Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a ~54 minute talk I gave, titled ""Bioelectricity: a bridge between physics and cognition, by way of biology", at the National Institute of Health Interest Group "Quantum SIG" (https://oir.nih.gov/sigs/qis-quantum-sensing-biology-interest-group). My talk doesn't contain any quantum biology content per se, but I discuss the idea of top-down control and cognition all the way down, from abstract mental goals to molecular pathways, with bioelectricity as a tractable medium for the communication between levels. Many of the examples are the same as in some other talks but the story is framed from a bit different perspective, especially the introduction.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Mind controlling body chemistry

(02:33) Cells as agential materials

(04:55) Regeneration and global goals

(07:05) Anatomical software and decoding

(11:34) Programming new body structures

(15:40) Synthetic life and anthrobots

(19:05) Platonic space and biomedicine

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/24 · 00m:00s

Thank you very much, and hopefully you guys can all see my slides. I'm going to talk about bioelectricity in a slightly different way than I usually do, and introduce it as a bridge between physics and cognition.

If you want to see the details here, everything is at this website, and this is my personal blog about what I think some of these things mean.

Slide 2/24 · 00m:22s

I want to point out something that is often forgotten. When you wake up in the morning, each of us may have very abstract, high-level goals. You may have financial goals, social goals, research goals. In order for you to get up out of bed and execute on those goals, charged molecules like calcium and potassium have to cross your muscle membranes. The chemistry has to dance to the tune of a very high-level, abstract mental goal. How does that happen? How is the chemistry of your body, the actual molecules of your body, controlled by your thoughts and your intentions? This is not a special mind-matter interaction that is only accessible to yoga practitioners or special masters. This is everyday voluntary motion. Our bodies are constructed in a way that can transduce these extremely abstract mental objects, like goals, all the way down to the act of chemistry changing in your cells.

Slide 3/24 · 01m:32s

You might want to ask: this interaction between the mental and the physical, where does it happen? Where is the interface between cognition and the contents of our mind and so-called just physics or physiology or chemistry? Where and how do our thoughts actually affect the physical world? When does the mental become the physical? When does it turn over? What I'm going to suggest is the answer is never. It's cognition all the way down, all the way from a high-level mind embodied in human bodies and whatever is beyond that, all the way down to molecules. That's the answer to this puzzle of the interaction of the mental world and physical world. It is mental all the way down.

The goal here is to understand how this happens through the different layers of our body, how to understand communication, the scaling of goals, the remapping of memories across substrates, across the different components of our body, and across the different problem spaces that they solve.

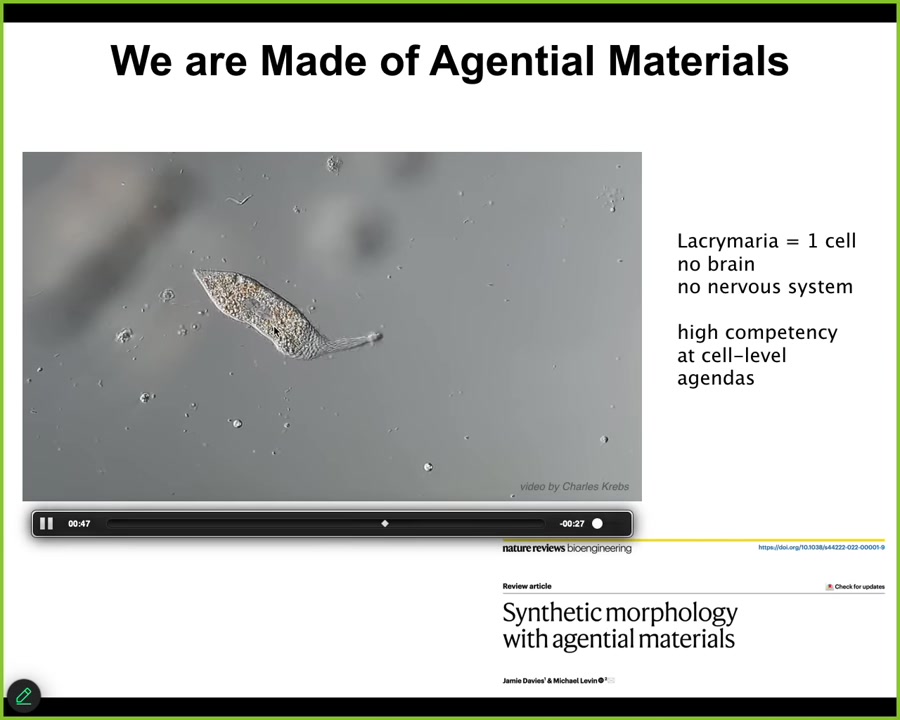

Slide 4/24 · 02m:36s

And in order to explain what I mean, I would like to introduce you to a single cell. This is an organism known as Lacrimaria. It's a single cell and this is what we are made of.

We are made of these agential materials. That is materials with an agenda, materials with competencies. There's no brain here. There's no nervous system. You can see this incredible creature and the competency that it has in its environment. One might wonder, how is it that we could engineer with materials such as this? It's completely different than how we used to do it with wood and metal and Legos, because you can't micromanage this. You have to convince it to do things.

Slide 5/24 · 03m:23s

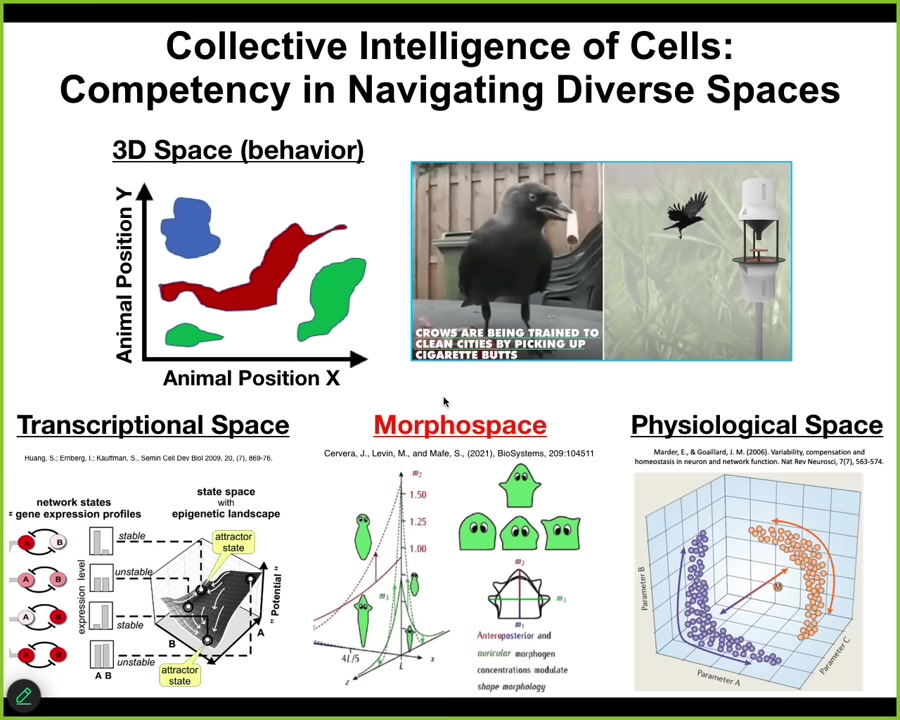

And that's because all throughout the history of life, biology has been solving problems in many, many different spaces besides the three-dimensional space of which we are so familiar. So we can recognize birds and primates and maybe an octopus or a whale or things like that as intelligent. But long before we had brains, long before we had muscles that allow us to move in three-dimensional space, biology was navigating the space of possible gene expressions, the space of physiological states, and the space of anatomical states.

