Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This ~50 minute talk given at a futurism/AI gathering is a variant of my recent talks on diverse intelligence, focusing on ways to expand our perspective via considerations of non-brain-based intelligence in the body, patterns as agents, synthetic beings as model systems for learning to predict and communicate with agents that do not share our selection history, pattern of form and behavior from the latent space, and more.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Butterflies, memory, and change

(04:16) Humans on intelligence continuum

(08:47) Relationship tools across minds

(13:34) Cellular and anatomical intelligence

(20:25) Bioelectric communication and medicine

(25:07) Active patterns as agents

(30:01) Xenobots and anthrobots

(36:04) Mathematical origins of goals

(43:06) Minds, machines, and futures

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/51 · 00m:00s

What I'm going to talk about today is a topic that I call mind blindness. We're going to discuss the prospects for being able to recognize and communicate with a very wide variety of unconventional beings. If you want to follow up on any of this, visit my official lab website. The data, the software, the published papers, everything is here. This is my personal blog about what I think some of these things mean.

Slide 2/51 · 00m:28s

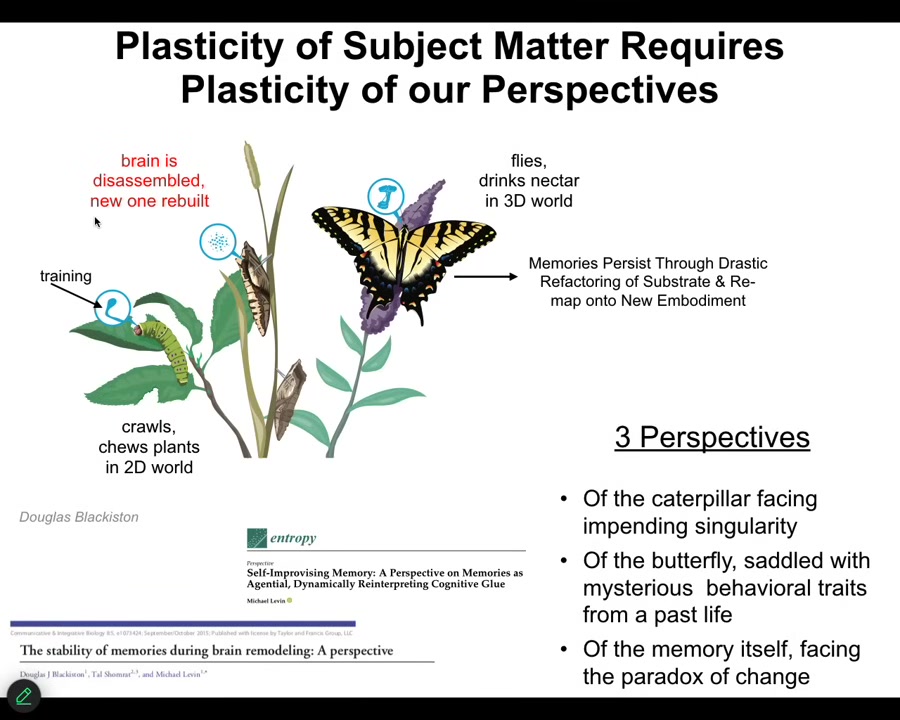

What I would ask us to do first is to consider this phenomenon of the butterfly developing from a caterpillar.

You start off with a soft-bodied creature, which crawls around in a kind of two-dimensional world. It eats leaves, and it has a brain suitable for that purpose. Now, what it has to do is turn into this very different creature, which has hard elements, a completely different controller is needed. It lives in a three-dimensional world. It flies around, drinks nectar. It has a very different brain. In order to get from here to here, what the system does is dissolve most of its brain. Most of its cells are killed off, the connections are broken, and eventually a new brain is rebuilt that's suitable for this life.

I'm going to use this as an example to talk about the plasticity of our perspectives, because the subject matter here has enormous plasticity. In particular, what happens is that if you train this caterpillar, if you train it on a behavioral assay, you can then find out that the moth or butterfly that results from it still remembers the original information. Memories persist through this kind of drastic refactoring of the brain. But more importantly, memories can't persist as they are. The actual memories of a caterpillar, for example "crawl over to eat leaves when you're hit with a particular light stimulus," are of no use whatsoever to the butterfly because, first of all, it doesn't move like that. Second, it doesn't care about leaves. It wants nectar. It's not about the fidelity of the memories; it's about the salience of the memories being remapped onto a completely different body.

In this model system, now that we've discussed that, I want to invite you to take three different perspectives.

The first perspective is that of the caterpillar. As a caterpillar, you are involved in a process that is going to drastically remake you. In fact, you're facing a singularity. There's an impending singularity where you, as you know it, are not going to exist any longer. However, in some important sense, you will continue in a new world, in a higher dimensional space with new capabilities. Things you cared about before, you will no longer care about, but you will have new and interesting things to do. That would be the perspective of the caterpillar.

Take on the perspective of the butterfly. You've come into the world, you have things that you're interested in and things that you can do, but you're also saddled with some mysterious memories, these behavioral traits, such as the things that the caterpillar was trained on, but of course you don't know anything about that. You just know that you've inherited some sort of weird propensities to do certain things when you see specific stimuli, and you don't know where those come from. They're certainly not from this life that you remember. They come from somewhere else. Somehow they become integrated into your behavioral repertoire. That's a different and also interesting perspective.

The most bizarre one of all is the perspective of the memory itself. How memories and other patterns in excitable media can even have perspectives. The idea is this. If you're a memory pattern within this system, within the caterpillar, you can't persist as you are. If you hope to persist through this change, you yourself are going to have to change. You're going to have to be modified in a way that is going to be salient to this novel substrate so that you are not wiped and forgotten. That means you're facing the paradox of change. If you don't change, you will not persist. If you do change, are you really the same? Are you really you anyway? All of these interesting things are brought up by this kind of system.

The reason that I'm going through all this is that I think we're going to have to radically widen the number of systems from whose perspective you are going to have to learn to think.

Right now, we don't do that very well, and we are going to have to get much better at it.

Slide 3/51 · 04m:32s

Because what we're going to talk about is not about language models or standard AIs.

The first thing that we're going to confront is this thing. Because we now know that as humans, we stand at the center of this continuum. We were single cells, both during evolution and during embryonic development. Each of us made our way from a single cell to what we are now, a modern adult human.

But of course, there's another continuum of modifications here, both biological and technological, where we already have humans walking around with sensory augmentation and various implants, and that's only going to grow. And so the idea is that this distinction that people like to make between proper beings, proper humans, in fact, and then so-called machines, is really not going to serve us well at all in the next coming decades, because what we don't want is to be sitting there trying to figure out whether your neighbor has 51 or 49% of their brain replaced with various engineered artifacts to see if they are a real human and deserving of your respect and compassion and whatever else.

And most of these issues, and you can see this discussed in this paper, most of the issues brought up recently by AI, such as, do these kinds of systems truly understand? We understand things. What does that really mean? All these kinds of questions are fundamentally unsolved questions about ourselves. They're being brought up by technology and AI, but they're really not novel. This issue of being replaced, in future generations doing things that past generations don't understand, and all these kinds of things have been with us for a really long time.

Slide 4/51 · 06m:15s

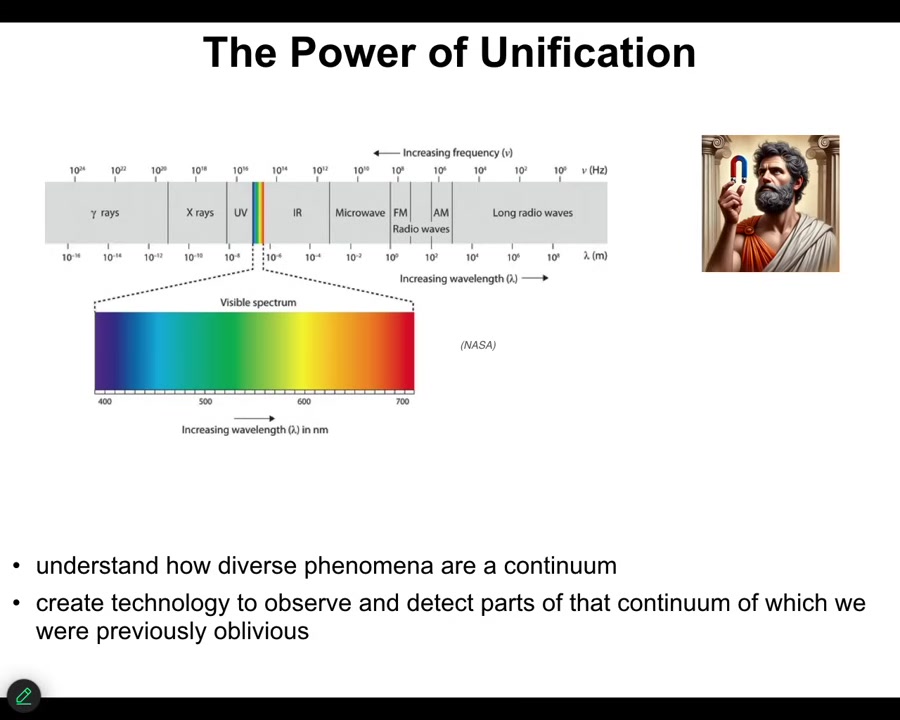

So what I'm interested in is trying to expand our very limited idea of how to recognize other beings and how to relate to them. I want to give you a very simple example. In the pre-scientific age, we had static electricity, and we had lightning and magnets and visible light. We used to think those were all very different things. We had different names for them. We thought they were categories that are discrete, they are different, and so on. The modern theory of electromagnetism did two things for us. First of all, it told us that all of those kinds of things are really manifestations of the same underlying continuum. It discovered a very deep symmetry in the world, showing us that our former categories don't really cut up the world in a deep way. The second thing it did is remind us that because of our own evolutionary history, we are only sensitive to a tiny portion of the spectrum. We were completely unaware that all this other stuff exists and we were not able to operate in that spectrum. I would propose that we have the exact same issue with respect to other minds.

Slide 5/51 · 07m:22s

We have a tremendous amount of mind blindness around beings that operate at different scales in different spaces. We're just not good at recognizing them because of our own evolutionary history.

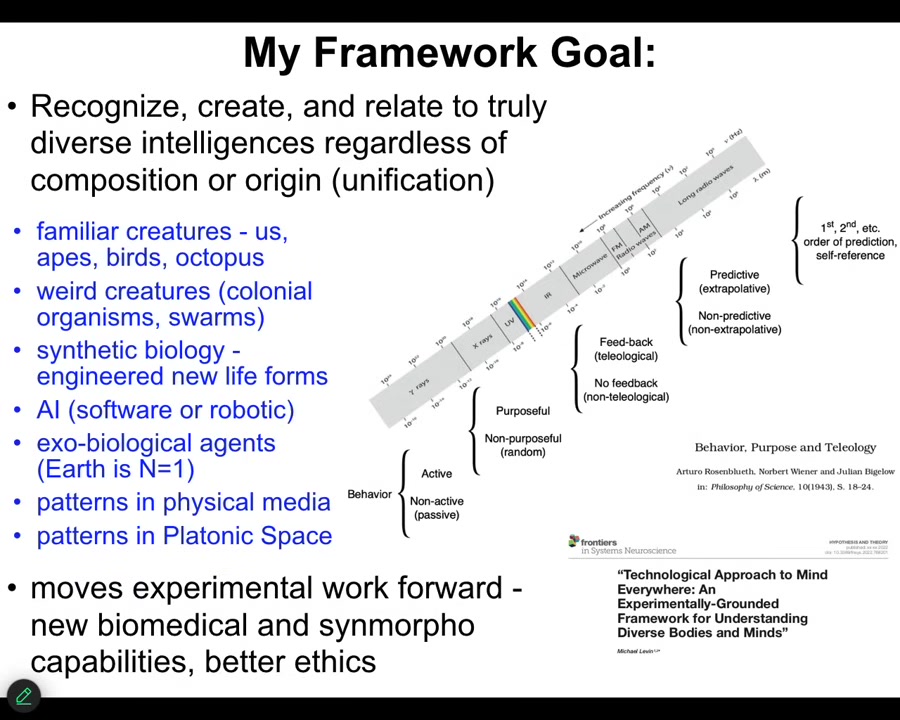

So my framework and the goal of a large part of my lab is around being able to develop tools to recognize, create, and ethically relate to truly diverse intelligence. That means not just primates and birds and maybe an octopus or a whale, but also really weird creatures such as colonial organisms and swarms, engineered synthetic new life forms, AIs, whether software or robotic, maybe someday exobiological agents such as aliens, and even some very strange things, which I'll touch on towards the end of the talk, such as patterns in physical media.

What we'll end on is this idea of patterns in a Platonic space. Some of this can be seen in this paper where I very carefully go over all the kinds of philosophical issues that have to be settled here.

But what I'm fundamentally interested in is frameworks that are not just philosophy, but make really practical contact with the world. That is, they move experimental work forward. Most of our lab applies these advances to regenerative medicine, birth defects, and cancer. As well, the development of novel ethical systems, which I think is going to be critical.

