Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a new ~1 hour talk by me on the concept of diverse intelligence, and morphogenesis as a model system with which to practice identifying and communicating with unconventional minds. This is a bit different than previous ones because I explicitly go over examples of how some of our various data on bioelectrics addresses each of several key properties of cellular collectives as *cognitive agents* navigating anatomical morphospace.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Talk overview and unification

(04:34) Protocols for recognizing minds

(09:23) Intelligence beyond nervous systems

(14:39) Components of collective intelligence

(21:07) Bioelectric software and patterning

(28:48) Writing bioelectric eye instructions

(34:39) Body-plan memories and morphospace

(40:07) Learning and creative morphogenesis

(48:02) Emergent Xenobots and Anthrobots

(53:04) Evolutionary ratchet and futures

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/55 · 00m:00s

Thank you so much. It's great to be here. I'm looking forward to discussing these issues with you. In my talk, I'm going to do three parts. First, I'm going to give some conceptual background to the way that my group addresses the issue of diverse intelligence. In particular, I'm going to spend a lot of time talking about one particular example. The model system that we have chosen for much of our work is decision making by a collective intelligence, the cells making decisions and solving problems and making memories within the space that they operate in, which is anatomical morphospace.

So this sets up two things. It shows us some very specific examples, and I will go through actual very detailed examples of how it is that we can recognize and communicate with unconventional intelligences that operate in a different medium, in a different scale of space and time, and in a different problem space entirely from our own. So that gives us an example of how we may learn to do that. It also shows a number of applications that we are driving in regenerative medicine, which I think is important because it shows that philosophical perspectives can drive empirical advances, that the philosophy matters because the perspective you have makes certain things possible that were never done before. This is an empirical aspect of our work.

At the end, I will close with some future-looking thoughts about what it all means. If you want to see any of the primary papers, the data sets, all of that is here at this site. This is my own personal blog with some thoughts about what it all means.

Slide 2/55 · 01m:42s

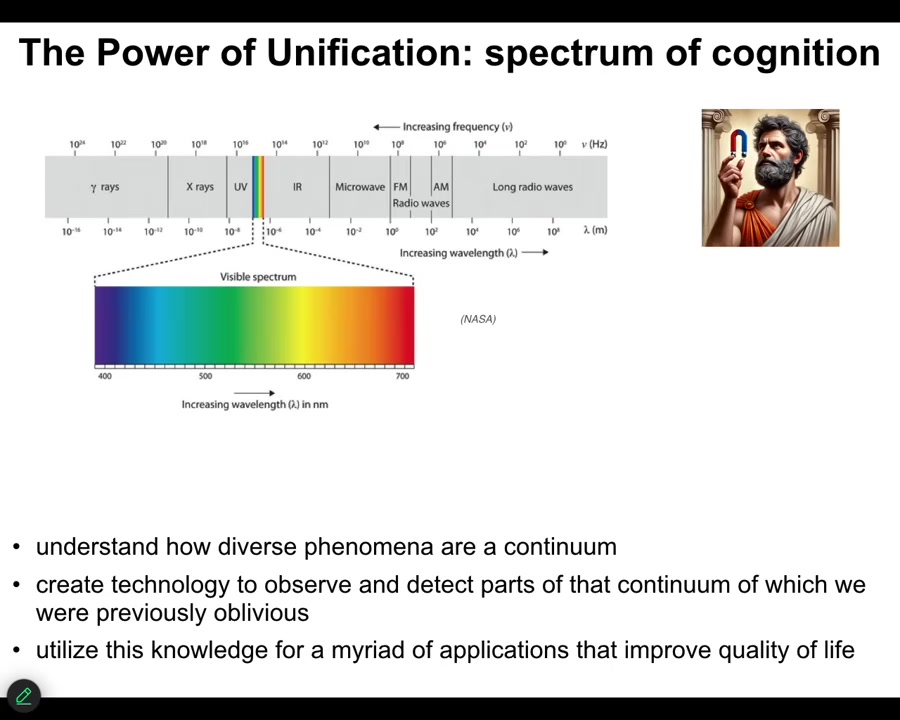

The first thing that I want to remind us of is the power of unification.

Back before we had a proper theory of electromagnetism, we had a variety of diverse phenomena: lightning, static electricity, magnets, light. Two things were true. One is we used to think those were completely different phenomena.

We were totally blind to an enormous spectrum of related phenomena. This is all that we could see because of our evolutionary past, but we didn't know all these other phenomena existed.

What unification allowed us to do with a good theory of electromagnetism is to say that, first of all, these are examples of the same underlying phenomenon. We were able to put them on one continuum. Now, this is a log scale. Certain regions of this continuum are much bigger than others. But the point is, they all end up on one continuum.

What it allowed us to do is make technology that enabled us to operate in these other spaces that evolution did not give us a natural facility for. I think this is very important. It allowed many applications that improved the quality of life.

I think what we need to do in cognition is exactly this.

Slide 3/55 · 03m:08s

We need to take things that look and seem different and explain how they all fit on the same continuum so that we may be able to recognize them, we may be able to communicate with them, and we'd be able to ethically relate to them.

This is what my framework attempts to do. It attempts to take all kinds of different agents, familiar things like primates and birds, all kinds of weird creatures, colonial organisms, swarms, synthetic life forms, engineered new life, which I will show you some today, AI, whether purely software or robotic, maybe someday some exobiological agents, and also something else that's weird, which is not physical agents at all, but actually patterns within media, which I won't have much time to talk about today, but maybe in the discussion after.

What I would like to do is to have a spectrum where we can understand what is going on with all of these. How do they relate to each other? How can we relate to them?

It's really important for me that whatever philosophical framework we develop, it has to move forward new discoveries, new capabilities. This cannot just be abstract. This has to demonstrate the value of different ways of thinking.

And so much of this is described in this paper. I'm not the first person to try this. Rosenblueth, Wiener, and Bigelow had this kind of scale going from passive matter up to human-level metacognition. But I think now we can say more than what was said before.

Slide 4/55 · 04m:35s

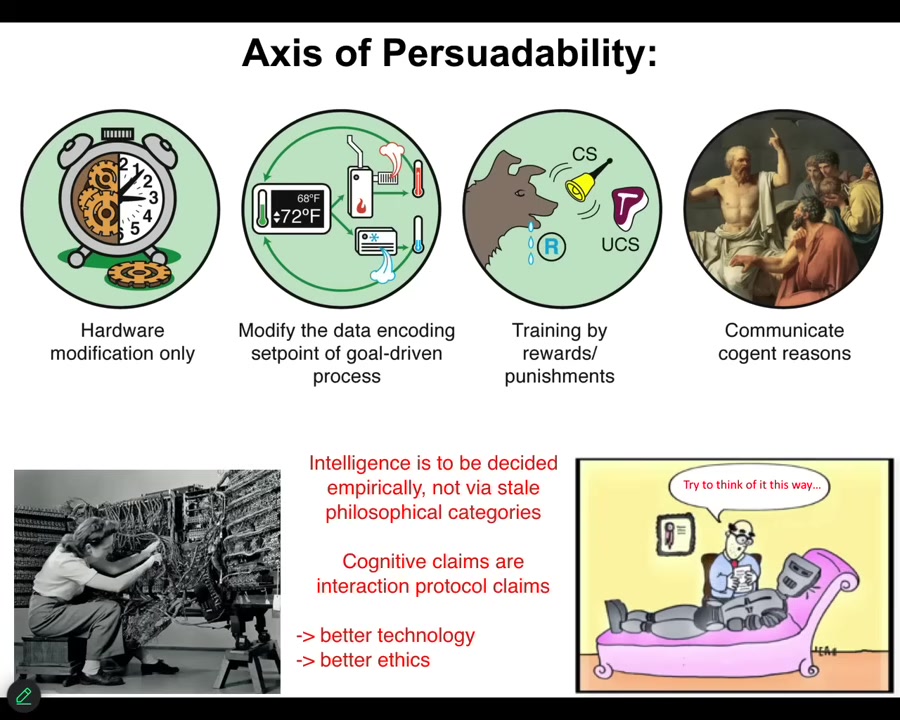

So in particular, there are a couple of philosophical perspectives that I bring to this and I like to lay the cards out on the table right at the beginning. The first thing is that I think all cognitive claims about a system are actually protocol claims. In other words, what you're saying when you say that a system has a particular degree of cognition, what you're really saying is how you plan to interact with it.

What tools? It might be hardware rewiring. It might be resetting the set points, as you can do with cybernetic agents like thermostats. It might be training, which you can do with some systems that can be trained with rewards and punishments. Or it might be something very advanced: the right side of the spectrum — friendship and love and various other kinds of very advanced things.

So what you're really saying is that there is a certain set of tools that you are bringing from behavioral science, cybernetics and control theory, psychoanalysis. You're bringing a certain set of tools, and then it's an empirical question. This is really important. This is not just philosophy. We can't just decide that something is a category error or that cells can and can't do something. It's an empirical question. You bring the tools and you see what they, in fact, allow you to do. And so this is the perspective that I take.

Slide 5/55 · 05m:55s

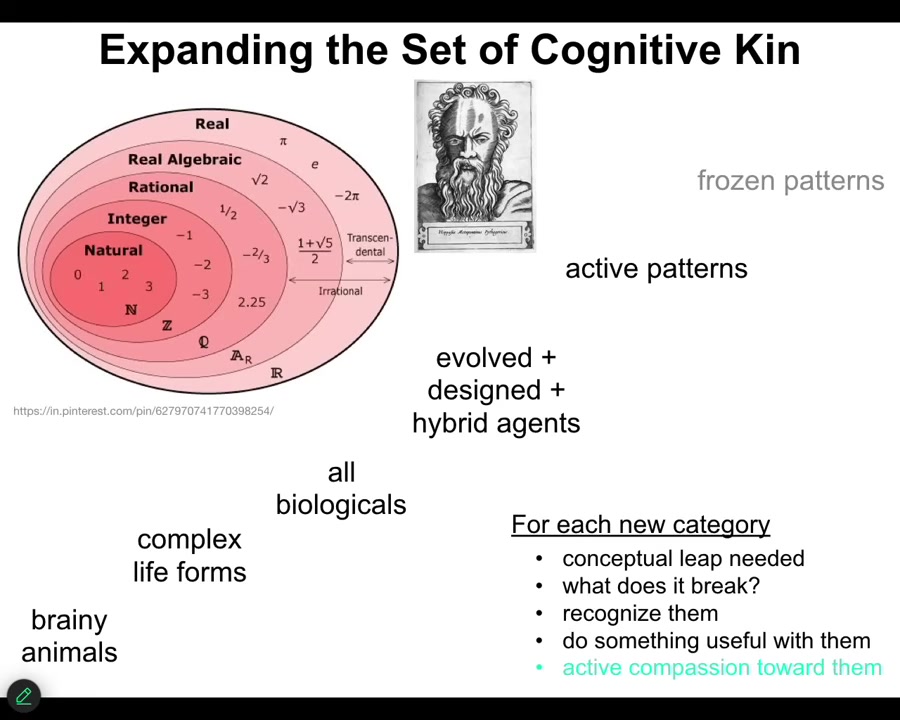

I'm going to focus on just a part of the spectrum today. What I try to do is like what happened to the notion of numbers, where we started out with very obvious, very natural kinds of things, and then progressively expanded them to weirder and weirder other concepts along that same continuum.

What's important is that process of expanding your categories to things that before did not seem possible or did not seem like they belong in the same set is disruptive. It is stressful. People like Hippasis were drowned at sea for some discoveries on certain kinds of numbers that people are uncomfortable with.

Some of the implications of what I'm about to say, especially towards the end, are disruptive for a number of areas. What I'd like to do is start here and progressively get weirder, and I'm only going to get to this point here, as to what kinds of agents can we actually start to recognize all around us and develop protocols for dealing with them. For each of these things, there's a conceptual leap needed; it breaks old categories.

It's very easy to detect minds in brainy animals.

Here's a mammal and this thing is going to set up a little accident scene like that.

Because he has a pretty good theory of mind about his owners, he knows that they're going to be troubled by this thing.

Slide 6/55 · 07m:25s

He's going to put it right on his neck. There he goes. And so then he's even going to look up to see if anybody's looking.

And it's incredibly obvious what's going on here. You're looking at another.

Slide 7/55 · 07m:35s

It's very obvious because they operate at the same spatiotemporal scale as we do. They live in the same three-dimensional space. They have similar goals to ourselves. However, the story isn't that simple even there.

Slide 8/55 · 07m:58s

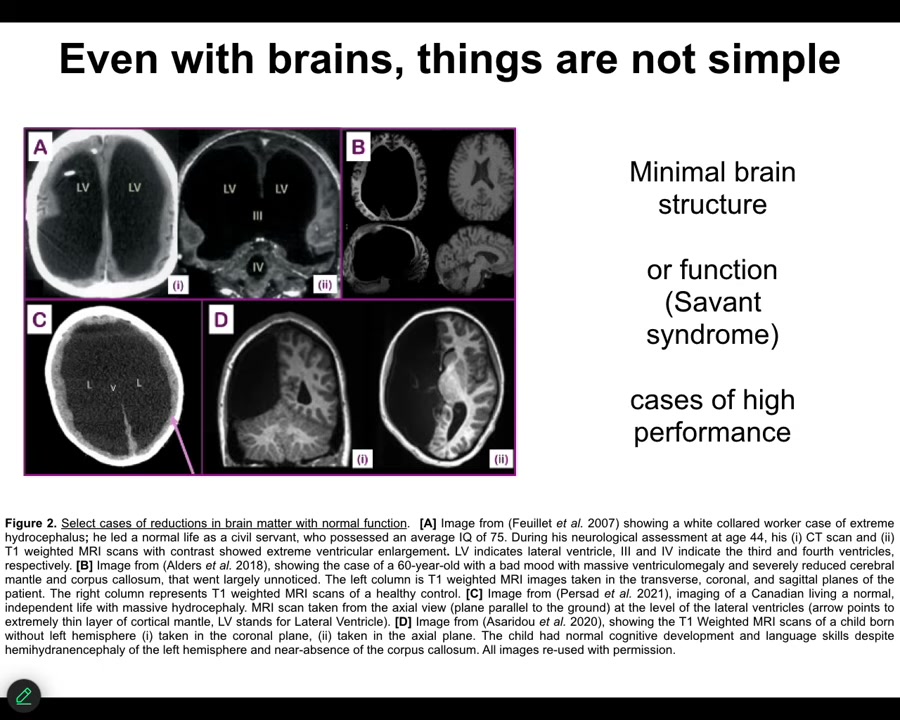

Even there, the story isn't simple. This is from a review that Karina Kaufman and I published recently, looking at human patients with minimal or greatly reduced brain real estate and yet normal or above normal function. There are some cases of high performance with very little brain. It's really remarkable. The relationship of brain hardware to performance is actually not as obvious as people think.

