Watch Episode Here

Listen to Episode Here

Show Notes

In this 1-hour TAME talk, we explore the Technological Approach to Mind Everywhere and how bioelectricity scales simple cells into collective intelligences that shape anatomy. Learn why morphogenesis can be seen as problem solving in morphospace, how developmental bioelectricity serves as a medium for memory and decision-making, and what synthetic bioengineering means for new bodies, minds, and future ethics.

CHAPTERS:

(00:00) TAME and nested cognition

(11:25) Intelligence in abstract spaces

(29:43) Morphogenesis as collective intelligence

(50:45) Bioelectric memories and xenobots

PRODUCED BY:

SOCIAL LINKS:

Podcast Website: https://thoughtforms-life.aipodcast.ing

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3pVafx6EZqXVI2V_Efu2uw

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/thoughtforms-life/id1805908099

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/7JCmtoeH53neYyZeOZ6ym5

Twitter: https://x.com/drmichaellevin

Blog: https://thoughtforms.life

The Levin Lab: https://drmichaellevin.org

Lecture Companion (PDF)

Download a formatted PDF that pairs each slide with the aligned spoken transcript from the lecture.

📄 Download Lecture Companion PDF

Transcript

This transcript is automatically generated; we strive for accuracy, but errors in wording or speaker identification may occur. Please verify key details when needed.

Slide 1/50 · 00m:00s

Which is a collection of ideas that I call "Technological Approach to Mind Everywhere" (TAME).

What I'm going to describe today is the idea that what bioelectricity does is it scales a basal cognition into a collective intelligence. In particular, I'm going to talk about the collective intelligence of morphogenesis or anatomical control. I'm going to tie that into a few other things.

If anybody wants to get hold of me afterwards, all of the contact info, the papers, and the primary data are at these two websites.

Slide 2/50 · 00m:39s

So the main points that I'd like to transmit are these tips for today. I take the view that the question of whether a system is cognitive, intelligent, and so on is a bad question, because it presupposes a binarization that doesn't exist. The real question for any given system is how much and what kind of intelligence, agency, and so on that system has. We need to frame it as an engineering problem. It's not a question of philosophy where some people will say thermostats don't have any agency. We can't say that from an armchair. It has to be an engineering problem.

The way it's a scientific or an engineering problem is that we need to assign to any given system whatever degree of intelligence or agency gives you the best prediction and control over that system. Okay, so it's a little bit like Dennett's intentional stance in that way, but it's a very practical, pragmatic approach. It's designed to drive forward a research agenda.

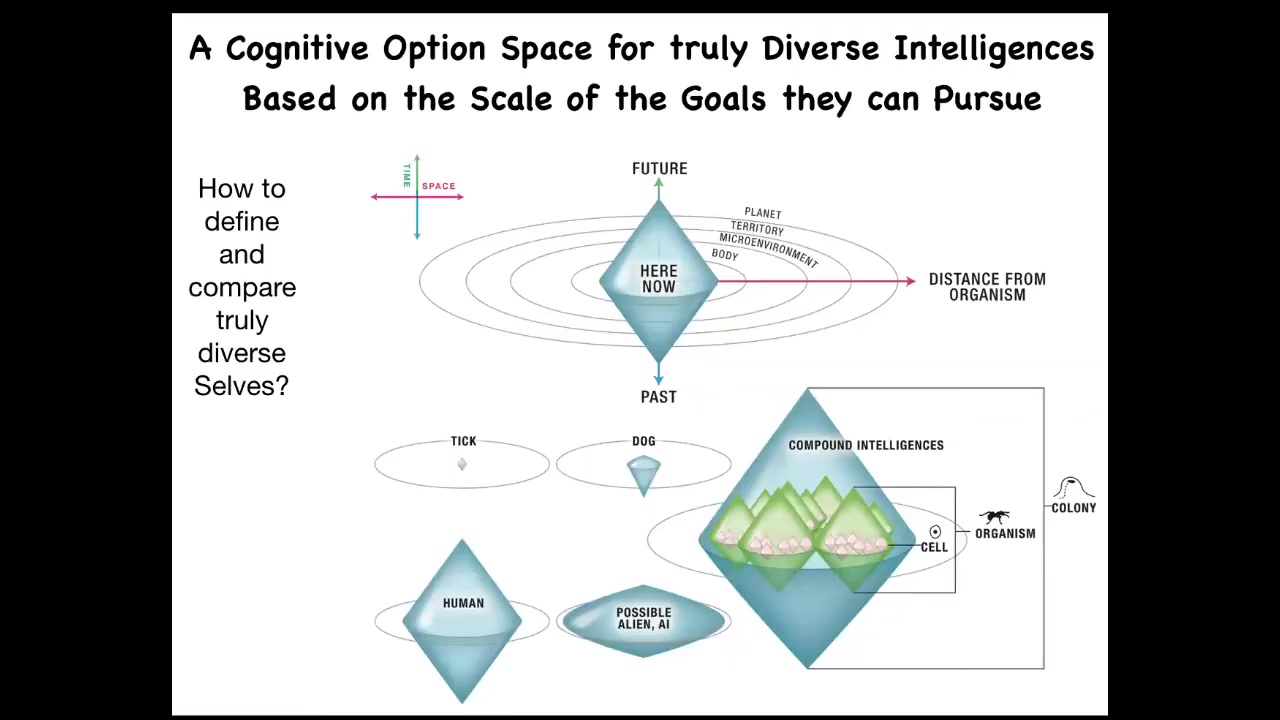

What I'd like to do is develop a framework that allows us to directly compare truly diverse intelligences, and you'll see what I mean by this. I've developed a framework around the scale of the goals that any given agent can pursue. The goals that are within that range define a sort of cognitive light cone of the kinds of things that agents can pursue and the kinds of goals that they can represent.

Morphogenesis is best understood not as a set of molecular mechanisms, but as an unconventional collective intelligence. It solves problems in morphospace, and an extension of the methods of neuroscience to bioelectricity outside the brain, or developmental bioelectricity, provides an interesting new lens on this problem of how you integrate diverse competent subunits into one higher-level cognitive structure.

I'm going to close with some interesting data from synthetic bioengineering in our lab and then talk about the future, which provides an astronomically large option space for new kinds of bodies and minds that are going to stretch our ability to use existing frameworks and terminology thrown around all the time, such as machine and robot, that are going to need to be completely revamped.

So the goal of the framework that I'm working on is to enable comparison of truly diverse intelligences that has nothing to do with their composition, meaning whether they're wet and biological or electronic or some other exotic material, or their origin story, meaning whether they are designed, evolved, or some combination of both. This means that we need to be able to compare and think about not only the familiar creatures that we're used to, but also very weird ones like colonial organisms and swarms, and novel engineered life forms. I'll show some examples of these today.

Of course, artificial intelligences are being produced and will increasingly be produced, and perhaps at some point even exobiological agents. At the very least, we should have an idea of how we would recognize one if we came across one. The key to this framework is that it has to move experiment forward. It has to be empirical and has to drive novel experiments.

I want to start off by trying to pull at the edges of typical model systems that people use and highlight some novel aspects, then move into what we've done in terms of this technological approach, and then show some novel organisms.

So let's start off by thinking about the typical example that people work with: some animal. They say here's my rat and it has memory and we know what the agent here is. It's the rat and it has memories that it's formed and it has preferences.

One of the interesting things about biology is that it's extremely plastic, and this is going to be a theme throughout the talk. Here's a typical life cycle.

You've got this soft-bodied creature, this caterpillar that crawls and chews plants. It's got a brain suitable for driving an organism of that type. Then it has to turn into an entirely different creature, which is hard-bodied and has to fly and drink nectar, has a completely different brain. During this transition from here to there, the brain is largely liquefied, the connections are broken down, many of the cells die. But what does remain is information, learned information. So things that the caterpillar learns are recovered in the behavior of the butterfly or moth.

So this has very important implications for understanding what memory is in the first place. How do you store information in a medium that's completely malleable and changes on the fly? It drives us to ask important questions, not only what's it like to be a caterpillar or a butterfly, but what's it like to be a caterpillar slowly changing into a butterfly? Because this is not some very long-term evolutionary process that we can zoom in and just look at individual animals. This happens during the lifetime of a single cognitive agent.

So we have to think about this plasticity. Every animal and plant has this issue because we all develop from one cell. And so there's this process of you start off as a collection of cells, eventually you're uncontroversially a cognitive agent. What happened in between and how did that work?

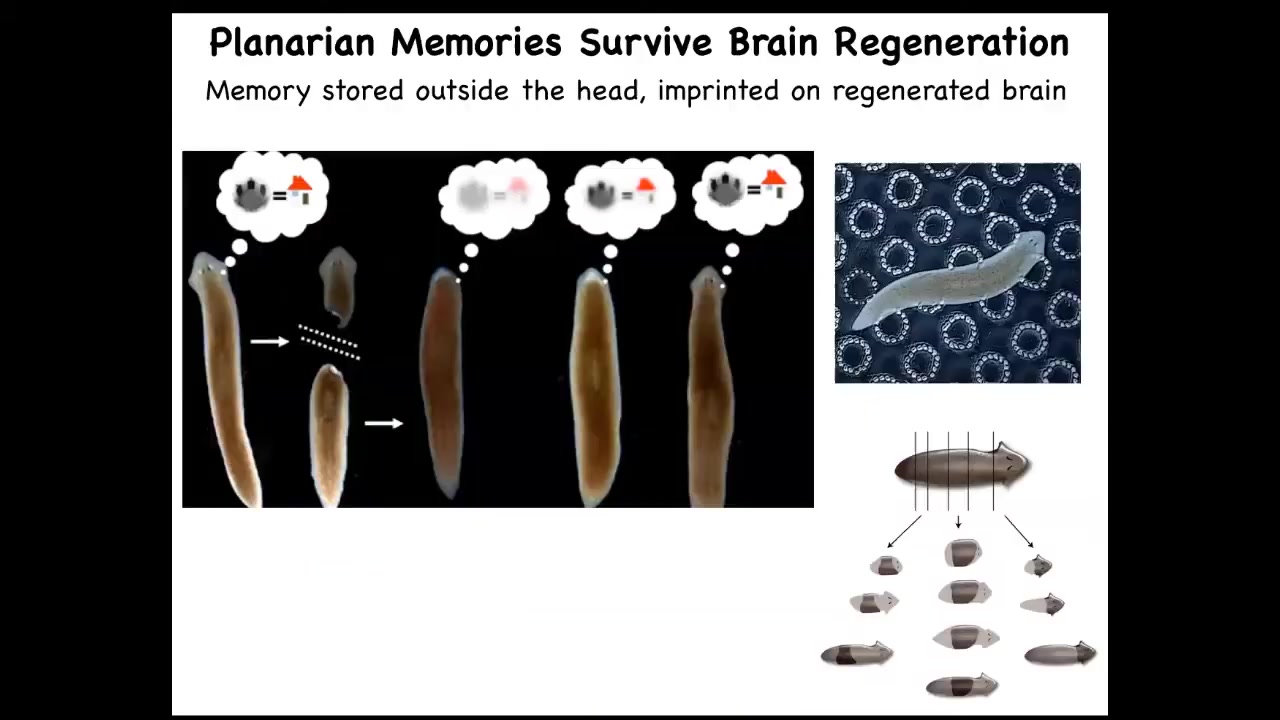

Slide 3/50 · 06m:48s

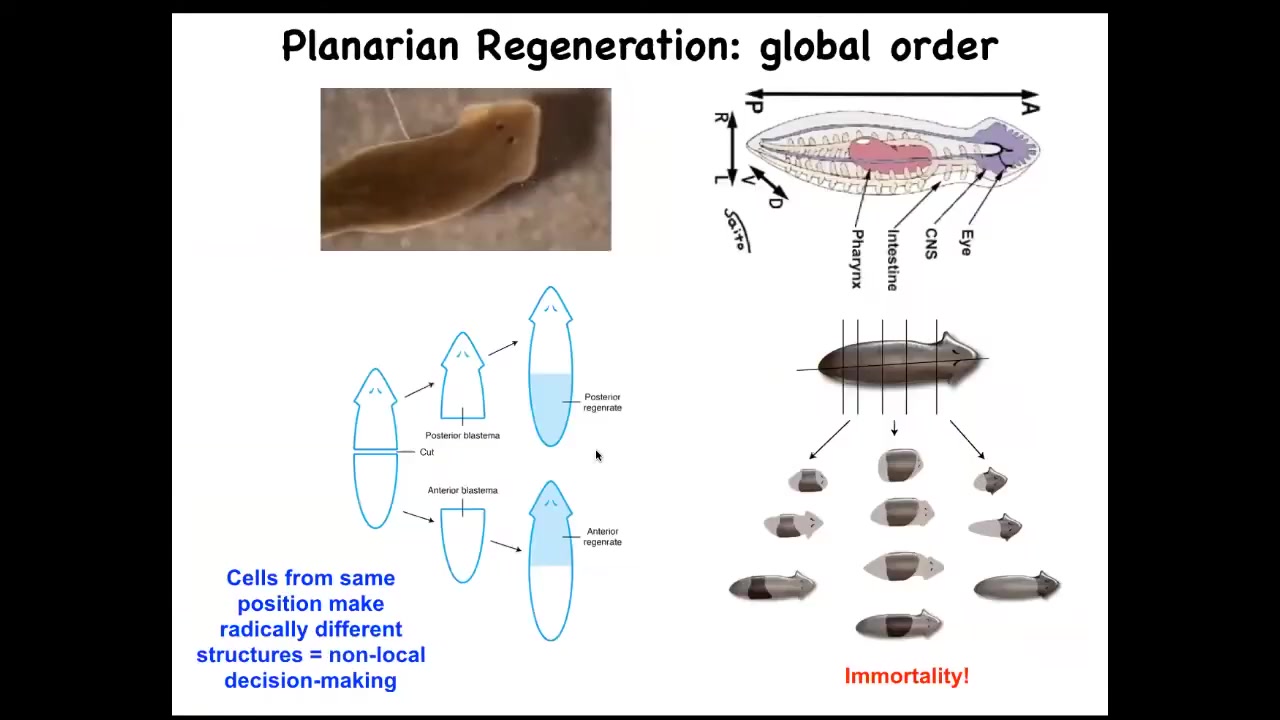

Even this happens even more drastically in planaria. These are the champions of regeneration: you can cut them into pieces and every piece gives rise to a complete worm. You can train them. You can train them on the fact that they're fed on this bumpy laser-etched little surface, and then you can cut off their heads. They have a true brain, all the same neurotransmitters that you and I have. The tail will sit there for eight days doing nothing. Eventually they will grow a new brain. This animal, now with this new brain, remembers the original information.

The rest of the body contains, presumably, some amount of that information, and it imprints it onto this novel brain as it's developing so that it can drive behavior. This plasticity of memory moving from one place to another raises the question: if we take memory to be some kind of indicator of individual identity, once you've chopped up a planarian into pieces, what happens to the original individual? It's gone, but on the other hand, it's now become 10 other individuals with similar memories. All of the old Philosophy of Mind 101 questions about duplicators are accurate and perfectly doable in this creature. It happens.

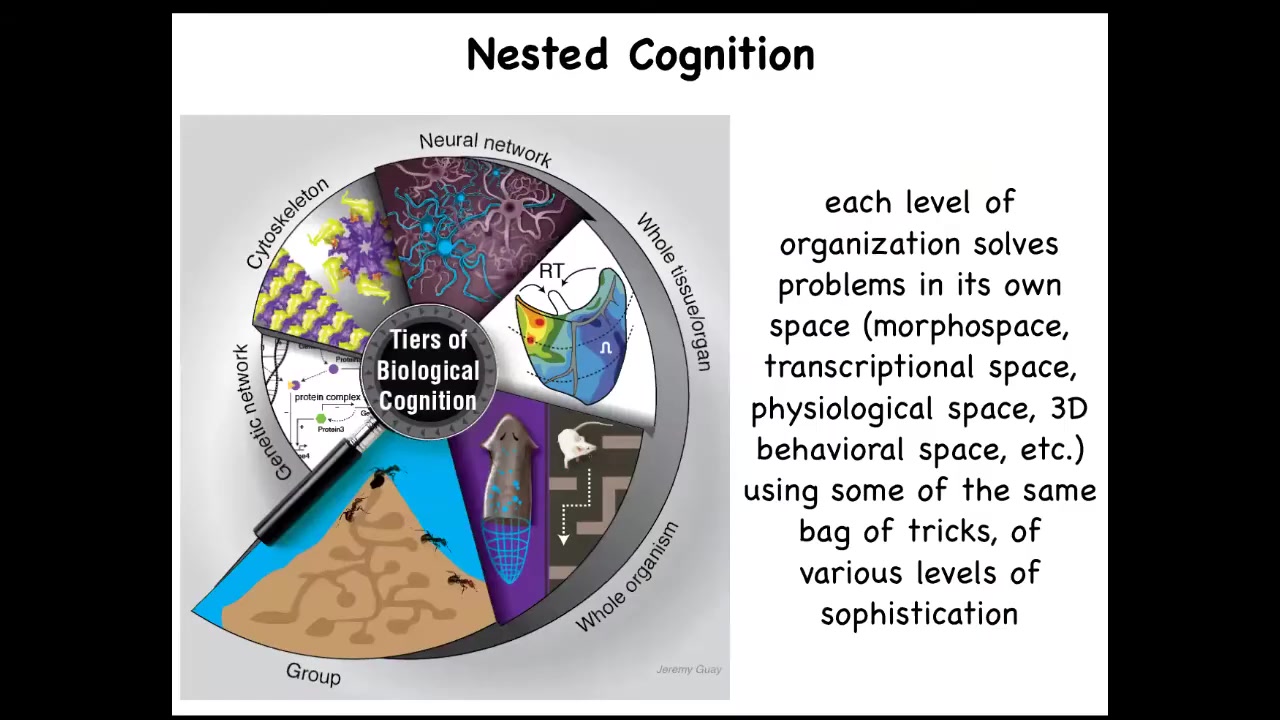

Slide 4/50 · 08m:13s

So what we're interested in is this idea of nested cognition, not simply the obvious fact that living things are a nested-doll architecture where the swarm is made of individuals, which are made of organs, made of tissues and so on, but that every level here is not merely structural, but solves problems in its own space. So molecular networks have kinds of memories and optimization that they can do. At every level, you have a system with the ability to solve problems in its own special space.

Slide 5/50 · 08m:54s

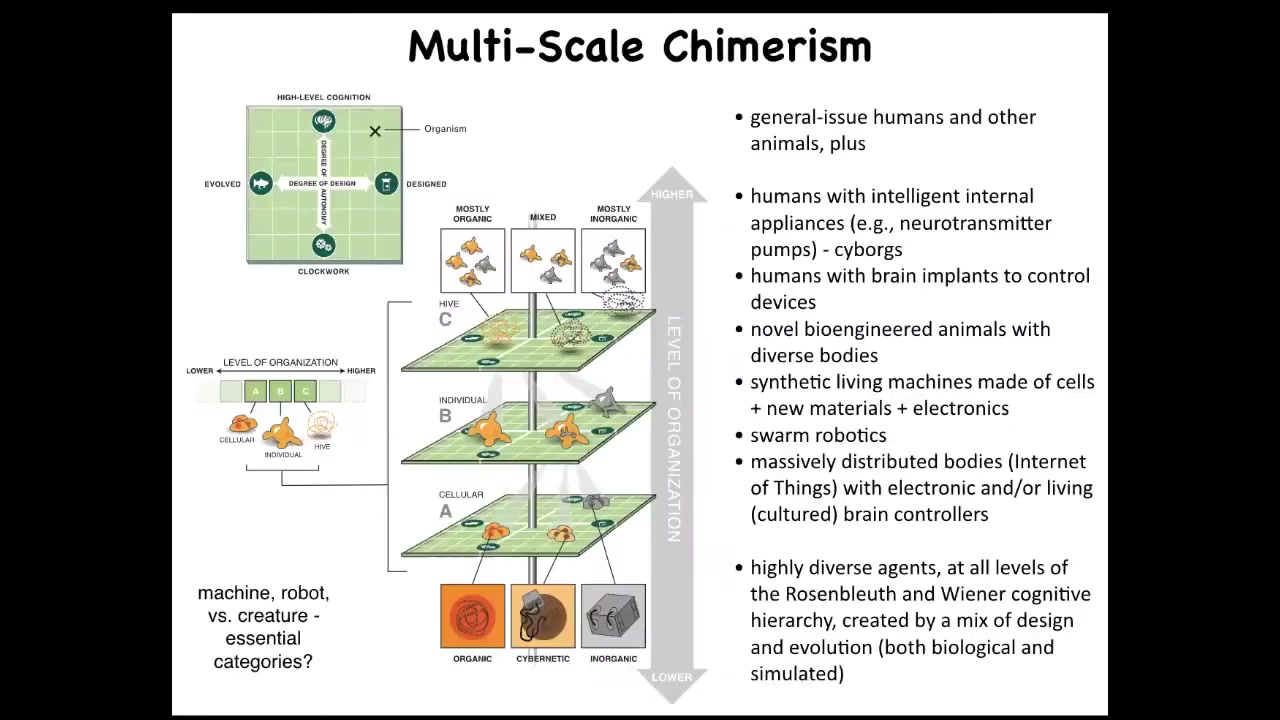

One of the things we can do is in any multi-scale system like this, we can now swap out components.

Within any organism, for example, at the cellular level, at the organ level, at the swarm level, you can replace its original evolved components with novel things that we have engineered. You can put in things that are anywhere on this plane that ranges from very passive materials all the way to smart materials and smart kinds of artifacts, and they might be evolved and they might be designed. There's an incredible interoperability in life, which allows you to change out the components on the fly. Everything works together. We already have humans that drive prosthetic limbs and wheelchairs with their minds. We have hybrots, which are robots with biological tissues driving them. We have hybrids and chimeras.

The interesting thing about being able to make all of these novel types of agents is that they will land somewhere on this continuum. This is Wiener and Rosenblueth's continuum of cognition. You can see here that while there are phase transitions to more advanced capabilities, it isn't a binary line. There are many different types of simple to complex cognitive capacities. All of these things, which we've never seen before, will have to be placed somewhere by experiment because we won't be able to assume. It won't be like it is now where you can look at something and say that looks like a fish and we know more or less where fish land. We're going to have things that we have absolutely no idea of their capacities because they don't look like anything that we've ever seen before.

Can I ask a question there? Can you go back one slide?

You mentioned phase transitions here in this framework. Do they suggest what the physical mechanism is behind that phase transition or is this more conceptual phase transition?

Yes, I will suggest a couple of examples. They're not meant to be exhaustive. I'm sure there are many others, but I will show you one or two that I think are required for this. Let's take a look at this.

