Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a 1 hour talk by Michael Levin to an audience of biomedical engineering students.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) Introduction to agential materials

(06:07) Cellular memory and competencies

(13:24) Morphospace and anatomical compiler

(20:00) Goal-directed regeneration mechanics

(29:01) Bioelectric networks beyond brains

(33:41) Bioelectric control of morphology

(40:35) Hidden competencies and cancer

(44:41) Xenobots and emergent behaviors

(49:10) Anthrobots and agential therapies

(53:22) Future biomedicine and closing

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/52 · 00m:00s

If you want to follow up on any of the specific details, all the peer-reviewed stuff is here. There are some more diverse thoughts in this blog, and you can always find me at michael.levin@tufts.edu.

Slide 2/52 · 00m:14s

I'd like to convey the following main points today. First, I'm going to talk about how our bodies operate in a multi-scale competency architecture, a kind of problem-solving intelligence at every level of organization. I'm going to argue that definitive regenerative medicine will require us to understand the collective intelligence of groups of cells and how to communicate goals to them in one of the spaces that they live in, which is anatomical amorphous space.

I'm going to talk about a set of mechanisms which are endogenous bioelectrical networks, and they're becoming a highly tractable interface for top-down control of behavior of this collective intelligence. The tools are now coming online to read and write pattern memories into this protocognitive medium.

I'm going to show you some applications in birth defects, regenerative repair, and cancer, and, because we're focusing on bioengineering, talk about how we go beyond traditional forms. To be able to heal, restore, and make new kinds of living structures, we have to understand the agential material that we're working with.

Slide 3/52 · 01m:20s

Now, across the spectrum of different types of materials, people have been working for thousands of years with passive materials, and now we're getting into active matter and computational material. The interesting thing about changing the type of material is that different techniques and technologies become appropriate, different strategies. When you're dealing with a passive material, the good news is that everything stays where you put it. You basically construct whatever you want piece by piece, bottom up. But the bad news is that all of its functionality is on you as the engineer; you have to make the pieces do everything that you want this machine to do.

As we move rightward on the spectrum, we enter what we're going to talk about here called agential materials. These are materials with an agenda. You can think about building a tower out of Legos. As you construct a tower out of these Legos, it's quite easy to do, except that if it falls over, that's it. That's the end. You might think about constructing a tower out of dogs. What's different there is that they're not going to stay where you put them if you use the technologies and approaches appropriate for passive material. But they do offer an interesting interface, which is learning. If you train them to stay like this, then you gain something different, which is that if you knock the tower over, it's self-healing. They will get right back up. The idea there is that you need to use the appropriate approach to the level of agency of your medium.

Slide 4/52 · 02m:56s

And so this ends up being a discussion that a lot of people have about machines versus organisms. And so is your body a machine? Is it more than a machine? And so on. And what I want to transmit is this idea of context-dependent, observer-dependent fluidity and how we think about these things.

So if you have an orthopedic surgeon, you definitely want that orthopedic surgeon to think of your body as a machine because they're going to use the appropriate tools, chisels and hammers. But then they send the patient home to heal. And when that patient heals, there is all kinds of stuff going on to get from here to here that actually isn't captured by this paradigm at all. And if there's any kind of psychological component to this, to whatever happened to that patient, you definitely don't want a psychotherapist who thinks of the patient as this kind of machine. So there are multiple levels and multiple different approaches. And some of the most interesting work is done by people like Fabrizio Benedetti, who says he works on placebo effects, and we'll get to this by the end of the talk. Words and drugs have the same mechanism of action. And this is incredibly deep. It really gets to the bottom of what the living organism actually is as a multi-scale system that spans a high-level cognitive content all the way down to the movement of molecules across cells.

Slide 5/52 · 04m:13s

What you can think about is this idea that this spectrum of different kinds of systems can be placed on what I call an axis of persuadability.

This is a way to think about these systems from the perspective of the engineer to ask, what are the kinds of tools, what are the approaches that I can use for these kinds of systems? Back here, when you have simple machines, hardware modification is the only game in town. You're not going to convince it of anything. You're not going to reward or punish it. You have to be rewiring the hardware.

You get into some cybernetic approaches with things that have goals, so homeostats and thermostats. There are some interesting systems which allow learning, different kinds of training. Of course we have human-level and whatever's beyond that as far as metacognition.

One question that we have to ask is where do groups of cells fit into this kind of spectrum? In other words, if we are bioengineers and we're interested in understanding our material, do we have to assume, as many people assume, that it lives somewhere down here and hardware rewiring is really the way to go? Or might we find that there are some tools from these other disciplines that are amenable to this?

This is critical because a lot of people treat this as a philosophical problem: those are just cells. They don't have memories or they can't have goals. I want to emphasize that this is an empirical question. You can't decide these things by armchair commitments to philosophical views; you have to do experiments.

That means taking some tools and concepts from other disciplines that are appropriate up here and asking the question, what new purchase on control and prediction and construction and invention and novel capabilities does that give us with our cellular material?

Slide 6/52 · 06m:07s

Developmental biology is really critical for all of these things because it teaches us something very profound, that physics becomes mind slowly and gradually. All of us at one point were an unfertilized oocyte, a simple cell, a little bag of chemicals, which people could look at and say, this is clearly amenable to the laws of chemistry and physics, but there's no mind there. It's just chemistry. But eventually we become something like this or even something like this.

What's critical about developmental biology is that it offers no sharp dividing line where you say, that's when we went from chemistry to mind. This is a slow, gradual process. So the self-assembly of the body and the scale up of cognition actually happen together. And this is what we need to understand if we're going to understand what cognitive processes are going on here and, both evolutionarily and developmentally, antecedents that we can take advantage of for engineering.

Slide 7/52 · 07m:17s

This is the kind of stuff we're made of. This is what our cells are like. This happens to be a lacrimaria. It's a free-living organism. There's no brain, there's no nervous system, there are no stem cells. This is one cell. And this creature is handling all of its physiological, metabolic, and behavioral needs in one cell. It's highly competent in the tiny goals that this thing has about its state of affairs around this little radius.

Slide 8/52 · 07m:46s

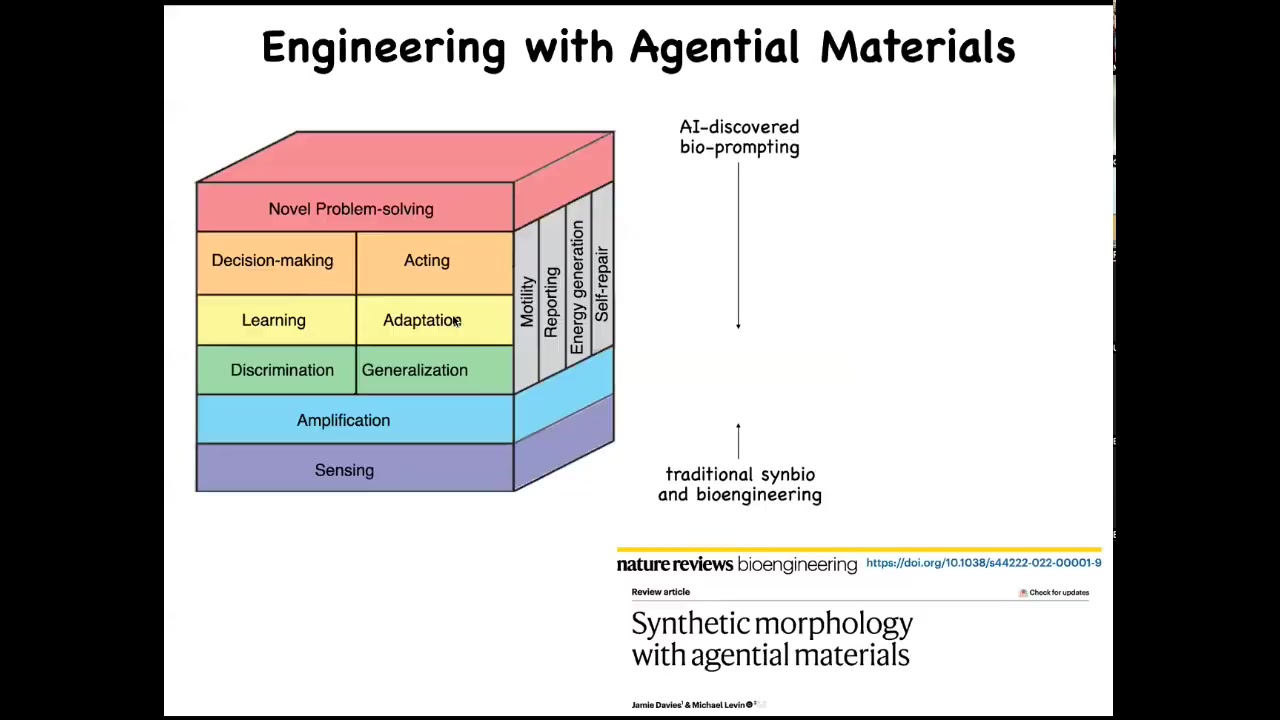

When we engineer with these kinds of materials, what you are able to do is take advantage of an incredible toolkit that evolution has been preparing for over a billion years of all of these kinds of competencies that otherwise you as the engineer would have to bake in yourself. When you're dealing with cells, they already do sensing, amplification, signal discrimination; they do learning, they do decision making. They solve new problems. All of this is there for you in the material.

Slide 9/52 · 08m:19s

It's not just at the level of individual cells, even below the cell level, something as simple as a gene regulatory network or a pathway, a set of molecules that interact with each other, can do several different kinds of learning, including habituation, sensitization, associative conditioning, Pavlovian kinds of learning. All of that is present long before you get to a cell and certainly long before you get to a neuron or a brain. So what I'm going to do next is try to show you some of the competencies of the medium, just to give you a few facts that you may not have seen in your biology so far. So you can start to get a feel for this amazing material that we're working in.

Slide 10/52 · 09m:00s

The first thing I'll show you is this tadpole. There are no eyes. Here are the nostrils, the mouth, the brain, the spinal cord, and the gut back here. This is a tadpole. What you'll see is that we prevented the primary eyes from forming, but we made an eye appear on its back. We'll talk about that in a little bit.

We made this machine to automate the behavioral testing of small model systems with light cues. What you find out is that these animals can see quite well. If you look where the optic nerve is, this eye does make a single optic nerve. It goes out. It doesn't go to the brain. It synapses on the spinal cord here. These animals can see. You don't need additional generations of evolution. You don't need selection. Just in one generation, by radically changing the sensory motor architecture, it's fine. The brain can recognize the information coming in here on this weird, itchy patch of tissue on its back as visual data. They can learn in visual cues and so on. The plasticity is amazing.

Slide 11/52 · 10m:06s

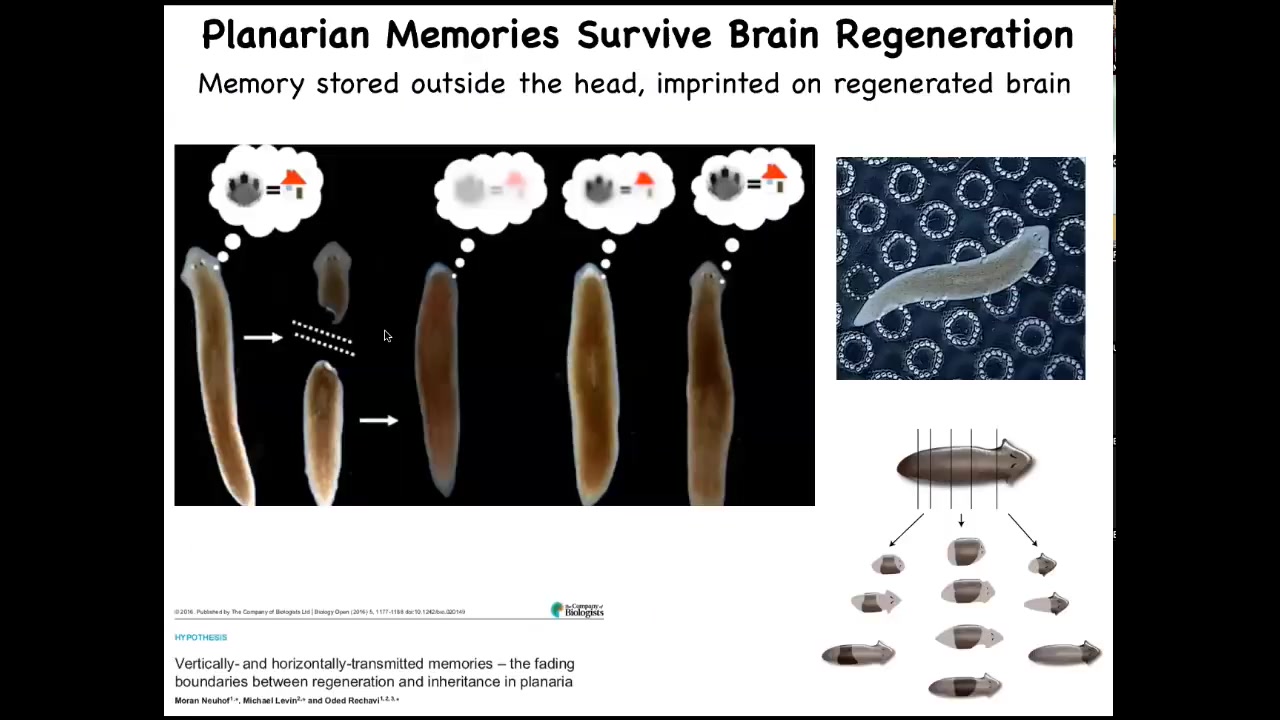

That gets even more incredible when you think about some other model systems. These are planaria. They are flatworms. One of the cool things about flatworms is that they regenerate their bodies. They regenerate from any fragments that you cut. The record is something like 275 pieces. They are also immortal, really interesting organisms. What you can do is train them. If you train them and then cut off their heads, which contains their brain, the tail will sit there doing nothing until they regrow a new head. When they regrow a new head and behavior resumes, you find out that they remember the original information.

Where is the information during this regenerative process when all you've got is a tail? The next question is how is that information imprinted onto the new brain as it develops. You might think about applications in human medicine where in a few years, patients with 6, 7, 8 decades of memories, personality, and so on have to have portions of their brain replaced with a progeny of naive stem cells. In some kind of degenerative brain therapeutics, what's going to happen to that patient? What's going to happen to their cognition, their memories, and so on? Here you see the interface between the memories of the body: the morphogenetic memory that enables you to regenerate the same pattern, and the behavioral memory of events in three-dimensional space, and how those two things come together.

