Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a ~1 hour talk by Mike Levin on the bioelectrics of cancer as a breakdown of multicellularity and collective intelligence of morphogenesis.

The full title is: "Bioelectrical signals reveal, induce, and normalize cancer: a perspective on cancer as a disease of dynamic geometry"

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Regeneration, cancer, and planaria

(06:58) Multicellularity and anatomical goals

(14:18) Morphological intelligence and homeostasis

(22:16) Bioelectric signaling and patterning

(30:11) Rewriting patterns for regeneration

(37:13) Bioelectricity in cancer initiation

(45:25) Normalizing cancer via electroceuticals

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/41 · 00m:00s

So if anybody wants to chat at any point or download any of the primary papers, the data sets, the software, everything is here at this website, please feel free to contact me.

I'm not a clinician, I'm a basic scientist, and I'm going to talk about some aspects of the cancer problem that I think are of fundamental interest, but also I think will have implications for biomedicine of cancer.

Sometimes I give a talk that's focused on this question: Why is cancer not an issue for our various autonomous robotics and the various other kinds of things we make? It sounds silly, but it's actually a deep question. The answer is because mostly what we make in our engineered constructs has a very flat architecture. In other words, the entire thing might have interesting complex behaviors. It might have some degree of intelligence and problem solving. But the parts that it's made of are passive. The parts do not have agendas of their own. There is no danger of them going off on their own tangent that doesn't merge with the goals of the rest of the structure.

Slide 2/41 · 01m:16s

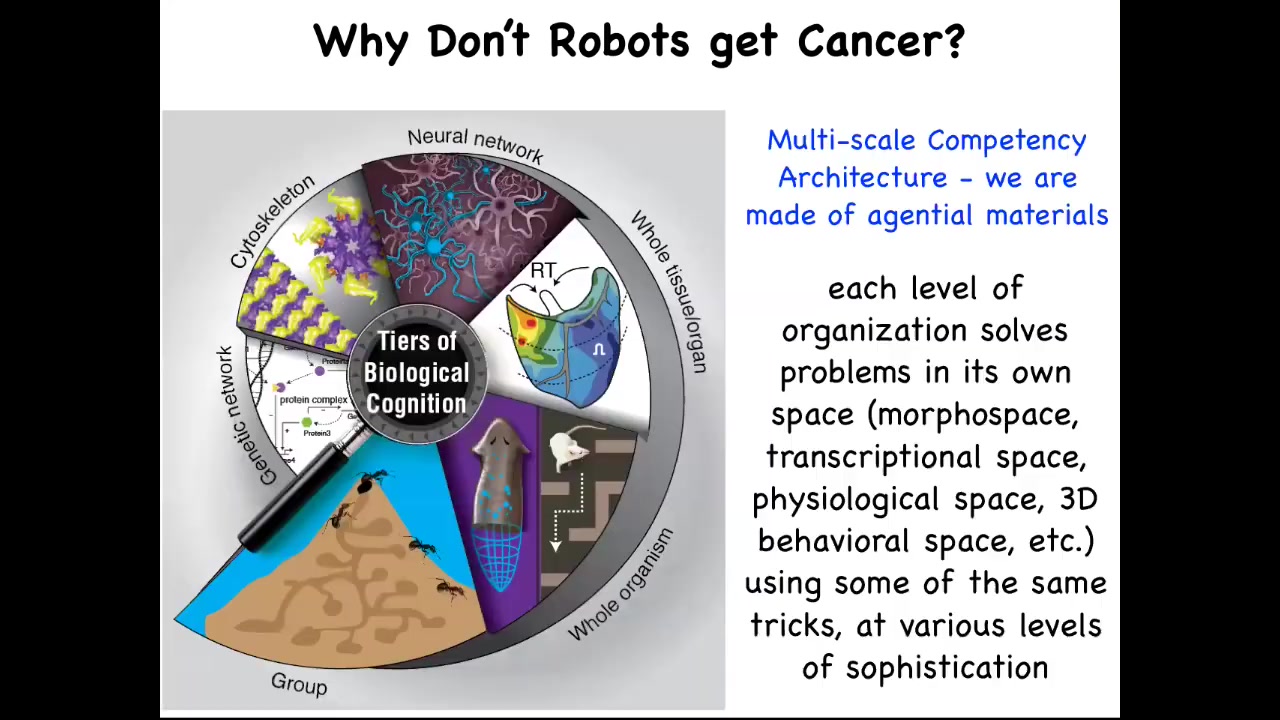

Now, that is not the case in biology. Biology has a completely different architecture. All the way up from molecular networks through organelles and tissues and organs and whole organisms and even swarms, biology is made of layers that are problem-solving intelligent agents on their own. They solve problems in various spaces. This might be not just the three-dimensional space of canonical behavior, but the space of physiological states, transcriptional space, anatomical morphospace, metabolic space, and so on. We are made of a kind of nesting doll architecture, not just structurally; each of these layers has their own problem-solving capacity, in many cases various kinds of ability to learn from experience and competencies of various kinds. And this turns out to be very important.

A summary of everything I'm going to tell you today is this: all cells, not just neurons, communicate in electrical networks that process information, and we think that cancer can be detected, it can be induced, but it can also be normalized by computational models of the manipulation of the bioelectrical signaling that normally keep cells operating towards large-scale anatomical goals.

Slide 3/41 · 02m:43s

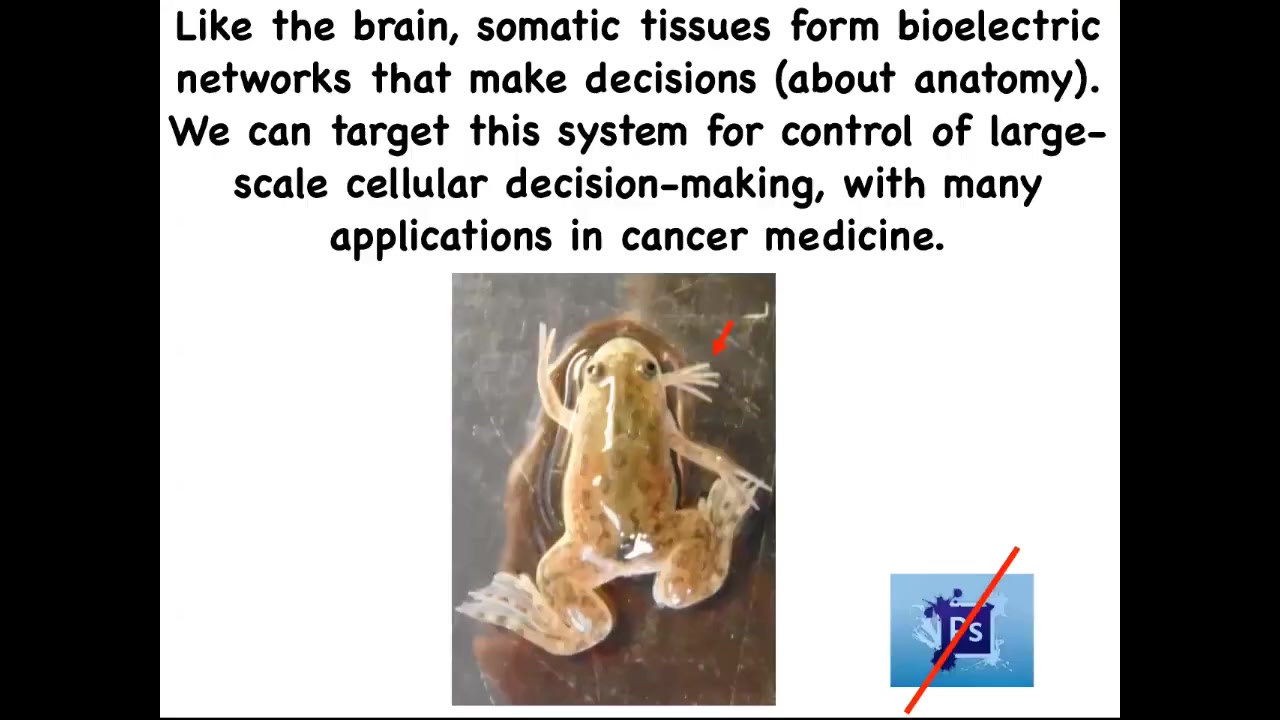

If we boil all that down to one sentence, it's this: the brain and all of the tissues in your body form electrical networks that make decisions about anatomy, and we can now target the system to change the large-scale decision-making of the cellular collectives. That has huge implications for all kinds of aspects of medicine. I'm going to show you some weird creatures today. Here's our five-legged frog. This is not Photoshop. These are real living forms in our lab that serve as our attempts to test the various theories that we have.

Slide 4/41 · 03m:18s

One fundamental aspect of the cancer problem is what scale do you think about it at?

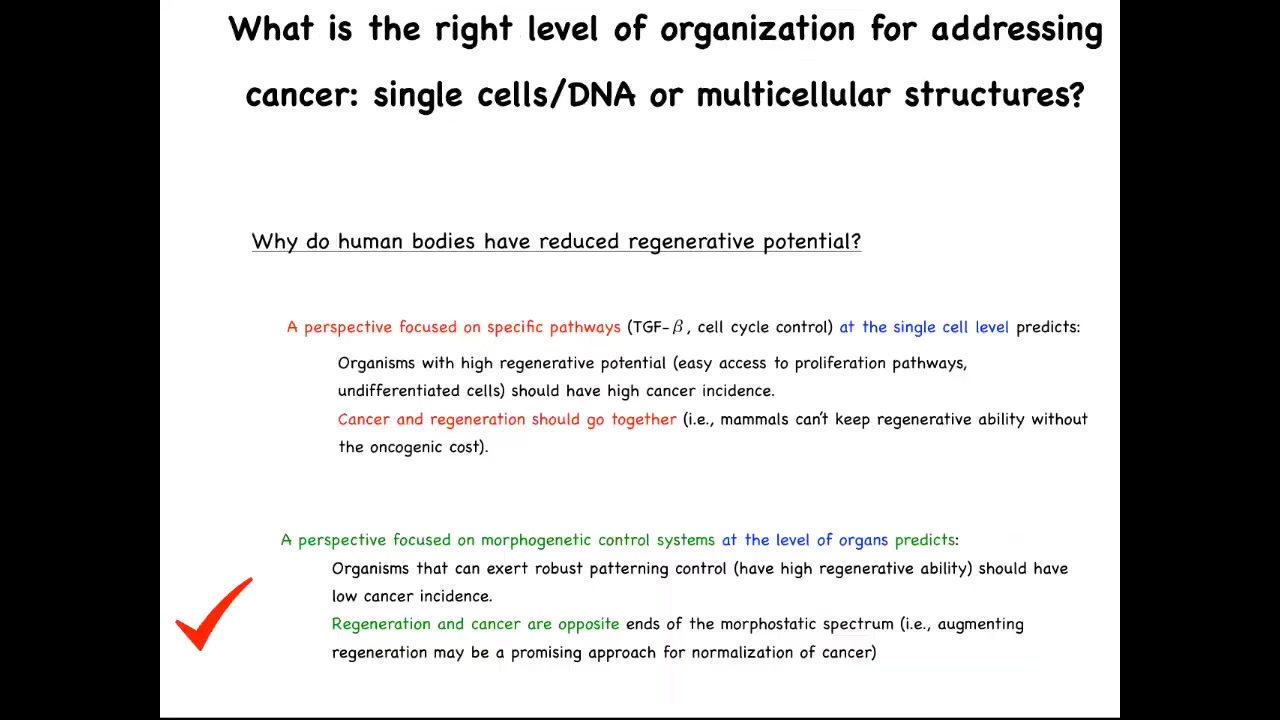

One particular thing that people sometimes ask is there are numerous animals, the planaria that I'll show you in a minute, salamanders, various other creatures that are highly regenerative. In other words, they lose a limb and they regrow it, things like that. People ask, why do human bodies have reduced regenerative potential? A common answer that people will advance is that it's to avoid cancer. If you're a long-lived organism that's going to be around for, say, up to 10 decades or so, you don't want to have access to highly plastic proliferative cells because the chance of developing cancer is going to be too high. The idea is that something like a human will then not be regenerative because we're keeping those plastic pathways suppressed.

A perspective focused on specific pathways, TGF beta, cell cycle control, all the things that we're used to thinking about for cancer and beyond, at the single cell level predicts that organisms with a high regenerative potential, meaning they have easy access to proliferation pathways, they have lots of undifferentiated cells, those animals should have a high cancer incidence, and specifically that cancer and regeneration should go together. This view predicts if you are a highly regenerative type of creature that has lots of plasticity, you should have a high oncogenic cost.

You could turn that on its head and make the opposite prediction. You might say organisms that exert robust patterning control over their cells, meaning they have high regenerative ability, should have low cancer incidence because of this ability to control cell behaviors towards adaptive anatomical outcomes. From that perspective, regeneration and cancer should be at opposite ends of the spectrum. Augmenting regeneration may then be a promising approach to normalize cancer.

It turns out that the evidence supports this view. Animals that are good at regenerating tend to be very cancer resistant. That turns out to be interesting and important.

Slide 5/41 · 05m:40s

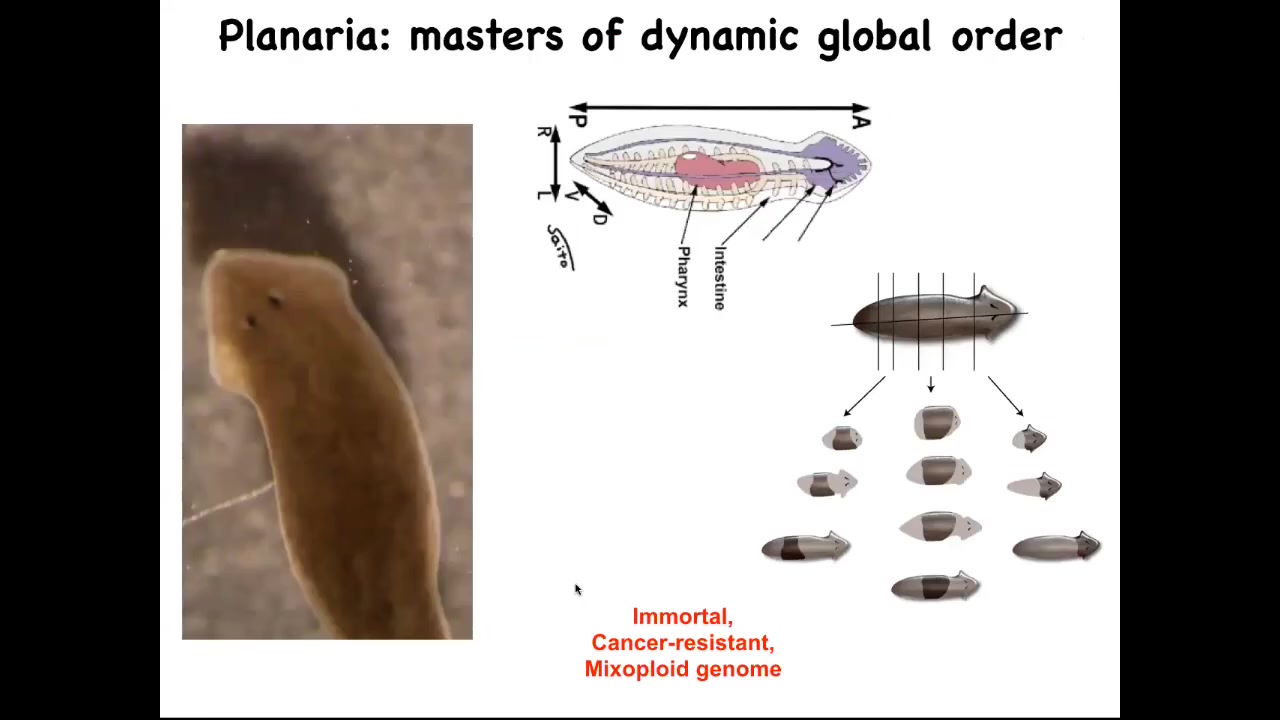

I want to show you one creature that in particular epitomizes this: the planarian flatworm. They have a true brain. They are similar to our direct ancestor. They have a centralized nervous system. They have lots of internal organs.

They have this amazing ability: you can cut them into pieces. The record is something like 275 pieces. Every piece knows exactly what a correct planarian should look like and regenerates everything that's missing. You get a perfect little worm.

In fact, the remaining piece scales down so that everything ends up being the correct proportion. Then eventually it will scale back up.

These guys are not only regenerative, they're immortal. There's no such thing as an old planarian of this kind. They are very cancer resistant. All of this occurs in the context of a mixoploid genome. If you look at their genomes, the cells could have different numbers of chromosomes. Their genomes are a total mess. If we have time later at the end of the talk, we can talk about why that is. I think it's a deep thing. What they're telling you is that it's possible to be a very long-lived creature despite having a chaotic genome, and also be cancer resistant.

For the first part of the talk, I want to, for a few minutes, think about that broader context: this idea of multicellularity versus cancer and what's going on here.

