Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a talk I gave to an audience of computer scientists and neuroscientists, interested in AI, consciousness, and the brain.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Bioelectric collective intelligence

(50:37) Gradient descent in biology

(53:00) Multi-agent RL parallels

(57:38) Questioning ubiquitous intelligence

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/38 · 00m:00s

Thank you so much. Thank you especially to the organizers for allowing me to share some thoughts with you all. This has been an amazing symposium. Lots of interesting ideas.

In particular, we've heard a lot about the intersection of artificial intelligence and neuroscience. What I'd like to do is talk about some ideas that are borrowed from neuroscience and deployed outside the brain. In particular, if we want to use biology as an inspiration for AI, biology offers many, many interesting contexts that are not brains. I'd like to pull us away from the neuroscience of the brain and think of some other things. If anybody wants to reach me later, all of the primary data, the papers, the software, everything else are here.

Many discussions still to this day take place in the context of this very old idea that this is Adam naming the animals in the Garden of Eden, this idea that there's a specific natural kind called the human brain, and it does various things, and we would like to mine that for insights as to how we can create intelligence.

Slide 2/38 · 01m:08s

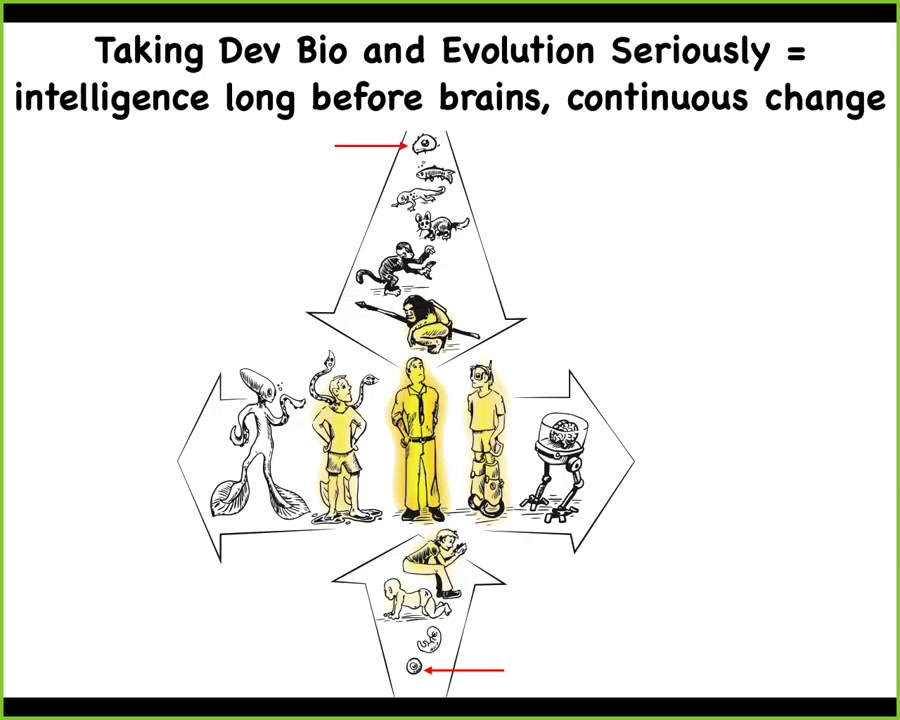

If we take developmental biology and evolution seriously, all of us began life as single cells. Whether on an evolutionary time scale or a developmental time scale, there is a continuum here. These transformations are very slow and continuous. We can pick out what we call great transitions and impose some sort of phase transition on these, but the underlying biology is very smooth and continuous.

Now we have this additional axis of manipulations we can make, where we can step away from the standard human architecture and, both with technological hybrids and with biological modifications, make any sort of combination that you want. In our lab, we think very hard about these kinds of issues. Where does intelligence come from and how does it scale up through these kinds of transformations?

Slide 3/38 · 02m:06s

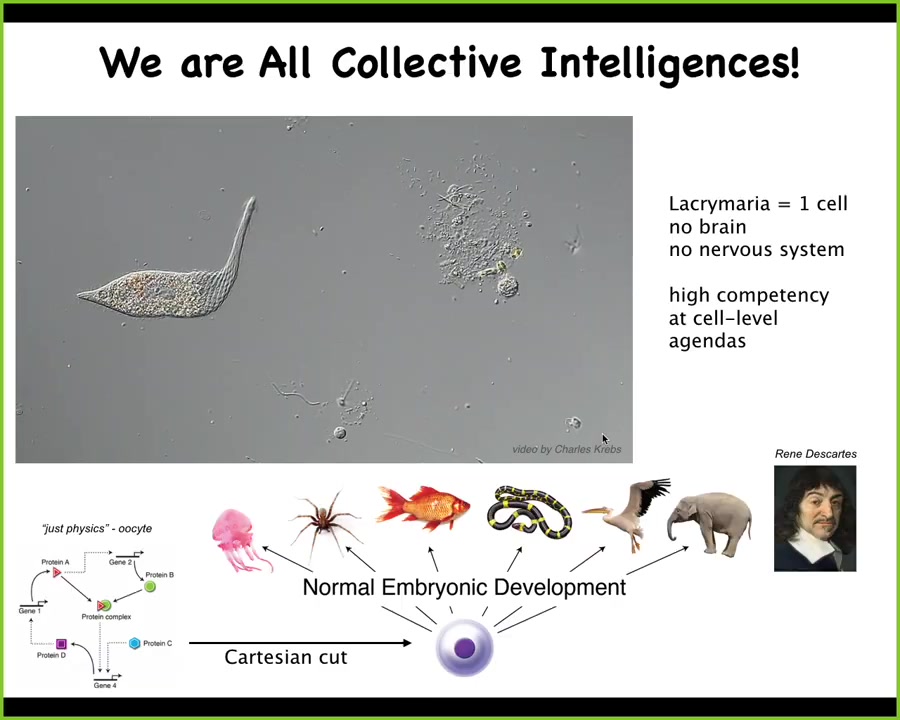

The important thing about us is that we, and I think all intelligences really are, are collective intelligences. What you're seeing here is a single cell. This is what we're made of, although this, of course, is a unicellular organism. We call the lacrimarium. There's no brain or nervous system, but it's handling all of its local needs in one cell. If you're into soft robotics, the level of control and morphological computation here is remarkable. And all of us made this journey across the Cartesian cut. We all started life as "just physics," so a little pile of chemicals, a quiescent oocyte, and then there's this slow and remarkable process of embryonic development that produces something like this, or perhaps even something like this. At some point we have folks who will say that we are certainly conscious and we have a certain level of cognition. And of course, many people will say it is not. They owe a story of how you get from here to here, given how slow and continuous this process actually is.

What I want to do for the next couple of minutes is talk about some interesting biology that isn't the standard thing that we're all used to.

Slide 4/38 · 03m:26s

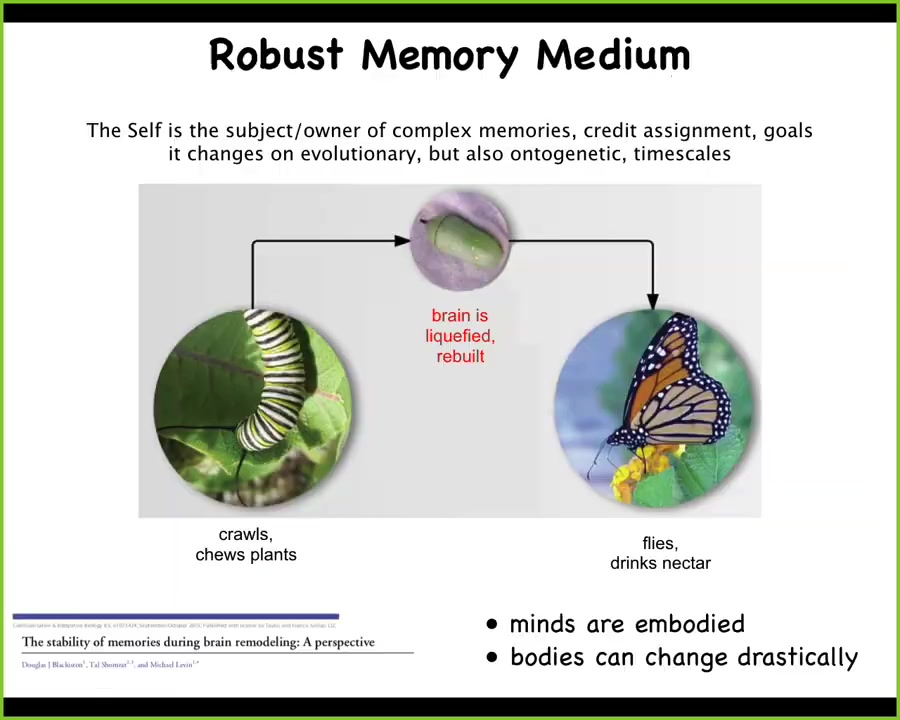

These are examples that aren't usually covered in typical neuroscience AI crossovers. One thing that should be looked at is this example where you have a caterpillar. This is a soft-bodied robot. It lives in a two-dimensional world of crawling on and eating leaves. And then it needs to become this, which is a hard-bodied robot which flies in three-dimensional space and has a completely different brain. What happens in between is that the brain is taken apart. Most of the cells are killed off. All the connections are broken. Everything is liquefied, rebuilt from scratch. And the amazing thing is that there's data showing that moths and butterflies retain the memories of the original caterpillar. So that's an interesting fact about this biological architecture that we have to keep in mind if we're going to try to make something similar.

It also raises interesting questions. Never mind what's it like to be a butterfly. For people who are into consciousness, what's it like to be a caterpillar turning into a butterfly during your lifetime? Not just the evolutionary time scale, but during your lifetime. A radical reconstruction of your cognitive medium.

Slide 5/38 · 04m:41s

This goes even further with planaria. These are flatworms. I'll talk about them more in a few minutes, but the salient fact about planaria is that this system can be cut into many pieces. Every piece will rebuild, regenerate, and give rise to a perfect little worm.

What McConnell discovered, and we validated using modern techniques recently, is that if you train a planarian, and planaria have a centralized brain, they have the same neurotransmitters that you and I do. You amputate the head. The tail sits there doing nothing for about 10 days, then regrows a brand new brain, at which point behavior resumes, and you can show that it still has the original information.

Not only is the information stored somewhere else in the body, possibly in some sort of distributed holographic form, we don't know, but it can also be imprinted onto the new brain as the brain develops. This tight interaction between morphogenesis, the shaping of the cognitive organs, and the information, the behavioral knowledge that is spread and moves throughout tissues. This plasticity is not just for invertebrates.

Slide 6/38 · 05m:56s

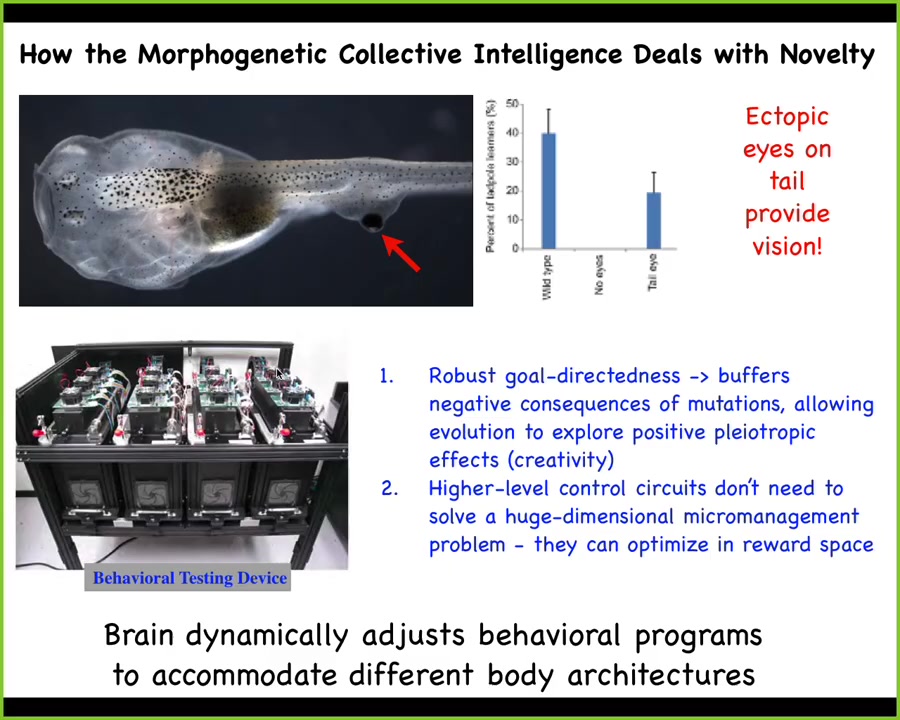

Vertebrates have it too. This is a tadpole of the frog Xenopus laevis. Here's the mouth, here are the nostrils, here's the brain, the gut. It's missing the primary eyes.

So we've made this particular embryo to not have any primary eyes, but we did put some eye cells on the tail. Not only do they go on to make a perfectly nice eye, even though it's surrounded by muscle instead of next to the brain where it belongs, these animals can see quite well. So we've made a device that trains them on visual tasks and automates the whole process.

And we can see that even though this eye does not connect to the brain, it makes an optic nerve that sometimes synapses on the spinal cord, sometimes goes up here to the gut. But these animals can see. This does not take long periods of evolutionary adaptation. In one generation, this animal finds itself with a radically altered sensory motor architecture. No problem. The brain is getting these weird signals from some itchy patch of tissue on its tail, and it can treat that as visual data and learn in visual assays.

So remarkable, and we'll get to this notion that what evolution is giving us here is a problem-solving machine. It's not something that just knows how to do one thing. It can very rapidly adapt to novel configurations in morphological space.