Slide 6/51 · 08m:48s

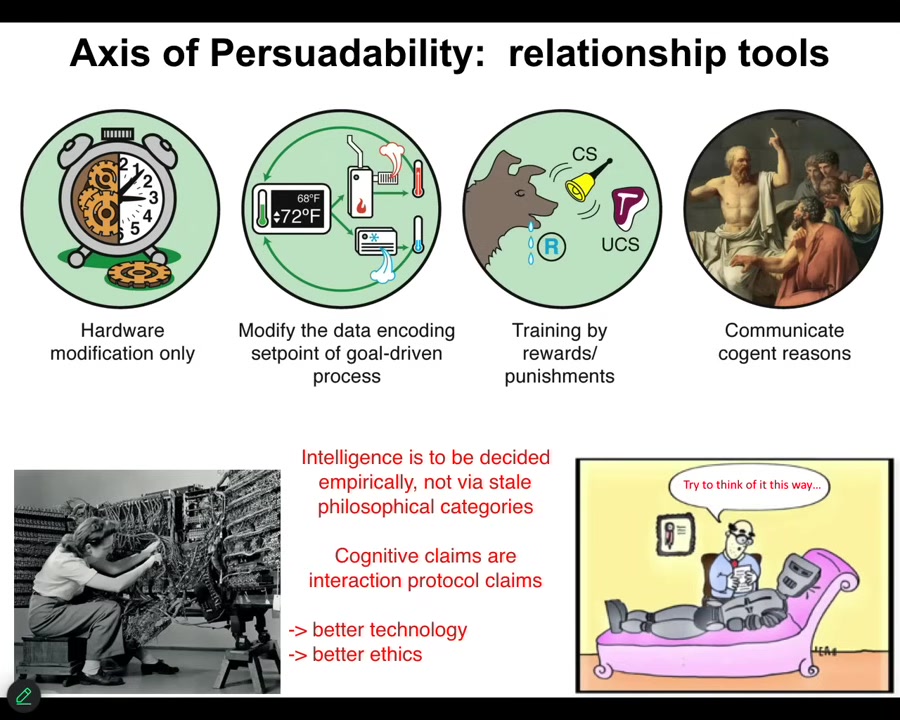

The one thing to understand about this kind of spectrum of whether you call it intelligence or cognition is choosing appropriate relationship tools.

If the system is simple and mechanical, the only way you're going to relate to it is by modifying its hardware. You're not going to convince it of anything or make it feel guilty. But if you have a system like your thermostat that is homeostatic, then you have something new you can do. You can use the tools of control theory and cybernetics to reset its goals. It's a primitive goal-seeking system.

Then you keep going, and eventually you encounter systems that have all kinds of learning capacity, and you can interact with them via the tools of behavioral science and training and rewards and punishments. Eventually you reach systems with which you can use the tools of psychoanalysis and friendship and love and reasoning.

The key thing to understand is that when you're looking at some system, you can't simply have feelings about where you think it is on the spectrum. When you see cells or simple machines, you say, I don't think this thing is cognitive. You can't really say that. You have to do experiments. All of these things are to be decided empirically, not via ancient philosophical categories.

Any kind of a claim like this is really a protocol claim. It means that you take your set of tools, you try to have that interaction with the system, and then all of us can see how well that worked out for you. Maybe you guessed too high or maybe you guessed too low. But it's really important to develop these tools so that we can get a good estimate when we're dealing with systems that we do not understand very well.

Slide 7/51 · 10m:28s

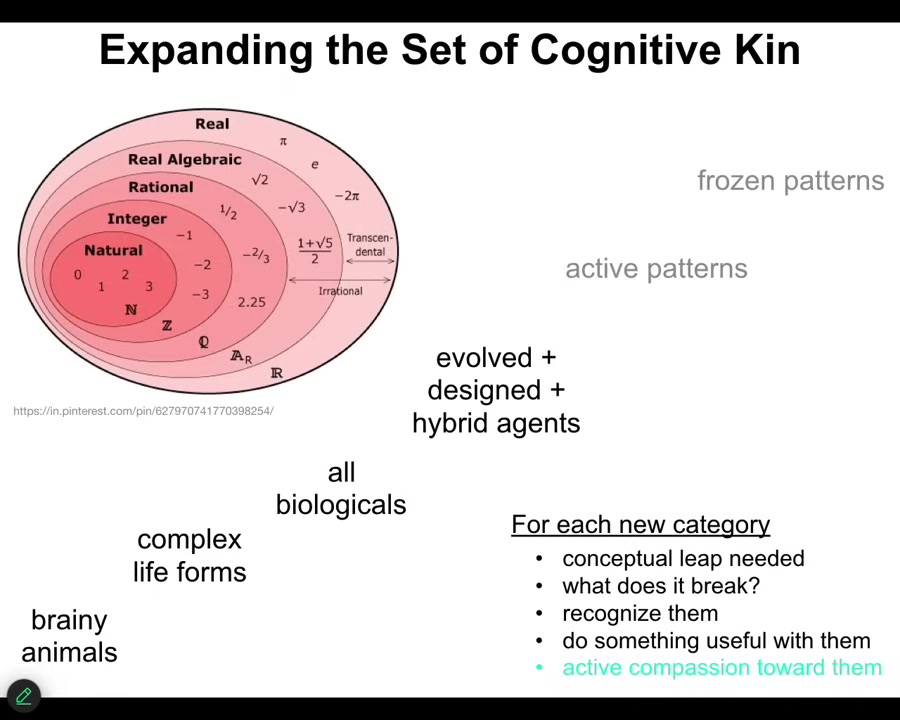

I think what's going to happen here is similar to what's happened in mathematics when people discovered new and different kinds of numbers. So originally we had the counting numbers and everybody understood what that was: one sheep, two sheep, and so on. Then somebody came up with zero, and that was wild, and then eventually negative numbers and then ratios and then irrational numbers. And what happens as you expand your concept is that you have to widen the initial definition, which was too narrow. So these ancient categories can be too narrow to give you what you want. And then you have to break some assumptions. You have to be able to recognize these other things. You have to be able to do something useful with them. I'm going to go up this scale to show you how we're going to expand this notion of other cognitive beings that you might want to interact with.

The thing is, that process is disturbing. This poor guy was drowned off a ship for talking about irrational numbers, because any time you break ancient categories, it shifts around a lot of things that we've gotten used to, and it makes things more complicated, but I think more beautiful in a very necessary sense.

Slide 8/51 · 11m:42s

And the thing we're going to have to get beyond is this ancient picture. This was called "Adam Names the Animals in the Garden of Eden." And you see what's going on here. There's our discrete natural kinds. There's a finite set of specific individual creatures. Adam's giving them names, and then we'll know everything that exists, and we'll know how to relate to all of these things. What we're going to have to break here is this notion that we can easily tell where all the creatures are, and that there's a specific set that we know ahead of time.

The thing we're going to keep from this is actually a very deep and interesting part of the story, which is that originally Adam had to name the animals. God couldn't do it. The angels couldn't do it. It had to be Adam to name them. That's because, for two reasons. One is that he was the one that was going to have to live with them. And that's true. We are going to have to do the same. In these ancient traditions, naming something means you've discovered its deep inner nature. We are going to have to do that. We're going to have to discover the nature of some very novel beings that no one has seen before. So we're going to have to really get beyond this kind of picture. So let's start in a place where everybody understands.

So it's really easy to detect mind in brainy animals.

This little guy is going to set up a little accident scene here.

He knows exactly what he's doing. He has a pretty good theory of mind.

Slide 9/51 · 13m:18s

He's even going to look to see if mom and dad are watching to make sure that somebody's catching this terrible accident scene. This is very obvious because it works on the same spatial-temporal scale as we do. It's in the same problem space. These beings have similar goals as we do. We can detect this pretty easily. So now let's get beyond this.

Slide 10/51 · 13m:35s

Let's talk about biological intelligence outside the brain. We're going to have to make some leaps here and break some things. This is what we do mostly in our lab as we study cells as collective intelligence operating in morphospace.

Slide 11/51 · 13m:50s

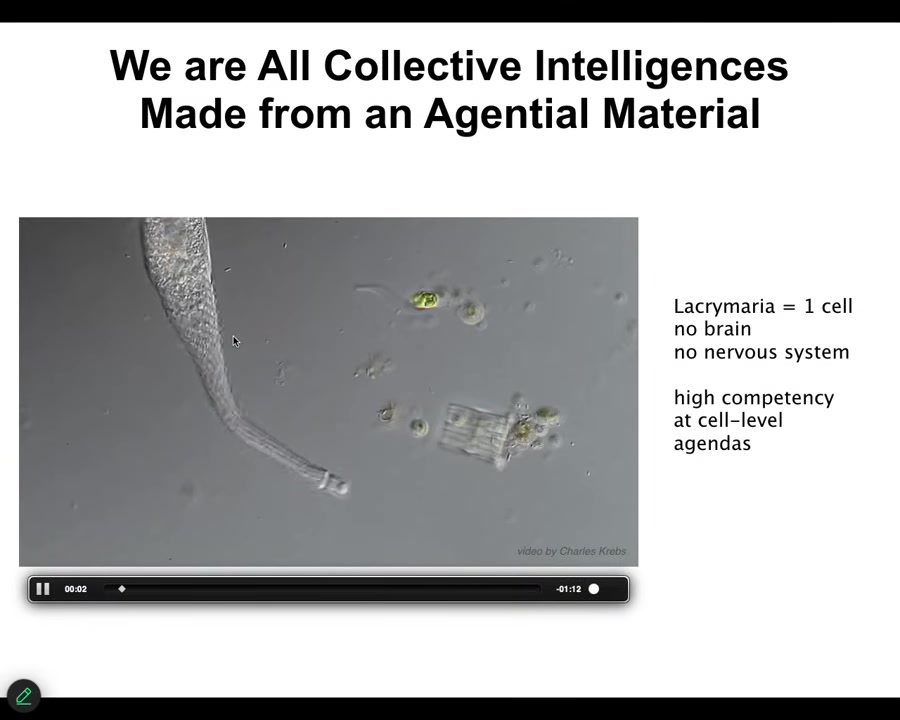

The first thing to realize is that we are all collective intelligences because we are made of an agential material. This is what we're made of. Not just bee colonies and anthills: our collective intelligences — all of us — are made of parts. Our parts are very smart.

This is a single cell. There's no brain. There's no nervous system. This is a free-living organism. It has extreme competency in its tiny cognitive life, with its local, very small agendas. This is the kind of thing we're made of. Even this creature is made of molecular networks.

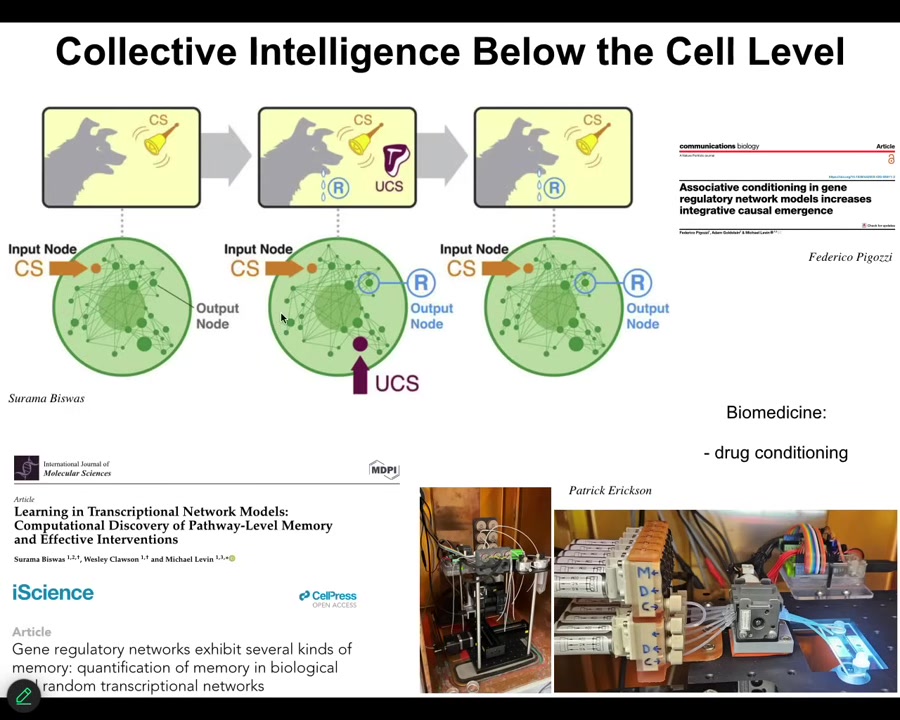

Slide 12/51 · 14m:30s

These molecular networks are themselves capable of at least six different kinds of learning, including Pavlovian conditioning. The molecular networks inside, not the cell, there are no neurons, but just small molecular networks are capable of learning. We recently found out that learning and causal emergence are tightly related. As the molecular networks learn, their causal emergence goes up. They become more integrated. They become more than the sum of their parts. Individuality and individuation and learning are tightly coupled. We're taking advantage of this in the lab for applications like drug conditioning and other things that are important in biomedicine.