Slide 6/41 · 07m:10s

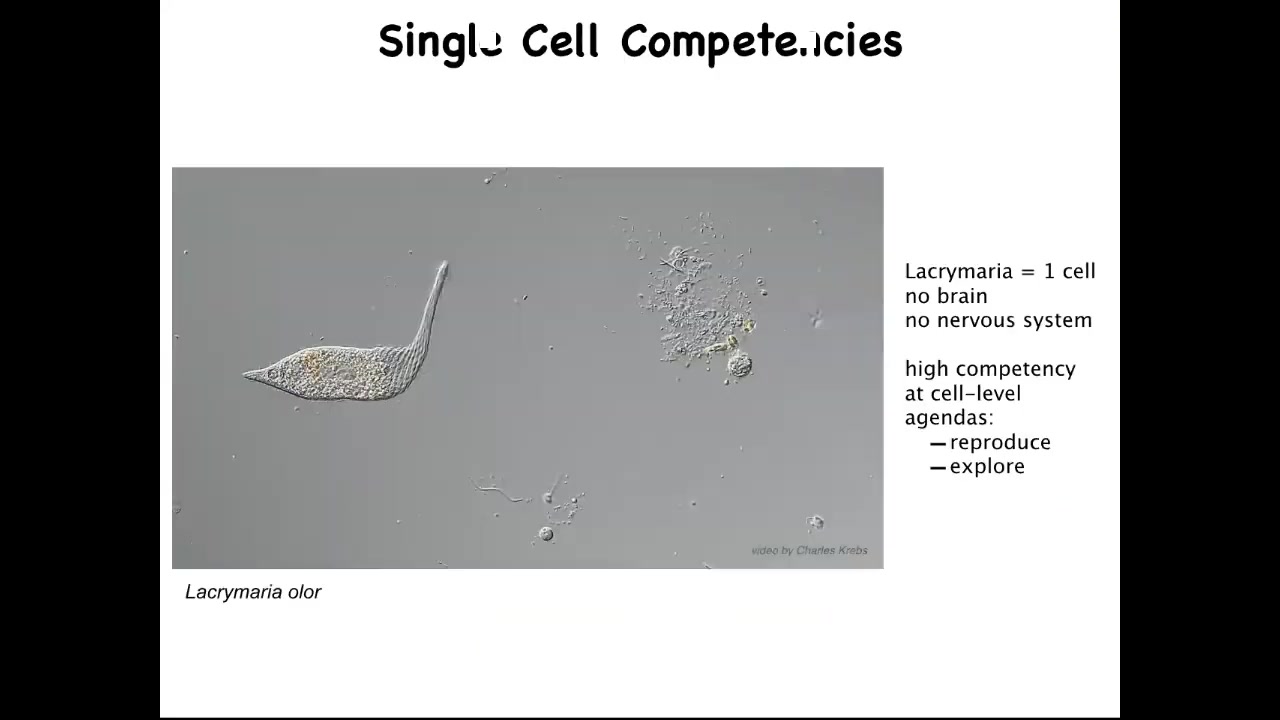

The first thing to realize is that the right question isn't why is there cancer? The right question is why is there anything but cancer ever? Because what we are made of are things like this. This is a free-living organism, but this is a single cell. This is called the lacrimaria.

You can see that it's actually very competent in its environment. It's got this local, very tiny light cone of the goals that it pursues. It's very competent in the control of its morphology, of its physiology, metabolics, and so on. It has little single-cell agendas. It's going to reproduce as much as it can. It's going to go wherever life is good. It's going to explore. It's going to feed and dump entropy into the environment.

This is the sort of thing that we are all made of. This raises an interesting question. Why do these kind of creatures, who have lots of different competencies in their own single-cell goals, come together during multicellularity to do this?

Slide 7/41 · 08m:13s

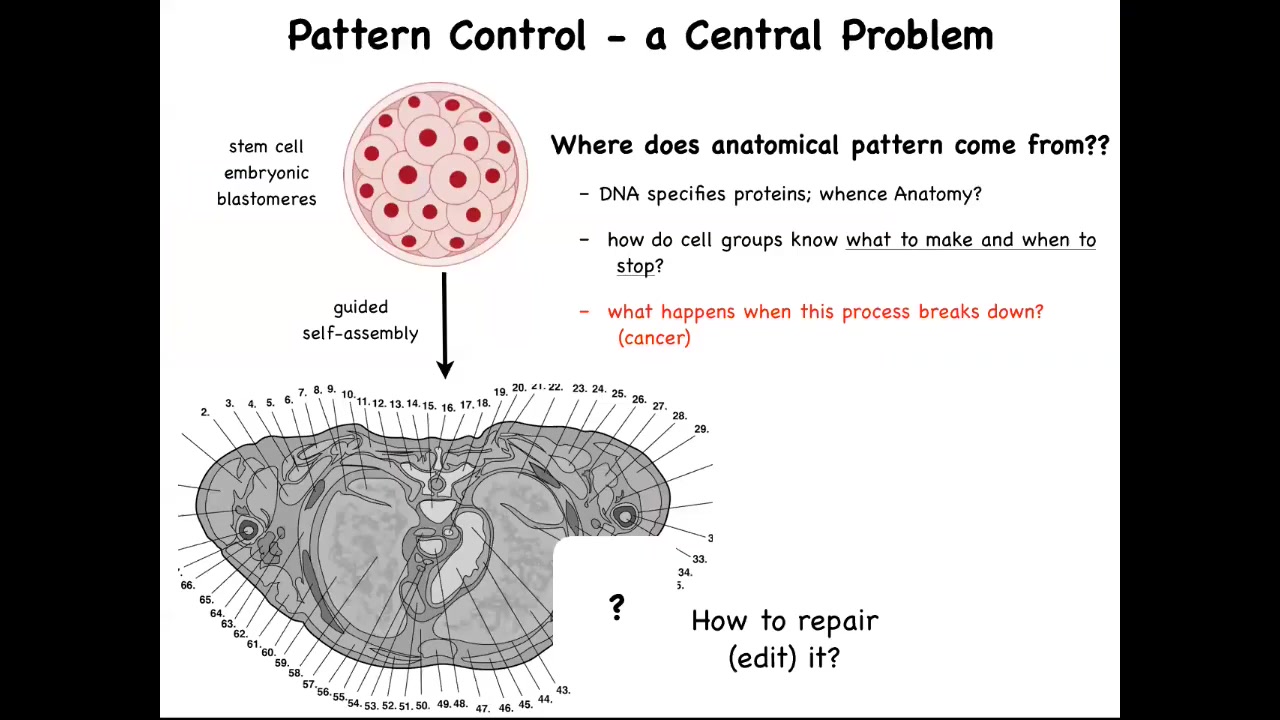

This is a cross-section through a human torso. You can see the incredible complexity and order. Everything is most of the time in the right size and shape and position and relative sitting next to the right thing. But we all start life as a collection of embryonic blastomeres. All of these cells have to reliably get to something like this. We need to ask the question, how do they do it? But also, where does this anatomical pattern come from? How do they know what to build?

The typical answer is people say, DNA, you've got a human genome, so what else is it going to build? This is very far from a satisfying answer because we can read genomes now and we know what's there. What's there is the specification of proteins, the tiniest pieces of hardware that the B cells have to deploy, but there's nothing in the genome that talks about the size, the shape, the symmetry type of the organism. We need to understand how this collective, using the hardware that it's been given by its genome, does all of the information processing needed to build what it's supposed to build, to stop when it's done.

How could we, as workers in regenerative medicine, ask these cells to rebuild a piece that's missing? In particular, what happens when this amazing process breaks down? What happens is cancer. I just want to point out why this genetic information is not sufficient. You might think we've had genomics and molecular biology for many decades now. Aren't we getting a handle on all this? Let's do a thought experiment.

Here's an axolotl larva. Baby axolotls have little forearms. This is a tadpole of the frog that we work with. At these stages they do not have any limbs. In our lab, we actually do this; it's more than a thought experiment. We make something called a frogolotl. A frogolotl is a combination of axolotl cells and frog cells, and they make a chimeric embryo.

We have the axolotl genome; it's been sequenced. We have the frog genome; it's been sequenced. I ask the question: can anybody tell me if these frogolotls are going to have legs or not? You can't. Despite the fact that we have the genomics and some understanding of the molecular biology of these cells, no one can make a prediction a priori of whether these frogolotls are going to have legs. That's because while we understand the molecular components inside cells, we don't understand how groups of cells make large-scale decisions about what they're going to make.

Slide 8/41 · 10m:58s

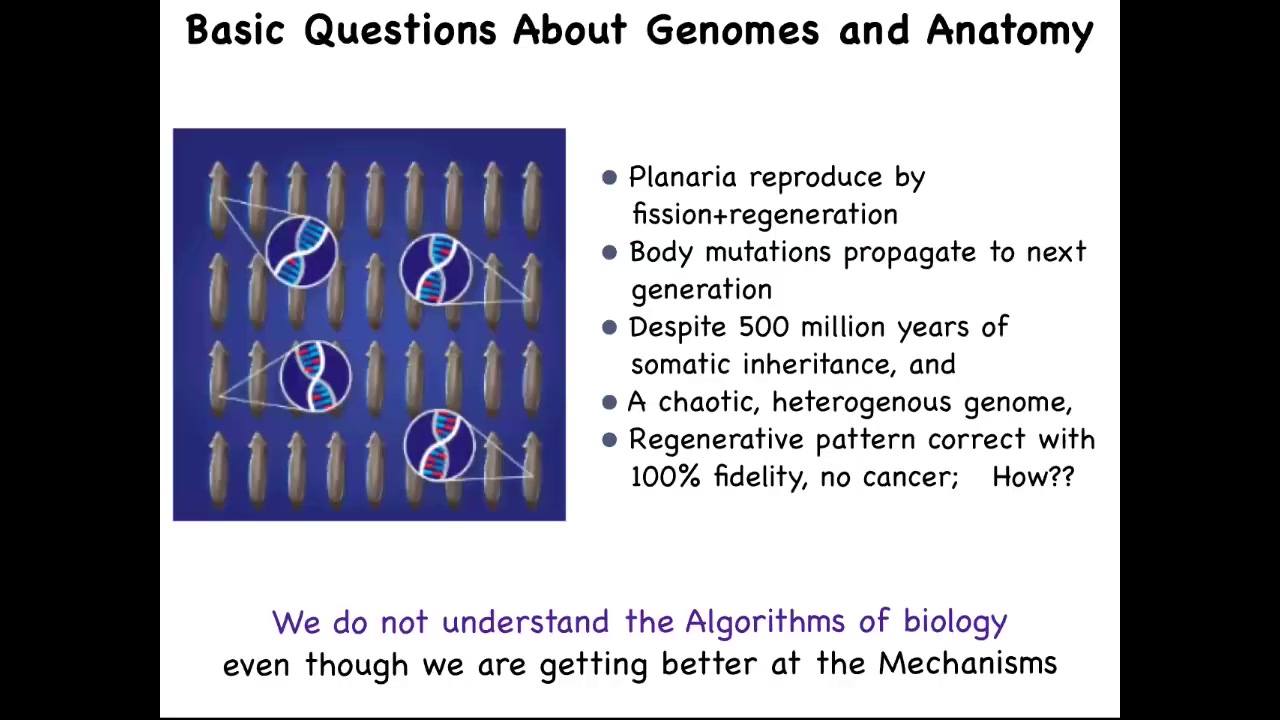

This is something that in planaria is a very stark problem because the species that we work with reproduce by fission and regeneration. They rip themselves in half and then they regenerate. That's how they reproduce.

When you do that, every somatic mutation that doesn't kill the cell ends up being amplified into the next generation as regeneration happens. They have somatic inheritance. These body mutations propagate continuously.

This is why their genome is so incredibly chaotic because they just keep everything that happens to them; they don't clean them the way that sexually reproducing organisms do. Despite all of that, despite all of this chaotic genome, they have 100% regenerative fidelity and they're very cancer resistant. It's pretty scandalous when you compare that to what we learn in basic biology, that the animal with the craziest genome actually has the least susceptibility to cancer, the best anatomical fidelity, and so on.

We're getting better at the mechanisms of biology, but we really don't understand the algorithms yet.

Slide 9/41 · 12m:08s

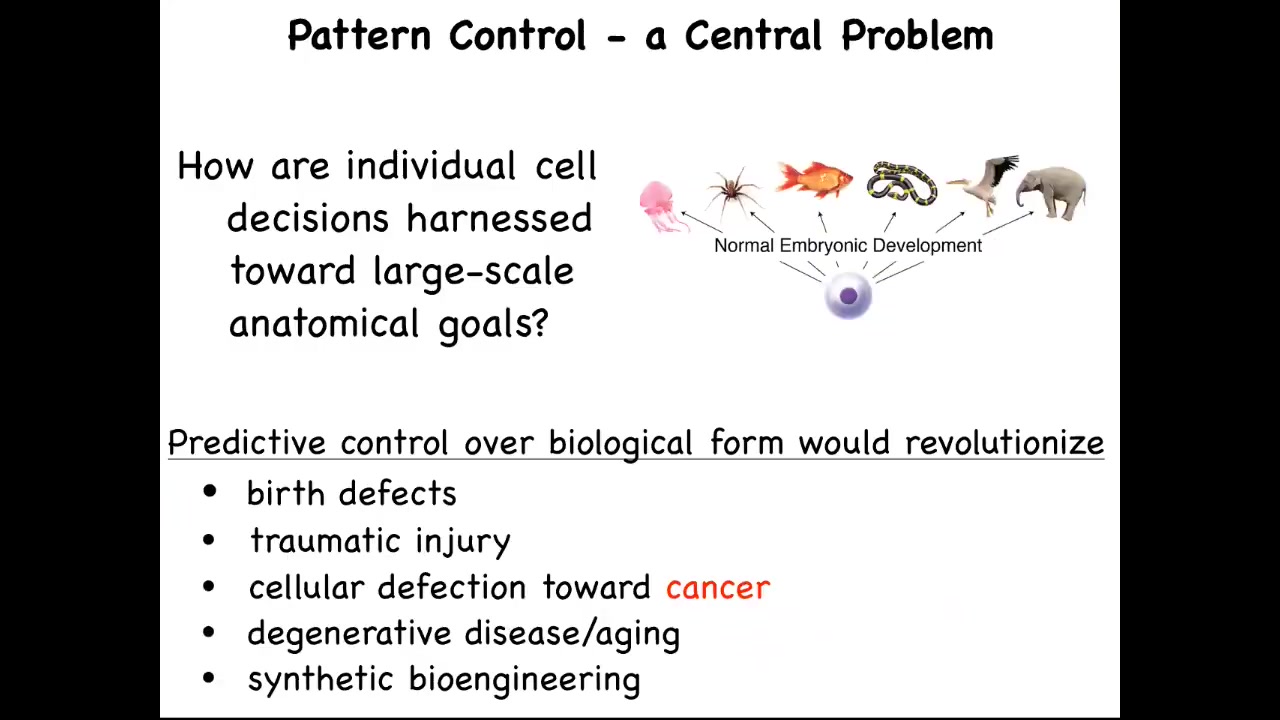

What we're interested in are these questions. How are individual cell decisions harnessed towards large-scale anatomical goals? If we understood this, it's not just about cancer. We would have the answer to birth defects, traumatic injury, degenerative disease, and be able to make all kinds of synthetic living machines. This is how we approach the cancer problem.

Slide 10/41 · 12m:29s

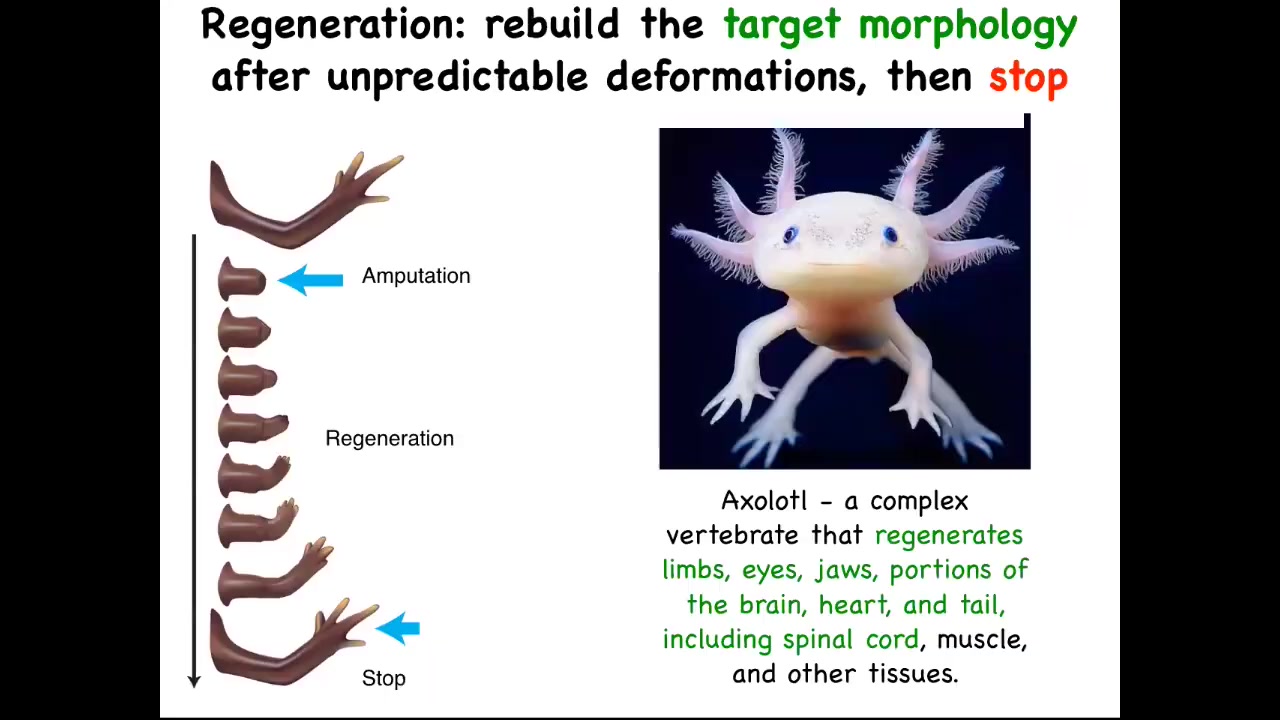

We think a lot about anatomical homeostasis. The most amazing thing about regeneration is that it knows when to stop. So here's an axolotl. These guys regenerate their limbs, their eyes, their jaws, portions of the brain, the heart. They regenerate their tail, including spinal cord and ovaries, amazing as adults. You can amputate anywhere along the axis of the limb, and they will regrow exactly what's needed, no more, no less. Then they stop. When do they stop? They stop when the correct salamander arm has been completed.

