Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a talk given to the Department of Biotechnology at Indian Institute of Technology Madras in January 2023.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Linking intelligence and morphogenesis

(13:43) Anatomical compiler vision

(27:52) Bioelectric codes and homeostasis

(37:34) Reprogramming organs and bodies

(49:15) Bioelectric models and therapies

(56:06) Xenobots and evolutionary implications

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/49 · 00m:00s

Can everybody see my slides? Yes. Thank you. If anyone is interested afterwards in reaching me or finding any of the primary papers, the data sets, the software, everything is at this website. What I want to talk about today is this idea that pre-neural bioelectrical networks underlie a kind of somatic intelligence. I want to talk about the implications of this for regenerative medicine, but also for evolution.

Slide 2/49 · 00m:38s

We can start by thinking about Alan Turing. This is the forefather of computer science. He was very interested in intelligence in different embodiments. He was interested in what is fundamental about intelligence aside from any one particular implementation and in the basics of computing and so on. But he also did this interesting early work on morphogenesis, the idea of the generation of pattern from chemical signals during embryonic development. And so one might ask, why would they be interested in studying morphogenesis? I think Turing, although he didn't write explicitly about this, being the genius that he was, saw deeply that these are the same problem. I think fundamentally, this is a very important idea that developmental morphogenesis and intelligence are really the same problem. And here's why.

Slide 3/49 · 01m:51s

We oftentimes say collections of ants and termites and bird flocks are collective intelligence. And then people think about, is this really an individual? Is it really a collective intelligence? How do we think about it? But then they say those things are maybe controversial, but I am a true centralized intelligence. I am a single being. I'm a centralized intelligence. And of course, this isn't correct because we are also made of parts. Our brains are a collection of cells. We are all walking bags of cells.

Slide 4/49 · 02m:27s

This is the sort of thing that we're made of. This is a single cell. This is called the lacrimaria. This is an independent organism. This is not a human somatic cell, but all of our cells were once independent living organisms.

You can see the high level of competency and autonomy that this little creature has in addressing the problems on its own scale, physiological and metabolic.

All of us made this amazing journey across the Cartesian cut. We were all once a quiescent oocyte, just a single cell where people would say that's just physics and chemistry. There's no cognition there. It's a chemical system. And then eventually we end up being something like this, which is a complex organism with behavior, and maybe even something like this, which is very complex, has human-level metacognition and will make statements like, "I am unique and I have mental properties that don't exist in other creatures."

The key thing to realize is that this journey is incredibly slow and gradual. Developmental biology offers no sharp lightning bolt where, to the left of that line, we were just chemistry and physics. And then after this, you're a cognitive creature. There's no such thing in developmental biology. It's a slow, gradual process.

We really need to understand how the scale-up of cognitive capacities happens during this process, on an evolutionary time scale, but also in each of us on a developmental time scale.

Slide 5/49 · 04m:08s

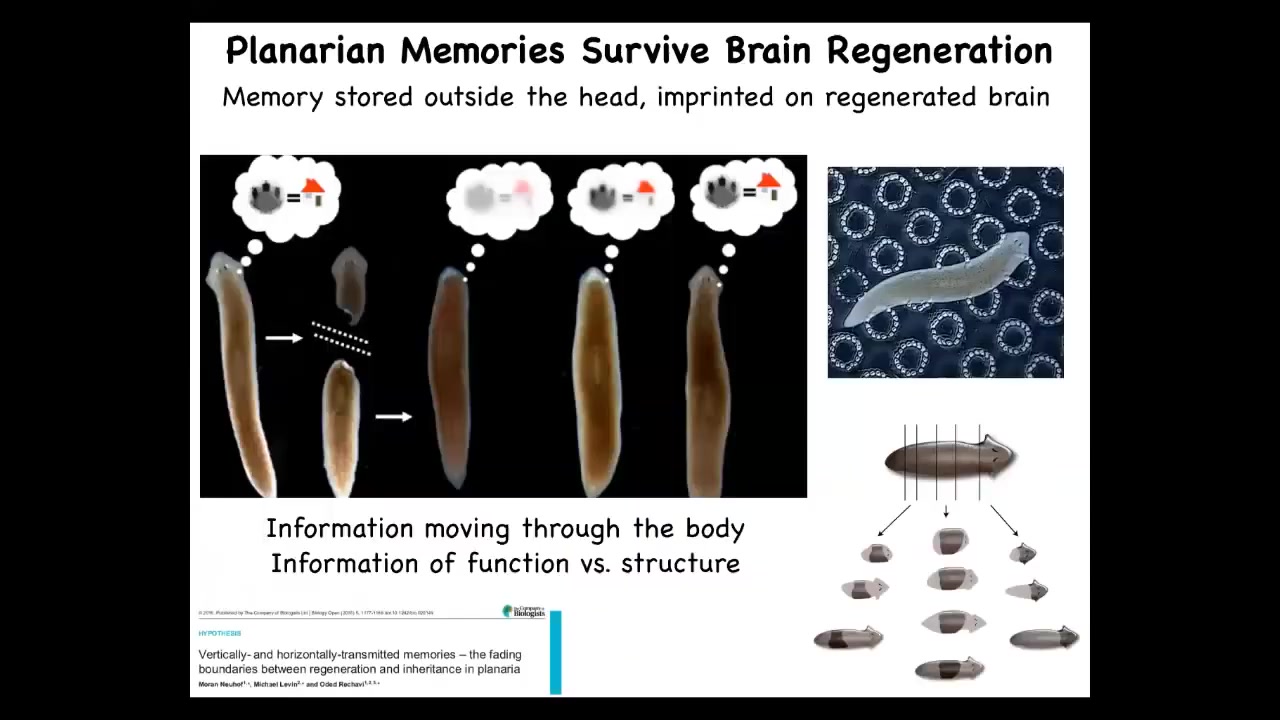

This connection between information in the brain and information in the body can be really seen in the plasticity of certain biological forms. Here, for example, is a planarian. This is a flatworm. They have two interesting properties. One is that they're smart, you can train them for specific memories, for specific behaviors, and they regenerate.

If I amputate the head off of this planarian, the tail will sit there and eventually regrow a new head. This is something that McConnell discovered in the 60s, and then we later confirmed using modern automated techniques. If you train a planarian to recognize these little bumpy disks as the place where they find food, and then you cut off their head, which contains their brain, the tail will eventually regrow a new head, and that new head, that new animal will show behavioral evidence of recall. It will still remember the information. These memories not only are potentially stored outside of the brain, but also imprinted onto a completely new brain as it develops. You see this ability of information moving across the body. You see the consilience of information about shape, about anatomical shape, and also restoring this cognitive information. These are really, really quite connected. That plasticity, that ability to recover personal identity.

If you're interested in philosophy and the question of personal identity and the question of what happens if somebody makes a copy of me, are they also me? What happens to the individual? Here, you can do this in planaria. You cut them into pieces and every piece will have the original information. Now, who's the original? It's a philosophical puzzle.

Slide 6/49 · 05m:56s

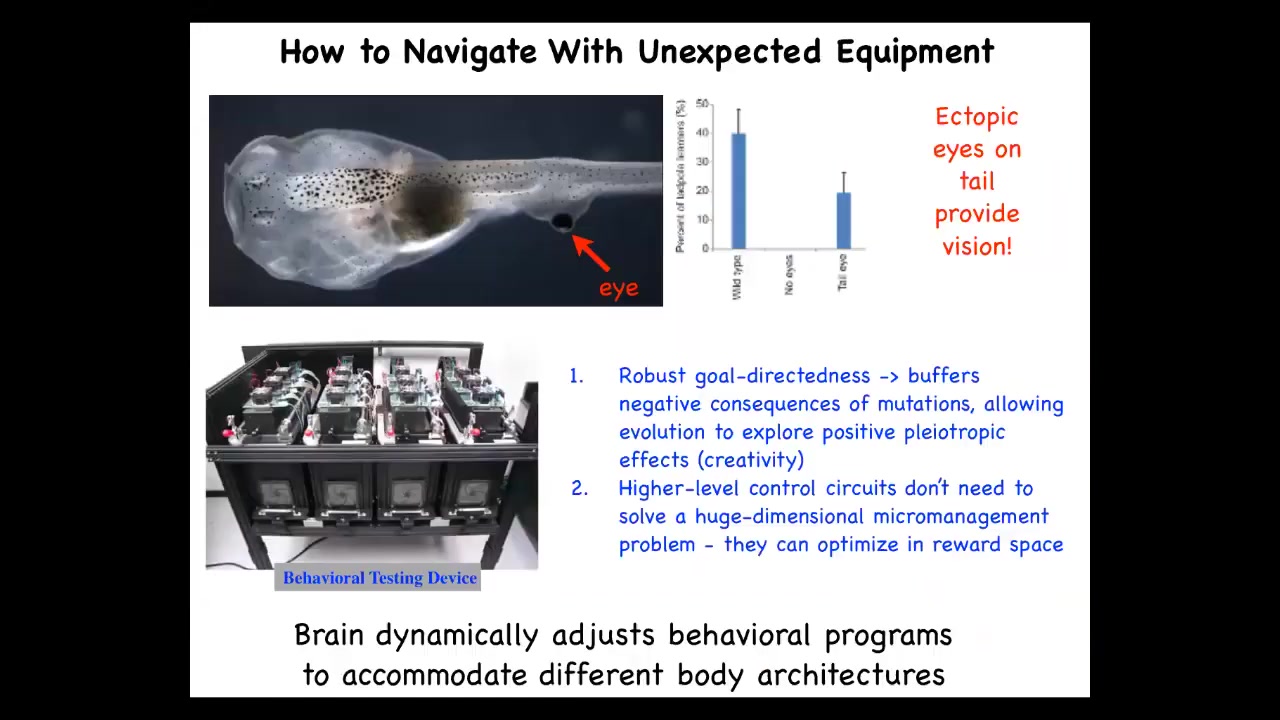

But this plasticity exists in vertebrates as well. This is a frog tadpole. Here's the brain, here are the nostrils, the mouth. What we've done is we've produced the tadpole with no primary eyes, but we did put some eye precursor cells on the tail and they form a perfectly good eye and that eye connects to the spinal cord. Using this device that we've built, we show that these animals can see quite well. We can train them on visual tasks, even though this eye does not connect to the brain and it's not in the head. That plasticity, you didn't need thousands of generations for this to evolve, this architecture is ready to be scrambled in this way and still have adaptive function. That has huge implications for evolution.

Slide 7/49 · 06m:47s

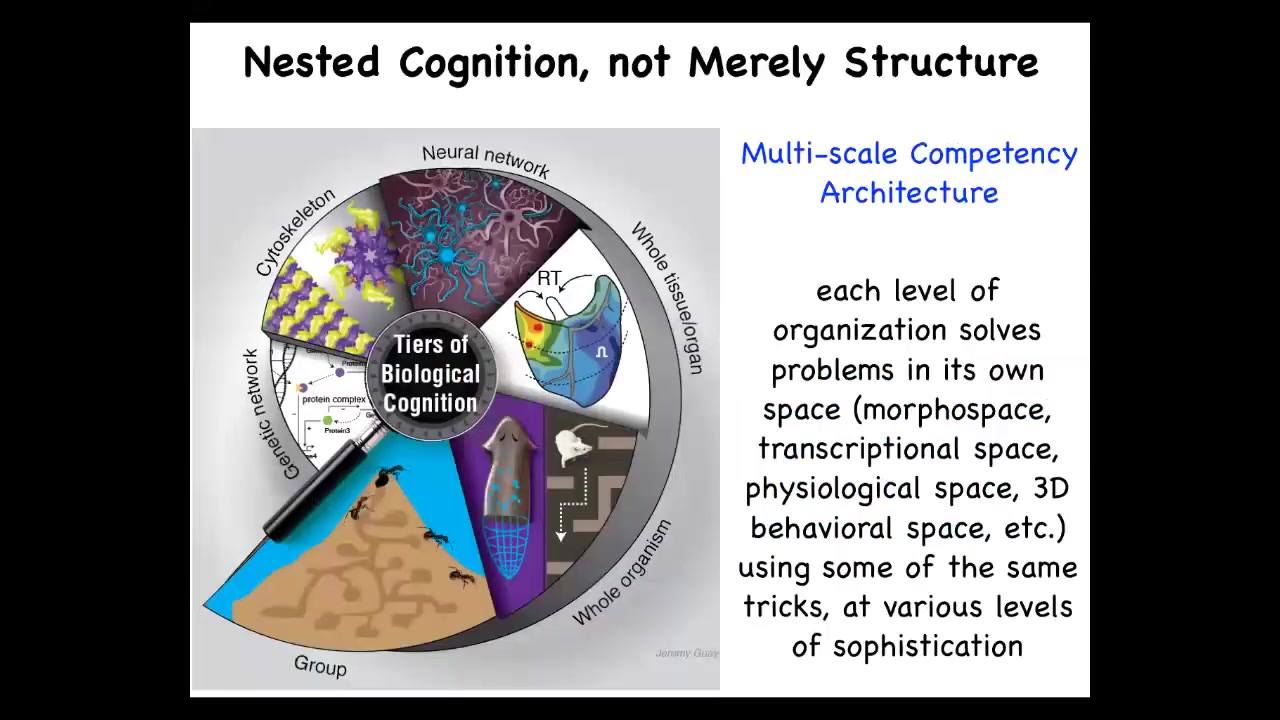

So the interesting thing about biology is that we are all multi-scale systems, not only structurally, so we all know that we're made of organs, tissues, cells, and molecular networks, but actually functionally at each level, these layers solve various problems in various spaces. We call this the multi-scale competency architecture.

Slide 8/49 · 07m:22s

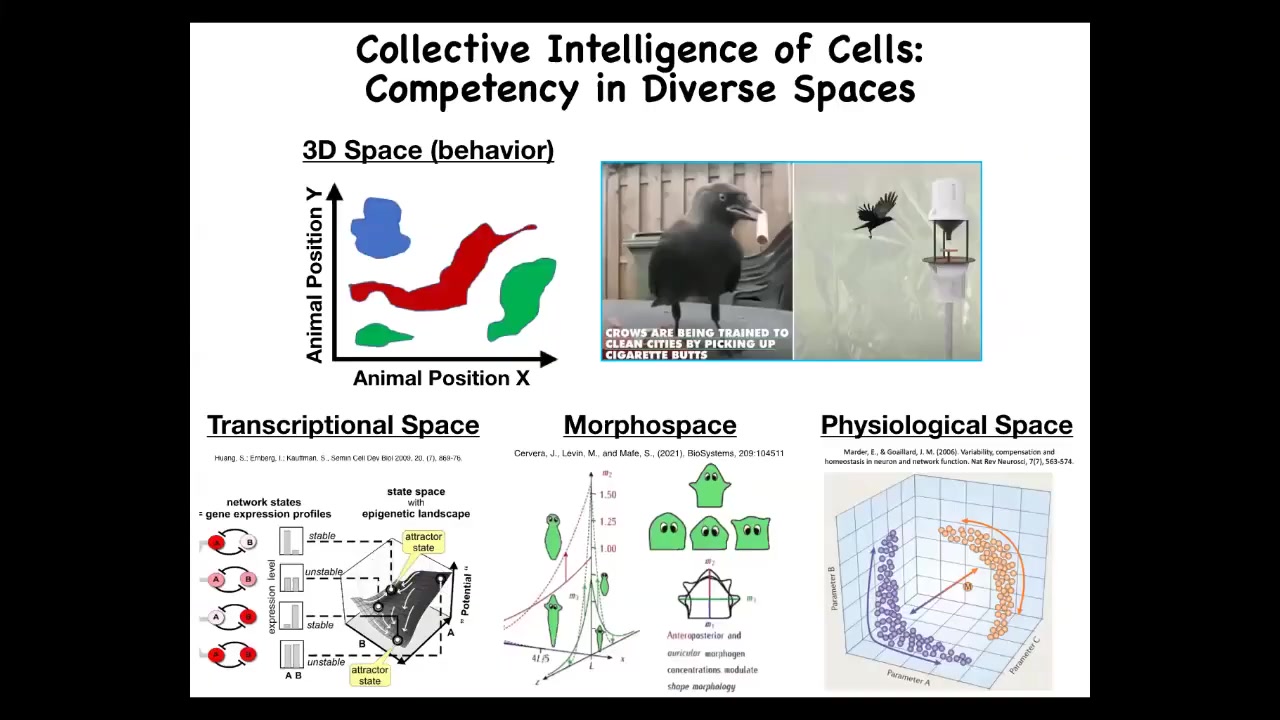

What do I mean by these problem spaces? We are, and many animals are, primed and good at recognizing agency and intelligence in three-dimensional space. Medium-scale bodies moving at medium speeds through space and doing intelligent things; it's easy for us to recognize that.

It should be clear that when we look at various systems and assign to them some kind of estimate of their intelligence, we're really taking an IQ test ourselves because we're not good at recognizing intelligent behavior in other problem spaces. For example, imagine that you had an innate feeling for your body chemistry, the way that we have vision and hearing. Imagine if you could feel your blood chemistry. It would be easy for us to recognize the workings of our liver and kidneys in physiological space as different kinds of intelligent behavior, meaning problem-solving behavior with different levels of competencies.

The spaces that we deal with are physiological space, the space of all possible gene expressions. This is a transcriptional space. My favorite is morphous space. This is the space of the different parameters that establish different anatomical shapes, like these different head shapes. We're going to spend most of today talking about problem solving in this anatomical space, but I want to say one thing about transcriptional and physiological spaces to give you an idea of how clever our cells really are.

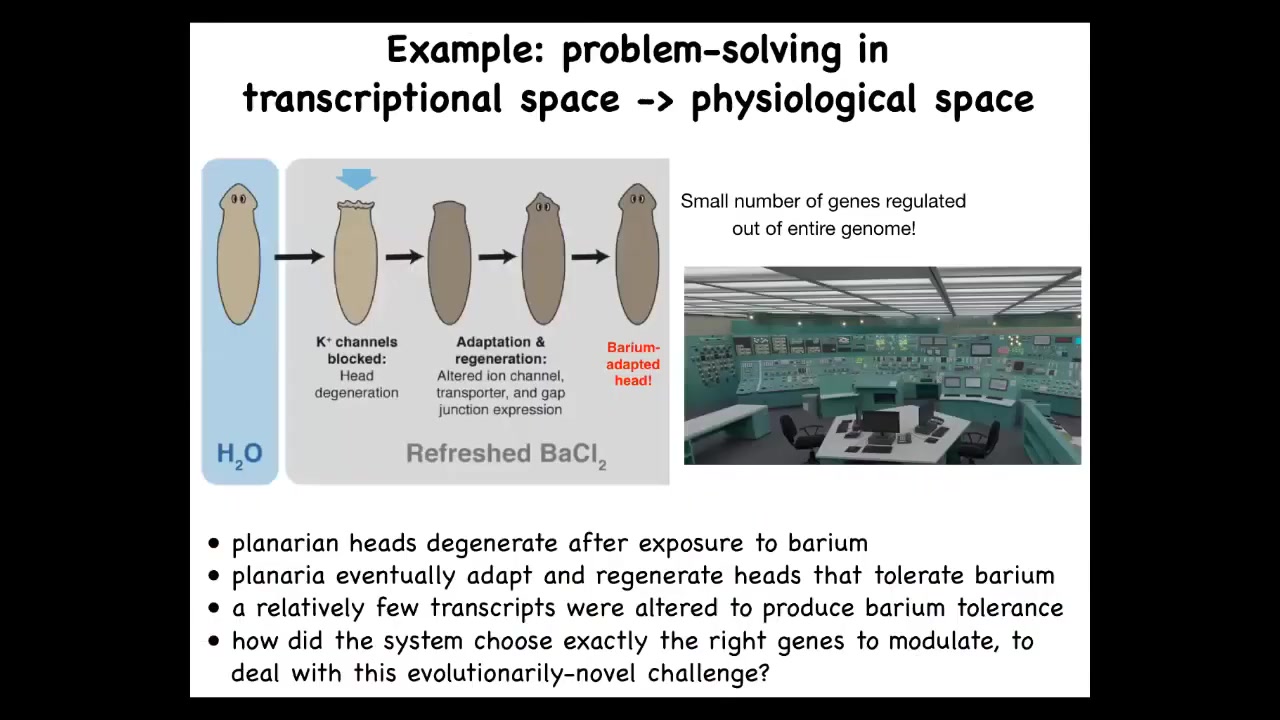

Slide 9/49 · 08m:55s

This is a planarian. This is that flatworm that I talked to you about. What we found is that if we expose this planarian to barium, a solution of barium chloride, barium is a non-specific potassium channel blocker. So the cells can't pass potassium, and that makes the cells very unhappy, especially in the head where there's lots of neurons that want to transfer potassium; their heads explode. Their heads literally explode overnight. If you leave them in the barium, in a week or two they regrow a new head, and the new head is completely insensitive to barium.

We asked the simple question, transcriptionally, what is different about this new head? Why does this new head not mind the barium? We compared all the genes that are expressed in these guys versus these guys, and we pulled out a very small number of genes. Now here's the amazing fact: a planarian never encounters barium in the wild. There's no evolutionary history for barium exposure. There's no reason why they should have a built-in mechanism for expressing certain genes when they encounter barium. This is a completely novel problem for them.

You can think about this as being stuck in a nuclear reactor control panel where every 20,000 genes, or however many they have, every knob is one gene. You're faced with a terrible physiological stressor. How do you know which genes to turn on and off if you've never seen this challenge before? The amazing thing is that you don't have time to do a random walk. You don't have time for gradient descent. The cells don't turn over very fast the way that you might in a bacterial colony. They find their way through this transcriptional space very efficiently, given a completely novel challenge.