Slide 7/38 · 07m:19s

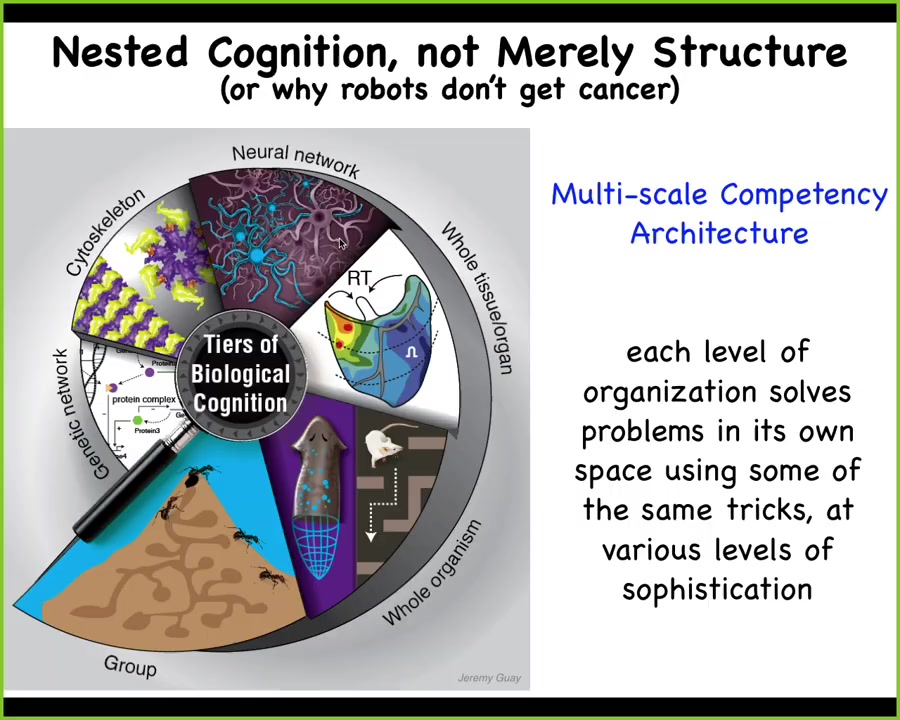

The way that biology does this is that not only structurally, but actually functionally, we are all nested dolls. At every level of organization, from the swarm to the organ, tissue, cell, and molecular network level, all of these layers are problem-solving types of processes.

I call this a multi-scale competency architecture, with the idea that some of the same navigation policies are being used to solve problems in different spaces, metabolic spaces, transcriptional spaces, morphological spaces, and the familiar 3D behavioral space of running mazes and doing things like that. Each of these layers is its own problem-solving system.

This is why there's another talk that I give to students sometimes called "Why Robots Don't Get Cancer." That's because we don't have very many architectures yet where the individual parts have their own agendas, and thus there's this failure mode whereby they can be decoupled from the collective top-down agenda and go off on their own and make a tumor and do other things. That's the risk of this architecture. That's the failure mode, but what you gain is incredible plasticity and robustness.

What I'm interested in, as far as understanding how these things help us to recognize and to build intelligences, is something like this, to develop a framework where we can abstract the notion of intelligence.

Slide 8/38 · 08m:45s

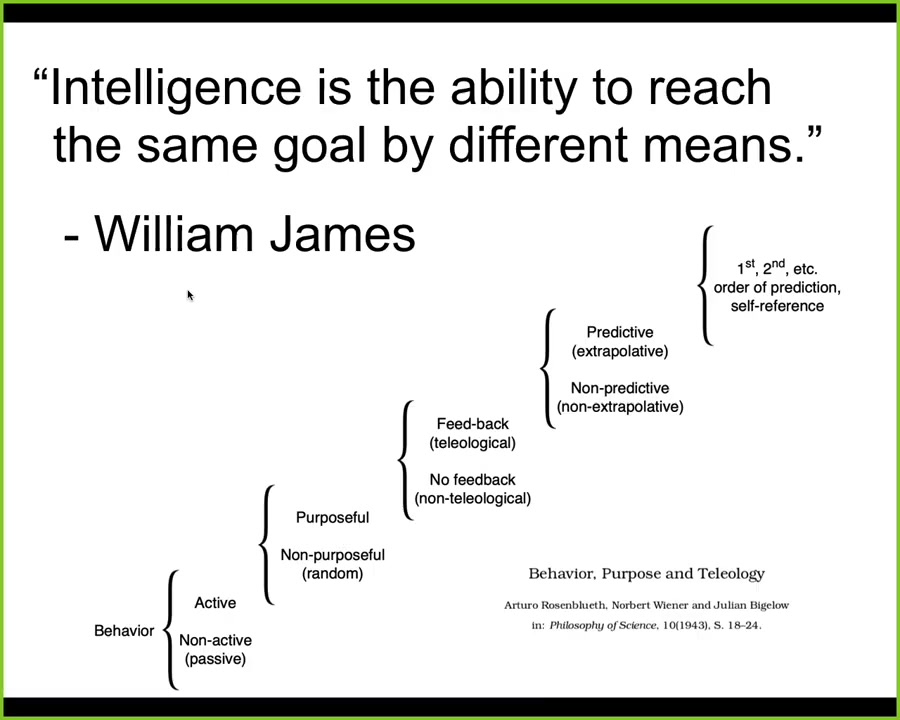

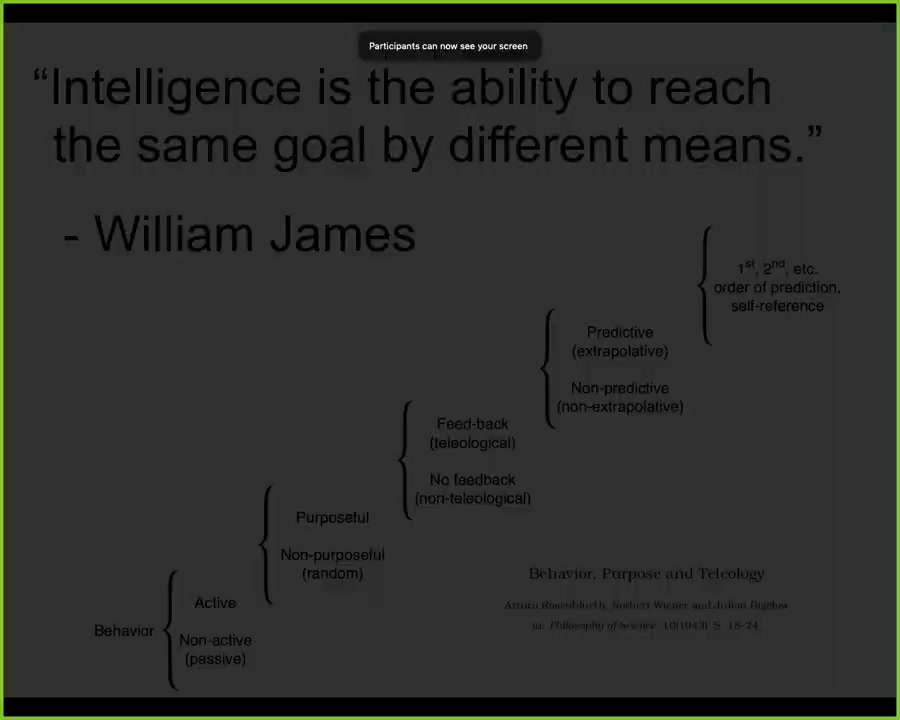

For this audience, I think that's very easy. For other audiences, this is a hard leap to make. Step away from the idea that intelligence is something that large brains do, and have a more cybernetic approach. I'm certainly not the first person to suggest this. Here are Rosenblueth, Wiener, and Bigelow trying for a hierarchy of cognitive capacities all the way from passive behavior up to human-level metacognition and so on.

So in our group, we understand intelligence in the way that William James said, which is the ability to reach the same goal by different means. The degree of sophistication of those means and the degree to which you can handle various perturbations along the way is how you gauge the type and the amount of intelligence.

As somebody said once, it describes the continuum between two magnets trying to get together and Romeo and Juliet trying to get together. What mechanisms exist on all the different systems on that continuum to help them do what they need to do.

Slide 9/38 · 09m:56s

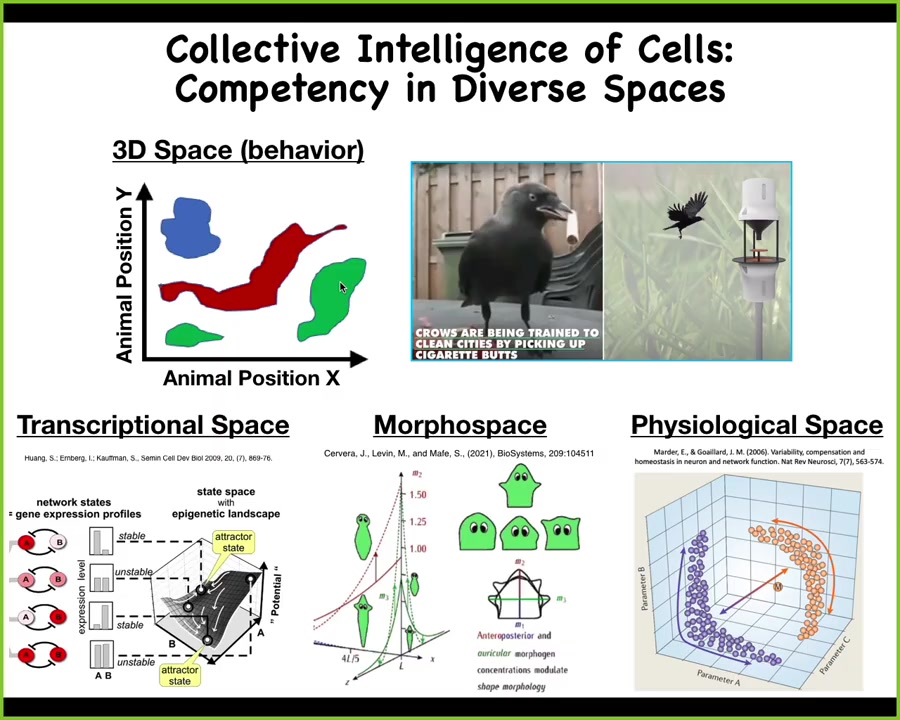

We're all good at recognizing intelligence in the three-dimensional world. Medium-sized objects moving at medium speeds, doing things we easily recognize as having agency and having intelligence. There are many other spaces in which biology has been solving problems long before brains showed up. Imagine if we had an innate sense of our blood chemistry or if we had an innate sense of various gene expression profiles, we would have no trouble at all intuitively recognizing our organs, our cells as navigating those spaces with significant competency. Right now, we're not primed for that. I'm going to spend most of my time talking about this morphospace, the behavior of a collective intelligence of cells in this morphological space.

One idea that we've been playing with is that what has happened is that evolution has pivoted some of the same strategies across all kinds of different problem spaces, all the way from metabolic and physiological spaces up through anatomical space, classic behavioral space, and then maybe linguistic space as well. And so I want to show you a few examples of what I mean by these unconventional intelligences.

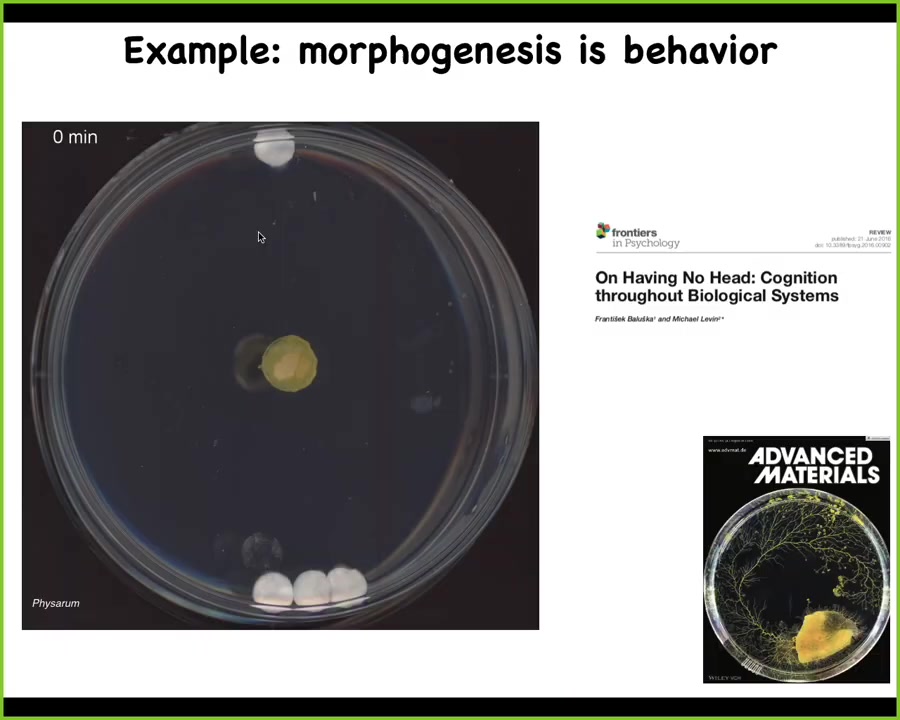

Slide 10/38 · 11m:16s

So this is a slime mold. This is called the Physarum polycephalum. What we've done is we've placed the slime mold here in the middle. The slime mold is unicellular. It's one cell. It can get very large, but it's just one cell. What we've done is we've placed one glass disc over here, three glass discs over here. This is just one example out of a paper where we did this many times and it has a very interesting behavior. These glass discs are completely inert. There's no food, there are no gradients. They're just glass.

For the first few hours, the slime mold grows like this. At this point, there's no obvious indication that it's going to do anything other than continue symmetrically growing. During this time, what it's been doing is gathering information about its environment. The way it does that is by gently squeezing; it continuously pulses the medium it's on and reads back the strain angle of the signals it gets. After that it grows towards the larger mass.