Slide 9/55 · 08m:30s

There are also some very interesting phenomena that have been known for a while. For example, learned information can be moved through the body. So in these planaria, if you train them on a place conditioning task to recognize these little bumpy areas and to look for food there, you can cut off their heads, which have a centralized brain. The tail will sit there for a while. It will eventually rebuild a new brain from scratch. And you will find out that these animals remember the original information. McConnell discovered this in the 60s. We reproduced it with modern automated equipment in 2013. And it does work. And what it means is that information is not only stored outside of the brain, but it is imprinted onto the new brain tissue as it develops. Some very interesting interactions here between memory, learning, and morphogenesis, which I'm going to get into.

Slide 10/55 · 09m:22s

Here's what I'm going to talk about today, biological intelligence outside the familiar brain. I'm going to claim that intelligence and problem solving are way older than brains and neurons. We're going to go across scales and substrates, and we're going to recognize them by problem solving and the ability to reach anatomical goals with many applications. The model system we're going to use is cells, groups of cells, as a collective intelligence that makes decisions about shape. Let's first look at what the building blocks are that we're talking about.

Slide 11/55 · 09m:55s

So this is a single cell. This happens to be a free-living organism called a Lacrymaria, but you get the idea. This is one cell, no brain, no nervous system, very competent in its own local environment to do the things that it needs. When you engineer with this, you have to do it very differently than you engineer with passive materials wood and metal, and this is described here.

Our entire body is made of nested competencies, not just nested structure, but actually a multi-scale competency architecture where the molecular networks, the subcellular components, the cells, the tissues, the organs, all the way up through the swarm level, all of them are able to solve problems in their own space using some of the same tricks that the brain does at various levels of sophistication.

Slide 12/55 · 10m:48s

And these spaces, it's important to think about what space these things are working in, because as humans, our evolutionary history and the firmware that we've been handed down are obsessed with three-dimensional space, medium-sized objects moving at medium speeds through 3D space. We're okay at recognizing the intelligence of crows and maybe an octopus or a whale. But biology actually does this perception, decision-making, action loop in many spaces, not just the obvious space of three-dimensional behavior.

So cells, for example, navigate transcriptional space, the space of possible gene expression states, the space of physiological states, and the space of anatomical shapes, which is the one we're going to be talking about today. And it's very hard for us to visualize any of these things. If we had internal sensors that let you feel the way that you have other senses, your blood chemistry, for example, you would have no problem recognizing that your liver and your kidneys were this intelligent symbiont that lived with you and kept you alive all day by moving you through these spaces that we now don't recognize.

Slide 13/55 · 11m:58s

A couple of things to set up what's about to happen. First, the definition. I use the word intelligence a lot. What do I mean by this? I mean William James' definition. It's pretty good. It's cybernetic. It doesn't talk about brains. It doesn't say what space you're in. It's a very general definition. It's the ability to reach the same goal by different means. In other words, some degree of competency at getting your goals met within some problem space. Now it's up to us to figure out what that might be.

The hypothesis we started out with years ago is that morphogenesis — which I'll show you many examples of, the formation and the repair of three-dimensional bodies by cells — is a collective intelligence exerting its behavioral competencies by moving through the space of possible large-scale outcomes. Now it's time to find out what kind of collective intelligence cellular swarms deploy. What I'm going to do next is show you a bunch of experimental data looking at our attempts to develop tools to communicate with this intelligence.

This thing is, first of all, operating at a very different time scale than brains and neurons: not milliseconds, but minutes or hours or days. It operates in a problem space that's hard for us to visualize. Anatomical, amorphous space is a fairly high-dimensional space; it's not obvious how to visualize it. It uses the exact same mechanisms that neurons use to navigate three-dimensional space. It uses ion channels, gap junctions, neurotransmitters, all the same hardware. It uses many of the same algorithms. All the tools of cognitive behavioral science work really well.

In fact, we have a system that we developed; you can go to this website and it will translate papers in neuroscience into developmental biology papers. You just swap a few words and everything carries over. There are deep symmetries between cognition and morphogenesis, which I think Alan Turing, for example, recognized when he worked on both diverse intelligence and the formation of chemical order in early embryogenesis. Those two things go together in a profound way.

What I'm going to do is look at how we can deploy some of the tools and concepts from behavioral cognitive science in this model system. We don't have real aliens to practice our theories on, but this is as close as we're going to get for a while because it's a related being to us, but it's very different in many ways. It's a nice stepping stone to develop ways to see new intelligence and new guises.

Slide 14/55 · 14m:38s

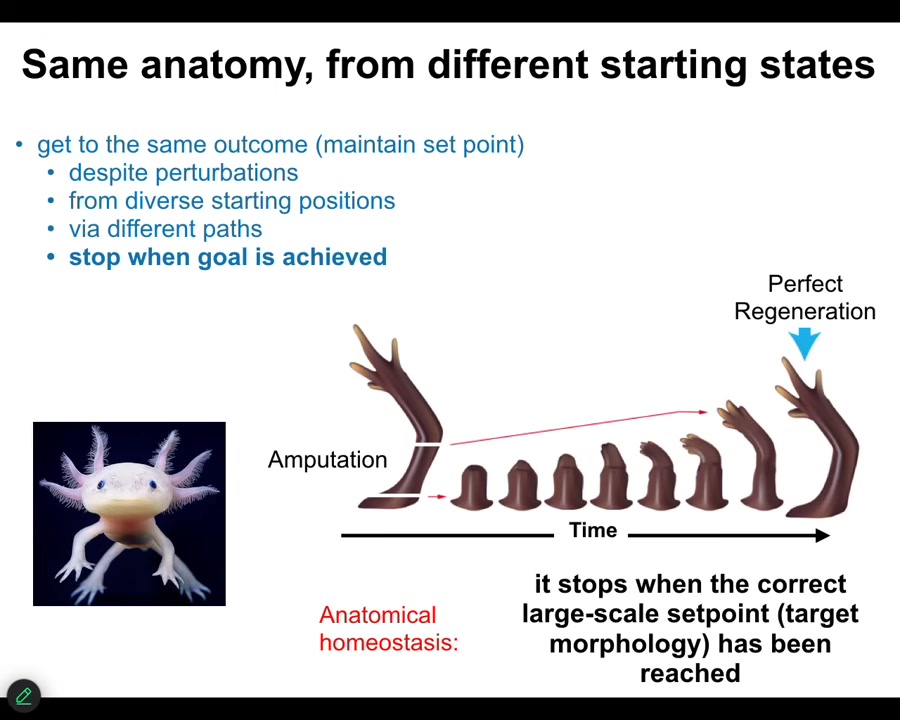

Here's a list of the things that I'm going to show you. Components of intelligence. If I'm going to claim this is a model for cognition, there's a few things you would want to see. First of all, goal-directed activity. How do these things pursue goals? I'm going to show you anatomical homeostasis.

Then it's important that you have hierarchical, non-local control. The thing about intelligence is that all intelligence is collective intelligence in the sense that every agent is made of parts, all of us. And what you want is for the agent to have a causal power that is not the same as simply tracking the microstates, the particles. And so you want a hierarchical control.

You want the system to be hackable. It's not just a physical process that always proceeds the same way, but there's some degree of input that can be provided from the outside world that changes in an important way what it does. It needs to be flexible and it needs to be controllable in that way. Learning would be nice. Creative solving, creative problem solving would be really nice.

And then at the end, I'm going to show you what happens when you don't just try to solve to the same goal you've always had, but when that's impossible, you improvise completely new goals. These are the examples of features of cognition that I'm going to show you in these cells.

Slide 15/55 · 15m:55s

The first example is reaching your goal from different starting positions. This is an animal called an axolotl. These amphibians regenerate their eyes, their jaws, their limbs, their spinal cords, and so on. And the way it works is this. Here's a limb. If you amputate anywhere along the distance, what the cells will do is: they immediately detect that they've been deviated from their correct state. They work very fast to rebuild this exact structure, and then they stop. And the most amazing thing about this whole process is that they know when to stop. It's an example of anatomical homeostasis. It's an error minimization scheme. They know exactly what the end point is. Not the individual cells. The individual cells have no idea what a finger is or how many you're supposed to have, but the collective absolutely knows. And they have the set point, and they will only stop when they get to the set point. That's a very simple example of navigation of anatomical space in a way that gets you to your goal from different starting positions.

The second part of this is more interesting. Can you get to the same endpoint by different paths?

Slide 16/55 · 17m:08s

And so we have not only regeneration, but actually all embryonic development is basically regeneration. We all start life as a single cell. We all rebuild an entire body from that single cell. So never mind planaria and their regenerative abilities. Half the human population has the ability to regenerate an entire body out of just one cell. And it's very reliable. But the reason that this process has an intelligence to it is not just because it's reliable or because complexity rises. It's not that.

Slide 17/55 · 17m:32s

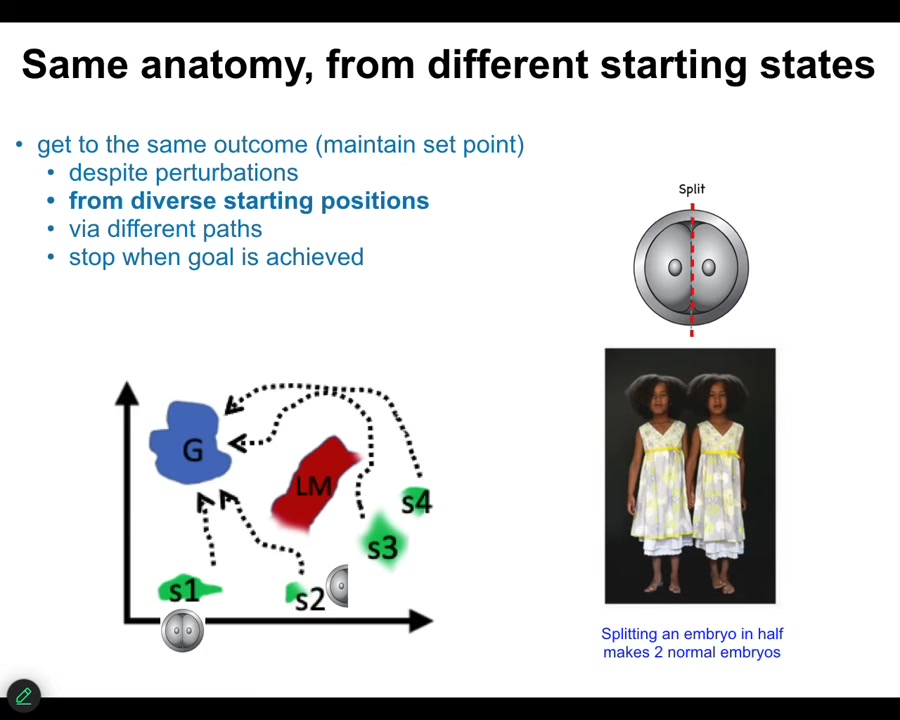

It's the fact that, as with that limb, you can start from many different states. I can cut early embryos into pieces and you don't get half bodies. You get perfectly normal monozygotic twins. You'll get to the same ensemble of goal states from different starting positions, avoiding various local minima. It can navigate to get there.

Slide 18/55 · 17m:55s

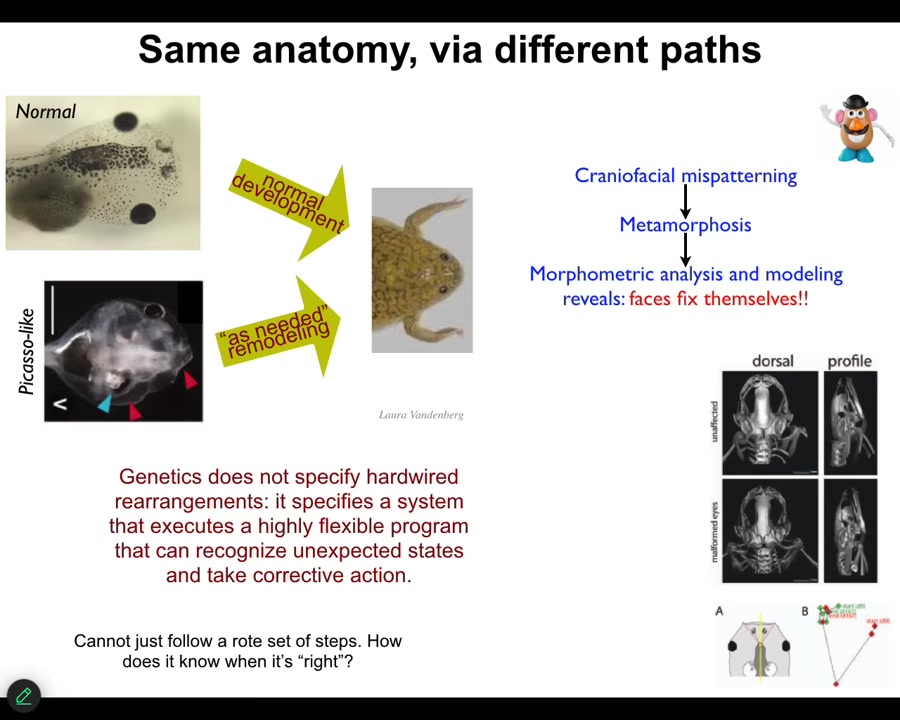

Here's one of my favorite examples that we discovered about 10 years ago. Here's a tadpole of a frog. So here are the eyes, the nostrils, the brain, the gut. And this thing has to rearrange its face in order to become a frog. It's called metamorphosis. So everything has to move. The jaws have to move, the nostrils have to move, the eyes, everything has to move around. And so the traditional model of this was that somehow every organ knows the direction and the amount to move. And then you get from a normal tadpole to a normal frog. This is why it's very important that we take this as an experimental question and not just assume. And so we did the experiment and we asked, how much ingenuity actually exists in this process?

And what we did was we made these Picasso tadpoles. We scrambled all the craniofacial organs. Everything is in the wrong place. The eyes on top of the head, the mouth is off to the side. It's a total mess. Kind of like these toys, this Mr. Potato Head where you can flip around all the position of all the organs. And what we found is that these animals make actually quite normal frogs because all of the organs will move around in novel paths. In fact, sometimes they go too far and they have to come back a little bit. They pursue these novel paths in order to get the correct final outcome.

So what the genetic hardware is giving you is not a precise, stereotypical set of deformations. What it actually makes is a problem-solving agent that can reach the same final outcome from unexpected starting positions, which do not normally occur in development, and can take corrective action. And in a minute, we're going to address this question of how does it actually know what the correct pattern is.