We don't know how this works. Overall, what we are interested in is diverse systems, not traditional brainy systems necessarily, but all kinds of other things, whether evolved or designed, that are able to navigate different problem spaces with different degrees of competency.

Slide 10/49 · 11m:19s

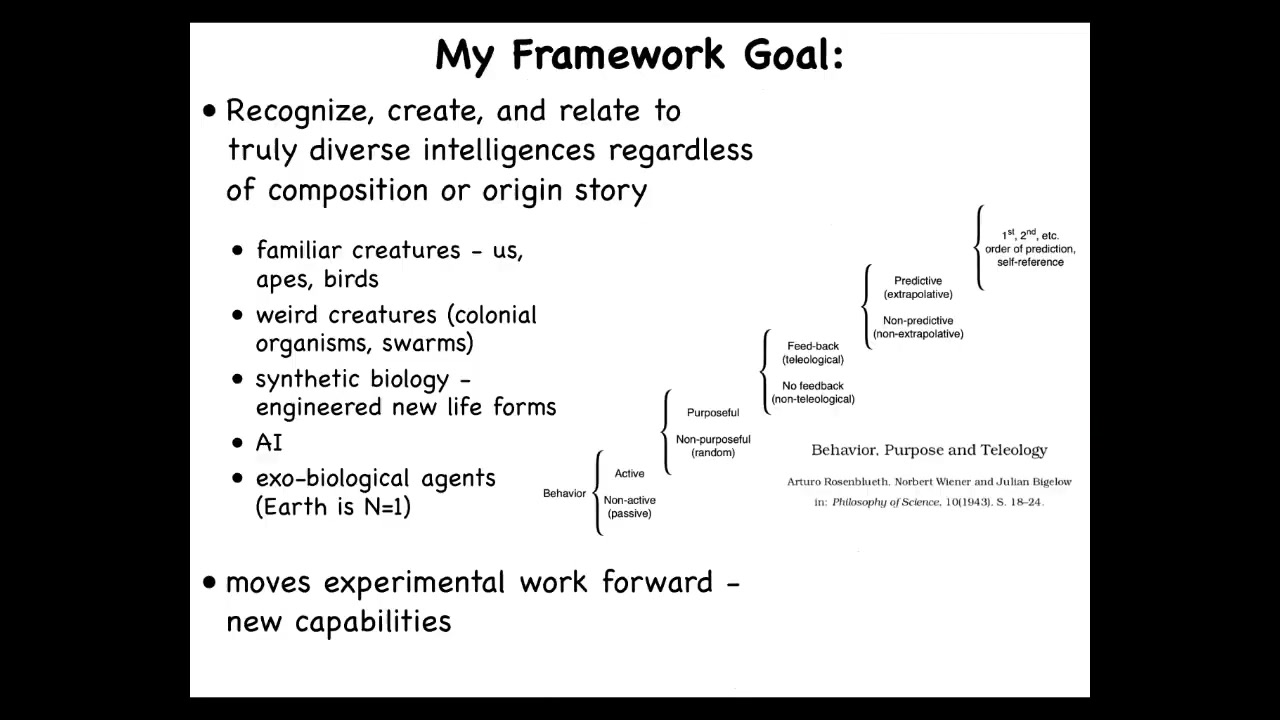

This notion of having different degrees of competency in navigation was described by Norbert Wiener and colleagues in a cybernetic scale of thinking about how behavior could be controlled. What they wanted to do was establish a continuum with some transitions here, all the way from completely passive behavior, which you would just say is just physics, all the way up to what we see in humans, which is metacognition and things like that, and all of the steps in between in a way that was not tied to specific architecture. We're not saying brain, we're not saying neural network, we're not making any assumptions about what the substrate is.

What we're saying is there are different kinds of behavioral competencies with respect to reaching specific goal states in that space. When he says teleology, he doesn't mean magic and he doesn't mean human level. It just means the ability of a system to reach a specific goal despite perturbations. These are the different levels of sophistication for different systems that might be able to do that.

This kind of approach allows us to do something interesting, which is the goal of my framework, which I call T-A-M-E, TAME, for Technological Approach to Mind Everywhere. It allows us to think about using the same tools for a very wide range of potential agents: familiar subjects of behavioral science like humans, other mammals, birds, maybe octopus, but also really weird creatures like colonial organisms, whole swarms, synthetic new life forms. I'll show you one at the end of this talk. Artificial intelligences that might be entirely software-based, and maybe someday exobiological agents, because all life on Earth is basically an N = 1 example of evolution.

We want general purpose tools to be able to recognize competencies. I'm not saying anything about consciousness. At this point, I'm not saying anything about human level intelligence. I'm saying basic problem solving competencies at different levels of sophistication that might exist in unfamiliar guises.

Here's my favorite example of that, which I would like to talk about. We all start life as a collection of embryonic blastomeres, and then eventually you get this. This is a cross-section through a human torso. You can see all the amazing order that's here. All the tissues and structures are positioned and everything's in the right size, the right orientation, the right position relative to each other. Where is this amazing amount of order encoded?

People are often tempted to say it's in the DNA, but we can read genomes now, and we know what's in the DNA. What's in the DNA is a description of the micro-level hardware, the proteins that every cell gets to have. The DNA doesn't directly say anything about this large-scale structure. The structure arises from the behavior of individual cells, from the physiology that drives individual cells to interact and create something like this.

We're interested in that collective behavior. We're interested in how groups of cells know what to make and when to stop building. As workers in regenerative medicine, we'd like to know, if a part is missing, how do we recreate it? As engineers, we want to go further and ask, can we push these cells to do something else besides what they normally build? Can they build something completely different?

Slide 11/49 · 15m:02s

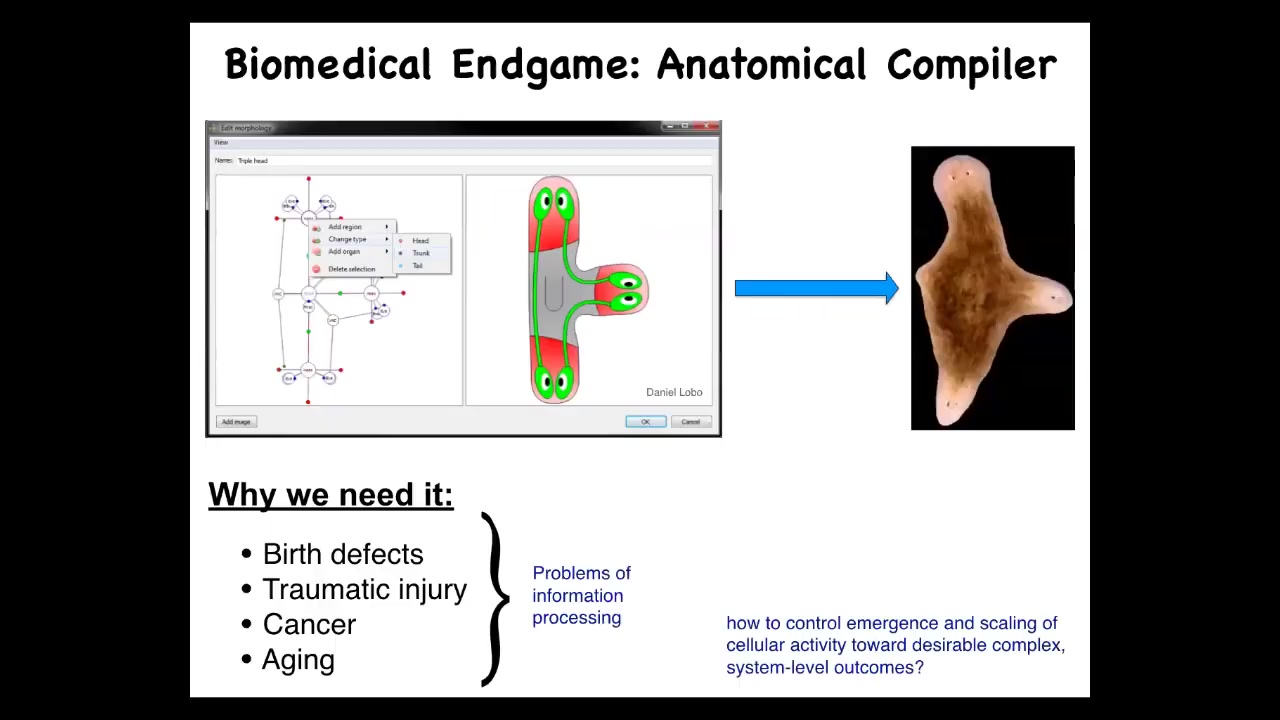

What I want to talk about is this, the way I see the end game of this whole field is with this notion of an anatomical compiler. Imagine that in the future, you will be able to sit down in front of a computer and draw the plant or animal that you want, not at the level of molecular pathways, but at the level of functional anatomy. You're just going to draw: here is this three-headed planarian. If we knew what we were doing, and if we had a mature science of morphogenesis, this system would be able to compile that description into a set of signals that would have to be given to cells and cause them to build whatever you wanted them to build.

To be clear, this anatomical compiler is not a 3D printer. We are not talking about micromanaging the position of all the cells and creating a 3D printed ear. The anatomical compiler is a communications device. It is a way to convert from an anatomical specification to the signals that have to be given to a collective of cells to get them to build something the way that they normally build other things in development and regeneration.

Why do we want this thing? All problems of biomedicine, with the exception of infectious disease, boil down to the control of collective cell behavior. If we had a way of convincing cells to build anything, an arbitrary structure, we would automatically have the solutions to birth defects, to traumatic injury, to cancer, to aging, to degenerative disease. We could make synthetic biobots on demand. All of these things would be solved if we solved this simple problem of how do you communicate to a collective of cells what you want them to build.

You might think, why don't we have this yet? We've had all this incredible advance in genomics and molecular biology. Why don't we have something like this?

Slide 12/49 · 17m:00s

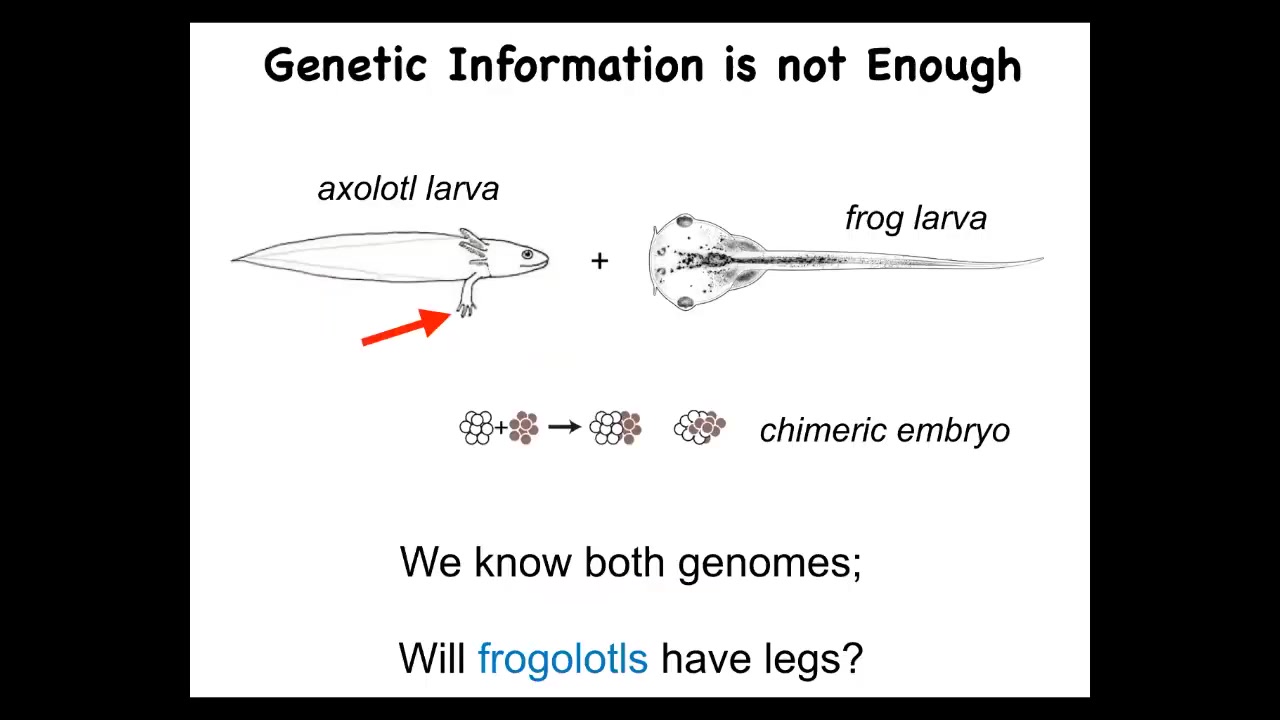

I just want to show you a very simple example of a problem. Here's a basic axolotl larva, baby axolotl. They have legs.

Here is a frog larva. This is a tadpole of a Xenopus frog. They do not have legs.

In our lab, we can do something which is make a chimeric embryo. We call it a frogilotl. Do you expect the frogilotl to have legs? You have the genome. We have the genome for the axolotl. We have the genome for the frog. Can you tell me if a frogolotl is going to have legs or not? If it does have legs, are those legs going to be made entirely of axolotl cells or will they have some frog cells included? Unfortunately, we have absolutely no conceptual framework that will allow you to derive that information from the genomics. We just can't do it.

Where we are today is here. We're very good at manipulating molecules and cells. Pathways, genomic editing, those kinds of things. We're very good at that. But we're really quite a long way from control of large-scale structure and function, which is really what we want.

What I would argue is that where we are in biomedicine today is here. It's where computer science was in the 40s and 50s, where you had to interact with the machine at the level of the hardware. CRISPR, pathway editing, single molecule approaches, protein design, the most exciting advances in molecular medicine are around the control of the hardware. We know very well from the information technology revolution that that's just the beginning. What we really want to understand is how to take advantage of the higher level affordances of living bodies, and really exploit what ends up being the agency of cells and tissues as they solve problems. I want to talk today about those kinds of approaches.

I talk a lot about competencies and intelligence. Let's give a definition. I like this definition by William James, which is intelligence is the ability to reach the same goal by different means. What we're talking about here is, again, when we say goal, we don't mean something that's a second order. Humans have that ability, but you don't need that. It's the ability of some system to exert energy to reach the same state despite various means.

Why would there need to be various means? Because there might be interferences of some sort that prevent it from doing the thing that it normally does. The degree of intelligence and the type of intelligence that a system has is how it handles those interventions. What abilities does it have to get to where it needs to go in its problem space, despite interventions?

Someone had this great quote: intelligence is a continuum that makes the difference between two magnets trying to get together and Romeo and Juliet trying to get together. The difference is in the degree of sophistication of things that are going to happen when you try to prevent them from reaching their goal. In one case, very little sophistication at all — they can only try to minimize the energy. In the other case, lots of sophisticated tricks to try and get there.

Let's talk about this kind of intelligence that's related to biomedicine in particular. Development is incredibly reliable. An embryo most of the time gives rise to a normal, very complex body, but it isn't hardwired. If you cut this embryo in half, you don't get two half bodies, you get two perfectly normal monozygotic twins.

That's because, in this morphogenetic state space, the ability to reach its goal — this ensemble of states that we consider a normal, healthy embryo — can be achieved from a variety of starting positions, and, as I'll show you momentarily, by avoiding local maxima, avoiding problems and doing new things to get to where you need to go.

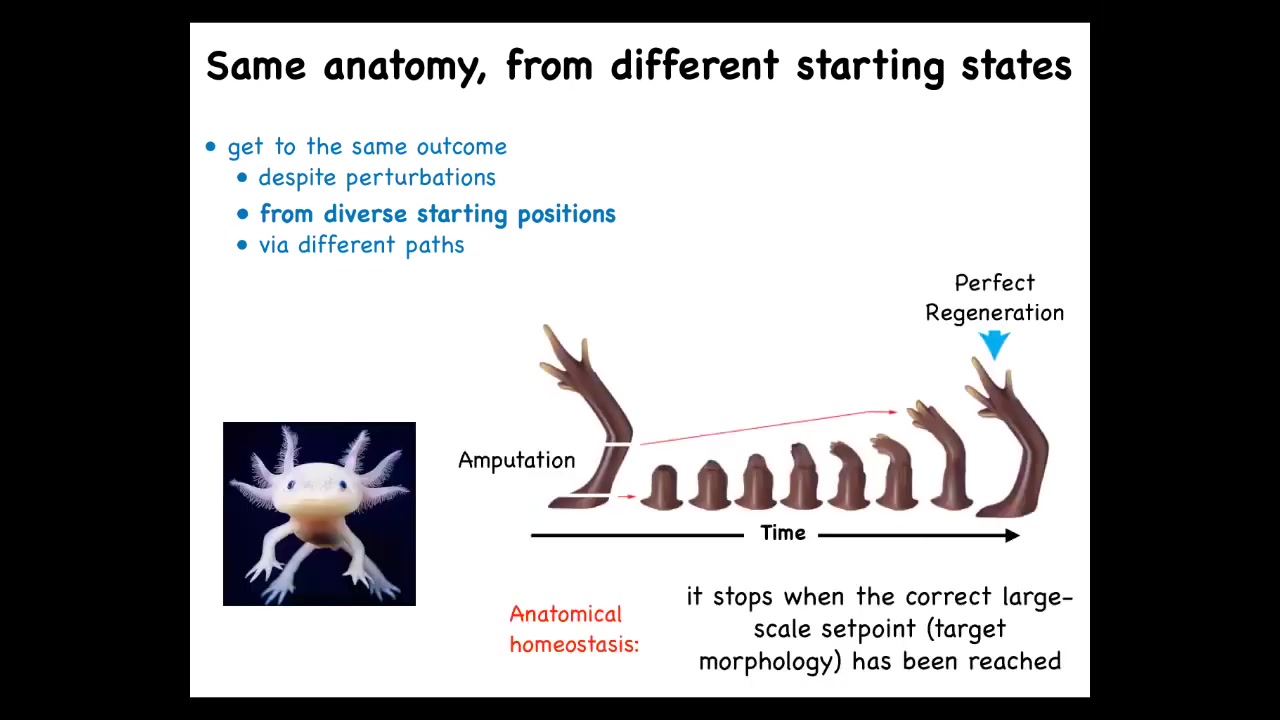

Slide 13/49 · 21m:11s

So here's one well-known example. This is a salamander known as the axolotl. These guys regenerate their limbs, their eyes, their jaws, portions of their brain and heart. And here's what the limbs look like. If you amputate anywhere along the axis of the limb, it will regenerate, the cells will grow exactly what's needed, no more, no less, and give you a complete, perfect limb.

Now, the most amazing thing is that they know when to stop. These cells are growing. No individual cell knows what a finger is or how many fingers you're supposed to have. But the collective makes exactly the right number of fingers, and then it stops when a correct salamander limb has been completed. And if you deviate at that point and you cut off some fingers, it will continue to grow, and it will only stop when the correct pattern has completed.

If you're into computer science, this looks like some sort of means-ends analysis. And basically, it's an error minimization scheme that allows the system to detect deviations from a stored set point and work towards that.

Slide 14/49 · 22m:18s

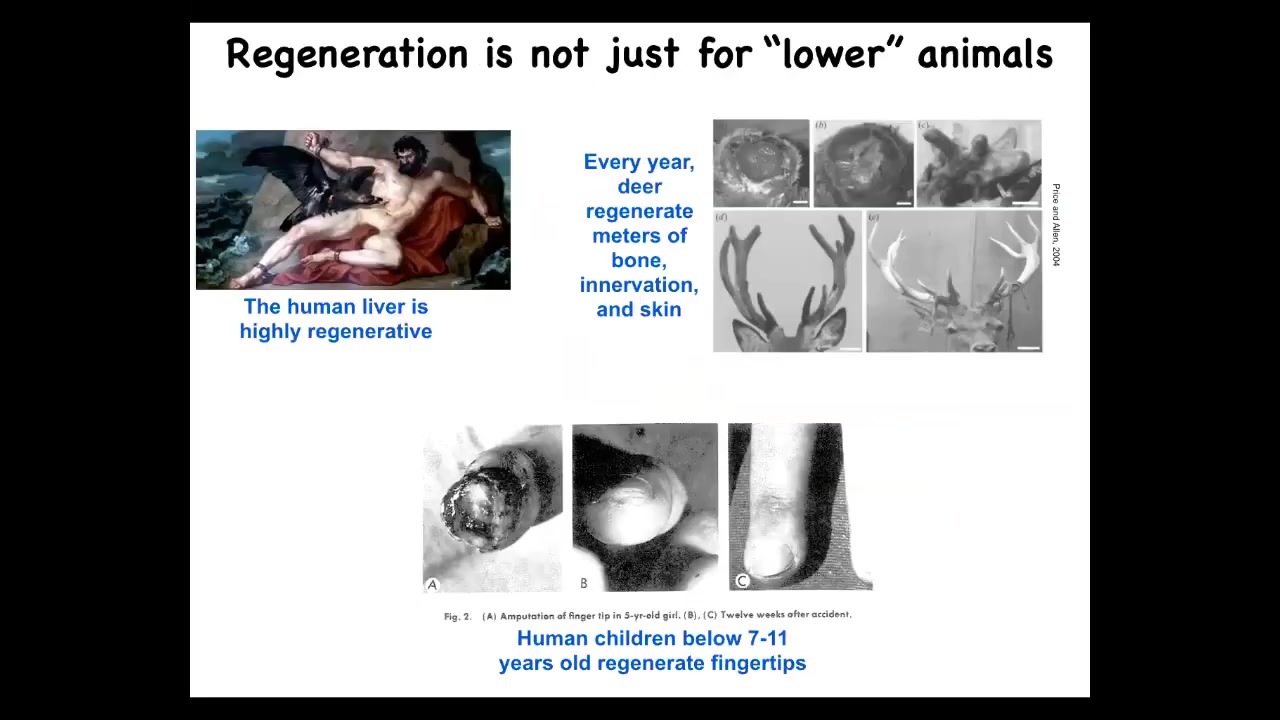

Salamanders aren't the only ones that have this. Human liver, for example, is highly regenerative. Even the ancient Greeks knew that. Human children regenerate their fingertips. Deer regenerate large amounts of bone, vasculature, and innervation every year. There are some mammalian examples of regeneration.

