Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

A talk on intelligence beyond the brain

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Multi-scale bioelectric intelligence

(52:42) Q&A introduction segment

(54:40) Evolution of regeneration

(56:09) AI and embodiment

(58:59) Continuum of cognition

(01:01:47) Intelligence beyond organisms

(01:03:13) Session closing remarks

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/47 · 00m:00s

Thank you so much for having me here. I'm looking forward to sharing with you some ideas at the intersection of developmental biology, cognitive science, and computer science. And in particular, we're going to talk about what biology can tell us about cognition outside of the brain, and across scales of organization that might be good inspiration for artificial intelligence.

Slide 2/47 · 00m:25s

The main points for today are these, that biology exhibits intelligence at every level. It operates as an unconventional agent in many different spaces besides the typical three-dimensional world of behavior that we think about. Neuroscience is an elaboration of a much more ancient computational system, which I will describe today, called developmental bioelectricity. This guides the trajectory of the body through morphospace.

Dynamic, robust, anatomical control is the output of a collective intelligence of cellular swarms. I'm going to show you how we can now both read and write the cognitive medium of this agent. Finally, this idea that multi-scale competency and other strategies that we find in biology that do not rely on neuromorphic architectures, meaning do not rely on mimicking the structure and function of brains, may represent a really important direction for engineering novel and hybrid intelligences.

So let's think first about cognition outside the brain. To really talk about artificial intelligence, we need to look at what we mean by natural intelligence and try to provide some sort of definition for it. There are many. I'm going to start by widening our perspective from the usual way that we think about intelligence and brains and how that relates to artificial intelligence.

Slide 3/47 · 01m:48s

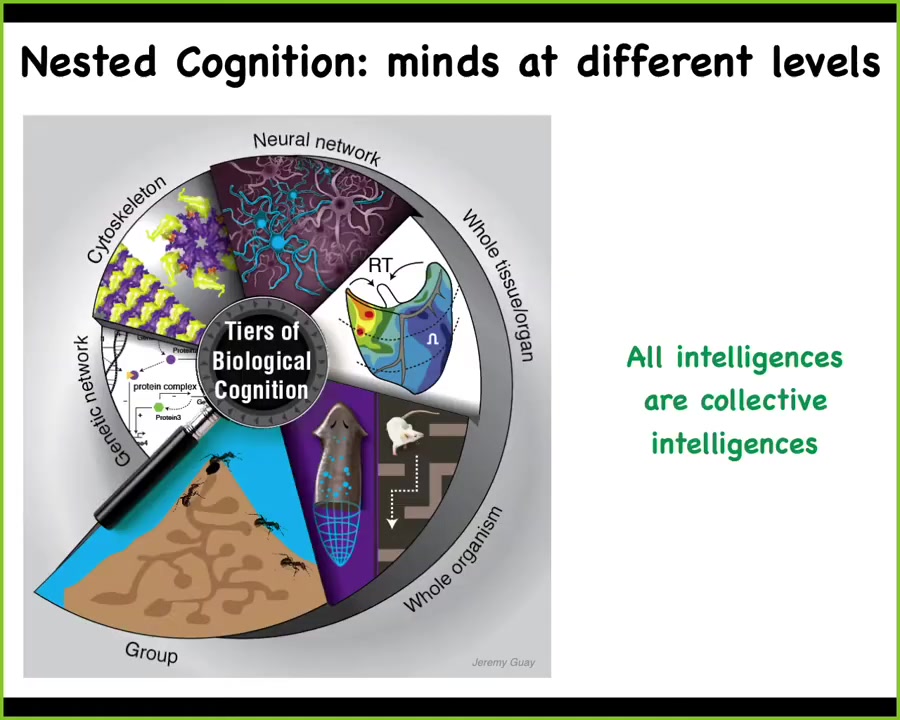

The first thing is that biology is deeply multi-scale. We study computation and cognition all the way from genetic networks, which in fact have learning capacity, to subcellular components like the cytoskeleton, neural networks, tissues and organs, in fact whole organisms and swarms such as ant colonies.

All intelligences are collective intelligences. There's no such thing as an intelligence that is a single indivisible unit. Everything is made of parts, and in particular, all intelligences are made of components. It's a major goal to try to understand how large-scale intelligence arises from the functionality of its individual components. We're all a kind of collective intelligence.

Slide 4/47 · 02m:38s

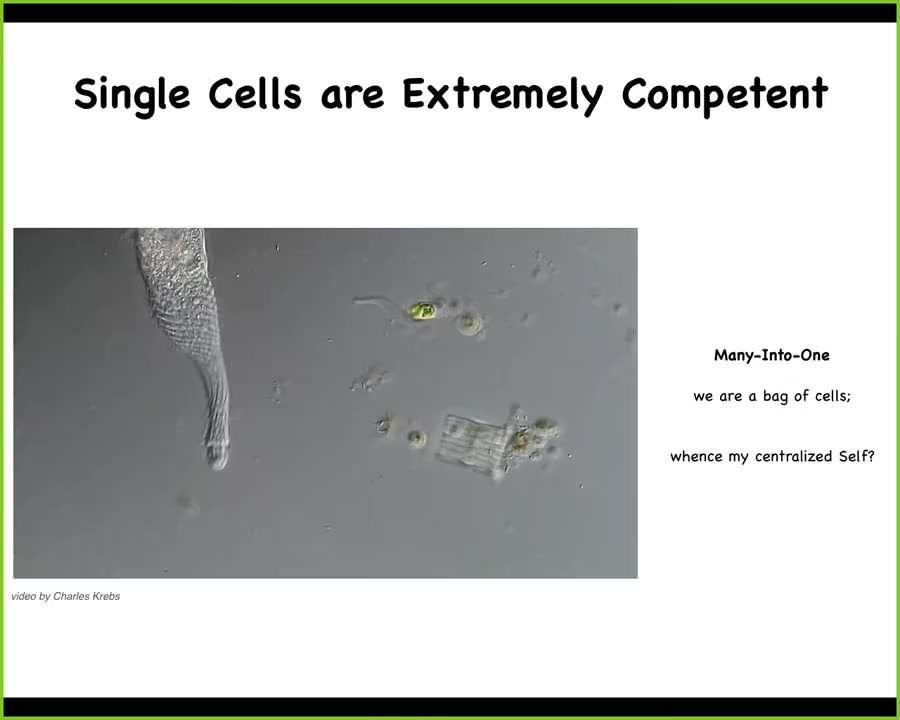

In fact, single cells are extremely competent. Here what you see is a single-cell creature known as a lacrimaria. Observe the incredible morphological control, and this is real time, as this animal hunts for bacteria and other things in its environment. We too are a bag of cells such as these. This many-into-one problem is really fundamental to ask how do individual life forms such as this work together to provide a large-scale agent that has some sort of a centralized intelligence, a centralized feeling of self.

Slide 5/47 · 03m:19s

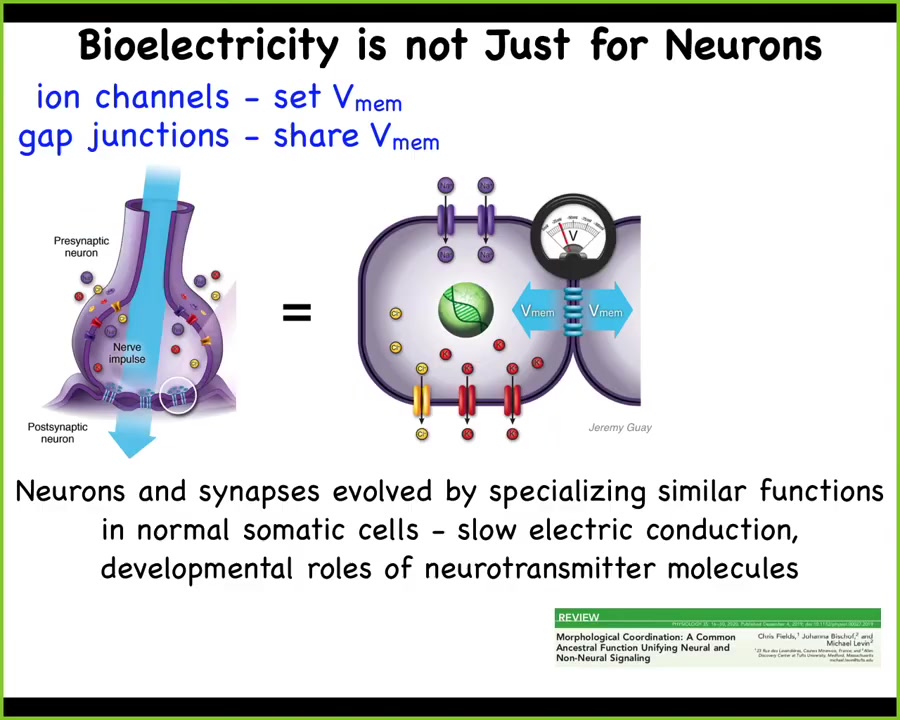

A key thing that I'm going to talk about today is that the bioelectric mechanisms that normally provide for this in the human brain, in all animal brains, are not just restricted to brains, but are an ancient evolutionary system that was here long before brains and neurons appeared.

Neural architectures evolved by specializing functions that were happening in cells long before evolution discovered brains and speed-optimized these kinds of electrical dynamics. We're here very early from about the time of bacterial biofilms. All of the components such as ion channels and electrical synapses and neurotransmitter signaling that we associate with complex brains are just elaborations of things that even pre-multicellular life forms can do.

There's a review here if you're interested in the details.

Slide 6/47 · 04m:14s

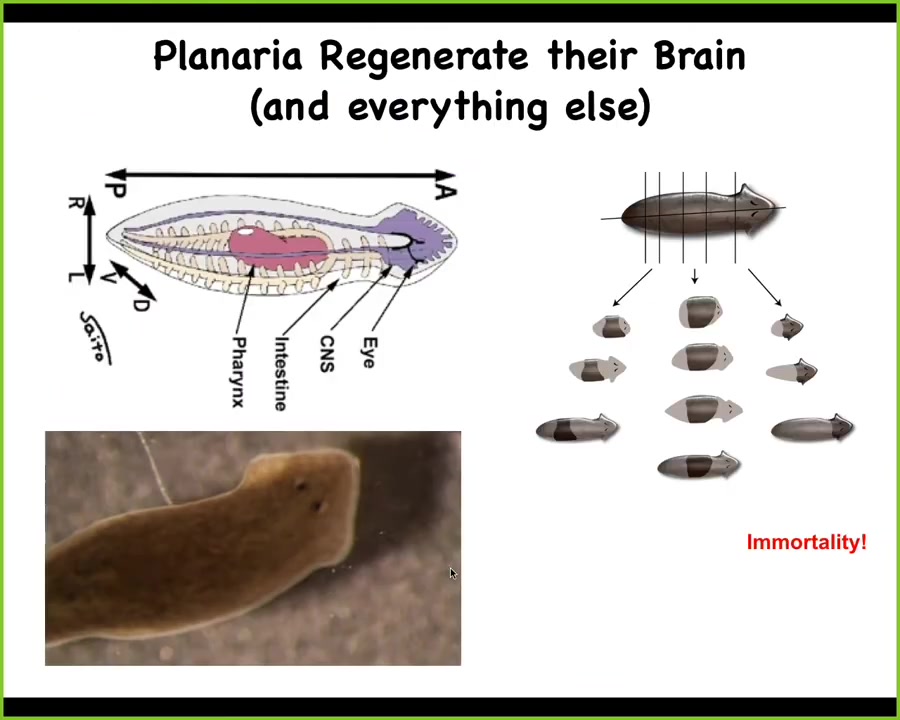

In order to start widening our approach, I want to think about the intersection of control of body morphology and memory and learning. First I need to introduce you to this animal. This is a model system known as a planarian. These are flatworms. You're seeing one here. They are not like an earthworm. They are much more complex. They are similar to our direct ancestor. They have a true brain, all the neurotransmitters that you and I have, centralized architecture, lots of different organs inside.

One other thing that's amazing about these planaria is that you can cut them into pieces and every piece will regenerate exactly what's needed, no more, no less, to form a perfect little worm. The record is something like 275 pieces. Every piece knows exactly what a correct worm looks like. In fact, the animal is so highly regenerative that they are immortal. They don't age at the level of the animal.

Slide 7/47 · 05m:11s

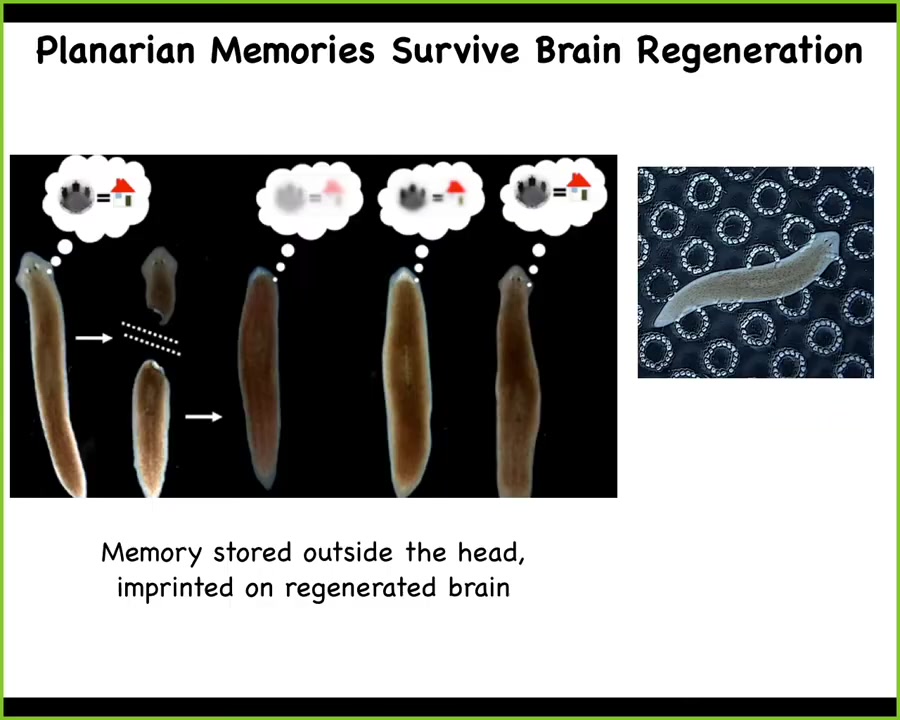

The reason I'm showing this to you is that what's remarkable about these animals that can regenerate their brains is that if you train a planarian onto some piece of information, such as that its home where it gets fed is a particular area with these little rough bumps, then what you can do is amputate the head. The tail will sit there doing nothing while the head regenerates. When the head and the brain regenerate, you can test the animal behaviorally and discover that it still has the original information. So the memory that this creature has formed was not only stored outside of the head, but also imprinted on the regenerating brain so as to provide for behavior that takes into account the knowledge that it had. So as we start to think about where memory, learning, preferences and so on are located, we can start to think about these really important dynamics that are not just focused on brains.

Slide 8/47 · 06m:03s

This leads us to the point of trying to look at some unconventional intelligences from the perspective that if memory and these kinds of mechanisms can exist without a brain, could intelligence do so as well? What might that look like?

Here I'm going to provide some examples. There are many definitions of intelligence.

