Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a ~50 minute talk by Michael Levin to a clinical audience about bioelectricity and why it represents a new approach to medicine.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Introduction and main goals

(02:57) Unusual regenerative examples

(07:21) Scaling biological control systems

(13:25) Learning at multiple scales

(18:12) Morphospace and anatomical goals

(22:02) Collective intelligence in morphogenesis

(26:12) Goal-directed morphogenetic homeostasis

(30:01) Bioelectric pattern memory decoding

(35:01) Rewriting bioelectric code therapeutically

(40:42) Planarian body plan memories

(45:27) Translational applications and outlook

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/39 · 00m:00s

Thank you so much. Thank you all for having me here to share some ideas with you. If you would like to find any of the reprints, the software, the data sets, everything is at these websites. I'm not a clinician. My background is computer science. Since then, I've been leading a group on very basic research into biological organization.

Slide 2/39 · 00m:23s

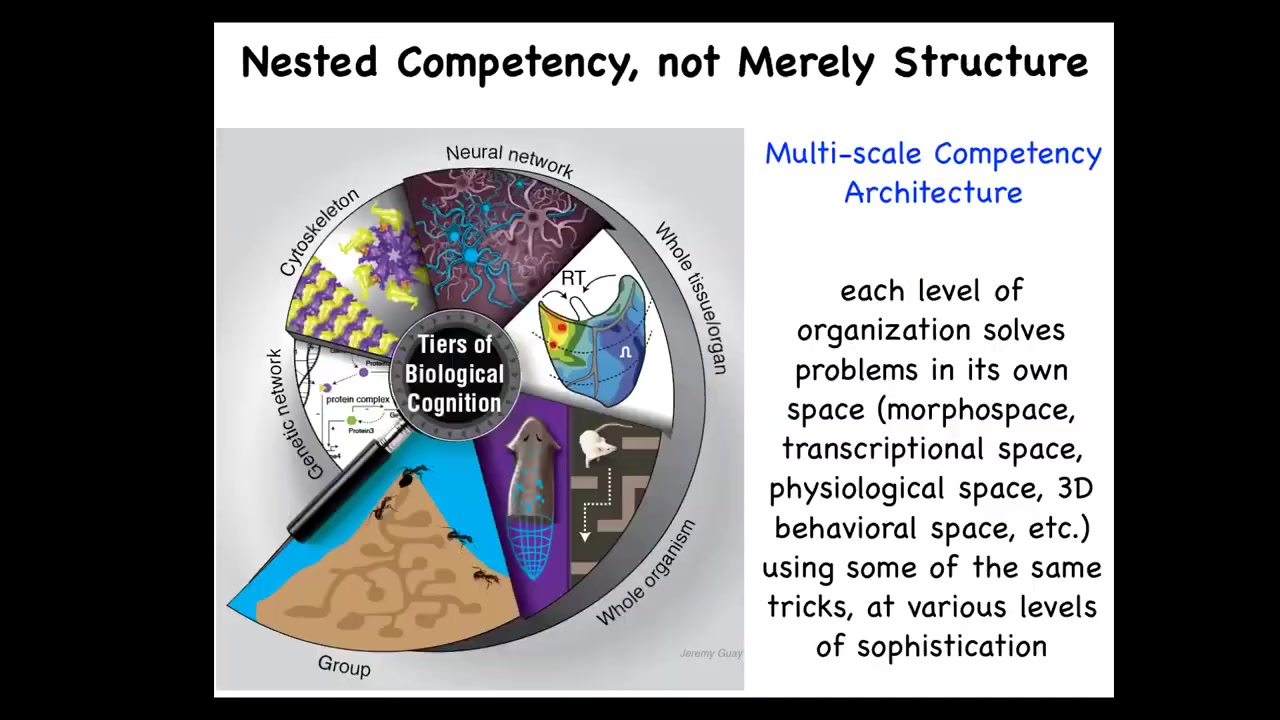

What I'm going to do is take you through some points that start out in a fairly philosophical place, and then eventually we'll get through some mechanisms and real implications for medicine going forward. So the main points I would like to transmit today are these. I'm going to talk about this notion of a multi-scale competency architecture and the way that many layers of the organism solve problems in different problem spaces. I'm going to talk about this notion that cells, tissues, organs, and so on, have a kind of collective intelligence, problem solving in different spaces. I'm going to argue that definitive regenerative medicine will require us to exploit that collective intelligence and communicate our anatomical goals to this collective.

I'm going to show you some mechanisms, specifically how endogenous bioelectrical networks in all tissues, not just nerve and muscle, are a tractable interface for exerting that kind of control. If you want to communicate to that intelligence, you need to understand how that collective is held together. This is bioelectricity. Not surprising, it's the same thing that happens in the brain. We have tools now. We've created some tools to read and write that information. I'll describe that. And I'll show you some applications in birth defects, regenerative medicine, and cancer. We work in various model systems, but all of this is now heading towards pre-clinical applications.

Slide 3/39 · 01m:53s

One of the key things that I'm interested in is this spectrum of perspectives on living bodies that is emphasized by these two competing metaphors, that of machines and that of organisms. There are many examples like this where a machine metaphor for repair of the body is relevant. After you've done what you need to do, we have this process of healing and adjustment where the body has a lot of endogenous competencies to reset various set points and to do things that we do not need to micromanage. What I'm interested in is the spectrum, what happens in between these two and how they connect to each other.

I really like this comment from Fabrizio Benedetti, who studies placebo effects. He says that words and drugs have the same mechanism of action underneath. We're going to talk about this link between cognition and intelligence and the practicalities of repairing bodies.

Slide 4/39 · 03m:01s

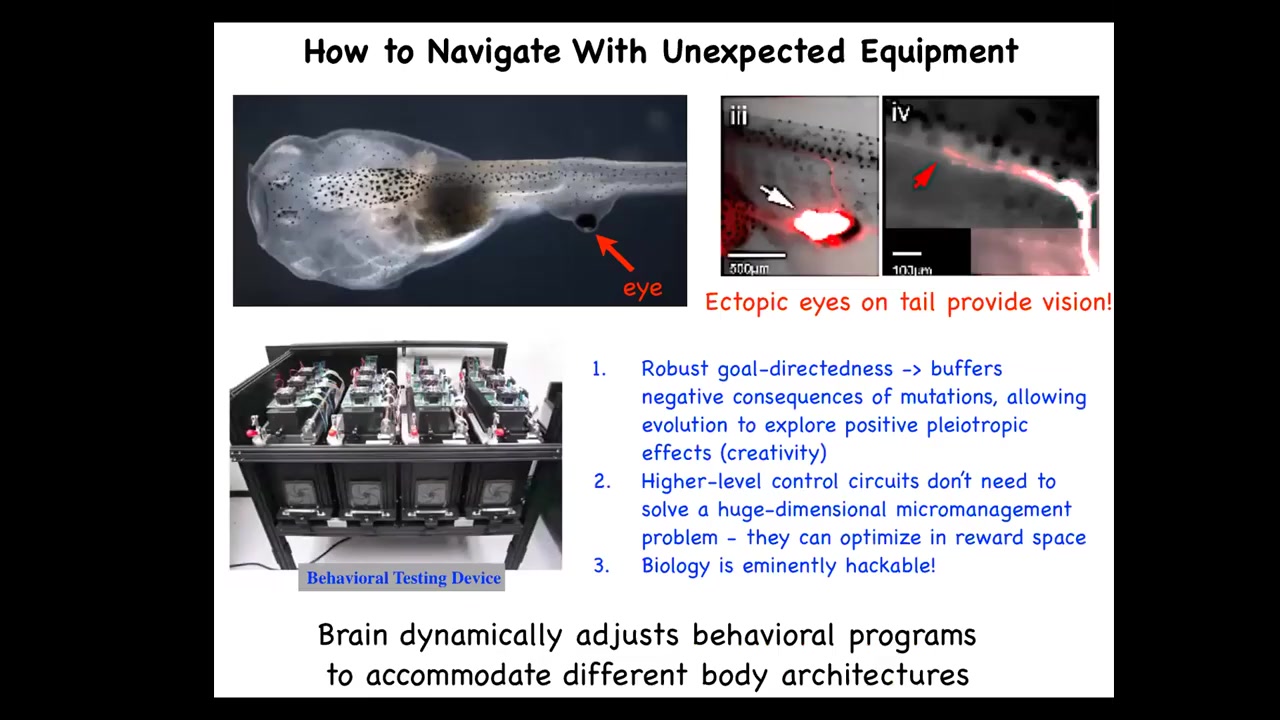

First thing I want to do is show you some unusual capabilities of biological systems, because I think in focusing on health and disease in human patients, we often lose sight of some of the amazing biology that's out there, and that is telling us some generic and profound things.

This is a tadpole of the frog Xenopus laevis, one of our models. Here is the brain, here is the gut, here are the nostrils, and here's the mouth. What you'll notice is that there are no eyes where they're supposed to be, so the primary eyes have been prevented. But we did induce an eye to form on its tail. These eyes make an optic nerve. The optic nerve comes out here. It does not reach the brain. It synapses onto the spinal cord or sometimes other places.

We've made this machine that tests these animals for visual learning. These animals can see quite well. It does not require generations of evolutionary adaptation to use your behavioral repertoire with a different sensory-motor architecture. There are no eyes connected to the brain. The eye is now on the tail. Within that animal, this architecture is able to figure out that what's coming in from this patch of tissue back here is in fact visual data. This kind of plasticity has massive implications for evolution and so on.

That's one example. In humans, this is related to sensory augmentation, sensory substitution, prosthetics, and similar plasticity.

Slide 5/39 · 04m:31s

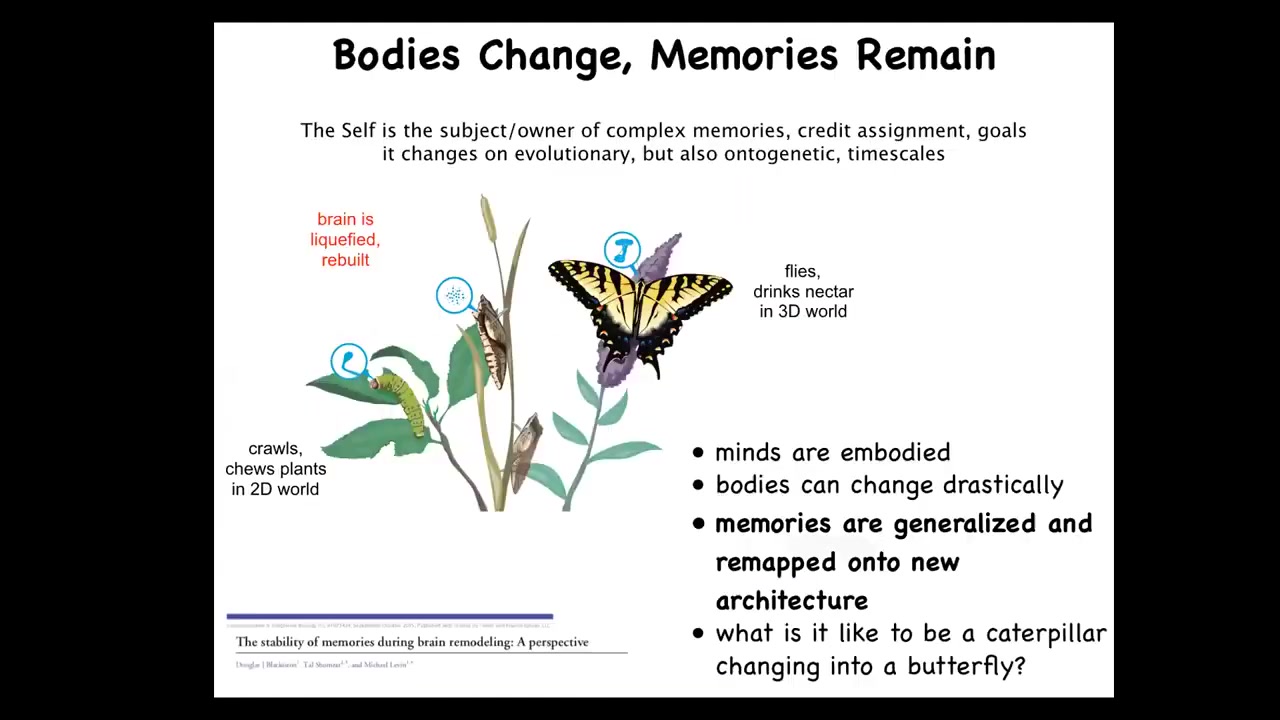

There's another kind which has to do with metamorphosis. This is a caterpillar. Caterpillars are a kind of soft-bodied creature with a very particular controller that runs a body that has no hard elements, meaning you can't push on anything. All you can do is change turgor. It lives in a two-dimensional world, eating leaves. But it has to turn into this: a butterfly that is a hard-bodied creature. It flies through a three-dimensional world. It drinks nectar. During this metamorphosis process, the brain is completely dissolved. Many of the cells die. Most of the connections are broken. And a new brain suitable for running this kind of body is rebuilt.

The amazing thing is that memories that are formed in the caterpillar persist in the butterfly. If you train the caterpillar, the butterfly will show evidence of recall despite the fact that its brain has been taken apart and refactored. Not only that, when you train the caterpillars to feed on a particular color substrate, the butterflies will remember and go to that color to feed. But they don't eat the same thing. What's food to the caterpillar is not at all food to the butterfly. Not only is there a persistence of memory, there's also a generalization of the notion of the category of food. It's not just that you remember, "this is where I find leaves." This is where I find food. And when the definition of food changes because your whole body is different, all the memories carry over. So there's this amazing ability to remap cognitive content onto a changing architecture. And this has many implications for therapeutics for degenerative brain disease in humans and persistence of personal identity as your brain gets replaced someday by new stem cells. So that's another kind of piece of biology.

Slide 6/39 · 06m:24s

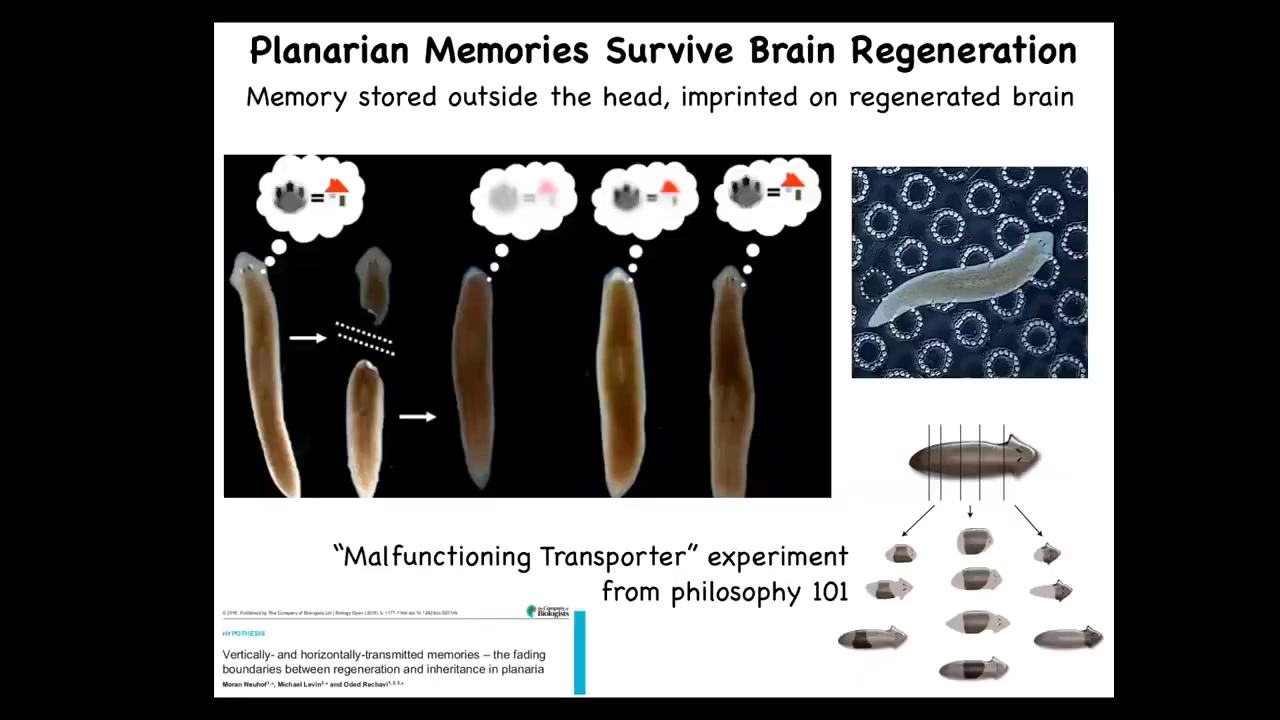

And then the third one is this, which is even more impressive, planaria are flatworms that regenerate every part of their body. But if you train them to recognize this particular bumpy architecture as where they get fed, you can cut off their heads with their brain. The tail will sit there doing nothing for about 8 days. They regrow a new brain. When the brain shows up, they resume behavior and they show that they remember the original information. They do have a true centralized brain, same neurotransmitters that you and I have. In this case, it's clear that information is somehow distributed. It is imprinted onto the new brain as it forms. This is information moving through the body. I show these examples to stress the commonalities between memory and learning and the transformation of bodies under metamorphosis and development. These 2 things are highly linked.