Slide 12/52 · 11m:38s

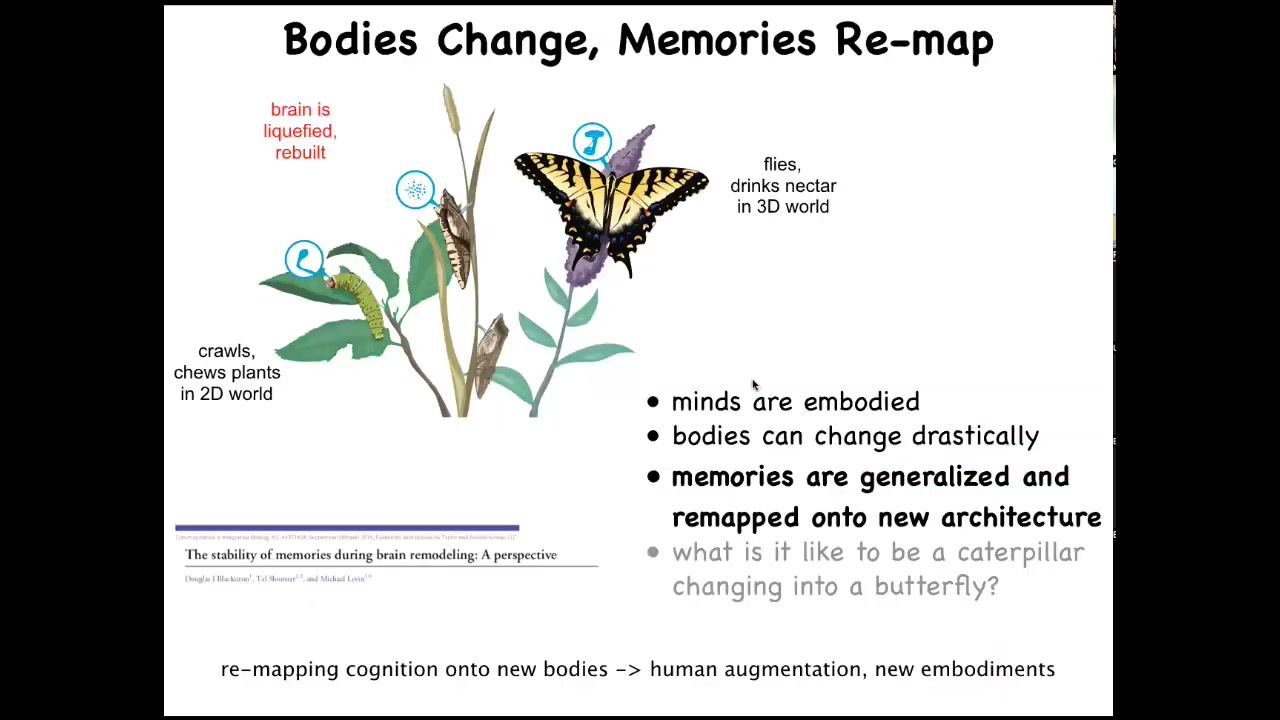

To me, one of the most interesting cases is this. This is a caterpillar. These guys are a kind of soft-bodied robot. They have no hard elements. The controller here is this brain suited for driving that type of embodiment. They live in a two-dimensional world. They crawl around and they eat leaves. But they have to become this: a hard-bodied flying kind of thing, which lives in a three-dimensional world. And it has a very different brain.

During metamorphosis, the brain is basically dissolved. Most of the cells are killed off, but the memories remain. If you train the caterpillar by giving it leaves on a particular color disk, the butterfly will remember that fact. The most amazing thing here is that butterflies don't eat the same things that caterpillars do. Caterpillars eat leaves, the butterfly doesn't care about leaves, it likes nectar. That means that during this process, not only do you have to store information despite the drastic refactoring of the medium, which is, again, the brain and the central nervous system, but you also have to remap and generalize from finding leaves to finding a global category called food. And whatever that food is to you now, that is what you're going to remember.

So it's really interesting to see how specific memories are generalized and then imprinted onto a new physical architecture in a way that preserves their salience. The information you learned in this life, you have a different life and a different body, and you don't have the details of the information, but you have the generalized lessons. We don't have even the beginnings of an understanding of how all that actually works. But it has implications for human augmentation, new embodiments through cyborg architectures.

Slide 13/52 · 13m:24s

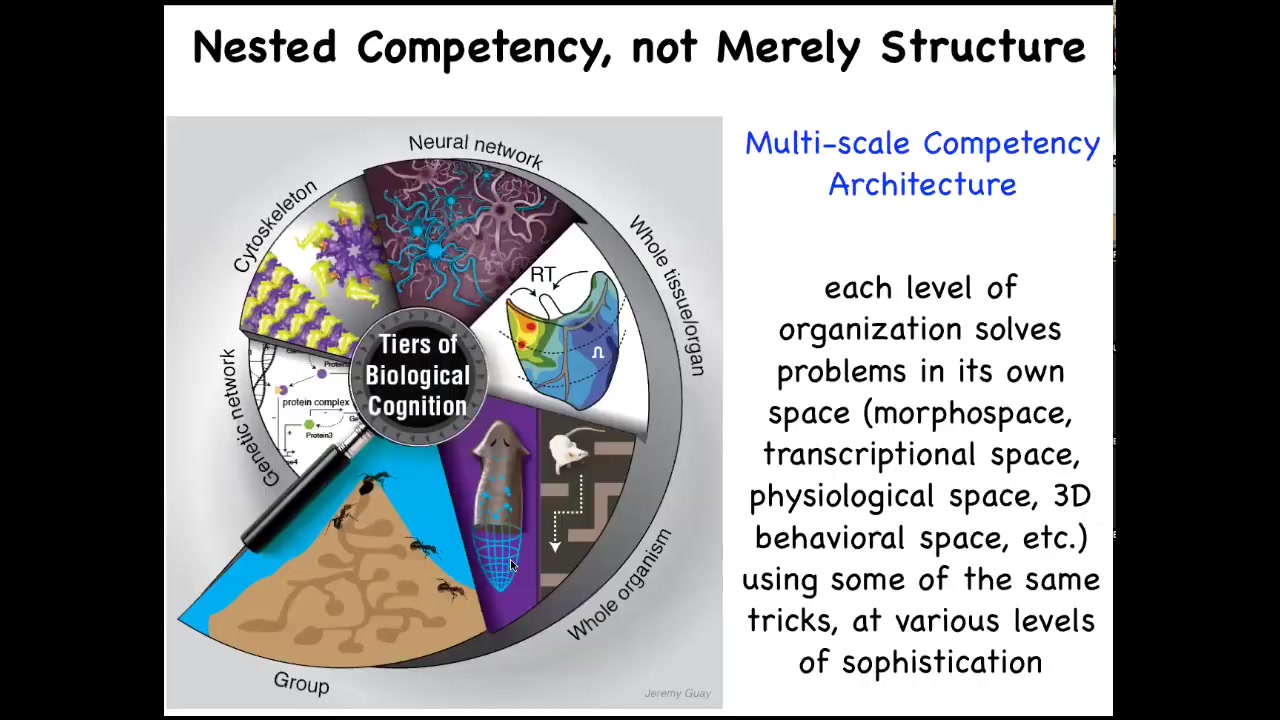

So the reason that we have these amazing capacities in the living world is that all living beings are made of a nested multi-scale competency architecture where it's not just structurally that you're made of organs, which are made of tissues and cells and so on. But at every level of organization, these structures are solving problems. Each of them has little agendas in different spaces, different scales of problems, and they're all very good at solving these problems. And this architecture is responsible for a lot of the magic that we can take advantage of as bioengineers.

Slide 14/52 · 13m:59s

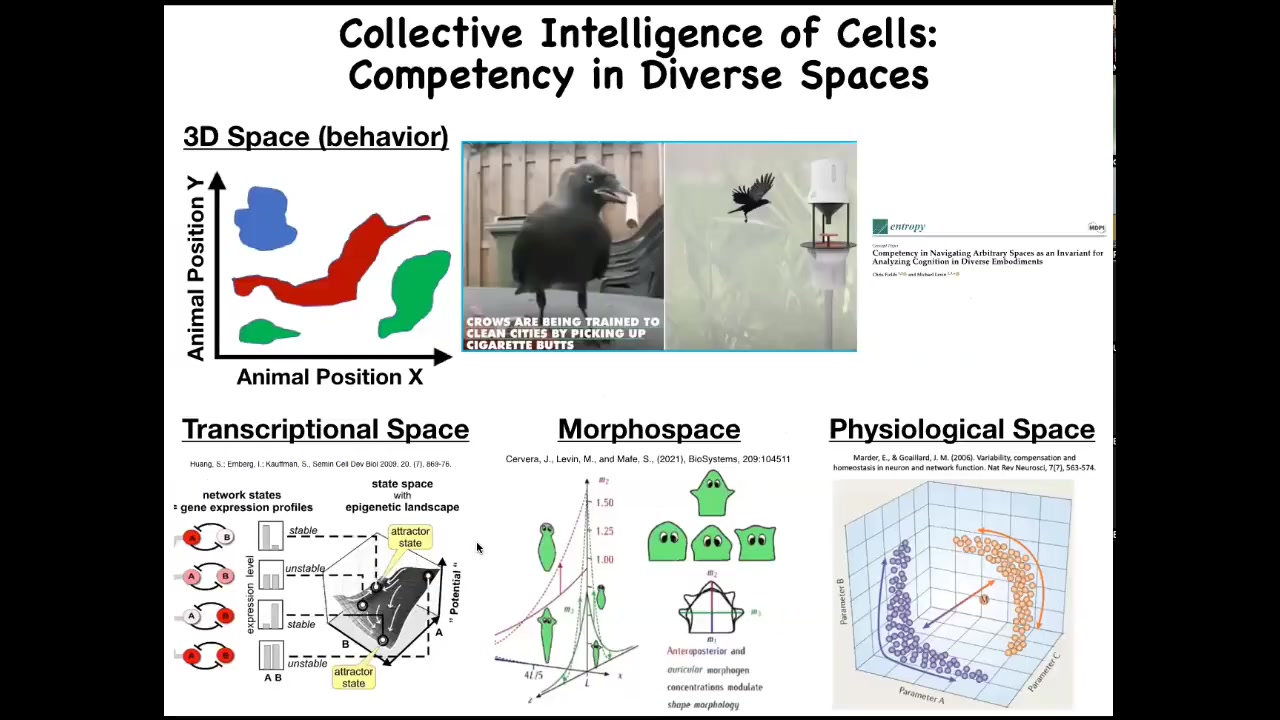

When I talk about problem solving, we have to realize that we as humans are pretty good at recognizing intelligent behavior in three-dimensional space performed by medium-sized agents moving at medium speeds. Our cognitive system is prime for that. So we understand dogs and apes and birds and maybe an octopus or a whale.

But there are all these other spaces in which living things strive and navigate and suffer and have successes and failures. There are transcriptional spaces of all possible gene expressions, physiological state spaces, and what we'll talk about most of all today, which is anatomical morphospace. These things are hard for us to recognize intelligence operating in these different spaces.

But just imagine if we had evolved with a primary sense of our blood chemistry. If you could directly feel, let's say, 20 different parameters, the way you do with taste and smell, I think we would have no trouble realizing that our liver and our kidneys were intelligent agents navigating these spaces and solving problems.

Slide 15/52 · 15m:15s

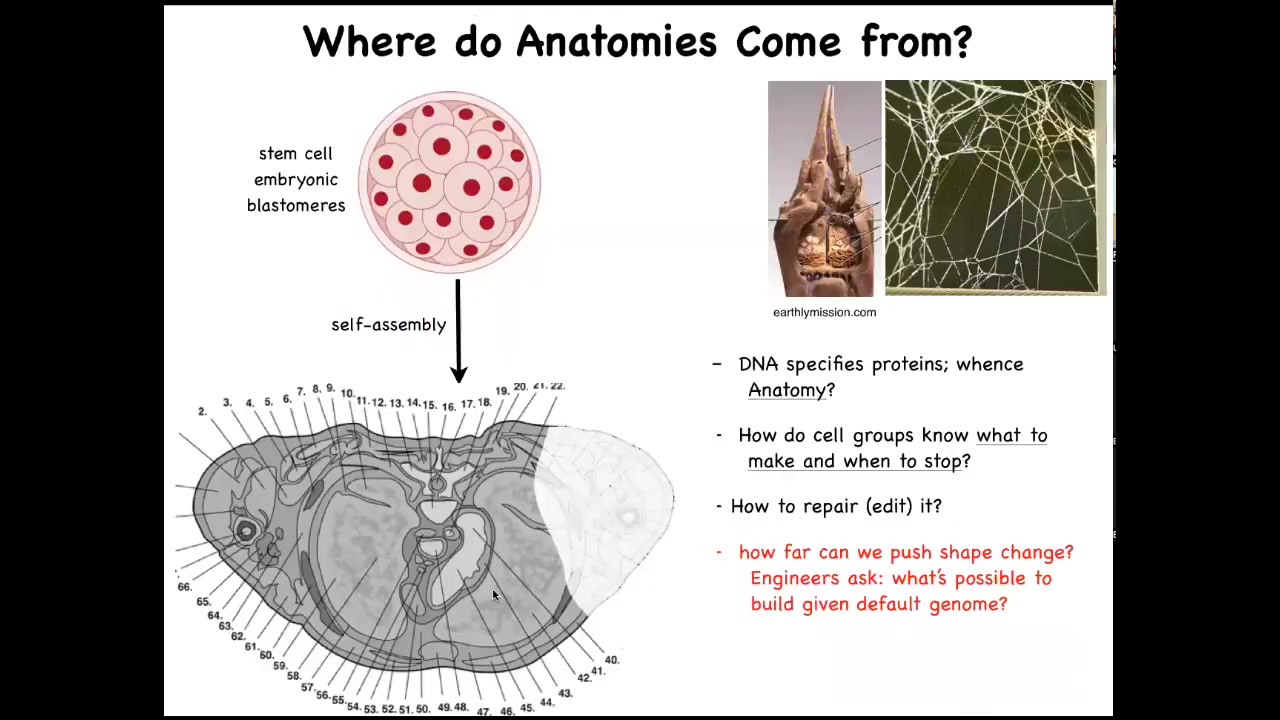

Let's talk about anatomical morphospace. How do collections of cells navigate that anatomical space? I'm going to make the argument that quite literally, groups of cells are a collective intelligence that navigates anatomical space. To understand why this is, let's consider this scenario.

