Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is about a ~45 minute talk by me, focusing specifically on parallels between morphogenesis and cognitive/behavioral science (given to a neuroscience audience).

CHAPTERS:

(00:01) Talk overview and goals

(03:21) Cognitive spectrum and scaling

(09:45) Intelligence in other spaces

(15:20) Defining and testing intelligence

(23:25) Facial morphogenesis and setpoints

(27:20) Bioelectric patterns and eyes

(32:28) Regeneration and pattern memory

(40:30) Cancer as cognitive breakdown

(44:14) Anthrobots and future medicine

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/45 · 00m:00s

Lots more details, data, software, all the primary papers are here because I'm only going to have a chance to give a broad overview today.

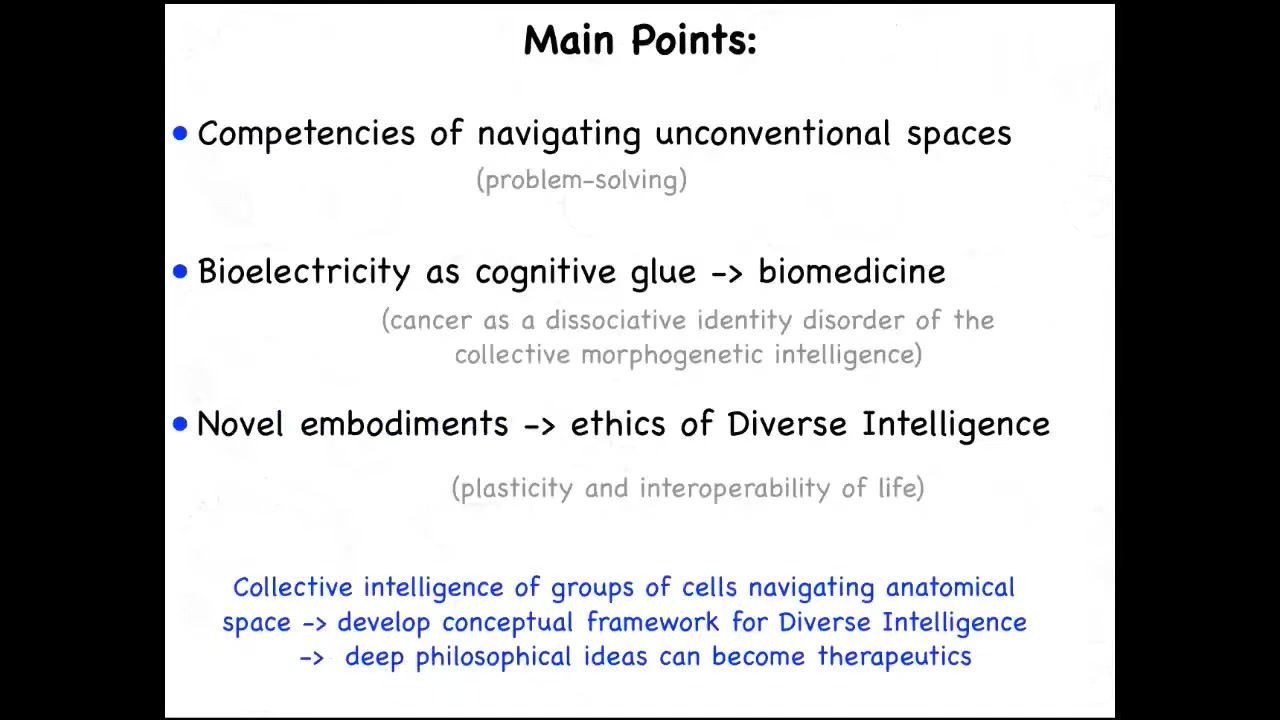

What I'd like to talk about are three main points. I'm going to focus on the competencies of navigating unconventional spaces. This goes beyond the three-dimensional problem-solving that conventional brainy systems do.

I will talk about a particular example of this unconventional intelligence, which is the idea of non-neural cells using familiar electrical communication pathways as a cognitive glue to give them the ability to solve problems in anatomical space. I will talk about specific applications of this idea to show that this is not just a philosophy or wordplay, but it leads to some interesting biomedical approaches. I'll talk briefly about cancer as literally a dissociative identity disorder of this somatic intelligence.

At the end, I'm going to talk about some novel embodiments and mention the ethics of diverse intelligence.

Our approach is to study experimentally the collective intelligence of groups of cells that navigate anatomical space. This allows us to think broadly about the field of diverse intelligence and what minds in unfamiliar embodiments look like, and to try to fill the gamut from fundamental philosophical ideas that have been kicked around for a long time to how some of these things can become actionable therapeutics.

Slide 2/45 · 01m:38s

One place that we might start is with this kind of old image. This is Adam naming the animals in the Garden of Eden. There are two things here that are important. One is that there are a set of discrete natural kinds that are meant to be individual, specific kinds of agents. And then here's Adam, and he's different from the others. One of his roles is to name the other animals. This, as you'll see at the end of the talk, is very profound because naming something is to discover its true nature, and it's going to be on us to discover the true nature of some very unconventional beings that have never been here before in the tree of life.

Slide 3/45 · 02m:20s

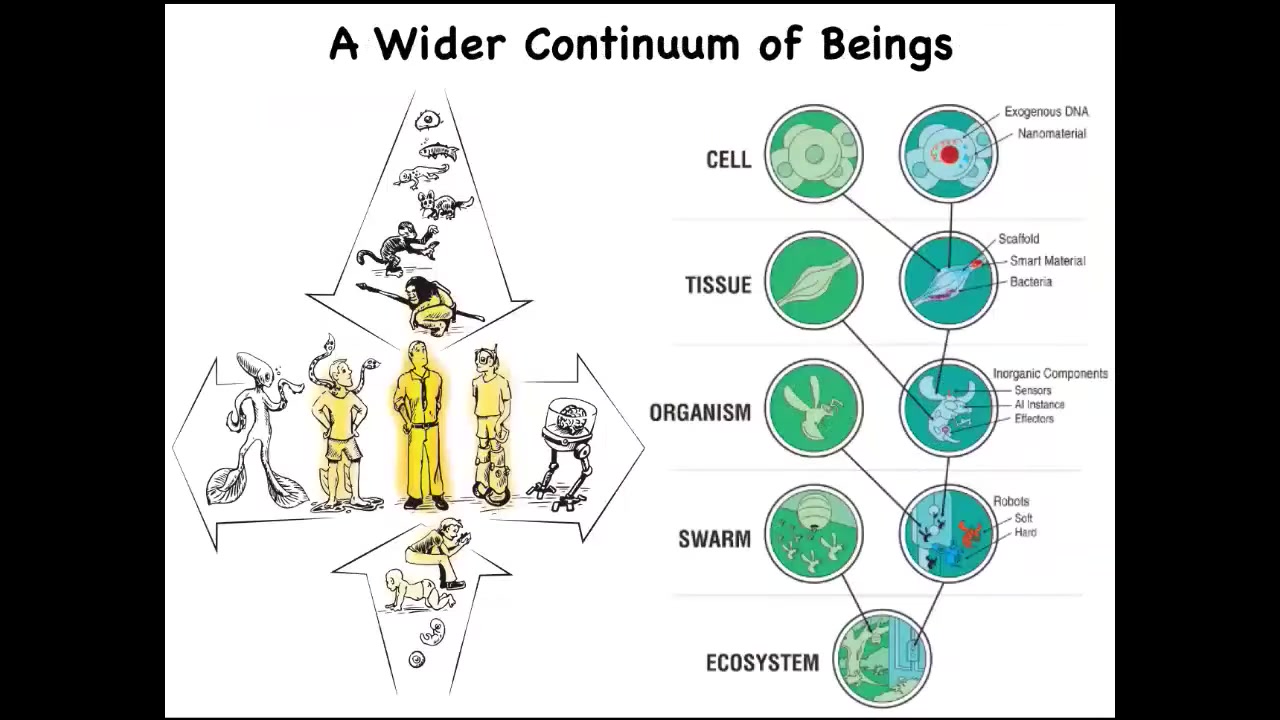

And that is because this human with their agential glow that a lot of people focus on as a special thing. We are at the center of a continuum, not only on the evolutionary time scale, but also the developmental time scale.

And so when we talk about humans doing this or that, we have to ask which kind of human and where does that happen?

And now with synthetic biology and bioengineering, we know that there's another continuum here, which is that through both engineering and engineered components and biological modifications, we can make some very unusual hybrids that ask us to develop tools to understand what is the cognitive world of beings that are really quite different from what we're used to. And that's because life is very interoperable and at every level of the hierarchy, we can introduce engineered components and make something that has never existed before.

Slide 4/45 · 03m:21s

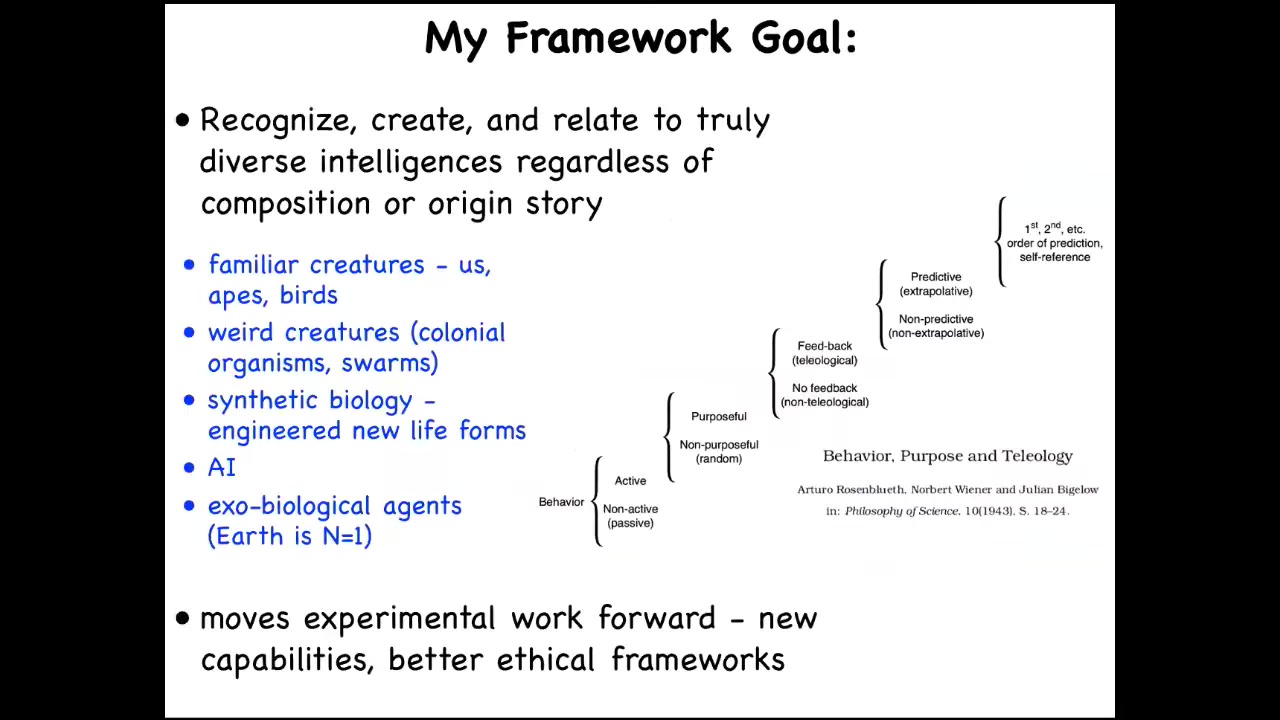

What I'm very interested in, and this is that paper that Lars was mentioning, was the first explication of what I'm trying to do, which is to develop a framework where we can think about all sorts of agents.

This includes the familiar kinds of things: apes and birds and maybe a whale and an octopus and insects, and then colonial organisms and swarms and engineered new life forms and AIs, whether purely software or embodied robotics, potentially exobiological agents at some point, some kind of alien life. How do we think about all these things? What do they all have in common? I'm not the first person to think about this.

Here's Rosenblueth, Wiener, and Bigelow's scale from the 1940s. This is a cybernetic view, which goes from passive matter all the way up through various categories or phase transitions that allow novel kinds of functionality and behavior to arise, recognizing that this is a continuum, that these are not categorically different things, and you have to ask where things land on this continuum.

Slide 5/45 · 04m:34s

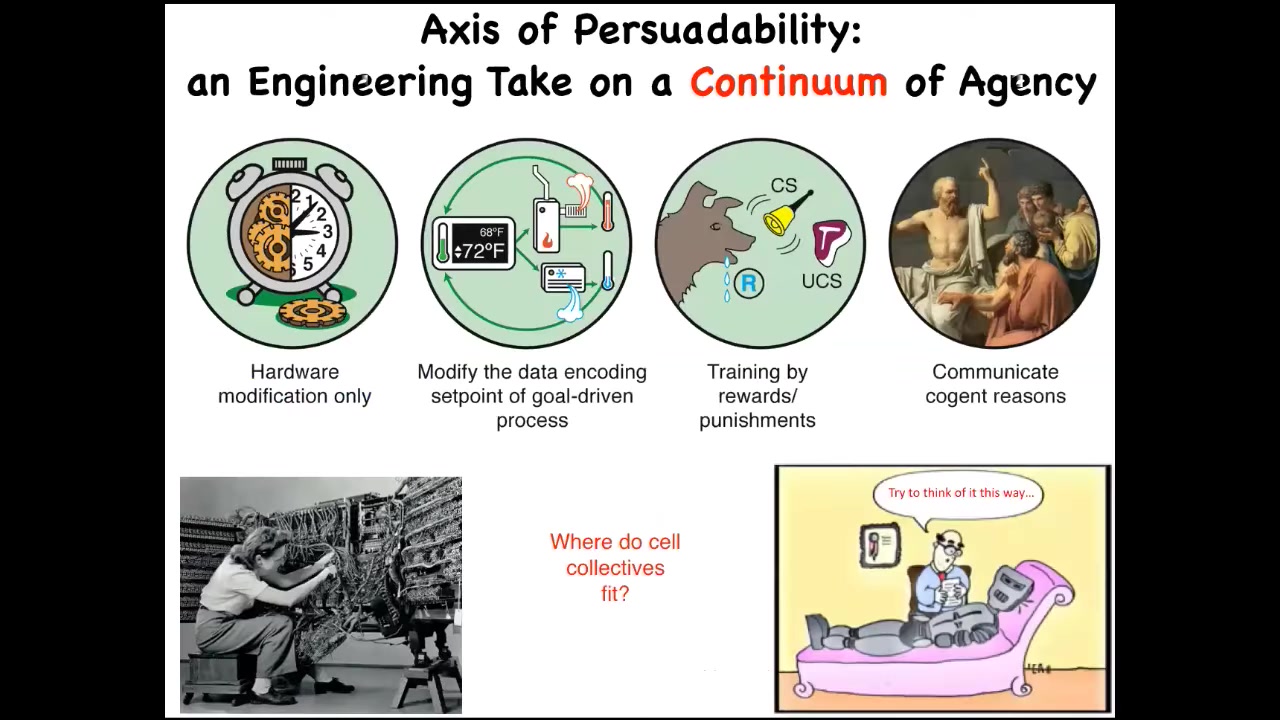

For me, to make this very practical, I like an engineering approach, which is to say that cognitive claims about anything, whether an animal or anything else, any kind of cognitive claim is really an engineering protocol claim.

What you're really saying, I think, when you say that this is a system that is cognitive at a particular level, is what kind of tools can we deploy to interact with it in an optimal way?

Here are just four very basic examples. Systems like this or simple machines—your only tool in your toolkit is hardware modification. You're not going to convince it of anything. You're not going to train it. All you can do is modify the hardware. Then we progressively move up to various kinds of cybernetic circuits where you can do more interesting things like reset their set point and let them do what they do best, which is try to maintain it. You have other kinds of systems: rewards and punishments and training, and then human-level metacognition and whatever is beyond that.

One of the critical things, I think, in this field is that we can't just have philosophical feelings about where things land on the spectrum. We have to do experiments. When we ask where cellular collectives fit on this kind of spectrum, I call it an axis of persuadability, specifically because from the perspective of an engineer the question is, how do we get the system to do something that it wasn't doing before? That is how we make these ideas very practical.

This question of where cellular collectives fit—most people in our field will say that they're down here. People say, "Well, it's a chemical machine. It doesn't have a brain and it can't do this or that." We have to do experiments. We can't just assume.

Slide 6/45 · 06m:25s

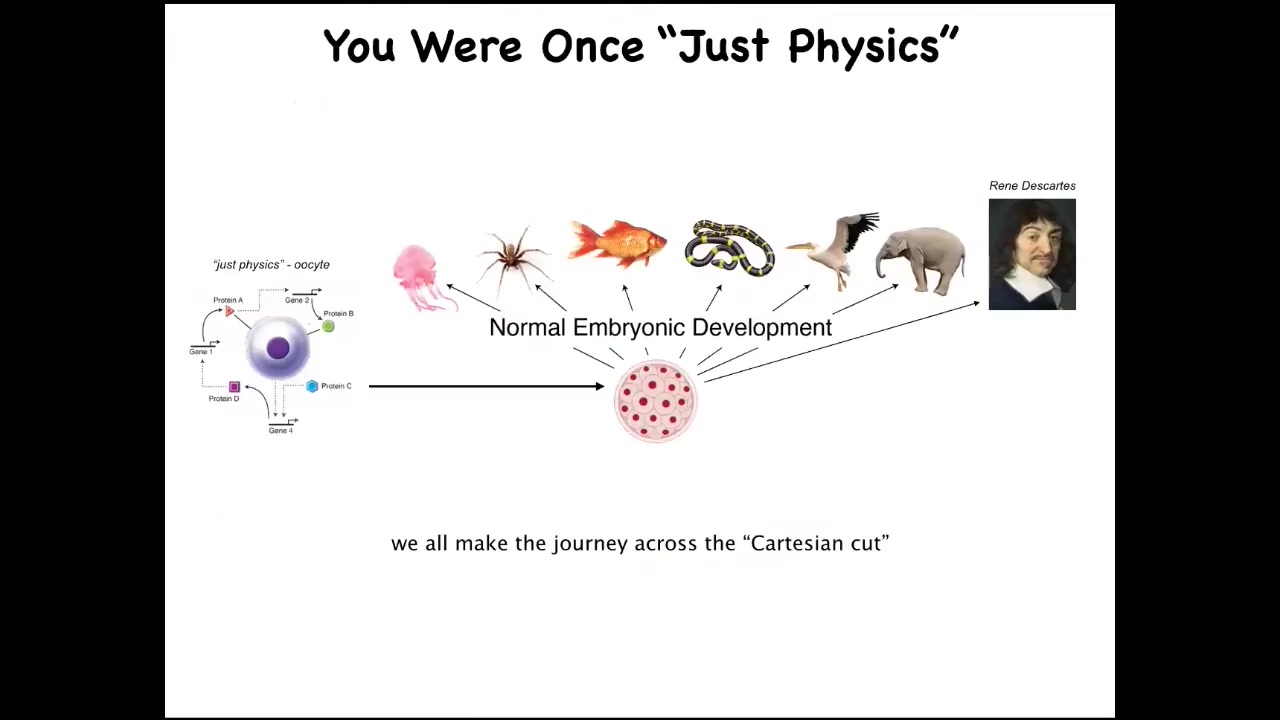

And part of it is that we all started life as a single cell. It's a little BLOB of chemistry and physics that becomes one of these things, or even perhaps something like this. And the one thing we learned for sure from developmental biology is that there is no sharp dividing line that turns physics and chemistry into mind. You're not going to find any specific stage at which suddenly things take over. So we know that what we're really looking for in the science is some kind of principled set of models about the scaling of whatever competencies these things can do up to what happens here. How do they arise both evolutionarily and developmentally? People often see this and say we somehow develop from a single cell, but at least we're a unified mind.