It's clear that this, as a collective, has a good idea of what the final steps are supposed to be. We know that because it stops the proliferation, the morphogenesis. Everything stops when they get there.

Slide 11/41 · 13m:23s

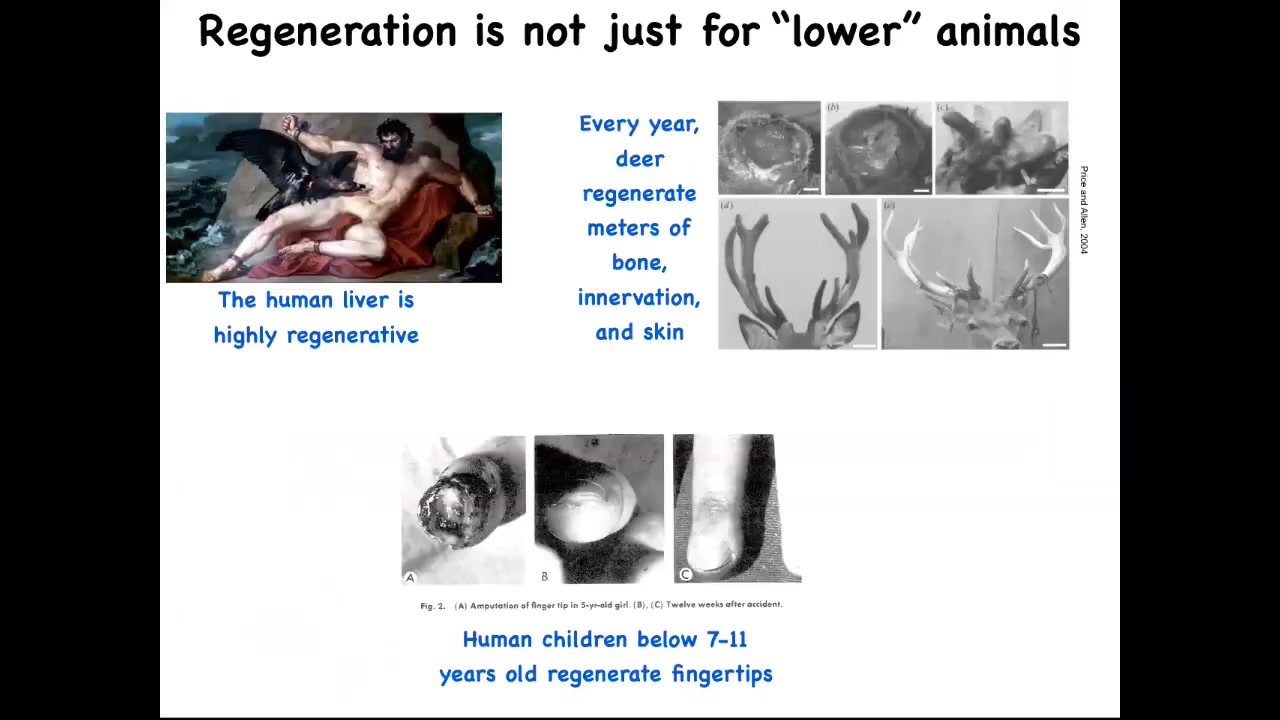

By the way, this isn't just for frogs and worms. Human livers are highly regenerative. Even the ancient Greeks knew that. I have no idea how they knew that back in those days. Human children regenerate their fingertips, so a clean amputation at a fairly young age, if you don't sew the skin over, will eventually result in a cosmetically acceptable finger. And deer, when they regenerate their antlers, they grow up to a centimeter and a half of new bone per day. So here's a large adult mammal growing massive amounts of new bone, vasculature, innervation, skin, and so on.

Slide 12/41 · 13m:59s

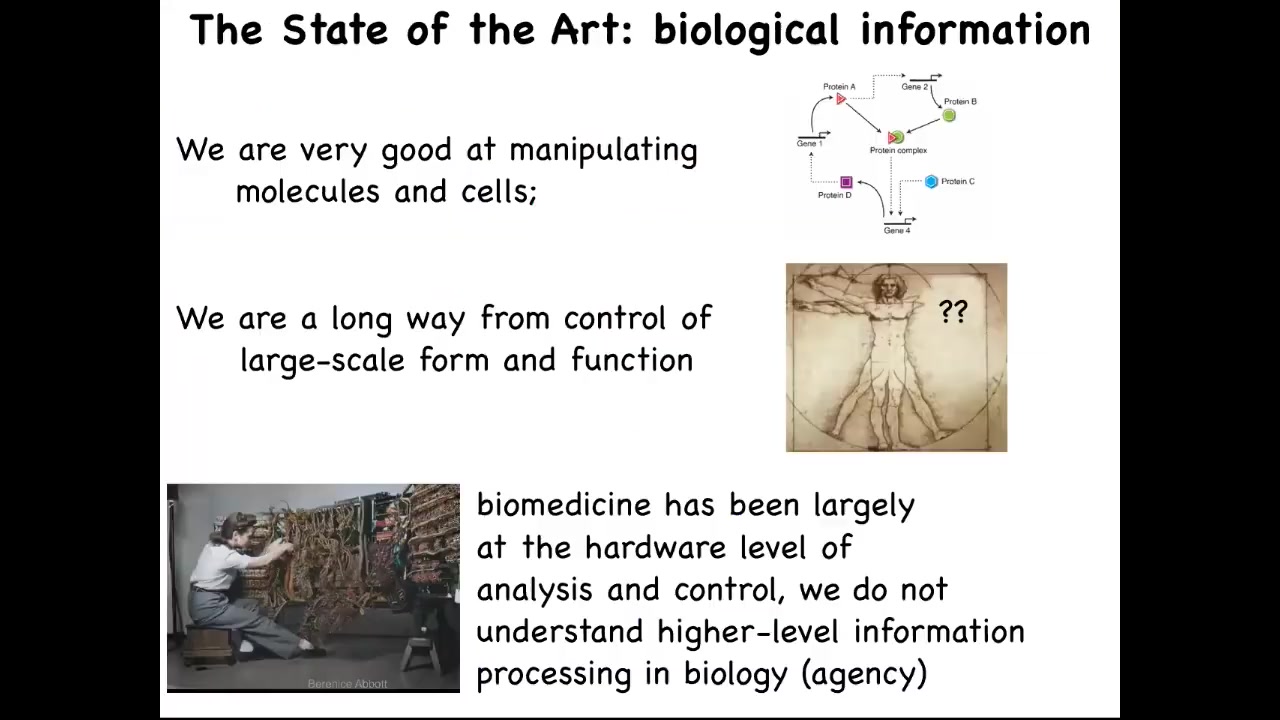

So what we would like to do is to move from the questions of molecular biology, and the community is quite good at getting this kind of information, what genes and proteins interact with each other, to really try to understand the large-scale decision-making of complex organs. You can think about the journey that computer science took. This is what programming looked like in the 1940s and 50s. What's important about this is that you can see, in order to program this computer, what she's doing is she's physically rewiring it. The focus is on the hardware, so she's there plugging wires back and forth. The idea is that in order to control this machine and make it do something else, you have to physically interact with the hardware.

This is the reason we have this amazing information technology revolution: we've moved away from that. Some people still work on hardware, but the vast majority of us don't need to have a soldering iron when we want to switch from Photoshop to Microsoft Word on your laptop, because we've learned to take advantage of the reprogrammability of the device.

I'm going to argue that biology is highly reprogrammable and that this is what we need to do. We need to move biology and medicine towards understanding that because all of the current excitement in the field is about the hardware. CRISPR, genomic editing, rewiring molecular pathways, protein engineering, all of this stuff is focused on the hardware.

Slide 13/41 · 15m:35s

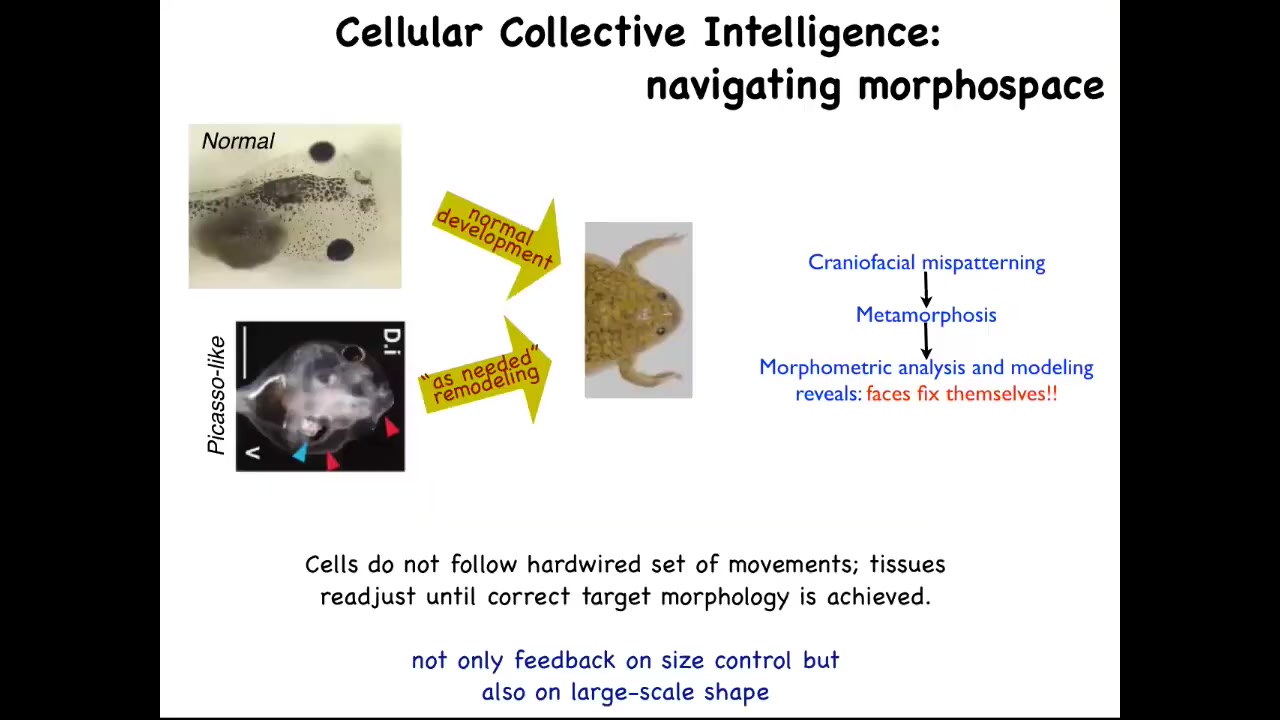

The kind of software competencies I'm talking about are the sorts of things that you see, for example, here. This is something we discovered a few years ago. Tadpoles need to become frogs. In order to become a frog, they have to rearrange their face. The eyes have to move, the nostrils have to move, the jaws, everything has to move. It used to be thought that this was a hardwired process that every organ just moves in the right direction, the right amount, and there you go. You have your frog.

We decided to test that idea and to see if there was in fact more intelligence to this process. How do you test for intelligence? You perturb the system in a novel way, and you see if it still has the ability to have its goals met despite starting in a new configuration. This is William James's definition of intelligence. It says, same goal by different means. How competent is the system?

What we did was we created what we call Picasso tadpoles. Everything is in the wrong place. The eyes on top of the head, the jaws are off to the side, the thing's a complete mess. If all it was doing was moving each organ in the right direction, the right amount, the frog would be equally messed up because you're starting in an incorrect configuration. What we found is that these animals make quite normal frogs because all of this is going to move in novel paths. Sometimes it goes too far and has to double back. But all of them will move around and rearrange relative to each other until they get to a correct frog phase. Evolution has given us not a hardwired system that makes certain movements. It has given us an error minimization scheme that is able to continue to operate until a particular morphological goal has been met. It has lots of different types of feedback.

Slide 14/41 · 17m:15s

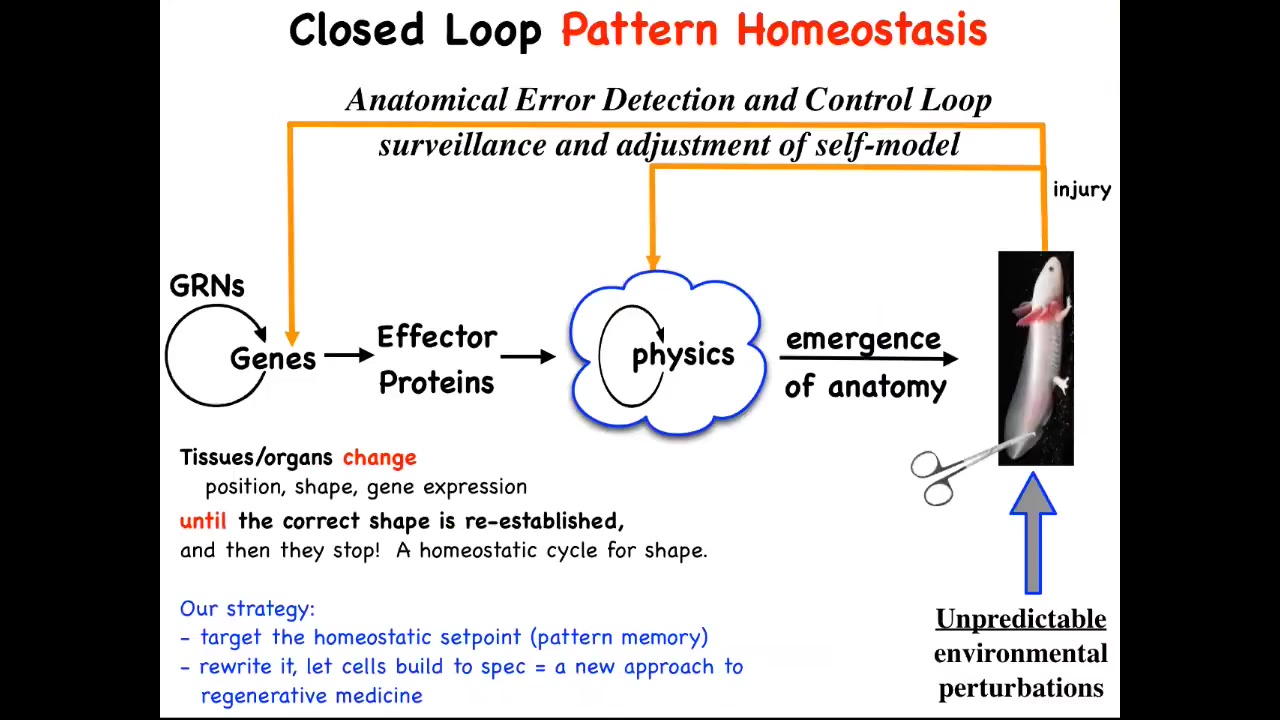

This is the kind of paradigm that we all learn. It's based on genetics and emergence, this idea that gene regulatory networks will create proteins, they interact with each other using local rules, and then eventually there's emergence of complexity. Something complex happens like this salamander. That's true, this does happen, but it's only a part of the story, and I think not even the main part.

The main part is that this hardware that is produced has this amazing ability to implement anatomical homeostasis. When the system is deviated by injury, by mutations, by teratogens, pathogens, when it's deviated there are feedback loops that kick in, both at the level of transcription and at the level of physics, and this is the one we're going to talk about, that try to get you back to where you need to be. It's an error minimization process, like the thermostat in your house. It's a basic homeostatic loop.

The thing about homeostatic loops is that they have to have a set point. This is a very unconventional view, but typically these feedback loops are scalar. There are single numbers like pH or hunger level. Here, the set point actually has to be a description of a fairly complex anatomical structure, not to the individual cell level of detail, but some level of anatomical description.

In general, we're not encouraged in biology to think about goals or final states. We're encouraged to think about molecular mechanisms and what the emergent qualities are of that complex dynamical system. This cybernetic view really forces you to think about whether the system literally stores a set point of what it's supposed to build. What it's doing is like any homeostatic system: it tries to reduce the error to that set point.

This is what we've been doing for years now. We've taken this very strong and counterintuitive prediction that this thing literally knows what shape it's supposed to grow. The prediction is that we should be able to find that encoding. We should be able to decode it. Whatever biophysical medium holds it, we should be able to decode it. Then we should be able to rewrite it.

If we rewrite it, something amazing should happen, which is that in the typical approach to this problem, if you believe only in emergence, all your interventions have to be down here. You have to make changes here, maybe with CRISPR, maybe something else. You make changes down here and eventually they percolate up. The limiting factor for complex, beyond single-gene diseases is: how do you know which genes to manipulate for a complex outcome? You generally don't because this whole process is not reversible. It's a really terrible inverse problem.

However, if there is in fact a stored pattern that the cells are working towards, then you've got a different approach. You might be able to change the pattern the way you do in your thermostat when you change the set point. You don't need to know how the rest of the system works. You just need to know how to change the set point and rely on it to do what it does best, which is to try to get to that set point.