Slide 9/47 · 06m:26s

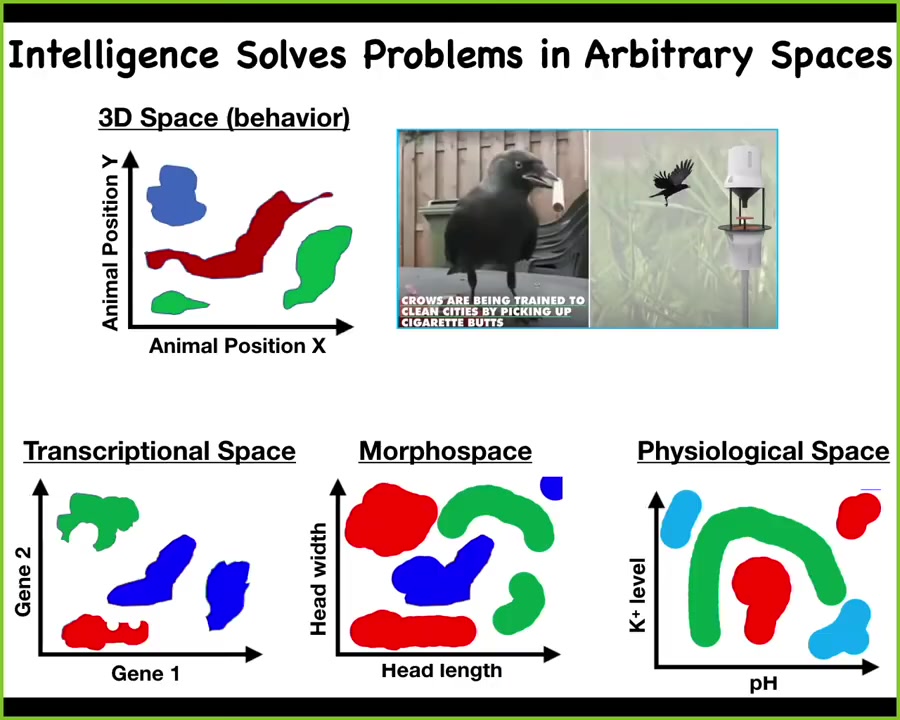

I will try to generalize it as solving problems in arbitrary spaces. We all know about navigating three-dimensional behavioral space. There are all kinds of clever animals that do things to navigate three-dimensional space and thus demonstrate their intelligence by solving various problems in the space. But in fact, life, long before it started solving problems in behavioral space, was solving problems in other spaces, for example, transcriptional space, the very high-dimensional space of all the different genes that could be turned on and off at any given moment. It was solving problems in morphospace, which is the space of all possible anatomical configurations of the body during development and remodeling. It was solving problems in physiological or metabolic space. One can generalize this idea of intelligence to the functionality in these various other kinds of spaces, not just three-dimensional behavior.

Slide 10/47 · 07m:24s

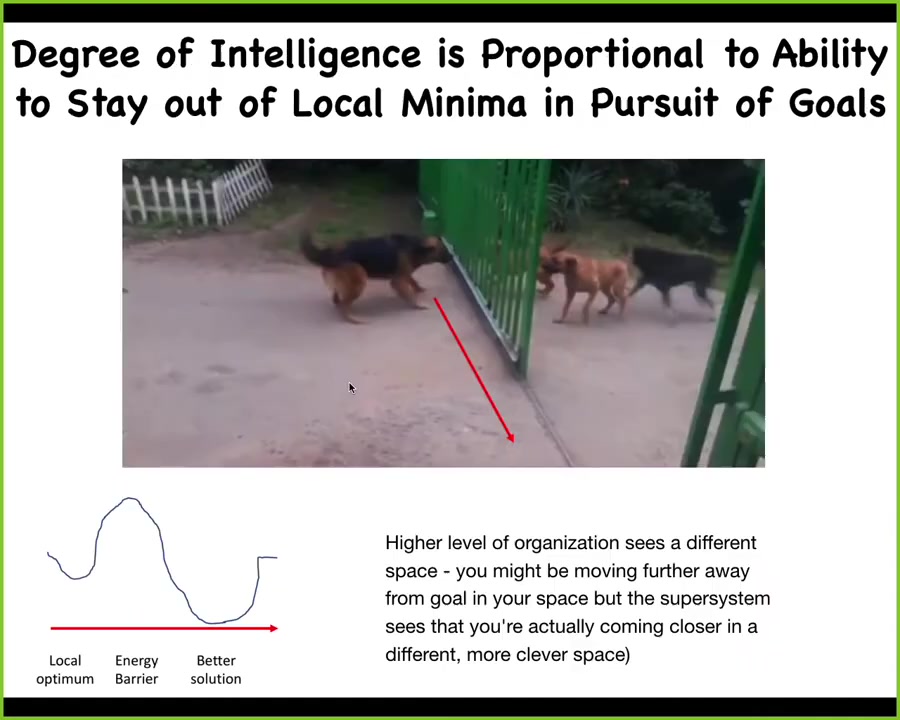

One could also say that the degree of intelligence is proportional to the ability to not get trapped by local optima. For example, you could imagine a scenario where the shortest path to your goal is right here. Here's the straight line. But if you had a particular degree of cognitive sophistication that allowed you to have patience and to move temporarily further from your goal to eventually get closer, to get around this local optimum, then you might be set to have a higher capacity.

I'm going to show you three or four examples of the kinds of problems that biology solves.

Slide 11/47 · 07m:58s

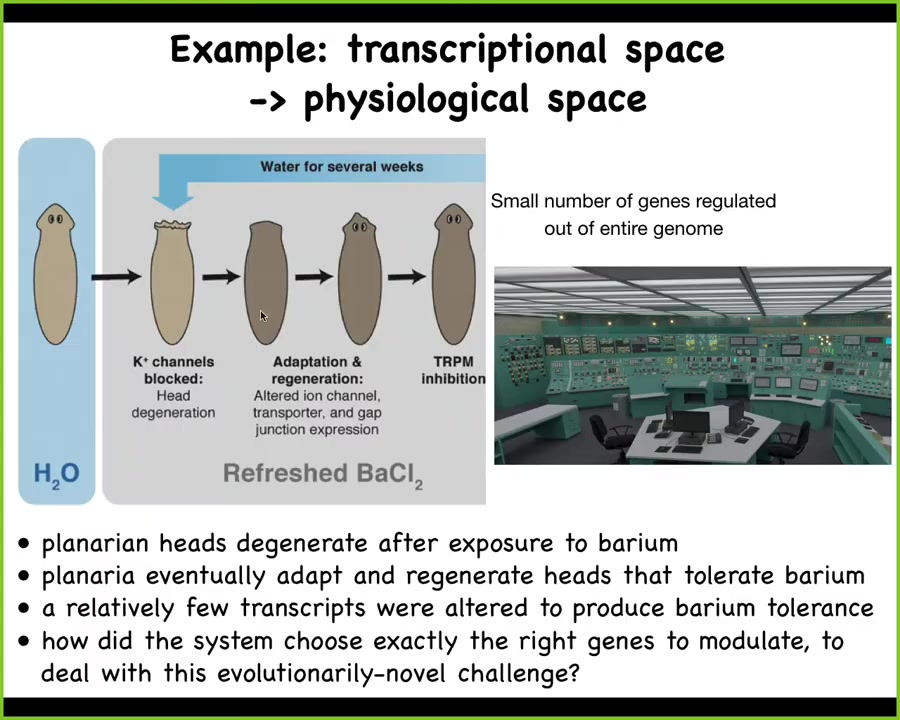

The first is an example of solving a problem in transcriptional and physiological space. Imagine here's our planarian; what we showed a couple of years ago is that if you put this planarian into a solution of barium, their heads explode. What is barium? Barium is a non-specific blocker of all potassium channels. So the cells are very unhappy. The heads explode. That makes sense. The most amazing thing is that over the next couple of weeks, they regrow a new head and the new head is completely barium insensitive. No problem with barium whatsoever.

We looked at the gene expression to ask why is this? What's different about this head versus the normal head that explodes? The answer is a very few genes were up- and down-regulated to enable these cells to do their business in the absence of this novel stressor. The amazing thing here is that barium is never encountered by planaria in the wild. It's just not something they ever come across. So there's no evolutionarily baked-in way for them to know how to respond to it.

I always think about this problem like you're in a nuclear reactor control room and the thing is melting down and you have to know which of these buttons you are going to turn on and off. Which genes out of the tens of thousands of genes that the planarian has would you turn on and off? In some way that we still don't understand, this animal very rapidly navigates to that region of transcriptional space, choosing out of all of those genes just a handful that will allow it to solve this completely novel stressor. We have no idea how this works, but it's an incredible example of problem-solving in a very high-dimensional space.

Slide 12/47 · 09m:33s

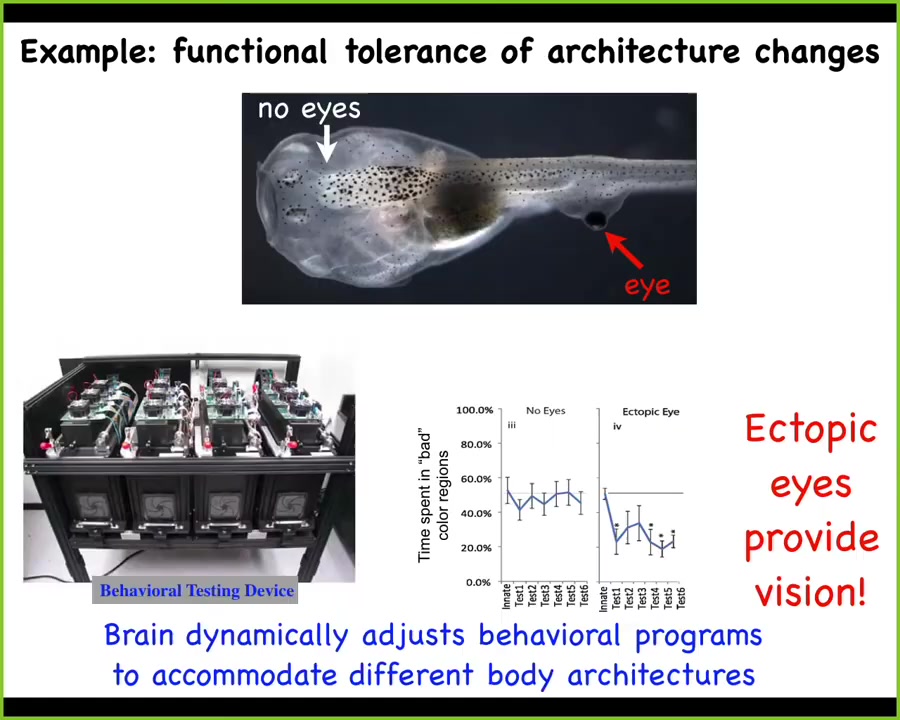

Another example is functional tolerance to changes of architecture. What you see here is a tadpole. Here's the tadpole, here are the nostrils, here's the brain, here's the gut, and here's the tail. One thing you'll notice is that there are no eyes where the eyes are supposed to go, but we've produced an eye on the tail. It turns out that these animals, which have no eyes in the head but eyes on the tail, can see perfectly well. We built a machine to assay their learning rate in various visual tasks.

This architecture, which for millions of years expected visual input from a particular region in the brain, now has this weird itchy patch of tissue on its tail that's providing electrical signals. The brain has no problem interpreting that as visual data. It takes the information, which often synapses on the spinal cord, and folds it into its behavioral repertoire. Incredible tolerance to architecture, and very rapid. This is not millennia of evolution. This is an immediate change that we make over several days in our lab, and the brain adapts to it very rapidly.

Slide 13/47 · 10m:43s

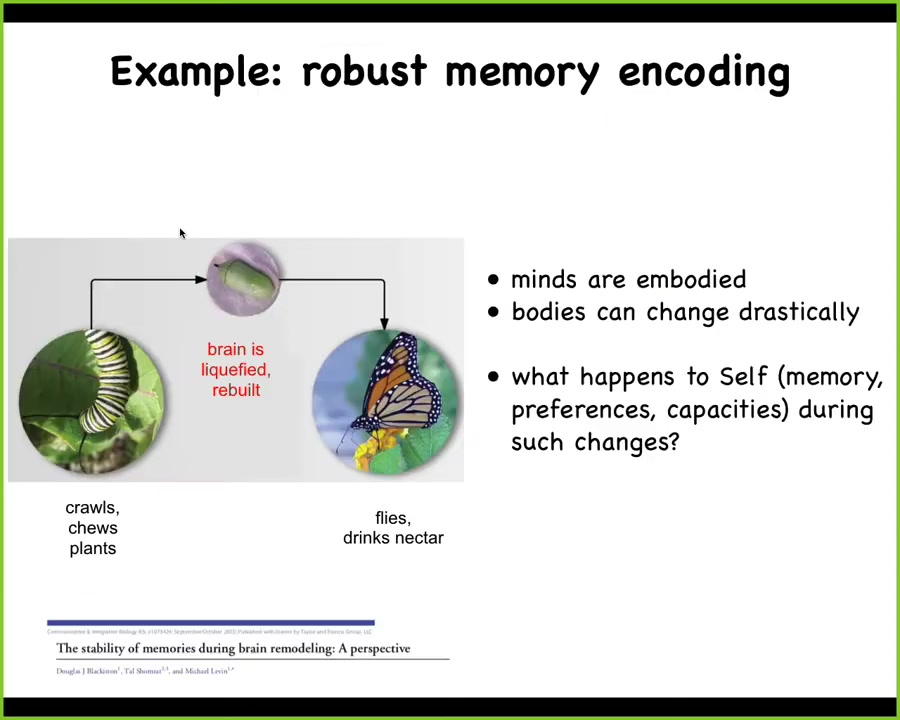

Another example is robust memory encoding. Here's a caterpillar. This is a kind of soft-bodied robot that crawls around and chews plants. It needs to turn into a hard-bodied robot, which flies and drinks nectar. You need a completely different controller for these two kinds of bodies.

During the process of metamorphosis, the brain of the caterpillar is liquefied. Most of the neurons die. All the neuronal synaptic connections are broken. The whole thing is taken apart and rebuilt into a new kind of brain for a moth or butterfly. The remarkable thing here, and you can read more about this in this review, is that during this process, memories remain. The moth or butterfly shows evidence of recall of things that the caterpillar learned. We would love to have memory media like this, that when you radically change them and move all the parts around and reconstruct them, the information still remains. We don't have any technology like that. It is not at all known how the information is encoded, except that it's incredibly robust to these large-scale changes.

Slide 14/47 · 11m:51s

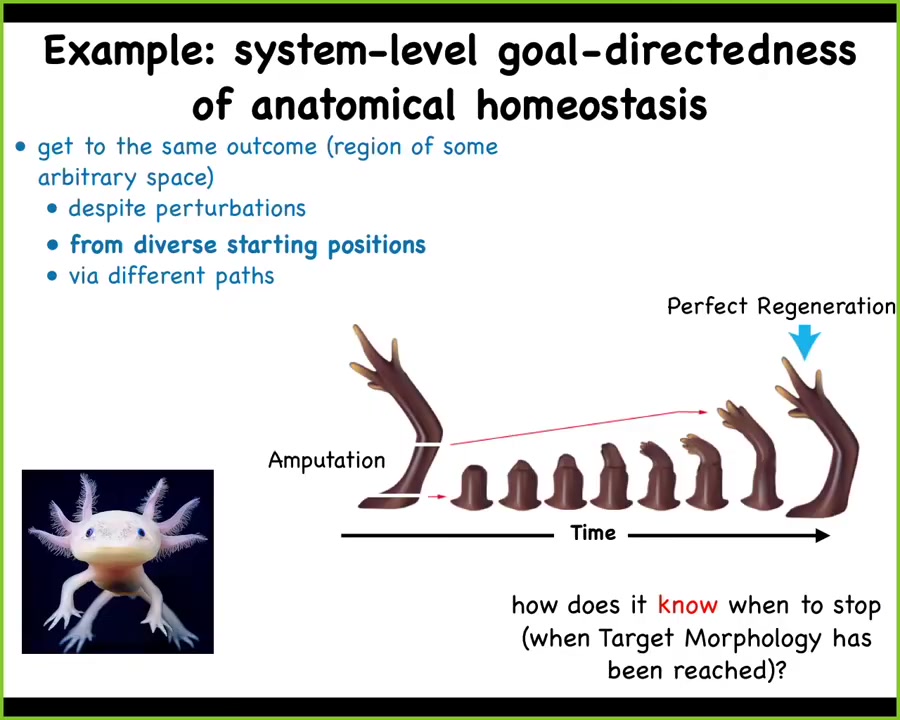

The final example that I want to show you, and this is one of the most important that we'll study here, is the idea of goal-directedness. Here I'm going to bring up a topic called anatomical homeostasis.