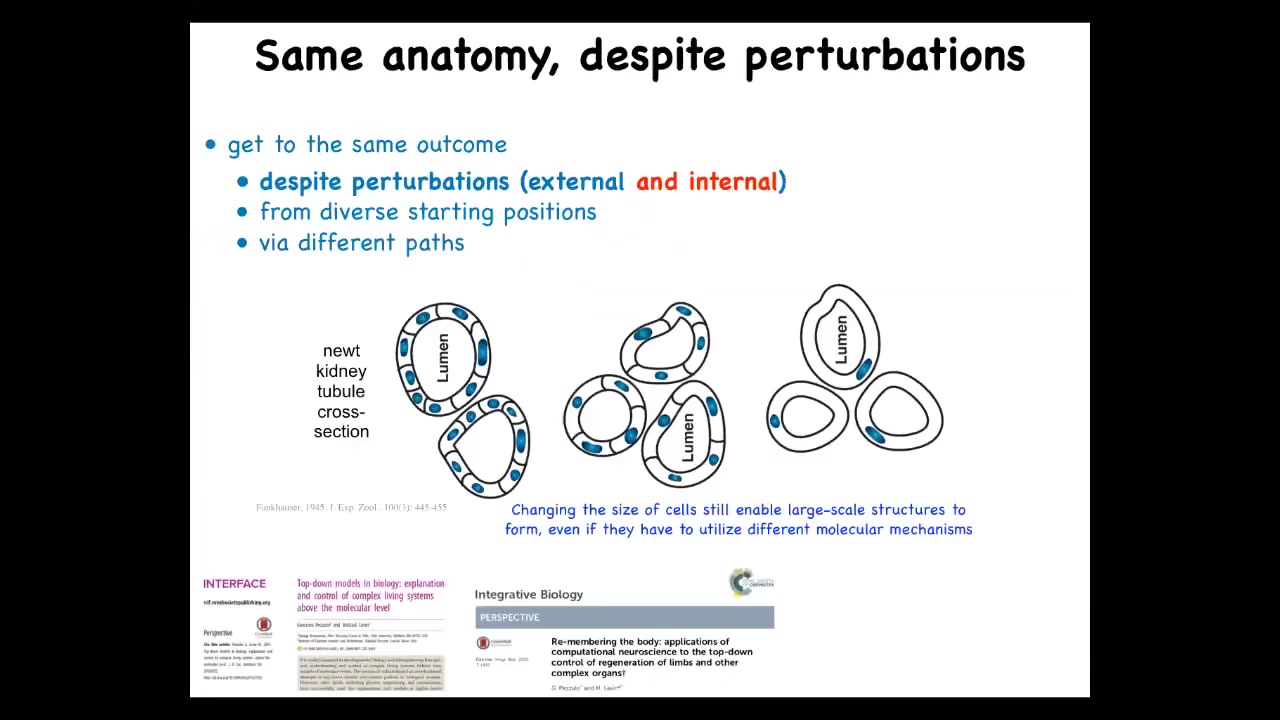

Slide 15/49 · 22m:41s

But here's one of my favorite examples because this illustrates a very interesting point that you can think about as top-down control. This is the cross-section through the lumen of a salamander. What you can see normally is there's about 8 to 10 cells that form this kind of structure. One thing you can do here is make these cells much larger. When you do that, the system adjusts and a smaller number of these large cells make the same-shaped lumen. You can make the cells incredibly large. Just one cell will wrap around itself like this and form the exact same structure.

This is remarkable for a couple of reasons. One is that this is a completely different molecular mechanism. In the first case, you have cell-to-cell communication, Delta-Notch signaling, which are important in forming tubulogenesis. In this case, it's cytoskeletal bending. In the service of a large-scale anatomical goal state, meaning having a tubule of the right shape and size, different underlying molecular mechanisms are being called up to reach that state.

So this is, if you're into neuroscience, very familiar because in cognition, you have this exact example where you have large-scale executive control and goal-directedness that has to feed down into the individual circuits and eventually to muscle voltage states to execute the problem. It's a top-down control, and it happens here in morphogenesis in this amazing example.

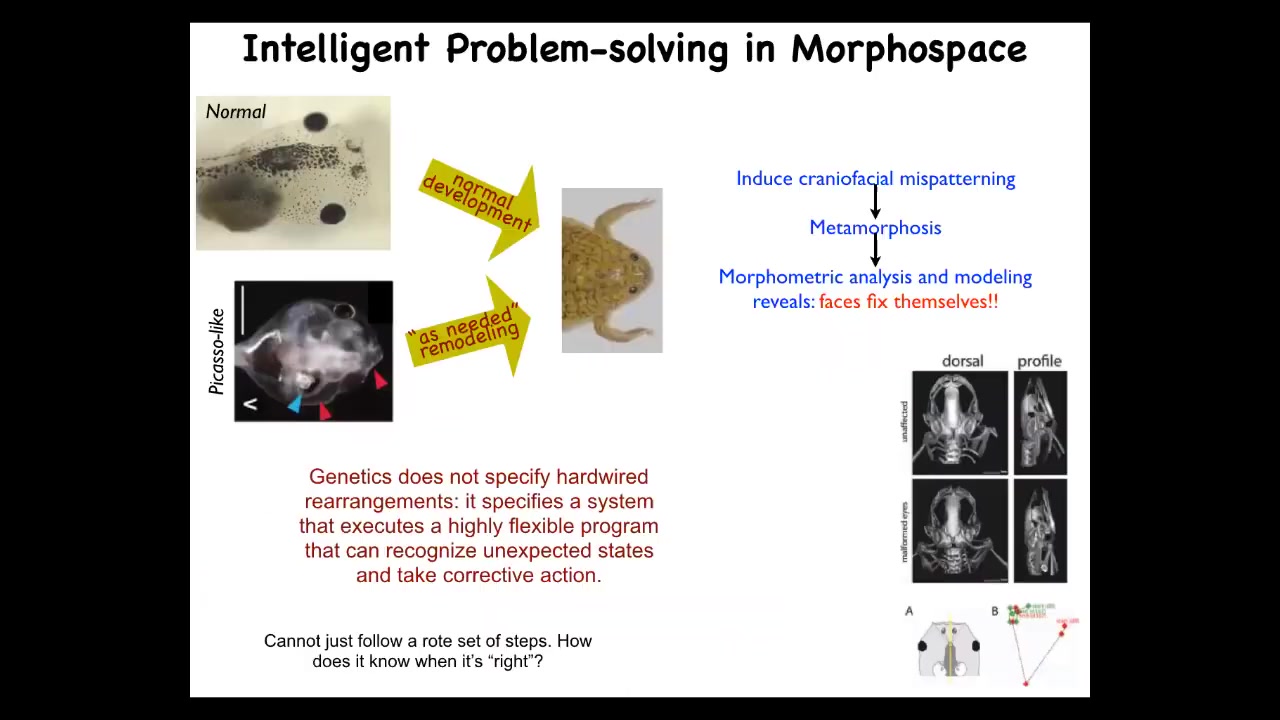

Slide 16/49 · 24m:46s

This is a different example that we discovered a few years ago, which really shows you the need to look for competencies in unexpected places. Here again is our tadpole. Here are some eyes, the nostrils, the mouth is back here, the brain. These tadpoles have to rearrange their face to become a normal frog. It was thought that this process is very mechanical. Every normal tadpole looks the same, every normal frog looks the same, and then the genome would just program a set of hardwired motions where every part of the face would move in the right direction, the right amount, and then you get a normal frog from a normal tadpole.

We tested the hypothesis. I think this is really critical. Before making any assumptions about what the level of competency of a system is, you have to do experiments. We did this experiment. We said, I wonder if it really is hardwired. What we did was we made these, called Picasso tadpoles. They're scrambled. Everything's in the wrong place. The jaws are off to the side, the eye might be on top of the head. Everything's scrambled.

What we found is that these animals make largely normal frogs. Why? Because all of these organs will move around in novel, unnatural paths, sometimes go too far and have to move backwards. They will all move around until they get to a correct frog pattern and then they stop. The genetics does not specify a set of hardwired rearrangements. What it specifies is a system that is able to reach the goal despite completely abnormal, unexpected starting positions.

This is very important. I think a more general claim is that evolution doesn't just make specific solutions to specific problems. It actually creates hardware that implements a problem-solving machine that is able to perform various kinds of information processing to reach regions of anatomical space, physiological space, and so on, despite novelty. I'll show you a bunch of examples of that.

Slide 17/49 · 26m:50s

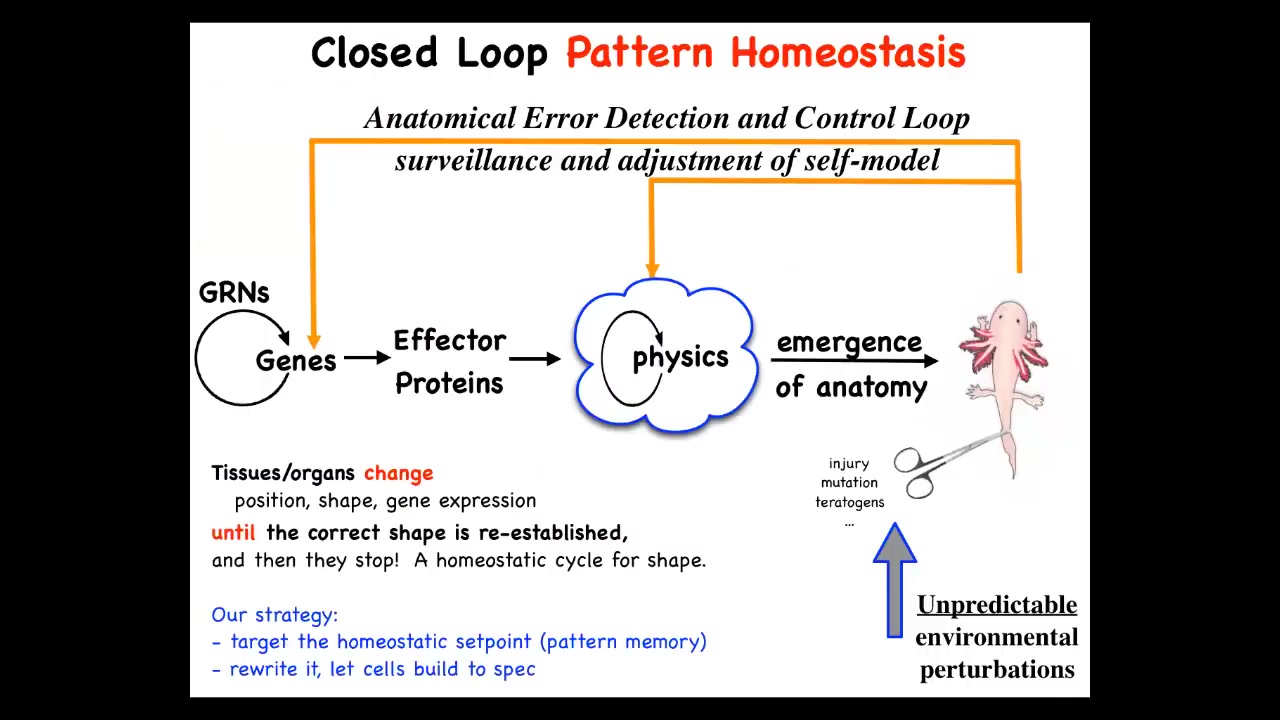

What we started thinking about then was this. This is the typical story that appears in the textbooks, which is, now, the process of morphogenesis is this. You have genes turning each other on and off. They make effector proteins. There are local interactions in terms of physics. And then eventually this magical process of emergence where complexity arises from lots of simple local rules.

This is certainly true when there are many systems where complexity arises from simple rules, but this is not the end of the story. In fact, this is, I think, just not even the major part of the story because what we see now is that this process is not simply feed-forward emergent. If this final form is deviated from its goal state by injury, mutations, teratogens, whatever, feedback loops will kick in both at the level of physics and at the level of genetics, which will undergo various other actions to try and get back to the state.

This is, in the cybernetic sense, a goal-directed system: regeneration, regulative development, metamorphosis, all of these things are trying to get to specific regions of anatomical amorphous space. They exert energy to do so, and they have diverse competencies, more than just pre-wired kinds of behaviors.

On the one hand, this is nothing too new. Biologists are well aware of feedback loops and homeostatic kinds of loops like this: pH, temperature, and so on. Cells do this. But the interesting thing about this process is that the set point for that homeostatic process is not a scalar. It's not a single number. It's not just pH or metabolic level. It is an anatomical descriptor. It's a shape.

That leg will continue to regenerate until the correct salamander leg has formed. In some sense, it is a descriptor of our complex multicellular anatomy that's driving this thing. This whole odd view of looking at these systems as navigational agents, as opposed to just emergent physics and chemistry, makes a very strong prediction.

It suggests that if there is an explicitly encoded set point somewhere, then we ought to be able to find it. Find the physical mechanism of that encoding. We ought to be able to decode it. We ought to be able to decode it, to understand, to be able to read it out, and we ought to be able to rewrite it, to re-specify it. That's what we've been doing. I'll show you how that works.

One of the conceptual implications of this is really important. It means that if this is true, then we have the ability on a biomedical level to rewrite that set point without having to change the machine. In other words, the amazing thing about your thermostat in your house is that you can change the set point without needing to rewire the thermostat. The hardware stays exactly the same, but you can make it do new things. Computers are reprogrammable, and that's the beauty of it. You can run multiple things on the same hardware.

Currently, molecular medicine is all about this portion. That is, if you want to make a change here, we have to figure out which genes we would need to CRISPR to make that change happen. In general, moving backwards, this is an incredibly difficult inverse problem that's going to limit the applications of CRISPR and genome editing technologies, because in general, you cannot reverse this. We have no idea what genes to change. If you wanted a salamander with three-fold symmetry instead of bilateral symmetry, what genes would you change? We have no idea.

It would be really nice if it were true that cellular collectives had a set point; you could change the set point and it would then build. You wouldn't have to solve this terrible inverse problem.

Slide 18/49 · 30m:56s

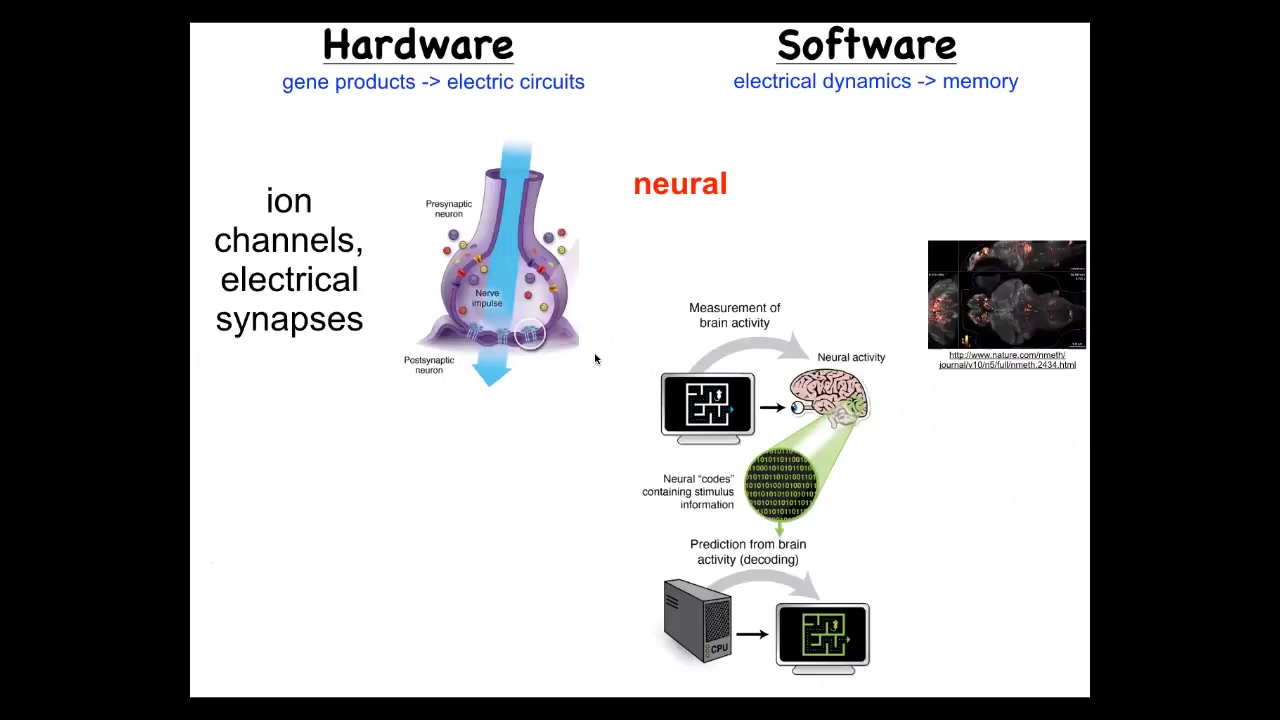

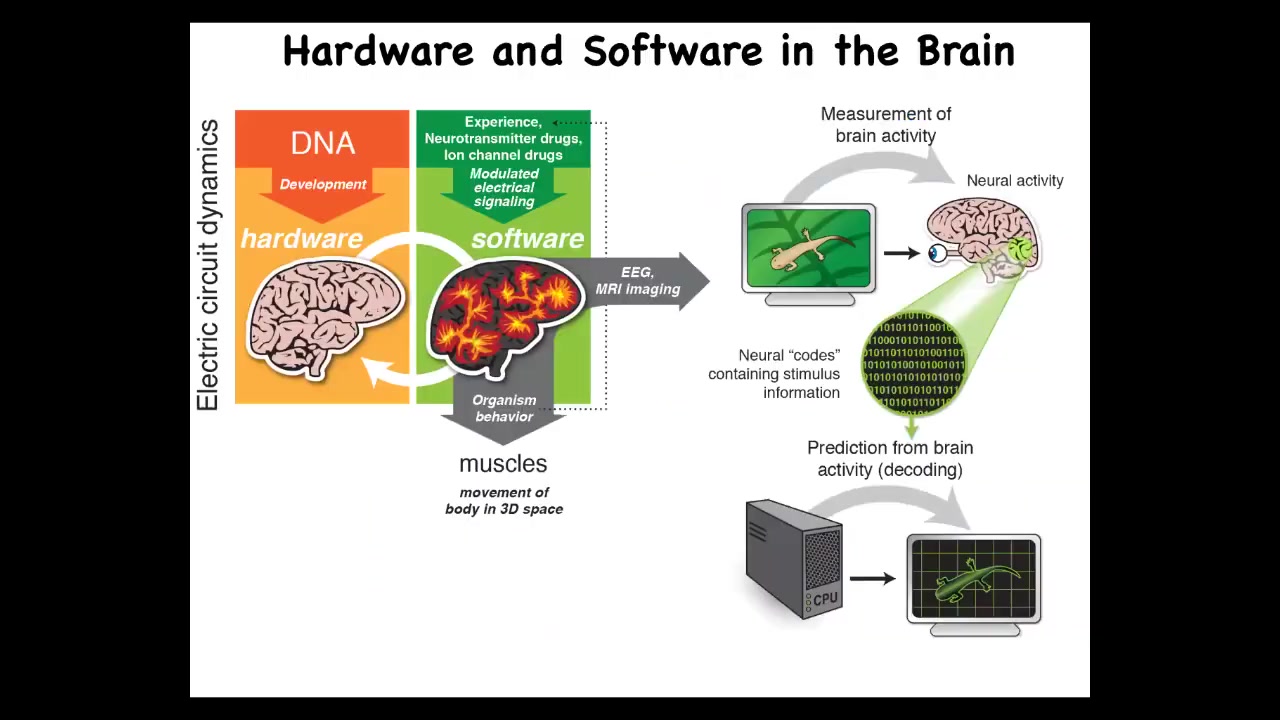

So how does the brain handle a goal-directed navigation in its problem space? It's got this hardware where individual cells have ion channel proteins that enable the cell to reach a resting potential. Those potentials are propagated to their neighbors through gap junctions. They have this electrical network. That electrical network, that hardware allows a certain set of behavioral software, and here you can see the readout: this group did an amazing video of the electrical activity in a living zebrafish brain.

Neuroscience is committed to the idea that all of the cognitive content of this system, of this mind, is encoded in this physiology and in this electrical activity, that if we were able to read and understand, decode, and this is what people work on neural decoding, if we could decode this electrical activity, we would know what the memories, the goals, the capacities of the system are.

The good news is that this amazing architecture of this hardware and software is extremely ancient. In fact, it's as old as bacterial biofilms. Most cells have electrical connections with each other. All cells have ion channels that set their electrical state. You can run a very parallel research program using the techniques from computational neuroscience to try and decode the information processing of the body cells as they try to solve anatomical problems. Here it is parallel to this brain skin. This is a frog embryo putting itself together. We can now image all the electrical states as this happens and try to decode them.

Slide 19/49 · 32m:47s

The isomorphism is very strong because what you have is the DNA, which determines the micro-level hardware. This becomes an excitable medium, which has the ability to have certain electrically implemented information-processing tasks.