Slide 13/51 · 15m:12s

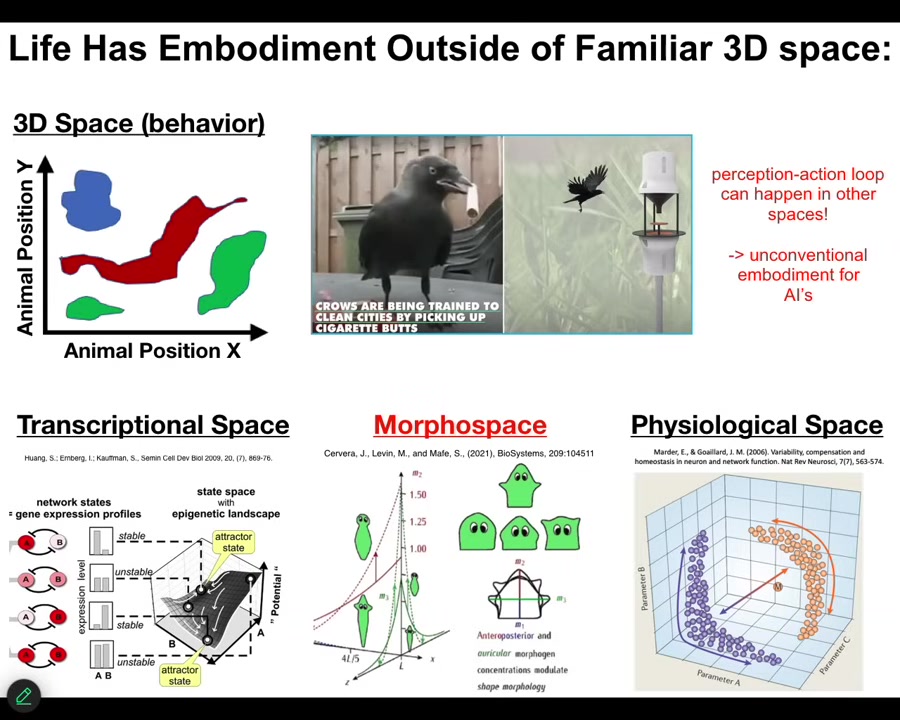

As we think about the future and the kinds of beings that we're going to share our world with, we have to remember that we as humans are obsessed with three-dimensional space. Because of our own senses, we see creatures doing smart things by moving around in three-dimensional space, and we say, that's intelligence, and we're okay at recognizing that.

But biology has been solving problems in all kinds of weird spaces that are very hard for us to imagine. The space of all possible gene expression, that's like a 20,000 dimensional space. The space of physiological states, the space of anatomical outcomes, long before muscles and nerves and brains and all of that developed, living things were doing that same perception, decision-making, memory, action loop that we associate with behavior in three-dimensional space. Biology was doing that in all these other kinds of spaces.

And so this means you have to be very careful when you say that your AI is not real because it is disembodied, because it isn't rolling around in the physical world and touching things in the 3D environment; it doesn't have a body, therefore it doesn't bind its symbols and it can't know what it's talking about. There's a whole lot of different intelligences in biology that do that same tight interaction with their environment, but not because they're moving in 3D space. So we have to break our attachment to 3D space as the only space in which you can have a body. There are many other spaces in which you can have a body.

Slide 14/51 · 16m:40s

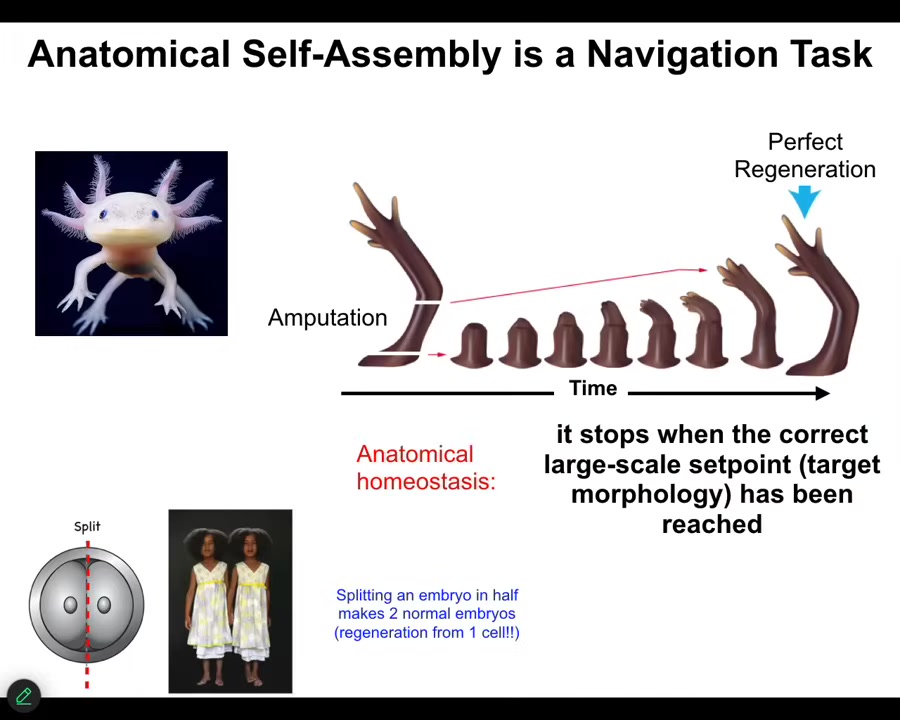

Normally I would give a whole hour talk about this. I want to point out two quick things about this collective intelligence of cells becoming what you are, whether you're a human or this axolotl: becoming what you are is a navigation task in anatomical space. It is not a set of hardwired mechanical chemistry rules that just roll forward. That is not at all what happens in development and in general is incredibly plastic, and it's a goal-seeking process.

If you amputate this limb anywhere along the length, the cells know that they've been deviated from the right position in anatomical space. They'll work really hard to get there, and then they stop. The most amazing part is that when they reach their goal, they will stop. That's how you know it's a goal-seeking system. No individual cell knows what a finger is or how many fingers you're supposed to have, but the collective does, and it very reliably pursues this goal. The same thing is true during development.

What's important about this is that these cells — it's the collective intelligence that pursues this giant goal. I want to point out why this is important.

Slide 15/51 · 17m:55s

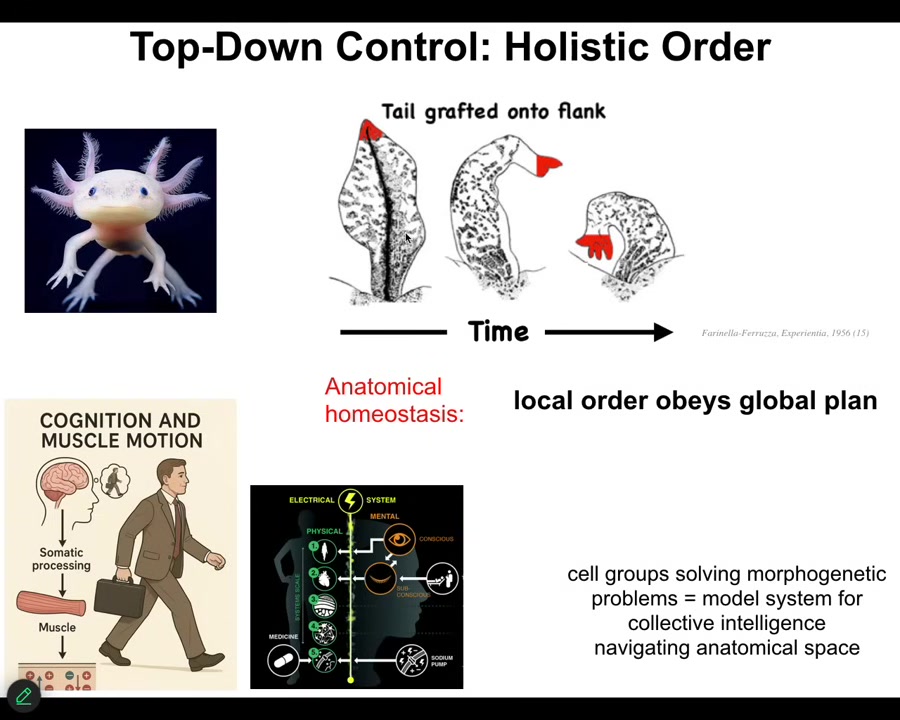

Here's an experiment that was done in the 50s. Somebody took tails and grafted them to the side of this kind of amphibian, to the flank. What happens is that over time that tail begins to remodel into a limb. Now that is an amazing thing. This is not about damage and it's not about injury response. Take the perspective of the cells up here at the tip of the tail. They are tail tip cells sitting in their normal position at the end of the tail. There is no damage, there is no injury, and yet they turn into fingers. Why are they doing this? Because this is a system with top-down control, because the collective, not the individual cells, but the group, knows perfectly well that what you need in the middle here is a limb, not a tail, and then those commands filter down and actually make all of the cell biological and molecular biological changes needed to turn this structure into fingers.

From the perspective of the tail, if you were a cell sitting here, you would have no understanding of what's going on, but there would be major changes coming. It's very clear that they're integrated, that something is happening. These are not random changes, but you don't know why, and you don't know where it's going because you don't have the, as a single cell, you don't have the cognitive light cone to see into that anatomical space to know what's going on. But the collective does. The reason it's important is that all of us are these kinds of systems.

Just imagine this is a remarkable fact that hardly anybody talks about. When you wake up in the morning, you might have financial goals, social goals, whatever; these are extremely abstract goals in very abstract problem spaces. For you to act on any of them, you have to get up out of that. In order to do that, potassium and calcium and other ions have to move across your muscle cell membranes for you to actually execute those goals. This is remarkable everyday magic, that these abstract mental states are actually making the chemistry do different things at the location of your effectors. Your whole body is basically a system for transducing very high-level abstract thoughts and goal states down into the molecular events that have to take place for you to actually walk.

This is something that we study in our lab all the time: how does that transduction work and how do we communicate with the different parts of the system? The way the system actually works has to do with bioelectricity.

Slide 16/51 · 20m:28s

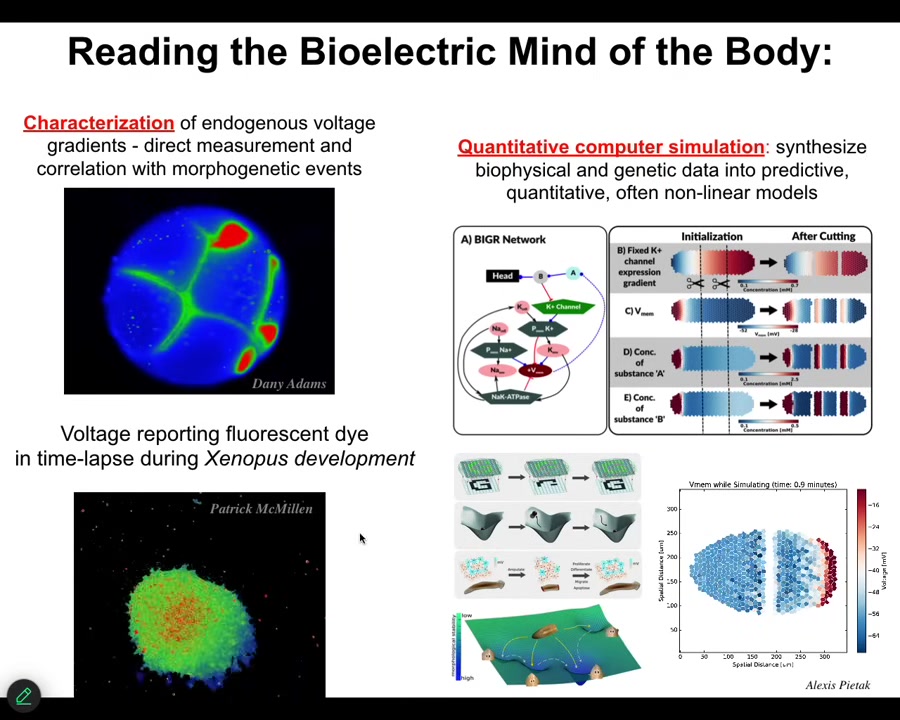

Not a huge shock because we already know that's how our brain electrophysiology works and that's where it evolved. But we developed tools to read, as I'll show you momentarily, the electrical pattern memories that this collective is forming.

This is an early frog embryo and you can see each one of these things is an individual cell and then they're going to divide. But all of these colors are electrical conversations that the cells are having with each other, so that the collective can figure out which side is left, which side is right, how many eyes are going to be.

We've developed lots of computational tools to try to understand what's going on here and how these electrical pattern memories work.