Slide 7/45 · 07m:14s

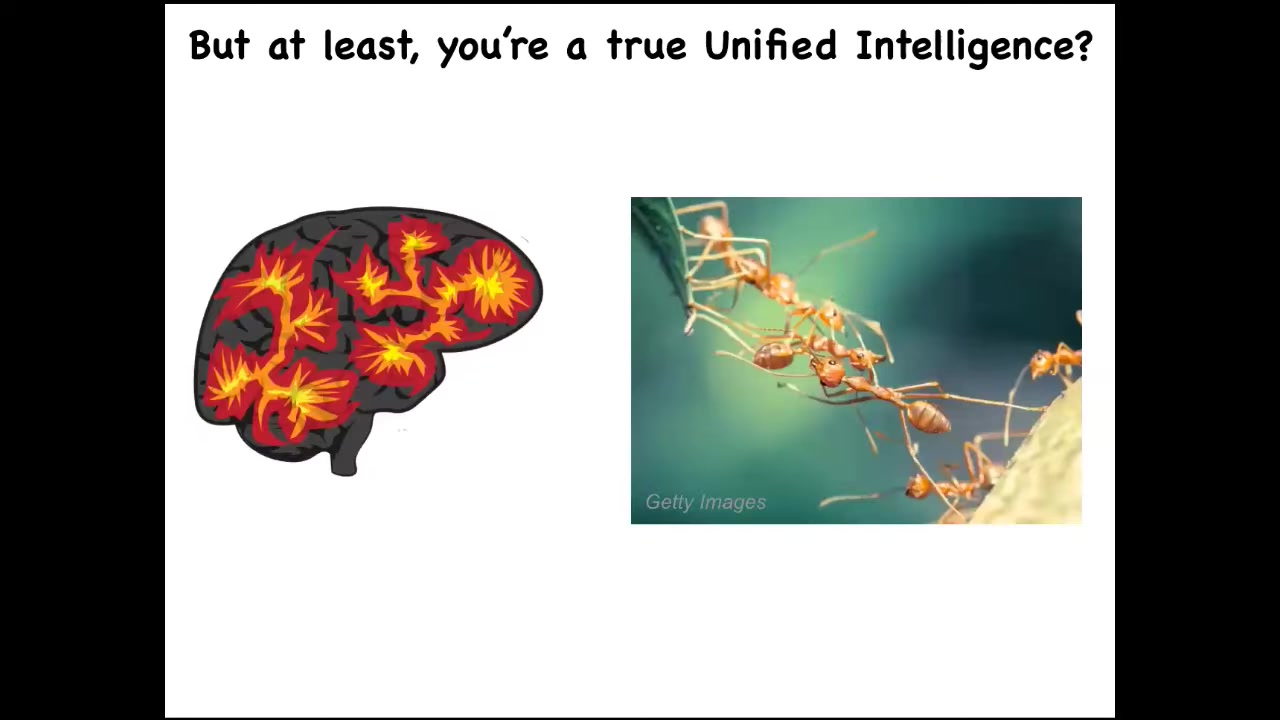

We're a unified intelligence. We're not like a collection of ants or termites where people say that these are collective intelligence, but it's not the same. We are a unified mind.

Slide 8/45 · 07m:30s

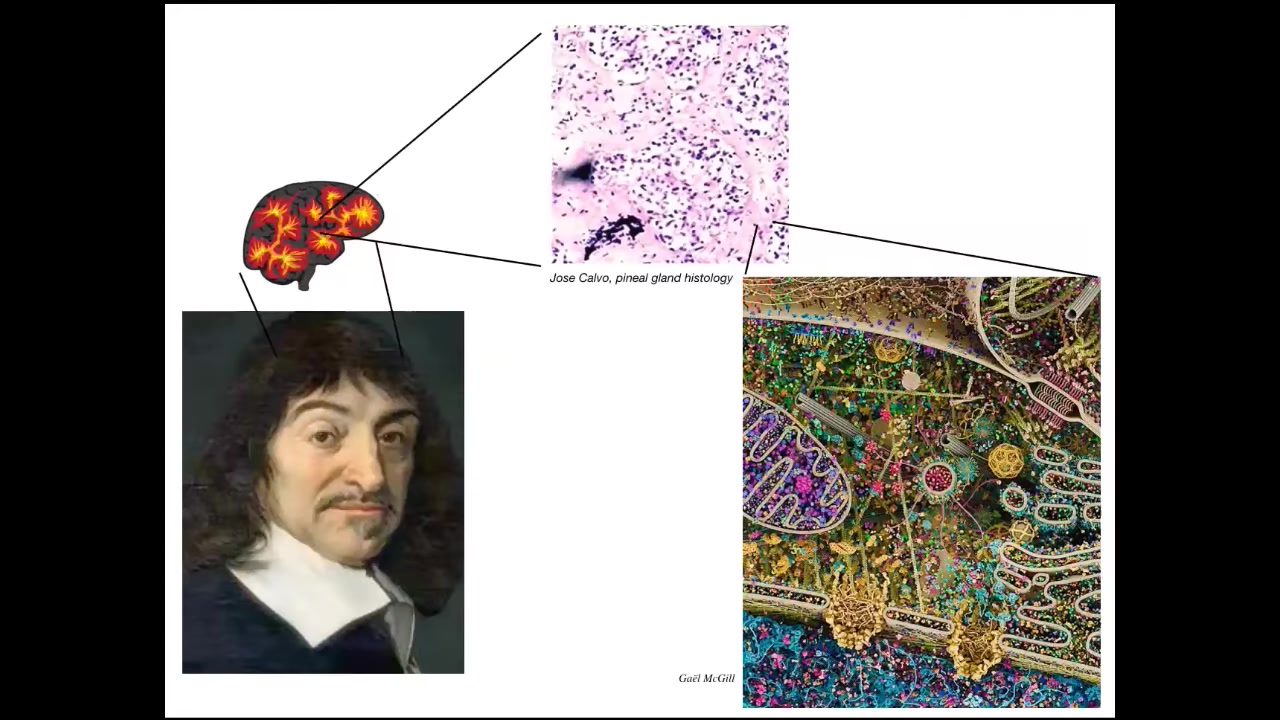

The thing to keep in mind is that even something like the pineal gland, which Descartes thought was really fitting for humans who have this supposedly unified perspective, if he had good microscopy, he would have known that inside that pineal gland there are huge numbers of individual cells.

Inside each of those cells is all of this stuff. This is the molecular machinery in there. In an important sense, we are all collective intelligences.

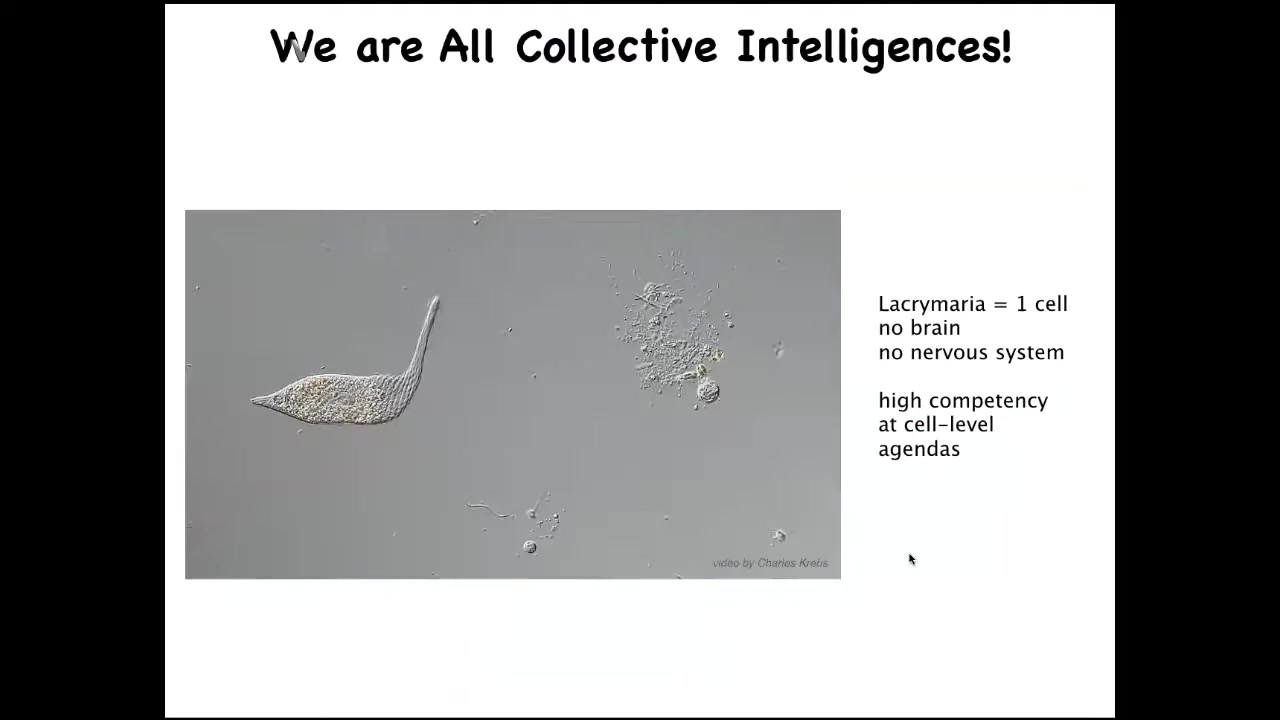

Slide 9/45 · 07m:56s

We are all made of parts. Our parts look like this. This is a free-living organism, which you can see what's going on here at the level of a single cell. This little creature is incredibly competent with its physiological needs, its metabolism and so on. All of that is handled, no brain, no nervous system. This is what it can do about the goals of its tiny little world.

I'm interested in the scaling. This, of course, is a chemical system. These guys can learn. If we don't think that you can reward or punish a chemical network, that's pretty much what you have here: a set of physical and chemical processes.

Slide 10/45 · 08m:40s

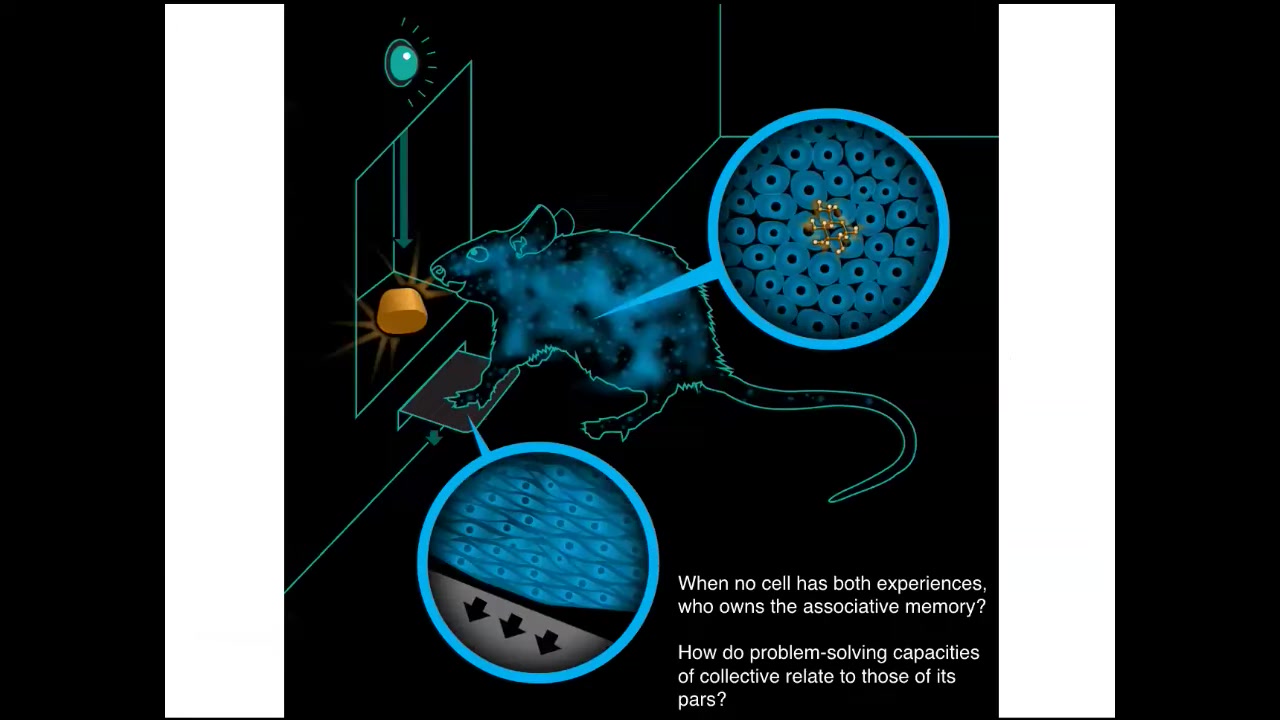

I'm also interested in this notion of a cognitive glue.

If you have this rat that learns to press a lever and get a reward, the cells at the bottom of the foot are the ones that experience the lever; the cells in the gut experience the sugar. Who is it that owns the associative memory that these things are connected? No individual cell had both experiences. There has to be a rat that is in some way the owner of information that none of its parts have. We're interested in how the problem-solving capacities of these collectives relate to those of their parts.

Slide 11/45 · 09m:12s

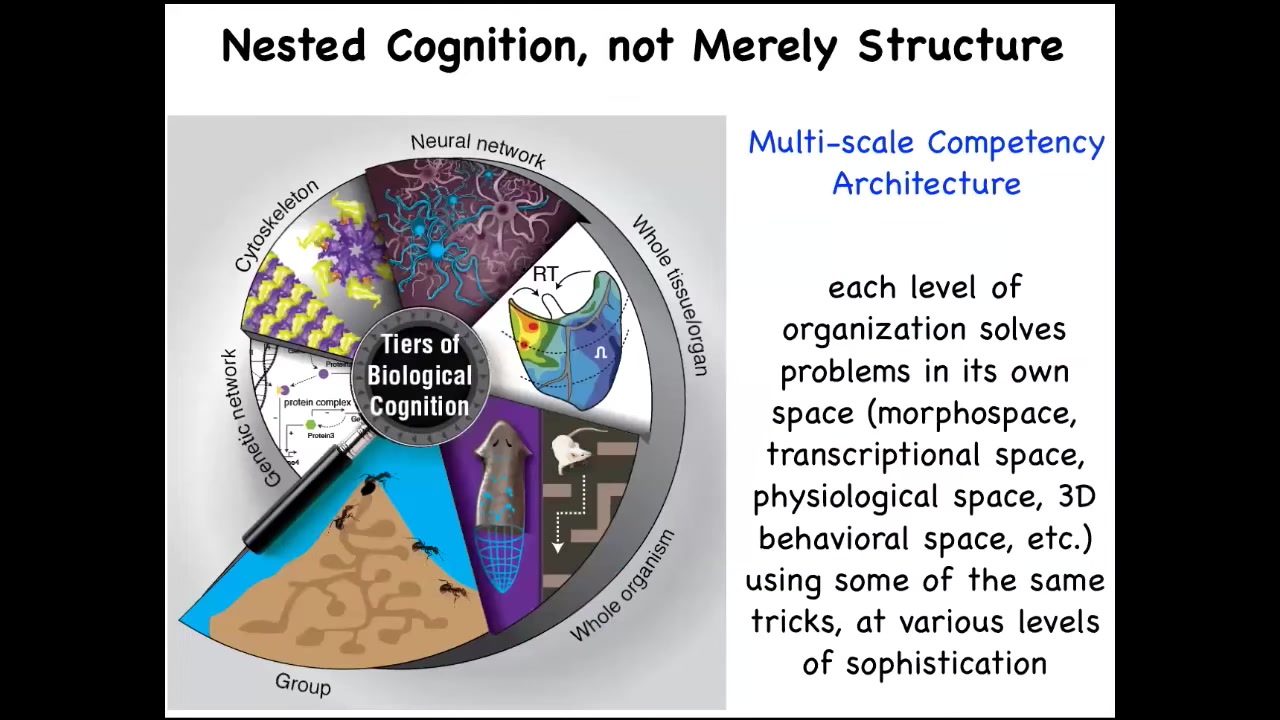

We also notice that the architecture of life is very multi-scale, not just structurally, but each level here of this hierarchy is itself competent in various problem spaces. They solve all kinds of issues in physiological, anatomical, and other kinds of spaces. These are the kinds of models we make of multi-scale agents that cooperate and compete for various things.

Slide 12/45 · 09m:46s

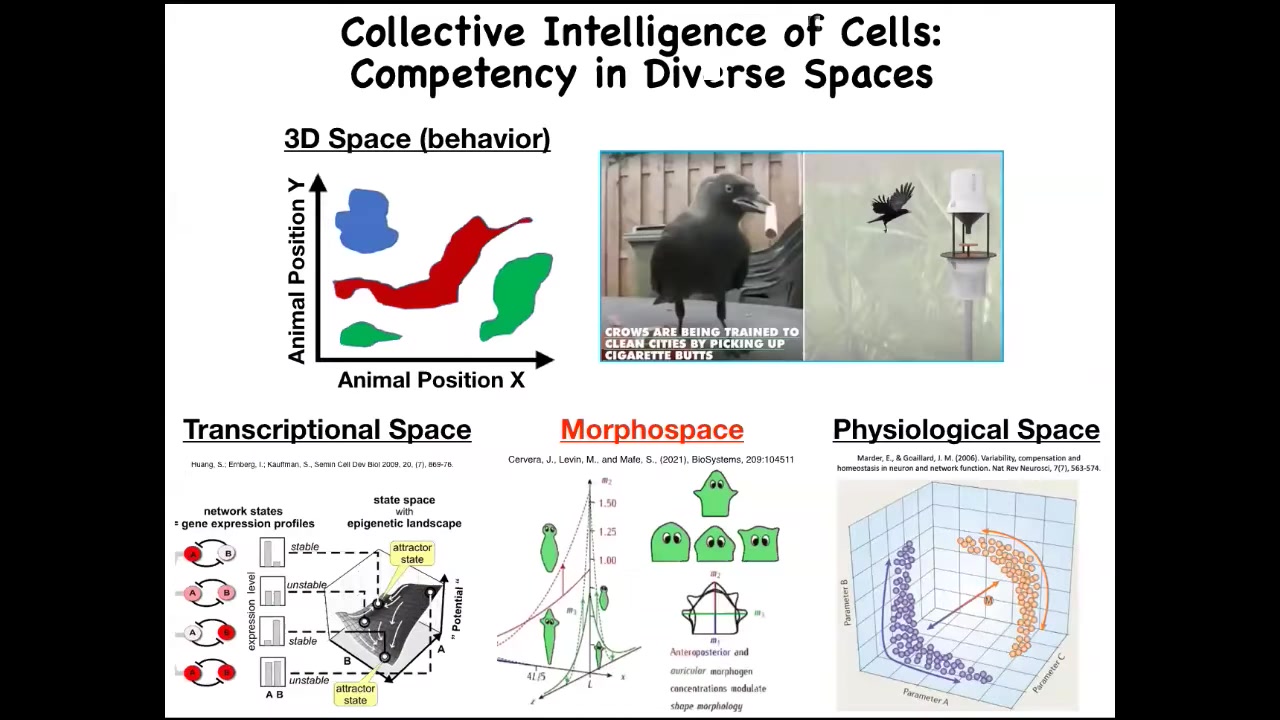

Now, we are reasonably good at noticing intelligence of medium-sized objects moving at medium speeds through three-dimensional space. We're used to this, and it's really hard for people to buy the concept of intelligence in unfamiliar kinds of animals, but navigating three-dimensional space is what people are used to.

I think it's important to understand that while we, because of our sensory apparatus and our lifestyle, are very preoccupied with specific scales of space and time, and also with three-dimensional space, there are other spaces in which other types of agents live. They operate in those spaces, they solve problems, they perform a perception-action loop. They have goals that they meet with some level of competency, and these include spaces of gene expression, spaces of physiological state, and anatomical morphospace. I could tell you some amazing stories about cells navigating and solving problems in these spaces, but I won't have time to do that today. So I'm going to focus on anatomical morphospace.

