and all of our amazing collaborators. We have funding from a variety of sources. Here are the companies that have supported our work. And most of all, I thank the model systems because they really do all the hard work and all the heavy lifting. Thank you so much. And I will stop here and take any questions.

Slide 62/83 · 1h:02m:38s

That was really a fascinating talk. We have quite a few questions already. We'll jump right into them. The first question is from an anonymous attendee.

Do you have any comments on plants and how this collective cellular intelligence plays into those sorts of organisms?

Slide 63/83 · 1h:02m:58s

There's a robust corner of the field of diverse intelligence that works on plant cognition. Learning in plants, decision making in plants, memory, all that. I think it's super interesting work. There is absolutely no problem. A lot of people get worked up about talking about plant intelligence. There are much more minimal systems that have degrees of what is usefully called intelligence, meaning that we can apply tools from behavioral science to much more primitive things than plants.

Absolutely, plants have aspects of this.

Slide 64/83 · 1h:03m:32s

I do. There's a whole other talk I give on that topic.

Slide 65/83 · 1h:04m:05s

There are some interesting feedback loops between biological intelligence and what has come out of recent research in machine learning. In particular, we have some amazing examples of problem solving in the living world that we do not know how to duplicate with any of our technology. Plants could solve tricky inverse problems that we have no clue how to handle.

I do think that there's going to be a bi-directional synergy between these two areas where the biology helps the machine learning get to better algorithms, which in turn helps us leverage up the competencies of the living material. I think it's an exciting time.

Slide 66/83 · 1h:04m:52s

Another question from an anonymous attendee. You mentioned we don't know where this collective cellular intelligence comes from or how it works. What are the prevailing theories or hypotheses?

I don't think I meant that we don't know anything about how it works.

We now know quite a bit about some of the key features.

We could talk about exactly what happened.

The key thing, I'll just give you one simple piece of it.

Slide 67/83 · 1h:05m:30s

Imagine that you're starting out with a little tiny homeostatic agent where the cognitive light cone is very small, all it cares about is one local variable. And the goal is how do you combine that into a network which is able to now store set points that are much bigger. They're bigger in terms of information content, they're bigger in space and time, and they operate in other problem spaces.

Slide 68/83 · 1h:05m:52s

We have a bunch of computational modeling work showing what are at least some of the connection policies that are necessary and sufficient for that to happen. In order to do that, there are some memory wiping properties that you need. For example, systems have to be connected in a way that makes it hard for each piece to know whether a particular memory belongs to it or to its neighbor, because that then wipes the individuality to the point where now this collective goal directedness takes over.

Some interesting pieces have to do with stress propagation and the idea of stress sharing, that other components, stress becomes your stress. In an important way that gives a kind of a collective identity to the system.

Slide 69/83 · 1h:06m:35s

There's some other stuff. Those are the things that are beginning to be known. That's not terribly mysterious at this point. What is completely open is the ability to predict specific goals. What we don't know right now at all is when we make a collective system, social structures, political structures, swarm robotics — we make collective intelligences all the time.

We have very little ability to predict what their competencies are going to be and what specific goals they are going to have.

And so that's the problem.

We understand a little bit of something about the scaling now. Being able to guess what it's going to want to do after you've made a collective system, I think, is an existential level problem for humanity going forward.

Slide 70/83 · 1h:07m:32s

It's a really important science that we really need to develop.

Another anonymous question. Do you have any thoughts on the Tuatara, since they're ancient creatures with unusual DNA structure? I admit that I have no idea what that is. Maybe they can ask another question that is a little more explanatory. How do you spell that? T-U-A-T-A-R-A. It's on the Q&A. Thank you. That's something for me to look up.

The next question is from Dean. Your slide of injecting a tumor into an embryo showed clustering and isolation, while a true malignancy involves infiltrations without a clean border. Is this contrast an inconsistency, and is there a therapeutic opportunity? To be clear, we did not inject the tumor.

What we did was we injected a human oncogene into a few cells in the embryo.

Slide 71/83 · 1h:08m:45s

The first thing that cells do when they express these oncogenes, and it's an open question why they do that, is they disconnect electrically from their neighbors. That oncogene prevents the cell from having good connections to its neighbors. As soon as it disconnects from its neighbors, it does what any amoeba does in the environment: it over-proliferates and it starts to migrate. And then some of them will try to come back and form. They're trying for multicellularity, so they'll make a tumor, but it's not a good organ or anything like that.

There are many therapeutic opportunities here because not only do they go off and have this metastatic behavior, but they convince some other cells to do the same.

This is also seen in clinical cases: these cancer-associated fibroblasts.