Slide 6/50 · 11m:28s

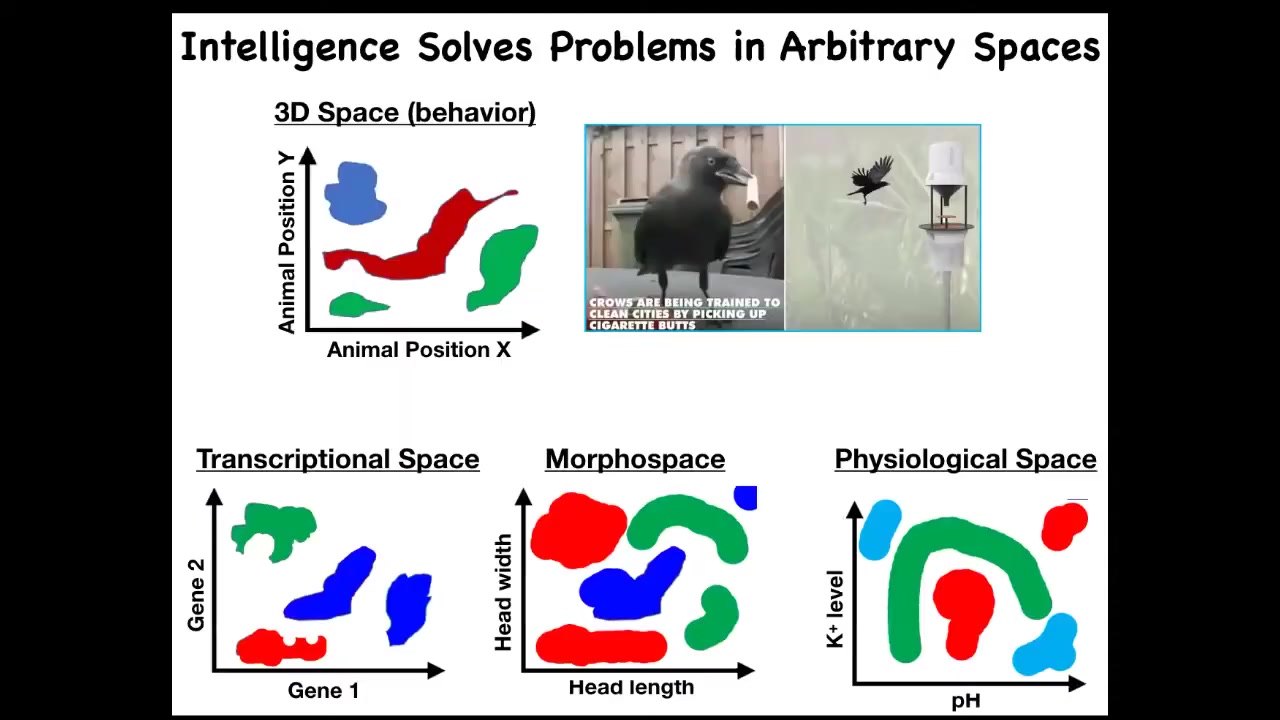

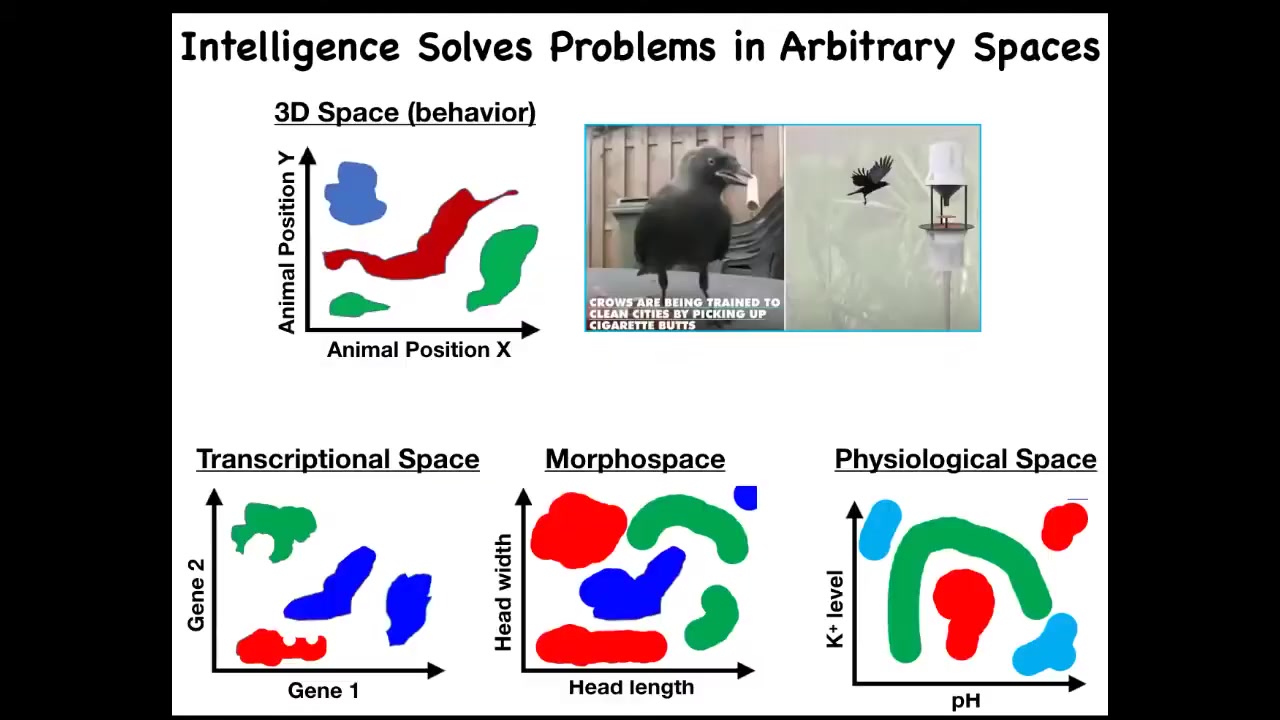

One thing that I would like to do is to generalize this issue of intelligence. There are many definitions of intelligence. I'm not claiming this is the only one, but it's one useful one. This idea of solving problems in arbitrary spaces is powerful because we're used to things like this, where intelligence is a type of behavior, meaning movement in three-dimensional space.

We are surrounded by intelligences that solve problems in gene expression space, in anatomical morphospace, which I'll show you many examples of today, and physiological space. The reason, I think, that we are very good at recognizing intelligence of this type is because all of our sensory organs point outwards. Our training set of noticing other systems behaving is all about things moving in three-dimensional space. If we had sensors that routinely examine the states of our inner organs, it would be really easy for us to recognize our liver, our pancreas as fairly intelligent types of agents operating in physiological space and transcriptional space, solving problems. If we had access to our developmental stages, we would actually be able to recognize morphospace as well. We traditionally don't have any of these. I'm going to try to expand to that.

We can define intelligence as the ability to navigate in these various spaces. I've just, for the purposes of the slide, knocked it down to two dimensions each, but these are very high, especially this one is a very high-dimensional space.

Slide 7/50 · 13m:12s

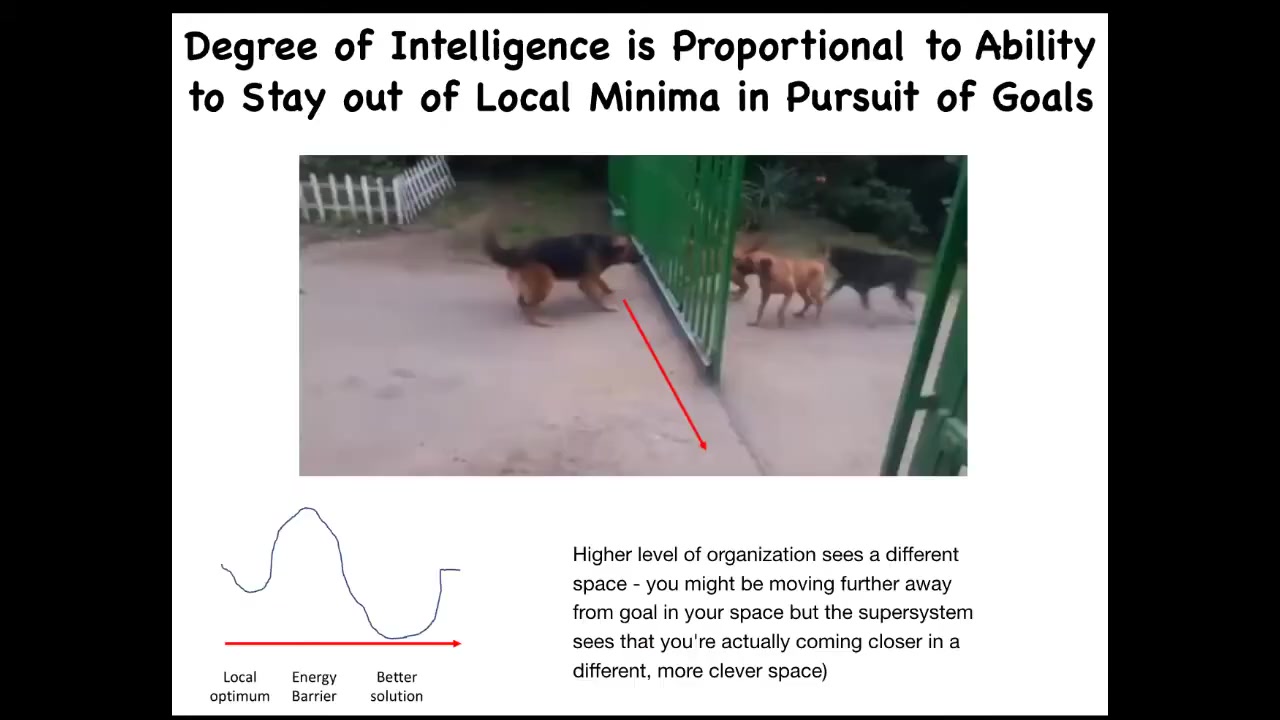

And one can also say that your amount of intelligence or your degree of intelligence is your competency to pursue goals in that state without getting trapped by local minima. So here, for example, there's the goal which this animal wants to get to. In order to come around and actually get there, he would have to temporarily get further away from the goal. It's not a direct line to where he's going, but higher levels of organization allow a higher IQ for systems that can actually navigate to a better maximum without getting trapped. And so your ability to do that is a kind of estimate of your intelligence. We'll get to another metric momentarily.

Slide 8/50 · 13m:57s

We can see that perhaps what evolution did was to pivot some of the same tricks in solving these problems. Very early life had to solve problems only in metabolic space, but then eventually genes came along and you had to solve problems in a transcriptional and physiological space. Eventually multicellularity meant you had to solve problems in morphospace. And eventually when nervous systems and muscles came along, you had to solve problems in three-dimensional space. Could it be that evolution makes use of some of the same principles to solve problems in these different spaces? Here's a transitional form.

Slide 9/50 · 14m:32s

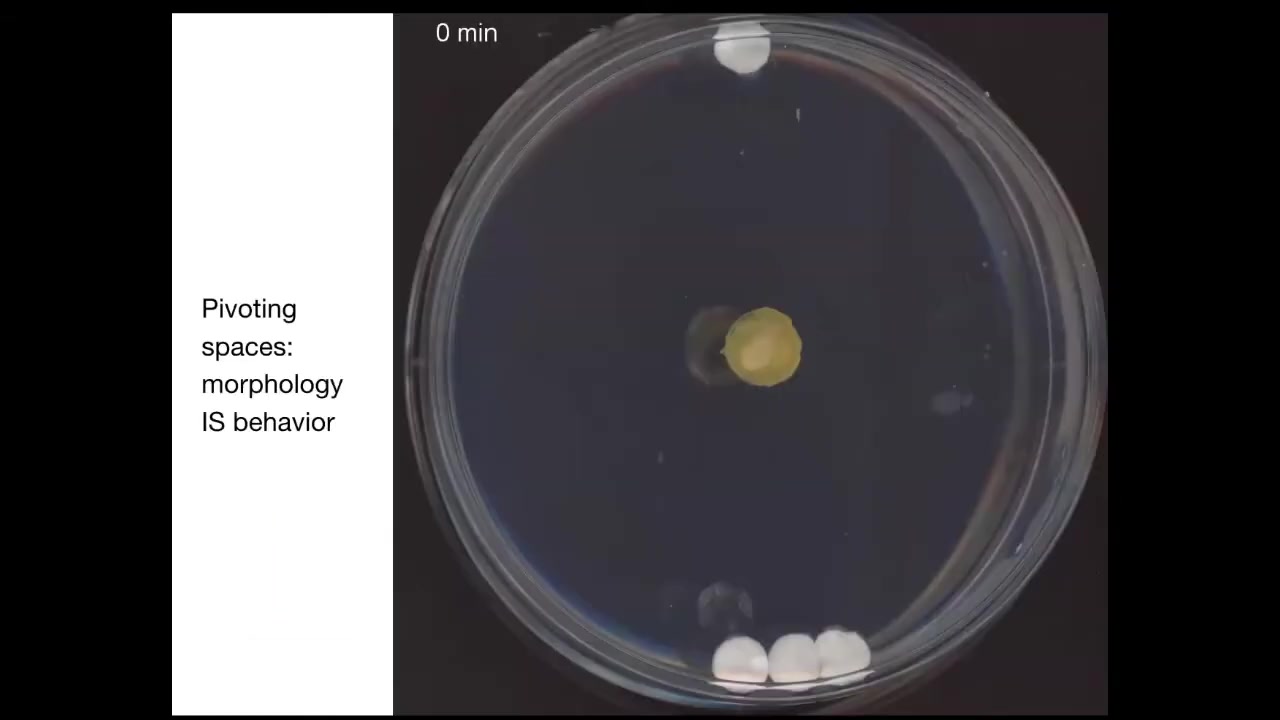

This is a slime mold known as Physarum. In this system, I'm going to play this movie momentarily; its behavior is its morphology.

What you're catching here by studying this organism is that pivot point of an organism where two of those spaces intersect, where learning to solve problems by changing your shape is in fact solving problems in three-dimensional behavior.

To show you an example, this is something we discovered a couple of years ago. If you put the slime mold down here, you put one glass disc up here, you put three glass discs back here. There's no food on these discs. They're completely inert, just glass. The only thing it has to go on is mass. But as it turns out, using a kind of sonar, sensing of pressure waves and tension in the environment, it's able to build a picture of the distribution of mass. What it will do is for the first few hours, it just grows out equally here. This is about four hours. Then at this point, it figures out where the bigger mass is, and that's where it goes. This is quite reliable. It always prefers the bigger mass, and it always goes to the bigger mass first. The behavior of this animal in solving this problem is in fact morphology. All it can do is change its body shape.

By the way, this whole thing is one cell.

Slide 10/50 · 16m:00s

One way to start thinking about very unconventional intelligence is, you ask yourself, what do all intelligences have in common? If it's not what they're made of, and if it's not how they got here, meaning evolution, design, whatever, the question is, what do they have in common? I think one useful, not exclusively, not the only thing, but one useful invariant is their ability to pursue goals.

You can map out, I've collapsed it into 3 dimensions of space here and then one at a time. It's like a Minkowski diagram in relativity. You can map out the size of the goals that any given agent can represent. This is not the size of their sensory reach or the size of their activity, but the size of the goals that they can represent.

If you're a very simple organism like a bacterium or a tick, you probably have very limited memory in the past, very limited predictive power forward. And all you're doing is measuring very local concentrations and things you care about, sugar or butyrate. Your cognitive light cone is quite small.

If you're another more sophisticated animal, you might have some considerable memory going backwards. You might have predictive capacity going forwards. You will still never care about what happens in two weeks and the next town over. It's just impossible. Your cognition is not capable of holding on to goals of that magnitude.

If you're a human, you might have an immense cognitive light cone. You may be working towards world peace and literally exerting efforts to manage the state of things on a planetary scale. You may be depressed because some of your goals are so far in the future, they extend any plausible lifespan that you may have. Uniquely, humans can have this problem.

If you're an alien or some sort of AI, you might have a weirdly shaped cone that's bigger, smaller, or different than what we're used to. All of these are compound. Your cells, your organisms, and your tissues will have their own different types of cognitive light cones.

By focusing on the goal directedness of this, a couple of interesting things happen. The first thing that happens is that it allows you to compare directly systems that are extremely different from each other. The other thing that it does is it gives you some insight into a notion of stress if we label stress as the driver between the target goal state, where you'd like to be, and where we are now.

Because, if you tell me what you're stressed out about or the things that are capable of stressing you, I can guess where you are on this kind of continuum. If the only thing you can be stressed about is the local concentration of glucose, you're one type of organism. If you're stressed about the future of the global stock market, you're a very different kind of agent.

Slide 11/50 · 19m:12s

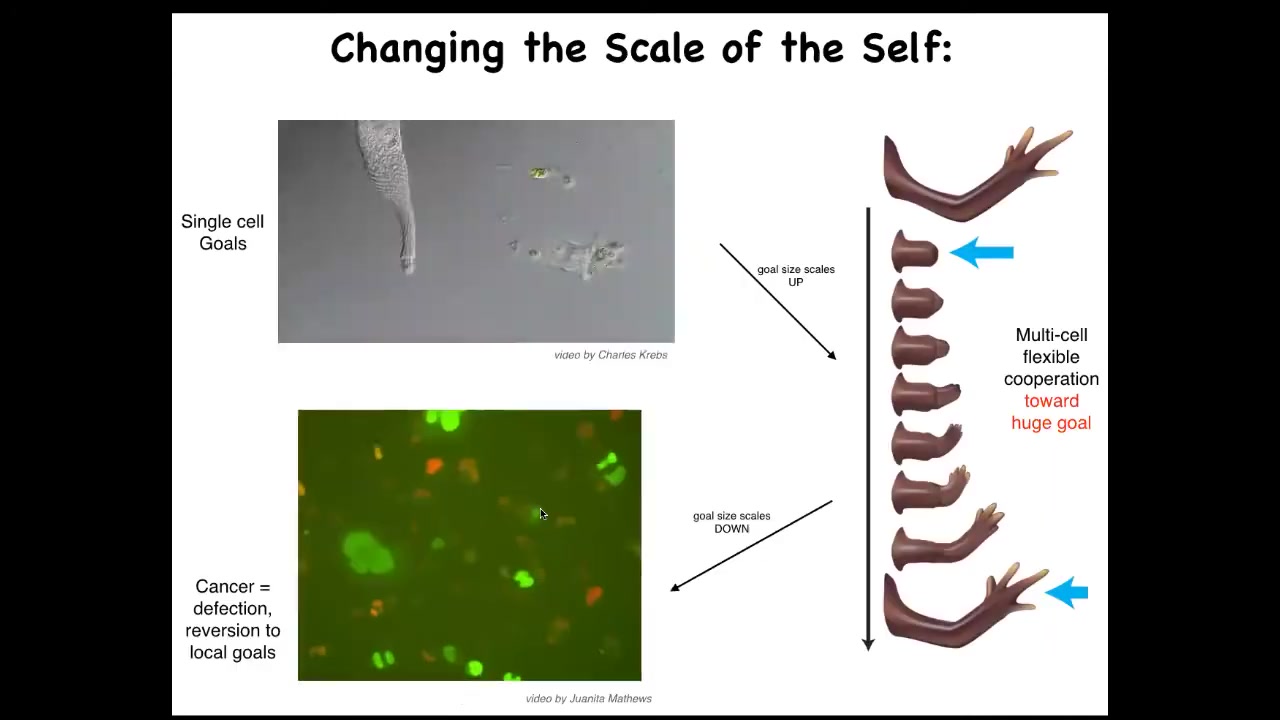

One thing that we see then is that the scale of the goals on which you are working can shift during your lifetime. This is a single-celled organism. It's called the lacrimaria. This little guy handles all of its single-cell goals. There's no brain, there's no nervous system, but all of its anatomical, its physiological, its metabolic goals are all handled on a very small scale here.

But when cells work together, they can work on very large goals. Here's one example, multicellular organisms like the salamander. If you were to amputate this limb, what the cells will do is they will immediately recognize that there's a problem, and they will work together, including the death of many of them, because programmed cell death is an important part of this. They will work together to rebuild this very large structure, this limb. They will stop working when their goal is complete. When does regeneration stop? When the correct structure is finished. They recognize the structure is complete, and the collective stops working. Individual cells don't know anything about this. They don't know what a finger is. They don't know what the length of a hand is. Individual cells can only handle local goals, but collectives can handle very large goals.

Unfortunately, that scale-up process can break down. During the lifetime of this animal, one individual cell can become disconnected from the collective. What happens then is that the goals on which it's working shrink back down to its unicellular past. What you're seeing here is glioblastoma. These are cancer cells. The dream of each one of these cells is to become two cells and to go where life is good, and that is all. They are not going to be working on anything useful like an organ or a tissue. They will at best make a tumor, but they're just metastasizing as amoebas, and they treat the rest of the organism as just environment.

Slide 12/50 · 21m:22s

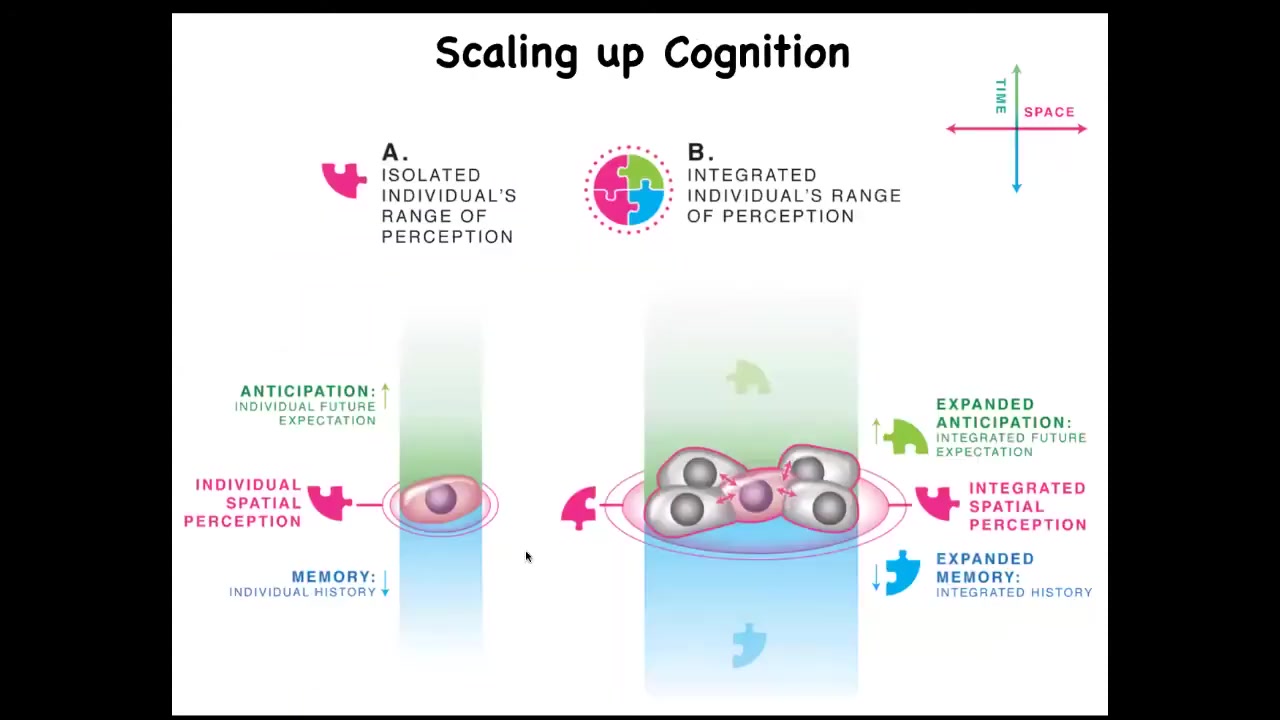

What we have to keep an eye on, and this is where bioelectricity is going to come in momentarily, is that individual cells have an incentive. An individual cell on the same scale has predictive value, memory, and local quantities that it's trying to minimize or maximize.

