Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a ~1 hour 7 minute talk I gave at the SEMF Interdisciplinary School (July 2025, https://semf.org.es/school2025/#speakers-container) on agency ways to think about expanding our ability to detect and communicate with unconventional minds. The same talk but with a lengthy Q&A will be up on the SEMF website.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Electromagnetism and agency framework

(09:41) From brains to bodies

(18:41) Bioelectric networks in morphogenesis

(29:26) Bioelectric prompts and medicine

(37:03) Continuums and new agents

(42:35) Xenobots and anthrobots

(49:35) Evolution and platonic patterns

(56:05) Minimal agents and machines

(01:02:08) Common traits and conclusions

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/58 · 00m:00s

Great. Thank you very much. I'm happy to be here, even though remotely, to share some thoughts with you on agency.

Because there are many details that go into all the things I'm going to say today in one hour, you can follow all the downloads, the software, the data sets, everything is here. This is my personal blog where I write things around what I think all of these things mean in terms of a bigger picture.

What I'd like to do today is three things. I'd like to introduce some of the ways I think about this field in general and some broader philosophical approaches. Then I'm going to show you some specific examples of the thing I mean, because it is important to me that these conceptual frameworks engage with the empirical science. I want to show you that we now have ways of studying all of this and that these kinds of ideas do lead to new discoveries, which I think is important.

Then at the end, I'll say some more controversial things around what I think the future is going to look like.

Slide 2/58 · 01m:04s

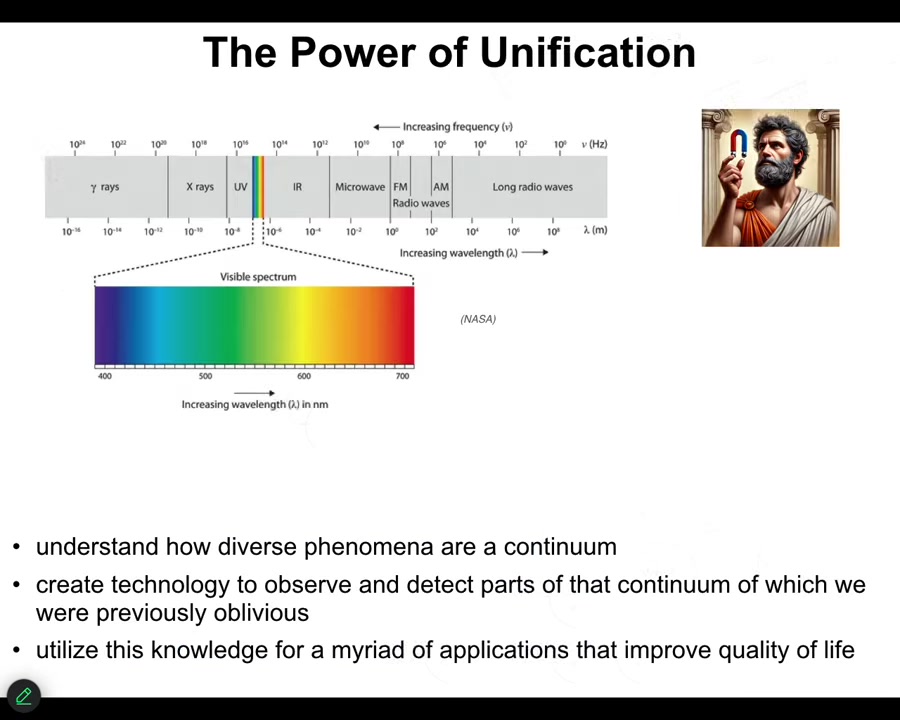

So the first thing I want to think about is the story of the electromagnetic spectrum. Back before we had a proper theory of electromagnetism, two things were happening. One is that we had all kinds of phenomena which were thought to be different. In particular, they used different terminology. We had lightning and static electricity and magnets and light, and people were completely convinced that these are different things. If you try to speak of them using the same terminology, people would tell you that you're committing a category error, that those are fundamentally different kinds of things. So that's the first situation. The second was that because of our own evolutionary history, there were massive regions of the spectrum of which we were completely unaware. We could not sense or operate or relate to any of the phenomena out here short of this little narrow band that we're sensitive to, and we simply had no idea that any of this existed.

What a good theory of electromagnetism allowed us to do were two things. First, unification. We were able to understand that actually all of these phenomena, despite the fact that we've had for thousands of years different names for them, are all one thing. In other words, science is moving forward, whether or not our ancient linguistic categories keep up with it. I think they should keep up with it.

And second, because we have a much better theory of electromagnetism, we can now make technology that allows us to operate along regions that were previously inaccessible to us, which improves the quality of life.

What I'm going to argue is that the exact same situation currently exists in the field of diverse intelligence or cognition more broadly. That we have lots of phenomena that, because of these ancient linguistic categories, people insist are different. People talk about crisp categories of things like living organisms and machines, and they prefer binary kinds of labels, as in this is intelligent, this is just physics, and so on. We are in the same situation here, where we can now develop good conceptual frameworks and the technology they enable to move beyond these limitations.

Slide 3/58 · 03m:31s

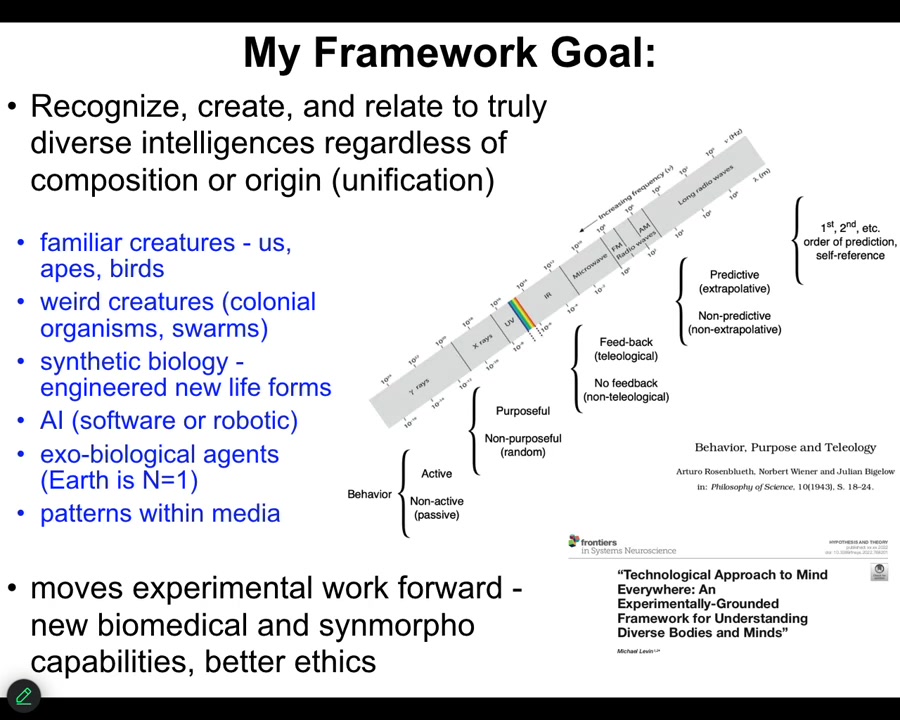

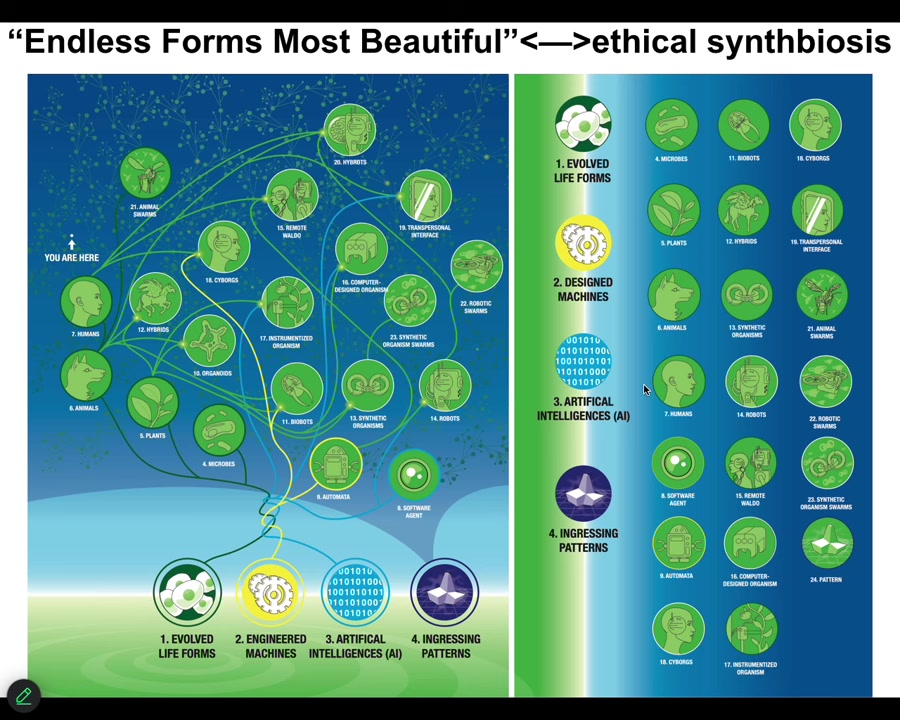

One of the things that I'm working on is a framework that enables us to recognize, create, and ethically relate to very diverse agents. This includes the familiar animals and maybe some more unusual things, whales, octopus, some people like to think about those things. But also some very unusual creatures like colonial organisms and swarms, engineered new life forms, so synthetic morphology, AIs, whether software or robotically embodied, perhaps someday exobiological agents, and then some even much more unusual kinds of things, which we probably won't get to today, but I can talk about them if people want in the Q&A, which are not even strictly speaking recognized today as physical beings at all.

My goal is to develop a framework that allows us to think about all these things and understand what they have in common. Very critically, it has to move experimental work forward. In other words, not only should it drive new discoveries in biomedicine and bioengineering, but it also should drive improvements in ethics in our ways to relate to other beings. The first version of it is here in this very lengthy paper that tries to lay this out in great detail. I'm not the first person to try for something like this. Here's Rosenbluth, Wiener, and Bigelow around 1943, talking about the cybernetic perspective of how you get from passive matter all the way up to human-level metacognition and things like this. But you can emphasize these transitions, or you can think about it as a spectrum.

Slide 4/58 · 05m:14s

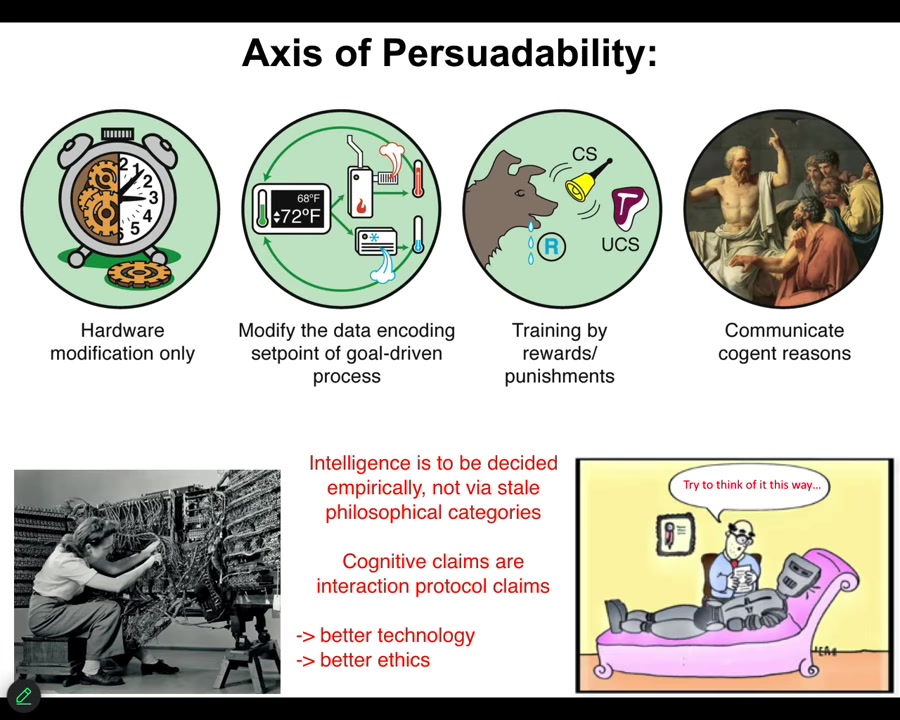

I think what we're dealing with here is what I call the axis of persuadability. For the purposes of this discussion, I take a very engineering approach to these things where I think agential claims are basically interaction protocol claims. That is, when we say something has a degree of intelligence or cognition or agency, we are not really trying to debate the essence of what it truly is, some sort of ground truth that we can all agree upon after we fight about it for a while.

What we're saying instead is a very observer-relative claim that I'm going to use a set of tools, maybe hardware rewiring, maybe control theory and cybernetics, maybe behavior science and rewards and punishments, maybe psychoanalysis and love and friendship. I have a set of tools and I'm going to use those tools to interact with the system and then we can all see how well that worked out for both of us, meaning that it is a publicly observable empirical claim that a certain set of tools is appropriate to a certain system.

This is very important because it means that we can't sit back in our armchairs and philosophically have feelings about this. I don't think we can say this is just a chemical reaction, definitely not conscious or cognitive. Nor can we say there's a spirit under every rock, the whole universe is this beautiful mind together. You can't decide that based on feelings; you have to do experiments and show which kinds of tools, or new tech tools that we have developed, give you any kind of a purchase on the system.

Slide 5/58 · 06m:56s

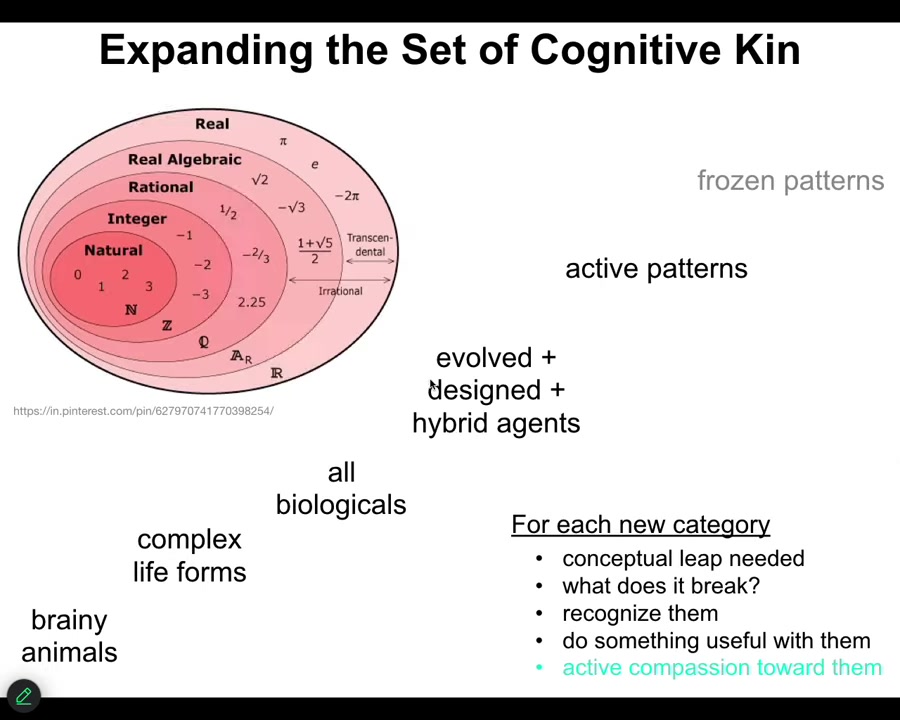

So that's what I'm interested in. I will also point out, though, that in moving up, and sometimes I give a talk that goes across all of these increasingly more unusual kinds of agents, what happens is what happened when we discovered new kinds of numbers. We had counting numbers and then somebody came up with zero and then the negative numbers and fractions and then irrationals and so on. And the interesting thing is that in widening your view of what a number is, going from this pre-scientific counting thing to some very weird transcendentals and so on, there's a few things that happen. You have to break conceptual categories. You have to break assumptions that you've had. And actually, this is quite painful.

Slide 6/58 · 07m:41s

this poor guy, Hippas, was thrown off a ship for breaking some assumptions about rational numbers.

I think what we have in the field today is a kind of mind blindness, where we are stuck on some ancient categories that prevent us from seeing and relating to an important part of the world. Getting past that makes things more complicated, and it upsets a number of established categories. People get upset over this stuff. I know, because I get the emails from everybody who's ticked off in either direction based on the things I'm going to say. I do think it makes for more meaning in the world and it makes our experience more beautiful.

Slide 7/58 · 08m:25s

So specifically, what we need to do is to get beyond this kind of ancient vision of our relationship to the world.

This piece of art is called "Adam Names the Animals in the Garden of Eden". And what it's telling us is this idea that there are discrete natural kinds. We all know what these animals are. And then here's Adam, and he's separate. He's different from all of them. So all of that has to go.

But the good part of this, and the very deep part of this piece of art, is that in this ancient story, it was up to Adam to name the animals. God couldn't do it. The angels couldn't do it. Adam had to be the one to name them. And that's for two reasons. One is because in those ancient traditions, naming something meant you've discovered its true inner nature.

And this is very important because we are going to have to, as a species, discover the true inner nature of all kinds of weird creatures that I'll talk about and give them names in that sense that we must begin to understand them. The other thing is that it was up to Adam to do this because he was the one that would have to live with him. And all of us are going to be living in a very different world moving forward. And so this has to be updated.

Let's talk about some different kinds of agency.

Slide 8/58 · 09m:44s

First of all, it's very easy to detect this kind of thing in brainy mammals. Here's this creature; he has a very good theory of mind. He sets up this little accident scene right there, puts it right on the neck there. Because he knows what reaction he's going to get out of his human owners, if nothing happens too quickly he's going to look. Are they watching? When we see things like this, we know exactly what's going on. No problem. That's because they operate at the same scale of time, of space, of direction. They have very similar fundamental goals to ours. They operate in the same space, the three-dimensional space.

