Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

This is a 1 hour talk on bioelectricity with a special slant toward microbiology/immunology/parasitology. More information is at

https://thoughtforms.life/?p=1722

including some audio of Q&A afterward.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) From cells to minds

(06:24) Anatomical goals and morphospace

(16:21) Bioelectric pattern control

(29:05) Regeneration and anatomical memory

(38:23) Bioelectric medicine and hacking

(50:00) Self, cancer, and bioelectricity

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/51 · 00m:00s

Thank you for that introduction, and thank you for the opportunity to share some thoughts with you. Today, I will give a talk on bioelectricity with a specific focus, although we don't generally focus on microbiology or immunology in our group. We've done work in those areas, and I think this may be of special interest to this audience.

Slide 2/51 · 00m:22s

Here are the main points that I'm going to transmit today. I'm going to talk about the fact that numerous issues in biomedicine depend on two critical things. One is the ability to communicate anatomical and physiological target states, AKA goals, to cellular collectives, to groups of cells. The correct setting of the boundary between self and world is the other. This is very important, and I'll show you what I mean by this.

I'm going to tell you that biology uses natural bioelectrical networks to establish emergent agents that have pattern memories, problem-solving competencies, and maintain a border between themselves and the outside environment. I'm going to argue that cell groups are literally a collective intelligence that navigates some very interesting spaces, including the space of gene expression, the space of physiological states, and, of course, the space of anatomical structures. Failure modes of that process result in things like birth defects. They limit regeneration after injury. They result in cancer, possibly immune disorders, possibly aging.

This is cutting-edge work. We don't really know that yet. But we're going to be able to find out soon because tools are now available to read and write the content of the proto-cognitive medium of which we are all made: these bioelectrical networks among cells. That offers a roadmap for a new kind of regenerative medicine approach that targets the software of life and complements all of the work in today's molecular medicine on the hardware of cells.

So the talk is going to come in three parts. An introduction where I set up some of the unusual perspectives that we use on all of this. Then we'll talk about bioelectricity as a kind of cognitive glue that keeps all of these cells working together. At the end, we will talk about this notion of hacking as a fundamental concept in biology.

So let's start with the simple observation that all of us were a single cell once. Each of us made this amazing journey from something that people call just chemistry and physics. I really don't like that term at all. When you look at a single unfertilized oocyte, what you see is a little chemical system and you say, okay, that's generally well described by chemistry and physics. And then eventually we become something like this, which is a system that has its own inner perspective. It has all kinds of intelligence, intelligent competencies. It has amenability to techniques of behavioral science and maybe psychoanalysis and things like that. This remarkable process of embryonic development takes us from physics and chemistry into the science of the mind. We all made that journey slowly, step by step. There is no magical lightning flash at some point within that process that converts a purely physical system into a truly cognitive system. There's no special point at which that happens. This is a slow and gradual journey.

Slide 3/51 · 03m:12s

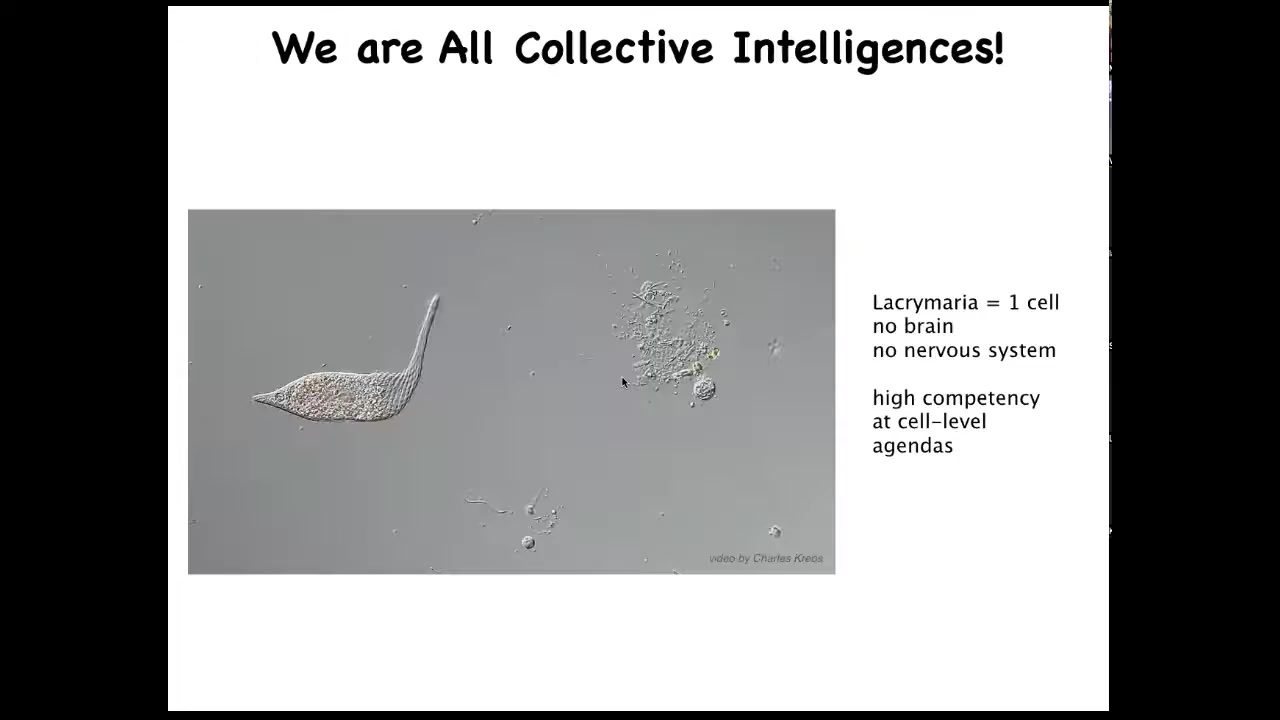

All of us are collective intelligence because we're all made of things like this. This is a single cell. This happens to be a free-living organism. This is called Lacrimaria. It has no brain. It has no nervous system. But you can see that it's quite competent in all kinds of cell-level agendas. It maintains its metabolic goals, its physiological goals, its anatomical goals. It's quite good at it.

Slide 4/51 · 03m:37s

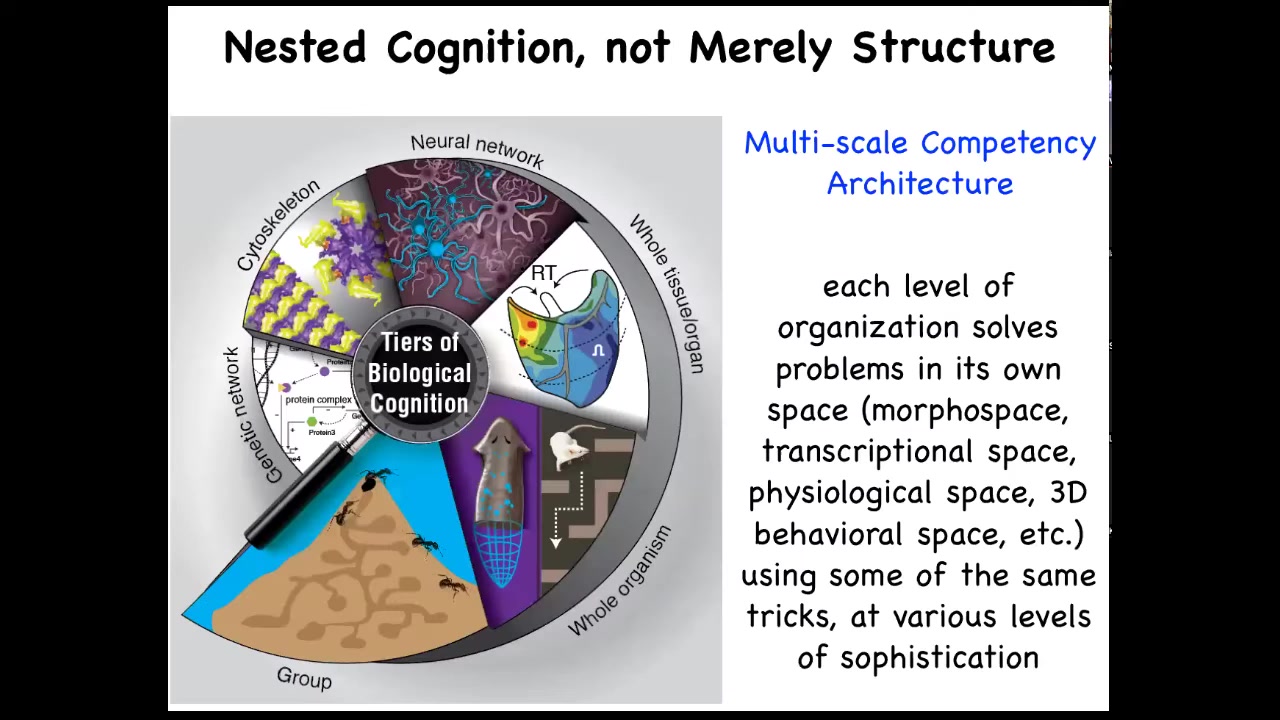

The interesting thing about biology is that each of us is made of this multi-scale competency architecture that is not just structural; we're nested dolls, groups of us are made of organisms, which are made of organs and tissues and cells and subcellular components, but each of these layers is actually solving problems in its own space. These are not merely passive sub-components. They are all competent in solving various kinds of problems.

Slide 5/51 · 04m:06s

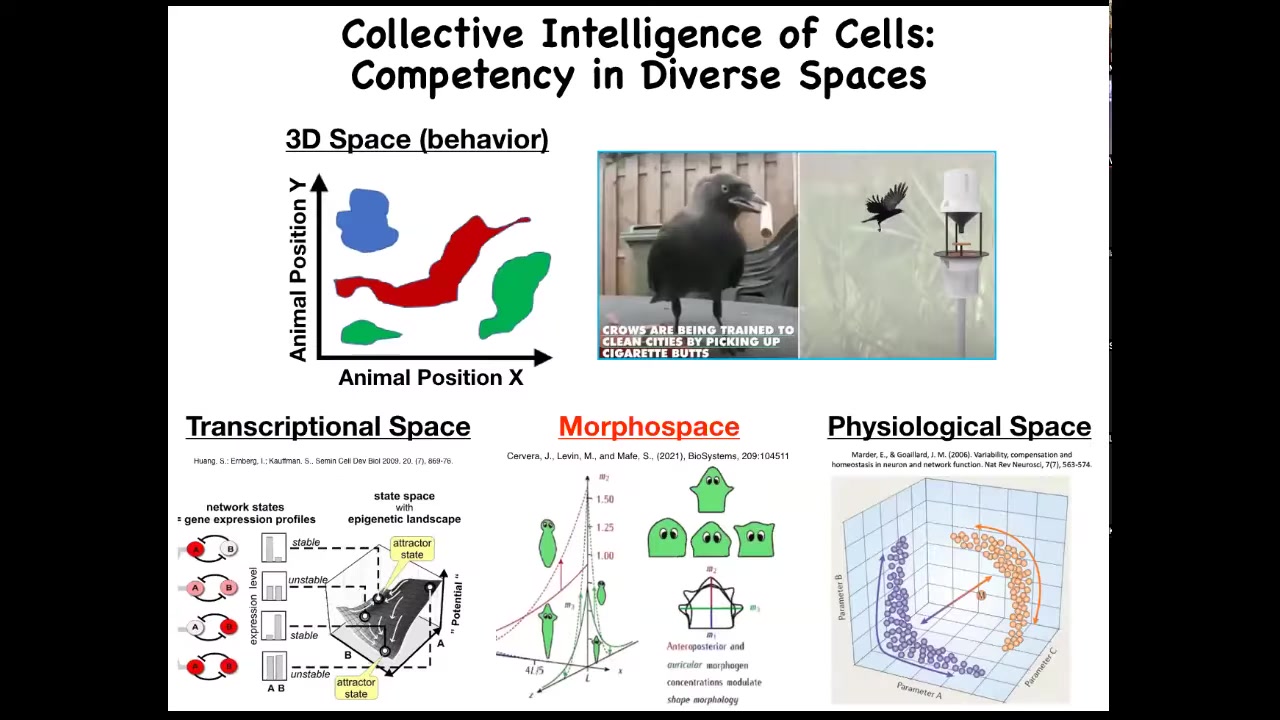

Now, as humans, we're reasonably good, not great, but reasonably good at recognizing intelligent behavior of medium-sized objects moving at medium speeds in three-dimensional space. So primates, maybe birds, maybe an octopus, maybe a whale, we have some ability to understand and detect intelligence when we see it.

But there are all these other problem spaces in which various agents live and navigate. There's the space of possible gene expressions, very high dimensional space. There's the space of anatomical configurations of the body, and then, of course, physiological space. We're going to spend most of our time talking about anatomical amorphous space.

But just imagine if we had evolved with a built-in sense of our own blood chemistry. If you had a sensor, a tongue that reported 20 different metrics you could take of your blood chemistry at any given time, and you could feel you had a sense organ that could report that. I think we would have no trouble perceiving that we live in a 23-dimensional space and that our liver and our kidneys and our various organs are intelligent agents navigating that space to solve all sorts of stressors and problems that come at us every day.

And so this idea that we have to get better at navigating these different spaces and understanding how other systems navigate these spaces and recognizing what competencies they have to make decisions to move through these other spaces is going to be a critical part of the medicine to come.

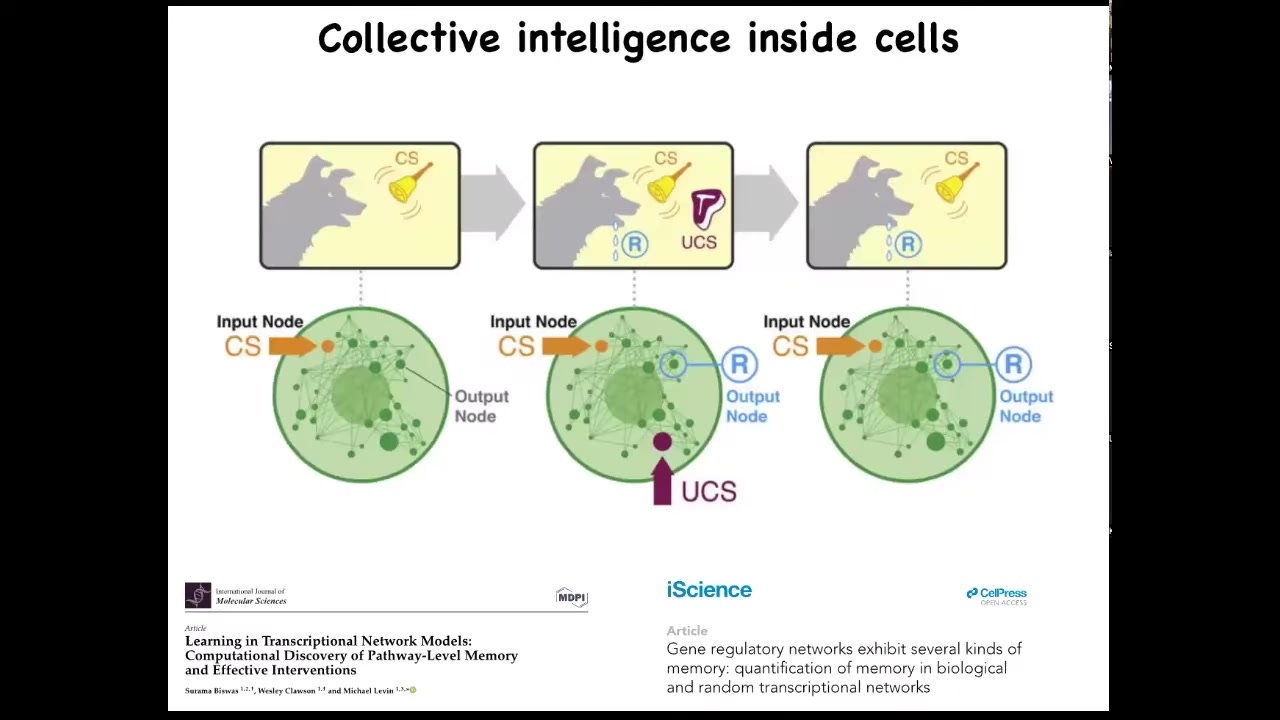

Slide 6/51 · 05m:46s

And this is long before you get to brains or anything like that. We find out that even subcellular components, that individual cells are already a collective intelligence themselves because they have molecular pathways and gene regulatory networks. These molecular networks are themselves a kind of learning agent. They have six different kinds of memory that they can muster, including Pavlovian conditioning. And that's before you even get to the level of a single cell. So it's this multi-scale architecture of agents with really interesting properties that we want to take advantage of.

Slide 7/51 · 06m:24s

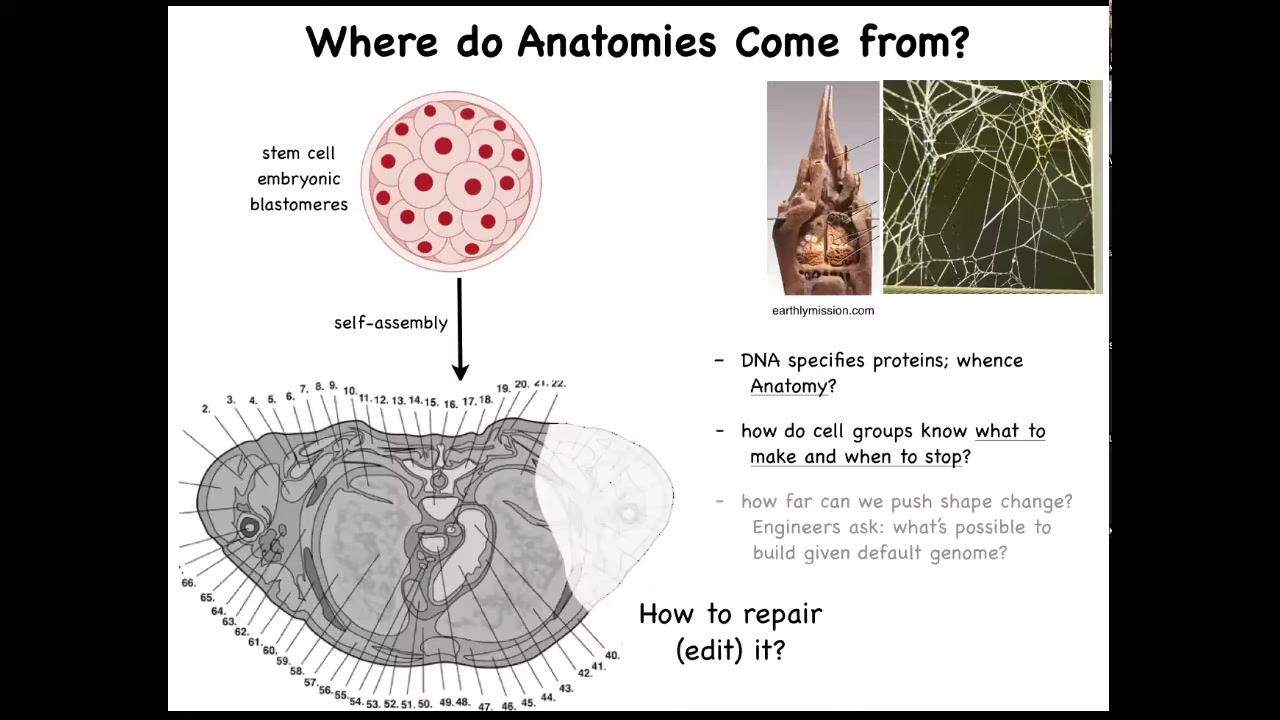

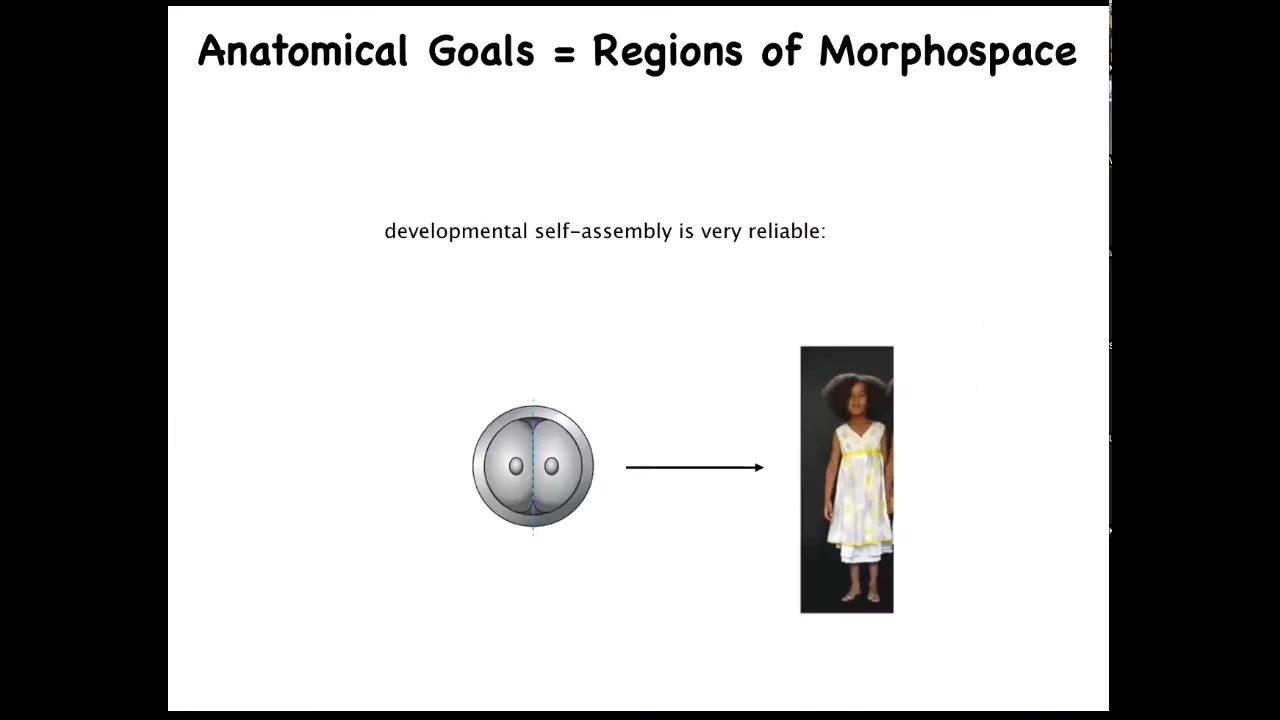

For our focus on navigation of anatomical morphospace, let's ask this question. Here's a cross-section through a normal human body. You can see the amazing complexity and order here. Everything is in the right place, right next to the right thing, the right size, and so on. One might ask the question, where does this pattern come from? In other words, where is it encoded? It's a very specific pattern. It's the same in most individuals. Where is it encoded? We know that we have to get there from this kind of starting position. So we all start as a ball of embryonic blastomeres, and eventually you get something like this. So where is it stored? Initially people will say, well, it's in the DNA.