But surrounding yourself with copies of yourself in a multicellular setting has an important advantage. It gives you improved predictive value because the thing that is the most predictive for you and the least surprising is yourself. This ties in nicely with Carl Friston's active inference framework, or surprise minimization, and suggests that in attempts to predict and manage their environment, cells can get together and become a larger network, which has a spatially bigger area of measurement that it can take. It has more computational capacity for prediction and memory.

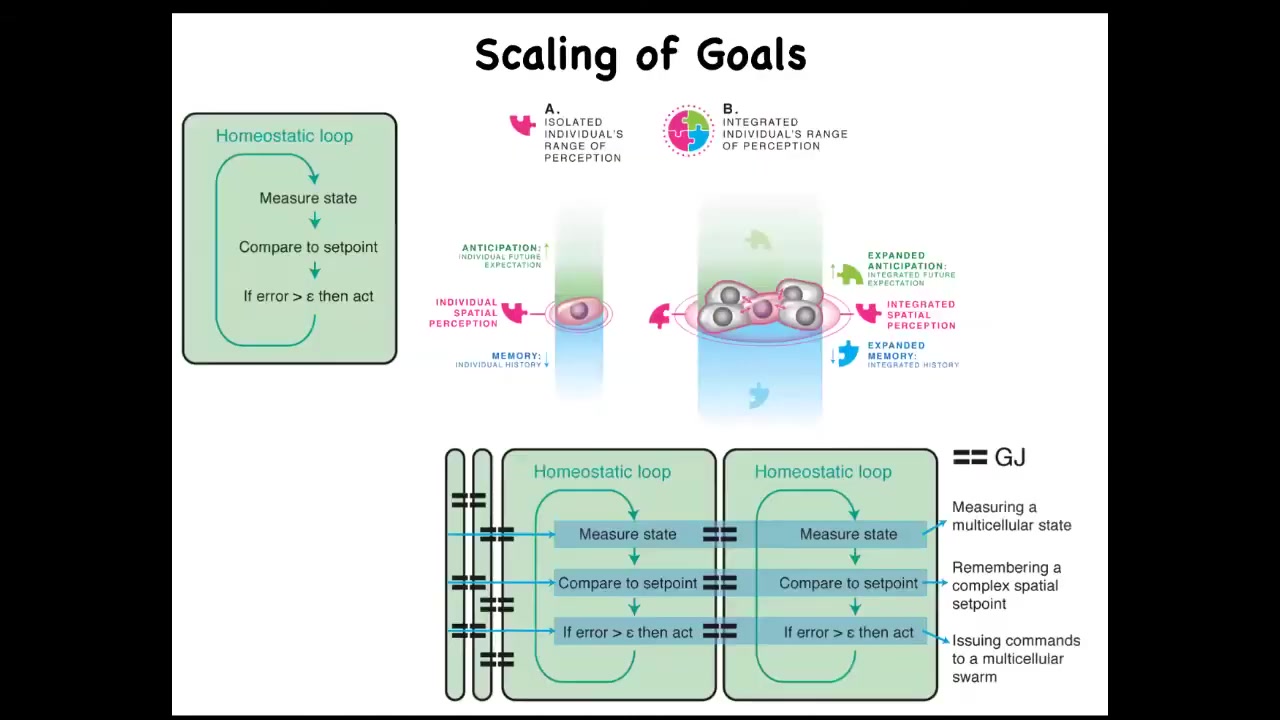

What happens now is that whereas single cells can only measure and react to very small local things, the point of what it's trying to do is to take measurements of things it cares about, decide whether it needs to make adjustments towards the state it prefers, and then run that homeostatic cycle again and again to try to stay in a good area. Collections or networks, by virtue of connecting to each other, can measure, can represent, and can work towards larger goals. Their goals inflate. We're going to get into this in some detail.

Slide 13/50 · 23m:03s

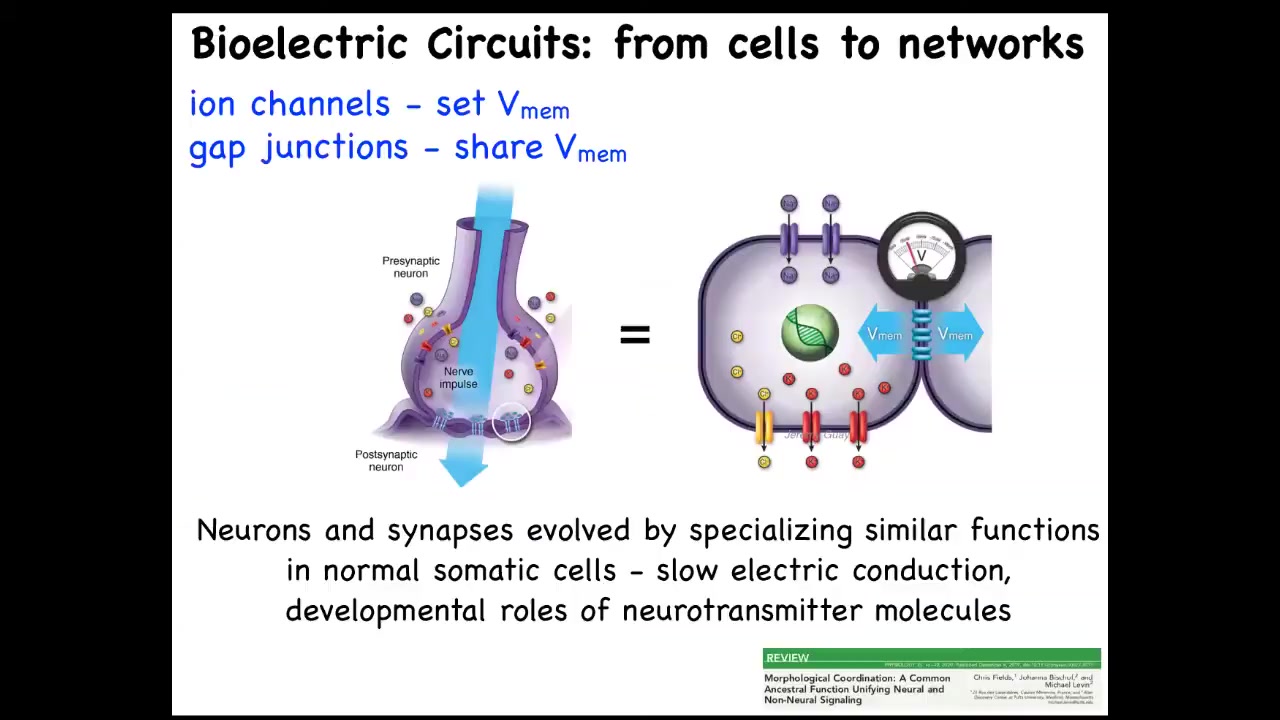

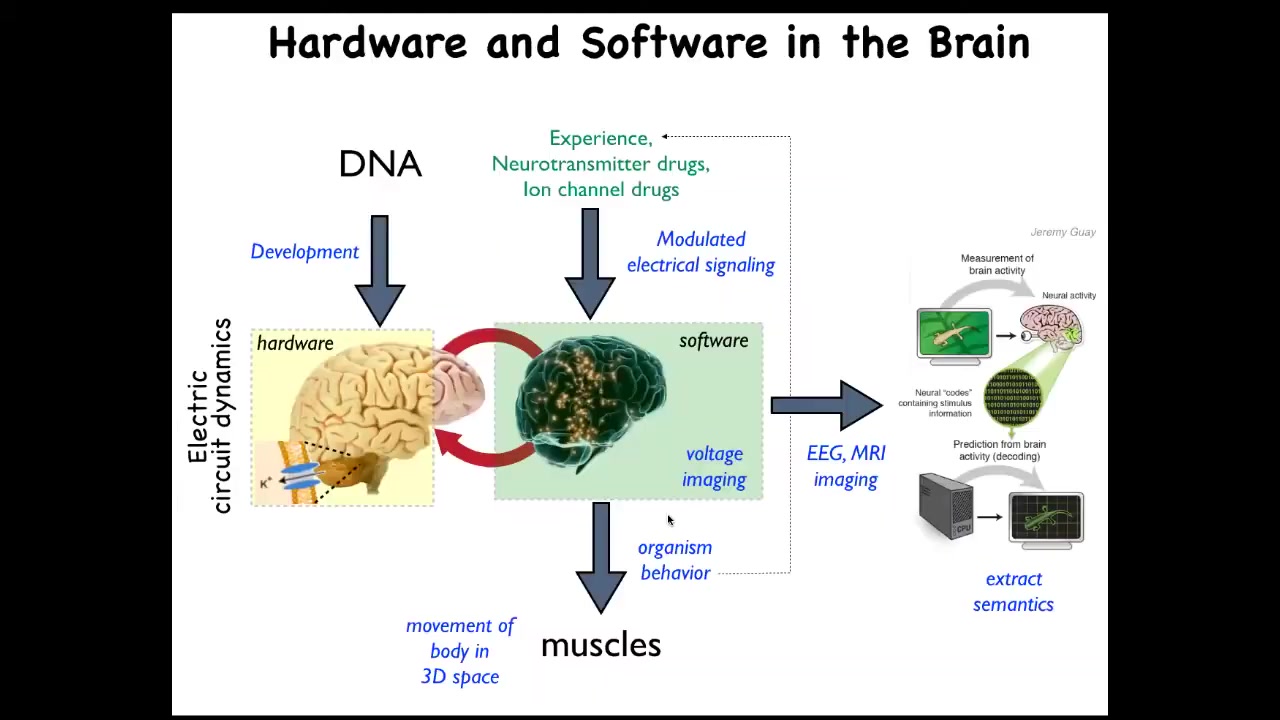

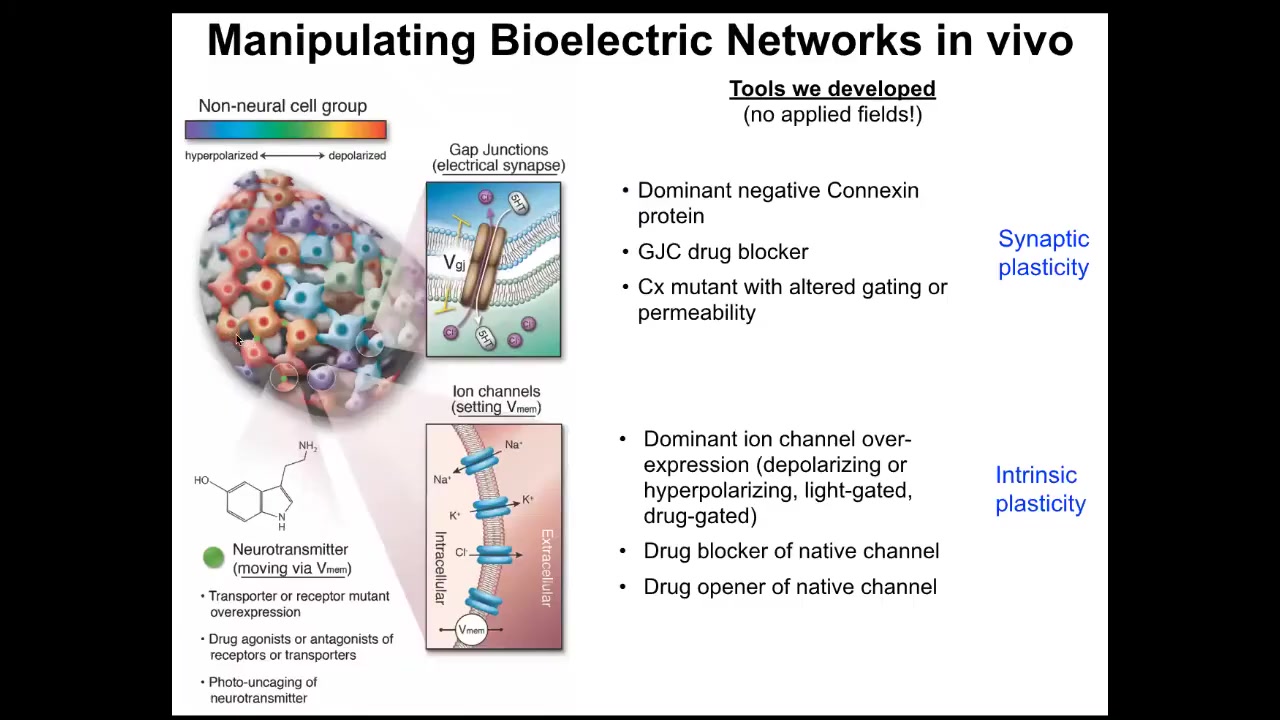

The thing to keep in mind is that we have one example that a lot of folks have worked on over the centuries, which is in the brain. How do individual neurons tie together such that you get the ability to pursue goals, let's say behavioral goals, that don't belong to any one individual neuron. This architecture won't surprise anyone here. The hardware looks like this. We have cells connected to their neighbors by these electrical synapses known as gap junctions. They have ion channels on their surface. Every cell sets a voltage, and they can communicate that voltage to their neighbors. Somehow this architecture is really key to binding individual cells into larger collectives that can pursue larger goals.

Now, the interesting thing is that neurons did not arise out of nowhere. They didn't just suddenly discover all this stuff. Evolution found this system around the time of bacterial biofilms. Bacterial biofilms already use the same scheme to coordinate their activity. As a result of that ancient origin, every cell in your body has ion channels. Most of them have these gap junctions to their neighbors. This idea of using electricity to form networks is how we make computers, but evolution beat us to it by a long margin. You can read more about that there. To give you a simple example, that type of model makes a simple prediction.

Slide 14/50 · 24m:37s

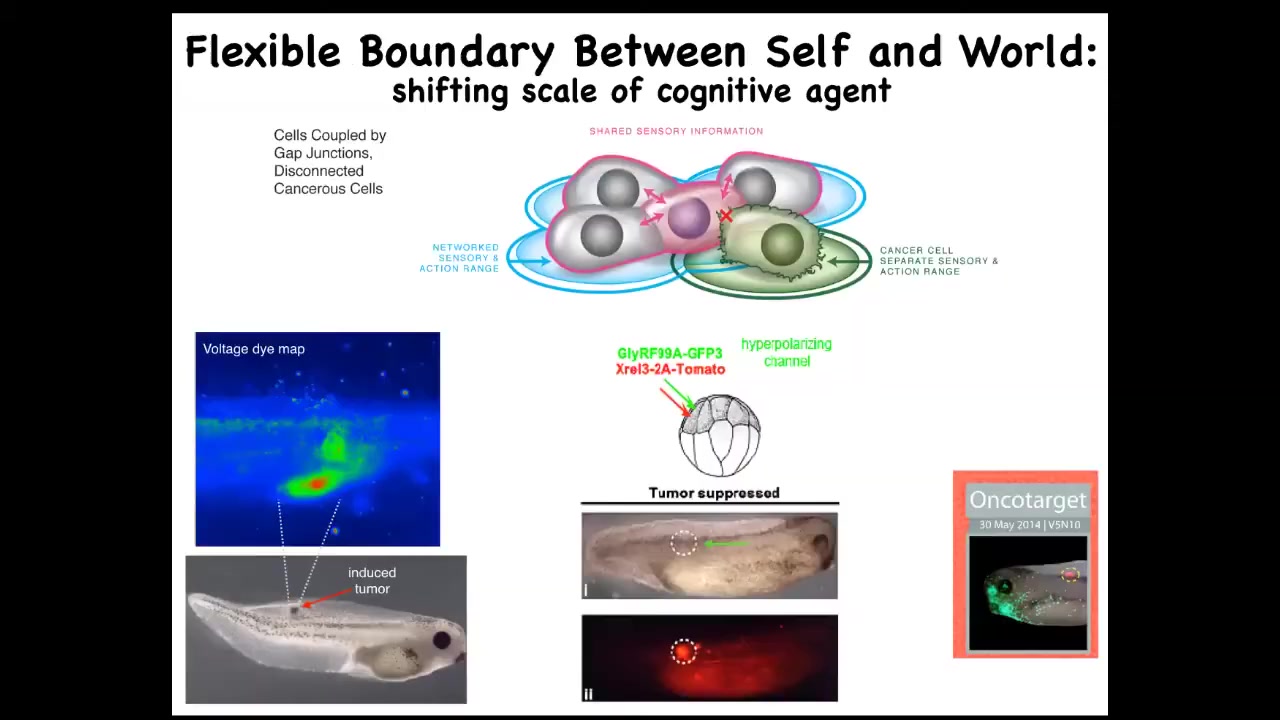

The prediction is, could we use the electrical connectivity specifically between cells and their neighbors as a marker and a control knob on the defection known as cancer. What happens is when you inject a human oncogene into this frog embryo, eventually it'll make this tumor. Even before the tumor becomes apparent, you can already see this is a voltage-sensitive reporter dye where you can get a map of all the electrical activity. You can already see that these cells are depolarized. That's the first thing that oncogenes do: they cause an electric state that shuts down the gap junctions, they decouple from their neighbors, and you get this metastatic process, as the cells with not necessarily any genetic damage, because you can cause this with lots of different mechanisms. They will now simply treat the rest of the animal as external environment. They'll crawl to wherever life is good. They'll reproduce as much as they can. They're on their own now. Cancer, from this perspective, is no more selfish than any other cell type. It's just that the self is now smaller.

What happens is that in a multicellular body the self is quite large because all of the cells are connected and they're working on a very large thing. As soon as you break that connection, your self is tiny and the rest of the animal might as well be external environment. The good news is that once we've understood that, you can go back in and mis-express an ion channel that forces the electrical state to be such that the gap junctions remain open. When you do this, here's the oncogene still blazingly expressed. This can be a nasty thing like KRAS and so on. It's blazingly expressed, but there's no tumor. The cells behave perfectly normally. If you were to sequence them, you'd find the mutation, you'd predict there'd be a tumor and you'd be wrong because the bioelectric state actually trumps the state of the hardware, trumps the genetic state. You can suppress tumorigenesis this way or in fact induce it by artificially breaking these connections. What's magic about the binding here is these gap junctions.

Slide 15/50 · 26m:53s

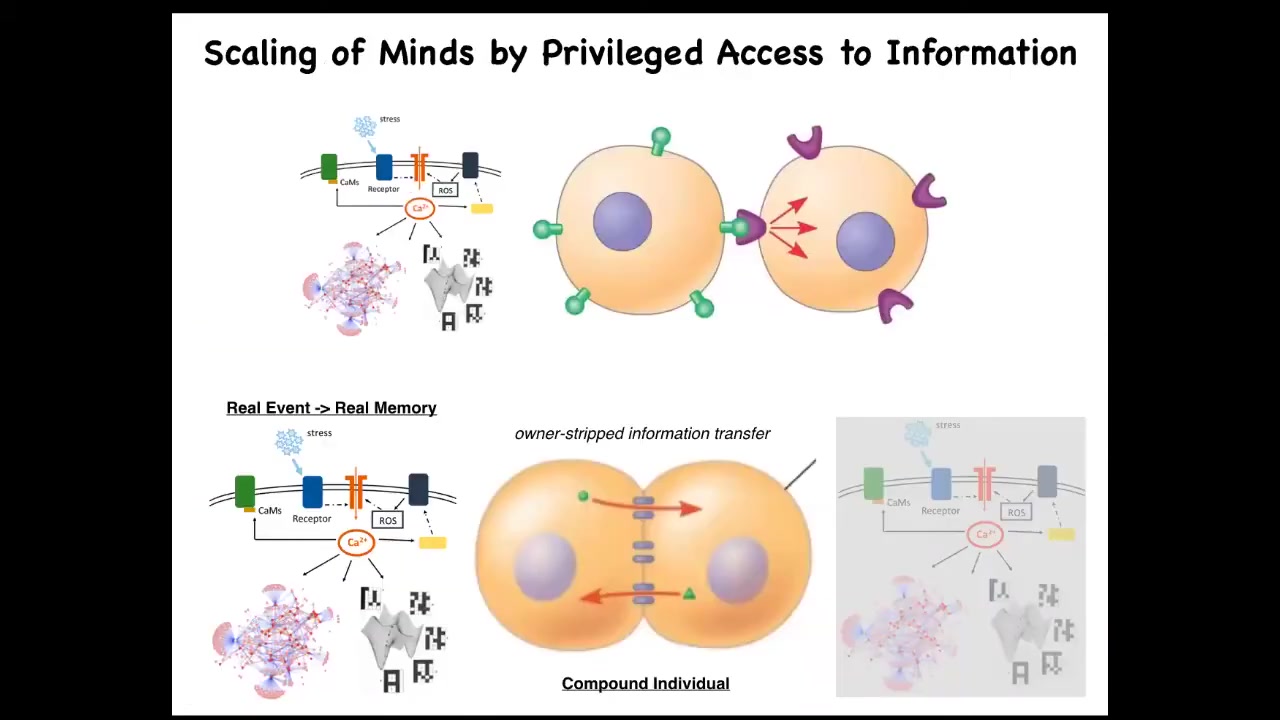

We'll take just a couple minutes to think about this. When you have two cells signaling to each other in a normal way, an external ligand comes along and hits a receptor. This cell is very clear on the fact that the signal came from the outside. Therefore, it can ignore it, can do various things in response to it.

Gap junctions are magic in the following way. When two cells are connected by gap junctions, each cell gets privileged direct access to the internal milieu of the other cell. That means that if something happens on this side, some stress or injury triggers a calcium flux, that flux is going to propagate to its neighbor, and the calcium has no metadata on it that tells it where it came from. Once this cell experiences some second messenger calcium, it has no way to tell whether that's a memory belonging to this cell or to the neighbor. As far as this cell is concerned, it's a false memory because this cell wasn't the one that got stressed. But as far as this collective is concerned, it's absolutely a vertical memory.