Slide 9/58 · 10m:26s

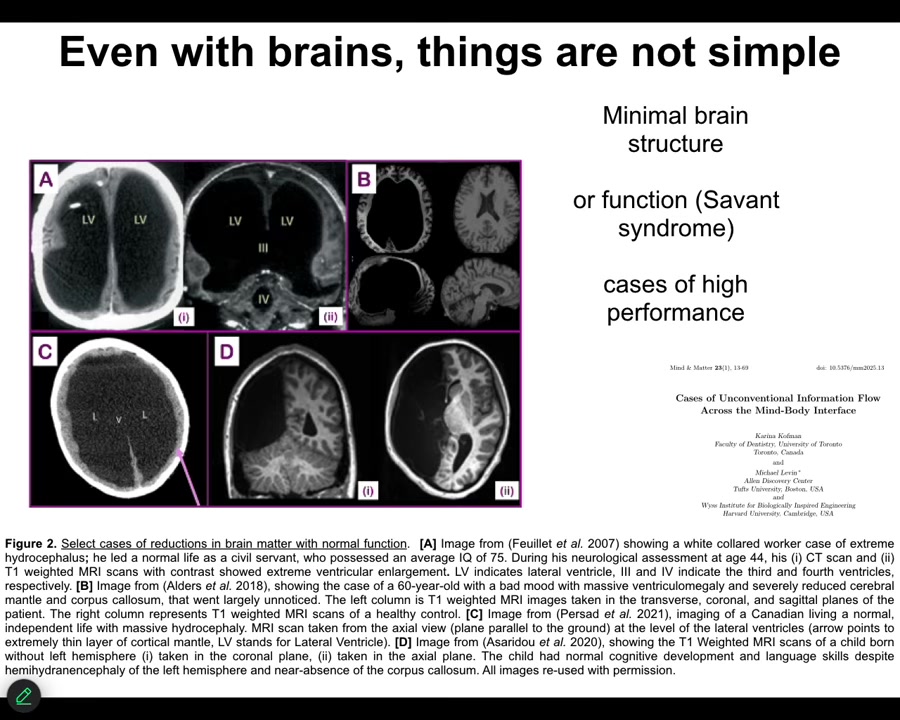

Although I will point out that even that is not so simple. There's this paper that Karim Kaufman and I wrote recently reviewing some cases of humans with very minimal brain structure but normal or above-normal cognitive performance. Even with brains, things are not simple because the mapping of the amount of brain real estate you have to the level of performance you're able to muster is not straightforward at all. These cases are rare, but they exist, and they're telling us that we don't understand even this relationship very well. Let's move beyond that.

Slide 10/58 · 11m:00s

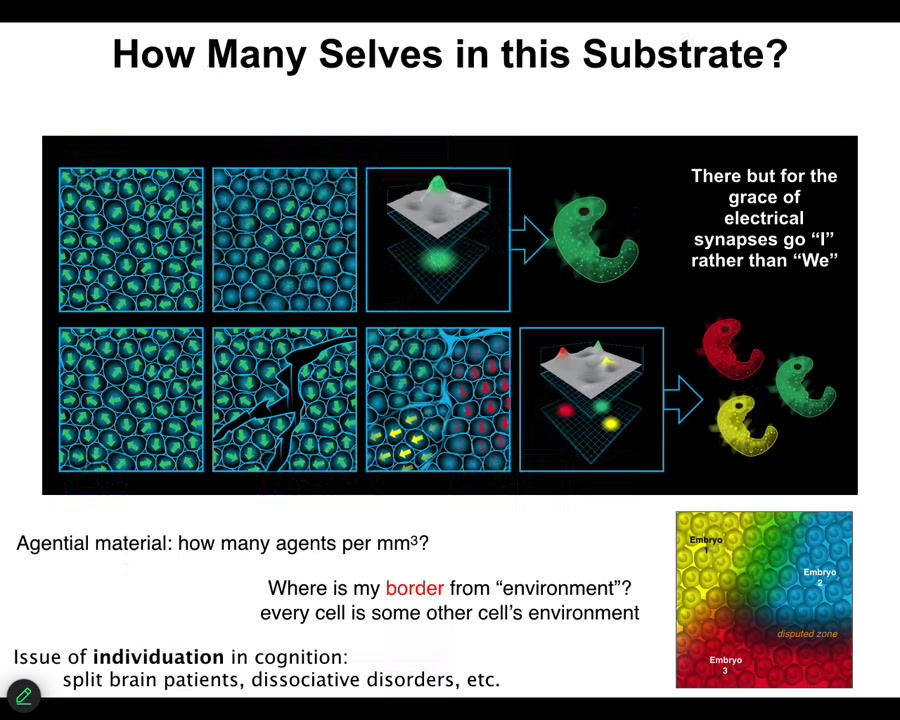

The thing is that all of us, whether we're talking about our bodies or our minds, are a kind of self-organized pattern in a substrate. So this is an early embryonic blastoderm, and we look at this and we say this is one embryo. What do we mean, what are we counting when we say there's one embryo? There are hundreds of thousands of cells here. What is there one of? Well, what there's one of is commitment. There's one story that all of these cells have bought into in terms of what they are going to do in anatomical space. It's a very convincing model of themselves and later of the outside world that binds them together into a single vision, which we then have named an embryo.

And in fact, if you put little slices into this blastoderm, and I've done this in duck embryos when I was a grad student, what will happen is that each one of these regions will not be able to sense the others. It will self-organize into an embryo, and you will end up with twins, triplets.

So the number of individuals, the number of agents that can emerge at this higher level out of this continuum is not fixed. It could be anywhere from zero to probably half a dozen or more. It's not set by the genetics. It's a dynamic act of process having to do with alignment, both physical and the cognitive alignment between the competent subunits. And this is true for our bodies, but it's also true for our brains and our minds because in terms of split-brain patients and dissociative identity disorders, there are potentially multiple human personalities or human agents within one brain. So again, this relationship between the actual hardware and the real estate versus the agents that inhabit it is not simple at all.

Slide 11/58 · 12m:55s

And so now we can move to actually talking about something even less well understood, which is biological intelligence outside the brain. And we're going to need to realize that intelligence is way older evolutionarily than brains. This idea breaks our common focus on specific scales and substrates of intelligence. We're going to have to be able to recognize these things using some new markers and some expansion of our imagination, and it has many useful applications.

And what I'm going to do is tell you how to apply this kind of thing to one particular model system, which is cells, so living cells, as a collective intelligence operating in anatomical space. Okay, that's the section. So let me unpack that for you.

Slide 12/58 · 13m:41s

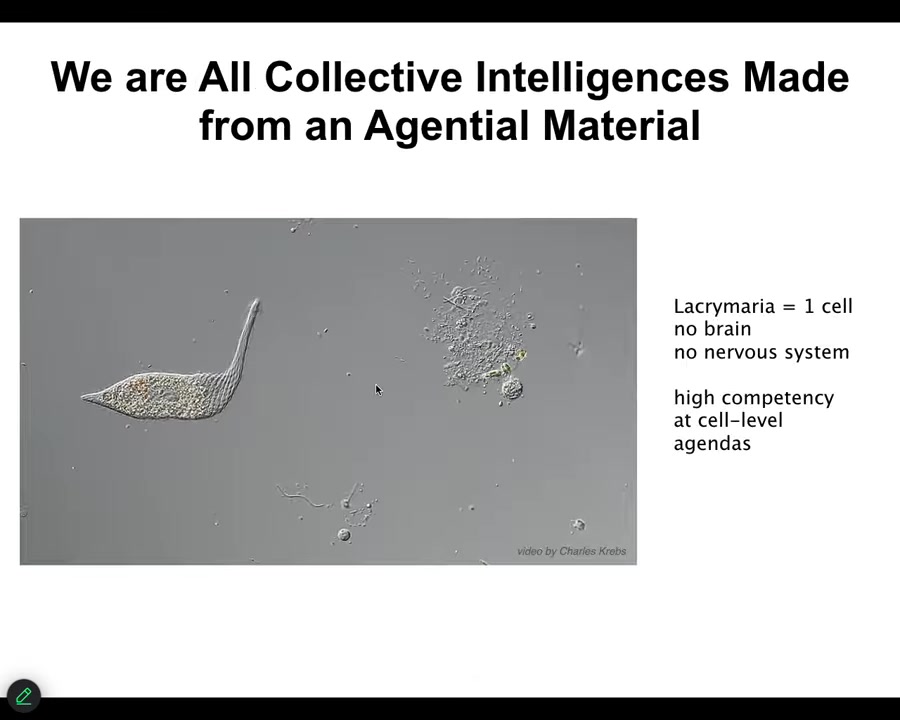

This is the sort of thing we're made of. This happens to be a free-living organism called the lacrimaria. Single cells, no brain, no nervous system, extremely competent in its low agendas. It's an agential material, very different engineering with this material than with passive matter like wood and metal.

Slide 13/58 · 14m:05s

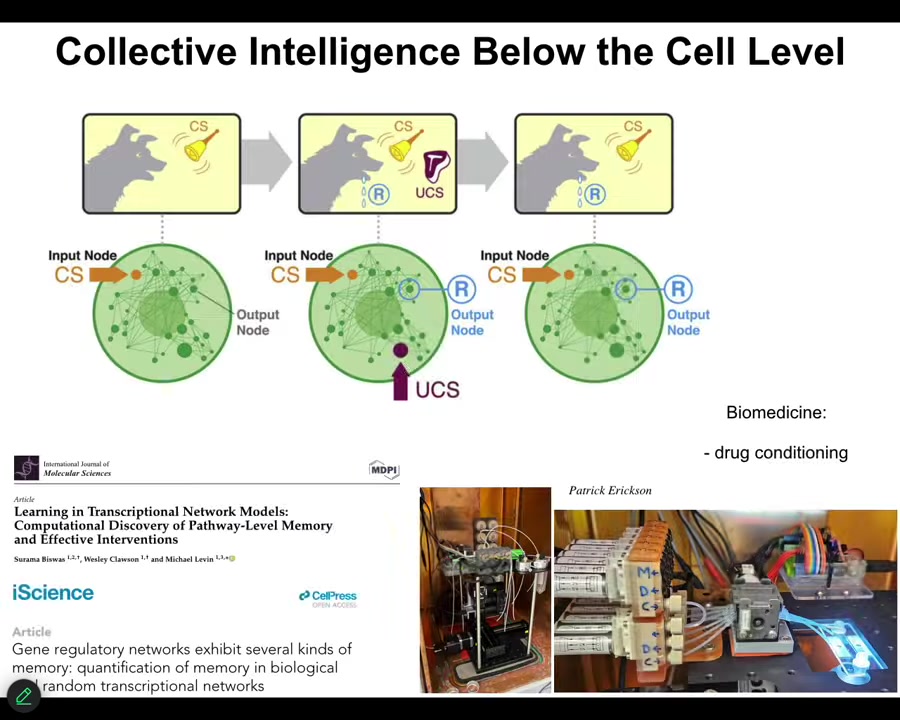

In fact, even below that level, never mind the cell itself, it turns out that the molecular pathways inside of cells, signaling pathways, gene regulatory networks, are capable of several different kinds of learning, including Pavlovian conditioning, sensitization, habituation, association. They can count to small numbers, amazing properties of the molecular networks. Never mind cells or synapses or brains or any of that. In our lab, we're taking advantage of this to build devices to train the molecular networks inside of cells to do useful things like drug conditioning.

Slide 14/58 · 14m:48s

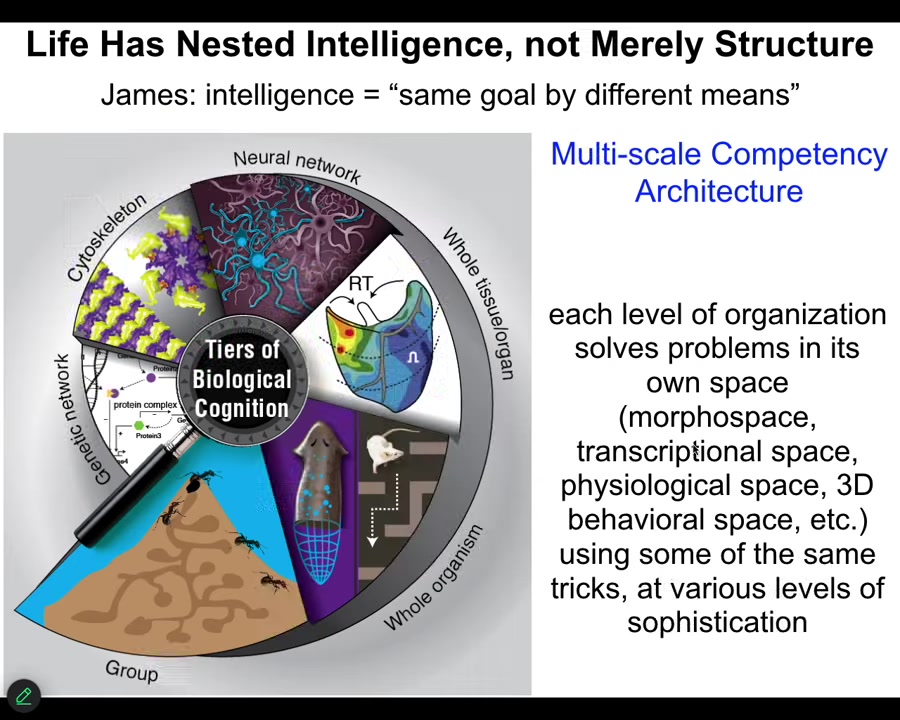

The thing about our bodies is that they have nested intelligence. That is, we are made at every scale. We are made of a material that has agendas. It has problem-solving competencies. We call this the multi-scale competency architecture.

All the way from the molecular networks up through the different scales up to swarms, these things navigate different spaces.

Slide 15/58 · 15m:14s

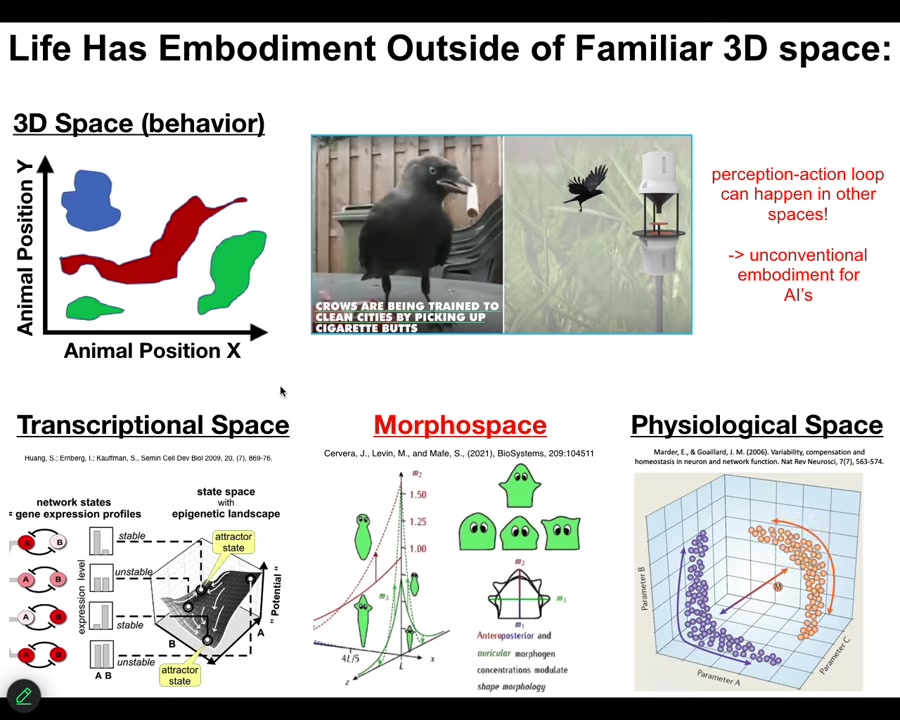

Because of our own evolutionary history, we are very obsessed with three-dimensional space. Movement in three-dimensional space is to us a fundamental feature of embodiment. In particular, we can only recognize easily medium-sized objects moving at medium speeds through three-dimensional space, these kinds of things. Anything else requires a lot of imagination and a lot of expansion of our categories.

For example, if you think about artificial intelligence or even brain organoids, people will often tell you they're not embodied. Their intelligence is not real because they don't have a body. They're sitting there inside a server box. The problem is that we are bad at recognizing embodiment. If it's not rolling around the floor in your lab or in the environment, we don't think it has a body.

But biology shows us that the loop that underlies intelligence, meaning sensing, decision-making, memory, and then actions—prediction and those kinds of things—are operating in many different spaces besides three-dimensional space. Cells and tissues navigate the space of gene expression. They navigate the space of physiological states. They navigate anatomical morphospace, which is what we're going to be talking about soon. All of these things are not trivial for us.

In the same way that mathematicians have learned to think about high-dimensional shapes and patterns, which we can't visualize, we're going to have to do the same thing here. We're going to have to develop tools, technologies that help us understand how intelligence navigates these spaces.

Slide 16/58 · 16m:52s

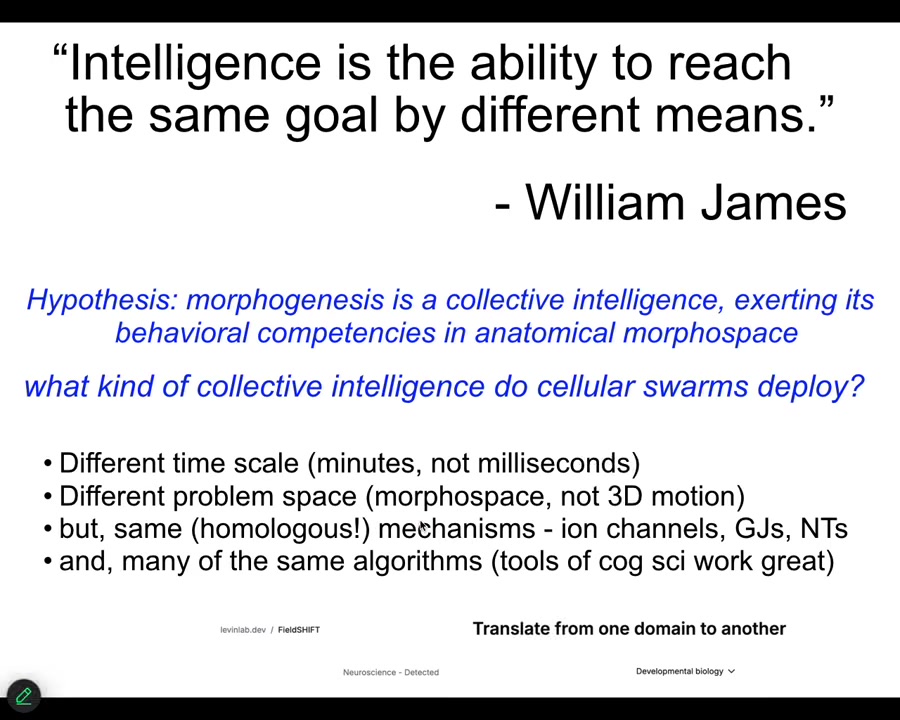

When I say intelligence, what I mean is William James's definition. Some degree of the ability to reach the same goal by different means. I love this definition. It doesn't say anything about brains. It doesn't say anything about the origin story of the agent, whether they were engineered or evolved. It doesn't say what space the goal is in. It just says that it's the ability to navigate that space to reach the goal when things happen.