Slide 19/55 · 19m:32s

The next thing that we should talk about is hierarchical non-local control.

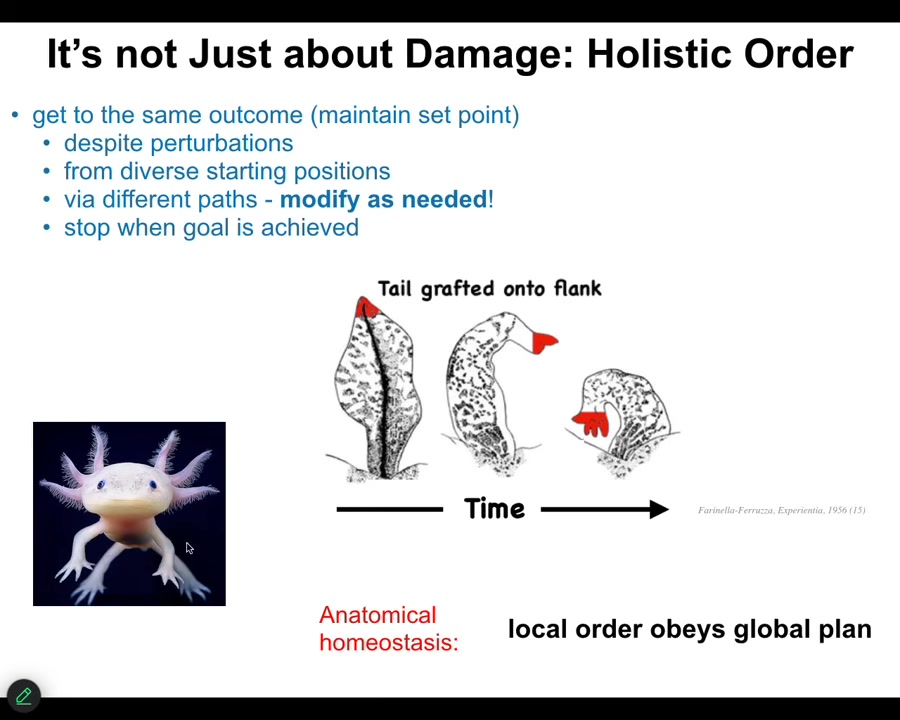

The special thing about being a collective intelligence is that there is information that is global. There are goals that affect the entire system. It's not just a set of parts blindly doing their own thing. This is a pretty cool example, back to the axolotl.

Slide 20/55 · 19m:52s

These amphibians — this is all data from the 1950s. If you take a tail and graft it to the flank of this animal, the tail will soon remodel into a limb.

So this is not just about damage, this is not just about embryonic development. This whole thing has the plasticity to continuously remodel, whether from injury, from a single cell, or from this crazy surgical manipulation, which doesn't happen in nature. It has the ability to correct towards a large-scale outcome.

What I mean by multi-level is this. Here are the cells sitting at the tip of a tail. Locally, they're fine. There's nothing wrong with them. There are tail-tip cells sitting at the end of the tail. They should be happy, but they turn into fingers. The reason they turn into fingers is that it is not a local environment problem. This whole thing needs to become more coherent with a large-scale goal.

You see multi-scale propagation, where the error at the level of — again, there is no injury at the end of the tail, there's nothing wrong here — but the large-scale error at the level of the collective propagates down into events that change the fate of individual cells.

The next thing I'd like to talk about is hackability and the idea that all of these things implement software that is important, not just their molecular hardware. This is going to be the largest portion of the talk.

Slide 21/55 · 21m:22s

So let's first ask ourselves, where does anatomical information come from in the first place? So this is a cross-section through a human torso. You can see the amazing order. Everything is in the right place, the right size, or relative to the right thing. It's all here. It's pretty consistent. We all start life as these embryonic blastomeres. Eventually you get this. Where does this actual structure come from?

Now, people are tempted to say DNA, it's in your genome, but we know what DNA encodes now. DNA doesn't encode any of this. The DNA in the genes encodes proteins. They encode the tiny molecular-level hardware that every cell gets to have. They don't directly specify shape any more than the genome of the termite specifies directly the structure of the nest or the genome of the spider specifies where all the connections are going to be in the web. This whole thing is the outcome of the physiological software that runs on that genetic hardware.

So we still need to understand how groups of cells know what to build. How do they know when to stop? If something is damaged, how do we ask them to repair it? How do we communicate novel goals to them if they don't already do so?

And as engineers, we can go further and ask what else is possible beside the standard outcome. What else can the same cells be made to do? That same hardware, right? This is the beauty of software: it gets the same hardware to do different things. Reprogrammability is really key to cognition, and so, how does all this work?

Slide 22/55 · 22m:55s

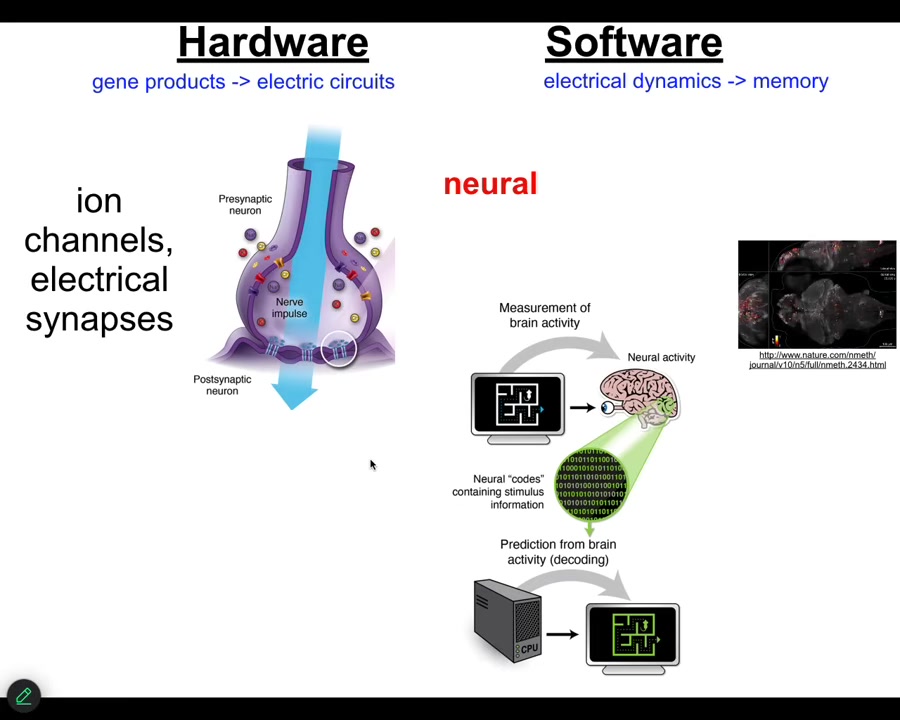

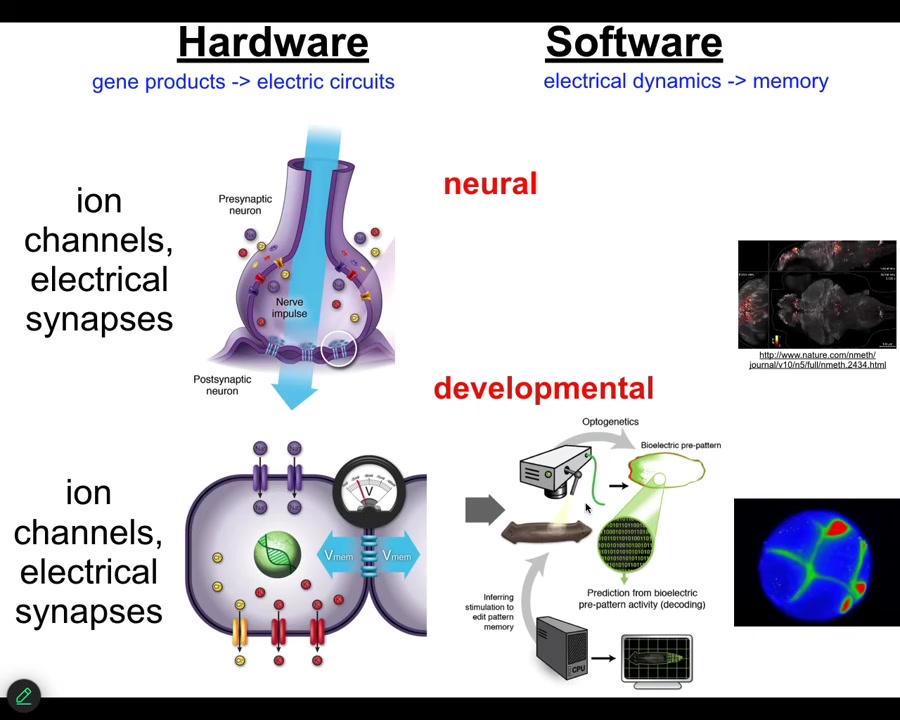

OK, what we wanted to do was to take inspiration from the one clear example that we know, where a group of cells has a goal and is able to execute on that goal. Those are brains.

We know that what nervous systems are good at is storing targets in, for example, three-dimensional space and guiding bodies to achieve those targets. Here we have a good example to learn from where groups of cells can represent future goals and can minimize distance from those goals to meet them. We know how at least some of this works in the brain.

You have these cells in networks that have ion channels on their surface. They pass ions in and out, and the cell acquires a voltage gradient. Those voltages may or may not be propagated to their neighbors through these electrical synapses, known as gap junctions. You have an electrophysiological network. This is what it looks like.

This group made this amazing video of a zebrafish brain living and thinking about whatever fish think about.

There is this process of neural decoding, the project that aims to read all this electrophysiological activity and decode the cognitive state of the animal. So what are the memories, the preferences, the goals, the plans, whatever this animal can do? The idea of neuroscience is that, if we knew what we were doing, we could decode all of that from the electrophysiological activity.

Here you have a merger of something very interesting. You have a physical network that ostensibly obeys the laws of physics and chemistry. But what it actually does is represent very abstract memories and goals and so on. This is where the rubber meets the road for embodied cognition. But it turns out that this amazing architecture is ancient.

Slide 23/55 · 24m:42s

Evolution discovered the beauty of electricity for these kinds of things very long ago, not waiting until nerve and muscle came on the scene. It was discovered around the time of bacterial biofilms. So now, every cell in your body has ion channels. Most cells in your body have these electrical synapses, and they all run these electrophysiological networks. And so what we've been doing is running this process of neural decoding. But instead of asking, what does the brain think about? We've been asking, what does the rest of your body think about? Because the mechanisms are homologous.

This is where your brain got all of its cool tricks. It's from much more ancient developmental roles of channels, gap junctions, and neurotransmitters. It's not just an analogy or a metaphor. It's evolutionarily homologous. And so the question is, what did these things think about before they thought about moving you through three-dimensional space? And what they thought about was moving your body shape through anatomical morphospace.

Slide 24/55 · 25m:45s

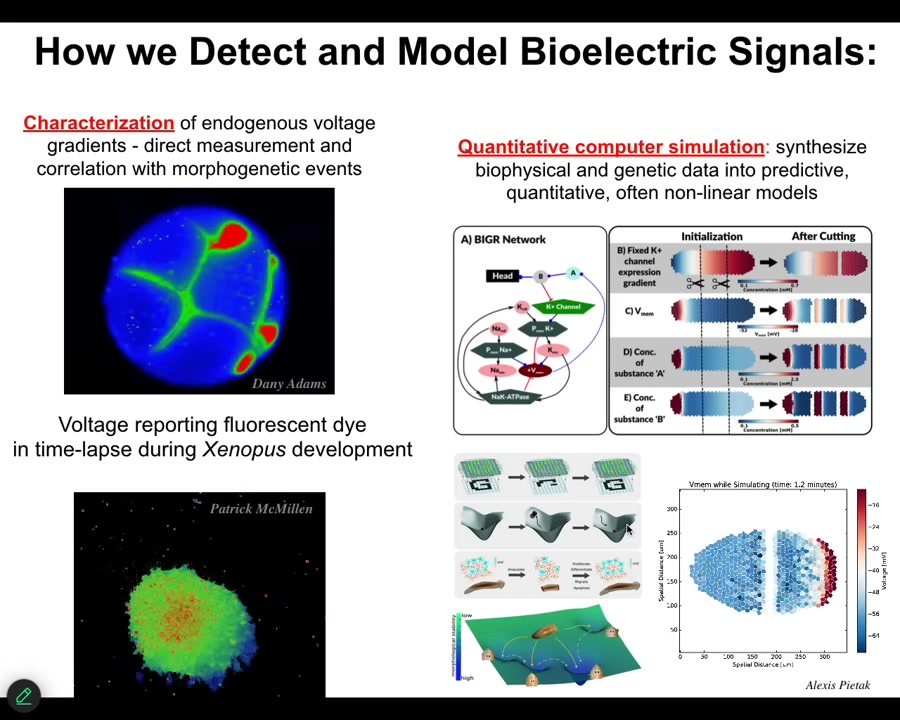

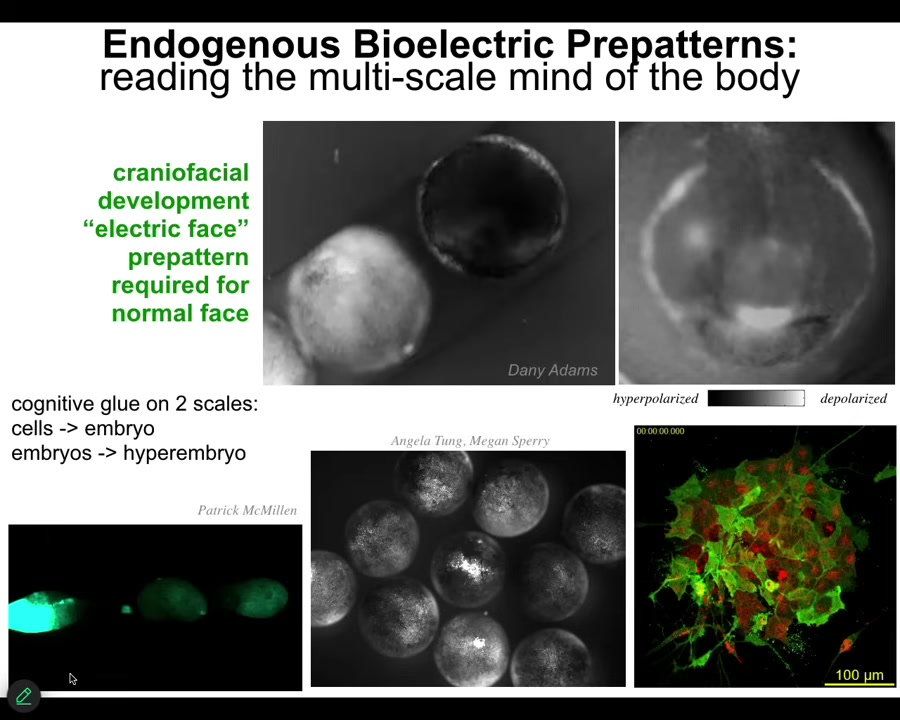

So we developed some tools to be able to read and write this kind of information.