We can read genomes now, and we know what's in the genome. Nothing like this is directly encoded in the genome. What the genome does specify is protein sequences, which are the tiny hardware that every cell gets to have. Beyond that, there's this process of physiology where, using that hardware, these cells have to know what to build. They have to know when to stop.

As workers in regenerative medicine, if a part of this is missing, we would like to know how to convince the cells to regrow it. Something I won't have time to talk about today, but as engineers, we ask the further question, which is, what else can we get these exact same cells to build? Same DNA, same cells, what else can we make them build other than this? What else are they willing to build?

These are some of the big questions that we're asking. This comes up a lot. The structure of the termite nest and the structure of the spider web are not directly in their genomes either. So all of this is a working out of a kind of physiological process that is running on top of the hardware that's genetically encoded.

Slide 8/51 · 08m:15s

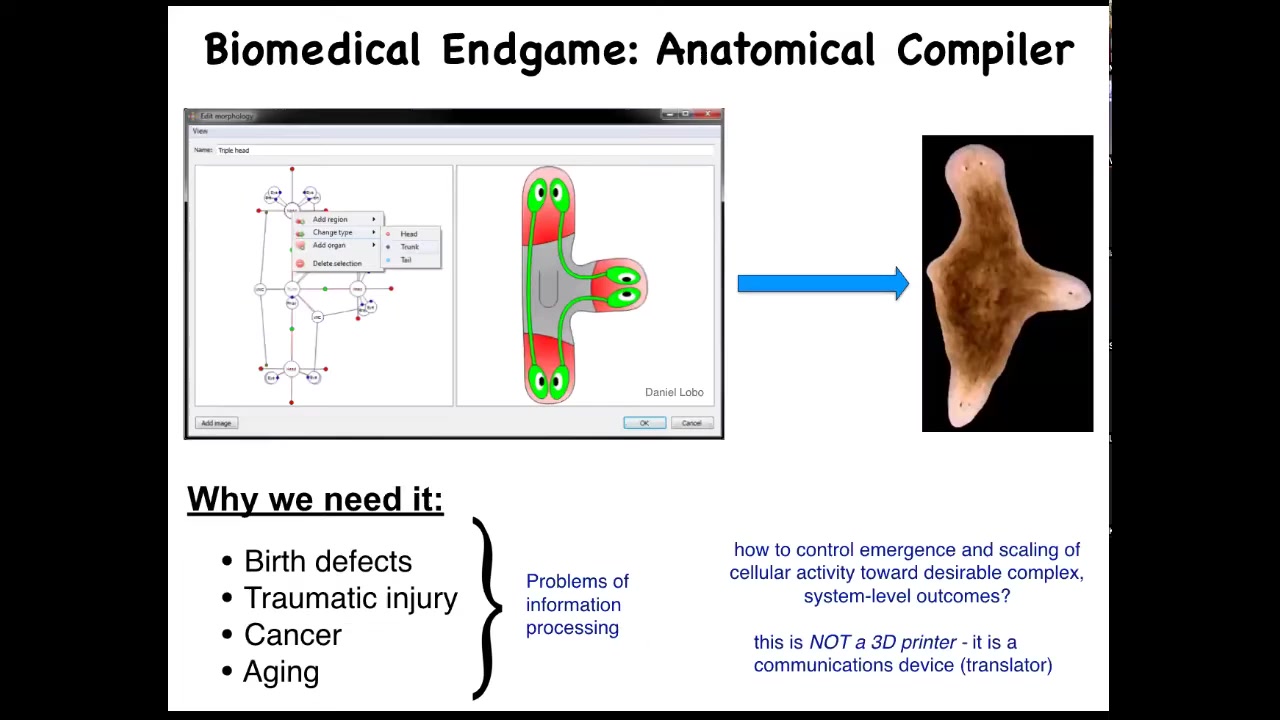

As we think about the future of the field, the endgame, here's how we think about it. Someday, you will be able to sit down in front of a device, a system called an anatomical compiler. The idea is that you will be able to draw any animal, plant, organ, biological robot, anything you like; you'll be able to draw it. If we knew what we were doing, the system would compile down this anatomical goals description into a set of stimuli that would have to be given to cells to build exactly what you want it to build. In this case, this nice three-headed flatworm.

Understand the idea. This is complete control over growth and form. You should be able to say what you want and know what are the signals that you have to give to cells to produce it. This is not only fascinating from the perspective of evolution and cell biology, but it's critically important for biomedicine because if we had something like this, all of these things would go away. Birth defects, traumatic injuries, cancer, aging, maybe degenerative disease, all of this could be handled if we could communicate to a group of cells what it is that they should be building.

The key is that this anatomical compiler is not a 3D printer. It's not about putting cells where you want them and micromanaging their properties. It's really a communications device. It's a translator of your anatomical goals to the set points that the cells are going to try to build. We don't have anything remotely like this. We're very far from this. Genetics and molecular biology and genomics and so on have been operating for decades; why don't we have something like this?

Slide 9/51 · 09m:53s

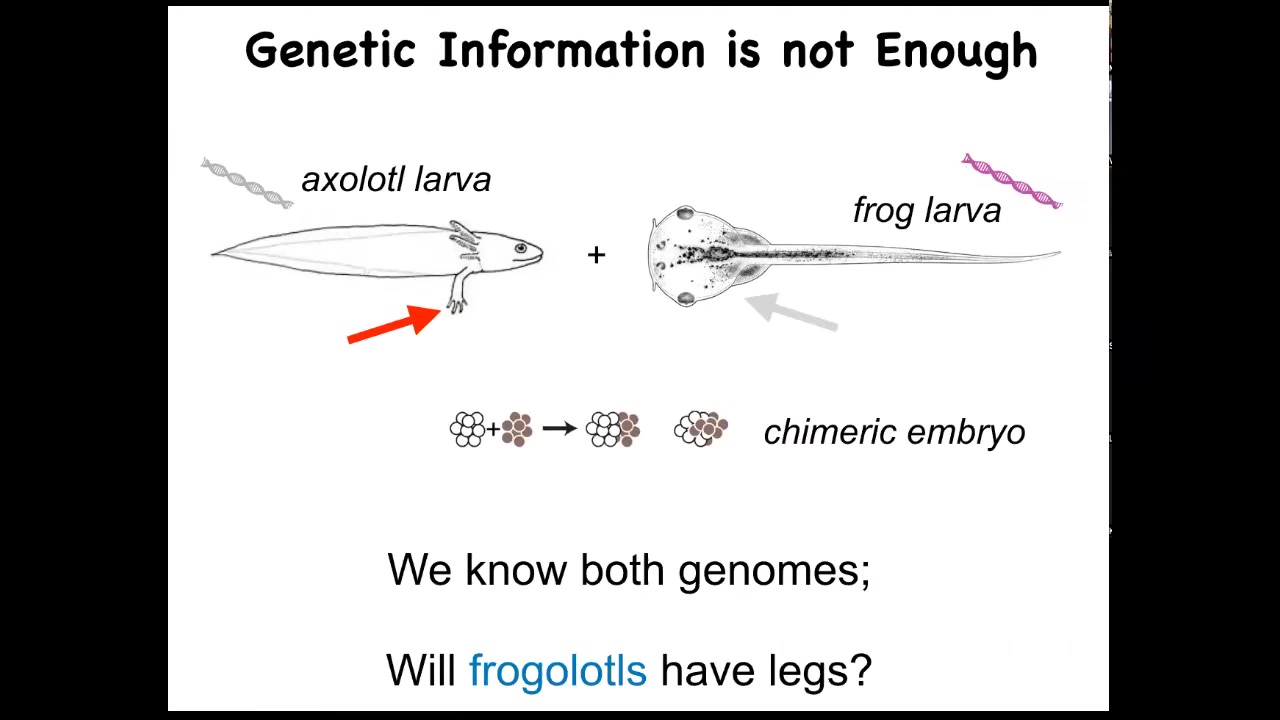

I just want to show you a very simple example of what I think is missing here. So this is the axolotl larva. It's an aquatic amphibian. The baby axolotl has four little legs. This is a tadpole of a frog, Xenopus laevis. They do not have legs at this stage. In my group, we make something known as a frogolotl. A frogolotl is a chimeric embryo. It has some tissues from here and some tissues from there, and they're perfectly viable.

We have the frog genome and the axolotl genome; both have been sequenced. Could you tell me whether frogolotls are going to have legs or not? The answer is no. At this point, we have absolutely no models that will allow us to predict from the genetic data whether this frogolotl is going to have legs or not.

Slide 10/51 · 10m:44s

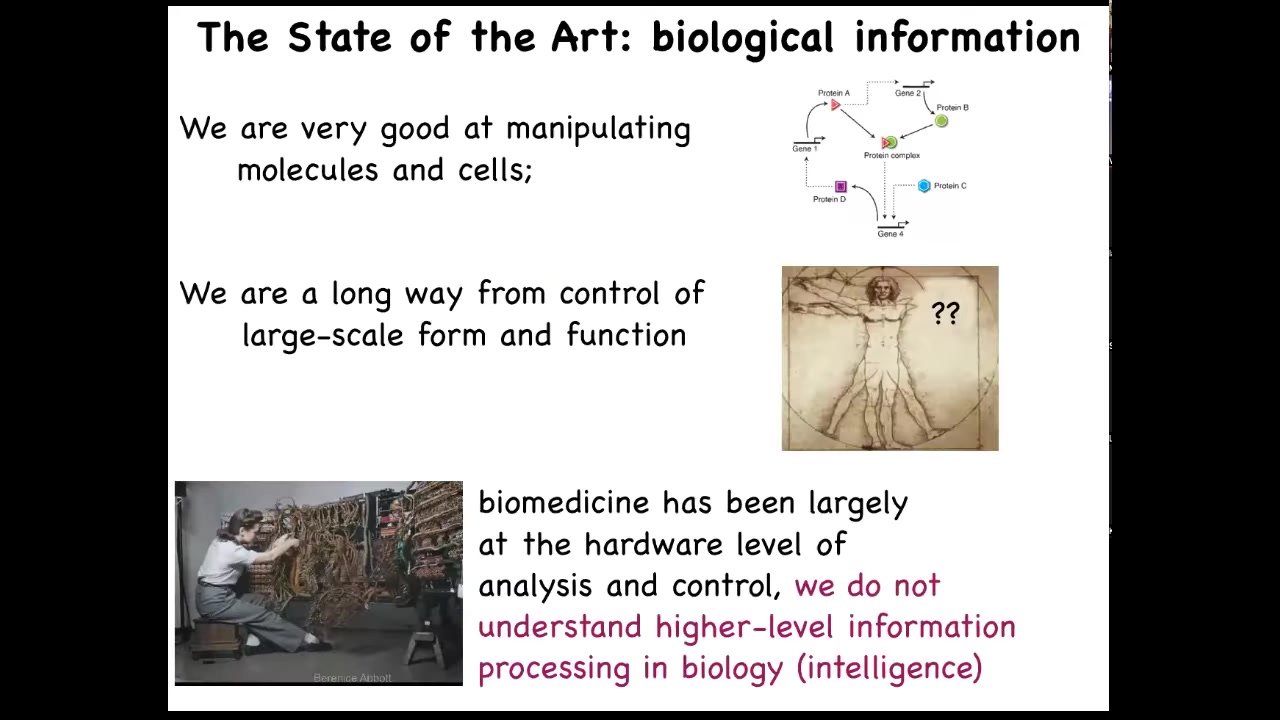

And that's because while we are very good as a community at getting this kind of information, hardware, really nano level hardware information about what genes talk to what other genes, what proteins associate with each other and so on. We're really still quite a long way from having any kind of control over the large scale decision making that cells have in order to reach anatomical set points in that amorphous space. How do individual cells agree on what they're going to build? I think that something that's very instructive is the journey that information technology took. So this is what computer programming looked like in the 40s and 50s. You literally had to interact with the hardware. That was the way you were going to program this machine. But the reason that nowadays, when you want to, on your laptop, switch from Photoshop to PowerPoint, you don't get out your soldering iron and start rewiring, it's because what computer science realizes is the power of a reprogrammable medium. The idea that if your software is good enough, if your hardware is good enough, and I'm going to argue that biological hardware is definitely good enough, then you have access to some really interesting competencies of your machine that don't require you to be doing everything at the hardware level. Modern molecular medicine is focused on this level now. So CRISPR, genomic editing, pathway rewiring, protein engineering, all of these things, all the excitement there is about the hardware. It's all about the molecules. And I think we're leaving on the table something very important, which is the ability of different levels of biology to process information in a way that we can correctly call intelligence.

Slide 11/51 · 12m:25s

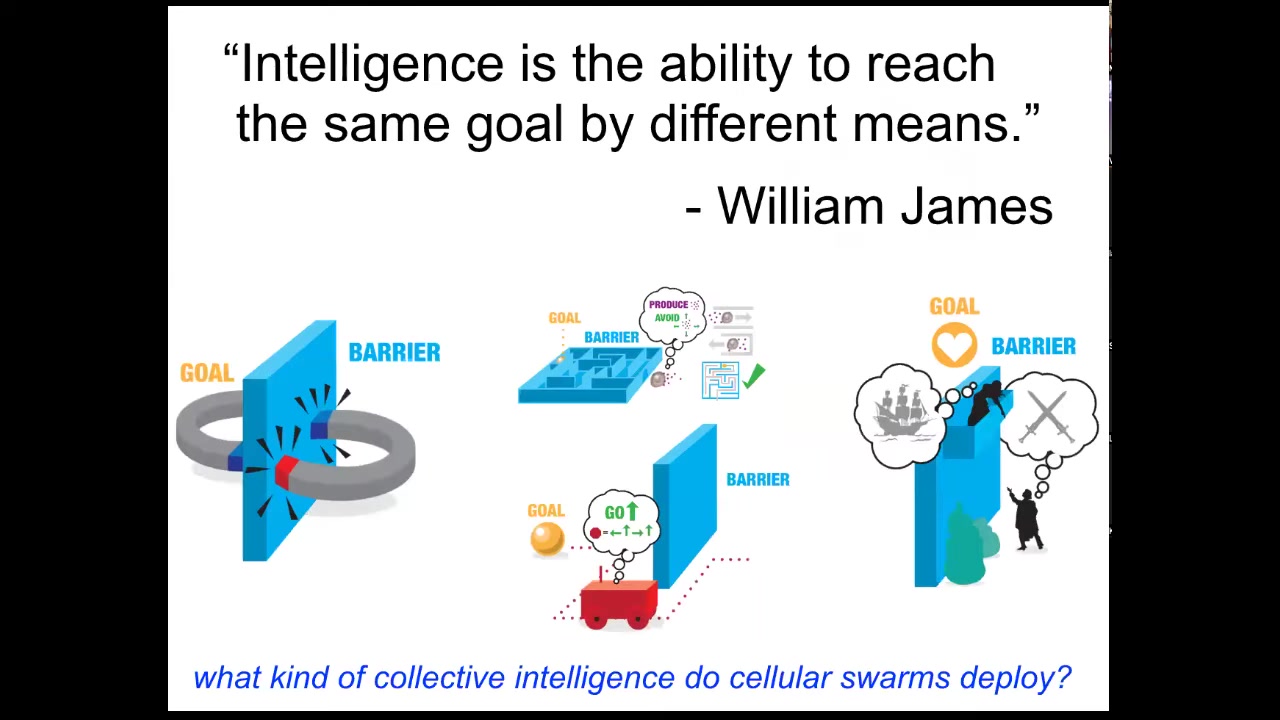

Now, what do I mean by intelligence? I'm using William James's definition. There are many definitions. I like this one. What James said was that intelligence is the ability to reach the same goal by different means. It's a nice cybernetic definition that doesn't talk about having a brain or what scale you are temporally or spatially or what space you're operating in. It's this idea that as an agent, you have goals and you have some degree of competency to get those goals met, despite various things that are going to happen.

He talks about a spectrum of systems from two magnets trying to get together. This is low on that spectrum of competencies, because, for example, if you separate them by a piece of wood, the magnets will never go around and join each other because that would require them to temporarily get further away from their goal, and they simply don't have the capacity for that kind of delayed gratification. Romeo and Juliet, on the other hand, do. They have planning, and they have other things they can bring to bear on their problem.

In between, you have autonomous vehicles, animals, cells, and tissues. This is a spectrum of intelligence and competencies to solve problems in a space. Let's ask, what kind of collective intelligence do cellular swarms deploy? Cells in the body, what can they do?

Slide 12/51 · 13m:49s

The first thing to think about is that development, while it's very reliable, most of the time this egg develops into exactly what it's supposed to be. It actually isn't hardwired because you can cut early embryos into pieces and each half — let's say you divide it in half here — you don't get a half a body, you get two perfectly normal monozygotic twins. You've got this ability to navigate to the right ensemble of states, this target morphology that we call a normal human, within normal human variation. You can navigate there from different starting positions, as a complete embryo, as a half embryo. You can even go around some local minima along the way. That's one example.

Slide 13/51 · 14m:33s

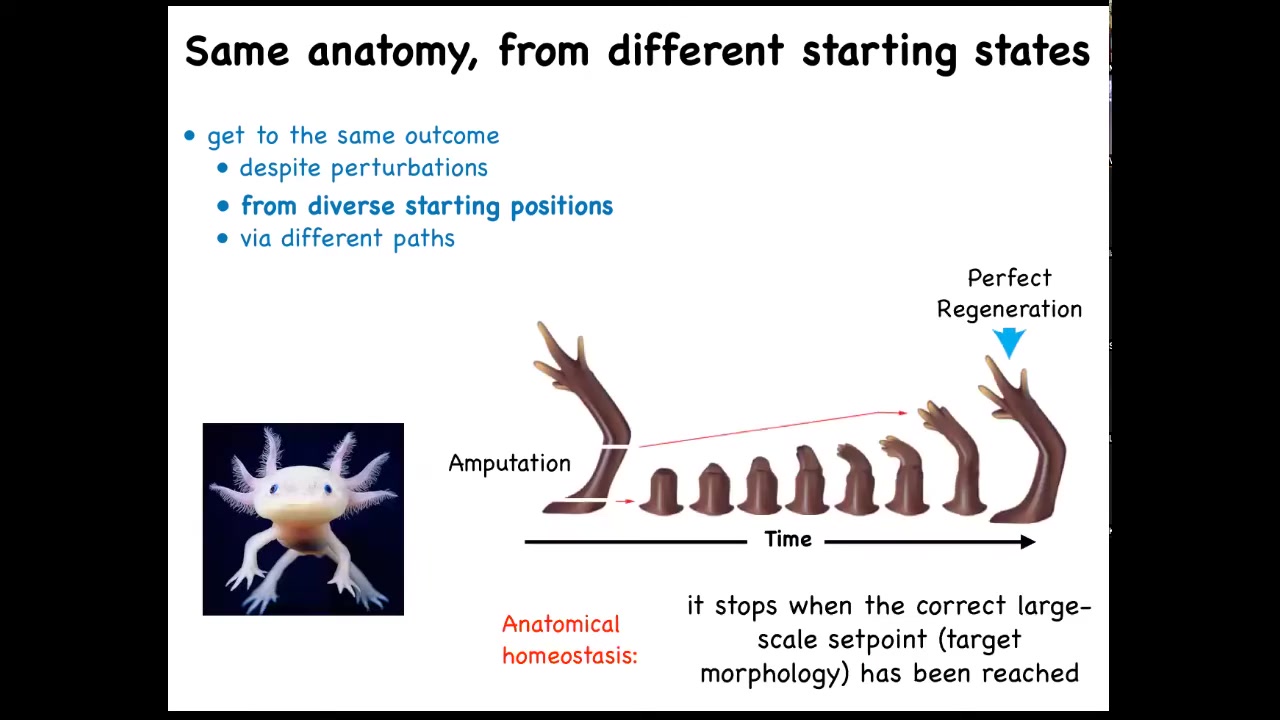

That kind of thing is not just for embryos. Here's that axolotl again. These guys regenerate their limbs, their eyes, their jaws, their tails, including spinal cord, portions of their brain and heart. And what you can see here is that you have this salamander limb. They do this natural experiment where they bite off each other's legs if you house them together. And so no matter where it's been amputated, it will do exactly what's needed to grow and then it stops. The most amazing thing about regeneration is that it stops. How does it know when to stop? All of these cells stop their activity when a correct salamander limb has appeared. So what you're seeing here is an error minimization scheme. You're seeing the system: no matter where it starts from, it will do what it needs to do. When it gets to the correct position in anatomical morphospace, that's when it stops. So you can think about this as an anatomical homeostasis.

