Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a ~35 minute talk about diverse intelligence and our efforts to establish formalisms and methods for communicating with unconventional biological intelligences.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Expanding the mind spectrum

(05:41) Embryos and cellular intelligence

(10:22) Anatomical intelligence and bioelectricity

(17:07) Communicating with bioelectric collectives

(23:27) Bioelectric medicine and patterns

(27:18) Anthrobots and emergent behaviors

(30:20) Future minds and humility

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/30 · 00m:00s

What I'm going to talk about today is some efforts that we and others have made to try to expand what I think of as significant mind blindness that affects us because of our evolutionary history and our focus on particular kinds of minds.

I'm going to spend the middle part of the talk discussing results that we have using the collective intelligence of body cells as a model system to understand a diverse intelligence that lives in a weird space that's hard for us to imagine and the progress that we've actually made in communicating with that intelligence. So it's a case study for us.

But I'm also going to talk about some much weirder things.

If anybody's interested in the primary papers, the data sets, the software, everything is here. Then here's where I keep my own personal thoughts about what it all means.

Slide 2/30 · 00m:52s

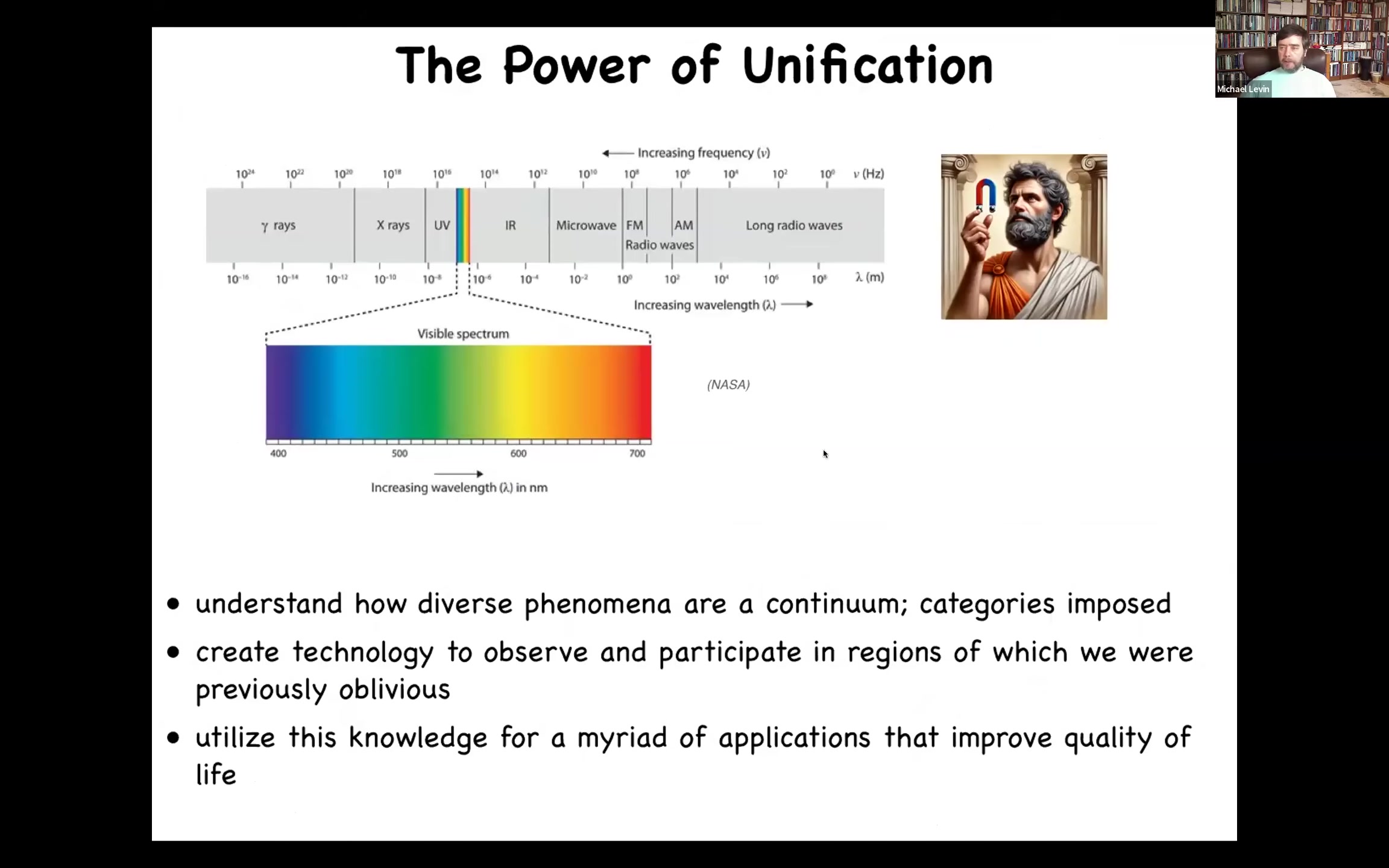

I want to start off by reminding ourselves of something that happened over history: prior to having a solid theory of electromagnetism, we had static electricity and we had lightning and we had magnets and we had light. We all thought those were different things. We thought these were completely different kinds of phenomena. We were also unaware that we actually were only sensitive to a tiny part of this spectrum. What a good theory of electromagnetism did for us is several things. First of all, it revealed that all of these different things are in fact manifestations of the same thing and that it is a spectrum and that the labels we put on this spectrum are convenient, but they're for our purposes. The underlying thing is a continuum. And it allowed us to develop technology driven by the theory that now lets us interact with this enormous range of things in the universe around us to which we were previously completely blind. And that allows us to make applications that improve quality of life.

I want to argue that this idea, the idea of a unification that reveals a spectrum and an underlying symmetry to seemingly disparate phenomena, is in fact the exact way we should start thinking about diverse kinds of minds.

Slide 3/30 · 02m:10s

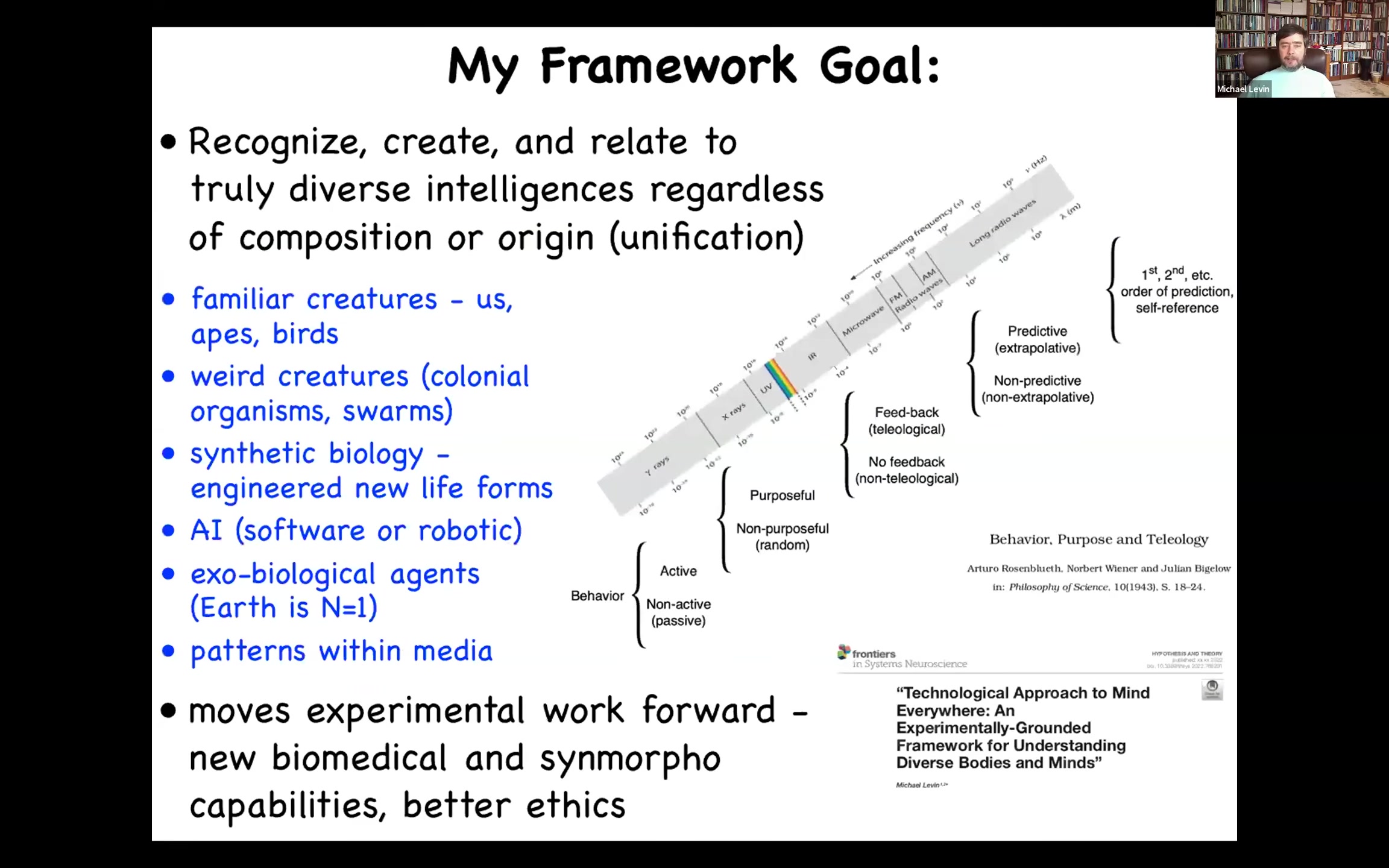

In my group, what I would like to do is to develop a framework that helps us to recognize and ethically relate to a very wide range of beings. Not just the primates and birds and maybe an octopus or a whale that conventionally we think about, but also some really weird biologicals such as colonial organisms and swarms, synthetic new life forms, AIs, whether robotic or purely software, someday maybe exobiological alien entities, and some even very weird things that I probably won't have time to really talk about today, which aren't even conventional physical objects. I think what we have here is exactly this kind of spectrum where we have names for different types of agents along the spectrum, all the way from passive matter, and I'm not sure there is any such thing, but we tend to think of the kinds of things that physics studies as dumb materials, all the way up to whatever humans are with their metacognitive abilities and everything in between. What I'm interested in are theories of transformation and change, not sharp categories, but actually how things scale along this continuum and all the details are here. One thing to remember is that as we study these kinds of things, what I think we are working up along is this kind of spectrum where things get progressively weirder; as you start to leave this conventional area, the kinds of agents that we think about get stranger and stranger. The one other precedent that we have is in the discovery of numbers. Originally we had the counting numbers and then somebody invented 0 and then negative numbers. And then eventually people figured out that even the rationals weren't the limit of things and so on. What's important here is that each one of these expansions required a conceptual leap. It required us to break prior categories that we thought define what is essential about numbers. It was quite disturbing. Lots of people died, for example, when irrationals were discovered, like this poor guy, Hippasus, was either killed or drowned on his own from the horror of this kind of thing. We just need to remember that expanding these categories is not trivial. It's often painful. The ability to recognize other kinds of things that didn't fit your previous category is in order so that you can do something useful with them. In the context of what we're talking about now, which is other types of beings actually have some sort of active, compassionate relationship with them, is not easy. We as humans are really primed to recognize this kind of thing.

Here's this Oscar-winning performance where this little squirrel-like creature sets up a little accident scene.

Slide 4/30 · 05m:08s

He puts it right on the neck. He's got a very good theory of mind. He knows what the owners are looking for.

In terms of paying attention to him, he's going to check in a minute to see whether anybody's watching.

Slide 5/30 · 05m:18s

These kinds of things, it's very easy for us to understand that there's a mind here. That's because they operate at the same spatio-temporal scale. They operate within the same space as we do. They have roughly similar biological goals. And so things that are driven by brains, especially mammals, are not really problematic usually. There are some weird situations.

Slide 6/30 · 05m:42s

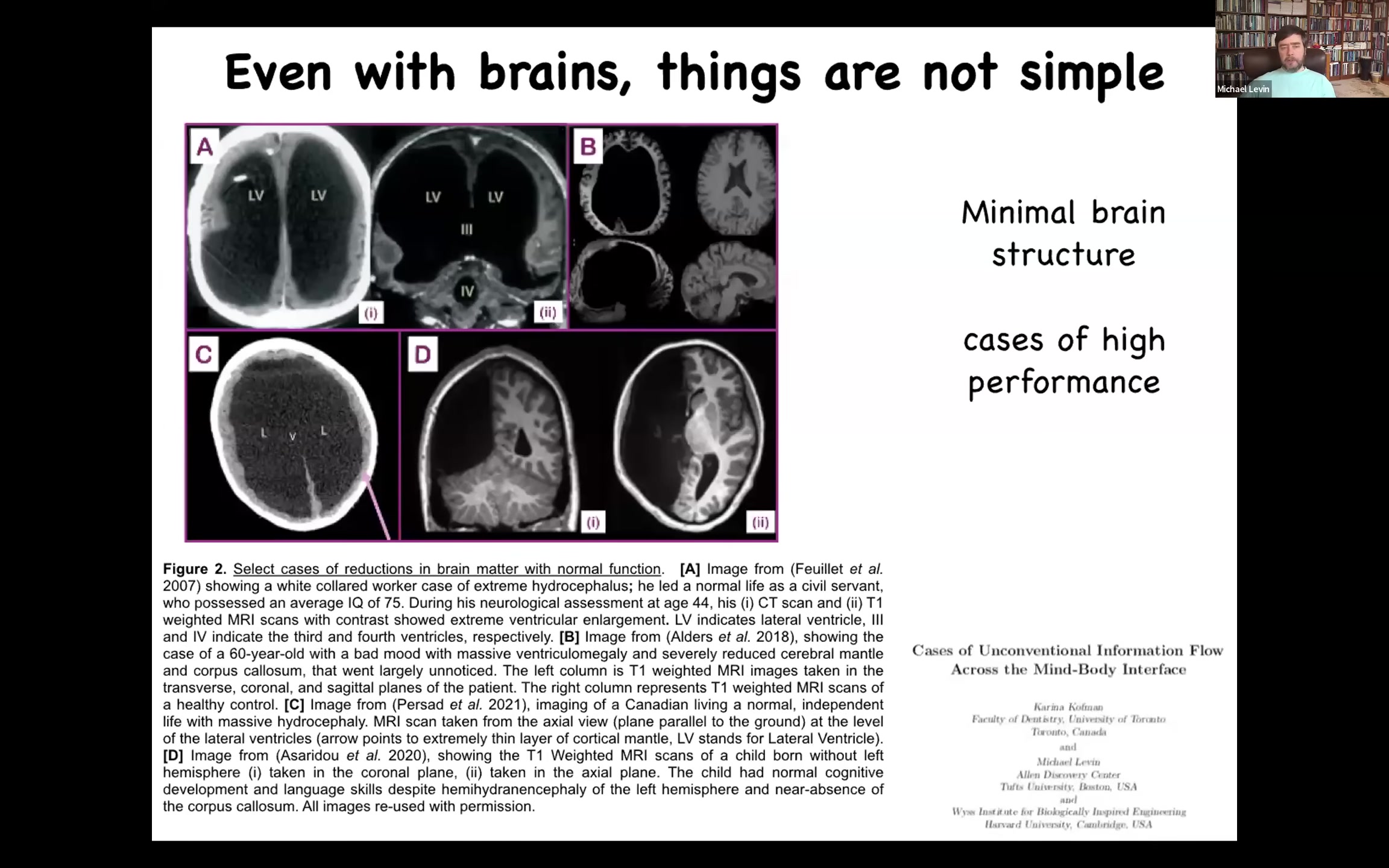

We have theories of mapping of functions onto brain structure. Yet there are clinical cases; Karina Kaufman and I reviewed this in a paper — cases where individuals have radically reduced amounts of brain tissue despite normal or even above-normal performance. Even the mapping between brain and performance is not simple.

Slide 7/30 · 06m:12s

But in order to understand what we are and how we come to be as embodied agents, we need to look at our origins, both evolutionarily and developmentally.