We all start life like this, a group of embryonic blastoderm and blastomeres, rather, and then eventually you have this cross-section through a human torso. Look at all the incredible complexity that's here. All normal humans have this amazing order of everything being the right size and shape next to the right thing. Where does this pattern come from?

People often say DNA, but we can read genomes now; we know that none of this is directly in the DNA. What the DNA actually specifies is proteins, the micro-level hardware that every cell gets to have. All of this is the result of the physiological software performed by cells.

We really need to understand how cell groups know what to make and when to stop.

In regenerative medicine, we'd like to know how to repair missing parts: how do we convince these cells to build them again?

For today, we'll talk more about how far we can push this. As engineers, we'd like to know what's possible. What if you wanted these cells to build something completely different?

We understand now that this is a problem of information. The structure of the body is not directly in the genome any more than the structure of a nest is laid out in the genome of termites or the structure of a web is specified in the genome of a spider. This is all physiological software that we need to understand.

In order to embark on this journey and figure out what this all means, it's important to think about the end game.

Slide 16/52 · 17m:00s

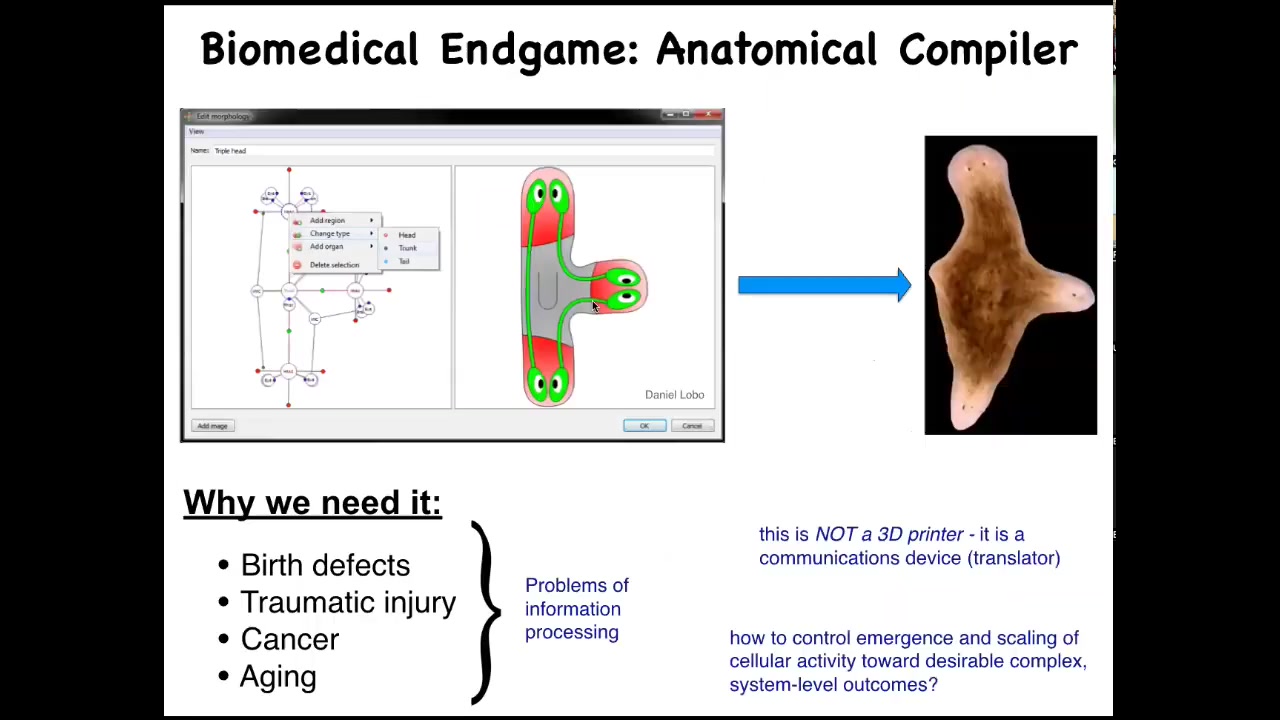

What are we trying to do here? What's the end of this field? When do we think we've succeeded and we can all go home? You can think about this as something we call the "anatomical compiler." Someday you will be able to sit down and draw at the level of the anatomy, not molecular pathways, but at the level of the anatomy: you'll be able to draw the animal, plant, biobot, or organ that you want, whatever it is. And what the system will do is compile that anatomical description into a set of stimuli that have to be given to those cells to build exactly that — in this case, this nice three-headed flatworm.

Why do we need it? Besides the foundational issues of evolution and computation and so on, this is an incredibly practical problem because if we had something like this, if we had a way to convince cells to build whatever we wanted them to build: birth defects, traumatic injury, cancer, aging, degenerative disease — all of these problems would go away. Bio-robotics would take off. This is central. Our failure to communicate goals to groups of cells is responsible for a huge part of the unmet need of biomedicine.

What's important is that this thing is not a 3D printer. It's not about putting individual cells where they go. It's a communications device. It's about translating our goals to that of the collective so that they can deploy their morphogenetic skills. You might think, why don't we have this? Molecular biology and genetics have been going gangbusters for decades. Why don't we already have this?

Slide 17/52 · 18m:33s

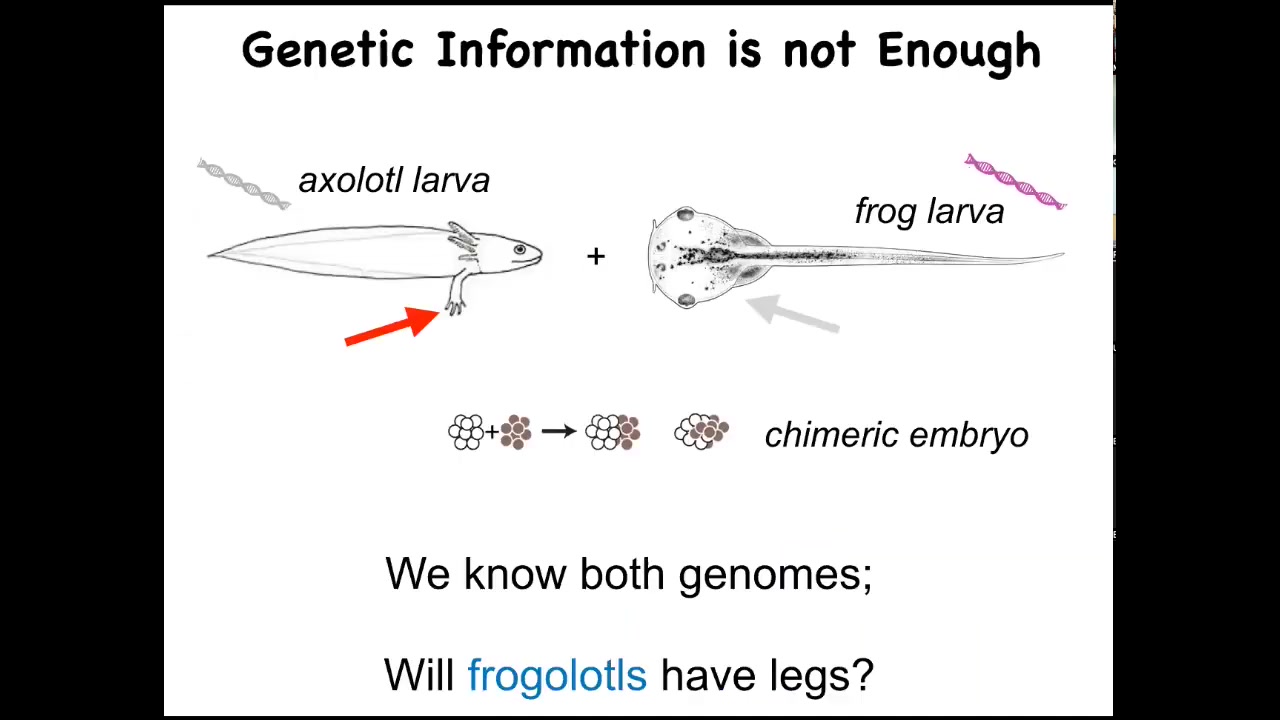

Here's a baby axolotl. Baby axolotls have the little four legs. Here's a frog tadpole. They do not have four legs at this stage.

In my group, we make something called a frogolotl. A frogolotl is a bunch of embryonic axolotl cells and a bunch of embryonic frog cells. They make a lovely chimeric embryo.

I tell you that we have the genome of the axolotl. It's been sequenced. We have the genome of the frog. That's been sequenced. I give you those genomes and ask a simple question: Would the frogolotl have legs or not? We don't have the beginnings yet of a science to figure that out from this kind of genomic data.

Slide 18/52 · 19m:13s

And so here's where we are. We're very good at manipulating molecules and cells. All the exciting approaches nowadays, genome editing, CRISPRs, stem cell biology, pathway rewiring, protein engineering, all of these kinds of things, are down at the level of the hardware. But what we really don't understand at all and what we would like to control is anatomy. How do large-scale collections of cells make decisions about what to build? And so I'm going to make the argument that biology today, and biomedicine in particular, is where computer science was in the 50s and 60s. This is how you did programming back then. You were down at the level of the hardware and you had to interact with the hardware. But the reason that nowadays on your laptop, when you need to go from PowerPoint to Microsoft Excel, you don't get out your soldering and start rewiring is because computer scientists perfected this remarkable hierarchy of tools to deal with software, to reprogram certain kinds of media. And I think this is what we're just beginning to realize in biology. And we need to understand the intelligence and the reprogrammability of our medium.

Slide 19/52 · 20m:20s

Now, I've used the word intelligence several times. What do I mean by it? Here's the definition I like: William James' definition: The ability to reach the same goal by different means.

This is a cybernetic definition because it doesn't talk about what kind of brain you have. It doesn't specify what sort of problem space you're operating in. It's much deeper than that. It talks about different levels of competency to reach specific goals when the system is stymied or deviated from that goal.

For the next few minutes, let's talk about what kind of intelligence do cells deploy? What problems do they solve? When I say that groups of cells are a collective intelligence, what do I mean? Here's one example.

This is a cross-section through the kidney tubule of a newt. Normally there's 8 to 10 cells that work together to produce that. One thing you can do with these animals is prevent cell division at early stages, which means every cell ends up with multiple copies of its genome. You get polyploid newts, 4N, 6N, 8N. When that happens, the cells get bigger, but the newt stays the same size. If you look at the cross-section, a smaller number of bigger cells are now involved.

You can still make a normal newt if you've got the wrong amount of DNA. If your cell size is incorrect, they will adjust. The most amazing part of all is that if you make absolutely gigantic cells, these are 5N or 6N newts, one cell will bend around itself and still give you the same kind of structure. The reason that's remarkable is that this is cell-to-cell communication; this is normal tubulogenesis. This is some sort of cytoskeletal bending. It's a different molecular mechanism.

Think of what you have here, two key points. One is that this is downward causation in the sense that in the service of an anatomical goal, different molecular mechanisms are being called up. Your medium is good at finding the tools that it has to get the job done when things change. There's that definition of intelligence.

Think about the problem that newts have coming into the world. Fundamentally, you don't know how many copies of your genome you're going to have. You don't know the size of your cells. You don't know how many cells you're going to have. You don't know any of that. You can't afford to take your evolutionary priors too seriously or overtrain on them, as machine learning folks like to say. You have to solve this problem from scratch.

Because of the prevalence of mutation, not only can you not count on your environment to be exactly the same as it was, you can't even count on your parts to be the same as they were. Your own components are not going to be the same because of mutation, evolutionary change, and environment throws a wrench into everything too.

What evolution actually makes is problem-solving machines. You can't afford to do the same thing every single time.

Anatomical goals in morphospace means a single human egg reliably gives rise to an anatomically normal human, but so do half embryos and quarter embryos and things like that. When you cut an early embryo into pieces, you don't get half bodies, you get perfectly normal monozygotic twins, triplets, quadruplets, and so on. That's because they can get to the same ensemble of states, this goal state in anatomical space corresponding to the normal human target morphology. You can get there from different starting positions and avoid some local maxima.

That type of navigation of space is shocking. We don't have any machines that do this. We're not good at making engineering that works like this. We don't have anything that you can cut into pieces and it still figures out what to do, rebuilds, and remaps old memories if you decide to change the structure the way that butterflies do.

Slide 20/52 · 24m:02s

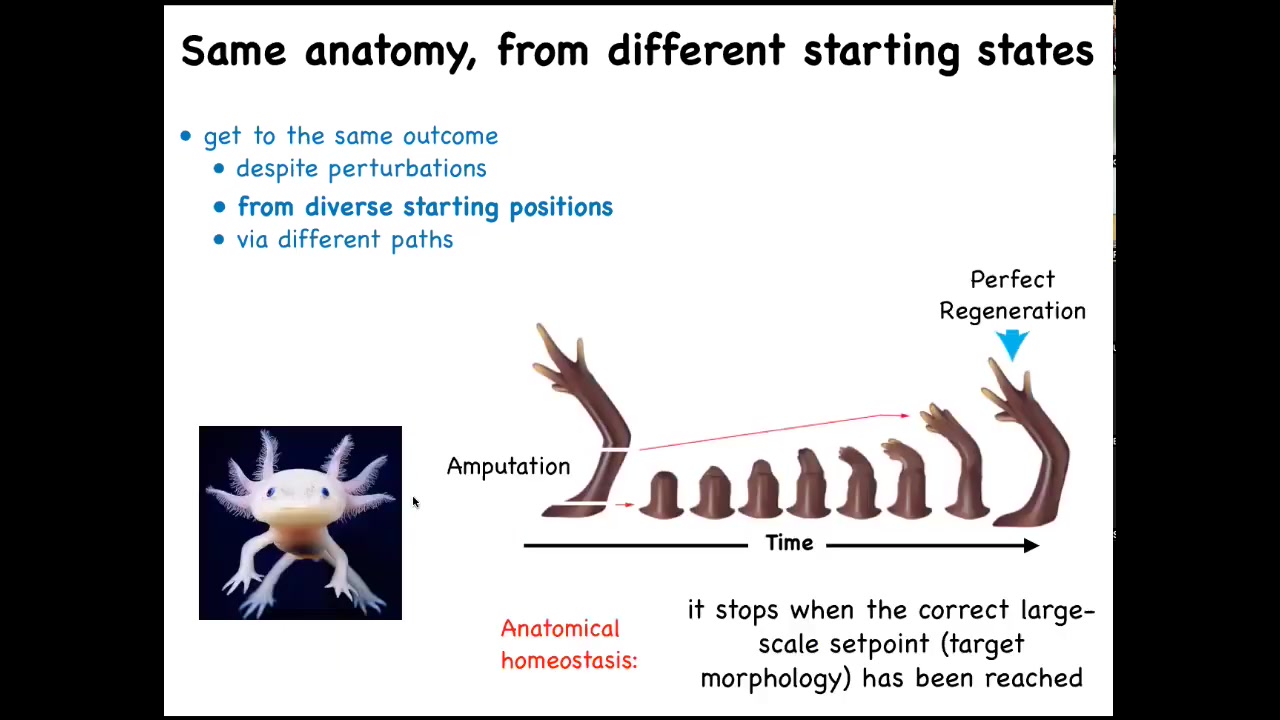

That kind of process is not just for embryos. Some animals keep it throughout their lifetime.