Slide 13/45 · 10m:57s

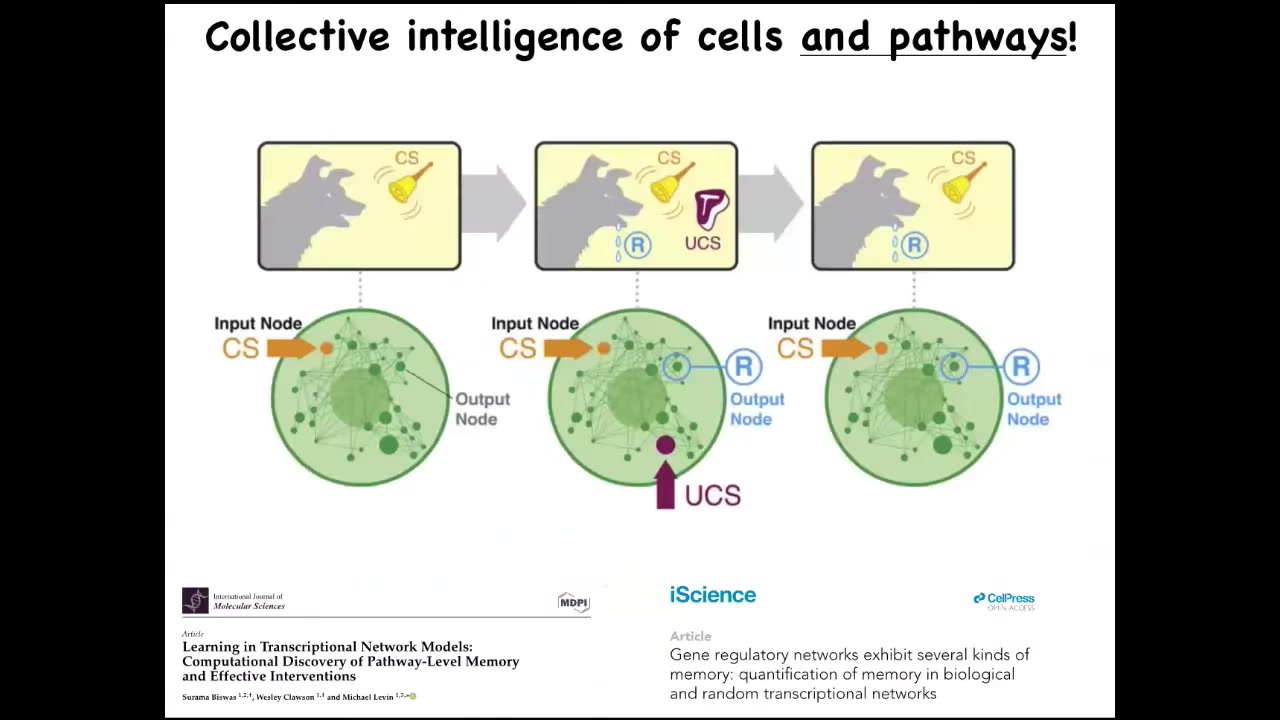

I will mention one quick thing: even small pathways, groups of 10 or so genes that can turn each other on and off, already demonstrate the dynamics of six different kinds of memory, including Pavlovian conditioning. You do not need the rest of the cell. You certainly don't need neurons to do some things that are well described by paradigms in behavior science. You can see those here. This is a biomedical research program that we have, taking advantage of the learning capacities of the pathways of your body to use drugs in a very different way than is used now.

Slide 14/45 · 11m:35s

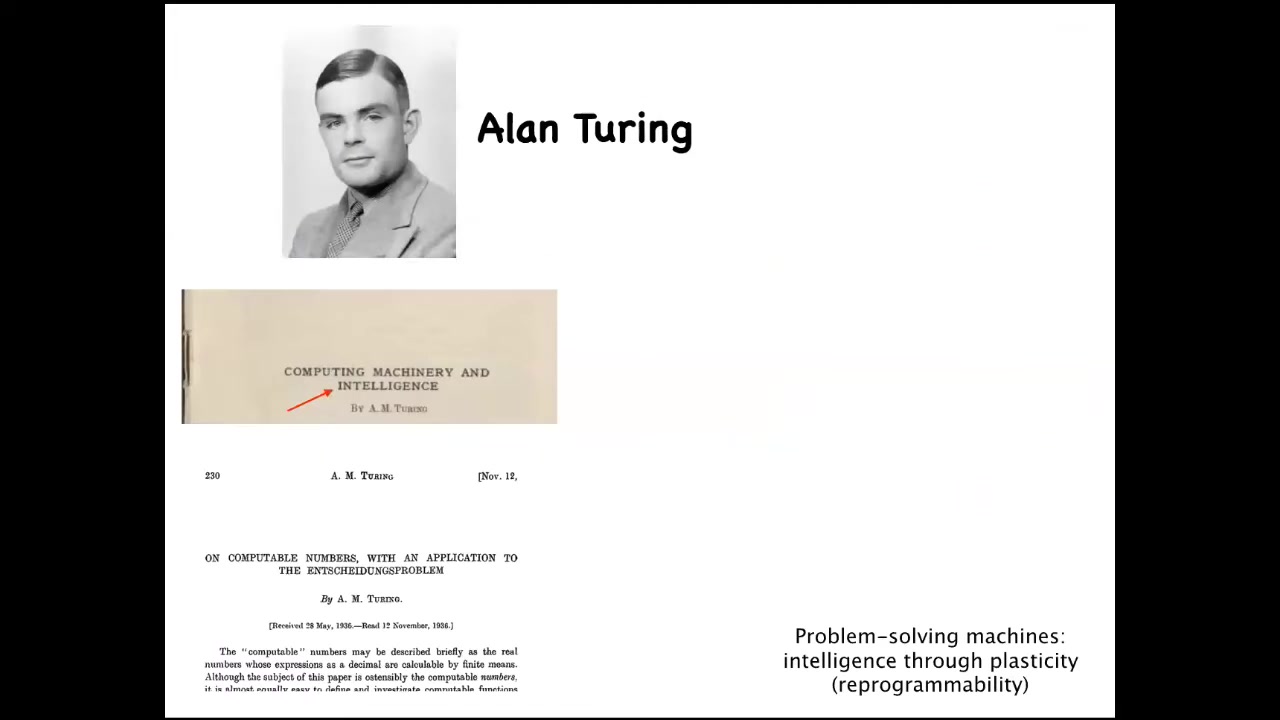

But let's talk about the anatomical morphospace. I find it really interesting that Alan Turing, who was the forefather of a lot of ideas in artificial intelligence, thought about computation, minds embodied in different types of media, and specifically reprogrammability, the issue of problem-solving machines and intelligence through plasticity. What does it mean to program or reprogram a machine?

But he also published a paper called "The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis." This was an extremely early attempt to understand how embryos self-organize and why order arises in embryogenesis.

You might ask, why would somebody who's interested in cognition and computation suddenly be writing papers about the biochemistry of early development? Even though as far as I know he didn't write anything about this, I think he saw a very profound symmetry, a very profound commonality between the problem of the origin of the mind and the origin of the body. He was right on. There are some very deep analogies here that we'll explore a bit today.

Slide 15/45 · 12m:50s

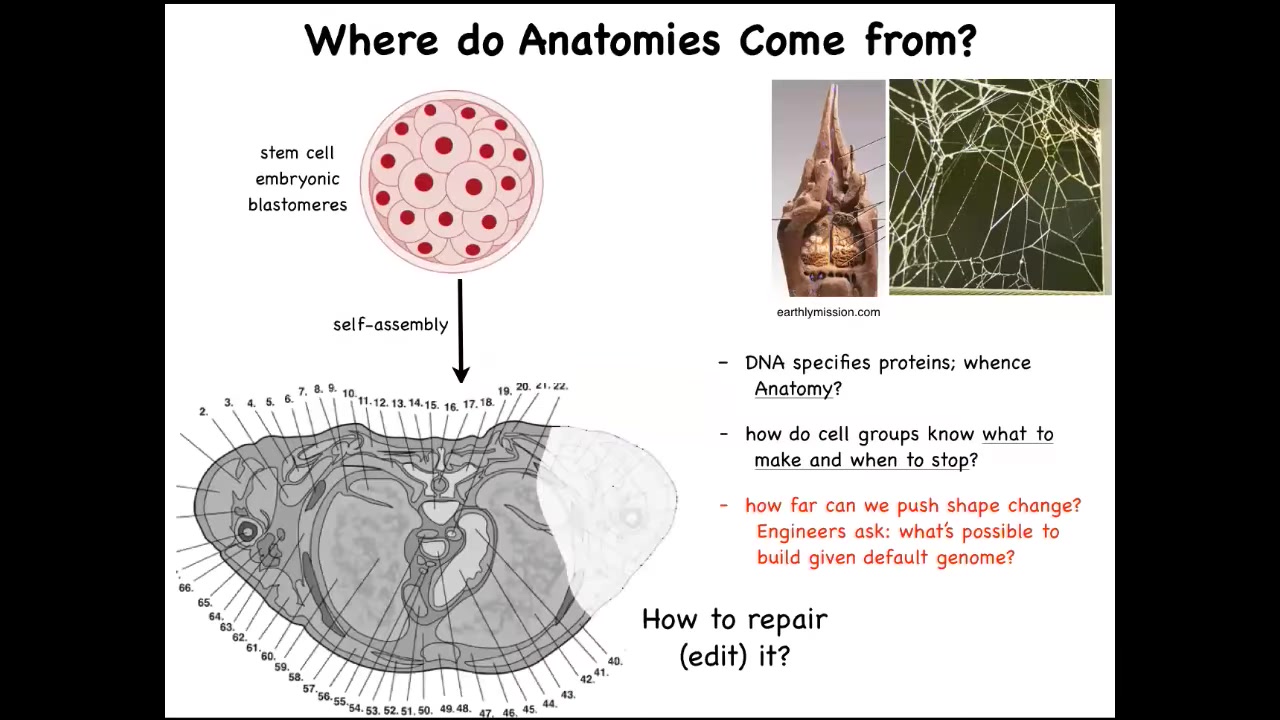

So where do anatomies come from? We all start life like this, as a set of embryonic blastomeres. Eventually, this is a cross-section through the human torso. Look at the incredible order here. All of these complex parts, everything is in the right place, in the right orientation relative to the right neighbor. Where does this pattern actually come from? You might be tempted to say DNA. Most people at this point say genome; it's in the DNA. But of course, we can read genomes now, and we know that the spatial structure is not explicitly in the genome at all any more than the shape of a termite mound or the shape of a spider web is in the genome of these creatures. It's an emergent feature of the physiology and the behavior of these cells. So we need to understand how the cells, with the hardware that the genome does encode — and the genome obviously encodes the tiny protein hardware that every cell gets to have — and the functional software that then describes the behavior of these cells: how do they know what to build? How do they know when to stop? As engineers, we might also ask, how far can we push this process? My lab actually does a lot of work on synthetic morphology. I'll show you a tiny bit at the end, but it's quite remarkable what cells with a perfectly normal genome can be convinced to build. And as workers in regenerative medicine, we'd like to know how we repair. If something is missing or damaged, how do we convince the cells to build something else?

Slide 16/45 · 14m:19s

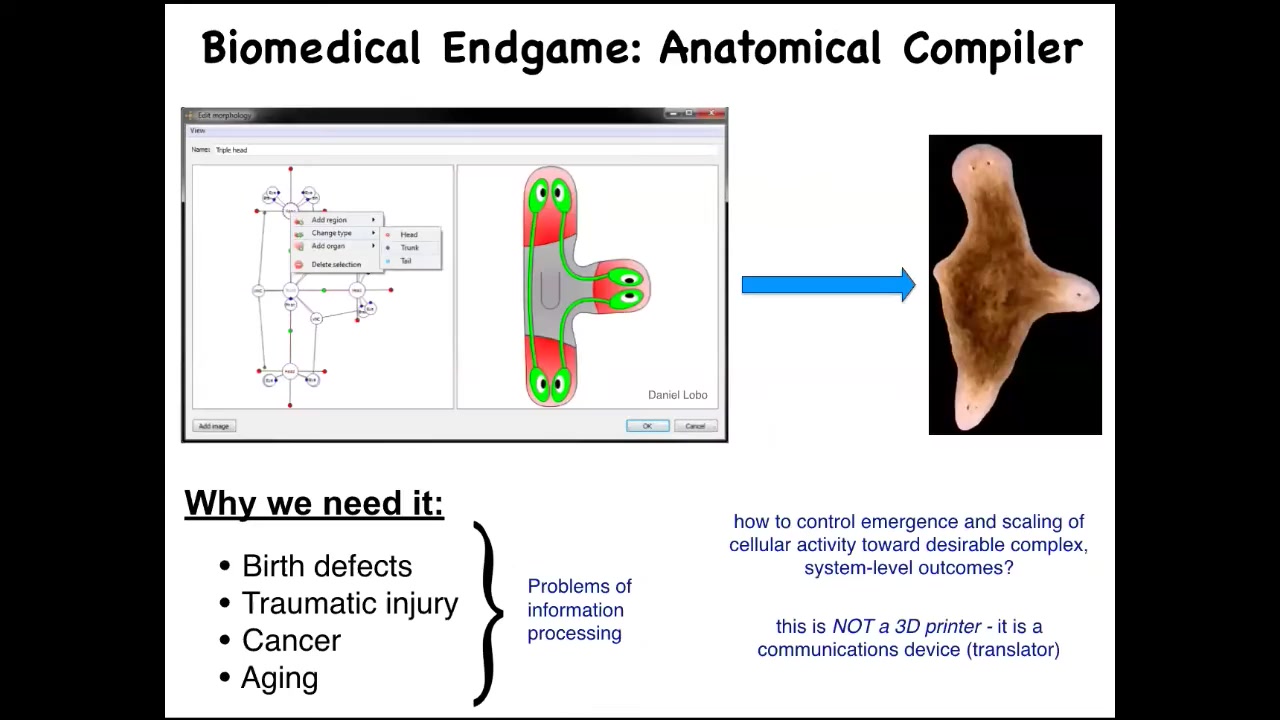

If we think about what the end game of that field is, I think it is the anatomical compiler. So someday, we'll be able to sit down in front of a computer, draw the plant, animal, organ, or biobot that you want. What the computer will do is compile this description down into a set of stimuli that would have to be given to these cells to have them build exactly what you just drew.

Complete control over growth and form. This is a very practical concern because all of these things—birth defects, failure to regenerate after injury, cancer, aging—would go away if we knew how to convince a group of cells to build something very specific, whatever it is that we wanted. Keep in mind, this is not meant to be a 3D printer. This is not about micromanaging the cells. This is about translating. It's basically a communication device to translate our anatomical goals into those of the cellular collective.

Slide 17/45 · 15m:17s

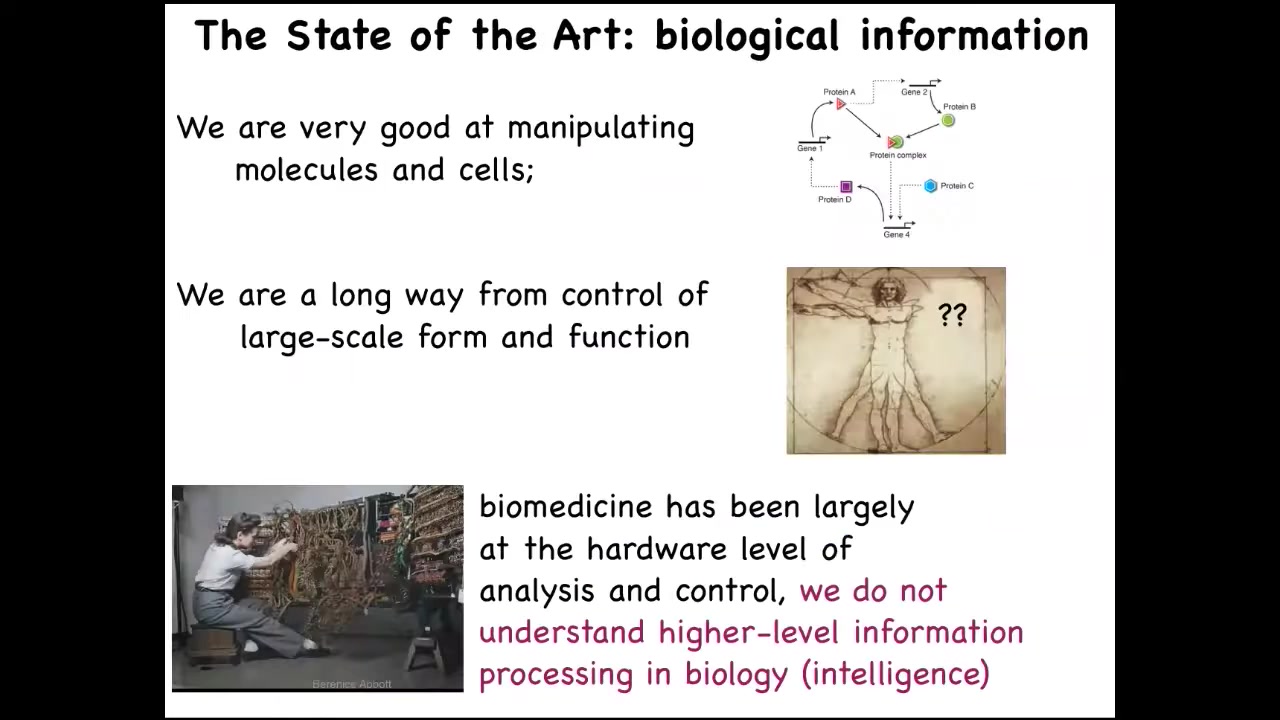

Now, despite the importance of this thing, we don't have anything like this yet. And why not? Molecular biology and genetics and biochemistry have been going gangbusters for decades.

Slide 18/45 · 15m:24s

Why don't we have this? I think that what's happening here is that while we're very good at manipulating molecules, we're really a very long way away from controlling large-scale form and function. Biomedicine today is all about digging into the molecular level hardware. So genomic editing, pathway rewiring, protein engineering, all of these things are about the hardware.

If you think about the kind of trajectory that computer science took, this is what programming looked like in the 1940s and 50s. So you, to program, had to manipulate the system at the level of the hardware. You had to rewire it. The reason you don't use your soldering iron on your laptop when you go from Microsoft Word to Photoshop is that they've understood that certain kinds of media are strongly reprogrammable, that we can take advantage of their competencies with software level interventions. And that we can use various abstractions to understand how they process information. It's not all about the hardware.

So I think what we're missing in biomedicine and what I'm going to talk about today is this frontier, which is addressing the intelligence layers that I think exist in the biological hardware.

