Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a ~50 minute talk by me (given at IIT Mandi yesterday) on bioelectricity from the perspective of both, a path to regenerative medicine of birth defects, injury repair, and cancer, and a model system for learning to communicate with unconventional collective intelligences.

CHAPTERS:

(00:01) Introduction and anatomical compiler

(04:16) Intelligence across biological scales

(11:10) Morphogenetic intelligence and plasticity

(20:06) Bioelectric networks as interface

(26:05) Cancer and cognitive disconnection

(32:18) Reprogramming developmental anatomy

(39:11) Regeneration, morphoseuticals, and AI

(43:50) Anthrobots and future minds

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/42 · 00m:00s

Thank you for having me here. Today, I'm going to talk about the role of bioelectric networks as the interface to a new kind of intelligence, and in particular, the intelligence of the body. This has two major implications. One is the biomedical aspects, and the other is that this is a model system for how to identify and communicate with diverse intelligences that are not like us. If you want to follow any of the details, download the papers, the data sets, the software, everything is here at this site. This is my personal blog about what I think all of these things mean.

Slide 2/42 · 00m:40s

The main points that I would like to transmit to you today are these. First, I'm going to tell you about bodies as a multi-scale competency architecture that there is a problem-solving intelligence at every level, from molecular networks to organs to collections of individual animals. I'm going to claim that definitive regenerative medicine is going to require exploiting the collective intelligence of this material and the communication of anatomical goals to the agential material of life. I'm going to show you that bioelectrical networks are a very tractable interface for top-down control of anatomical outcomes.

We have tools now available to read and write the pattern memories into this proto-cognitive medium, and we're going to be able to re-specify what it is that the cells want to build. This is going to give rise to, and already has given rise to, applications in birth defects, regenerative repair of injury, and cancer. These things are now heading towards the clinic. The bigger context is that morphogenesis is an amazing model system for the study of diverse intelligence, learning to communicate with and relate to truly unconventional agents in novel embodiments.

Slide 3/42 · 01m:51s

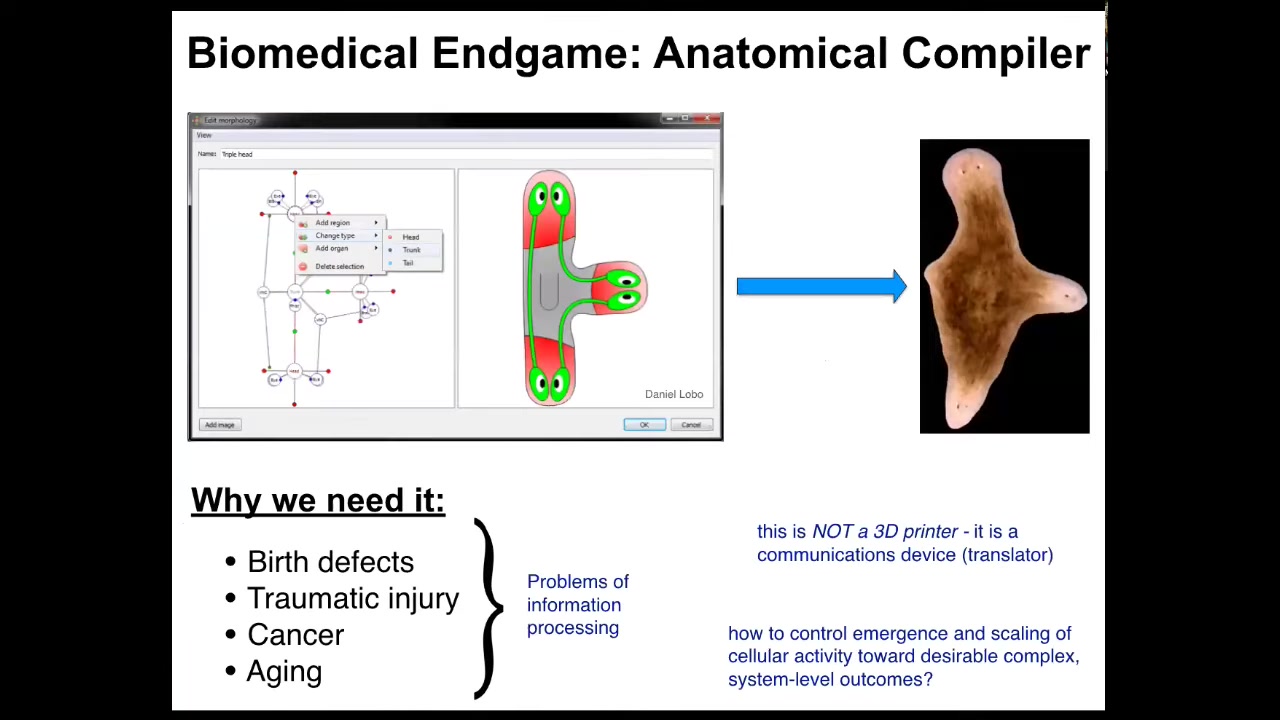

The first thing I want to start with is the end game. Where is this all going? Where's the field of regenerative medicine going? I think we can think about the place that we want to get to with the notion of an anatomical compiler. The idea is that someday you will be able to sit in front of a computer and draw the plant, animal, organ, biobot, whatever, draw any kind of a living construct. And what the system will do is compile that anatomical description into a set of stimuli that would be given to individual cells to get them to build whatever you want them to build. If we had something like this, all of these medical problems would go away. Birth defects, traumatic injury, cancer, aging, degenerative disease, this would all be gone because you could communicate to cells what you want them to build, healthy new organs. All of these things are really limited by the problem of communication and information processing. We do not know how to get cells to build specific structures. This is very important. This device is not some kind of a 3D printer where we're going to micromanage the properties of cells and tissues. It is a translator. It's a communications device.

Slide 4/42 · 03m:01s

We need this because currently in the field, this is what we're very good at.

Figuring out which proteins and genes interact with which other proteins and genes. At the cellular level and the molecular level, we have a lot of information.

We're a very long way away from being able to repair things like missing limbs and organs and having biomedical treatments that actually fix anything as opposed to suppress symptoms while you're taking a drug. That's because biomedicine and biology in general today are where computer science was in the 50s. You can see how she's reprogramming this computer by physically rewiring the hardware.

The idea is that modern molecular medicine is all about the hardware. Everything is done at the molecular level. All the exciting approaches are genome editing, protein engineering, and pathway rewiring. We're focused down into the lowest molecular hardware of life.

But we don't understand the software, the physiological software that underlies information processing in biology. In order to understand it and to take advantage of it for health applications, we need to understand the intelligence of the material that we're working with.

Slide 5/42 · 04m:15s

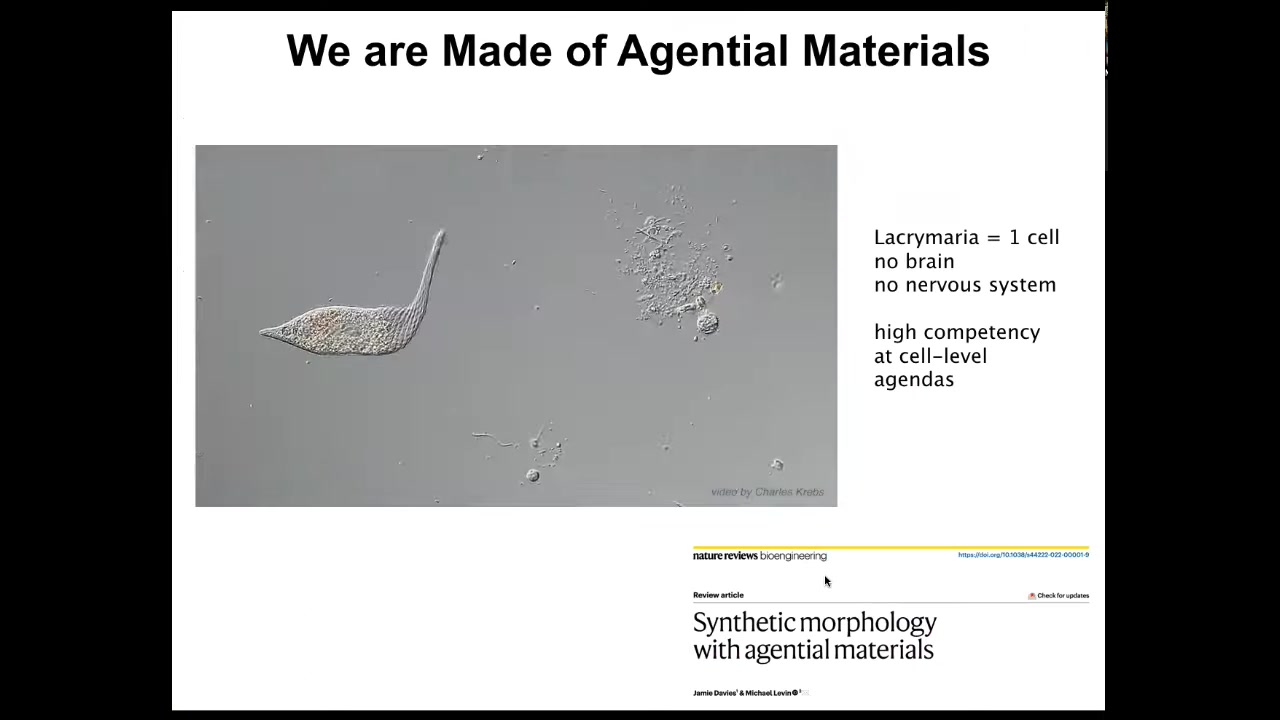

This is the thing we're made of. This is a single cell. This is an organism known as a lacrimaria, one cell. No brain, no nervous system, but extreme competency at its own tiny agendas.

We are all made of individual cells. Here, Jamie Davies and I talk about what it's like to engineer with this material. It's very different than engineering with metal and plastic. Completely different.

A set of tools is needed to engineer the material with agendas, in particular, because it's not even that the cells are where the intelligence starts.

Slide 6/42 · 04m:50s

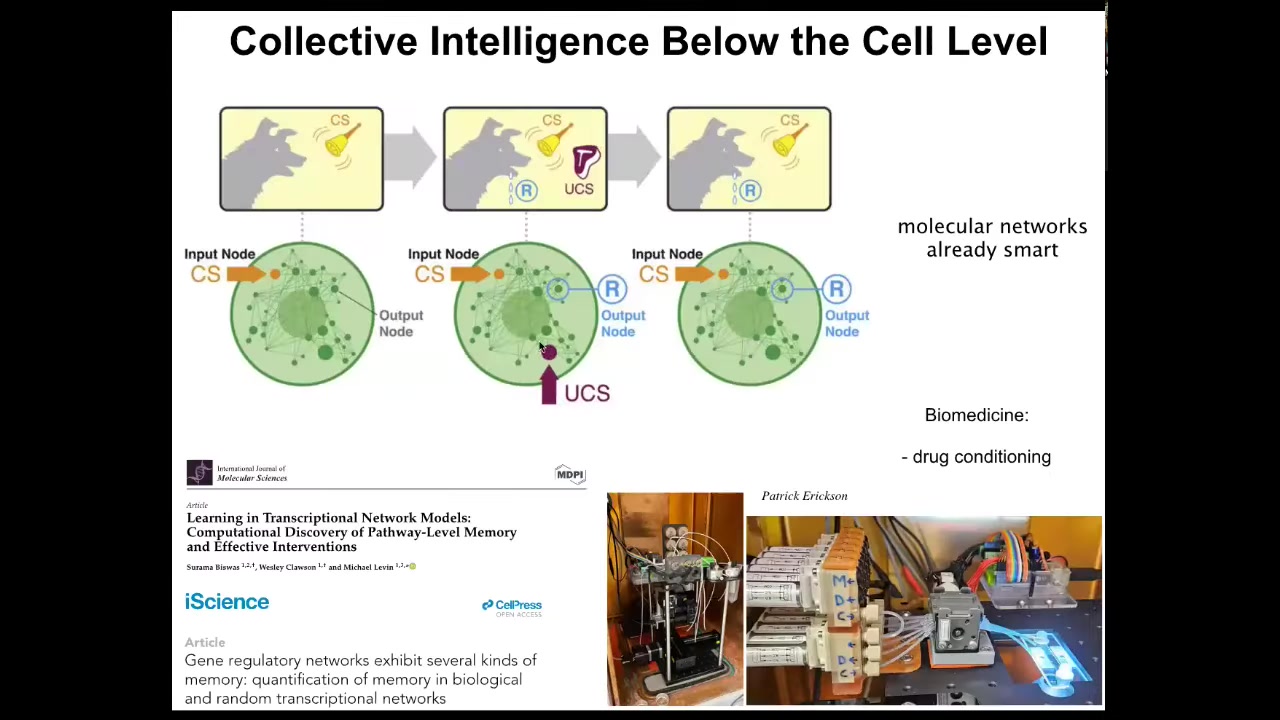

Even below the cell level, the molecular pathways inside of individual cells are already capable of six different kinds of learning, including Pavlovian associative conditioning. So we've shown this in a number of papers, and we're using this to train individual cells and molecular pathways in the lab for things like drug conditioning and other applications. The material has intelligence at every level.

Slide 7/42 · 05m:17s

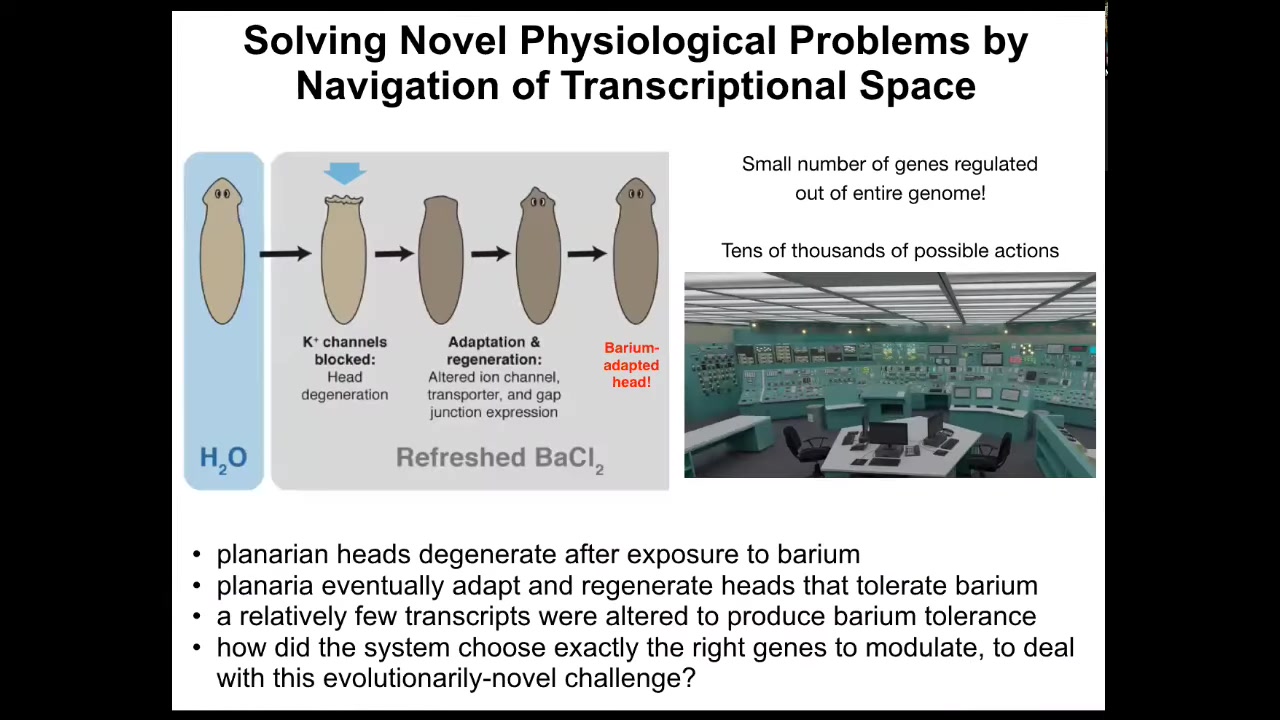

I can show you a few examples. Here's an example of problem solving at the transcriptional and physiological level. We have these flatworms, these planaria. You put them in a solution of barium. In barium, all the potassium channels are blocked. The head explodes. Literally, overnight, they lose their heads because the cells are so unhappy about not being able to pass potassium. But within a short time, it regrows a new head, and the new head is completely adapted to barium. It grows just fine.

What happened? We checked, and it turns out that these barium-adapted planaria expressed a handful of genes, about a dozen genes, differently than standard planaria. What this means is that under a new stressor, barium, which planaria have never seen before, these cells improvise a solution out of tens of thousands of possible genes. They very quickly identify a dozen genes to solve their problem. It's sitting in this nuclear reactor that's melting down. There are a million buttons. You don't have time to randomly try all the buttons to see what happens. You have to have some strategy for knowing what to do to solve your problem. Cells are very good at taking physiological stressors and using the tools at their disposal, including their genetics; their genome is a tool to be used. They improvise a solution.