Here's your axolotl. These guys regenerate their eyes, their jaws, their tails, including spinal cord, their limbs, their ovaries. If you amputate, whether here or anywhere, it will immediately start to grow and morph and then eventually rebuild and stop.

Two amazing things. One is that it grows exactly what's needed from wherever you cut. It only does what's missing. When does it stop? It stops when the correct salamander arm has been completed. That's remarkable because that means it has to know where it's going. It has to know what the end goal of their journey through anatomical space is.

The reason it's a goal is not just because it's complex and it's an outcome of a bunch of chemistry happening in parallel. What you're seeing here is a high level of effort, measured in metabolic cost and so on, to get back to the correct state when it has been deviated from that state.

Slide 21/52 · 25m:09s

I'll point out that this is not just about worms and salamanders. Human livers regenerate, human children regenerate their fingertips, and deer, large adult mammals, regenerate huge amounts of bone, innervation, vasculature, and skin when they're regenerating their antlers — up to a centimeter and a half of new bone per day. It's an interesting question why we're generally not that good at it.

Slide 22/52 · 25m:34s

To remind us what we're talking about, this kind of goal-directed navigation in anatomical space looks something like this. These tadpoles have to become frogs. Here are the eyes, the mouth. They have to rearrange all these organs to go from tadpole to frog. The null hypothesis has always been that it's a hardwired process. Each one of these organs travels the right direction and the right amount. You get from a normal tadpole to a normal frog. We decided to test that: how much intelligence does this really have? We created what's called Picasso tadpoles. These are scrambled: the eyes on the side of the head, the mouth is off to the top. Everything's scrambled. What you find is that these animals make quite normal frogs because all of these components will undergo novel motions and they won't stop until they get to the right place. Sometimes they go too far and have to double back. Eventually everything settles on the correct frog face. The genetics does not give you hardware that moves things in a prescribed fashion, it gives you an error minimization scheme. It gives you a system that can try to minimize errors from a specific set point.

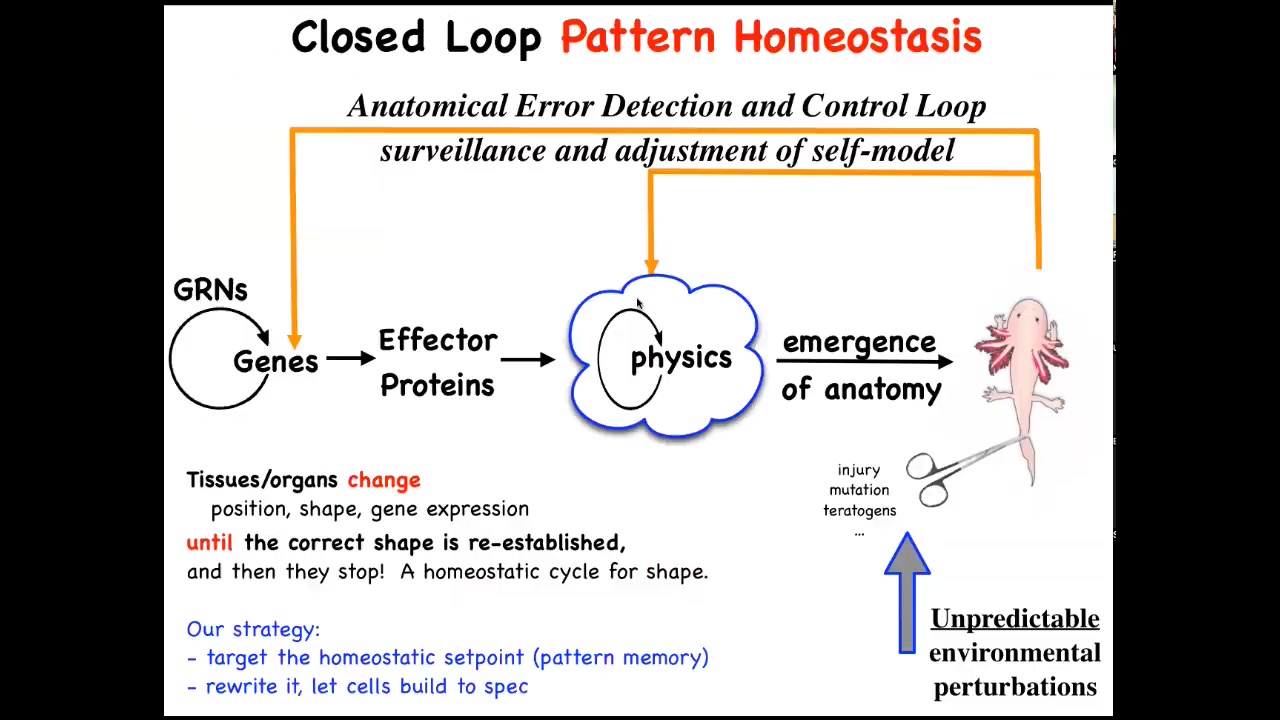

Slide 23/52 · 26m:44s

That means that, to the standard view of developmental biology, which is what you see in your textbooks, you have some gene regulatory networks and then some proteins that interact via physics. And then there's this magical process of emergence.

Eventually, if you crank on these rules in parallel, something complex will come out. All of this is true. There are plenty of ways to get emergent complexity, but that's not the whole story. In fact, I think that's not even the most interesting part of the story. What's more important are these feedback loops, which will try to regain that target morphology when you deviate from it.

And so this means injury, but also mutations and teratogens and various other ways to get away from this set point. Thinking about this suggests a couple of things.

First of all, biologists know all about feedback loops and homeostasis, but typically we think about scalars like pH, temperature, hunger level—single numbers. Here, the set point is going to have to be something complex, like an anatomical representation of the thing you're trying to build. How could we possibly store a goal state like this in tissue? How could tissue remember an anatomical or geometric pattern?

This weird way of thinking about things, molecular biologists don't love because you're not supposed to talk about goals. You're supposed to talk about chemistry and chemical pathways. But since the 40s, we've had a mature science of machines with goals. It's not scary or magical anymore. We can think about these things now.

This way of thinking about it makes some strong predictions. It predicts that you should be able to find, decode, and then rewrite whatever mechanism is keeping this set point, because all homeostatic systems have to store a set point. It also predicts that if you are successful in rewriting that set point, you shouldn't have to make changes down here, which is very difficult.

If you want to make system-level changes, what genes do you change? Usually we have no idea because reversing this is extremely hard. It's a very hard inverse problem. But you should be able to change the set point and then the cells will do what they do best, which is build to it.

But how could a collection of cells possibly remember, and I use that word on purpose, what the correct state is going to be?

Slide 24/52 · 29m:16s

We know from neuroscience that certain collections of cells are very good at remembering goal states and trying to implement them intelligently, and that would be brains. The way that system works is you have these electrical networks which use ion channels to set voltage gradients. They have electrical synapses that spread information through the network. And that hardware supports all of the amazing software of cognition.

Here's a zebrafish brain that this group imaged, and it's the commitment of neuroscience to neural decoding: that if we just knew how to decode this physiology, we would be able to extract the memories, the preferences, the behavioral repertoire of this animal. In neuroscience, we have the beginnings of a science that links electrophysiology to mental cognitive content, to goals, to various kinds of intelligent problem-solving activities.

But this is not unique to brains. Every cell in your body has ion channels. Most cells have electrical connections to their neighbors. What if we could steal a bunch of techniques and approaches from neuroscience and apply them to other cells that also form electrical networks? That leads to questions like early embryos. This is voltage imaging that we develop, much like here, but instead of the brain, you're looking at the early frog embryo. What do cells think about long before there are brains or muscles or movement in the 3D world? What is this electrical network thinking about? This is what we study.

Slide 25/52 · 30m:57s

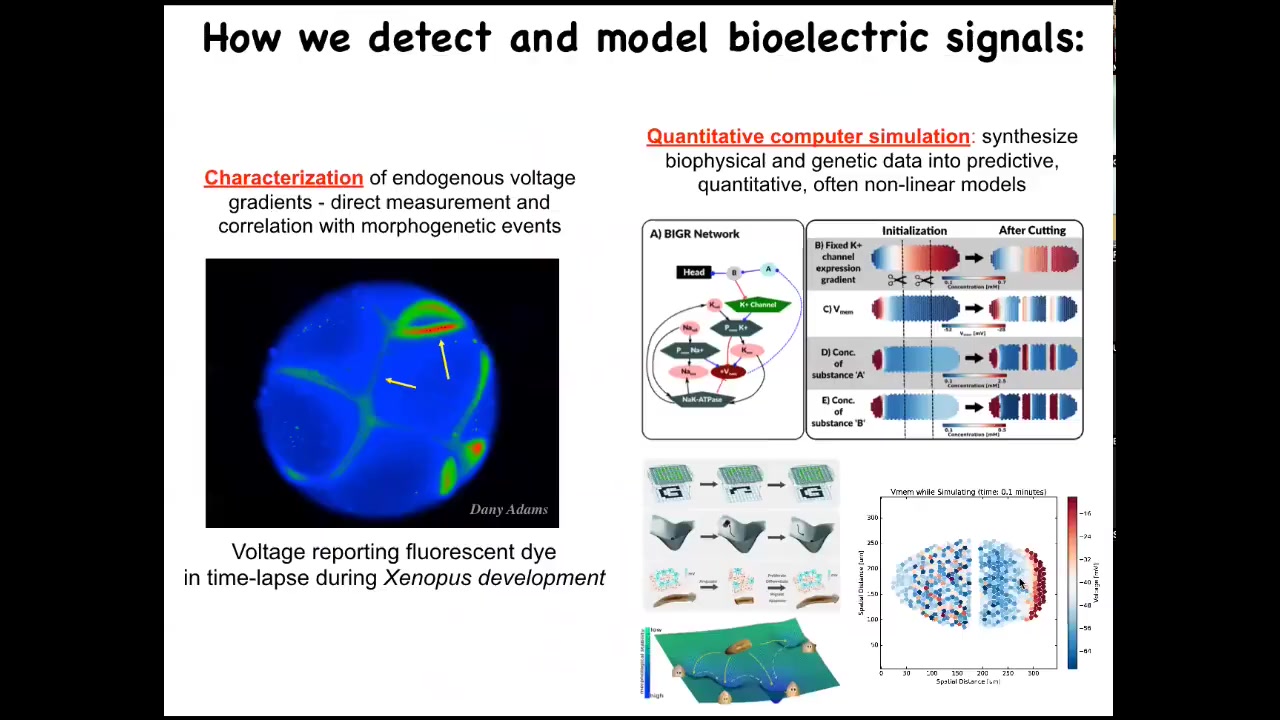

We developed some tools. The first tool is voltage imaging, to characterize the information flow through the system. We do this by voltage-sensitive fluorescent dyes, or sometimes genetically encoded voltage reporters. We do a lot of computational modeling to try to understand these and predict these dynamics.

Slide 26/52 · 31m:19s

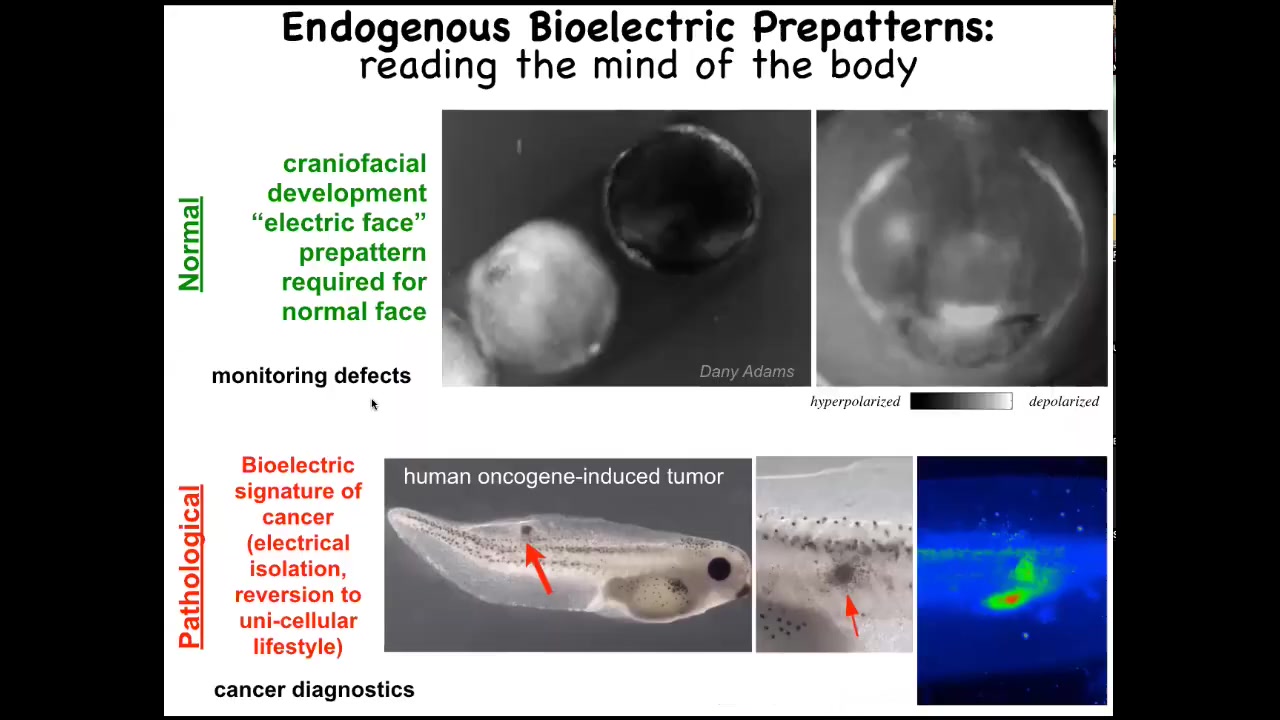

Let me show you two patterns that are particularly interesting. One is the electric face. This is a time-lapse video of a frog embryo putting its face together. The brightness corresponds to voltage, to resting potential. This is one frame out of that video. What you see is that the future structure of the face is already laid out in the electrical properties of that ectoderm. Here's where the eye is going to be, here's where the mouth is going to be, here are the placodes; the animal's left eye comes in slightly later. This pattern is a necessary part of normal development because if we change this pattern, the gene expression required to pattern the face and the ultimate anatomy are all altered. The bioelectric code is literally showing you where all the different regions of the face are going to be.