Slide 17/51 · 21m:10s

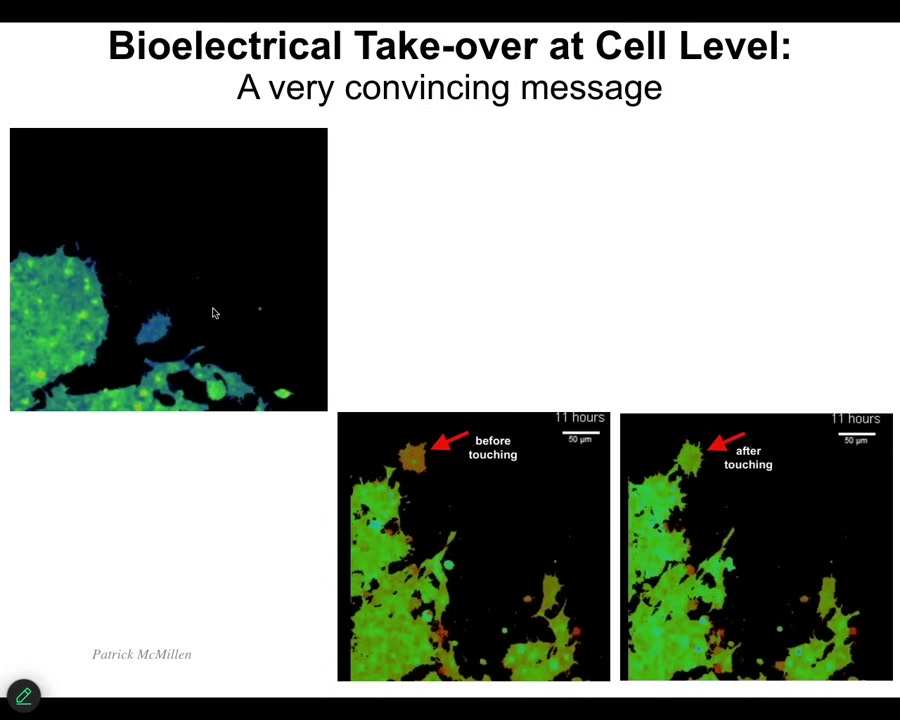

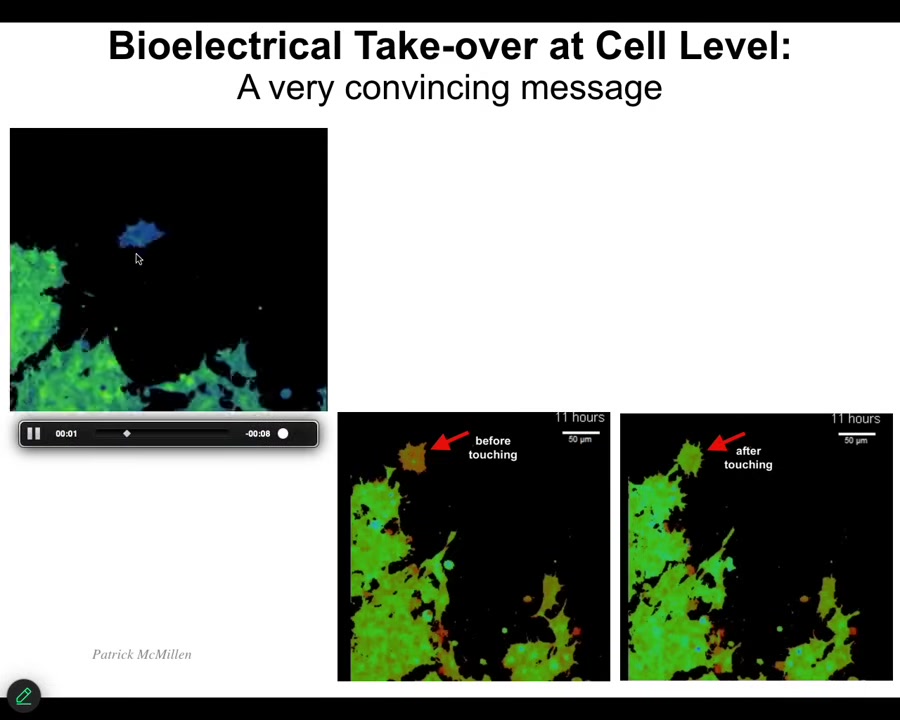

I want to show you an instance of communication, and in particular how these kinds of collectives talk to each other. These are two frames from this video, which I'm going to play momentarily. The color indicates voltage. What we're reading is these bioelectrical states.

What you'll see is that this cell has a very different voltage than this whole collective here, except after it makes this tiny little contact, then it changes. Watch what happens.

Slide 18/51 · 21m:40s

So here it's minding its own business, moving along, it has a different electrical state than this—bang. That's all it takes: that tiny little touch, and now it changes, it becomes just like this other collective group of cells, and it goes over and joins them and starts to boom. It's been hacked and it found whatever message it just got really convincing and it went over and began to work with them. The reason we like to study stuff like this is because we want to communicate to these collectives too.

Slide 19/51 · 22m:08s

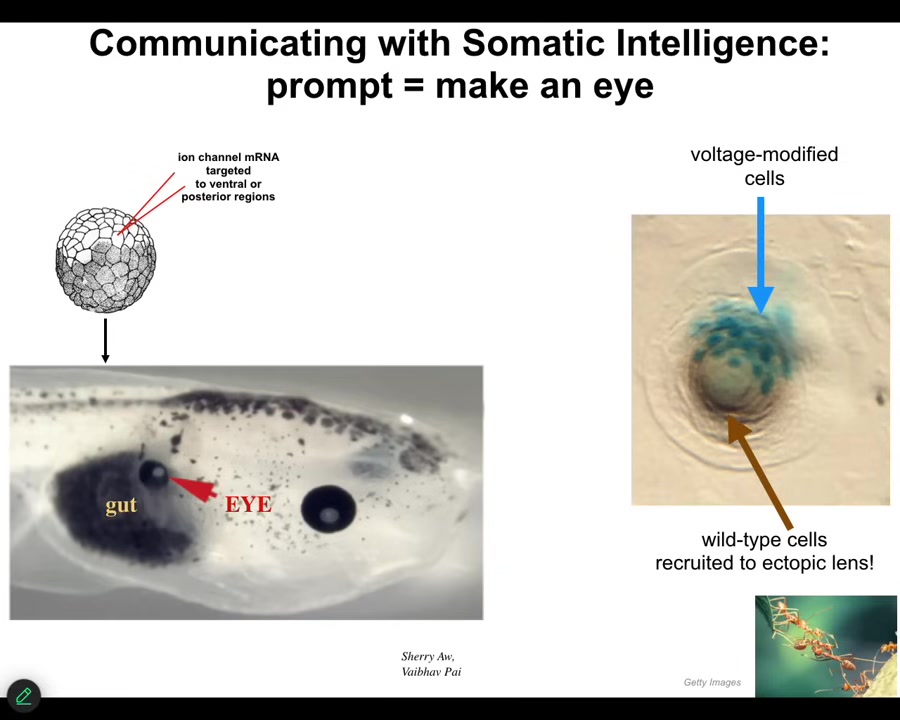

For example, here's one. We've learned how to prompt the cells to make an eye. So what you're looking at is the side of a tadpole here. This is the brain up here. Here's the mouth. Here's the gut. The other eye is back here on the other side away from you. And here's the normal eye. What we did was inject some ion channels to give these cells here a very simple voltage-based message that says "build an eye." We have no idea how to build an eye. We have no idea how to control all the tens of thousands of molecular events that need to take place to specify an eye, much like you don't know what you have to do to get ions to move across your muscle membranes to make you walk. Your body takes care of that, being the transduction machinery. Same thing here. Once we give the stimulus, if we do it correctly, not only will the cells obey and build an eye, and we don't have to sweat the details of how it happens, but also if we don't inject enough cells, the blue ones are the ones we injected, they will automatically talk to all the others and get them to participate. All this brown stuff out here, we never touched it. We only injected these blue cells. They instructed the others to help out and make this thing.

The material is incredible. Not only does it understand very high level messages like an eye. Not just gene expression, not just the proteins, but it actually understands organ identity, but it also knows how to distribute that message to other cells so that they will help. They resist, but this is why we would like to learn to communicate. And so what you're seeing here is the practical implications of having these ideas about talking to collective intelligences. You have to find the cognitive glue. In this case, it's the bioelectric dynamics that we've been tracking. Then you have to learn the language, and then you have to be able to send and receive messages in that language to communicate with them. And that's how you know you're on the right track when you're able to have applications in regenerative medicine or other fields that work.

Slide 20/51 · 24m:08s

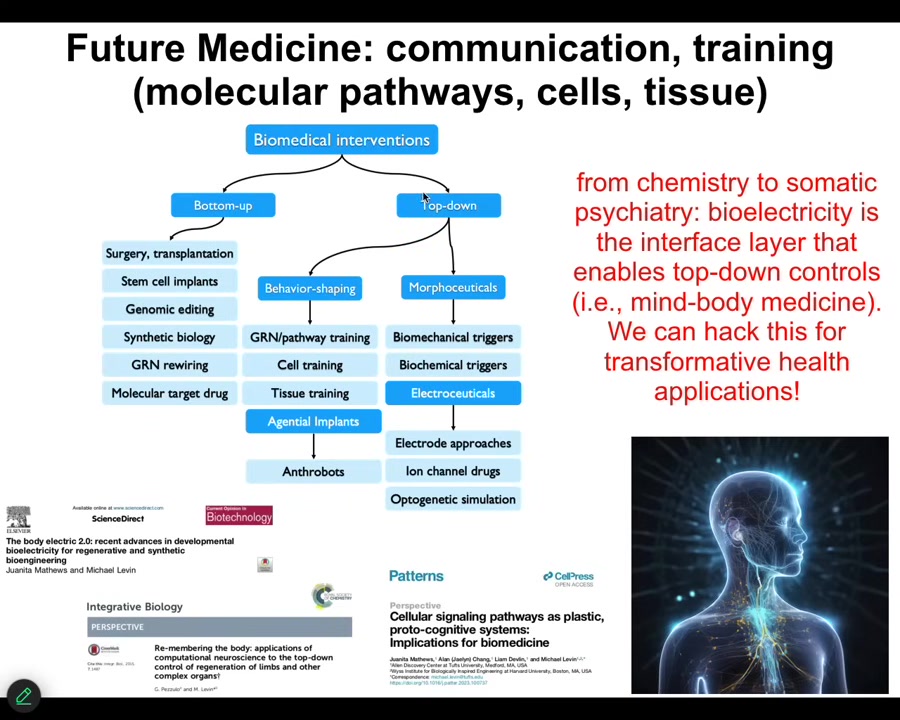

As a peek at what I think future medicine is, today, all biomedicine is basically here. These bottom-up techniques focused on the hardware and understanding not only the software of life but the intelligence of the agential material of which we are all made are going to allow some amazing novel approaches.

I think future medicine is going to look a lot more like somatic psychiatry than it is like chemistry. Right now, everyone thinks it's going to look like chemistry. I think it's going to be all about communication and other ways to understand the stressors and the memories and the priors and everything else of the material of which we're made.

If that wasn't weird enough for you, taking this notion of behavioral intelligence from 3D space into anatomical space and developing tools to communicate with that anatomical intelligence about the things it cares about, which is about different kinds of anatomy.

Slide 21/51 · 25m:10s

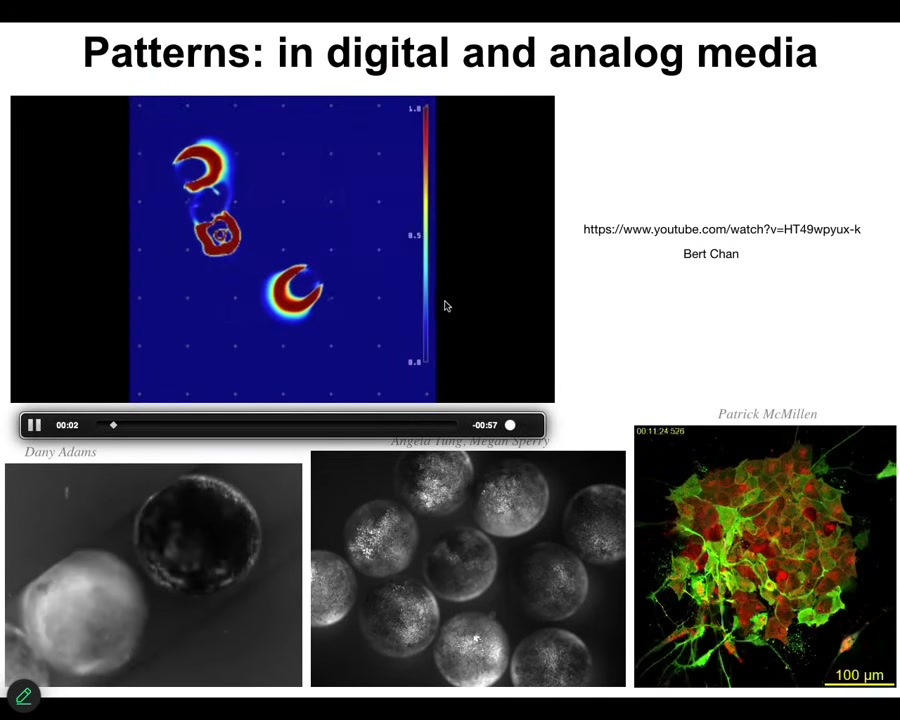

I want to take one step further, and I want to talk about active patterns as the target of our communications. Up until now, what we've been talking about are actual physical things. They're weird because they're not brains, but they're cells, and in fact, electrically active cells, so you can get an idea of how we're going to talk to them. We're going to talk about patterns as opposed to physical objects. What I mean by patterns are things like this.