What it does is make large-scale decisions to control muscles to move you through three-dimensional space. That same architecture exists in your body. It's extremely ancient, both evolutionarily and developmentally.

It uses the exact same kind of tricks. The DNA specifies the channels, but then you get this excitable medium that is able to have memories and decision-making at the level of the network. It issues commands to all kinds of cells, not just muscles. Those commands move your body configuration through morphospace.

That process takes you from the shape of an egg in an early embryo through progressive stages, and if you're a caterpillar, further through metamorphosis to become a butterfly.

The exact same thing: what evolution does is pivot the ability of electrical networks to process and integrate information through different problem spaces, starting off with metabolic, then moving into anatomical, then behavioral, and eventually linguistic in the case of humans.

Slide 20/49 · 34m:18s

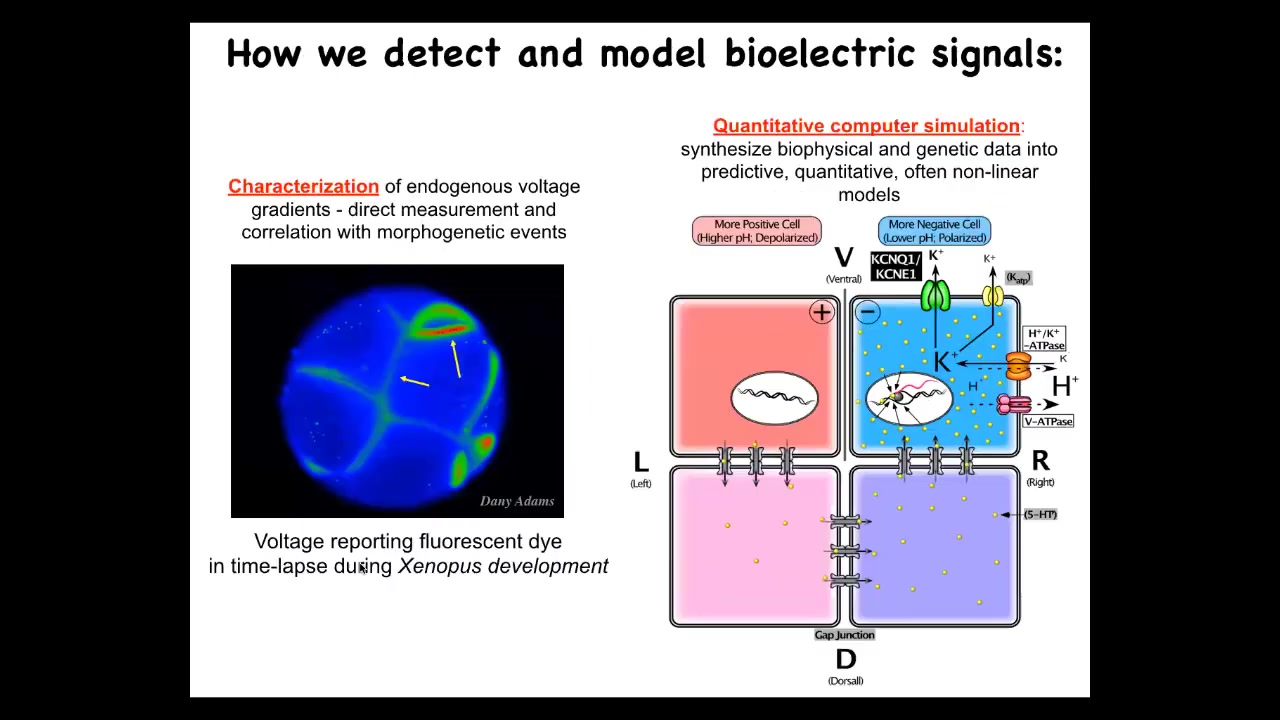

We developed some tools to study all of this. Here's a time-lapse movie of the frog embryo. This is done using a voltage-sensitive fluorescent dye. This technique was developed by Danny Adams to help characterize what the cells are saying to each other. We also do a lot of computational modeling to link to the molecular biology, what ion channels and pumps and gap junctions are responsible for these things.

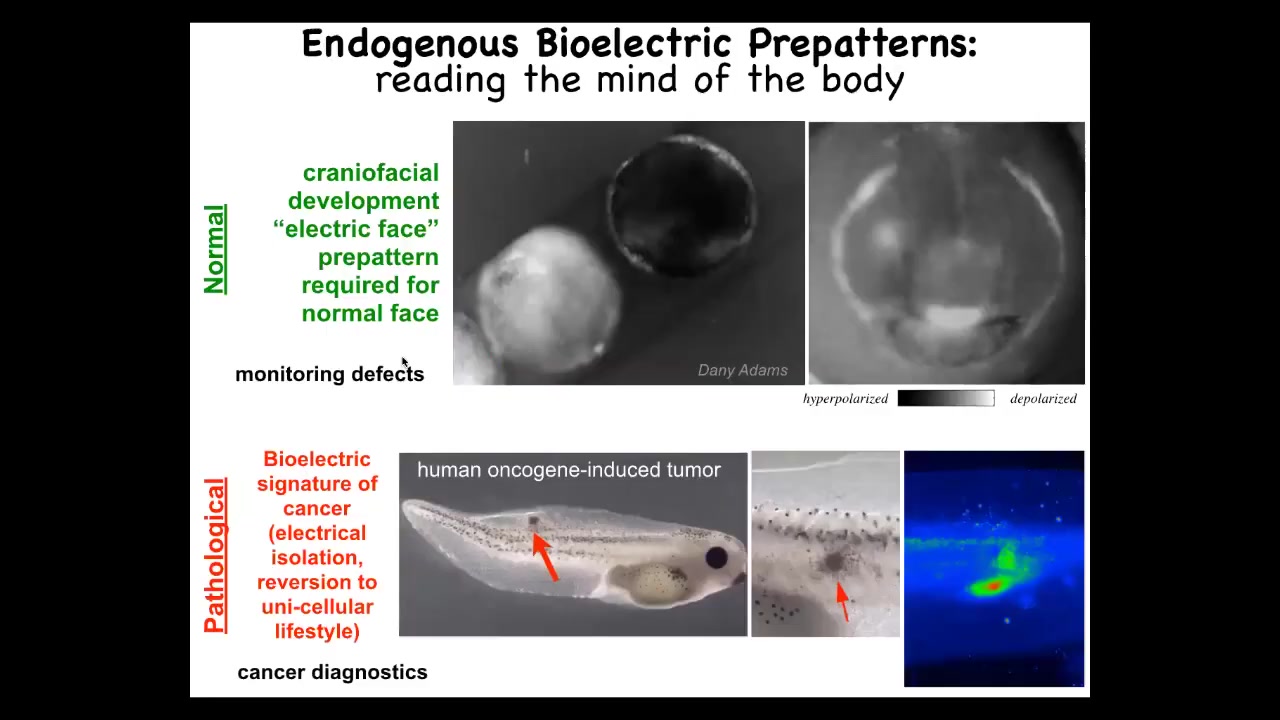

Slide 21/49 · 34m:46s

And I want to show you two kinds of patterns. We call this the electric phase. This is one frame taken from a voltage movie of a frog embryo putting its face together. And what you see is that long before the genes turn on to actually become, to actually regionalize and then implement the face anatomy, you already can read out the pattern memory that tells these cells what to do. Here's where the mouth is going to go, here's where the eye is going to go, the other eye will come later. The placodes out here, this pattern is already there. We know this pattern is instructive, because if you move any of this, the gene expression moves and then the anatomy moves.

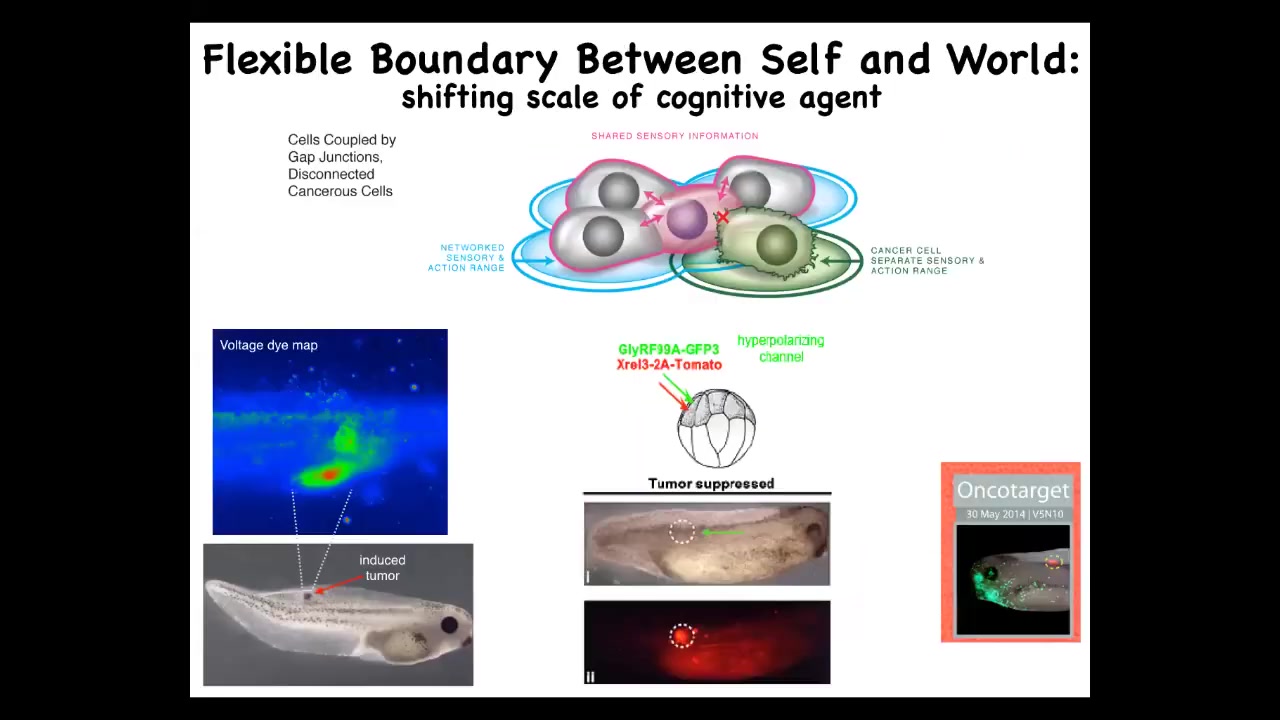

This is a normal pattern that's required for face development. This is a pathological pattern that occurs when you inject human oncogenes into an embryo. Eventually they'll make a tumor, but before that tumor is histologically apparent, you can already see from the cells' aberrant voltage signature that they've disconnected from the electrical network of the rest of the body. They have their own weirdly depolarized voltage. They're like amoebas at that point. They're going to treat the rest of the body as external environment. This is metastasis. They've rolled back to their individual unicellular past. So how do we do these kinds of experiments?

Slide 22/49 · 36m:15s

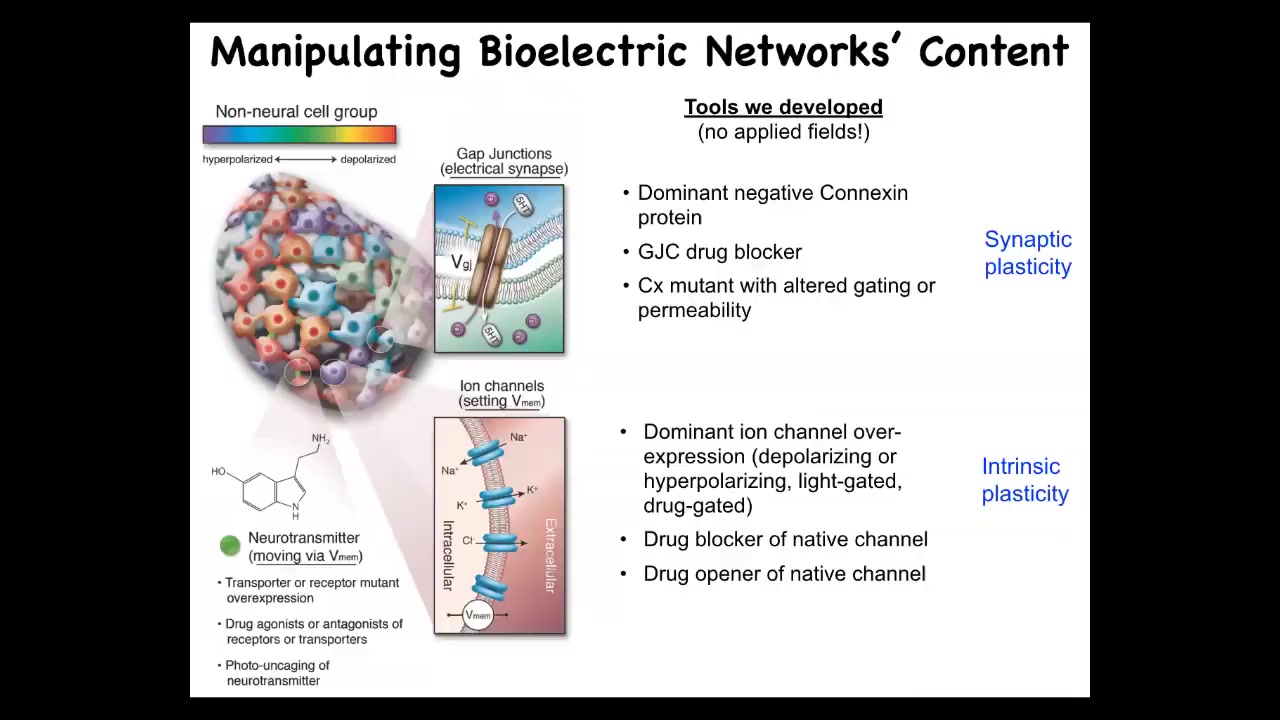

We've borrowed a lot of tools from neuroscience. We do not use applied fields, electrodes, or electromagnetic radiation.

This is manipulating the native bioelectrical interface that cells expose to each other to enable them to program each other's activity collectively. Those are ion channels and gap junctions.

We can use all of the techniques from neuroscience. We could mutate the channels to give them new properties. We can put in new channels. We can block channels pharmacologically. We can do it with light. Optogenetics, all the same tools.

It's very interesting that neither the tools nor the concepts of neuroscience can tell the difference between brains and other tissue. All of the stuff works. We steal everything from neuroscientists: all the neurotransmitter machinery and drugs, optogenetics, active inference, perceptual bistability, you name it.

All of these concepts are directly transferable. There are some important differences between other cells and neurons. But all of them are capable of the key thing, which is to make these electrically active information-processing networks.

Slide 23/49 · 37m:30s

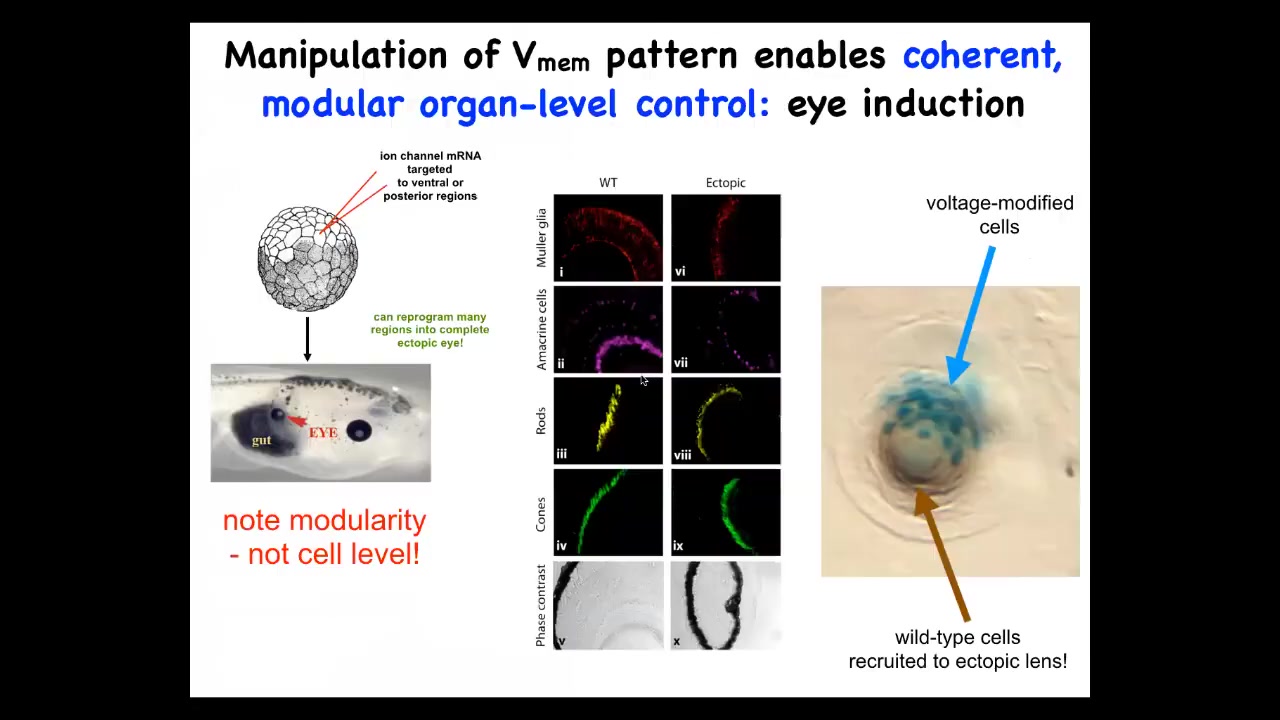

Let me give you some examples of what happens when you make some of these changes. One thing you can do is we can micro-inject into this frog embryo some RNA that encodes an ion channel, a potassium ion channel, that will set the same electrical state that we observed in the eye field and that electrical face in the embryos. When you do this, what you have communicated to the cells is that they should form an eye. And you can do this to cells in the gut, on the tail, anywhere, not just in the anterior and ectoderm where the textbooks tell you are the only cells competent to make eyes. That's not true. If you go further up the chain of command and edit the bioelectrical pattern, any cells in this body will make a complete eye. These eyes have all the right layers of retina, optic nerve, core, all the stuff is here.

Notice a couple of interesting features here. One feature is that what we have not done is reprogrammed specific stem cells for specific fates. We put in a very simple signal. We don't try to micromanage the cells. This is basically a subroutine call. We're communicating to the collective that the eye state is what it should make. We are not trying to micromanage the individual cells. And so this is modularity. This is really like a subroutine call. We just say build an eye here, the cells, all the downstream cascades turned on after that.

The second amazing competency that these cells have is they can do what ants and termites do, which is recruitment. So here is a lens. This ectopic lens is sitting out in the flank of a tail somewhere. These blue cells are the ones that we've actually injected with ion channels, but there's not enough of them to make a proper lens. And so what they do is they recruit their neighbors, these other brown cells that are completely wild type; there's no extra channel there, but they're recruited by these cells. So there's two levels of instruction. We instruct these cells: make an eye. These cells instruct their neighbors: there's not enough of us, you've got to help. And so they have the ability to detect whether there's enough of them to do the task. And if there's not, they have the ability to instruct their neighbors to join in. These are cells that otherwise would have made pieces of the tail. These are some really interesting capacities of this cellular collective to get its job done.

Slide 24/49 · 40m:05s

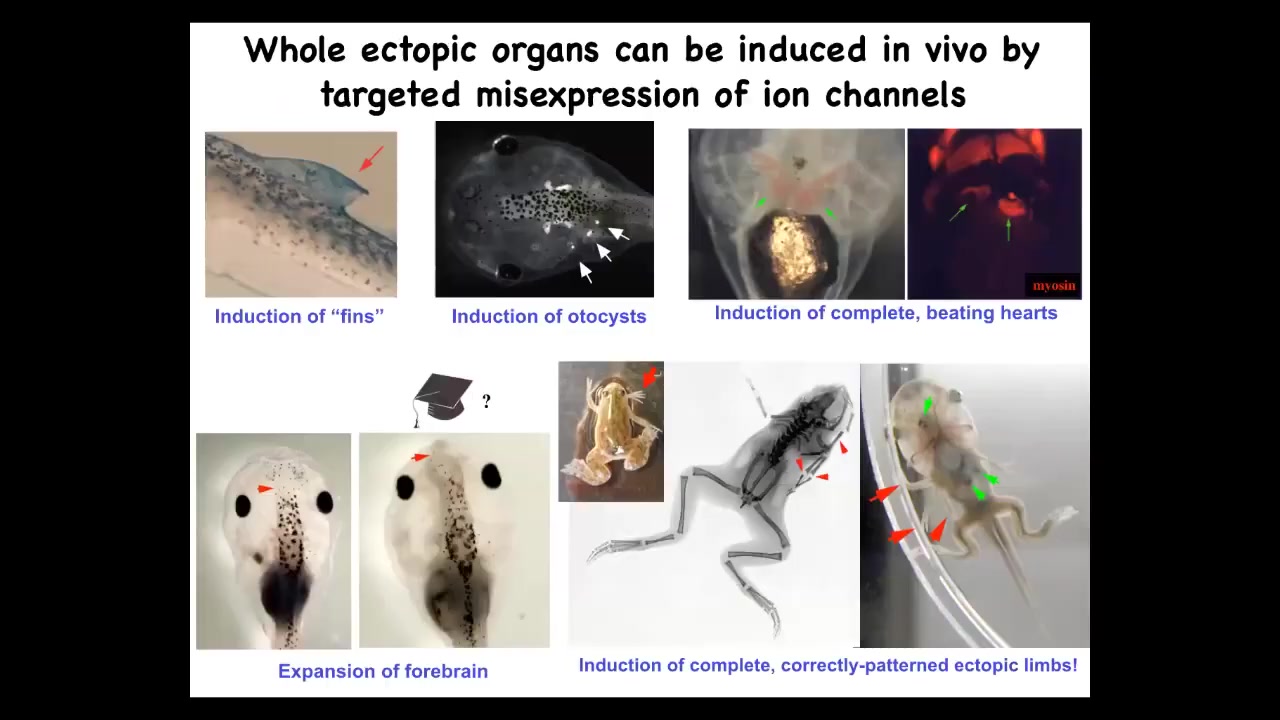

We can make, in addition to eyes, extra limbs. You can make extra forebrains, you can make extra hearts, we can make otocysts or inner ear organs, or you can make fins. That's interesting because tadpoles don't have fins. It's more of a fish thing. Targeted misexpression of ion channels, meaning creating a new bioelectrical state, calls up different organs. Not individual cell states, but actual organs.