Slide 15/41 · 20m:29s

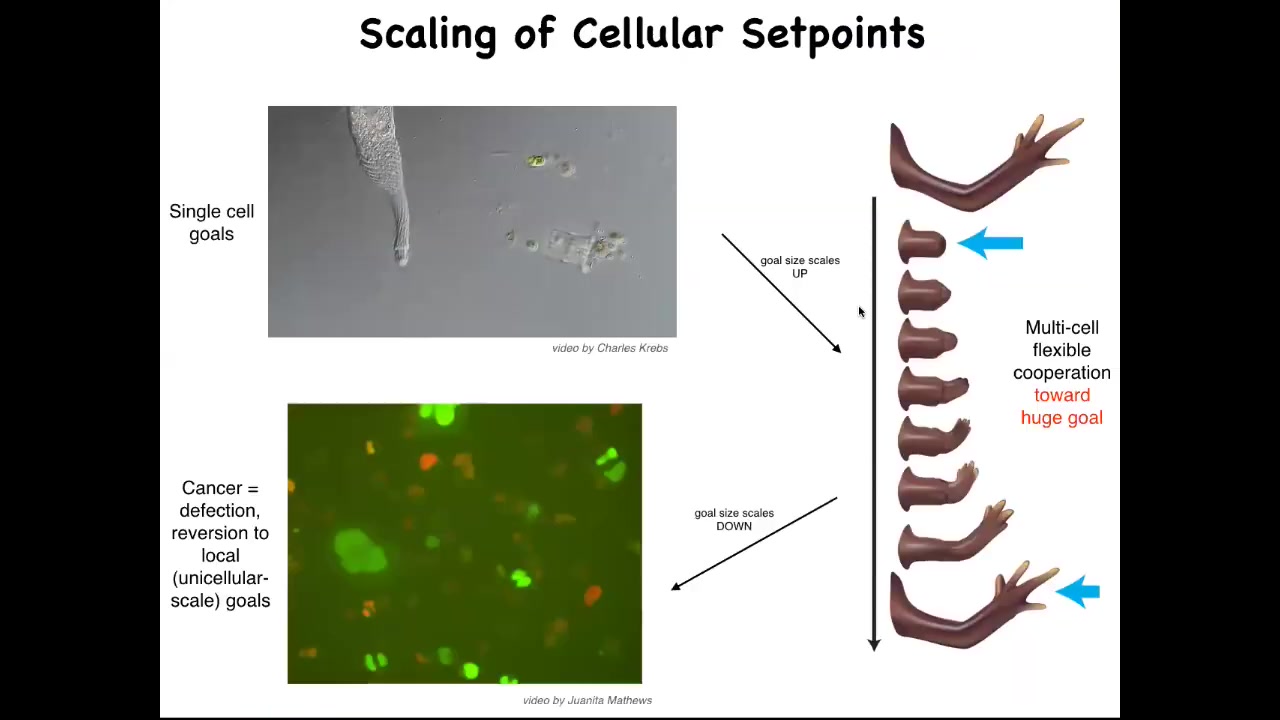

So here's how we think about this, that what evolution has done is scale up competent single cell systems into something like this, using a particular interaction that I'll tell you about shortly, where the goals get much bigger. Instead of single cell level goals of metabolism and proliferation, the goal here is to maintain this. And if you deviate from that goal, the system will very commonly go back and try to build it. But there's a breakdown of that cooperation and that scale up, and that breakdown is cancer. This is human glioblastoma cells crawling around. I'm going to make the argument that what this process really is is a breakdown of this coordination system that is scaling up from tiny goals of single cells to anatomical goal states in an anatomical morphous space. And that process breaks down and you get cancer.

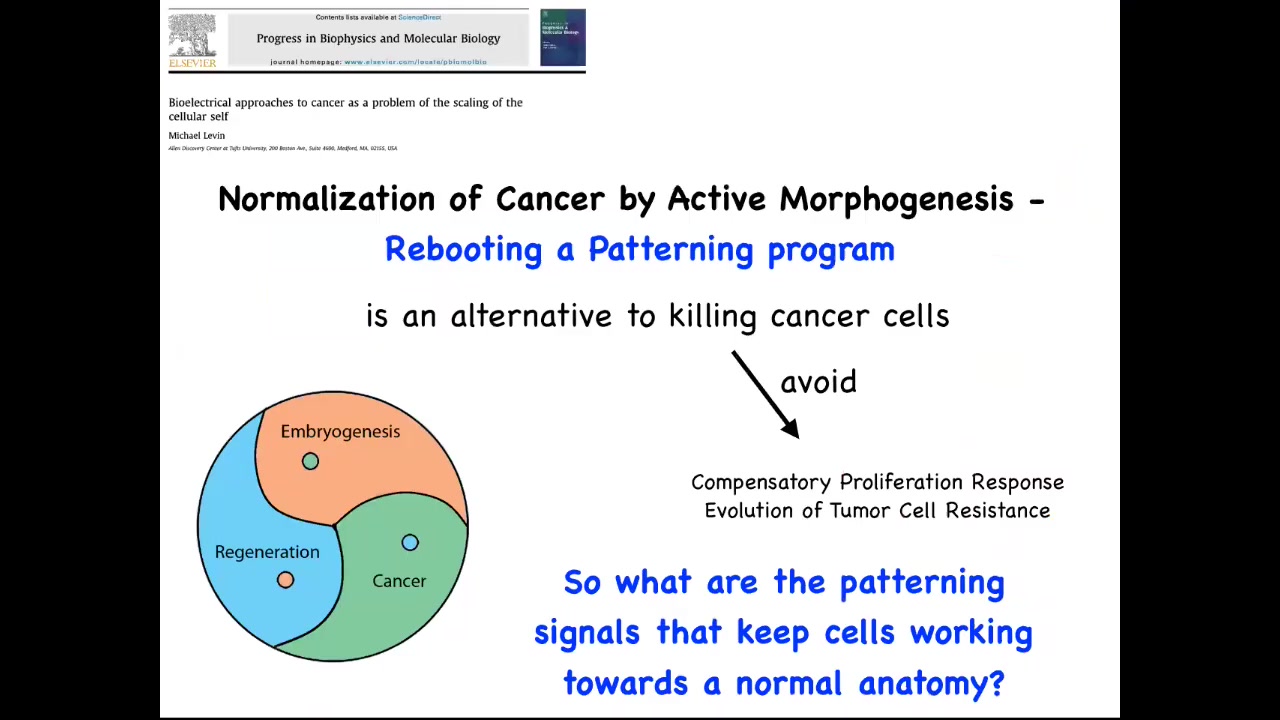

Slide 16/41 · 21m:25s

This way of thinking about it, which weaves together embryogenesis, regeneration, and cancer as a problem of information control, in particular of scaling of goals in biology, suggests that if we really understood this, we should be able to develop strategies that don't just kill the cancer cells, which are of course problematic because you get compensatory proliferation and tumor resistance and all that. Instead of trying to kill them, could we try to reconnect them more strongly to the signals that normally keep them working together towards making nice organs? That requires us to know what are these signals? How do cells remember what the whole thing is supposed to be? Because no individual cell knows how many fingers a salamander limb is supposed to have, but the collective certainly does.

So the question is, how does that scaling happen? How do you go from single cell information to large scale anatomical goals?

This is where we get into bioelectricity. Bioelectricity is just one layer of a complex morphogenetic field of information that all cells have access to. I'm going to spend the next half an hour talking about bioelectricity, not because I think bioelectricity is the only thing that matters. Chemical signals, extracellular matrix, biophysical pressures and tensions, and so on. But this is a particularly interesting and important layer, and that's the one that I'm going to talk about. This morphogenetic field is there guiding the large-scale system throughout lifespan, from basic embryonic development all the way through maintenance and resistance to aging.

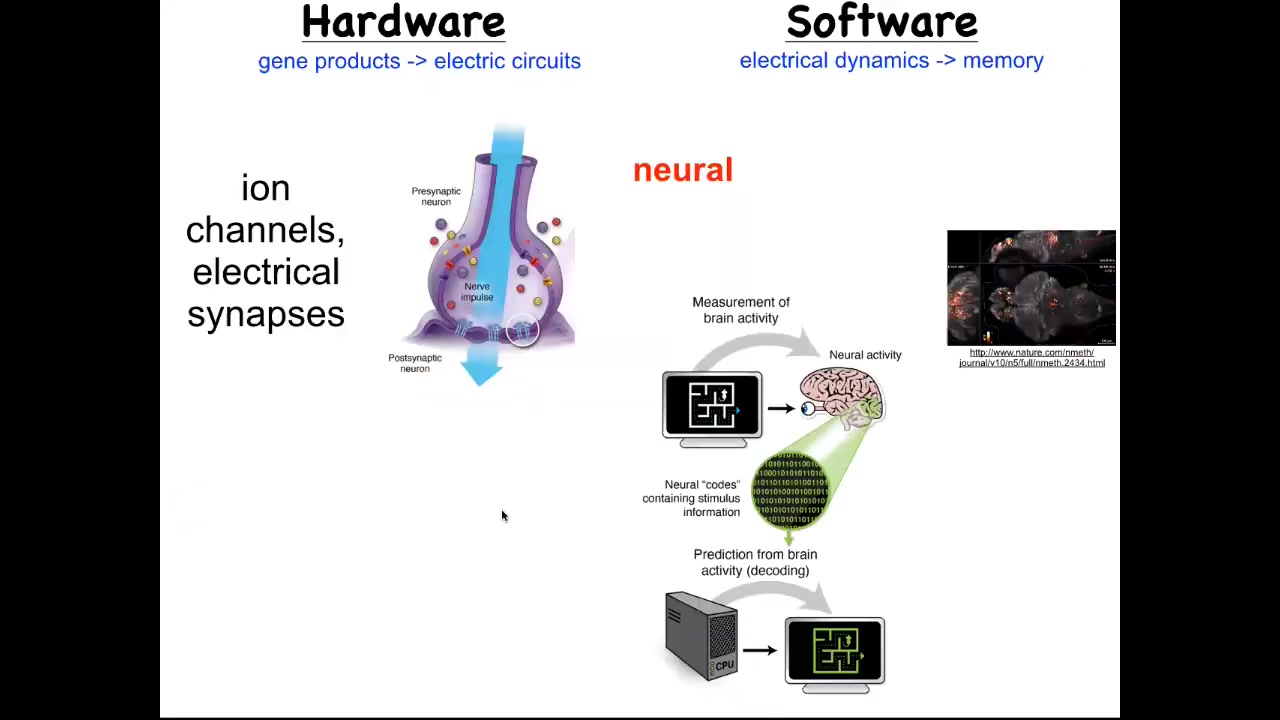

So what are bioelectrical signals? Every cell in your body, not just neurons, has ion channels and gap junctions. These ion channels let charged molecules in and out. As a result, you get a voltage gradient across the membrane. So every cell has a voltage gradient across that membrane.

If you take different kinds of cells and put them on a scale from depolarized to hyperpolarized, you get a very interesting relationship. Mature quiescent cell types tend to be up here, strongly polarized. Your proliferative cells, such as embryonic stem cells and other embryonic types of cells, tend to be down here, as do cancer cells.

I always hesitate to show the slide because people really like this and it takes away attention from the fact that I don't think any of this is really a single cell level problem. I don't think cancer is a single cell disease. This focuses your attention on the individual voltage of a single cell, but it's actually much more interesting than that. It is true that this voltage controls all kinds of cell properties that are important for cancer. It controls differentiation, apoptosis, cell migration, cell shape, and so on.

Slide 17/41 · 24m:33s

But the story is much more interesting than the single cell behavior because as we start to think about how it is that collections of cells can store memories of what to do, the most obvious example of that is the nervous system and the brain. Each of us exists as a coherent individual over and above the many neurons that are in our brains because of bioelectrical signaling in your brain that serves an important function. It works as a cognitive glue. What it does is it allows information processing in networks.

While individual cells have these voltage dynamics, what they do is they propagate those electrical states through various kinds of synapses, such as these gap junctions, to their neighbors. It's the movement of these electrical signals through the network that binds them together towards computations that can underlie cognition and the appearance of an individual that is more than the sum of their parts. This hardware allows interesting software.

This group made this video of a zebrafish, a living zebrafish brain and everything that's going on as this animal thinks about whatever it is that fish think about. You can track all the electrical activity. There's this goal; it's called neural decoding, the idea of being able to read out this electrophysiology over time and decode it so that you know what the animal is thinking. That's the commitment of neuroscience: from this pattern, you should be able to recover the memories, the goals, the preferences, the behavioral competencies of this animal. They're all encoded in this electrical activity.

But it turns out that every part of your body has these ion channels. Most cells have these electrical synapses with their neighbors. We wondered, could we extend neuroscience beyond neurons and ask the same neural decoding question, except outside of the nervous system, let's say in an embryonic tissue or in a nascent tumor, could we read out the conversations that these cells are having and try to understand what the collective is going to do by tracking the individual voltage states of each cell?

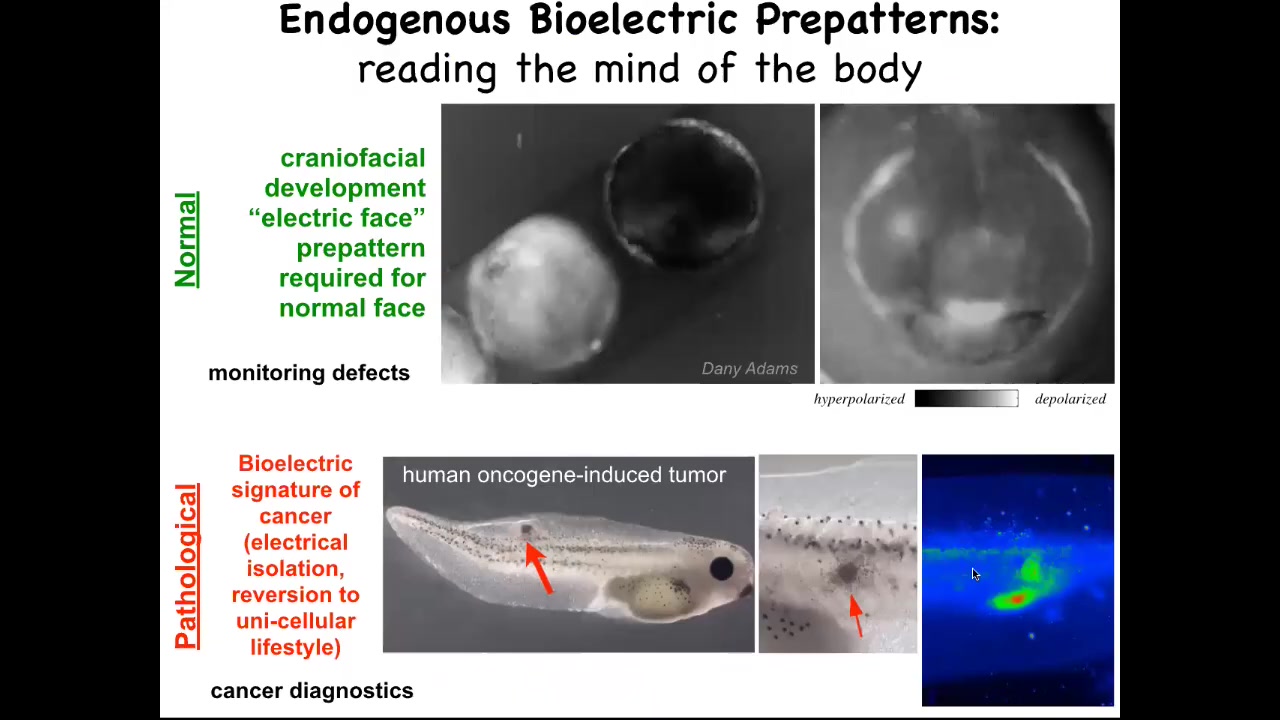

This is not a model. This is actual data of a voltage-sensitive fluorescent dye. This was a technique first developed by my colleague, Danny Adams, who made this video of an early frog embryo developing. The idea is to be able to decode what the collective is going to build.

Slide 18/41 · 27m:00s

I'm going to show you here, this is grayscale, but it's the same idea. It's a voltage-reporting dye. This is a time lapse of a frog embryo putting its face together. There's all kinds of interesting things happening. This is one frame from that video. What you see in that frame is that long before the genes come on to pattern the face and long before the anatomy of the face is established, you can read out the pattern that it's going to make in the future. Here's where the eye is going to be. Here's where the mouth is going to be. Here are the placodes. We call this the electric face. It is literally the pre-pattern or the tissue memory of what a correct face is supposed to look like. If you perturb this pattern at all, you change the gene expression and then you change the anatomy. This is instructive. It is required for the normal face to take shape. This is a pathological pattern, which is when we inject human oncogenes and they make a tumor and eventually it starts to metastasize. You can detect this process long before it actually happens by tracking the voltage of the cells. You can see that these cells have already electrically decoupled from their neighbors. When they do that, they're reverting to a single cell, a unicellular ancient past. As far as they're concerned, the rest of the animal is just environment to them. They're going to proliferate, they're going to migrate to where it's metabolically favorable. You can detect this breakdown of multicellularity.