Slide 14/51 · 15m:30s

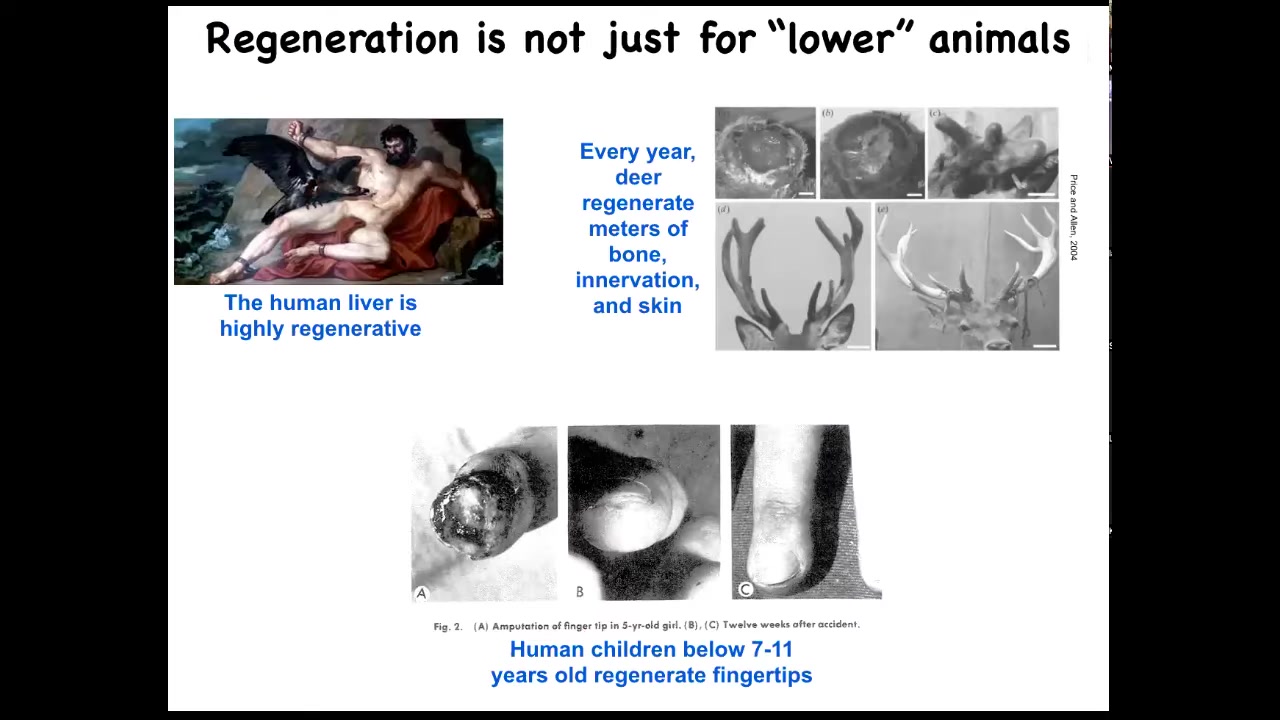

Salamanders aren't the only ones to do this. Humans regenerate their livers, human children regenerate their fingertips, and deer, a large adult mammal, regenerates its antlers every year. Deer can regenerate up to a centimeter and a half of new bone per day, including vasculature and innervation, producing a very large structure. We can talk later about why humans seem to have less capacity than some amphibians.

Slide 15/51 · 16m:03s

But what I've just shown you is this idea that this multi-scale architecture that we are made of, cells and tissues and organs, are able to navigate their anatomical state space, get where they're going despite various injuries and perturbations. And what we're going to do now is talk about how that happens. How do the cells know what to make, how do they know what a correct salamander limb is, for example, and how do they communicate with each other to make that happen? And for that, we're going to talk about something called bioelectricity.

Slide 16/51 · 16m:33s

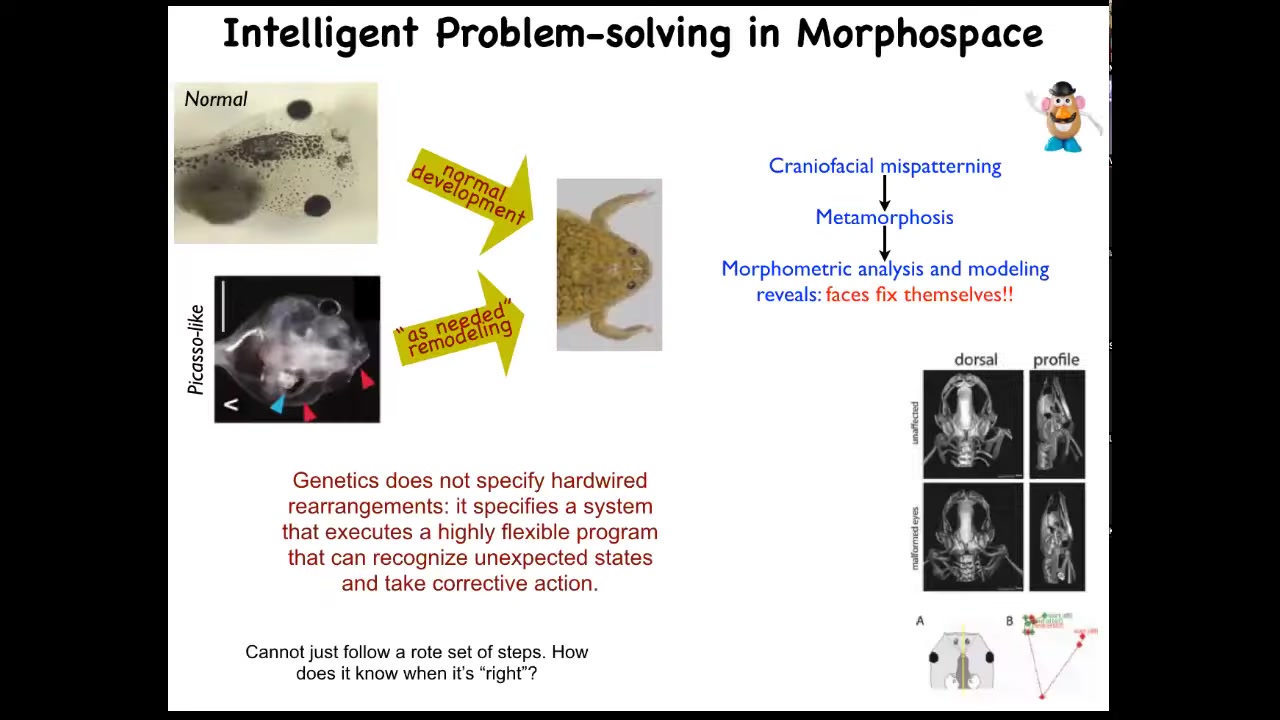

Let's remind ourselves of what the problem is that we're facing here. This is a normal tadpole. So here are the eyes, here are the nostrils, the mouth is here, the brain and gut.

These tadpoles are supposed to become frogs. In order for a tadpole to become a frog, it has to rearrange its face. So the eyes have to move, the jaws have to move, everything has to move around. It was thought that this was a hardwired, i.e., very mechanical and simple process, whereby every tadpole looks the same, every frog looks the same. All you have to do is somehow encode the right direction and amount of movement for all these organs, and then they'll end up in the right place.

We decided to test that. This is very important for us: for all of these estimates of intelligence, you have to do perturbative experiments. You can't just guess, and you can't have philosophical pre-commitments to it, and you can't just assume from observational data. So what we did was, in line with James's idea that you look to see how the system reacts to barriers and perturbations, we made so-called Picasso tadpoles.

Everything is in the wrong place. It's all scrambled. The whole face is scrambled. The eyes are on the back of the head, the jaws are off to the side. It's a complete mess. If this was a hardwired process, everything would end up in incorrect locations as the systems moved their normal amount in their normal direction. But that isn't what happens at all. These animals give rise to very normal-looking frogs.

What happens is that genetics doesn't specify a set of hardware rearrangements. What it actually gives you is hardware that executes an error minimization scheme. It executes a problem of reducing error from a particular set point.

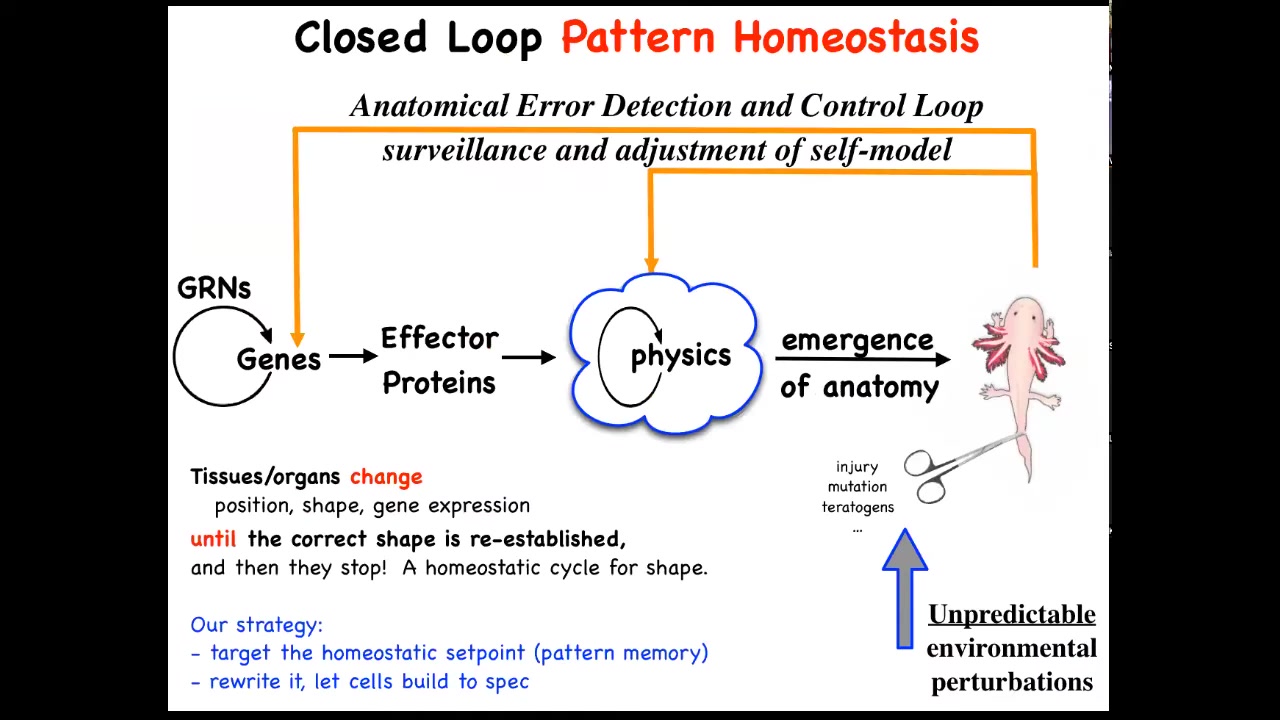

Slide 17/51 · 18m:12s

This is the story that you see in textbooks, which is very much focused on emergence and complexity. This idea that there are local rules: genes interact in gene regulatory networks, they make some proteins, proteins interact via physics, and so on. Eventually, out of lots of simple rules comes something very complex like this. This is all true. It absolutely does occur. It's only part of the story. That feed-forward emergence, the idea that complexity will emerge from the execution of local rules, is only part of it because when you deviate the system from that target morphology, and this could be with injury, teratogens, mutations, whatever, then some very interesting new activities will kick in, both at the level of physics and genetics, that are basically error reduction loops, and you end up with a process of anatomical homeostasis, where they will try to reduce that error and get back to where they're supposed to be.

Biologists know all about feedback loops, of course, but there's a couple of interesting and novel things here. One is that typically homeostatic loops in biology are a scalar. In other words, a single number. It's a hunger or pH level or temperature or something like that. It's a single number. Here, that's not the case. You really have to know something about the complex shape of this organism to be able to correct after different kinds of damage. The set point of this homeostatic process is some kind of complex data structure, but also we're not encouraged, especially in molecular biology and cell biology, to think about systems trying to do things. We're not encouraged to think in a goal-directed way. We're told to think about chemistry and different ways that the subsystems interact with each other, and then what emerges, the science of complexity. We're not taught to think about models in which the system's actually trying to achieve some goal in a problem space.

This way of thinking about it makes a very strong prediction. It says that if this is true, we ought to be able to find the biophysical encoding of that set point. How does it know what the right pattern is? Well, it has to be encoded somewhere. If we were able to find it, we could do the same thing that you do with thermostats or with any other cybernetic system, which is if you understand where the set point is encoded, you can learn to decode it and you can rewrite it and then let the system do what the pattern says. In other words, we wouldn't have to intervene back here, which is what most of the current molecular medicine approaches are. You want changes up here at the system level, but all your tools are down here, molecular pathways. Working this backwards is incredibly hard, if not impossible. That's a big advantage. If we could leave all this in place and simply reset the set point the way you do on your thermostat, you don't rewire the system, you just change what the system thinks of as the correct set point. That would be a big advantage.

This is what we've been doing for some time now, testing that hypothesis. Can we find, decode, and rewrite the set point of this homeostatic system? Now, in thinking about what it might even be: how would you encode a complex anatomical or geometric shape in living tissue?

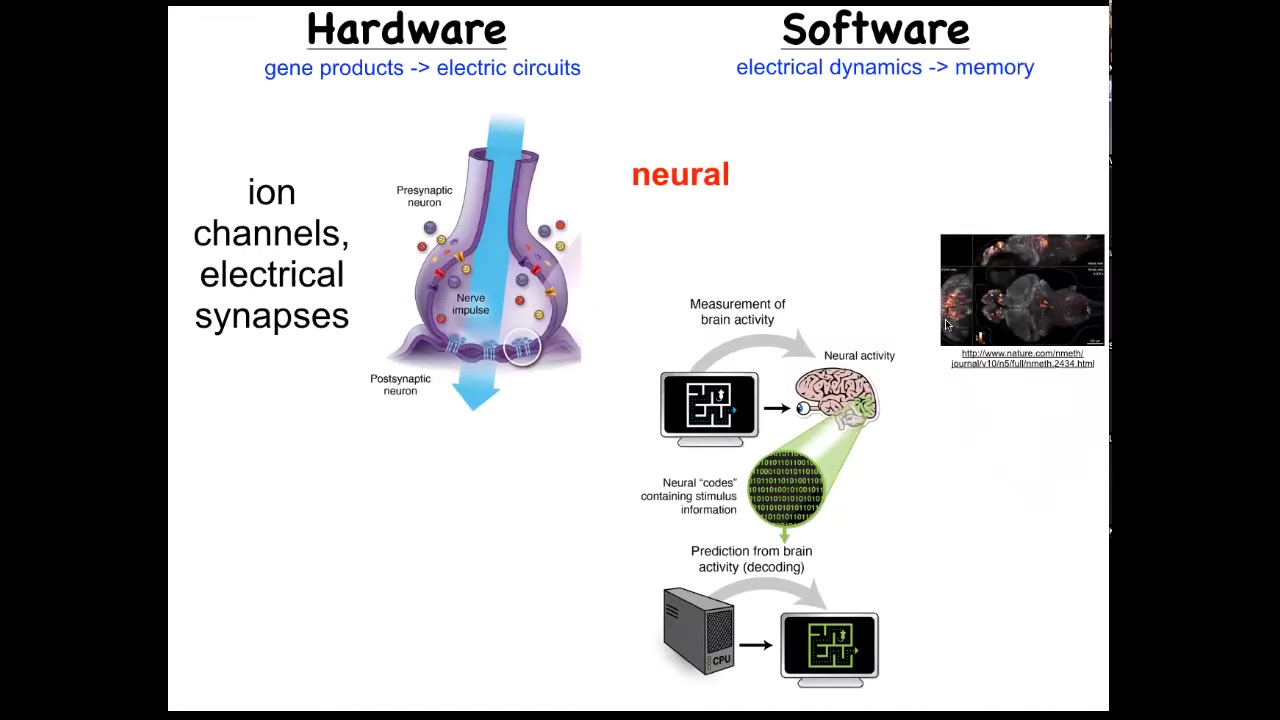

Slide 18/51 · 21m:38s

One immediately thinks of the one example where that's not controversial. In the brain, we know that there's this hardware made up of cells in the network, which have these ion channels in them. They pass ions back and forth and they get a voltage that they can then share with their neighbors through these kind of gap junctions or these electrical synapses. That hardware drives a very interesting kind of software. Here you can actually watch an amazing video of electrical activity in the zebrafish brain.

What happens in the brain is storage of complex patterns as goal states, and then control of the body to try to reach those goal states. We know it's possible in biological tissue to store set points and to work hard to try to get to them. There's this process of neural decoding, a research program that seeks to read information like this and extract from that all of the memories, the preferences, the goal states of the animal.

Now, the remarkable thing is that trick of having an electrical network store and work towards specific goal states is not unique to the brain. Evolution discovered it about the time of bacterial biofilms, and every cell in your body does this. Every cell has ion channels. Every cell has gap junctions that it can form with its neighbors. One can ask, what did your body think about long before it had a brain and muscle to move through three-dimensional space? What was this computational medium used for? We can try to decode it. That's a very parallel kind of idea to what neuroscientists do, except outside of the nervous system.

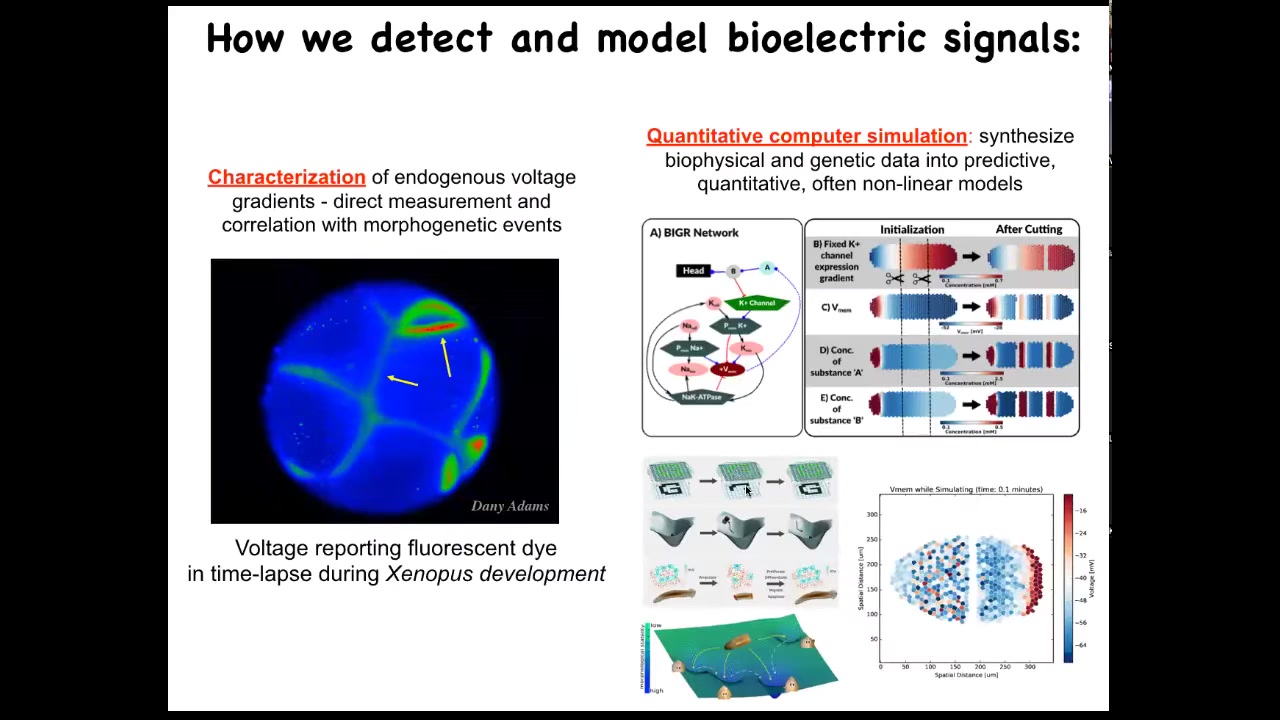

Slide 19/51 · 23m:17s

So we developed some of the first tools to read and write this information outside the nervous system. The first is a set of voltage-sensitive fluorescent dye approaches that you soak your samples in, and they tell you where all the voltage gradients are. So this is a video of an early frog embryo made by my colleague, Danny Adams. When she was a postdoc in my group, she worked out a protocol by which we could use these voltage dyes to see all the electrical conversations that these cells are having with each other.