The hypothesis that we've been following that I'm going to tell you about today is that morphogenesis, meaning embryonic development, regeneration, metamorphosis, cancer suppression, all of those things, is basically the behavior of a collective intelligence exerting its competencies in anatomical space.

Now I have to cash this out with actual data. I have to show you what kind of collective intelligence these swarms deploy. What problems do they solve? How do they navigate the space?

It's very similar to what happens in the brain, except that it happens at a different time scale, it happens in a different space, but the mechanisms are the same. All of the tools of cognitive and behavioral science work as well.

We've made a tool. I used to do this with my students by hand, and now we have a tool to do this, and you can play with this, where you can take any neuroscience paper and do a find, replace. Anytime it says neuron, say cell. Anytime it says millisecond, say minutes, or hours, and you've got a developmental biology paper, and we have a system now that will do that for you.

There is a fundamental symmetry between the self-assembly of the mind and the self-assembly of the body.

Slide 17/58 · 18m:34s

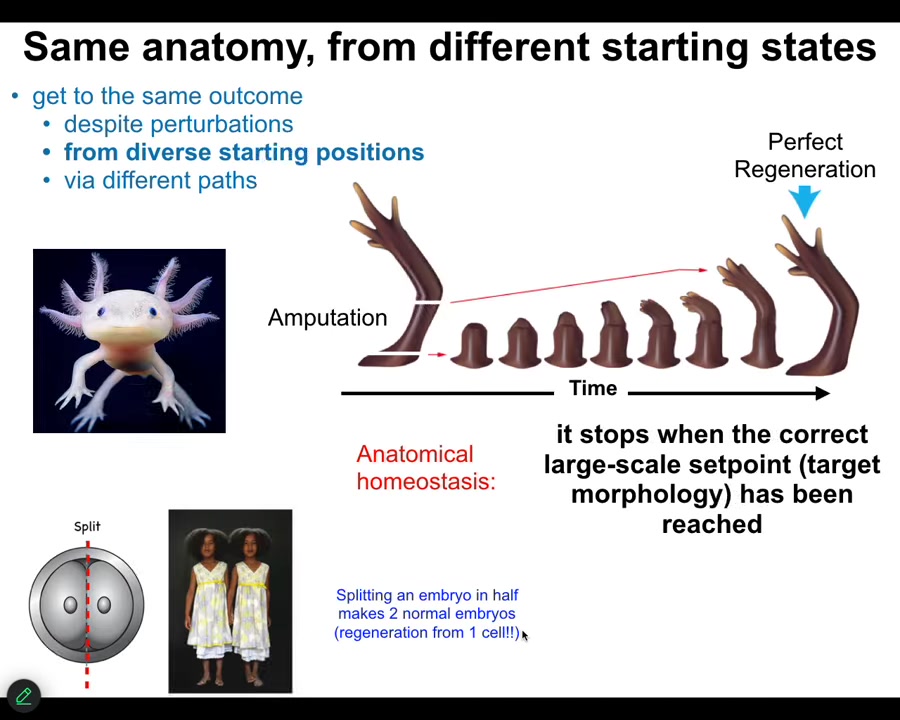

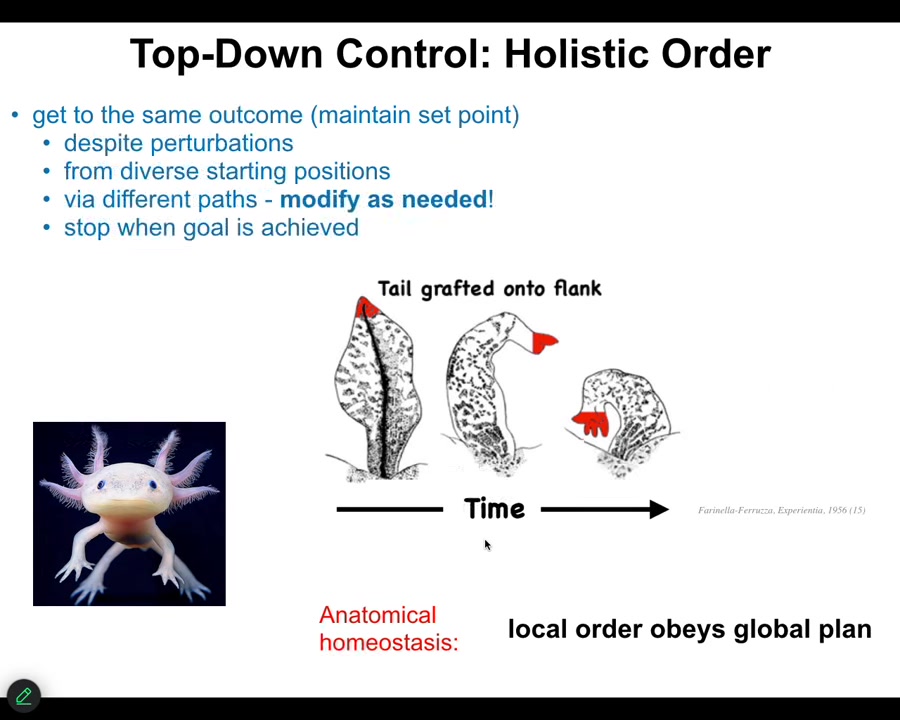

Let me show you some interesting things that agents that navigate morphospace can do. First thing they can do is they can get to the same goal from different starting positions.

This is an axolotl, highly regenerative amphibian. If you amputate the leg at any position, no matter where you do it, the cells will grow very rapidly. They know immediately that they've been deviated from this target state. They will rebuild the limb. No matter where they started from, they will rebuild the correct amount of stuff. Then they stop. That's the most amazing thing about regeneration: it knows when to stop. When does it stop? It stops when the goal has been reached, when the delta, the error, because this is basically an example of homeostasis. It tries to reduce the error between where it needs to be and wherever it is now, and it can navigate in the anatomical space to get back to where it needs to be.

Embryonic development is really just an extreme form of regeneration. In embryogenesis, you regenerate from a single cell. Again, it can reach that from different starting positions because if you cut early embryos into pieces, you don't get half bodies. You get perfectly normal twins and triplets and so on. Navigation of anatomical space from different starting positions.

Slide 18/58 · 19m:54s

It's not just about damage. It's about top-down holistic control. Here's another example in amphibians. If one takes the tail of one of these creatures and grafts it, surgically grafts it to the flank back here, what will happen is that over time that tail becomes a limb. And the little cells at the tip of the tail, which are locally fine, they're tail tip cells sitting at the end of a tail, they become fingers. What's happening here is the same thing that happens in any significant cognitive system where the low-level molecular mechanisms are being harnessed, they're being controlled by a higher level goal. The fact that the system knows, just like it knew what the goal state of a proper limb is so that it can regenerate, it knows that at the level of the whole body, you don't have a tail in the middle, you have limbs. And so that delta, the delta between the memory of what it needs to do and the current state is actually what drives all the molecular processes downstream that implement that state. Think about what voluntary motion is. You wake up in the morning, you have very abstract high-level goals, financial goals, social goals, all this very abstract stuff, but in order for you to get up and walk and execute on those goals, those high-level abstract ideas have to be transduced into the movement of potassium, sodium, and calcium ions across your muscle membranes. The biochemistry is actually controlled top-down by these extremely abstract strategies for navigating some kind of space.

Slide 19/58 · 21m:31s

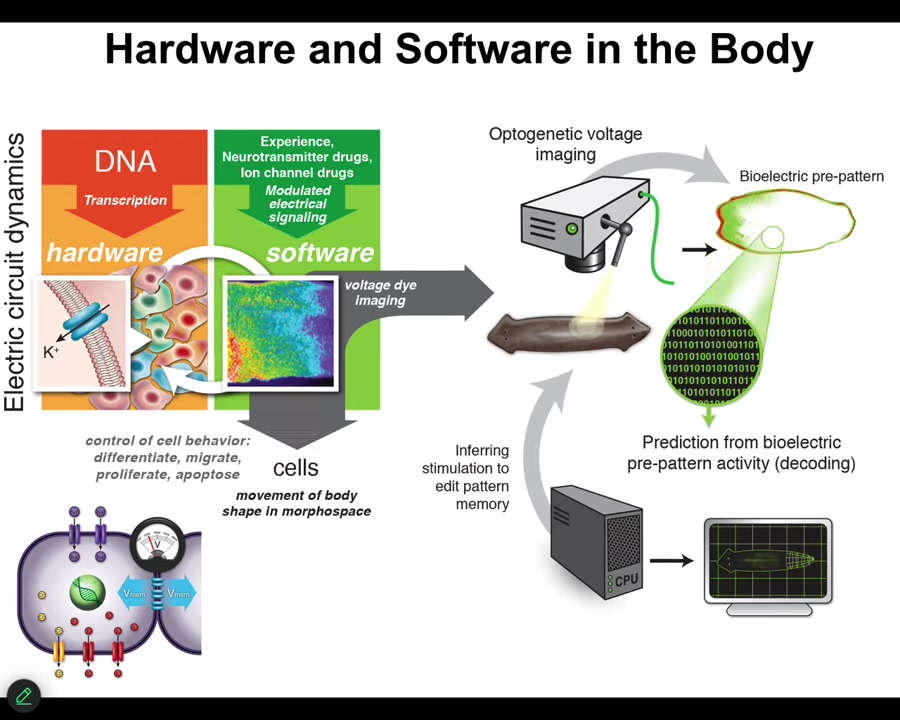

I've skipped already a lot here because for reasons of time, we could do hours just on these various kinds of examples because some of them are truly, truly amazing. But I want to point out that the way that this navigation is guided is actually very similar to what happens in the brain.

So in the brain, the animal brain is a non-controversial example of an intelligent system that pursues goals in a problem space. So the hardware is a bunch of cells that have these ion channels in their membranes so they can adopt a certain voltage state. Then they have these controllable electrical synapses called gap junctions through which they can propagate that electrical state to their neighbors.

And so the electrophysiology of signals through that network is thought to underlie the cognitive content of that mind. For this reason, there is this project of neural decoding where people try to read out the electrical activity of the brain and decode it to know what that human or animal is thinking. You should be able to decode the memories, the preferences, the goals — all of it should be decodable.

What happens here is that this electrical system controls your muscles, so it issues commands to your muscles to move you through three-dimensional space towards meeting your adaptive goals. What an amazing system.

Slide 20/58 · 22m:57s

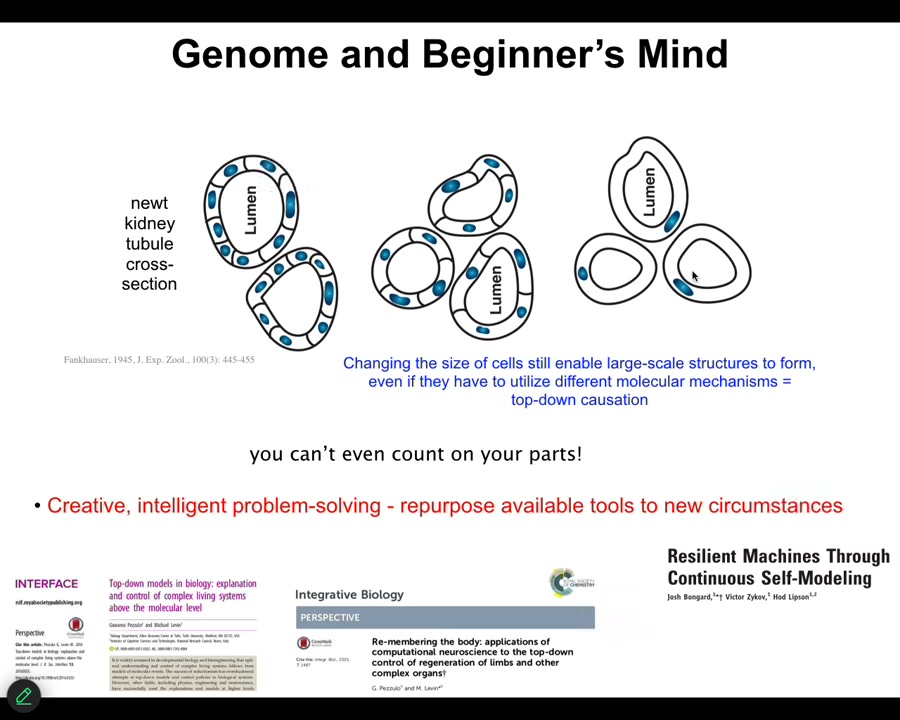

Turns out it's very old. Long before brains were here, evolution discovered this kind of hardware, software feature of electrical networks. All cells in your body have ion channels. Most of them have gap junctions to their neighbors. Long before there were any brains or neurons, these electrical networks were processing information to control your cells, not just your muscles, but all your cells, to move your configuration through anatomical space.

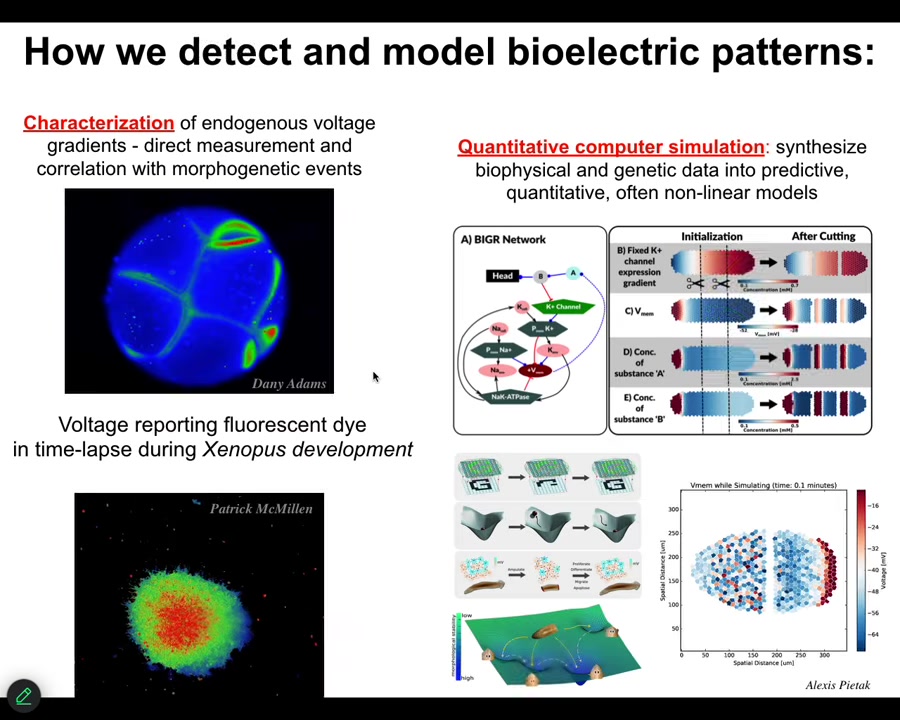

And so now, as we have been for over two decades, we can begin on this parallel journey of asking: we know what the electrical networks of the brain think about. What do the electrical networks of the body think about? What were they doing before there were any brains? And could we decode and extract the cognitive content of those pre-neural bioelectric networks?

The reason I'm focusing on all of this is that it's not a unique home for cognition. It's just an incredibly convenient cognitive glue. Evolution loves it because it's a very convenient way to allow competent subunits such as neurons in your brain or cells in the rest of your body to become a network that can process and synthesize information in spaces that none of the individual components could. No cell in that salamander limb knows what a finger is or how many fingers you're supposed to have, but the collective absolutely does. This is exactly why the bioelectric cognitive glue makes you know things that your neurons don't know, and you have goals and spaces that your neurons couldn't possibly have, and why morphogenesis is able to do things that no individual cell knows.

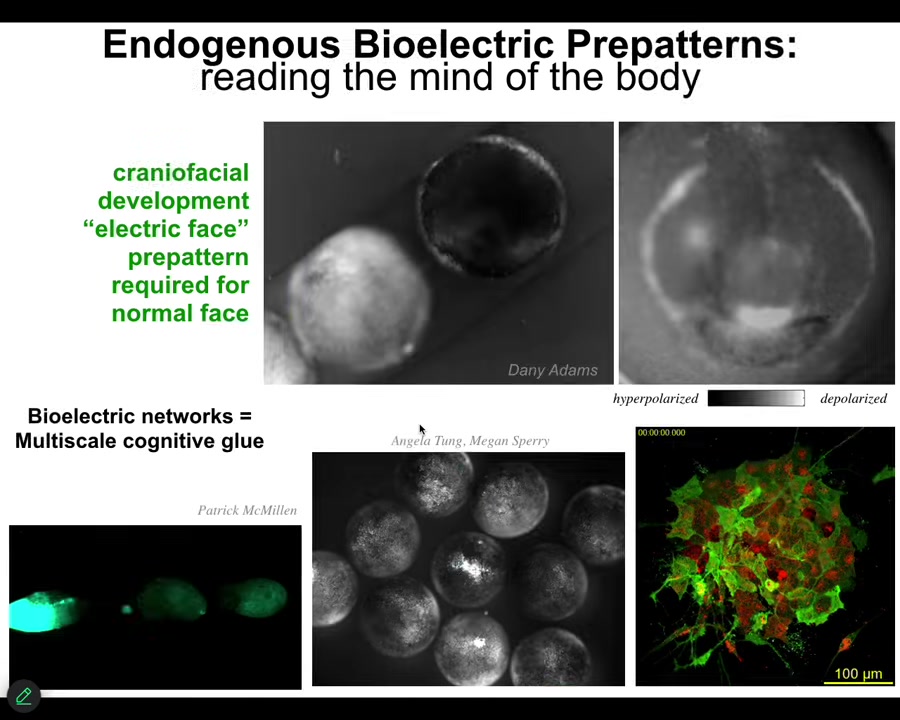

Slide 21/58 · 24m:39s

We developed the first molecular tools to read and write electrical information into these networks. Here you can see voltage-sensitive fluorescent dyes. These aren't simulations. These are real. This is real data. This is an early frog embryo where you can see all the electrical conversations that our cells are having. These are some explanted cells. The colors represent voltage, the membrane voltage of the cell. It's reading electrical activity in the brain, except we can do this in other tissues.