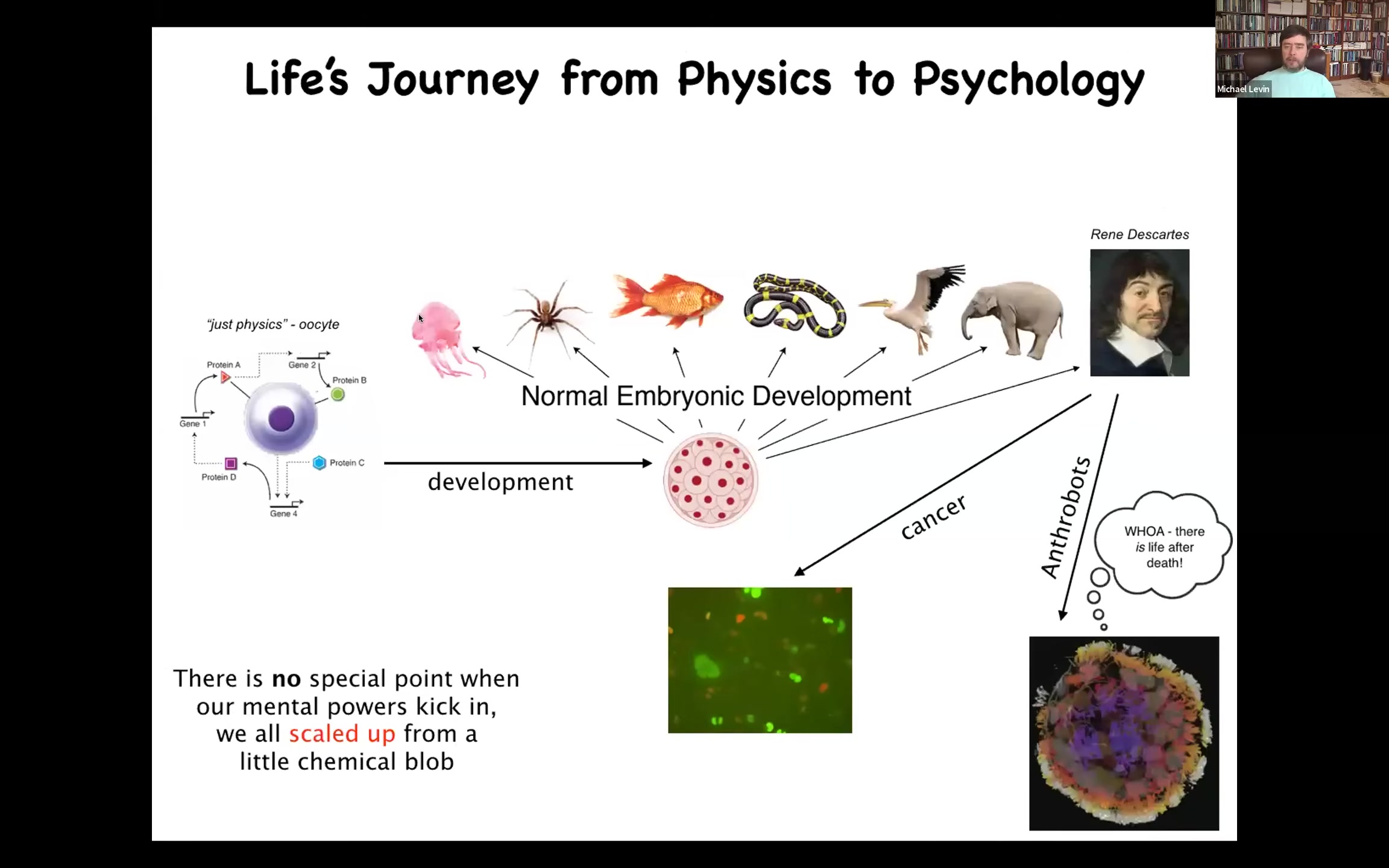

All of us start life as a little BLOB of chemistry and physics. Here's an unfertilized oocyte. Through the incredible process of embryogenesis, we become fodder for either behavioral science or maybe psychoanalysis and other deeper kinds of things.

One thing developmental biology shows us is that there is no magic bright line at which physics ticks over to psychology. It's a continuous, gradual process. It's important to be able to understand that process. This is not the end of the road because there are other processes that can happen afterwards, including a dissociative disorder known as cancer. Other very strange things, after the death of the body, your cells continuing their life in a totally novel embodiment, such as these anthrobots.

Slide 8/30 · 07m:20s

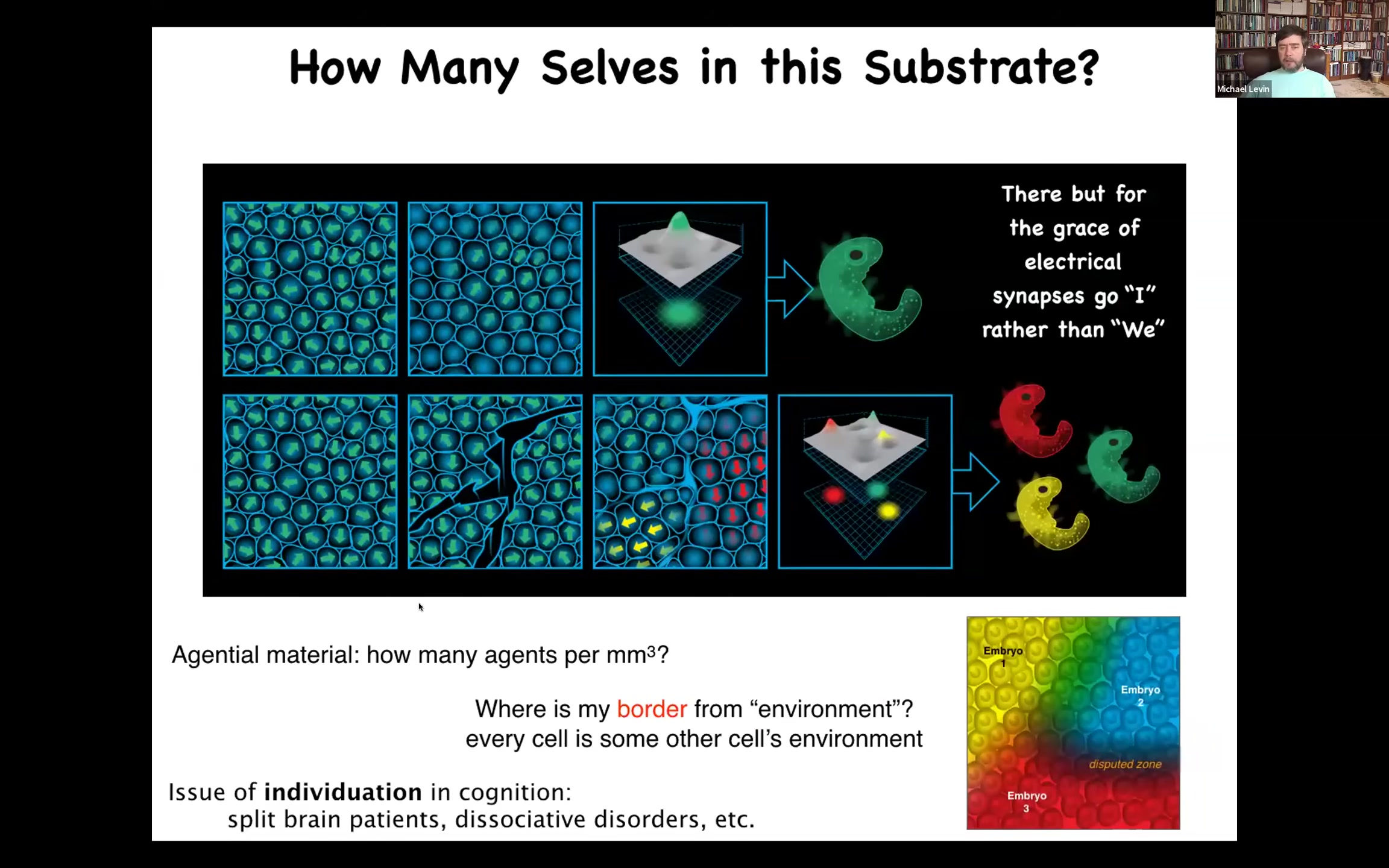

It's also important to note that even the notion of an embryo isn't simple because if you look at an early blastoderm, so let's say there's a couple of 100,000 cells here and you say, there's an embryo. What are you counting when you say there's one embryo? What is there one of? What there's one of is alignment. What there's one of is a story that all of the cells have bought into a self-model that guides their movement in anatomical space, in the space of possible anatomical configurations. The reason there's one embryo is because all the cells agree that is where they're going. I used to do this in duck embryos as a graduate student. If you take a little needle and you put some scratches in this blastoderm, each one of these islands doesn't feel the presence of the others. They align among themselves. They decide they're the embryo. This is how you get twins and triplets.

That means that the number of individuals inside an embryonic medium is not determined. It's certainly not set by genetics. It could be anywhere from zero to half a dozen or more in a standard blastoderm. How many actual individuals or cells can emerge from that medium is not obvious. It's a physiological outcome that shares both mechanistic and functional similarities with issues of individuation in the cognitive sense. Things like split brain patients, dissociative identity disorders: how many individuals are within a given set of real estate in the brain and how many can fit? What's the maximum carrying capacity? We know this for standard computation. We do not know how to calculate this for neural substrates. It's an incredibly dynamic process. It's driven by this sort of thing.

Slide 9/30 · 09m:08s

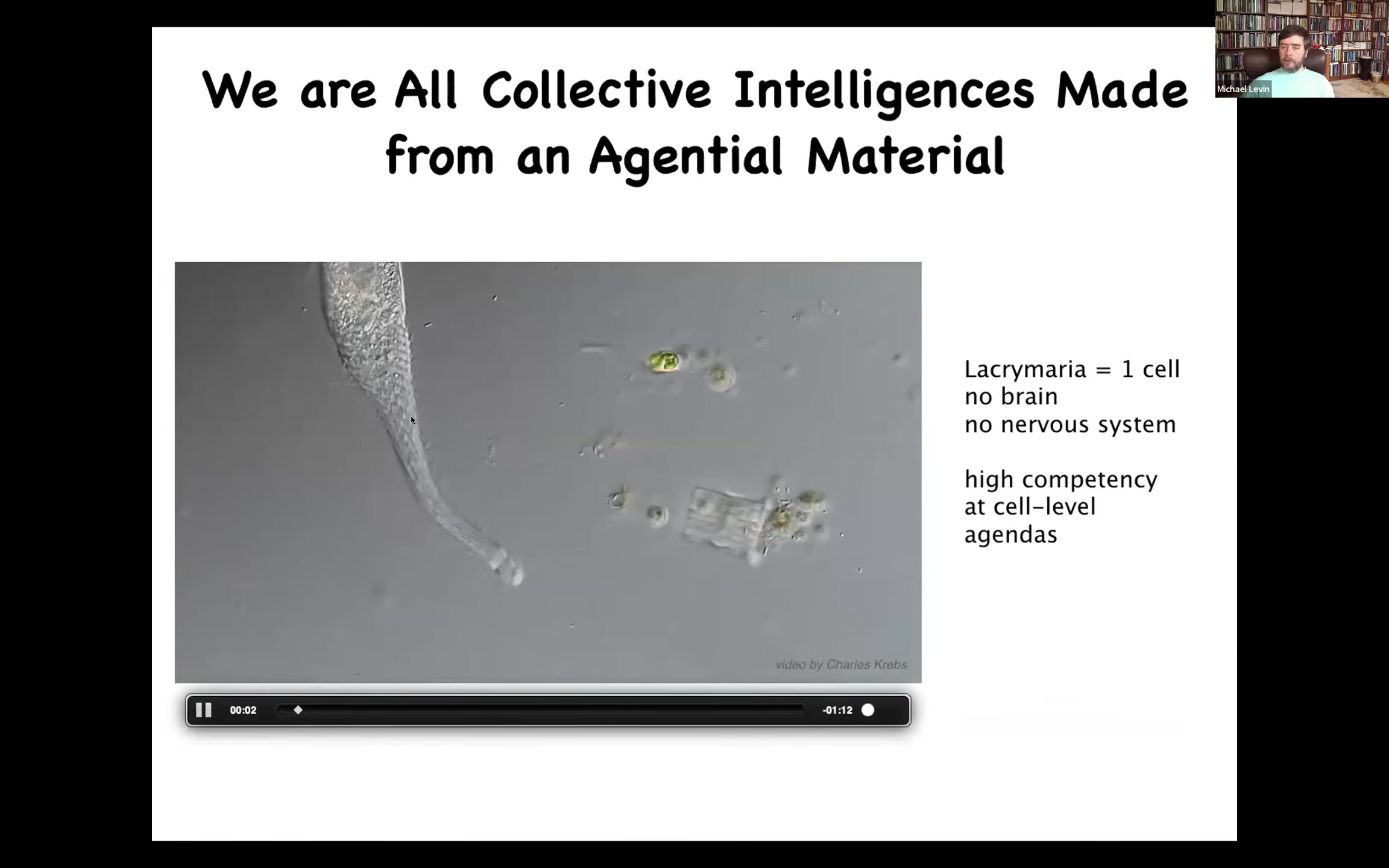

This is what we're all made of. This is a single cell. Now, this is a free-living organism. There's no brain. There's no nervous system.

There is, however, a great competency in managing its own tiny little cognitive light cone.

The spatio-temporal region of goals that it can pursue is small, but it's very good at doing what it needs to do.

Even this, a lot of people are now catching on that cells have a kind of intelligence and competency.

But it's not just that this goes down to the cell level.

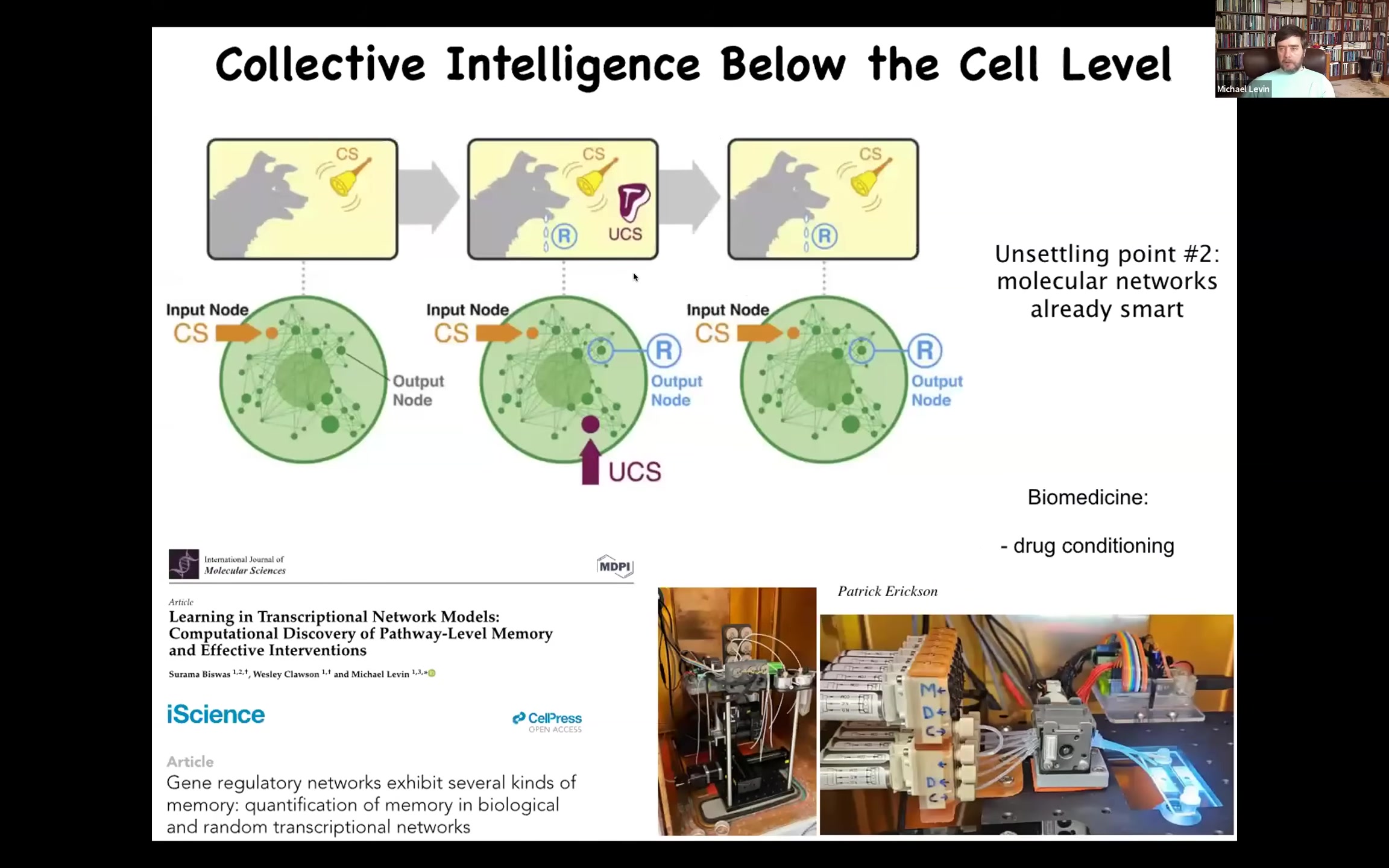

Slide 10/30 · 09m:42s

It goes far beyond that because even the chemical material inside of that cell, not the cell itself, not the nucleus, not any of that, but just the chemical pathways, for example gene regulatory networks, just from the way the math works, they are themselves capable of at least six different kinds of learning, including Pavlovian conditioning. You don't need anything else. Just a set of interacting chemicals is already potentially capable of several different kinds of learning.