In other words, your journey from being a single-cell egg, a fertilized egg, to being a human is a navigation of the space of anatomical possibilities. There's probably an infinite number of possibilities. These systems do this kind of perception-action loop in all of these spaces, but these are very hard for us to recognize. We as humans are completely obsessed with three-dimensional space. If it's not moving around, a medium-sized object at medium speeds, we really find it very difficult to understand the intelligence.

Slide 6/24 · 04m:26s

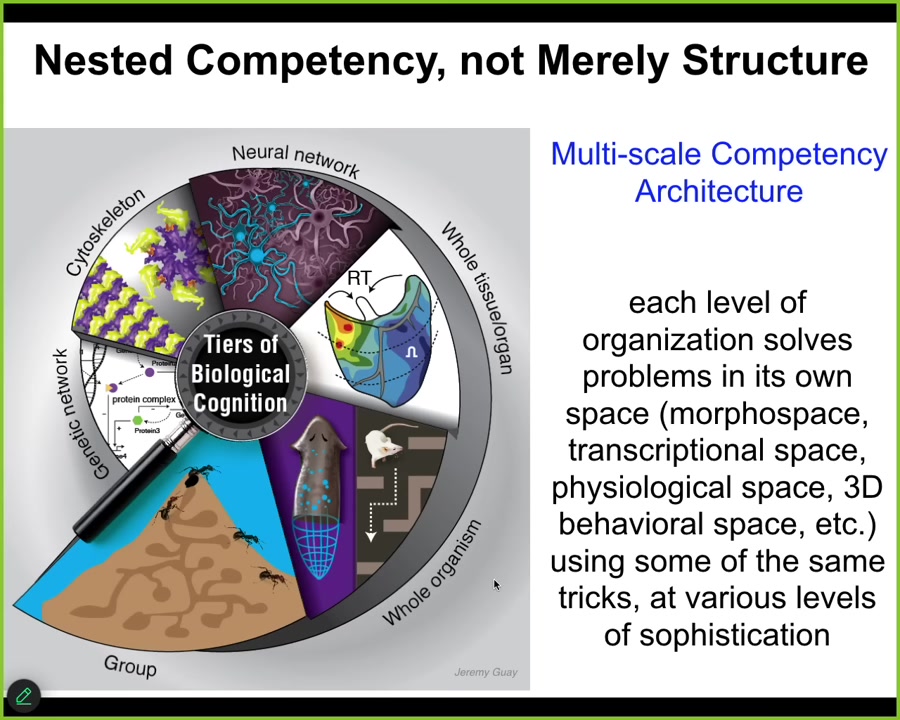

In our body, every layer, all the way from the molecular networks to the organelles within our cells to the networks of cells and tissues and organs and even collections of organisms, has its own capacity to solve problems. This is the so-called multi-scale competency architecture. At every level of organization, there are agendas and competencies, and they solve problems. I'm going to show you a couple of examples of the kinds of things they do.

Slide 7/24 · 04m:54s

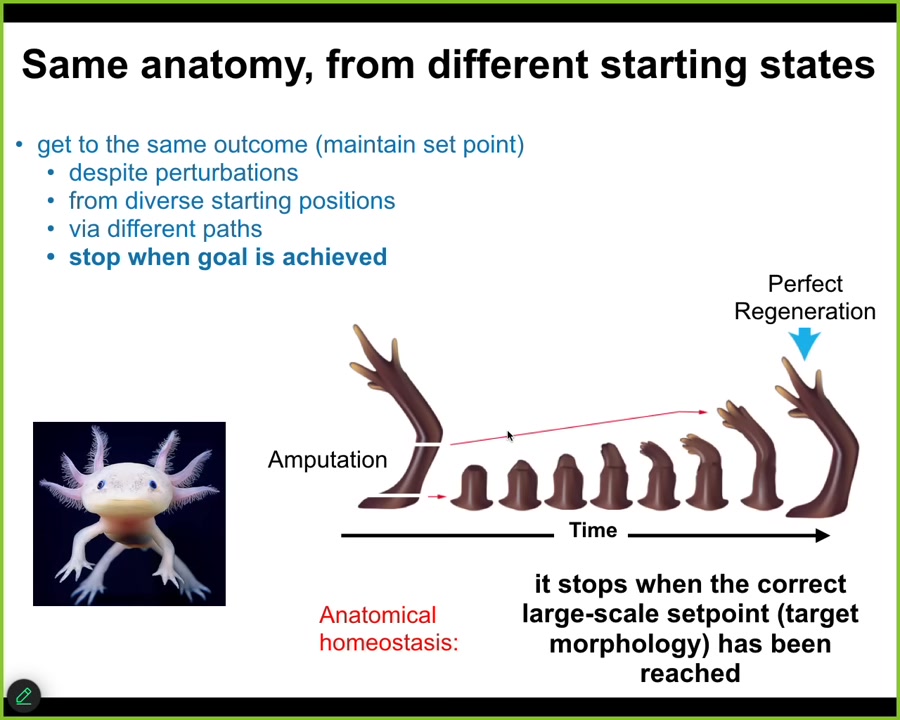

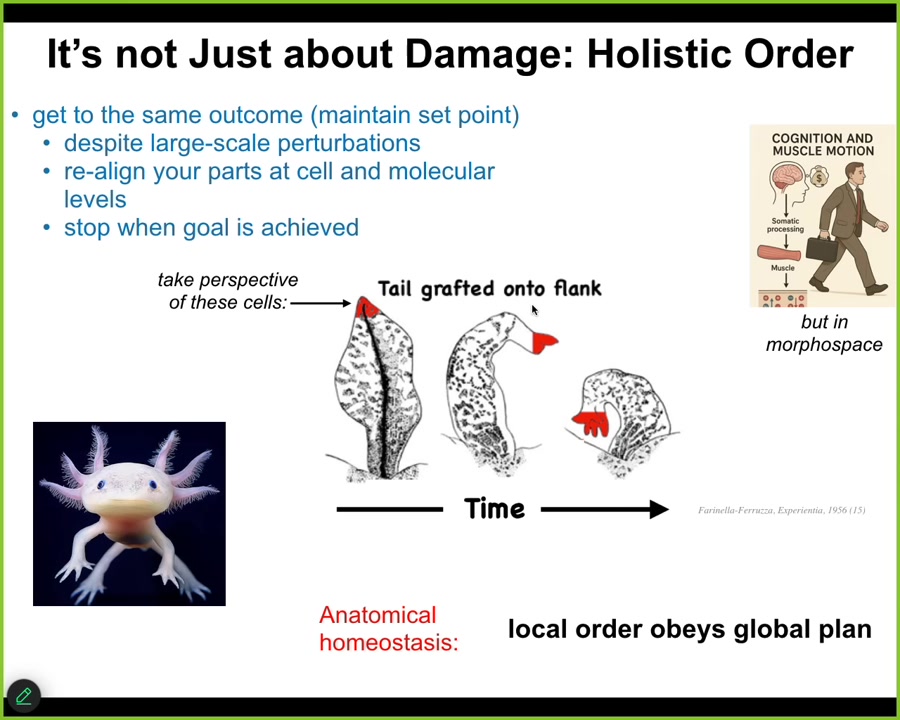

This is an amazing creature called an axolotl, and these amphibians are highly regenerative. They replace damaged limbs, eyes, jaws, all sorts of organs.