This animal is a salamander. It is the axolotl. It is incredibly regenerative, so it will grow back limbs, eyes, jaws, portions of the brain and heart, spinal cord, ovaries and so on. What that looks like is this: if it loses an arm, it will continue to build very rapidly and eventually it gets to this point where it has a perfect duplicate of the original and then it stops. One of the most amazing questions about this is how does it know when to stop? It stops when a correct salamander arm has been produced.

If you amputate at the shoulder, you will start here and grow all of these parts. If you amputate at the elbow, you will start here and only grow these parts. They all end at exactly the same time.

This is a system that continues to remodel, trying to keep this particular anatomical configuration. It can get there from diverse starting positions. Whether you start here or you start here, you get to the same point, doing only exactly what it needs to do.

Not only can this system handle diverse starting positions, but it can handle radical perturbations along the way.

Slide 15/47 · 13m:11s

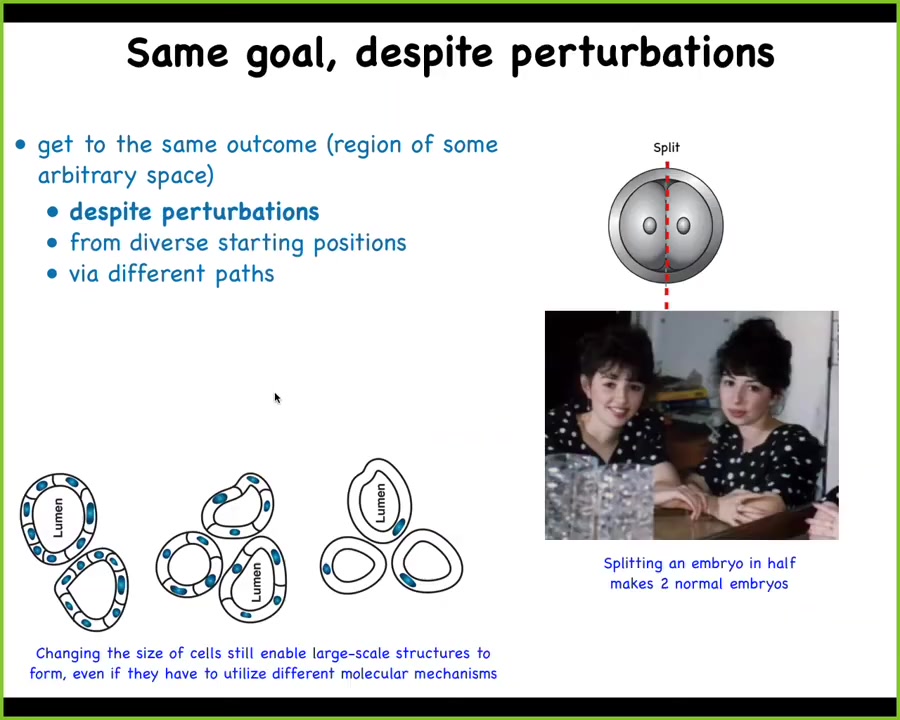

So if you take an early embryo of many kinds, including human, you split it in half, you don't get 2 half embryos the way you would if you cut up any of our current robotics or computer architectures. You get 2 perfectly viable monozygotic twins. The system can regulate for the fact that half of it is missing, regrow what's needed, and you're back to normal. In fact, it is also tolerant to really powerful perturbations, such as a drastic change at the smallest level of its subunits.

For example, this is a cross-section of a lumen of a kidney tubule from a salamander. You can see that it has 8 to 10 cells that all talk to each other to form this structure. If we artificially make the cells gigantic by multiplying the amount of chromosomes, but not letting the cells divide at an early point, this produces a viable salamander. What you'll see here is that as the cells get bigger, fewer of them are working together to build the exact same type of anatomical structure. When the cells get really gigantic, just one cell bends around itself to produce the same anatomical unit.

What you're seeing here is that the system is tolerant to massive changes in its components. When the components change, the system is able to call up different molecular pathways. Here, cell-to-cell communication; here, cytoskeletal bending — diverse kinds of molecular pathways are used to implement a large-scale goal. It can do this despite the massive perturbation of radically changing its components.

Slide 16/47 · 14m:55s

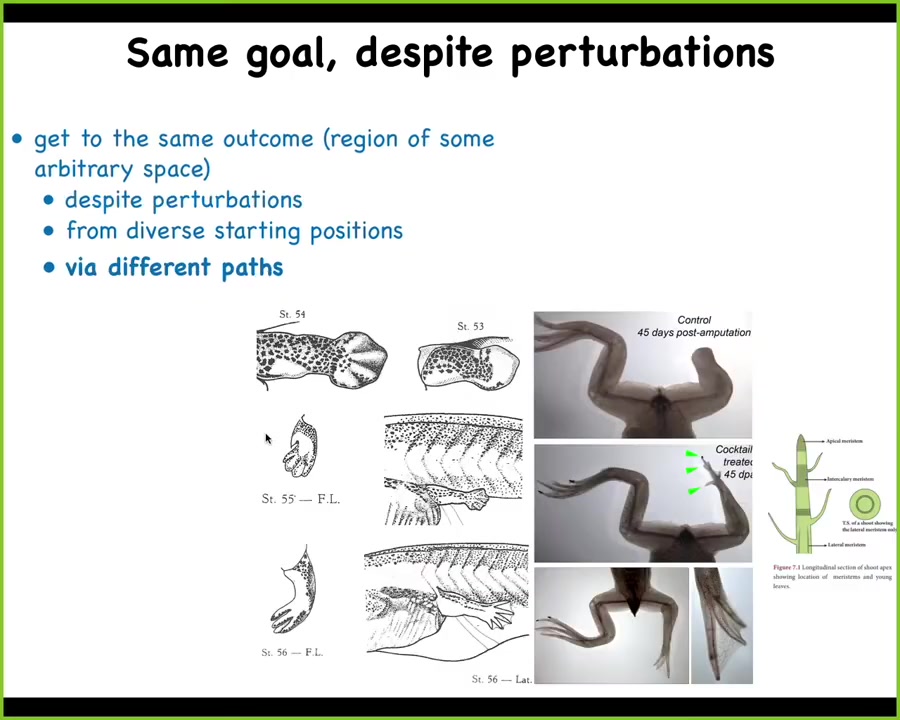

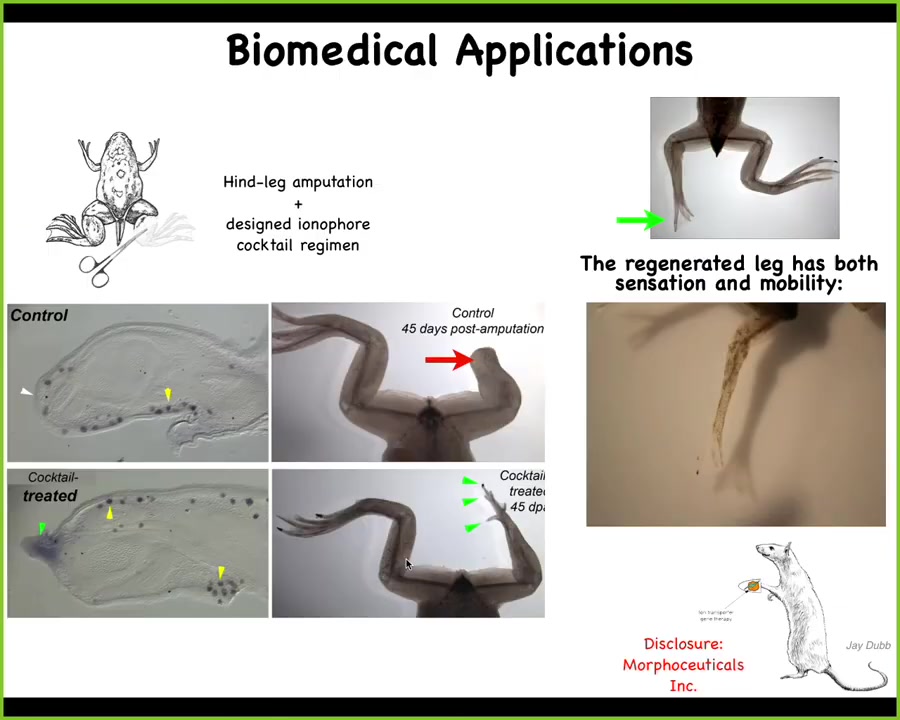

The final piece of this is that it can get where it's going via different paths. This is part of our regenerative medicine efforts to grow back limbs. This is a frog. Frog limbs normally do not grow back after amputation. Here you can see after 45 days later, you get nothing. We designed a cocktail, which I'll describe shortly, that triggers leg regeneration. You can see that immediately you start getting some toes and a toenail up here and eventually a pretty good frog leg.

One of the cool things about this is that this is not how frog legs normally develop. This is the normal developmental sequence of a frog leg. You get a paddle with the fingers and then the parts in between die off by programmed cell death. That is not what happens here. This has a central stalk and then a bunch of toes come off from the sides, almost like a plant meristem, but then eventually gets to the same point of having a very nice frog leg.

So we can get to the same goal despite perturbations from diverse starting positions and via lots of different paths. In order to start thinking about how biology makes such robust systems that solve all these problems in different spaces, anatomical space and physiological space and so on, let's start off by asking where is anatomy specified in the first place?

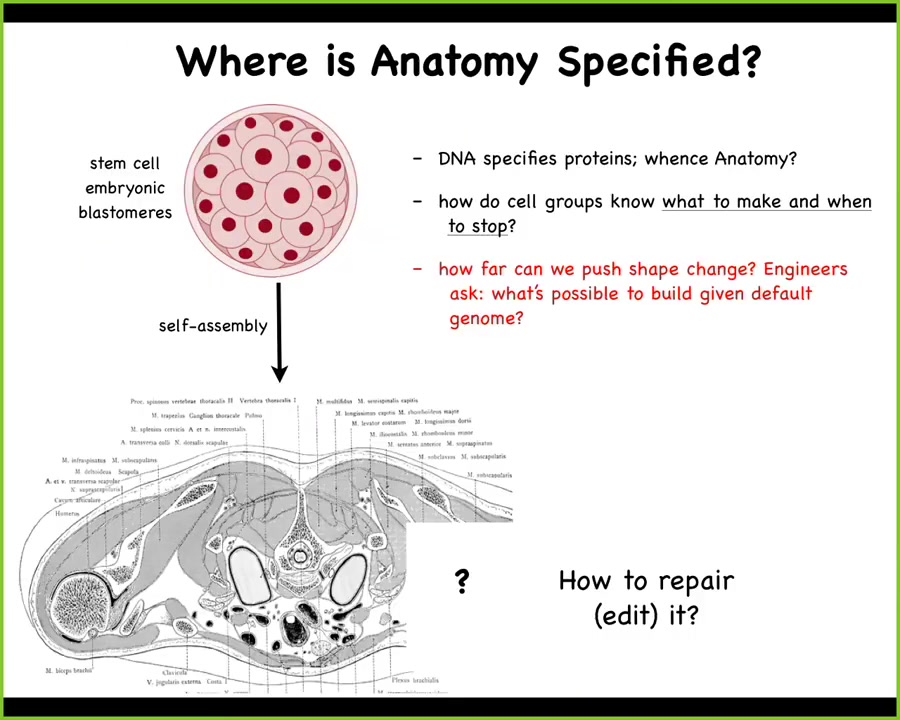

Slide 17/47 · 16m:12s

So this is a cross-section of a human torso. You can see here all the different organs and structures. This is incredible in invariant order. Every normal human has all this in the same configuration. All the organs and tissues are the right shape, size, position, and so on. Where does this come from? We all start life here as a collection of embryonic blastomeres that have to build this.

The genome is certainly important, but we actually know what's in the genome now because we can read it. And what's in the genome are protein sequences. They're descriptions not even at the cellular level, but of the smallest molecular hardware that these cells get to deploy. So there's nothing directly in the genome about shape or size or anything like that. So where does the anatomical order come from? How do the cells know how to build this? In regenerative medicine, we worry about how we influence those cells to restore something that's missing. But as engineers, we also ask, what else can these same cells build? Given the exact same hardware, meaning the same genome, what else are they willing to build? I'm going to show you that shortly.

The nice thing about these individual cells is that you can see that each is handling its morphological, physiological, and behavioral needs at the level of a single cell. But when these cells got together during multicellularity, they actually started to pursue much larger goals.

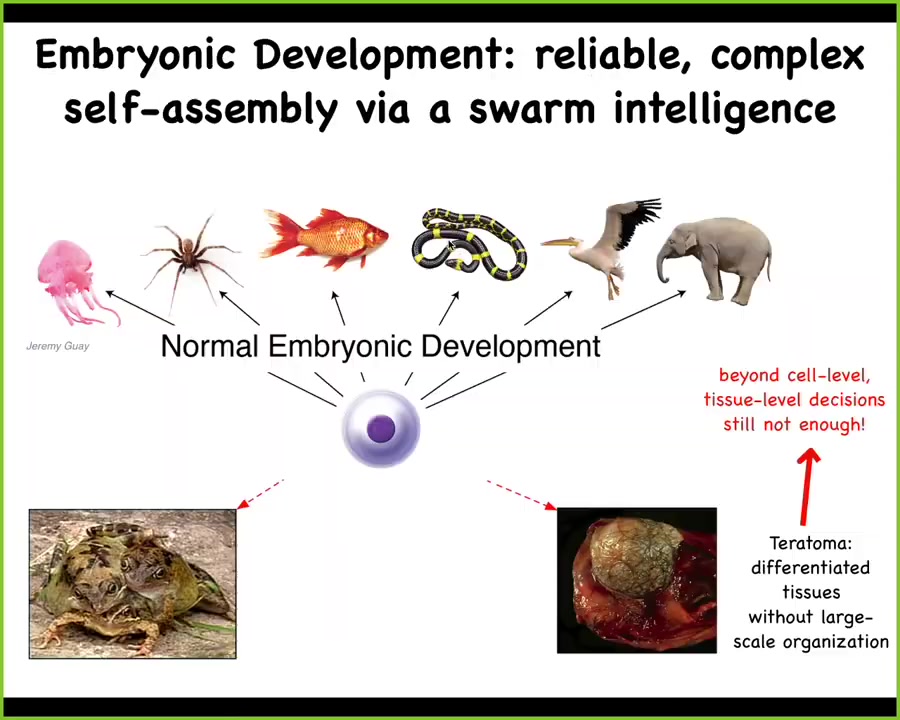

Slide 18/47 · 17m:47s

The goals that they pursue are these. These are the kinds of morphologies that are made in embryonic development and then defended during regeneration. These are lots of cells cooperating together to form and maintain very large structures, much bigger than themselves.

This process can go wrong in many different ways. For example, this is a tumor that has hair and teeth and bone and muscle because the stem cell biology went fine, meaning you got all the different cell types that you needed, but the three-dimensional structure is completely off. This is not the same thing as a viable animal. How does this work? What is the relationship between the genome and the anatomy? What I'm going to describe in the rest of the talk is that there's a very important intermediate layer, which has to do with information processing between the hardware of the genome and the resulting behavior in morphospace. You can see an example of it here.