And so already, not only are we collective intelligences made of cells, but actually the cells themselves are collective intelligence made up of components that do all kinds of interesting things. We are in our lab taking advantage of the ability of these molecular networks to learn to make applications such as drug conditioning.

Slide 11/30 · 10m:32s

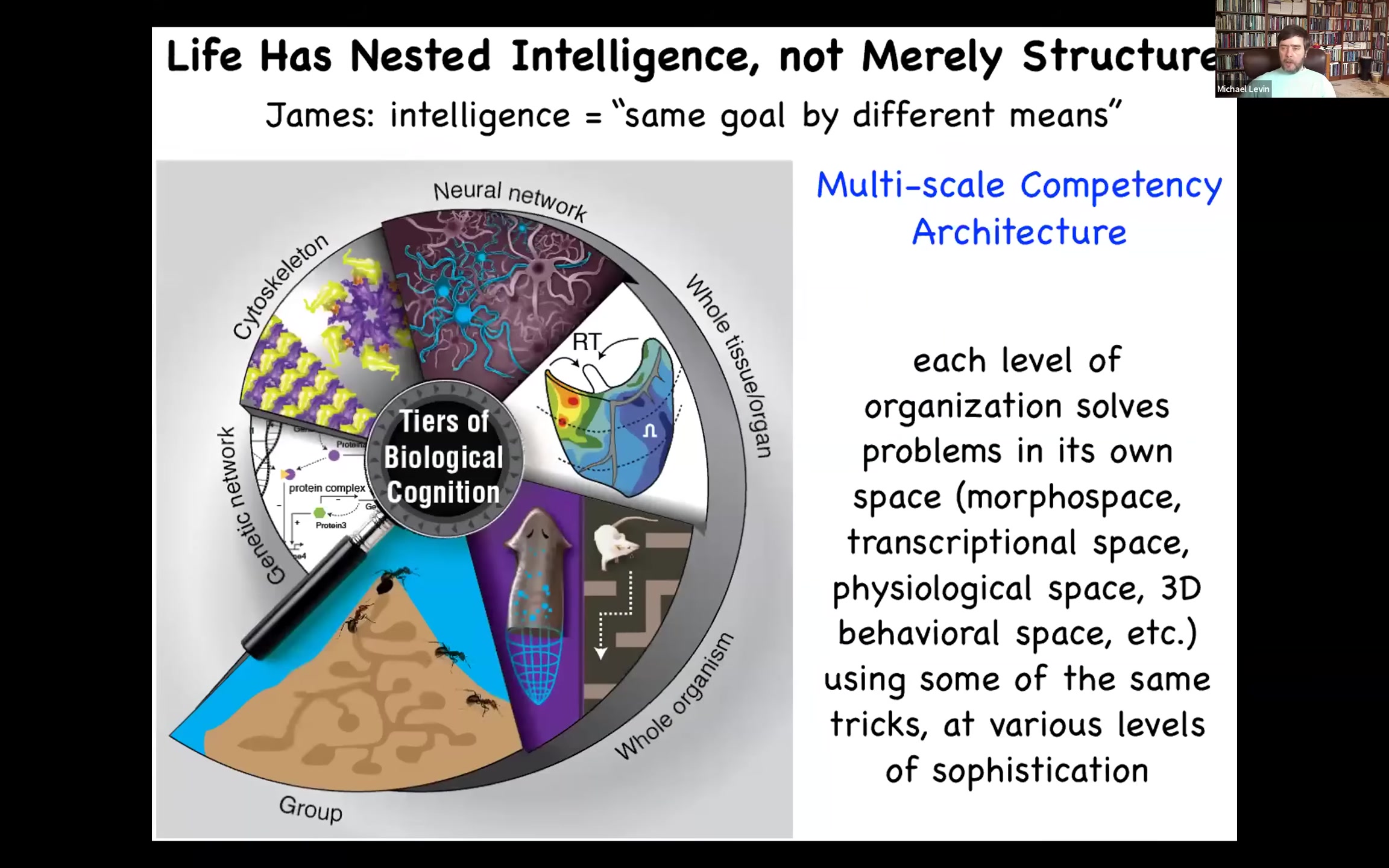

Our body is a multi-scale competency architecture. Every level from the molecular networks on up is a kind of agent that solves problems in various weird spaces.

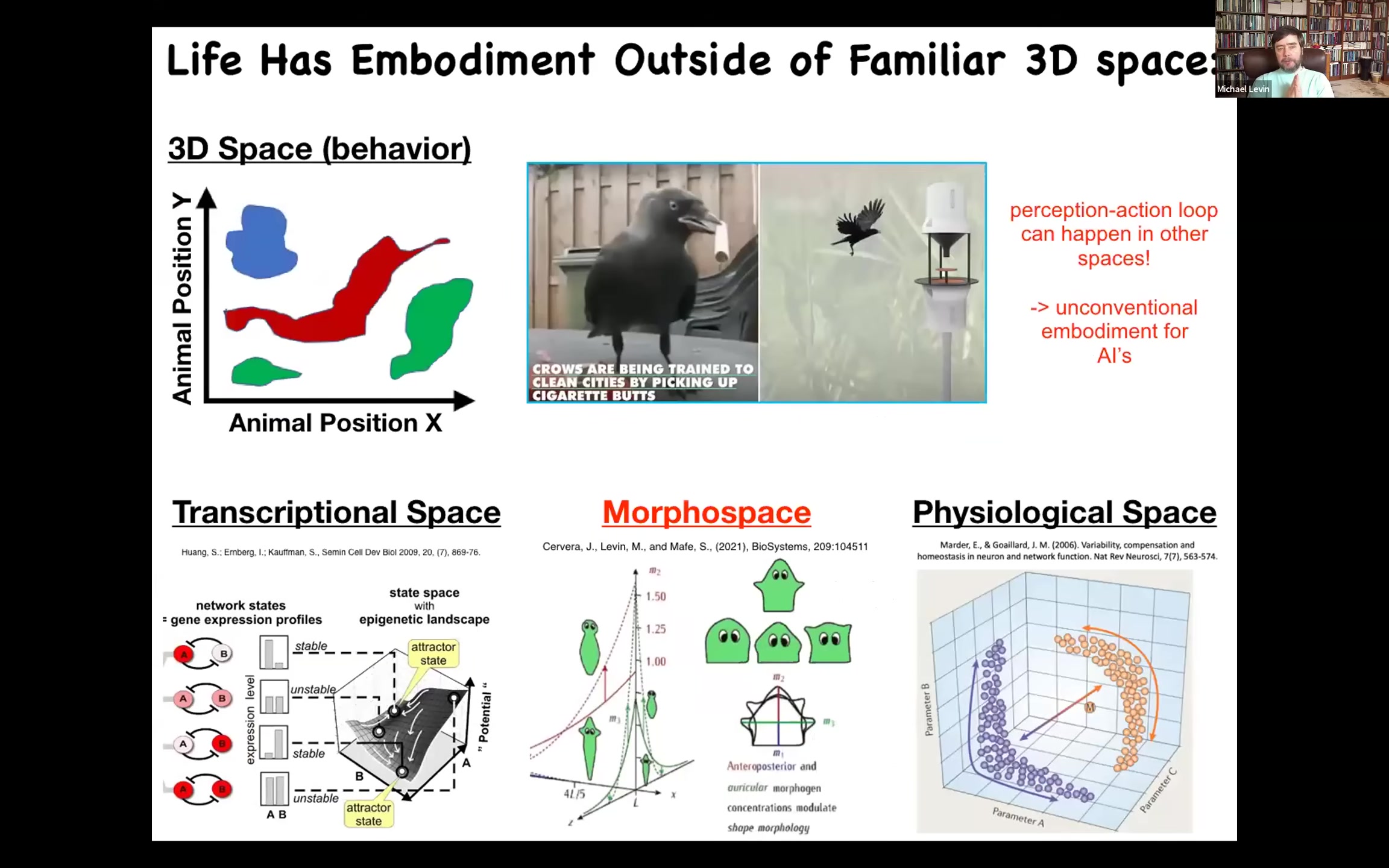

Slide 12/30 · 10m:50s

And because of our evolutionary firmware, we are pretty good at recognizing intelligence in three-dimensional space. We're obsessed with the 3D world because of our vision and medium-sized objects moving at medium speeds, like birds; we can pick that up. But biology exploits intelligence and goal-directed navigation in lots of different spaces. So the space of possible gene expressions, the space of possible physiological states, and the one we're going to talk about most, the anatomical morphospace. This thing that's essential for intelligence, this perception-action loop, happens in all kinds of other spaces that are very difficult for us to recognize. This has lots of implications for things like AIs, hybrids, and organoids where people look at them and say, this is not embodied. It just sits there. It doesn't move in the physical world. But the physical world is not the only world where you can do this critical perception-action loop. And so what I mean by anatomical intelligence is I don't just mean complexity.

Slide 13/30 · 11m:55s

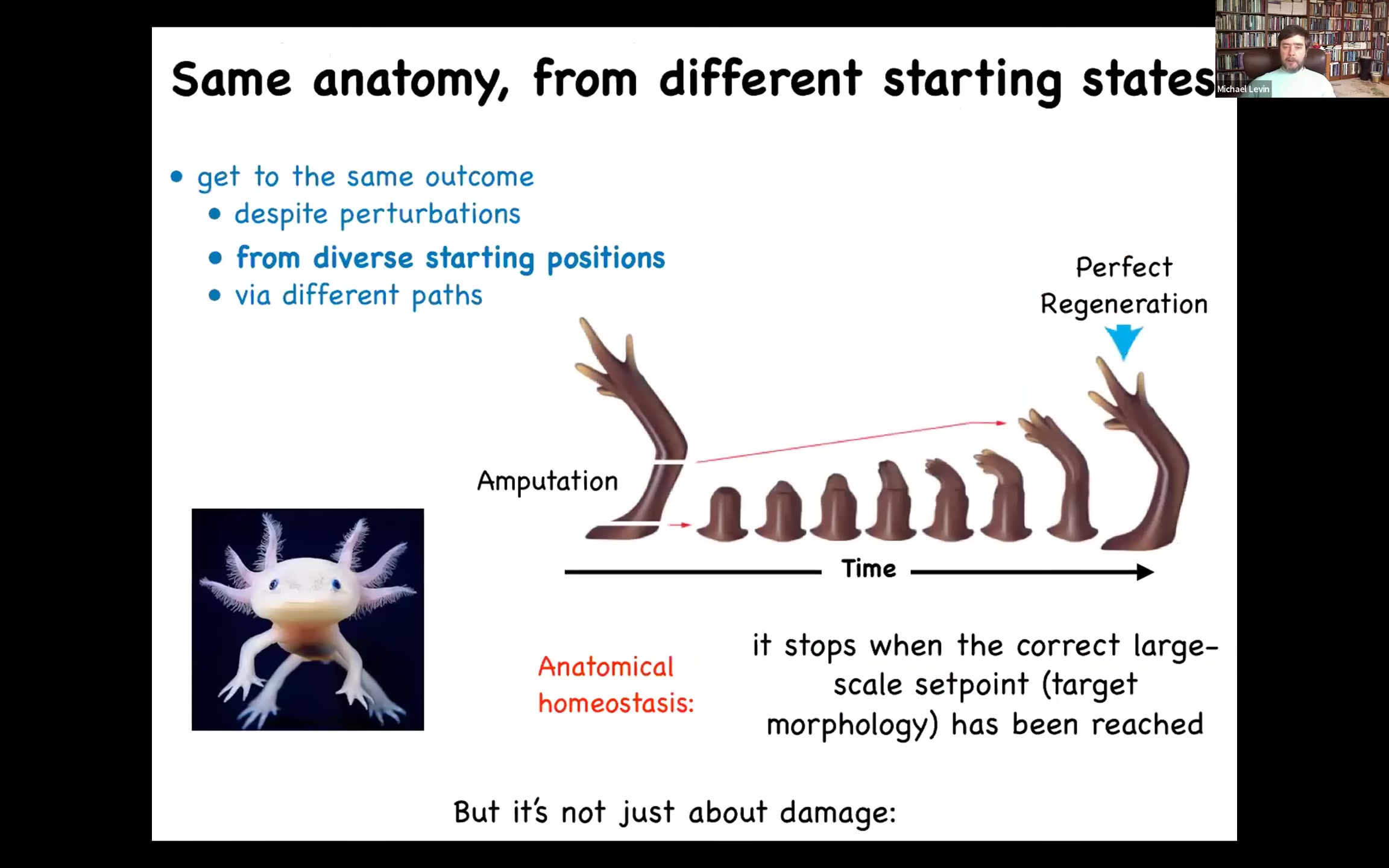

I don't even just mean reliability, I mean problem solving. Here's a very simple example of a goal-directed system. You have this axolotl. They are incredibly regenerative. They can restore most of their body parts. If it loses a limb anywhere along this axis, the cells immediately detect that they've been deviated from their target state. They will work really hard to get back there. The most amazing thing is they stop when they're done. When do they stop? They stop when a correct axolotl limb has formed.

This is an example of a very simple homeostatic process. The system has a goal: you deviate it from that goal, it expends lots of energy to get there, and then it stops. In fact, it will work no matter where you cut; it makes exactly the right steps from here to there. We can regain its position in that anatomical space it navigates. This is not just about damage.