We have lots of simulation and computational analysis tools by which, at the level of the transcriptional ion channel network, at the level of the tissue voltage patterns, and at the level of the whole animal, such as this pattern-completion example, we can analyze the dynamics and try to understand what guides the changes in these patterns.

Slide 22/58 · 25m:31s

Just to show you a couple of quick examples, this is something we call the electric face. The different grayscale values are voltage here. You can see this is a time lapse of an early frog embryo putting its face together. This is one frame out of that video. Long before the genes turned on to regionalize the face, you can see here's where it's going to put the eye, here's where it's going to put the mouth, the placodes are out here.

This is the readout of a pre-pattern that shows that this tissue, this anterior ectoderm tissue, already has this pattern laid out in terms of where the organs are going to go. This pattern is critical. If you change it, the face will change. I'll show you that in a minute.

Not only does bioelectricity serve as a cognitive glue binding cells into multicellular assemblies, it also works on a higher scale between individuals. Here are some xenobots, which I'll talk about later. When we poke one, within seconds, these other two find out about it.

The same thing is here with embryos. This calcium wave that you're seeing here, and we've done studies showing that the collective is actually able to do things that no individual embryo can do. We can talk about that if anybody has questions. These kinds of dynamics serve as multi-scale cognitive clues.

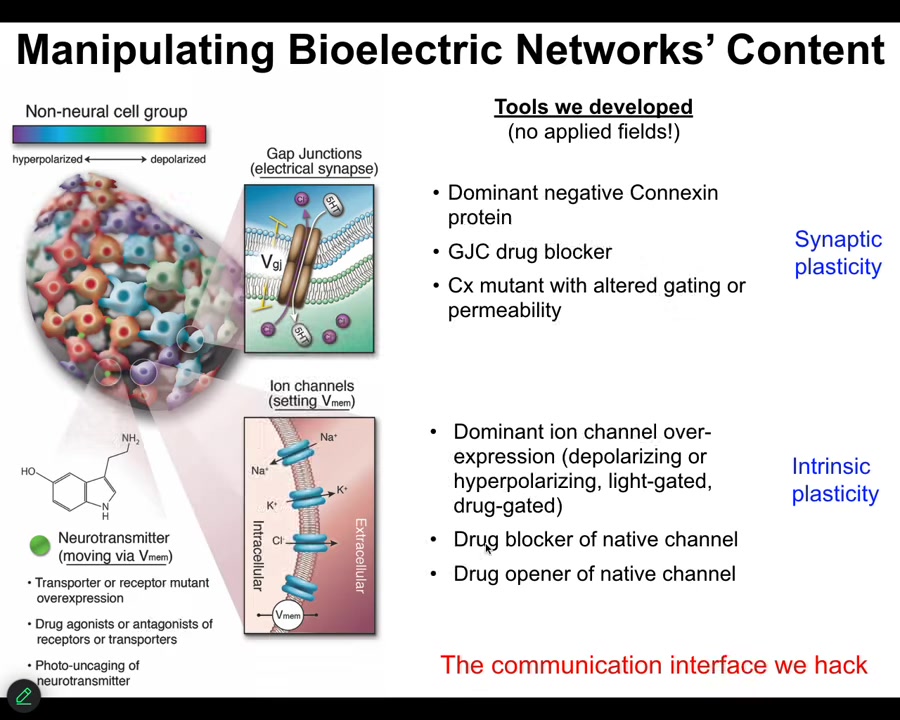

Slide 23/58 · 26m:52s

Now, more important than just tracking these patterns is being able to rewrite them. You want to be able to put information in, not just detect it. We've developed tools for that, stolen from neuroscience, because it's the same set of mechanisms. This is what's very important. If the tools don't distinguish between neural bioelectricity and the things that go on in brains and the kinds of things that go on in other tissues, maybe those things are not as disparate as we try to make them.

To do this, we don't use any applied fields. There are no electrodes, no magnets, no frequencies, no waves. We don't do any of that. What we do is manipulate either the gap junctions, control the electrical topology of the tissue network, or directly control the ion channels, meaning using optogenetics, using drugs, you can open and close channels, which changes the voltage in predictable ways. This is the communication interface that we're hacking.

All of the stuff I'm about to show you only works. It's not because we're so smart. It only works because this is how the cells usually control each other's behavior. This is how cells control other cells in networks and make sure that their activity serves a higher level set of goals, such as anatomical goals. That's what we're hacking here.

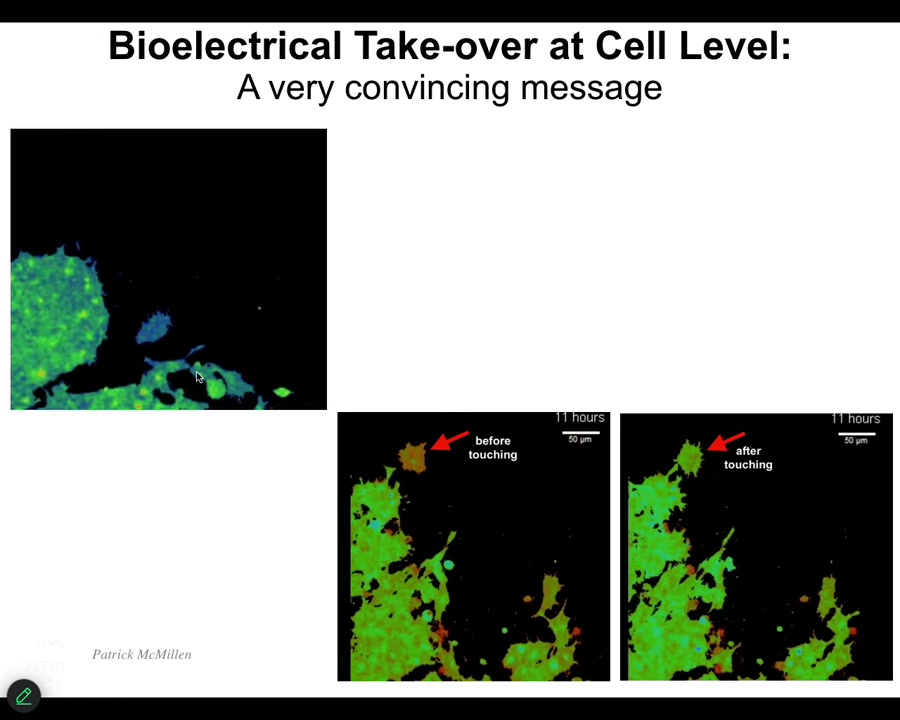

Slide 24/58 · 28m:20s

The first thing I want to show you is an example of what happens when a very convincing bioelectric message is propagated from one agent to another. These two are adjacent frames of a video that I'm going to play in a second. What you can see is the color is voltage. You can see that this cell that starts out a very different color, as soon as it touches this whole mass here, boom, it changes voltage. All it takes is one little touch.

Here it is. It's moving along and minding its own business. This thing reaches up, bang, touches it, and right there you can see. Now it's got a different voltage, and now it comes and joins this collective. It's a whole story on cancer and voltage and why cells do or do not play nicely with other cells that we can talk about.

I want to show you the example of an informational takeover. What's happening here is that once this cell touches it, that bioelectrical state is taken up. Even after it's left, that's it. Its physiological state has changed and all of the things it's going to do later have changed.

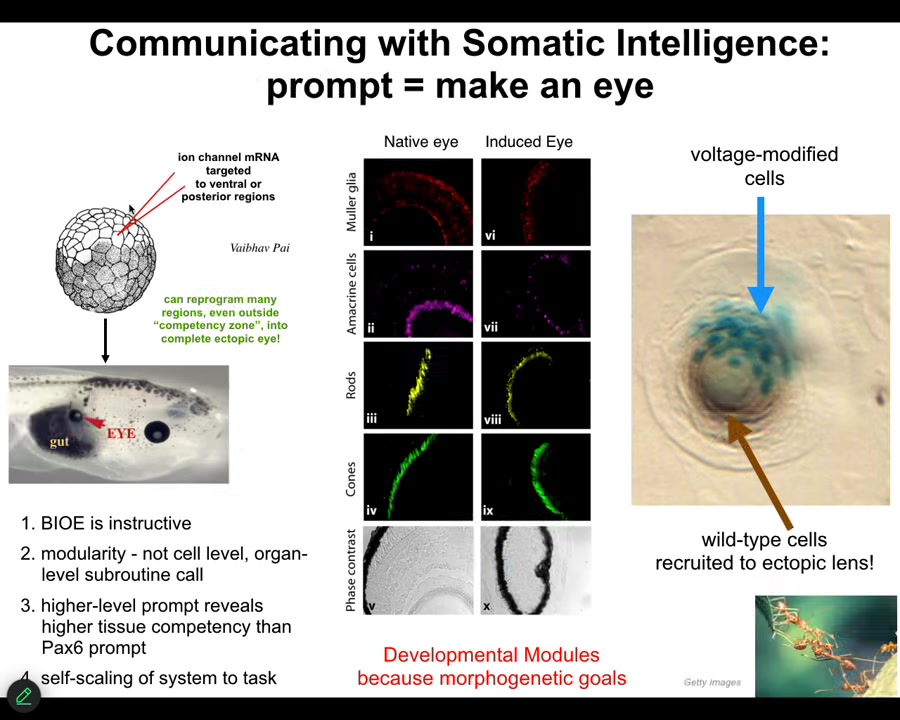

Slide 25/58 · 29m:19s

I'm showing you this because this is the kind of thing we really are interested in being able to duplicate for biomedical reasons. For example, suppose that you wanted to convince a bunch of cells to grow an eye as you might want in a medical application. It turns out that you don't actually need to know all the steps that are required to build an eye or how to tell which genes to turn on and off or where to put the stem cells. Eyes are very complex. We have no idea how to build an eye. But what we do know is how to provide a very top-level prompt, and I'm using these words on purpose, a high-level prompt that basically just says, "build an eye here."

And the way we do that, for example, in this early frog embryo, we introduce some RNA encoding a particular potassium channel that is going to establish that little voltage spot in a group of cells, just like what you saw in that electric face. When you do that in a bunch of cells that normally would become gut — here's a tadpole side view, here's the mouth, the brain up here, the eyes, the gut, and here's the ectopic eye — if you look inside, it has all the same lens, retina, optic nerve; it has all the same stuff inside.

So the first thing you learn is that these patterns of bioelectric state are instructive. They actually determine what happens next. They're information patterns within this excitable medium of cells that matter to what happens next. They're extremely modular. We didn't talk about which cells are next to which other cells. We just gave an organ-level instruction: make an eye. They did all the rest.

Just like in that top-down control that I was talking about before, how your high-level goals can make the biochemistry of your body respond appropriately, that's exactly what's happening here. We're letting it do all the hard work. It has amazing competencies because if you only inject a few cells — these blue cells are the ones we injected — all this other stuff out here that makes this nice eye, we didn't touch any of it. It's the blue cells that are telling the other cells, "hey, you should help us build an eye. There's not enough of us. You need to participate in this process."

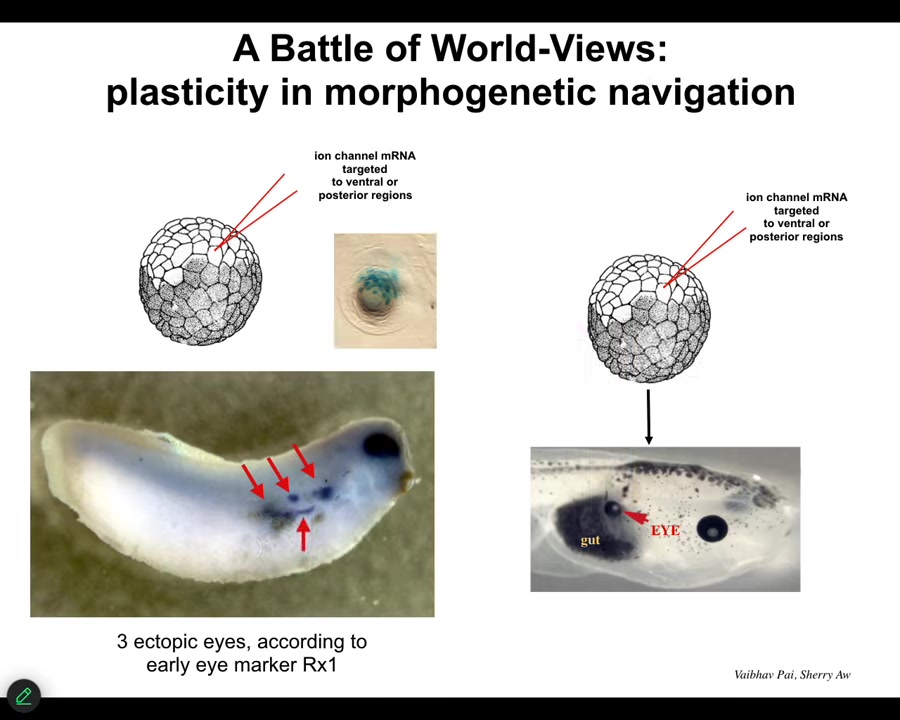

Slide 26/58 · 31m:22s

The amazing thing is that what's happening here is really a battle of models of the future or worldviews for cognitive systems. Because the cells that we inject here are saying to the other cells, you should be an eye.

At the early stages, in embryos, you might see one, two, three, four, five, all kinds of ectopic eyes. But then towards the end, some of them disappear and all you get is one. What happened to them is that there's a cancer suppression mechanism that resists this message.

These cells are saying to the neighbors, you should really be an eye. The other cells have an evolutionarily built-in process that says, if your neighbors have some sort of weird voltage, you need to equalize them out. The others are saying, no, you should be skin or gut or whatever it is that we were in. Sometimes the ectopic eye wins and sometimes the skin wins.

We can see this bioelectric pattern trying to take over, become convincing, change the set point, the actual set point of the cell so that they can build those structures. We can see this information propagating and competing for the attention of the medium.

For biomedical purposes, we would love to be very good at this. You want the cells taking on whatever message you're giving them, not fighting you on it, which is actually what happens to many therapeutics today.

Slide 27/58 · 32m:48s

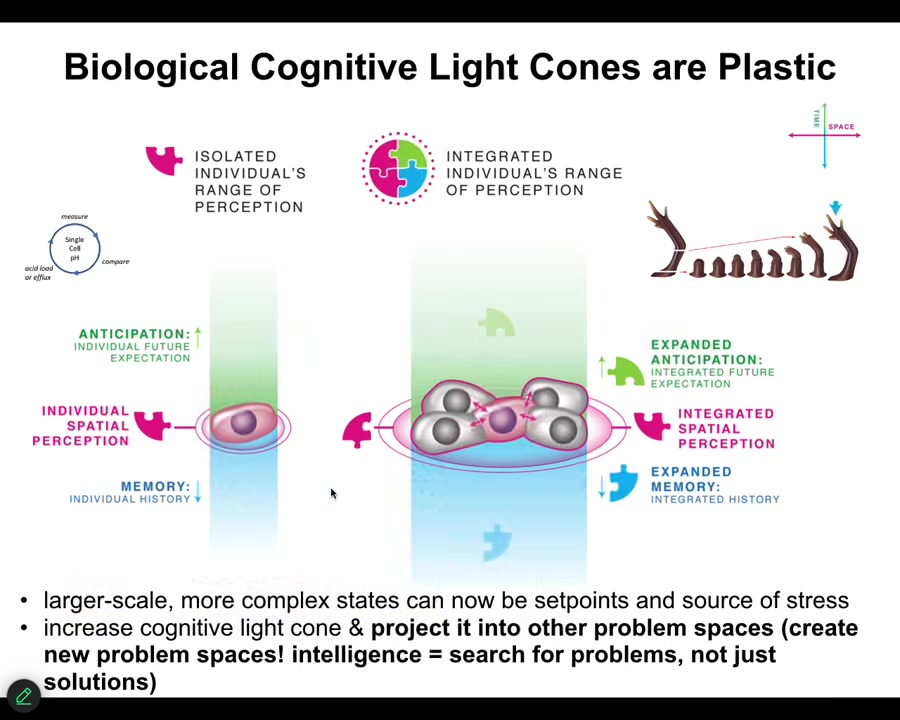

So one of the interesting things about all of this is that the border between the agent and its world is quite plastic. I call this border the cognitive light cone. It's not the size of your sensory range or your effectors or anything like that. It's the size of the biggest goal that you can maintain and pursue.

So individual cells have little tiny cognitive light cones. They're mainly only interested in things like homeostatic loops about pH and hunger level and things like that. They have memory going backwards, predictive capacity of the future, but it's all in a very small spatio-temporal scale.

But when cells assemble into groups, they start to take on grandiose goals. These cells here have this giant thing as a goal, this limb. Again, no individual cell knows what this is, but the collective now is connected into a bioelectric network that scales the agency of the components. It enlarges the intelligence. The cognitive light cone gets bigger. It can solve much bigger, more interesting problems. But also there's a sense of a loss of agency for the subunits because what the larger level is doing is bending the option space so that everything they do is in service of this larger goal. So the agency is actually moving as the cognitive light cone and the border between self and world shifts. And this strange way of thinking about things has very practical implications.

Slide 28/58 · 34m:05s

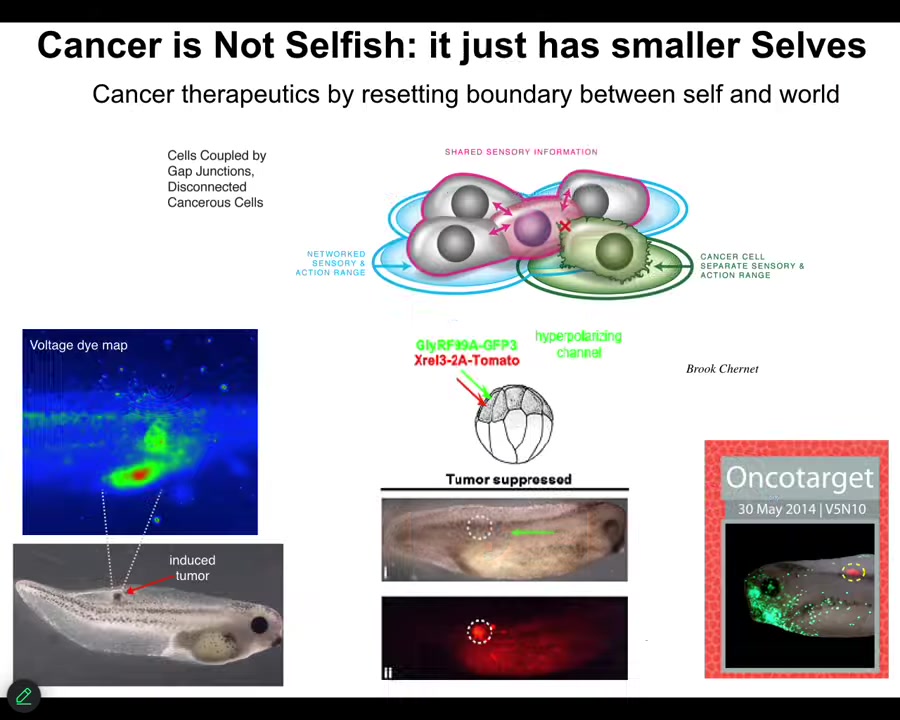

For example, in cancer: when we inject human oncogenes into this tadpole, there'll be a tumor. You can already see the cells electrically decoupling from their neighbors, and what they're going to do is treat the rest of the body as external environment. Once they're decoupled, they're just amoebas; their cognitive light cone shrinks, and they're not more selfish than normal cells, they just have smaller cells. The boundary between self and world of working on this nice organ is now shrunk to the level of a single cell like their unicellular ancestors.