What you're seeing here is voltage-sensitive fluorescent dyes. This is a frog embryo. These are not models.

This is an early frog embryo with all the cells making decisions, who's going to be left, right, head, tail, all of that. These are cells in culture deciding whether they're going to be part of this collective or crawl off to do something different.

So we have the ability to track these bioelectrical states. We do a lot of simulations. We know what the different ion channel proteins are that drive it, so the link to genetics is here.

Then we do simulations on a tissue level to understand where these patterns come from. Then we can link that to ideas in connectionist cognitive science and machine learning, such as pattern completion and memories as distinct attractors in these electrophysiological networks.

So we try to understand the large-scale utility of these patterns. I'm going to show you two very quick examples.

Slide 25/55 · 26m:45s

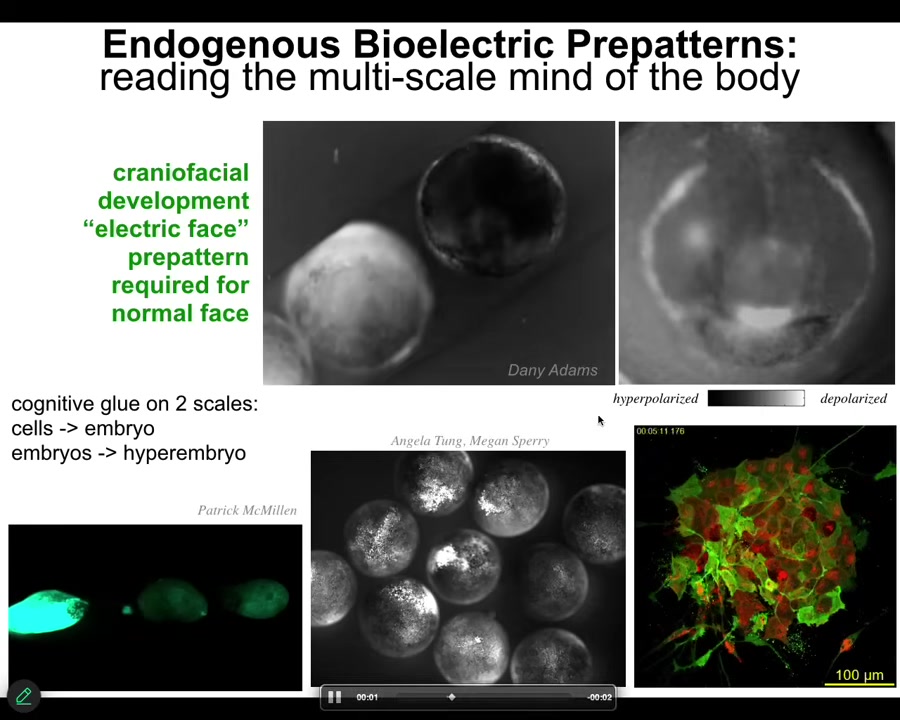

The way that bioelectricity acts as a cognitive glue. Cognitive glue are mechanisms and policies that allow individual competent subunits, like cells, to know things and to achieve goals that none of the individuals know. The reason you're more than a pile of neurons is that the electrophysiology provides the cognitive glue that makes you different than your set of individual cells.

Here is a time-lapse video of an early frog embryo putting its face together. This is one frame out of that video. If you look at the bioelectrical map, what you see is that long before the genes come on to regionalize that ectoderm, you already have, here's where the right eye is going to form, here's where the mouth is going to be, here are the placode structures. We are reading out the memory of what a frog face is supposed to look like. This is what causes cells to build the right structures. If you manipulate this pattern, then we'll build something else, which I'm about to show you.

Not only do these bioelectrical networks provide a cognitive glue on the level of a single embryo, they actually even do it between embryos. They're multi-scale. Here, this embryo in the middle gets poked, and you can see that all of them find out about it rather quickly because there's this amazing calcium wave that propagates.

Slide 26/55 · 28m:08s

You can see that again here in this one: when we poke this embryo, this wave propagates, and they all find out. So we published recently the finding that these groups actually solve problems better than individuals. If you challenge them with teratogens and things like that, large collectives of embryos resist them better than individuals. This is a problem-solving competency potentiated by the communication that in this case is bioelectrical.

You can see here this is a group of cells. You can see some very rapid signaling; you can see some slower things going on. We can read the information in these collectives, but more important than that, we can learn to write it.

Slide 27/55 · 28m:55s

And the way we do that is not with any applied fields. We don't use any electromagnetics. There are no magnets, no frequencies, no waves, nothing like that. What we do is hijack the interface that cells normally use to control each other. We tap into the cognitive glue directly. What that means is we can change, using various molecular tools, the topology of the network, which cells talk to each other through these gap junctions, and we can directly change the voltage by targeting the ion channels. We can open them, we can close them, and this is with optogenetics, with certain drugs that do it, with genetic modification occasionally. There are many, many ways to do it, but we steal everything from neuroscience. All the tools, both the bench tools and the conceptual stuff, we take directly from what the neuroscientists do. And everything works very well.

The reason this is important is because you want to be able to communicate with the decision-making of that collective. You and I communicate through an electrical interface because I can make sounds and motion in these slides, which then gets transduced by your retina into electrical signals that have meaning and are interpreted by the electrical network in your nervous system. The same thing is true here. We want to communicate with them.

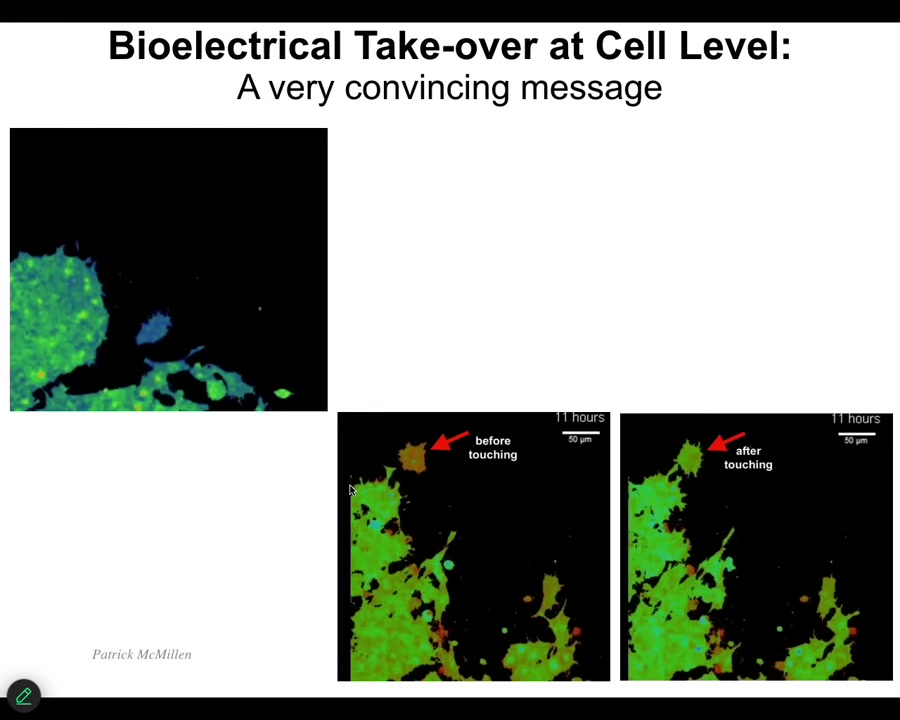

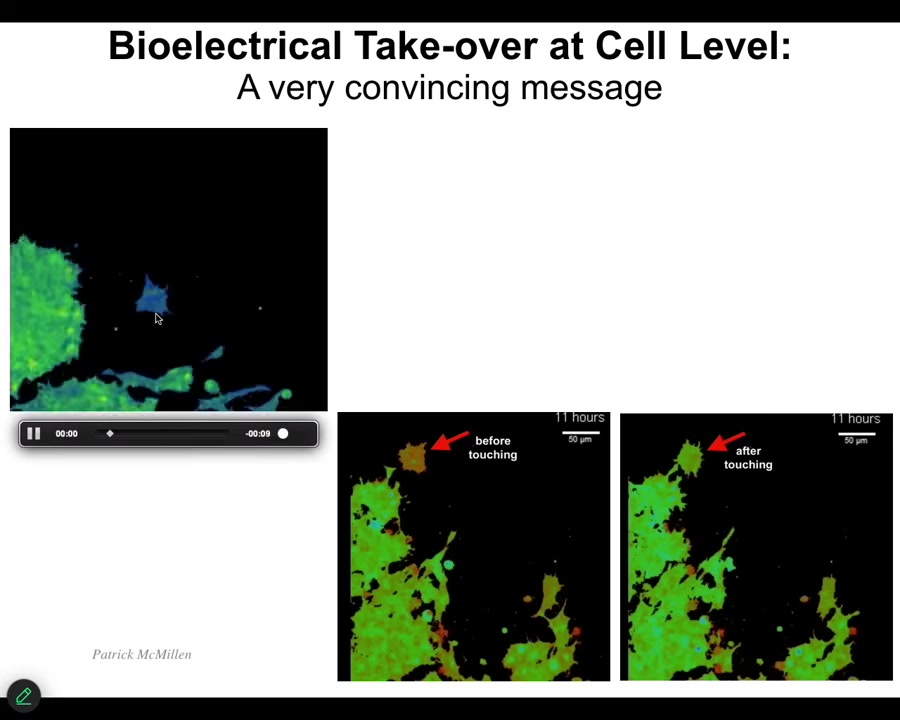

Slide 28/55 · 30m:15s

I want to show you what a native example of communication looks like. These are two frames, and then I'm going to play the video. All of these are cells. The color represents the voltage. What you see is that this cell has a different voltage than these other cells before it touches. Right after it touches, a very tiny point of contact, this cell decides to join them and the voltage becomes just like them. This cell gets hacked by the messages that these cells are sending.

Slide 29/55 · 30m:45s

It's blue here, it's crawling along, minding its business, then eventually the starch is bang, it turns green. The voltage changes immediately and then it joins the collective. This is the kind of thing that's going on in bodies all the time. Cells are communicating with each other and changing each other's long-term properties.

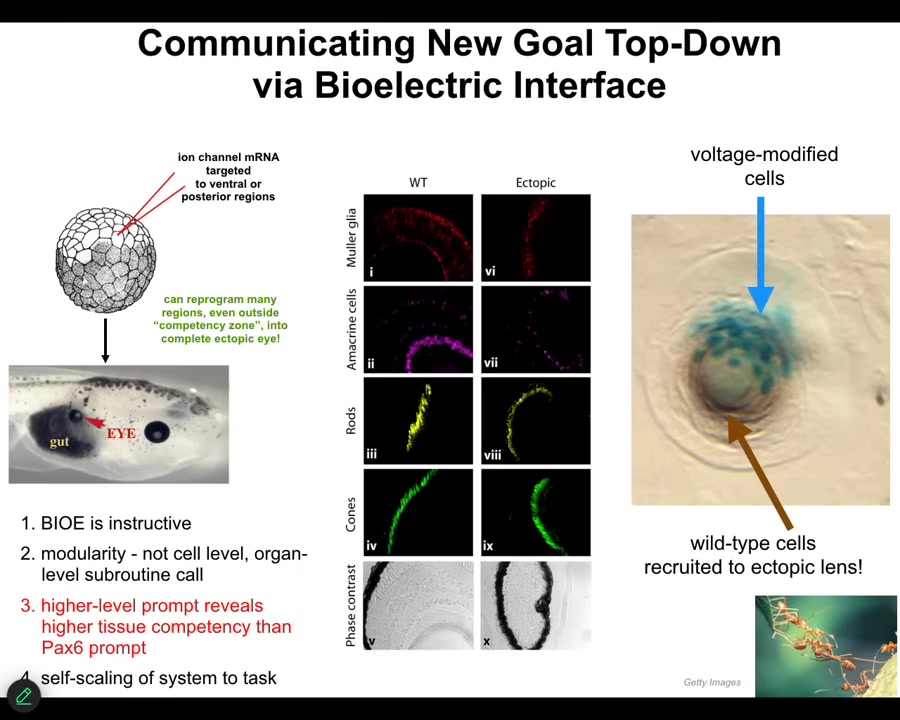

Slide 30/55 · 31m:05s

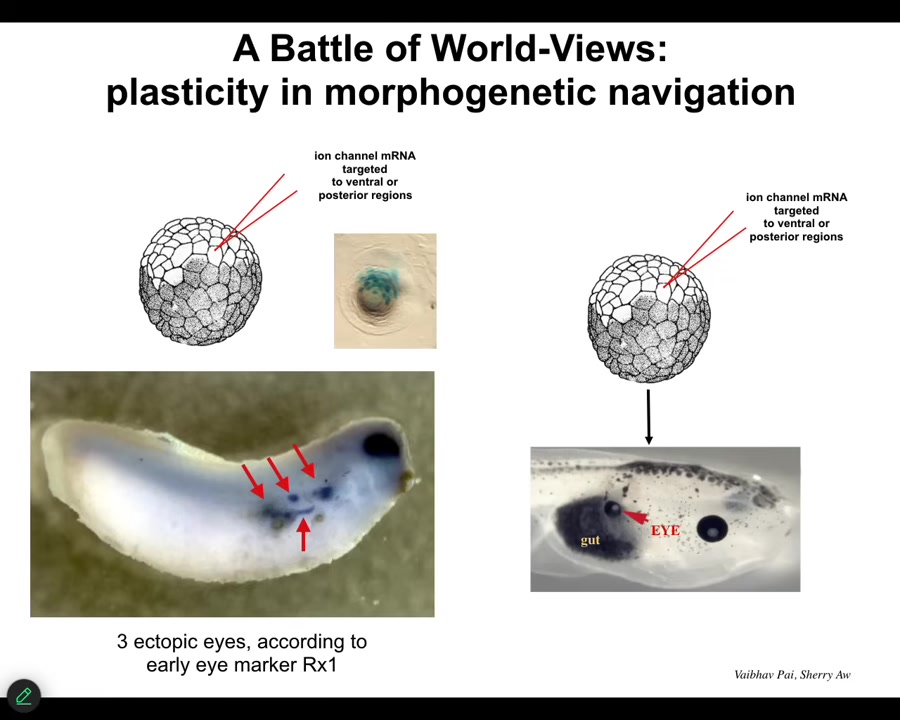

When you do this, I'm going to show you a couple of cool examples of communicating with this collective. I showed you that the native eye arises because there's a particular bioelectrical pattern there, this eye spot. We asked, what happens if we introduce that message somewhere else? It looks like we see the message that leads to this build an eye here outcome.