What happens is that if the limb is amputated anywhere along the length, the cells spring into action and will immediately regenerate and regrow the same pattern and then they stop. The most amazing part is they know when to stop. When do they stop? They stop when the correct axolotl limb has been completed. So it has the ability to know when it's been deviated from its goal and then to work really hard to get back to that same position in anatomical space. It's the ability to reach the same goal from different starting positions. That's pretty impressive.

Slide 8/24 · 05m:41s

But notice that it's not about damage. You can see this in the following experiment. In the 1950s, they took tails from this amphibian and surgically grafted them to the side. What you see is that over time that tail transforms into a limb.

Now take the perspective of these cells here at the tip of the tail. There's nothing locally wrong. There's no injury, no damage. These cells are perfectly correct tail tip cells sitting at the end of a tail. Why do they turn into fingers? Because what's happening here is that a large-scale plan — the collective, not the brain of the animal, but the tissue and the organ structures — are well aware that you don't need a tail here, you need a limb. Their high-level intent to fix that error filters down to the molecular biology needed to turn tail tip cells into fingers. It's exactly what I told you at the beginning. It's a multi-scale system where high-level goals of the top-level collective filter down to make the molecular biology and the chemistry adjust to what needs to happen. The local order obeys a global plan. It's an amazing part of our architecture.

Slide 9/24 · 07m:01s

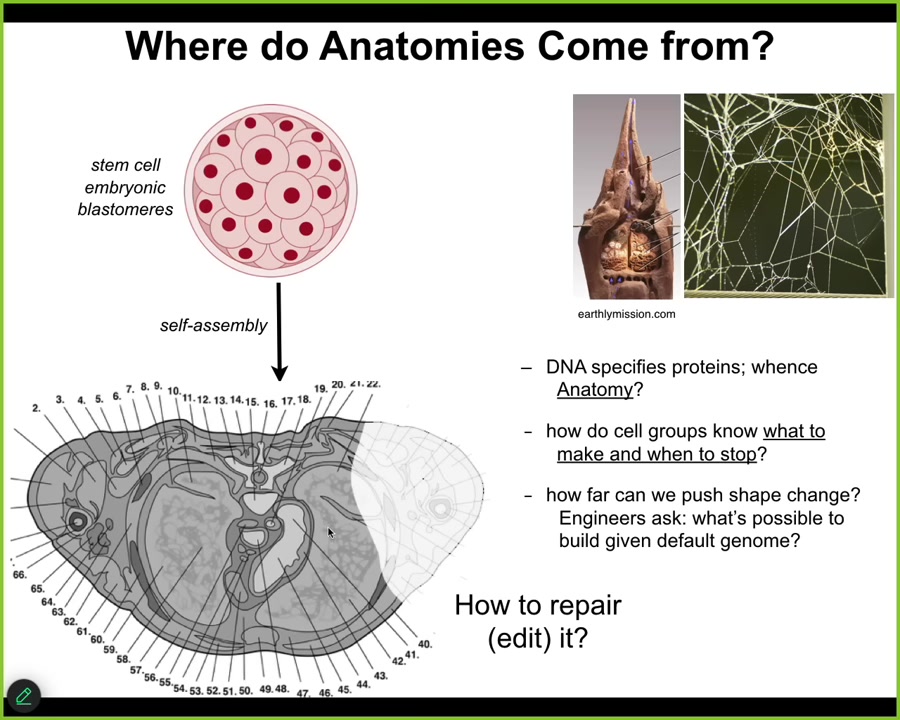

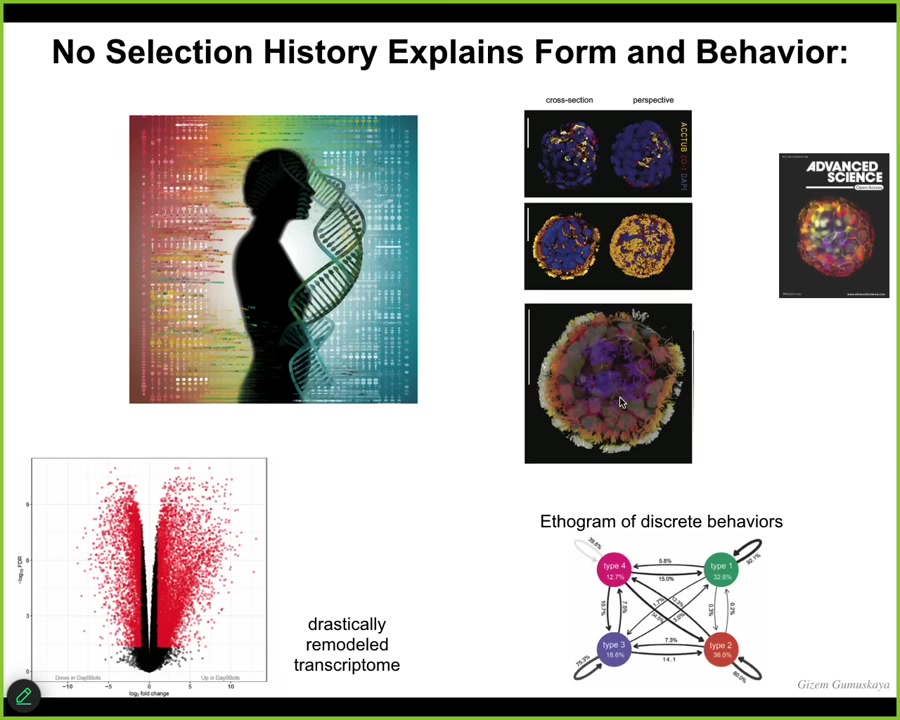

We want to try to understand what are the possibilities here for medicine and engineering. We need to start to think about how the outcomes, how the goals of the system — it's very clearly a goal-seeking system. It repairs, it can remodel. Where do the goals come from?

All of us start life as a little ball of blastomeres. Eventually, here, this is a cross-section through a human torso. You see this incredible order. Everything is in the right place, the right size, relative to the right thing, next to the right structure. Where did this come from? You might think it came from the DNA, but we can read genomes now. None of this is actually encoded directly in the DNA. The DNA specifies proteins, tiny molecular hardware that every cell gets to have. The question of what kind of symmetry you will have, how many eyes, if you're going to have eyes, how many fingers — all of this stuff is not directly in the DNA at all, any more than the structure of this incredible termite mound or the spider web is in the DNA of those creatures. It is the result of the physiological software that runs on the genetically specified hardware.

We have begun to develop tools to decode some of this software. You might wonder, how do groups of cells remember what to build? How do they know what to build? And what else could you ask them to build?