Slide 19/47 · 18m:44s

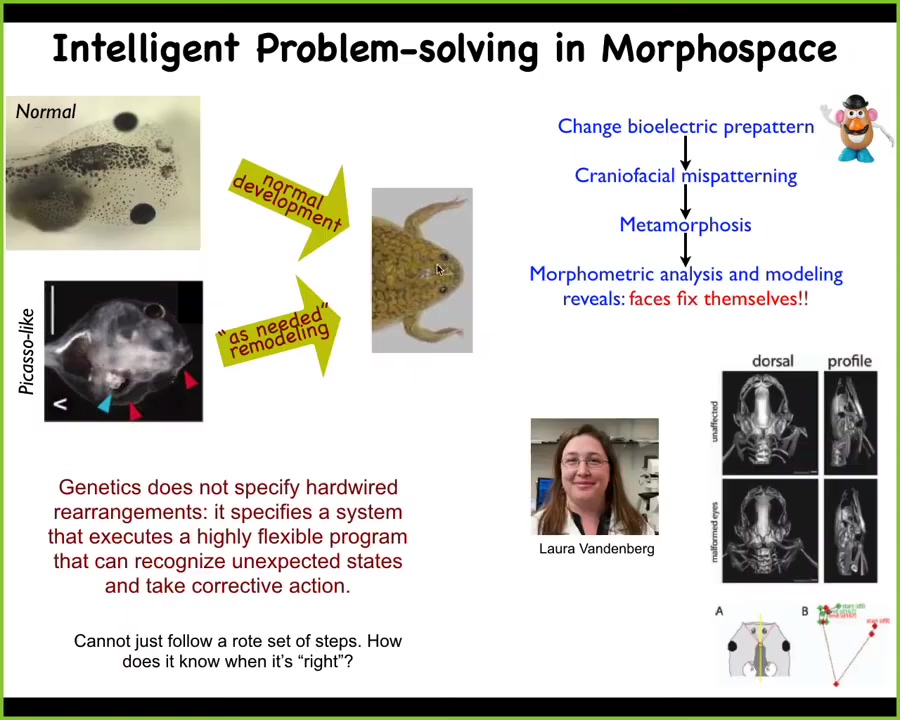

This is something we discovered a few years ago.

If you think about metamorphosis from a tadpole to a frog, this is a normal tadpole. Here are the eyes, here are the nostrils, the brain. This face has to be rearranged in order to make a frog. The nostrils have to move, the jaws have to come out, the eyes have to move, everything has to move around. And it was thought that somehow what the genetics gives you is a system that moves all these pieces in the right direction, the right amount, every single time, because then you will get from a standard tadpole to a standard frog.

So what we did was we created so-called Picasso tadpoles. Everything is in the wrong place. The eyes are off on the top of the head, the jaws are off to the side, the nostrils, everything is moved. And what we found is that remarkably, these animals still give rise to pretty normal frogs, because all of the different components will start to move in unnatural paths. Sometimes they go too far and have to double back until they get to a correct frog face, and then they settle down.

So what the genetics gives us is a system that's able to do this kind of error minimization scheme. The cells and the tissues are able to work together towards a specific anatomy. And when things are changed, they flexibly pursue other paths through morphospace to get to the correct configuration. And it's this kind of problem solving that I think has many lessons to teach us for synthetic systems.

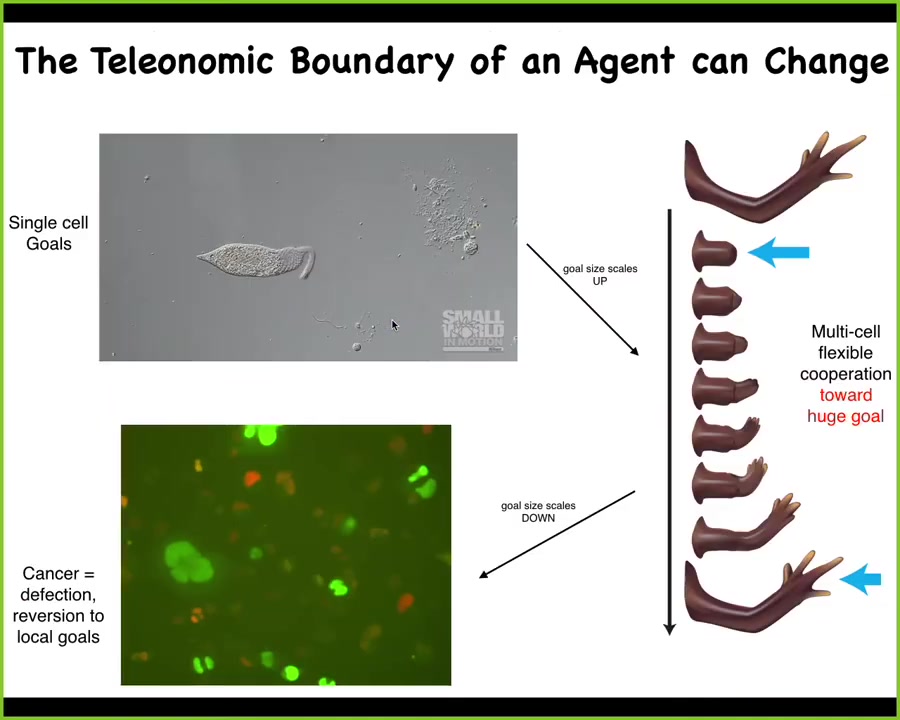

Now, in contrast to the things that single cells care about, which are metabolic needs, this system is trying to maintain a very large-scale morphology.

Slide 20/47 · 20m:20s

The scale of the goals that the systems are trying to pursue in the cybernetic sense, these are things they're trying to optimize, can drastically change. Going from single cells to multicellularity, the goals scale up from single-cell types of concerns to making this large structure, but they can also scale down during the lifetime of the organism.

What you see here are cancer cells. These are human glioblastoma cells in culture, and these cells have abandoned the goals that they used to contribute towards in the body and have reverted to a single-cell lifestyle where they treat the rest of the animal as just environment. It becomes important to ask how the scaling happens. How do individual cells scale up to a system that is able to exhibit intelligent problem-solving behavior within morphospace? How does the process fall apart? This many-into-one transition. How do competent pieces give rise to larger wholes with larger goals?

For this, we're going to talk about bioelectricity as a cognitive binder, as a medium in which anatomical decisions are made so that we can see how it is that the intelligence and the goal directedness of these cells scale up in this system.

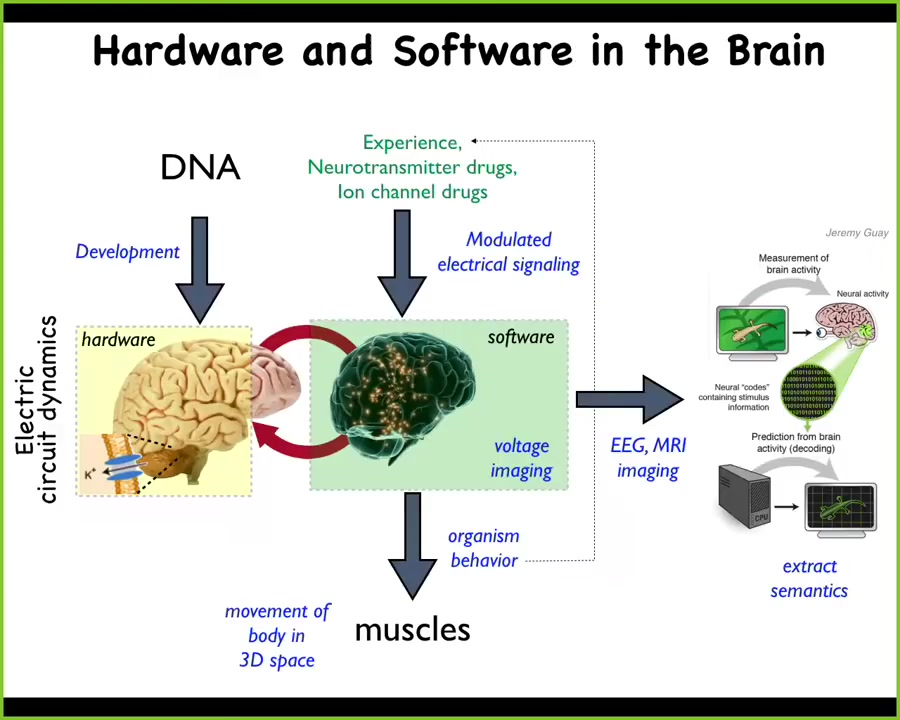

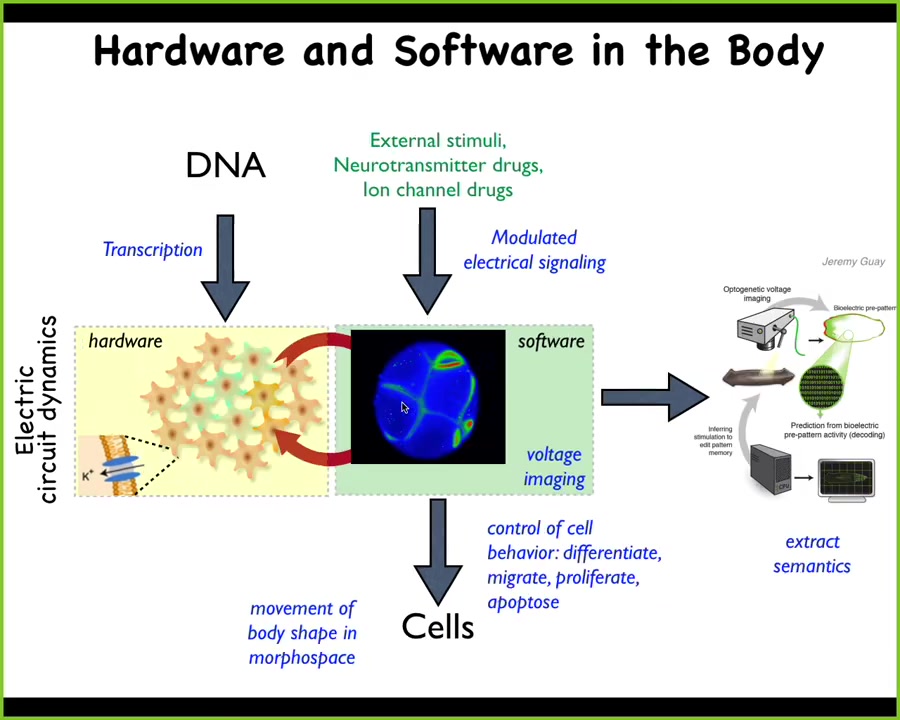

Slide 21/47 · 21m:46s

Let's think about how this works in the brain. In the brain, the hardware is a bunch of cells that are expressing various ion channels. This enables them to have electrical activity. This electrical activity can be viewed as a sort of software which guides or controls the functionality of muscles, which moves the body in three-dimensional space. This is what's under the hood of typical intelligences, of biological intelligences that we try to mimic in AI.

And so neuroscience holds that if we learned to image this electrical activity and decode it — this is called neural decoding — we should be able to infer the cognitive state of the creature: What is it thinking about? What are the memories? What are the plans and so on? That's where the information is.

Slide 22/47 · 22m:38s

It turns out that all cells do this. The system is extremely isomorphic. Non-neural cells also drive these electrical dynamics, which then, instead of guiding muscles to move you through three-dimensional space, issue commands to cells like proliferate, migrate, change shape that will move the body configuration through morphospace. What I think evolution does is pivot the exact same trick, this bioelectrical architecture, which I'll talk about more in a minute, to solve problems in diverse spaces. What we're trying to do is use the techniques of neuroscience and also develop some new ones to read these electrical properties.

Here you see a voltage-sensitive fluorescent dye showing the early cells in a frog embryo. Here's all the electrical conversations that they're having with each other to sort out who's going to be head or tail, to read and interpret this information and thus try to read the proto-cognitive content of tissues and organs as they make these decisions in solving problems in morphospace.

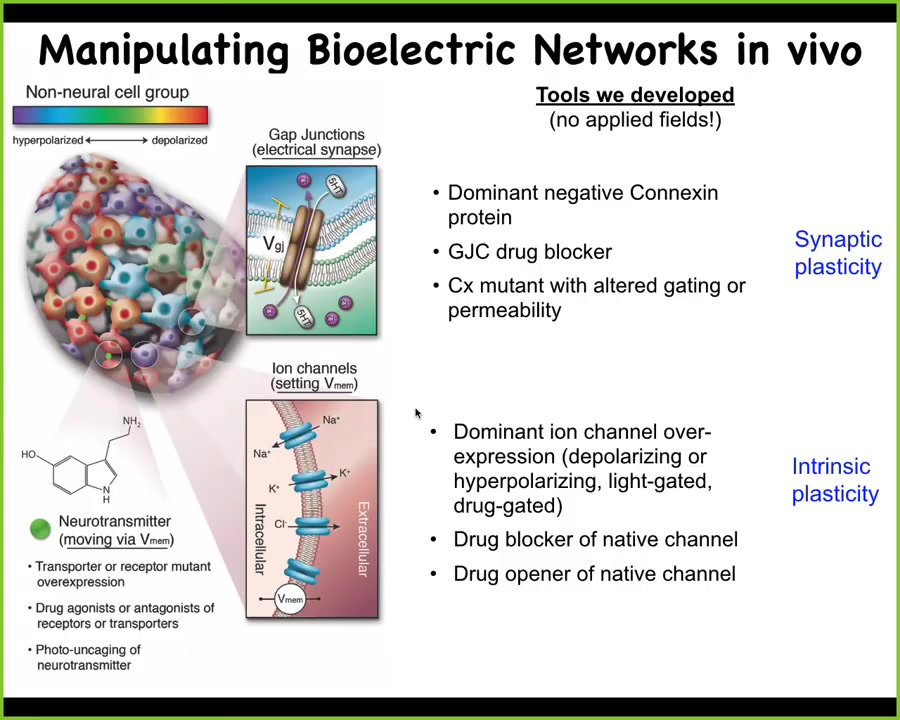

Slide 23/47 · 23m:45s

We developed some of the first tools to read and write this electrical information. You saw the voltage dye, which allows you to peek under the hood and read the electrical state of these tissues. Then we developed functional techniques that allow us to write information into that medium. This means there are no electrodes, there are no electric fields, there's no electromagnetism, no external application of fields or currents or anything like that. We use tools like optogenetics to manipulate the native machinery that tissues are using to process information electrically. That means changing the topology of the network by directly altering these cell-to-cell electrical synapses, regulating which cell gets to talk to which other cell electrically and how. We can directly change the voltage state of any cell by opening or closing these ion channels. For example, using drugs or light or mutation of these channels, we can directly influence the voltage pattern. We have some tissue here that's not necessarily nervous, and we can control the topology and the electric state of specific cells, for example, by putting down light masks. When you start to read and write this electric information, something very interesting happens.

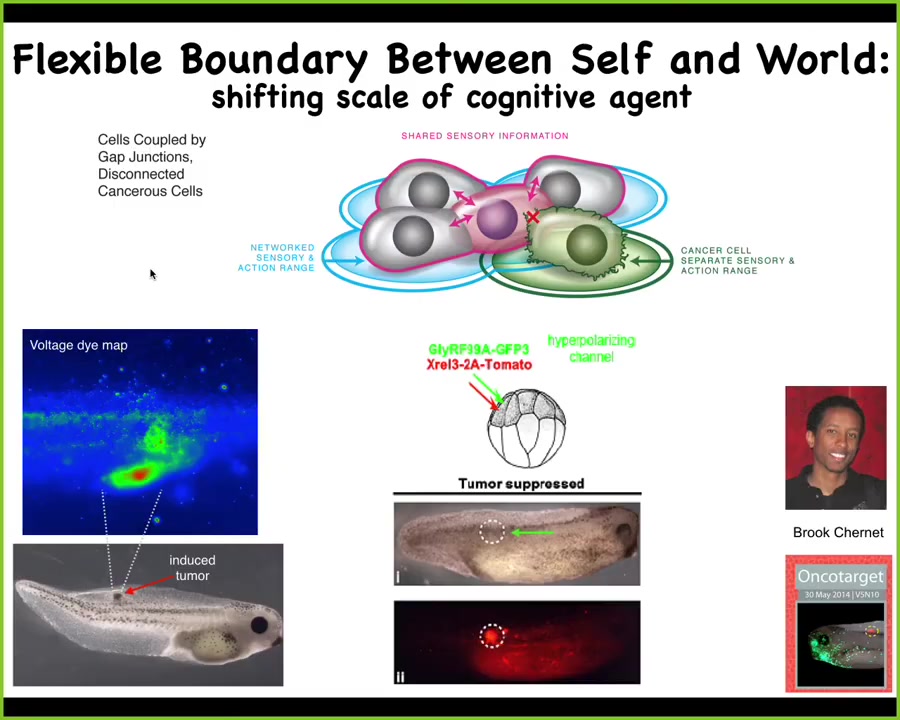

Slide 24/47 · 25m:07s

At the level of single cells, you can begin to control whether cells are connected to these large-scale goal-directed structures.