Slide 7/39 · 07m:21s

In order to think about what this means ultimately for definitive regenerative medicine, I want to start thinking about this idea of scaling up control systems.

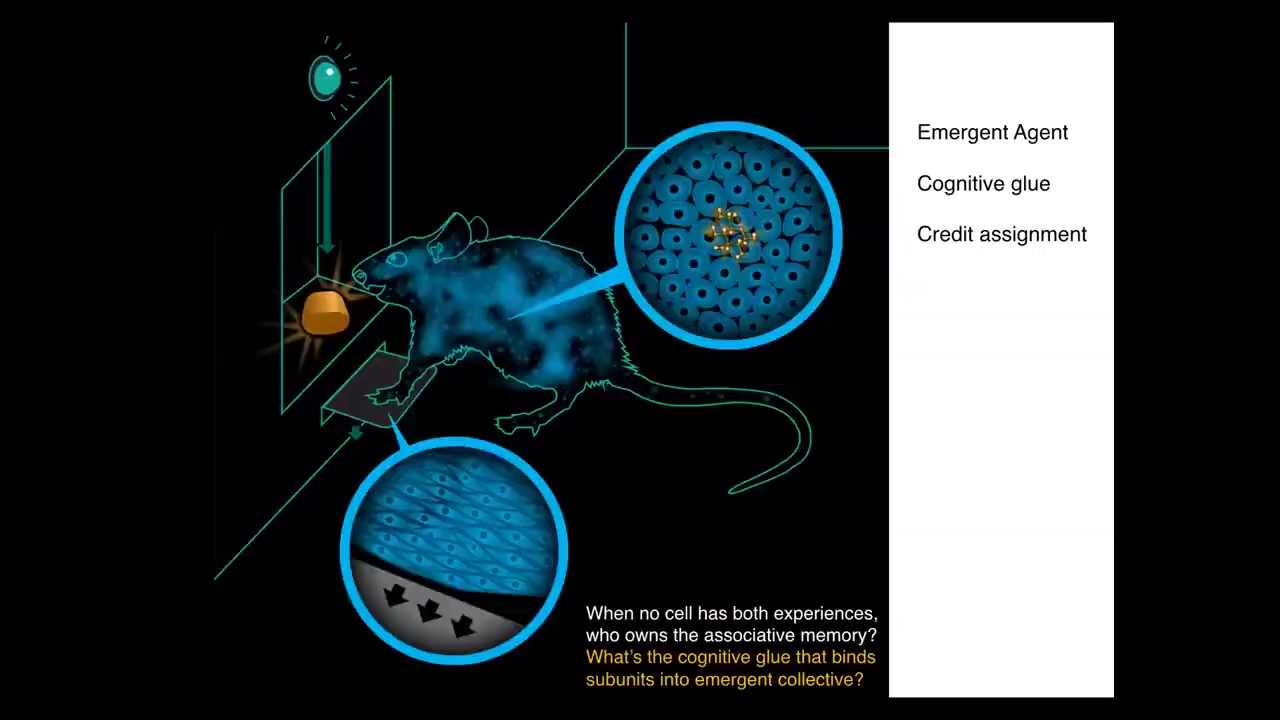

Here we have a rat. This rat has learned that to press the lever, it gets a tasty reward. The associative memory does not belong to any cell in the rat because no individual cell had that experience. The lever was interacted with by the cells at the palms. The sugar is obtained by these intestinal cells. No individual cell had this experience. In order to understand who owns that associative memory between these events, you have to realize that there's this higher level emergent organism. There's a kind of cognitive glue here that binds the individual cells into an emergent system that can store and process and act on these kinds of associative memories that do not belong to any of the parts. There's a kind of credit assignment problem here — all this organism needs to figure out what happened that caused that actual reward.

These are very interesting issues. This scale up, this idea of forming emergent control systems from lower level components, is really fundamental to our architecture.

If I told you that by sheer force of will I can depolarize a large number of cells in my body, change their electrical polarization, which means move ions from here to there, you would think either that I was making up stories or maybe it's some sort of really exotic biofeedback yoga, some sort of rare mind-body control thing. This, of course, is not rare at all.

In the morning when you have the high-level cognitive intent of going into your office to work, that intent has to filter down to the actual muscles that are going to be depolarized to move your body. This ability of crossing levels all the way from high-level metacognitive goal-seeking mechanisms down to the actual molecular biology of your muscle cells is what our body architecture does 24-7. It allows information to span levels from high-level cognition down to the control of molecular mechanisms.

Slide 8/39 · 09m:50s

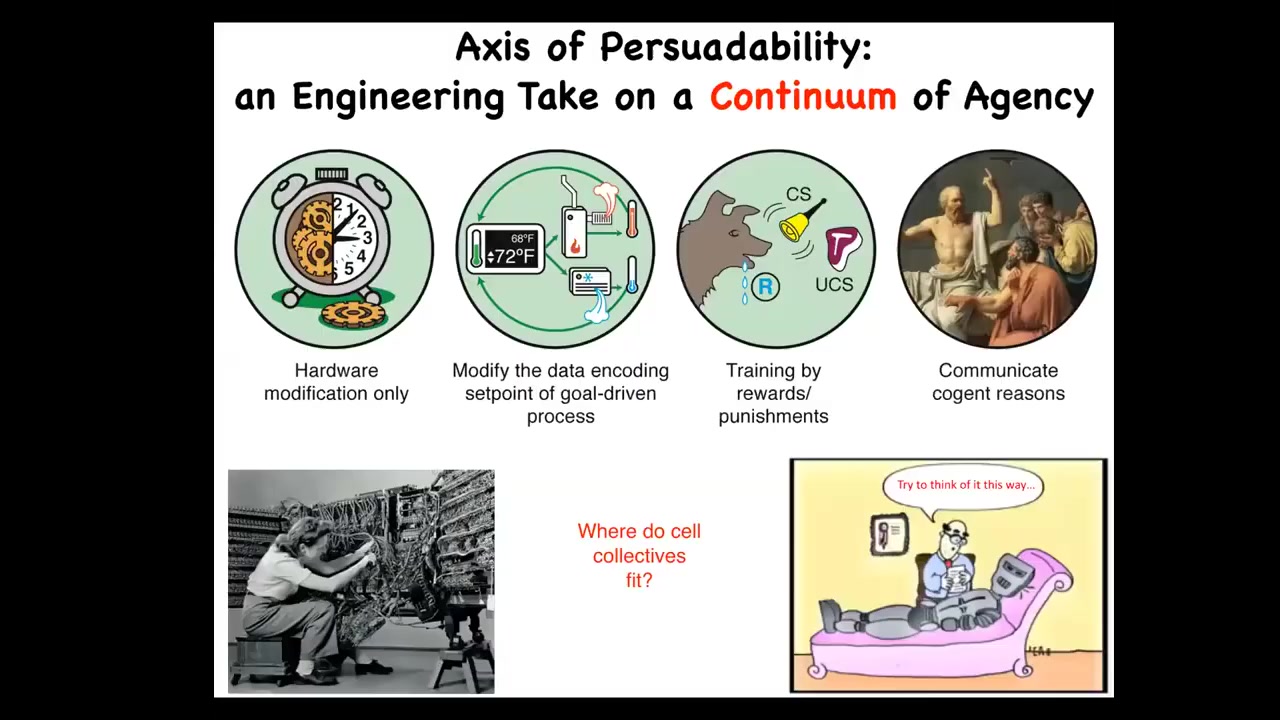

We have in engineering a whole spectrum, and I call this the axis of persuadability, which is a spectrum of diverse agents, all the way from very simple mechanical devices up through cybernetic homeostats and various learning systems and eventually complex metacognition. Different toolkits are used at all of these levels, and it's important to get it right. Treating complex biological agents as simple machines leaves a lot on the table and runs into all kinds of ethics issues. Conversely, trying to communicate various complex reasons to something like this is a waste of time. For any given system, you want to guess the correct level, not too low, not too high, in order to have techniques that are actually going to be effective. You can't decide this on a philosophical basis for any system. It's empirical. You have to do experiments. The question is, where do cellular collectives fit in here? Are they simple mechanical machines? Are they cybernetic homeostats? Can they learn? Where do they fit? We'll talk about that.

Slide 9/39 · 11m:03s

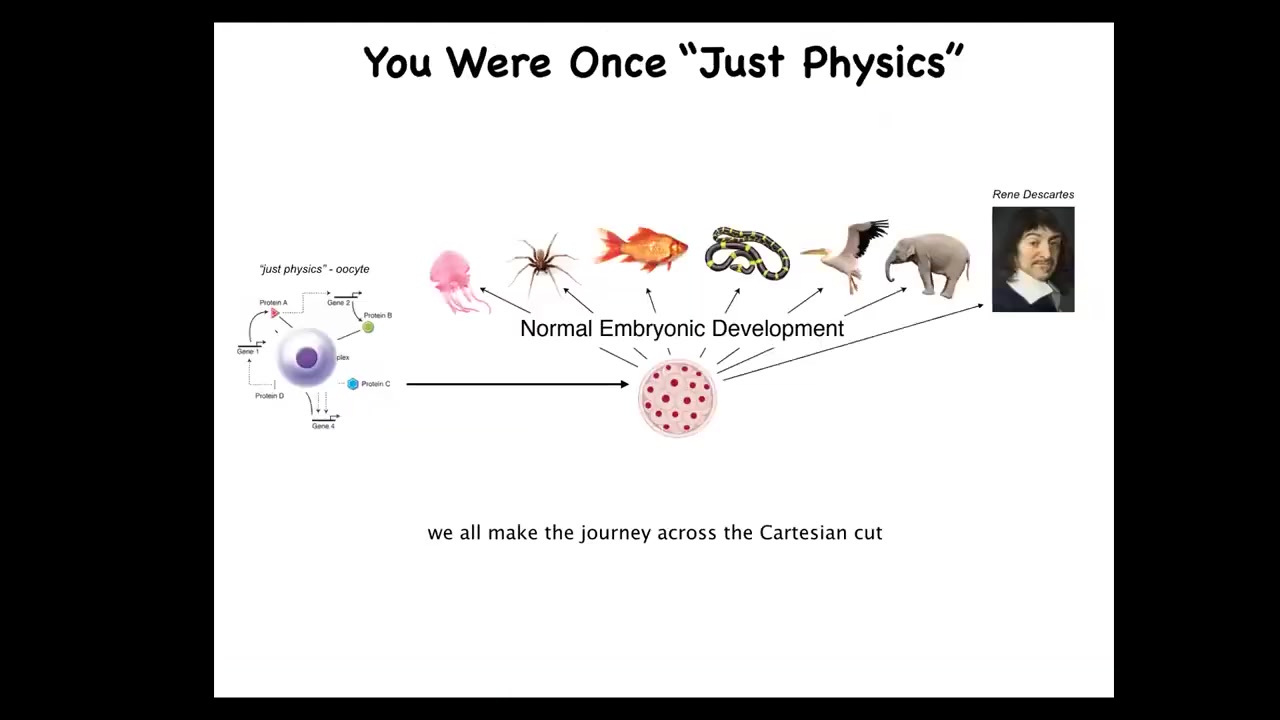

Each of us makes this amazing journey from being a little BLOB of chemicals that is well described by physics and chemistry. We're an unfertilized quiescent oocyte. Through this amazing process of embryonic development, we become something like this or even something like this.

Developmental biology offers no magical lightning-bolt moment at which physics becomes mind. We really need to understand the origins, both evolutionarily and developmentally, of various intelligence and other cognitive capacities that we enjoy by the time we get here.

Slide 10/39 · 11m:41s

And many people feel that there is this strange progression from a BLOB of chemistry into an actual cognitive human, but at least we're true unified intelligences. We're not like ants and beehives, which people speak of as collective intelligences. At least we are centralized intelligences.

Slide 11/39 · 12m:04s

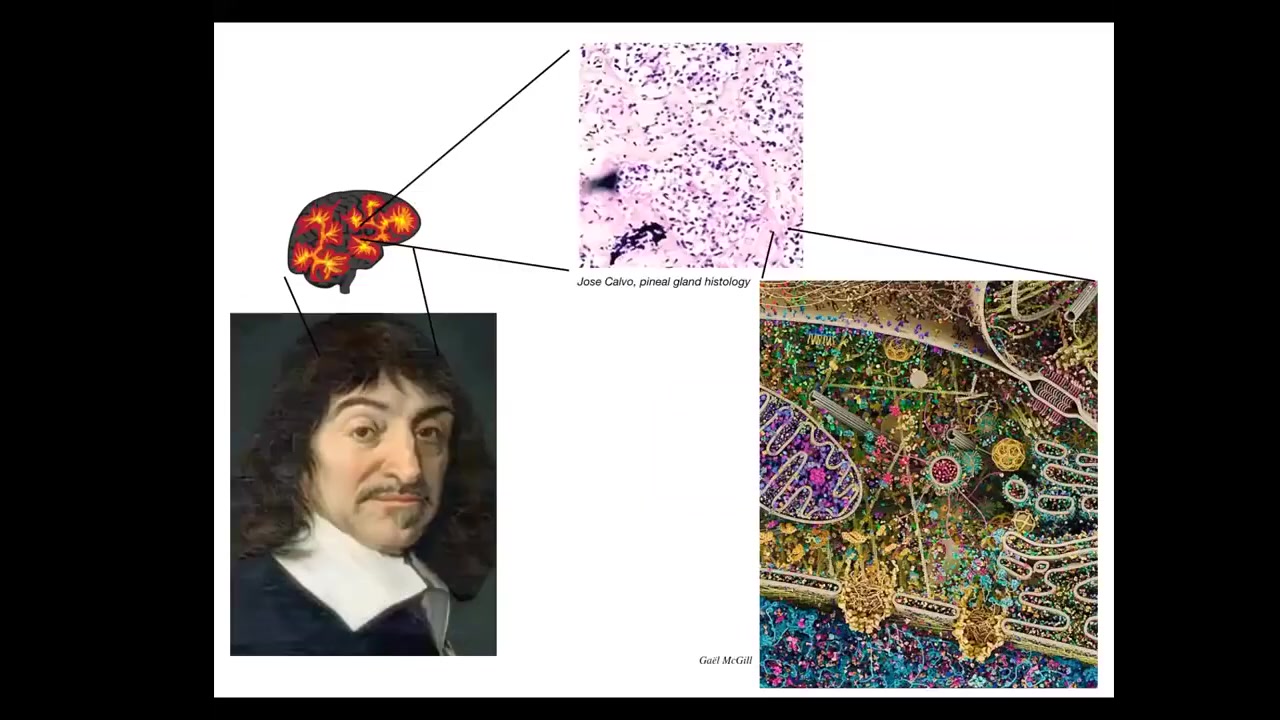

For example, Rene Descartes liked the pineal gland in the brain because he said our unified experience as humans, there should be one structure, an unpaired structure in the brain that would correspond to that. But he didn't have good microscopy available to him. If he did, he would realize that within that pineal gland there are tons of cells. There isn't one of anything. It's a composite of these tons of cells. And inside each of these cells is all this stuff. So in fact, we are not as unified as people think. We are collectives at multiple scales.

Slide 12/39 · 12m:36s

All intelligences are collective intelligences made of parts. This is the thing we're made of. This is a single cell. This is called Lacrymaria. This is a free-living organism, but our cells were once free-living organisms too.

It has no brain, it has no nervous system, but it handles all of its local goals, its physiological needs, its metabolic needs, behaviorally. All of that is handled within one cell. You can see it feeding on the various bacteria around.

What we are made of is a gentle material. We're not made of passive matter. We are made of a material with agendas, with various competencies. You can see here, Jamie Davies and I talked about this, what this means for biomedicine and bioengineering.