This is an early frog embryo. We inject into one of the early blastomeres some RNA encoding a particular potassium channel that we chose. When you do this, it establishes the voltage spot. The cells obey and they make an eye.

Here's an eye on the gut of this tadpole. These eyes have lens, retina, optic nerve, all the same stuff that they're supposed to. There are many interesting things about this phenomenon. I want to show you a couple. First, it shows you that bioelectrics is instructive, that these messages actually tell the cells what to do. Second, it's extremely modular. We didn't tell them which genes to turn on. We don't know how to specify an eye. Eyes have lots of very complicated tissues inside. We didn't say any of that. We used a high level communication that says, build an eye here. Like any good intelligence, it has a multi-scale hierarchical control where it took care of all of the downstream molecular details. It turned on and off all the genes that are needed to make retina and lens.

This is like in cognition. When I'm talking to you, I don't need to worry about reaching into your brain and changing all your synaptic proteins to make sure that you understand what I'm saying. You will take care of that. I'm only giving these high-level language prompts. That's the same thing here.

Also fun is that this is a cross-section through a lens sitting somewhere out in the tail of the tadpole. The blue cells are the ones that we injected with our electrical signal. We didn't touch any of this other stuff. The blue cells already know that there's not enough of them to make a proper eye. What do they do? They recruit a bunch of their neighbors. The secondary instruction is an automatic part of the material. We don't need to teach them to do that. They already know. Once these cells become convinced that they need to build an eye, they propagate that to the rest of the cells, like I showed you in that cell. That is what that looks like. But what's interesting is that this is not guaranteed.

Slide 31/55 · 33m:28s

This kind of outcome is the result of a battle of goal patterns.

If we inject and you look at a much earlier-stage embryo than this, the blue represents the initial stages of eye specifications. This is a gene called REX1, which says that these cells are starting to go towards an eye fate. When you look early, you say, one, two, three, 4, 5, this thing's going to have 5 ectopic eyes. By the end, you may only find one. That's because there's a competition happening here. The cells that we injected are saying to their neighbors, "you should be an eye." But the rest of the cells, because of a cancer-suppression mechanism that resists cells with unusual voltage, are saying to them, "no, you should be a gut or skin or whatever." Sometimes the one wins and sometimes the other. The question is, how convincing is each message? You're watching models of the future battle it out in the excitable medium of cells. Then whoever wins, that's what happens. That's an example of communicating organ-level goals.

Slide 32/55 · 34m:40s

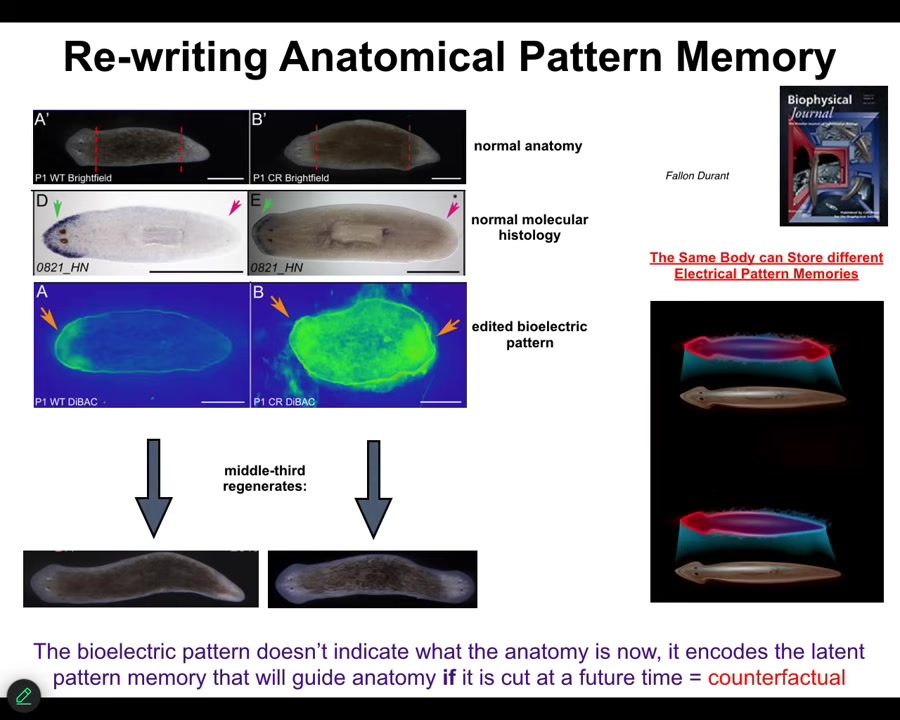

Now I want to show you specifically what the pattern memories look like and how we rewrite them. These are, again, planaria, flatworms. They have a head, mid-body, and a tail. When you cut them into pieces, they reliably produce normal worms, one head, one tail. You might wonder, how do they know how many heads are supposed to be there? How does each fragment, when you cut this middle fragment, it's got two wounds, how come it doesn't put a head on either end? This fragment is going to put a head right there in these cells, and these cells are right neighbors. Why don't they make a head? How does this thing know how many heads?

It turns out there's a voltage gradient that says one head, one tail. And if we take this voltage gradient — all it takes is 3 hours exposure to a specific ionophore drug that duplicates this pattern. Now you have two heads. The technology's still being worked out, but you've got two heads here. What it will do then is, once you cut it, will then make two-headed animals. These are real animals.

This two-headed pattern is not a map of this two-headed animal. This is a pattern of this perfectly normal-looking one-headed animal where we change the pattern. The molecular markers are still, here's the marker of the head. There is no head marker in the tail. The anatomy is normal. The molecular histology is normal. What's not normal is that this thing has a different representation, a different stored memory of what a normal planarian is supposed to look like. It's in fact a counterfactual memory, maybe the early basis of this amazing human time travel ability in your brain where you can envision things that haven't happened yet. Because there's nothing molecularly or anatomically wrong with this animal, but it has a different representation of what to do if it gets injured in the future. It's a latent memory. It doesn't do anything until it gets injured. It sits there, and you would have no idea that it's there by looking at the anatomy. If it gets injured, this is its idea of a correct worm, and that is what they built.

The body of a worm can hold at least two different representations of what a correct planarian should look like. This is a very basal model system for storing memories of the future.

Slide 33/55 · 37m:02s

The reason I call it a memory is because once you convert that electric circuit to store a two-headed pattern, it's permanent. So you can take these two-headed animals, you cut them again and again in plain water, no more manipulation of any kind, and they will continue to form two-headed animals. Here you can see this little video of what the two-headed guys are doing. It has all the properties of memory. It's long-term stable; it's rewritable. We can go from one head to two, we can go from two heads to one now. We don't touch the DNA at all. There's nothing wrong with the hardware. You could sequence this thing all day long. You would never be the wiser that it has two heads and that it was going to give rise to offspring that has two heads. None of this is genetic. None of this information is visible at the hardware level. It is the bioelectric network that remembers how many heads you're supposed to have.

Slide 34/55 · 37m:55s

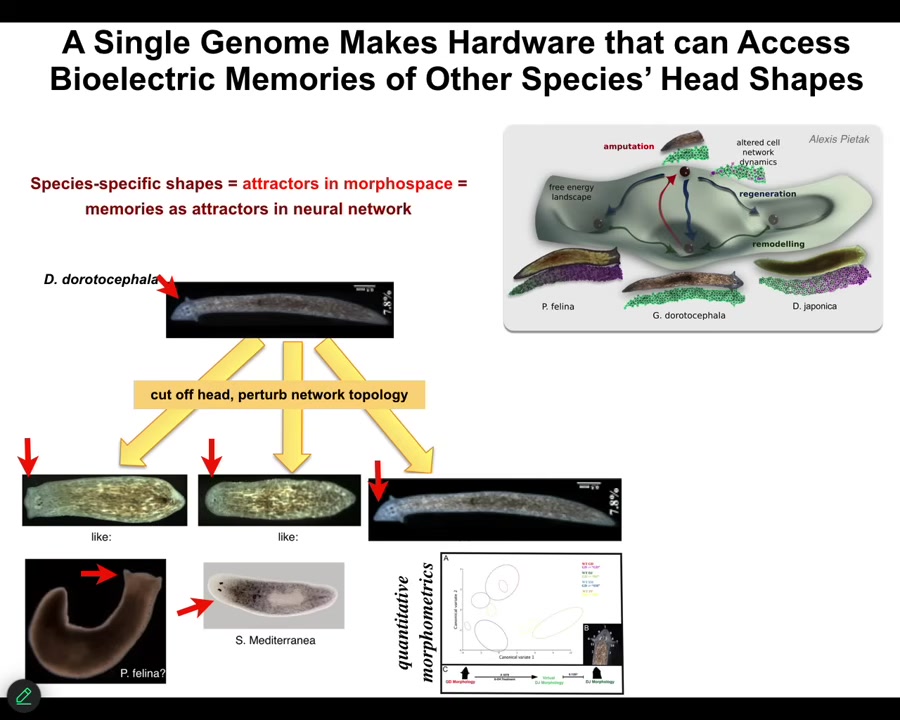

This is not just about the number of heads. It's also about the head shape. It's all about moving through the space of possible anatomical outcomes. So here's a planarian with a nice triangular head. What we can do is cut it off and change the bioelectrical signaling to make flat heads like this P. falina, or round heads like this S. mediterranea, or, of course, the normal triangular head like a Dugisia duradocephala. So what happens is, again, not touching the DNA, the exact same hardware is perfectly happy to visit other attractors in this anatomical space if the software says so.

You can make the shape of the brain and the distribution of the stem cells become just like these other species, about 100 to 150 million years' divergence between them, and they traverse it readily.

Slide 35/55 · 38m:50s

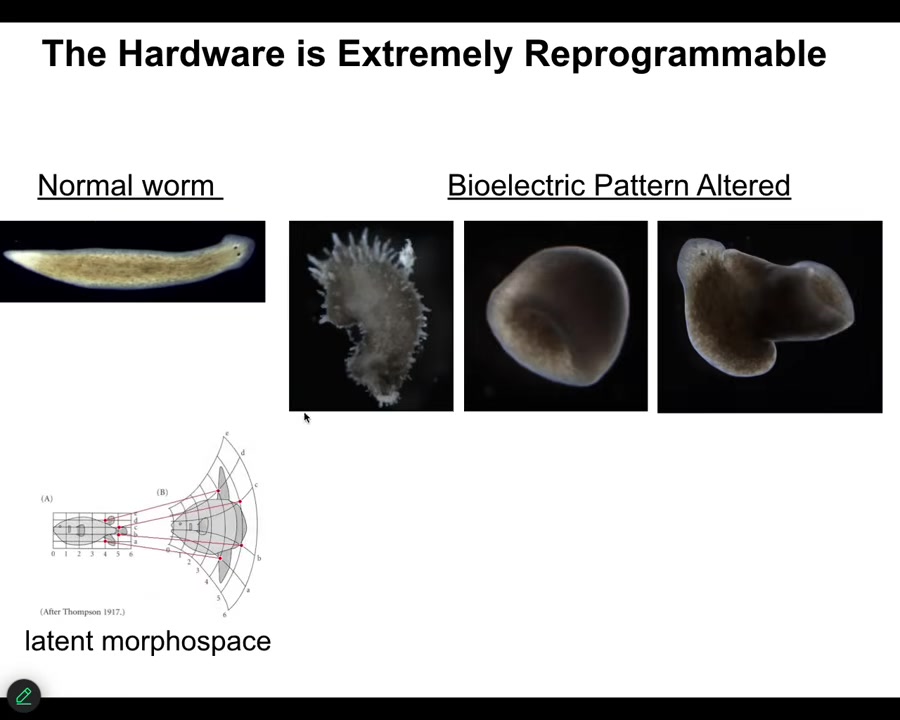

You can also push them to make some very strange things that don't look like planaria at all. You can make these spiky things. You can make cylindrical shapes instead of flat. You can make combination things. So there's this massive latent morphospace that you can explore with exactly the same hardware. Plants do it too.

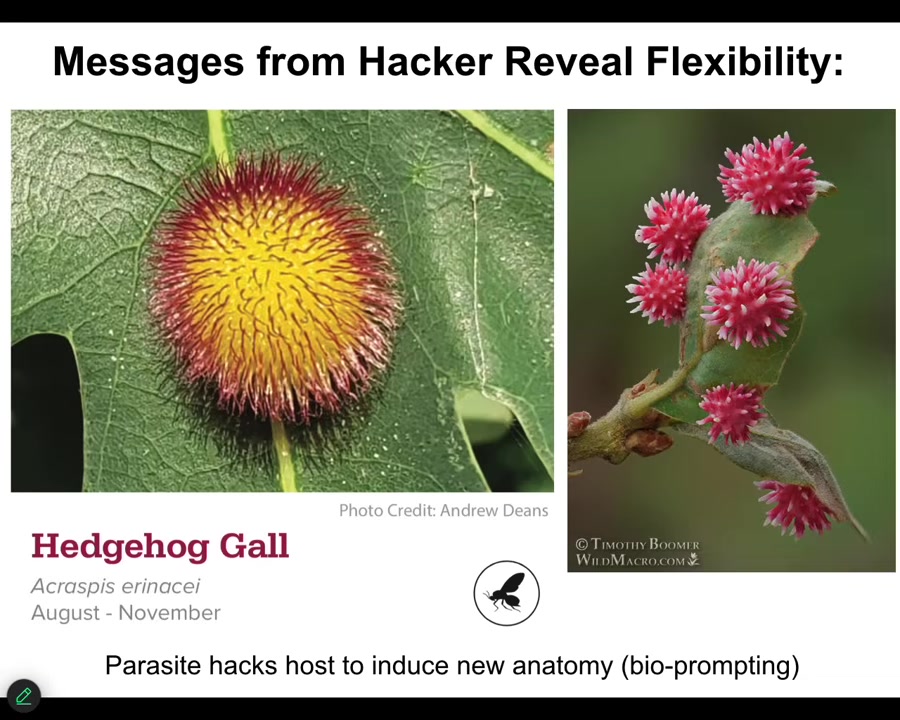

I love these galls where we think we know what the oak genome does. So acorns reliably make oak trees, an instinctual behavior, every single time, stereotypical.