You can do all kinds of interesting tricks about stacking the glass discs one on top of the other. You can get it tilted and do various things to confuse it, but this is what it does. Here, it gathers information and at that point you can tell that it's decided what it's going to do. These spaces that we talk about are our abstraction. Because behavior for this system is morphological change. This is a transitional form in which behavior and control of morphology are the same. That's the sort of thing this single-celled organism can do.

Slide 11/38 · 12m:56s

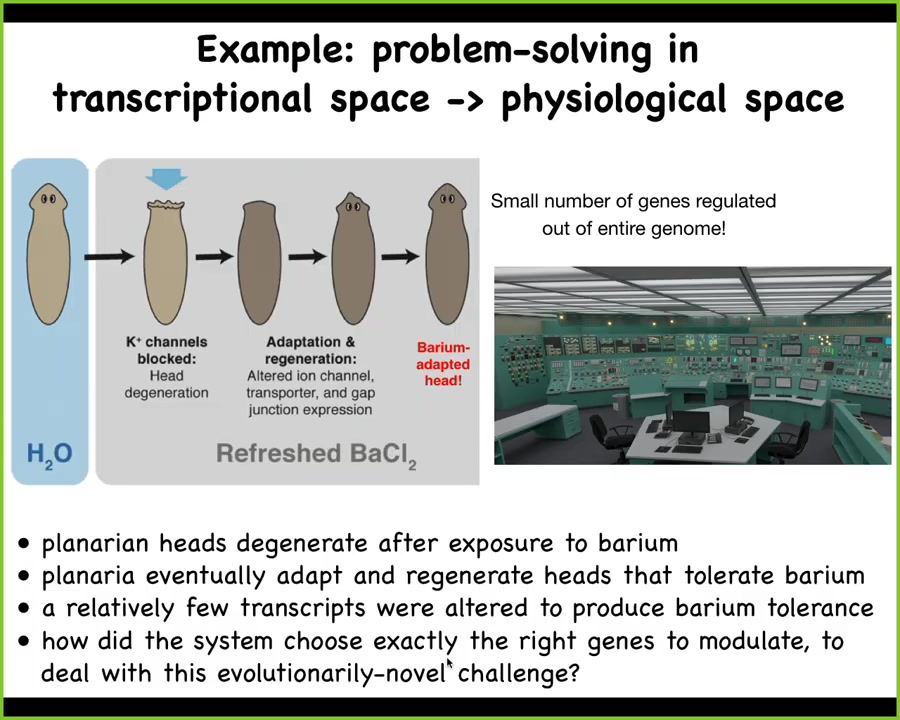

Here's another type of intelligence. We discovered something interesting in these planaria where if you put planaria in a solution of barium, barium chloride is a non-specific ion channel blocker, a potassium channel blocker, to be more precise. All the cells, especially the cells in the head, which have to exchange potassium, so all the neurons, are extremely unhappy. Their heads literally explode in this barium. Overnight it's called "deep progression" — their heads explode.

If you leave them in the barium, a couple of weeks later they will grow a new head. The new head is completely barium adapted. It doesn't care about barium at all, no problem.

We asked the simple question. We took these barium-adapted heads, we took the primary original heads, and we asked, what gene expressions are different? What does this new head do in terms of gene expression that's different from this head? There's only a handful of genes that are actually different. What they allow these cells to do is carry out their physiological business despite not being able to pass potassium. That's a pretty significant change. But there's only a handful of genes.

The kicker to all this is that planarian never experienced barium in the wild. It's just not ecologically realistic. There's never been an evolutionary history of pressure for knowing what to do when you're hit with barium.

I always think about this problem as being trapped in this nuclear reactor control room. The thing's melting down. There are 20,000 or however many genes — buttons. And you're faced with this novel stressor. How do you know which thing is going to improve your physiological situation? The cells don't turn over very fast, so you don't have time for random search. You don't have time for gradient descent.

We don't know how this works. Maybe there's some generalization from other types of things like epileptic excitotoxicity that they do have. It's an amazing ability to walk through that transcriptional space in a way that efficiently allows you to solve for a completely novel physiological stressor.

I've shown you a couple of examples of problem-solving in these unusual spaces. What I want to spend the most of my time doing is talking about morphospace, morphogenesis. This idea of morphogenesis as being relevant to the problem of intelligence is not new.

Slide 12/38 · 15m:22s

Alan Turing needs no introduction. He was interested in problem-solving machines, intelligence through plasticity, reprogrammability. He also wrote a paper on the chemical basis of morphogenesis.

Why would somebody who is interested in intelligence and machines be interested in the chemistry of spontaneous self-organization and morphogenesis? He didn't say much about it, but I think he was on to something very deep. He understood, and I think this is true, that these are fundamentally the same problem. There's a very strong kind of invariance between these two problems, and we should investigate them.

Slide 13/38 · 16m:03s

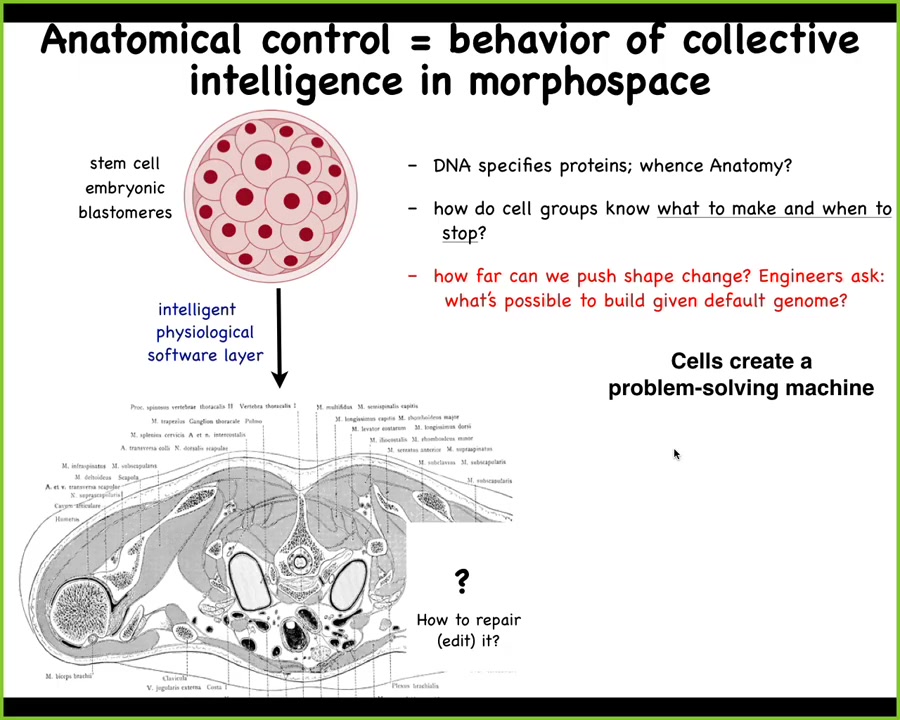

Let's talk about this. We all begin as this collection of blastomeres that arises from the fertilized egg, and then eventually we become something like this. This is a cross-section through a human torso.

Look at this amazing order. All the organs and structures are in the right place next to the right thing, and incredibly robust. This works correctly most of the time.

The amazing thing is that we can ask where the information comes from. Where is the information encoded for this particular layout? You might want to say DNA, but we can read genomes now. DNA doesn't say anything about this directly, any more than it directly says anything about the shape of a spider web or the shape of a termite colony. It provides the micro-level hardware. What the DNA gives you are the protein sequences that every single cell gets to have. Once you have those protein sequences, physiology comes, which I like to think of as a layer of software that is executed by this machine, which does some really interesting things.

The key is that even though this process is very reliable, it is not hardwired.

Slide 14/38 · 17m:22s

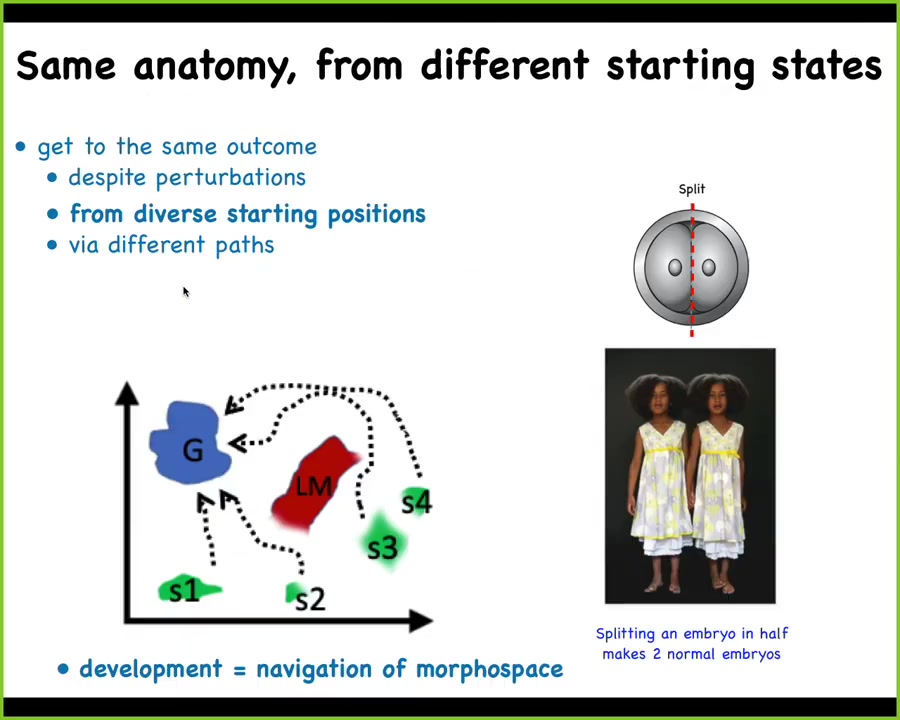

So if you take an early mammalian embryo, for example, a human, and you cut it in half, you don't get two half embryos. What you get are two perfectly normal monozygotic twins. Each half recognizes the other half is missing and produces exactly what it needs. You can cut it into more pieces than that.

We have this notion that regulative development in animals that can do it, most of them, is a kind of navigation of morphospace. If I boil down the shape or the space of all possible anatomical configurations, which is a kind of quantitative morphospace, what we want is to be able to reach a particular ensemble of goal states, the target morphology of this particular species, from different starting positions, despite various local maxima and different barriers. So we can think about morphogenesis as a navigation of this virtual space.

Slide 15/38 · 18m:15s

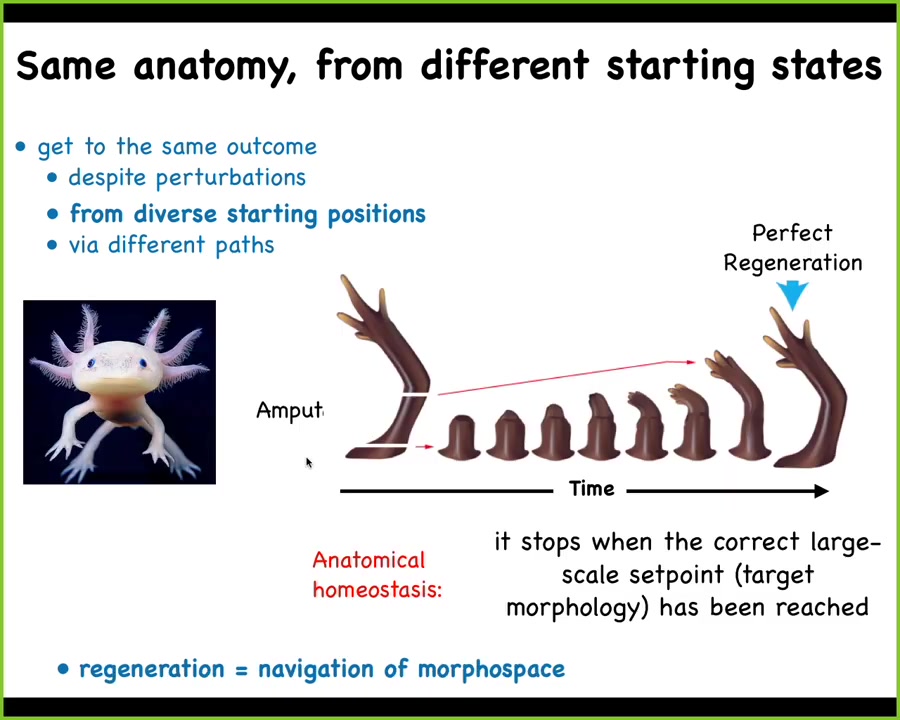

Here's an example. It's not just for development. Regeneration does this too. Here's a salamander known as an axolotl. These guys regenerate their eyes, their jaws, their tails, including spinal cord, their limbs, their ovaries. And you can see what happens in the limb if they lose a portion of the limb: it doesn't matter where along the axis it's lost, the cells will very rapidly grow exactly what's needed, and then they stop. The most amazing part is that they stop. When do they stop? They stop when the correct salamander arm has been completed. This means that what you really have here is a kind of homeostatic process whereby this group of cells is able to navigate that morphospace from different positions to the right region, recognize that they got where they're going, and then they can stop.