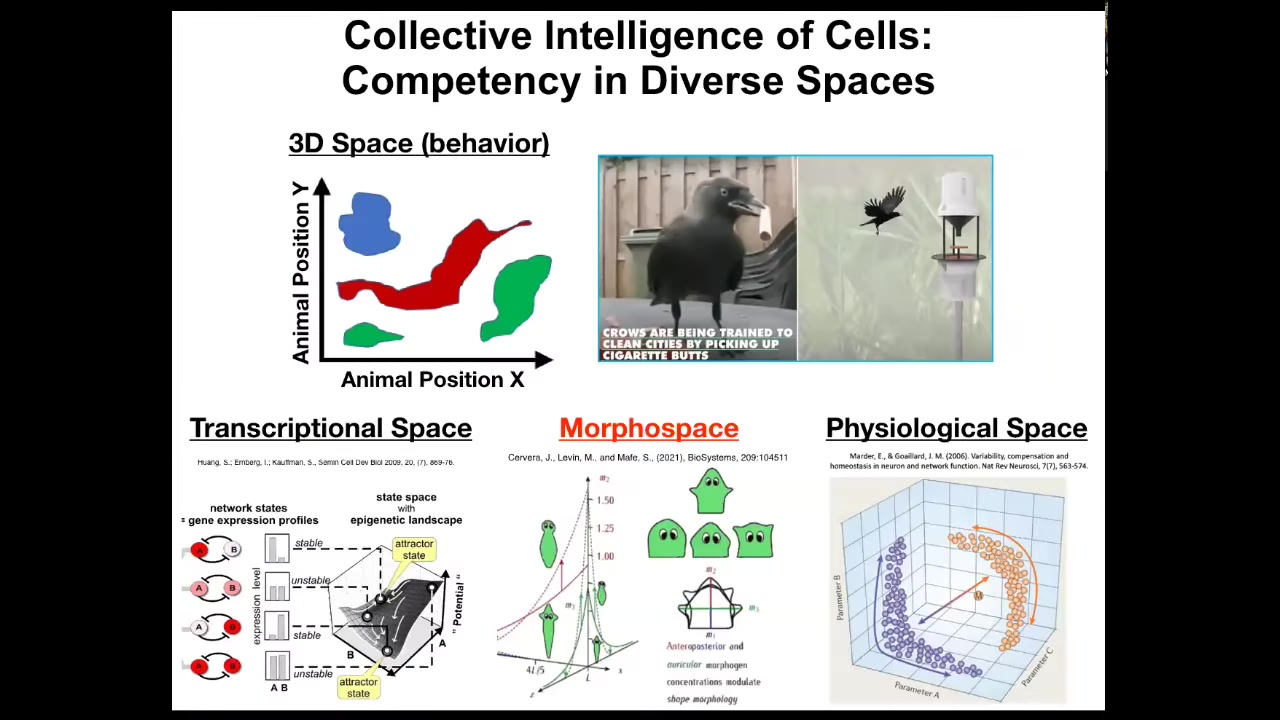

This happens in many different kinds of spaces. In your body, all the way from the molecular networks to the subcellular organelles to the tissues, all of these systems live in their own space, and they are able to navigate that space adaptively to solve problems, to learn, and so on.

Slide 8/42 · 06m:58s

And as humans, we're pretty good at recognizing intelligence in three-dimensional space, that is of medium-sized objects moving at medium speeds in 3D space, like birds and primates. But we're really not very good at noticing intelligence when the body is very large or very small or very fast or very slow. Our own evolutionary firmware limits what we natively can see.

And biology uses all of these other spaces. It navigates transcriptional space, the space of physiological states, the space of possible anatomical states. This is the one we're going to talk about today, the most anatomical morphospace. So I'm emphasizing the idea of biology not as a set of mechanical, open-loop processes, but actually as systems that are primarily navigation systems that are moving around in various spaces and trying to achieve specific states within those spaces, aka they have goals and they have different competencies of reaching those goals.

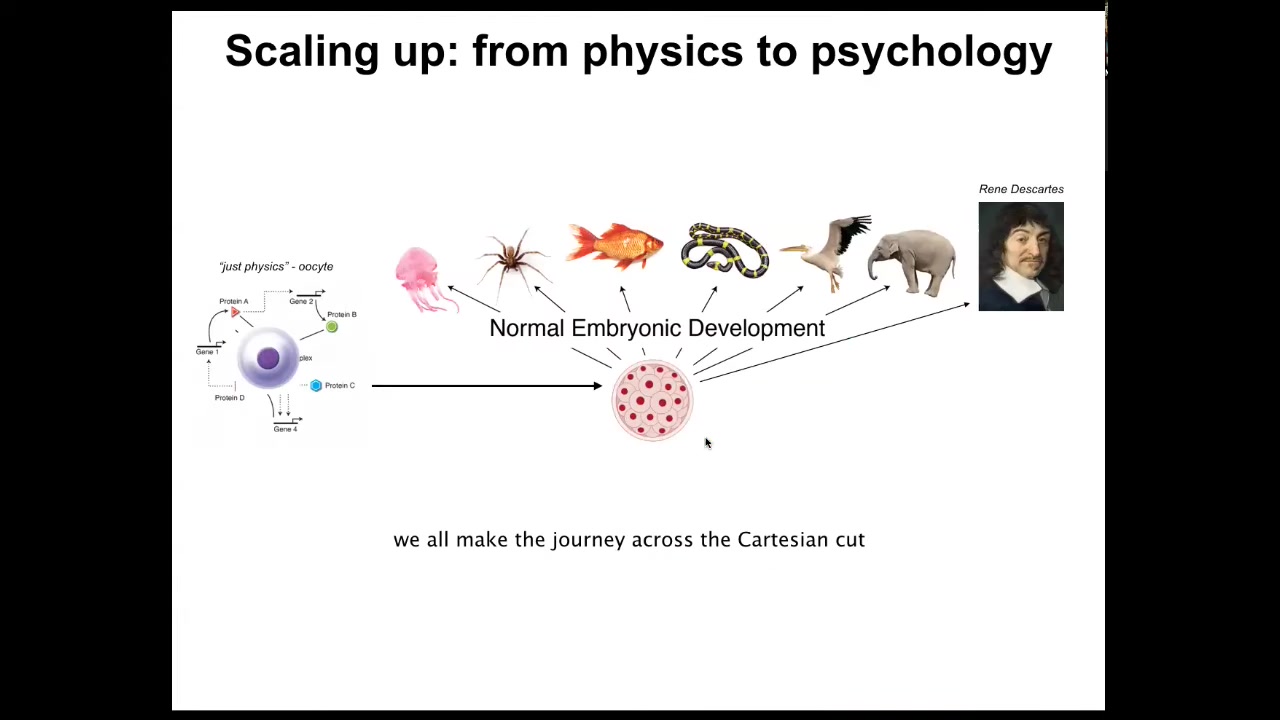

Slide 9/42 · 08m:00s

And this is the journey that we all took. We all started life as a little unfertilized oocyte, a quiescent little BLOB of chemicals. Then gradually, we become one of these things, or maybe even something like this. Incredible complexity. But you'll note that in development, there is no magic time point at which we suddenly become a mind. This is slow and gradual. It's not an issue of categories of dumb matter versus intelligent beings. This intelligence is baked in at the very bottom into the molecular networks that underlie even cells. And it's a gradual process of scaling up, expanding the cognitive light cone, projecting it into new spaces as you leave the domain of physics and chemistry and you enter eventually the domain of behavioral science, psychiatry, psychoanalysis, and so on.

Slide 10/42 · 08m:56s

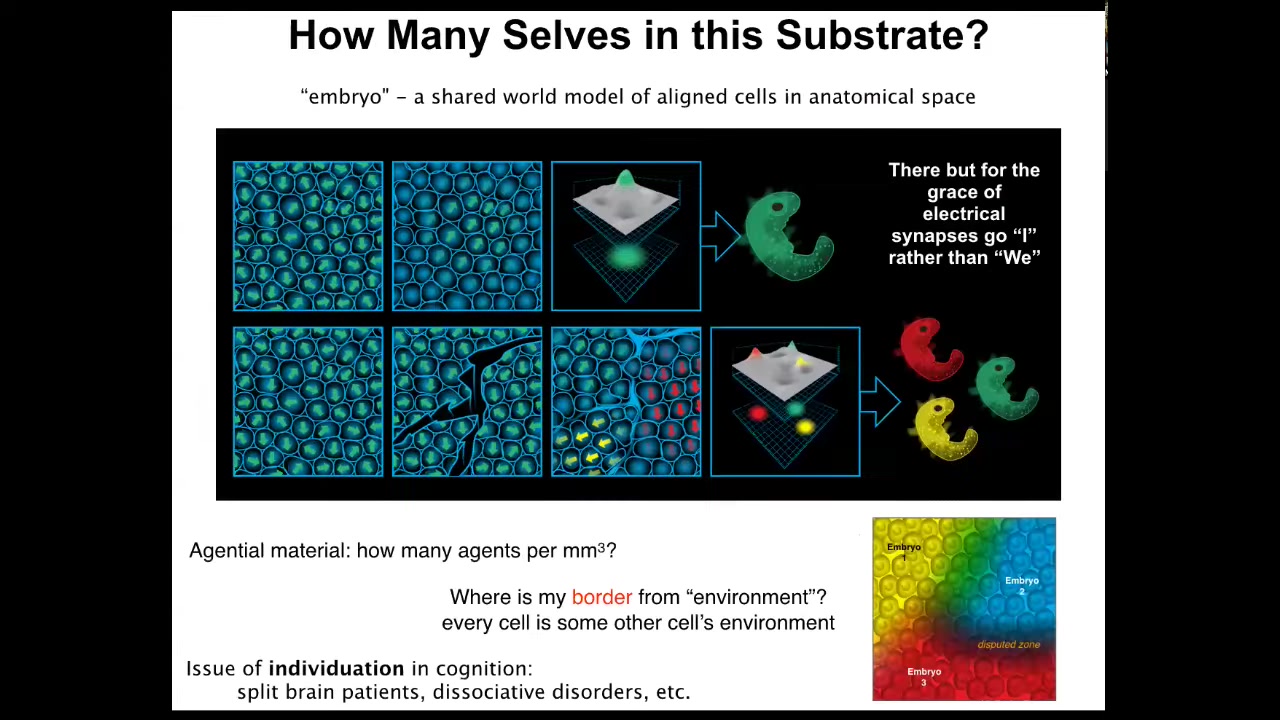

What happens is that these embryos self-organize. It's interesting to ask how many individuals are within a single embryo and what is an embryo?

Here's an embryonic blast that is maybe 100,000 cells at this point. The reason we call this an embryo and not just a pile of cells is because of alignment, both physical alignment, but more importantly, teleological alignment: these cells are all committed to the same goal, the same story of what they should be doing, where they should be going in anatomical amorphous space. An embryo is a shared world model. That's what it is. That convinces all of the cells that they're going to work together to one particular outcome.

But if we make scratches in this blastoderm, each of these islands actually becomes its own embryo. This has been known for a long time. All of these cells will self-organize and eventually you will get twins, triplets, and so on. So the question of how many individuals, how many minds can emerge out of this blastoderm is not fixed by the genetics. It is a dynamic thing. Just like bodies self-organize out of an excitable medium, they each acquire the cognition that is needed to navigate this world. It can be anywhere from zero to half a dozen or more distinct individuals that can form out of this one blastoderm.

This raises questions about the maximum carrying capacity, like how many human minds can actually be produced out of a single embryo. It also links to issues of the same kind of thing in cognition. In other words, split brain patients, dissociative identity disorders, and how many different minds can inhabit the same brain. That's basically the same question here.

So developmental biology is at the very center: not only is it a requirement to understand for things like regenerative medicine, but also for deep questions of mind. What are we, where did we come from — all of this has its root in the self-organization of the material substrate of life and mind.

Slide 11/42 · 11m:10s

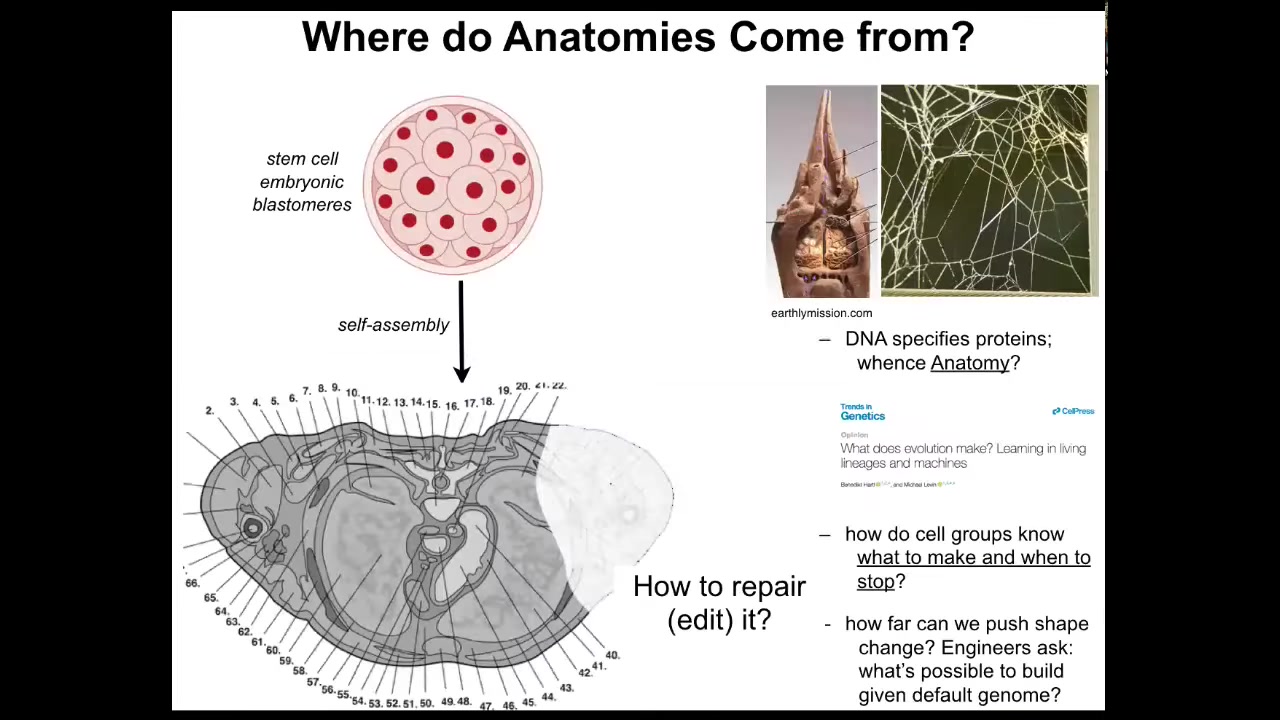

So these anatomies, we need to understand where they come from. Here's a cross-section through a human torso. You can see amazing detail, everything is in the right place, next to the right thing, the right size and shape. We start as a bag of embryonic blastomeres. Where is this shape coming from? How do the cells know what to do? A lot of people will immediately say the genome, but we can read genomes. Now we know that the genome doesn't directly say anything about any of this. The genome specifies proteins, the tiny molecular hardware that every cell gets to have. We wrote this paper recently talking about what the genome actually is. The genome doesn't specify this any more than the termite genome directly specifies the structure of the termite nest or the spider genome tells you the shape of the spider web. These are all software outputs. The genome specifies the hardware.

We need to understand how that software works. How do cells know what to make and when to stop? If something is missing or damaged, how do we repair it? As you'll see at the end of this talk, as engineers, we'd also like to ask, what are the limits of plasticity? The exact same cells with the same genome, what else can they be induced to build?

I think the answer to all of these questions lies directly through the concept of intelligence.

Slide 12/42 · 12m:38s

What I mean by intelligence is this. It's William James's definition. It's the ability to reach the same goal by different means. It's a very cybernetic definition. It doesn't say you have to have a brain. It doesn't say what kind of goals they are. They don't have to be in three-dimensional space, and they can be in other kinds of spaces. But it's the degree of ingenuity you have to reach your goal state when things change and in novel circumstances.

What kind of collective intelligence do cellular swarms deploy? I call it a collective intelligence because we are all collective intelligences. In fact, all intelligence is collective intelligence because it's made of parts. We are made of many different cell types, including neurons. We know things that our individual cells don't know because of the process of collective intelligence and the cognitive glue that binds them together and aligns them toward a single world model and a self model. I'll show you that bioelectricity is one of those important cognitive clues.

Let's talk about morphogenetic intelligence. First, we know that development is very reliable. Most of the time, from an embryonic state you get exactly the species-specific target morphology. This is not why I call it intelligence. It is not because it's reliable. It is not because there's an increase in complexity. Those things are very cheap. It's really easy to have systems that reliably have some kind of outcome and raise complexity while they're doing it. Intelligence is the ability to meet your goal when things change.

The first thing we know is that we can cut embryos into pieces and you don't get half embryos; you get perfectly normal monozygotic twins and triplets, and so on. We know that embryos can navigate that anatomical space and reach this ensemble of goal states despite perturbations and local minima. When you start them in different positions, they will do what's needed to move through that space and get where they're going. This is a system that can get to the same outcome from different starting positions.