The fact that you, as a cell, here have engrams, memory molecules, traces of experience that you cannot distinguish whether they belong to you or to this other cell — that blurring of identity, who the memories belong to, is what scales the system into a larger collective. The partial erasure of an individual's ability to keep track of which memories really belong to them binds this into a larger-scale cognitive whole that now operates on all the information. So the benefit is that you're now more clever. You have more computational capacity. You now have information you didn't have before and couldn't have had before.

But the downside is that these individual cells don't really exist anymore. There's a collective which consists of them both. You can scale that up and look at how information propagates through these networks in a way that erases the distinction between one and another and makes a greater whole.

Can I have a question now?

I guess a two-part question. First, do we know or have a rough idea of when gap junctions evolved biologically? And second, it sounds like you're creating a framework where any particular system of information or biophysical information pathways would lead to this compound individual creation on the larger sense itself. You're giving us an illustration of how that might work. Is that right?

Two things. Gap junctions are pretty ancient, but even before that, it doesn't actually have to be a gap junction. I've pushed this idea into a roboticist working in a completely different medium. It doesn't have to be an actual gap junction. It has a few features that are important to reproduce, which gap junctions meet, but even bacterial — there's some kind of bacterial thing where they dock with each other that has the same property. It has to wipe ownership information on whatever molecules come through it, and it has to be able to be gated, being open and closed. Even as far back as bacteria, before true gap junctions evolved, those already existed. But gap junctions are themselves voltage sensitive, at least some are, which gives you an extra level of control, which is why it's so much better in metazoan organisms.

As far as what this means for scaling: yes, anything that meets some functional criteria would contribute to that scaling. It doesn't actually have to be a gap junction, but I think that's what evolution did. That's how evolution does it.

Okay, let's look at some specific examples. Now, one of the things I'm interested in is morphogenesis and why, if we're into cognition, we're talking about morphogenesis. What does that have to do with it?

I want to address it starting over here.

Slide 16/50 · 31m:13s

One of the things we'd like to do is what I use with colleagues and communities that aren't necessarily into cognition at all, but it's a way to try to make people care about this stuff because I think it's very deep and fundamental.

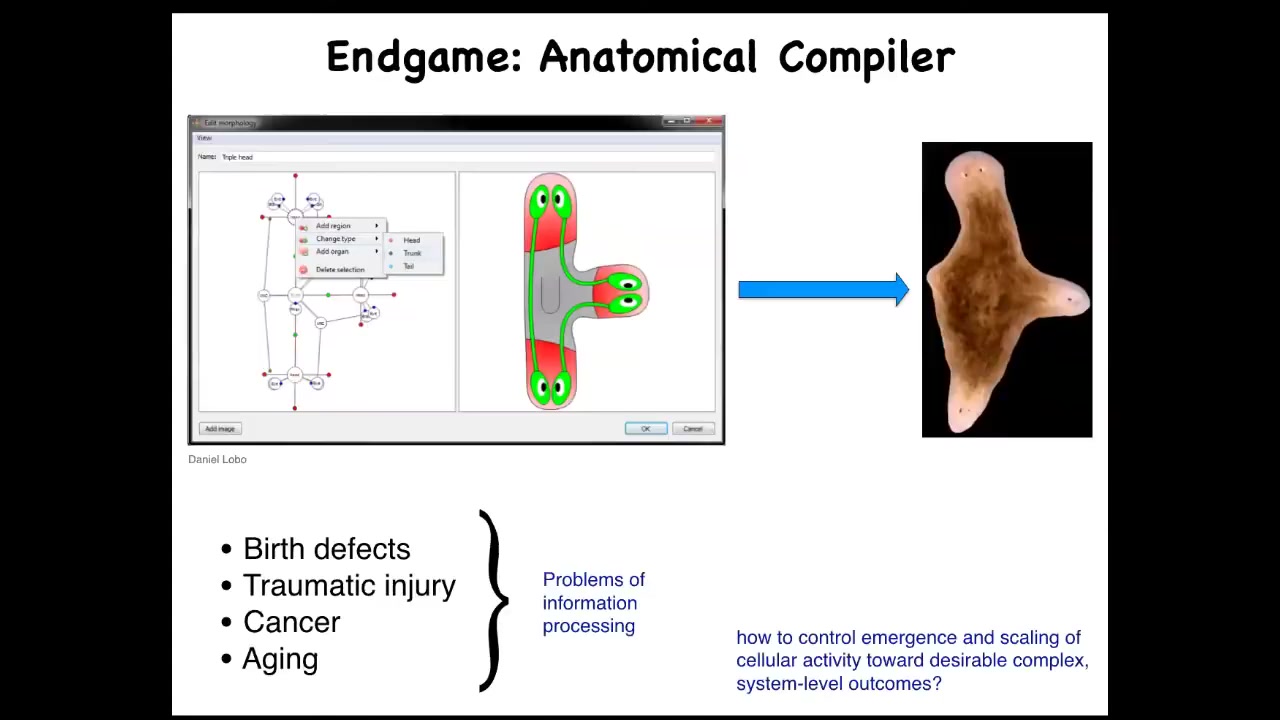

What everybody would like to have is an anatomical compiler. What you'd like to do is to be able to draw the animal or plant that you want, not at the level of genes or molecules or pathways, but you actually draw what you care about, which is anatomy, functional anatomy. If we knew what we were doing, this piece of software would compile our drawing into a set of stimuli that would have to be given to cells to get them to build whatever it is that you want them to build.

Why would we want this if we had this? We could address almost every problem of medicine with the exception of infectious disease. Birth defects, regenerating organs after traumatic injury, reprogramming tumors, reversing aging, all of this would be possible. If we knew how to tell cells what they should be building. It's very instructive to ask, why don't we have this? We are about as far away from this as you can get, despite all the amazing progress in genetics and biochemistry.

Slide 17/50 · 32m:33s

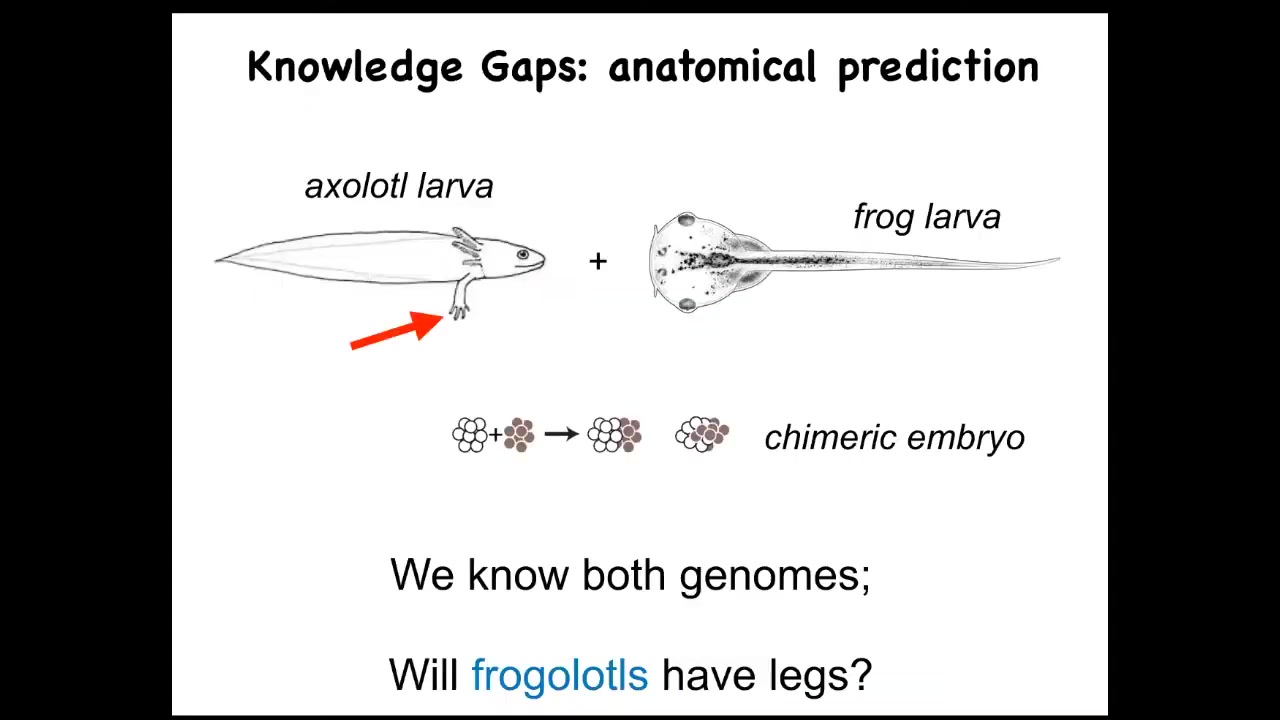

Let's just ask a simple question. Here's an axolotl larva. These guys have legs. Baby axolotls have little legs. Frog larvae do not have legs. They're just tadpoles. We have made chimeric embryos that are partly axolotl cells and partly frog cells. We make these frogolotls. I ask a simple question. Are frogolotls going to have legs?

We have the axolotl genome. We have the frog genome. How come no one can tell me whether frogolotls will have legs? Part of it is because we really don't have a good understanding of how cellular collectives make decisions. We know the properties of the hardware of individual cells. We know what proteins they're going to have. We don't know how the collective makes decisions about what it's going to build.

Slide 18/50 · 33m:22s

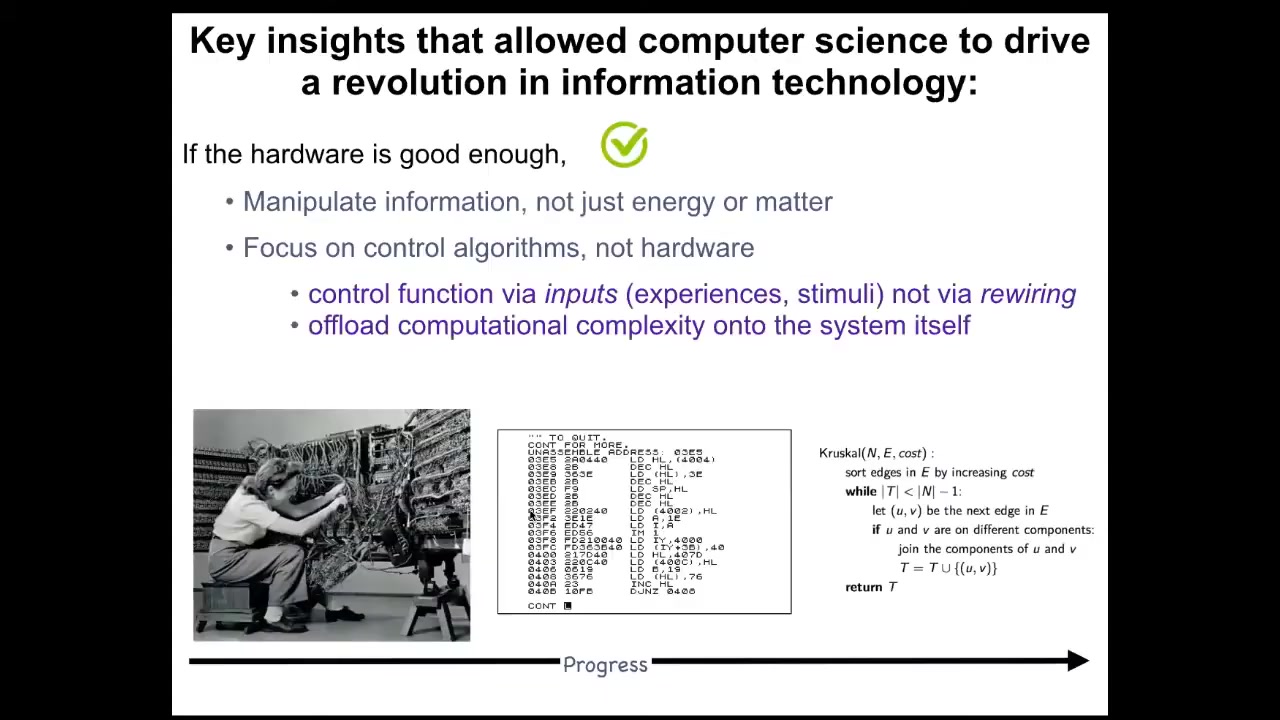

And all of molecular medicine, this is the chart of progress of computer science, where back in the day, in order to reprogram a computer, you had to physically change the hardware around. You have to move wires. Nowadays, I say to my students, be in constant awe that when you move from Microsoft Word to Excel, you don't get out your soldering iron and start changing the hardware, because that is what molecular medicine does. All of molecular medicine currently is focused down here. It's all about, we're going to edit the genome, we're going to change pathways, promoters, we're going to change molecular networks. And what computer science shows us is that actually, if your hardware is good enough, and I think the biological hardware is definitely good enough, you can do something much more interesting. You don't have to rewire the hardware. You have to understand the software that binds the pieces into large-scale collective behaviors, such as following an algorithm that you can then understand and manipulate.

Slide 19/50 · 34m:18s

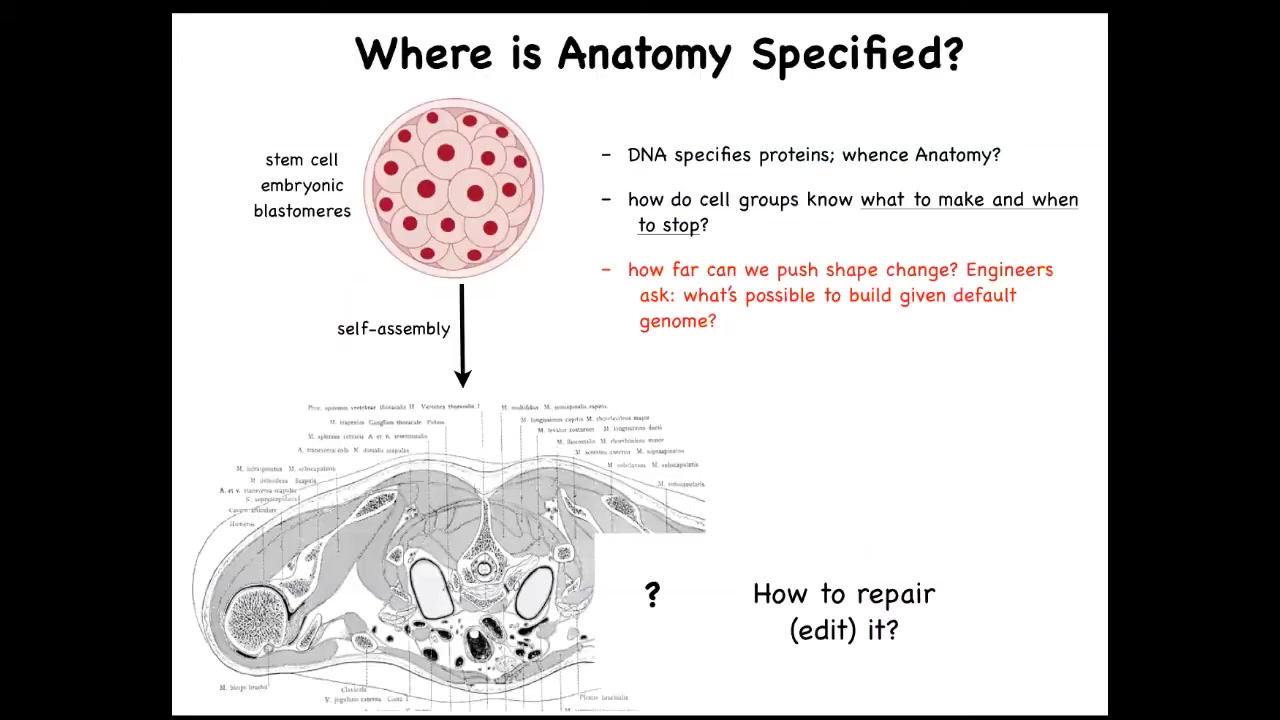

Let's just look at how this works. Here's the cross-section through a human torso. Look at this amazing invariant order. All of the tissues and organs, everything is in exactly the right place, next to each other, right size, the right shape. It all started life like this: a collection of blastomeres descending from a fertilized egg. Where did this pattern come from? Where did this order come from? People are tempted to say DNA, but we can read genomes now. When you read a genome, you don't see any of this. What you see when you read a genome is protein sequences. You see the hardware that every single cell gets to have, but there's nothing directly in the genome about the size, the shape, the symmetry type. We really need to understand this process of how cell collectives know what to make and when to stop. As workers in regenerative medicine, we'd like to know if a piece of this is missing, what do we communicate to the cells to get them to rebuild it? As engineers, we'd like to ask, how far can we go with this? Can we get the cells to make something completely different? Can we get them to build something else with the same genome?

So as I've already shown you, individual cells are very competent on their local scale. The cool thing is that when they get together in multicellular organisms, that scaling that I was talking about allows them to represent, as a much larger network, goal states that are much bigger.

Slide 20/50 · 35m:46s

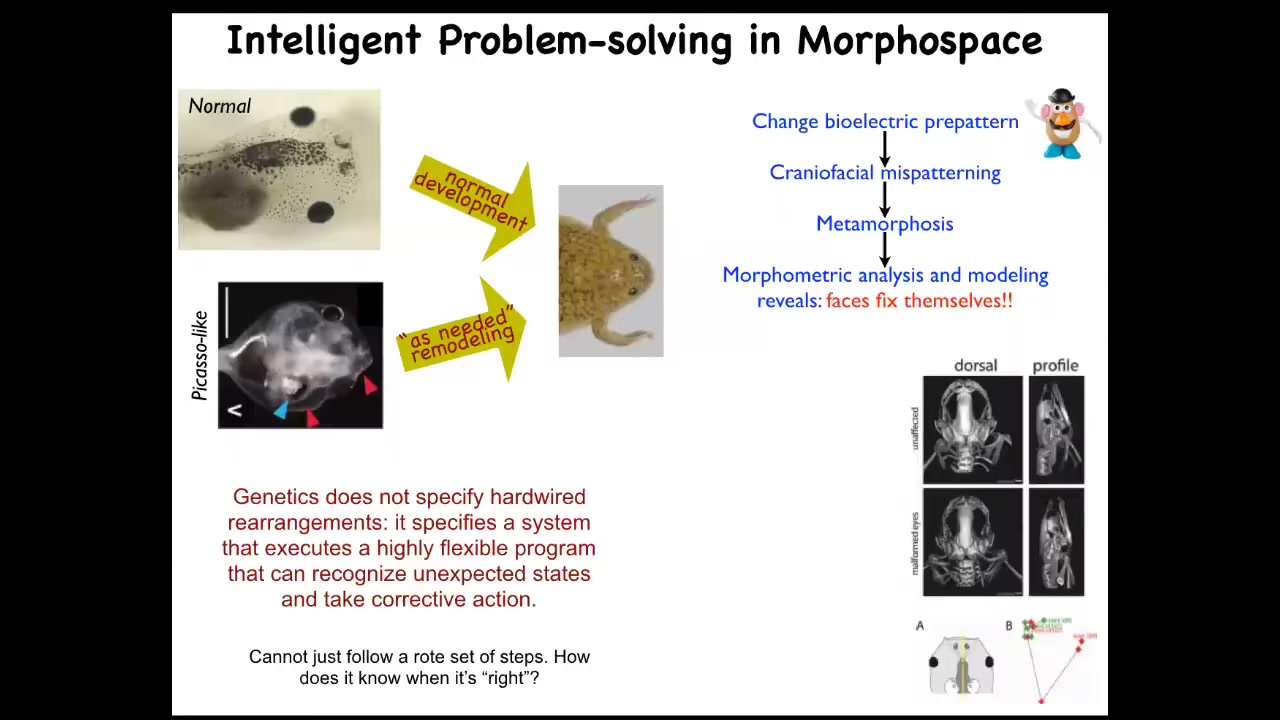

I'll show you a simple example of this. Here's a tadpole. Here's the brain, here's the gut, here are the eyes, here are the nostrils. In order for this tadpole to become a frog, it has to move the various organs around. The eyes have to move forward, the jaws have to come out, everything has to move.

In the past it was thought that all tadpoles look the same and all frogs look the same. As long as everything is a hardwired set of movements, you get a normal frog from a normal tadpole. What we did was make so-called Picasso tadpoles—tadpoles where everything is in the wrong place. The eyes on the side of the head, the jaws are over here, everything is completely mixed up. These things largely make pretty normal frogs because all of the different organs will continue to move in abnormal paths, sometimes doubling back if they go too far, until they get to a correct frog shape and then things stop.

This is a system. It's not that the genetics somehow specifies these hardwired rearrangements. What in fact it gives you is a piece of hardware that can execute an error minimization scheme. It knows the correct set point and is able to keep deforming, even if it starts in an abnormal state, until the error is as small as it can possibly get.

Slide 21/50 · 37m:07s

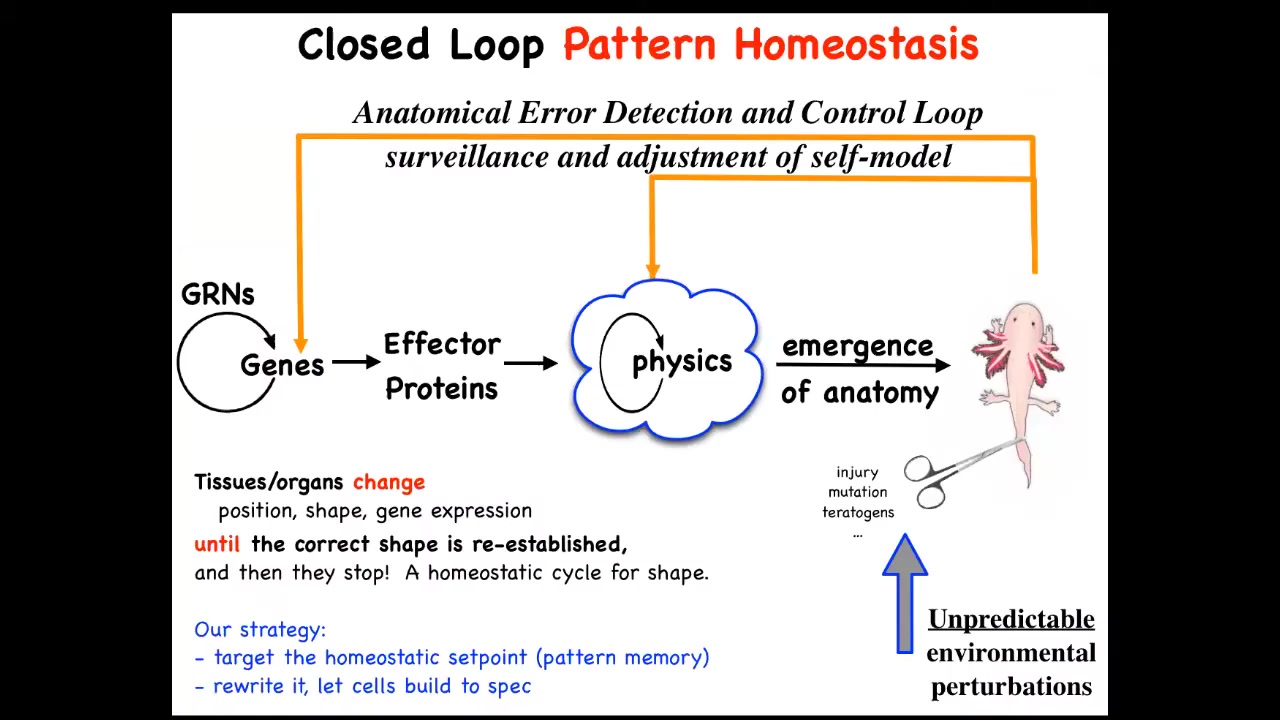

This down here is the standard story of developmental biology, and it's all focused on emergence. You have gene regulatory networks, you have some physics, and eventually if you do a lot of this in parallel, out will emerge some complex form. But what's really important about this is that there are actually feedback loops where when the system gets away from the set point by injury, by disease, by mutation, by pathogens, whatever, teratogens, these feedback loops kick in and try to minimize that error.