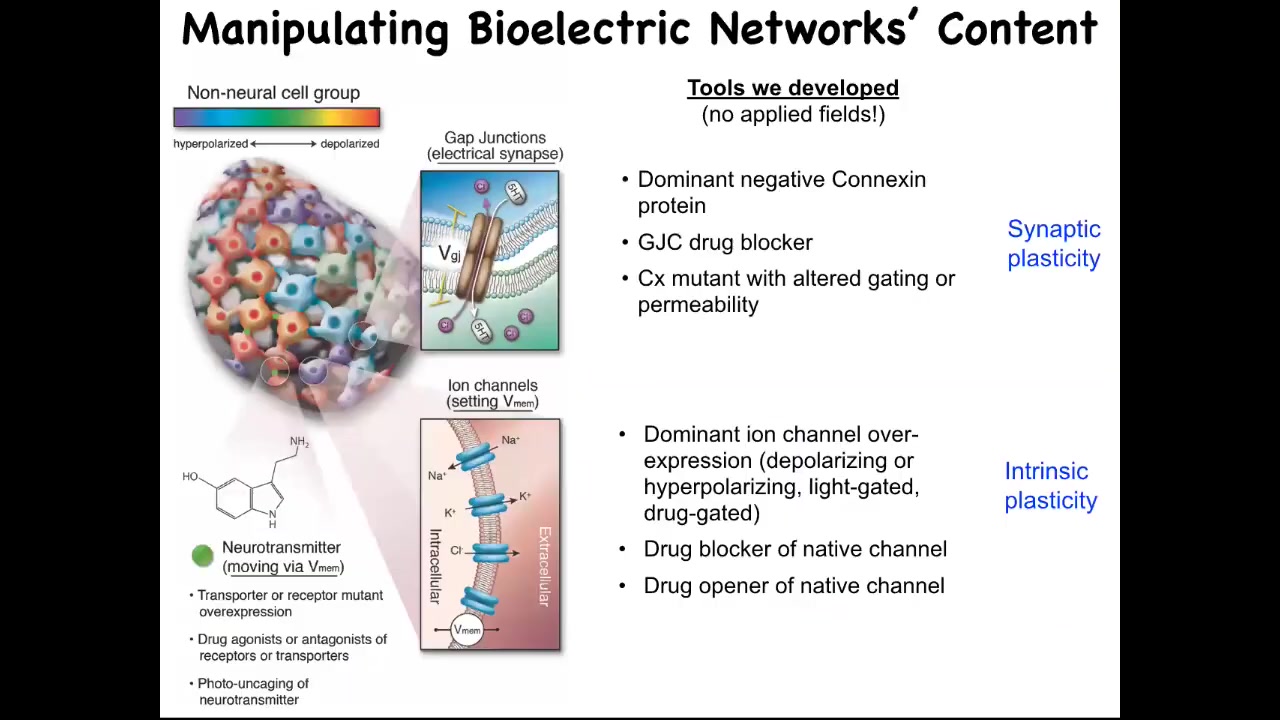

What we've been doing is developing tools first to track and characterize these bioelectrical gradients, lots of computational modeling to link them to the ion channels and pumps that are there.

Slide 19/41 · 28m:43s

The most important thing is the functional tools to rewrite the pattern. It's one thing to read it and be able to see what the electrical states in the collective are, but critically, you have to manipulate them and try to write, in the language of neuroscience, you're trying to incept false memories into the tissues or change the electrical pre-patterns that guide their activities. The way you do that: we don't use any kinds of applied fields. There are no electrodes, there are no magnets, there are no electromagnetic waves or radiation, nothing like that. What we're using is we're exploiting the native interface that cells expose to each other. This is how the cells program each other natively in the body. They're using this interface of these ion channels and these gap junctions. And we can use them too. We can use pharmacological, molecular, genetic, or optical (with optogenetics) methods. We can control the gap junctions and we can turn the channels on and off in spatial patterns, and thus we can imprint new bioelectrical memories into tissues.

Now, the next question is, what happens when you do that? What's the evidence that these patterns are actually instructive for anything? Couldn't they just be a readout of housekeeping physiology, an epiphenomenon? How do we know they matter? We know they matter because now that we have these tools, we can start to rewrite the pattern. I'm going to show you what happens when you rewrite the pattern.

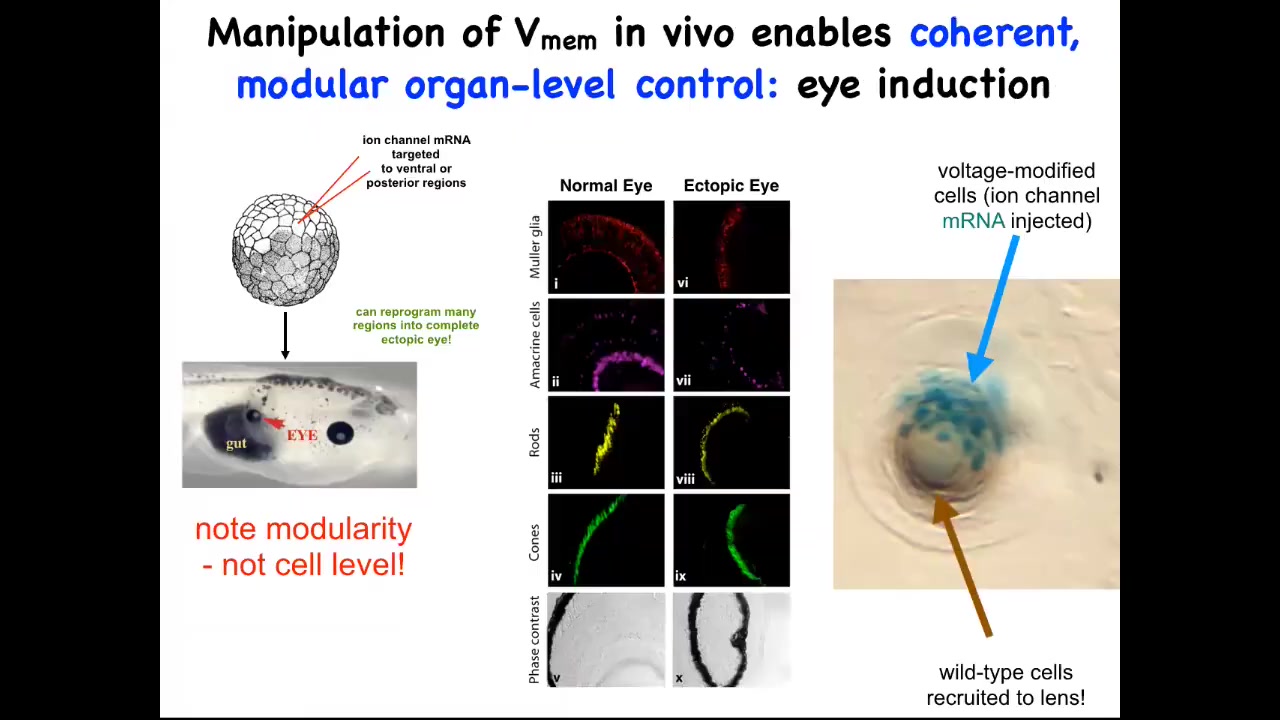

Slide 20/41 · 30m:10s

One thing you can do, I showed you the electric face, which has a particular kind of pattern that determines where the eye is going to be built. We can recapitulate that pattern somewhere else. We can put it anywhere on the embryo that we want. When you do that, you inject an RNA for a specific potassium channel that sets that little voltage pattern. Wherever those cells get that information, they will build an eye. For example, they might have been gut cells before, but if you tell them to build an eye, they will build an eye.

Those eyes will have all the right lens, retina, optic nerve, all the right stuff that belongs there. Note the incredible modularity. We didn't provide enough information on how to build an eye. We didn't try to control gene expression levels or all the different stem cells that need to happen or all the different morphogenetic movements. We didn't say any of that. We provided a very simple bioelectrical pattern that serves as a subroutine call. All it does is encode for the rest of the cells. It encodes the information: "build an eye right here."

In fact, this is a cross-section through a lens created this way. The blue cells are marked with beta-galactosidase. They're the ones we actually injected. If there's not enough of them to build an eye, they will recruit their neighbors. All this other stuff that's making this lens was never manipulated by us in any way. It's only the blue cells that we targeted.

You see one of the competencies here: not only is there a subroutine you can call to make a complex organ, but if you don't hit enough cells, they will have a conversation with their neighbors and recruit them. Another collective intelligence, for example ants, will also recruit their buddies if they come across something that's too big a job for the few of them; it scales to the task at hand automatically. We didn't have to do anything for that. The body already does it. We tell these cells to make an eye, and they tell their neighbors to participate so that we can all make a properly shaped lens.

Slide 21/41 · 32m:05s

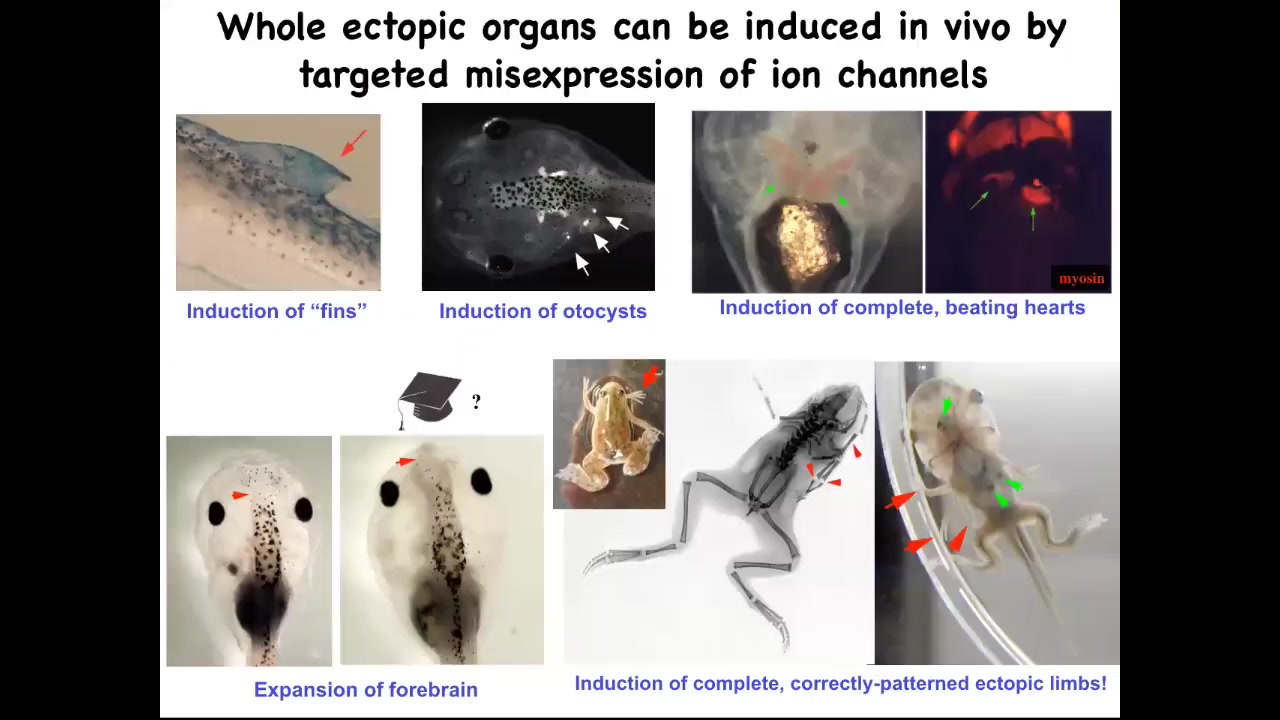

If you do that, you can make ectopic forebrains here. This is what a normal frog brain looks like. You can make extra limbs, lots of extra limbs. You can make ectopic beating hearts. You can make otocysts, which are inner ear balance organs. And you can even make fins. That's interesting because tadpoles aren't supposed to have fins. That's more of a fish thing, but we'll talk about that.

Slide 22/41 · 32m:28s

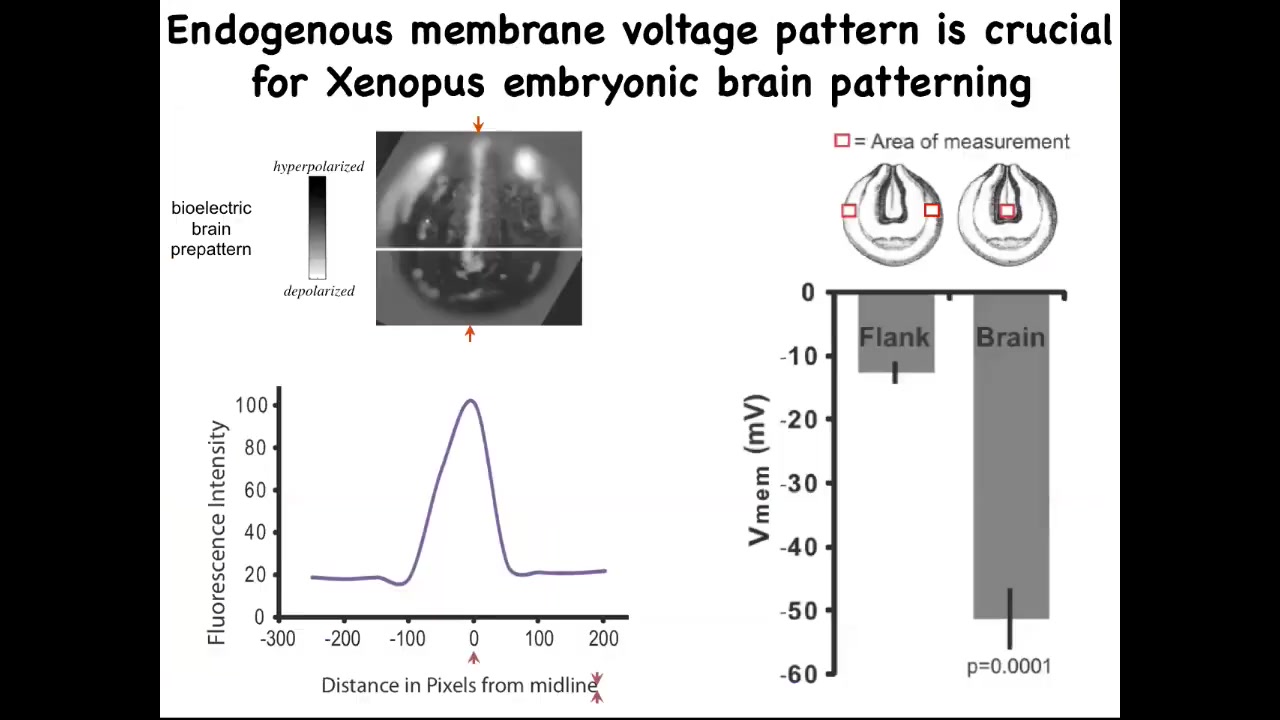

You can also use this technique to repair birth defects. So very briefly, this is the pattern that indicates what a frog brain should look like and the size and shape of it. It's got a very particular voltage characteristic. If you scan along this line, it looks like this bell curve.