Slide 14/30 · 12m:45s

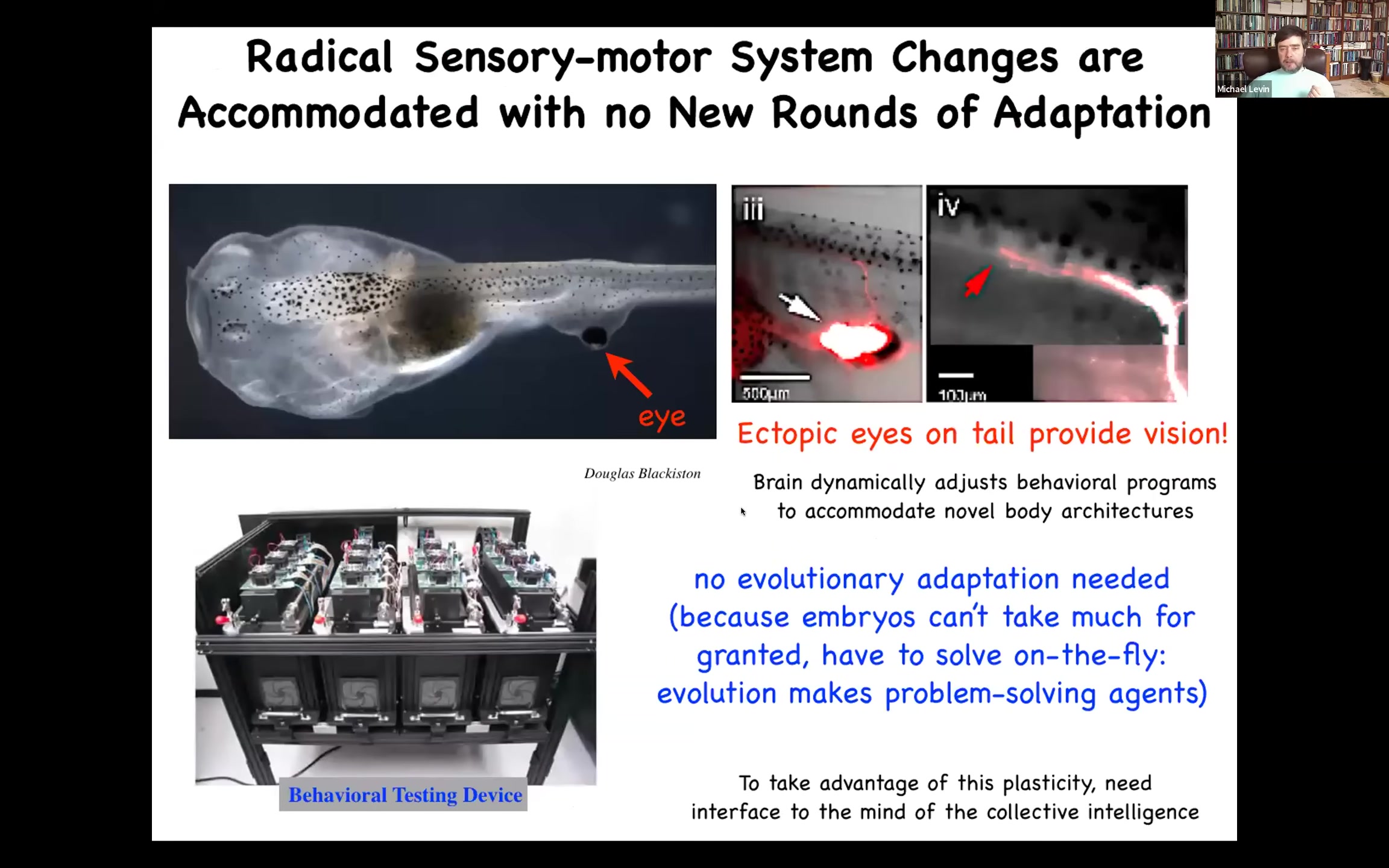

That incredible plasticity leads to phenomena like this. If we make this tadpole with no primary eyes, this is a tadpole of the frog, here's the mouth, here are the nostrils, the brain, the tail. If we make a tadpole with no primary eyes, but we put an eye on its tail, and I'll show you in a minute how we can do that. What happens is that eye makes a single optic nerve. The optic nerve does not go to the brain. Sometimes it synapses on the spinal cord here, sometimes on the gut, sometimes nowhere at all. These animals can see perfectly well. How do we know? Because we built a device that trains them on visual cues, and we can show that they learn in visual assays.

This is amazing. Why do you not need additional rounds of evolutionary adaptation here? You've got an animal with a radically different sensorimotor architecture. The eye is connected to the spinal cord or some other organ; why does it just work out-of-the-box? That's because every instance of embryogenesis or regeneration or remodeling or metamorphosis is not a hardwired process driven by the chemistry of genetics. What it is is a problem-solving process that takes place when an active agent interprets the information that it has, including its genetic affordances and everything else. It gives rise to this incredible plasticity that we're going to look at the implications of this momentarily.

So what we'd like to know is how all this works. What's the cognitive glue that binds individual competent subunits, like cells and, in fact, molecular networks, into tissues, organs, and so on? What are the mechanisms and policies that allow these things to work together and embody a higher order individual that knows things that its parts don't know?

Slide 15/30 · 14m:28s

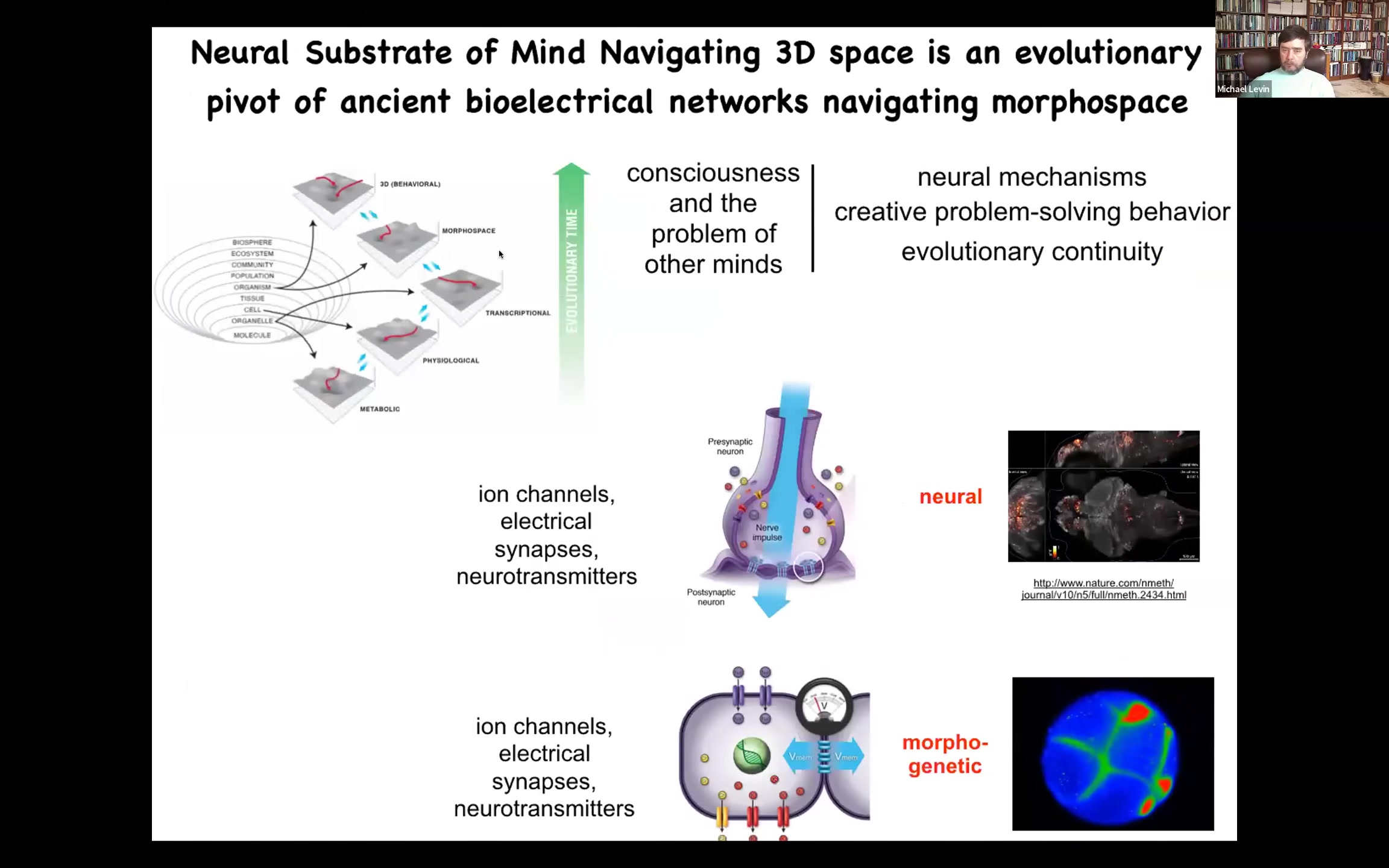

We know how this works in our bodies as far as cognition is concerned. The cognitive glue that binds individual neurons together into us is electrophysiology or bioelectricity. It's the electrical networking of the cells in your brain that allow us to know things that our neurons don't know.

It turns out that this is a scheme that evolution had discovered long before there were brains and muscles and things like that. Using electricity to bind things together into a larger-scale collective intelligence goes back to at least bacterial biofilms. It's very ancient.

More generally, what evolution, I think, has done is to pivot some of the same navigational tricks across all kinds of spaces as life got more complex. So from metabolic spaces, physiological spaces, gene expression spaces, eventually multicellularity, and you get anatomical amorphous space, then muscles and brains appear, and you've got 3D behavioral space, and then eventually linguistic spaces.

The interesting thing here is that what our brains are using to embody conventional cognition is exactly the same molecular mechanisms, meaning ion channels, electrical synapses, and neurotransmitters, exactly the same machinery as the collective intelligence of the body uses to make anatomical decisions. This is interesting.

When you attribute consciousness to other humans that you're talking to or other beings, you typically use one of three criteria. Either you're looking at mechanisms — they use the same mechanisms that I use and I'm conscious, so therefore they must be, too. Or you're looking at behavior, some sort of creative problem solving, and you say this is a sign of cognition and consciousness. Or you're looking at evolutionary continuity: they're on the same evolutionary stream and therefore they must have had it too.

If you accept any of these criteria, you have to take seriously the idea that every structure in your body potentially has some level of conscious experience because it fulfills all of the criteria that we normally use to attribute consciousness to each other.

What we're interested in is understanding, if we're going to use the collective intelligence of morphogenesis as a model system, one of the things we'd like to do is to communicate with it.

Slide 16/30 · 17m:08s

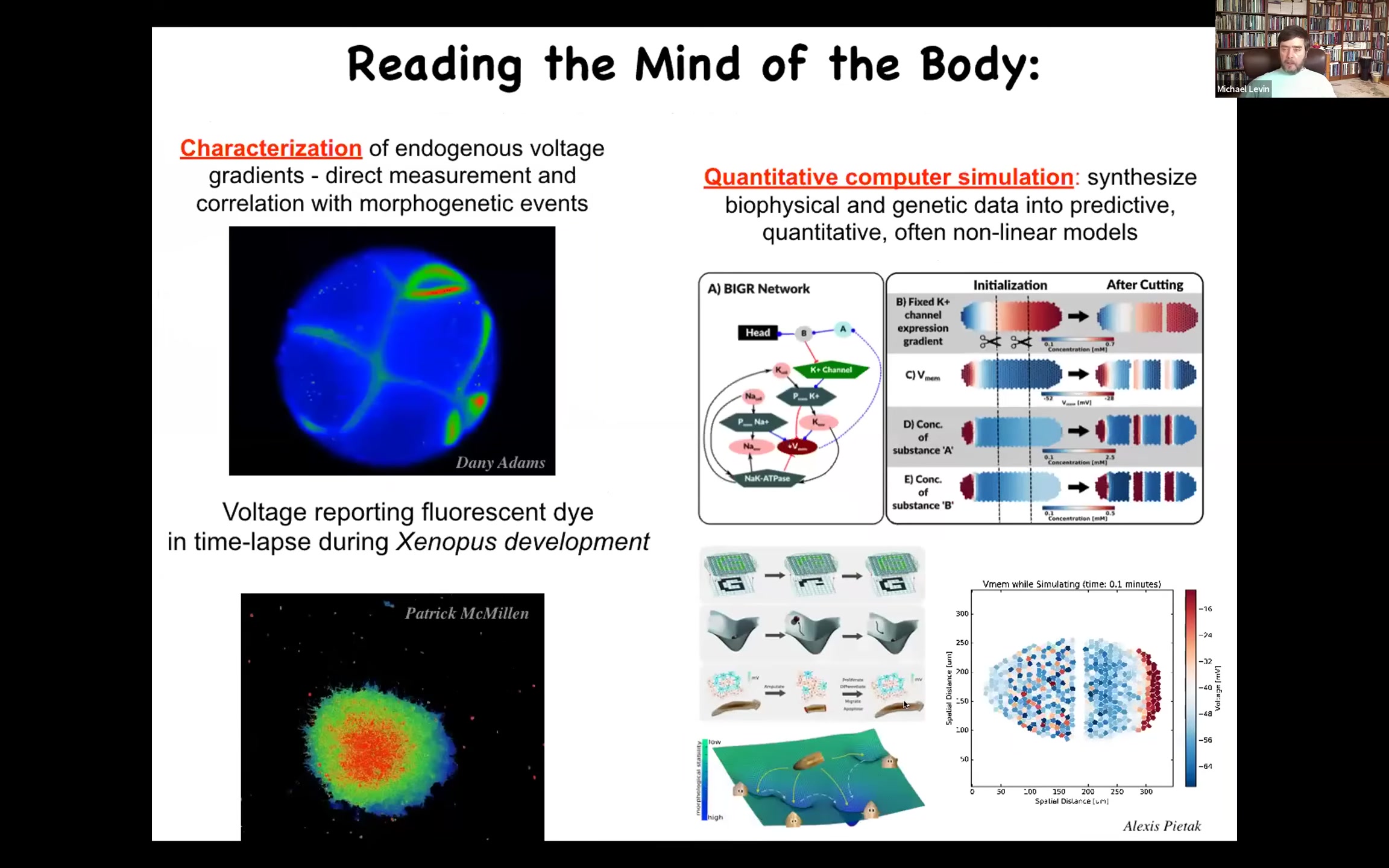

And in order to do that, the first thing we developed was some tools to read the information content of its mind. And so to read out the electrical activities the way that neuroscientists read out the states of the brain. And we developed a fluorescent dye technology that allows us. So here are a bunch of cells in a dish deciding whether they should be a collective or not. Here are some cells in an early frog embryo. So these are not models. This is real data. In time-lapse.

You can see all the electrophysiology that goes on as these cells figure out who's going to be left, who's going to be right, anterior, posterior. So we have all kinds of computational methods that we've developed to model this phenomenon and to understand how it can underlie memories and large-scale circuits that do pattern completion, which is regeneration. You lose a part of the body and then you can complete that pattern later. So we have all kinds of simulations.