I have to say this is definitely not the standard story of developmental biology. Biologists certainly know about feedback loops, but we're used to feedback loops that are very local quantities, like scalars — pH, hunger level, temperature. Whereas what you have here is the set point of this homeostatic process. Think of your thermostat. Your thermostat has this kind of feedback loop. The set point for this process is some coarse-grained anatomical description of what a correct body looks like.

People tend not to like this because it reminds them of teleology, the idea that this is a goal-directed process. But fortunately, since cybernetics in the 40s, we've had a mature science of systems that are goal-directed objects, and they don't need to be artifacts, don't need to be second-order metacognition. You don't need to know you have goals in order to have goals. You just have to have this error minimization loop.

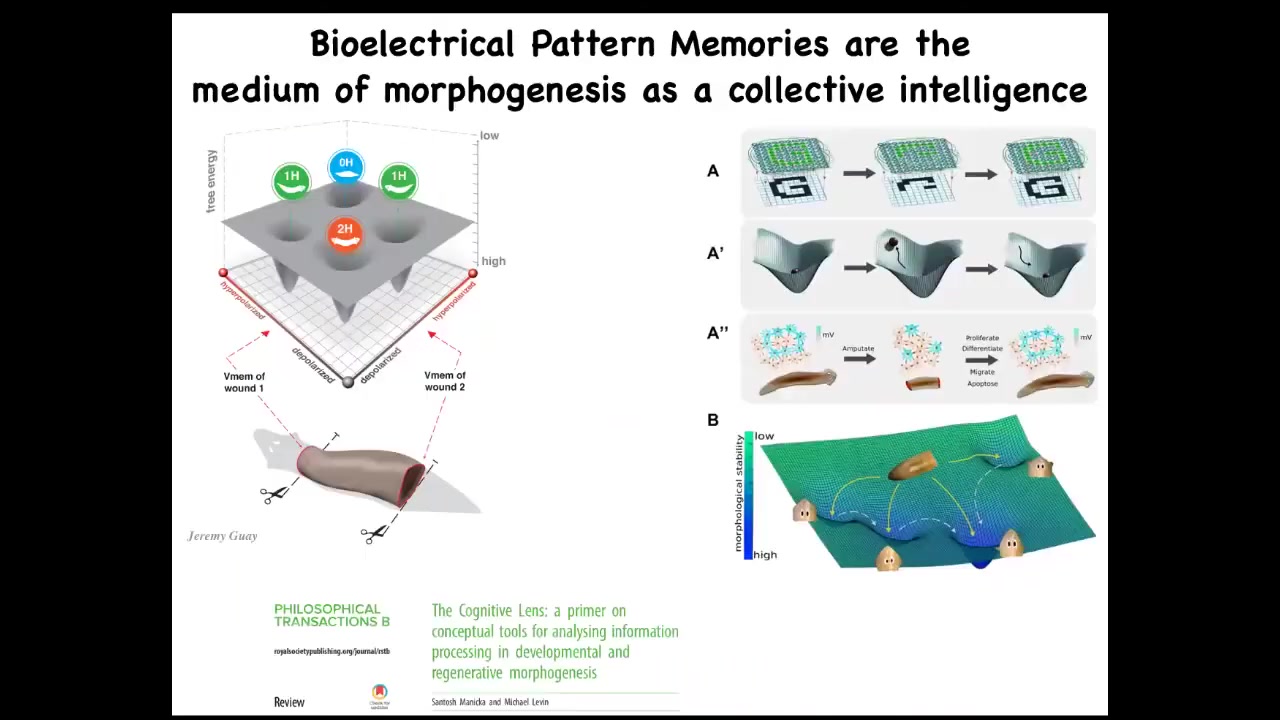

This raises a number of questions which existed even before this was formalized, which is how does it know when to stop regeneration? The most amazing thing about regeneration is that it stops when the right thing is finished. How does it know what the correct pattern is? In our lab for years now, what we've been doing is following the strong and unusual prediction of this model, which is that we ought to be able to find the encoding, the pattern memory that tells these things what a correct shape is, and we ought to be able to learn to decode it, and we ought to be able to learn to rewrite it.

And the thing about that scaling is that these memories: living things are homeostats built upon homeostats.

Let's talk about this first.

Slide 22/50 · 39m:35s

Individual cells all have a homeostatic loop about things that individual cells care about, which might be a pH, hunger level, voltage, or other variables. They all execute these loops, and the set points they use are fairly small. So these are small cognitive light cones.

But when they connect in networks, what it allows the collective to do is measure very large states, such as, for example, the distance between this bone and that bone, or the distance between the eyes, or in fact how many eyes I have or how many fingers I have. Those kinds of things can be measured by coupled homeostats. Coupled systems can actually measure a very large state, and that enables these large systems to work in more complicated problem spaces.

Slide 23/50 · 40m:35s

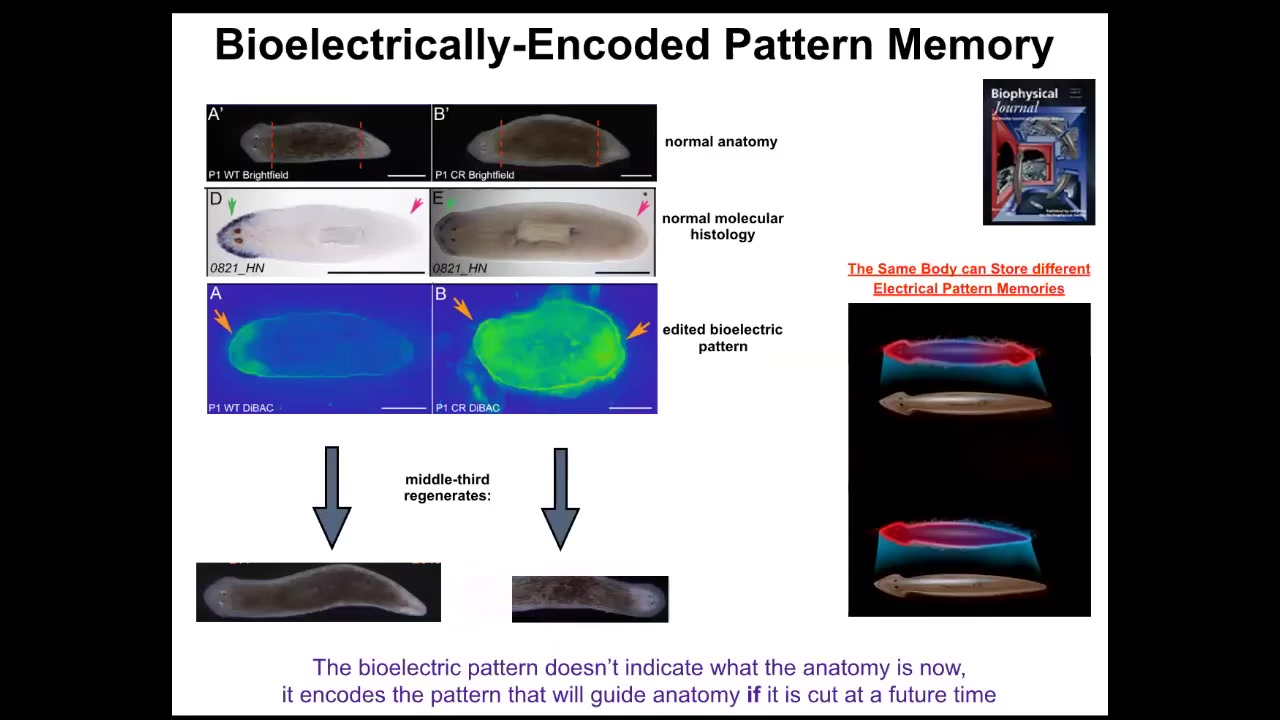

We already know that this happens in the brain. There you have these coupled electrical networks and the resulting behavioral control software. The commitment of neuroscience, or at least of standard physicalist neuroscience, is that you ought to be able to read all the electrical states, you should be able to decode them, and eventually you have neural decoding. You will be able to recover the memories, the preferences, the goals, and so on of this agent. Because of this mapping, the fact that all cells are actually doing this, we have a very similar research program. Can we learn to decode the electrical activity of non-neural networks and extract the semantic content of this collective agent operating in morphospace, an anatomical space?

Slide 24/50 · 41m:27s

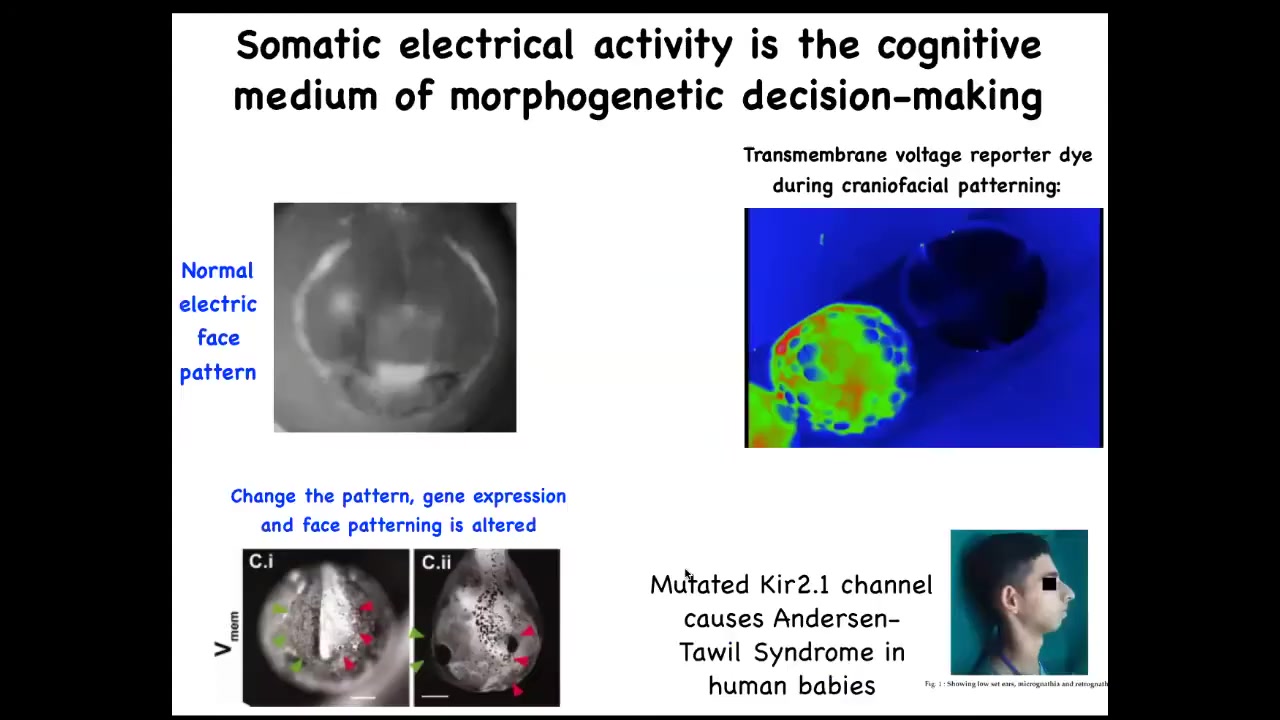

I'll show you examples of what these pattern memories look like. Here's a frog embryo putting its face together. This is a time lapse. In grayscale, this is one frame out of that video. You can already see this is voltage, this is a voltage-sensitive fluorescent dye.

This is showing you in time lapse what all the voltages are. You can already see the outlines of the face. This is a subtle scaffold that drives the downstream gene expression that then drives the cell differentiation and cell movements that create the face. Here's where the animal's right eye is going to go; the left eye lags a little bit. That's where the mouth and the placodes are; everything is already decided.

The reason I'm showing you this pattern, this example, is because in this case, the pattern memory actually looks like the thing it's supposed to represent. That's usually not the case. This is a rare example that's easy to understand.

If you mess with this electrical pattern, you will recapitulate the birth defects that occur in humans and other model systems from mutations, for example, of various ion channel genes. If this pattern isn't correct, the face will not be correct.

What we see here is a normal endogenous instructive bioelectric pattern memory that tells the cells how to make a frog face. I've already shown you a pathological example of that in the cancer dye experiments. What we did beyond being able to observe these things and characterize them is steal a bunch of tools from neuroscience that enable us to rewrite these things in vivo.

Slide 25/50 · 43m:00s

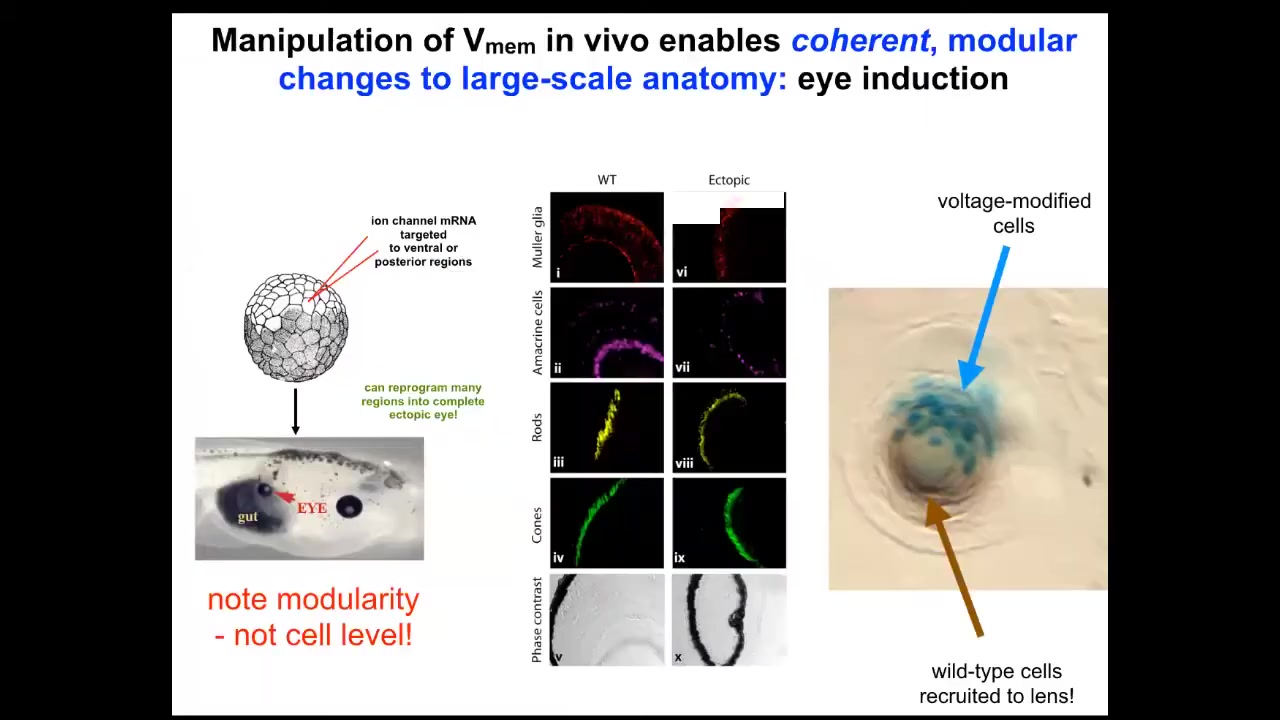

All the same things that people do to work on synaptic plasticity or intrinsic plasticity — no applied electric fields, no electromagnetics, no magnetic component at all. This is molecular physiology to target the channels and gap junctions that are normally operating here. We can control the gap junctions, meaning which cells talk to which other cells, or we can set directly the voltage by opening and closing ion channels. We can use optogenetics, we can use ion channel drugs, all the same stuff that neuroscientists use. When you do this, you can go in and do what in neuroscience is called inception of false memories, which people like Tonegawa at MIT have done.

Slide 26/50 · 43m:46s

If I go in here into this frog embryo and I inject a bunch of ion channel RNA, encoding a particular ion channel, to create an eye-specific electrical state in cells that are going to be gut. These cells by default would have made a gut. But if I give them a pattern that says, no, make an eye here, what do the cells do? They make an eye. These eyes can have all the same layers: retina, optic nerve, lens. And there's actually a very cool phenomenon where if we only target a certain number of cells, the blue tells you which cells we actually targeted. What they will next do is recruit their neighbors, which we didn't directly target, to help them make the right shape and size of eye. There are two instruction events. By the bioelectrical pattern, we instruct these cells that they're supposed to be making an eye, and then they instruct their neighbors to join with them and to execute this particular goal of making this lens. This is a lens sitting out on the flank of an embryo somewhere. And they instruct their neighbors.

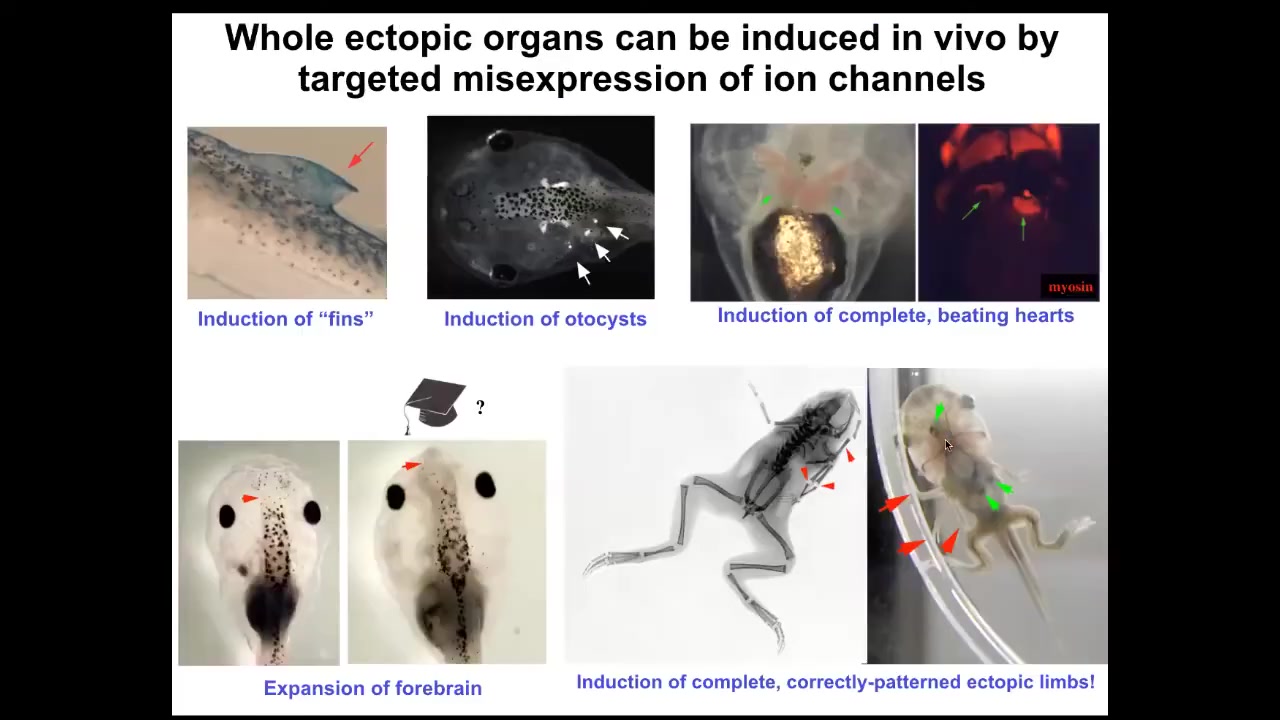

Slide 27/50 · 44m:51s

Using these false pattern memories, we can induce fins, although tadpoles aren't supposed to have fins. You can get otocysts or inner ears. You can get ectopic hearts. You can get ectopic forebrain. You can get new legs or new limbs.

You have some ability to re-specify the goal, the large-scale anatomical goal states on which these cells are going to work. What we have not done is micro-specify cell types. People will often say, can you turn a stem cell into a particular type of cell? Maybe, but what this layer of control is supposed to be is not for that. It's not for micromanaging individual cell activities. It's for telling the whole large collective what it is that it should be working on. There are patterns that indicate different types of organs. This is not about individual cell behavior. This is about the instructive pattern of a large collective.

Now let's look at how the memory works.

Slide 28/50 · 45m:56s

And so, in planaria we've been studying this. Planaria have this amazing property that you can cut them into pieces. The record is, I think, 275 or something like that. And every piece will regrow exactly what's missing, no more, no less. In fact, the other tissue will shrink so that the whole tiny little worm is in perfect proportion. They're so good at this, they're immortal. So there's no such thing as an old planarian. They live forever.

All of the cells cannot simply be watching their local environment to know what to do, because if you cut an animal in half like this, the cells at the back end here need to make a tail, the cells at this end need to make a head, but they were exact neighbors until you separated them with a scalpel. So they can't simply know locally; they have these radically different anatomical fates. They have to communicate with the rest of the fragment to say, what else is here? Do we have a head? Which way are we facing? What do we need to do?