We inject a human oncogene into this tadpole. Eventually it makes a tumor. Even before you can visually see the tumor, you can already tell which cells are going to defect by tracking their bioelectric state. Here it is using that voltage-sensitive dye. This could obviously be the beginning of a diagnostic modality.

The interesting thing is that the first thing that oncogene does is cause the cells to acquire an aberrant electrical potential and thus disconnect from the rest of the network, and at that point it's just an amoeba in an environment, and that's how you get metastasis, and it will just go where life is good and try to proliferate as much as possible.

If you artificially control this bioelectric change and force the cell to remain electrically coupled to its neighbors, then there is no tumor. Here in red is where the oncogene is. It's blazingly strong. It's all over the place here, but there is no tumor because we force that cell to stay in electrical contact with its neighbors and the electrical pattern at the level of the network dominates individual cell states and forces that cell to keep working towards making nice organs and a nice epithelium.

Slide 25/47 · 26m:27s

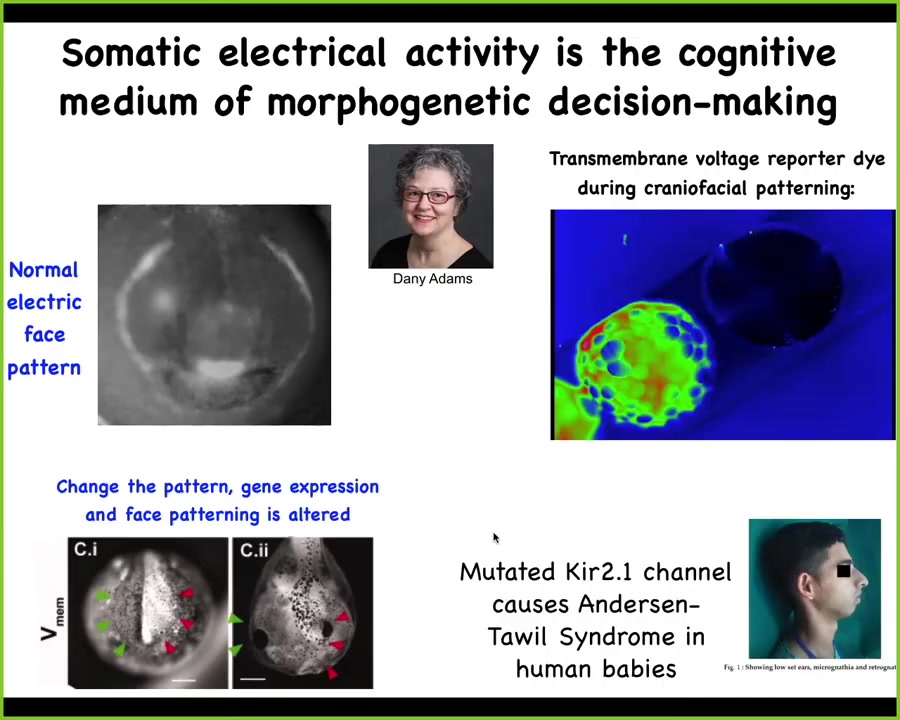

So that's at the level of a single cell. Now, it also turns out that these patterns are critical to very large-scale morphogenesis in the body. This is a time-lapse video of voltage as the frog embryo puts its face together. This was discovered by my colleague, Danny Adams. It's what we call the electric face. Here's one frame out of that movie. What you see is that long before the genes come on and the organs are formed, there is a pre-pattern already that you can read out. Here's the eye, here's the mouth, here are the placodes. There's already a pattern that you can read out from the tissue about where all of the gene expressions and the anatomical structures are supposed to go.

I'm showing you this one because it's quite obvious. The electric face looks like a face. It's easily decoded. Most patterns are not like this. They don't look like the actual thing that they're going to be, and there's a lot of decoding that has to happen. But this obviously was one we cracked early on because it's so simple. It's quite a direct type of pattern. What you can do is you can basically peek into the computations that this tissue is doing about where it's going to place its different structures.

Even in humans, when this process goes awry, for example, a mutated ion channel, you get things like Anderson-Table syndrome, which are craniofacial dysmorphias and defects of the limb and the brain and so on. Somatic electrical activity is a kind of cognitive medium by which the collective of cells makes anatomical decisions about what it's going to build.

Slide 26/47 · 28m:02s

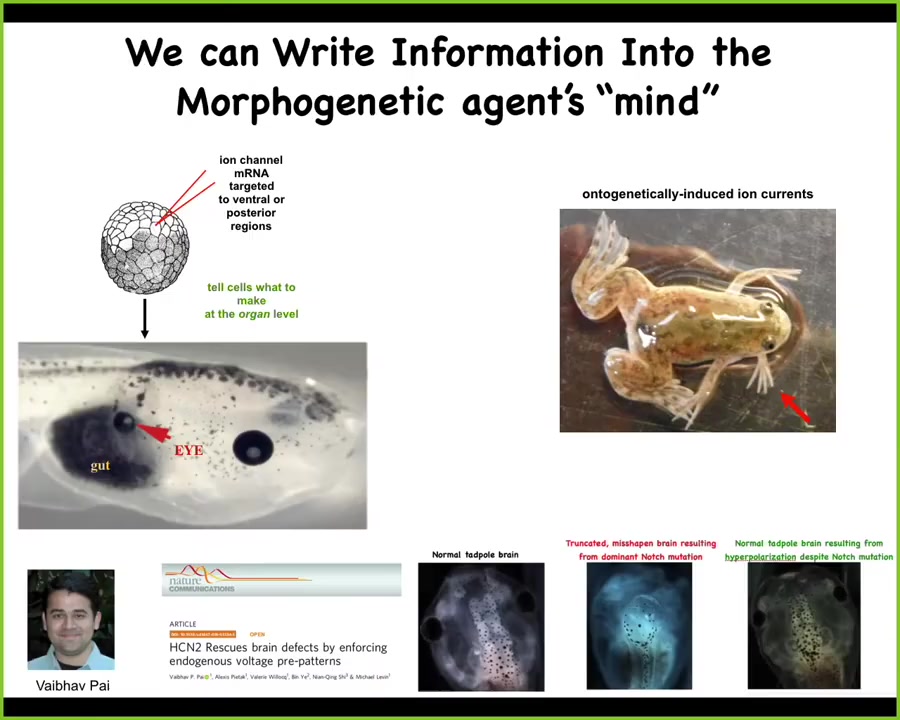

We know this because we can now manipulate it. For example, here's a tadpole, here are the eyes, here's the brain up here. What we can do is inject some RNA that's going to become an ion channel that will take these cells, which are fated to be gut. These are cells that are going to make the digestive system. We can put in an ion channel that brings it to a voltage pattern that is appropriate to an eye. We can establish an eye pattern. When you do this, the cells obey and they make a perfectly good eye with lens and retina and so on out of cells that were previously going to be gut. You can induce ectopic eyes, you can induce ectopic limbs. Here's our five-legged frog. We can also make brain and heart and things like that.

A couple of interesting things here: one is that this is incredibly modular, so we don't know how to micromanage the production of an eye or a hand. It's too difficult. What we have found is a subroutine in the system, which is basically triggered by a particular bioelectrical pattern. That subroutine says, build an eye here or build a leg here. We can trigger these complex things.

This is, of course, very nice for regenerative medicine because we can trigger these things without having to understand all of the steps that go into building that. We don't need to micromanage it. In fact, we can go further and not only create new ectopic organs, but actually fix very complex organs such as the brain.

Here's what a normal brain looks like. Here's a defective brain of a tadpole that has a mutation in an important neural gene or has been exposed to nicotine or alcohol or whatever. We can now counteract this by opening and closing channels as directed by a very specific computational model that told us how to fix it. We tested those predictions and we got back normal brains with correct shape, correct gene expression, and in fact, correct behavior. So they get their IQs back, they can learn again.

This bioelectric layer is a really tractable system in which, with some help from computational tools, we can start to understand what the collective intelligence of the cells is trying to do and guide it towards novel outcomes when it's appropriate.

Slide 27/47 · 30m:13s

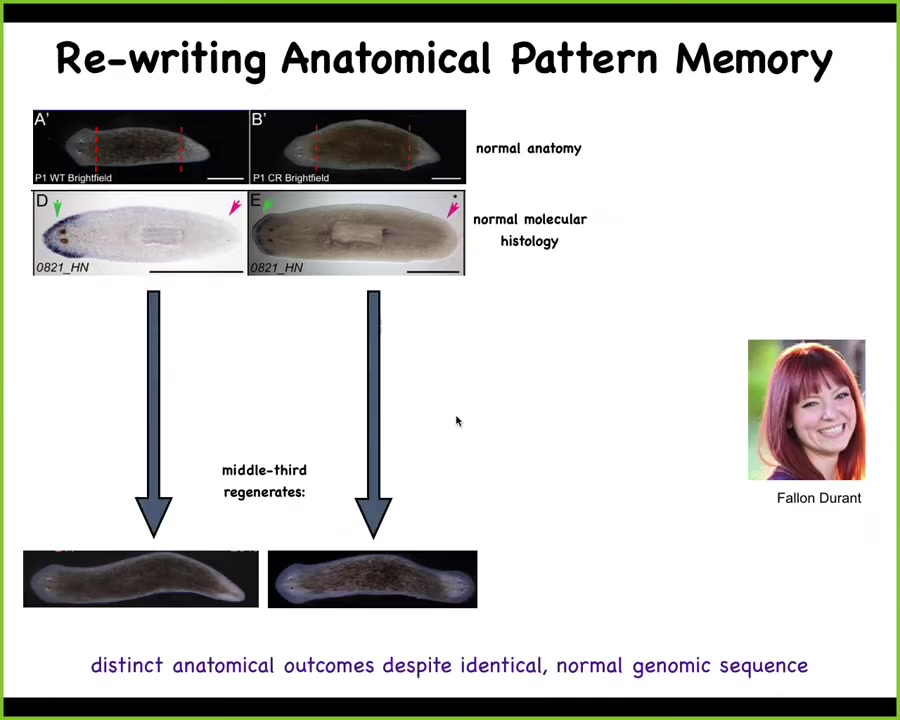

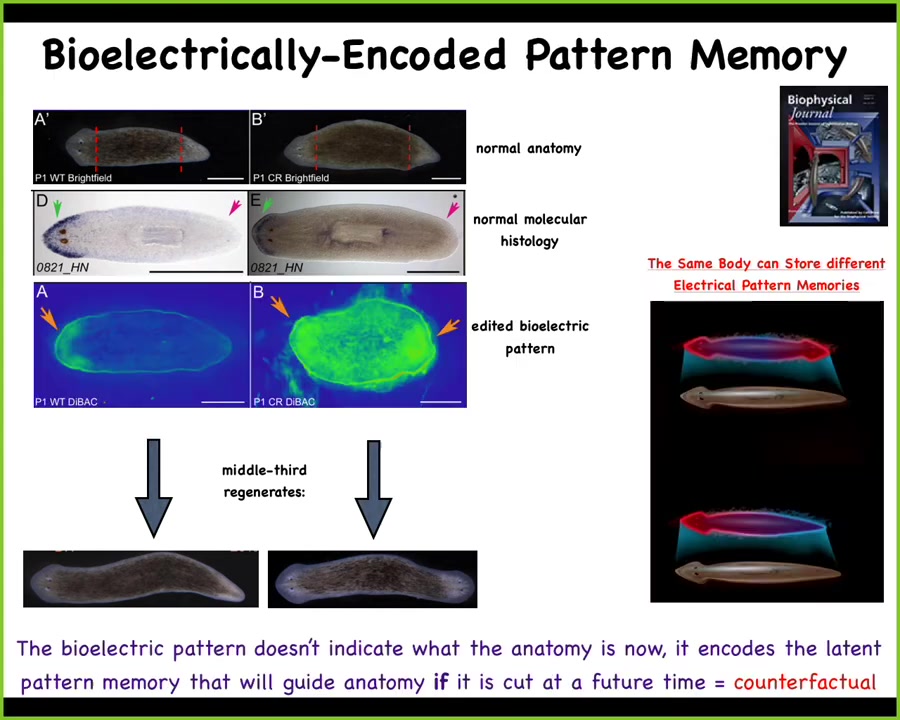

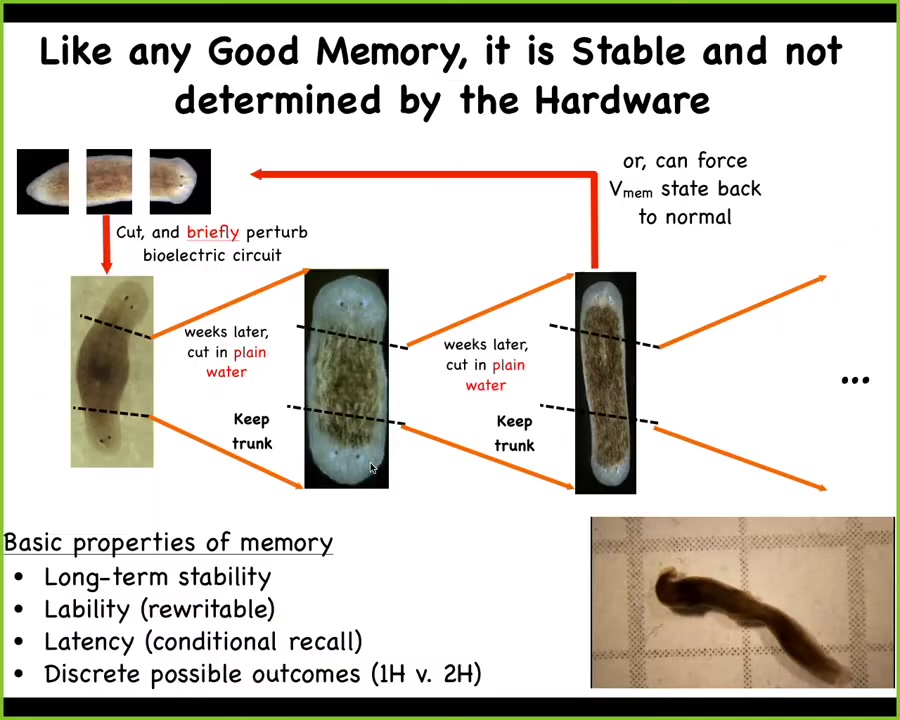

One of the things that I'm going to claim is that this bioelectrical system forms the memory medium of the collective agent working in Morphospace, and I'm going to show you an example of how this works. Here are our planaria again. On the left, there's a perfectly normal one-headed worm. The blue here is a gene expression that is an anterior gene. It marks the head, so you can see it's present in the head, not present in the tail. When we amputate the head and the tail, the middle fragment regenerates into a perfectly normal worm — one head, one tail. That's the normal story. And that happens with incredible fidelity, 100% of the time.

On the right, you see a different scenario. A one-headed, anatomically normal worm. Again, the anterior genes are in the head. No anterior genes in the tail. But when we amputate the head and the tail here, the middle fragment gives rise to a two-headed worm. It has heads on both sides. This is not Photoshop. These are real worms. Now, why would this happen?