There's absolutely a clinical opportunity here to communicate with those cells: reconnect them to their neighbors, but also give them the signals that they're expecting to hear from those neighbors that would lead them to pursue anatomical goals instead of an amoeba-like lifestyle.

Slide 72/83 · 1h:09m:52s

The next question is from Paul. He says, "Fascinating research. How far are we from applying some of the knowledge from your work to generating healthy cells, like a replacement liver or kidney or whatever?"

I try not to give time estimates because it's impossible to know exactly what's going to happen on the research side, on the funding side, and so on. But I will say that we've solved the leg regeneration problem in frogs, which normally don't regenerate their legs. We're moving this into mice now.

Slide 73/83 · 1h:10m:30s

And we have a company meeting that at least somebody believes that this is going to head for the FDA in our lifetime. So that's about as close as I can get. I expect to see, I'm 55, so take that for what it's worth. I expect to see in my lifetime some of these approaches regenerating complete complex organs in patients. I think it's going to happen.

Slide 74/83 · 1h:10m:55s

That would be tremendous. Next question is from Christopher. Can we exert control of those decisions at the macroscopic level yet, for instance, to breed frog allotiles and have some of them grow legs and some not grow legs from the same genome? There are a couple of pieces to that.

Slide 75/83 · 1h:11m:18s

So, exerting control at the macroscopic level, a lot of the techniques that we have don't require us to have any fine cell level specificity to where we target. So we can do that.

The planaria, the two-headed planaria, in fact, tear themselves in half and each half regenerates and you get two worms. The two-headed planaria reproduce as two-headed.

That is a permanent line of planaria and there's not a thing wrong with them genetically.

You can imagine if we took some of those two-headed animals and threw them in the Charles River.

One hundred years from now, some scientists would come along and scoop up some samples and say, a speciation event, two-headed animals and one-headed animals. Let's sequence the genome and see what the speciation event is.

Of course, there's nothing wrong with their genome. So we can already do this.

The frogilotls, I don't really expect that to breed true, but we will eventually have an answer.

Slide 76/83 · 1h:12m:22s

The bigger thing is nobody fundamentally cares if ****** models will have one leg or two. The key is whether they have legs or not. The key is that we need a science of being able to predict such things, and we don't have it. All the molecular biology, sequencing, and genomics in the world are not handling this. So we're missing quite a bit here.

Slide 77/83 · 1h:12m:42s

Okay, and we have one more question from Christopher. Should matter in the body other than cells with DNA, for example, water or iron content in the blood, be considered part of the collective intelligence or as an external input or resource accessible to the members of the group intelligence?

Here's what I would say.

One of the important components of any intelligence is the various scratch pads that it uses to keep information.

Many of those scratch pads are themselves not biotic. Cells can use the extracellular matrix as a kind of stigmergy to deposit various molecules that they pick up later.

A kind of memory medium, the way that ants use the surrounding ground as a memory medium by putting down pheromones.

I think absolutely cells will use. I don't think cells care whether the stuff they interact with is living or not.

They will exploit anything in their environment to solve the problems that they have. I absolutely think there's a bunch of abiotic stuff, including bacteria, including water, which has interesting properties, minerals, that are part of the problem solving that cells are using.

I would think they're part of it.

Slide 78/83 · 1h:14m:05s

This is a small follow-up question that he included. Are dead skin cells and hair cells still part of the collective intelligence even after they're dead? There are two things there.

Slide 79/83 · 1h:14m:18s

So that would depend, and I don't know the answer, but it's a good research program. That would depend on whether other cells are using the dead skin and hair cells for some computation, and they may be. That's an empirical question.

But dead is an interesting thing.

There's a whole research program in a project that I'm part of where we're trying to ask what it means. Look at the Xenobots.

Slide 80/83 · 1h:14m:45s

The original frog that they came from is certainly dead. It's gone. There is no frog. But the cells, none of the cells are dead. The cells are all alive. In fact, the Xenobots have a whole other lifestyle and they live for however long they live. Dead is also not easy to define anymore.

Slide 81/83 · 1h:15m:05s

The last question here is more on Tuataras. It says they're living fossil creatures whose bodies look much the same as they did in dinosaur times, but whose DNA evolves very rapidly. Interesting. Thank you for that. I will look it up. I've never heard it.

That's it for the questions and we're right at the time limit. So any final comments you wanted to make, Michael?

No, just thank you for listening. Great questions.

Slide 82/83 · 1h:15m:38s

I appreciate very much your interest. If anybody needs me, michael.levin@tufts.edu.

Slide 83/83 · 1h:15m:42s

I'm happy to hear from you. And thank you, Michael, for a really fascinating talk. Thank you so much. Thank you everyone for attending today and have a great weekend. Thank you. Bye-bye everyone.