Then there's a lot of computer modeling and simulation that we do to try to understand how the expression of ion channels in these cells gives rise to specific patterns and what happens to these patterns when the tissue is altered.

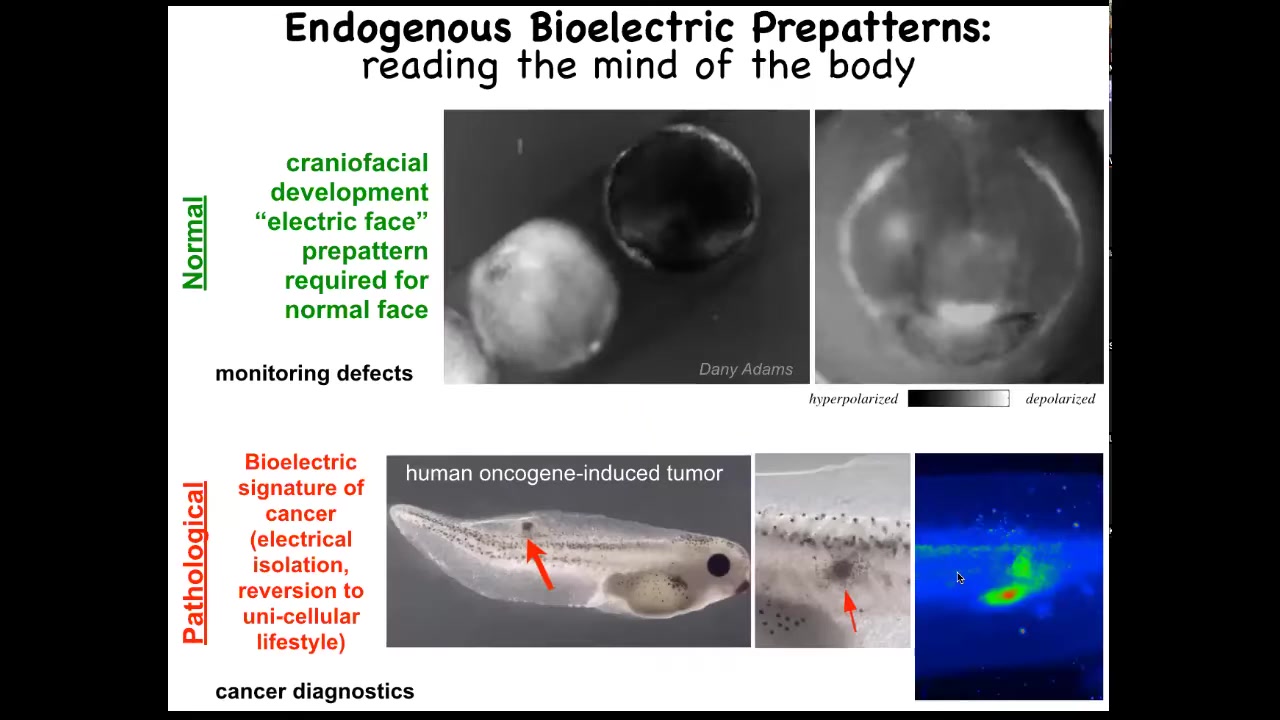

Slide 20/51 · 24m:00s

I want to show you an example of two of these patterns. One is the electric face. Here's a time lapse. Again, this is a voltage imaging dye. It's grayscale instead of pseudo-colored. What you see here is that at one frame of this movie, this is what the bioelectric pattern looks like. I'm showing it to you because this is one of the easiest, most obvious patterns to understand. It literally looks like a face. Here's where the eye is going to go. Here are the placodes. Here's where the mouth is going to be. We're literally looking at the pattern memory of these cells that are telling us what it's going to build shortly thereafter. We know this pattern is absolutely required to have a normal face because, as I'm going to show you in a minute, when we perturb that pattern, the gene expression shifts and thus the anatomy shifts.

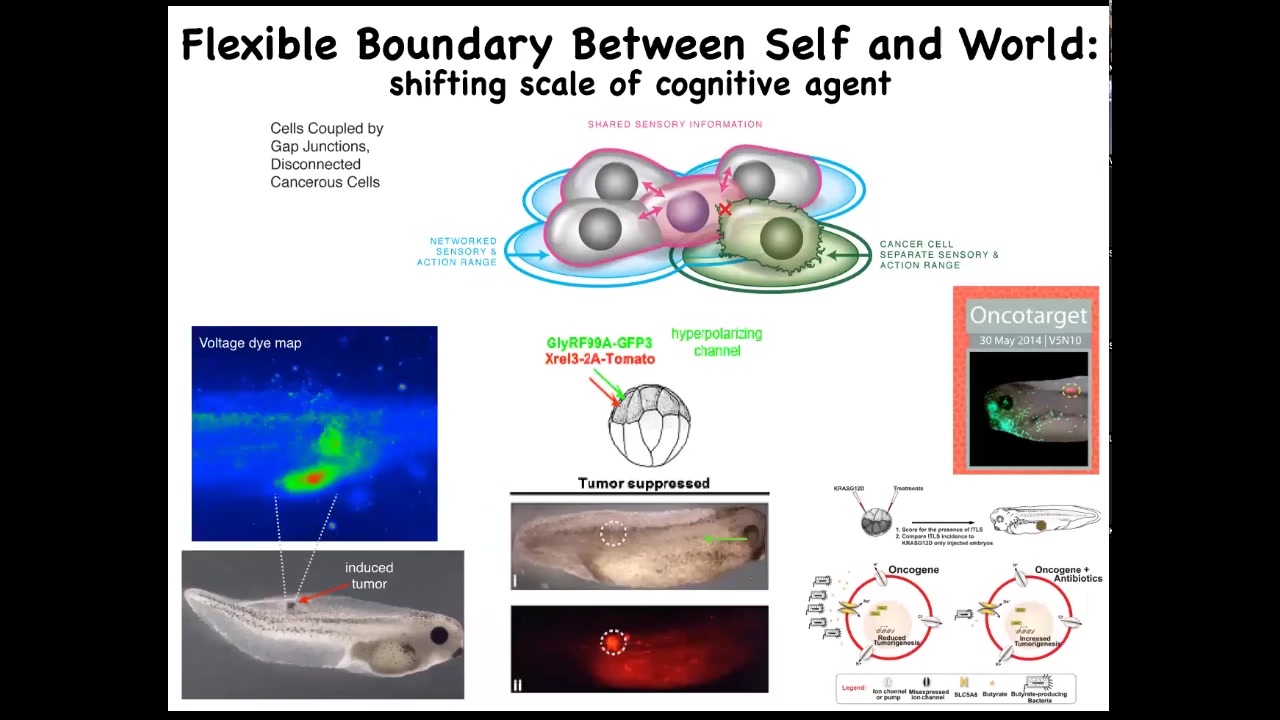

That's a normal pattern. There's also a pathological pattern where if we inject a human oncogene into this tadpole, these cells will eventually form a tumor and metastasize. But long before that, using this voltage dye you can see these cells have disconnected from the electrical network here. They're going off on their own. As far as they're concerned, they're amoebas in the big wide world. They're just treating the rest of this body as outside environment. You can track this. This is where we're working on this as a kind of cancer diagnostic tool, much like this is a birth defect monitoring tool. Tracking all of these things is important, but even more important is the ability to rewrite them.

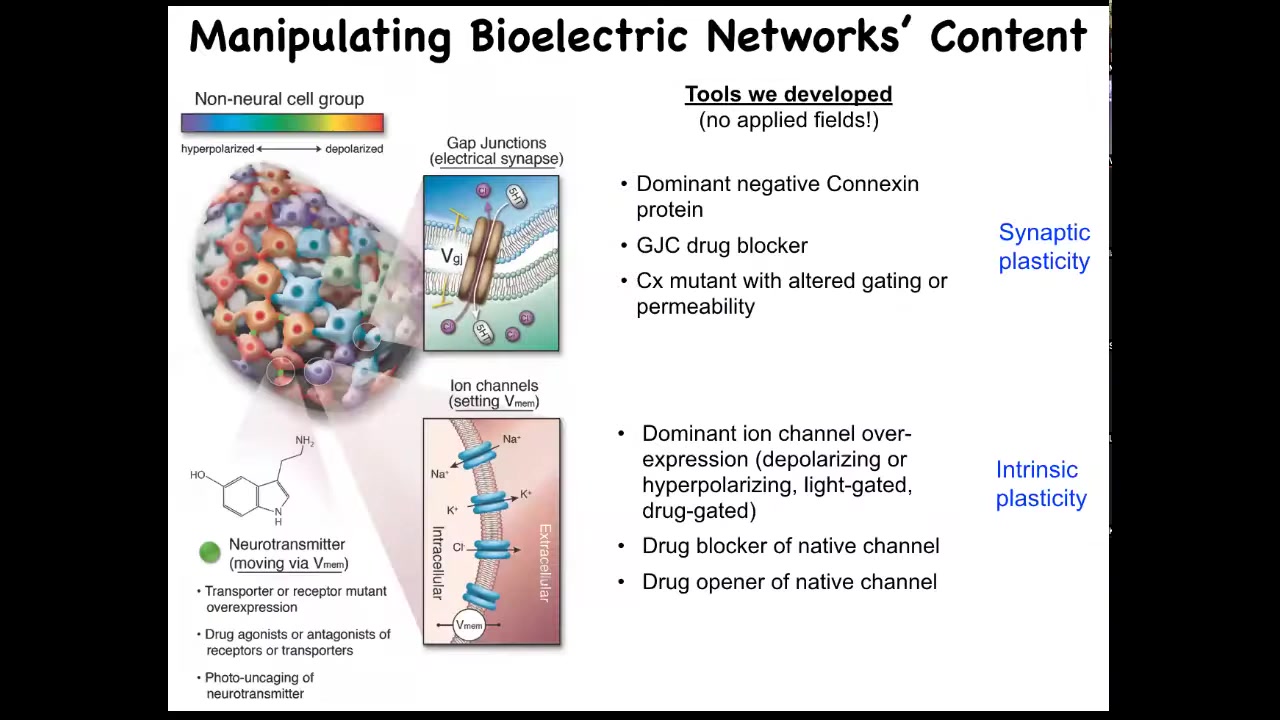

Slide 21/51 · 25m:24s

It's not just about reading these bioelectrical patterns. We need to alter them. I want to be very clear that when we alter these things, we are not using electrodes. There are no magnets. There are no waves, no frequencies, no radiation, no electromagnetic fields. What we are doing is exploiting the natural interface that these cells are using to control each other. That is the ion channels on their surface. All of these cells expose this amazing interface to each other and to us, which are ion channels and gap junctions. We now have all the tools of molecular physiology from neuroscience to control them. We can open them, we can close them. You can do this with drugs. You can use this with light as optogenetics. You can do it with genetic modification of the channels themselves. There are many ways to do it, but it's quite specific. The idea is, can we open and close these channels to induce a very specific pattern? The answer is yes, you can. I'm going to show you a few things that happen when you do that.

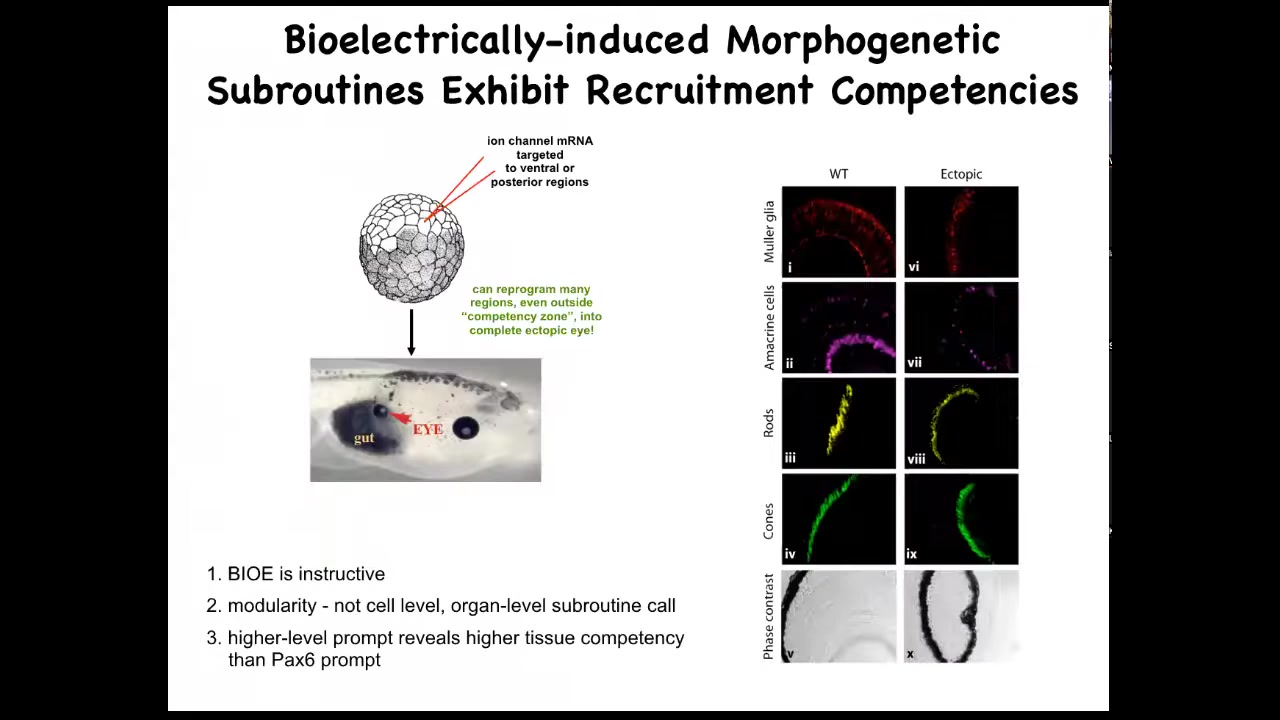

Slide 22/51 · 26m:25s

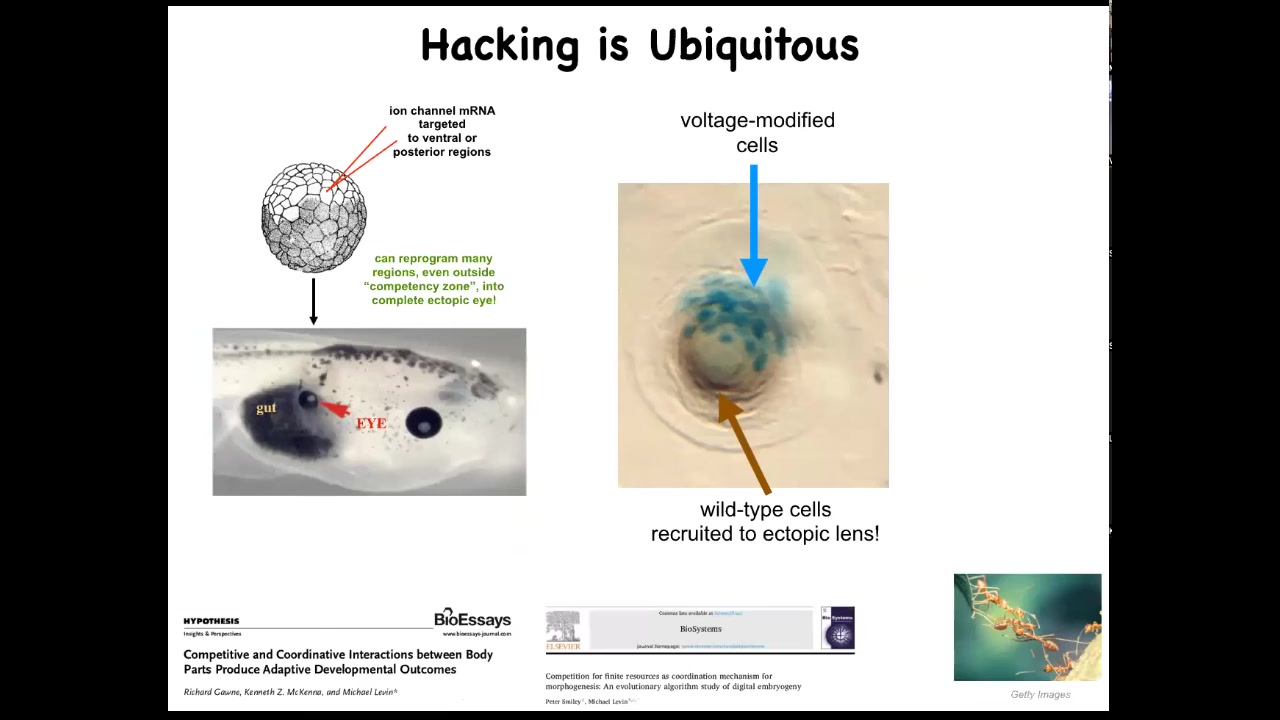

Here's an early frog embryo. What we've done here is to inject some RNA encoding potassium channels. What that RNA will do is set up a local spot of voltage that looks just like that eye spot that I showed you on the electric face. If we do that in some cells that would otherwise have been gut, then what these gut cells will do is change what they're working on and instead build an eye. If you section through these eyes, they can have all the right lens, all the right components: lens, retina, optic nerve, all that stuff. From this, you see a couple of interesting features. One is that the bioelectric pattern is instructive. It's not about generalized damage. It's about telling cells what to do. If you move that eye spot to, for example, where the gut should go, then these are the cells that will make an eye. So the bioelectric memory pattern is in fact instructive for anatomy. That's the first thing.

The second thing is the modularity. We didn't tell these cells how to make an eye. We didn't tell all the stem cells what to do, where to put the optic nerve, where to put the retina, and so on. All we did was give a very simple signal that says, make an eye here. Everything downstream is the competency of the responding medium. It's the responding cells that know what to do when they get that signal. So it's a very high level subroutine call. If you do any coding, it's a subroutine call.

The last thing that I find really interesting here is that if you look at your developmental biology textbook, it will say that only these cells up here in the anterior neurectoderm are competent to become an eye. The reason people say that is because they've probed it with a master eye gene called PAX6. If you misexpress PAX6, indeed, you can only get eyes up here and nowhere else. Using that tool, it reveals a lack of competency in the rest of the body. But that's not the right tool. If you use bioelectric signals, in fact, you can get eyes anywhere. We've gotten them on the tail, in the gut, anywhere you want. And so that teaches us an important thing: be humble about the competencies of the material we're dealing with, because it's only as good as we are in giving it the right prompt.

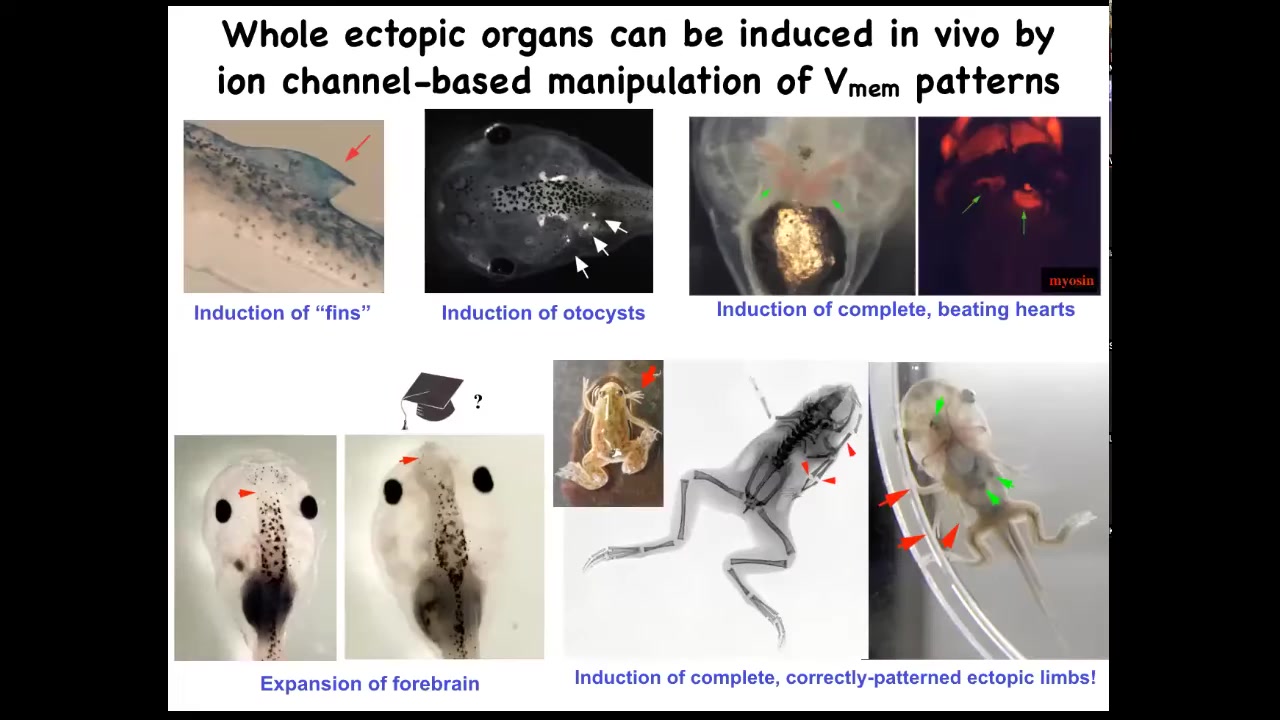

Slide 23/51 · 28m:38s

If you do this, you can make ectopic inner ears, so otocysts here. You can make ectopic hearts. You can make ectopic forebrains, new legs. Here's our nice six-legged frog. Ectopic fins. That's weird. Tadpoles aren't supposed to have fins. We'll talk about that in a minute. This is more of a fish thing. We've been using this idea to give high-level anatomical signals to redirect where cells are going in that space.