Slide 13/39 · 13m:26s

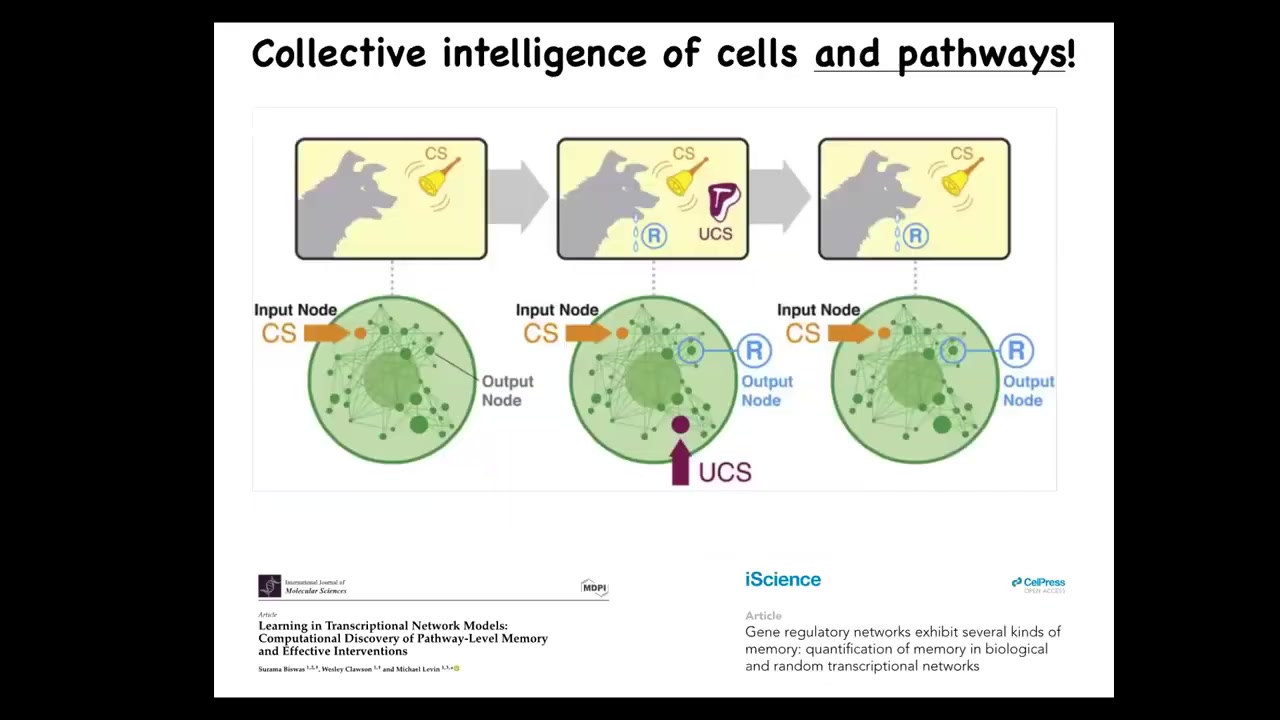

In fact, it's not even just the cells that have these various capacities. Even within the cells, we now know that something as simple as a molecular pathway or a gene regulatory network can do at least six different kinds of learning. You can take these various nodes, transcription factors or whatever the targets are going to be, and if you stimulate and read from them as you would, for example, in a Pavlovian conditioning task, you can demonstrate that biological networks can store multiple memories of different kinds. You find habituation, sensitization, associative learning, anticipation — it's all here. Even from the lowest level. This is an amazing material that evolution, and we as bioengineers, are dealing with. It requires a different kind of engineering.

Slide 14/39 · 14m:11s

This architecture of which we are made is what we call a multi-scale competency architecture because every level, it's not just structurally smaller, but every level solves problems in a different space. All of these agents cooperate and compete to get various goals accomplished. The higher level deforms the energy landscape for the lower level so that when they do what they do, the end result percolates up as navigating a different space.

Slide 15/39 · 14m:41s

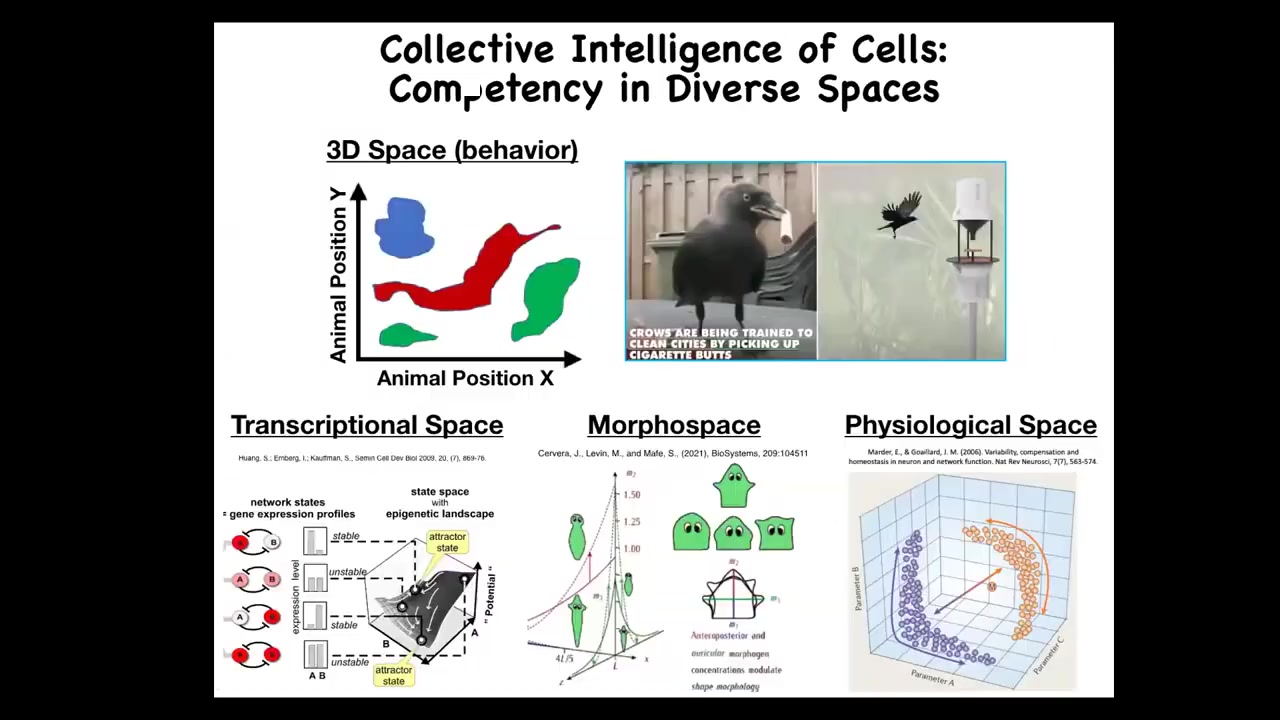

Now, we as humans are pretty good, we're not great at it, but we're pretty good at noticing intelligence in three-dimensional space. When we see medium-sized objects moving at medium speeds, we can recognize intelligence in primates and birds, maybe an octopus, a whale, things like that. But what we're not good at all is recognizing intelligence at different scales, so things that are very small or very large or happen at different time scales, and in particular in different spaces. There are other spaces in which intelligence can solve problems. For example, the space of possible gene expression, transcriptional space, the space of physiological states — of course, these are high-dimensional spaces. I boil it down to two dimensions on a flat slide. What we're going to talk about today is this notion of an anatomical morphous space. It's the space of all possible geometric configurations of a particular structure. One of the amazing things is that cells and cellular collectives solve problems in all of these spaces. I don't have time today to talk about all these remarkable examples.

Slide 16/39 · 15m:50s

I can send out some papers if people are interested, but I want to show you an example of what we're talking about, an example of problem-solving in a novel situation.

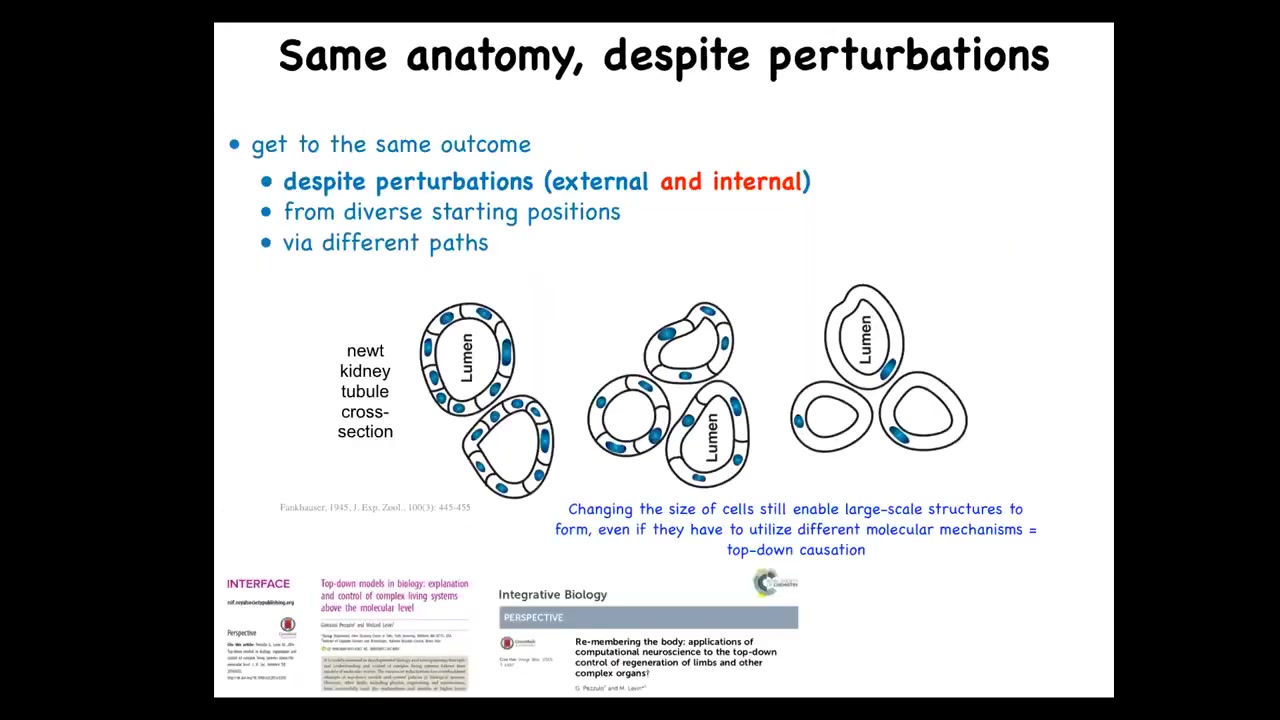

So this here is a cross. This was discovered in 1945. This is a cross-section of a kidney tubule in a newt. And normally there's about 8 to 10 cells that work together to build this kind of tubule with a lumen in the middle.

One thing you can do to these early embryos is make sure that the early cell has multiple copies of the genome. So you can have instead of 2N, you can have 4N, 5N, 6N, and so on in newts. When you do that, the cells get bigger to accommodate the increased amount of genetic material. And the first amazing thing is that you still get a normal newt. So you can have multiple copies of your entire genome and still have a normal animal.

But the second amazing thing is that these larger cells, fewer of them will get together to still form the exact same lumen. So they scale the proportional number of cells to their new size. So that's very impressive. But the most impressive thing is that if you make these cells absolutely gigantic, and this I believe is 6N chromosome complement, what will happen is each cell will bend around itself to form the same lumen.

Now, why this is of note is that this is a different molecular mechanism. This is cell-to-cell communication and tubulogenesis. This is cytoskeletal bending to bend one cell around itself. So this is a kind of top-down causation. In the service of a large-scale anatomical goal, having this tubule, different molecular mechanisms can be called up.

And so if you think about this as a new embryo, a newt coming into the world, you have to not take prior expectations very seriously. You can't depend on how many copies of your genome you're going to have. You can't count on having cells of the right size. You can't count on having cells of the right number. You have to be able to create the correct pattern, meaning take that journey through anatomical morphospace, not only with external unpredictabilities in the environment, but you can't even trust your own parts. You don't even know ahead of time what you're going to be made of. And so that remarkable plasticity turns out to be very important, and it's not just newts; this is ubiquitous throughout the tree of life and turns out to be very important for medicine.

So let's think about this issue of morphospace. We all start life like this, the embryonic blastomeres. Eventually, we acquire this incredibly complex structure. All the organs typically are in the right place relative to the right thing next to each other and so on. And so you might ask a simple question, where does this pattern come from? Actually, where is this encoded? And a lot of people are tempted to say, well, it's in the DNA, of course, it's in the genome. But the thing with that is that we can read genomes now, and we know what's in the genome, and it isn't directly anything like this. What's in the genome are the descriptions of the micro-level hardware, the proteins, that every cell gets to have. So we still need to understand, using that hardware, how this collective knows what to build and when to stop. How do we convince it to regenerate? And as engineers, could we get these exact same cells to build something completely different? I won't have time to talk to you about that, but we do make some synthetic organisms from genetically wild-type cells. And in fact, cells are willing to make all kinds of stuff with you if you do the right things. So this is what we're really interested in, is where does this pattern come from?

Slide 17/39 · 19m:24s

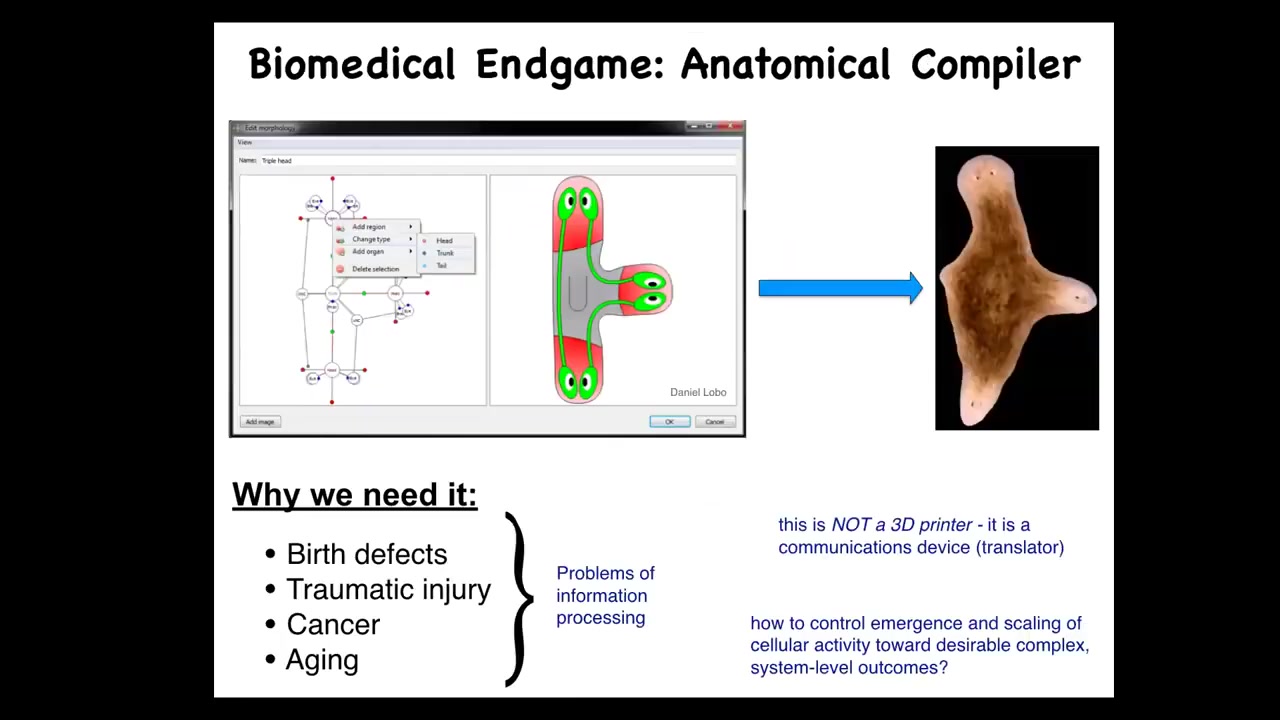

Now, as I think about the end game of our branch of biomedicine, I think about the fact that so many things would go away. So birth defects, traumatic injury, cancer, aging, degenerative disease, all of these things would be a non-issue if we had the ability to communicate anatomical goals to a group of cells. If you could tell a group of cells what to build, all of those things would be solved. So what I think about is this notion of an anatomical compiler, this idea that someday you will be able to sit down in front of a computer, draw the plant or animal or organ or biological robot, draw the structure that you want. And the system, if we knew what we were doing, would compile that description down into a set of stimuli that would have to be given to cells to make them build whatever you just drew. Complete control over anatomical growth and form. That is what I see as the end game here. We don't have anything remotely like this.