This is a pathological pattern that we see when we inject human oncogenes into tadpoles. Eventually they'll make a tumor; it has a bunch of metastases here. You can already see these cells long before this is visible. You can already see these and can tell where it's going to happen by looking at where the cells are disconnecting from their neighbors and acquiring an abnormal voltage potential. At that point, they just think of themselves as amoebas, the rest of the body is just external environment. They go where they want, they eat what they want, and you get metastases.

These are techniques for monitoring these bioelectrical states.

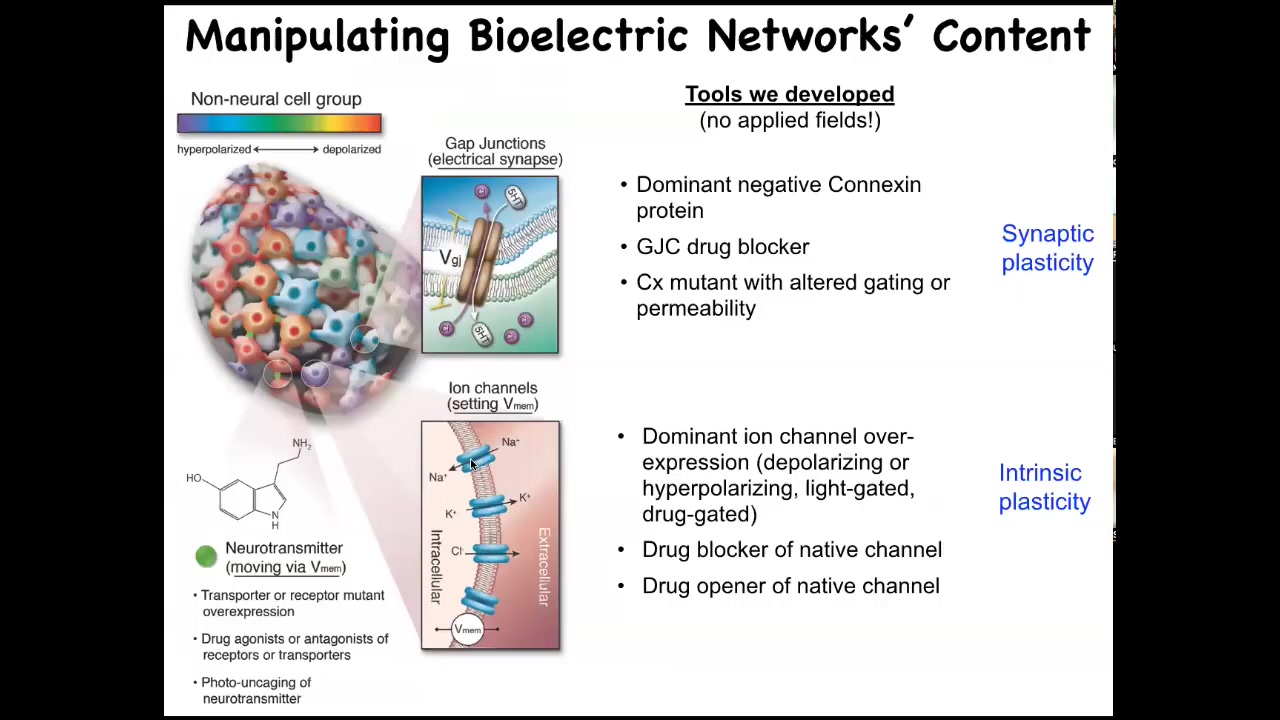

Slide 27/52 · 32m:49s

But now we've also developed techniques to write information back into them. We do not use electrodes. We do not use electromagnetic radiation. There are no fields. There are no waves. There are no magnets. All of this is done by manipulating the external interface, the bioelectric interface that cells normally use to hack each other. And that means ion channels on their surface to set voltage state and gap junctions, these electrical synapses to convey that voltage state to the neighbors in the network.

We can use all the stuff that neuroscience uses. We can use various ion channel and gap junction modifying drugs. We can mutate them genetically. We can do optogenetics and use light. What happens when you do this? What is this electrical information in the body used for? Let's modify it and see what happens. That's what we started to do when we first developed some of these tools to use these molecular reagents to control the bioelectrical state of these networks.

Slide 28/52 · 33m:50s

I'm going to show you a couple of examples that I like. This is one where we use RNA encoding certain potassium channels to express it in early cells and to induce the kind of voltage pattern that you saw in the eye spot of that electric face. When you do that, you find out that what you've done is told these cells to make an eye, but you can do that anywhere. That is the information the cells use to decide what they should be. If you tell a bunch of gut cells that they should be an eye, that's what they make. We can make these eyes anywhere in the animal. They have the lens, optic nerve; they have all that stuff.

From this, we learn a couple of things. First, the bioelectric pattern is instructive. It's not just a matter of we screwed up some voltage and then the animal is sick and doesn't make the right tissues. It's actually instructive. You can make an entire new organ by telling it what to do.

We find out that information is quite modular. We didn't give it a lot of details. In fact, we didn't say how to make an eye. We have no idea how to make an eye. What we've told it was a very simple signal, which is basically a high-level subroutine call that says make an eye here. Everything else is handled by the material. This is back to this concept of the competency of your material. The material already knows how to make an eye, but what you need to figure out is how to convince it that that's the path that it should be following.

We also find that if you prompt it with the right signal, you can actually get it to do things that normally it won't do. When you're reading your developmental biology textbook, it will say that the cells behind this anterior rectoderm are actually incompetent to form an eye. That's because it was probed with the so-called master eye gene called PAX6. If you do that, you don't get eyes past this. But if you use the right prompt, which is this bioelectrical signal, then they're competent. You can get this anywhere in the body. That reminds us to be humble about what are the competencies of the tissue. If you don't know what your material does, that may be a limitation of the material, or it may be a limitation of us and our understanding. Assigning intelligence to materials is basically us taking an IQ test ourselves in terms of what we understand about how this works.

If you only get a few cells — the blue ones are the ones we injected — they will recruit their neighbors. All of this other stuff here was never modified by us. They recruit their neighbors to help them finish the task. We didn't teach them to do that. They already do that, like many other collective intelligences such as ants and termites: if a couple of ants find something interesting and they can't carry it to the nest, they'll recruit others to help. The cells do the same thing here.

This is another kind of application where we looked at limb regeneration. Frogs, unlike salamanders, do not regenerate their limbs at certain stages.

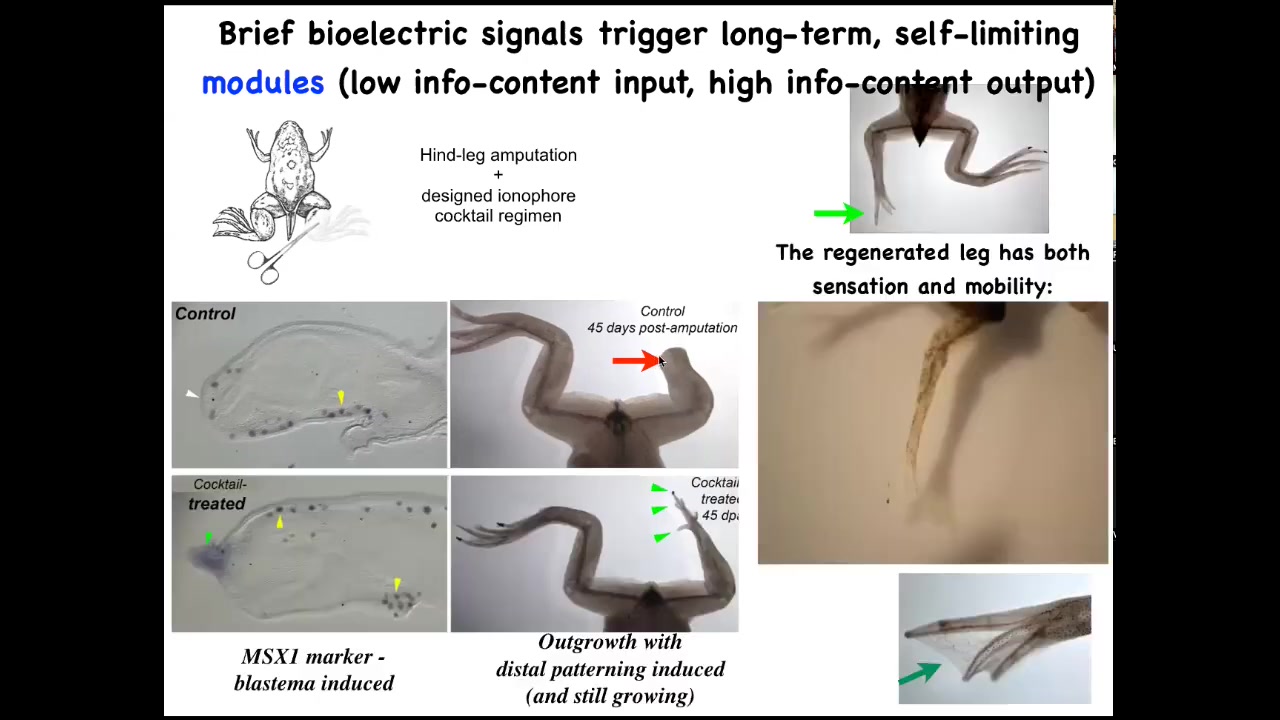

Slide 29/52 · 36m:53s

Here it is. We amputate. Forty-five days later there's nothing, but we were able to come up with a cocktail that, after a very brief stimulus, triggers the whole. Here's MSX1, a pro-regenerative marker. By 45 days, you've already got some toes, you've got a toenail, and eventually a pretty respectable-looking leg that is touch-sensitive and motile. The latest work on this, 24-hour stimulation, leads to a year and a half of leg growth. We don't touch it during that time at all. This is not about micromanagement. This is not about controlling gene expression or where the cells go. This is about convincing the cells right at the beginning that they need to go down the regeneration path, not the scarring path. And then after that, the system takes care of it.

Slide 30/52 · 37m:38s

We are now trying to move this into mammals. I have to do a disclosure here because David Kaplan and I have this company called Morphoceuticals, Inc., where we are trying to push that technology using wearable bioreactors, which David's lab builds for mice and hopefully eventually for the clinic.

Slide 31/52 · 37m:55s

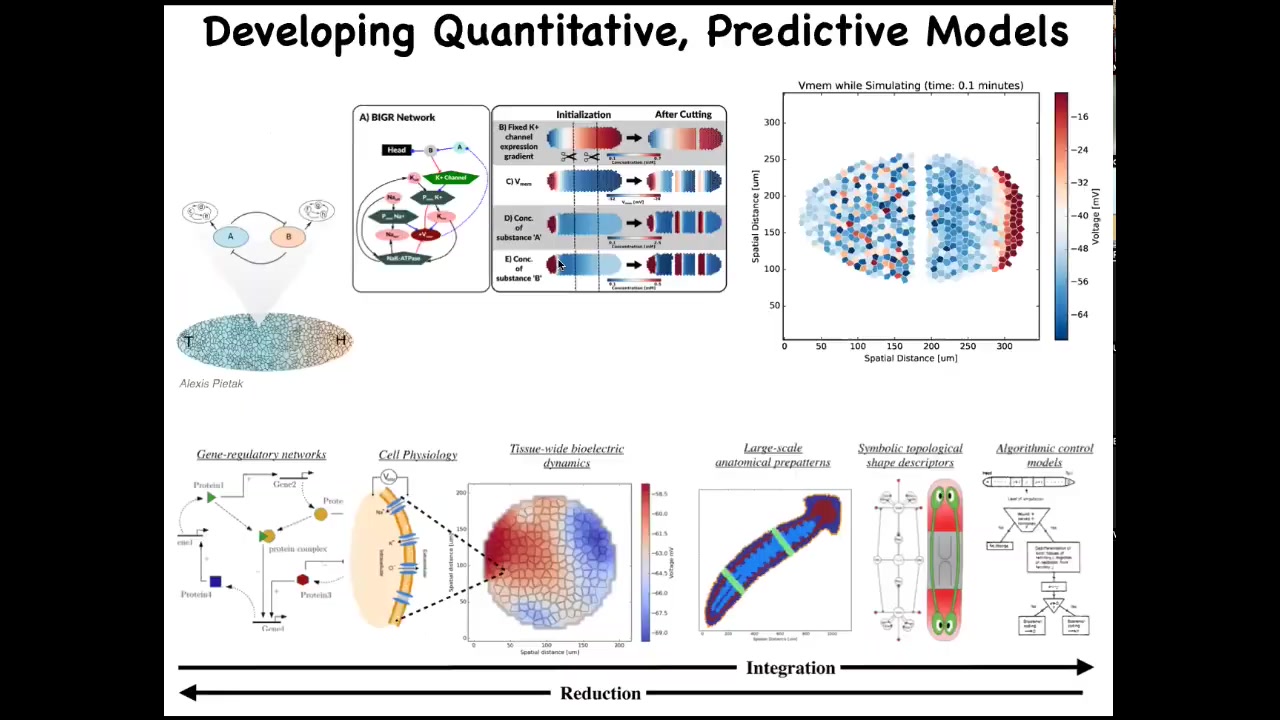

The goal here is to develop a computational pipeline that goes all the way from the beginning of understanding which channels are even expressed in my cells down to understanding the bioelectrical tissue dynamics, large-scale kinds of anatomical decision-making, and eventually a computational and algorithmic description of how different regions decide their shape and size, which makes it much easier to then make changes. We want a full-stack simulator where we can understand this.