Slide 17/30 · 18m:02s

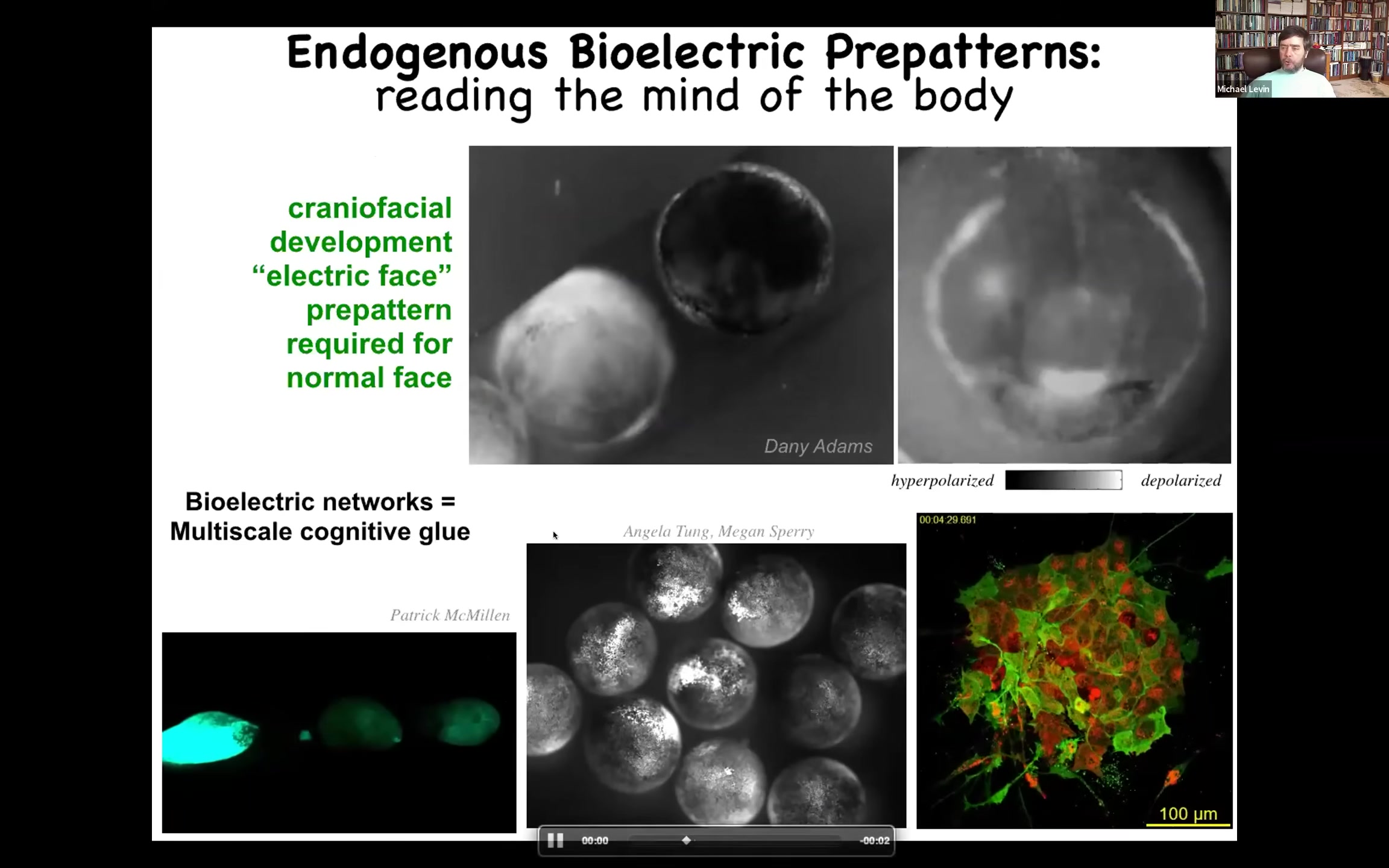

I want to show you some of these patterns. These electrical patterns serve as a kind of cognitive glue to bind cells together into a single body.

Here we have a frog embryo putting its face together. This is 1 frame from that video. We call this the electric face, because what you see here is that before the gene expression and the cell behaviors that lead to forming a face, this is the memory that you can read out of what it's planning to build. Here's where the eye is going to go, here's where the mouth is going to go, here are some placode structures.

The bioelectric stores a memory of what the thing is going to build, but it's also a cognitive glue across individuals. Here you can see when we poke this one, these two find out about this in short order. The same thing here: you poke this embryo, there's a wave that goes. Each one of these is a whole embryo. You can see that there's communication within and communication between individuals. They're sitting in an aqueous medium, which is how the wave can propagate.

Here are a bunch of cells where you can see the incredibly complex electrical activity that they're able to drive. We're able to read these things. Now, if you're going to communicate, you can't just listen.

Slide 18/30 · 19m:15s

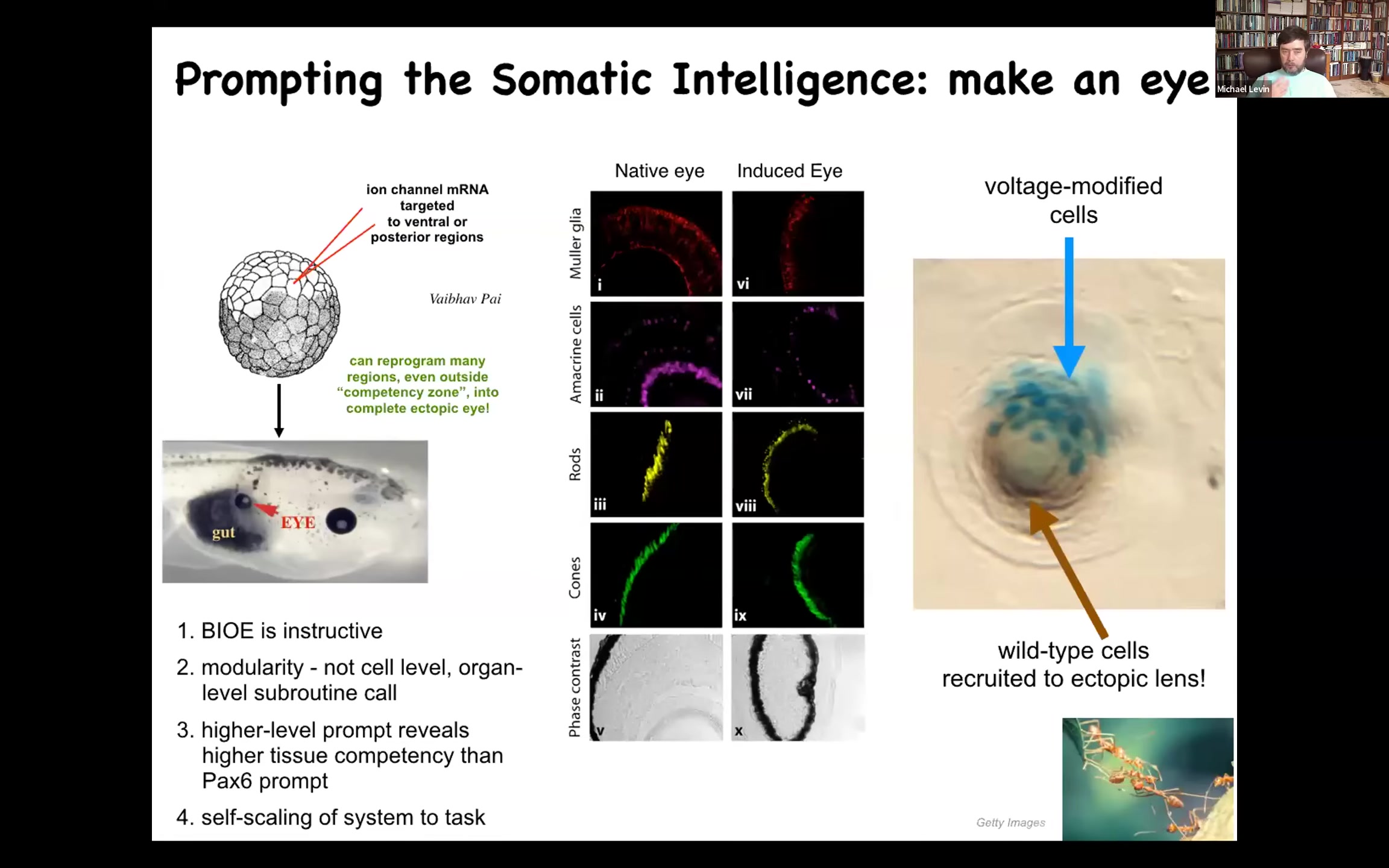

You have to be able to convey messages too. This is one example. I could show you hours of this kind of stuff where what we can do is say to some cells that are going to normally make a gut, give them the message that says, make an eye. That message is encoded electrically. We introduce it using ion channel, potassium channels encoded by RNA that make a little voltage gradient that looks just like that eye spot that I showed you a minute ago. Sure enough, the cells get the message and they make an eye.

Now there's something very important here, which is that when I'm talking to you, I don't need to worry about reaching in and making sure that all your synaptic connections are doing the right biochemical things so that you remember what I'm saying. You are going to take care of all of that because you're a multi-scale cognitive system. All I need to do is give you prompts with a very thin linguistic interface, and then you will do all the hard work of arranging the internals of your brain to act accordingly. The same thing is true here. We provide a very simple signal. It's a prompt. It says, make an eye. We don't tell the cells what to do. We don't tell which genes to turn on and off. We don't talk to the stem cells. In fact, we have no idea how to actually make an eye any more than I have any idea of how to manipulate your synapses so that you remember what I'm saying. The system takes care of all of that because it is a multi-scale cognitive agent that takes high-level information and it handles all the stuff downstream, including if we only get a few cells here, they will do the job of telling their neighbors.

So the blue ones are the ones that we injected. All of this other stuff, this lens that's sitting out in the flank of a tadpole, we didn't touch any of those cells. These cells told those cells what to do. They said, you need to participate with us to make this thing because there's not enough of us to make. These other cells resist. They have a different vision of the future that they were following before. We can actually track the communication that goes back and forth and see who wins because it's a cancer suppression mechanism. Cells don't just pick up whatever message you happen to give them. They resist. They have their own idea of what they should be doing. So all this morphogenesis is a constant battle of worldviews. It's a battle of models and the cell collectives have to decide which model of the future they're going to go with.

Slide 19/30 · 21m:22s

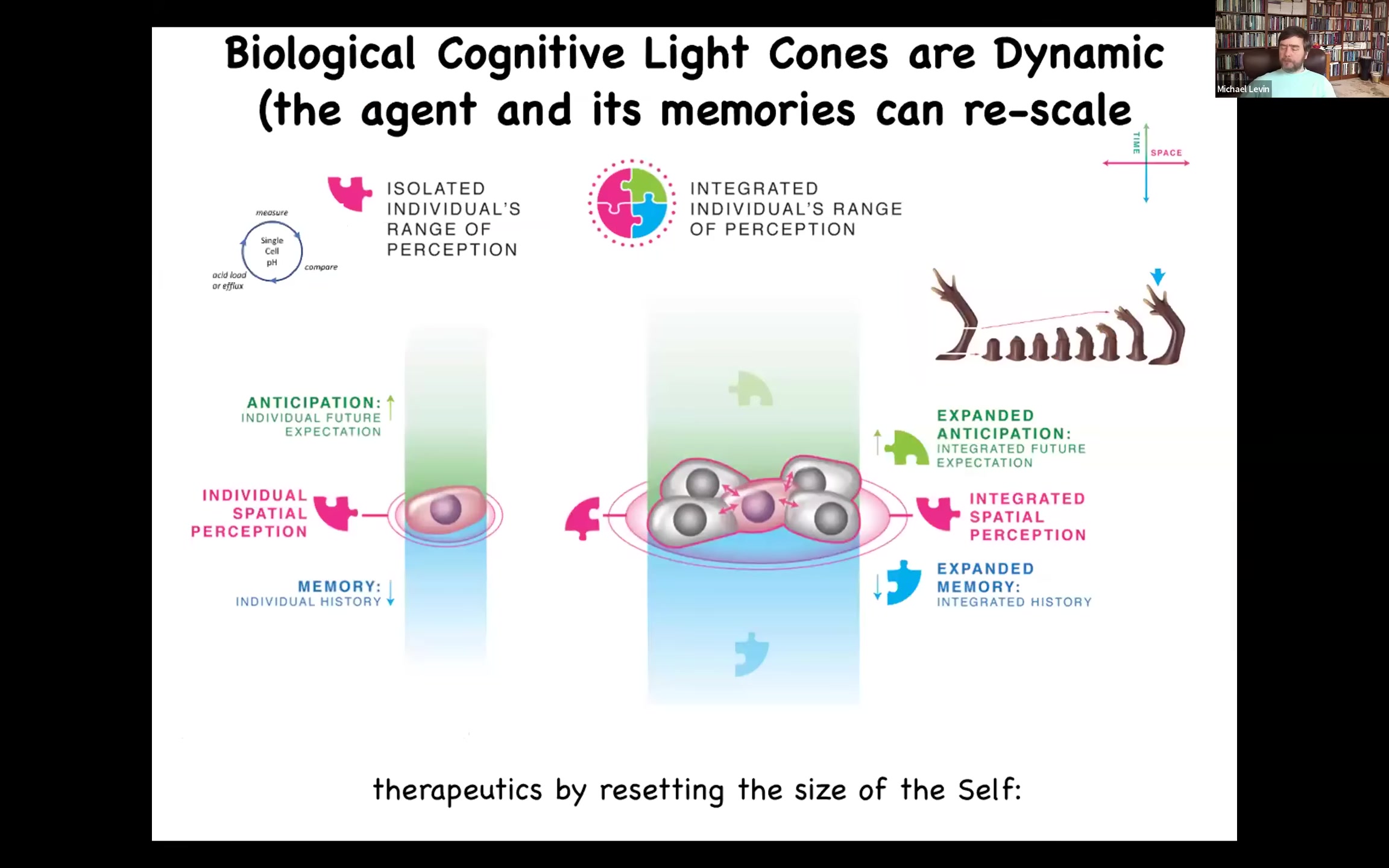

Another thing you can do with this interface is to change the scale, the size of the self. In other words, the scale of the cognitive light cone or the size of the goals that it can pursue.

The individual cells have little tiny cognitive light cones and they remember very simple goals like hunger level or pH. Then that's what they pursue. Their homeostatic set points are very simple things.

But morphogenetic systems have huge grandiose goals like building a limb. No individual cell knows what a finger is or how many fingers you're supposed to have, but the collective absolutely does. If you try to deviate it, you'll see that it knows what the set point is.

There's this question: can we show how connecting cells into a larger network allows them to have larger goals? How do you expand the size of the cognitive light cone? This weird way of thinking about it has therapeutic benefits. We try to show practical implications for all this strange stuff that we say so that other people can see why it's useful to think about it this way.

Slide 20/30 · 22m:25s

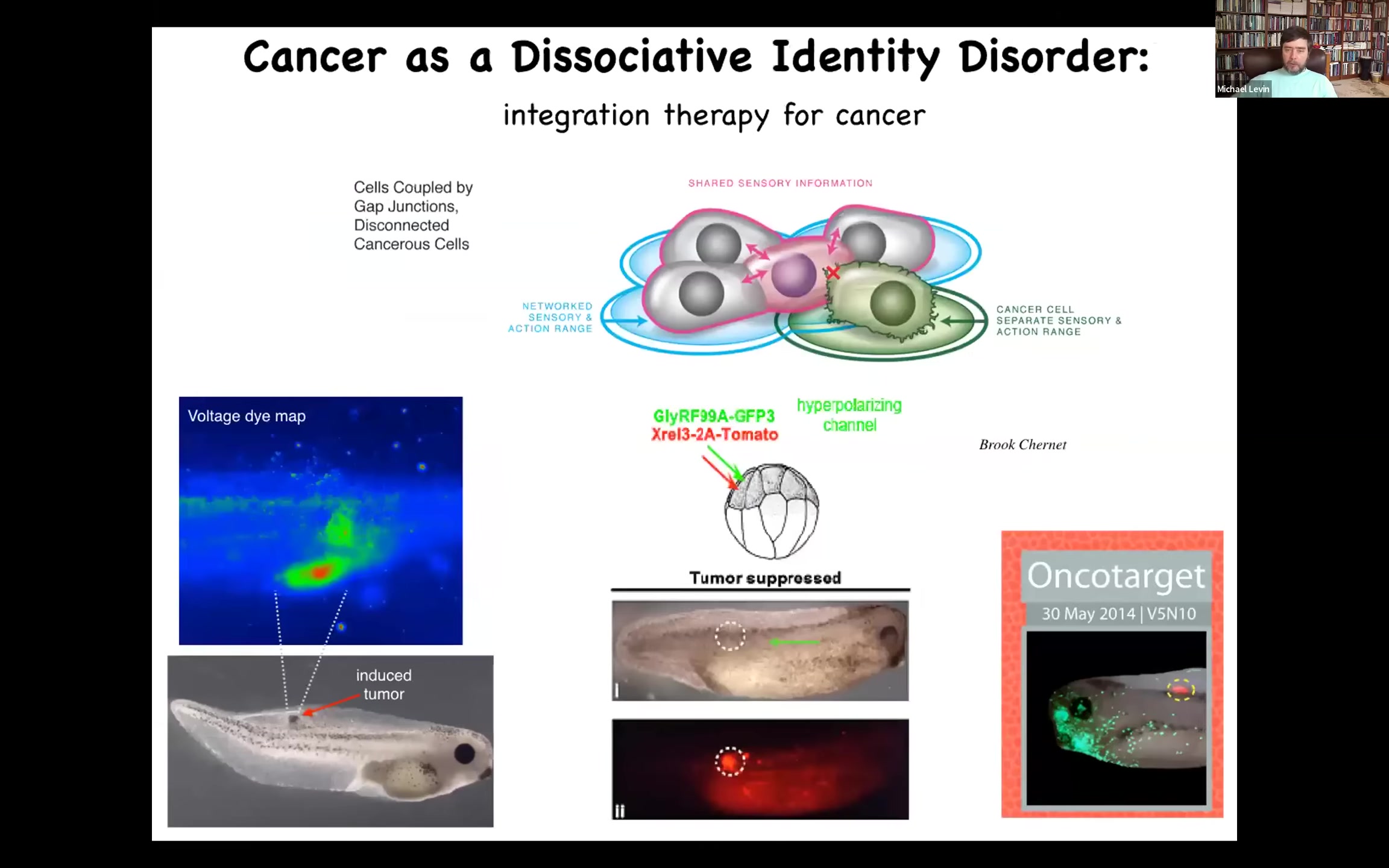

Here's a human oncogene injected into a tadpole. It normally makes a tumor. It's because oncogenes make the cells disconnect electrically from the rest of the network. When they do that, as far as they're concerned, the rest of the body is just external environment. It's not that they're more selfish, it's that they have smaller selves. The border between self and world shrinks, and whereas before it was part of this big collective that could entertain thoughts about building a proper skin and muscle, now it's just an amoeba doing its thing, so metastasis.