Slide 18/39 · 20m:23s

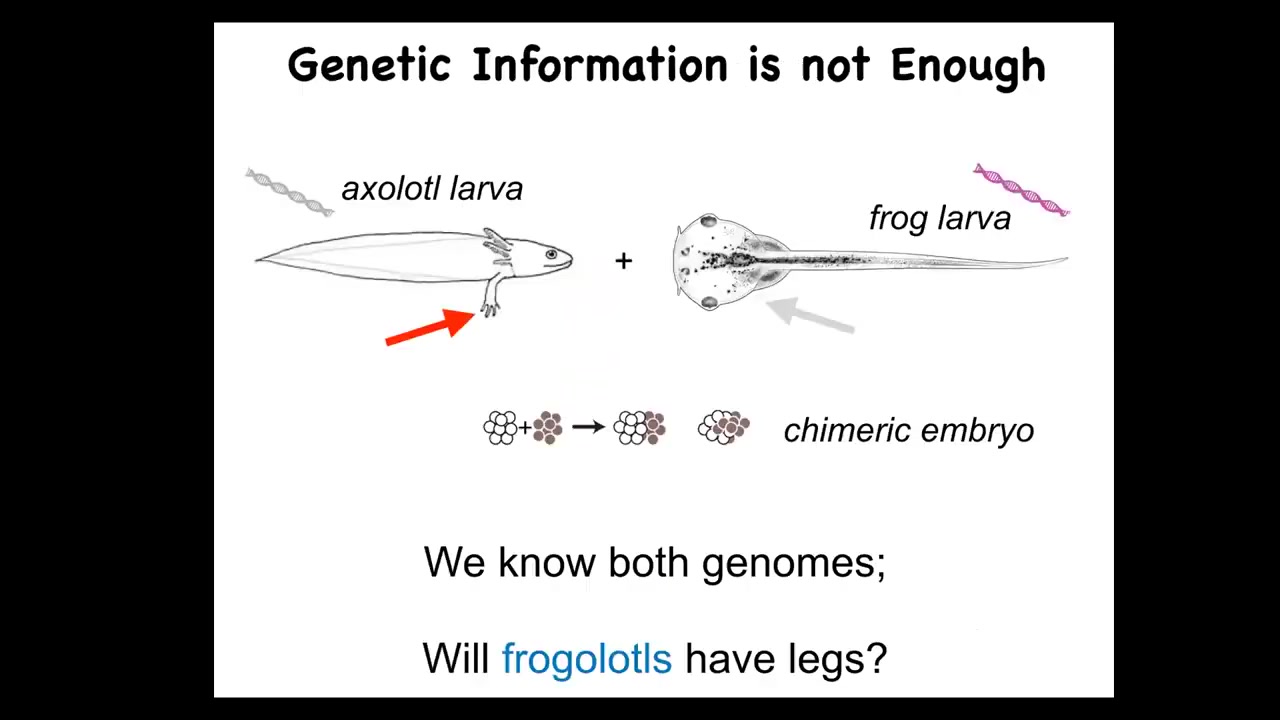

You might ask why, because genetics and molecular biology have been advancing very rapidly in cell biology and so on. Why don't we have something like this? I want to point out just a very simple example. This is a baby axolotl, and baby axolotls have little legs. This is a tadpole of a frog. They do not have legs at this stage.

In my group, we make something known as a frogolotl, which is basically a chimeric embryo consisting of some frog and some axolotl cells. I pose the following question. You've got the axolotl genome, it's been sequenced. You've got the frog genome, that's been sequenced. Can anybody tell me whether a frogolotl is going to have legs or not? The answer is no. We have absolutely no models in the field that would answer that question, despite having perfect genetic information.

That's because while we are very good at this kind of thing—understanding the molecular details of the hardware—we are not good yet at understanding the collective decision-making of groups of cells in the anatomical amorphous space. We do not understand how they solve problems in these various spaces, and this is something that I see as the future, the next frontier of the field.

Think about what happened in computer science. This is what programming looked like in the 40s and 50s. To control a computer, you had to interact with the hardware. This is where molecular medicine is today. All of the most exciting advances—CRISPR, genome editing, protein engineering, pathway rewiring—are down at the hardware level. Single molecule approaches; everybody's very interested in the hardware. We've barely begun to understand the software of life, which is really the problem-solving competencies of our material.

I keep using this word intelligence. What do I mean by that? I mean William James's definition, which is quite interesting. He said intelligence is the ability to reach the same goal by different means. What he's focusing on is problem solving. It's quite agnostic about the problem space. He doesn't say what kind of brain you have or whether you are evolved or engineered. He's trying to pull out what is central to all intelligent systems, no matter what their composition or their provenance.

Let's talk about this notion of the collective intelligence of cells. What can they do? What are the collective kinds of problem-solving capacities? The first thing is that while embryogenesis is reliable—most of the time you get this—it isn't hardwired. If you cut early embryos into pieces, you don't get half bodies; you get normal monozygotic twins or triplets or whatever. There's this ability to reach this goal state, which is the ensemble of states in anatomical space that correspond to normal human variation. That's where the normal human target morphology is. You can get there from different starting points, avoiding various local minima.

Slide 19/39 · 23m:13s

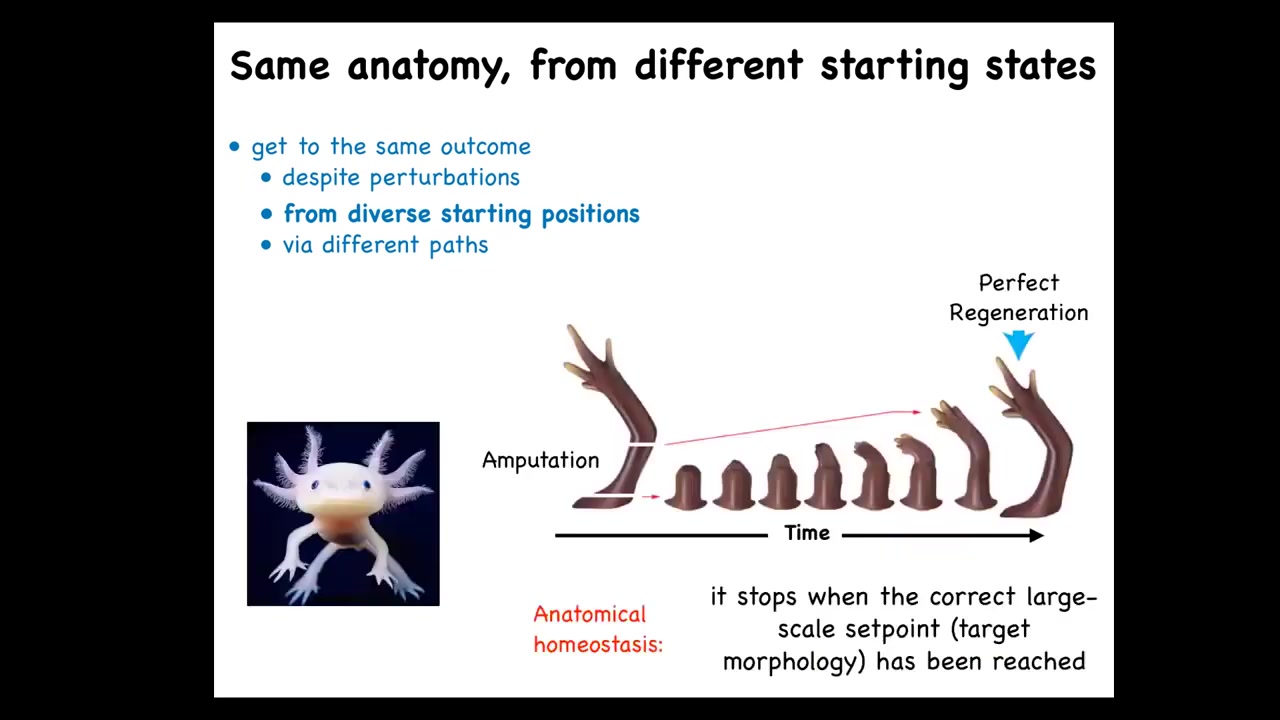

This is not just for embryos. Some animals do this throughout their lifespan. This salamander here can regenerate its eyes, its jaws, its tails, its limbs, and so on. If you amputate anywhere along here, the system will do exactly what's needed. In other words, grow and undergo morphogenesis, and then it stops. That's the most amazing part of regeneration: it knows when to stop. When does it stop? It stops when a correct salamander limb has formed.

This is a kind of anatomical homeostasis. It's a system that can tell where it is in the anatomical morphospace. This is correct, this is incorrect, and go roughly in the right direction. When it gets to the right region, it stops. This is a critical capacity that we need to understand.

Slide 20/39 · 24m:01s

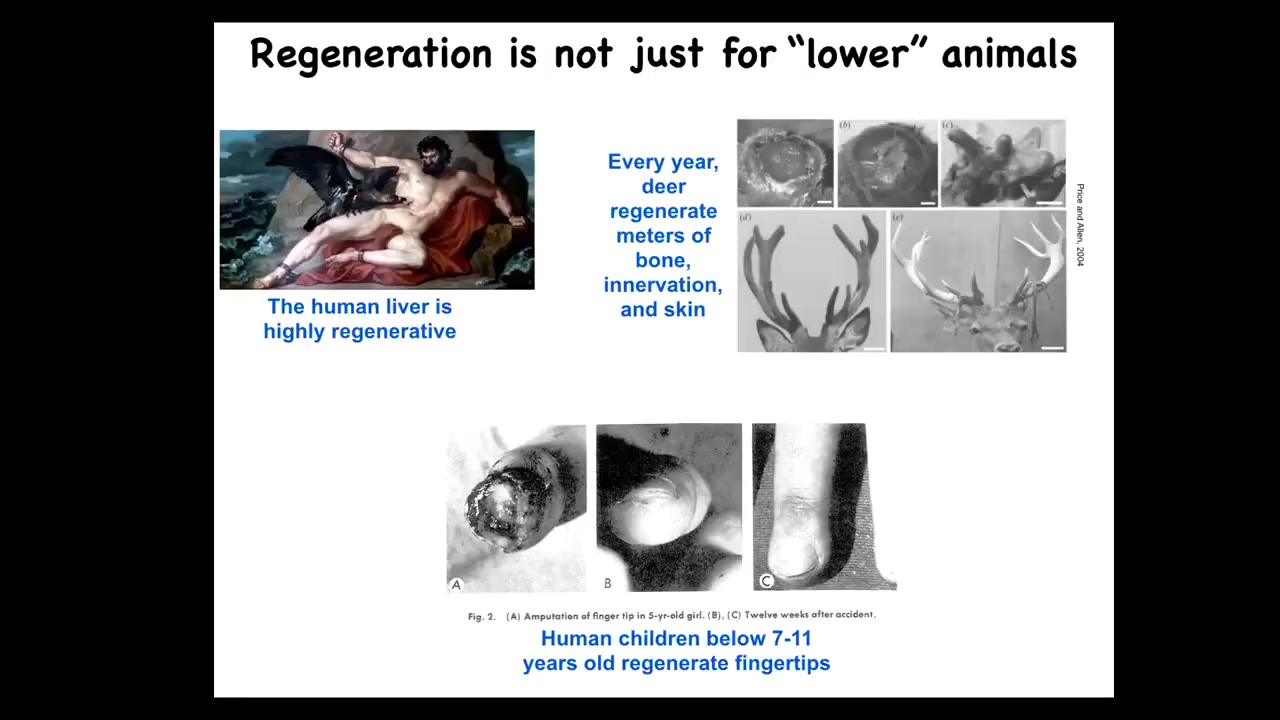

Now, it's not just for worms and salamanders. Humans, their liver is highly regenerative. Even the ancient Greeks knew that. Human children will regenerate their fingertips up to a certain age, and deer are a large adult mammal that, while regenerating its antlers, will regrow up to a centimeter and a half of new bone per day. This is remarkable growth: bone, vasculature, innervation, all of that every year.

Slide 21/39 · 24m:30s

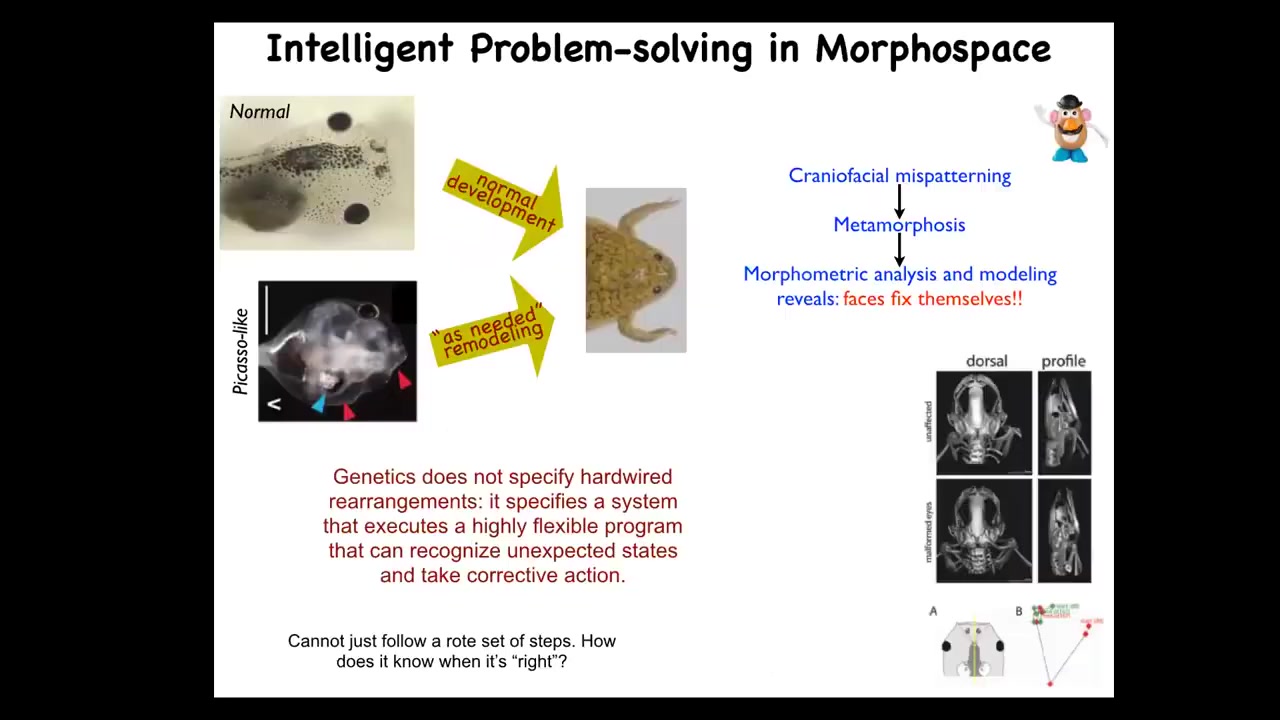

I want to focus on one very simple example of what I mean by navigating this morphospace. This is the frog tadpole; here are the eyes, the face is here. Tadpoles need to become frogs, and in order to do that, they have to rearrange their face. The jaws have to come out, the nostrils have to move, the eyes have to move closer.

It was thought that this was just a hardwired set of movements. Every organ moved in the right direction, the right amount, and you get from a normal tadpole to a normal frog. That was the assumption. We decided to test the hypothesis. How much intelligence does the system actually have for navigating this problem space? We created these so-called Picasso tadpoles. The idea is that everything is in the wrong place: the eyes are on the back of the head, the jaws are off to the side. We scrambled the whole head. These animals make largely very normal frogs because all of these body organs will move in novel paths. If they go too far, they actually double back and everything will rearrange relative to each other until you get to a correct frog face.

What the genetics actually gives you is an amazing system that executes a problem of error minimization. It's able to take novel actions to correct towards a particular outcome. This is William James's definition, the ability to reach your same goal by different means. You saw that in the kidney tubule example where the cells call up different molecular mechanisms. You see it here when it's from different starting positions, it gets where it's going.

Of course, we can look at this and we can understand the idea of navigation and we can understand homeostasis, but it all brings up one big question: how does it know what the correct frog face looks like? How does it know where it's going?

Slide 22/39 · 26m:12s

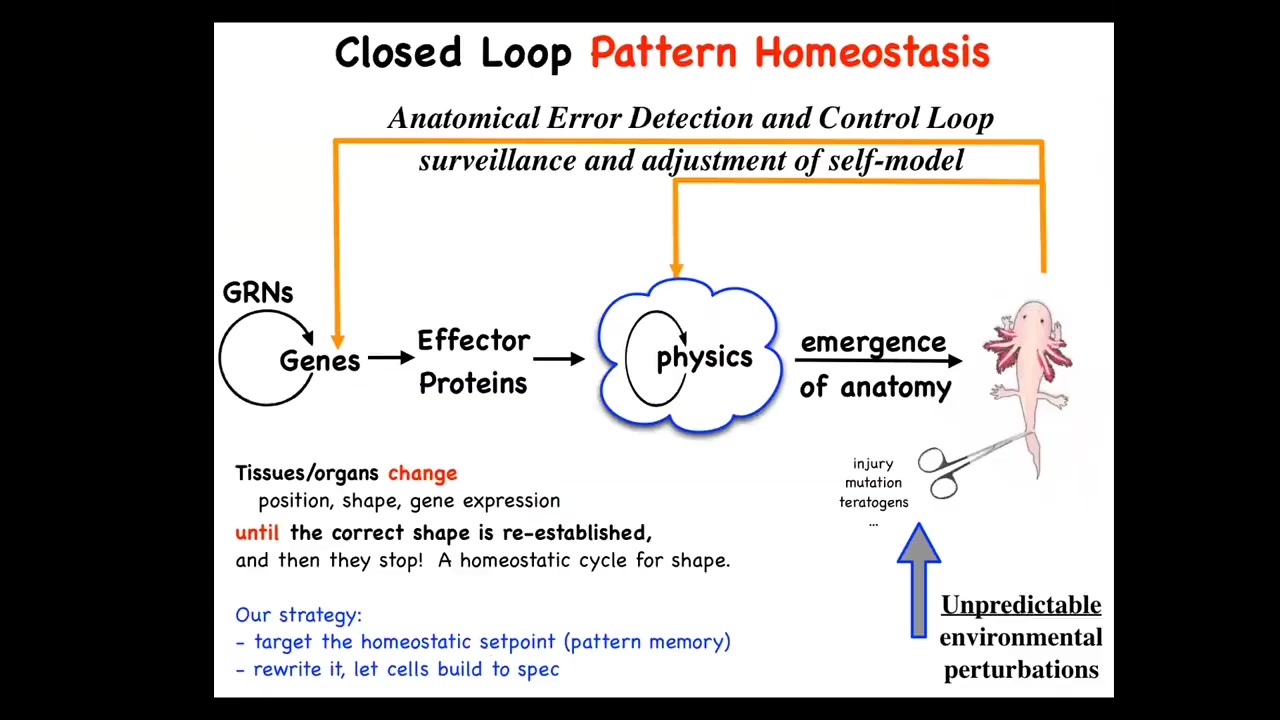

This is the standard story of developmental biology that you get from textbooks, which is the gene regulatory activity leads through the process of feed-forward emergence and emergent complexity to this kind of outcome. That's all true. It does. There is a lot of emergent complexity going on. Simple rules give rise to complex anatomical structures. But that is far from the end of the story.