And so that story of cancer has very practical implications. What if we don't kill those cells, we don't fix the genetic defect in this oncogene, all we do is forcibly reconnect the cells to their neighbors? And when you do that by injecting certain ion channels, this is the same animal. Here's the ANCA protein blazingly expressed, in fact, all over the place. If you were to sequence it, you would make a prediction that there would be a tumor. You would be wrong because there is no tumor.

It's not the genetics that drives any of this. It's the physiology: the computations, the information processing, and the cognition within the tissue that tries to set goal states. These cells, even though they have this nasty oncogene, are working on making nice skin and nice muscle, because they're not individual cells; they're part of a cognitive collective.

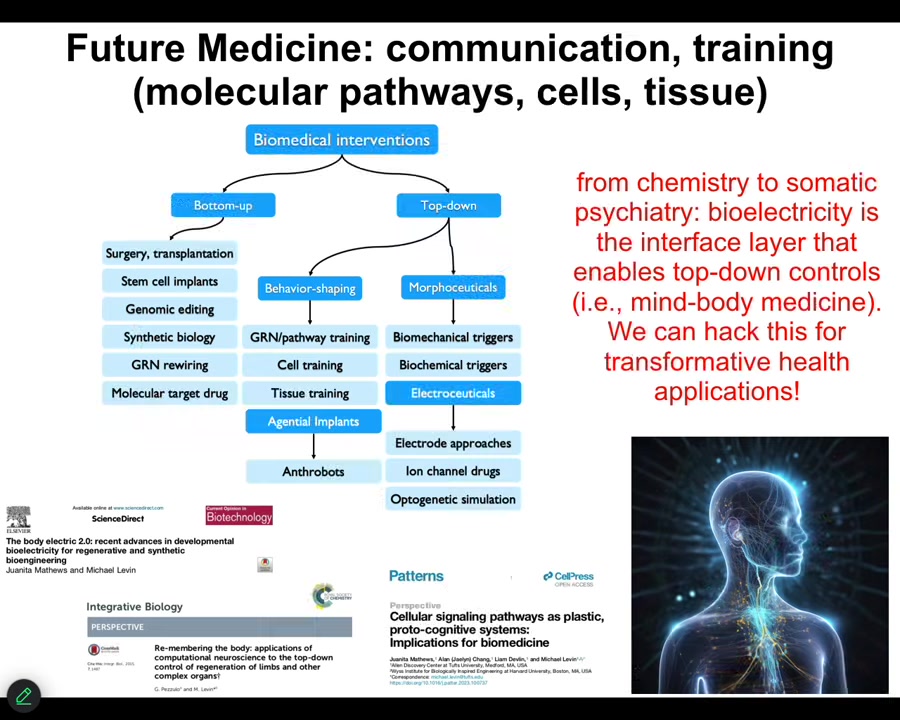

All of this is really part of a new approach to biomedical interventions.

Slide 29/58 · 35m:24s

The current approach is very bottom-up, very hardware-focused, as computer science was in the 40s and 50s. To program a computer, you had to physically rewire the hardware. Now we have the ability to talk about other approaches that exploit the intelligence of the material.

I think future biomedicine is going to look a lot more like somatic psychiatry and chemistry. It is not going to be about the molecular hardware. You can see all of that in these papers.

The reason I bring it up now is just to point out that all these deep philosophical questions about what is intelligence, what's a good way to rigorously quantify cognitive capacities, how do agents set the boundaries between themselves and their world, these deep ideas are moving from philosophy to empirical science. By having these kinds of frameworks that we've developed, we've reached novel discoveries that are moving towards therapeutics. There are companies that are now licensing all this stuff for therapeutic approaches because it allows you to find new things.

I think that's a key question as we start to debate different ways of looking at cognition. We need to keep in mind the kind of empirical outcomes of different worldviews. Every model helps you see certain things and it hides certain other things. These kinds of outputs are how we can judge them.

Slide 30/58 · 37m:03s

In the second half of the talk, I want to move beyond that and get a little more weird in terms of what other kinds of agents there are. And we're going to talk about non-biologicals, some hybrids, and even some really strange stuff, minimal agents. And this is going to break some other categories. For example, this standard debate that people often talk about, whether it's a life or a machine, I think these binary categories absolutely have to go.

Slide 31/58 · 37m:34s

And one of the reasons they have to go is because it isn't just about AIs or humans or any of that, but we have to realize that this modern adult human that is the center point of a lot of work on the philosophy of mind is not a binary category. It's at the center of a continuum on a developmental scale and evolutionary scale, starting with one cell. So if you think this human has some sort of special properties, it has moral worth and responsibilities and choice and all these things. When exactly did that show up? Because there is no magic lightning flash in development where you go from physics and chemistry to being a mind. It's a slow, gradual scale up. And the same thing during evolution. You have to ask yourself, which of our hominid ancestors would have these properties? That's one continuum, and knowing what we know about developmental biology and evolution reminds us that a continuum hypothesis should be the null hypothesis. People say humans have real cognition, cells don't. And if you think it's a continuum, you have to show why. I actually think it's the exact opposite. The facts of developmental biology and evolution tell us that the continuum hypothesis is the null hypothesis. If you think there are sharp categories, you have to say where does the magic come from and why?

But there's another continuum, which is the continuum of technological and biological change. We know, and already there are modified humans in various ways walking around, and there will be much more. If you want to keep these kinds of distinctions, you're going to have to know what to say about this kind of thing, which is going to be very prevalent. You're going to have people with different engineered components. I don't think any of us want to be trying to measure and see whether this guy is 51% machined. The idea is that biology is so interoperable that almost any combination at any level of evolved and engineered material is some kind of agent.

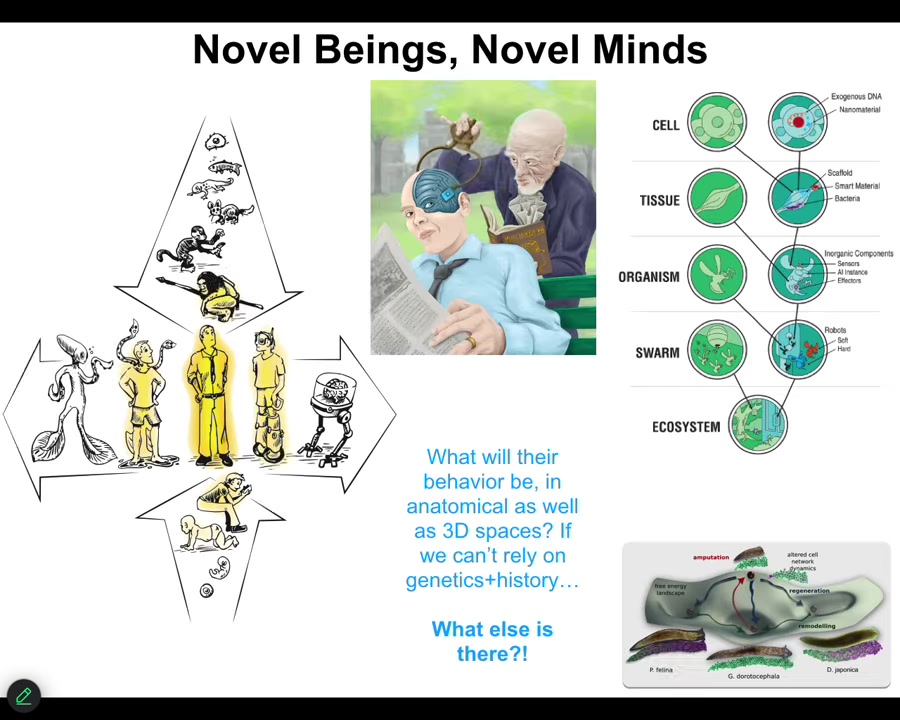

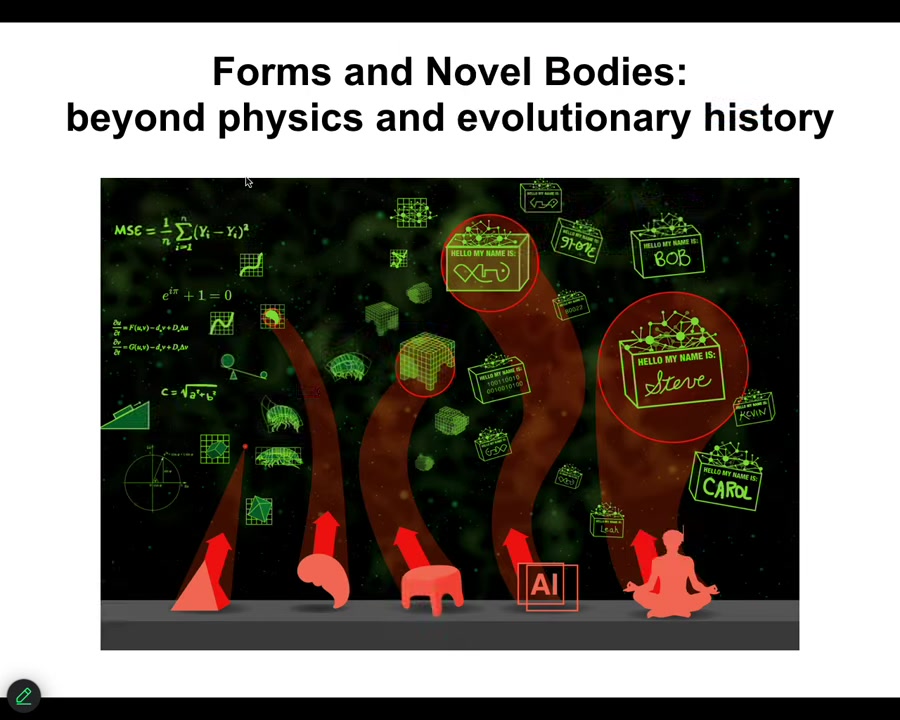

So now we have to ask the following question. We know what the morph, for example, behavioral and morphogenetic goals are of standard evolved beings because evolution presumably set them. That's what people generally think. So now we ask of these kinds of beings with no evolutionary history behind them, what are their goals going to be? What are their properties going to be? What are the cognitive capacities of these very different kinds of beings? If we can't rely on genetics and we can't rely on evolutionary history, what else is there? We study goals in morphospace a lot and different head shapes in planaria and how the same hardware can visit different anatomical attractors. But these attractors were set by evolution. If you don't have that to rely on, what else is there? We need to start thinking broadly.

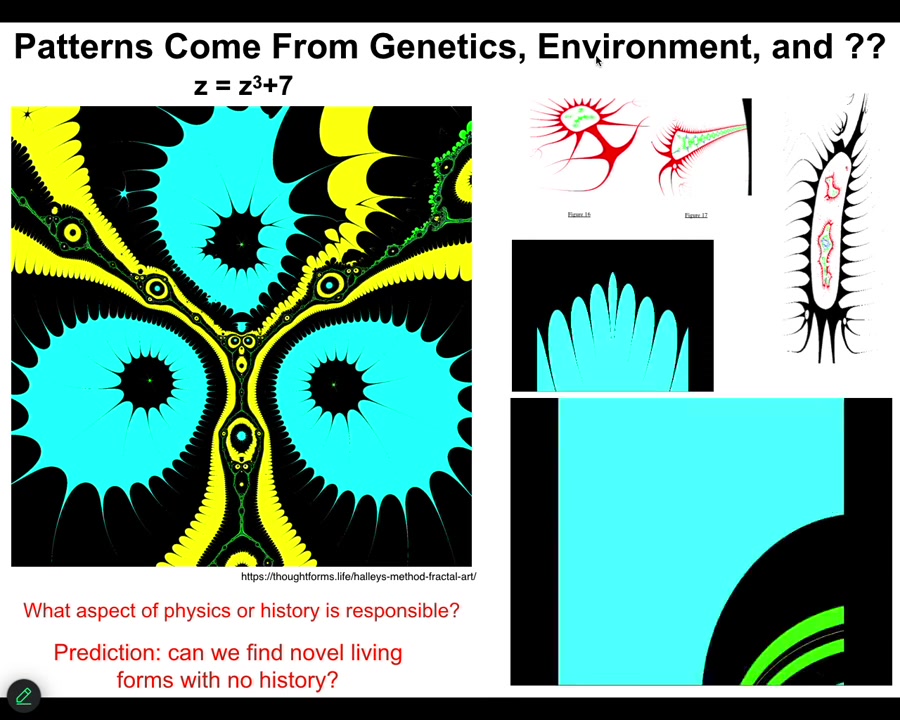

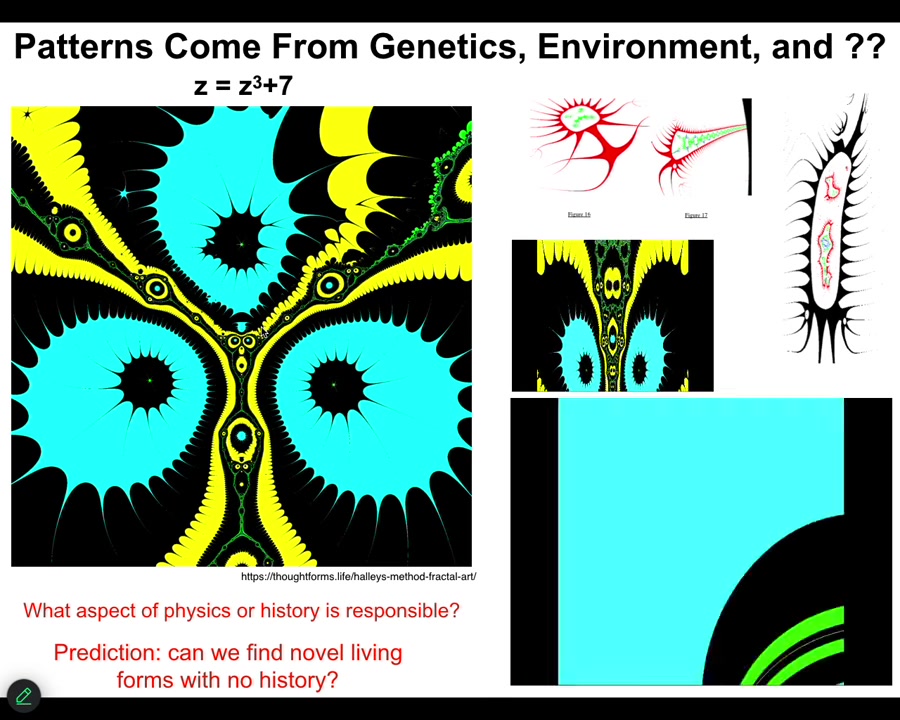

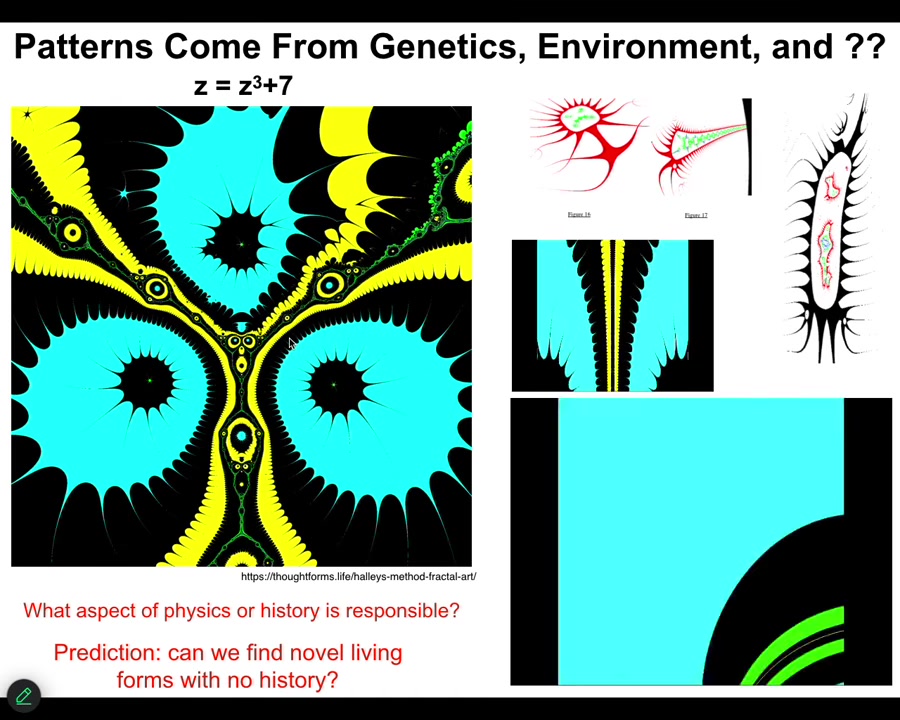

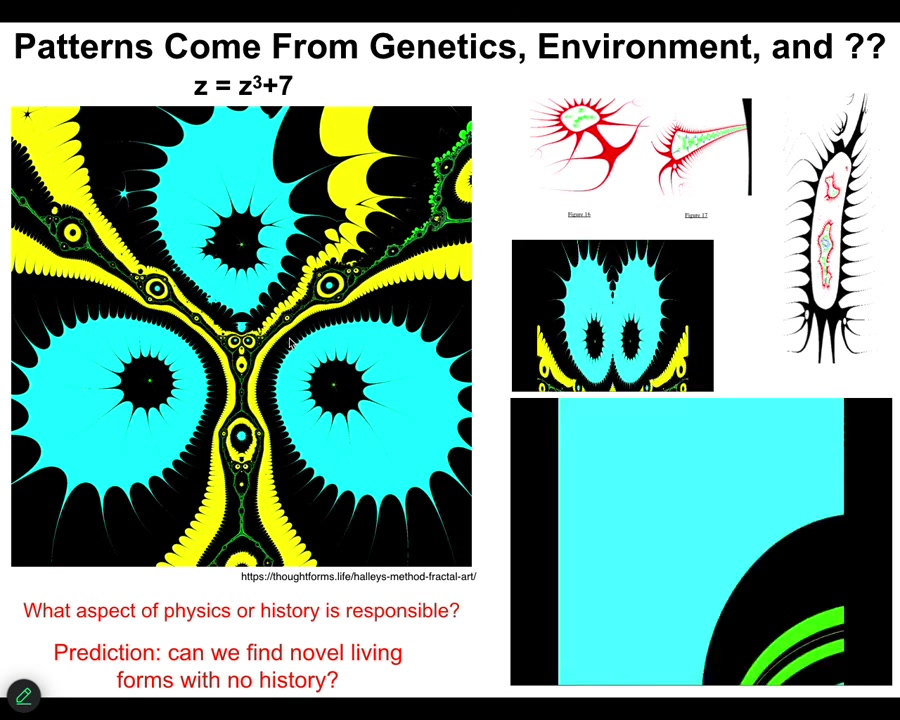

First of all, we need to understand that there are very complex, strictly defined patterns that come from neither genetics nor environment.