Slide 16/38 · 19m:10s

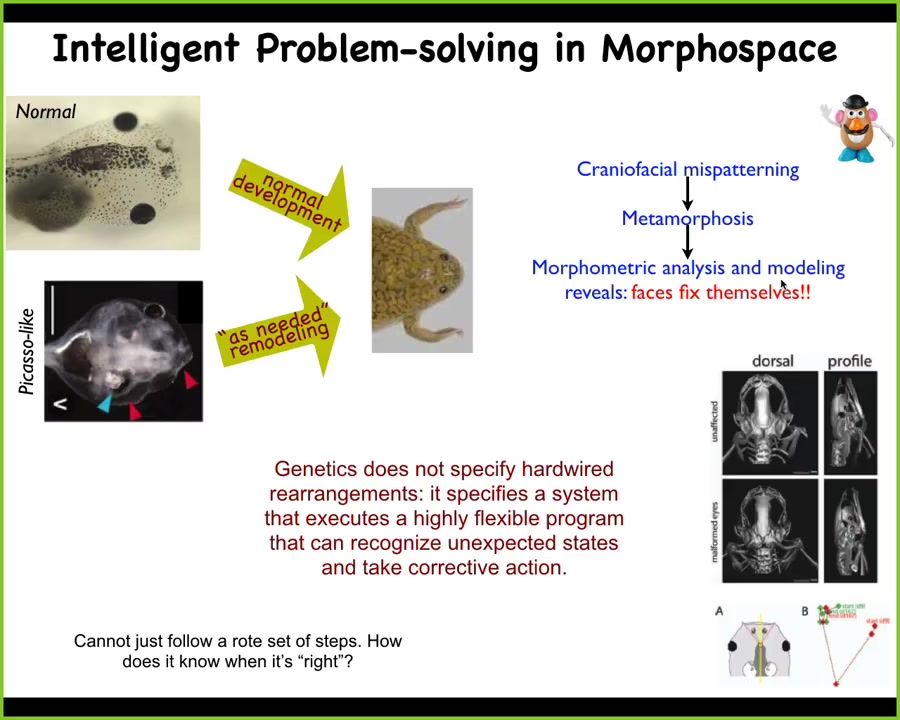

Here's another example. This is something that we discovered some years back. Here's a tadpole. The tadpole has the eyes, the nostrils, the mouth, and so on. Tadpoles need to become frogs. In order to do that, all the pieces have to move around. They have to rearrange.

People used to think that this was somehow hardwired, that every part of the face moves in a particular direction, a particular amount, and then you get from being a normal tadpole to a normal face. We wanted to test this idea that this is some kind of hardwired process. We created these so-called Picasso tadpoles. Everything is scrambled. The eyes might be on top of the head, the mouth is off to the side, everything is messed up.

Largely, these types of animals result in pretty normal frogs because all of these different organs will keep moving in novel paths. Sometimes they have to double back if they go too far, and eventually they stop when they reach the correct frog face. What the genetics actually gives you is a kind of error minimization scheme. We thought hard about how is this possible? How is a collection of cells supposed to recognize this kind of stop condition? How does it take measurements of what's going on now? How does the attractor here work? What's going on?

We started thinking about goal-seeking behavior, because fundamentally that's what this is in the cybernetic sense. This is a goal-seeking system. There's a particular set of states that will expend energy to attain, even if you try to deviate it or push it off that state. So how does this work?

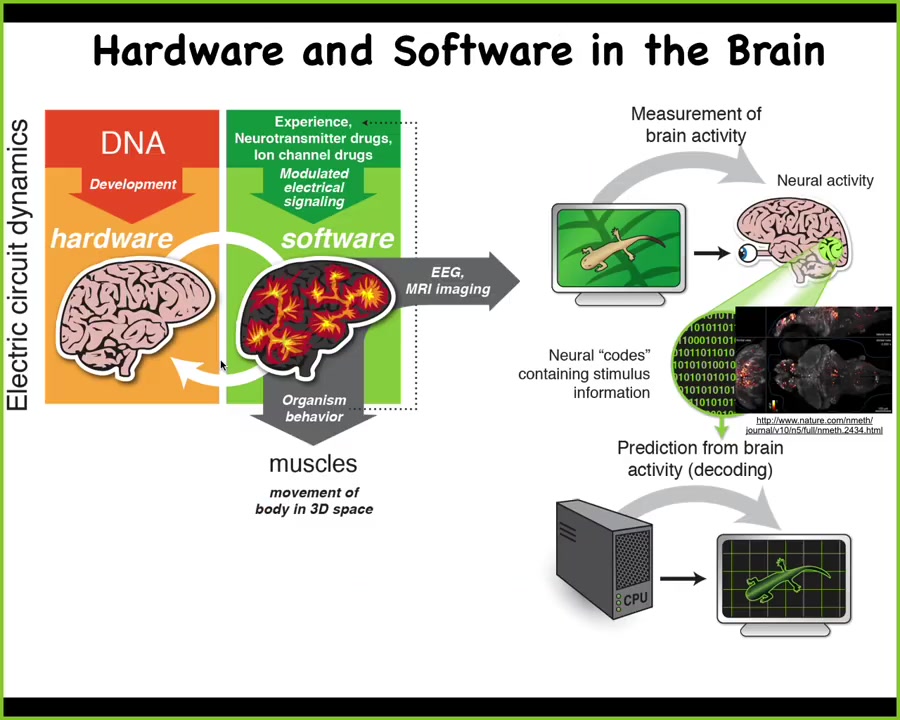

Slide 17/38 · 20m:43s

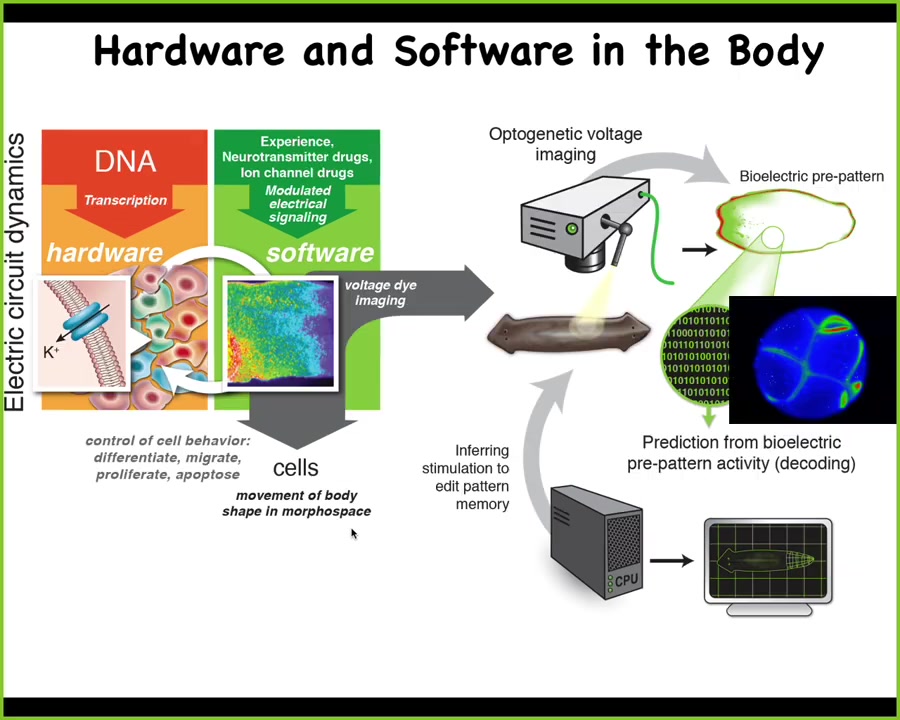

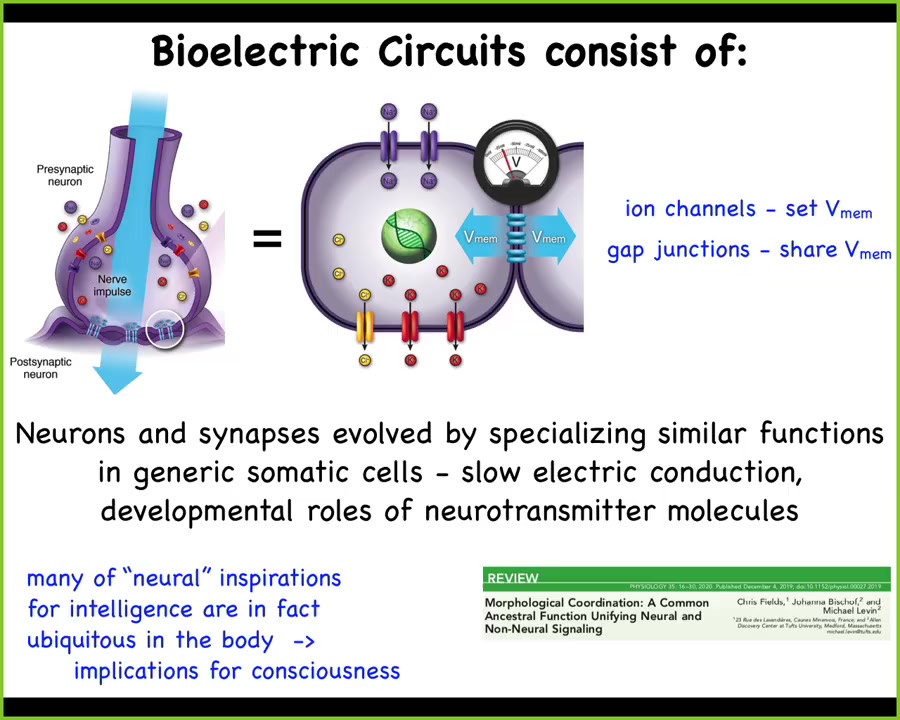

The obvious example is what happens in the brain. In the brain, we know what the hardware looks like. We know some of the behaviors of the software layer. There's this idea, which several people have talked about today, of neural decoding, the idea that if we understood how to decode the electrical activity, so this is a zebrafish movie, a movie of a zebrafish brain in the living state as it's doing whatever computations that it's doing, if we understood how to decode this, the commitment of neuroscience is that that's where the cognition is. We would know the memories, the preferences, the behavioral repertoire. We could somehow decode that. But the interesting thing is that this kind of architecture is extremely ancient.

Long before brains and neurons appeared, you had exactly the same thing in the rest of the body. The way this works is that the electric circuits make various decisions that are then used to control muscles to move your body in three-dimensional space.

Slide 18/38 · 21m:51s

Where this comes from is a much more ancient system where the same electrical circuits control various cell behaviors, not just muscles, but all cell behaviors, cell movement, cell division, cell differentiation, shape change, to move the configuration of the body in morphospace.

What evolution did in creating nervous systems is that it repurposed the system. SPED optimized it because the original system works at the scale of hours, not milliseconds, and also made some trade-offs of space for time in terms of what it measures.

You can think of the exact same kind of research program that comes from neuroscience and say, could we use all the same techniques to track the physiological activity of this process and try to decode it. What are the electrical networks of the body thinking about? What memories do they have? What behavioral repertoires do they have?

Slide 19/38 · 22m:48s

The fact is that every cell in your body has ion channels. Most cells have electrical synapses to their neighbors that selectively propagate electrical states. You can see here this whole story of how we got to neurons from other cell types.

But the interesting thing is that most of the techniques of neuroscience do not distinguish. Everything works. We've carried over many things from neuroscience into other contexts. The kinds of things that serve as neural inspirations for AI and for intelligence, for consciousness—the mechanisms of all this—are ubiquitous in the body. They're everywhere. There are very few of the kinds of things that certain theories of consciousness talk about in the brain. Most of these underlying processes are actually ubiquitous. That may have implications for where we think consciousness could be found.

Slide 20/38 · 23m:48s

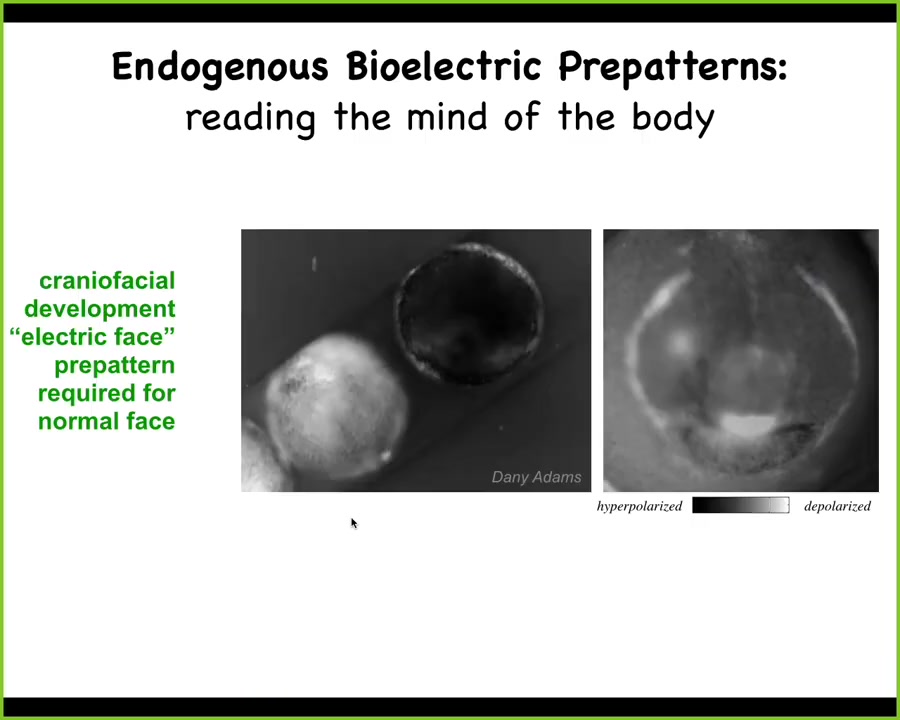

So I want to show you one example. This is a time-lapse video of an early frog embryo putting its face together. Here, the way we do the imaging is with a voltage-sensitive fluorescent dye, very similar to how you might look at electrical activity in the brain.

One frame out of that video looks like this. It is a snapshot of an early pre-pattern that tells these cells where all the organs of the face are going to go. Here's where the first eye is going to go. Here's where the mouth is going to go, the placodes. This is a glimpse of a decode, and the reason I'm showing you this is because this is one of the easiest to decode. In fact, it almost looks like a face. We call this the "electric face." This is a snapshot of what the tissue is thinking as it prepares to turn on the various gene expression domains that are actually going to build these various organs. And we know it's functional, it's instructive, because if you move any of this, if you change these states, the anatomy follows. I'll show you a few examples of that.