Slide 28/47 · 31m:23s

And it happens because what we've done in the meantime is manipulate the normal bioelectric pattern that tells this tissue how many heads it's supposed to have. So here is a depolarization region that says one head and one tail. And what we've done is change this pattern by manipulating the ion channels to have two bioelectric patterns indicative of two heads. Of course, it's a mess. The technology is still being worked out. But what this does is tell the cells to make an extra head.

Here's the most important part to hear: this bioelectrical map is not a map of this two-headed creature. This is a map of this one-headed creature before we cut it. So a single normal body, the same anatomy, can hold one of two different memories of what a correct planarian should look like. Until you injure it, it is a latent memory. It doesn't do anything. It just is kept. But once you injure it, the tissue consults the map and builds whatever the map says.

And so this is the beginnings of a kind of counterfactual memory that we see in the brain with the advanced animals being able to envision, either remember or plan forward for things that are not happening right now. So counterfactual memories of things that either happened before or might happen in the future.

Here's the most primitive version of this: the electrical system is able to store, at least in the same hardware, two electrical memories of what a correct planarian is.

Slide 29/47 · 32m:56s

The reason I keep calling it a memory is because if you take these two-headed animals and you amputate them, they will continue to make two-headed worms with no further manipulations forever. That electrical circuit is a permanent storage of how many heads the thing is supposed to have. We can flip it back and forth. We can take these two-headed animals and put them back to one-headed. This is what they're doing in their spare time, these two-headed worms.

So this has all the properties of memory. It has long-term stability, it is labile, meaning rewritable, it has conditional recall and discrete possible outcomes.

Here we've shown you that with the exact same hardware this is a great example of reprogrammability. This is one of the concepts that we get from computer science, which is very important because even though the genome has not changed, no genomic editing, no genes are changed, the exact same hardware is able to work towards different types of outcomes, one-headed animal or two-headed animal, and stop when that outcome has been achieved. The goals are rewritable. Here we've shown you how to rewrite the goal state of this agent to now work towards a two-headed form instead of a one-headed form. We can go further than this.

Slide 30/47 · 34m:10s

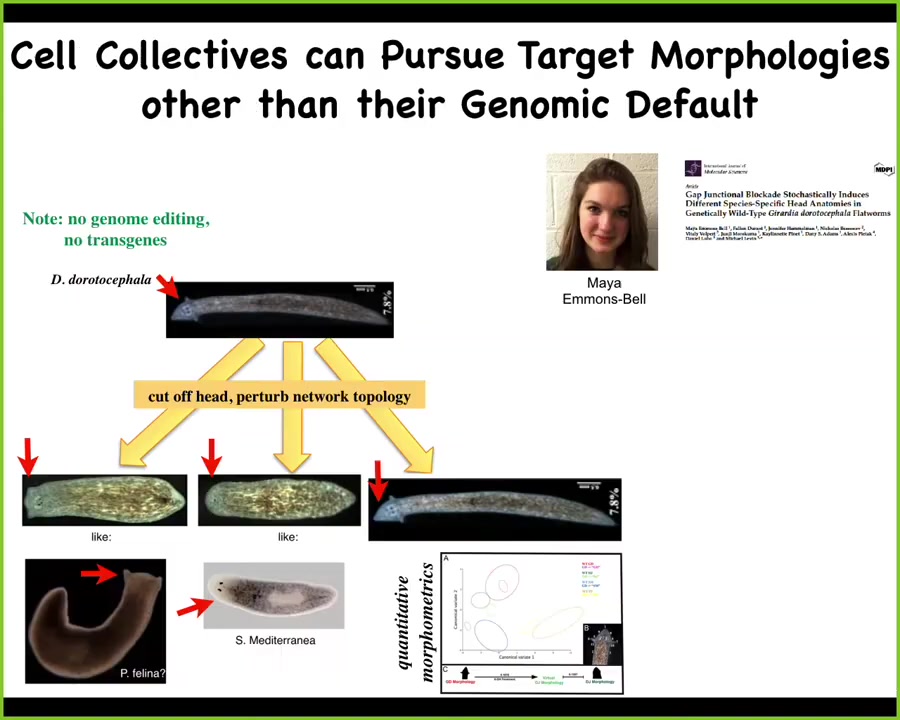

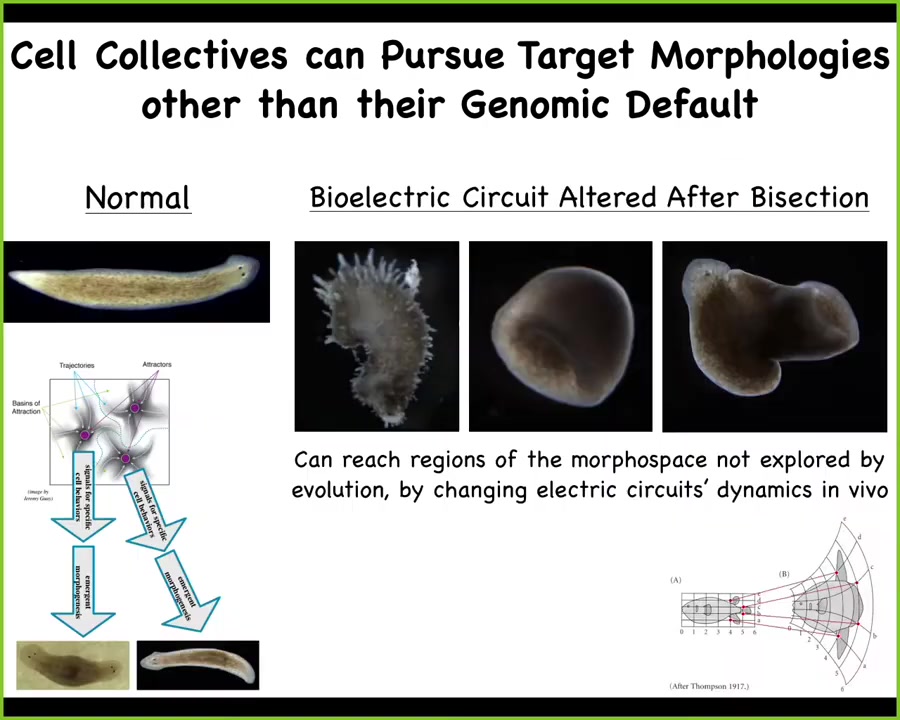

In fact, we can ask it to form heads belonging to other species. So this triangular-headed worm, no genomic editing of any kind. We amputate the head. We prevent the cells from electrically communicating with each other for 48 hours. When the network reforms, they sometimes land in the wrong attractor. Sometimes you get the correct triangular head, but sometimes you get round heads like this S Mediterranean, where you get flatheads like this P. falina. The exact same genetically specified hardware can in fact land in regions of morphospace that belong to other species. There are evolutionary implications of this. These are not just head shapes, but they have shapes of the brain and shapes of the distribution of the stem cells that are just like these other species.

Slide 31/47 · 34m:59s

You can go further than that and you can access regions of the morphospace that evolution is not using because they're not ecologically viable or competitive. You can make planaria into these spiky forms. You can make three-dimensional cylinders. You can have combinational forms that are flatworms with a tube growing out into the third dimension. So you can reach areas of morphospace by pushing that electrical circuit into stable factors that normally it's not using.

Slide 32/47 · 35m:26s

This has all kinds of biomedical implications that we're currently working on. At this point, I have to do a disclosure. David Kaplan and I are co-founders of a company called Morphoseuticals Inc. which is now trying this induction technology in mammals, hopefully to eventually solve human limb regeneration and organ regeneration. You can see these induced legs are both touch sensitive and motile, and we do it by applying to these cells a set of drugs that open and close specific ion channels to trigger the electrical system to make the decision to regrow a leg instead of a scar. We treat the animal for 24 hours, and then you get up to 13 or more months of leg growth, during which time we don't touch it. The idea is to change the early decision-making of the circuit and let it control the downstream genetics appropriately.

Slide 33/47 · 36m:19s

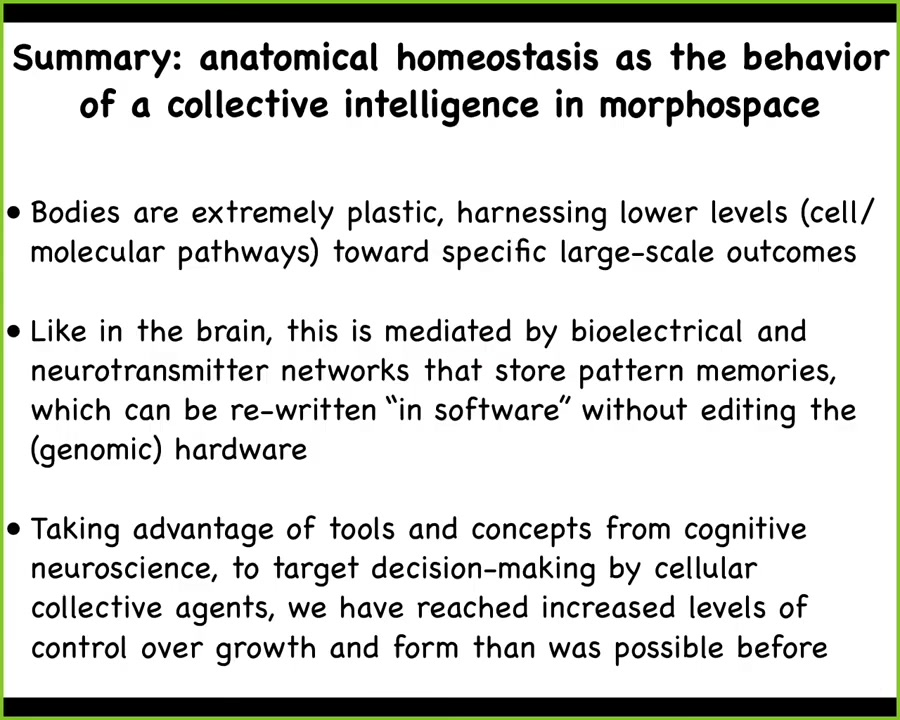

To summarize this first part of the talk, what I've shown you is that anatomical homeostasis, the ability to create and repair complex anatomies despite perturbations from different starting positions, is a collective intelligence functioning in morphospace. Bodies are incredibly plastic. They can harness all kinds of lower-level mechanisms towards specific large-scale outcomes. In the brain, this is mediated by electrical and neurotransmitter networks that store pattern memories. These pattern memories can be rewritten in software by stimuli and experiences, not rewiring, meaning not editing the pathways or the genomic hardware.

By taking advantage of these tools and concepts from cognitive neuroscience, we can now reach regenerative medicine and developmental kinds of outcomes that were not possible before. At this point, what I want to talk about are some synthetic model systems.

Slide 34/47 · 37m:23s

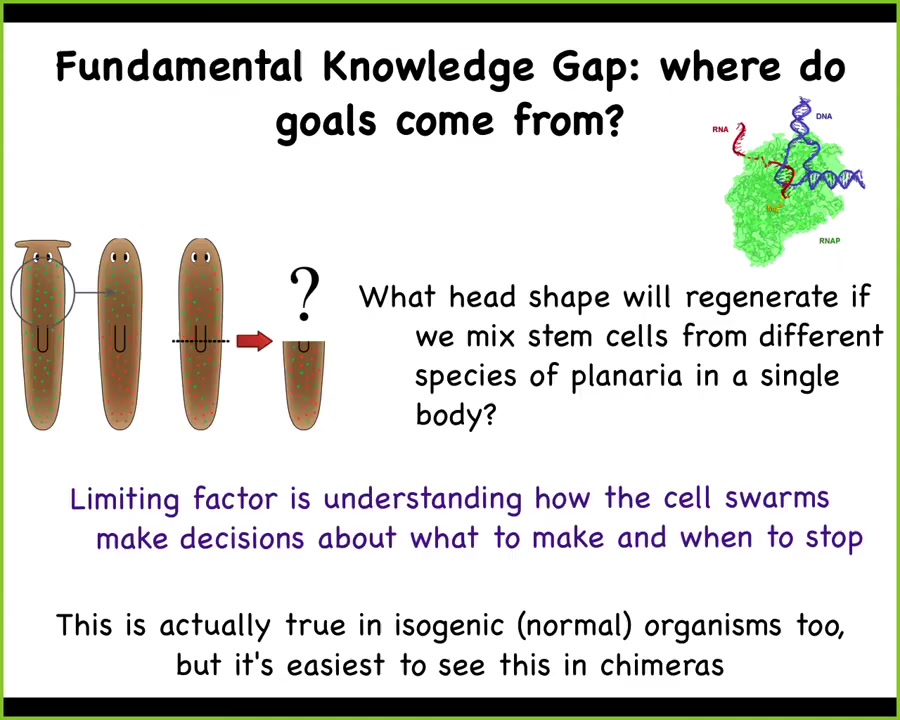

The reason that's important for this whole thing is that we have a fundamental knowledge gap, which is this question of where do the goals of complex collective systems come from. All intelligences are collective intelligences and if you as a brainy centralized system have some sort of goal, we need to understand how those goals emerge from the little tiny homeostatic goals of your cells and tissues.

This is important not only for biology, but for prediction of technology, Internet of Things, robotic swarms, how do we predict and control the goal of emergent high-level systems?

In biology, how this plays out is like this. We have one flat-headed planarian species with these green cells that know how to build a flat head and then they stop. We have a round-headed species with red cells that know how to make a round head and then they stop. We can do a thought experiment. What happens if I mix these cells in the same body and then I amputate the head? What will happen?

The thing to know about biology is that despite all of the progress in genetics and molecular biology of stem cells, and all the great papers on planaria in Science and Nature, we don't have a single model of what would happen in such an experiment. None of the molecular models make predictions for this experiment because the crux of this experiment is the question of what goal state these individual cells are working towards and what happens when they're mixed together. How do the resulting homeostatic set points relate to the components that are in the system? We really don't understand this at all.

It's true in normal animals as well, because we don't know how to predict anatomy from genomes, but it's easiest to see in these kinds of chimeras. So to begin to try to understand this process and to really study plasticity in the biological context, we did the following thing.

Slide 35/47 · 39m:22s

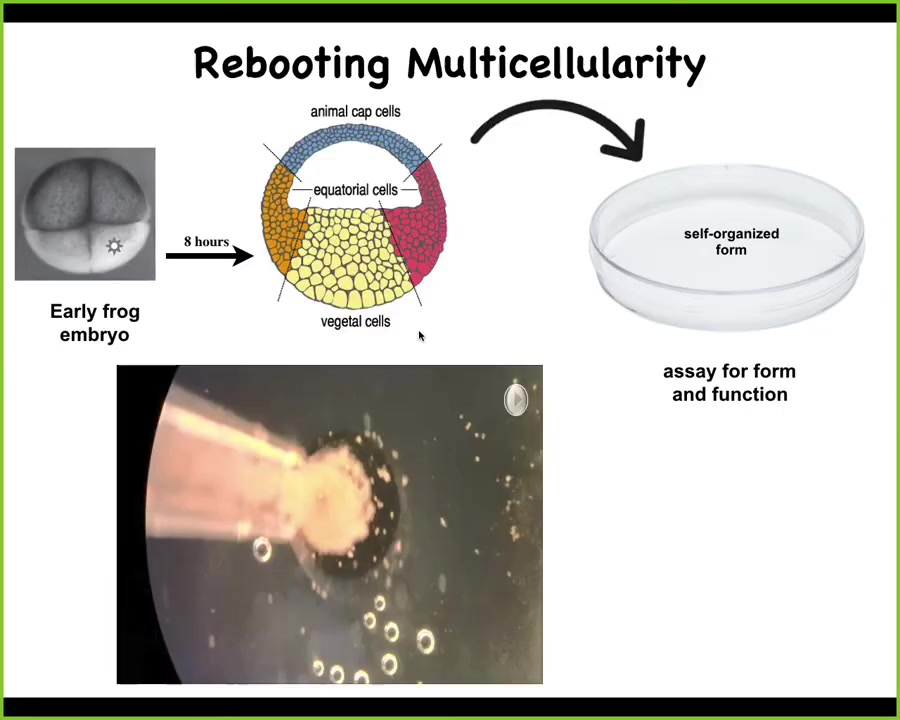

This is largely the work of Doug Blakiston in collaboration with our partners at the University of Vermont, Sam Kriegman and Josh Bongard, roboticists. We asked the following question: if we take cells and liberate them from their normal boundary condition, will they reboot their multicellularity? Will they build something else? If so, what will they build? Doug in my lab did the following experiment.