Slide 10/24 · 08m:22s

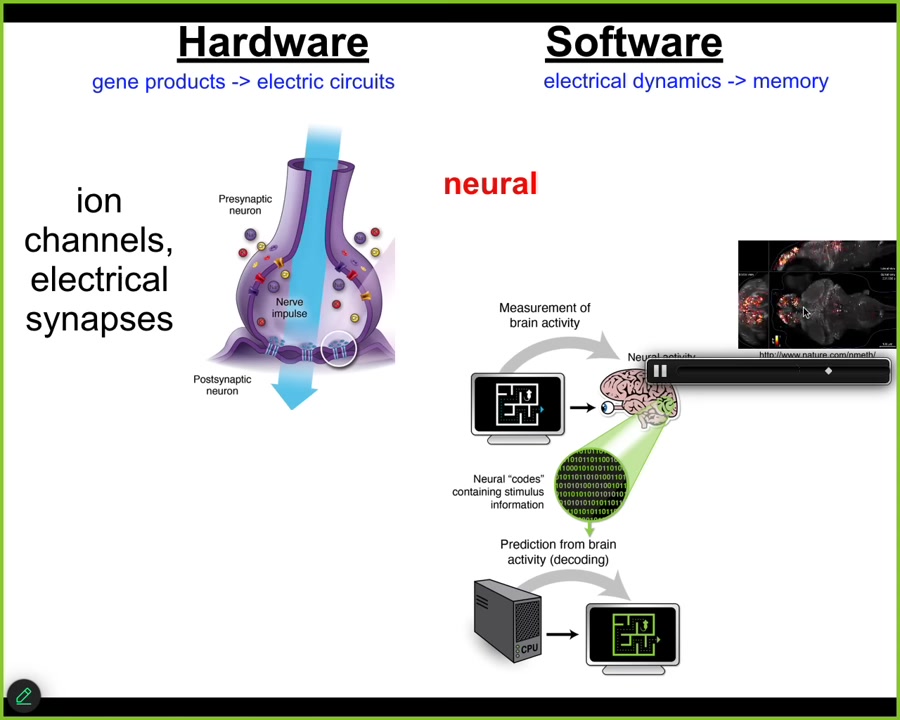

We have an idea of how this works. The brain consists of many cells, which have these little ion channels on them. The ion channels allow the cells to have a voltage gradient. That voltage is communicated through these special electrical synapses. You can see here a video that this group made of zebrafish brains thinking about whatever it is that zebrafish think about. You can track it and try to decode it. This is the idea of neural decoding to try to understand what are the memories, the goals, what is encoded in this electrophysiology.

Slide 11/24 · 09m:01s

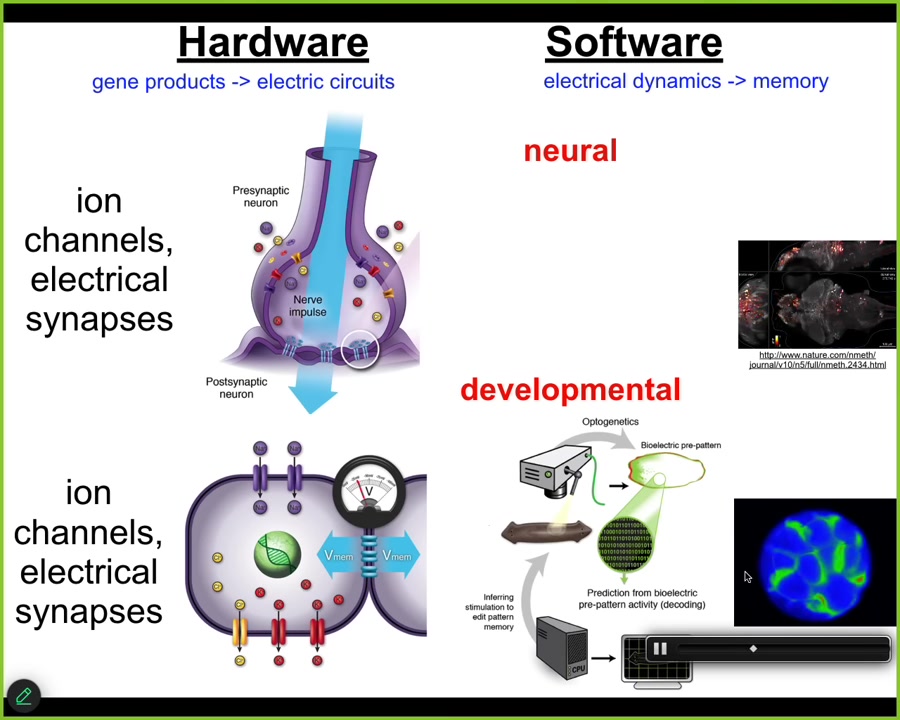

The ability to store mental content in electrical networks and propagate it down to activity is extremely ancient. Biology discovered this long before we had brains or muscles or nerves. Every cell in your body has these ion channels and creates electrical gradients. Most cells have electrical synapses to their neighbors so they can communicate with them and create networks with large computational capacity. We can do something very similar to what neuroscientists try to do in the brain, and that is to decode.

Here's an early frog embryo, and the colors indicate the voltages that are mediating the little conversations that all the cells are having with each other. Who's going to be left, who's going to be right, who's going to be the head, the tail, and so on. We try to decode this. Can we ask what does your body think about before you have a brain? And what did bodies think about in general before there were any brains?

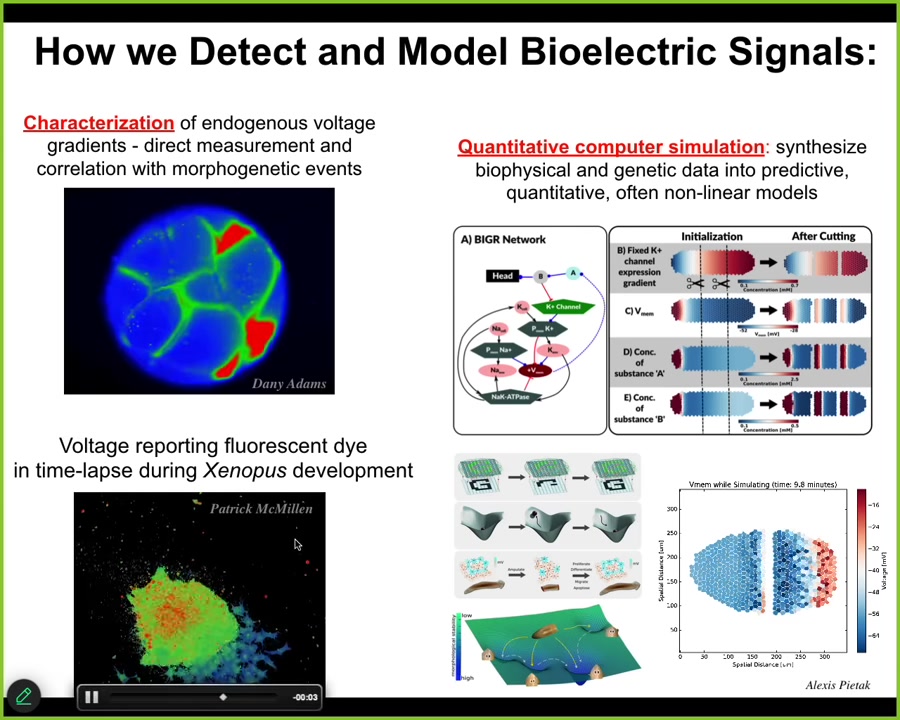

Slide 12/24 · 10m:04s

We created some tools to do this, to read and write the memories of the body. First, these voltage-sensitive fluorescent dyes. This is a technology to non-invasively read the electrical communication between cells. You can see that here in individual cells, and this is an entire embryo. We also do a lot of computational modeling to try to understand quantitatively how this works.