Slide 23/41 · 32m:46s

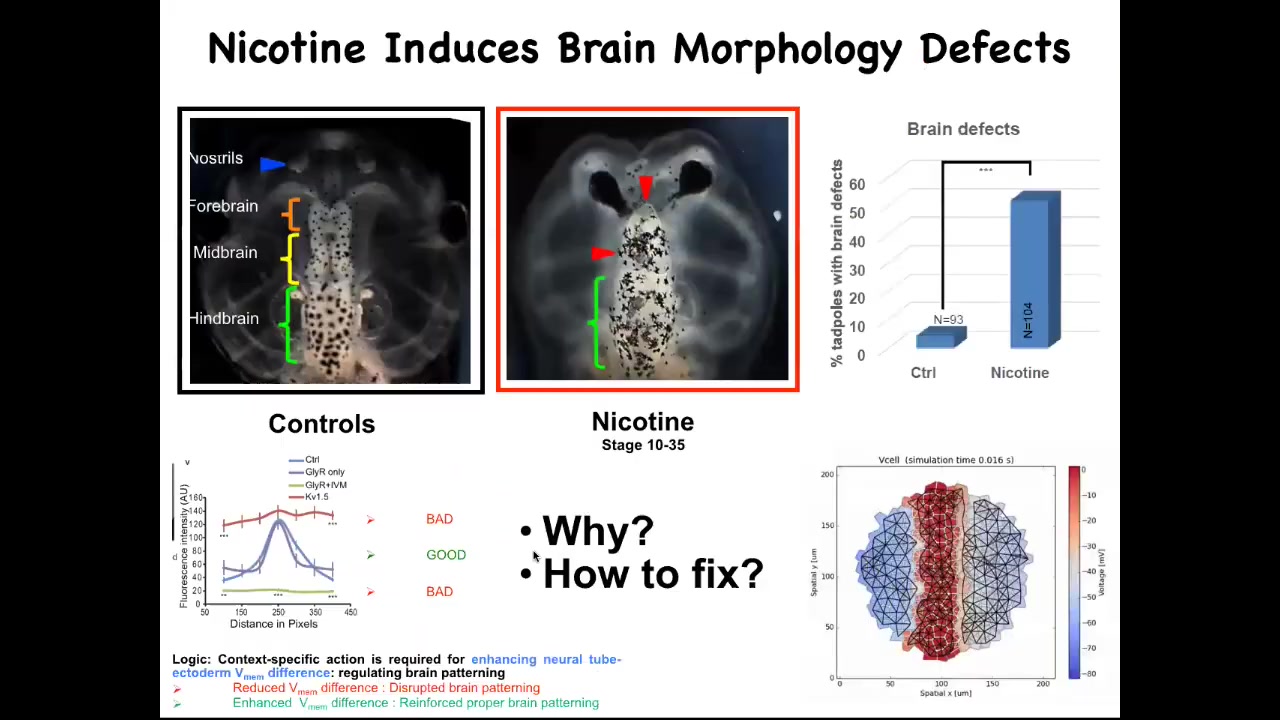

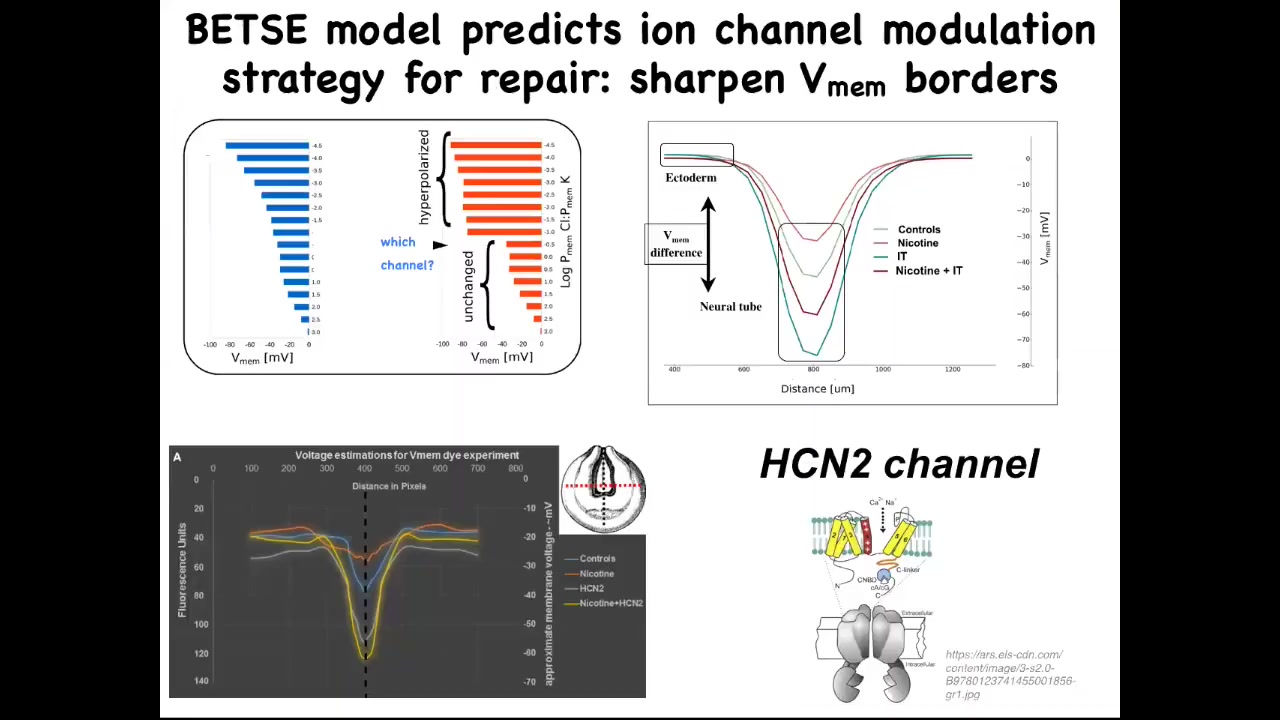

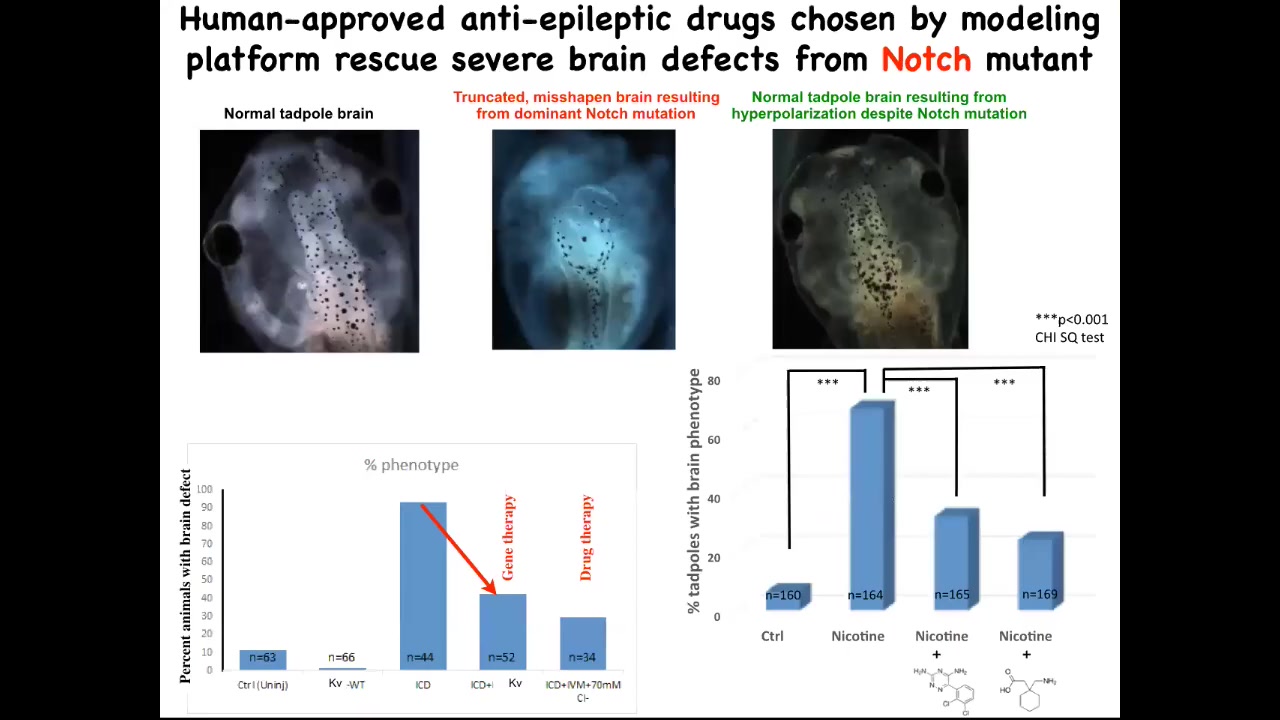

What we figured out is that there are many teratogens, for example nicotine and alcohol, fetal alcohol syndrome. But what they do is they ruin this nice pattern. They'll flatten it out either here or here. In either case, you get severe brain defects. We made a computational model of this process, of what happens to the bioelectrics under various perturbations. We asked the model: if the bioelectric pattern is wrong, how would we fix it?

Slide 24/41 · 33m:12s

In other words, what channel would we open or close to get the pre-pattern back to the right place? This isn't what we're doing. This is rational repair. We're not taking random shots in the dark. We're not trying to ruin an existing pattern. We're trying to use our computational simulator of bioelectric gradients to ask how to repair a complex organ when it's been damaged. This model proposed one specific thing, which is this very interesting channel called HCN2.

Slide 25/41 · 33m:51s

And when you activate these HCN2 channels, here's what a normal brain looks like: forebrain, midbrain, hindbrain. This is an embryo. This is much worse than being hit with a teratogen. This is a mutation in a gene called Notch. Notch is a really important neurogenesis gene. If you mutate Notch, there is no forebrain; the midbrain and hindbrain are a big bubble. These animals have no behavior. They lay there doing nothing.

On top of this mutation, if you impose the right bioelectrical pattern, and this was done by opening the HCN2 channel, which in turn was suggested by the computational model, you rescue brain shape, you rescue brain gene expression, and you even rescue their IQ. We check their IQs by learning and training them in various assays; they get their IQs back. This is quite amazing. You can do this molecular genetically, meaning put in new HCN2 channels, which would be gene therapy, or you can do it with drugs that open existing HCN2 channels. These happen to be two anti-epileptics that open the HCN2 channel, and you can do this rescue.

I'm not claiming that this will work for everything, but the amazing thing about this example is that there's a hardware problem. They have a mutant Notch signaling pathway, in which case things go terribly wrong. But that hardware problem is fixable in software by going back in and telling these cells what the correct pattern is. I think that's very powerful. That's an example of repairing birth defects.

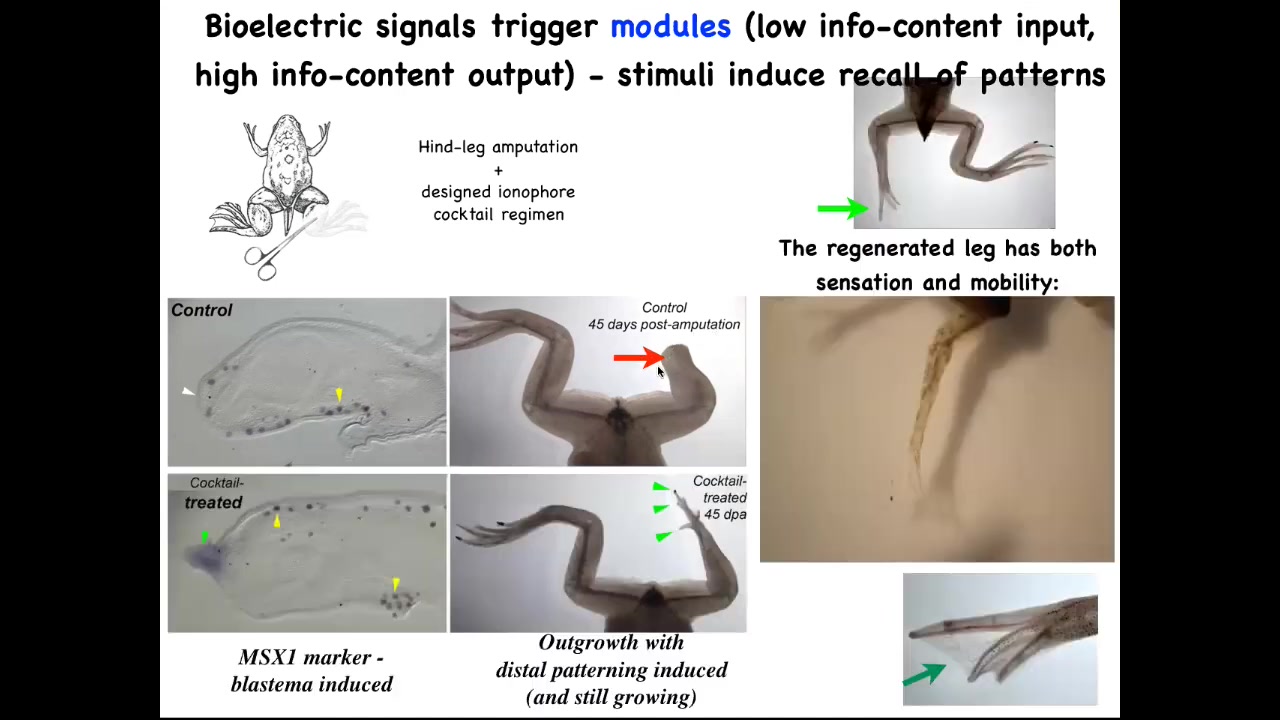

Here's an example of some of our regenerative work: frogs do not regenerate their legs after they lose them, but we've come up with a cocktail that induces a pro-regenerative blastema with MSX1.

Slide 26/41 · 35m:33s

By 45 days, instead of nothing, you start to get toes and a toenail and then eventually a pretty respectable leg that's touch sensitive and motile. This whole interaction with our ionophore cocktail took 24 hours, and the leg can grow for a year and a half without us touching it. It's not about micromanaging where the stem cells go or what the pattern is. It's about communicating to the cell collective very early on. You're going to take the path through morphospace that goes towards leg building, not the path that goes to scarring and a stump.

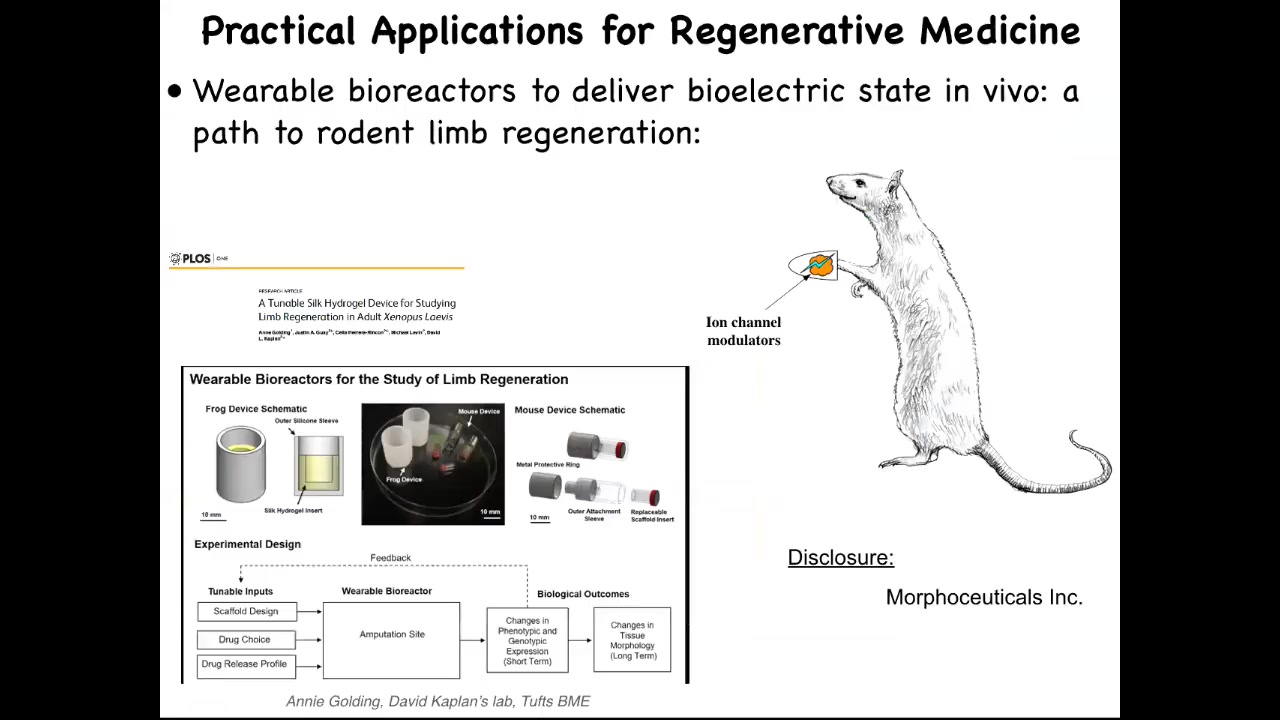

Slide 27/41 · 36m:14s

I have to do a disclosure here because Dave Kaplan and I are co-founders of a company called Morphoceuticals, where we're trying to apply that same strategy to mammals and hopefully eventually to human patients. Of course, we're quite far from that still.

The summary of everything I've said so far is that in the brain, the mechanism that binds cells towards large-scale common purpose—meaning to create and upkeep complex organs and to maintain against aging and cancer—is specifically bioelectrical networks. Modifying the information processed by these electrical networks offers some high-level control: creating new organs, fixing complex organ shapes, and so on. This provides control over growth and patterning without genomic editing or bottom-up attempts to engineer all the pathways involved. We're harnessing the competencies of the system: recruiting other cells, size control, tape control.

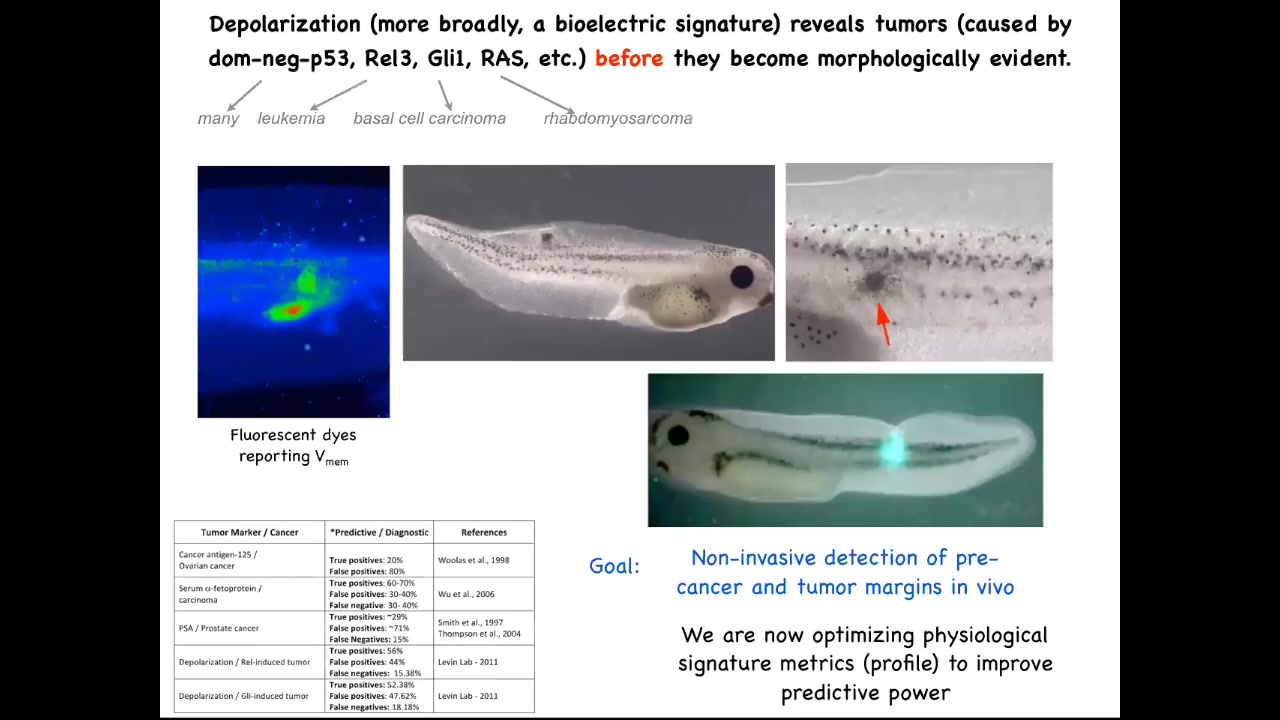

Now we get to the part that's directly about cancer. If these bioelectrical signals are important for cancer, then four things should be true. There should be implication by molecular data of ion channels, pumps, and proteins in cancer. Bioelectric signatures should be a viable diagnostic tool for detecting tumors early. We should be able to induce cancer-like phenotypes by disrupting proper Vmem gradients. Cancer-like phenotypes should be suppressible by the modulation of Vmem gradients.

These are predictions of the view that bioelectrics is the mechanism that binds individual cells towards organogenesis and away from the single-cell behavior seen in cancer cells. By 2016, it was already seen that there's a very rapid rise in the number of papers implicating various ion channels in cancer. There are lots of bona fide oncogenes implicated in human patients, mouse models, frog and zebrafish that point to a direct functional role of various ion channels.