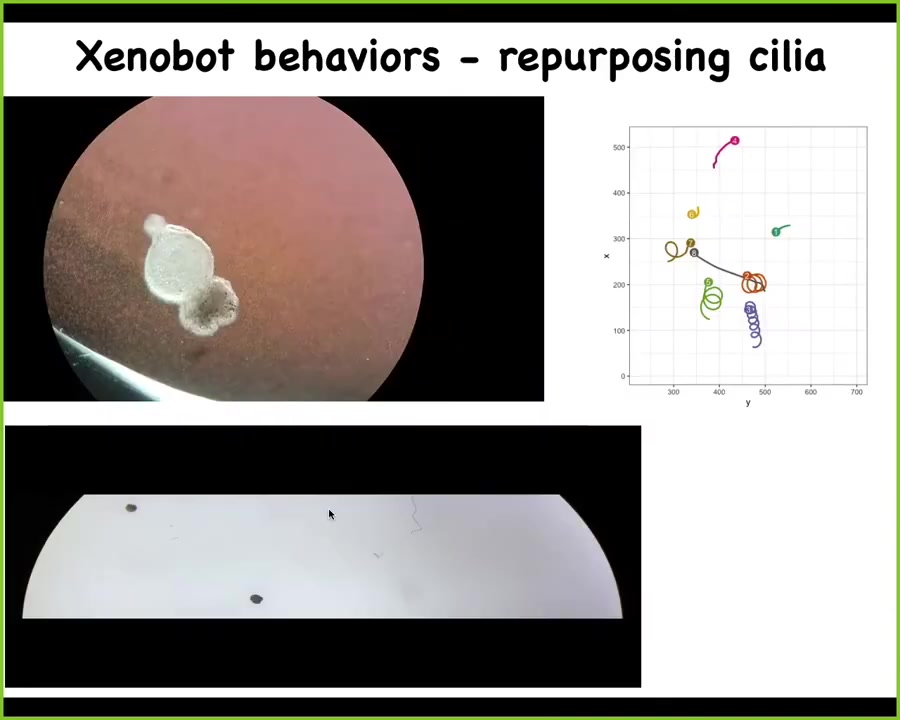

Slide 36/47 · 39m:51s

He took an early frog embryo. He isolated a bunch of these cells, which are basically fated to become skin. Then he put them in a separate little environment overnight and asked them what they're going to do in the absence of all this other stuff that normally instructs them. In the absence of the rest of the embryo, all of these cells; this is a time-lapse. Overnight they coalesce together. The flashing is calcium signaling. Eventually they start communicating with each other. After that, they form a novel creature.

Slide 37/47 · 40m:29s

They form something we call a Xenobot. For Xenopus laevis, that's the kind of frog we're using, and it's a kind of biobot.

You can see here, they make these round structures that swim along. The reason they can swim is because they're covered with cilia, these tiny hairs that row against the water. You can see one moving along. Here is an example of two of them. They have very diverse moving regimes. This one is going in circles. This one is patrolling back and forth. They have the ability to do both straight motion and circular motion. This one here is going on a much longer journey. These two are sitting quietly for the time being, so you can see diverse behaviors.

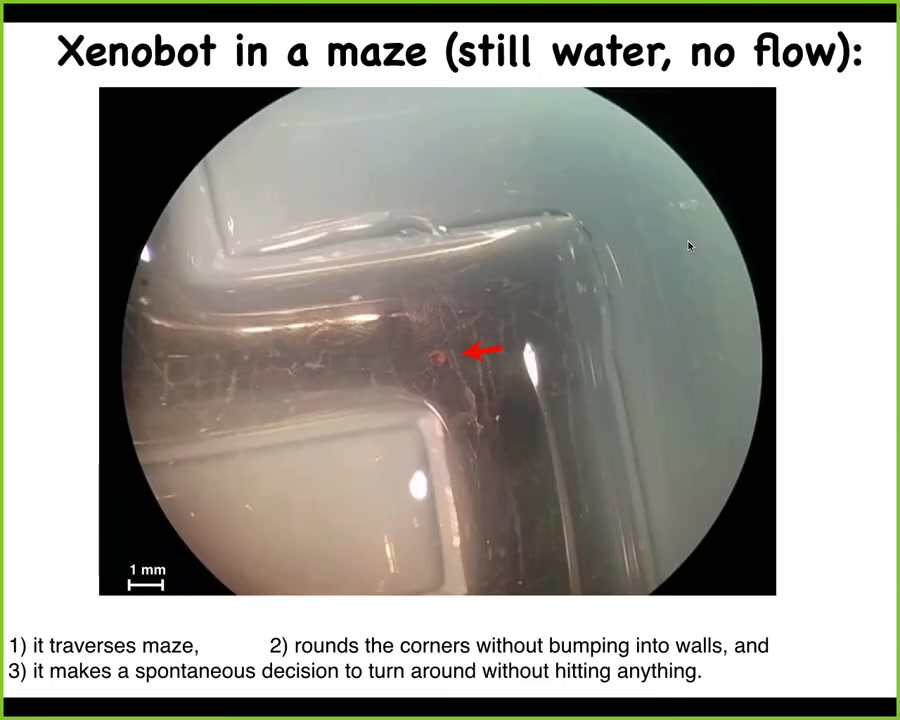

Slide 38/47 · 41m:11s

What I'm going to show you now is what happens in a maze. This is a perfectly still water maze. There's no flow. There are no gradients; it's completely still. You can see what this Xenobot is doing. It's able to traverse the path. It rounds the corners without bumping into the wall. As it goes forward, it doesn't have to hit the opposite wall to take this turn. It takes a turn. Over here, for some internal dynamics reason that we don't understand, it decides to turn around and go back where it came from. They have all sorts of interesting behaviors.

They are regenerative. If you cut it in half, you can see the amazing amount of force through that 180-degree hinge that has to be deployed to sew this thing back up into its normal Xenobot shape.

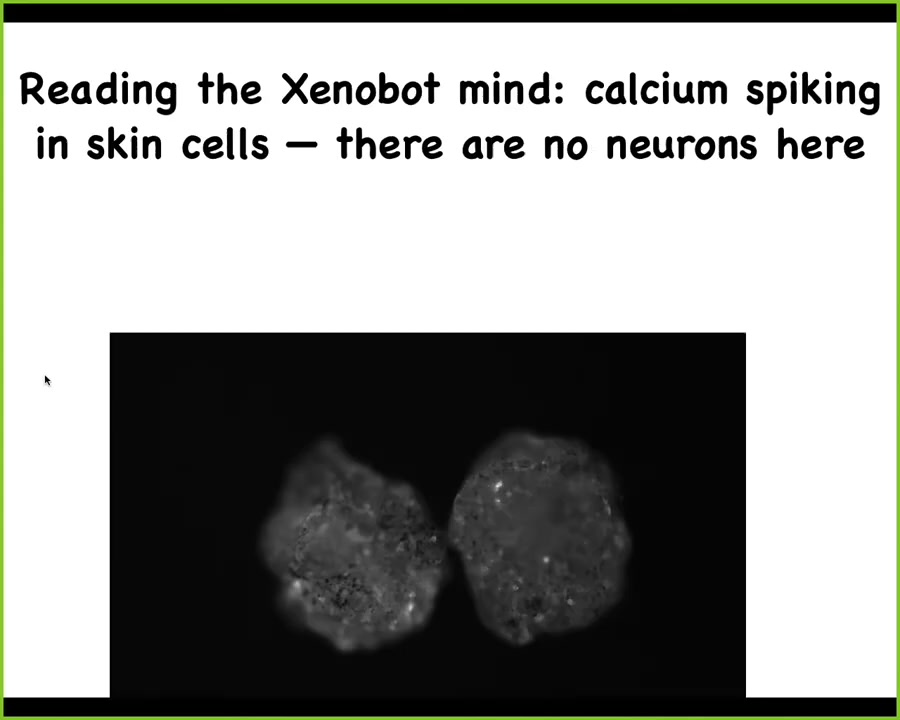

Slide 39/47 · 41m:58s

In fact, as I've shown you, they have all kinds of interesting calcium spiking, which looks very much like what you would see if you did calcium imaging of a living brain, a zebrafish brain. There are no neurons here. All of the movement, all of the interactions, the different motion types, the ability to regenerate, these types of electrical and calcium dynamics, all of this happens just in skin. This is a creature that doesn't look anything like a tadpole or a frog embryo. It has all these novel capacities that were developed by skin in the 48 hours after we liberated them from the animal.

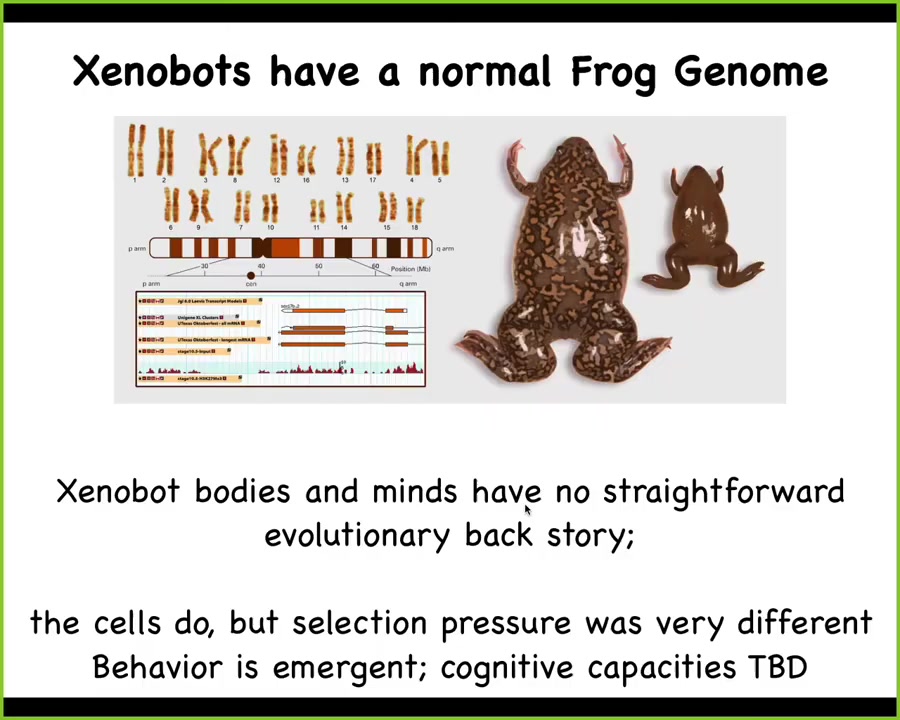

Slide 40/47 · 42m:42s

The amazing thing is that these Xenobots have a perfectly normal frog genome. The molecular hardware is exactly the same. We have not edited them. If you were to sequence them, all you would ever see is Xenopus laevis. If you're used to seeing something like this associated with a frog genome, this would be your prediction of what you're seeing.

The interesting thing about Xenobots is that they have no straightforward evolutionary origin. For all living creatures on Earth, if you ask why they have the properties that they have — why they fly, why they see at a certain wavelength, why they swim — the answer is always the same: because for millions of years their ancestors were selected for X, Y, Z. In this case, this isn't true. The individual cells have, of course, an evolutionary history, but they were selected to sit quietly on the outside of the tadpole and keep out pathogens. We don't know what their cognitive capacities are yet. We're trying to train them and see their preferences. What we see is this remarkable plasticity where cells from a standard genome can be abstracted into a new environment, and within 48 hours they put together a coherent organism with morphology and behavior that is completely different from their genomic default. That plasticity is really remarkable. That's not something we could have predicted ahead of time from anything we know about their hardware. We can use this now as the beginnings of a system to try to understand where these goal states come from.

Slide 41/47 · 44m:19s

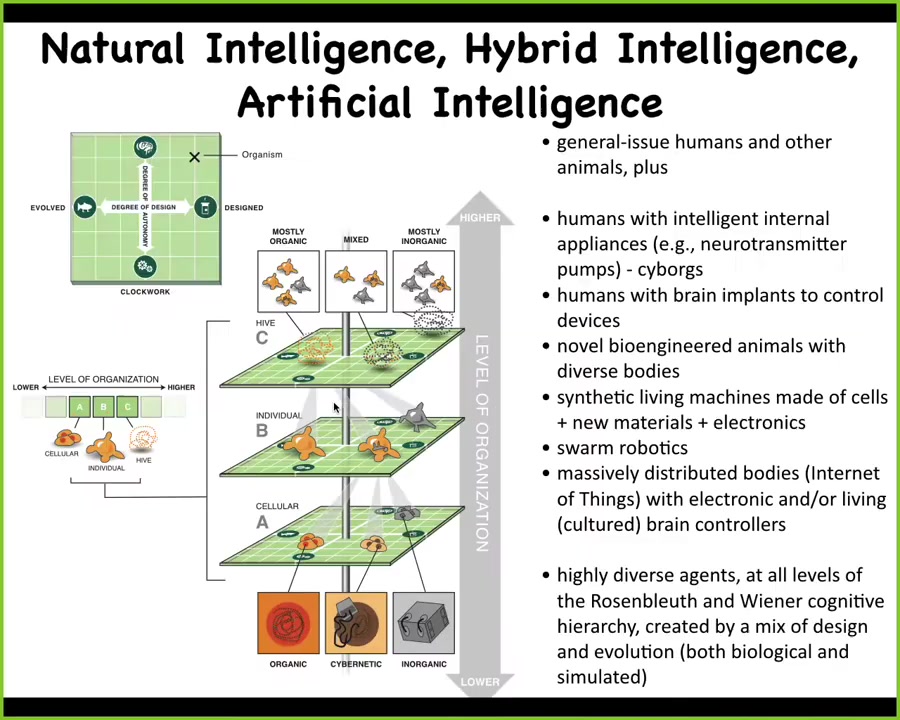

Now to come back to the big questions and finish up. There's a spectrum all the way from natural intelligence to artificial intelligence, and in between lie hybrid intelligences, which are already being made and which we are increasingly going to encounter.

At every level of organization, from the materials to the cellular to the organ and so on, we can make changes now. We can put in organic components, inorganic components, or smart materials, nanomaterials, cells from different tissues, all kinds of software-controlled subsystems, and we can mix them in any organization at any level. Whatever it is that you're putting in can be anywhere on this spectrum from a very simple machine to something that's quite complex, and it can be evolved or designed.

We already have humans with intelligent appliances such as neurotransmitter pumps, these kinds of cyborgs. We have humans with brain implants that allow them to directly control devices such as wheelchairs and prosthetics. We have lots of novel engineered animals, hybrids, where living brains are connected to robotic bodies to drive them around.

This now opens up an incredible option space of different creatures.