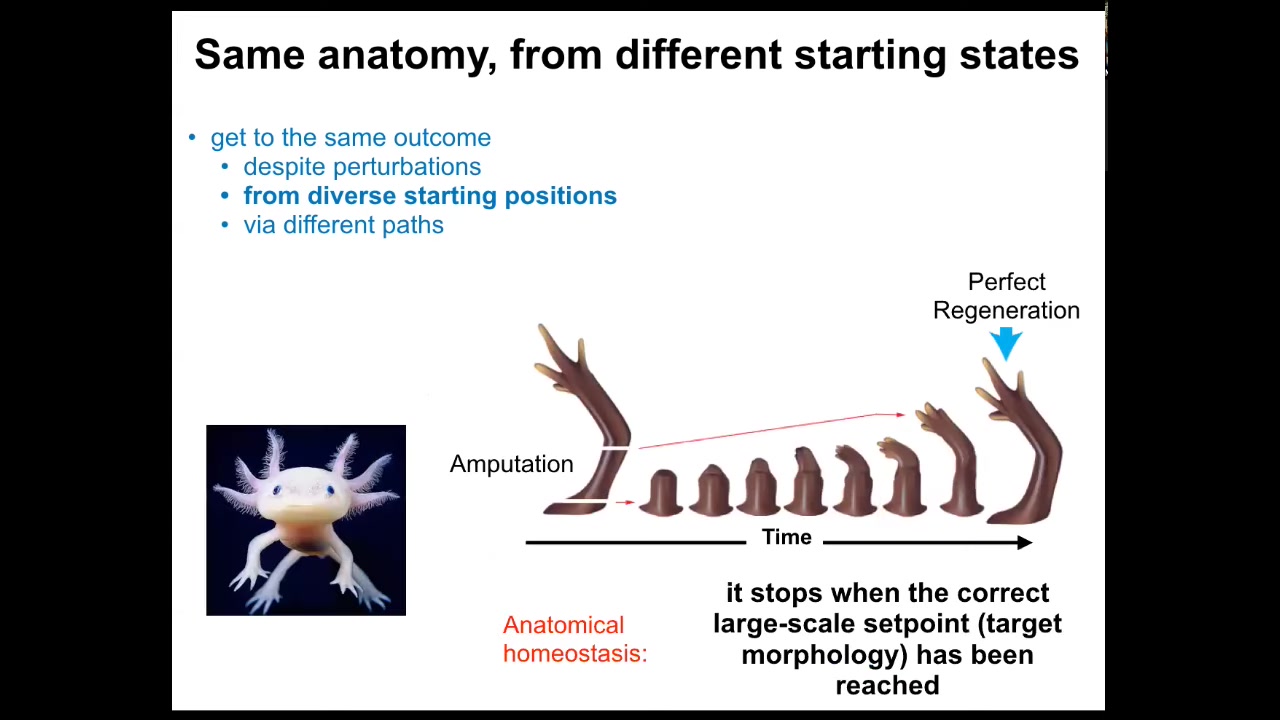

Slide 13/42 · 14m:42s

In fact, some systems can do it throughout their life. This is an axolotl. This amphibian regenerates its eyes, its jaws, its limbs, its spinal cord, portions of the brain and heart. Here you can see what happens. If it's amputated anywhere along the length of this appendage, the cells immediately can tell that something's different. They've been deviated from their point in morphospace, from their goal state. They will grow very quickly. They will make the correct pattern, and then they stop. When do they stop? They stop when the correct salamander or other animal limb has been produced.

This is an example of anatomical homeostasis. It's a system that has a goal state. When you deviate it from that goal state, it will do its best to get back to that goal state. It reduces the error between where it is and where it wants to be. It knows where it wants to be because once it gets there, then everything stops; remodeling and growth stop.

Notice that this is not just about repair, and it's not just about damage. It's a much more interesting system. If you take a tail from an amphibian and graft it onto the flank, what you will see over time is that it actually transforms into a limb. The cells at the end of the tail, which are locally perfectly fine, they're tail end cells sitting at the tip of a tail, but they become fingers. This whole thing remodels. It's a non-local event. There's nothing wrong up here, but all of them remodel because it seeks to be within the correct overall morphology with the rest of the animal, and being a tail in the flank is not it.

You have the situation of anatomical homeostasis, where the local order here obeys a global plan. This is really critical in all cognitive systems. The whole point is to guide the parts towards large-scale goals that they don't know anything about. It's a kind of a top-down control system.

Slide 14/42 · 16m:34s

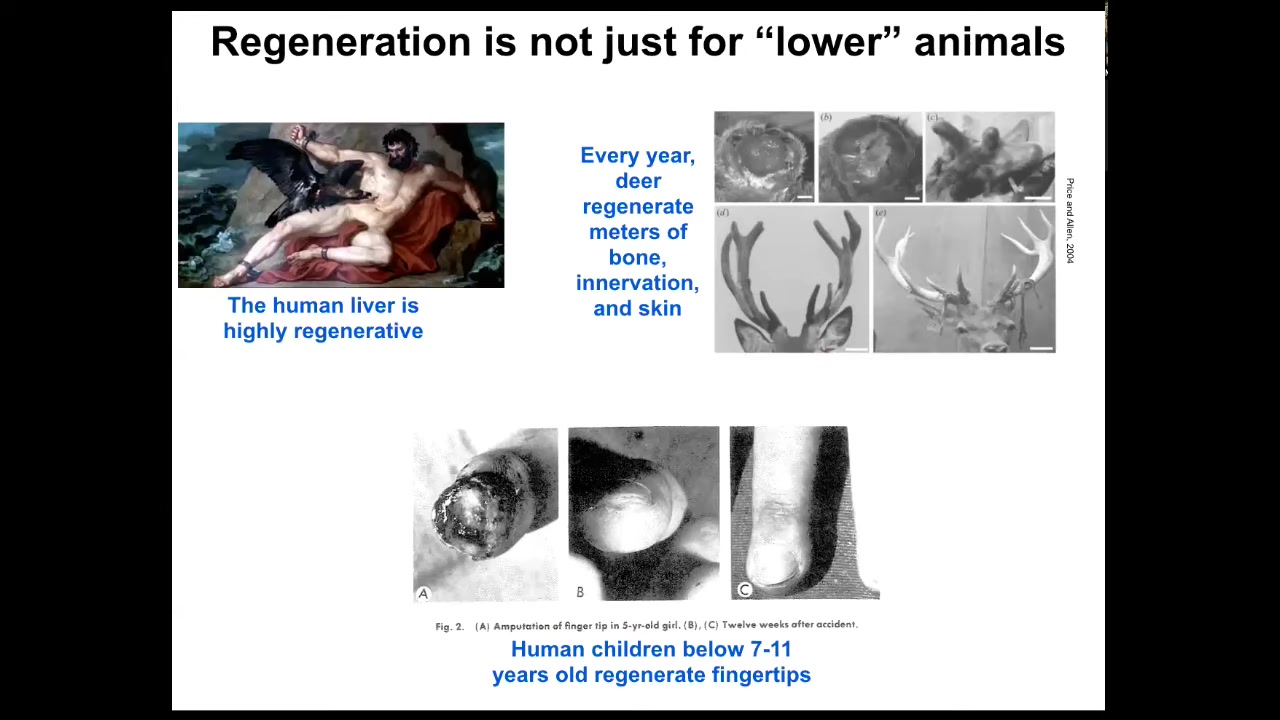

This regeneration is not just for so-called lower animals. Mammals can do it somewhat. Humans regenerate their liver. Even the ancient Greeks knew that. I have no idea how they knew that, but they did. Deer regenerate every year huge amounts of bone, innervation, and vasculature as they regrow. They can grow a centimeter and a half of new bone per day. It's an amazingly rapid process. Even human children below a certain age tend to regenerate fingertips. If they lose a fingertip, you don't need to do anything. They will regenerate and often have a very good cosmetic outcome. We have a little bit of this property and our goal is to enhance this for biomedicine.

Slide 15/42 · 17m:14s

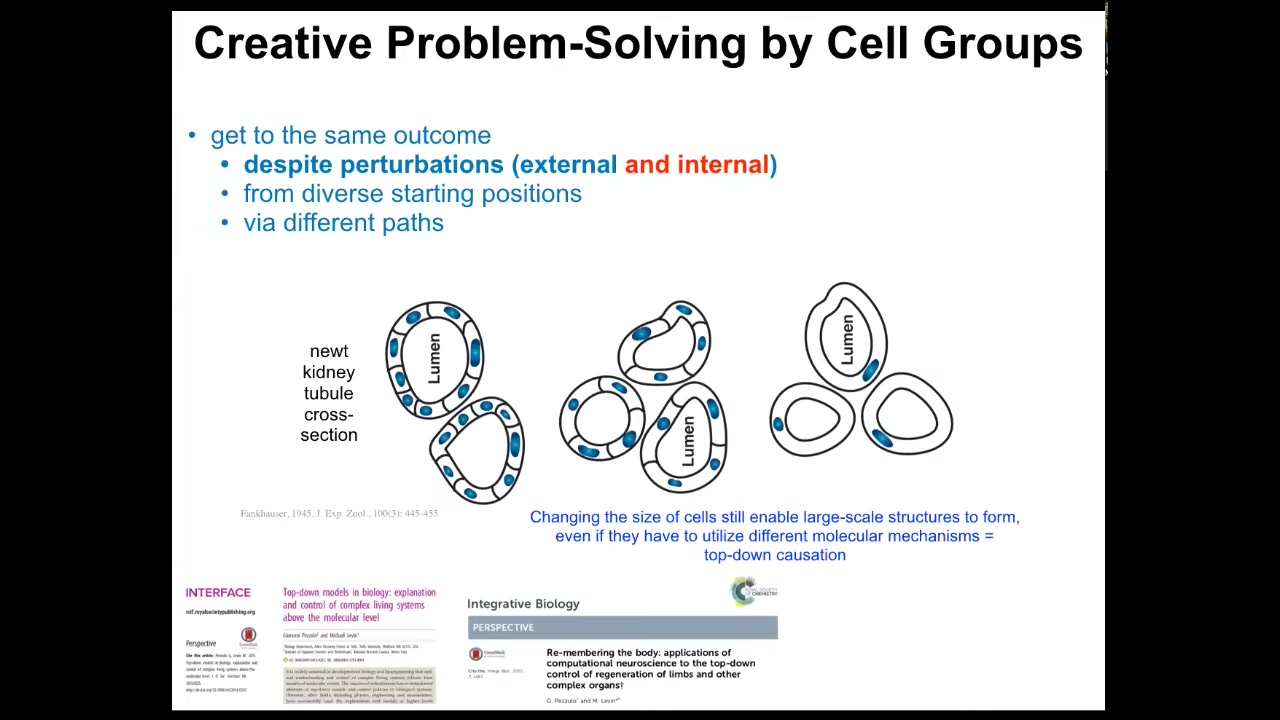

I've shown you a couple of examples of this intelligence. This is perhaps my favorite. It's the idea that living things have to respond not only to external perturbations, such as injury, but they also can't trust their internal parts.

Over time — that's for two reasons: biology uses an unreliable medium. As a cell, you never know how many copies of any molecule you have, or whether your genes have been mutated through lineages.

Here's my favorite example. This is a cross-section through a kidney tubule in the newt. Normally, 8 to 10 cells work together to form this structure with a lumen in the middle. One thing you can do is make newts with extra copies of their genetic material. If you do that, the nuclei get bigger, the cells get bigger to accommodate, but the newt stays the same size. That's because fewer, bigger cells will make exactly the same structure.

The first amazing thing is that it doesn't matter how many copies of your genetic material you have. You have extra instructions. You still get a normal newt. If your cells are bigger, the size of the organ adjusts to the cell size.

And then the most amazing thing happens when you make truly gigantic cells. When the cell gets so big that only one cell will fit, it bends around itself, leaves a hole in the middle, and gives you the same large-scale structure.

On the one hand, this is remarkable because this is a kind of top-down causation that is the hallmark of any IQ test. The idea is that in the service of your goal — making this structure — you pick different molecular mechanisms: cell-to-cell communication, cytoskeletal bending. In this case, you use different mechanisms at your disposal to solve the problem. This is standard IQ-test stuff. You're given a set of objects and told, "These are the tools you have." Try to make something happen out of these tools creatively.

This is a remarkable example of creative problem solving, because think of what this means. If you're an embryo coming into the world, what can you count on? You can't count on your environment. Who knows what's going to happen there? You can't even count on your own parts. You don't know how many copies of your genome you're going to have. You don't know how big your cells are going to be. You don't know how many cells you have. You still have to get the job done regardless.

This is one of those examples of the amazing plasticity of the living material to reach its goals. Later in this talk, I'm going to show you what it does when those goals are completely unreachable. What it does is find new goals, but I'll show you that.

In the meantime, it's able to reach its goals by reusing the tools it already has in novel ways.

We can ask, how is all this happening? How are cells cooperating and coordinating together to solve these problems and to reach goal states? What could it mean mechanistically for a set of cells to have a goal and try to meet it?

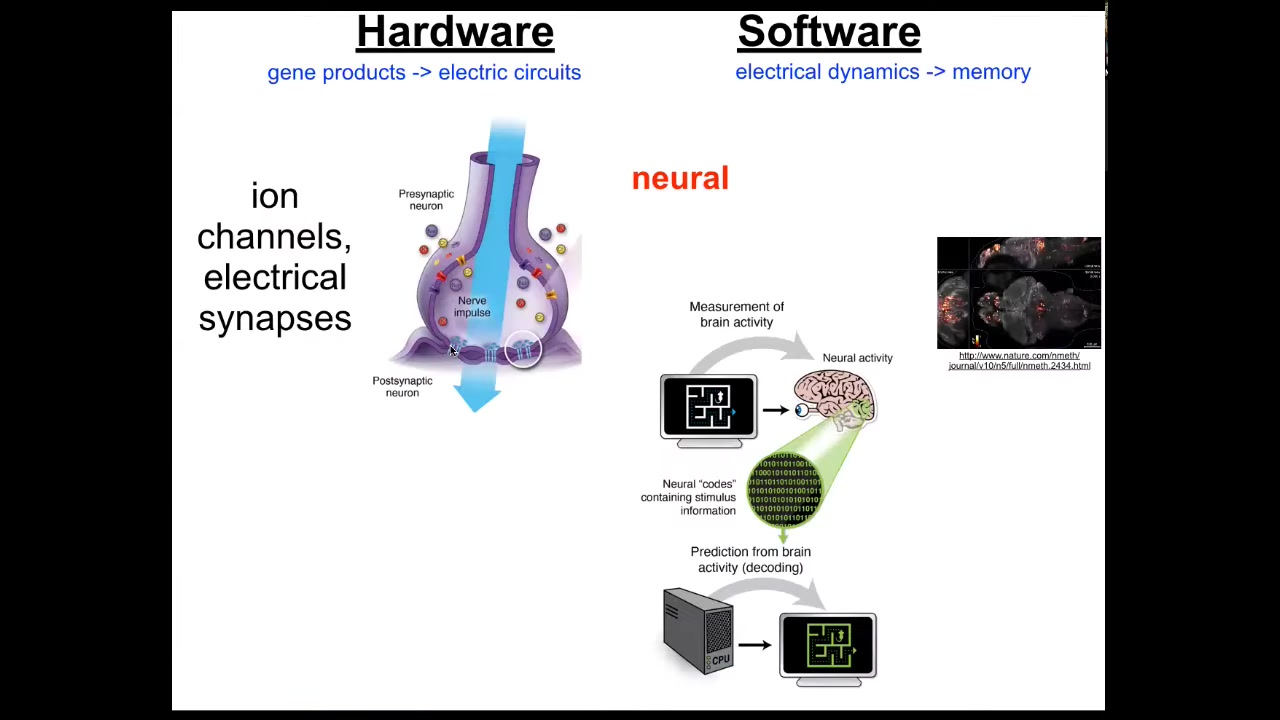

Slide 16/42 · 20m:18s

We have an example of this in neuroscience. We already know that as a neural, brainy organism, you have a set of cells that can keep goals and pursue them, and that's your brain. The way that works is there's this hardware, which is basically a network of cells that have little proteins in their membrane called ion channels. They use ions like potassium, sodium to establish a voltage gradient between inside and outside. That gradient can propagate to their neighbors through these electrical synapses known as gap junctions. That's the network. That's the hardware.

The software is this amazing electrophysiology. Here it is in a living zebrafish brain that underlies all the decision-making of the system. There's this project of neural decoding where neuroscientists hope that by recording and then decoding the electrophysiological activity, they will have access to interpreting the memories, the preferences, the goals. All of the cognitive aspects of the animal or the human patient are encoded in this electrophysiology.

It turns out that evolution discovered this amazing system long before brains came on the scene. Every cell of your body has ion channels. Most of them have gap junctions to their neighbors. We can, and have done for some years, try the same project of decoding the electrophysiology of your body to understand what the somatic intelligence is thinking about.

We know what your neural intelligence thinks about. In animals, it thinks about moving them through three-dimensional space. But your bioelectric networks of the rest of your body, which were discovered around the time of bacterial biofilms, are incredibly ancient in evolution; what they think about is how to move the configuration of your body through anatomical space.