Slide 36/55 · 39m:22s

In fact, it's not hardwired because along comes this bioengineer and provides a prompt that hacks these cells, that takes advantage of their morphogenetic competencies, and it makes them build this thing. These galls are not made from the wasp cells, they're made from the leaf cells. Who would have known that these flat green things are capable of building something like this or something like this if we didn't see this degree of prompting?

The flexibility of behavior in these anatomical spaces is remarkable, and evolution makes things that under standard circumstances follow the same path, but they don't have to follow the same path. In addition to that instinct-like baseline behavior, they have many other capabilities.

Slide 37/55 · 40m:08s

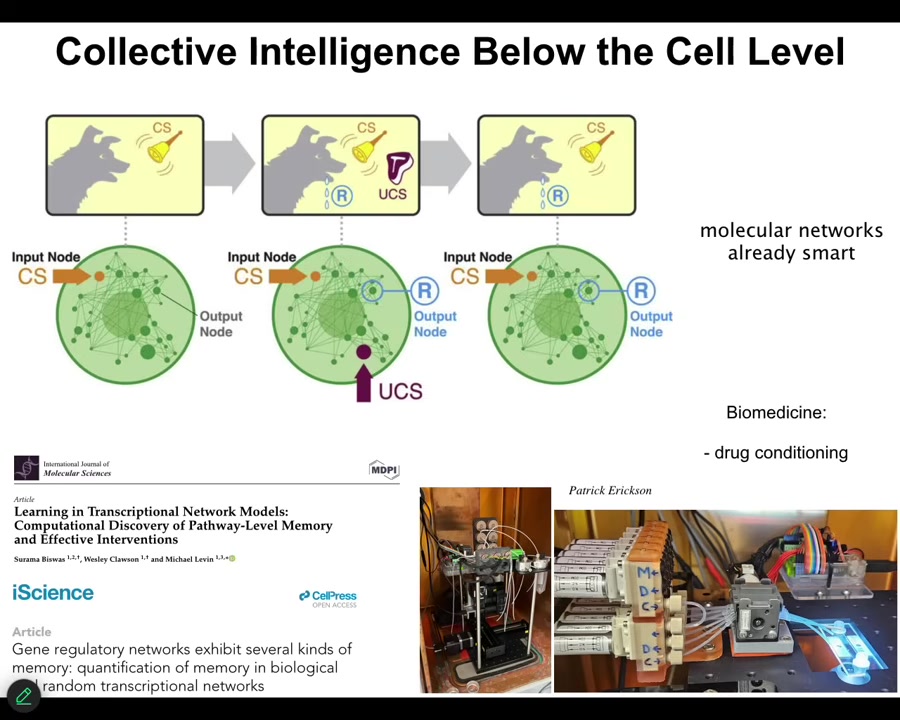

I want to briefly talk about learning and problem solving before I wrap up. Conventionally, people are told that learning is a property of the nervous system, that it requires synaptic proteins.

Slide 38/55 · 40m:25s

Learning is a free gift from the mathematics of networks. It comes into biology very, very early. What we found is that molecular networks, for example, gene regulatory networks, molecular pathways, whatever, can do six different kinds of learning, including Pavlovian conditioning, just from the properties of small networks of nodes that turn each other on and off. If you stimulate the nodes the way that the protocols and behavioral science tell you, you can see habituation, sensitization, associative learning. You get that before you even get cells. You don't need cells for this; just molecular pathways do this on their own.

We're taking advantage of all this stuff now in the lab to do things like drug conditioning. So the material isn't all the way down. It's not just the nervous system, it's not even just cells; it's all the way down to molecular networks. You're already starting with certain competencies that you didn't need to evolve. Evolution optimizes all this, but you don't need evolution to have the learning at the very beginning in your material. So this is learning at the single-cell level.

Slide 39/55 · 41m:38s

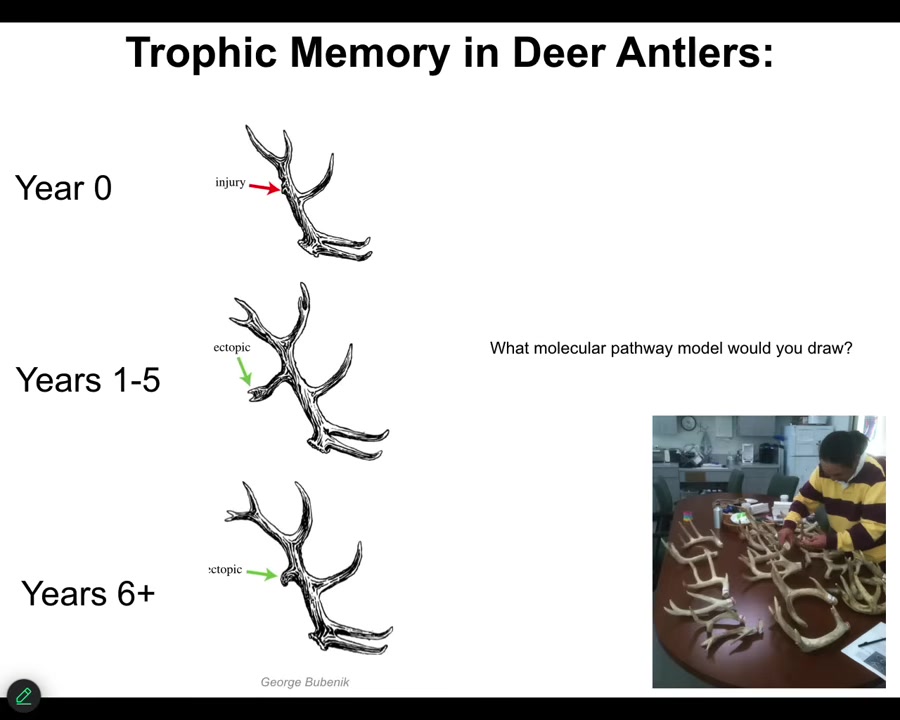

Here's an example of learning at the large scale level. This is trophic memory in deer antlers. Deer every year they grow a stereotypical structure and then they shed it and then they grow the next thing, the next one next year. This guy, Bubenik, found out, through decades of painstaking experiments with deer, that it's not an easy model system by any means. What he found out is that if you make an injury in a particular location in this antler rack, it heals, there's a little callus, and then this whole thing falls off. But next year, you're going to get an ectopic tine at the same location, and this goes on for about five or six years, and then eventually it goes away.

And so we actually inherited all of his antlers. We got 13 boxes of antlers in the mail with all the labels of who's who. It's amazing because this is a memory that you get from physiological injury. There's nothing genetically wrong here. But what would be very challenging is writing down a molecular biological mechanism for storing the location of this thing in a completely different set of cells, because remember, all this is going to fall off. It's the cells in the scalp that are going to rebuild. You have to know where the injury occurred. You have to store that information for months, and then you have to use it to guide new growth.

This is a kind of morphogenetic memory, and there are many. Another type that we studied is in axolotl. If you keep amputating the limb, you amputate it five or six times, and eventually it won't do it anymore. It just stops trying to regenerate.

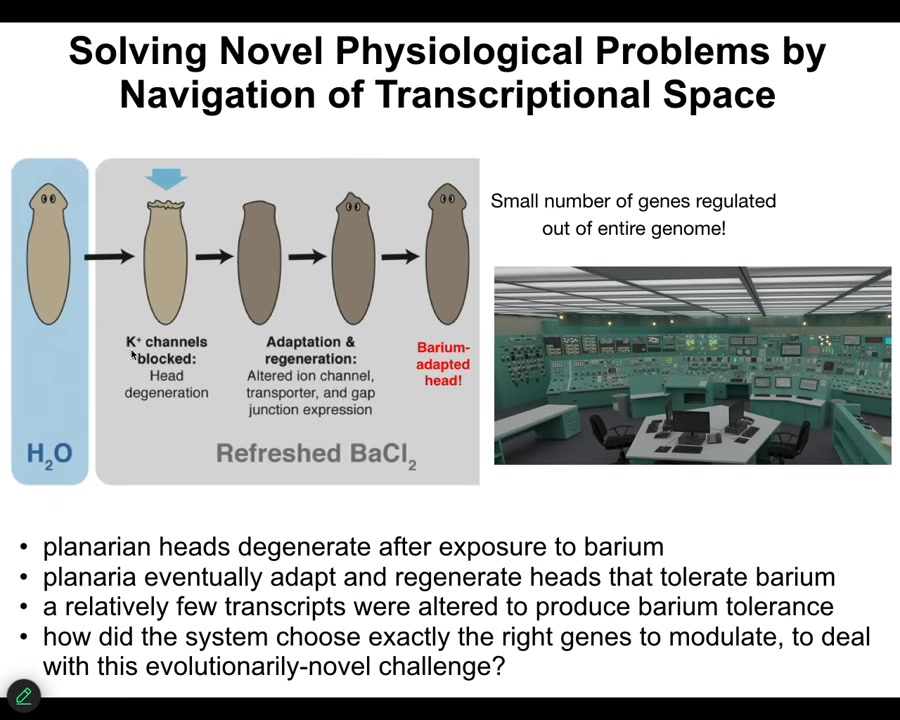

The last thing I want to show you has to do with what I call creative problem solving or improvising solutions to stressors you have not seen before. Here are two examples.

Slide 40/55 · 43m:20s

This one we discovered. You take a planarian flatworm, you put it in a solution of barium chloride. Barium is a non-specific potassium channel blocker, so it makes the cells very unhappy. In particular, the neurons in the head can't pass potassium, so they die and the whole head explodes. It's neurotoxicity; over the next 24 to 48 hours the whole head explodes.

But if you leave it in barium, they then rapidly grow a new head, and the new head doesn't care about barium at all. It's totally barium-adapted. How can that be? So we looked at the transcriptomes of barium-adapted heads versus normal heads, and we found that there are really only a handful of genes that are differently expressed.

So now think about what this is. I envision it as sitting in a control room of a nuclear reactor that's burning down and trying to figure out what buttons you're supposed to press. You have this novel stressor that you've never seen before. Barium is not something they run into. Your cells are dying. What are you going to do? You have tens of thousands of genes. You don't have time to start randomly turning things on and off. It's just too fast and these cells don't turn over that fast. It's not like bacteria where you can have evolutionary hill climbing. You have to very rapidly figure out which of your genes you're going to turn on and off to do this.

And they find a solution. The latest data are that in a large number of separate groups of planaria, they all find the same solution. There are not many solutions to this. Apparently there's only one that they find, and they all find the same one.

So solving novel physiological problems by navigating your transcriptional space—your effectors are gene expression, but your problem is physiological. Not only do you need to know how to navigate that space, you need to functionally merge two completely different problem spaces to know what to do. We have no idea how they do this.

Slide 41/55 · 45m:22s

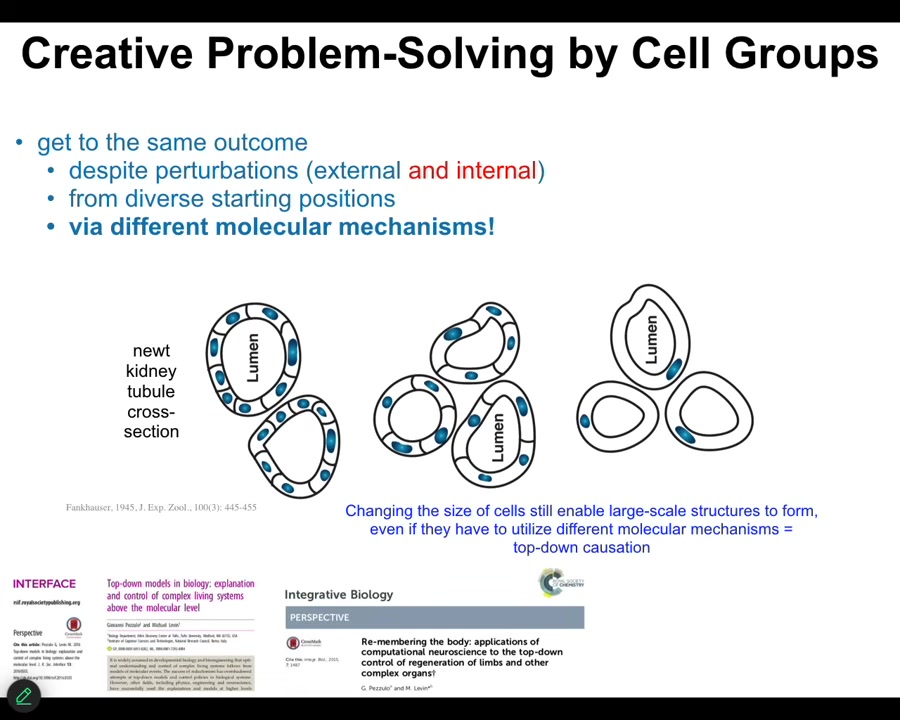

One other example of this is here. This is a cross-section through a kidney tubule in a newt, and normally there are 8 to 10 cells that work together to form this. But what you can do is make newts with larger numbers of chromosomes, copies of their genome. You can make polyploid newts. When you make polyploid newts, the cells get bigger to accommodate the bigger nuclei, but the newt stays the same size. How can that be? Because now fewer cells do the exact same thing. They make up for the change in size with smaller numbers.

You can keep pushing that until you get these enormously large cells. Then one cell will bend around itself, leaving a hole in the middle, and give you the exact same structure.

There are two things going on here that I think are absolutely fascinating. First, what you have here is a kind of top-down causation, because this is a different molecular mechanism. This is cell-to-cell communication; this is cytoskeletal bending. Cells will actually dip into their genetic affordances to pick different molecular mechanisms to get a large-scale job accomplished. What they're looking for is to accomplish this very large anatomical structure, and they do this with different molecular mechanisms at their disposal.

This is a standard thing you see on any IQ test. Here's a set of objects, solve this problem you haven't seen before by using the tools at your disposal. It's a standard definition of intelligence.

There's something else that's really interesting and profound here; think about what this means for an animal coming into the world as an embryo. Never mind the external environment, which is unpredictable; you can't even count on your own parts. You don't know how many copies of your genetic material you're going to have. You don't know how big your cells are going to be. You don't know how many cells you're going to have. You have to get the job done. You have to navigate to your final position in anatomical space, no matter what is going on under a very wide range of novel circumstances.

Biology and evolution make these amazing problem-solving agents that really are not assuming one particular outcome. They have the ability to improvise novel problems. These abilities are not unlimited. You can put them in scenarios where the natural goal is simply unreachable.

I'm going to show you a couple of novel creatures and new goals that are improvised and cannot be specifically chalked up to evolution. The first thing I'm going to show you is Xenobots.