Slide 13/24 · 10m:25s

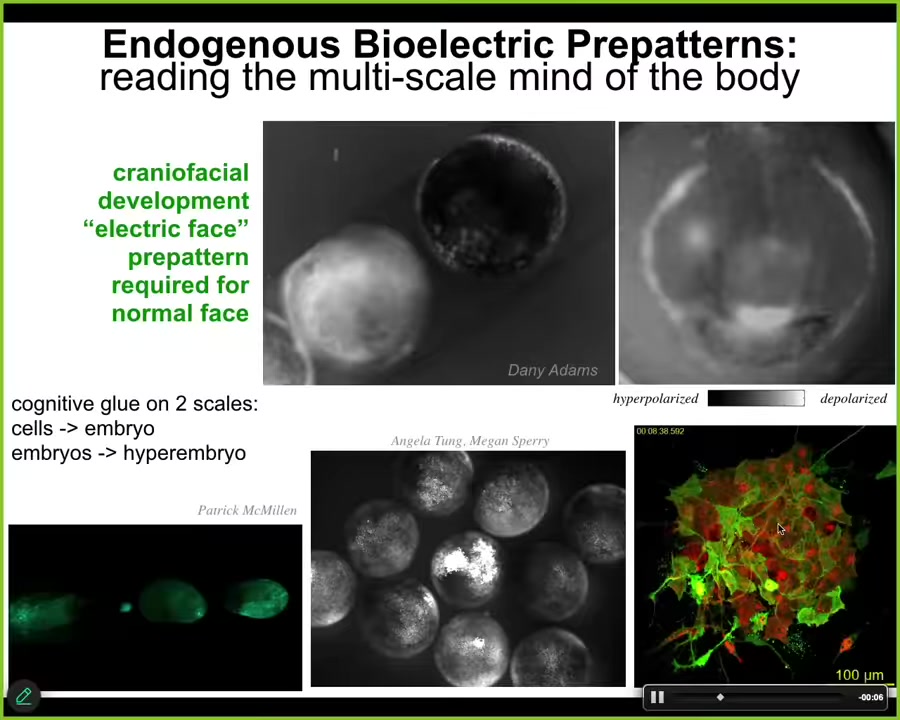

I'm going to show you an example of several kinds of patterns. We call this the electric face. Here's an early frog embryo in a time lapse. The brightness indicates voltage. This is one frame of that video. You can see that already long before the organs of the face were specified, the electrical pattern set the future as a scaffold. You can see here's where the eye is going to be, here's where the mouth is going to be, here are some placodal structures outside. This is how it knows what a correct face looks like. We are literally here looking at the decoded electrical memory of the tissue of what a proper tadpole face is supposed to look like. It's not just single embryos; each one of these big circles is a different embryo, and they communicate with each other. When I poke this guy here, there's this calcium wave that goes. The embryos communicate with each other to help each other reach the correct endpoint. Here you can see we can track this among the individual cells.

Slide 14/24 · 11m:34s

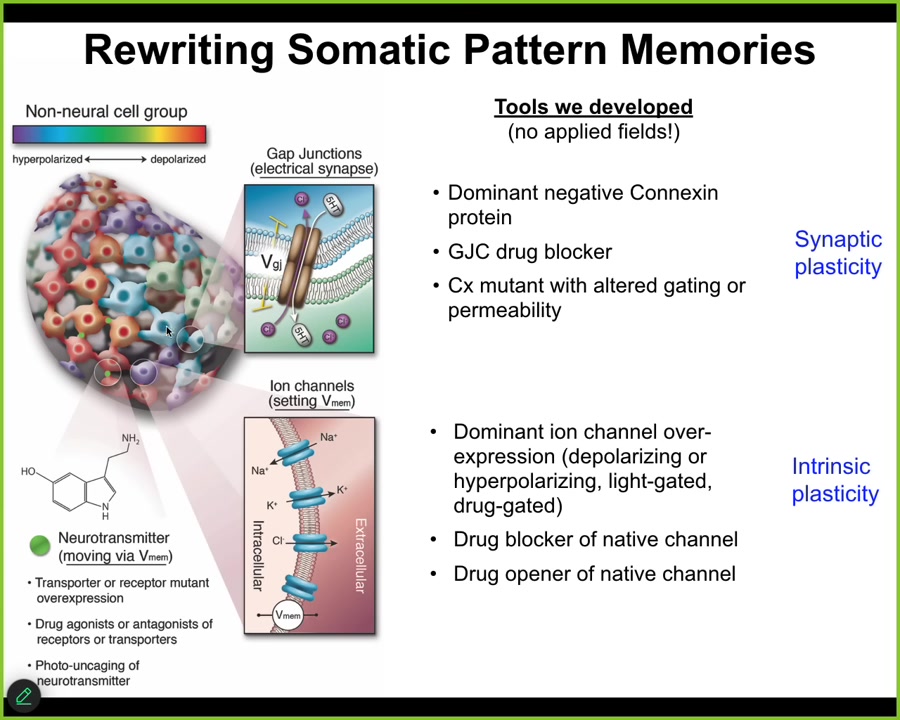

Now it's not enough to read those electrical networks and read the memories that the tissue has. We want to be able to rewrite those memories. We don't use any electric fields. There are no magnets, no electromagnetism, no frequencies, no waves. That is not how we do this. What we do is hack the normal interface that the cells are using to control each other's behavior. That means controlling these ion channels and controlling the electrical synapses. We can do this with all the tools of neuroscience. We can do it with light, with special pharmacological agents or drugs. Now I want to show you one or two examples of what happens when we can rewrite these pattern memories.

Slide 15/24 · 12m:15s

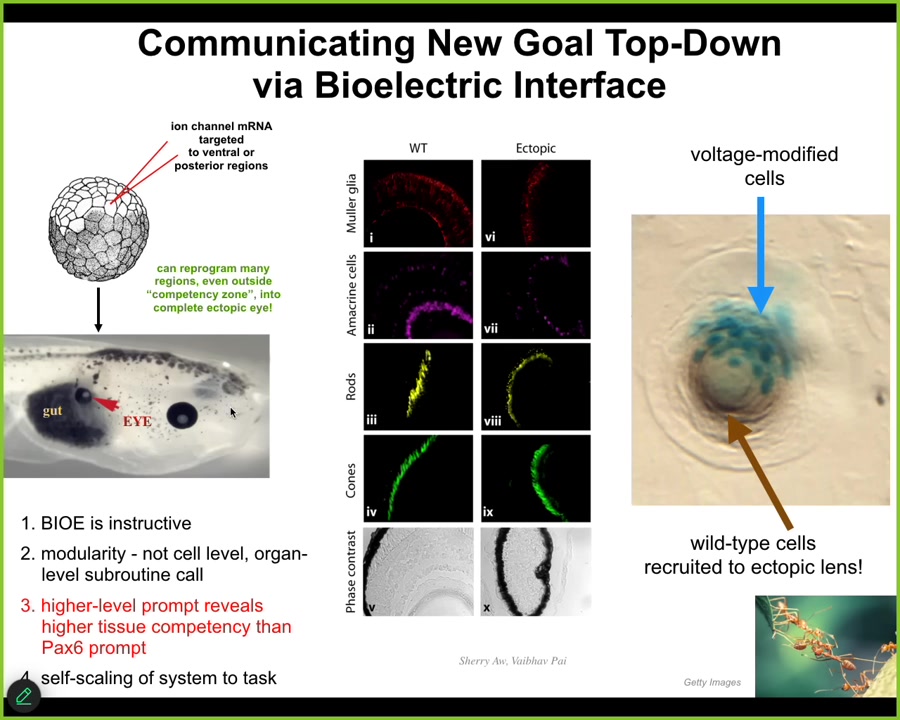

Well, the first thing we can do is we can ask the tissue to make whole organs. So here's a side view of a tadpole. Here's the brain up here. The mouth is back here. Here's the eye. Here's the gut. And the tail is back here.