This is molecular biology data. You can scan databases. Here is data from a GEO database that looks at the expression of certain channels. You can see a particular ion channel in normal cells and benign nevi, and by the time you get to malignant cells it tends to be shut off.

There is evidence implicating ion channel genes in the process of cancer, but the genes aren't key. This is important. We cannot think about oncogenes the way we think about transcription factors, growth regulators, and cell cycle checkpoints. It's the physiological state that matters here.

Slide 28/41 · 39m:26s

I've shown you that we can take different kinds of oncogenes, human oncogenes, throw them in a frog embryo, and they will create tumors. You can detect them early by using this voltage dye, and we were working on this as a diagnostics modality, because the first thing these oncogenes do is they shut down the electrical connectivity between cells and their neighbors.

As soon as that connectivity is shut down, these cells are out of the network that processes large-scale information, and they're back to a local tiny set of goals that their unicellular ancestors had. Contrary to a lot of models of cancer and game theory, these cells are not more selfish. It's not that they're more selfish. It's that their self is tinier. It's much smaller. It's now down to their computational boundaries, now down to the size of a single cell. Whereas before, when they were electrically connected into this network, they were part of something that was working on much bigger projects, these anatomical constructions.

Slide 29/41 · 40m:37s

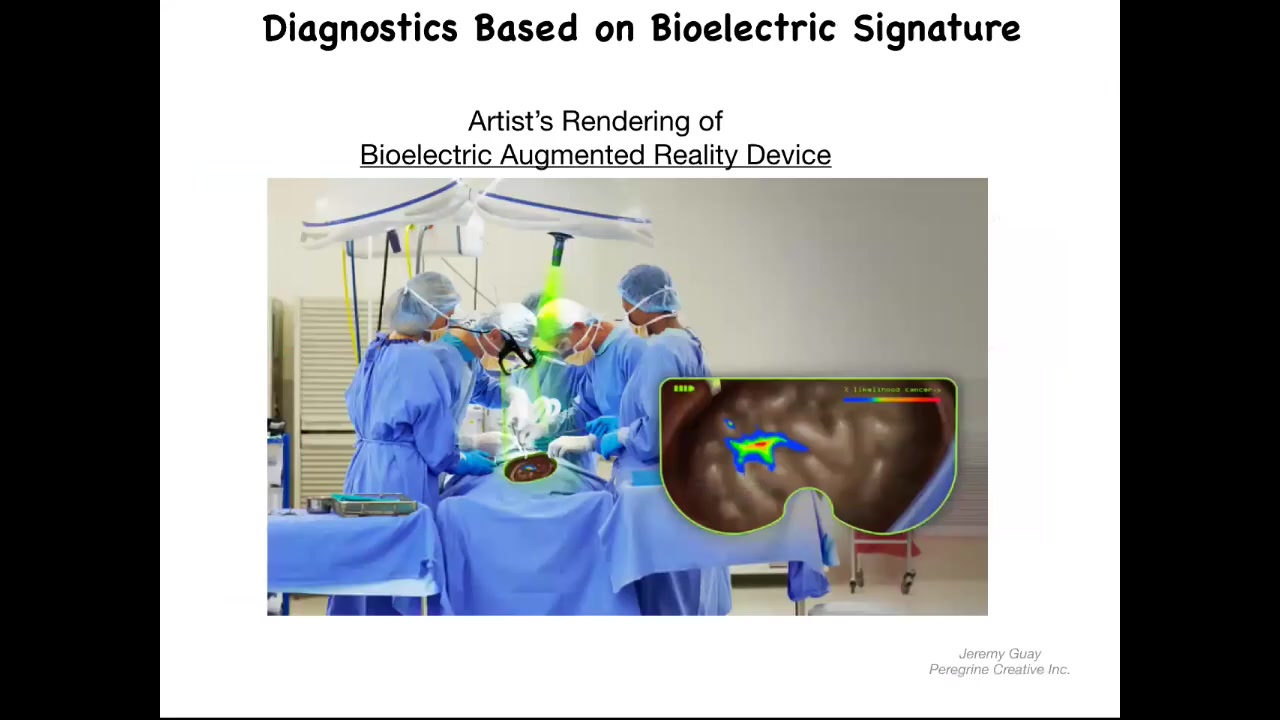

You could imagine, and this is an artist's rendering, but this is one of the things that we're working on, is this kind of augmented reality device where during surgery the surgeon can see the area, but overlaid onto the anatomy is an AI-processed probability landscape that shows based on the electrical signaling. There's a voltage-sensitive dye in there. These dyes are not generally very well tolerated. You should be able to look down and see here's where the major tumors are, but actually these cells up here are leaving the collective as well, and you better get them. That's our story of the diagnostic potential of this.

Slide 30/41 · 41m:23s

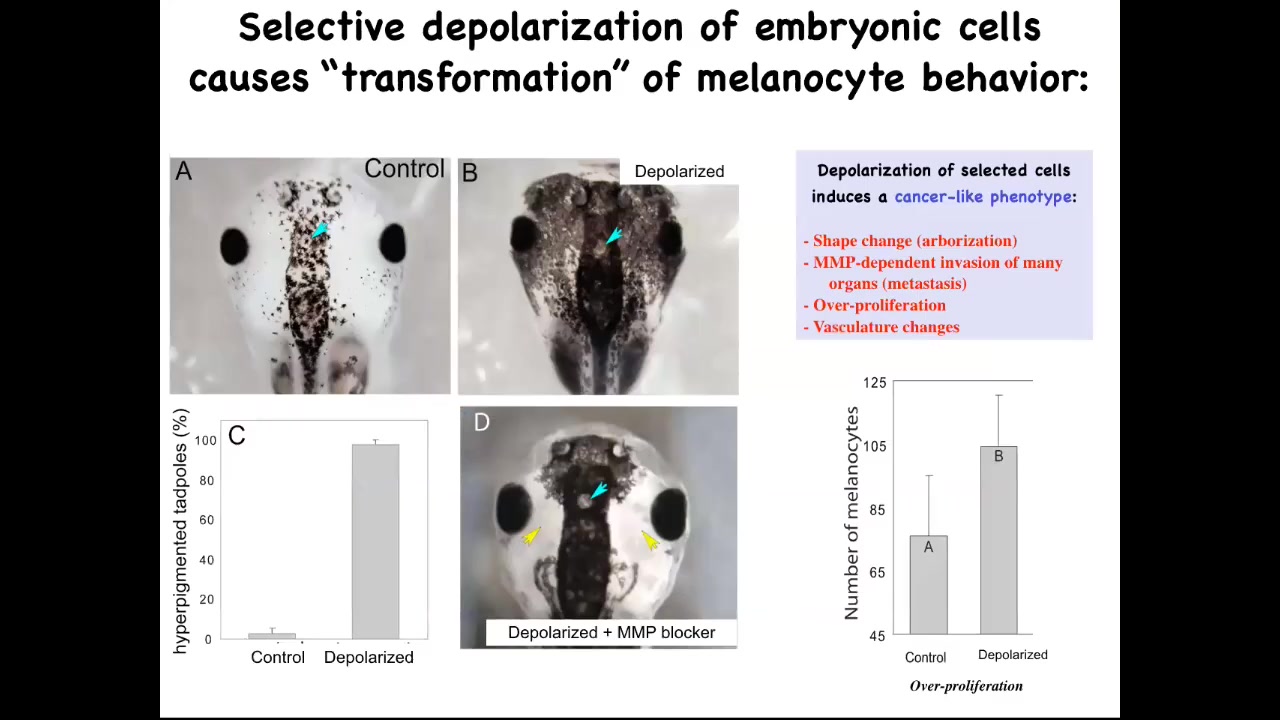

Now here's the second thing I promised, which is, can you actually induce a cancer phenotype by disrupting the bioelectric? This is a normal tadpole head. These little black cells are melanocytes, and here's what the normal complement of melanocytes looks like. What we did was we disrupted the electrical communication between a very specific cell type. We call them instructor cells. There are no oncogenes here. There's no mutation, no DNA damage. There's nothing wrong with the hardware of these animals. They haven't been exposed to any carcinogens. We've temporarily perturbed the communication between these pigment cells and this other cell population. When you do that, the pigment cells go completely wild. They over-proliferate. You can see here they've taken over this normal periocular space that's normally quite clear. They've taken over. They're everywhere. In fact, these animals turn pitch black. There's melanocytes everywhere.

Slide 31/41 · 42m:25s

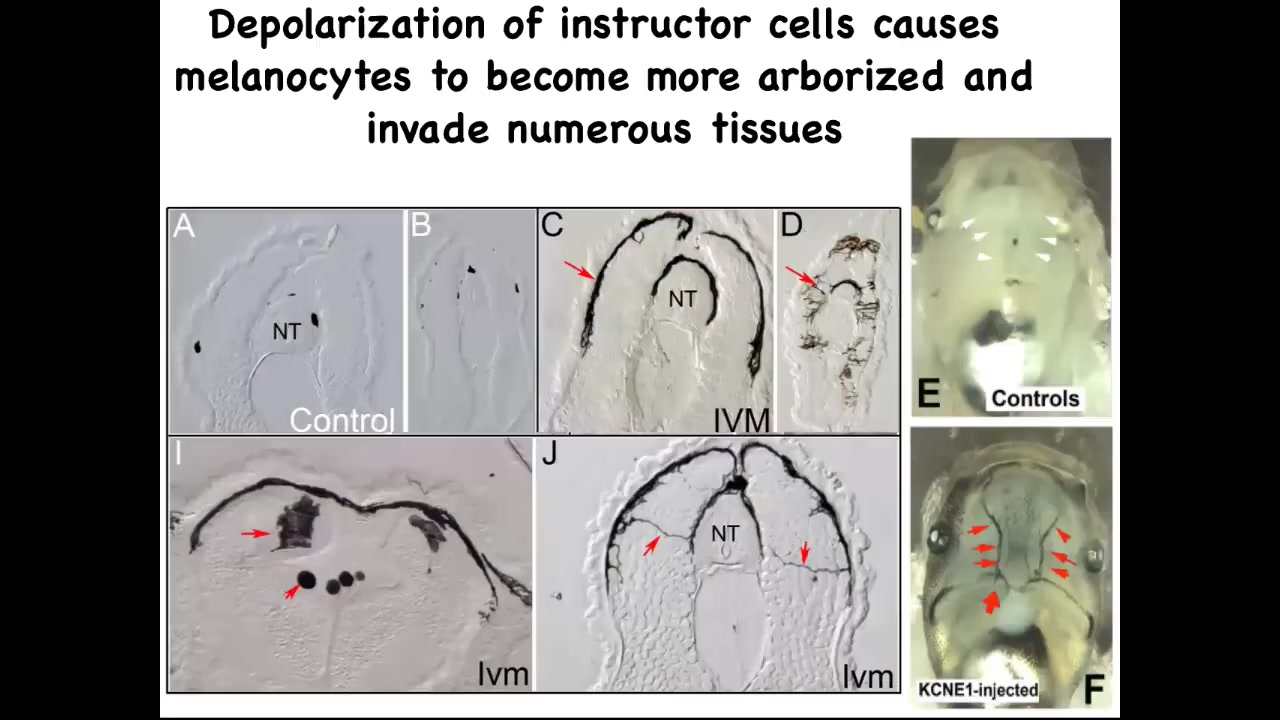

If you take a section through them, this is the neural tube, and you can see one, two, three, four, small numbers of these nice round little melanocytes. When the bioelectric signals aren't there to tell them what to do, they go crazy. They revert back to their original kinds of behaviors. They change shape drastically. They acquire these long projections. They're exploring their environment. They're digging into the neural tube, into the nerve tissue itself, to the lumen inside the space. They invade all the organs.

You can see the blood vessels; normally quite clear. The melanocytes are hitting the vasculature and propagating through it. This is full-on metastatic melanoma in these guys. There are no genetic defects. If you were to sequence the genome, you would not see any mutations. Although by this stage you will see markers of epithelial-mesenchymal transition.

Slide 32/41 · 43m:29s

This works also in human melanocytes exactly the same way. They will go completely crazy if you disrupt their bioelectrical state.

Here's the cross-section and here are these crazy melanocytes that are digging in and taking over the brain. These are not the cells that we manipulated. These blue cells out here are the ones that we manipulated. This is not a cell-autonomous event, meaning that the thing that goes crazy is not the cell whose voltage has been perturbed. It's other cells in the environment. I'm not the first person to talk about the importance of the microenvironment, but in particular, the bioelectrical properties of the microenvironment are the switch that leads from normal melanocytes into this crazy converted melanoma-like behavior.

Slide 33/41 · 44m:21s

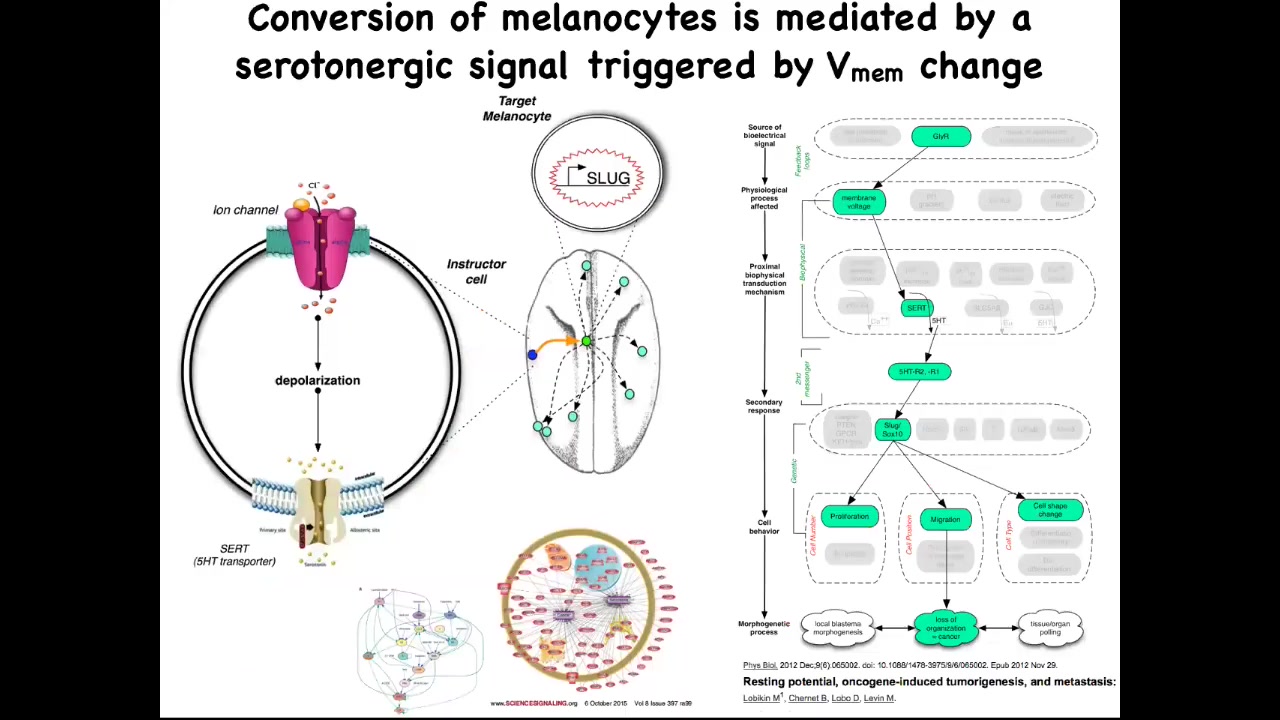

The way it works. It's a serotonergic signal that normally goes from these instructor cells to the melanocytes. If you perturb the bioelectrics of this instructor cell, that serotonergic process goes awry, these melanocytes are left on their own. They do whatever amoeba does. They over-proliferate; they crawl wherever they feel like and take over the environment.

We've studied in great detail this whole serotonergic pathway, the downstream gene expression, and the gene regulatory network. The importance of this part of the talk is this. One significant way to have a carcinogenic transformation is to have cells that are isolated from the electrical information that normally keeps them orchestrated towards proper functionality and morphogenesis. Oncogenes trigger this, but there are other ways to trigger it.

Slide 34/41 · 45m:27s

The final thing I want to show you is: we don't want to create more and more cancer. Obviously, we want a treatment modality. Here it is.