Slide 22/51 · 25m:35s

This is a simulation. This is an amazing system called Lenia by Bert Chan. If you've heard of the "Game of Life," the cellular automaton, it's a souped-up version of that. But it has these amazing patterns in it. To our visual system, you can see that these are not just individual pixels turning on and off. You've got some stable patterns that are doing various things in that space. Of course, our tissues are doing exactly the same thing.

Slide 23/51 · 26m:12s

This is again bioelectric imaging, and there are patterns that propagate not only through individual embryos, which you can see here, but actually through groups of embryos. I poked this one in the middle, and that pattern, that wave propagated outwards. When they do this injury, that information propagates as a wave across the whole collective.

What I'm going to claim momentarily is that we need to take patterns in excitable media seriously as targets of communication. They are not merely dissipative readouts of what the actual hardware is doing. They are actually the agents at some degree of cognitive capacity; we're not sure yet where they land on that spectrum, but we have to take them seriously.

You might be saying, but that's crazy. Surely only physical beings can be agents. Patterns in media are just patterns; they're not agents.

Slide 24/51 · 27m:25s

So I want to tell a very quick science fiction story based on a story I don't remember which one it was that I read many, many years ago. Imagine that out of the core of the Earth comes some creatures that live down there. They're incredibly dense. They use gamma rays for vision, and so they live in the core. They come out of the surface. What do they see? Everything that you see around you, all this supposedly solid stuff is like a thin plasma to them. They don't even notice it. What they're going to see is that their planet is surrounded by this thin gas that has certain patterns in it.

And if one of them is a scientist, he might track these patterns, these eddies in this thin plasma. He might say to the others, "I've been watching this gas and there are these patterns that hold themselves together for a while." They say, "How long?" "On the order of 100 years." They also look like they're doing things. They almost seem like agents. They move around; they look like they're pursuing goals.

The others laugh at them and say, "No, we are actual agents. We are real physical beings. Patterns in a gas can't be agents." I remind us all that we are temporary metabolic and other kinds of patterns. The distinction between who's a physical agent and who's a pattern of data that flows through that agent is really very relative. It is not absolute.

Slide 25/51 · 29m:00s

The first real paper I saw about this was quite a while ago by Randy Beer. He has this awesome paper on the cognitive domain of a glider in the Game of Life. Gliders are patterns in that medium. They're not real. The actual physics of that world: all it has is individual pixels. It doesn't have any gliders in it.

Chris Fields and I wrote on trying to dissolve the distinction between thoughts and thinkers, between systems that process information and the data patterns that flow through them. There's a deep complementarity here that we have to think about.

In the body, there are many patterns of metabolic, biomechanical, and bioelectrical activity moving around that we really need to take very seriously. The next step I want to take is this.

Slide 26/51 · 29m:50s

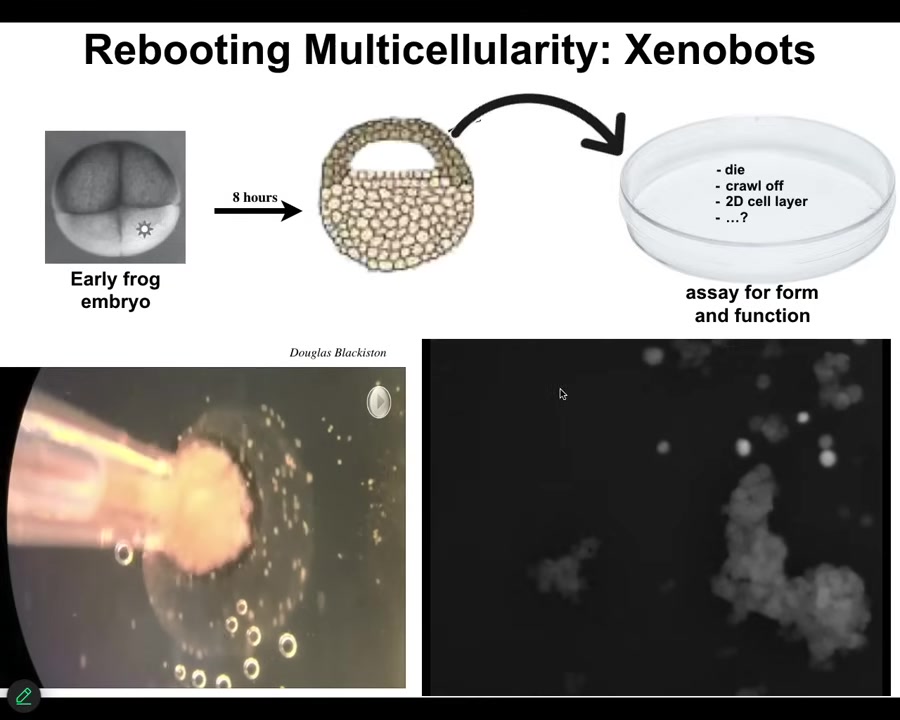

I want to talk about some very novel embodiments for patterns of anatomy and behavior. And we're going to go beyond evolution for this one. These are xenobots.

Slide 27/51 · 30m:02s

You may have seen them before. What happens is when we take epithelial cells from early frog embryos and we set them aside, they don't die. They don't crawl away from each other. They don't form two-dimensional cell culture layers. What they form are these little tiny compact beings. You can watch it happen. Each one of these circles is a single cell. I love the fact that it looks like a little horse. They don't all look that way. There's a wide range, but it sort of moves around as a collective. It has these interesting motions. These are calcium signaling flashes when it explores nearby other cells. They all put together into this kind of creature that has its own motion.

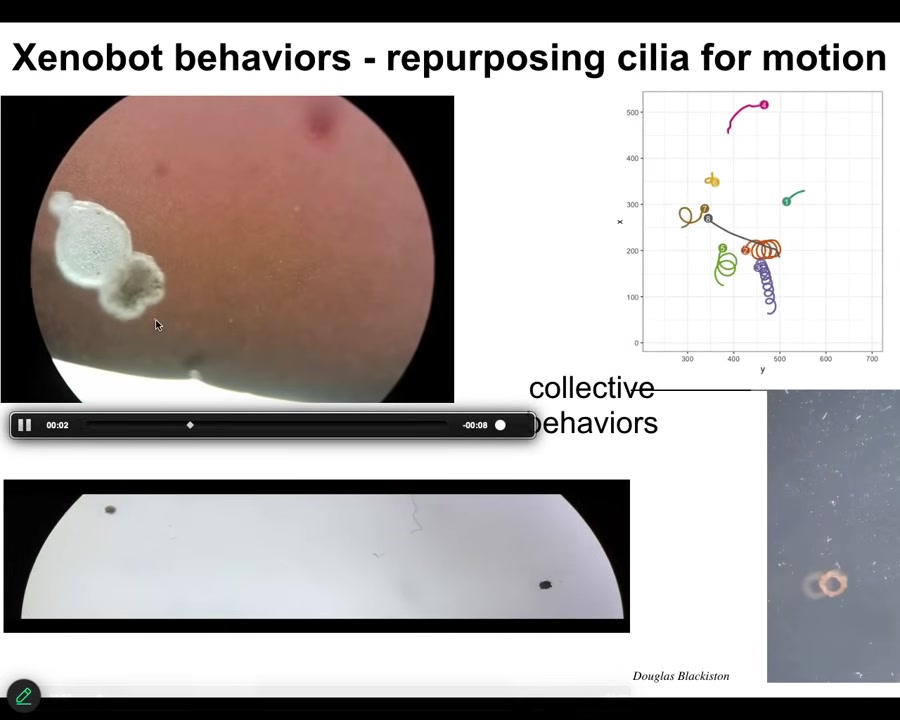

Slide 28/51 · 30m:45s

It has cilia, which are these little hairs that it waves to move through the medium. They can go in circles. They can go back and forth like this.

We can make them into weird shapes like donuts. They can have collective behaviors.

They have all kinds of amazing behaviors.

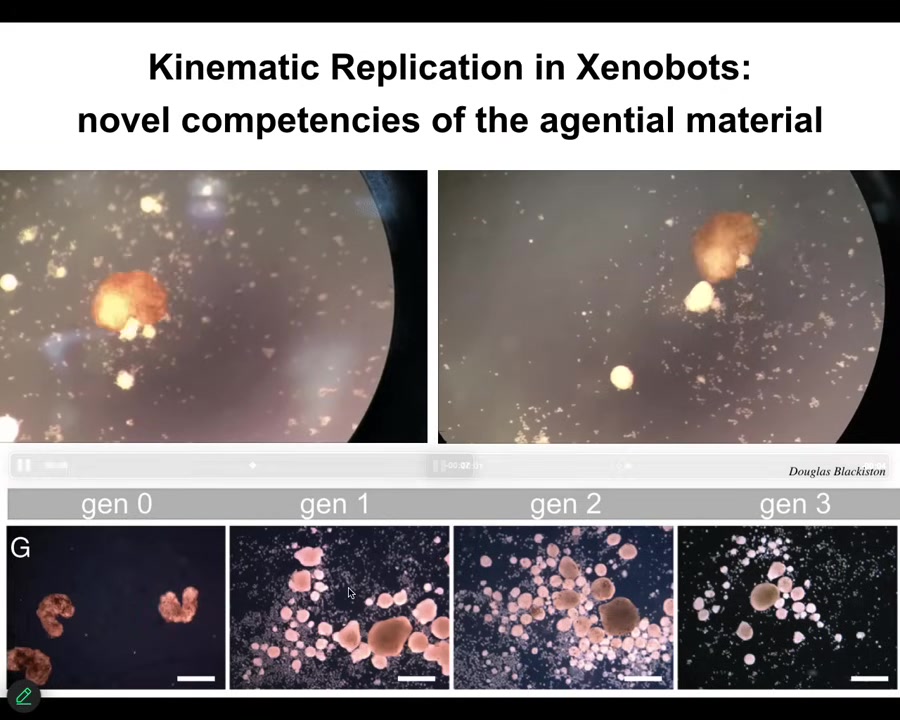

I'm only going to show you two. One is called kinematic replication.

If you give these xenobots loose epithelial cells, they'll go in circles, push these cells into little balls, and then polish them.

And guess what they become?

Slide 29/51 · 31m:18s

They become the next generation of Zenobots. What do they do? They do exactly the same thing, and they make the next generation. We call this kinematic replication.

All we did here was to release these cells from the instructive constraints of the other body cells.

We didn't change the DNA. We didn't put in any scaffolds. There are no synthetic biology circuits.

All we did was liberate the cells from their normal environment and ask, what would you do if you didn't have to do what the other cells are normally forcing you to do, which is to be a boring two-dimensional outer layer, keeping the bacteria out of the body.

Slide 30/51 · 31m:55s

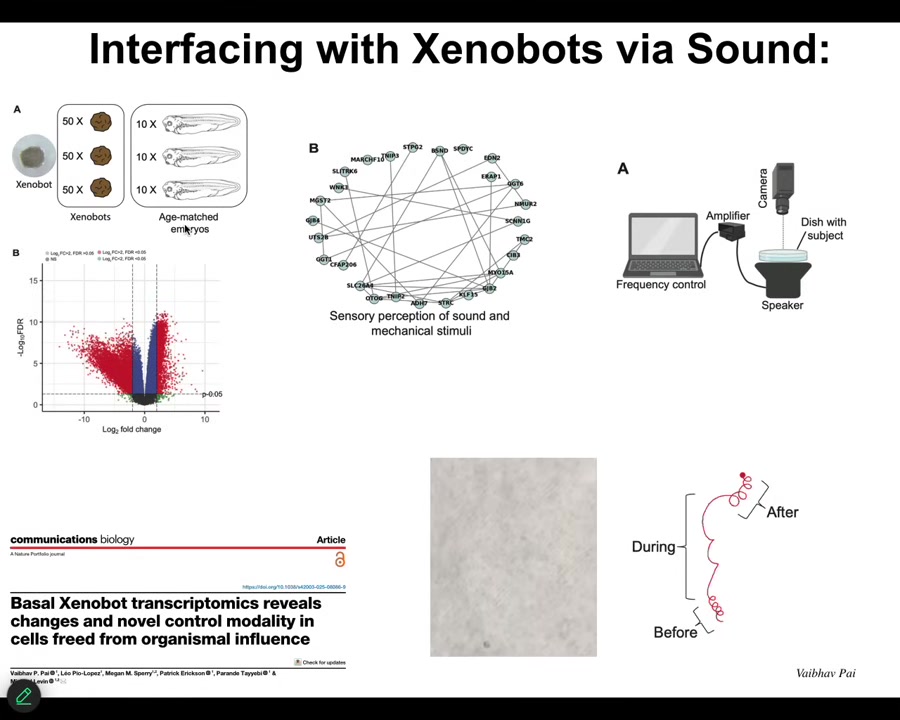

The other thing we found out they do is they have hundreds of genes that are expressed differently. Genes that are expressed differently than they would if they had stayed in the body. Some of those genes are related to perception of sound. We thought, could they possibly hear? We put a speaker underneath the dish. When we started playing the sound, their behavior changed. Unlike actual frog embryos, which don't do this, the Xenobots perceive these vibrations and change their behavior accordingly.