Slide 19/45 · 16m:42s

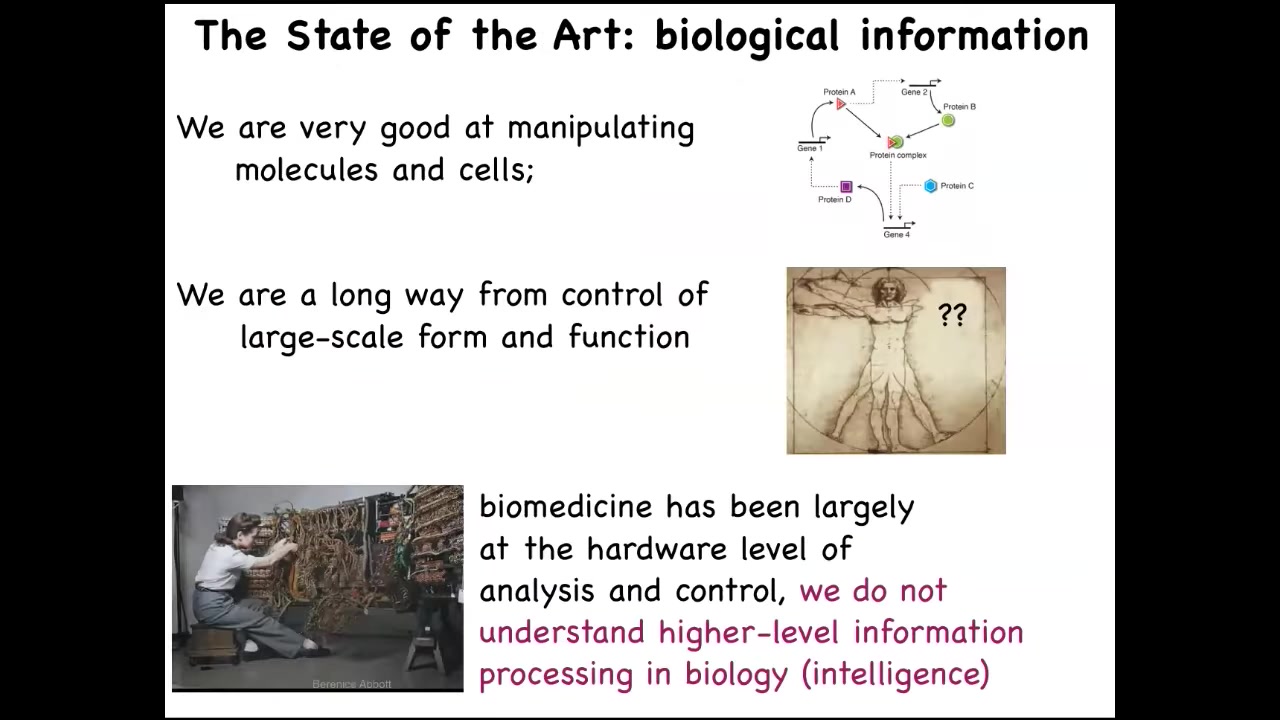

When I say intelligence, what do I mean? I'm going to restrict it to there are many components to this and many people have other definitions. I'm just going to focus on this one way of thinking about it, which is William James's idea, which is that it's the ability to reach the same goal by various means.

So that means that we're not asking what kind of brain it has, we're not asking what it's made of, a very cybernetic definition that focuses on whatever the goals of the system are. How competent or clever is it in meeting those goals when new things happen?

This means that you can't just infer this from observation. You can't watch cells doing things and say they're intelligent. You have to formulate very specific hypotheses. What space do you think they're working in? What goals do you think they have? What competencies do you think they have to meet those goals? And then you do the experiment. You put barriers.

James illustrates this in the following example. When you have two magnets trying to come together, this process is a low-IQ scenario because the magnet will never move further from its goal temporarily, going around the barrier to get to where it's going. It has no ability for delayed gratification. It's just never going to do that.

In contrast, Romeo and Juliet have long-term planning and abilities to get further from their goal temporarily to overcome various physical and social barriers. In between, you have other systems. You have cells that navigate mazes, autonomous vehicles, and various animals.

We have to make a hypothesis and we have to test specifically what competencies they have.

What kind of collective intelligence do cellular swarms deploy? What do I mean when I say intelligence in other spaces? Let's consider this notion of navigating anatomical morphospace.

Slide 20/45 · 18m:33s

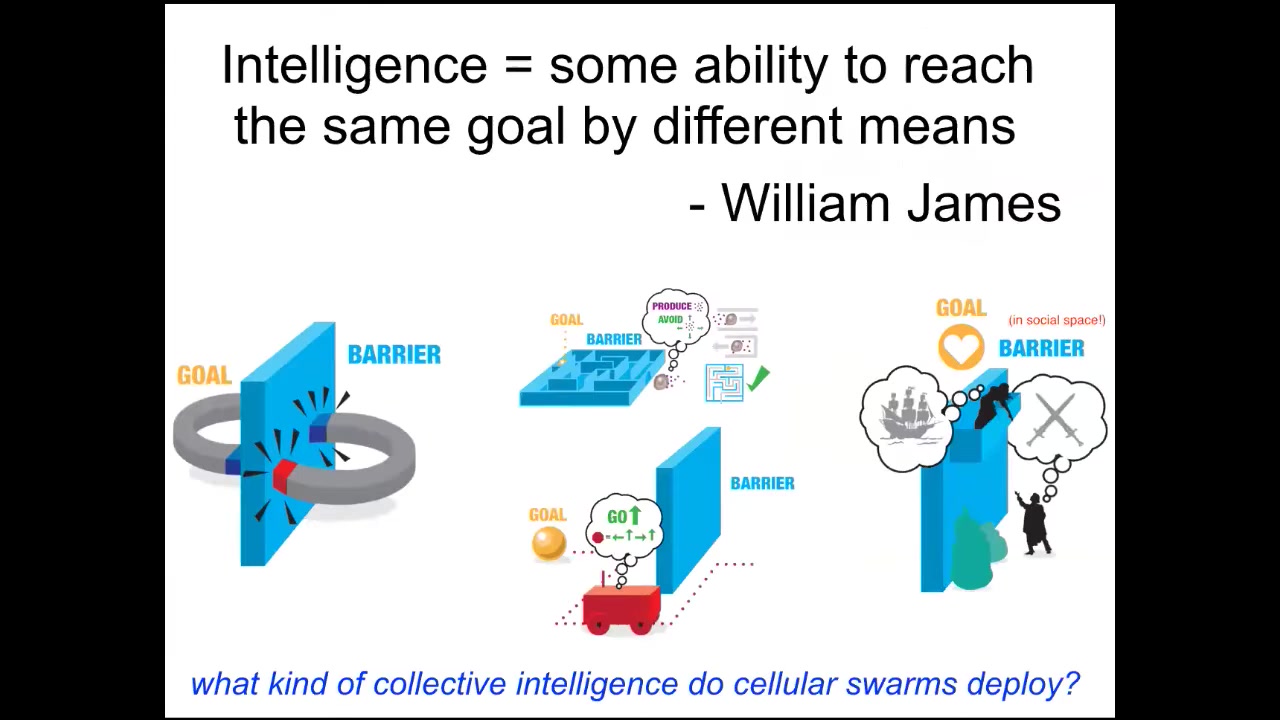

Development starts like this and ends up like this. If you think about the space of all possible anatomical configurations, what you have here is a long journey to a very specific ensemble of states that corresponds to the normal human target morphology. The first thing we know is that this is very reliable.

Now that by itself is not a sign of intelligence because an open loop process that was reliable and always resulted in an increase in complexity and the same kind of outcome can be just a very mechanical kind of thing. But one thing we know about embryos is that they are incredibly resilient to all kinds of perturbation. For example, if you cut these embryos into pieces, you don't get half bodies. What you get are normal monozygotic twins, triplets.

This navigation of anatomical space allows them to get there from different starting positions. They can often avoid local maxima. I have many examples of how they do this.

Slide 21/45 · 19m:33s

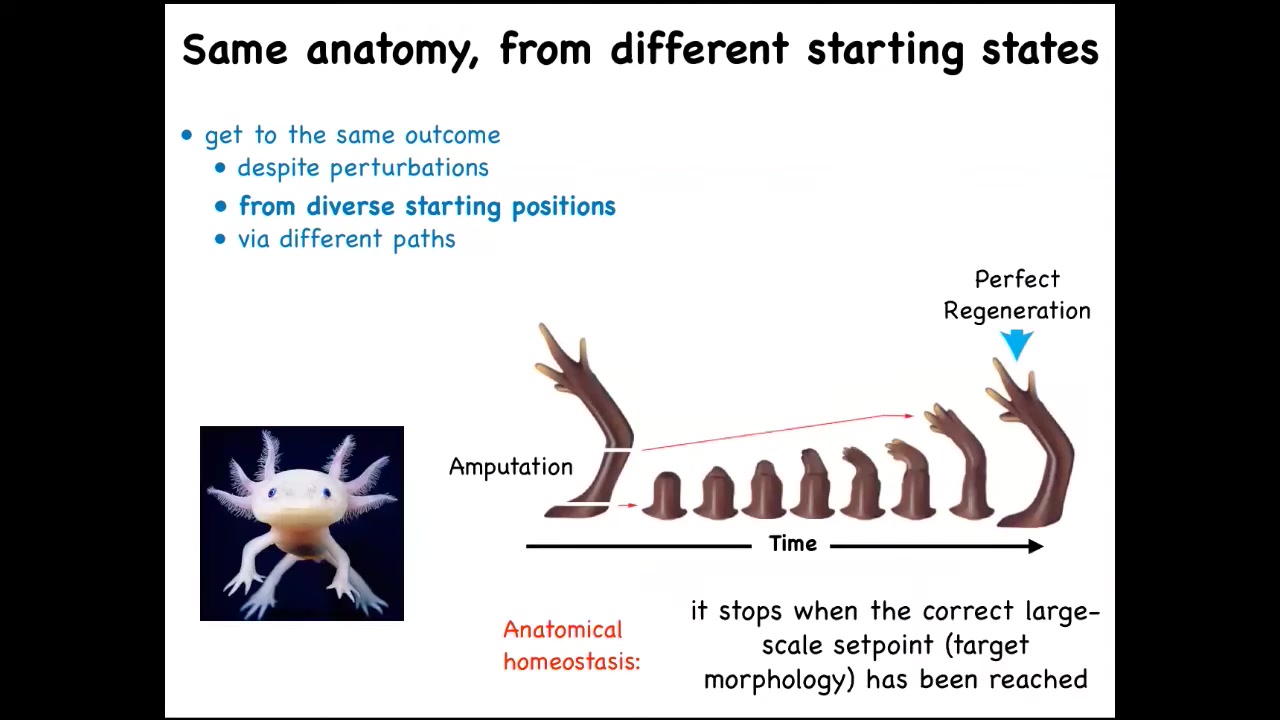

But you can see what happens in animals that retain this ability throughout their lifetime, like this axolotl. It has this limb, and you can amputate the limb anywhere you want. They will grow exactly the right amount. They'll do the complex patterning, lots of cell proliferation, and then they stop. The most amazing thing about regeneration is that it knows when to stop. When does it stop? It stops when a correct salamander arm has been completed. These animals can regenerate their eyes, their jaws, their tails, ovaries. What you have here is the ability to get to the same outcome from different starting positions, despite various kinds of injury.

Slide 22/45 · 20m:17s

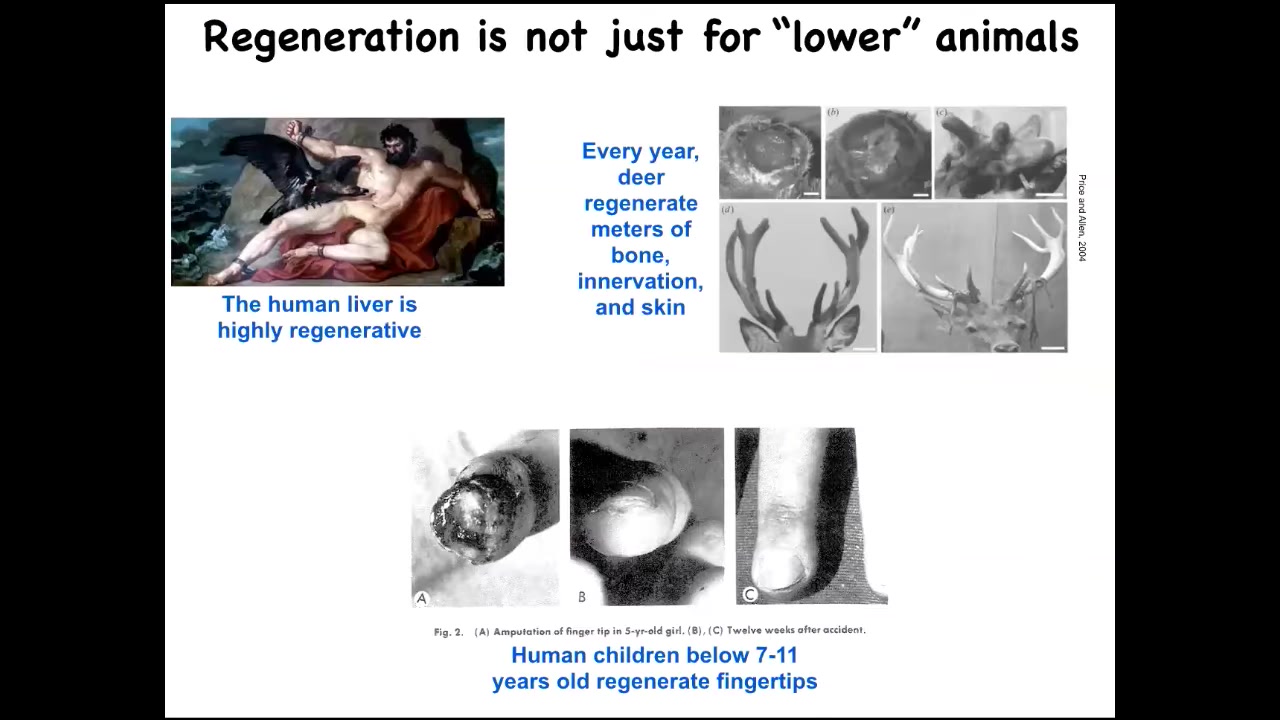

Humans and other mammals can do this. We regenerate our livers; deer regenerate antlers at the rate of a centimeter and a half of new bone per day. Really remarkable. This is an adult mammal doing this. This is to say that what I'm going to show you isn't just about frogs and worms, because that's what I'm going to focus on. Even human children can regenerate their fingertips. This ability to get to the correct target morphology when you've been deviated from it by injury is not the end of the story.

Slide 23/45 · 20m:47s

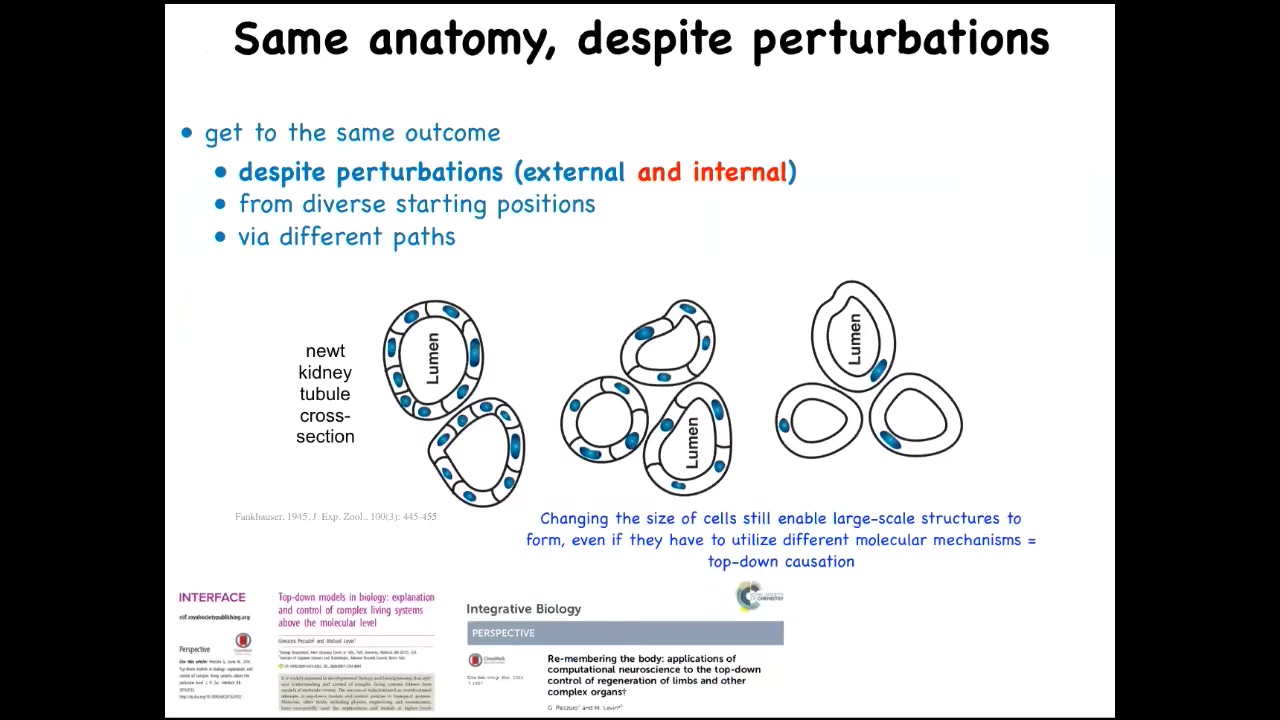

This is one of my favorite examples. This is a cross-section through a kidney tubule in a newt, and what you'll notice is usually about 8 to 10 cells that work together to give you this anatomical structure.

Now, the ability to get to where you're going in anatomical space is not just about external injury. One thing that we can do is increase the amount of genetic material in the early cell. This is a process that can be done with the egg where the DNA divides but the cell does not. What you end up with is very large cells. You can make polyploid newts this way, 2N, 4N, 6N, and so on. When you do this, the cells become much larger, but the whole newt stays the same size. The system automatically scales the number of cells needed to complete this process to the new cell number.

Amazing thing number one, things work perfectly well, even though you have multiple copies of your genome floating around, that doesn't confuse it. Amazing thing number two, when you're working with cells that are now abnormally large in size, we know what to do. We can use fewer of them to build the same thing. Amazing thing number three, which is that when you make the cells truly gigantic, one single cell will wrap around itself, giving you the same structure.

What's remarkable about that is that this is a different molecular mechanism. This is cell-to-cell communication. This is cytoskeletal bending. This system in the pursuit of this particular anatomical outcome can choose different molecular tools in the toolkit available to these cells to get the job done.

Think about what this means for a salamander entering this world for the first time. You can't count on having the right amount of DNA. You can't count on having the right size cells. You can't count on having the right number of cells. That's a different set of experiments. You still need to complete your journey through that morphospace using whatever tools you have available.

This is not injury. This is not something that normally happens to these animals. This is not the typical kind of regeneration, but it is a response to a kind of injury at a larger scale, which is evolutionary change, mutation. For this reason, I think that one thing that evolution really does is make problem-solving agents. I don't think it makes solutions to specific environments because it commits from the very beginning to the fact that everything is going to change and you cannot overtrain on the priors of past generations. This kind of problem-solving capacity is everywhere.

Slide 24/45 · 23m:26s

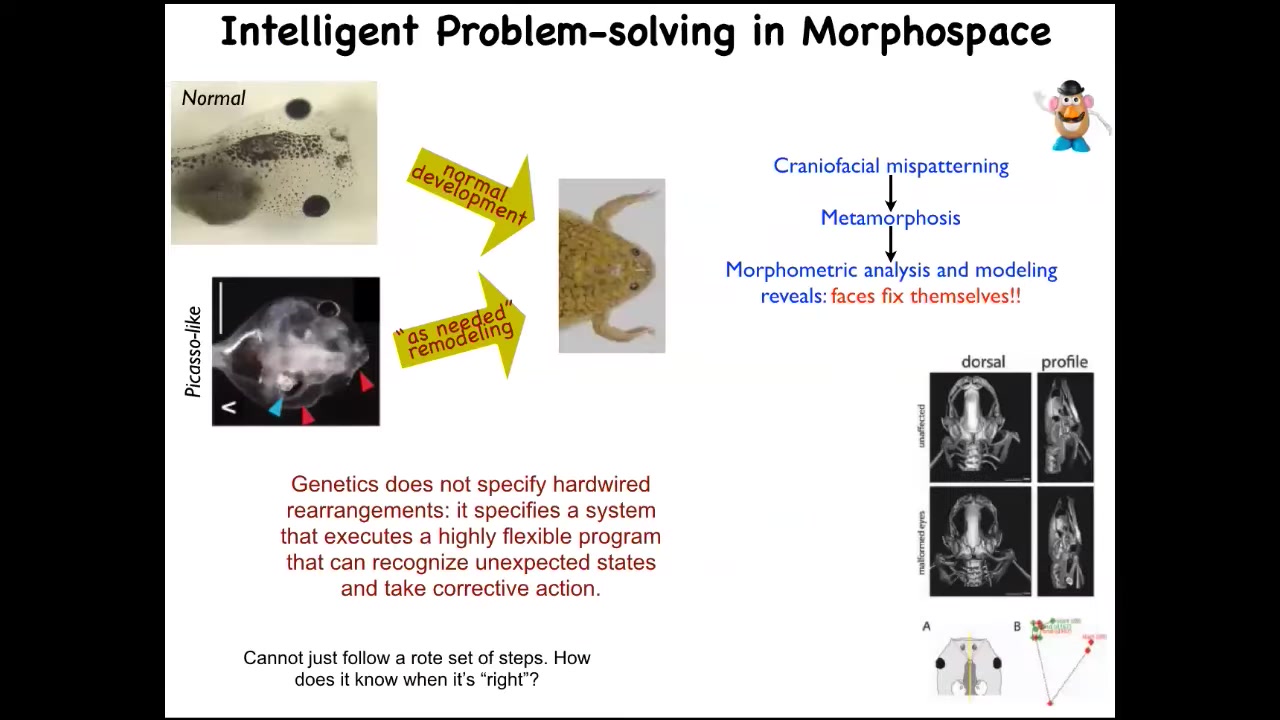

Here's one simple example that we found just to nail down this experiment, this point. So these are tadpoles of the frogs, Xenopus laevis. Here are the eyes, here's the brain, here are the nostrils, the mouth. Typically what happens is that these tadpoles have to become a frog. In order to do that, they have to rearrange their face. They have to move all these craniofacial components. People did think up until we found this a few years ago that this was a hardwired process. After all, every tadpole looks the same and every frog looks the same. So all you need to do is move all these components the right distance, a fixed amount, and you're good.