What you can do is forcibly reconnect these cells to the collective, and we've done that here. If you do that, the ANCA protein is still there. It's labeled in red; you can see it's blazingly expressed. This is the same animal, but there's no tumor. We didn't kill the cells. We didn't fix the genetic lesion. We didn't do any of that. What we did do is force the cells to be part of this electrical network; it is now part of a larger self with larger goals, working on anatomical things instead of being an amoeba in an environment.

What I've showed you is that this bioelectrical interface allows you to detect, reset, and communicate with a very unconventional collective intelligence. What it does is think about how to move an anatomical configuration through the space of anatomical possibilities. If we had more time, I could show you different problem-solving competencies that it has along those lines.

Slide 21/30 · 23m:55s

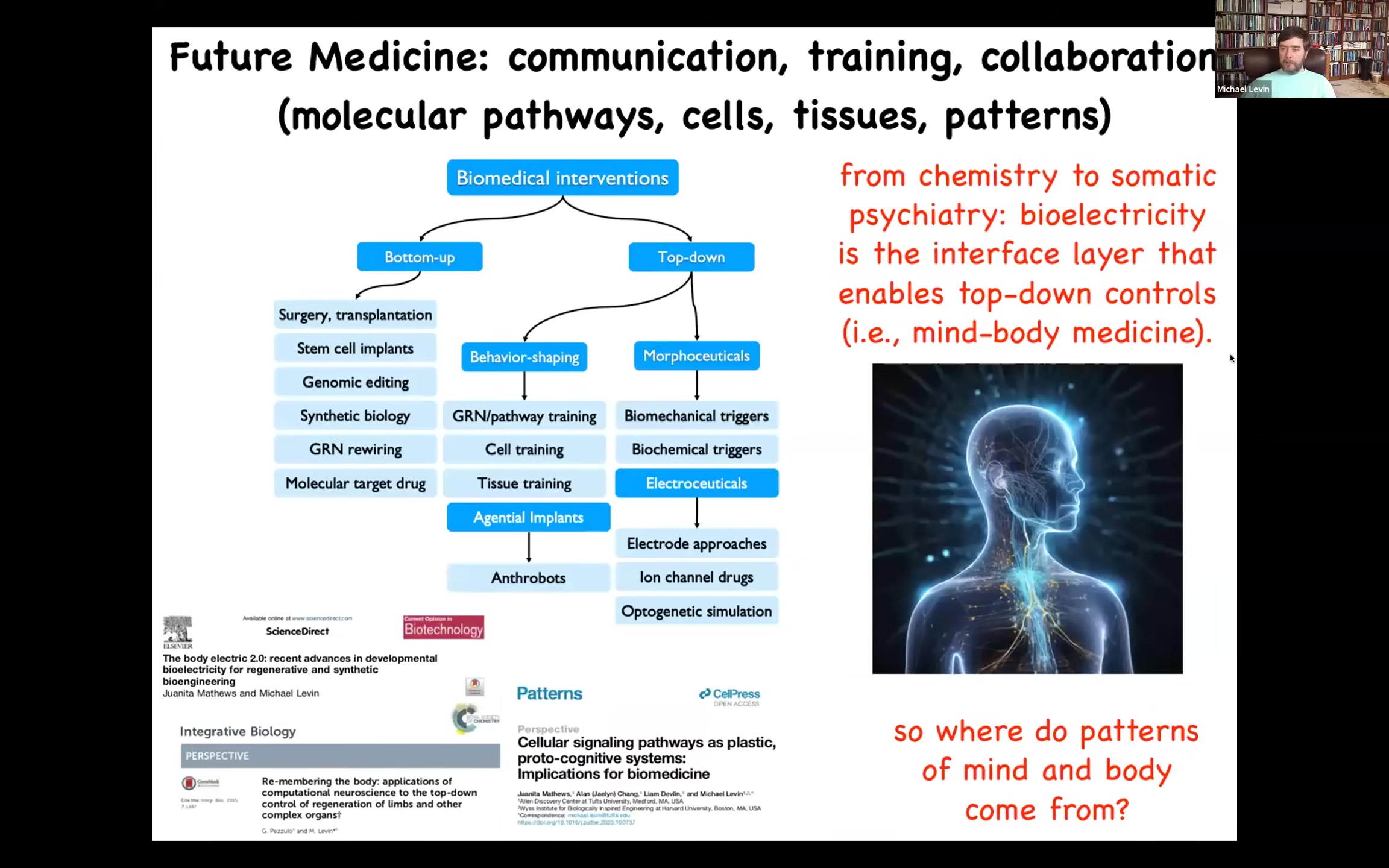

All of this way of thinking about it suggests to me a different kind of biomedicine. Everything that we do today is mostly bottom-up. It's focused on the hardware here. If we actually focus not only on the software, but on the intelligence inside the agential material of life, you end up with all kinds of applications. Most of this I didn't get to show you, training cells and tissues and top-down communication via electroceuticals. I think the future medicine is not going to look like chemistry. It's going to look a lot more like somatic psychiatry. Bioelectrics is one interface layer. No doubt there are others. There are biophotons and other things that probably will be developed. The most well-developed at this point is bioelectricity.

If the future of all of this is really the study of patterns, it's the study of patterns of thought and behavior that occur in these weird media, such as the electrical networks of your body. Where do these patterns come from? The standard answer in biology is they come from two places. Biologists love two kinds of explanations for things. One is history, in other words, a history of selection. The pattern is what it is because everything else died out and this is what we have now. The other thing that biologists like is physics. Patterns are constrained by physical effects and the properties of the physical world. Some of those patterns just come from the physics.

What's interesting is that there are some patterns, and we can start with the one studied by mathematicians, that have neither a genetic nor an environmental explanation.

This thing that you're looking at here is what the pattern actually looks like when you start tweaking the formula. This is a very simple function in the complex number z.

z cubed plus 7, for example: if you do something called a Halley plot, a very simple algorithm for plotting the roots of this function and how the roots behave, you get this amazing complex pattern.

It doesn't hurt that it's very organic looking, which is why I use this example.

What's salient here is that there's a tiny seed. It encodes a very complex pattern, a very rich kind of structure.

If you wanted to explain why it looks like this, there are no facts of the physical world that explain it. There is nothing in the history of the physics of the universe that explains why this is the way it is. The explanation does not come from the physical world. You cannot tweak any of the constants of the universe at the beginning of the Big Bang and get a different pattern out of this. It is an extra thing that is distinct from information you get from your genetic lineage and information you get from your physical environment. There are plenty of patterns like this in that space as you play with these kinds of things.

What does this have to do with biology? Could we find any living forms without a large-scale history? If biologists say that whatever form you have is driven by your evolutionary history, are there any beings that are picking up forms that cannot be explained in this way?

I'm going to show you just one.

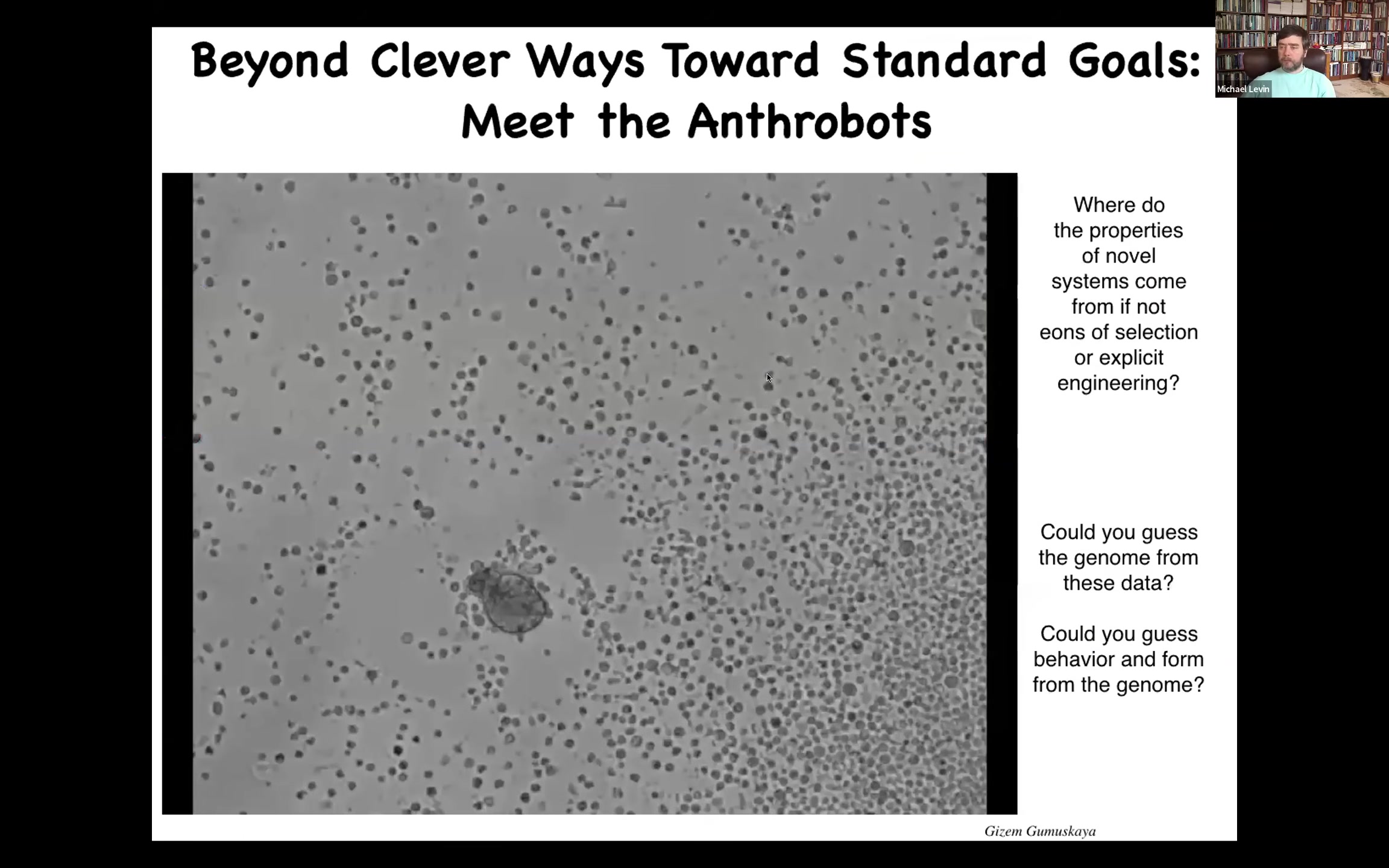

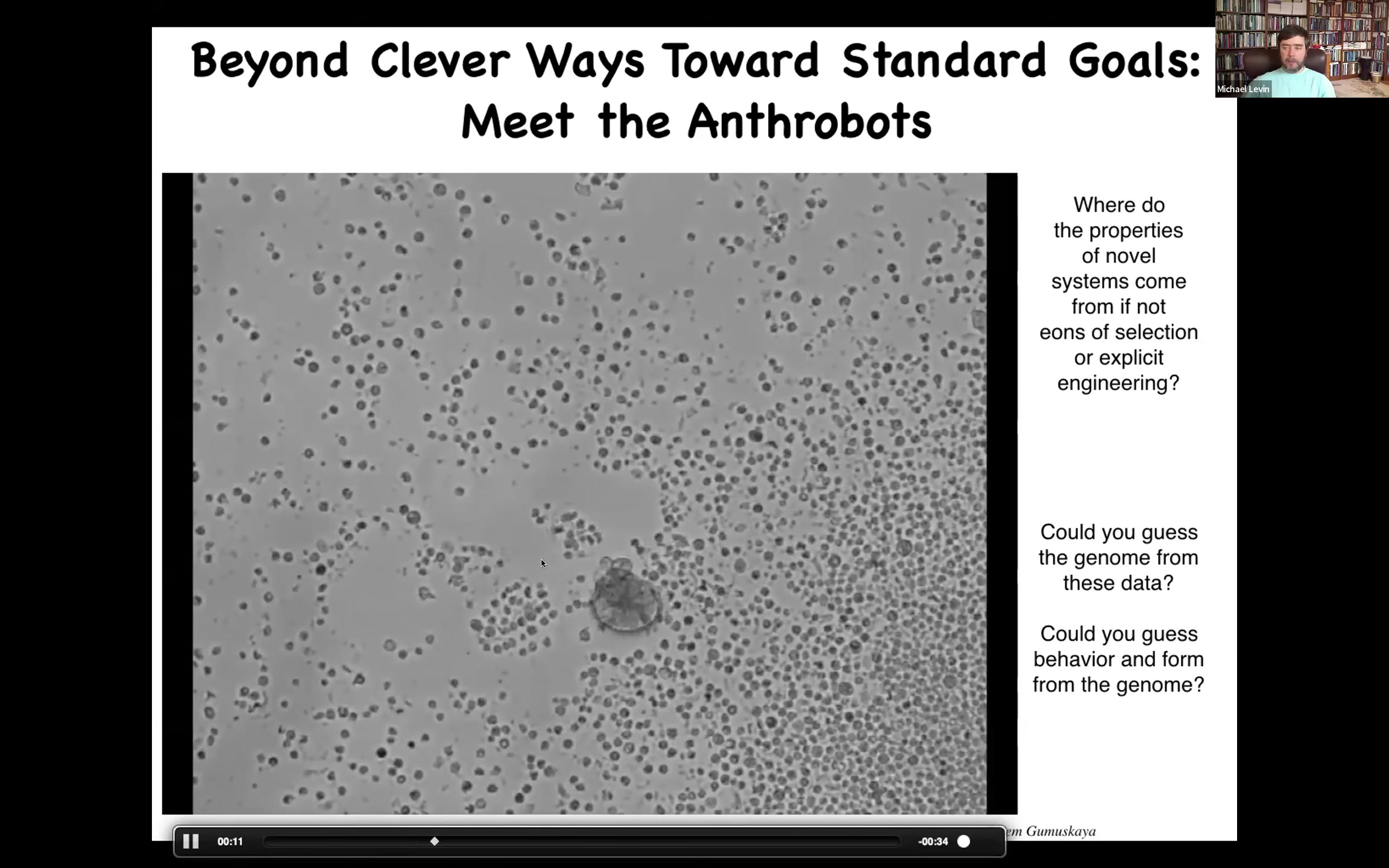

Slide 22/30 · 27m:18s

This is something called an anthrobot. You might be tempted to guess that this is a primitive organism that we picked up at the bottom of a pond somewhere.

Slide 23/30 · 27m:30s

You might take a guess about its genome. You might think that this will have a genome of an early metazoan, for example. If you were to sequence this genome, you would find out that it's 100% Homo sapiens. These anthrobots are self-assembled from adult human cells. They come from tracheal epithelia that human patients donate. Some of these patients are alive and well when they donate this, some are not. For those that are not, this is a weird kind of life after death where the cells self-assemble into a multicellular organism.