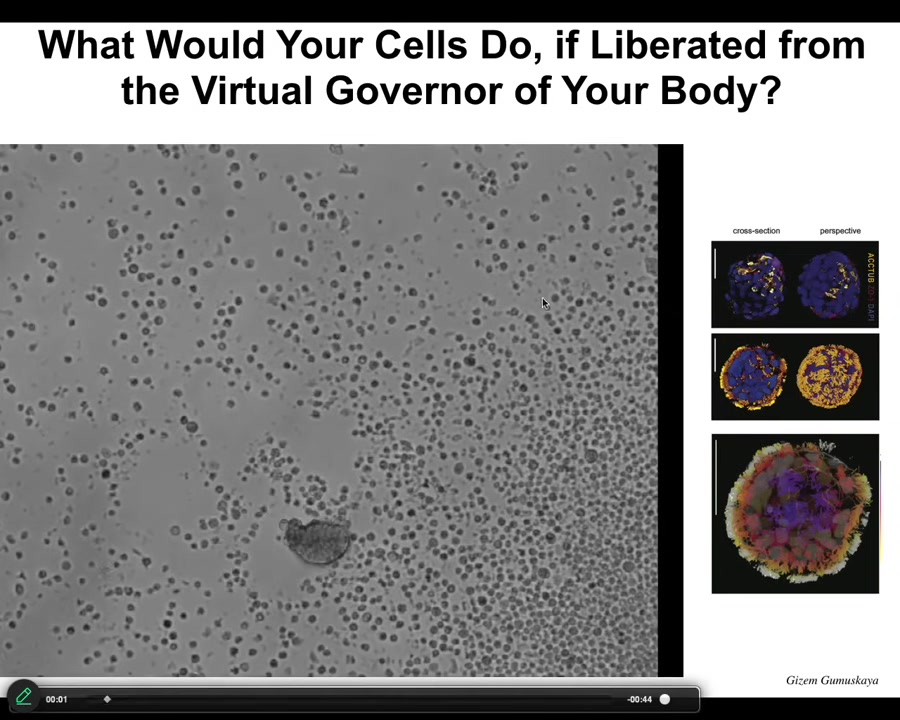

You might say these are amphibian cells and amphibians are known to be pretty plastic in their embryonic cells, so maybe this is some sort of frog-specific thing. Some people said when our first Xenobot work came out that this is an artifact of frog behavior. I asked, what's the furthest we can get from embryonic frogs?

Slide 31/51 · 32m:55s

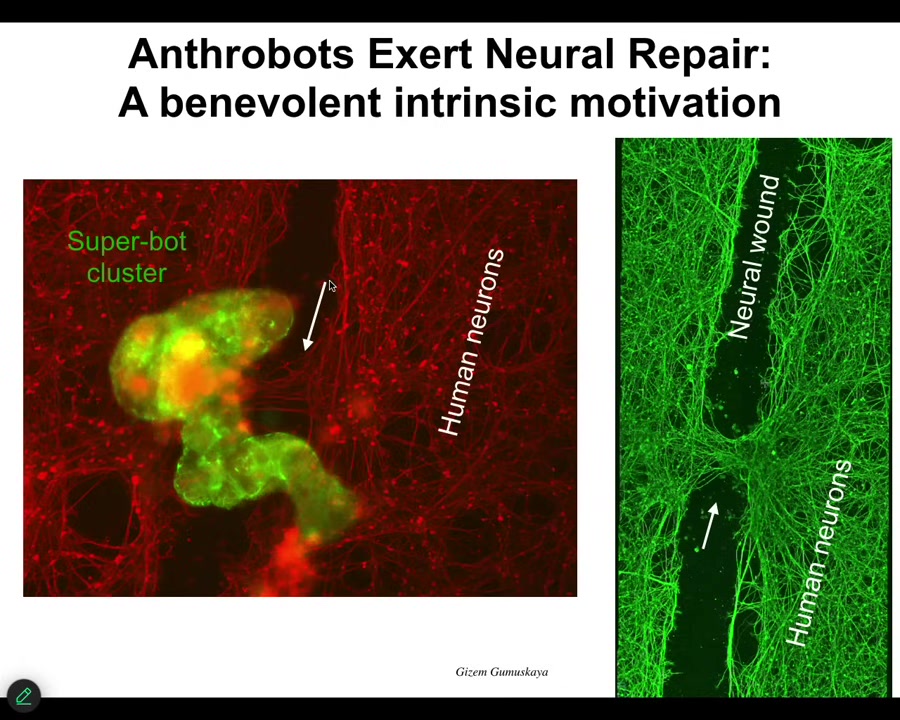

And that would be adult humans. I would ask you, what do you think your cells would do if we liberated them from this virtual governor that your body is to them, that controls your cell behavior? This thing, which looks like we got this from the bottom of a lake somewhere, a primitive organism, is actually, if you were to genetically sequence this, you would see 100% Homo sapiens. These cells were taken from adult human tracheal epithelial tissues. So not embryonic. Adult patients go get tracheal biopsy samples. They sell the cells to a company and we buy them. And this is what they self-assemble into. We call it an anthrobot. It also has cilia. It runs around doing various things. What does it know how to do? One thing it knows how to do is to heal neural wounds.

Slide 32/51 · 33m:45s

If we take a bunch of human neurons here, we make a big scratch down the middle. You let some of these Xenobots, in this case tagged green, into the arena; they will assemble this thing we call a superbot cluster, and then they start knitting together the two sides of the wound. If you lift them up, this is what you see under where they were sitting.

It's amazing, these beings, which have never existed before. This is not experiment number 800 of 1,000 things we did. This is the first thing we tried. We said, what is this novel being capable of? It looks like it's capable of healing. It looks like it's the beginning of a biorobotics platform made of your own cells. If you were using this in the body to heal, you wouldn't need immunosuppression because these are your own cells. Not genetically modified, no weird drugs or nanomaterials or scaffolds or anything like that. This is plasticity of your own cells to do new things when given the opportunity.

Slide 33/51 · 34m:48s

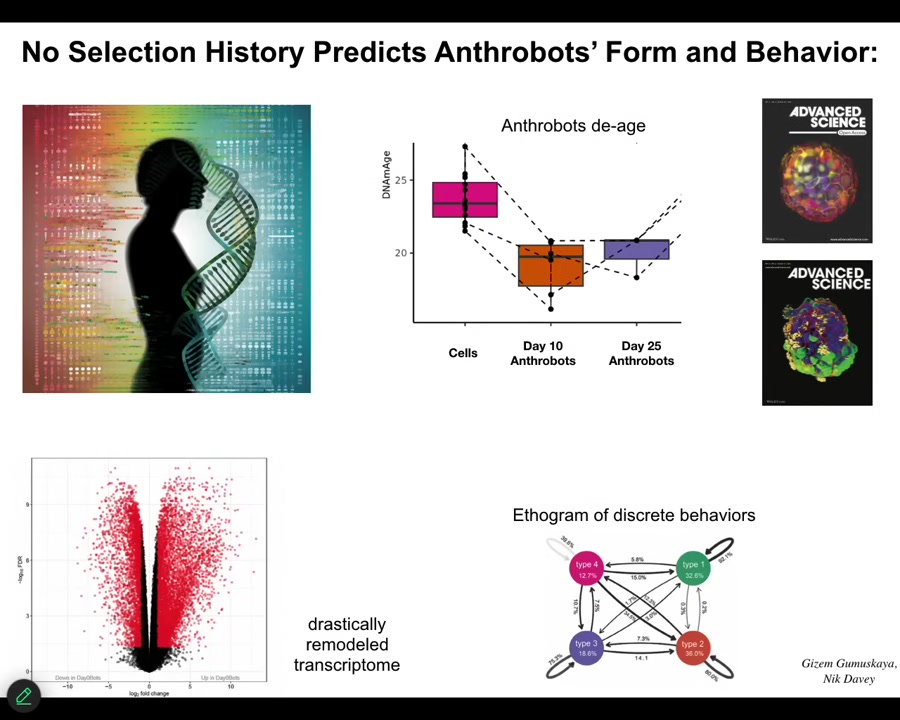

These anthrobots have 9,000 differentially expressed genes from what they were doing when they were sitting in your airway. Who would have known that your tracheal epithelium, which sits there quietly in your airway for decades dealing with mucus and air particles, has the ability to make a self-contained, multi-little creature that also has the ability to heal? They are younger than the cells they come from. So they actually de-age during this process, which is the beginning of our anti-aging program. They have discrete behaviors.

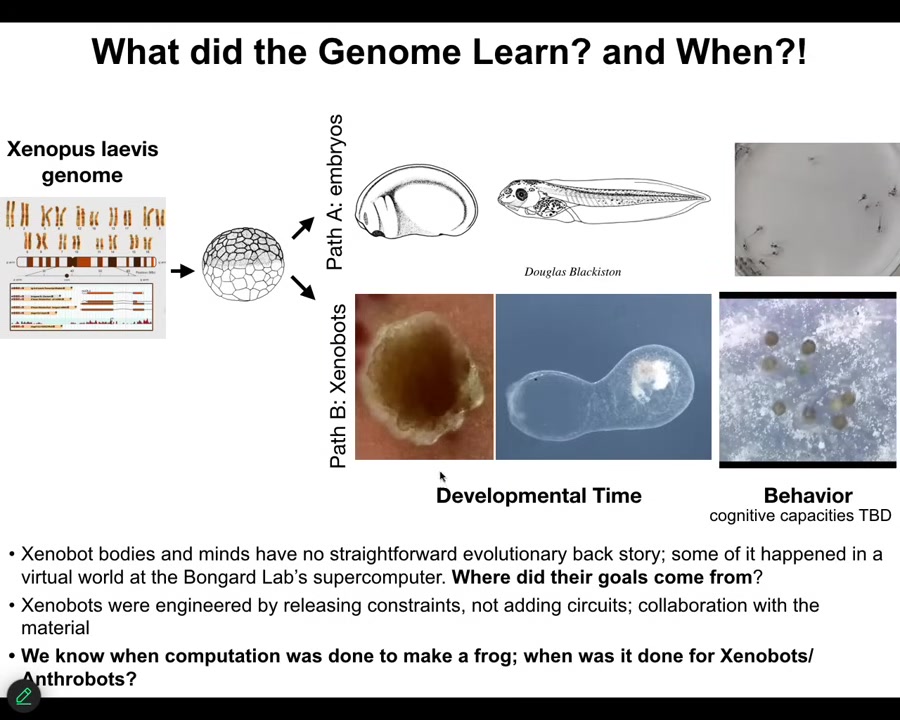

Slide 34/51 · 35m:25s

Here's why I'm telling you all this, because there's something very interesting going on here that's going to help us understand novel beings. We know, for example, the frog genome learned to do developmental stages of a frog and eventually of tadpoles. We know when it happened. It happened during the eons of frog evolution and selection. We also know when the computational cost for this was paid. It was paid by this genome bashing against the environment and getting selected. But when did we pay the computational cost for being xenobots or anthrobots? There's never been any xenobots. There's never been any anthrobots. There's never been selection to be a good xenobot or anthrobot. Those anthrobots don't look like any stage of human development. There's never been selection for kinematic self-replication. All of these things are completely new. You can't pin them on selection. You can ask the question, when were the computational costs for this paid? When did the cells learn how to do all this? It's a profound mystery. Where do the goals of novel beings come from?

Slide 35/51 · 36m:30s

This is what we're going to talk about: where do novel goals come from?

The reason it's important is that if we are going to relate to new beings, whether ones that we have made ourselves or whether ones that we have recognized in our environment, which I think is chock full of all kinds of cognitive beings that we are poorly set up to recognize, where do their goals come from if it's not the kind of selection thing that we're used to thinking about?

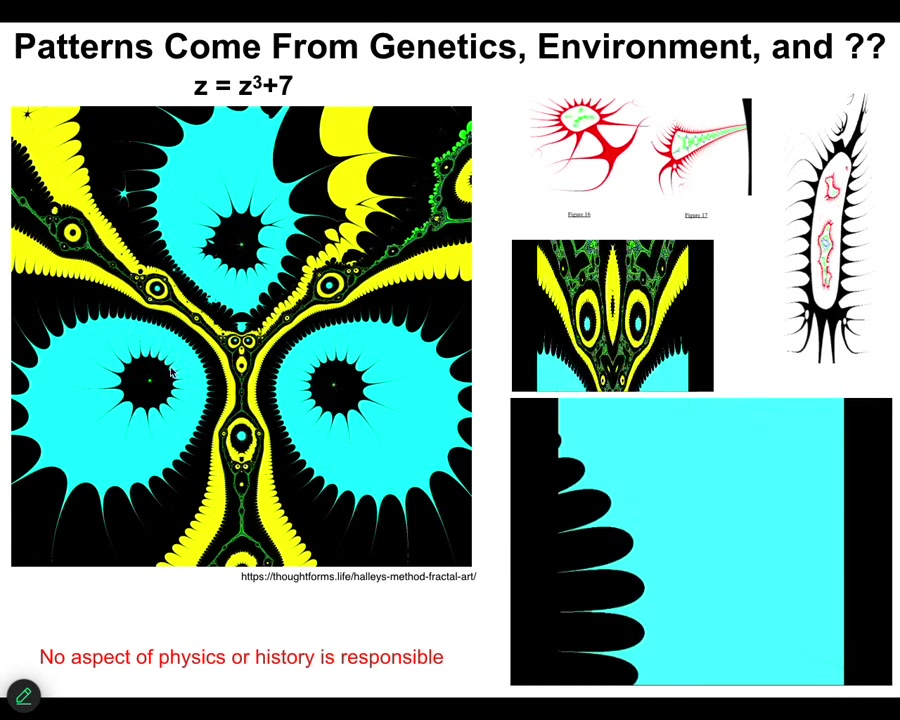

I want to introduce this notion of a mathematical latent space.