Slide 29/50 · 47m:00s

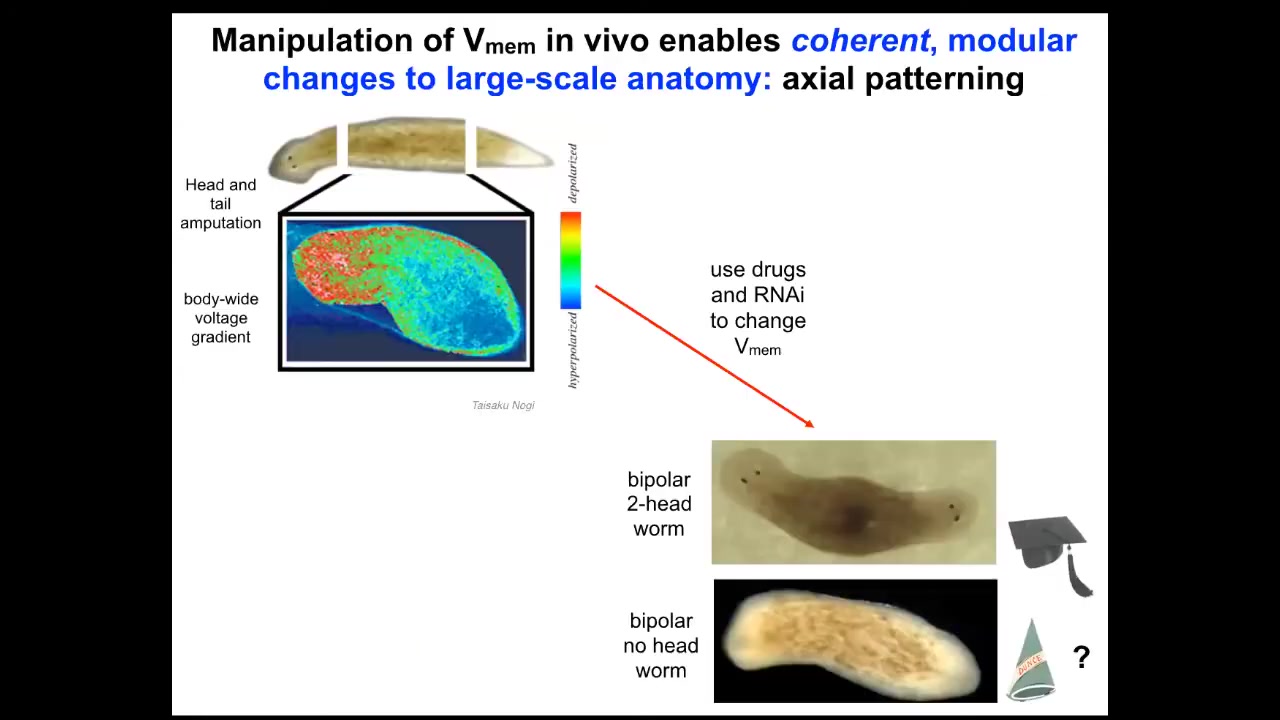

So that happens by virtue of a bioelectrical pre-pattern, this kind of voltage distribution that says to this fragment, one head, one tail. And in fact, if we go in and we depolarize this region to edit this memory to say, no, actually you should have two heads, then this is what you get. The cells are perfectly happy to build to that shape. You can get two heads, you can get no heads. Now we can ask, I've been calling this thing a memory and it's time to cash that out.

Slide 30/50 · 47m:26s

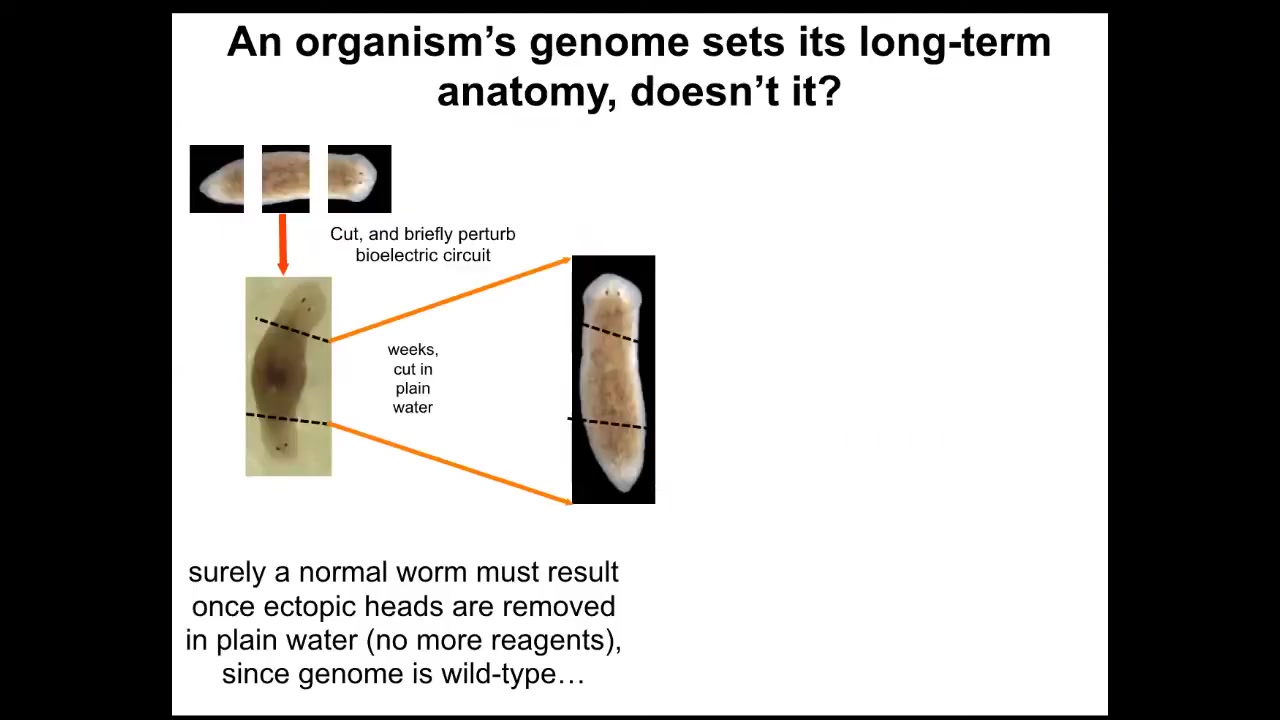

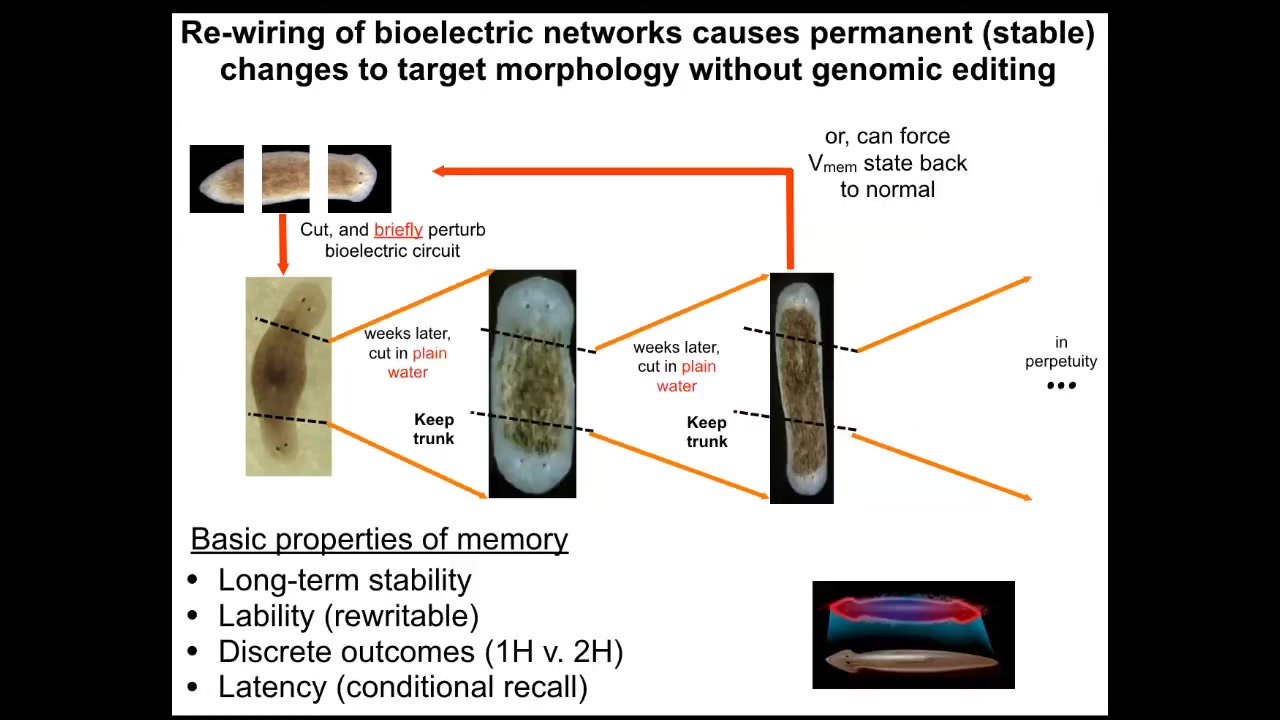

Why have I been doing that? If we take this two-headed animal and we ask a question, we're going to remove the primary head. We're going to remove this crazy secondary head that formed. We're going to leave the nice normal middle gut fragment. There's nothing genomically wrong with it. We haven't touched the genome. This was all purely bioelectrically modified. We're going to let this middle fragment regenerate in plain water. The standard paradigm says you're going to get a one-headed worm because the ectopic tissue is gone. The genome is wild type. There's no drugs anywhere around anymore. It's plain water. You're going to go back to your normal shape and make a one-headed worm. But the interesting thing is that if you look at the electrical circuit that actually determines this, it has two stable attractors, one at the single head state and one at the double head state. That's suspicious. Why would that be?

Slide 31/50 · 48m:19s

It turns out that if you were to do this, what you'd get is continuation of the two-headed phenotype. These animals make two-headed worms in perpetuity, as far as we can tell.

The genome is identical. You're not going to get this information by sequencing their genome. The answer to how many heads a planarian is supposed to have is stored in the steady state of a real-time electrical circuit, just like volatile RAM, that keeps this information. We can shift it back. We know how to go from a two-headed animal back to a one-headed animal.

Slide 32/50 · 48m:55s

What I want to show you is that this is the beginning of a really interesting, powerful example. Somebody asked me at the beginning, what are the triggers of the phase transitions in that in Wiener and Rosenbluth's cognitive diagram? Here's one example. Take a look at this: a single-headed planarian right here. It is anatomically normal. It has gene expression of anterior genes in the anterior end, not in the posterior end. It has a bioelectrical gradient that says one head, one tail. If you cut it, it makes a normal worm.

This animal, anatomically normal, again, gene expression normal. But what we've done is we've manipulated it such that it has an electrical pattern memory that says, no, two heads. What happens when you cut this animal here is you get a two-headed animal. But really critically, this electrical pattern is not the electrical pattern of this guy. This is the electrical pattern of this guy. So a single body can hold at least one of two different ideas of what a correct planarian is supposed to look like. It's a latent pattern memory. It doesn't do anything until you injure the animal. At that point, the cells consult it and make what it says.

This is the beginning of counterfactual memory. This is an electrical circuit that lets you remember things that are not true right now. This is the very basis of the ability to hold a counterfactual, to represent a counterfactual state. It represents something that is not true right now, because this is not the answer to how many heads I have right now. This is the answer to how many heads I am supposed to have. Until you get injured, those two things don't really collide. Once you get injured, that mismatch drives the morphogenesis.

So where is that memory stored then? If it appears spontaneously. Sorry, I don't understand.

Nothing here appears spontaneously. This is the default electrical pattern that arises from the circuit comprising the ion channels that evolution has given us. It's a default attractor.

We can go in and, because that circuit has this remarkable memory ability — it will remember when you set it to a different state and keep the new state — force a two-headed pattern, and then it will stick. It will remember. It's like a flip-flop. There's a default; you hold it in a particular state, and you can flip it from zero to one. This is exactly the same thing. It's a bioelectrical circuit that reliably self-organizes this pattern, but it also has the memory that if you change it, it will keep the new pattern.

In the absence of injury, the cells ignore it. It's a latent memory, but then it's recalled upon injury. If you want to know where the electric memory is, you're looking at it the same way that if we were to take a flip-flop, the smallest piece of RAM that stores one bit of information, you would see, in fact, I have a cartoon somewhere that shows you how it works. It's exactly like this. If you were to plot the voltage of that flip-flop, you would see it low on one side, high on the other, or vice versa, depending on whether it was zero or one.

Slide 33/50 · 52m:16s

This is a bridge between biophysical circuits that we study in the planarian and the kind of electrical computations that we see in neural networks that do cool things, remember pieces of a pattern. So it's well understood in machine learning how it is that an artificial neural network can be trained on a pattern. Part of that pattern is deleted. The network is able to reproduce the whole thing.

This is a fairly mature field that combines dynamical systems theory and these ideas in connectionist roots of intelligence. This is the link.

This is how you go from just physics. A lot of people say, I can see how the circuit works. That's not memory, that's just physics. This is how you go from just physics to the ability to store memory, to pattern completion, to counterfactual memories, first in morphospace, to have a memory of where you should be in morphospace, and later on, once muscles and nerves evolve, to pivot that same system to say, this is where I should be in three-dimensional space, because I now have place cells and various other things that let me do pattern completion on things I see with my retinas. This is how that transition happens.

And that's one important jump on that Wiener and Rosenbluth scale. What's cool about all of this, pattern memories, is it's actually very deep.

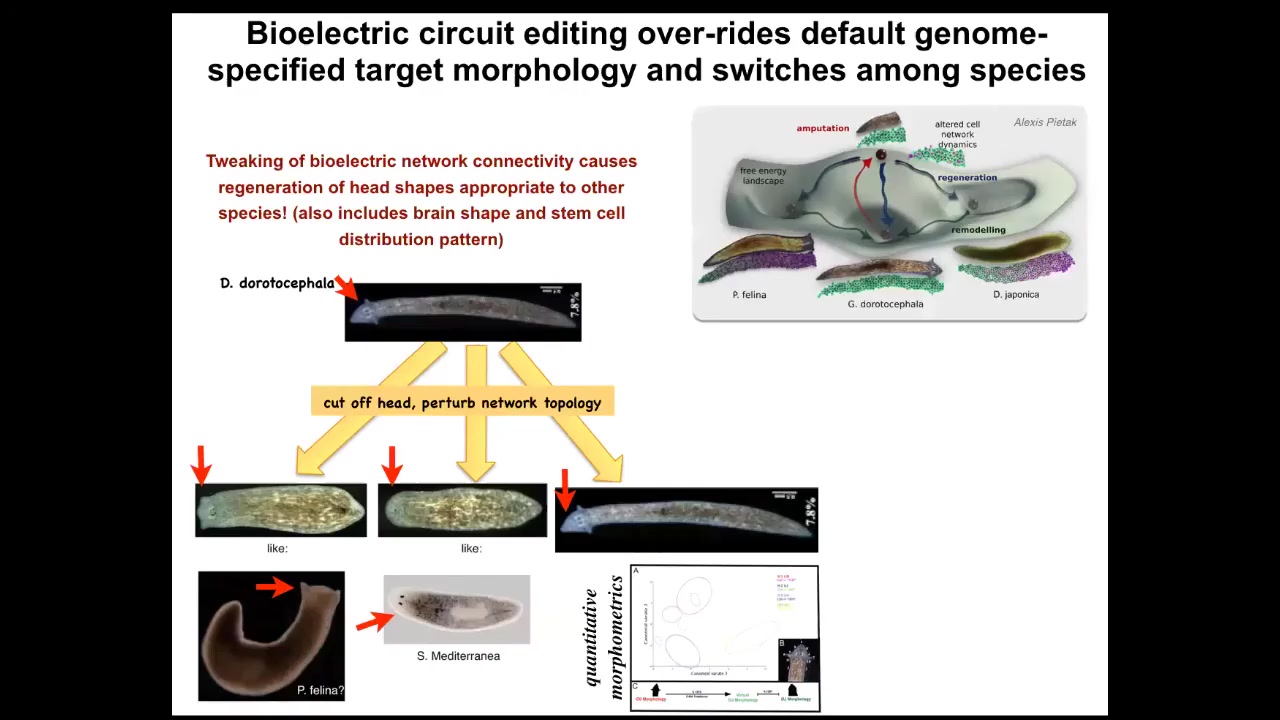

Slide 34/50 · 53m:55s

Not only can you get multiple different heads, but you can also get heads belonging to other species. I cut off the head, I perturbed the electrical connectivity between these cells so they can't communicate with each other for about 48 hours. Then I withdraw the blocker, which is regular general anesthesia. They settle back down. In some percentage of cases, they find their correct attractor, but in many cases, they find other attractors belonging to other species of worm about 150 million years distant — roundheads like this S. mediterranean or flatheads like this P. felina. Not only the head shape but the shape of the brain and the distribution of the stem cells change.

The morphospace is defined by the different potential attractors of this electrical circuit. Normally the species-specific head shape is very stable, but you can perturb the system, raise the temperature of the system, and let it fall back down. When it falls back down, it doesn't always land in the correct attractor, and the frequency with which you get these animals is proportional to the genetic distance between them. It's reasonable to see how evolution explores and canalizes this space.

Slide 35/50 · 55m:19s

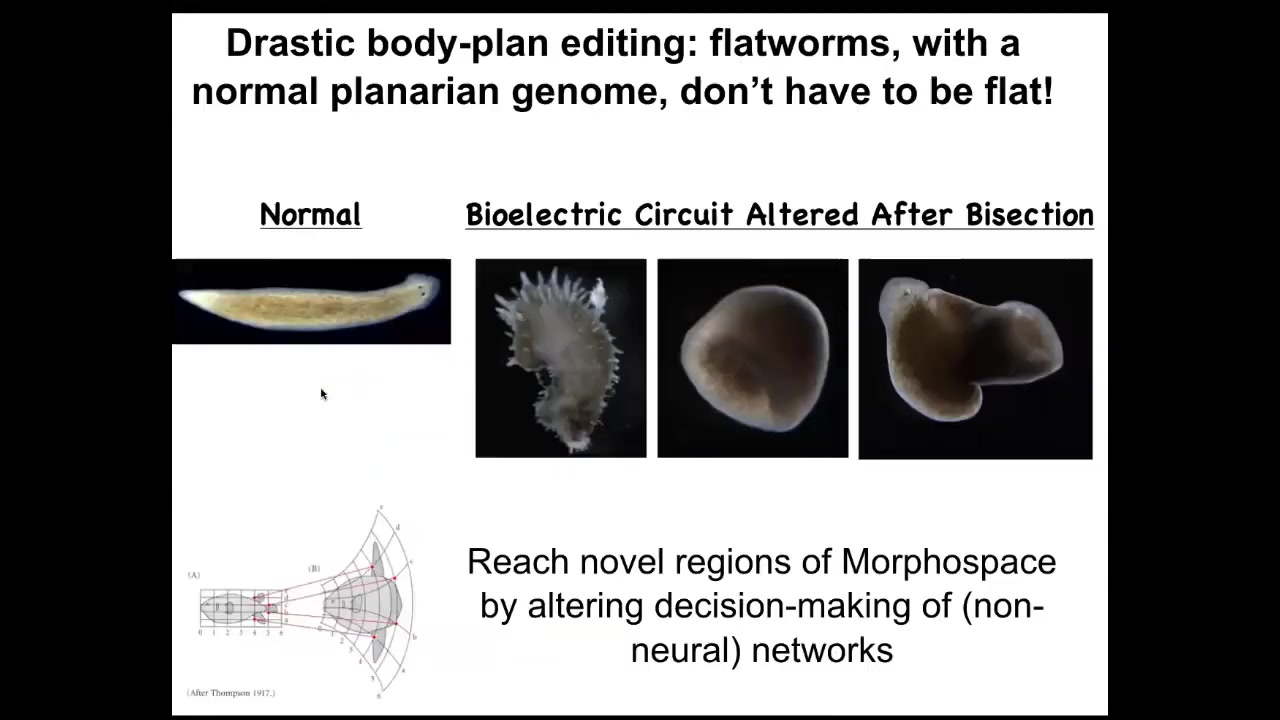

You can go further and reach areas of morphospace that evolution does not utilize. You can make flatworms that are not flat at all. They're spiky or they're cylindrical or a combination of both. So there's a ton of things that standard, perfectly standard wild-type genetically identical cells can achieve if you modify the information content in the electrical circuit that's telling them what the collective is working on.