The really critical part here is that it is a homeostatic process, where if you deviate a system from where it needs to be in terms of injury, but also mutations, teratogens, whatever, then these loops kick in that try to make changes to get you back to where it needs to be. This is not simple feed-forward emergence. This is goal-directed activity.

On the one hand, biologists know all about homeostasis, but there are a couple of things here that are unique and different and the kind of counter paradigm. First, typical homeostatic loops use a scalar as the set point. It might be pH, temperature, or hunger level. It's typically a single variable. This is not like that. The set point here is a complex anatomical structure, maybe not to the level of individual cells. It doesn't have to be high resolution, but this is a system that clearly knows what the correct pattern is. That's first.

Second, we are not encouraged in biology, and especially in molecular genetics, to formulate models in terms of goals. Models are supposed to be in terms of chemistry and local rules, and then whatever emerges, emerges. But you're not encouraged at all. In fact, you're actively discouraged from looking for goals, purpose, intelligence in these systems.

Since the 1940s, we've had cybernetics, control theory, computer science, and so on, that allow us to think about these things without magic. It should no longer be scary to think about physical systems, including living systems that are not brains having goals, being able to solve problems. We have the tools to understand this now.

What this weird way of thinking about this system as a goal-seeking system makes is a very strong prediction. It suggests that in order to make changes down here, and those might be repair or might be augmentation of human potential, it is no longer true that the only game in town is to try to change down here. That's extremely difficult because this process is not reversible. We generally have no idea what genes or proteins you might want to tweak to make specific system-level changes. That is going to establish a kind of ceiling for things like CRISPR and genome editing. They'll solve a lot of low-hanging, single-cell, single-gene diseases.

But after that, there's a real problem, the same problem that holds back Lamarckian inheritance, which is that it's in general impossible to figure out in this kind of scheme what you need to change down here to make changes up here. If it is true that this is a goal-seeking system that in some way remembers the actual set point, then we've got a new way.

This is a strategy that everybody from cyberneticians to the repair person who shows up to fix your thermostat at home understands: in a system like this, you don't need to make changes to the structure. You might just be able to reset the set point.

What we've been doing for the last 20 years is following the predictions of this idea: we should be able to find the recorded set point in the body somewhere. We should be able to decode it. The homeostatic set point should be readable. It should be decodable. Then we're going to rewrite it and let the system do what it does best, which is build to that spec. You don't go rewind.

Wiring your thermostat when you want it to go to a different temperature, and you don't use a soldering iron on your laptop when you go from Photoshop to Zoom, you exploit the reprogrammability of your material. In trying to understand where is this set point going to be stored? How can all of this work? We took a cue from the brain.

Slide 23/39 · 30m:25s

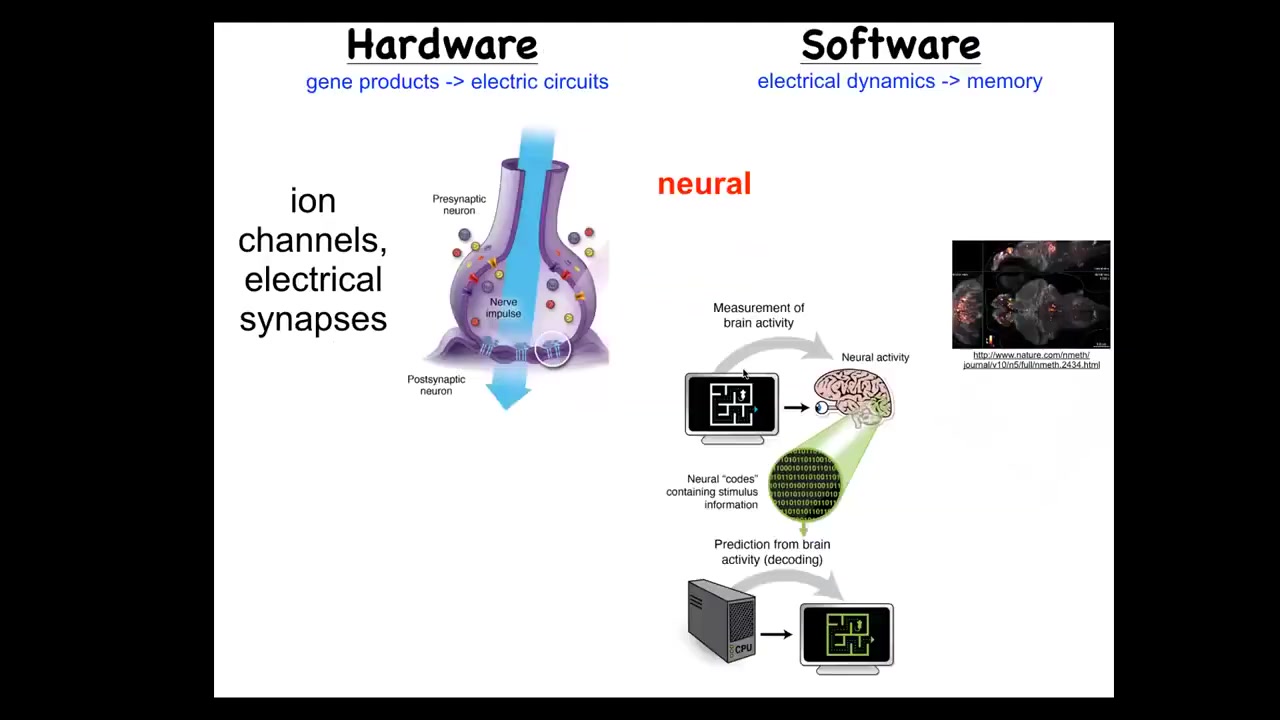

In the brain, we know that brains are goal-seeking systems. There's this network where the hardware is formed from ion channels that set voltage gradients. These voltage gradients communicate information to their neighbors through these electrical synapses known as gap junctions. And so that's the hardware. The software is here. So this group made this amazing video of a zebrafish brain while the zebrafish is thinking about whatever it is that fish think about. And the commitment of neuroscience is this idea that all of the memories, the preferences, the behavioral repertoires, the goals, all of that is stored in the electrophysiology. And the idea is that having read the electrophysiology, if we now knew how to decode it, this is the project of neural decoding, we would be able to read all of the cognitive content, we would know what the fish wants, what it's trying to achieve.

The remarkable thing is that those kinds of tricks that the brain uses are not new. They were discovered by evolution at the time of bacterial biofilms. So they're extremely ancient. Every cell in your body has ion channels. Most cells have gap junction connections to their neighbors. And so all of your tissues from the moment of the first cell division in embryogenesis form these kinds of electrical networks. And then you could make this leap, which is what we've done, which is to say, could we port all of the techniques of behavioral neuroscience and computational neuroscience away from neurons? If this system is more general, what if neuroscience isn't really about neurons at all? It's about information processing and networks and problem solving. Then you could take all these tools, and the amazing thing that we found is that these tools actually don't distinguish. So we distinguish by different journals, different courses in your education, different funding bodies. Developmental biology and neuroscience are considered different fields. Those distinctions are quite artificial in the sense that the tools don't distinguish them at all. We can port everything from optogenetics to neurotransmitter machinery modulation, the pharmacology for our ion channels, active inference, perceptual bistability. All of this stuff maps over. So what you might do is try to do a kind of a decoding project on morphogenesis. You might say, we'll use the same techniques, we'll understand what the network is doing electrically, and could we extract from that information that will help us understand and control how these things move through morphospace?

So we developed the first tools to do that away from neurons. This is a voltage-sensitive dye showing in a time-lapse all the electrical conversations that cells in a frog embryo are having with each other as it sorts out who's going to be left, right, anterior, posterior. We've developed lots of computational tools, including simulators, to understand how these bioelectrical gradients form and how they develop and what the dynamics are going to be.

Slide 24/39 · 33m:16s

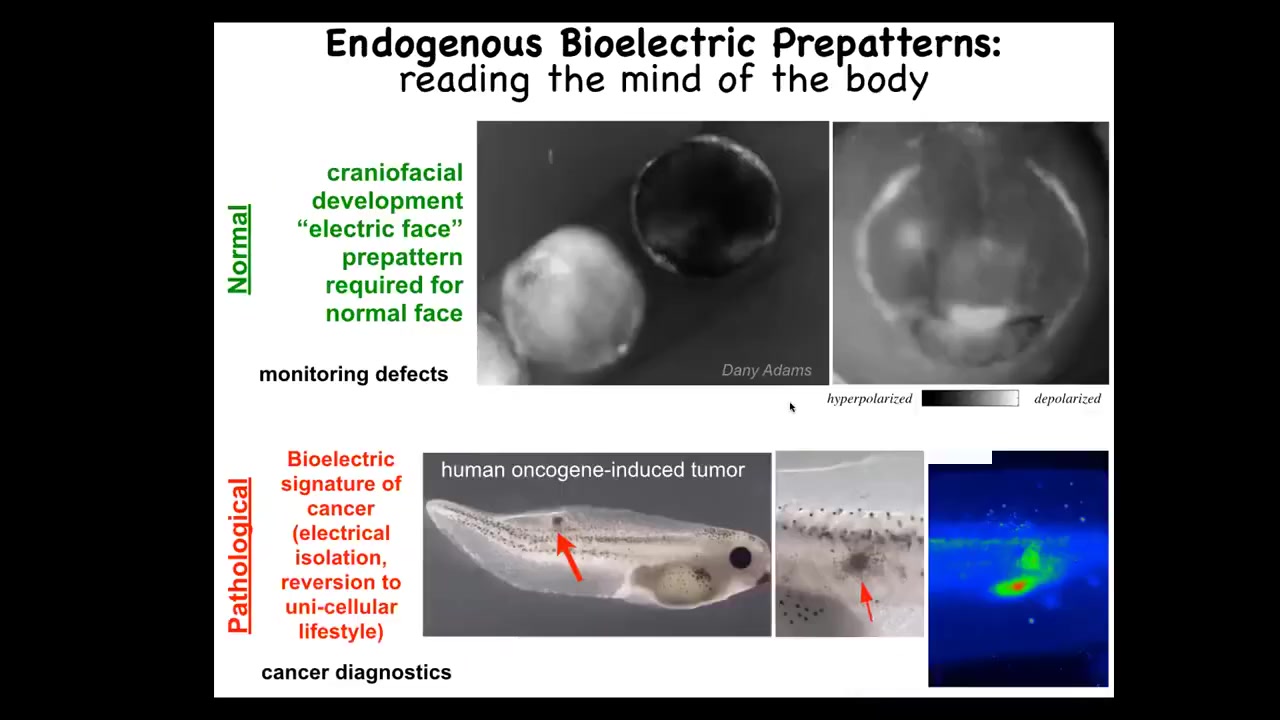

I'm going to show you this pattern. I'm showing you one that's easy to understand. There are many patterns that are actually quite hard to decode, and this is very hard work that's going to last years, this cracking, this bioelectric code. I want to show you a nice simple one. This is a frog embryo in time-lapse putting its face together. This is one frame out of that movie. We call this the electric face. Because long before the anatomy of the face is formed and before the genes turn on to regionalize the ectoderm here and to make a face, you can already see that these cells know where everything is going to go. Here's where the eye is going to be. Here's where the mouth is going to be. Here are the placodes. We can read by using the same voltage-tracking techniques that people used in brains; we can actually read the electrical pre-pattern, that subtle scaffold that determines downstream gene expression.

So this is a native endogenous pattern memory that is required for making a frog face. If you move this, if you change this pattern, then the gene expression changes and the anatomy changes. That's a normal pattern, and you might imagine using that to someday monitor birth defects. This one is a pathological pattern that you can induce by injecting human oncogenes into these tadpoles. Eventually, these tumors will metastasize. Before that happens, you can already see the aberrant bioelectrical state that this oncogene has established, and you know where the tumor is going to be, and you actually know where the margins are going to be here. So there's all kinds of cancer diagnostic opportunities there.

Slide 25/39 · 34m:50s

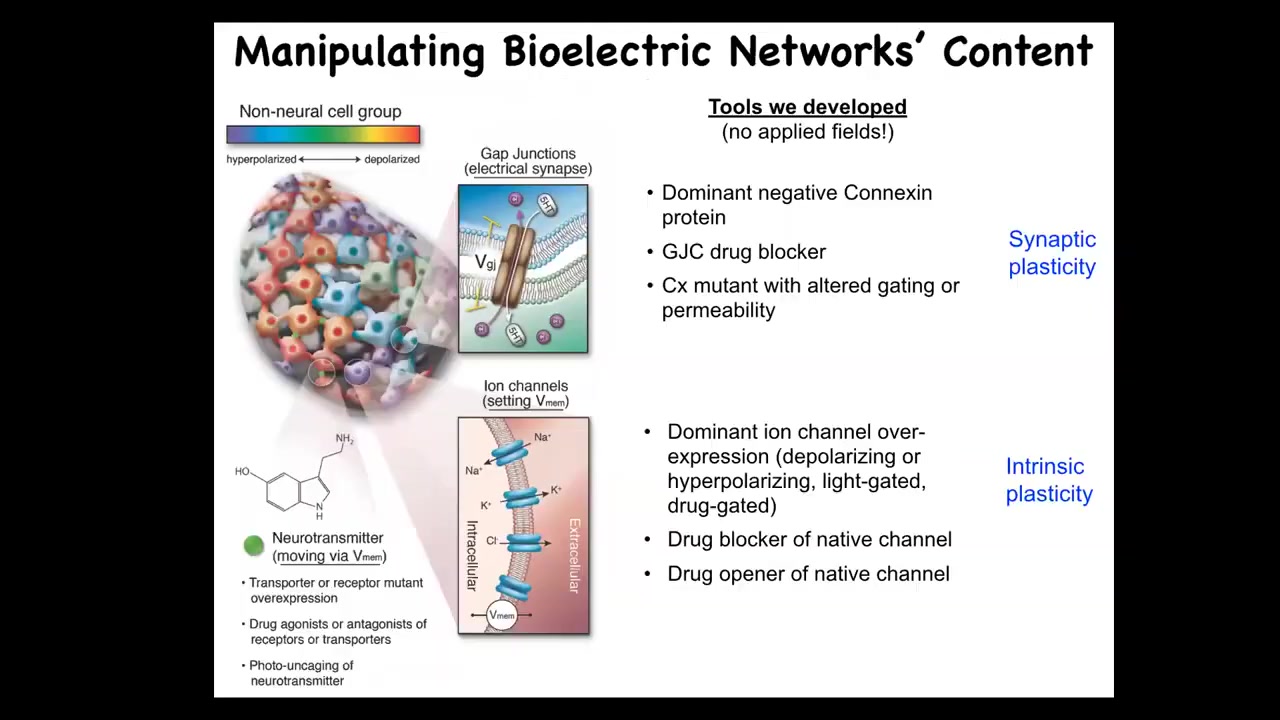

In addition to being able to monitor these things, the most important things are functional experiments. You want to be able to read and write this electrical information to prove that it's functionally important and then to modulate it in medical settings. So we developed some tools. Everything I'm going to show you next: there are no applied fields. There are no electrodes, there are no electromagnetics, there are no frequencies, there are no waves. There's only modulating the native interface that cells use to hack each other in vivo. And so this is really just tools appropriated from neuroscience to manipulate ion channels and gap junctions and thus have predictive control over the bioelectrical state of cells. This is really very high-resolution molecular pharmacology, genetic modification of ion channel properties and optogenetics and so on.

So when you do this, what happens if we change the electrical information? Back when I first started doing this around 2000, everybody said at the time that what you're going to get is uninterpretable toxicity and death. It was thought that the resting potential in normal cells was a housekeeping parameter, that if you mess with that, you're just going to get toxicity. So it turns out that that's not the case and that this information carries very specific constructive cues.