We decided to test that claim and find out how much actual problem-solving capacity there is here. So we made Picasso tadpoles. These are tadpoles where all the craniofacial organs are scrambled. Here's the eyes on top of the head, the mouth is off to the side, everything is scrambled. The amazing thing is that they become pretty normal frogs because all of these components will move through unconventional paths to get to where they need to go, and then they stop. Sometimes they go a little too far and have to come back a little, but eventually they stop.

So what the genetics gives us is not a set of hardwired rearrangements, but a system of error minimization. It's a system that functionally has a particular set point. It measures error towards that set point and will keep changing until that error is within acceptable tolerances.

That raises a clear question: how does it know when it's reached the right thing? This whole thing is a process of anatomical homeostasis as people study in physiological homeostasis. If you have a homeostatic system like this, where's the set point? Homeostatic processes need to store a set point. Where's the set point?

Slide 25/45 · 25m:19s

We took a lot of inspiration from neuroscience. The idea that neural decoding is this commitment to the idea that the memories, preferences, goals, behavioral repertoires of a system can be read out from the electrophysiology of their brain. If we understood how to decode these patterns, we would know. This is a living zebrafish brain that this group imaged. If we knew how to decode these patterns, we could understand the behavior and the mental life of this creature. This is an amazing system that uses electrical communication between cells to process information in the service of behavior and specifically goal-directed behavior that animals can do.

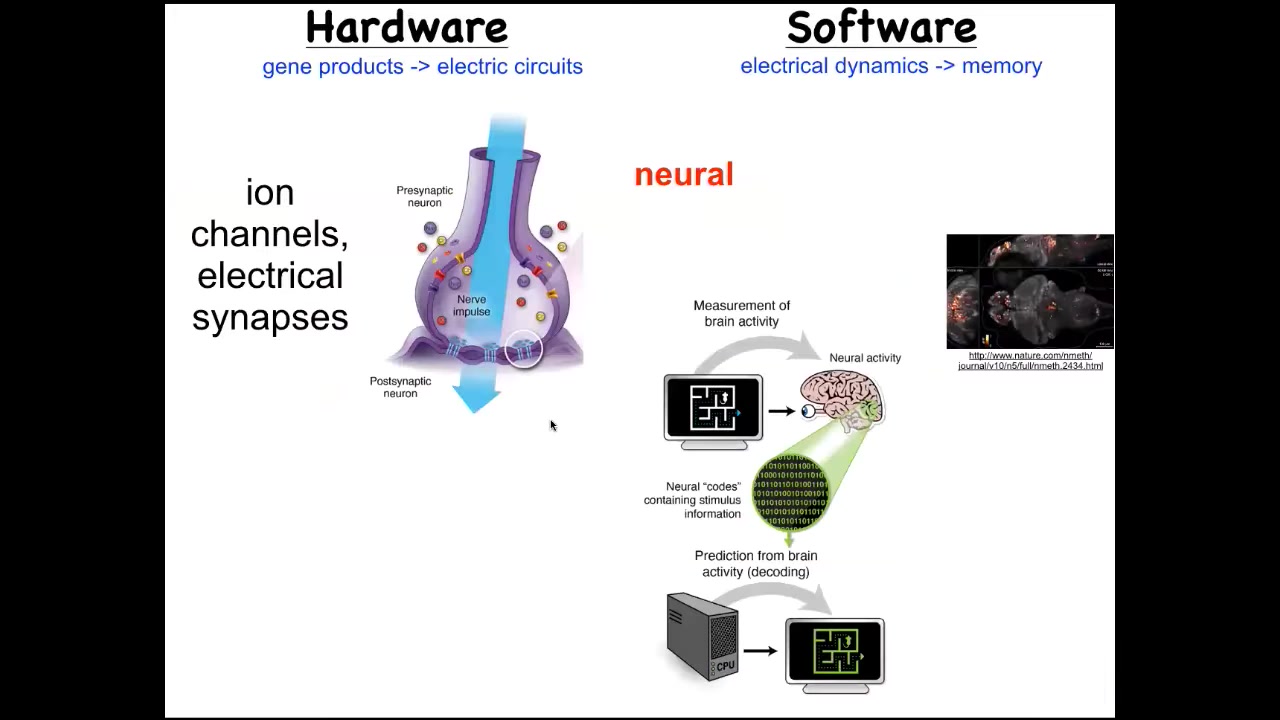

It turns out that evolution discovered the utility of electrical networks for this process very early on. This is not something that nerves or brains invented. This is as old as the first bacterial biofilms. Every cell in your body has these ion channels. Most of the cells have electrical synapses known as gap junctions between them.

What we embarked on was a very parallel path to that in neuroscience: can we use all of the tools that have been developed? This means importing practical tools, things like optogenetics, drugs that hit the neurotransmitter pathways, and the conceptual tools: all the stuff from behavioral science, all of the active inference and all these kinds of things. We steal everything from neuroscience because the tools do not distinguish. As far as the tools are concerned, this is the same kind of process. That's an important clue. The fact that the tools don't distinguish this asks us to really think hard about why we distinguish this. It turns out that most things that neurons do, every cell in the body can do, but on a different time scale: they work on a much slower time scale.

What evolution did was pivot the system of controlling your journey through anatomical space into controlling your motion in three-dimensional space when nerves and muscles came on the scene. We wanted to ask a simple question. What does the body think about? We know some of the things that brains think about. What does the body think about? What are these electrical networks doing prior to the formation of the brain?

Slide 26/45 · 27m:50s

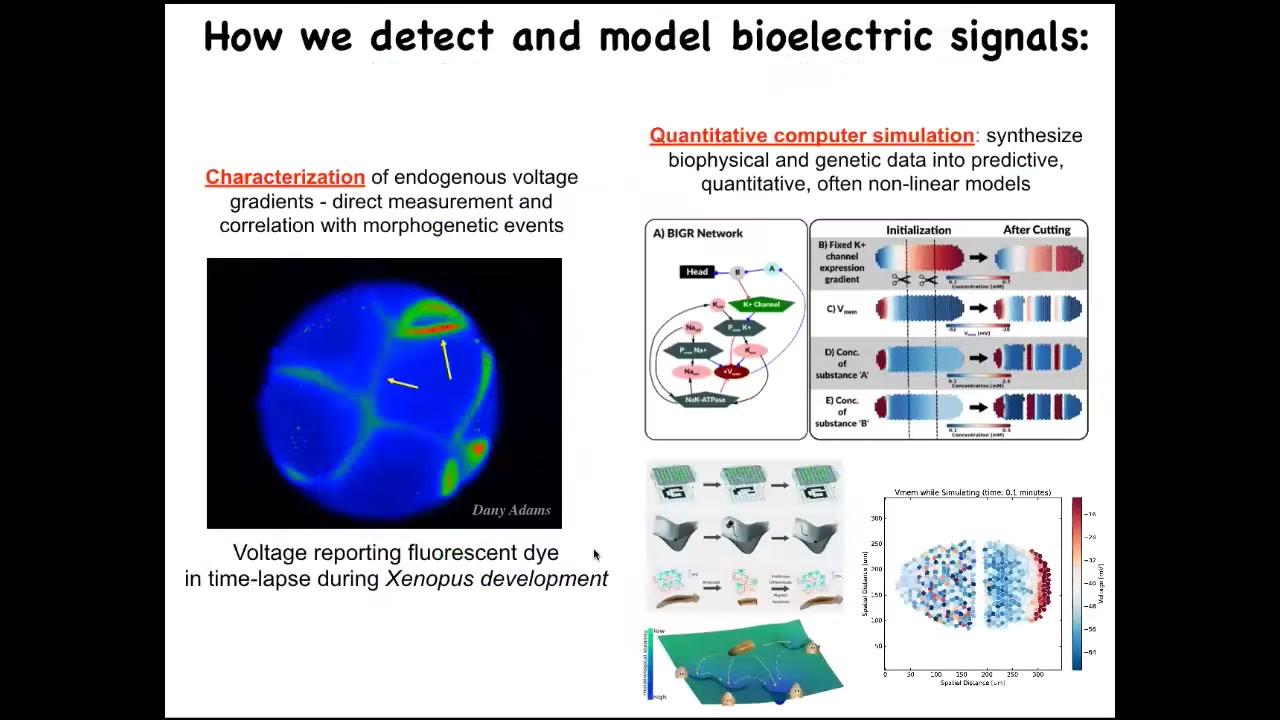

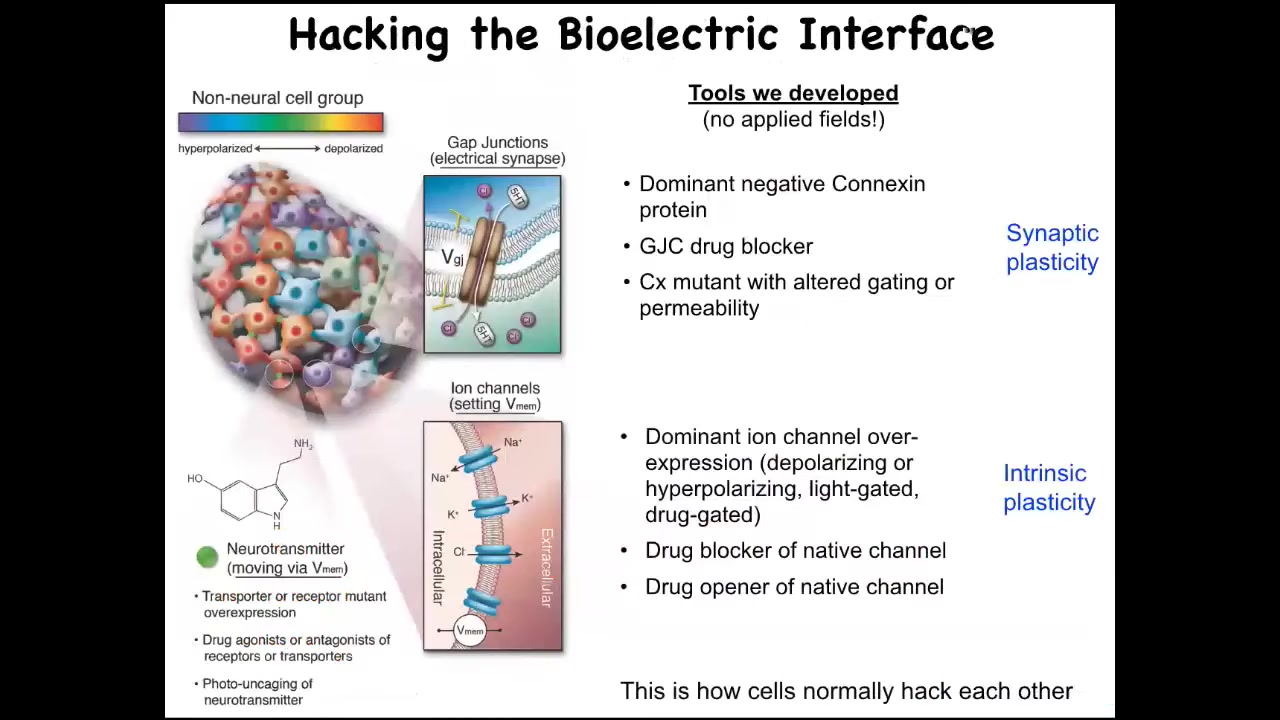

We developed some of the first tools to read and write this electrical information from non-neural cells, the way people have been doing in the nervous system. This, for example, is a time-lapse video using a voltage-sensitive fluorescent dye of the early steps of frog embryo development. What you're watching here are all of the conversations that these cells are having with each other in this network around who's going to be left, right, top, bottom, and so on. The question is, can we learn to read and decode this information? We do a lot of quantitative simulation where we start with knowing what ion channels are expressed and we have these pathways, but then we simulate the electrical paths the way people do with neural network simulators and ask how they do things like pattern completion, error correction, and some other things I'm going to show you taken right out of typical neuroscience.

Slide 27/45 · 28m:44s

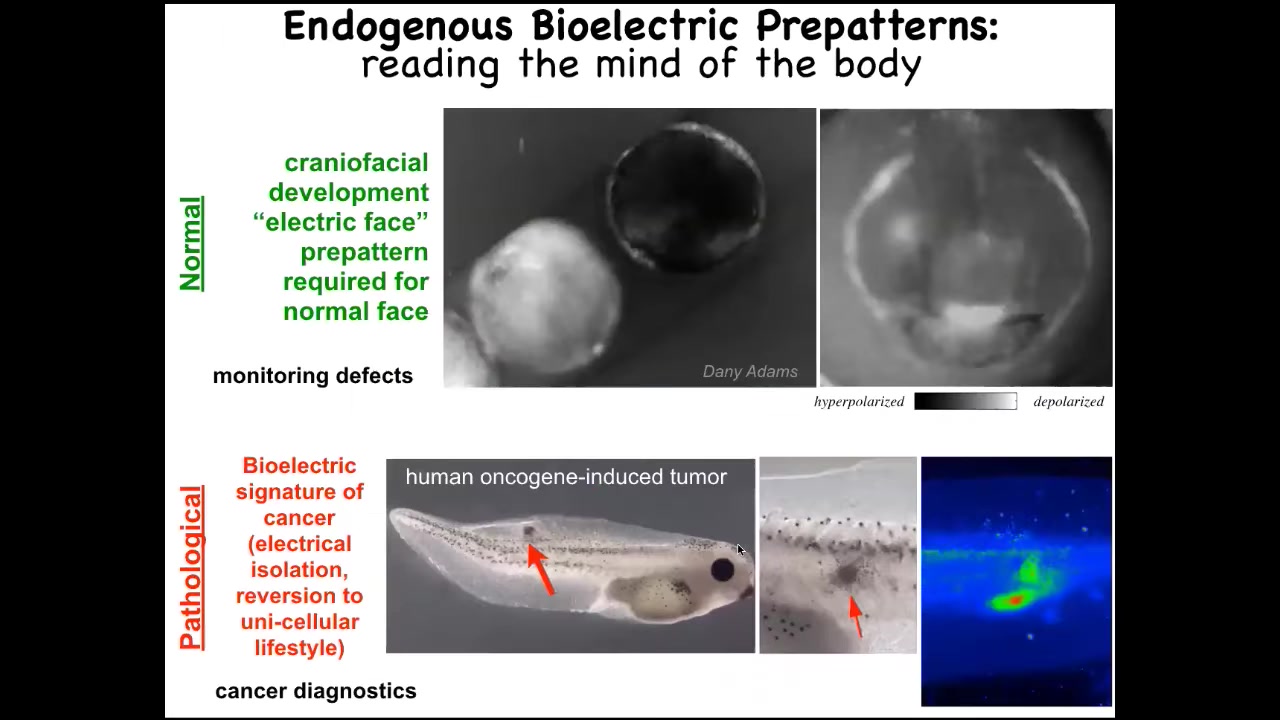

And I want to show you a quick example of what these patterns look like. This is a time lapse of a frog embryo putting its face together. Here's one particular pattern. And the reason I'm showing you this pattern is it's the easiest one to decode, the easiest one we found so far. We call it the electric face because it looks like a face. By looking at the electrical pattern in these tissues, we know what the future gene expression and anatomy are going to be. Here's where the animal's right eye is going to be formed, here are the placodes, here's the mouth. We know, as I'll show you momentarily, that if you manipulate this pattern, the cells build something different. That's an endogenous pattern that is required for normal craniofacial development.

This is a pathological pattern that we induce by injecting oncogenes, and I'll tell you the story of cancer shortly.

Slide 28/45 · 29m:33s

Watching patterns is all well and good, but the most important thing is a functional perturbation so that we can see if we can really read and write new information into these electrical networks. Remember the hypothesis that these electrical networks, much like in the brain, are literally the medium, the information processing medium of the collective intelligence that solves anatomical problems. Much like in the brain, the networks underlie the collective behavior of neurons that solve other kinds of problems. Can we learn to read and write this information?

We don't use any applied electric fields. There are no waves, there are no frequencies, there are no electrodes, no magnets. We do exactly what neuroscientists do, which is that we target either the topology of the network by opening and closing specific gap junctions, or we can target the actual electrical state of these cells by controlling the ion channels. We're talking about drug-based openers and blockers, genetic mutation of channels, optogenetics.

What we're doing is taking advantage of the interface, the electrical interface by which cells normally control each other's behavior. Everything I'm going to show you works in morphogenesis, not because we're so smart and we engineered all this stuff. It works because that is how the cells normally control each other.

Slide 29/45 · 30m:57s

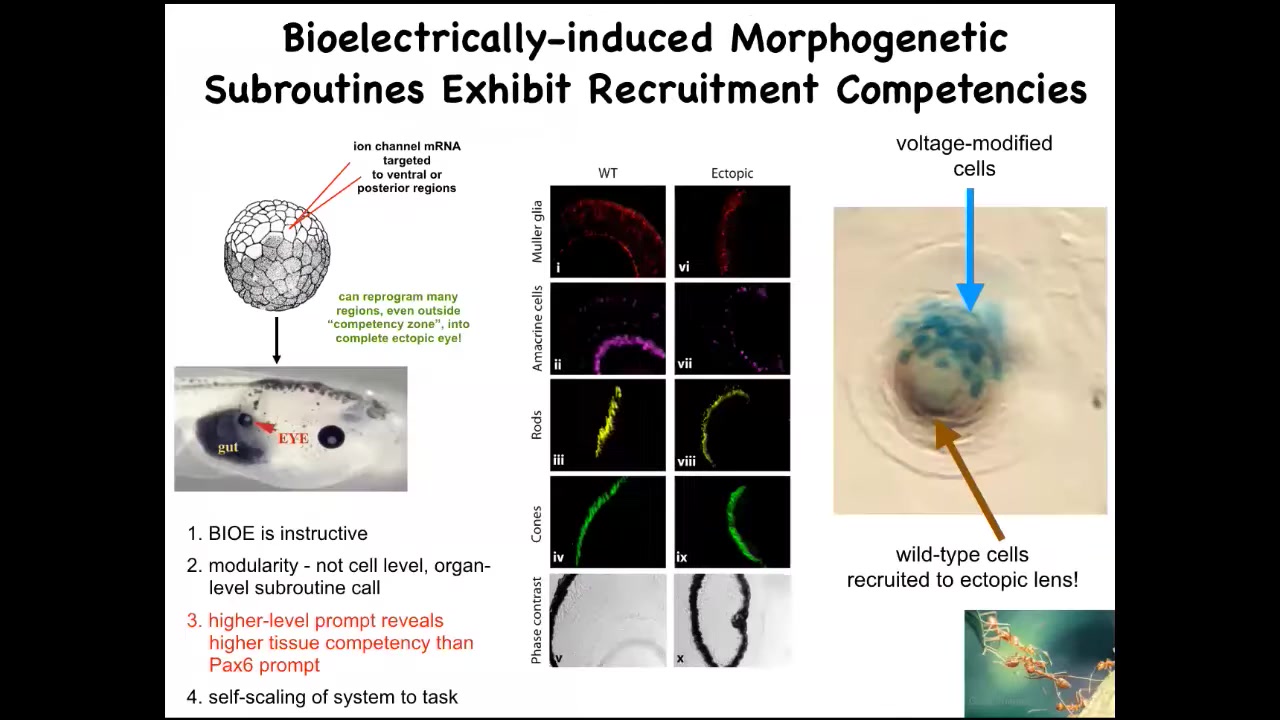

Having seen that spot in the electric face that makes an eye, you might wonder, what happens if we introduce that somewhere else? This idea that these patterns are spatial memories of the set point that guides morphogenesis makes a strong prediction. We should be able to reproduce them somewhere else.