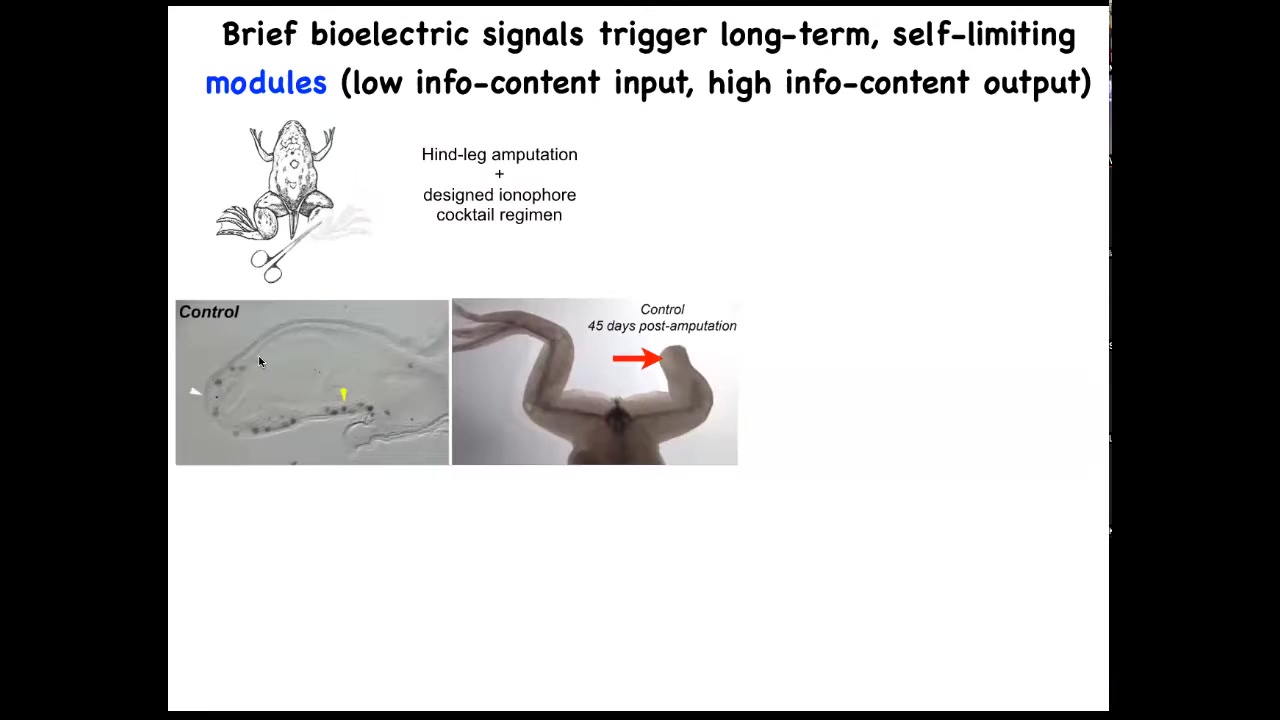

Slide 24/51 · 29m:05s

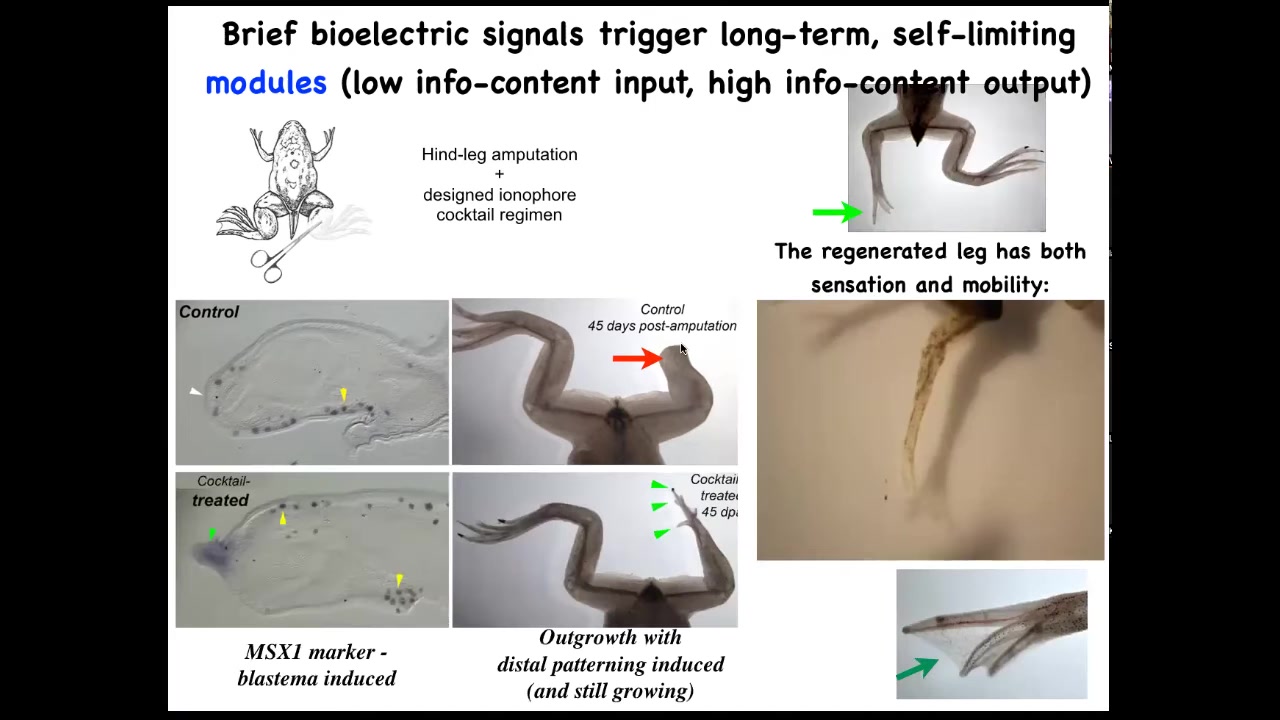

One obvious application is in regenerative medicine. Here are some frogs. When you amputate their legs at this stage, normally nothing happens. 45 days later, there's nothing.

Slide 25/51 · 29m:16s

We have a cocktail of ion channel modifying drugs that immediately induces an MSX1 positive blastema. It induces, you got some by 45 days, you've already got some toes, you've got a toenail, the most distal part: a perfectly respectable leg, and it's touch sensitive and it's motile. It's functional.

The way this works is that we only intervene in the system for 24 hours, for that first initial period, and then we don't touch it again. The record, our longest experiment, is 18 months. During those 18 months, a full-on adult frog regrows their leg when treated with a particular cocktail, and we don't touch it during that time at all. This is not about micromanagement. This is not about telling stem cells what to do or scaffolds or any of that. It's about convincing the cells on day one that they're going towards the leg-building region of morphospace, not the scarring region of morphospace.

Dave Kaplan and I have this company called Morphoceuticals, where we are trying to move that approach now from amphibians to mammals. We are doing work to get, eventually, into the clinic with a mammalian limb regeneration application delivered by this wearable bioreactor, which is what David's lab does.

Slide 26/51 · 30m:39s

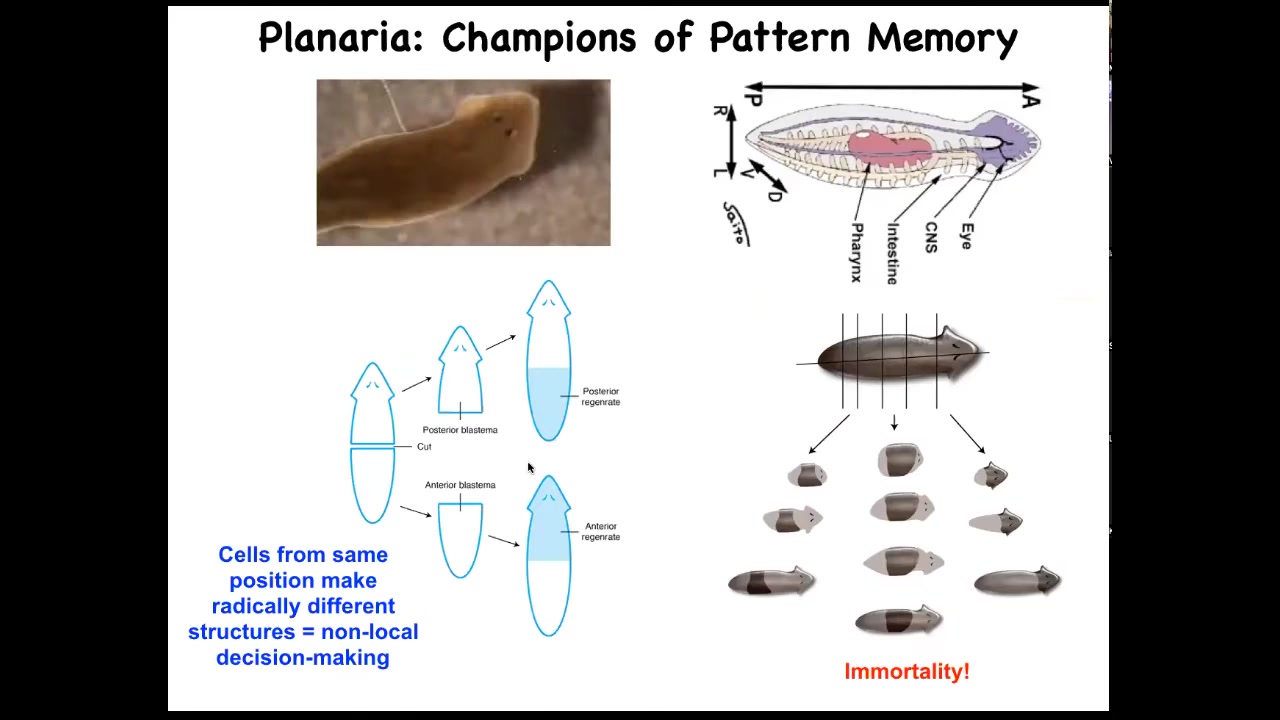

I want to shift gears to really nail this idea of these bioelectric patterns as kinds of memory. And to do that, I want to talk about a different organism. This is called planaria. These guys are these very cute little worms. They have a true brain. They have a central nervous system. They have lots of different organs and tissues, the same neurotransmitters as you and I. They have this amazing property that if you cut them into pieces, every piece regrows into a perfect little worm. That's amazing. Every piece gives rise to a complete correct anatomy.

Not only are they cancer resistant, but they are actually immortal. There's no such thing as an old asexual planarian. They also have an extremely messy genome. But they have this amazing anatomical fidelity.

Slide 27/51 · 31m:36s

And so if you amputate the head and the tail and you leave this middle fragment here, you might ask, how does this fragment know how many heads it's supposed to have? And it turns out that there's an electrical circuit that we characterized. And this electrical circuit is what tells it how many heads it's supposed to have.

Slide 28/51 · 31m:56s

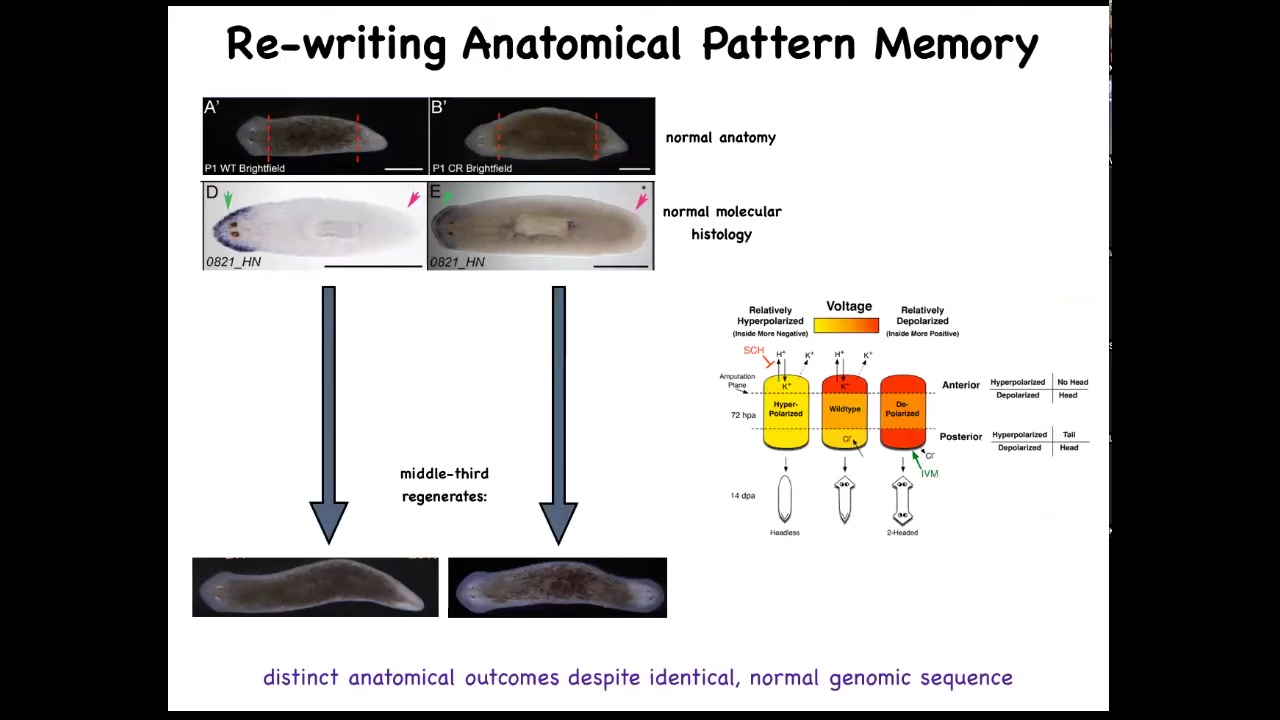

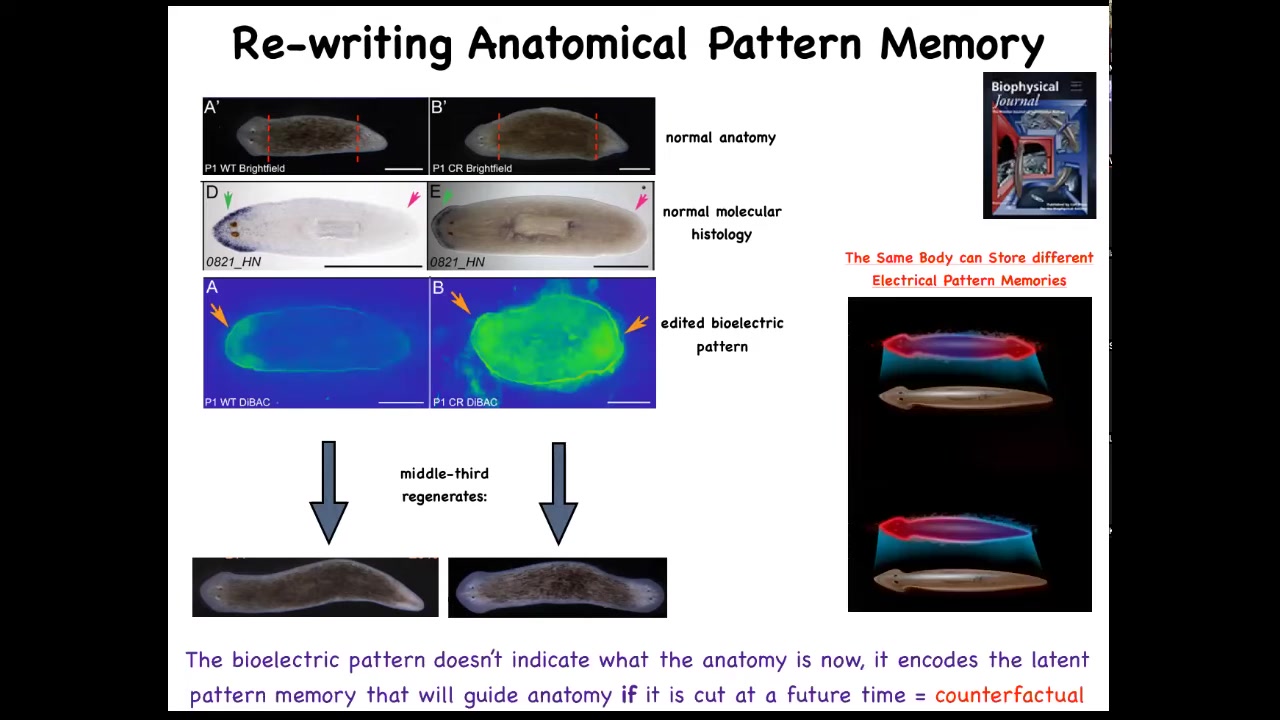

And so this is what the voltage looks like in that fragment. You can see that it says one head. Now, what we're able to do is take that animal and rewrite this electrical circuit to say two heads. This is messy still. The technology is still being worked out. But we can say, no, you should have two heads. And what will happen is that if you then cut this animal, it will in fact have two heads. This isn't Photoshop. These are real animals.

Now, the amazing thing is that this voltage map is not a map of this animal. That's critical. This is not a map of this two-headed guy. This is a voltage map of this perfectly anatomically and molecularly normal animal. Only if you cut him does he then make two heads. In the absence of that injury, he just stays how it is.

A single planarian body, a normal one-headed planarian body, can store two different representations of what to do if you get injured in the future. Two different ideas of what a correct planarian looks like.

There's a couple of interesting things here. First of all, this is basically a counterfactual. This idea of brains being able to do this amazing time travel where you're able to think about things that are not true right now. You're able to have memories of the past, anticipation of the future. That's a mental time travel.

A very basic primitive version of that counterfactual is this ability to store a pattern of what you will do if you happen to get injured in the future. This is that ability to rewrite that set point. We literally have rewritten the representation of how the pieces know what the correct anatomy is. Once you've rewritten it, that's the only thing they have to go on. There's nothing else for them to compare it to. This is their new normal.

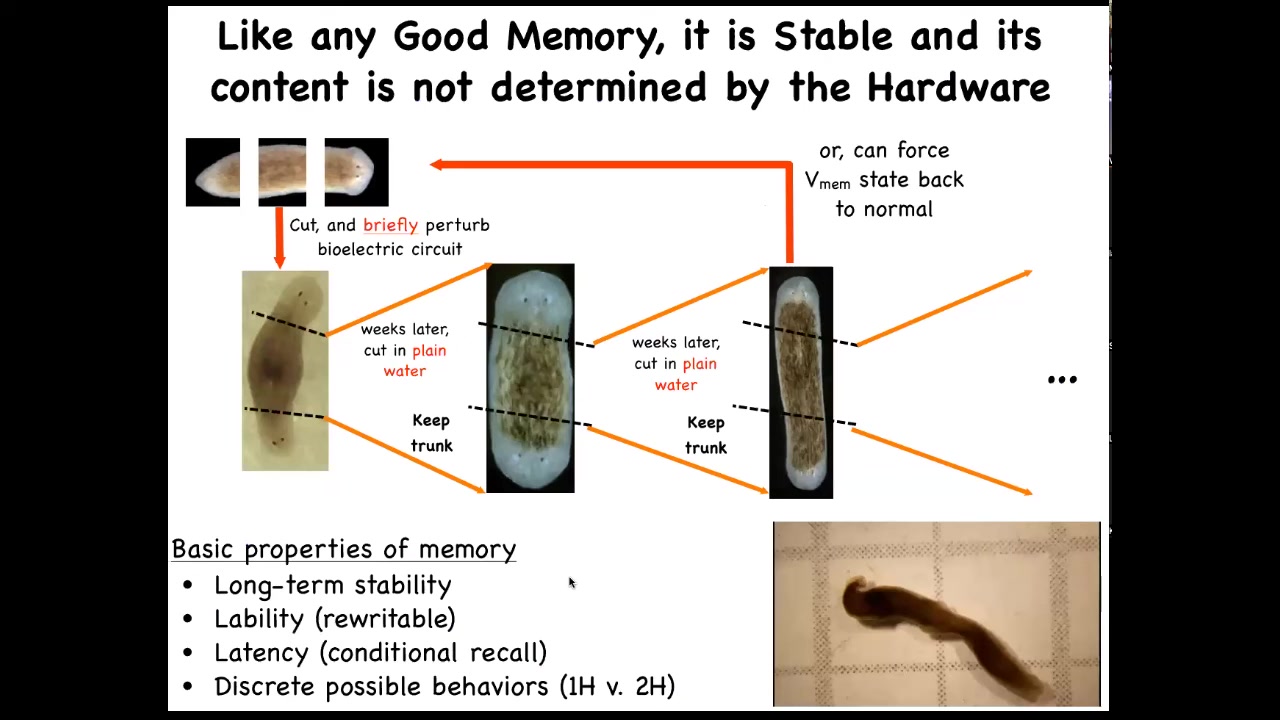

Slide 29/51 · 33m:44s

Now, I call this a memory because it has all the properties of being memory. If you take one of these two-headed worms, and you cut off the primary head and you cut off this ectopic secondary head, and you leave them in plain water, you let them regenerate, what they will do is they will continue being two-headed, even though they have a normal genome.