Slide 17/42 · 22m:12s

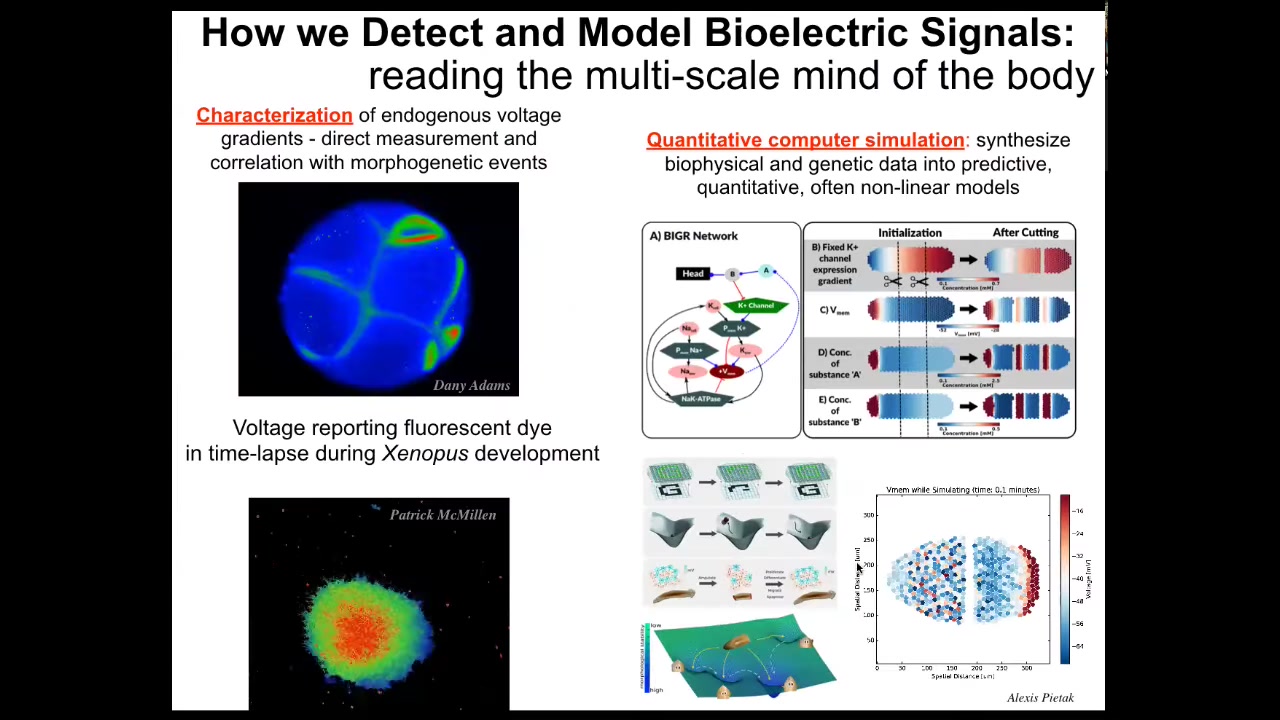

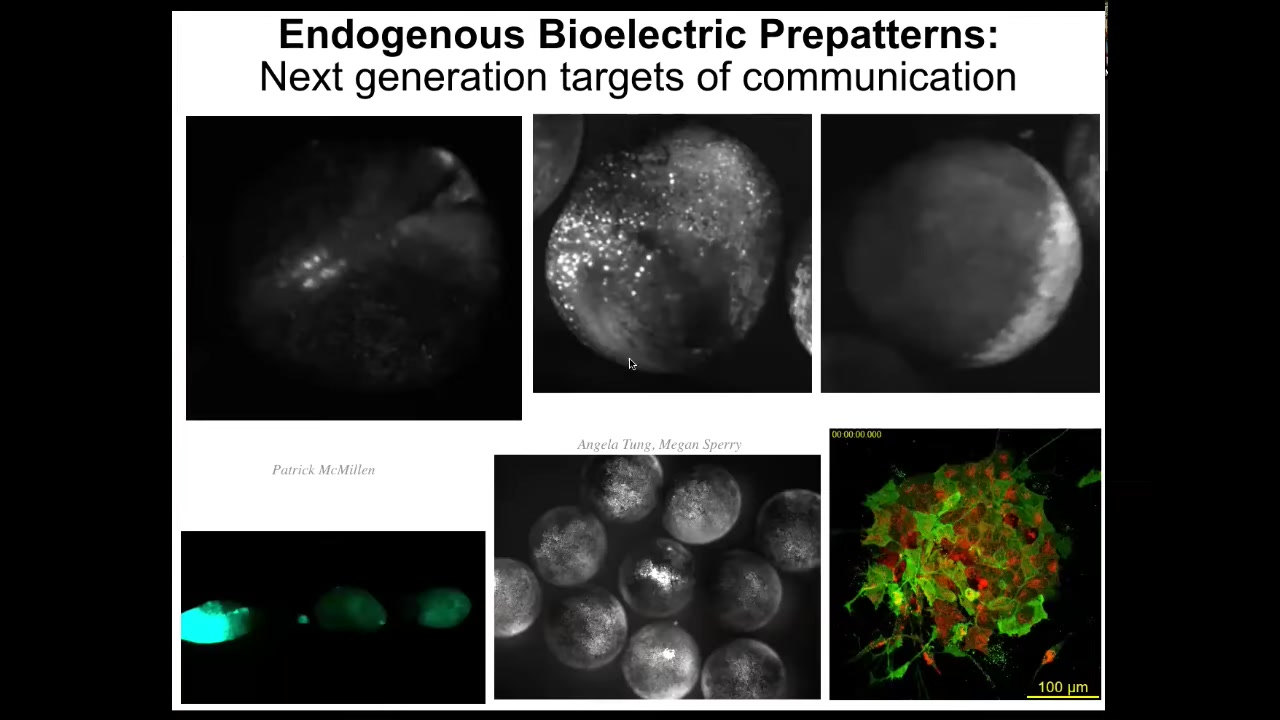

We've developed some tools. First, voltage-sensitive fluorescent dye imaging to be able to read and write these, or to detect changes in these electrical properties of cells.

The idea is that we can scan, here's an early frog embryo, here are some cells in the dish making decisions as to whether they're going to join this mass or crawl off. The colors represent voltage. These are not models; this is real data. We're able to now watch all the conversations that cells are having with each other in all the electrical patterns that occur.

We do a lot of computer simulations connected to the molecular biology of which channels and pumps are expressed. The quantitative simulation at the tissue level is then connected to ideas in, for example, machine learning, such as pattern completion or regeneration, where you can see here's what the network remembers and, when parts are missing, how it can restore that memory.

Slide 18/42 · 23m:08s

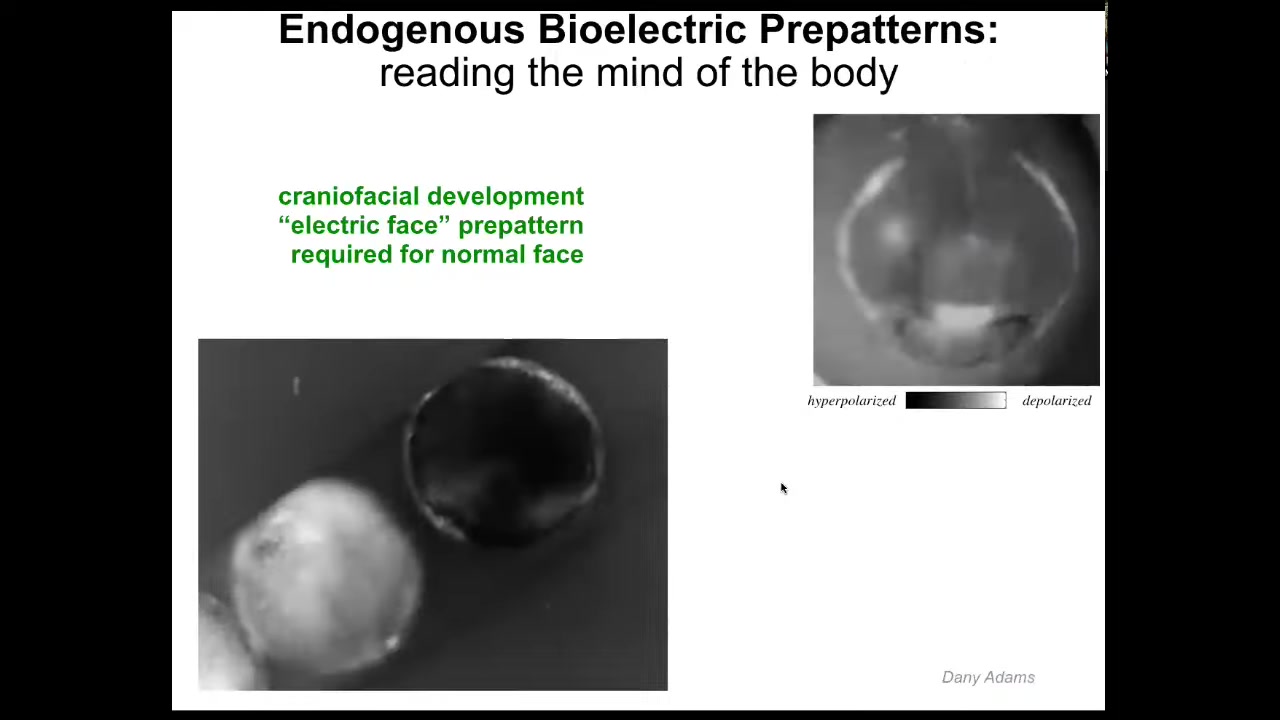

Let me show you a couple of specific patterns. This is what we call the electric face.

This is an early frog embryo putting its face together in time lapse. What you can see here, again, is that the color and the grayscale are different levels of voltage. What you see here is there's a lot going on, but this is one frame. Even before the genes turn on to regionalize the face, you already have a subtle scaffold, a pre-pattern, an energetic pre-pattern to the anatomy that says, here's where the eye is going to be, here's where the mouth is going to be, here are the placodes. This tissue already knows what a frog face looks like. If you change this pattern, then everything downstream—gene expression and anatomy—will follow.

Slide 19/42 · 23m:50s

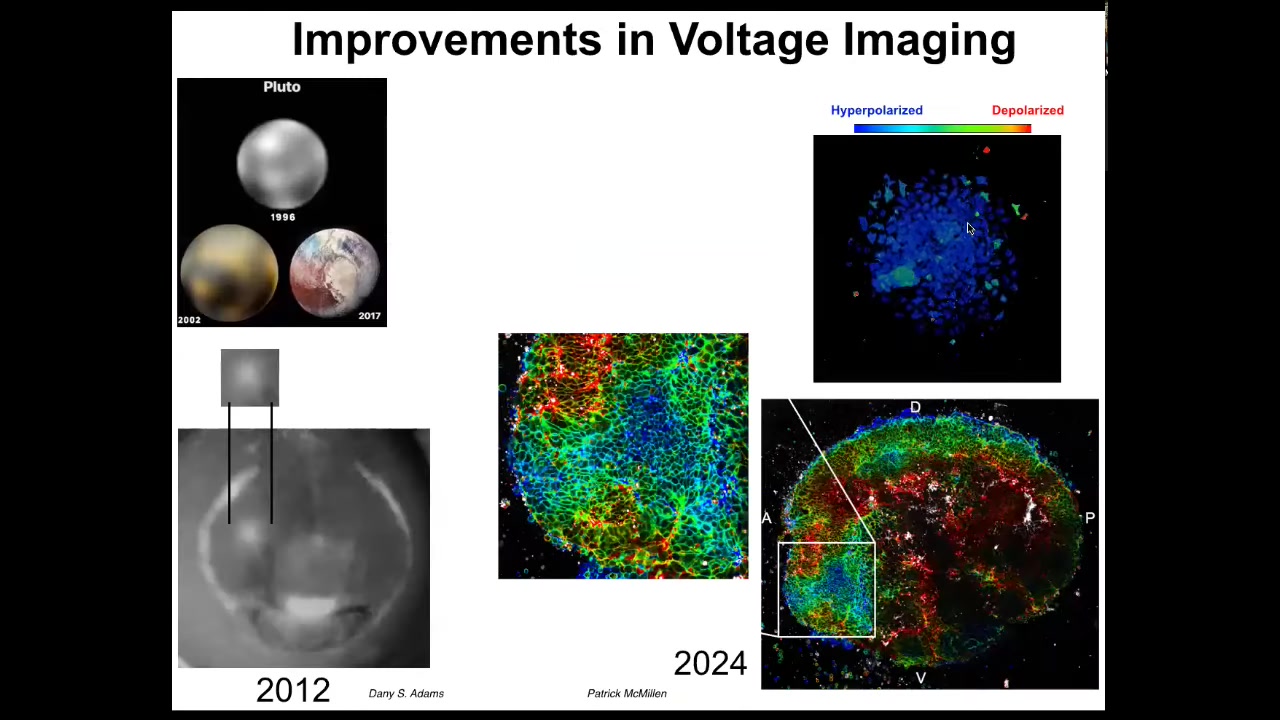

These improvements in voltage imaging have been amazing. I like this as an example. In astronomy, in 1996, this is what we had for Pluto. This was the best image we had for Pluto in 1996. By 2002 it looked like this, but by 2017 it looked like this. This is Pluto at the edge of our solar system.

This imaging is the same thing. This is what an eye spot looked like in 2012. Now we have imaging that looks like this, where we can see individual cells, we can track the voltage, and we can see the incredible complexity of the data that are actually being processed by these tissues.

Slide 20/42 · 24m:31s

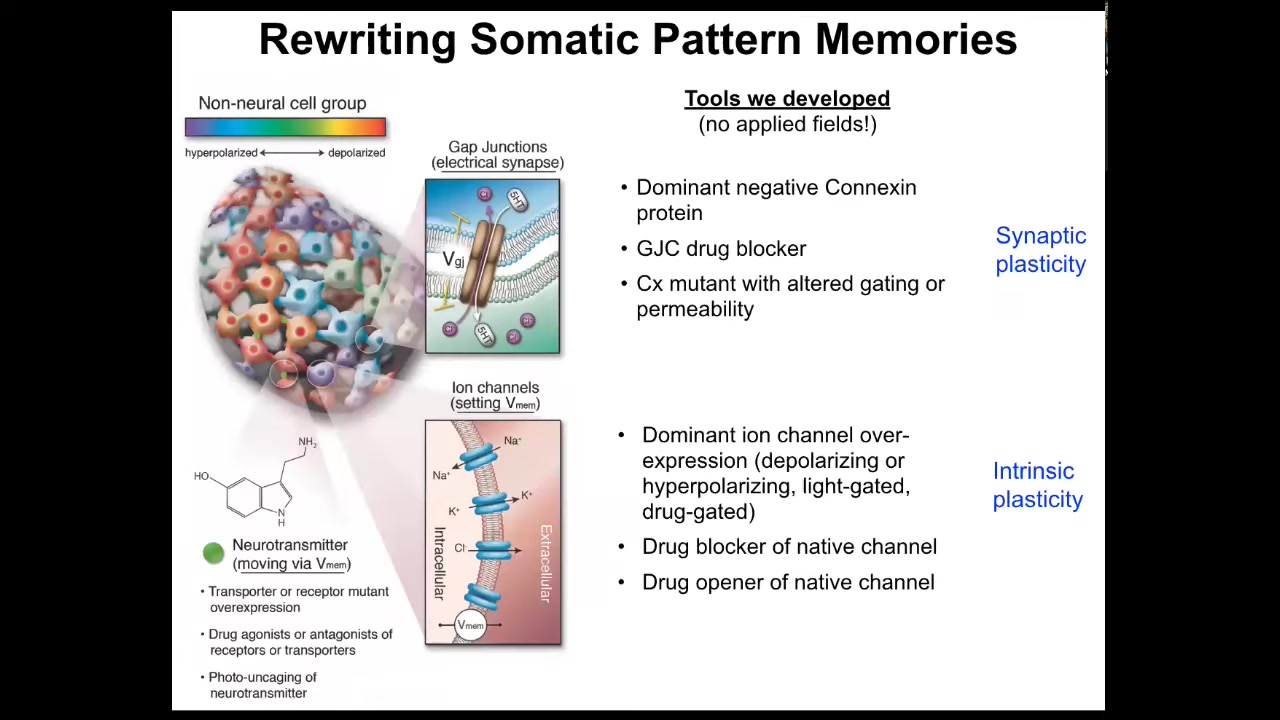

But tracking these patterns is not sufficient. You need to be able to change them. It's not just about characterizing what happens. You need to be able to write the information in.

The way we do that is we use no applied fields. There are no waves, frequencies, electromagnetic radiation, no magnets, no electrodes. What we do instead is manipulate the interface that cells are normally using to control each other. Here are the electrical synapses between cells and we can open and close them. And here are the actual ion channels that set the voltage states, and we can open and close them using drugs, optogenetics, or introducing mutant channels that have different properties. We steal all the tools of neuroscience because this is fundamentally the same problem.

One of my arguments is that neuroscience is not about neurons at all. It's about the scaling of intelligence from cells to larger collectives. All of the tools of neuroscience — the bench tools, the techniques, and the concepts, everything from active inference, perceptual bistability, memory models — can be remapped onto developmental biology. It all works the same way. Because what evolution did in creating the neural phenomena that we're used to is sped-up bioelectrical signaling. So instead of minutes, things in the brain take milliseconds. It projected into a new space; in addition to navigating anatomical space, once you have nerve and muscle you can navigate three-dimensional space, but everything else is the same.

Now it's time for me to show you what you can actually do with this, because I claim that this bioelectrical interface and this way of thinking about bioelectrical signaling as the cognitive glue that binds individual cells toward larger purpose is an amazingly useful interface to make some changes that are important for medicine. I'm going to show you those.