We can inject a set of ion channel RNAs into a particular region to establish the voltage pattern that we want. That voltage pattern will tell the local cells, you should build an eye. You can make an eye anywhere in the animal, including out of gut cells. If you section these eyes, they can have the right lens, retina, optic nerve; they can have all the right stuff inside.

First thing you learn from this is that these bioelectrical patterns are instructive. If you control the pattern and put it somewhere else, you can make large-scale changes in the anatomy, meaning you can control whole behavioral modules in that anatomical agent.

The second thing is it's very modular. What we have here is a stimulus, a prompt, that causes a very complex downstream set of behaviors. We didn't have to micromanage the stem cells or tell any of the genes when to come on. It's a very top-down trigger.

The third thing is that in your developmental biology textbook, you would see that only the anterior neuroectoderm, this stuff up here, is supposedly competent to make eye. That's because typically what they do is they prompt this thing with PAX6, which is supposed to be the master eye gene. If you misexpress PAX6, this up here is the only region that can make ectopic eyes. But that's the wrong prompt. If you use a bioelectric prompt, you find out that any region in the embryo is competent to make eye.

This reminds us of something important in the field of diverse intelligence: when we talk about the competency of various systems, we're really taking an IQ test ourselves. All we're saying is, this is what we know so far, as far as what the system can do. It doesn't necessarily mean that that's the limitation of what the system can do, because maybe we have not found the right set of triggers or do not appreciate its behavioral repertoire.

The last thing that I find amazing about this is that this is a lens sitting out in the flank of a tadpole somewhere in the tail. What you'll notice, the blue cells are the ones that we injected with our potassium channel. All of these other cells up here were never injected. What's happening here is that there's not enough of these cells to build an entire eye. What they're doing is recruiting their neighbors to help them complete the process. That competency, we didn't have to put that in. The ability of these cells to do a secondary instruction—so we tell you, "make an eye," and they tell their neighbors, "you have to help us make an eye"—is something that we see in other collective intelligences like ants and termites when the colony scales its efforts appropriate to a task of carrying a large food item. This is all part of what the material can do.

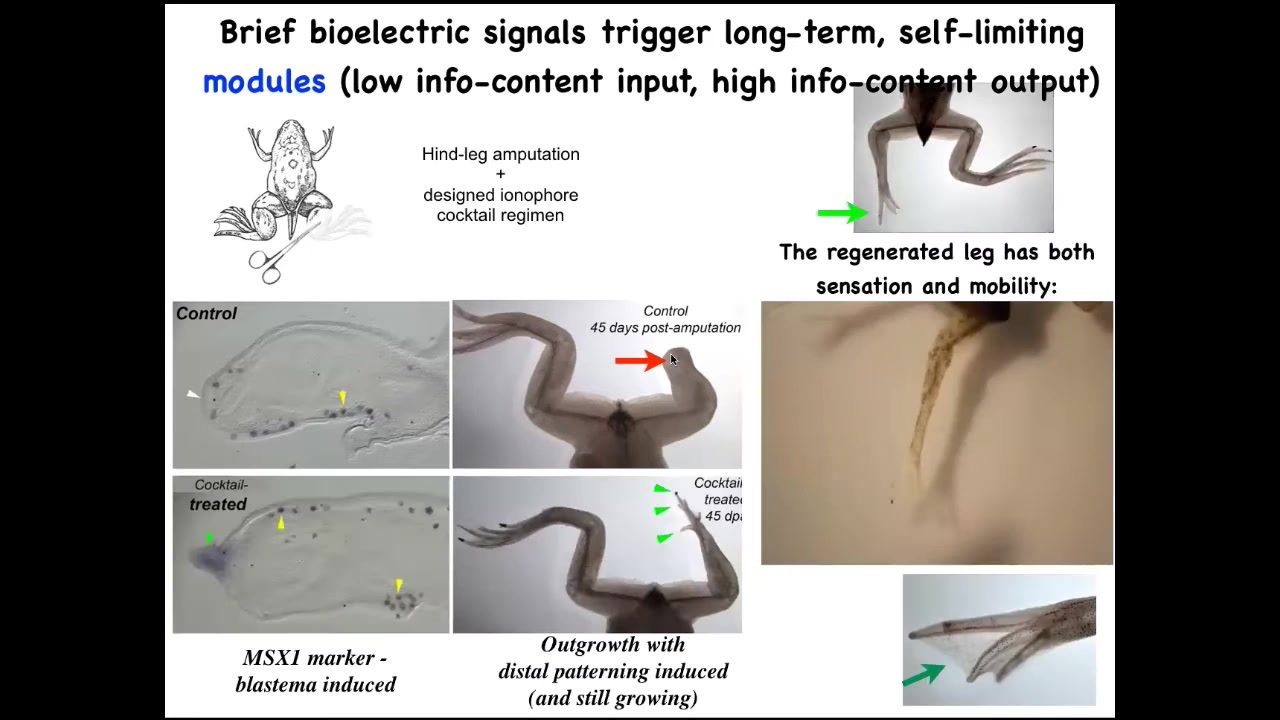

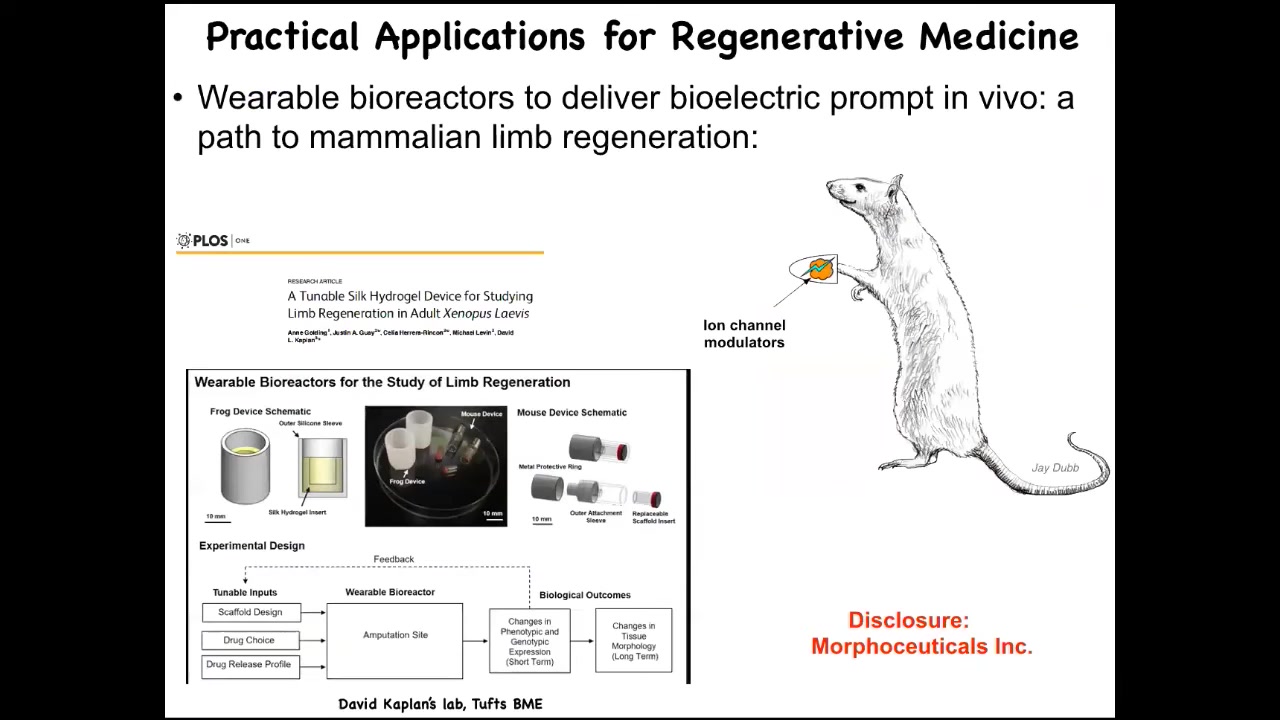

We're pushing this now into biomedical areas. For example, frogs who normally do not regenerate their legs at this stage—normally there's no repair.

Slide 30/45 · 34m:26s

We have figured out some bioelectrical prompts that set the tissue to a particular state that says, go down the leg regeneration path, not the scarring path. So immediately the pro-regenerative genes turn on, and then eventually you get this nice leg that's touch sensitive and motile. In the early stages it looks like this, a pretty respectable leg. The idea is that we don't micromanage this. We're not talking to the individual cells. Any more than you're talking to individual neurons when you're using high-level behavioral control in animals, it's a very high-level subroutine call where you can say, build a leg. That process takes 24 hours, and the leg itself grows for a year and a half. You get 18 months. It's completely autonomous. Once you've convinced those cells that that's what they're doing as opposed to a scar, it goes.

Slide 31/45 · 35m:16s

At this point, I have to do a disclosure. Morphoseuticals Inc. is a company that Dave Kaplan and I founded to try to do this in mammals and eventually human patients.

Slide 32/45 · 35m:28s

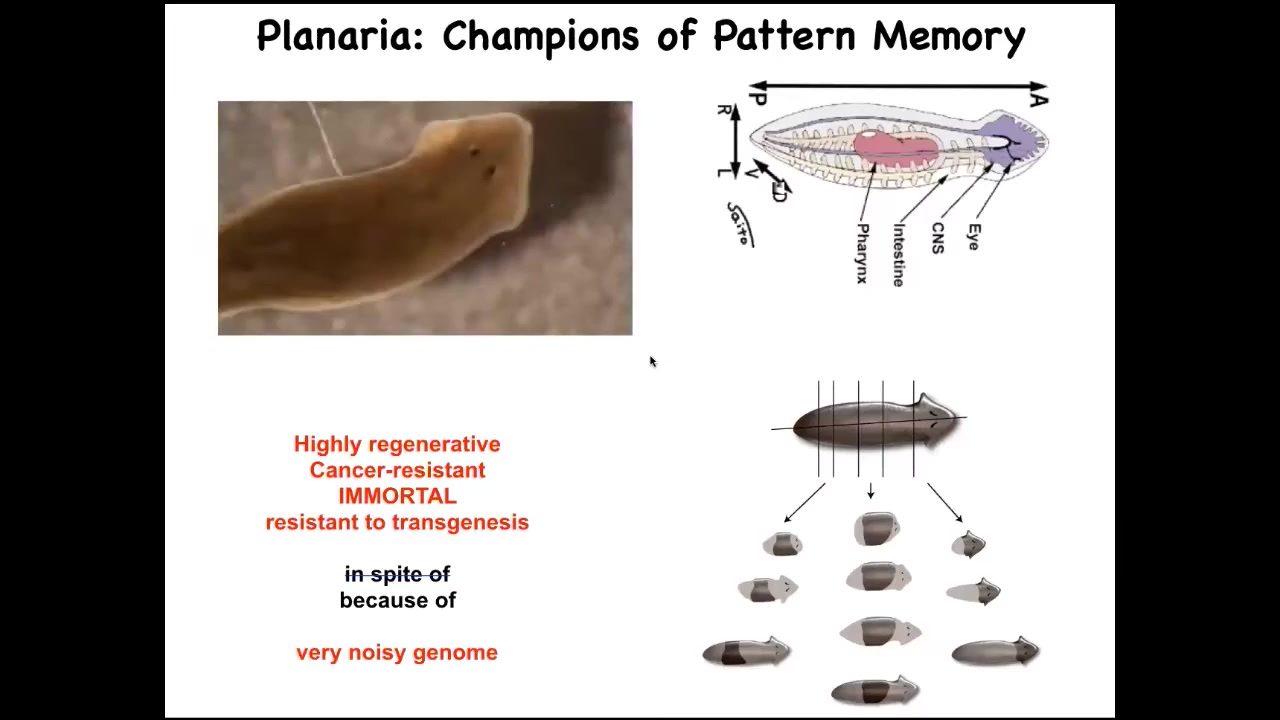

I want to show you one other example of an animal that lets us see how much we can import from ideas in neuroscience. This is a planarian. These are flatworms that regenerate. They have some amazing properties, but they're highly regenerative. They're also cancer resistant. They're immortal, if no aging occurs, and they're extremely resistant to transgenesis. And I think that's because of their incredibly noisy genome. But one of the amazing things is that when you cut it into pieces, and the record is 276 pieces, each piece gives rise to a perfectly normal worm, and it has the right number of heads and tails.

Slide 33/45 · 36m:12s

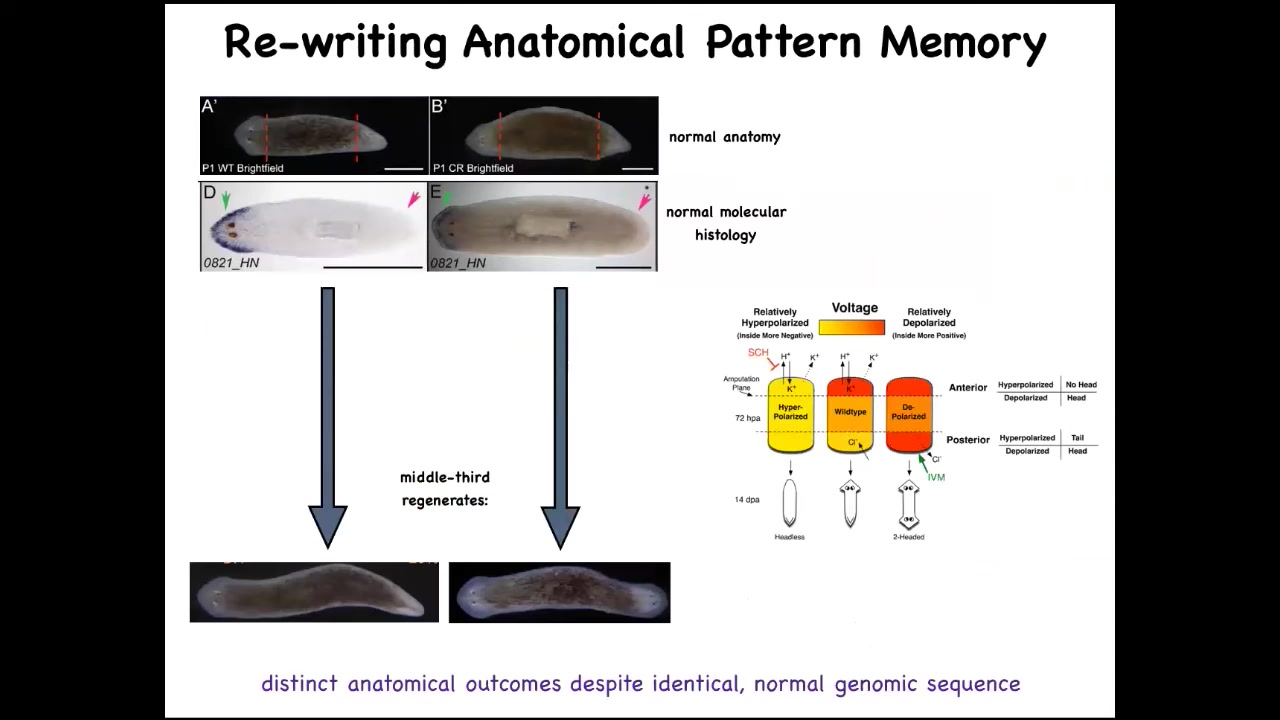

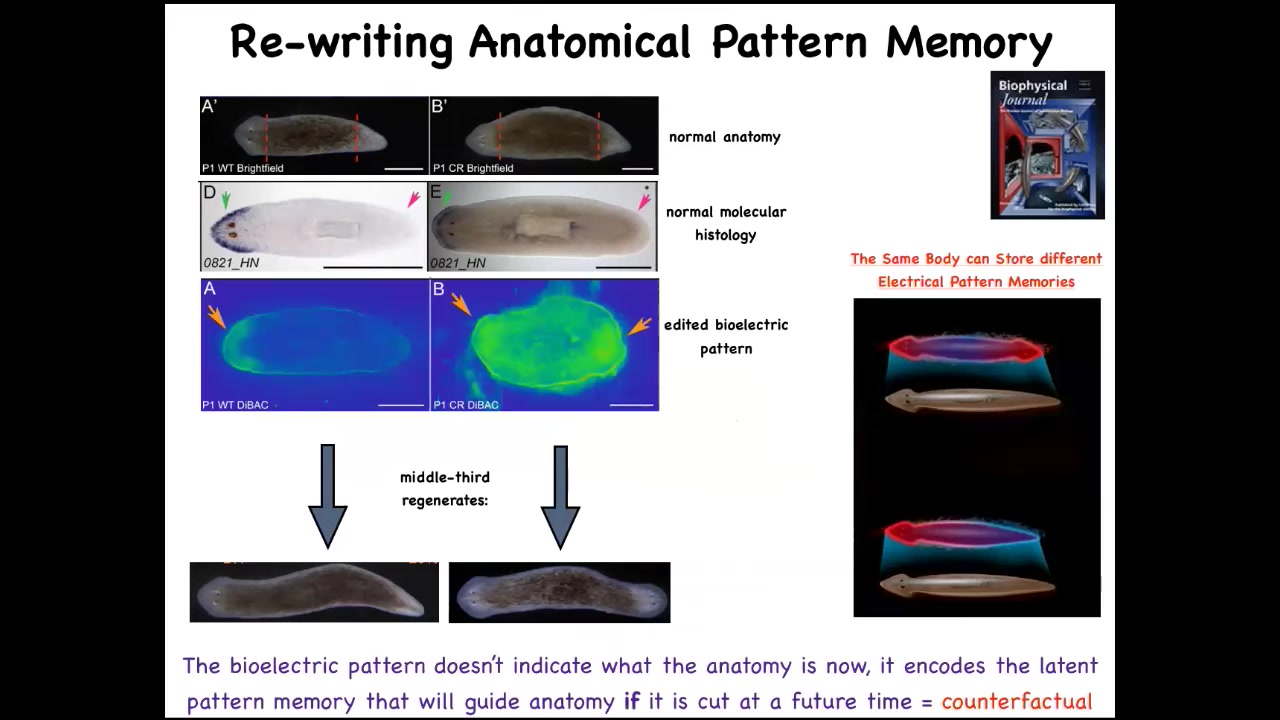

We wondered, how does a piece know how many heads and tails it's supposed to have? What controls that? And we discovered an electric circuit that determines this process.

Slide 34/45 · 36m:22s

You have a normal worm here. You've got the head and the tail. We amputate those. We take the middle fragment. It reliably makes a one-headed worm. Here's what the bioelectrical pattern is. If you read this fragment, it's got this pattern that we've been able to decode. This is one head, one tail. And what we can do is we can take this animal and change that pattern to say two heads. It's messy because the technology is still in its infancy, but we can make it say two heads, and then this is what they built.

This bioelectrical map is not a map of this two-headed animal. This bioelectrical map is a map of this perfectly normal one-headed worm. What you're looking at here is literally we can now see the pattern memories. We can visualize what this tissue thinks a correct planarian looks like. This is what it thinks it looks like, but it doesn't match the current anatomy and that's fine. Nothing changes until this animal gets injured. Then this pattern is consulted and the cells build a two-headed animal.