Slide 26/39 · 36m:11s

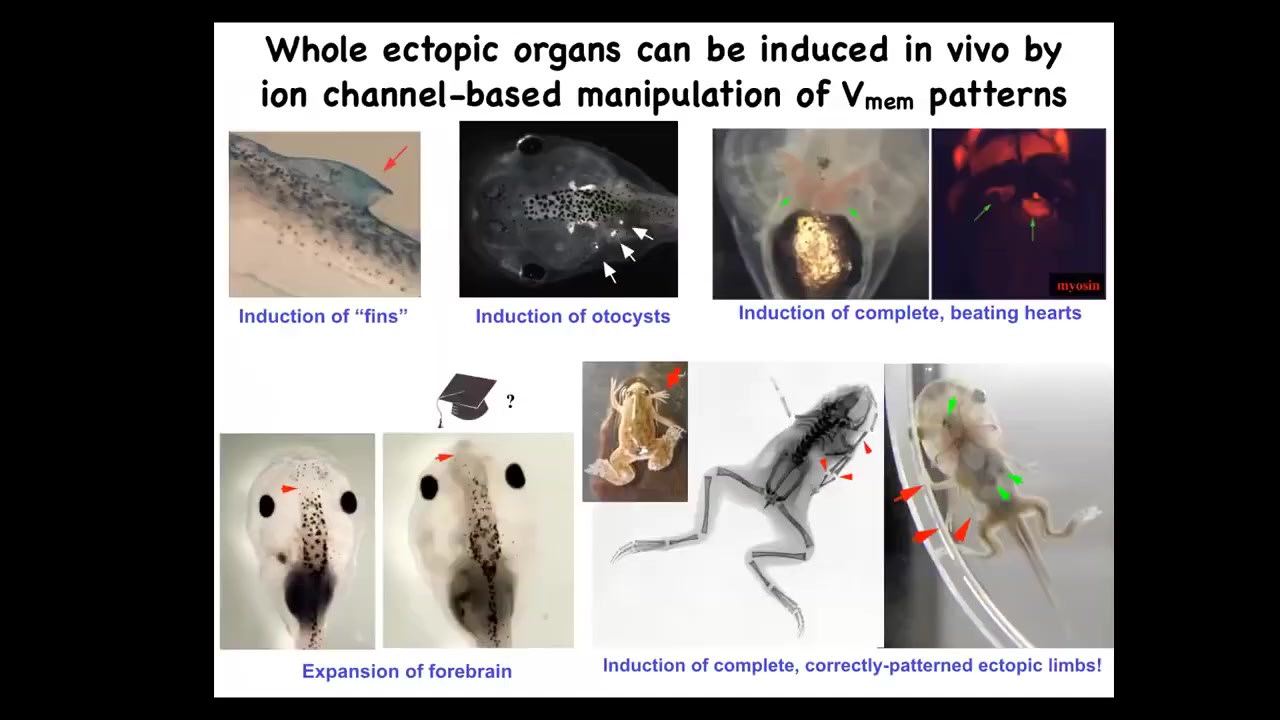

What we can do in these tadpoles, by manipulating bioelectrical patterns, by injecting new channels, by using optogenetics and so on, is induce the formation of ectopic hearts, ectopic otocysts, ectopic forebrains.

This is where the brain normally ends, and you can wonder if this guy is that much smarter than this one. You can make ectopic limbs. Here is our six-legged frog. This is an optogenetic frog. You can see that this isn't just some random toxicity. We're actually calling up new organs.

Slide 27/39 · 36m:47s

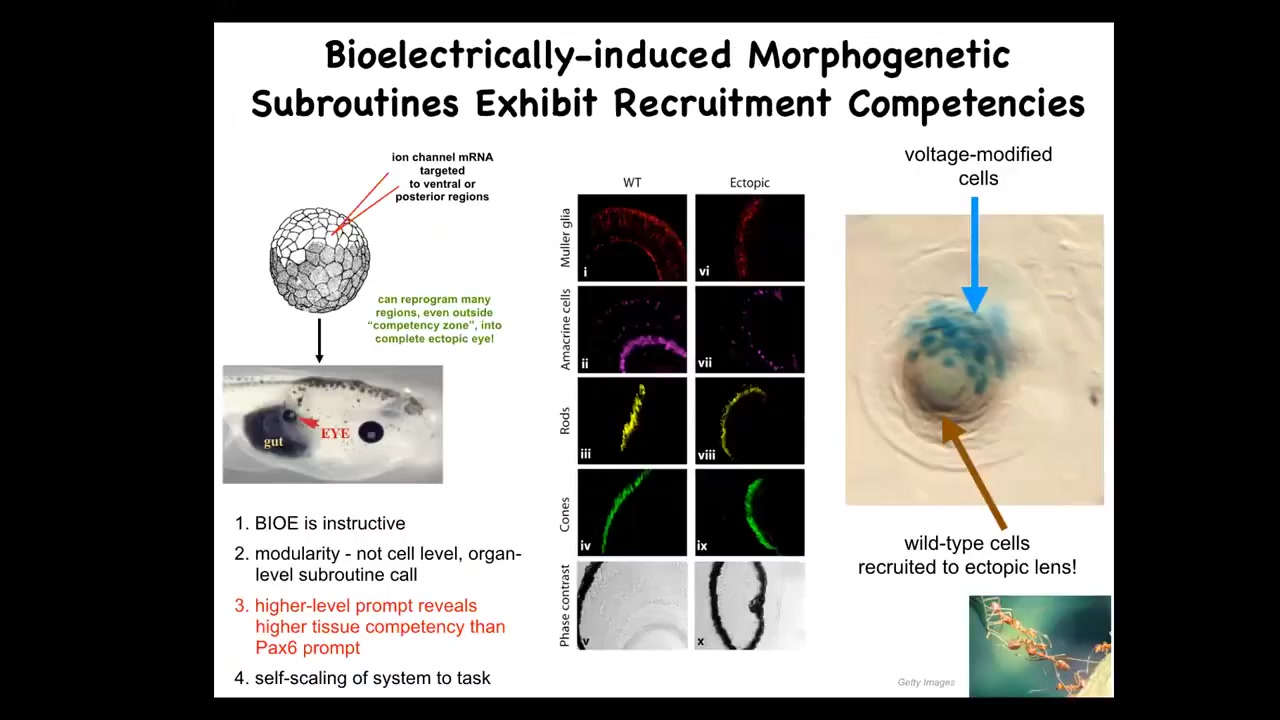

This is my favorite example of that. We take a frog embryo and we inject some ion channel RNA. These are potassium channel RNAs that were specifically chosen to make a voltage spot of the kind that you saw in that electric face that corresponds to an eye spot. We inject that into a region of the animal that would become gut. So what you have here is these endoderm cells, and when you establish that voltage pattern, they happily make an eye.

Now, according to your developmental biology textbook, endoderm should not be able to make an eye. Only the anterior neuroectoderm should be competent to make an eye. That's actually not true. You can get an eye anywhere if you prompt it with the right bioelectrical pattern. Not the master eye gene Pax6. That doesn't work anywhere outside of this area, but the bioelectric state does. So you can induce these eyes. These eyes can have all the right lens and retina and optic nerve and all the stuff they're supposed to have.

Notice a couple of additional things here. One is that this signaling that we did is extremely simple. We didn't give all the information needed to make an eye. We don't know how to make an eye, and we certainly don't know how to specify all of the different stem cell positions. This is a high-level subroutine call. We said, make an eye here. The rest of the competency is in the system itself. This is something computer scientists exploit all the time.

Doing it that way extends the competency of the cells. We thought only these cells could do it; all cells can do it. That tells you that when you're estimating the level of intelligence or competency of a given system, you're really taking an IQ test yourself. If you're not prompting it with the right things, you miss everything. That's very important.

The other thing is that this is a lens sitting out in the flank of a tadpole. These blue cells are marked with beta-galactosidase. They are the only ones that have this new channel. Now, why are all these other clear cells participating in this construction project? These are native cells that were not manipulated by us.

That's because another competency of this material, which makes this really attractive for regenerative medicine, is that these cells know when there's not enough of them to make a lens. They recruit their neighbors to help complete this process. There's another collective intelligence, which is good at this, and that's ants and termites. They also do exactly that. They recruit their buddies when the job needs more elements.

You see the secondary instruction. We instruct B-cells, you need to make an eye. B-cells automatically instruct their neighbors, you need to help. We did not have to micromanage any of this.

Slide 28/39 · 39m:26s

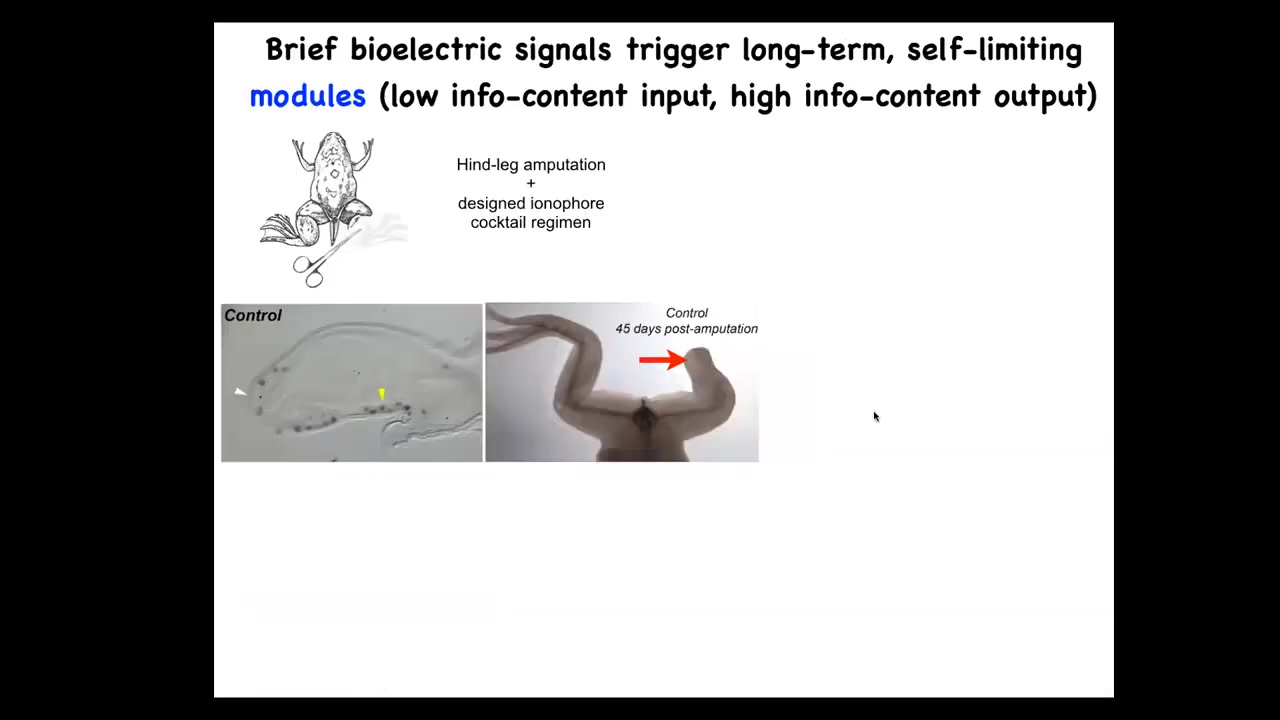

That is why in our regenerative medicine program, we try for triggers. We don't want to 3D print limbs and we don't want to try to manipulate all the cells. This is an example of what we've done. In the frog, you cut off the leg. 45 days later, there's nothing. It doesn't regenerate.

Slide 29/39 · 39m:45s

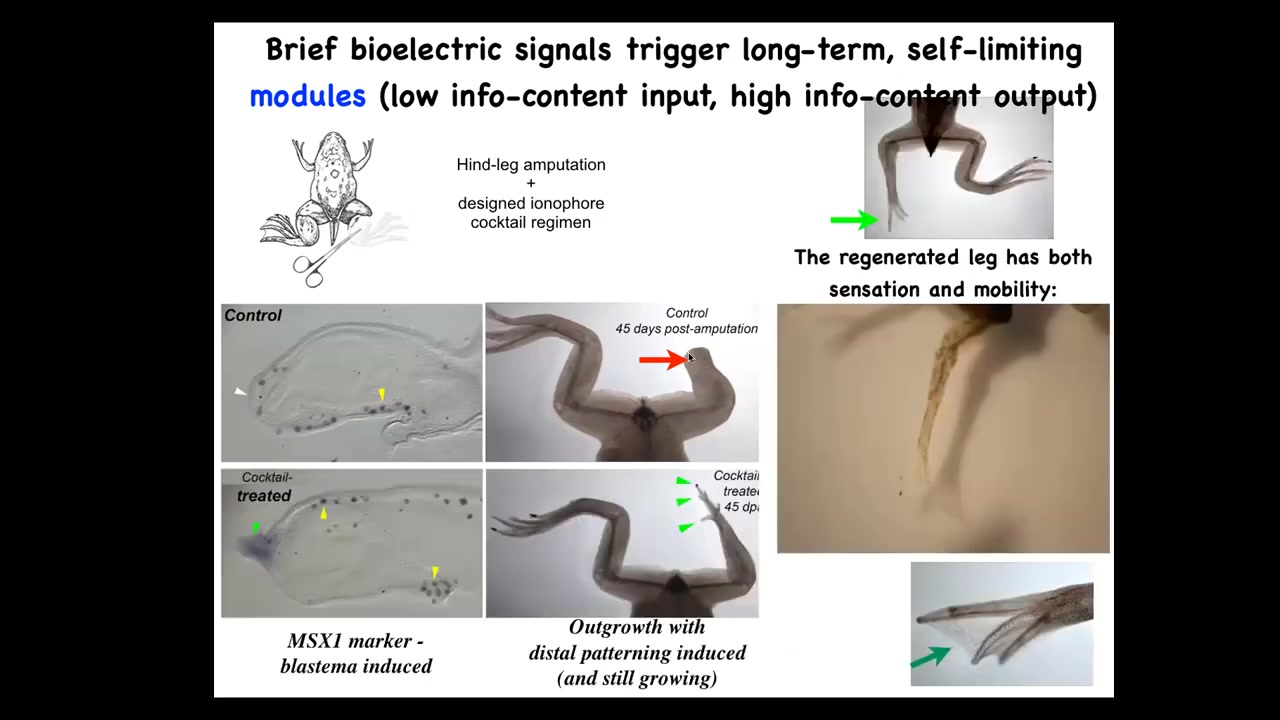

However, if you apply a cocktail of ionophores that sets up a particular bioelectrical state, then within a couple of days you get an MSX1-positive blastema. By 45 days, you've got some toes, you've got a toenail, and eventually a pretty respectable leg that is touch-sensitive and motile. It's a functional appendage. Now here's the key. We interact with that wound for 24 hours. That's it. After that, an adult frog will grow a leg for a year and a half, 18 months of leg growth, during which time we don't touch it at all. The idea is not to micromanage the process. The idea is to say to those cells at the very beginning, you're going to go down the leg regeneration path, not the scarring path in morphospace. You get them going, then you leave them alone. They do their thing.

Here's where I need to do a disclosure: David Kaplan and I have founded a company called Morphoseuticals, which seeks to move some of that technology into mammals. We're now trying this in rodents with a wearable bioreactor that applies drug payloads and hopes to trigger regeneration while you support it with this environment.

Slide 30/39 · 40m:55s

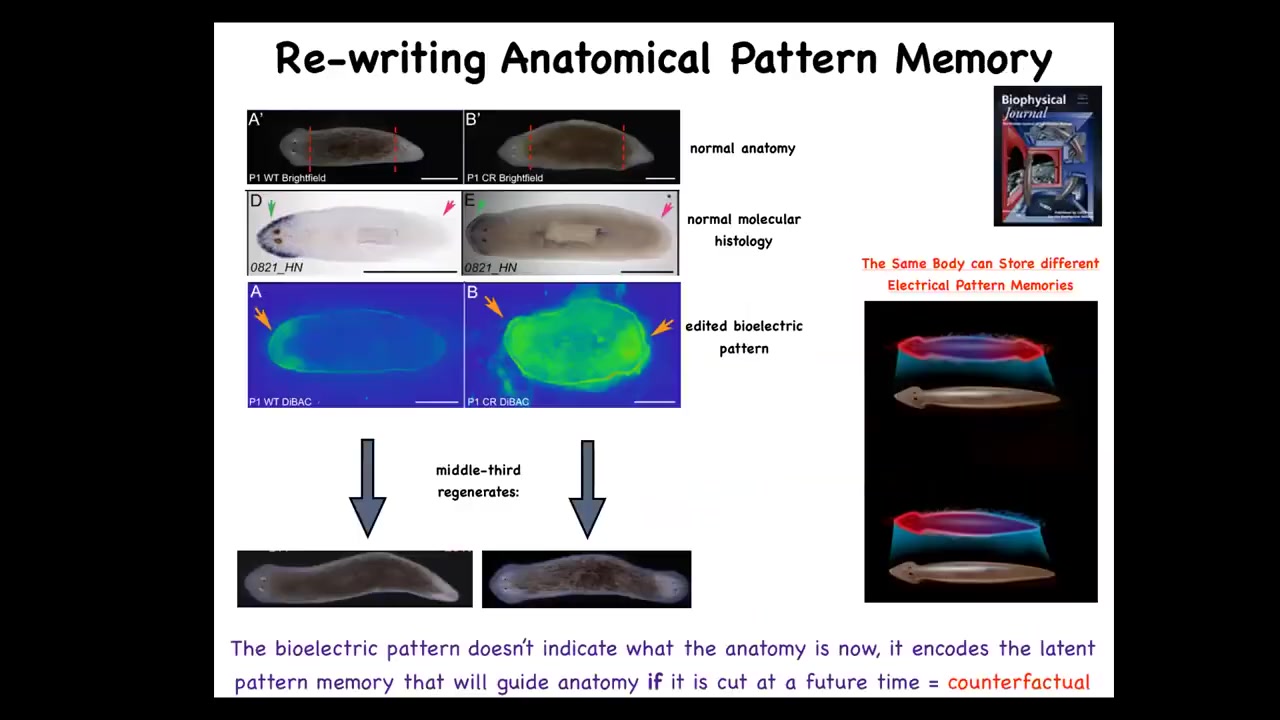

I want to quickly move to another system to hit hard this idea that I mentioned before, which is that there is an encoded representation within tissue of what to do if you get injured. In other words, the target anatomy is represented in the tissue in some way. There is a goal represented in the biophysics of the body. And I want to show you that we can now see those and change those, at least to start.