Slide 32/52 · 38m:26s

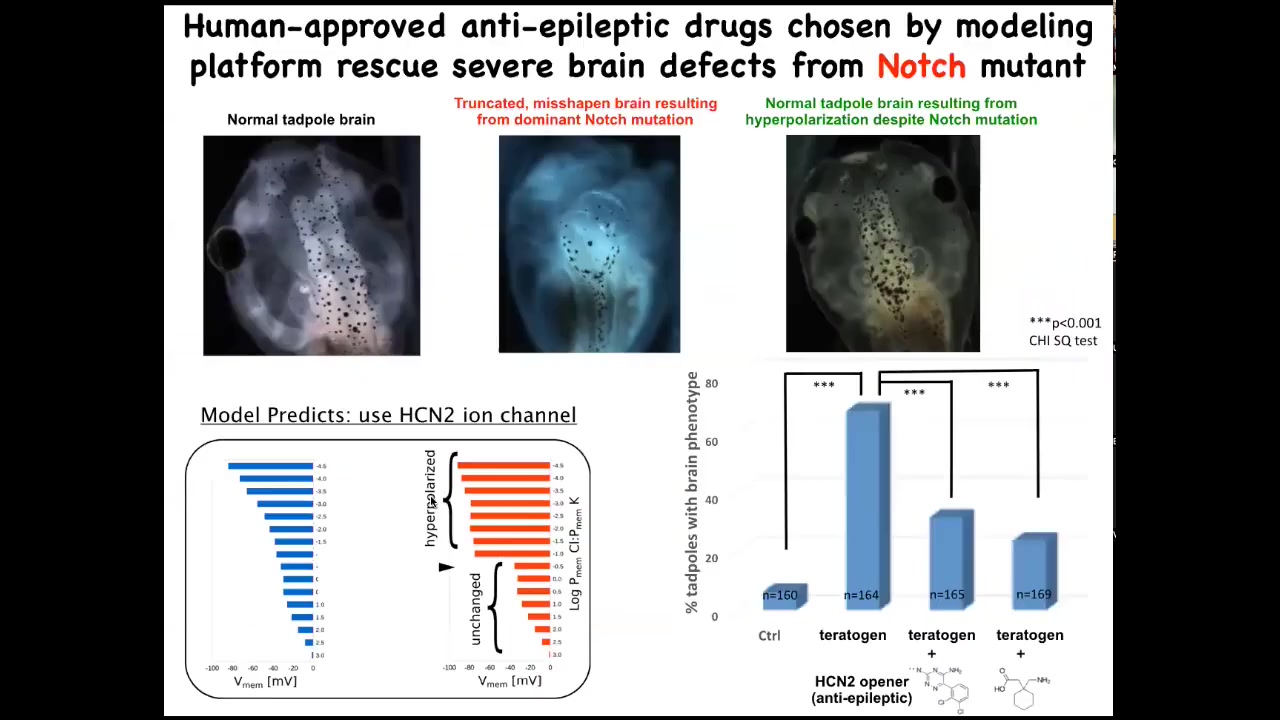

We're only at the very early stages of this, but one thing that we can already do is make repairs in quite complex organs. This is a normal tadpole brain. Here's a completely disorganized brain induced by a dominant Notch mutation. You can see the forebrain is basically gone, the midbrain and the hindbrain are a bubble. They have no behavior. They're just very drastic defects.

We had a computational model that told us we could open certain channels to reinforce the endogenous bioelectrical pattern that tells cells how to make a normal brain. If you do this, despite the Notch mutation being there — Notch is a very important neurogenesis gene — and it happens to be this HCN2 ion channel, if you activate or mis-express some of these channels, you get back a normal brain. Not only normal structurally and molecularly, but their behavior is normal, their IQ comes back to normal, indistinguishable from controls.

In some cases, and I'm not saying this is always going to be the case, you can fix certain hardware defects. This Notch mutant is a hardware defect. You can fix some hardware problems in software if you have the computational platform that can show you how to do that.

Slide 33/52 · 39m:42s

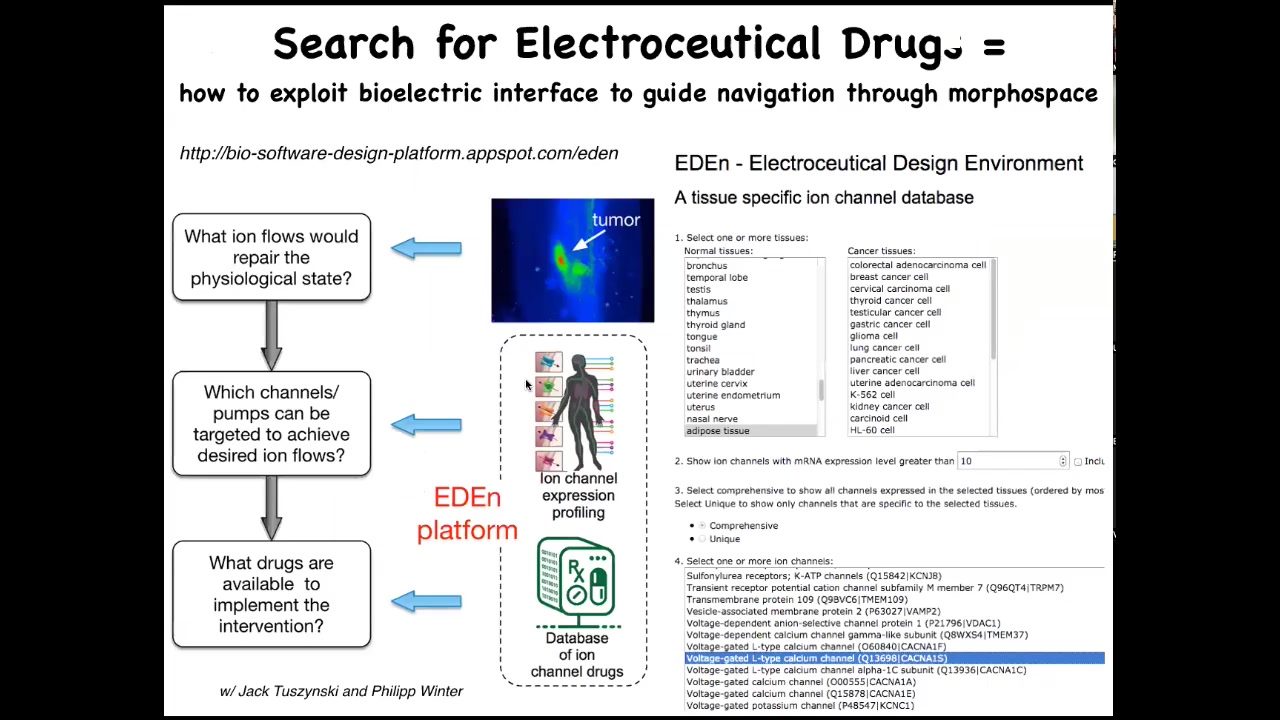

What we are working on is this notion that at some point there's going to be a workflow like this where you start with an incorrect bioelectrical state, say a tumor. You already have a database of physiomic data. That doesn't exist yet. We're working hard to start to generate some of that data that tells you what the correct state is for that tissue or organ.

Then the simulator would be able to say, these are the ion channels you need to open or close to convert the incorrect state to the correct state. Then you go and you look for drugs. Something like 20% of all drugs are ion channel drugs. This is a huge platform of electroceuticals out there that could potentially be repurposed for these kinds of bioelectric interventions if we had a system for choosing them. You can start to play with that there.

All of this so far has been about how to get back to normal. Injury, birth defects, cancer — how do we get back to normal? But as engineers, I want to start thinking beyond that.

Slide 34/52 · 40m:50s

One interesting fact is that development is very deceiving. It's deceiving because it is so reliable, because it works so well most of the time. When you look at an acorn, and you know that all of the time the acorns develop into trees, you get the feeling that what the oak genome has learned to do is to make these things nice, flat, green, same kind of patterns all the time. But it turns out humans are not the only bioengineers.

Slide 35/52 · 41m:18s

And there's this little guy, these wasps that lay embryos, they lay eggs on these leaves. And what they're able to do is to hack the surrounding cells to build something like this: a gall. These galls have this amazing kind of complex structure. There are lots of different kinds of galls. So what you find out is that, first of all, this idea that what the genome only knows how to do is this is wrong. Actually, it knows how to do something very different. Instead of flat green, it makes these round, red, spiky things. That leads us to the realization that were it not for this wasp, we would have no idea what these cells are capable of. Nobody would ever guess that these same cells with that same exact genome—there's no genomic modification here—but it knows how to do this. The ability of that hardware to go there is, we wouldn't know that. And that leads to the question of what else is possible. So if we understood the bio-prompting a little better. What else can we make these cells do? And this idea that evolution uses this kind of hacking universally, it's all over the place. This is not micromanaging the genome. It is, in fact, exploiting the competencies of the material.

Slide 36/52 · 42m:39s

One of the things that the material is quite good at is scaling up its goals. Let's remember that individual cells have little tiny goals. The states that they're working towards are physiological, metabolic, things on the scale of a single cell, both in time and space. What evolution and development allow them to do is to join together large goals in anatomical space.

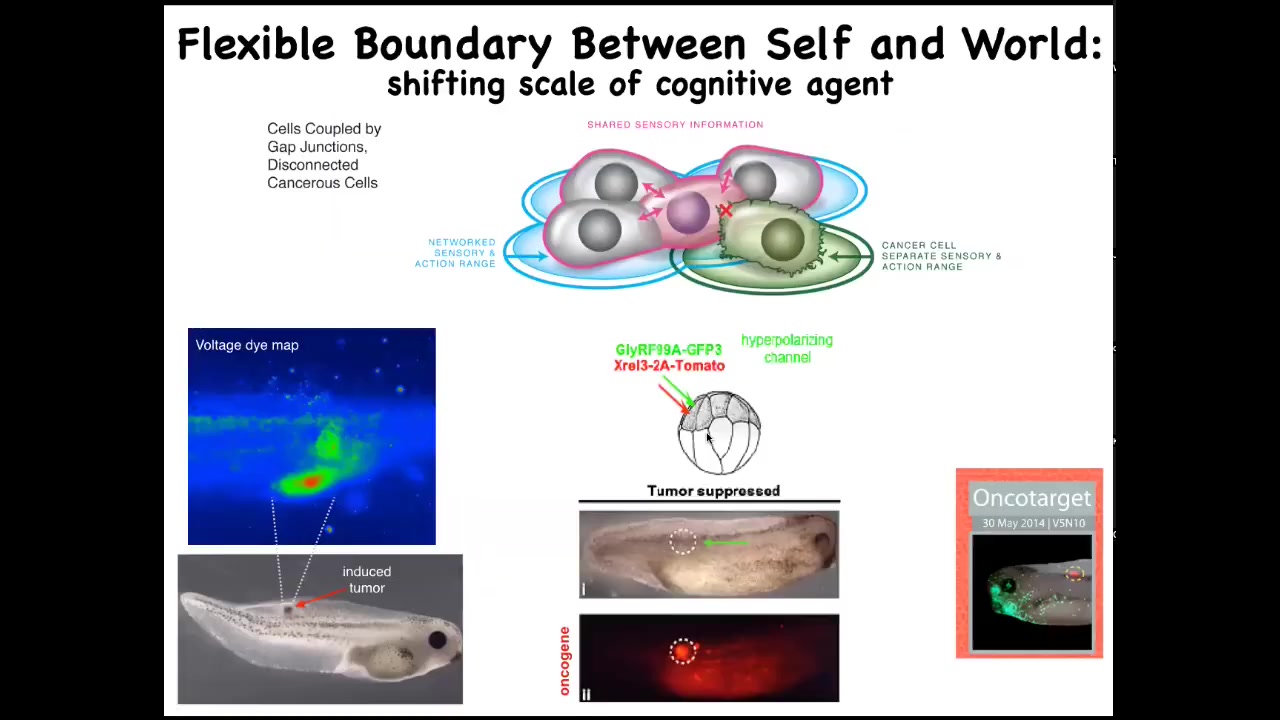

But that process has a failure mode. That failure mode is cancer. You can see here: when individual cells disconnect from this electrical network, they treat the rest of the body as external environment, then they roll back to their ancient unicellular kinds of behaviors. They're not more selfish. Cancer cells are not more selfish than regular cells. Their selves are smaller. You can see this kind of inflation and scaling of the boundary between self and world.

Slide 37/52 · 43m:41s

And so that leads to an interesting strategy that we can use: an anti-cancer approach — could we actually force the reconnection of cells to the rest of the body? Here's this experiment. We induce a nasty human oncogene, KRAS mutation. Typically, they'll make a tumor, and in fact, this is the same animal here. These cells are very strongly expressing the oncogene, but there's no tumor. That's because we also expressed a particular ion channel that forces these cells, despite what the oncogene is trying to tell them, to remain electrically connected to their neighbors and hooked into the pattern memory that we should be building — nice skin, the muscle, kidney and so on, as opposed to going off and being amoebas.

This interplay between the collective goals and the individual goals allows us to start asking questions about how we reset those goals and where they come from in the first place. You might think that where they come from in the first place has to be evolution. Evolution over the eons has set these goals. In the last little bit of the talk, what I want to discuss is some synthetic systems where they're beginning to show us that things are not so simple.