Slide 21/42 · 26m:29s

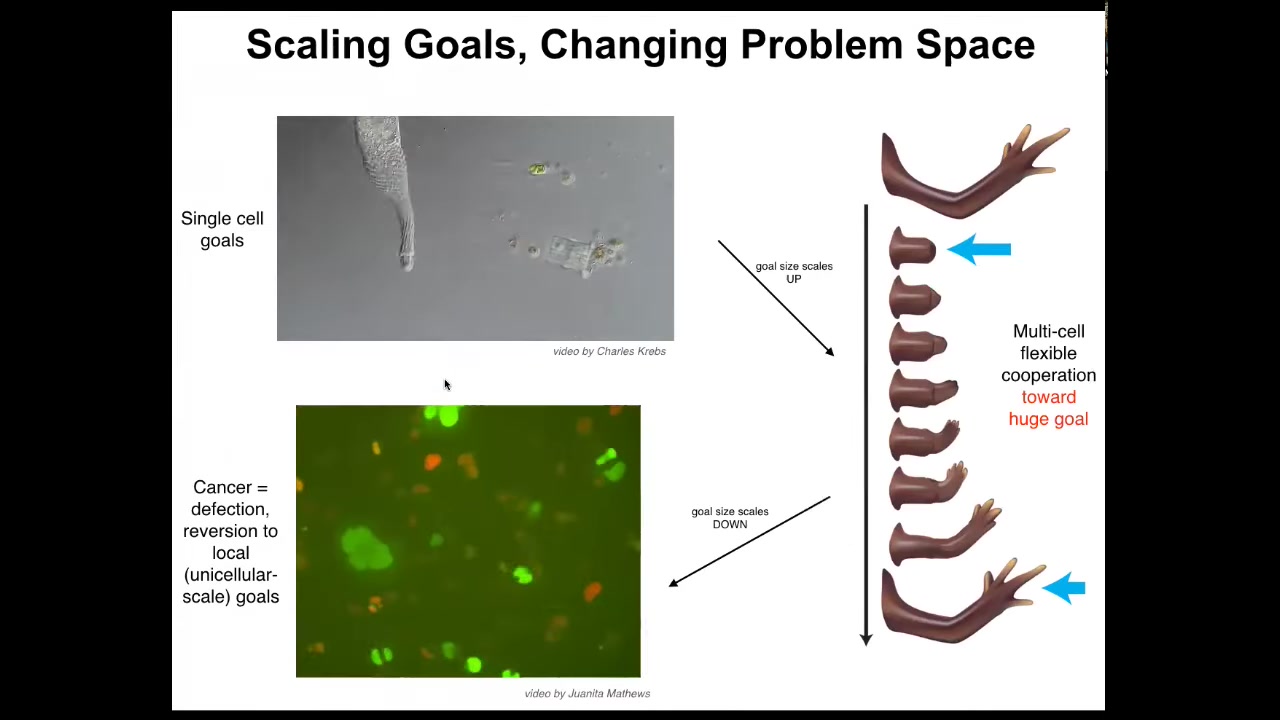

Let's think about the cognitive light cone of this system. Here's an individual cell. Individual cells have tiny cognitive light cones. Cognitive light cone is defined as the size of the largest goal that the system can have. That's my definition when I set up that concept to capture this idea that the kinds of goals you can have determine your level of intelligence. These systems only care about metabolic and physiological states in a tiny region. They have a little bit of memory and anticipation potential, but it's very small, both in space and time. That cone is very small.

But during evolution and development they join networks, and networks have, compared to these cells, a huge cognitive light cone. For example, the goal of this system is to remain this limb. If you try to deviate it, it will try to get back there. That's how you know it's a goal, because when you deviate the system, it tries to come back. Whereas these cells work on tiny goals, this thing is working on a giant construction project. It's immense. It's an entire limb. No individual cell knows what a finger is or how many fingers you're supposed to have. Individual cells don't know that, but the collective certainly does. Whereas this cell was adaptively trying to reach its local goals, this system adaptively reaches this giant goal. One thing we can think about is the scaling and the changes of the size of that cognitive light cone, but it can also shrink. This is glioblastoma. This is what happens when individual cells disconnect from that electrical network. They can no longer remember this big goal they were working on. They go back to their ancient unicellular lifestyle, which is to be an amoeba and the rest of the body is just an environment.

Slide 22/42 · 28m:21s

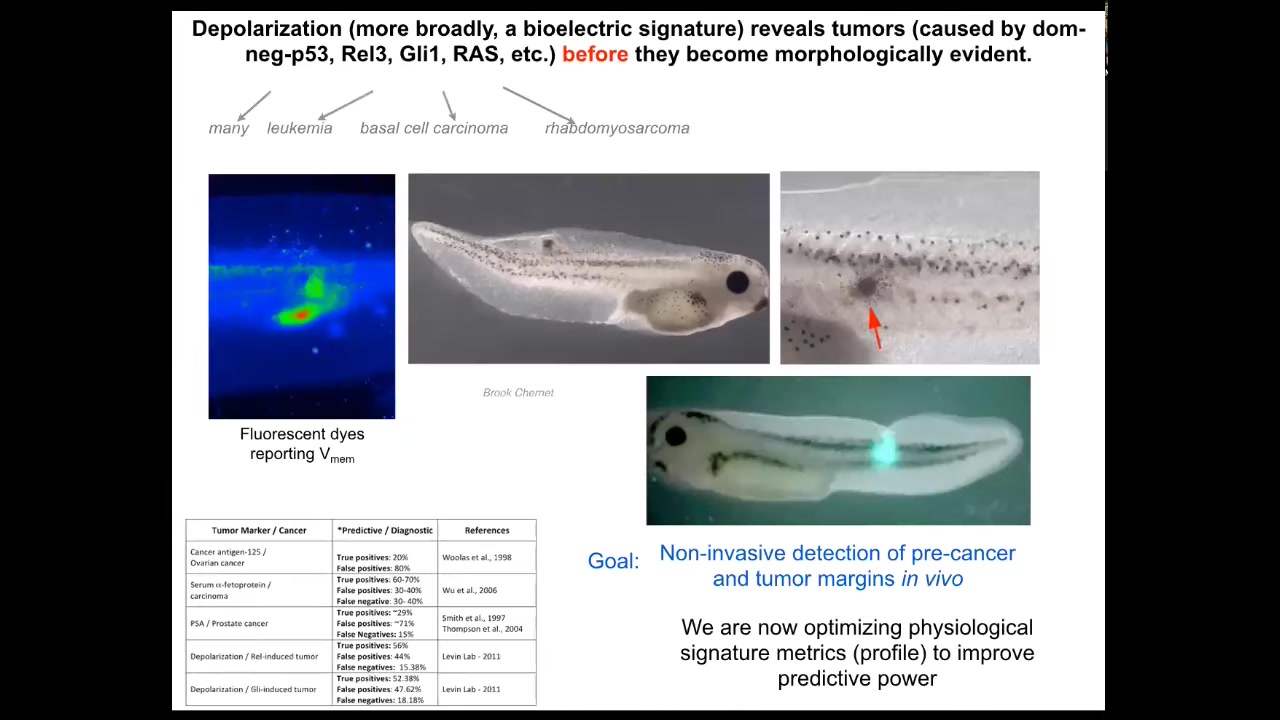

What happens in the body — this is the tadpole system; these are frog larvae. When we inject human oncogenes, they get tumors. Here they are, the tumors start to metastasize. But at very early stages, you can tell with the voltage dye where the tumor is going to be, because here's where the cells are disconnecting from the network and establishing their own aberrant voltage gradients; as far as they're concerned, they're just amoebas. This is just external environment. That boundary between self and world, instead of being this giant self, has now shrunk for these cells. They are now tiny little cells. This is a diagnostic modality, of course.

We're working on a device like this where surgeons will be able to look down during the operation and, using voltage dyes, see where the margins of the tumor are and where there are any rogue cells so they know exactly what they can cut. This is an artist's rendition of a thing we're working on.

Slide 23/42 · 29m:21s

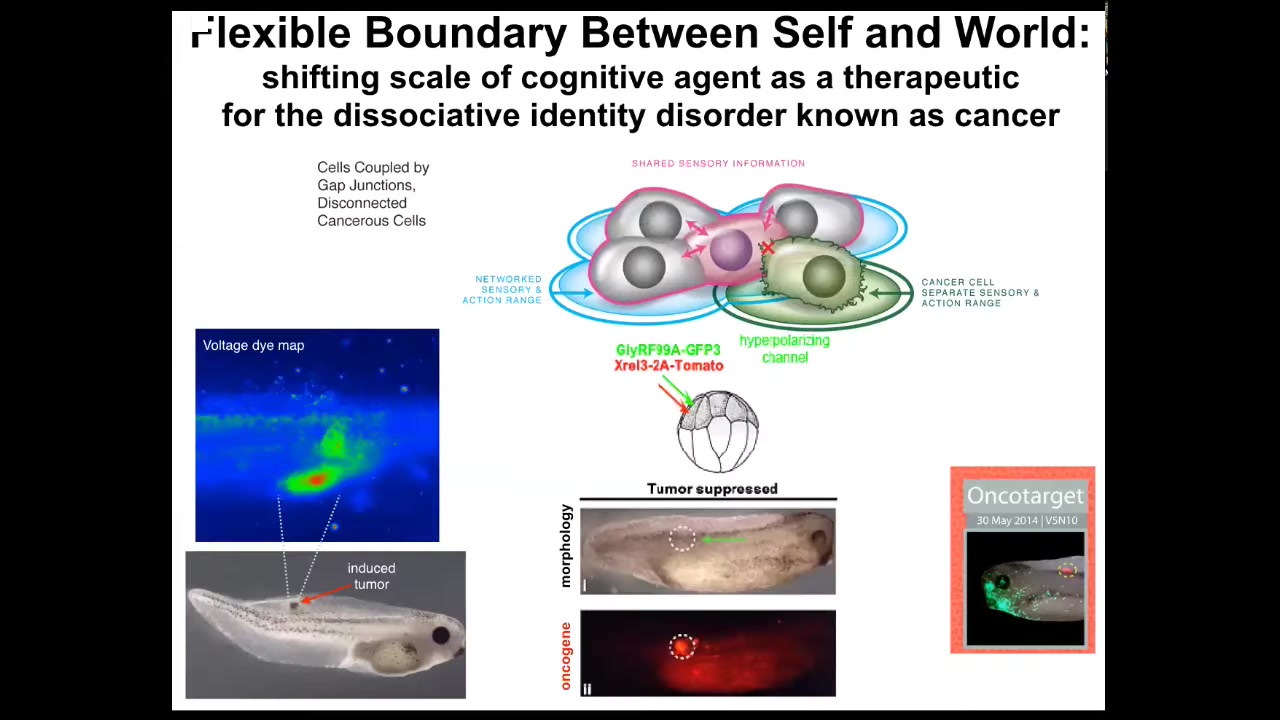

What's even more important than diagnostics is the idea that you can intervene here. What we did is we said, what if we don't kill the cells? We don't try to fix the oncoprotein or anything like that. All we're going to do is reconnect them, forcibly reconnect them to the rest of the network.

The oncogene is telling you to disconnect and go be an amoeba. We are just going to tell you to connect. We're not going to tell you what to do. We're not going to repair the gene. We're just going to tell you to connect.

The way we do that is by injecting ion channel RNA into cells that force the cell voltage to be such that the gap junctions are open and they're connected. This is an example of what you see here in the full data set in a couple of Oncotarget papers where the oncoprotein is. You can see we labeled it in red fluorescence. It's very strong. It's everywhere.

This is the same animal. There's no tumor. Even though the oncoprotein that normally makes tumors is here strongly, there's no tumor. Because it's not the genetics that drives, it's not the hardware that determines the outcome, it's the software. When these cells are connected into a network, the network remembers how to make nice muscle, nice skin, all the things it's supposed to make. It's not going to make a tumor.

Slide 24/42 · 30m:35s

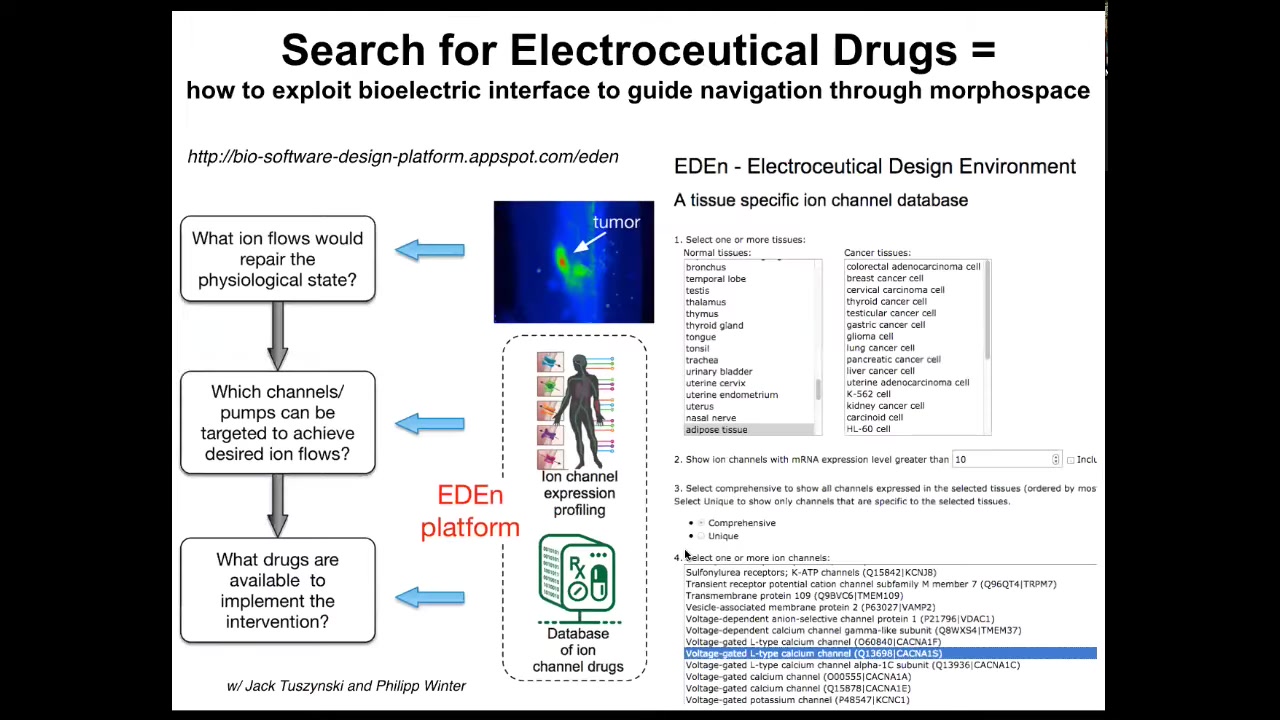

What we're doing now is trying to develop a computational platform where you can actually choose various tissues, whether cancer or normal, which enables us to know what channels and pumps exist. Those are your targets for intervention. There's a computational platform that will tell you if you want to change the state from this to this, which ion channels do you need to open and close? This is a platform for searching. We call it the electroceutical design environment. The idea is that you'll be able to exploit the many, many ion channel drugs. Something like 20% of all drugs are ion channel drugs. This is an incredible toolkit of electroceuticals that we're going to deploy to try to re-inflate that cognitive light cone as a therapeutic.

In particular, this view of cancer as literally a dissociative identity disorder. Cancer is a dissociative identity disorder of the somatic intelligence, and you can reintegrate if you understand the physiology, the electrophysiology, and you're able to bind the cells back into a collective.

This is some of our first work on using this in mammalian cells, and this is an example of glioblastoma, identifying electroceuticals that actually normalize the cells and make them quite normal.

Slide 25/42 · 32m:04s

The first example I've shown you is that we understand the scaling of the cognitive light cone, we understand what the electrical networks are doing, we can start to reset that boundary and that leads to a novel therapeutic for cancer.

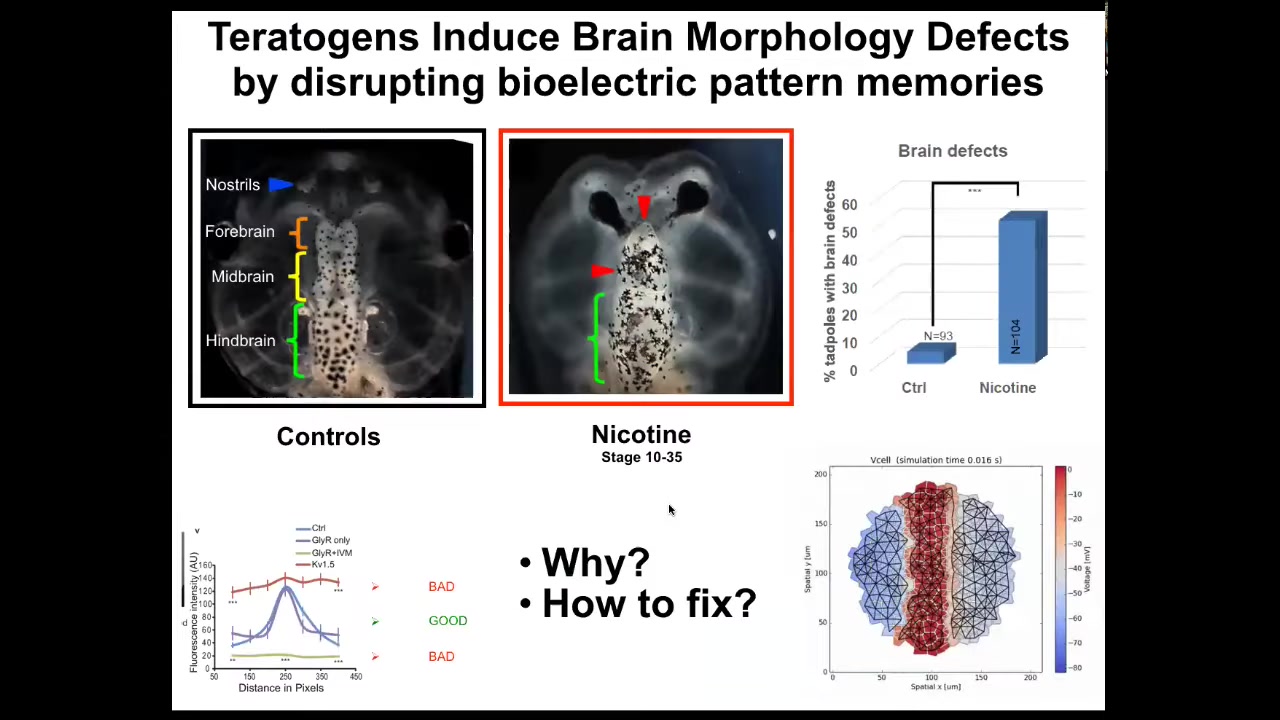

Now I want to talk about birth defects. There are many ways to screw up embryonic development that the cells cannot overcome. Nicotine, for example, alcohol, many different things.