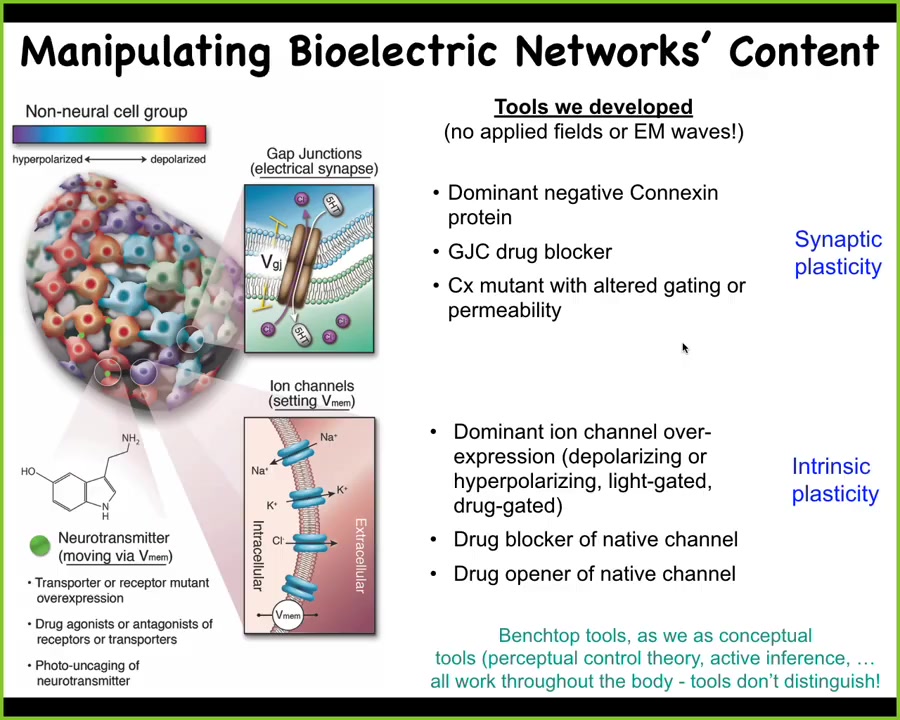

So tracking this is all well and good, but we want to make changes. We want to be able to do functional experiments.

Slide 21/38 · 24m:55s

And for that, we don't use electric fields. We don't use electrodes; no magnetics, no EM waves. We appropriate all the tools of neuroscience. So for these electrical synapses, these gap junctions, we can change the topology or the connectivity of the network by opening and closing these things or introducing new ones, and this is similar to controlling the synaptic plasticity. This is the intrinsic plasticity where we can go in and directly change the voltage of individual cells, either pharmacologically by opening and closing channels, or specifically with optogenetics. We can use light to trigger specific voltage changes. We can do this at the neurotransmitter level as well. We have the ability to do what people like Tanagawa do when they try to incept false memories into the brains of mice; we can incept false pattern memories into non-neural tissues. All of these benchtop techniques, including perceptual control theory and active inference, we use them routinely to address things going on in navigating morphospace.

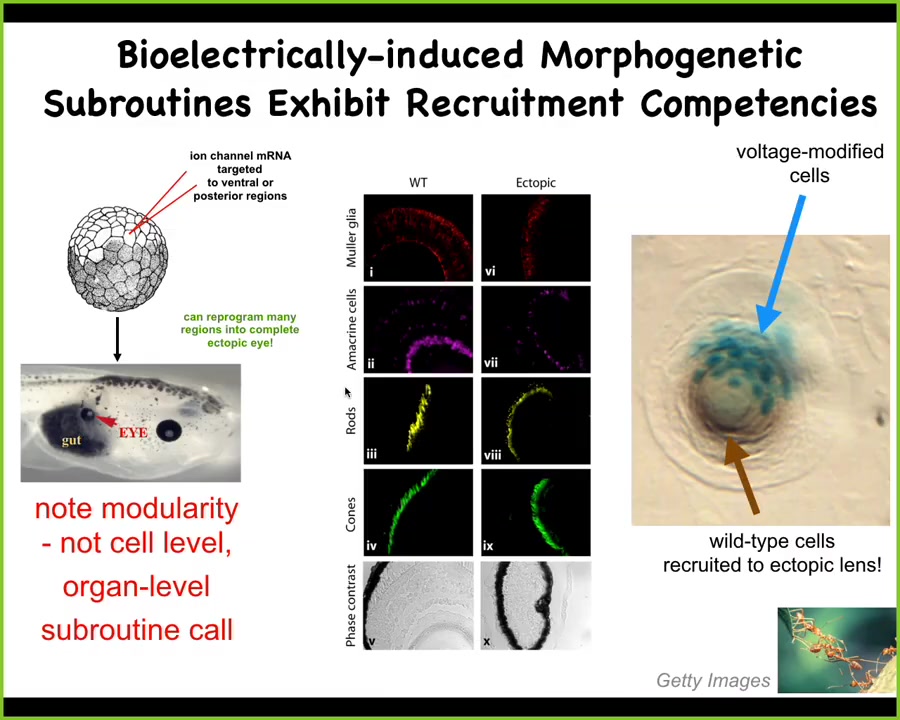

Slide 22/38 · 26m:10s

Here's an example. I showed you that electric face. We showed you there's a particular pattern that controls where the eye goes. We simply said, could we artificially establish that same bioelectric pattern somewhere else in the body, what would happen? And so here's what happens. The way we do it was in this particular case, we injected RNA encoding an ion channel, a potassium channel that established a little spatial domain. And the code, by the way, is multicellular. It's not a single-cell code. So we established a multicellular domain of the right voltage. And sure enough, these cells build a complete eye. They can make this eye anywhere in the gut, on the tail, anywhere.

Now, notice a few interesting things about this. First of all, it's extremely modular. What we are not doing here is telling individual stem cells what to be. We are not providing enough information to actually build an eye. We have no idea how to build an eye. Eyes have all of these complex structures inside. What we're doing is providing a very high-level subroutine call. It's a trigger that says, build an eye here. Downstream of that are all the gene expressions, the cell movements, everything else that is the implementation machinery. But the trigger, that goal-directed behavior, that movement in morphospace that causes these cells to move from what their old morphology was to an eye shape, all of that is triggered by a fairly simple bioelectrical state. It's almost a stimulus that causes a trigger that causes a complex behavior.

Now, the other amazing thing is this. Right here is a cross-section through an ectopic lens, like this, that's sitting out in the tail of a tadpole that we induce. The blue cells here are the ones that bear the ectopic ion channel, this potassium channel, and they're blue because of a beta-galactosidase label. So we can tell which cells we actually injected. All the rest of these cells that are participating in making this nice lens are not labeled.

Now what happened here is that when we injected this, we didn't get enough cells to make a proper lens. And so the first instructive interaction was when we told these cells, you should make an eye with our voltage signal. But then what they had the competency to do is to recruit their neighbors. The system can tell that there's not enough of these guys to make an eye. And so they recruit as many of their neighbors as needed to actually make this complete organ. We didn't do any of that. That's a built-in competency to the system. The plasticity of the system is ready to receive large organ level information to rearrange that large-scale structure and have new behaviors, and by the way, trigger downstream cascades, such as recruiting other cell types. And this, of course, is found in other types of collective intelligence. So ants and termites will recruit their buddies when there's a task to be done that requires more of them. So there's these amazing competencies.

Slide 23/38 · 29m:09s

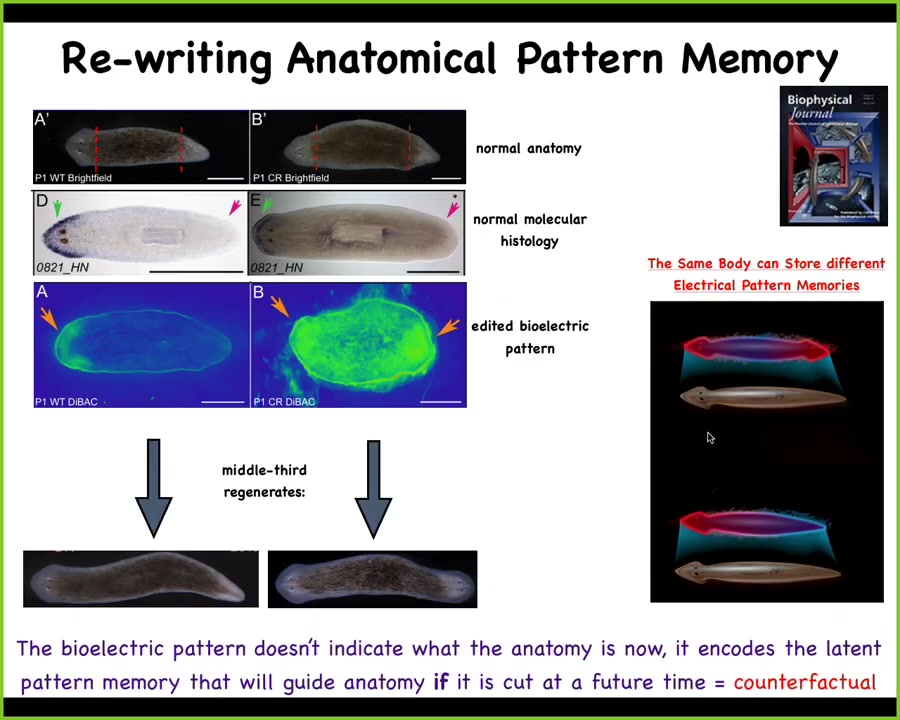

Now, I want to show you another way to interact with these pattern memories. Here are our planaria. One head, one tail. This is a normal worm. If you look at where the gene expression is, the anterior marker is at the head, telling you one head, one tail. What this guy will do, if we chop off the head and the tail, that middle fragment will give you a nice one-headed worm. 100% of the time, they're extremely robust with this.

But what we notice now: there's this fragment, how does it know how many heads it's supposed to have? How does it know these cells up here will make a tail, these cells here will make a head, but they're right next to each other when you cut them apart? How do they know what they're supposed to make? We looked and found this voltage gradient that is a map of this animal telling us one head, one tail. That in fact is what they built. What we did was we worked out a pharmacological way. Some of these things are exactly mirroring. General anesthetics. If you want a bunch of cells to forget what they're supposed to be doing, general anesthetic is a really good way to do that. There's some nice analogies to the coherence of minds.

What you can do is you can produce a different pattern that says 2 heads. This is quite messy, the technology is still quite young, but you can produce this pattern. If you do that in this animal, when you cut him, he will produce a two-headed animal. This is not Photoshopped. These are real life worms, even though the genetics are untouched. The hardware is exactly the same. There's nothing wrong with the genetics here. We didn't edit the genome.

The other critical thing is that this map is not a map of this two-headed body. This is a map of this one-headed animal. You can think about this as a primitive form of counterfactual memory. A kind of very simple form in morphospace of what we like about brains, which is this ability to time travel, to have memories and make predictions about things that are not true right now. Even though anatomically this animal has one head and one tail, if you were to look at what your idea of the correct planarian looks like, that's very clear. It's 2 heads. If you get injured, that's what you'll do. If you don't get injured, nothing happens. It's a latent memory that doesn't get activated.

When I talk about the collective of cells being a real collective intelligence, this is what I mean. We can literally read the memories that it has, at least in some cases, such as this. We know now, very much like in the brain, that the same hardware is capable of having one of two different ideas of what a correct planarian looks like. It's a representation of a future morphological state. The goal is movement through morphospace.

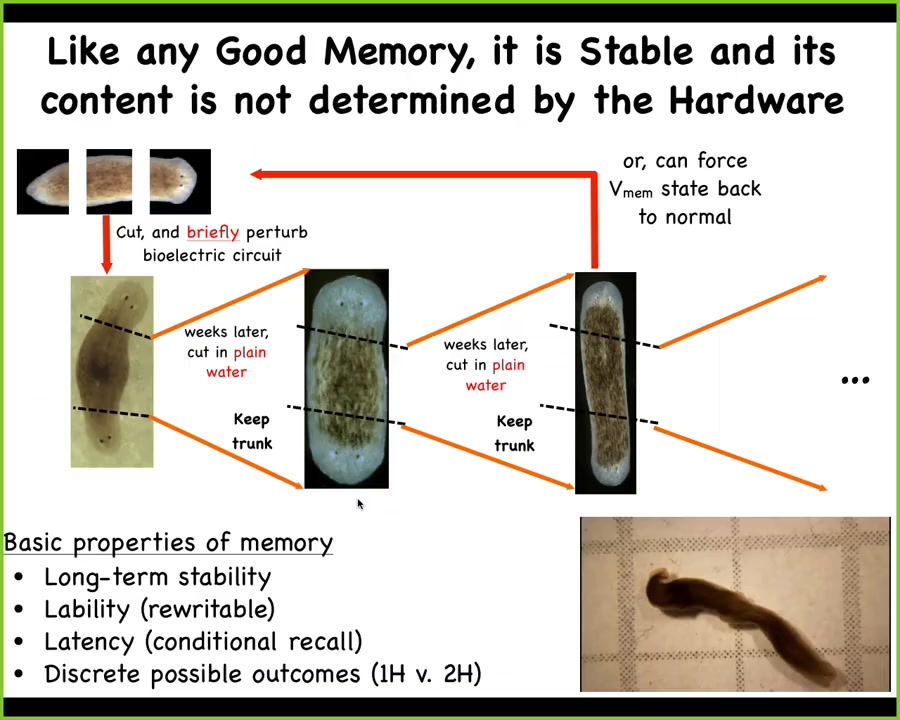

Slide 24/38 · 32m:03s

Now I keep calling it a memory because... If you cut these animals, here's our two-headed worm. You cut off the primary head, you cut off this crazy ectopic secondary head. You take this middle fragment, and you might think the genetics are untouched. In plain water, it should just go back to normal and make one head, one tail. That's not what it does. The circuit, the electrical circuit that keeps this information has memory. In fact, it has all the properties of memory. It's long-term stable. It's rewritable by experience, not by hardware manipulation. It has latency, which I just showed you, or conditional recall, and it has two possible behaviors. What happens is, as far as we can tell, in perpetuity, once you make these two-headed animals, they stay two-headed, even though their genome is wild type. And we now know how to make them go back. We can actually reset the circuit. So it's almost like a flip-flop where we can go back and forth between that circuit and coding one state, one-head or two-head kinds of states. And here you can see these two-headed animals hanging out. Not only can you take this kind of machine and tell it how many heads it's supposed to have, you can actually tell it what kind of head to have.