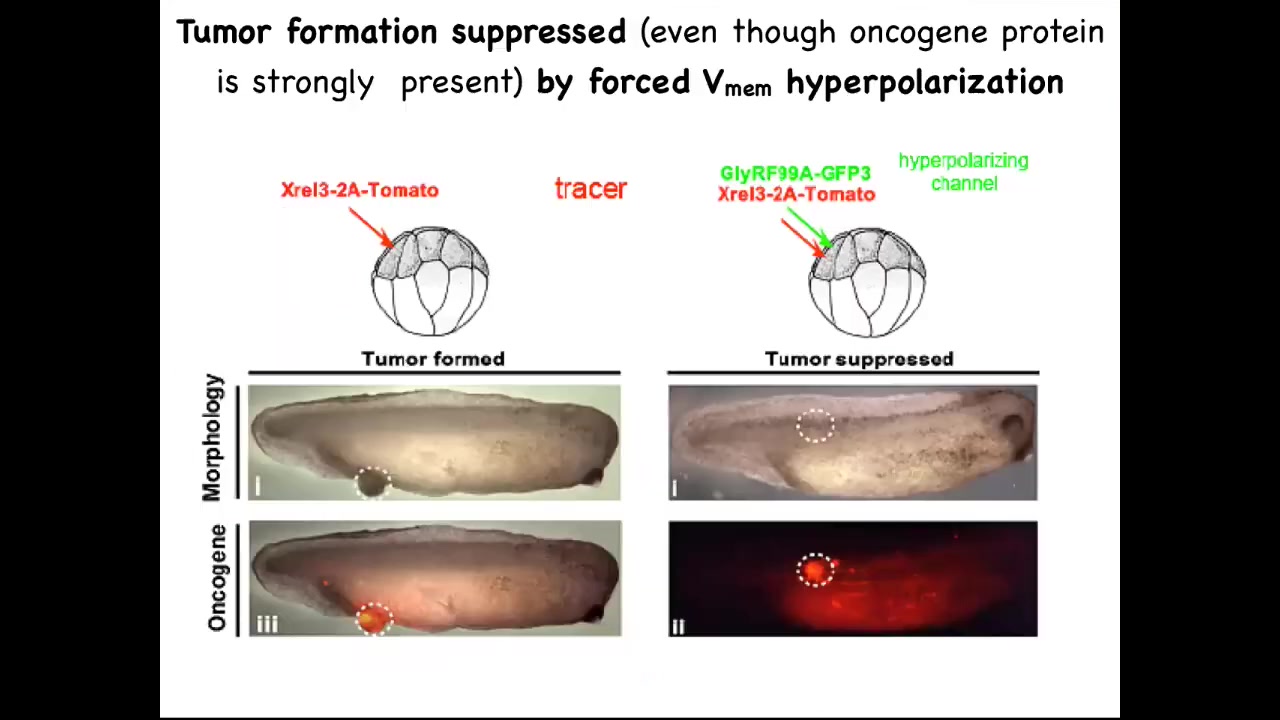

One of the things we can do is inject these oncogenes, even nasty KRAS mutations. The oncogene is labeled with fluorescent red protein, in this case tomato, so you can see it. Here it is.

What we know is that if we co-inject a particular ion channel RNA that we've chosen to resist, to fight. What this oncogene is going to do is it's going to try to tell the cells to depolarize and disconnect from their neighbors. This ion channel is going to dominate that. It's going to say, fine, you have the oncogene, but you're not going to be able to depolarize it. We're going to keep you connected to all of the neighbors.

This is the same animal. Here's the bolus of where the oncoprotein was expressed. It's all over the place. If you sequence this and you find it's full of this oncogene—definitely going to make a tumor—and there is no tumor.

Because what drives the outcome is not the genetic state, it's the physiological state. I've already shown you an example of this. I've shown you in the frog brain. You could have a Notch mutation and if you sequence it, the prediction would be that you're going to have terrible defects. That's not what drives. What drives is the bioelectric state. You can override this hardware defect with a particular physiological state. These same cells are not dead. They just continue participating in normal morphogenesis.

Slide 35/41 · 46m:58s

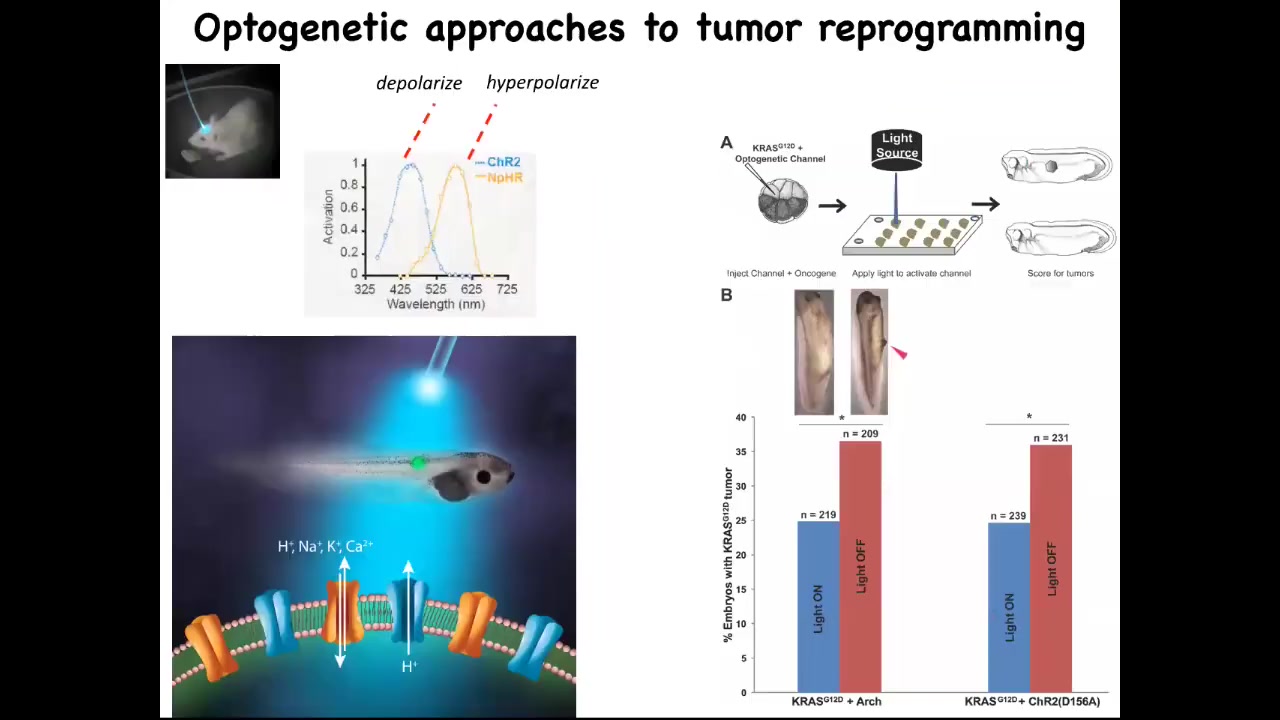

Now you can do this with light. Here's an example of optogenetics. We just use optogenetic technology that we took from neuroscientists, and you can knock down the incidence of these tumors significantly by using light to trigger the right kind of channel.

Slide 36/41 · 47m:13s

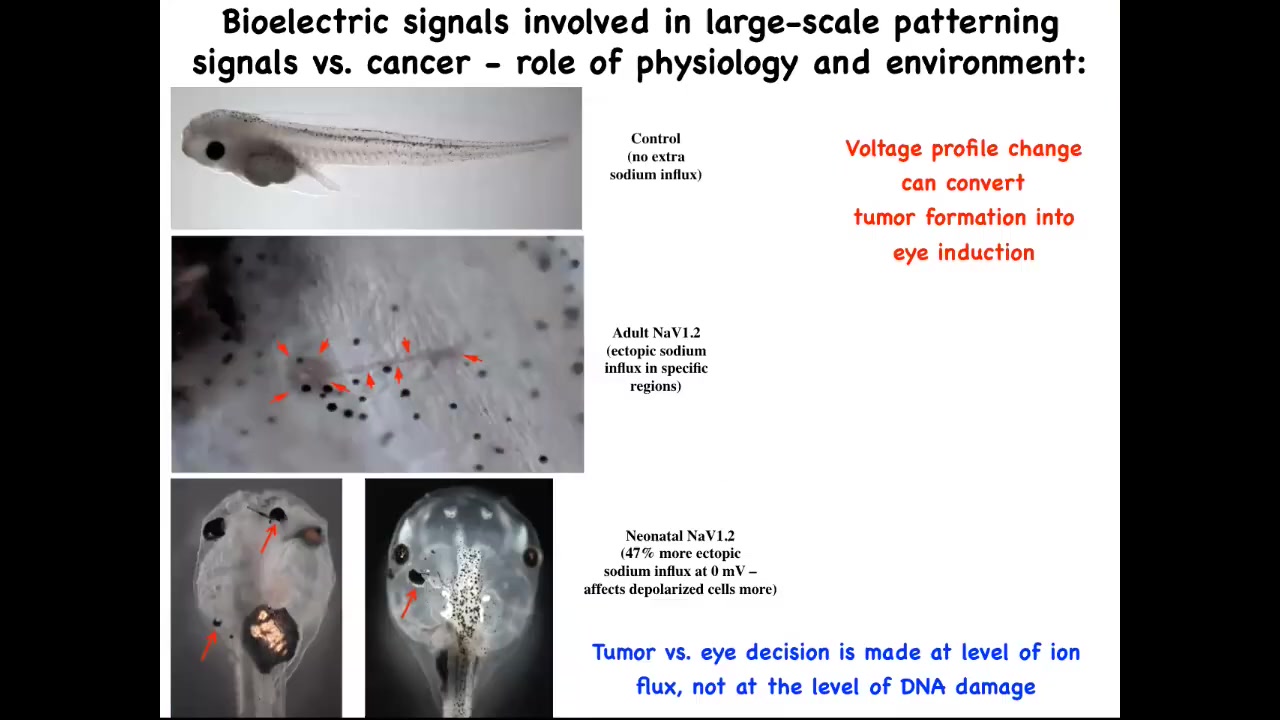

In fact, here's a normal tadpole and here's the tail. Whether you get a tumor and these kinds of metastatic events, whether you get a tumor or whether you get an ectopic eye is determined by the amount of sodium in the medium, because we were using a sodium ion channel to do this. The sodium ion channel is not like a transcription factor that always has the same effect. It's a physiological element whose activity depends on how much sodium there is. So whether you get a tumor or an eye is actually determined by a physiological parameter, namely how much sodium is in the medium, not at the level of DNA damage or anything like that.

Slide 37/41 · 47m:58s

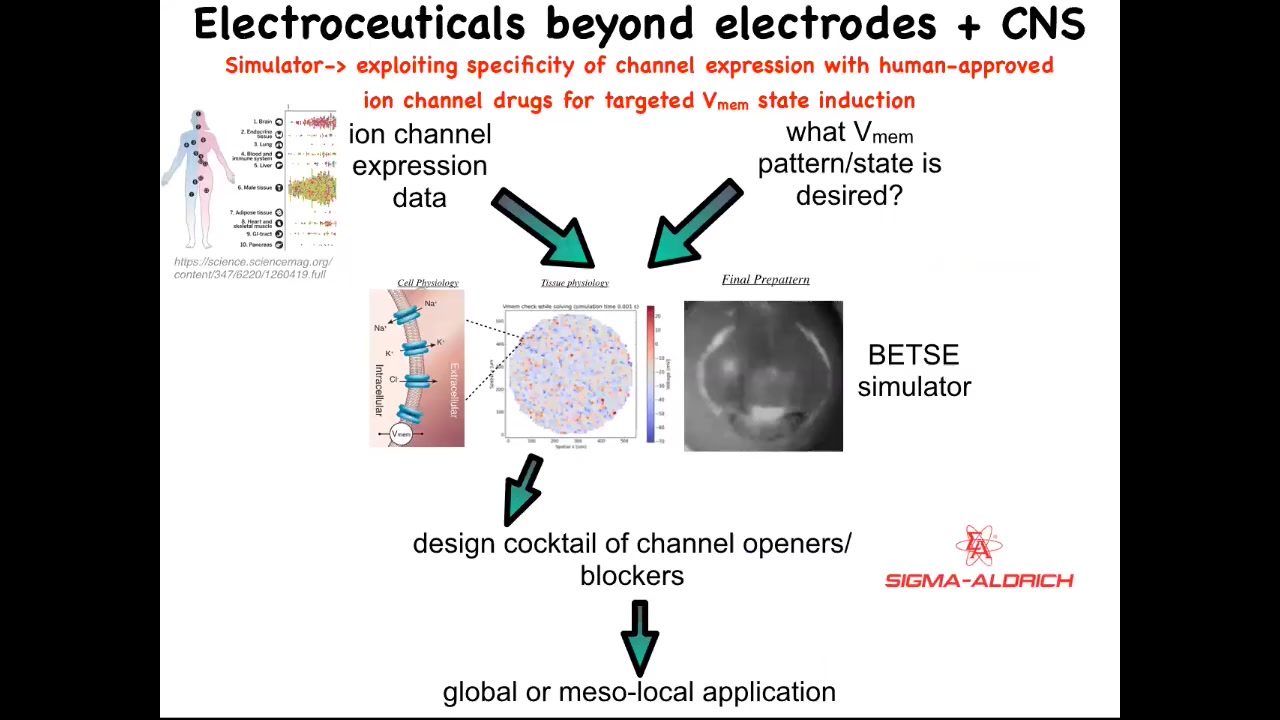

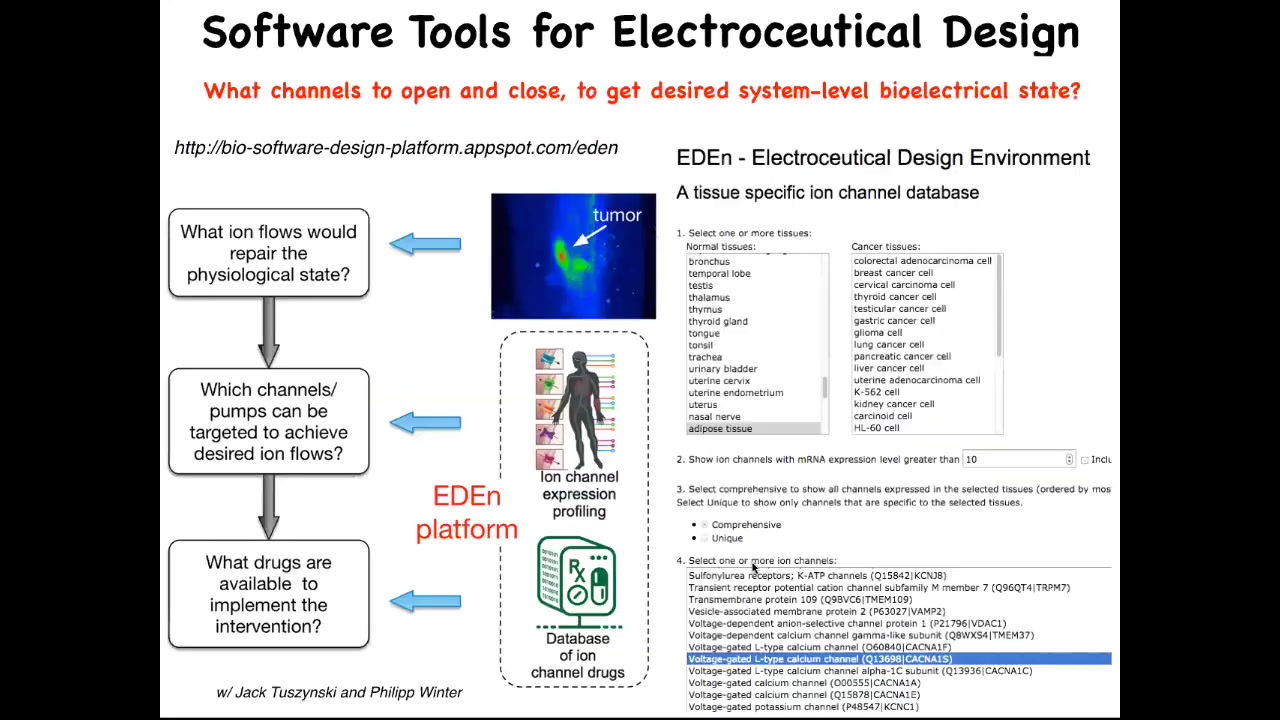

Putting all this together, our framework for addressing all this is this idea of electroceuticals, of using existing ion channel drugs with our computational models that tell us what's going to happen when you open and close certain channels. We know which channels there are because human tissues are extensively profiled, and that feeds into the model. The one thing that is largely missing today is the physiomics of what are the correct bioelectrical states for all the organs. We have no idea for humans, and we only know this for certain animal model systems. This is where a lot of the work has to happen: to understand what the correct bioelectrical state is. Then we have a simulator that can tell you how to get from the wrong state to the correct state. That helps you pick from an existing, huge library; something like 20% of all drugs are ion channel drugs, a potentially huge library of electroceuticals.

Slide 38/41 · 48m:52s

You can play with this a little bit. This is online, the beginnings of this platform. It's freely accessible. You can pick different types of tissues. You can pick either cancers or normal. It will tell you what channels there are. If you pick specific channels, it'll tell you what drugs because you can search DrugBank.

Slide 39/41 · 49m:17s

We've begun this process. Now moving this from frog. This is our first paper on human glioblastoma. It's in vitro. What we're using is some of these drugs that were picked by this process that I just told you, on glioblastoma cells, and there are all kinds of interesting effects in preventing proliferation, partial reprogramming to differentiation, possibly normalization. Stay tuned. This is very much work in progress. We need in vivo experiments, but we're slowly moving now into mammalian context.

Slide 40/41 · 49m:55s

Here's the summary of the whole thing. Cancers are fundamentally a disorder of the scaling of cellular competencies. Individual cells can get certain goals met, for example, overgrowth and migration, but in normal bodies, they are kept harnessed towards much larger grandiose anatomical goals, but this process can break down. That process is mediated by bioelectrical signaling, which is why bioelectrics can be used to detect, induce, and reprogram cancer cell behavior.

In the nervous system, we can instruct cell behavior without having to change the genome. You don't need to change your genome to learn new things or to acquire new goals. We are now developing pharmacological and optical strategies towards discovery of electroceuticals for normalizing cancer. There's a huge role for machine learning and AI, but also for getting this physiomic data that has been neglected in favor of transcriptomics and proteomics.

The future directions, what we and our partners are working on, is to refine that physiological signature. Optical non-invasive diagnostics for pre-cancer and tumor margins and surgery, to refine control methods for voltage in mammalian systems. Specifically, the bigger picture here is to crack the bioelectric code, to induce normalization towards normal tissues and organs using ion channel drugs that are already in human use, meaning they're already approved.

Slide 41/41 · 51m:36s

I will stop here. I want to thank the students and postdocs who did all the work, our many collaborators, our technicians, our funders. I have two disclosures. Morphoseuticals is the limb regeneration company. Astonishing Labs is the company we're doing all the cancer diagnostics with. Most of all, I thank the animal model systems because they do all the heavy lifting. Thank you, and I will take questions.