You can see this is a frog tadpole head. Here's the forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain. The eyes are out here. If it's exposed to certain teratogens, there are defects. The brain structure is messed up. The eyes are connected to the forebrain instead of being out here, lots of problems.

We created a computational model that asks the question, What's going on with the bioelectric pre-pattern in these cases? When the pattern is incorrect, how can we correct it? What channels and pumps can we target to go back to the correct bioelectrical patterns? This is why it's important to understand the tissue-level rules governing the transition of electrical states. These are not single-cell phenomena. These are large-scale phenomena.

Slide 26/42 · 33m:18s

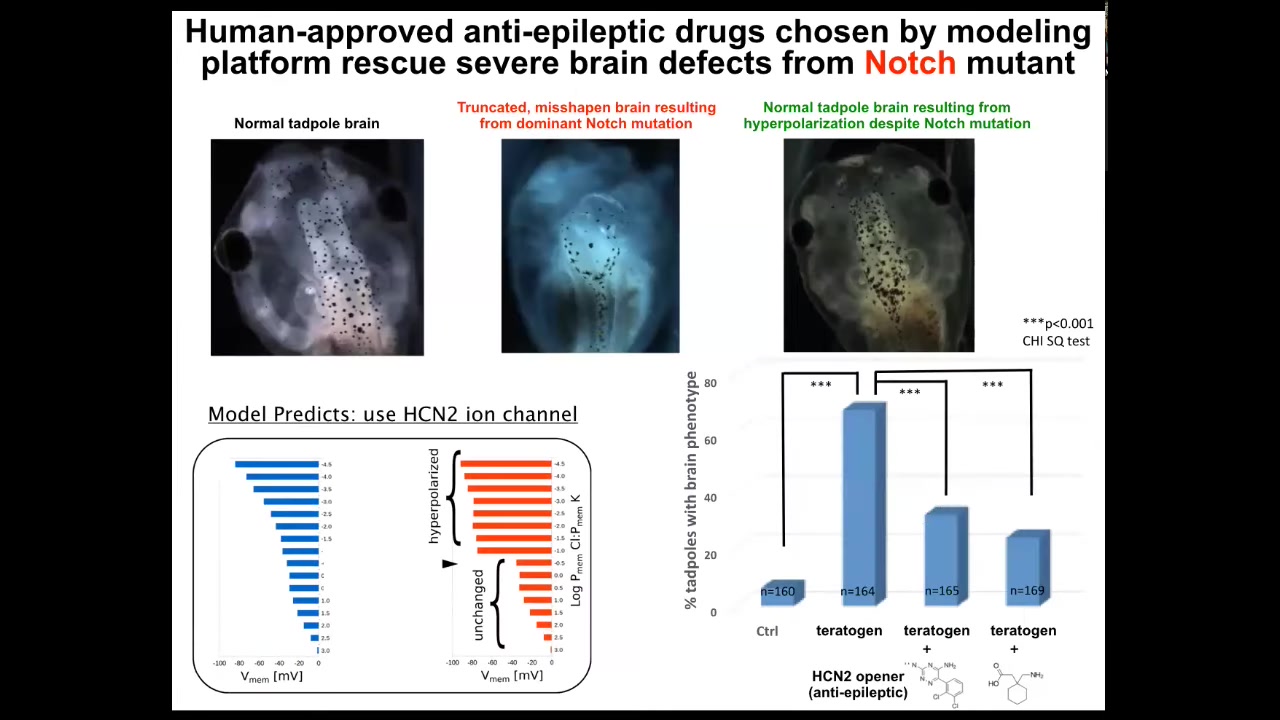

When we did that, the model did something quite amazing. It predicted this particular channel, this HCN2 channel, as a kind of sharpening filter that it predicted would repair the bioelectric pattern that went wrong in these kinds of embryos.

I'm going to show you what I think is the most impressive target out of all of the papers on this that we had, which is the mutation of this notch gene. Notch is a very important neurogenesis gene. If you mutate it here in the forebrain, midbrain, hindbrain, the animals bearing the notch mutation — it's dominant — there's no forebrain. The midbrain and hindbrain are a bubble filled with water. They have no behavior. They do nothing. They just lay there.

What we found is that if we did what the model predicts, which is to crank up this HCN2 channel, everything goes back to normal: the brain shape, the brain gene expression, and even behavior. We tested their learning rate, and they learn at the same rate as controls. Everything goes back to normal, even though they still have this notch mutation.

This is an example of correcting in software: using the physiological modulation of the decision-making of cells of how to build a brain can override genetic defects. I'm not saying that will be true in every case, but in some cases you can fix certain kinds of hardware defects in software by communicating new goals.

Our model is now to the point where it can actually suggest very specific targets. We used two anti-epileptics that are already in human use for this new purpose to open these HCN2 channels and induce this kind of repair.

What we're trying to do here is by using this electrical interface, by opening and closing specific channels, we're trying to transmit specific goal states to the cells so that we can control what they build.

Slide 27/42 · 35m:19s

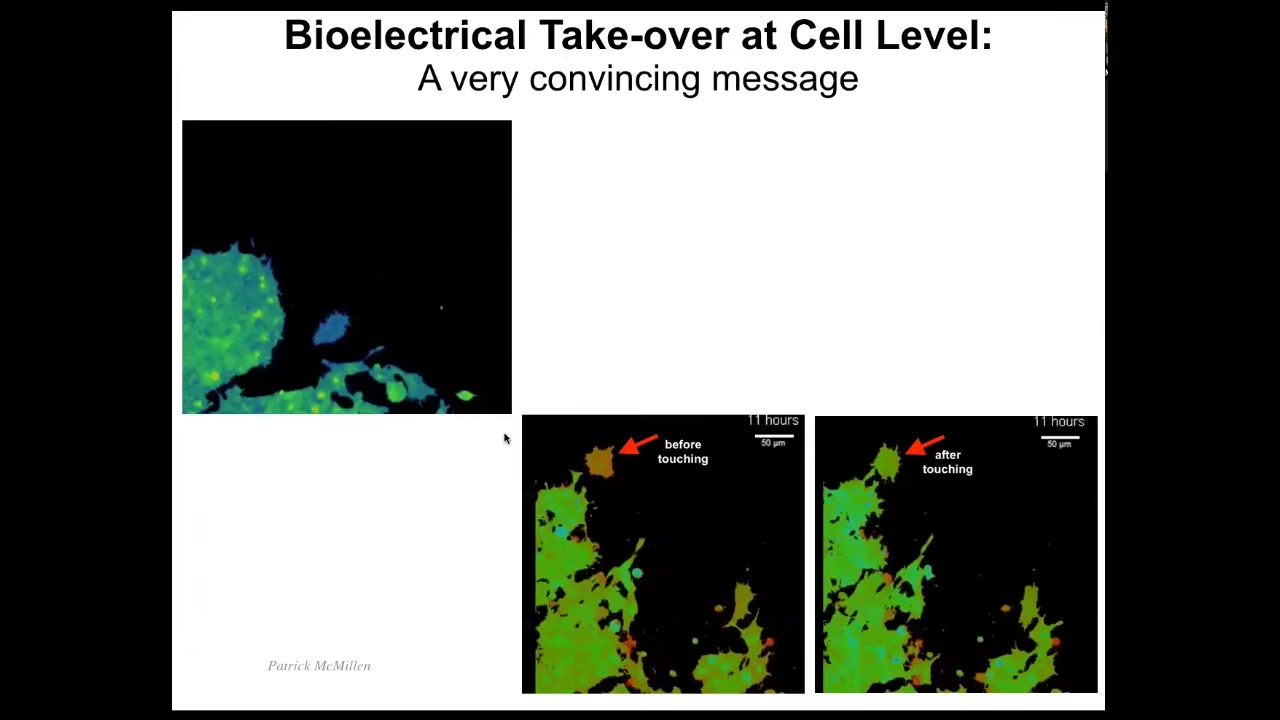

You can see here it's very interesting how certain kinds of messages can completely alter cell decision making. Here are cells, the color represents voltage, and you can see that this cell is quite depolarized until it touches this cell; it only takes a tiny touch, and it turns completely into this, it acquires the same voltage state as these guys from the tiniest contact. Here you can see it.

Here it is, it's blue, it's crawling along. Now it's going to make contact — tiny little touch — and it's convinced. It's already acquired the same voltage state as the rest and joined the collective. These electrical signals are extremely powerful, and we need to learn from these cells how to make signals that convincing so that we can every time get the response we want.

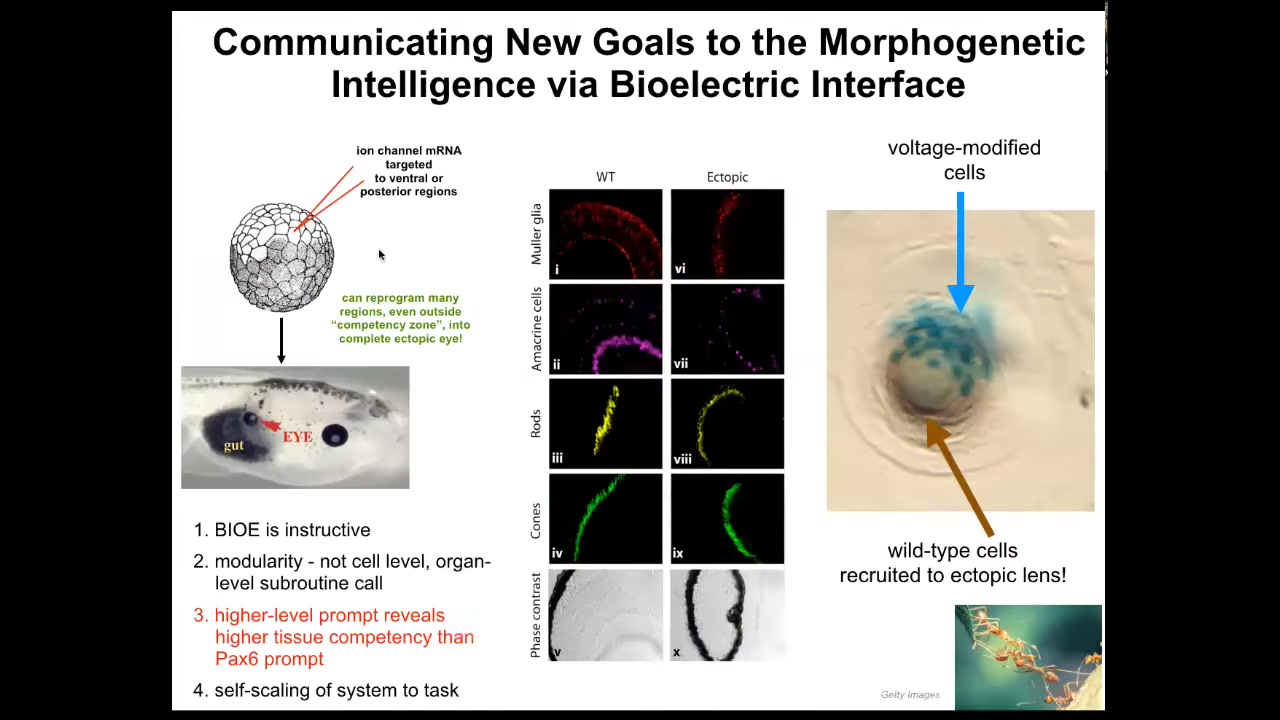

Slide 28/42 · 36m:08s

What kind of response might we want? Well, here's an example. I showed you in that electric face, there's a particular voltage spot that says, make an eye here. It indicates the position of the eye. We asked, what if we reproduce that same voltage state somewhere else in the animal? We took RNA encoding a particular potassium channel, which will induce that voltage state, and injected it into cells that will be part of the gut or the tail or somewhere else. Sure enough, the cells get the message; they make an eye. These eyes can have all the same lens, retina, optic nerve, all the same stuff that they're supposed to.

Keep in mind, this is extremely modular, meaning that we don't know how to make an eye. We don't tell the cells what to do, where the stem cells go, what genes to turn on and off. They already know all of that. All we need to do is give them a very high-level message, that high-level subroutine call that says make an eye. If we're convincing, they will take up the message and they will not only make an eye, but actually, if you only inject a few cells, this is a lens sitting out in the tail somewhere of a tadpole. The blue ones are the ones we actually injected. What they do is they recruit all their neighbors because it's not enough of them to make a good eye. They recruit all these other cells that were never injected by us. It's a secondary induction. Once you convince these cells that they need to make an eye, they go ahead and convince all the other cells that they should participate with them.

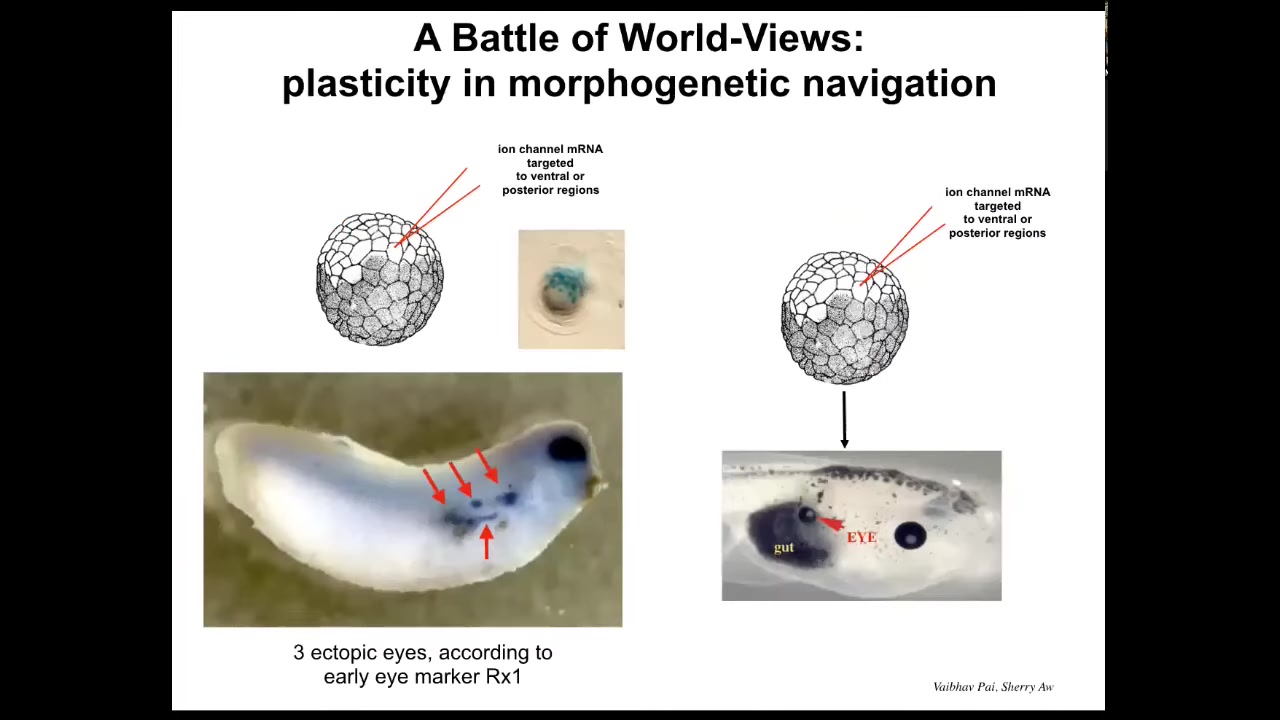

Slide 29/42 · 37m:33s

But when I say convince, I mean that literally because in this state, in this kind of system, there is a battle of worldviews. There is a battle of models of what the future should look like.

Because if you do this at an early stage, you will see a number of ectopic eye spots. Each one of these blue things is the expression of Rx1, which is an early eye marker. And so you can look at the SEM and you say, we're going to have at least three ectopic eyes, maybe more. But in the end, you often only get one. What happened? Or in fact, none. What happened? It's because while our signal is saying BNI, the surrounding cells have a cancer suppression mechanism, which says if you are next to a cell which has some kind of weird voltage that's not like you, try to convince it to have the normal voltage. In other words, wipe out or resist what we are trying to do. I showed you a minute ago how cells do that by touching and converting the voltage of the neighboring cells.

So what's happening here is really a battle of two worldviews. Should we be an eye or should we be skin or gut, and sometimes one wins, sometimes the other wins. We're still only at the early stages of understanding what makes certain messages more convincing to these cells. Why do some patterns win in some cases? This is also important for understanding why we get cancer in certain scenarios and not others.