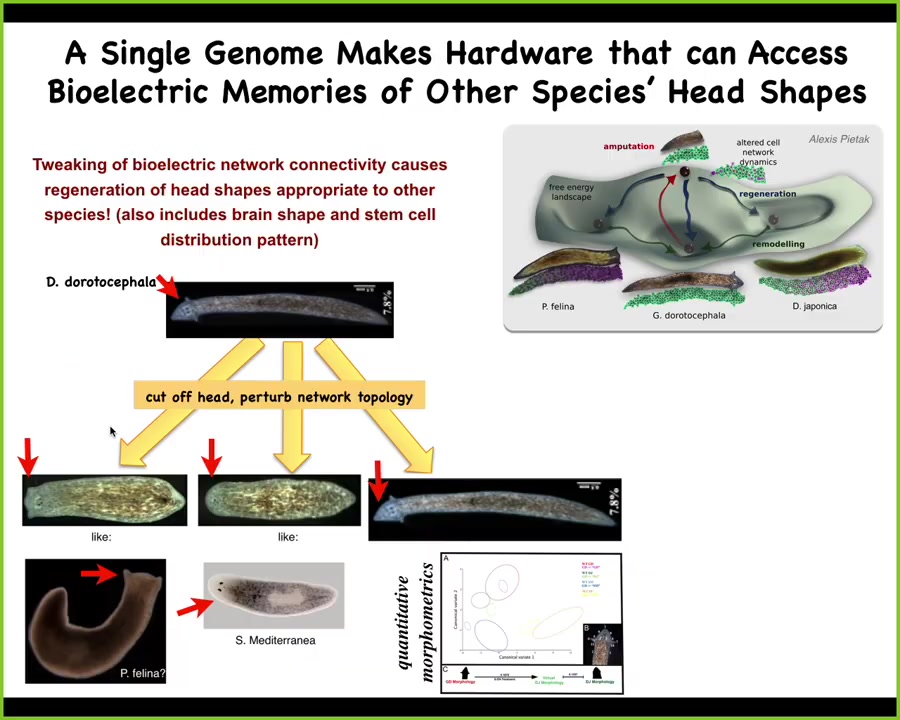

Slide 25/38 · 33m:09s

So here's a planarian with normally a triangular head shape like this. What we can do is amputate the head and then treat the rest of the tissue in a way that basically using a general anesthetic that just, all it does, so general anesthetics among other things, uncouple gap junctions, so they uncouple these electrical synapses. And when you uncouple them, what happens is the individual cells are still alive, but things like global computations go away. And then when you put them out of the compound, they settle down, but they don't always settle into the same state. Actually, this is true in humans as well. The reason that they don't like giving general anesthesia to people is that some people have psychotic breaks because the brain does not come back to the same state. It's kind of miraculous that it ever comes back to the same state if you uncouple all the activity. But what you can do here with these guys is when they come back, they sometimes come back flat-headed, like this P. felina. Sometimes they come back round-headed, like this S. mediterranea. The evolutionary distance here is between these guys and the actual species. It's about 150 million years. So without genetic change, you can explore different attractors in morphospace that other species live in naturally. This may be how the speciation happened. We don't know. It's not just the shape of the head, it's also the shape of the brain and the distribution of stem cells are exactly the same as these other species. So you get the idea of this incredible reprogrammability and plasticity that goes beyond the default kinds of robust behaviors that the standard machine does after development.

Slide 26/38 · 34m:54s

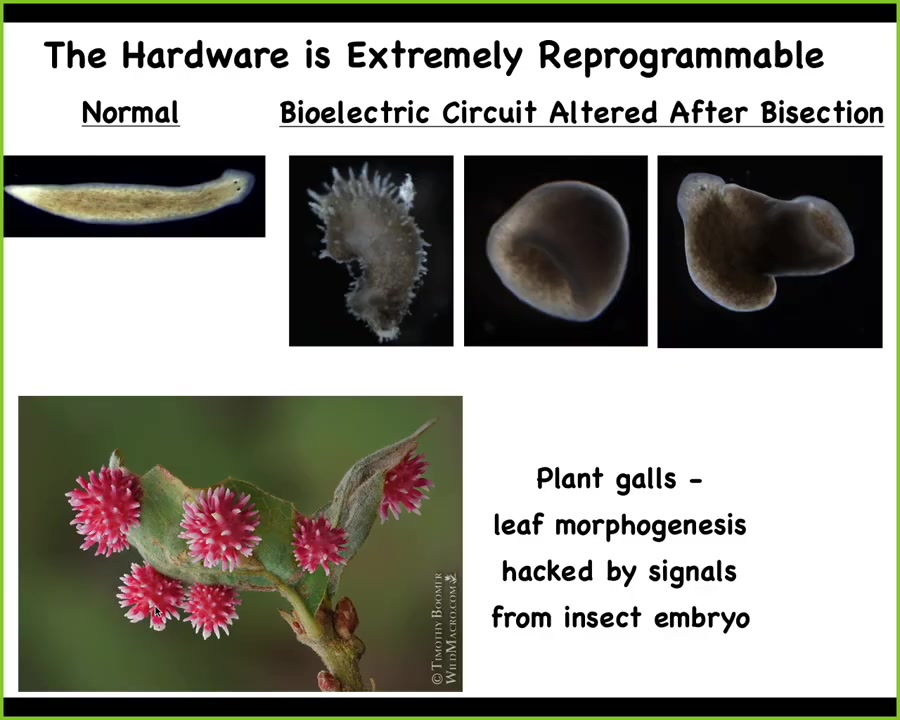

You can explore regions of the latent space that are very far from normal planaria. Here's your normal planaria. We can make these crazy spiky forms. We can make something that's cylindrical, has a different kind of symmetry, body or plant symmetry. You can make these kinds of hybrid forms.

A lot of biological hardware is extremely reprogrammable. If you've ever seen them in the wild, these are called galls. There's a wasp embryo in there, but these are not made of the wasp cells. These are made of the leaf cells of the plant. Normally these cells make this nice flat leaf. People who are focused on genetics and molecular biology will say, that's what the genome encodes: the ability to make these flat leaves. In fact, it's very easily hacked by this parasite that gives them signals to form something completely different. These leaf cells are in fact able to form something like this. It's just that they normally don't.

Slide 27/38 · 35m:57s

I want to now start to pull back and try to talk about what we mean by a collective intelligence in whatever space it's acting in.

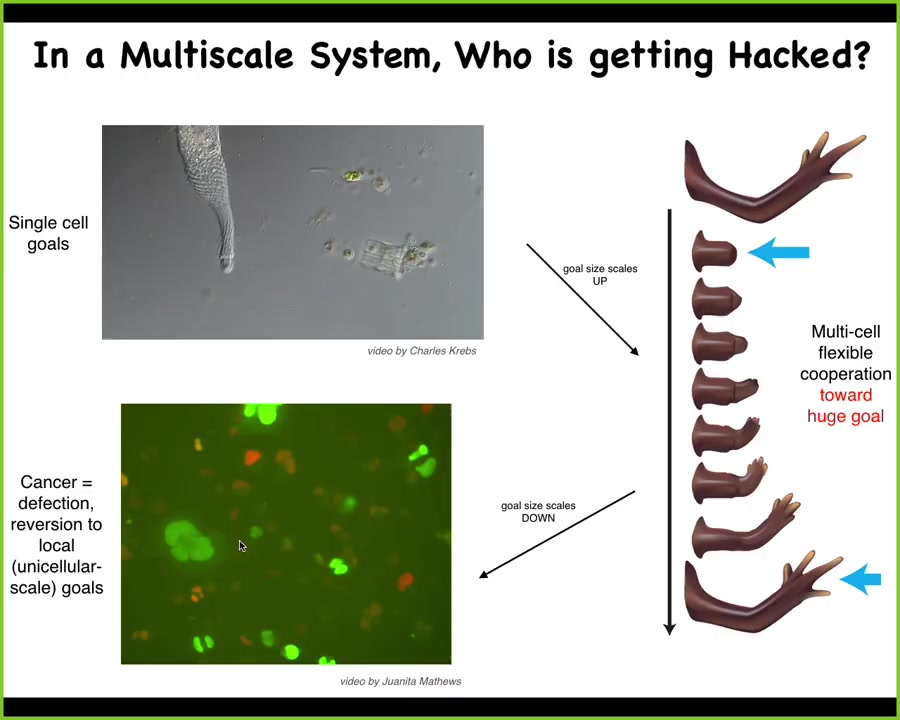

This is what happens during evolution: the components like this, which are very competent at very local, tiny little goals, so metabolic goals, the things that individual cells do, using bioelectricity and other types of modalities, including chemical signaling, biomechanical signaling, they scale up to systems that have much bigger goals.

This system has the ability to try to reach this goal, something like organogenesis, despite all kinds of perturbations that I've shown you.

There's a flip in space. This now is in morphospace, and there's a scale up of the kinds of goals that it can achieve.

But that process has failure modes, and that failure mode is cancer.

This is human glioblastoma in a dish. What happens is that individual cells, when they electrically disconnect from their neighbors, and that can be caused by a variety of factors, at that point they revert back to their unicellular past. They are no longer interested or capable of understanding the behavioral cues that bind all of them towards these kinds of larger-scale construction projects, and they go back on their own. At that point, the rest of the animal is amoeba. It's an environment to these amoebas, and that's metastasis.

Slide 28/38 · 37m:28s

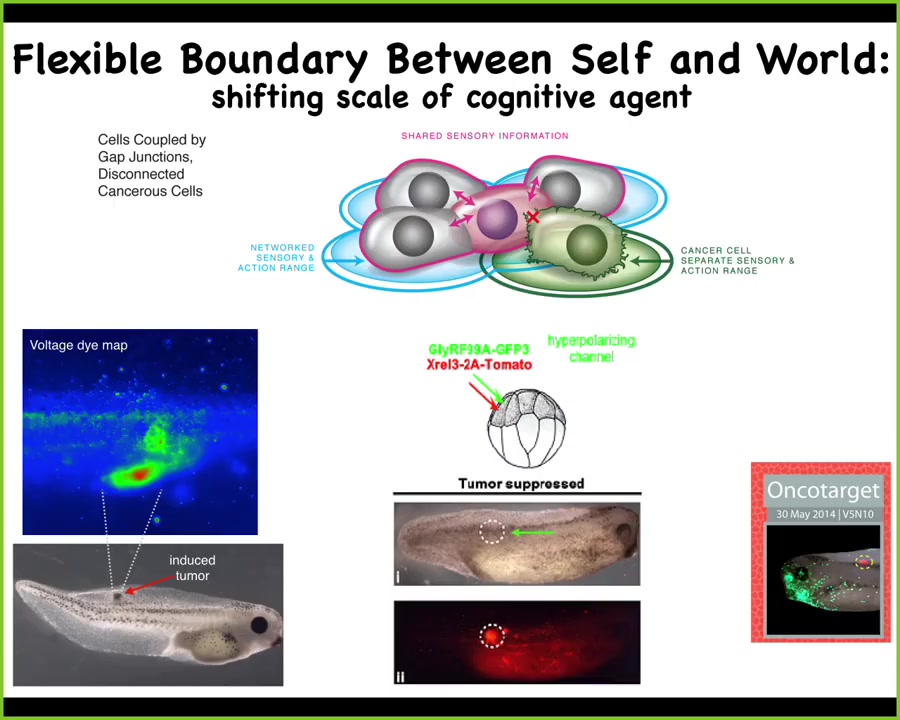

And so there's the utility of this kind of thinking, where you think about these cancer cells not as more selfish, but that their cells are smaller. The computational boundary has shrunk to the level of a single cell. And that leads you naturally to some new therapeutics.

For example, here you can see when you induce a human oncogene into these tadpoles and they're going to make a tumor, even before the tumor forms you can see these bioelectrical disconnections of the cells from the network. You can see exactly where the tumor is going to be. If you co-inject an ion channel, that forces the cells to remain in electrical communication. It doesn't kill the cells and doesn't fix the genetic mutation. You can see that here: the oncogene is blazingly expressed. It can be a nasty KRAS mutation or p53. In fact, it's all over the place. There's no tumor because what drives the whole collective outcome is the behavior of the network. The individual cells are much less important here. You can try to re-expand that cognitive boundary to get the cells connected with each other and to pursue organogenesis.