Slide 36/50 · 55m:49s

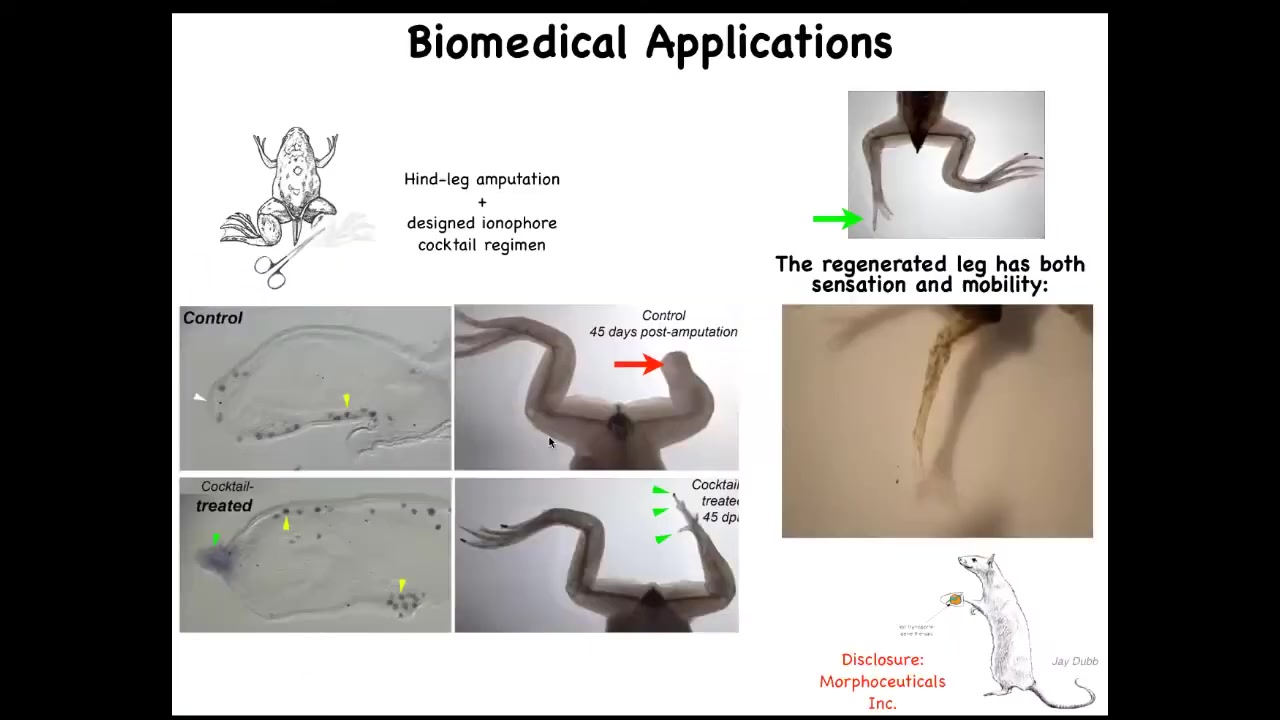

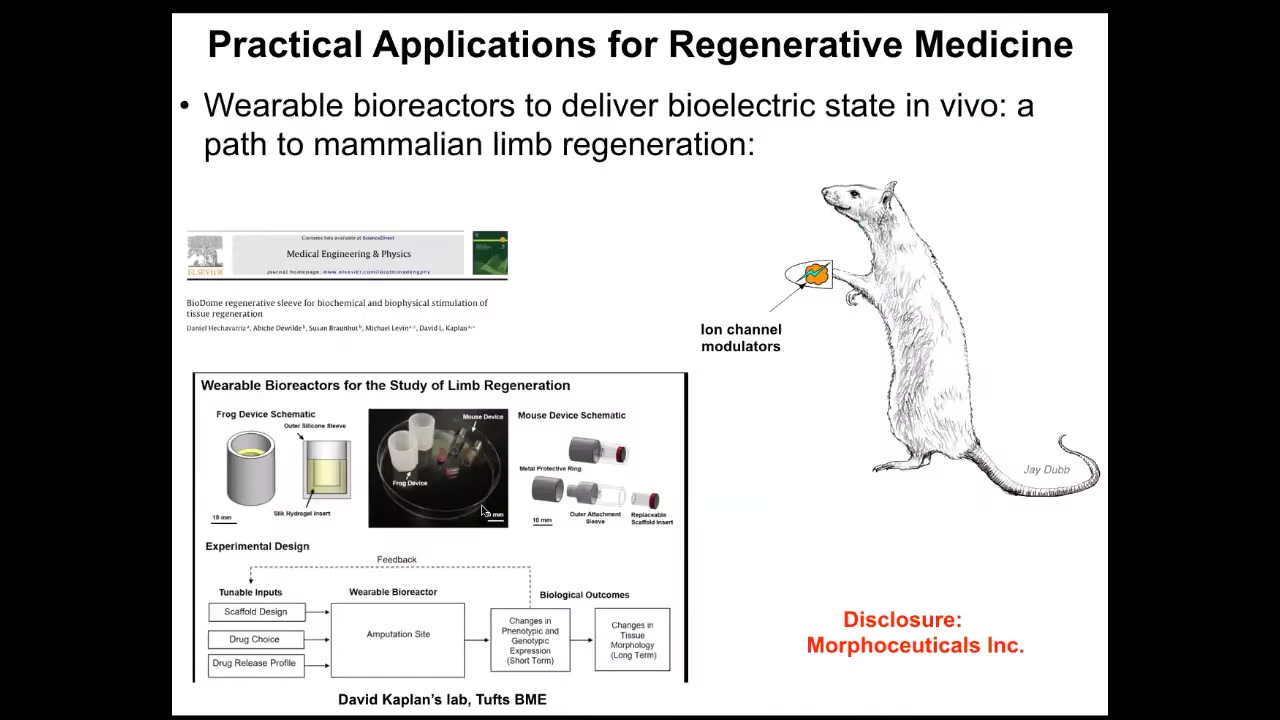

This has all kinds of biomedical applications. This is how we learn to grow back legs on animals that normally don't grow them back, frogs. We're able to induce this regenerative response. I have to do a disclosure here. David Kaplan and I are co-founders of a company called Morpheceuticals, Inc., because we're now trying to induce regeneration in mammals and eventually in humans.

Slide 37/50 · 56m:14s

Using these wearable bioreactors. Just a couple more things I want to show you.

But the idea is that we should be making a full stack model all the way from the genetic networks that set up the hardware of every cell, these ion channels, to the electrical dynamics, the symmetry breaking and amplification dynamics that give you these bioelectrical patterns, and to the very large scale dynamics by which these patterns indicate organs, and ultimately to infer algorithmic descriptions of this so that we can make changes here in a way that we can easily understand, not trying to micromanage at this level, which is hopeless in the long run.

We're using machine learning to help us discover these networks and interventions to ask, how do I need to stimulate a particular circuit to get a particular outcome?

Slide 38/50 · 57m:20s

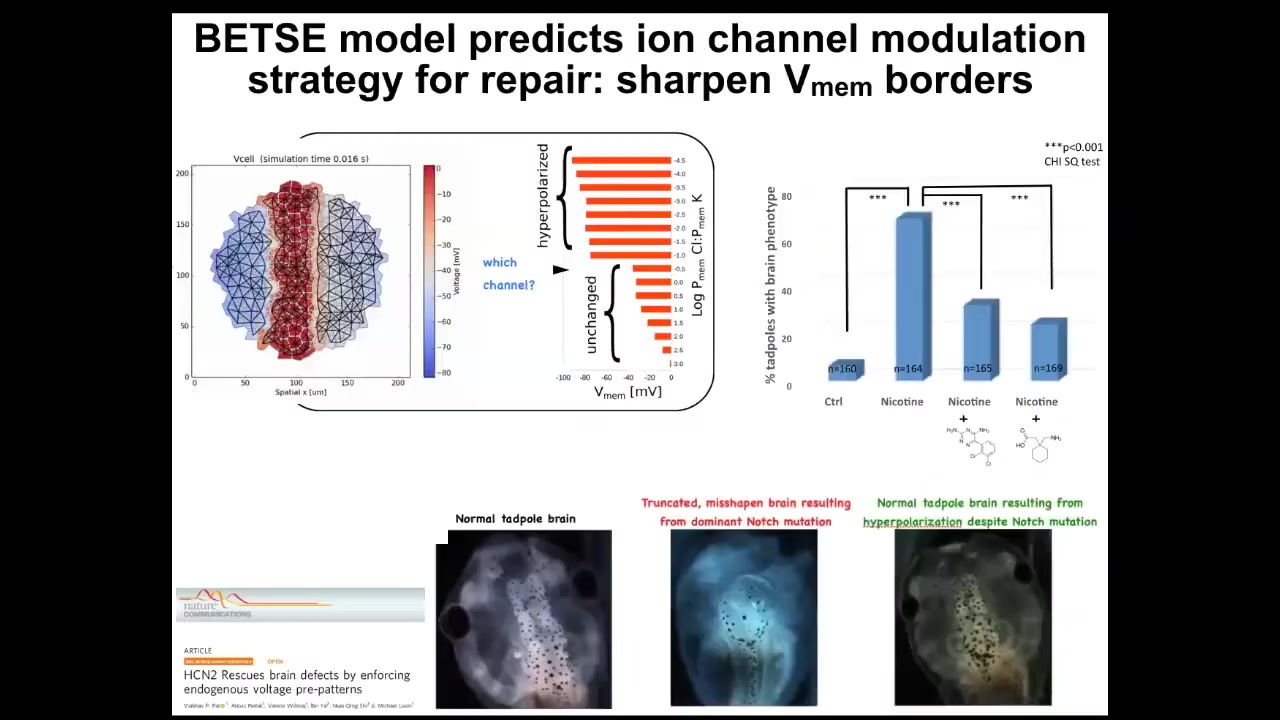

One simple example is fixing a really complicated birth defect.

Here's a normal brain: forebrain, midbrain, hindbrain. Here's an animal with a genetic mutation; it works the same way with alcohol poisoning, fetal alcohol syndrome, and so on. This brain: the forebrain is gone; the midbrain and hindbrain are a bubble.

If we make a computational model of this electric circuit and ask it what channels to open or close to recover the correct memory from this state, it actually suggests a drug that already exists. In fact, it's human-approved and targets a specific channel. These animals get their brains back despite the fact that the gene is still mutated, and they get their brain structure back and their IQs back; their learning rates are indistinguishable from controls.

Slide 39/50 · 58m:09s

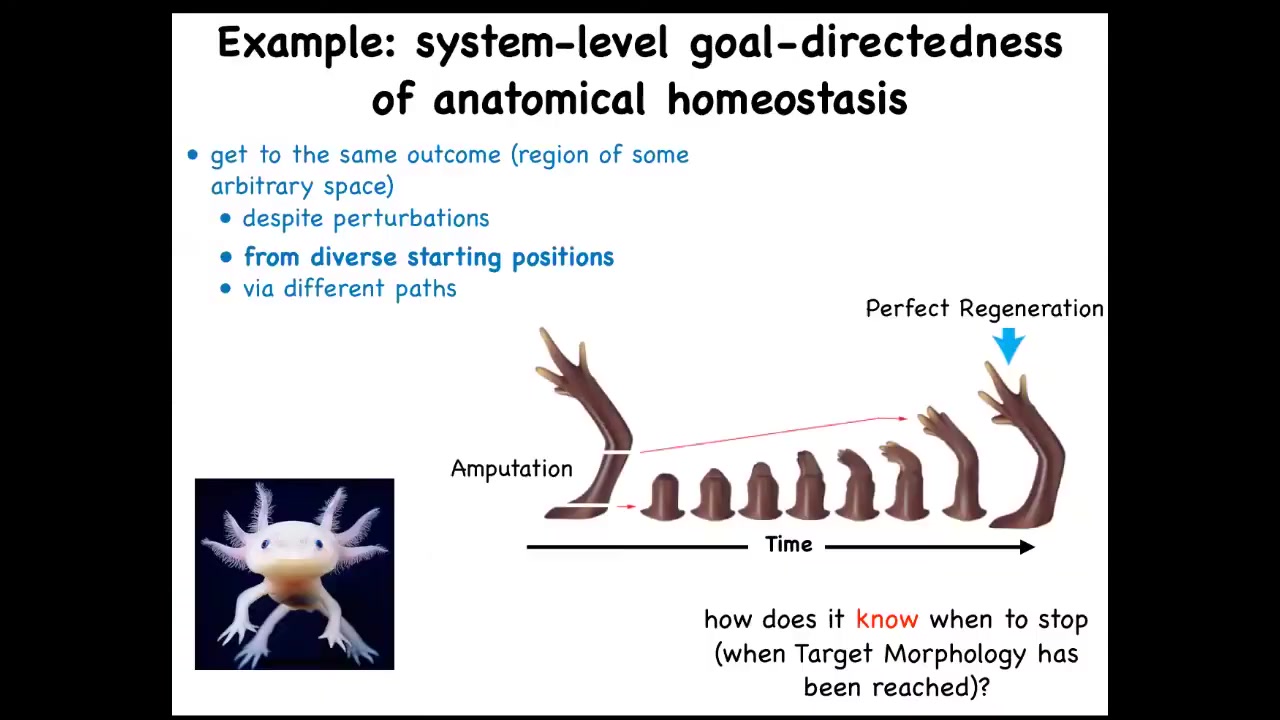

What I want to get to at the end is coming back to the idea of biological goals. We talked about the fact that in regeneration, it tries to get back to this particular state, depending on wherever you start. If you start here, it'll start here. If you amputate here, it'll just grow back from here, and it gets to its correct state. The ability of cells to do this is quite remarkable.

Slide 40/50 · 58m:38s

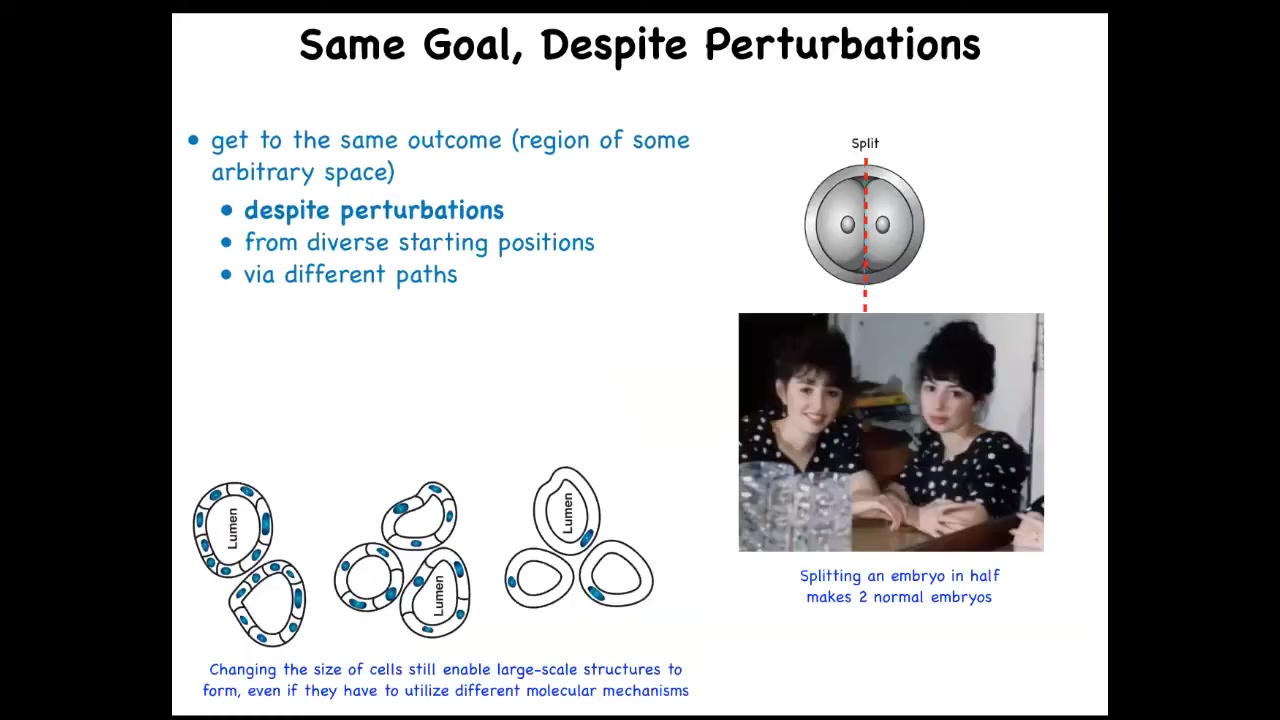

What you can do is, and this is very old work, this is a cross-section of a kidney tubule in newts, normally made of 8 to 10 cells. You can make polyploid newts, which have giant cells. As you increase the size of the cells, fewer and fewer of them are needed to make the same lumen. If you make the cells truly immense, one cell will bend around itself and give you that same lumen. So different molecular mechanisms are being called up in the service of a large-scale goal. So that's very interesting, and for people who want to think about top-down causation and so on, it's quite important. The idea is that you can get to the same goal despite various perturbations along the way.

These are serious perturbations. For example, if the early embryo is cut in half, you don't get two half embryos; you get two perfectly normal monozygotic twins. Or you can make the cells much bigger. We don't have any technology where you can just change the size of all the components and everything works just as well. This ability is very close to William James's definition of intelligence as being able to get to the same goal with various means.

When we regenerate these frog legs, they don't grow back the same with the same path through morphospace as development; they actually look more like plants. You get the single stalk with a toenail and then these off to the side, and eventually you get the same leg, but it's not the same path at all.

Slide 41/50 · 1h:00m:16s

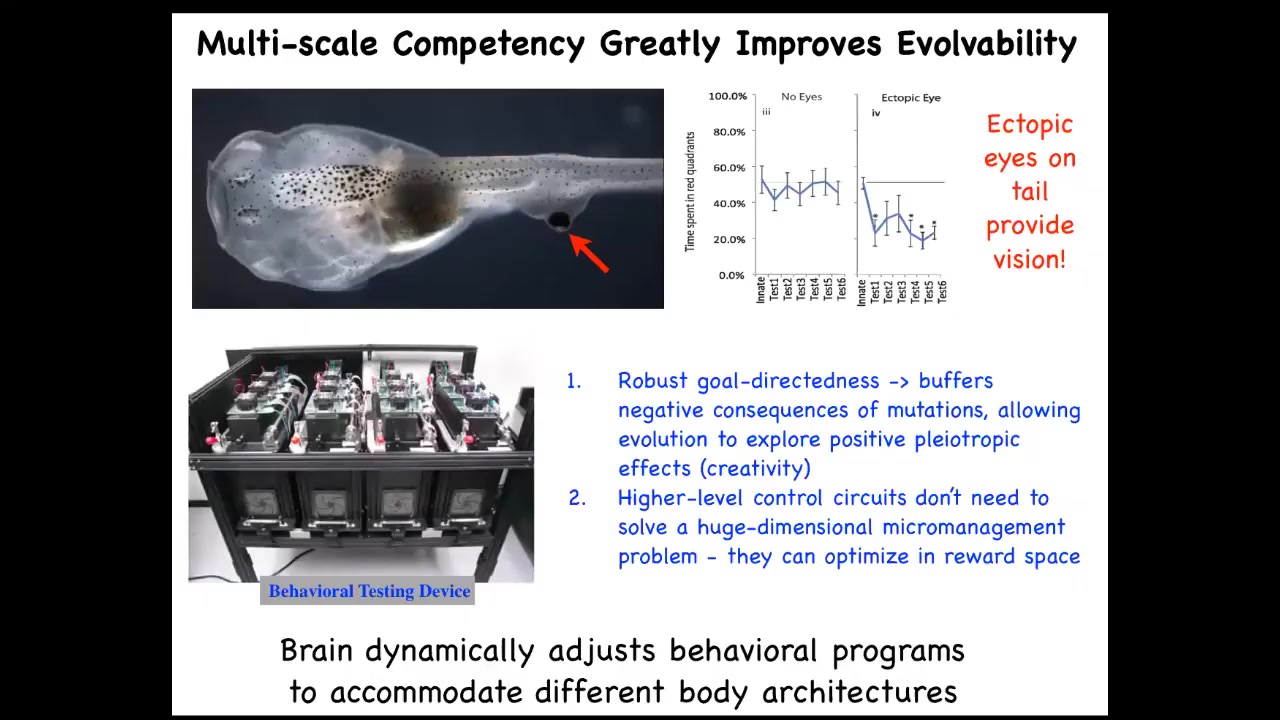

All of these systems are able to navigate morphospace in novel ways to get to where they're going. Even functionally, if we take a tadpole and we remove the primary eyes and we put an extra eye on its tail, this eye connects to the spinal cord, doesn't connect up to the head.

These animals can see perfectly well. They can learn; we have this machine that trains them for visual behavior.

You can see the advantage for evolution is massive. Instead of evolving specific solutions to specific problems, we evolve a kind of multi-scale competency architecture, where all the parts are competent to get various things accomplished, and that allows you to solve problems you have not seen before. It means that this kind of robust goal directedness buffers the negative consequences of mutations. If you have a mutation that's useful, but it puts the eye somewhere else, no problem. Things still work. You don't have a dead embryo.

It means that the higher level control circuits don't need to solve this immensely difficult high-dimensional micromanagement problem. Instead, they bend the reward space for the subunits that are just pursuing their local thing.

This is at the very end. I know I'm already at an hour. I just want to show you the artificial organisms.

Slide 42/50 · 1h:01m:32s

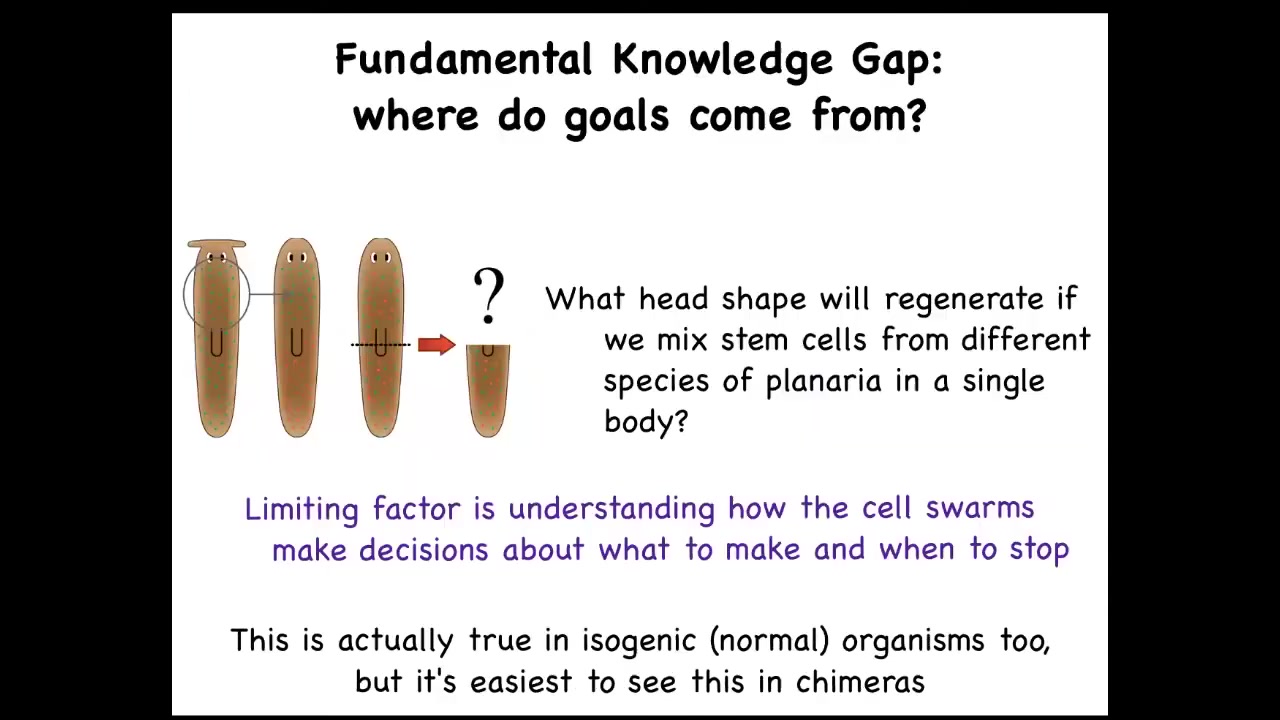

What we wanted to do was to really ask about this idea of where do goals in these spaces come from? What is the actual origin?

What I've shown you are systems that can get to the same goal intelligently, but then there's a question of where do these goals come from. You can see this right away. Asking very simple questions: what if I mix the stem cells from different kinds of planaria with round and flat heads? What are they going to make? We don't have any models yet; the field, despite all the progress on stem cell biology, has no model that will make a prediction on what happens if you make a chimera mix. They said, what will be the anatomical goal state of an agent made up of these different types of cells?