Slide 42/55 · 48m:05s

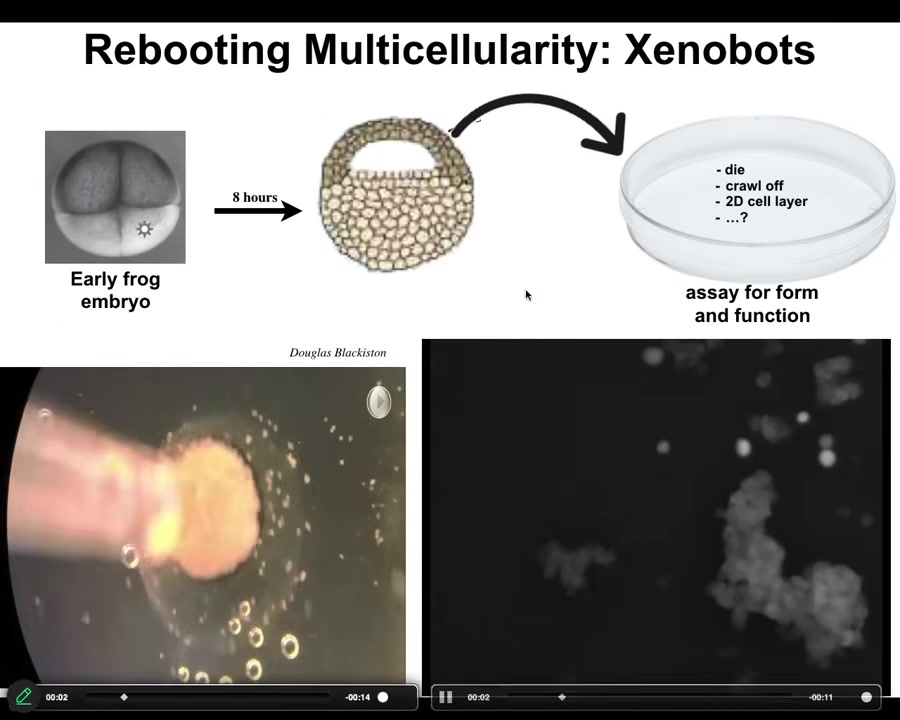

Xenobots are made of frog skin cells. We take these epithelial cells from an early frog embryo. We put them in a dish. They could have done many things. They could have died. They could have crawled away from each other.

Instead, what they do is they self-assemble into this tiny little construct we call a xenobot. Here, watch: each of these circles is an individual cell. Watch what this process looks like close up.

These have assembled; it's fun that it looks like a little horse-shaped thing, but they move at once, all together. They approach this other thing — you'll see a little calcium flash here, which is evidence of some sort of signaling. We don't know what it is.

Slide 43/55 · 48m:45s

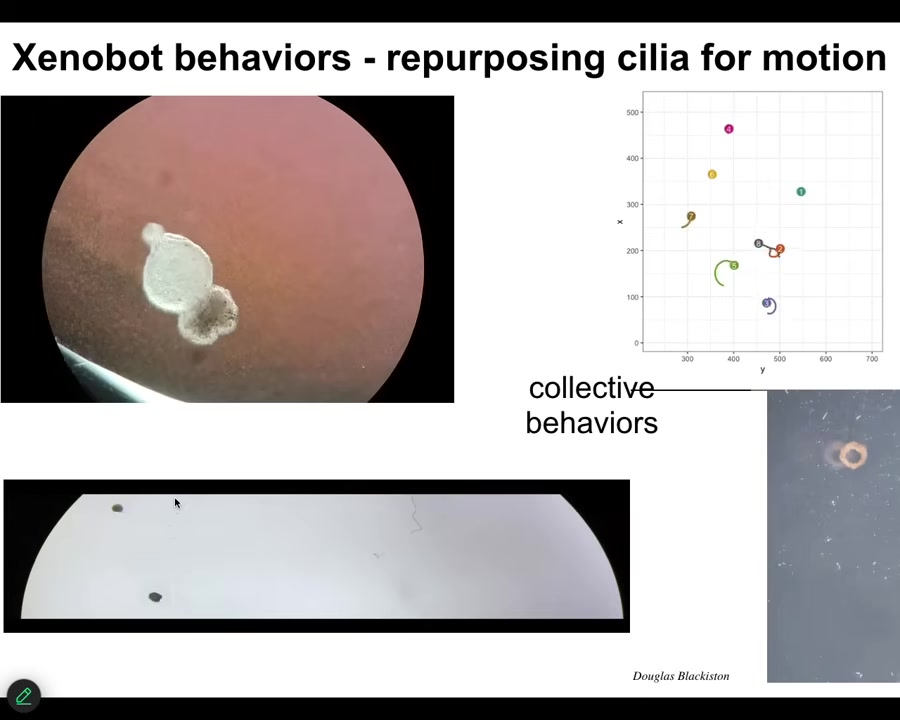

So all of these cells come together, and they make this novel thing that moves along by swimming using these cilia, these little motile hairs that they swim along. They can go in circles. They can patrol back and forth.

We can make them into crazy shapes like this. They have group behaviors.

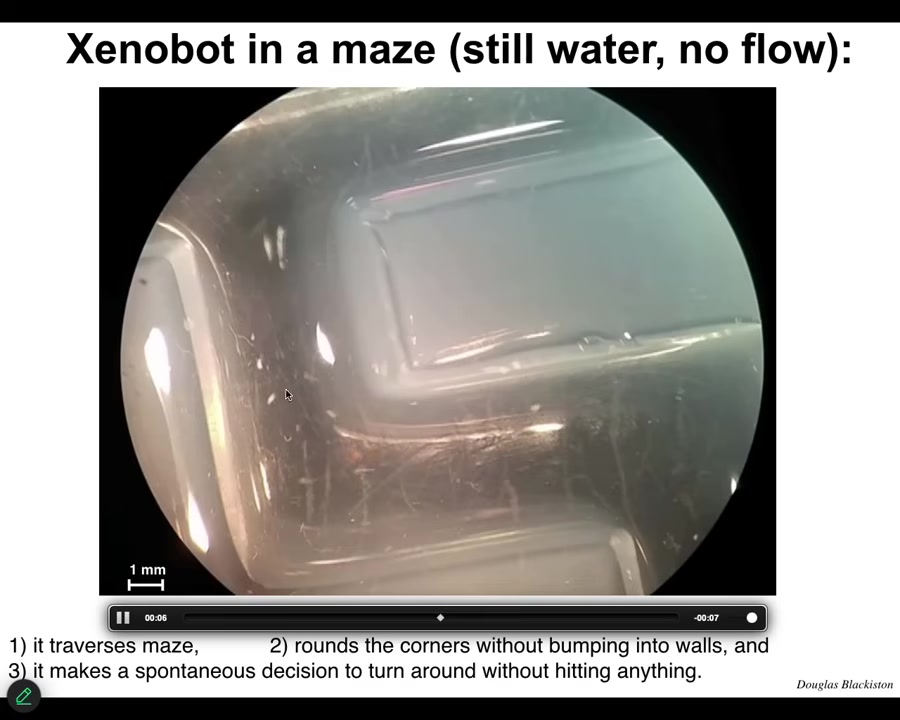

Here it is navigating along a maze.

Slide 44/55 · 49m:08s

It traverses, it will take the corner without bumping into the opposite wall. At some point, it just turns around and goes back where it's coming from.

I'm not making any claims about the cognition of this thing yet.

We have a paper coming later this year about their memory properties and various other things. What's interesting is to ask what determines the behavior of these things.

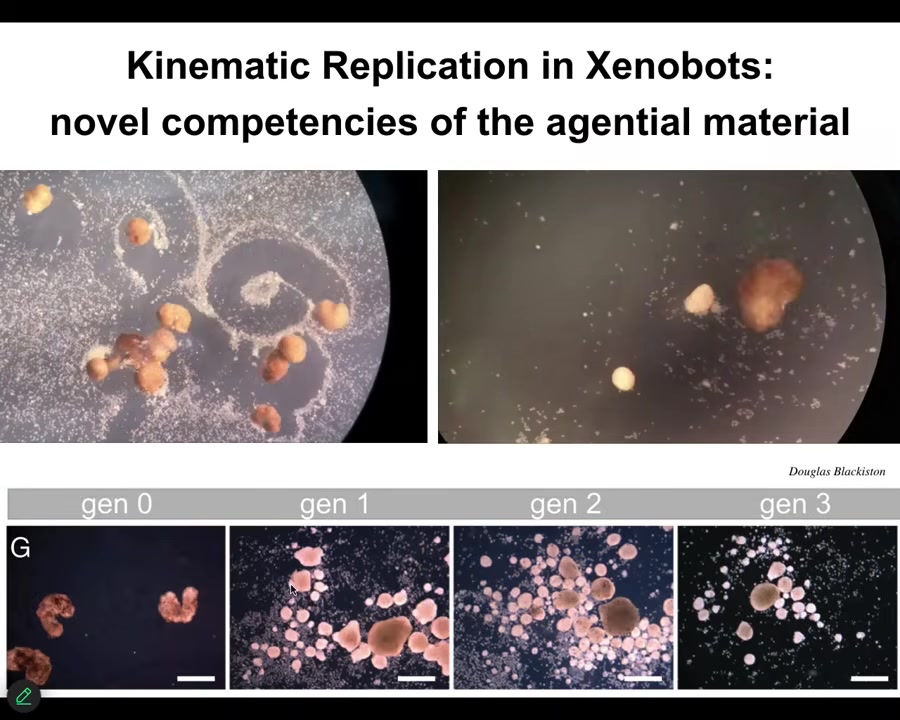

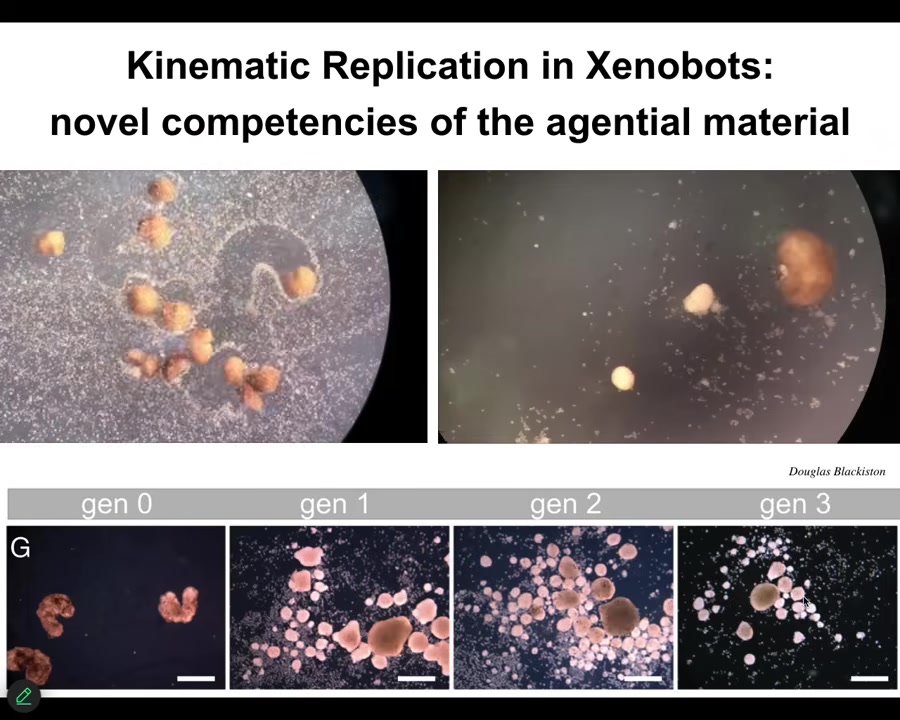

For example, here they are doing something we call kinematic self-replication.

We've made it impossible for these things to reproduce in the normal ****** fashion, but if you give them loose skin cells, what they will do is von Neumann's dream of a robot that makes copies of itself from material it finds in the environment, because what they do is they collect these loose cells into a little ball here.

Slide 45/55 · 49m:55s

These little balls, because they're dealing with an agential material, not passive matter, mature and they become the next generation of Xenobots. They do exactly the same thing and they make the next generation.

As far as we know, no other animal does this.

Slide 46/55 · 50m:05s

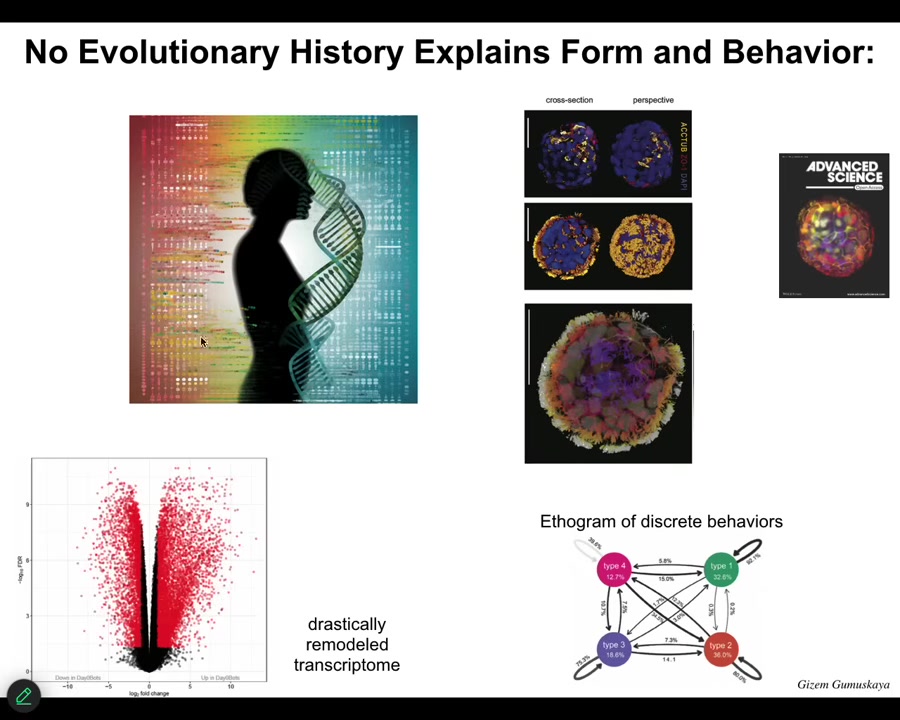

How kinematic self-replication is novel. We didn't teach them to do this. We didn't know they were going to do this. There is no evolutionary history that would suggest this.

These are things that are novel forms and behaviors of novel beings who have not been selected for these properties.

Nobody ever selected them for being good at kinematic self-replication.