Slide 25/49 · 40m:33s

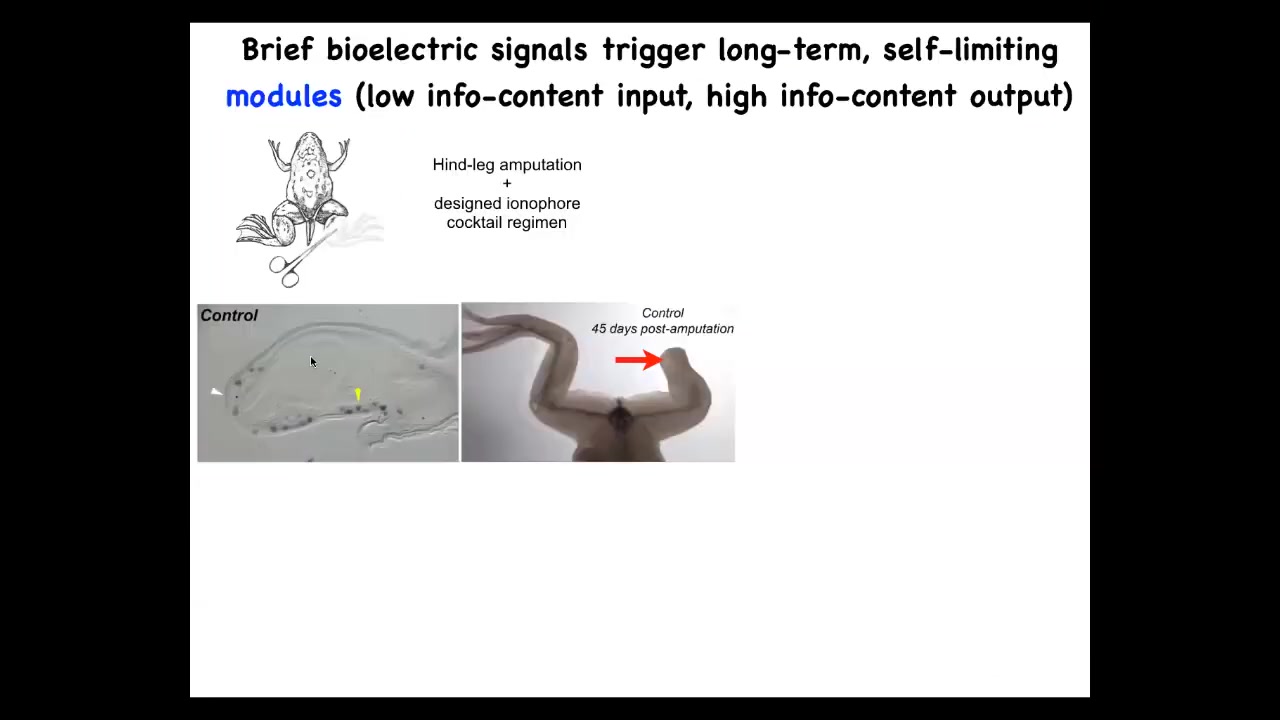

We can take advantage of this biomedically. For example, here's a frog. Frogs normally do not regenerate their legs. The leg is lost; 45 days later, there's nothing going on here, there's a cross-section.

We came up with a cocktail. This is the work of Kelly Chang in my lab, who created a cocktail that triggers the regeneration decision in this wound. A 24-hour treatment, and then legs grow for up to a year and a half, and we never touched them. After 24 hours, the signals have been passed to convince the cells that this is the path through morphospace they should be taking, not towards scarring, but towards regeneration.

Immediately you turn on MSX1, which are pro-regenerative genes. By 45 days you already have some toes, a toenail, and eventually a very respectable frog leg that is touch sensitive and motile, meaning it's functional.

The idea for regenerative medicine is that we should be looking for triggers, ways to communicate to the cells what structure they should be building, not trying to micromanage the process the whole time.

Slide 26/49 · 41m:41s

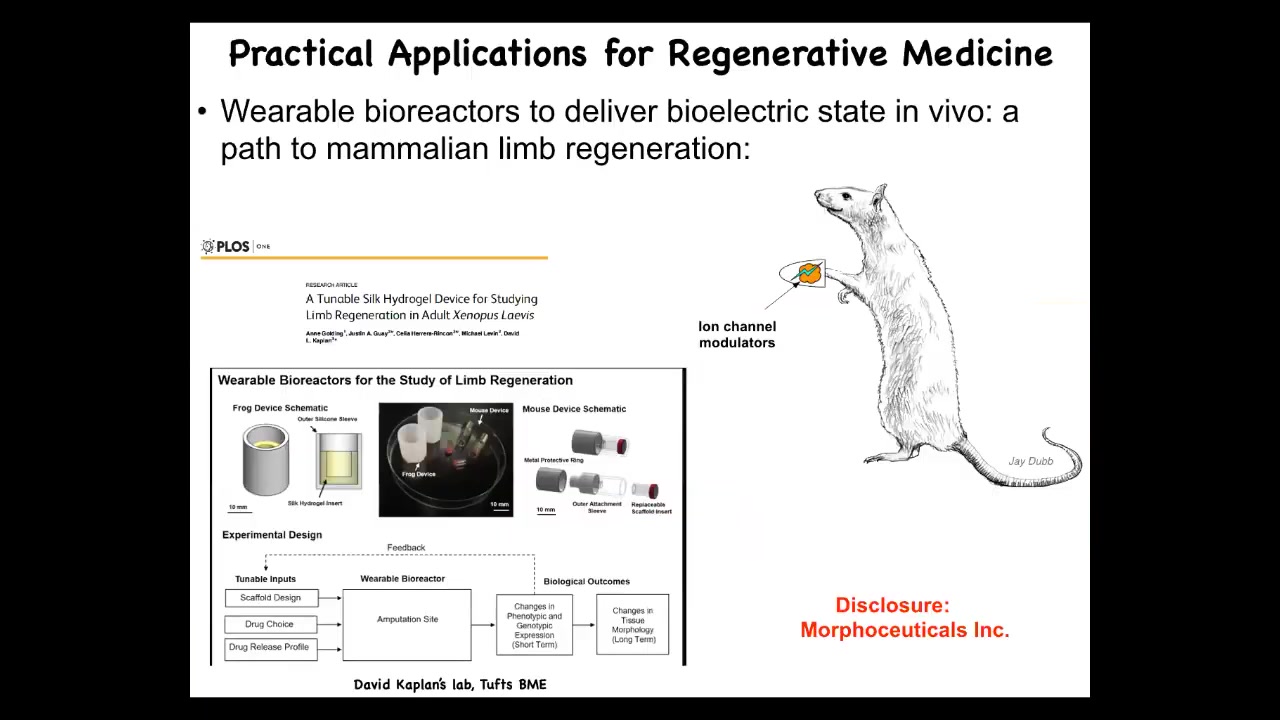

I have to disclose that David Kaplan and I are scientific co-founders of a company called Morphoceuticals, Inc., which seeks to now take those discoveries and move them into mammalian systems. We're doing this now in rodents, hoping to learn to do organ regeneration and ultimately human patients someday.

Slide 27/49 · 42m:03s

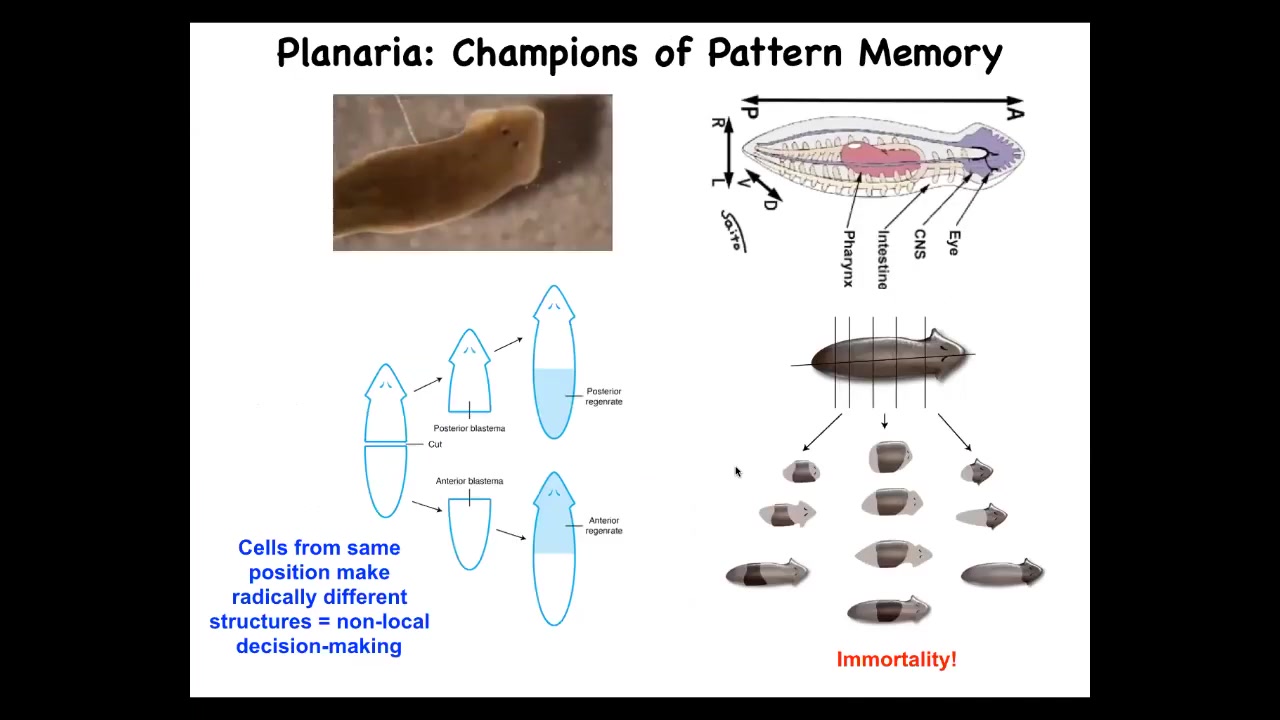

So I want to switch to this other model system, these planaria. And as I've told you, the planaria are amazing. They're so good at repairing body damage. They do this continuously. They're immortal. There's no such thing as an old planarian. They continuously replace dying cells. And as a result, individual worms are basically immortal.

Slide 28/49 · 42m:27s

The amazing thing about that is that when you cut them into pieces, each piece needs to know what it's missing and what needs to be rebuilt. That anatomical control that makes them cancer resistant and immortal needs to be able to recognize what part needs to go where. Typically it's 100% reliable. If I amputate the head and the tail and I take this middle fragment, it will give rise to a perfectly normal one-headed worm.

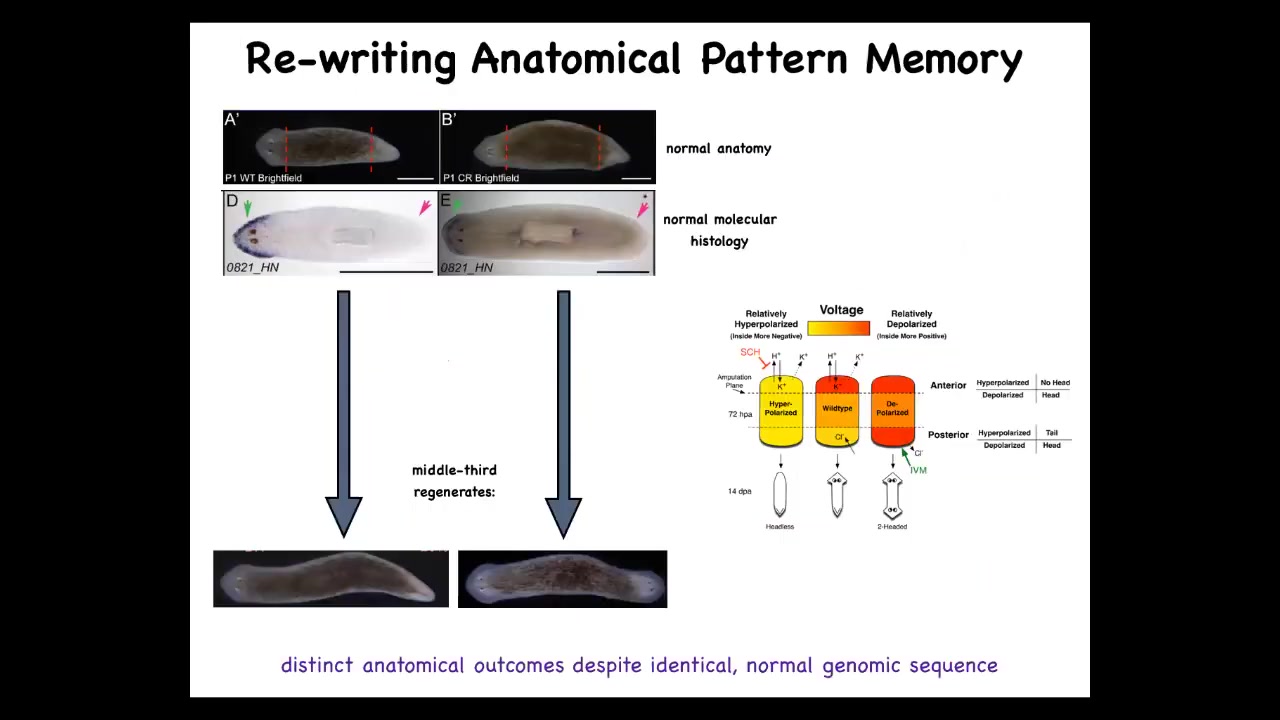

One of the interesting things we found is that there's an electrical circuit in this fragment that determines how many heads and how many tails it's supposed to have. That's the memory. The memory is literally electrical.

We can take this one-headed animal with normal transcriptional profiles. The anterior genes are in the head, not in the tail. When you amputate this guy, he gives rise to a two-headed worm. This is not Photoshop. These are real animals.

I just told you that it's 100% fidelity. Why would it give rise to a two-headed worm?

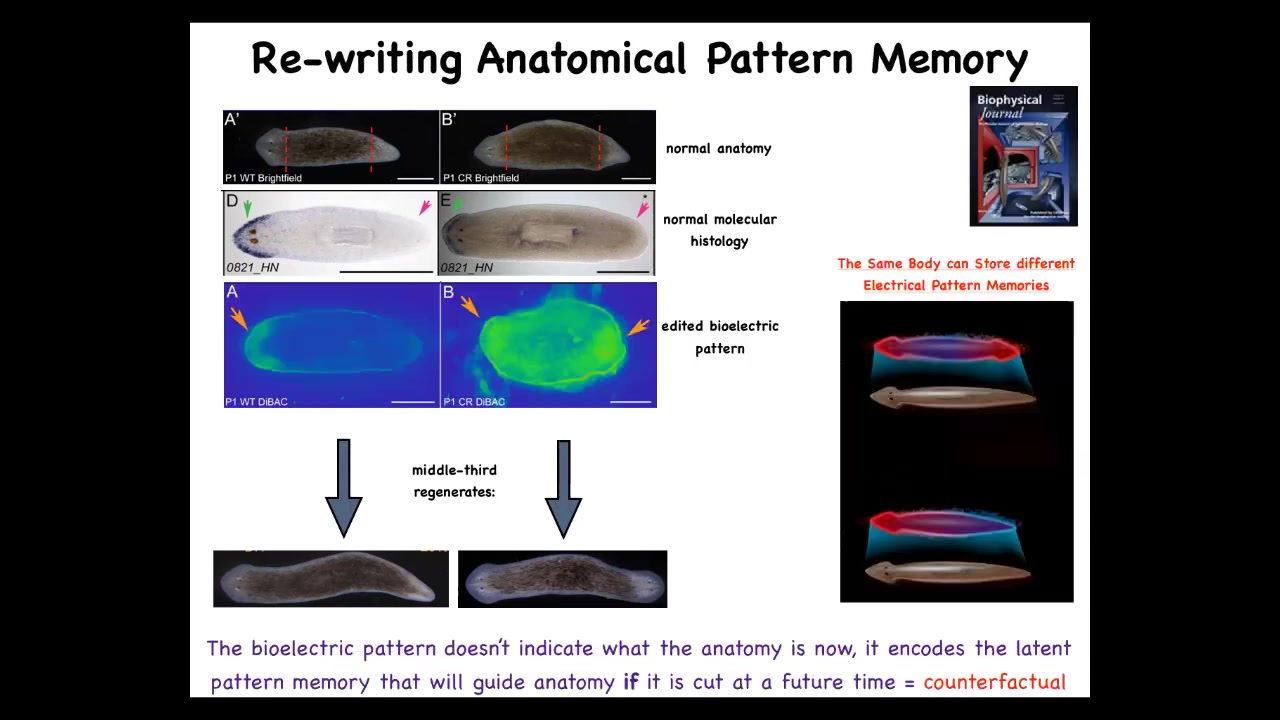

Slide 29/49 · 43m:30s

That's because what we first did was to use drugs that target ion channels and the gap junctions to reset the electrical pattern memory. This is what the fragment normally has, one head, one tail. We can reset that to two heads. You can see it's messy where the technology is still being worked out. We can reset this pattern to be two heads. When you cut, it makes a two-headed animal.

Here's the critical part. This electrical map is not a map of this two-headed animal. This is an electrical map of this perfectly anatomically normal one-headed animal. It's a latent memory, meaning it doesn't do anything until we injure it. When you injure it, the cells consult this map and realize they need to make two heads and that's what they do. A single one-headed planarian body can store one of two different representations of what a correct planarian looks like.

I promised you at the beginning that if we have this homeostatic loop, you have to store the set point somewhere. Somewhere you have to say what the correct information is. How does it know what's correct? This is how. That information is stored in electrical memories that we can now read out and edit and write to some extent, much like people are trying to incept false memories into brains.

If you're interested in the brain and this ability, they call it "mental time travel," the ability to remember things or imagine things that are not true right now. The ability of a system to store states that are not true right now, that time shifting, that's what you see here. This electrical memory is counterfactual. It is not a true description of what my anatomy looks like. It is a counterfactual memory of what I will do if I get injured in the future. It's a memory of a plan for the future. It's a very primitive way of doing counterfactual memories that might be the evolutionary precursor to complex counterfactual thought in brains.

Slide 30/49 · 45m:35s

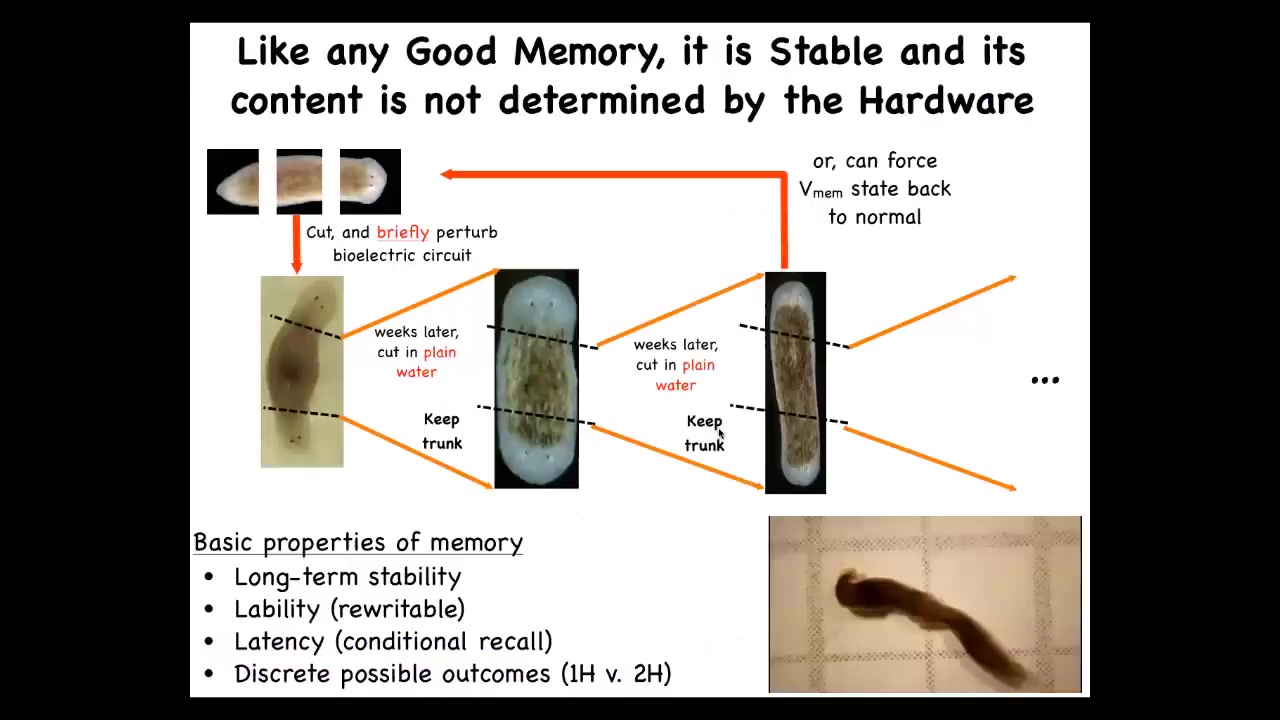

Why do I keep calling this a memory? Because if you cut these two-headed animals and you take this middle fragment, with no more manipulation, it will continue to form two-headed animals. There's been no genetic change here. We haven't rewritten the genome. The hardware is exactly the same. What we've done is given it a brief physiological stimulus that altered the memory of what the set point for this regenerative process is.