Slide 43/50 · 1h:02m:17s

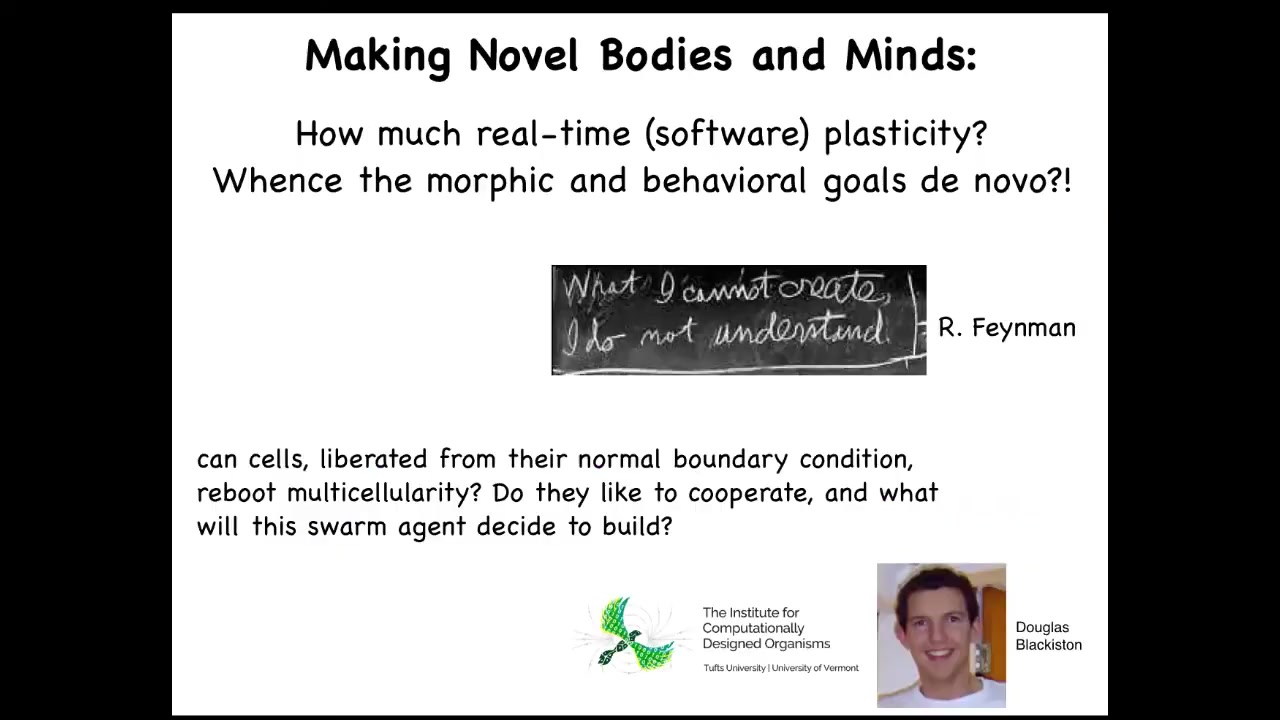

What we did was in partnership with Josh Bongard's lab at the University of Vermont, and with Doug Blackiston, who is a staff scientist in my group and who led the biology. Sam Kriegman did all the computer science. We asked a simple question: can we make a completely novel organism from standard genetically normal cells and ask what the goals of this organism are going to be, both anatomically and behaviorally?

Slide 44/50 · 1h:02m:43s

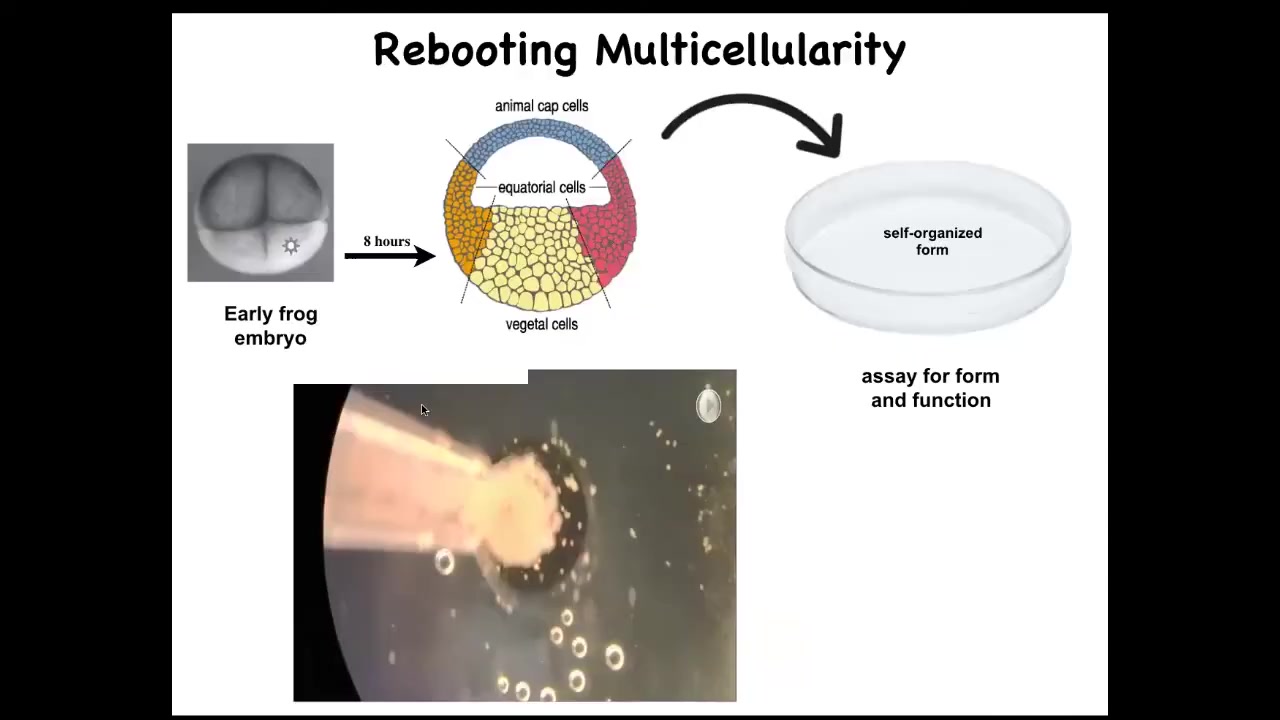

What we did was we liberated some skin cells from the frog embryo. We didn't add anything, no transgenes, but we took away something. We took away the instructive interactions with the rest of the animal.

We took some of these skin cells, we put them aside in this little depression. We gave them a chance to reimagine their multicellularity. What are they going to do? They could have done a lot. They could have died. They could have made a flat monolayer. They could have crawled off and separated from each other.

Slide 45/50 · 1h:03m:12s

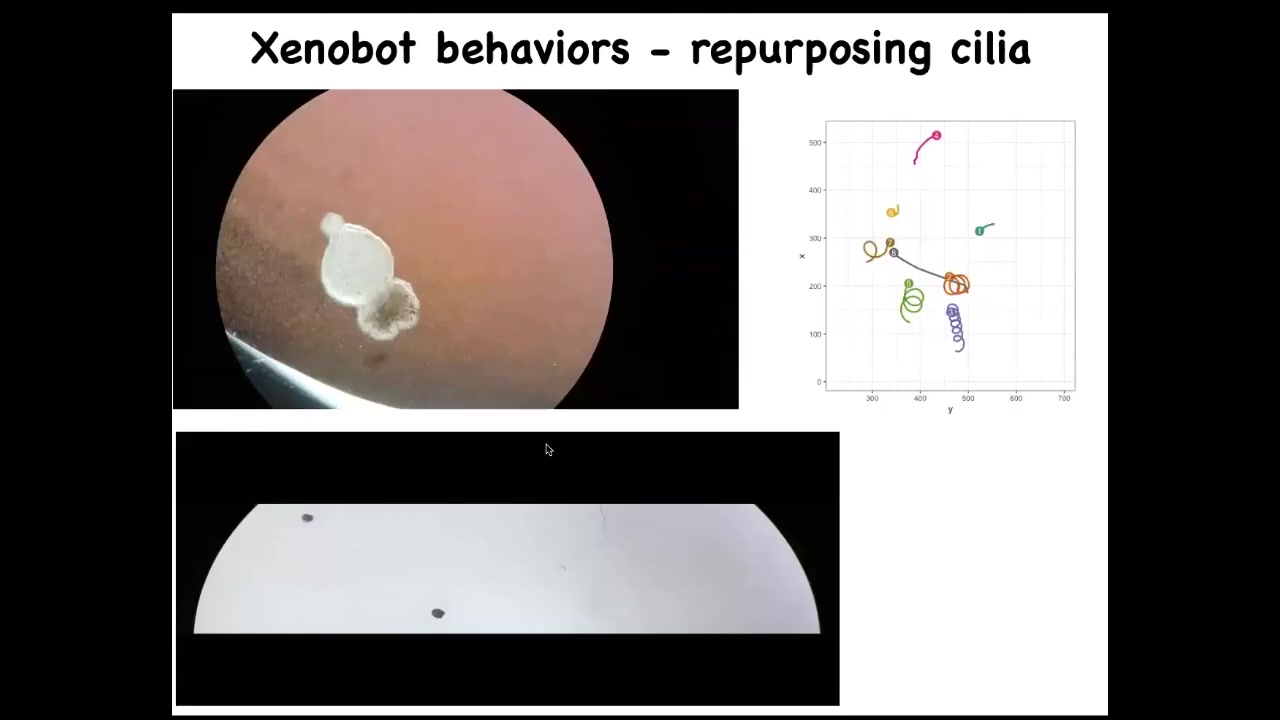

Instead, what they did was they made this little creature, we call it a xenobot, because it's a biobot made of Xenopus laevis cells. It uses the little hairs that these cells normally use to redistribute mucus on the surface of the frog. It uses them to swim now, to row against the environment. And they can go in circles, they can patrol back and forth. Here's some tracking data showing different behaviors of these guys.

Slide 46/50 · 1h:03m:36s

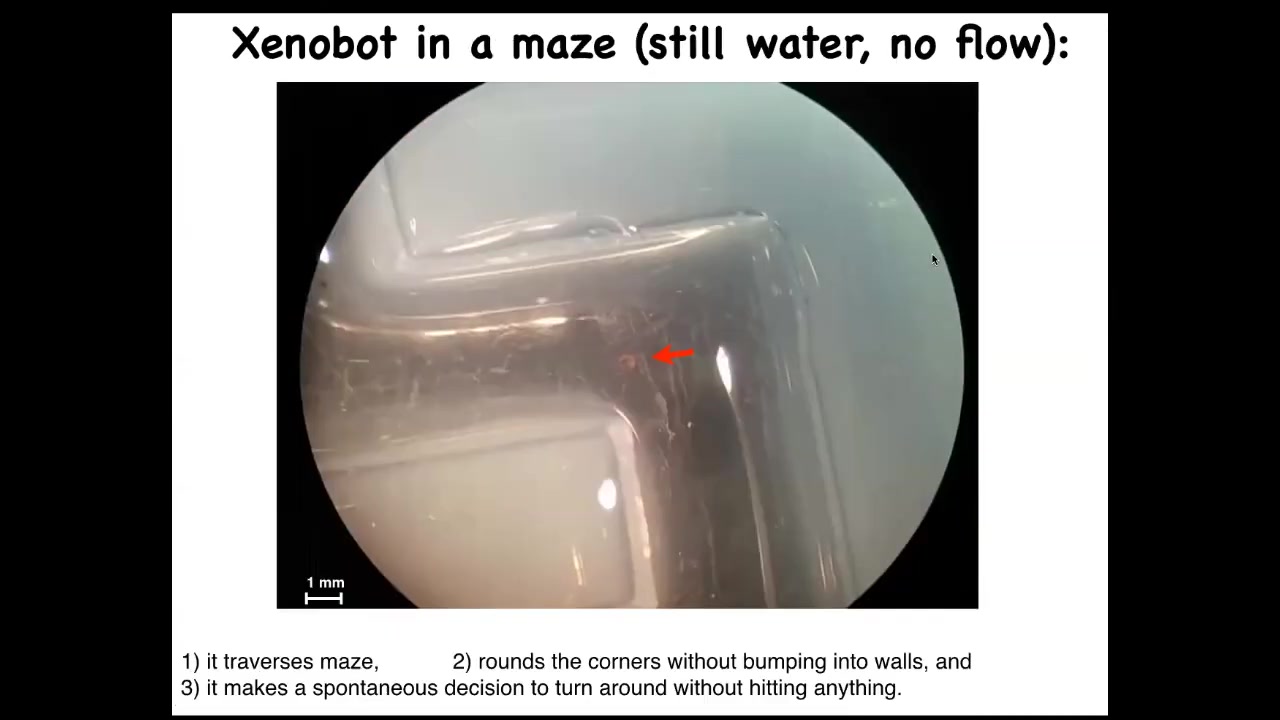

They can do a maze. This is flat; there's no water movement in this. It is completely still water. There's no gradients, there's nothing, but you can see it navigate. I'm going to show you this again. It's very interesting. So it moves forward. Now at this point, without hitting the opposite side, it decides to take the corner. At this point, something like proto-free will kicks in, and for no reason that we know, just purely internally, it just turns around and says, forget it, there's nothing here for me, and it comes back to where it came from. We have no idea what processes are going on. We're going to investigate this, but you're watching the very beginnings of self-directed motion. This is just skin. There's no brain, there's no nervous system.

They self-repair. If you cut them in half, they basically try to seal back to their original shape.

Slide 47/50 · 1h:04m:32s

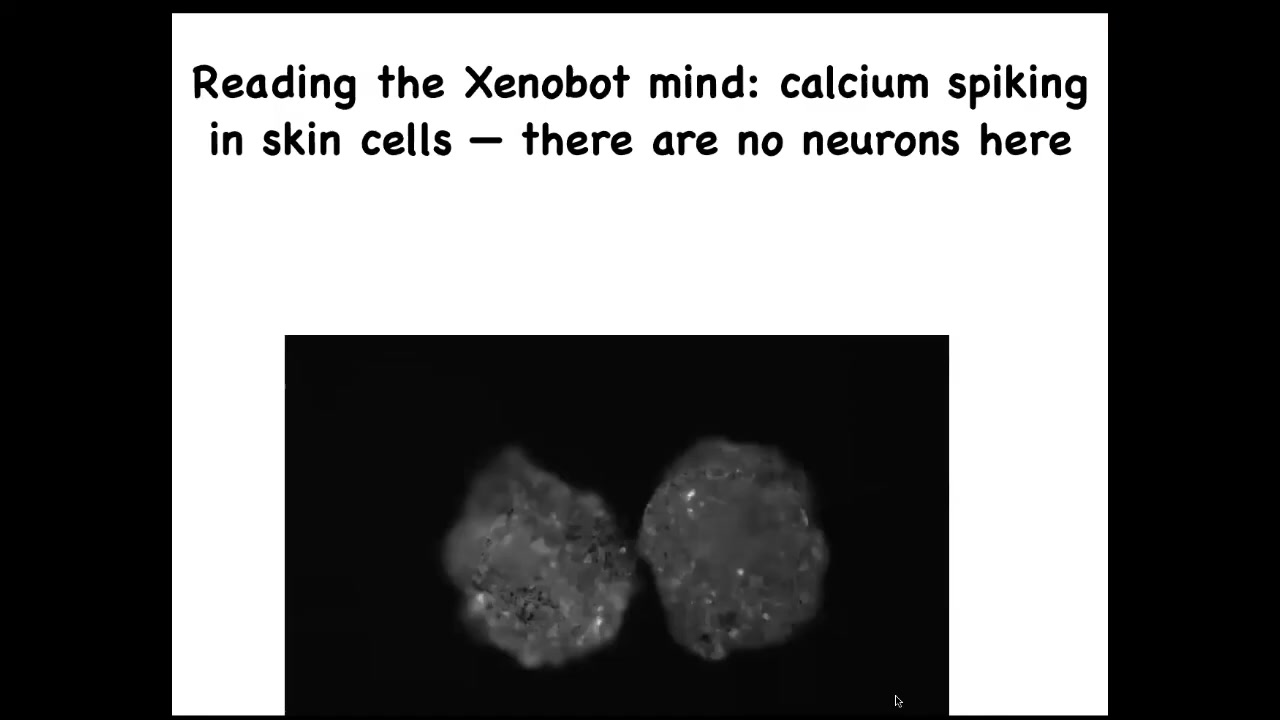

If you express a calcium reporter, a calcium signaling reporter, you can see that, and then we glue two of them down so they don't move. It's very brain-like. This is exactly the kind of imaging you get when you do calcium imaging in a zebrafish brain or a mouse brain. Again, there's no neurons. This is all being done by skin.

Slide 48/50 · 1h:04m:55s

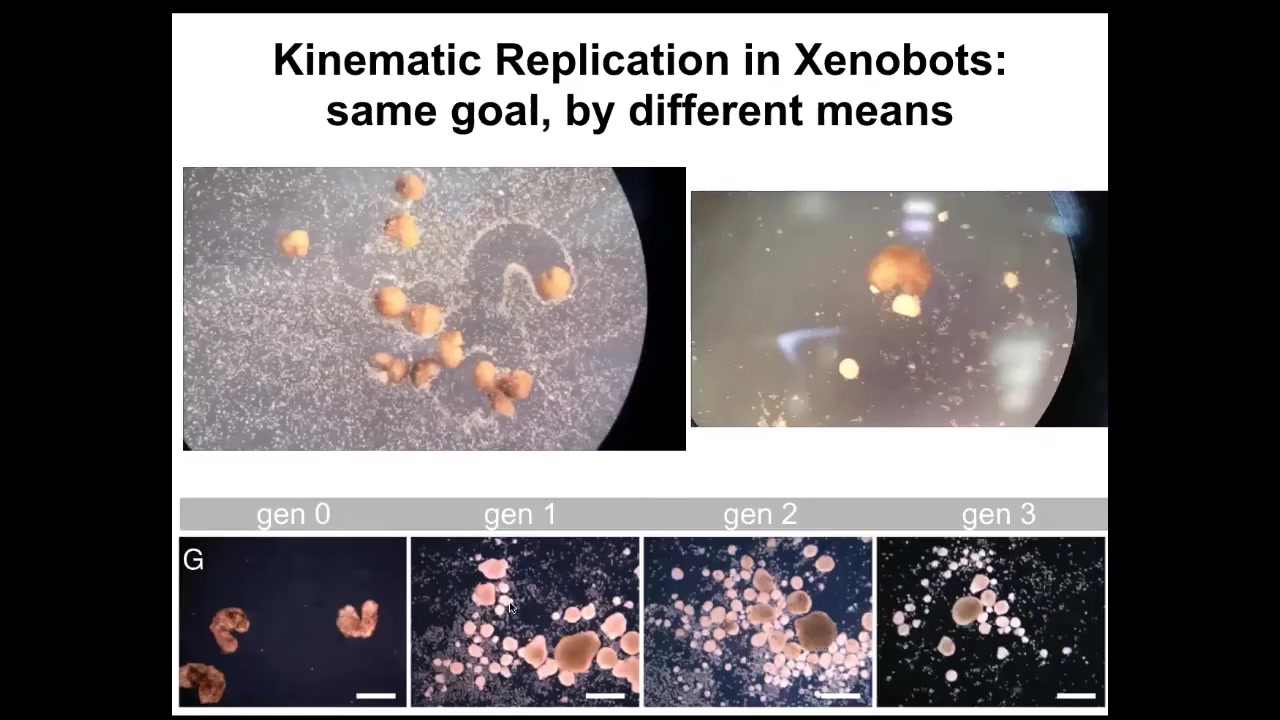

And then the most amazing thing, which we, this paper just came out a week ago, is that being deprived of the normal ability to reproduce, which frogs do with sperm and egg, these skin cells still figured out a way to make copies of their new organism, these new xenobots, which is kinematic self-replication. If you put them in a field of cells, they will run around. They will push these cells into piles. They will corral them like little sheepdogs. They'll just corral them and they will assemble them into little blobs. Guess what these blobs become? These blobs become the next generation of xenobots. And they will do exactly the same thing. And so we can make up through four generations so far. And so the same goal by different means.

And the amazing thing is, sometimes I've done versions of this talk where I show people these organisms, I don't tell them what it is. At the end, I say, can you, Nikki, do you have a question? I'll say, what do you think this is? And people will say, you got it out of the bottom of a pond somewhere, it's clearly some organism. And they'll say, we got the genome, we sequenced the genome and say, oh, the genome, that's great. Now we'll get to the bottom of what this is.

Slide 49/50 · 1h:06m:19s

The genome was 100% Xenopus laevis. What's interesting about these creatures is that, uniquely on the face of the earth, these guys don't have a straightforward evolutionary backstory. For every other animal, if you ask why do they have a particular shape or size or a color or behavior or whatever, the answer is the same. Because eons of selection have shaped them to do specific things. These guys have never existed before. There was never any selection in the frog lineage to be a great xenobot. And so the fact that within 48 hours, these cells can self-assemble a coherent new organism with its own characteristic novel behavior and way of reproducing — where did those come from? Selection pressure has always been to be a nice skin cell and sit on the surface of the tadpole and keep out the bacteria. So this is just the beginning.

I think that what we're going to have, because of all these technologies, is the merger of evolved materials, different cell types from different creatures, design materials, nanomaterials, micro robotics, and of course software, in every possible combination, hybrids, cyborgs, everything that when Darwin looked out into the ecosystem and saw all this variety he called "endless forms most beautiful," will be a small little corner of this enormous option space of novel creatures with new bodies and new minds, which are going to have collective goals and collective cognitive capacities that we will have to discover because we're sure not going to be able to guess them by comparing them to anything.

Slide 50/50 · 1h:08m:08s

So this is it. This is the end. To summarize that, I think anatomical homeostasis, the ability to reach anatomical goals, is an instructive kind of intelligence, which tells us something about different ways of scaling and different ways of solving problems. And it suggests all kinds of new biomedical approaches which we are pursuing. One way to look at selves is via the boundaries of the kinds of goals they are capable of pursuing. Developmental bioelectricity is interesting because it's not just another piece of physics that you have to pay attention to in development. It is actually the medium, the medium of memory and decision-making for that collective intelligence of cells, that group of cells trying to achieve a particular outcome despite all kinds of perturbations. Now we can target these pattern memories to control behavior without micromanagement. We're working on even higher level systems, training tissues to specific outcomes, the way you would train an animal. I will argue that evolution creates problem-solving agents, not specific solutions to specific problems. A great question for the future, which we're going to try to address, is where does the ability to generalize come from? If evolution is supposed to be so short-sighted and reward immediate benefit, why is it producing things that are so good at generalizing to environments they've never seen before in novel solutions? I think that's a very deep puzzle. Synthetic bioengineering is going to enable a huge option space of new bodies and new minds, which is going to require us to redefine a lot of terminology and a lot of concepts that we've had, not to mention the new ethics that isn't based on what you're made of and how you got here. Lots more detail in these papers, and many more papers I'm happy to send out to anybody who wants.

I want to thank the students and postdocs who did all the work that I showed you today, our funders, and the animals; they do all the heavy lifting here. That's it.