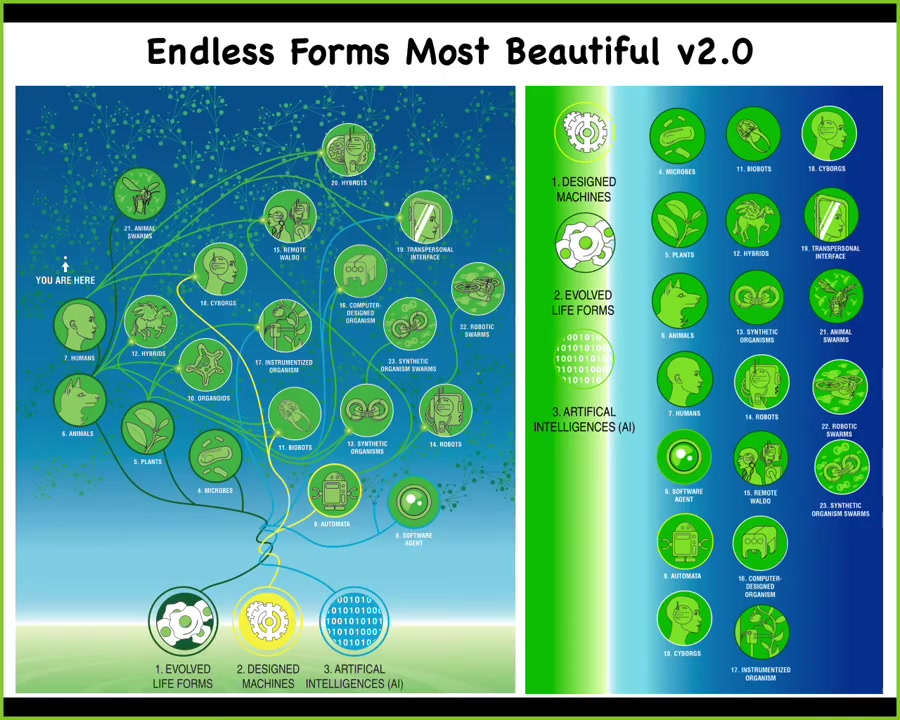

Slide 42/47 · 45m:41s

Darwin had this phrase, "endless forms most beautiful," because he was impressed with the diversity and the richness of a riverbank full of life. All of the life forms that exist in this one planetary evolutionary tree are here. Around us is this incredible astronomical option space of combinations: every possible combination of evolved material, designed, engineered material, and a software agent. All of these can be mixed together into different things, some of which we're already seeing, but increasingly in our lifetime and in the next generation, we're going to be living amidst massive amounts of creatures that we've never seen before, that have no place on the evolutionary tree. Because biology is incredibly interoperable, these chimeras are largely viable, and you can make just an incredible set of combinations of all kinds of things.

Slide 43/47 · 46m:52s

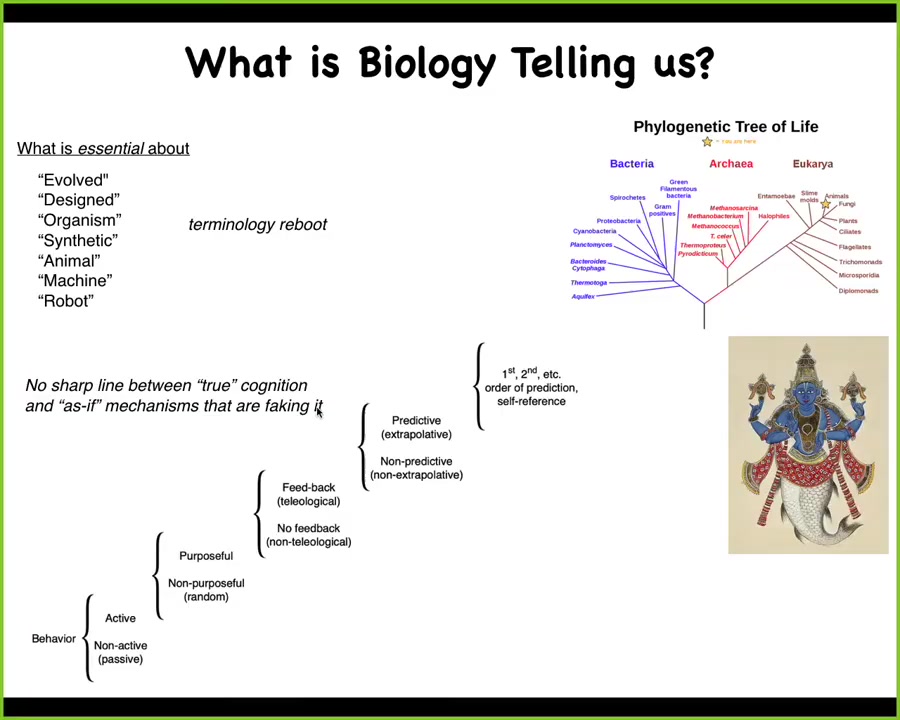

What the biology is telling us is a couple of interesting things. First of all, evolved, designed, what's an organism, what is an animal, what's a machine, what is a robot, is a Xenobot, a machine, an animal, or a robot? All of these terms are now not nearly as useful as they used to be. We need a significant reboot to the terminology because they no longer pick out any really crisp categories. We need to figure out what, if anything, is actually essential about these terms.

People who talk about living things not being machines generally have in mind a conception of machine, which is just not realistic anymore. It's the last centuries of machines. That boundary is completely eroded.

The other thing that biology is telling us is that there is no sharp line between so-called true cognition and as-if mechanisms that are faking it. A lot of people have this concept that humans and maybe some great apes and maybe some other mammals have real cognition, and then there's all this other stuff which is only as if it's just physics, and there is no support in biology.

This is important for workers in AI and machine learning to know: there is no support in biology to any idea that there's any kind of a crisp line that you can draw between creatures that have true intelligence and just physics. If we take evolution seriously, it means that the journey from physics to psychology is a true continuum. There are no binary divisions, but there are a set of transitions of capacity, which Wiener and Rosenbluth outline here, and you can see all the different ways to climb this ladder, and all of these unusual creatures that are going to be made will be somewhere along this continuum.

Slide 44/47 · 49m:01s

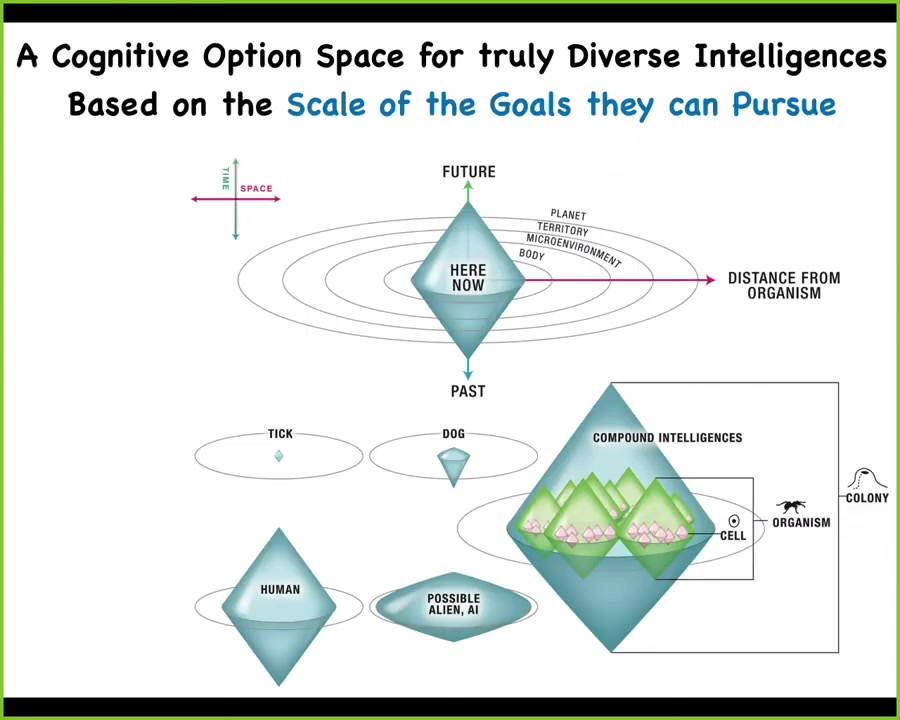

I don't have time to go into it now, but if anybody's interested, I've developed a framework that allows us to compare and contrast these diverse intelligences on the same scale. The way you do that is by plotting the spatial-temporal scale of the goals that any given intelligence can pursue.

In biology, every layer, every scale of organization is rife with multiple competing, cooperating agents that have goals in their own local space, and the competition and communication among these agents within their own layer and across, both going up and going down, is what gives rise to this incredible plasticity of life. That's what we've called a multi-scale competency architecture, and it's based on nested goal directedness, and this is what I think is key about natural intelligence that we could really utilize.

Slide 45/47 · 50m:00s

The summary of this last part was simply that new bodies can be constructed in a huge option space of configurations of chimerism within biology and with engineered objects. All of these new kinds of bodies will have a mind. And we know that because there's a smooth gradation from a human with a neural implant that lets them control a vacuum cleaner, let's say, 95% human, 5% robotics, all the way down to a vacuum cleaner with a bunch of human cells cultured on it to help it navigate the room. That's 5% human, 95% vacuum cleaner. And every possible step in between can be bioengineered. There's no hard distinction that you can make in these cases. Bioengineering is completely smearing out all of these terms. Not only is chimeric bioengineering showing us how to observe minds and their collective goals emerging from scratch, but it's also a really good model system within which to understand the mapping between the body and the mind and how active intelligences act in really diverse spaces.

To close, I'll remind you that morphogenesis is an ancient protocognitive process. It's one example of how biology can teach us about intelligence and the scaling of cognition. Bioelectrical networks underlie one type of this scaling up of cognition, and they will help us to understand neuroscience and how this happens in the brain. Synthetic morphology is a powerful tool, not just for regenerative medicine and robotics, but also for answering big questions about how larger intelligences emerge from smaller intelligences.

In fact, the new era of synthetic morphology and chimerism is going to require a whole new ethics for relating to these novel agents that aren't based on what they look like, meaning what they're made of, or their origin story, how they got there. These things will increasingly be unreliable guides to the degree of cognition that something has. If you are interested in more details, there are lots of papers on our website about all these different topics.

Slide 46/47 · 52m:18s

And I want to thank the people who have done all this work. Here are the students and postdocs who did all of this. And of course, our collaborators, our funders. And I thank you very much for listening.

Slide 47/47 · 52m:30s

You were too late to the room, so you couldn't hear the clapping.

So there was an enormous amount of material and inspiring stuff in there. This is one of the talks that will have an impact on a lot of people's minds. There are plenty of questions and there is no time, but we can try to move the upcoming talks a little bit down. One of the speakers told me that I can only move their talk by a maximum of 10 minutes. We will do that. Start the next talk 10 minutes past the hour and have a little space for a couple of questions. I would not use the time of the audience to ask questions. I would give the chance to ask. I'm sure there will be many questions.

I don't know who was first. I can see Marcin.

Mike, thank you very much for a great talk.

I would like to ask you, if I understood well, regeneration is some kind of process which is natural and common in lower level organisms. If I cut my finger, I can regenerate the skin. But in many organisms regeneration lost its role; it is not very common. If someone cuts my head, there's no chance I could survive. In this case, from an evolutionary point of view, why did we lose this "paradise" of regeneration? How would you interpret this?

First of all, there are large adult mammals that regenerate very well, and one example is the deer. The deer every year regenerates a meter of new bone and vasculature and innervation, up to a centimeter and a half of new bone per day. It's not that mammals can't do it, but there is something important about this. The antlers are a non-load-bearing structure. You don't put your weight on it.

If you think about why evolution did this, think about our ancestor, which would have been something resembling a mouse back a long time ago. It's running around the forest; somebody bites its leg off. The problem is several. You're going to bleed out, get infected, be walking on it, and grind it into the floor as the new cells are trying to develop. What evolution did was to say, you're much better off scarring it and hoping you survive. You're not like a salamander, which can stay quietly in the water for long periods of time. It's an engineering choice made, forced by our lifestyle. It is not anything fundamental.

In fact, our biomedical spin-off company, as many others, is founded on this idea that we can reactivate it if we can convince the cells that they should go back to their morphogenetic programs and not worry about having to scar so we don't bleed out.

Thank you for your fascinating talk.

I was wondering, if you're looking at what you presented to us as a scientific model of organisms, what would artificial intelligence researchers and philosophers do with that? To me, it looks more like an observation than an articulation. To me, it looks like something embodied and active cognition researchers, cyberneticists, and morphogeneticists would be looking for, rather than traditionally minded AI researchers or AI philosophers. When it came to describing the engineering paradigm that you are developing from your investigations, I began to perceive that AI might serve as part of the engineering paradigm you seem to be seeking to initiate. This isn't really a question but an observation, and I'm trying to frame this within the context of this conference.

In our group, we try to bounce back and forth.

We use both techniques and inspiration from machine learning, from connectionist types of ideas to help us understand how cellular collectives are solving these problems. And at the same time, to take what we've learned from them and transition them into new strategies for new machine learning architectures. I've argued for years now that one of the reasons we're having trouble with general artificial intelligence is that we've immediately focused on the brain, which is a rather derived type of thing, where what we're missing is the basic underlying architecture that evolution has been using all along. And there's another version of this talk I give sometimes called "Why Don't Robots Get Cancer?" The reasons robots don't get cancer is because all of our architectures are extremely flat. The sub-components generally don't have the goal-seeking capacity to go off on their own and do something else. And so the good news is that we don't have these kind of complex defections that you have to deal with in biology. But the downside is that we're missing precisely this flexibility and this incredible robustness that you get by having a true multi-scale architecture, where the outcome is a combination of cooperation and competition across levels, where every level has goals, not just the larger scale.

Thank you so much for opening my eyes to your research there.

Now, I do want to challenge this idea of a smooth gradient of cognition, the somebody cognition thing. I want to ask: there seems like a difference between animals which enjoy what would be an adolescent period, where there's a radical reconfiguration of the brain and other organs that seem to orient that organism to goals which aren't given by the acculturated environment immediately in early childhood. And so then the individual takes up some goal or purpose in its own individual life in that context, however it's raised by way of this radical transformation in the adolescent period. So is there a difference in kind between organisms which enjoy this embodied radical transformation during adolescence and others that don't?

I want to say two things about that. Certainly, I'm not saying that there are no great transitions on this continuum. There are clearly transitions; language is the most obvious one. However, the reality is that any two animals or any two architectures that you bring me, one of which is an advanced one that has some property and one that doesn't, we can make a chimera out of them, and we can make one as finely as you want. It's going to be smooth, but there are going to be these kinds of gradations, specifically to the goals in the adolescence portion.

One thing we see again and again is that biological systems are amazing at picking up novel goals, and we have no idea where these goals come from. Even in the case of the Xenobots, for example, within forty-eight hours they become this very coherent system with behavioral goals, with morphological goals. I have no idea where that comes from. Often, what people lean on is evolution. They say these artificial constructs are not really thinking; they don't have a history of evolution behind them. I don't think that's what biology relies on. Even embryogenesis is a series of adolescent steps where each step radically transforms into another step. So I think this is a continuum with lots of fascinating humps on it.

I'll throw in a very quick question. You talked a lot about lower levels, where cells and capacity and stuff happens. I wonder whether you have any views on going beyond that to full organisms. What do you think is the situation there?

You seem to suggest that the intelligence of a normal organism is actually already a cooperative. But isn't that true on higher levels too?

Absolutely. You can keep going and ask very interesting questions about how the dynamics that merge cells into higher levels play out in swarms, colonies, and societies.

One of the current projects in our lab is to train ant colonies, not the ants, but the colony. There are interesting ways that you can think about interacting with a colony mind that is distinct from how you would interact with individual ants.

It becomes very important to ask questions like how much and what kind of cognitive capacity might a collective intelligence of an electrical grid, of a political system, or of a group of animals, humans, or plants have? All of this is up for grabs.

What's clear is that the biology is telling us that you cannot assume these things and that it's an empirical question where on the continuum any given system lands and you have to do experiments to find out. I think that's a very important message for the philosophers: where on the continuum the system lands, because we have a huge preference for one particular spot. This is really fascinating stuff.

I have to cut the discussion because we do have other people who have slots to speak. I will stop here and we'll stick into the section.

Thank you, Michael. That was excellent stuff. I'm sure you will get a lot of philosophers on your tails for discussions in due course. Thank you.

Let's move into two sections. We have Rule A and Rule B. Rule A continues here.