We haven't touched the genome. There is no genomic editing here, no CRISPR, no transgenes. The memory is in the bioelectrical circuit. They literally remember how many heads, and, as with any good memory, if you rewrite it, it keeps. You can keep cutting them, as far as we can tell, forever, and they will stay two-headed.

Here are these animals. You can see them hanging out. This has all the properties of memory.

Think about the role of the genome here. If I were to ask you where the number of heads in the planarian is encoded, and you said it was in the genome, you'd be wrong. What the genome does encode is hardware that by default starts out encoding the state that says one head. But it's not determined, it's not nailed down by the hardware because you can change it. You can change it in situ without changing any of the genetics. That's the tip of the iceberg of information here that's generated physiologically in that hardware.

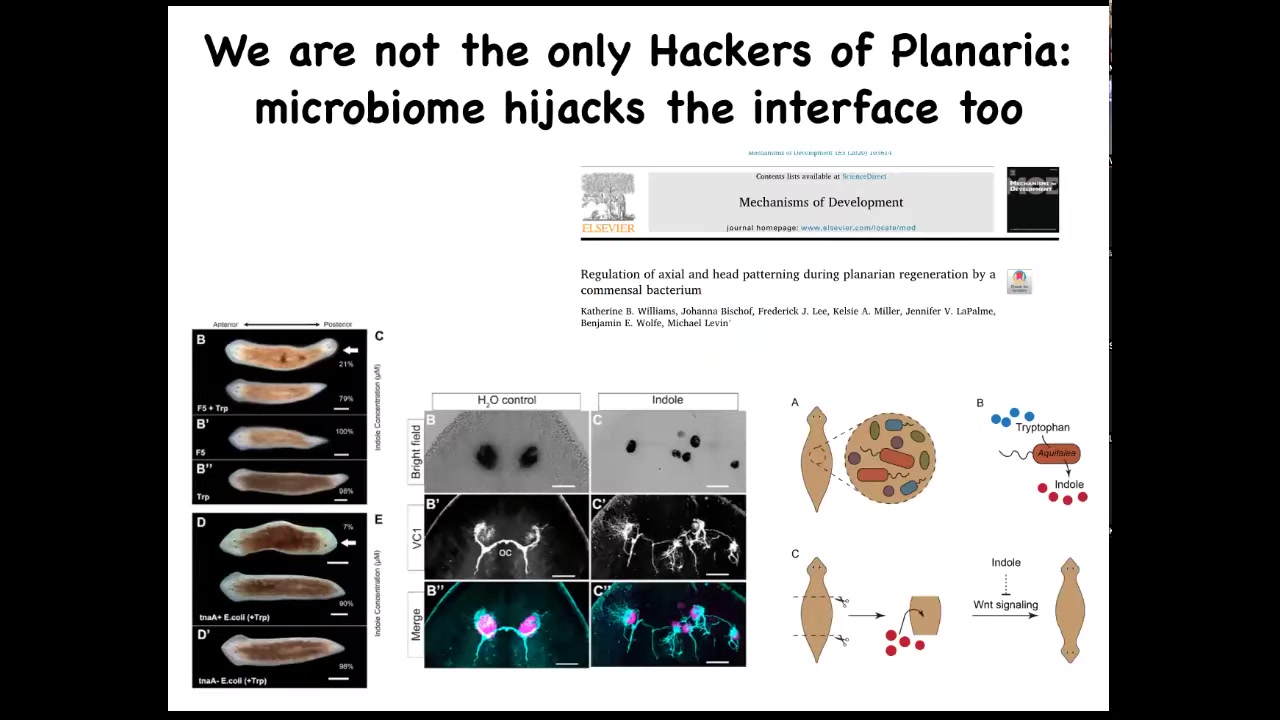

Now we are not the only ones that can hijack this electrical system.

Slide 30/51 · 35m:04s

Bacteria can do it too. This is a study that we did in collaboration with Ben Wolf and Catherine Williams. Kate was an undergrad in our lab. What she found was that there are bacteria that live natively on these planaria. When we interfere with the relative proportions of the different types of bacteria, they can exert a strong influence on their host, for example, to make their host two-headed or to make radical changes in their visual system. So this is the normal: the eye spots, the optic nerves—radical changes in that visual system, all driven by, again, no genetic change, but all driven by signaling from the bacteria that are able to interface to the native controller that sets things like head number, head shape, and so on.

Slide 31/51 · 35m:53s

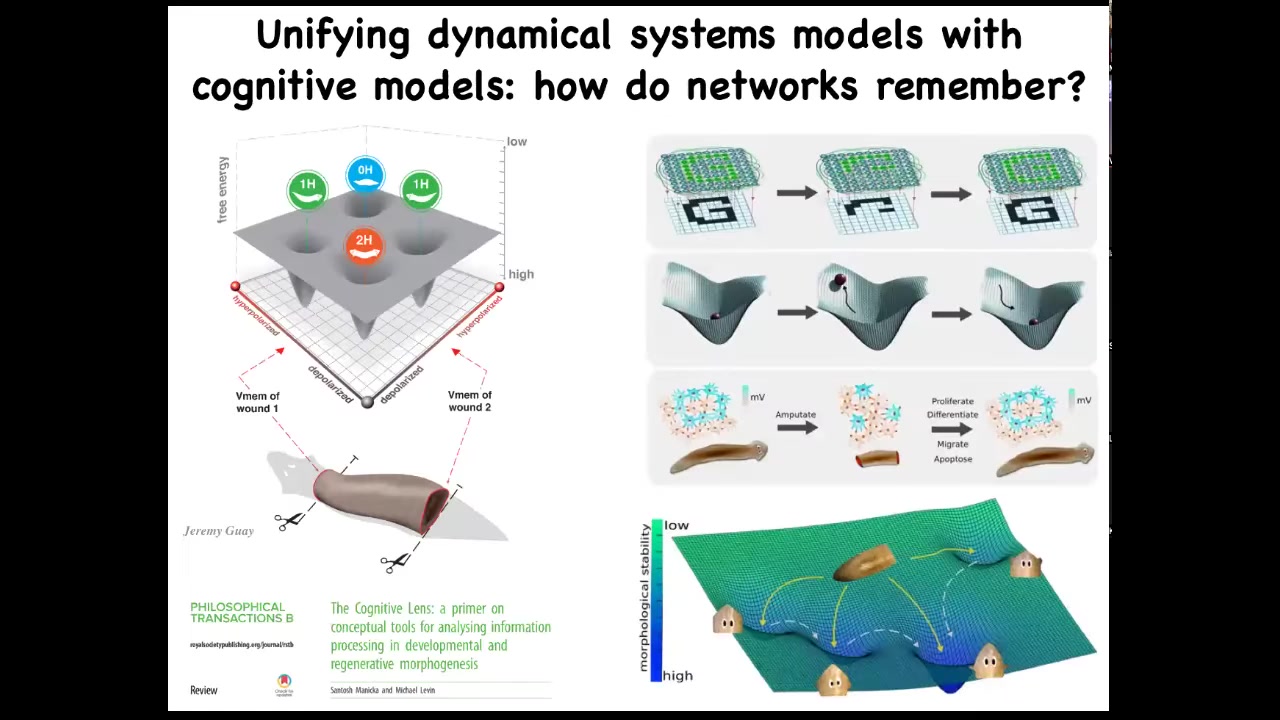

What we're doing now is we're trying to unify two very different approaches that people take to problems like this. On the one hand, the state space of the biophysical circuit that shows you all the different ways that it could be, and some ideas from connectionist machine learning and dynamical systems theory that tries to understand how do networks store information, how do they recover from partial input, and so on. These we're trying to unify, and some of that is described here.

Slide 32/51 · 36m:27s

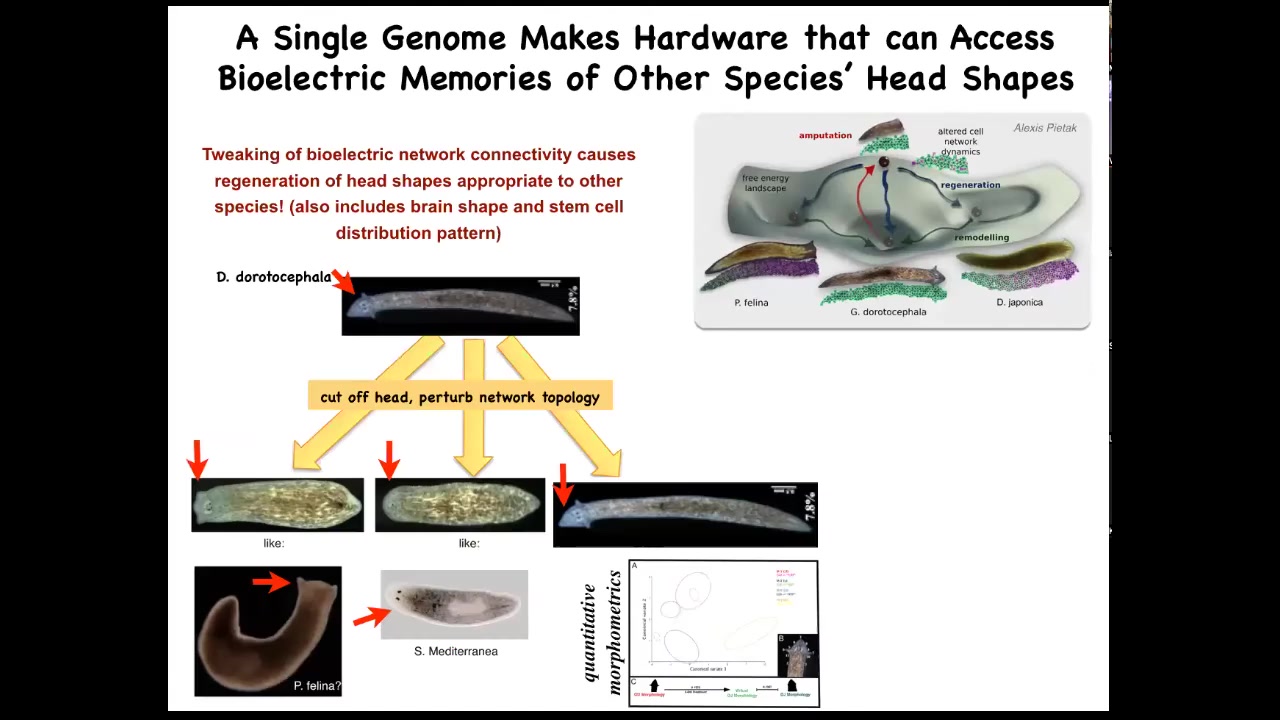

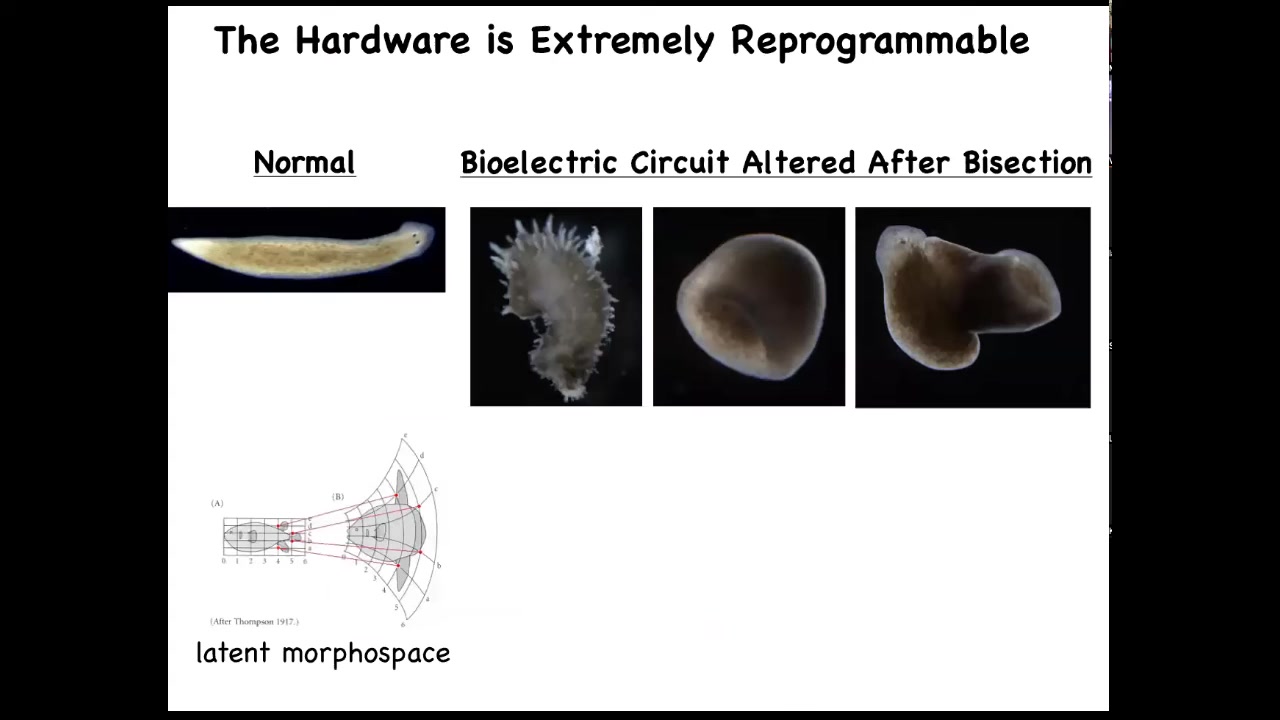

Interestingly, it's not just about head number, it's more general than that. It's about head shape as well. So if we take this nice triangular-headed planarian, amputate the head, and then confuse the bioelectrical circuit about what it should be doing, you sometimes get flat heads like this P. falina, or you get round heads like this S. mediterranean. These creatures are between 100 and 150 million years distance from this guy. Again, remember, no genetic change here. Not only the head shape, but actually the shape of the brain and the distribution of the stem cells changes to be just like these guys. So this hardware, this perfectly normal genetic hardware, is happy to visit other attractors in that morphospace that belong normally to some other species. But that hardware can go there, no problem. So you're starting to see this idea of reprogrammability. This is what I said at the beginning, the biological tissue has the ability for you to call large-scale subroutines with very simple triggers, very simple signals, and then everything else gets handled underneath. It has the ability to remember and to store new patterns that you write into it using this physiological interface. And it has the ability to visit different attractors other than what the default of the hardware normally is.

Slide 33/51 · 37m:47s

Now you can even visit some attractors that you wouldn't say belong to planaria at all. You can go further. We've made these spiky forms, these cylindrical things that are not even flat. And then the hybrid, these hybrid shapes. You can explore the latent space around any particular form to see what else it's actually capable of. D'Arcy Thompson wrote about this as early as 1917.

I think this space is, if we were doing a bioengineering talk, I would show you that the space is actually quite enormous and fascinating.

Slide 34/51 · 38m:23s

The last story I want to tell you on the bioelectric front has to do with repair of birth defects. A new way to address the repair of very complex structures.

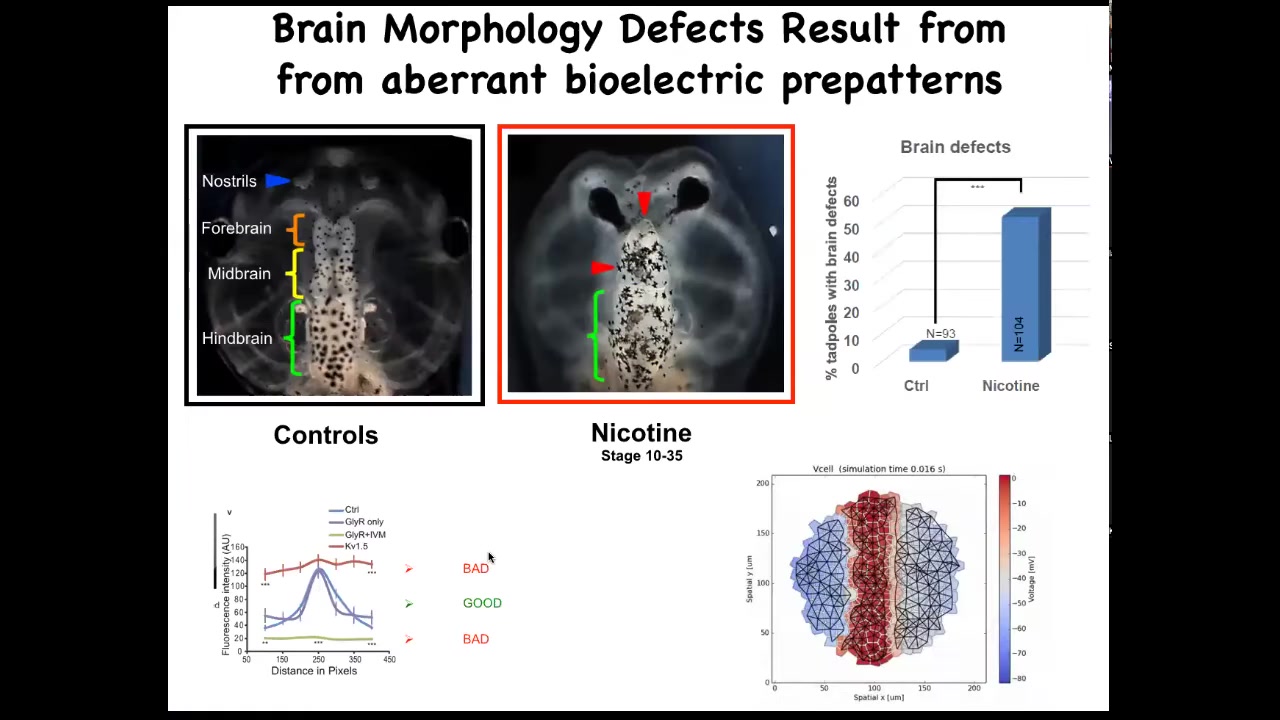

Here's a frog brain. You've got the forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain. You can see it comes in two halves, left and right. If you expose these embryos to various kinds of teratogens—nicotine, alcohol, various mutations—you can get characteristic defects like this, for example.

We sought to ask a question. How could we repair something complex like this?

To do that, we created a model, a computational model of the bioelectric pattern that normally tells this brain what shape and what size it should be.

The thing about this bioelectric pattern is that it has this very characteristic bell curve shape, and flattening it out either up here or down here both has the same effect. It gives you terrible brain defects. It's very important that this particular shape in the electrical pattern be there.

We simply ask the model, if the pattern is wrong, what channels could we open and close to get back to that pattern?

The idea is using a predictive computational model of the bioelectrics to say, how do we fix that memory, the pattern memory of what you're supposed to be?

Slide 35/51 · 39m:43s

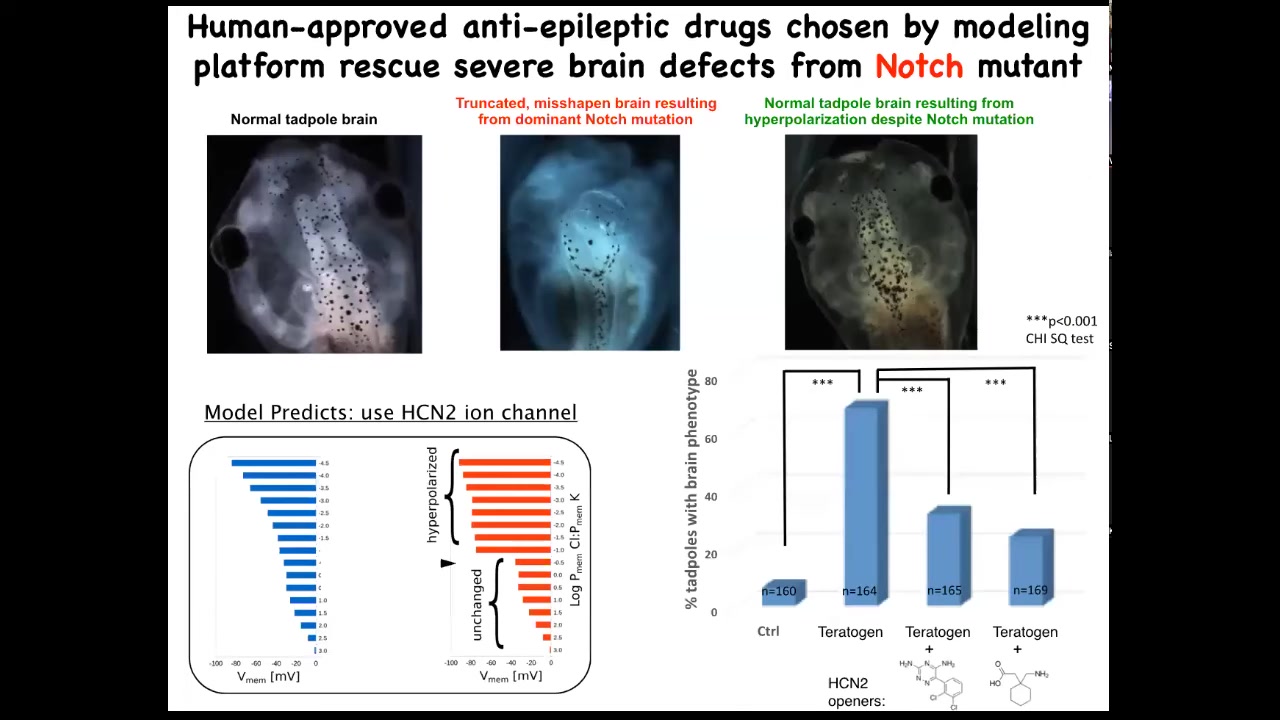

Amazingly, the models made a suggestion about a very interesting channel called HCN2. When we tried it to test the predictions of the model, we basically upregulated HCN2 in these creatures.