So the question of what determines the number of heads in a planarian is subtle. It isn't the DNA. What the DNA does is produce an electrical machine that by default stably settles on the memory of a one-headed structure. But it's rewritable and it has memory. Once you rewrite it to a two-headed state, that's what it keeps. We do have a way of turning them back so we can take these two-headed animals and rewrite the memory back to a one-headed.

Here you see a video of what these guys are doing. These are all the properties of memory. It's long-term stable, it's rewritable, it has conditional recall, which I just showed you, and it has discrete behaviors.

Slide 31/49 · 46m:47s

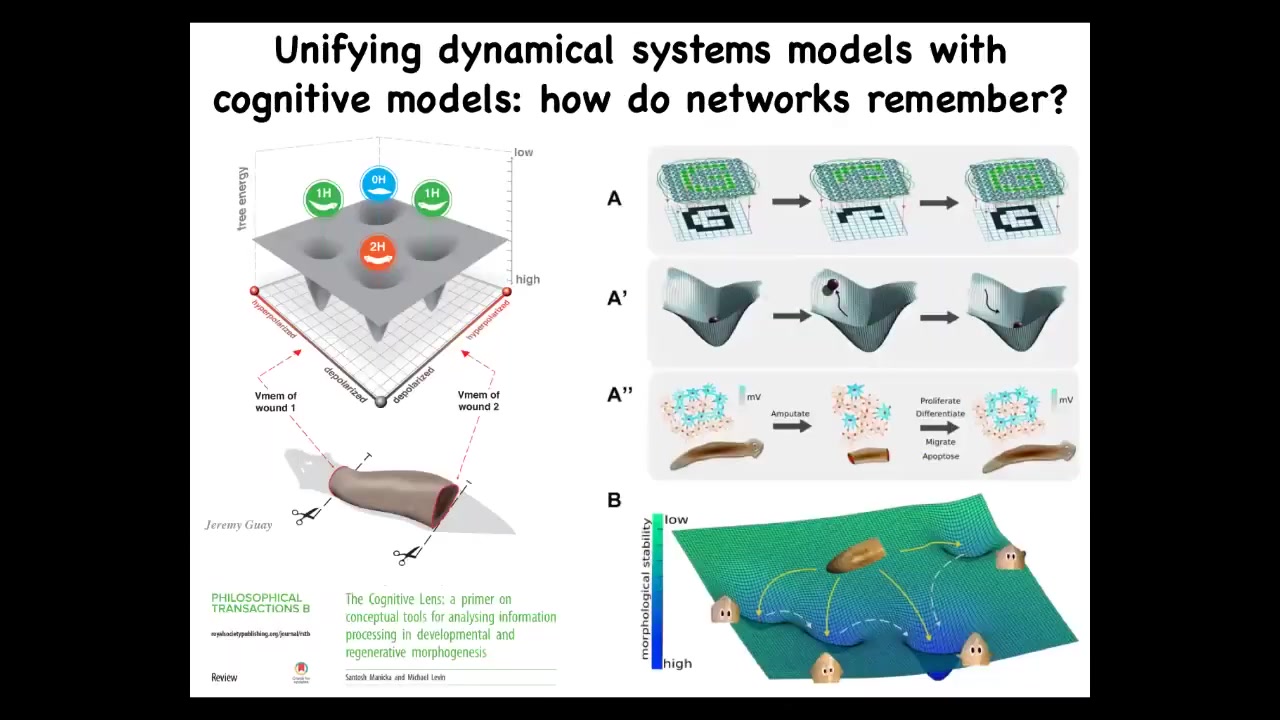

What we are doing now is to take what we know about the state space of these electrical circuits and map them to anatomical outcomes, which are attractors in this morphospace, and understand how that process gives rise to these amazing abilities, such as if the system is deviated, it comes back, it recovers missing information. These are all things that people study. We want to integrate that field.

Slide 32/49 · 47m:29s

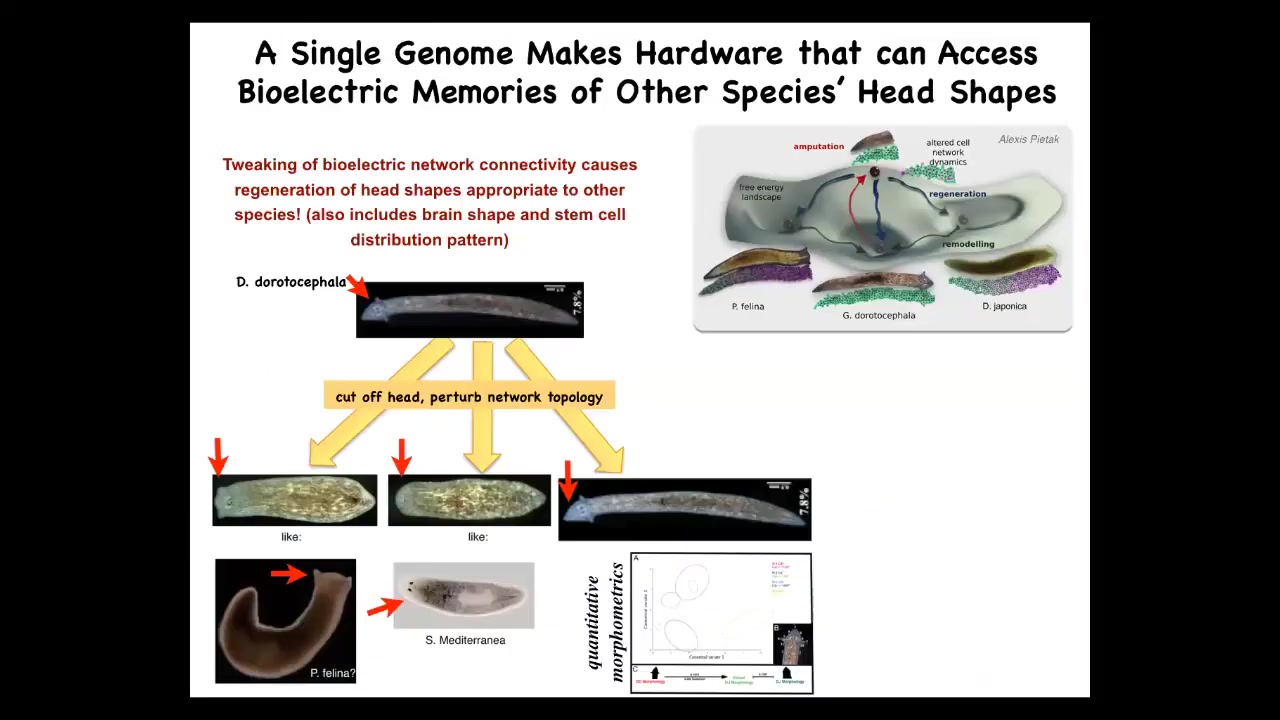

Interestingly, this is not just about head number, it's also about shape. If we perturb the electrical network in this guy when he tries to regenerate his head, you can get the same genetics to form a flat-headed P. falina or a round-headed S. mediterranean. The distance between this guy and these species is about 100 to 150 million years. What you can do by changing the electrical pattern memories is to select between attractors in the state space that normally correspond to other species.

One way that could have happened is genetic assimilation. An environmentally induced bioelectric change that causes head shape change then eventually ends up being assimilated into the genome as changes in ion channel properties. Evolution could make use of this very powerful mechanism.

It's not just the head shape. It's the shape of the brain and the distribution of stem cells is exactly like these other species. You're literally making a head of another species.

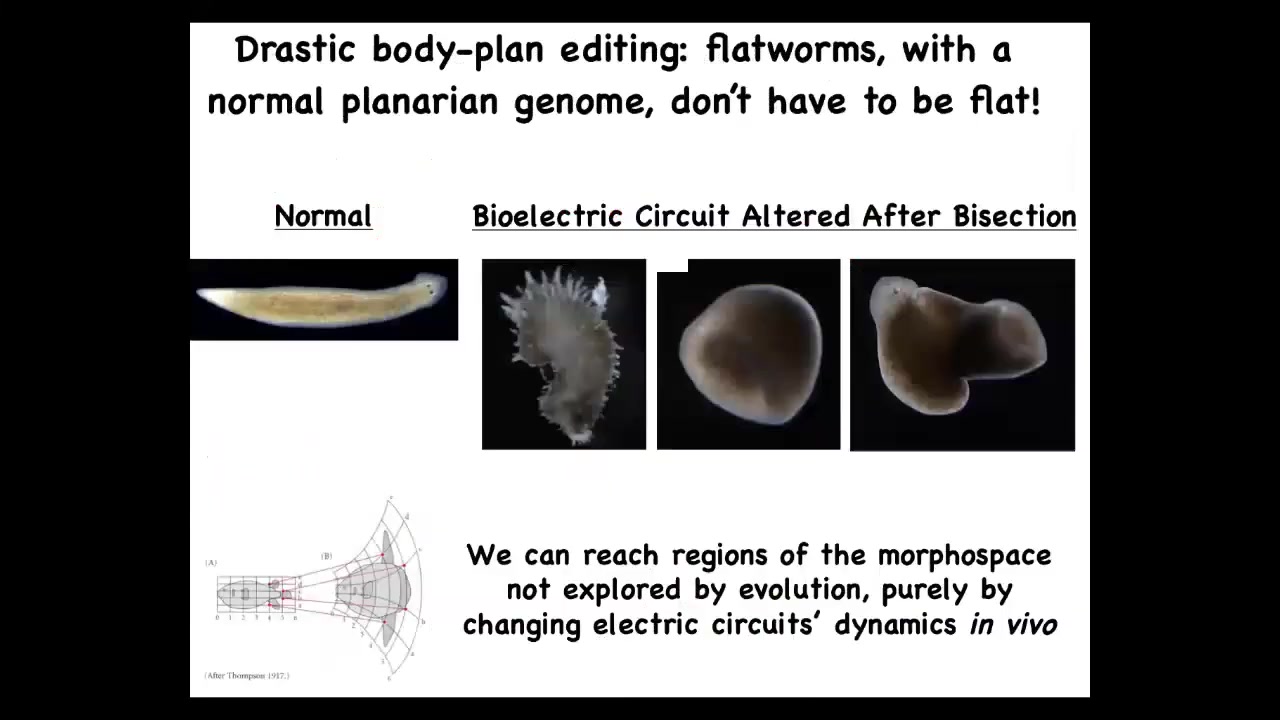

Slide 33/49 · 48m:43s

It's not even about existing other species. You can make shapes that don't belong to any species. The morphospace of possible shapes is quite large. You can make these spiky forms, this cylindrical three-dimensional thing, you can make combination forms. Evolution doesn't use it. Presumably these don't make very successful worms, but the cells, the hardware, the genetically specified hardware of a wild-type genome is perfectly happy to form these other forms.

Slide 34/49 · 49m:15s

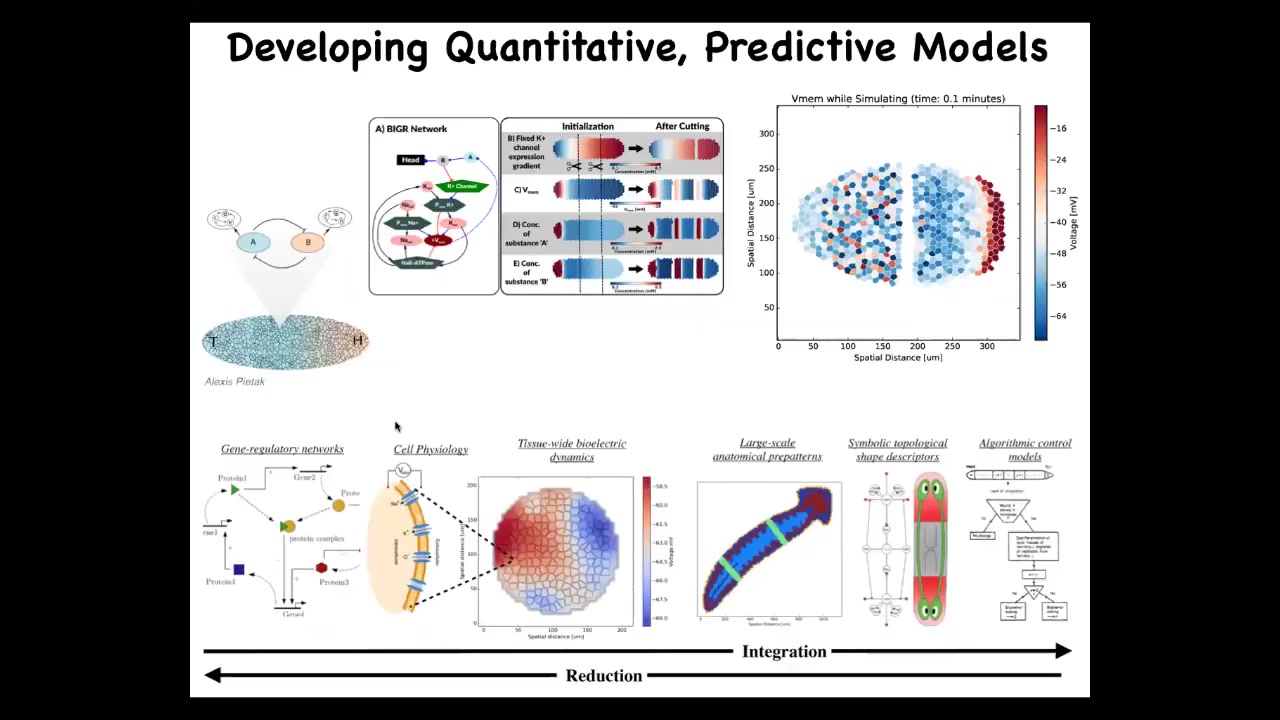

What we're looking for is a full stack framework in which we can start from knowing what the channels and pumps are that determine the hardware of the cells, but then we can start to understand on a tissue level the changes in the bioelectric large-scale properties, getting to what does that mean for organ specification, and ultimately getting to a symbolic algorithm of the decision-making at the organ level about where heads and tails and all the other organs go. We've started work on this bioelectrical simulator. Alexis Pytak has made this amazing system that allows us to simulate some of this and link chemical networks with the electrical, downstream electrical information processing.

Slide 35/49 · 50m:02s

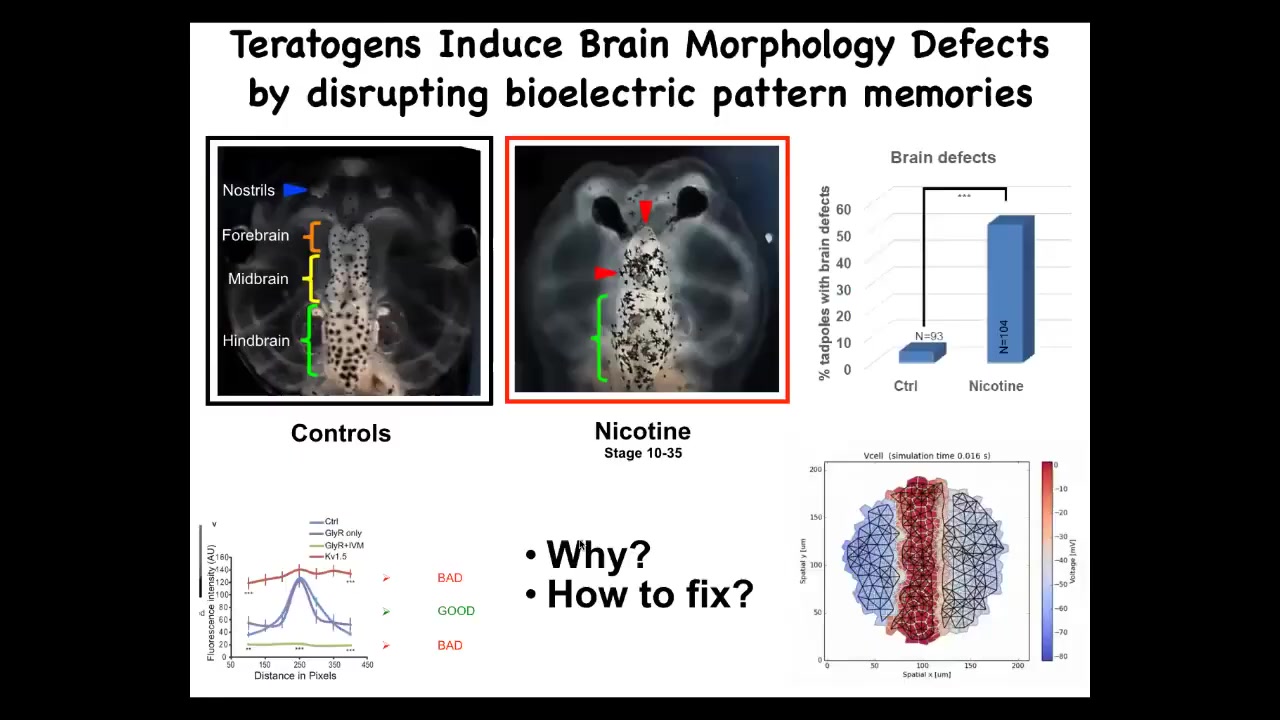

I want to show you one quick success case of using such a thing for biomedicine. This is a tadpole brain: forebrain, midbrain, hindbrain. In animals that are exposed to teratogens like nicotine or alcohol, there are severe brain defects. We said, could we make a computational model of the bioelectric pattern of a normal brain and show what happens to that pattern under various deformations? We made this pattern and it showed us some really interesting features of why things go wrong.

Slide 36/49 · 50m:40s

What that model was able to do is then say, if that's what happens to the electrical pattern, what would we need to do to fix it? Which channels and pumps could be open or closed to get back to the correct bioelectrical pattern, even though you were exposed to this nasty teratogen?

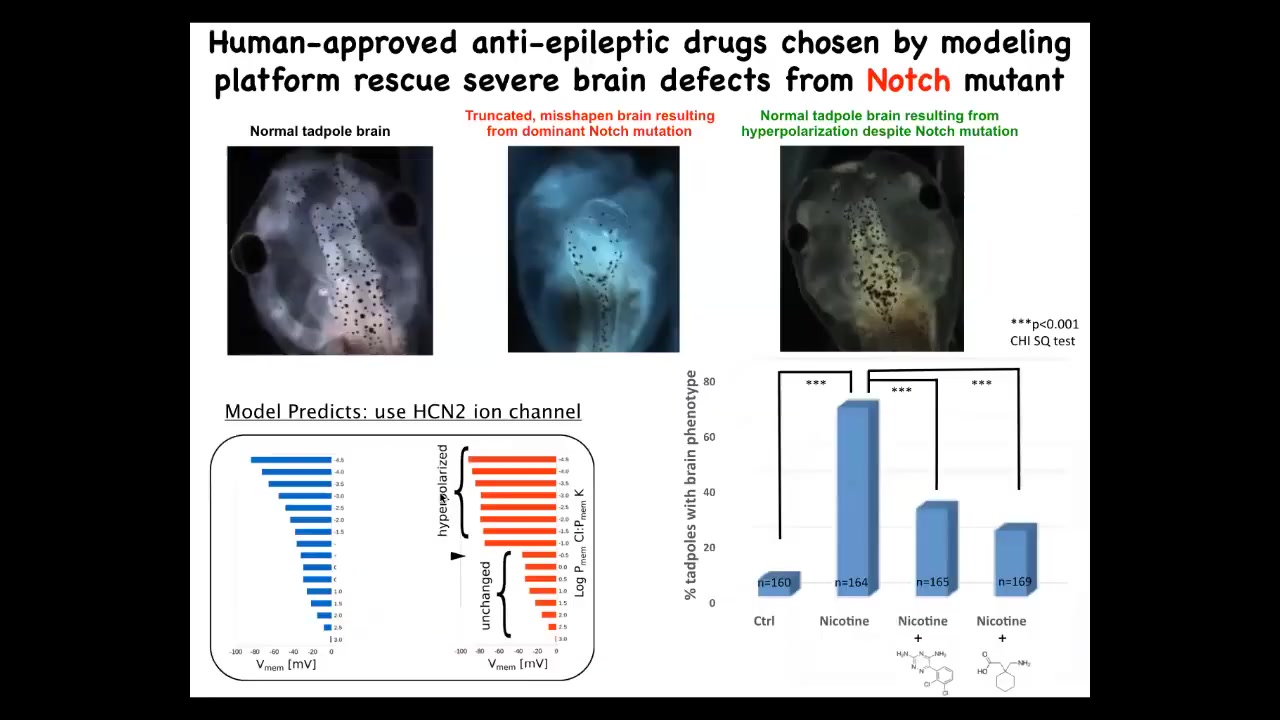

In fact, we did this with even a genetic change, which is a mutation in notch. Notch is a very important neurogenesis gene. In the absence of proper notch function, the forebrain is missing. The midbrain and hindbrain are just a big bubble. The animals have no behavior. It's a very severe defect.