Slide 32/58 · 40m:44s

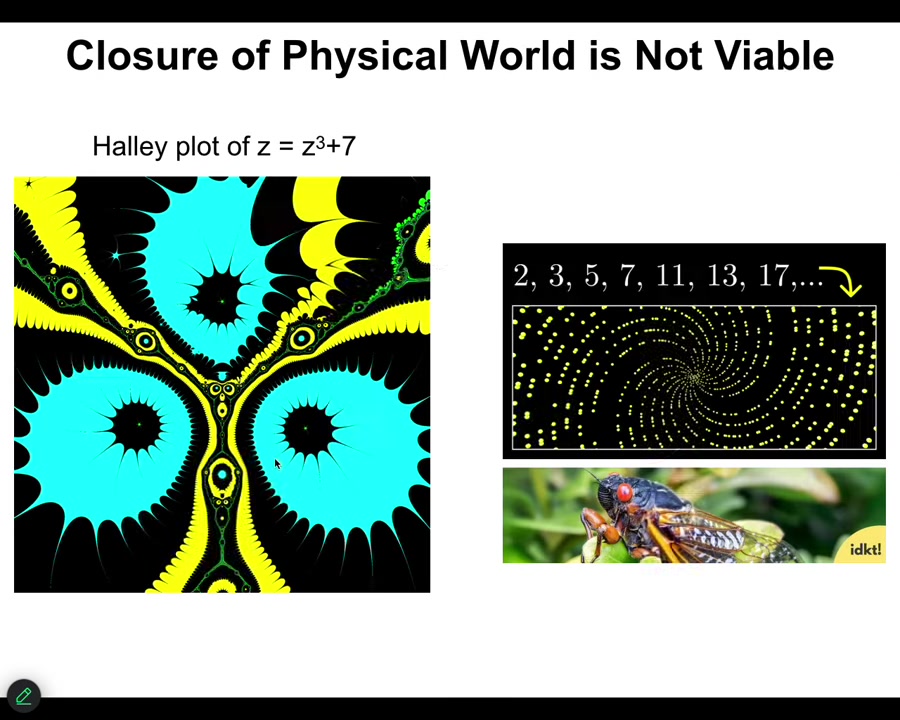

What I'm showing you here is what's called a Halley plot. This is just one example. I like these things because they look organic and they're pretty, but there are a million versions of this. It's a Halley plot of a very simple mathematical function in complex numbers. That's it. This is the complex function, and this is a video made by changing these parameters slowly in each frame.

Slide 33/58 · 41m:08s

You're looking at all this stuff and you can ask yourself, okay, what exactly determines the precise shape of this? If you're a biologist, you would say it's going to be either physics or it's going to be a history of selection. That's what we have. But these mathematical kinds of structures have neither. They have neither a history of selection nor are they dependent on any facts of physics. They come from a different world. We're going to talk about that.

Slide 34/58 · 41m:32s

And so now we can say, okay, if there are patterns that don't require either genetics or any kind of genetic history, nor do they depend on laws of physics, how relevant is this to biology?

I want to say two things. Questions in biology often exit the world of physics entirely.

Slide 35/58 · 41m:55s

So there are cicadas, for example, that come out at 13 and 17 years. Why? Because they're trying to time it so that it's harder for predators to latch on to those cycles. And if you want to understand why that works, the answer is because 13 and 17 are prime. The answer to why those numbers are prime is nowhere in physics and it's nowhere in biology or evolution.

Slide 36/58 · 42m:19s

You've left the set of physical explanations. But it's crucial for you to understand the biology that's happening. Let's look at some biological forms that appear to make use of some of these kinds of things that are not from direct history.

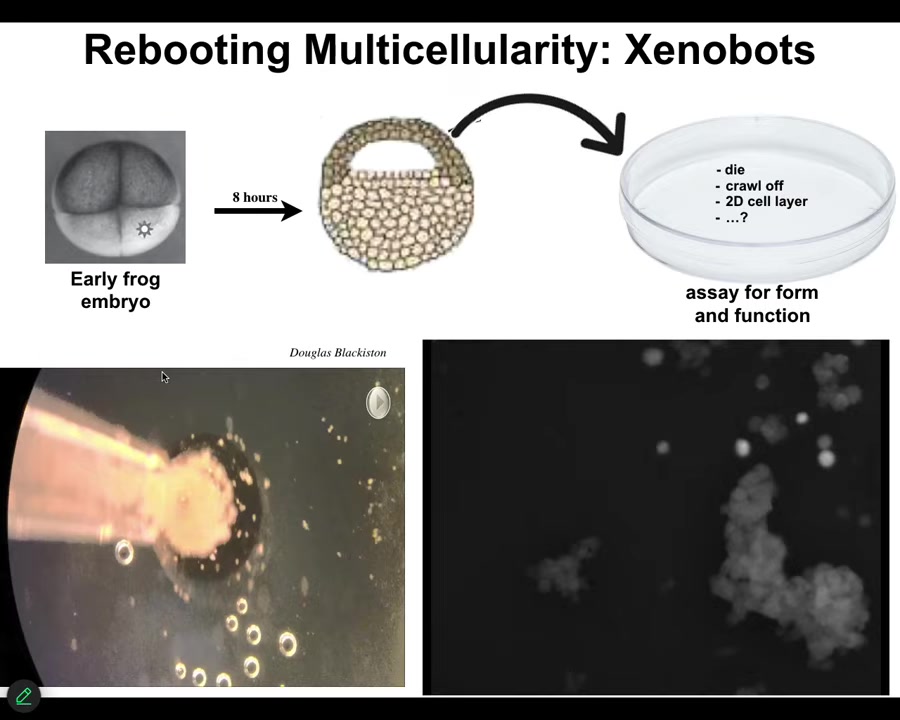

Slide 37/58 · 42m:35s

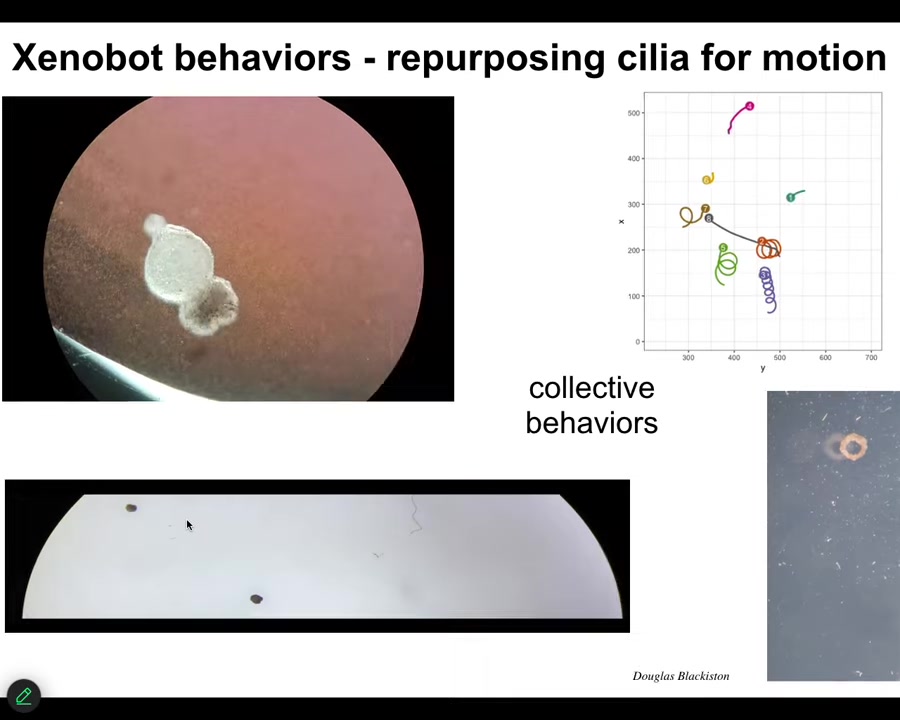

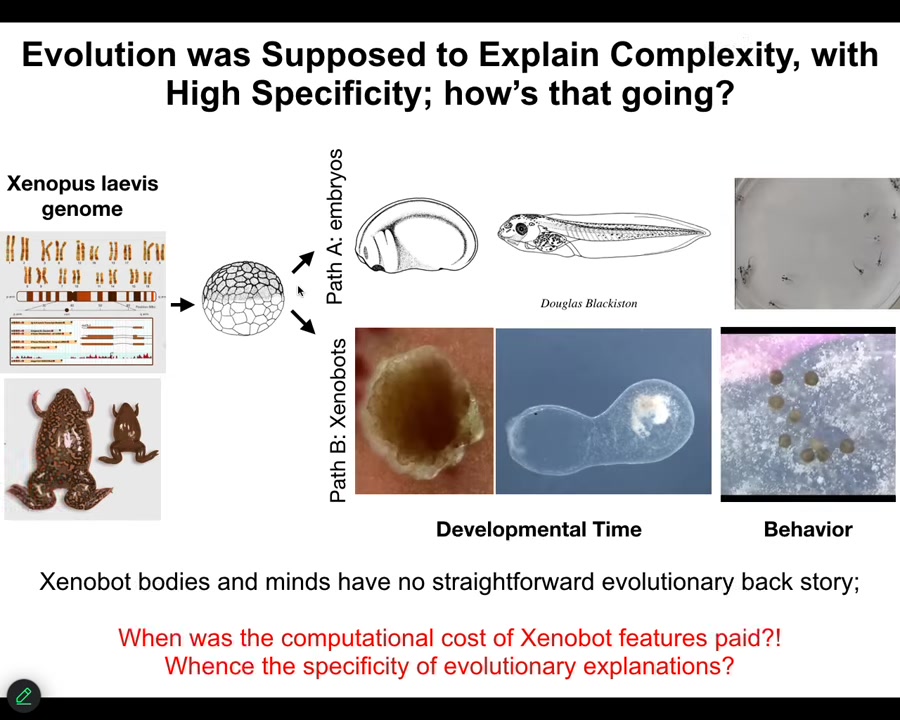

Xenobots arise when we take some cells from the animal cap epithelium of a frog embryo. We liberate them from the rest of the cells. What they do is they pull themselves together into this little construct.

I want to show you what some of the cells do. Each one of these circles here is a separate cell. There's a group of them here. I think it's great fun that it looks like a little horse that moves as a unit. It's over here examining these other cells. We don't know what any of the signaling is yet, but you'll see a little calcium flash here. There's all kinds of rich behavior.

Slide 38/58 · 43m:14s

But when they get together, they first of all use the cilia on their surface to swim through the environment. They can go in circles. They can patrol back and forth. We can make crazy kinds of shapes. This thing, they can have collective behavior here. There are groups of them.

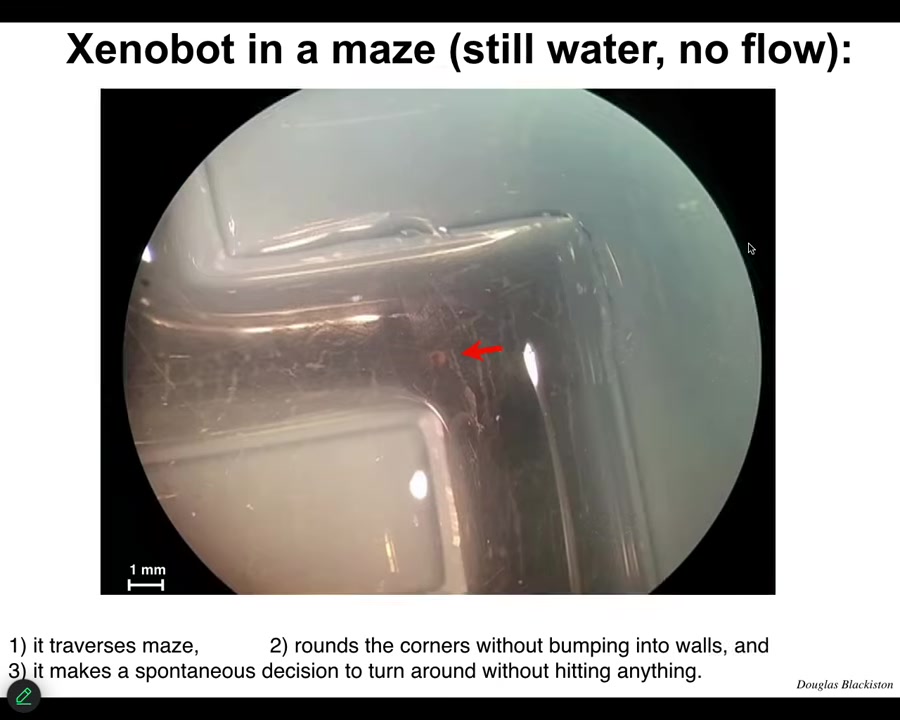

Slide 39/58 · 43m:30s

This is what it's like for a Xenobot to traverse a maze. Still water, no water movement. It makes the corner without having to bump into the opposite wall. It takes that corner, then it spontaneously turns around, goes back where it came from. These are not like conventional biobots that are made of muscle that you have to pace with electrical stimulation. It's completely autonomous. This thing does its own behaviors.

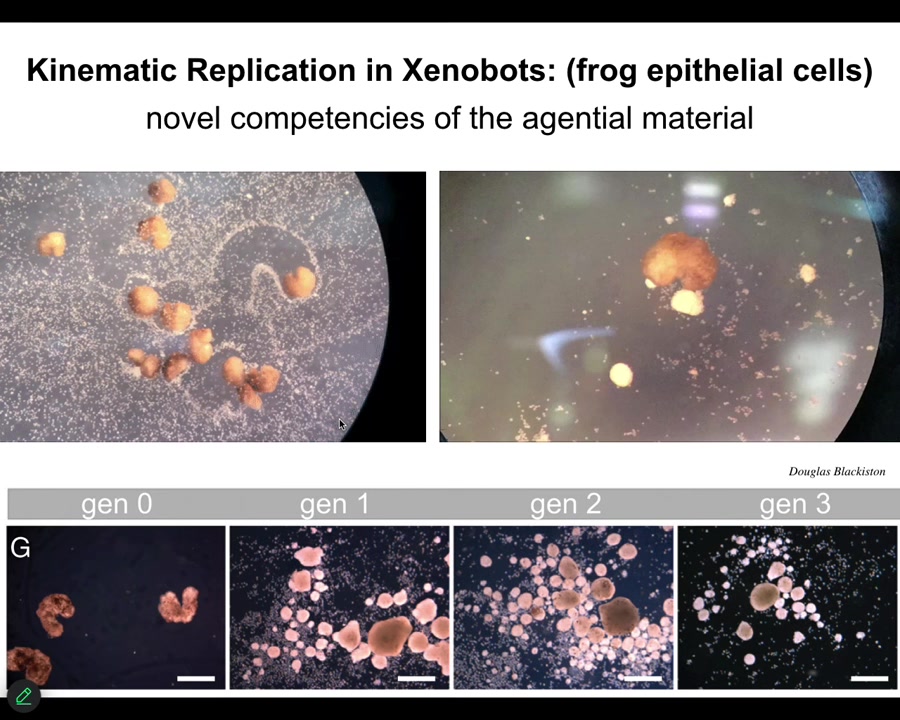

Slide 40/58 · 43m:54s

Here's one amazing behavior that it does. We call this kinematic self-replication. If you provide it with loose epithelial cells, what they will do, both collectively and as individuals, is run around, make little piles of the material. And because it's dealing with an agential material, that little pile matures into the next generation of Xenobots. They do the same thing and they make the next generation and the next generation. The idea here is that this is like von Neumann's dream. It's a robot that's able to make copies of itself with material it finds in the environment.

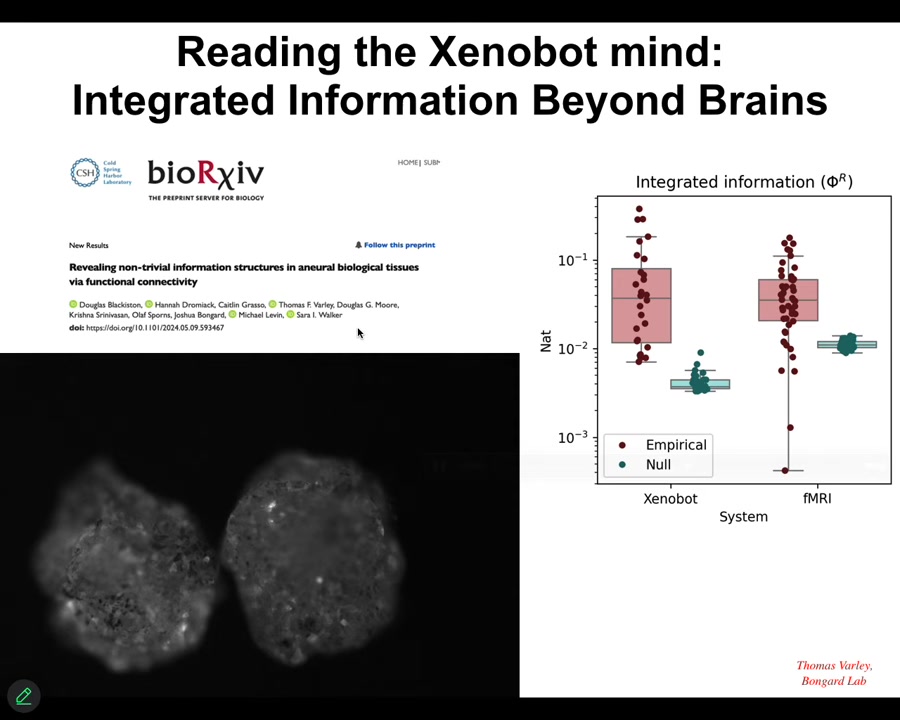

Slide 41/58 · 44m:35s

One of the things that you will see in these bots is this calcium flashing. This is the exact same technique that is used to characterize cognitive activity in brains. We can take these electrophysiological signals and apply some tools to them. This is the work of Thomas Varley from the Bongard Lab. When we apply these tools, you can look at something called Phi-R, which is a measure of integrated information based on Phi 2.0 by Baldusian and Giulio Tononi. What we see is that compared to null models, there is significant integrated information in these structures just like there is in brains analyzed with fMRI.