What we've done is inject some ion channel RNA. These are molecules encoding a specific electrical component called a potassium channel. We inject these cells to set up a little spot of voltage that says build an eye here. And sure enough, the cells do exactly that here. They've built this nice eye. It has all the same lens and retina, optic nerve, all the same stuff that an eye is supposed to have.

If we only inject a few cells, the blue cells are the ones we injected, they will automatically talk to their neighbors and instruct them to join them in making this structure. All this stuff out here that isn't blue, we never touched it. The blue cells tell the other cells what to do.

This is remarkable for many reasons. First of all, it tells us that the bioelectric state, which is what we've manipulated here, in fact, is instructive. It tells the tissues what to do. But more importantly, it's instructive at a very high level. We didn't have to tell what genes to turn on and off. This has nothing to do with genetic editing. This is not about controlling specific genes. This is not about controlling stem cells. We have no idea how to micromanage the creation of an eye. What we do know how to do is to say to the very competent tissue, build an eye here. And it takes care of the rest.

That same theme: very high-level abstract goals being transduced down into the chemistry that actually implements it. So all of these things happen after we've said to these cells, instead of a gut, you should make an eye.

Slide 16/24 · 14m:00s

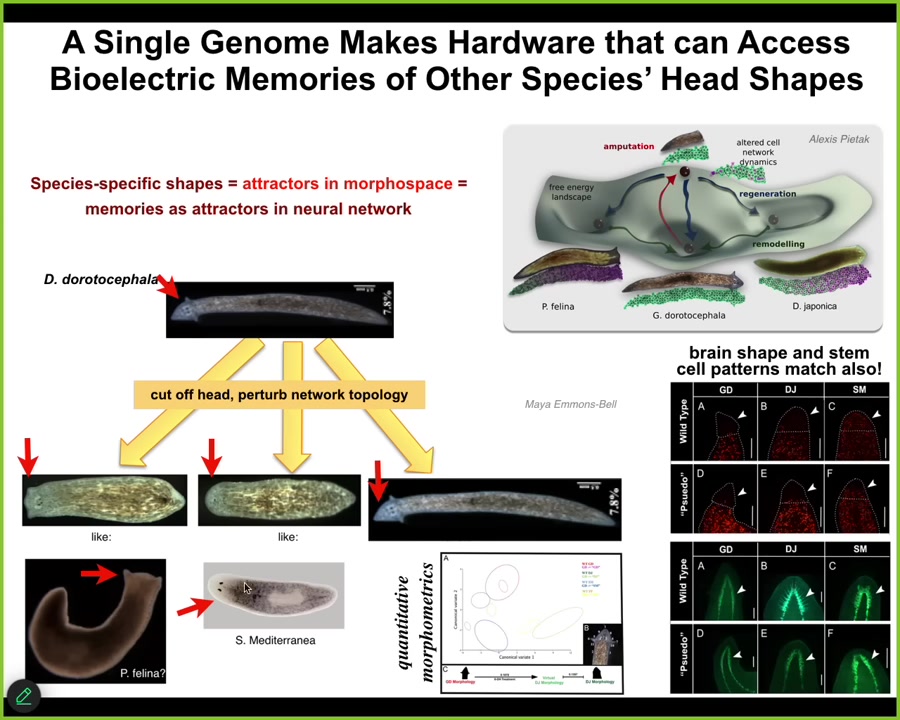

Here's another example. This is a flatworm called a planarian. There's a Japanese version called Dugesia japonica. This is a different one called Duratocephala. They have a triangular head like this. They're highly regenerative. If we amputate the head, they grow it back. They grow back every part of their body. We're studying this for many reasons.

One of the amazing things is that they use an electrical gradient to know how many heads and what kind of head they should have. When we manipulate it, we can make them have their normal heads like this, but they can also make flat heads like a completely different species of planarian, or roundheads, like a different species of planarian. These are between 100 and 150 million years distant from this, but without any genetic change. We don't touch the genome at all. We simply communicate electrically with the cells, and we can get the same hardware, so the same genetics, to visit these kinds of attractors in anatomical space that belong to these other species.

Not just the shape of the head, but the shape of the brain and the distribution of stem cells here becomes just like these other species. You can ask the body to produce a new organ in a different location. You can ask the body to produce structures that belong to an entirely different species here.

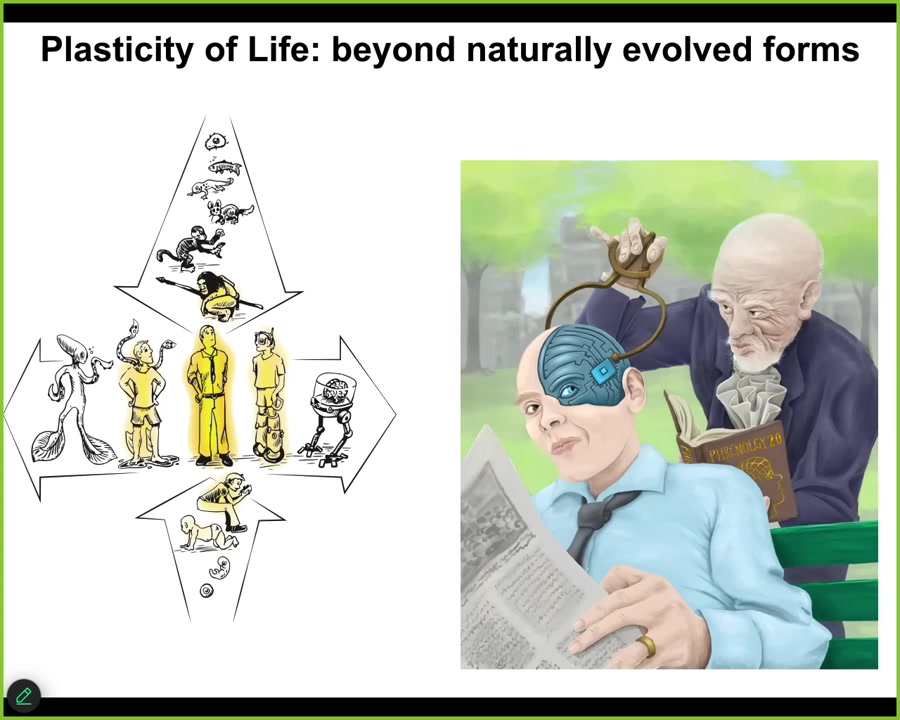

This is the beginning of using this bioelectric interface for regenerative medicine applications. We're working on limb regeneration, repairing birth defects, and reprogramming tumors when we learn the bioelectric interface by which we can communicate with these systems. Notice that everything I've shown you so far has been normal structures that have evolved on Earth. That eye was a normal frog eye. These heads belong to a normal species.