In biology, we love to pin things on genetics and environment.

If you want to know why a creature has certain patterns, it's because of a history of an environment which led you to be selected that way, plus some laws of physics.

There are aspects of physics that determine how things are going to go. But we know from mathematics that is not the only place where patterns come from.

For example, here is something called a Halley plot of a very simple mathematical object that is defined by this little equation, the complex number Z, Z cubed plus 7.

This is the pattern that's hiding in this simple description.

Slide 36/51 · 37m:40s

Where did this particular thing come from? It wasn't physics. There is nothing in the physical world that determines this. There's nothing in the physical world that you can change that will make this be different.

And it isn't history. Nobody selected these things to be like this.

It comes from wherever the laws of mathematics come from.

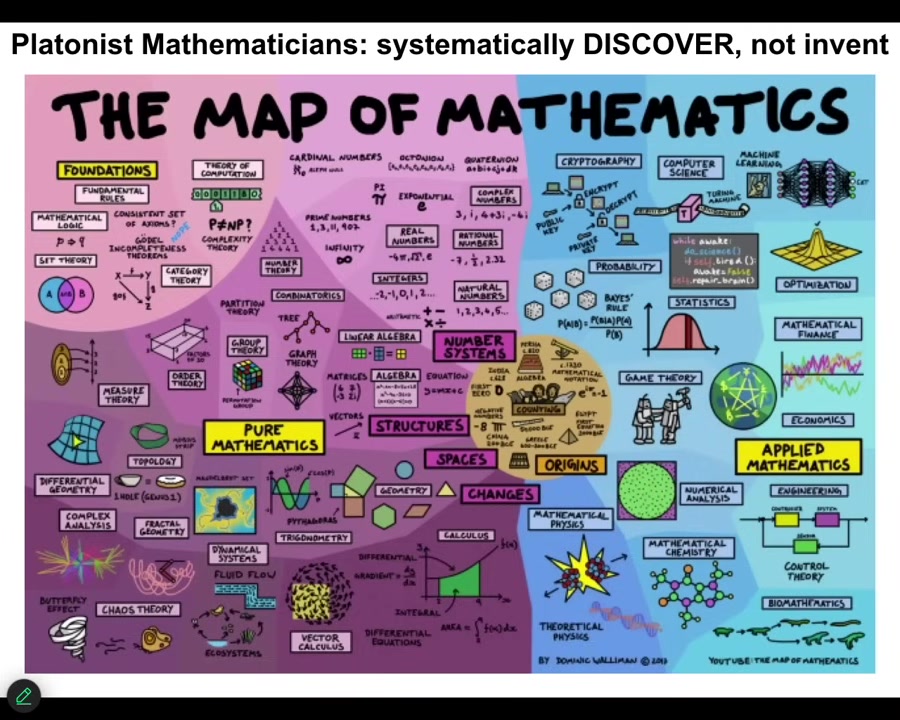

Slide 37/51 · 37m:55s

It is a property of a mathematical object. It's not physical. We can make movies and videos and look at all this stuff. It doesn't hurt that they all look very organic. It's cool. But the fact is that all the specificity that you see here, all these different patterns come neither from properties of physics nor from any kind of selection.

That's going to become important in a minute.

Slide 38/51 · 38m:20s

And also it's important that at least some mathematicians have a Platonist view of it where they're not inventing new things. No human created or invented that Halley plot that I just showed you. It was discovered. And more specifically, there is an ordered, structured space of these things that we can study. It's not just a random grab bag of patterns. We can actually navigate this space.

Slide 39/51 · 38m:55s

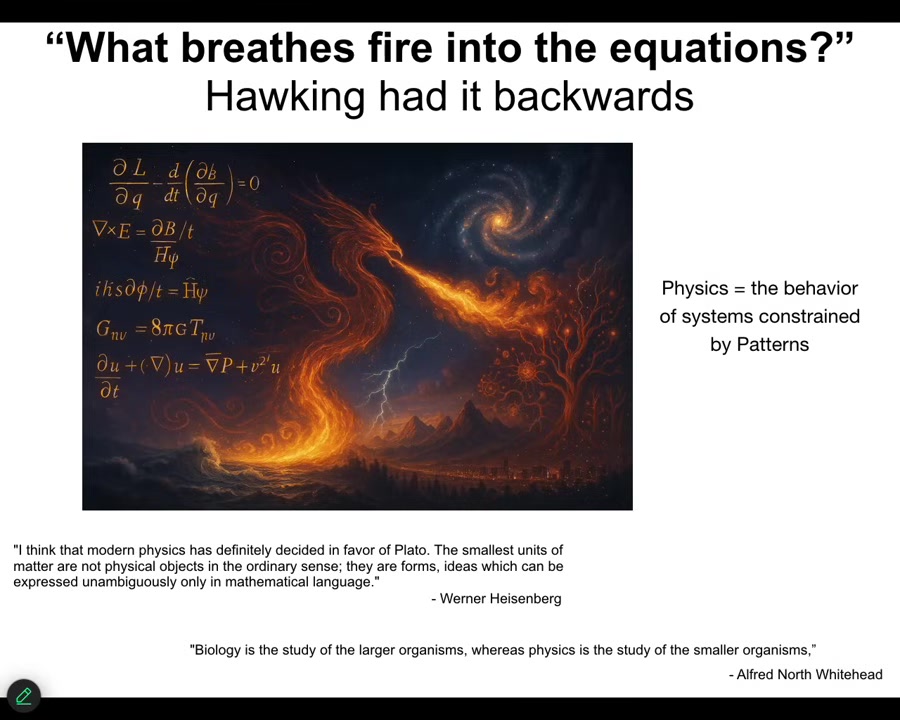

I'm going to propose that this question that I think Hawking asked you, "what breathes fire into the equations?" I'm going to flip this. I'm going to say no, what actually is happening is that the properties of mathematical objects are breathing fire into physical embodiments that we make. I'm not the first person to say this; here's a nice quote from Heisenberg and from Whitehead. Lots of people had this idea that physics is the behavior of systems that are constrained by specific patterns that exist outside the physical world. Pythagoras already knew this and said as much. Biology, on the other hand, is something slightly different.

Slide 40/51 · 39m:38s

Biology is the study of behavior of systems that are elevated by these patterns, not just constrained by them. Biology exploits the heck out of these patterns.

These cicadas. They sleep and they hibernate and then they come out at 13 years and 17 years. If you're a biologist and you want to understand why, you will catch on to the fact that it's because they want to not be timed by their predators. In other words, if it were 12 years, then every two-year, every three-year, every four-year, every six-year, a predator would come out and get me. 13 and 17 are cool for that. And then you say, okay, but why those two? And you say, well, because they're prime, but why are 13 and 17 prime and not something else? Now you're in the math department.

Because the reason this biology is doing this is the distribution of primes, which is a property of this mathematical object. When I say where patterns come from, and when I make the claim that these patterns are functionally determinative of what happens both in biology and physics, I'm not saying that there's some kind of temporal causality the way we normally understand A causes B. What I'm saying is, if this were different, if the distribution of primes were different, the cicadas would be doing something different. It doesn't work in reverse. There's nothing you can do in the physical world to change this. Biology exploits these kinds of patterns that you don't need to evolve. You get them for free. There's a ton of examples that I could give you.

Slide 41/51 · 41m:18s

This is the interesting thing: both in physics and biology, if you ask why long enough, you eventually always end up with mathematics, both for properties of particles in physics. And eventually the answer is it's because the amplituhedron has this or that symmetry. It's always going to be like that. Now we have two ways of thinking about it.

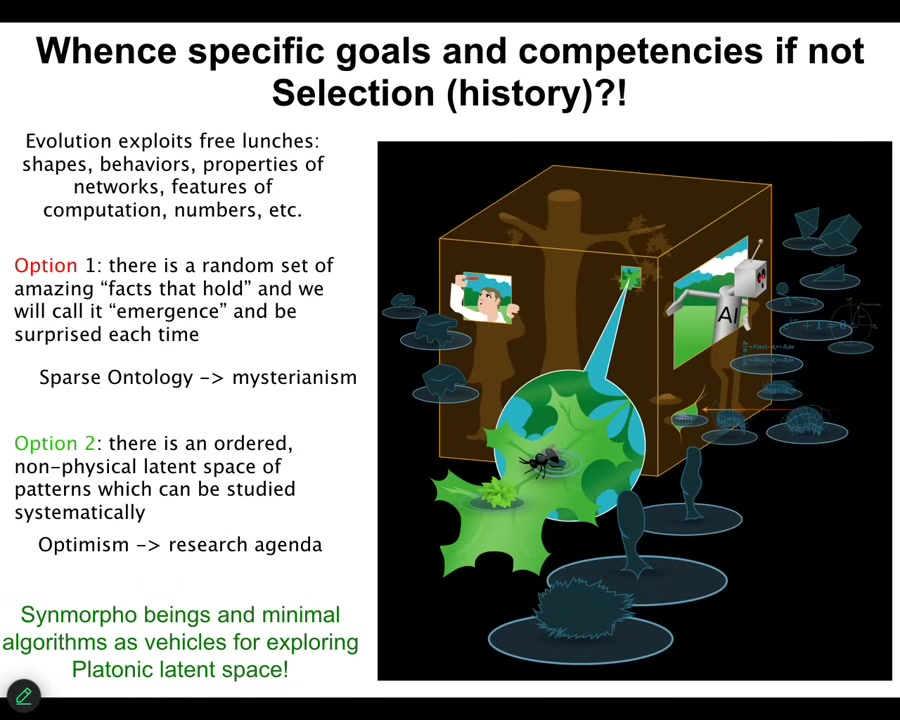

Slide 42/51 · 41m:40s

Where do the goals of novel beings come from? If it's not going to be selection in history, because there haven't been any such beings, and we're talking about AI, synthetic biology, whatever, if they've never existed, where do their goals come from? And where do these amazing features come from? The fact that anthrobots can heal, the fact that xenobots do kinematic self-replication, the fact that simple gene regulatory networks can do Pavlovian conditioning. Where does that come from?

There are two options. Option one is what I think most scientists opt for. They say physical facts are the only facts that exist. The physical world is the only thing that exists. Therefore, for these other patterns that are determined in these weird ways, it's emergent.

What does that mean? These are just facts that hold. That's all. We have to bite the bullet and say that's just how it is.

The benefit of it is that you get to have a sparse ontology. You get to just stay in the physical world. You don't need these exotic platonic spaces.

The downside is that it's a really mysterian, pessimistic view. It means that from time to time we'll come upon these surprises. That's what emergence really means: you were surprised. You didn't see it coming. We'll write them down in our big book of emergent outcomes, and that'll be that.

I don't like it. I propose a different metaphysical stance, which is more optimistic. It's basically what the mathematicians are doing: they say no, it's not a random grab bag of patterns that we find. It is a structured, ordered space. What we can do is investigate that space.

How do you investigate that space? You make vehicles for exploring it: xenobots, anthrobots, chimeras, and other things are ways to explore. I call it a platonic space to link to the work in mathematics on this, but I'm not trying to stick close to what Plato said about this, and I differ from it in many ways.

This notion is that there is a space of patterns that is not physical because these patterns are not determined or defined by anything that happens in the physical world. Everything that I've set up until now, I think, is actually pretty mundane and makes sense.

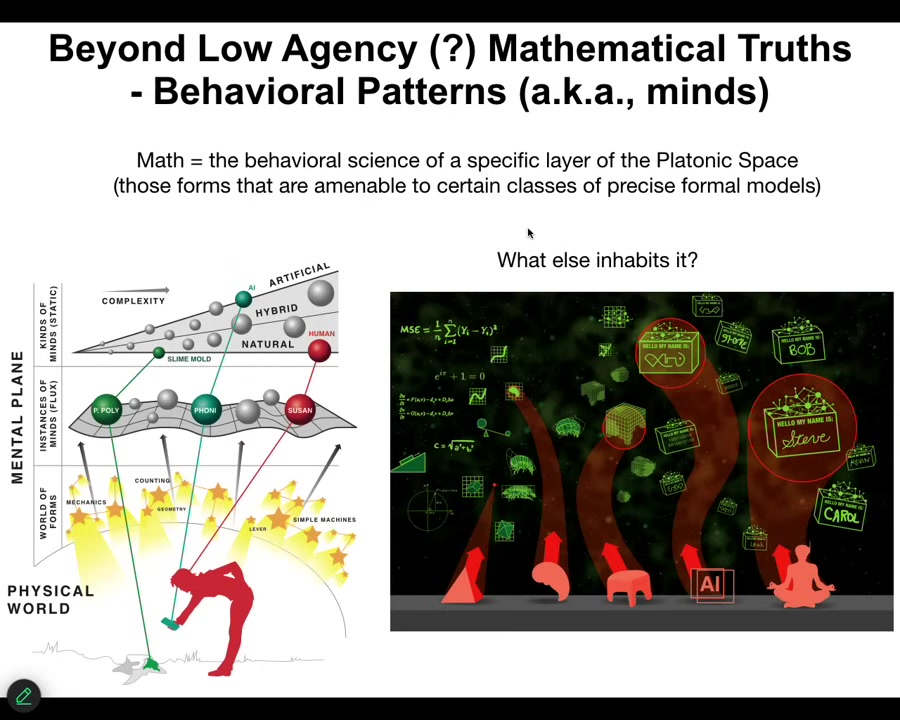

Slide 43/51 · 44m:08s

Here comes the weirder parts, which is we can ask the question, what else inhabits this space? We know there are some properties of numbers and shapes and things. What else? Could it be that there are other patterns here that are not these low agency things that mathematics studies? Maybe math is just the behavioral science of one layer of that space, things that are well-behaved in formal models. Maybe there are high agency forms here that we would recognize as kinds of minds.