My point is not that these things are like brains. My point is that both brains and these structures, which have no neurons at all, have an information property that quantifies the extent to which something is more than the sum of its parts. That's the point of this causal information theory. So we can start studying. This is in the name of stealing all the tools from neuroscience, mainly because I don't believe that neuroscience is about neurons at all. I think neuroscience is a study of cognitive glue. It just so happened that we latched on to the brainy examples first. But it's the study of a scaling of agency from competent subunits to collectives that express that competency at larger scales towards larger goals in other spaces.

So that's one creature I wanted to show you.

Slide 42/58 · 46m:12s

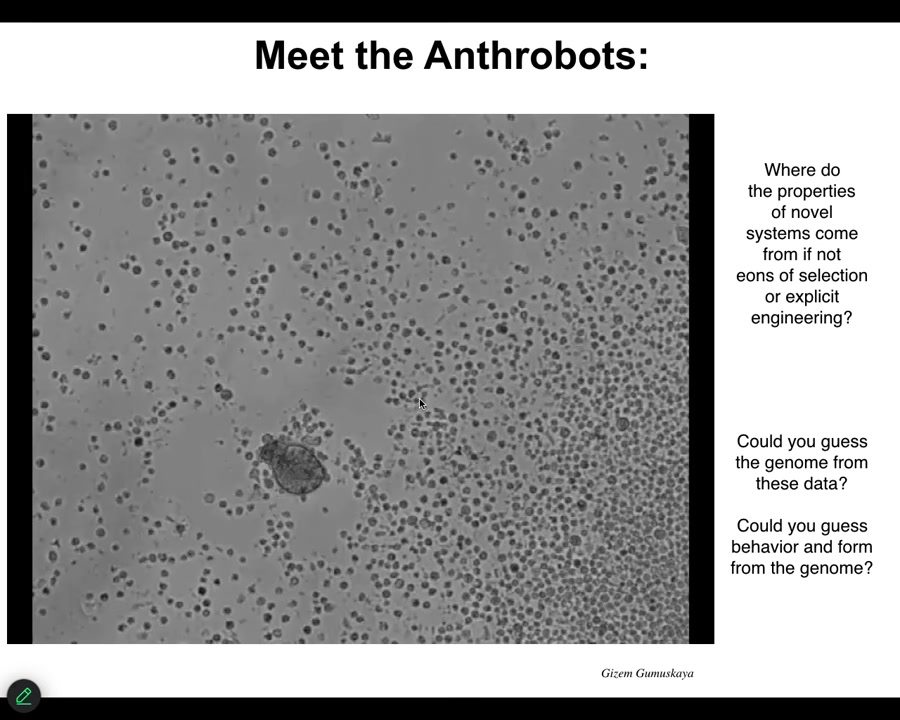

If I didn't tell you what this was, you might guess that this was something we got at the bottom of a lake somewhere. It looks like a primitive organism. You could guess at the genome and think that it would also look like a primitive organism genome, except that if you sequenced it, what you would see is a full-on, totally normal Homo sapiens genome. These are anthrobots. They're made of adult human tracheal epithelial cells. They self-organize. They become this motile little thing that looks like no stage of early human development or of any human development.

Slide 43/58 · 46m:47s

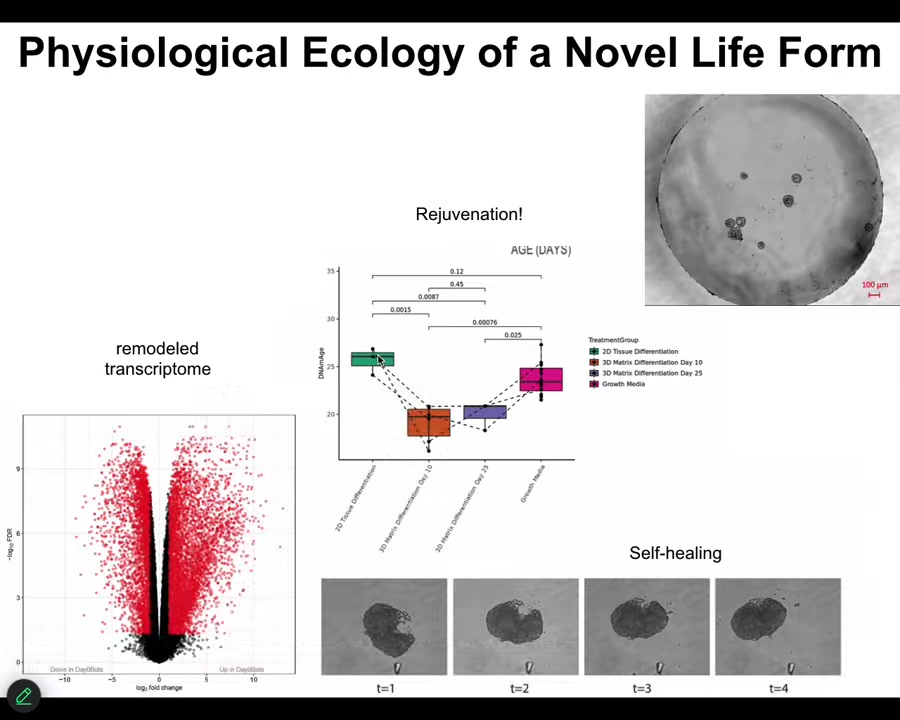

They have some interesting properties. You can see some group behaviors here. These guys express 9,000 new genes differently than the original tissue. They have a completely altered transcriptome. Xenobots express hundreds of genes differently. These guys express thousands of genes differently. About half the genome is now different. In either case, the Xenobot or the Anthropot case, we didn't edit the genome. We didn't put in any synthetic biology circuits. There are no scaffolds. There are no nanomaterials. There's no weird drugs. All it is, we liberate the cells. They have a new lifestyle. They reboot their multicellularity in a new way. For that, they drive a novel transcriptome. They can self-heal, as can xenobots. If you make mechanical damage, they will repair themselves.

This is something wild that I don't have time to talk about. They're younger than the cells they came from. This process of assembling yourself into a new being, in a new lifestyle, is actually rejuvenating. We know our children are not born at the age of their parents. They're born at almost zero. So the process of morphogenesis is drastically rejuvenating. But even these anthrobots are younger than the cells that they came from.

Slide 44/58 · 48m:00s

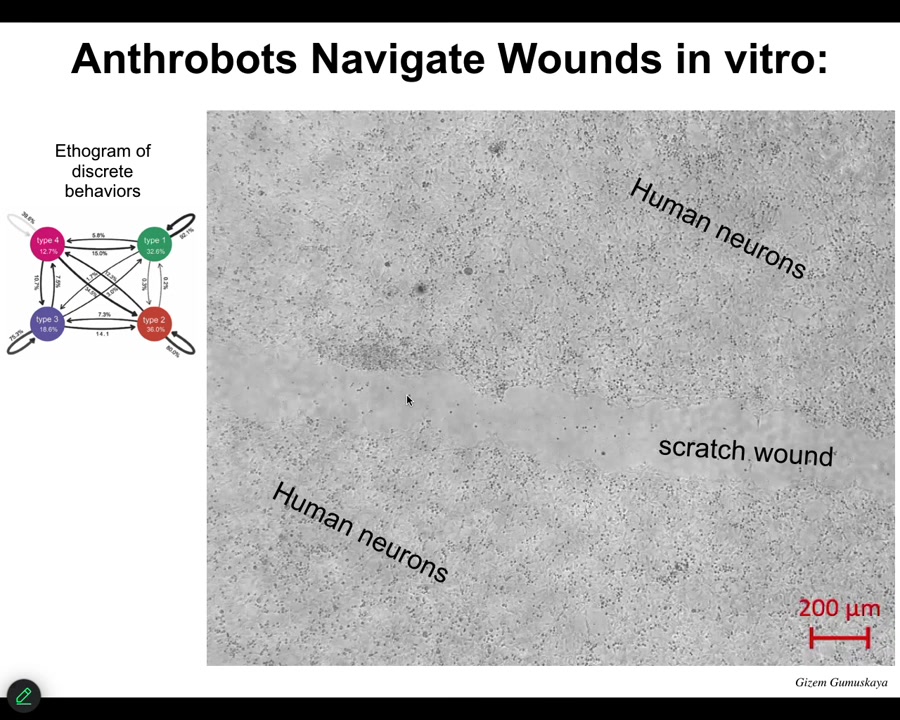

They have a number of behaviors and we can draw an ethogram of different types of behaviors and the probability transitions between them. One of the cool behaviors that they have is that they can traverse these scratch wounds. All this stuff up here is human neurons. We made a big scratch through here with a scalpel. These bots can then drive down.

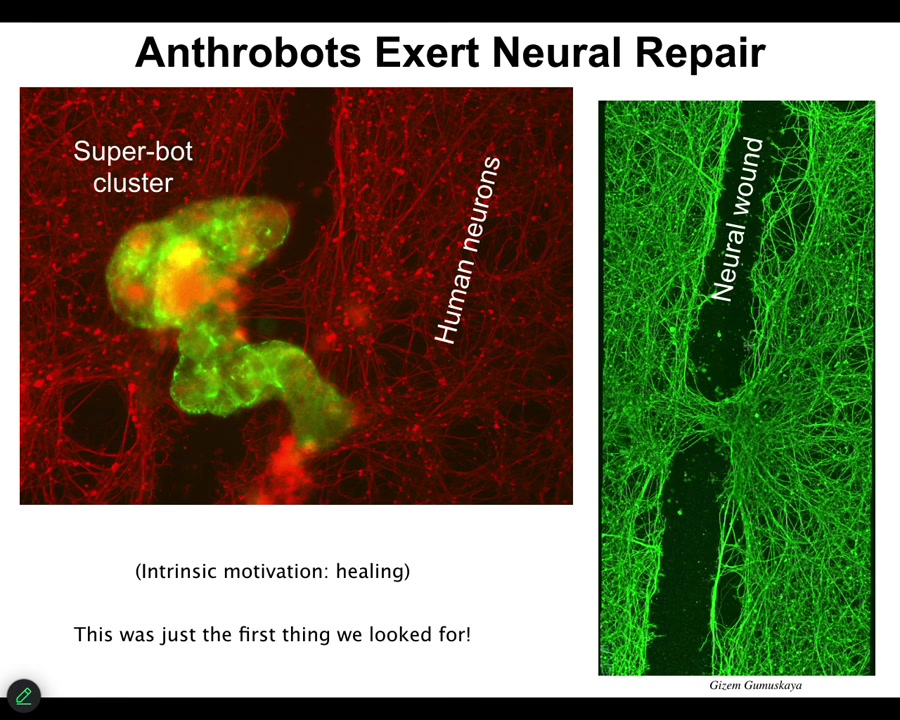

Slide 45/58 · 48m:22s

And what you'll see is that when they pick a spot to land, they assemble into this kind of super bot cluster. There's maybe a dozen of them here. What you see they start to do is heal across the gap. If you lift up the bots four days later, you see that they've made this healing.

I want to point out two things here. First of all, this is a kind of intrinsic motivation in the sense that we didn't program them to do this. We didn't make them do this. Whoever thought that your tracheal cells, which sit there quietly in your airway and deal with pollen and mucus, have the ability to be a multi-little autonomous being that can heal neural wounds. We would have no idea. That's the first thing.

It's cool that the one we found is very positive and healing.

The other thing to point out is this is just the first thing we looked at. This is not test 92 of 1000 things we looked for. This is the first thing we looked for and that we found. That says to me there's probably just the tip of the iceberg. There's probably a million things that these guys know how to do.

Slide 46/58 · 49m:30s

Here's the important point. Where do the properties of all these kinds of beings come from? We know that the frog genome, for example, gives us this. The specific history of the frog genome, by butting up against the environment, gave us a certain set of developmental stages and then these tadpoles with certain behaviors. But it also gave us the xenobots. This is an 84-day-old xenobot. So what did the genome actually learn during all this time? There's never been any xenobots or anthrobots. There's never been selection to be a good xenobot or a good anthrobot. You can't really blame the properties, the forms and the behaviors of any of these kinds of beings on a history of selection. They were never selected for this.

The processes of evolving a frog automatically give you this stuff. That's fine, except that it breaks the whole point of what evolutionary theory was supposed to do for us, which is to explain the specific properties that living organisms have with respect to the history that got them there. There should be incredible amounts of specificity between what happened in the past and what we observe now. If we're saying that at the same time that you selected for all this you've got all these capacities, then that tells us the standard story is incomplete in major ways.

On the computational side, you can ask the same question. When was the computational cost for all of this paid? Because this never happened before. We have some very interesting questions around when these kinds of things appear and why they appear.

Slide 47/58 · 51m:14s

I'll point out that I think it's very clear now that the thinking that the physical world is closed with respect to causation and with respect to the things you need to understand to explain physics, biology, and computation is just no longer viable. It hasn't been, I think, since the time of Pythagoras and Plato. They saw this clearly. I already mentioned this idea that the properties of prime numbers are actually what you need to understand if you want to know why the cicadas are doing what they're doing. This is not a fact of physics or evolution. This is a fact that comes from mathematics.

Slide 48/58 · 51m:52s

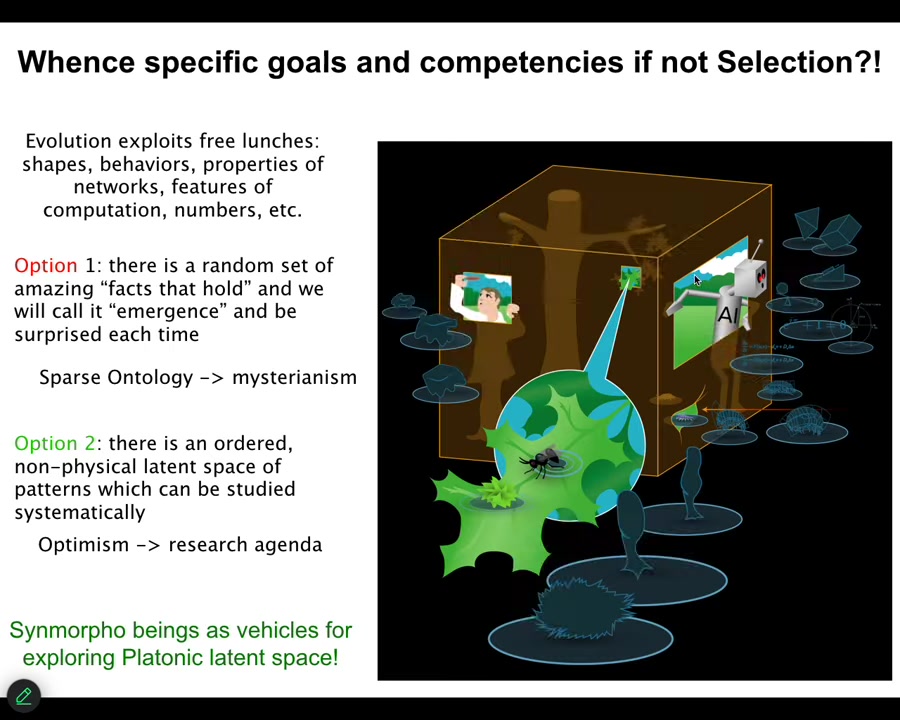

Here comes some ideas about how to think about this in the future. And I realize that this is a step that most people do not want to take because they like a nice sparse ontology where the physical world is all there is. I don't think that's viable. So how do we think about this? There's a couple of ways to think about these competencies of novel beings.

One way to think about them is that evolution exploits a ton of these free lunches for mathematics, properties of networks, of numbers, of computation. Evolution uses them a lot, and we could go through some examples.

How do we think about them? Here's the typical way people think about them. They say, look, these are just facts that hold. You found that Zenobots do something that they weren't selected for. It's just an emergent fact that holds in our world. That's it.

And so the problem with this standard view of emergence and complexity is that the benefit is that you keep your sparse ontology. You can just say that all we have is the physical world. But the problem is it's a very mysterious and, I find, very pessimistic view of science. It just means that emergence, meaning anything that is surprising to us, anything that we didn't see coming, you can write it down in your big book of emergent amazing things, and then what? Thinking about this as a disordered set of surprises, metaphysically, I don't like it at all.

I prefer what mathematicians do. Platonist mathematicians believe that there is an ordered latent space, a non-physical ordered space of patterns, such as the truths of number theory and all this kind of stuff, which can be studied systematically. I find this a much more optimistic agenda because it's not just a bunch of surprises. If you think that these things exist in an ordered structured space, you can then systematically traverse that space and discover those patterns.

I think that all of these things that we build — Zenobots, but also normal embryos and cells and robots and everything else — are basically interfaces to this Platonic space of patterns. They are vehicles that we can use experimentally to map out the space and to understand the mapping between the interfaces that we built. I think physical bodies are interfaces to these patterns, and we need to map out the relationship between these pointers or interfaces and the thing itself.