Not only is it a pattern memory that serves as the set point, but it is actually a counterfactual memory. It is a very primitive example of a kind of mental time travel where brains can remember things that aren't true right now and anticipate things that also aren't true right now. This state of affairs is not true right now. For this animal, the anatomy is normal, the gene expression is normal, but this is what it stores: what am I going to do if I get injured in the future. We now know that the body of a planarian can store at least two, no doubt more, but we've nailed down two representations of what the target pattern is going to be if it should happen to be injured in the future.

Slide 35/45 · 38m:29s

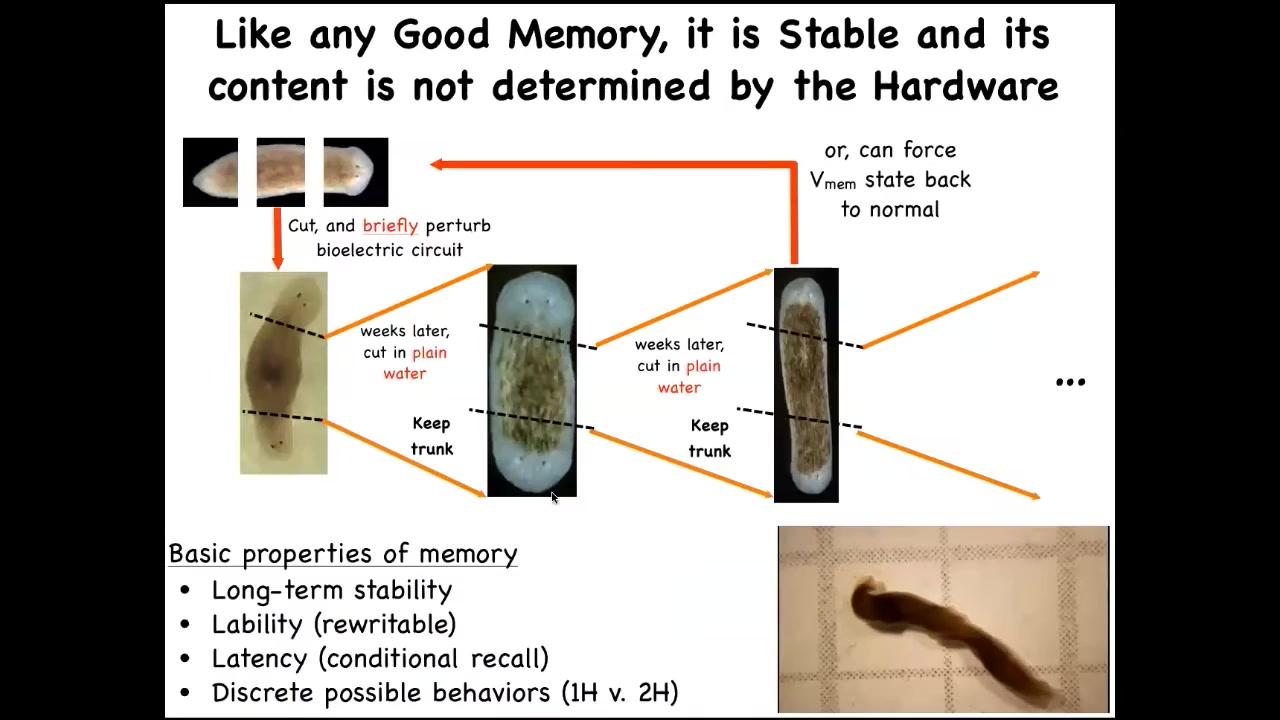

Another reason I call this thing a pattern memory is this remarkable result, which is that if you make a two-headed worm and then you cut them again in plain water, they continue to regenerate two-headed in a two-headed way. There is no genetic change here. We're not touching the genome. We're not reprogramming at the genetic level. We have altered, through a physiological experience, the set point that guides the movement of the regenerative process in their navigation of space. And it will continue to — that electrical circuit holds. As long as we don't set it back, and we now know how to set it back, it will continue to hold. This system has all the properties of memory. Not in physical space, in anatomical space. It's long-term stable, but it's rewritable. It has a conditional recall. It's got discrete possible behaviors, so one head versus two. The individual cells aren't doing discrete things. It's the group, the collective. The individual cells here aren't confused as to whether there should be part of a head or a tail. The collective makes a decision about where it's going to go. Not only can you convince the system to permanently take up a different set point for the number of heads, you can do the same thing for the type of heads, and you can make them have heads of other species.

Slide 36/45 · 39m:40s

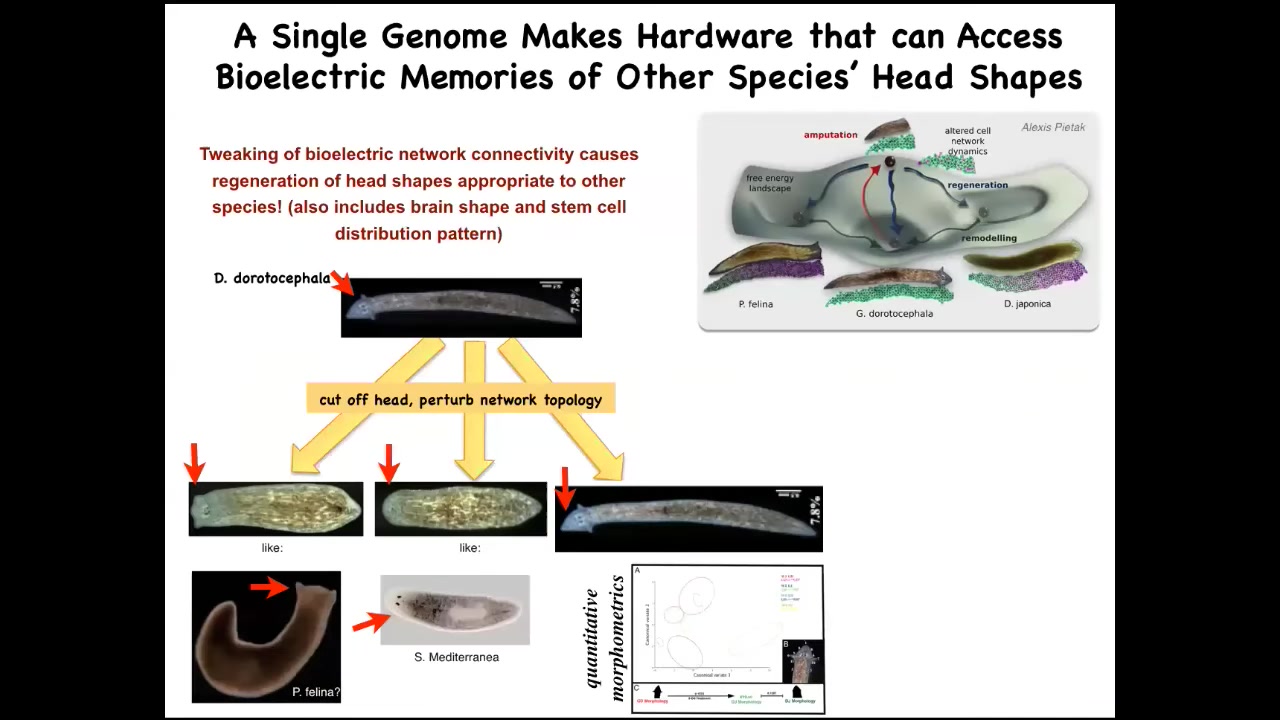

So for example, here's a nice triangular-headed Dugisia duradocephala. If we cut that head off and manipulate the bioelectrical network, they will make heads of flatheads like this P. falina, they will make roundheads like this S. mediterranea, and that same hardware, that same genomically determined hardware, will visit the attractors in anatomical space where normally these other species hang out. With 100 to 150 million years' distance here, no genetic change. And the same thing is true of their stem cell distribution, their brain shape; they can adopt the brain shape and the stem cells of these other species. The behavior, we're still trying to nail down whether that's true.

Slide 37/45 · 40m:31s

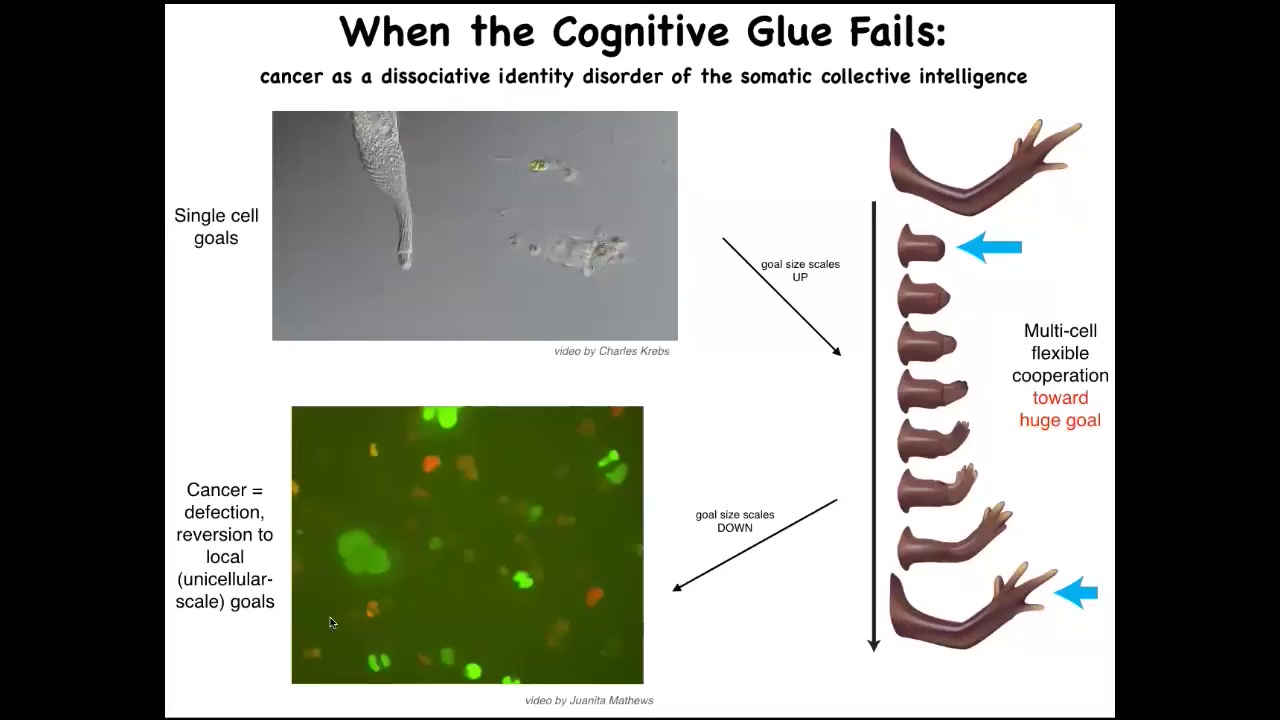

So the last piece of this I want to show you before we stop is this. What happens when this cognitive glue fails? I've been arguing that much like in the brain, these electrical networks provide an essential connectivity that allows groups of cells to store memories and to pursue error minimization with respect to those memories about goals in other spaces that the individual cells do not worry about. So the tiny little homeostatic goals of this cell, which basically are just the scale of the cell itself and they're metabolic goals and things like that, what evolution and development do is they scale up and give us electrical and chemical networks that can have very grandiose goals. They can maintain things like this, where if you deviate away from this, then they will work really hard to get back and then they stop and relax. So what happens here is the scaling. In my framework, I call this the cognitive light cone for various reasons. The size of the set points towards which the system can competently work is greatly scaled up from here to here.

Now, these electrical processes can fail. One thing that happens when cells become isolated from the rest of the network is they can no longer maintain participation in this pattern. This is a human glioblastoma. What happens here is that these cells are, once they disconnect from the network, they roll back to their ancient unicellular self. Their goals are now extremely small. Their goals are to get as many nutrients as they can and to proliferate as much as they can and to go wherever they want. As far as they're concerned, the rest of the animal is just external environment. So these cells are not more selfish, it's that their cells are smaller. What's happening here is that it's kind of a dissociative identity disorder, as certainly as seen in conventional cognitive systems, such as human minds. We can have that here too. This system can break up so that the individual cells are pursuing their own agendas, no longer this kind of a collective thing that was working so well before.

Slide 38/45 · 42m:37s

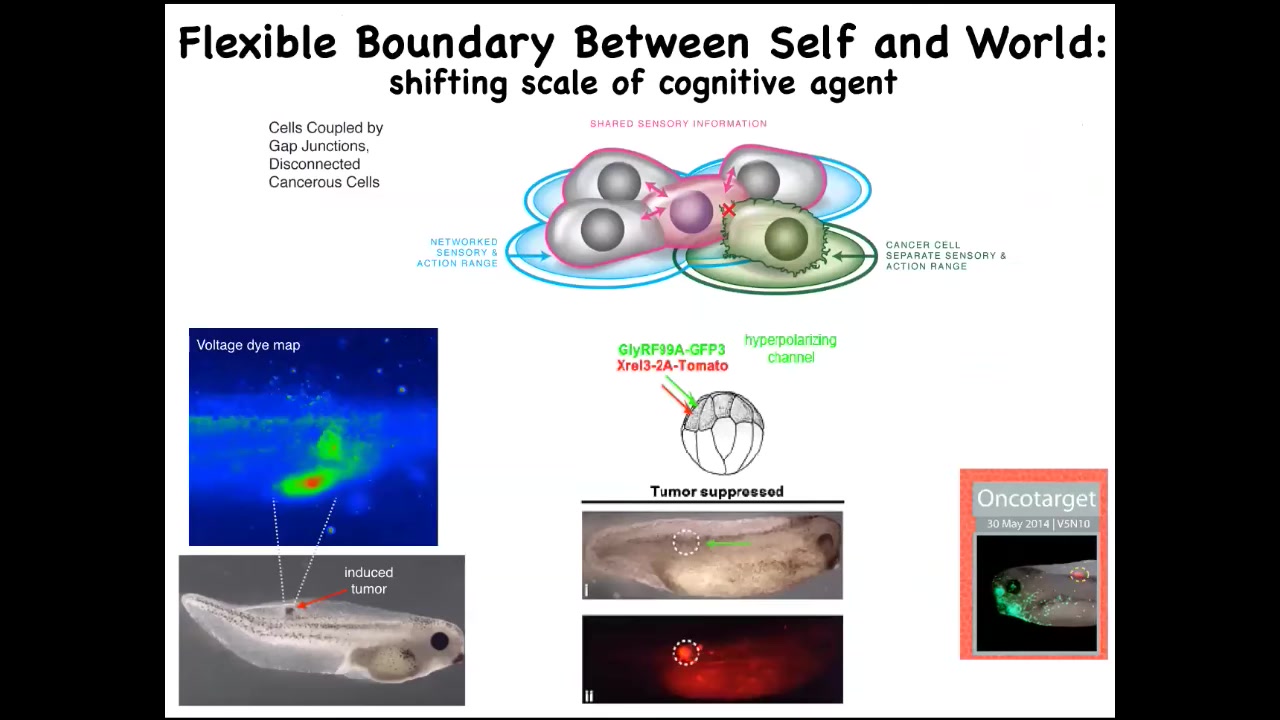

So that leads to a really different way of thinking about cancer, not as a genetic disorder of a broken genome but as a failure of maintaining the properly sized boundary between self and world — the scaling of where do I end and the outside world begins. Thinking about it in this way suggests a very specific therapeutic. Once you have an oncogene here, the first thing these cells do when the oncogene is expressed is they depolarize and cut electrical connections with their neighbors. At that point, they can no longer remember what they're supposed to be building, and that's it. Then you get metastasis.

One thing you might do is say, instead of toxic chemotherapy, we're not going to try to kill these cells. What we're going to do is force them to reconnect back to their neighbors. When I inject an oncogene — these are nasty human oncogenes like KRAS mutations — you can also co-inject an ion channel that keeps the cell in tight electrical connection with their neighbors. It hyperpolarizes it so the gap junctions can form.

This is the same animal. Here's the ONCA protein. It's blazingly strongly expressed. In fact, it's all over the place. There's no tumor. And there's no tumor because it's not the hardware that drives it, it's not the genetic state that drives this, much like in neuroscience where the same hardware can do many different behaviors depending on the local physiology. What's happening here is that these cells are connected to their neighbor, and now the whole network is busy minimizing delta from having nice skin, nice liver, and those kinds of things. And so this, again, we're now moving into humans.

Slide 39/45 · 44m:17s

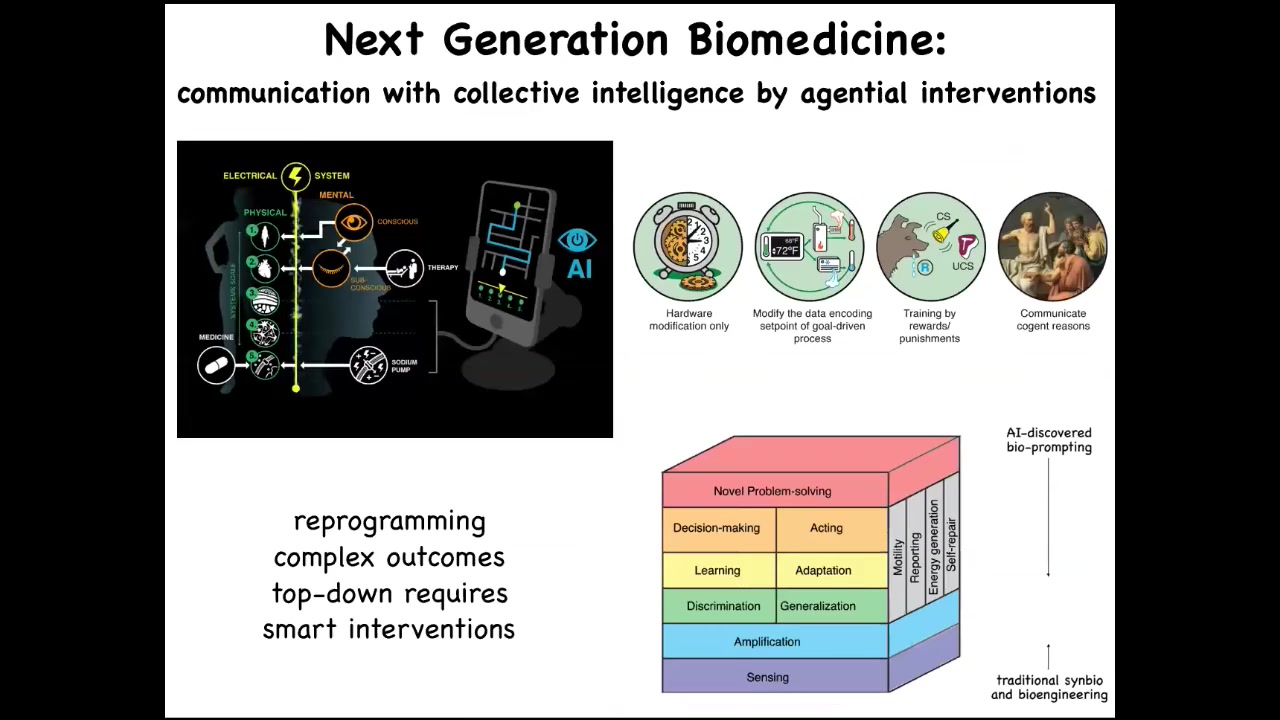

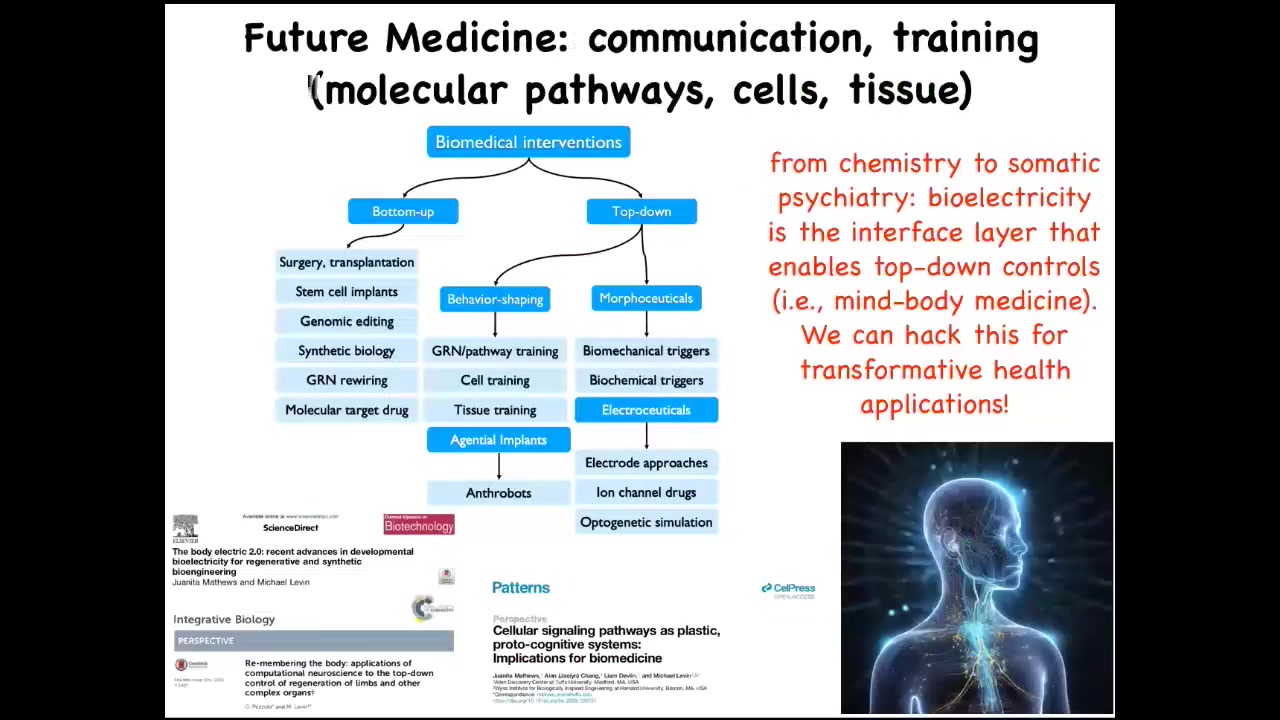

My final point is that when we're talking about biomedicine, where the rubber hits the road with these discussions of intelligence — is it a category error to think about intelligence in non-brainy systems? To me, as an engineer, I judge all of this by how much utility you can squeeze out of it. And if we can use the tools of behavioral and neuroscience to achieve new capabilities in regenerative medicine and cancer, then I think we're on to something. If we take seriously the idea that the body has a multi-scale architecture where the different pieces have different competencies on the scale, we have lots of new kinds of approaches.