What I'm showing you is that understanding the dynamics of the bioelectric patterns is a way to do things like create whole organs, specify a complete eye, for example, where we actually don't know how to micromanage that process.

Slide 30/42 · 39m:11s

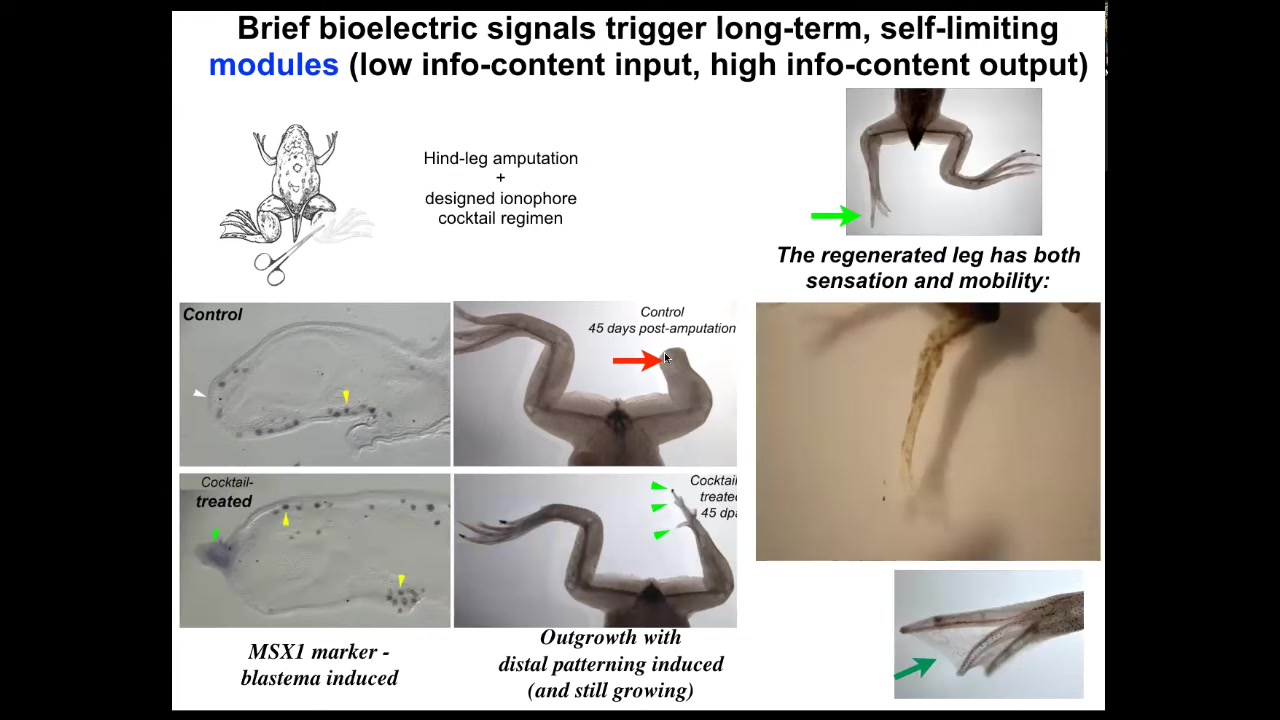

We're moving this forward into regenerative medicine of other structures like appendages.

Here's a frog. Unlike axolotls, frogs do not regenerate their legs. Here, 45 days later, there's nothing.

Slide 31/42 · 39m:28s

With a cocktail that we've designed that is applied for the first day, within 45 days, you already get some toes. You've got a toenail here. The anterior-most structures early on, all of the pro-regenerative genes like MSX1 are turned on. You can see this leg is touch sensitive and motile. It's functional and actually a pretty respectable leg by the time it's done.

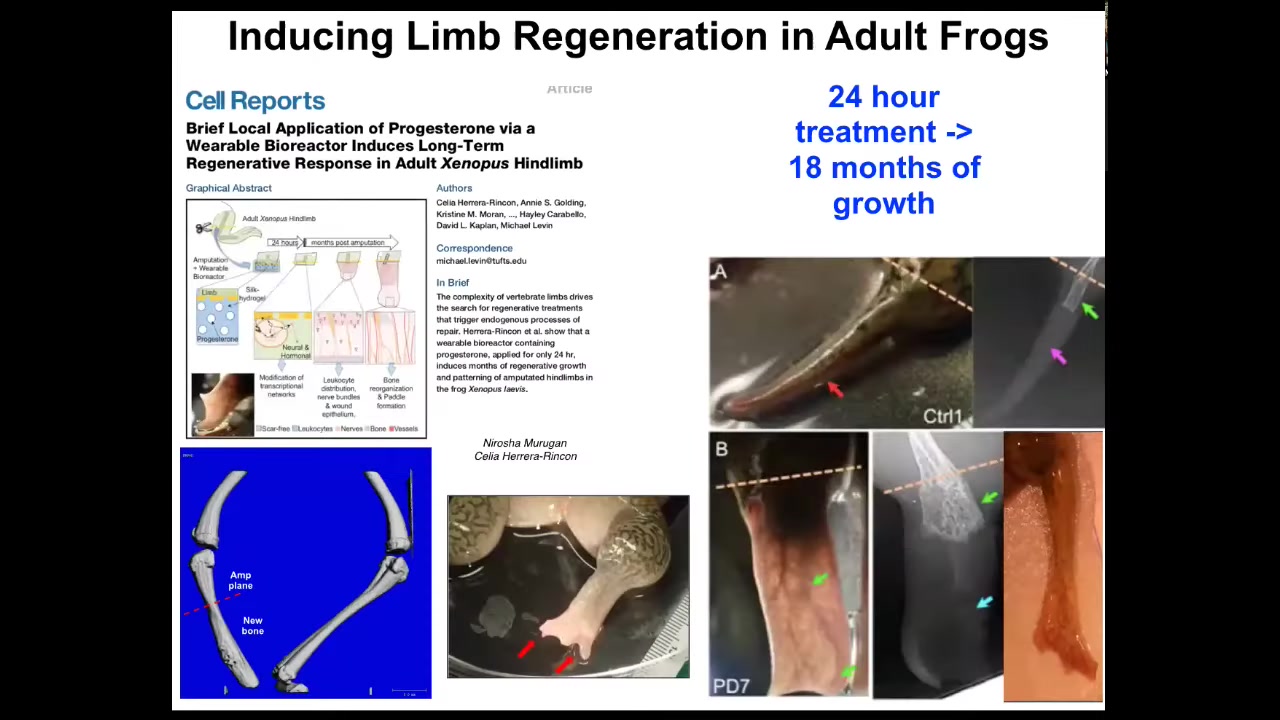

Slide 32/42 · 39m:49s

The amazing thing here is that we only intervene for 24 hours. The way this works is you do the amputation, then you put a wearable bioreactor that contains some ion channel modulating chemical compounds. That only lasts 24 hours. Then you get a year and a half of leg growth here. During that time, we don't touch it at all. The idea is not to micromanage it. This is not about scaffolds or putting specific 3D printing cells or working with stem cells. It's not about any of that. It's about convincing the cells at the very beginning, in the first 24 hours, you're going to go down the leg path versus you're going to go down the scarring path, and that's it. Then you leave it alone because it's a competent system that navigates that space on its own. We don't need to tell it how to do that. It already knows how to do that. This is what we're interested in: developing triggers for these kind of very complex applications.

I have to do a disclosure because Dave Kaplan and I are co-founders of this company called Morphoceuticals, which is now moving this to mammals and hopefully eventually to patients.

Slide 33/42 · 40m:57s

These bioelectrical signals are not only binding individual cells into a larger scale collective, but they are active patterns in themselves. If you see here, there's a wide range of phenomena.

Each one of these is a separate embryo. It's not a single cell. You can see there are patterns that go between embryos. When I poke this one, these guys find out about it because of this wave. Within an embryo, there are amazing wave phenomena. You can see here it looks like certain cellular automata.

The patterns themselves are the targets of intervention. That is, we are not just seeking to communicate with the cells, the physical agents, we're actually seeking to communicate with the patterns. The patterns that move through the tissue have computational capacity. As William James said, thoughts are thinkers as well. Patterns within media are agents that can do computation and that we need to be able to target.

Slide 34/42 · 41m:59s

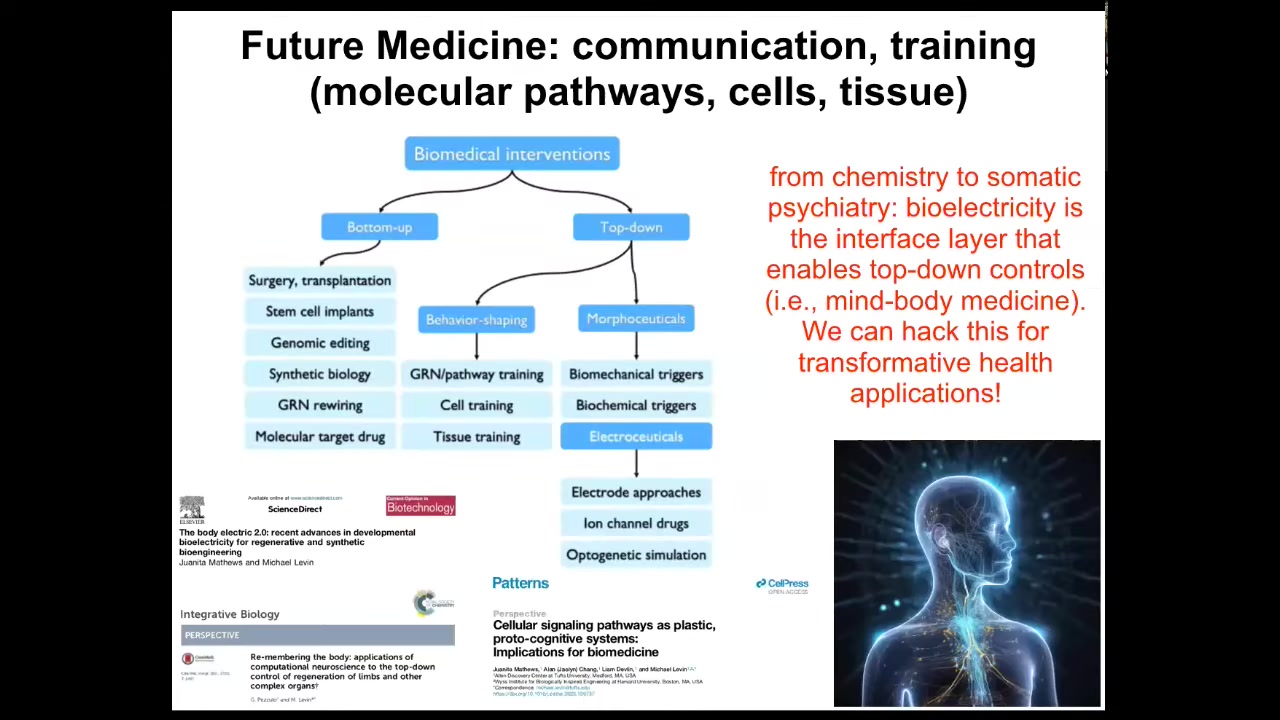

This is what the future of biomedicine looks like.

There are two major groups of interventions. Everything up until now has been these kinds of bottom-up things. They're all things that target the hardware and hope that you eventually get the correct system-level response. But there's also this amazing emerging field of top-down approaches, including training cells and tissues. All kinds of electroceuticals are a special category of morphoseuticals, which are, again, interventions that don't try to micromanage the system, but actually try to communicate and collaborate with the intelligence and the problem-solving navigational capacity of these systems at all scales. That's why I think future medicine is going to look a lot more like a kind of somatic psychiatry, not chemistry. Bioelectricity is not the only layer, but it's a great layer to start to understand this. All of that is described in detail here.

Slide 35/42 · 43m:02s

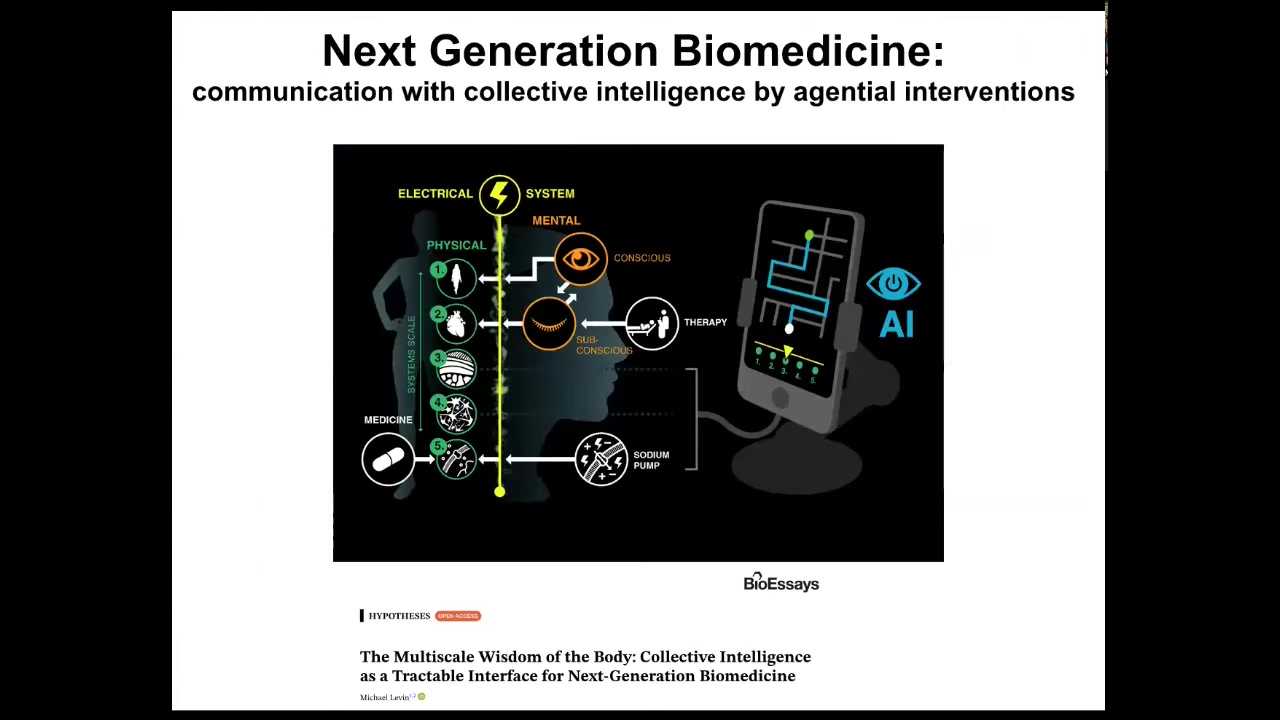

What we're doing now to make this even easier is to use AI and other tools to begin to communicate with all the different layers. The bioelectric layer goes from subcellular components up through the mind of the patient. At every level, there are new agents to communicate with.

We are developing AI tools to do that, as well as a robotic platform. This is work with Josh Bongard's lab at UVM and Don Ingber's group at the Wyss Institute to create a platform where robotics, actual laboratory robotics, can be driven by AI to improve our ability to communicate with these things.

Slide 36/42 · 43m:51s

And the last thing I want to show you is to bring this back to where we started.

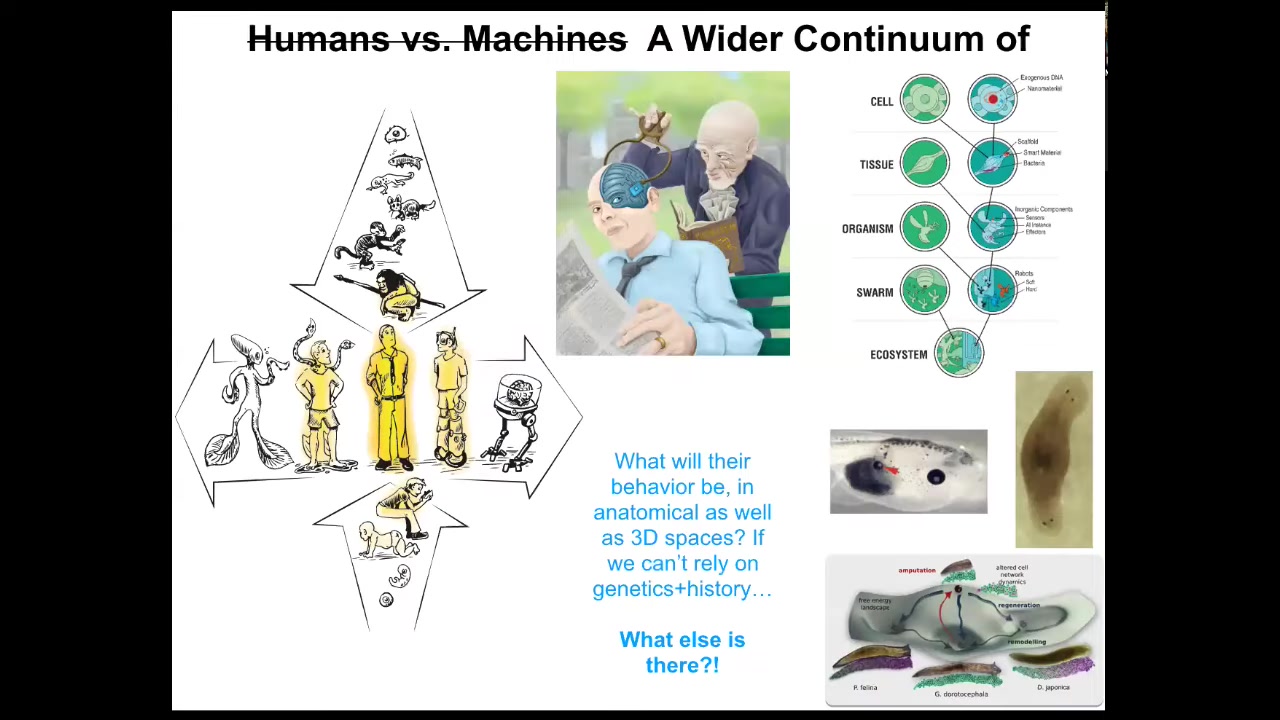

This is all fundamentally not about regenerative medicine. The medical applications are a really exciting outcome, but they're just an application of a much, much deeper question. A deeper question is, what kind of minds can be embodied in the physical world, and what is the spectrum of intelligence that exists in unconventional embodiments?