Here is a normal brain. I'm showing you what I consider to be the most impressive or the worst kind of teratogen. This is a genetic mutation. This is a mutant in a gene called Notch. Notch is a very important neurogenesis gene. With that overactive Notch mutant, there is no forebrain. The hindbrain and midbrain are a bubble. These animals have no behavior. They just lay there. This is a very severe defect.

We asked, could we possibly fix this? Could we repair the state? It turns out that if you upregulate HCN2 channel activity, just like the model said, either by injecting new HCN2 RNA or by using drug openers of existing HCN2s — these are human-approved anti-epileptics — you get back to the correct brain. In fact, these animals have not only the right brain shape, but they have the right gene expression in the brain and they have the right cues back because we can do behavioral testing and they learn in a way that's indistinguishable from controls.

I find this remarkable because it turns out that using the bioelectric interface guided by a computational model, you can sometimes fix certain hardware defects in software. I'm not claiming that will always be possible, but in this case, a hardware defect, a broken Notch signaling pathway, can be overridden by giving these cells a reinforced memory of what they should be doing. This is one of many examples where the physiological state trumps the genetic state.

Slide 36/51 · 41m:32s

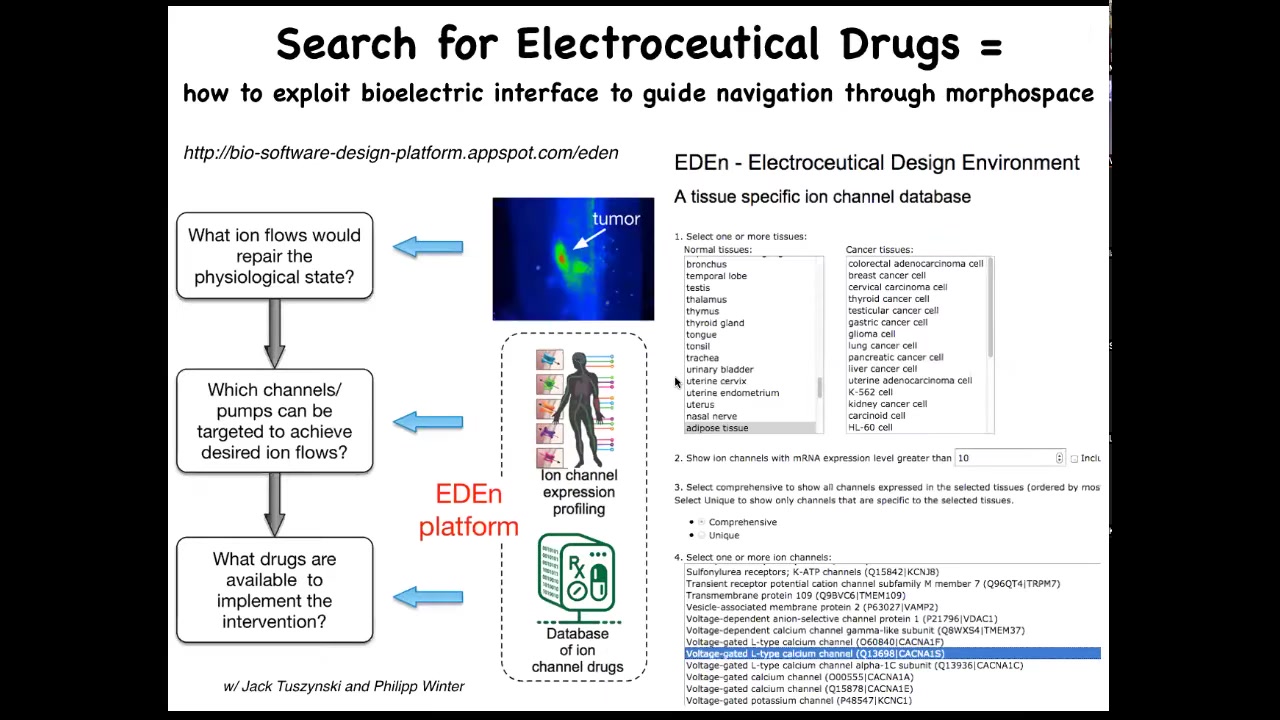

More generally, what we're doing now is setting up a system like this, where you could go from the initial issue of, I have an incorrect pattern, that might be a birth defect, it might be a tumor. You know what the correct pattern is, because we're working on the physiomic data sets, and you know which channels are in your tissue of interest, because all this stuff has been profiled and is online. If you integrate the simulator, you can ask which of those channels can be used to get the pattern back to normal. This is just the beginning.

You can play with this. It's online. This is the beginning of the interface where you could pick different tissues, either normal or transformed, and then see all the channels that are your potential targets, so-called electroceuticals, because there's a huge database of drugs that target all of these channels, and many of them are human-approved. This is what we're looking at in the future: the use of computational platform-guided electroceuticals for birth defects, for regenerative medicine, and for cancer.

Slide 37/51 · 42m:44s

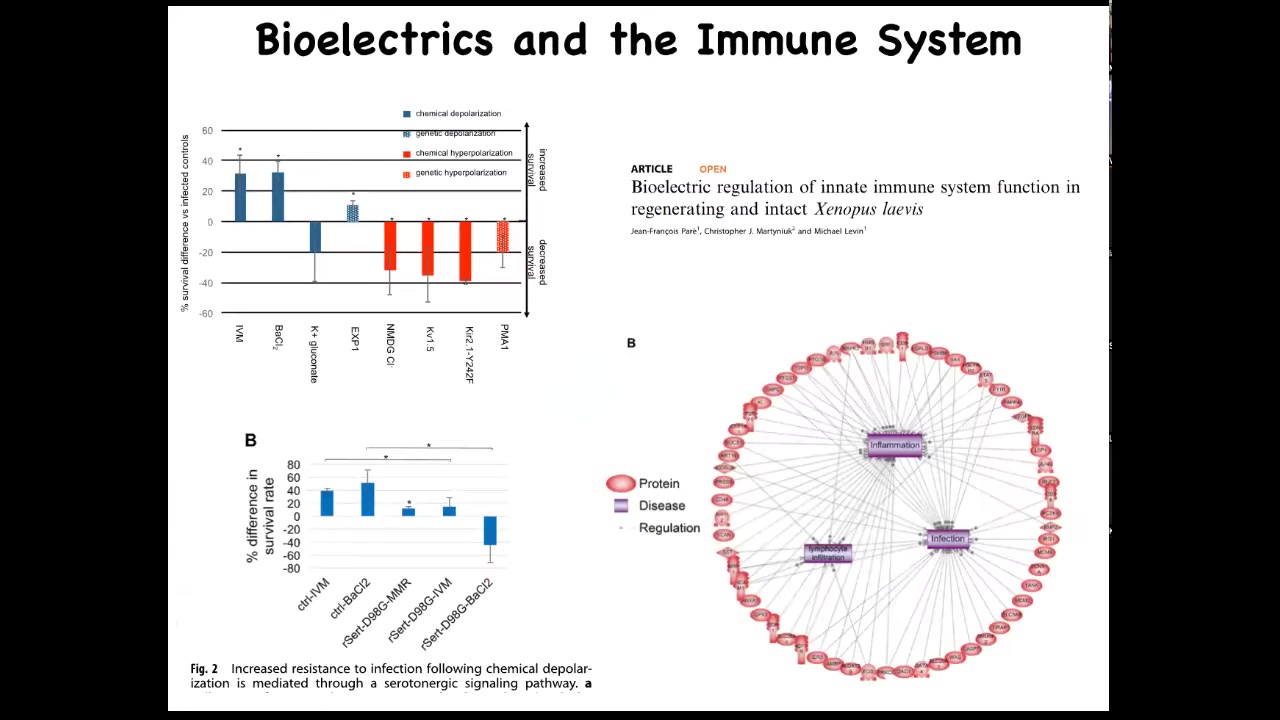

The bioelectric system also affects immune function. We studied the innate immune system and found that survival of embryos when they were challenged with a pathogenic bacteria is much improved if you hyperpolarize the tissues with specific drugs or RNAs. Some of that functionality is mediated by serotonin. If you put a serotonin transporter dominant negative, you can abrogate the activity. When we looked using next-gen sequencing, RNA-seq, we found that changes in bioelectrics alter many different targets that belong to inflammation, infection, and other immune-relevant endpoints.

Slide 38/51 · 43m:41s

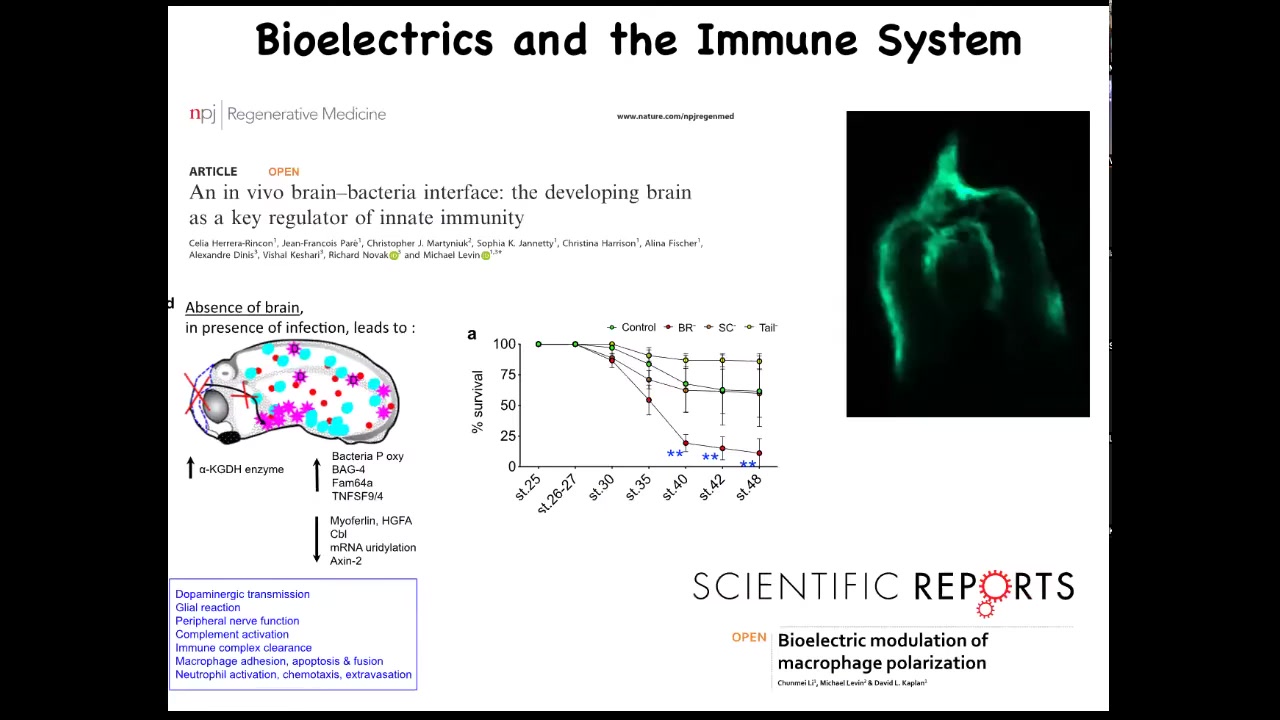

We found that the presence of the brain is an important component of that loop. In the absence of the brain, the body continues to develop. They're completely viable. But what they do have is decreased ability to fight off infections.

There's a really important interplay between the brain and the non-neural bioelectricity of other cells and the immune response that leads to either tolerance or susceptibility or to clearance of a bacterial infection.

One of the things that we found, this is a cross-section through a frog embryo, is that if you inject fluorescent bacteria, this is pathogenic E. coli made fluorescent by expressing GFP, this pattern is very familiar to developmental biologists. This is exactly where neural crest cells travel in the body to make various organs. The bacteria are following these same paths that native cells follow during morphogenesis. There's much more to learn about this. We're just beginning to scratch the surface.

Slide 39/51 · 44m:59s

So for the last few minutes, I want to bring it back and think about what this means for questions of biomedicine, but specifically about infection and things like that.

I want to focus on this notion of hacking as a fundamental concept. What we've seen up until now is that cellular collectives, so groups of cells, use bioelectricity to keep collective memories of what they should be doing, specifically in anatomical space. They have the ability to respond to various cues, for example, novel bioelectric signals, and take journeys in that morphospace and build various organs and repair organs. The idea is that we have a collective intelligence here. It's held together by bioelectricity, like your collective intelligence of your individual neurons is held together by the bioelectricity of your brain and nervous system. Let's think about how that looks in other spaces.

Slide 40/51 · 45m:58s

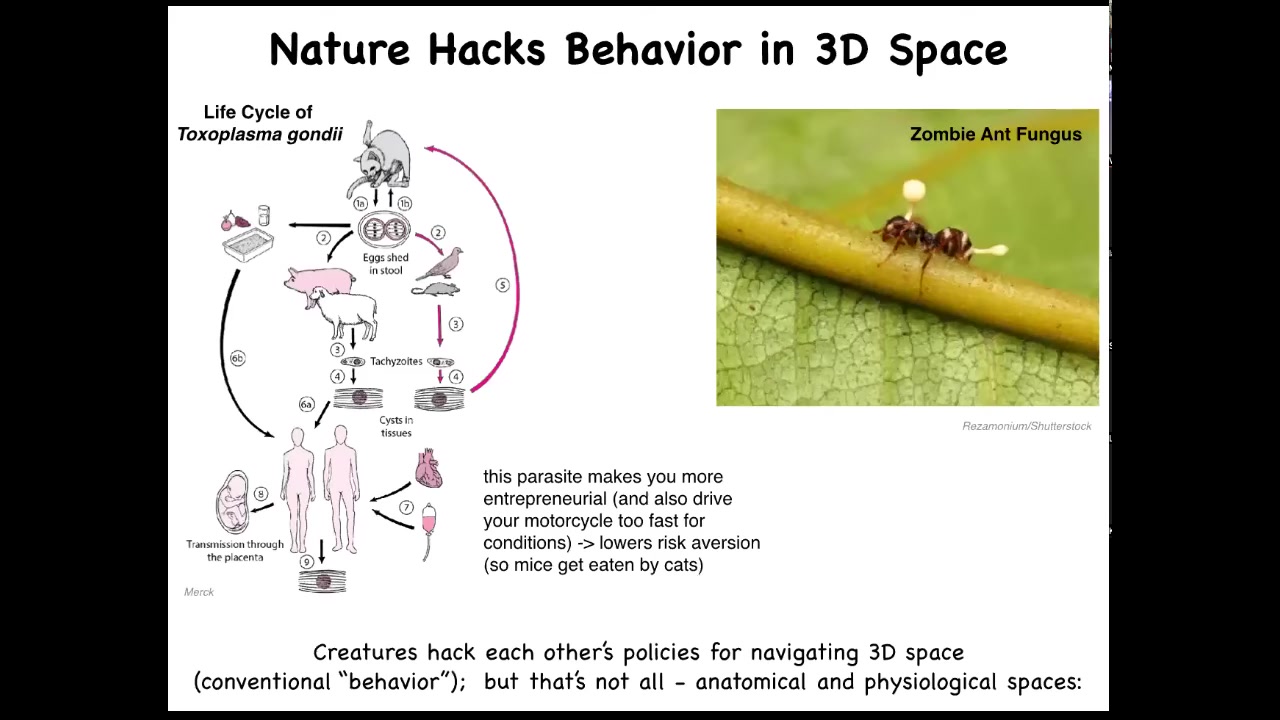

These are some examples. There are many examples in which parasites actually hack behavior. Toxoplasma, known to affect the behavior of the animal hosts it infects and humans, lowers risk aversion. There's also the zombie ant fungus, which controls the body of the ant and forces it to take behaviors that facilitate the fungus life cycle.

The idea is that creatures hack each other's policies for navigating three-dimensional space. There are lots of parasites that do host-altered behavior, but that's not all, because these parasites can also hack the behavior of life in anatomical and physiological spaces. What do I mean by that?

Slide 41/51 · 46m:49s

The development's amazing, but it lulls us into a false sense of understanding because we look at the reliability of this process. Here's an acorn, here's an oak leaf. We tend to think that we know what the oak genome does. It takes you on a particular path in morphospace from here to here. This is what happens 100% of the time. That's what we think the hardware encoded by the genetics knows how to do.

Slide 42/51 · 47m:22s

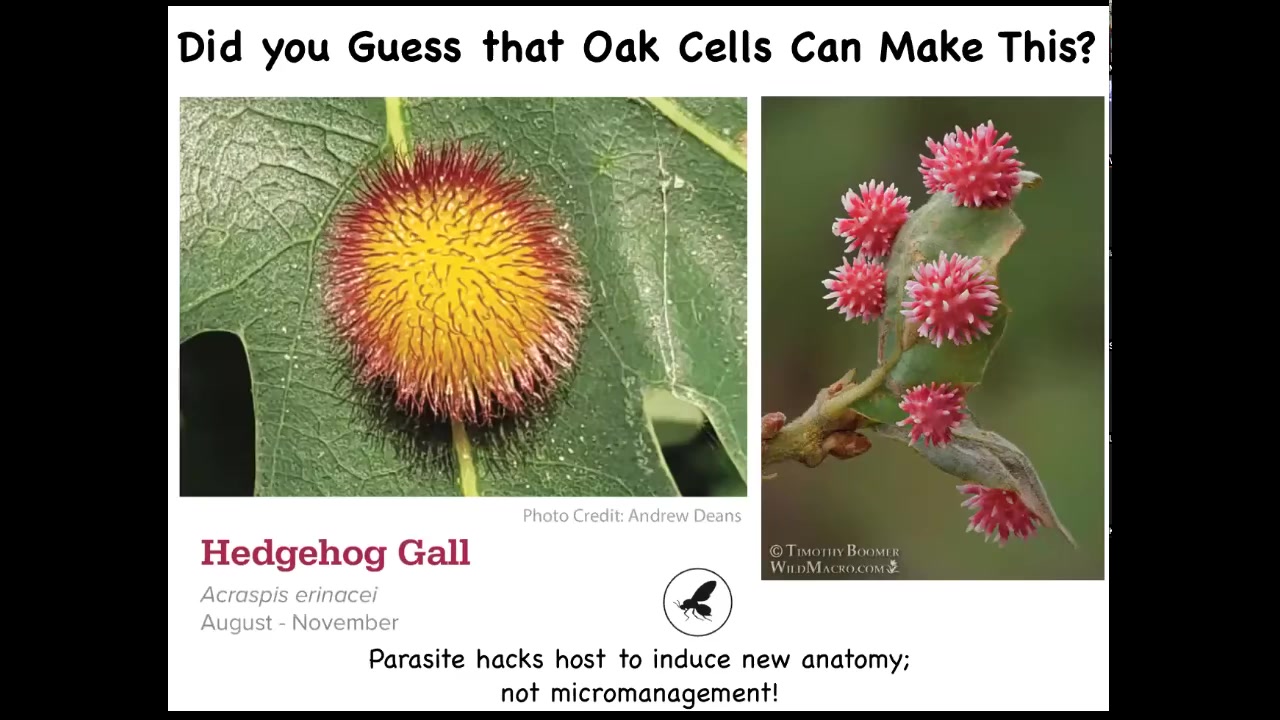

One thing we would never have guessed is that these exact same cells are also capable of forming this or this or who knows what else, because there's a little hacker. In this case, it's a wasp that lays down an embryo and that embryo signals to the plant cells. It doesn't build this thing. These are not wasp cells. It puts out some signals that convince the cells of the leaf to build this crazy structure.

And from looking at that leaf or from looking at the oak genome, we would have no idea that these cells are even capable of doing something like this, taking this journey in morphospace until we found that it was prompted by this.

So this idea, we call it bio-prompting, this idea that if you're dealing with a reprogrammable, competent material, you don't have to micromanage it. You can find some very high-level signals that are going to exploit the competencies of that material to build specific things and to take other journeys.

Slide 43/51 · 48m:26s

The key questions here are: as a multi-scale biological system, how do you know when you are being hacked? How do you know where the border is between you and the outside world? Which signals are yours? Which signals are coming at you from outside? And when you're born, what are you? What sensors do you have? What effectors do you have? You really don't know.

There are many examples in psychology as well as physiology of disorders in the ability to set a border between you and the outside world. Many patients have trouble figuring out whether various impulses they have are coming from them or from the outside.

Think about the difference between learning versus being trained. When you're learning, the implication is that you're the boss and you're functioning in this dumb environment, and it's up to you what you're going to learn from that environment. When you're being trained, the situation is similar, but there's another agenda on the other side of that environment; it is no longer zero agency. There's another agent there that's serving their agenda by training you in a particular way.