Slide 38/52 · 44m:59s

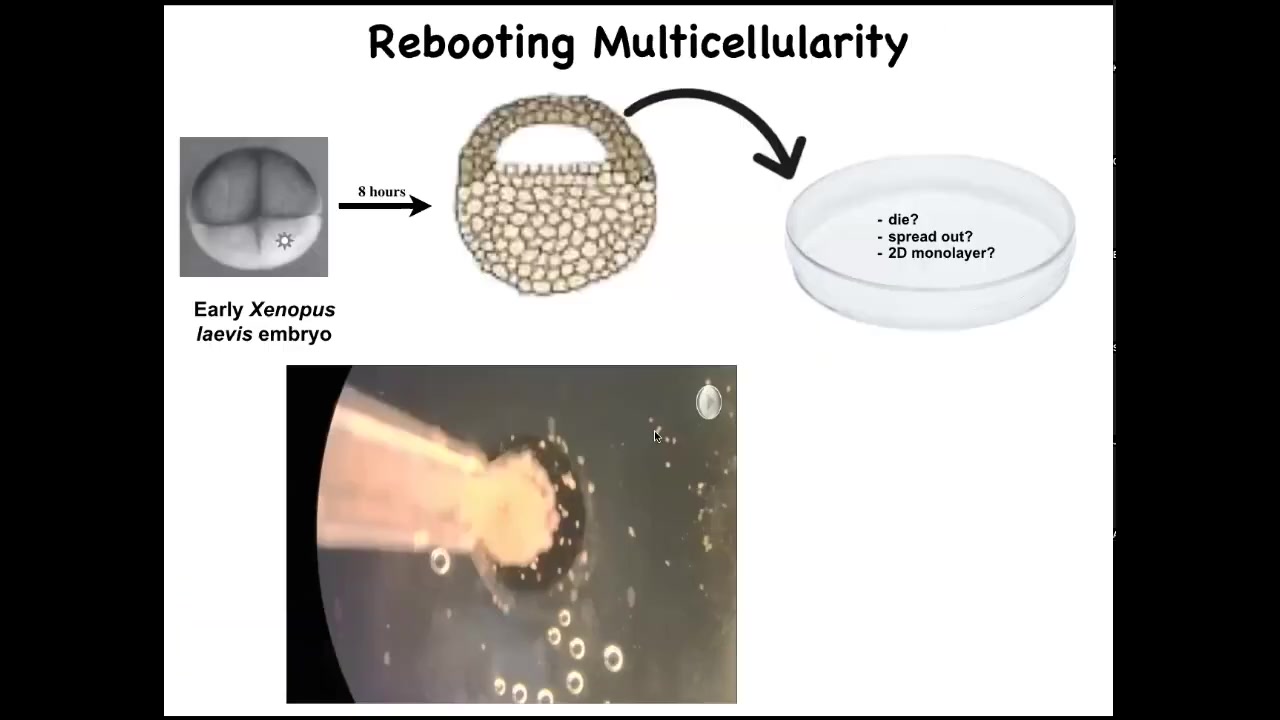

I want to introduce you to these things, which are called Xenobots. And what we started doing was to take some early ectodermal cells off of a frog embryo, liberate them and put them in a petri dish. They could do a number of things. They could die. They could spread out and walk away from each other. They could form a two-dimensional monolayer. What they do instead is they coalesce together into this little organoid-looking thing. And then they start to move.

Slide 39/52 · 45m:30s

They start to swim around because they have little cilia. They have little hairs on their surface that are normally used by frogs and tadpoles to move mucus down their bodies. But in this configuration, they can use it to swim. They row against the water and they swim. They can go in circles and patrol back and forth like this, and they can have collective behaviors. We call them Xenobots because Xenopus laevis is the name of the frog, and we think they're a bio-robotics platform. So Xenobots.

Slide 40/52 · 46m:01s

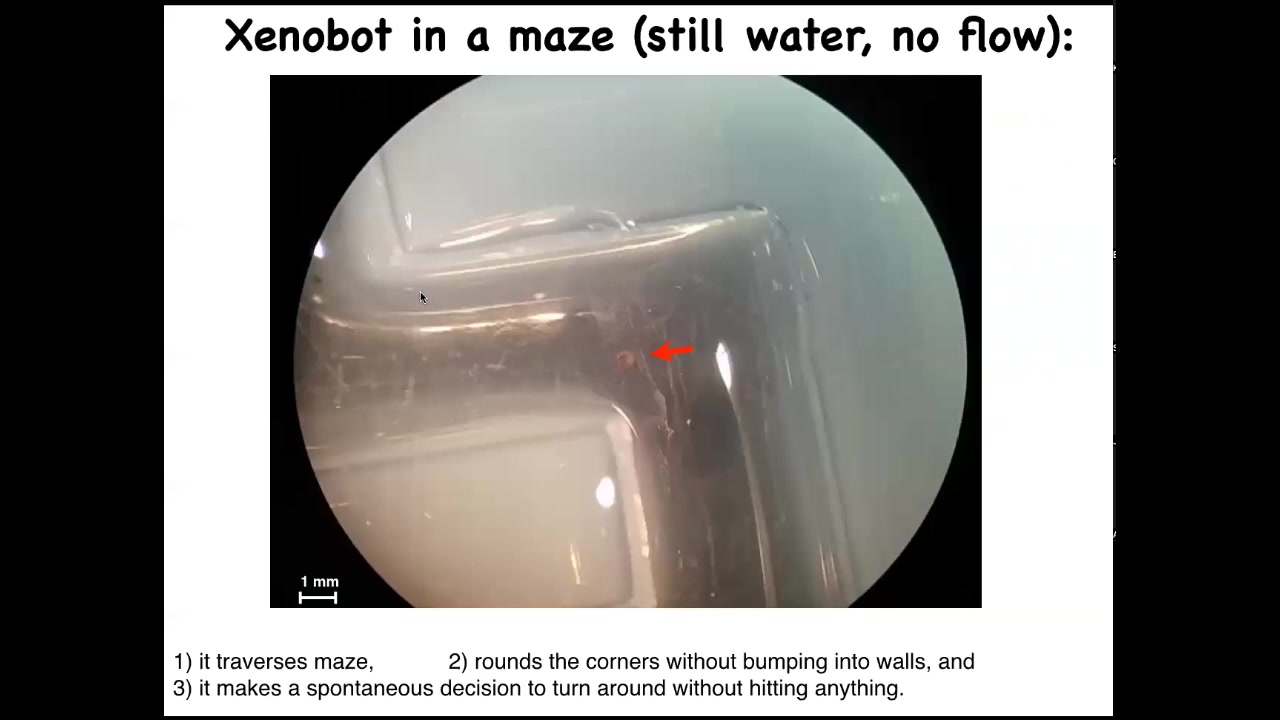

Here's a Xenobot doing a maze. Watch what happens. It swims down here. At this point, it takes the corner without having to bump into the opposite wall. Then, due to some internal dynamics we don't understand, it decides to turn around and go back where it came from. They have autonomous behavior — we're not pacing it, we're not controlling it. It has autonomous swimming behavior. Lots of interesting behaviors.

Slide 41/52 · 46m:25s

We're visualizing calcium signaling. We can use all the tools that people use to analyze electrical activity in brains, information theory, and so on. But there are no neurons here. These are epithelial cells. They have lots of interesting computations going on that can be read out through this calcium.

Slide 42/52 · 46m:46s

They self-repair. If you cut them in half, look at all the force that it had to generate through that hinge to fold this thing up. They go back to their Zenabot form.

Slide 43/52 · 47m:01s

If you give them a bunch of loose skin cells here, what they will do is they will, both independently and in groups, they will work together to collapse them into these little piles, and they polish the little piles.

And because they're working with an agential material too, just like we were when we made the Zenobots, these little piles become the next generation of bots. They mature and they go on and they do exactly the same thing. And so you have a kinematic replication. They're making copies of themselves from stuff they find in the environment. This is von Neumann's dream, a robot that finds materials and makes copies of itself. So that leads to an interesting engineering question, which is, what did the hardware learn during evolution?

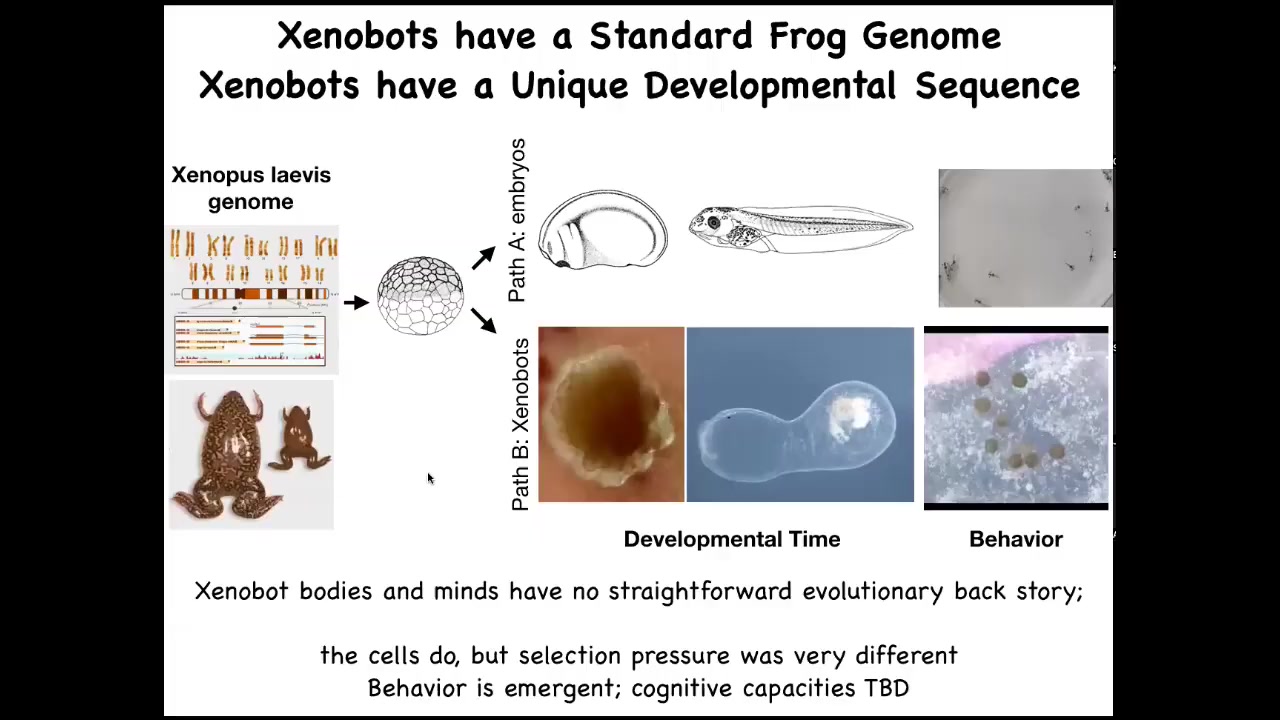

Slide 44/52 · 47m:41s

Here's the Xenopus genome. Typically, it goes through a very stereotypical set of steps. Here's embryogenesis, and then eventually you get tadpoles with this behavior.

But these cells can also make xenobots with their own weird developmental progression. They have different behaviors. This is really important. If there's never been any xenobots, there's never been any selection to be a good xenobot; where does this come from? Where do these behaviors and capabilities come from? We once again remember that it is not just about selection; it is about the fact that evolution makes some very reprogrammable, very competent problem-solving hardware that in novel configurations can do different things.

We didn't give these cells any new genes, no weird nanomaterials. All we did was liberate them from the rest of the body. What you see is that their normal behavior is the result of them being hacked by these other cells to serve a certain purpose and have a boring two-dimensional life on the outside of the animal, being a barrier to pathogens. But liberated from all that, they have a completely different type of existence. Being able to look at your material through its point of view and ask who's hacking whom with what and how much is a really critical part of your toolkit going forward, I think.

Slide 45/52 · 49m:12s

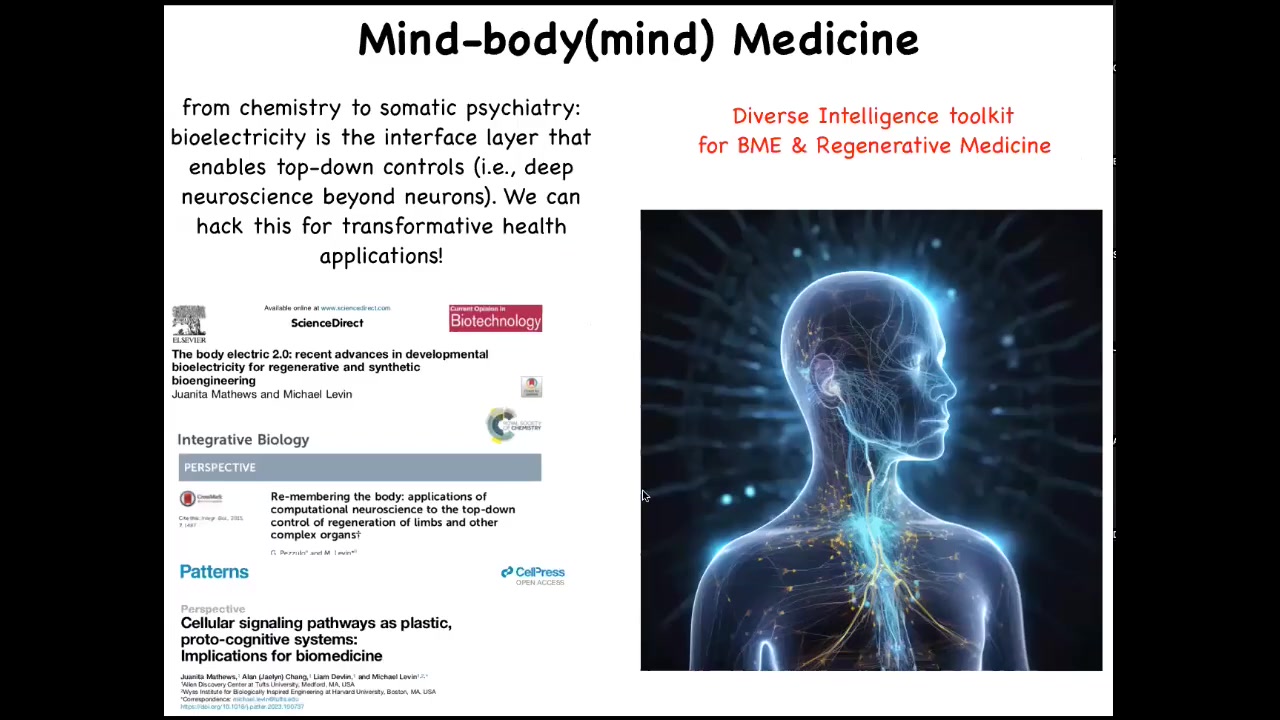

And so next generation bioengineering and biomedicine is going to be using tools of AI and tools from other disciplines, neuroscience beyond neurons, to play along this whole axis of complexity and cognition all the way up from cognitive things and conscious ones, for example in Benedetti's study where people are told they're given a particular neuroactive compound and then their brain chemistry actually shows the effects of that compound, even though all they got was placebo.

So this idea that what we're going to be doing is taking advantage of the information processing, the memories, the competencies of the different levels of the medium.

And one idea that is relevant here is the notion of having an impedance match between the technique that you're using, the intervention, and the target that you're reprogramming. So up till now, we mostly use drugs, we use various materials, and those are pretty low agency interventions. But could we design higher agency interventions to really match the agency of the material that we're trying to deal with? But I want to show you what I think of as a promising platform in the future.