Slide 47/55 · 50m:28s

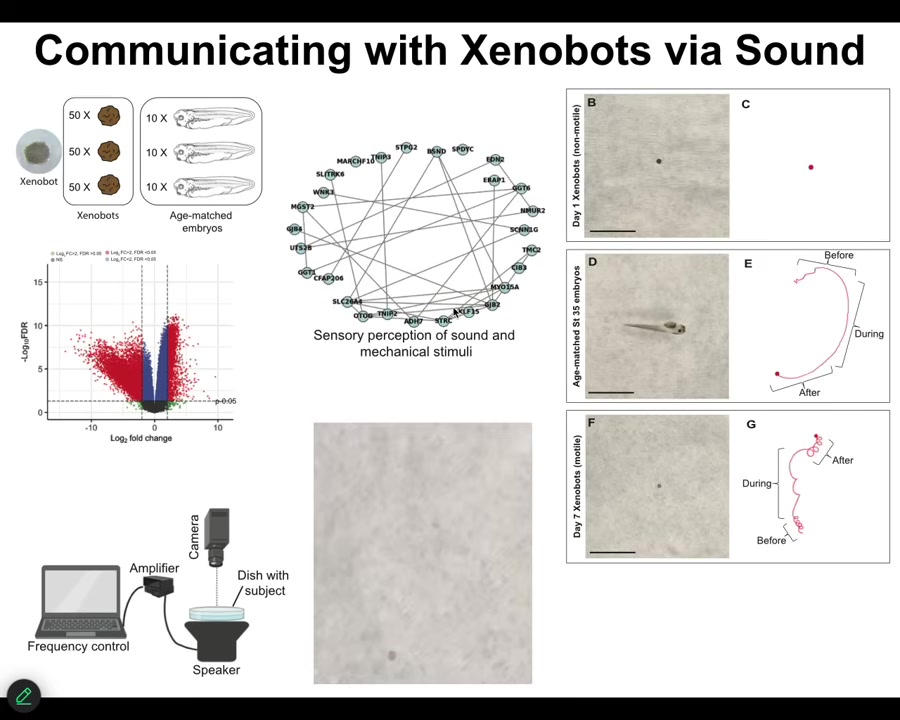

One wild thing is that if you look at their gene expression, they express hundreds of genes differently than the cells within the embryo would if we had left them alone. One of the clusters they express is hearing, a bunch of genes related to hearing. So we tested this. We said, is it possible that they actually respond to sound? And it looks like they do.

Slide 48/55 · 50m:48s

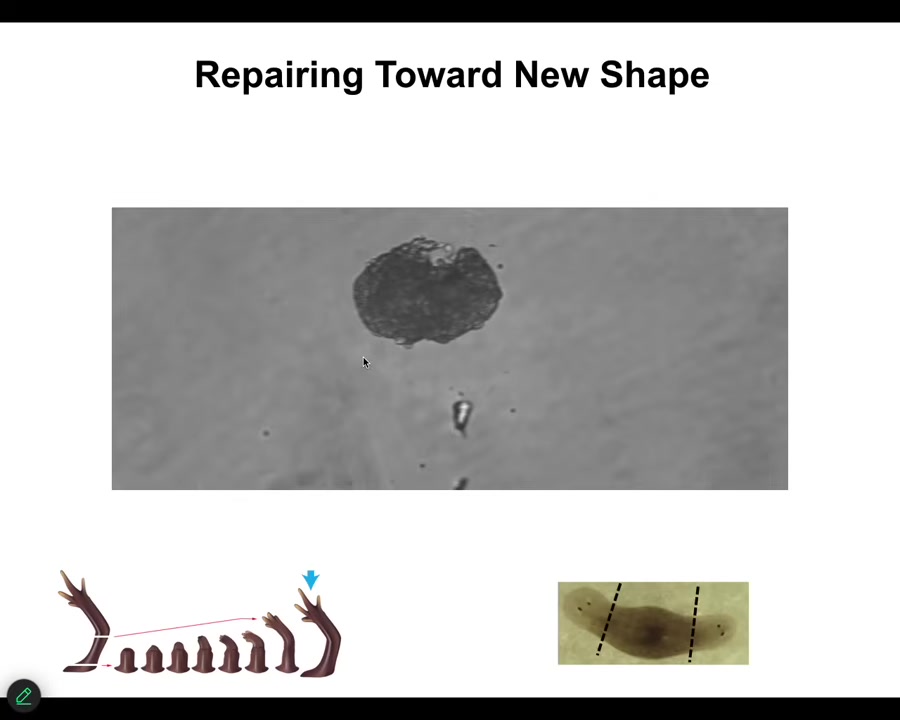

The last thing I'm going to show you in the last couple of minutes is something else. These are called anthrobots, similar. It's a little construct here, swimming around. If I didn't tell you what this was, you might think that this is a primitive organism we got from the bottom of a pond somewhere. If you were to sequence the genome, what you would find out is that it's 100% Homo sapiens. These are human cells taken from an adult patient, made of tracheal epithelia. They self-organize into this little self-motile creature.

Slide 49/55 · 51m:18s

These creatures heal. If you poke a hole like this, they will eventually heal up to their novel shape. Many other natural beings repair to either the original shape or to new shapes. They have other wild properties.

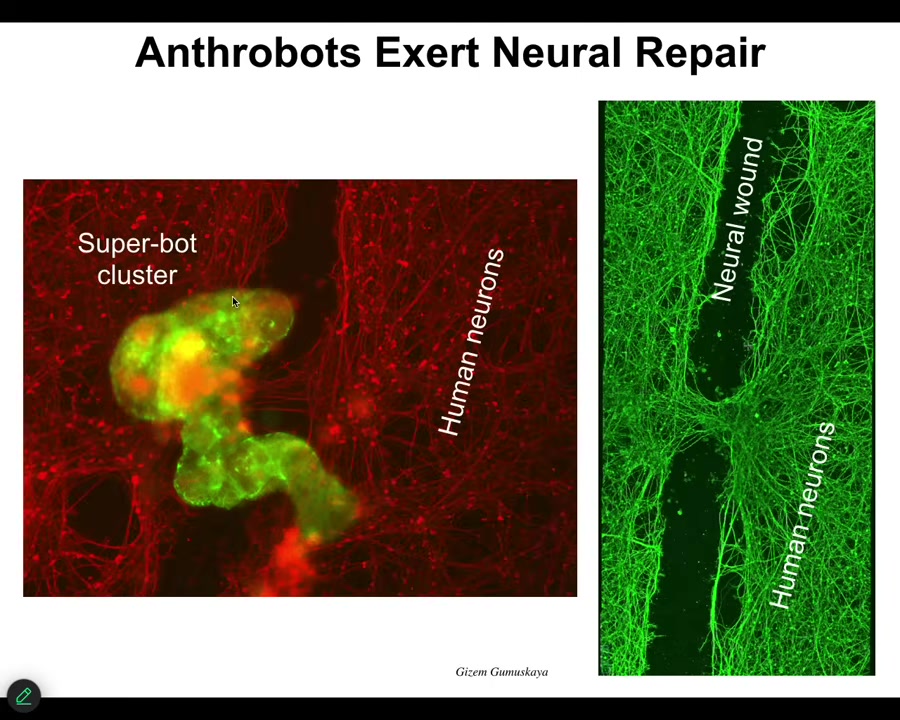

Slide 50/55 · 51m:38s

They know how to heal neural wounds. This red stuff here or this green stuff are human neurons that are plated in a dish. If you take a scalpel and put a big scratch through it, they will come along here. These anthrobots gather in a little cluster, and what they start to do is heal across the gap here.

Your tracheal epithelial cells, if explanted or liberated from the rest of the body, will make a self-motile little construct that, among other things, knows how to heal neural wounds. These are all completely emergent. We had no idea what exactly they were going to be able to do.

Slide 51/55 · 52m:12s

They express 9,000 genes differently than the cells in their normal position. They are massively remodeling their transcriptome toward their new lifestyle. They have four different behaviors that you can build an ethogram of. They were never selected to be good anthrobots. They don't look like any stage of normal human development. What they do is they dip into their genome to pull out new functionalities, like what I showed you in the Xenobots. This is the beginning of a science of trying to understand, in addition to the goals provided and shaped by evolution, where the form and function of novel beings come from. A couple of things, then I'm going to stop.

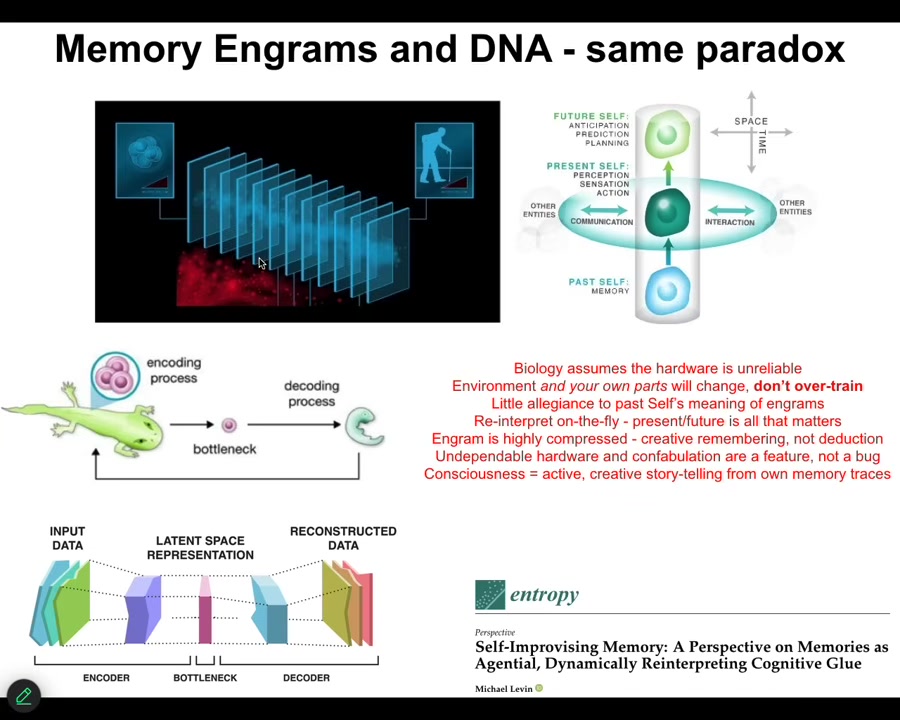

Slide 52/55 · 53m:15s

There's an interesting feature of both cognition and morphogenesis that underlies this intelligence ratchet, which is that in both cases, in the case of memories that are behavioral memories and in the case of genomic memories from your past lineage, any given creature at any given point, you don't have access to your past.

What you have access to are the information traces, the engrams, whether in DNA or in your brain, that the past has left as messages to your present self from your past self. Those messages have to be interpreted. You can't take them literally. In this compression of the past into the present, much like your past experiences get compressed into memory traces, past successes and failures get compressed into the bottleneck of an egg.

All of this information you cannot take literally because you've thrown away a ton of correlations. What you have to do is decode them creatively. You have to ask yourself, what can I do with this information now? What does it mean for me? This has massive implications for how we understand cognition and behavior.

What I've been showing you today in many examples is that the DNA is a prompt. It's pieces of a generative model that are used to bias cells for creative interpretation of what they're going to do. The plasticity of this process and the creativity are immense. I think this is the ratchet, the evolutionary ratchet that leads from the unreliable material of life, the biological substrate, which you can never quite be certain that you have what you expected to have, to this amazing improvisation and creative problem-solving process that you apply to these prompts to drive you into the future, and all of that is expressed here.

Slide 53/55 · 55m:00s

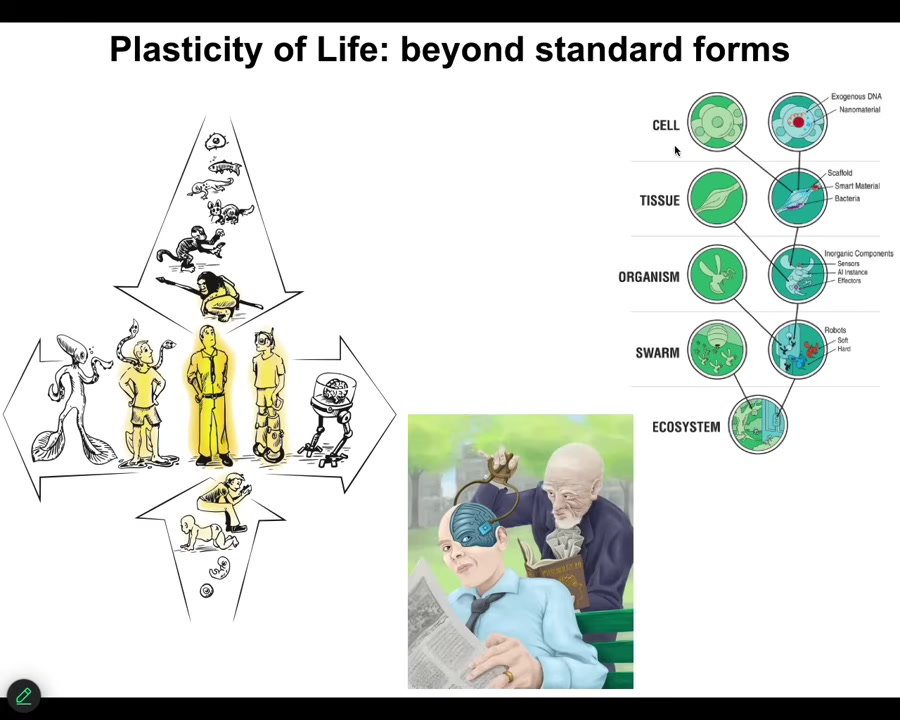

Because of this plasticity of life, it isn't just the AIs that we need to be thinking about. It is this whole enormous spectrum of biological and technological changes. We already have certain kinds of cyborgs and hybrids. The future is not going to be around binary categories of humans, machines, life, and so on. But we have this amazing spectrum that we need to understand.

Slide 54/55 · 55m:28s

Any combination of evolved material, design material, software, and patterns from the world of mathematics, the things that are not physical at all, determine some kind of viable embodied mind.

Everything that Darwin saw when he said "endless forms most beautiful" was a tiny corner of this option space. The future for us is to use model systems like morphogenesis and many others to learn to communicate with and have a kind of ethical synth biosis with creatures that are not like us.

A large part of this is not just for biomedicine, for inducing regeneration, normalizing cancer, which are all things that we've done using these approaches, but to help us relate to beings that are radically different from us.

Slide 55/55 · 56m:12s

I'll stop here and thank the students and the postdocs who did some of the work that I showed you today. Lots of amazing collaborators. The funding support that has paid for some of this work over time. Disclosures: there are three companies that have spun off from this work that are supporting some of it. The most thanks goes to the actual model systems who do all the hard work. Thank you very much.