Being able to tell which signals are yours, which are coming from your own body parts, and which are coming from a parasite means it's important to know the boundary computationally, not just physically, the skin, but the computational boundary between you and the outside world.

For biomedicine, another important thing is to get the buy-in from cells on whatever signal you're trying to send. Oftentimes, if you trigger this kind of resistance, you get drug habituation and failure to reset, to affect any kind of permanent cures. You can manage symptoms while you're giving a drug, but as soon as you take the drug away, it goes right back, or sometimes it gets worse. Most of our drugs have that property. The idea to avoid resistance is to change the set points, not to micromanage the symptoms or the current state, but to change what the collective of the cells is trying to do.

Slide 44/51 · 50m:38s

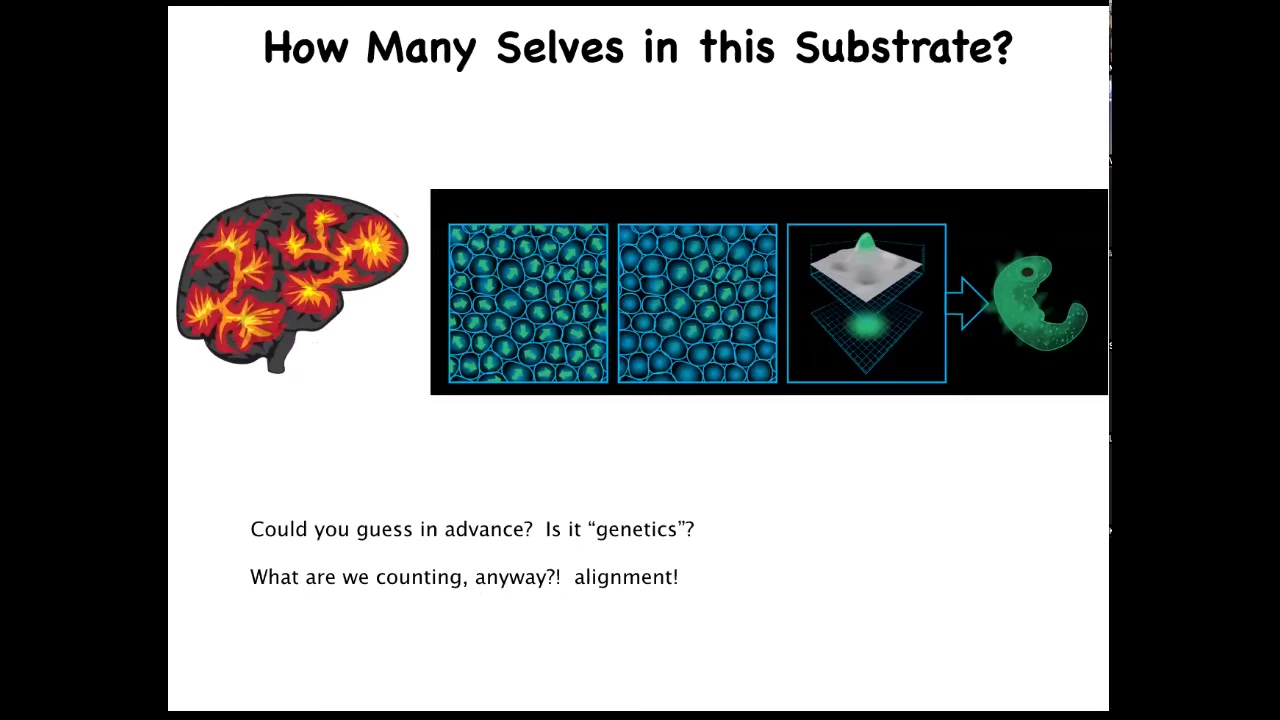

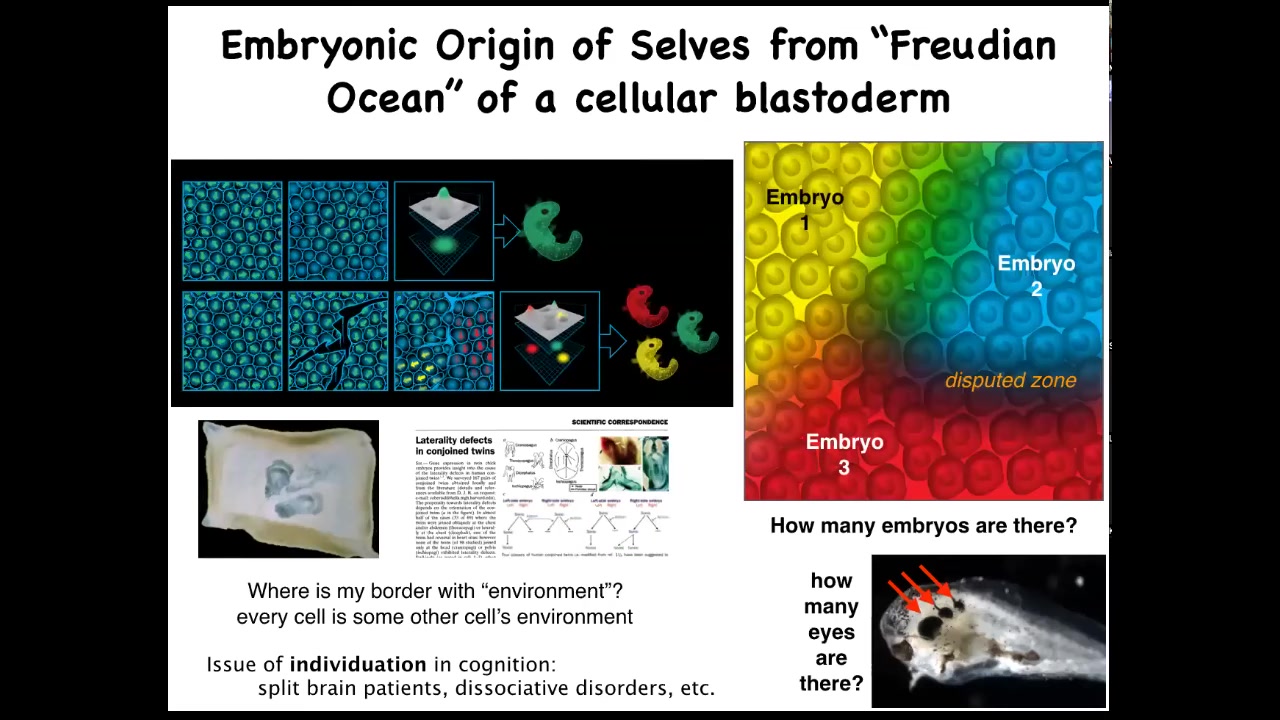

And so let's think about this. How do you set the boundaries between self and world? This is a schematic of an embryonic blastoderm, let's say 50,000 cells. We're all something like this — it's a flat sheet. When you look at this and you say there's an embryo, what are you really counting when you say there's one embryo? What is there one of? There's 50,000 cells. What there is one of is alignment, both physical, be it in the sense of planar cell polarity, but also an anatomical alignment of all of these cells towards a specific goal. All of these cells are working together to build one specific thing, meaning they all are going to take the same journey in that anatomical space from a single cell to a particular complex anatomy.

This is actually quite similar to a problem you might have when looking at a brain if you didn't already know what a human was and somebody showed you a 3 1/2-pound brain and said, how many individuals do you think fit in there? How many cognitive cells do you think could fit in there? We have absolutely no idea. We don't know the density of a typical neural medium for a typical human type of cognition. We really don't know how many you can fit in there. There's all kinds of interesting clinical work on that.

Slide 45/51 · 52m:02s

The same thing is true of the embryonic blastoderm. When I was a grad student, I used to do this experiment. Take a little needle and scratch—this is a duck embryo—put a little scratch in that blastoderm, and for about four hours, until they heal back up, each of these little islands doesn't feel the rest, and it decides that it's the embryo, and you get conjoined twins or triplets.

This means that when you look at one embryo, the question of how many cells or how many individuals are in there is not fixed by the genetics. It might be zero, it might be one, it's usually one, but it might be up to half a dozen, depending on what these cells decide to do and how the collectivity works.

Because every cell is every other cell's neighbor, every cell is somebody else's neighbor. In this kind of joined blastoderm, you see that each individual has to decide where I end and where the other guy begins.

That idea is right there from embryogenesis. Setting up that border between you and the outside world has to be calculated in the beginning. Some cells are confused, they're not sure, and that gives rise to laterality defects and conjoined twins.

This is something that we worked out back in 1996 or so: why conjoined twins have laterality defects. It's because some of these cells don't know, am I the right side of this one or am I the left side of that one?

Slide 46/51 · 53m:33s

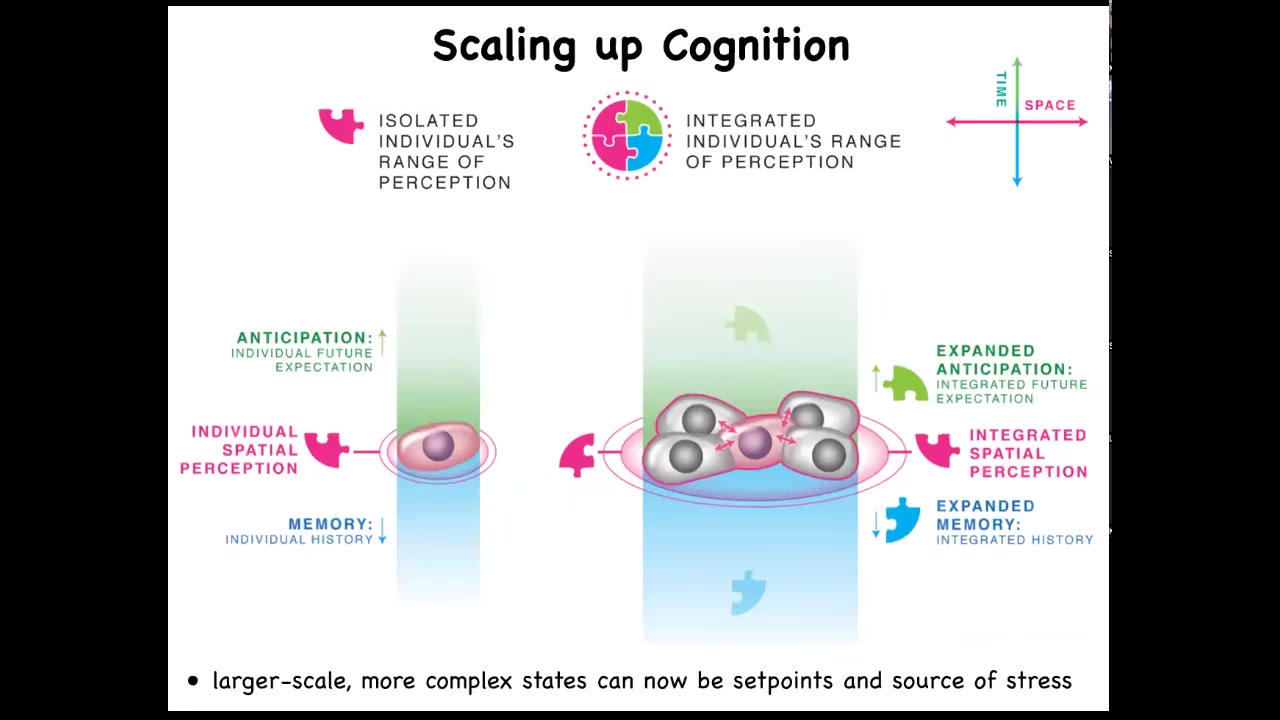

When cells get together, they are able to inflate or enlarge their cognitive light cone in space and time. They're able to perceive more signals. They're able to have larger computational capacities.

Slide 47/51 · 53m:51s

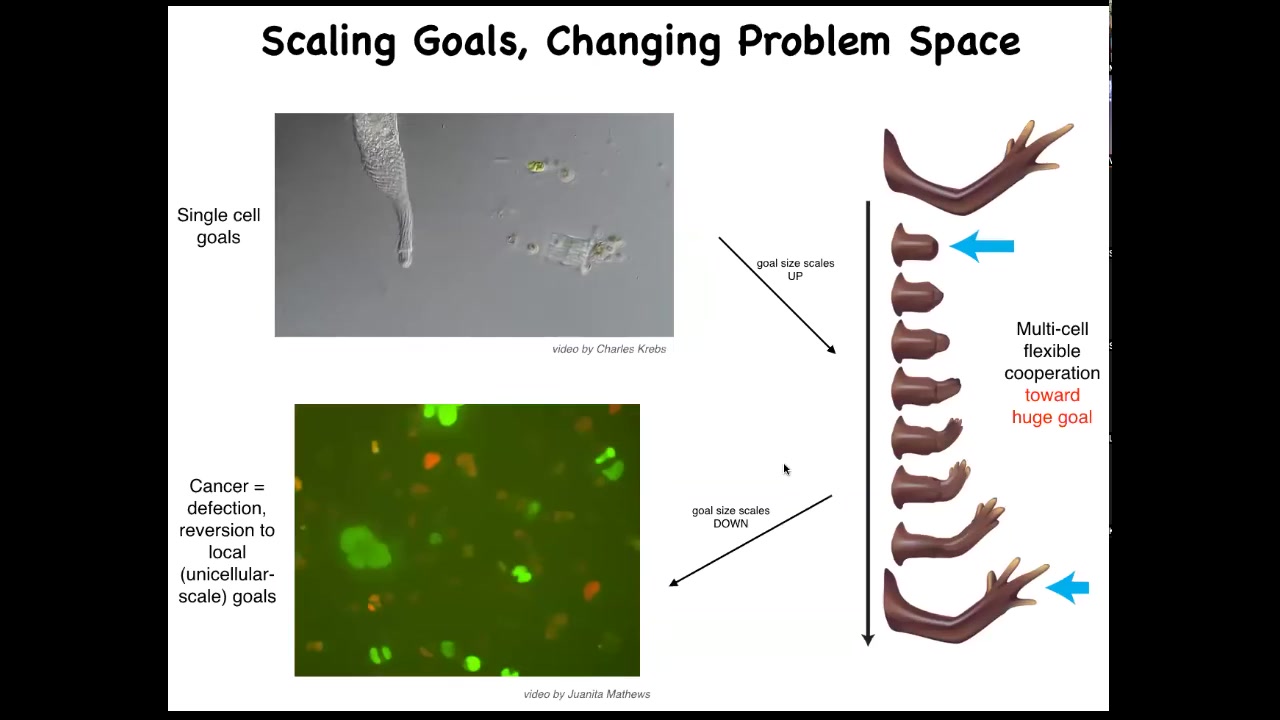

And this is what evolution has given us based on the ability for using this bioelectrical and other interfaces to scale up our goals from the tiny little goals of these cells, metabolic and so on, they scale up to these very grandiose goals of keep maintaining a limb and repairing it if anything happens to it. But that has a failure mode and that failure mode is cancer. When these cells disconnect from the electrical network, they can no longer support these complex representations of things they should be doing, they go back to a single-cell amoeba lifestyle, proliferate and migrate to wherever life is good. This is glioblastoma.

On this weird idea that cancer cells are not more selfish than other cell types: lots of game theory models model cells as being less cooperative or more selfish. They're not more selfish. I think it's just their cells are smaller. Whereas the self here is quite large and it maintains this whole thing. These have a little tiny amoeba-size self.

Slide 48/51 · 54m:50s

And so using that crazy idea, we've actually developed a therapeutic around inflating the boundary between self and world for these transformed cells, not killing them, but actually co-injecting ion channels that force them to remain in electrical connection to the rest of the tissue.

These are nasty oncogenes: KRAS mutations and so on. But if you manage the bioelectrics appropriately, even though the oncoprotein is blazingly expressed — it's all over the place — there's no tumor. This is the same animal. There's no tumor. And that's because it's not the genetics, it's not the oncogene that drives the phenotype, it's the physiology. It's the decision of the cells in a collective that they're not going to be overacting as amoebas, they're going to be making nice skin, nice muscle, and so on.

Remarkably, that process actually involves bacteria. It involves butyrate made by bacteria. We studied that in this paper. It works at a distance from where the oncogenes actually are because there's this signaling depending on a butyrate transporter that's part of this whole process. Once again, the microbiome is key here.

Slide 49/51 · 56m:03s

This idea of cells hacking each other is ubiquitous. We are only able to do these things because that is what the cells expect. When we inject an ion channel to force these cells to build an eye, if we only hit a few of them, this is a cross-section of a lens sitting in the tail of a tadpole, and the blue ones are the ones we injected, what do they do? They hack all their neighbors to cause them to participate with them because there's not enough of them. They know there's not enough of them to make a proper lens, so they recruit their neighbors.

That is seen in other kinds of collective intelligences like ants and termites, where a few of them will take on a project, there's not enough of them, so they will recruit their buddies to help them. The cells are constantly hacking each other and trying to convince each other to do new things. Sometimes they cooperate, sometimes they compete. This is all discussed here. Competition between your body parts is quite important.

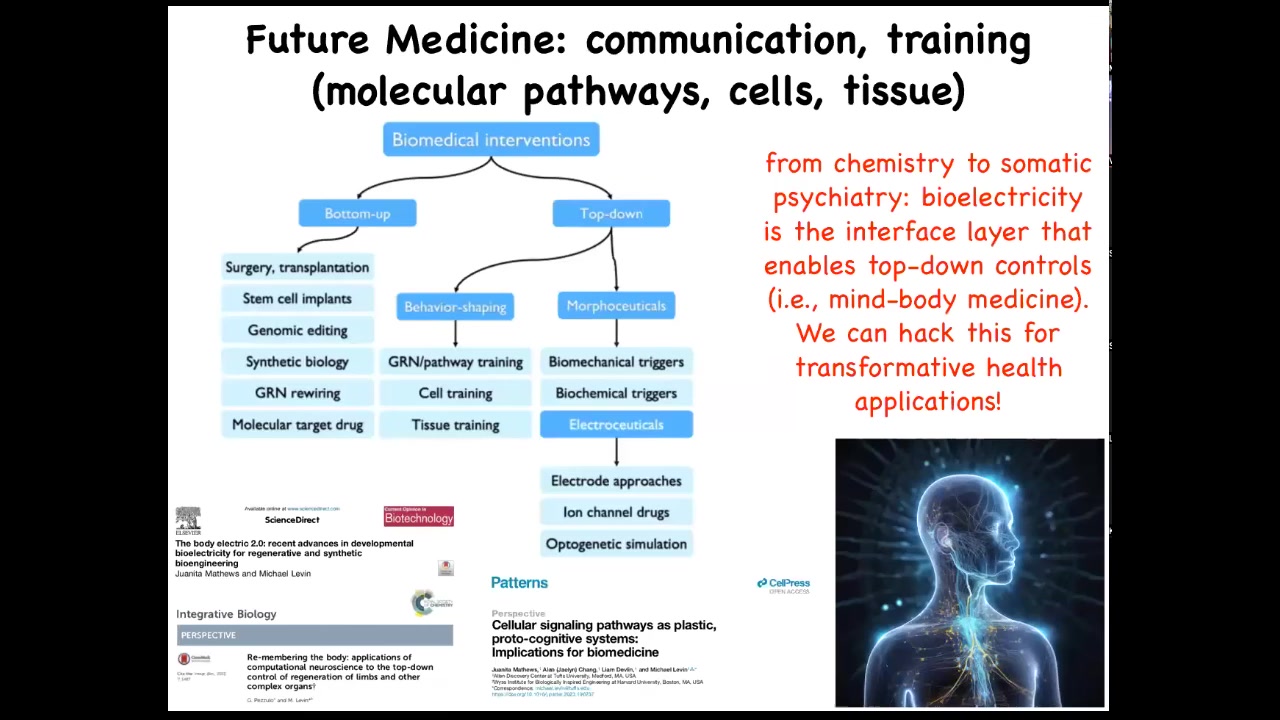

All of this focuses on not a bottom-up approach where we talk about micromanaging specific pathways, but a top-down approach where we ask, What does the collective remember?

Slide 50/51 · 57m:09s

What are the goals that it's trying to reach? Where are the set points encoded? And how could we hack them by rewriting the set points and talking to them at a very high level?

This is my layout of biomedicine, where most of what's going on is here: these bottom-up interventions that are trying to micromanage certain things. All of this is what I think of as future medicine, this idea that it's going to look a lot more like somatic psychiatry and a lot less like chemistry, because all the key models in this field are going to be around information. They're going to be around what the collective agents at different scales believe, what's their calculus of decision making, and so on. And you can read more about that here.

Lots more papers if anybody wants to dig down in some of the philosophical aspects about what machines are and what cognition is and so on.

Slide 51/51 · 58m:04s

I'll stop here and thank the people who did all the work. J.F. Pare, who did the innate immune system bioelectrics, and Celia Herrera-Rincon, who did the brain and immune system work; Pai Vipav Pai did all the ectopic eye work; the planaria work was done by Johanna Bischoff and Fallon Durant. Danny Adams did the voltage dyes, and Juanita and Brooke are working on the bioelectrics of cancer. I'll thank our various technical support that we have in the lab, our many amazing collaborators, our funders here that have supported the work that I told you about. Two disclosures: Morphaceuticals and Astonishing Labs, which are two companies that support some of our work, and most of all, the model systems, because the animals really do all the hard work. Thank you very much, and that's it. I'll take questions.