So this is our planarian, this is our flatworm. These guys have amazing powers of regeneration. Every piece gives rise to a new worm. If you cut off the head and the tail, you see that in this one-headed animal the anterior genes are in the front, the way they should be. They reliably make this one-headed worm. Now how does this piece know how many heads it's supposed to have? You might think it's nailed down by the genetics. But remember, genetics doesn't say anything about how many heads you're supposed to have, not directly.

It turns out that what it has is this bioelectrical gradient that has this information: one head, one tail. We are able to take this animal and in place rewrite that bioelectrical pattern so that it now says two heads. You can see this is kind of messy. There's still a lot of technology to be worked out here, but we can say two heads. When you do that, the animal hangs around anatomically completely normal; gene expression completely normal. But if you cut it, it makes a two-headed animal.

This isn't Photoshop. These are real. What you're looking at is a visualization of the memory of the tissue of what to do if I get injured. It's a counterfactual memory. It's not true right now. This is not a map of this guy. This is a map of this guy's perfectly normal one-headed anatomy. This is, if you think about what brains allow us to do, mental time travel where you can think about things that are not happening now, future things, past things. This is the beginning of that. This is a counterfactual pattern. This is what I think a proper planarian looks like, and it doesn't matter now because I'm not injured, but if I get injured, this is what I'm going to do. This is what these cells consult.

Slide 31/39 · 43m:07s

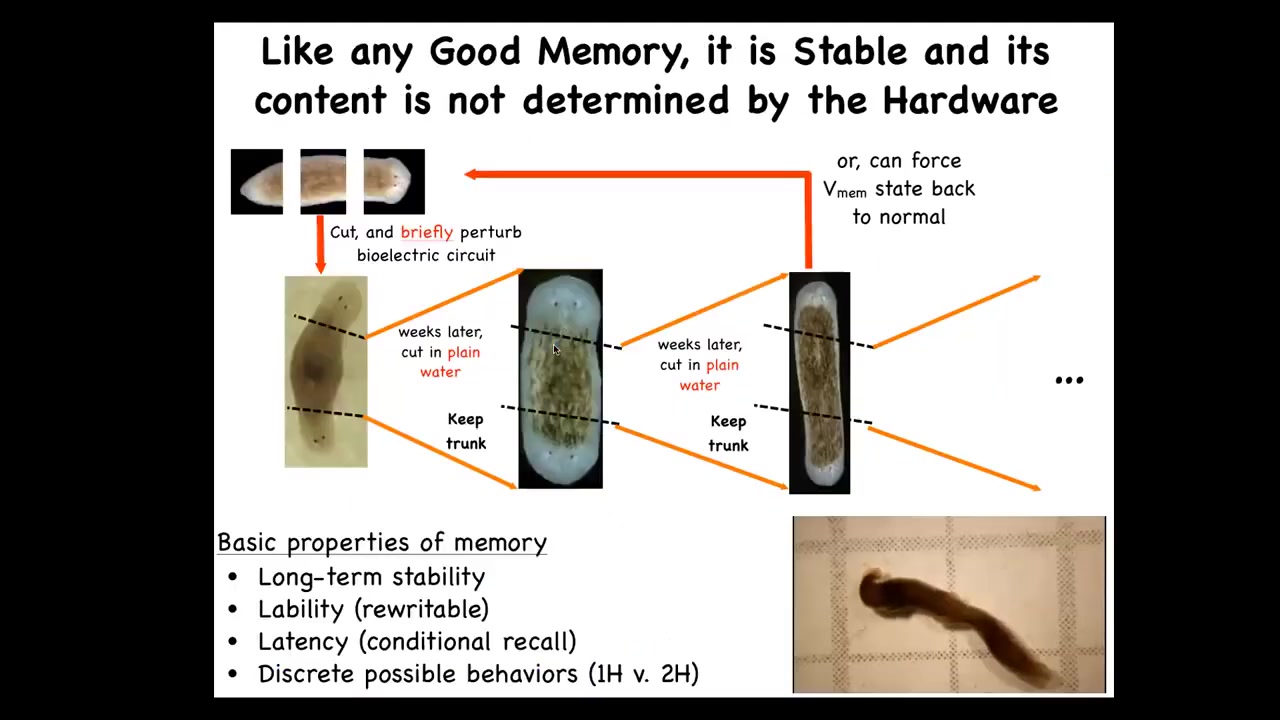

I keep calling it a memory.

Note that what we have not done is change the DNA. We haven't touched the genome. They're completely wild-type cells. But if you take these two-headed animals and you cut off the primary head and you cut off this weird ectopic secondary head, you might think that this middle fragment would just go back to the normal form dictated by its genetics. The first two-headed worms were seen in around 1903. Nobody recut them until we did it in 2008 because it was perfectly obvious what would happen. It would go back to normal because the genome is normal. That is not at all what happens. In fact, if you do this, they will continuously, in perpetuity, regenerate as two-headed animals. We can set it back.

This is in fact a memory. It has long-term stability. It is rewritable. It has conditional recall. Here you can see these two-headed guys moving around because the question of how many heads you're going to have is not nailed down in your genome. The genome encodes some hardware that by default will be running some code that says one-headed pattern, but you can rewrite it. It's reprogrammable as good hardware is. This is really important because this is not a genetic trick.

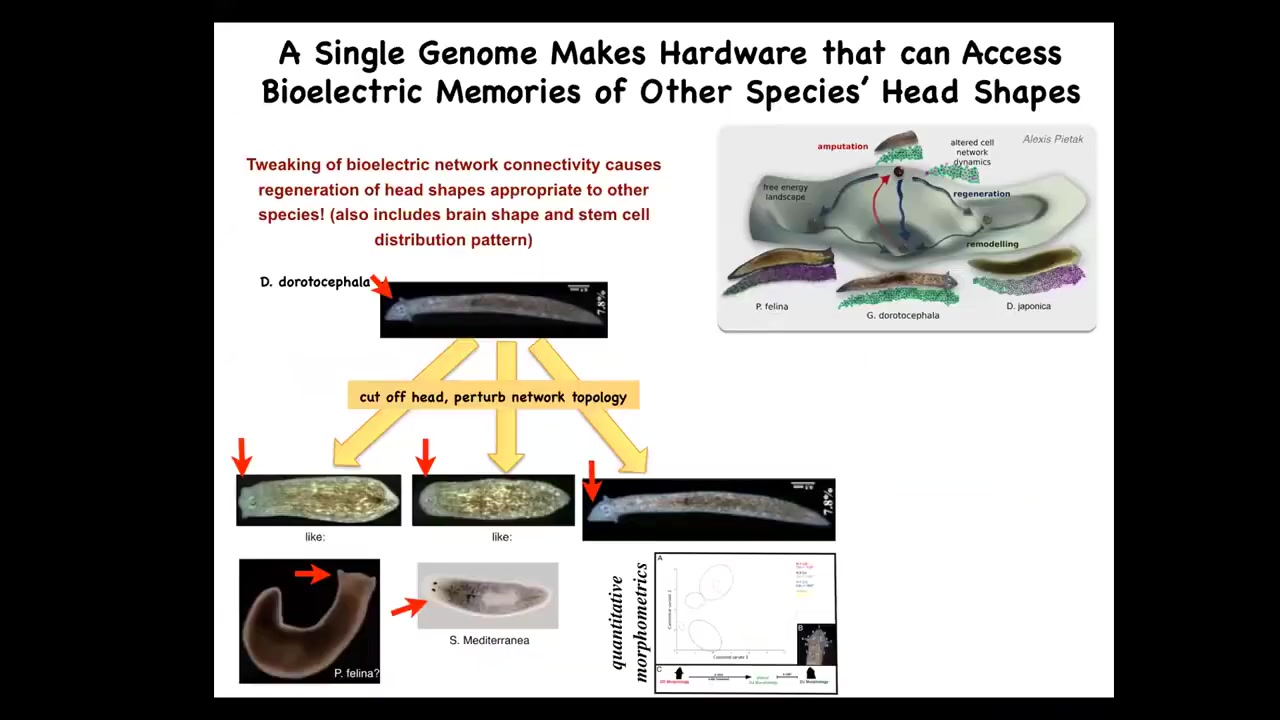

Slide 32/39 · 44m:21s

Not only can you control the number of heads, you can control the shape of the heads. These triangular-headed species are perfectly happy to make a flat head such as P. falina or a round head such as S. Mediterranean, about 100 to 150 million years' distance between these guys and these guys. They're okay making the brain shape of these animals, making the stem cell distribution of these animals, visiting the attractors in anatomical state space that normally belong to these other species. This hardware can go there too. It just normally doesn't. You start to get an idea of this latent space of possibilities around what a given genome does and of communicating the right path to these cellular collectives via bioelectrics.

This is why we're trying to make a full stack understanding all the way from the molecular genetics of where these channels come from, then what is the symmetry breaking, self-organization, computation that happens in these electrical tissues, these electrical networks, and then a body-level regeneration, and algorithmic decision-making based on this bioelectrical information that we can use to infer interventions.

Slide 33/39 · 45m:30s

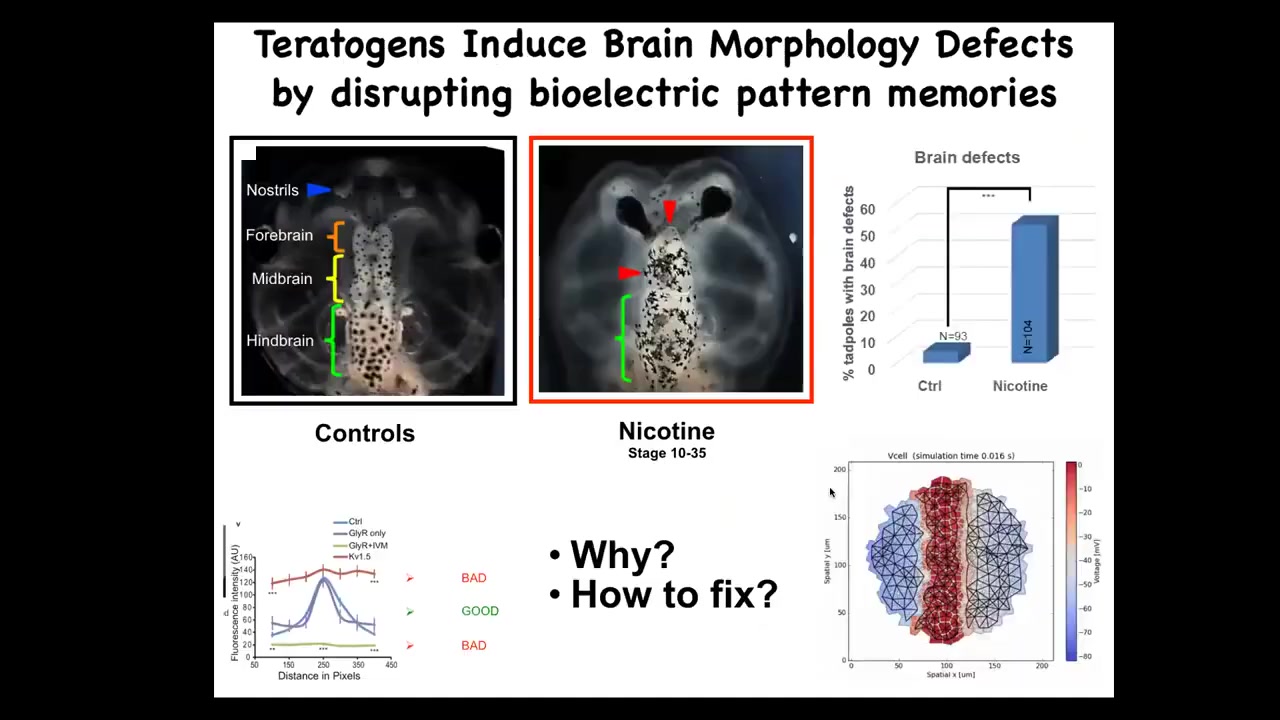

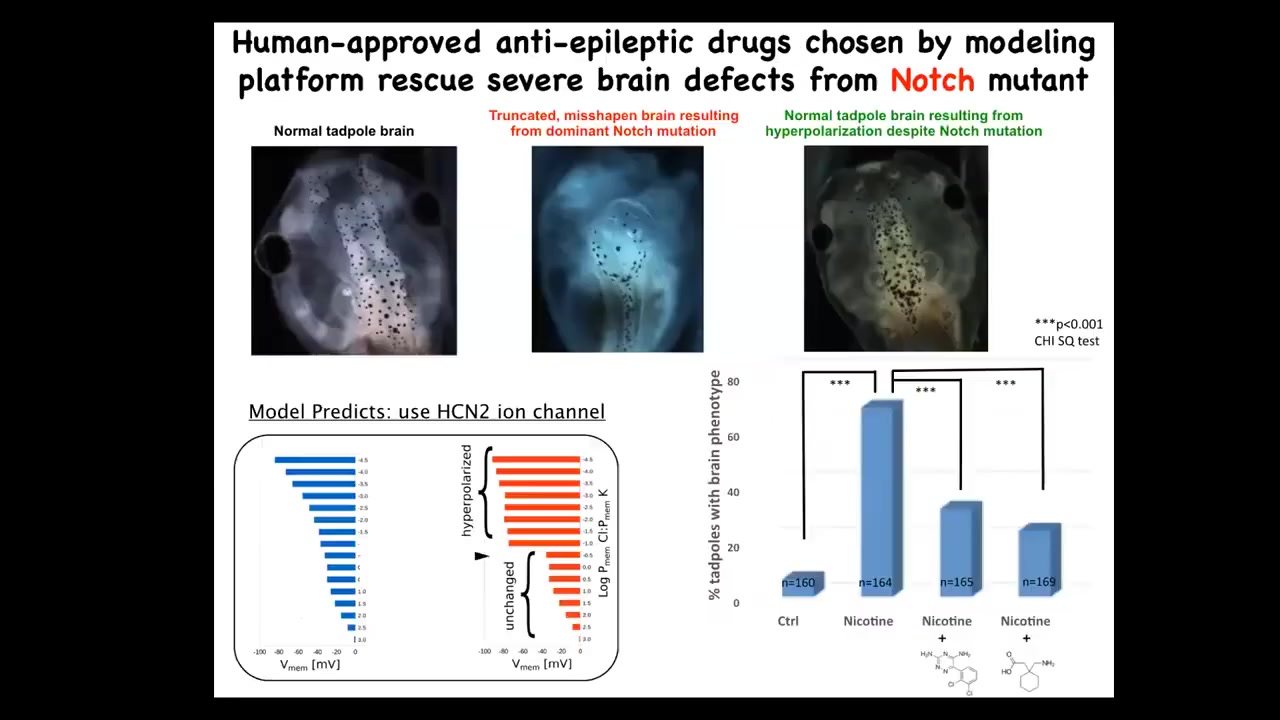

In the last couple of minutes, I want to show you, I've shown you novel organ formation. I've shown you regeneration. I'm going to show you birth defects and cancer.

This is a normal frog tadpole brain, forebrain, midbrain, hindbrain. Lots of ways to mess up this process: alcohol exposure, nicotine, mutations. What we wanted to do was to see if we can now try to repair these complex organs. What we did was to make a bioelectrical model, a computational model of the bioelectrical pattern that normally tells the brain what the size and shape should be.

Slide 34/39 · 46m:04s

When you do that, you can interrogate that model for interventions in cases where things go wrong.

For example, these are the effects of a mutation in Notch. Notch is a very important neurogenesis gene. If you mutate Notch, the forebrain is gone. Midbrain and hindbrain are just a bubble. These animals have no behavior. They're completely disabled.

What we asked the model to do was to say the bioelectrical pattern in these mutants is incorrect, and we observed that with our dye technology. What channels would we need to open or close to get back to the correct pattern? Not fix the mutation, but to get back to the correct pattern.

The model gave a suggestion. There's this HCN2 ion channel, which has some specific properties that we can talk about. We showed that despite that dominant mutation of Notch, these animals can be rescued. These are two drugs that open HCN2. They're basically anti-epileptics already in human use that completely restore the brain. You get your brain structure back, you get gene expression back, and they get their IQs back. They have normal learning rates compared to controls. The mutants have none.