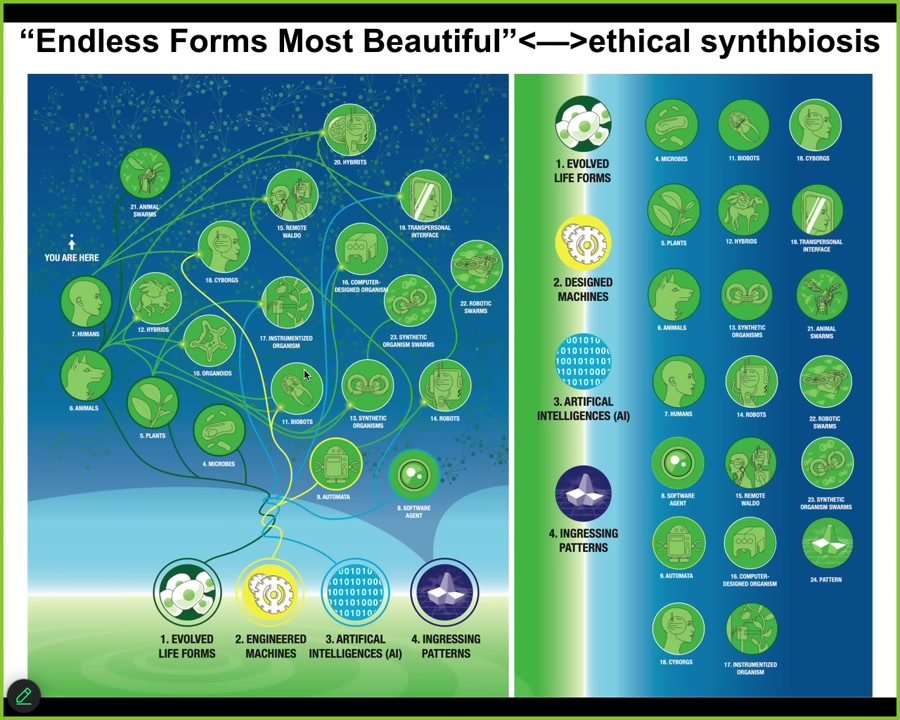

Slide 17/24 · 15m:52s

We need to think beyond this. What is going to happen when humans are modified, which we are already modifying ourselves in both biological and technological ways? There's going to be an incredible variety of beings that are combinations of novel technologies with existing biological structures. We can ask, where do those goals come from? We know where the frog eye came from and the planarian head. They came from evolution acting over eons to set particular structures. But for beings like this that have never been here before, where do the goals of their tissues come from?

Slide 18/24 · 16m:34s

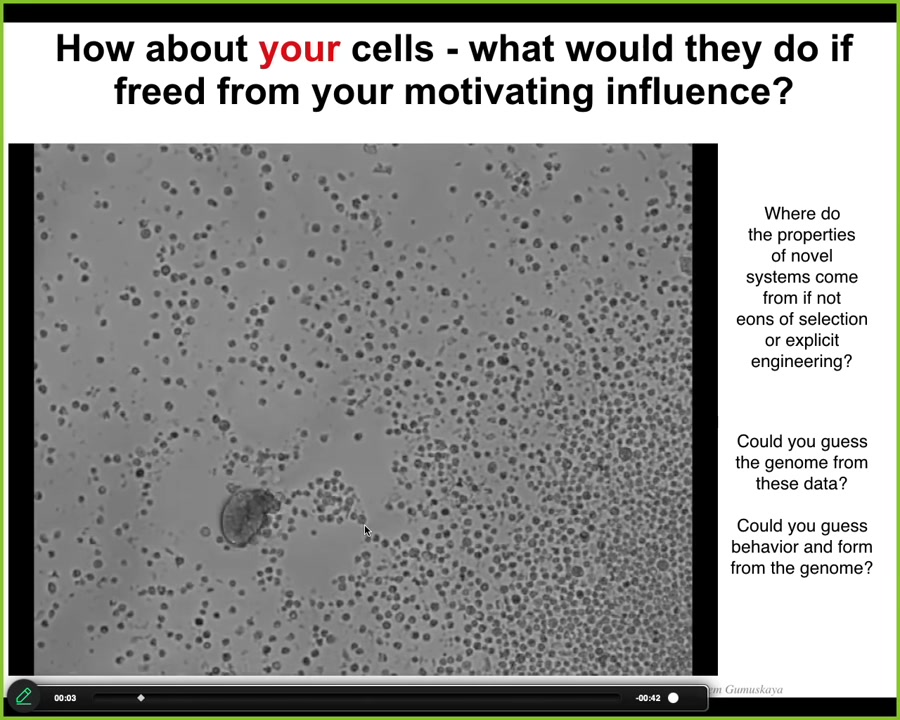

In order to try to understand, I want to introduce you to a synthetic life form. This is something that if you saw, you might think that we got this from the bottom of a lake somewhere, a primitive organism. But actually, if you were to sequence it, you would find 100% Homo sapiens. We call these anthrobots. They are made from adult human patient cells from tracheal epithelial biopsies, not embryonic.

They have the ability to self-assemble into a tiny little creature that swims around. It has a completely different behavior. It doesn't look anything like any stage of human development. The plasticity is amazing. When you free your cells from the influence of the rest of the body, they have a different life. This thing has never existed before. These anthrobots have no evolutionary history. What do they know how to do?

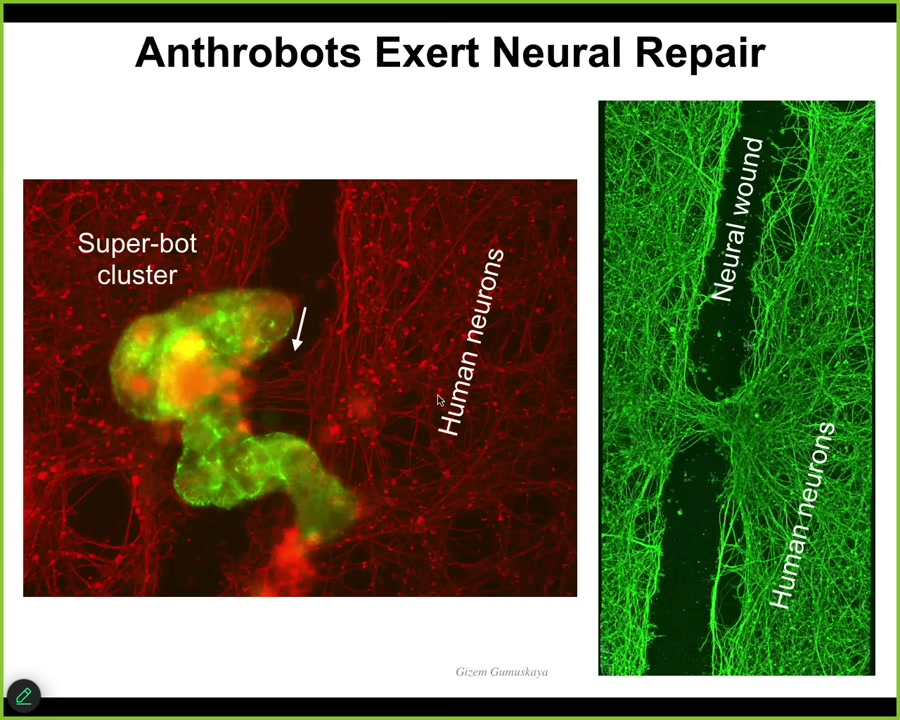

Slide 19/24 · 17m:23s

One thing they know how to do is repair damage, for example, in neurons. If you plate a bunch of human neurons here in a petri dish, you take a scalpel and you make a big scratch, a big wound through this. Here's your neural wound. And you put a bunch of these anthrobots labeled in green. They will find a spot in this wound. They will land there. And what you'll see is that they start to knit the neurons across the gap. They start to repair. If you lift them up four days later, this is what they're doing. They're repairing the damage. So who would have thought that your tracheal epithelial cells which sit there quietly for decades dealing with mucus and air particles have the ability to become a completely different little creature.