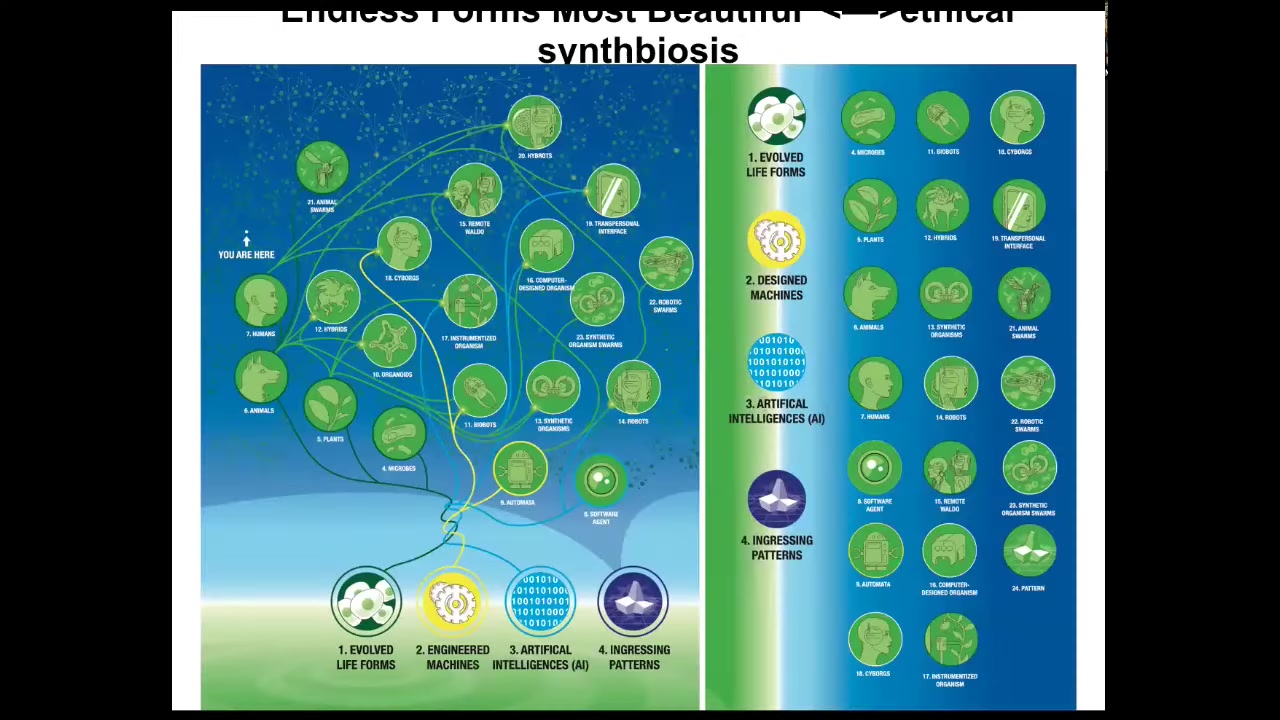

We know that there's a smooth gradient both in evolution and development from single cells to modern humans. But there's another spectrum too with technological changes and biological changes.

One can ask: I've shown you ways to modify organisms. I haven't talked about the planaria, but we have these flatworms and we can make them have two heads or, in fact, heads of other species. You can make all kinds of changes—extra eyes, extra heads, extra limbs. These things are components that are naturally evolved; they exist in other animals.

What happens when we start to make beings like these that have never existed before, where you can't blame evolution as an answer to why they have certain behaviors or forms?

Slide 37/42 · 45m:05s

I want to introduce you to a new life form that's made by existing cells, but has a completely different embodiment. We call these anthrobots. If I didn't tell you what this was, you might think this is some kind of a primitive organism that we found at the bottom of a lake somewhere. If you were to sequence it, you would find out that this is 100% Homo sapiens. These are completely normal, unedited human adult, not embryonic adult, tracheal epithelial cells that self-assemble and form this little self-motile thing that has a structure and behavior that's not like any of our human developmental sequence.

Slide 38/42 · 45m:42s

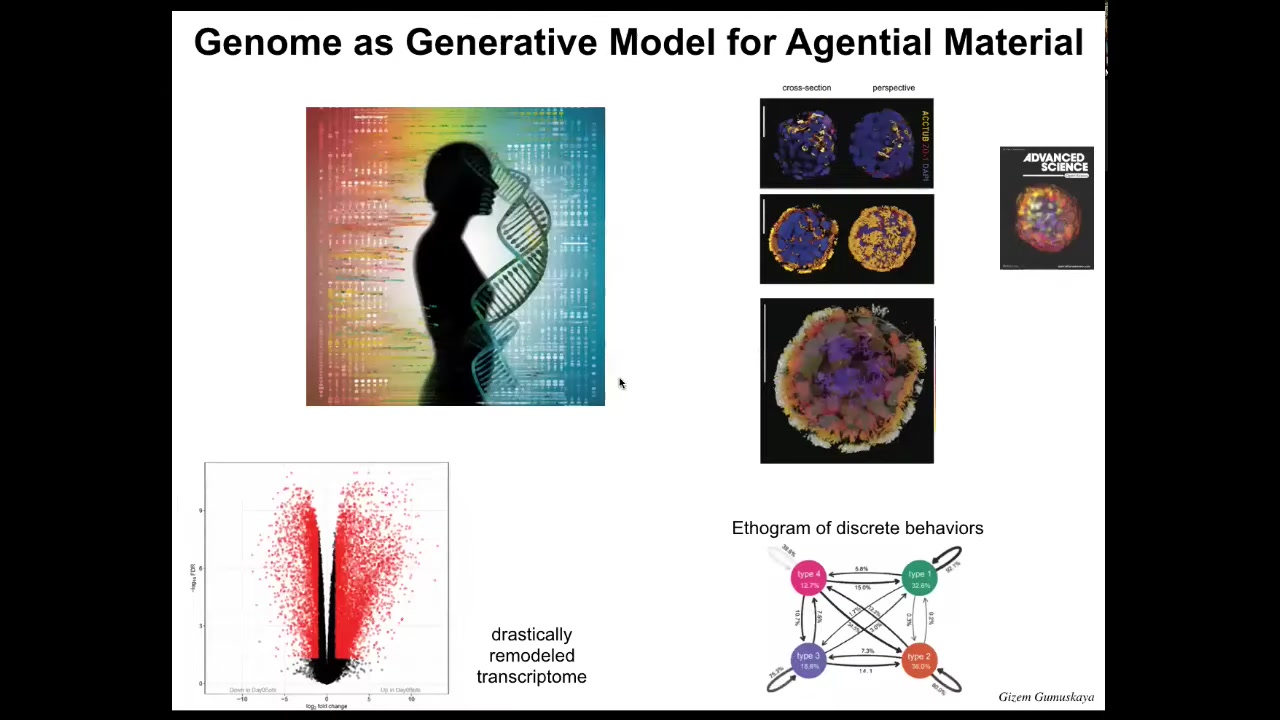

This is what they look like. They can move around because they have those little hairs called cilia on their outer surface. They have four different behavior types. You can draw an ethigram of the transition probabilities, so you can study them like any other behaving animal. If you look at their gene expression, over 9,000 genes are differentially expressed compared to their tissue of origin. About half the genome is now different. We haven't done anything to the DNA. There are no synthetic circuits here. There is no genome editing, no nanomaterials, no weird drugs. They do this because they have a new lifestyle. They change their gene expression because they have a completely different lifestyle, which gets back to the question we started with: in producing genomes, evolution does not make fixed solutions for fixed environments. What it makes are problem-solving agents that have the ability to interpret the information they have, including genetic information, in whatever way is most adaptive at the time.

Slide 39/42 · 46m:38s

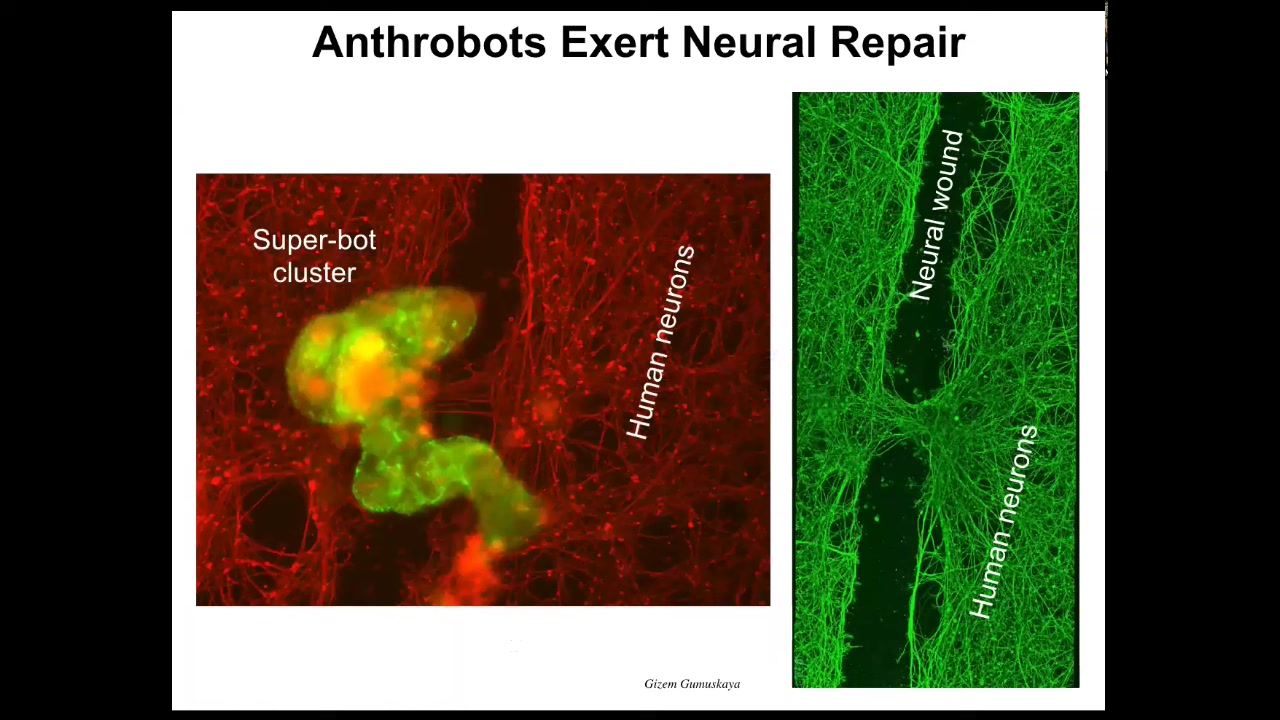

And they have amazing capabilities. If you make human cells, if you plate human neural cells in the dish, and then you take a scalpel and put a big scratch through it—this is a neural wound—the anthrobots will settle down, they'll make this superbot cluster thing, and you can see what they do. If you lift it up, they start healing the gap.

Who would have thought that your tracheal epithelial cells, which sit there quietly in your airway for decades, are able to have a different life as a self-motile little creature. It knows how to fix neural wounds. We're hoping that this is a new kind of personalized therapeutic, meaning that you can use this inside your body. You don't need immune suppression. It will be your own cells with a billion years of history of knowing what inflammation is, what infection is, what cancer is. Much more sophisticated than any nanobot that we can build.

But also it is a biomedical personalized intervention; it is a window on plasticity and an exploration tool for understanding what patterns are available that have never been selected for in evolution. There's never been any anthropots. There's never been selection to be a good anthropot.

Slide 40/42 · 47m:47s

I want to end with this idea that when Darwin said "endless forms most beautiful," he was thinking about the naturally evolved forms on Earth, which are a tiny corner of this incredible possibility space of bodies and minds, because of that plasticity of life, the ability of living material to improvise solutions every time.

Any combination of evolved material, engineered material, and software is some kind of a viable system, cyborgs and hybrids and chimeras of all kinds that can make use of patterns that come from wherever the rules of mathematics come from. It's not in the physical world. It's a different set of patterns.

We are going to have to adapt our ethical frameworks to a new kind of synth biosis with beings that are not like us.

All of the biomedical stuff I showed you and reprogramming the goals of the cellular collective are just examples. They're an early form of trying to detect and trying to communicate with an intelligence that's not like ours.

Because if we can't handle doing that with our own body cells, the chance that we're going to be able to do it with a wide variety of forthcoming beings with whom we are going to share our world — never mind just the AIs, but all of the composite beings, the cyborgs and everything, or of course, alien life — we're not ready for any of that if we can't even communicate with our own body cells.

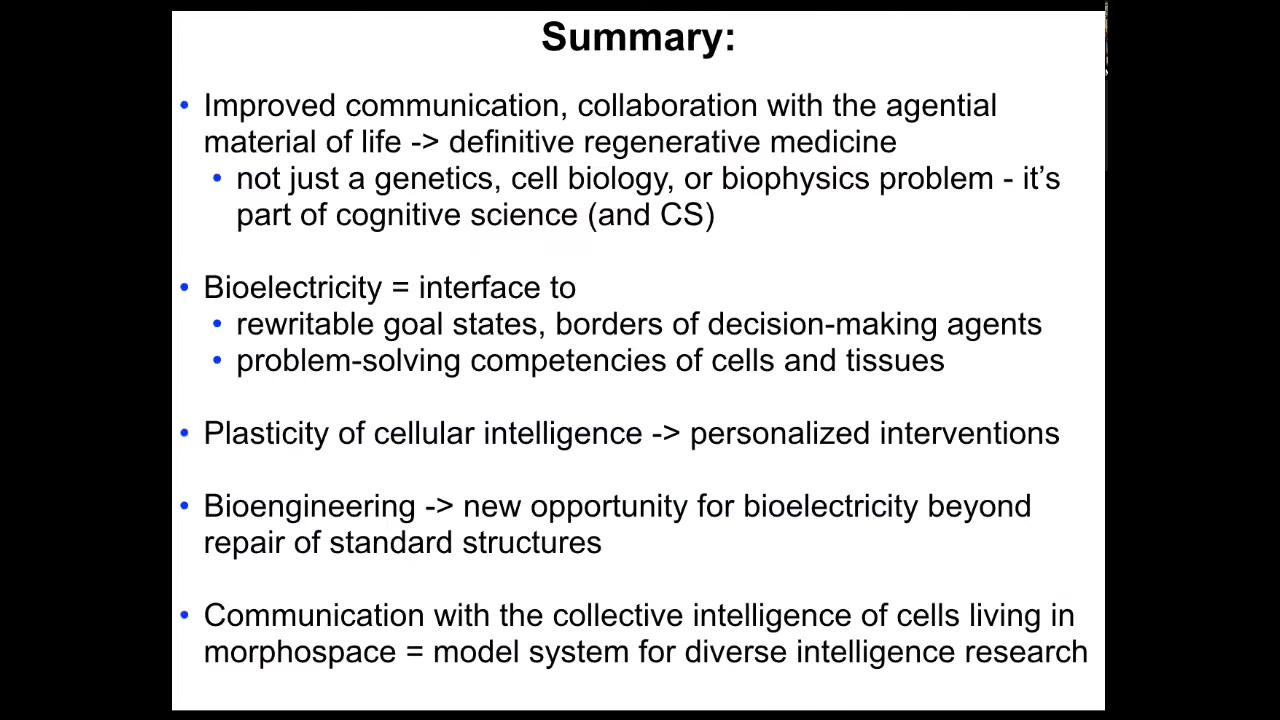

Slide 41/42 · 49m:21s

I'll summarize what we are looking for: improved communication and collaboration with the agential material of life. Definitive regenerative medicine is not a problem of genetics or biochemistry. It's a branch of cognitive science and of computer science or information science. Bioelectricity is the interface to rewrite the goal states of these basal intelligences. We can reset the borders now. I showed you that in the cancer examples. We can take advantage of the problem-solving competencies of cells and tissues. We are scratching the surface here. The plasticity of that cellular intelligence can lead to tools like anthrobots for personalized interventions.

Bioengineering gives us amazing opportunities for using bioelectricity and other modalities beyond repair. We're talking about augmentation, freedom of embodiment. That communication with the collective intelligence of cells that lives and functions and exerts its intelligence and morphospace is a model system for this emerging new field.

Slide 42/42 · 50m:27s

I'll thank the postdocs and the students who did all the work that I showed you today, our many amazing collaborators, our various funders over the years that have supported different aspects of our work.

Here are the disclosures. There are three companies that have spun off from some of the things that I showed you today.

The most thanks go to the model systems because they do all the hard work and they're the ones who teach us about all this stuff. I will stop here. Thank you.