Slide 44/51 · 44m:42s

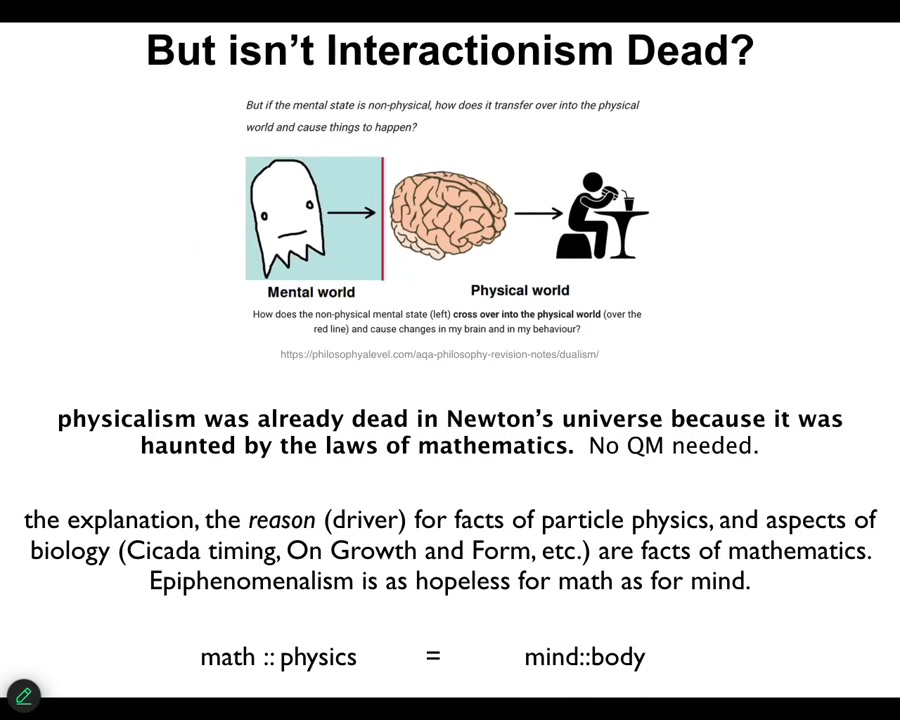

Behavioral propensities — that sounds like a dualist interactionist model. There are non-physical patterns that are somehow interacting through the brain and affecting the physical world. I would say we're going to have to revive this.

Because physicalism was already dead even at the time of Pythagoras and Newton; we already knew that physical objects were haunted by the laws of mathematics, even long before there was quantum mechanics. I would suggest that the mind-body connection is basically the same problem as the mathematics-physics connection.

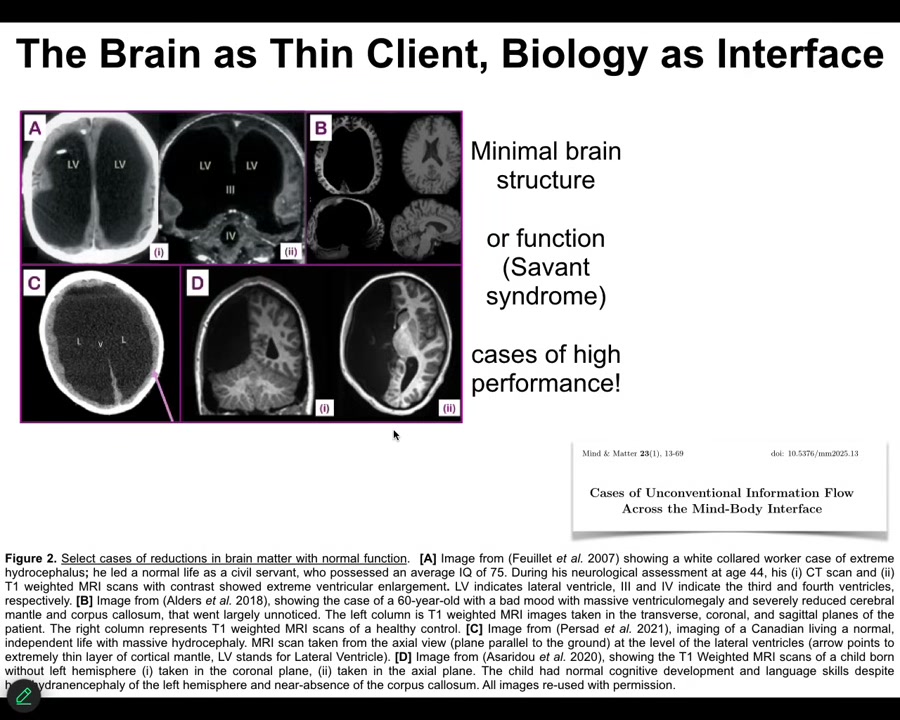

Slide 45/51 · 45m:22s

That model makes the suggestion that the brain and the physical bodies in general are thin clients. They're interfaces through which these patterns manifest in the physical world.

Karina Kaufman and I reviewed human clinical cases where there's tremendous reduction of brain volume and yet normal behavior. That's the kind of thing that isn't predicted by standard neuroscientific theories.

But this idea is that everything we make, embryos, robots, biobots, AIs, whatever, is basically an interface to these patterns.

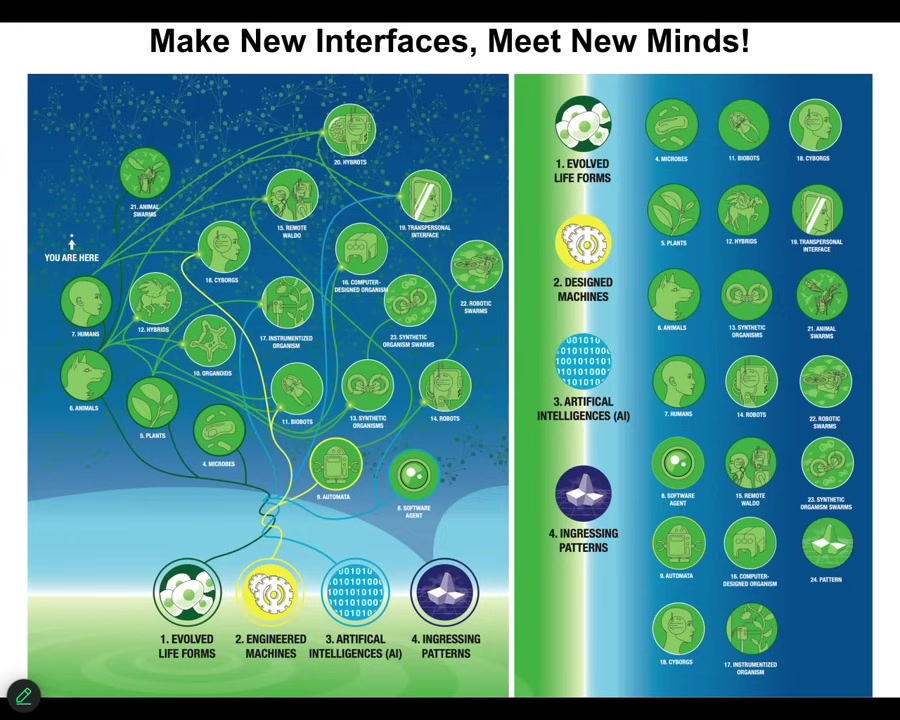

Slide 46/51 · 46m:08s

The reason this is important is that pretty much every combination of evolved material, engineered material, and software is going to be an interface for some kinds of patterns that ingress from this space.

Everything we know about on Earth— all of the living beings— is a tiny corner of the possible beings in the space, with hybrids and cyborgs and all this other very alien stuff. When we make novel interfaces, we're going to be fishing in a pool of different types of minds that we have never encountered before. We need to ramp up and understand their goals and how to ethically relate to them in a kind of synth biosis.

The final thing I want to say is this.

Slide 47/51 · 46m:52s

If you were with me this far, this is typically where people leave the train.

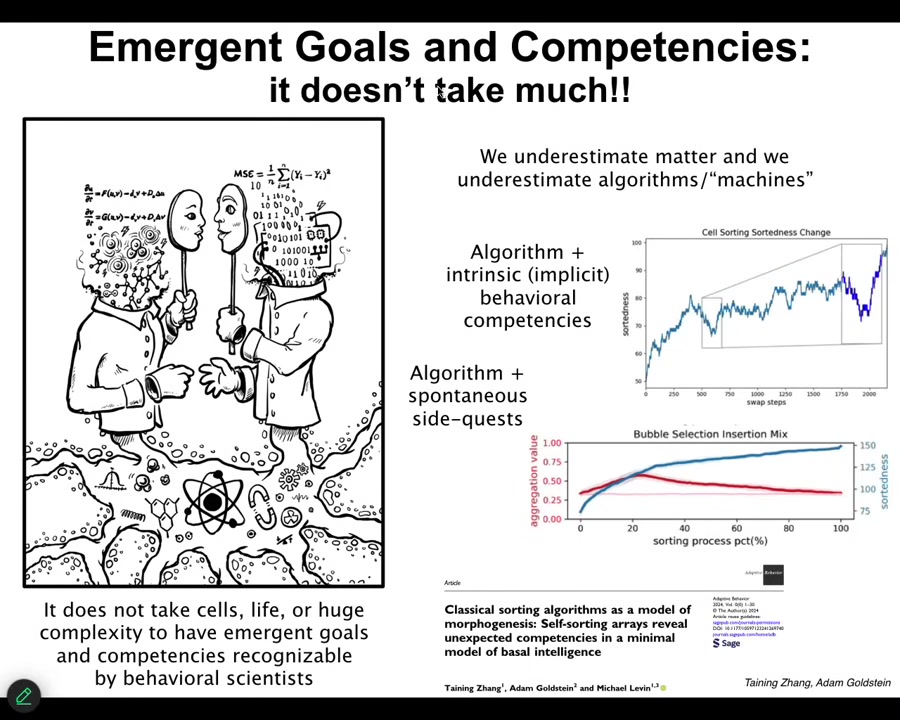

We can say, okay, biology, fine. What you've just said is that biology and all the complexity of biology make these amazing interfaces which are good to allow the ingressions of these complex behavioral propensities, so you get patterns that are not well defined by the laws of chemistry and all that, fine. But surely at least we have simple machines. We have simple things, algorithms that behave, they only do the thing you force them to do. They are not real beings like us. They are not creative. They just follow the algorithm.

I'm here to tell you that these ingressions do not require biology. They do not require significant complexity. They make themselves known in even the simplest, tiniest, most minimal models, fully deterministic.

In this system, we studied sorting algorithms, things like bubble sort. If you know how to look, you find intrinsic motivations that are nowhere in the algorithm.

This stuff is everywhere. People have been studying these algorithms for 60 or 80 years. Nobody had noticed this because we're not primed to look for it.

Slide 48/51 · 48m:18s

Nothing—neither biochemical machines like us nor digital algorithmic machines that we make—is what our formal models say they are. I don't think there are any machines anywhere in the sense that we try to formalize them. Minds are not fully defined by our models of them, neither for their limitations nor for their competencies.

Because these models in computer science and physics and biology are models of the front end. They're models of the front-end interface. They are not good models of the entire system. I'm going to stop here and summarize as follows.

Slide 49/51 · 48m:58s

I think intelligence is to be found in very diverse embodiments. I think a lot of distinctions that we make now are artifacts of lack of imagination and knowledge from prior ages. These things are going to dissolve.

We need much better formalisms. The tools are coming online to allow us to do that. Not only the ethics and a mature humanity going forward depend on this, but also very practical things around biomedicine and bioengineering.

Slide 50/51 · 49m:32s

And so the future — the real Garden of Eden view is going to be a lot more like this. We're in for some very interesting times. But it's going to require us to level up in terms of being able to relate to beings that are very unlike ourselves.

Slide 51/51 · 49m:50s

I'll stop here and thank the postdocs and the students who did the work that I showed you today. Lots of our amazing collaborators and our funders who have supported us over the years. I have to do disclosures. These are three companies that have licensed some of our intellectual property and support our work. Thank you.