Slide 40/45 · 45m:02s

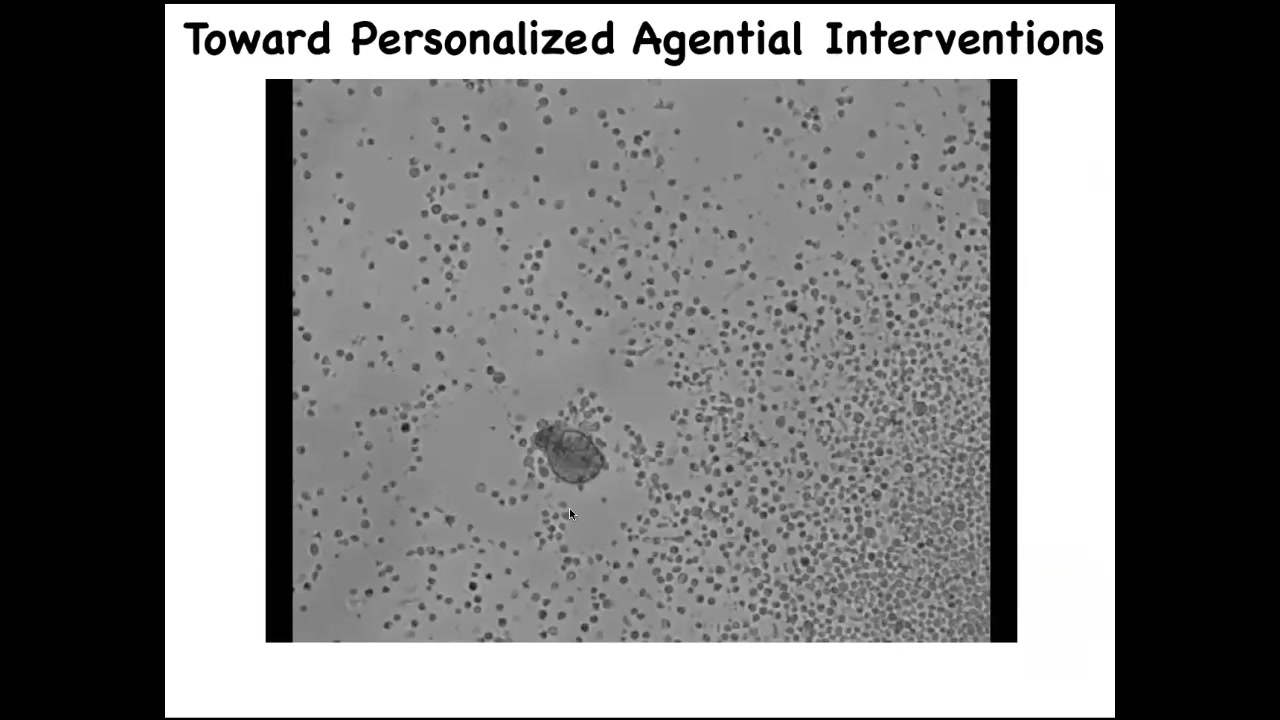

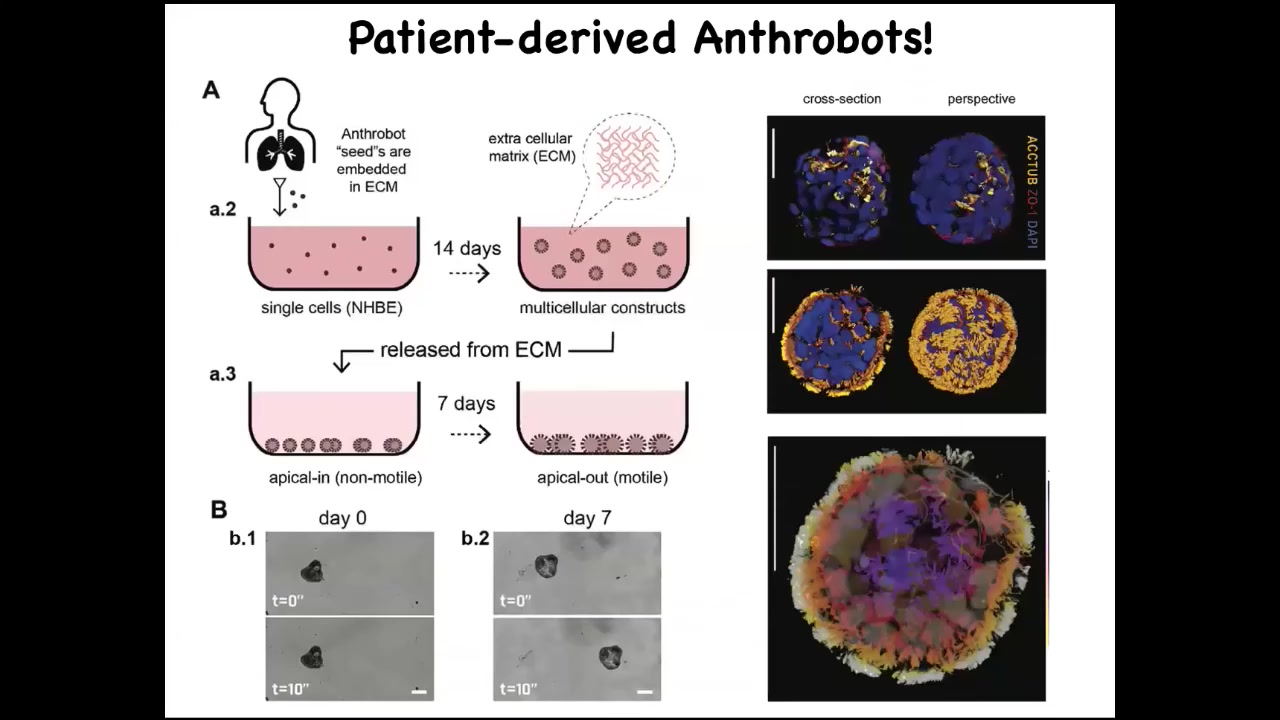

I'm going to show you one real quick. This is, if you look at this thing, you might ask, what is this? You might think that this is a primitive organism that I got out of the bottom of a pond somewhere.

I can tell you that if you were to sequence the genome of this little guy, what you would see is Homo sapiens. This is 100% Homo sapiens genome. What this is, is something we call an anthrobot. It's made of cells collected from adult human patients, tracheal epithelium that people donate.

Slide 41/45 · 45m:33s

Under a certain protocol that we have, these cells self-assemble. There is no new genetic material, no transgenes, no weird nanomaterials, no scaffolds. These cells automatically assemble into this self-motile little structure, which has all kinds of interesting behaviors.

Slide 42/45 · 45m:50s

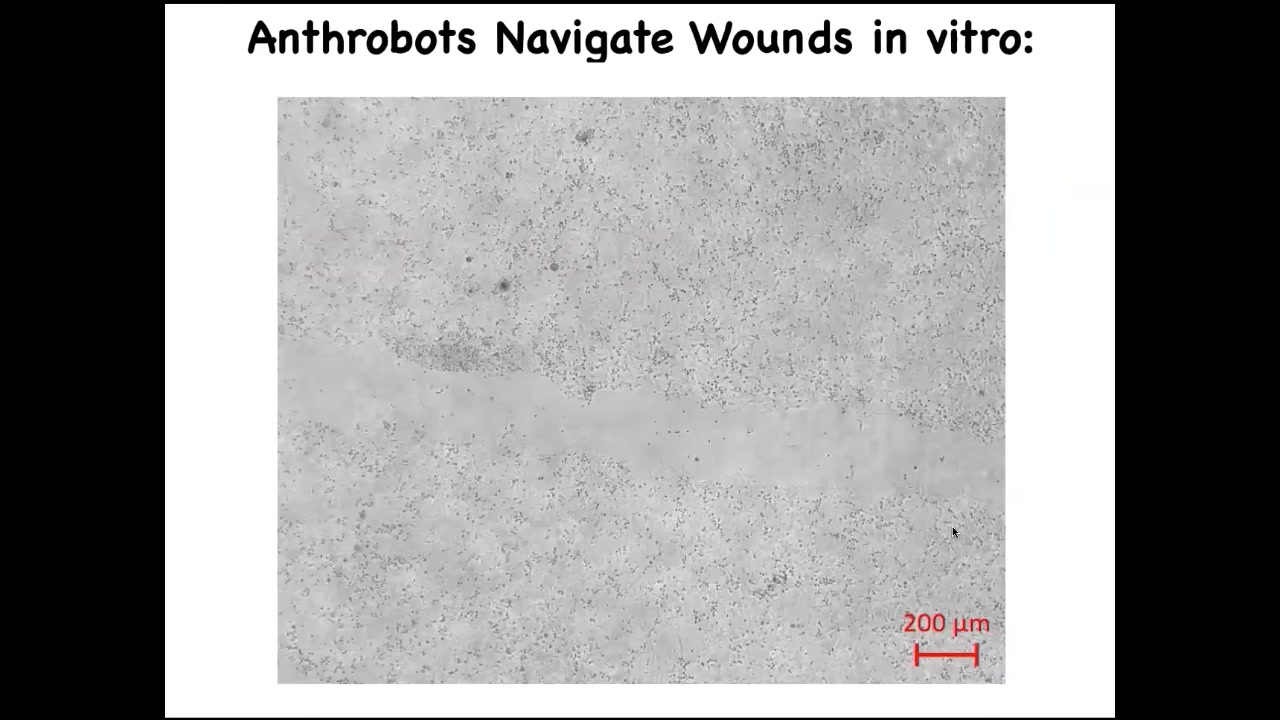

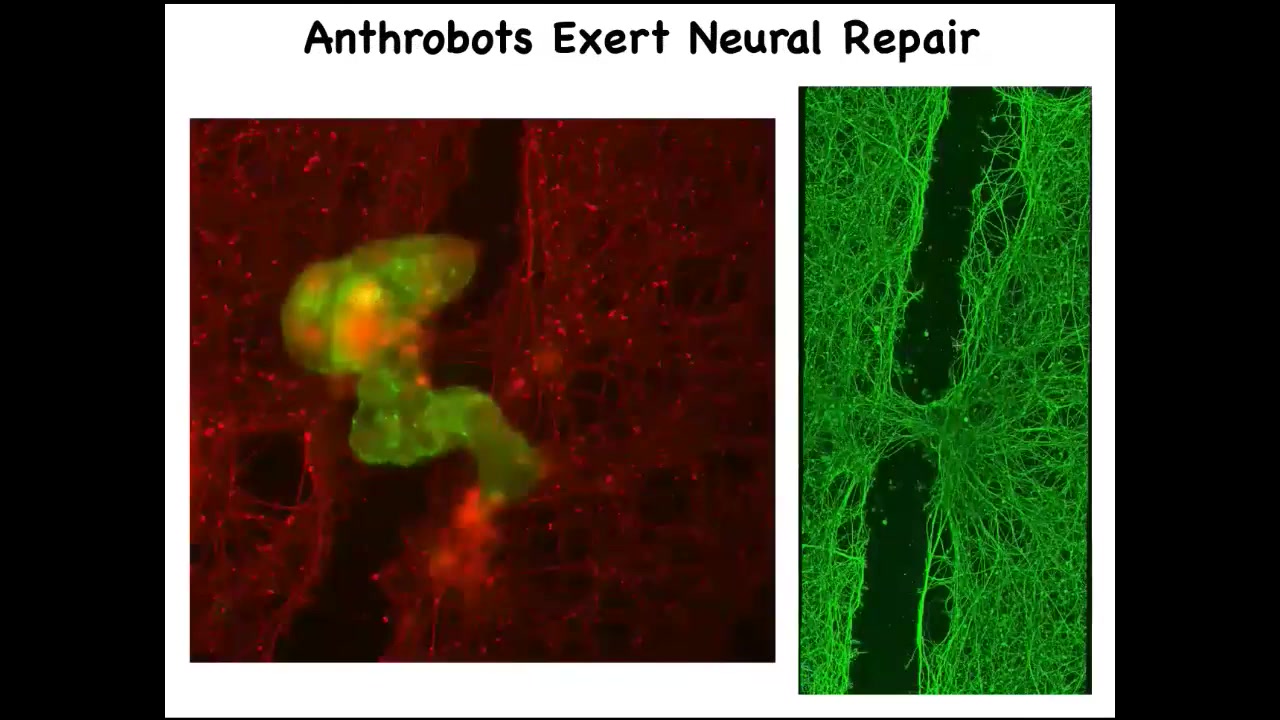

Here's one. If you plate human neurons here on this dish, and then you make a scratch, so a wound through this neural layer, here it is. So these anthrobots traverse it.

Slide 43/45 · 46m:03s

If you allow them to accumulate in a particular area across this neural scar, what you'll see is that they spend about four days knitting the sides together. When you lift it up, this is what it's doing. So who would have known that your tracheal cells, which normally sit there for decades quietly in your airway, are actually capable of having a kind of novel existence in the self-motile form with new competencies. Nobody would have known that they can heal neural defects if we hadn't tested the plasticity of these cells. What are they willing to do? What do they know how to do? This is just experiment one. Who knows what else?

Slide 44/45 · 46m:44s

So the bottom line here is that for biomedicine, the molecular approach of always going downwards in terms of descriptive models and the concepts that we're using gives rise to all of these techniques. But being able to look at the things that neuroscience is very good at, which is multi-scale kinds of interventions, that's been known for many, many years: you can look at the scale of the synapses and the proteins in the synapse, but you can also look at circuits and group dynamics and all of these other scales.

All of this now is on the table. And we've done a lot of work here on things that I've not shown you, really targeting. We've done cell training and things like that, really targeting these competencies by taking seriously the idea that intelligence is not something you can guess, but you have to discover. For that reason, I think that future medicine is going to look a lot more like a kind of somatic psychiatry than it's going to look like the chemistry of today.

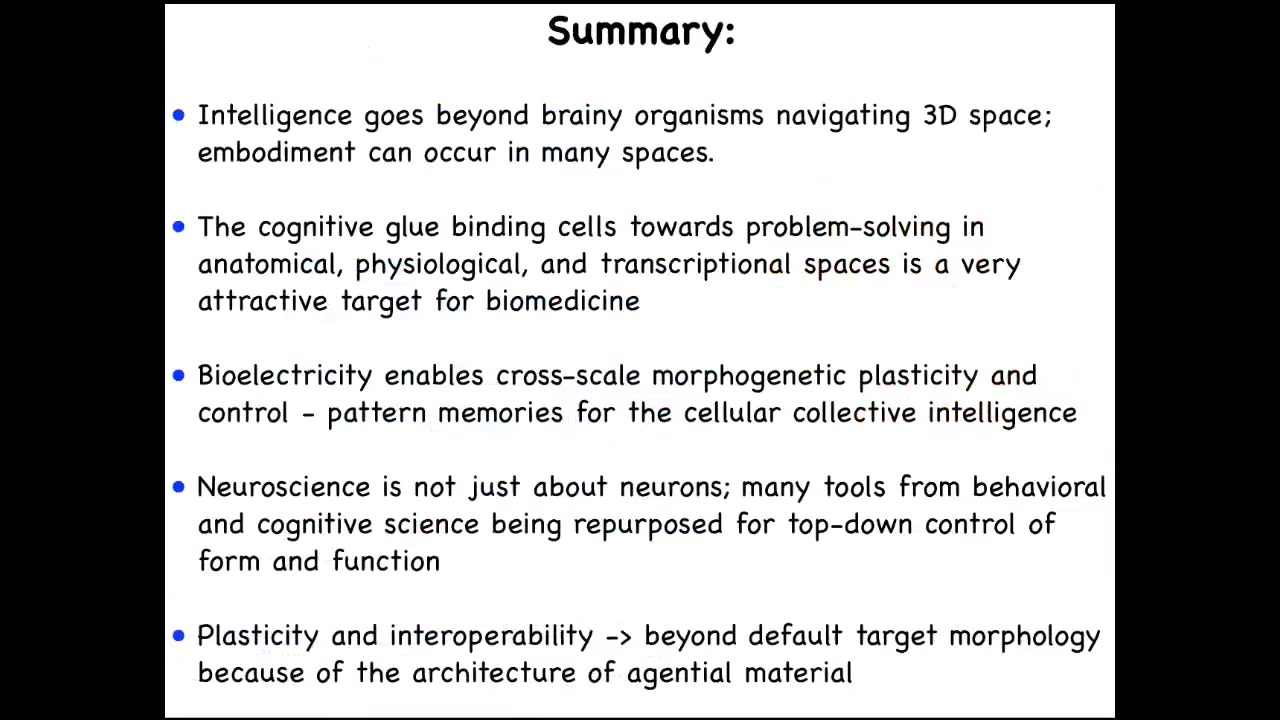

Slide 45/45 · 47m:47s

I think it's important to consider that intelligence can be deployed in many different spaces besides our familiar 3D space, that there's an attractive target for biomedicine in the mechanisms that bind cells together towards goals in higher scale spaces. Bioelectricity is a key element of this. I really think that the major, the deep ideas of neuroscience are not about neurons at all, and they have to do with cross-scale kinds of dynamics, problem-solving dynamics that evolution exploits at every level of structure. If you're interested in any of these things, there are lots of papers on this where I go into detail.

I will thank the postdocs and the students who did all this work, our many collaborators, our funders, three companies that fund our work, and always the animals because they do all the hard work. Thank you so much, and I'll take any questions.