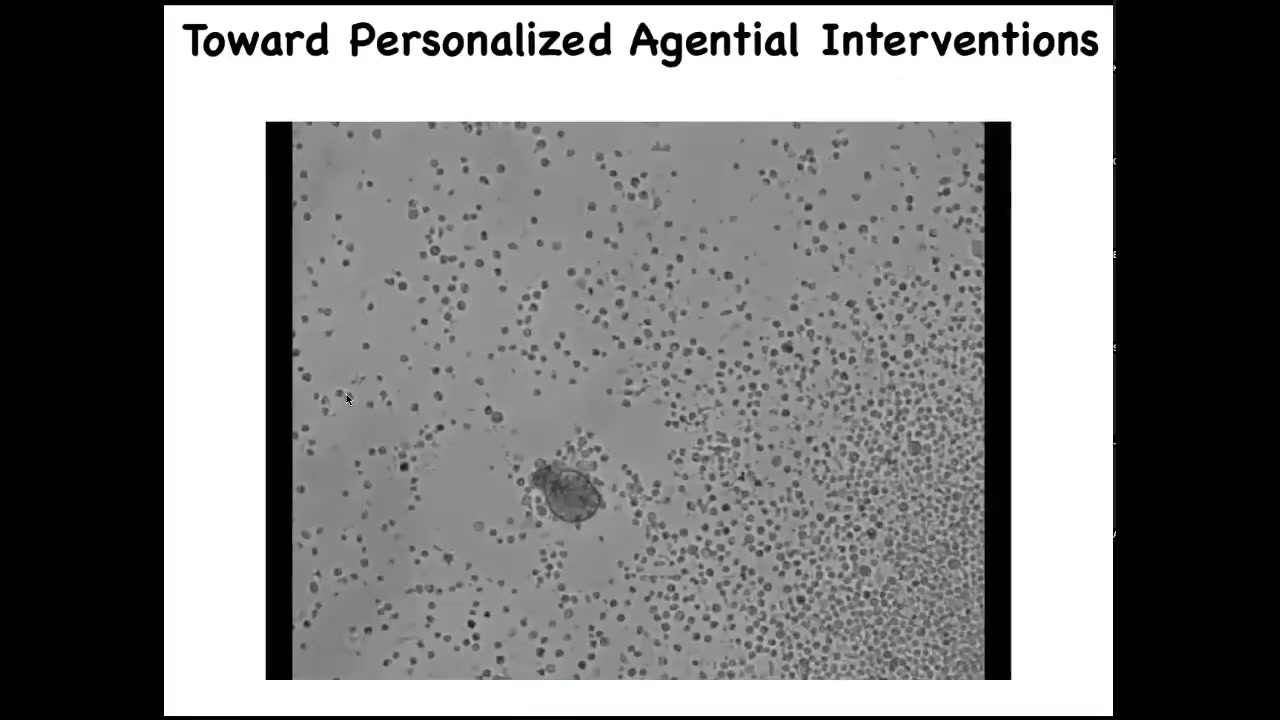

Slide 46/52 · 50m:38s

This is towards personalized, agential interventions. Here it is, this little thing is swimming around. If I were to show this to you and ask you what this is, you might think that this is some primitive animal we got from the bottom of a pond somewhere. But if you sequence the genome, you find something interesting: 100% Homo sapiens. These are human cells, and this is an anthrobot. The way it's the Xenobot, but it comes from human patients. This is what it looks like.

Slide 47/52 · 51m:09s

They come from human tracheal epithelium donated by adult patients during biopsies. We have a particular path for them, a protocol in which they also become ciliated on the outside, just like our xenobots. They then undergo all kinds of interesting behaviors. Here's one.

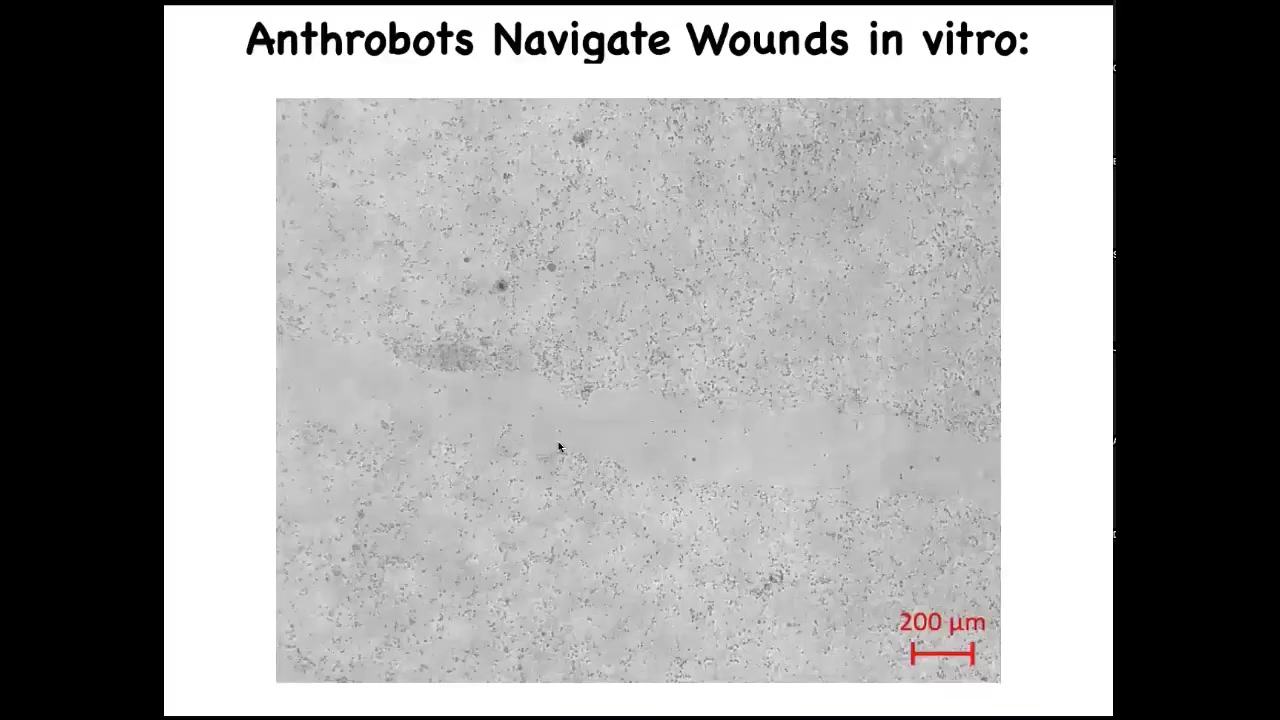

Slide 48/52 · 51m:28s

What it's doing is traversing this scratch that we made. This stuff out here is iPS-derived human neural cells. This lawn of neurons—we put a scratch through it. This is a wound assay where you ask what happens if you damage a bunch of these nerves. You saw that the Anthrobot navigates.

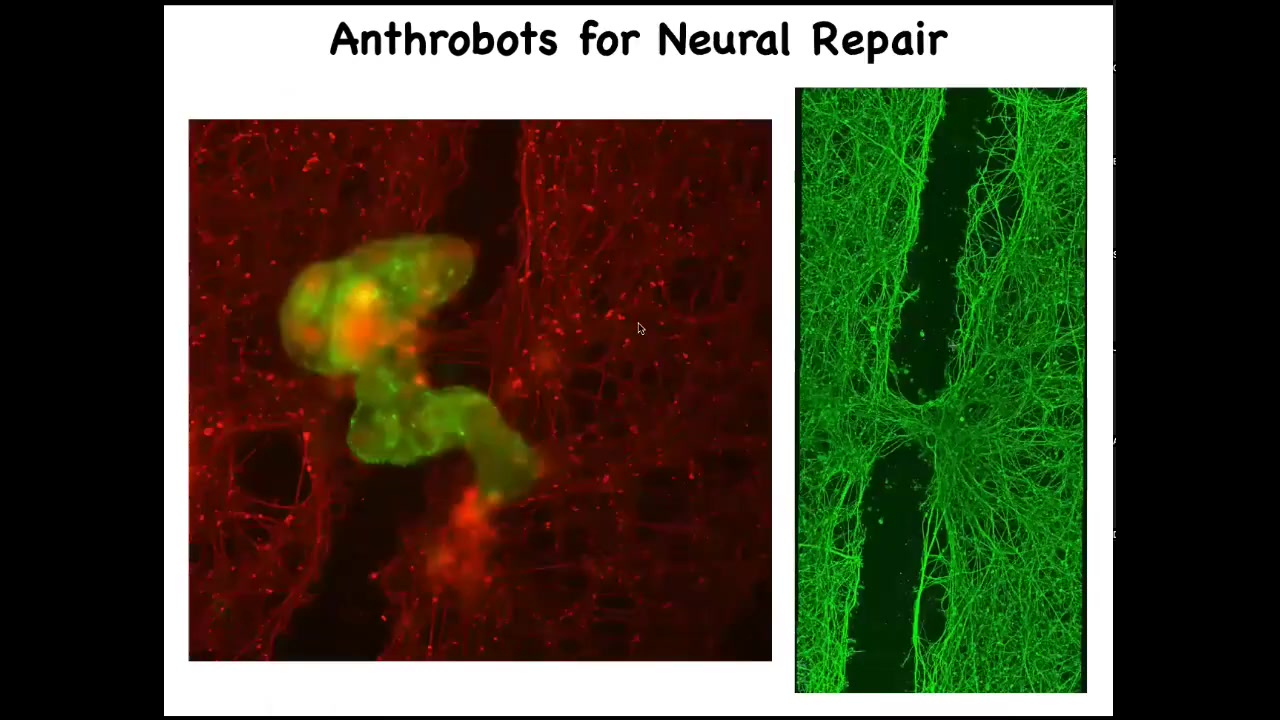

Slide 49/52 · 51m:52s

If a bunch of them settle into this gap, here we call this a super bot or a bridge bot. This is something that we recently found: if you leave them there for about four days, they actually start to knit together the sides of the gap. Here's what it looks like once you've lifted up the bot.

This is a PhD student in my group, Gizem Komushkaya, who did all this anthrobot work. Imagine, in the future, your own body cells, no transgenes, no gene therapy, can be deployed to help repairs. Who would have known that your tracheal cells that sit there quietly for decades are able to form a little biobot that moves around on its own and heals neural wounds? What other kinds of capabilities do they have? We don't know. This is the first thing we try. They probably have all kinds of other competencies. They don't require any immune suppression because they're made of your own cells.

Slide 50/52 · 53m:05s

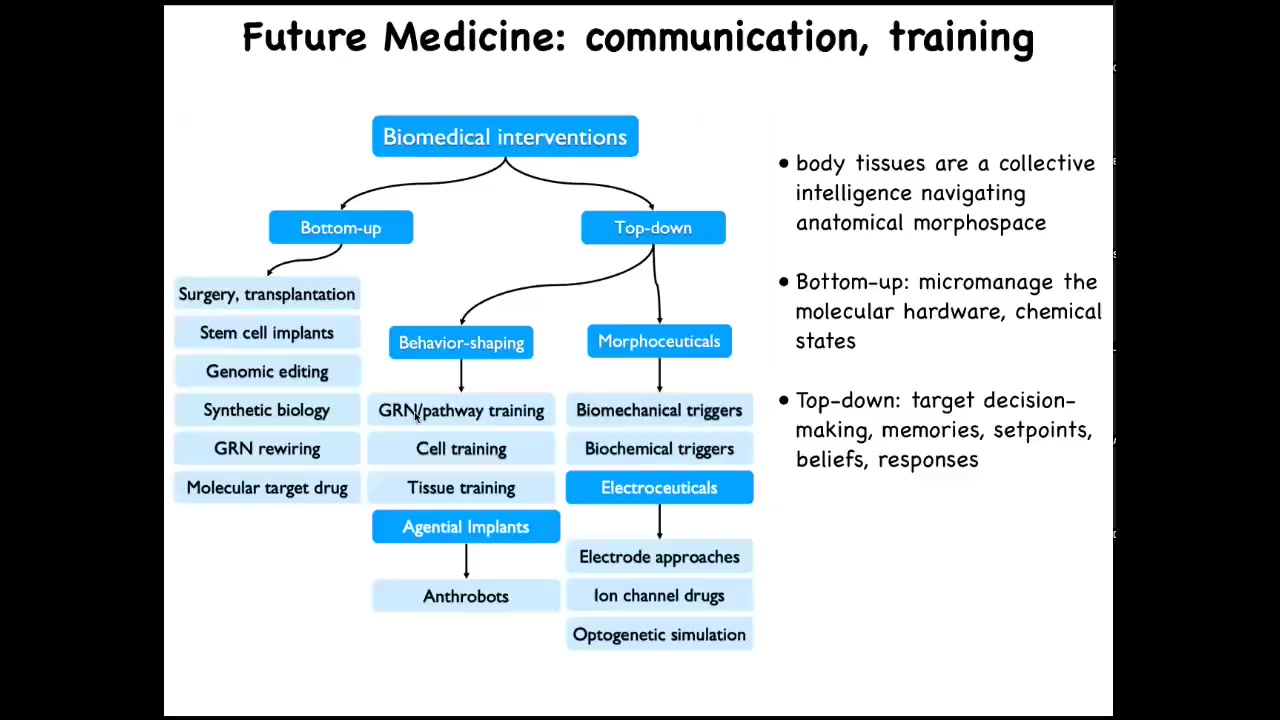

They share with you the priors about what health and disease is, which low agency interventions like drugs and implants are not going to have. So this is what I think of as the landscape for biomedicine going forward. This is all the familiar bottom-up tools that we have today. But complementing them is this whole developing area of top-down interventions, including behavior shaping, which we didn't even talk about as far as training cells and tissues, and then using agential implants and things like that. The various morphoceuticals, including electroceuticals, are being used to rewire not the hardware, but actually to change their behavioral landscape. So the idea is that you're not micromanaging their molecular state. What you're doing is targeting their decision-making, their memories, their set points, their beliefs, literally the models they make of their micro-environment based on past experience — are they going to fight you on the things that you want them to do.

Slide 51/52 · 54m:12s

The diverse intelligence community, who work on understanding problem solving and intelligence in unconventional substrates, have a lot to say to biomedical engineers and regenerative medicine workers. These two fields need to come together in an important way. The medicine of the future is going to be much more like somatic psychiatry, less like chemistry. Bioelectricity is at least one. There may be others, but it's at least one interface that enables us to exploit the mind of the body. If you want to go deeper, a lot of the more general, more philosophical stuff is in these papers.

I want to thank all the people who did the work.

Slide 52/52 · 55m:00s

The grad students and the postdocs who did all the things I showed you today. Lots of collaborators, our funders, and, of course, three disclosures. Here are three companies that have supported some of the work that I've shown you today. Jeremy Gay is the amazing graphic artist who makes all our illustrations and, most of all, the model systems, because they have the hardest job of all and teach us about all these amazing things. Thank you so much and I will take questions.