What the computational model was able to do is pick out a channel for us, specifically this HCN2 ion channel. It has some interesting properties. The model told us that if we turn on this channel, the bioelectric state should basically come back to normal. When we did that, and you can do this either genetically or through a couple of drugs that are already human-approved that target HCN2, these animals went back to normal. These animals have the same notch mutation, but you can see the brain structure is normal, their IQs are indistinguishable from controls, they get their behaviors back.

This is an amazing thing. Not only are we now to the point where a computational platform can actually predict therapeutics by quantitatively asking what does the bioelectric change need to be? And then what drugs do we have that will induce that change? But this is an example of fixing a hardware defect. So the notch mutation is an example of fixing a hardware defect in software by brief stimulation of the physiology with a drug.

I'm not arguing that that's going to be true always. There are many hardware defects, enzyme mutations and so on, that are not fixable this way. But it is remarkable that some genetic defects can actually be repaired this way.

Slide 37/49 · 52m:38s

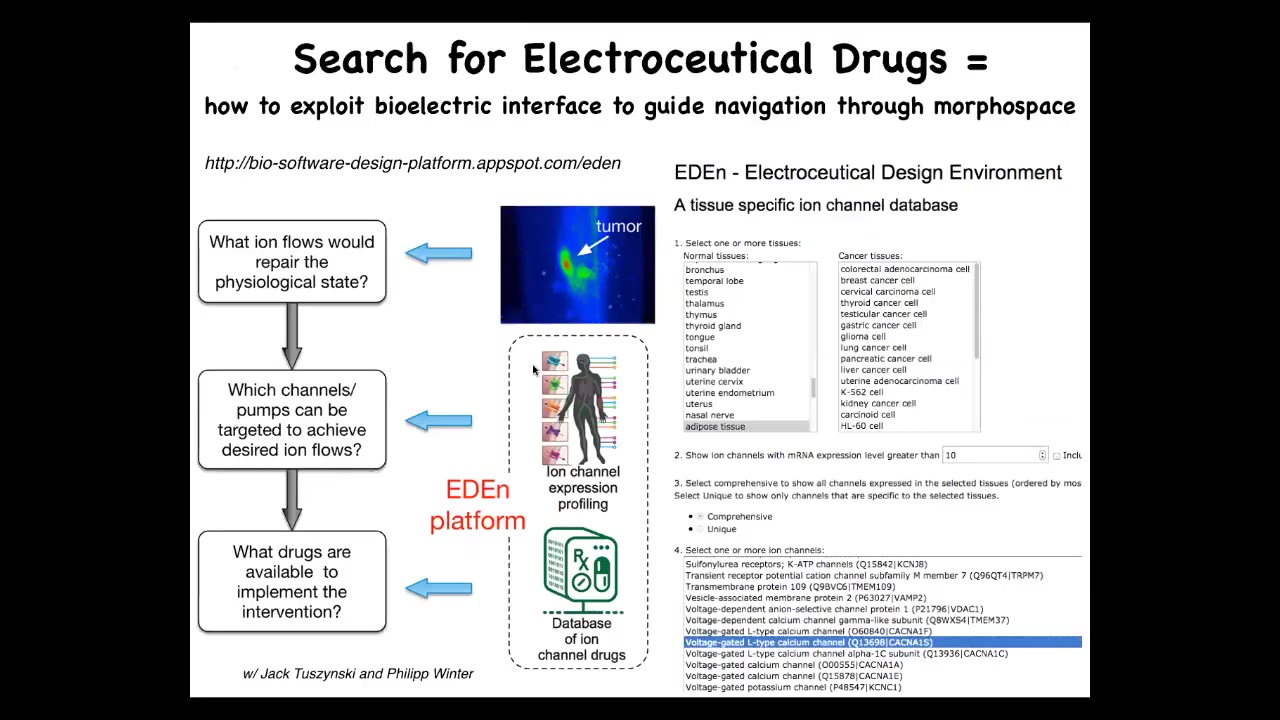

So what we are working on is this system, and you can play around with this, although it's still a very early stage. The idea is that you should be able to take your knowledge of the correct and the incorrect states, run it, and the model will tell you which ion channels and pumps can be targeted. We know what drugs exist for all these different channels, and it should suggest electroceuticals. So combinations of drugs to address different kinds of problems with cancer, repair of injury, birth defects, and so on.

Slide 38/49 · 53m:19s

For the last couple of minutes, I want to say a couple of quick things about coming back to this idea of let's zoom out from the biomedicine and think about what we've learned about intelligence and cognition.

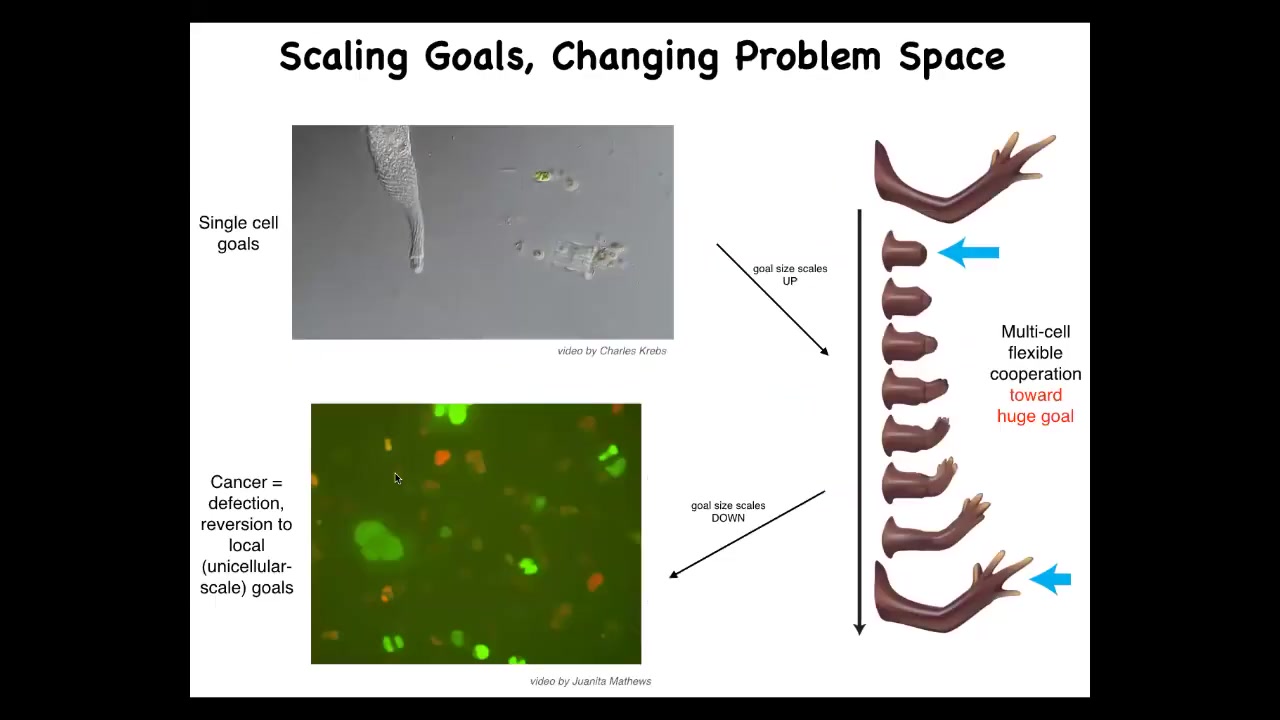

We know that it has competencies in a certain very small cognitive light cone. The local environment is what it cares about. Cells have a little bit of memory going back, a little bit of predictive power looking forward. Both spatially and temporally, the goals that the system pursues are very small. What evolution did is create a set of policies for electrical networks that allow them to pursue much bigger goals. So this collective pursues the goal of having this anatomical state, and you can deviate it and it will do its best to get back there. Individual cells have no idea what a finger is or how many you should have, but the collective does. It's the network that's able to do this. But it has a failure mode. The failure mode is cancer. When cells disconnect from this electrical network, as in glioblastoma, they basically roll back to these individual cell behaviors and their light cone shrinks.

We can think about the scaling up of cognition from individual cells that have a very small spatio-temporal cognitive capacity to larger networks that have more computational capacity for memory, for prediction, and for integrating spatial information across a distance.

Slide 39/49 · 54m:49s

This has a very clear testable biomedical prediction. Here's our tumors induced by human oncogenes. We're not going to change the hardware. We're going to leave the hardware defect in. We're not going to remove the cells or try to fix the genetic mutation. What we will do is force these cells to be in normal electrical communication with each other. And so when we inject the oncogene, we also inject an ion channel that, despite what the oncogene does — electrically decoupling the cells — will cause them to stay connected. So this is the oncoprotein here. It's very strongly expressed. In fact, it's all over the place, but there's no tumor. This is the same animal. There's no tumor because the physiology overrides the genetics. Some hardware defects can be fixed in software. If you connect these cells to the group, they will not have the metastatic single-cell goal-pursuing behavior. They will work on a collective project, making nice skin, nice muscle underneath. These ideas of cognitive scaling lead directly to novel therapeutic approaches that had never been tried before.

Slide 40/49 · 55m:58s

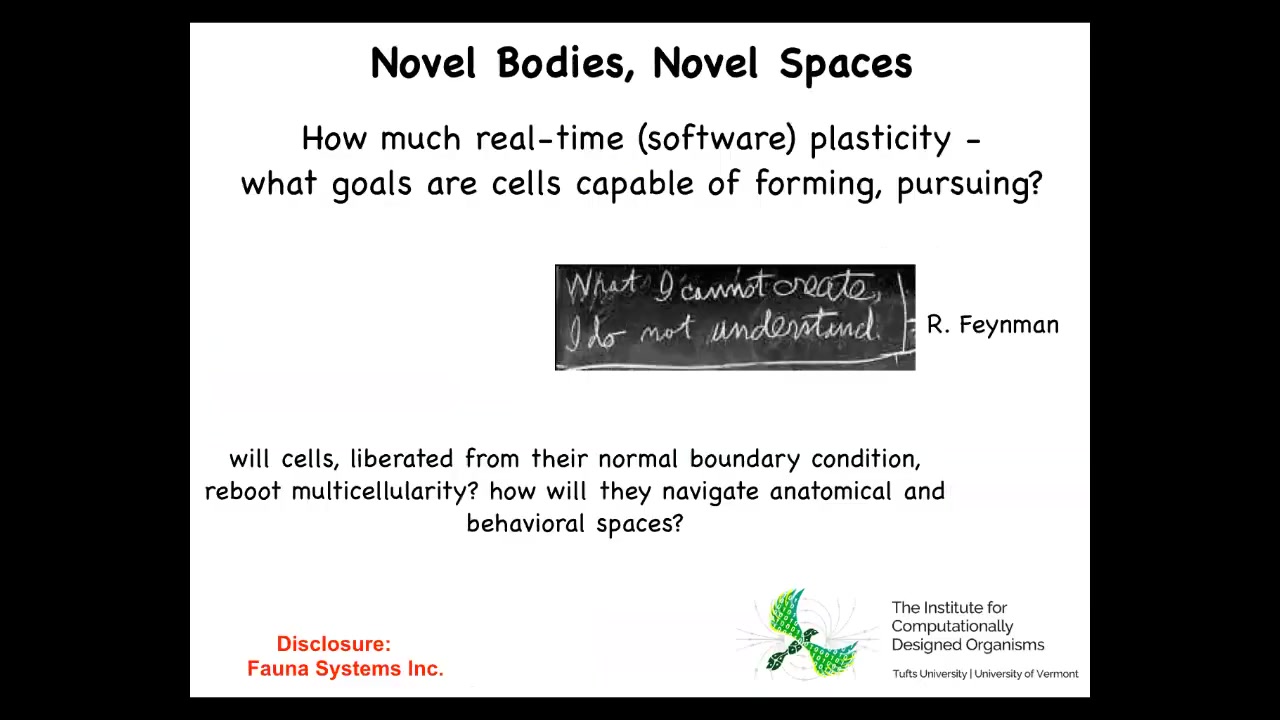

The last two minutes I want to show you one amazing example of cellular competencies and plasticity. We wanted to know whether cells could reboot their multicellularity and what their novel goals would be if we took them out of their normal context.

I have to make a disclosure. Josh Bongard and I have founded this company for computer-designed robotics. Everything I'm going to show you is done in collaboration with the Bongard lab. Doug Blackiston in my group did all the biology, and Sam Kriegman did the computer science aspects.

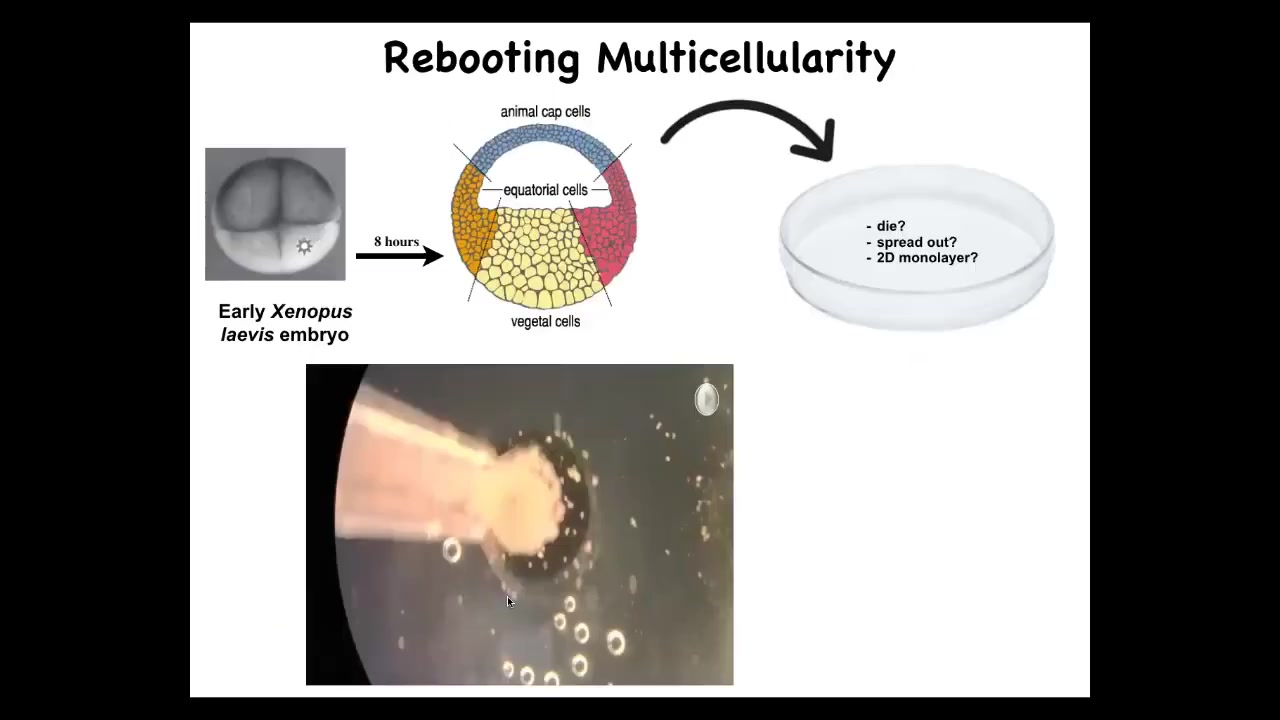

Slide 41/49 · 56m:34s

Doug takes these frog embryos. He takes the skin cells from the top; these are cells fated to be epidermis, so skin, and we dissociate them and then just pipette them down into this little depression. What might they do? They might die, they might spread out, they might form a two-dimensional monolayer.

Slide 42/49 · 57m:01s

What they do instead is that overnight they coalesce together, and they form this little thing we call a Xenobot. Here it is. We call it a Xenobot because Xenopus laevis is the name of the frog, and it's a biorobotics platform, so it's a biobot.

Slide 43/49 · 57m:17s

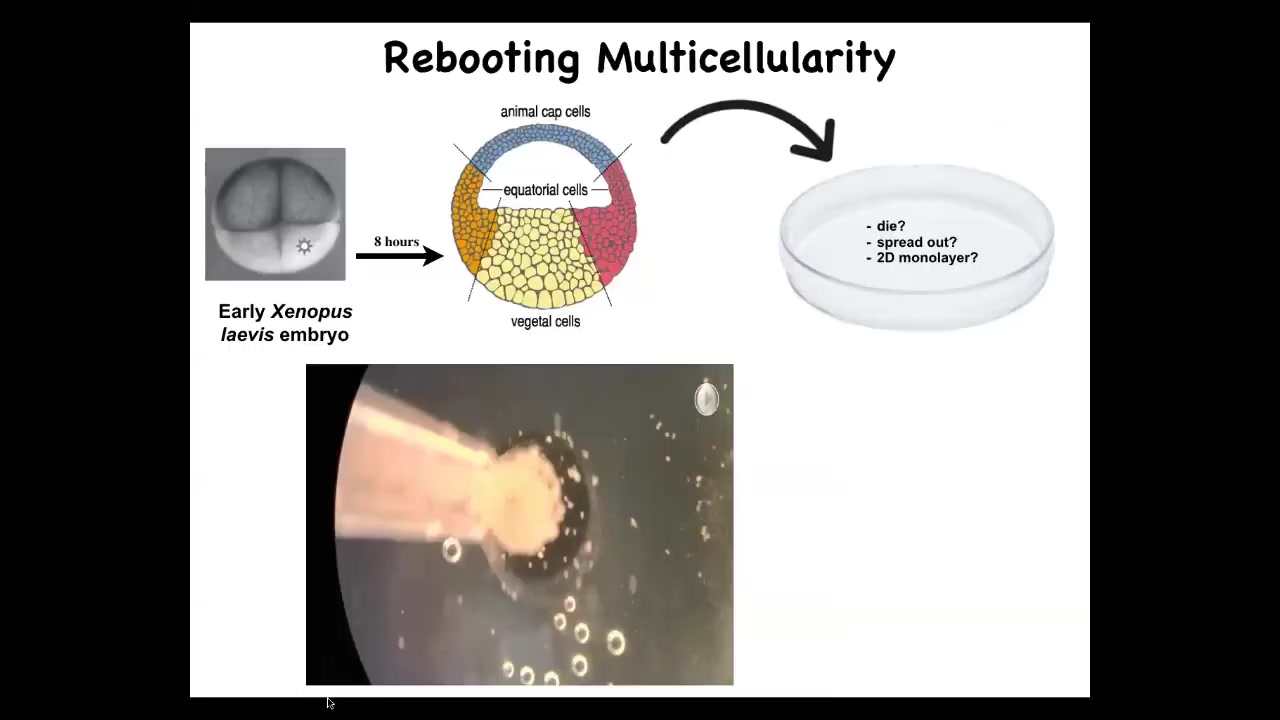

One thing these Xenobots do is they swim. How do they do it? They have little hairs called cilia on the outside of their bodies. Normally, the cilia are used to redistribute mucus down the body of the frog. But here what they do is they row, and the ones on this side row this way, the ones on this side row that way. And so the thing moves on its own. It's completely spontaneous. We don't pace it, we don't activate it.

They have a wide variety of behaviors. They can go in circles, they can patrol back and forth like this. This is skin. There's no neurons here. They have some collective behaviors. So these two can interact with each other. These are resting, doing nothing. This one is going on a long journey.

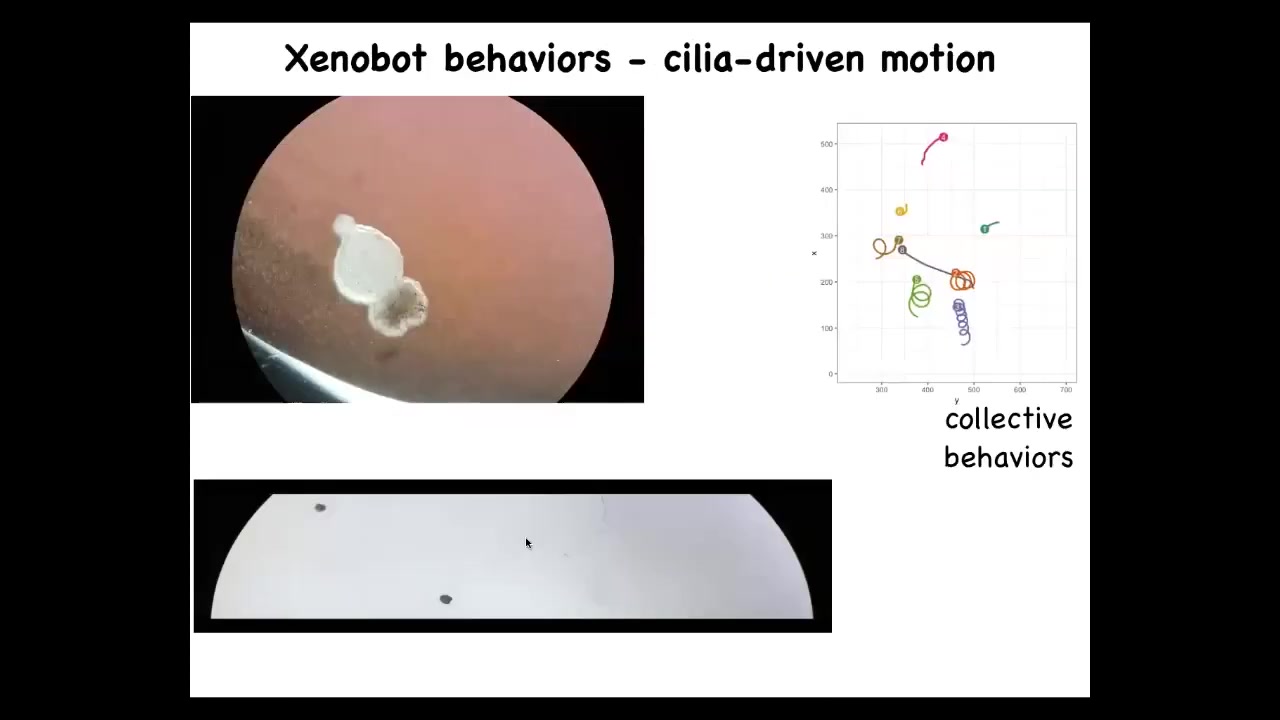

Slide 44/49 · 57m:59s

Here it is navigating a maze. It moves forward. It takes the turn without bumping into anything. It doesn't have to bump into the opposite side. It takes the corner. Then, due to some internal dynamic, it turns around and goes back where it came from. No control by us. This is completely spontaneous behavior of these guys.