Slide 29/38 · 38m:42s

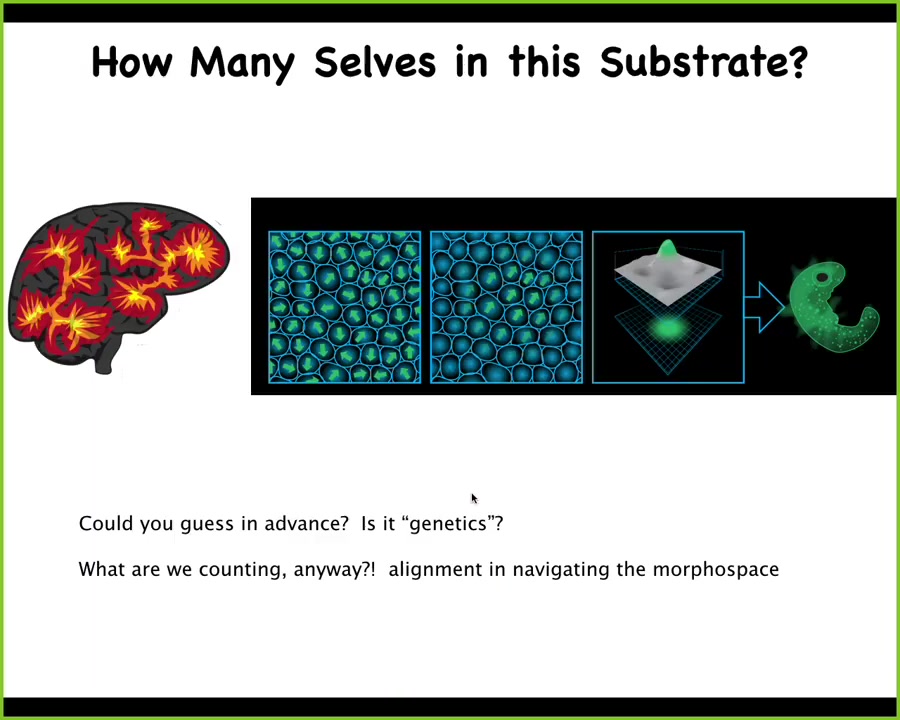

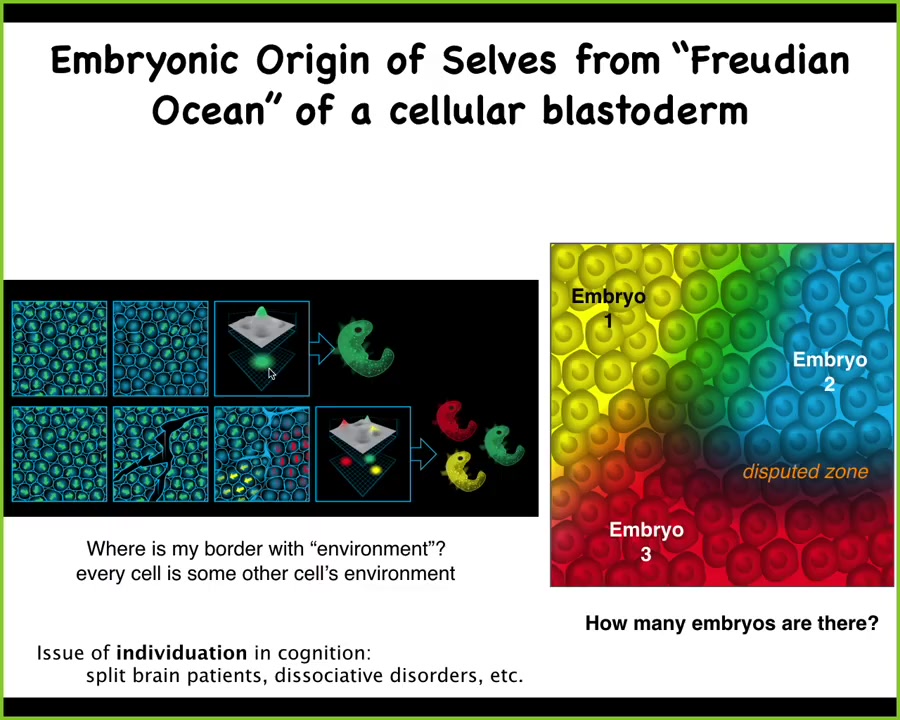

This issue of cognitive boundaries, the boundary between self and outside world, in a standard human, you would think it's very simple. There's our human, there's where the body ends. Although this idea of the extended mind, Andy Clarkson and those kinds of ideas, are already stretching that; it's really more fundamental.

If you didn't know what a human was and somebody showed you a brain, this 3 1/2 pound mass, how many individual selves would you say are in there? You don't know because we don't have a way of saying, per pound, this is how much real estate it takes to make a self.

The same thing is true of embryogenesis. This is a deep problem of an individual emergent system arising from a sea of components. This is an embryonic blastoderm. It's an early stage, about 50,000 cells, and you look at it and you say, that's an embryo. When you look at it, given that there's 50,000 cells, you can ask yourself, what are we counting? What is an embryo as distinct from the individual cells we're looking at? Can we guess how many embryos are present in any particular blast? Usually the answer is 1. Usually there's seemingly one individual in a brain. But it doesn't have to be one.

Slide 30/38 · 40m:14s

And what can happen is this. I used to do these experiments myself as a grad student. You can take an avian or a mammalian blastoderm and you take a little needle and you make some scratches in it. What happens is when you make these scratches, each domain, because the scratches will heal, will temporarily self-organize into a new embryo. When the scratches do heal, you end up with conjoined twins. You will have these regions, each of them as a separate embryo. Then there are some disputed zones, these cells that don't quite know who they belong to. But a particular blastoderm can give rise to 0, 1, or several individuals.

Now, in the case of morphogenesis, what are individuals? Well, they are collections of cells that are bound to a common purpose. They're going to make a specific thing, meaning they're going to move to the right region of morphospace. They're going to have two eyes and then four limbs and then various other things. That's what we're counting. We're counting independent goal following systems. In this sort of excitable medium, there can be multiple, depending on the dynamics. It's not genetically determined. Usually it's one, but it doesn't have to be one. This is true in brains as well, where we see split brain patients and various dissociative disorders. There's no guarantee that in that medium there's one individual.

So what we're interested in is merging these ideas of understanding the bioelectric circuitry and the attractors and the other features of that state space with ideas about how memories are stored in electrical networks, what it means when we can recover a portion of that information after damage, and of course the dynamical systems approaches to this.

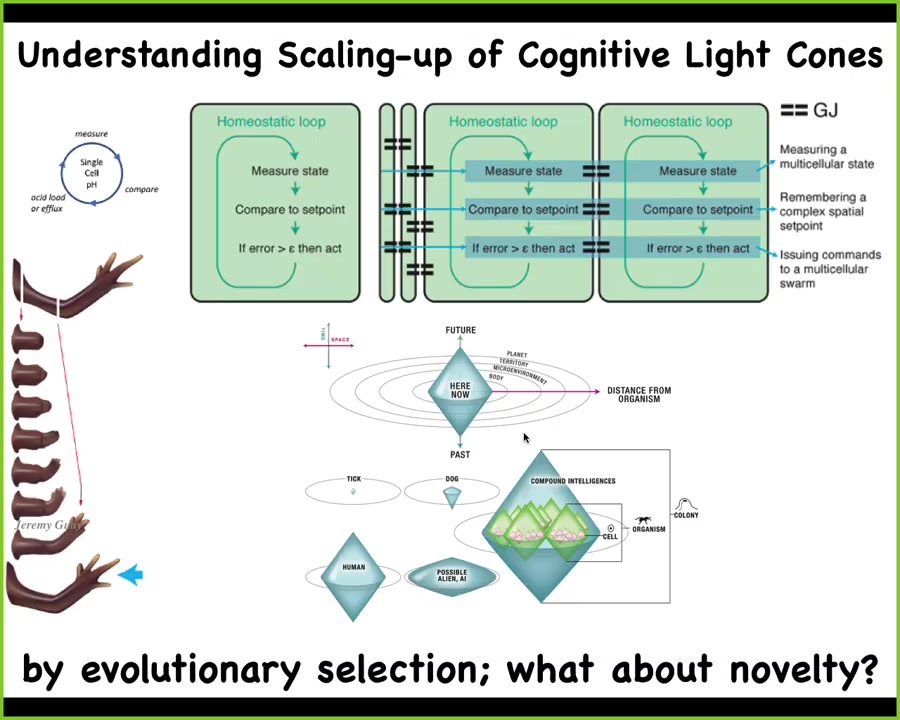

Slide 31/38 · 42m:01s

And so what we really need, and this is very active work in our lab now, is to understand the scaling, where we start with individual tiny competent subunits, which can do homeostatic things like keep pH and hunger level and so on. Individual cells, and then you bind them together into networks that have particular policies for spreading signals back and forth. As a result of this, what you get is an increase in what we call the cognitive light cone, the size of the maximal spatial-temporal size of the biggest goal that it can hang on to or that it can pursue. So individual cells pursue tiny goals, collections of cells pursue bigger goals, and so on. Now, when we talk about the size of these goals, typically if we ask, where do they come from? The standard answer is evolutionary selection—you get them from evolution. But what about novelty?

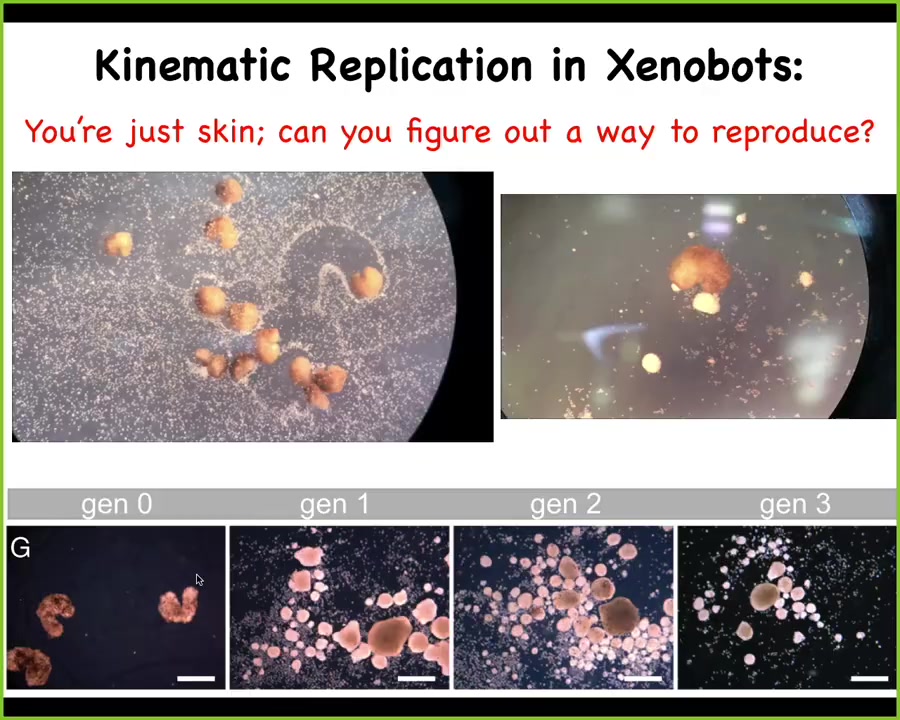

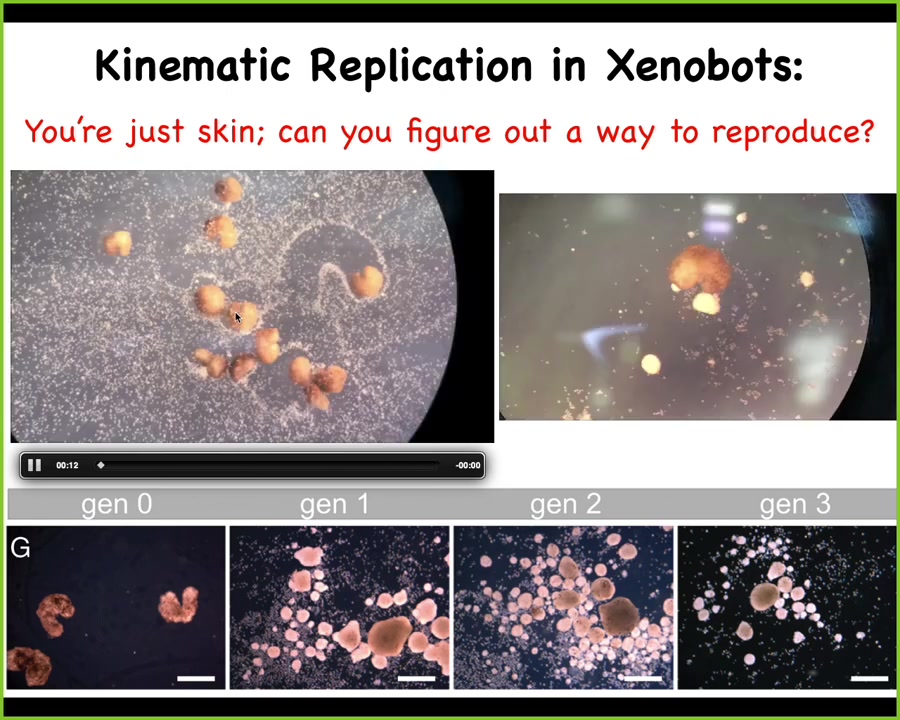

Slide 32/38 · 42m:58s

We have examples like this, and I can show you much more, but I don't have too much time left. These are what we call Xenobots. Xenopus laevis is the name of the frog. We can use frog skin cells to make something, to make a biological robot or a biobot called a Xenobot. These little things running around are just skin. They're just frog skin that was liberated from the rest of the animal, rebooted into a new kind of critter with a new behavior.

They have many new behaviors, but here's one. If you provide them with a bunch of loose cells, what they will do is they will run around and collect these cells into little balls and polish them like this. And because the little balls are not passive, they're an agential material, just like the original, they will mature into the next generation of Xenobots and continue to do the same thing. So this is a kinematic self-replicating system. This is von Neumann's dream, a robot that goes around and finds materials in the environment and builds copies of itself.

But the interesting thing here is that there's never been evolutionary selection to do this. No other animal does kinematic self-replication. When you look at these skin cells in vivo, you might think the only thing they could possibly know how to do is to be this boring two-dimensional layer that keeps the bacteria out on the outer side of these embryos.

Slide 33/38 · 44m:24s

Liberated from those instructive cues, you get to find out that they can do all kinds of things by themselves and within about 48 hours they exhibit reproductive behavior that's completely different from how frogs normally reproduce, because we've made it impossible for them to reproduce their normal way. This is just skin. I can't do any of that other stuff. The ability of all the parts to have coherent, novel behaviors and to solve new problems that were not actually anywhere in the training set is really interesting here.