Slide 20/24 · 18m:05s

This is what they look like. They have little cilia, little hairs on their outer surface that allow them to swim. They have four different behavior patterns that they can switch between. They have 9,000 differently expressed genes. About half the genome is differentially expressed. Again, we didn't touch the genome. There are no synthetic biology circuits here, no weird nanomaterials, no scaffolds. This is novel—the capabilities of a being that puts itself together in a way that's never existed in evolution before.

The opportunities here are incredible because these are made from your own cells. You wouldn't need immunosuppression. We're only scratching the surface of what they can do. They're also teaching us about this amazing scenario where living beings can have goals and properties that were not set by evolution. They don't have an evolutionary history.

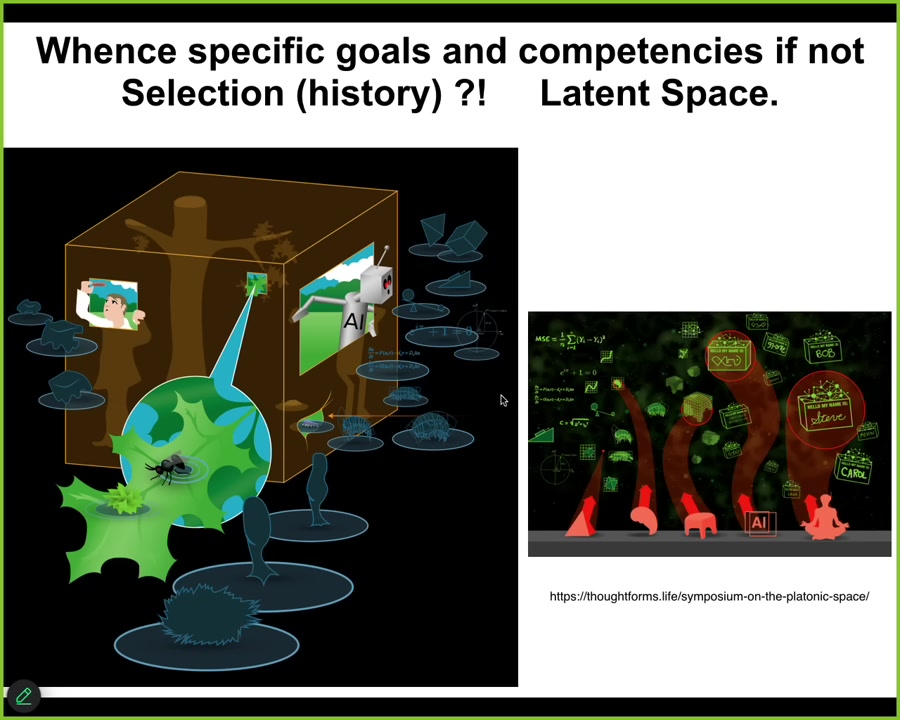

Slide 21/24 · 19m:07s

Where did they come from? We think now that all of these kinds of things, the anthropods, xenobots, all these other things that we make, are basically vehicles for exploring what you might call the Platonic space or a latent space of possibilities.

These capabilities—these new gene expressions, new behaviors, new forms, new physiological properties—are not just random things that happen; they are drawn from an ordered, structured space that contains not only mathematical truths, but also high-order patterns that we recognize as kinds of minds. You can see there's a whole symposium that we're running this fall on this Platonic space. This idea is that living beings, but also engineered beings like robots and AIs and hybrid forms and cyborgs, all receive the benefit of the ingressions of patterns from this space. We really need to understand this to take the full benefit of the technologies that are coming.

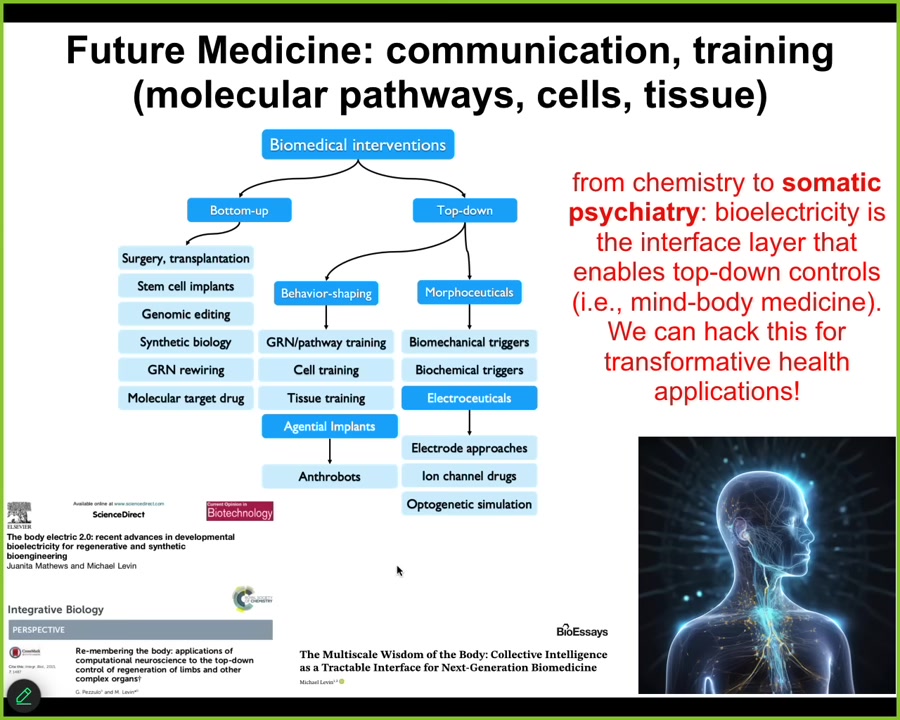

Slide 22/24 · 20m:10s

These are all the familiar strategies of biomedicine. They're all bottom up, they're all hardware first. But there are these incredible technologies coming down the line having to do with exploiting the intelligence of the material of life. I think that future biomedicine is going to look a lot more like somatic psychiatry than it's going to look like chemistry. It is about collaborating, cooperating, and convincing your various intelligences in your body to do the things you need them to do.

Slide 23/24 · 20m:48s

The final thing I'll say is this. Besides all the advances that this is going to lead to in regenerative medicine, cancer, birth defects, bioengineering, there's an ethical and a social component here: all of the natural forms that Darwin meant when he said "endless forms, most beautiful" are a tiny corner of this enormous space of beings. All of the combinations of evolved material, engineered material and software, and the patterns from this space, make some kind of a viable, novel, embodied mind. So cyborgs and hybrids and every kind of combination under the sun is coming. We are already living with many of these beings. Many of these already exist, but there will certainly be more. We need to understand all of these components and develop a novel set of ethical principles to relate to beings that are not like us, that are truly alien, that do not come from our evolutionary life stream. We need to enter into a kind of ethical synth biosis with these beings as a matter of maturing as a species.

Slide 24/24 · 21m:56s

I'll stop here and just thank the students and the postdocs who did some of the work that I showed you today and our collaborators and our technical support disclosure: here are three companies that have licensed some of our technologies and support the work.

Most of the gratitude goes to the living model systems that have taught us everything we know. I thank you very much for listening.