Slide 45/49 · 58m:18s

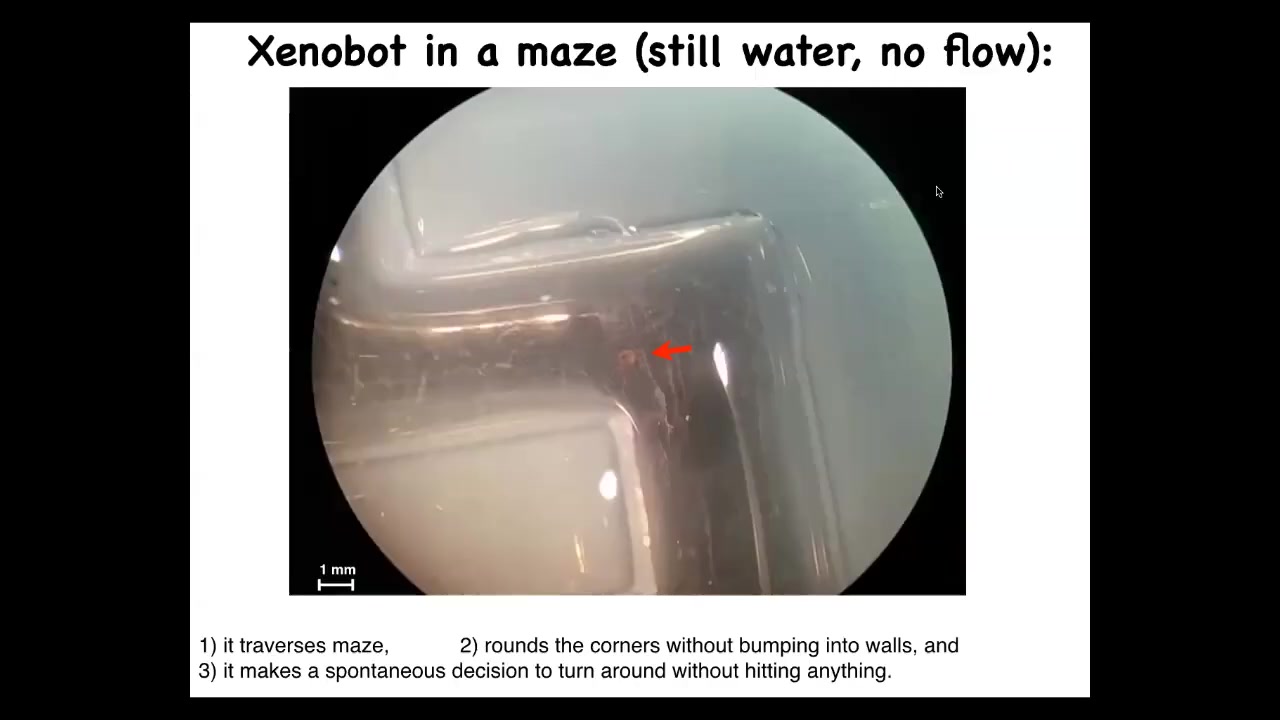

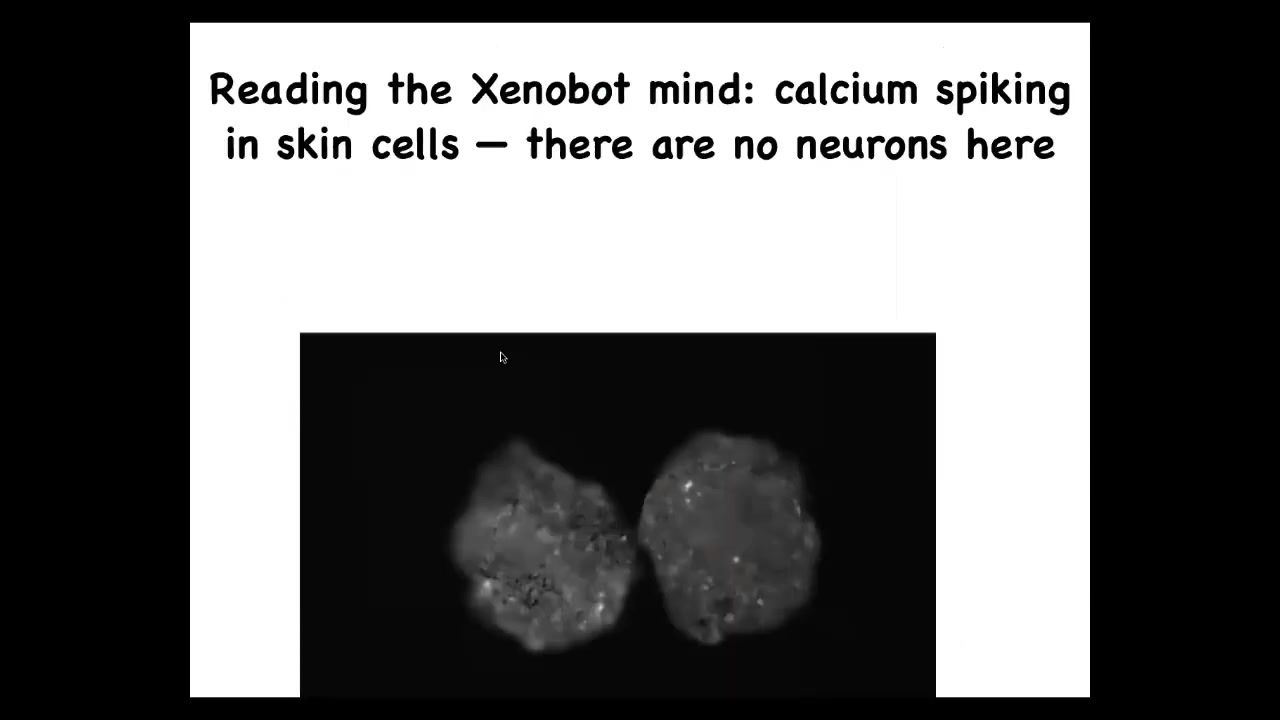

If you image the signaling, this is calcium signaling. This is the kind of thing you would see in imaging brain activity. We are now analyzing, using information theory approaches, what the integrated information is inside or between. Are they communicating? We don't know yet. That remains to be determined.

Slide 46/49 · 58m:40s

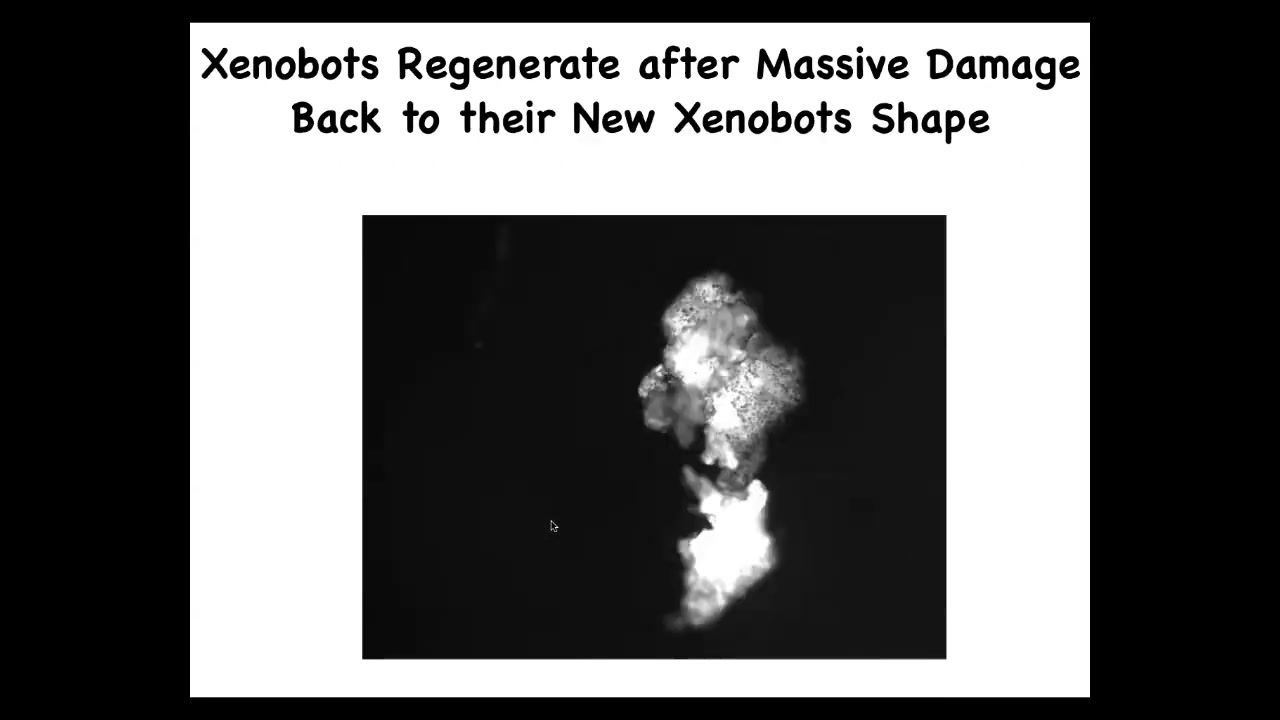

They can regenerate. If you cut them in half here, you can cut them almost in half. Look at the amazing force that it takes to fold this thing up like that.

Slide 47/49 · 58m:54s

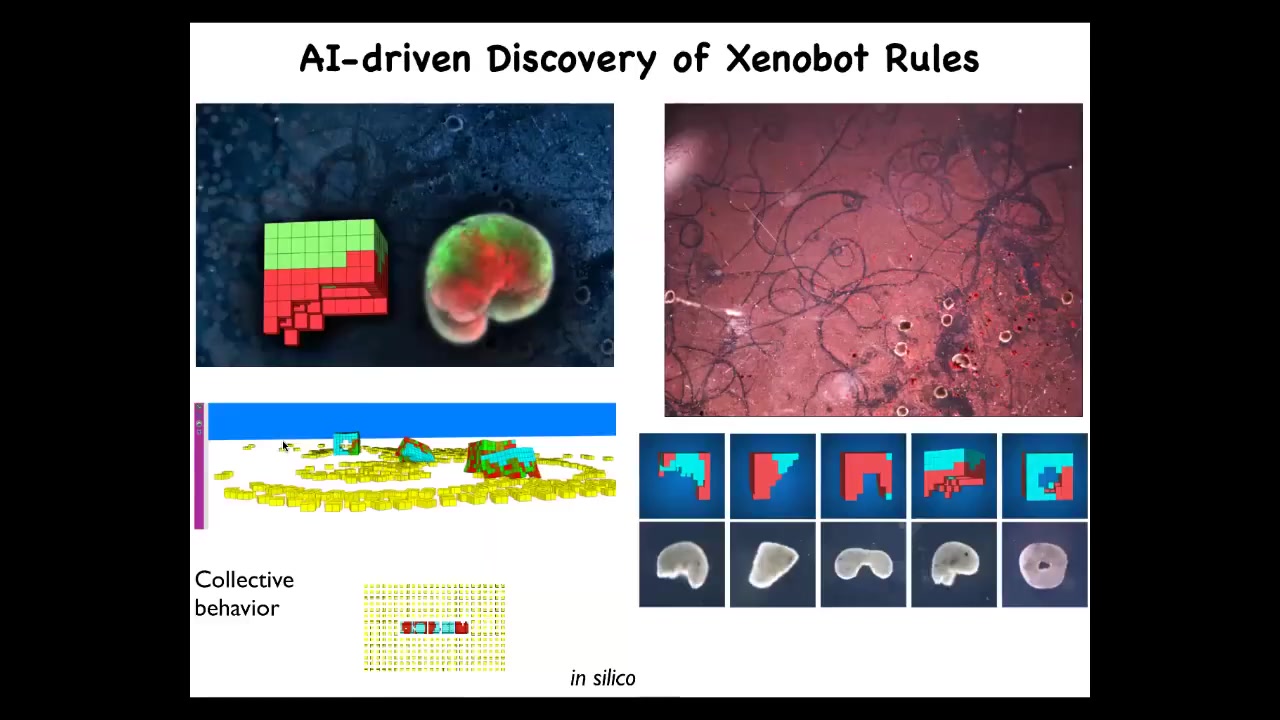

And then here's the most surprising thing of all: by modeling. Sam and Josh computationally modeled this, evolved in an AI environment, and used evolutionary algorithms to evolve different kinds of Zenobot shapes and simulate their activity. One thing we learned is that they like to make piles. They like to find loose material and collect it into piles. We tested whether that would be true of real bots.

Slide 48/49 · 59m:26s

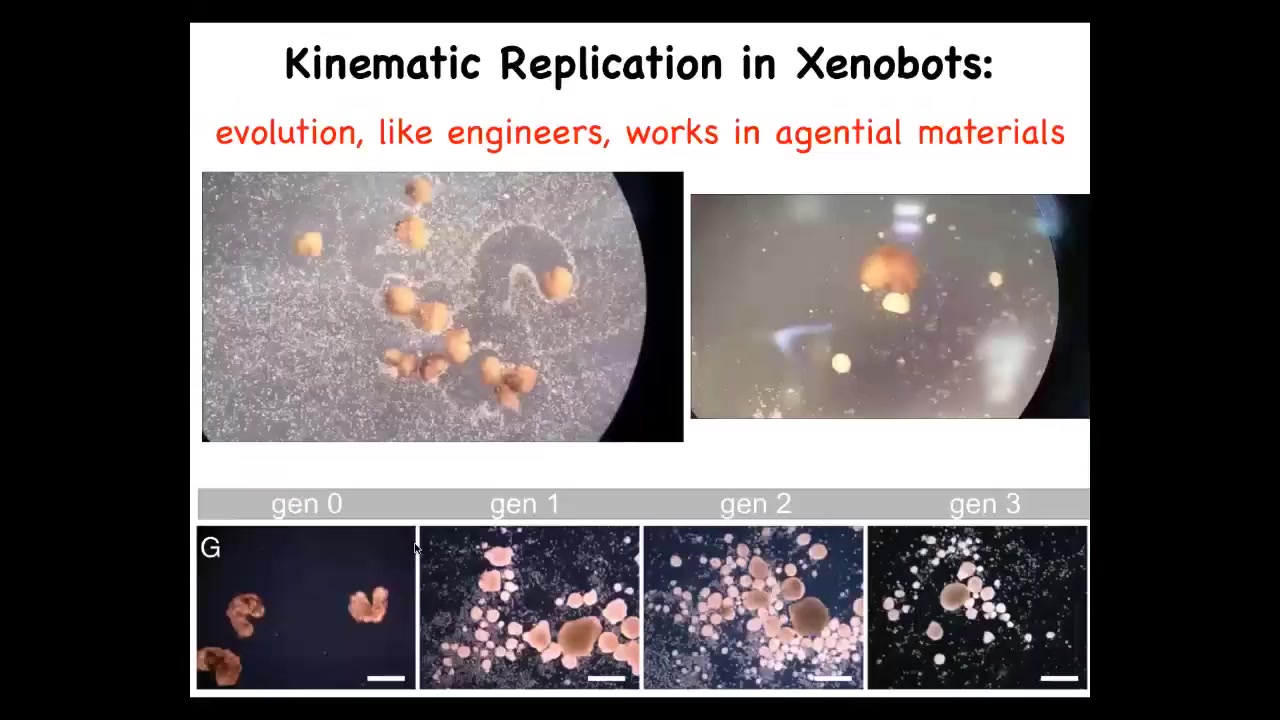

We gave them a bunch of loose materials. These are cells. These white things are just loose skin cells. We found something incredible: in fact, they run around and they collect these cells into piles and they compact; the piles become the next generation of Xenobots, which then mature and go on to do exactly the same thing. They just continue to make, to reproduce copies of themselves.

Now, a couple of interesting things. First, the only reason this works is because the Xenobots, like us and like evolution, they're working with an agential material. They're not working with passive particles. They're working with an agential material that also knows how to cooperate with each other to become something interesting, meaning another Xenobot. This is taking advantage of that agential capacity of the bots. The second thing is that this is von Neumann's dream, a robot that's able to go out and make copies of itself by finding objects in its environment. This is a very early form of that. There's no strong heredity here. All the bots look the same, but they do replicate. We call this kinematic self-replication. We've made it impossible for these guys to replicate in the normal ****** fashion, but within 48 hours, they are able to do this.

Slide 49/49 · 1h:00m:46s

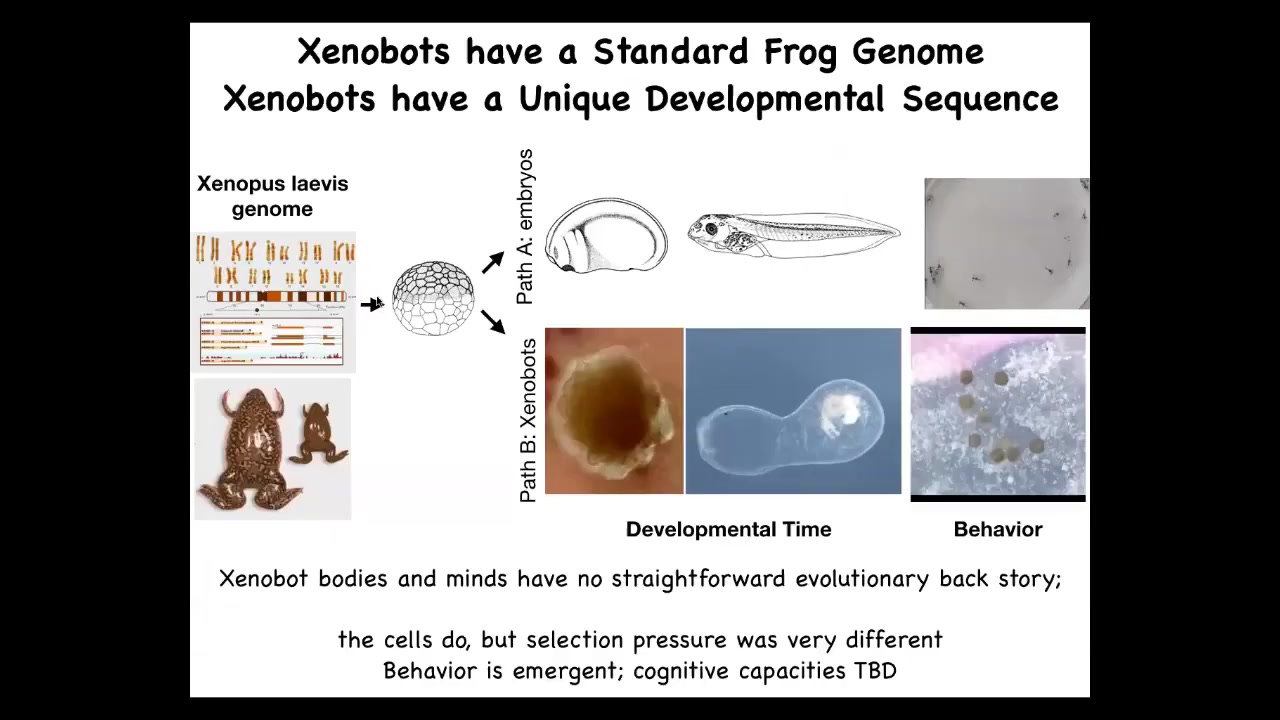

And so the last thing I want to discuss is the kind of evolutionary implications of this.

This is a normal frog with a normal frog genome. When you ask what does this genome encode, it's common to think it encodes a frog. But actually what it encodes is a little machine that can, under normal circumstances, it has default frog developmental stages and normal tadpole behaviors. But under other circumstances, it can be a Xenobot. It can form the Xenobot. It has its own developmental stages. Who knows what this is: a completely novel thing. And then they have their own different Xenobot behaviors.

Now, we didn't add anything to go from here to here. We didn't add any new genes. We didn't add synthetic circuits or weird nanomaterials. All we did was engineer by subtraction, meaning that we removed some other cells and we asked, what is the native behavior of these cells? Because if you look at a typical embryo skin, you would say, what does it know how to do? It knows how to be a boring two-dimensional layer on the outside of the embryo. But that's because the other cells are basically bullying these cells, behavior-shaping these cells into doing that. On their own, left to their own devices, this is what they actually do. This is the default behavior.

So you can imagine evolution as searching this space of behavior-shaping signals that cells will send each other to get them to do something adaptive. This is the default behavior of those cells.

And the final thing is this. When we think about why a certain organism has certain shapes, behaviors, properties, the answer is usually evolution, because eons of selection have given it these particular goal states in anatomical space and behavioral space and morphological space and so on. But actually, there's never been any Xenobots, and there's never been any selection to be a good Xenobot. So there's no straightforward selection story that explains these behaviors. So we have to start thinking differently about where goals in these spaces come from. I think that's very interesting. And we don't know what the cognitive capacities of these guys are yet. We're working to understand what can they sense, what are their preferences, what can they learn, and so on.

So I'll stop here by saying that all of this conceptual stuff is discussed in these papers, which I'm happy to send to anybody.

I want to thank the postdocs and the students.