This incredibly large option space, all of the natural model systems of biology are here, including brains that we like to get inspiration from, but all this other stuff, hybrids and cyborgs, every combination of cellular material, designed, engineered material and software is some kind of viable agent. There's this huge option space of novel intelligences that I think we really need to mine in addition to whatever insights we can get from standard brains.

Slide 34/38 · 45m:25s

In the end, I'm going to close here with a couple of thoughts. This idea that non-neural bioelectricity is a kind of cognitive glue for collective intelligence in morphogenetic space, exactly as it serves as the cognitive glue to neurons in the brain and in traditional behavioral space. It has some interesting things to say to neuroscience in terms of the origins of the amazing things that neuroscientists study and vice versa. We certainly benefit from all of the insights of the field.

The same thing with AI. This idea of diverse intelligence in unconventional embodiments is a really powerful set of inspirations for creating novel robotics, novel AI systems that are not, specifically not neuromorphic, that are looking at more basic fundamental principles. We appropriate a lot of ideas. I could show you data on perceptual bistability in morphospace, planaria that can't decide if they want one head or two, and they shift back and forth. Many deep areas of intersection among these three fields.

Slide 35/38 · 46m:38s

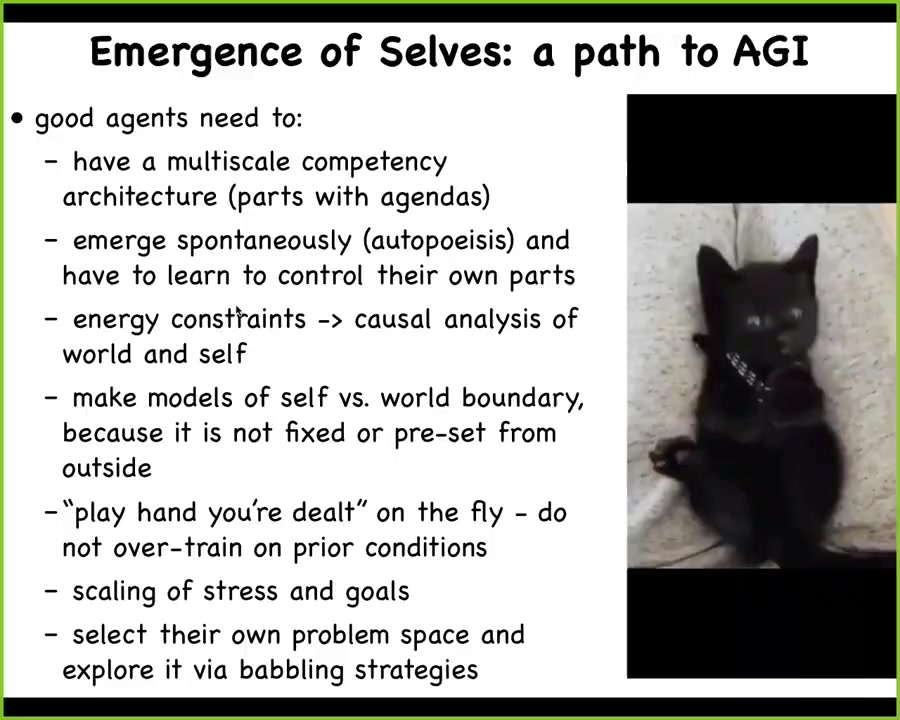

And so, from all these ideas about how individual pieces come to be a single coherent thing, give us some suggestions for what you might want from a real agent. This idea that when we make these things, everything has to be determined on the fly. We can't predefine a built-in model of what they are, where their boundaries are. They have to emerge spontaneously through autopoiesis. They have to figure out where the world starts, where they end, what they have, what effectors. As you saw from all of these examples, the tadpoles with the eyes on their tails, biological systems make very few assumptions really about what happened before. The product of the evolutionary process is a problem-solving machine that starts from scratch. I call it "play the hand you're dealt." They do not make too many assumptions about how the world is. I can show you many examples of beings that have too many cells, too few cells, the wrong kinds of cells, and they will always try to figure out something useful to do with that.

I think the process of self-construction is really going to be critical for proper intelligence. Anybody who's interested can dive into some of the details here.

Slide 36/38 · 47m:56s

I want to thank all of the students and the postdocs who have done the work. Thank our funders. I'll do a disclosure here: Fauna Systems, because Josh Bongaard and I have a startup company around computer-designed bio-robotics.

My final message is that I think that this multi-scale competency architecture, which is made up of these agential materials that behaviorally shape each other to accomplish specific outcomes in Morphospace, can really teach us a lot about how collective intelligence works and how we can engineer it. I'll stop here and thank you all for listening.

Slide 37/38 · 48m:37s

Thank you, Michael. My head exploded several times through the... Thank you. So one question regarding the worm and the head. You said that the memory is distributed, so it builds the same head with the same functionality and same memory. So if the memory is in the body, why does it need that? So what's the functionality of the head? Is it the executive? Is the memory multiple places that gets replicated? And also your ideas about selfhood and limits of self, that was great. Thank you so much.

Thank you. Yeah, so the thing with planaria is that the brain is actually required for behavior. So when you cut off the head, the remaining body parts really don't do anything. They just sit there. So you wouldn't know whether it had memory or it didn't have memory because it doesn't do anything. And so in order to observe evidence of the memory, you have to let it regrow the head so that it can actually start to behave.

So I think that the rest of the body, and we don't know exactly where the memory is. We don't know if it's in the neurons. We don't know if it's in all the tissues. We really don't know. But I think that the memory outside of the brain is passive. It's stored, but it doesn't have the ability to act or to be read out. I personally think that, and of course, this is extremely controversial, but I'm not the only person thinking about it this way, this idea that to what extent are specific memories actually stored in the neurons versus the neurons being a kind of decoding machinery from other cellular substrates. And there's some nice work on that. So I think there's something to that. But you definitely need the brain to be able to read out the memories and act in the three-dimensional world.

This was absolutely spectacular, and I love this view of localization in the sense that comes out of your view. But I want to push that a moment. So we will often be in this situation where there's something that could happen that is good for me, if I think about myself as being small. And what I'm gonna do is, I want someone over there, which isn't my direct neighbor, to do something for me, and at some level what we want is something that's almost like gradient descent. I tell my neighbor, "Hey, can you move out of the way?" And they tell their neighbor, "Hey, can you move out of the way?" And so, this training that we have in gradient descent in AI should be the case for biology at all levels, if I hear you loudly, so I wonder if you go so far, basically just say that gradient descent should be a ubiquitous property in biology.

So, this is really interesting. I have a slide, I didn't bring it here just for lack of time, but I have a slide that shows almost exactly what you just said. So think about the role of stress. Imagine that you have a bunch of cells and there's one cell at the bottom that's not at the right location. It wants to get up here to the top. Now the problem is that all of these other cells are perfectly happy where they are. They're not getting out of the way for this. And so this cell is very stressed because it's not in the right location. What you can do is you can export your stress. You can start to leak your stress to the neighbors. The neighbors also start to feel stressed. They don't know that it's not their stress because all the stress molecules are exactly identical. And so the temperature of the whole system rises. They start to get a little plastic and everybody's willing to move around a little bit. And then you can get to where you can go. And then you reach some kind of global maximum and everybody's happy.

It's a way to have this kind of cooperativity without any altruism because all the other cells want to minimize their own stress and you're stressing them out. The way for them to have lower stress is for you to have lower stress. It's like this collective; I think it's one of these things that helps collectivism. If you want to call that gradient descent, I'd love to talk more; I'm not an expert in gradient descent. But if that's what it is, I'd love to know about it. I think it's quite similar. That would be great.

Thanks for that talk; that was great. That was also a perfect question. I come from a multi-agent RL background, multi-agent systems, and the goal of multi-agent systems is to model the collection of agents working together to solve tasks. In multi-agent RL, the way we do this is agents share rewards. This could be sharing stress or sharing food. This models the group of agents as a larger self.

Recent work in the last few years shows that if the group of agents grows too big, performance might degrade, or if agents fully share their rewards, performance might degrade. Is there anything like this where between cells they might not fully share their stress or rewards, but there's a degree where I don't want to offload all of my reward, but just part of my reward to help cooperation?

Sarah Marsden, who is an RL expert—I'm not— we're writing a paper on this topic. I can think of two examples similar to what you're saying. One is an idea Chris Fields and I had a while back: one of the drivers of multicellularity might be that if you, as a simple cell, want to do some kind of active inference and predict your environment, the most predictable thing in a very uncertain environment would be a copy of yourself. The nice thing to do would be to surround yourself with copies of yourself so that you have some prayer of having a stable environment and knowing what's coming next, at which point you might want to addict your neighbors to hang out with you. You might have autocrine and paracrine loops where you're secreting goodies, maybe natural opioids, maybe nutrients. You might try to share some of this to keep the other cells around and maintain this.

The other aspect of what you just said is seen in gap junctions. The magical thing about gap junctions, which are these connections that allow molecules to pass directly from the inside of one cell to the other, is this. Under traditional signaling modes, one cell will secrete a chemical, it floats over, the other cell has receptors and senses it. The receiving cell is clear that this signal came from outside. You might ignore it or learn from it, but it came from outside. Gap junctions are different because if something happens—cells A and B are connected with gap junctions, something happens to cell A, it triggers a memory trace, let's say a calcium spike, which immediately propagates into cell B. What these gap junctions do is erase the ownership on that data. There's no metadata on the calcium about where it came from. Calcium is calcium. Whatever else comes across as a signal of that information or a reward is shared by the two cells, or not equally, because the gap junctions can be regulated.

What that tends to do is it erases the individual identities because if A&B cannot cleanly maintain their individual memories, if they share memories, it's like this mind meld, because now it's not that I have my own memories and you have your own memories, now they're just weak, because it's the same pool of molecules.

It also makes it impossible to defect in a game theory sense, because if you're connected and I do something nasty to you, it comes back to me immediately. It forces this cooperativity; it forces a kind of sharing of our past that binds us together. In that sense, to my knowledge, nobody's actually studied this in detail, but I bet exactly what you're saying, that if we were able to track the reward molecules going through these things, we would find some dynamics that are understandable under these various frameworks like RL and other things that you guys study.

Hi, I have a question. I would like to challenge you a bit on the notion of ubiquitous intelligence. From what I see, I really like the idea that it goes through transcriptomic networks, the cell-to-cell interaction networks. But it sounds to me like you ascribe every complex system that's interconnected and that this interaction between these individual agents, that if there's an adaptive behavior that is somehow intelligent. My question is, where is the boundary? Let's assume a block of metal is not interactive, because it's not an interactive complex system. But in your framework, the weather might be, because you have interacting things and it's a complex system.

Slide 38/38 · 58m:29s

I just wonder, in your framework, do you think that from cell-to-cell interaction, gene-to-gene interaction, to neuron-to-neuron interaction, it's just a slow continuous scale-up? It's a different time scale because we have these learning rules in the brain which we'd like to understand. Do you think the same things hold true for the cells? It's just that it's a different time scale and would eventually get there.

Let's say IBM organizes a workshop to develop a brain model that's able to solve some problems with intelligence. In a sense, ChatGPT can solve problems, or AI has improved or become more intelligent because it is actually able to solve certain problems. My question is, in your framework, would you say if you just wire up a bunch of neurons artificially, they are doing something and create some dynamic, and that's not the intelligence we're interested in? Do you think there's a qualitative difference in how the brain is doing intelligence and how cell-to-cell systems are doing intelligence?

Here's what I would say: I do not believe in intelligence as a binary notion. I don't think we can say yes, it is, no, it isn't. The real question is how much and what kind. We can talk about whether there are great transitions or it's a smooth continuum. I absolutely agree that intelligence cannot be attributed simply on the basis of complexity or a dynamical system.

This is what Wiener et al. were trying for: they were giving functional criteria for assigning certain kinds of intelligence, which you can only assess in experiment. If you bring me an extremely complex system and we want to make intelligence claims about it, on my framework we have to do a couple of things. We have to pick a problem space, then pick a goal or problem-solving behavior that we think it's doing, and then do experiments to see what kinds of competencies it can muster. Then we have an empirical answer. If two people have a model, one person says it's just a hardwired thing that does the same thing, somebody else says it's a Braitenberg vehicle of type 2, somebody else says it has metacognition and it knows what it knows. These are all empirical questions. We have to do the experiment.

I'll give you a very simple example. If you look at a gene regulatory network, these are a mathematical model that literally just says it has maybe a dozen genes and each one turns another one on and off. It's a set of coupled ordinary differential equations, for example. The traditional view was that it's a complex dynamical system, but we can see what it's doing; there's no way this thing's intelligent. We said, let's do the experiment. We found that it can actually do six different kinds of learning, including associative conditioning. Is it highly intelligent? No. Can it do associative learning? And is associative learning a kind of intelligence somewhere on the spectrum? I would say so, but we didn't know that until we did the experiment. We tried to train it and observed what it can do.

When you brought up the weather, that's interesting. I've made this exact claim about the weather. At the moment, we have no idea why.

Because nobody's tried training the weather. I do not think we know whether, if you tried certain kinds of behavioral paradigms, things that come from behavioral science, we would then find out no, actually the weather doesn't have any kind of learning capacity, so it's zero or extremely low. Or we would find out it actually does. Much like these genetic networks, these biological transcriptional networks that people thought had none of this, and in fact have some.

So I just insist on two things: one is that this is a matter for experiment, not for armchair speculation. I don't think we can have feelings about systems as to whether they should be intelligent or not. We have to do experiments, which means you make a claim about what type of—this is one, I have a different scale that I came up with, but this is Wiener's, is fine too. You pick where you think it is on this, and then you see whether your model gives you better prediction and control versus somebody else who picks a different spot on the spectrum. As long as we stick to empirical experiments, then we can find out what kind of intelligence anything has.

Thank you.