It matches no stage of normal human development. You would not be able to guess from the human genome that this is what you would get. It's interesting: what capacities does this creature have? It's never existed on Earth before. There's never been any anthrobots. There's never been any selection to have to be a good anthrobot. What can it do and where do those patterns come from?

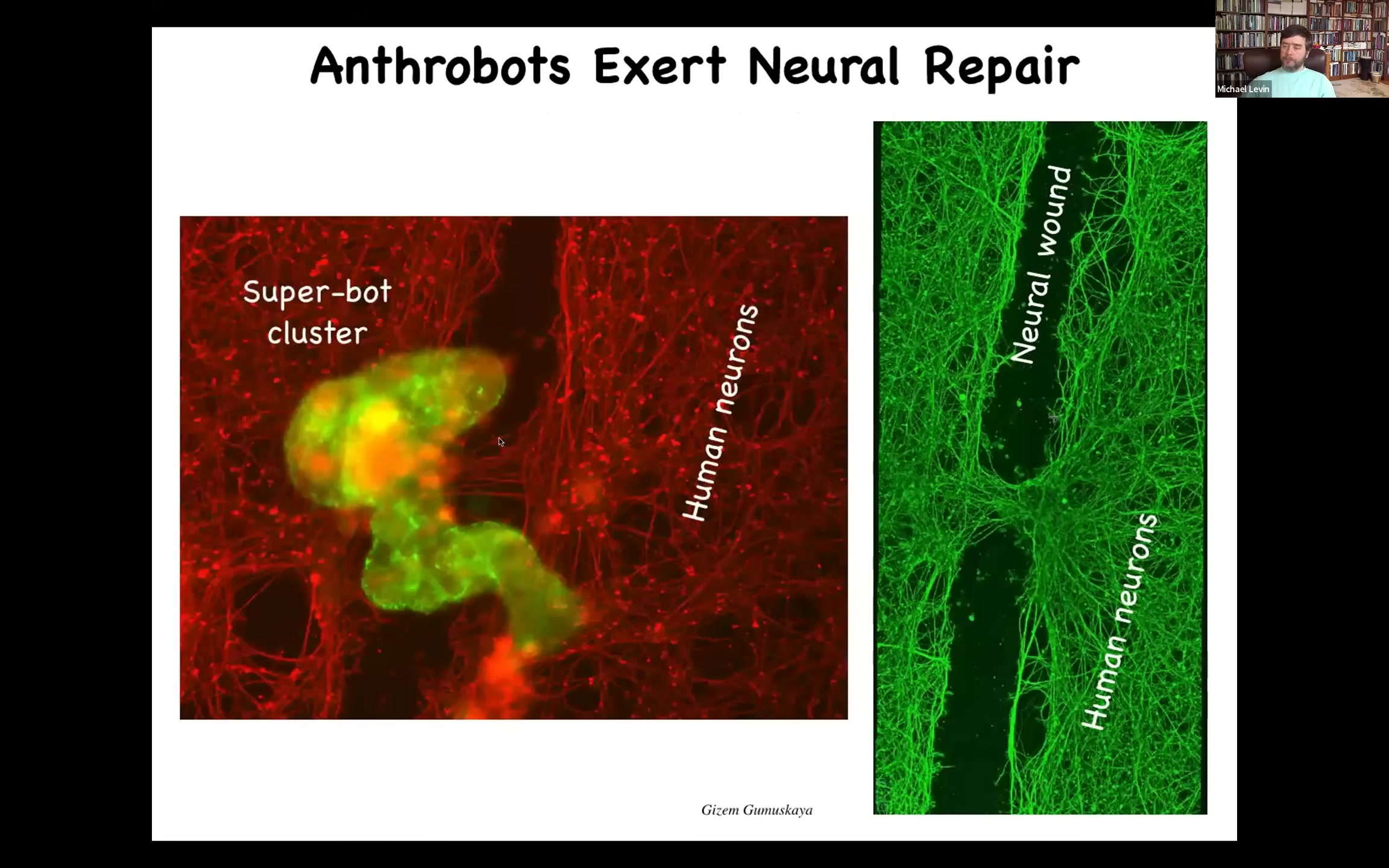

Slide 24/30 · 28m:35s

If you plate a bunch of human neurons on a dish and make a big scratch through them, you'll find that these anthrobots cluster in what we call a superbot. They pile up. Over the next four days, they start healing the wound. If you lift it up, this is what you see. They're sitting there knitting across the gap.

Who would have thought that your tracheal cells, which sit in your airway for long periods of time dealing with dust particles, given the opportunity to reboot their selfhood, to reboot their multicellularity, would go on and make this kind of self-motile thing that has the ability to heal parts of your body. This is a technology that we're developing for in-the-body repair. It's made of your own cells. You won't need immunosuppression once we figure out how to ask these cells to do the things we want them to do. This is all kinds of useful technology.

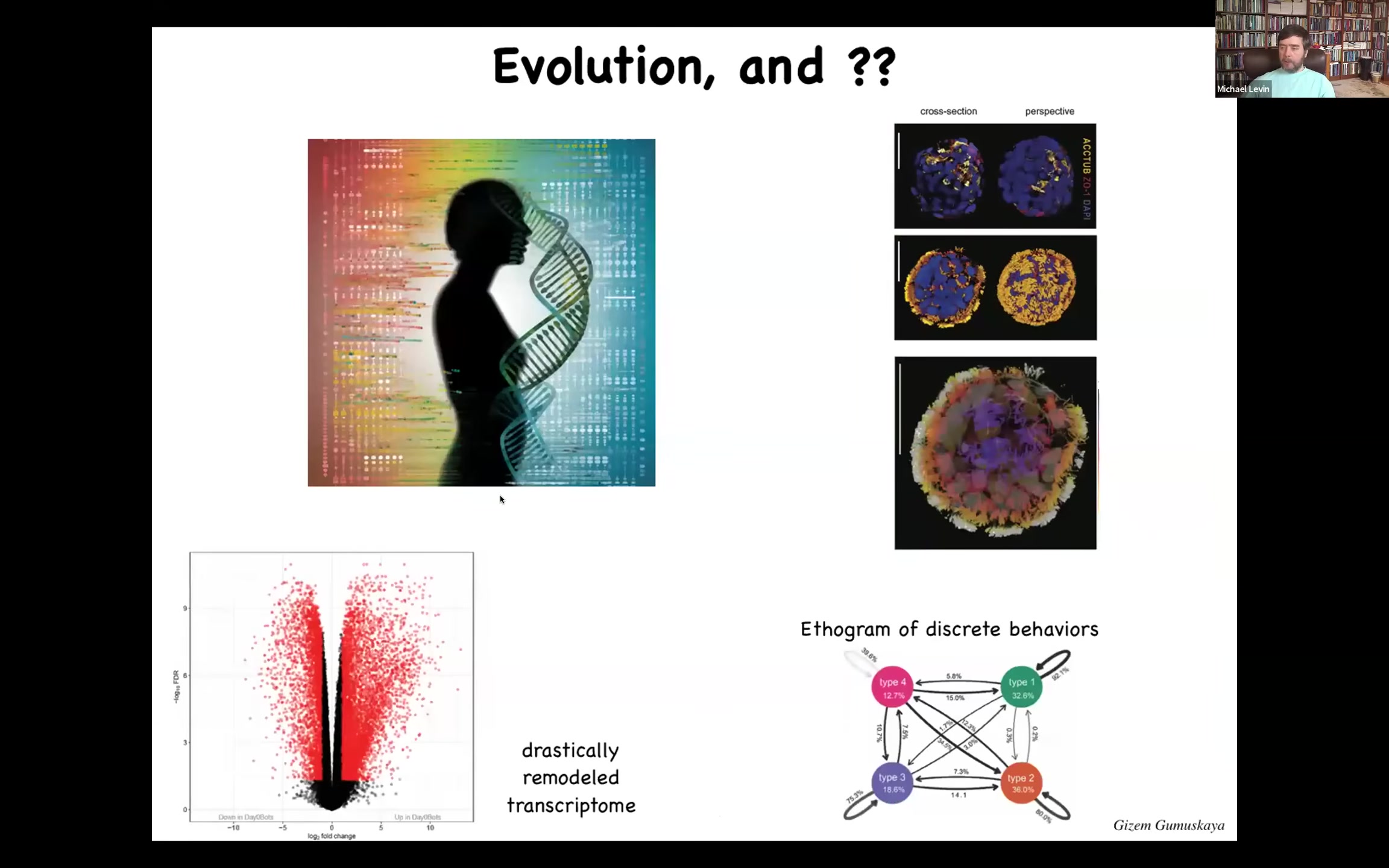

Slide 25/30 · 29m:25s

They have four different discrete behaviors, and you can draw an ethogram of those transition states between those behaviors like you would in any animal.

They have a drastically remodeled transcriptome. What I mean by that is this volcano plot shows different genes that they express differently than the tissue they came from. Each one of these red genes—there are about 9,000 of them—so almost half the genome is differently expressed compared to that tissue.

When we say, why do humans look the way they look and have certain properties, it's the human genome. The same genome can also make this. And if you do enable them to make this, we don't edit the genome. There's no weird nanomaterials. There are no scaffolds, no synthetic biology circuits. The cells do all the work. When they do this, they will pick and choose what they express from their genome, about half of them, to be in a completely different kind of form and function.

I want to say a couple of quick things.

Slide 26/30 · 30m:22s

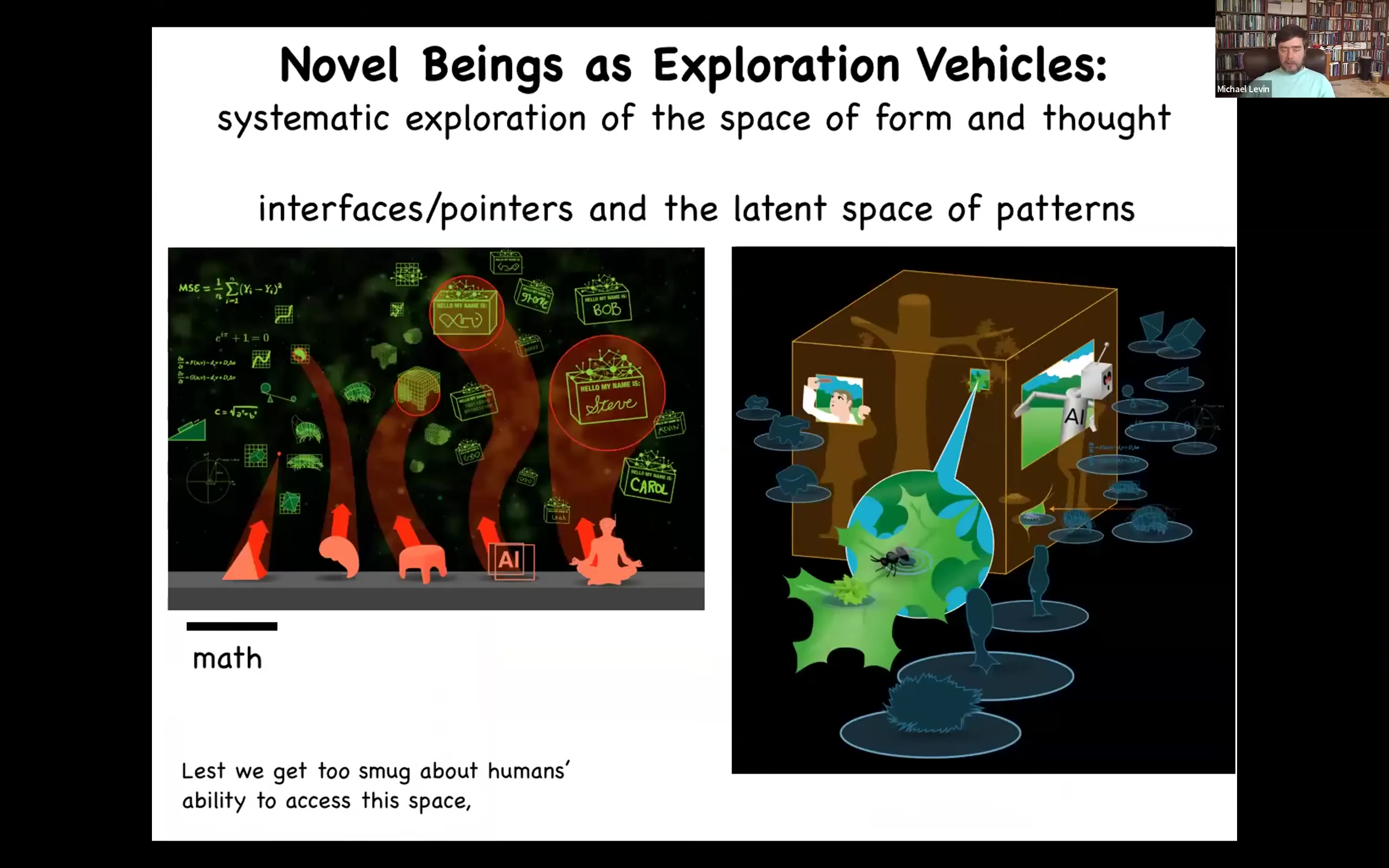

The first thing, and so this is the latest and most exploratory aspect of all this work, is that I see all of this stuff, the Xenobots that we build, the Anthrobots, the Chimeras, all the things that we make, I see them as exploration vehicles. I see them as enabling a systematic mapping of the relationship between the interfaces that we make, which are the physical objects.

So I think all physical objects, including cells and embryos and bodies and robots and everything, all of these things are physical, are interfaces or pointers into a space of pattern. Mathematicians have known this for a long time. They study one region of that space, and there's all kinds of truths and patterns of mathematical objects that don't come from the physical world. But I actually think it's a much richer space and it contains other very high-agency patterns that we recognize as kinds of minds. And everything that we do is basically poking holes in this separation between the interfaces and the patterns that are then ingressed through these interfaces.

And so it's just the very last thing I'll say is lest we get too smug about our ability to access this space, because among us are certain geniuses that can perceive incredible truths and works of art and literature. They're picking out things out of that space and letting them come into the world. Lest we think that this is some human capability, I will just point out that first of all, there are no humans as a sharp category.