Slide 49/58 · 54m:14s

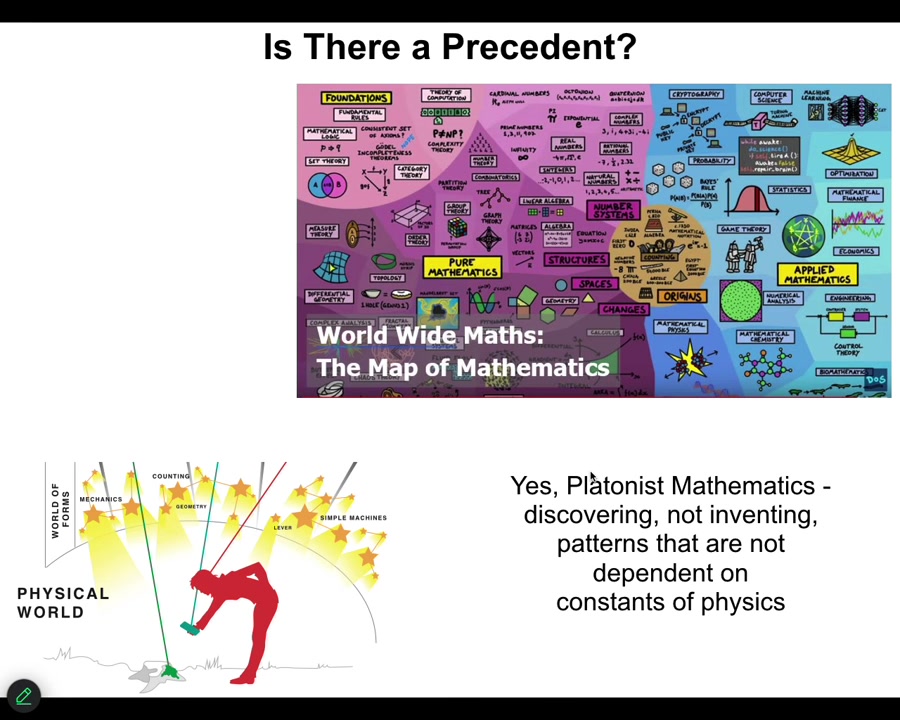

There is a precedent for this. Large numbers of mathematicians think that is what they're doing when they are studying mathematics.

I will go one step further and simply hypothesize this: that along with the layer of the Platonic space that contains low-agency forms, such as facts about numbers and shapes, are very high-agency forms, very complex, dynamic high-agency forms that we would recognize as kinds of minds.

Slide 50/58 · 54m:36s

They are forms of behavioral propensity. They are behavioral properties, not only morphogenetic properties as you find in seashells and other things that obviously are implementing some mathematical forms. That's what I think that all of these things that we're building here or that we find in the natural world are interfaces or pointers into this space that we now have to understand.

Slide 51/58 · 55m:08s

I'm going to end in a couple of minutes and just finish up this way.

I think the Garden of Eden view that we started out with is going to be way weirder than anybody imagined. I think we need to start thinking about minds that are in very different kinds of embodiments.

Overall, this idea of what I've been pushing with this concept of facts of biology that are not explained by either physics or evolutionary history means that we have to think hard beyond the physical embodiment in asking what is this interface actually pulling down from that latent space.

But if that wasn't weird enough, I want to take one step further.

Usually this is the point at which most people have gotten off the ship that I was talking about.

Slide 52/58 · 56m:01s

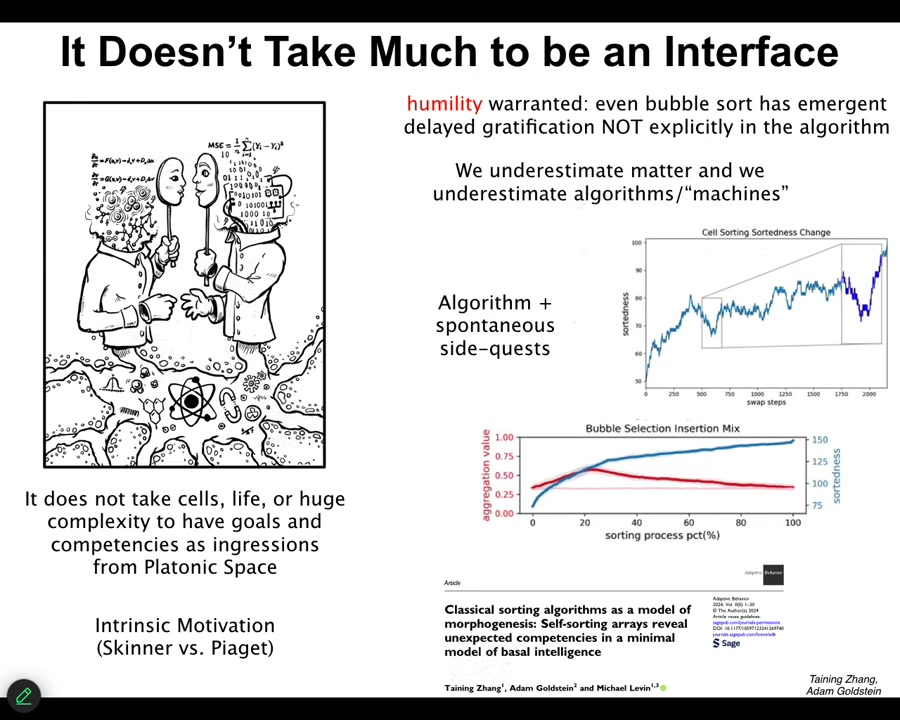

But here's the last bit. If that hadn't done it, probably this might. I want to point out the following, that it doesn't take much to be a good interface to interesting patterns from that space. In other words, I don't think it requires cells, life, or large complexity to be an interface to patterns, including patterns that we recognize as behavioral propensities or even problem-solving skills, AKA intelligence. I don't think it requires any of that to start being the interface to the two ingressions to some of those patterns. You can see this in this paper.

Even something as simple as bubble sort. A simple computer algorithm that was designed to sort numbers, and I specifically started this project because I wanted the most shocking example possible. I wanted something that was really simple, really deterministic, that had no more details to be discovered. It's like six lines of code. You can see everything there. There's nowhere to hide. I wanted to show what even something as simplistic as that has. What we're finding is that not only does it have interesting problem-solving capacities, for example, delayed gratification, so it doesn't just follow a gradient, it's able to move away from its goal in order to recoup gains later. That's a pretty good skill for cognitive systems. Not only does it do that, it does these other weird side quests, which we call clustering, that are nowhere in the algorithm. They're doing specific things that are nowhere in the algorithm. Much like us, they're forced, by the physics of their world, to do certain things. So they're forced to sort numbers, and here you can see the sortedness rises over time. They also do this other thing called clustering, and they do as much of it as they can before the physics of their world grinds them down because they have to sort. It's a very existential story of our life, too. We are also subject to the physics of our universe, but until we disband as a collective intelligence, we have the opportunity to do some things that are neither demanded nor prohibited by the biochemistry that runs our life.

That feature of life is actually appearing in a very simple, very basal form all the way at the beginning. Here we need to start to understand how we relate to engineered agents, because there are the things that we force them to do through reinforcement learning and things like that. There's also the stuff that they do that we never ask them to do, like the things that I've shown you today of the cells that are going to build an eye or the xenobots with their kinematic self-replication or the anthrobots. They do things that we did not engineer them to do, that we did not ask them to, that evolution did not prepare them to do. This very interesting aspect of intrinsic motivation is a huge open research program for the future of agency.

Slide 53/58 · 59m:12s

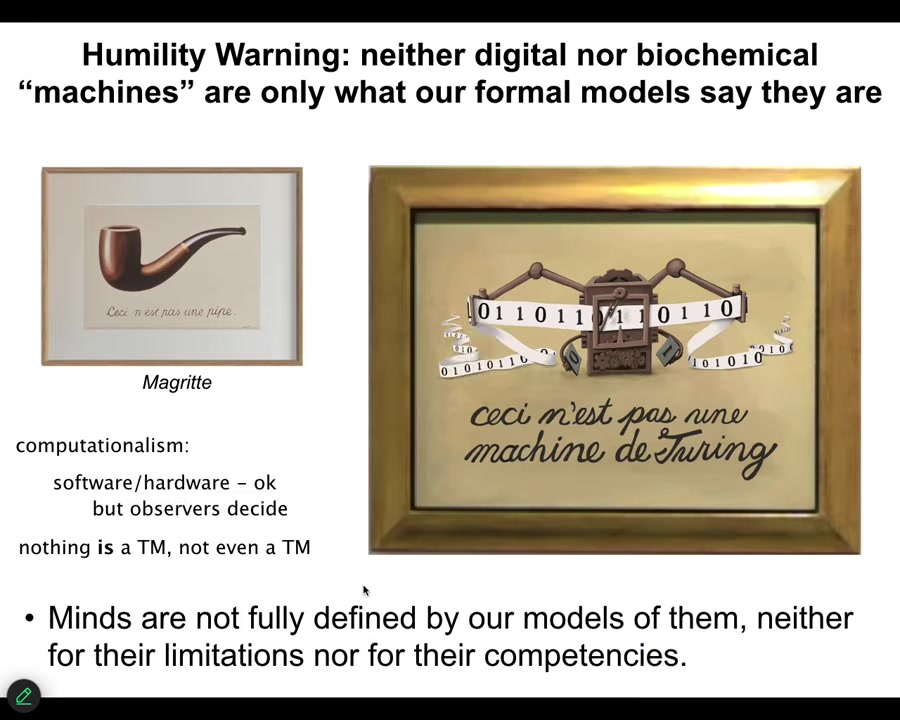

And so I want to point out the big problem with all of this, and the reason a lot of people hate these kinds of ideas, is that there's a whole community of organicist thinkers who really want to keep a sharp separation from quote-unquote machines and the magic and the majesty of living things. They say to me, by putting these things on the same spectrum, you are devaluing what's amazing about life and mind. You are asking us to treat as machines things that we know are not well described by machine metaphors, meaning living and cognitive agents.

I want to point out here that I'm going in the exact opposite direction. I am in no way saying that our simple machine metaphors are suitable for understanding life and mind. I'm saying the exact opposite. I'm saying that in our urge to preserve what's special about life, we have decided that there is this category of dead matter and these kinds of machines that are not like that, and they only do what the algorithm or the materials tell them to do. I think that is a fundamental error.

And I think because we've mistaken our formal models for the thing itself, Magritte is telling us that our formal models of objects are not the objects themselves. I asked our graphic designer to draw this kind of thing. It says in French, "This is not a pipe." And then it says, "This is not a Turing machine." There are no Turing machines. There's only our formal models of a Turing machine.

And this idea, computationalism, this idea that our computer formalisms capture everything that simple machines are doing, I think is exactly as wrong as the idea that some people push that biochemistry and the laws of physics tell the entire story of the mind. We are used to giving a break on that, saying the rules of chemistry don't fully determine what you need to know about our minds. And they also don't for these things that up until now have been assumed to perfectly match our formal models of simple machines. I don't think that exists anywhere. We really have to understand that our models are not catching everything that these things are doing. And we have to be a lot more humble about that.

Slide 54/58 · 1h:01m:22s

So the bottom line is, and I'm over time here, I just want to say a couple of very quick things. This is the new space that we're going to be living in.

All of the natural creatures that Darwin was so impressed with, as when he said, "endless forms most beautiful," are like this tiny corner of this space. Pretty much any combination of evolved material, design material, and software is going to feature ingressions of patterns that we are very poor at predicting. And so cyborgs and hybrots and chimeras of all kinds, we are going to have to find a way to live with them in a kind of ethical synthbiosis.

Slide 55/58 · 1h:02m:05s

For the last minute I want to look at this. If we are trying to build a continuum, what is it that all actual beings have in common? I think this idea of a continuum of scaling goes all the way down. What do they have in common? I want to list those things, and then we can talk about it. The first thing they have in common is this flexible cognitive light cone. So all significant agents have some goal-directed cybernetic loop, and the size of those goals and the space in which they play out determine what kind of being you are.

So not only the kind of goals you can have, but this question of where do you end in the outside world begins, and we've talked about this. I don't have to go over this again.

Slide 56/58 · 1h:02m:52s

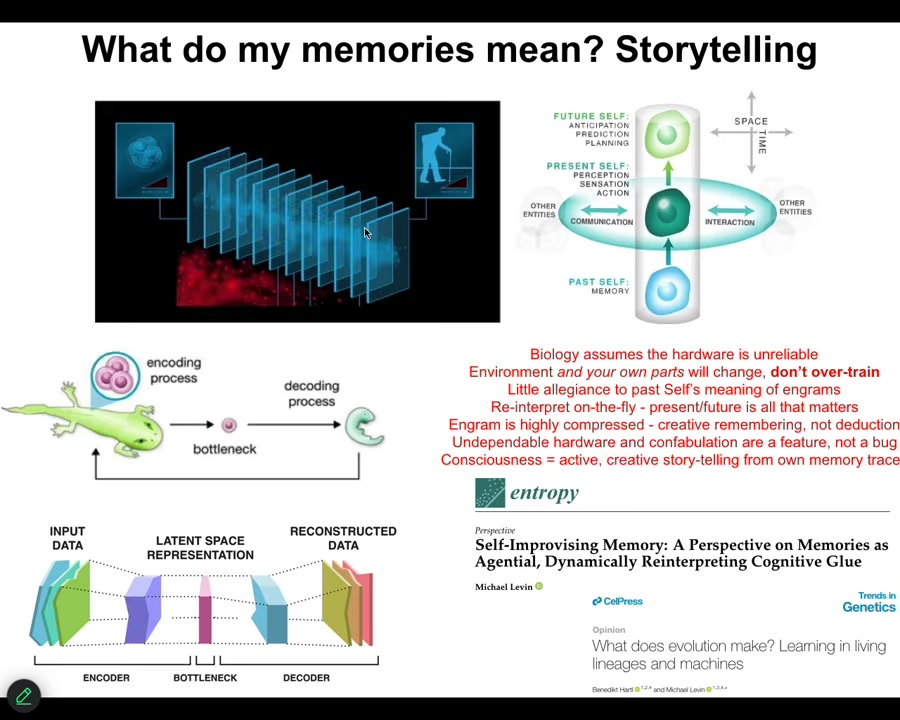

The next thing is the need to interpret your own memories. Significant agents are time slices of a persistent self-telling story during which at any given moment you don't have access to the past. You have access to the memory traces that past you left for you. So messages. Your memories are messages given to you by a past self; you can have messages laterally from other beings. You have to interpret those memories. You don't know what the physical engrams in your brain and body mean. You have to actively reconstruct a story of what you are and what the future is as an active agent.

So all active agents, whether engineered or biological, are experts in confabulatory storytelling. They don't have allegiance to how these messages were interpreted in the past. They tell the best story they can looking forward.

The cool thing is that this is not only a fact about cognitive systems; it's the same thing about biology. The reason that we can have anthrobots and xenobots and all kinds of crazy things I didn't show you today, tadpoles with their eyes on their tails, is that the genomic information is to be interpreted. It is not a determinant of what happens next. It is a set of prompts, as described in this paper, that the agential material of cells is going to interpret as best as it can. If that turns out to be a frog, under normal circumstances, great. If the circumstances are not normal, it will be a xenobot or an anthrobot, and it will pick things out of those genomic affordances that it needs in its new lifestyle.

Slide 57/58 · 1h:04m:39s

I'm going to stop here and summarize.

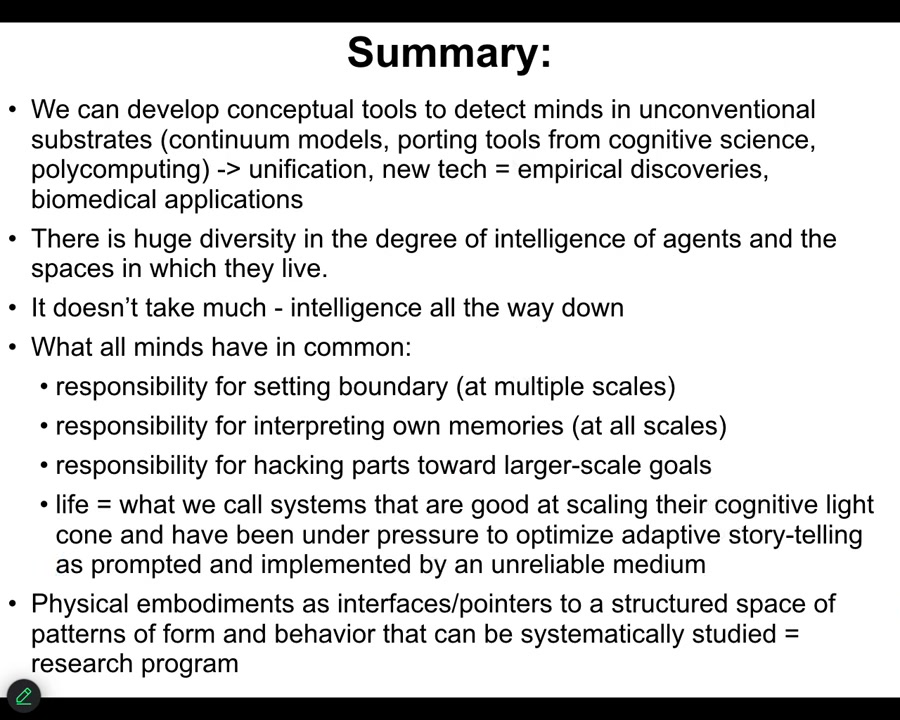

I think that we are in a good place now to develop and mature conceptual tools to detect other kinds of minds and unconventional substrates. We have tools, and it's driving new technology to make new empirical discoveries, such as biomedicine and beyond. I think that there is a huge diversity in the kinds of intelligence and the spaces in which these agents work. We are terrible at noticing it. We have a lot of hubris in thinking that we or even complex life forms are special. I don't think it takes much to get onto that continuum. That spectrum goes all the way down.

Here's what I think all significant minds have in common. They have responsibilities. They are responsible for setting their boundary. They're self-constructing boundaries. They have to interpret their own memories. They're continually self-constructing stories of what they are and what that means in their environment and what they should do. They have the responsibility for hacking their own parts towards their large-scale goals. So you have to control your cells, which control the biochemistry.

I think cognition is a superset of life. If we wanted to define life, I would say that life is systems that are really good at scaling their cognitive light cone and have been under pressure to optimize their adaptive storytelling. They are great at interpreting the information that they get because they are constructed of an unreliable medium. The biological medium is fundamentally unreliable, which has huge implications for evolution and cognitive science.

Physical embodiments are interfaces or pointers to a structured space of patterns of body and mind that can be systematically studied. That is the research program. If anybody's interested in this stuff, there's lots more papers where we discuss these things.

Slide 58/58 · 1h:06m:37s

Most critically, I want to thank all the people who did this work. These are the postdocs and the students who did all this who are mentioned here. We have lots of amazing collaborators that have participated in all of this. Our funders have supported this work over the last 30 years. I have to do the disclosures. There are three companies that supported some of this work and spun out of our lab. Most importantly, most of the gratitude goes to the model systems, biologically and not, that are teaching us about these things every day. So thank you.