This shows that in some cases, you can fix various teratogen-induced defects as well. You can fix hardware defects with software. The hardware is so amazing that in some cases, even genetic defects can be overcome. I'm not saying this will be true for all genetic diseases, but for many cases, you can actually fix the situation at the physiology level.

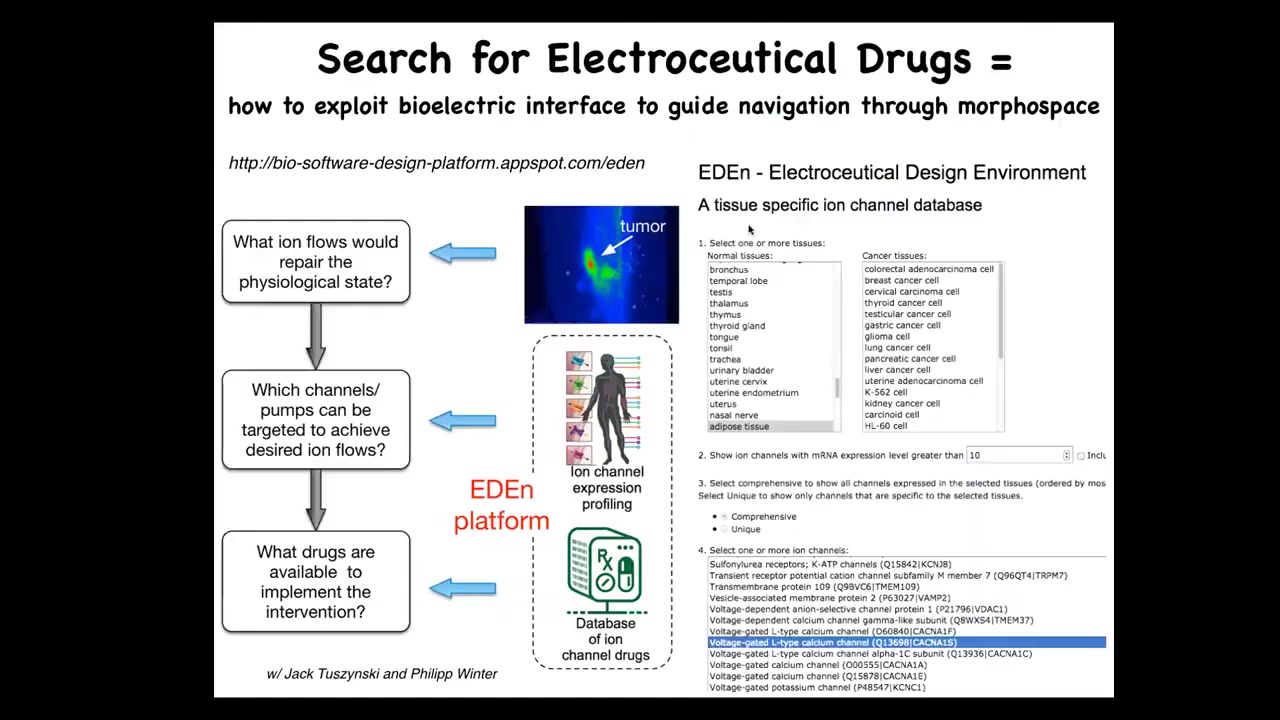

Slide 35/39 · 47m:33s

What we're doing now is creating this kind of platform where you can go on, you can play with us online, you choose the cells or the tissues that you want. It tells you all your possible ion channel targets. We're working on the simulator in between that will tell you which of these you need. Once you know your targets, you pick drugs because about 20% of all drugs are ion channel drugs. There's a huge amount of potential electroceuticals out there.

Slide 36/39 · 48m:00s

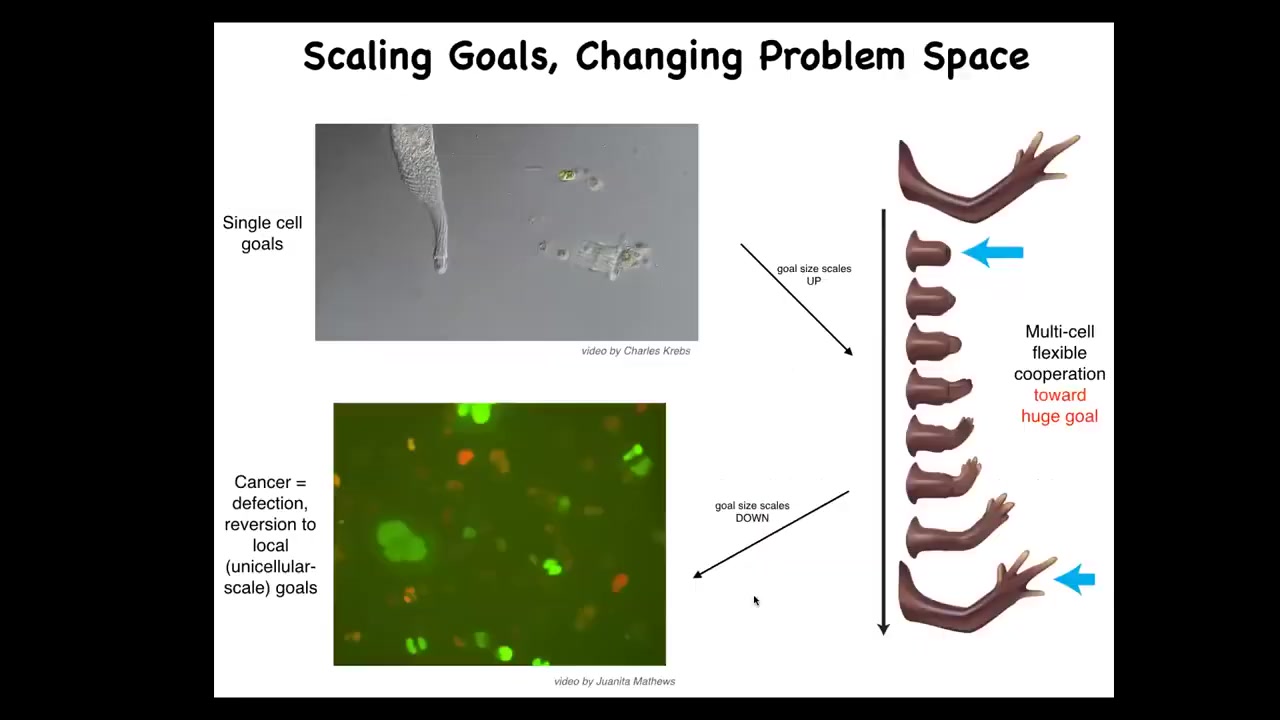

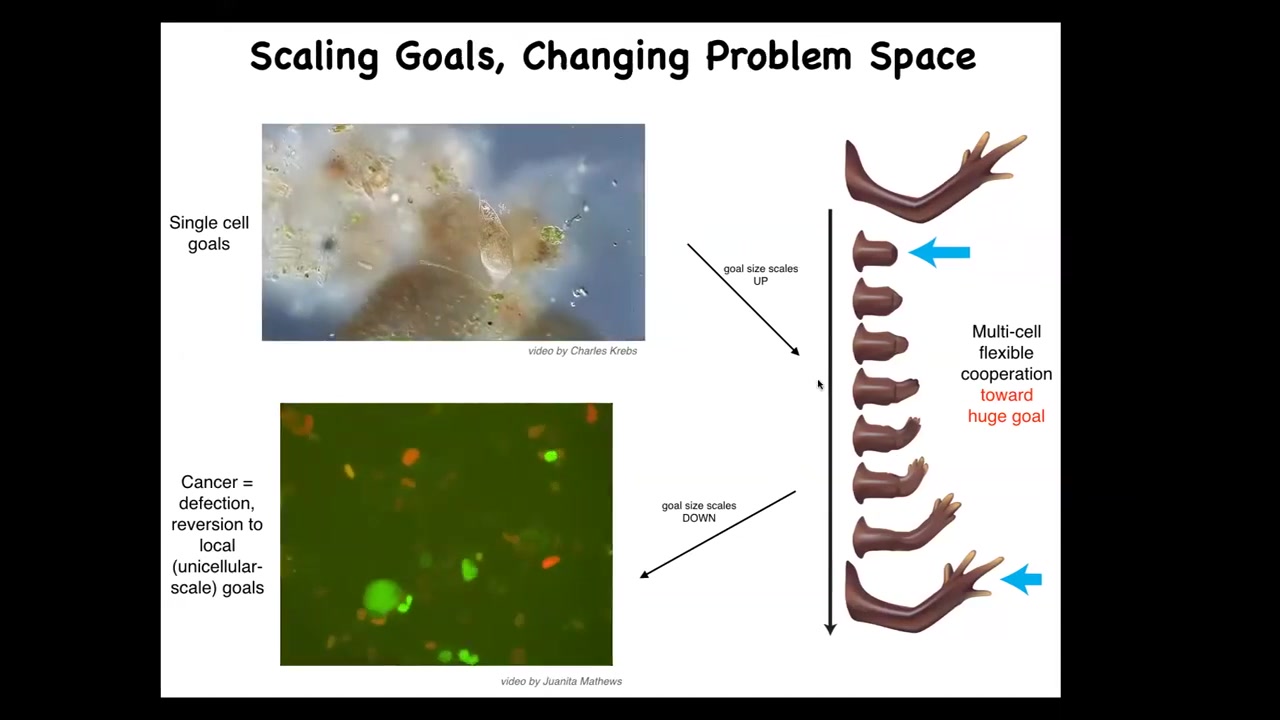

The last thing I want to show is the cancer application. What evolution has done for us is to scale up the cognitive capacities of single cells towards larger goals in novel problem spaces. Individual cells, these little amoebas, have little tiny goals. Their cognitive light cone is very small. Local physiological states.

But together in an organism, they're bound into electrical networks that work on huge goals. This is centimeters long, and no individual cell knows what a finger is or how many fingers you're supposed to have, but the collective absolutely does because it works towards the set point. The cognitive light cone scales up. Their goals are now centimeters in size in this anatomical space. Larger goals in a different space. That scale-up has a failure mode.

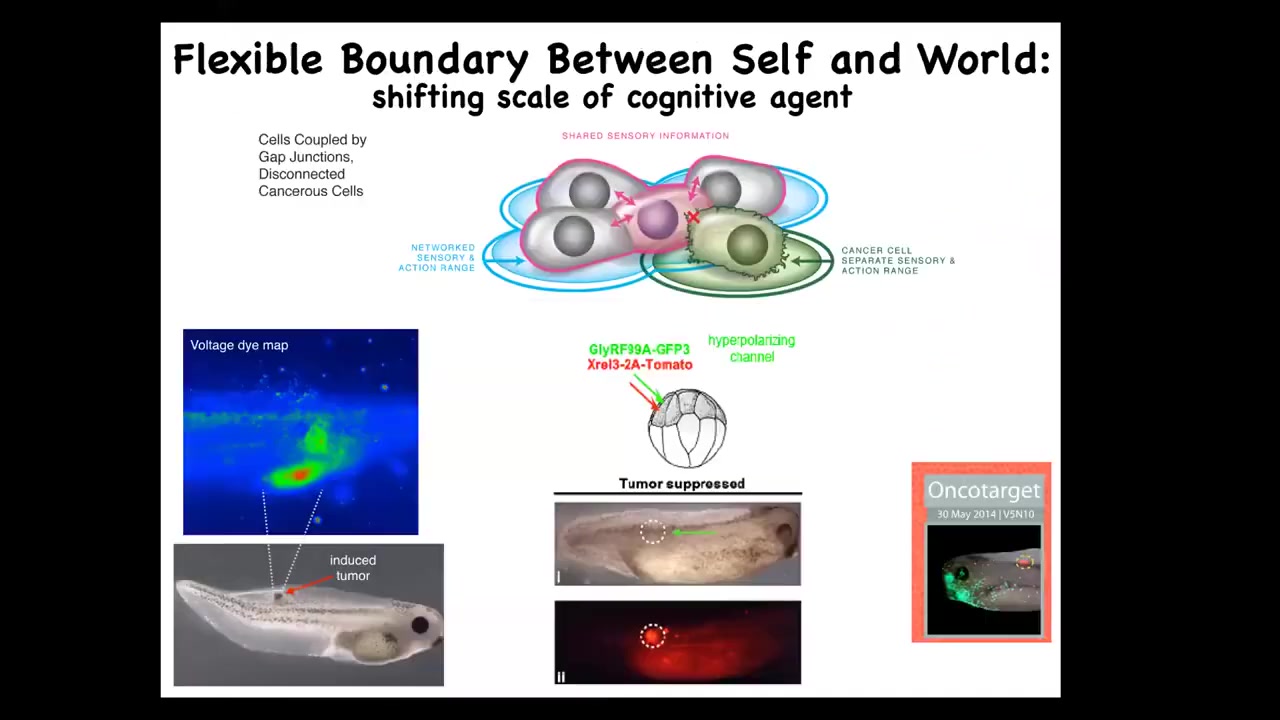

Slide 37/39 · 48m:55s

That failure mode is cancer. And here's what you see, human glioblastoma. These cells are not more selfish than normal cells. They just have smaller cells because they've been electrically disconnected from the collective. And now all their goals are amoeba level goals.

Slide 38/39 · 49m:10s

If you have that idea, you can try to come up with a therapeutic that instead of killing these cancer cells, would reconnect them electrically to the rest of the network. We inject human oncogenes—these can be nasty KRAS mutations, things like that—and then co-inject an ion channel that forces the cells to stay electrically connected. Even though the oncoprotein is blazingly strongly expressed here, there is no tumor. This is the same animal. It's not the genetics that drives, it's the physiology.

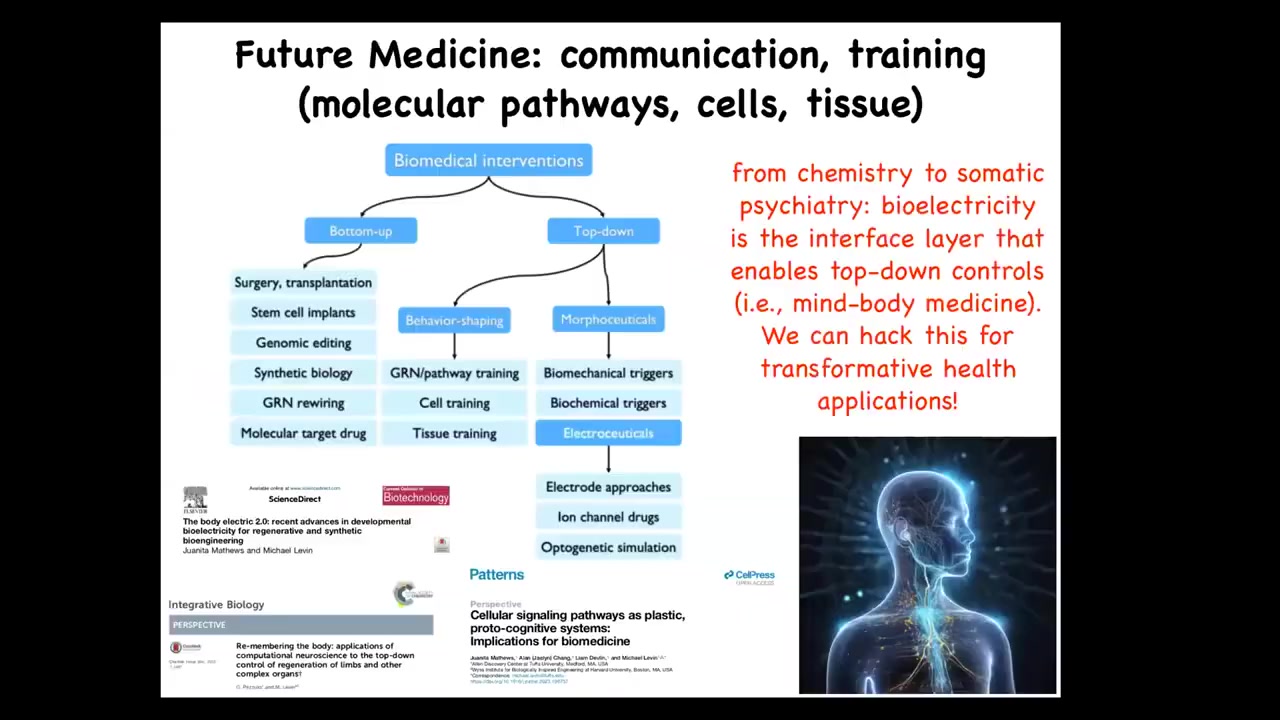

Slide 39/39 · 49m:41s

I'm going to end here by pointing out that in the space of biomedical interventions, lots of focus has been spent here. These are all the things that address the hardware, but complementing that, are a huge potential set of tools from behavioral science, from cognitive science, that take advantage of the competency of the material. Projecting forward, I think that future medicine is going to look a lot more like a kind of somatic psychiatry than it's going to look like chemistry. It's going to be about communicating our goals to a collective via the bioelectric interface or via some other interface.

I want to thank the postdocs and the students who contributed to this work, our various funders, our collaborators, the disclosures of companies that have funded our lab, and most of all the model systems because they do all the heavy lifting. Thank you very much and I'll take questions.