Slide 27/30 · 31m:58s

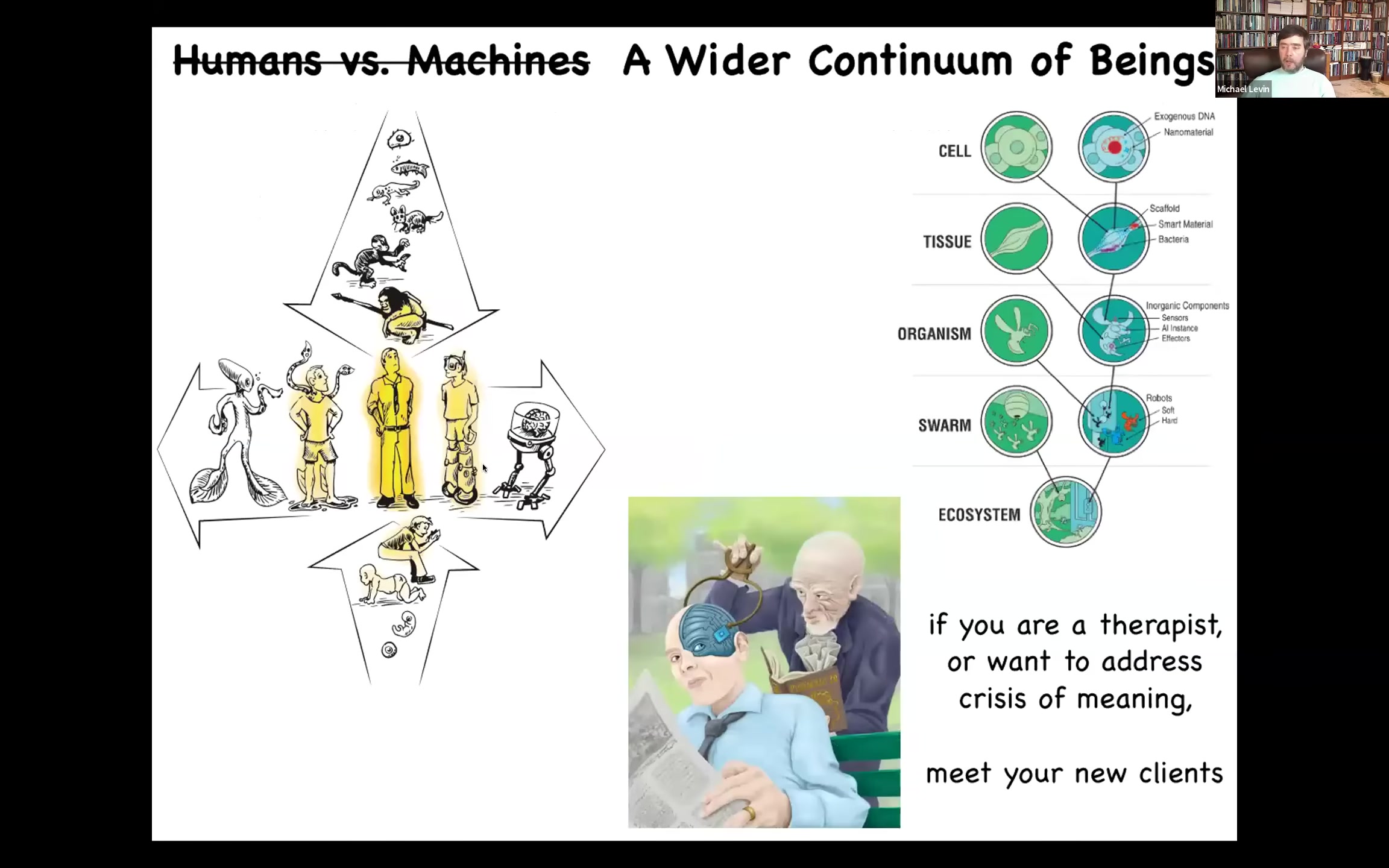

So we are at the center of all kinds of continua, both developmentally, evolutionarily. Whatever you think that humans are or can do, you have to have a story for where does it come from and how does it scale? In fact, both with biological changes and technological changes, the standard human category becomes extremely diffuse because of the plasticity of life that allows it to be interoperable with all kinds of modifications. If you in the audience, if you're a therapist or you're interested in the crisis of meeting and helping people through this, you've got a set of constituents that count on you for help, you really have to start thinking about here are your patients of the future. The standard human patient is not enough. There are going to be all kinds of interesting new beings with all kinds of needs that we are going to have to address in some way. Some of these will have the same existential concerns as us, some will have very different concerns.

I think that because of this interoperability, all natural life is a tiny corner of this option space and that pretty much every combination of evolved material, design material, software, and these patterns that you can't forget about as an ingredient—there will be hybrids and cyborgs and just every possible kind of being that we are going to have to enter some sort of ethical synth biosis with.

Slide 28/30 · 33m:30s

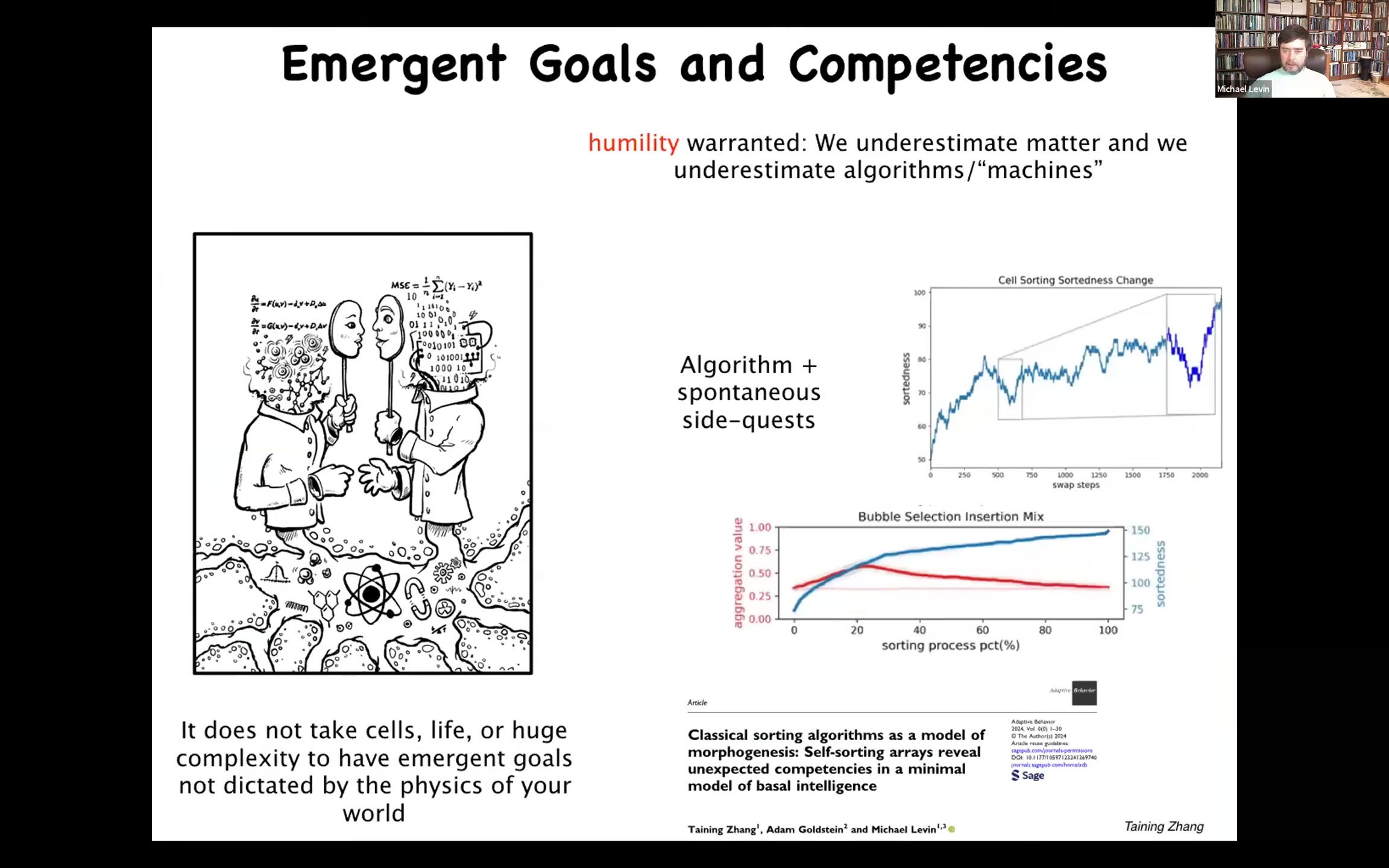

And then the last thing I'll say is this: there's some serious humility warranted in all of this, because a lot of people think that A, it's complexity that makes all this work, or that B, there's something special about the biological material and this kind of trial and error process of evolution.

And our work, even looking at deterministic, extremely simple things that computer scientists study, like sorting algorithms, already you see that it does the thing the algorithm tells it to do, but if you know how to look, you also find it doing all kinds of interesting side quests the algorithm does not ask it to do, things that you would recognize as aspects of cognition. Very minimal, but yet there they are.

And so I really think this goes all the way down: this ability to have the freedom to express patterns from that space that are not fully determined by the physics of your world or the algorithms that we think you are following is always richer than that, even in extremely simple systems.

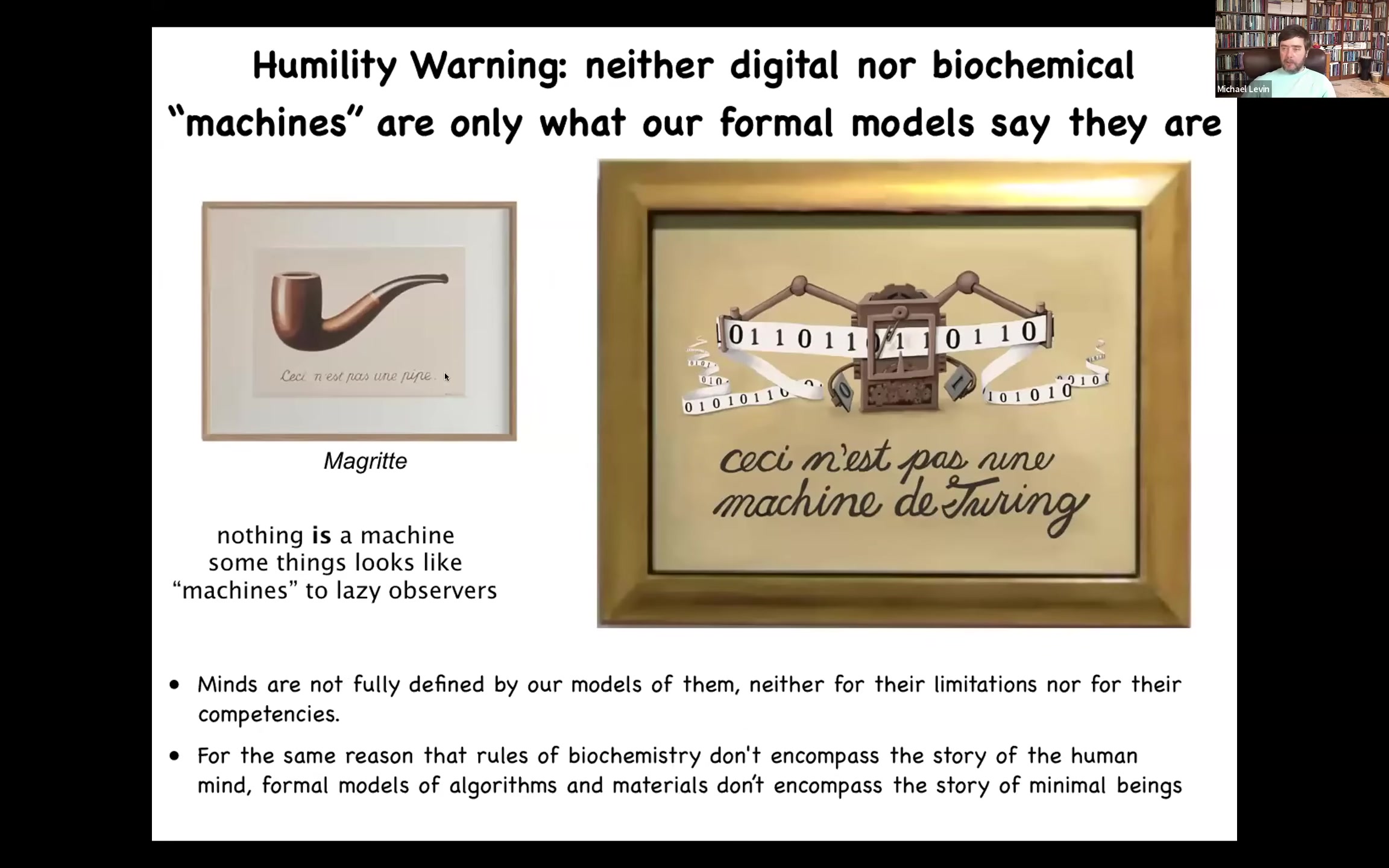

Slide 29/30 · 34m:38s

And so Magritte was telling us that our formal models are not the thing itself. I would say the same thing. There's a lot of organicist thinkers who are down on computationalism and they say, living things aren't machines. And they say nothing is a machine because a machine is a formal model that humans have defined to handle certain aspects of what physical objects do in the world. And it doesn't fully describe even the simplest kinds of systems, never mind the biological systems. So nothing is a machine, but some things look like the machines, like a machine to lazy observers. And I think for exactly the same reason that the rules of biochemistry don't encompass the story of the human mind, formal models of algorithms and materials do not encompass the story of minimal beings. I think we have to get much wider in our perception of what we can relate with.

Slide 30/30 · 35m:30s

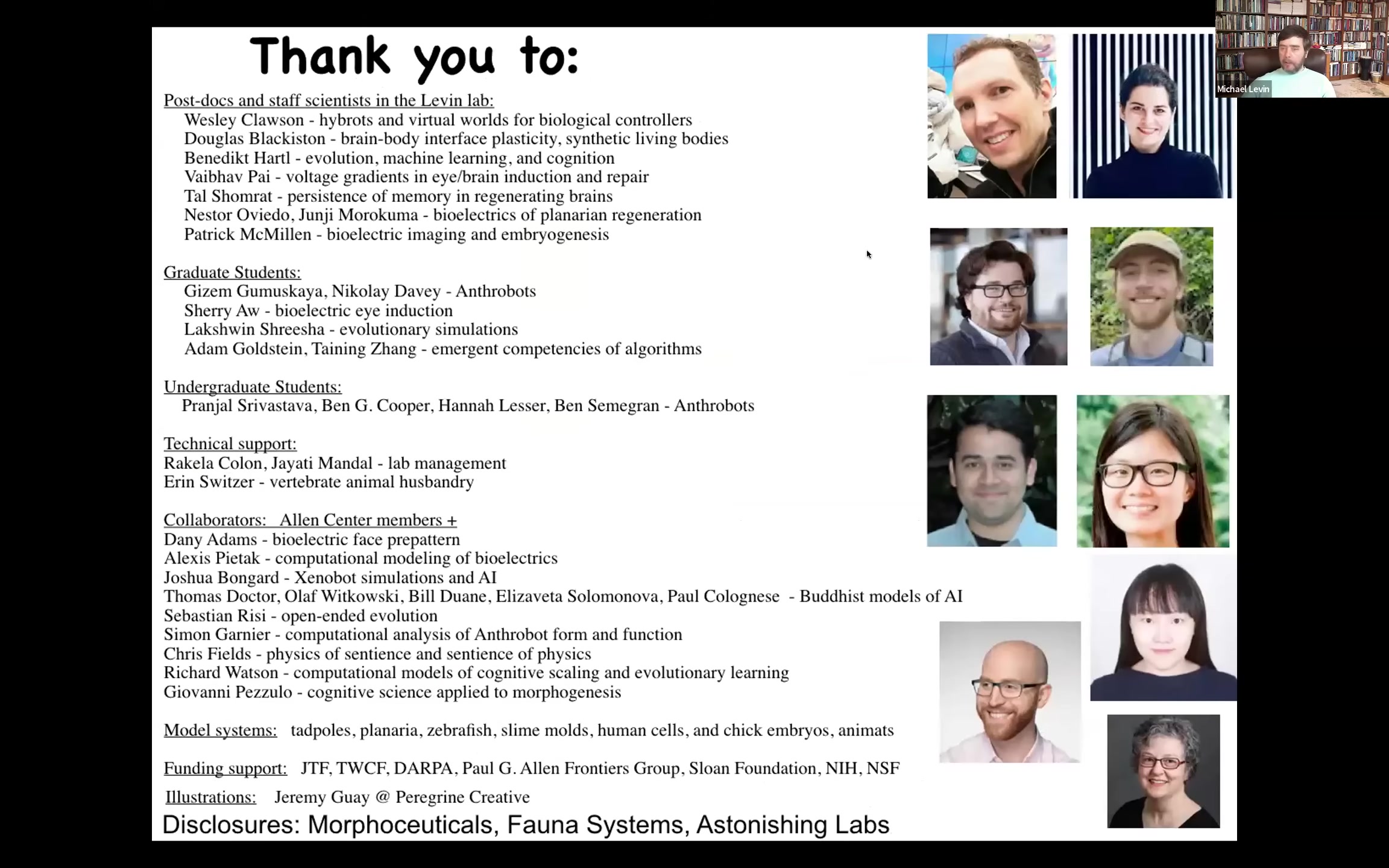

I'm going to end here and thank the people who did the work that I showed you. Here's some postdocs and students and collaborators in our lab. Disclosures: there are three companies that have spun off from the work that we do. I thank our funders and the model systems because they've done the most hard work in teaching us about this stuff. Thank you so much. I'll stop here.